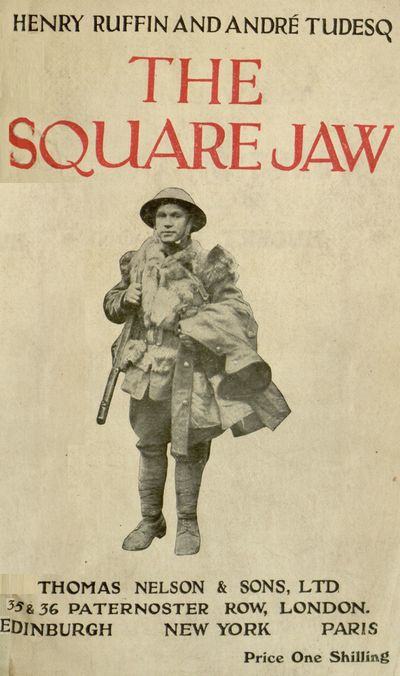

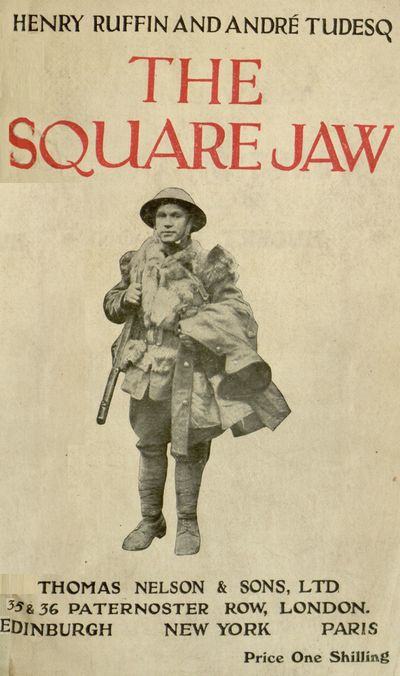

Title: The Square Jaw

Author: Henry Ruffin

André Jean Tudesq

Release date: March 27, 2015 [eBook #48592]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

HENRY RUFFIN AND ANDRÉ TUDESQ

THOMAS NELSON & SONS, LTD

35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON.

EDINBURGH NEW YORK PARIS

Price One Shilling

BY

HENRY RUFFIN AND ANDRÉ TUDESQ.

Translated from the French.

THOMAS NELSON & SONS,

35 AND 36, PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C.

EDINBURGH. NEW YORK. PARIS.

| PART I.—BATTLE OF THE ANCRE. | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | The Impromptu Victory | 7 |

| II.— | In Front of the Munich Trench | 11 |

| III.— | The Real Supermen | 14 |

| IV.— | Surprises of a Moonlit Frosty Night | 17 |

| V.— | The Battle Reopens | 20 |

| VI.— | On the Edge of the Fray | 23 |

| Epilogue | 24 | |

| PART II.—THE SQUARE JAWS. | ||

| I.— | The Welding of French and British | 31 |

| II.— | How the Australian Contingent Voted in France in Face of the Enemy | 35 |

| III.— | Boelcke's Land of Promise | 40 |

| IV.— | The Square Jaw | 45 |

| V.— | The Relief | 49 |

| PART III.—THE ARMIES OF THE NORTH. | ||

| I.— | The Preparation of the Canadians | 56 |

| II.— | Arras, the Wounded Town | 60 |

| III.— | The Ground of Heroic Deeds | 63 |

| IV.— | A Dinner of Generals | 66 |

| V.— | War in the Black Country | 68 |

| VI.— | The Art of Saving | 71 |

| VII.— | "Brothers in Arms" | 73 |

| PART IV.—IMPRESSIONS OF "NO MAN'S LAND." | ||

| I.— | As in a Picture of Epinal | 79 |

| II.— | A Hero After the Manner of Roland | 81 |

| III.— | Midnight in the Front Line | 84 |

| IV.— | Through the Mine Area | 87 |

| V.— | The Menace of the Golden Virgin | 91 |

| VI.— | "Ronny" | 94 |

| VII.— | Piping Out the Day | 96 |

| VIII.— | Y Gully | 98 |

| IX.— | Christmas Night in "No Man's Land" | 100 |

THE BATTLE OF THE ANCRE.

THE IMPROMPTU VICTORY.

The Ancre Front, 13th November.

You read the reports. The names of the places that have been taken, the calculations of the gains, the numbers of the prisoners, leave you cold. Words! words! It is on the field of battle, amidst the thunder of the guns and the magic glow of fires, that one should read the bulletins of victory.

This evening a heady, irresistible joy took possession of the Army. The prisoners were pouring in. The men were singing in their quarters. Upon a front 3-1/2 miles wide and nearly 1-1/2 deep our Allies had broken the German lines on both sides of the Ancre.

They have been giving me details of the battle. From hour to hour, here, in the midst of the troops, I am being told the incidents of the fighting. A risky privilege!

The despatches which come to us; the despatch riders who, at the utmost speed of their motor-cycles, bring us reports through the ruts and mud of the roads; the messages of the telegraph—everything has assumed a heroic quality. A feverish joy quivers in every face. Even the bell of the telephone follows, strangely, the measure of our heart-beats.

"We owe this victory to our quickness," a Colonel tells me. "This battle was an impromptu." The word is a picture. It is absolutely right.

At six o'clock—that is to say, in the grey light of the[Pg 8] morning—after a short but annihilating artillery preparation, the divisions posted in the first line dashed forward through the fog and drizzle. The objective was three villages—Beaumont-Hamel and Beaucourt on the North bank of the river, and, on the South, Saint Pierre-Divion.

Let me tell you something of the country and its difficulties.

Swamps, soggy undulations formed by the trenches and the convoys, a wet, clayey soil, into which one sinks to the waist. Mud everywhere. Slime everywhere. One must slide down the funnels and holes that the shells have made. Thus the waves of the assault gather for their onset. The Germans had constructed defences formed of five lines of trenches, each alternated with at least three rows of barbed wire entanglements. The chevaux de frise and other obstacles covered, in places, a space over 200 yards wide.

On the one hand and on the other the banks of the Ancre ran up into bluffs like buttresses. Since his failure of the 1st of July, the enemy has cut among these natural protections deep trenches which wind along parallel to the course of the river. He has also set up on the slopes powerful machine-gun emplacements and blockhouses with mortars.

The English advance went like clockwork. The secret had been well kept; the evening before, the troops of this sector were quite unaware that an advance was to take place.

An absolute determination inspired both officers and men. The result of the attack was never in doubt. The trenches were taken by storm, together with those who manned them. It was a veritable harvest of men. The fourth line was taken at the point of the bayonet in eighteen minutes.

At eight in the morning we attacked the outskirts of the three villages. Beaumont-Hamel was the first to be taken, with its garrison. Before Beaucourt we were brought to a halt by machine-gun fire. Saint Pierre-Divion was outflanked.[Pg 9] The artillery increased its range and cut short all counter-attacks.

By nine o'clock the objective was gained with complete success. The fog grew thicker. The fire of the heavy guns and the barrage fires followed one another without pause.

Through twilight gloom and the mists of low-lying clouds monstrous lightnings flicker across this spectral landscape. The smallest hill is a Sinai. In a leap of nearly 1-1/2 miles the batteries have advanced at the same pace as the troops, taking such cover as Heaven sends them. All this sector smokes and roars to its farthest extremities. It is as if there were dragons squatting everywhere by the hundred and spitting flame. Fires break out, blushing palely through the fog. Stores of munitions explode behind the villages. It is like the brute thunder of the earthquake.

The fiercest fighting developed at Beaumont-Hamel, where the ground is full of great caves that run into one another. In these there was plenty of room for four companies.

Next, the centre of interest shifted to the South bank of the Ancre, where Y Gully commands the passage of the river and the road to Beaucourt. This ravine, upon which three months' work had been spent, was a positive arsenal. Every 20 yards along it there was a machine-gun. The Germans believed it to be impregnable. This evening the English had their own guns in it.

