Title: Wonder Tales from Many Lands

Author: Katharine Pyle

Release date: February 24, 2015 [eBook #48351]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED

BY

LONDON

GEORGE G. HARRAP & COMPANY LTD.

2 & 3 PORTSMOUTH STREET KINGSWAY W.C.

AND AT SYDNEY

First published August 1920

Printed in Great Britain

by Turnbull & Spears, Edinburgh

| PAGE | |

| LONG, BROAD, AND SHARPSIGHT | 9 |

| A Story from Bohemia | |

| THE DWARF WITH THE GOLDEN BEARD | 30 |

| A Slavonic Fairy Tale | |

| THE GREAT WHITE BEAR AND THE TROLLS | 55 |

| A Story from the Norse | |

| THE STORY OF THE THREE BILLY GOAT GRUFFS | 61 |

| A Story from the Norse | |

| THE STONES OF PLOUVINEC | 67 |

| A Tale from Brittany | |

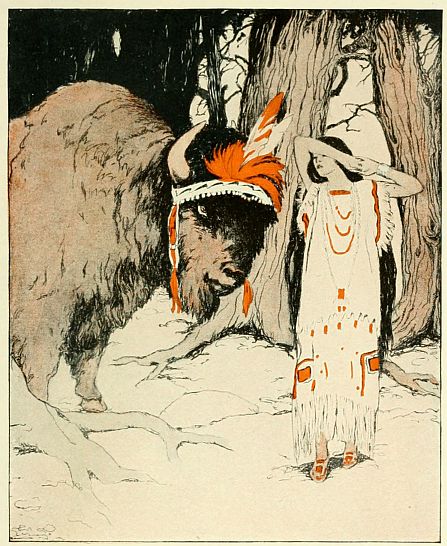

| THE KING OF THE BUFFALOES | 81 |

| An American Indian Tale | |

| THE JACKAL AND THE ALLIGATOR | 88 |

| A Hindu Fairy Tale | |

| THE BABA YAGA | 93 |

| A Russian Fairy Tale | |

| TAMLANE | 99 |

| A Story from an Old Scotch Ballad | |

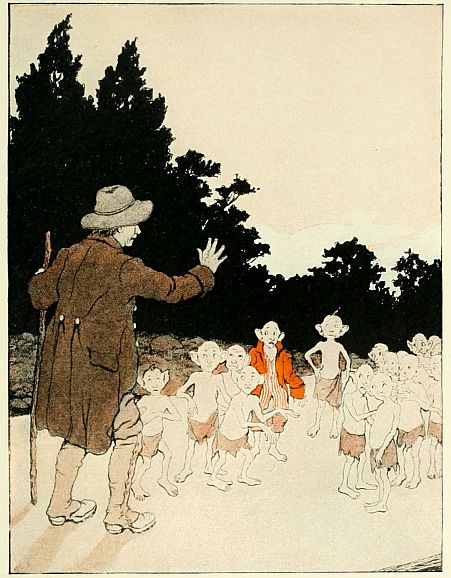

| THE FARMER AND THE PIXY | 104 |

| [6]An English Fairy Tale | |

| RABBIT’S EYES | 109 |

| A Korean Fairy Tale | |

| MUDJEE MONEDO | 114 |

| An American Indian Tale | |

| DAPPLEGRIM | 126 |

| A Tale adapted from the Norse | |

| THE FISH PRINCE | 146 |

| A Hindu Folk Tale | |

| THE MAGIC RICE KETTLE | 161 |

| A Korean Story | |

| THE CROW PERI | 178 |

| A Persian Story | |

| THE FOUR WISHES | 199 |

| A German Story | |

| WHY THE ANIMALS NO LONGER FEAR THE SHEEP | 229 |

| A French Creole Story | |

| PRINCESS ROSETTA | 240 |

| A French Fairy Tale |

| PAGE | |

| The Baba Yaga and Peter | Frontispiece |

| There was a great black raven in the room with them | 28 |

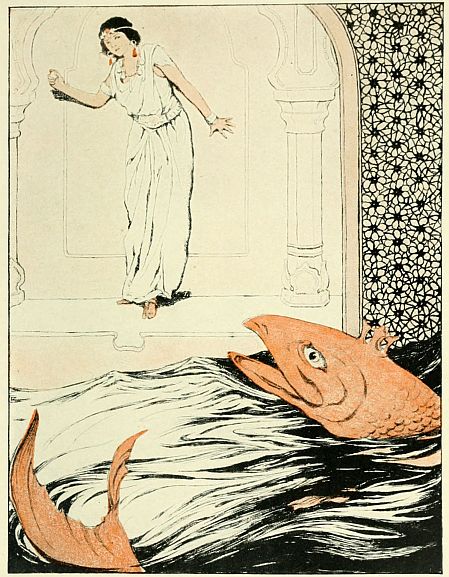

| He spoke to her in the softest voice he could manage | 82 |

| Then it was a swan that beat its wings in her face | 102 |

| “Not so fast, my fine little fellow,” he said | 106 |

| She managed to throw the third stone at him | 152 |

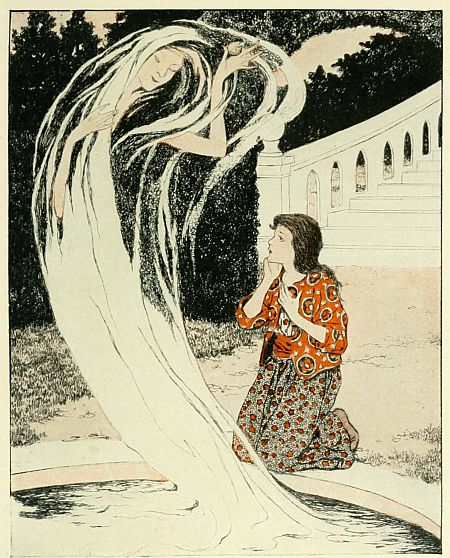

| “Do not be afraid, my child,” said the nixie to Matilda | 202 |

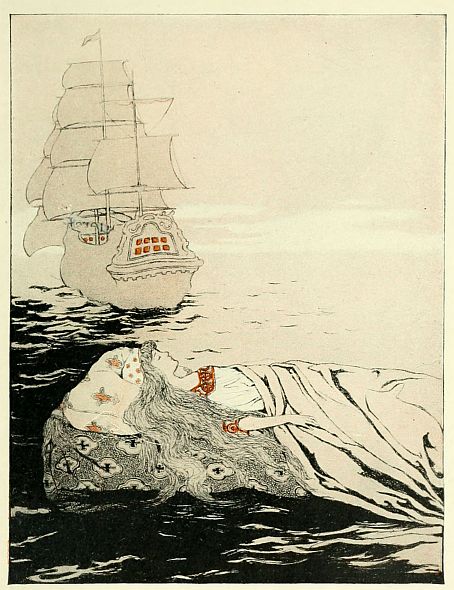

| The mattress upon which she lay had floated on and on | 248 |

THERE was once a King who had one only son, and him he loved better than anything in the whole world—better even than his own life. The King’s greatest desire was to see his son married, but though the Prince had travelled in many lands, and had seen many noble and beautiful ladies, there was not one among them all whom he wished to have for a wife.

One day the King called his son to him and said, “My son, for a long time now I have hoped to see you choose a bride, but you have desired no one. Take now this silver key. Go to the top of the castle, and there you will see a steel door. This key will unlock it. Open the door and enter. Look carefully at everything in the room, and then return and tell me what you have seen. But, whatever you do, do not touch nor draw aside the curtain that hangs at the right of the door. If you should disobey me and do[10] this thing, you will suffer the greatest dangers, and may even pay for it with your life.”

The Prince wondered greatly at his father’s words, but he took the key and went to the top of the castle, and there he found the steel door his father had described. He unlocked it with the silver key, stepped inside, and looked about him. When he had done so, he was filled with amazement at what he saw. The room had twelve sides, and on eleven of these sides were pictures of eleven princesses more beautiful than any the Prince had ever seen in all his life before. Moreover, these pictures were as though they were alive. When the Prince looked at them, they moved and smiled and blushed and beckoned to him. He went from one to the other, and they were so beautiful that each one he looked upon seemed lovelier than the last. But lovely though they were, there was not one of them whom the Prince wished to have for a wife.

Last of all, the Prince came to the twelfth side of the room, and it was covered over with a curtain, and the curtain was of velvet richly embroidered with gold and precious stones. The Prince stood before it and looked at it and looked at it. He tried to peer under its edges, but he could see nothing; never in all his life had he longed for anything as he longed to lift that curtain and see what was behind it.

