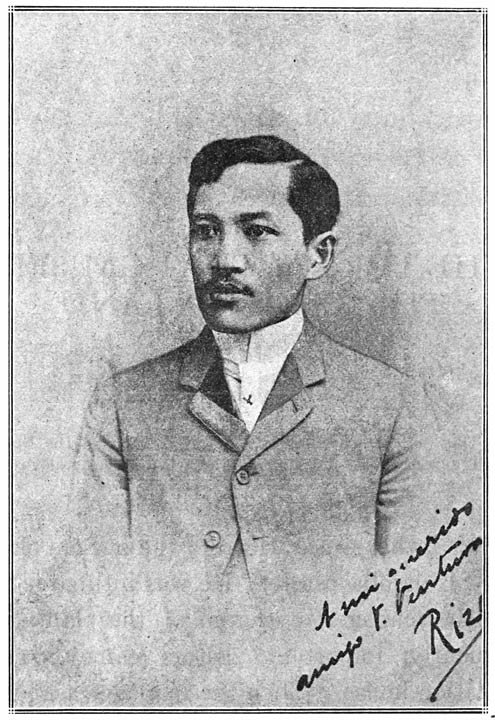

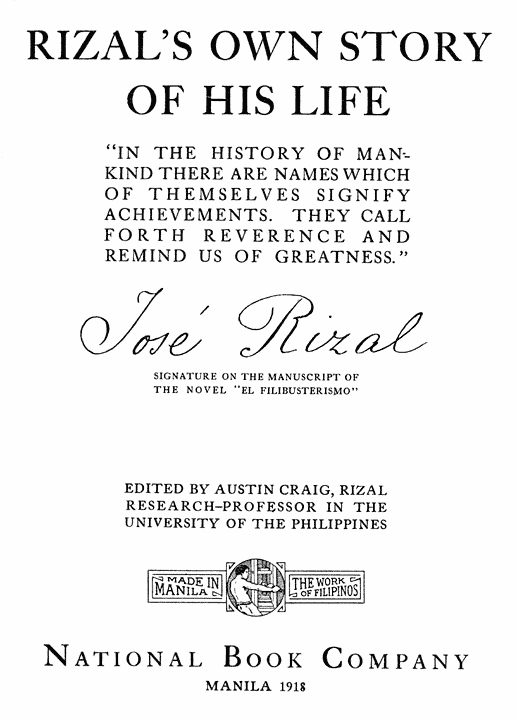

RIZAL.

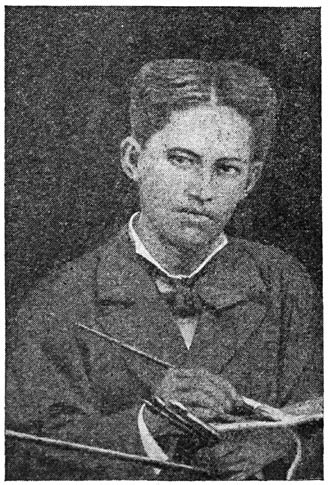

Sketched by himself in Berlin when he was twenty-five years old. Physicians then told him that he had consumption; but with care, and fresh air, he soon became well again.

[2]

