Title: Montreal, 1535-1914. Vol. 2. Under British Rule, 1760-1914

Author: William H. Atherton

Release date: February 12, 2015 [eBook #48244]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Charlene Taylor, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (https://archive.org/details/toronto)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Montreal 1535-1914, Volume II (of 2), by William Henry Atherton

| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See

https://archive.org/details/montrealunderthe02atheuoft Project Gutenberg has the other volume of this work. Volume I: see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/47809/47809-h/47809-h.htm |

By WILLIAM HENRY ATHERTON, Ph. D.

Qui manet in patria et patriam cognoscere temnit Is mihi non civis, sed peregrinus erit

VOLUME II

ILLUSTRATED

THE S. J. CLARKE PUBLISHING COMPANY MONTREAL VANCOUVER CHICAGO 1914

The history of “Montreal Under British Rule” is the “Tale of Two Cities”, of a dual civilization with two main racial origins, two mentalities, two main languages, and two main religions. It is the story of two dominant races growing up side by side under the same flag, jealously preserving their identities, at some times mistrusting one another, but on the whole living in marvelous harmony though not always in unison, except on certain well defined common grounds of devotion to Canada and the Empire, and of the desire of maintaining the noble traditions and the steady progress of their city.

Montreal of today is a cosmopolitan city, but it is preponderatingly French-Canadian in its population. This fact makes it necessary to give especial attention to the history of two-thirds of the people. There has, therefore, been an effort in these pages, while recognizing this, to respect the rights of the minority, and open-handed justice has been observed.

The position of a dispassionate onlooker has been taken as far as possible in the narration of the domestic struggles in the upbuilding of the city through the crucial turnstiles of Canadian history under British rule—the Interregnum, the establishment of civil government, the Quebec act, the Constitutional act, the Union, and the Confederation. This attitude of equipoise, while disappointing to partisans, has been justified if it helps to present an unbiased account of different periods of history and serves to maintain the city’s motto of “Concordia Salus”—a doctrine which has been upheld throughout this work. Tout savoir c’est tout pardonner.

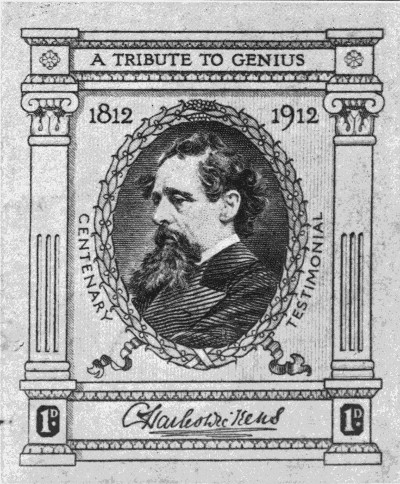

Charles Dickens in his visit to Montreal in 1842 observed that it was a “heart-burning town.” There is no need to renew the occasion for such a title in the city of today.

It only remains to express thankful indebtedness to those, too numerous to mention, who have assisted in the compilation of certain information otherwise difficult of access, and also to thank a number of friends, prominent citizens of Montreal, who in connection with the movement for city improvement and the inculcation of civic pride have encouraged the author to embark on the laborious but pleasant task of preparing this second volume of the history of “Montreal Under British Rule,” as a sequel to the first volume of “Montreal Under the French Régime.”

WILLIAM HENRY ATHERTON.

December, 1914.

In presenting the second volume to the reader the writer would observe that its first part deals mainly with the story of city progress under the various changes of the political and civic constitution, with certain chapters of supplementary annals and sidelights of general progress. The second part treats in detail, for the sake of students and as a reference book, the special advancement of the city through its various eras in religion, education, culture, population, public service, hospital, charitable, commercial, financial, transportation and city improvement growth, and in so doing the author has desired to present the histories of the chief associations that have in the past or in the present been mainly responsible for the upbuilding of a no mean city.

W.H.A.

PART I

CONSTITUTIONAL AND CIVIC PROGRESS

CHAPTER I

THE EXODUS FROM MONTREAL

1760

“THE OLD ORDER CHANGETH, GIVING PLACE TO NEW”

| AMHERST’S LETTER REVIEWING EVENTS LEADING UP TO THE CAPITULATION—THE SURRENDER OF ARMS—THE REVIEW OF BRITISH TROOPS—THE DEPARTURE OF THE FRENCH TROOPS—END OF THE PECULATORS—VAUDREUIL’S CAPITULATION CENSURED—DEPARTURE OF THE PROVINCIAL TROOPS—ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF THE COLONY—DEPARTURE OF AMHERST—THE TWO RACES LEFT BEHIND. NOTES: (1) THE EXODUS AND THE REMNANT.—(2) THE POPULATION OF CANADA AT THE FALL | 3 |

CHAPTER II

THE INTERREGNUM

1760-1763

MILITARY GOVERNMENT

| BRIGADIER GAGE, GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL—THE ADDRESS OF THE MILITIA AND MERCHANTS—GOVERNMENT BY THE MILITARY BUT NOT “MARTIAL LAW”—THE CUSTOM OF PARIS STILL PREVAILS—COURTS ESTABLISHED—THE EMPLOYMENT OF FRENCH-CANADIAN MILITIA CAPTAINS IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE—SENTENCES FROM THE REGISTERS OF THE MONTREAL COURTS—GOVERNOR GAGE’S ORDINANCES—TRADE—THE PORT—GAGE’S REPORT TO PITT ON[viii] THE STATE OF THE GOVERNMENT OF MONTREAL—THE PROMULGATION OF THE DECLARATION OF THE DEFINITIVE TREATY OF PARIS—REGULATIONS CONCERNING THE LIQUIDATION OF THE PAPER MONEY—LEAVE TO THE FRENCH TO DEPART—LAST ORDINANCES OF GAGE—HIS DEPARTURE | 13 |

CHAPTER III

THE DEFINITIVE TREATY OF PARIS

1763

THE NEW CIVIL GOVERNMENT

| THE DEFINITIVE TREATY OF PEACE—SECTION RELATING TO CANADA—CATHOLIC DISABILITIES AND THE PHRASE “AS FAR AS THE LAWS OF GREAT BRITAIN PERMIT”—THE TREATY RECEIVED WITH DELIGHT BY THE “OLD” SUBJECTS BUT WITH DISAPPOINTMENT BY THE “NEW”—THE INEVITABLE STRUGGLES BEGIN, TO CULMINATE IN THE QUEBEC ACT OF 1774—OPPOSITION AT MONTREAL, THE HEADQUARTERS OF THE SEIGNEURS—THE NEW CIVIL GOVERNMENT IN ACTION—CIVIL COURTS AND JUSTICES OF THE PEACE ESTABLISHED—MURRAY’S ACTION IN ALLOWING “ALL SUBJECTS OF THE COLONY” TO BE CALLED UPON TO ACT AS JURORS VIOLENTLY OPPOSED BY THE BRITISH PARTY AS UNCONSTITUTIONAL—THE PROTEST OF THE QUEBEC GRAND JURY—SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATIONS IN 1766 TO SUIT ALL PARTIES—GOVERNOR MURRAY’S COMMENT ON MONTREAL, “EVERY INTRIGUE TO OUR DISADVANTAGE WILL BE HATCHED THERE”—MURRAY AND THE MONTREAL MERCHANTS—A TIME OF MISUNDERSTANDING. NOTE: LIST OF SUBSEQUENT GOVERNORS | 25 |

CHAPTER IV

CIVIC GOVERNMENT UNDER JUSTICES OF THE PEACE

1764

| RALPH BURTON, GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL, BECOMES MILITARY COMMANDANT—FRICTION AMONG MILITARY COMMANDERS—JUSTICES OF PEACE CREATED—FIRST QUARTER SESSIONS—MILITARY VERSUS CITIZENS—THE WALKER OUTRAGE—THE TRIAL—WALKER BOASTS OF SECURING MURRAY’S RECALL—MURRAY’S DEFENSE AFTER HIS RECALL—THE JUSTICES OF THE PEACE ABUSE THEIR POWER—CENSURED BY THE COUNCIL AT QUEBEC—COURT OF COMMON PLEAS ESTABLISHED—PIERRE DU CALVET—CARLETON’S DESCRIPTION OF THE “DISTRESSES OF THE CANADIANS” | 35 |

CHAPTER V

THE PRELIMINARY STRUGGLE FOR AN ASSEMBLY

THE BRITISH MERCHANTS OF MONTREAL

| “VERY RESPECTABLE MERCHANTS”—A LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ON BRITISH LINES PROMOTED BY THEM—INOPPORTUNE—VARIOUS MEMORIALS TO GOVERNMENT—THE[ix] MEETINGS AT MILES PRENTIES’ HOUSE—CRAMAHE—MASERES—COUNTER PETITIONS | 45 |

CHAPTER VI

THE QUEBEC ACT OF 1774

THE NOBLESSE OF THE DISTRICT OF MONTREAL

| THE GRIEVANCES OF THE SEIGNEURS—MONTREAL THE HEADQUARTERS—“EVERY INTRIGUE TO OUR DISADVANTAGE WILL BE HATCHED THERE”—PETITIONS—CARLETON’S FEAR OF A FRENCH INVASION—A SECRET MEETING—PROTESTS OF MAGISTRATES TODD AND BRASHAY—PROTESTS OF CITIZENS—CARLETON’S CORRESPONDENCE FOR AN AMENDED CONSTITUTION IN FAVOUR OF THE NOBLESSE—THE QUEBEC ACT—ANGLICIZATION ABANDONED | 51 |

CHAPTER VII

THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR OF 1775

MONTREAL THE SEAT OF DISCONTENT

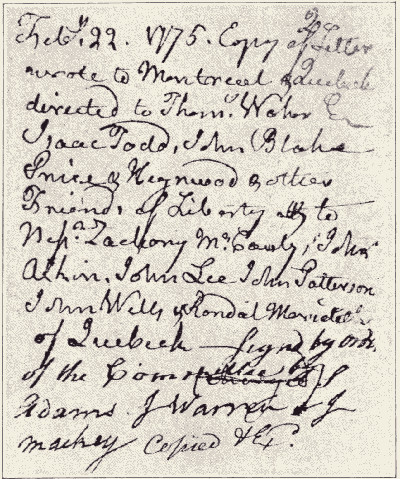

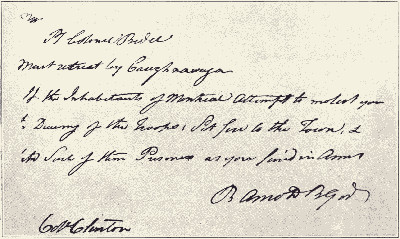

| THE QUEBEC ACT, A PRIMARY OCCASION OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION—MONTREAL BRITISH DISLOYAL—THE COFFEE HOUSE MEETING—WALKER AGAIN—MONTREAL DISAFFECTS QUEBEC—LOYALTY OF HABITANTS AND SAVAGES UNDERMINED—NOBLESSE, GENTRY AND CLERGY LOYAL—KING GEORGE’S BUST DESECRATED—“DELENDA EST CANADA”—“THE FOURTEENTH COLONY”—BENEDICT ARNOLD AND ETHAN ALLEN—BINDON’S TREACHERY—CALL FOR VOLUNTEERS FEEBLY ANSWERED—MILITIA CALLED OUT—LANDING OF THE REBELS—ENGLISH OFFICIAL APATHY—MONTREAL’S PART IN THE DEFENCE OF CANADA—THE FIRST SOLELY FRENCH-CANADIAN COMPANY OF MILITIA—NOTE: THE MILITIA | 63 |

CHAPTER VIII

MONTREAL BESIEGED

1775

THE SECOND CAPITULATION

| ETHAN ALLEN—HABITANTS’ AND CAUGHNAWAGANS’ LOYALTY TAMPERED WITH—PLAN TO OVERCOME MONTREAL—THE ATTACK—ALLEN CAPTURED—WALKER’S FARM HOUSE AT L’ASSOMPTION BURNED—WALKER TAKEN PRISONER TO MONTREAL—CARLETON’S FORCE FROM MONTREAL FAILS AT ST. JOHN’S—CARLETON[x] LEAVES MONTREAL—MONTREAL BESIEGED—MONTGOMERY RECEIVES A DEPUTATION OF CITIZENS—THE ARTICLES OF CAPITULATION—MONTGOMERY ENTERS BY THE RECOLLECT GATE—WASHINGTON’S PROCLAMATION | 71 |

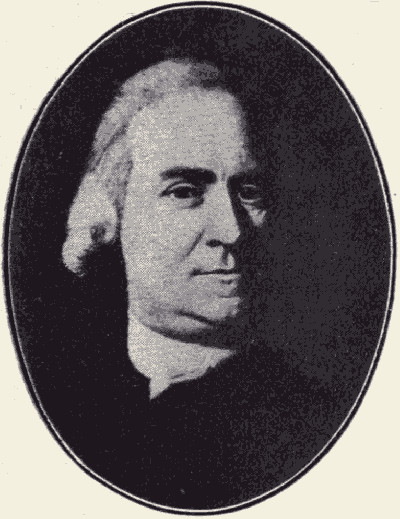

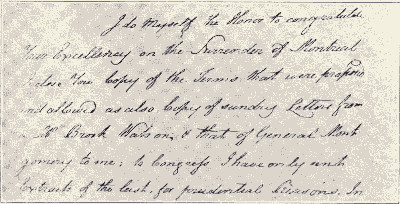

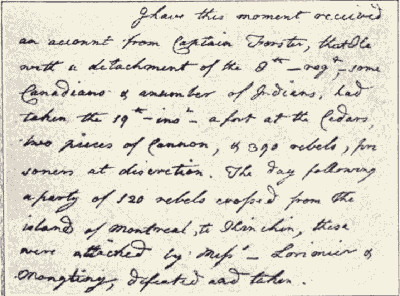

CHAPTER IX

MONTREAL, AN AMERICAN CITY SEVEN MONTHS UNDER CONGRESS

1776

THE CONGRESS ARMY EVACUATES MONTREAL

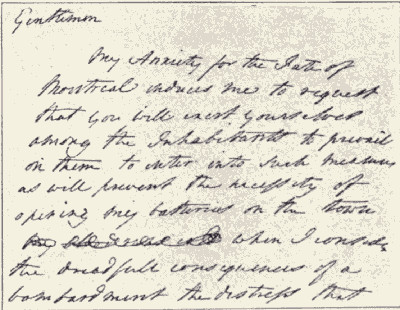

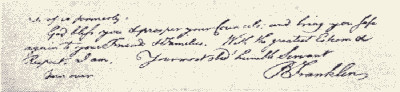

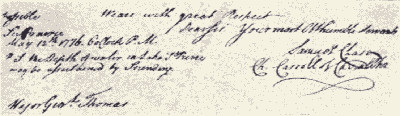

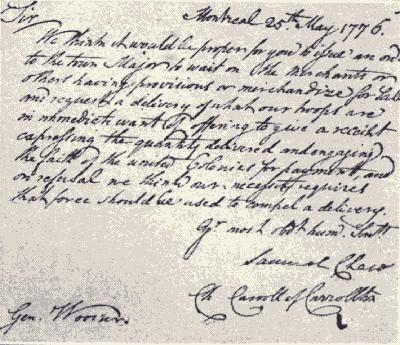

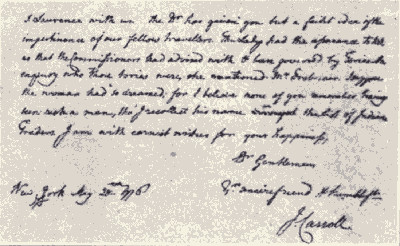

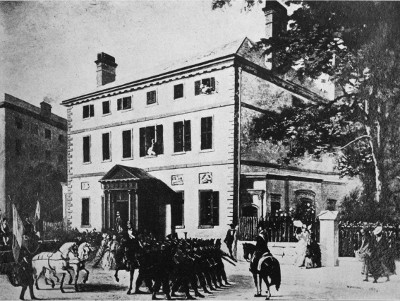

| MONTREAL UNDER CONGRESS—GENERAL WOOSTER’S TROUBLES—MONEY AND PROVISIONS SCARCE—MILITARY RULE—GENERAL CONFUSION—THE CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY, AMERICAN HEADQUARTERS—THE COMMISSIONERS: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, SAMUEL CHASE AND CHARLES CARROL—FLEURY MESPLET, THE PRINTER—THE FAILURE OF THE COMMISSIONERS—NEWS OF THE FLIGHT FROM QUEBEC—MONTREAL A STORMY SEA—THE COMMISSIONERS FLY—THE WALKERS ALSO—THE EVACUATION BY THE CONGRESS TROOPS—NOTES: I. PRINCIPAL REBELS WHO FLED; II. DESCRIPTION OF DRESS OF AMERICAN RIFLES | 79 |

