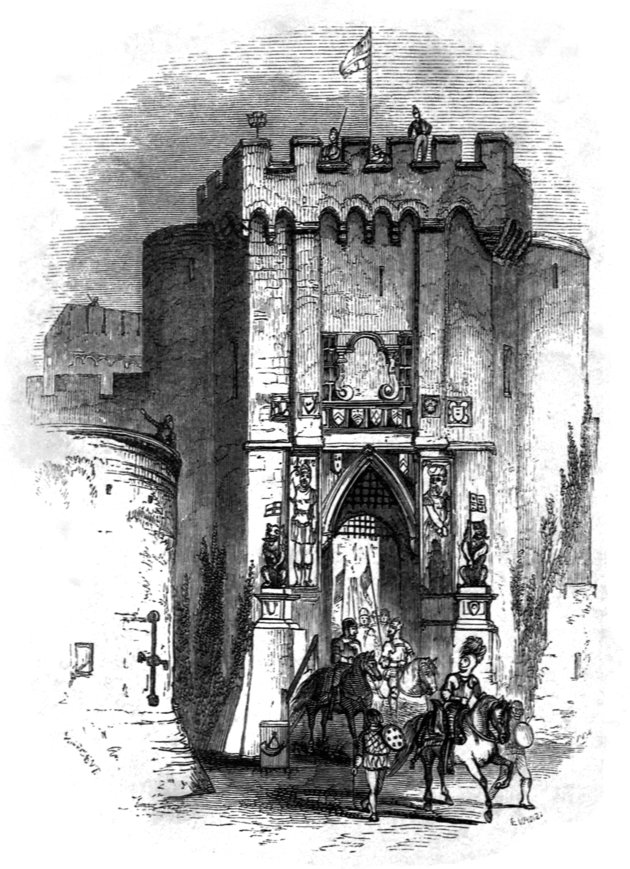

SOUTHAMPTON BAR IN THE OLDEN TIME.

Title: Glimpses of Nature, and Objects of Interest Described, During a Visit to the Isle of Wight

Author: Mrs. Loudon

Release date: February 6, 2015 [eBook #48183]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, David Maranhao and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

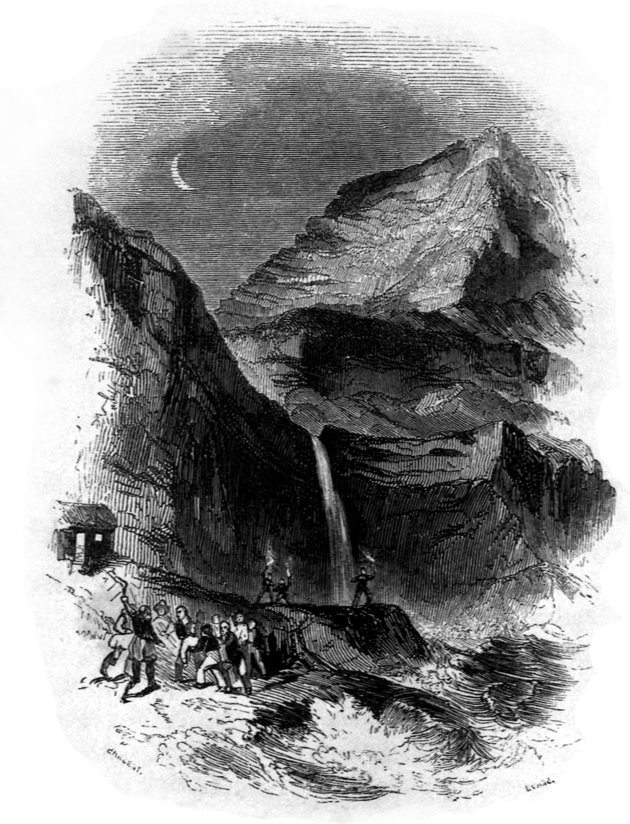

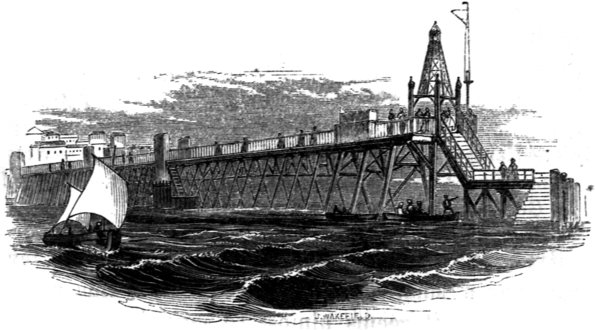

SOUTHAMPTON BAR IN THE OLDEN TIME.

On the 21st of August, 1843, Mr. Loudon, my little daughter Agnes, and myself, set out, from Bayswater, to make the tour through the Isle of Wight which is recorded in the following pages.

That tour has since acquired a melancholy importance in my eyes, from being the last I ever took with my poor husband, whose danger I was quite unconscious of when I wrote the book, though his death took place in less than a month from the day of its publication. This circumstance made the book painful to me, and I never looked at it again till now I have been reading it over for revision; and it is impossible to describe the vivid interest with which I recall every incident that took place, and every word that was uttered.

In preparing this second edition, I have added a chapter on shells and sea-weed, but in other respects I have made no alteration, save a few verbal corrections; as the principal object I had in view, in writing down all we saw and heard during this excursion, was to show how much may be observed and learnt while travelling, even through a well-known country and under ordinary circumstances. I think it of the utmost importance to cultivate habits of observation in childhood; as a great deal of the happiness of life depends upon having our attention excited by what passes around us. I remember, when I was a child, reading a tale called “Eyes and No Eyes,” which made a deep impression on my mind; and which has been the means of procuring me many sources of enjoyment during my passage through life. That little tale related to two boys, both of whom had been allowed half a day’s holiday. The first boy went out to take a walk, and he saw a variety of objects that interested him; and from which he afterwards derived considerable instruction, when he talked about them with his tutor. The second, a little later, took the same walk; but, when his tutor questioned him as to how he liked it, he said he had thought it very dull, for he had seen nothing; though the same objects were still there that had delighted his companion. I was so much struck with the contrast between the two boys, that I determined to imitate the first; and I have found so much advantage from this determination, that I can earnestly recommend my young readers to follow my example. The use of travelling is, that it affords us more opportunities of observation than we could have at home; but, if we do not avail ourselves of these opportunities, we may travel over the whole globe without reaping any advantage. I trust the young people who may read these pages will so far profit by them as to notice all they see, and, particularly, to look for objects of natural history in their walks, whether at home or by the sea-side; and, in return, I promise them that they will find a thousand sources of amusement that before they had no idea of.

Bayswater,

March 9, 1848.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I.—Terminus of the Southampton Railroad at Vauxhall.—Truth and Falsehood.—Reaping.—Flint in Straw.—The river Mole.—The Wey.—Canals and Locks.—Poppies and Opium.—Limestone and Chalk.—Gleaners.—Ruins at Basingstoke.—Southampton Bar.—Sir Bevis and the Giant Ascabart. | 8 |

| Chapter II.—Passengers down the River.—Sea-nettles.—Netley Abbey and Fort.—View of the Isle of Wight.—Adventure of the Portmanteau.—Landing at West Cowes.—Crossing the Medina.—Salt Works at East Cowes. | 28 |

| Chapter III.—Morning Walk through West Cowes.—Ride to Newport.—Carisbrook Castle.—Children of Charles I.—Donkey Well.—Chapel of St. Nicholas.—Boy Bishop.—Archery Meeting.—History of the Isle of Wight.—Bows and Arrows. | 53 |

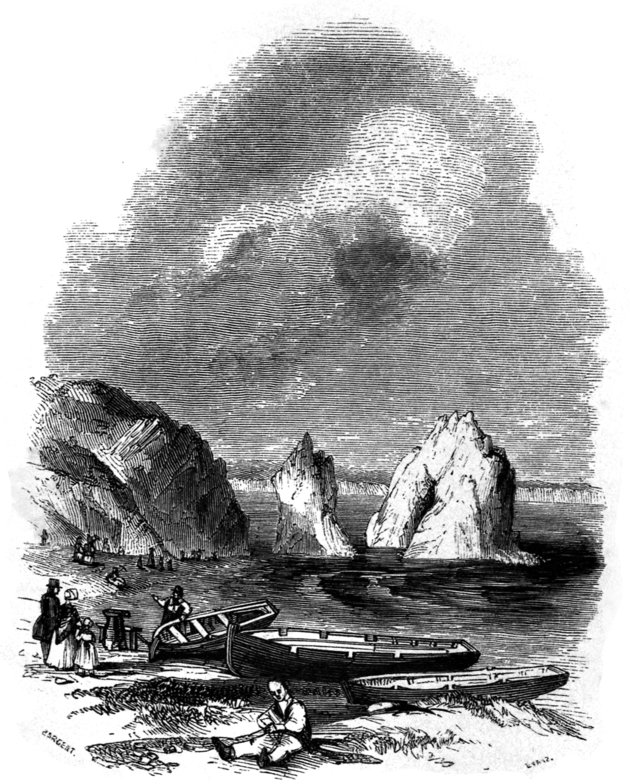

| Chapter IV.—Departure from Carisbrook.—Road to Freshwater.—Yarmouth.—House where Charles II. was entertained by Admiral Sir Robert Holme.—Freshwater.—Rocks.—Roaring of the Sea.—Birds.—The Razor-bill and Guillemot.—Sea-weed. | 75 |

| Chapter V.—Young Londoner and Neptune.—Disobedience of the Young Fisherman.—Fossils.—Fine Water.—Alum Bay.—The Needles.—Old Couple.—Dull Road.—Fertility of the Isle of Wight. | 97 |

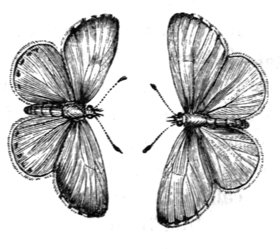

| Chapter VI.—Management in Household Affairs.—Undercliffe.—Alexandrian Pillar.—Light-house of St. Catherine.—Little Church of St. Lawrence.—Churchyard.—St. Lawrence’s Well.—Ventnor.—Wishing Well, and Godshill.—Beautiful Butterflies.—Pulpit Stone.—St. Boniface.—Arrival at Shanklin. | 135 |

