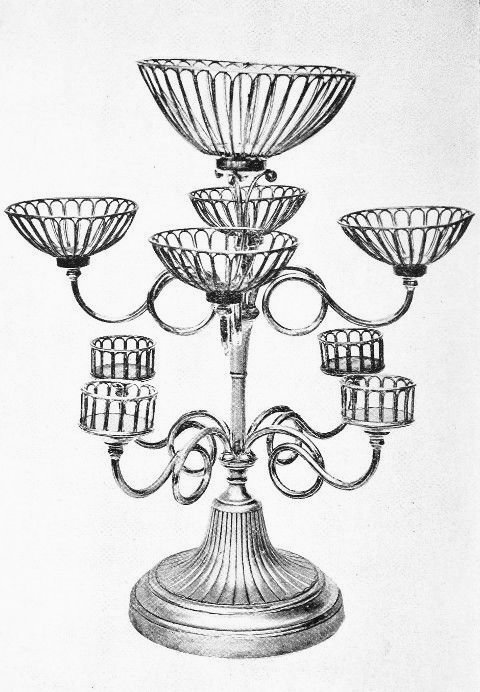

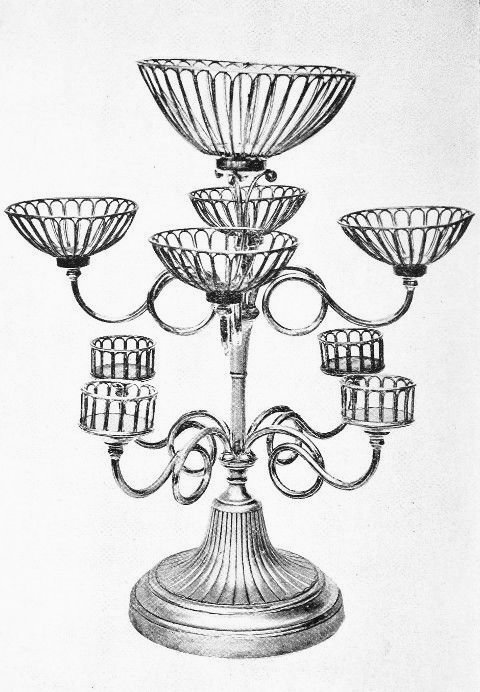

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CENTREPIECE.

On circular base, with nine plated wire baskets for glass dishes on spiral branches.

Date 1775-1780.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

Frontispiece.

Title: Chats on Old Sheffield Plate

Author: Arthur Hayden

Release date: March 1, 2015 [eBook #48392]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Karin Spence and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

CHATS ON OLD

SHEFFIELD

PLATE

COMPANION VOLUME BY THE SAME AUTHOR

CHATS ON OLD SILVER

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

Appendix.—Tables of Date Letters, London (1598-1905)—Table

of Differences in Shields, London

(Elizabeth to George V)—Illustrations of

Marks, London, Provincial, Scottish and Irish

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CENTREPIECE.

On circular base, with nine plated wire baskets for glass dishes on spiral branches.

Date 1775-1780.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

Frontispiece.

BY

ARTHUR HAYDEN

AUTHOR OF "CHATS ON OLD SILVER," "CHATS

ON OLD CLOCKS" ETC.

WITH FRONTISPIECE AND 58 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

INCLUDING 5 PAGES OF MAKERS' MARKS

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE

| First published | 1920 |

| Second Impression | 1924 |

(All rights reserved)

TO MY FRIEND

WALTER IDRIS,

IN APPRECIATION OF

KINDRED RECOGNITION

[7]

Many readers have importuned me to write a companion volume to my Chats on Old Silver, to complete the chain of evolution of the metal-smith's art in regard to silver plate and silver plated ware. Accordingly this volume appears as a complementary and companion volume to that on "Old Silver," and although the former describes the history and character of the silversmiths' work from Elizabeth to Victoria, the present volume covers a much shorter period, approximately a hundred years, when the plater's skill, in what is now generally known as old Sheffield Plate, of superimposing a thin sheet of silver on a copper base, won a triumph in the great art of simulation until it was superseded by the modern electro-plating process.

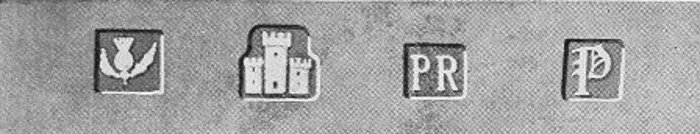

The invention was discovered and first practised at Sheffield, but it soon covered a wider area, and plated ware by fusion and rolled was made at Birmingham, London, Nottingham and elsewhere. But it still retains the name of Sheffield Plate, and nothing can remove this title from the public mind, although it is a misnomer. "Sheffield [8] Plate" is Sheffield solid silver duly assayed at the Sheffield Assay Office, which has existed since 1773, and bears the crown as the town mark together with the maker's initials and the date letter, the same as sterling silver plate assayed at London, Birmingham, Chester, Edinburgh, Dublin, or any other of the assay offices. Sheffield Plated Ware is a copy or simulation of real plate. It was, as this volume shows, possessed of considerable artistic qualities, it was fashioned by craftsmen who were masters of a clever technique, and it is, if not a lost art, certainly an art not practised in the old methods nor with the same exactitude nowadays, and as such it is worthy of the serious attention of the collector.

As to its artistry purists may cavil at its imitativeness. Although "imitation is the sincerest form of flattery" the contemporary silversmiths of London and elsewhere were far from flattered. They began to be alarmed at the growth of the manufacture, and protective Acts of Parliament were passed to safeguard the interests of silversmiths against competition by silver platers.

In regard to technique I have given sufficient details to enable collectors to identify their possessions and to take a further interest in details of craftsmanship.

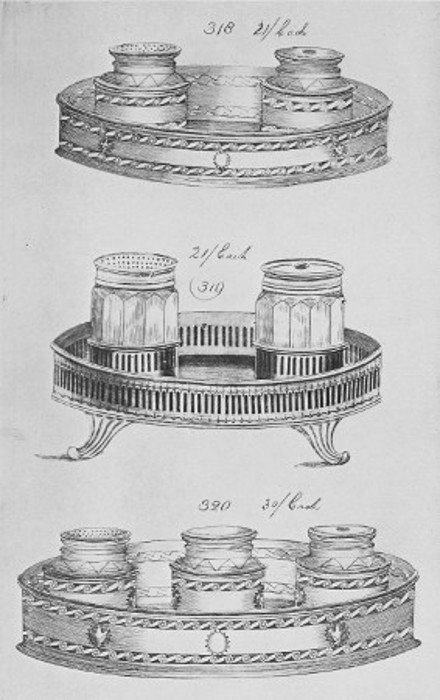

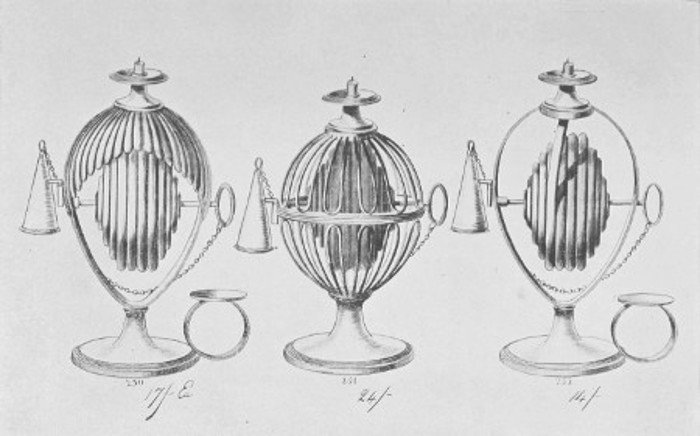

By permission of the Board of Education I am reproducing several designs from the copper-plate illustrations of the old Catalogues and [9] Pattern Books issued to buyers of their wares on the Continent of Europe by the leading firms of Sheffield in the eighteenth century.

In regard to information concerning the manufacture of plate by fusion at Dublin I am under an obligation to Dudley Westropp, Esq., of the National Museum, Dublin, for notes embodied herein relating to the importation of Sheffield plated ware into Ireland and its attempted manufacture there.

I have also to acknowledge the kindness of G. Harry Wallis, Esq., F.S.A., of the Nottingham Museum and Art Gallery, for the inclusion of illustrations of several examples.

The Corporation of Sheffield have allowed me to have special photographs taken of examples exhibited in the Public Museum, Sheffield, and I am indebted to the Curator, E. Howarth, Esq., for his courtesy in enabling this to be carried out successfully.

I have had access by the kindness of collectors to several representative collections. I am especially indebted to B. B. Harrison, Esq., for enabling me to illustrate herein many fine examples from his choice collection.

To Walter H. Willson, Esq., I have to express acknowledgment for allowing me to reproduce illustrations of specimens of old Sheffield plated ware that have passed through his hands for many years, and for much information afforded me in connection with the old technique.

[10]

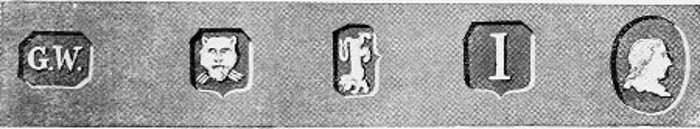

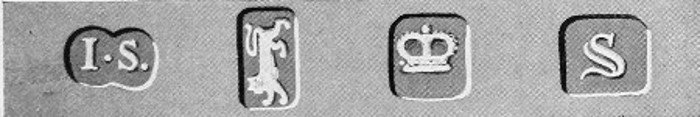

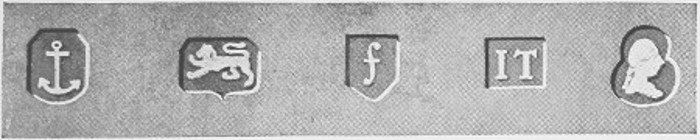

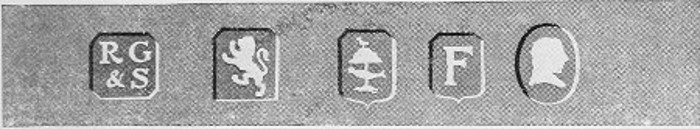

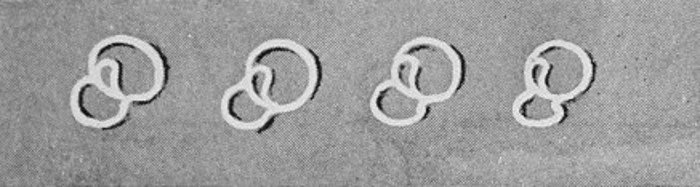

In regard to marks on old Sheffield and other plated ware, in view of strictures on marks laid down by Acts of Parliament, I have come to the conclusion that marks on old Sheffield plated ware are somewhat negligible, as they lack the authoritative exactitude of those placed by law on silver plate. There were marks when the Sheffield makers simulated silver marks till they alarmed the silversmiths and were stopped by statute. Then came a hiatus. Then again they adopted trade marks plentifully found, but these marks are not always found on examples of the best period. So in adjudging old Sheffield plated ware, marks have a subsidiary place, and they are accorded a subsidiary place in this volume.

I submit this volume unhesitatingly to lovers of old Sheffield plated ware as a carefully considered exposition of what was produced for a hundred years, consisting of fine design, exquisite balance, and wonderful technique, till plating became a scientific process and electro-plating became of common usage. But this is modernity.

ARTHUR HAYDEN.

[11]

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | 7 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | 13 | |

| CHAPTER I | ||

| INTRODUCTION | 17 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| EARLY DAYS (THE INVENTION OF SILVER-PLATING BY FUSION AT SHEFFIELD) | 43 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| CANDELABRA AND CANDLESTICKS | 79 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| SALT CELLARS AND MUSTARD POTS | 133 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| CAKE BASKETS, DECANTER STANDS (COASTERS), DISH OR POTATO RINGS, INKSTANDS AND TAPER HOLDERS | 159 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| TEAPOTS, TEA AND COFFEE SETS, TEA KETTLES, COFFEE POTS, SUGAR BASINS | 187[12] | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| SOUP TUREENS, HOT WATER JUGS, THE SUPPER TABLE | 217 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| CENTREPIECES | 243 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| CLOSE PLATING | 259 | |

| APPENDIX, MARKS ON OLD SILVER (1753-1840) | 271 | |

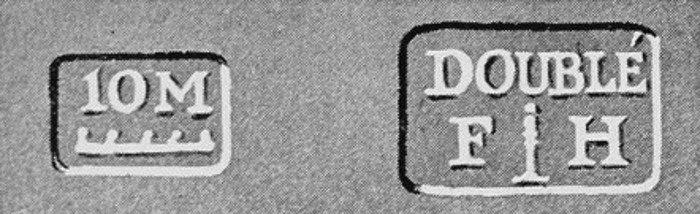

| APPENDIX, MARKS ON OLD SHEFFIELD PLATE (1753-1840) | 285 | |

| INDEX | 297 | |

[13]