CHAPTER X

THE ASSEMBLY AT LAST

1776-1791

THE CONSTITUTIONAL ACT OF 1791

| REOCCUPATION BY BRITISH—COURTS REESTABLISHED—CONGRESS’ SPECIAL OFFER TO CANADA—LAFAYETTE’S PROJECTED RAID—UNREST AGAIN—THE LOYALTY OF FRENCH CANADIANS AGAIN BEING TEMPTED—QUEBEC ACT PUT INTO FORCE—THE MERCHANTS BEGIN MEMORIALIZING FOR A REPEAL AND AN ASSEMBLY—HALDIMAND AND HUGH FINLAY OPPOSE ASSEMBLY—MEETINGS AND COUNTER MEETINGS—CIVIC AFFAIRS—THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A PROJECTED “CHAMBER OF COMMERCE”—THE FIRST NOTIONS OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS—THE MONTREAL CITIZENS’ COMMITTEE REPORT—THE UNITED EMPIRE LOYALISTS—THE DIVISION OF THE PROVINCE PROJECTED—THE CONSTITUTIONAL ACT OF 1791. NOTE: MONTREAL NAMES OF PETITIONERS IN 1784 | 87 |

CHAPTER XI

THE FUR TRADERS OF MONTREAL

THE GREAT NORTH WEST COMPANY

| MERCHANTS—NATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS ORIGINS—UP COUNTRY TRADE—EARLY COMPANIES—NORTH WEST COMPANY—CHARLES GRANT’S REPORT—PASSES—MEMORIALS—GEOGRAPHICAL[xi] DISCOVERIES—RIVAL COMPANIES—THE X.Y. COMPANY—JOHN JACOB ASTOR’S COMPANIES—- ASTORIA TO BE FOUNDED—THE JOURNEY OF THE MONTREAL CONTINGENT—ASTORIA A FAILURE—THE GREAT RIVAL—THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY—SIR ALEXANDER SELKIRK—THE AMALGAMATION OF THE NORTH WEST AND HUDSON’S BAY COMPANIES IN 1821—THE BEAVER CLUB | 97 |

CHAPTER XII

FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY DESIGNS

MONTREAL THE SEAT OF JACOBINISM

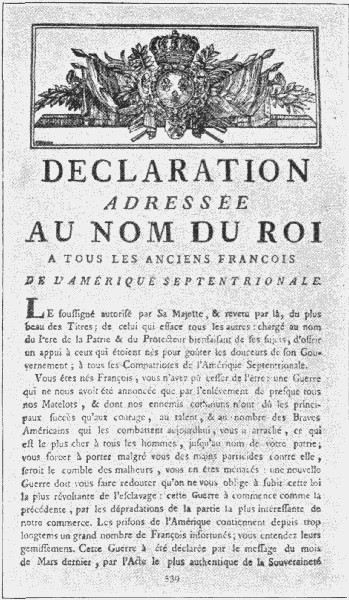

| THE ASSEMBLY AT LAST—MONTREAL REPRESENTATIVES—FRENCH AND ENGLISH USED—THE FRENCH REVOLUTION—MUTINY AT QUEBEC—THE DUKE OF KENT—INVASION FEARED FROM FRANCE—MONTREAL DISAFFECTED—ATTORNEY GENERAL MONK’S REPORT—THE FRENCH SEDITIONARY PAMPHLETS—PANEGYRIC ON BISHOP BRIAND—MONTREAL ARRESTS—ATTORNEY GENERAL SEWELL’S REPORT—M’LEAN—ROGER’S SOCIETY—JEROME BONAPARTE EXPECTED | 105 |

CHAPTER XIII

THE AMERICAN INVASION OF 1812

MONTREAL AND CHATEAUGUAY

FRENCH CANADIAN LOYALTY

| THE CAUSES OF THE WAR OF 1812—THE CHESAPEAKE—JOHN HENRY—HOW THE NEWS OF INVASION WAS RECEIVED IN MONTREAL—THE MOBILIZATION—GENERAL HULL—THE MONTREAL MILITIA—FRENCH AND ENGLISH ENLIST—MONTREAL THE OBJECTIVE—OFFICIAL ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF CHATEAUGUAY—COLONEL DE SALABERRY—RETURN OF WOUNDED—THE EXPLANATION OF THE FEW BRITISH KILLED | 115 |

CHAPTER XIV

SIDE LIGHTS OF SOCIAL PROGRESS

1776-1825

| THE “GAZETTE DU COMMERCE ET LITTERAIRE”—A RUNAWAY SLAVE—GUY CARLETON’S DEPARTURE—GENERAL HALDIMAND IN MONTREAL—MESPLET’S PAPER SUSPENDED—POET’S CORNER—THE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY DISCUSSED—FIRST[xii] THEATRICAL COMPANY: THE “BUSY BODY”—LORD NELSON’S MONUMENT—A RUNAWAY RED CURLY HAIRED AND BANDY LEGGED APPRENTICE—LAMBERT’S PICTURE OF THE PERIOD—MINE HOST OF THE “MONTREAL HOTEL”—THE “CANADIAN COURANT”—AMERICAN INFLUENCE—THE “HERALD”—WILLIAM GRAY AND ALEXANDER SKAKEL—BEGINNINGS OF COMMERCIAL LIFE—DOIGE’S DIRECTORY—MUNGO KAY—LITERARY CELEBRITIES—HERALD “EXTRAS”—WATERLOO—POLITICAL PSEUDONYMS—NEWSPAPER CIRCULATION—THE ABORTIVE “SUN”—A PICTURE OF THE CITY IN 1818—THE BLACK RAIN OF 1819—OFFICIAL, MILITARY AND ECCLESIASTICAL LIFE—ORIGIN OF ART, MUSIC, ETC. | 123 |

CHAPTER XV

BUREAURACY vs. DEMOCRACY

THE PROPOSED UNION OF THE CANADAS

| REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT—MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS—FRENCH-CANADIANS AIM TO STRENGTHEN THEIR POLITICAL POWER—THE “COLONIAL” OFFICE AND THE BUREAUCRATIC CLASS VERSUS THE DEMOCRATIC REPRESENTATIVE ASSEMBLY—L. J. PAPINEAU AND JOHN RICHARDSON—PETITIONS FOR AND AGAINST UNION—THE MONTREAL BRITISH PETITION OF 1822—THE ANSWER OF L.J. PAPINEAU—THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL—THE BILL FOR UNION WITHDRAWN. NOTES: NAMES OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE FROM 1796 TO 1833—MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY FOR MONTREAL DISTRICT, 1791-1829—PETITION OF MONTREAL BRITISH—1822 | 133 |

CHAPTER XVI

MURMURS OF REVOLUTION

RACE AND CLASS ANTAGONISM

| “CANADA TRADE ACTS”—LORD DALHOUSIE BANQUETED AFTER BEING RECALLED—MOVEMENT TO JOIN MONTREAL AS A PORT TO UPPER CANADA—THE GOVERNOR ALLEGED TO BE A TOOL—EXECUTIVE COUNCIL—RIOTOUS ELECTION AT MONTREAL—DR. TRACY VERSUS STANLEY BAGG—THE MILITARY FIRE—THE “MINERVE” VERSUS THE GAZETTE AND HERALD—THE CHOLERA OF 1832—MURMURS OF THE COMING REVOLT—MONTREAL PETITION FOR AND AGAINST CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES—MR. NELSON BREAKS WITH PAPINEAU—THE NINETY-TWO RESOLUTIONS—MR. ROEBUCK, AGENT FOR THE REFORM PARTY, ADVOCATES SELF-GOVERNMENT—FRENCH-CANADIAN EXTREMISTS—THE ELECTIONS—PUBLIC MEETING OF “MEN OF BRITISH AND IRISH DESCENT”—TWO DIVERGENT MENTALITIES—THE CONSTITUTIONAL ASSOCIATIONS—PETITIONS TO LONDON—LORD GOSFORD APPOINTED ROYAL COMMISSIONER—HIS POLICY OF CONCILIATION[xiii] REJECTED—MR. PAPINEAU INTRANSIGEANT—RAISING VOLUNTEER CORPS FORBIDDEN—THE DORIC CLUB—“RESPONSIBLE” GOVERNMENT DEMANDED | 139 |

CHAPTER XVII

MONTREAL IN THE THROES OF CIVIL WAR

1837-1838

| THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL TO REMAIN CROWN-APPOINTED—THE SIGNAL FOR REVOLT—FIRST INSURRECTIONARY MEETING. AT ST. OURS—DR. WOLFRED NELSON—CONSTITUTIONAL MEETINGS—THE PARISHES—THE SEDITIONARY MANIFESTO OF “LES FILS DE LIBERTE” AT MONTREAL—REVOLUTIONARY BANNERS—IRISH REJECT REVOLUTIONARY PARTY—MGR. LARTIGUE’S MANDEMENT AGAINST CIVIL WAR—THE FRACAS BETWEEN THE DORIC CLUB AND THE FILS DE LIBERTE—RIOT ACT READ—THE “VINDICATOR” GUTTED—MILITARY PROCEEDINGS—WARRANTS FOR ARREST—PAPINEAU FLIES—RELEASE OF PRISONERS AT LONGUEUIL—COMMENCEMENT OF HOSTILITIES—ST. DENIS—LIEUTENANT WEIR’S DEATH—GEN. T.S. BROWN—ST. CHARLES—ST. EUSTACHE—CAPTURE OF WOLFRED NELSON—SECOND MANDEMENT OF BISHOP LARTIGUE—DAY OF THANKSGIVING—CONSTITUTION SUSPENDED—THE INDEPENDENCE OF CANADA PROCLAIMED BY “PRESIDENT NELSON”—THE REGIMENTS LEAVE THE CITY—LORD DURHAM ARRIVES—AMNESTY AND SENTENCES—DURHAM RESIGNS—THE SECOND INSURRECTION—MARTIAL LAW IN MONTREAL—SIR JOHN COLBORNE QUASHES REBELLION—STERN REPRISALS—ARRESTS—TRUE BILLS—POLITICAL EXECUTIONS—“CONCORDIA SALUS” | 149 |

CHAPTER XVIII

PROCLAMATION OF THE UNION

1841

HOME RULE FOR THE COLONY

| THE DURHAM REPORT—THE RESOLUTIONS AT THE CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY—LORD SYDENHAM—THE PROCLAMATION OF UNION AT MONTREAL—RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT AT LAST | 159 |

CHAPTER XIX

RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT UNDER THE UNION

| KINGSTON THE SEAT OF GOVERNMENT—THE RACE CRY RESUSCITATED—LAFONTAINE—RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT—MONTREAL ELECTIONS—RESTRICTION[xiv] REMOVED ON FRENCH LANGUAGE IN PARLIAMENT—FREE TRADE MOVEMENT—FINANCIAL DEPRESSION—GEORGE ETIENNE CARTIER—REBELLION LOSSES BILL—THE BURNING OF THE PARLIAMENT HOUSE—THE MONTREAL MOVEMENT FOR ANNEXATION WITH THE STATES—“CLEAR GRITS” AND THE “PARTI ROUGE”—THE RAILWAY AND SHIPPING ERA—THE CAVAZZI RIOT—THE RECIPROCITY TREATY—EXIT THE OLD TORYISM—CLERGY RESERVES AND SEIGNEURIAL TENURE ACTS—THE MILITIA ACT—MONTREALERS ON THE ELECTED COUNCIL—THE Année Terribe OF 1857—THOMAS D’ARCY MC GEE—QUEBEC TEMPORARY SEAT OF GOVERNMENT—PROTECTION FOR HOME INDUSTRIES—CONFEDERATION BROACHED IN MONTREAL—THE TRENT AFFAIR—ST. ALBAN RAID PROSECUTIONS—THE REMODIFIED CIVIL CODE—FENIAN RAID EXCITEMENT IN MONTREAL—OTTAWA SEAT OF GOVERNMENT—THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICAN ACT—CONFEDERATION | 163 |

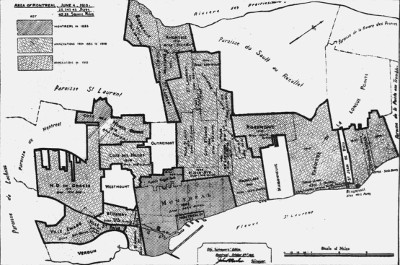

CHAPTER XX

THE MUNICIPALITY OF MONTREAL

| EARLY EFFORTS TOWARDS MUNICIPAL HOME RULE—1786—1821—1828—THE FIRST MUNICIPAL CHARTER OF 1831—THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF MONTREAL—JACQUES VIGER FIRST MAYOR—THE RETURN TO THE JUSTICES OF THE PEACE—LORD DURHAM’S REPORT AND THE RESUMPTION OF THE CORPORATION IN 1840—CHARTER AMENDMENT, 1851—FIRST MAYOR ELECTED BY THE PEOPLE—CHARTER AMENDMENT OF 1874—THE CITY OF MONTREAL ANNEXATIONS—CIVIC POLITICS—THE NOBLE “13”—1898 CHARTER RECAST, SANCTIONED IN 1899—CIVIC SCANDALS—THE “23”—JUDGE CANNON’S REPORT—THE REFORM PARTY; THE “CITIZENS’ ASSOCIATION”—REDUCTION OF ALDERMEN AND A BOARD OF CONTROL, THE ISSUE—THE WOMEN’S CIVIC ASSOCIATIONS—THE NEW REGIME AND THE BOARD OF CONTROL—FURTHER AMENDMENTS TO CHARTER—THE ELECTIONS OF 1912—ABOLITION OF THE SMALL WARD SYSTEM ADVOCATED—THE ELECTIONS OF 1914—A FORECAST FOR GREATER MONTREAL—SUPPLEMENT: LIST OF MAYORS—CITY REVENUE | 181 |

