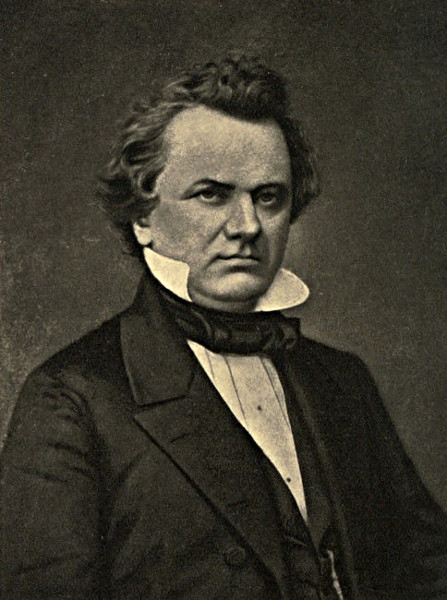

STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS

Title: Charles Sumner: his complete works, volume 05 (of 20)

Author: Charles Sumner

Release date: January 20, 2015 [eBook #48035]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS

iiCopyright, 1900,

BY

LEE AND SHEPARD.

Statesman Edition.

Limited to One Thousand Copies.

Of which this is

Norwood Press:

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

ITS NECESSITY, PRACTICABILITY, AND DIGNITY;

WITH GLANCES AT

THE SPECIAL DUTIES OF THE NORTH.

Address before the People of New York, at the Metropolitan Theatre, May 9, 1855.

The principles of true politics are those of morality enlarged; and I neither now do nor ever will admit of any other.—Burke, Letter to the Bishop of Chester: Correspondence, Vol. I. p. 332.

True politics I look on as a part of moral philosophy, which is nothing but the art of conducting men right in society, and supporting a community amongst its neighbors.—John Locke, Letter to the Earl of Peterborough: Life, by Lord King, Vol. I. p. 9.

Malus usus abolendus est.—Law Maxim.

All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them; for this is the Law and the Prophets.—Matthew, viii. 12.

Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice.

Rogers, Pleasures of Memory.

Through the influence of the late Dr. James W. Stone, an indefatigable Republican, a course of lectures was organized in Boston especially for the discussion of Slavery. This course marks the breaking of the seal on the platform. Mr. Sumner undertook to open this course, which was to begin in the week after his address before the Mercantile Library Association; but he was prevented by sudden disability from a cold. His excuse was contained in the following letter.

“Hancock Street, 23d November, 1854.

“My dear Sir,—An unkindly current of air is often more penetrating than an arrow. From such a shaft I suffered on the night of my address to the Mercantile Library Association, more than a week ago, and no care or skill has been efficacious to relieve me. I am admonished alike by painful consciousness and by the good physician into whose hands I have fallen, that I am not equal to the service I have undertaken on Thursday evening.

“Fitly to inaugurate that course of lectures would task the best powers in best health of any man. Most reluctantly, but necessarily, I must lose sight of the inspiring company there assembled in the name of Freedom to sit in judgment on Slavery, and postpone till some other opportunity what I had hoped to say. You, who know the effort I have made to rally for this occasion, will appreciate my personal disappointment.

“It is my habit to keep my engagements. Not for a single day have I been absent from my seat in the Senate during the three sessions in which duty has called me there; and never before, in the course of numerous undertakings to address public bodies, at different times and in different places, has there been any failure through remissness or disability on my part.

“Pardon these allusions, which I make that you may better understand my feelings, now that I am compelled to depart for the moment from a cherished rule of fidelity.

“Ever faithfully yours,

“Charles Sumner.

“Dr. Stone.”

Failing to open the course, Mr. Sumner closed it, on his return from Washington in the spring, with the following address, which he was called to repeat in the same hall a few days later. Yielding to friendly pressure, he consented to repeat it at several places in New York, among which was Auburn, the residence of Mr. Seward, by whom he was introduced to the audience in the following words.

“Fellow-Citizens,—A dozen years ago I was honored by being chosen to bring my neighbors residing here to the acquaintance of a statesman of 4Massachusetts who was then directing the last energies of an illustrious life to the removal of the crime of Human Slavery from the soil of our beloved country,—a statesman whose course I had chosen for my own guidance,—John Quincy Adams, ‘the old man eloquent.’

“He has ascended to heaven: you and I yet remain here, in the field of toil and duty. And now, by a rare felicity, I have your instructions to present to you another statesman of Massachusetts, him on whose shoulders the mantle of the departed one has fallen, and who more than any other of the many great and virtuous citizens of his native Commonwealth illustrates the spirit of the teacher whom, like us, he venerated and loved so much,—a companion and friend of my own public labors,—the young ‘man eloquent,’—Charles Sumner.”

In the city of New York the same address formed the last of an Antislavery course. It was delivered in the Metropolitan Theatre, before a crowded audience, May 9, 1855. Mr. Sumner had never before spoken in New York. He was introduced by Hon. William Jay, in the following words.

“Ladies and Gentlemen,—I have been requested, on the part of the Society, to perform the pleasing, but unnecessary, office of introducing to you the honored and well-known advocate of Justice, Humanity, and Freedom, Charles Sumner. It is not for his learning and eloquence that I commend him to your respectful attention; for learning, eloquence, and even theology itself, have been prostituted in the service of an institution well described by John Wesley as the sum of all villanies. I introduce him to you as a Northern Senator on whom Nature has conferred the unusual gift of a backbone,—a man who, standing erect on the floor of Congress, amid creeping things from the North, with Christian fidelity denounces the stupendous wickedness of the Fugitive Law and the Nebraska Perfidy, and in the name of Liberty, Humanity, and Religion demands the repeal of those most atrocious enactments. May the words he is about to utter be impressed on your consciences and influence your conduct.”

The reception of the address attested the change in the public mind. Frederick Douglass, who was present, wrote:—

“Metropolitan Theatre was literally packed, and, for two hours and a half, the vast audience, with attention unwearied, and with interest rising with every sentence which dropped from the speaker, indorsed sentiments which many of the same parties would five years ago have stoned any one for uttering.”

The Tribune said:—

“Mr. Sumner’s speech last night was the greatest oratorical and logical success of the year, and was most enthusiastically praised by the largest audience yet gathered in New York to hear a lecture.”

The interest was such, that he was constrained, much against his own disposition, to repeat it in Brooklyn, where he was introduced by Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, and then again at Niblo’s Theatre, New York, where he was introduced by Joseph Blunt, Esq. The concluding words of Mr. Beecher were as follows.

“I am to introduce to you a statesman who follows a long train of representatives and statesmen who were false to the North, false to Liberty; and then they made a complaint that there was no North! It was because the North lost faith in her recreant children. It lost faith in its traitors, and not in Liberty. But now, if the haughty Southerners wish to engage in any more conflicts of this kind, I think they will have to find some other than the speaker to-night with whom to break a lance. [Loud cheers.] I do not wish merely to introduce to you the ‘honorable gentleman’ sent from Massachusetts as a United States Senator; my wish is to do better than that; I wish to introduce to you the MAN,—Charles Sumner. [Loud applause.]”

The Tribune spoke thus of these meetings:—

“That a lecture should be repeated in New York is a rare occurrence. That a lecture on Antislavery should be repeated in New York, even before a few despised ‘fanatics,’ is an unparalleled occurrence. But that an Antislavery lecture should be repeated night after night to successive multitudes, each more enthusiastic than the last, marks the epoch of a revolution in popular feeling; it is an era in the history of Liberty. Niblo’s Theatre was crowded last evening long before the hour of commencement. Hundreds stood through the three hours’ lecture. We give a full report of the words, but only of the words.”

Other newspapers were enthusiastic in their comments.

The National Era, at Washington, in printing the address, said of its delivery in Metropolitan Hall:—

“Mr. Sumner closed, as he had continued, amid loud and protracted applause. Especially at the point when he said that the Fugitive Slave Bill must be made a dead letter, the audience seemed wild with enthusiasm. Handkerchiefs waved from fair hands, and reporters almost forgot their stolid unconcern.”

