Title: Mademoiselle de Maupin, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Théophile Gautier

Illustrator: François-Xavier Le Sueur

Édouard Toudouze

Translator: I. G. Burnham

Release date: May 8, 2015 [eBook #48894]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Laura Natal & Marc D’Hooghe

Chapter XII — Her supple, yielding body shaped itself to mine like wax and took its whole exterior outline as exactly as possible:—water would not have found its way more scrupulously into every irregularity in the line.—Thus glued to my side, she produced the effect of the double stroke that painters give to the shadow side of their picture in laying on their color.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

MADEMOISELLE DE MAUPIN — VOLUME II

IN THE RUSTIC CABIN Fronts.

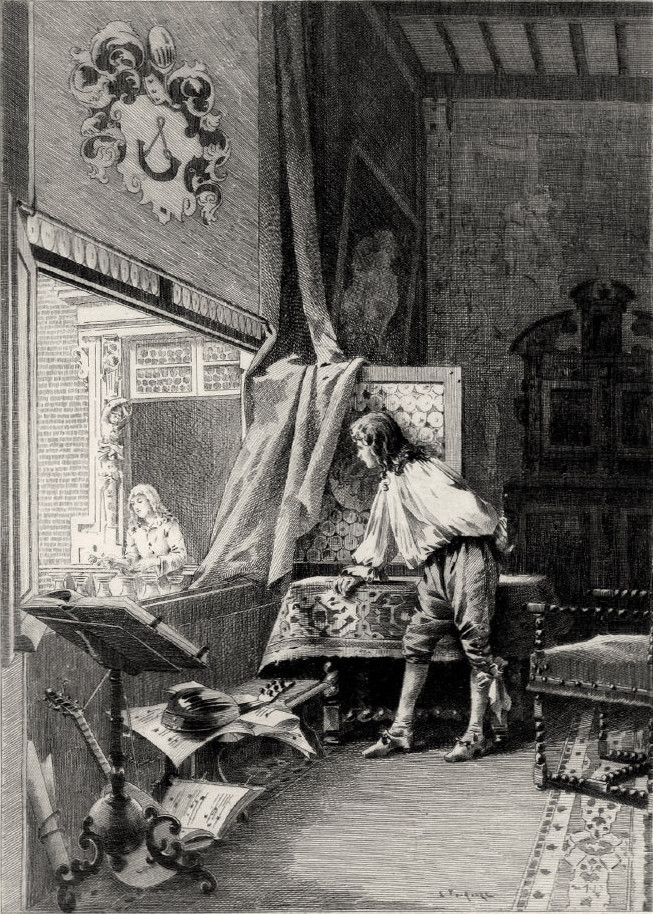

D'ALBERT WATCHES THÉODORE

AT THE HOTEL DU LION-ROUGE

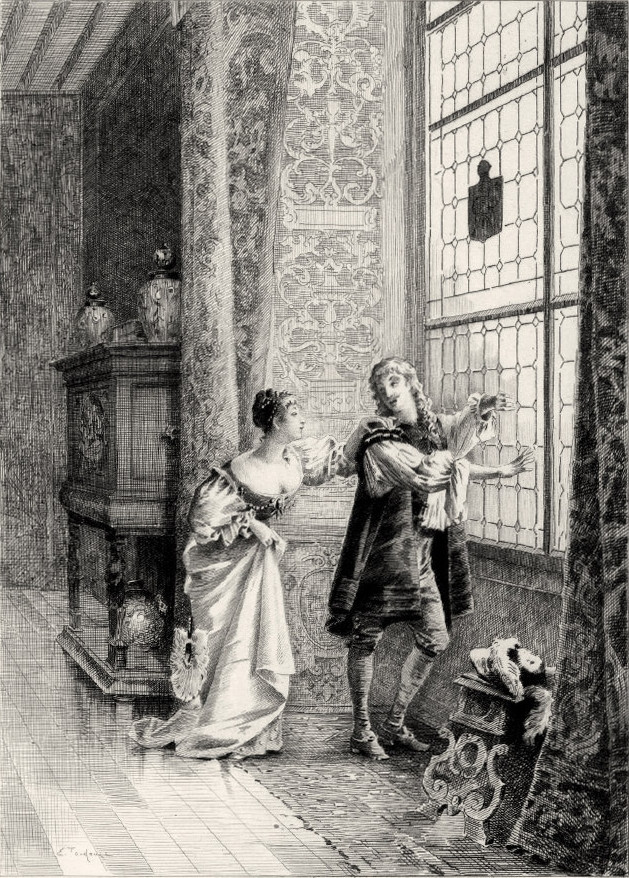

BEFORE THE REHEARSAL

AN EMBARRASSING SITUATION

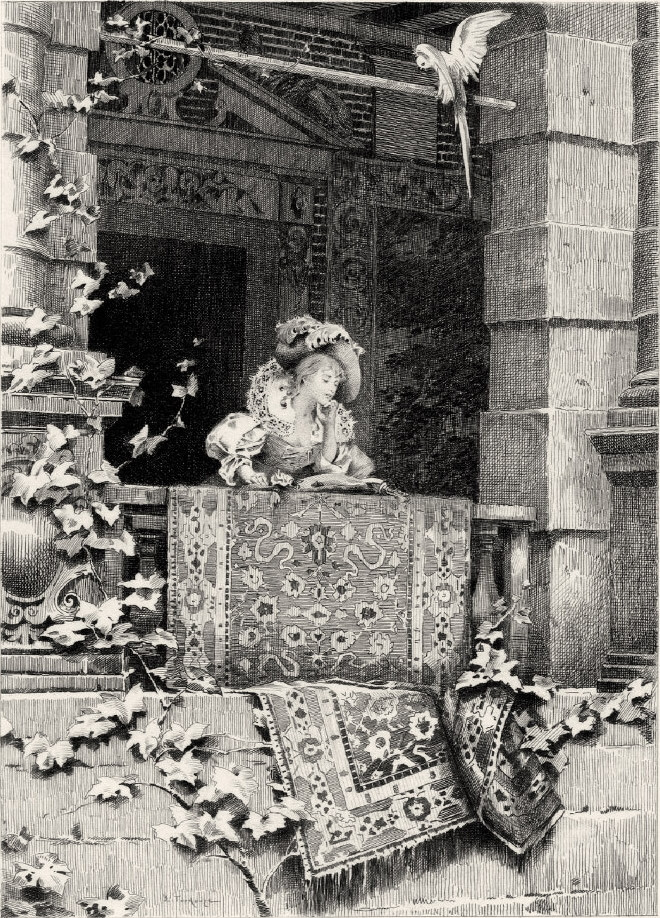

AT THE WINDOW OF THE CHATEAU

THE DUEL

ARRIVAL IN THE TOWN OF C——

D'ALBERT'S SURPRISE

THE REALIZATION

That is the fact.—I love a man, Silvio.—I tried for a long while to deceive myself; I gave a different name to the sentiment I felt, I clothed it in the guise of pure, disinterested friendship; I believed that it was nothing more than the admiration I have for all beautiful persons and all beautiful things; I walked for several days through the deceitful, laughing paths that wander about every new-born passion; but I realize now in what a deep and terrible slough I have become involved. There is no way of concealing the truth from myself longer; I have examined myself carefully, I have coolly considered all the circumstances; I have gone to the bottom of the most trivial details; I have searched every corner of my heart with the assurance due to the habit of studying one's self; I blush to think it and to write it; but the fact, alas! is only too certain.—I love this young man, not with the affection of a friend, but with love;—yes, with love.