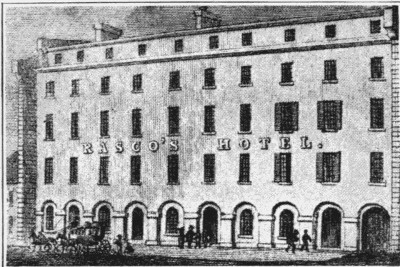

CHAPTER XXI

SUPPLEMENTAL ANNALS AND SIDELIGHTS OF SOCIAL LIFE UNDER THE UNION

| FOREWORD—MARKED PROGRESS GENERAL—THE EMBRYONIC COSMOPOLIS—THE DEEPENING OF LAKE ST. PETER—FOUNDATION OF PHILANTHROPIES—LIVING CHEAP—THE MONTREAL DISPENSARY—RASCO’S HOTEL AND CHARLES DICKENS—PRIVATE THEATRICALS—MONTREAL AS SEEN BY “BOZ”—DOLLY’S AND THE GOSSIPS—THE MUNICIPAL ACT—ELECTION RIOTS—LITERARY AND UPLIFT MOVEMENTS—THE RAILWAY ERA COMMENCES—THE SHIP FEVER—A RUN ON THE SAVINGS’ BANK—THE REBELLION LOSSES BILL AND THE BURNING OF PARLIAMENT HOUSE—RELIGIOUS FANATICISM—GENERAL D’URBAN’S FUNERAL—A[xv] CHARITY BALL—THE GRAND TRUNK INCORPORATORS—EDUCATIONAL MOVEMENTS—THE “BLOOMERS” APPEAR—M’GILL UNIVERSITY REVIVAL—THE GREAT FIRE OF 1852—THE GAVAZZI RIOTS—PROGRESS IN 1853—THE CRIMEAN WAR OF 1854—THE PATRIOTIC FUND—THE ASIATIC CHOLERA—THE ATLANTIC SERVICE FROM MONTREAL—ADMIRAL BELVEZE’S VISIT—PARIS EXHIBITION PREPARATIONS—“S.S. MONTREAL” DISASTER—THE INDIAN MUTINY—THE FIRST OVERSEAS CONTINGENT—THE ATLANTIC CABLE CELEBRATED—A MAYOR OF THE PERIOD—THE RECEPTION OF ALBERT EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALES—FORMAL OPENING OF THE VICTORIA BRIDGE—THE GREAT BALL—“EDWARD THE PEACEMAKER”—THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR—MONTREAL FOR THE SOUTH—FEAR OF WAR—CITIZEN RECRUITING—THE MILITARY—OFFICERS OF THE PERIOD—PEACE—THE SOUTHERNERS—THE WAR SCARE—THE BIRTH OF MODERN MILITIA SYSTEM—THE MILITARY FETED—CIVIC PROGRESS—FENIAN THREATS—D’ARCY MCGEE—SHAKESPEARE CENTENARY—GERMAN IMMIGRANTS’ DISASTER—ST. ALBAN’S RAIDERS—RECIPROCITY WITH THE UNITED STATES TO END—ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE CITY COUNCIL—THE FIRST FENIAN RAID—MONTREAL ACTION—MILITARY ENTHUSIASM—THE DRILL HALL—A RETROSPECT AND AN APPRECIATION OF THE LATTER DAYS OF THE UNION | 195 |

CHAPTER XXII

CONSTITUTIONAL LIFE UNDER CONFEDERATION

FEDERAL AND PROVINCIAL INFLUENCE

| MONTREAL AN IMPORTANT FACTOR IN FEDERAL AND PROVINCIAL POLITICS—CONFEDERATION TESTED—CARTIER AND THE PARTI ROUGE AT MONTREAL—ASSASSINATION OF THOMAS D’ARCY M’GEE—THE HUDSON’S BAY TRANSFER—THE METIS AND THE RIEL REBELLION—LORD STRATHCONA—THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY BILL—RESIGNATION OF SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD—SECOND FENIAN RAID—THE “NATIONAL POLICY”—VOTING REFORM—TEMPERANCE BILL—ORANGE RIOTS—SECOND NORTH WEST REBELLION—THE “SIXTY-FIFTH REGIMENT”—THE MANITOBA SCHOOL QUESTION—PROMINENT CITIZENS—BRITISH PREFERENTIAL TARIFF—BOER WAR—“STRATHCONA HORSE”—THE NATIONALIST LEAGUE—RECIPROCITY AND FEAR OF ANNEXATION—THE ELECTIONS OF 1911—NAVAL BILL—PROVINCIAL POLITICS—MONTREAL MEMBERS—PROVINCIAL OVERSIGHT OVER MONTREAL—HOME RULE—THE INTERNATIONAL WAR OF 1914—THE FIRST CONTINGENT—MONTREAL’S ACTION | 219 |

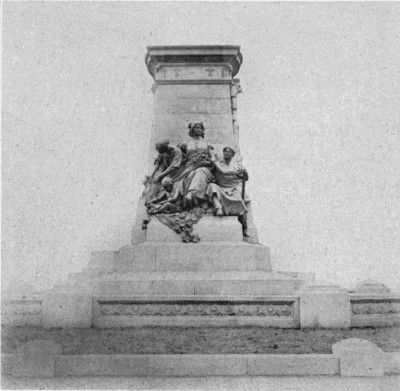

CHAPTER XXIII

SUPPLEMENTAL ANNALS AND SIDELIGHTS OF SOCIAL LIFE

UNDER CONFEDERATION

1867-1914

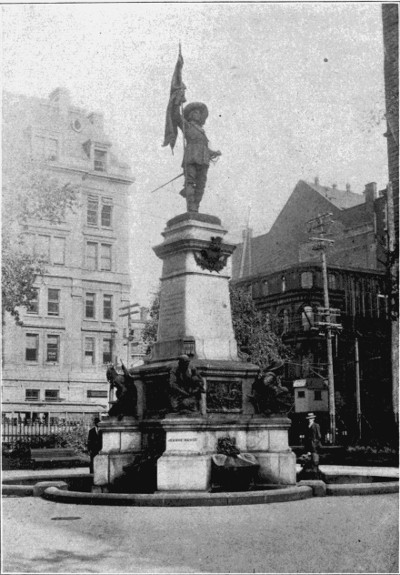

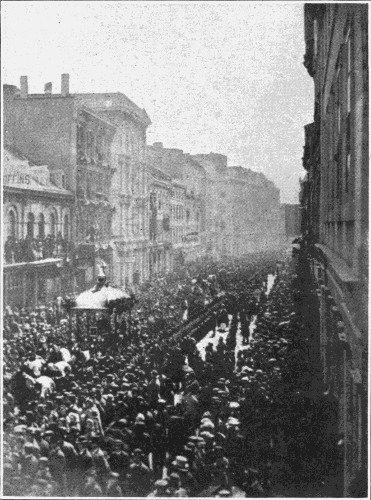

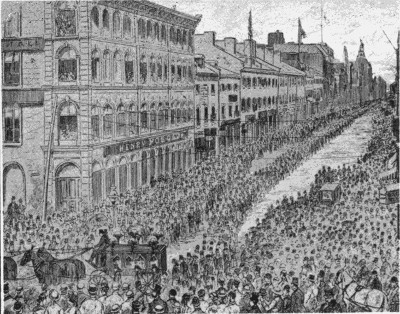

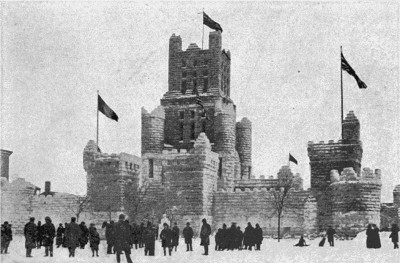

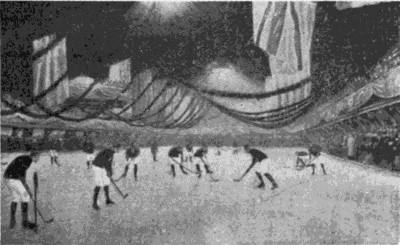

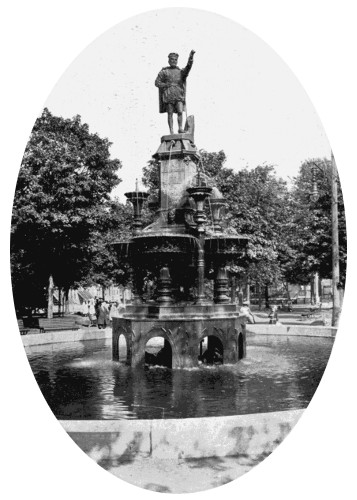

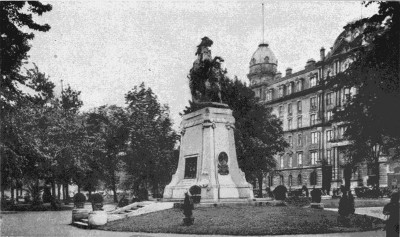

| CONFEDERATION—IMPRESSIONS OF—FUNERAL OF D’ARCY M’GEE—PRINCE ARTHUR OF CONNAUGHT—THE SECOND FENIAN RAID—THE “SILVER” NUISANCE—ORGANIZATION[xvi] OF CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILROAD—RUN ON A SAVINGS BANK—FUNERAL OF SIR GEORGE ETIENNE CARTIER—NEW BALLOT ACT—THE “BAD TIMES”—THE NATIONAL POLICY—THE ICE RAILWAY—THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILROAD CONTRACT—THE FORMATION OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF CANADA—OTHER CONGRESSES—THE FIRST WINTER CARNIVAL—FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF ST. JEAN BAPTISTE ASSOCIATION—THE GREAT ALLEGORICAL PROCESSION AND CAVALCADE—THE MONUMENT NATIONAL—THE RIEL REBELLION—SMALLPOX EPIDEMIC AND RIOTS—THE FLOODS OF 1886—THE FIRST REVETMENT WALL—THE JESUITS ESTATES BILL AND THE EQUAL RIGHTS PARTY—LA GRIPPE—THE COMTE DE PARIS—ELECTRICAL CONVENTION—HISTORIC TABLETS PLACED—THE TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF VILLE MARIE—THE BOARD OF TRADE BUILDING BURNT—THE CITY RAILWAY ELECTRIFIED—HOME RULE FOR IRELAND—VILLE MARIA BURNT—THE “SANTA MARIA”—CHRISTIAN ENDEAVOURERS CONVENTION—THE CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY AS A PUBLIC MUSEUM—MAISONNEUVE MONUMENT—LAVAL UNIVERSITY—QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE—MONTREAL AND THE BOER WAR—THE VISIT OF THE DUKE AND DUCHESS OF CORNWALL—TURBINE STEAMERS—A JAPANESE LOAN COMPANY—FIRST AUTOMOBILE FATALITY—FIRES AT MCGILL—ECLIPSE OF SUN—THE WINDSOR STATION ACCIDENT—THE “WITNESS” BUILDING BURNT—THE OPENING OF THE ROYAL EDWARD INSTITUTE—GREAT CIVIC REFORM—THE DEATH OF EDWARD VII—THE “HERALD” BUILDING BURNT—THE EUCHARISTIC CONGRESS—MONTREAL A WORLD CITY—THE DRY DOCK—THE “TITANIC DISASTER”—CHILD WELFARE EXHIBITION—MONTREAL AND THE WAR OF 1914 | 231 |

PART II

SPECIAL PROGRESS

CHAPTER XXIV

RELIGIOUS DENOMINATIONS

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

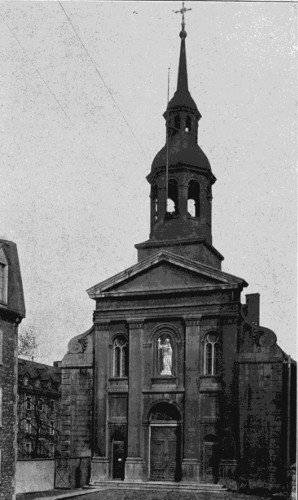

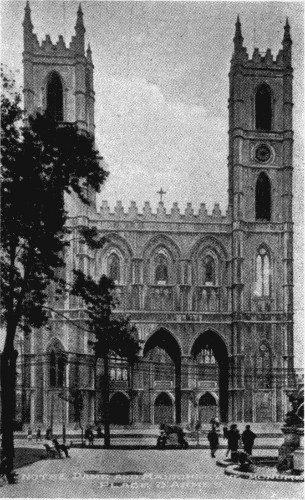

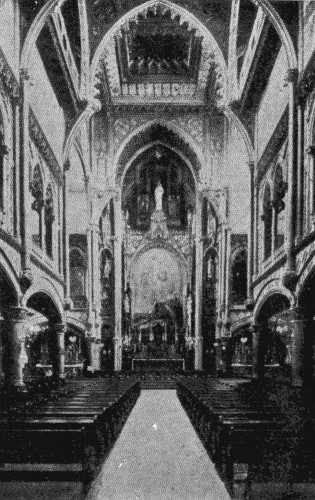

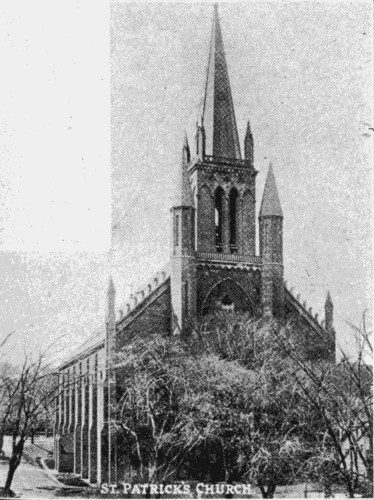

| EARLY CHAPELS AND CHURCHES—THE FIRST PARISH CHURCH—OTHER CHURCHES STANDING AT THE FALL OF MONTREAL—NOTRE DAME DE VICTOIRE—- NOTRE DAME OF PITIE—THE “RECOLLET”—THE PRESENT NOTRE DAME CHURCH—ERECTION AND OPENING—THE “OLD AND NEW”—THE TOWERS AND BELLS—THE ECCLESIASTICAL DIOCESE OF QUEBEC—THE BISHOPS OF MONTREAL—THE DIVISION OF THE CITY INTO PARISHES—THE CHURCHES AND “RELIGIOUS”—ENGLISH-SPEAKING CATHOLICS—ST. PATRICK’S, IRISH NATIONAL CHURCH, ETC. NOTE: THE “RELIGIOUS” COMMUNITIES OF MEN AND WOMEN | 251 |

CHAPTER XXV

OTHER RELIGIOUS DENOMINATIONS

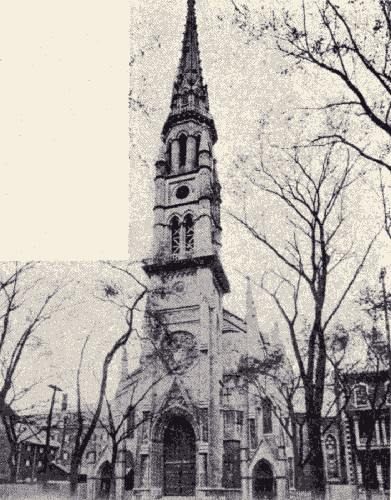

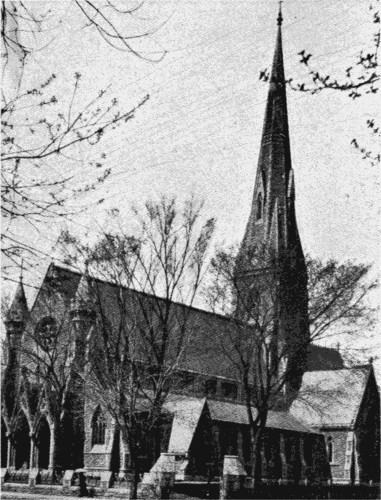

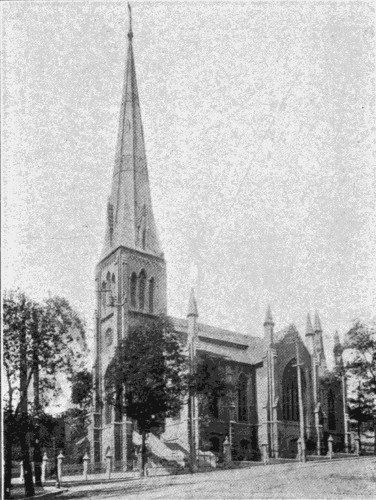

ANGLICANISM—EARLY BEGINNINGS—FIRST “CHRIST CHURCH”—THE BISHOPS OF MONTREAL—HISTORY OF EARLY ANGLICAN CHURCHES.

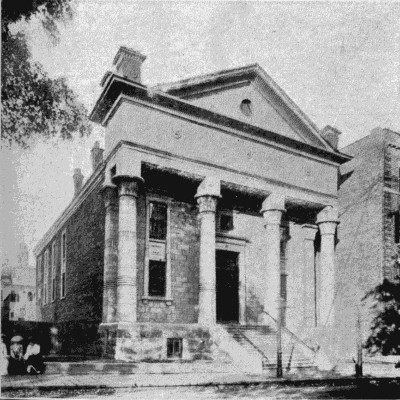

PRESBYTERIANISM—ST. GABRIEL’S STREET CHURCH—ITS OFFSHOOTS—THE FREE KIRK MOVEMENT—THE CHURCH OF TODAY.

METHODISM—FIRST CHAPEL ON ST. SULPICE, 1809—THE DEVELOPMENT OF METHODIST CHURCHES.

THE BAPTISTS—FIRST CHAPEL OF ST. HELEN STREET—FURTHER GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT—PRESENT CHURCHES.