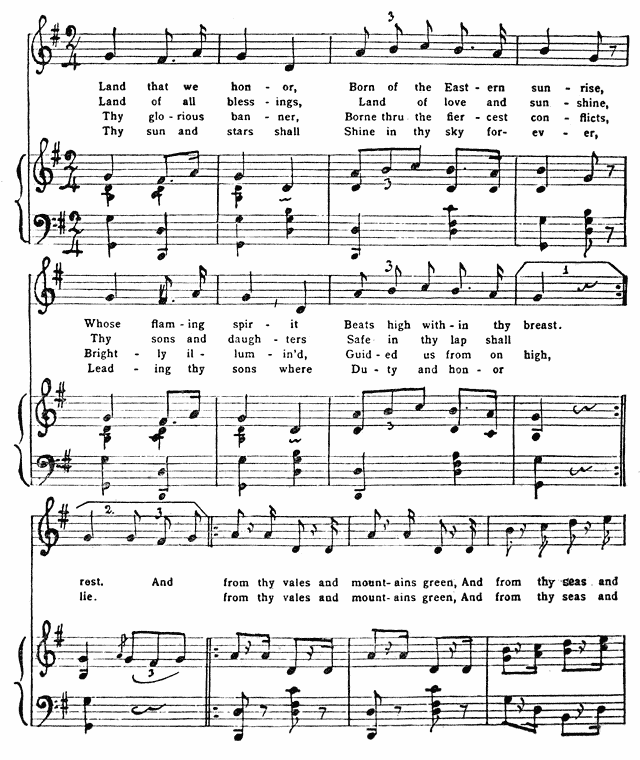

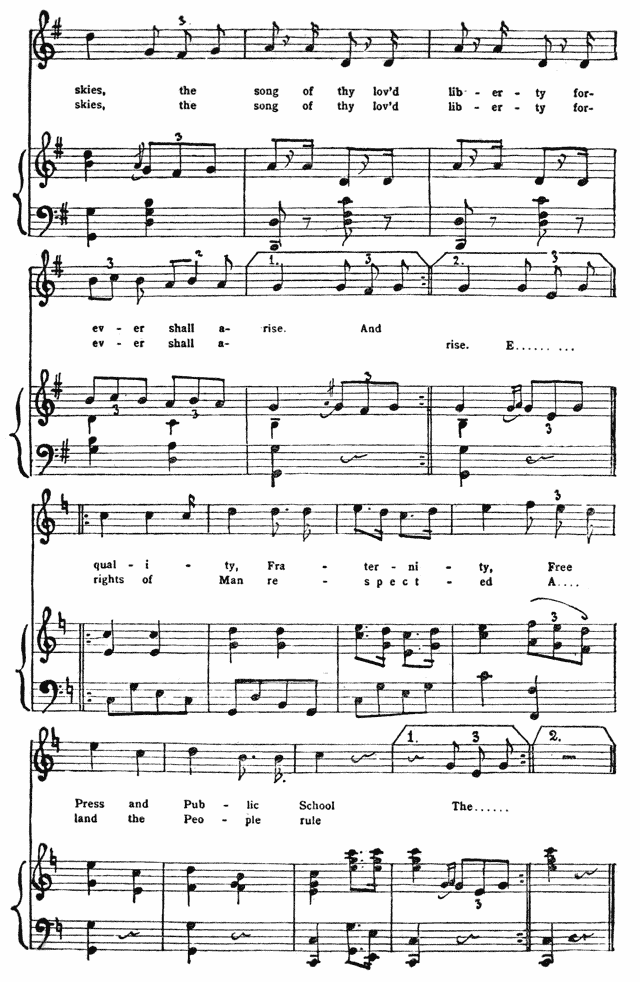

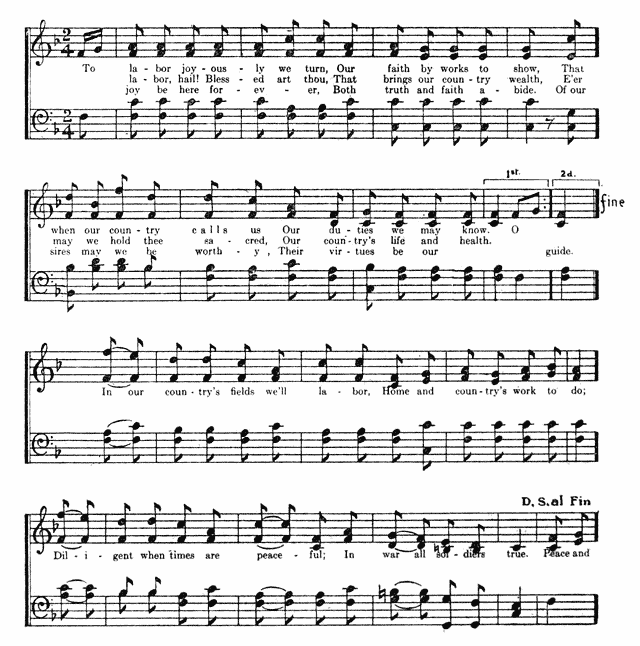

RIZAL’S “HYMN TO LABOR”

Words by José Rizal

(Arranged from Chas. Derbyshire’s translation; lines in different order.)