At last his longing grew so great that he could[11] withstand it no longer. He laid his hand upon the folds and drew it aside, and when he had done so, his heart melted within him for love and joy. For there was the portrait of a maiden so fair and lovely that all the other eleven beauties were as nothing beside her.

The Prince stood and looked at her, and she looked back at him, and she did not blush or beckon to him as the others had done, but rather she grew pale.

“Yes,” said the Prince at last, “you and you only shall be my bride, even though I should have to go to the ends of the world to find you.”

When he said that, the picture bowed its head gravely.

Then the Prince dropped the curtain and left the room and went down to where the old King was waiting for him. As soon as he came before his father, the old man asked whether he had found the room and entered it.

“I did,” answered the Prince.

“And what did you see in the room, my son?”

“I saw a picture of the maiden whom I wish to have for a wife.”

“And which of the eleven was it?”

“It was none of the eleven; it was the twelfth—she whose portrait hangs behind the curtain.”

When the old King heard this, he gave a cry of grief. “Alas, alas, my son! What have you[12] done! Did I not warn you not to lift the curtain and not to look behind it?”

“You warned me, my father, and yet I could not but look, and now I have seen the only one whom I will ever marry. Tell me, I pray of you, who she is, that I may go in search of her.”

“Well did I know that misfortune would come upon you if ever you entered that room. That Princess whom you have seen is indeed the most beautiful Princess in all the world, but she is also the most unfortunate. Because of her beauty, she was carried away by a wicked and powerful Magician who wished to marry her. To this, however, she would not consent. He still keeps her a prisoner in an iron castle far away beyond forest, plain, and mountain at the very end of the world. Many princes and heroes and brave men have tried to rescue her, but none has ever succeeded. They have lost their lives in the attempt, and the Magician has turned them all into stone statues to adorn his castle. And now you are determined to throw away your life also.”

“That may be,” said the Prince; “and yet it may also be that I shall succeed even though others have failed. At any rate, I must try, for I cannot live without her.”

When the King found that his son was determined to go, and that nothing could stay him, he gave him a jewelled sword and the finest steed in his stable and bade him God-speed.

So the Prince set out with his father’s blessing, and he rode along and rode along until at last he came to a forest that was so vast there seemed to be no end to it. In this forest he quite lost his way. He was therefore very glad when he saw some one trudging along in front of him.

The Prince rode on until he overtook the man, and then he reined in his horse and bade him good day.

“Good day,” answered the man.

“Do you know the ways through this forest?” asked the Prince.

“No, I know nothing about them, but that never bothers me. If at any time I think I am going in the wrong direction, it is easy to right myself.”

“How is that?” said the Prince.

“Oh, I have the power of stretching myself out to any length, and if I lose my way I have only to make myself tall enough to see over the tree-tops, and then I can easily tell where I am.”

“That must be very curious. I should like to see that,” said the Prince.

Well, that was easy enough, and the man would be glad enough to oblige him. So he began to stretch himself. He stretched and stretched and stretched until he was taller than the tallest tree in the forest. His head and body were quite lost to sight among the branches, and all that the Prince could see were his legs and feet.

“Is that enough?” the man called down to the Prince.

“Yes, that is enough,” answered the Prince, and he had to shout to make himself heard, the man’s head was so far away.

Then the man began to shrink. He shrank and shrank until he was no taller than the Prince himself.

“You are a wonderful fellow,” said the Prince. “What is your name?”

The man’s name was Long.

“And what did you see up there?”

“I saw a plain and great mountains beyond, and still beyond that an iron castle, and it was so far away that it must be at the very end of the world.”

“It is that castle that I am seeking,” said the Prince, “and now I see that you are the very man to guide me there. Tell me, Long, will you take service with me? If you will, I will pay you well.”

Yes, Long would do that, and not for the sake of the money either, but because he had taken a fancy to the Prince.

So the Prince and his new servant travelled along together, and presently they came out of the forest on to a plain, and there, far in front of them, was another man also travelling along toward the mountains.

“Look, Master!” said Long. “Do you see[15] that man? His name is Broad. You ought to have him for a servant too, for he is even more wonderful than I am.”

“Call him, then,” said the Prince, “and I will speak with him.”

No, Long could not call him, for Broad was too far away to hear him, but he could soon overtake him. So Long stretched himself out until he was tall enough to go half a mile at every step. In this way he soon overtook Broad and stopped him, and then he and Broad waited until the Prince had caught up to them.

“Good day,” said the Prince to Broad.

“Good day,” answered Broad.

“My servant here tells me that you are a very wonderful person,” said the Prince. “What can you do that is so wonderful?”

What Broad could do was to spread himself out until he was as broad across as he wished to be.

“I should like to see that,” said the Prince.

Very well! Nothing was easier, and Broad was willing to show him. “But first,” said Broad, “do you get behind those rocks over yonder. Otherwise you may get hurt. And now I will begin.”

“Quick! quick, Master!” cried Long, in a voice of fear. “We have not a moment to lose,” and he ran at full speed and crouched down behind the rocks. The Prince followed him, and[16] he also got behind the rocks, but he did not know why Long was in such a hurry, nor why he seemed so frightened. He soon saw, however, for when Broad began to spread, he spread so fast and with such force that unless the Prince and Long had been behind the rocks, they would certainly have been pushed against them and crushed.

“Is that enough?” cried Broad, after he had spread out so wide that the Prince could scarcely see across him.

“Yes, that is enough.”

So Broad began to shrink, and soon he was no fatter than he had been before.

“Yes, you are certainly a very wonderful fellow, and I should like to have you for a servant,” said the Prince. “Will you come with me also?”

Yes, Broad would come, for a master who was good enough for Long was good enough for him too. So now the Prince had two servants. He rode on across the plain toward the mountains, and the two followed him.

After a while they came to a man sitting by the way with a bandage over his eyes. The Prince stopped and spoke to him.

“Are you blind, my poor fellow, that you wear a bandage over your eyes?”

“No,” answered the man, “I am not blind. I wear the bandage because I see too well without it. Even now, with this bandage, I can see as clearly as you ever can. If I take it off, I can see[17] for hundreds of miles, and when I look at anything steadily my sight is so strong that the thing is riven to pieces, or bursts into flame and is burned.”

“That is a very curious thing,” said the Prince. “Could you break yonder rock to pieces merely by looking at it?”

“Yes, I could do that.”

“I would like to see it done,” said the Prince.

Well, the man was ready to oblige him. So he took the bandage from his eyes and fixed his gaze on the rock. First the rock grew hot, and then it smoked, and then, with a great noise, it exploded into tiny fragments, so that the pieces flew about through the air.

“Yes, you are even more wonderful than these other two,” said the Prince, “and they are wonderful enough. How are you called?”

“My name is Sharpsight.”

“Well, Sharpsight, will you take service with me, for I need just such a servant as you?”

Yes, Sharpsight would do that; so now the Prince had three servants, and they were such servants as no one in the world ever had before.

They travelled along over the plain, and at last they came to the foot of the mountain that lay between them and the iron castle.

“Now we must either go over it or round it,” said the Prince; “and which shall it be?”

“No need for that, Master,” answered Sharpsight.[18] “Just let me unbandage my eyes, but be careful you are not struck by any of the flying pieces when the mountain begins to split.”

So the Prince and Broad and Long took shelter behind a clump of trees, and then Sharpsight uncovered his eyes. He fixed his eyes on the mountain, and presently it began to groan and split and splinter. Pieces of sharp rock and stones flew through the air. It was not long before Sharpsight’s gaze had bored a way straight through the mountain and out on the other side. Then he put back the bandage over his eyes and called to the Prince that the way was clear.

The Prince and his companions came out from their shelter, and when they saw the way that Sharpsight had made through the mountain they could not wonder enough. It was so broad and clear that ten men could have ridden through it abreast.

With such a way before them it did not take them long to go through the mountain, and then they found themselves in the country beyond, and a black and terrible land it was too. Nowhere was there any sound or sign of life. There were fields, but no grass. There were trees, but they bore neither leaves nor fruit. There was a river, but it did not flow, and there was light, and yet they saw no sun. But darker and gloomier than all the rest was the castle which[19] rose before them. It was the iron castle where the Black Magician lived.

There was a moat round the castle and an iron bridge across it. The companions rode across the bridge, and no sooner were they over than the bridge rose behind them and they were prisoners.

They could not have turned back even if they had wished to, but none of them had any thought of such a thing.