CONGREGATIONALISM—CANADA EDUCATION AND HOME MISSIONARY SOCIETY—FIRST CHURCH ON ST. MAURICE STREET—CHURCHES OF TODAY.

UNITARIANISM—FIRST SERMON IN CANADA, 1832—ST. JOSEPH STREET CHAPEL—THE CHURCHES OF THE MESSIAH.

HEBREWS—SHEARITH ISRAEL—SHAAC HASHOMOYIM AND OTHER CONGREGATIONS.

SALVATION ARMY—ITS GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT.

OTHER DENOMINATIONS.

| A RELIGIOUS CENSUS OF MONTREAL FOR 1911 | 271 |

CHAPTER XXVI

1760-1841

SCHOOL SYSTEM OF MONTREAL BEFORE THE CESSION

| NEW MOVEMENT FOR BOYS—THE COLLEGE OF MONTREAL—THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH EDUCATION—THE FIRST ENGLISH SCHOOLMASTERS BEFORE 1790—A REPORT OF 1790 FOR THE SCHOOLS OF CANADA—THE DESIRE TO REAR UP A SYSTEM OF PUBLIC EDUCATION—THE JESUITS’ ESTATES—THE “CASE” AGAINST AMHERST’S CLAIM TO THE JESUITS’ ESTATES AND FOR THEIR DIVERGENCE TO PUBLIC EDUCATION—NEW ENGLISH MOVEMENT FOR A GENERAL SYSTEM OF EDUCATION—THE ACT OF 1801—THE ROYAL INSTITUTION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF LEARNING—NEVER A POPULAR SUCCESS—ITS REFORM IN 1818—A COUNTERPOISE—THE FABRIQUE ACT OF 1824—REVIEW OF SCHOOLS UNDER THE ROYAL INSTITUTION—SUBSIDIZED SCHOOLS—REVIEW OF CATHOLIC SCHOOLS—LAY SCHOOLS—LORD DURHAM’S REPORT ON EDUCATION. NOTE: THE JESUITS’ ESTATES | 293 |

CHAPTER XXVII

1841-1914

THE SCHOOL SYSTEM AFTER THE UNION

THE RISE OF THE “SCHOOL COMMISSIONS OF MONTREAL”

EDUCATION AFTER THE REBELLION—THE EDUCATIONAL ACT OF 1846—THE PERSONNEL OF THE FIRST CATHOLIC AND PROTESTANT COMMISSIONERS—NORMAL[xviii] SCHOOLS—THE AMENDED SCHOOL ACT OF 1868-69—THE CHARTER—THE PROTESTANT HIGH SCHOOL—THE PROTESTANT COMMISSIONERS, 1869-1914—HISTORY OF SCHOOLS—LIST OF CATHOLIC COMMISSIONERS, 1869-1914—PRESENT SCHOOLS UNDER COMMISSION—INDEPENDENT CATHOLIC SCHOOL COMMISSIONS—THE ORGANIZATIONS COOPERATING WITH THE CENTRAL COMMISSION—“NUNS”—“BROTHERS”—“LAITY.”

| NOTE: SECONDARY EDUCATION—TECHNICAL AND COMMERCIAL—VOCATIONAL | 305 |

CHAPTER XXVIII

UNIVERSITY DEVELOPMENT

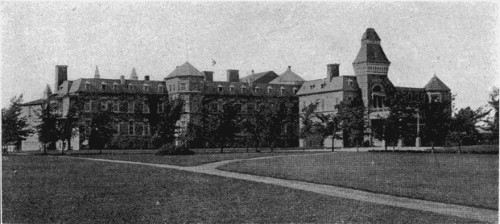

I. M’GILL UNIVERSITY

THE ROYAL INSTITUTION—JAMES M’GILL—CHARTER OBTAINED—THE “MONTREAL MEDICAL INSTITUTE” SAVES M’GILL—NEW LIFE IN 1829—THE RECTOR OF MONTREAL—THE MERCHANTS’ COMMITTEE—M’GILL IN 1852—THE HISTORY OF THE FACULTIES—BUILDINGS—DEVELOPMENT SINCE 1895—RECENT BENEFACTORS—MACDONALD COLLEGE—THE STRATHCONA ROYAL VICTORIA COLLEGE FOR WOMEN. NOTE: THE UNION THEOLOGICAL MOVEMENT—THE JOINT BOARDS OF THE CONGREGATIONAL, ANGLICAN, PRESBYTERIAN AND WESLEYAN AFFILIATED COLLEGES.

II. LAVAL UNIVERSITY (MONTREAL DISTRICT)

| THE STORY OF ITS COMPONENT PARTS—EVOLUTION FROM THE “ECOLES DE LATIN”—COLLEGE DE ST. RAPHAEL—ENGLISH STUDENTS—COLLEGE DECLAMATIONS—THE PETIT SEMINAIRE ON COLLEGE STREET—THE COLLEGE DE MONTREAL—THE SCHOOLS OF THEOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY, CLASSICS, LAW AND MEDICINE—THE APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION “JAM DUDUM”—DESCRIPTION OF THE UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS—AFFILIATED BODIES—THE FACULTIES AND SCHOOLS. NOTE: NAMES OF EARLY “ENGLISH” STUDENTS AT THE “COLLEGE” | 325 |

CHAPTER XXIX

GENERAL CULTURE

I. THE LIBRARY MOVEMENT

FRENCH:—L’OEUVRE DES BONS LIVRES, 1844—THE CABINET DE LECTURE PAROISSIAL, 1857.

ENGLISH:—“MONTREAL LIBRARY” AND MONTREAL NEWS ROOM, 1821—MERCANTILE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION, 1844—THE FRASER INSTITUTE, INCORPORATED 1870—ITS EARLY LITIGATIONS—ITS PUBLIC OPENING IN 1885—OTHER LIBRARIES.[xix]

II. LITERARY AND LEARNED SOCIETIES

THE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, 1827—THE MECHANICS INSTITUTE, 1828—LA SOCIETE HISTORIQUE, 1856—CONFERENCE DES INSTITUTEURS, 1857—THE “INSTITUT CANADIEN”—CERCLE LITTERAIRE DE VILLE MARIE, 1857—UNION CATHOLIQUE, 1858—(THE GUIBORD CASE)—THE ANTIQUARIAN AND NUMISMATIC ASSOCIATION, 1862—THE “ECOLE LITTERAIRE” 1892—ST. JAMES LITERARY SOCIETY, 1898—THE “DICKENS’ FELLOWSHIP” 1909—OTHER LITERARY ASSOCIATIONS—THE “BURNS SOCIETY”—THE ALLIANCE FRANCAISE—THE CANADIAN CLUB, 1905.

III. ARTISTIC ASSOCIATIONS

FOREWORD:—INTELLECTUAL AND ARTISTIC EXCLUSIVENESS.

ART:—EARLY ART IN CANADA—THE MODERN MOVEMENT—THE MONTREAL SOCIETY OF ARTISTS—THE ART ASSOCIATION OF MONTREAL—ITS HISTORY—ITS PAINTINGS—MONTREAL ART COLLECTIONS—THE ART SCHOOL—MONTREAL ARTISTS—THE WOMAN’S ART SOCIETY—THE CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY—THE ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS—THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF CANADA—OUTSTANDING ARTISTS.

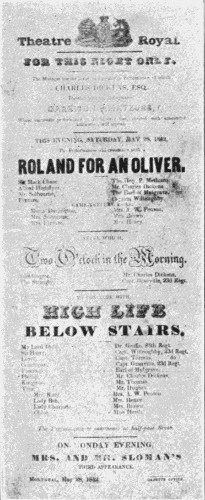

THE DRAMA:—PLAYS IN 1804—THE FIRST THEATRE ROYAL BUILT IN 1825—THE SECOND OPENED IN 1850—OTHER THEATRES TO THE PRESENT—AMATEUR THEATRICAL ASSOCIATIONS—THE DRAMATIC LEAGUE.

MUSIC:—MODERN SOCIETIES—SOCIETE DE STE CECILE—SOCIETE DE MONTAGNARDS—AMATEUR MUSICAL LEAGUE—MENDELSSOHN CHOIR—MONTREAL PHILHARMONIC—INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC.

| NEWSPAPERS:—MONTREAL HISTORIES | 349 |

CHAPTER XXX

NATIONAL ORIGINS OF THE POPULATION

1834, THE YEAR OF THE SIMULTANEOUS ORIGIN OF THE EARLIEST NATIONAL SOCIETIES.

ST. JEAN BAPTISTE ASSOCIATION—REORGANIZATION IN 1843—THE “MONUMENT NATIONAL”—EDUCATION AND SOCIAL AMELIORATIONS—THE FRENCH-CANADIAN SPIRIT—PRESIDENTS.

ST. GEORGE’S SOCIETY—A CELEBRATION IN 1821—OBJECT—EARLIEST OFFICERS—THE HISTORY OF ST. GEORGE’S HOME—PRESIDENTS.

ST. ANDREW’S SOCIETY—ORGANIZATION AND FIRST OFFICERS—JOINT PROCESSIONS OF NATIONAL SOCIETIES—EARLIEST CHARITABLE ACTIVITIES—THE HEALTH OF THE POPE—THE LORD ELGIN INCIDENT—THE CRIMEAN WAR—SUBSCRIPTION TO A PATRIOTIC FUND—THE HISTORY OF ST. ANDREW’S HOME BEGINS—THE HISTORY OF ST. ANDREW’S HALL—CONDOLENCE ON DEATH OF D’ARCY MCGEE—PRESIDENTS.

ST. PATRICK’S SOCIETY—ORIGINALLY NON-DENOMINATIONAL—EARLY PRESIDENTS—THE REORGANIZATION IN 1856—FIRST OFFICERS—FIRST SOIREE—FIRST ANNIVERSARY DINNER—NATIONAL SOCIETIES PRESENT—THE TOASTS—IRISH[xx] COMPANIES IN CORPUS CHRISTI PROCESSION—IRISH PARLIAMENTARY REPRESENTATION—T. D’ARCY M’GEE—EMIGRATION WORK—ST. PATRICK’S HALL—PRESIDENTS.

IRISH PROTESTANT BENEVOLENT SOCIETY—EARLY MEMBERS—WORKS—PRESIDENTS.

GERMAN SOCIETY—HISTORY AND PRESIDENTS.

WELSH SOCIETY—ORIGINALLY THE “WELSH UNION OF MONTREAL”—AFTERWARD—ITS OBJECT—PRESIDENTS.

NEWFOUNDLAND SOCIETY—ORIGIN—PRESIDENTS.

THE ZIONIST MOVEMENT—THE JEWISH COMMUNITY.

| OTHER NATIONAL ASSOCIATIONS AND CENSUS OF POPULATION FOR 1911 | 369 |

CHAPTER XXXI

PUBLIC SAFETY SERVICES

FIGHTING FIRE—DARKNESS—FLOODS—DROUGHT

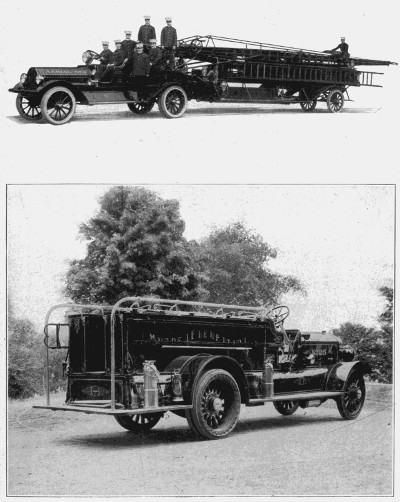

1. FIRE FIGHTING—THE FIRE OF 1765—“THE CASE OF THE CANADIANS OF MONTREAL”—THE EXTENT OF THE FIRE—FIRE PRECAUTIONS SUGGESTED—OTHER HISTORICAL FORCES—THE MONTREAL FIRE FORCES OF THE PAST AND PRESENT.

2. THE LIGHTING OF MONTREAL—OIL LAMPS, 1815—GAS, 1836—ELECTRICITY—FIRST EXPERIMENTS IN THE STREETS, 1879—THE ELECTRIC LIGHTING COMPANIES—NOTES ON INTRODUCTION OF THE TELEGRAPH—FIRE ALARM—ELECTRIC RAILWAY.

3. FLOODS, EARLY AND MODERN, 1848, 1857, 1861, 1865, 1886—THE PRACTICAL CESSATION IN 1888.

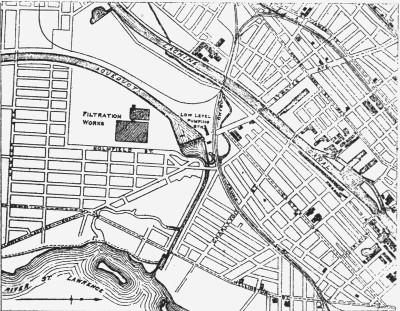

| 4. THE CITY WATER SUPPLY—THE MONTREAL WATER WORKS—PRIVATE COMPANIES—THE MUNICIPAL WATER WORKS—THE PUMPING PLANTS—THE WATER FAMINE OF 1913 | 397 |

CHAPTER XXXII

LAW AND ORDER

JAILS—POLICE SERVICES—COURTHOUSE—LAW OFFICERS

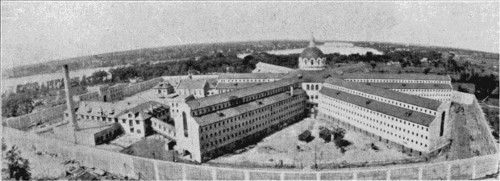

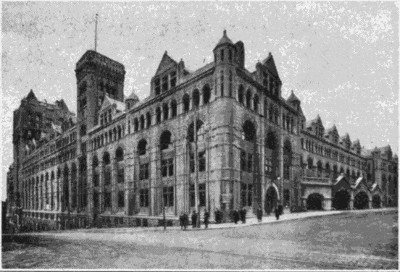

| EARLY PUNISHMENTS—FIRST CASES OF THE MAGISTRATES—GEORGE THE “NAGRE”—“EXECUTION FOR MURDER”—OTHER CRIMES PUNISHED BY DEATH—SOLDIER DESERTIONS—A PUBLIC EXECUTION—THE JAILS—- THE JAIL TAX TROUBLES—OBNOXIOUS TOASTS—THE NEW JAIL OF 1836—ITS POPULATIONS—THE NEW BORDEAUX PRISON—OTHER SUPPLEMENTARY PRISONS—THE EARLY POLICING OF MONTREAL—THE LOCAL POLICE FORCE OF 1815—THE POLICE FORCE AFTER THE REBELLION OF 1837-1838—POLICE CHIEFS—MODERN LAW COURTS AND JUDGES—THE HISTORY OF THE BAR—THE BAR ASSOCIATIONS OF MONTREAL—THE RECORDERS—THE ARCHIVES.[xxi] SUPPLEMENT—THE JUDGES OF THE HIGHER COURTS FROM 1764 TO 1914—THE SHERIFFS OF MONTREAL—THE PROTHONOTARIES—THE COURTHOUSE SITES—THE BATONNIERS | 413 |

CHAPTER XXXIII

HOSPITALS

THE HOTEL DIEU: JEANNE MANCE—THE HOSPITALIERES OF LA FLECHE—THE HOTEL DIEU CHAPEL—ST. PATRICK’S HOSPITAL—THE MIGRATION TO PINE AVENUE—THE PRESENT MODERN HOSPITAL.

THE GENERAL HOSPITAL: “THE LADIES BENEVOLENT SOCIETY”—THE HOUSE OF RECOVERY—THE MONTREAL GENERAL HOSPITAL—ITS BENEFACTORS AND ITS ADDITIONS—THE EARLY TRAINING OF NURSES—THE ANNEX OF 1913.

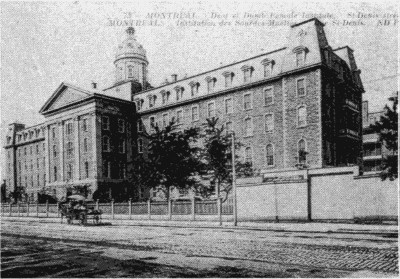

THE NOTRE DAME HOSPITAL: THE LAVAL MEDICAL FACULTY—THE OLD DONEGANI HOTEL—THE LADY PATRONESSES—MODERN DEVELOPMENT.

