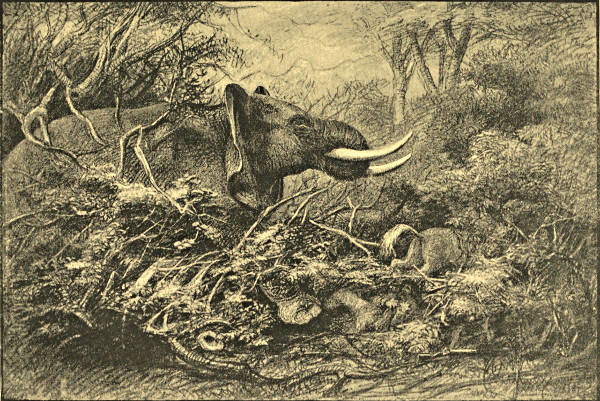

THE LION’S LAST CHARGE

Title: Big Game Shooting, volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Clive Phillipps-Wolley

Illustrator: Charles Whymper

Release date: March 25, 2015 [eBook #48584]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The Badminton Library

OF

SPORTS AND PASTIMES

EDITED BY

HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF BEAUFORT, K.G.

ASSISTED BY ALFRED E. T. WATSON

BIG GAME SHOOTING

I.

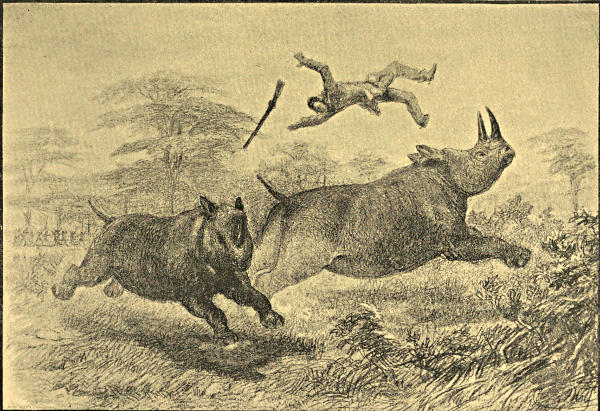

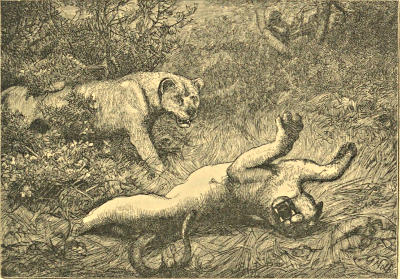

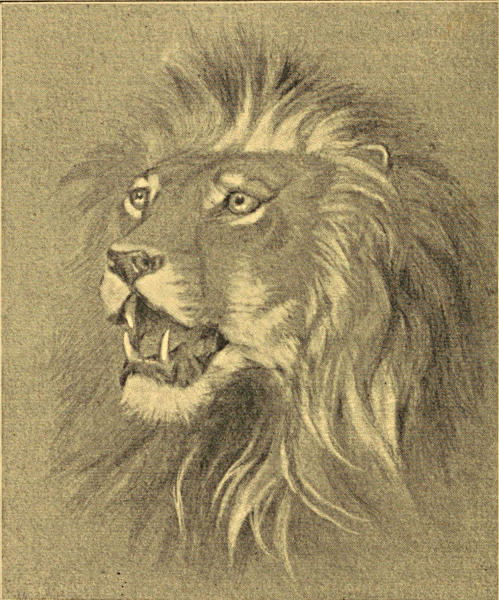

THE LION’S LAST CHARGE

BY

CLIVE PHILLIPPS-WOLLEY

WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY

SIR SAMUEL W. BAKER, W. C. OSWELL, F. J. JACKSON,

WARBURTON PIKE, AND F. C. SELOUS

VOL. I.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY CHARLES WHYMPER, J. WOLF

AND H. WILLINK, AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

1894

All rights reserved

Badminton: May 1885.

Having received permission to dedicate these volumes, the Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes, to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, I do so feeling that I am dedicating them to one of the best and keenest sportsmen of our time. I can say, from personal observation, that there is no man who can extricate himself from a bustling and pushing crowd of horsemen, when a fox breaks covert, more dexterously and quickly than His Royal Highness; and that when hounds run hard over a big country, no man can take a line of his own and live with them better. Also, when the wind has been blowing hard, often have I seen His Royal Highness knocking over driven grouse and partridges and high-rocketing pheasants in first-rate[Pg viii] workmanlike style. He is held to be a good yachtsman, and as Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron is looked up to by those who love that pleasant and exhilarating pastime. His encouragement of racing is well known, and his attendance at the University, Public School, and other important Matches testifies to his being, like most English gentlemen, fond of all manly sports. I consider it a great privilege to be allowed to dedicate these volumes to so eminent a sportsman as His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, and I do so with sincere feelings of respect and esteem and loyal devotion.

BEAUFORT.

BADMINTON

A few lines only are necessary to explain the object with which these volumes are put forth. There is no modern encyclopædia to which the inexperienced man, who seeks guidance in the practice of the various British Sports and Pastimes, can turn for information. Some books there are on Hunting, some on Racing, some on Lawn Tennis, some on Fishing, and so on; but one Library, or succession of volumes, which treats of the Sports and Pastimes indulged in by Englishmen—and women—is wanting. The Badminton Library is offered to supply the want. Of the imperfections which must[Pg x] be found in the execution of such a design we are conscious. Experts often differ. But this we may say, that those who are seeking for knowledge on any of the subjects dealt with will find the results of many years’ experience written by men who are in every case adepts at the Sport or Pastime of which they write. It is to point the way to success to those who are ignorant of the sciences they aspire to master, and who have no friend to help or coach them, that these volumes are written.

To those who have worked hard to place simply and clearly before the reader that which he will find within, the best thanks of the Editor are due. That it has been no slight labour to supervise all that has been written, he must acknowledge; but it has been a labour of love, and very much lightened by the courtesy of the Publisher, by the unflinching, indefatigable assistance of the Sub-Editor, and by the intelligent and able arrangement of each subject by the various writers, who are so thoroughly masters of the subjects of which they treat. The reward we all hope to reap is that our work may prove useful to this and future generations.

THE EDITOR.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | On Big Game Shooting Generally By Clive Phillipps-Wolley. | 1 |

| II. | South Africa Fifty Years Ago By W. Cotton Oswell, and Biographical Sketch by Sir Samuel W. Baker. | 26 |

| III. | Second Expedition to South Africa By W. Cotton Oswell. | 88 |

| IV. | Later Visits to South Africa By W. Cotton Oswell. | 119 |

| V. | With Livingstone in South Africa By W. Cotton Oswell. | 142 |

| VI. | East Africa—Battery, Dress, Camp Gear, and Stores By F. J. Jackson. | 154 |

| VII. | Game Districts and Routes By F. J. Jackson. | 166 |

| VIII. | The Caravan, Headman, Gun-bearers, etc. By F. J. Jackson. | 176 |

| IX. | Hints on East African Stalking, Driving, etc. By F. J. Jackson. | 185 |

| X. | The Elephant By F. J. Jackson. | 204 |

| XI. | The African Buffalo By F. J. Jackson. | 214 |

| XII. | The Lion By F. J. Jackson. | 236 |

| XIII. | The Rhinoceros By F. J. Jackson. | 251 |

| XIV. | The Hippopotamus By F. J. Jackson. | 269 |

| XV. | Ostriches and Giraffes By F. J. Jackson. | 275 |

| XVI. | Antelopes By F. J. Jackson. | 279 |

| XVII. | The Lion in South Africa By F. C. Selous. | 314 |

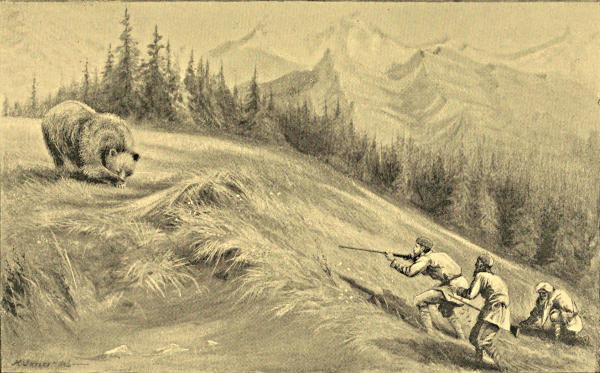

| XVIII. | Big Game of North America By Clive Phillipps-Wolley. | 346 |

| XIX. | Musk Ox By Warburton Pike. | 428 |

| INDEX | 437 |

(Reproduced by Messrs. Walker & Boutall)