Such extracts might be multiplied. Beyond these was the testimony of individuals gratified at the hearing obtained for cherished sentiments. One wrote from Philadelphia as follows.

“I cannot forbear, not for your gratification, but for my own, to testify my unbounded sympathy and satisfaction in the Three Days’ Ovation of May that you have enjoyed in New York, in reward of your faithful sentinelship on the ramparts of Liberty in that sin-beleaguered fortress, the Capitol at Washington, faithfully supporting the cause of the weak against insolence and haughty vulgarity.… You have gloriously and faithfully withstood obloquy and reproach: the hour of triumph is now well assured.”

Another wrote from Albany:—

“I have never read anything so magnificent as your Lecture in the Independent. How I wish I could have heard it! Letters from judges in such matters inform me that no speech in New York for many years has produced such a sensation.”

Count Gurowski, writing from Brattleboro’, Vermont, expressed his enthusiastic sympathy, and at the same time predicted the adverse feeling among slave-masters.

“I have just finished the reading of your admirable Oration. I am en extase. I was near to cry.… But you have thrown the gauntlet once more to the ‘gentlemen from the South,’ bravely, decidedly, and pitilessly. Do not be astonished, if they shall send you, covered with laurels as you are, to Coventry. This undoubtedly they will do.”

These extracts show something of public sentiment at this stage of the great contest with Slavery. From this time forward the discussion broadened and deepened.

History abounds in vicissitudes. From weakness and humility, men ascend to power and place. From defeat and disparagement, enterprises are borne on to recognition and triumph. The martyr of to-day is gratefully enshrined on the morrow. The stone that the builders rejected is made head of the corner. Thus it always has been, and ever will be.

Only twenty years ago, in 1835, the friends of the slave in our country were weak and humble, while their great undertaking, just then showing itself, was trampled down and despised. Small companies, gathered together in the name of Freedom, were interrupted and often dispersed by riotous mobs. At Boston, a feeble association of women, called the Female Antislavery Society, sitting in a small room of an upper story in an obscure building, was insulted and then driven out of doors by a frantic crowd, politely termed at the time “gentlemen of property and standing,” which, after various deeds of violence and vileness, next directed itself upon William Lloyd Garrison,—known as the determined editor of the “Liberator,” and originator of the Antislavery Enterprise in our day,—then ruthlessly tearing him away, amidst savage threats and with a halter about his neck, dragged him through the8 streets, until, at last, guilty only of loving liberty, if not wisely, too well, this unoffending citizen was thrust into the common jail for protection against an infuriate populace. Nor was Boston alone. Even villages in remote rural solitude broke out in similar outrage,—while large towns, like Providence, New Haven, Utica, Worcester, Alton, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, became so many fiery craters overflowing with rage and madness. What lawless violence failed to accomplish was urged next through forms of law. By solemn legislative acts, the Slave States called on the Free States “promptly and effectually to suppress all those associations within their respective limits purporting to be Abolition Societies”;[1] and Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and New York basely hearkened to the base proposition. The press, too, with untold power, exerted itself in this behalf, while pulpit, politician, and merchant conspired to stifle discussion, until the voice of Freedom was hushed to a whisper, “alas! almost afraid to know itself.”

Since then, in the lapse of few years only, a change has taken place. Instead of those small companies, counted by tens, we have now this mighty assembly, counted by thousands; instead of an insignificant apartment, like that in Boston, the mere appendage of a printing-office, where, as in the manger itself, Truth was cradled, we have this Metropolitan Hall, ample in proportion and central in place; instead of a profane and clamorous mob, beating at our gates, dispersing our9 assembly, and making one of our number the victim of its fury, we have peace and harmony at unguarded doors, ruffled only by generous competition to participate in this occasion; while Legislatures openly declare their sympathies, villages, towns, and cities vie in the new manifestation, and the press itself, with increased power, heralds, applauds, and extends the prevailing influence, which, gushing from every fountain, and pouring through every channel, at last, by quickening power of pulpit, politician, and merchant, swells into an irresistible tide.

Here is a great change, worthy of notice and memory, for it attests the first stage of victory. Slavery, in all its many-sided wrong, still continues; but here in this metropolis—ay, Sir, and throughout the whole North—freedom of discussion is at length secured. And this, I say, is the first stage of victory,—herald of the transcendent future.

Nor is there anything peculiar in the trials to which our cause has been exposed. Thus in all ages is Truth encountered. At first persecuted, gagged, silenced, crucified, she cries out from the prison, the rack, the stake, the cross, until at last her voice is heard. And when that voice is really heard, whether in martyr cries, or in earthquake tones of civil convulsion, or in the calmness of ordinary speech, such as I now employ, or in that still, small utterance inaudible to the common ear, then is the beginning of victory! “Give me where to stand and I will move the world,” said Archimedes; and Truth asks no more than did the master of geometry.

Viewed in this aspect, the present occasion rises above any ordinary course of lectures or series of political meetings. It is the inauguration of Freedom. From this time forward, her voice of warning and command cannot be silenced. The sensitive sympathies of property, in this commercial mart, may yet again recognize property in man; the watchful press itself may falter or fail; but the vantage-ground of free discussion now achieved cannot be lost. On this I take my stand, and, as from the Mount of Vision, behold the whole field of our great controversy spread before me. There is no point, topic, fact, matter, reason, or argument, touching the question between Slavery and Freedom, which is not now open. From these I might aptly select some one, and confine myself to its development. But I should not in this way best satisfy the seeming requirement of the occasion. According to the invitation of your Committee, I was to make an address introductory to the present course of lectures, but was prevented by ill-health. And now, at the close of the course, I am to say what I failed to say at its beginning. Not as Caucus or as Congress can I address you; nor am I moved to undertake a political harangue or constitutional argument. Out of the occasion let me speak, and, discarding any individual topic, aim to exhibit the entire field, in its divisions and subdivisions, with metes and bounds.

My subject will be The Necessity, Practicability, and Dignity of the Antislavery Enterprise, with Glances at Special Duties of the North. By this enterprise I do not mean the efforts of any restricted circle, sect, or party, but the cause of the slave, in all its forms and under all its names,—whether inspired by11 pulpit, press, economist, or politician,—whether in the early, persistent, and comprehensive demands of Garrison, the gentler tones of Channing, or the strictly constitutional endeavors of others now actually sharing the public councils of the country. To carry through this review, under its different heads, I shall not hesitate to meet the objections urged against it, so far at least as I am aware of them. As I speak to you seriously, I venture to ask your serious attention even to the end. Not easily can a public address reach that highest completeness which is found in mingling the useful and the agreeable; but I desire to say that it will be my effort to cultivate that highest courtesy of a speaker which is found in clearness.

I begin with the NECESSITY of the Antislavery Enterprise. In the wrong of Slavery, as defined by existing law, this necessity is plainly apparent; nor can any man within the sound of my voice, who listens to the authentic words of the law, hesitate in my conclusion. A wrong so grievous and unquestionable should not be allowed to continue. For the honor of human nature, and the good of all concerned, it must at once cease. On this simple statement, as corner-stone, I found the necessity of the Antislavery Enterprise.

I do not dwell, Sir, on the many tales which come from the house of bondage: on the bitter sorrows undergone; on the flesh galled by manacle, or spurting blood beneath the lash; on the human form mutilated by knife, or seared by red-hot iron; on the ferocious scent of bloodhounds in chase of human prey; on the sale of fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, brothers and sisters,12 little children, even infants, at the auction block; on the practical prostration of all rights, all ties, and even all hope; on the deadly injury to morals, substituting concubinage for marriage, and changing the whole land of Slavery into a by-word of shame, only fitly pictured by the language of Dante, when he called his own degraded country a House of Ill Fame;[2] and, last of all, on the pernicious influence upon master as well as slave, showing itself too often, even by his own confession, in rudeness of manners and character, and especially in that blindness which renders him insensible to the wrongs he upholds. On these things I do not dwell, although volumes are at hand of unquestionable fact, and also of illustrative story so just and germane as to vie with fact, out of which I might draw, until, like Macbeth, you had “supped full with horrors.”

