Title: Harper's Young People, August 16, 1881

Author: Various

Release date: April 26, 2015 [eBook #48803]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| Vol. II.—No. 94. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, August 16, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"UNHAPPY."—From a Painting by Greuse.

"UNHAPPY."—From a Painting by Greuse.

It was one fine morning in early summer that Sam Finney rose a full hour earlier than usual, quickly disposed of his breakfast, hurried through his chores, and then hastened off down the main street of the village to the steamboat dock.

Here he seated himself atop of a pile, and watched for the appearance of the Laura Pearl, the "favorite steamer" that formed the principal connecting link between the quietness and oysters of Fair Farms and the bustle and markets of the city.

As a general thing, Sam did not take much interest in the arrival of the Laura, as she was familiarly called; but to-day she was to bring with her Tom Van Daunton and his new row-boat.

Now Tom was a city boy, and had only passed one summer at Fair Farms; still, that was long enough to allow of his becoming the most intimate friend of Sam, who had lived in the little village all the twelve years of his life. Together the two had rowed, crabbed, fished, and fallen overboard to their hearts' content, the only drawback to their complete happiness consisting in the fact that they had never had a boat exactly suited to their wants. Sam's father, to be sure, owned two or three, but all were used by his older brothers for clamming and oystering, while the Van Dauntons' Whitehall was very safe and pretty, but altogether too large for two boys not yet in their teens.

Nevertheless, as has been said, the lads managed to enjoy themselves immensely: and now that Tom's father had given him as a birthday present a sum of money with which to have a boat built for his own use, there seemed to be no limit to the good times ahead.

Tom had promptly hastened to inform his friend by letter of the luck they were in, asking at the same time for suggestions as to the sort, size, and color of the prospective craft.

And now it was all finished, and to-day the Van Dauntons, and Tom, and the boat were expected at the pretty little Swiss cottage on the river-bank, which was just across the road from the Finney farm.

"Hip! hip! hurrah! Here she comes!" sung out Sam, as the Laura Pearl shot into view from behind the point; and he waved his hat with such energy that he nearly fell off the top of the pile on the back of a big hard-shell crab that was clinging to the bottom of it.

He saved himself, however, and as the Laura ran up alongside, dexterously caught her stern line, and placed it over the post.

"Bravo! well done!" shouted somebody from the upper deck, and there was young Van Daunton, looking a little pale after his winter in the city, but just as good-natured as ever, while at his feet lay the Breeze, the wonderful new, oiled, cedar boat, fifteen feet long, rather narrow, yet very trim, and with seats for four persons.

The Breeze was carefully lifted down, and placed on the wharf, from whence she was launched that very afternoon, with her two pretty flags flying fore and aft, and an admiring crowd of fishers and crabbers as spectators.

And all summer long the boys' interest in the boat never lessened; for when they became tired of rowing for rowing's sake, they pretended the Breeze was a steamboat, with Tom and Sam taking turns as Captain and Engineer, while little Vincent, as passenger, cheerfully consented to be picked up and set down anywhere on the route, as long as there was plenty of sand for him to play in.

With this new idea in their heads, the lads had rigged up a bell under one of the forward seats, which was connected with the stern, where the Captain steered, by a string, and by this means all directions as to stopping and starting were given precisely as on the Laura Pearl or any other steam vessel.

It was one afternoon late in the season that the boys determined to venture upon a more extended trip than any they had hitherto undertaken.

"'Twould be great fun to cruise along the bay shore, with land on only one side of us." It was Sam who spoke, and thus suggested the voyage, as he had afterward good cause to remember. "We might leave Vin in one of the little coves there, and then steer out toward the sea. What do you say, Captain?"—for it happened to be Tom's turn at the "wheel."

What could the latter say but that he was of the same mind? And as the day was fine, it was decided to put the brilliant idea into effect without delay; for around the point to the bay shore and back was no trifling distance, and it was already past one.

"Lucky the tide's with us," remarked Sam, as he answered the bell by pushing off and rowing leisurely down stream.

"But it's pretty near low water now, so you'll have to hurry up if you want it to help you all the way;" and Tom cast a nautical eye shoreward to see how great an extent of snails was exposed.

The Breeze was, as Sam had predicted, a very easy-going boat, and now, propelled by his strong young arms, and aided materially by the outflowing tide, she went along at such a rate as to create quite a strong namesake of hers in the heated air, which blew refreshingly in Tom's face as he guided his craft through the windings of the Leafic channel.

And now they had rounded the point, and the wide expanse of the bay, stretching far off to the city on the one side, and to the ocean on the other, was before them.

"Oh dear! how hot I am!" said Vin, eying with envy a clump of stunted cedars that grew close to the shore on their left.

"So am I," returned his brother; "but duty calls us to explore still further these watery wastes, so we'll just set you down here, where you can amuse yourself by making railroads in the sand till we come back." And as he spoke, Tom pulled on his left tiller-rope, and then gave Chief Engineer Finney the signal to slow up, as they ran into a convenient little cove.

Vin lost no time in getting out and seeking the scanty shade which the trees afforded, and then the two "big boys" pushed off again, promising to call for their passenger in about half an hour.

"And now for the 'bright blue sea,'" cried Tom, as he turned the Breeze's bow in the direction of Europe.

Further and further in the rear the clump of cedars was left, and still the sandy cape that marked the division between sea and river appeared as far away as ever. Finally Tom, losing patience at their seemingly slow progress, took one of Sam's oars, and together the two made the boat fly through the water.

But if the Captain had remained at his post in the stern a little while longer, he would have noticed something ahead that might have led him to turn around and hasten back instead of hurrying onward. That something was what at first seemed to be merely a harmless white cloud rising out of the ocean, but which grew ever larger and larger as it advanced toward the land.

And still the boys, eager to pass beyond the line of breakers on their right, wasted not an instant in turning round to look before them, until at last they gained their point, left the white-capped billows behind them, and the next moment awoke to the fact that they were completely enveloped in the densest fog. Where but a few seconds previous all had been bright and beautiful, there was now naught apparent but the heavy curtain of mist, blotting out the blue of sea and sky and all the glorious sunshine.

For half a minute the boys were so amazed that they just sat and stared mutely at as much as they could see of one another; and then, with the single cry of "Vin!" Tom splashed his oar into the water, and began to row the boat around. But in which direction should he head it? Where was the clump of cedars now? or where, in fact, was anything but fog, thick and penetrating, shrouding everything?

"Oh, Sam, what shall we do?—which way shall we go?" exclaimed poor Tom, for an instant losing his wonted courage and hopefulness as he thought of his ten-year-old brother off there alone on that barren beach waiting and watching for them to come back for him.

"Maybe the fog'll lift soon," replied Sam. "They don't generally last long this time of year." And the lad endeavored to speak cheerfully, although his heart beat fast and loud, for was it not he that had first proposed the foolish expedition?

"But I can't sit here, and do nothing but wait. It's too awful. Oh, if we only had a compass!" And Tom gazed out into the mists about him as if determined to pierce through their heavy folds.

At that moment a sharp, short whistle was sounded disagreeably close at hand, and served to add a new terror to the situation. A vessel might run them down.

"Quick! the bell!" shouted Sam; and snatching up the string, he rang it at regular intervals all through the terrible hours that followed.

Meanwhile Tom, unable to remain quiet, had caught up the other oar, and begun pulling in the direction of—he knew not where. Presently a splashing sound of wheels was heard, then the whistle's shrill note of warning, and the next instant the Breeze was tossed to and fro like a cork in the swell of a passing steamer.

The boys grew pale as they realized the extremity of their danger, and clutched the sides of the boat to save themselves from being thrown out.

And yet they were quite helpless. Even little Vin, alone there on that deserted shore, was to be envied, for he was at least in temporary security.

Tom still rowed slowly on, while Sam strained his eyes to the utmost, and kept up the monotonous ringing of the bell. Neither of the lads said much; but the expression of Tom's face, although all its usual bright color had left it, showed that he was determined to bear up bravely to the end, whatever that might be.

The water still remained quite smooth; even the long easy swells were growing less and less noticeable, and the boys were beginning to hope that they were at least headed for the shore, when—thump went the boat into a great black object, and both gave themselves up for lost.