You, whom I have loved so dearly, Silvio, my dear, my only friend and companion, have never made me feel anything of the sort, and yet, if there ever was under heaven a close, warm friendship, if ever two hearts, although utterly different, understood each other perfectly, ours was that friendship and ours those two hearts. How many swiftly-flying hours have we passed together! what endless conversations, always too soon ended! how many things we have said to each other that no one ever said before!—We had, each in the other's heart, the window that Momus would have opened in man's side. How proud I was to be your friend, although younger than you—I so foolish, you so sensible!

My feeling for this young man is really incredible; no woman ever disturbed my peace of mind so strangely. The sound of his clear, silvery voice acts upon my nerves and excites me in a most peculiar way; my soul hangs upon his lips, like a bee upon a flower, to drink the honey of his words.—I cannot brush against him as we pass without shivering from head to foot, and in the evening, when the time comes to say good-night and he gives me his soft, satiny hand, my whole life rushes to the place he has touched and I can feel the pressure of his fingers an hour after.

This morning I looked at him for a long while without his seeing me.—I was hidden behind my curtain.—He was at his window which is exactly opposite mine.—This part of the chateau was built toward the close of the reign of Henri IV.; it is half of brick, half of unhewn stone, according to the custom of the time; the window is long and narrow, with stone lintel and a stone balcony.—Théodore—for you have already guessed of course that he is the young man in question—was leaning in a melancholy attitude on the rail, and seemed to be deep in meditation.—Draperies of red damask with large flowers, half drawn aside, fell in broad folds behind him and served as a background.—How beautiful he was, and what a marvellous effect his dark, sallow face produced against the dark red! Two great bunches of hair, black and glossy, like the grape clusters of Erigone of old, fell gracefully along his cheeks and made a charming frame for the pure and delicate oval of his beautiful face. His round, plump neck was entirely bare and he wore a sort of dressing-gown with flowing sleeves not unlike a woman's robe. He held in his hand a yellow tulip, at which he plucked pitilessly in his reverie, throwing the pieces to the wind.