| Old Sheffield Plated Centrepiece | Frontispiece |

| Chapter I.—Introduction | PAGE |

|---|---|

| Soup Tureen and Fruit Dish carved in Pear-wood | 29 |

| Wedgwood Dessert Basket and Dessert Centrepiece | 33 |

| Group of Silver Lustre Ware and Glass Candlesticks | 37 |

| Chapter II.—Early Days | |

| Knives, with Medallion of Shakespeare | 51 |

| Wine Label, Buttons | 51 |

| Group of Patch Boxes | 55 |

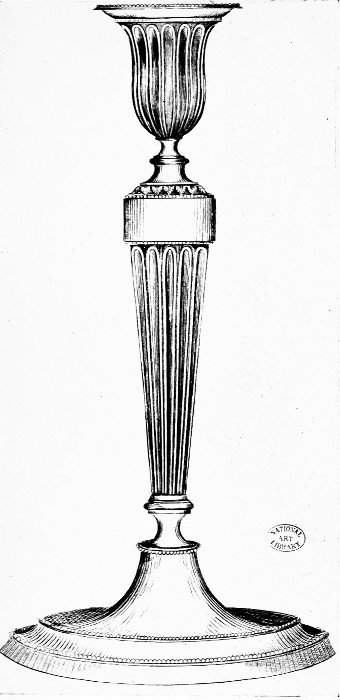

| Candlestick, 1775, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 65 |

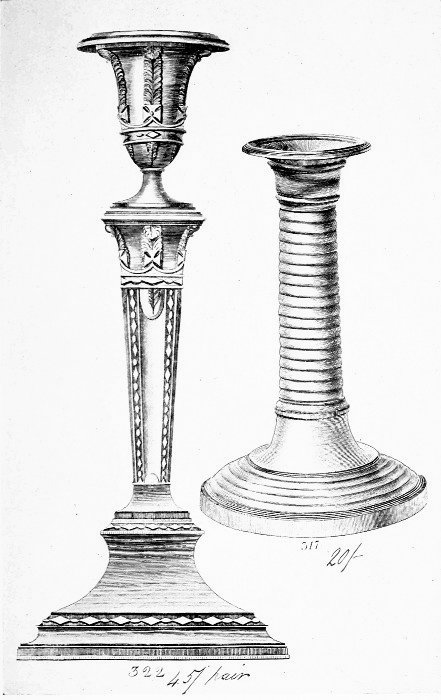

| Candlestick, 1795, Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 69 |

| Candlesticks, 1797, Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 75 |

| Chapter III.—Candelabra and Candlesticks | |

| Candlestick, 1785 | 83 |

| Candelabrum, 1800 | 87 |

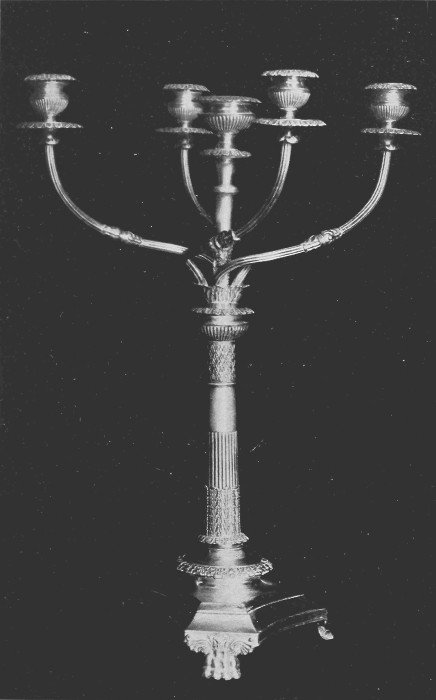

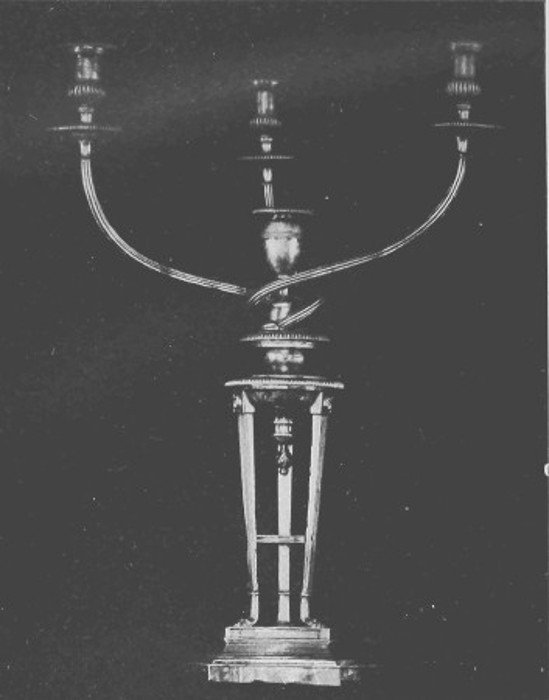

| Candelabrum (7-lights), 1820 | 91 |

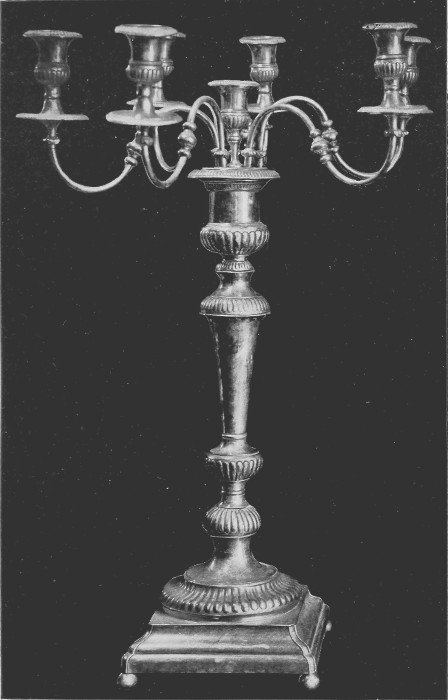

| Candelabrum (5-lights), 1810 | 93 |

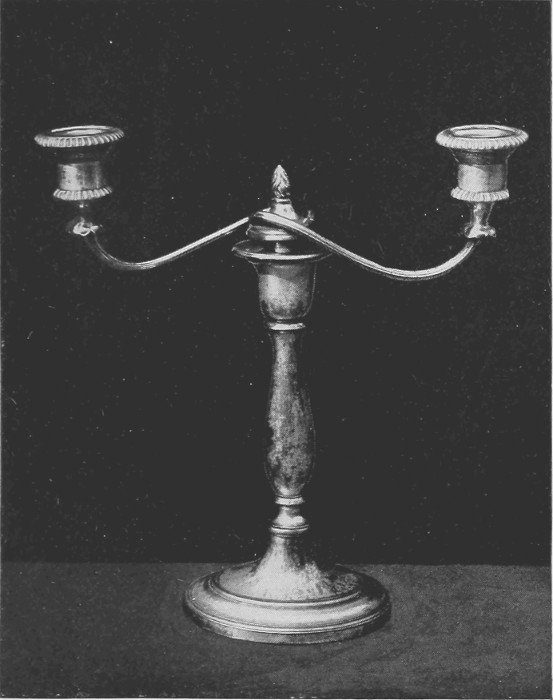

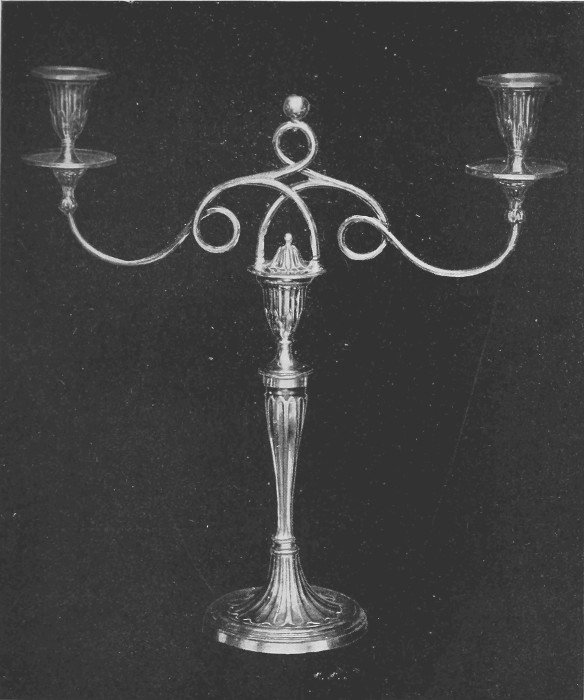

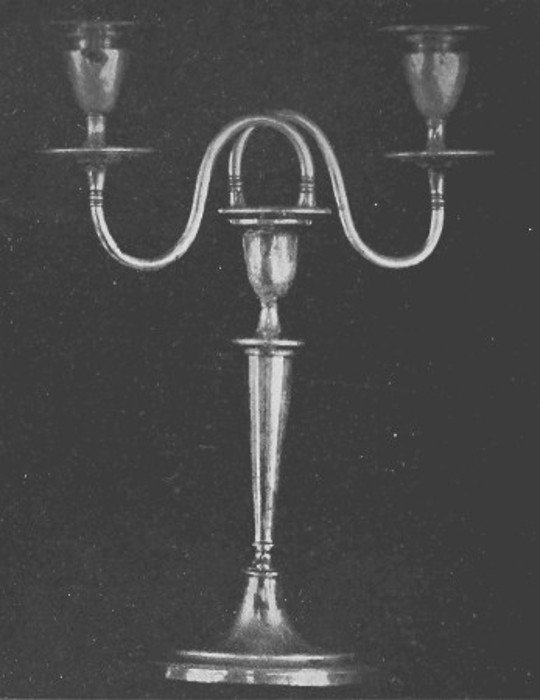

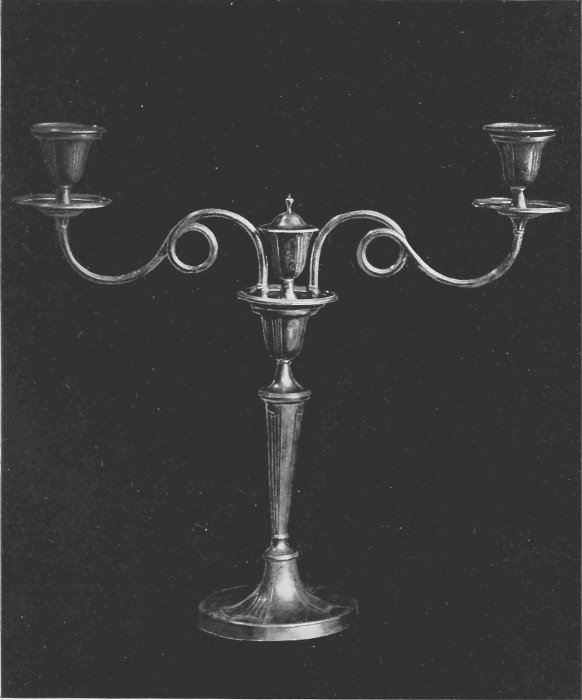

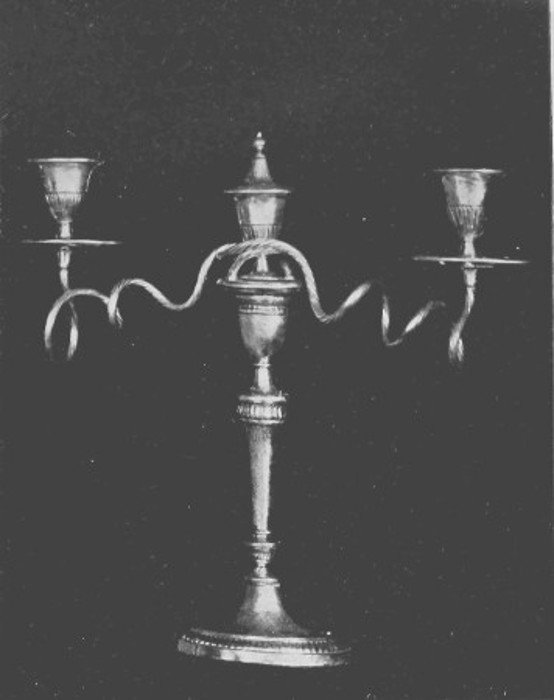

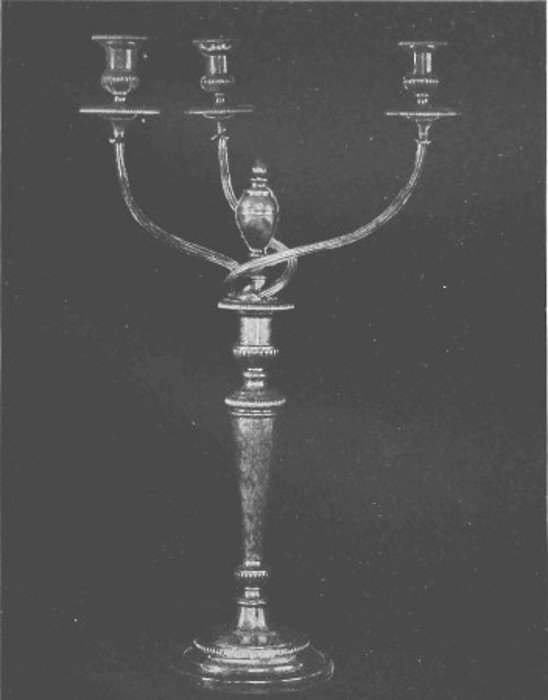

| Candelabrum (2-lights), 1790 | 97 |

| Candelabra, 1790 | 101 |

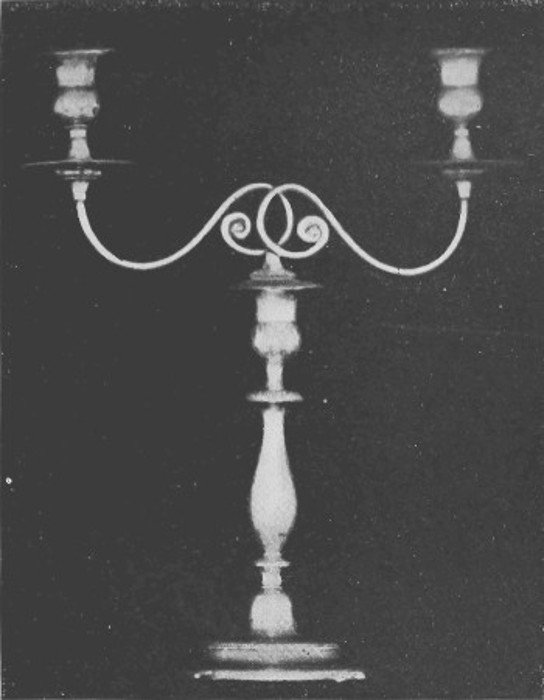

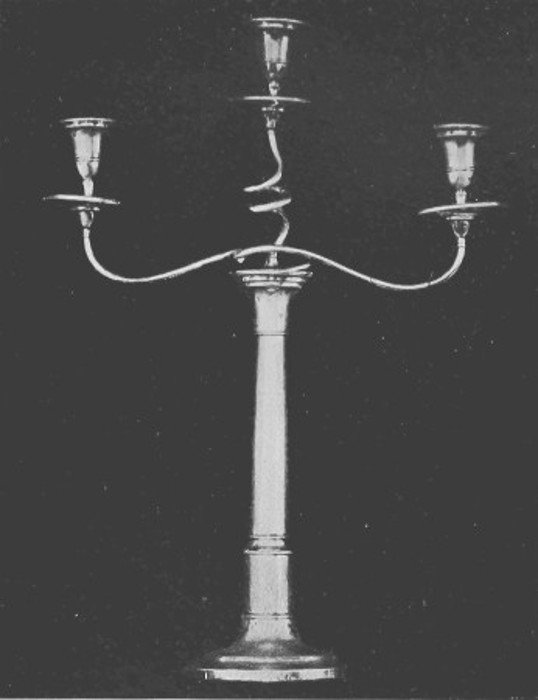

| Candelabrum (Single twist), 1790 | 103 |

| Candelabrum (Double twist) | 107 |

| Candelabrum, 1795; Candelabrum, 1790-1795 | 111 |

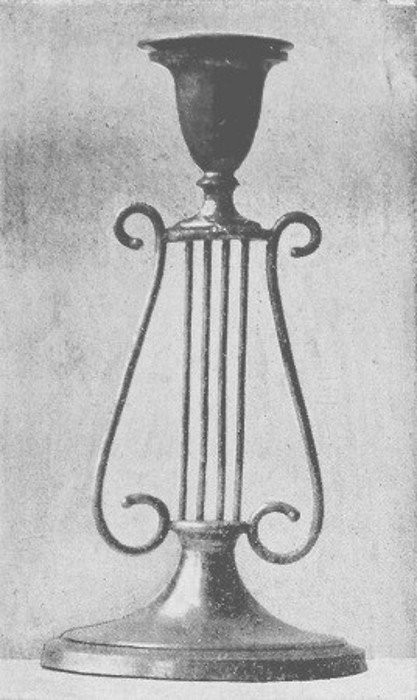

| Candelabrum, Small, Candlestick, Lyre Design | 113 |

| Candelabrum (3-lights), 1805; Candelabrum (4-lights), 1810 | 117 |

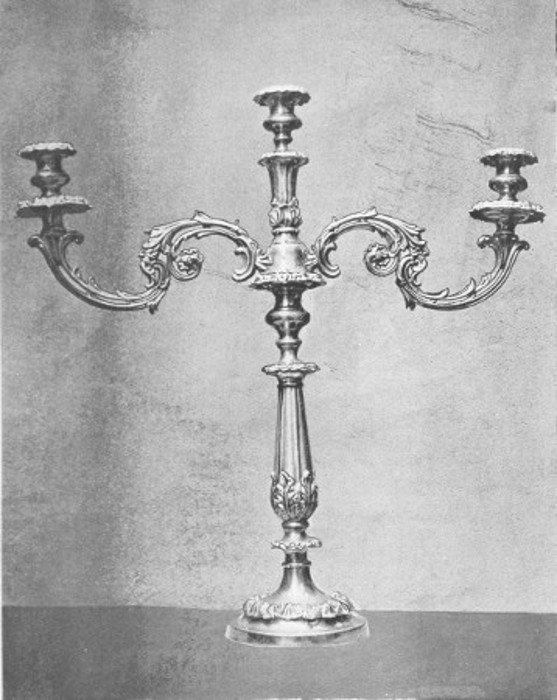

| Candelabrum (3-lights), 1820 | 121[14] |

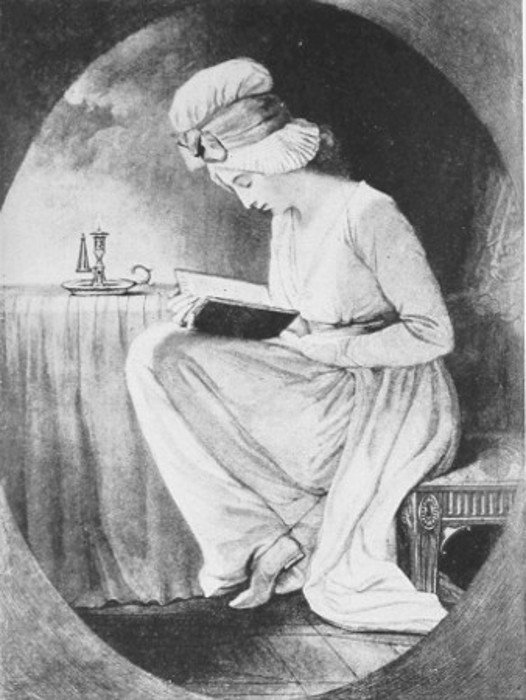

| Old Print Serena (after Romney) Chamber Candlesticks | 123 |

| Table Candlesticks, 1765, 1770, 1795 | 127 |

| Table Candlesticks, 1780, 1790, 1795 | 129 |

| Table Candlesticks, 1810, 1820, 1830 | 129 |

| Chapter IV.—Salt Cellars and Mustard Pots | |

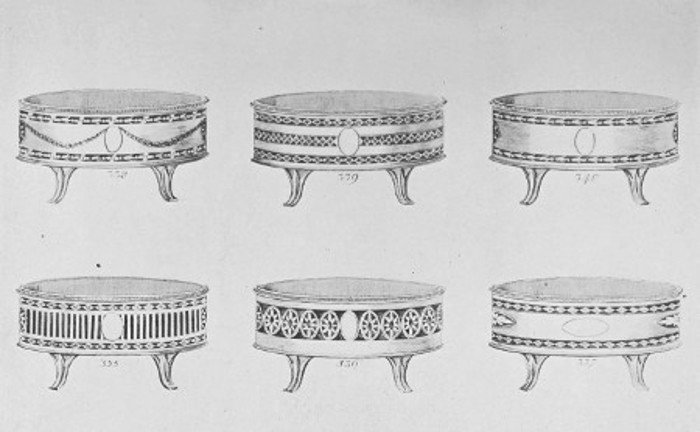

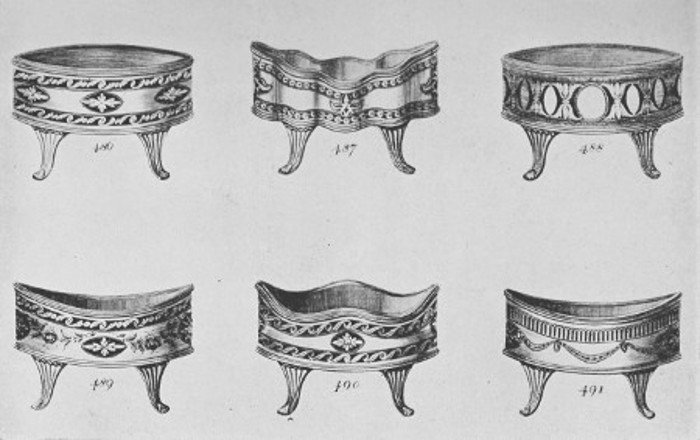

| Salt Cellars, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 137 |

| Salt Cellars, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 141 |

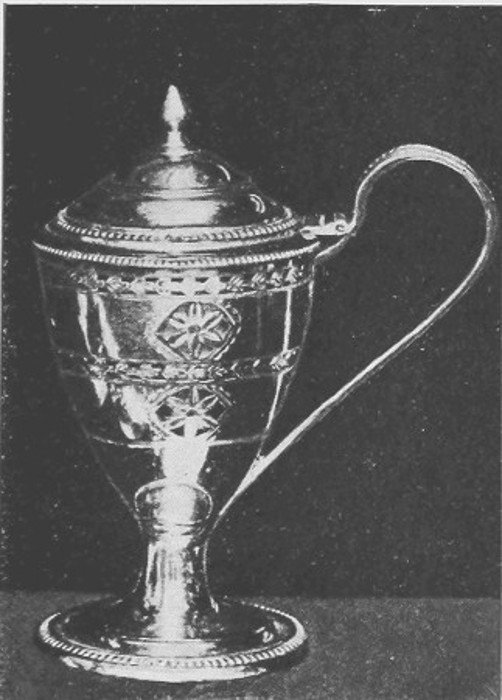

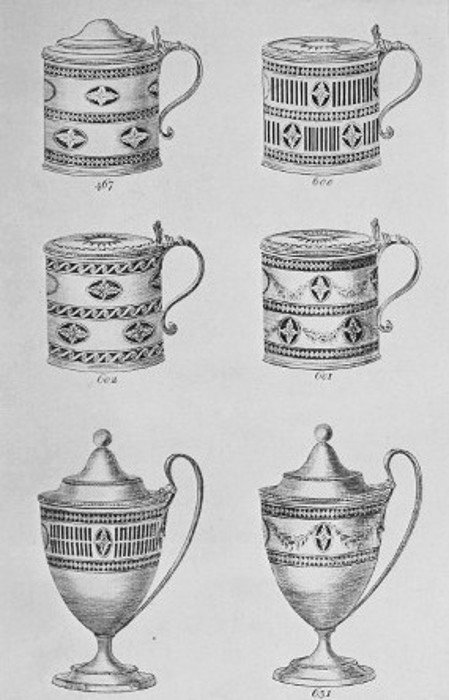