| ARTIST | |||

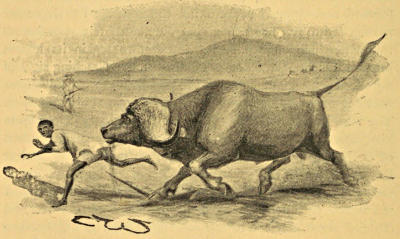

| The Lion’s Last Charge | C. Whymper | Frontispiece | |

| A Close Shot | Major H. Jones | to face p. | 8 |

| Molopo River | Joseph Wolf | ” | 10 |

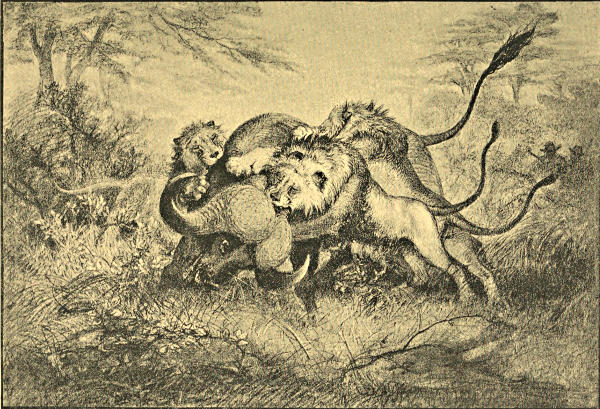

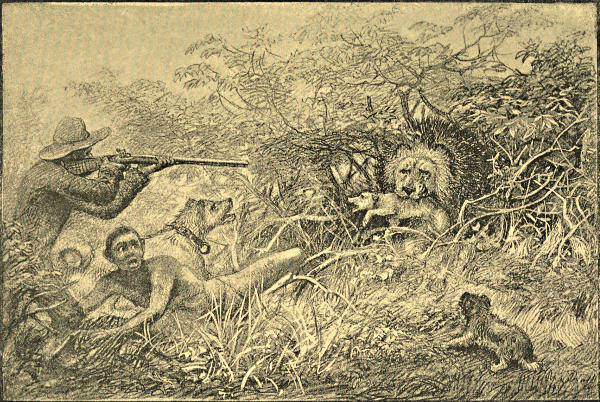

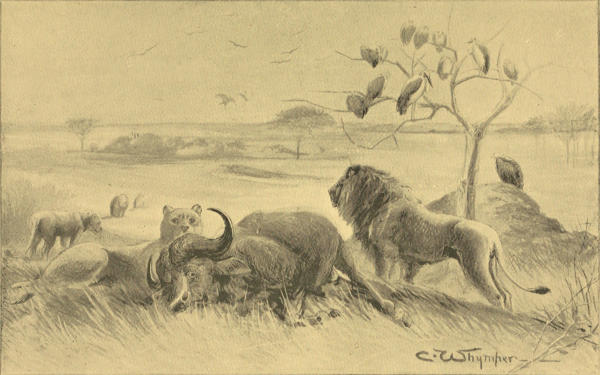

| Odds—3 to 1 | ” | ” | 90 |

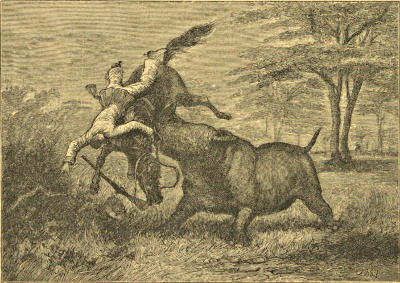

| Feeling both Horns of a Dilemma | ” | ” | 116 |

| The Drop Scene | ” | ” | 120 |

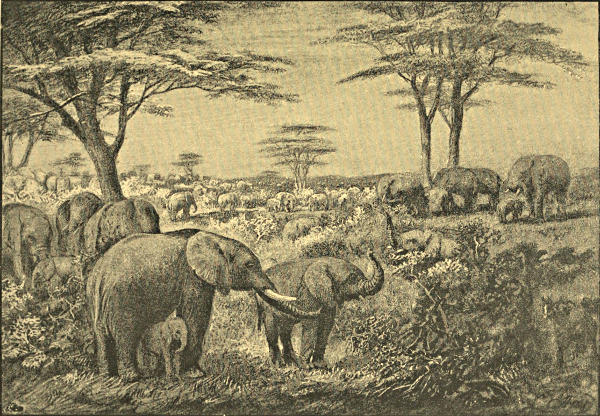

| Elephants—Zouga Flats | ” | ” | 128 |

| Threatening of Elephantiasis | ” | ” | 140 |

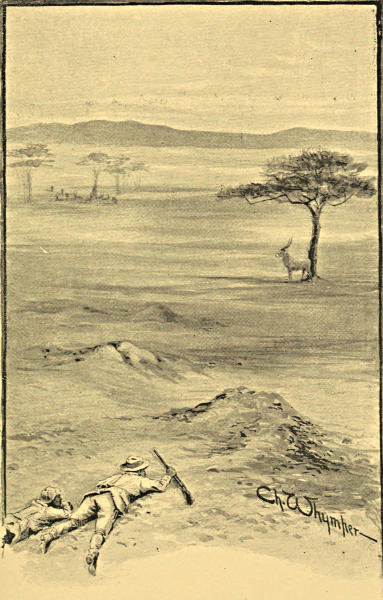

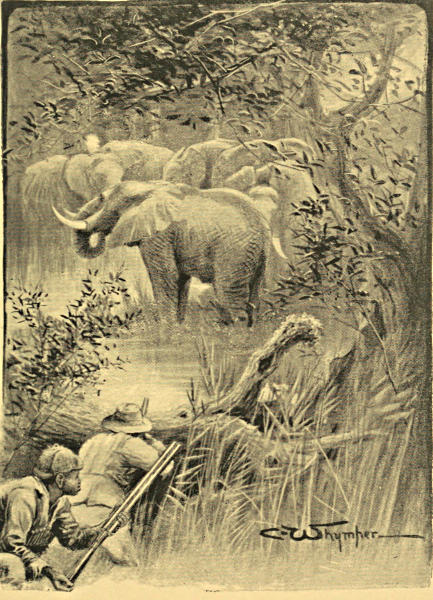

| A Difficult Stalk | C. Whymper | ” | 166 |

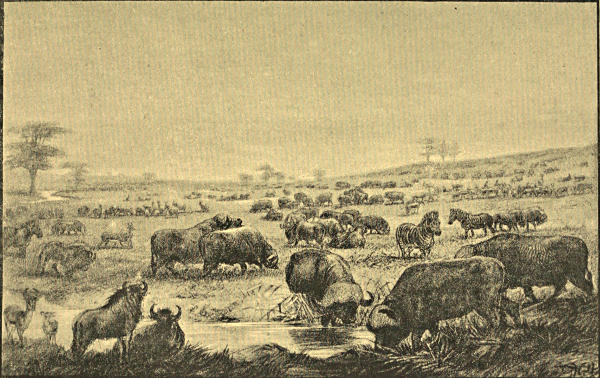

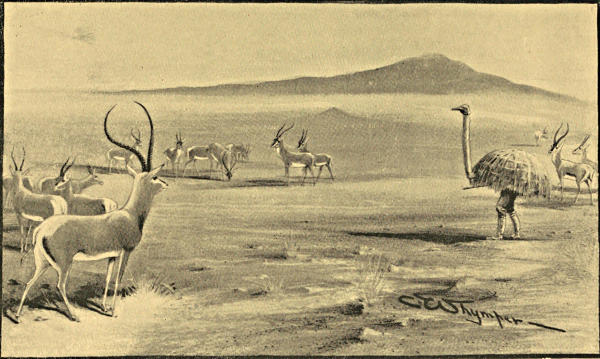

| ‘Teeming with Game’ | ” | ” | 174 |

| Camp with Boma at side | From a photograph by E. Gedge | ” | 176 |

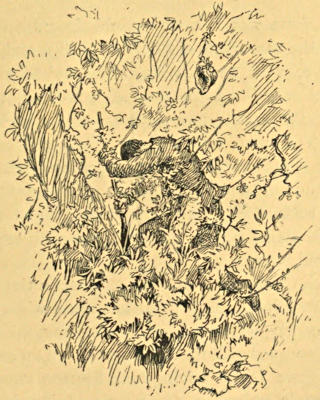

| The Bushman’s Stratagem | C. Whymper | ” | 198 |

| Resting the 4-bore on the fallen Tree | ” | ” | 212 |

| Good Guides | ” | ” | 244 |

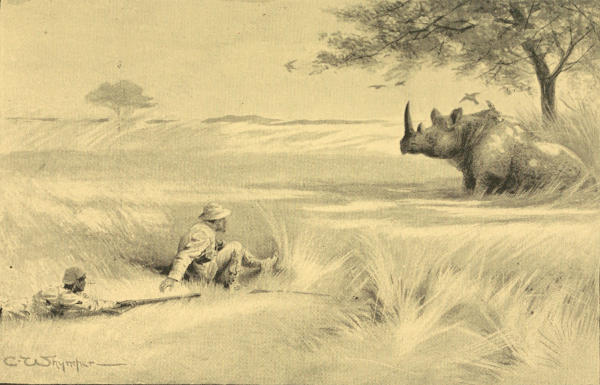

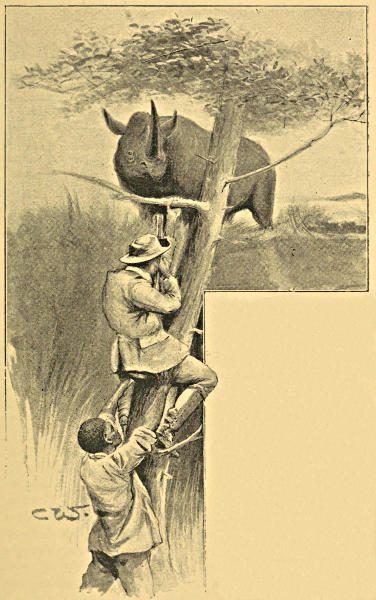

| The Rhino raised herself like a huge Pig | ” | ” | 258 |

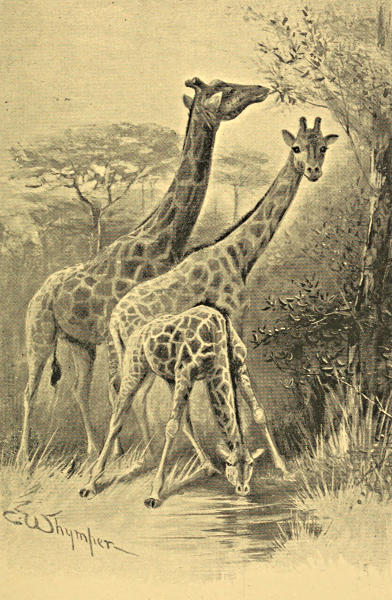

| A Family Group | ” | ” | 276 |

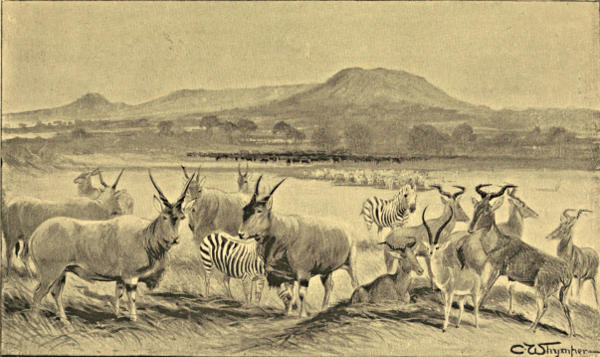

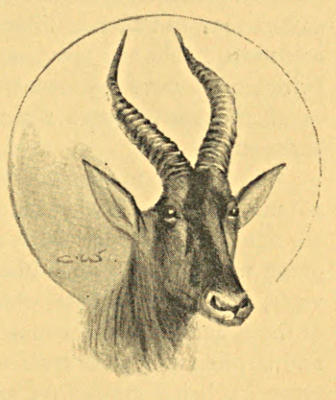

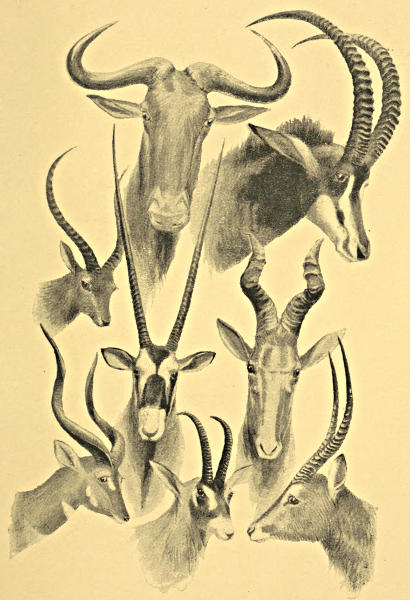

| A Group of South African Antelopes | ” | ” | 314 |

| Standing still as Stone Images | ” | ” | 368 |

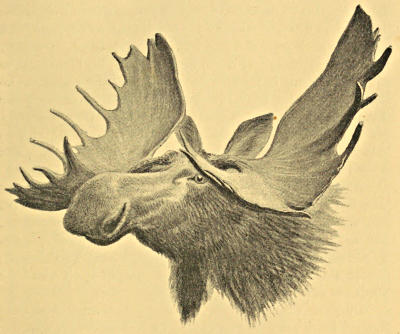

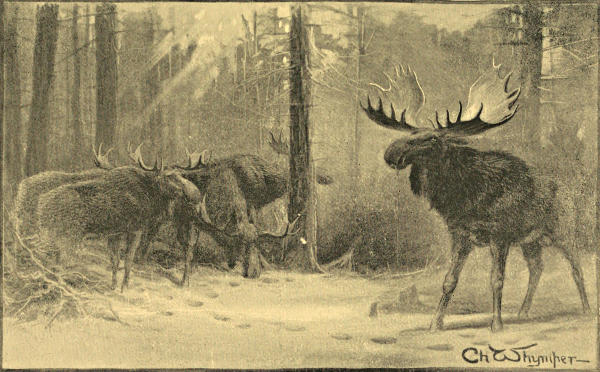

| Moose at Home | ” | ” | 398 |

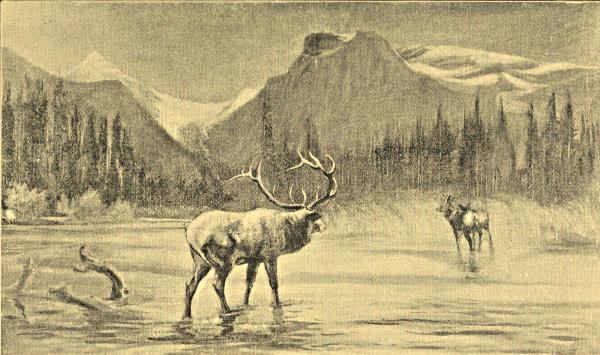

| Wapiti in the Emerald Pass, British Columbia | C. W., from a photograph | ” | 402 |