The Prince struck with his sword upon the great door of the castle, and at once it opened before him, but when he entered he saw no one. Before him was a great hall, and on either side of it was a long row of stone figures. These statues were all figures of knights and kings and princes. The Prince looked at them and wondered, for they were so lifelike that it seemed scarcely possible to believe that they were of stone.

He and his companions went on farther into the castle, and everywhere they found rooms magnificently furnished, but silent and deserted. Nowhere was there any sign of life.

Last of all they entered what seemed to be a dining-hall. Here was a table set with the most delicious things to eat and drink. There were four places about the table, and one of them was somewhat higher than the others, as though intended for the prince or king.

“One might think this table had been set for us,” said the Prince. “We will wait for a while, and then, if no one comes, we will eat, at any rate.”

They waited for some time and then took their places at the table. At once invisible hands filled the goblets and other invisible hands passed the dishes.

The Prince and his companions ate and drank all they wished, and then they rose from the table, meaning to look farther through the castle.

At this moment the door opened and a tall man with a long grey beard came into the room. From head to foot he was dressed entirely in black velvet, even to his cap and shoes, and round his waist his robe was fastened with three iron bands. In one hand was an ivory wand, curiously carved; with the other he led a lady so beautiful, and yet so pale and sad-looking, that the heart ached to look at her. The moment the Prince saw her he knew her as the one whose picture he had seen behind the golden curtain—the one whom he had said should be his bride.

The Magician, for it was he, spoke at once to the Prince. “I know why you have come here, and that you hope to win this Princess for your bride. Many others have come here with the same wish and have failed. Now you shall have your turn. For three nights you must watch here with her. If each morning I return and find her[21] still with you, then you shall have her for a bride after the third morning. But if she is gone, you shall be turned into a stone statue, such as those you have already seen about my palace.”

“That ought not to be a hard task,” said the Prince. “Gladly will I watch with her for three nights; if in the morning you find her gone, I am willing to suffer whatever you will. But my three companions must also watch with me.”

Yes, the Magician was willing to agree to that, so he left the lady there with the four, and then went away, closing the door behind him.

As soon as the Magician had gone the Prince and his followers made ready to guard the room so that no one could come in to take the lady away, nor could she herself leave without their knowing it.

Long lay down and stretched himself out until he encircled the whole room, and anyone who went in or out would have to step over him. Sharpsight sat down to watch, while Broad stood in the doorway and made himself so broad that no one could possibly have squeezed in past him. Meanwhile the Prince tried to talk to the lady, but she would not look at him nor answer him.

In this way some time passed, and then suddenly the Prince began to feel very drowsy. He tried to rouse himself, but in spite of his efforts his eyes closed, and he fell into a deep sleep.

It was not until the early morning that he woke.[22] Then he roused himself and looked about him. His companions too were only just opening their eyes, for they, like himself, had been asleep, and the lady was gone from the room.

When the Prince saw this he began to groan and lament, but his companions told him not to despair.

“Wait until I see if I can tell you where she is,” said Sharpsight. He leaned from the window and looked about.

“Yes, I see her,” he said. “A hundred miles away from here is a forest. In that forest is an oak-tree. On the topmost bough of that oak-tree is an acorn, and in that acorn is the Princess hidden.”

“But what good is it to know where she is unless we can get her back before the Magician comes?” cried the Prince. “It would take us days to journey there and to return.”

“Not so long as that, Master,” answered Long. “Have patience for a moment until I see what I can do.” He then stepped outside and made himself so tall that he could go ten miles at a step. He set Sharpsight on his shoulder to show him the way, and away he went, and he made such good time that he was back in the castle again before the Prince could have walked three times round the room.

“Here, Master,” he said, “here is the acorn. Take it and throw it upon the floor.”

The Prince threw the acorn upon the floor, and[23] at once it flew open, and there stood the Princess before him.

Hardly had this happened when the door opened and the Magician came into the room. When he saw the Princess he gave a cry of rage, and one of the iron bands about his middle broke with a loud noise.

He looked at the Prince, and his eyes flashed as if with red fire. “This time you have succeeded in keeping the Princess with you,” he cried, “but do not be too sure that you can do the same thing again. To-night you shall try once more.”

So saying he went away, taking the Princess with him. In the evening he came again, and again he brought the Princess.

“Watch her well,” said he to the Prince, with an evil smile. “Remember, if she is not still here to-morrow morning you will share the fate of the others who have tried to watch her and have failed.”

“Very well,” answered the Prince. “What must be must be, and I can only do my best.”

The Magician then went away, leaving the Princess with them as before.

The Prince and his companions had determined that this night they would stay awake, whatever happened, but presently their eyelids grew as heavy as lead, and soon, in spite of themselves, they all fell into a deep sleep.

When they awoke the day was breaking, and[24] the Princess had again disappeared. The Prince was ready to tear his hair with despair, but Sharpsight bade him take heart.

“Wait until I take a look about,” he said. “If I cannot see her, then it will be time for you to despair.”

He leaned from the window, and first he looked east, and then he looked west, and then he looked toward the north. “Yes, now I see her,” he said, “but she is far enough away. Two hundred miles from here is a desert. In that desert is a rock, in that rock is a golden ring, and that ring is the Princess.”

“That is far away indeed,” groaned the Prince, “and at any moment the Magician may be here.”

“Never mind, Master,” cried Long. “Two hundred miles is not so far when one can go twenty miles at a step.” He then made himself twice as tall as the day before, and taking Sharpsight on his shoulders he set out for the desert.

It was not long before he was back again, and in his hand he carried the golden ring. “If it had not been for Sharpsight,” he said, “I would have been forced to bring back the whole rock with me, but he fixed his eyes upon it, and at once it split into a thousand pieces and the ring fell out. Here! Take the ring, Master, quick, and throw it upon the floor.”

The Prince did so, and as soon as the ring touched the ground it was transformed into the Princess.

At this moment the Magician opened the door and came into the room. When he saw the Princess he stopped short, and his face turned black with rage and fear. At the same moment the second band about his middle flew apart.

“Ah, well!” he cried to the Prince, “no doubt you think you are very clever, but remember there is still another night, and next time you may not prove so lucky in keeping the Princess with you.”

So saying he went away with the Princess, and the Prince saw him no more until evening. Then for the third time he came, and brought the Princess with him.

“Watch her well,” said he, “for I promise you will not have so easy a task this time as you have had before.”

Then he went away, and the four comrades set themselves to watch. But again all happened as it had before. In spite of themselves they could not stay awake. First they nodded and then they snored, and then they fell into such a deep sleep that if the walls had fallen about them they would not have known it. For this was an enchanted sleep that the Magician had thrown upon them in order to take away the Princess.

Not until day began to dawn did the four awake, and when they did there was nothing to be seen of the Princess.

“Well, she is not here in the room,” said[26] Sharpsight, “so methinks I’d better look outside.”

Then he leaned from the window, and for a long time he looked about him. At last he spoke. “Master, I see the Princess, but to bring her back will not be such an easy task as it was before. Three hundred miles from here is a sea. At the bottom of the sea is a shell. In that shell is a pearl, and that pearl is the Princess. But to bring that pearl up from the sea is a task for Broad as well as Long.”

“Very well,” said the Prince, “then Long must take Broad with him on one shoulder. Only make haste and return again quickly, in heaven’s name, or the Magician may be here before you are back, and we shall be turned into stone.”

Well, the three servants were willing enough to be off. Long stretched himself out until he was three times as tall as he had been the first time, and that was the most he could stretch. Then he went away, thirty miles at a step. At that rate it was no time before he came to the sea. But the sea was fathoms deep, and the shell lay at the very bottom of it, and try as he might he could not reach it.

“Now it is my turn,” said Broad. Then he lay down and put his mouth to the sea and began to drink. He drank and drank and swelled and swelled until it was wonderful to see him, and in the end he swallowed so much of the water that[27] it was easy enough for Long to reach down and pick up the shell.

“And now we must make haste,” cried Sharpsight, “for as I look back at the castle I see that the Magician is already waking.”

At once Long took his companions on his shoulders and started back the way he had come. But Broad had drunk so much water and was so heavy that Long could not go as fast as he otherwise would. “Broad, you will have to wait here, and I will come back for you later,” he cried, and with that he threw Broad down from his shoulder as though he had been a sack full of grain.

Broad had not been expecting such a fall and was not prepared for it. He gasped and choked, and then the sea he had swallowed rose all about them; it filled the valley and washed up over the foot of the mountains. Long was so tall that he was able to wade out of it, though the water was up to his waist, and Sharpsight too was safe, for he was on Long’s shoulder; but Broad was like to have been drowned. He only saved himself by catching hold of Long’s hand, and so he was drawn out of the water and up on dry land.