"It's a ship," thought Tom, momentarily expecting the dark waters to close over his head.

"Help! help! We've run into a steamer!" cried Sam, tugging away in a crazy fashion at the bell-cord.

But, as it turned out, the great black object was neither a ship nor a steamer, but a huge buoy, and instead of being lost, the lads were saved; for, attaching themselves to this marker of shoals, they were out of the course of vessels, and all that was necessary for them to do was to wait.

And this they did patiently, although it proved a hard task, with the thought of Vin all alone there on that distant beach. Sam kept up the sounding of the bell, for it was a sort of company for them, while Tom counted the minutes on his watch until it grew to be after five, when a faint glimmering became perceptible through the mist, and gradually the fog lifted and rolled away.

And now where did the young mariners find themselves? Why, half way up the bay in the direction of the city, and a long pull they had of it back to the clump of cedars.

But on arriving here no Vin was to be seen, and the boys were beginning to grow quite desperate in their anxiety, when Sam stumbled upon the following, written in the sand:

"Don't worry about me. I am going to walk home by the bridge at Leafic.

"Vin."

"It's a good four miles," said Tom, "and I know he's never been over the road."

But when they came in sight of the Van Dauntons' wharf, there was Vin on the end of it, anxiously looking out for them.

Fig. 1.—POISON-IVY.

Fig. 1.—POISON-IVY.

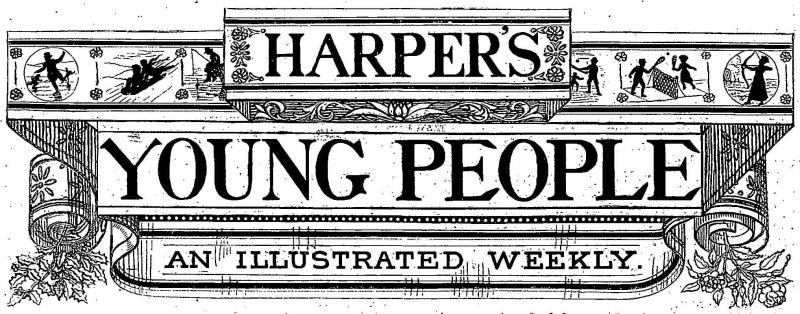

At this season of the year, when so many of our young folks are gathering wild flowers, ferns, berries, leaves, and mosses in the woods and along the hedges, I can not think of a more useful lesson in wood and field botany than that which teaches how to know and distinguish two of the most poisonous vegetable substances to be met with in the woods. I mean the poison-ivy, poison-oak, and mercury-vine, which are the common names for one and the same vine, found climbing up the trunks of trees, on rail, board, and stone fences, over rocks and bushes, in waste lands and meadows. In fact, everywhere and anywhere it can secure a foot of ground, no matter how poor, or how much exposed to the scorching rays of the sun, this wretched vine prospers, happy and contented to spread out its poisonous arms hidden beneath its glossy and graceful foliage. In Fig. 1 is shown a close study from nature of a specimen growing at the west end of Coney Island, where it is to be found in abundance between the highest sand-dunes on the north and south sides of the island. Here when the ivy has a chance to climb up a tree or bush, up it goes, throwing out its aerial rootlets in all directions. But when growing away from any support, in the sand which is being constantly displaced by the strong ocean winds, it then grows stout, erect, and bush-like. Under these peculiar circumstances of growth it has received the name of poison-oak, and was supposed by many botanists to be a separate variety, though in fact the poison ivy and oak are one and the same thing. When the stem of the poison-ivy is wounded, a milky juice issues from the wound. The leaves, after being separated from the vine, turn black when exposed to the air.

Fig. 2.—VIRGINIA CREEPER.

Fig. 2.—VIRGINIA CREEPER.

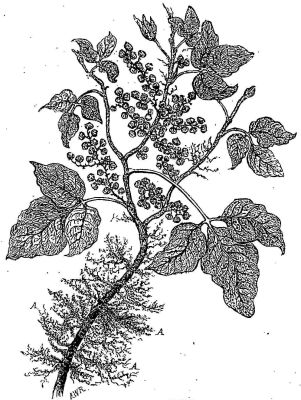

The stem of the vine is nearly smooth in texture; the aerial rootlets (Fig. 1, A A A), which start from all parts of the stem, are of a bright brown color when young. The masses of berries when unripe are of a light green color; when ripe, of an ashen gray. Below the mass of this year's berries are generally to be found those of last year. The leaf has a smooth and somewhat shiny texture, and curves downward from the midrib. To many people the slightest contact with the leaves of the ivy will produce poisoning. I have known of instances where persons in passing masses of ivy-vine, particularly when the wind was blowing from the vine toward the passer-by, became severely poisoned. One of our most beautiful native vines, the so-called Virginia creeper, which frequently grows side by side with the ivy, is often mistaken for it, and blamed for the evil doings of its neighbor, and yet is so innocent and beautiful a vine that I have figured it in full fruit (Fig. 2). The Virginia creeper has a leaf consisting of five lobes, which are distinctly notched, and which curve upward from the midrib. Instead of aerial rootlets like the ivy, it has stout tendrils more or less twisted and curled, often assuming the form of a spiral spring. These tendrils are provided with a disk by means of which an attachment is made to any object within reach (see Fig. 2, B B).

The stem has the appearance of being jointed. The[Pg 660] berries are large and grape-like in the form of the cluster, and when ripe are of a deep blue color, with heavy bloom. In the fall of the year the leaves turn to a deep red and brownish-red color.

The poison-sumac, swamp-sumac, or dogwood (Fig. 3) is ten times more severe in its poisoning qualities than the poison-ivy. It grows from six to ten feet in height, in low marshy grounds. The berries are smooth, white, or dun-colored, and in form and size closely resemble those of the ivy.

Fig. 3.—POISON-SUMAC.

Fig. 3.—POISON-SUMAC.

This sumac is terrible in its effects, often causing temporary blindness. Some years ago it became the fashion to wear immense wreaths and bunches of artificial flowers inside and outside of ladies' bonnets. The flower-makers, being hard pressed for material, made use of dried grasses, seed-vessels, burrs, and catkins; these were painted, dyed, frosted, and bronzed to make them attractive. I became greatly interested in the business and the ingenuity displayed, and spent much time examining the contents of milliners' windows. On one occasion when standing before a very fashionable milliner's window on Fourteenth Street, I was horror-stricken on discovering that an immense wreath of grayish berries which constituted the inside trimming of a bonnet was composed entirely of the berries of the poison-sumac, just as they had been gathered, not a particle of varnish, bronze, or other material coating them. The bonnet, when worn, would bring this entire mass of villainous berries on the top and sides of the head, and a few of the sprays about the ears and on the forehead. Stepping into the store, I addressed the proprietor, and asked her if she knew that the bonnet was trimmed with the berries of one of the most poisonous shrubs known in the United States. After staring at me in a sort of puzzled way, she informed me that I was mistaken; that she had received those flowers from Paris only a week ago.

"Madam," I replied, "there must be a mistake somewhere, for those are the berries of the poison-sumac, which does not grow in Europe."

She gave me one angry look, asked me to please attend to my own business, and swept away from me to the other end of the store.

A few days after this I read in the daily papers an account of the poisoning of a number of small girls employed in a French artificial flower manufactory in Greene Street. I at once guessed the cause. I visited the factory mentioned, introduced myself to the proprietor, told him what I knew about the poison berries—and was rudely requested to make myself scarce. After these two adventures I made up my mind to keep my botanical knowledge (poisonous though it might be) to myself.

When in the army I came across a very curious case of poisoning with swamp-sumac and poison-ivy. A creature having the form of a human being, and wearing the uniform of a soldier, was found in a solitary tent, which was pitched in an abandoned and desolated plantation. This creature's body had the appearance of having been scalded, and his eyesight was nearly gone: in fact, we were afraid to touch him, fearing that he had some terribly infectious disease. But why was he there, alone and deserted?—not even a sanitary guard over him to prevent all communication except by the doctors. He did not seem to care to talk much about himself or his situation, or state why his comrades had left him there to die. Being on the march, all we could do was to leave him extra rations, water, and tobacco. But we afterward learned from members of his regiment that to avoid duty and an engagement he had poisoned himself by building a fire of green poison-ivy and swamp-sumac, and had actually submitted himself to a vapor-bath of these two poisonous materials. He was a professional bounty-jumper, and had taken this means to get out of the army. He was never heard of afterward, as he fell into the hands of the enemy where his comrades left him.

