Title: The Bases of Design

Author: Walter Crane

Release date: January 13, 2015 [eBook #47967]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

i

ii

iii

THE BASES

OF DESIGN

BY WALTER CRANE

LONDON

GEORGE BELL AND SONS

1902

iv

First Edition, Medium 8vo, 1898.

Second Edition, Crown 8vo, 1902.

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

v

TO CHARLES ROWLEY, J.P. CHAIRMAN OF THE MANCHESTER MUNICIPAL SCHOOL OF ART, TO WHOSE ENERGY, SYMPATHY, AND ENTHUSIASM THE SCHOOL, IN ITS NEWER DEVELOPMENT, OWES SO MUCH, AND TO MY FORMER COLLEAGUES OF THE TEACHING STAFF, AS WELL AS TO ALL STUDENTS, I DEDICATE THIS BOOK.

vi

vii

THE substance of the following chapters originally formed a series of lectures addressed to the students of the Manchester Municipal School of Art during my tenure of the directorship of Design at that institution.

The field covered is an extensive one, and I am conscious that many branches of my subject are only touched, whilst others are treated in a very elementary manner. Every chapter, indeed, might be expanded into a volume, under such far-reaching headings, to give to each section anything like adequate treatment.

My main object, however, has been to trace the vital veins and nerves of relationship in the arts of design, which, like the sap from the central stem, springing from connected and collective roots, out of a common ground, sustain and unite in one organic whole the living tree.

In an age when, owing to the action of certain economic causes—the chiefest being commercial competition—the tendency is to specialize each branch of design, which thus becomes isolated from the rest, I feel it is most important to keep in mind the real fundamental connection and essential unity of art: and though we may, as students and artists, in practice be intent upon gathering the fruit from the particular branch we desire to make our own, we should never be insensible to its relation to other branches, its dependence upon the main stem and the source of its life at the root. viii

Otherwise we are, I think, in danger of becoming mechanical in our work, or too narrowly technical, while, as a collective result of such narrowness of view, the art of the age, to which each individual contributes, shows a want of both imaginative harmony and technical relation with itself, when unity of effect and purpose is particularly essential, as in the design and decoration of both public and private buildings, not to speak of the larger significance of art as the most permanent record of the life and ideals of a people.

My illustrations are drawn from many sources, and consist of a large proportion of those originally used for the lectures, only that instead of the rough charcoal sketches done at the time, careful pen drawings have been made of many of the subjects in addition to the photographs and other authorities.

It may be noted that I have freely used both line and tone blocks in the text and throughout the book, although I advocate the use of line drawings only with type in books wherein completeness of organic ornamental character is the object. Such a book as this, however, being rather in the nature of a tool or auxiliary to a designer's workshop, can hardly be regarded from that point of view. The scheme of the work, which necessitates the gathering together of so many and varied illustrations as diverse in scale, subject, and treatment as the historic periods which they represent, would itself preclude a consistent decorative treatment, and it has been found necessary to reproduce many of the illustrations from their original form in large scale drawings on brown ix paper touched with white, as well as from photographs which necessarily print as tone-blocks.

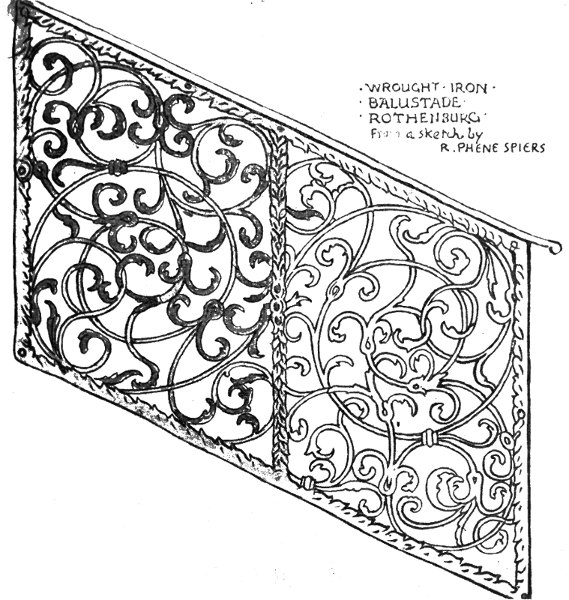

I have to thank Mr. Gleeson White for his valuable help in many ways, as well as in obtaining permission from various owners of copyright to use photographs and other illustrations, and also the publishers, who have allowed me the use of blocks in some instances—Mr. George Allen for a page from "The Faerie Queene"; Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew and Co. for the use of the "Punch" drawings; and Messrs. J. S. Virtue and Co. for the use of photographs of carpet weaving and glass blowing, which were specially taken for "The Art Journal." My thanks are also due to Mr. Metford Warner (Messrs. Jeffrey and Co.) for the use of his photo-lithographs of my wall-paper designs issued by his firm; to Mr. R. Phené Spiers for the use of his sketch of the iron balustrade from Rothenburg; to Mr. T. J. Cobden-Sanderson for photographs of two of his recent bookbindings; to the executors of the late Rev. W. H. Creeny for permission to reproduce two of the illustrations from his "Monumental Brasses on the Continent of Europe" (now published by Mr. B. T. Batsford); also to Mr. Harold Rathbone, who kindly allows me to reproduce the cartoons by Ford Madox Brown in his possession; to Mr. J. Sylvester Sparrow for the practical notes on painting glass; and to Mr. Emery Walker for help in several ways in the preparation of the book.

Kensington,

November, 1897.

x

THIS reprint of "The Bases of Design" gives me an opportunity to correct a few errors which had inadvertently crept in on its first appearance, and also to add a word here and there.

I venture to hope that the book may prove more useful and accessible to students in its present form.

Kensington,

November, 1901.

xi

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | OF THE ARCHITECTURAL BASIS | 1 |

| II | OF THE UTILITY BASIS AND INFLUENCE | 48 |

| III | OF THE INFLUENCE OF MATERIAL AND METHOD | 91 |

| IV | OF THE INFLUENCE OF CONDITIONS IN DESIGN | 123 |

| V | OF THE CLIMATIC INFLUENCE IN DESIGN—CHIEFLY IN REGARD TO COLOUR AND PATTERN | 160 |

| VI | OF THE RACIAL INFLUENCE IN DESIGN | 191 |

| VII | OF THE SYMBOLIC INFLUENCE, OR EMBLEMATIC ELEMENT IN DESIGN | 222 |

| VIII | OF THE GRAPHIC INFLUENCE, OR NATURALISM IN DESIGN | 259 |

| IX | OF THE INDIVIDUAL INFLUENCE IN DESIGN | 302 |

| X | OF THE COLLECTIVE INFLUENCE IN DESIGN | 350 |

| xii | ||

| xiii | ||

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS |

||

|---|---|---|

| PAGE | ||

| Three typical Constructive Forms in Architecture—Lintel, Round Arch, Pointed Arch. | 5 | |

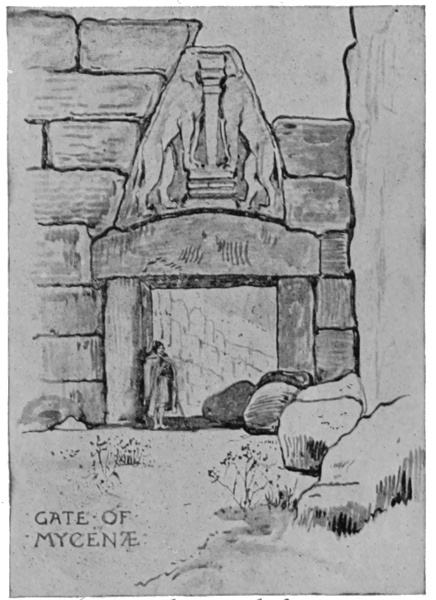

| Gate of Mycenæ. | 6 | |

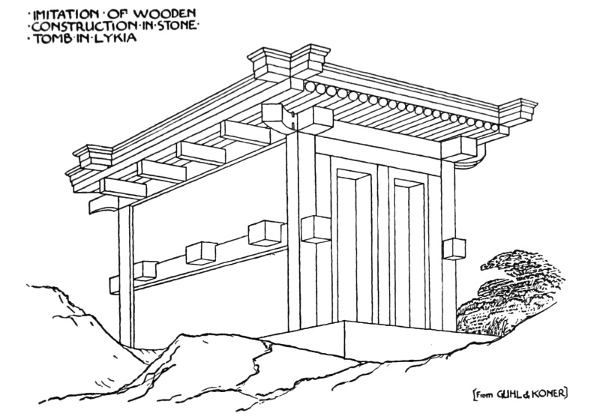

| Imitation of Wooden Construction in Stone Tomb in Lycia. | 7 | |

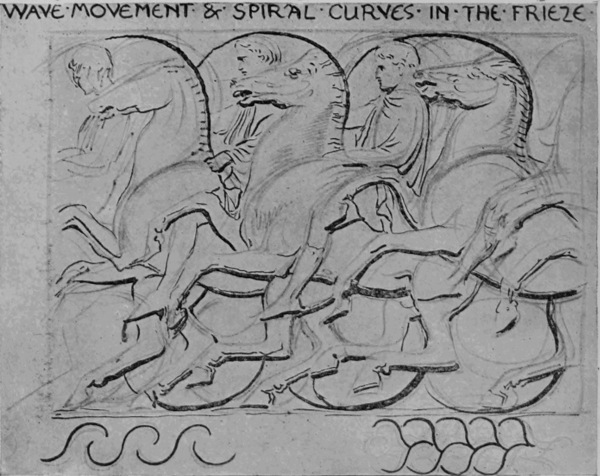

| Ornamental lines in the Frieze of the Parthenon. | 8 | |

| Metope of the Parthenon, showing relation and proportions of the masses in relief to the ground. | 9 | |

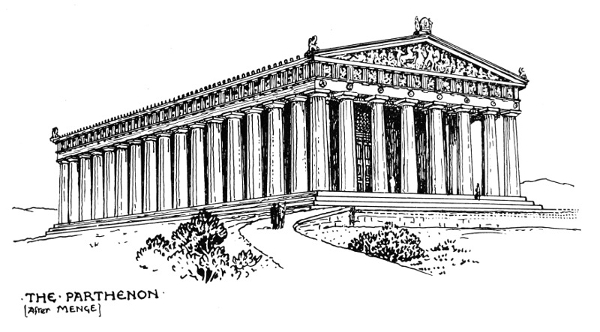

| The Parthenon. | 11 | |

| The Parthenon—Eastern Pediment, sketches showing relation of lines of sculpture to angle of Pediment. | 12 | |

| The Parthenon—Elevation showing portion of Pediment, Frieze and Columns. | 13 | |

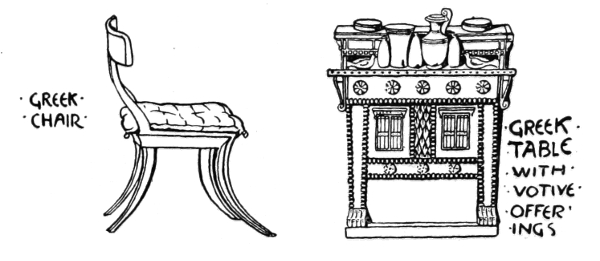

| Architectural influence in design of small accessories (Greek). | 15 | |

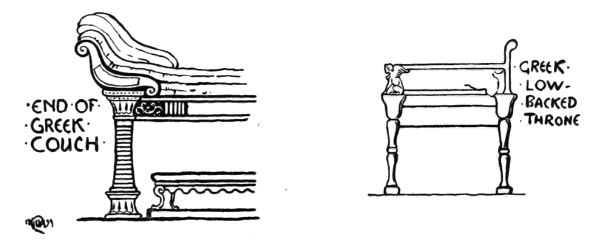

| Section of the Colosseum. | 17 | |

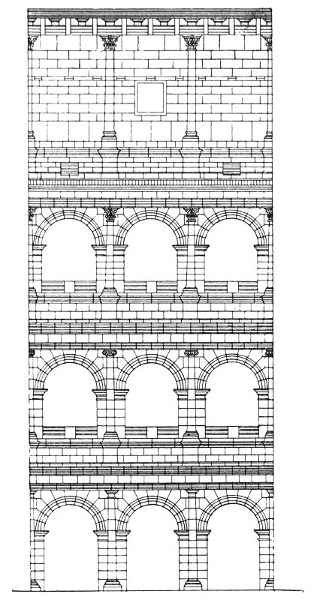

| Hanging the Festal Garland—Visit of Bacchus to Icarius. | 18 | |

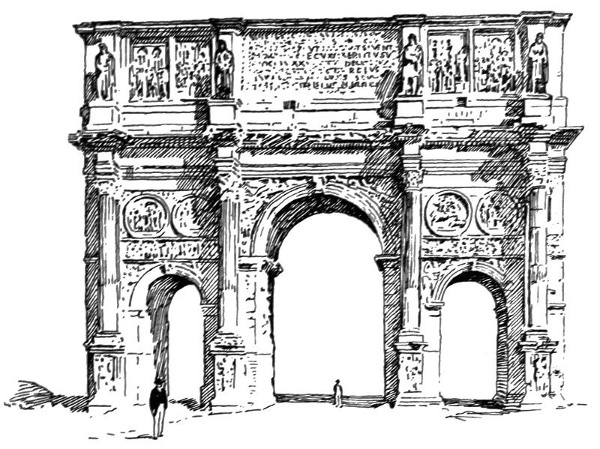

| Arch of Constantine. | 19 | |

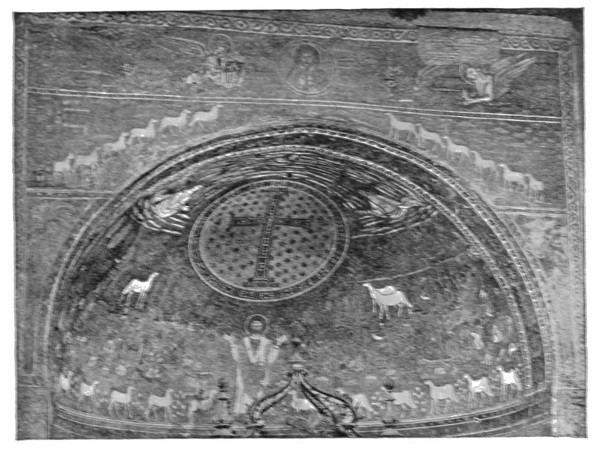

| Mosaic, St. Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna. | 21 | |

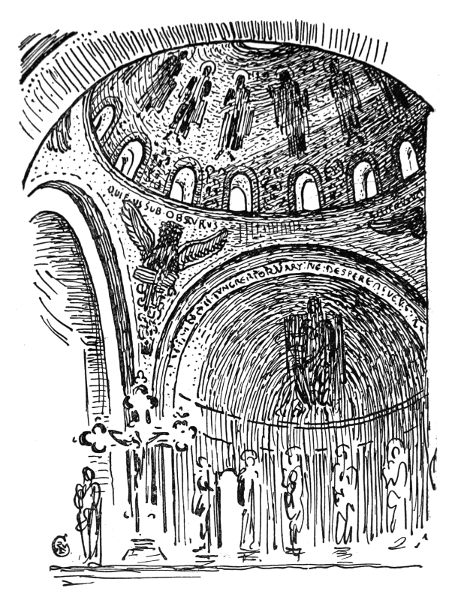

| Part of Interior of Dome of St. Mark's, Venice. | 23 | |

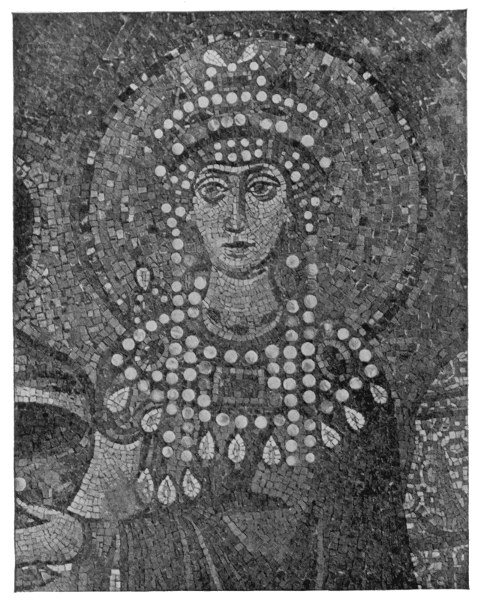

| Mosaic of the Empress Theodora, St. Vitale. | 24 | |

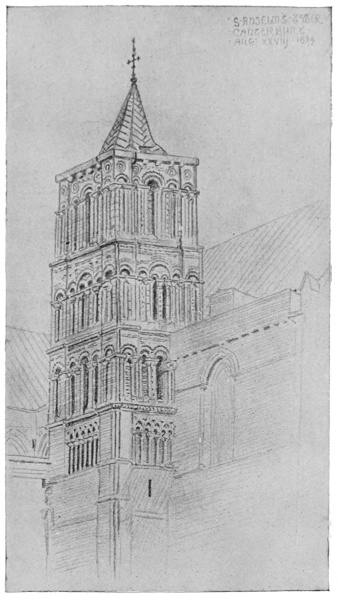

| Anselm's Tower, Canterbury. | 27 | |

| Transitional Arcade, South Transept, Canterbury. | 28 | |

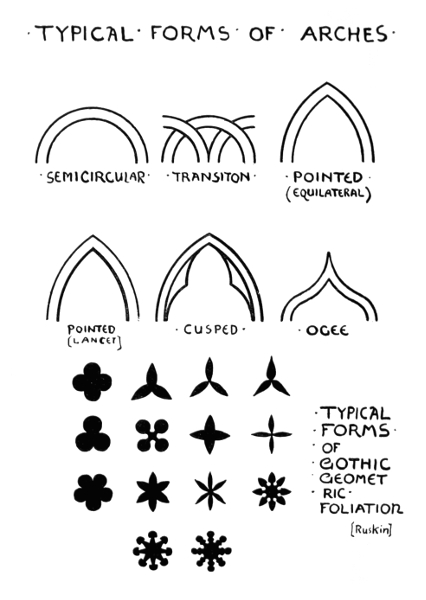

| Typical Forms of Arches. | 30 | |

| Typical Forms of Gothic Geometric Foliation. | 30 | |

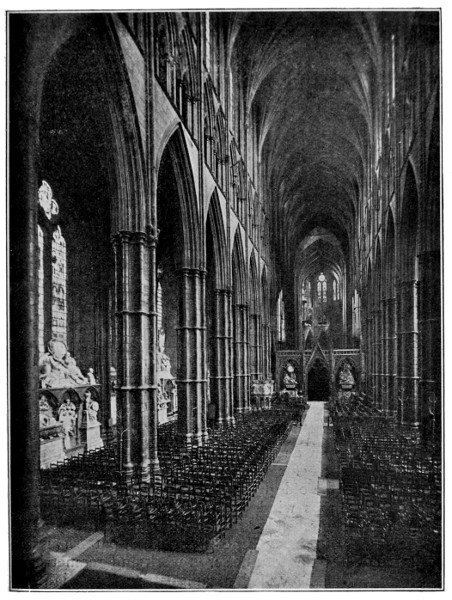

| Westminster Abbey: the Nave, looking east. | 31 | |

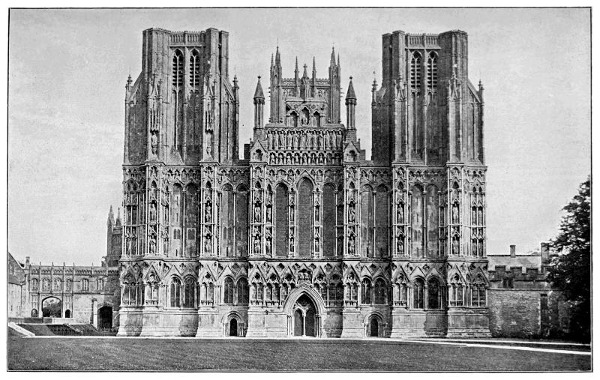

| Wells Cathedral, West Front. | 33 | |

| Westminster Abbey, Fan Tracery in Henry VII.'s Chapel. | 35 | |

| The Five Sisters of York. | 37 | |

| Details of Tomb, Winchelsea Church (1303). | 38 | |

| Fourteenth Century Canopied Tomb, Winchelsea Church. | 39 | |

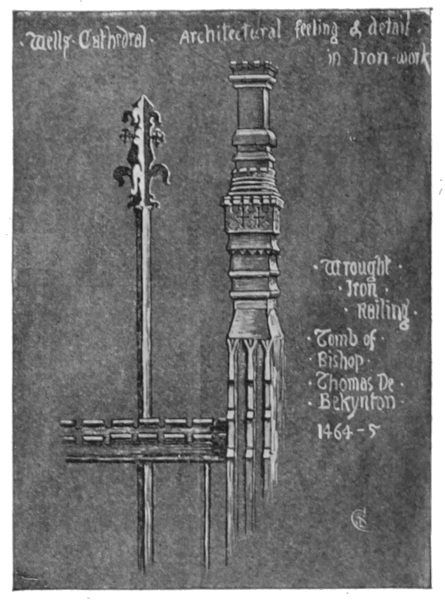

| Wrought-iron Railing, Wells Cathedral. | 40 | |

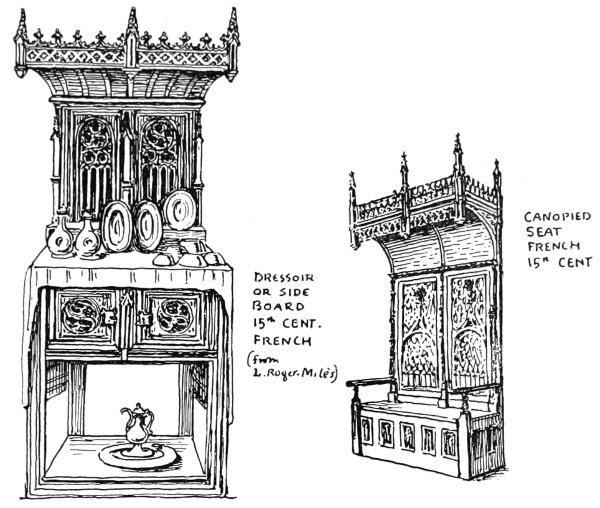

| Canopied Seat and Sideboard, French Fifteenth Century. | 41xiv | |

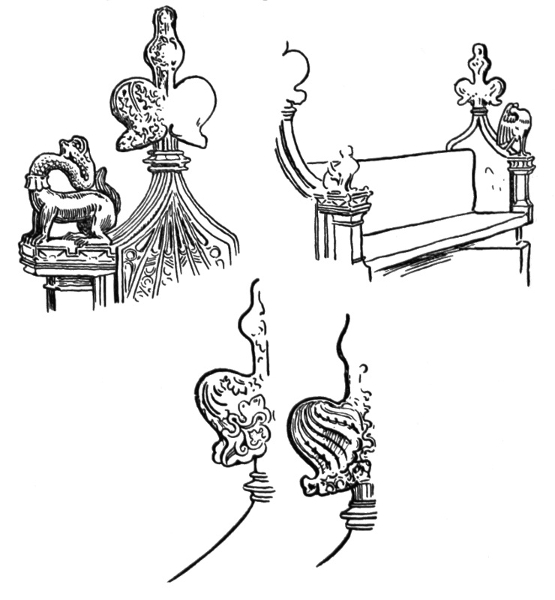

| Carved Bench-ends, Dennington Church, Suffolk. | 42 | |

| Brocade Hanging, from the Annunciation, by Memling. | 43 | |

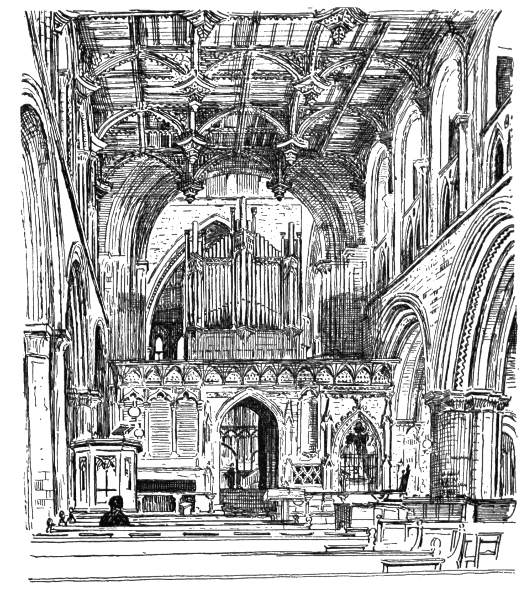

| St. David's Cathedral. | 44 | |

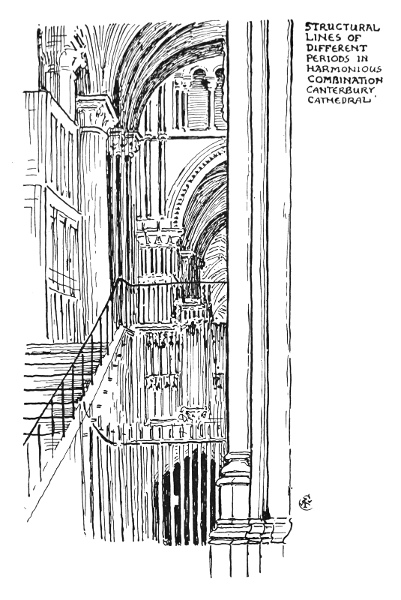

| Structural lines of different periods in harmonious combination, Canterbury Cathedral. | 45 | |