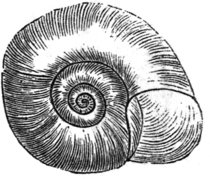

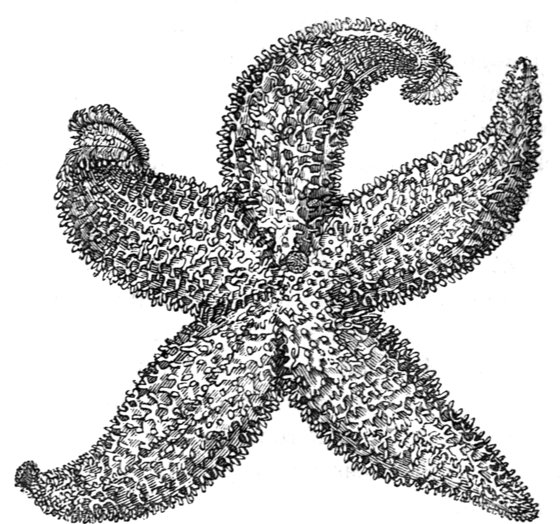

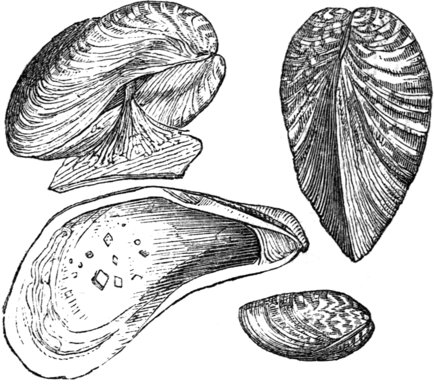

| Chapter VII.—Consequences of Carelessness.—Beach at Shanklin.—Lobster-pots.—Planorbis.—Marsh Snail.—Sea Rocket.—Starfish.—Crabs and Lobsters.—Sea-weed:—Mode of drying it.—Mussels.—Shanklin Chine.—The split Shoe.—Shops at Shanklin. | 155 |

| Chapter VIII.—Shanklin continued.—Siphonia or Sea-Tulip.—Zoophytes.—Sponges.—Corals.—Shells: Anomia; Scallop-shell; Cockle-shell; Whelk; Solen, or Razor-shell; Mactra or Kneading Trough; Mya. | 177 |

| Chapter IX.—Sandown Bay.—Culver Cliff.—Sandown Fort.—High Flood.—Girl and Dog.—Poultry.—Hares.—Butterflies.—Ichneumon Fly.—Myrtles.—Brading.—Bembridge.—St. Helen’s.—Arrival at Ryde. | 198 |

| Chapter X.—Ryde.—Handsome Shops.—Binstead.—Wootton Bridge.—Newport.—East Cowes.—Horse Ferry.—Steam Boat.—Arms of the German Empire.—Return home. | 213 |