“That was a pretty trick to play upon me,” he gasped and spluttered.

But Long had no time to answer him, for already Sharpsight was whispering in his ear that the Magician had awakened and was now[28] on his way to the Prince. He caught Broad by the belt and swung him up on his shoulder, and this he could easily do, because now Broad was so shrunken that he was quite light.

In two more steps Long had reached the castle, but already the Magician was opening the door of the chamber where the Prince was.

“Quick! Quick!” cried Sharpsight. “Throw the pearl in at the window.”

And indeed there was no time to be lost. Long threw the pearl in through the window, and the moment it touched the floor it turned into the Princess. She stood there before the Prince, no longer pale and sad, but smiling and as rosy as the dawn.

Already the Magician was in the room, with an evil smile upon his face. When he saw the Princess standing there he gave a cry so loud and terrible that the whole castle shook with it. And now the third iron band that was about his waist broke.

At once the black velvet robe that had been held about him by the bands rose and spread into two great black wings. His eyes shrank, his nose grew long and sharp, and instead of the Magician there was a great black raven in the room with them. Heavily flapping, it rose from the ground. Three times round the room it flew, croaking mournfully, and then out through the window.

And now through all the castle arose a stir and hum of life. The stone figures in the hall stirred and looked about them, and stepped down, no longer cold dead stone, but living, breathing people. They were those who had come to the castle to search for the Princess, and had been bewitched by the Magician and turned into statues; the evil charm was broken, and they were alive once more.

When they found that it was the Prince and his followers who had delivered them they did not know how to thank them enough. They could not even grudge the Princess to the Prince, for it was he who had brought them back to life. They all said they would return with the Prince to his own country, so as to be at the wedding when he was married to the Princess.

And what a wedding it was! There was enough cake and ale for all to feast to their hearts’ content.

The old King was so happy that he at once made over the kingdom to his son, that he and his bride might reign.

As for the three companions, they ate and drank till they were full, and then they set out into the world again. The Prince begged and entreated them to stay with him, but they would not. They were too fond of travelling about the world, and for all I know they may be in some corner of it still.

THE Princess Beautiful was the daughter of the King of the Silver Mountains, and she was no less lovely than her name. Because of her beauty many heroes and princes came to her father’s kingdom, all seeking her in marriage. The Princess cared for none of them, however, except the young Prince Dobrotek. Him she loved with all her heart, and her father was quite willing that she should choose him for a husband, for the Prince was rich and powerful as well as handsome.

The marriage between them was arranged, and the guests from far and near were invited to attend. Among those asked was a dwarf who had also been a suitor for the hand of the Princess.

This dwarf was a very powerful magician, and as he was very malicious as well as powerful, he was greatly feared by every one. He was scarcely two feet high, and so ugly that it was enough to frighten one only to look at him. His great pride was his beard, which was seven feet long, and every hair of it was of pure gold. Because of its length he wore it twisted round[31] and round his neck like a golden collar. Thus he avoided tripping over it at every step.

When this dwarf heard that the Princess was to marry Dobrotek he was filled with rage and chagrin. In spite of his hideousness he was so vain of his beard that he could not imagine why the Princess should have chosen another instead of himself. He swore that even still she should take him for a husband, and that if she did not do this then she should marry no one. However, he said nothing of this vow to anyone. He accepted the invitation to the wedding, and when the day came he was one of the first of the guests to arrive.

All went to the church and took their places, and when the Prince and Princess stood before the altar they were so handsome that every one was filled with admiration.

The priest opened his book and was just about to make them man and wife when a frightful noise arose outside. It was a sound of whistling and roaring and rending. Then the doors were burst open, and a terrible hurricane swept into the church.

The guests were so frightened that they hid themselves under the seats, but the storm touched none of them. It swept up the aisle and caught up the Princess Beautiful as though she were a feather. The Prince threw his arms about her and tried to hold her. But he could do nothing[32] against such a hurricane. She was torn from his grasp and swept out of the church and away, no one knew whither.

When the storm was over the people came out from under the seats and looked about them, but look as they might they could see no bride. Only the Prince was standing before the altar, tearing his hair with despair because the Princess was lost to him.

And well might he despair, for the hurricane that had carried the Princess away was no common storm. It had been raised by the wicked enchantments of the dwarf, and had swept Princess Beautiful far away, over plain and mountain, over sea and forest, to the very castle of the dwarf himself. There she was lying in an enchanted sleep, and it would be a bold man who could hope to rescue her.

When the King of the Silver Mountains found his daughter gone he was in a terrible rage. “It was for you to save her,” cried he to the Prince. “She was your bride, and you should have lost your life before you allowed her to be torn from you.”

To this the Prince answered nothing, for he thought the same himself. Yet who can stand against magic? Only enchantment, indeed, could have prevailed against him.

“Go!” cried the King, “find her and bring her back to me, or your life shall answer for it.”

The Prince wished nothing better than to go in search of his bride. Life was worth nothing to him without her, and at once he made ready to depart. He was in such haste that he stopped for neither sword nor armour, but leaped upon his horse and rode forth as he was.

On and on he rode, many miles and many leagues, but the farther he rode the less he heard of the Princess, and the more he despaired of ever finding her. At last he entered a forest so dark and vast that it seemed to have no end. As he rode on through the shadows he suddenly heard a sharp and piteous cry. He looked about him to see whence it came, and presently he found a hare struggling in the clutch of a great grey owl.

The Prince had a kind heart. He seized a stick and quickly drove the owl away from its prey. For awhile the hare lay stretched out and panting, but presently it recovered itself.

“Prince,” it said to Dobrotek, “you have saved my life, and I am not ungrateful. I know why you are here and whom you seek. To rescue the Princess Beautiful will be no easy task. It was the Dwarf of the Golden Beard who raised the tempest that carried the Princess away. Even now he holds her a prisoner in his castle. Whoever would rescue her must first overcome the dwarf, and to do this one must be in possession of the Sword of Sharpness.”

“And where is that sword to be found?” asked the Prince.

“On a mountain many leagues away. It is guarded by a dragon who keeps watch over it night and day. Only when the sun is at its highest does the dragon sleep, and then but for a few short minutes. To gain possession of the sword one must ride the wild horse that lives here in the forest and that moves faster than the wind.”

“And can I find that horse and ride him?”

“It can be done. Under yonder rock lies a golden bridle. It has lain hidden there for over a hundred years. With it lies a golden whistle. The sound of that whistle will call the horse, wherever he is. But he is very terrible to look upon, for his eyes are like burning coals, and he breathes smoke and fire from his nostrils. He will come at you as though to tear you to pieces, but do not be afraid. Cast the bridle over his head, and he will at once become quite tame and gentle. Then you can ride him wheresoever you wish. He will bear you to the mountain where the dragon lies and will help you to gain possession of the sword.”

The Prince thanked the hare for its advice. He lifted the rock from its place, and there beneath it lay the golden bridle and the golden whistle. The Prince took up the bridle, and at once the whole glade was filled with light; and[35] no wonder, for the bridle was studded with precious stones and glittered like the sun. He raised the whistle to his lips and blew upon it loud and clear.

At once, from far away in the forest, came a loud sound of neighing, and of galloping hoofs. The wild horse was coming. On and on it came, nearer and nearer. Its eyes shone like coals of fire, and the leaves were withered on either side of it because of its fiery breath.

It rushed at the Prince as though it would tear him to pieces; but he was ready for it, and as soon as it was near enough he threw the bridle over its head. At once the fire faded from its eyes. Its breath grew quiet, and it stood there as gentle and harmless as a lamb.

“Master,” it said to Dobrotek, “I am yours now. Whatsoever you wish me to do, I will do, and I will bear you wherever you wish to go.”

“First, then,” said the Prince, “I wish you to carry me to the mountain where I can find the Sword of Sharpness.”

“Very well, Master, I will do so. But before we start on such a dangerous adventure as that you should be properly armed. Do you enter in at one of my ears and go on until you come out of the other.”

At once it seemed to the Prince as though the horse’s ear were a great cave opening out before him. He entered in and went on and on, though[36] it was very dark there in the horse’s head. Presently he saw another opening before him, and that was the horse’s other ear. He came out through it and found himself in the forest again, but now he was clothed as a warrior prince should be, in shining armour, and he held a sword in his hand.

“That is right,” said the horse. “Now mount and ride, for we have far to go.”

So the Prince said good-bye to the friendly hare and thanked it again. He mounted upon the horse’s back and away they went like the wind. Soon they were out of the forest, and the dark was left behind them. On they went and on they went, until they came within sight of a smoking mountain; there the horse stopped.