Chapter IX — This morning I looked at him for a long while without his seeing me.—I was hidden behind my curtain.—He was at his window which is exactly opposite mine.—***Théodore—for you have already guessed of course that he is the young man in question—was leaning in a melancholy attitude on the rail, and seemed to be deep in meditation.

One of the shafts of light that the sun projected on the wall cast its reflection on the window, and the picture took on a warm golden tone that the most chatoyant of Giorgione's canvases might have envied.

With that long hair waving gently in the wind, that marble neck thus uncovered, that ample robe enveloping the form, those lovely hands protruding from the sleeves like the pistils of a flower peeping from among their petals, he seemed not the handsomest of men but the loveliest of women,—and I said to myself in my heart: "He is a woman, oh! he is a woman!"—Then I suddenly remembered an absurd thing I wrote to you long ago, you know, about my ideal and the way in which I was surely destined to meet her; the beautiful dame in the Louis XIII. park, the red and white chateau, the terrace, the avenues of old chestnuts and the interview at the window; I gave you all the details before.—And there it was—what I saw was the exact realization of my dream.—There was the style of architecture, the effect of light, the type of beauty, the coloring and the character I had longed for;—nothing was lacking, except that the lady was a man;—but I confess that at that moment I had entirely forgotten that.

It must be that Théodore is a woman in disguise; it cannot be otherwise. His excessive beauty, excessive even for a woman, is not the beauty of a man, were he Antinous, the friend of Adrian, or Alexis, the friend of Virgil.—He is a woman, parbleu! and I am a fool to have tormented myself so. In that way everything is explained as naturally as possible, and I am not such a monster as I thought.

Does God put such long, dark, silky fringes upon a man's coarse eyelids? Would he tinge our vile, thick-lipped, hairy mouths with that bright, delicate carmine? Our bones, hewn with reaping-hooks and roughly jointed, do not deserve to be swathed in flesh so white and delicate; our battered skulls were not made to be bathed in waves of such lovely hair.

O beauty! we are made only to love thee and adore thee on our knees, if we have found thee—to seek thee incessantly throughout the world, if that happiness has not been vouchsafed us; but to possess thee, to be thou ourselves, is possible only for angels and women. Lovers, poets, painters and sculptors, we all seek to erect an altar to thee, the lover in his mistress, the poet in his song, the painter in his canvas, the sculptor in his marble; but the source of everlasting despair is the inability to give tangible form to the beauty one feels, and to be enveloped by a body which does not realize the idea of the body you understand to be yours.

I once saw a young man who had stolen the bodily form I ought to have had. The villain was just what I would have liked to be. He had the beauty of my ugliness, and beside him I looked like a rough drawing of him. He was of my height, but stronger and more slender; his figure resembled mine, but possessed a refinement and dignity that I have not. His eyes were of the same shade as mine, but they had a sparkle and an animation that mine will never have. His nose had been cast in the same mould as mine, but it seemed to have been retouched by the chisel of a skilful sculptor; the nostrils were more open and more passionate, the flat surfaces more sharply defined, and it had a heroic cast of which that respectable part of my countenance is entirely devoid. You would have said that nature had tried first to make that perfected myself in my person.—I seemed to be the blotted and unsightly rough draft of the thought of which he was the copy in fine type. When I saw him walk, stop, salute the ladies, sit down and lie down with the perfect grace that results from beautiful proportions, I was seized with such horrible melancholy and jealousy as the clay model must feel as it dries up and cracks in obscurity in a corner of the studio, while the haughty marble statue, which would not exist but for it, stands proudly erect on its carved pedestal and attracts the notice and the enthusiastic praise of visitors. For after all that rascal was simply myself cast a little more successfully and with less unruly bronze that worked itself more carefully into the hollow places of the mould.—I consider him very insolent to strut about thus with my form, and to play the braggart as if he were an original type; at the best, he is simply a plagiarist from me, for I was born before him, and except for me nature would never have had the idea of making him as he is.—When women lauded his good manners and the charms of his person, I had a most intense longing to rise and say to them: "Fools that you are, praise me directly, for this gentleman is myself, and it is a useless circumlocution to send him what comes back to me."—At other times my fingers itched to strangle him and to turn his soul out of that body that belonged to me, and I hovered about him with clenched fists and compressed lips, like a nobleman hovering around his palace, in which a family of beggars have taken up their abode during his absence, perplexed as to the best means of casting them out.—The young man is a stupid creature, by the way, and succeeds so much the better on that account.—And sometimes I envy him his stupidity more than his beauty.—The dictum of the Gospel as to the poor in spirit is not complete: they shall inherit the kingdom of Heaven; I know nothing about that, nor do I care; but there is no doubt that they inherit the kingdom of earth—they have money and fair women, that is to say, the only two desirable things in the world.—Do you know a man of spirit who is rich, or a youth of courage and of any sort of merit who has a passable mistress?—Although Théodore is very beautiful, I have never desired his beauty, and I prefer that he should have it, rather than I.

