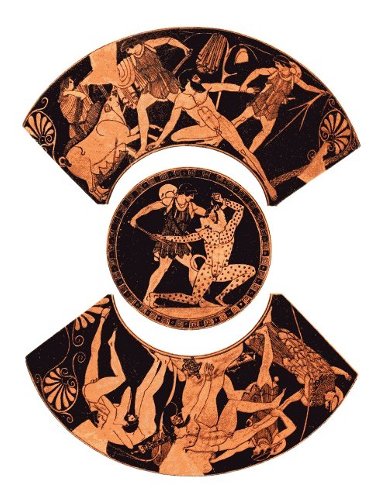

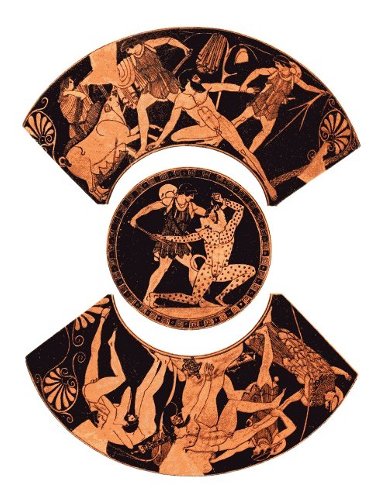

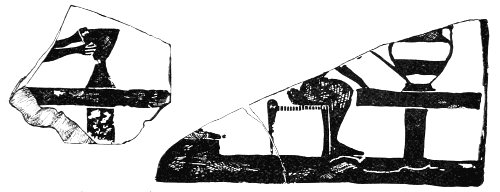

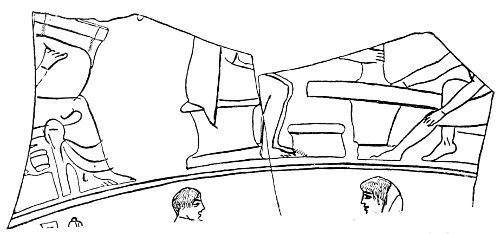

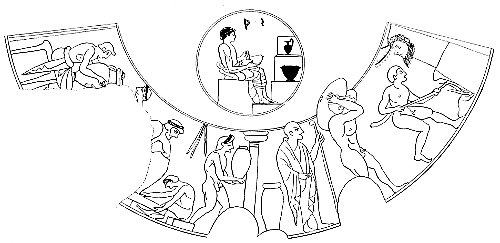

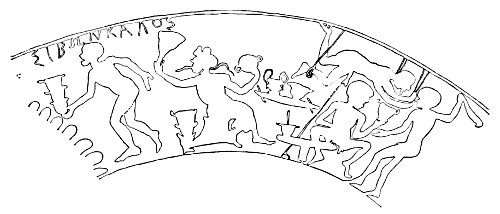

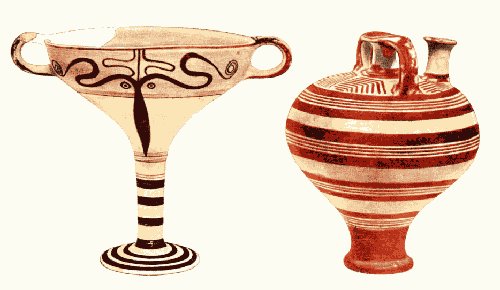

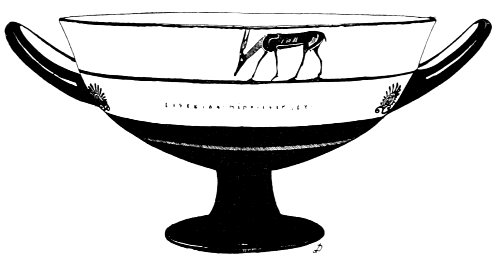

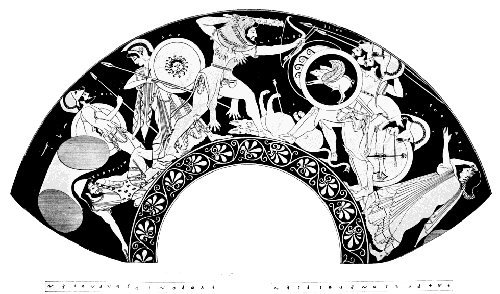

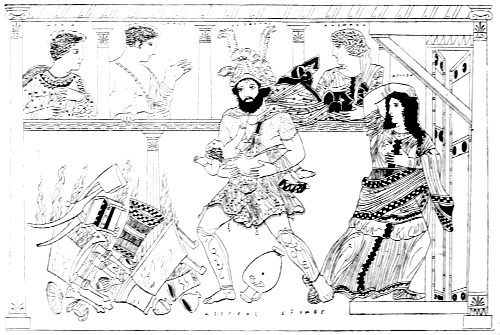

KYLIX BY DURIS.

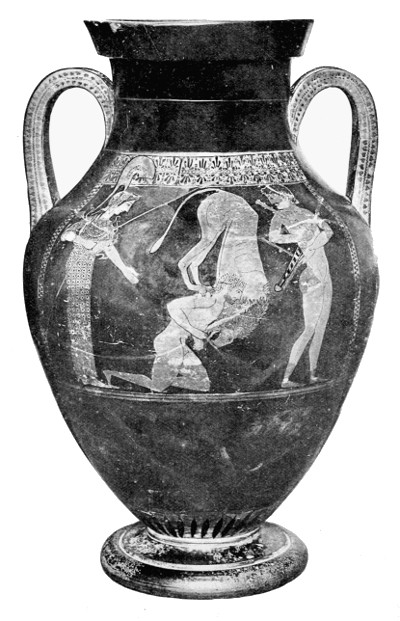

THE LABOURS OF THESEUS.

(British Museum).

Title: History of Ancient Pottery: Greek, Etruscan, and Roman. Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: H. B. Walters

Samuel Birch

Release date: February 7, 2015 [eBook #48154]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by KD Weeks, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

Minor errors in punctuation and formatting have been silently corrected. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered during its preparation. The end note also discusses the handling of the many Greek inscriptions.

Volume II of this text is available separately at Project Gutenberg at:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/48155

References to Volume II are linked as well for ease of navigation.

KYLIX BY DURIS.

THE LABOURS OF THESEUS.

(British Museum).

In 1857 Dr. Samuel Birch issued his well-known work on ancient pottery, at that time almost the first attempt at dealing with the whole subject in a comprehensive manner. Sixteen years later, in 1873, he brought out a second edition, in some respects condensed, in others enlarged and brought up to date. But it is curious to reflect that the succeeding sixteen years should not only have doubled or even trebled the material available for a study of this subject, but should even have revolutionised that study. The year 1889 also saw the completion of the excavations of the Acropolis at Athens, which did much to settle the question of the chronology of Attic vases. Yet another sixteen years, and if the increase in actual bulk of material is relatively not so great, yet the advance in the study of pottery, especially that of the primitive periods, has been astounding; and while in 1857, and even in 1873, it was impossible to do much more than collect and co-ordinate material, in 1905 Greek ceramics have become one of the most advanced and firmly based branches of classical archaeology.

It therefore implies no slur on the reputation of Samuel Birch’s work that it has become out of date. Up till now it has remained the only comprehensive treatise, and therefore the standard work, on the subject; but of late years there has been a crying need, especially in England, of a book which should place before students a condensed and up-to-date account of Greek vases and of the present state of knowledge of the subject. The present volumes, while following in the main the plan adopted by Dr. Birch, necessarily deviate therefrom in some important particulars. It has been decided to omit entirely the section relating to Oriental pottery, partly from considerations of space, partly from the impossibility of doing justice to the subject except in a separate treatise; for the same reason the pottery of the Celts and of Northern Europe has been ignored. Part I. of the present work, dealing chiefly with the technical aspect of the subject, remains in its main outlines much as it was thirty years ago; but the other sections have been entirely re-written. For the historical account of vase-painting in Birch’s second edition one chapter of forty pages sufficed; it now extends to six chapters, or one quarter of the work. The subjects on the vases, again, occupy four chapters instead of two; and modern researches have made it possible to treat the subjects of Etruscan and Roman pottery with almost the same scientific knowledge as that of Greece.

A certain amount of repetition in the various sections will, it is hoped, be pardoned on the ground that it was desirable to make each section as far as possible complete in itself; and another detail which may provoke unfavourable criticism is the old difficulty of the spelling of Greek names and words. In regard to the latter the author admits that consistency has not been attained, but his aim has been rather to avoid unnecessary Latinising on the one hand and pedantry on the other.

Finally, the author desires to express his warmest acknowledgments to all who have been of assistance to him in his work, by their writings or otherwise, especially to a friend, desiring to be nameless, who has kindly read through the proofs and made many useful suggestions; to the invaluable works of many foreign scholars, more particularly those of M. Pottier, M. Salomon Reinach, and M. Déchelette, he owes a debt which even a constant acknowledgment in the text hardly repays. Thanks are also due to the Trustees of the British Museum for kind permission to reproduce their blocks for Figs. 75, 109, 118, 125, 128, 131, 138, 185, 191, and 197, to M. Déchelette for permission to reproduce from his work the vases given in Figs. 224, 226, and to the Committee of the British School at Athens for similar facilities in regard to Plate XIV. (pottery from Crete). Lastly, but by no means least, the author desires to express to Mr. Hallam Murray his deep sense of obligation for the warm interest he has shown in the work throughout and for the pains he has taken to ensure the success of its outward appearance.

London, January 1905.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v |

| CONTENTS OF VOLUME I | ix |

| LIST OF PLATES IN VOLUME I | xiii |

| LIST OF TEXT-ILLUSTRATIONS IN VOLUME I | xv |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANCIENT POTTERY | xix |

| NOTE ON ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS WORK | xxxvi |

| PART I | |

| GREEK POTTERY IN GENERAL | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| Importance of study of ancient monuments—Value of pottery as evidence of early civilisation—Invention of the art—Use of brick in Babylonia—The potter’s wheel—Enamel and glazes—Earliest Greek pottery—Use of study of vases—Ethnological, historical, mythological, and artistic aspects—Earliest writings on the subject—The “Etruscan” theory—History of the study of Greek vases—Artistic, epexegetic, and historical methods—The vase-collections of Europe and their history—List of existing collections | 1–30 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| SITES AND CIRCUMSTANCES OF DISCOVERY OF GREEK VASES | |

| Historical and geographical limits of subject—Description of Greek tombs—Tombs in Cyprus, Cyrenaica, Sicily, Italy—Condition of vases when found—Subsequent restorations—Imitations and forgeries—Prices of vases—Sites on which painted vases have been found: Athens, Corinth, Boeotia, Greek islands, Crimea, Asia Minor, Cyprus, North Africa, Italy, Etruria—Vulci discoveries—Southern Italy, Sicily | 31–88 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE USES OF CLAY | |

| Technical terms—Sun-dried clay and unburnt bricks—Use of these in Greece—Methods of manufacture—Roof-tiles and architectural decorations in terracotta—Antefixal ornaments—Sicilian and Italian systems—Inscribed tiles—Sarcophagi—Braziers—Moulds—Greek lamps—Sculpture in terracotta—Origin of art—Large statues in terracotta—Statuettes—Processes of manufacture—Moulding—Colouring—Vases with plastic decoration—Reliefs—Toys—Types and uses of statuettes—Porcelain and enamelled wares—Hellenistic and Roman enamelled fabrics | 89–130 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| USES AND SHAPES OF GREEK VASES | |

| Mention of painted vases in literature—Civil and domestic use of pottery—Measures of capacity—Use in daily life—Decorative use—Religious and votive uses—Use in funeral ceremonies—Shapes and their names—Ancient and modern classifications—Vases for storage—Pithos—Wine-amphora—Amphora—Stamnos—Hydria—Vases for mixing—Krater—Deinos or Lebes—Cooking-vessels—Vases for pouring wine—Oinochoë and variants—Ladles—Drinking-cups—Names recorded by Athenaeus—Kotyle—Skyphos—Kantharos—Kylix—Phiale— Rhyton—Dishes—Oil-vases—Lekythos—Alabastron—Pyxis—Askos—Moulded vases | 131–201 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| TECHNICAL PROCESSES | |

| Nature of clay—Places whence obtained—Hand-made vases—Invention of potter’s wheel—Methods of modelling—Moulded vases and relief-decoration—Baking—Potteries and furnaces—Painted vases and their classification—Black varnish—Methods of painting—Instruments and colours employed—Status of potters in antiquity | 202–233 |

| PART II | |

| HISTORY OF GREEK VASE-PAINTING | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| PRIMITIVE FABRICS | |

| Introductory—Cypriote Bronze-Age pottery—Classification—Mycenaean pottery in Cyprus—Graeco-Phoenician fabrics—Shapes and decoration—Hellenic and later vases—Primitive pottery in Greece—Troy—Thera and Cyclades—Crete—Recent discoveries—Mycenaean pottery—Classification and distribution—Centres of fabric—Ethnography and chronology | 234–276 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| RISE OF VASE-PAINTING IN GREECE | |

| Geometrical decoration—Its origin—Distribution of pottery—Shapes and ornamentation of vases—Subjects—Dipylon vases—Boeotian Geometrical wares—Chronology—Proto-Attic fabrics—Phaleron ware—Later Boeotian vases—Melian amphorae—Corinth and its pottery—“Proto-Corinthian” vases—Vases with imbrications and floral decoration—Incised lines and ground-ornaments—Introduction of figure-subjects—Chalcidian vases—“Tyrrhenian Amphorae” | 277–327 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| VASE-PAINTING IN IONIA | |

| General characteristics—Classification—Mycenaean influence—Rhodian pottery—“Fikellura” ware—Asia Minor fabrics—Cyrenaic vases—Naukratis and its pottery—Daphnae ware—Caeretan hydriae—Other Ionic fabrics—“Pontic” vases—Early painting in Ionia—Clazomenae sarcophagi | 328–367 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| ATHENIAN BLACK-FIGURED VASES | |

| Definition of “black-figured”—The François vase—Technical and stylistic details—Shapes—Decorative patterns—Subjects and types—Artists’ signatures—Exekias and Amasis—Minor Artists—Nikosthenes—Andokides—“Affected” vases—Panathenaic amphorae—Vases from the Kabeirion—Opaque painting on black ground—Vase-painting and literary tradition—Early Greek painting and its subsequent development | 368–399 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| RED-FIGURED VASES | |

| Origin of red-figure style—Date of introduction—Καλός-names and historical personages—Technical characteristics—Draughtsmanship—Shapes—Ornamentation—Subjects and types—Subdivisions of style—Severe period and artists—Strong period—Euphronios—Duris, Hieron, and Brygos—Fine period—Influence of Polygnotos—Later fine period—Boeotian local fabric | 400–453 |

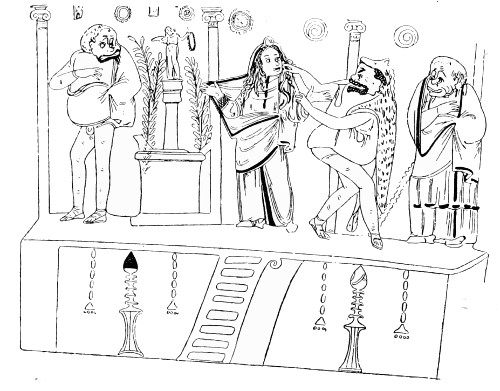

| CHAPTER XI | |

| WHITE-GROUND AND LATER FABRICS | |

| Origin and character of white-ground painting—Outline drawing and polychromy—Funeral lekythi—Subjects and types—Decadence of Greek vase-painting—Rise of new centres—Kertch, Cyrenaica, and Southern Italy—Characteristics of the latter fabrics—Shapes—Draughtsmanship—Influence of Tragedy and Comedy—Subjects—Paestum fabric—Lucanian, Campanian, and Apulian fabrics—Gnathia vases—Vases modelled in form of figures—Imitations of metal—Vases with reliefs—“Megarian” bowls—Bolsena ware and Calene phialae | 454–504 |