| ARTIST | ||

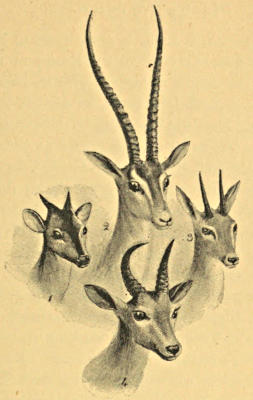

| Springbuck, Steinbuck, Blesbuck and Reedbuck | C. Whymper | 1 |

| Over the fallen Timber | 11 | |

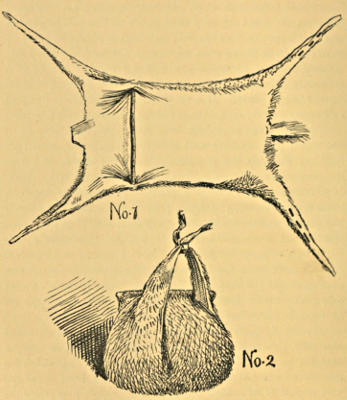

| Skin and Pack | 14 | |

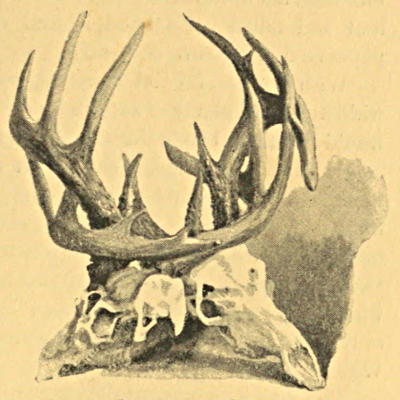

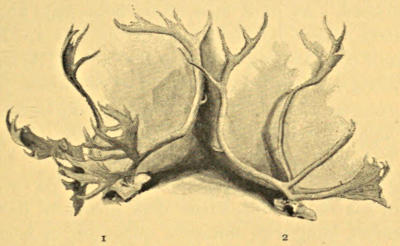

| Interlaced Antlers | From a photograph by J. Lord | 17 |

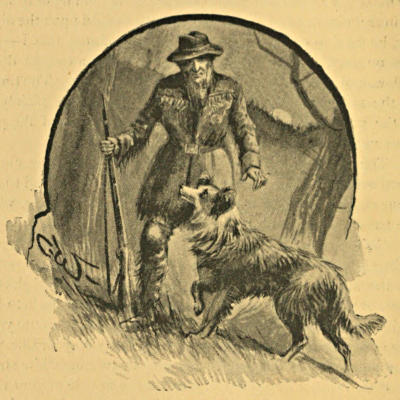

| Poor Old Sam | C. Whymper | 24 |

| Vignette | H. Willink | 25 |

| Death of Superior | J. Wolf | 52 |

| A Night Attack, Lupapi | 66 | |

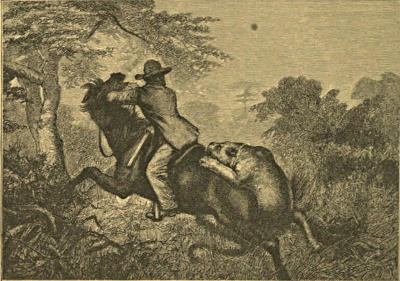

| ‘Post equitem sedet “fulva” cura’ The Lioness does the scansion | 70 | |

| Death of Stael | 102 | |

| Maneless Lions | 131 | |

| Dead Buffalo | From a photograph by E. Gedge | 154 |

| Easy Stalking Country | C. Whymper | 168 |

| At last the Bull took a few steps forward | 193 | |

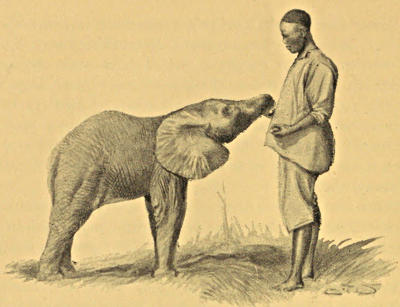

| A Baby Elephant | C. W., after a photograph by E. Gedge | 204 |

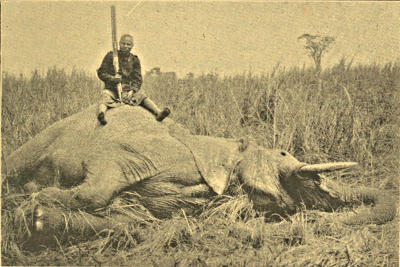

| Dead Elephant | From a photograph by E. Gedge | 213 |

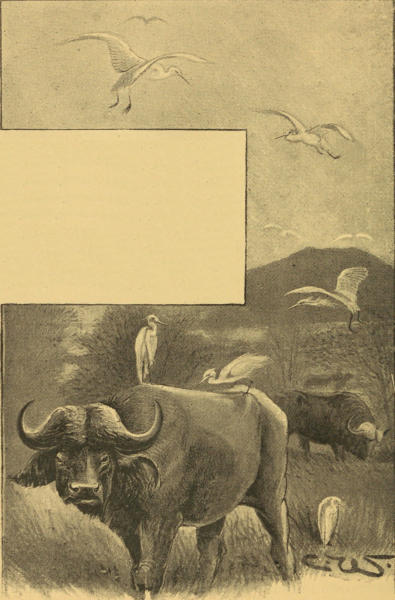

| Bull Buffalo | 216 | |

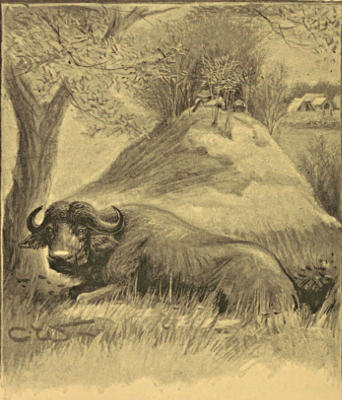

| Blissful Ignorance | C. Whymper | 224 |

| ‘Often attended by Birds’ | ” | 226 |

| The Buffalo was close upon him | ” | 234 |

| Dead Rhinoceros and Gun-bearer | From a photograph by F. J. Jackson | 252 |

| ‘I was knocked over’ | C. Whymper | 262 |

| ‘In this awkward position’ | ” | 267 |

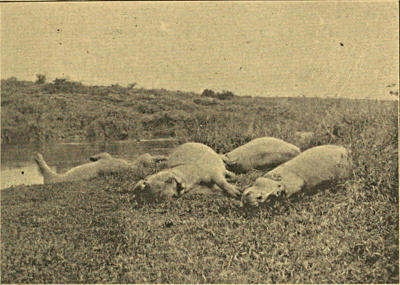

| Dead Hippos | From a photograph by E. Gedge | 269 |

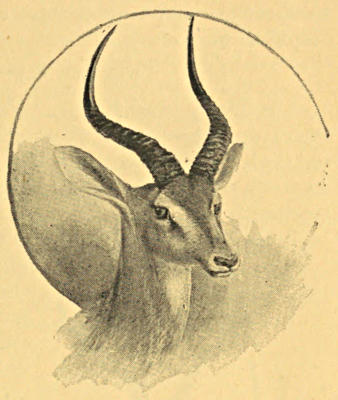

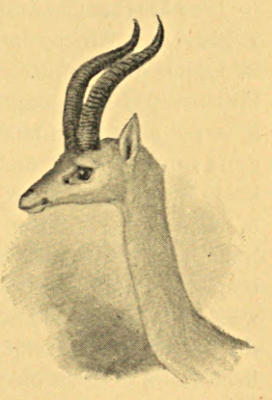

| C. Harveyi, G. Petersi, N. Montanus, and C. Bohor | C. Whymper | 279 |

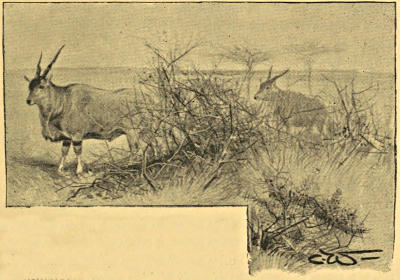

| Plan of an Oryx Stalk | F. J. Jackson | 281 |

| Plan of a Gazella Grantii Stalk on Rombo Plain | 282 | |

| Plan Of an Hartebeest Stalk | 283 | |

| Bubalis Jacksoni | C. Whymper | 291 |

| Oryx Collotis and Bubalis Cokei | ” | 294 |

| Kobus Kob | 297 | |

| Adult and Immature Gazella Grantii | 298 | |

| The Walleri | 307 | |

| B. senegalensis | C. Whymper | 311 |

| My best Lion | 326 | |

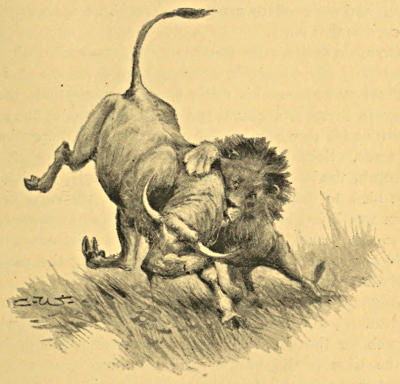

| ‘Springing upon his Victim’ | C. Whymper | 337 |

| My best Koodoo | 344 | |

| Puma (Felis concolor) | C. Whymper | 349 |

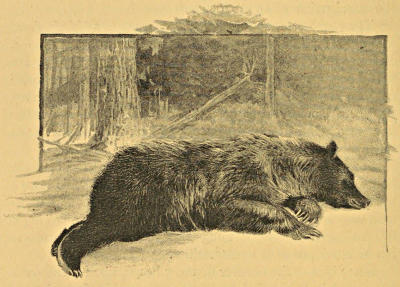

| Dead Grizzly | From a photograph by A. Williamson, Esq. | 352 |

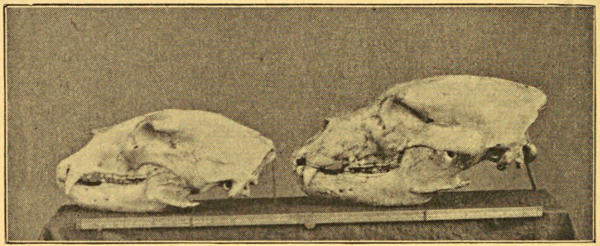

| Specimen Skull of Black Bear and Grizzly Bear | From a photograph | 354 |

| ‘Spring in the Woods’ | C. Whymper | 370 |

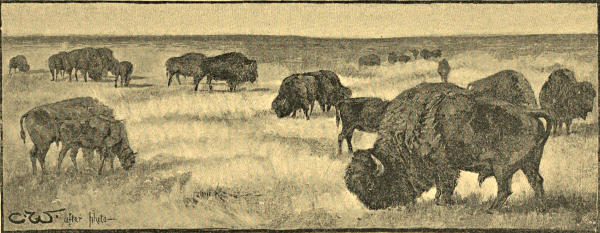

| Colonel Bedson’s herd of Buffaloes | C. W., from a photograph | 379 |

| A Pile of Buffalo Bones | C. Whymper | 380 |

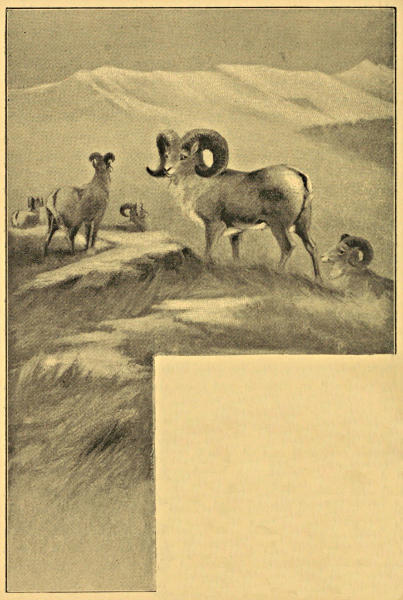

| A Group of Bighorn | 382 | |

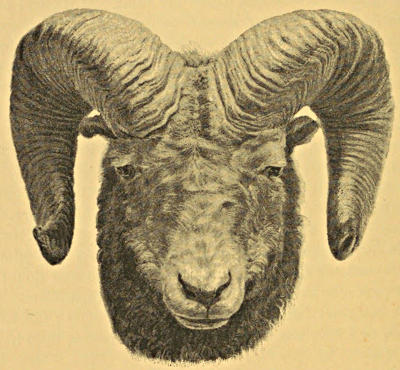

| Mr. Arnold Pike’s great Ram | From a photograph | 386 |

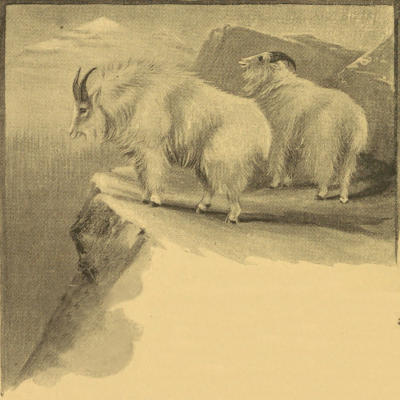

| Rocky Mountain Goats | 390 | |

| Antilocapra americana | C. Whymper | 393 |

| A Herd of Pronghorns | ” | 395 |

| The Record Head | From a photograph | 397 |

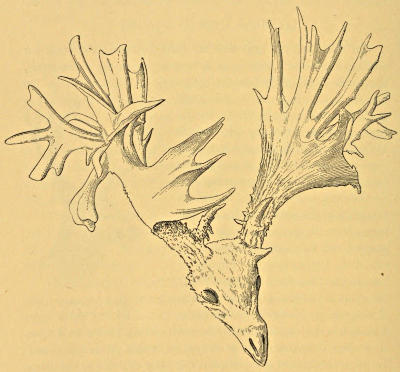

| Abnormal Palmated Wapiti Head | 414 | |

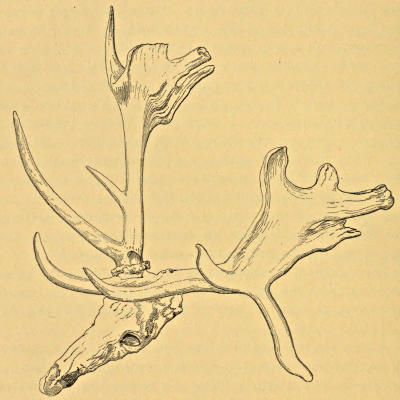

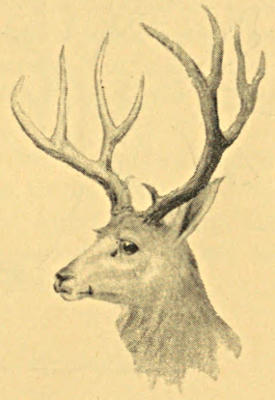

| Woodland and Barren Ground Caribou Antlers | C. Whymper | 415 |

| Typical Mule Deer (C. macrotis) | From a photograph | 419 |

| Abnormal Head of Mule Deer | 420 | |

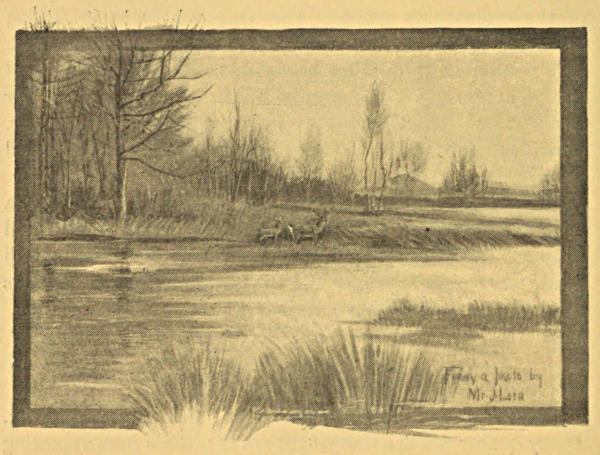

| The White-tail’s Haunt | C. W., from a photograph by J. Lord | 422 |

| Guanaco, C. paludosus, C. columbianus | C. Whymper | 425 |

| Musk Ox | 428 | |

| Vignette | H. Willink | 435 |

1 Springbuck. 2 Steinbuck. 3 Blesbuck. 4 Reedbuck.

By Clive Phillipps-Wolley

It may be asked, as to these volumes, why ‘Big Game Shooting’ should find a place in a series devoted to British sports and pastimes, whereas, except the red deer, there is no big game in Great Britain?

It is true that there is no big game left in Britain; but if the game is not British, its hunters are, and it is hardly too much to say that, out of every ten riflemen wandering about the world at present from Spitzbergen to Central Africa, nine are of [Pg 2]the Anglo-Saxon breed.

It may be asked, again, what justification there is for the animal life taken, and for the time and money spent in the pursuit of wild sport?

That, too, is an easy question to answer. Luckily for England, the old hunting spirit is still strong at home, and the men who, had they lived in Arthur’s time, might have been knights-errant engaged in some quest at Pentecost, are now constrained to be mere gunners, asking no more than that their hunting-grounds should be wild and remote, their quarry dangerous or all but unapproachable, and the chase such as shall tax human endurance, human craft, and human courage to the uttermost.

If in these days of ultra-civilisation an apology is needed for such as these, let it be that their sport does no man any harm; that it exercises all those masculine virtues which set the race where it is among the nations of the earth, and which but for such sport would rust from disuse; that if the hunter of big game takes life, he often enough stakes his own against the life he takes; and if he be one of the right sort, he never wastes his game.

Incidentally, however, the hunter does a good deal for his race and for the men who come after him; something for science, for exploration, and even for his worst enemy—civilisation.

In Africa, hunting and exploration have gone hand in hand; in America the hunters have explored, settled, and developed much of the country, replacing the buffalo with the shorthorn and the Hereford; while in India, not the least amongst those latent powers which enable us to govern our Asiatic fellow-subjects is the respect won by generations of English hunters from the native shikaries and hillmen.