| Mustard Pots, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 145 |

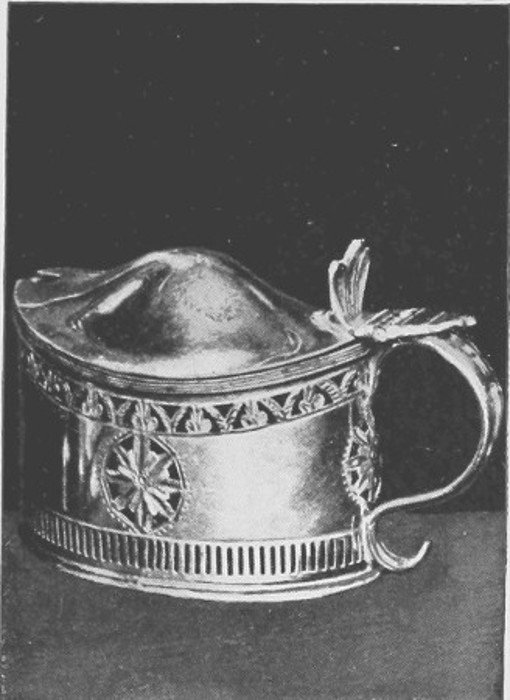

| Mustard Pots, 1775, 1785, 1790 | 149 |

| Mustard Pots, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 151 |

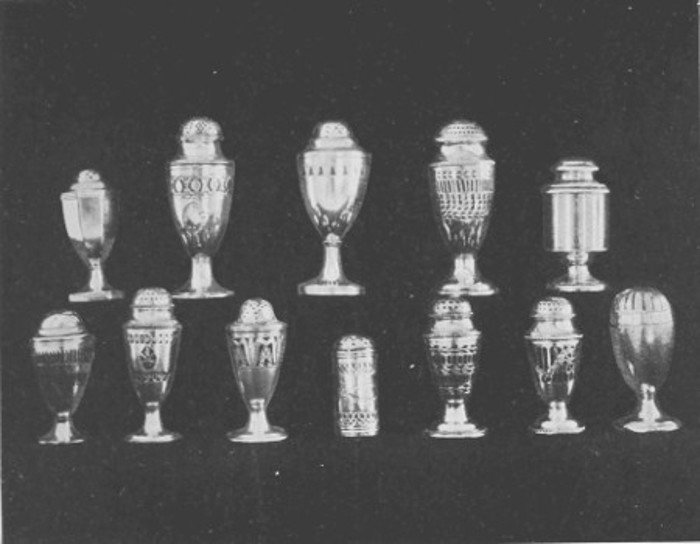

| Pepper Casters, Group of | 155 |

| Mustard Pots, Group of | 155 |

| Chapter V.—Cake Baskets, Decanter Stands, Dish Rings, Inkstands, Etc. | |

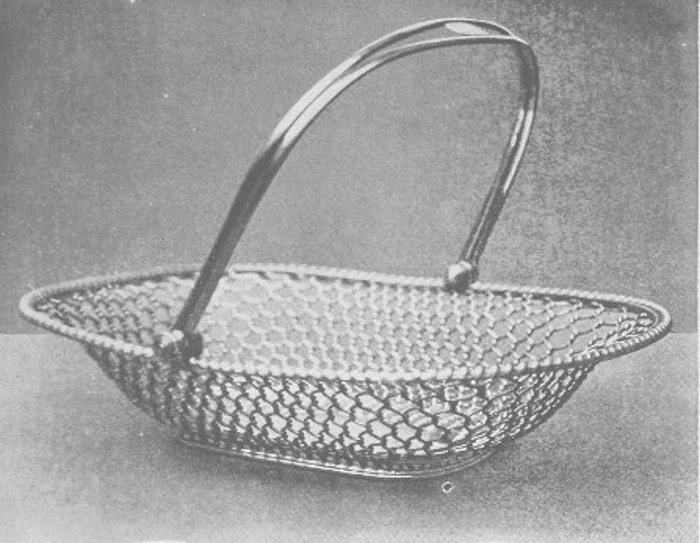

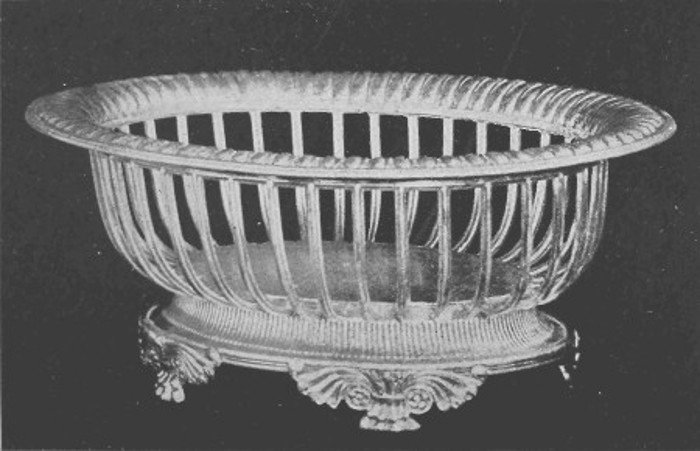

| Cake Baskets, Wire Work, 1800, 1810 | 163 |

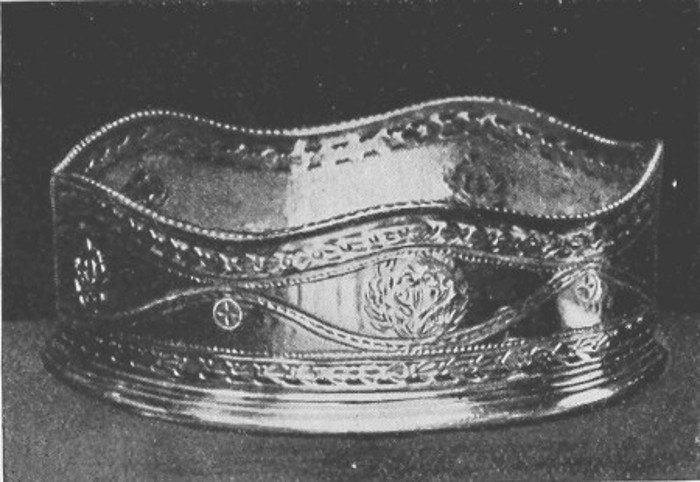

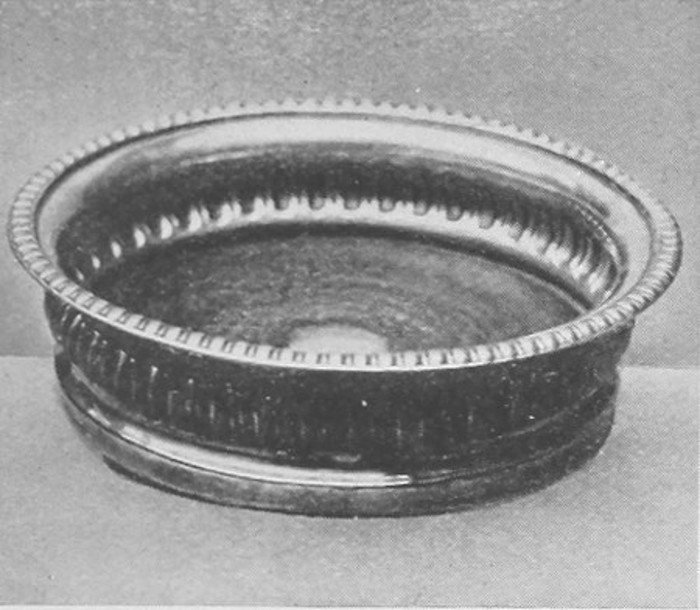

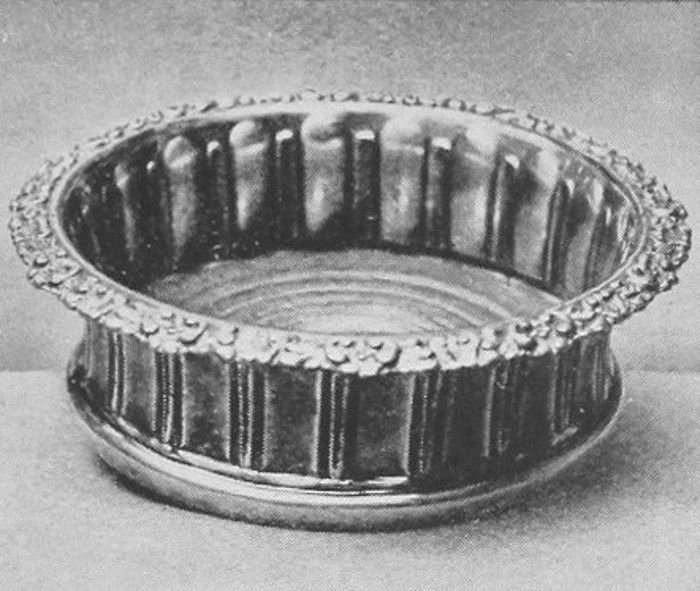

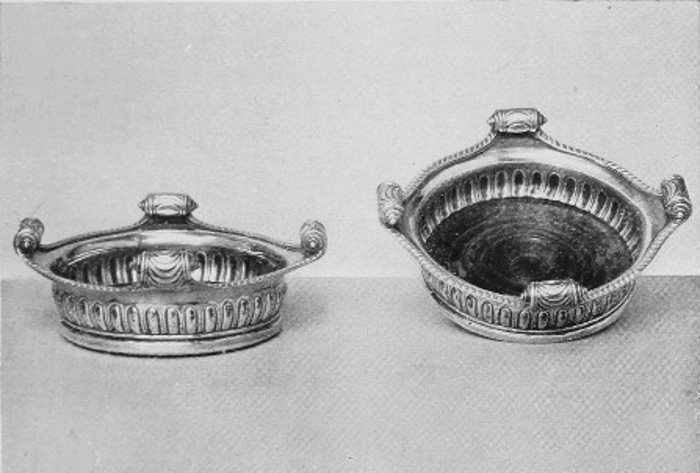

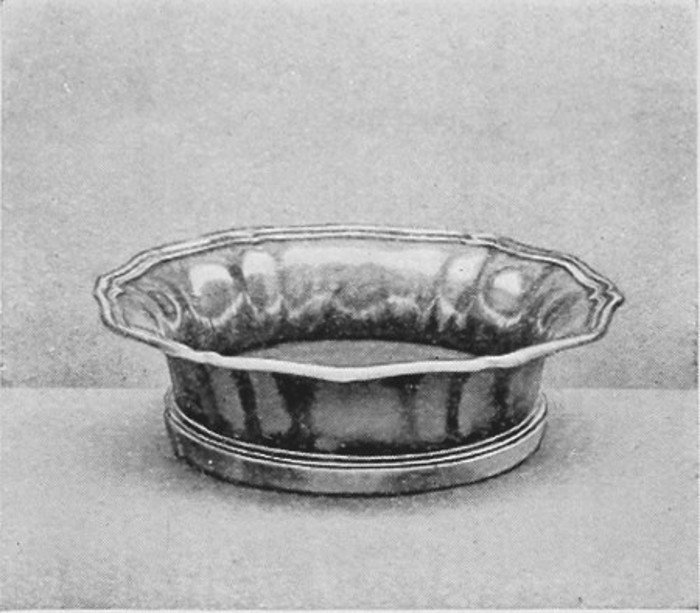

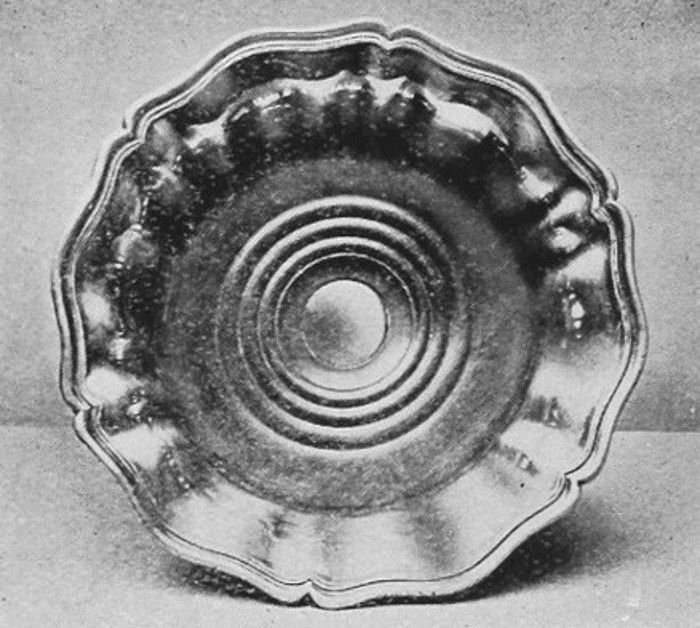

| Decanter Stands (Coasters), Group of, 1785-1790 | 167 |

| Decanter Stands (Coasters), Group of, 1805, 1810, 1815 | 169 |

| Decanter Stands (Coasters), Group of, 1805, 1820 | 173 |

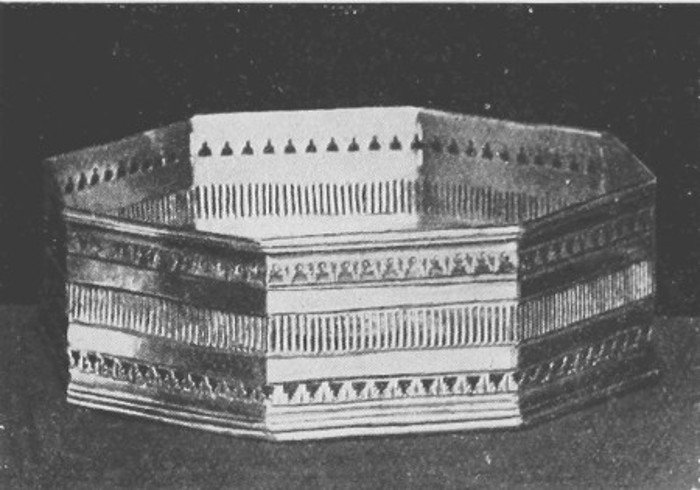

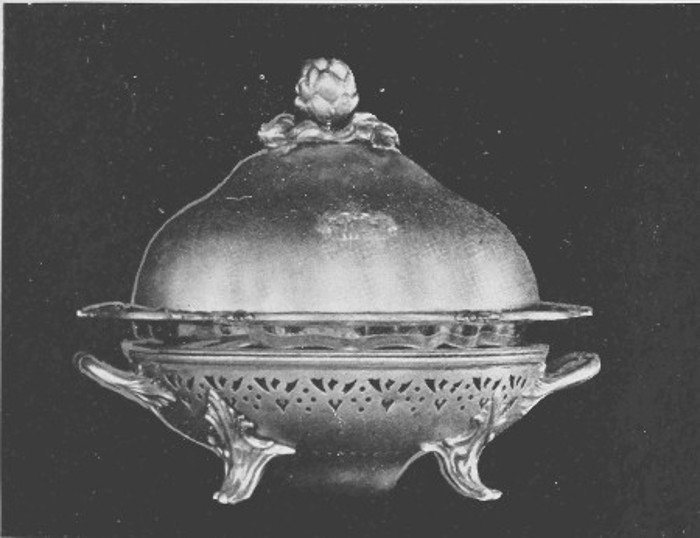

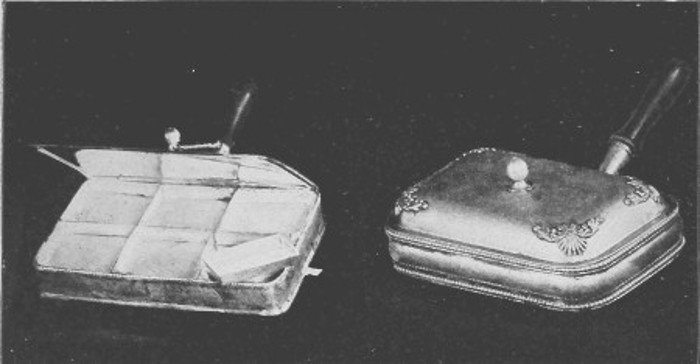

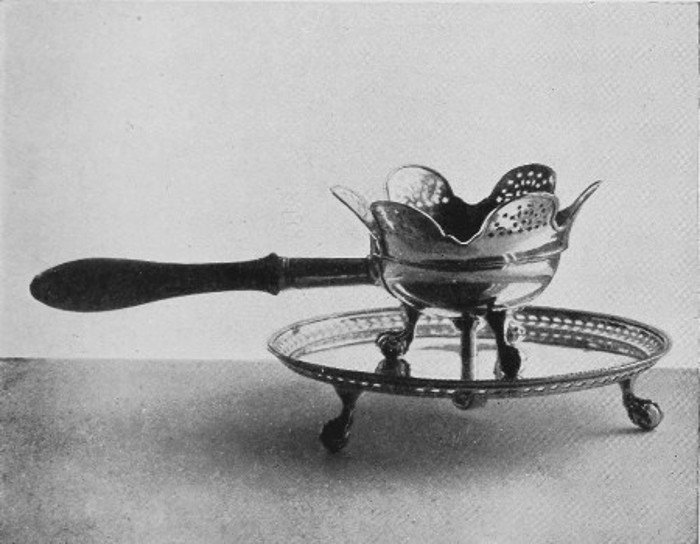

| Butter Dish | 175 |

| Dish or Potato Ring | 175 |

| Inkstands, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 179 |

| Taper Holders, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 183 |

| Chapter VI.—Teapots, Tea Kettles, Coffee Pots, Sugar Basins | |

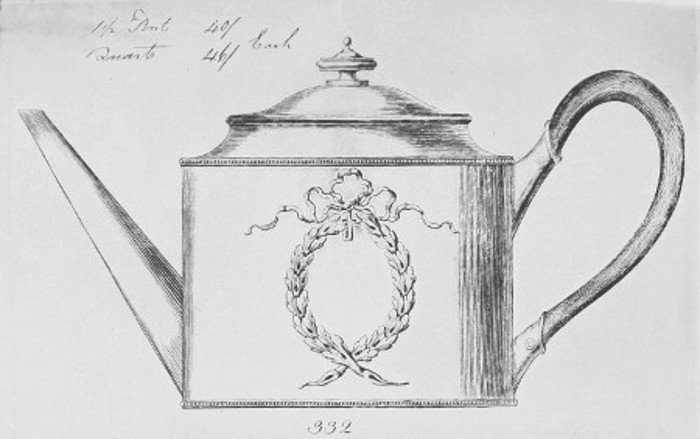

| Teapot, 1792, from Old Pattern Book (18th century) | 191 |

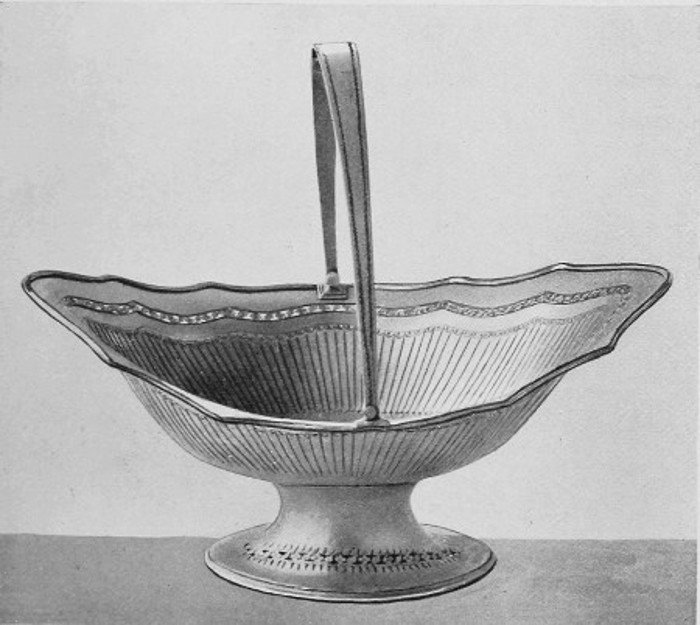

| Teapot and Tea Caddies, Cake Basket | 193 |

| Tea and Coffee Sets, 1810, 1820 | 197 |

| Tea and Coffee Sets, 1825, 1830 | 199 |

| Tea Urn, 1810 | 203 |

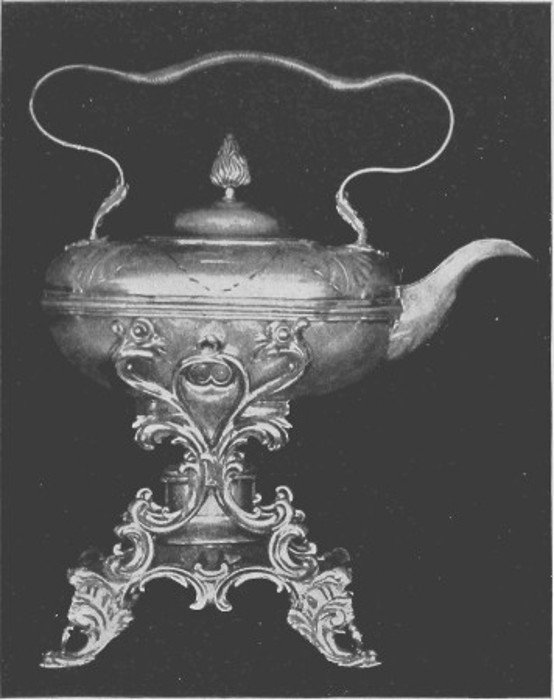

| Tea Kettles and Stands, 1805, 1820 | 207 |

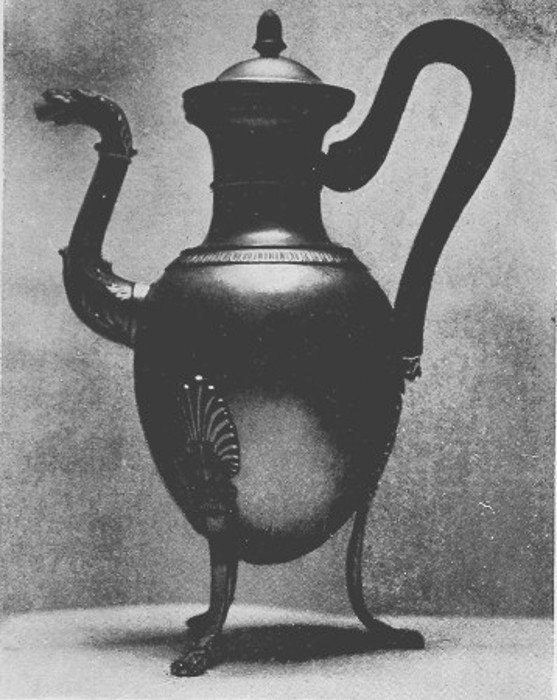

| Coffee Pot, French, Silver-plated; Sugar Baskets, Pierced Work | 211 |

| Sugar Baskets, 1825 | 213[15] |

| Chapter VII.—Tureens, Hot Water Jugs, Etc. | |

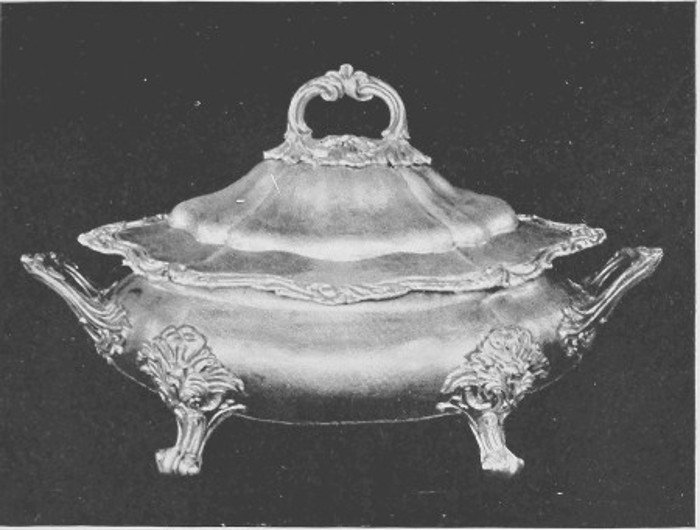

| Soup Tureen, 1805 | 221 |

| Soup Tureens, 1815, 1825 | 225 |

| Soup Tureen, 1815 | 229 |

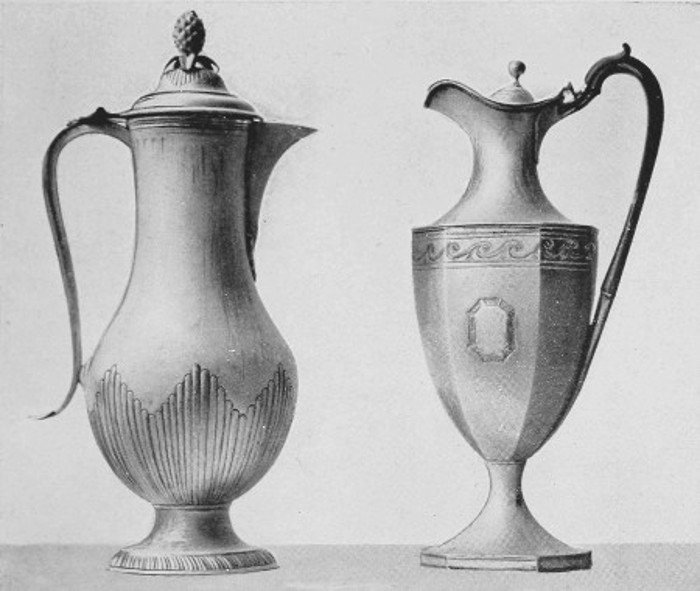

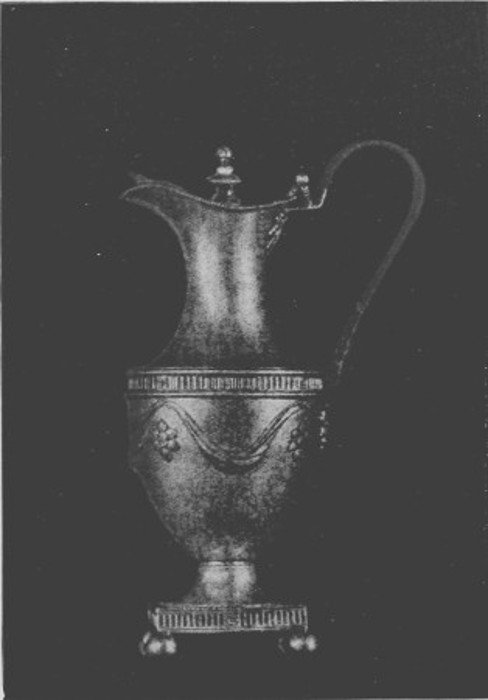

| Hot Water Jugs (2) | 229 |

| Entrée Dishes, 1815, 1825 | 233 |

| Hot Water Jug, Adam style, 1770 | 235 |

| Toasted Cheese Dishes, 1800, 1810 | 239 |

| Pipe Lighter, 1783 | 239 |

| Chapter VIII.—Centrepieces | |