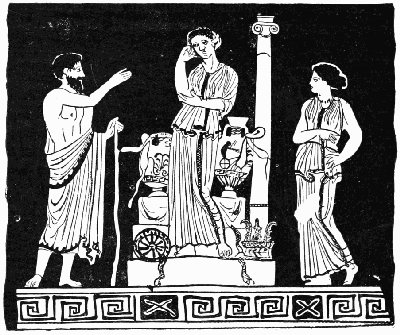

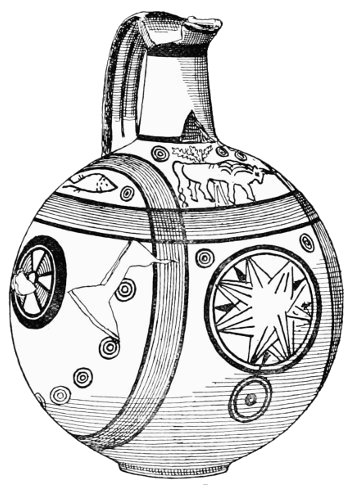

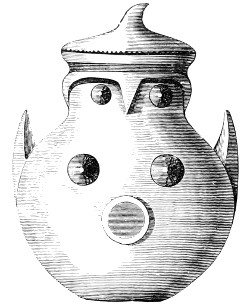

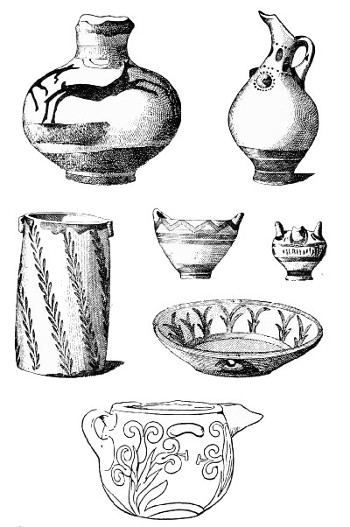

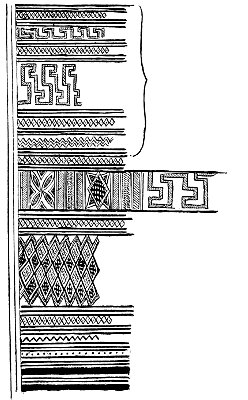

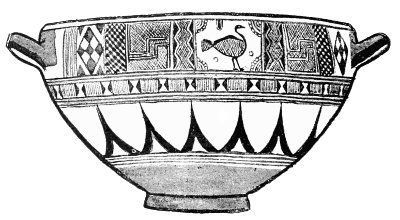

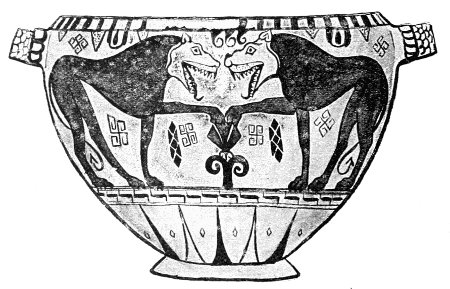

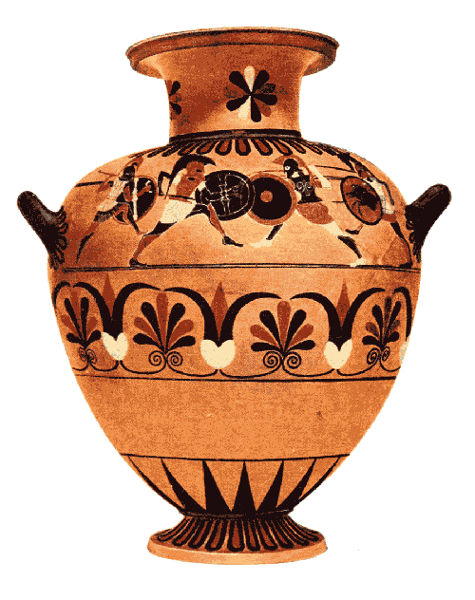

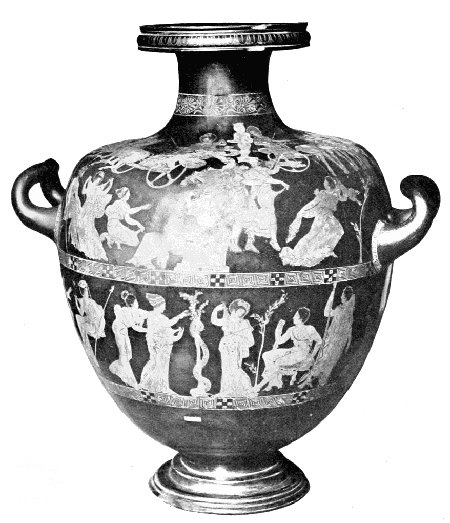

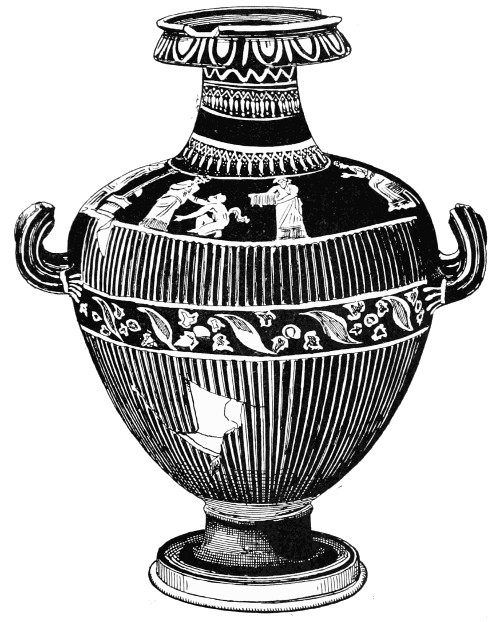

| PLATE | ||

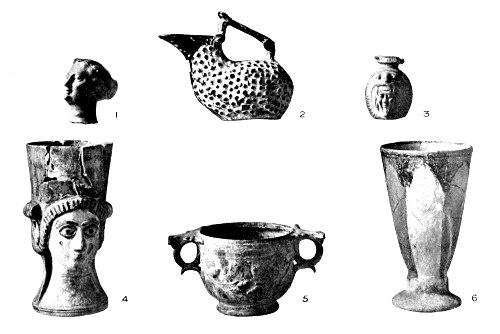

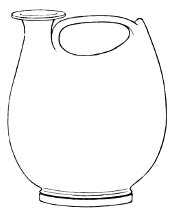

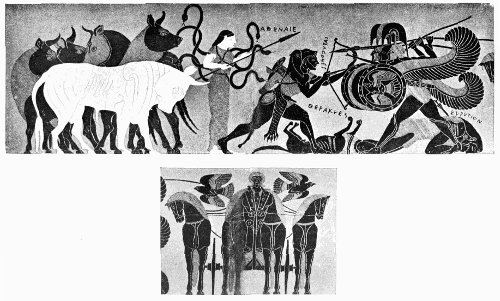

| I. | Kylix signed by Duris: Labours of Theseus (colours) | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | ||

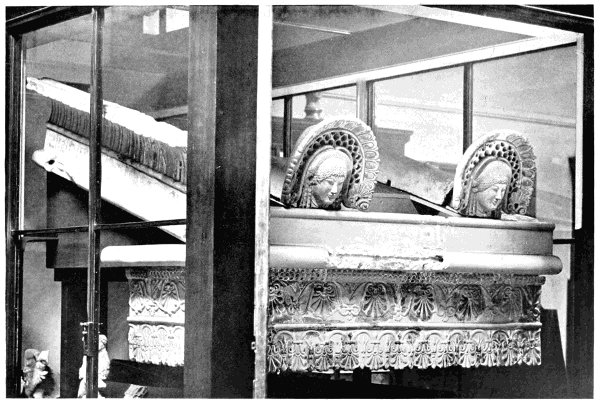

| II. | Archaic terracotta antefixes | 98 |

| III. | Restoration of temple at Civita Lavinia | 100 |

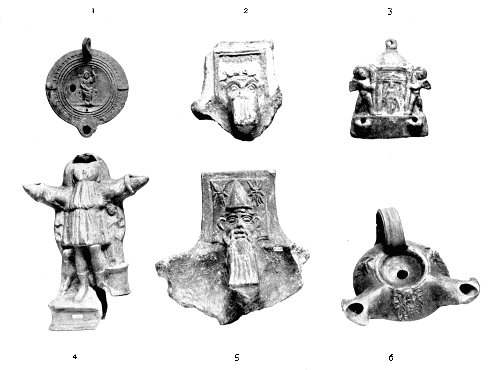

| IV. | Greek lamps and “brazier-handles” | 106 |

| V. | Moulds for terracotta figures | 114 |

| VI. | Terracotta vases from Southern Italy | 118 |

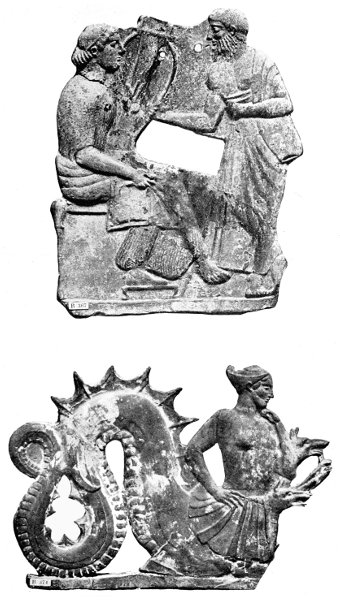

| VII. | “Melian” reliefs | 120 |

| VIII. | Archaic terracotta figures | 122 |

| IX. | Terracotta figures of fine style | 124 |

| X. | Porcelain and enamelled wares | 128 |

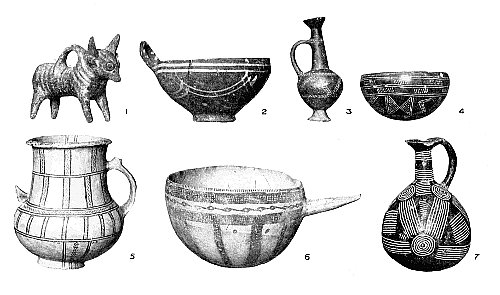

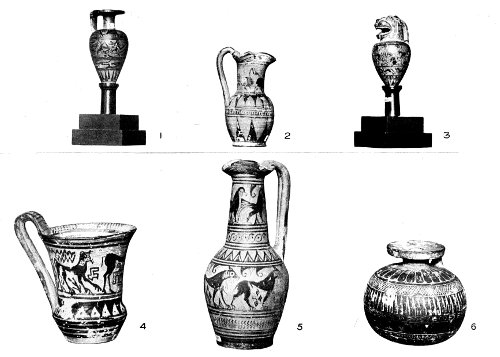

| XI. | Cypriote Bronze-Age pottery | 242 |

| XII. | Mycenaean vases found in Cyprus | 246 |

| XIII. | Cypriote “Graeco-Phoenician” pottery | 252 |

| XIV. | Example of Kamaraes ware from Palaiokastro, Crete (from Brit. School Annual) | 266 |

| XV. | Mycenaean vases (colours) | 272 |

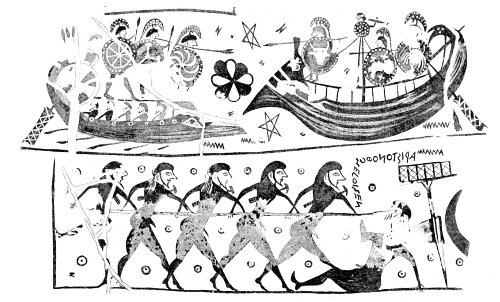

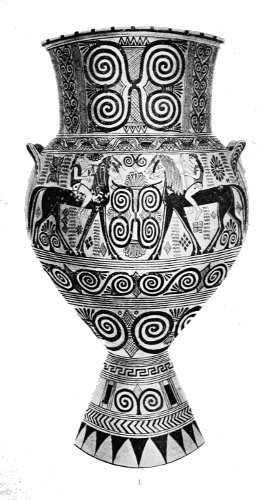

| XVI. | Subjects from the Aristonoös krater in the Vatican (from Wiener Vorl.) | 296 |

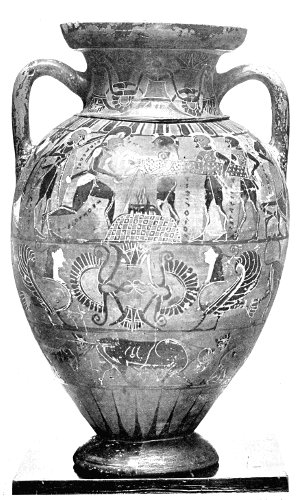

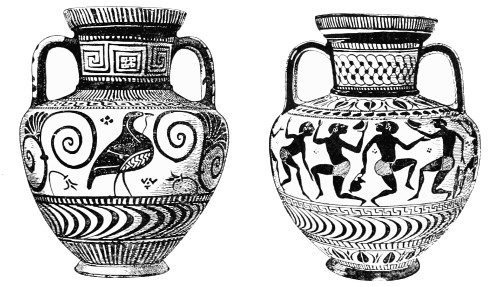

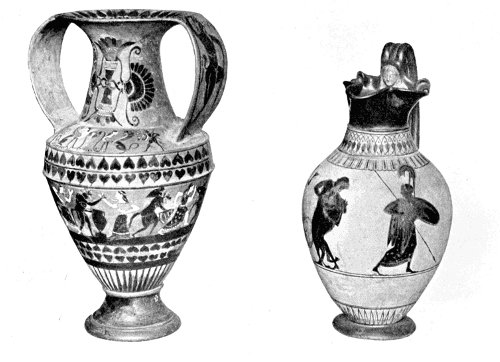

| XVII. | Phaleron, Boeotian, and Photo-Corinthian vases | 300 |

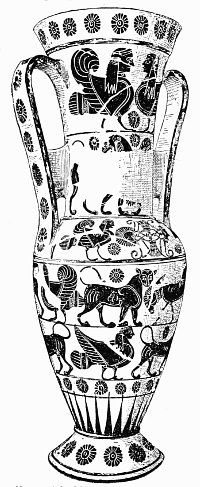

| XVIII. | Melian amphora in Athens (from Conze) | 302 |

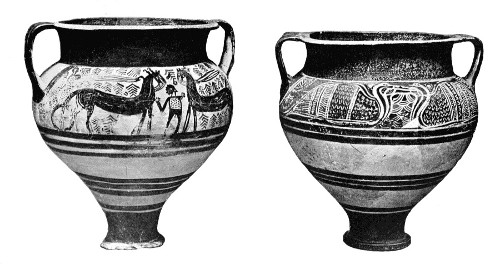

| XIX. | Proto-Corinthian and Early Corinthian vases | 308 |

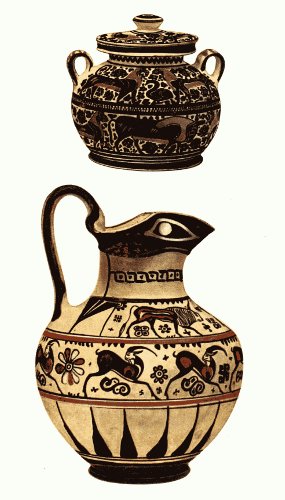

| XX. | Corinthian pyxis and Rhodian oinochoë (colours) | 312 |

| XXI. | Later Corinthian vases with figure subjects | 316 |

| XXII. | Chalcidian vase in Bibl. Nat., Paris: Herakles and Geryon; chariot | 320 |