All these I put aside,—not because I do not regard them of moment in exhibiting the true character of Slavery, but because I desire to present this argument on grounds above all controversy, impeachment, or suspicion, even from slave-masters themselves. Not on triumphant story, not even on indisputable fact, do I now accuse Slavery, but on its character, as revealed in its own simple definition of itself. Out of its own mouth do I condemn it. By the Law of Slavery, man, created in the image of God, is divested of the human character, and declared to be a mere chattel. That this statement may not seem to be put forward without precise authority, I quote the law of two different States. The Civil Code of Louisiana thus defines a slave:—

“A slave is one who is in the power of a master to whom he belongs. The master may sell him, dispose of his person,13 his industry, and his labor. He can do nothing, possess nothing, nor acquire anything but what must belong to his master.”[3]

The law of another polished Slave State gives this definition:—

“Slaves shall be deemed, sold, taken, reputed, and adjudged in law to be chattels personal, in the hands of their owners and possessors, and their executors, administrators, and assigns, to all intents, constructions, and purposes whatsoever.”[4]

And a careful writer, Judge Stroud, in a work of juridical as well as philanthropic merit, thus sums up the law:—

“The cardinal principle of Slavery, that the slave is not to be ranked among sentient beings, but among things, is an article of property, a chattel personal, obtains as undoubted law in all of these [Slave] States.”[5]

Sir, this is enough. As out of its small egg crawls forth the slimy, scaly, reptile crocodile, so out of this simple definition crawls forth the whole slimy, scaly, reptile monstrosity by which a man is changed into a chattel, a person is converted into a thing, a soul is transmuted into merchandise. According to this very definition, the slave is held simply for the good of his master, to whose behest his life, liberty, and happiness are devoted, and by whom he may be bartered, leased, mortgaged, bequeathed, invoiced, shipped as cargo, stored as goods, sold on execution, knocked off at public auction, and even staked at the gaming-table on the hazard14 of a card or die. The slave may seem to have a wife; but he has not, for his wife belongs to his master. He may seem to have a child; but he has not, for his child is owned by his master. He may be filled with desire of knowledge, opening to him the gates of joy on earth and in heaven; but the master may impiously close all these gates. Thus is he robbed, not merely of privileges, but of himself,—not merely of money and labor, but of wife and children,—not merely of time and opportunity, but of every assurance of happiness,—not merely of earthly hope, but of all those divine aspirations that spring from the Fountain of Light. He is not merely restricted in liberty, but totally deprived of it,—not merely curtailed in rights, but absolutely stripped of them,—not merely loaded with burdens, but changed into a beast of burden,—not merely bent in countenance to the earth, but sunk in law to the level of a quadruped,—not merely exposed to personal cruelty, but deprived of his character as a person,—not merely compelled to involuntary labor, but degraded to a rude thing,—not merely shut out from knowledge, but wrested from his place in the human family. And all this, Sir, is according to the simple Law of Slavery.

And even this is not all. The law, by cumulative provisions, positively forbids that a slave shall be taught to read. Hear this, fellow-citizens, and confess that no barbarity of despotism, no extravagance of tyranny, no excess of impiety can be more blasphemous or deadly. “Train up a child in the way he should go” is the lesson of Divine Wisdom; but the Law of Slavery boldly prohibits any such training, and dooms the child to hopeless ignorance and degradation. “Let there be light” was the Divine behest at the dawn of Creation,—and15 this commandment, travelling with the ages and the hours, still speaks with the voice of God; yet the Law of Slavery says, “Let there be darkness.”

But it is earnestly averred that slave-masters are humane, and slaves are treated with kindness. These averments, however, I properly put aside, precisely as I have already put aside the multitudinous illustrations from the cruelty of Slavery. On the simple letter of the law I take my stand, and do not go beyond what is there nominated. The masses of men are not better than their laws, and, whatever may be the eminence of individual virtue, it is not reasonable to infer that the body of slave-masters is better than the Law of Slavery. And since this law submits the slave to their irresponsible control, with power to bind and to scourge, to shut the soul from knowledge, to separate families, to unclasp the infant from a mother’s breast, and the wife from a husband’s arms, it is natural to conclude that such enormities are sanctioned by them, while the supplementary denial of instruction gives conclusive evidence of their full complicity. And this conclusion must exist unquestioned, just so long as the law exists unrepealed. Cease, then, to blazon the humanity of slave-masters. Tell me not of the lenity with which this cruel law is tempered to its unhappy subjects. Tell me not of the sympathy which overflows from the mansion of the master to the cabin of the slave. In vain you assert these instances. In vain you show that there are individuals who do not exert the wickedness of the law. The law still endures. Slavery, which it defines and upholds, continues to outrage Public Opinion, and, within the limits of our Republic, more than three millions of human beings, guilty only of a skin16 not colored like your own, are left the victims of its unrighteous, irresponsible power.

Power divorced from right is devilish; power without the check of responsibility is tyrannical; and I need not go back to the authority of Plato, when I assert that the most complete injustice is that erected into the form of law. But all these things concur in Slavery. It is, then, on the testimony of slave-masters, solemnly, legislatively, judicially attested in the very law itself, that I now arraign this institution as an outrage upon man and his Creator. And herein is the necessity of the Antislavery Enterprise. A wrong so transcendent, so loathsome, so direful, must be encountered, wherever it can be reached; and the battle must be continued without truce or compromise, until the field is entirely won. Freedom and Slavery can hold no divided empire; nor can there be any true repose, until Freedom is everywhere established.

To the necessity of the Antislavery Enterprise there are two, and only two, main objections,—one founded on the alleged distinction of race, and the other on the alleged sanction of Christianity. All other objections are of inferior character, or are directed logically at its practicability. Of these two main objections let me briefly speak.

1. I begin with the alleged distinction of race. This objection assumes two different forms,—one founded on a prophetic malediction in the Old Testament, and the other on professed observations of recent science. Its importance is apparent in the obvious fact, that, unless such distinction be clearly and unmistakably established,17 every argument by which our own freedom is vindicated, every applause awarded to the successful rebellion of our fathers, every indignant word ever hurled against the enslavement of white fellow-citizens by Algerine corsairs, must plead trumpet-tongued against the deep damnation of Slavery, black as well as white.

It is said that Africans are the posterity of Ham, son of Noah, through Canaan cursed by Noah, to be the servant of his brethren, and that this malediction has fallen upon all his descendants, including the unhappy Africans,—who are accordingly devoted by God, through unending generations, to unending bondage. Such is the favorite argument at the South, and more than once directly addressed to myself. Here, for instance, is a passage from a letter recently received. “You need not persist,” says the writer, “in confounding Japheth’s children with Ham’s, and making both races one, and arguing on their rights as those of man broadly.” And I have been seriously assured, that, until this objection is answered, it will be vain to press my views upon Congress or the country. Listen now to the texts of the Old Testament which are so strangely employed.