| Centrepieces, 1790, 1810 | 247 |

| Centrepiece, with Female Figures | 251 |

| Chestnut Dish; Fruit Basket, 1810 | 255 |

| Appendix | |

| Marks on Silver Plate | 275, 279, 283 |

| Marks on Old Sheffield Plate | 287, 291 |

[17]

I

INTRODUCTION

IMITATION AS A FINE ART

ECONOMIC SUBSTITUTION

EUROPEAN IMITATIVENESS

PARALLELS IN ENGLISH CRAFTSMANSHIP

EARLY PLATING

SILVER PLATERS AT SHEFFIELD

[19]

Imitation as a fine art—Economic substitution—European imitativeness—Parallels in English craftsmanship—Early plating—Silver platers at Sheffield.

Imitation is no new thing in art. Indeed it may be advanced as an axiom that no art worthy of the name has ever come into being without inheriting the traditions and technique of some preceding motifs. Bizarre movements have at one time and another seized artists and craftsmen, they have become anarchist in regard to all previous art postulates, and produced somewhat chaotic and formless results. The fantastic jazz in art circles known as L'Art Nouveau some years ago, temporarily upset the balance of the younger generation of designers, spent its force in unchecked licence, and ended so ignominiously that it is now entirely forgotten, nor has it left any permanent impression upon succeeding schools.

Now and again imitation has been resorted to by well-known masters to flagellate the taste of their own day. Embittered by constant [20] praise of old works they have made imitations of old masters' styles and foisted them on their critics until at such moment they divulged their authorship and pricked the bubble of the undue adoration of the ancients. Pierre Mignard fabricated a Magdalen and through the complicity of a dealer it was sold as a newly discovered Guido to the Chevalier de Clairville. Presently it was noised about that the painting was by Mignard. Le Brun, the great painter, pronounced it to be a Guido and in his best manner. The jest had gone far enough, the owner, Mignard, Le Brun, and the critics met to settle the affair. Le Brun and the critics adhered to their belief in its authenticity. Mignard protested otherwise, and said he had painted the work over the portrait of a cardinal, and as proof dipped a brush in oil and disclosed the cardinal's hat. Le Brun, bursting with anger, satirically exclaimed, "Always paint Guido but never Mignard." But the canvases of Mignard and Le Brun both hang together in the leading galleries of Europe.