| XXIII. | “Tyrrhenian” Amphora: The death of Polyxena | 324 |

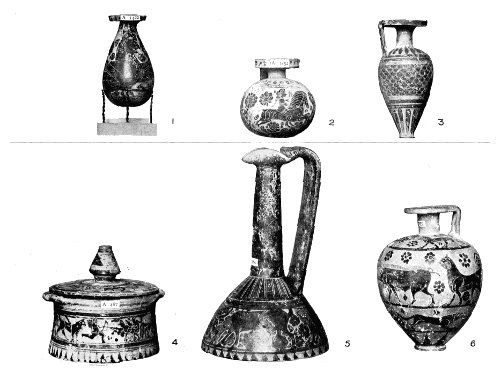

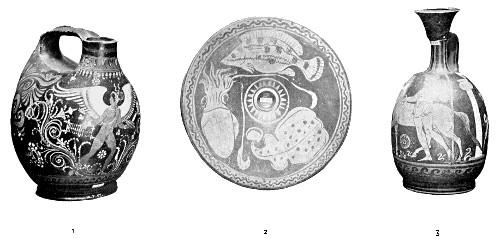

| XXIV. | Rhodian and Naucratite wares | 336 |

| XXV. | Situla from Daphnae; later Ionic vase in South Kensington | 352 |

| XXVI. | Caeretan hydria (colours) | 354 |

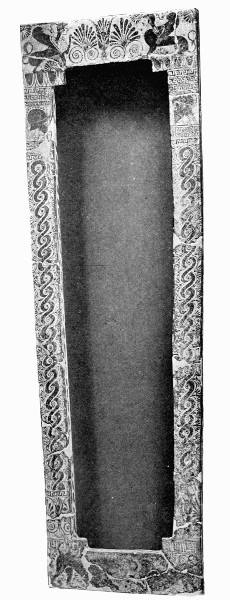

| XXVII. | Painted sarcophagus from Clazomenae | 364 |

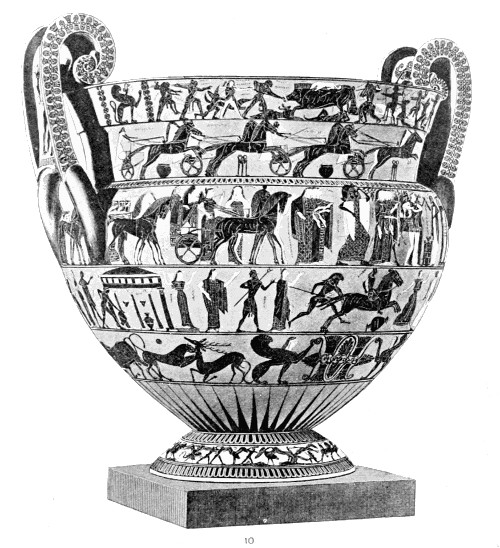

| XXVIII. | The François vase in Florence, general view (from Furtwaengler and Reichhold, Gr. Vasenm.) | 370 |

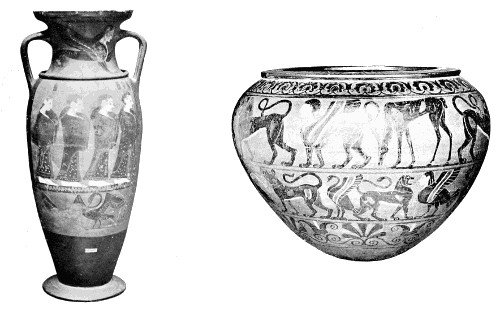

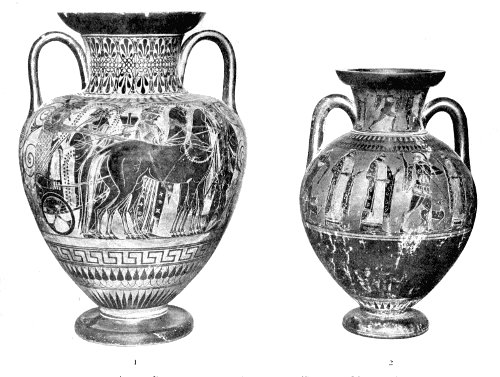

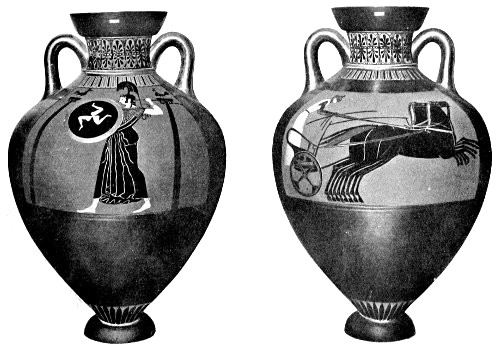

| XXIX. | Attic black-figured amphorae | 380 |

| XXX. | Vases by Nikosthenes | 384 |

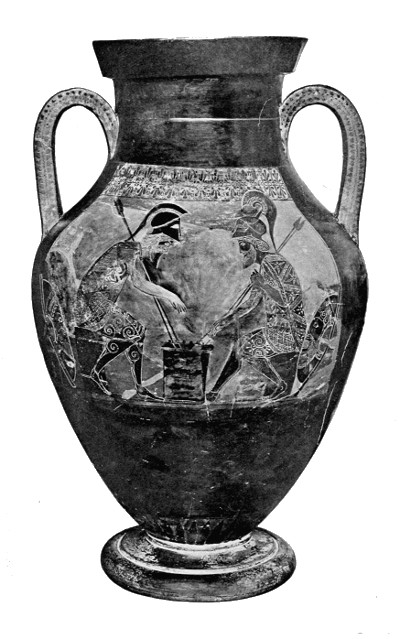

| XXXI. | Obverse of vase by Andokides: Warriors playing draughts (B.F.) | 386 |

| XXXII. | Reverse of vase by Andokides: Herakles and the Nemean lion (R.F.) | 386 |

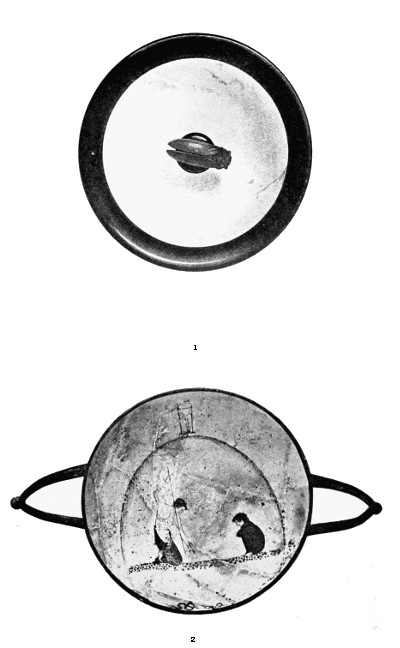

| XXXIII. | Panathenaic amphora, earlier style | 388 |

| XXXIV. | Panathenaic amphora, later style | 390 |

| XXXV. | Vases with opaque figures on black ground (Brit. Mus. and Louvre) | 394 |

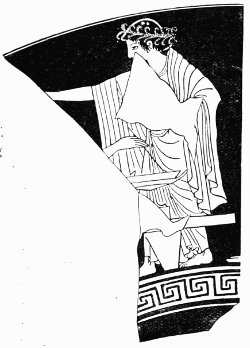

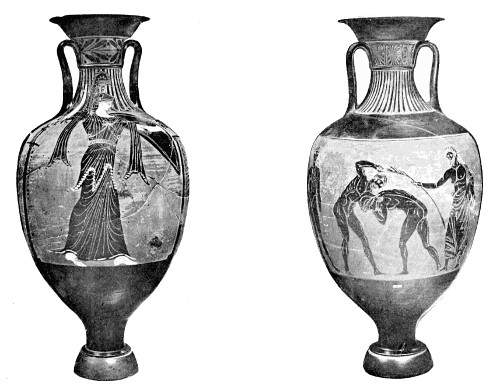

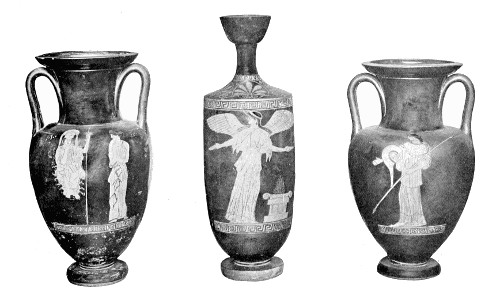

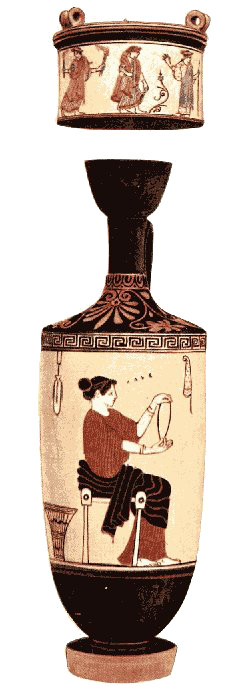

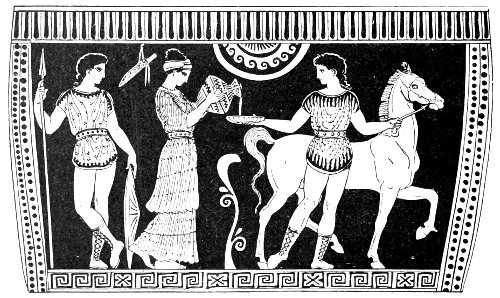

| XXXVI. | Red-figured “Nolan” amphorae and lekythos | 412 |

| XXXVII. | Cups of Epictetan style | 422 |

| XXXVIII. | Kylix at Munich signed by Euphronios: Herakles and Geryon (from Furtwaengler and Reichhold) | 432 |

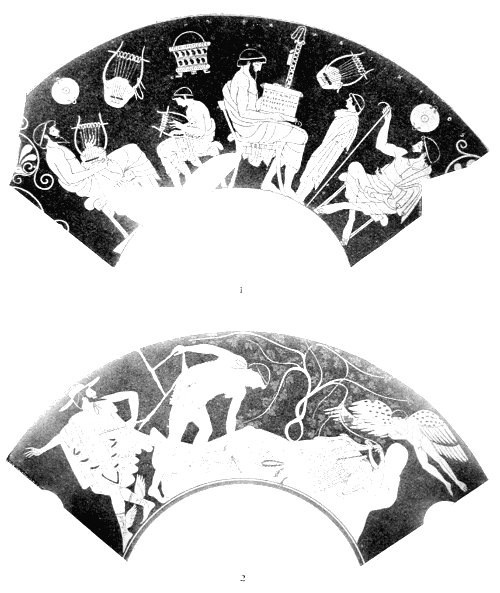

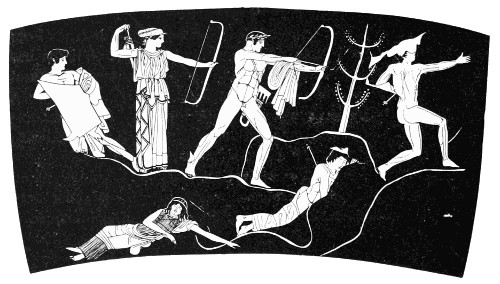

| XXXIX. | Kylikes by Duris at Berlin and in the style of Brygos at Corneto (from Baumeister) | 436 |

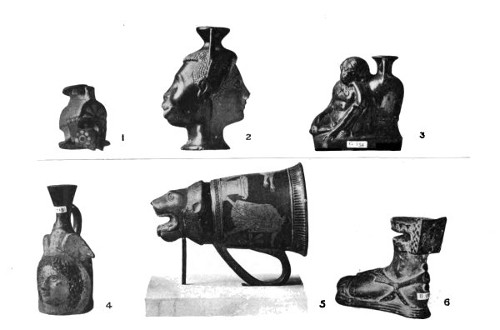

| XL. | Vases signed by Sotades (Brit. Mus. and Boston) | 444 |

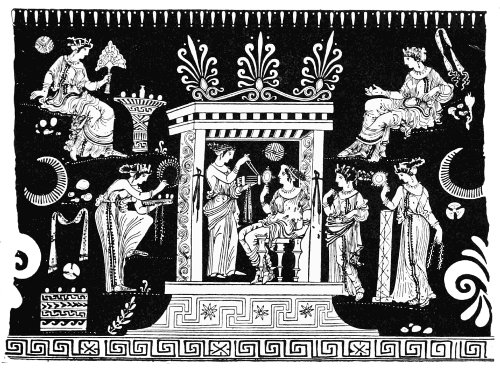

| XLI. | Hydria signed by Meidias | 446 |

| XLII. | Vases of “late fine” style (colours) | 448 |

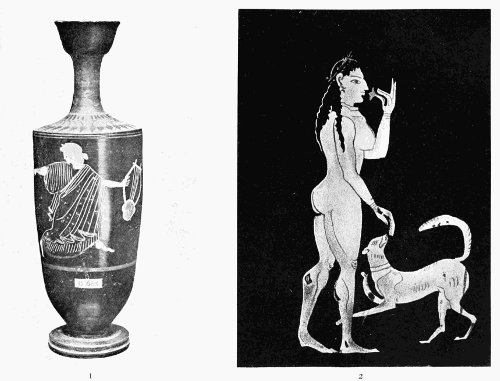

| XLIII. | Polychrome white-ground vases (colours) | 456 |

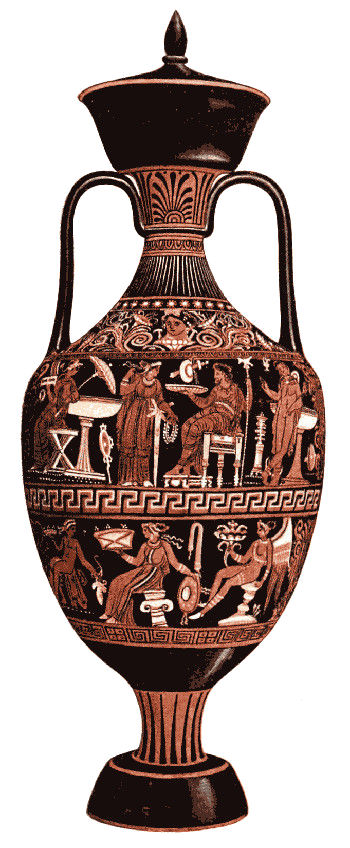

| XLIV. | Campanian and Apulian vases | 484 |

| XLV. | Apulian sepulchral vase (colours) | 486 |

| XLVI. | Vases modelled in various forms | 492 |

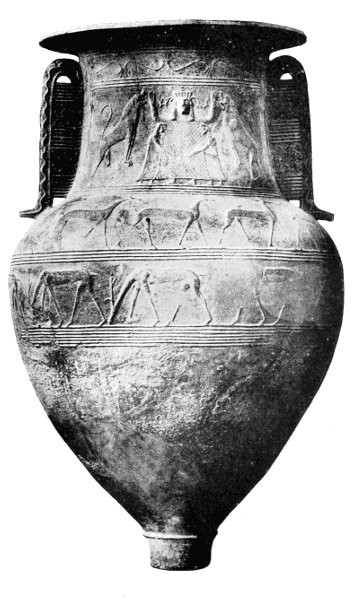

| XLVII. | Archaic vase in Athens with reliefs (from Ἐφημερὶς Ἀρχαιολογική) | 496 |