Those strange passions of which the elegies of the ancient poets are full, which used to surprise us so and which we could not conceive, are therefore possible, nay, probable. In the translations we made of them, we used to substitute names of women for the names we found. Juventius was changed to Juventia, Alexis became Ianthe. The comely youths became lovely maidens, and thus we reconstituted the unnatural seraglio of Catullus, Tibullus, Martial, and the gentle Virgil. It was a very gallant occupation, which proved simply how little we understood the genius of the ancients.

I am a man of the Homeric days;—the world in which I live is not mine, and I have no comprehension of the society that surrounds me. Christ did not come to earth for me; I am as great a pagan as Alcibiades and Phidias.—I have never been to Golgotha to pluck the passion-flowers, and the deep stream that flows from the side of the Crucified One and forms a red girdle around the world has not bathed me in its waves;—my rebellious body refuses to recognize the supremacy of the soul, and my flesh does not understand why it should be mortified.—To me the earth is as fair as heaven, and I think that the correction of physical form is virtue. Spiritual matters are not my forte, I like a statue better than a phantom and high noon better than twilight. Three things delight my soul: gold, marble, and purple,—brilliancy, solidity, color. My dreams are made of those, and all the palaces I build for my chimeras are constructed with those materials.—Sometimes I have other dreams—of long cavalcades of snow-white horses, without saddle or bridle, ridden by handsome, naked young men, who pass upon a band of deep blue as on the friezes of the Parthenon; or deputations of maidens crowned with fillets, with tunics with straight folds and ivory citterns, who seem to wind about an enormous vase.—There is never any mist or haze, anything indistinct or uncertain. My sky has no clouds, or, if it has any, they are solid clouds, carved with the sculptor's chisel, made from blocks of marble that have fallen from the statue of Jupiter. Mountains with sharply-outlined peaks rise abruptly along its edges, and the sun, leaning on one of the highest summits, opens wide its yellow lion's eye with the golden eyelids.—The grasshopper chirps and sings, and the corn bursts its sheath; the vanquished shadow, unable to withstand the heat, musters its platoons and takes refuge at the foot of the trees; everything is radiant and glowing and resplendent. The slightest detail acquires substance and becomes boldly accentuated; every object assumes robust shape and color. There is no place for the tameness and reverie of Christian art.—That world is mine.—The brooks in my landscapes fall in carved streams from a carved urn; between those tall, green reeds, as resonant as those of Eurotas, you see the gleam of the rounded, silvery hip of some naiad with sea-green hair. In yonder dark oak forest Diana passes, her quiver on her back, with her flying scarf and her buskins with interlaced bands. She is followed by her pack and her nymphs with the melodious names.—My pictures are painted in four tones like those of the primitive painters, and often they are only colored bas-reliefs; for I love to put my finger on what I have seen and to follow the curve of the contours into its deepest recesses; I consider everything from every point of view and walk around it with a light in my hand.—I have contemplated love in the old-fashioned light, as a bit of sculpture more or less perfect. How is the arm? Not bad.—The hands do not lack delicacy.—What think you of that foot? I think that the ankle has no nobility, and that the heel is commonplace. But the neck is well placed and well shaped, the curved lines are wavy enough, the shoulders are plump and well modelled.—The woman would make a passable model and several portions of her would bear to be cast.—Let us love her.

I have always been like this. For women I have the glance of a sculptor, not that of a lover. I have been anxious all my life about the shape of the decanter, never about the quality of its contents. If I had had Pandora's box in my hands, I believe I never should have opened it. I said just now that Christ did not come to earth for me; nor did Mary, the star of the modern Heaven, the gentle mother of the glorious Babe.

