Title: A Year with the Birds

Author: W. Warde Fowler

Illustrator: Bryan Hook

Release date: April 10, 2015 [eBook #48677]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Shaun Pinder, Stephen Hutcheson, Carol Spears,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

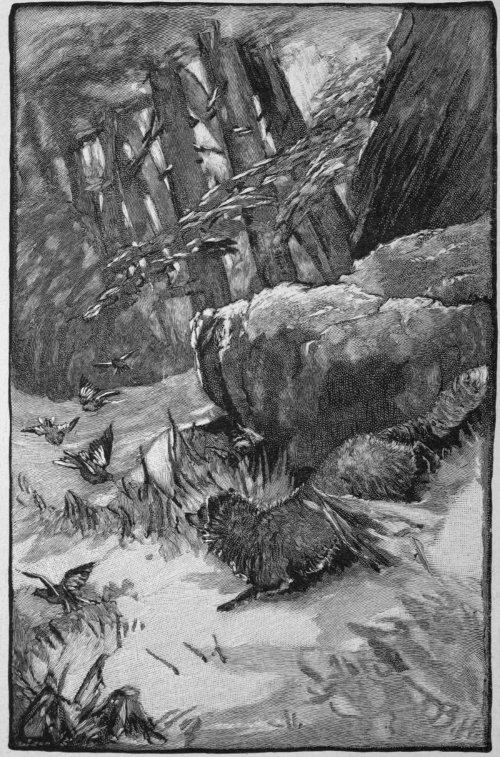

Fox and Snow-finches.—p. 100.

BY

W. WARDE FOWLER

AUTHOR OF “TALES OF THE BIRDS,” ETC.

“L’uccello ha maggior copia di vita esteriore e interiore, che non hanno gli altri animali. Ora, se la vita è cosa più perfetta che il suo contrario, almeno nelle creature viventi: e se perciò la maggior copia di vita è maggiore perfezione; anche per questo modo séguita che la natura degli uccelli sia più perfetta.”—Leopardi: Elogio degli uccelli.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRYAN HOOK

THIRD EDITION ENLARGED

London

MACMILLAN AND CO.

AND NEW YORK

1891

Richard Clay and Sons, Limited,

LONDON AND BUNGAY.

First two editions published elsewhere. Third edition, 1889; Reprinted, 1891.

PATRI MEO

QVI CVM AVCVPIS NOMINE

AVIVM AMOREM

FILIO

TRADIDIT

This little book is nothing more than an attempt to help those who love birds, but know little about them, to realize something of the enjoyment which I have gained, in work-time as well as in holiday, for many years past, from the habit of watching and listening for my favourites.

What I have to tell, such as it is, is told in close relation to two or three localities: an English city, an English village, and a well-known district of the Alps. This novelty (if it be one) is not likely, I think, to cause the ordinary reader any difficulty. Oxford is so familiar to numbers of English people apart from its permanent residents, that I have ventured to write of it without stopping to describe its geography; and I have purposely confined myself to the city and its precincts, in order to show how rich in bird-life an English town may be. The Alps, too, are known to thousands, and the walk I have described in Chapter III., if the reader should be unacquainted with it, may easily be followed by reference to the excellent maps of the Oberland in the guide-books of Ball or Baedeker. The chapters viii about the midland village, which lies in ordinary English country, will explain their own geography.

One word about the title and the arrangement of the chapters. We Oxford tutors always reckon our year as beginning with the October term, and ending with the close of the Long Vacation. My chapters are arranged on this reckoning; to an Oxford residence from October to June, broken only by short vacations, succeeds a brief holiday in the Alps; then comes a sojourn in the midlands; and of the leisurely studies which the latter part of the Long Vacation allows, I have given an ornithological specimen in the last chapter.

Some parts of the first, second, and fifth chapters have appeared in the Oxford Magazine, and I have to thank the Editors for leave to reprint them. The third chapter, or rather the substance of it, was given as a lecture to the energetic Natural History Society of Marlborough College, and has already been printed in their reports; the sixth chapter has been developed out of a paper lately read before the Oxford Philological Society.

The reader will notice that I have said very little about uncommon birds, and have tried to keep to the habits, songs, and haunts of the commoner kinds, which their very abundance endears to their human friends. I have made no collection, and it will therefore be obvious to ornithologists that I have no scientific knowledge of structure and classification beyond that which I have obtained at second-hand. And, indeed, if I thought I ix were obtruding myself on the attention of ornithologists, I should feel as audacious as the Robin which is at this moment, in my neighbour’s outhouse, sitting on eggs for which, with characteristic self-confidence, she has chosen a singular resting-place in an old cage, once the prison-house of an ill-starred Goldfinch.

There are few days, from March to July, when even the shortest stroll may not reveal something of interest to the careful watcher. It was pleasant, this brilliant spring morning, to find that a Redstart, perhaps the same individual noticed on page 120, had not forgotten my garden during his winter sojourn in the south; and that a pair of Pied Flycatchers, the first of their species which I have known to visit us here, were trying to make up their minds to build their nest in an old gray wall, almost within a stone’s throw of our village church.

Kingham, Oxon.

April 24, 1886.

My little book, which never expected to spread the circle of its acquaintance much beyond its Oxford friends, has been introduced by the goodwill of reviewers to a wider society, and has been apparently welcomed there. To enable it to present itself in the world to better advantage, I have added to it a new chapter on the Alpine birds, and have made a considerable number of additions and corrections in the original chapters; but I hope I have left it as modest and unpretending as I originally meant it to be.

During the process of revision, I have been aided by valuable criticisms and suggestions from several ornithological and bird-loving friends, and particularly from Rev. H. A. Macpherson, A. H. Macpherson, Esq., O. V. Aplin, Esq., and W. T. Arnold, Esq., whose initials will be found here and there in notes and appendices. I have also to thank Archdeacon Palmer for most kindly pointing out some blemishes in the chapter on the Birds of Virgil.

W. WARDE FOWLER.

Lincoln College, Oxford.

Nov. 19, 1886.

Though my knowledge of birds has naturally grown fast since I wrote these chapters, I have thought it better, except in one instance, to resist the temptation of re-writing or interpolating for this edition. The book stands almost exactly as it was when the second edition was issued; but the list of Oxford birds is omitted, as Mr. Aplin’s work on the Birds of Oxfordshire, shortly to be published by the Clarendon Press, will embody all the information there given. I regret that the frontispiece, drawn for the original edition by my friend Professor W. Baldwin Spencer, can no longer be reproduced.

I wish to express my thanks to Mr. B. H. Blackwell, of Oxford, not only for the care and pains he bestowed upon the issue of the former editions, but for the ready courtesy with which he fell in with my wish to transfer the book to the hands of Messrs. Macmillan.

W. W. F.

June 4, 1889.

PAGE

For several years past I have contrived, even on the busiest or the rainiest Oxford mornings, to steal out for twenty minutes or half an hour soon after breakfast, and in the Broad Walk, the Botanic Garden, or the Parks, to let my senses exercise themselves on things outside me. This habit dates from the time when I was an ardent fisherman, and daily within reach of trout; a long spell of work in the early morning used to be effectually counteracted by an endeavour to beguile a trout after breakfast.

By degrees, and owing to altered circumstances, 2 the rod has given way to a field-glass, and the passion for killing has been displaced by a desire to see and know; a revolution which I consider has been beneficial, not only to the trout, but to myself. In the peaceful study of birds I have found an occupation which exactly falls in with the habit I had formed—for it is in the early morning that birds are most active and least disturbed by human beings; an occupation too which can be carried on at all times of the day in Oxford with much greater success than I could possibly have imagined when I began it. Even for one who has not often time or strength to take long rambles in the country round us, it is astonishing how much of the beauty, the habits, and the songs of birds may be learnt within the city itself, or in its immediate precincts.