Victory everywhere! Three villages taken; more than 2,000 prisoners counted already! I have just been to see them. They are encamped along the edge of an immense bivouac. All about them the heaviest of the guns spit out, minute by minute, their delicate ton-weight mouthfuls. The prisoners are identified, questioned, and searched. A dazed stupor is all that their terrified faces declare. They have suffered very little damage, for most of them have been surprised in their caves and dug-outs. Many of them[Pg 10] are still wearing their helmets. Their officers have accepted their bad fortune, one would say, gladly. There is nothing of bravado in their carriage. The Tommies surround this encampment curiously. With a friendliness that is very touching they offer, some cigarettes, others food. Generosity on the one side; a growing astonishment on the other. The German soldiers, nearly all Silesians, accept these things with a sort of childish gratitude.

The motor-ambulances move here, there and everywhere over the clayey fields, where the wheels of the ammunition wagons have drawn mighty furrows, like those that peaceful toil once made here. One hardly sees the faces of these men. They are blanks, for their thoughts are elsewhere, within. On the other hand, one's attention is seized by such things as their feet, mere lumps of clay, that at times the red touch of a swathed wound enlivens. Motor-'buses—as in London—run upon the roads. Those who are lightly wounded crowd to the top. One of them wears a pointed helmet, where shines the two-headed eagle. Others hang the Iron Cross upon their caps. They are all laughing and joking like schoolboys.

The road to Bapaume, to the north, is almost all free. From to-day begins, on this side, the siege of that town, which the Germans have converted into a stronghold. All over the plain the English are lighting camp-fires: and in perfect safety, since the enemy's line has retired about 1-1/2 miles. The skirl of bagpipes, the scream of fifes, the choruses of the men, rise into the foggy night. It proves the truth of the saying: "To live truly is to live perilously."

Victory! And the battle goes on.

IN FRONT OF THE MUNICH TRENCH.

Beaumont-Hamel, 15th November.

That two-hour tramp through a few kilometres of trenches was a heart-breaking business. We floundered through holes, we were swallowed up in bogs, while the mud that fell from the parapets gradually spread itself over our oilskins. A steel helmet becomes wonderfully heavy after an hour or so, and a dizzy headache soon tormented us, from the constant right-angled turns which we were obliged to make, like so many slaves at a cornmill. But what a reward has been ours since our arrival!

Here we are, seated at the horizontal loophole of a quite new observation post, in the front line, in the very trench from which, the day before yesterday, the English launched their attack.

In front, towards the left, is Beaumont-Hamel. Out of this heap of rubbish start up three-cornered bits of wall, which give to these ruins the look of a dwarf village. On the hillside a mangled copse looks like those guileless charcoal strokes which one sees in a child's drawing. To the right—Beaucourt. Here the ruin is absolute. I have hunted in vain for any trace of man's handiwork. Even the dust of the stones has blown away.

A few hundred yards ahead of us the men have just rushed forward. With rifles held high they spring from the parapet into the open. They look like an army of ants, that now moves along in a stream, now closes together like a vice, now marks time, now plunges into vast funnels, and again, at racing speed, surges up the gentle slope. The barbed-wire entanglements cover acres of ground; they are the eleventh line of the German defences. In many places the wires are so closely bunched together that the balls cannot pass through them.

At least a brigade is engaged. One can see the company[Pg 12] leaders quite plainly. The shells are bursting everywhere, throwing up furious fountains of black smoke with which bits of earth and iron are mingled. The rolling clouds of the shrapnel seem to frame one regiment.

Ah! Bad luck! That one was well timed which burst over there on the right, just above the company that was lying down there. The damage must have been serious. Men lie on the ground who will never pick themselves up again. A cloud, the colour of absinthe, hangs sullenly over those little khaki spots.

On the right, on the left, in front, behind, with a disquieting skill and precision, the Germans pile barrage upon barrage. Meanwhile, without a pause, the troops advance across this hell. I can follow, with the naked eye, every movement of an active young officer, who is wearing a light yellow overcoat, and who is charging at the head of his company, with a cane under his left arm and a revolver in his right hand as calmly as if he were strolling along Regent Street or Piccadilly.

The human wave, breaking through the barrage, disappears suddenly in the earth. It is as if a chasm had opened to swallow all these men at a gulp. And now, listen! For the gunfire is punctuated with sharp detonations. It sounds like a shrill drumming, swelled by furious shouts and cries of agony. The Tommies have entered the enemy's lines. After a short period of bombing, they advance, yard by yard, with the bayonet. Round the blockhouses the machine-guns rattle. We listen anxiously to these thousand voices of the attack. Every man has vanished. The field of vision is empty. Only the variegated smokes of the different shells spread themselves slowly abroad. The uncertainty is unbearable. Half an hour later we learn from the telephone that the attack has succeeded. The brigade has done its work. We have just witnessed, on the north bank of the Ancre, the capture of an important trench, or rather redoubt, nearly 450 yards away from Beaumont—the Munich Trench.

Here again there has been a famous haul of prisoners. More than 300 unwounded soldiers have been compelled to surrender. In a short time the first of them cross in front of our observation post. They are haggard, covered with mud, and their eyes are the eyes of trapped beasts. Two of them, converted into impromptu stretcher-bearers, are carrying a wounded officer on a stretcher that is soaked in blood.

And now the battle increases everywhere in violence. We hear that on this side of Beaucourt some strong reserves, collected there by the Germans, have just been surrounded and taken prisoners. A whole brigade staff has fallen into the hands of the English. More than 5,000 prisoners have been counted already. It will take at least two days to count all that have been taken. A genuine victory!

The "tanks" have played an honourable part in the battle, and I have just seen two of them at work. My impressions may be summed up in these words: a huge amazement and satisfaction.

One of them, which has been christened The Devil's Delight, did marvels at Beaucourt. This deliberate leviathan, having placed itself boldly at the head of the advancing flood of men, took up its position at the entrance of the ruined village. At first the Germans fled. Then, one by one, they came back. With machine-guns, bombs, rifles and mortars they endeavoured to pierce its double shell. Nothing availed. Squatted on its tail, the terrific tank lorded it there like a king on his horse. It made no objection whatever to being approached. Some sappers tried to place bombs under it, to blow it sky high. Inside it the crew shammed dead. The Germans took heart. Ten, twenty, thirty men, armed with screw-jacks and mallets laboured to overthrow it. But what could even two battalions have accomplished against this patient mastodon, whose skin was steel and whose weight was 800 tons? A colonel, mad with rage, fired the eight barrels of his revolver at it, point-blank. If the tank[Pg 14] could have laughed it must have burst with delight. Its sense of humour is a strictly warlike one.

After a full quarter of an hour of silence the Germans, believing that the crew had been destroyed and that the monster was helpless, surrounded it boldly and in considerable numbers. Thereupon, unmasking its machine-guns, and opening fire from its sides, the terrible creature began to hack them in bits, mow them down in heaps, drill them full of holes and slay them by the dozen.

A giant miller, grinding death!

An hour later, when the larger part of the English troops succeeded in reaching Beaucourt, they found the Germans, dead and dying, piled around the tank. The tank says little, but to the point.

Three cheers for Mademoiselle Devil's Delight!

THE REAL SUPERMEN.

"We are consolidating our positions."

(English Communiqué, 16th November.)

Here is a story.

Some time ago, on the North bank of the Ancre, in the Beaumont-Hamel Sector, everyone was affected with a curious boredom. Nothing happened: very little artillery fire; not so much as a pretence at an attack. It was a dead calm. The bombs were all asleep. Muscles grew slack. Enthusiasm staled. Boredom, that worst misery of trench life, reigned supreme.

One evening this slackness among the troops—and it was as bad on one side as on the other—produced a curious result. Among the Germans, a homesick Silesian began to sing some of the carols of his own country. His voice rose[Pg 15] freshly into the fresh night. At the same time on the English side, a Highlander, stirred by the sweetness of the autumn evening, blew a few shrill notes upon his fife. The voice of the man and the fife supported one another, and so a concert began, a concert of old songs, the simple happy songs of the peasant. The English shouted to the Germans, "Give us Gott Strafe England!" and the Germans obliged with the "Song of Hate." "Encore! Encore!" cried the Highlander, whose fife was seeking to catch the air that the enemy was singing. The song began again, the fife supporting it. Then it was taken up by all the English. But to what sort of a rhythm! The "Song of Hate," slow as plain song, had suddenly become, as it crossed the trenches, a crazy, jerky, rollicking ragtime, a tune for the can-can. The Germans supposed that they were being chaffed. By way of applause, they let fly a shower of bombs. To this compliment the English replied in kind. Then the night closed down upon a boredom more dreadful than ever.