| Matting. | 49 | |

| Primitive Rush Mat. | 50 | |

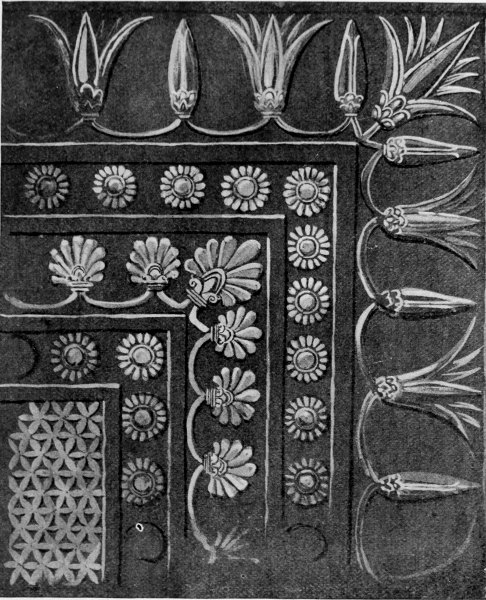

| Assyrian Border. | 50 | |

| Assyrian enamelled Tile. | 51 | |

| Greek Anthemion Ornament. | 52 | |

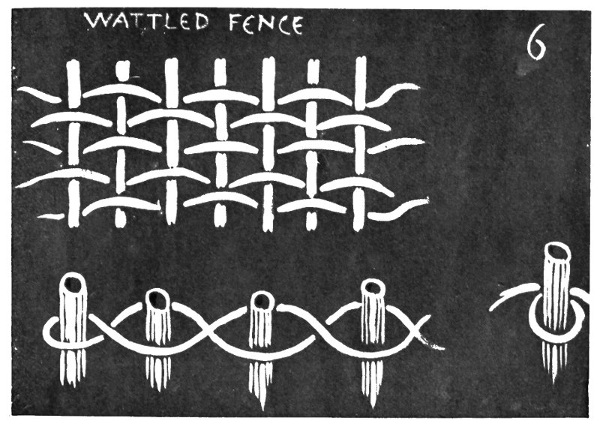

| Wattled Fence. | 52 | |

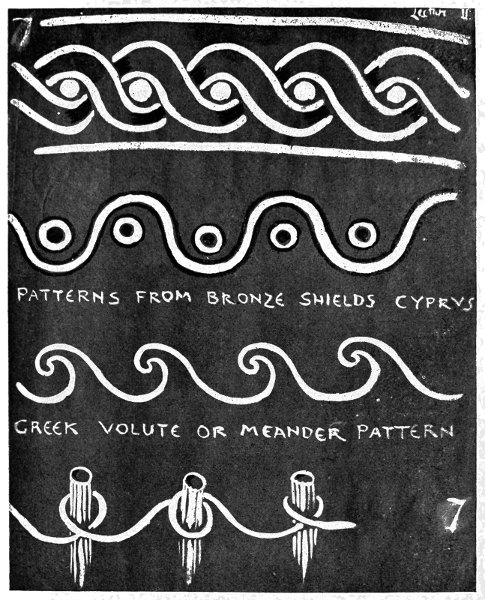

| Ancient Volute Ornament. | 53 | |

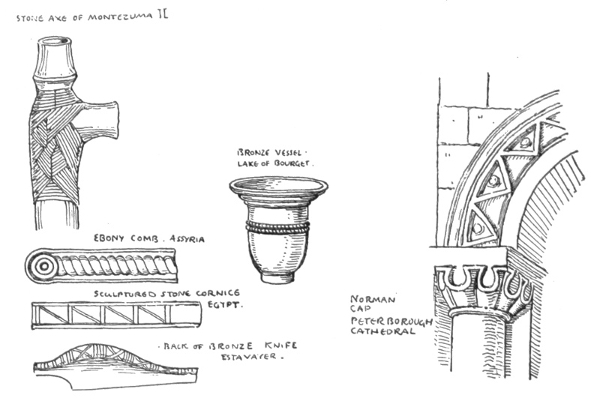

| Types of Decoration derived from Thonging. | 54 | |

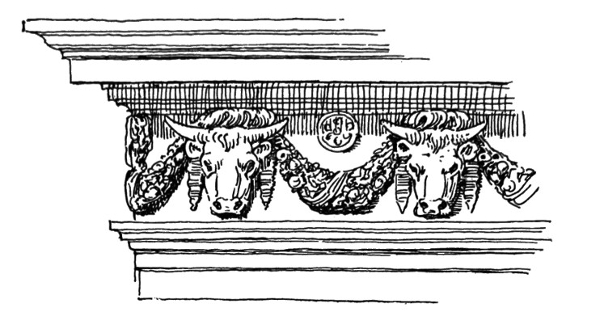

| Frieze of the Temple of the Sybil at Tivoli. | 55 | |

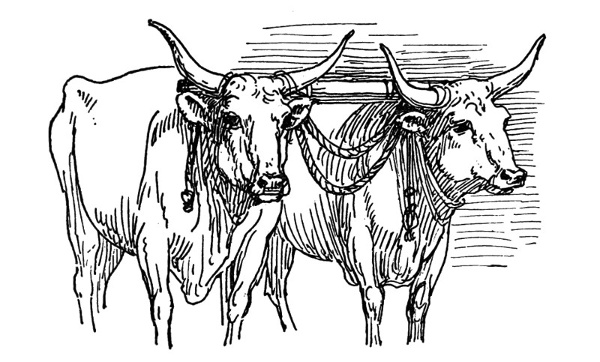

| Yoke of Oxen, Carrara. | 55 | |

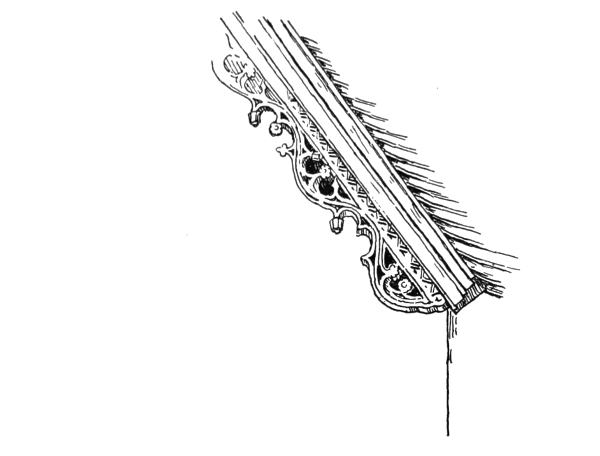

| Barge-board, Ightham Mote House. | 57 | |

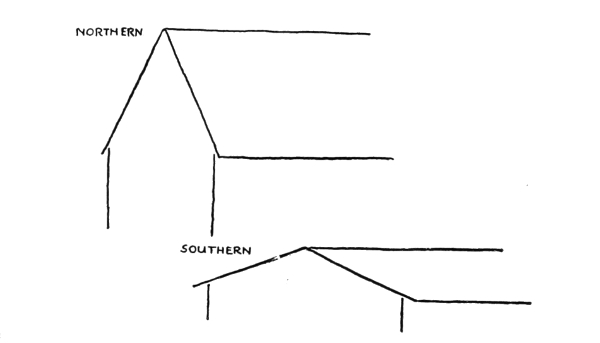

| Types of Gables. | 57 | |

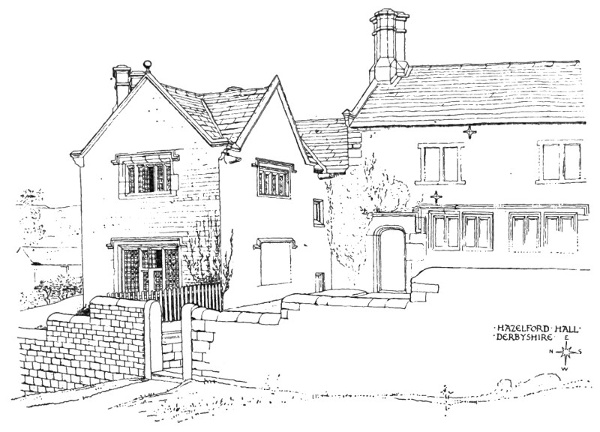

| Hazelford Hall, Derbyshire. | 59 | |

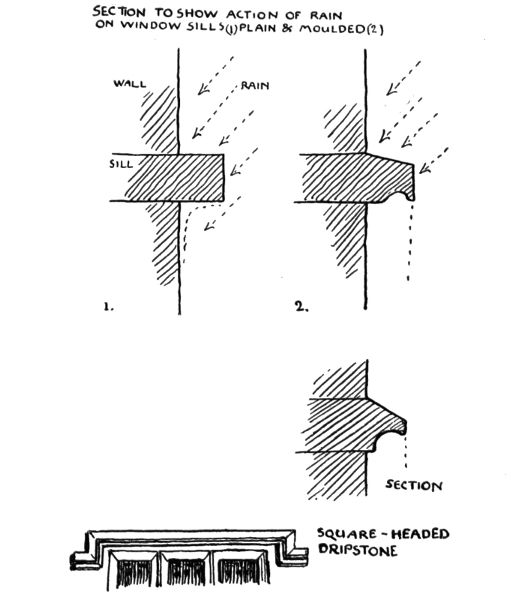

| The Principle of the Dripstone. | 60 | |

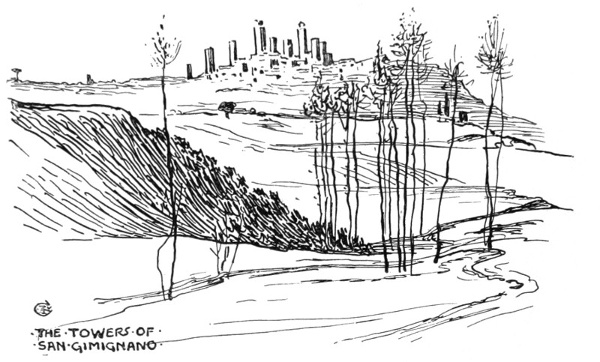

| Towers of San Gimignano. | 61 | |

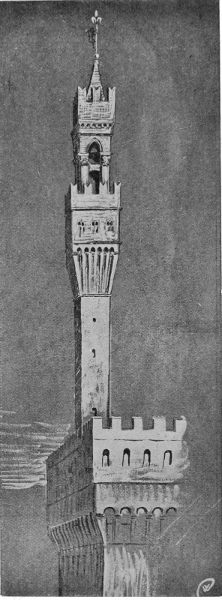

| Tower of the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. | 63 | |

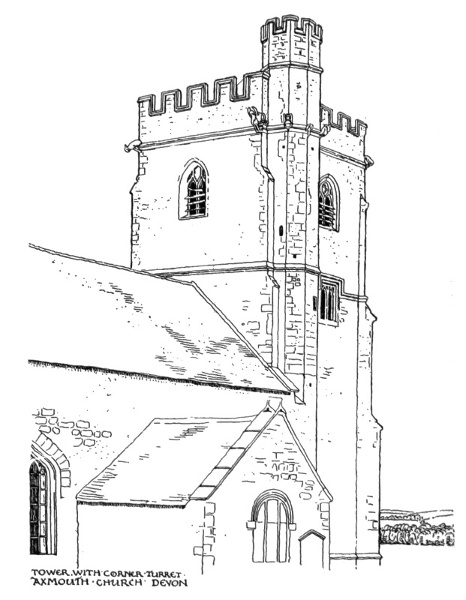

| Tower with corner Turret, Axmouth Church, Devon. | 64 | |

| Cut Brick Chimneys, Leigh's Priory, Essex. | 65 | |

| Brick Chimney, Framlingham Castle. | 66 | |

| Cast-iron Fire-dog, St. Nicholas's Hospital, Canterbury. | 67 | |

| Cast-iron Grate Back, Bruges. | 68 | |

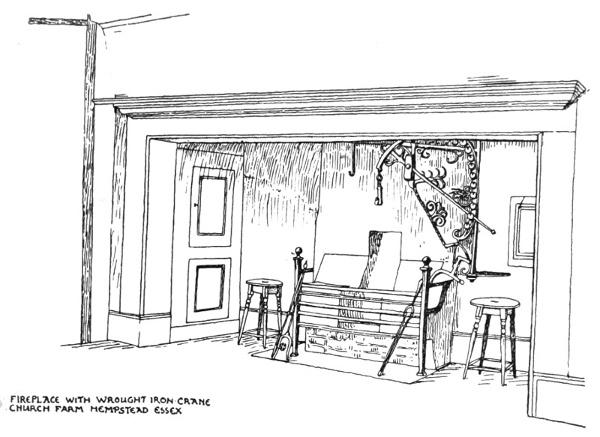

| Fireplace with wrought-iron Crane, Church Farm, Hempstead, Essex. | 69 | |

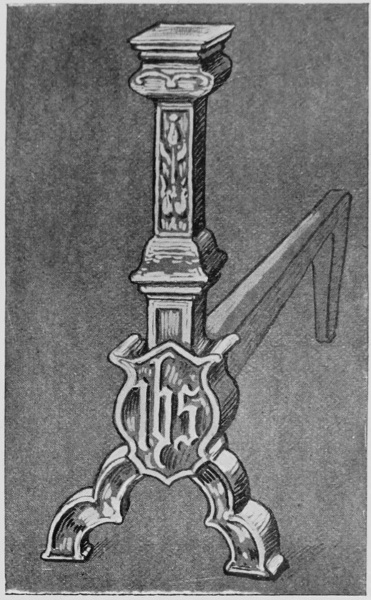

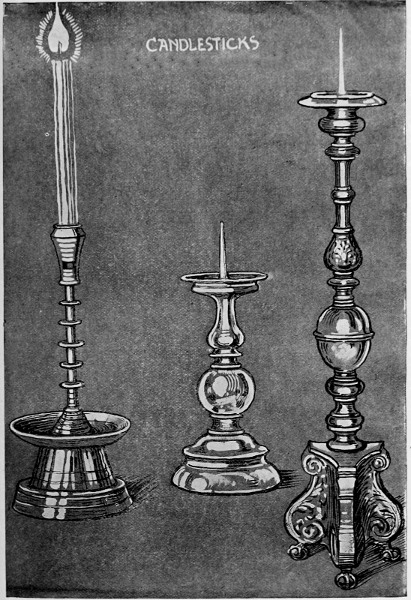

| Candlesticks. | 71 | |

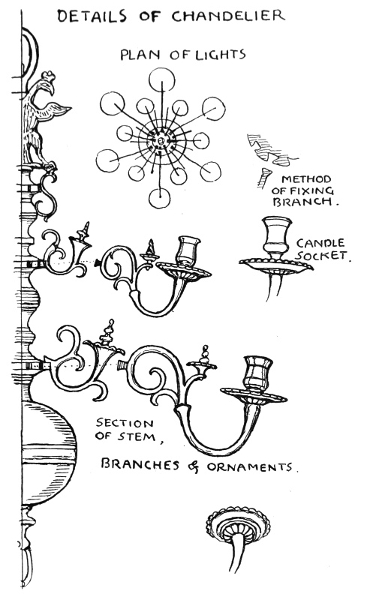

| Brass Chandelier, German Seventeenth Century. | 74 | |

| Details of above. | 75 | |

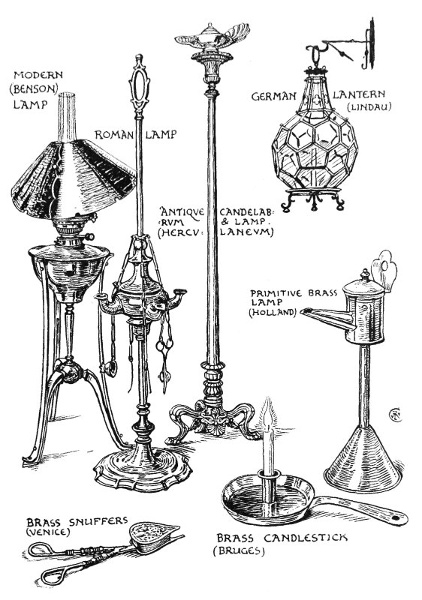

| Lamps, Candlestick, and Snuffers. | 77 | |

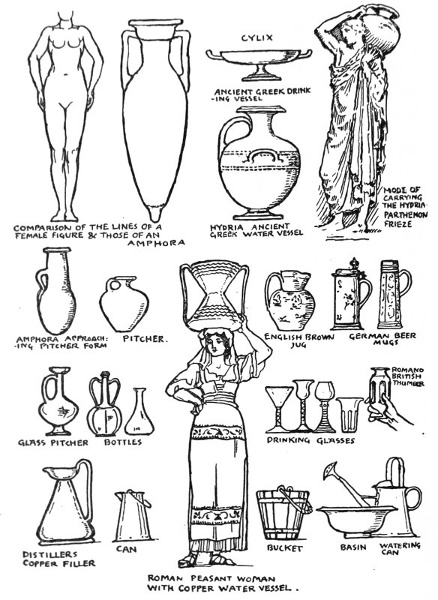

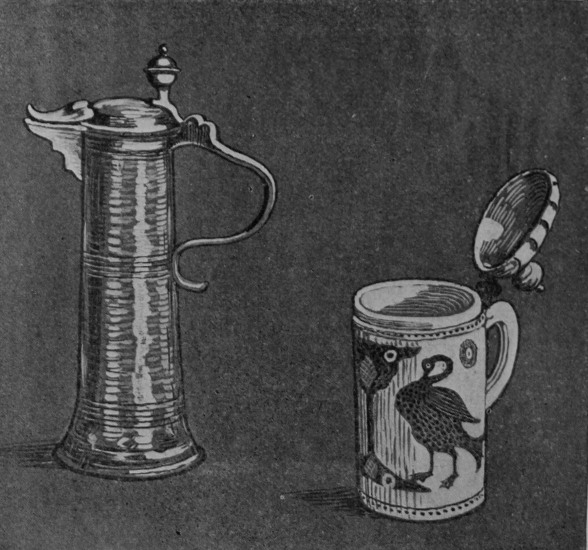

| Drinking Vessels, etc. | 81 | |

| German Beer Mugs. | 82 | |

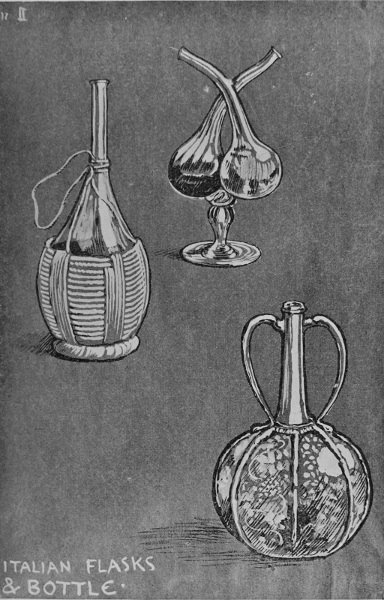

| Italian Flasks and Bottle. | 83 | |

| Pitcher from Rothenburg. | 87 | |

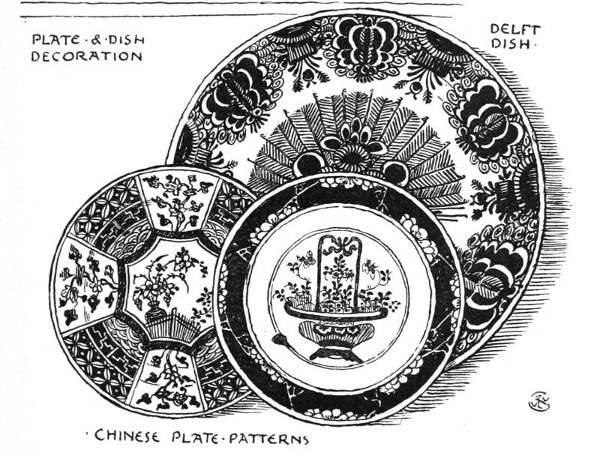

| Plate and Dish Decoration. | 87 | |

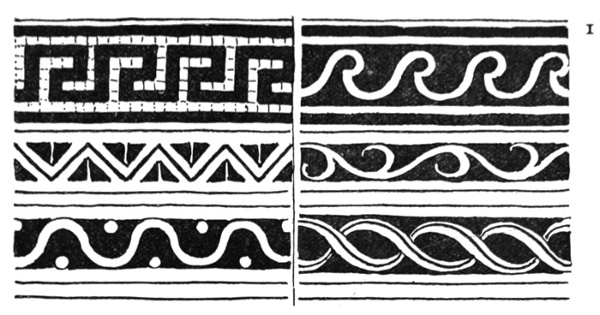

| Typical Border Systems. | 89 | |

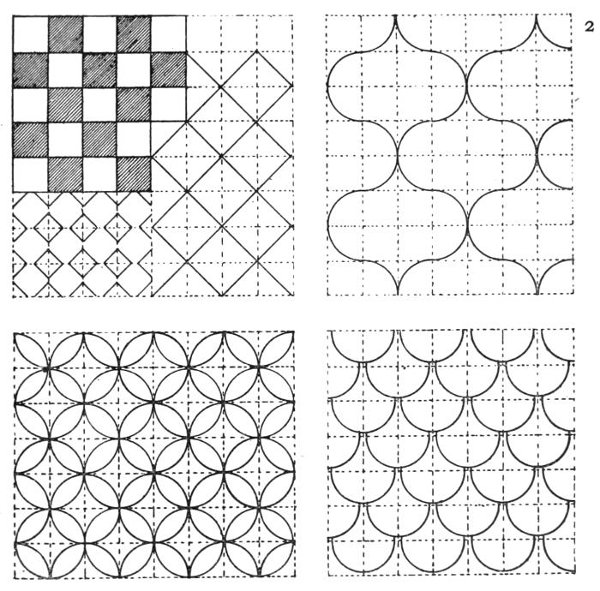

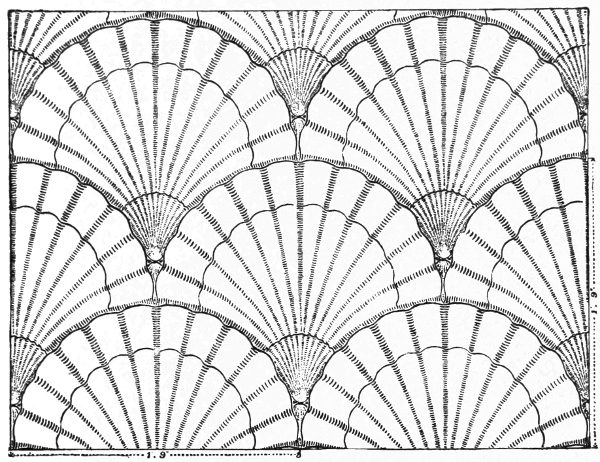

| Persistent Pattern Plans, Rectangular Basis. | 89 | |

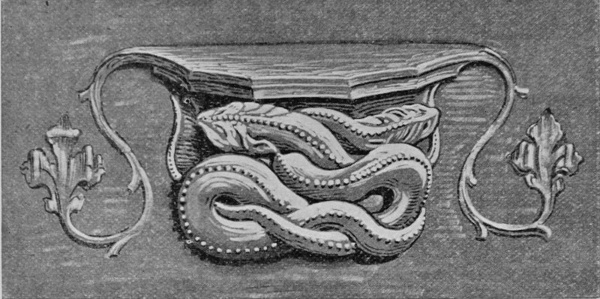

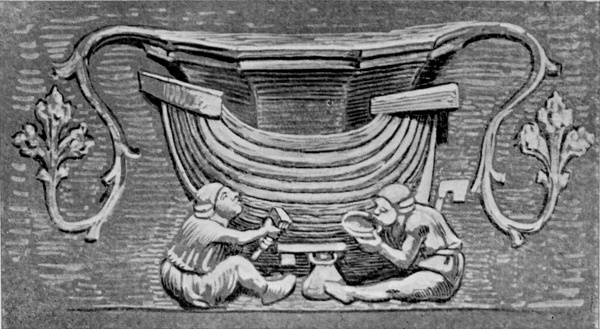

| Corbel, Fourteenth Century, Dennington Church, Suffolk. | 92 | |

| Misereres, St. David's Cathedral. | 93, 94 | |

| Scandinavian Clay Vessel. | 95 xv | |

| Modern Egyptian Clay Vessel. | 97 | |

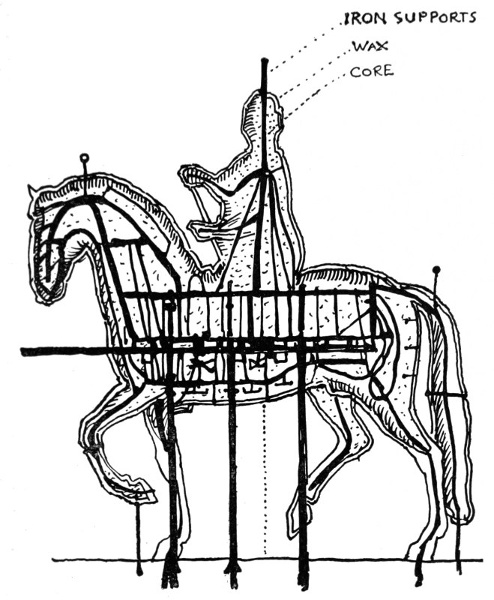

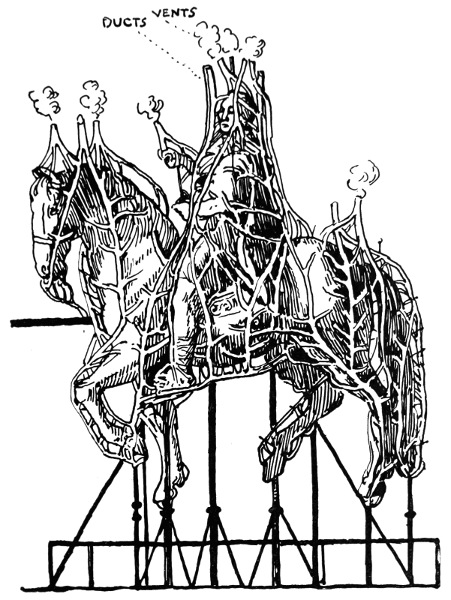

| Bronze Statue of Louis XV. by Bouchardon, showing internal Iron-work and Core. | 99 | |

| The same, showing distribution of Ducts and Vents. | 101 | |

| Wrought-iron Gates, St. Lawrence, Nuremberg. | 103 | |

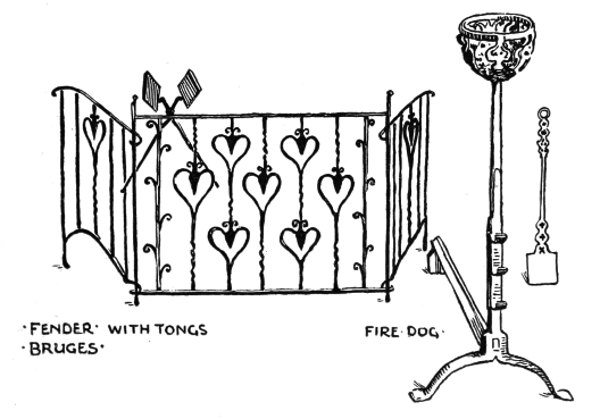

| Wrought-iron Fender, Tongs, Fire-dog and Shovel, Bruges. | 103 | |

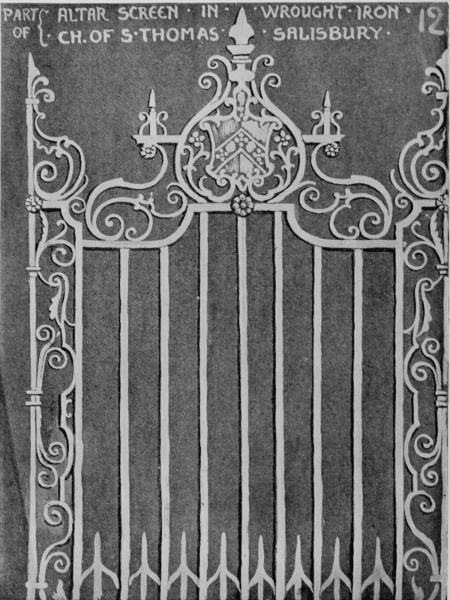

| Wrought-iron Altar Screen, St. Thomas's, Salisbury. | 104 | |

| Wrought-iron Balustrade, Rothenburg, from a sketch by R. Phené Spiers. | 105 | |