Often and long have I stood beneath the stone foliage of cathedrals, in the uncertain light from the stained-glass windows, at the hour when the organ moaned of itself, when an invisible finger was placed upon the keys and the wind blew through the pipes,—and I have buried my eyes deep in the pale azure of the Madonna's sorrowful eyes. I have followed piously the emaciated outline of her face, the faintly-marked arch of her eyebrows; I have admired her smooth, luminous forehead, her chastely transparent temples, her cheek bones tinged with a dark, maidenly flush, more delicate than the peach bloom; I have counted one by one the lovely golden lashes that cast their trembling shadow on her cheeks; I have distinguished, in the half-light in which she is bathed, the fleeting outlines of her slender, modestly bent neck; I have even, with audacious hand, raised the folds of her tunic and seen without a veil that virgin bosom, swollen with milk, that was never pressed by any save divine lips; I have followed the tiny blue veins in their most imperceptible ramifications, I have placed my finger upon them to force the celestial fluid to gush forth in white threads; I have brushed with my lips the bud of the mystic rose.

Ah well! I confess that all that immaterial beauty, so fleet-winged and so vaporous that one feels that it will soon take flight, made a very slight impression on me.—I like the Venus Anadyomene better, a thousand times better.—The antique eyes, turned up at the comers, the pure, sharply-cut lip, so amorous and so well adapted to be kissed, the full, low forehead, the hair, wavy as the sea, and knotted carelessly behind the head, the firm, lustrous shoulders, the back with its thousand charming sinuosities, the small, closely-united breasts, all the rounded, tense outlines, the broad hips, the delicate strength, the evident superhuman vigor in a body so adorably feminine, delight me and enchant me to a degree of which you, the Christian and the virtuous man, can form no idea.

Mary, despite the humble air that she affects, is much too haughty for me; the tip of her toes, swathed in white bands, hardly rests upon the globe, already turning blue in the distance, on which the ancient dragon writhes.—Her eyes are the loveliest on earth, but they are always looking up toward the sky or down at her feet; they never look you in the face,—they have never served as a mirror to a human form.—And then, I do not like the clouds of smiling cherubs who circle about her head in a light vapor. I am jealous of those tall virile angels, with floating hair and robes, who so amorously crowd about her in the pictures of the Assumption; the hands clasped together to support her, the wings fluttering to fan her, displease and annoy me. Those dandies of heaven, coquettish, over-bearing youngsters, in tunics of light and wigs of gold thread, with their beautiful blue and green feathers, seem to me too gallant by far, and if I were God, I would be careful how I gave my mistress such pages.

Venus comes forth from the sea to visit the world—as befits a divinity who loves men—alone and naked.—She prefers the earth to Olympus, and has more men than gods for lovers; she does not envelop herself in the languorous veils of mysticism; she stands, her dauphin behind her, her foot upon her shell of mother-of-pearl; the sun strikes upon her gleaming breast, and with her white hand, she holds in the air the wavy masses of her lovely hair, in which old father Ocean has scattered his most perfect pearls.—You can see her; she conceals nothing, for modesty was invented only for the ugly, it is a modern invention, the offspring of Christian contempt for form and matter.

O old world! all that thou didst revere is despised; thy idols are overthrown in the dust; emaciated anchorites, dressed in rags and tatters, bleeding martyrs, their shoulders torn by the tigers of thy circuses, have perched upon the pedestals of thy beautiful, charming gods;—Christ has enveloped the world in His shroud. Beauty must needs blush for itself and put on a winding-sheet.—Ye comely youths with your limbs rubbed in oil, who struggle in the lyceum or the gymnasium, under the brilliant sky, in the sunlight of Attica, before the marvelling crowd; ye maidens of Sparta who dance the bibase, and who run naked to the summit of Taygetus, resume your tunics and chlamydes;—your reign is past. And ye, moulders of marble, Prometheuses in bronze, break your chisels:—there will be no more sculptors.—The palpable world is dead. A dark, lugubrious thought alone fills the immense void.—Cleomenes is going to the weavers' shops to see what folds the cloth or linen takes.

Virginity, thou bitter weed, born in soil drenched with blood, whose blanched and sickly flower blossoms painfully in the damp shade of cloisters, beneath a cold shower of lustral water;—thou rose without perfume, bristling with thorns, thou hast replaced for us the lovely, joyous roses, bathed in spikenard and Falernian, of the dancing girls of Sybaris!

The ancient world knew naught of thee, unfruitful flower; thou didst never form a part of its wreaths whose perfume intoxicated;—in that lusty, healthy society thou wouldst have been disdainfully trodden under foot.—Virginity, mysticism, melancholy—three unknown words—three new diseases, brought to earth by Christ.—Ye pallid spectres, who inundate our world with your frozen tears, and who, with your elbows on a cloud and your hands on your breasts, can say nothing but "O death! O death!" ye could never have stepped foot upon that earth, peopled with indulgent, madcap gods!