“Master,” said he, “do you see that mountain in front of us and the smoke that rises over it?”

Yes, the Prince saw it.

“That smoke is the breath of the dragon that guards the Sword of Sharpness. Just now he is awake, and if we were to venture within reach he would soon scorch us to cinders with his breath. There are, as the hare told you, only a few short minutes at midday when he sleeps, and when we may approach him safely. To gain the sword I must, in those few minutes, cross the plain before us and climb the mountain. Only I, who go like the wind, could do such a thing, and even for me it will be difficult. We may both lose our lives in the attempt.”

“Nevertheless, we must try it,” said the Prince, “for unless I can gain the sword, and free the Princess from the dwarf, life is worth nothing to me.”

“Very well,” answered the horse. “Then we will attempt it, for you are my master.”

So all the rest of that day the horse and the Prince lay hidden, for it was already afternoon. Through the night and the next morning they waited, and the Prince could see the flames and columns of smoke that the dragon breathed forth. But as the sun rose high in the heavens the dragon became sleepy, and the flames burned lower and with less smoke. At last the sun was at its height.

“And now, Master, is our time,” cried the horse. With that he galloped out on to the plain and made for the mountain. On he flew as fast as the wind, and faster. The Prince could hardly breathe, and he could not see at all, so fast the horse went. The plain was crossed, the mountain climbed, but already the dragon was awakening. “Quick, quick! the sword. There it lies beside him!” cried the horse.

The Prince stooped and caught up the Sword of Sharpness, and in that instant the dragon awoke. It reared its head and seemed about to devour the Prince, but when it saw what he held in his hand it dropped its crest and fawned at his feet.

“You are my master,” it said, “for you hold[38] the Sword of Sharpness. But do not kill me. Spare my life, and I will give you advice that may save your own.”

“What is the advice?” asked the Prince.

“When you reach the dwarf’s castle (for I know that you are going there, and why), you may with this sword be able to overcome the dwarf. But after you have done that, you must cut off his beard and carry it away with you. It will serve as proof that you and you alone have slain him. You must also fill a flask with water from the fountain in the midst of the garden. It is the Water of Life, and you will need it. You will need the Cap of Invisibility too that the dwarf sometimes wears upon his head. All three of these things you must have. Do not neglect what I tell you, for if you do evil will certainly come upon you.”

“It is well,” said the Prince. “I will remember what you say, and if no good comes of it, no harm can either.”

So saying, the Prince drew his own sword from its sheath and left it on the mountain, taking the Sword of Sharpness in its place. Then he rode down the mountain and away over the plain. Once he looked back, but he saw neither flame nor smoke behind him. The dragon lay there as harmless as any worm, for with the Sword of Sharpness all its power was gone.

On and on rode the Prince, so fast that the[39] wind was left behind, and at last he and his horse came within sight of a castle all of iron. About it was a wall that was seven times the height of a man, and this also was of iron.

“Look, Prince,” said the horse. “That is the dwarf’s castle that we see before us.”

Then on they went again and never stopped until they reached the castle gate. Beside the gate hung a great brazen war trumpet. The Prince lifted it to his lips and blew upon it such a blast that it was like to split the ears of those who heard it. Again he blew, and once again.

“And now, Master, take out the sword from its sheath and make ready, for the dwarf will soon be here,” said the horse.

Meanwhile the Princess Beautiful had been living behind those iron walls, and she had been not unhappy, though she had often grieved because Prince Dobrotek was not with her.

When the dwarf had caused her to be swept away by the hurricane he had thrown her into an enchanted sleep, and in this sleep she lay until she was safely placed in a room that the dwarf had specially prepared for her. This room was made entirely of mirrors, only divided here and there by curtains of cloth of gold. These curtains were embroidered with scenes from the dwarf’s own life and from the life of the Princess. In the mirrors Beautiful could see her own beauty repeated endlessly. The furniture of the room[40] was all of gold, curiously carved, and the cushions were embroidered with gold and precious stones.

When the Princess opened her eyes and looked about her she did not know where she was. She had no remembrance of the storm that had brought her hither. She remembered only that she had stood beside Prince Dobrotek in the church, and that a great noise had arisen outside. After that she had known nothing until she awoke in this chamber.

She arose from the couch where she was lying and began to examine the room. All the light came from a dome overhead. She could find neither doors nor windows, and she wondered much how she had been brought into a room like this.

While she was looking about her she heard a noise behind her that made her turn quickly. At one side the mirrors had swung apart like doors, and through this opening came a procession of enormous black slaves bearing a golden throne in their midst. Upon this throne sat the Dwarf with the Golden Beard. The slaves set the throne down in the middle of the room and at once withdrew, closing the mirrored doors behind them.

When the Princess saw the dwarf she was very much alarmed. She at once suspected that it was he who had brought her here, and that he meant to keep her a prisoner until she would consent to marry him.

The dwarf stepped down from the throne and[41] approached her with a smiling air, but she shrank away from him into the farthest corner of the room.

The dwarf was magnificently dressed. His beard had been brushed till it shone like glass, and he had thrown it over one arm as though it were a mantle. But in his left hand he carried a cap of some coarse grey stuff that was in strange contrast with the rest of his dress.

“Most beautiful Princess,” said he, “you are welcome indeed in my castle. None could be more so, and I hope to make you so happy that you will be more than content to spend your life here with me.”

“Miserable dwarf!” cried the Princess, “do you really think you will be able to make me stay here with you? Do you not know that Prince Dobrotek will come in search of me soon? He will certainly find me! Then he will punish you as you deserve for your insolence.”

The Princess was trembling now, but with rage rather than fear. The dwarf seemed not at all disturbed by her anger, however.

“Beautiful one,” he said, still smiling, “you are even more beautiful when you are angry than when you are pleased. Let Prince Dobrotek come. I fear him not at all. But do not let us waste our time in talking of him. Instead let us talk of ourselves, and of how pleasantly we will pass our days together.”

So saying, the dwarf came close to the Princess and attempted to take her hand. But instead of permitting this, the Princess gave him such a blow upon the ear that he fairly staggered under it. His beard slipped from his arm, and in trying to steady himself he tripped on it and fell his length upon the floor.

The Princess laughed maliciously. At the sound of her laughter the dwarf became filled with fury. His eyes flashed fire as he scrambled to his feet. “Miserable girl!” he cried. “Do you dare to laugh? The time will come when you will feel more like weeping, if not for me then for yourself. Some day you will be glad enough to receive my caresses. Now I will leave you, and when I come again it will be in a different manner.” So saying, he gathered up his beard and rushed through the mirror door, closing it behind him.

His words, and his manner of going, frightened the Princess. She again began to look about her for some way of escape. Suddenly she saw upon the floor the grey cap that the dwarf had carried in his hand. He must have dropped it when he fell, and he had been too angry to notice that he was leaving it behind. She picked it up and stood turning it thoughtfully in her hands. Then, without considering why she did so, she placed it upon her head. She was standing directly in front of a mirror at the time. To her amazement,[43] the moment she had the cap on her head every reflection of her vanished from every mirror in the room. The Princess could hardly believe her eyes. She might have been thin air for any impression she made upon the glass. She took the cap from her head, and immediately her reflections appeared again in the mirrors. She replaced it, and they vanished from sight. Then the Princess knew that she held the Cap of Invisibility—the cap that causes anyone who wears it to become invisible.

As she stood there with the cap still upon her head, the mirror door was burst open and the dwarf rushed into the room. His dress was disordered and his eyes glared wildly.

He looked hastily about him, but he could see neither the cap nor the Princess. At once he knew that she had found the cap and had put it on.

“Ah, ha!” he cried to the invisible Princess. “So you have found it! You have put it on, and hope so to escape me. But I know you are still here, even though I cannot see you. I will find you, never fear.”

Spreading his arms wide, he rushed about the room, hoping to touch the Princess and seize her, but as he could not see her she was easily able to escape him. Now and then he stopped and listened, hoping the Princess would make some sound that would tell him where she was, but at[44] these times Beautiful too stood still. She did not move, she scarcely breathed, lest he should hear her.

Suddenly the Princess saw something that gave her a hope of escape. The dwarf had neglected to fasten the swinging mirror behind him when he entered. She flew to it and pushed it open. Beyond lay a long corridor. Down this the Princess fled, not knowing where it would lead her.

But the dwarf saw the mirror move, and guessed she had passed out through it. With a cry of rage he sprang after her.