THE WESTERN HOSPITAL: THE BISHOPS COLLEGE MEDICAL FACULTY—THE WOMEN’S HOSPITAL.

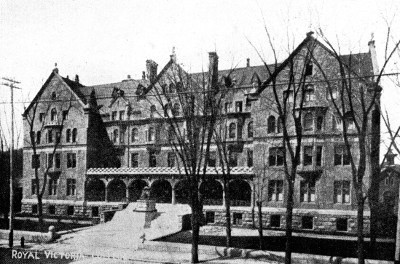

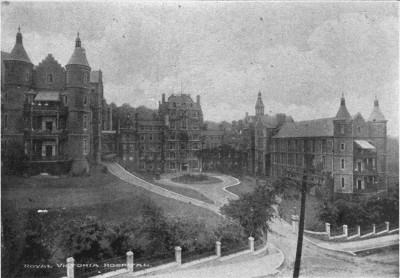

THE ROYAL VICTORIA HOSPITAL: IN MEMORY OF QUEEN VICTORIA—ITS DESCRIPTION—ITS INCORPORATION—ITS EQUIPMENT.

THE HOMEOPATHIC HOSPITAL: FIRST ORGANIZED WORK—INCORPORATION—THE FIRST HOSPITAL—THE FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS—THE PHILLIPS TRAINING SCHOOL FOR NURSES.

THE HOSPITALS FOR THE INSANE: EARLY TREATMENT OF INSANE—THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE HOSPITALS ST. JEAN DE DIEU AT LONGUE POINTE AND THE PROTESTANT ASYLUM AT VERDUN.

CIVIC HOSPITALS: THE SMALLPOX HOSPITAL—“CONTAGIOUS” HOSPITALS—HOSPITAL ST. PAUL—ALEXANDRA HOSPITAL.

TUBERCULOSIS DISPENSARIES: THE ROYAL EDWARD INSTITUTE—PIONEER TUBERCULOSIS CLINIC IN CANADA—PUBLIC HEALTH EXHIBITIONS—THE INSTITUTE BRUCHESI: ITS DEVELOPMENT—THE GRACE DART HOME—CIVIC AID.

CHILDREN’S HOSPITALS: THE CHILDREN’S MEMORIAL HOSPITAL—STE. JUSTINE.

OTHER HOSPITAL ADJUNCT ASSOCIATIONS.

| NOTE: MEDICAL BOARDS: PRIVATE, PROVINCIAL, MUNICIPAL | 433 |

CHAPTER XXXIV

SOCIOLOGICAL MOVEMENTS

| I. | CARE OF THE AGED, FOUNDLINGS AND INFANTS. | |

| II. | RELIEF MOVEMENTS. | |

| III. | SICK VISITATION AND NURSING BODIES. | |

| IV. | MOVEMENTS FOR THE “UNFORTUNATES.” | |

| V. | VOCATIONAL TRAINING FOR THE HANDICAPPED. | |

| VI. | IMMIGRATION WORK. | |

| VII. | HUMANITARIAN MOVEMENTS FOR BOYS. | |

| VIII. | HEBREW SOCIAL WORKS. | |

| IX. | COOPERATIVE MOVEMENTS. | |

| X. | MOVEMENTS FOR SAILORS AND SOLDIERS. | |

| XI. | TEMPERANCE MOVEMENTS. | |

| XII. | THE IMPROVEMENT OF THE CONDITIONS OF WORKERS. | |

| XIII. | RECENT SOCIAL MOVEMENTS. | |

| XIV. | MUNICIPAL CHARITIES. | 457 |

CHAPTER XXXV

COMMERCIAL HISTORY BEFORE THE UNION

| MONTREAL’S EARLY BUSINESS FIRMS—A PROPHECY AT BEGINNING OF NINETEENTH CENTURY—CULTIVATION OF HEMP—ST. PAUL STREET—SLAVES IN MONTREAL—DOCTORS AND DRUGS IN 1815—WHOLESALE FIRMS IN 1816—FIRST MEETING OF COMMITTEE OF TRADE—NOTRE DAME STREET—M’GILL STREET—FRENCH CANADIAN BUSINESSES—SHIP CARGOES—THE SHOP FRONTS IN 1839 | 527 |

CHAPTER XXXVI

COMMERCIAL HISTORY SINCE THE UNION

THE RISE OF MODERN MANUFACTURES AND INDUSTRIES

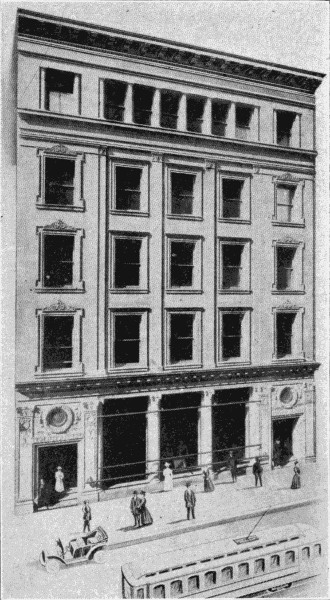

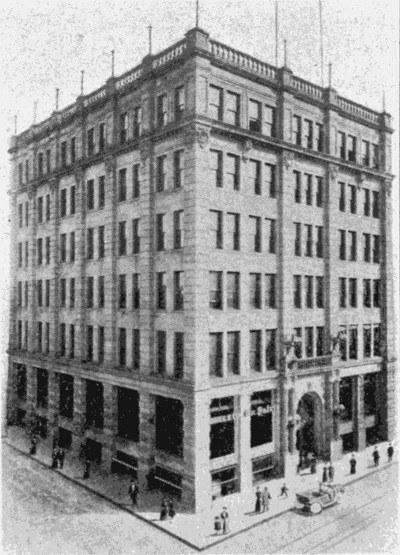

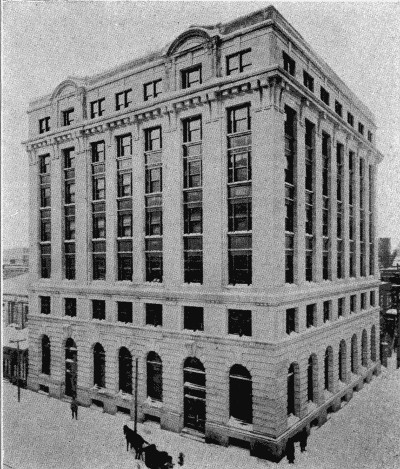

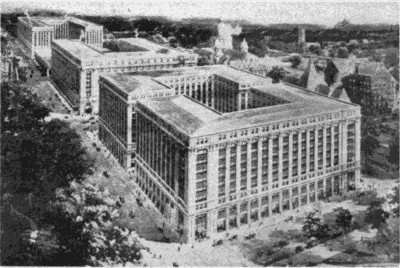

| MONTREAL CENTER OF CANADIAN TRADE—LORD ELGIN’S OPINION OF THE CANADA CORN ACT—TRADE DEPRESSION BEGINNING IN 1847—SUGAR AND FLOUR INDUSTRIES—THE PANIC OF 1860—A PROSPEROUS DECADE—ANOTHER DEPRESSION—THE NATIONAL POLICY—PROSPERITY AGAIN IN THE EIGHTIES—ST. CATHERINE STREET—THE RISE OF FURTHER INDUSTRIES—THE RISE OF THE COMMERCIAL ASSOCIATIONS—THE COMMITTEE OF TRADE—ITS ACTIVITIES—THE BOARD OF TRADE—ITS ACTIVITIES IN CANAL, PORT, RAILWAY, CANADIAN AND EMPIRE EXPANSION—ITS INTEREST IN CIVIC GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL CIVIC BETTERMENT—ITS BUILDING—ITS SOCIAL FUNCTIONS—THE “CHAMBRE DE COMMERCE”—ITS ORIGIN—THE OTHER MERCHANTS’ ASSOCIATIONS OF THE CITY—A TRIBUTE TO THE MERCHANTS OF MONTREAL. NOTES: PRESIDENTS OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—CENSUS (1912) OF MONTREAL MANUFACTURES | 535 |

CHAPTER XXXVII

FINANCE

MONTREAL BANKING AND INSURANCE BODIES

I. BANKING: HAMILTON’S PLAN FOLLOWED BY THE FIRST BANK OF THE UNITED STATES IN 1791-1792, THE ATTEMPTED CANADA BANKING COMPANY AT[xxiii] MONTREAL—DELAY THROUGH AMERICAN WAR OF 1812-1815, RENEWED AGITATION FOR A BANK CHARTER FOR MONTREAL—1817, THE FIRST BANK OF MONTREAL WITHOUT A CHARTER—ITS FIRST OFFICERS—OTHER BANKS FOLLOW—THE QUEBEC BANK—THE RIVAL “BANK OF CANADA”—THE BANK OF BRITISH NORTH AMERICA—MOLSONS BANK—THE MERCHANTS BANK—BANQUE JACQUES CARTIER, PREDECESSOR TO BANQUE PROVINCIALE—THE ROYAL BANK—THE BANQUE D’HOCHELAGA—THE MONTREAL CITY AND DISTRICT BANK—BANKS WITH HEAD OFFICES ELSEWHERE—MONTREAL BANK CLEARINGS WITH CANADIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN CITIES.

| II. INSURANCE: THE PIONEER FIRE INSURANCE COMPANY OF CANADA—THE “PHOENIX”—THE “AETNA”—IN THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES—THE GREAT FIRE OF 1854—LATER COMPANIES. A. LIFE INSURANCE: THE PIONEER COMPANIES—THE SCOTTISH AMICABLE AND SCOTTISH PROVIDENT COMPANIES. B. MISCELLANEOUS INSURANCE | 553 |

CHAPTER XXXVIII

TRANSPORTATION

I

SHIPPING—EARLY AND MODERN

BY RIVER AND STREAM

MONTREAL HEAD OF NAVIGATION—LAKE ST. PETER—JACQUES CARTIER’S DIFFICULTIES—THE GRADUAL DEEPENING OF THE CHANNEL—THE LACHINE CANAL IN 1700—ITS FURTHER HISTORY—MONTREAL THE HEAD OF THE CANAL SYSTEM OF CANADA.

II

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MONTREAL SHIPPING

A—SAILING VESSELS

BIRCH BARK CANOE—BATEAU—DURHAM BOAT—SHIPBUILDING IN MONTREAL.

B—STEAM VESSELS

JOHN MOLSON’S ACCOMMODATION, 1809—PASSENGER FARES BETWEEN MONTREAL AND QUEBEC—PASSAGE DESCRIBED—THE TORRANCES—INLAND NAVIGATION—THE RICHELIEU AND ONTARIO COMPANY—THE FIRST UPPER DECK STEAMER TO SHOOT THE LACHINE RAPIDS.

C—ATLANTIC LINERS

| THE ROYAL WILLIAM FIRST OCEAN STEAMER AND PIONEER OF THE OCEAN LINERS—ITS CONNECTION WITH MONTREAL—MAIL SERVICE TO MONTREAL—THE GENOVA—- ARRIVAL IN MONTREAL IN 1853—DINNER TO CAPTAIN PATON—THE CRIMEAN WAR—THE MONTREAL OCEAN STEAMSHIP COMPANY—THE FIRST CANADIAN ATLANTIC SHIP COMPANY—THE ALLAN LINE—EARLY BOATS—MAIL CARRIERS—1861 DISASTERS—SUBSEQUENT SUCCESS—THE PRESENT MONTREAL ALLAN SERVICE—THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY STEAMSHIP LINES—OTHER LINES—THE SHIPPING AND THE WAR OF 1914—THE GREAT ARMADA | 569 |

CHAPTER XXXIX

TRANSPORTATION

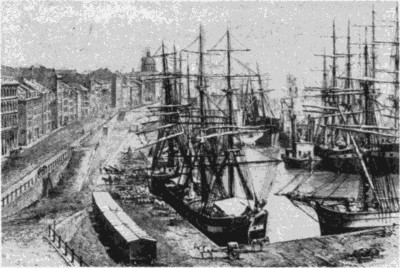

I

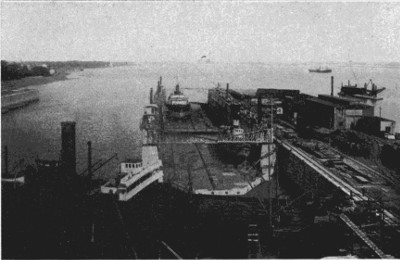

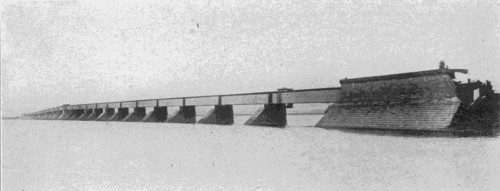

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PORT OF MONTREAL—HERIOT’S DESCRIPTION IN 1815—T.S. BROWN IN 1818—THE ISLAND WHARF—THE CREEK—THE PRIMITIVE WHARVES—THE “POINTS”—THE RIVER FRONT—THE SPRING FLEET—FIREWOOD RAFTS—TOW BOATS—THE EVERETTA—AN ACCOUNT OF 1819—BOUCHETTE’S PLAN OF 1824—THE FIRST HARBOUR COMMISSIONERS, “THE TRINITY BOARD”—FIRST REPORT—LATEST REPORT—EARLY ENGINEERS—REVIEW OF HARBOUR IN 1872—A TRANSFORMATION FROM 1818—GRAIN ELEVATORS—NUMBER OF VESSELS—MARKET AND WOOD BOATS—THE BONSECOURS MARKET—1875 PLAN FOR IMPROVEMENT NOW CARRIED OUT—FLOATING DOCK—DESCRIPTION OF PRESENT HARBOUR—ITS FACILITIES FOR FURTHER DEVELOPMENT—THE DESIRE TO LENGTHEN THE SHIPPING SEASON.

II

HARBOUR COMMISSIONERS—THE HARBOUR COMMISSIONERS FROM 1830 TO THE PRESENT TIME.

III

| CUSTOMS—SHIPPING FEDERATION—THE PILOTAGE AUTHORITY—IMPORTS AND EXPORTS | 585 |

CHAPTER XL

TRANSPORTATION BY RAIL

IV

MONTREAL AND THE RAILWAYS OF CANADA

MONTREAL THE CENTRE OF RAILWAY COMMUNICATION—THE FIRST RAILWAY—THE SNAKE RAIL AND THE “KITTEN”—“THE CHAMPLAIN AND THE ST. LAWRENCE”—THE[xxv] SECOND RAILWAY. THE ATLANTIC AND ST. LAWRENCE—THE AMALGAMATION INTO THE GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY COMPANY.

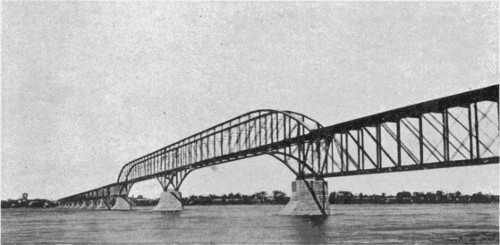

1. ITS HISTORY—ITS PRESIDENTS—AN INTERESTING REPORT AT CONFEDERATION—NEW FREIGHT YARDS—CHAS. M. HAYS AND THE GRAND TRUNK PACIFIC RAILWAY—THE BUILDING OF THE VICTORIA BRIDGES BY THE GRAND TRUNK RAILROAD.

2. THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY—ITS FINANCIERS—TWIN TO CONFEDERATION—OPPOSITION TO PROMOTERS—EARLY FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES—NO BIG FORTUNES MADE—ROLLING STOCK—A REAL EMPIRE BUILDER—HELPING NEW INDUSTRIES—HUGE LAND HOLDINGS—IRRIGATION OF BARREN LANDS.

| 3. OTHER SYSTEMS—THE “INTERCOLONIAL”—THE CANADIAN NORTHERN AND ITS MOUNTAIN TUNNEL | 607 |

CHAPTER XLI

TRANSPORTATION BY ROAD

I

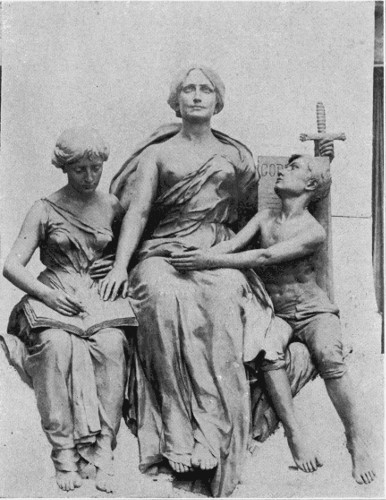

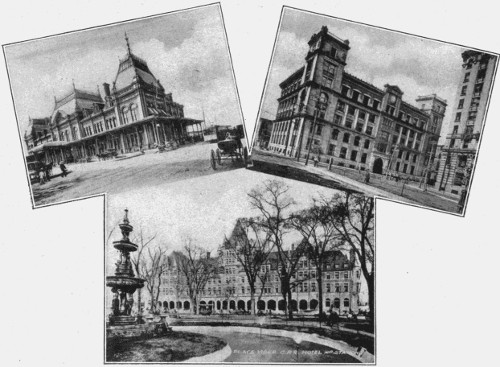

THE ANCIENT AND MODERN POSTAL SERVICE OF MONTREAL

ANCIENT ROADS—THE “GRAND VOYER”—GOOD ROADS MOVEMENT—THE EVOLUTION OF ROADS—“POST” MASTERS RECOGNIZED IN 1780—THE EARLY POSTAL SYSTEM OF MONTREAL AND BENJAMIN FRANKLIN—BURLINGTON THE TERMINUS—EARLY LETTER RATES—MAIL ADVERTISEMENTS—THE QUEBEC TO MONTREAL POSTAL SERVICE—EARLY POSTOFFICE IN MONTREAL—OCEAN AND RAILWAY MAIL SERVICE—THE PRESENT POSTOFFICE—ITS HISTORICAL TABLETS BY FLAXMAN—THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE POSTAL SYSTEM—THE POSTMASTERS OF MONTREAL.

II

STREET TRANSPORTATION

MODERNIZING MONTREAL

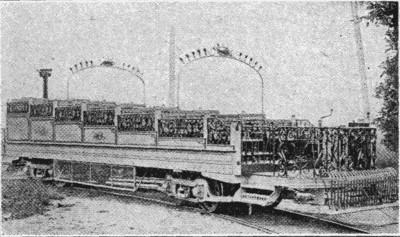

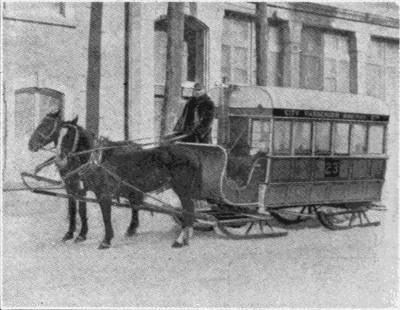

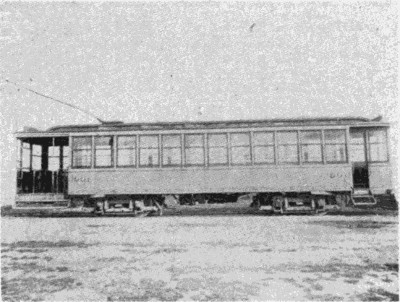

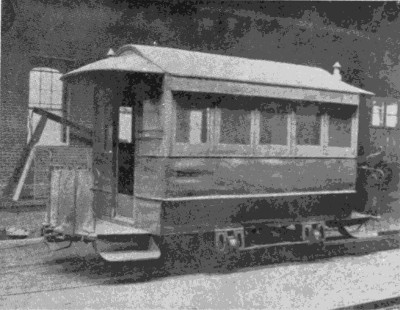

| MONTREAL IN 1861—THE STREET RAILWAY MOVEMENT—THE “MONTREAL CITY PASSENGER RAILWAY COMPANY” CHARTERED—THE HISTORY OF THE COMPANY—ITS FIRST PROMOTERS—EIGHT PASSENGER CARS, SIX MILES, HORSE SERVICE IN 1861—THE OPENING UP OF THE STREETS—WINTER SERVICE OF SLEIGHS—1892 THE BEGINNING OF ELECTRIC ERA—THE CONVERSION OF THE SYSTEM INTO ELECTRIC TRACTION—THE GRADUAL GROWTH OF THE COMPANY | 623 |

CHAPTER XLII

1760-1841

CITY IMPROVEMENT FROM THE CESSION

UNDER JUSTICES OF THE PEACE

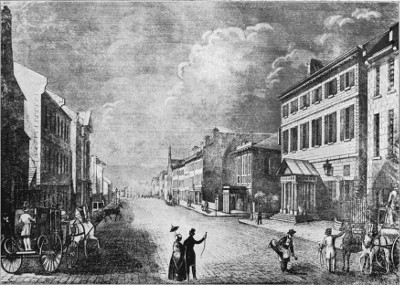

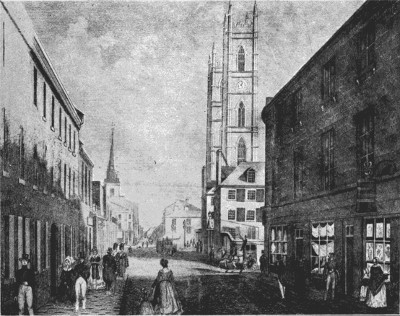

| EARLY STREET REGULATIONS—A PICTURE OF MONTREAL HOUSES IN 1795—FURTHER STREETS OPENED—A “CITY PLAN” MOVEMENT IN 1799—HOUSES AT THE BEGINNING[xxvi] OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY—MAP OF 1801—CITY WALLS TO BE DEMOLISHED—CITADEL HILL REMOVED—FURTHER IMPROVEMENTS—ROAD COMMISSIONERS—PICTURE OF 1819—IMPROVEMENTS DURING THE TRANSITIONAL PERIOD OF THE JUSTICES AND THE MUNICIPALITY—PICTURE OF 1839 BY BOSWORTH | 635 |

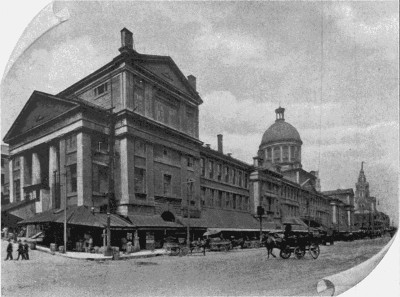

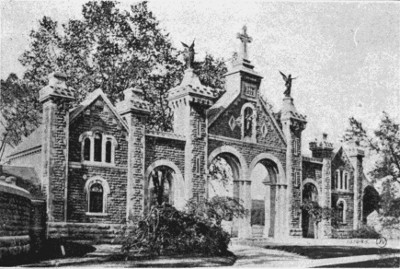

CHAPTER XLIII

1841-1867

CITY IMPROVEMENT AFTER THE UNION

UNDER THE MUNICIPALITY

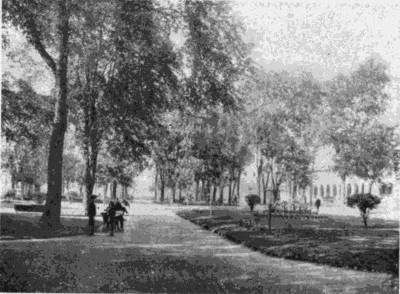

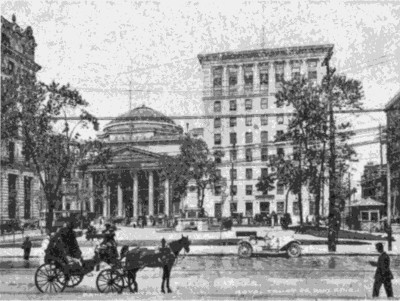

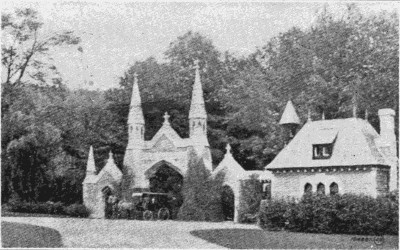

| GREAT STRIDES AT THE UNION—THE EARLY MARKET PLACES—THE BONSECOURS MARKET—OTHER MARKETS—PUBLIC PLACES—THE EARLY SQUARES—PRESENT PARKS—THE EARLY CEMETERIES—THE FIRST JEWISH CEMETERY—THE DORCHESTER STREET PROTESTANT CEMETERY—DOMINION SQUARE—MOUNT ROYAL—COTE DES NEIGES—OTHER CEMETERIES—GENERAL CITY IMPROVEMENT—AREAS OF PUBLIC PLACES | 641 |

CHAPTER XLIV

1867-1914

CITY IMPROVEMENT SINCE CONFEDERATION

THE RISE OF METROPOLITAN MONTREAL

THE METROPOLITAN ASPECT OF MONTREAL IN 1868—EDUCATIONAL BUILDINGS—THE CITY STREET RAILWAY AIDS SUBURBAN EXTENSION—FORECAST OF ANNEXATIONS—THE CITY HOMOLOGATED PLAN—THE ANNEXATION OF SUBURBAN MUNICIPALITIES IN 1883—TABLE OF ANNEXATION SINCE 1883—PREFONTAINE’S REVIEW OF THE YEARS 1884-1898—IMPROVEMENTS UNDER THE BOARD OF CONTROL—A REVIEW OF THE LAST TWO DECADES OF METROPOLITAN GROWTH—THE CHANGES DOWNTOWN—THE GROWTH UPTOWN.

| STATISTICAL SUPPLEMENTS: 1. STATEMENT OF BUILDINGS. 2. REAL ESTATE ASSESSMENTS. 3. RECENT BUILDINGS ERECTED OR COMPLETED. 4. THE METROPOLITAN POPULATION; COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON THE POPULATION OF MONTREAL WITH THE CITIES OF THE CONTINENT. 5. OF THE WORLD. 6. OPTIMISTIC SPECULATIONS FOR THE FUTURE. 7. VITAL CITY STATISTICS IN 1912. 8. A PLAN FOR “GREATER MONTREAL”—THE HISTORY OF THE PRESENT MOVEMENT | 651 |

CONSTITUTIONAL AND CIVIC PROGRESS

| CHAPTER | |

| I | THE EXODUS—“The Old Order Changeth, Giving Place To New.” |

| II | THE INTERREGNUM—Military Rule. |

| III | THE TREATY OF PARIS—New Civil Government. |

| IV | CITY GOVERNMENT UNDER JUSTICES OF THE PEACE. |

| V | PRELIMINARY STRUGGLES FOR AN ASSEMBLY—The Case For The Merchants. |

| VI | THE QUEBEC ACT—1774. The Case For The Noblesse. |

| VII | REVOLUTIONARY WAR OF 1775. |

| VIII | MONTREAL BESIEGED. |

| IX | MONTREAL AN AMERICAN CITY. |

| X | THE ASSEMBLY AT LAST. 1791. |

| XI | THE FUR TRADERS. |

| XII | FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY DESIGNS. |

| XIII | THE INVASION OF 1812-1813. |

| XIV | ANNALS AND SIDELIGHTS. |

| XV | BUREAUCRACY AND DEMOCRACY. |

| XVI | MURMURS OF REVOLUTION. |

| XVII | IN THE THROES OF CIVIL WAR. |

| XVIII | PROCLAMATION OF UNION—Responsible Government. |

| XIX | UNDER THE UNION. |

| XX | THE MUNICIPALITY OF MONTREAL. |

| XXI | ANNALS AND SIDELIGHTS. |

| XXII | UNDER CONFEDERATION. |

| XXIII | ANNALS AND SIDELIGHTS. |

HISTORY OF MONTREAL

THE EXODUS FROM MONTREAL

1760

“THE OLD ORDER CHANGETH, GIVING PLACE TO NEW”

AMHERST’S LETTER REVIEWING EVENTS LEADING UP TO THE CAPITULATION—THE SURRENDER OF ARMS—THE REVIEW OF BRITISH TROOPS—THE DEPARTURE OF THE FRENCH TROOPS—END OF THE PECULATORS—VAUDREUIL’S CAPITULATION CENSURED—DEPARTURE OF THE PROVINCIAL TROOPS—ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF THE COLONY—DEPARTURE OF AMHERST—THE TWO RACES LEFT BEHIND. NOTES: (1) THE EXODUS AND THE REMNANT.—(2) THE POPULATION OF CANADA AT THE FALL.

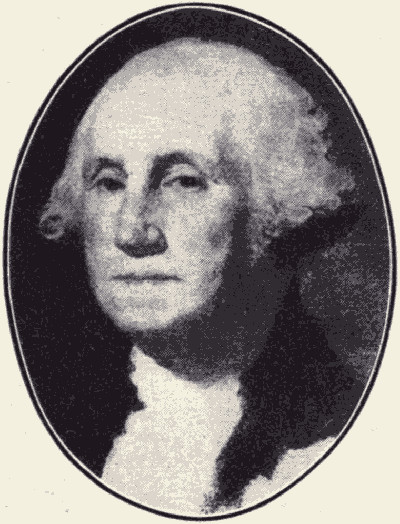

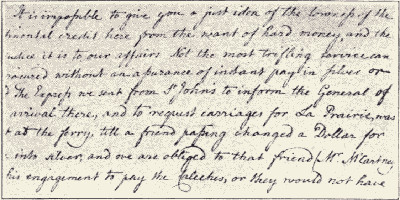

On the capitulation of Montreal in the grey of the early morn of September 8, 1760, British Rule began and the Régime of France was ended. On the 9th the victorious Amherst wrote his official account to the Honourable Lieutenant Governor Hamilton. The details therein will serve to recapitulate the history of the final downpour on Montreal during the days preceding its fall, with the new era commencing, and accordingly we present it to our readers.

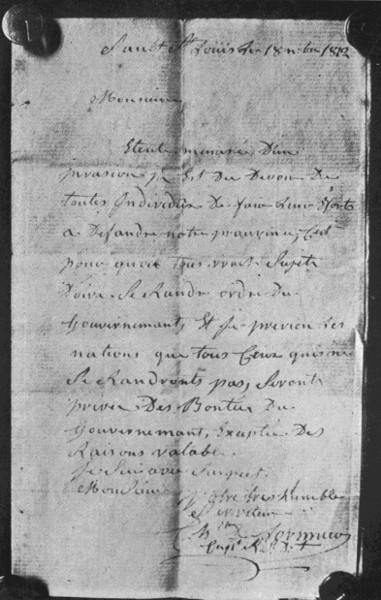

“Camp of Montreal,

9th September, 1760.

Sir:

In Mine of the 26th ultimo I acquainted You with the progress of the Army after the departure from Oswego and with the Success of His Majesty’s Arms against Fort Levis, now Fort William Augustus, where I remained no longer than was requisite to make Such preparations as I Judged Essentially necessary for the passage of the army down the River, which took me up to the 30th.

In the morning of the following day I set out and proceeded from Station to Station to our present Ground, where we arrived on the 6th in the evening, after having in the passage sustained a loss of Eighty-Eight men drowned,——Batteaus of Regts. seventeen of Artillery, with Some Artillery Stores, Seventeen[4] Whaleboats, one Row Galley staved, Occasioned by the Violence of the Current and the Rapids being full of broken Waves.

The Inhabitants of the Settlements I passed thro’ in my way hither having abandoned their Houses and run into the Woods I sent after them; Some were taken and others came of their own Accord. I had them disarmed and Caused the oath of Allegiance to be tendered to them, which they readily took; and I accordingly put them in quiet possession of their Habitations, with Which treatment they seemed no less Surprised than happy. The troops being formed and the Light Artillery brought up, the Army lay on their Arms till the Night of the 6th.