| PAGE | |

| Southampton Bar in the Olden Time | 25 |

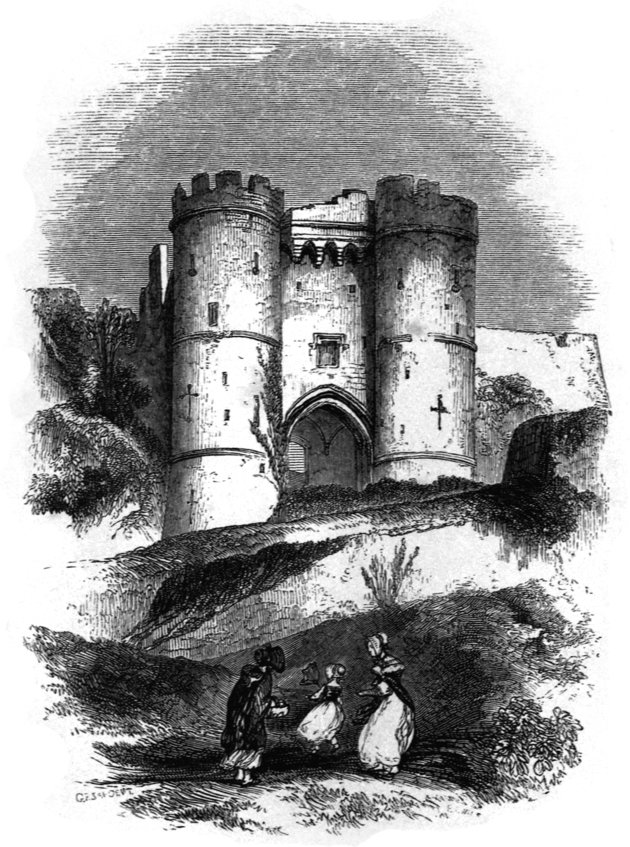

| Carisbrook Castle | 59 |

| Arched Rock at Freshwater | 84 |

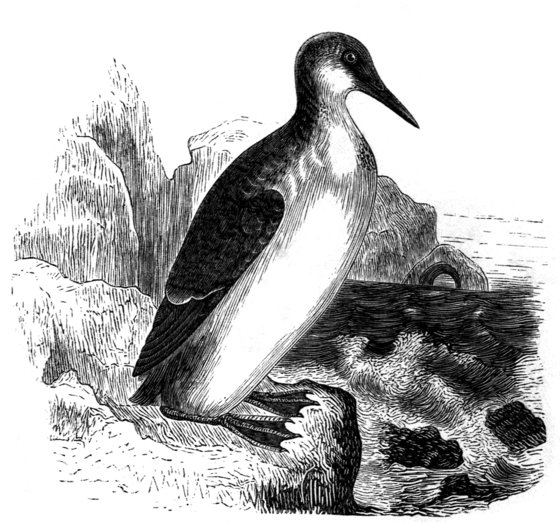

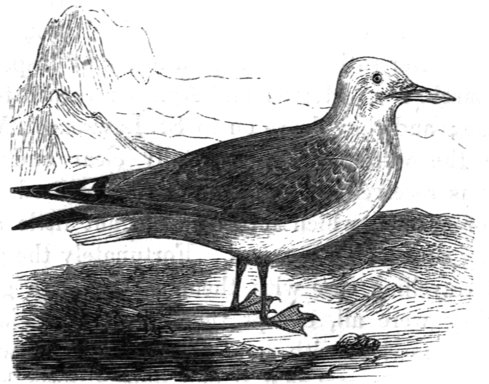

| Guillemot | 92 |

| Black Gang Chine | 133 |

| FIG. | PAGE | |

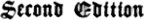

| 1. | Medusa, or Sea-Nettle | 30 |

| 2. | Sea-Jellies | 32 |

| 3. | The Portuguese Man-of-War | 37 |

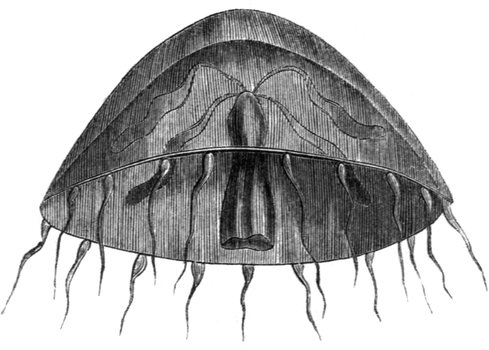

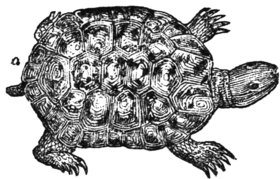

| 4. | Tortoise | 55 |

| 5. | Carisbrook Gate | 59 |

| 6. | King Charles’s Window | 60 |

| 7. | Ground-Ivy | 83 |

| 8. | The Spotted Medick | 83 |

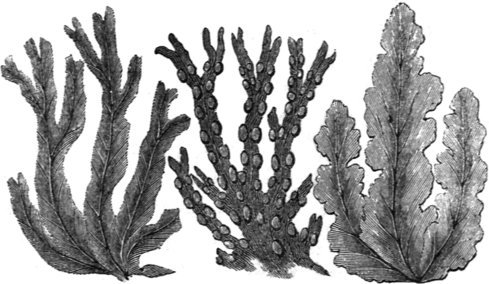

| 9. | Winged Fucus; Bladder Fucus; Tangle | 88 |

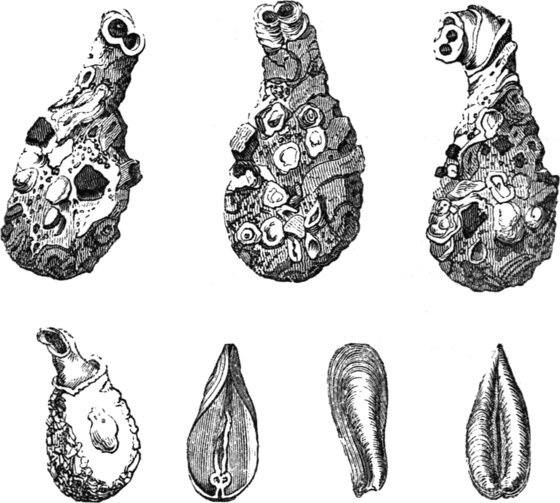

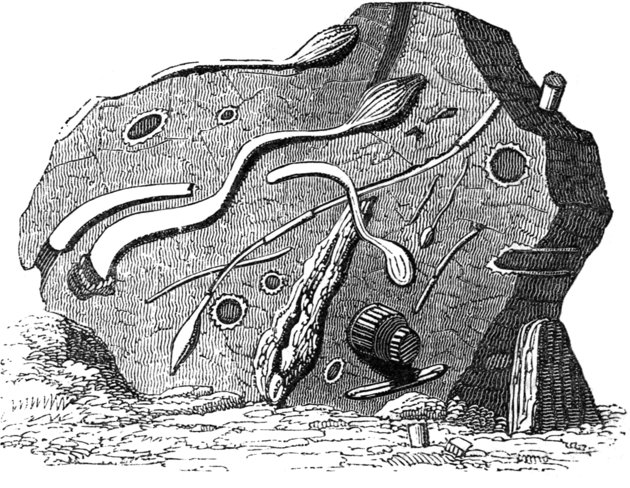

| 10. | Burrowing Molluscs | 113 |

| 11. | Section of Alum Bay | 115 |

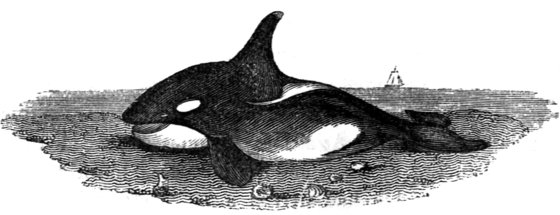

| 12. | Grampus | 116 |

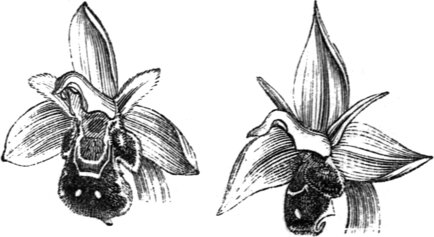

| 13. | The Bee Orchis | 120 |

| 14. | Plant of Crosswort | 124 |

| 15. | The Kittiwake Gull | 146 |

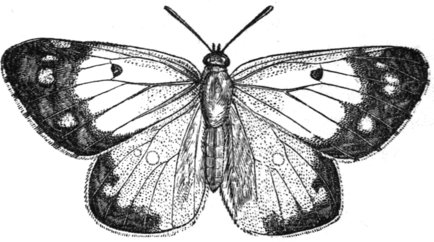

| 16. | The Azure Blue Butterfly | 152 |

| 17. | The Horny Snail | 159 |

| 18. | The Marsh Snail | 160 |

| 19. | The Star-fish, or Five-Fingers | 162 |

| 20. | Irish Moss, or Carrageen | 167 |

| 21. | Duck’s Foot Conferva | 168 |

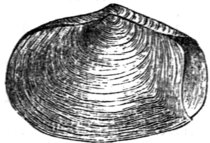

| 22. | Freshwater Mussels | 171 |

| 23. | Mass of Fossils containing the Siphonia, or Sea-Tulip | 179 |

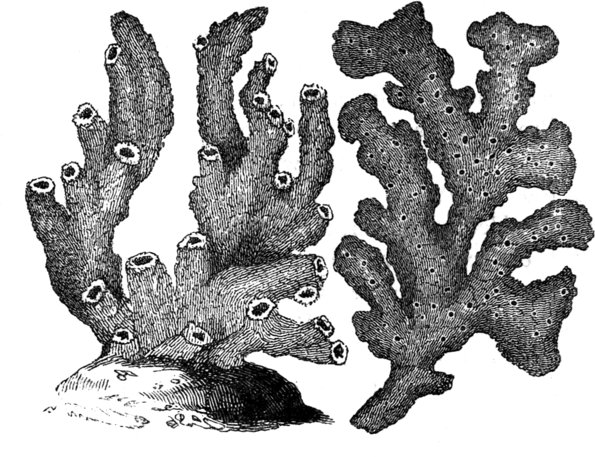

| 24. | Sponges | 183 |

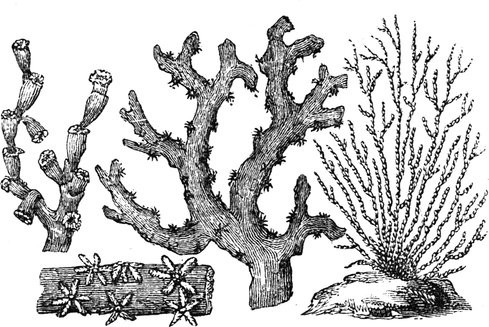

| 25. | Corals | 185 |

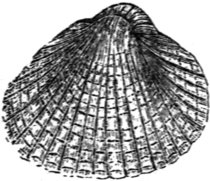

| 26. | Saddle-Shaped Anomia | 186 |

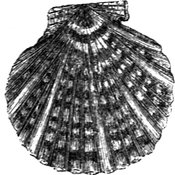

| 27. | Scallop Shell | 188 |

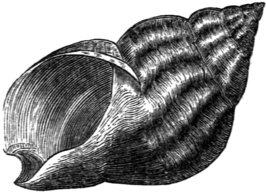

| 28. | Whelk (Buccinum) | 190 |

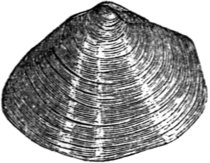

| 29. | Truncated Gaper; Solen, or Razor-Shell; Common Cockle; the Kneading-Trough | 192 |

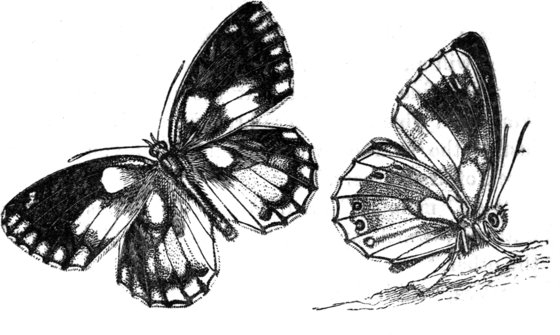

| 30. | The Marbled-White Butterfly, or Marmoress | 203 |

| 31. | The Clouded-Yellow Butterfly | 205 |

| 32. | Ichneumon Fly on a Floret of the Flowering Rush | 206 |

| 33. | Ryde-Pier | 214 |

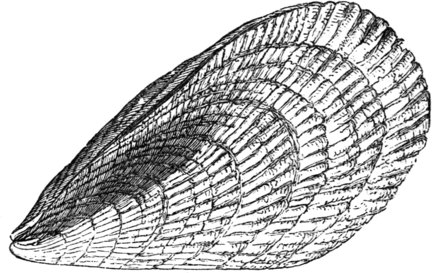

| 34. | Ribbed Mussel | 215 |

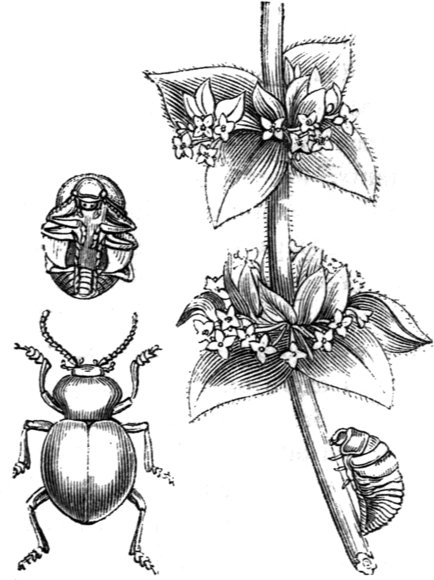

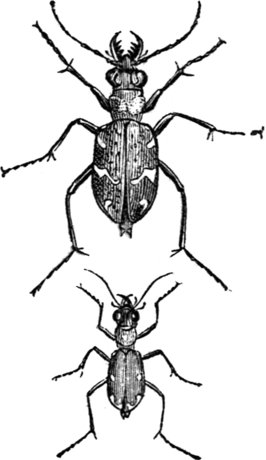

| 35. | Tiger Beetles | 219 |

| 36. | Helix virgata; Bulimus articulatus | 222 |

| 37. | Arms of Germany | 228 |

Agnes Merton was one day sitting in rather a melancholy mood on the swing in her garden, without swinging, and apparently lost in thought. It was a very odd place for meditation, but little girls do choose strange places sometimes; and Agnes at this moment felt very sad and uncomfortable on various accounts. Her papa had been in a bad state of health for some time, and Mrs. Merton’s attention had been so entirely occupied by him, that Agnes had been comparatively neglected by her mother. Her papa also could not be troubled with her, although he was very fond of her when he was well; sick people cannot bear the fatigue of children. Agnes had no sisters, and only a daily governess, who stayed with her but a short time, so that during the greater part of the day the poor child was left entirely to her own resources, and children so young as Agnes cannot always be reading. Agnes was at this time particularly unfortunate, as even her favourite cat, Sandy, had gone away about three weeks before, and nobody knew what had become of him. In this state of things every amusement seemed to have lost its zest, and after swinging a short time with the air of a person who was performing a task, rather than one who was enjoying a pleasure, Agnes sat, as we have before said, on her swing, apparently quite lost in thought, and, indeed, so absorbed that she started when her mother laid her hand upon her shoulder, and asked her if she would like to go to the Isle of Wight?

It is impossible to describe what a change these few words produced in the feelings of the little girl, and she replied with her countenance beaming with delight, “Oh yes, mamma, very much indeed!”

“Your papa,” resumed Mrs. Merton, “has been ordered to try change of air for the benefit of his health, and he has determined to go to the Isle of Wight for a week. At first he intended leaving you at home, but at my earnest desire he has consented to take you with us, upon condition of your giving no trouble.”

“Oh, mamma,” interrupted Agnes, “I will not give any trouble at all.”

“Perhaps you are hardly aware of what you are promising,” said Mrs. Merton, smiling; “your papa has determined on taking no servant with him, so that you must dress and undress yourself, and take care of your own clothes.”

“But, mamma,” said Agnes, “shall we not have poor little Susan?”

“No,” replied Mrs. Merton; “there will only be your papa, besides you and me: and as my time will be principally occupied in attending on him, you must contrive to take care of yourself.”

Agnes laughed; “I think I am quite old enough to do that,” said she.

“We shall see,” replied her mother. “You must also dine and take all your meals with us; as it will probably not be convenient for us to stay to take any refreshment at the time you have been used to dine.”

This, so far from being a hardship, Agnes thought the most delightful part of the whole, as she had long considered dining at six o’clock as one of the great desiderata of life; but Mrs. Merton continued: “You must also never complain of being hungry or thirsty; but act as much as possible as if you were really a woman, since we are going to treat you like one.”

“I am afraid, mamma,” said Agnes, “that will be very hard.”

“If you do not think you can undertake to do all I wish, you must stay at home; and I have no doubt your aunt Jane will be so kind as to take care of you while we are away. But I think you are quite capable of all that will be required of you. You are now ten years old, and you knew how to pack up a trunk when you were only seven. You shall have a pretty little black portmanteau entirely to yourself, and you shall have a list of everything that is put into it, so that you may know when all your things are right.”

Agnes was delighted with the idea of taking care of her own trunk; particularly as her mamma consented, at her earnest request, to leave the choice of what clothes she would take entirely to herself. Agnes was very fond of managing, and of giving directions to her maid, Susan, who was called immediately; for as this was Saturday, and they were to set out on Monday, there was no time to be lost. Susan was almost as much delighted as her little mistress with the task; and both felt of extraordinary importance when they found themselves alone with the open portmanteau before them, and close to the wardrobe from which it was to be filled. Both Susan and her young mistress were, however, soon very much puzzled to know what to decide on. Agnes at first had looked out nearly all the clothes she had, but it was soon found that the pretty little black portmanteau would not hold half the things that had been laid out. A fresh selection was therefore necessary, and several of the pretty frocks were put back into the drawer.

“Oh, I must have that, Susan,” said Agnes, stretching out her hands after her favourite blue, which was being taken away.

“Very well, miss,” said Susan. “Then suppose you take that, and leave this,” laying down the blue and taking up an equally favourite pale pink.

“Oh no,” cried Agnes; “I must have that, it is so prettily made.”

“Suppose you take all your coloured frocks,” said Susan, “and leave your white ones?”

“But, mamma says she always likes me best in white,” said Agnes.

“Well, then, we will take the whites,” said Susan, “and leave the coloured ones.”

Agnes sighed deeply. “Oh dear,” cried she, after a short pause; “I wish mamma were here to decide for me. I thought it would be so delightful to have everything my own way, but now the time is come I do not like it at all. I see it saves a great deal of trouble to have some one to direct, and to tell one what to do. I am sure I wish mamma would come and tell me, for I am quite tired of being my own mistress;” and as she spoke Mrs. Merton entered the room; for she had been in an adjoining apartment, and, overhearing the wishes of her little daughter, had come to her assistance. Under Mrs. Merton’s directions the box was soon packed, and Agnes was astonished to see how rapidly her difficulties had vanished.