Tune of “The Wearing of the Green”

[3]

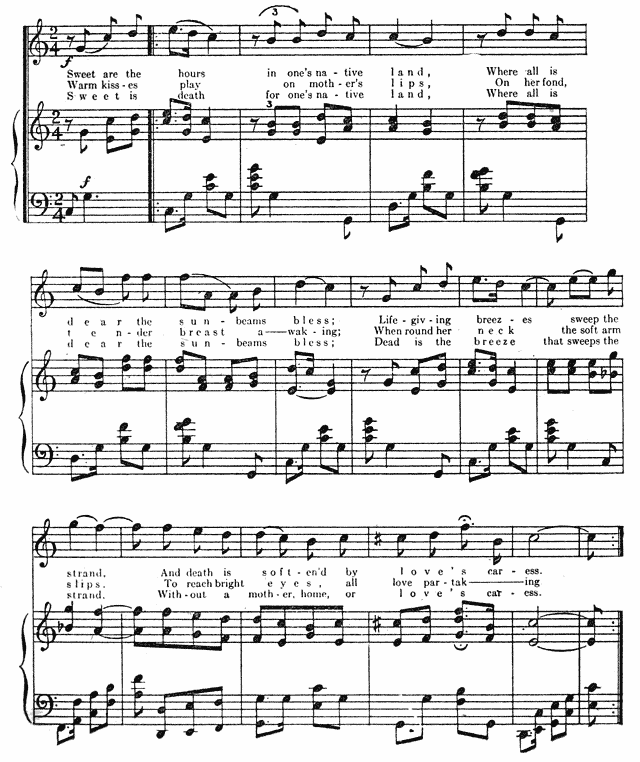

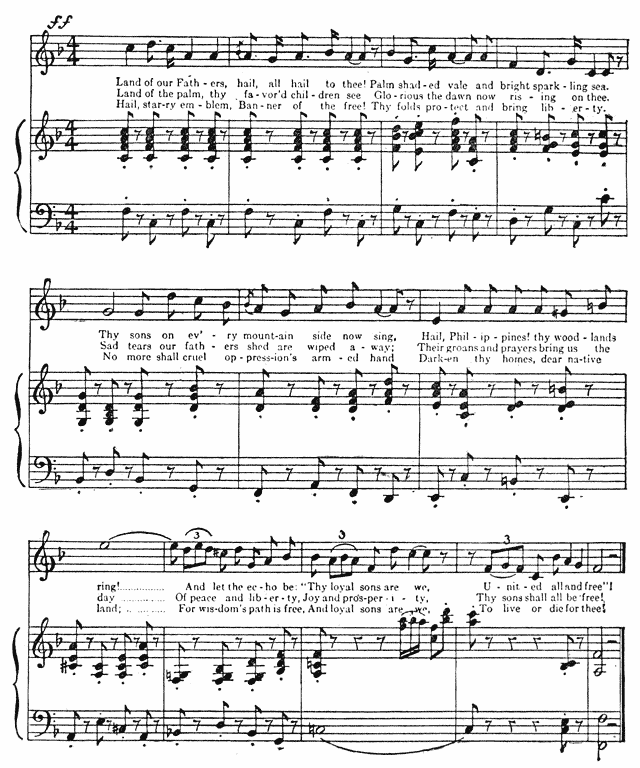

RIZAL’S “MARIA CLARA’S LULLABY”

MANILA 1918

[6]

COPYRIGHT 1918 BY AUSTIN CRAIG

Registered in the Philippine Islands

Rizal’s Painting of his Sister Saturnina

(Afterwards Mrs. Manuel Hidalgo)

Printed in the United States of America

(Philippine Islands)

Press of E. C. McCullough & Co., Manila, P. I. [7]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. W. W. Marquardt suggested this book.

Miss Josephine Craig advised and assisted in the selections.

Hon. C. E. Yeater read and criticised the original manuscript.

Miss M. W. Sproull revised the translations.

Dean Francisco Benitez acted as pedagogical adviser.

Miss Gertrude McVenn simplified the language for primary school use.

Mr. John C. Howe adapted and arranged the music.

Mr. Frederic H. Stevens planned the make-up and, in spite of wartime difficulties, provided the materials needed.

Mr. Chas. A. Kvist supervised the production.

Mr. C. H. Noronha, who, in 1897, in his Hongkong magazine Odds and Ends, first published Rizal’s farewell poem “My Last Thought”, was the careful and obliging proofreader.

Assistant Insular Architect Juan Arellano, a colleague of the editor on the Dapitan Rizal national park committee, designed the sampaguita decorations.

Mr. A. Garcia achieved creditable illustrations out of poorly preserved photographs whose historical accuracy has not been impaired by the slightest embellishment.