The fact is, that for several obvious reasons, Oxford is almost a Paradise of birds. All the conditions of the neighbourhood, as it is now, are favourable to them. The three chief requisites of the life of most birds are food, water, and some kind of cover. For food, be they insect-eaters, or grub-eaters, they need never lack near Oxford. 3 Our vast expanse of moist alluvial meadow—unequalled at any other point in the Thames valley—is extraordinarily productive of grubs and flies, as it is of other things unpleasant to man. Any one can verify this for himself who will walk along the Isis on a warm summer evening, or watch the Sand-martins as he crosses the meadows to Hincksey. Snails too abound; no less than ninety-three species have been collected and recorded by a late pupil of mine. The ditches in all the water-meadows are teeming with fresh-water mollusks, and I have seen them dying by hundreds when left high and dry in a sultry season. Water of course is everywhere; the fact that our city was built at the confluence of Isis and Cherwell has had a good deal of influence on its bird-life. But after all, as far as the city itself is concerned, it is probably the conservative tranquillity and the comfortable cover of the gardens and parks that has chiefly attracted the birds. I fancy there is hardly a town in Europe of equal size where such favourable conditions are offered them, unless it be one of the old-fashioned well-timbered kind, such as Wiesbaden, Bath, or Dresden. The 4 college system, which has had so much influence on Oxford in other ways, and the control exercised by the University over the government of the town, have had much to do with this, and the only adverse element even at the present day is the gradual but steady extension of building to the north, south, and west. A glance at a map of Oxford will show how large a space in the centre of the town is occupied by college gardens, all well-timbered and planted, and if to these are added Christchurch Meadow, Magdalen Park, the Botanic Garden, and the Parks, together with the adjoining fields, it will be seen that there must be abundant opportunity for observations, and some real reason for an attempt to record them.

Since the appearance in the Oxford Magazine, in May, 1884, of a list of “The Birds of Oxford City,” I have been so repeatedly questioned about birds that have been seen or heard, that it is evident there are plenty of possessors of eyes and ears, ready and able to make use of them. There are many families of children growing up in “the Parks” who may be glad to learn that life in a town such as Oxford is, does not exclude 5 them from some of the pleasures of the country. And I hold it to be an unquestioned fact, that the direction of children’s attention to natural objects is one of the most valuable processes in education. When these children, or at least the boys among them, go away to their respective public schools, they will find themselves in the grip of a system of compulsory game-playing which will effectually prevent any attempt at patient observation. There is doubtless very much to be said for this system, if it be applied, like a strong remedy, with real discriminating care; but the fact is beyond question, that it is doing a great deal to undermine and destroy some of the Englishman’s most valuable habits and characteristics, and among others, his acuteness of observation, in which, in his natural state, he excels all other nationalities. It is all the more necessary that we should teach our children, before they leave home, some of the simplest and most obvious lessons of natural history.

So in the following pages it will be partly my object to write of the Oxford birds in such a way that any one of any age may be able to recognize 6 some of the most interesting species that meet the eye or ear of a stroller within the precincts of the city. And with this object before me, it will be convenient, I think, to separate winter and summer, counting as winter the whole period from October to March, and as summer the warm season from our return to Oxford in April up to the heart of the Long Vacation; and we will begin with the beginning of the University year, by which plan we shall gain the advantage of having to deal with a few birds only to start with, and those obvious to the eye among leafless branches, thus clearing the way for more difficult observation of the summer migrants, which have to be detected among all the luxuriousness of our Oxford foliage.

I shall call the birds by their familiar English names, wherever it is possible to do so without danger of confounding species; but for accuracy’s sake, a list of all birds noticed in these pages, with their scientific names according to the best, or at any rate the latest, terminology, will be given in an appendix.

When we return to Oxford after our Long 7 Vacation, the only summer migrants that have not departed southwards are a few Swallows, to be seen along the banks of the river, and half-a-dozen lazy Martins that may cling for two or three weeks longer to their favourite nooks about the buildings of Merton and Magdalen. Last year (1884) none of these stayed to see November, so far as I could ascertain; but they were arrested on the south coast by a spell of real warm weather, where the genial sun was deluding the Robins and Sparrows into fancying the winter already past. In some years they may be seen on sunny days, even up to the end of the first week of November, hawking for flies about the meadow-front of Merton, probably the warmest spot in Oxford. White of Selborne saw one as late as the 20th of November, on a very sunny warm morning, in one of the quadrangles of Christchurch; it belonged, no doubt, to a late September brood, and had been unable to fly when the rest departed.

It is at first rather sad to find silence reigning in the thickets and reed-beds that were alive with songsters during the summer term. The 8 familiar pollards and thorn-bushes, where the Willow-warblers and Whitethroats were every morning to be seen or heard, are like so many desolate College rooms in the heart of the Long Vacation. Deserted nests, black and mouldy, come to light as the leaves drop from the trees—nurseries whose children have gone forth to try their fortune in distant countries. But we soon discover that things are not so bad as they seem. The silence is not quite unbroken: winter visitors arrive, and the novelty of their voices is cheering, even if they do not break into song; some kinds are here in greater numbers than in the hot weather, and others show themselves more boldly, emerging from leafy recesses in search of food and sunshine.

Every autumn brings us a considerable immigration of birds that have been absent during the summer, and increases the number of some species who reside with us in greater or less abundance all the year. Among these is the familiar Robin. My friend the Rev. H. A. Macpherson, in his recently published Birds of Cumberland, tells us that in that northern county the 9 Robins slip quietly away southward in autumn. And it is in September and October that every town and village in the south of England is enlivened by their numbers and the pathetic beauty of their song; a song which I have observed as being of finer quality in England than on the continent, very possibly owing to a greater abundance of rich food. I have been even tempted to fancy that our English Robin is a finer and stouter bird than his continental relations. Certainly he is more numerous here at all times of the year, and he may travel where he pleases without fear of persecution; while the French and German Robins, who for the most part make for Italy in the autumn, return in spring in greatly diminished numbers, owing to the incurable passion of the Italians for “robins on toast.”

It does not seem that they come to us in great numbers from foreign shores, as do many others of our common birds at this time of the year; but they move northwards and southwards within our island, presumably seeking always a moderately warm climate. At Parsons’ Pleasure I have seen 10 the bushes literally alive with them in October and November, in a state of extreme liveliness and pugnacity. This is the great season of their battles. Most country-people know of the warfare between the old and young Robins, and will generally tell you that the young ones kill their parents. The truth seems to be that after their autumnal moult, in the confidence of renewed strength, the old ones attack their offspring, and succeed in forcing them to seek new homes. This combativeness is of course accompanied by fresh vigour of song. Birds will sing, as I am pretty well convinced, under any kind of pleasant or exciting emotion—such as love, abundance of food, warmth, or anger; and the outbreak of the Robin’s song in autumn is to be ascribed, in part at least, to the last of these. Other reasons may be found, such as restored health after the moult, or the arrival in a warmer climate after immigration, or possibly even the delusion, already noticed, which not uncommonly possesses them in a warm autumn, that it is their duty to set about pairing and nest-building already. But all these would affect other species also, and the 11 only reason which seems to suit the idiosyncrasies of the Robin is this curious rivalry between young and old.

The Robins, I need not say, are everywhere; but there are certain kinds of birds for which we must look out in particular places. I mentioned Parsons’ Pleasure just now; and we may take it very well as a starting-point, offering as it does, in a space of less than a hundred yards square, every kind of supply that a bird can possibly want; water, sedge, reeds, meadows, gravel, railings, hedges, and trees and bushes of many kinds forming abundant cover. In this cover, as you walk along the footpath towards the weir, you will very likely see a pair of Bullfinches. They were here the greater part of last winter, and are occasionally seen even in college and private gardens; but very rarely in the breeding-season or the summer, when they are away in the densest woods, where their beautiful nest and eggs are not too often found. Should they be at their usual work of devouring buds, it is well worth while to stop and watch the process; at Parsons’ Pleasure they can do no serious harm, and the 12 Bullfinch’s bill is not an instrument to be lightly passed over. It places him apart from all other common English birds, and brings him into the same sub-family as the Crossbill and the Pine-Grosbeak. It is short, wide, round, and parrot-like in having the upper mandible curved downwards over the lower one, and altogether admirably suited for snipping off and retaining those fat young juicy buds, from which, as some believe, the Bullfinch has come by his name.[1]

Parsons’ Pleasure, i. e. the well-concealed bathing-place which goes by this name, stands at the narrow apex of a large island which is formed by the river Cherwell,—itself here running in two channels which enclose the walk known as Mesopotamia,—and the slow and often shallow stream by which Holywell mill is worked. The bird-lover will never cross the rustic bridge which brings him into the island over this latter stream, without casting a rapid glance to right and left. Here in the summer we used to listen to the 13 Nightingale, or watch the Redstarts and Flycatchers in the willows, or feast our eyes with the splendid deep and glossy black-blue of the Swallow’s back, as he darted up and down beneath the bridge in doubtful weather. And here of a winter morning you may see a pair of Moorfowl paddling out of the large patch of rushes that lies opposite the bathing-place on the side of the Parks; here they breed in the summer, with only the little Reed-warblers as companions. And here there is always in winter at least a chance of seeing a Kingfisher. Why these beautiful birds are comparatively seldom to be seen in or about Oxford from March to July is a question not very easy to answer. The keeper of the bathing-place tells me that they go up to breed in ditches which run down to the Cherwell from the direction of Marston and Elsfield; and this is perhaps borne out by the discovery of a nest by a friend of mine, then incumbent of Woodeaton, in a deserted quarry between that village and Elsfield, fully a mile from the river. One would suppose, however, that the birds would be about the river, if only to supply their voracious 14 young with food, unless we are to conclude that they feed them principally with slugs and such small-fry. Here is a point which needs investigation. The movements of the Kingfisher seem to be only partly understood, but that they do migrate, whether for short or long distances, I have no doubt whatever.[2] On the Evenlode, another Oxfordshire river, which runs from Moreton-in-the-Marsh to join the Isis at Eynsham, they are rarely to be seen between March and September, or August at the earliest, while I seldom take a walk along the stream in the winter months without seeing one or more of them.