Nor is this a solitary instance of the pique of artists for lack of discernment in contemporary criticism. Goltzius, that masterly exponent of strongly graved lines on the copper, produced and published six prints in the style of Albert Dürer, Lucas van Leyden and others, and one, the Circumcision, was sold as one of Dürer's finest achievements. These six engravings of Goltzius are known among his work as the [21] "masterpieces." They are certainly masterly imitations, and he executed them to show his critics that though his was a new style, yet he could if he chose slavishly follow the manner of the old masters. These are instances of imitation used ironically as a weapon to pour scorn on the mediocrity and want of knowledge of critics.

In pictures there have been whole generations of imitators and copyists. The continent in the eighteenth century was flooded with sham Correggios, Claudes, Poussins, and Cuyps, and many English painters, afterwards well known, did not disdain to make copies for the dealers of old masters' pictures. David Allan, called the "Scottish Hogarth," was an adept in copying chalk drawings from the old masters; and many artists eked out a pitiable existence as copyists while waiting for the public to acclaim their original work. John Jackson copied the head of Reynolds for Chantrey which could have passed for the original by Sir Joshua. A Rubens he painted in the presence of the students of the Royal Academy was acclaimed as faithful to the original. He was unequalled in such facsimile imitations. Henry Liverseege, in the early days of the nineteenth century, copied Vandyck, Rubens, and Teniers with such skill that few could say which was the original and which the copy. Two pictures, one by Sir Edwin Landseer, and the other a copy, were to be sold on successive days at auction. The painter, strolling [22] in to the auction room on the day before the copy was sold, mistook it for his own work.

At the galleries of the Fine Art Society, in Bond Street in 1875, an exhibition was held of a series of facsimiles of Turner drawings in the National Gallery lent by Ruskin and executed for him by Mr. Ward. Of these replicas, Ruskin said in a note: "I have given my best attention during upwards of ten years to train a copyist to perfect fidelity in rendering the works of Turner, and have now succeeded in enabling him to produce facsimiles so close as to look like replicas—facsimiles which I must sign with my own name to prevent their being sold for real Turner vignettes."

Economic Substitution.—But imitation has many phases. Modern photography in copying the great works of old masters has made it possible to study their works with exactitude in the dimensions of black and white, and if the work is an etching or an engraving the reproduction claims a closer relationship with the original. The art of engraving from painters' work is imitative to the extent that it depicts the same subject and takes its initial inspiration from the painted canvas. But it claims a much higher regard—the great school of interpretative engravers translated painting into terms of black and white.

Economically, therefore, it will be seen that there is a real reason why imitative art, on whatever plane it finds itself, should hold its [23] place. In a broad sense it has had a mission. It is true, as Goethe said, that "There are many echoes but few voices"; but the echoes have their value too until they reverberate into nothingness and new voices arise. As a substitute, therefore, for unattainable works of art any medium that will so successfully simulate the original as to convey the lines and the grace, the colour and the harmony, though in a lesser degree than the original, is to be welcomed for its own sake.

There are many occasions when sacrifices have had to be made and when prototypes have been destroyed and substitutes have arisen which have artistically filled the hiatus, if only for the time being. For instance, the extravagance of Louis XIV in regard to sumptuous silver passed all bounds. At a fête at Versailles in 1668 on each side of the royal buffet was elevated on a portico ten feet high a grand silver guéridon bearing a massive silver girandole which lighted the buffet, accompanied by numerous large silver vases. On the table and steps of the buffet, which reached the height of twenty-five feet, were arranged twenty-four massive bowls of fine workmanship—these were separated by as many large vases, cassolettes and girandoles of great beauty. There were on the table twenty-four large silver jardinières full of flowers, in front was a great silver cistern shaped like a shell, at the two extremities were four guéridons, six feet high, surmounted by silver [24] girandoles. Two other tables for the ladies were similarly equipped with masterpieces of the silversmiths' art.

In 1688 the Grande Monarque needed money to carry on his wars, and he issued an edict forbidding the manufacture of such massive silver, and sent all his plate to the Mint. So all this fine work, designed, made by Claude Ballin, Pierre Germain, Montars and other celebrated craftsmen after designs by Le Brun, was melted down; happily the pieces were first drawn by the artist goldsmith Delaunay and their forms are preserved. The king made it compulsory that the fine plate of the nobility should be sacrificed too, and in consequence most of the fine old silver was melted down.

But here comes the imitative note. The age of sumptuous silversmiths' work was followed by an age of fine pottery. Beautifully decorated earthenware and porcelain became fashionable. Rouen made a special service for Louis XIV, and a great impetus was given to the art of the factories of Moustiers, Marseilles and Nevers, and thus the nobles of France had their banquets from the clay of the potter instead of from the vessels of the silversmith.

As will be shown later the relationship between the art of the potter and that of the silversmith has always been somewhat closely allied. The designs of the one have, although not necessarily adapted to a differing technique, been boldly taken and assimilated in results that [25] leave their note of incongruity to be criticized by collectors and connoisseurs to-day.

European Imitativeness.—In order to arrive at a closer appreciation of the niceties of imitation, perhaps it would be better to commence by attempting to understand what is originality and where it can be found. But that would entail a great amount of study. In porcelain one would have to follow the attempts of the Dutch school of potters and bow down in admiration to Meissen, where the first true porcelain was made in Europe. All else is imitative, including Sèvres and Wedgwood and Worcester. Nor does imitation stand arrested at technique, it follows slavishly the oriental prototype in design. We find pagodas and Chinese landscapes, and little figures which meant so much in a language of symbolism, scattered promiscuously on Delft beakers and on Bow cups. Wedgwood, in his Portland Vase, copied a prototype of blue glass. In his classic subjects in relief on his vases and his cameos he builded on the reputation of Greek and Roman types translated through the brain of John Flaxman, and there was a school of potters who came second-hand after Wedgwood and imitatively carried on his classic style.

The whole of the school of decorating furniture in lac is imitated from the East, and a poor imitation at best.

What the glass-worker did at Venice was copied over the Alps in Germany. It suffered in translation and finally became something new. [26] The bulbous appendages to German glass were the crescendo note of the Italian more reticent ornament. When the Murano glass-worker added the tiny griffin-like symbolized version of the small sea-horse found in the Adriatic to the handles of his tazzas, he added a touch of grace and beauty. But the German developed these into chimerical beasts.

In an examination of European art one wonders where imitation ends and where originality begins. Originality unfortunately often begins just at that point when the original touch of genius is lost sight of and when banal excrescences are added, meaningless and offensive.

But originality and fertility of design often begin when experimentalists set out to produce one thing and realized another, and commenced a new technique and became original in so doing. The search for the philosopher's stone was futile, the old alchymists in their laboratories, though they never found the means of transmuting baser metals into gold, made experiments which begat the results of modern science.

Impulses are carried out in various countries in accordance with national limitations. The East African negro who patiently covers a gin bottle with bead-work, proudly displayed as native art by a missionary society in London, is obeying the instinct to embellish and add his own genius to that of the alien. He knows the value the white man puts on [27] the spirit bottle, and he worships afar off at the same shrine.

Parallels in English Craftsmanship.—In regard to Sheffield plated ware, if it be advanced that it was imitative of old silver and therefore negligible, we must claim as a parallel old English earthenware, where, although the technique differed from that of the potting of porcelain, it did simulate porcelain, and examples of the one are found in replica of the other. As to production the reason for imitativeness is often to effect economy. Nor should this be anathema in art. Undoubtedly Staffordshire and all its products struck hard at the English porcelain factories. But, in spite of its initial imitativeness and its wary regard for competitive lines, it did win a path of its own. There the parallel ceases because earthenware was made in England prior to porcelain.

Imitativeness in various arts is common enough. The glass-worker and the potter copied the silversmith. The cabinet-maker was indebted to both and vice versa. We find acanthus ornament in wood and in metal, the strapwork of the Tudor carver on wood and on silver. The cupid in metal on the Stuart clock case is duplicated in the stretcher of the chair carved in walnut, and is found in stone at Hampton Court and St. Paul's in similar ornament. Wedgwood snatched the topographical designs from copper-plate engravings to decorate his service for Catherine II of Russia, depicting English country seats and views. Chippendale [28] borrowed from the Chinese, and echoed Marot, the French designer, in his original designs which burst upon the town in his Director.

Nor does it seem to trouble the collector of china overmuch that Worcester copied oriental models and even used a spurious Chinese mark, that Bow boldly proclaimed itself as "New Canton," and copied Worcester, and that Lowestoft copied both. The invention of transfer printing upon china is claimed by Worcester, by Liverpool and by Battersea, and all three employed designs which were not original. The whole school of designs transfer-printed upon china is imitative, many of them had already appeared as illustrations to books.

Take another art, that of stipple engraving printed in colours. Here indeed is an imitative art. An engraving in black and white is a translation of a subject in colours. When printed in colours it sets out to be imitative of another art. But collectors have not been shy to give as much as four figures for some of these eighteenth century colour prints, greater prices even than the original paintings would bring under the hammer. The subject is illimitable and provocative of much argument.

[29]

SOUP TUREEN AND LADLE CARVED IN PEAR-WOOD.

(At the Wedgwood Museum at Etruria.)

FRUIT DISH AND STAND CARVED IN PEAR-WOOD.

(At the Wedgwood Museum at Etruria.)

As interesting examples showing the versatility of designers, and that potters and silversmiths and woodworkers not only touched at many points but actually assimilated designs more proper to [31] another technique in which they were working. The technique of the metal workers should have little to recommend its adoption by the cabinet-maker, yet we find tea caddies in Chippendale's Director which have details certainly more fit to be executed as mounts by the French ormulu workers than by the English wood-carvers, even though in soft mahogany. Josiah Wedgwood availed himself of many suggestions from other fields than that of pottery. A Soup Tureen and Ladle carved in pear-wood is at the Museum at Etruria to prove this excursion of his for models. This illustration (p. 29) clearly shows a design, although executed in wood, having certain ornaments which more properly belong to the technique of the silversmith.

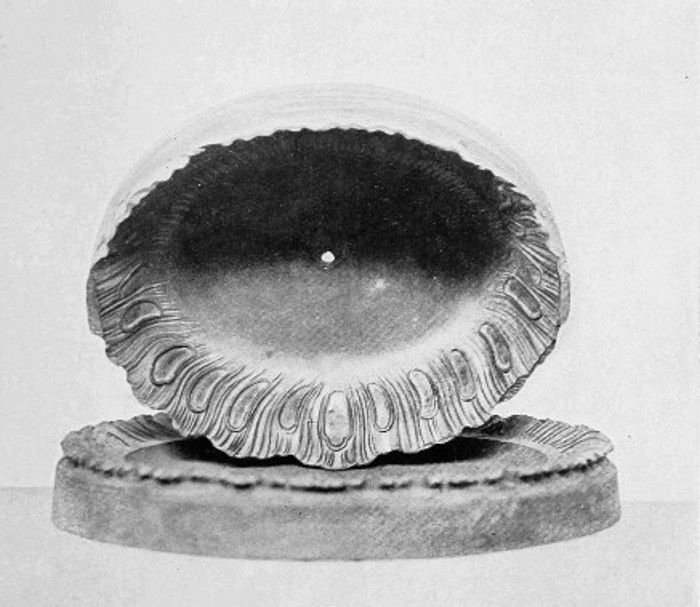

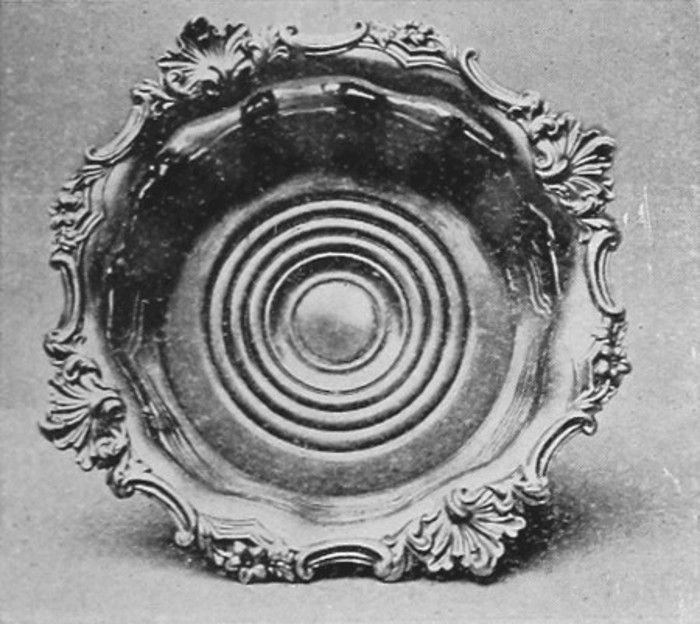

Another carved pear-wood model is that of a Fruit Dish and Stand. Here again there peeps forth not so much the technique of the wood-carver as the peculiar and more easily obtainable ornament of the metal worker. It might be a Sheffield plated Decanter Stand or Coaster.

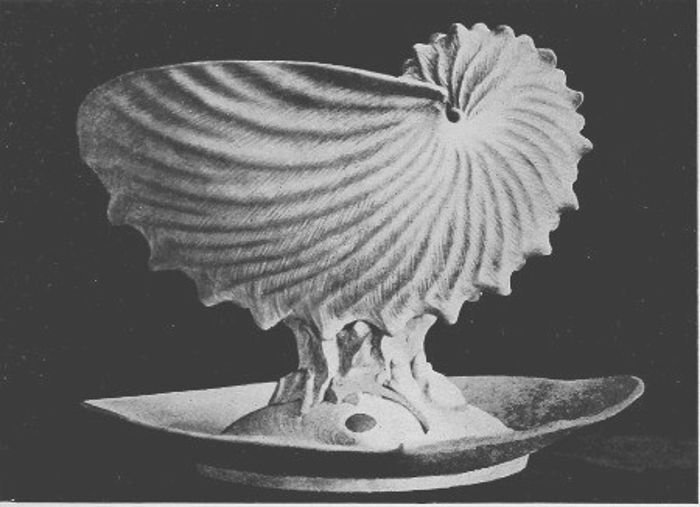

Josiah Wedgwood's collection of shells provided him with many a model for his cream ware dishes. He has used the small flattish escallop like shells—Pholus Æstatus, Pectem Japonicum, Area Antiquat and others, with great effect and crudely suggested the natural colours. In these the silversmiths helped themselves liberally to Wedgwood's models and we find innumerable single shell designs prevalent since their [32] adoption in pottery by Wedgwood. It would similarly appear that they were equally indebted to him for another of his bold replicas of nature in the fine Dessert Centrepiece (illustrated, p. 33). As spoon-warmers and for other purposes the silversmith found this model from old Josiah's conchological collection remarkably practical and accordingly lost no time in imitating it.

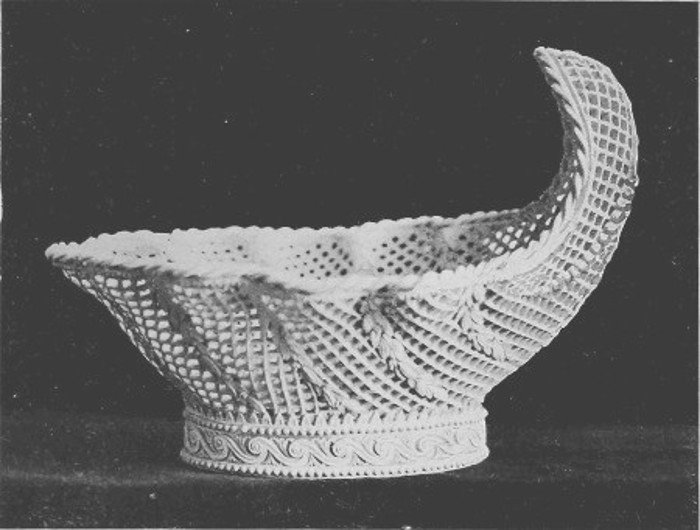

Another Wedgwood piece, a Dessert Basket (illustrated, p. 33) proves that Josiah had his own back, for the pierced ornament is distinctly taken from the silversmith and is more proper to his art than to that of the worker in clay.[1] "One can trace the motives of much of his work, both as to form and decoration, in the collections of various kinds which he was amassing, and in his constant intercourse with the metal-workers of Sheffield and Birmingham. To the former source he was indebted for the designs derived from objects of natural history, particularly shells and plants; to the latter source he owed many shapes and methods of decorative treatment which were used for silver plated ware." His introduction of diapers and other conventional designs in pierced and perforated work come straight from the Sheffield silver platers, and this style of ornamentation done in the same county as Sheffield, at the Leeds pottery, was carried to its extreme limit by Messrs. Hartley Green & Co., who became the most successful imitators of Wedgwood's cream ware, about the year 1783.