And the entire establishment of Messrs. E.C. McCullough & Company—printers, pressmen and bookbinders—labored zealously and enthusiastically to do credit to the imprint: “Made in Manila—The Work of Filipinos”. [8]

The Memory of Rizal is kept alive in many ways:

1. A province near Manila bears his name.

2. The anniversary of his death is a public holiday.

3. A memorial school has been built by the Insular Government in his native town.

4. His home in exile has been made a national park.

5. The first destroyer of the future Philippine navy is named “Rizal”.

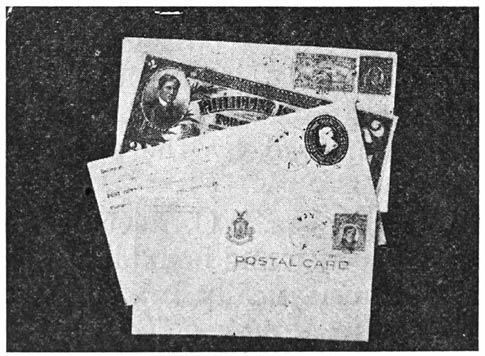

6. Rizal’s portrait appears on the two-peso bill.

7. Rizal’s portrait appears on the two-centavo postage stamp.

A 2-centavo postage stamp

A two-peso bill

A 2-centavo stamped envelope

A Philippine post card

[9]