I look upon woman, after the ancient fashion, as a beautiful slave destined to minister to our pleasures.—Christianity has not rehabilitated her in my eyes. To me she is still something dissimilar and inferior to us, whom we adore and with whom we toy, a plaything more intelligent than if it were made of ivory or gold, and having the power to pick itself up if it is dropped on the ground.—I have been told, because of that, that I have a low opinion of women; it seems to me, on the contrary, to show that I have a very high opinion of them.

Upon my word I cannot see why women are so eager to be looked upon as men.—I can understand that they might long to be boa-constrictors, lions or elephants, but that they should long to be men passes my comprehension. If I had been at the Council of Trent when this important question was discussed, namely, whether woman is a man, I should most certainly have given my opinion in the negative.

I have in the course of my life written some amorous verses, or at all events some that claimed to be so considered.—I have just read over a part of them. The modern idea of love is absolutely lacking.—If they were written in Latin distiches instead of in French rhymes, they might be taken for the work of a wretched poet of Augustus's time. And I am amazed that the women, for whom they were written, did not take serious offence at them instead of being charmed with them.—To be sure, women understand no more about poetry than cabbages and roses, which is very natural and simple, they being themselves poetry, or at least the best instruments of poetry: the flute does not hear or understand the tune that you play upon it.

In these poems I speak of nothing but golden or ebon locks, the miraculous fineness of the skin, the roundness of the arm, the small size of the feet and the refined shape of the hand, and they all end with an humble entreaty to the divinity to accord as speedily as possible the enjoyment of all those beautiful things.—In the finest passages, there is naught but garlands suspended at the door, showers of roses, incense, a succession of Catullian kisses, delicious, sleepless nights, quarrels with Aurora coupled with injunctions to the aforesaid Aurora to withdraw behind old Tithonus's saffron-colored curtains;—there is splendor without heat, resonance without vibration.—They are rhythmical, polished, written with sustained interest; but, through all the refinements and veils of expression, you can feel the sharp, stern voice of the master trying to assume a softer tone in speaking to the slave.—Not, as in the erotic poems written since the Christian era, does a heart ask another heart to love it, because it loves; there is no smiling, azure lake inviting a brook to plunge into its bosom that they may reflect together the stars of heaven; no pair of doves spreading their wings at the same time to fly to the same nest.

Cynthia, you are fair; make haste. Who knows if you will be alive to-morrow?—Your hair is blacker than the lustrous flesh of an Ethiopian maiden. Make haste; in a few years slender silvery threads will glide in among its dense masses;—these roses smell sweet to-day, to-morrow they will have the odor of death and will be only the dead bodies of roses.—Let us inhale your roses so long as they resemble your cheeks; let us kiss your cheeks so long as they resemble your roses.—When you are old, Cynthia, no one will care aught for you, not even the lictor's assistants if you should pay them, and you will run after me whom you repulse to-day. Wait until Saturn has furrowed with his nail that pure and gleaming brow, and you will see how your threshold, now so besieged, so implored, so covered with flowers and so wet with tears, will be avoided, accursed and covered with weeds and nettles.—Make haste, Cynthia; the smallest wrinkle may serve as a grave for the greatest love.

That brutal, imperious formula summarizes the ancient elegy; it constantly comes back to that; that is its main argument, the strongest, the Achilles of its arguments. After that it hasn't very much to say, and when it has promised a robe of byssus of two colors and a string of pearls of equal size, it is at the end of its tether.—It also includes almost all of what I find most conclusive under such circumstances.—I do not, however, always confine myself to this somewhat restricted programme, and I embroider my poor canvas with a few threads of silk of different colors, picked up here and there. But these threads are short or knotted together twenty times and do not cling firmly to the woof. I speak politely of love because I have read many beautiful things on the subject. Only an actor's talent is needed for that. With many women this external appearance is enough; the habit of writing and using the imagination prevents me from falling short in such matters, and every mind at all experienced, by applying itself to the task, can readily attain that result; but I do not feel a word of what I say, and I keep repeating, in an undertone, with the poet of old: "Cynthia, make haste."