From Africa to Siberia the story of exploration has never varied. The world’s pioneers have almost invariably belonged to one of two classes. It has been the love of sport, or the lus[Pg 3]t of gold, which has led men first to break in upon those solitudes in which nature and her wild children have lived alone since the world’s beginning. Hunters or gold prospectors still find the mountain passes, through which in later days the locomotives will rush and the world’s less venturous spirits come in time to reap their harvests and make fortunes in the footsteps of those who ask nothing better than to spend their strength and wealth in the first encounter with an untrodden world, living as hard as wolves, and content to think themselves rich in the possession of a few gnarled horns and grizzled hides. As for us who are Englishmen, it is well for us to remember that in most lands in which we shoot we are but guests, and the beasts we hunt are not only the property of the natives, but one of their most important sources of food supply. Bearing this in mind, we should be moderate in the toll we take of the great game, and considerate even of those who may not be strong enough to enforce their wishes. The recklessness of one man in a country where foreigners are few may suffice to damn a whole nation in the eyes of a prejudiced people, and it is worth while to recollect that any one of us who strays off the world’s beaten tracks may serve for a type of his nation to men who have never seen another sample of an Englishman.

Looked at from any point of view, the wholesale slaughter of big game must be condemned by every thinking man. The sportsman who in one season is lucky enough to obtain a dozen good heads does no harm to anybody, and probably does good to the bands of game in his district by killing off the oldest of the stags or rams. But the man who kills fifty or a hundred foolish ‘rhinos’ (beasts, according to Mr. Jackson, which any man can stalk) in one year, or scores of cariboo at the crossings during their annual migration in Newfoundland, or deer and sheep by the hundred in America, shocks humanity and does a grave injury to his class. The waste of good meat is quite intolerable; kindly natured men hate to hear of the infliction of needless pain, and waste of innocent animal life; good sportsmen recoil in disgust from a record of butchery misnamed[Pg 4] sport, for, according to the very first article of their creed, it is the difficulty of the chase which gives value to the trophies. If there were no difficulties, no dangers, no hardships, then the sport would have no flavour and its prizes no value. The mere fact that a man can kill as many of any particular kind of animal as he pleases should be sufficient to make him let that beast alone, unless he wants it for food, as soon as he has secured (say) a couple of fine specimen heads. Finally, to look at this question from the lowest and most selfish standpoint, the wholesale slaughter of wild game in foreign countries should be discouraged unanimously by all who love the rifle, since men who kill or boast of having killed exceptionally large bags of big game in any country are extremely likely to arouse the natural and proper indignation of local legislators, who have it in their power to close their happy hunting grounds to all aliens for the fault of a few individuals, not by any means typical of, or in sympathy with, their class.

On the other hand, it would be well if some of those of our own race, who should know better, would be less ready to call other men butchers merely because they have killed large quantities of game. Everything depends upon the circumstances connected with the slaying. If a man needs and can utilise a hundred antelope, surely he has as good a right to kill them as if he were killing a hundred sheep for market. There are occasions when not only does the hunter’s skill win the regard of savages who value nothing in friend or foe more than real manhood, but it is absolutely necessary to kill game in order to keep a native following in food. Without the hunter’s skill, food would have to be bought or looted from hostile natives, a feud engendered which might end in the shedding of other blood than that of the beasts, and a serious obstacle be thus raised in the path of the pioneers of civilisation and trade.

Our big game sportsmen have made more friends than foes, have always contrived to feed their men, and the very greatest of[Pg 5] them have never shed a drop of native blood. Where gallant Oswell or Selous have been, there are no blood feuds against the English to hamper an expedition of their countrymen.

So much for the ethics of Big Game Shooting; as to the practical side of it, let it be said at once that it is impossible upon paper to teach any man to become a successful big game hunter. Upon the hillside or in the forest, with an expert to guide him, with the floating mists to teach him something of the way of the winds, with game tracks or the game itself before him, each man has to learn for himself, and even then he learns more from his own mistakes than from anyone else. To be really successful a man wants so many things; he needs so many qualities combined in his own person. To be a good shot means but little. The man who can win prizes at Wimbledon may be a successful deer-stalker, but it by no means follows that he will be. He has one good quality in his favour, but even that quality varies with the varying conditions under which he shoots. With his pulses steady, his heart beating regularly, his wind sound, his digestion unimpaired, his eyes free from moisture, with the distances measured off for him, and with a bull’s-eye to shoot at, he may make phenomenal scores; but when he has been living upon heavy dampers and strong tea taken at irregular intervals, his digestion may become impaired. When he has toiled all day and come fast up a steep incline at the end of a long stalk, his pulse will not be steady, his sides may be heaving like those of a blown horse, his eye may be dimmed by a bead of sweat which will cling to his eyelash and fall salt and painful into his eye just when it should be at its clearest. The distances are not marked for him, and the atmosphere varies so much at different altitudes, that it is not always easy to judge how far he is from his quarry, and that quarry, instead of being marked in black and white for his convenience, has an awkward trick of being just the colour of the hillside, with an outline which at 200 yards melts into the background and becomes one with its surroundings.