On the 7th, in the morning, two Officers came to an advanced post with a Letter from the Marquis de Vaudreuil referring me to what one of them, Colonel Bouguinville, had to say. The Conversation ended with a Cessation of Arms till 12 o’Clock, when the Proposals were brought in; Soon after I returned them with the terms I was willing to grant, Which both the Marquis de Vaudreuil and Mons. de Lévis, the French General, were very strenuous to have softened; this Occasioned Sundry Letters to Pass between us During the day as well as the Night (when the Army again lay on their Arms), but as I would not on any Account deviate in the Least from my Original Conditions and I insisted on an Immediate and Categorical answer Mr. de Vaudreuil, soon after daybreak, Notified to me that he had determined to Accept of them and two Sets of them were accordingly Signed by him and me and Exchanged Yesterday when Colonel Haldimand, with the Grenadiers and the Light Infantry of the Army took Possession of One of the Gates of the town and is this day to proceed in fulfilling the Articles of the Capitulation; By which the French Troops are all to lay down their arms; are not to serve during the Continuance of the Present War and are to be sent back to Old France as are also the Governors and Principal Officers of the Legislature of the Whole Country, Which I have now the Satisfaction to inform You is entirely Yielded to the Dominion of His Majesty. On which Interesting and happy Event I most Sincerely Congratulate you.

Governor Murray, with the Troops from Quebec, landed below the Town on Sunday last & Colonel Haviland with his Corps (that took possession of the Isle aux Noix, Abandoned by the enemy on the 28th) Arrived Yesterday at the South Shore Opposite to My Camp. I am, with great regard,

Sir,

Your most Obedient,

Humble Servant

Jeff Amherst.

The Honourable Lt. Governor Hamilton.

(Endorsed by Hamilton, Camp Montreal, 7 ber, 1776. General Amherst, received by Post Tuesday, 23d September.)”1

Haldimand, as directed by Amherst on the 9th, received the submission of the troops of France.

In the French camp, de Lévis reviewed his forces—2,132 of all ranks. In his Journal they are thus summarized:

| Officers present | 179 | |

| Soldiers | 1953 | |

| —— | ||

| 2132 | ||

| Officers returned to France | 46 | |

| Soldiers invalided | 241 | |

| —— | ||

| 287 | ||

| —— | ||

| Total | 2419 | |

| Soldiers described as absent from their regiments | 927 | |

| —— | ||

| 3346 |

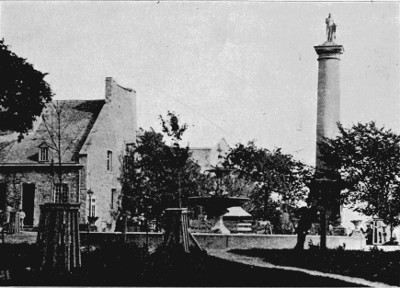

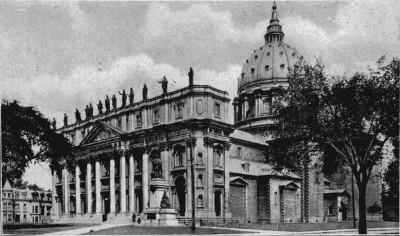

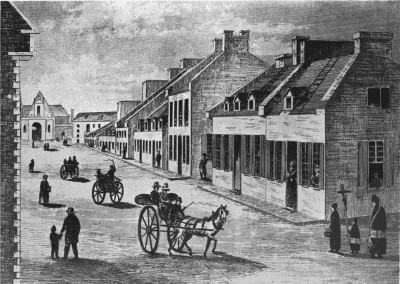

FORTIFICATIONS OF MONTREAL, 1760

There on the Place d’Armes yielded up their arms, all that was left of the brave French warriors who had no dishonour in their submission, surrendering only to the overwhelming superior numbers of the English conquerors. With de Lévis was the able de Bourlamaque and the scholarly soldier de Bougainville, with Dumas, Rocquemaure, Pouchot, Luc de la Corne and so many of the heroes of Ticonderoga and Carillon. There too was de Vaudreuil, the Governor General, Commander-in-Chief, and last governor of New France, with his brother, the last Governor of Montreal under the Old Régime. Haviland’s entourage and the British troops present could not but admire their late opponents.

The only jarring note of the ceremony was the absence of the French flags from the usual paraphernalia to be delivered up. The omission is thus signaled by Amherst, in his official report of the submission, who after mentioning the surrender of the two captured British American stands of colours goes on to say that there were no French colours forthcoming: “The Marquis de Vaudreuil, generals and commanding officers of the regiment, giving their word of honour that the battalions had not any colours; they had brought them with them six years ago; they were torn to pieces and finding them troublesome in this country they had destroyed them.”

They had however been but recently destroyed, for the “Journal” of de Lévis, written by him Cæsar-like in the third person, tells how, after being unable to shake the determination of de Vaudreuil to capitulate without the honours of war, de Lévis, in order to spare his troops a portion of the humiliation they were to undergo, had ordered them to burn their colours to avoid the hard condition of handing them over to the enemy. “M. le Chevalier de Lévis voyant avec douleur que rien ne pouvoit faire changer la determination de M. le Marquis de Vaudreuil voulant épargner aux troupes une partie de l’humiliation quelles alloient subir, leur ordonna de brûler leurs drapeaux pour se soustraire à la dure condition de les remettre aux ennemis.”2 (Cf. Journal des Campagnes du Chevalier de Lévis en Canada, 1756-1760. Edited by l’Abbé H.R. Casgrain, Montreal, C.O. Beauchemin et fils, 1889.)

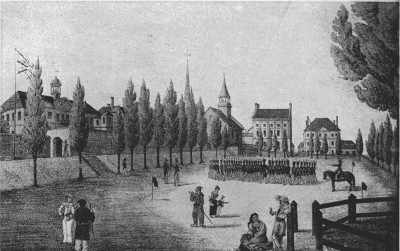

On the 11th Amherst turned out his whole force and received Vaudreuil on parade. Between these two, friendly relations had been established. Place d’Armes was again a scene of colour with the presence of the British regiments led by Murray, Haviland, Burton, Gage, Fraser the gallant Highlander, Guy Carleton, who was to become the famous viceroy of Canada and to die Lord Dorchester, Lord Howe, and the scholarly Swiss soldier Haldimand. There were present, too, Sir William Johnston, the baronet of the Mohawk Valley and leader of the six nations, Major Robert Rogers of the famous rangers,3 with his two brothers, and others of note. No doubt de Vaudreuil’s suite was not far off with de Lévis, de Bourlamaque, de Bougainville, Dumas, Roquemaure, Pouchot, Luc de la Corne, with the nefarious Intendant Bigot and all the principal officers of the colony who had been in Montreal, the headquarters of government since the fall of Quebec.

During the three following days the town was definitely occupied by the British, and the arrangements completed for the departure of the French Regulars. The regiments of Languedoc and Berry, with the marine corps, were embarked on the 13th; the regiments of Royal Rousillon and Guyenne on the 14th; on the 16th the regiments of La Reine and Béarn. On the 17th de Lévis, with de Bourlamaque, started for Quebec; de Vaudreuil and Bigot left on the 20th and 21st. By the 22nd every French soldier had left Montreal, except those who had married in the country and who had resolved to remain in it and transfer their allegiance to the new government.4

Fate had dealt a severe blow to the brave defenders of Canada whom we now find sailing from Montreal to France, which would appear to have abandoned them. The regulars and the colonial troops, in spite of their jealousies and emulations, were brave men, and duly honoured as such by the British soldiery who saw the vessels bearing on the broad St. Lawrence so many of those who had recently disputed the long drawn out strife for the conquest of Canada. Speaking of this, “the most picturesque and dramatic of American wars,” Parkman continues: “There is nothing more noteworthy than the skill with which the French and Canadian leaders use their advantages; the indomitable spirit with which, slighted and abandoned as they were, they grappled with prodigious difficulties and the courage with which they were seconded by regulars and militia alike. In spite of occasional lapses, the defence of Canada deserves a tribute of admiration.”—(“Montcalm and Wolfe,” Vol. II, p. 382.)

The departures from Montreal and Quebec must have been indeed heart-rending. That from Montreal, since the fall of Quebec, the home of all the high officials of the civil, religious and military governments, was the most striking, as the natural leaders of the colony were mostly there. “There repassed into Europe,” says the French Canadian historian, F.X. Garneau, “about 185 officers, 2,400 soldiers valid and invalid, and fully 500 sailors, domestics, women[7] and children. The smallness of this proved at once the cruel ravages of the war, the paucity of embarkations of succour sent from France, and the great numerical superiority of the victor. The most notable colonists at the same time left the country. Their emigration was encouraged, that of the Canadian officers especially, whom the conquerors desired to be rid of and whom they eagerly stimulated to pass to France. Canada lost by this self-expatriation the most precious portion of its people, invaluable as its members were from their experience, their intelligence and their knowledge of public and commercial affairs.”5 (Bell’s translation, Vol. II, p. 294.)

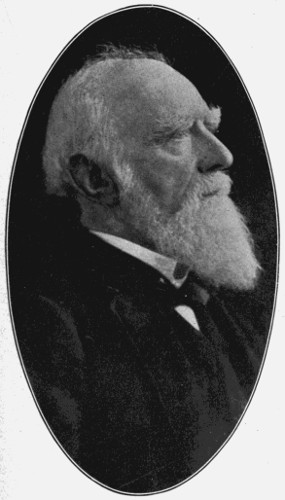

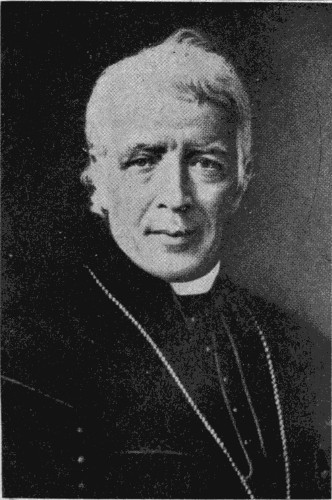

SIR GUY CARLETON

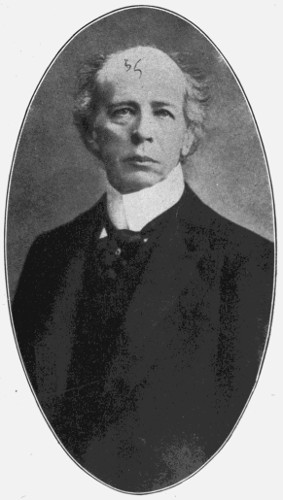

GENERAL JAMES MURRAY

LORD JEFFREY AMHERST

The clergy, however, solidly remained at their posts to build up the self-esteem of the people and to rear up a loyal race. Hence the respect and gratitude due to them by the French Canadians of today.

Yet there were many of whom the country was well rid, such as Bigot, Cadet, Péan, Bréard, Varin, Le Mercier, Pénisseault, Maurin, Corpron and others, accused of the frauds and peculations that helped to ruin Canada. A great sigh of relief might well have escaped from the French who had been ruined by them.

Most of the ships provided by the English government weathered the November gales. The vessel L’Auguste containing Saint-Luc de la Corne, his brother, and others, after being storm-tossed and saved from conflagration, finally drove towards the shore, struck and rolled on its side, and became wrecked on the Cap du Nord, Ile Royale. La Corne, with six others, gained the shore, and he reached Quebec before the end of the winter, as his journal tells us. His name was to become familiar at Montreal under the British régime.

The sloop Marie, which had been fitted up to receive the Marquis de Vaudreuil, his family and staff, had an early mishap between Montreal and Three Rivers, having run aground.

M. de Vaudreuil and the staff of officers of the colony arrived at Brest on the English vessel L’Aventure under a flag of truce, with 142 passengers from Canada. Thence, de Vaudreuil wrote to the minister of mariné. On December 5th the latter wrote back acknowledging this letter and that of September from Montreal containing the articles of capitulation, with papers relating thereto. A précis of this letter to Vaudreuil reveals that, although the king was aware of the condition of the colony, in default of the reinforcements it was unable to receive, yet, after the hopes the governor had given, by his letters in the month of June, of holding out some time longer, and his assurances that the last efforts would be put forth to sustain the honour of the king before yielding, His Majesty did not expect to learn so soon of the surrender of Montreal and of the whole colony. Granting the force of all the reasons which led to the capitulation, the king was nevertheless considerably surprised, and less satisfied, at having to submit to conditions so little to his honour, especially in the face of the representations which had been made to him by M. de Lévis on behalf of the military corps of the colony. The king, in reading the memorandum of these representations, which the minister was unable to avoid placing before him, saw in it that, notwithstanding the slight hope of success, Vaudreuil was still in a condition,[8] with the diminished resources remaining to him, to attempt an attack or a defence that might have brought the English to grant a capitulation that would have been more honourable for the troops. The king left him at liberty to remain at Brest for the time, for his health. With regard to the officers who were with him, they could retire to their families or elsewhere. It was sufficient for him to be informed of their place of residence.—(“Canadian Archives,” Vol. III, p. 313.)

Not only was Vaudreuil censured for the capitulation of Montreal, but finally he had the honour of being placed in the Bastille with the peculators whom we have above mentioned.6 His release, however, was speedy. Whatever his gains might have been from trading in the early part of his career, e. g., as Governor of Louisiana, he reached France from his government of Canada a poor man. The trial of those accused of peculation lasted from December 1, 1761, till the end of March, and on December 10, 1763, the president of the commission rendered his final decision. Vaudreuil with five more were relieved from the accusation, but he died in 1764 less from age than from sorrow.

“In the course of his trial he stood by the Canadian officers, now being slandered by Bigot. ‘Brought up in Canada myself,’ said the late Governor General, ‘I knew them, every one, and I maintain that almost all of them are as upright as they are valorous; in general the Canadians seem to be soldiers born; a masculine and military training early inures them to fatigues and dangers. The annals of their expeditions, their explorations, and their dealings with the aborigines abound in marvelous examples of courage, activity, patience under privation, coolness in peril, and obedience to leaders during services which have cost many of them their lives, but without slackening the ardour of the survivors. Such officers as these, with a handful of armed inhabitants and a few savage warriors, have often disconcerted the projects, paralyzed the preparations, ravaged the provinces, and beaten the troops of Great Britain when eight or ten times more numerous than themselves. In a country with frontiers so vast, such qualities were priceless.’ And he finished by declaring that he would fail in his duty to those generous warriors, and even to the state itself, if he did not proclaim their services, their merits and their innocence.”—(Bell’s translation of Garneau, Vol. II, p. 298.)

Governor Carleton, writing in 1767 to Lord Shelburne, confirms this tribute.[9] “The new subjects could send into the field about eighteen thousand men well able to carry arms, of which number, above one-half have already served with as much valour, with more zeal, and more military knowledge for America, than the regular troops of France that were joined with them.”

Vaudreuil might also have paid a compliment to the brave women of New France, who, like Madeleine de Verchères and others, were ready to fight with the men, and who were true women and wives. “Brave and beautiful,” George III summed them up in a compliment paid at his court in London after the conquest to Madame de Léry, the wife of Chevalier de Léry, the engineer who repaired the fortifications of Montreal: “If all the Canadian ladies resemble you, I have truly made a fine conquest.”

It must not be thought that the departure of the French colonial officers was an entire abandonment of the project of regaining the country. They were to be retained for the French service and possibly for future use in Canada.7 They were called to Tourraine and there held at the king’s pleasure under pay, to all intents and purposes officers in the French service, and liable to be sent on any service.

“The British provincial troops were sent from Montreal at an early date. The New Hampshire and Rhode Island regiments crossed the river and proceeded to Chambly, thence went to Crown Point. The Connecticut troops were ordered to Oswego and Fort Stanwix; the New York and New Jersey regiments to the lately named Fort William Augustus, at the head of the rapids, and to Oswegatchie (Ogdensburg). Rogers, with four hundred men, bearing letters from Vaudreuil instructing the forts to be given over, was sent to Detroit, Miami, St. Joseph and Michillimackinac.8 Moncton at the same time received orders to forward regular troops to take permanent possession of these forts.”—(Kingsford, “History of Canada,” Vol. IV, p. 409.)

The troops that were to remain in Montreal for the winter were now established in their quarters. The French Indians in the neighbourhood were summoned to the city and requested to bring their prisoners; they appeared with several men, women and children, and Johnston established rules and regulations for their future government.