I have told you this story as a sort of commentary upon the epigram in which a certain colonel explained this very successful two days' battle: "Our attack, like our victory, was an impromptu."

To capture three villages and eleven lines of the enemy's defences upon a front 3-1/2 miles wide and nearly 1-1/2 deep, is pretty good. To take a haul of nearly 6,000 prisoners out of their dug-outs and caves and other quarters—that is not to be sneezed at either. But to organise the territory that has been taken and to consolidate it, working night and day under the constant fire of the enemy—that is perhaps a less glorious business, but it is a thing more difficult to accomplish than any attack.

For two long hours of the night my friend Ruffin, of the Agence Havas, and I, conducted by our guide, the major, tramped it through the trenches in order to reach those which lie under Beaumont. Steel helmet on head, first-aid equipment and gas mask under arm, we went on between[Pg 16] the two walls of this roundabout road, our feet sticky with mud and our eyes continually dazzled. Rockets soared into the air to burst and then go out like those Roman candles which blossom into sprays of slowly moving stars. One might have thought that some unseen juggler, over there on the blazing skyline, was manipulating huge fiery plates.

The trenches were swarming with soldiers, the reliefs who were going back to billets, and the reserves who were taking their places; the sappers and pioneers, with their picks and shovels, who, protected by the machine-guns, repair the shelters wherever they have given way; the ambulance men and the stretcher-bearers; the grave diggers; the supplying sections, who bring up the cases of grenades, before ever they appear with food. This crowd of dim men, ten feet underground, moved like a silent river.

One hardly thought of talking. To-night, when they are consolidating the conquered positions, the opposing artilleries were engaged in a terrific duel. The barrage fires of the Germans followed one another every quarter of an hour, each one lasting seven minutes, and each minute an eternity, when, every second, there fell not less than 100 shells. To protect those who were at work the English artillery set up curtain fires, which smashed every preparation for a counter-attack. Marmites, shells, shrapnel, hurtled from either side of the single line which had been snatched from this Inferno.

An odd scent of roasted apples catches us by the throat; our eyes begin to stream in a detestable fashion. "Look out for the acid drops!" cries our major. We know this bit of soldiers' slang, which means the lachrymatory shells. We quickly put on our masks. In perfect safety, crouched against the wall of the trench, in the company of a hundred unknown comrades, we wait until the poisonous gust of yellow smoke has blown away. Through the eye-pieces of our masks everything seems to be enveloped in some fabulous steam; the pale lightning of the guns, the ghastly[Pg 17] discs of the English rockets, the red stars of the German. But one sound: the clatter of the machine-guns near us, a muffled thunder as of a rising sea.

In this muddy ditch we are like some lost gang of divers.

And in the meantime, 100 yards ahead of us, in the midst of choking gases and the tempest of the machine-guns, soldiers—heroes—have never ceased their work.

They hammer nails, they drive in stakes, they sink piles, they knot together into spider nets the tangled strands of the barbed wire. All honour to them! These are the Supermen.

SURPRISES OF A MOONLIT FROSTY NIGHT.

A true Walpurgis Night of heroes and warriors. It is not on the summit of the Brocken that I have witnessed it, but, looking out over the plain of the Ancre, from a tree. This tree, every evening, is wreathed with the fumes of asphyxiating shells. Its woolly streamers of shrapnel smoke are like the foliage around a heraldic crown.

As soon as twilight is come, aeroplanes cross the neighbouring lines and attack this tree with their machine-guns. It is treated like a combatant. Herein, perhaps, lies the secret of its clumsy strength and beauty. It stands upon its hill, solid and straight. It holds its ground as few men could do. It is a French ash that stands upon the field of battle in the very middle of the British Army.

It has become an observation post. One climbs it by a straight ladder 160 feet long. In its highest fork one of the engineers has made a wooden box, bound together with barbed wire, with a little canvas to hide it. Field-glasses, maps, range-finders are there. All the gusts of the autumnal breeze blow through it. Up here, too, men are pitched about as if they were in the mizzen-top of a cruiser. Strange nest for war eagles!

"Perfect weather for flying," the major tells me.

A clear, frosty, moonlight night broods over the black distances of the plain. The river and its swampy edges glisten like silver coins. No sign of life. Only the guns, all round the horizon, roar beneath their crests of lightning.

Imagine that after blinding yourself with a very tight and thick bandage you suddenly open your eyes. Glowing discs, will o' the wisps, haloes, flashing rainbows, a whole ballet of lights spins upon your retina. Up here, that is the spectacle that each night brings. The battlefield appears to be electrified. At one moment, sharp, stabbing flashes, cold arrows of light. It is the English guns shelling the enemy. The next, radiances which divide, spread out fanwise, or blossom like flowers. They are German marmites or crapouillots.

The sounds of the guns intersect one another. They are hard and dry, when some battery, near by, opens fire; dull, soft and muffled, according as the distance becomes greater. A stroke upon a gong, followed by a long metallic shriek, high in the air, announces a heavy shell. After a hoarse scream a machine-gun begins to crackle, rending both air and men.

It is all one vast intermittent hurly-burly, lightning flashing low down, V-shaped sheaves of red fire. And all is, each time, unexpected, cruelly inconsequent, magnificent and devastating.

Thousands of men are there, and thousands upon thousands, all over this plain of the Ancre. There they lie, buried in their trenches, their nerves like stretched wire, ready to spring forward on the instant.

From here we can see one of the last sectors to be conquered.

It is land over which the offensive has passed.

And our hearts ache as we remember that down there, near this swamp, it is not even in ill-made trenches that the English sections are keeping their watch, but, simply,[Pg 19] in shell-holes, where the water lies deep, holes whose sides have been hastily shored up—veritable human hells.

The fireworks did not keep us waiting. About ten o'clock, a certain unwonted nervousness becoming evident among the Germans, the two English trenches of the first line let off a bouquet of rockets. Balls of light, red, blue or green, climbed 90 feet into the air. For a moment they rose, hesitatingly, like toy balloons at the end of a string, then burst into stars or sheaves, lighting up, as with a ghastly daylight, this neutral ground, this "no man's land," which the scattered corpses of the patrols alone inhabit. After each flight of rockets the guns came savagely to life, and, below our watch-tower, even in greater numbers, even more furious, other batteries, and yet others, proclaimed their presence. "Barrage!" one of the short-lived fire-balls demanded over to the west. The firing increased, pounding the sector from end to end. This light from fairyland, then, was nothing but a cry for help! In a moment the Ancre and its swamps were blushing.

The moon began to veil herself with small round clouds. "Watch out for the aeroplanes," our staff-major told us again. In a quarter of an hour his warning was justified.

The snarl of engines filled the milky spaces of the sky. Two squadrons against two. The English searchlights found the enemy for a moment, then lost him. Then from every crest and from smallest hollow the anti-aircraft guns began their barrage. In the sky nothing could be seen but the commas of flame and blazing curves, which marked where the shrapnel and the shells had burst. The machine-guns chattered like an applauding crowd.

A few planes succeeded in crossing the barrage. It was magic—of another kind.

One, two, five incendiary bombs were thrown by the enemy. The eye was dazzled as by a sudden appearance[Pg 20] of the aurora-borealis. The night became a ghastly day. Thick columns of smoke rose into the air, then, half-way to the clouds, swelled up like the tops of palm-trees. And thus they remained, twenty minutes after the explosion, without dissolving, steady against the wind, turning themselves into canopies and domes and a preposterous hedge of giant parasols.

One might have thought that some fabulous forest had just sprung up, filled with domed palaces of fantastic shape.