“And he [Noah] said, Cursed be Canaan: a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant.”[6]

That is all; and I need only read these words in order to expose the whole—transpicuous humbug. I am tempted to add, that, to justify this objection, it is necessary to maintain at least five different propositions, as essential links in the chain of the African slave: first,18 that by this malediction Canaan himself was actually changed into a chattel,—whereas he is simply made the servant of his brethren; secondly, that not merely Canaan, but all his posterity, to the remotest generation, was so changed,—whereas the language has no such extent; thirdly, that the African actually belongs to the posterity of Canaan,—an ethnographical assumption absurdly difficult to establish; fourthly, that each descendant of Shem and Japheth has a right to hold an African fellow-man as chattel,—a proposition which finds no semblance of support; and, fifthly, that every slave-master is truly descended from Shem or Japheth,—a pedigree which no anxiety or assurance can prove. This plain analysis, which may fitly excite a smile, shows the fivefold absurdity of an attempt to found this revolting wrong on any

The small bigotry which finds comfort in these texts has been exalted lately by the voice of Science, undertaking to suggest that the different races of men are not derived from a single pair, but from several distinct stocks, according to their several distinct characteristics; and it is haughtily argued, that the African is so far inferior as to lose all title to that liberty which is the birthright of the lordly white. Now I have neither time nor disposition, on this occasion, to discuss the question of the unity of races; nor is it necessary to my present purpose. It may be that the different races of men proceeded from different stocks; but there is but one great Human Family, in which Caucasian and African, Chinese and Indian, are all brothers, children of one Father, and19 heirs to one happiness,—alike on earth and in heaven. “Star-eyed Science” cannot shake this everlasting truth. It may exhibit peculiarities in the African, by which he is distinguishable from the Caucasian. In his physical form and intellectual character it may presume to find the stamp of permanent inferiority. But by no reach of learning, no torture of fact, no effrontery of dogma, can any science show that he is not a man. And as a man he stands before you an unquestionable member of the Human Family, entitled to all the rights of man. You can claim nothing for yourself, as man, which you must not accord to him. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which you proudly declare to be your own inalienable, God-given rights, and to the support of which your fathers pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor, are his by the same immortal title that they are yours.

2. From the objection founded on alleged distinction of race, I pass to that other founded on alleged sanction of Slavery by Christianity. Striving to be brief, I shall not undertake to reconcile texts often quoted from the Old Testament, which, whatever their import, are all absorbed in the New; nor shall I stop to consider the precise interpretation of the familiar phrase, Servants, obey your masters, nor seek to weigh any such imperfect injunction in the scales against those grand commandments on which hang all the Law and the Prophets. Surely, in the example and teachings of the Saviour, who lifted up the down-trodden, who enjoined purity of life, and overflowed with tenderness even to little children, human ingenuity can find no apology for an institution which tramples on man, which defiles woman, and sweeps20 little children beneath the hammer of the auctioneer. If to any one these things seem to have the license of Christianity, it is only because they have first secured a license in his own soul. Men are prone in uncertain, disconnected texts to find confirmation of their own personal prejudices or prepossessions. And I—who am no theologian, but only a simple layman—make bold to say, that whoever finds in the Gospel any sanction of Slavery finds there merely a reflection of himself. On a matter so irresistibly clear authority is superfluous; but an eminent character, who as poet makes us forget his high place as philosopher, and as philosopher makes us forget his high place as theologian, exposes the essential antagonism between Christianity and Slavery in a few pregnant words, which, by recalling the spirit of our Faith, are more satisfactory than whole volumes of ingenious discussion. “By a principle essential to Christianity,” says Coleridge, “a person is eternally differenced from a thing; so that the idea of a Human Being necessarily excludes the idea of property in that Being.”[8]

With regret, though not with astonishment, I learn that a Boston divine has sought to throw the seamless garment of Christ over this shocking wrong. But I am patient, and see clearly how vain is his effort, when I call to mind, that, within this very century, other divines in another country sought to throw the same sacred vesture over the more shocking slave-trade,—and that, among many publications, a little book was then put forth by a reverend clergyman, with the title, “The African Trade for Negro Slaves shewn to be consistent with Principles of Humanity and with the Laws21 of Revealed Religion.”[9] Thinking of these things, I am ready to say, with Shakespeare,—

In support of Slavery, it is the habit to pervert texts and to invent authority. Even St. Paul is vouched for a wrong which his Christian life rebukes. Much stress is now laid on his example, as it appears in the Epistle to Philemon, written at Rome, and sent by Onesimus, a servant. From the single chapter constituting the entire epistle I take the following ten verses, most strangely invoked for Slavery.

“I beseech thee for my son Onesimus, whom I have begotten in my bonds; which in time past was to thee unprofitable, but now profitable to thee and to me; whom I have sent again. Thou, therefore, receive him, that is, mine own bowels: whom I would have retained with me, that in thy stead he might have ministered unto me in the bonds of the gospel; but without thy mind would I do nothing; that thy benefit should not be as it were of necessity, but willingly. For perhaps 22he therefore departed for a season that thou shouldest receive him forever; not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved, specially to me, but how much more unto thee, both in the flesh and in the Lord! If thou count me, therefore, a partner, receive him as myself. If he hath wronged thee, or oweth thee aught, put that on mine account: I Paul have written it with mine own hand, I will repay it: albeit I do not say to thee how thou owest unto me even thine own self besides.”[10]

Out of this affectionate epistle, where St. Paul calls the converted servant, Onesimus, his son, precisely as in another epistle he calls Timothy his son, Slavery is elaborately vindicated, and the great Apostle to the Gentiles made the very tutelary saint of the Slave-Hunter. Now, without invoking his real judgment of Slavery from his condemnation on another occasion of “men-stealers,” or what I prefer to call slave-hunters, in company with “murderers of fathers and murderers of mothers,” and without undertaking to show that the present epistle, when truly interpreted, is a protest against Slavery and a voice for Freedom,—all of which might be done,—I content myself with calling attention to two things, apparent on its face, and in themselves an all-sufficient response. First, while it appears that Onesimus had been in some way the servant of Philemon, it does not appear that he was ever held as chattel; and how gross and monstrous is the effort to derive such a wrong out of words, whether in the Constitution of our country or in the Bible, which do not explicitly, unequivocally, and exclusively define this wrong! Secondly, in charging Onesimus with this epistle to Philemon, the Apostle recommends him as23 “not now a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved,” and he enjoins upon his correspondent the hospitality due to a freeman, saying expressly, “If thou count me, therefore, a partner, receive him as myself”: ay, Sir, not as slave, not even as servant, but as brother beloved, even as the Apostle himself. Thus, with apostolic pen, wrote Paul to his disciple, Philemon. In these words of gentleness, benediction, and equal rights, dropping with celestial, soul-awakening power, there can be no justification for a conspiracy, which, beginning with the treachery of Iscariot and the temptation of pieces of silver, seeks, by fraud, brutality, and violence, through officers of the law armed to the teeth, like pirates, and amidst soldiers who degrade their uniform, to hurl a fellow-man back into the lash-resounding den of American Slavery; and when any one thus perverts this beneficent example, allow me to say that he gives too much occasion to doubt his intelligence or his sincerity.

Certainly I am right in stripping from Slavery the apology of Christianity, which it has tenaciously hugged; and here I leave the first part of my subject, asserting, against every objection, the Necessity of our Enterprise.

I am now brought, in the second place, to the Practicability of the Enterprise. And here the way is easy. In showing its necessity, I have already demonstrated its practicability; for the former includes the latter, as the greater includes the less. Whatever is necessary must be practicable. By a decree which is a proverb of tyranny, the Israelites were compelled to make bricks without24 straw; but it is not according to the ways of a benevolent Providence that man should be constrained to do what cannot be done. Besides, the Antislavery Enterprise is right; and the right is always practicable.

I know well the little faith of the world in the triumph of principles, and I readily imagine the despair with which our object is regarded; but not on this account am I disheartened. That exuberant writer, Sir Thomas Browne, breaks into ecstatic wish for some new difficulty in Christian belief, that his faith may have a new victory; and an eminent enthusiast went so far as to say, “I believe because it is impossible,”—Credo quia impossibile. No such exalted faith is now required. Here is no impossibility; nor is there any difficulty which will not yield to faithful, well-directed endeavor. If to any timid soul the Enterprise seems impossible because it is too beautiful, then do I say at once that it is too beautiful not to be possible.

Descending from these summits, let me show plainly the object it seeks to accomplish; and here you will see and confess its complete practicability. While discountenancing all prejudice of color and every establishment of caste, the Antislavery Enterprise—at least so far as I may speak for it—does not undertake to change human nature, or to force any individual into relations of life for which he is not morally, intellectually, and socially adapted; nor does it necessarily assume that a race, degraded for long generations under the iron heel of bondage, can be taught at once all the political duties of an American citizen. But, Sir, it does confidently assume, against all question, contradiction, or assault whatever, that every man is entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; and, with equal confidence, it25 asserts that every individual who wears the human form, whether black or white, should be recognized at once as man. When this is done, I know not what other trials may be in wait for the unhappy African; but this I do know, that the Antislavery Enterprise will then have triumphed, and the institution of Slavery, as defined by existing law, will no longer shock mankind.