Many a man who shoots well at a mark is a poor shot in the woods; but luckily the converse of this proposition is also true. Again, strength and endurance, steady nerve and quick eyes count for much, but they alone will not make a man successful.

The strong young hunter is often the worst. Likely enough he does the work for the work’s sake, laughs at mountain-sides, and, like a friend of our own, starts at dawn, travels all day, tells us at night of peaks at fabulous distances on which he has stood, but comes back empty-handed, simply because he is too strong, too fast, and runs over ground leaving behind him, or ‘jumping’ out of range, game which a feebler man might have seen when crawling slowly over the hillside or sitting down for a frequent rest. One really good Western sportsman we know advocates a very different system. ‘Camp,’ he says, ‘near where game is, look out for likely places, and then go and sit about near them all day long. If the game comes to you, you’ll probably get it; if it don’t you won’t, and you wouldn’t any way. Somehows,’ he generally adds, ‘them bull elicks allus did have longer legs than mine, d—n ’em.’

Perhaps a knowledge of natural history is almost better than either great physical powers or exceptional skill with the rifle. If you watch a first-rate tennis-player, it will seem to you that tennis is a very easy game. The second-rate player performs prodigies of activity to get into the right place in time, but the first-rate man never seems to be obliged to exert himself at all. He always is where he ought to be. So it is with the good man to hounds. His place at the fence is the easiest, and yet he never seems to swerve or pick his place. In every case it is the same. Knowledge of the game helps all the men in the same way, and each in his own fashion picks his place; but he picks it long beforehand. The tennis-player knows where the return must come, the hunting man sees the weak place by which he means to go out at the very moment that he comes in to a field, and in like manner the big game hunter gets to where the big ga[Pg 7]me is because he has calculated beforehand where it ought to be, and experience and knowledge of the beasts’ habits, and a certain instinct which some men have, do not mislead him.

First, then, study the habits of wild animals generally. They are much the same all the world over, and a man may learn a great deal by the side of an English covert, when the rabbits and pheasants are running before the beaters, which he can turn to good use when hunting bigger game.

Why do you suppose some men always seem to get more shots than others; why do the birds always rise better to them than to you? Pure luck you think, and they perhaps don’t deny it. Don’t believe it. The true sportsman knows by instinct what tussock of grass will hold a rabbit as he goes by it, and if a rabbit is there he won’t let it lie whilst he passes. You won’t see him swing round, saving himself a bit and leaving the likeliest corner in a big field unbeaten. The birds would have sneaked down into the ditch and stopped there whilst you wheeled by thirty or forty paces off, but our friend puts them up; and if when those rabbits at the covert-side were bolting just out of range between you and him, you think he dropped his white pocket-handkerchief on the drive by mistake, you don’t know your man. That handkerchief just turned them enough to bring them close by him, and he had awful luck you know, and fired six shots to your one.

That is the way in big game shooting too. Partly from experience, and partly by instinct, some men know where to look for a beast, and know the ways of it when found. Study then the habits of beasts generally to begin with, and then those of the particular beast you are going to hunt. Learn what it feeds on at different seasons of the year, and where its food is to be found; learn at what time of day it feeds, and at what time it lies down. Most animals feed early and late, just at dawn and just at the edge of night, sleeping when the sun warms them, using what Nature sends them instead of supplying the place of the sun with a blanket as we do. Many beasts are almost entirely nocturnal in their feeding hours, and these not [Pg 8]only such as one would naturally expect to prowl by night—tigers, lions and suchlike—but ibex and mountain beasts which feed on nothing worse than grass. Just at and before dawn most beasts are up and feeding, probably because that is the coldest time in the twenty-four hours; the beasts become chilled and restless, and Nature warns them that food and motion are the best cures for the evils they are suffering from.

Learn too, with the utmost care for yourself, upon which of its senses each particular beast relies, for all do not rely upon the same sense. The sense of smell is perhaps the most universal safeguard of the beasts which men hunt, but all are not as keen of scent as the cariboo, nor all as wonderfully quick and long-sighted as the antelope, of whom Western men say that he can tell you what bullet your rifle is loaded with about as soon as you can make him out on the skyline. A bear is so short-sighted as to be almost blind on occasion, and no beasts seem capable of quickly identifying objects which are stationary, though all catch the least movement in a second. This of course is where the man who rests often gets an advantage. If a beast is stationary in timber, for instance, you may often look at him for a minute after your Indian has found him before making him out; but if he but flick his ear or turn a tine of his antler ever so little, it will catch your eye at once.

In still hunting for wapiti or other timber-loving deer, a broken stick will warn every beast within a quarter of an hour’s tramp; but on a mountain-side, where stones are constantly falling from the action of sun and wind and rain, ibex, sheep and other mountain beasts will often take but little or no notice of the stones you dislodge during your climb. Only be careful that these stones do not fall too often or at too regular intervals.

A CLOSE SHOT

In Scotland stalking is almost the only form of hunting deer; in America and other wild countries there are two principal forms of sport—stalking and still hunting; the one practised in comparatively open country and in the mountains, and the other in those dense forests where, partly from choice and [Pg 9]partly because it has been much hunted, most of the big game now harbours. In this series stalking has already been dealt with, so that with this form it is only necessary to deal briefly here. The wind is the stalker’s deadliest foe, and in many of the countries known best to the writer (sheep countries for the most part) there are days in each week when it is wiser to stay in camp or hunt in the timber down below, rather than risk disturbing game when the winds are playing the devil in Skuloptin. Take your Indian’s advice, and stop at home on such days as these; play picquet with your friend, look after your trophies, or write up your diary.

To any but the youngest hunters it seems superfluous to say that you must hunt up or across the wind; to remind them of what a score of authorities have said before about the lessons to be learnt from the drifting mist-wreaths; to warn them to take care that they see the beast before the beast sees them, and to this end to be careful in coming over a rise in the ground; to put only just so much of their head above the skyline as will enable them to see the country beyond, and even then to bring that small part of their body up very slowly and under cover of some friendly bush-tussock or boulder. In eighteen years’ hunting the writer has met many men who might be forgiven for believing that wild game never lies down, for whenever they have seen it, it has been on its feet, looking at them. And no wonder, for some of them would even ride up to the top of a bluff before looking to see what lay in the valley beyond. And yet, even after such a mistake as this, there is a chance sometimes of retrieving your error if the wind is in your favour. If, for instance, in riding from camp to camp you suddenly come in full view of a stag, with a hind or two, walking in the early morning along the ridge of the next bluff to that upon which you and your Indians are riding, say a word to your men, and let them either ride slowly on or stop absolutely stationary in the same spot, whilst you slide out of your saddle and creep away on[Pg 10] your belly amongst the grass. Above all, they must keep in full view of the stag, and if they do this, in nine cases out of ten the stag will not notice that you have gone, and whilst he stares intently at the strange objects which he knows to be at a safe distance from himself, you will have time to get round and make a successful stalk. Even the hinds will be too intent on watching the other men to keep a proper look-out in your direction. And this brings up another point. Take care of the hinds and of those lean grey-faced ewes. The ram and the stag are blunderers and reckless, especially in love-time; but the ewes are as suspicious and wary as schoolmistresses, and must always be watched carefully. If for a moment you see the grey faces turn in your direction, keep still; keep still as a statue, even though you have raised yourself upon your hands to peer over and have found out too late that your palms are pressing upon the thorny sides of a bunch of prickly pears. It will come to an end at last, though that fixed regard seems never ending; but in any case, if you want a shot you must be still, for if you try to lower your head and hide whilst they are looking at you, you might just as well go home. This rule applies in another instance. If you should by chance come upon a beast unawares, stand stock still at once; don’t try to hide if it is a deer; don’t try to bolt if it is something more dangerous. If you stand still, beasts are slow to identify objects, and your deer may not be badly scared or your bear may pass on with only a suspicious stare; but if you attempt to hide, your deer will certainly show you his paces over fallen timber, or your bear or tiger if bad tempered may charge.

But you ought very seldom to run into beasts in this way, if you keep your eyes open for ‘sign,’ i.e. tracks, droppings, freshly broken twigs, and places where deer have been browsing, and if, as you ought to, you take a good long time to scan every valley carefully before you enter it. Of course you must not keep your eyes on the ground looking for tracks—this is a fatal trick of a ‘tender foot’—but you can see tracks well enough with eyes looking well ahead of you; and indeed, if you are following a trail, you will find it more easily by looking for it yards ahead of you than you will by searching for it at your feet.

MOLOPO RIVER

Again, in looking for game you have at first to learn what to look for. The deer you are likely to see will not be standing broadside on, with head aloft like Landseer’s ‘Monarch,’ but will be a long blur of brown on a hillside, with head stretched out almost flat upon the ground in front of it, crouching (if it has seen you) more like a rabbit than a lordly stag, or else it will be but a patch of brown which moves between the boles of the pines, or a flickering ear, or a gleaming inch or so of antler, or, worse than all, a flaunting white flag bobbing over the fallen timber if it is a deer, or a dull white disc moving up towards the skyline if it is a sheep which you have stirred from amongst those grey boulders for one of which you mistook it.

Over the fallen timber

A common error which men make is to depend too much upon the eyes of their gillie. That an Indian has better sight than a white man is an article of many a man’s creed. I believe it to be a mistake. The Indian is trained, he knows what to look for, and is looking for it. The average white man who takes an Indian with him does not know what to look for, and is relying upon his Indian’s eyes. Consequently the Indian sees the game first, tries to point it out to his master, who finds it just about the time that the beast has stood as long as it means to, and is on the move by the time that the white man, flurried by his Indian’s oft-repeated ‘Shoot! shoot!’ has found out what he is to shoot at. Of course the result is[Pg 12] a miss. If, instead of allowing his Indian to go ahead and do the spying, the gunner had gone ahead, he would in the course of a few weeks have learnt to find his own game, and when he had found it he would have secured for himself those first invaluable seconds when the beast was still standing uncertain of danger and for the moment at his mercy. If only a man is enough of a woodsman to find his way back to camp and to find again the game he has killed, he will do far better to go alone than with the best of guides. Two pair of eyes may be better than one, but one pair of feet make less noise than two, and the man who finds his own game, and chooses his own time to shoot, is far more likely to kill than the man who presses the trigger at the dictation of an excitable redskin. That ‘Shoot, shoot’ has lost many a head of game.

Don’t be in a hurry when you have sighted game. If it has not seen you it is not likely to move, and if it has you can’t catch it. Take your time. Light a pipe if the wind is right, and if it isn’t the deer will object to your smell quite as much as to the smell of tobacco. Having lighted your pipe, con the ground over carefully, and plan out your stalk at your leisure. It may be that you have come across sheep in an utterly unapproachable position, lying down for their midday siesta. If so, lie down for yours too, keeping an eye open to watch their movements. Towards evening first one old ram will get up and stretch himself (and perhaps turn round and lie down again) and then another; but eventually they will feed off slowly over the brow, and then you can run in and make your stalk. If there is a good head in the band your patience will not be without its reward. Again, when you have made your stalk and are safe behind your boulder at 150 or 200 yards from your beast, don’t be in a hurry. If your eyes are dim and you cannot see your foresight clearly, shut your eyes and wait. There is no more reason why the beasts should see you now than half an hour ago. Wait till your hand is steady and your eye clear; don’t look too much at the coveted horns (as my gillies always said that I did); shoot not at the whole beast, but at the vital part behind or[Pg 13] through the shoulder; and remember that you have worked days perhaps for the chance you will either take or miss in the next few seconds. Remember that a man shoots over three times for every once he shoots too low. Put your cap under your rifle if you are going to shoot from a rock rest; shoot from a rest whenever you can, and if you miss the first shot, do as the Frenchman wanted to when pheasant shooting, i.e. wait until he stops. If it is a ram or a deer, unless he has seen or winded you, it is a thousand to ten that he will stop within 50 yards or so to look back to see what frightened him before leaving the country. When he stops you will get another chance at a stationary object, and one shot of this kind is worth a good many ‘on the jump.’ If a beast does not look likely to stand again after the first shot, a sharp whistle will sometimes stop him.