I have often been accused of being a knave and a pretender.—No one on earth would like so well as I to speak freely and to empty his heart!—but as I have no idea or sentiment in common with the people about me,—as there would be a hurrah and a general hue and cry at the first true word I spoke, I have preferred to keep silent, or, if I speak, to give utterance only to idiotic remarks that are received everywhere and entitled to privilege of citizenship.—I should receive a warm welcome if I said to women such things as I have just written to you! I fancy that they wouldn't much relish my way of looking at things or the view I take of love.—As for the men, I cannot tell them to their faces that they are wrong not to walk on four legs; and in truth I have a more favorable opinion of them.—I have no desire to quarrel at every word. What difference does it make after all what I think or what I don't think? that I am sad when I seem cheerful, cheerful when I have an air of melancholy! No-body is inclined to cry out at me because I don't go about naked; may I not dress my face as well as my body? Why should a mask be more reprehensible than a pair of breeches, and a lie than a corset?

Alas! the earth revolves about the sun, roasted on one side, frozen on the other. There is a battle in which six hundred thousand men cut and slash at one another; it is the loveliest day imaginable; the flowers are coquettish beyond words and boldly throw open their gorgeous breasts even under the horses' feet. To-day a fabulous number of worthy deeds are done; it rains in torrents, there is snow and thunder and lightning and hail; one would say that the world was coming to an end. The benefactors of humanity are covered with mud up to their middle like dogs, unless they have a carriage. Creation mocks pitilessly at the creature and lets fly stinging sarcasms at every turn. Everybody is indifferent to everybody else, and everything lives or vegetates according to its own law. Whether I do this or that, whether I live or die, whether I suffer or enjoy, whether I dissemble or speak frankly, what matters it to the sun or the turnips or even to mankind? A wisp of straw fell on an ant and broke his third leg at the second joint; a rock fell upon a village and crushed it; I do not believe that one of those disasters brings more tears than the other to the golden eyes of the stars. You are my best friend, if that word is not as hollow as a bell; if I should die, it is perfectly certain that, however distressed you might be, you wouldn't go without your dinner even for two days, and that, notwithstanding that terrible catastrophe, you would continue to enjoy your game of backgammon.—Who of my friends, who of my mistresses will remember my names and baptismal names twenty years hence, and who would recognize me in the street, if I should pass by with a coat that was out at the elbows?—Oblivion and annihilation, that is the end of man.

I feel as utterly alone as possible, and all the threads that lead from me to external things and from them to me have broken one by one. There have been few instances where a man who has retained the power to judge his impulses has reached such a degree of brutishness. I resemble a decanter of liquor which has been left uncorked and from which the spirit has evaporated completely. The liquid has the same appearance and the same color; taste it, you will find it as insipid as water.

When I think of it I stand aghast at the rapidity of this decomposition; if this continues I must pickle myself or I shall inevitably rot, and the worms will attack me, as I no longer have a soul, and that alone marks the distinction between a body and a corpse.—Not more than a year ago I still had something human about me;—I moved about and sought enlightenment. I had one thought that I cherished more than all the rest, a sort of goal, an ideal; I longed to be loved, I dreamed the dreams common to youths of that age,—less vague, less chaste, to be sure, than those of ordinary young men, but contained nevertheless within reasonable bounds. Gradually all the incorporeal part of me became detached and faded away and naught remained at the bottom but a thick layer of coarse slime. The dream became a nightmare and the chimera a succubus;—the world of the soul closed its ivory doors in my face; I no longer understand anything except what I touch with my hands; I have dreams of stone; everything condenses and hardens about me, nothing wavers, nothing vacillates, there is no air or breath; matter weighs me down, takes possession of me, crushes me; I am like a pilgrim who should fall asleep on a summer's day with his feet in the water, and wake in winter with his legs caught and embedded in the ice. I no longer desire the love or friendship of any one; even glory, that resplendent halo that I so craved for my brow, no longer arouses the slightest desire in my mind. There is but one thing, alas! that stirs my pulses now, and that is the horrible desire that draws me toward Théodore.—This is the sum of all my moral notions. Whatever is physically beautiful is good, whatever is ugly is bad.—If I should see a lovely woman whom I knew to be the wickedest creature on earth, adulteress and poisoner, I confess that it would make no difference to me and would in no wise interfere with my taking delight in her, if I found the shape of her nose what it should be.

This is my idea of supreme happiness:—A large square building with no outside windows: a large court-yard, surrounded by a colonnade of white marble, a crystal fountain in the centre with a jet of quicksilver after the Arabian fashion, orange-trees and pomegranates in boxes, arranged alternately; overhead a deep blue sky and a bright yellow sun;—tall greyhounds with pointed muzzles would lie sleeping here and there; from time to time barefooted negroes with gold ringlets about their legs, and beautiful, slender white maid-servants, dressed in rich and fanciful costumes, would pass in and out under the arches, baskets on their arms or jugs on their heads. And I should be seated, silent and motionless, beneath a magnificent canopy, surrounded by piles of cushions, a great tame lion under my elbow, the bare breast of a young female slave under my foot by way of hassock, and smoking opium in a long jade pipe.