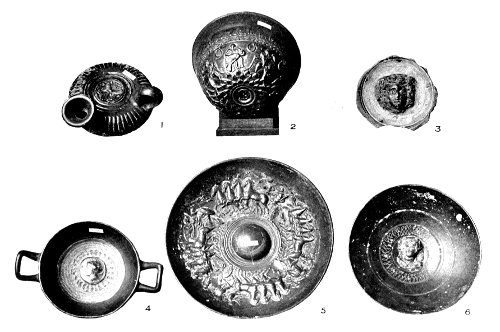

| XLVIII. | Vases of black ware with reliefs (Hellenistic period) | 500 |

| FIG. | PAGE | ||

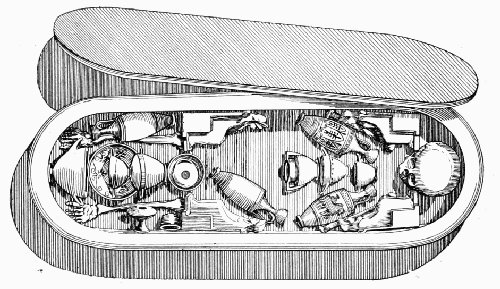

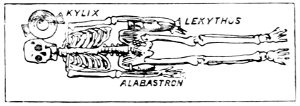

| 1. | Coffin containing vases, from Athens | Stackelberg | 34 |

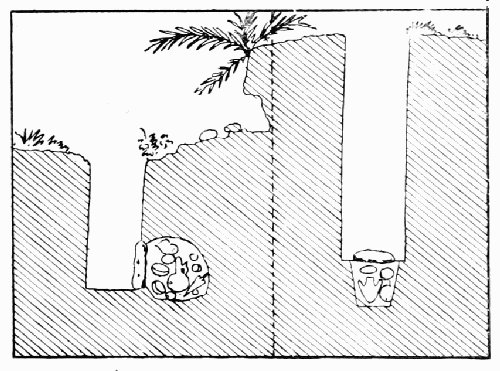

| 2. | Bronze-Age tombs in Cyprus | Ath. Mitth. | 35 |

| 3. | Tomb at Gela (Sicily) with vases | Ashmol. Vases | 37 |

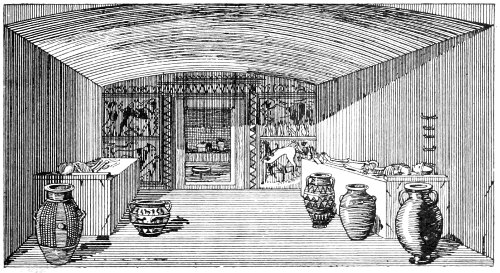

| 4. | Campana tomb at Veii | Campana | 39 |

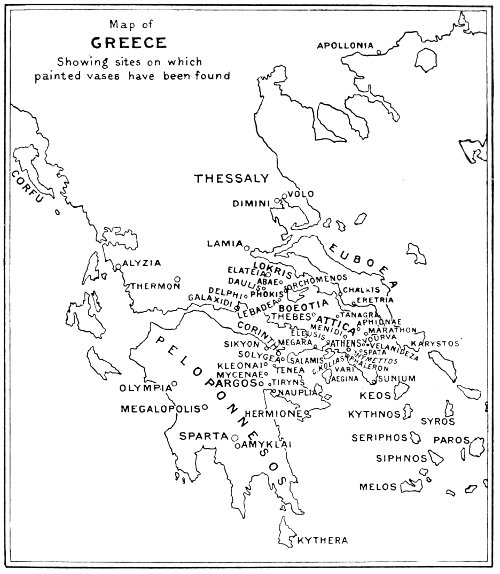

| 5. | Map of Greece | 47 | |

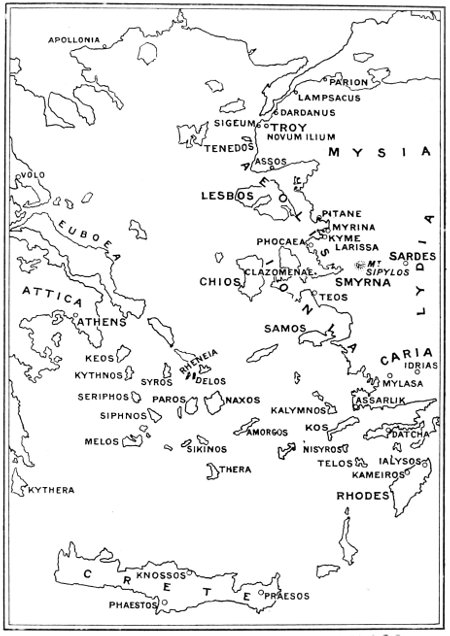

| 6. | Map of Asia Minor and the Archipelago | 63 | |

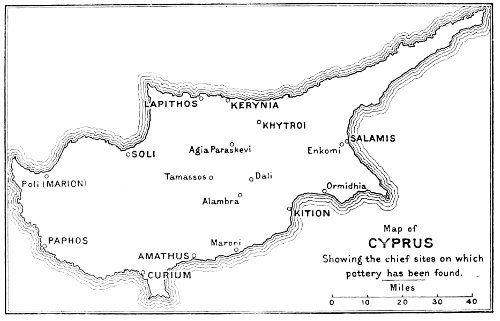

| 7. | Map of Cyprus | 66 | |

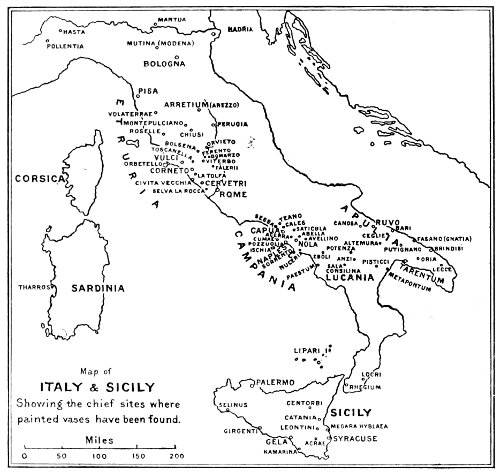

| 8. | Map of Italy | 70 | |

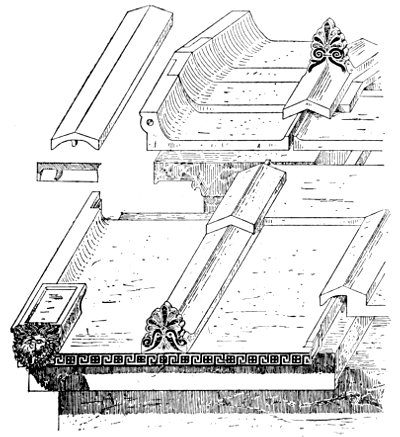

| 9. | Diagram of roof-tiling, Heraion, Olympia | Durm | 93 |

| 10. | Antefix from Marathon | Brit. Mus. | 99 |

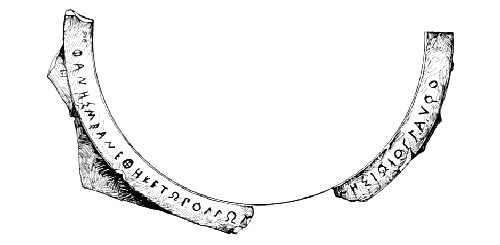

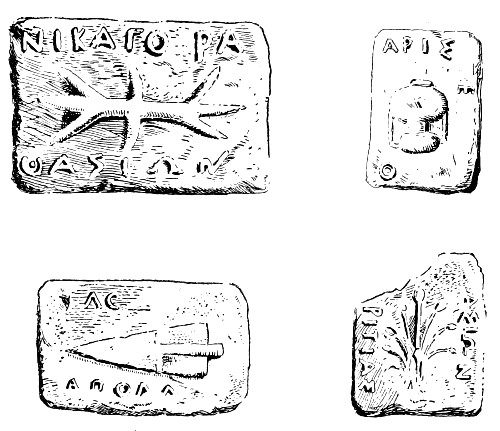

| 11. | Inscribed tiles from Acarnania and Corfu | Brit. Mus. | 102 |

| 12. | Ostrakon of Megakles | Benndorf | 103 |

| 13. | Ostrakon of Xanthippos | Jahrbuch | 103 |

| 14. | Hemikotylion from Kythera | Brit. Mus. | 135 |

| 15. | Child playing with jug | Brit. Mus. | 137 |

| 16. | Dedication to Apollo (Naukratis) | Brit. Mus. | 139 |

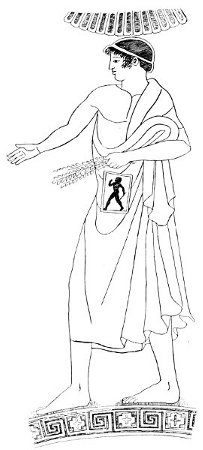

| 17. | Youth with votive tablet | Benndorf | 140 |

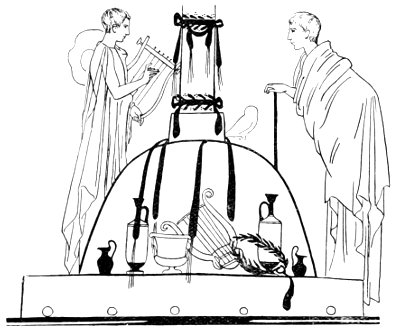

| 18. | Vases used in sacrifice | Furtwaengler and Reichhold | 141 |

| 19. | Funeral lekythos with vases inside tomb | Brit. Mus. | 143 |

| 20. | Vases placed on tomb (Lucanian hydria) | Brit. Mus. | 144 |

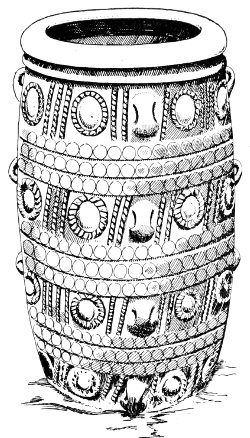

| 21. | Pithos from Knossos | 152 | |

| 22. | Greek wine-jars | Brit. Mus. | 154 |

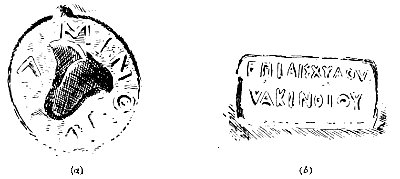

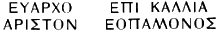

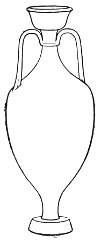

| 23. | Amphora-stamps from Rhodes | Dumont. | 156 |

| 24. | Amphora-stamps from Thasos | Dumont. | 158 |

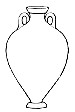

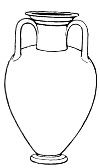

| 25. | “Tyrrhenian” amphora | 160 | |

| 26. | Panathenaic amphora | 160 | |

| 27. | Panel-amphora | 161 | |

| 28. | Red-bodied amphora | 161 | |

| 29. | “Nolan” amphora | 162 | |

| 30. | Apulian amphora | 162 | |

| 31. | “Pelike” | 163 | |

| 32. | Stamnos | 164 | |

| 33. | “Lekane” | 164 | |

| 34. | Hydria | 166 | |

| 35. | Kalpis | 166 | |

| 36. | Krater with column-handles | 169 | |

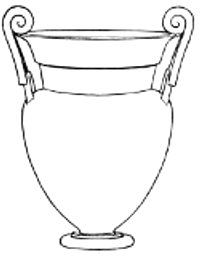

| 37. | Volute-handled krater | 170 | |

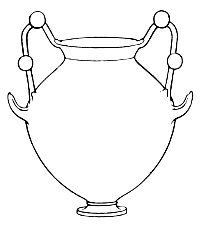

| 38. | Calyx-krater | 170 | |

| 39. | Bell-krater | 170 | |

| 40. | Lucanian krater | 172 | |

| 41. | Psykter | 173 | |

| 42. | Deinos or lebes | 173 | |

| 43. | Oinochoë (7th century) | 177 | |

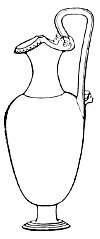

| 44. | Oinochoë (5th century) | 177 | |

| 45. | Prochoös | 178 | |

| 46. | Olpe | 178 | |

| 47. | Epichysis | 179 | |

| 48. | Kyathos | 179 | |

| 49. | Kotyle | 184 | |

| 50. | Kantharos | 188 | |

| 51. | Kylix (earlier form) | 190 | |

| 52. | Kylix (later form) | 191 | |

| 53. | Phiale | 191 | |

| 54. | Rhyton | 193 | |

| 55. | Pinax | 194 | |

| 56. | Lekythos | 196 | |

| 57. | Lekythos (later form) | 196 | |

| 58. | Alabastron | 197 | |

| 59. | Aryballos | 197 | |

| 60. | Pyxis | 198 | |

| 61. | Epinetron or Onos | 199 | |

| 62. | Askos | 200 | |

| 63. | Apulian askos | 200 | |

| 64. | Guttus | 200 | |

| 65. | Potter’s wheel, from Corinthian pinakes | Ant. Denkm. | 207 |

| 66. | Potter’s wheel (vase of about 500 B.C.) | Ath. Mitth. | 208 |

| 67. | Boy polishing vase; interior of pottery | Blümner | 213 |

| 68. | Seilenos as potter | 216 | |

| 69. | Interior of furnace (Corinthian pinax) | Ant. Denkm. | 217 |

| 70. | Interior of pottery | Ath. Mitth. | 218 |

| 71. | Red-figured fragment, incomplete | 222 | |

| 72. | Studio of vase-painter | Blümner | 223 |

| 73. | Vase-painter varnishing cup | Jahrbuch | 227 |

| 74. | Vase-painter using feather-brush | Jahrbuch | 228 |

| 75. | Cypriote jug with concentric circles | Brit. Mus. | 251 |

| 76. | Cypriote vase from Ormidhia | Baumeister | 254 |

| 77. | “Owl-vase” from Troy | Schliemann | 258 |

| 78. | Deep cup from Troy | Schliemann | 259 |

| 79. | Vase in form of pig from Troy | Schliemann | 259 |

| 80. | Double-necked vase from Troy | Schliemann | 259 |

| 81. | Vases from Thera | Baumeister | 261 |

| 82. | Mycenaean vases with marine subjects | Brit. Mus. | 273 |

| 83. | Ornamentation on Geometrical vases | Perrot | 283 |

| 84. | Geometrical vase with panels | Brit. Mus. | 284 |

| 85. | Boeotian Geometrical vases | Jahrbuch | 288 |

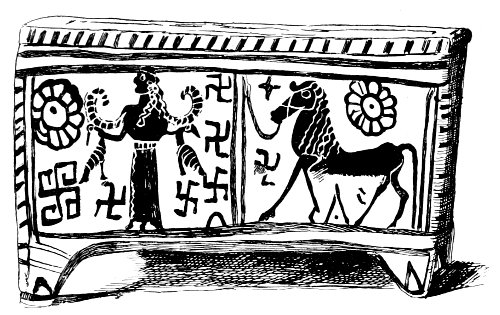

| 86. | Coffer from Thebes (Boeotian Geometrical) | Jahrbuch | 289 |

| 87. | Burgon lebes | Brit. Mus. | 296 |

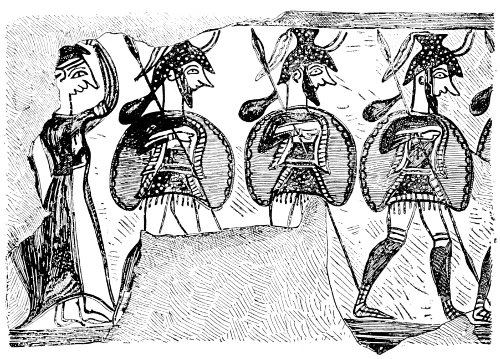

| 88. | Warrior vase from Mycenae | Schliemann | 297 |

| 89. | Proto-Attic vase from Vourva | Ath. Mitth. | 299 |

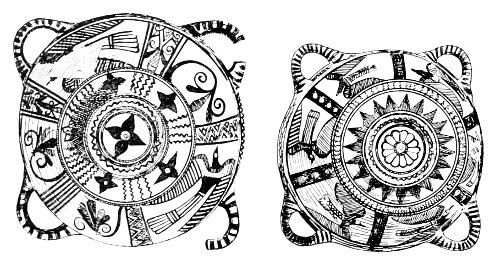

| 90. | The Dodwell pyxis (cover) | Baumeister | 316 |

| 91. | Vases of Samian or “Fikellura” style | Brit. Mus. | 337 |

| 92. | The Arkesilaos cup (Bibl. Nat.) | Baumeister | 342 |

| 93. | Cyrenaic cup with Kyrene | Brit. Mus. | 344 |

| 94. | Naukratis fragment with “mixed technique” | Brit. Mus. | 346 |

| 95. | “Egyptian situla” from Daphnae | Brit. Mus. | 351 |

| 96. | Kylix by Exekias | Wiener Vorl. | 381 |

| 97. | Vase by Amasis: Perseus slaying Medusa | Brit. Mus. | 382 |

| 98. | Vase from Temple of Kabeiri | Brit. Mus. | 392 |

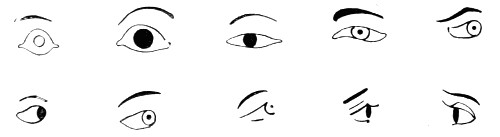

| 99. | Diagram of rendering of eye on Attic vase | Brit. Mus. Cat. | 408 |

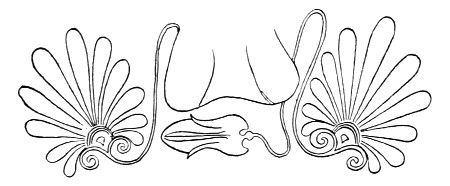

| 100. | Palmettes under handles (early R.F.) | Jahrbuch | 414 |

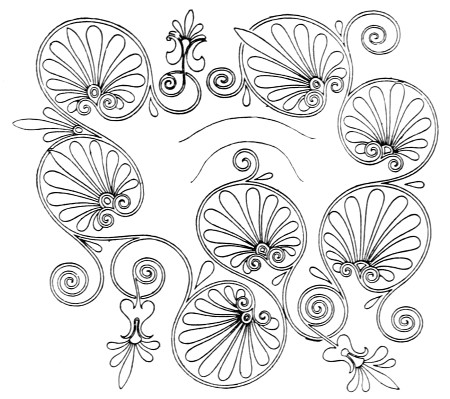

| 101. | Palmettes under handles (later R.F.) | Riegl | 415 |

| 102. | Development of maeander and cross pattern | Brit. Mus. Cat. | 416 |

| 103. | Krater of Polygnotan style: Slaying of Niobids (Louvre) | Mon. dell’ Inst. | 442 |

| 104. | Boeotian kylix | Brit. Mus. | 452 |

| 105. | Burlesque scene: Herakles and Auge | Jahrbuch | 474 |

| 106. | Apulian sepulchral vase | Brit. Mus. | 477 |

| 107. | Vase by Assteas in Madrid | Baumeister | 480 |

| 108. | Lucanian krater: Departure of warrior | Brit. Mus. | 482 |

| 109. | Hydria with opaque painting on black ground | Brit. Mus. | 489 |

| 110. | Phiale with Latin inscription | Brit. Mus. | 490 |

American Journal of Archaeology. Baltimore and Boston, 1885, etc. In progress. (Amer. Journ. of Arch.)