“I cannot think how it is, mamma,” said she, “that you have been able to arrange in a moment what gave me so much trouble and vexation. You have done everything just as I wished, and as I would have done it myself, if I could have made up my mind; and yet my governess often tells me that I am self-willed, and like to have my own way; now, it appears to me that I actually did not know what my own way was, till you came and showed me.”

“The reason you had so much difficulty in deciding,” said Mrs. Merton, “was that your judgment required to be guided by experience, a quality in which young people are necessarily deficient. When you are as old as I am, and have travelled as much, you will be able to decide as rapidly as I did in this matter; as you will know by experience what things are likely to be most useful.”

Terminus of the Southampton Railroad at Vauxhall.—Truth and Falsehood.—Reaping flint in straw.—The river Mole.—The Wey.—Canals and Locks.—Poppies and Opium.—Limestone and Chalk.—Gleaners.—Ruins at Basingstoke.—Southampton.—The Bar.—Sir Bevis and the Giant Ascabart.

On Monday morning Agnes did not fail to awake in time, and after an early breakfast the party proceeded to the railroad. It was a very long ride from Bayswater to the station at Nine Elms, and Agnes thought it longer than it really was. At length, however, they arrived, and Agnes watched with considerable anxiety her black leather portmanteau taken off the carriage with the rest of the luggage. She was once going to tell the porter to take particular care of it, but observing that her mother did not speak she also remained silent, and followed Mrs. Merton into a large room, in which a man stood behind a kind of counter, receiving money and giving tickets. When it was Mrs. Merton’s turn, the man fixed his eyes on Agnes, and said abruptly, “How old are you?”

“I was ten last October,” replied Agnes, very much surprised at this question. Mrs. Merton then laid three sovereigns on the counter, which the man took up, giving her three tickets in return, with which she walked away in silence, and joining Mr. Merton they both walked to the railway carriages followed by Agnes, who could not at all understand the meaning of what had taken place. She did not like to ask any questions, as she had promised not to be troublesome, but she could not help thinking of the man’s strange behaviour; and when her mamma, who saw her puzzled look, asked what she was thinking about, she ventured to inquire what the man meant by speaking to her only, and why he took any interest in knowing her age. “I suppose,” said she, “he must have some little girls of his own, and that he wanted to know if I were the same age; but I wonder whether he thought me short or tall.” Mrs. Merton smiled, and replied that she really believed the man had never thought about it.

“Why did he ask my age, then?” inquired Agnes, rather vexed at her mamma’s indifference.

“To know how much you were to pay for your place,” replied Mrs. Merton. “If you had been under ten, I should have paid only half price for you.”

“But why did he not ask you such a question as that?”

“He was probably afraid that I should not tell him the truth.”

“But surely, mamma,” cried Agnes, her face flushing, and her eyes sparkling with indignation, “the man could never think you would demean yourself so much as to tell a falsehood for the sake of ten shillings.”

“If he had known me,” replied Mrs. Merton quietly, “I hope he would not have suspected me of telling a falsehood for the sake of any sum.”

An old gentleman who was their fellow-traveller, was very much amused at Agnes’s indignation, and began to tease her by telling her that her mamma was in the habit of telling stories every day; and when Agnes indignantly denied his assertion, he asked her if she thought her mamma had never written “your humble servant” at the end of a letter, without meaning that she was ready to act as a servant to the person she addressed; and whether she did not often say she was glad or sorry to hear some particular piece of news, when she did not, in fact, care much about it. Agnes began to look puzzled, and Mrs. Merton, not liking this mocking style of conversation, as she knew the necessity of keeping a strict line in a child’s mind between truth and falsehood, tried to turn her daughter’s attention to the objects they were passing. It is very strange that sensible and well-informed men should often take as much pleasure in confusing the thoughts of a poor innocent child, as vicious boys do in tormenting a harmless dog. This gentleman, whose name they afterwards found was Mr. Bevan, was a well-intentioned, good-hearted man, who would have been shocked at the thought of hurting Agnes by treading on her foot, or pushing her down; and yet, while he would have shrunk from wilfully inflicting on her a trifling bodily hurt which could only have caused a temporary suffering, he had no hesitation in doing a serious injury to her mind. It is true he only wished to amuse himself by watching the play of her countenance, without thinking of the consequences; and that if she had been his child he would have been the first to correct her for telling a falsehood: but his mocking strain roused the first doubt that had ever crossed the mind of Agnes as to whether it was possible to tell a falsehood without meaning any harm. Hitherto she had been truth itself, and still nothing would have induced her to tell a falsehood wilfully: but she was puzzled, as she was not old enough to distinguish between positive assertions, and mere conventional phrases, to which nobody attaches any precise meaning; and that perfect confidence in the holiness and power of truth, which is so beautiful a feature in the youthful mind, was shaken. Mrs. Merton wished to prevent her daughter’s mind from dwelling on the subject, and pointing to a corn-field, she asked Agnes, if she knew what corn it was. Before, however, the child could answer, a young man who sat opposite told her with a patronizing air, that it was wheat.

“You may know it,” continued he; “by its close heads. Barley and rye have long bristles, and oats have loose heads.”

Agnes now began to be interested in the wheat-fields they were passing; and her mamma made her observe the curious curved knife called a sickle, which is used in reaping corn; and the manner in which the corn was tied up in sheaves after it was cut, and the sheaves afterwards placed together in shocks, with their heads leaning towards each other, and a sheaf reversed over the top to keep the grain dry.

“But why do women reap?” asked Agnes; “you told me mowing was too difficult for them, and surely it is nobler to cut corn than grass.”

“Reaping requires less strength than mowing, as the sickle is neither so heavy nor so cumbrous as the scythe.”

“What part of the wheat produces the flour?”

“Can you not guess?”

Agnes hesitated, and then said, timidly and blushing, “I am not quite sure, but I think it is the seed.”

“Right,” cried Mr. Merton, who, being an excellent botanist himself, was always glad to turn his daughter’s attention to the peculiarities of plants. “Now tell me if you know any thing particular about the straw.”

“I believe it is hollow and jointed.”

“It is; and, what is more, it is not composed entirely of vegetable matter, but partly of stone; for every wheat straw contains enough flint to make a glass bead.”

“Oh, papa,” cried Agnes, “now you must be joking.”

“Indeed I am not. If a wheat straw be held in the flame of a candle, it will first turn to white ashes; and, if these ashes be still exposed to the flame, they will gradually melt into an imperfect sort of glass. When hay-ricks are burnt, there is always left a mass of dark, flinty matter, which closely resembles the dross sometimes thrown out of a glass-house.”

“How very curious!” cried Agnes.

“Did you ever see wheat in flower, my dear,” asked Mr. Bevan.

“Never, sir,” replied Agnes; and then, turning to her father, she said: “I suppose the gentleman wishes to make game of me; for wheat has no flowers,—has it papa?”

“Certainly, it has flowers, for it has perfect seeds; and all plants that have perfect seeds must have flowers. The flowers of the wheat are, however, inconspicuous, as they have no petals.”

While this conversation was passing, the train had kept whirling on, and Mrs. Merton had remarked two or three things that she thought worthy of the notice of her little daughter: she now called her attention to the windings of the river Mole, which has received its strange name from the manner in which it creeps along, and occasionally appears to bury itself under ground, as its waters are absorbed by the spongy and porous soil through which it flows. Agnes was very anxious to hear more of this curious river.

“It is remarkable,” said Mrs. Merton, “that it is not navigable in any part of its long course of forty-two miles; and that occasionally when the weather has been dry a long time, it disappears altogether. At the foot of Box-Hill, near Dorking, with regard to this phenomenon, it is supposed that there are cavities, or hollow places, under ground, which communicate with the bed of the river, and which are filled with water in ordinary seasons, but, in times of drought, become empty, and absorb the water from the river to refill them. When this is the case, the bed of the river becomes dry, and Burford bridge often presents the odd appearance of a bridge over land dry enough to be walked on. The river, however, always rises again about Letherhead, and suffers no further interruption in its course.”

While Mrs. Merton was speaking, the train had continued whirling on, and they had long passed the sluggish Mole, and had caught a glance of the more useful Wey; a river of about the same length as the Mole, but which has the advantage of being navigable for a great part of its course; and Agnes had watched the inhabitants of the little cottages which bordered the line of the railway trimming their gardens, and spreading their seeds out to dry in the sun. She had been amused, in one place, observing the careful manner in which a stack of faggots had been thatched, to keep it from the rain; and, in another, by observing the delight of a number of pigs, which had been turned into a stubble field, from which the corn had just been carried; and which ran about, grunting and capering, in a manner which none but pigs could ever accomplish. The train now passed another stream; and Agnes asked what river it was. “It is not a river,” said Mrs. Merton, “but the Basingstoke canal.”

“How do you know it is a canal, mamma?” asked Agnes.

“Its banks are straight and regular,” said Mrs. Merton, “which shows that they have been formed artificially; and the water is as deep close to the bank as it is in the centre: whereas, in rivers, the banks are generally irregular, and the water is shallower near them. Besides, there can be no doubt about this being a canal, for there, you see, is a lock.”

“Now, mamma,” said Agnes, “you have told me a great many things that I do not understand. I thought a canal had been only to supply the place of a river; and, if that is the case, I do not see why its banks should be different; and I do not know what you mean by a lock.”

“It is true,” said Mrs. Merton, “that a canal is intended to supply the place of a river, in as far as it is useful for carrying boats; but most rivers are only deep enough in the centre for this purpose, and a great deal of ground is lost on both sides: but, when a canal is dug, it is an object to save as much ground as possible; and, therefore, the trench that is dug is equally deep in all its parts, and perfectly level at the bottom. Now, when a country is hilly, the only way in which the canal can be kept level at the bottom is, by having it in two or more parts, of different levels, each one distinct from the other; as, otherwise, all the water from the high part would run into the low part: and these little canals are joined together by means of what are called locks. Each lock is a kind of oblong well, with a pair of strong, water-tight gates at each end; the lock being just the same depth as the difference between the higher and lower parts of the canal. When a boat comes along the higher part of the canal, the gates at that end of the lock are opened, and a sufficient quantity of water flows in, to allow the boat to float in at the same level. As soon as the boat is completely within the lock, the upper gates are closed, and the gates which communicate with the lower level of the canal are opened, when the water flows out, and the boat sinks gradually down to the lower level.”

“See, mamma,” cried Agnes, “there is a boat coming close to a lock; but it is in the lower part of the canal: what will they do now?”

“They will open the lower gates of the lock till the water has descended to the level of that part of the canal which contains the boat, which will then float in; and, I suppose, you can guess what will then take place.”