When poisoned with ivy or sumac (they are all sumacs), if time and cooling medicines are taken, the poison will slowly exhaust itself; but it is a tedious and slow operation. A cure which is in use with the Indians of California and the Territories is to eat a few of the leaves after the poison has made its appearance on the skin. The Editor of Harper's Young People tells me that he has tried this method, and that in his case it effected a complete cure within twelve hours.

On the following morning Tim and Sam were awakened very suddenly by a confused noise which appeared to come from the kitchen below, and which could not have been greater had a party of boys been engaged in a game of leap-frog there.

A woman's screams were heard amid the crashing of furniture as it was overturned, the breaking of crockery, and the sounds of scurryings to and fro, while high above all came at irregular intervals the yelp of a dog.

This last sound caused Tim the greatest fear. A hasty glance around the room had shown him that Tip, who had been peacefully curled up on the outside of the bed when he last remembered anything, was no longer to be seen; and without knowing how it could have happened, he was sure it was none other than his pet who was uttering those cries of distress.

In a few moments more he learned that he was not mistaken, for Tip rushed into the room, his tongue hanging out, his stub of a tail sticking straight up, and looking generally as though he had been having a hard time of it.

Before Tim, who had at once leaped out of bed, could comfort his pet, a voice, sounding as if its owner was sadly out of breath, was heard crying, "Sam! Sam! Sammy!"

"What, marm?" replied Sam, who lay quaking with fear, and repenting the fact that his desire for candy had led him into what looked very much like a bad scrape.

"Did a dog just come into your room?"

"Yes, marm."

"Throw something at him, and drive him out."

For an instant Sam clutched the pillow as if he would obey the command; but Tim had his arms around Tip's neck, ready to save him from any injury, even if he was obliged to suffer himself.

"Why don't you drive him out?" cried Mrs. Simpson, after she had vainly waited to hear the sound of her son's battle with the animal.

"Why—why—why—" stammered Sam, at a loss to know what to say, and trembling with fear.

"Are you afraid of him?"

"No, marm," was the faltering reply.

"Then why don't you do as I tell you?"

"Why—why, Tim won't let me," cried Sam, now so frightened that he hardly knew what he did say.

"Why, what's the matter with the boy?" Tim heard the good woman say; and then the sound of rapid footsteps on the stairs told that she was coming to make a personal investigation.

Sam, in a tremor of fear, rolled over on his face, and buried his head in the pillow, as if by such a course he could shelter himself from the storm he expected was about to break upon him.

Tim was crouching in the middle of the floor, his face close down to Tip's nose, and his arms clasped so tightly around the dog's neck that it seemed as if he would choke him.

That was the scene Mrs. Simpson looked in upon after she had been nearly frightened out of her senses by a strange dog while she was cooking breakfast. She had tried to turn the intruder out of doors, but he, thinking she wanted to play with him, had acted in such a strange and at the same time familiar manner that she had become afraid, and the confusion that had awakened the boys had been caused by both, when neither knew exactly what to do.

Mrs. Simpson stood at the room door looking in a moment before she could speak, and then she asked, "What is the meaning of this, Samuel?"

Sam made no reply, but buried his face deeper in the pillows, while the ominous shaking of his fat body told[Pg 662] that he was getting ready to cry in advance of the whipping he expected to receive.

"Who is this boy?" asked the lady, finding that her first question was likely to receive no reply.

Sam made no sign of life, and Tim, knowing that something must be said at once, replied, piteously, "Please, ma'am, it's only me an' Tip."

Sam's face was still buried in the pillows; but the trembling had ceased, as if he was anxious to learn whether his companion could free himself from the position into which he had been led.

"Who are you, and how did you come here?" asked Mrs. Simpson, wonderingly.

Tim turned toward the bed as if he expected Sam would answer that question; but that young man made no sign that he had even heard it, and Tim was obliged to tell the story.

"I'm only Tim Babbige, an' this is Tip. We was tryin' to find a place to sleep last night, when we met Sam, an' after we'd found the cow we went down to the store an' bought some candy, an' when we come back Sam was goin' to ask you to let me sleep in the barn, but you was in bed; so he said it was all right for me to come up here an' sleep with him. I'm awful sorry I did it, an' sorry Tip acted so bad; but if you won't scold, we'll go right straight away."

Mrs. Simpson was by no means a hard-hearted woman, and the boy's explanation, as well as his piteous way of making it, caused her to feel kindly disposed toward him. She asked him about himself; and by the time he had finished telling of the death of his parents, the cruel treatment he had received from Captain and Mrs. Babbige, and of his desperate attempt at bettering his condition, her womanly heart had a great deal of sympathy in it for him.

Then Tim added, as if it was the last of his pitiful story, "Me an' Tip ain't got anybody who cares for us but each other, an' if we don't get a chance to work, so's we can get some place to live, I don't know what we will do." Then he laid his head on the dog's nose, and cried as though his little heart was breaking, while Tip set up a series of most doleful howls.

"You poor child," said the good woman, kindly, "you're not large enough to work for your living, and I don't know what Mr. Simpson will say to your being here very long; but you shall stay till we see what can be done for you, whatever he says. Now don't cry any more, but dress yourself, and come down stairs, and help me clean up the litter the dog and I made. Sam, you lazy boy," she added, as she turned toward her half-concealed son, "get up and dress yourself. You ought to be ashamed for not telling me last night what you were about."

Then patting Tim on the head, the good woman went down stairs to attend to her household duties.

As soon as the sound of the closing door told that his mother had left the room, Sam rolled out of bed, much as a duck gets out of her nest, and said, triumphantly, to Tim, who was busy dressing, "Well, we got out of that scrape all right, didn't we?"

Tim looked up at him reproachfully, remembering Sam's silence when the affair looked so dark; but he contented himself with simply saying, "Yes, it's all right till we see what your father will say about it."

"Oh, he won't say anything, so long as mother don't," was the confident reply; and the conversation was broken there by Tim going down stairs to help Mrs. Simpson in repairing the damage done by Tip.

Before he had been helping her very long, he showed himself so apt at such work that she asked, "How does it happen that you are so handy at such things?"

"I don't know," replied Tim, bashfully, "'cept that Aunt Betsey always made me help her in the kitchen; an' I s'pose it comes handy for a feller to do what he must do."

By the time Sam came down stairs the kitchen presented its usual neat appearance, and he was disposed to make light of his mother's fright; but she soon changed his joy to grief by telling him to go to the spring for a pail of water.

Now if there was one thing more than another which Sam disliked to do, it was to bring water from the spring. The distance was long, and he believed it was unhealthy for him to lift as much weight as that contained in a ten-quart pail of water. As usual, he began to make a variety of excuses, chief among which was the one that the water brought the night before was as cool and fresh as any that could be found in the spring.

Tim, anxious to make himself useful in any way, offered to go; and then Sam was perfectly willing to point out the spring, and to generally superintend the job.

"Tim may go to help you," said Mrs. Simpson, "but you are not to let him do all the work."

Sam muttered something which his mother understood to mean that he would obey her, and the boys left the house, going through the grove of pine-trees that bordered quite a little pond, at one side of which, sunk deep in the earth, was a hogshead, into which the water bubbled and flowed from its bed under the ground.

But Sam was far more interested in pointing out objects of interest to himself than in leading the way to the spring. He showed Tim the very hole where he had captured a woodchuck alive, called his attention to a tree in which he was certain a family of squirrels had their home, and enlarged upon the merits of certain kinds of traps best calculated to deceive the bushy-tailed beauties.

Tim did not fancy this idea of idling when there was work to be done; and as soon as he saw the spring, he hurried off, in the middle of a story Sam was telling about a rabbit he caught the previous winter.