Annali dell’ Instituto di corrispondenza archeologica. Rome, 1829–85. (Ann. dell’ Inst.) Plates of vases re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire des Vases, vol. i. (1899).

Annual of the British School at Athens. London, 1894, etc. In progress. (Brit. School Annual.)

Antike Denkmäler, herausgegeben vom kaiserl. deutschen Institut. Berlin, 1887, etc. In progress. A supplementary atlas to the Jahrbuch. (Ant. Denkm.)

Archaeologia, or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. London, 1770, etc. Issued by the Society of Antiquaries. In progress.

Archaeological Journal, issued by the Royal Archaeological Institute. London, 1845, etc. In progress. Numerous articles on Roman pottery, etc. in Britain. (Arch. Journ.)

Archaeologische Zeitung. Berlin, 1843–85. Vols. vii.–xxv. have the secondary title Denkmäler, Forschungen und Berichte. (Arch. Zeit.) Plates of vases re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. i. (1899).

Archaeologischer Anzeiger. Berlin, 1886, etc. In progress; a supplement bound up with the Jahrbuch (new acquisitions of museums, reports of meetings, etc.). (Arch. Anzeiger.)

Archaeologische-epigraphische Mittheilungen aus Oesterreich-Ungarn. Vienna, 1877–97. Now superseded by Jahreshefte. (Arch.-epigr. Mitth. aus Oesterr.)

Athenische Mittheilungen. Athens, 1876, etc. In progress. Organ of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. (Ath. Mitth.)

Berichte der sächsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften. Leipzig, 1846, etc. In progress. Important articles by O. Jahn, 1853–67. (Ber. d. sächs. Gesellsch.)

Bonner Jahrbücher. Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande. Bonn, 1842, etc. In progress. Important for notices of pottery, etc., found in Germany, and for recent articles by Dragendorff and others on Roman pottery (Arretine and provincial wares, vols. xcvi., ci., cii., ciii.). (Bonner Jahrb.)

Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique. Athens and Paris, 1877, etc. In progress. (Bull. de Corr. Hell.)

Bullettino archeologico Napolitano. Naples, 1842–62. Ser. i. 1842–48. New ser. 1853–62. Re-edited by S. Reinach, 1899. (Bull. Arch. Nap.)

Bullettino dell’ Instituto di corrispondenza archeologica. Rome, 1829–85. Chiefly records of discoveries in Italy and elsewhere. (Bull. dell’ Inst.)

Classical Review. London, 1887, etc. In progress. Reviews of archaeological books and records of discoveries.

Comptes-Rendus de la Commission impériale archéologique. Petersburg, 1859–88. Edited by L. Stephani. With folio atlas, re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. i. (1899). (Stephani, Comptes-Rendus.)

Ἐφημερὶς Ἀρχαιολογική. Athens, 1883, etc. (new series). In progress. Plates of vases, 1883–94, re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. i. (1899). (Ἐφ. Ἀρχ.)

Gazette archéologique. Paris, 1875–89. (Gaz. Arch.)

Hermes. Zeitschrift für classische Philologie. Berlin, 1866, etc. In progress.

Jahrbuch des kaiserlichen deutschen archaeologischen Instituts. Berlin, 1886, etc. In progress. With Arch. Anzeiger (q.v.) as supplement and Antike Denkmäler (q.v.) as atlas. (Jahrbuch.)

Jahreshefte des oesterreichischen archaeologischen Institutes. Vienna, 1898, etc. In progress. (Jahreshefte.)

Journal of Hellenic Studies. London, 1880, etc. In progress. With atlas in 4to of plates to vols. i.–viii., and supplementary papers (No. 4 on Phylakopi). (J.H.S.)

Journal of the British Archaeological Association. London, 1845, etc. In progress. A few articles on Roman pottery in Britain. (Journ. Brit. Arch. Assoc.)

Monumenti antichi, pubblicati per cura della R. Accad. dei Lincei. Milan, 1890, etc. In progress. (Mon. antichi.)

Monumenti inediti dell’ Instituto di corrispondenza archeologica. Rome, 1829–85 (with supplementary volume, 1891). Re-edited (the plates of vases) by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. i. (1899). (Mon. dell’ Inst.)

Monuments Grecs, publiés par l’Association pour l’encouragement des Études grecques. Paris, 1872–98. (Mon. Grecs.)

Monuments Piot. Fondation Eugène Piot. Monuments et mémoires publiés par l’Académie des Inscriptions. Paris, 1894, etc. In progress.

Museo italiano di antichità classica. 3 vols. Florence, 1885–90. Plates of vases re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. i. (1899). (Ath. Mitth.)

Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, communicate alla R. Accademia dei Lincei. Rome and Milan, 1876, etc. In progress. Important as a record of recent discoveries in Italy and Sicily. (Notizie degli Scavi.)

Philologus. Zeitschrift für das klassische Alterthum. Göttingen, 1846, etc. In progress. With occasional supplementary volumes.

Revue archéologique. Paris, 1844, etc. In progress (four series, each numbered separately). (Rev. Arch.)

Römische Mittheilungen. Rome, 1886, etc. In progress. Organ of German Institute at Rome. (Röm. Mitth.)

Adamek (L.). Unsignierte Vasen des Amasis. Prague, 1895 (Prager Studien, Heft v.).

Amelung (W.). Personnificierung des Lebens in der Natur in den Vasenbildern der hellenistischen Zeit. Munich, 1888. See also Florence.

Anderson (W. F. C.). See Engelmann and Schreiber.

Antiquités du Bosphore cimmérien. 3 vols. Petersburg, 1854, fol. Vases, etc., found in the Crimea. (Re-edited in 8vo by S. Reinach, 1892.)

Arndt (P.). Studien zur Vasenkunde. Leipzig, 1887. Adopts Brunn’s theory of the late Italian origin of black-figured vases.

Athens (National Museum). Catalogue des Vases peints, by M. Collignon and L. Couve. Paris, 1902. With atlas of photographic plates. The fragments from the Acropolis form the subject of a separate catalogue (in preparation).

Aus der Anomia. Collected articles, some relating to vases. Berlin, 1890.

Baumeister (A.). Denkmäler des klassischen Alterthums. 3 vols. Munich, 1884–88. Excellent illustrations of numerous vases accompanying the articles, which are arranged alphabetically in dictionary-form. The article Vasenkunde, by Von Rohden, is useful, but now somewhat out of date. (Baumeister.)

Beger (L.). Thesaurus Brandenburgicus selectus. 3 vols. Köln, 1696, fol. Publishes vases belonging to the Elector of Brandenburg (see Vol. I. p. 16).

Benndorf (O.). Griechische und sicilische Vasenbilder. Berlin, 1869–83, fol. Chiefly funerary vases and later fabrics. (Benndorf, Gr. u. Sic. Vasenb.) See also Wiener Vorlegeblätter.

Berlin. Beschreibung der Vasensammlung im Antiquarium, by A. Furtwaengler. Berlin, 1885. 2 vols. With plates of shapes.

Bloch (L.). Die zuschauenden Götter in den rothfig. Vasengemälden. Leipzig, 1888.

Blümner (H.). Technologie und Terminologie der Gewerbe und Künste. 4 vols. Leipzig, 1875–86. (Vol. ii. Arbeit in Thon, for pottery and terracottas; vol. iii. for building construction.) Out of date in some particulars, but still exceedingly useful, and fairly well illustrated. (Blümner, Technologie.)

Boeckh (A.) and others. Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum. 4 vols. Berlin, 1828–77, fol. Vol. iv. contains many vase-inscriptions. (Boeckh, C.I.G.)

Böhlau (J.). Aus ionischen und italischen Nekropolen. Leipzig, 1898, 4to. Indispensable for the study of Ionic vase-fabrics. (Böhlau, Aus ion. u. ital. Nekrop.)

Bologna (Museo Civico). Catalogo dei vasi, by G. Pellegrini. Bologna, 1900. (Plates and cuts.)

Bolte (J.). De monumentis ad Odysseam pertinentibus capita selecta. Berlin, 1882, 8vo.

Bonn. Das akademische Kunstmuseum zu Bonn, by R. Kekulé. Bonn, 1872.

Bonner Studien. Aufsätze aus der Alterthumswissenschaft R. Kekulé gewidmet. Berlin, 1890. Collected papers, including several on Greek vases.

Boston. Catalogue of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman vases in the Museum of Fine Arts. Boston, 1893. By E. Robinson. Now withdrawn, owing to re-numbering and extensive subsequent accessions, for which see Boston Museum Reports (below).

Boston Museum Reports, 1895, etc. In progress from 1896. Issued annually, with full details of new acquisitions, describing many unique specimens. (Boston Mus. Report.)

Böttiger (C. A.). Griechische Vasengemälde. Weimar and Magdeburg, 1797–1800.

—— Kleine Schriften. 3 vols. Dresden, 1837–39.

Bourguignon Collection. Sale Catalogue, 18 March 1901. Paris, 1901. (Best vases not included.)

Branteghem (A. van). See Froehner.

British Museum. Catalogue of the Greek and Etruscan Vases. Vol. i., by C. Smith, in preparation. Vol. ii., Black-figured vases, by H. B. Walters (1893). Vol. iii., Red-figured vases, by C. Smith (1896). Vol. iv., Vases of the later period, by H. B. Walters (1896). (Referred to as B. M. Cat. of Vases, or B.M. with number of vase.)

—— Designs on Greek Vases, by A. S. Murray and C. Smith. 1894, fol. (Plates of interiors of R.F. kylikes.)

—— White Athenian Vases, by A. S. Murray and A. H. Smith. 1896, fol.

—— Terracotta Sarcophagi, by A. S. Murray. 1898, fol. (The sarcophagi from Clazomenae, Kameiros, and Cervetri; see Chapters VIII. and XVIII.)

—— Excavations in Cyprus (Enkomi, Curium, Amathus). 1900. By A. S. Murray, H. B. Walters, and A. H. Smith.

Bröndsted (P. O.). A brief description of 32 ancient Greek painted vases, lately found at Vulci by M. Campanari. London, 1832, 8vo.

Brongniart (A.). Traité des Arts Céramiques, ou des Poteries considerées dans leur Histoire, leur Pratique, et leur Théorie. 3rd edn., 1877. 2 vols., with Atlas. (Brongniart, Traité.) See also Sèvres.

Brunn (H.). Geschichte der griechischen Künstler. 2 vols. Stuttgart, 1859. The second volume has some account of the vase-painters then known.

—— Probleme in der Geschichte der Vasenmalerei. Munich, 1871, 4to. Theory of Italian origin of B.F. vases.

—— Neue Probleme in der Geschichte der Vasenmalerei. Munich, 1886.

—— Griechische Kunstgeschichte. 2 vols. (incomplete). Munich, 1893–97. Deals with some of the earlier fabrics.

—— Kleine Schriften. Vol. i. Leipzig, 1898. In progress. See also Lau.

Bulle (H.). Die Silene in der archaischen Kunst. Munich, 1893.

Burlington Fine Arts Club. Catalogue of objects of Greek Ceramic Art (exhibited in 1888), by W. Froehner. (Mostly vases from Branteghem Collection.)

—— Catalogue of Exhibition of Ancient Greek Art, 1903, by E. Strong and others. A revised édition de luxe (1904) with plates.

Cambridge (Fitzwilliam Museum). A Catalogue of the Greek vases in the Fitzwilliam Museum, by E. A. Gardner. Cambridge, 1897. With plates.

Canessa (C. and E.). Collection d’Antiquités, à l’Hôtel Drouot, 11 May 1903, 4to. Paris, 1903. A sale catalogue of an anonymous collection containing several interesting vases.

Canino (Prince Lucien Bonaparte of). Muséum Étrusque de L. Bonaparte, prince de Canino. Fouilles de 1828 à 1829. Vases peints avec inscriptions. Viterbo, 1829, 4to. With atlas of plates, of which only one part was published.

—— Catalogo di scelte Antichità Etrusche trovate negli Scavi del Pr. di Canino, 1828–29. Viterbo, 1829, 4to.

Caylus (A. C. P. de). Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques et romaines. 7 vols. Paris, 1752–67, 4to. (Vases given in vols. i. and ii.)

Cesnola (L. P. di). Cyprus: its ancient cities, tombs, and temples. (With a chapter on the pottery, by A. S. Murray.) London, 1877, 8vo.

Christie (J.). Disquisitions upon the Painted Vases, and their connection with the Eleusinian Mysteries. London, 1825, 4to. (See Vol. I. p. 21.)

Collignon (M.). See Athens, Rayet.

Commentationes philologae in honorem T. Mommseni. Berlin, 1877, 4to. Several useful papers on vases.

Conze (A.). Melische Thongefässe. Leipzig, 1862. Folio plates.

—— Zur Geschichte der Anfänge griechischer Kunst. Vienna, 1870, 8vo. See also Wiener Vorlegeblätter.

Corey (A. D.). De Amazonum antiquissimis figuris. Berlin, 1891, 8vo.

Couve (L.). See Athens.

Daremberg (C.) and Saglio (E.), and subsequently E. Pottier. Dictionnaire des antiquités grecques et romaines. Paris, 1873, etc. In progress (to M in 1904). (Daremberg and Saglio.) Special reference should be made to the articles Figlinum, Forma, Lucerna, and those on vase-shapes. The bibliographies are very exhaustive.

Dennis (G.). The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria. 2 vols. London, 1878 (2nd edn.), 8vo. Introductory matter on vases antiquated; useful as record of discoveries, etc. (Dennis, Etruria.)

Des Vergers (N.). Étrurie et les Étrusques. 2 vols. and atlas. Paris, 1862–64. Some fine vases published.