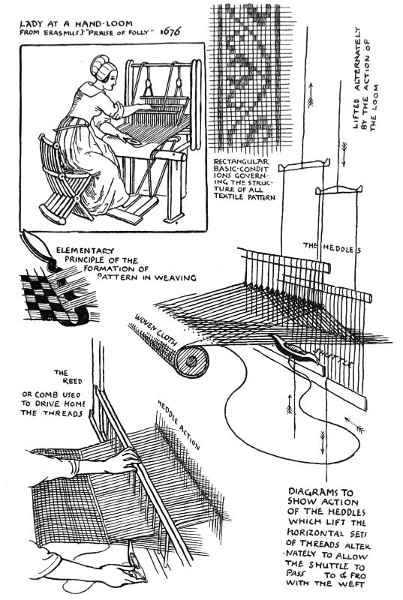

| Lady at a Hand Loom, from Erasmus's "Praise of Folly" (1676). | 107 | |

| Diagrams showing the principle of the Loom. | 107 | |

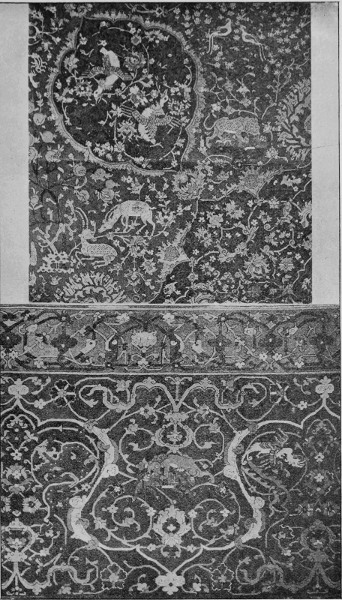

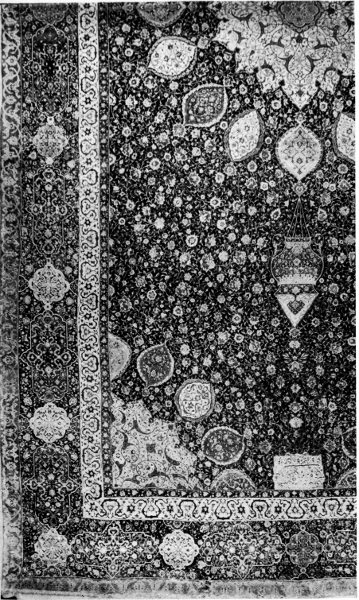

| Persian Carpet, South Kensington Museum. | 109 | |

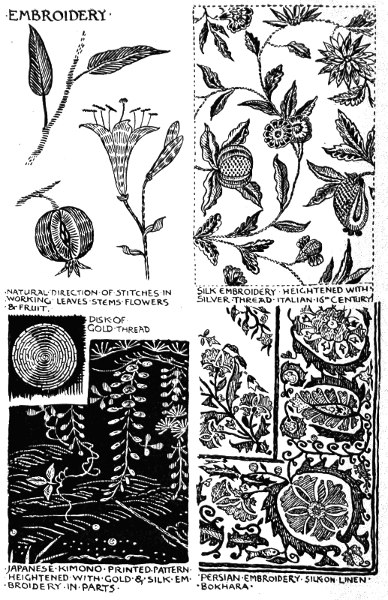

| Embroidery. | 114 | |

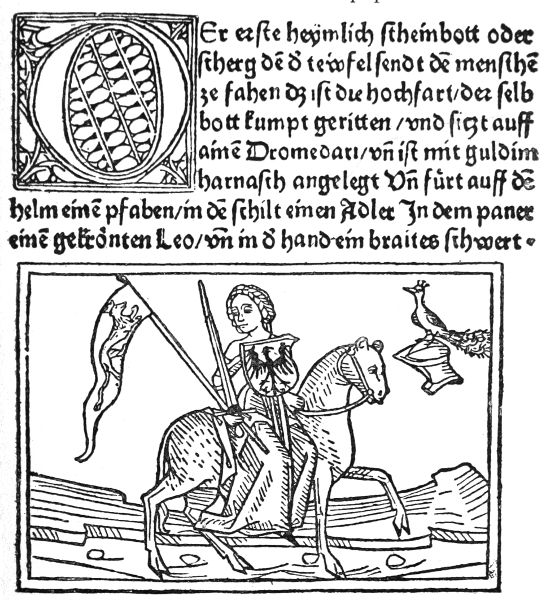

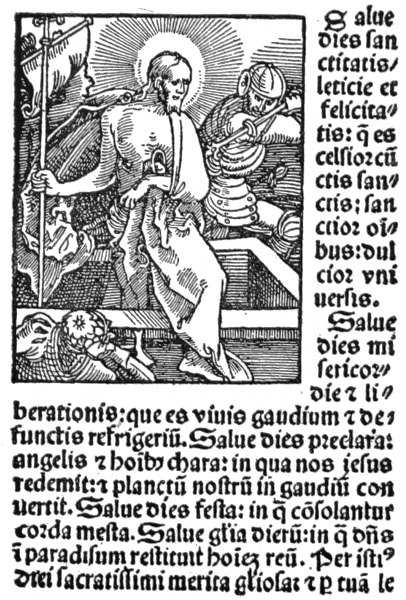

| Facsimile of a page from the "Buch von den Sieben Todsünden" (Augsburg, 1474). | 117 | |

| Hans Baldung Grün, facsimile of a page from "Hortulus Animæ" (Strassburg, 1511). | 118 | |

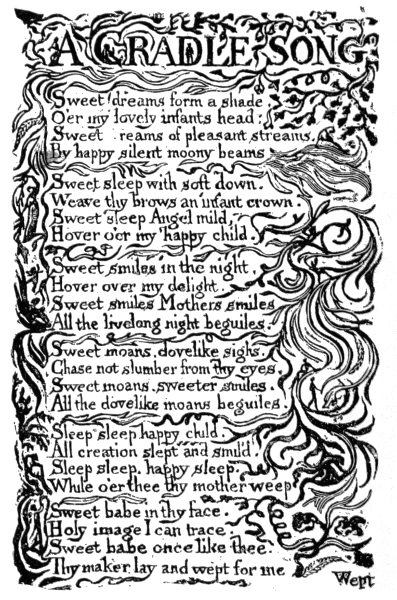

| William Blake, "A Cradle Song". | 120 | |

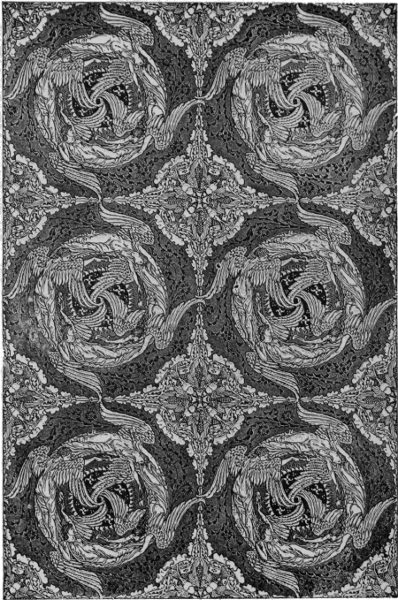

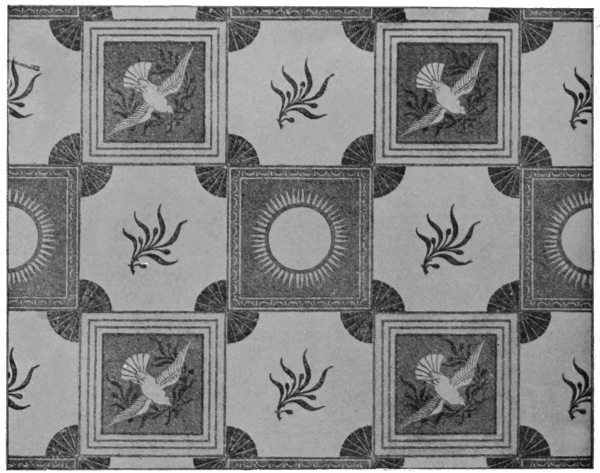

| Ceiling Papers. Designed by Walter Crane. | 124, 125, 126 | |

| Repeating Pattern Wall-paper. Designed by Walter Crane. | 127 | |

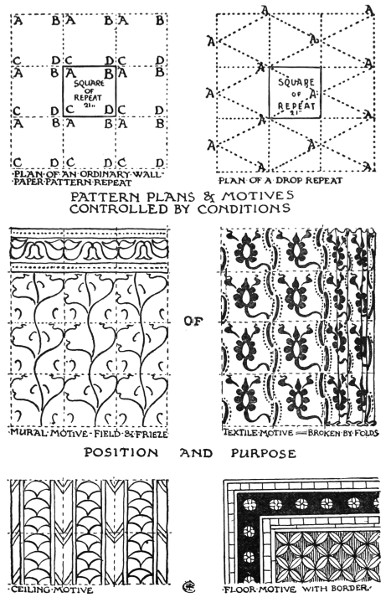

| Pattern Plans and Motives controlled by conditions of Position and Purpose. | 129 | |

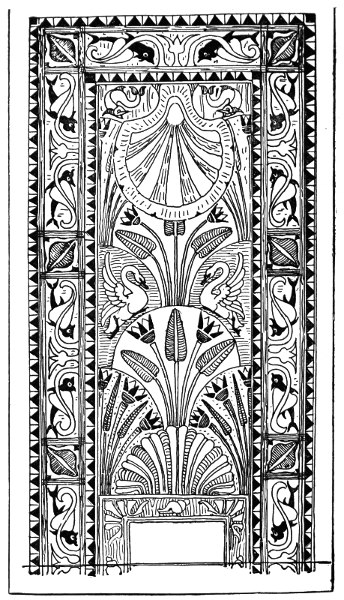

| Floor Motive, sketch design for inlaid wood, by Walter Crane. | 130 | |

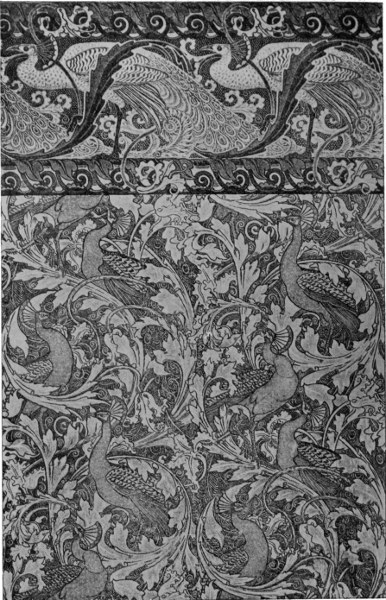

| Drop Repeat Wall-papers. Designed by Walter Crane. | 132, 134 | |

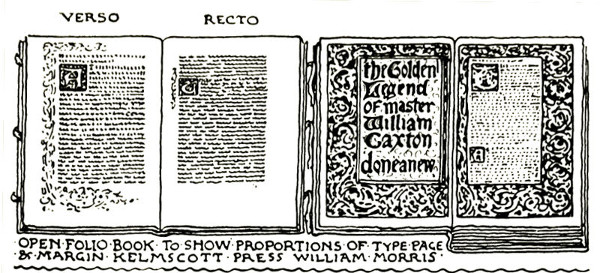

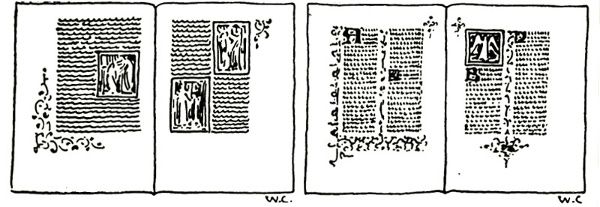

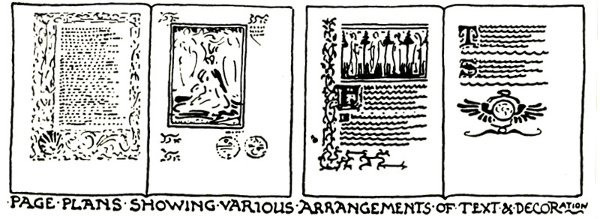

| Page Plans, showing various arrangements of Text and Decorations. | 137 | |

| Page from "The Glittering Plain" (Kelmscott Press). | 139 | |

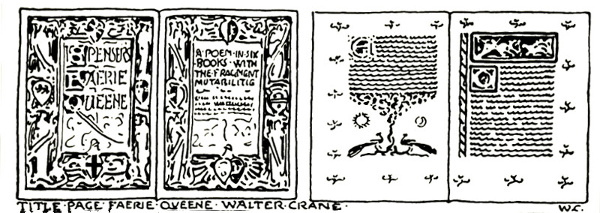

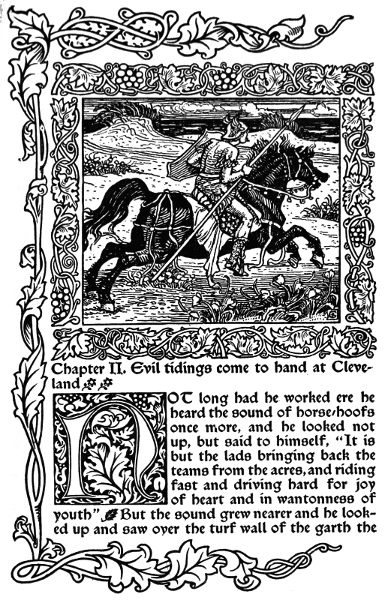

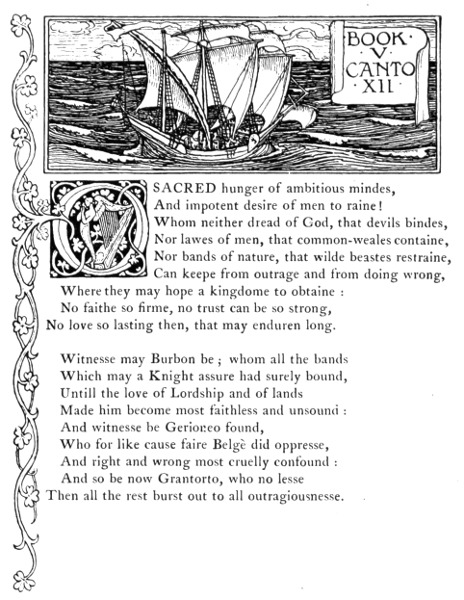

| Page from Spenser's "Faerie Queene" (Walter Crane). | 140 | |

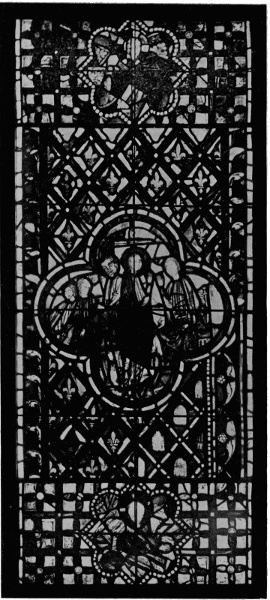

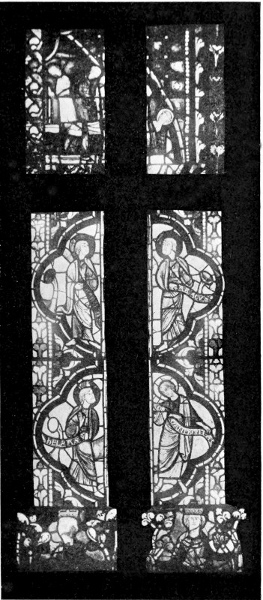

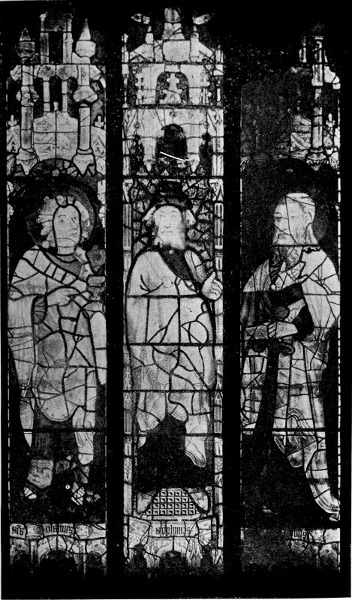

| Thirteenth Century Glass from the Sainte Chapelle, Paris (South Kensington Museum). | 142, 143, 145 | |

| Sixteenth Century Glass from Winchester College Chapel (South Kensington Museum). | 147 | |

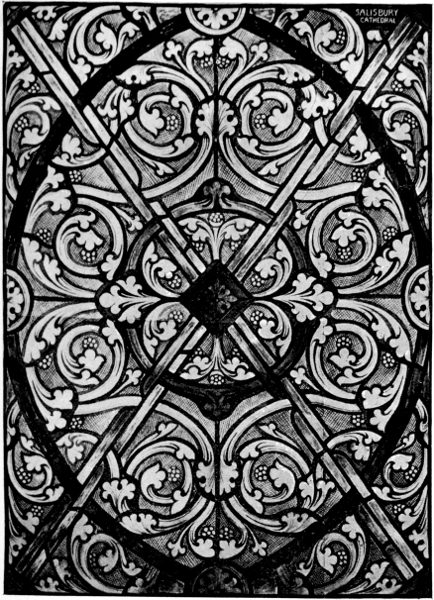

| Thirteenth Century Glass Grisaille, Salisbury Cathedral. | 151 | |

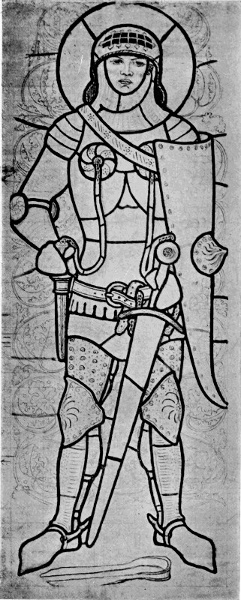

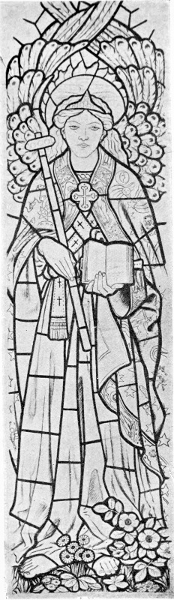

| Cartoons for Glass, showing lead design, by Ford Madox Brown. | 152, 153 | |

| Modern Glass, designed and executed by J. S. Sparrow. | 157 | |

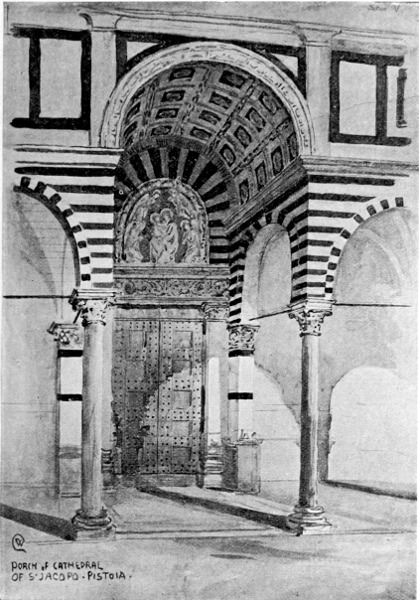

| Porch of Cathedral of S. Jacopo, Pistoia. | 165 | |

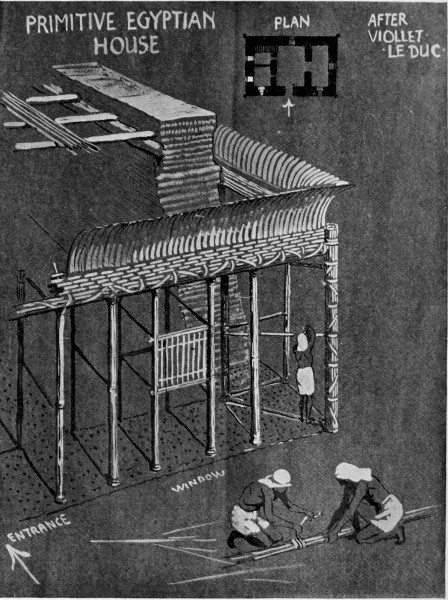

| Primitive Egyptian House, after Viollet le Duc. | 168 | |

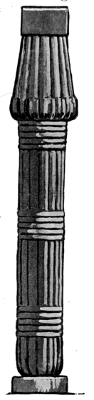

| Column from Temple of Luxor. | 169xvi | |

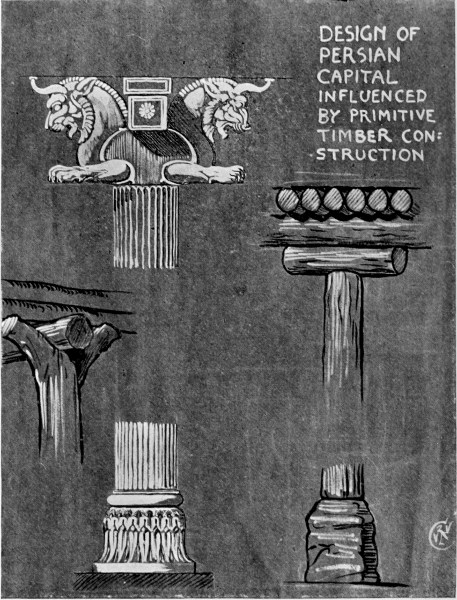

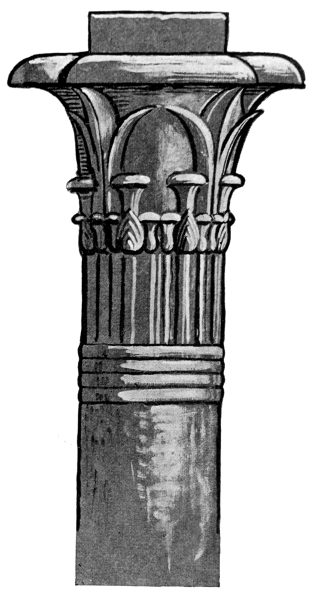

| Persian Capital, influenced by Primitive Timber Construction. | 170 | |

| Lotus Capital, Philæ. | 171 | |

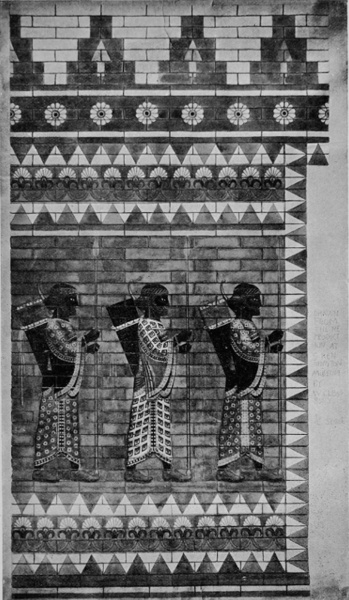

| Frieze in coloured and glazed Bricks, Palace of Susa (from the Reproduction in the South Kensington Museum), drawn by W. Cleobury. | 173 | |

| Holy Carpet of the Mosque at Ardebil (South Kensington Museum). | 177 | |

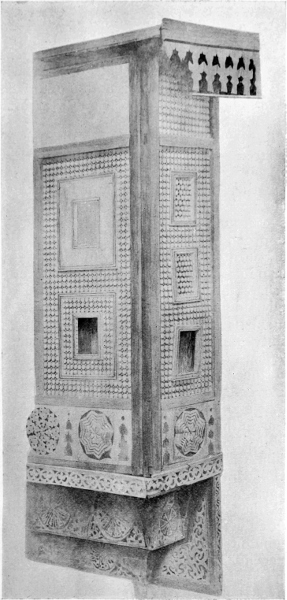

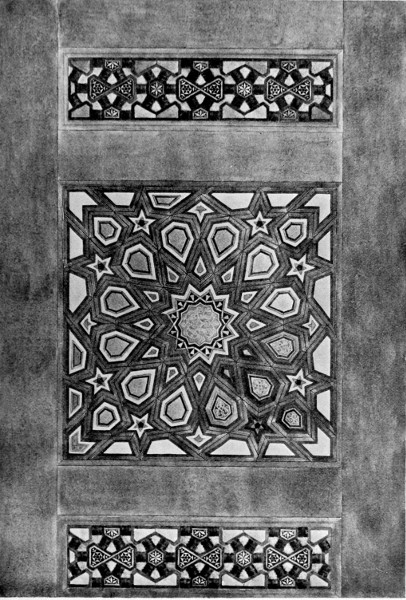

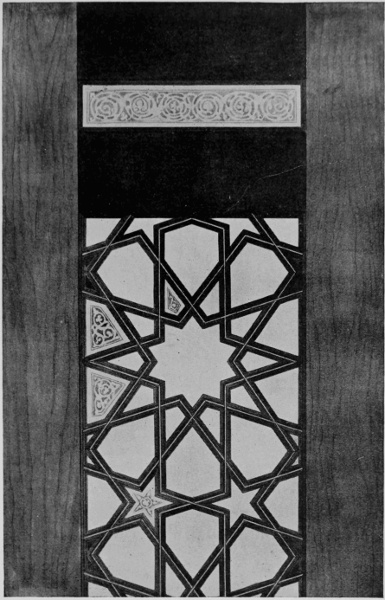

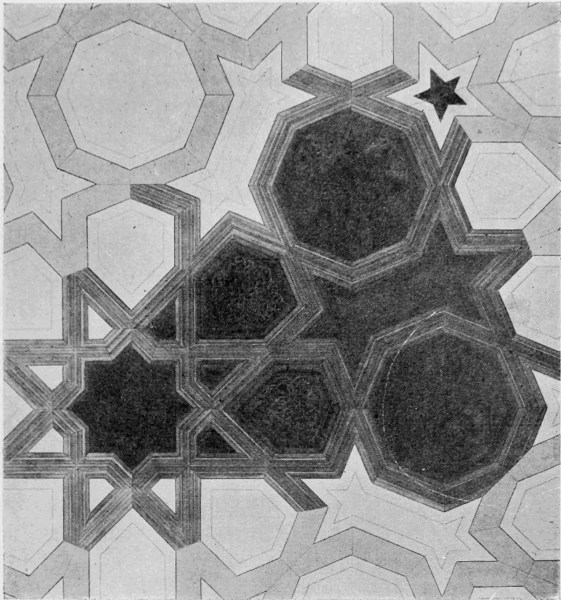

| Arab Casement from Cairo (South Kensington Museum), drawn by W. Cleobury. | 181 | |