In this work, the first essential, practical requisite is, that the question shall be openly and frankly confronted. Do not put it aside. Do not blink it out of sight. Do not dodge it. Approach it. Study it. Ponder it. Deal with it. Let it rest in the illumination of speech, conversation, and the press. Let it fill the thoughts of the statesman and the prayers of the pulpit. When Slavery is thus regarded, its true character will be recognized, as a hateful assemblage of unquestionable wrongs under sanction of existing law, and good men will be moved to apply the remedy. Already even its zealots admit that its “abuses” should be removed. This is their word, not mine. Alas! alas! Sir, it is these very “abuses” that constitute its component parts, without which it would not exist,—even as the scourges in a bundle with the axe constituted the dread fasces of the Roman lictor. Take away these, and the whole embodied outrage disappears. Surely that central assumption—more deadly than axe itself—by which man is changed into a chattel, may be abandoned; and is not this practicable? The associate scourges by which that transcendent “abuse” is surrounded may, one by one, be subtracted. The “abuse” which substitutes concubinage for marriage, the “abuse” which annuls the parental relation, the “abuse” which closes the portals of knowledge, the “abuse” which tyrannically usurps all the labor26 of another, now upheld by positive law, may by positive law be abolished. To say that this is not practicable, in the nineteenth century, is a scandal upon mankind, and just in proportion as these “abuses” cease to have the sanction of law will the institution of Slavery cease to exist. The African, whatever may be then his condition, will no longer be the slave over whose wrongs and sorrows the world throbs at times fiercely indignant, and at times painfully sad, while with outstretched arms he sends forth the piteous cry, “Am I not a man and a brother?”

In pressing forward to this result, the inquiry is often presented, To what extent, if any, shall compensation be allowed to slave-masters? Clearly, if the point be determined by absolute justice, not the masters, but the slaves, are entitled to compensation; for it is the slaves who, throughout weary generations, have been deprived of the fruits of their toil, all constantly enriching their masters. Besides, it seems hardly reasonable to pay for the relinquishment of disgusting “abuses,” which, in their aggregation, constitute the bundle of Slavery. Pray, Sir, by what tariff, price-current, or principle of equation, shall their several values be estimated? What sum shall be counted out as the proper price for the abandonment of that pretension—more indecent than the jus primæ noctis of the feudal age—which leaves woman, whether in the arms of master or slave, always a concubine? What bribe shall be proffered for restoration of God-given paternal rights? What money shall be paid for taking off the padlock by which souls are fastened down in darkness? How much for a quit-claim to labor now meanly exacted by the strong from the weak? And what compensation shall be awarded27 for the egregious assumption, condemned by reason and abhorred by piety, which changes man into a thing? I put these questions without undertaking to pass upon them. Shrinking instinctively from any recognition of rights founded on wrongs, I find myself shrinking also from any austere verdict which shall deny any means necessary to the great consummation. Our fathers, under Washington, did not hesitate, by Act of Congress, to appropriate largely for the ransom of white fellow-citizens enslaved by Algerine corsairs; and, following this example, I am disposed to consider the question of compensation as one of expediency, to be determined by the exigency of the hour and the constitutional powers of the Government,—though such is my desire to see the disappearance of Slavery, that I could not hesitate to build a Bridge of Gold, if necessary, for the retreating fiend.

The Practicability of the Antislavery Enterprise is constantly questioned, often so superficially as to be answered at once. I shall not take time to consider the allegation, founded on assumptions of economy, which audaciously assumes that Slave Labor is more advantageous than Free Labor, that Slavery is more profitable than Freedom, for this is all exploded by official tables of the census,—nor that other futile argument, that the slaves are not prepared for Freedom, and therefore should not be precipitated into this condition, for this is no better than the ancient Greek folly, where the anxious mother would not allow her son to enter the water until he had learned to swim.

As against the Necessity of the Antislavery Enterprise there were two chief objections, so also against its28 Practicability there are two,—the first founded on alleged danger to the master, and the second on alleged damage to the slave himself.

1. The first objection, founded on alleged danger to the master, most generally takes the extravagant form, that the slave, if released from his present condition, would “cut his master’s throat.” Here is a blatant paradox, which can pass for reason only among those who have lost their reason. With absurdity having no parallel except in the defences of Slavery, it assumes that the African, when treated justly, will show a vindictiveness he does not exhibit when treated unjustly,—that, when elevated by the blessings of Freedom, he will develop an appetite for blood never manifested when crushed by the curse of bondage. At present, the slave sees his wife ravished from his arms,—sees his infant swept away to the auction-block,—sees the heavenly gates of knowledge shut upon him,—sees his industry and all its fruits unjustly snatched by another,—sees himself and his offspring doomed to servitude from which there is no redemption; and still his master sleeps secure. Will the master sleep less secure when the slave no longer smarts under these revolting atrocities? I will not trifle with your intelligence, or with the quick-passing hour, by arguing this question.

There is a lofty example, brightening the historic page, by which the seal of experience is affixed to the conclusion of reason; and you would hardly pardon me, if I failed to adduce it. By a single Act of Parliament the slaves of the British West Indies were changed at once to freedmen; and this great transition was accomplished absolutely without personal danger of any29 kind to the master. And yet the chance of danger there was greater far than among us. In our broad country the slaves are overshadowed by a more than sixfold white population. Only in two States, South Carolina and Mississippi, do the slaves outnumber the whites, and there not greatly, while in the entire Slave States the whites outnumber the slaves by millions. It was otherwise in the British West Indies, where the whites were overshadowed by a more than sixfold population. The slaves were 800,000, while the whites numbered only 131,000, distributed in different proportions on the different islands. And this disproportion has since increased rather than diminished, always without danger to the whites. In Jamaica, the largest of these possessions, there are now upwards of 400,000 Africans, and only 15,000 whites; in Barbadoes, the next largest, 120,000 Africans, and only 16,000 whites; in St. Lucia, 24,000 Africans, and only 900 whites; in Tobago, 14,000 Africans, and only 160 whites; in Montserrat, 7,000 Africans, and only 150 whites; and in the Grenadines, upwards of 6,000 Africans, and only about 60 whites.[11] And yet the authorities in all these places attest the good behavior of the Africans. Sir Lionel Smith, Governor of Jamaica, in a speech to the Assembly, declares that their conduct “amply proves how well they have deserved the boon of Freedom”;[12] the Governor of the Leeward Islands dwells on30 “the peculiarly rare instances of the commission of grave or sanguinary crimes amongst the emancipated population of these islands”;[13] and the Queen of England, in a speech from the throne, has announced that the complete and final emancipation of the Africans had “taken place without any disturbance of public order and tranquillity.”[14] In this example I find new confirmation of the rule, that the highest safety is in doing right; and thus do I dismiss the objection founded on alleged danger to the master.

2. I am now brought to the second objection, founded on alleged damage to the slave. It is common among partisans of Slavery to assert that our Enterprise has actually retarded the cause it seeks to promote; and this paradoxical accusation, which might naturally show itself among the rank weeds of the South, is cherished here on our Northern soil among those who look for any fig-leaf with which to cover indifference or tergiversation.