A night very fruitful of surprises—barrages, rockets, anti-aircraft firing, a battle of aeroplanes, incendiary bombs. Truly the Great Game, this!

I left my watch-tower tree like a man who has saved his soul from the black powers of sorcery.

THE BATTLE REOPENS.

18th November.

The Battle of the Ancre, which for a moment had died down, began again this morning, at dawn, with a new violence.

The English had only paused just long enough to oil the vast machine, which has now resumed its regular, methodic movements; and the latest news permits us to anticipate a fresh and substantial success.

The scene of these last events has been rather different from that which witnessed the English advance of the 12th and 13th of November. This, one may say in passing, proves the elasticity of the British offensive.

If the eye travels, on the map, to the right, beyond the positions in which the last battle was fought, it follows a line almost parallel to the valley of the Ancre. To-night, then, the English, not pursuing this theoretically correct line, inclined their front slightly to the[Pg 21] South, to the centre of a line drawn between Thiepval and Le Sars. This re-entering angle formed an obvious obstacle to the domination of the Ancre valley upon the whole of this part of the British front. For this reason General Sir Douglas Haig decided to abolish it.

Hence the movement of this morning.

The attack was elaborately prepared, and with the utmost secrecy, and was launched at dawn.

At the moment of writing this telegram the reports that are coming in from the scene of action show that the operation is being carried out, within the limits assigned, very successfully. To employ an expression coined by one of their own number, the Boche prisoners are "pouring" to the rear.

This morning the weather, so fine during the last three days, was extremely unfavourable to any movement of troops. There had been heavy snow during the night, and for the first time this winter our Allies fought in the snow. About 8 o'clock, the temperature having risen, a thaw set in. After that it was in foul mud that they did their fighting.

In order to understand properly the British manœuvres on the two banks of the Ancre, we must remark that yesterday, the 17th of November, the English had executed a movement which obviously aimed at assisting to-day's operations.

Shortly, by outflanking the village of Beaucourt to the East, they had carried their foremost positions, by yesterday evening, as far as the little wood of Hollande. Now it is clear that any advance in this direction seriously menaces Grandcourt and those positions on the north bank of the Ancre, which the British troops attacked this morning.

A superior staff-officer remarked lately in my hearing that the German line, throughout the recent fighting, has exhibited points of varying strength. He attributed this circumstance to the work of the English artillery. The[Pg 22] resistance which the enemy had been able to offer had varied directly with the effectiveness of the English gunfire.

It is also noticeable that the German losses in killed, prisoners and missing are considerably greater than the corresponding losses among the English. This result is apparently due to the fact either that the Germans surrender more readily than the English, or that the British artillery causes the enemy to sustain the heavier damage in dead and wounded, or else finally that, unlike the English, the Germans do not include their lightly wounded in the total of their losses.

Whatever the causes may be, that the issue of this battle has been disastrous for the Germans becomes daily more evident. It appears now that they are thinking of shortening their line where it is opposed to the British Army between Puisieux-les-Monts and Grandcourt. Under the increasing pressure of our Allies, the Germans, who are convinced that Grandcourt must soon fall, are entrenching themselves with feverish haste upon a new line, which unites Puisieux with Miraumont.

The enemy, using Puisieux as the pivot of his retiring movement, would thus describe an angle whose depth, from Puisieux to the Ancre, is about 2 miles, and whose width, between Grandcourt and Miraumont, is about 1-1/4 miles.

It is possible, however, that the British offensive may to some extent disorganise the beautiful and geometric symmetry of this new "strategic retreat" of the Germans.

ON THE EDGE OF THE FRAY.

19th November.

Yesterday was a good day for the English. Our friends were successful on nearly the whole front which they attacked. The only difficulty which they encountered—and this was not serious—was on their left centre; that is to say, to the South of Grandcourt. Thereabouts the ground favoured the defence, for it is cut up into a number of deep gorges, where the Boches had constructed redoubts and "nests" of machine-guns.

But, on the other hand, the Canadians did wonders on the left, pushing their patrols right up to the Western outskirts of Grandcourt.

The advance of the British troops on the North bank of the Ancre to the East of Beaucourt has caused the fortified village of Grandcourt to be menaced on more than one side.

They say that yesterday the German artillery made a very weak reply to the fire of the British guns. This is certainly not due to any shortage of material or ammunition suffered by Prince Rupert in this quarter. It is well known, on the contrary, that he has concentrated against the English an enormous quantity of these things. This weakness of the German reply must be due either to the destructive precision of the British fire, or to the formation of that line of resistance, about which I told you yesterday, in the rear of the present front.

The German prisoners who have been taken during the day say that the Boches suffered comparatively little damage, during the attack, from the British fire, since they were in dug-outs of great strength and depth. But when the infantry arrived they found themselves hemmed helplessly in on all sides, and were forced to surrender en masse.

The same prisoners cannot sufficiently praise the performance of the tanks, about which they speak with a kind of awful admiration. They always use the same word when they describe these armour-plated monsters: "Marvellous! Marvellous!"

They say that the German troops in the first line are well enough fed, but that as soon as they go into reserve or are given a rest their diet is at once restricted.

THE CHARNEL-HOUSE.

19th November. Evening.

On this November Sabbath the belfries of Contay, Warloy, Senlis and a dozen other villages of Picardy are sending forth through the fog their regular summons to vespers. It is very cold, and the snow which fell the other night has become foul mud, in which men, beasts and wagons flounder and splash.

The Tommies in their quarters have made a rather more careful toilet than usual, and are now gathered, in some neighbouring field or under some shed out of which a church has been improvised, to listen to the words of their chaplains. Peace, it would seem, reigns everywhere.

Only, alas! in appearance. For overpowering the voices of priests and sound of bells the guns begin their booming out a few paces away. Peace has not dwelt, this many a day, either in Englebelmer or in Mesnil, which offer to the eyes of the passer-by the spectacle of their desolated ruins, their silent belfries, their indescribable sadness. Nor does Peace dwell, assuredly, on this battlefield where you see these quagmires, these dead, bare[Pg 25] fields that, one would say, have been trampled by generations of men; these deserted trenches that have fallen in here and there; these networks of barbed wire, to-day, happily, no longer of any service; these shattered wagons, these rusting weapons; these gun shelters which dart lightning; these parks of munitions and materials; these strayed horses; these lines of muddy, brooding men—in a word, all this wretchedness—and, over all, covering everything as with a veil, this sky that seems heavy with threats, with hostility.

Yet, before the war, few of the countrysides of France can have breathed a more sweet and perfect spirit of peace. A soldier who was here last spring, before ever men had come hither to destroy one another, told me of the delight which he took in this pleasant corner of Picardy. "It was," he said, "a landscape by Claude Lorraine."

We were halted at the head of a small valley which runs easily downwards, near Mesine, towards the Ancre, and we were looking out across the country. At our feet the river, coming from the East, turned in a gentle curve towards the South, and was lost to sight in the direction of Avelun and Albert. The stream, considerably swollen by the recent rains, wound slowly between marshes and flooded fields.

The tall poplars of the valley, stripped of their leaves as much by the bullets as by the rough weather, moved gently in the breeze. Yesterday a dozen villages saw themselves reflected in the Ancre, and clothed the neighbourhood of the river with a share of their own prosperity. They were, among others, Mesnil, Hamel, Beaumont and Miraumont on the North bank. Thiepval, Saint Pierre-Divion and Grandcourt on the South. But the same devices of man that have massacred the trees of the valley and stripped Thiepval of its forest, have levelled these fortress-villages with the ground, and it is in vain that to-day we may hope to distinguish them[Pg 26] from the rest of this dismal country. Even as we looked, the shells of the opposing artilleries blotted out the last traces of Grandcourt. The guns, for ever the guns! They are the only sign of life in all this land of Death.

The little cemetery at Hamel, which we passed on our road, was not likely to dissipate these gloomy thoughts. In what a condition the battle has left it! It lay, unfortunately for itself, just between the two lines, English and German. But, indeed, it is no more and no less sad a sight than all that surrounds it; no more, no less than Beaumont; no more, no less than Beaucourt, to which we have now come.