ILLUSTRATIONS

- Page

- Rizal’s pencil sketch of himself 1

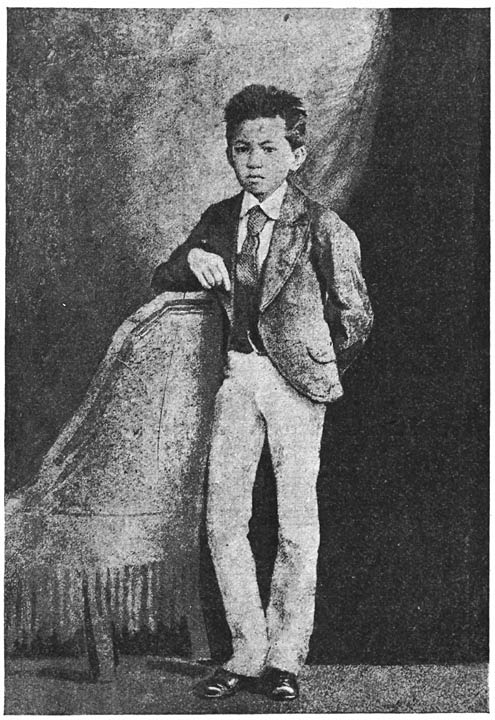

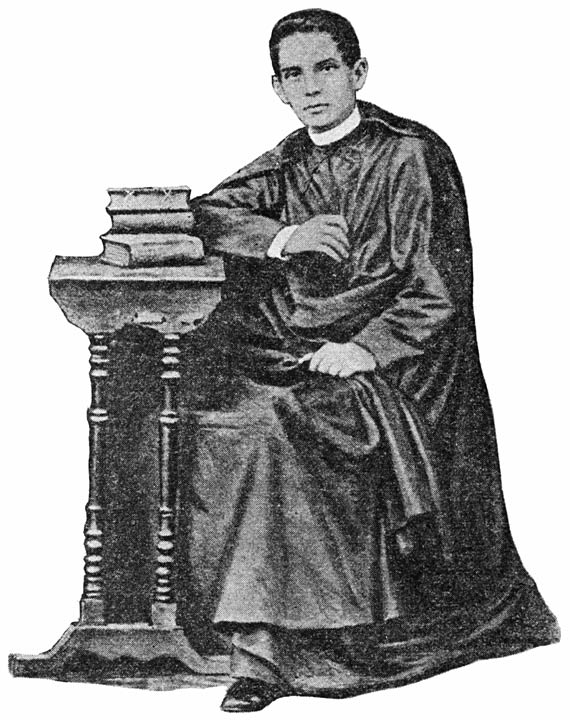

- Rizal at 14 4

- Rizal’s painting of his sister Saturnina 6

- Rizal’s portrait on Philippine postage and money 8

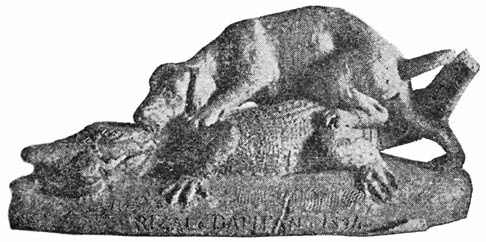

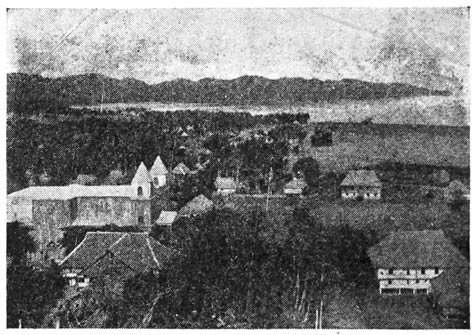

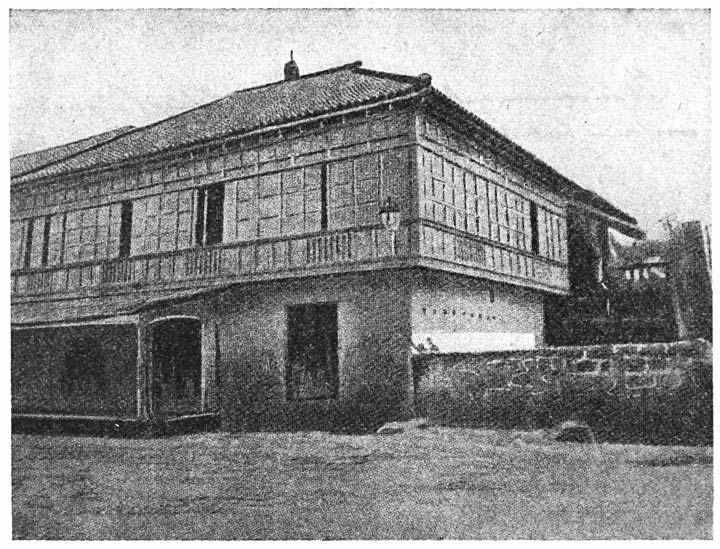

- Rizal’s home, Kalamba 12

- Rizal’s mother and two of his sisters 16

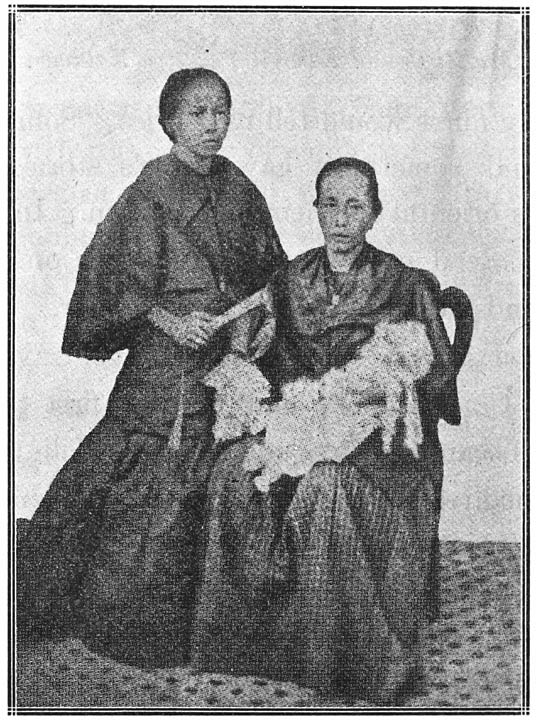

- Clay model of dog and cayman combat 17

- Where Rizal went to school in Biñan 18

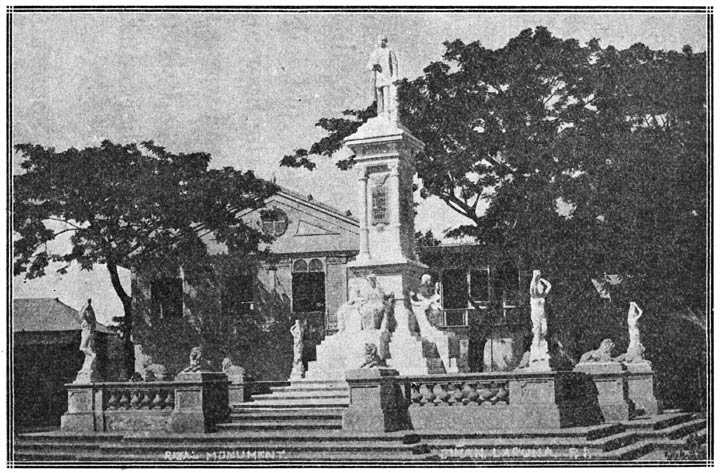

- Rizal monument, Biñan 24

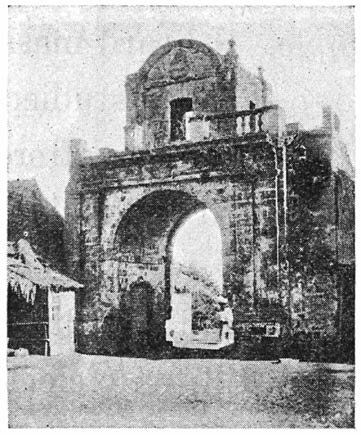

- Santa Rosa Gate, on Biñan-Kalamba road 26