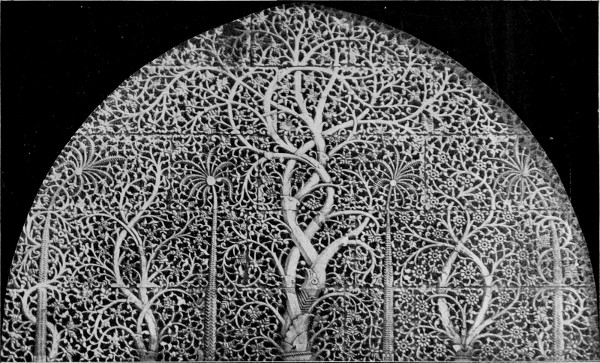

| Carved stone lattice Window from the Mosque of the Palace of Ahmedabad. | 183 | |

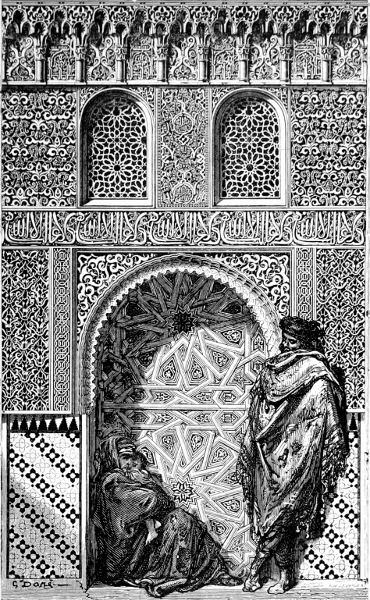

| Portion of the Alhambra, drawn by Gustave Doré. | 187 | |

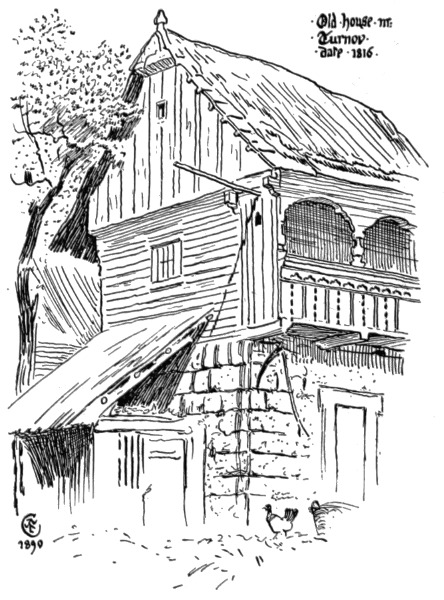

| Old House in Turnov, dated 1816. | 188 | |

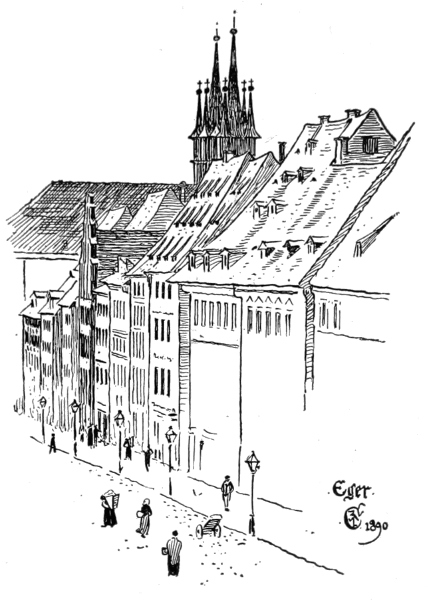

| Street in Eger. | 189 | |

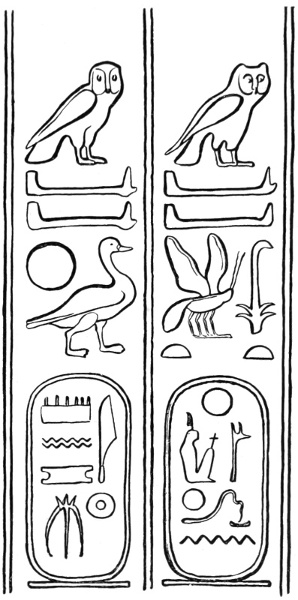

| Egyptian Hieroglyphics, Tomb of Beni Hasan (XIXth Dynasty). | 195 | |

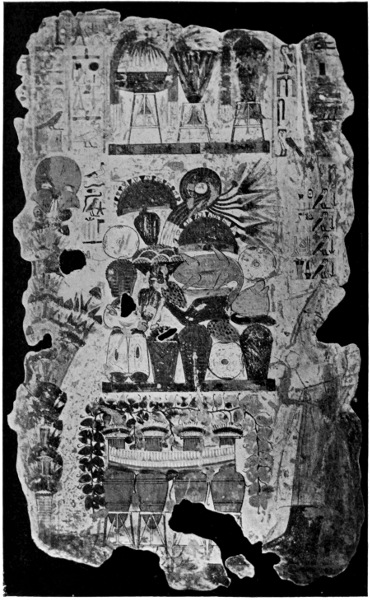

| Altar with Offerings, Egyptian Mural Painting, Thebes. | 196 | |

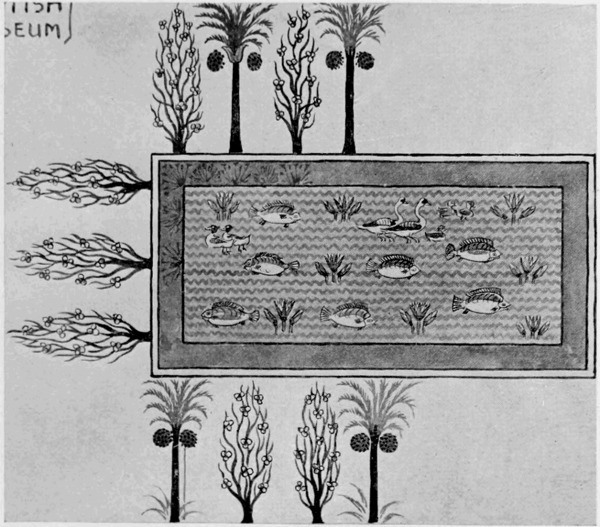

| Egyptian Wall-painting (British Museum). | 197 | |

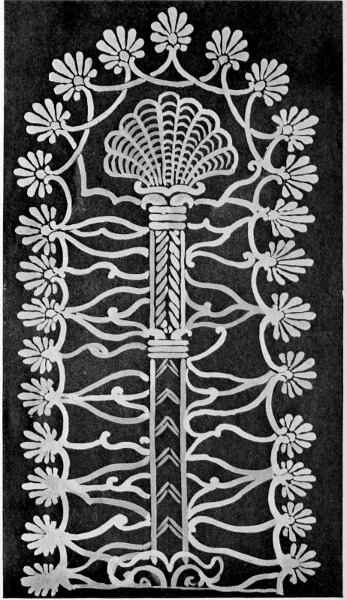

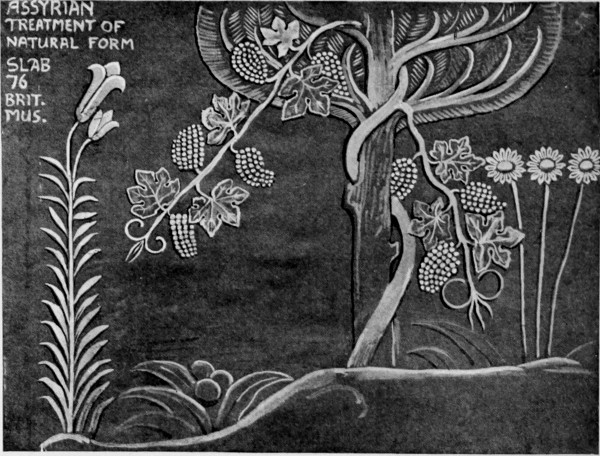

| Assyrian Tree of Life. | 198 | |

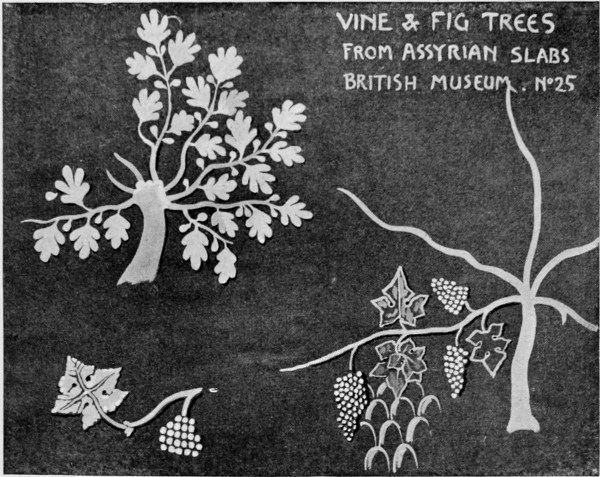

| Assyrian Bas-reliefs (British Museum). | 199, 200, 201 | |

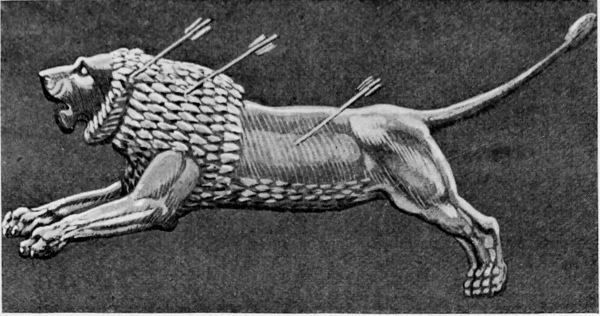

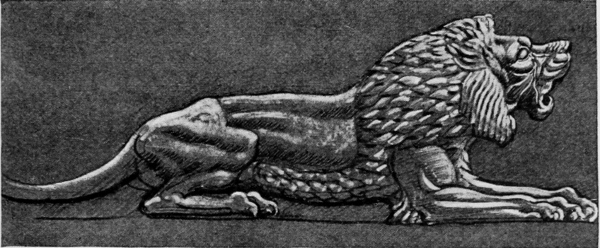

| Assur Beni Pal, Assyrian Lions from the British Museum. | 203 | |

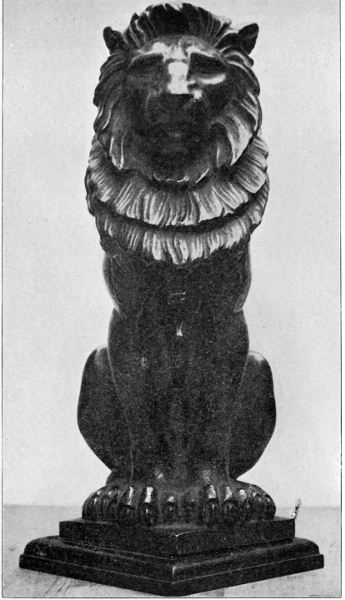

| Lion modelled by Alfred Stevens and cast in iron. | 205 | |

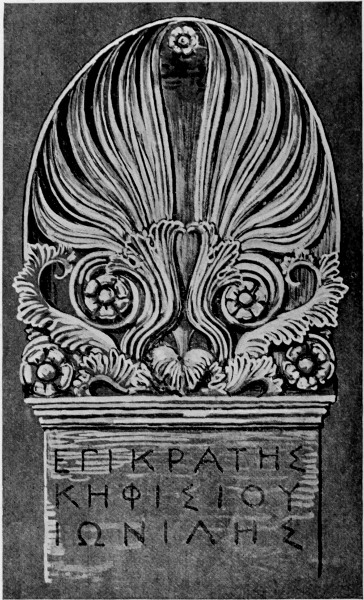

| Greek Stele or Head-stone. | 206 | |

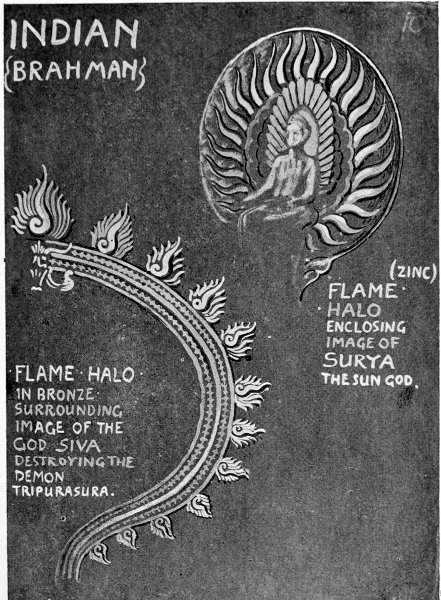

| Indian Flame Halo or Nimbus. | 207 | |

| Persian Pomegranate forms, from a goat-hair Carpet (South Kensington Museum). | 208 | |

| Celtic design, from a Cross at Campbeltown, Argyllshire. | 209 | |

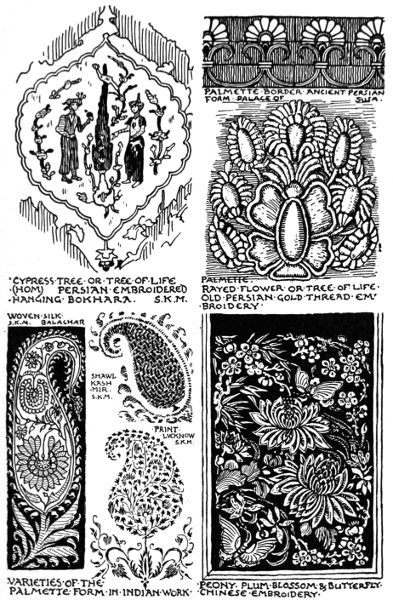

| Typical ornamental Forms in Persian, Indian, and Chinese designs. | 211 | |

| Arabian Fourteenth Century carved and inlaid Pulpit, Cairo (South Kensington Museum), drawn by W. Cleobury. | 213, 215 | |

| Panel in carved and inlaid Wood, from the Mosque of Tooloon in Cairo, Fourteenth or Fifteenth Century Saracenic. | 217 | |

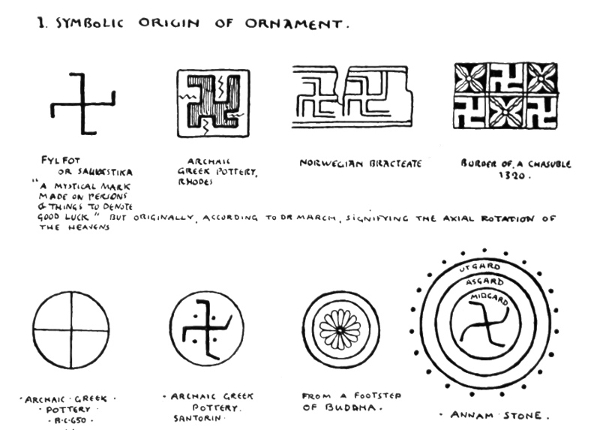

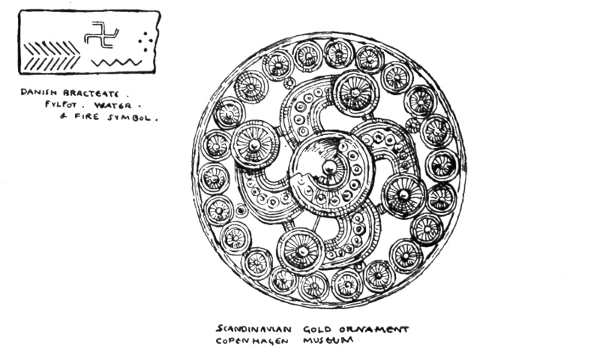

| The Fylfot or Sauvastika, and its incorporation in ornament. | 224 | |

| Primitive Symbols, Sun, Fire, Water. | 224 | |

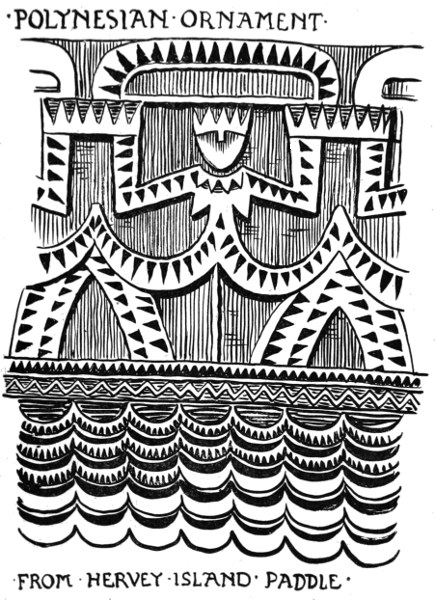

| Polynesian Carved Ornament, from Hervey Island Paddle. | 225 | |

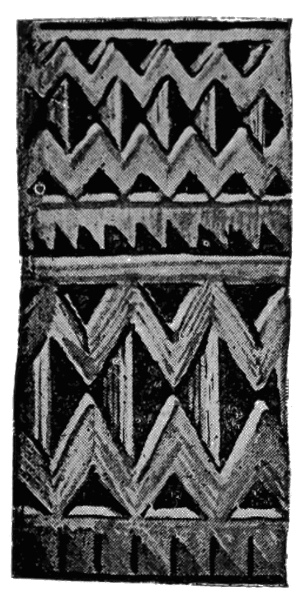

| Polynesian Ornament—Evolution of the Zigzag. | 227 | |

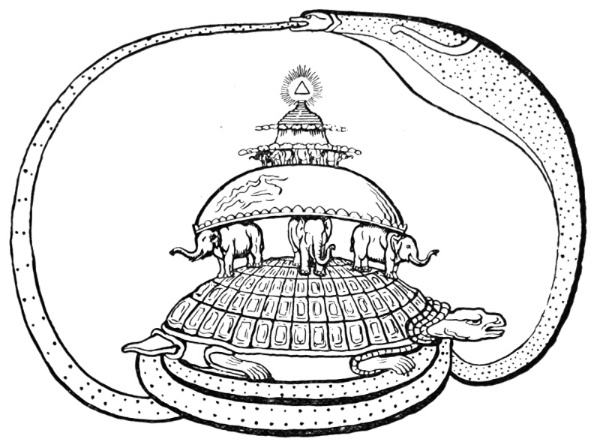

| Hindu Symbol of the Universe. | 229xvii | |

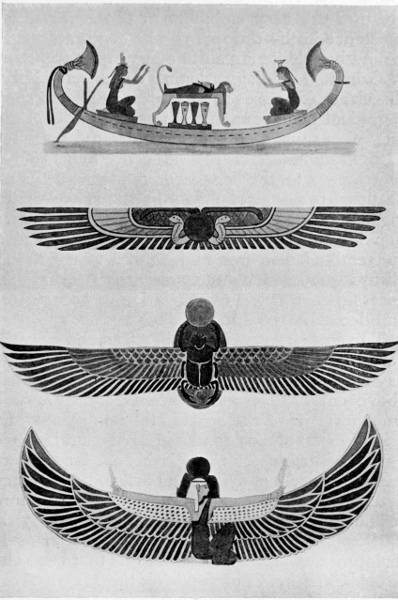

| Examples of Egyptian Symbolism. | 231 | |

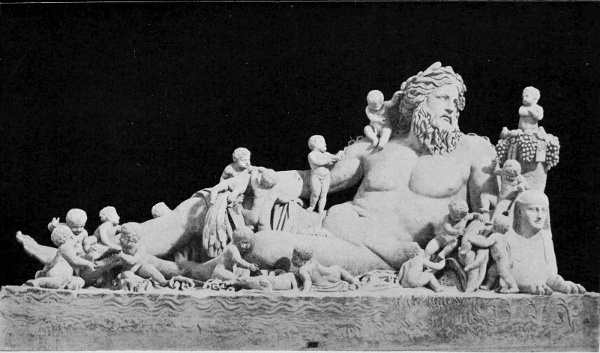

| Il Nilo (Vatican, Rome). | 235 | |

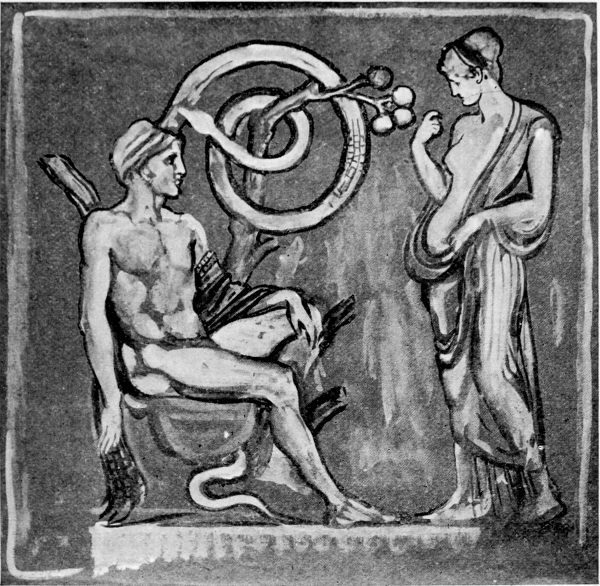

| Venus and Paris—the Apples of the Hesperides (from a relief at Wilton House). | 237 | |

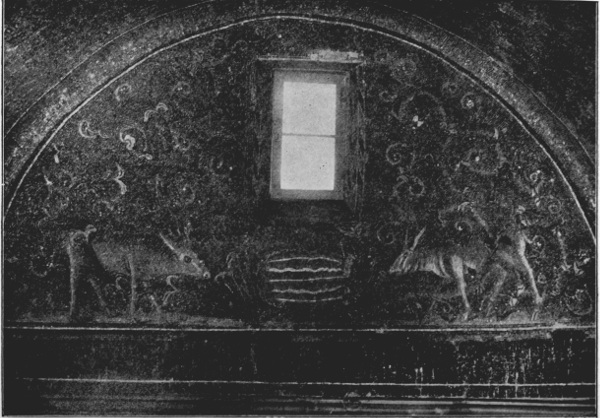

| Christian Emblem: Stags Drinking (Mausoleo di Galla Placidia, Ravenna). | 240 | |

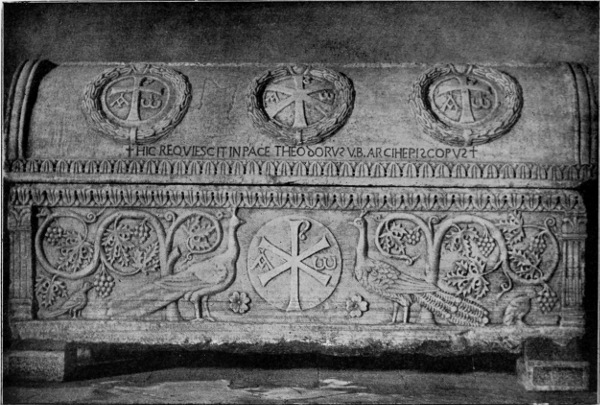

| Christian Emblem: Peacocks and Vine (Sarcophagus, St. Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna). | 241 | |

| Fra Angelico, Angel (Uffizi, Florence). | 242, 243 | |

| Orcagna, Fiends from "The Triumph of Death," Fresco (Campo Santo, Pisa). | 245 | |