"What's the use of bein' in such a rush?" asked Sam, as, obliged to end his story, he ran after Tim. "Mother don't want the water till breakfast's ready, an' that won't be for a good while yet. Jest come over on this side the pond, an' I'll show you the biggest frog you ever saw in your life, that is, if he's got out of bed yet."

"Let's get the water first, an' then we can come back an' see everything," said Tim, as he hurried on.

"But jest come down here a minute, while I see if I can poke him out of his hole," urged Sam, as he picked up a stick, and started for the frog's home.

Tim paid no attention to him; he had been sent for water, and he did not intend to waste any time until that work had been done. He leaned over the side of the hogshead to lower the pail in, when Sam shouted, "Come here; I've found him."

But Tim went on with his work; and just as he had filled the pail, and was drawing it up, he heard a cry of fear, accompanied by a furious splashing, which, he knew could not come from a frog, however large he might be.

Dropping his pail, at the risk of having it sink beyond his reach, he looked up just in time to see a pair of very fat legs sticking above the water at that point where the frog was supposed to reside, and to hear a gurgling sound, as if the owner of the legs was strangling.

For a single moment Tim was at a loss to account for the disappearance of Sam, and the sudden appearance of those legs; but by seeing Tip run toward the spot, barking furiously, and by seeing the stick which was to have disturbed the frog in his morning nap floating on the water, he understood that Sam had fallen into the pond, without having had half so much fun with the frog as he expected.

Tim, now thoroughly frightened, ran quickly toward his unfortunate companion, calling loudly for help.

When he reached the bank from which Sam had slipped, the legs were still sticking straight up in the air, showing that their owner's head had stuck fast in the mud.

By holding on to the bushes with one hand, and stretching out the other, he succeeded in getting hold of Sam's trousers, at which he struggled and pulled with all his strength. Although it could hardly be expected that so slight a boy as Tim could do very much toward handling so heavy a body as Sam's, he did succeed in freeing him from the mud, and in pulling him to the surface of the water.

After nearly five minutes of hard work, during which Tip did all he could to help, Tim succeeded in pulling the fat boy into more shallow water, where he managed to get on to his feet again.

AFTER VISITING THE FROG'S HOME.

AFTER VISITING THE FROG'S HOME.

A mournful-looking picture he made as he stood on the bank, with the water running from every point of his clothing, while the black mud in which he had been stuck formed a cap for his head, and portions of it ran down over his face, striping him as decidedly as ever fancy painted an Indian.

He was a perfect picture of fat woe and dirt, and if he had not been in such peril a few moments before, Tim would have laughed outright.

He was evidently trying to say something, for he kept gasping for breath, and each time he opened his mouth it was filled with the mud and water that ran from his hair.

"What is the matter?" asked Tim, anxiously. "Are you hurt much?"

"No—no," gasped Sam; "but—but I saw the frog."

This time Tim did not try to restrain his mirth, and when Mrs. Simpson, who had been startled by Tim's cries for help, arrived on the spot, she found nothing very alarming.

Master Sam received a severe shaking, and was led away to be cleaned, while Tim and Tip were left to attend to the work of bringing the water.

At breakfast, where Sam ate so heartily that it was evident he had not been injured by his bath, the question of what should be done about allowing Tim to remain was discussed by Mr. and Mrs. Simpson.

The farmer said that a boy as small as he could not earn his salt, and it would be better for him to try to find a family who had no boys of their own, or go back to Captain Babbige, where he belonged. He argued, while Tim listened in fear, that it was wrong to encourage boys to run away from their lawful protectors, and was inclined to make light of the suffering Tim had told about.

Fortunately for the runaway, Mrs. Simpson believed his story entirely, and would not listen to any proposition to send him back to Selman. The result of the matter was that Mr. Simpson agreed to allow him to remain there a few days, but with the distinct understanding that his stay must be short.

This was even more than the homeless boy had expected, and he appeared so thankful and delighted at the unwilling consent, that the farmer began to think perhaps there was more to him than appeared on the surface, although he still remained firm in his decision that he was to leave the farm as soon as possible.

In 1857, the first postage stamp was issued in Ceylon. The design was the head of Victoria, to the left, in a circular medallion, printed in lilac, and was of the value of one halfpenny. This solitary stamp was soon after followed by a more extensive series, consisting of the following values and colors: 1d., blue; 2d., green; 4d., red; 5d., red-brown; 6d., brown-violet; 8d., maroon; 9d., brown-violet; 10d., vermilion; 1s., lilac-blue; 1s. 9d., green; 2s., blue. The general design was the head of Victoria; to the left, on an oval disk, the frame-work varying in some of the values.

These stamps were all unperforated, that is, not separated by little round holes, and except the ½d., were printed on paper having a star as a water-mark in the paper, a star being on each stamp in the sheet.

In 1861, perforation of the sheets was introduced, and we find all the values named above, except the ½d. and the 1s. 9d., perforated, with no change in the color. In 1863, the ½d., 6d., 9d., and 1s., printed without water-mark, were perforated. In 1864, all the values thus far enumerated, excepting the 1s. 9d., were printed on paper with water-mark CC and crown—Crown Colony. In 1867, the 2d. was printed in yellow, the 5d. in green, and the 10d. in orange, and a 3d. of new design, printed in rose, was introduced. In 1869, the 1d. stamp appeared in a new dress.

In 1872, the rupee became the sole standard of value, with decimal subdivisions. The rupee was divided into 100 cents, the cent of Ceylon being nearly equal to one-half cent of our money. In conformity with this change of currency, an entirely new issue of stamps took place. The general design was as formerly, the frame-work of each stamp differing in details. The values and colors are: 2c., bistre; 4c., gray-blue; 8c., yellow; 16c., lilac; 24c., green; 36c., blue; 48c., rose; 96c., gray-green. Later, the series was supplemented by three additional values—34c., 64c., and 2r. 50c.

For official purposes some of the values had the word "Service" printed upon them. The values so utilized were 1d., 2d., 3d., 6d., 8d., 1s., and 2s.

In 1861, a series of stamped envelopes of exquisite design was put in circulation. The colors corresponded to the colors of the adhesives, and were of the following values: 1d., 2d., 4d., 5d., 6d., 8d., 9d., 1s., 1s. 9d., 2s. These envelopes were afterward suppressed, and a single value, four cents, issued. Another change was made in the design of this value, which now corresponds to the old 5d.

Postal cards were introduced in 1872, value 2c., in lilac, and lately Postal Union cards of the value of 6c. and 8c. were placed in use. There have also been several series of fiscal stamps, ranging in value as high as 1000 rupees.

Ceylon is an island in the Indian Ocean, separated on the northwest from continental India by the Gulf of Manaar. It is 271 miles long from north to south, and in its greatest width 137 miles. In 1505, the Portuguese adventurer Almeida landed at Colombo, the present capital, and found the island divided into several kingdoms. In 1517, the first Portuguese settlement was effected, and gradually the whole western coast was in possession of Portugal. The fanatical zeal and remorseless cruelty of the Portuguese led to their downfall, when, after several attempts, the Dutch finally succeeded in driving the Portuguese from the country.

The first intercourse of the English with Ceylon took place in 1763. On the breaking out of war between Great Britain and Holland, an English force was sent to Ceylon, and in 1796 succeeded in gaining possession of the coasts. The interior was still ruled over by the native Kings; but in 1815 the last of them, a tyrant of the worst type, was captured, and subsequently died in exile, ending with him a long line of sovereigns, whose pedigree can be traced through upward of two thousand years. About the same time, by treaty, the whole island came into possession of the English.

The language of about seventy per cent. of the people is Cingalese, and of the remaining people, save the Europeans, the language is Tamil. The stamp-collector, who has the two-cent postal card, will find the English inscriptions on the card in both these languages.

NO USE CRYING OVER SPILLED MILK.

NO USE CRYING OVER SPILLED MILK.

Jamie was thinking. Well, what of that? Boys often think, don't they? No, indeed, that's just what they don't do; at least Jamie couldn't remember when he had seated himself deliberately to make a business of thinking before this occasion. And now he sat with a puzzled face, and a line between his eyes, so deep in thought that neither the coaxing fore-paws of Nep the dog nor the sound of clinking marbles could arouse him. The question with Jamie was just this: Should he continue to hide Neppie from the eye of man, and thus be happy in the secret knowledge that at last he owned a pet of his very own, who came and went at his bidding, and gave him love for love, or should he take him to the dog pound and earn his thirty cents as well as the others who rejoiced in the title of "dog-catcher"?