At the end of the corridor was a barred door. Beautiful had scarcely time to unfasten this door and run through before the dwarf reached it. But once outside the door she found herself in a wide and open garden. Here she could pause and take breath. The dwarf had no means of knowing in which direction she had gone. He could not hear her footsteps upon the soft grass, and the rustling of the wind among the leaves prevented his hearing the sound of her dress as she moved.

For a while the dwarf ran up and down the garden, hoping some accident might bring him to the Princess. But he grasped nothing except empty air. Discouraged, he turned back to the castle at last, muttering threats as he went.

After he had gone the Princess began to look[45] about her. She found the garden very beautiful. There were winding paths and fountains and fruit trees and pergolas where she could rest when she was weary. She tasted the fruit and found it delicious. It seemed to her she could live there for ever very happily, if only her dear Prince Dobrotek were with her.

As for the dwarf, in the days that followed the Princess quite lost her fear of him, though he often came to the garden in search of her. After a time she even amused herself by teasing him. She would take off her cap and allow him to see her. Then, as he rushed toward her, she would put it on again and vanish from his sight. Or she would run just in front of him, singing as she went, that he might know where she was. The poor dwarf would chase madly after the sound. Then, when it seemed that he was just about to catch her, she would suddenly become silent and step aside on the grass, and laugh to herself to see him run past her, grasping at the air.

But this was a dangerous game for the Princess to play; she was not always to escape so easily. One day she was running before him, just out of reach, and calling to him to follow, when a low branch caught her cap and brushed it from her head. Immediately she became visible.

With a cry of triumph the dwarf caught the cap as it fell and thrust it in his bosom. Then he seized the Princess by the wrist.

“I have you now, my pretty bird. No use to struggle. You shall not escape again.”

In despair the Princess tried to tear herself loose from his hold, but the dwarf’s fingers were like iron.

At this moment from outside the gate sounded the loud blast of a war trumpet. At once the dwarf guessed that it was Prince Dobrotek who blew it, and that he had come in search of the Princess.

Suddenly, and before Beautiful could hinder him, he drew her to him and breathed upon her eyelids; at the same time he muttered the words of a magic charm.

At once the Princess felt her senses leaving her. In vain she strove to move or speak. In spite of herself her eyes closed, and she sank softly to the ground in a deep sleep.

As soon as the dwarf saw that his charm had worked he caused a dark cloud to gather about him, which entirely hid him from view. Rising in this cloud, he floated high above the iron walls and paused directly over Prince Dobrotek. He drew his sword and made ready to slay the bold Prince who had come against him.

Dobrotek looked up and wondered to see the dark cloud that had so suddenly gathered above him.

“Beware!” cried the wild horse loudly. “It is the dwarf. He is about to strike.”

Scarcely had he spoken when the darkness drew down about them. Through this darkness shot a flash as bright as lightning. It was the dwarf’s sword that had struck at the Prince. But swift as the stroke was, the horse was no less swift. He sprang aside, and the sword drove so deep into the earth that the dwarf was not able to draw it out again.

“Strike! Strike!” cried the horse to Dobrotek. “It is your chance!”

Dobrotek raised the Sword of Sharpness and struck into the cloud, and his blow was so sharp and true that the dwarf’s head was cut from his body and fell at the Prince’s feet.

Dobrotek alighted, and cutting off the dwarf’s beard, he wound it about him like a glittering golden belt. Then, leaving the head where it lay, he opened the gate and went into the garden.

He had not far to go in his search for Beautiful, for she was lying asleep upon the grass close to the gate. Dobrotek was filled with joy at the sight.

“Princess, awake! awake!” he cried. “It is I, Dobrotek. I have come to rescue you.”

The Princess neither stirred nor woke. Her lashes rested on her cheeks, and she breathed so gently that her breast scarcely moved.

“Master,” said the horse, “this is no natural sleep. It is some enchantment. Take up that cap that lies beside her. Then fill your flask at[48] the fountain of the Water of Life and let us go. Do not try to wake her now. When it is time, you can do so by sprinkling upon her a few drops of the water. But first let us make haste to leave this place, for it is still full of evil magic.”

Dobrotek was not slow to do as the horse bade him. He filled a flask with the Water of Life and hid the Cap of Invisibility in his bosom. Then, lifting the Princess in his arms, he mounted the horse and rode back with her the way they had come.

It was not long before they reached the place where the Prince had saved the hare from the owl in the forest. Here the Prince found his own horse. It had not wandered away, but had stayed there, browsing on the grass and leaves and drinking from a stream near by.

“And now, Prince,” said the wild steed, “it is time for us to part. Light down and take the bridle from my head. Put it back again where you found it, and cover it with the rock; but keep the whistle by you. If ever you need me, blow upon it, and I will come to your aid.”

Dobrotek did as the steed bade him. He lighted down and took the bridle from its head. He put it in the hole where he had found it and rolled back the rock upon it. Then the horse bade him farewell, and tore away through the forest, neighing as it went and breathing flames of fire.

After it had gone the Prince felt very weary. He had not yet awakened the Princess, but had laid her, still asleep, upon the soft moss of the forest. Now he stretched himself at her feet, and at once fell into a deep slumber.

Now it so chanced that while he was asleep King Sarudine, the King of the Black Country, came riding through the forest. He too had been a suitor for the hand of the Princess, but he had been refused. When he heard that she had been spirited away, and that Prince Dobrotek had gone to seek for her, he also determined to set out on the same mission. He hoped that he might be the first to find her and so win her for his bride. For the King, her father, had sent out a proclamation that whoever could find the Princess Beautiful and rescue her should have her for his wife.

What was the amazement of Sarudine, as he came through the lonely wood, suddenly to see the Princess lying there asleep, with Dobrotek at her feet.

At first he drew his sword, thinking to kill the Prince; but after a moment’s thought he put it back in its sheath. Then bending over Beautiful he very quietly lifted her in his arms, mounted his horse, and rode away with her.

Dobrotek was so wearied with his adventures that he slept on for some time, not knowing that the Princess had again been stolen from him.

But when at last he woke and found her gone, he was like one mad, so great was his despair. He rushed about hither and thither through the forest, calling her name aloud, and seeking her everywhere, but nowhere could he find her.

Suddenly he bethought him of his golden whistle, and putting it to his lips he blew so loud and shrill that the forest echoed to the sound. At once the great grey horse came galloping through the forest to him.

Dobrotek ran to meet it. “Tell me,” he cried, “you who know all things, where is Beautiful? She has been stolen from me, and I cannot find her.”

“She is no longer here in the forest,” answered the horse. “She has been carried away by King Sarudine. He has taken her back to her father’s castle, and now he claims her as his bride, for he says that he is the one who found and rescued her. But she still sleeps her enchanted sleep, and none can waken her. You alone can do this, for you have the Waters of Life. Hasten back to the castle, therefore, but before you go to waken her, put on the Cap of Invisibility. King Sarudine fears you, and he has set guards about the castle with orders to slay you if you attempt to enter. All their watchfulness will be in vain, however, if you wear the cap upon your head.”

The advice was wise, and Dobrotek at once[51] did as the horse told him. He drew out the cap and put it upon his head. So he became invisible. Then he rode away in the direction of the country of the Silver Mountains.

He rode on and on, and after a while he came to where the first line of guards was set. They heard the galloping of a horse, and looked all about them, but they could see no one, so he passed in safety. Not long after he came to a second line of soldiers, and he went by them unseen also. Then he passed a third line of guards, and after that he was at the palace.

The Prince entered in, and went from one room to another, and presently he came to the great audience hall. There sat the King upon a golden throne. At his right hand sat King Sarudine, and at his left the Princess lay upon a golden couch, and so beautiful she looked as she lay asleep that the Prince’s heart melted within him for love. He lifted the cap from his head, and there they all saw him standing before them.

The King of the Black Mountains turned pale and trembled at the sight of him, but the old King gave a loud cry of surprise. He had thought that Prince Dobrotek had met his death long ago, or that if he lived he would be afraid to return to the Silver Mountain Country without bringing the Princess with him.

“Rash Prince!” he cried; “what are you[52] doing here? Do you not fear to appear before me, having failed in your search?”

“I did not fail,” answered the Prince, “there lies the Princess, and were it not for me she would still be a prisoner in the castle of the Dwarf of the Golden Beard.”

“How is that?” asked the King.

Then Dobrotek told them his story. He told of how he had become master of the wild horse in the forest, of how he had gained possession of the Sword of Sharpness, and then of how he had ridden to the dwarf’s castle and slain him in battle. He also told how he had brought the Princess away with him, how he had fallen asleep in the forest, and of how the King of the Black Country had stolen Beautiful from him while he slept.