“Oh yes,” said Agnes, “the lower gates will be closed as soon as the boat is completely within the lock, and the upper ones opened.”

“You are quite right,” said her mother: “and, in this way the boat will be raised to the higher level of the canal.”

“I do declare, they are opening the gate now,” cried Agnes, leaning out of the window of the railway carriage as far as she possibly could. “How I do wish the train would stop a moment, and let me see the boat float in.”

But it was of no use: the train whirled on; and poor Agnes, instead of watching the machinery of the lock, was obliged to sit down, and listen to a lecture from her mamma, on the impropriety of hanging out at the windows of any carriage, and of those belonging to rail-roads more particularly. Some time passed almost in silence, till at last Mr. Bevan asked Agnes if she did not admire the pretty flowers in the corn-fields they were passing.

“Those poppies are very pretty, certainly,” said Agnes; “and I should admire them very much in a garden; but I do not like them in a corn field, because papa says they are a proof of bad farming.”

The old gentleman laughed at this, and asked Agnes if she knew the use of poppies, and that opium was made from them.

“Not from that kind, I believe, sir,” said Agnes. “It is the white poppy, is it not, mamma, that produces the opium?”

“Yes,” returned Mrs. Merton; “and it requires a hotter and drier climate than that of England to produce it in perfection. The best opium,” continued Mrs. Merton, “is obtained from Turkey; and, in that country, there are whole fields covered with poppies; and there are people whose principal business it is to watch when the petals of the flowers are falling, and then to wound the unripe capsule of each flower with a double-bladed lancet, so that the milky juice may exude. This milky juice becomes candied by the heat of the sun; and, being scraped off the following morning, forms what is called opium.”

They now passed through a deep cutting of a grey, partially-shining rock, which Mrs. Merton told Agnes was limestone. A little further the rocks became chalky, with narrow rows of flints embedded in them; which looked as though the high bank had been originally a chalk wall, with a row of broken bottles along the top, on which other chalk walls of a similar description had been built. Farther on, the banks of the cutting were formed of more crumbly materials, and appeared to consist entirely of loose sand and powdered chalk.

“What a variety of soils we are going through!” said Agnes.

“Not so great as you imagine,” returned her mother. “Chalk is but another form of limestone, and flint but another form of sand; and these two earths are almost always found together.”

They had now reached the Basingstoke station; and, while some of the passengers were getting down, Agnes amused herself in counting the number of gleaners in a field from which the corn had just been carried.

“There are eighty-two,” said she, after a short pause.

“Eighty-two what?” asked her mother.

“Gleaners,” said Agnes, directing her mother’s attention to the field, which, indeed, was nearly filled with people. The attention of the other passengers was now turned towards the field; and they all agreed that the corn must have been carried in a very careless manner to have left so many ears behind.

“It is a good thing for the poor people in the neighbourhood,” said Mr. Bevan.

“But,” said Mr. Merton, “it is hard for the farmer, who has been at the expense of ploughing and manuring, harrowing and sowing, and who is now deprived of his just profits by the negligence of his servants.”

The train soon moved on a little, and Agnes’s attention being attracted by the ruins of a church which stood on a little eminence near the road, she eagerly asked what it was.

“Those,” said the old gentleman, “are the ruins of a chapel, dedicated to the Holy Ghost, which is said to have been erected in the reign of Edward IV., and to which a school was formerly attached; but the school was shut up during the Civil Wars, and the building reduced to the state in which you now see it.”

“It is a fine ruin,” said Mrs. Merton.

“Yes,” returned the old gentleman; “and there is some fine carving about it, (if you were near enough to see it,) which was added in the reign of Henry VIII.”

“Was it not at Basingstoke,” asked Mr. Merton, “that Basing-House stood, so celebrated for its defence against Cromwell?”

“That was at Old Basing,” replied Mr. Bevan, “which was formerly a town, and a larger place than this: the word stoke signifying a hamlet. But things are reversed now; for Old Basing has become a hamlet, and Basingstoke a town.”

Agnes was very much interested in this conversation; as she had seen Mr. Charles Landseer’s beautiful painting of the taking of Basing house; and she now found how much a little knowledge of the subject adds to the interest you feel in a picture.

“Is the population of Basingstoke large?” asked Mr. Merton.

“There are about four thousand inhabitants, I think,” said the old gentleman, “rather less than more.” He then added, “I believe we are now only about thirty miles from Southampton.”

“Only thirty!” The distance is nothing on a rail-road,—an affair of about an hour or so; but how different it would be to a feeble mother, carrying a heavy child! How different to an exhausted wanderer, struggling to reach his longed-for home! Then, indeed, a distance of thirty miles would seem an undertaking almost heart-breaking, and scarcely to be accomplished; but time and space are always relative, and, in measuring them, we are apt to judge by our feelings, rather than by the reality.

After leaving Basingstoke, the train proceeded with great rapidity. Andover was the next station; and here numerous carriages were waiting to convey passengers to Salisbury, Exeter, and all the intermediate towns. Winchester next appeared in sight; and soon that ancient city, with its fine cathedral and antique cross, lay below them. Then they reached, and passed, the river Itchen, which winds backwards and forwards, like a broad riband floating in the wind. They were now within a few miles of Southampton; and, as they rapidly advanced, they began to feel the fresh breeze from the water. They still hurried on, and soon the masts of the shipping appeared in sight. The train now stopped, that the passengers might give up their tickets. This was soon done; and the train whirled on again to Southampton. They descended at the terminus; and having their luggage conveyed to the pier, they had it placed on board one of the steam-packets, which, they were told, would sail in about an hour. Having finished this business, Mr. Merton sat down on one of the seats on the pier, while Mrs. Merton and Agnes walked back to take a glance at the town.

The town of Southampton consists principally of one long, broad street, which ascends from the sea up a hill. This street is divided nearly in the middle by a curious old gate, called the bar; and which was, in fact, one of the gates of the ancient town. Towards this monument of antiquity, Mrs. Merton and Agnes bent their steps; and Mrs. Merton explained to her daughter, that bar was the Saxon name of gate.

“Oh, yes,” cried Agnes, “you know we say Temple Bar; and I remember that the gates in York are called bars: but mamma, what are those curious figures in front?”

“They are said to be the figures of a knight, renowned in romance, called Sir Bevis, of Hampton, and of Ascabart, a giant whom he slew.”

“The giant Ascabart is alluded to in the first canto of Scott’s Lady of the Lake; and many legends are told of his conqueror Sir Bevis, who appears to have resided near Southampton, at a place still called Sir Bevis’s Mount.”

“I suppose these figures below are Sir Bevis’s arms,” said Agnes; “if there ever was such a person.”

“I do not wonder that you have not full faith in Sir Bevis,” said Mrs. Merton, smiling; “but for my own part, I believe that all the heroes of romance we hear about in different places are real personages, though their deeds have been so exaggerated as to make us doubt their existence.”

“But the arms, mamma,” repeated Agnes,—“whose do you think they are?”

“Most of them are probably those of the persons who have repaired the gate, at different times; and I think those of Queen Elizabeth are in the centre. The queer-looking animals that sit below, however, most probably belonged to Sir Bevis, as they appear of the same date as his figure.”

They now took a rapid glance at the very handsome shops which lined the High-street on both sides, and returned to the pier, where they found the steam-packet just ready to start.

Passengers down the River.—Sea-nettles.—Netley Abbey and Fort.—View of the Isle of Wight.—Adventure of the Portmanteau.—Landing at West Cowes.—Crossing the Medina.—Salt Works at East Cowes.

The pier at Southampton has only been erected a few years, and it is called Victoria-pier, because it was opened by her present Majesty, shortly before her accession to the throne. Mrs. Merton and her daughter walked rapidly along it; for the bell had already rung, and the steam-packet was on the point of starting when they arrived. For a few minutes after they came on deck, they were too much hurried to observe anything particular, but Agnes had the pleasure of seeing that her dear little portmanteau was quite safe among the rest of the luggage. The day was fine, and the water sparkled in the sun-beams, as the steam-boat pursued its way rapidly down the river.

The first thing that attracted Agnes’s attention, was the appearance of some workmen who were taking up a few of the upright pieces of wood which supported the pier. These piles were bored through in several places; and Mrs. Merton asked her if she could tell the cause.

“The cause is the Pholas, or Stone-piercer,” said Agnes. “I remember, mamma, you told me all about that curious shell-fish long ago; and that the piles are now obliged to be covered with nails driven into them, to prevent them from being bored through: but I never saw any of the piles before.” She had not much time to look at them now; as, though the wind was against them, the steam-packet flew on as rapidly as the railway-train had done: and, as Mrs. Merton gave her arm to her husband, who was walking up and down the deck, Agnes knelt on the seat near the side of the vessel, to watch the little billows as they rose up rapidly, and broke against it. But her attention was soon engaged by some curious little animals which were seen in the water, and which appeared like fairy umbrellas, opening and shutting occasionally as they floated along. Some of these curious creatures were rather large, with a kind of fringe round the lower part; and others had what appeared to be a fleshy cross on their summit, which was of a bright purple. They were so numerous that Agnes thought she should like to catch one or two, and she leant over for that purpose; but her little arms were not long enough to reach the water. A young man who saw her trouble was about to assist her, when the old gentleman who had been their fellow traveller by the rail-road stopped him. “You had better not touch them,” said he; “they will sting you.”

Fig. 1.

MEDUSA, OR SEA-NETTLE.

“Sting!” cried Agnes, “can such beautiful creatures sting?”

“Yes,” replied Mr. Bevan, “if you were to take them into your hand, you would find an unpleasant tingling, which would be followed by heat and pain, like the smarting produced by the sting of a nettle.”

“The vulgar people here, call them Chopped Ham,” said a young man, with a book in his hand; “and they say that the sting is the mustard that is usually eaten with Ham. In the Legends of the Isle of Wight,” continued he, glancing at his book, “this strange name is supposed to allude to a chieftain of the name of Ham, who was killed and chopped in pieces near Netley Abbey, and who has given his name, not only to Southampton, but to Hampshire.”

“I should like to get some of these curious creatures in spite of their stinging,” cried Agnes; “they are so beautiful. They look like fairy parasols, continually opening and shutting, but made of the finest gauze, and trimmed with long fringe; and see, there are some tinted with all the colours of the rainbow.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Merton, “the poet says,

“How very pretty, mamma,” cried Agnes.

“These lines are very pretty,” said Mr. Merton, “and, moreover, they have a merit not very common in poetry, for they exactly describe the sea-nettles, as they are called, with which you are so much delighted.”

“Sea-nettles!” cried Agnes, “it seems a pity that they have not a prettier name.”

Fig. 2.

SEA-JELLIES (Acalepha).

“They are also called Medusæ, or jelly-fish,” said Mrs. Merton.