- Model of a Dapitan woman at work 28

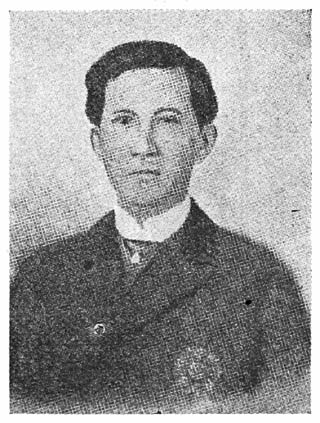

- Rizal’s uncle 29

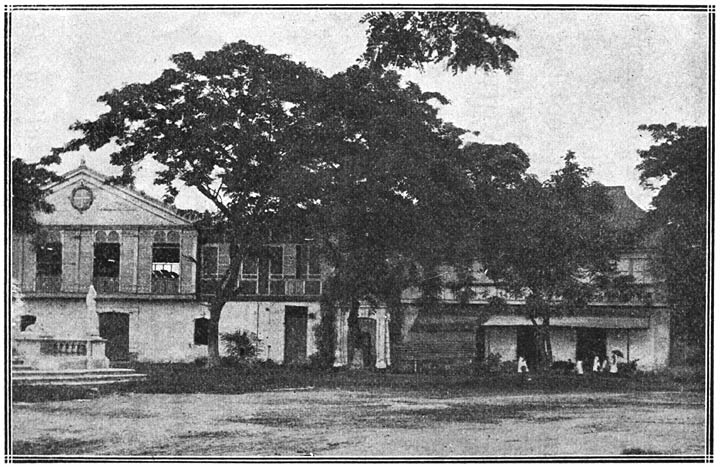

- Rizal’s uncle’s home in Biñan 30

- Guardia Civil soldier 31

- Rizal’s mother 33

- Rizal’s father 34

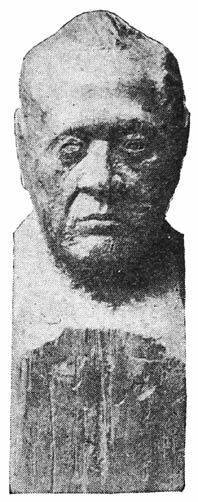

- One of Rizal’s teachers, Terracotta bust by Rizal 36

- Padre Sanchez, Rizal’s favorite teacher in the Ateneo 37

- Carving of the Sacred Heart, made by Rizal in the Ateneo 44

- Wooden bust of Rizal’s father 45

- Rizal at 18 48

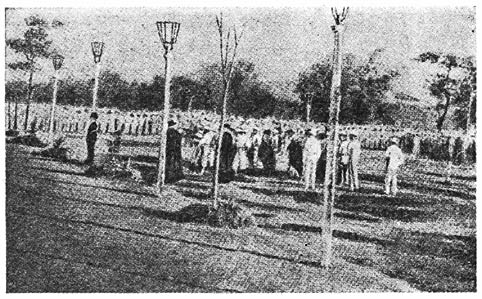

- Rizal’s sacrifice of his life 57

- Professor Burgos 58

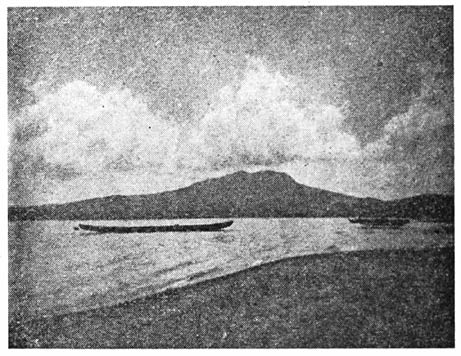

- The lake shore at Kalamba 60

- A Manila school girl, drawn by Rizal 62[10]