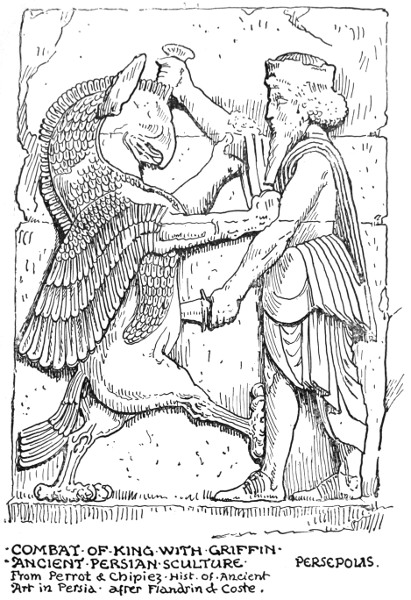

| Combat of King with Griffin (Ancient Persian Sculpture, Persepolis). | 247 | |

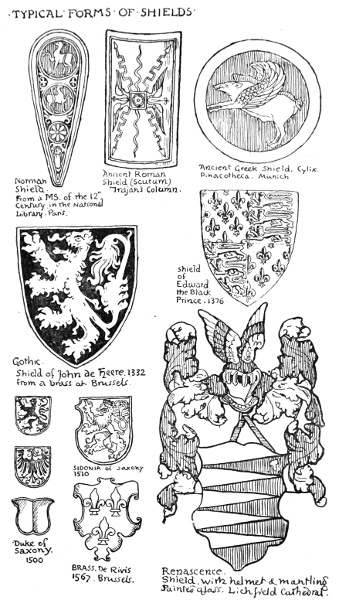

| Typical Forms of Shields and of Heraldic Treatment. | 249 | |

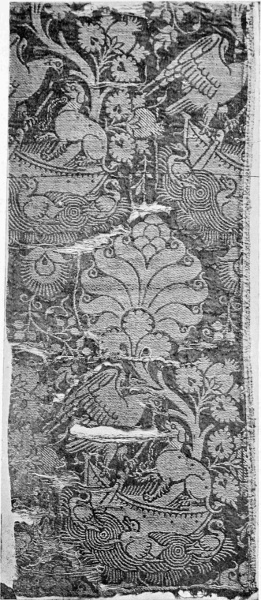

| Sicilian Silk Tissue, Twelfth century (South Kensington Museum). | 251 | |

| Alciati's Emblems, designed by Solomon Bernard, Ex Bello Pax, Fortune, Ambition, Avarice. | 253, 254, 255, 256 | |

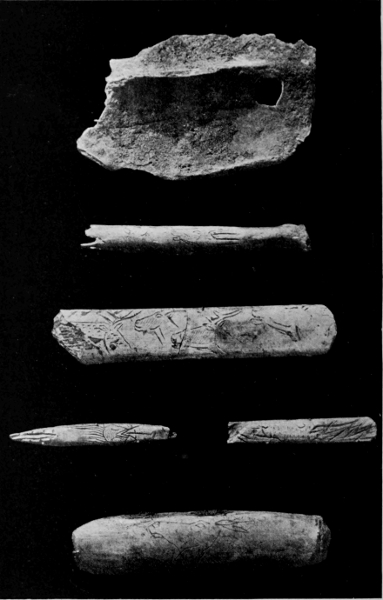

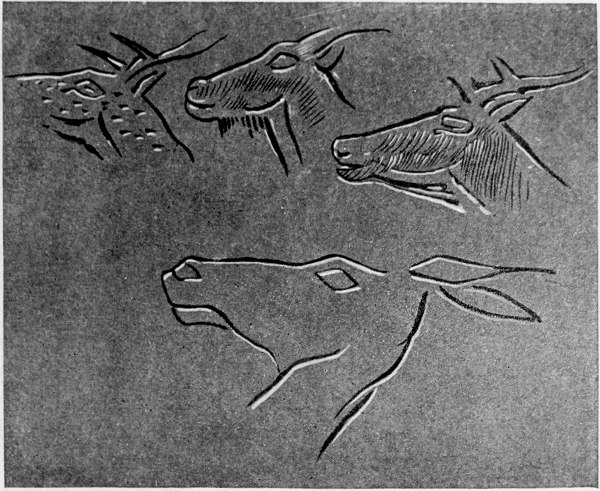

| Prehistoric Graphic Art of the Cave Men. | 260, 261 | |

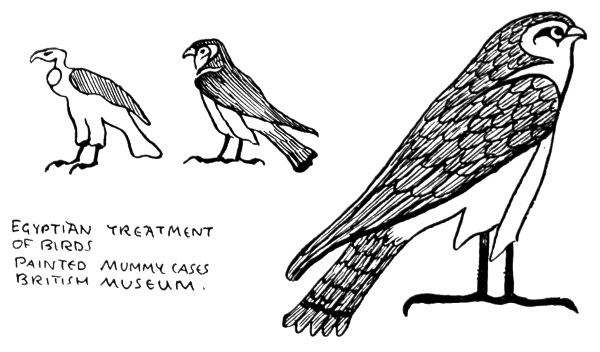

| Egyptian Treatment of Birds (from painted Mummy Cases, British Museum). | 264 | |

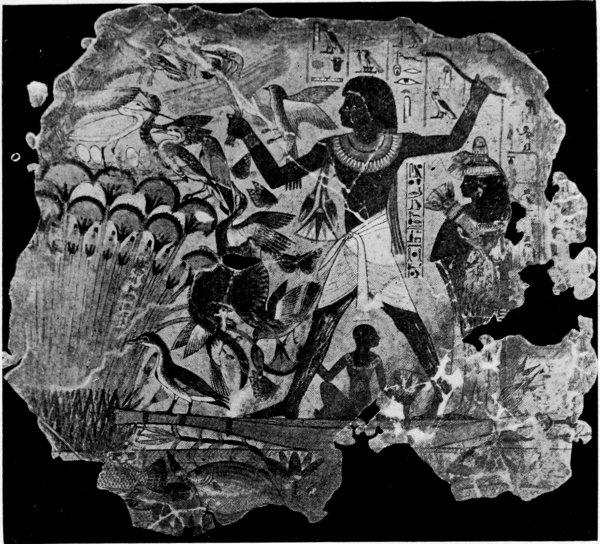

| A Fowler, Wall-painting, XIXth Dynasty (British Museum). | 265 | |

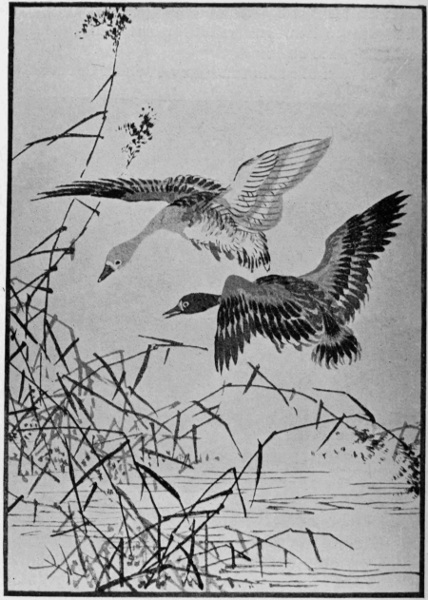

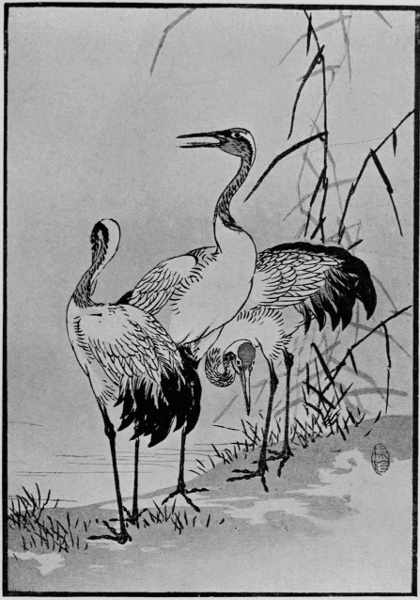

| Japanese Graphic Art (from "The Hundred Birds of Bari"). | 266, 267 | |

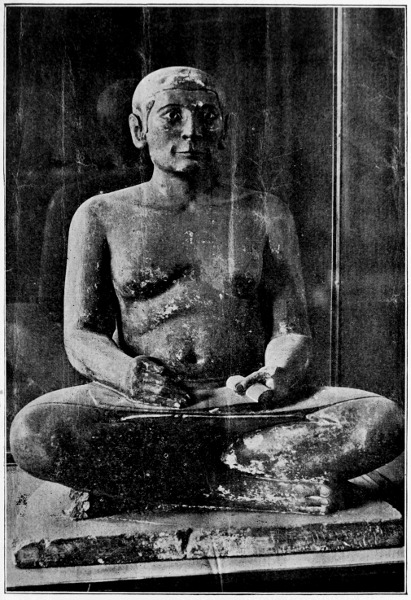

| Egyptian Scribe, Portrait Statuette, Vth or VIth Dynasty (Louvre). | 269 | |

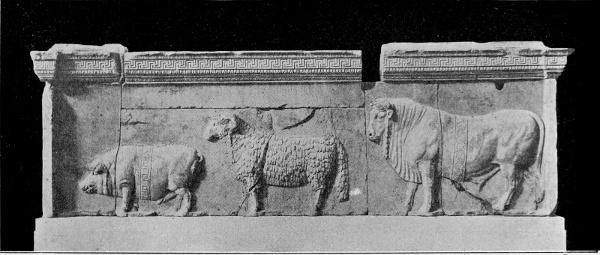

| Sculptured Frieze discovered in the Forum, 1872. | 271 | |

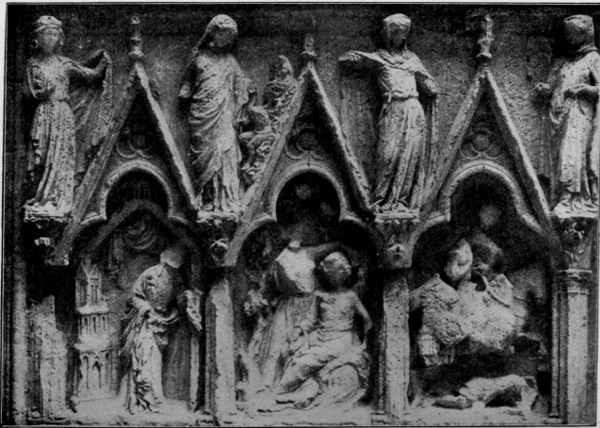

| Auxerre Cathedral, Thirteenth Century Sculpture. | 272 | |

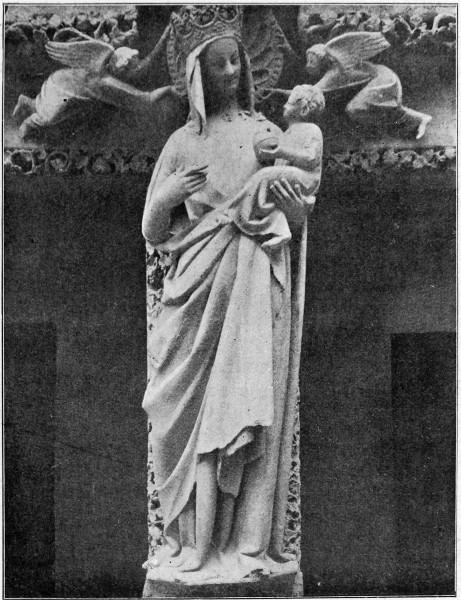

| Amiens Cathedral, Fourteenth Century Sculpture. | 273 | |

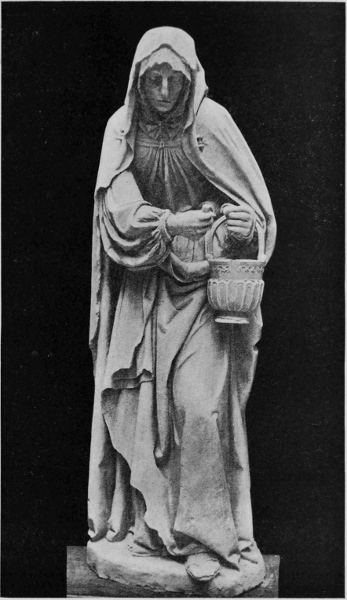

| Statue of St. Martha (St. Urbain, Troyes). | 275 | |

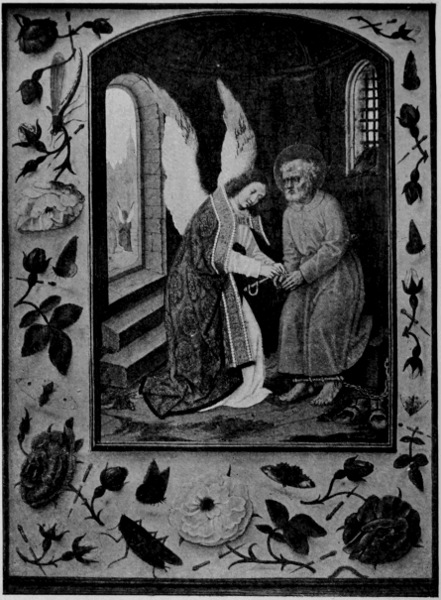

| Memling, "Deliverance of St. Peter" (Grimani Breviary). | 276 | |

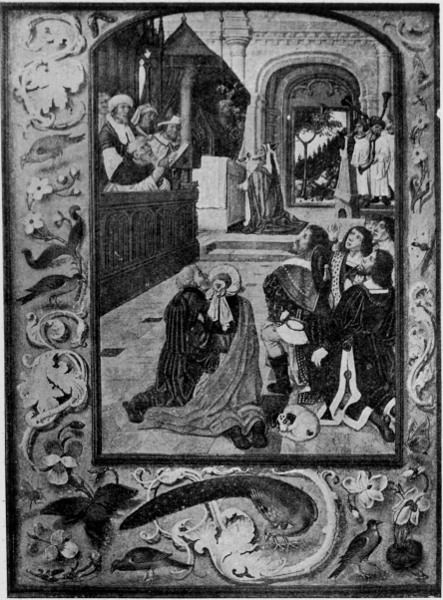

| Memling, "David placing the Ark in the Tabernacle" (Grimani Breviary). | 277 | |

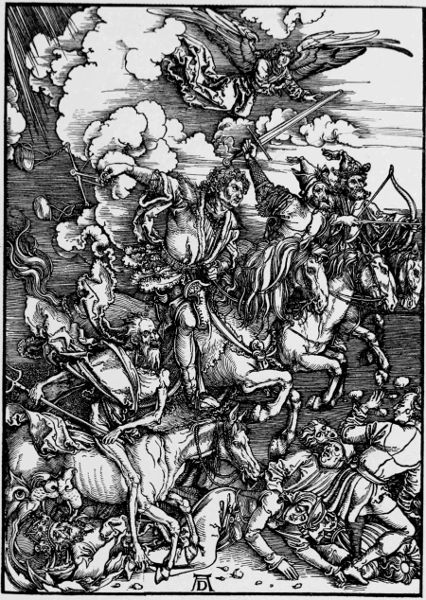

| Albert Dürer, "The Apocalypse". | 279 | |

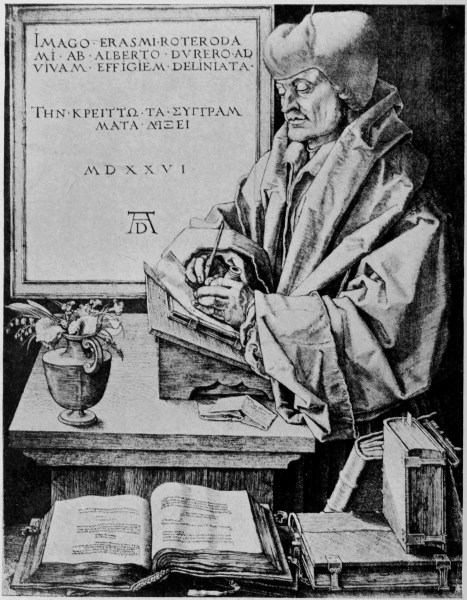

| Albert Dürer, Portrait of Erasmus (1526). | 280 | |

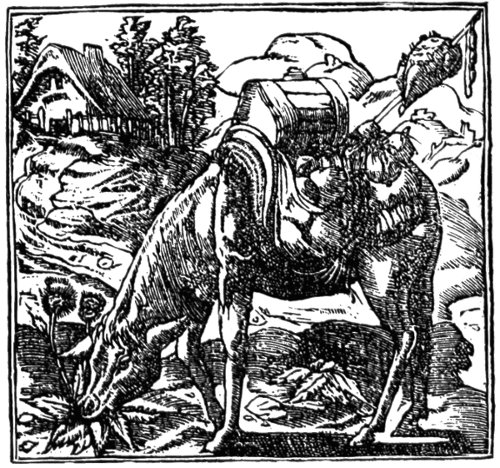

| Albert Dürer, "The Cannon" (1513). | 281 | |

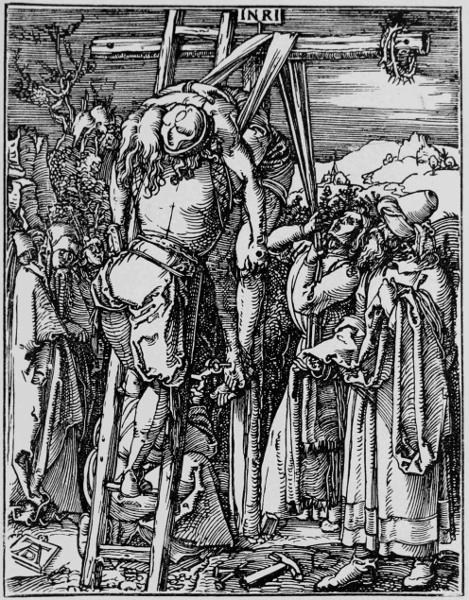

| Albert Dürer, The taking down from the Cross ("Little Passion"). | 283 | |

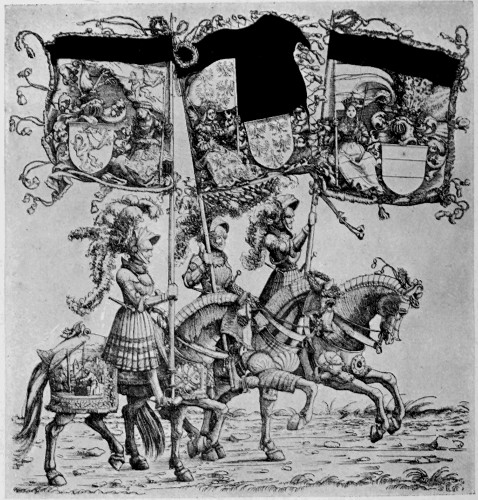

| Hans Burgmair, Group of Knights from "The Triumphs of Maximilian". | 284 | |

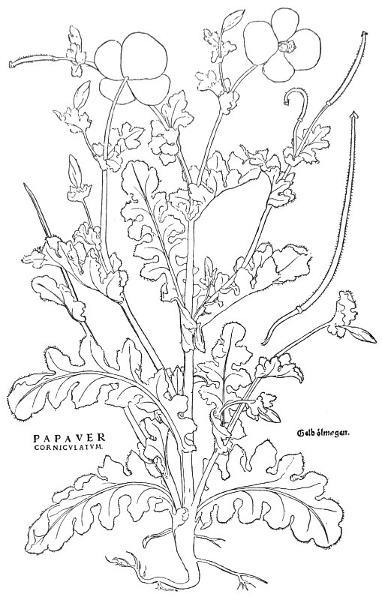

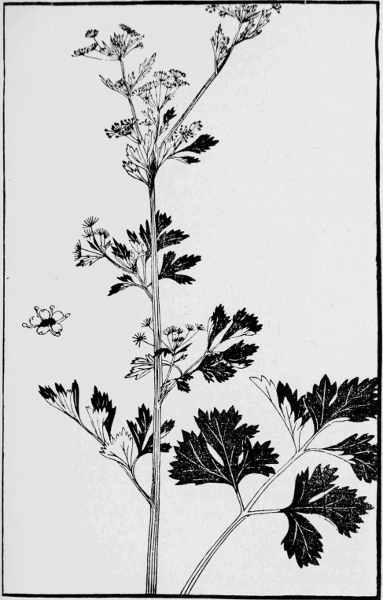

| Horned Poppy, from Fuchsius' "De Historia Stirpium" (1542). | 287xviii | |

| Japanese Plant Drawing. | 288, 289 | |

| Brass of Joris de Munter and Wife (Bruges, 1439). | 291 | |

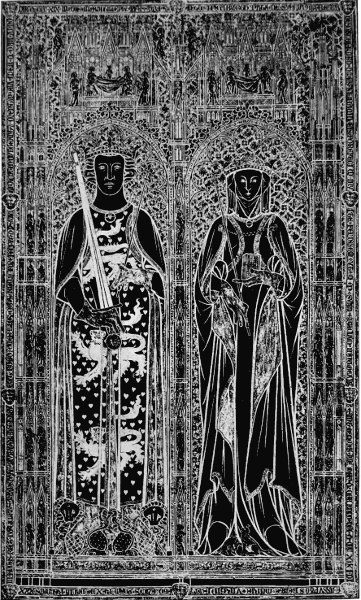

| Brass of King Eric Menved and Queen Ingeborg of Denmark (Ringstead, 1319). | 293 | |

| Charles Keene, Drawing from "Punch". | 295 | |

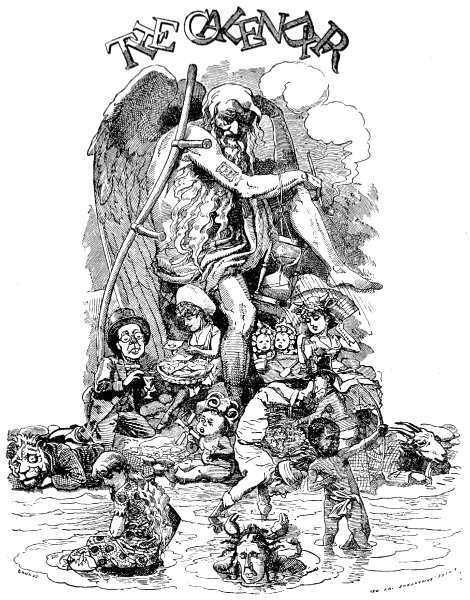

| Linley Sambourne, Drawing from "Punch". | 297 | |

| Phil May, Drawing from "Punch". | 299 | |

| Simone Memmi, Fresco containing portrait of Cimabue and Contemporaries (S. M. Novella, Florence). | 307 | |

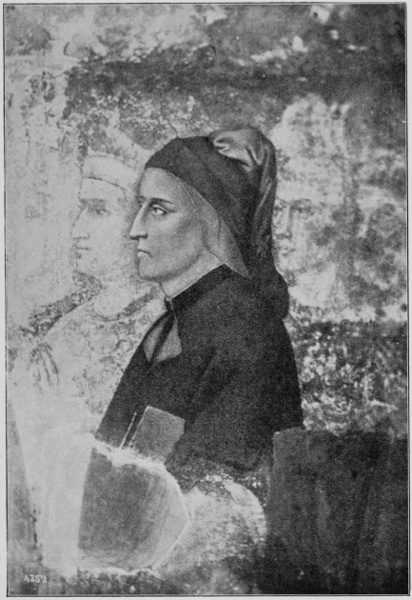

| Giotto, Portrait of Dante (Pretorian Palace, Florence). | 309 | |

| Giotto, Frescoes (Arena Chapel, Padua). | 310, 311 | |

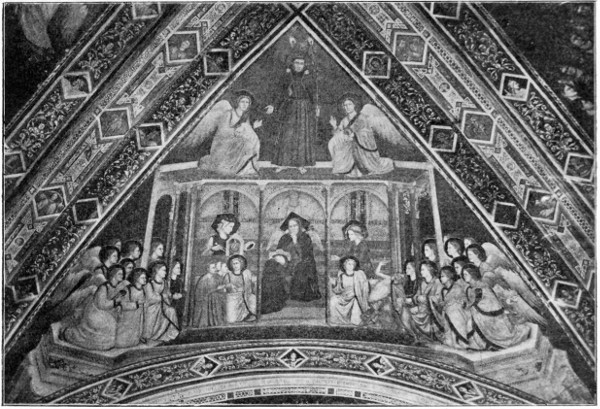

| Giotto, Frescoes (Assisi). | 312, 313 | |

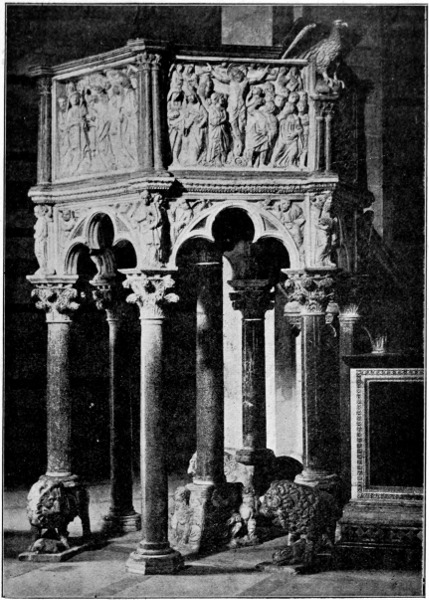

| Niccolo Pisano, Pulpit (Baptistery, Pisa). | 315 | |

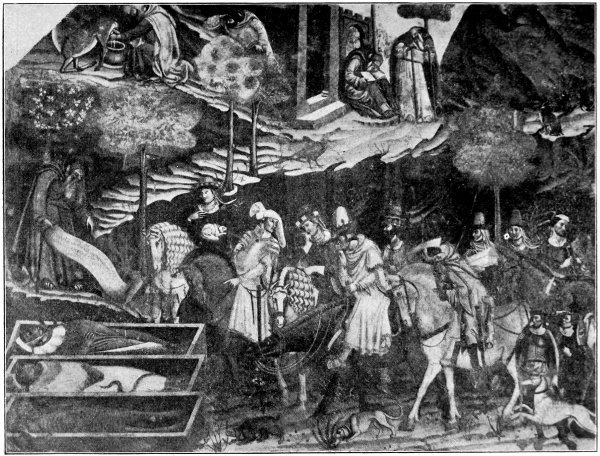

| Orcagna, "Triumph of Death," Fresco (Campo Santo, Pisa). | 317 | |

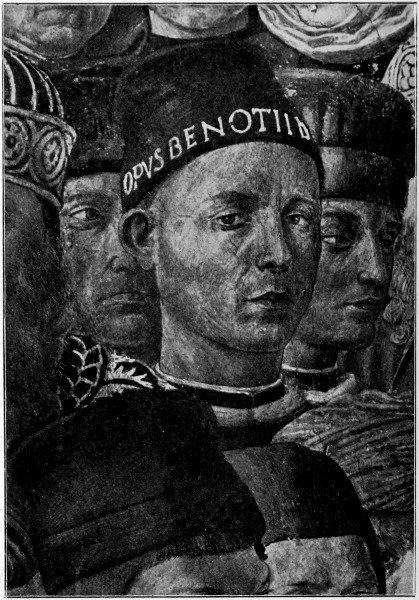

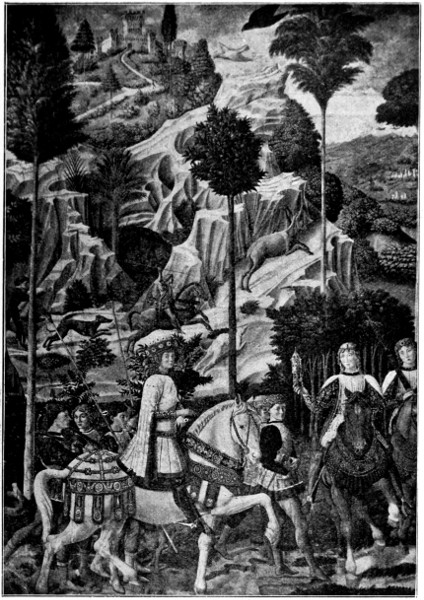

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Frescoes (Riccardi Chapel, Florence). | 318, 319, 320, 321 | |