“Are they alive, mamma?” said Agnes.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Merton, “and they belong to the humblest class of animated nature, called Zoophytes, which form the connecting link between animals and plants. These creatures have no head, but only a mouth, which opens directly into the stomach, and the fringe that you observe consists of numerous slender arms with which they seize their prey and which are armed with small hooks, so fine as scarcely to be seen without a microscope. It is these hooks catching the flesh which occasion the pain that is felt when they are touched.”

“If you were to take one up in your hand,” said Mr. Bevan addressing Agnes, “you could not keep it long, for these creatures decay, and, in fact, melt into water as soon as they are dead. They are only seen on fine warm days like the present; for when the weather is cold, they sink to the bottom. They are very beautiful at night, when they become luminous, and appear like a host of small stars, rising to the surface, and again disappearing, as though dancing on the sea. There are a great many different kinds, and those of the tropical regions are very large and brilliant.”

They now came in sight of Netley Abbey, and there was a great rush to see it. Agnes, however, was very much disappointed, as its appearance from the water was very different from what she had expected.

“I thought it would be something beautiful like Melrose Abbey,” said she, “and it is only like a common church.”

“What you see,” said Mrs. Merton, “is the Fort, and you cannot judge of the beautiful effect of the ruins of the Abbey unless you were on shore.”

“That fort, or castle,” said Mr. Bevan, “was erected by Henry VIII., after the spoliation of the abbey, which was built about 1238, and the name of Netley is a corruption of its old name of Lettely, which signified a pleasant place.”

“Are there many legends connected with the Abbey?” asked Agnes.

“Several,” returned the old gentleman. “Among other things it is said, that a carpenter of Southampton, named Taylor, had once bought the ruins, with a view of taking them down, and selling the materials; but a spirit appeared to him in a dream for three nights in succession, and warned him not to do so. He disregarded the warning, however, and had just taken a person to the Abbey to make a bargain with him for the frame-work of one of the old windows, when a part of the ruin fell upon his head and killed him on the spot.”

“That is a very useful legend,” observed Mr. Merton, “as it has probably served to protect the ruins.”

“No doubt it has,” returned Mr. Bevan, “as it is firmly believed. There are several other stories of money being buried, and of the guardian spirit of the abbey appearing to protect its treasures whenever they are in any danger of being found.”

“These stories,” said Mr. Merton, “are common to most old monasteries; and they have probably arisen from the popular belief that much greater wealth was possessed by the abbots at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII. than was found by the commissioners, and that consequently some of it must have been hidden.”

“The most remarkable story about Netley,” said the old gentleman, “I will relate to you if you like to hear it.”

The people all crowded round him eagerly, and he began as follows: “In the ancient times, when Netley was inhabited by a community of monks, there were certain underground passages, the opening to which was only known to the abbot, the prior, and two of the oldest monks. When one of these chanced to die, the entrance to these secret passages was confided to another; but it was never known to more than four at a time, and they took a solemn oath never to reveal it. What was contained in these mysterious passages was never known. Even the rough soldiers of Henry VIII., when they demolished the monastery, respected its secret; till, at length, in modern times, a gentleman of the town of Southampton was determined to explore the subterranean vaults of Netley, and having with great pain and difficulty cleared an opening, he entered with a lantern in his hand, and a lighted candle fixed at the end of a long stick. He and his light soon disappeared, and those who had followed him to the opening remained a long time watching for his return. At length they began to grow uneasy, and they were just debating whether they should follow him, when suddenly footsteps were heard rattling along the subterraneous passages, and the gentleman rushed out, crying, ‘Block up the opening, block up the opening!’ He gazed wildly for a moment and then fell down, and instantly expired, probably from the effects of the dangerous gas which is generally found in places that have been long closed up.”

Mrs. Merton, who did not like the deep interest with which her little daughter had listened to this tale, now again directed her attention to the Medusæ.

Fig. 3.

THE PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR.

“We call them Portuguese men-of-war,” said one of the sailors as he passed by.

“That is curious enough,” said the old gentleman, “for there is a kind of Zoophyte which is common in the West Indies, the proper English name of which is the Portuguese man-of-war; but it is very different from these. When seen floating on the water, it looks like a little weaver’s shuttle; but it is in fact a bladder inflated with air, having a ridge down the back like a cock’s comb, beautifully tinted with rose colour, the bladder itself being of a purplish hue at both ends. Below hang a number of thread-like appendages, some of which are straight, and some twisted, and all of which are of a beautiful dark blue or purplish hue. The animal possesses the power of contracting and dilating its bladder, and raising up the narrowest part, so as to make it serve for the purposes of a sail. There is also a little hole in the narrow part of the bladder, only large enough to admit a very fine bristle; through this the animal appears to squeeze out the air when it wishes to descend.”

“I have often seen the Portuguese men-of-war,” said a naval officer who stood near them. “I dare say there are fifty sorts of these creatures in the West Indies, and there are a great many also of the Medusæ, which are a thousand times more beautiful than those we have been looking at here.”

“There are many different kinds of sea-jellies, or bubbles,” said Mr. Merton, “in the British seas, and it is said that many kinds were found formerly, which now appear to be extinct. It is even supposed that the curious marks in the old red sandstone of Forfarshire, which are called Kelpies’ feet, are occasioned by sea-jellies having been left by the sea on the sandstone, and lain there till decayed.”

“The Kelpies were supposed to be water-spirits,—were they not?” said the young man.

“Yes,” replied Mr. Bevan: “I remember, when travelling in the Highlands, hearing many strange stories about them.”

While they were conversing in this manner, the steam-boat made rapid progress, and they now approached Calshot Castle, a fort situated on a small head-land jutting into the sea.

“That fort,” said the old gentleman, “was built in the time of Henry VIII., to protect the entrance to Southampton water; and it is still used as a garrison, though the force it contains is but small. We are now in the Solent Sea, which divides the mainland from the Isle of Wight; and there,” he continued, “is the Island itself.”

They all turned to look; and Agnes was very much astonished to find it so near.

“How do you like the Isle of Wight?” asked her mamma.

“It looks a pretty mountainous country,” said Agnes; “and more like Scotland than any thing I have before seen in England.”

“You will find it very different,” said the old gentleman, turning to Agnes, “when you see it nearer.”

“Every thing is on a much smaller scale,” said Mrs. Merton; “but there is certainly some resemblance.”

At this moment the steam-boat stopped, and the passengers were desired to walk on shore at West Cowes. Agnes was deeply interested in watching the porters, who seized the luggage, and were carrying it off without asking where it was to go to; while several sailors surrounded the steam-boat, crying out, “Want a boat, want a boat, sir,—East Cowes, sir.” As Mr. Merton was very much fatigued with his journey, Mrs. Merton’s attention was entirely devoted to him; and, telling the porter to take their luggage to the Fountain Hotel, she gave her arm to her husband, to assist him to leave the vessel. Agnes was preparing to follow them, when, to her great dismay, she saw a man seize her own dear black leather portmanteau, and toss it into a boat going to East Cowes. She positively screamed; and, running to the edge of the vessel, she cried out, “Oh! do not take that! That is mine.”

“Yours,” cried a good-natured-looking sailor, who was standing in the boat taking in the luggage; “and are you not going with this party, then?”

“No,” said Agnes, trembling and panting for breath, “I am going to West Cowes,—to the Fountain. My papa and mamma are gone there.”

“Here,” cried the sailor; “I dare say the child is right;” calling to a young sailor who stood on the deck of the steam-packet; “Take this portmanteau, and go with that little girl to the Fountain.” At this moment the mate of the steam-packet came down to see what was the matter; and, having heard Agnes’s story, he asked what name was on the portmanteau; and, finding all was right, he told the boy to take it to the Fountain: Agnes following him, in a state of great agitation, but very much pleased at having saved her property. They had scarcely stepped on shore, when they met Mrs. Merton, who, having seen her husband comfortably placed on a sofa, had become uneasy at Agnes’s not following them, and had returned to the pier in search of her. When Mrs. Merton saw her little girl pale and trembling, she was very much alarmed; but, when she heard the story, she praised Agnes for the courage she had displayed, instead of scolding her, as she had been about to do, for her delay. Agnes was, however, too much agitated to feel her usual pleasure at her mother’s praises. It was the first time she had ever acted for herself in her life; and, though she had done right, she felt the bad effect of the over excitement. Mrs. Merton now offered sixpence to the boy who had carried Agnes’s portmanteau on shore, but he refused it. “Oh! no,” said he; “the young lady is quite welcome;” and, declaring that his father would be very angry with him if he took anything, he hurried into the Fountain: and putting down his burthen in the hall, he ran off, without allowing Mrs. Merton to say another word. As the pier at West Cowes is, indeed, the yard of the Fountain Inn, Mrs. Merton and Agnes had not far to go; but, as Mr. Merton had wished to take some repose after his fatigue, Mrs. Merton satisfied herself with ordering dinner at the bar, and walked out into the little narrow streets of Cowes with her daughter.

The first object that Mrs. Merton had in view, was to order a carriage, to take them round the Island on the morrow; and, for this purpose, she went into a fruit-shop nearly opposite the front door of the inn, where she saw a ticket offering carriages for hire. Mrs. Moore, for that was the name of the greengrocer, was a very nice person; and Mrs. Merton soon made an arrangement with her, that a little open carriage should be ready for them at nine the following morning. Mrs. Merton then asked Agnes, where she would like to walk; and Agnes having expressed a strong desire to visit East Cowes, as being the place to which her portmanteau had been so nearly conveyed, Mrs. Merton asked Mrs. Moore, which was the best mode of going.

“Oh! there are two ways, ma’am,” said Mrs. Moore. “You can either go by the ferry, at a penny a piece, or you can go in a boat from the pier, and pay a shilling.”

“Oh, let us go in the ferry-boat,” cried Agnes; “I never was in a ferry-boat in my life.”

Mrs. Merton having ascertained that the ferry-boat was perfectly safe, and that respectable people frequently went by it, determined to indulge her daughter, and they set off in the direction that was pointed out to them. The walk was not a very agreeable one; it was up a narrow street, and a rather steep hill. This appeared very extraordinary both to Agnes and her mamma, as people generally descend to water. At last, however, after a very disagreeable walk, and inquiring their way several times, they began to descend the hill, and soon reached the ferry, where the boat being just ready to go, they took their seats. Agnes and her mamma were both very much amused at the old man who rowed them across.

“I thought ferry-boats had generally a rope to keep them steady,” said Mrs. Merton.

“So they have for the horse-ferries,” said the old man; “but as for this, I can row it as well without a rope as with one. But it is not everybody that can do that, that is true enough.”

As the old man spoke, he gave a vigorous pull, and as he did so, his grey hair blew back from his ruddy and sun-burnt face; while his whole figure presented a striking picture of the good effect which a life of moderate, but regular, labour in the open air has upon the human frame.