A little in front of Beaucourt is a small hill, a sort of spur, lying towards the South-west. On the morning of the 13th of November it faced precisely in the direction whence the British attack was about to be launched. Even in its present state one can, from the lie of the ground and from the débris which is found scattered everywhere about, form some faint idea of what the Boches had made out of this natural fortress.

The British infantry, however, never hesitated a moment to storm the place, and their impetuosity was such that in 18 minutes it was in their hands.

If you do not know the price at which the English, like ourselves, bought this victory, go out upon this advanced work of Beaucourt. Take your courage in both hands and look about you. See there that group of fallen soldiers, the glorious victors of the Ancre, who lie still untouched, by the side of the Boches whom they have dragged down with them to death, after hand-to-hand struggles that no words may describe. Looking like pilgrims clothed in homespun, the English stretcher-bearers, now grave-diggers, "tidy up" the field of battle.

Poor and dear Tommies! They have fallen with their faces to the German trench. They fought with their heads, as do ours, for there is not a shell-hole of[Pg 27] which they have not taken advantage during their advance against their enemy. They have fought, also, like lions, since they have gained the victory.

One of them, a great, athletic-looking fellow with black hair, has fallen head forwards into a shell-hole. His poor, shattered body is drained of blood, but his face is a fiery red, as if his rage had risen there as he died.

Another, of slighter, more fragile frame, lies on his back, his legs apart, with a ball through his forehead. Close beside him are the bomb which he was about to throw and a tiny French-English dictionary. May we not say that he has witnessed with his blood to the friendship of two great nations?

Beside another, who has been hideously wounded, the wind turns over the leaves of a soldier's Bible.

But enough! My eyes can bear no more. And I hasten away from this scene, over which, like the sound of mighty organs, the great guns chant their huge and terrible chorus.

To free ourselves from this nightmare we went to visit the gunners in their shelters. It was three in the afternoon, and we had only just discovered that we had not yet lunched. A big fellow, who chattered like a magpie and was built like a Hercules, lit two candles for us, stirred the fire which was crackling in an earthen stove, spread a newspaper for our table-cloth, and offered us a seat on a case of jam-jars. Our sandwiches seemed delicious; our tea, the best in the world; our hovel, a palace; our candles, an illumination.

A joy, hitherto unknown, in being merely alive gave a priceless quality to the smallest pleasures of existence. We listened with the most intense interest and an unaccustomed delight to the talkative soldier, while he instructed us about the price of sugar in England.

Meanwhile, his battery, just beside us, went on killing Germans.

The spirit of Dickens hovered over that wretched hut.

Suddenly I noticed that my companion had fallen into a brown study, and I fancied that he was back upon that hill by Beaucourt. "Come, come!" I said. "What are you thinking about now?"

"I am thinking," the Englishman replied, "that we are bound to avoid war if we can, but that when war comes we are bound to meet it like men."

THE SQUARE JAWS.

THE WELDING OF FRENCH AND BRITISH.

Not all things can be welded together. There are metals which are wholly unsympathetic, and even for those which are not we require the services of the plumber and his solder.

It is the glory and the good fortune of the British and French Armies that, from the first day of the war, they have shown themselves fitted—and eager—to become one; and that they have discovered, to this end (and continue daily to employ them), plumbers of the first class and lead in abundance.

Let us understand one another. To say "joining," "soldering," is not to say "fusion," and the theory of united action upon a united front does not necessarily imply that out of two friends a single individual is wrought. A poilu might say that it is possible to be very good comrades without sleeping in the same bed.

For Germany such fusion would have been a danger, and she has always avoided it. Although she has carried her partnership with her allies to the length of making them her slaves, she has been very careful to allow nothing like a mingling of breeds in the forces which are at her disposal. The German Army has, for instance, resisted every temptation to admit into its ranks any of its Austrian friends. For it believes that it is possible to be too friendly.

Germany has confined herself, where this is in question, to giving her weakened allies no more help than can be obtained from her officers, commissioned and non-commissioned,[Pg 32] or from the specialised activities of her artillery and engineers. Beyond this she has but one thought—at any cost to insure unity of action between her forces and those of her allies.

From this it follows that to bring about a real fusion of two or more allied armies upon one front is a tactical achievement of the first importance. Such a fusion—the essential condition of all united effort that is to possess a real value—becomes, from its very nature, the principal object of the enemy's attack. The history of this war shows, if one may say so, nothing but a series of attempts, upon one side or the other, to prevent or destroy the cohesion of the opposing forces. (Mons; the first and second Battles of Ypres; the Russian-Rumanian Armies and the Army of the East; the junction of the Italians near Vallona with the Army of Salonika, etc.) But it is not enough that this fusion should exist. It is also vital—as we shall presently see in the case of the Franco-British forces—that it should be both elastic and solid.

Since it is agreed that in war-time each month counts as a year, we may say that it is now two months since the French and British Armies celebrated their silver wedding. Age has weakened neither the strength nor the love of the partners to this marriage. We can say confidently that, since the day when "the contemptible little Army of General French" first shook hands with our pioupious, the friendship has never been interrupted. For all his passionate desire to accomplish the destruction of the bond which the two countries have willingly exchanged for their individual liberty, the enemy's efforts have been fruitless.

Even during the gloomy days of the retreat from Mons and Charleroi the union of the two Armies remained unimpaired. While one of them, overwhelmed by numbers, found itself compelled to retire, the other, without any proper understanding of the reason, and[Pg 33] with no thought for anything but the maintenance of the connection, complied at once with the manœuvre, though not without exacting a heavy toll from its enemies.

A few days later the victory of the Marne was to reward these mutual sacrifices for the common cause.

A cloud had passed. Others followed. Again and again the enemy, furious at the perfect understanding which existed between his opponents and dreading what the consequences of it might be to himself, determined to make an end of it. The two battles of Ypres were the fruit of this resolution, to shatter the unity of the French and British Armies.

For one moment they believed that they had succeeded.

This was on the 24th April, 1915, when, by the use of asphyxiating gas, till then unknown to us, they had driven in one corner of the Ypres salient. We know that it was the gallantry of the Canadians that saved the day and closed the opening breach.

Since then the chain has never been weakened. Nay, in the North it has never been so much as stretched.

This, however, has not been the case with the connection between the British Army and the main body of the Armies of France. The continual addition of new units to the British forces was bound to cause frequent changes, here, in the geographical distribution of the adjoining troops. Can France ever forget the day when she learned that silently, without a hitch, and under the very noses of the Germans, the British front had suddenly been extended from Loos to the Somme? A mother who meets, after years, the son whom she has last seen as a child, must feel a surprise not unlike that with which France discovered that the Armies of her Allies had become so large. Who knows but that we may soon be again delighted in the same way? I say "delighted," not "surprised," for our Allies have taught us to forget to be astonished by anything they may do.

And so, every time that the British front is extended, this elasticity of the fusion of the Armies is to be observed.

It is clear that these rearrangements can in no way affect its solidity, since it is this very fusion which has made possible not only the terrific offensive of the 1st July last, but also its uninterrupted prosecution.

Only a very happy combination of circumstances could have brought about this miracle—for it is one—which to explain is to show that it must last as long as the war shall go on.

First of all, it is due to the perfect understanding which exists between the General Staffs of the two Allied Armies. It is, indeed, an achievement to set men of different races, if of equal courage, side by side. But this is not enough. Much more need is there of a unity of command which shall see that the best use is made of all this determination, brought together from sources so widely sundered, so that the utmost measure of mutual support and cohesion may result from the efforts of units which, though they work alongside of one another, are strangers. Now it is this very thing which is evident in the combined operations of the British and French Armies, at all times and particularly since the opening of the offensive in Picardy. The Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, and General Foch—whom one may perhaps describe as the keystone of the combination—have shown themselves, in this connection, to be as good psychologists as they are tacticians.

The troops of neither nation—and this should be made very clear—have in any case experienced the smallest embarrassment in following out the commands of their leaders. Whenever either English or French have been able to give one another any kind of support, they have done it faithfully and readily. The "fusion" is not a thing of maps; it is not to be found in this place or that; it is a spiritual verity.