This bird is one of those which owe much to the Wild Birds Act, of which a short account will be found in Note A, at the end of this volume. It may not be shot between March and August, and though it may be slaughtered in the winter with impunity, the gun-licence and its own rapid flight give it a fair chance of escape. Formerly it was a frequent victim:

By green Rother’s reedy side

The blue Kingfisher flashed and died.

Blue is the prevailing tint of the bird as he flies from you: it is seldom that you see him coming towards you; but should that happen, the tint that you chiefly notice is the rich chestnut of the throat and breast. One Sunday morning, as I was standing on the Cherwell bank just below the Botanic Garden, a Kingfisher, failing to see me, flew almost into my arms, shewing this chestnut hue; then suddenly wheeled, and flashed away all blue and green, towards Magdalen Bridge. I have seen a Kingfisher hovering like a dragon-fly or humming-bird over a little sapling almost underneath the bridge by which you enter Addison’s Walk. Possibly it was about to strike a fish, but unluckily it saw me and vanished, piping shrilly. The sight was one of marvellous beauty, though it lasted but a few seconds.

One story is told about the Kingfisher, which I commend to those who study the varying effects of colours on the eye. Thompson, the famous Irish naturalist, was out shooting when snow was lying on the ground, and repeatedly saw a small brown bird in flight, which entirely puzzled him; at last he shot it, and found it to be a Kingfisher 16 in its full natural plumage.[3] Can it be that the swift flash of varying liquid colour, as the bird darts from its perch into the water, is specially calculated to escape the eye of the unsuspecting minnow? It nearly always frequents streams of clear water and rather gentle flow, where its intense brightness would surely discover it, even as it sits upon a stone or bough, if its hues as seen through a liquid medium did not lose their sheen. But I must leave these questions to the philosophers, and return to Parsons’ Pleasure.

The island which I have mentioned is joined to Mesopotamia by another bridge just below the weir; and here is a second post of observation, with one feature that is absent at the upper bridge. There all is silent, unless a breeze is stirring the trees; here the water prattles gently as it slides down the green slope of the weir into the deep pool below. This motion of the water makes the weir and this part of the Cherwell a favourite spot of a very beautiful little bird, which 17 haunts it throughout the October term.[4] All the spring and early summer the Gray Wagtail was among the noisy becks and burns of the north, bringing up his young under some spray-splashed stone, or the moist arch of a bridge; in July he comes southwards, and from that time till December or January is constantly to be seen along Cherwell and Isis. He is content with sluggish water if he can find none that is rapid; but the sound of the falling water is as surely grateful to his ear as the tiny crustaceans he finds in it are to his palate. For some time last autumn (1884) I saw him nearly every day, either on the stonework of the weir, or walking into its gentle water-slope, or running lightly over the islands of dead leaves in other parts of the Cherwell; sometimes one pair would be playing among the barges on the Isis, and another at Clasper’s boat-house seemed quite unconcerned at the crowd of men and boats. It is always a pleasure to watch them; and though all Wagtails have their charm 18 for me, I give this one the first place, for its matchless delicacy of form, and the gentle grace of all its actions.

The Gray Wagtail is misnamed, both in English and Latin; as we might infer from the fact that in the one case it is named from the colour of its back, and in the other from that of its belly.[5] It should be surely called the Long-tailed Wagtail, for its tail is nearly an inch longer than that of any other species; or the Brook-Wagtail, because it so rarely leaves the bed of the stream it haunts. All other Wagtails may be seen in meadows, ploughed fields, and uplands; but though I have repeatedly seen this one within the last year in England, Wales, Ireland, and Switzerland, I never but once saw it away from the water, and then it was for the moment upon a high road in Dorsetshire, and within a few yards of a brook and pool. Those who wish to identify it must remember its long tail and its love of water, and must also look out for the beautiful sulphur yellow of its under parts; in the spring both male and female have 19 a black chin and throat, like our common Pied Wagtail. No picture, and no stuffed specimen, can give the least idea of what the bird is like: the specimens in our Oxford Museum look “very sadly,” as the villagers say; you must see the living bird in perpetual motion, the little feet running swiftly, the long tail ever gently flickering up and down. How can you successfully draw or stuff a bird whose most remarkable feature is never for a moment still?

While I am upon Wagtails, let me say a word for our old friend the common Pied Wagtail, who is with us in varying numbers all the year round. It is for several reasons a most interesting bird. We have known it from our childhood; but foreign bird-lovers coming to England would find it new to them, unless they chanced to come from Western France or Spain. Like one or two other species of which our island is the favourite home, it is much darker than its continental cousin the White Wagtail, when in full adult plumage. Young birds are indeed often quite a light gray, and in Magdalen cloisters and garden, where the young broods love to run and seek food on the beautifully-kept turf, almost every variety of youthful plumage may be seen in June or July, from the sombrest black to the brightest pearl-gray. Last summer, I one day spent a long time here watching the efforts of a parent to induce a young bird to leave its perch and join the others on the turf: the nest must have been placed somewhat high up among the creepers, and the young bird, on leaving it, had ventured no further than a little stone statue above my head. The mother flew repeatedly to the young one, hovered before it, chattered and encouraged it in every possible way; but it was a long time before she prevailed.

The mother flew repeatedly to the young one, hovered before it, chattered and encouraged it in every possible way.—p. 21.

Let us now return towards the city, looking into the Parks on our way. The Curators of the Parks, not less generous to the birds than to mankind, have provided vast stores of food for the former, in the numbers of birches and conifers which flourish under their care. They, or their predecessors who stocked the plantations, seem to have had the particular object of attracting those delightful little north-country birds the Lesser Redpolls, for they have planted every kind of tree in whose seeds they find a winter subsistence. 22 Whether they come every winter I am unable to say, and am inclined to doubt it; but in 1884, any one who went the round of the Parks, keeping an eye on the birches, could hardly fail to see them, and they have been reported not only as taking refuge here in the winter, but even 23 as nesting in the summer. A nest was taken from the branch of a fir-tree here in 1883, and in this present year, if I am not mistaken, another nest was built. I failed to find it, but I several times saw a pair of sportive Redpolls at the south-east corner of the Parks.[6]

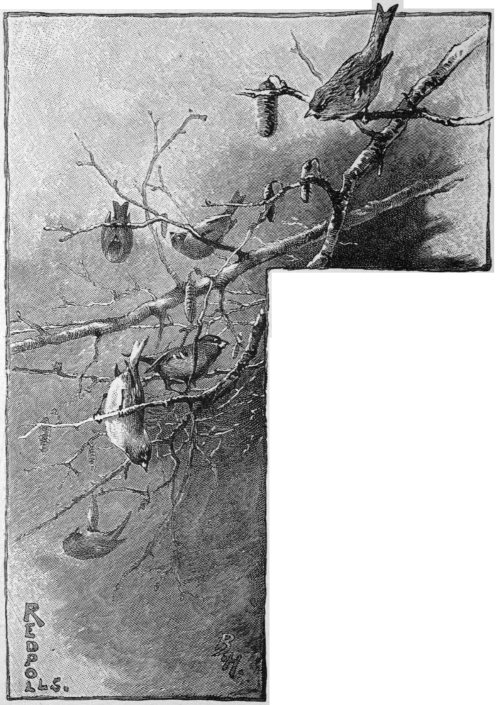

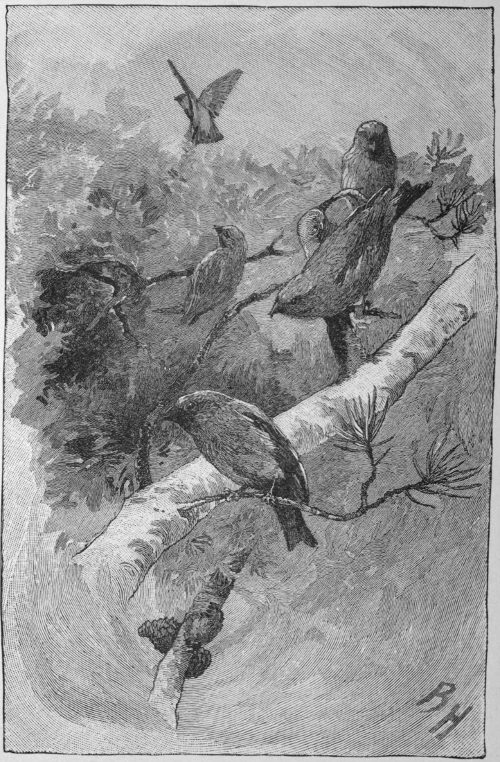

These tiny linnets at work in the delicate birch-boughs.—p. 23.