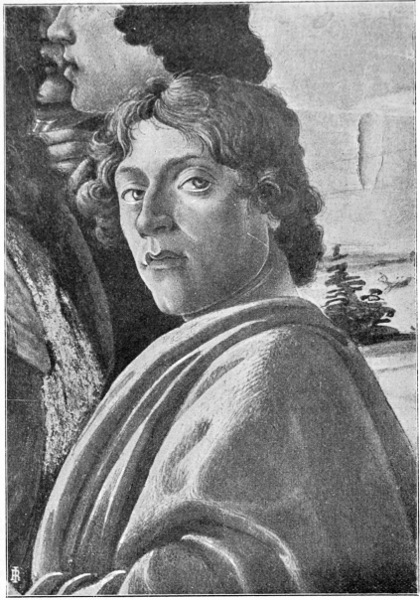

| Botticelli, Detail from "The Adoration of the Magi" (Uffizi, Florence). | 323 | |

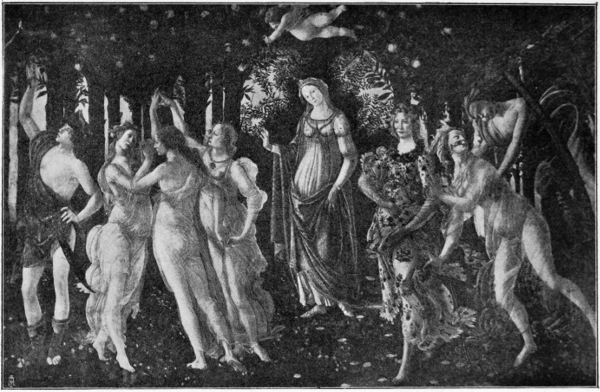

| Botticelli, "La Prima Vera" (Academy, Florence). | 325 | |

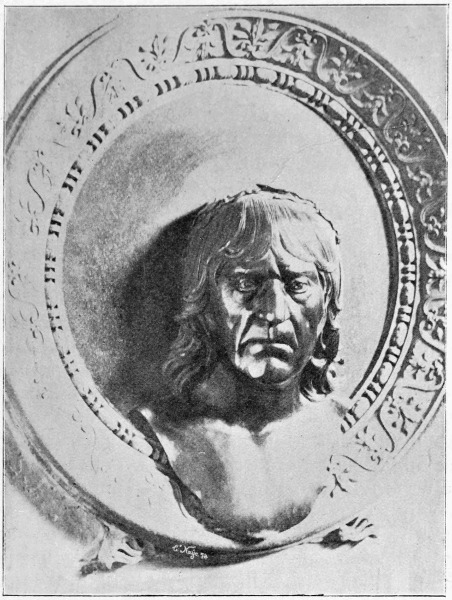

| Mantegna, Bronze Monument (S. Andrea, Mantua). | 327 | |

| Mantegna, "The Triumph of Julius Cæsar," from Andrea Andreani's woodcut. | 331 | |

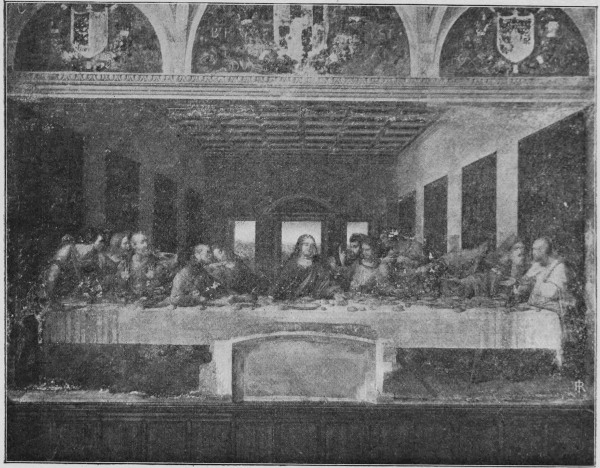

| Leonardo da Vinci, "The Last Supper" (Milan). | 335 | |

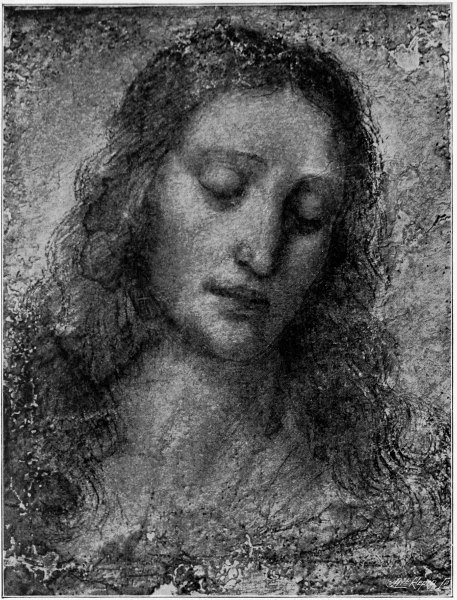

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Head of Christ. | 337 | |

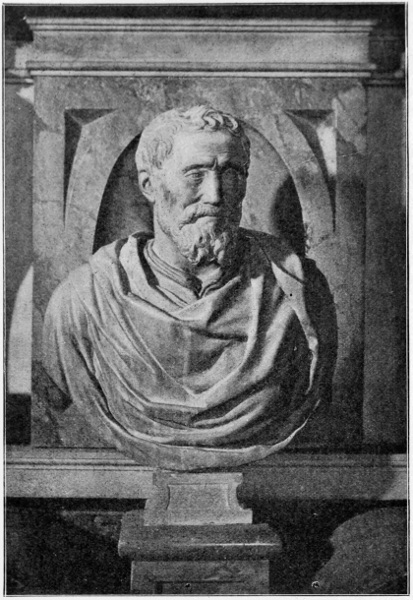

| Bust of Michael Angelo (S. Croce, Florence). | 339 | |

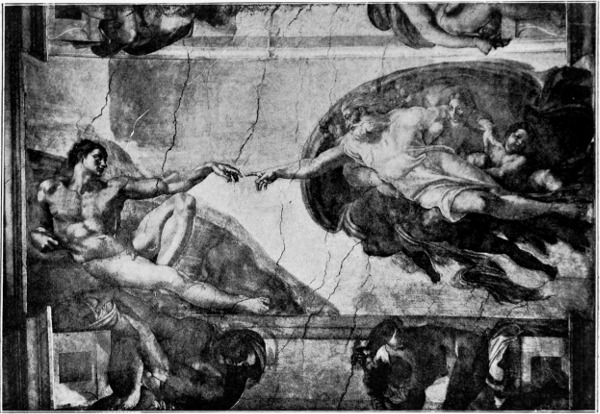

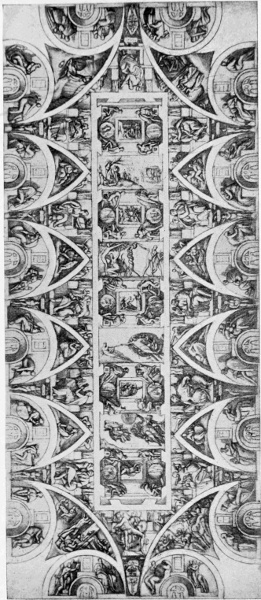

| Michael Angelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel ("The Creation of Man"). | 341 | |

| Michael Angelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. | 343 | |

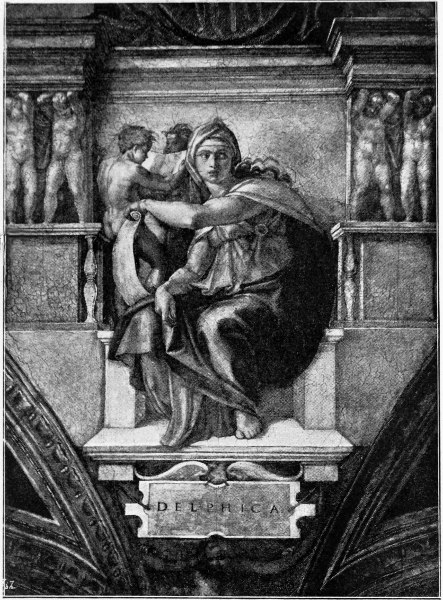

| Michael Angelo, The Delphic Sibyl (Sistine Chapel). | 345 | |

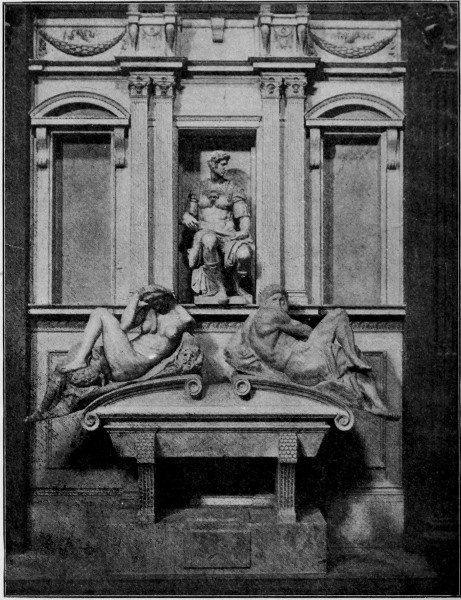

| Michael Angelo, Tomb of Giuliano de Medici (Florence). | 346 | |

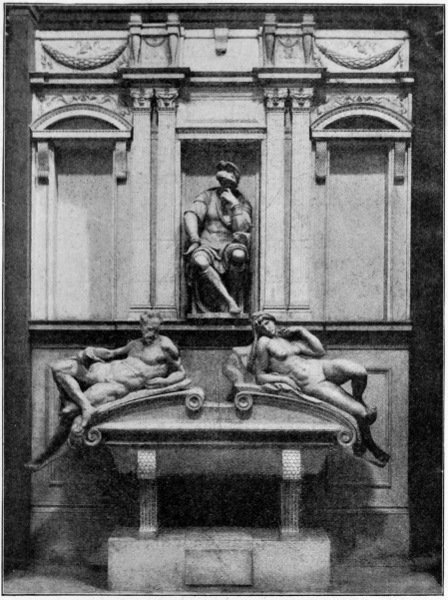

| Michael Angelo, Tomb of Lorenzo de Medici (Florence). | 347 | |

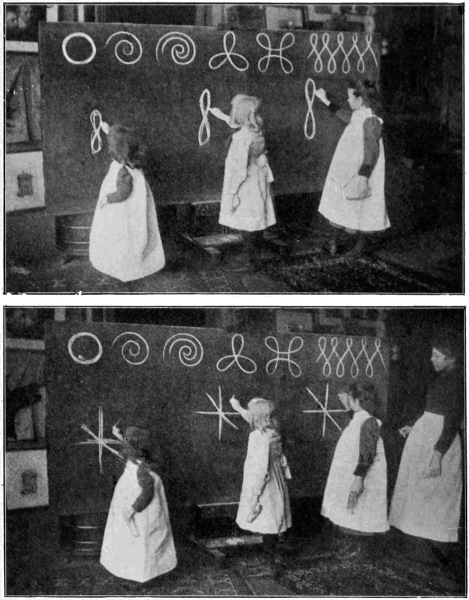

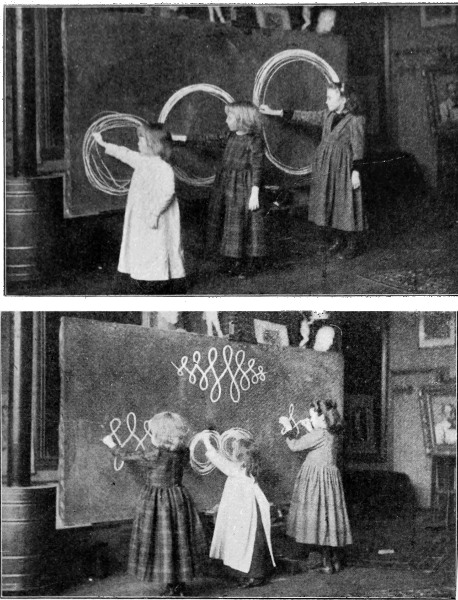

| Natural variation in Repetition of Ornamental Forms—Primary School Children drawing on the blackboard, Philadelphia. | 356, 357 | |

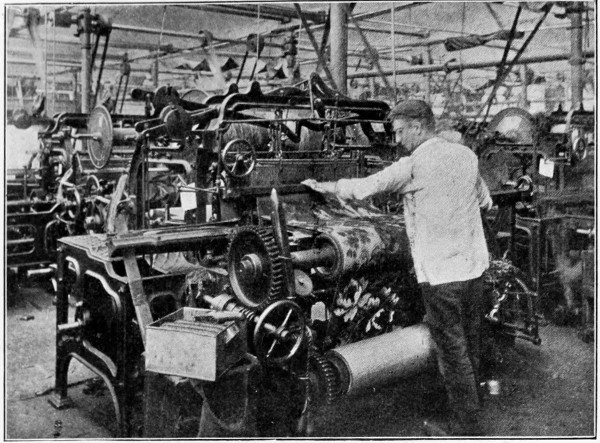

| Axminster Carpet Weaving. | 361 | |

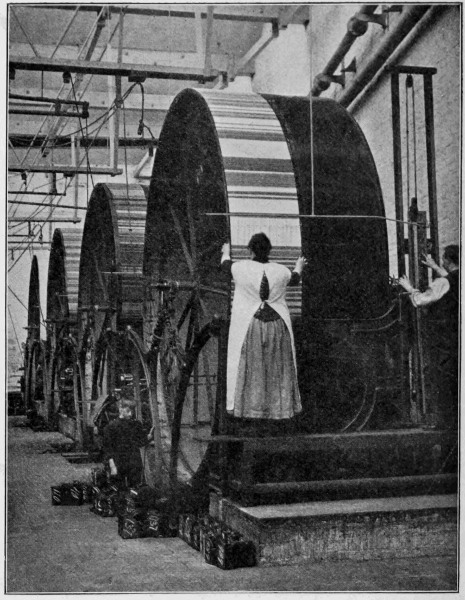

| Tapestry Carpet Weaving. | 362 | |

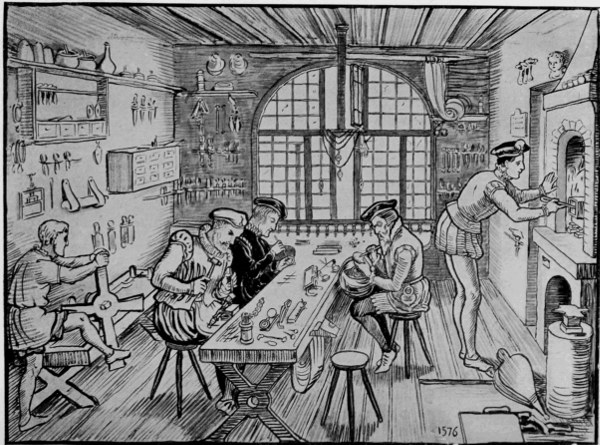

| Interior of the Atelier of Etienne Delaune, Paris, 1576. | 364 | |

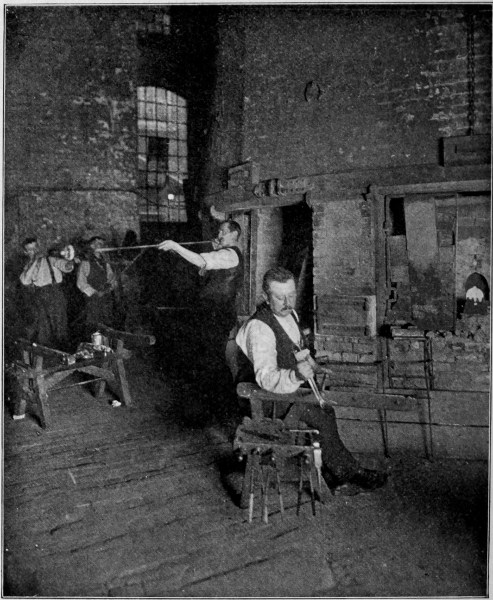

| Glass Blowing. | 366 | |

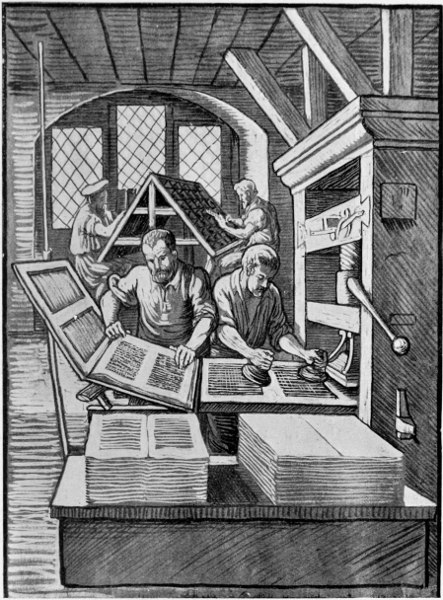

| Interior of a Printing Office, Sixteenth Century, from Jost Amman. | 367 | |

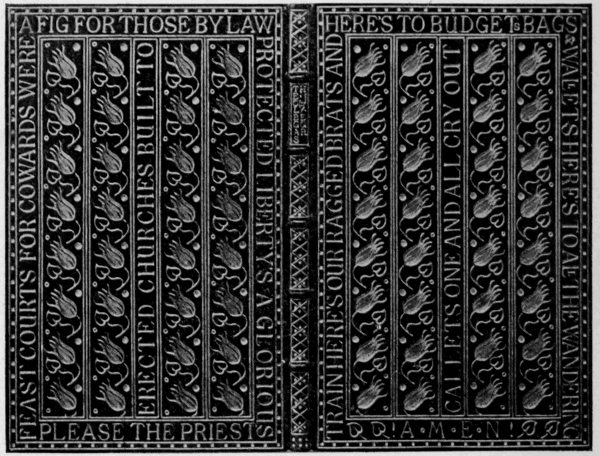

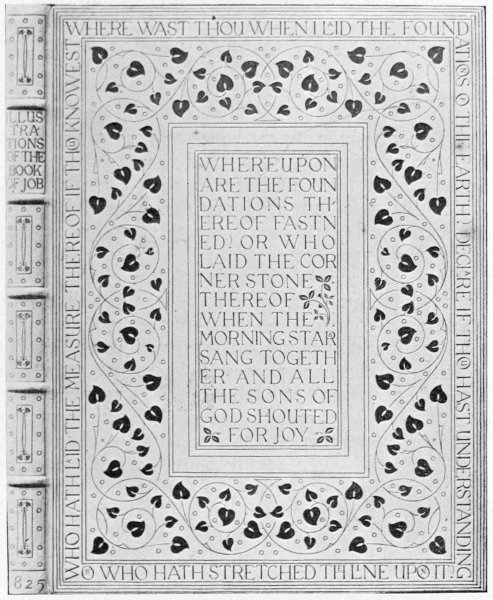

| Gold-Tooled Bindings, by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson. | 370, 371 | |

1

OF THE BASES OF DESIGN

WHEN we approach the study of Design, from whatever point of view, and whatsoever our ultimate aim and purpose, we can hardly fail to be impressed with the vast variety and endless complexity of the forms which the term (Design) covers, understanding it in its widest and fullest sense.

From the simplest linear pattern, or bone scratchings of primitive man, to the most splendid achievements in mural decoration of the Italian Renascence—or, shall we say, from the grass mat of the first plaiter to the finest Persian carpet: or from Stonehenge to Salisbury Cathedral—the range is enormous, and were we to attempt to trace, step by step, the true relation between the diverse and multitudinous characteristics which such contrasts suggest, we should be tracing the course of the development of human thought and history themselves.

When we stand amazed in this labyrinth—this enchanted and beautiful wood of human invention which the history of art displays, we might be content to gaze at the loveliness of particular forms there, and simply enjoy, like children, the beauty 2 of the trees and flowers; gathering here and there at random, and casting them aside again when we were tired, without a thought as to their true significance.

If, however, we desire to find some clue to the labyrinth—something which will explain it in part, at least, something which will give us a key to the relation of these manifold forms, and enable us to place them in harmonious order and coherence, we shall presently ask:

(1) How and whence they derived their leading characteristics?

(2) Upon what basis have they been built up? and

(3) What have been the chief influences which have determined, and still determine, their varieties?

Let us try to address ourselves to these questions, since, I believe, even if we only end as we begin, by inquiry, that, in the course of that inquiry, by study, by comparison, and careful observation, we shall be able greatly to clear our path, and find much to help us as individual students and practical workers in art.

(1) The first arts are, of course, those of pure utility, which spring from the primal physical necessities of man: which are concerned in the maintenance of life itself—the art or craft of the hunter and the fisherman, the tiller of the soil, the hewer of wood and the drawer of water: but seeing that next to securing sufficiency of food, the efforts of man are directed towards providing himself with shelter, both of roof and raiment, and since most of the arts of the creative sort must be practised 3 under shelter of some kind, and that all of them contribute in some way towards the building or adornment of such shelter, I think we shall find the true basis and controlling influences, which have been paramount in the development of decorative design, in the form and character of the dwellings of man and their accessories; from the temples he has raised to enshrine his highest ideals—these temples themselves being but larger and more monumental dwellings—to the tomb, his last dwelling-place. We shall find, in short, the original and controlling bases of design in architecture, the queen and mother of all the arts.

In asserting this one does not lose sight of the view that all art is, primarily, the projection or precipitation in material form of man's emotional and intellectual nature; but, being projected and taking definite shape, it becomes subject to certain controlling forces of nature, of material, of condition, which re-act upon the mind; and it is with these controlling forces and conditions, and the distinctions which arise out of them, that we are now concerned.

Such distinctions as exist, for instance, in the feeling, the plan and construction of those patterns intended to be laid upon the floors (as in carpets or tiles), and such as are intended to cover ceilings and walls (as in plaster-work, textile hangings or wall papers), obviously arise from the relative positions of floor, walls, and ceilings, and the differences between horizontal and vertical positions; and these conditions are necessarily part and parcel of the constructional conditions of the dwelling itself. 4

The first shelter may be said to have been the shelter of nature without art—the Tree and the Cave, the first homes of man; although he was probably not by any means the first animal to hide among the woods and the rocks, since he had many and formidable foes to dispute with or disturb him in possession. It is noticeable that such art as is associated with this strange and remote chapter of man's existence on the earth—the art-instinct which impelled the primitive hunter to incise the bone and stone implements he used with the images of the animals he hunted—is purely graphic, and does not show any feeling of that adaptive ornamental quality characteristic of what we call decorative design, which would seem to belong to a more highly organized condition of society. "Among the primitive Greeks," remarks Messrs. Guhl and Köner in their Life of the Greeks and Romans, "fountains and trees, caves and mountains, were considered as seats of the gods, and revered accordingly, even without being changed into divine habitations by the art of man." But, as proving literally that art springs out of nature, the cave itself led to a development of architecture, as in some early Greek tombs where the cave, or cleft in the rocks, is utilized and added to by masonry; or where the rock itself was carved and hollowed, as in the rock-cut temples of Egypt and India. To which some trace the origin of columnar architecture.

The Tent of the Asiatic wandering tribes, and the wattled and wooden Hut of the western and northern, come next in the order of human dwellings, and not only may we trace certain types of 5 pattern design to both sources, but it would seem as if both the tent and the hut, and perhaps the wagon of the Aryans, had had their influence upon the more substantial stone structures which succeeded them. When tribes became communities, townships were founded, and more fixed and settled habits of life prevailed.

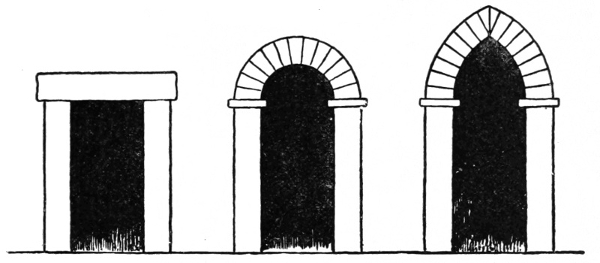

DIAGRAM TO SHOW THE THREE TYPICAL FORMS OF ARCHITECTURE:

I

Now we may broadly group the principal types of architectural form and construction in three principal divisions, following Professor Ruskin, namely:

1. The architecture of the Lintel (or column and pediment).

2. The architecture of the Round Arch (or vault and dome).

3. The architecture of the Pointed Arch1 (or vault, gable, and buttress).

6

Of the first we may find the simplest type in Stonehenge; we may find it in equally massive, and almost as primitive form at Mycenæ, in the famous Gate of the Lions, remarkable as being the earliest known example of Greek sculpture: we may find it more developed in the Greek temples of ancient Egypt, at Karnac, Thebes and Philæ, and we may see it in its purest form in the Parthenon at Athens.

GATE OF MYCENÆ.

The derivation and development of the Greek Doric temple from its prototype of wooden construction has frequently been demonstrated, and the tombs in Lycia furnish striking illustrations of this close imitation and perpetuation in stone of a system and details belonging to wood; and it is instructive to compare its features with corresponding parts in the Parthenon, and to observe how closely they agree. It is a curious instance of that love for and clinging to ancient and traditional forms, that with the art and all the resources of Athenian civilization, the 7 form and construction of its temples remained much the same, and may be considered as only glorified enlargements in marble of their wooden predecessors, retaining all the characteristic details of those primitive structures.