[1] Josiah Wedgwood, by Professor Church, 1903.

[33]

WEDGWOOD CREAM WARE DESSERT BASKET.

Showing fine pierced work.

(Reproduced by the courtesy of Messrs. Josiah Wedgwood & Sons.)

WEDGWOOD CREAM WARE DESSERT CENTREPIECE.

Designed from Josiah Wedgwood's collection of shells.

(In the Museum at Etruria.)

(Reproduced by the courtesy of Messrs. Josiah Wedgwood & Sons.)

[35]

The illustration (p. 37) shows the competitive repetition of design contemporary with Sheffield plate. The potter found earthenware, covered with a fine platinum glaze, was a colourable imitation of silver plate. If the squire had his plate and persons of lesser degree more economically inclined had their Sheffield plate, the cottager could have a fine, glittering array of silver lustre vessels. Nor was the glass-worker behindhand in coming into the field, as the illustration shows.

Early Plating.—In early days silver was used sparingly before the Spanish fleets from South America had poured silver into Europe. Ancient drinking vessels of wood such as the mazer, a drinking bowl much like a punch bowl, were decorated with silver bands. Cocoa-nut cups were similarly decorated. By the end of the sixteenth century, solid silver had replaced most of these forms for use in the spacious days of Elizabeth. The early records show that certain goldsmiths were guilty of mals outrages. In the fourteenth century gold was debased by mixing it with glass, silver by adding lead or fine sand. Latten and brass vessels were silvered and passed off as being of solid silver. One Edward Bor in 1376 was summoned before the mayor and aldermen of London to make answer "that he had silvered 240 buttons of latone and 34 circlets of latone for purses called gibesers (gipcières) and had [36] maliciously purposed and imagined to sell the same for pure silver in deceit of the people"; both he and a confederate one Michael Hakeneye were sent to Newgate prison. Another case of John of Rochester in 1414 is recorded where he counterfeited mazer bands in copper and brass, plated over with silver.

It is interesting to read that "no artificer nor another other man shall gild nor silver any such locks, rings, beads, candlesticks, harness for girdles, chalices, hilts nor pommels of swords, powder boxes, nor covers for cups made of copper or latten, upon pain to forfeit to the King one hundred shillings every time, and to make satisfaction to the party grieved for his damages. But that (chalices always excepted) the said artificers may work ornaments for the Church of copper and latten, and the same gild or silver, so that always in the foot or some other part of such ornament the copper and latten shall be plain, that a man may see whereof the thing is made for to eschew the deceit aforesaid."

As to the hall marks on silver[2] the series of Acts of Parliament relating to the assaying, marking and regulating wrought plate and ascertaining the standard "for the good and safety of the public," covers a long period. British hall marks possess a reputation extending over three hundred years. Heavy penalties were exacted for fabrication of marks. In France in 1724 an edict was passed declaring sentence of death against those who counterfeited stamps or insert or solder stamps on other plate.

[2] See Chats on Old Silver, by Arthur Hayden, pp. 25-63.

[37]

GROUP OF SILVER LUSTRE WARE.

Coffee Pot. Basin. Teapot.

The Staffordshire potter's imitation of silver.

GLASS CANDLESTICKS.

Late eighteenth century.

[39]

It is thus evident that baser metals had from time immemorial been plated with silver, and, given an unprotected public, many such frauds could be perpetrated by skilful and unscrupulous craftsmen. In fact they were perpetrated. In 1767 a working silversmith was prosecuted by indictment upon Stat. XXVIII Edward I and Stat. VI George I, cap. 11 for soldering bits of standard silver to tea-tongs and shoe-buckles which were worse than standard and sending the same to the Goldsmiths' Company Assay Office at London in order fraudulently to obtain their marks to the same. In France from 1753 to 1759 a set of regulations to be observed by silversmiths in the profession of their art enacts that "They shall not make the rims turned over full of solder, in form of hammered edges to basins, dishes and plates; nor shall they under pretext of joining, solder on to them other bottoms."

The methods employed prior to the invention of the plating by fusion and rolling in sheets at Sheffield was known as French plating. Throughout the eighteenth century clock cases were silvered by this method, and successive layers of silver could be applied to any thickness required.

Silver Platers at Sheffield.—The platers set out frankly as a school of copyists to imitate silver plate. They laid a thin imposition [40] of silver on copper and rolled it and dealt with the sheets as if they were solid silver. They suffered from many disadvantages which they eventually overcame; they competed directly, and more directly, than did the Staffordshire potters with the silversmiths. The potter snatched the silver models and so did they. But he had less reason than they because he left his proper technique as a worker in clay in so doing. It was no new thing to plate baser metals with silver or with gold. But the method by which it was accomplished and the rolled-out sheets were new. To rush into a general industry to expend great capital on it, to launch it on the market, to compete with the richest and closest corporation of goldsmiths in the world, was a new and audacious venture, and this Sheffield did, and the designs partook of the character of the finest produced by the experienced workers in silver plate.

It is an incongruous situation wherein this school of imitators, who set out diffidently to simulate silver and were presently met by severe statutes of the realm and with severe penalties for producing marks simulating those of the assay offices, overrode the tide that set against them and were finally acknowledged by statute as genuine craftsmen to be protected in a great industry, and Sheffield obtained an assay office of her own, with overlordship over her platers.

In comparison with the other assay offices both Sheffield and Birmingham own titles which seem to convey that the assay offices [41] came into being as a protective measure; they were to be watch-dogs over the silver platers in their district. In 1773 there were, among others, the "Wardens and Commonalty of the Mystery of Goldsmiths of the City of London," the "Incorporation of Goldsmiths" of Edinburgh, and the "Fraternity or Company of Goldsmiths" of Dublin. But the assay offices established at Sheffield and Birmingham were to be "The Guardians of the Standard of Wrought Plate," which is suggestive in the circumstances.

Competitive rivalry in art has often ended in the undoing of a particular school where imitation was pushed to fulsome lengths. When the wood engraver simulated the actual cracks in the canvases of the subjects he was copying on his block he showed a decadence which shortly led to his extinction. But the Sheffield platers never added blemishes of their own to the silver they copied. They produced faithful copies. They selected fine examples and they stood supreme in what they set out to do, until, by a later process, they were superseded.

[43]

II

EARLY DAYS

THE INVENTION OF SILVER PLATING BY FUSION

THOMAS BOULSOVER OF SHEFFIELD (1704-1788)

A WORLD OF KNICK-KNACKS

THE SHEFFIELD SILVER-PLATING PROCESS

EARLY SHEFFIELD PLATED PRODUCTIONS

JOSEPH HANCOCK

THE RISE OF THE BIRMINGHAM AND OTHER SILVER PLATERS

THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE GREAT PERIOD OF SHEFFIELD PLATING

CONTEMPORARY SILVERSMITHS AND THEIR ART

[45]

The invention of silver plating by fusion—Thomas Boulsover of Sheffield (1704-1788)—A world of knick-knacks—The Sheffield silver-plating process—Early Sheffield plated productions—Joseph Hancock—The rise of the Birmingham and other silver platers—The commencement of the great period of Sheffield plating—Contemporary silversmiths and their art.

It was in the year 1743 that a fortunate accident led to the discovery that copper and silver could be fused together, and happily the value of the momentary happening led to the further development of the process and the final perfected invention of plating silver on copper which laid the foundation of a great and flourishing art industry which brought wealth and renown to Sheffield and extended to other centres. The old method of plating continued with various improvements for a hundred years until superseded. During the years 1750 to 1790 some of the best examples were issued and a stream of fine work duplicating the silver plate of the period, and not excluding examples simulating earlier Queen[46] Anne styles, was poured out. Its excellence of craftsmanship and its cheapness not only won the approval of the English public but attracted the attention of Continental buyers, and contemporary with the catalogues of Joseph Wedgwood issued in French and other languages we find that the Sheffield and Birmingham silver platers similarly issued illustrated catalogues with designs showing what they were producing.

Thomas Boulsover of Sheffield (1704-1788).—According to some accounts Thomas Boulsover was a button maker, a spur maker or a cutler, probably he was all three, and employed in the making of these and other metal articles then manufactured at Sheffield. He is spoken of as an "ingenious mechanic." He was probably a practical workman who had a small shop where articles were brought for repair. It was in connection with the repair of a knife handle which was partly copper and partly silver that owing to an accident in the soldering the copper and the silver fused together. Although to his credit he immediately realized the possibilities of his discovery, he was possibly too poor a man to do more than carry out further experiments in a small way and make buttons and snuff boxes and minor articles by his process. His name is sometimes spelt as Bolsover, but it would appear that in the records at Sheffield he registered under the name of Thomas Boulsover and Co., which is possibly more correct; although in days when[47] duchesses spelled their title as "dutchess" matters of a letter or two were not considered very important even in names.

The following extract from the Derby Mercury, September 17, 1788, is an interesting obituary notice of Boulsover:

"On Thursday se'night died at Whitely Wood, near Sheffield, Mr. Thomas Bolsover aged eighty-four. This Gentleman was the first Inventor of Plated Metal: which like many other curious Arts was discovered by Accident. About the year 1750 (at which Time he kept a Cutler's Shop at Sheffield), Mr. Bolsover was employed to repair a Knife Haft which was composed of Silver and Copper; and having effected the Job, the cementing of the two Metals immediately struck him with the practicability of manufacturing Plated Articles, and he presently commenced a Manufacture of plated Snuff Boxes and Buttons. Consequently from Mr. Bolsover's accidental Acquirement, the beneficial and extensive Trade of plated goods had its origin. He has been justly esteemed one of the most ingenious Mechanics that Sheffield can boast." The name Bolsover, says the writer in the Derby Mercury, suggests a Derbyshire origin.

There is little doubt that among the earliest articles to which Boulsover turned his attention were buttons. Silver was in the time of Boulsover being sold at approximately six shillings per oz., and, in view of the cost of solid silver articles, the invention of a presentable process that would[48] lessen the cost came at an opportune moment. It must be remembered, too, that there was a duty of sixpence per ounce upon silver. In 1784 there was an additional duty of sixpence imposed. In 1804 the duty was increased to one shilling and sixpence per ounce, and it is interesting to note that in 1815 by 55 George III, cap. 185 the counterfeiting of the King's head duty mark was made a felony punishable by death. Nor did the invention, although coming at a ripe moment when economies were desirable, seem likely to receive financial support; for the establishment of an industry on a great basis, for the very same motives which necessitated economy, prevented capital from being embarked on what might have been a hazardous enterprise. At that time the country was in a disturbed condition. In 1742 Walpole's administration came to an end. His fall was occasioned by his foreign policy, which was based on friendship with France. He was succeeded by Carteret. His "Drunken Administration," as it was termed, was not likely to instil confidence in the country. He cared solely for foreign politics. "What is it to me," he said, "who is judge, or who is bishop. It is my business to make kings and emperors and to maintain the balance of Europe." In 1744 France declared war against England, and preparations for war were made in America and India. In 1745 Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender, landed in Scotland, was given a public[49] banquet by the ladies of Edinburgh, defeated Sir John Cope at Prestonpans, and marched across the border and through England as far as Derby. His troops must have passed through Sheffield, and with civil war in the heart of the country, and at his threshold, Boulsover no doubt quietly pursued his vocation and added to his experiments. He made snuff boxes and buttons, and patch boxes, and possibly buckles, and waited for a better day.

It is interesting to notice the inauguration of our two great china factories about this date. Derby was not likely to commence a new industry with the Pretender rattling his sabre in the city in 1745. But we find Worcester commencing operations in 1751, followed by Derby in 1756. There is stated to have been a political significance in the advent of the former. It appears that in the cathedral city in spite of its loyalty to the reigning house there was a growing Jacobite influence. It was thought that the establishment of a factory would enable the Whigs to win the election contests which had gone to the Jacobite party. But we do not remember to have heard any such association with Sheffield in regard to the establishment of the Sheffield plating industry. It seems to have been purely a trade venture and supported by local influence and capital.

It is not generally known that for a long period Sheffield has made use of Swedish iron for the manufacture of the best steel. Nor is it public[50] property that "Made in Sheffield" frequently meant that razors, knives, surgical instruments, scissors, etc., were made at Solingen in Germany, and sent as "blanks" to be finished in Sheffield. The Master Cutlers of Sheffield cannot have been aware of these happenings. We speak of pre-war days when we have seen at Solingen much that should shame Sheffield.

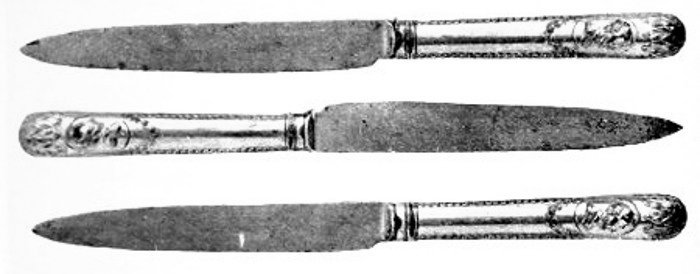

In the early knife handles illustrated (p. 51) the sheet is very thin, and the design is stamped and both halves of the handle soldered together. The thin pointed steel blade is characteristic of old examples. It had not yet arrived to the stage of the trade mark with name of firm "made in Sheffield." There is a fault in design. The object of ornament is to be seen and admired. When these knives were set on a table, the head of Shakespeare in the medallion was upside down. This is a small detail, but details such as these were carefully studied at Sheffield at a later date and ornament used to its fullest capacity.

In regard to the particular design of the head of Shakespeare. There

is a reason for its existence. It comes straight from the days of

the great Shakesperian revival by David Garrick, where in 1741 he

acted Richard III for the first time. Quin and Cibber were outshone

by this new actor, who drew the fashionable world of St. James's to

his little house in Goodman's Fields. He became an idol. In 1742 with

Mrs. Woffington he acted in Dublin for a season and [51]

[53]created a

great sensation. In 1747 he was joint lessee of Drury Lane Theatre.

A Chelsea figure represents him as Richard III and, in complement to

the new worship of Shakespeare who had been forgotten for a hundred

years. Addison had omitted him from his "Account of the greatest

English poets," and Steele did not include him in his essay "A Dream

of Parnassus" in the Spectator. Sheffield, quick to seize an idea of

marketable value, stamped the little medallion of Shakespeare on her

knife handle with an eye to fashionable demands of the day.

OLD SHEFFIELD KNIVES.

With steel blades and plated handles with medallion of Shakespeare.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

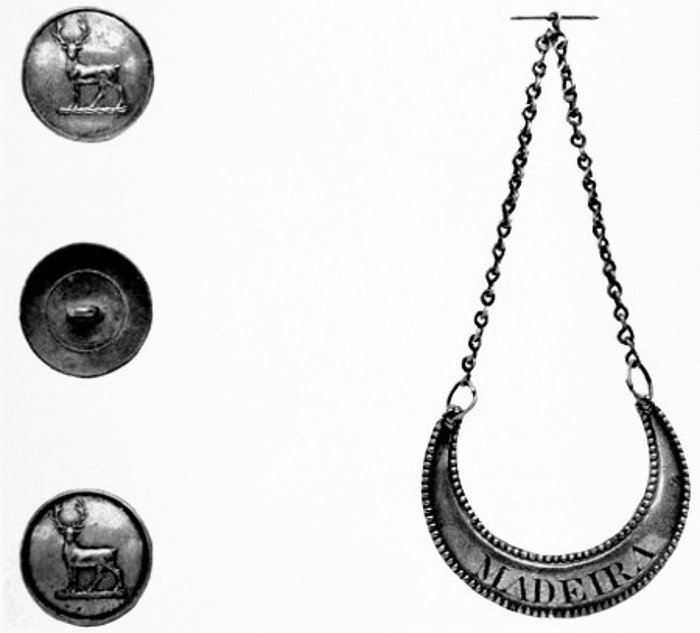

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED BUTTONS. OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED WINE LABEL.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

Buttons were also a strong feature in early days, and continued as a leading feature to the end of the Sheffield plated period. Firms were established in London who carried on this branch till quite a late date. It is stated that a plated button was the first article made by Boulsover. In Ireland John Roche, of Usher's Quay, Dublin, also produced buttons in this style. The designs were stamped according to order. The illustration (p. 51) shows the type with copper shank firmly soldered on to the back. Possibly Army buttons of the same date were similarly made. Collectors have a field here for search and research.