You will hear, especially from Americans, who very often can shoot uncommonly well with the Winchester, and from Indians, who are the poorest shots in the world, of extraordinary shots at long ranges. Pay no attention to them. If you cannot get within 200 yards of game, except antelope in an open country, you are a poor stalker; and rely upon it more game is killed within 80 yards than is fired at over 200. Indians get what game they kill, not by their fine shooting at long ranges, but by their clever creeping and stalking. At the same time, there is a limit to everything, and if you attempt to get too close, a glimpse of your cap, which would only make a deer stare at 150 yards, will make him dash off as if wolves were after him at 50 yards.

Having dropped your stag, lie still (if you have wounded him only, this is still more necessary) and reload, as many a man has been terribly disappointed at seeing a deer which he considered was ‘in the bag’ get up and go off from under the very muzzle of an unloaded rifle. But your stalk may end without your getting a shot. Some puff of wind of which you had no suspicion may warn your quarry before you get within range of him, and if this happens, watch which way he goes, and do you go by another way, for he will put every beast he passes in his flight upon the ‘qui vive.’

In case of wounded game do not be in too great a hurry to follow it. A wounded beast which is pressed will go on travelling just out of range of you until night falls, even though you can see a hind leg, broken high up, swinging loosely at every step he takes; but the same beast will lie down very soon if he has not seen or winded his enemy; his wound will stiffen, and in an hour he will be easy enough to stalk again and kill.

Skin and pack

When you kill your stag, don’t cut his throat, as a Tartar would do, high up, thereby spoiling the head for mounting, but plunge your knife into his chest. This will let out the blood and not spoil the neck. If, when you kill, you are far from home, and want to pack your venison home yourself, the Indian fashion of packing and carrying is the simplest that I know. It is done thus:—

After grallocking, skin your deer and cut off his head. Skin well down the legs, cutting off the feet at the fetlock joint, and spread the skin out with the hair downwards. Now cut from a bush near by a stick about as thick as your thumb, about three inches shorter than the width of the skin just behind the forelegs. Lay this on the skin and stretch the skin over it, driving in the points of the stick so as to hold the skin taut at the width of the stick. Next cut two or three little holes in the skin of each hind leg, and sew the two legs together by pushing a small twig through alternate holes in the skin of either leg. This will make the hind legs into a loop or handle. Now cut up what meat you want into joints of convenient size, pack them neatly on the skin behind the stick, fold up your pack and bring the stick through your loop, so that the ends of it overlap and hold against the loop; put the loop over your forehead or your shoulders, and there you are with a fairly convenient satchel full of meat on your back, the hairy side of the skin against your coat, and a sufficiently soft strap of skin across forehead or chest to carry the weight. All this can be done on the spot with no more adjuncts than your skinning knife and a bush to cut twigs from. The only difficulty is that the head must be arranged as an extra pack or must be called for on a subsequent occasion.

But your beast, though down, may not be dead, and apart from the caution already given to load before going up to a fallen beast, there is another worth giving. Many a man has lost his life by being too anxious to handle his prize. One instance of a fine young fellow maimed for life by a panther whose mate he had killed, and whom he was too anxious to[Pg 16] handle without sufficient investigation of the position, occurs to me as I write, and an attempt of my own to turn over a wapiti which was not quite dead elicited such a vigorous kick from the leg I was hauling upon as sent me flying some yards into the scrub. If the deer had had free play for his leg, he might have done worse than make me a laughing stock for my Indians.

When you get your shot be careful where you place it, and if the beast is moving towards you, let him pass before firing, if possible. If it is only a deer, a raking shot, striking him even a little far back and travelling transversely through him, will be much more likely to go through vital organs and stop him than one fired from in front; and, besides, a shot of this kind is not so likely to reveal the shooter at once to the beast and elicit a charge, if the beast is a dangerous one, as when fired right into his face.

Don’t, unless absolutely compelled to, fire at dangerous game above you. A wounded beast naturally comes down hill, and you are likely to be in its way if you fire from below; besides, a wounded beast will come quicker down hill than up. If your beast should charge you, stand still and go on shooting. Your chance may be a poor one, but in nine cases out of ten it is the best you have got.

Interlaced antlers

But if after all your care, and even after you have heard (or think that you have heard) the bullet smack upon your stag’s shoulder, he should show absolutely no sign of being hit, except perhaps a slight shiver or contraction of his muscles—if even he should turn and bolt at headlong speed—do not be at once discouraged; no, not even if you should follow him for many hundred yards without finding a single splash of blood upon the trail. Don’t listen to your Indian, if you have reason to think that you held straight, even though appearances justify his assertion that you made a clean miss. That little spasmodic shiver is a hopeful sign. When you see your stag do this, you may be very sure that he is hard hit in a vital spot, and he will not go far. It he starts off at racing pace, he will probably pitch over on his head, dead, at the end of a hundred yards; and[Pg 17] even if he does not bleed at first, follow him persistently: flesh wounds often bleed more freely than more dangerous ones, and it is quite on the cards that you will at last find that your stag was hit after all (far back, perhaps), and you may get him, although the shot hardly deserved such a prize. In any case it is your duty as an honest sportsman to do your utmost to find out whether you have wounded a beast, and, if so, to do all in your power to secure him and put an end to his pain, rather than leave him to take a better chance which may offer.

The greater part of what has been written so far applies either to shooting big game generally or to stalking: a word or two may well be devoted to still hunting—a form of the chase much practised in America and other well-wooded countries.

Almost every fresh form of sport brings a fresh set of muscles, a hitherto little used sense or mental quality, into play, so that an all-round sportsman should be that very exceptional animal, a man in the full possession of all his faculties.

On the mountains a man depends upon his feet and upon his eyes; in the woods he has to place at least as much reliance upon his ears as upon his eyes; whilst his feet in still hunting are to the beginner the very curse and bane of his existence.

Except in wet weather or to a redskin, still hunting is an impossibility in any true sense of the term. When for weeks[Pg 18] in Colorado there has not fallen one drop of rain, when sun and wind have parched the whole face of Nature, every twig and every fallen leaf upon the forest floor become absolutely explosive, and the merest touch will make them ‘go off’ with a report loud enough to be heard in London.

Damp weather is, then, the first essential for successful still hunting; but even then, when the leaves crush noiselessly under foot and fallen twigs bend instead of snapping, the utmost patience and care are necessary.

With a pair of good shooting boots, English made, with wide welts and plenty of nails in them—boots, for choice, which would run about two to the acre—with his rifle over his shoulder, and a handful of loose change in the pocket of his new American overalls, any average young man may go confidently into the best woods in America, certain that in a fortnight of hard work he will see nothing except what Van Dyke calls ‘the long jumps’ (i.e. tracks of startled deer) or those waving white flags popping over the fallen logs which those gunners only may hope to stop who habitually shoot snipe with a Winchester.

The man who is generally successful as a still hunter is he who knows the haunts and habits of the deer, who travels slowly in the woods, constantly stopping to listen and look ahead, who not only takes care to wear clothes of the softest material, with moccasins or tennis-shoes upon his feet, but who always has a hand ready to move an obstinate briar or obstructive rampike gently out of his way before it has time to rasp against his clothes or trip him and pitch him upon his head.

The first thing to remember in entering upon this sport is that every live thing in the woods is watching and listening at least three parts of its waking life, and that your only chance of success is to catch it off its guard in those rare moments when it is either feeding or moving, and therefore making a noise itself. A moving object is more easily seen than a stationary one, therefore do you stand or sit still from time to time among thick cover on some ridge or other commanding posi[Pg 19]tion, and watch the woods, peer through the thickets, and make certain that they are untenanted, before you blunder through them. When a log upon which your eyes have been dwelling idly for several minutes gets up as you move, and goes off with a snort, before you can get your rifle to your shoulder, you will realise more thoroughly how hard it is to distinguish stationary game in cover. Keep your ears, too, on the alert: a bear will move through a dry azalea bush, when he pleases, almost less noisily than a blackbird, and his great soft feet make far less sound on the dead leaves than yours do. Slow ears are almost as bad as slow eyes in still hunting; but do not condemn either your eyes or ears as worse than the natives’ until the eyes have learned from experience what to take note of, and the ears which are the sounds worth listening to. In time the language of the forest will become plain to you, whether it is spoken in the voices of birds and beasts, in the rustlings and scurryings amongst the bushes, or written in tracks upon the great white page of new-fallen snow at your feet; but at first your ears will send many a false message to your brain.

In the intensity of the stillness the fir cones which the squirrels drop make you start, expecting to see the bushes divide for a bull moose at least to pass through them: at night, when you are watching by the river for bear, you think that you hear distinctly the ‘splosh, splosh’ of the grizzly’s feet as he wades down the shallows towards you. Not a bit of it: it is only a foolish kelt who has run himself aground and is trying to kick himself off again into deep water. On the other hand, that grating of one bough against another which you fancied that you heard may have been a ‘bull elk’ burnishing his antlers against a cottonwood-tree, that far-away whistle of the wind may have been a fragment of a forest monarch’s love-call, and that angry squirrel across the canyon was actually chattering not because he had seen you, but because he was disturbed by a bear passing by the log on which he was sitting.

But the language of the woods can only be learnt by residence amongst them, and this is especially true of the written[Pg 20] language of tracks, which is to my mind one of the few things utterly beyond a white man’s powers ever thoroughly to master. Such proficiency as a man may acquire in tracking he must acquire for himself in the woods, since any essay upon it would need more illustrations than words to make the meaning plain.

Fishing is said to require patience. Believe me, still hunting requires more. Although you have toiled all day and seen nothing; although you are hot, ‘played out,’ and therefore intensely irritable (perhaps you have even a touch of fever upon you); although every log on your way home ‘barks’ your shins, and every tendril clings to your ankle—you must keep your temper; and even when that thorny creeper hooks you by the fleshy part of your nose, you must not swear—at least, not aloud. If you do, at the very moment that the words leave your lips, the only beast you have seen all day will get up with a contemptuous snort from the other side of the bush in front of you.

But when all is written that can be written upon ‘still hunting,’ there is still much which can only be taught in the woods—or, if on paper, then it has been done already, as well as man could possibly do it, in the pages of the best book ever written by an American, Van Dyke’s ‘Still Hunter.’ I am glad to have a chance of acknowledging my indebtedness to this author. Whatever I know of still hunting I have learned from his book and from experience, and have never yet known my two teachers disagree.

There is only one word which I would add here, but it is the most important that I shall write. There is one danger in still hunting in the woods more terrible than any other which the big game hunter can encounter: the danger, I mean, of accidentally shooting his fellow-man.

Make a rule for yourself before you go into the woods, and keep it as the first of sylvan commandments: Never, under any pretence whatever, pull your trigger until you know not only what you are shooting at, but also at what part of your beast you are shooting.