Amherst remained in Montreal till September 26th, when he went down the river to Quebec. He left on October 5th and on the 18th was on Lake Champlain, thence to Albany, which he left on the 21st to arrive in New York on the 28th of October. He never visited Canada again, but he left it, however, well organized.

Immediately after the capitulation of Montreal he had occupied himself with the establishment of a provisional military government with tribunals to administer justice summarily until a definite form of government should be determined. The French division of the province into the three administrative districts of Quebec, Three Rivers and Montreal was maintained. In a despatch to Pitt dated October 4, 1760, from Quebec (Amériques et Indes Occidentales, No. 699), Amherst renders an account of all the dispositions which he had made since the date of the capitulation of Montreal. Although the greater part of these were[10] military matters, the following items concerning the civil administration may be found:

September 15; I have sent officers with detachments to the different villages to collect the arms and to make them take the oath of allegiance.

September 16; I have named Colonel Burton governor of Three Rivers.

September 17; I have given order to the militia of the town (Montreal) and of the suburbs to give up their arms and to take the oath of allegiance next day, immediately after the embarkation of M. de Vaudreuil.

September 22; I have named Brigadier General Gage governor of Montreal.

On the same day he published a proclamation for the government of Three Rivers similar to the one for Montreal, dated merely September, 1760 (“Amériques et Indes Occidentales”), in which arrangements are made for the transaction of business and amicable arrangements with the new government and the troops.

The new government was only, however, of an ad interim nature, for it was not certain that England would keep Canada. It was this thought that reconciled the Canadians to the new situation.

Meanwhile the British Flag floated over Citadel Hill.

The country was now British. France had been tried in the balance and found wanting. It had lost, through its wavering policy, a fair domain and a noble people. This poignant loss was voiced by de Vaudreuil, the deposed governor general, who, in spite of his faults, was a true Canadian and had visions of its future as one of the proudest jewels in the crown of France, for was it not La Nouvelle France? On quitting his beloved country he paid it this homage in a letter to his minister:

“With these beautiful and vast countries, France loses 70,000 inhabitants9 of a rare quality; a race of people unequaled for their docility, bravery and loyalty. The vexations they have suffered for many years, more especially during the five years preceding the reduction of Quebec—all without a murmur, or importuning the king for relief—sufficiently manifest their perfect submissiveness.”

The qualities, they had then, remain still the mark of those of the same race living in Montreal of today.

As their predecessors took the oath of allegiance to King George II, and became good Britishers, so have their descendants remained today, in the days of George V. “What perished in the capitulation of Montreal,” says Parkman, “was the Bourbon monarchy and the narrow absolutism which fettered the life of New France throughout the Old Régime. What survives today is the vigour of two races striving to make Canada strong and free and reverent of law.”

NOTE I

THE EXODUS AND THE REMNANT

Judge Baby of Montreal, in an article in the Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3d Edit., Vol. II, p. 304, has combatted very successfully[11] the traditional view started by Bibaud and followed by Garneau that after the capitulation of Montreal, and the Treaty of Paris, 1763, the seigneurs, the men of learning, and the chief traders and others of the directing classes, left the country. This emigration was from the town but the country places were untouched. He proves that a great many remained outside the civil and military party who had governed the country, and the soldiery who were taken officially to France; that many of the young colonial officers who had thought to have a chance to follow a career in the army or navy of France shortly returned at the call of their fathers whose interest in their lands and whose poverty, heightened by the depreciation of the paper money, would not have induced them to begin life again in France; that even of those who did go to France there were very many who returned, as they had intended; hence the recurrence of names, in the history after the cession, made familiar before it. The long list given by Judge Baby of Seigneurs and gentlemen proved by him to have remained, strengthens his case. An interesting list of French-Canadians remaining in Montreal engaged in business at this time is also given by him as follows:

Guy, Blondeau, Le Pellé De LaHaye, Lequindre Douville, Perthuis, Nivard St. Dizier, Les freres Hervieux, Gaucher-Gamelin, Glasson, Moquin, St. Sauveur, Pothier, Lemoine de Monnière, De Martigny, De Couagne, Desauniers, Mailhot, St. Ange-Charly, Dumas, Magnan, Mitiver, L’Amy, Bruyère, Pierre Chaboillez, Fortier, Lefèbre du Chouquet, Courtheau, Vallée, Cazeau, Charly, Carignan, Auger, Porlier frère, Pommereau, Larocque, Dumeriou, Roy-Portelance, De Vienne, De Montforton, Sanguinet, Campeau, Laframboise, Vauquier, Guillemain, Curot, Dufau, Campion, Lafontaine, Truillier-Lacombe, Périneault, Arillac, Léveillé, Bourassa, Pillet, Hurtubise, Leduc, Monbrun, Landrieu, Mezière, Hilbert, Tabeau, Sombrun, Marchesseau, Avrard, Lasselle, Dumas St. Martin, Beaubien-Desrivières, Réaume, Nolin, Cotté, St. Germain, Ducalvet, L’Eschelle, Beaumont.

The Judge gives the names of many jurisconsults who remained in the country, three of whom eventually became members of the Superior Council; also of doctors; the great majority of the notaries remained in the country. In summing up, he finds “130 seigneurs, 100 gentry, 125 traders of mark, twenty-five jurisconsults, and men of law, twenty-five to thirty doctors and surgeons, notaries of almost the same number”—“were these not,” he asks, “sufficient to face the political, intellectual and other needs of the population then in Quebec, Montreal and Three Rivers?”

NOTE II

POPULATION OF CANADA AT THE FALL

M. de Vaudreuil’s estimate of 70,000 population has been challenged by Dr. Kingsford (“History of Canada,” Vol. IV, p. 413).

Amherst before leaving Canada obtained a census of the population which he reported as 76,172 by parishes and districts.

| Parishes | Companies of Militia | Number of Militia | Total of all souls | |

| Montreal | 46 | 87 | 7,331 | 37,200 |

| Three Rivers | 19 | 19 | 1,105 | 6,388 |

| Quebec | 43 | 64 | 7,976 | 32,584 |

| —— | —— | ——— | ——— | |

| 108 | 170 | 16,412 | 76,172 |

The census must have been obtained through the French and there is no ground for supposing that they would designedly furnish an incorrect statement. It does not, however, accord with the previous or subsequent tables of population.

The population in 1736 was 39,063; 1737, 39,970; 1739, 42,701; 1754, 55,009. In the fifteen years between the last two dates the population increased 12,003, something less than one-third. If we apply this increase to the next six years we may be justified in estimating the increase at one-eighth, which would place the population at 62,000. It is not provable that in these six years of war the population could have increased upwards of 20,000,—five-elevenths—nearly half of the former total. In 1761 the three governors were called upon to furnish a census of their several districts. The reports were:

| (Gage) Montreal | 24,957 |

| (Burton) Three Rivers | 6,612 |

| (Murray) Quebec | 30,211 |

| ——— | |

| Total of | 61,780 |

“I am inclined, therefore,” says Kingsford, “to estimate the French population of Canada in 1760 at 60,000 souls, the number of which hitherto has been generally accepted as correctly representing it.”

At the same time Doctor Kingsford placed too much reliance on the census of 1761. It is well known that fear of conscription and other bogies caused the census returns of French-Canadian inhabitants to be minimized for many a long day under British rule. If Amherst’s census of 76,172 is correct, as well as the 61,780, that of the year 1761, then a loss of 14,392 is to be accounted for.

FOOTNOTES:

1 From R. McCord’s collection.

2 A detailed and romantic account of their burning on St. Helen’s Island is to be found in “L’Ile de Ste. Helène, Passè, Présent et Avenir, par A. Achintre et J.A. Crevier, M.D., Montreal, 1876.” I have found no historical proof of them being burnt there.—Ed.

3 Major Rogers’ picture in ranger uniform long decorated the shops of London. His bold, bucanneering deeds caught the popular fancy. The late Lord Amherst recalled long afterward how certain verses traditional in his family had been taught the children of successive Amhersts so long that the meaning of the allusion was forgotten until quite recently, when it was found that they referred to Rogers.

4 The French troops were only able to leave Quebec on the 22nd and 25th of October.—“Can. Arch. A. and W.I.,” 95, p. 1.

5 See Appendix for Judge Baby’s criticism and qualification of the extent of this exodus.

6 The accused numbered fifty-five. Among those condemned either to banishment from France or restitution and fines were: Bigot, the Intendant, Varin, his sub-delegate, and Duchesnaux, his secretary; Cadet, commissary general of Canada, and his agent, Corpron; Péan, captain and aide-major of the marine troops in Canada; Estèbe, the keeper of the King’s stores in Quebec; (all these had operated in Montreal directly or through their agents); Martel de St. Antoine, keeper of the King’s store at Montreal; Maurin, Pénisseault, merchants and operators in Cadet’s offices in this city; and Le Moyne-Despins, a merchant employed in furnishing provisions to the army. See “Montreal Under the French Régime,” Vol. I.

7 In 1767 Guy Carleton feared an uprising in Canada on the probable return of this body of officers. See letter to Lord Shelburne. (Constitutional Documents—Shortt & Doughty.)

8 Rogers reached New York, on his return from Detroit, the following February. Owing to the setting in of winter he had been unable to proceed to other forts. He reported that he had found one thousand Canadians in the neighbourhood of Detroit.—“Can. Arch. A. and W.I., 961,” p. 219.

9 See note at the end of this chapter.

THE INTERREGNUM

1760-1763

MILITARY GOVERNMENT

BRIGADIER GAGE, GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL—THE ADDRESS OF THE MILITIA AND MERCHANTS—GOVERNMENT BY THE MILITARY BUT NOT “MARTIAL LAW”—THE CUSTOM OF PARIS STILL PREVAILS—COURTS ESTABLISHED—THE EMPLOYMENT OF FRENCH-CANADIAN MILITIA CAPTAINS IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE—SENTENCES FROM THE REGISTERS OF THE MONTREAL COURTS—GOVERNOR GAGE’S ORDINANCES—TRADE—THE PORT—GAGE’S REPORT TO PITT ON THE STATE OF THE GOVERNMENT OF MONTREAL—THE PROMULGATION OF THE DECLARATION OF THE DEFINITIVE TREATY OF PARIS—REGULATIONS CONCERNING THE LIQUIDATION OF THE PAPER MONEY—LEAVE TO THE FRENCH TO DEPART—LAST ORDINANCES OF GAGE—HIS DEPARTURE.

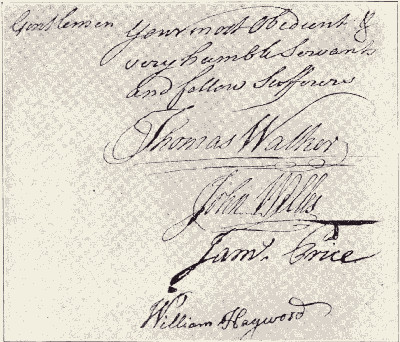

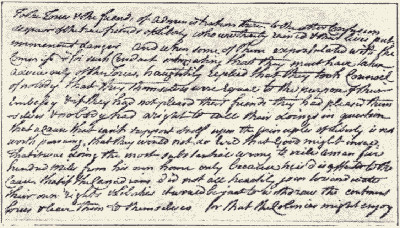

Brigadier Gage was appointed governor of Montreal on September 21, 1760.1 He early won the esteem of the townspeople. All his ordinances manifest the desire to act in accordance with justice and in harmony with the people. Montrealers recognized this and shortly after the death of George II, which took place on October 25th, expressed their confidence in their rulers in an address written in English and French. The English version as inserted in the New York Gazette is as follows:

“To his Excellency, General Gage, governor of Montreal and its dependencies.

“The address of the officers of militia and merchants of the city of Montreal.

“Cruel Destiny has thus cutt short the Glorious Days of so Great and so Magnanimous a Monarch! We are come to pour out our Grief unto the paternal Bosom of Your Excellency, the Sole Tribute of Gratitude of a People who will never cease to Exalt the mildness and Moderation of their New Masters. The General who has conquered us has rather treated Us as a Father than a Vanquisher and has left us a precious Pledge2 by name and deed of his Goodness to Us. What acknowledgements are we not beholden to make for so many Favours? Ha! They shall be forever Engraven in our Hearts in Indelible Characters. We Entreat Your Excellency to continue us the Honour of Your Protection. We will endeavour to Deserve it by Our Zeal and by the Earnest Prayers We shall ever offer up to the Immortal Being for Your Health and Preservation.” (Canadian Archives, A. & W., I, 96, I, page 327.)

The mildness and moderation of the “New Masters” was particularly shown by the retention of existing laws and customs. It will be recalled that Vaudreuil, in the Articles of Capitulation had asked that “French and Canadians should be continued to be governed according to the customs of Paris and the laws and usages established for this country and should not be subject to any other laws than those established under the French dominion.” Whereupon Amherst had replied that this had been answered by the preceding article and especially by the reply to the last (Article 41), asking that the British government should only require a strict neutrality of the Canadians, which said curtly: “They become subjects of the king”—a non-committal reply, which at first looked severe but was, as the conscientious historian, Jacques Viger,3 has said, just and reasonable under the circumstances. In the event, Amherst granted more than his answer would suggest, for during the Interregnum, the French and British incomers continued to be governed according to the custom of Paris. Hence the gratitude expressed through General Gage was well deserved.

The period of the Interregnum, now beginning (September 8, 1760, to August 10, 1764), which was to last until the promulgation of the treaty of Paris, and the official publication by Governor General Murray of his civil appointment, has been called erroneously by several French historians, “La Regne Militaire,” a term suggestive of military despotism and summary justice. Commander Jacques Viger, M. Labrie, Judge Mondelet and others rejected this erroneous misnomer in the columns of the Journal “La Bibliotheque Canadienne,” being edited in 1827 by Bibaud, the well known historian. For, after examining the documents of the period they came to the conclusion that the name of La Regne Militaire could only be merited because, as most of the official men of the law having been in Government employ had left the country and new justices had to be created who should judge according to “les lois, formes et usages” of the country, the government devolved perforce on the military men and of the “milices,” the only educated men left besides the clergy.

This is made clear by a memoir of October 15, 1777, to the British government on the subject of the administration of justice, drawn up by Judges Panet, Mabane and Dunn, of whom Pierre Panet had been one of the greffiers at Montreal, and the others had had close relations with the military judges. Their testimony is therefore convincing. They state:[15] “Though Canada was conquered by His Majesty’s arms in the fall of 1760, the administration in England did not interfere with the interior government of it till the year 1763. It remained, during that period, as formerly, with three districts, under the separate command of military officers who established in their respective districts, military courts under different forms, indeed, but in which, according to the policy observed in wise nations towards a conquered people the laws and usages of Canada were observed in the rules of decision.”

The basis of the new military government was the placard issued by General Amherst from Montreal on the 22d of September, 1760, in which he announced the new order of the government for the old and new subjects, and outlined the new form of military government throughout the three districts, by the appointment in each parish of the officers of the militia, the commandant of the regular troops and a third court of further appeal to the governor, as the future demonstrators of justice, and then left it to the local governors of the other two divisions of the country to establish their own courts. These officers of militia were the most competent at the time to carry on the traditional “custom of Paris” as they were mostly appointed from the Seigneurs of the district and the educated class.

Accordingly on October 28, 1760, General Gage issued his orders establishing tribunals of militia officers to regulate civil disputes among individuals and a second tribunal of appeal before the regular military court, with a final court of appeal to himself.

The rest of the document deals with police prohibitions to the inhabitants, not to harbour deserters or to traffic with the soldiers for their arms, clothing, etc., or any other of their accoutrements; it orders chimneys to be swept once a month, and other precautions against fire; carpenters were to be prepared with an adz, the inhabitants with an axe and bucket; also arrangements for safety against snow from falling from houses, the cleansing of the portions before the house and the disposal of garbage, the keeping of the roads and bridges in good order, and regulations concerning the sale of provisions brought in by the country people, the sale to be made in the common market place with the prohibition to town merchants to forestall the citizens by buying up the supplies brought in. The militia captains being no lawyers, were only required by Amherst to dispense law and justice as best they could, being limited to civil cases.