This peculiar form of complaint is an old device, instinctively employed on other occasions, until it ceases to be even plausible. Thus, throughout all time, has every good cause been encountered. The Saviour was nailed to the cross with a crown of thorns on his head, as a disturber of that peace on earth which he came to declare. The Disciples, while preaching the Gospel of forgiveness and good-will, were stoned as preachers of sedition and discord. The Reformers, who sought to establish a higher piety and faith, were burnt at the stake as blasphemers and infidels. Patriots, in all ages, striving for their country’s good, have been doomed to31 the scaffold or to exile, even as their country’s enemies. Those brave Englishmen, who, at home, under the lead of Edmund Burke, espoused the cause of our fathers, shared the same illogical impeachment, which was touched to the quick by that orator statesman, when, after exposing its essential vice, in “attributing the ill effect of ill-judged conduct to the arguments which had been used to dissuade us from it,” he denounced it as “absurd, but very common in modern practice, and very wicked.”[15] Ay, Sir, it is common in modern practice. In England it has vainly renewed itself with special frequency against Bible Societies,—against the friends of education,—against the patrons of vaccination,—against the partisans of peace,—all of whom have been openly arraigned as provoking and increasing the very evils, whether of infidelity, ignorance, disease, or war, which they benignly seek to check. To bring an instance precisely applicable to our own,—Wilberforce, when conducting the Antislavery Enterprise of England, first against the Slave-Trade, and then against Slavery itself, was told that those efforts, by which his name is now consecrated forevermore, tended to increase the hardships of the slave, even to the extent of riveting anew his chains. Such are precedents for the imputation to which our Enterprise is exposed; and such, also, are precedents by which I exhibit the fallacy of the imputation.

Sir, I do not doubt that the Enterprise produces heat and irritation, amounting often to inflammation, among slave-masters, which to superficial minds seems inconsistent with success, but which the careful observer32 will recognize at once as the natural and not unhealthy effort of a diseased body to purge itself of existing impurities; and just in proportion to the malignity of the concealed poison will be the extent of inflammation. A distemper like Slavery cannot be ejected like a splinter. It is too much to expect that men thus tortured should reason calmly, that patients thus suffering should comprehend the true nature of their case and kindly acknowledge the beneficent cure; but not on this account can it be suspended. Nor, when we consider the character of Slavery, can it be expected that men who sustain it will be tranquil. Conscience has its voice, and will be heard in awful warning hurrying to and fro in the midnight hour. Its outcry is more natural than silence.

In the face of this complaint, I assert that the Antislavery Enterprise has already accomplished incalculable good. Even now it sweeps the national heart, compelling it to emotions of transforming power. All are touched,—the young, the middle-aged, the old. There is a new glow at the household hearth. Mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters are aroused to take part in the great battle. There is a new aspiration for justice on earth, awakening not merely a sentiment against Slavery, such as prevailed with our fathers, but a deep, undying conviction of its wrong, and a determination to leave no effort unattempted for its removal. With the sympathies of all Christendom as allies, already it encompasses the slave-masters by a moral blockade, invisible to the eye, but more potent than navies, from which there can be no escape except in final capitulation. Thus it has created the irresistible influence which itself constitutes the beginning of success.

Already are signs of change. In common speech, as well as in writing, among slave-masters, the bondman is no longer called slave, but servant,—thus, by soft substitution, concealing and condemning the true relation. Newspapers, even in the land of bondage, blush at the hunt of men by bloodhounds,—thus protesting against an unquestionable incident of Slavery. Other signs appear in the added comfort of the slave,—in the enlarged attention to his wants,—in the experiments now beginning, by which the slave is enabled to share in the profits of his labor, and thus finally secure his freedom,—and, above all, in the consciousness among slave-masters that they dwell now, as never before, under the keen observation of an ever-wakeful Public Opinion, quickened by an ever-wakeful Public Press. Nor is this all. Only lately propositions were introduced into the Legislatures of different States, and countenanced by Governors, to mitigate the existing Law of Slavery; and almost while speaking, I have received drafts of two different memorials, one to the Legislature of Virginia, and the other to that of North Carolina, asking for the slave three things, which it will be monstrous to refuse, but which, if conceded, will take from Slavery its existing character: I mean, first, the protection of the marriage relation; secondly, the protection of the parental relation; and, thirdly, the privilege of knowledge. Grant these, and the girdled Upas tree soon must die. Sir, amidst these tokens of present success, and the auguries of the future, I am not disturbed by complaints of seeming damage. “Though it consume our own dwelling, who does not venerate fire, without which human life can hardly exist on earth?” says the Hindoo proverb; and the time is even now at hand, when the34 Antislavery Enterprise, which is the very fire of Freedom, with all its incidental excesses and excitements, will be hailed with similar regard.

It remains to show, in the third place, that the Antislavery Enterprise, which stands before you at once necessary and practicable, is commended by inherent Dignity. Here reasons are obvious and unanswerable.

Its object is benevolent; nor is there in the dreary annals of the Past a single enterprise more clearly and indisputably entitled to this character. With unsurpassed and touching magnanimity, it seeks to benefit the lowly whom your eyes have not seen, and who are ignorant even of your labors, while it demands and receives a self-sacrifice calculated to ennoble an enterprise of even questionable merit. Its true rank is among works properly called philanthropic,—the title of highest honor on earth. “I take goodness in this sense,” says Lord Bacon in his Essays, “the affecting of the weal of men, which is that the Grecians call Philanthropia, … of all virtues and dignities of the mind the greatest, being the character of the Deity; and without it, man is a busy, mischievous, wretched thing, no better than a kind of vermin.”[16] Lord Bacon was right, and perhaps unconsciously followed a higher authority; for, when Moses asked the Lord to show him his glory, the Lord said, “I will make all my goodness pass before thee.”[17] Ah! Sir, Peace has trophies fairer and more perennial than any snatched from fields of blood, but, among all35 these, the fairest and most perennial are the trophies of beneficence. Scholarship, literature, jurisprudence, art, may wear their well-deserved honors; but an enterprise of goodness deserves, and will yet receive, a higher palm than these.

In other aspects its dignity is apparent. It concerns the cause of Human Freedom, which from earliest days has been the darling of History. By all the memories of the Past, by the stories of childhood and the studies of youth, by every example of magnanimous virtue, by every aspiration for the good and true, by the fame of martyrs swelling through all time, by the renown of patriots whose lives are landmarks of progress, by the praise lavished upon our fathers, are you summoned to this work. Unless Freedom be an illusion, and Benevolence an error, you cannot resist the appeal. Who can doubt that our cause is nobler even than that of our fathers? for is it not more exalted to struggle for the freedom of others than for our own?

Its practical importance at this moment gives to it additional eminence. Whether measured by the number of beings it seeks to benefit, by the magnitude of the wrongs it hopes to relieve, by the difficulties with which it is beset, by the political relations which it affects, or by the ability and character it enlists, the cause of the slave now assumes proportions of grandeur which dwarf all other interests in our broad country. In its presence the machinations of politicians, the aspirations of office-seekers, and the subterfuges of party, all sink below even their ordinary insignificance. For myself, Sir, I see among us at this time little else by which an honest man, wishing to leave the world better than he found it, can be tempted out upon the exposed36 steeps of public life. I see little else which can afford any of those satisfactions an honest man should covet. Nor is there any cause so surely promising final success:—

It is written that in the last days there shall be scoffers, and even this Enterprise, thus philanthropic, does not escape their aspersions. As the objections to its Necessity were twofold, and the objections to its Practicability twofold, so also are the aspersions twofold,—first, in the form of hard words, and, secondly, by personal disparagement of those engaged in it.