The ferry-boat was soon across the river; and when Mrs. Merton and her daughter had landed at East Cowes, and were walking on the terrace in front of the Medina Hotel, Agnes could not help observing to her mother, that she thought the old man very conceited; “and it is such a ridiculous thing for a man to be proud of, too,” added she; “rowing a common ferry-boat.”

“My dear Agnes,” said her mother in a serious tone, “I have several times observed in you a tendency to look with contempt upon persons and things that you consider beneath you. It is true that you have many advantages which this ferryman has not. Fortunately for you, your parents are rich enough to allow you teachers to instruct you, servants to wait upon you, and a variety of comforts and indulgences which this ferryman can neither enjoy himself, nor give to his children. But these are merely accidental advantages. Circumstances might arise which would reduce you in a moment to a greater degree of poverty than this man, as, in fact, if we were obliged to live by the labour of our hands, he would be far superior to us from his activity and vigour. He is, though an old man, evidently in the enjoyment of robust health and great strength; and I am quite sure if your papa and I were obliged to row a ferry-boat for our support, we could neither of us do it half so well as he does.”

“Oh! but mamma,” said Agnes, “there is no danger of our being reduced to poverty, is there?”

“Not that I am aware of,” said Mrs. Merton; “but it is impossible to say what may happen. As your papa is not in trade he is not liable to those sudden and violent changes which frequently affect the commercial part of the community; but still many things may happen that would occasion a severe reverse. You know in the time of the French Revolution, many persons of a much higher rank than ours were reduced to the greatest distress, and even Louis Philippe, the present King of the French, was obliged to teach in a school for his support.”

They had now reached a part of the beach where the pebbles were very rough, and as Agnes was much interested in what Mrs. Merton was saying, she did not pay proper attention to where she was going, and at this moment she stumbled over a piece of wood. This obliged her to look more carefully at her feet, and as the road was now become very rough, Mrs. Merton thought it better not to proceed any farther along the beach, but to return to the terrace, where the road was smooth. They did so, and had not walked far, when they saw a skate that had just been caught, lying on the beach, panting, and opening and shutting its mouth, which was in the middle of its body on the under side. Agnes shuddered as she looked at it. “I wish they would throw it back into the water, mamma,” said she.

“We can hardly expect that,” returned her mother; “but I wish the fishermen in this country would stab their fish as soon as they have caught them, as I have heard fishermen do in the east. The skate is a kind of ray, and belongs to the same genus as the Torpedo. The thornback, or maid, belongs also to this genus. Do you remember the little things, that looked like little leather purses, that we used to find among the sea-weed at Brighton?”

“Oh yes! the fishermen called them skate barrows; but you told me they were the eggs of the skate.”

They now walked on in silence for a short time, till Agnes’s attention was caught by a building which some men were busily employed in pulling down.

“What is that, mamma?” cried she: “and why are those people taking off the roof?”

Mrs. Merton pointed to a portion of the walls that remained standing, and on which the words “salt-works” might still be read.

“Salt-works!” repeated Agnes; “what is salt made of, mamma?”

“Salt,” said Mrs. Merton, “can hardly be said to be made, as it is a mineral which is formed naturally in the earth, and which we procure in three different ways. Sometimes it is dug out of the salt-mines, as at Northwich in Cheshire, and in the Austrian dominions; but this kind of salt is coarse and dark-coloured. Another way of procuring it is from salt-springs; that is, from water which has become saturated with salt in its passage through the earth, as at Nantwich and other places in Cheshire, and at Droitwich in Worcestershire; and this salt is what we have in common use. The last kind of salt is what is made from the sea-water, and most of the works that have been erected for this purpose in England are in Hampshire, particularly in the Isle of Wight.”

“And how do they get the salt out of the salt-water?” asked Agnes.

“By boiling it,” said her mother, “in large shallow pans, such as that which you see before you.”

While they were examining the pans, Agnes asked her mother a great many questions respecting the salt-works, and Mrs. Merton told her, that the salt obtained from sea-water is of so much coarser kind than that obtained from the salt-springs, that it is principally used for curing meat, and for manuring the land.

“Ah!” said Agnes, “that reminds me of a question that I have often wished to ask you, mamma. When I was at Shenstone, my cousin George told me that salt would be excellent manure for my plants, and I put some on my annuals, which were just coming up, and, would you believe it, mamma, it killed them every one.”

“That,” said Mrs. Merton, “was because the manure was too strong for them, and you no doubt put a great deal too much. Salt, to do good to plants, should be given to them in very small quantities, as, though all plants require some mineral substances to be mixed with their food to keep them in health, it is in such small quantities that in some plants it is only in the proportion of one to four thousand; and where mineral substances are required in the greatest quantity for the nourishment of a plant, it is only in the proportion of about ten to one thousand.”

“I do not think I quite understand that, mamma,” said Agnes.

“Well,” returned Mrs. Merton, “at any rate you will remember, that though a very small quantity of salt may be useful to plants, a large quantity will kill them, and that, consequently, it is much safer for inexperienced gardeners not to give them any.”

“I remember once being told that all the places that produce salt end in wich; but the name of this place is Cowes.”

“I have heard that the word wich is derived from the Saxon, and that it signifies a salt-spring,” said Mrs. Merton, “but of course that does not apply to salt procured from the sea.”

Mrs. Merton and her daughter had now reached the beach, and ordering a boat from one of the boatmen lounging about, they stepped into it to return to West Cowes.

“But, mamma,” said Agnes, who was still thinking of the salt-works, “is this the water they use for making salt? This is the Medina, and not the sea, and the Medina is a river, is it not?”

“This part of the Medina,” said Mrs. Merton, “is what is called an estuary; that is, an arm of the sea mixed with the waters of a river; the water of this estuary is salt, and affected by the tides as far as Newport.”

“What makes the waters of the sea salt?” asked Agnes.

“That is a very difficult question to answer,” said her mother, “but it is supposed that rivers carry salt from the earth they run through, into the sea; and as the water in the sea is continually being evaporated by the heat of the sun, the quantity of salt, in proportion to the quantity of water, soon becomes much greater in the sea than in the river, and hence the water becomes much salter.”

“Why, mamma,” cried Agnes, “that is just what is done in the salt-pans.”

“You are right,” returned her mother. “The salt manufacturers observing the process of nature, have imitated it as well as they could, by applying artificial heat to evaporate the water. What is called bay-salt, is formed by the sea-water left in the clefts of the rocks by the tide evaporating naturally, and leaving a saline crust behind; and this salt takes its name from the sea-water being frequently thus left in bays. But see, here is the Fountain Inn, where I have no doubt your papa is waiting dinner for us.”

Morning Walk through West Cowes.—Ride to Newport.—Carisbrook Castle.—Children of Charles I.—Donkey Well.—Chapel of St. Nicholas.—Boy Bishop.—Archery Meeting.—History of the Isle of Wight.—Bows and Arrows.

The next morning Agnes and her mamma both rose early; and as Mr. Merton felt inclined to take some repose, they went out by themselves to take a walk before breakfast. They were advised to visit the Parade and the Castle; and, accordingly, they bent their way down the main street of the town, and soon found themselves on the beach. They strolled gently along a terrace, supported by a sea-wall, till they arrived at a part which was semicircular, and which was backed by a small battery, pierced for eleven guns. This wall forms the boundary of the garden of a moderate-sized house, which, they were told, was called the Castle. This building had been formerly a fort, built by Henry VIII., at the same time as Calshot Castle, for the purpose of defending the coast against the attacks of pirates, which were then frequent in this sea; but it has been so completely modernised, that it now retains nothing of a castle but the name. They saw a great many bathing-machines, which are very common here, as the gravelly beach permits the machines to be used at all states of the tide. After satisfying themselves with this walk, Mrs. Merton and her daughter turned up a beautiful lane, which afforded them a most magnificent prospect; commanding the Solent Sea, Calshot Castle, and the tall Tower of Eaglehurst, seated on the neighbouring cliffs. In a small garden that they passed, they saw a tortoise crawling slowly along; and Agnes, who disliked slow movements exceedingly, expressed her pity at its miserable fate.

“Nothing is destined by the all-merciful Creator to a miserable fate, Agnes,” said her mother; “and I am confident that every creature has a particular kind of happiness allotted to it, though our ignorance may prevent us from seeing in what it consists. The tortoise is also curiously and wonderfully made: as it has neither force to resist its enemies, nor swiftness to fly from them, it has been provided with a shield of amazing strength, under which it can draw its head, and thus remain in perfect safety from the attacks of birds of prey; yet it can, when necessary, put forth its head again, so as to see and enjoy all around it.”

Fig. 4.

TORTOISE.

Agnes was very much interested in this, and would have willingly staid some time to watch it; but this Mrs. Merton could not permit, as they had no time to spare: and, on their return to the inn, they found breakfast ready, and Mr. Merton waiting for them. He was, indeed, very impatient to set off; as it was now after eight o’clock, and the carriage was to be at the door at nine. “We shall soon be ready,” said Mrs. Merton; “for everything is packed up, and we shall not be long taking our breakfast.”

“That is, if you can get anything to eat,” said Mr. Merton; “for I never saw waiters so slow as these are.”

Not discouraged by these remarks, Mrs. Merton sat down to table; and she and Agnes, whose appetites were sharpened by their morning walk, soon contrived to make an excellent breakfast; though Mr. Merton, who was rendered more fastidious by ill health, could scarcely get anything that he could like. At nine exactly the little carriage was at the door; and Agnes, after running up stairs into the bed-room, to make quite sure that nothing had been left behind, placed herself beside the driver, rejoicing that she had taken the precaution of packing up her portmanteau before she went out. Mr. and Mrs. Merton sat behind; and thus the whole party were enabled to have a distinct view of the country they passed through.

The ride from West Cowes to Newport does not, however, contain anything very striking; and, as the distance is only five miles, they were not long in reaching the town of Newport, which is remarkable for its neatness, though it has little else to recommend it. Our party called at the Post-office; and Mrs. Merton and Agnes visited the church and church-yard, while Mr. Merton was reading his letters.

The Church at Newport was built in the year 1172, in the reign of Henry II., and was dedicated to St. Thomas à Becket. There is nothing remarkable in the Church, excepting the stone which marks the burial-place of Elizabeth, daughter of Charles I., who died at the age of fifteen, while a prisoner in Carisbrook Castle; and the handsome monument erected to the memory of Sir Edward Horsey, who was governor of the island in the time of Queen Elizabeth. In the church-yard there was pointed out to them a grave containing six persons of the name of Shore, who all died on the same day; and this having attracted the attention of Agnes, Mrs. Merton asked an explanation, when the guide told them, that this unfortunate family were coming from the West Indies, on board the ship Clarendon; and, as they intended remaining some time in the Isle of Wight, a house had been taken for them at Newport, looking into the church-yard. The Clarendon was wrecked off Blackgang Chine, on the 11th of October, 1836; and this unfortunate family were among the passengers. It is said all was prepared for them in the house; and even a dinner had been cooked by order of a near relative of theirs, who was anxiously awaiting their arrival when their dead bodies were brought to Newport.