Living side by side, dying under one another's eyes,[Pg 35] English and French are acquiring a mutual respect and confidence which cannot fail to strengthen their fighting power.

"After all the proofs of their resolution and intrepidity," wrote Field-Marshal French in a report, of June, 1915, upon the gas attacks, "which our valiant Allies have given throughout the campaign, it is quite unnecessary for me to dwell upon this incident, and I will only express my firm conviction that if there are any troops on earth who could have held their trenches in the face of an attack as treacherous as it was unforeseen, it is the French divisions that would have done it."

Which is the more admirable—the General who speaks of his Allies in such generous terms, or the soldiers who inspired such words?

HOW THE AUSTRALIAN CONTINGENT VOTED IN FRANCE IN FACE OF THE ENEMY.

8th December, 1916.

What Frenchman has not met, at least once, in Paris or some other of our large towns, one of these stout lads who wear the uniform and carry the equipment of the British soldier, but are to be distinguished from him by that khaki-coloured, broad-brimmed felt hat, which the Boers have immortalised?

Of a height generally above that of the average Frenchman, with broad shoulders, an alert glance, a free and easy air; a skin that is often tanned; a horseman from boyhood, slow to tire, reckless in battles and of a hot temper—such is the Australian soldier, one of the world's foremost fighting men.

His courage, which the enemy regards with a peculiar[Pg 36] distaste, has earned him heavy fighting everywhere throughout the war. Let us recall, shortly, some of his chief performances.

The first division sent by Australia to the assistance of the Mother Country towards the end of 1914 was employed on the defences of Egypt and the Suez Canal. These sterling horsemen did splendid work in this field of operations, and for four months lived in the desert, exposed to continual attack.

Next, the Australian troops, augmented by certain units of New Zealanders, disembarked on the Gallipoli Peninsula at the left of their English comrades. Hardly were they on shore before they began a series of battles which never stopped for a week. They held, at very great cost, the bit of ground which had been taken from the Turks, and during four months two divisions of them lived, Heaven knows how, on a space of less than a third of an acre.

Then came the Evacuation of Gallipoli. The Australians returned to Egypt, there to rest between December, 1915, and the 1st of April, 1916, on which day they made their appearance on the Western front.

Since that time the Australians have fought on French soil.

They have to thank their splendid reputation that they are always to be found wherever the most glory is to be won. It was they who took Pozières, during the Somme offensive, and the farm at Mouquet, and measured their strength, throughout those epic days, against that of the Prussian Guard.

Such is the Army which, quite recently, has held its Elections under the very guns of the Germans.

For this Army, whose valour is already almost legendary, is also among the most democratic Armies of the world. No one is more jealous of his independence than the Australian. If he loves and admires his comrades-in-arms, the French poilus, it is, no doubt,[Pg 37] because, having long misunderstood them, after the fashion of strangers towards all things French, he cannot to-day find words enough to do justice to their military qualities and their unselfish courage. But it is also, and, above all, because his heart goes out naturally to the French people under arms, to this democracy which in so many ways resembles his own country, Australia the Free. Like the French soldier, the Australian loves his fun; like him, he is light-hearted, always singing. And each of them glories in the knowledge that beneath his soldier's uniform is a citizen and an elector of a noble country.

These reflections will help us to understand why the Australian Government has been led to hold a referendum of its Expeditionary Force in France.

As you know, the people of Australia were concerned with the business of deciding for or against the introduction of compulsory military service into their country. Mr. Hughes, the Premier of New South Wales, who did France the honour to visit it at the beginning of this year, was the originator of this referendum. The result, for reasons which I will presently mention, was a majority against conscription for Australia.

To enable the Australian contingent to vote was the simplest thing in the world. Voting booths were prepared at Contay, a small village between the Ancre and the Somme, close to the firing-line. As fast as the sections left the trenches to go back into billets, each officer, non-commissioned officer and man was given two voting papers. On one the word "Yes" was printed; on the other, "No." The voting lasted a month—the time between reliefs—at the end of which period about 100,000 papers had been collected in the ballot-boxes at Contay. It is strange that the majority of the Australian contingent voted against compulsory service for Australia.

Why?

Let no one imagine that it was because these heroes[Pg 38] have become opponents of the war; nor is it even because they think that their country has done enough.

They have voted against compulsory service, first of all, for a reason of a general nature, which applies to the whole of this body of Australian electors—namely, because the Australians have a horror of all moral compulsion and a burning love of liberty. These soldiers have also been influenced by another objection: they fear lest to introduce a professional Army into Australia may be to infect their nation with a spirit of militarism which is not at all to their taste.

And the proof that the negative result of the referendum has in no way weakened the determination of Australia to pursue the war to a victorious end and in complete accord with the Mother Country, is that, on the one hand, the Australian contingent persists, after, as before, recording its vote, in splendidly performing its duty at the front; and that, on the other hand, Australia continues to send to the battlefields of Europe thousands of fresh volunteers.

Hurrah for Liberty! Down with the Boches! In this motto the quality of the Australian troops is perfectly expressed. This quality one meets with again in the war song, the species of Marseillaise, which the Australians sing to-day when they are on the march in France.

Here are its words in full:

1st Verse.

Chorus.

2nd Verse.

Chorus.

3rd Verse.

Chorus.

BOELCKE'S LAND OF PROMISE.

On the 28th of October, six Halberstadters and Aviatiks attacked two English aviators in the neighbourhood of Pozières. During the fight six fresh enemy machines came to the assistance of their friends. At the end of five minutes of furious fighting two German machines collided. Pieces of the machines fell, and one of them descended toward the East. The fight lasted 15 minutes, at the end of which time all the enemy machines were driven off.

It is probable that it was during this fight that Captain Boelcke was killed. It was, in fact, at this date that the German wireless stated that Boelcke had been killed owing to a collision in the air.

In a letter which he wrote to a friend a few days before his tragic and still unaccountable death, Boelcke, the best-known and most successful of the German aviators, said:

"The Somme front is a positive land of promise. The sky is filled with English airmen."

Boelcke expressed, under the guise of a kind of sporting self-congratulation, the astonishment of his fellows at the way in which the British flying service had developed.

A large number of documents found upon German prisoners give evidence of a no less striking kind upon the same point.

"Our air service," says one of them, "practically ceased to exist during the Battle of the Somme. At times the sky seemed black with enemy machines."

Another says:

"We are so inferior to our opponents in our air service that when hostile machines fly over our own lines[Pg 41] we have no recourse but to hide ourselves in the earth. Now and then a few of our machines attempt to go up, but it is only a drop in the bucket."

Finally, for one must not pursue this subject too far, a General Order has been issued to the German Army to the effect that when troops are marching they must halt and take cover whenever a British machine is known to be in their vicinity; for the English are in the habit of flying sufficiently low over the invaded territory to use their machine-guns against moving troops and convoys.

To this evidence from enemy sources I may perhaps add my own. I assert, then, as definitely as it is possible to do it, that one of my most agreeable surprises, during my visit to the British front, was the discovery of the great numbers and unceasing activity of the British aeroplanes. Whether I was in the firing-line or behind it, my attention was being constantly drawn to the movements of the British air service.

On the 15th of September the total number of hours during which flying was carried on upon the British front was 1,300. Reckoning that each aviator flies, on an average, for two hours, it is possible to form an idea of the number of machines which were in the air on that day.

During the last Battle of the Ancre the British planes of every kind, for bombing, fighting and directing the gunfire, seemed always to be over the German lines; and on one fairly still day I was able to count as many as 30 of them in the air at once, and this on a comparatively narrow sector.

Behind the lines I went to see numerous aviation camps, instruction camps, depôts of munitions, etc. They were like so many beehives, models of organisation, order and method. The pilots, the observers, the mechanics, everyone, seen at close quarters, gave me an impression of a very unusual power and intelligence, and[Pg 42] inspired me with the same confidence with which their own mastery of the air has so long filled them, ever since, indeed, they wrested it from the enemy.

Perhaps it may not be labour lost if, in order to get a right understanding of the present very satisfactory and praiseworthy position, we review shortly the history of British military aviation since the beginning of the war.