It is one of the prettiest sights that our whole calendar of bird-life affords, to watch these tiny linnets at work in the delicate birch-boughs. They fear no human being, and can be approached within a very few yards. They almost outdo the Titmice in the amazing variety of their postures. They prefer in a general way to be upside down, and decidedly object to the common-place attitudes of more solidly built birds. Otherwise they are not remarkable for beauty at this time of year; their splendid crimson crest—the “Bluttropf,” as the Germans aptly call it—is hardly discernible, and the warm pink of their breasts has altogether vanished.

Before we leave the Parks I must record the fact that an eccentric Jack-snipe, who ought to have considered that he is properly a winter bird in these parts, was several times flushed here by the Cherwell in the summer of 1884, and the natural inference would be that a pair had bred somewhere near. Col. Montagu, the most accurate of naturalists, asserted that it has never been known to remain and breed in England; yet the observer in this case, a well-known college tutor who knows a Jack-snipe when he sees it, has assured me positively that there was no mistake; and some well-authenticated cases seem to have occurred since Montagu wrote.[7]

There are plenty of common birds to be seen even in winter on most days in the Parks, such as the Skylark, the Yellow-hammer and its relative the Black-headed Bunting, the Pied Wagtail, the Hedge-sparrow, and others; though lawn-tennis, and cricket, and new houses and brick walls, are slowly and surely driving them beyond the 25 Cherwell for food and shelter. But there are some birds which may be seen to greater advantage in another part of Oxford, and we will take the short line to Christchurch Meadow, past Holywell Church, doubtless the abode of Owls, and the fine elms of Magdalen Park, beloved by the Woodpigeons.

All this lower part of the Cherwell, from Holywell mill to its mouth at the barges, abounds in snug and secure retreats for the birds. In Addison’s Walk, as well as in the trees in Christchurch Meadow, dwell the Nuthatch and the Tree-creeper, both remarkable birds in all their ways, and each representative of a family of which no other member has ever been found in these islands. They are tree-climbing birds, but they climb in very different ways: the Creeper helping himself, like the Woodpeckers, with the downward-bent feathers of his strong tail; while the Nuthatch, having no tail to speak of, relies chiefly on his hind claw. These birds are now placed, on account of the structure of their feet, in a totally different order to that of the Woodpeckers, who rank with the Swifts and the Nightjars.

One is apt to think of the Creeper as a silent and very busy bird, who never finds leisure to rest and preen his feathers, or to relieve his mind with song. When he does sing he takes us a little aback. One spring morning, as I was strolling in the Broad Walk, a Creeper flew past me and fixed himself on the thick branch of an elm—not on a trunk, as usual—and uttered a loud and vigorous song, something after the manner of the Wren’s. I had to turn the glass upon him to make sure that there was no mistake. This is the only occasion on which I have ever heard the Creeper sing, and it seems strange that a bird with so strong a voice should use it so seldom.

I have never but once seen the Green Woodpecker in Oxford, and that was as he flew rapidly over the Parks in the direction of the Magdalen elms. If he lives there, he must be known to the Magdalen men, but I have not had intelligence of him. The fact is that he is a much wilder bird than his near relation, the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, who is, or was, beyond doubt an 27 Oxford resident. A correspondent of the Oxford Magazine, “R. W. R.,” states that this bird bred outside his window at Trinity a few years ago, “but has not done so lately for reasons of his own, of which I approve.” Another correspondent, however, reports him from Addison’s Walk; and Mr. Macpherson of Oriel, whose eye is not likely to have erred, believed that he saw one in the Broad Walk a few years ago. I myself have not seen the bird nearer Oxford than Kennington; but I am pretty sure that it is commoner and also less shy than is generally imagined, and also that the ornithologist who sees it is not likely to mistake it for another bird: its very small size—it is not so large as a sparrow—its crimson head, and its wings, with their black and white bars, making it a conspicuous object to a practised eye.[8]

A blackbird proceeded calmly to take his bath in the fountain.—p. 30.

Christchurch Meadow is a favourite home of the Titmice. I believe that I have seen all the five English species here within a space of a very few days: English, not British, for there is one other, the Crested Tit, of which I shall have more to say in another chapter. A family of Longtails, or Bottle-tits, flits from bush to bush, never associating with the others, and so justifying its scientific separation from them. Another family is to be seen in the Parks, where they build a nest every year. These delightful little birds are however quite willing to live in the very centre of a town, indifferent to noise and dust. A Marsh-tit was once seen performing its antics on a lamp-post in St. Giles. A Great-tit built its nest in the stump of an old laburnum, in the little garden of Lincoln College, within a few yards of the Turl and High Street; the nest was discovered by my dog, who was prowling about the garden with a view to cats. I took great interest in this brood, which was successfully reared, and on one occasion I watched the parents bringing food to their young for twenty minutes, during which time they were fed fourteen times. The ringing note of this Great-tit or his relations is the first to be heard in that garden in winter-time, and is always welcome. The little Blue-tit is also forthcoming there at times. One Sunday morning I saw a Blue-tit climbing the walls of my College quadrangle, almost after the manner 30 of a Creeper, searching the crannies for insects, and even breaking down the crust of weathered stone. Among memories of the rain, mist, and hard work of many an Oxford winter spent among these gray walls, “haec olim meminisse juvabit.”

But I have strayed away from Christchurch Meadow and the Botanic Garden. Here it is more especially that the Thrush tribe makes its presence felt throughout the autumn. In the Gardens the thrushes and blackbirds have become so tame from constant quiet and protection, that, like the donkeys at Athens of which Plato tells us, they will hardly deign to move out of your way. A blackbird proceeded calmly to take his bath, in the fountain at the lower end near the meadow, one morning when I was looking on, and seemed to be fully aware of the fact that there was a locked gate between us. Missel-thrushes are also to be seen here; and all these birds go out of a morning to breakfast on a thickly-berried thorn-bush at the Cherwell end of the Broad Walk, where they meet with their relations the Redwings, and now and then with 31 a Fieldfare. The walker round the meadow in winter will seldom fail to hear the harsh call of the redwing, as, together with starlings innumerable, and abundance of blackbirds, they utter loud sounds of disapproval. There is one bush here whose berries must have some strange ambrosial flavour that blackbirds dearly love. All the blackbirds in Oxford seem to have their free breakfast-table here, and they have grown so bold that they will return to it again and again as I teasingly walk up and down in front of it, merely flying to a neighbouring tree when I scrutinize them too closely in search of a lingering Ring-ousel. Who ever heard of a flock of blackbirds? Here, however, in November, 1884, was a sight to be seen, which might possibly throw some light on the process of developing gregarious habits.[9]

Rooks, Starlings, Jackdaws, and Sparrows, which abound here and everywhere else in 32 Oxford, every one can observe for themselves, and of Sparrows I shall have something to say in the next chapter; but let me remind my young readers that every bird is worth noticing, whether it be the rarest or the commonest. My sister laughs at me, because the other day she found an old copy of White’s Selborne belonging to me, wherein was inscribed on the page devoted to the Rook, in puerile handwriting, the following annotation: “Common about Bath” (where I was then at school). But I tell her that it was a strictly accurate scientific observation; and I only wish that I had followed it up with others equally unimpeachable.