As soon as Mrs. Merton and Agnes re-entered the carriage, they proceeded to the pretty little village of Carisbrook, catching several views of the Castle on their route. Mr. Merton, who did not feel equal to the fatigue of visiting the Castle, remained at a little public-house, opposite the church, called the Bugle Inn, while Mrs. Merton and Agnes walked to the Castle. The wind had been high all the morning, but it had now increased so much, that, when Mrs. Merton and Agnes ascended the Castle hill, it almost blew them back again. At the gate were some old women, sitting at a fruit-stall; and, though neither Agnes nor her mamma had any inclination to buy fruit, one old woman followed them up the hill, and was so importunate that they could hardly send her away. “Do ask the lady to buy this beautiful fruit for you, Miss,” said the old woman, holding up a miserable green peach, that looked as if it had fallen from the tree before it had attained half its proper size.

“I don’t want such a miserable-looking thing as that,” said Agnes, wrapping her cloak around her, though it was with great difficulty that she did so, on account of the wind.

CARISBROOK CASTLE

“It’s a peach, and not an apple, Miss,” said the woman. Agnes was quite provoked to have it supposed that she, a botanist’s daughter, did not know a peach from an apple; and, turning round angrily, told the woman to get away, and not to dare to be so troublesome. Unfortunately, however, while Agnes was scolding the old woman for teasing her, a sudden gust of wind, operating upon the broad surface of the cloak, actually blew her a short way down the hill before she could recover herself. The old woman laughed; and Agnes, who was quite indignant, declared that Carisbrook Castle was the most disagreeable place she had ever seen in her life.

Fig. 5.

CARISBROOK GATE.

“It is rather soon to say that,” said Mrs. Merton; “when you have only yet seen its ancient gate, and a troublesome old woman on the outside of it.”

The man whose office it was to show the castle now opened the gate, and called their attention to its antiquity. “These towers,” said he, “are of the age of Edward IV., and look, ladies, at this ancient wooden door, it is of equal antiquity.” They looked at the wooden door, which was indeed very old and very much dilapidated; but Mrs. Merton could not help suspecting that its workmanship was of more modern date than that which the man assigned to it, particularly as the arms of Elizabeth were emblazoned over the gateway. She pointed these out to the man, who replied, “The Castle was repaired and fortified in the reign of Elizabeth, when the whole country trembled with dread at the apprehension of the invasion of the Spanish Armada. Look at those ruins on the left. There is the window at which the unfortunate Charles I. attempted to escape, but his most Sacred Majesty being, as the historians describe him, of portly presence, the window was too small to admit of his passing through it.” They now ascended the dilapidated steps of the keep, but Agnes was too cross and too much annoyed by the wind, to admire the beautiful prospect that presented itself. They, therefore, descended again, as well as the wind would permit them, the seventy-two stone steps by which they had mounted, and repaired to the well-house, to visit the celebrated donkey. When they first entered Agnes was a little disappointed to see the donkey without any bridle or other harness on, standing close to the wall, behind a great wooden wheel.

Fig. 6.

KING CHARLES’S WINDOW.

“Oh, mamma,” cried she, “I suppose the donkey will not work to-day, as he has no harness on?”

“I beg your pardon, miss,” said the man; “this poor little fellow does not require to be chained like your London donkeys, he does his work voluntarily. Come, sir,” continued he, addressing the donkey; “show the ladies what you can do.” The donkey shook his head in a very sagacious manner, as much as to say, “you may depend upon me,” and sprang directly into the interior of the wheel, which was broad and hollow, and furnished in the inside with steps, formed of projecting pieces of wood nailed on, the hollow part of the wheel being broad enough to admit of the donkey between its two sets of spokes. The donkey then began walking up the steps of the wheel, in the same manner as the prisoners do on the wheel of the treadmill; and Agnes noticed that he kept looking at them frequently, and then at the well, as he went along. The man had no whip, and said nothing to the donkey while he pursued his course; but as it took some time to wind up the water, the man informed Mrs. Merton and her daughter while they were waiting, that the well was above three hundred feet deep, and that the water could only be drawn up by the exertion of the donkeys that had been kept there; he added, that three of these patient labourers had been known to have laboured at Carisbrook, the first for fifty years, the second for forty, and the last for thirty. The present donkey, he said, was only a novice in the business, as he had not been employed much above thirteen years; and he pointed to some writing inside the door, in which the date was marked down. While they were speaking the donkey still continued his labour, and looked so anxiously towards the well, that at last Agnes asked what he was looking at. “He is looking for the bucket,” said the man; and in fact, as soon as the bucket made its appearance, the donkey stopped, and very deliberately walked out of the wheel to the place where he had been standing when they entered.

“Pretty creature,” said Agnes; “how sagacious he is!”

“He is very cunning,” said the man; “and he knows when the bucket has come to the top as well as I do.”

The man now threw some water into the well, and Agnes, who had heard that the water made a great noise in falling, after listening attentively for a second or two was just going to express her disappointment at not hearing it, when she was quite startled by a loud report, which seemed to come up from the very bottom of the well.

“Oh! surely,” cried she, “that never can be the same water that you threw down such a long time ago?”

“It is, indeed, miss,” said the man; “the water is five seconds in falling.”

“Five seconds!” cried Agnes; “why, that is only the twelfth part of a minute; surely it must have been much longer than that!”

“Time,” said Mrs. Merton, “often appears to us much longer or shorter than it really is, according to the circumstances in which we are placed. Thus, as we are accustomed to hear a splash of water thrown into other water, the very moment we see it fall, the time that elapsed between your seeing this water fall and hearing it splash, appeared to you much longer than it really was.” The man then let down a lighted lamp; and Agnes, who watched its descent, was astonished to see how it dwindled away, till at last it appeared like a little star, and she saw its reflection on the water.

They had now seen all that was interesting in the “Well House;” and having left it, they were about to cross to the chapel on the opposite side of the court, when they met the old gentleman who had been their fellow-traveller in the railway carriage and in the steam-boat. He seemed very glad to see them again, and was much amused with Agnes’s account of all the wonders that she had seen in the “Well House.”

“And no doubt,” said he, “you have also seen the window through which Charles attempted to escape; but are you aware that two of his children were confined here after their father was beheaded?”

They replied that they had seen the tomb of the Princess Elizabeth at Newport.

“Ay,” said the old gentleman; “she was said to be poisoned, but I believe the poor thing died of grief. She was called Miss Elizabeth Stuart, and her brother Master Harry; and it is said that the poor things almost broke their hearts when they found nobody knelt to them, or kissed their hands. It was said that the Parliament intended to apprentice Elizabeth to a mantua-maker; but she died, and disappointed them, and two years afterwards Cromwell sent the little Duke of Gloucester to the Continent.”

“We were going to the chapel,” said Mrs. Merton; “will you walk in with us?”

“This chapel,” said he, pointing to that to which they were bending their steps, “is dedicated to St. Nicholas, the patron Saint of children, students, sailors, and parish clerks.”

“What an odd mixture!” said Mrs. Merton, smiling.

“St. Nicholas,” continued Mr. Bevan as they entered the chapel, “was a child of extraordinary sanctity; so much so, indeed, that even when a baby at the mother’s breast, it was said he refused to suck on the fast days appointed by the Romish Church. As he grew older his devotion became so apparent that he was called the boy bishop; and it was in his honour that the curious festival bearing that name was instituted in the Romish Church.”

“I have often heard of the festival of the boy bishop,” said Mrs. Merton; “but I was not aware that it was instituted in honour of St. Nicholas.”

“What was the ceremony of the boy bishop?” asked Agnes.

“It was one of those strange festivals in the Romish Church,” said Mrs. Merton, “in which people were permitted, and even encouraged, to ridicule all the things which, during the rest of the year, they were taught to consider sacred, and to hold in the highest reverence.”

“The festival of the boy bishop,” observed Mr. Bevan, “is of remote antiquity, and it is said to have been practised on the Continent long before it was introduced into Britain; though we find that, in the year 1299, Edward I., on his way to Scotland, heard mass performed by one of the boy bishops, in the little chapel at Heton, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne.”

“And even that is above five hundred years ago,” remarked Mrs. Merton.

“On St. Nicholas’s day,” resumed Mr. Bevan, “the 6th of December, a boy was chosen, at each of our principal cathedrals, from amongst the choristers, to represent a bishop; and to this boy all the respect and homage was paid that would have been offered to a bishop, if he had really been one. His authority lasted until St. Innocent’s day, the 28th of December; and during this time he walked about in all the state of a bishop, attired in a bishop’s robes, with a crosier in his hand, and a mitre on his head. If one of these boy bishops died within the period of his office, he was buried with all the pomp and form of a real bishop; and there is, in fact, a monument in Salisbury Cathedral, representing a boy, about ten or twelve years old, attired in episcopal orders.”

“What a very curious thing!” said Agnes.

“This, I suppose then,” said Mrs. Merton, “is the reason why St. Nicholas is represented as the patron of children?”

“Yes,” said the old gentleman, “and he was considered the patron of students, from the following story:—St. Nicholas was Bishop of Myra, and an Asiatic gentleman, sending his two sons to be educated at Athens, desired them to call upon St. Nicholas at Myra to receive his benediction. They intended to do so, but unfortunately the landlord of the Inn where they put up, perceiving that they had plenty of money, murdered them in their sleep, and cutting their bodies into pieces, salted them, and put them into a pickling tub, used for pickling pork. St. Nicholas had a vision of this in a dream; and going the following morning to the Innkeeper, he desired him to show him the tub where he kept his pickled pork. The Innkeeper at first endeavoured to excuse himself, but, at length, he was compelled to obey; when St. Nicholas, uttering a prayer, the mangled pieces of the poor young men jumped out of the tub, and re-uniting themselves, fell at the feet of the holy bishop, thanking him for having restored them to life. It is on this account that, in ancient pictures, Saint Nicholas is generally represented with two naked children in a tub.”

“I think I have heard, when on the Continent,” said Mrs. Merton, “that St. Nicholas was also the patron of young girls; and that in convents, when the novices had behaved well, it was pretended that he had stuffed their stockings with sugar plums during the night.”

“Yes,” returned the old gentleman, “and nearly the same fiction was resorted to by parents; who, when they wished to make presents to their children, used to tell them that, if they left their windows open at night, and had been quite good, St. Nicholas would come through the open window and leave them something pretty or nice.”