England had not wished for war, nor had she prepared for it, and while aviation seemed to her a marvellous achievement of the human brain, she was far from thinking that she was bound to make use of it in order to injure mankind. This is why her military air service, like her whole Army, was in no more than an embryonic condition when she found herself faced with the grim reality of this war.

Far more than the exigencies of the campaign on the continent, it was the repeated raids of the Zeppelins over England which caused her to devote herself to the development of her aviation.

The undertaking bristled with difficulties. We should be wrong, were we in France, to suppose that we are the only people the story of whose aviation has been marked by crises. Our Allies, though their practical nature is proverbial among us, were forced to experiment and grope their way for a long time before they could arrive at a solution of the many knotty problems of aerial defence.

A complete lack of any central authority, a division or responsibility between the various staffs, nobody to decide as to how machines should be employed or how built, waste of every kind—the English have experienced all these troubles. But how admirably they have surmounted them! The proof is that now the only resource of the Germans is a servile imitation.

This spirit of imitation among the Germans has shown itself most markedly in these last weeks, during the process of the Battle of the Ancre. The Germans set out[Pg 43] by collecting a large number of aeroplanes on a very narrow front. Then they began to show some signs of taking the initiative with a daring to which we were little accustomed.

Did they really hope to wrest the mastery of the air from the English? I do not know. In any case their attempt began badly; for when, 40 in number, they met 30 of the British machines, they could discover no better way of saving themselves than by flight, after a quarter of their number had been put out of action.

It was about this time that General von Groener, a man of energy and resolution, called upon the German aeroplane factories to increase their output; and that Mr. Lloyd George in England, while giving publicity to this new effort of Germany, exhorted his fellow-countrymen not to allow themselves to be overtaken by their enemy.

Boelcke may rest in peace. His land of promise can only grow greater and breed birds more rapidly.

After this, what need one say more of the technical skill and the often heroic courage of the British aviator?

The French and British airmen form, indeed, one great family of heroes, and our men have, in King George's Army, cousins who are as like them as brothers.

At this point I will do no more than offer for your consideration a document and a story.

The document is a letter, sent from Germany to his friends by an English aviator, Lieutenant Tudor-Hart, on the 25th of this July. I should blame myself were I to alter one word of it.

"I was," he writes, "with Captain Webb at between 12,000 and 15,000 feet above the German lines, when we saw eight German machines coming towards us from the South-west. They were higher than we were, and we went towards them to attack them. Two of them passed about 300 yards above our heads. I opened fire on one and they replied together.

"I signed to Webb to turn so that I might fire at the[Pg 44] other machine, behind us; but he made a spurt forward with the machine. I looked round to see what had happened, but Webb pointed to his stomach and fell forward upon the controls. I fancy he must have died almost immediately. His last thought had been to save the machine.

"It at once began to swing in the direction of the German lines, and I was compelled to return to my machine-gun, in order to fire on a plane which was getting too close. The other machines never stopped firing at us. My only hope was to make for our lines, but I could not manage to push Webb out of the pilot's seat, and I was obliged to manœuvre above the hood.

"I had to fire so often that it became impossible for me to guide the machine. At last, constantly under fire, I planed down towards a field near by and tried to land. I saw a number of men with rifles, and I thought that I might be killed before being able to set the machine on fire.

"One wing having struck the earth, the machine was smashed, and I was thrown out. I got off with one side paralysed, one ankle and one rib broken. I was very well treated, and the German flying men behaved towards me like sportsmen and gentlemen."

It is in this way that the paladins of this war both conduct and express themselves.

And now for the story.

There was once in England a rich man who interested himself in Art and Politics. His name was Lord Lucas. Life had always smiled upon him, and he had returned her smile. Had he wished it, he might have spent his life in slippered ease and lived from day to day without a care.

Choosing, rather, to become a soldier, he joined the Expeditionary Forces during the South African War. He was wounded and lost a leg, but this in no way deterred him from being of service to his country.

When the European War broke out, Lord Lucas was the Minister for Agriculture in the Asquith Cabinet.

He felt shame to be engaged in such a vapid business as Politics now appeared, and he resigned. Next we find him volunteering for the British air service. In spite of his artificial leg, he went through his training, was hurt, got cured, and returned to his work and never rested until he had flown over the German lines. One day Lord Lucas, millionaire, artist, ex-Cabinet Minister, and, above all, soldier, failed to return to his squadron. The Boches alone know whether he is dead or a prisoner.

The man who told me the story of this splendid life was the best friend of Lord Lucas, and he was worthy to be it. I asked this soldier, a peer himself and himself wounded, if in England, as in France, commissions in the air service were much sought after. In reply, he pointed to two great birds, and said: "We admire them, Monsieur, as you do, and, like you, we envy them."

THE SQUARE JAW.[A]

[A] Of the two articles which follow, the first ("The Square Jaw") was written on the 9th of December, during the crisis caused by the successive resignations of Mr. Lloyd George and Mr. Asquith.

The second ("The Moral of the British Armies") was written on the 19th of the same month, the day after Germany made her official offer of peace.

The British soldier does not concern himself with Politics. It is not in his character to do so; moreover, any such conduct is against the rules of his profession. And so, since discipline "is the first weapon of Armies," the British soldier respects it above everything else.

The Englishman has a passion and a profound respect for method. Method requires that Politics should[Pg 46] be the business of Ministers and Politicians, and that war should be carried on by soldiers. Method, says the Englishman, demands that everyone should stick to his own work and his own place. Without this, anarchy must ensue. Now there cannot well be anything less anarchical than the British Army.

It is their order and discipline which most powerfully and most quickly impress the Frenchman who is permitted to live for a time among the Armies of England. These qualities, let me hasten to add, are also the least superficial, and thus afford the surest test of the value of these Armies.

Observe that it is not by collecting together a body of indifferent natures, passive temperaments and personalities more or less irresponsible, that this order and discipline have been infused into the British Army. The level of capacity of this Army is, moreover, by no means a low one; for it is one of the most intelligent Armies in Europe or in the whole world. The common soldier is not of one class, to the exclusion of all others. He does not represent one section only of British opinion. His corporate mind is therefore in no way a limited one.

As a volunteer, he thronged into England, at the beginning of the war, from every quarter of the globe, and by this voluntary act at once proclaimed his intelligence. To-day, as a conscript, he represents, more than ever before, the completeness of his country's will.

As for the officers, who differ from our own in their essentially aristocratic character, in them we see the direct expression of all those qualities of brain and heart which distinguish the leading elements of British society.

And so, if this army does not concern itself with Politics, if it is thoroughly disciplined, if it contents itself with "making war," it is because it prefers to do these things.

It is, moreover, excellently informed of everything which happens outside itself, whether in England or elsewhere,[Pg 47] and in this respect differs considerably from the German Army which lies beyond its trenches. A Boche prisoner, recently taken, owned that neither the newspapers of his country nor any letters ever reached the German troops in the front lines. As each day comes, its history is told to our enemies by word of mouth only; that is to say, after the fashion which best suits their rulers.

Among the English there is very little heard or said about peace, or about the objects for which they are fighting; but they read, and they read continually. The soldier follows the course of events as well in his letters as in his newspaper.

And in what does his knowledge consist? What does he know?

He knows that the Army to which he belongs owes much to that French Army which he admires so deeply, and by whose side he is proud to fight for the interests which their natures share. He knows that to the British Army is secured, from now onwards, one of the chief factors of invincible and victorious strength—numbers. He knows approximately the number of his effectives, and he would gladly, by crying it aloud, shake the confidence of the enemy and confirm that of his friends.

He knows also that the second factor of his strength—material—while it is already considerable and probably equal to that which his opponents possess—does not represent a quarter of what the coming year will produce. He knows, from having done it again and again since July, that not only can he resist the enemy, but defeat him; and he awaits confidently the hour of triumph.

Hence his firm, his unshakable determination to obtain victory on his own terms; hence, also, it follows that no thought or hope of a premature peace ever disturbs his mind.

And if no one else remained to fight, he would go[Pg 48] on, for—he says it himself, and one cannot but believe him—he has "a square jaw."