1. The hard words are manifold as the passions and prejudices of men; but they generally end in the imputation of “fanaticism.” In such a cause I am willing to be called “fanatic,” or what you will; I care not for aspersions, nor shall I shrink before hard words, either here or elsewhere. They do not hurt. “My dear Doctor,” said Johnson to Goldsmith, “what harm does it do any man to call him Holofernes?” From that great Englishman, Oliver Cromwell, I have learned that one cannot be trusted “who is afraid of a paper pellet”; and I am too familiar with history not to know that every movement for reform, in Church or State, every endeavor for Human Liberty or Human Rights, has been thus assailed. I do not forget with what facility and frequency hard words are employed: how that grandest character of many generations, the precursor of our own Washington, without whose example our Republic might have failed, the great William, Prince of Orange,37 founder of the Dutch Republic, the United States of Holland,—I do not forget how he was publicly branded as “a perjurer and a pest of society”; and, not to dwell on general instances, how the enterprise for the abolition of the slave-trade was characterized on the floor of Parliament, by one eminent speaker as “mischievous,” and by another as “visionary and delusive”; and how the exalted characters which it enlisted were arraigned by still another eminent speaker,—none other than that Tarleton, so conspicuous as commander of the British horse in the Southern campaigns of our Revolution, but more conspicuous in politics at home,—“as a junto of sectaries, sophists, enthusiasts, and fanatics”; and yet again were arraigned by no less a person than a prince of the blood, the Duke of Clarence, afterwards William the Fourth of England, as “either fanatics or hypocrites,” in one of which categories he openly placed William Wilberforce.[19] Impartial History, with immortal pen, has redressed these impassioned judgments; nor has the voice of the poet been wanting:—

But the same impartial History will yet re-judge the impassioned judgments of this hour.

2. Hard words have been followed by personal disparagement, and the sneer is often raised that our Enterprise lacks the authority of names eminent in Church and State. If this be so, the more is the pity on their account; for our cause is needful to them more than38 they are needful to our cause. Alas! it is only according to example of history that it should be so. It is not the eminent in Church and State, the rich and powerful, the favorites of fortune and of place, who most promptly welcome Truth, when she heralds change in the existing order of things. It is others in poorer condition who open hospitable hearts to the unattended stranger. This is a sad story, beginning with the Saviour, whose disciples were fishermen, and ending only in our own day. Each generation has its instances. But the cause cannot be judged by any such indifference. Strong in essential truth, it awaits the day, surely at hand, when all will flock to its support. As the rights of man are at last recognized, the scoffers, now so heartless, will forget to scoff.

And now, Sir, I present to you the Antislavery Enterprise vindicated, in Necessity, Practicability, and Dignity, against all objection. If there be any which I have not answered, it is because I am not aware of its existence. It remains that I should give a practical conclusion to this whole matter, by showing, though in glimpses only, your Special Duties as Freemen of the North. And, thank God! at last there is a North.

Mr. President, it is not uncommon to hear persons among us at the North confess the wrong of Slavery, and then, folding the hands in absolute listlessness, ejaculate, “What can we do about it?” Such we encounter daily. You all know them. Among them are men in every department of human activity,—who perpetually buy, build, and plan,—who shrink from no labor,—who are daunted by no peril of commercial39 adventure, by no hardihood of industrial enterprise,—who, reaching in their undertakings across ocean and continent, would promise to “put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes”; and yet, disheartened, they can join in no effort against Slavery. Others there are, especially among the youthful and enthusiastic, who vainly sigh because they were not born in the age of Chivalry, or at least in the days of the Revolution, not thinking that in this Enterprise there is opportunity for lofty endeavor such as no Paladin of Chivalry or chief of the Revolution enjoyed. Others there are who freely bestow means and time upon distant, inaccessible heathen of another hemisphere, in islands of the sea; and yet they can do nothing to mitigate our graver heathenism here at home. While confessing that it ought to disappear from the earth, they forego, renounce, and abandon all effort to this end. Others there are still (such is human inconsistency!) who plant the tree in whose full-grown shade they can never expect to sit,—who hopefully drop the acorn in the earth, trusting that the oak which it sends upward to the skies will shelter their children beneath its shade; but they do nothing to plant or nurture the great tree of Liberty, that it may shield with its arms unborn generations of men.

Others still there are, particularly in large cities, who content themselves with occasional contribution to the redemption of a slave. To this object they give out of ample riches, and thus seek to silence the monitions of conscience. I would not discountenance any activity by which Human Freedom, even in a single case, may be secured; but I desire to say that such an act—too often accompanied by pharisaical pretension, in contrast40 with the petty performance—cannot be considered essential aid to the Antislavery Enterprise. Not in this way can impression be made on an evil so vast as Slavery,—so widely scattered, and so exhaustless in its unnatural supply. The god Thor, of Scandinavian mythology, whose power surpassed that of Hercules, was once challenged to drain dry a simple cup. He applied it to his lips, and with superhuman capacity drank, but the water did not recede even from the rim, and at last the god abandoned the trial. The failure of even his extraordinary prowess was explained, when he learned that the cup communicated, by invisible connection, with the whole vast ocean behind, out of which it was perpetually supplied, and which remained absolutely unaffected by the effort. And just so will these occasions of charity, though encountered by the largest private means, be constantly renewed; for they communicate with the whole Black Sea of Slavery behind, out of which they are perpetually supplied, and which remains absolutely unaffected by the effort. Sir, private means may cope with individual necessities, but they are powerless to redress the evils of a wicked institution. Charity is limited and local; the evils of Slavery are infinite and everywhere. Besides, a wrong organized and upheld by law can be removed only through change of the law. Not, then, by occasional contribution to ransom a slave can your duty be done in this great cause, but only by earnest, constant, valiant effort against the institution, against the law, which makes slaves.

I am not insensible to the difficulties of this work. Full well I know the power of Slavery. Full well I know all its various intrenchments in the Church, the41 politics, and the prejudices of the country. Full well I know the wakeful interests of property, amounting to many hundred millions of dollars, which are said to be at stake. But these things can furnish no motive or apology for indifference, or any folding of the hands. Surely the wrong is not less wrong because gigantic; the evil is not less evil because immeasurable; nor can the duty of perpetual warfare with wrong and evil be in this instance suspended. Nay, because Slavery is powerful, because the Enterprise is difficult, therefore is the duty of all more exigent. The well-tempered soul does not yield to difficulties, but presses onward forever with increased resolution.

But the question recurs, so often pressed in argument, or in taunt, What have we at the North to do with Slavery? In answer, I might content myself by saying, that, as members of the human family, bound together by cords of common manhood, there is no human wrong to which we can be insensible, nor is there any human sorrow which we should not seek to relieve; but I prefer to say, on this occasion, that, as citizens of the United States, anxious for the good name, the repose, and the prosperity of the Republic, that it may be a blessing and not a curse to mankind, there is nothing among all its diversified interests, under the National Constitution, with which, at this moment, we have so much to do; nor is there anything with regard to which our duties are so irresistibly clear. I do not dwell on the scandal of Slavery in the national capital, of Slavery in the national territories, of the coastwise slave-trade on the high seas beneath the national flag,—all of which are outside State limits, and within the exclusive jurisdiction of Congress, where you and I, Sir, and42 every freeman of the North, are compelled to share the giant sin and help to bind its chain. To dislodge Slavery from these usurped footholds, and thus at once relieve ourselves from grievous responsibility, and begin the great work of Emancipation, were an object worthy an exalted ambition. But before even this can be commenced, there is a great work, more than any other important and urgent, which must be consummated in the domain of national politics, and also here at home in the Free States. The National Government itself must be emancipated, so that it shall no longer wear the yoke of servitude; and Slavery in all its pretensions must be dislodged from a usurped foothold in the Free States themselves, thus relieving ourselves from serious responsibility at our own door, and emancipating the North. Emancipation, even within the national jurisdiction, can be achieved only through emancipation of the Free States, accompanied by complete emancipation of the National Government. Ay, Sir, emancipation at the South can be reached only through emancipation of the North. And this is my answer to the interrogatory, What have we at the North to do with Slavery?

But the answer may be made yet more irresistible, while, with mingled sorrow and shame, I portray the tyrannical power which holds us in thraldom. Notwithstanding all its excess of numbers, wealth, and intelligence, the North is now the vassal of an OLIGARCHY, whose single inspiration comes from Slavery. According to official tables of our recent census, the slave-masters, all told, are only THREE HUNDRED AND FORTY-SEVEN THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-FIVE;[21] and yet this small company43 now dominates over the Republic, determines its national policy, disposes of its offices, and sways all to its absolute will. With a watchfulness that never sleeps and an activity that never tires, the SLAVE OLIGARCHY asserts its perpetual and insatiate masterdom,—now seizing a broad territory once covered by a time-honored ordinance of Freedom,—now threatening to wrest Cuba from Spain by violent war, or hardly less violent purchase,—now hankering for another slice of Mexico, merely to find new scope for Slavery,—now proposing once more to open the hideous, Heaven-defying Slave-Trade, thus replenishing its shambles with human flesh,—and now, by the lips of an eminent Senator, asserting an audacious claim to the whole group of the West Indies, whether held by Holland, Spain, France, or England, as “our Southern islands,”[22] while it assails the independence of Hayti, and extends its treacherous ambition even to the distant valley of the Amazon.