"I want that thirty cents, that's one thing sure and certain," thought Jamie, "an' if I don't get it by luggin' Neppie to the pound, I won't get it anyway, and that's just another certain sure thing. I sha'n't get rich waitin' fur Aunt Betty to give me a cent now and then; and there's Tom Blake got his pockets full half the time. But when a fellow cares for a dorg, he kinder hates to go back on 'im. And Nep cares for me, too, and he wouldn't think I'd be such a mean chap. Now if Aunt Betty didn't hate dorgs so bad, I'd ask her to let me keep 'im fair an' square, and then I shouldn't have to be 'fraid he'd bark every minute, and let folks know I was hiding 'im[Pg 666] here under this old box, tied, poor old feller, so he can't move hardly. There comes Jack Jones. Wish he'd keep away, and let a feller think a moment in peace."

Along came Jack, jingling some money in his hand. "Hello, Jim, whose dorg yer got?"

Jamie passed his arm caressingly about the dog's neck, and replied, "Mine, of course; who d'yer think, Jack Jones?"

"Ain't yer goin' to take him to the pound? See here," displaying three silver tens in his soiled palm to Jamie's envious brown eyes. "Got 'em at the pound just now for catching a dorg. Goin' to the circus to-night. Big show, I tell yer. Can't yer come along?"

Jamie's eyes began to widen and grow shiny. The circus? Oh, wouldn't he like to go! But Aunt Betty only kept a little store, and had hard work to keep herself and chubby-faced little nephew in bread and butter, and as for giving him money to go to the circus, why, Jamie knew he might as well hope to catch stars. So he only shook his head, and Jack passed on with the parting advice, "Better sell that dorg, and earn thirty cents, and come along."

Again Jamie plunged deeply into thought, forgetting to pet and fondle his four-footed companion according to his usual custom during these stolen visits.

About ten days before our introduction to the little boy, a lady living in one of the handsome houses out on one of the avenues, where each house has its own garden, and where there is always a sweet suggestion of real country, happened to look out of her window one morning, and exclaimed, anxiously: "There is that dog again, Bridget. What shall we do to get rid of him? He'll be sure to bite Nellie some day, and it is a shame the dog-catchers don't come out here."

Then she went in haste down to the front gate, and Bridget followed with the gardener's rake and hoe, with which to "shoo" the intruder away. Although he was frightened, yet Mr. Dog did not seem inclined to leave the fence a little further down; and no wonder, for there was little Miss Nellie, the three-year-old baby, sticking her wee fat hand through the railing, and smilingly feeding the four-footed tramp with the cake mamma had just given her. Poor, hungry, strange dog! no friends, no home: no wonder it was hard for him to leave the only friend he had found in his vagrant life.

But despite Nellie's cry, "Me love doggie," the rake and hoe did valiant duty, and the intruder was driven away.

Just then Master Jamie came whistling along, returning from an errand for Aunt Betty.

"Here, boy," called the lady, "I'll give you ten cents if you'll only catch that horrid dog, and take him to the pound, or anywhere away from here. They'll give you thirty cents if you take him to the pound. He doesn't seem to belong to anybody, so you can earn your money, if you like, quickly."

Without much trouble, Jamie secured the dog, and lifted him in his arms, glad of the chance for making the promised sum. But before he had gone very far he found the dog so gentle and inclined to be so playful that he began to think it would be nice if he could only keep him all the time. It seemed such a pity that a nice dog like that should go to the pound. Jamie's warm little heart rebelled against anything so dreadful, and by the time he had reached his own street his mind was fully made up; and so the new pet had been hidden all this time, while Jamie had paid him many a stolen visit in his secluded home.

But at last it seemed impossible to keep the secret any longer from Aunt Betty, and this is why we found Jamie thinking so intently, and troubling himself with a question to him very serious.

For some moments after Jack had left him, Jamie thought over the matter, hesitating between the pound and Aunt Betty in regard to his favorite, until at last the dog, which Jamie had named Nep, reminded his master of his presence by poking his cold nose as far into Jamie's neck as possible, and laying his fore-paws gently upon his arm. The boy could not resist that, and in a moment he had squeezed Neppie's breath almost out of his body, and exclaimed, "I'll just keep you, you darling; you shall stay with me." Then bravely he walked into Aunt Betty's store, with the dog close at his heels, and made a full confession.

The old lady looked unusually prim and severe just at that moment, owing to an unprofitable customer, who had only littered the counter, and left no pennies behind. So it happened that Jamie had come at the wrong time with his request; but he didn't know it, you see, and he plunged into the business at once, and stammered through to the end, while Aunt Betty looked over her spectacles, and eyed him and the trembling dog severely.

"Keep that creetur? No, sir; not a bit of any such thing. Get him away from here this very instant. The idee—a dog in my shop! Massy sakes alive! Shoo, sir! shoo! Go out, dog, this minute."

An emphatic shake of her foot convinced poor Nep that the old lady was not the friend Jamie had been; and Jamie himself, with a sorrowful face, took his abused treasure back to the old box.

"I'll have to take yer to the pound to-morrer, old fellow," he whispered in Nep's ear, and went back to the store.

That night it rained hard, and the wind blew a gale; and little Jamie, remembering his captive pet, thought he would plead once more with Aunt Betty for the dog.

"Just this one night, auntie, please let him come in out of the wet, and to-morrow I'll take him to the pound, and give you the thirty cents."

Now Aunt Betty's heart wasn't all ice, by any means, and she did pity the poor animal out in the storm. So she finally consented that for this one time he could sleep inside, and she hoped never to see him again.

Then Nep was called in, and told to lie under the table; and as Jamie soon after lighted his little lamp and went to bed, the old lady closed her shop window, and sat down to read the paper. Before she knew it, her tired eyes had closed, and she was in the land of Nod.

It was only a few moments, however, before she felt something tugging violently at her dress, and the sound of barking greeted her ears as she opened her eyes. The lamp had burned low down, but by its dull glow she discovered that it was the dog that had awakened her, and that he was then doing his best to squeeze his body between the floor and a low-seated lounge near the fire-place. Then Aunt Betty saw a slender tongue of flame and smoke creep from under the sofa, and knowing that she had put one or two old papers behind there the day before, she sprang up with a cry to Jamie, and drawing the sofa out, placed her foot upon the blazing papers.

Then the terrified Jamie remembered that after he had lighted his lamp he had tossed the still burning match into the empty grate, as he supposed, but instead of that it must have fallen behind the sofa, with the result as above. It had taken some time for the flame to fairly burn; but Aunt Betty and Jamie would have fared badly, I'm afraid, if it had not been for the faithfulness and watchfulness of the good little dog that had aroused Aunt Betty's ire so greatly only that afternoon. It was very careless of Jamie, and a lesson to him, but it brought one good result for him, after all, for Nep didn't go to the pound the next day, nor any day, in fact. And as Aunt Betty said the other morning, while feeding Jamie's pet with her own hands, "For all she couldn't abide dogs and sich, yet there was sich things as being onreasonable, and that she never would be, not if she knew it."

"It's going to rain, you dear little bird:

Fly into your house; don't stop for a word."

"Yes, I saw a black cloud as I sat on the tree,

But I care not for rain—I have feathers, you see."

"You have feathers, I know, but your little pink feet

Will be numb with the cold when the cruel rains beat."

"Oh no; I shall tuck them up snugly and warm,

Close under my body, all safe from the storm."

"But the branches will rock, and the dark night will come:

Oh, do, little bird, fly away to your home!"

"Never fear, pretty one, as I rock I shall sing,

And how soundly I'll sleep with my head 'neath my wing!"

"Oh, birdie, dear birdie, I'd like much to know

How you're always so happy, blow high or blow low."

"Don't you know we've a Father who cares for me?

And that is the reason I'm happy and free."

"Well, miss, how can I serve you?"

Mr. Searle, the grocer of Nunsford, spoke rather sharply, bending over his counter in the twilight, and looking half contemptuously upon his customer.