Once in a while the observance of this rule may lose you a beast which you might have crippled, and eventually secured if you had taken a snap shot at the grey thing which you saw moving in the bushes. But, on the other hand, instead of killing a bear or a buck, it is much more likely that your snap shot will wound some poor devil of a hind, who will sneak away to die in anguish somewhere in the thick covert where none but the jackal will benefit by her death; or else you may do as I once actually did—hit a bear in the seat of his dignity, thereby arousing his very righteous indignation in a way that is dangerous to the offending party; or, worse still, you may (as I nearly did) fire upon your own gillie or friend, whose moccasined footfall is very like a bear’s tread, and whose sin in wandering across your beat would be too severely punished by death.

In all seriousness, it has always seemed to me that any man who, whilst out shooting, kills another in mistake for game deserves to be tried for his life, unless he be a very young beginner—and young beginners should hunt by themselves. There is no excuse for shooting a man. If the shooter could not tell that that at which he fired was a human being, much less could he tell at what part of his beast he was shooting, and a random shot ‘into the brown’ of a beast is unsafe, unsportsmanlike, and brutally cruel.

Finally, do not be tempted to use complicated sights in still hunting. When you have followed deer under pines heavy with snow, through sal-lal bush which looks like deep billows of the same, only to find, the first time, that your Lyman sight is down, and the second time that though erect the peephole is full of ice, you will recognise the merits of a Paradox with the simplest sights for wood shooting in any weather as thoroughly as the writer does, and whilst admitting the merits of the Lyman sight for long-range shooting in the open, eschew all but such simple sights in timber.

There are, of course, other ways of hunting big game besides those already dealt with. Almost any game may be[Pg 22] driven, from lions in Somaliland and tigers in the Terai to chamois in the Alps and sheep in North America, and there is no doubt that sufficient excitement and a good deal of sport may be got out of the day’s work; but, after all, the beaters who out-climb the Spanish ibex (as described by Mr. Chapman in his ‘Wild Spain’) and the natives who risk their lives in the driving, have always seemed to the present writer to be the men who did the work, and were principally responsible for the success of the day’s sport. To the guns who are posted by the organiser of the beat little advice can be given, except to obey orders, stick to their posts, be careful not to shoot at anything until it has passed them—or, at any rate, at anything which is in such a position with regard to the beaters and other guns as to make it unsafe to fire—to keep their attention concentrated upon the business in hand, to make all arrangements for concealment and ease in shooting directly they are posted, and then to keep quiet. There is not quite enough in this form of sport for the gun to do to please some men, but de gustibus non est disputandum.

Night shooting is another form of sport, sometimes rendered necessary by the shyness and nocturnal habits of such beasts as the grizzly and the Caucasian ibex. There are charms in night watching peculiar to the hour, which appeal particularly to the naturalist and lover of outdoor life; there is a certain fascination in the mystery of the night, the gloom of the great woods, and the awful stillness of the white peaks; while the children of the forest always seem more natural and less suspicious at night than at any other time. But it needs every charm which the night can boast to tempt a man to sit hour after hour in the shadow, without stirring, without speaking, without even thinking of anything except the sport in hand, whilst the rain runs down his spine in a strong stream, or a cold wind catches his body, heated by the tramp to the ambuscade, and slowly freezes it. If you must shoot at night, be careful about the wind: find out as well as you are able from what quarter you may expect your bear, and take care that your wind[Pg 23] does not reach him before he reaches the carcase by which you are hidden. Choose a spot where you have some chance of making out his outline against the sky if he should come, and whether you are watching by a carcase or by a salmon pool, be satisfied with a distant inspection of the bait, i.e.—don’t go and walk about all round it, &c.

Bears are especially shy of returning to a carcase when they know that men are about, one grizzly that I know of in British Columbia having defeated a very well-known Indian sportsman by making a circuit round the carcase before coming in to feed. If in that circuit he caught no taint of human kind upon the night air, he used to come in and sup; but if he found that I——y was on guard, he used to go quietly home to a canyon down below, and wait for a more favourable opportunity. The tracks in the morning told the whole story, of course, as plainly as if the unfortunate sportsman had been a witness of the performance.

The principal difficulties in this kind of shooting are to keep sufficiently quiet to induce your bear to come, and to see your sights sufficiently to kill him, even at short ranges, when he has come.

Go to the spot as lightly clad as possible, carrying any spare things you can on your arm; don’t hurry or overheat yourself on the way to your ambush, and put on a spare flannel shirt or coat, or whatever it is you are carrying, before you begin to feel chilled. Take a little sheet of macintosh with you to secure you a dry seat, and if you have no fancy night sights on your rifle, you can make a rough but serviceable one by twisting white string or cotton with a large knot in it round the muzzle of your rifle, while the thumb and finger of your left hand, as they embrace your rifle barrels, may be held a little apart to make a very coarse backsight. This is only a more or less clumsy Indian device, but it is considerably better than nothing if you get caught in the dark with no better appliances. After all, a sport which keeps you up all night, and in camp without any exercise all day, and which depends for success so entirely upon the good will of the bear, is not one to hanker after.

By the way, when you have shot your bear (if you should shoot him), and when you have taken his hide off, be careful how you pack it upon any ordinary pony. A spark applied to a powder magazine is hardly more astounding in its effects than the application of a fresh bear-skin to the back of some of the meekest of cayuses. A perfect Dobbin which belonged to the writer shook his faith in horseflesh for ever by cutting his legs from under him as if they had been carried away by a round shot, merely because Dobbin had been asked somewhat suddenly to carry the hide of a two-year-old black bear.

Poor old Sam

In all American sport, dogs are used from time to time by the trappers and meat hunters who make hunting a business, and a thoroughly broken collie, such as accompanied the wr[Pg 25]iter and Mr. Arnold Pike in an expedition to Colorado, would be invaluable to any still hunter, as this dog would not run in without orders, would precede his master at a slow walk in timber, regularly pointing in any direction from which he got wind of a deer, would take his owner up to it at a walk, would run a wounded beast to bay, follow and worry at the heels of a bear, and keep the camp secure from the inroads of inquisitive strangers or the all-devouring burros of our train. But such dogs as ‘Pup’ are rare, and the old gentleman to whom he belonged informed me that an offer of $500 for him would not be entertained, though his own whole ambition in life was to make double that sum to buy a farm and settle down, as at 65 he was beginning to think that he was almost too old to stay all the year in the woods. Poor old Sam! When one is too old for the woods, it [Pg 26]should be almost time to ‘turn in’ for that last sleep.

By W. Cotton Oswell

By Sir Samuel W. Baker

One man alone was left who could describe from personal experience the vast tracts of Southern Africa and the countless multitudes of wild animals which existed fifty years ago in undisturbed seclusion; the ground untrodden by the European foot; the native unsuspicious of the guile of a white intruder. This man, thus solitary in this generation, was the late William Cotton Oswell. He had scarcely finished the pages upon the fauna of South Africa when death seized him (May 1, 1893) and robbed all those who knew him of their greatest friend. His name will be remembered with tears of sorrow and profound respect.

Although Oswell was one of the earliest in the field of South African discovery, his name was not world-wide, owing to his extreme modesty, which induced him to shun the notoriety that is generally coupled with the achievements of an explorer. Long before the great David Livingstone became famous, when he was the simple unknown missionary, doing his [Pg 27]duty under the direction of his principal, the late Rev. Robert Moffat, whose daughter he married, Oswell made his acquaintance while in Africa, and became his early friend.

At that time Oswell with his companion Murray allied themselves with Livingstone to discover a reported lake of the unknown interior, together with Mrs. Livingstone and their infantine family. This expedition was at the private cost of Oswell and Murray; but, in grateful remembrance of the assistance rendered by Livingstone in communicating with the natives and in originating the exploration, Oswell sent him a present of a new waggon and a span of splendid oxen (sixteen animals), in addition to a thorough outfit for his personal requirements.

Livingstone, in the ‘Zambesi and its Tributaries,’ dwelt forcibly upon the obligation imposed upon him by Oswell’s generosity; but, having submitted the manuscript to his friend for revision, Oswell insisted upon disclaiming the title of a benefactor. After the discovery of the Lake ’Ngami by Livingstone and his party, Oswell received the medal of the French Geographical Society; he was therefore allied with Livingstone, who was the first explorer of modern times to direct attention to the lake system of Africa, which has been developed within the last forty years by successive travellers.

Oswell was not merely a shooter, but he had been attracted towards Africa by his natural love of exploration, and the investigation of untrodden ground. He was absolutely the first white man who had appeared upon the scene in many portions of South Africa which are now well known. His character, which combined extreme gentleness with utter recklessness of danger in the moment of emergency, added to complete unselfishness, ensured him friends in every society; but it attracted the native mind to a degree of adoration. As the first-comer among lands and savage people until then unknown, he conveyed an impression so favourable to the white man that he paved the way for a welcome to his successors. That is the first duty of an explorer; and in this Oswell well earned the proud title of a ‘Pioneer of Civilisation.’

As these few lines are not a biography, but merely a faint testimony to one whose only fault was the shadowing of his own light, I can sincerely express a deep regret that his pen throughout his life was unemployed. No one could describe a scene more graphically, or with greater vigour; he could tell his stories with so vivid a descriptive power that the effect was mentally pictorial; and his listeners could feel thoroughly assured that not one word of his description contained a particle of exaggeration.

I have always regarded Oswell as the perfection of a Nimrod. Six feet in height, sinewy and muscular, but nevertheless light in weight, he was not only powerful, but enduring. A handsome face, with an eagle glance, but full of kindliness and fearlessness, bespoke the natural manliness of character which attracted him to the wild adventures of his early life.

He was a first-rate horseman, and all his shooting was from the saddle, or by dismounting for the shot after he had run his game to bay.

In 1861, when I was about to start on an expedition towards the Nile sources, Oswell, who had then retired from the field to the repose of his much-loved home, lent me his favourite gun, with which he had killed almost every animal during his five years’ hunting in South Africa. This gun was a silent witness to what its owner had accomplished. In exterior it looked like an ordinary double-barrelled rifle, weighing exactly ten pounds; in reality it was a smooth-bore of great solidity, constructed specially by Messrs. Purdey & Co. for Mr. Oswell. This useful gun was sighted like a rifle, and carried a spherical ball of the calibre No. 10; the charge was six drachms of fine-grained powder. There were no breech-loaders in those days, and the object of a smooth-bore was easy loading, which was especially necessary when shooting from the saddle. The spherical ball was generally wrapped in either waxed kid or linen patch; this was rolled rapidly between the hands with the utmost pressure;[Pg 29] the folds were then cut off close to the metal with scissors, and the bullet was again rolled as before. The effect was complete; the covering adhered tightly to the metal, which was now ready for ramming direct upon the powder-charge, without wads or other substance intervening. In this manner a smooth-bore could be loaded with great rapidity, provided that the powder-charge was made up separately in the form of a paper cartridge, the end of which could be bitten off, and the contents thrust into the barrel, together with the paper covering. The ball would be placed above, and the whole could be rammed down by a single movement with a powerful loading rod if great expedition should be necessary. Although the actual loading could thus be accomplished easily, the great trouble was the adjustment of the cap upon the nipple, which with an unsteady horse was a work of difficulty.

This grand old gun exhibited in an unmistakable degree the style of hunting which distinguished its determined owner. The hard walnut stock was completely eaten away for an inch of surface; the loss of wood suggested that rats had gnawed it, as there were minute traces of apparent teeth. This appearance might perhaps have been produced by an exceedingly coarse rasp. The fore-portion of the stock into which the ramrod was inserted was so completely worn through by the same destructive action, that the brass end of the rod was exposed to view. The whole of this wear and tear was the result of friction with the ‘wait-a-bit’ thorns!