It is important, in the present condition of affairs, that the French public should make no mistake as to the opinions of the British soldier concerning the war and its sure conclusion.

About this no one can be under any delusion. Everywhere on the British front there is but one opinion—that the war must be carried through to the end; that is to say, till the inevitable victory of the Allies has come to pass; and that it would be a crime against the Homeland, the Allies and those comrades who have fallen, to listen to proposals for a peace which would be consistent with neither the intentions nor the interests of England and her Allies.

During my visit of two months I have seen the larger part of the British front from the Somme to the Yser. Everywhere I have met with the same spirit of determination. This state of mind may be explained in various ways; the perfect confidence which the British Army feels in its Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, "the lucky," as the soldiers call him; the regular growth in the numbers of the effectives, which, though I may not disclose these figures, exceed the estimates of them usually made in France; the tremendous development of material and in the output of munitions; the magnificent successes gained on the Somme and the Ancre, which have given rise to the certainty of being able to defeat an enemy formerly said to be invincible; etc., etc.

Without doubt, the war goes slowly. Tommy admits it, but he begs you to observe—and justly—that on every occasion when his infantry has come to grips with the Germans it has invariably beaten them.

"Besides," he thinks, "perhaps it is not absolutely essential, in order to win the war and place England and her Allies in a position to dictate their own terms, that our Armies should hurl themselves forward in one final[Pg 49] and costly advance over the shattered lines of the Germans." The British soldier is fond of comparing the Western battle front to an immense boxing ring, of which the complex systems of barbed wire which stretch from the North Sea to Belfort form the ropes. The war, on the West, has been fought within these limits since the Marne. It is possible that it will see no change of position up to the end.

But, as in a boxing match, it is not necessary, in order to win, to drive one's opponent over the ropes and out of the ring; in the same way it may happen that the German Army is "knocked out" in the positions where it is fighting to-day.

That, at least, is the opinion of the British soldier.

It is, indeed, no more than a paraphrase of that dictum, pronounced not long ago by General Nogi, and as true of the ring as it is of war: "Complete victory is to him who can last a quarter of an hour longer than the other fellow."

Tommy has no intention—no more than has his friend the poilu—of playing the part of "the other fellow."

THE RELIEF.

The scene is an old trench of the French first line. It is midday. It is raining. It goes on raining. It has always rained. The sector is fairly quiet, and has been for an hour or so. Tommy sees a chance to write a letter.

Here in his dug-out—a miserable shelter which oozes water everywhere—squatted on the straw that becomes filth the moment it is thrown down, he is telling his friends in Scotland all his small sorrows and hopes; he is wishing them "A Happy New Year."

Suddenly his pen falters; the writer considers, stops writing, and, addressing the second-lieutenant as he goes by: "Beg pardon, sir," he asks, "may I say that they have moved out?"

"Certainly not," says the lieutenant, apparently horrified by such a question. "It is absolutely forbidden to say anything about this business. Do you understand, all of you?"

"But—but," someone ventures to say, "everyone in England knows about it already. The papers ..." and they show the lieutenant some newspapers which have come that morning. The officer takes them, glances at them, smiles, and says: "Oh, these journalists!"

On the front page of the paper a striking photograph is exhibited, showing an incident of the taking over by the British of the French front. Underneath is the following description:

"Tommy takes over the French trenches. French soldiers looking on at the arrival of British troops who are relieving them. This important operation took place at the front, at Christmas-time, silently, secretly and with complete success. The enemy, who was in many places no more than a few yards distant, never had any suspicion of this change, which has greatly extended the British lines and eased the strain which our gallant Allies have endured upon the Western front.

"This military manœuvre affords the best reply to the manœuvres of Germany in the direction of peace."

And so Tommy continues his letter in some such fashion as this:

"Now that the thing is done, I may tell you that we have left the sector of —— in order to come down farther South, where we have relieved the French. It has been a fine chance to see our brave Allies at work, and I am tremendously proud to have taken their place in the lines.

"The thing has been done very well, although it[Pg 51] wanted a lot of care and was very dangerous. You can imagine that if the Boches had had any notion of what we were at, they would not have failed to do their level best to stop us or make it difficult for us; for it must make them very savage to see our 'contemptible little Army' always extending its flanks, without wearing thin anywhere, and so setting free first-rate troops for the French to use elsewhere.

"We came among the Frenchmen on Christmas Day.

"The roads were all as busy as on the day before the offensive on the Ancre in front of Beaumont-Hamel. We never stopped meeting French troops and wagons, which were going back towards the railway.

"We exchanged civilities with the poilus which neither they nor we understood the least bit. But I may tell you that it was pretty clear to me that they were not sorry to be giving up their places to us.

"On the 25th of December, after supper, we left our last camp and marched through the night for many hours, till we came to this French trench where I am writing to you now.

"The poilus were at their posts. It'll be a long time before I forget that sight.

"Although they were far dirtier and more tired than were we, the French, as they themselves say, 'had the smile.' If we had been allowed to make any noise, we should have cheered them. But we were only 38 yards from the Boche line.

"The officers and the non-commissioned officers gave the orders in whispers. They had interpreters to help them.

"As for me, I was at once told off to do sentry in the place of a great French chap, with a beard, who was a good 15 years older than I.

"As I understood a bit of French, I was able to make out most of what he said to me.

"'Good evening, my lad,' says he. 'You're a good[Pg 52] fellow to come and let me out of this. Shake hands, won't you?'—I didn't understand everything; French is so difficult—and he added: 'And now, young 'un, open your eyes and keep them skinned.'

"Then he gave me a great deal of very sound advice, showing me in which directions I must keep a good look-out, and telling me to have a care of a blackguardly German machine-gun which never has done sweeping their parapet.

"When he had finished with this he took his rifle out of the loophole, and I put mine there in its place. And that's how the big relief was carried out on Christmas night."

At this point Tommy was forced to interrupt his long letter, for the Germans had at last got news of the relief and were attacking the sector. In vain.

Next day Tommy finished thus:

"My poilu was right. This corner can hardly be called a quiet one, and Fritz is a bad boy, there's no doubt about it. Thanks for your Christmas parcel. The pudding was A1. Good-bye.

"Tommy."

THE ARMIES OF THE NORTH.

Flat calm on both sides of the Ancre; calm—or something like it—on the Somme. Let us take advantage of this apparent truce to get into rather closer touch with the British Army.

By this eight-day tour (though it has seemed, while we have been making it, a kind of intermezzo between two acts of the offensive) we had intended, particularly, to demonstrate to ourselves, by our study of the events and those who have enacted them, the dauntless determination with which our Allies, not satisfied to defend the heroic heritage which these battlefields of 1915 have bequeathed to them, now prepare for the future.

In telling these experiences, one has to play the Censor over oneself. And so we may say nothing of the most important things of all. Everywhere throughout this countryside mighty Armies, in the most perfect secrecy, are doing their business, scattering, with prodigal hand, the seed of future victory. And the harvest will surely be gathered. And if, at this time of heart-breaking uncertainty, our journey enables us to do no more than declare that great things are assuredly preparing, this alone will make it worth our having undertaken it.

We did not set out, we three, with our permits from the General Headquarters, to make a sentimental pilgrimage over the battlefields that lie between Lorette and the trenches of French Flanders. No; it was a reconnaissance that we made—into the Future. These sketches of the British Armies are, thus, no more than a study of latent forces.

THE PREPARATION OF THE CANADIANS.

We spent the first two days among the Canadians. Let me recall a few of their performances. They sustained, in front of Ypres, the first great gas attack launched by the Germans. During the offensive in Picardy, being sent into the front line on the 15th of September or thereabouts, they stormed Courcelette and Martinpuich, and consolidated their forward positions on one side towards Grandcourt, on the other towards Le Sars. The rest of them kept the enemy contained.

To sum them up—an Army full of robust qualities, an Army of young athletes, inured by their own home-life to the physical hardships of the trenches, regardless alike of cold, fog and mud. An Army, too, of formidable size, since to-day its numbers are greater than those of the whole British Expeditionary Force of 1914.