She was a tall girl of fifteen, rather old-looking for her years, but with a face so evidently designed by Nature for blooming color, dimples, and good-humor, that its lines of care and want were peculiarly painful.

"Well, miss," repeated the grocer, as his customer hesitated.

"I should like a few things, Mr. Searle," said the young girl, speaking in a decidedly un-English although sweet, clear voice, "but I must tell you first it will have to be on credit—for just a little longer. I am sure we shall soon be able to pay you."

Mr. Searle's face was puckered into doubtful lines by this request. "Well, it's three weeks now," he said, slowly. "It's not usual, miss—"

"I know—I know," said the girl, eagerly, and looking at him with such a strained, wistful expression that Searle's heart melted. "I know, and I shall very soon have something—"

"Well, then, we'll let it go," said Searle, with real good-humor; and he busied himself supplying his customer's modest wants—half a pound of tea, a pound of sugar, some dried herrings, and a few candles.

"There," he said, placing the parcels in her hands. "I hope your mother is better, miss," he added, kindly.

The girl's eyes were full of sudden tears. "A little, thank you, Mr. Searle," she said; and then, holding her small parcels carefully, she hurried away, disappearing in the wintry dusk, while Mr. Searle called out to his wife:

"That's the American young lady again. Hanged if I can understand it. They're high-born, I'm sure; but wot's keeping them starving here in Nunsford is wot I can't tell."

"And you've give more credit?" said the sharp voice of his wife, as that lady's thin figure appeared in the doorway of the shop parlor. "Well, Searle, you are easy took in."

"Never mind, Sairey," answered Searle. "I couldn't look at that child's white face, and let her go 'ungry."

Mrs. Searle slammed the parlor door expressively, while her husband turned to watch the arrival of some more distinguished customers.

Meanwhile the American girl was hurrying on in the wintry twilight down the High Street of the quaint old town, where the lamps were just beginning to be lighted, and where many people, hastening homeward with that expectant look that seems to mean a cheerful fireside and cozy supper, made the young girl think sadly of her own desolation. Nora Mayne had a stout little heart: she was accustomed to trying to feel brave, to forcing herself to think cheerfully both of the present and the future, but I am afraid that just then it seemed rather hard work. She and her mother were almost at the end of their resources, friendless and alone in a strange English town.

As she went along, slackening her pace a little as she passed the dear old Abbey Church, Nora thought over the last year, deciding in her own mind that it had been a great mistake to try their fortunes in England. Just a year before, Mr. Mayne's death left his widow and child with a few hundred dollars, and almost no friends, in a Connecticut village. Mr. Mayne had been a visionary man. Nora remembered brief periods of luxury, followed by want and loneliness. Her life had been a wandering one, for Mr. Mayne rarely staid long in any one place; and the girl was early accustomed to leading a lonely life among her books, not caring to make friends she might leave on the morrow. At her father's death Nora and her mother had come to England, hoping to find employment among some of the widow's early friends. Mrs. Mayne's girlhood had been spent in England—a bright, luxurious period, of which Nora never tired of hearing; but death, and the long silence of years, had scattered all traces of that happy past. The associations of twenty years before seemed to have vanished as though the whole story had been a dream. Months passed in London and in the little town of Nunsford, which Mrs. Mayne remembered in that happy "long ago," and now mother and daughter were living from week to week, no longer hopeful, only waiting for some chance to take them home again. Meanwhile illness had been added to their trials; Nora had the new misery of seeing her mother suffer while she vainly searched for some employment. Day after day she returned to their humble lodging tired and disappointed; yet even on this evening, feeling it so difficult to face the future with any hope, there lurked somewhere in the dim corner of her heart a confidence in "to-morrow."

Nora only allowed herself to linger a moment by the old church. It was her favorite haunt; the gray walls, the bit of cloister, the solemn pathway with its tombs and archway of leafless trees—how she loved it all! It was so like the pictures she had seen of England—so peaceful, when her heart was full of anxieties, so bright on the winter mornings, with sunshine among the fir-trees and the ivied door outside, and a flood of light from the old stained-glass windows within! Nora had learned to know every nook and corner near the old abbey; and how great was her delight the day she found a short-cut from the High Street, past the grayest wall, the end of the grammar school with its quaint bit of thatched roof, and around by the beautiful brick-walled Deanery garden.

That Deanery garden was another source of comfort to little Nora. She fancied all manner of stories connected with it. She knew that once the house had been a monastery, and, later, a famous manor, and now it looked as if it might contain any romance, however picturesque or poetic.

It was a beautiful old house, with many turrets and gabled ends. It stood in the midst of a garden that even in winter-time seemed to have a bloom of its own. There are many winter flowers in Devonshire. These colored the Deanery garden faintly, and filled the girl's heart with pleasure as she caught glimpses of them on her lonely walks. Sometimes the garden gate stood open; often in passing, Nora saw the Dean's daughters with their governess going in or out. Once as she stood in the morning sunshine that fell warmly on the brick wall, Nora had[Pg 668] seen an invalid lady carried out to a Bath-chair, followed by a tall servant in livery and a pretty, slim young girl. The lady had a beautiful face framed in white hair; she flashed a look on Nora in her shabby gown standing in the cruel sunlight—a wistful, pathetic little figure, with something worth remembering in her eager eyes. The young lady at her side was drawing on a long glove, and Nora saw the sparkle of her pretty rings. In spite of the lady's wan face, it all suggested comfort, and prosperity,' sunshine, warmth; the green things of life seemed to little Nora to be shut in, and to come out of that quaint old garden. She stood still, fancying herself unseen, as the lady was placed in the Bath-chair, her young companion arranging her fur wraps comfortably.

"Thanks, dear," the lady said, in a sweet low voice. Then she glanced back at some one within the Deanery garden. "Penelope is with me," she said, smiling.

"That is her name, then," thought the little watcher, sighing, as the Bath-chair was wheeled away. "And what a lovely face! what a sweet way she had with the poor lady! Oh, but it is easy to take care of sick people who have plenty of money!" cried the poor child to herself, thinking of her mother in need at home.

But Nora never saw "Penelope" again. She watched often, wondering if the pretty young figure would not appear in the garden or out of the old wall door. Gradually she began to think of her as a "story-book" girl—some one to build up a romance about, while her own life was dragging on with such bitter anxieties.

Nora's destination was not very far from the Deanery. It was an old-fashioned Berlin wool shop, the upper floors of which were let in lodgings. She passed the shop window quickly, and entering by a side door, hurried up the old oak staircases to a room on the top floor. A fire was burning low, faintly illuminating the dreary room, with its stiff furniture and inartistic decoration. Mrs. Mayne was pillowed in an easy-chair before the fire.

"Here I am, mamma," said Nora, cheerfully; "and now you shall have a good cup of tea."

Mrs. Mayne answered with a faint smile; but it pleased her to watch her daughter's lithe figure moving quickly about, as she stirred the fire into a brighter blaze, made the tea, and wheeled a little table into the glow. Nora's languid looks were always reserved for the moments she was by herself. She kept up a cheerful flow of conversation while the kettle boiled, and she prepared a second cup of tea, and toasted a fresh round of bread to tempt her mother's appetite.

A sharp little knock sounded on the door.

"That is Mrs. Bruce," exclaimed Nora, bending over her mother's chair, as the door opened on the fat, good-humored-looking figure of their landlady.

MRS. BRUCE ASKS A FAVOR.—Drawn by E. A. Abbey.

MRS. BRUCE ASKS A FAVOR.—Drawn by E. A. Abbey.

"I beg your pardon, 'm," said Mrs. Bruce, standing still, with folded arms, "but could miss do me a favor?"

"Certainly," exclaimed Nora.

"Then would you mind stopping harf an hour in the shop for me? I must go hout, and there ain't a soul to leave in it. There won't be a many coming in at this hour. If you'll come down with me, I'll give you a hidea of some of the prices, though most of the things is marked."

Nora eagerly assented, and leaving the candle and a book near her mother, she followed Mrs. Bruce down the staircases to the Berlin wool shop, which was comfortably warmed and lighted. A broad window full of gay wares fronted the street. Within were the usual contents of such a shop—Berlin wools, fancy-work, patterns, and the like. Nothing out of the common, but for Nora Mayne the shop always possessed a curious fascination.