Oswell invariably carried his gun across the pommel of his saddle when following an animal at speed. In this manner at a gallop he was obliged to face the low scrubby ‘wait-a-bits,’ and dash through these unsparing thorns, regardless of punishment and consequences, if he were to keep the game in view, which was absolutely essential if the animal were to be ridden down by superior pace and endurance. The walnut stock thus brought into hasty contact with sharp thorns became a gauge, through the continual friction, which afforded a most interesting proof of the untiring perseverance of th[Pg 30]e owner, and of the immense distances that he must have traversed at the highest speed during the five years’ unremitting pursuit of game upon the virgin hunting-grounds of Southern Africa. I took the greatest care of this gun, and entrusted it to a very dependable follower throughout my expedition of more than four years. Although I returned the gun in good condition, the ramrod was lost during a great emergency. My man (a native) was attacked, and being mobbed during the act of loading, he was obliged to fire at the most prominent assailant before he had time to withdraw his ramrod. This passed through the attacker’s body, and was gone beyond hope of recovery.

There could not have been a better form of muzzle-loader than this No. 10 double-barrel smooth-bore. It was very accurate at fifty yards, and the recoil was trifling with the considerable charge of six drams of powder. This could be increased if necessary, but Oswell always remained satisfied, and condemned himself, but not his gun, whenever a shot was unsatisfactory. He frequently assured me that, although he seldom fired at a female elephant, one bullet was sufficient to kill, and generally two bullets for a large bull of the same species.

Unlike Gordon Cumming, who was accustomed to fire at seventy and eighty yards, Oswell invariably strove to obtain the closest quarters with elephants, and all other game. To this system he owed his great success, as he could make certain of a mortal point. At the same time the personal risk was much increased, as the margin for escape was extremely limited when attacking dangerous game at so short a distance as ten or fifteen paces. When Oswell hunted in South Africa, the sound of a rifle had never disturbed the solitudes in districts which are now occupied by settlers. The wild animals have now yielded up their territory to domestic sheep and cattle; such are the rapid transitions within half a century! In those days the multitudes of living creatures at certain seasons and localities surpassed the bounds of imagination; they stretched in countless masses from point to point of the horizon, and[Pg 31] devoured the pasturage like a devastating flight of locusts. Whether they have been destroyed, or whether they have migrated to far distant sanctuaries, it is impossible to determine; but it is certain that they have disappeared, and that the report of the rifle which announces the advance of civilisation has dispersed all those mighty hosts of animals which were the ornaments of nature, and the glory of the European hunter. The eyes of modern hunters can never see the wonders of the past. There may be good sport remaining in distant localities, but the scenes witnessed by Oswell in his youth can never be viewed again. Mr. W. F. Webb, of Newstead Abbey, is one of the few remaining who can remember Oswell when in Africa, as he was himself shooting during the close of his expedition. Mr. Webb can corroborate the accounts of the vast herds of antelopes which at that time occupied the plains, and the extraordinary numbers of rhinoceros which intruded themselves upon the explorer’s path, and challenged his right of way. In a comparatively short period the white rhinoceros has almost ceased to exist.

Where such extraordinary changes have taken place, it is deeply interesting to obtain such trustworthy testimony as that afforded by Mr. Oswell, who has described from personal experience all that, to us, resembles history. He was accepted at that time as the Nimrod of South Africa, ‘par excellence,’ and although his retiring nature tended to self-effacement, all those who knew him, either by name or personal acquaintance, regarded him as without a rival; and certainly without an enemy: the g[Pg 32]reatest hunter ever known in modern times, the truest friend, and the most thorough example of an English gentleman. We sorrowfully exclaim, ‘We shall never see his like again.’

By W. Cotton Oswell

I have often been asked to write the stories of the illustrations given in the chapters on South Africa, but have hitherto declined, on the plea that the British public had had quite enough of Africa, and that all I could tell would be very old. As I now stand midway between seventy and eighty I trusted I might, in the ordinary course of nature, escape such an undertaking; but in the end of ’91 the best shot, sportsman and writer that ever made Africa his field—I refer to my good friend Sir Samuel Baker—urged me to put my experiences on paper; and Mr. Norton Longman at the same time promising that, if suitable, he would find them a place in the Badminton volume on ‘Big Game,’ I was over-persuaded, made the attempt, and here is the result.

The illustrations are taken from a set of drawings in my possession by the best artist of wild animal life I have ever known—Joseph Wolf. After describing the scene, I stood by him as he drew, occasionally offering a suggestion or venturing on two or three scrawling lines of my own, and the wonderful talent of the man produced pictures so like the reality in all essential points, that I marvel still at his power, and feel that I owe him most grateful thanks for a daily pleasure. Many of the scenes it would have been impossible to depict at the moment of their occurrence, so that even if the chief human actor had been a draughtsman he must have trusted to his memory. Happily I was able to give my impressions into the hands of a genius who let them run out at the end of his fingers. They are rather startling, I know, when looked through in the space of five minutes; but it must be remembered that they have to be spread over five years, and[Pg 33] that these are the few accidents amongst numberless uneventful days. I was once asked to bring these sketches to a house where I was dining. During dinner the servants placed them round the drawing-room, and on coming upstairs I found two young men examining them intently. ‘What’s all this?’ one asked. ‘I don’t know,’ the other replied. ‘Oh, I see now,’ the first continued, ‘a second Baron Munchausen; don’t you think so?’ he inquired, appealing to me. We were strangers to each other, so I corroborated his bright and certainly pardonable solution; but they are true nevertheless. I have kept them down to the truth: indeed, two of them fall short of it. I am very well aware that there are two ways of telling a story, one with a clearly defined boundary, the other with a hazy one, over which if your reader or hearer pass but a foot’s length he is in the realms of myth. I think I had my full share of mishaps; but I was in the saddle from ten to twelve hours a day for close upon five seasons, and general immunity, perhaps, induced carelessness. I may say now, I suppose, that I was a good rider, and got quickly on terms with my game. I was, however, never a crack shot, and not very well armed according to present notions, though I still have the highest opinion of a Purdey of 10-bore, which burnt five or six drachms of fine powder, and at short distances drove its ball home. This gun did nearly all my work. I had besides a 12-bore Westley-Richards, a light rifle, and a heavy single-barrelled one carrying two-oz. belted balls. This last was a beast of a tool, and once—I never gave it a second chance—nearly cost me my life, by stinging, without seriously wounding, a bull elephant. The infuriated brute charged nine or ten times wickedly, and the number might have been doubled had I not at last got hold of the Purdey, when he fell to the first shot. We had no breech-loaders in those days, save the disconnecting one, and that would have been useless, for we had to load as we galloped through the thick bush, and the stock and barrel would soon have been wrenched asunder or so strained as to prevent their coming accurately into contact again.

The Purdey gun has a second history which gives it more value in my eyes than the good work it did for me. I lent it to Baker when he went up the Nile, and it had the honour, I believe, of being left with Lady Baker to be used, if required, during her husband’s enforced absences. Baker returned it to me with a note apologising for the homeliness of the ramrod—a thornstick which still rests in the ferrules—adding that having to defend themselves from a sudden attack, his man Richarn, being hard pressed whilst loading, had fired the original ramrod into a chief’s stomach, from which they had no opportunity of extracting it.

I am sorry now for all the fine old beasts I have killed; but I was young then, there was excitement in the work, I had large numbers of men to feed, and if these are not considered sound excuses for slaughter, the regret is lightened by the knowledge that every animal, save three elephants, was eaten by man, and so put to a good use. I have no notes, and though many scenes and adventures stand out sharply enough, the sequence of events and surroundings is not always very clear. If my short narrative seems to take too much the form of a rather bald account of personal adventure, I must apologise; and I may add that the nature and habits generally of the animals I met with are now so well known, and have over and over again been so well described by competent writers, that my relations with a few individuals of their families must be the burden of my song.

I spent five years in Africa. I was never ill for a single day—laid up occasionally after an accident, but that was all. I had the best of companions—Murray, Vardon, Livingstone—and capital servants, who stuck to me throughout. I never had occasion to raise a hand against a native, and my foot only once, when I found a long lazy fellow poking his paw into my sugar tin. If I remember right, I never lost anything by theft, and I have had tusks of elephants, shot eighty miles from the waggons, duly delivered. One chief, and one[Pg 35] only, wanted to hector a little, but he soon gave it up. And with the rest of the potentates, and people generally, I was certainly a persona grata, for I filled their stomachs, and thus, as they assured me, in some mysterious way made their hearts white.

There is a fascination to me in the remembrance of the past in all its connections: the free life, the self-dependence, the boring into what was then a new country; the feeling as you lay under your caross that you were looking at the stars from a point on the earth whence no other European had ever seen them; the hope that every patch of bush, every little rise, was the only thing between you and some strange sight or scene—these are with me still; and were I not a married man with children and grandchildren, I believe I should head back into Africa again, and end my days in the open air. It is useless to tell me of the advantages of civilisation; civilised man runs wild much easier and sooner than the savage becomes tame. I think it desirable, however, that he should be sufficiently educated, before he doffs his clothes, to enjoy the change by comparison. Take the word of one who has tried both states: there are charms in the wild; the ever-increasing, never-satisfied needs of the tame my soul cannot away with.

But I am writing of close upon fifty years ago. Africa is nearly used up; she belongs no more to the Africans and the beasts; Boers, gold-seekers, diamond-miners and experimental farmers—all of them (from my point of view) mistakes—have changed the face of her. A man must be a first-rate sportsman now to k[Pg 36]eep himself and his family; houses stand where we once shot elephants, and the railway train will soon be whistling and screaming through all hunting-fields south of the Zambesi.

Reduced from 12 st. 2 lb. to 7 st. 12 lb. by many attacks of Indian fever caught during a shooting excursion in the valley of the Bhavany River, I was sent to the Cape as a last chance by the Madras doctors; indeed, whilst lying in a semi-comatose state, I heard one of them declare that I ought to have been dead a year ago; so all thanks to South Africa, say I! I gained strength by the voyage, and, shortly after reaching Cape Town, hearing that a Mr. Murray, of Lintrose, near Cupar Angus, had come from Scotland for the purpose of making a shooting expedition to the interior, I determined to join him. The resolve was carried out early in the spring of 1844 (the beginning of the Cape winter); we started out from Graham’s Town to Colesberg, buying on the way horses, oxen, dogs, waggons, and stores, crossed the Orange River, and set our faces northwards. We were all bitten in those days by Captain—afterwards Sir Cornwallis-Harris, whose book, published about 1837, was the first to give any notion of the capabilities of South Africa for big game shooting, and, Harris excepted, ‘we were the first that ever burst into that “sunny” sea’-as sportsmen. Murray was an excellent kind-hearted gentleman, rather too old perhaps for an expedition of this kind, as he felt the alternations of the climate very much; and no wonder, for I have known the thermometer to register 92° in the shade at 2 p.m., and 30° at 8 p.m. I was younger, and though still weak from the effects of fever, the dry air of the uplands daily gave me vigour, and the absolute freedom of the life was delightful to me. Just at first I had to become accustomed to the many little annoyances of missing oxen, strayed horses, &c.; but when our waggons became our home, and our mi[Pg 37]gratory state our life, all anxious care vanished. Things would be put right somehow; there was no use worrying ourselves; what had been yesterday would be to-morrow. What though the flats between the Orange and Molopo Rivers were full of sameness, they were also full of antelope, gnu, and quagga. These, with the bird and insect life, were all fresh, and made the world very bright around us. These upland flats have been so often described, that I will not bore the reader unnecessarily with an account of them, and besides, I am not writing of the country or its appearance, but have merely undertaken to try and give some idea of the game that once held possession of it; and, indeed, I doubt very much if I could convey any notion at the present time of what it was some fifty years ago, for all the glamour of the wildness and abundant life has long passed away.