Disney (J.). Museum Disneianum, being a description of a collection of various ancient fictile vases in the possession of J. D. (now at Cambridge). London, 1846, 4to.

Dubois-Maisonneuve (A.). Introduction à l’étude des vases antiques d’argile peints. Paris, 1817, fol. (Dubois-Maisonneuve, Introd.)

Dumont (A.). Inscriptions céramiques de Grèce. Paris, 1872, 8vo. (Inscriptions on handles of wine-amphorae.)

—— Vases peints de la Grèce propre. Paris, 1873. (Reprinted from the Gazette des Beaux Arts.)

—— Les Céramiques de la Grèce propre; histoire de la peinture des vases grecs depuis les origines jusqu'au V. siècle avant Jésus-Christ. Illustrations by J. Chaplain. Revised by E. Pottier. 2 vols. Paris, 1888–90. Vol. i., on earlier vase fabrics (now becoming out of date); plates mostly of later vases. Vol. ii., miscellaneous papers (vases, terracottas, etc.). (Dumont-Pottier.)

Endt (J.). Beiträge zur ionischen Vasenmalerei. Prague, 1899, 8vo. (Endt, Ion. Vasenm.)

Engelmann (R.). Bilder-Atlas zum Homer. Leipzig, 1889. Translated by W. F. C. Anderson: Pictorial Atlas to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, London, 1892. (Engelmann-Anderson.)

—— Archaeologische Studien zu den Tragikern. Berlin, 1900. Eranos Vindobonensis (collected papers). Vienna, 1893, 8vo.

Fea (C.). Storia dei vasi fittili dipinti che si trovano nell’ antica Etruria. Rome, 1832. (Dealing with “Etruscan” theory.)

Festschrift für Johannes Overbeck (collected papers). Leipzig, 1893, 4to.

Festschrift für Otto Benndorf zu seinem 60. Geburtstage gewidmet (collected papers). Vienna, 1898, 4to.

Fiorelli (G.). Notizia dei vasi dipinti rinvenuti a Cuma nel 1856. Naples, 1857. Plates reproduced in Bull. Arch. Nap. (q.v.).

Flasch (A.). Angebliche Argonautenbilder. Munich, 1870.

—— Die Polychromie der griechischen Vasenbilder. Würzburg, 1875.

Florence. Führer durch die Antiken in Florenz, by W. Amelung. Munich, 1897.

Förster (P. R.). Hochzeit des Zeus und der Hera, Relief der Schaubert’schen Sammlung in .... Breslau. Breslau, 1867, 4to.

—— Der Raub und die Rückkehr der Persephone. Stuttgart, 1873.

Froehner (W.). Choix de vases grecs inédits de la collection du Prince Napoléon. Paris, 1867, fol.

—— Deux peintures de vases grecs de la nécropole de Kameiros. Paris, 1871, fol.

—— Musées de France. Recueil de monuments antiques. Paris, 1873, fol.

—— Collection de M. Albert B(arre). Paris, 1878, 4to. (Sale catalogue.)

—— Collection Eugène Piot, Antiquités. Paris, 1890. (Sale catalogue.)

—— Collection van Branteghem. Brussels, 1892, fol., with plates. (Sale catalogue.)

—— Collection d’antiquités du Comte Michael Tyszkiewicz. Paris, 1898. (Sale catalogue.)

And see Burlington Fine Arts Club, Marseilles Mus.

Furtwaengler (A.). Eros in der Vasenmalerei. Munich, 1875, 8vo.

—— Collection Sabouroff. 2 vols. (the first giving vases). Berlin, 1883–87, 4to. (Also a German edition; the vases now in Berlin.)

—— Orpheus, Attische Vase aus Gela (in 50tes Winckelmannsfestprogr., 1890).

—— Neuere Fälschungen von Antiken. Munich, 1899, 4to.

—— and Loeschcke (G.). Mykenische Thongefässe. Berlin, 1879, obl. fol.

—— —— Mykenische Vasen: Vorhellenische Thongefässe aus dem Gebiete des Mittelmeeres. Berlin, 1886, 4to, with atlas in fol.

—— and Reichhold (C.). Die griechische Vasenmalerei, Auswahl hervorragender Vasenbilder. Munich, 1900, etc. Text by A. F. and C. R.; plates (separate) by C. R. And see Berlin, Genick.

Gardner (E. A.). See Cambridge, Naukratis.

Gardner (P.). See Oxford.

Gargiulo (R.). Cenni sulla maniera di rinvenire i vasi fittili Italo-Greci. Naples, 1831; 2nd edn., 1843.

—— Raccolta de Monumenti più interessanti del Real Mus. Borb. Naples, 1825–3-. 2 vols. of plates.

Genick (A.) and Furtwaengler (A.). Griechische Keramik. 4to. Tafeln ausgewählt und aufgenommen von A. G., mit Einleitung und Beschreibung von A. F. 2nd edn. Berlin, 1883, 4to.

Gerhard (E.). Antike Bildwerke. Munich, 1828–44. Text in 8vo and plates in fol.

—— Berlins antike Bildwerke. Berlin, 1836, 8vo.

—— Griechische und etruskische Trinkschalen des königl. Museums zu Berlin. Berlin, 1840, fol.

—— Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder. 4 vols. Berlin, 1840–58. (Gerhard, A. V.) Re-edited by S. Reinach, Répertoire, vol. ii. (1900).

—— Etruskische und campanische Vasenbilder des königl. Museums zu Berlin. Berlin, 1843, fol.

—— Apulische Vasenbilder des königl. Museums zu Berlin. Berlin, 1845, fol.

—— Trinkschalen und Gefässe des königl. Museums zu Berlin und anderer Sammlungen. Berlin, 1848–50, fol.

—— Gesammelte akademische Abhandlungen und kleine Schriften. 2 vols. in 8vo and atlas in 4to. Berlin, 1866–68. (Chiefly papers on mythology, illustrated by vases.)

Girard (P.). La Peinture antique. Paris, 1892. Vases as illustrative of Greek painting.

Gori (A. F.). Museum Etruscum. 3 vols. Florence, 1737–43, fol.

Gsell (S.). Fouilles dans la nécropole de Vulci, exécutées et publiées aux frais de Prince Torlonia. Paris, 1891, 4to.

Hancarville (P. F. Hugues, pseud. D’). Antiquités étrusques, grecques, et romaines, tirées du cabinet de M. Hamilton. 4 vols. folio, 1766–67.

Harrison (Jane E.). Myths of the Odyssey in art and literature. London, 1882, 8vo.

—— Mythology and Monuments of Ancient Athens (with translation from Pausanias, by M. de G. Verrall). London, 1890. Introduction important for vases relating to Attic cults.

—— Prolegomena to Greek Religion. Cambridge, 1903. Numerous vases interpreted with reference to mythology and religion.

—— and MacColl (D. S.). Greek Vase-paintings. London, 1894.

Harrow School Museum. Catalogue of the classical antiquities from the collection of the late Sir G. Wilkinson, by Cecil Torr. Harrow, 1887, 8vo.

Hartwig (P.). Die griechischen Meisterschalen des strengen rothfigurigen Stils. Stuttgart, 1893, 4to, with atlas in fol. Invaluable for a study of cups of R.F. period.

Helbig (W.). Das homerische Epos, aus den Denkmälern erlautert. 2nd edn. Leipzig, 1884, 8vo. (Vases used to illustrate civilisation of Homeric poems.)

—— Les vases du Dipylon et les naucraries. Paris, 1898, 4to.

—— Eine Heerschau des Peisistratos oder Hippias auf einer schwarzfigurigen Schale. Munich, 1898, 8vo.

—— Les Ἱππεῖς Athéniens. Paris, 1902, 4to. And see Rome.

Hermann (P.). Das Gräberfeld von Marion auf Cypern. Berlin, 1888, 4to. An account of the finds by O. Richter and others at Poli, Cyprus. (48tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.)

Heydemann (H.). Iliupersis auf einer Trinkschale des Brygos. Berlin, 1866, fol.

—— Humoristische Vasenbilder aus Unteritalien. Berlin, 1870. (30tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.)

—— Griechische Vasenbilder. Berlin, 1870, fol. (Chiefly vases at Athens.)

—— Nereiden mit den Waffen des Achill. Halle, 1879, fol.

—— Satyr und Bakchennamen. Halle, 1880. (5tes hallische Festprogr.). Numerous other monographs, chiefly Hallische or Winckelmannsfestprogramme. And see Naples.

Hirschfeld (G.). Athena und Marsyas. Berlin, 1872.

Hoppin (J. C.). Euthymides; a study in Attic vase-painting. Leipzig, 1896.

Huddilston (J. H.). Greek Tragedy in the light of vase-paintings. London and New York, 1892.

—— Lessons from Greek Pottery. London and New York, 1902. With bibliography.

Inghirami (F.). Monimenti etruschi o di etrusco nome. Ser. 5. Vasi fittili. Fiesole, 1824, 4to.

—— Galeria Omerica. 3 vols. Fiesole, 1831–36.

—— Etrusco Museo Chiusino. 2 vols. Fiesole, 1832–34, 4to.

—— Pitture di vasi fittili. 4 vols. Fiesole, 1833–37.

—— Pitture di vase etruschi. 4 vols. Florence, 1852–56. (A second edition of the preceding work.)

Jahn (O.). Telephos und Troilos. Kiel, 1841, 8vo.

—— Ueber Darstellungen griechischer Dichter auf Vasenbildern. Leipzig, 1861. (From Abhandl. des sächs. Gesellsch. viii.)

—— Archaeologische Aufsätze. Greifswald, 1845, 8vo.

—— Archaeologische Beiträge.Berlin, 1847, 8vo.

—— Beschreibung der Vasensammlung Königs Ludwigs in der Pinakothek zu München. Munich, 1854, 8vo. (Vasens. zu München.) The Einleitung (Introduction) gives a résumé of the whole subject.

—— Ueber bemalte Vasen mit Goldschmuck. Leipzig, 1865, 4to.

—— Die Entführung der Europa auf antiken Kunstwerken. Vienna, 1870, 4to.

Jatta (G.). Catalogo del Museo Jatta (at Ruvo). Naples, 1869, 8vo.

Karlsruhe. Beschreibung der Vasensammlung der grossherzoglichen vereinigte Sammlungen zu Karlsruhe, by H. Winnefeld. 1887, 8vo.

Karo (G.). De arte vascularia antiquissima quaestiones. Bonn, 1896, 8vo.

Kekulé (R. von, now Kekule von Stradonitz). See Bonn.

Kirchhoff (A.). Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Alphabets. 4th edn. Gütersloh, 1887.

Klein (W.). Euphronios; eine Studie zur Geschichte der griechischen Malerei. 2nd edn. Vienna, 1886, 8vo.

—— Die griechischen Vasen mit Meistersignaturen. 2nd edn. Vienna, 1887, 8vo.

—— Die griechischen Vasen mit Lieblingsinschriften. 2nd edn. Vienna, 1898.

Knapp (P.). Nike in der Vasenmalerei. Tübingen, 1876, 8vo.

Kopenhagen. De malede Vaser i Antikkabinettet i Kjöbenhavn. Kopenhagen, 1862. Catalogue of the vases, by S. Birket Smith. (Referred to as Kopenhagen, with number of vase.)

Kramer (G.). Ueber den Styl und die Herkunft der bemalten griechischen Thongefässe. Berlin, 1837.

Krause (J. H.). Angeiologie. Halle, 1854, 8vo. (Study of vase-shapes and their names.)

Kretschmer (P.). Die griechischen Vaseninschriften ihrer Sprache nach untersucht. Gütersloh, 1894.

La Borde (A. de). Collection des vases grecs de M. le Comte de Lambert. 2 vols. Paris, 1813–28, fol. The vases are now at Vienna. Re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, vol. ii. (1900).

La Chausse (M. A. de = Caussius). Romanum Museum. Rome, 1690; 3rd edn., 1746.

Lanzi (L.). Dei vasi antichi dipinti volgarmente chiamati Etruschi. Florence, 1806.

Lau (Th.), Brunn (H.), and Krell (P.). Die griechischen Vasen, ihre Formen und Decorationssystem. Plates and text. From originals at Munich. Leipzig, 1877. (Brunn-Lau, Gr. Vasen.)

Lenormant (C.) and De Witte (J.). Élite des monuments céramographiques. 4 vols. Paris, 1837–61, 4to. (Él. Cér.)

Letronne (J. A.). Observations sur les noms de vases grecs. Paris, 1833.

London. See British Museum.

Longpérier (H. A. Prévost de). Musée Napoléon III. Choix de monuments antiques ... Texte explicatif par A. de L. Paris, unfinished, 1868–74, 4to.

Louvre. See Paris.

Lützow (C. von). Zur Geschichte des Ornaments an den bemalten griechischen Thongefässen. Munich, 1858.

Luynes (H. d’A. de). Description de quelques vases peints, étrusques, italiotes, siciliens et grecs. Paris, 1840, fol. The vases are now in the Bibliothèque Nationale. Re-edited by S. Reinach, Répertoire, ii, (1900).

MacColl (D. S.). See Harrison.

Macpherson (D.). Antiquities of Kertch, and researches in the Cimmerian Bosphorus, etc. London, 1857, 4to. (Discoveries in the Crimea.)

Madrid (Museo arquelogico nacional). Catalogo del Museo, by A. G. Gutierrez and J. de D. de la Rada y Delgado. Part i. Madrid, 1883, 8vo.

Marseilles. Catalogue des antiquités grecques et romaines du Musée, by W. Froehner. 1897.

Martha (J.). L'Art Étrusque. Paris, 1889, 4to.

Masner (K.). See Vienna.

Mayer (M.). Die Giganten und Titanen in der antiken Sage und Kunst. Berlin, 1886.

Mélanges Perrot. Paris, 1902, 4to. (Collected papers in honour of Perrot.) (Recueil de mémoires concernant l’archéologie classique, la littérature, et l’histoire anciennes, dedié à Georges Perrot.)

Micali (G.). Storia degli antichi popoli Italiani. 3 tom. Firenze, 1832, 8vo. With atlas entitled Monumenti per servire alla storia, etc. Fol.

——— Monumenti inediti a illustrazione della storia degli antichi popoli italiani. Florence, 1844, 8vo, plates in fol. Vases found in Etruria. (Micali, Mon. Ined.)

Milchhoefer (A.). Die Anfänge der Kunst in Griechenland. Leipzig, 1883, 8vo.

Milliet (P.). Études sur les premières périodes de la céramique grecque. Paris, 1891.

Millin (A. L.). Peintures des vases antiques. 2 vols. Paris, 1808–10, fol. The Introduction of Dubois-Maisonneuve (q.v.) was published uniform with this. Re-edited by S. Reinach in 4to, Paris, 1891. (Millin-Reinach.)

Millingen (F.). Ancient Unedited Monuments of Grecian Art. 2 vols. in one. London, 1822–26. (Millingen, Anc. Uned. Monum.)

——— Peintures antiques de vases grecs, tirées de diverses collections. Rome, 1813, fol. Re-edited by S. Reinach in 4to, Paris, 1891. (Millingen-Reinach.)

——— Peintures antiques de vases grecs de la collection de Sir J. Coghill. Rome, 1817, fol. Re-edited by S. Reinach in Répertoire, ii. (1900).

Morgenthau (J. C.). Ueber den Zusammenhang der Bilder auf griechischen Vasen. I. Die schwarzfigurigen Vasen. Leipzig, 1886. 8vo.

Moses (H.). A collection of antique vases, etc., from various museums and collections. London, 1814.

——— Vases from the collection of Sir Henry Englefield. London, 1848.

Mueller (E.). Drei griechische Vasenbilder. Zurich, 1887. 4to.

Müller (K. O.). Denkmäler der Alten Kunst. 1832–69, obl. fol. 2 vols. (2nd re-edited by F. Wiestler).

—— —— Theil ii. 3rd edn., 1877. Text 4to; plates, 1881, obl. fol.