Union Grove, Wisconsin.

In one of the April numbers of Young People I noticed an article entitled, "How to Build a Catamaran." It reminded me of the catamarans I used to see on the surf at Madras, and I thought the boys would like to hear something about them. The name catamaran is taken from two Tamil words, meaning literally "tied trees." Along the coast of South India and Ceylon hundreds of catamarans may be seen dancing up and down the sparkling surf. They are made of three or four mango logs fastened together securely with ropes made from the palmyra-tree. Sitting on deck as our ice-ship, the Robert, approached Madras, it looked as if there were a great many dark figures standing on the water. The boats were invisible, and only the figures seemed coming closer, until they drew so near that we could see under the water the logs on which the fishermen were standing. Every man had a long pole in his hand, with which he guided his curious craft. The fishermen were nearly naked, so that getting wet did not trouble them very much. The hot Indian sun poured down on their heads, but they did not seem to mind it.

Often when sitting on the veranda of our sea bungalow in Ceylon, looking over the blue waves of the Bay of Bengal, we would see the fishermen wade out from the shore, dragging their catamarans until they reached deep water, when, gracefully skipping on, off they would go, paddling skillfully over the white caps of the surf, till they almost disappeared in the blue distance. After a while they would come safely back, balancing their rudderless barks carefully till they were beached on the sand. Then they would go to the bazar or market with the fish they had caught, the long pole resting on their black shoulders. Probably the readers of Young People would not enjoy a sail on a catamaran in India, but the little Hindoo boys enjoy it very much, and are expert and daring in the management of their boats.

There is another queer craft, called a "dhomy," of which you may hear at another time.

Émile de R.

Ottawa, Kansas.

We have a very kind cousin who sends Young People to my little sister. During the days of "Toby Tyler" one of our intimate friends came up every Thursday to read the story with us. One of us would read aloud, pausing now and then to wipe away the tears which would come. Every morning when papa went down town my little three-year-old sister would say, "Don't forget to bring 'Toby' to-night." I am very glad Mr. Otis is writing another story.

We used to have a hen which we called Speck. In one of her broods was a white chick, whose name was Minnie. When Minnie was half grown, Speck had some more little ones, which Minnie seemed to think were as much hers as they were Speck's. Whenever she had anything to eat she called them to share it, and really took as good care of them as Speck did. While Speck was sitting on the eggs, Minnie would get on the nest behind her. One day papa went out to the chicken-coop, and Speck with her brood was on one of the nests, covering as many chicks as she could with one wing, while little Miss Minnie on the other side was covering as many as she could with her wing.

The other day some little swallows fell down through the chimney into the fire-place in mamma's room. They were too young to fly, so we put them in a basket, and hung it on a tree. The mother bird heard their cries, and came and fed them, but in two days the poor things died.

It has been warmer here lately than ever before in Kansas.

Evelyn.

Luzerne, Warren County, New York.

Although I wrote once before, and my letter was not published, I will try again; for I know the Editor must be very busy if he reads all the letters the young people send to Our Post-office Box. I enjoy all the stories very much. "Mildred's Bargain" was excellent.

An Indian was here lately who had three rattle-snakes. He got them from Lake George, and was trying to tame them, but one of them bit him. To cure him they had to give the poor man liquor to drink till he was intoxicated.

Belle N.

Willimantic, Connecticut.

I must tell you about my poor pet kitty. She was black and white, and I thought her splendid, but she was run over by a train, and there were some very sober faces here that day, you may be sure. I have a dog now. His name is Prince, and as he does not like kittens, we have to get along without any. He is eight years old. We have had him about a year.

My brother George is six years old, and I am nine, and we both take great comfort in reading Young People.

Mary W. H.

We are very sorry so dreadful a fate befell your little kitty. If Prince were younger, you might teach him to be friendly with Madam Puss and her kits; but as he is eight years old, which is a quite dignified and "settled" age for a dog, you will have to let him keep his opinions. A kind, intelligent dog is, we think, as satisfactory a pet as a cat.

Edna, Minnesota.

I have been meaning for a long time to write to Young People, and thank the young friend who sends me the paper. I enjoy reading it very much, as I do all other good reading matter. I am driving three horses on a sulky plough. I have broken thirty acres of prairie this summer. I have to strap myself to the seat, as I have no legs to steady me. I like this work, and am very sorry the season is so nearly over.

Elmer P. Blancherd.

The tragic fate of a family of bantams is touchingly told in these rhymes by a little correspondent:

Nine little bantams were pecking at the shell;

One got free too soon, and fell down the well.

Eight little bantams nestled close at night;

A weasel snatched one, and fled out of sight.

Seven little bantams wandered in the lane;

A hawk pounced on one; it ne'er was seen again.

Six little bantams were eating crumbs of bread;

A greedy bantam took too much, and fell down dead.

Five little bantams were playing in the barn;

The horse stepped on one of them, but did the rest no harm.

Four little bantams watched the ducks swim;

One tumbled over the pond's grassy rim.

Three little bantams were in their mother's care;

A rooster pecked one, and then were left a pair.

Two little bantams trod the world together;

Cook killed one of them, and pulled out every feather.

One little bantam, brave in colors rare,

Won the very highest prize at the county fair.

L. G. R., Louisville, Ky.

Chelsea, Massachusetts.

I would like to tell the readers of Young People about a pretty pair of white mice which my father gave me. About a month ago, when I went to feed them, I found a very cunning little one in the nest. He has grown to be almost as large as the big ones. Last Friday I was away all day, and when I came home I went to play with my pets, when I found five more little ones.

The next evening I heard a noise in the kitchen, and when I went to see what it was, I saw my cat with the poor little mother mouse in her mouth. When she saw me coming she started to run, but I caught her by the tail, and got it away from her. Alas! it only lived a few seconds. Oh! I felt dreadfully.

I tried to feed the little ones, but they were so young they could not eat, and they grew so weak that my mother said it would be a mercy to drown them. I felt very sad about this, but I put them in a box, and that in a pail of water, and they were soon out of their misery. I buried them in my garden, under my plum-tree. I have only two left.

My father would not allow me to punish the cat, because he said it was her nature. I have, besides my mice, two cats and a canary. My brother has three rabbits. He has gone this afternoon to get me a turtle.

L. B. G.

Bay Ridge, Long Island.

We have two dogs, and we call them Tip and Becky. We have a Polly, and she is sick. I had a paroquet, but a cruel dog killed it. This is my first letter to any paper, although I am twelve years old.

Jennie B. F.

Newark, New Jersey.

I am a little boy ten years old. I have taken the Young People only three weeks, and I like it very much. "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" is splendid. I liked it so well that I borrowed the back numbers, and read it all through. I am very sorry that the President was shot, and I want to tell you that he does not forget the boys and girls. I wrote him a letter telling him I was very glad that he was elected, and he in return sent me a handsome photograph of himself. I think all the more of it now, and if he should die, money could not buy it.

Milton W. D.

Verona, Italy.

When I was in Milan I went to the National Exposition, and there I saw how silk was made from the very beginning—a thing which interested me very much. The silk-worm was feeding upon the leaves of the mulberry-tree. Afterward it wound about itself an oval ball of silk, which is called a cocoon. The cocoon was then put into boiling water to kill the worm and find the end of the silk, which was wound off by machinery in large skeins. The natural colors of the cocoons are white, buff, and yellowish-green. The skeins are dyed to make the other colors of silk used. Some of the cocoons were saved until the worm changed into the butterfly, and then the butterfly was put into a lace bag to lay its eggs, which next spring will produce more silk-worms.

I saw ribbons of different colors of silk being made; also saw the manufacture of satins and velvets. All the women and girls who were working at the machines wore the same kind of head-dress; it was composed of silver pins, fastened at the back of the head, and standing out like a fan.

In the evening I went to the Gallery of Victor Emanuel, which is a favorite place for those who wish to promenade. It is several blocks long, and in the shape of a cross, with stores on all sides, and the buildings quite high. Over all is an arched roof of glass, which at night is brilliantly lighted by gas, making it look very pretty. I watched the way they lighted up the dome: a man wound up a little locomotive, which went round on a track with a lighted torch, and in a few minutes the gallery was as bright as day.