But more out-of-the-way birds will sometimes come to Oxford, and I have seen a Kestrel trying to hover in a high wind over Christchurch Meadow, and a Heron sitting on the old gatepost in the middle of the field. Herons are often to be seen by the river-bank in Port Meadow; and it was here, some years ago, that Mr. W. T. Arnold, of University College, was witness of an extraordinary attack made by a party of three on some small birds. Port Meadow constantly entices 33 sea-birds when it is under water, or when the water is receding and leaving that horrible slime which is so unpleasant to the nose of man; and in fact there is hardly a wader or a scratcher (to use Mr. Ruskin’s term)[10] that has not at one time or another been taken near Oxford. Sometimes they come on migration, sometimes they are driven by stress of weather. Two Stormy Petrels were caught at Bossom’s barge in the Port Meadow not long ago, and exhibited in Mr. Darbey the birdstuffer’s window. And a well-known Oxford physician has kindly given me an interesting account of his discovery of a Great Northern Diver, swimming disconsolately in a large hole in the ice near King’s Weir, one day during the famous Crimean winter of 1854-5; this splendid bird he shot with a gun borrowed from the inn at Godstow. During the spring and early summer of 1866, our visitors from the sea-coast were constant and numerous. Even the beautiful and graceful little Tern (Sterna Minuta) 34 more than once found his way here; and on the second occasion saved his own life by the confidence which he seemed to repose in man. ‘I intended to shoot it,’ wrote a young friend of mine, ‘but relented when I saw how tame and trustful it was.’

Specimens of almost all such birds are to be seen in the bird-cases of the Museum, and occasionally they may be seen in the flesh in the Market. Both Market and Museum will give plenty to do on a rainy day in winter:—

Ubi jam breviorque dies et mollior aestas

Quae vigilanda viris!

All the birds mentioned in the last chapter are residents in Oxford, in greater or less numbers according to the season, except the Fieldfares 36 and Redwings, the Grey Wagtail, and the rarer visitors: and of these the Fieldfares and Redwings are the only true winter birds. They come from the north and east in September and October, and depart again in March and April. When we begin our Summer Term not one is to be seen. The berries in the meadow are all eaten up long before Lent Term is over, and though these are not entirely or even chiefly the Redwing’s food, the birds have generally disappeared with them.

They do not however leave the country districts till later. When wild birds like these come into a town, the cause is almost certain to be stress of weather; when the winter’s back is broken, they return to the fields and hedges till the approach of summer calls them northwards. There they assemble together in immense flocks, showing all the restlessness and excitement of the smaller birds that leave us in the autumn; suddenly the whole mass rises and departs like a cloud. Accounts are always forthcoming of the departure of summer migrants, and especially of the Swallows and Martins, and there are few who 37 have not seen these as they collect on the sunny side of the house-roof, or bead the parapet of the Radcliffe building, before they make up their minds to the journey. But few have seen the Fieldfares and Redwings under the same conditions, and I find no account of their migration, or at least of what actually happens when they go, in any book within my reach as I write. But on March 19, 1884, I was lucky enough to see something of their farewell ceremonies. I was walking in some water-meadows adjoining a wood, on the outskirts of which were a number of tall elms and poplars, when I heard an extraordinary noise, loud, harsh, and continuous, and of great volume, proceeding from the direction of these trees, which were at the time nearly half-a-mile distant. I had been hearing the noise for a minute or two without attending to it, and was gradually developing a consciousness that some strange new agricultural instrument, or several of them, were at work somewhere near, when some Fieldfares flew past me to alight on the meadow not far off. Then putting up my glass, I saw that the trees were literally black with birds; and as long as 38 I stayed, they continued there, only retreating a little as I approached, and sending foraging detachments into the meadow, or changing trees in continual fits of restlessness. The noise they made was like the deep organ-sounds of sea-birds in the breeding-time, but harsher and less serious. I would willingly have stayed to see them depart, but not knowing when that might be, I was obliged to go home: and the next day when I went to look for them, only a few were left.

These birds do not leave us as a rule before the first summer visitors have arrived. In the case I have just mentioned, the spring was a warm one, and the very next day I saw the ever-welcome Chiff-chaff, which is the earliest to come and the latest to go, of all the delicate warblers which come to find a summer’s shelter in our abundant trees and herbage.

I use this word ‘warbler’ in a sense which calls for a word of explanation: for not only are the birds which are called in the natural history books by this name often very difficult to distinguish, but the word itself has been constantly used to denote a certain class of birds, without 39 any precise explanation of the species meant to be included in it. Nor is it in itself a very exact word; some of the birds which are habitually called warblers do not warble in the proper sense of the word,[11] and many others who really warble, such as the common Hedge-sparrow, have no near relationship to the class I am speaking of. But as it is a term in use, and a word that pleases, I will retain it in this chapter, with an explanation which may at the same time help some beginner in dealing with a difficult group of birds.

If the reader of this book who really cares to understand the differences of the bird-life which abounds around us, will buy for a shilling Mr. Dresser’s most useful List of European Birds,[12] he will find, under the great family of the Turdidae, three sub-families following each other on pages 7, 8, and 9, respectively called Sylvianae, 40 or birds of woodland habits, Phylloscopinae, or leaf-searching birds, and Acrocephalinae, or birds belonging to a group many of the members of which have the front of the head narrow and depressed: and under all these three sub-families he will find several species bearing in popular English the name of warbler. At the same time he will find other birds in these sub-families, which are quite familiar to him, but not as ‘warblers’ in any technical sense of the word; thus the Robin will be found in the first sub-family, and the Golden-crested Wren in the second. But, leaving out these two species, and also the Nightingale, which is a bird of somewhat peculiar structure and habits, he will find four birds in the first sub-family belonging to the genus Sylvia, which are all loosely called warblers, and will be mentioned in this chapter as summer visitors to Oxford, viz. the Whitethroat (or Whitethroat-warbler), the Lesser Whitethroat, the Blackcap, and the Garden-warbler; he will also find two in the second, belonging to the genus Phylloscopus, the Chiff-chaff and the Willow-wren (or Willow-warbler), 41 and two in the third, belonging to the genus Acrocephalus, the Sedge-warbler and the Reed-warbler. Let it be observed that each of these three genera, Sylvia, Phylloscopus, and Acrocephalus, is the representative genus of the sub-family in this classification, and has given it its name; so that we might expect to find some decided differences of appearance or habit between the members of these genera respectively. And this is precisely what is the case, as any one may prove for himself by a day or two’s careful observation.

The birds I have mentioned as belonging to the first genus, i. e. Whitethroat, etc., are all of a fairly substantial build, fond of perching, singing a varied and warbling song (with the exception of the Lesser Whitethroat, of whose song I shall speak presently), and all preferring to build their cup-shaped nest a little way from the ground, in a thick bush, hedge, or patch of thick-growing plants, such as nettles. They also have the peculiarity of loving small fruits and berries as food, and are all apt to come into our gardens in search of them, where they do quite 42 as much good as harm by a large consumption of insects and caterpillars.

Secondly, the two kinds of birds belonging to the genus Phylloscopus, Chiff-chaff and Willow-warbler, are alike in having slender, delicate frames, with a slight bend forward as of creatures given to climbing up and down, in an almost entire absence of the steady perching habit, in building nests upon the ground with a hole at the side, and partly arched over by a roof of dried grass, in feeding almost exclusively on insects, and in singing a song which is always the same, each new effort being undistinguishable from the last. In fact these two birds are so much alike in every respect but their voices (which though unvarying are very different from each other), that it is almost impossible for a novice to distinguish them unless he hears them.

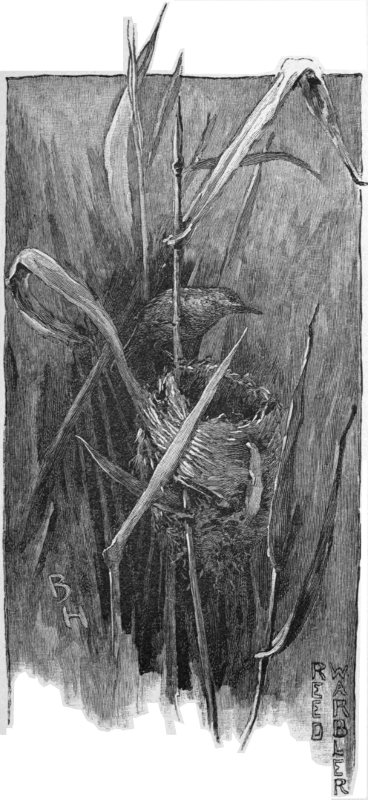

Thirdly, the two species belonging to the genus Acrocephalus, the Sedge- and Reed-warblers, differ from the other two groups in frequenting the banks of rivers and streams much more exclusively, where they climb up and down the water-plants, as their name suggests, and build a cup-shaped nest; and also in the nervous intensity and continuity of their song.