Munich. Beschreibung der Vasensammlung König Ludwigs in der Pinakothek, by O. Jahn. Munich, 1855. With admirable introduction. See also the guide (Führer) published in 1895. A new catalogue by Furtwaengler said to be in progress.

Murray (A. S.). Handbook of Greek Archaeology. London, 1892. (Chaps. i. and ii. deal with vases.) And see British Museum.

Museo Borbonico. Naples, 1824–57. 16 vols., 4to. Illustrations of the collections in the Naples Museum (Real Museo Borbonico). See also Gargiulo.

Museo Gregoriano. Museo Etrusci ... in Aedibus Vaticanis ... Monumenta. 2 vols. (vases in 2nd). Rome, 1842, fol. (Mus. Greg.)

Myres, J. L. See Nicosia.

Naples. Die Vasensammlungen des Museo Nazionale zu Neapel, by H. Heydemann. Berlin, 1872. See also Gargiulo, Museo Borbonico.

Naukratis, I. and II. Third and Sixth Memoirs of the Egypt Exploration Fund, by W. M. Flinders Petrie, E. A. Gardner, etc. London, 1886–88. Plates of pottery found at Naukratis, discussed in text by C. Smith and E. A. Gardner.

Nicosia (Cyprus Museum). A Catalogue of the Cyprus Museum, by J. L. Myres and M. Ohnefalsch-Richter. Oxford, 1899.

Ohnefalsch-Richter (M.). Kypros, the Bible, and Homer. 2 vols., text and plates. Berlin, 1893. Also a German edition. Useful for collected examples of Cypriote pottery and terracottas. See also Nicosia.

Overbeck (J.). Die Bildwerke zum thebischen und troischen Heldenkreis. 2 vols., text and atlas. Brunswick and Stuttgart, 1853–57. Lists of vases illustrating Theban and Trojan legends. (Overbeck, Her. Bildw.)

—— Griechische Kunstmythologie. Vols. ii.–iv. only published (Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Apollo, and myths connected with them). Leipzig, 1871–89. With atlas in fol. (Overbeck, Kunstmythol.)

Oxford (Ashmolean Museum). Catalogue of the Greek Vases in the Ashmolean Museum, by P. Gardner. Oxford, 1893. With coloured plates.

Panofka (T.). Vasi di premio illustrati. Florence, 1826.

—— Musée Blacas. Paris, 1829, fol. Vases mostly in B.M.

—— Recherches sur les véritables noms des vases grecs. Paris, 1829.

—— Antiques du cabinet du comte Pourtalès-Gorgier. Paris, 1834, 4to. (Panofka, Cab. Pourtalès.)

—— Bilder antiken Lebens. Berlin, 1843, 4to.

—— Griechinnen und Griechen nach Antiken skizzirt. Berlin, 1844, 4to.

—— Der Vasenbilder Panphaios. Berlin, 1848.

—— Von den Namen der Vasenbildner in Beziehung zu ihren bildlichen Darstellungen. Berlin, 1849, 4to.

—— Die griechischen Eigennamen mit καλός in Zusammenhang mit dem Bilderschmuck auf bemalten Gefässen. Berlin, 1850.

(And many other pamphlets with publication of vases, chiefly from the mythological point of view, but now out of date.)

Paris (Louvre). Catalogue des vases antiques de terre cuite, by E. Pottier. Paris, 1896, etc. In progress (two volumes issued, dealing with earlier fabrics). With accompanying atlas of photographic plates (2 vols., down to Euphronios).

Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale). Catalogue des vases dans le Cabinet des Médailles, by A. de Ridder. Paris, 1901–02. 2 vols. With plates.

Passeri (J. B.). Picturae Etruscorum in Vasculis. 3 vols. Rome, 1767–75, fol.

Patroni (G.). Ceramica antica nell’ Italia meridionale. Naples, 1897. A useful study of Greek and local fabrics of Southern Italy.

Pellegrini (G.). See Bologna.

Perrot (G.) and Chipiez (C.). Histoire de l’art dans l’antiquité. (Text by Perrot, plates by Chipiez.) In progress: 8 vols, published in 1882–1904. Vol. iii., Cypriote pottery; vol. vi., Mycenaean; vol. vii., Dipylon. (Perrot, Hist. de l’Art.)

Petersburg. Vasensammlung der kaiserlichen Ermitage, by L. Stephani. Petersburg, 1869. 2 vols.

Pollak (L.). Zwei Vasen aus der Werkstatt Hierons. Leipzig, 1900.

Pottier (E.). Étude sur les lécythes blancs attiques à représentations funéraires. Paris, 1883, 8vo. (Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises, No. 30.)

—— La peinture industrielle chez les Grecs. Paris, 1898, 8vo.

—— and Reinach (S.). La Nécropole de Myrina. 2 vols. Paris, 1887.

See also Daremberg, Dumont, Paris.

Raoul-Rochette. Monumens inédits d’antiquité figurée. Paris, 1833, fol.

—— Peintures antiques inédites. Paris, 1836, 4to.

Ravestein (E. de M. de). Musée de Ravestein; Catalogue descriptif. 2 vols. Liège, 1871–72, 8vo.

Rayet (O.) and Collignon (M.). Histoire de la céramique grecque. Paris, 1888. (More or less popular, and becoming out of date; well illustrated.) (Rayet and Collignon.)

Reinach (S.). Chroniques d’Orient. Paris, 1891–96. 2 vols. Reprinted from the Revue Archéol. (1883–95). Notes of discoveries, etc.

—— Répertoire des Vases Peints. Paris, 1899–1900. 2 vols. An invaluable re-editing, with outline reductions of the plates, of many publications of vases, with bibliographical notes and explanations appended. See Laborde, de Luynes, Tischbein, etc., and list of periodicals. (Referred to as Reinach, with number of volume and page. In Chapters XII.-XV. the references are all to this publication in preference to the original works.)

See also Millin, Millingen, Ant. du Bosph. Cimm., and Pottier.

Reisch (E.). See Rome.

Ridder (A. de). See Paris.

Riegl (A.). Stilfragen. Grundlegungen zu einer Geschichte der Ornamentik. Berlin, 1893, 8vo. A valuable study of early vegetable ornament on vases.

Robert (C.). Thanatos. Berlin, 1879, 4to. (39tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.)

—— Bild und Lied. Berlin, 1881, 8vo. On the relation of vase-paintings to the Homeric poems.

—— Archaeologische Märchen aus alter und neuer Zeit. Berlin, 1886, 8vo. Papers on various subjects, more or less controversial.

—— Homerische Becher. (50tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.) Berlin, 1890.

Robert (C). Scenen der Ilias und Aithiopis auf einer Vase der Sammlung des Grafen M. Tyszkiewicz. Halle, 1891, fol. (15tes Hall. Winckelmannsprogr.)

—— Die Nekyiades Polygnot. Halle, 1892. (16tes Hallisches Festprog.; a restoration of the painting on the basis of vases.)

—— Die Iliupersis des Polygnot. Halle, 1893. (17tes Hallisches Festprogr.; dealing similarly with that painting.)

—— Die Marathonschlacht in der Poikile und weiteres über Polygnot. (18tes Hallisches Festprogr.) Halle, 1895.

Roberts (E. S.). An Introduction to Greek Epigraphy. Part i. The archaic inscriptions and the Greek alphabet. Cambridge, 1887, 8vo.

Robinson (E.). See Boston.

Roehl (H.). Inscriptiones Graecae antiquissimae praeter Atticas in Attica repertas. Berlin, 1882, fol. (Roehl, I.G.A.)

Rohden (H. von). See Baumeister.

Rome (Vatican, Museo Gregoriano). Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen in Rom, by W. Helbig and E. Reisch. 2nd edn., 1899. 2 vols. In vol. ii. is given a full description of the best vases (about 250) in this collection; they are quoted as Helbig 1, 2, 3, etc., according to the numbers of the book. See also Museo Gregoriano.

Roscher (W. H.). Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie. Leipzig, 1884, etc. In progress (down to P in 1904). Many vases published in the later parts.

Ross (L.). Reisen auf die griechischen Inseln des ägäischen Meeres. Halle, 1840–52, 4 vols., 8vo.

—— Archaeologische Aufsätze. 2 vols. Leipzig, 1855–61. With plates in fol.

Roulez (J.). Choix de vases peints du Musée d’antiquités de Leyde. Gand, 1854. Re-edited by S. Reinach, Répertoire, vol. ii., 1900.

Ruvo (Museo Jatta). See Jatta.

Salzmann (A). Nécropole de Camiros. Paris, 1866–75, fol. Plates only.

Schliemann (H.). See Vol. I. p. 269.

Schneider (A.). Der troische Sagenkreis in der älteren griechischen Kunst. Leipzig, 1886.

Schneider (F. J.). Die zwölf Kämpfe des Herakles in der älteren griechischen Kunst. Leipzig, 1888.

Schneider (R.). Die Geburt der Athena. Vienna, 1880, 8vo.

Schöne (R.). Le antichità del Museo Bocchi di Adria. Rome, 1878, 4to.

Schreiber (Th.) and Anderson (W. C. F.). Atlas of Classical Antiquities. London, 1895, obl. 8vo. (Schreiber-Anderson.)

Schulz (H. W.). Die Amazonenvase von Ruvo, erklärt und in Kunsthistorischer Beziehung betrachtet. Leipzig, 1851, fol. See Reinach, Répertoire, vol. ii.

Sèvres Museum. Description méthodique du Musée Céramique de Sèvres, by A. Brongniart and D. Riocreux. Paris, 1845. 2 vols., with atlas of plates.

Sittl (K.). Die Phineusschale und ähnliche Vasen mit bemalten Flachreliefs. Würzburg, 1892.

Smith (A. H.). See British Museum.

Smith (Cecil). Catalogue of the Forman Collection of Antiquities (illustrated). London, 1899. And see British Museum.

Smith (S. B.). See Kopenhagen.

Stackelberg (O. M. von). Die Gräber der Hellenen. Berlin, 1836, fol.

Stephani (L.). See Petersburg and Compte-Rendu.

Strena Helbigiana. (Collected papers in honour of W. Helbig.) Leipzig, 1900, 8vo.

Studniczka (F.). Kyrene, eine altgriechische Göttin. Leipzig, 1890.

Tanis II. Fourth Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund (Tell-Nebesheh and Defenneh). London, 1887. By W. M. F. Petrie and F. L. Griffith, with notes on the Daphnae pottery by A. S. Murray.

Thiersch (F.). Ueber die hellenischen bemalten Vasen, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die Sammlung des Königs Ludwigs von Bayern. Munich, 1849. From Abhandl. d. k. bayer. Akad., Philosoph.-philol. Classe, vol iv.

Thiersch (H.). Tyrrhenische Amphoren. Eine Studie zur Geschichte der altattischen Vasenmalerei. Leipzig, 1899.

Tischbein (W.). Collection of engravings from ancient vases (the second Hamilton Collection; see Vol. I. p. 17). 4 vols. Naples, 1791–95, fol. Re-edited by S. Reinach, Répertoire, vol. ii., 1900. About 100 plates were engraved for a fifth volume, never published.

Treu (W.). Griechische Thongefässe in Statuetten- und Büstenformen. Berlin, 1875, 4to. (35tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.)

Tyszkiewicz (Count M.). See Froehner.

Urlichs (C. L. von). Der Vasenmaler Brygos und die ruland’sche Münzsammlung. Würzburg, 1875, fol.

—— Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte. Leipzig, 1884, 8vo. See also Würzburg.

Ussing (J.). De nominibus vasorum graecorum disputatio. Copenhagen, 1844.

Vienna. Die Sammlung antiker Vasen und Terracotten im k. k. Oesterreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie, by K. Masner. Vienna, 1892. With plates.

Vogel (K. J.). Scenen euripideischer Tragödien in griechischen Vasengemälden. Leipzig, 1886.

Vorlegeblätter für archäologische Übungen. Vienna, 1869–91, fol. Plates without text. Series i.–viii. 1869–75, ed. A. Conze (chiefly R.F. kylikes, by Euphronios, Hieron, Duris). Series A-E, 1879–86, ed. O. Benndorf (chiefly R.F. kylikes). Third series, 1888–91 (3 vols.), ed. Benndorf and others (chiefly signed B.F. vases). (Wiener Vorl.)

Wallis (H.). Pictures from Greek Vases. The White Athenian lekythi. London, 1896.

Walters (H. B.). See British Museum.

Watzinger (C). De vasculis pictis tarentinis capita selecta. Darmstadt, 1899, 8vo.

Welcker (F. G.). Alte Denkmäler. 5 vols, and atlas. Göttingen, 1849–64.

Wernicke (K.). Die griechischen Vasen mit Lieblingsnamen. Berlin, 1890.

—— and Graef (B.). Denkmäler der antiken Kunst. Leipzig, 1899, etc. In progress. A new edition of Müller and Wieseler’s well-known work. Text and atlas.

Westropp (H. M.). Epochs of painted vases, an introduction to their study. London, 1856.

Wilisch (E. G.). Die altkorinthische Thonindustrie. Leipzig, 1892.

Winkler (A.). De inferorum in vasis Italiae inferioris repraesentationibus. Breslau, 1888, 8vo.

Winnefeld (H.). See Karlsruhe.

Winter (F.). Die jüngeren attischen Vasen und ihr Verhaltniss zur grossen Kunst. Berlin, 1885.

Witte (J. J. A. M. de, Baron). Description des antiquités et objects d’art qui composent le cabinet de feu M. E. Durand. Paris, 1836, 8vo.

—— Description d’une collection de vases peints et bronzes antiques provenant des fouilles de l’Étrurie. Paris, 1837, 8vo. [Another edition, 1857.]

—— Noms des fabricants et dessinateurs de vases peints. Paris, 1848, 8vo.

—— Études sur les vases peints. Paris, 1865, 8vo. (Extract from the Gazette des Beaux-Arts.)

—— Description des collections d’antiquités conservées à l’Hôtel Lambert (the Czartoryski collection). Paris, 1886, 4to. (Coll. à l’Hôtel Lambert.) See also Lenormant.

Würzburg. Verzeichniss der Antikensammlung der Universität Würzburg, by C. L. von Urlichs. 1865–72, 8vo.

Zannoni (A.). Gli Scavi della Certosa di Bologna. 2 vols., text and plates. Bologna, 1876, fol. (An account of excavations at Bologna; many illustrations of tombs and Greek vases.)

Athens. See Martha.

Berlin Museum. Ausgewählte griechische Terrakotten im Antiquarium des königliches Museum zu Berlin, herausgegeben von der Generalverwaltung. Berlin, 1903. See also Panofka.

Blümner (H.). Technologie und Terminologie. See above, p.xxi. Vol. ii. deals with method of working in clay (Thonplastik, p. 113 ff.).

Borrmann (R.). Die Keramik in der Baukunst. Durm’s Handbuch der Architektur, part i. vol. 4. Stuttgart, 1897. On the use of terracotta in classical architecture. See also Dörpfeld.

British Museum. Terracotta Sarcophagi, by A. S. Murray. London, 1898. See above, p. xxii.

—— Catalogue of the Terracottas in the British Museum, by H. B. Walters. London, 1903. See also Combe.

Campana (G. P.). Antiche opere in plastica. Rome, 1842–52, fol. Text incomplete; plates of architectural terracottas of the Roman period.

Combe (Taylor). A description of the collection of ancient Terracottas in the British Museum. London, 1810. Describes the Towneley figures and mural reliefs.

Daremberg (C.), Saglio (E.), and Pottier (E.). Dictionnaire des Antiquités. See above, p. xxiii. The article Figlinum in vol. ii. will be found useful.

Dörpfeld (W.), Graeber (F.), Borrmann (R.), and Siebold (K.). Über die Verwendung von Terrakotten am Geison und Dache in griechischen Bauwerke, (41tes Winckelmannsfestprogr.) Berlin, 1881. (On terracotta in architecture.)

Furtwaengler (A.). Collection Sabouroff. See above, p. xxiv. Vol. ii. contains plates of Tanagra figures, with useful text to each.