IMITATION OF WOODEN CONSTRUCTION IN STONE

TOMB IN LYKIA,

[From GUHL & KONER].

By these means, however, qualities of grandeur, joined with extreme simplicity, subtle proportions, and sparing, severe, but delicately chiselled ornament were gained; which, when heightened with colour in the broad and strong sunshine of Greece, seemed all sufficient, especially so when they formed the framework, or setting, of the most beautiful and noble sculpture the world has ever seen, as in the Parthenon.

To this sculpture, indeed, all the lines and proportions of the building seem to lead the eye, while it remains, whether in pediment, metope, or 8 frieze, an essential part of the architectural effect, and is strictly slab sculpture, or what may be considered as architectural ornament, for, as I have elsewhere said, we may fairly consider figure-sculpture to have been the ornament of the Greeks: just as one might say that picture writing and hieroglyphic were the mural decorations of the Egyptians.

ORNAMENTAL LINES IN THE FRIEZE OF THE PARTHENON.

WAVE MOVEMENT & SPIRAL CURVES IN THE FRIEZE.

These sculptures were evidently designed under the influence of the strongest architectural and decorative feeling, and were constructed upon a basis of ornamental lines. There is a certain rhythm and recurrence of mass, and line, and form in them throughout, and they have all been carefully 9 considered in relation to the places they occupy.

METOPE OF THE PARTHENON,

SHOWING RELATION & PROPORTIONS OF THE

MASSES IN RELIEF TO THE GROUND.

It is to be noted, too, that the sculptures are placed in the interstices of the construction; that is to say, not on the actual bearing parts. On 10 this point it is interesting to compare with the earlier forms of pure stone construction at Mycenæ. The lions over the Mycenæ Gate are carved upon a slab of stone placed in the triangular hollow left above the lintel to prevent it breaking under the great pressure of the heavy stones used. The triangular hollow may be seen without the slab in the doorway of Clytemnestra's house at Mycenæ. Here we have an early instance of the interstice left by the necessities of the construction being utilized as a decorative feature, significant in its design, showing the protecting image of the Castle of Mycenæ, much in the same way as we see the family arms sculptured over the gateways of our English mediæval castles.

Returning to the Parthenon, we see that the same principle is observable in the pediment and metope sculptures, the frieze of the cella being really a mural decoration consisting of facing slabs of marble. The building would doubtless stand without any of them, as a timber-framed house would stand without its boarding, or filling of brick or plaster; but it would be like a skeleton, or a head without its eyes—much, indeed, as time, bombardment, ravage, and the British Museum have left it now.

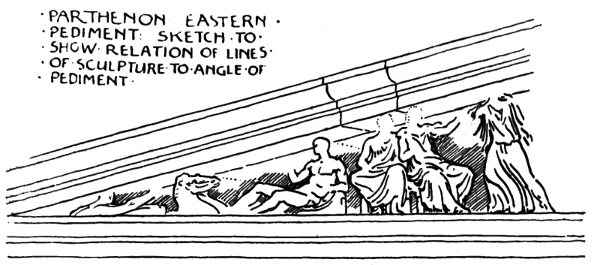

Before we leave the Parthenon, let me call attention to one prevailing principle, characteristic of its design in every part; for though following throughout the principles or traditions of wooden construction, no doubt its proportions and lines were consciously and carefully considered by the architect with a view to æsthetic effect. It is 11 12 the principle of recurring or re-echoing lines, a leading principle, indeed, throughout the whole province of Design, and one on the importance and value of which it is impossible to lay too much stress.

THE PARTHENON

[After MENGE].

PARTHENON EASTERN PEDIMENT—SKETCH TO SHOW RELATION OF LINES OF SCULPTURE TO ANGLE OF PEDIMENT.

PARTHENON EASTERN PEDIMENT—SKETCH TO SHOW RELATION OF LINES OF SCULPTURE TO ANGLE OF PEDIMENT.

To begin with the pediment. The main outline is delicately emphasized by the mouldings of the edge, which also serve as a dripstone—the practical origin, probably, of all mouldings. The groups of sculptured figures within the recess (which further serve to express the pitch of the roof) re-echo, informally, in the lines controlling their composition, as well as in the lines of limbs 13 14 and draperies, variations of the angle of the pediment. Thus, the groups of figures, full of action and variety as they are, are united and harmonized with the whole building; while, to avoid undue appearance of heaviness on the crest of the pediment and on the angles were placed anthemion bronze ornaments.

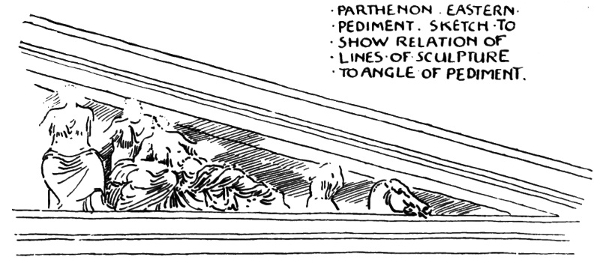

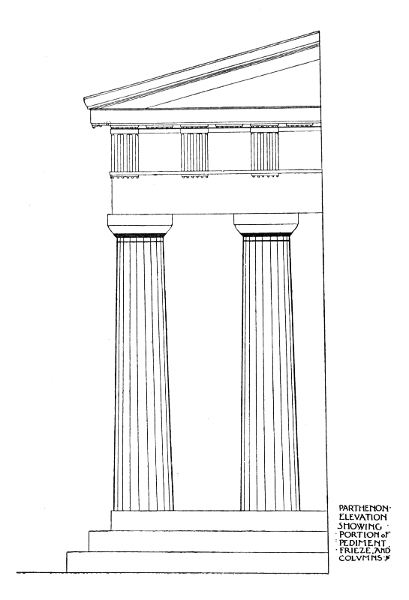

PARTHENON ELEVATION SHOWING PORTION OF PEDIMENT FRIEZE AND COLUMNS.

The cornice, again, is emphasized by mouldings marking the important horizontal lines of the building, re-echoed by the lines of the frieze, and counteracted and braced by the emphatic vertical lines of the triglyphs, and enriched by the little dentils below.

Then we come to the cap of the Doric column. It is simplicity itself. A thin square block of marble forms the abacus. The capital is a flattened circular cushion of marble, rounded at the sides in a diminishing curve to the head of the column, which terminates in a horizontal reeding. The column itself is delicately channelled with a series of lines which follow its outline, and give vertical expression to the idea of the support of the horizontal mass above, the column gradually diminishing from base to cap, entasized or slightly swelled in the middle to avoid the visual effect of running out of the perpendicular. The Doric columns spring boldly from the steps without base mouldings, the steps repeating the horizontal lines of the building again, and giving it height and dignity. The other variants of the Greek style will illustrate much the same principles in different degrees, and we may trace the value of proportions, and recurring lines, and different degrees of enrichment through the other four orders. 15

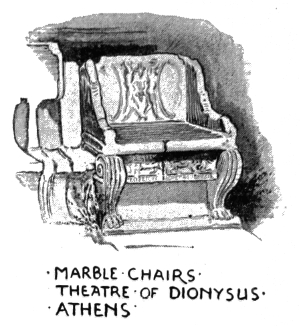

MARBLE CHAIRS, THEATRE OF DIONYSUS, ATHENS.

As designers, then, we can at least learn some very important lessons from lintel architecture generally, and from the Parthenon in particular, and chiefest amongst these are:

1. The value of simplicity of line.

2. The value of recurring and re-echoing lines.

3. The value of ornamental design and treatment of figures in low or high relief as parts of architectural expression

GREEK CHAIR.

GREEK TABLE WITH VOTIVE OFFERINGS.

END OF GREEK COUCH.

GREEK LOW-BACKED THRONE.

4. The value of largeness of style in the design and treatment of the groups and figures themselves, both as sculpture pure and simple and as architectural ornament.

When we come to examine the accessories of 16 Greek life, furniture, pottery, dress, we find them all characterized by the same qualities in design as we have just been noting in the architecture; the fundamental architectural feeling seems to pervade them. A simplicity of line, balance, and reserve of ornament distinguishes alike their seats and chairs and tables, caskets, vases and vessels, and the expressive lines of their dresses and draperies falling into the lines of the figure give life and variety, while they contrast with the severity of the architectural lines and planes.

Now, so far we have been considering the architecture of the lintel, and its bearing upon design, and the qualities and principles we may learn from it generally.

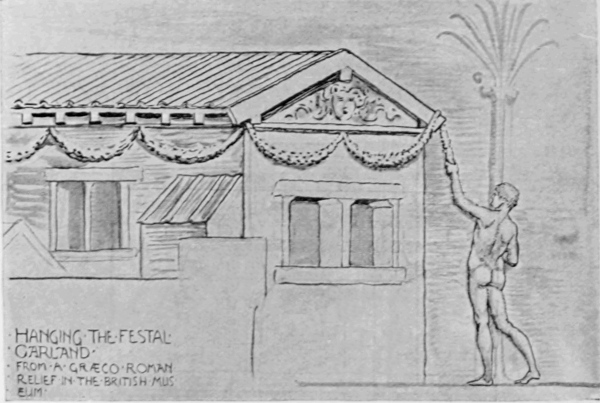

With the use of the round arch—invented, it is said, by the Greeks, but always associated with the Romans, who used it—quite different effects come in, with different motives and ideas in design. The Roman architecture, the round arch, fulfils the functions of both construction and ornament, on the same principle of recurrence, or repetition, we have noticed before; as, for instance, in the Colosseum, where the tiers of round arches which support the outer wall of the building serve both the constructive and decorative functions. With the use of the arch the arcade becomes a constructive feature of great decorative value, and takes the place in Roman and Romanesque buildings, with a lighter and more varied effect, of the columned Greek cella. Sunshine, no doubt, had much to do with its use, since a covered arcaded loggia, or porch in front of a building, so frequent in Italy, gave both shelter and coolness. The use of the 17 18 arch led to vaulting, and to the use of arch mouldings, enrichments, and to the covering the vaults with mosaic and painting, and the vaulting led to the dome, which, again, offered a splendid field for the mosaicist and the painter.

CONSTRUCTIVE & DECORATIVE USE OF ROUND ARCH & PILASTER FLAVIAN AMPHITHEATRE (COLOSSEUM) ROME.

The Romans borrowed all their architectural details from the Greeks, and varied and enriched them, adding many more members to the cornice mouldings, and carving stone garlands upon their friezes, to take the place of the primitive festal ones of leaves which were hung there, as in the relief of the visit of Bacchus to Icarius, a Romano-Greek sculpture in the British Museum.

HANGING OF THE FESTAL GARLAND,

FROM A GRÆCO ROMAN RELIEF IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

They (the Romans) fully realized the ornamental value of colonnades and porticoes, and they used the column, varying the orders, and translating them into pilasters freely as decorations on the façades and walls of their buildings, slicing up the 19 peristyles of temples, as it were, for the sake of their ornamental effect, cutting down the columns into pilasters, and placing them, with intervening friezes, one on the top of the other, masking the construction of the real building, a favourite device with the Renascence architects.

USE OF DECORATIVE SCULPTURE IN ROMAN ARCHITECTURE: THE ARCH OF CONSTANTINE.

Roman architecture may be considered really as a transitional style. While its true constructive characteristic is the round arch, every detail of the Greek or Lintel architecture is used both without and with the arch, and in the latter case the column frequently becomes a wall decoration in the shape of a pilaster, as well as the cornice, and is no longer made use of, as in true lintel construction, to support 20 the weight of the roof. In their viaducts and bridges and baths they were great builders with the arch, but, like some modern engineers, when they wanted to beautify they borrowed architectural ornament from the Greeks.

Nothing very fresh was gained for design in these adaptations except a certain heavy richness of detail in the sculptured cornices and friezes, and coffered ceilings. The use of the flat pilaster, however, led to the panelled pilaster with its elegant arabesque, which was afterwards revived and developed with such extraordinary grace and variety by the artists of the Renascence and carried from Italy westward.

With the round arch, too, several important decorative spaces were given to the designer, the spandrel, the panel, the medallion, all of which, with the frieze, may be seen utilized for the decorative sculpture on the arch of Constantine. The decorative use of inscriptions is also a feature in Roman architecture, and the dignity of the form of their capital letters was well adapted to ornamental effect in square masses upon their triumphal arches and along the entablature of their temples.

The Romans, too, brought the domed roof and the mosaic floor into use, and were great in the use of coloured marbles; also stucco and plaster work in interiors, the free and beautiful plaster work found in the tombs on the Latin Way being well known; so that on the whole we owe to them the illustration of the effective use of many beautiful arts, which the Italians have inherited to this day, though it must be said often with more skill than taste. 21

One might say, generally and ultimately, Roman art exemplified that love of show, and the external signs of power, pomp, splendour, and luxury which became dear as well as fatal to them, as they appear to do to every conquering people, until they are finally enervated and overcome as if by the Nemesis of their own supremacy.

MOSAIC, ST. APOLLINARE IN CLASSE, RAVENNA.

The art of Greece, one may say, on the other hand, at her zenith represented that love of beauty as distinct from ornament, and clearness and severity of thought which will always cling to the country from whence the modern world derives the germ of nearly all its ideas.

But when the seat of the empire was transferred to Constantinople, and Roman art, influenced by 22 Asiatic feeling, and stimulated and elevated by the new faith of Christianity, became transfigured into the solemn splendour of Byzantine art, the architecture of the round arch and the dome and cupola rose to its fullest beauty, and such buildings as St. Sophia at Constantinople, and St. Mark's at Venice, with the churches of Ravenna, mark another great and noble epoch in the arts of design.

Byzantine design, whether in building, in carving, in mosaic, or goldsmiths' work, impresses one with a certain restraint in the midst of its splendour; a certain controlling dignity and reserve appears to be exercised even in the use of the most beautiful materials, as well as in design and the treatment of form.

The mosaics of the Ravenna churches alone are sufficient to exemplify this. The artists seemed fully to realize that the curved surfaces of the dome, the half dome of the apse, or the long flat frieze above the arch columns of the nave of the basilicas, like St. Apollinare in Classe, afforded splendid fields for a splendid material, the cross light from the deep-set windows enriching the effect, and that everything might well be secondary to it. The same principle or feeling is seen in St. Mark's where the architecture is quite simple, the arches and vaulting without mouldings, nothing to interfere with the quiet splendour of the gold or blue fields of mosaic varied with simple typical figures, bold in silhouette, placed frankly upon them, emblems, boldly curving scroll-work, and inscriptions. The execution, too, is as direct and simple as the design. Such design and 23 decoration as this becomes an essential and integral part of the architectural structure and effect.

SKETCH OF PART OF INTERIOR OF DOME, S. MARK'S, VENICE.

MOSAIC OF THE EMPRESS THEODORA, T. VITALE, RAVENNA, SIXTH CENTURY.

Note the way in which the tesseræ are laid (in 24 the head of the Empress Theodora from St. Vitale at Ravenna, for instance). The cube is used as much as possible, but the cubes vary much in size, and are set often with very open joints, the cement 25 lines of the bedding showing quite clearly, and the surface of the work uneven, the tesseræ being worked, of course, from the front and in situ, presenting a varied surface of different facets which, catching the light at different angles, give an extraordinary sparkle and richness to the effect as a whole. In the head of Theodora the effect is enhanced by the discs of mother-of-pearl used for the head-dress.

In the laying of the tesseræ, too, note that the system is followed of defining the outlines with rows of cubes, and building up the masses (as in the nimbus) with concentric rows, as a rule, making the lines of the filling tesseræ follow as far as possible the line of the boundary tesseræ. This, of course, would naturally result as the simplest and most convenient, as well as most expressive, method of laying tesseræ, in defining form by means of small cubes, and is one of the conditions of the work, and when, as in these mosaics, so far from being refined away, or concealed, or any attempt being made (as in later times) to imitate painting, these conditions are boldly and frankly acknowledged, we see how its peculiar beauty, character, and the quality of its ornamental effect depends upon these very conditions.

This principle will be found to hold good and true throughout all art. Directly, from a false idea of refinement, or with the object of displaying mechanical skill, the craftsman is induced to try to conceal the fundamental conditions of his craft, and to make it ape the qualities of some totally different sort of work, he ceases to be an artist, at all events. The true artist in any material is he 26 who in acknowledging its conditions and limitations finds in them sources and opportunities of new beauty, and in being faithful to those conditions makes them subserve his invention.

After the decorative splendour of the Byzantine architecture, the Norman work left in our own land seems comparatively simple and plain as time has left it, but its remains show its Roman descent in the doorway and porch of many a quiet village church, as well as on a greater scale in so many of our cathedrals, which often illustrate, in a remarkable way, the transition or growth of one style out of another, the new evolved from the old.

At Canterbury, for instance, one reads the signs which mark the transformation of the Norman building into the Gothic. The first church founded by St. Augustine was Saxon. This was enlarged by Otho (938) as a basilica. This again was ruined by the Danes (1013). The Norman part of the present building was constructed by Bishop Lanfranc (1070), on to which was grafted, as it were, the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth century Gothic which distinguish it.

There is a tower on the south side of the transept known as Anselm's Tower (from Bishop Anselm, one of the Norman builders), and on the lower part runs an arcading of interlacing round arches, the tower itself being richly arcaded in several stories in round arches. But this lower band shows the period of transition, from the use of the round arch, to the pointed—the pointed lancet arches being formed by the interlacing of the round, so that we have here the actual birth of the pointed arch (at least, as a decorative feature), which leads 27 us to our next typical division and characteristic epoch of architectural style.

ANSELM'S TOWER, CANTERBURY.

We need not go out of our own country to find abundant illustrations of typical forms of pointed architecture. Almost any village church will give 28 us the main features—the characteristic plan of nave and chancel, curiously following the plan of the ancient Roman basilica—the public hall and law court in one, and perpetuating for us the type of ancient dwelling or hall which may be said to have prevailed from the time of Homer to the end of the Middle Ages, varying chiefly in external features and architectural detail.

The severe lancet arch is characteristic of the first phase of the Gothic, which gradually grew out of the severer Norman. The gable took a higher pitch, and to support the weight and thrust of towers and spires, buttresses were used, and these became, also, a striking and characteristic feature of the pointed arch, which completed in the thirteenth century the period of its first development.

Lancet arch, high-pitched gable, buttress (plain and pinnacled), spired and pinnacled tower—these are the leading constructive exterior characteristics, the carved work, somewhat restrained, and chiefly manifested in peculiar foliation of the capitals and corbels, and in the hollows of arch mouldings in rows of sharp cut dog teeth.

In the interior clustered shafts took the place of the solid round Norman piers, rising, as we see in our cathedral naves, to support lofty vaulted roofs, the ribs moulded and covered at their intersections by carved bosses.

Again we may note the principle of recurring lines which repeat and emphasize the form of the arched openings and the structural lines of the vaulting in the mouldings. This recurrence gives that effect of extraordinary grace and lightness combined with structural strength which is so striking 29 30 a characteristic of thirteenth century Gothic work, and of which there is no finer example than the nave of Westminster Abbey.

TRANSITIONAL ARCADE, SOUTH TRANSEPT, CANTERBURY.

TYPICAL FORMS OF ARCHES:

TYPICAL FORMS OF GOTHIC GEOMETRIC FOLIATION.

31

WESTMINSTER ABBEY: THE NAVE, LOOKING EAST.

32

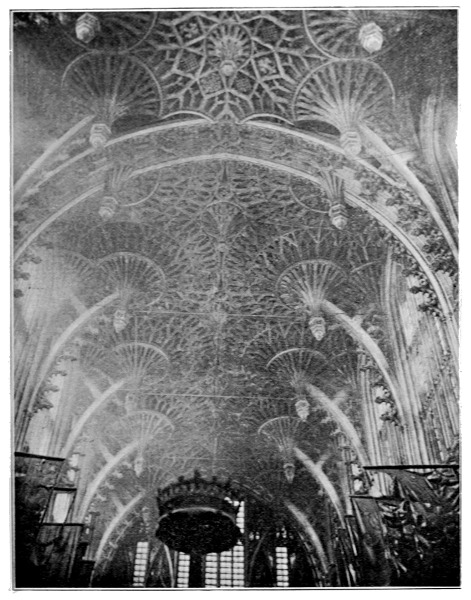

We noted that the Greeks used the interstices of their construction for their chief decoration, their figure sculpture, and to some extent the same plan is followed in Gothic architecture, where we find the tympanums of doors, the spandrels of arcades (as in the Chapter House at Salisbury or the angel choir at Lincoln), and canopied niches (as at Wells), used for figure sculpture; but, at the same time, the structural features themselves are emphasized by ornament to a far greater extent, as in caps, arch mouldings, the junctions of the vaulting, and the like; and increasingly so in the succeeding Decorated and Perpendicular periods, until we get vaulted roofs of fan tracery like those of King's College Chapel at Cambridge, or Henry VII.'s Chapel at Westminster.

But if we may say that the chief decorative glory of Greek architecture was its figure sculpture, as mosaic was of the Byzantine churches, so we may say that the traceried window, filled with stained and leaded glass, became the chief decorative glory of Gothic architecture.

Unhappily great quantities of glass have disappeared from our cathedrals and churches, from one cause or another, but from the relics that remain we may form some idea of the splendour and quality of the old glass.

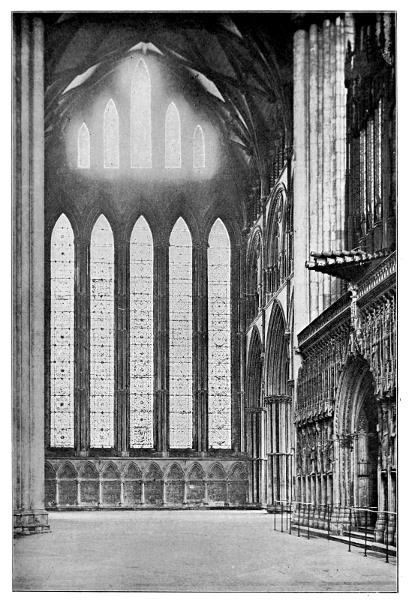

The famous windows of the south transept at York Minster, called "The Five Sisters," are good examples of the severer earlier style of pattern and colour, consisting of fine scroll-work and geometric forms, in which hatched grisaille patterns are heightened by bright points and lines of colour.

WEST FRONT OF WELLS CATHEDRAL.

Thirteenth century glass, where figures are used, 33 34 is characterized by the smallness of their scale in proportion to the window, and traces of Byzantine tradition in their drawing, intricate design, and deep and vivid colouring, the work being composed of small pieces of glass leaded together; the effect of the jewel-like depth and quality of the colour—deep crimsons, blues, and greens being much used—being increased by the close network of leading.

As windows, in the course of the evolution of the Gothic style, were made broader, or rather, the window opening proper from wall to wall being greatly increased in width and height, they were supported and divided into panels or lights by elaborate stone tracery, a tracery which becomes almost as distinct a province of design as the design of the glass itself—distinct from, yet in close relationship to the architecture of the building. The comparative slight divisions of the tracery, however, gave more scope to the stained glass designer, who shows very emphatic architectural influence in the elaborate canopies which surmount the figures occupying the separate lights of the windows from the thirteenth to the end of the fifteenth centuries, as well as in the general vertical arrangement of the lines of their composition. He gradually increased the scale of his figures and gave more breadth to his design, and brought it more into relation with the art of the painter and the sculptor, at the same time acknowledging with them, in the disposition of his figures in the space, and the disposition of the draperies and accessories, that architectural influence under which the artist and craftsman of the Middle Ages 35 36 worked with extraordinary freedom and fertility of invention, and yet in perfect harmony2—a sign of that fraternal co-operation and the effect of the formation of men into brotherhoods and guilds, which, coming in with the adoption of Christianity and the organization of the Church, remained through all the turbulence and strife of the time the great social force of the Middle Ages.

WESTMINSTER ABBEY, FAN TRACERY IN HENRY VII.'S CHAPEL, FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

It seems to me if we wish to realize the ideal of a great and harmonious art, which shall be capable of expressing the best that is in us: if we desire again to raise great architectural monuments, religious, municipal, or commemorative, we shall have to learn the great lesson of unity through fraternal co-operation and sympathy, the particular work of each, however individual and free in artistic expression, falling naturally into its due place in a harmonious scheme. Let us cultivate our technical skill and knowledge to the utmost, but let us not neglect our imagination, sense of beauty, and sympathy, or else we shall have nothing to express.

Through the thirteenth century onwards to the fifteenth Gothic architecture continued to develop, to pass through new phases, to take new forms, a living and growing style moving with the wants and ideals of men.