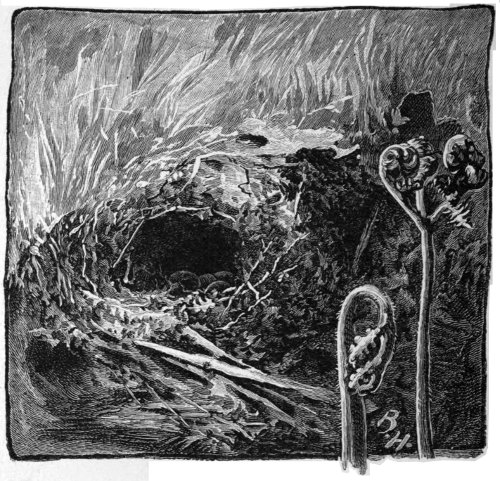

Reed Warbler.—p. 42.

These eight species, then, are the ‘warblers,’ of whom I am going to speak in the first place. They may easily be remembered in these three groups by any one who will take the trouble to learn their voices, and to look out for them when they first arrive, before the leaves have come out and the birds are shy of approach on account of their nests and young. But without some little pains confusion is sure to arise, as we may well understand when we consider that a century ago even such a naturalist as White of Selborne had great difficulty in distinguishing them; he was in fact the first to discover the Chiff-chaff (one of our commonest and most obvious summer migrants) as a species separate from the others of our second group. To give an idea of the progress Ornithology has made during the last century, I will quote Markwick’s note on White’s communication:—‘This bird, which Mr. White calls the smallest Willow-wren, or Chiff-chaff, makes its appearance very early in the spring, 44 and is very common with us, but I cannot make out the three different species of Willow-wrens, which he says he has discovered.’[13] Nothing but a personal acquaintance—a friendship, as I must call it in my own case—with these little birds, as they live their every-day life among us, will suffice to fix the individuality of each species in the mind; not even the best plates in a book, or the faded and lifeless figures in a museum. You may shoot and dissect them, and study them as you would study and label a set of fossils: but a bird is a living thing, and you will never really know him till you fully understand how he lives.

Let us imagine ourselves taking a stroll into the Parks with the object of seeing these eight birds, not as skeletons, but as living realities. The first to present themselves to eye and ear will be the two species of the second group, which may roughly be described (so far at least as England is concerned) as containing Tree-warblers. From the tall trees in St. John’s 45 Gardens, before we reach the Museum, we are certain on any tolerably warm day to hear the Willow-warbler, which has been the last few years extremely abundant; in Oxford alone there must have been two or three hundred pairs in the spring of 1885. From the same trees is also pretty sure to come ringing the two notes of the Chiff-chaff, which is a less abundant bird, but one that makes its presence more obvious. Let us pause here a moment to make our ideas clear about these two. We may justly take them first, as they are the earliest of their group to arrive in England.

When the first balmy breath of spring brings the celandines into bloom on the hedge-bank, and when the sweet violets and primroses are beginning to feel the warmth of the sun, you may always look out for the Chiff-chaff on the sheltered side of a wood or coppice. As a rule, I see them before I hear them; if they come with an east wind, they doubtless feel chilly for a day or two, or miss the plentiful supply of food which is absolutely necessary to a bird in full song. Thus in 1884, I noted March 20 as the first day on which 46 I saw the Chiff-chaff, and March 23 as the first on which I heard him. The next year, the month of March being less genial, I looked and listened in vain till the 31st. On that day I made a circuit round a wood to its sunny side, sheltered well from east and north, and entering for a little way one of these grassy ‘rides’ which are the delight of all wood-haunting birds, I stood quite still and listened. First a Robin, then a Chaffinch broke the silence; a Wood-pigeon broke away through the boughs; but no Chiff-chaff. After a while I was just turning away, when a very faint sound caught my ear, which I knew I had not heard for many months. I listened still more keenly, and caught it again; it was the prelude, the preliminary whisper, with which I have noticed that this bird, in common with a few others, is wont to work up his faculties to the effort of an outburst of song. In another minute that song was resounding through the wood.

No one who hails the approach of spring as the real beginning of a new life for men and plants and animals, can fail to be grateful to this little brown bird for putting on it the stamp and 47 sanction of his clear resonant voice. We may grow tired of his two notes—he never gets beyond two—for he sings almost the whole summer through, and was in full voice on the 25th of September in the same year in which he began on March 23rd; but not even the first twitter of the Swallow, or the earliest song of the Nightingale, has the same hopeful story to tell me as this delicate traveller who dares the east wind and the frost. They spend the greater part of the year with us; I have seen them still lurking in sheltered corners of the Dorsetshire coast, at the beginning of October, within sound of the sea-waves in which many of them must doubtless perish before they reach their journey’s end. And now and then they will even pass the winter with us: this was the case with one which took up his sojourn at Bodicote, near Banbury, in a winter of general mildness, though not unbroken, if I recollect right, by some very sharp frosts.

The Willow-warbler follows his cousin to England in a very few days, and remains his companion in the trees all through the summer. He has the same brownish-yellow back and yellowish-white 48 breast, but is a very little larger, and sings a very different song, which is unique among all British birds. Beginning with a high and tolerably full note, he drops it both in force and pitch in a cadence short and sweet, as though he were getting exhausted with the effort; for that it is a real effort to him and all his slim and tender relations, no one who watches as well as listens can have a reasonable doubt. This cadence is often perfect, by which I mean that it descends gradually, not of course on the notes of our musical scale, by which no birds in their natural state would deign to be fettered, but through fractions of one or perhaps two of our tones, and without returning upwards at the end; but still more often, and especially, as I fancy, after they have been here a few weeks, they take to finishing with a note nearly as high in pitch as that with which they began.[14] This singular song is heard in summer term in every part of the Parks, and in the grass beneath the trees there 49 must be many nests; but these we are not likely to find except by accident, so beautifully are they concealed by their grassy roofs. Through the hole in the upper part of the side you see tiny eggs, speckled with reddish brown, lying on a warm bedding of soft feathers; one of these was built last May in the very middle of the lawn of the Parsonage-house at Ferry-Hincksey, and two others of exactly the same build, one a Chiff-chaff’s, were but a little way outside the garden-gate, and had escaped the sharp eyes of the village boys when I last heard of them. Though from being on the ground they probably escape the notice of Magpies and Jackdaws and other egg-devouring birds, these eggs and the young that follow must often fall a prey to stoats and weasels, rats and hedgehogs. That such creatures are not entirely absent from the neighbourhood of the Parks, I can myself bear witness, having seen one morning two fine stoats in deadly combat for some object of prey which I could not discern, as I was divided from them by the river. The piping squeaks they uttered were so vehement and loud, that at the first moment I mistook them for 50 the alarm-note of some bird that was strange to me. In July, 1886, I saw a large stoat playing in Addison’s Walk, when few human beings were about, and the young birds, newly-fledged, were no doubt an easy prey.

One word more before we leave the Tree-warblers. In front of my drawing-room window in the country are always two rows of hedges of sweet peas, and another of edible peas; towards the end of the summer some little pale yellow birds come frequently and climb up and down the pea-sticks, apparently in search of insects rather than of the peas. These are the young Willow-warblers, which after their first moult assume this gently-toned yellow tint; and very graceful and beautiful creatures they are. I have sometimes seen them hover, like humming-birds, over a spray on which they could not get an easy footing, and give the stem or leaves a series of rapid pecks.

We have to walk but a little further on to hear or see at least two of our first group, the Sylviae, or fruit-eating warblers. As we pass into the Park by the entrance close to the house of the 51 Keeper of the Museum, we are almost sure, on any sunny day, to hear both Blackcap and Garden-warbler, and with a little pains and patience, to see them both. These two (for a wonder) take their scientific names from the characteristics by which sensible English folk have thought best to name them; the Blackcap being Sylvia atracapilla, and the Garden-warbler Sylvia hortensis. Mr. Ruskin says, in that delicious fragment of his about birds, called Love’s Meinie, that all birds should be named on this principle; and indeed if they had only to discharge the duty which many of our English names perform so well, viz. that of letting English people know of what bird we are talking, his plan would be an excellent one. Unluckily, Ornithology is a science, and a science which embraces all the birds in the world; and we must have some means of knowing for certain that we shall be understood of all the world when we mention a bird’s name. This necessity is well illustrated in the case of the warblers. So many kinds of them are there, belonging to all our three groups, in Europe alone, not to speak of other parts of the 52 world, that even a scientific terminology and description upon description have not been able to save the birds from getting mixed up together, or getting confounded with their own young, or with the young of other birds.