Wine labels, or as they were termed, "bottle tickets," offer, if not great variety of style of decoration, certain curious indications as to the wines and liqueurs they were intended to label. We illustrate a label used for "Madeira." But some of the others were for wines either[54] now known under more familiar names or forgotten altogether, such as: "Shrub," "Bucellas," "Xerez," and others.

The patch boxes (illustrated, p. 55) show the type of work executed in the early days. The plating was carried out on the exterior; the interior of these examples is bare copper. The left-hand example shows in its ornament the swirls and curves of the rococo style which Chippendale adapted and spiritualized in its translation. The right-hand specimen owes something to Dutch influence and to tobacco boxes which were common at the period. It is a genre subject, with the figure of a man standing and a lady reclining on a sofa. The middle patch box is in tortoiseshell and silver, and represents the fable of the Fox and the Crane. The sides and base of this box are plated, and, as in the case of the others, the interior is copper.

[55]

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED PATCH BOXES.

1. Rococo design with floral ornament. Interior of box copper.

2. Tortoiseshell, inlaid with silver. Fable subject: Fox and Crane.

3. Rococo border, with figures of man and woman. Interior of box copper.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

DETAIL OF ABOVE.

(In the collection of B. B. Harrison, Esq.)

A World of Knick-knacks.—The world of London and Bath had set the fashion in trinkets, as much affected by the masculine sex as by ladies of fashion. Buckles, clasps, etuis, snuff boxes were made in gold or silver gilt. But one Christopher Pinchbeck, who died in 1732, a "Clock and Watchmaker and Toyman," as he terms himself on his trade card with his engraved portrait, became a specialist in reproductions and replicas. It is of interest to quote the advertisement of the son of Pinchbeck in the Daily Post, November 17, 1732, as showing [57]what articles he made of a metal in imitation of gold, and with this as a parallel it will be possible to draw a conclusion as to the class of articles of a similar character which were made at Sheffield at a slightly later period:

"To prevent for the future the gross Imposition that is daily put upon the public by a great Number of Shopkeepers, Hawkers, and Pedlars, in and about this town, Notice is hereby given that the ingenious Mr. Edward Pinchbeck, at the Musical Clock in Fleet Street, does not dispose of one grain of his curious metal, which so nearly resembles Gold in Colour, Smell, and Ductility, to any person whatsoever; nor are the Toys made of the said Metal sold by any one person in England except himself: therefore Gentlemen are desired to beware of Impostors, who frequent Coffee Houses, and expose to sale Toys pretended to be made of this Metal, which is a most notorious Imposition upon the Publick. And Gentlemen and Ladies may be accommodated by the said Mr. Pinchbeck with the following curious Toys, viz. Sword-Hilts, Hangers, Cane-Heads, Whip-Handles for Hunting, Spurs, Equipages, Watch Chains, Coat Buttons, Shirt Buttons, Knives and Forks, Spoons, Salvers, Tweezers for Men and Women, Snuff Boxes, Buckles for Ladies' Breasts, Stock Buckles, Shoe Buckles, Knee Buckles, Girdle Buckles, Stock Clasps, Necklaces, Corrals." The advertisement goes on to enumerate "Watches and Astronomical Clocks, which newly[58] invented Machines are artfully contrived as to perform on several Instruments great variety of fine Pieces of Musick composed by the most celebrated Masters, with that Exactitude, and in so beautiful a manner that scarce any hand can equal them. They likewise imitate the sweet Harmony of Birds to so great a Perfection as not to be distinguished from Nature itself."

Pinchbeck articles are now collected. They display fine workmanship and artistic decoration, and true to the asservation of the inventor they have kept their colour in a wonderful manner.

The Sheffield Silver Plating Process.—It has been already shown that the superimposition of silver and gold on baser metals was not an unknown thing, and that many old statutes exist to prevent such wares being substituted for solid gold and silver plate. These earlier processes mainly depended on washing or laying on successive sheets or foils. The Boulsover process consisted in cutting off from a solid bar of copper a rectangular piece some three inches wide, twelve inches long, and about one inch in thickness. This was pure soft copper and easy to work. Later an alloy was made with the addition of a sixth part of brass making the base or body harder. One side of this copper block is carefully filed, extreme cleanliness being employed to exclude any dirt from the surface. A silver sheet of slightly lesser dimensions, after being made thoroughly flat[59] and kept perfectly clean on one side, is laid on the copper with the two prepared surfaces fitting upon each other. The silver was about a quarter of an inch in thickness. Over the silver is laid a piece of sheet iron the exact size of the silver. The three sheets are then tightly bound together by means of iron wire. The whole is then put into a furnace until it is red hot; at the exact moment when it is considered by the skilled workmen that the two metals had properly fused together the block was carefully taken from the furnace and put aside for cooling. It is obvious that if the workmen were careless and did not by constant practice know the correct length of time to allow the operation to continue in the furnace the result would have been a failure. The silver, instead of exactly fusing with the copper, would run over the edges and leave patches where the two metals had not properly adhered. It is the same in old processes such as the tempering of a sword. There are no exact rules, the craftsman must have a sure eye and be quick to act at a second's notice.

Those who have witnessed the cabinet-maker in the exactitude with which he commands his mastery over glueing parts, as is experienced in the manufacture of air-craft parts, know that given perfect conditions of temperature and glue of indubitable character the parts cannot be separated. Similarly in the Sheffield plating the silver adhered to the copper base and remained[60] a component part and not a layer likely to be disturbed by future bending or hammering.

The next stage in the process was the process of passing these blocks under steel rollers in the rolling mills. And during this operation it underwent several further stages of heating or annealing. Here again the workman has to ascertain to a nicety the exact moment to discontinue the firing, otherwise all would be ruined and the silver be burnt off the face of the copper. In glass blowing similar technical difficulties render the art one of great rapidity and quick judgment. At the last stage, by an act of misjudgment, all the previous work might be wasted and the piece turn out a wreck. The fire is a capricious agent. In pottery it is the same. Many a vase after being elaborately painted by the artist and fired in the ovens, owing to some accident, comes out a distorted and misshapen mass.

The result of this Sheffield plating was to produce a sheet which could be manipulated in the same manner as though it were solid silver. The interiors of vessels, it is true, showed the copper, but these were tinned till at a later date silver was placed on both sides of the copper and fused at the same operation in the furnace. In regard to the ornament a good deal found on old Sheffield plated ware was made by the use of dies, such as feet, handles, knobs, and were cast in two halves and soldered together prior to being affixed in their positions on the articles. In other forms[61] of decoration similar to that found on the silver plate of the day the same technique was employed in the repoussé work in producing a raised design on the exterior, that is, by means of hammering against a sand-bag, using a tool on the inside of the vessel. Chasing and engraving is done on the outside while the vessel is filled with sand or with some other composition.

This technique is not confined to Sheffield plated articles; it is the technique of the silversmith, where repoussé work receives its striking force by a tiny hammer from within the vessel; chasing with sunk lines, and elaboration and finishing the repoussé design, is done from the exterior.

In regard to designs, the productions duplicate some of the finest plate. At its best Sheffield plate realized its artistic responsibilities. It did not disseminate shoddy imitations of English plate. Its copies had the saving grace of being executed by men who understood the value of the originals. They worked faithfully in a more economic medium, but they did not debase the original design, and they were too clever to add meretricious touches of their own and mar work which they must have loved or they could not have copied it so truly.

Joseph Hancock of Sheffield.—Thomas Boulsover claims our regard for his invention and his steady application to it on a minor plane. But Joseph Hancock took longer views. He was a member of the Corporation of Cutlers in Sheffield,[62] and he it was who saw to what great uses the new invention could be put if handled on a great scale. He made candlesticks, teapots, salvers, and many other more important articles, and by so doing he raised the process above the snuff-box and button level and established commercially the great industry for which Sheffield has become famous.

Mills were erected for rolling out the ingots, skilled workmen were procured who had served their apprenticeship as silversmiths in London and elsewhere. Sheffield, almost concurrently with the great impetus given to the making of plated silver ware, began to make silver plate. But such solid silver had to be conveyed to London to receive the marks of the Goldsmiths Company of London to denote its standard quality. In regard to embarking on so novel an enterprise as raising a great industry founded on the designs of the silversmiths, there must have been many forebodings as to legal possibilities. The laws on the subject were very stringent. Persons had been fined and imprisoned in the reign of George II for manufacturing plate of lower value than the standard. In 1741 one Drew Drury of London stated that he was inadvertently concerned in making a stamp resembling the "Lion Passant," that he had never made any use of it, and that he had caused it to be broken. The Wardens of the Goldsmiths Company did not accept his confession and proceeded against him.

[63]

Among exceptions not required to be assayed were metal spouts to china, stone or earthenware teapots and shirt buckles or brooches. But silver shoe-clasps, patch boxes, salt shovels, tea strainers, caddy spoons, bottle tickets (wine labels), and all buckles except the above mentioned were, if silver, to be assayed.

It is remarkable to find the Sheffield silver platers somewhat incautiously flying in the face of the protective legislation in regard to silver plate and its marking. In fact, it appears that they recklessly placed three marks on some of the earlier ware resembling those on silver plate. In 1773 a Committee of the House of Commons was appointed to inquire into the manner of conducting the several assay offices in London, York, Exeter, Chester, Norwich, and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. York, Exeter, and Norwich, it was found, were not in operation and had closed down. In regard to evidence a Mr. W. Hancock, a silversmith of Sheffield, said that his work had been injured by scraping. He went to the Goldsmiths Hall of London and "gave some drink to the Assay Master and scraper, since which time his plate had been less damaged." Mr. Spilsbury said that scrapers had the opportunity to deliver to the assayer better silver than they scrape from the work, and that the assayer had the opportunity of favouring what silversmith he pleased. When his plate had been objected to he found that these difficulties were removed[64] on "giving drink at the Hall." This may be said to have been in keeping with the old tradition of the Goldsmiths Company of London, for we read that in 1359 one of the members of the Fellowship was found guilty of mals outrages. He prayed the mercy of the Company and offered them ten tuns of wine. He was duly forgiven on paying for a pipe of wine and twelve pence a week for one year to a poor man of the Company.

The Committee in their Report found in regard to Sheffield and probably Birmingham that "the artificers are now arrived at so great a perfection in plating with silver the goods made of base metal, that they very much resemble solid silver, and that if the practice which has been introduced of putting marks upon them somewhat resembling those used at the assay offices shall not be restrained, many frauds and impositions may be committed upon the public."

[65]

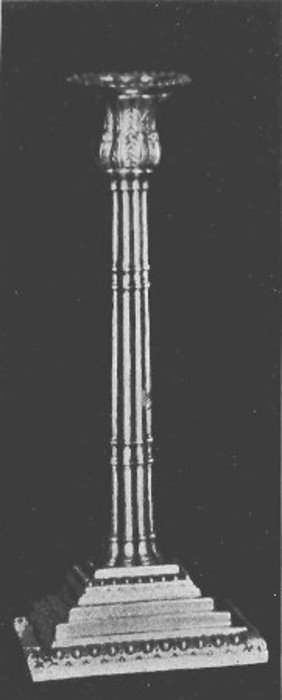

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CANDLESTICK.

Designed in Adam style, 1775. From copper-plate engraving in old catalogue issued by Sheffield makers to the Continental markets.

(At the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

(Reproduced by permission of the Board of Education.)

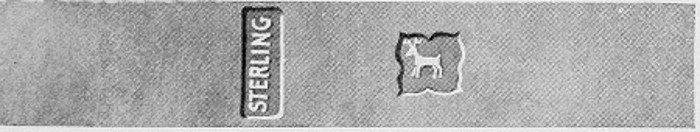

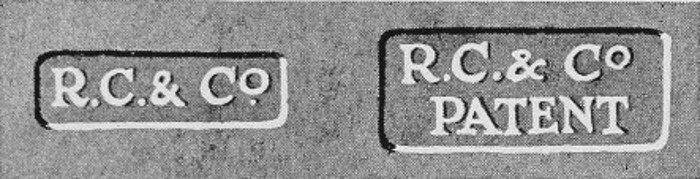

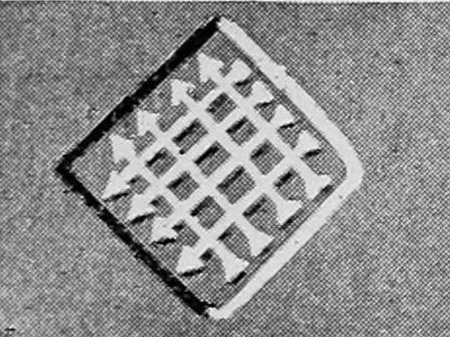

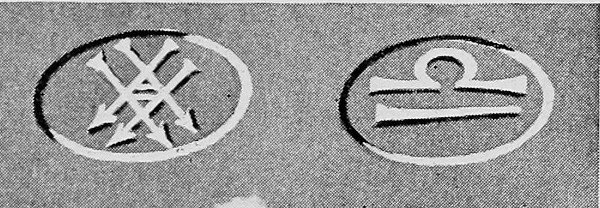

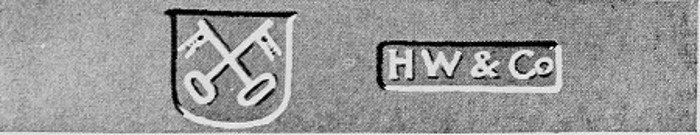

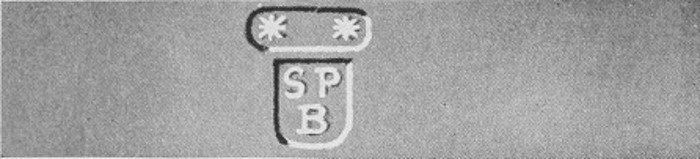

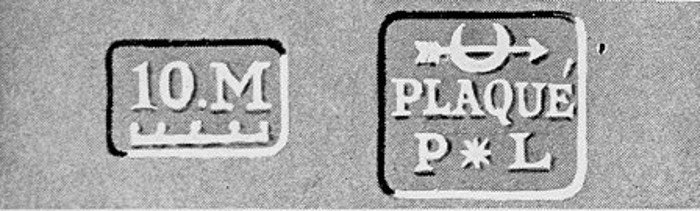

The result was to draw the teeth of the platers by appointing assay offices at Sheffield and Birmingham. The penalties laid down in the Act of 1773 put an end to silver plate being marked. In 1784 another Act was passed, 24 George III, cap. 20, which had some interesting stipulations concerning silver plated ware. "Whereas doubts have arisen whether a Manufacturer of Goods plated with Silver can make or strike his Name upon such Goods without incurring the said Penalty (one hundred pounds): and by reason of such Doubts the Manufacturers of Goods plated [67]with Silver have been deterred from striking their Names upon plated Goods, whereby a proper Distinction betwixt plated Goods of the different Manufacturers is prevented, and all Emulation in that Branch of Business is destroyed: to the certain and manifest Prejudice of the said Manufactory. For obviating such Doubts be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, that it shall be lawful for any Manufacturer of Goods plated with Silver within the said town of Sheffield, or within One Hundred Miles thereof, to strike or cause to be struck upon any Metal Vessel or Thing plated or covered with Silver, his or her Surname, or, in case of any Partnership the name of the Firm of such Partnership, and also some Mark, Figure, or Device, to be struck at the end of such Surname, or other Name of Firm: such Mark, Figure or Device not being the same or in Imitation of any Mark made use of by any Assay Office established by Law for assaying wrought Plate, without being subjected to any Penalty or Forfeiture for so doing; any Thing in the said Act to the contrary hereof notwithstanding."

A later clause lays it down that "it shall be Provided that every such Surname or Name or Firm as aforesaid, shall be in plain and legible characters, and struck with one Punch only."

The clause "within one hundred miles of Sheffield" included Birmingham, which gave a control to Sheffield; but the severe rules as to stamps being the surname or name of the firm[68] made the marking of Sheffield plated articles a cumbrous business and not much to the liking of the silver platers, although it must be regarded as a compliment that they were legally compelled to mark their ware so carefully, apparently for no other reason than that its resemblance to silver plate was so strong that it might be mistaken for the sterling article.

The Rise of the Birmingham and Other Silver Platers.—What Joseph Hancock did for Sheffield Matthew Boulton did for Birmingham. Prior to 1773 the mark used consisted of three stamps with two crowns and the letters B&F (Boulton and Fothergill); in 1784 the mark was two suns struck in duplicate and was registered as M. Boulton and Co. at the Sheffield Assay Office in accordance with the Act of 1784.

The 1773 Act (13 George III, cap. 52) made no provision for the Sheffield and Birmingham platers, but gave powers to the Sheffield and Birmingham Assay Offices. Certain portions of this were repealed, and provision made for the marking of plated ware. But this revision only applied to Sheffield and for some reason Birmingham was omitted, therefore the Birmingham platers, although silver could be assayed at Birmingham, had to put themselves under the ægis of the Sheffield Assay Office. Hence we find Boulton & Co. registering at Sheffield.