Heuzey (L.). Les Figurines antiques de terre cuite du Musée du Louvre. Paris, 1883, 4to. Plates, with brief text.

—— Catalogue des figurines antiques de terre cuite du Musée du Louvre. Vol. i. Paris, 1891. Deals with archaic terracottas (Rhodes and Cyprus). No more published.

Huish (M. B.). Greek Terracotta Statuettes, their origin, evolution, and uses. London, 1900. (The plates include some doubtful specimens.)

Hutton (Miss C.A.). Greek Terracotta Statuettes. (Portfolio monograph, No. 49.) London, 1899. An excellent résumé of the subject, with good illustrations.

Kekulé (R., now Kekule von Stradonitz). Griechische Thonfiguren aus Tanagra. Stuttgart, 1878, fol.

—— Die antiken Terracotten, im Auftrag des archäologischen Institutes des deutschen Reichs, herausgegeben von R. K. Stuttgart, 1880, etc., fol. In progress.

Vol. i. Terracotten von Pompeii, by A. von Rohden. 1880. Chiefly architectural.

Vol. ii. Terracotten von Sicilien, by R. Kekulé. 1884.

Vol. iii. Typen der griechischen Terrakotten, by F. Winter. 1903. In two parts. A Corpus of all known types of terracotta statuettes, with numerous illustrations and other useful information.

Martha (J.). Catalogue des Figurines en terre cuite du Musée de la Société Archéologique d’Athènes. Paris, 1880, 8vo. (Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises, Fasc. 16.)

Minervini (G.). Terre cotte del Museo Campano. Vol. i. Naples, 1880. Illustrations of architectural terracottas.

Panofka (T.). Terracotten des königlichen Museums zu Berlin. Berlin, 1842, 4to.

Paris (P.). Élatée, la ville, le Temple d’Athéna Cranaia. Paris, 1892. (Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises, Fasc. 60.) Contains some useful information on the subject.

Pottier (E.). Les Statuettes de Terre Cuite dans l’Antiquité. Paris, 1890. (Bibliothèque des Merveilles.)

Pottier (E.) and Reinach (S.). La Nécropole de Myrina. 2 vols., text and plates. Paris, 1887.

Rohden (H. von). See Kekulé.

Schöne (R.). Griechische Reliefs aus athenischen Sammlungen, herausgegeben von R. S. Leipzig, 1872, fol. Illustration and discussion of the “Melian” reliefs (see pls. 30–34).

Winter (F.). See Kekulé.

Artis (E. T.). The Durobrivae of Antoninus identified and illustrated. London, 1828, fol. Plates only; for accompanying text (by C. Roach-Smith) see Journ. of Brit. Arch. Assoc. i. p. 1 ff. Deals with pottery and kilns of Castor and neighbourhood.

Blanchet (A.). Mélanges d’Archéologie gallo-romaine, ii. Paris, 1902, 8vo. (Lists of potteries in Gaul on p. 90 ff.)

Blümner (H.). Technologie und Terminologie, etc. See above, p. xxi.

Brongniart (A.). Traité de la Céramique. See above, p. xxii.

Buckman (J.) and Newmarch (C. H.). Illustrations of the remains of Roman Art in Cirencester, the ancient Corinium. London and Cirencester, 1850, 4to. (Now somewhat out of date.)

Caumont (A. de). Cours d’antiquités monumentales; histoire de l’art dans l’Ouest de la France. 6 vols. Paris and Caen, 1830–41, 8vo, with atlas in oblong 4to.

Choisy (A.). L'Art de Bâtir chez les Romains. Paris, 1873, 4to. (For the use of bricks and tiles.)

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Berlin, 1863, etc., fol. In progress. The portions of the published volumes giving the inscriptions on vases, tiles, and lamps, under the heading Instrumentum Domesticum, are invaluable, especially vol. xv. (by H. Dressel) relating to Rome. (C.I.L.)

Déchelette (J.). Les Vases céramiques ornés de la Gaule romaine (Narbonnaise, Aquitaine, et Lyonnaise). 2 vols. Paris, 1904, 4to. An invaluable survey of the pottery of Central and Southern Gaul, with much new material. (Déchelette.)

Fabroni (A.). Storia degli antichi vasi fittili aretini. Arezzo, 1841, 8vo. (On the Arretine wares.)

Guildhall Museum. See London.

Hölder (O.). Formen der römische Thongefässe, diesseits und jenseits der Alpen. Stuttgart, 1897, 8vo.

Koenen (K.). Gefässkunde der vorrömischen, römischen, und frankischen Zeit in den Rheinlanden. Bonn, 1895, 8vo.

London (Guildhall Museum). Catalogue of the Collection of London Antiquities in the Guildhall Museum. London, 1903, 8vo.

—— (Museum of Practical Geology). Handbook to the collection of British Pottery and Porcelain in the Museum. London, 1893, 8vo.

Marini (G.). Iscrizioni antiche doliari, edited by G. B. de Rossi and H. Dressel. Rome, 1884, 4to.

Marquardt (J.). Handbuch der römischen Alterthümer (with T. Mommsen). Bd. vii., Privatalterthümer. Leipzig, 1879–82, 8vo. See p. 616 ff. for Roman pottery.

Mazard (H. A.). De la connaissance par les anciens des glaçures plombifères. Paris, 1879, 8vo. (On the enamelled Roman wares described in Vol. I. p. 129.)

Middleton (J. H.). The Remains of Ancient Rome. 2 vols. London, 1892, 8vo. (On the use of bricks and tiles at Rome.)

Plicque (A. E.). Étude de Céramique arverno-romaine. Caen, 1887, 8vo. (On the potteries of Lezoux.)

Roach-Smith (C). Collectanea Antiqua; etchings and notices of ancient remains, etc. 7 vols. London, 1848–80, 8vo. Useful for records of discoveries of Roman remains in Gaul and Britain.

—— Illustrations of Roman London. London, 1859, 4to.

Steiner (J. W. C). Codex Inscriptionum Romanarum Danubii et Rheni. 4 vols. Darmstadt, etc., 1851–61, 8vo. Contains many inscriptions on pottery and tiles not as yet published in the C.I.L.

Victoria County History of England, ed. by W. Page, etc. In progress. London, 1900, etc. Articles in the first volume of each separate county history, by F. Haverfield, dealing with all known Roman remains. Those of Northants and Hampshire are especially useful and complete.

Wright (T.). The Celt, the Roman, and the Saxon. Fourth edn., 1885. Still useful as a summary of Roman Britain, though out of date and inaccurate in many particulars.

Reference should also be made to the Bonner Jahrbücher (see above, p. xix), especially to the treatise by Dragendorff in vol. xcvi., and for German pottery to Von Hefner’s article in Oberbayrische Archiv für vaterlandische Geschichte, xxii. (1863), p. 1 ff.

For Bibliography of Roman Lamps, see heading to Chapter XX.

B.F. = Black-figured vases.

R.F. = Red-figured vases.

B.M. = British Museum.

Reinach = Reinach’s Répertoire des Vases (see Bibliography).

In the cases where particular vases are cited, as in Chapters XII.-XV., the name of the museum is given with the catalogue number attached, as B.M. B 1; Louvre G 2; Berlin 2000, etc. The vases in the Vatican Museum at Rome are quoted as Helbig, 1, 2, 3, etc. (see Bibliography, under Rome).

All other abbreviations will be found in the Bibliography.

Importance of study of ancient monuments—Value of pottery as evidence of early civilisation—Invention of the art—Use of brick in Babylonia—The potter’s wheel—Enamel and glazes—Earliest Greek pottery—Use of study of vases—Ethnological, historical, mythological, and artistic aspects—Earliest writings on the subject—The “Etruscan” theory—History of the study of Greek vases—Artistic, epexegetic, and historical methods—The vase-collections of Europe and their history—List of existing collections.

The present age is above all an age of Discovery. The thirst for knowledge manifests itself in all directions—theological, scientific, geographical, historical, and antiquarian. The handiwork of Nature and of Man alike are called upon to yield up their secrets to satisfy the universal demand which has arisen from the spread of education and the ever-increasing desire for culture which is one of the characteristics of the present day. And though, perhaps, the science of Archaeology does not command as many adherents as other branches of learning, there is still a very general desire to enquire into the records of the past, to learn what we can of the methods of our forefathers, and to trace the influence of their writings or other evidences of their existence on succeeding ages.

To many of us what is known as a classical education seems perhaps in these utilitarian times somewhat antiquated and unnecessary, but at the same time “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome” have not lost their interest for us, and can awaken responsive chords in most of our hearts. Nor can we ever be quite forgetful of the debt that we owe to those nations in almost every branch of human learning and industry. To take the most patent instance of all, that of our language, it is not too much to say that nearly every word is either directly derived from a classical source or can be shown to have etymological affinities with either of the two ancient tongues. Nor is it necessary to pursue illustrations further. We need only point to the evidences of classical influence on modern literature, modern philosophy, and modern political and social institutions, to indicate how our civilisation is permeated and saturated with the results of ancient ideas and thoughts. The man of science has recourse to Greek or Latin for his nomenclature; the scholar employs Latin as the most appropriate vehicle for criticism; and modern architecture was for a long time only a revival (whether successful or not) of the principles and achievements of the classical genius.

Now, those who would pursue the study of a nation’s history cannot be content with the mere perusal of such literary records as it may have left behind. It needs brief consideration to realise that this leaves us equipped with very little real knowledge of an ancient race, inasmuch as the range of literature is necessarily limited, and deals with only a few sides of the national character: its military history, its political constitution, or its intellectual and philosophical bent—in short, its external and public life alone. He who would thoroughly investigate the history of a nation instinctively desires something more; he will seek to gain a comprehensive acquaintance with its social life, its religious beliefs, its artistic and intellectual attainments, and generally to estimate the extent of its culture and civilisation. But to do this it is necessary not only to be thoroughly conversant with its literary and historical records, but to turn attention also to its monuments. It need hardly be said that the word “monument” is here used in the quasi-technical sense current among archaeologists (witness the German use of the word Denkmäler), and that it must bear here a much wider signification than is generally accorded to it nowadays. It may, in fact, be applied to any object which has come down to us as a memorial and evidence of a nation’s productive capacity or as an illustration of its social or political life. The student of antiquity can adopt no better motto than the familiar line of Terence:

For the very humblest product of the human brain or hand, a potsherd or a few letters scratched on a stone, may throw the most instructive light on the history of a race.

In no instance is this better seen than in the case of Assyria, where almost all that we know of that great and wonderful people is derived from the cuneiform inscriptions scratched on tablets of baked clay. Or, again, we may cite the stone and bronze implements of the primitive peoples of Europe as another instance where “the weak and base things of the world and the things that are despised” have thrown floods of light on the condition of things in a period about which we should have been completely in the dark so long as we looked only to literary records for our information. Nothing is so common that it may be overlooked, and we may learn more from a humble implement in daily use than from the finest product of a poetic or artistic intellect, if we are really desirous of obtaining an intimate acquaintance with the domestic life of a people.

Among the simplest yet most necessary adjuncts of a developing civilisation Pottery may be recognised as one of the most universal. The very earliest and rudest remains of any people generally take the form of coarse and common pots, in which they cooked their food or consumed their beverages. And the fact that such vast quantities of pottery from all ancient civilisations have been preserved to us is due partly to its comparatively imperishable nature, partly to the absence of any intrinsic value which saved it from falling a prey to the ravages of fire, human greed, or other causes which have destroyed more precious monuments, such as gold ornaments, paintings, and statues of marble or bronze. Moreover, it is always in the pottery that we perceive the first indications of whatever artistic instinct a race possesses, clay being a material so easy to decorate and so readily lending itself to plastic treatment for the creation of new forms or development from simple to elaborate shapes.

To trace the history of the art of working in clay, from its rise amongst the oldest nations of antiquity to the period of the decline of the Roman Empire, is the object of the present work. The subject resolves itself into two great divisions, which have engaged the attention of two distinct classes of enquirers: namely, the technical or practical part, comprising all the details of material, manipulation, and processes; and, secondly, the historical portion, which embraces not only the history of the art itself, and the application of ancient literature to its elucidation, but also an account of the light thrown by monuments in clay on the history of mankind. Such an investigation is therefore neither trifling in character nor deficient in valuable results.

It is impossible to determine when the manufacture of pottery was invented. Clay is a material so generally diffused, and its plastic nature is so easily discovered, that the art of working it does not exceed the intelligence of the rudest savage. Even the most primitive graves of Europe and Western Asia contain specimens of pottery, rude and elementary indeed, but in sufficient quantities to show that it was at all times reckoned among the indispensable adjuncts of daily life.

It is said that the very earliest specimens of pottery, hand-made and almost shapeless, have been discovered in the cave-dwellings of Palaeolithic Man, such as the Höhlefels cave near Ulm, and that of Nabrigas, near Toulouse; and pottery has also been found in the “kitchen-middens” of Denmark, which belong to this period. Such relics are, however, so rude and fragmentary, and so much doubt has been cast on the circumstances of their discovery, that it is better to be content with the evidence afforded by the Neolithic Age, of which perhaps the best authenticated is the predynastic pottery of Egypt.[1]

Abundant specimens of pottery have been found in long barrows in all parts of Western Europe; these are supposed to be the burial-places of the early dolichocephalic races, now represented by the Finns and Lapps, which preceded the Aryan immigration. The chief characteristic of this pottery is the almost entire absence of ornamentation. Neolithic man appears to have been far less endowed with the artistic instinct than his palaeolithic predecessor. Where ornament does occur, it appears to have a quite fortuitous origin: for instance, a kind of rope-pattern that appears on the earliest pottery of Britain and Germany, and also in America, owes its origin to the practice of moulding the clay in a kind of basket of bark or thread. It is also possible that cords of some kind were used for carrying the pots; and this reminds us of another characteristic of the earliest pottery, which, indeed, lasts down to the Bronze Age—namely, the absence of handles.

The baking of clay, so as to produce an indestructible and tenacious substance, was probably also the result of accident rather than design. This was pointed out as long ago as the middle of the eighteenth century by M. Goguet. In most countries the condition of the atmosphere precludes the survival of sun-dried clay for any length of time; moreover, such a material was more suitable for architecture (as we shall see later) than for vessels destined to hold liquids. Thus it is that Egypt, Assyria, and Babylonia alone have transmitted to posterity the early efforts of workers in sun-dried clay.

To return to the new invention. The savage conceivably found that the calabash or gourd in which he boiled the water for his simple culinary needs was liable to be damaged by the action of fire; and it required no very advanced mental process to smear the exterior of the vessel with some such substance as clay in order to protect it. As he found that the surface of the clay was thereby rendered hard and impervious, his next step would naturally be to dispense with the calabash and mould the clay into a similar form. These two simple qualities of clay, its plastic nature and its susceptibility to the action of fire, are the two elements which form the basis of the whole development of the potter’s art.

From the necessity for symmetrical buildings arose the invention of the brick, which must have superseded the rude plastering of the hut with clay, to protect it against the sun or storm. In the history of the Semitic nations the brick appears among the earliest inventions, and its use can be traced with various modifications, from the building of the Tower of Babel to the present day. It is essential that bricks should be symmetrical, and their form is generally rectangular. Their geometrical shape affords us a clue to ancient units of measurement, and the various inscriptions with which they have been stamped have elevated them to the dignity of historical monuments. Thus the bricks of Egypt not only afford testimony, by their composition of straw and clay, that the writer of Exodus was acquainted with that country, but also, by the hieroglyphs impressed upon them, transmit the names of a series of kings, and testify to the existence of edifices, all knowledge of which, except for these relics, would have utterly perished. Those of Assyria and Babylon, in addition to the same information, have, by their cuneiform inscriptions, which mention the locality of the edifices for which they were made, afforded the means of tracing the sites of ancient Mesopotamia and Assyria with an accuracy unattainable by any other means. The Roman bricks have also borne their testimony to history. A large number of them present a series of the names of consuls of imperial Rome; while others show that the proud nobility of the eternal city partly derived their revenues from the kilns of their Campanian and Sabine estates.