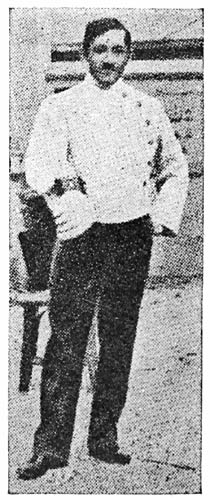

- Rizal in Paris 64

- Rizal at 30 66

- Crayon portrait of Rizal’s cousin Leonore 70

- Dapitan plaza and townhall 80

- Wooden medallion of Mrs. José Rizal 84

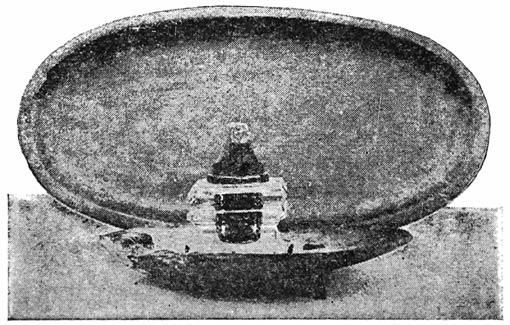

- Chalk pipehead, Rizal’s last modeling 86

- Rizal at 27 90

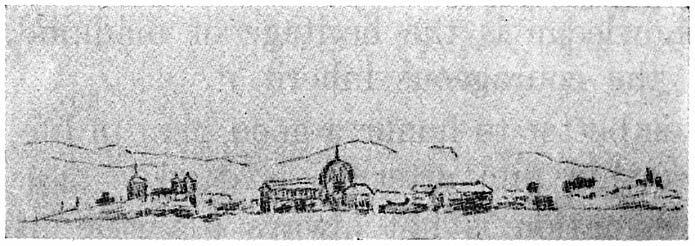

- Manila skyline, sketched by Rizal 92

- Rizal at 22 104

- Rizal at 24 106

- Rizal at 26 108

- Rizal at 28, from a group picture 110

- Rizal at 28, profile 114

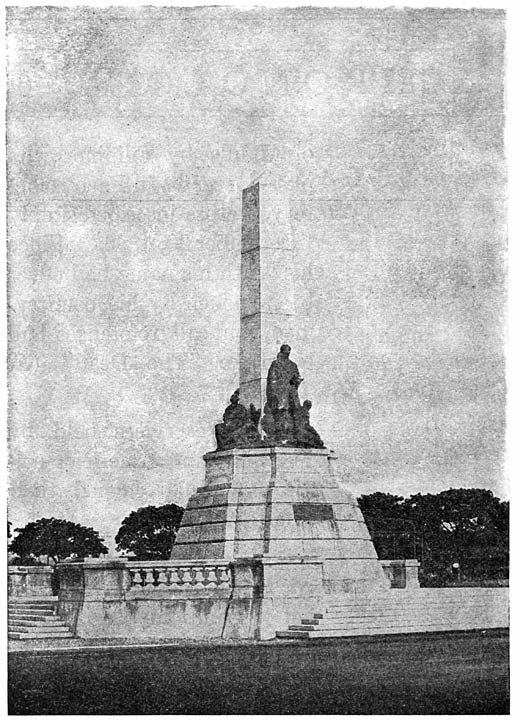

- Rizal Mausoleum, Luneta, Manila 118

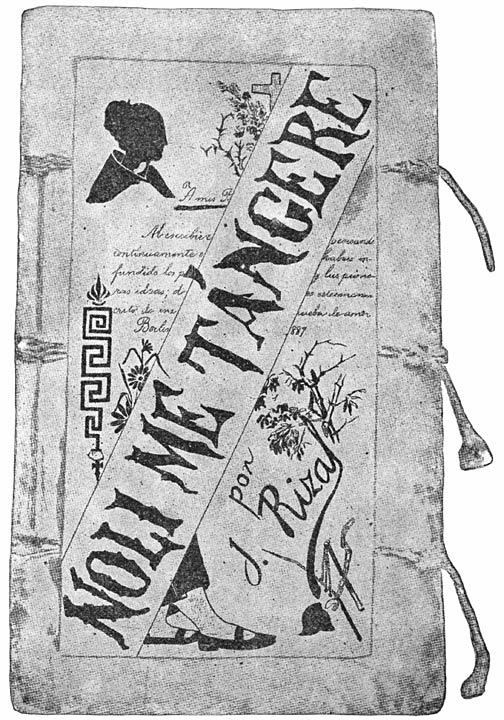

- Noli Me Tangere manuscript-cover design, by Rizal 120

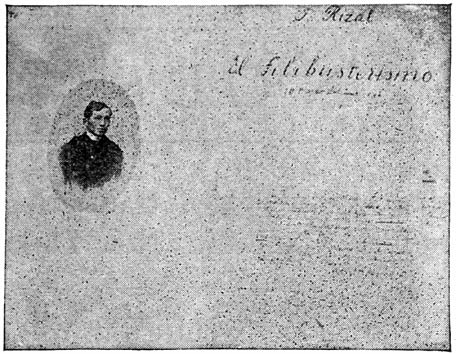

- El Filibusterismo manuscript-cover, lettered by Rizal 121

- Portrait of Rizal at time of finishing El Filibusterismo 121

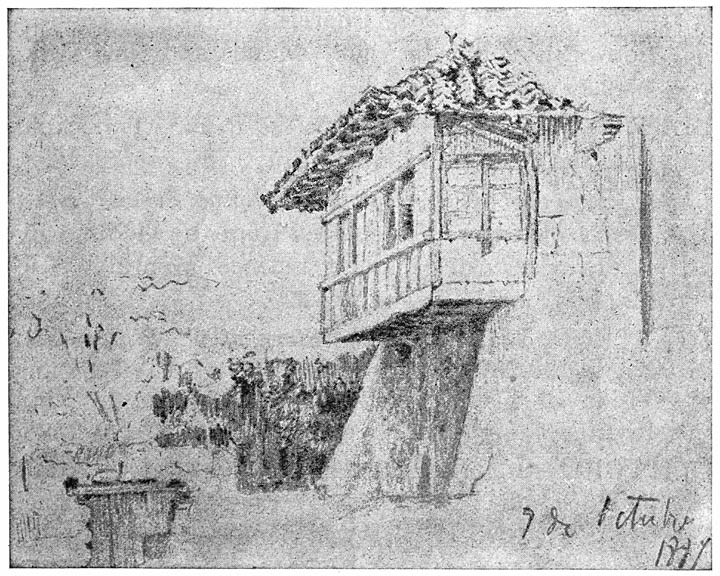

- Los Baños house where El Filibusterismo was begun, drawn by Rizal 121

- Diploma of Merit awarded Rizal for allegory “The Council of the Gods” 123

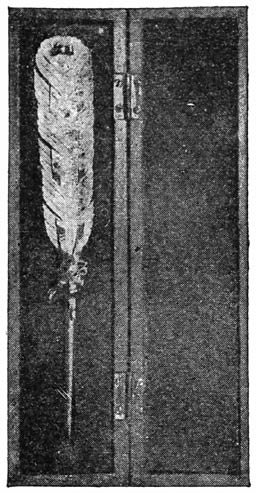

- Silver pen prize won by Rizal for poem “To Philippine Youth” 125

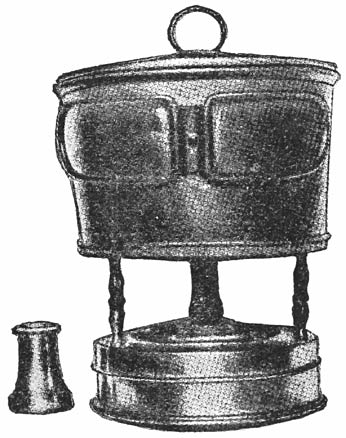