The old King listened attentively to all that Dobrotek told him. When the Prince had made an end to his story the old King turned to King Sarudine beside him.

“And what have you to say to this?” he asked. “Is this story true?”

“Much of it is true,” answered Sarudine, hardily, “but still more of it is false. It is true that it was the dwarf who carried Beautiful away. It is true that he kept her a prisoner, and that he was slain by the Sword of Sharpness. But it was I who won the sword and slew the dwarf, and it was I who rescued the Princess.[53] What better proof of this is needed than that it was I who brought her here?”

“That is only proof that you stole her from me,” cried the Prince. “The proof that I can offer is better still. If you slew the dwarf, where is his beard?”

To this the King of the Black Country could answer nothing, for he did not know where the beard was.

“Then I can tell you,” cried the Prince. With these words he threw aside his mantle, and there, wound about him like a glittering girdle, was the golden beard of the dwarf.

When the old King saw the beard he could doubt no longer as to which of the two had slain the dwarf and rescued the Princess. He turned such a terrible look upon Sarudine that the young King trembled.

“So you would have deceived me!” he cried. “You thought to win the Princess by a trick. Away! Away with you! Let me never see your face again; and if ever again you venture into my country, you shall be thrown into a dungeon and remain there as long as you live.”

Then, as Sarudine was hurried away by the guards, the old King turned again to the Prince. “You have indeed rescued the Princess,” he said, “but your task is still only half completed. She sleeps, and none can wake her. Until that is done, no man can have her for wife.”

“That is not such a hard matter, either,” said the Prince. With that he drew from his bosom the flask that held the Waters of Life and scattered a few drops upon the Princess.

At once she drew a deep breath and slowly opened her eyes. As soon as she saw the Prince she sprang to her feet and threw herself into his arms. The enchantment was broken, and she had awakened at last.

Then throughout the palace there was the greatest happiness and rejoicing. There never had been anything like the favours the old King heaped upon Dobrotek. The marriage between him and the Princess was again prepared for, and this time all went well. Nothing happened to interfere with the wedding, and the Prince and Beautiful were made man and wife. They loved each other all the more tenderly for the dangers they had shared, and from that time on they lived in all the happiness that true love brings.

THERE was once a man in Finmark named Halvor, who had a great white bear, and this great white bear knew many tricks. One day the man thought to himself, “This bear is very wonderful. I will take it as a present to the King of Denmark, and perhaps he will give me in return a whole bag of money.” So he set out along the road to Denmark, leading the bear behind him.

He journeyed on and journeyed on, and after a while he came to a deep, dark forest. There was no house in sight, and as it was almost night Halvor began to be afraid he would have to sleep on the ground, with only the trees overhead for a shelter.

Presently, however, he heard the sound of a woodcutter’s axe. He followed the sound, and soon he came to an opening in the forest. There, sure enough, was a man hard at work cutting down trees. “And wherever there’s a man,” thought Halvor to himself, “there must be a house for him to live in.”

“Good day,” said Halvor.

“Good day!” answered the man, staring with all his eyes at the great white bear.

“Will you give us shelter for the night, my bear and me?” asked Halvor. “And will you give us a bit of food too? I will pay you well if you will.”

“Gladly would I give you both food and shelter,” answered the man, “but to-night, of all nights in the year, no one may stop in my home except at the risk of his life.”

“How is that?” asked Halvor; and he was very much surprised.

“Why, it is this way. This is the eve of St John, and on every St John’s Eve all the trolls in the forest come to my house. I am obliged to spread a feast for them, and there they stay all night, eating and drinking. If they found anyone in the house at that time, they would surely tear him to pieces. Even I and my wife dare not stay. We are obliged to spend the night in the forest.”

“This is a strange business,” said Halvor. “Nevertheless, I have a mind to stop there and see what these same trolls look like. As to their hurting me, as long as I have my bear with me there is nothing in the world that I am afraid of.”

The woodcutter was alarmed at these words. “No, no; do not risk it, I beg of you!” he cried. “Do you spend the night with us out under the trees, and to-morrow we can safely return to our home.”

But Halvor would not listen to this. He was[57] determined to sleep in a house that night, and, moreover, he had a great curiosity to see what trolls looked like.

“Very well,” said the woodcutter at last, “since you are determined to risk your life, do you follow yonder path, and it will soon bring you to my house.”

Halvor thanked him and went on his way, and it was not long before he and his bear reached the woodcutter’s home. He opened the door and went in, and when he saw the feast the woodcutter had spread for the trolls his mouth fairly watered to taste of it. There were sausages and ale and fish and cakes and rice porridge and all sorts of good things. He tasted a bit here and there and gave his bear some, and then he sat down to wait for the coming of the trolls. As for the bear, he lay down beside his master and went to sleep.

They had not been there long when a great noise arose in the forest outside. It was a sound of moaning and groaning and whistling and shrieking. So loud and terrible it grew that Halvor was frightened in spite of himself. The cold crept up and down his back and the hair rose on his head. The sound came nearer and nearer, and by the time it reached the door Halvor was so frightened that he could bear it no longer. He jumped up and ran to the stove. Quickly he opened the oven door and hid himself inside, pulling the door[58] to behind him. The great white bear paid no attention, however, but only snored in his sleep.

Scarcely was Halvor inside the oven when the door of the house was burst open and all the trolls of the forest came pouring into the room.

There were big trolls and little trolls, fat trolls and thin. Some had long tails and some had short tails and some had no tails at all. Some had two eyes and some had three, and some had only one set in the middle of the forehead. One there was, and the others called him Long Nose, who had a nose as long and as thin as a poker.

The trolls banged the door behind them, and then they gathered round the table where the feast was spread.

“What is this?” cried the biggest troll in a terrible voice (and Halvor’s heart trembled within him). “Some one has been here before us. The food has been tasted and ale has been spilled.”

At once Long Nose began snuffing about. “Whoever has been here is here still,” he cried. “Let us find him and tear him to pieces.”

“Here is his pussy-cat, anyway,” cried the smallest troll of all, pointing to the white bear. “Oh, what a pretty cat it is! Pussy! Pussy! Pussy!” And the little troll put a piece of sausage on a fork and stuck it against the white bear’s nose.

At that the great white bear gave a roar and rose to its feet. It gave the troll a blow with[59] its paw that sent him spinning across the room. He of the long nose had it almost broken off, and the big troll’s ears rang with the box he got. This way and that the trolls were knocked and beaten by the bear, until at last they tore the door open and fled away into the forest, howling.

When they had all gone Halvor crawled out and closed the door, and then he and the white bear sat down and feasted to their hearts’ content. After that the two of them lay down and slept quietly for the rest of the night.

In the morning the woodcutter and his family stole back to the house and peeped in at the window. What was their surprise to see Halvor and his bear sitting there and eating their breakfasts as though nothing in the world had happened to them.

“How is this?” cried the woodcutter. “Did the trolls not come?”

“Oh, yes, they came,” answered Halvor, “but we drove them away, and I do not think they will trouble you again.” He then told the woodcutter all that had happened in the night. “After the beating they received, they will be in no hurry to visit you again,” he said.

The woodcutter was filled with joy and gratitude when he heard this. He and his wife entreated Halvor to stay there in the forest and make his home with them, but this he refused[60] to do. He was on his way to Denmark to sell his bear to the King, and to Denmark he would go. So off he set, after saying good-bye, and the good wishes of the woodcutter and his wife went with him.

Now the very next year, on St John’s Eve, the woodcutter was out in the forest cutting wood, when a great ugly troll stuck his head out of a tree near by.

“Woodcutter! Woodcutter!” he cried.

“Well,” said the woodcutter, “what is it?”

“Tell me, have you that great white cat with you still?”

“Yes, I have; and, moreover, now she has five kittens, and each one of them is larger and stronger than she is.”

“Is that so?” cried the troll, in a great fright. “Then good-bye, woodcutter, for we will never come to your house again.”

Then he drew in his head and the tree closed together, and that was the last the woodcutter heard or saw of the trolls. After that he and his family lived undisturbed and unafraid.

As for Halvor, he had already reached Denmark, and the King had been so pleased with the bear that he paid a whole bag of money for it, just as Halvor had hoped, and with that bag of money Halvor set up in trade so successfully that he became one of the richest men in Denmark.

THERE were once three Billy Goats who lived in a meadow at the foot of a mountain, and their last name was Gruff. There was the Big Billy Goat Gruff, and the Middle-sized Billy Goat Gruff, and the Little Billy Goat Gruff. They all three jumped about among the rocks in the meadow and ate what grass they could find, but it wasn’t very much.