If the Blackcap were not a Sylvia, he could not well be scientifically named after his black head, for other birds, such as Titmice, have also black heads, and I have frequently heard the Cole Tit described as the Blackcap. In any case he should perhaps have been named after his wonderful faculty of song, in which he far excels all the other birds of our three groups. Most people know the Blackcap’s song who have ever lived in the country, for you can hardly enter a wood in the summer without being struck by it; and all I need do here is to distinguish it as well as I can from that of the Garden-warbler, which may easily be mistaken for it by an unpractised ear, when the birds are keeping out of sight in the foliage, as they often most provokingly will do. Both are essentially warblers; that is, they sing a strain of music, continuous and legato, instead of a song that is broken up into separate 53 notes or short phrases, like that of the Song-thrush, or the Chiff-chaff. But they differ in two points: the strain of the Blackcap is shorter, forming in fact one lengthened phrase “in sweetness long drawn out,” while the Garden-warbler will go on almost continuously for many minutes together; and secondly, the Blackcap’s music is played upon a mellower instrument. The most gifted Blackcaps—for birds of the same species differ considerably in their power of song—excel all other birds in the soft quality of their tone, just as a really good boy’s voice, though less brilliant and resonant, excels all women’s voices in softness and sweetness. So far as I have been able to observe, the Blackcap’s voice is almost entirely wanting in that power of producing the harmonics of a note which gives a musical sound its brilliant quality; but this very want is what produces its unrivalled mellowness.

The other two members of our first group (we are still in genus Sylvia) are the two Whitethroats, greater and lesser, and we have not far to go to find them. They arrive just at the beginning of our Easter Term, but never come 54 to Oxford in great numbers, because their proper homes, the hedge-rows, are naturally not common objects of a town. In the country the greater Whitethroats are swarming this year (1885), and in most years they are the most abundant of our eight warblers; and the smaller bird, less seen and less showy, makes his presence felt in almost every lane and meadow by the brilliancy of his note.

Where shall we find a hedge near at hand, where we may learn to distinguish the two birds? We left the Blackcaps and Garden-warblers at the upper end of the Park; we shall still have a chance of listening to them if we take the walk towards Parsons’ Pleasure, and here in the thorn-hedge on the right hand of the path, we shall find both the Whitethroats.[15] As we walk along, a rough grating sound, something like the noise of a diminutive corn-crake, is heard on the other side of the hedge—stopping when we stop, and 55 sounding ahead of us as we walk on. This is the teasing way of the greater Whitethroat, and it means that he is either building a nest in the hedge, or thinking of doing so. If you give him time, however, he will show himself, flirting up to the top of the hedge, crooning, craking, and popping into it again; then flying out a little way, cheerily singing a soft and truly warbling song, with fluttering wings and roughened feathers, and then perhaps perching on a twig to repeat it. Now you see the white of his throat; it is real white, and it does not go below the throat. In one book I have seen the Garden-warbler called a Whitethroat; but in his case the white is not so pure, and it is continued down the breast. The throat of both Whitethroats is real white, and they have a pleasant way of puffing it out, as if to assure one that there is no mistake about it.

But how to distinguish the two? for in size they differ hardly enough to guide an inexperienced eye. There are three points of marked difference. The larger bird has a rufous or rusty-coloured back,[16] and his wing-coverts are of much 56 the same colour; while the back of the lesser bird is darkish or grayish brown. Secondly, the head of the lesser Whitethroat is of a much darker bluish-gray tint. But much the best point of distinction in the breeding season is in the song. As I have said, the larger bird warbles; but the lesser one, after a little preliminary soliloquy in an under-tone, bursts out into a succession of high notes, all of exactly the same pitch. It took me some time to find out who was the performer of this music which I heard so constantly in the hedges, for the bird is very restless and very modest. When I caught sight of him he would not stop to be examined closely. One day however he was kind enough to alight for a moment in a poplar close by me, and as I watched him in the loosely-leaved branches, he poured out the song, and duly got the credit for it.

We are now close to our old winter-station on the bridge over the mill-stream, and leaning over it once more on the upper side, we shall hear, if not see, both the remaining species of the warblers that Oxford has to show us. They are 57 the only species of River-warblers that are known to visit England regularly every year; these two, the Sedge-warbler and the Reed-warbler, never fail, and the Sedge-warbler comes in very large numbers, but only a few specimens of other River-warblers have been found out in their venturesomeness. Still, every young bird-hunter should acquaint himself with the characteristics of the rarer visitors, in order to qualify himself for helping to throw light on what is still rather a dark corner of English ornithology. These same species which we so seldom see are swarming in the flat lands of Holland, close by us, and why should they not come over to the island which birds seem to love so dearly?

But there is no doubt that birds have ways, and reasons for them, which man is very unlikely ever to be able to understand. Why, as Mr. Harting asks,[17] should the Reed-warbler be so much less “generally distributed” than the Sedge-warbler? That it is so, we can show well enough even from Oxford alone. You will find Sedge-warblers all along the Cherwell and the Isis, wherever there 58 is a bit of cover, and very often they will turn up where least expected; in a corn-field, for example, where I have seen them running up and down the corn-stalks as if they were their native reeds. But you must either know where to find the Reed-warbler, or learn by slow degrees. Parsons’ Pleasure is almost the only place known to me where

“The Reed-warbler swung in a nest with her young,

Deep-sheltered and warm from the wind.”[18]

There is, however, in this case, at least a plausible answer to Mr. Harting’s question. Owing to the prime necessity of reeds for the building of this deep-sheltered nest, which is swung between several of them, kept firm by their centrifugal tendency, yielding lovingly yet proudly to every blast of wind or current of water—owing to this necessity, the Reed-Warbler declines to take up his abode in any place where the reeds are not thick enough and tall enough to give a real 59 protection to himself and his brood. Now in the whole length of Isis between Kennington[19] and Godstow, and of Cherwell between its mouth and Parsons’ Pleasure, there is no reed-bed which answers all the requirements of this little bird. Now and then, it is true, they will leave the reeds for some other nesting-place; one of them sang away all the Summer Term of 1884 in the bushes behind the Museum, nearly half a mile from the river, and probably built a nest among the lilac-bushes which there abound. But that year they seemed to be more abundant than usual; and this, perhaps, was one for whom there was no room in the limited space of the reeds at Parsons’ Pleasure. Thick bushes, where many lithe saplings spring from a common root, would suit him better than a scanty reed-bed.[20]

There is no great difficulty in distinguishing Sedge- and Reed-warblers, if you have an eye for the character of birds. The two are very different in temperament, though both are of the same quiet brown, with whitish breast. The Sedge-bird is a restless, noisy, impudent little creature, not at all modest or retiring, and much given to mocking the voices of other birds. This is done as a rule in the middle of one of his long and continuous outpourings of chatter; but I one day heard a much more ridiculous display of impertinence. I was standing at the bottom of the Parks, looking at a pair or two of Sedge-warblers on a bush, and wondering whether they were going to build a nest there, when a Blackbird emerged from the thicket behind me, and seeing a human being, set up that absurd cackle that we all know so well. Instantly, out of the bush I was looking at, there came an echo of this cackle, uttered by a small voice in such ludicrous tones of mockery, as fairly to upset my gravity. It seemed to say, “You awkward idiot of a bird, I can make that noise as well as you: only listen!”—

The Reed-warbler, on the other hand, is quieter 61 and gentler, and utters, by way of song, a long crooning soliloquy, in accents not sweet, but much less harsh and declamatory than those of his cousin. I have listened to him for half-an-hour together among the bushes that border the reed-bed, and have fancied that his warble suits well with the gentle flow of the water, and the low hum of the insects around me. He will sit for a long time singing on the same twig, while his partner is on her nest in the reeds below; but the Sedge-warbler, in this and other respects like a fidgety and ill-trained child, is never in one place, or in the same vein of song, for more than a minute at a time.

It is amusing to stand and listen to the two voices going on at the same time; the Sedge-bird rattling along in a state of the intensest excitement, pitching up his voice into a series of loud squeaks, and then dropping it into a long-drawn grating noise, like the winding-up of an old-fashioned watch, while the Reed-warbler, unaffected by all this volubility, takes his own line in a continued prattle of gentle content and self-sufficiency.

These eight birds, then, are the warblers which at present visit Oxford. Longer walks and careful observation may no doubt bring us across at least two others, the Wood-warbler and the Grasshopper-warbler: the nest of the Wood-warbler has been found within three miles. Another bird, too, which is often called a warbler, has of late become very common both in and about Oxford—the Redstart. Four or five years ago they were getting quite rare; but this year (1885) the flicker of the red tail is to be seen all along the Cherwell, in the Broad Walk, where they build in holes of the elms, in Port Meadow, where I have heard the gentle warbling song from the telegraph wires, and doubtless in most gardens. The Redstart is so extremely beautiful in summer, his song so tender and sweet, and all his ways so gentle and trustful, that if he were as common, and stayed with us all the year, he would certainly put our Robin’s popularity to the proof. Nesting in our garden, or even on the very wall of our house, and making his presence there obvious by his brilliant colouring and his fearless domesticity, he might become, like his plainer cousin of the 63 continent, the favourite of the peasant, who looks to his arrival in spring as the sign of a better time approaching. “I hardly hoped,” writes my old Oberland guide to me, after an illness in the winter, “to see the flowers again, or hear the little Röthel (Black Redstart) under my eaves.”