- Alcohol lamp in which Rizal hid poem “My Last Thought” 125

[11]

CONTENTS

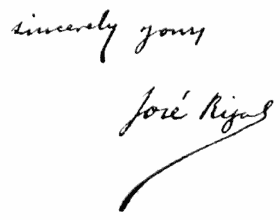

—Autographic quotation from Rizal.

- Page

- Rizal’s Song “Hymn to Labor” 2

- Rizal’s Song “Maria Clara’s Lullaby” 3

- My Boyhood 13

- My First Reading Lesson 49

- My Childhood Impressions 59

- The Spanish Schools of My Boyhood 61

- The Turkey that Caused the Kalamba Land Trouble 65

- From Japan to England Across America 69

- My Deportation to Dapitan 73

- Advice to a Nephew 81

- Filipino Proverbs 83

- Filipino Puzzles 84

- Rizal’s “Don’ts” 85

- Poem: Hymn to Labor 87

- Memory Gems from Rizal’s Writings 91

- Mariang Makiling 93

NOT BY RIZAL

- The Memory of Rizal 8

- Rizal Chronology 101

- A Reading List 119

- Philippine National Hymn (by José Palma) 126

- Song: Hail, Philippines (by H. C. Theobald) 128

[12]

Rizal-Mercado home, Kalamba. Here José Rizal was born. The family lost this building, along with most of their other property, in the land troubles. Governor-General Weyler sent soldiers to drive them out, though the first court had decided in their favor and an appeal to the Supreme Court had not yet been heard. Later, the upper part of the building was rebuilt.

[13]