[69]

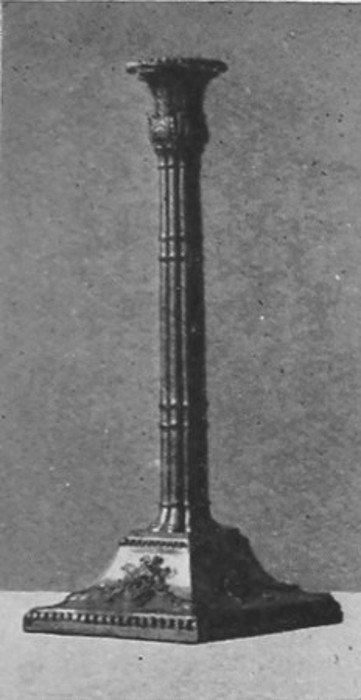

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CANDLESTICK.

From copper-plate engraving issued by eighteenth-century Sheffield plate makers to the Continental markets. Date 1795.

(At the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

(Reproduced by permission of the Board of Education.)

At Nottingham the silver plating industry was established, and in London it obtained so great [71]a stronghold that although it was born in Sheffield it died in London, as the craftsmen, although they found themselves somewhat moribund and a gradually dwindling body, owing to the newest invention from Sheffield—plating by electro-process—held on until some years after the new invention had extinguished the older styles elsewhere, but in the end silver plating by fusion and rolled plate work succumbed.

In regard to Ireland there is some evidence that an attempt was made to manufacture silver plate by fusion and rolling in the Sheffield manner. But very little fused plated ware was actually made in Dublin. Certain premiums were offered by the Irish government for "light plate" made in that country. Light plate evidently being understood to be plated ware. There are numerous notices and advertisements in Irish newspapers from about 1760 onwards announcing imports of Sheffield plated goods. There is no doubt that a considerable amount of Sheffield plated ware was imported into Ireland. The records of one firm show that between 1784 and 1804 plated articles to the value of £60,000 were exported from Sheffield to Ireland. Although the Dublin directories of the period show many names of Irish "silver platers," this is not evidence enough to establish the fact that any of these craftsmen worked in rolled plate; there is every likelihood that they plated small articles in the old manner and later, after the early years of the nineteenth[72] century, with the process known as "close plating." The name "Sly. Dublin" appears on a steel meat skewer plated with silver belonging to these latter days. There is, too, the possibility that some of the Sheffield platers actually exported rolled plate in sheets, though there is no direct evidence of this, as it would have been somewhat suicidal to place in the hands of other artificers the material to convert into what would have been practically Sheffield plated ware although made elsewhere.

But there is confirmation, although somewhat meagre, that plating by fusion was accomplished at Dublin, though apparently only practised to a small extent.

In 1779 the Goldsmiths Company of Dublin complained of the great amount of plated goods imported, and in 1783 the Dublin Society offered a premium of £150, being at the rate of 6 per cent. on value of Irish plate and light plated goods manufactured in Ireland, by rollers, between 1782-3 and 1783-4.

The records show that on November 25, 1784, the sum of £24 7s. was awarded to Christopher Haynes, goldsmith, of Dublin, being at the rate of 6 per cent. on the value of light plate goods entirely manufactured by him in Ireland by rollers, from 1st July, 1783, to 1st July, 1784; value £405 17s. 3d. It is further noted that a premium of £11 17s. 4d. was paid to John Lloyd, goldsmith, of Harolds Cross, Dublin, being 6 per[73] cent. on value of light plated goods manufactured by him in Ireland by rollers, value £197 3s. 3d.; and also premium of £2 2s. 11d. being 6 per cent. on value of plated goods manufactured by him in Ireland by rollers, value £35 10s. In 1792 "A Company of Manufacturers" in Abbey Street, Dublin, advertise plated metal for Button Makers at 4s. 4d. per pound.

The Great Period of Silver Plating.—Contemporary with the growth of Sheffield plating were influences which were very stimulating in regard to the fine and the applied arts. The quarter of a century from 1765 to 1790 teems with rich inventiveness on every hand. In 1768 Sir Joshua Reynolds became the first President of the Royal Academy, and he died in 1792. His brilliant canvases, with their Titian colours, and his children as graceful as those of Correggio, brought noonday into English art. Thomas Chippendale's Director was published in 1754, and the translations of great French styles acclimatized in this country. Horace Walpole built Strawberry Hill in 1750. In 1793 Sheraton's Cabinet Maker's and Upholsterer's Drawing Book appeared. Between these points a great influx of ornament and design burst upon the country. Flaxman was holding a mirror to the classic graces and Wedgwood was translating them into clay. Brothers Adam classicized certain parts of London. The Adelphi is typical. David Garrick lived in the Adelphi Terrace;[74] Antonio Zucchi painted his drawing-room ceiling, and a white marble mantelpiece chimney piece cost three hundred pounds. Great engravers were working in mezzotint and in line: stipple engravers under Bartolozzi's influence produced gems of English art printed in colours. A great outburst of work of permanent artistic quality stamps the period. Nor were the silversmiths behind in perpetuating glorious designs. Here then was the fine field in which the Sheffield platers could browse for inspiration. Their results justify their existence.

How great the industry became is reflected by the series of Design Books issued showing the patterns that Sheffield was able during a period of training of less than twenty years to send to the Continent and that, be it noted, in the days of Louis Seize. The illustrations of Candlesticks from these Design Books illustrated (pp. 65, 69, 75), are described in detail in Chapter III in relation to their technique and artistic features (pp. 86, 89).

Contemporary Silversmiths and Their Art.—For ten years of the reign of George II, and from 1760 to for thirty years of the reign of George III, English plate is remarkable for simple and practical designs embracing the exuberant ornament from the hand of Paul Lamerie and imbued with the classic spirit of Robert Adam. Its variety is a noticeable characteristic, and silver plated replicas carry on the tradition until the second or decadent period when cumbersome and unwieldy design overloaded ornament, and finicking details choked the fine inspirations that had come down from the past.

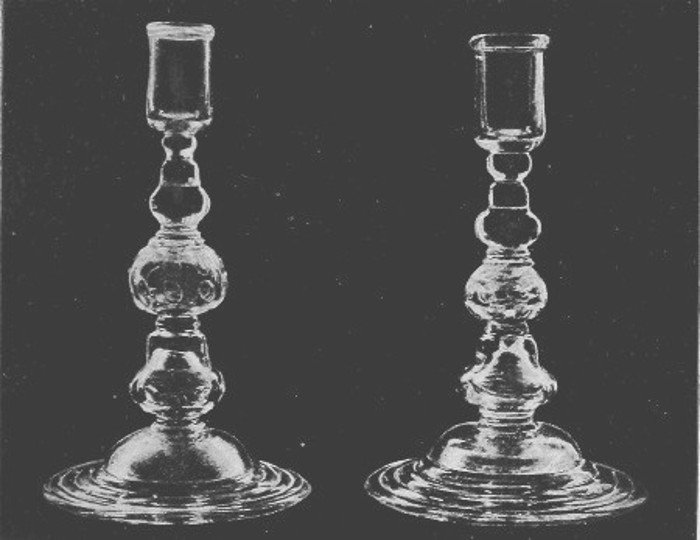

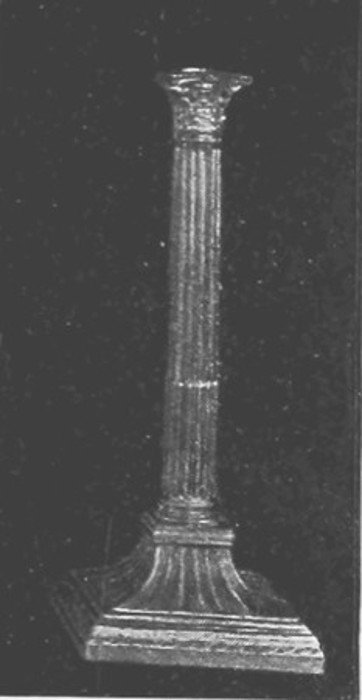

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CANDLESTICKS.

From old Pattern Book issued by R. C. & Co. (Robert Cadman & Co.) about 1797. The prices of the above examples (written in ink) are given at 20s. and 45s. per pair.

(At the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

(Reproduced by permission of the Board of Education.)

The cherubs' heads, the satyrs, the lion-masks, and the engraved and pierced work of Paul Lamerie extended from 1742. Thomas Gilpin was noted for his fine scrollwork; Peter Taylor has fine designs embodied in tea caddies engraved with Chinese figures and embellished with shell ornament. Isaac Duke with his sauce boats with handles formed as dragons and rich chasing and ornament holds high reputation. John Cafe, Edward Wakelin, John Swift and George Wickes all were of the middle eighteenth century and are well known. Daniells, William Shaw in 1785, Orlando Jackson and James Wilkes carried on the traditions. Peter Archambo, who worked a decade or two previously, had left a technique. The designs of Elston of Exeter are still honoured. At Dublin, R. Calderwood in 1750 and William Homer, of Dublin, and John Williams, of Cork, twenty years later were producing masterpieces of delicate artistry. And before the decadence came William Plummer and Paul Storr. It was therefore with no misgiving as to choice of rare design that the Sheffield plate workers set out to immortalize the work of these men with no less courage than did McArdell and the great school of mezzotinters in regard to the canvases of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

[79]

III

CANDELABRA AND CANDLESTICKS

EARLY TYPES

THE ADAM STYLE AND ITS PROMULGATION TO THE CONTINENT

THE CANDELABRUM

THE VARIETIES OF THE SPIRAL FORM

THE TRI-FORM CANDELABRUM

THE CHAMBER CANDLESTICK

THE EVOLUTION OF THE TABLE CANDLESTICK

[81]

Early types—The Adam style and its promulgation to the Continent—The candelabrum—The varieties of the spiral form—The tri-form candelabrum—The chamber candlestick—The evolution of the table candlestick.

In commenting upon early types of Sheffield plated candlesticks a good deal of past history has to go by the board. One does not need to discuss pricket candlesticks of ecclesiastical form. Unfortunately the exquisite Stuart examples, the symmetrically ideal forms of the Charles I period, so rarely found, and the finely balanced types of the Charles II, James II and the William period pass—as they were never duplicated by Sheffield.

Sheffield commences with George II and Sheffield ended with George III. Happily the banalities of the early-Victoria era never encompassed her craftsmen. Therefore, the early types of candlestick belong to the days of George II. They belong to the days when Boulsover looked to Joseph Hancock, the master cutler, for inspiration, and Joseph Hancock the cutler of Sheffield set out on a true path. A certain modernity was in[82] the air. The year 1751 had only 282 days, and the year 1752 only 355. The calendar was in process of reform. Joseph Hancock's types of the early days (we are speaking of 1750 to 1765) must have been the ordinary types made by the great silversmiths, though it may be imagined, as though in leading strings, Sheffield gently pursued her way with experimental copying.

To come to technique there were the edges of the silver and copper plate, an ugly witness of inferiority. These must be hidden somehow by godrooned edges, of solid silver maybe, rather than show the poverty of the rolled plate. If they were cast then there were the seams to screen from common observation. To this day the seams denote the genuineness of the old plate. Dies came into being. Portions were cast, ornaments were soldered together and attached to the article. At first there was always the factor determinable enough by close inspection that the silver was only on one side of the copper. The interior of vessels was copper, which was tinned. In candlesticks this was not a very formidable obstacle to successful imitation, as the nozzles could be French plated and otherwise concealed. The bottom could be plugged with a mahogany post and filled with solder, could be covered with shellac at the base and have a fine baize screen from all obtrusive gazers. But Sheffield soon got above and beyond any of these artifices.

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CANDLESTICK.

One of a pair, with finely shaped facets, decorated with leaf ornament. Date 1785.

(In the possession of G. H. Wallis, Esq., F.S.A.)

It is curious how collectors have come to love [83]

[85]the candlestick,

possibly it is because it represents something that vanished during the

horrible era of the gas chandelier and the paraffin lamp, and has been

resuscitated in later days in the form of an electric chandelier or in

electric standards. Electricity has galvanized the old candlestick and

the antique candelabrum into life. The Dutch hanging brass pendants are

now one of the stock lines of the electric fitter who furnishes the

villa in pseudo-Jacobean or pseudo-Georgian style. The shopwalker or

his satellites will pronounce empirically upon styles with the surety

of an encyclopædia. In consequence all electric lights are hall-marked

with "periods": they are "Adams" (sic), or "Chippendale," or

"Sheraton." Possibly collectors of another age may find shoddy written

over a lengthy period of our modern fitments for illumination.

The Adam Style and its Promulgation.—That Sheffield did great things in candlesticks is shown by a visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum. One of the finest examples of the classic style with urn shaped nozzle with classic pilaster column, both urn and base decorated with festoons in classic style, of the period of 1782, is a Sheffield silver candlestick. Sheffield was undoubtedly making fine silver candlesticks and candelabra at this period, and this is not unimportant in regard to the consideration of what she did as an echo of such work. During the last twenty years of the eighteenth century her output was[86] of the highest character. Since 1773, as we have shown, Sheffield had stood on her dignity as the proud possessor of an assay office with all the newly acquired rights of silversmiths jealous of infringements on so close a corporation. This had, without doubt, an enormous influence on the quality of the work perpetrated by the silver platers. Sheffield made a bid to become a silversmiths' centre and she has not lost her ancient ambitions to-day.

In the illustration given (p. 65) of a candlestick from a copper-plate engraving of pure Adam style, in date about 1775, it is seen how far Sheffield had advanced to be able to send such pattern books with designs broadcast to buyers of her ware on the Continent of Europe. This and another illustration (p. 69) indicate the class of candlestick Sheffield was prepared to export. Sheffield had not snatched at renown, she had won it. A series of Design Books of the period, from which we reproduce illustrations, establish the fact that Sheffield plated wares were as acceptable on the Continent as being something especially English, as were the equally original products of Wedgwood in pottery, and at a later date the Ironstone Ware of Mason, where it is said that he inflicted more injury upon the French potters than did the English fleet under Nelson.

OLD SHEFFIELD PLATED CANDELABRUM.

With two lights detachable for use of standard as a single light. Removable nozzles. Date about 1800. Showing signs of copper owing to bad usage.

(In the collection of Author.)

These are trade matters, but interesting withal, as they show the rapid

rise under careful and [87]

[89]

patient intuition of skilled craftsmen whose

resplendent models tempted the Continent to buy our replicas where

perhaps the original work was either not proffered for sale or was too

expensive for the continental market.

We give another illustration (p. 75) of two table candlesticks, 1797 in date, sent out, as the catalogue states, by R. C. & Co. (Robert Cadman and Company). In one example we have the favourite design of the ostrich feathers beloved of Hepplewhite and others in the chair backs of the same period. The classic influence of Adam is waning. There is nothing purely Grecian in the column. The Ionic pillar has long since disappeared. We have something as a substitute in design. The Maltese cross as a novelty finds itself as a feature in the design. It is composite, it is in a measure feeble in comparison with previous designs. It marks the oncoming period. It is just the sign of something confused in the design. We shall soon see something not only confused but extremely mixed and utterly banal with false and meretricious ornament, with little meaning except that here it stands, as ornament or as attempt at ornament, but as to balance or symmetry—that has been irretrievably lost. The age of decadence no one can explain. One marvels as much at ineptitude as at beauty in design.

Happily the Sheffield designers went backwards for some of their designs in a period that threatened decadence. The smaller of the candlesticks[90] (illustrated, p. 75) suggests the reticence and simplicity of a brass candlestick of the Stuart period. As such it must be regarded. It stands quietly unassailable in its English dignity.

A fine clean-cut example, in date 1785, of pure design, with facets sharply cut and decorated with acanthus leaf design in due subjection, is illustrated (p. 83). The urn stem and the urn nozzle determine the period, and the candlestick stands on a fine round base. Its clear defined reticence is almost like cut steel work on a minor plane of the same period, such as frames to cameos and later adapted to purses and chatelaines. Cut steel mounts to clock faces belonged to the coming Empire days. Here, in this candlestick illustrated, is an indication of facetted work as clean cut as glass, which in its working and in its technique is a metal too.

The Candelabrum.—Whatever may have been the varieties of the

hanging candelabrum in Dutch interiors, finely wrought brass and copper

with a variety of designs always pleasing and so attractive as to find

a ready duplication as a modern electric light candelabrum, we do not

find the table candelabrum at an early date in England. As days went