The Oxford Redstarts find convenient holes for their nests in the pollard willows which line the banks of the Cherwell and the many arms of the Isis. The same unvaried and unnatural form of tree, which looks so dreary and ghastly in the waste of winter flood, is full of comfort and adaptability for the bird in summer. The works of man, though not always beautiful, are almost always turned to account by the birds, and by many kinds preferred to the solitude of wilder haunts. Whether he builds houses, or constructs railways, or digs ditches, or forces trees into an unnatural shape, they are ready to take advantage of every chance he gives them. Only when the air is poisoned by smoke and drainage, and vegetation retreats before the approach of slums, do they leave their natural friends to live without the charm of their voices—all but that strange 64 parasite of mankind, the Sparrow. He, growing sootier every year, and doing his useful dirty work with untiring diligence and appetite, lives on his noisy and quarrelsome life even in the very heart of London.

Whether the surroundings of the Oxford Sparrows have given them a sense of higher things, I cannot say; but they have ways which have suggested to me that the Sparrow must at some period of his existence have fallen from a higher state, of which some individuals have a Platonic ἀνάμνησις which prompts them to purer walks of life. No sooner does the summer begin to bring out the flies among our pollard willows, than they become alive with Sparrows. There you may see them, as you repose on one of the comfortable seats on the brink of the Cherwell in the Parks, catching flies in the air with a vigour and address which in the course of a few hundred years might almost develop into elegance. Again and again I have had to turn my glass upon a bird to see if it could really be a Sparrow that was fluttering in the air over the water with an activity apparently meant to rival 65 that of the little Fly-catcher, who sits on a bough at hand, and occasionally performs the same feat with native lightness and deftness. But these are for the most part young Sparrows of the year, who have been brought here perhaps by their parents to be out of the way of cats, and for the benefit of country air and an easily-digested insect diet. How long they stay here I do not know; but before our Autumn Term begins they must have migrated back to the city, for I seldom or never see them in the willows except in the Summer Term.

These seats by the Cherwell are excellent stations for observation. Swallows, Martins, and Sand-martins flit over the water; Swifts scream overhead towards evening; Greenfinches trill gently in the trees, or utter that curious lengthened sound which is something between the bleat of a lamb and the snore of a light sleeper; the Yellow Wagtail, lately arrived, walks before you on the path, looking for materials for a nest near the water’s edge; the Fly-catcher, latest arrival of all, is perched in silence on the railing, darting now and then into the air for flies; the Corn-crake sounds 66 from his security beyond the Cherwell, and a solitary Nightingale, soon to be driven away by dogs and boats and bathers, may startle you with a burst of song from the neighbouring thicket.

Of the birds just mentioned, the Swifts, Swallows, and Martins build, I need hardly say, in human habitations, the Sand-martins in some sand- or gravel-pit, occasionally far away from the river. The largest colony of these little brown birds, so characteristic of our Oxford summer, is in a large sand-pit on Foxcombe Hill: there, last July, I chanced to see the fledgelings peeping out of their holes into the wide world, like children gazing from a nursery window. The destruction all these species cause among the flies which swarm round Oxford must be enormous. One day a Martin dropped a cargo of flies out of its mouth on to my hat, just as it was about to be distributed to the nestlings; a magnifying glass revealed a countless mass of tiny insects, some still alive and struggling. One little wasp-like creature disengaged himself from the rest, and crawled down my hand, escaping literally from the very jaws of death.

Before I leave these birds of summer, let me record the fact that last June (1886) a pair of swallows built their nest on the circular spring of a bell just over a doorway behind the University Museum; the bell was constantly being rung, and the nest was not unfrequently examined, but they brought up their young successfully. This should be reassuring to those who believe that the Museum and its authorities are a terror to living animals.

Nest on College Bell.

When the University year is over, usually about mid-June, responsibilities cease almost entirely for a few weeks; and it is sometimes possible to leave the lowlands of England and their familiar birds without delay, and to seek new hunting-grounds 69 on the Continent before the freshness of early summer has faded, and before the world of tourists has begun to swarm into every picturesque hole and corner of Europe. An old-standing love for the Alpine region usually draws me there, sooner or later, wherever I may chance to turn my steps immediately after leaving England. He who has once seen the mountain pastures in June will find their spell too strong to be resisted.

At that early time the herdsmen have not yet reached the higher pastures, and cows and goats have not cropped away the flowers which scent the pure cool breeze. The birds are undisturbed and trustful, and still busy with their young. The excellent mountain-inns are comparatively empty, the Marmots whistle near at hand, and the snow lies often so deep upon footpaths where a few weeks later even the feeblest mountaineer would be at home, that a fox, a badger, or even a little troop of chamois, may occasionally be seen without much climbing. If bad weather assails us on the heights, which are liable even in June to sudden snow-storms and bitter cold, we can 70 descend rapidly into the valleys, to find warmth and a new stratum of bird-life awaiting us. And if persistent wet or cold drives us for a day or two to one of the larger towns, Bern, or Zürich, or Geneva, we can spend many pleasant hours in the museums with which they are provided, studying specimens at leisure, and verifying or correcting the notes we have made in the mountains.

It is a singular fact that I do not remember to have ever seen an Englishman in these museums, nor have I met with one in my mountain walks who had a special interest in the birds of the Alps. Something is done in the way of butterfly-hunting; botanists, or at least botanical tins, are not uncommon. The guide-books have something to say of the geology and the botany of the mountains, but little or nothing of their fauna. I have searched in vain through all the volumes of the Jahrbuch of the Swiss Alpine Club for a single article or paragraph on the birds, and the oracles of the English Alpine Club are no less dumb.

Not that ornithologists are entirely wanting for 71 this tempting region; Switzerland has many, both amateur and scientific. A journal of Swiss ornithology is published periodically. Professor Fatio, of Geneva, one of the most distinguished of European naturalists, has given much time and pains to the birds of the Alpine world, and published many valuable papers on the subject, the results of which have been embodied in Mr. Dresser’s Birds of Europe. But what with the all-engrossing passion for climbing, and the natural indisposition of the young Englishman to loiter in that exhilarating air, it has come to pass that the Anglo-Saxon race has for long past invaded and occupied these mountains for three months in each year, without discovering how remarkable the region is in the movements and characteristics of its animal life.

I myself have been fortunate in having as a companion an old friend, a native of the Oberland, who has all his life been attentive to the plants and animals of his beloved mountains. Johann Anderegg will be frequently mentioned in this chapter, and I will at once explain who he is. A peasant of the lower Hasli-thal, in the canton of Bern, born before the present excellent system of 72 education had penetrated into the mountains, was not likely to have much chance of developing his native intelligence; but I have never yet found his equal among the younger generation of guides, either in variety of knowledge, or in brightness of mental faculty. He taught himself to read and write, and picked up knowledge wherever he found a chance. When his term of military service was over, he took to the congenial life of a guide and “jäger,” in close fellowship with his first cousin and namesake, the famous Melchior, the prince of guides. But a long illness, which sent him for many months to the waters of Leukerbad, incapacitated him for severe climbing, and at the same time gave him leisure for thinking and observing: Melchior outstripped him as a guide, and their companionship, always congenial to both as men possessed of lively minds as well as muscular bodies, has long been limited to an occasional chat over a pipe in winter-time.

But he remained an ardent hunter, and has always been an excellent shot: and it was in this capacity, I believe, that he first became useful to the Professor Fatio whom I mentioned just now. 73 He did much collecting for him, and in the course of their expeditions together, contrived to learn a great deal about plants, insects, and birds, most of which he retains in his old age. There is nothing scientific in his knowledge, unless it be a smattering of Latin names, which he brings out with great relish if with some inaccuracy; but it is of a very useful kind, and is aided by a power of eyesight which is even now astonishing in its keenness. I first made his acquaintance in 1868, and for several years he accompanied my brother and myself in glacier-expeditions in all parts of the Alps; but it has been of late years, since we have been less inclined for strenuous exertion, that I have found his knowledge of natural history more especially useful to me. He is now between sixty and seventy, but on a bracing alp, with a gun on his shoulder, his step is as firm and his enjoyment as intense, as on the day when he took us for our first walk on a glacier, eighteen years ago.