Alberto D. W.

Chardon, Ohio.

Young People is given me by my good grandpa. I gave him a pocket-knife which I found. I was five years old in April, and can not yet read, though I know all my letters, can make every one of them with a pencil, and can spell my name.

Both papa and mamma were formerly teachers. They and grandpa read the pretty stories aloud, and I look at the pictures.

My little sister, nearly two years old, has black eyes and curly hair. We play together, feed the chickens, make mud pies, and swing under the apple-tree. We have a steady horse named Betty, and a frisky two-year-old colt; two pussies, Tabby and Topsy; and Topsy has two kitties. Grandpa wants to go to New York, and get acquainted with Harper & Brothers.

Bessie H.

Orphans' Home, Rochester, Beaver County, Penn.

My uncle began sending me your paper last fall, and I like it very much. I am an orphan, and live at the Home in this place. It is a beautiful house, situated on a hill from which we have a very extensive view, seeing ten miles up and down the Ohio River. Last week we had examination in our school, and now we have vacation for two months. We have a large play-ground, several games of croquet, and a swing. I like "Paul Grayson," "Toby Tyler," "Mildred's Bargain," and "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" best of all your stories. I was thirteen years old the 19th of March last. Can you or any of the readers of Young People inform me how many cities in Egypt spoke the language of Canaan?

Luella M. H.

The language of Canaan was substantially the same as Hebrew. In this sense it was spoken in no Egyptian city. The Phœnician language spoken in Carthage was closely allied to the Hebrew. The Egyptian language itself shows a similar resemblance both to the Phœnician and Hebrew.

Detroit, Michigan.

I am deeply interested in the Young People, and think it is not only a paper from which much pleasure may be derived, but also one from which we can learn a great deal. I do not suppose this will find its way to the Post-office Box, but I shall feel much gratification if it does. I am thirteen years old. I have eight pretty rabbits, which are very cute.

Frank L. W. B.

Victoria, Texas.

If Mrs. Alice Richardson would like some numbers of Young People, she is welcome to some of mine. Jimmy Brown writes funny stories. I like "Toby Tyler," "Mildred's Bargain," "Susie Kingman's Decision," and "Aunt Ruth's Temptation" best of all. I would like to tell the little readers something about our birds. There is a mocking-bird that builds in our honeysuckle every spring. The dear little humming-bird sips the honey of our flowers.

Sadie E. S.

Germantown, New York.

I am twelve years old, and this is my first letter to the Post-office Box. I think "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" is splendid. My cousins were down from Albany, and we camped out for three or four days. We went fishing, and set our lines one night, and we caught an eel two and one-half feet long. Papa made me a present of a new set of harness. He lets me drive one of our horses, because it is gentle.

E. C. R.

Burlington, Kansas.

I live on a farm. My papa has a sheep ranch. I have a little brother six years old. I am ten myself. I have a pony, and a pet bird that will fight with me. When he wants to fight, he chirps to let me know. It is quite warm here now, with little rain. I think Judith W.'s letter was splendid.

Gracie May B.

Brooklyn, New York.

I have a little silver-fish for one of my pets, and every morning when I change the water I give him a fly. He has become so tame that he will take it out of my fingers, and as the fall is coming, I don't know what I shall feed him with. Will you please tell me what I can give him?

I think the Jimmy Brown stories are splendid. Papa asks me every Tuesday if there is anything by Jimmy, and if there is, he reads it aloud to us.

I am glad that Mr. Otis has written another story for Young People. His stories are so natural, and so very interesting![Pg 671] Can you tell me where Swaffham is? I think it must be in some of the British Possessions, for the postmark is on an English stamp. If you will please answer my questions, I shall be very much obliged.

Mamie E. F.

A prepared fish food is sold at the bird stores. We have given it to gold and silver fish, and they like it. Swaffham is a town of England, in Norfolk. It is situated on a height, and is one of the best-built towns in the county.

Plymouth, New Hampshire.

I am a boy eleven and a half years old, and the son of a Methodist minister. We have a beautiful home at the foot of the White Mountains, on the banks of the Pemigewasset River, about one hundred miles south of Mount Washington, and over one hundred miles north of Boston. I am collecting curiosities. I have already nice specimens of zinc, lead, amethyst, beryl, gypsum, agate, etc., among the minerals, also arrow-head, ivory-nut, Florida moss, etc. I hail the coming of your paper with delight, and long for Tuesday to arrive and bring it.

Fred S. K.

Abilene, Taylor County, Texas.

I am a little girl nine years old, and I live out on the Texas and Pacific Railroad, sixty-five miles from Fort Concha. I often find very lovely butterflies, white with brown-streaked wings. We see beautiful antelopes when we are out riding. Mamma has a phaeton, and a gentle horse called Frank. Josie and Earle (my two baby brothers) and I take long drives with mamma. There are many tarantulas here, resembling large hairy spiders. I have killed several. We sometimes see whole families of prairie-dogs—papa, mamma, and the little ones—on top of the hill, beside their holes, as we pass, and they bark loudly till we are close to them, when they wag their tails, and scamper off into their hiding-places.

We had to go out and fight prairie fire the other day. It came within a dozen rods of our home. We beat it out with coffee sacks.

I wish to exchange Texas moss, soil, and stones, for shells.

Hattie W. McElroy.

Agnes S.—If you have no acquaintances living near any of the historical trees mentioned in the article in No. 83, you might write to the postmaster of the place nearest the tree from which you wish to obtain a leaf, and ask him if his little daughter or sister will kindly procure one for you. A polite note, inclosing a stamped envelope, addressed to yourself, for the reply, will probably receive attention. You must not try this plan, however, until you have inquired among your friends, and ascertained that none of them know anybody to whom they can apply.

C. Whitty.—The specimen you inclosed in your note was sulphate of copper, commonly known as vitriol.

Student.—Short-hand.—Graham's Hand-Book of Standard Phonography is an excellent guide to the art of rapid writing. If you study hard, and follow the ample directions of Mr. Graham, taking every opportunity to practice "short-hand" reporting, you will become an adept. You can order this book through any bookseller, but Mr. Graham has an office at the Bible House, Fourth Avenue, New York.

Aurora J. M. C.—The authors of whom you inquire are not related.

"North Star."—The President of the L. A. W. is Mr. Charles E. Pratt, 597 Washington Street, Boston, Massachusetts. The badge of the League can only be procured by members.

J. Wilmer Cox.—A 36-inch bicycle will be large enough for you. You had better get a bicycle known as the "Mustang."

John M. Faglon, 25 Columbia Street, Brooklyn, New York, changes his offer for a bicycle from 36 to 40 inches to 42 to 46 inches.

Harry R. H.—Fiske & Co., 98 Fulton Street, or Ben Day, 48 Beekman Street, New York city, will give you the necessary information.

Willie and James Dudley withdraw from our exchange list.

Miss Mary T., W. F., and Others.—The address of Miss Judith Wolff is care of Mr. D. A. De Lima, 68 William Street, New York city.

Washington.—The site of our national capital was selected by General Washington, after whom it was named, and he laid out its general plan. It seemed desirable that the capital of the entire country should not be located in any State, and therefore the District of Columbia was set apart for the purpose of holding it. Your history will tell you that the District is formed of a portion of territory ceded by Maryland and Virginia. The situation was a very convenient one at the time the site of Washington was selected, and it still seems wisely chosen for many reasons, though in the summer season it is subject to malarial influences.

Miss J. F. B.—The answer to the Geographical Puzzle in No. 85 appeared in No. 88.

L. G. R. wishes to beg D. Van Buren's pardon for having sent the wrong stamps. She has just begun collecting stamps, and supposed those she sent were official. She discovered her mistake after having sent her letter. She will try to procure some real official stamps, and will send them if successful.

Leola C. Carter's address is changed from Ashland, Nebraska, to Rosebud Agency, Dakota Territory.

The following is a list of donations received previous to August 4 for the Young People's Cot in St. Mary's Free Hospital for Children, 407 West Thirty-fourth Street, New York city. The next list will be published October 4.