One day the Littlest Billy Goat Gruff looked up at the high mountain overhead, and he thought to himself, “It looks as though there were a great deal of fine grass up on the mountain. I believe I’ll just run up there all by myself, without telling anyone, and eat so much grass and eat so much grass that I’ll grow to be as big as anybody.”

So off the Little Billy Goat Gruff started without telling his brothers a word about it. He ran along, tip-tap, tip-tap, tip-tap, until at last he came to a wide river, with a bridge over it.

Now the Little Billy Goat did not know it,[62] but this bridge belonged to a great, terrible Troll, and the little goat had not gone more than half-way across when he heard the Troll shouting from under the bridge.

“Who’s that going across my bridge?” shouted the Troll in his great loud voice.

“It’s me, the Littlest Billy Goat Gruff!” answered the Little Billy Goat in his little bit of voice.

“Oh! it’s the Littlest Billy Goat Gruff, is it? Well, you won’t go much farther, for I’m the Troll that owns this bridge, and now I’m coming to eat you up.” And with that the Troll looked up over the edge of the bridge.

When the Little Billy Goat Gruff saw him, he was very much frightened. “Oh, dear, good Mr Troll, please don’t eat me up,” he cried. “I’m such a very little goat that I would scarcely be a mouthful for you. I have a brother who is a great deal bigger than I am; wait till he comes, for he’d make a much better meal for you than I would.”

“But if he’s much bigger than you are he may be tough.”

“Oh, no, he’s just as tender as I am.”

“And a great deal bigger?”

“Oh, yes, a great deal bigger.”

“Very well then, I’ll wait for him. Run along!”

So the little goat ran on, tip-tap! tip-tap![63] tip-tap! across the bridge, and on up the mountain to where he was safe. And glad enough he was to be out of that scrape, I can tell you.

Now it was not very long after this that the Middle-sized Billy Goat Gruff began to think he’d like to go up on the mountain too. He did not say anything about it to the Great Big Billy Goat Gruff, but off he set, all by himself—trap-trap! trap-trap! trap-trap! After a while he came to the bridge, where the Troll lived, and he stepped out upon it, trap-trap! trap-trap! trap-trap!

He’d barely reached the middle of it when the Troll began shouting at him in his great, terrible voice:

“Who’s that going across my bridge?”

“It’s me, the Middle-sized Billy Goat Gruff,” answered the Middle-sized Billy Goat in his middle-sized voice.

“Oh, it is, is it? Then you’re the very one I’ve been waiting for. I’m the Troll that owns this bridge, and now I’m coming to eat you up.”

At that the Middle-sized Billy Goat Gruff was in a great fright. “Oh, dear Mr Troll, good Mr Troll, please don’t eat me up! I have a brother that’s a great deal bigger than I am. Just wait till he comes along, for he’d make a much better meal for you than I would.”

“A great deal bigger?”

“Yes, a great deal bigger.”

“Very well then, run along and I’ll wait till he comes. Only the biggest goat there is is fit to make a meal for me.”

The Middle-sized Billy Goat was not slow to run along as the Troll bade him. He hurried across the river and up the mountain as fast as he could go, trappity-trap! trappity-trap! trappity-trap! And just weren’t he and his little brother glad to see each other again, and to be safely over the Troll’s bridge, and up where the good grass was!

And now it was the turn of the Big Billy Goat Gruff to begin to think he’d like to go up on the mountain too. “I believe that’s where the Little Billy Goat Gruff and the Middle-sized Billy Goat Gruff have gone,” said he to himself. “If I don’t look out they’ll be growing so fat up there that they’ll be as big as I am. I think I’d better go and eat the long green mountain grass too.” So the next morning off he set in the pleasant sunshine. Klumph-klumph! klumph-klumph! He was so big you could hear his hoofs pounding on the stones while he was still a mile away.

After a while he came to the bridge where the Troll lived, and out he stepped on it, klumph-klumph! klumph-klumph! and the bridge shook and bent under his weight as he walked. Then the Troll that lived under it was in a fearful rage. “Who’s that going across my bridge?” he[65] bellowed, and his voice was so terrible that all the little fish in the river swam away and hid under the rocks at the sound of it.

But the Big Billy Goat was not one bit frightened.

“It’s me, the Biggest Billy Goat Gruff,” he answered, in a voice as big as the Troll’s own.

“Oh, it is, is it? Then just stop a bit—for you’re the one I’ve been waiting for. I’m the Troll that owns this bridge, and now I’m coming to eat you up!” and with that the great grey Troll poked his head up over the bridge, and his eyes looked like two great mill-wheels, and they were going round and round in his head with rage. But still the Big Billy Goat was not one bit frightened.

“So you’re a Troll, are you! And you own this bridge, do you? And now you’re going to eat me up? We’ll just see about that:

When the Troll heard the Big Billy Goat talk to him that way he bellowed so that the Middle-sized Billy Goat and the Little Billy Goat heard him all the way up on the mountain where they were. He jumped up on the bridge and put down his big, bushy head and ran at the Billy Goat, and the Big Billy Goat put down his head and ran at the Troll, and they met in the middle[66] of the bridge. But the Billy Goat’s head was harder than the Troll’s, so he knocked him down and thumped him about, and then he took him up on his horns and threw him over the edge of the bridge into the river below, and the Troll sank like a piece of lead and never was seen or heard of again.

But the Big Billy Goat went on up the mountain; and you may believe that his two brothers were glad to see him again, and to hear that the great wicked Troll was gone from under the bridge.

And after that they all stayed up on the mountain together, and the smaller goats ate so much grass and grew so fat and big that after a while no one could have told one Billy Goat from the other.

IN the little village of Plouvinec there once lived a poor stone-cutter named Bernet.

Bernet was an honest and industrious young man, and yet he never seemed to succeed in the world. Work as he might, he was always poor. This was a great grief to him, for he was in love with the beautiful Madeleine Pornec, and she was the daughter of the richest man in Plouvinec.

Madeleine had many suitors, but she cared for none of them except Bernet. She would gladly have married him in spite of his poverty, but her father was covetous as well as rich. He had no wish for a poor son-in-law, and Madeleine was so beautiful he expected her to marry some rich merchant, or a well-to-do farmer at least. But if Madeleine could not have Bernet for a husband, she was determined that she would have no one.

There came a winter when Bernet found himself poorer than he had ever been before. Scarcely anyone seemed to have any need for a stone-cutter, and even for such work as he did get he was poorly paid. He learned to know what it meant to go without a meal and to be cold as well as hungry.

As Christmas drew near, the landlord of the inn at Plouvinec decided to give a feast for all the good folk of the village, and Bernet was invited along with all the rest.

He was glad enough to go to the feast, for he knew that Madeleine was to be there, and even if he did not have a chance to talk to her, he could at least look at her, and that would be better than nothing.

The feast was a fine one. There was plenty to eat and drink, and all was of the best, and the more the guests feasted, the merrier they grew. If Bernet and Madeleine ate little and spoke less, no one noticed it. People were too busy filling their own stomachs and laughing at the jokes that were cracked. The fun was at its height when the door was pushed open, and a ragged, ill-looking beggar slipped into the room.

At the sight of him the laughter and merriment died away. This beggar was well known to all the people of the village, though none knew whence he came nor where he went when he was away on his wanderings. He was sly and crafty, and he was feared as well as disliked, for it was said that he had the evil eye. Whether he had or not, it was well known that no one had ever offended him without having some misfortune happen soon after.

“I heard there was a great feast here to-night,” said the beggar in a humble voice, “and that all[69] the village had been bidden to it. Perhaps, when all have eaten, there may be some scraps that I might pick up.”

“Scraps there are in plenty,” answered the landlord, “but it is not scraps that I am offering to anyone to-night. Draw up a chair to the table, and eat and drink what you will. There is more than enough for all.” But the landlord looked none too well pleased as he spoke. It was a piece of ill-luck to have the beggar come to his house this night of all nights, to spoil the pleasure of the guests.

The beggar drew up to the table as the landlord bade him, but the fun and merriment were ended. Presently the guests began to leave the table, and after thanking their host, they went away to their own homes.

When the beggar had eaten and drunk to his heart’s content, he pushed back his chair from the table.

“I have eaten well,” said he to the landlord. “Is there not now some corner where I can spend the night?”

“There is the stable,” answered the landlord grudgingly. “Every room in the house is full, but if you choose to sleep there among the clean hay, I am not the one to say you nay.”