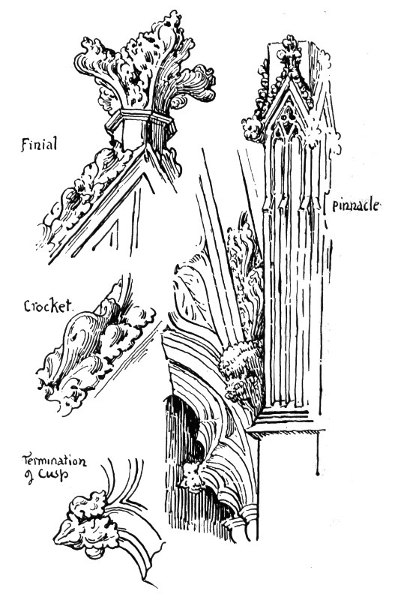

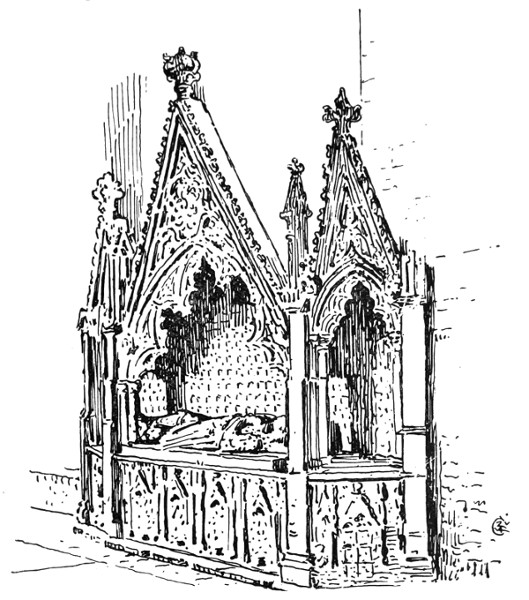

After the Early English comes the Decorated period, in which the mouldings and foliation become fuller, broader, and more ornate. To contrast decorated foliation and ornament with the earlier work, is like comparing the opening flower with 37 38 39 the bud. The ogee arch was invented, the crockets of the pinnacles and canopies grew and increased and became finer in form, the finials larger and more varied. The carved canopies and tabernacle work grew richer and more intricate. The foliage followed nature more closely. The figure subjects 40 of the carver were more freely treated, and dealt oftener with common life, with phantasy, or humour. The effigies of knight and lady, or priest, became more and more like portraits in stone or alabaster, the details of their dresses more rich, delicate, and beautiful. The maker of brasses showed a freer and more masterly hand, and greater sense of ornamental effect in the spacing and treatment of his figures. The work of the miniaturist and the scribe grew more and more delicate and exquisite in form, colour, and invention. The stained glass worker increased the scale of his figures, and varied the quality and treatment of his colours. The glazier invented new lead patterns; the wood carver revelled in stall work, screens, and misereres. The recessed and canopied tomb enriched the chantries of churches and cathedrals.

THE FIVE SISTERS OF YORK THIRTEENTH CENTURY.

DETAILS OF TOMB WINCHELSEA CH. 1303.

FOURTEENTH CENTURY CANOPIED TOMB, WINCHELSEA CHURCH.

Wells Cathedral Architectural feeling & detail in iron work.

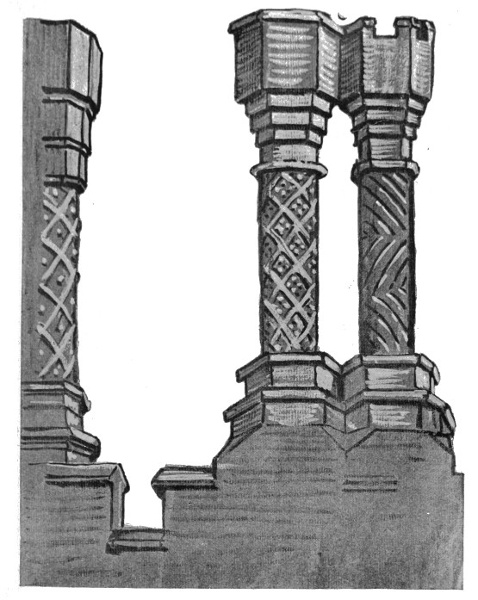

Beauty and invention of extraordinary fertility and richness characterized every form of art and handicraft associated with Gothic architecture. We can trace in each variety the architectural influence in every department of work. In some instances reproduction of actual architectural details and 41 characteristics, as, for instance, when the wrought-iron railing of a bishop's tomb (at Wells Cathedral, 1464-5) reproduced the battlement, buttress and pinnacle as motives, giving them, however, a free and fanciful rendering suited to the material.

DRESSOIR OR SIDE BOARD 15th CENT. FRENCH

(from L. Roger Milès)

CANOPIED SEAT FRENCH 15th CENT.

Abundant instances may be found of the fanciful treatment of architectural forms in furniture, textiles, in painting and carving, and metal work—the canopies over the heads of figures in stained glass, and inclosing figures upon brasses, are instances—shrines and caskets in the form of arcaded, and buttressed and pinnacled buildings, seats and chairs with canopied or arched backs, carved bench ends with "poppy head" finials and arched and foliated panels, censers in the form of shrines. The large gold brocaded stuffs used as hangings or coverings, and represented in miniatures and pictures of the 42 period. Very beautiful specimens are to be seen in the pictures of Van Eyck and Memling for instance.

CARVED BENCH-ENDS, DENNINGTON CHURCH, SUFFOLK.

In all these things we find a re-echo, as it were, of the prevailing foliated forms of Gothic architecture, repeated through endless variations, the controlling and harmonizing element throughout the design work of the Gothic periods, the form by which all seem to be harmonized and related, as the branches are related to the main stem, and as the plan of the tree may be found in the veining of the leaf. 43

The fourteenth century saw the development of a new phase of Gothic called Perpendicular. It is found united with the Early English and Decorated, as well as Norman, in nearly all our cathedrals.

BROCADE HANGING, FROM THE ANNUNCIATION, BY MEMLING.

At St. David's, for instance, there is a remarkable instance of a late Perpendicular timber roof, richly moulded and carved, with pendants, covering a Norman nave of 1180. Yet the effect is fine, and one feels glad that the restoring architect could find no authority for a Norman stone vaulting, otherwise we might have lost the rich timber roof for a modern idea of a supposititious Norman vault. The sketch (from the south side of the choir at Canterbury, p. 45), too, shows how harmoniously structural lines of different periods compose.

The chief characteristics of the late period of Gothic (Perpendicular) are a lower pitched arch, an elongated shaft, many clustered; caps and bases angular; ribs of vaulting richly moulded, or the vault covered with fan-like foliation in late examples, as in Henry VII.'s Chapel. Pinnacles begin to take the cupular form, details become 44 smaller, windows grow larger and are transversely divided by transoms or horizontal bars of stone, connecting and solidifying the many vertical mullions.

ST. DAVID'S CATHEDRAL.

A certain refinement of detail and line with a feeling for emphatic horizontals and verticals 45 46 comes in; and this feeling may be the indication of a reaction, as if the constructive and imaginative faculties of man were beginning to prepare for the next great change that was soon to sweep over the art of Europe.

STRUCTURAL LINES OF DIFFERENT PERIODS IN HARMONIOUS COMBINATION, CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL.

It might be said that gradually from that time architecture, as the supreme organic and controlling influence in the arts of design, gave up her prerogative of leadership, and since has rather been on the whole displaced in artistic interest by the other arts; or rather, with the change of the principle of organic growth out of use and constructive necessity in architecture for those of classical authority, archæology, or learned eclecticism, the different arts, more especially painting, began an independent existence, and, with the other arts of design, may be said to have been more individualized and less and less related both to them and to architecture ever since, reaching the extremest points of divergence perhaps in our own days.

It seems to me that, on the whole, there can be little doubt that architecture and the arts of design generally have suffered in consequence; and to bring them back to healthy and harmonious activity we must try to re-unite them all again upon the old basis.

I will terminate here my short sketch of architectural style and its influence, not attempting now to follow it in its later changes and adaptations to the increased complexities of human existence. My purpose has been rather to dwell upon the organic and typical forms of architecture, in my endeavour to trace the relationship between it and the art of design generally. 47

That relationship appears to me to consist chiefly in the control of constructive line and form, which all design, surface or otherwise, in association with any form of architecture is bound of necessity to acknowledge as a fundamental condition of fitness and harmony. Those essential properties of the expression of line, as they now seem, which give meaning and purpose to all design, appear to be derived straight from constructive necessities and the inseparable association of ideas with which they are connected; as, for instance, the idea of secure rest and repose conveyed by horizontal lines, or the sense of support and rigidity suggested by vertical ones may be directly traced to association with the fundamental principles of architectural structure, to the lintel and its support, to the laying of stone upon stone, and with this clue we might trace the expression of line through its many variations. 48

NEXT to the architectural basis influence in design, and, indeed, hardly separable from it, being another side of the constructive, adaptive art, we may fitly take the Utility Basis and influence.

This may be considered in two ways:

(1) In its effect upon pattern design and architectural ornament through primitive structural necessities.

(2) In its effect upon structural form and ornamental treatment arising out of, or suggested by, functional use.

(1) It is a curious thing that we should find the primitive ornamental motives bound up with the primitive structures and fabrics of pure utility and necessity, but such would appear to be the case.

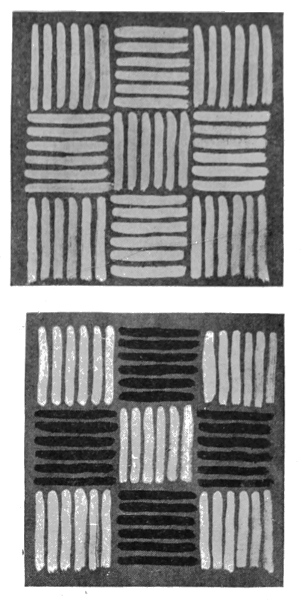

The plaiting of rushes to make a mat was probably one of the earliest industrial occupations, and the chequer one of the most primitive and universal of patterns. If we look at the surface effect of the necessity of the construction, the crossing of one equal set of fibres by another set at right angles, with the interlacement, a series of squares are produced, which alternate in tint if the colour of one set is darker than the sets which cross it (see illustration). 49 Emphasize this contrast and we get our chequer, or chessboard pattern, which, either as a pattern complete in itself, as in plaids and tartans, or as a plan, or effect motive in designing is, as I have said, perhaps the most universal and imperishable of all patterns, being found in association with the design of all periods, and still surviving in constant use among designers.

MATTING.

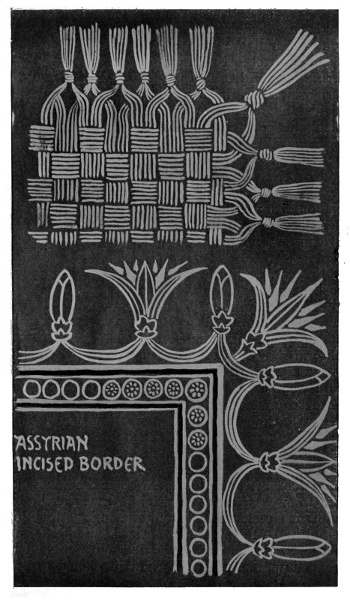

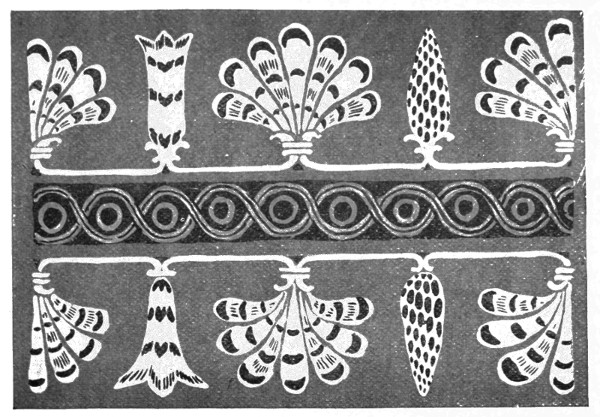

Let us follow the primitive rush mat a little further, however. As it lay on the primitive tent or hut floor its edges would take the sort of form shown on the following page. In ancient Assyrian, Egyptian, Persian, and Greek architecture we constantly find carved patterns used as borderings and figures, of the type given in the Assyrian example. Now, comparing this with the primitive matting, the suggestion is very strong of the probability of derivation of motive of patterns of this type from the same constructive source originally. In some instances, as on the enamelled tile from Assyria, the border reverses itself, but with the Greeks it finally took the upright direction, as in the Anthemion or honeysuckle border forms; but, however afterwards varied and enriched by floral form, its structural origin in plaited work is 50 51 always to be traced, and it seems to gain from it a certain strength and adaptability.

PRIMITIVE RUSH MAT AND ASSYRIAN BORDER.

Another type of ornament may be traced to the constructive necessities of wattle and wicker work, so much used by primitive man in the structure of his dwellings, and in primitive objects of use and service.

ASSYRIAN ENAMELLED TILE.

The various forms of volute, or spiral, and guilloche ornament, so much used by the ancients—Assyrian, Egyptian, and Greek—may be compared, in their structure and arrangement of line, with the form taken by the withy, or cord twisted around the upright canes or staves of a wattled fence, as seen in horizontal section. The primitive wattled structure gives the plans of these patterns. It certainly appears to account for their origin in a remarkably complete way. 52

GREEK ANTHEMION ORNAMENT.

WATTLED FENCE.

It is possible that another source which may have contributed to the evolution of the Greek spiral or volute was metal in the form of the thin beaten plates with which the primitive Greeks covered 53 parts of their interior walls; but these were later times, and it is also possible that the primitive metal worker took his motive from the wattling too.

ANCIENT VOLUTE ORNAMENT.

TYPES OF DECORATION DERIVED FROM THONGING.

Before metal was used, or nails or joinery were known, the method of fastening two things together, 54 such as the blade of a stone axe or hammer and its handle, was by thonging or tying them firmly together by strips of leather or thongs, and to this source again we might trace other types of pattern motives of very wide prevalence. In the first instances the thonging was imitated in metal-work when no longer used in the construction by way of ornament, as in various bronze implements existing; but later, starting from the tying and thonging motive, we get all sorts of variations, as in the zigzag of Norman arch mouldings, and in the earlier Celtic knotted work, which seemed partly a re-echo of some types of Eastern and classic ornament, unless we regard it as independently derived, like them, from primitive structure. It seems to make itself felt again in a new variety in the strap-work of our Elizabethan period, in which the ornament 55 apparently was a new blend of Gothic with classical details, with an infusion of oriental or Moorish feeling, filtered through Italy and Spain.

FRIEZE (TEMPLE OF THE SIBYL TIVOLI).

YOKE OF OXEN, CARRARA.

As an instance of architectural ornament, the motive of which seems taken from a piece of common every-day usage, we may note the frieze of the Roman circular Temple of the Sibyl at Tivoli, which is composed of the heads of oxen, alternating 56 with, and connected by, the curves of pendent floral garlands. To this day in Italy almost anywhere one may see this motive suggested by the appearance of the country ox wagon as it approaches along the road—the front view of the two oxen heads, with the level yoke across their necks, and the pendent connecting ropes hanging between.

It is probable, however, that whatever its origin, its suggestion was sacrificial, since the ox decked with garlands constantly figures in classical sculpture led before the altar to be slain, and this circumstance may equally have given rise to the sculptor's motive, just as we saw that the custom of decking the cornice of the Greek house with garlands suggested its perpetuation in stone carving by the classical architects.

It will be noted that those primitive sources to which we may trace motives in ornamental design, however, afterwards developed on purely ornamental lines, and because of their ornamental value, all of them have their beginnings in actual use and service, in physical and constructive necessity, and that they are closely associated with the form and character of the dwellings and temples of man.

(2) Turning now to the second division of our subject to consider "the effects upon form and treatment of surface arising out of, or suggested by, functional use," we shall still have to keep close to the dwelling, and constantly to remember the ever present architectural influence with the consideration of which we set out.

BARGE-BOARD, IGHTHAM MOTE HOUSE.

TYPE OF GABLES:

The angle of the pitch of the roof in buildings, for instance, which is so marked a characteristic in 57 the different types of architecture, was originally determined by the necessities of climate. One might say broadly that the acute, high-pitched Gothic roof means snow or bad weather, while the low-pitched classic roof means sunshine for the most part; or we might say that the one typified winter and the other summer. A house must still be built mainly for one or the other, though by 58 ingenuity and careful consideration of the points of the compass in choosing the site and planning, in the rare instances where free choice is still possible, something may be, and has been attempted, to fit all seasons; and it is this careful consideration of such points in our ancient buildings—say the old English manor houses, built to dwell in and to last—which gives that sense of homelike comfort and pleasure to the eye, perhaps, quite as much as the interest of their ornamental detail. A sunny garden terrace or arcaded front to the south to catch the winter sun—cool and shady rooms to the north for the summer—a sheltered porch to protect the guest against the weather. Such contrivances as these show that thought has been spent and care taken in the planning and building; that the builder or designer has been influenced by considerations of true utility—not in the bald and more modern sense of mere money or time saving appliance, but the truer economy of making a house livable. Here is a sketch of one of those old stone halls or manor houses of Derbyshire of the seventeenth century (Hazelford Hall), charmingly placed upon a hillside, so as to fit into or become part of the landscape, while it is really planned to live comfortably in, with due regard to the variation of the seasons and the winds. The living rooms face south and west.

Houses nowadays seem more built to sell than to live in (at least permanently), since I notice that often even when people build a house for themselves they constantly want to let it to somebody else. I should think that the gipsy van would suit modern habits exceedingly well. It 59 would be more picturesque than "a brick box with a slate lid," to which most of us are committed, and probably much less expensive in the long run. The only thing required to make it practicable on any scale is a trifling alteration in the land laws.

The origin of mouldings in architecture, as their use in the capacity of dripstones declares, was to serve a purely useful purpose—the alternating concavity and convexity of the members which generally characterize them affording escapement for the rain water, and keeping it away from the windows and doors.

HAZELFORD HALL, DERBYSHIRE.

To give a simple illustration of the principle. If the sill of a window, for instance, be left rectangular and perfectly level, the water would be likely to run inward through the window, or perhaps into the wall, but if sloped on the upper surface and hollowed beneath, the water would 60 tend to drop from the under outer edge clear of both window and wall.

SECTION TO SHOW ACTION OF RAIN ON WINDOW SILLS: (1)PLAIN & MOULDED(2).

This necessity led to motives in design and ornamental effect, and mouldings became valuable parts of æsthetic expression in architecture, affording means of emphasis, of giving the effect of receding planes, and of using the important principle of recurring lines to which I called attention in the first chapter. 61

The barge-board, too, so picturesque a feature in old timbered houses, had the same useful purpose to subserve in keeping the weather from injuring roof and wall.

Staircases with the necessary handrail, again, have led to beautiful form in design, not only in the planning of the staircase itself, which is so important a feature in every house, but in the interesting and varied design in the balusters supporting the handrail, and in newel heads, etc.

THE TOWERS OF SAN GIMIGNANO.

Towers and church steeples, which form such important and picturesque features in architectural (and, one might add, landscape) design, owed their existence, in the first place, to the necessities of watch, guard, and defence, and probably also means of communication by signals.

To the mediæval city, which, as it is now being realized, was a highly organized arrangement for mutual aid and defence, towers were of great importance both for watch and defence. They served as strong buttresses and vantage posts placed at 62 intervals along the inclosing city wall, and flanking the gateways. The boldness and grace of design in some mediæval towers is very notable. Those of Siena, for instance, and that town of towers, San Gimignano, of which I give a rough sketch to show the effect from a distance of the clustering towers, like a crown upon the hill top; above all, perhaps, is the famous tower of the Signoria or Palazzo Vecchio, the old city hall of Florence (thirteenth century). The Belfry of Bruges (thirteenth century), too, is another fine instance of boldness and grace of design. It had formerly a spire, which is shown in a sixteenth century picture, the background of a portrait by Pourbus, a Flemish painter, but the spire was twice destroyed by fire, and was not renewed a third time. But even as it stands the belfry is very striking, and, while it commands a vast prospect of the country round, it is also conspicuous all over the town, and a landmark to the flat country round about.

The towers of our own ancient village churches are generally battlemented, and the square ones often have a corner turret to give a more commanding view; and this again gives variety, and is a very picturesque feature. The battlements themselves (though intended for use in defence) are extremely ornamental features, and give relief and lightness to the parapet. In later Gothic times they were frequently fancifully pieced and filled with ornament, as on Magdalen Tower at Oxford. Their decorative value was perceived by the wood carver of the Gothic times, and they are constantly introduced in tabernacle work, screens, and furniture, where their use is purely decorative. 63

TOWER OF PALAZZO VECCHIO, FLORENCE.

Chimneys, again, afford an instance of a purely useful and serviceable object lending itself to ornamental treatment and becoming important as parts of the design of a building.

The first chimney in England is said to be the one existing in the Norman house at Christchurch, Hampshire. The common practice was to have the fireplace in the centre of the hall and let the smoke escape by a louvre in the roof, as may still be seen in the hall at Penshurst Place in Kent (fourteenth century); but in later times, especially in the Tudor period, the chimneys of brick are often 64 found full of invention and variety in design, and extremely rich in effect. I give sketches of some characteristic examples at Framlingham Castle and Leigh's Priory.

TOWER WITH CORNER TURRET, AXMOUTH CHURCH, DEVON.

The fine old brick chimney stacks one finds among the old farmsteads of Essex it is supposed 65 were built first and then the half-timbered house built around the brick stack.

CUT BRICK CHIMNEYS, LEIGH'S PRIORY, ESSEX.

BRICK CHIMNEY, FRAMLINGHAM CASTLE.

Other useful things connected with the fireside and the chimney corner, which are remarkable for 66 their adaptability in ornamental design, are the iron fire-dogs used to support the burning logs. We find them in great variety of shape and treatment, while their main or necessary lines remain the same. It is the standard or upright front part which affords a field for the inventive craftsman and designer. The fire-irons, too, are again purely useful in their object, but have become highly graceful and elegant in some of their forms.

The iron grate back (notably those of old Sussex), placed at the back of the fire against the chimney to protect the brick-work and radiate the heat, had again a purely useful function, but it has been the object of a great deal of fine and rich decorative design, chiefly of a heraldic or emblematic character, and many old examples exist. Cast iron has in modern times acquired a bad name (artistically speaking), but this is owing to its misapplication, as in railings or grills, where it endeavours 67 to usurp the place of wrought iron. In a flat panel or plain surface, such as a grate back affords, however, cast iron has a singularly good effect, and renders bold designs well. There are some fine heraldic grate backs in cast iron to be seen at Cheetham's Hospital, perhaps the most interesting building in the City of Manchester.

CAST-IRON FIRE-DOG, ST. NICHOLAS HOSPITAL, CANTERBURY.

I give a sketch of a quaint cast-iron chimney back of Gothic design from Bruges. At the Museum at the old Rath Haus there is a very good collection of examples. Somehow, with the modern, or rather mid-Victorian iron register fireplace all beauty and interest of design is lost. Though it should be remembered that a really fine artist and designer like Alfred Stevens spent his talent upon such things.

The conception of the thing, however, seems joyless and ugly, and in most surviving examples the ornament in endeavouring to be elegant becomes frittered and mean; and as to sheet-iron 68 stoves they seem to be under a ban of hideousness, which seems sad when one recalls the charming and cheerful earthenware stoves of Germany of Gothic and Renascence times, full of colour and invention. The revived use of tiled chimney, and recessed and basket grates, has done much to restore cheerfulness to our hearths.

CAST-IRON GRATE BACK.

Before we leave the chimney corner I might mention another bit of metal, important before the days of kitchen ranges as the chief cooking apparatus, 69 I mean the iron crane that is sometimes found still suspended in the wide chimneys of old farmhouses, made of wrought iron, twisted and curled, and with bright bosses of steel upon it, and great in hooks and hinges. Here is a sketch of a typical example in an Essex farmhouse.

FIREPLACE WITH WROUGHT IRON CRANE, CHURCH FARM, HEMPSTEAD, ESSEX.

Considerations of use, again, very evidently control design in lamps and candlesticks. A lamp necessitates: (1) a reservoir for the oil, and (2) a neck and mouth to hold the wick, and (3) a firm and steady stand. All these requisites are combined, with addition of handle, in the oldest and simplest form of lamp—the portable antique lamp to be carried in the hand. The reservoir is there, though small, and needing re-filling from a larger vessel (as was the case in the parable of the ten virgins).

These lamps were often placed upon the top of slender fluted tripod stands, to give light in 70 the house, or hung in clusters by chains from a branched stand like a tree. A combination of many of the characteristics of the antique lamp is found in the comparatively modern brass Roman lamp (now called antique, but till within a few years, and I believe still, commonly used by the people): we have the small reservoir, with four necks for the wicks, closely resembling in form the antique hand lamps. This is pierced by the shaft of the stand, which finishes in a ring handle at the top and terminates in a broad moulded stand, so that the lamp can be used for carrying or standing with equal facility. The little implements for trimming, snuffing, and extinguishing are suspended by small chains from the neck of the standard and add to the ornamental effect. Each part is made separately and screws together.

With the modern powerful lamps of mineral oil and circular wicks, much larger reservoirs are required, and modern lamps have tended to take the urn shape owing to this necessity, and they lose in beauty of line generally as they gain in body (much like people). A satisfactory type has been introduced by Mr. W. A. S. Benson, of copper, with a copper fan-like shade, which is generally a difficulty with a modern lamp; and the glasses also, while necessary, complicate the design and cannot be said to add to the beauty, as a rule. (See Illustration, p. 77.)

However, a lamp design can never get away from the primitive triple conditions of lamp structure with which we saw in its earliest form reservoir, neck for the wick, and stand—possibly handle—but within these demands of utility there is scope for 71 72 73 very great variations, and unlimited taste and invention.

CANDLESTICKS.

The candlestick, with which the hand lamp has something in common, is, however, quite distinct in character, seeing that it is formed to hold the combustible part in a solid, instead of a liquid form. Its requirements, therefore, are a firm stand (like the lamp), a reasonable height, on which to raise the light, another to hold the candle, and something to catch the melting grease.

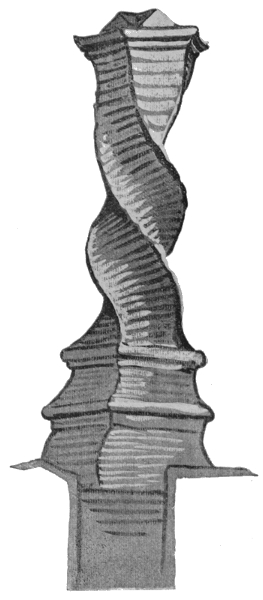

These conditions are satisfied in the form of the antique brass candlestick, but still better in the older Gothic form, or the church candlestick, which has a spike on which to hold the candle, instead of a hollow. A candlestick, therefore, should be true to its name and remain a stick, or moulded tubular column, though capable of development into the candelabrum, throwing out branches for extra lights from the central stem; a suggestive form, if sufficiently restrained, designed with taste.

The ancient hanging brass candelabra of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, or earlier, are very good in form as well as practical. There is a fine Gothic one in Van Eyck's picture in the National Gallery, "Jan Arnolfini and his Wife."