For all this tyranny there must be tools, and these are found through a new test for office, where Slavery is the shibboleth. Nobody, throughout this Republic, who cannot repeat the hateful word, is taken,—nobody, unless faithful to Slavery, is accepted for any post under the National Government. Yes, let it be proclaimed, that now at last, not honesty, not capacity, not fidelity to the Constitution is the test for office, but unhesitating support of Slavery. This is fidelity, this is loyalty, according to the new dispensation. And thus the strength of the whole people is transfused into this oligarchy. The Constitution, the flag44 itself, and everything we call our own, is degraded to this wicked rule.

And this giant strength is used with giant heartlessness. By cruel enactment, which has no source in the Constitution, which defies justice, tramples on humanity, and rebels against God, the Free States are made the hunting-ground for slaves, and you and I and all good citizens are pressed to join in the loathsome and abhorred work. Your hearts and judgments, swift to feel and to condemn, will not require me to expose here the abomination of the Fugitive Slave Bill, or its unconstitutionality. Elsewhere I have done this, and never been answered. Nor will you expect that an enactment so entirely devoid of all just sanction should be called by the sacred name of law. History still repeats the language in which our fathers persevered, when they denounced the last emanation of British tyranny which heralded the Revolution, as the Boston Port Bill; and I am content with this precedent. I have said, that, if any man finds in the Gospel any support of Slavery, it is because Slavery is already in himself; so do I now say, if any man finds in the Constitution of our country any support of the Fugitive Slave Bill, it is because that bill is already in himself. One of our ancient masters—Aristotle, I think—tells us that every man has a beast in his bosom; but the Northern citizen who has the Fugitive Slave Bill there has worse than a beast,—a devil! And yet in this bill, more even than in the ostracism at which you rebel, does the Slave Oligarchy stand confessed,—heartless, grasping, tyrannical,—careless of humanity, right, or the Constitution,—whose foundation is a coalition of wrong-doers, without even the semblance of decency,—while it degrades the Free45 States to the condition of a slave plantation, under the lash of a vulgar, despised, and revolting overseer.

Surely, fellow-citizens, without hesitation or postponement, you will insist that this Oligarchy shall be overthrown; and here is the foremost among the special duties of the North, now required for the honor of the Republic, for our own defence, and in obedience to God.

In urging this comprehensive duty, I ought to have hours rather than minutes; but in a few words you shall see its comprehensive importance. With the disappearance of the Slave Oligarchy, the wickedness of the Fugitive Slave Bill will drop from the statute-book,—Slavery will cease at the national capital,—Freedom will become the universal law of the national territory,—the Slave-Trade will no longer skulk along our coast beneath the national flag,—the Slave-marriage of the nation will be dissolved,—the rule of our country will be Freedom instead of Slavery,—the North will no longer be trampled on by the South,—the North will at last be allowed its just proportion of office and honor. Let all this be done, and much more will follow. With the disappearance of the Slave Oligarchy, you will possess the master-key to unlock the whole house of bondage. Oh, Sir! prostrate the Slave Oligarchy, and the gates of Emancipation will be open at the South.

Without waiting for this consummation, there is another special duty here at home, on our own soil, which must be made free in reality, as in name. And here I shall speak frankly, though not without a proper sense of the responsibility of my words. I know that I cannot address you entirely as a private citizen; but I shall say nothing here which I have not said elsewhere, and which46 I shall not be proud to vindicate everywhere. “A lie,” it has been declared, “should be trampled out and extinguished forever”; and surely you will do nothing less with a tyrannical and wicked enactment. The Fugitive Slave Bill, while it continues unrepealed, must be made a dead letter,—not by violence, not by any unconstitutional activity or intervention, not even by hasty conflict between jurisdictions,—but by an aroused Public Opinion, which, in its irresistible might, shall blast with contempt, indignation, and abhorrence all who consent to be its agents. Thus did our fathers blast all who became agents of the Stamp Act; and surely their motive was small, compared with ours. The Slave-Hunter who drags his victim from Africa is loathed as a monster; but I defy any acuteness of reason to indicate the moral difference between his act and that of the Slave-Hunter who drags his victim from our Northern free soil. A few puny persons, calling themselves Congress, with titles of Representatives and Senators, cannot turn wrong into right, cannot change a man into a thing, cannot reverse the irreversible law of God, cannot make him wicked who hunts a slave on the burning sands of Congo or Guinea, and make him virtuous who hunts a slave over the pavements of Boston or New York. Nor can any acuteness of reason distinguish between the original bill of sale from the kidnapper, by which the unhappy African was transferred in Congo or Guinea, and the certificate of the Commissioner, by which, when once again in Freedom, he is reduced anew to bondage. The acts are kindred, and should share a kindred condemnation.

One man’s virtue becomes a standard of excellence for all; and there is now in Boston a simple citizen whose47 example may be a lesson to Commissioners, Marshals, Magistrates, while it fills all with the beauty of a generous act. I refer to Mr. Hayes, who resigned his place in the city police rather than take part in the pack of the Slave-Hunter. He is now the door-keeper of the public edifice honored this winter by the triumphant lectures on Slavery. Better be a door-keeper in the house of the Lord than a dweller in the tents of the ungodly. Has he not chosen well? Little think those now doing the work of Slavery that the time is near when all this will be dishonor and sadness. For myself, long ago my mind was made up. Nothing will I have to do with it. How can I help to make a slave? The idea alone is painful. To do this thing would plant in my soul a remorse which no time could remove or mitigate. His chains would clank in my ears. His cries would strike upon my heart. His voice would be my terrible accuser. Mr. President, may no such voice fall on your soul or mine!

Yes, Sir, here our duty is plain and paramount. While the Slave Oligarchy, through its unrepealed Slave Bill, undertakes to enslave our free soil, we can only turn for protection to a Public Opinion worthy of a humane, just, and religious people, which shall keep perpetual guard over the liberties of all within our borders. On this from the beginning I have relied. On this I now rely. Wherever it is already strong, I would keep it so; wherever it is weak, I would strengthen it, until of itself it is an all-sufficient protection, with watch and ward surrounding the fugitive, surrounding all. And this Public Opinion, with Freedom as its countersign, must proclaim not only the overthrow of the Slave Bill, but also the overthrow of the Slave Oligarchy behind,—the48 two pressing duties of the North, essential to our own emancipation; and believe me, Sir, while they remain undone, nothing is done.

Mr. President, far already have I trespassed upon your generous patience; but there are other things pressing for utterance. Something would I say of the arguments by which our Enterprise is commended; something also of the appeal it makes to people of every condition; and something, too, of union, as a vital necessity, among all who love Freedom.

I know not if our work will be soon accomplished. I know not, Sir, if you or I shall live to see in our Republic the vows of the Fathers at length fulfilled, as the last fetter falls from the last slave. But one thing I do know, beyond all doubt or question: that this Enterprise must go on; that, in its irresistible current, it will sweep schools, colleges, churches, the intelligence, the conscience, and the religious aspiration of the land, while all who stand in its way or speak evil of it are laying up sorrow and shame for their children, if not for themselves. Better strive in this cause, even unsuccessfully, than never strive at all. The penalty of indifference is akin to the penalty of opposition,—as is well pictured by the great Italian poet, when, among the saddest on the banks of Acheron, rending the air with outcries of torment, shrieks of anger, and smiting of hands, he finds the troop of dreary souls who had been ciphers in the great conflicts of life:—