I cannot imagine paradise in any other form; and if God wills that I shall go there after my death, he will build me a little kiosk on that plan in the corner of some star.—Paradise as it is commonly described seems to me far too musical, and I confess in all humility that I am absolutely incapable of sitting through a sonata that should last only ten thousand years.

You see what my Eldorado is, my promised land; it is as good a dream as another; but it has this special peculiarity, that I never introduce any known face into it; that no one of my friends ever crossed the threshold of that imaginary palace; that no one of the women I have had has ever been seated beside me on the velvet cushions: I am always alone there in the midst of apparitions. I have never had an idea of loving all the female figures, all the lovely shades of young girls with which I people it; I have never fancied one of them in love with me.—In that seraglio of my fantasy, I have created no favorite sultana. There are negresses there, mulattresses, Jewesses with blue skin and red hair, Greeks and Circassians, Spaniards and Englishwomen; but they are to me simply symbols of coloring and feature, and I have them as one has all sorts of wine in his cellar and all species of humming-birds in his collection. They are pleasure machines, pictures that need no frame, statues that come to you when you have a fancy to look at them nearer at hand and call them. A woman has this incontestable advantage over a statue, that she turns of herself in whatever direction you choose, whereas you must make the circuit of the statue and station yourself where the best view is to be had—which is tiresome.

You must see that with such ideas I cannot remain in these times or in this world; for one cannot exist thus without regard to time and space. I must find something else.

Such a conclusion is the simple and logical result of such thoughts.—When one seeks only the gratification of the eye, symmetry of figure and purity of feature, one accepts them wherever he finds them. This explains the extraordinary aberrations of love among the ancients.

Since the days of Christ there has not been a single statue of man in which youthful beauty was idealized and reproduced with the care that characterizes the ancient sculptors.—Woman has become the symbol of moral and physical beauty: man has really been dethroned since the day the child was born at Bethlehem. Woman is the queen of creation; the stars join to form a crown for her head, the crescent moon deems it an honor to form a cradle for her foot, the sun gives her his purest gold to make trinkets, painters who wish to flatter the angels give them the features of women, and far be it from me to blame them for it.—Before the coming of the sweet-tempered, courteous dealer in parables, it was very different; men did not feminize the gods or heroes whom they wished to make seductive; they had their type, at once sturdy and delicate, but always masculine, however amorous the outlines, however smooth and devoid of muscles and veins the workmen may have made their divine legs and arms. They readily made the special beauties of women consistent with this type. They broadened the shoulders, they lessened the size of the hips, they gave more prominence to the breast, they accentuated more strongly the joints of the arms and thighs.—There is almost no difference between Paris and Helen. Wherefore the hermaphrodite was one of the most ardently-cherished chimeras of the ancient idolatry.

That son of Hermes and Aphrodite is, in very truth, one of the most attractive creations of pagan genius. It is impossible to imagine anything more ravishingly beautiful than those two bodies, both perfect, harmoniously melted together, those two types of beauty, so equal yet so different, which unite to form one that is superior to either, because they mutually soften each other and bring out each the other's good points: to one who adores form exclusively, can there be a more pleasing uncertainty than that due to the sight of that back, those doubtful loins, those legs, so strong and slender that you are in doubt whether they should be attributed to Mercury on the point of taking flight or Diana coming from the bath? The trunk is a combination of the most charming singularities; above the full round chest of the lusty youth rises with strange grace the swelling breast of a young virgin. Beneath the sides, well wrapped in flesh and feminine in their softness, you divine the muscles and the ribs, as in the sides of a young man; the stomach is a little flat for a woman, a little round for a man, and there is something vague and indecisive about the whole character of the body, which it is impossible to describe and which has a charm all its own.—Théodore would surely be a most excellent model of that kind of beauty; it seems to me, however, that in him the feminine element carries the day and that he has retained more of Salmacis than the Hermaphrodite of the Metamorphoses.

The strange part of it all is that I hardly think of his sex now, and that I love him with a sense of perfect security. Sometimes I try to persuade myself that this love is an abomination, and I tell myself so in the harshest possible way; but it comes only from the lips, it is an argument that I urge upon myself and fail to appreciate; it really seems to me that it is the simplest thing in the world and that any other in my place would do the same.

I look at him, I listen to him talk or sing—for he sings admirably—and I take an indescribable pleasure in it.—He seems to me so much like a woman that one day, in the heat of conversation, I called him madame inadvertently, whereat he laughed, and it seemed to me a decidedly forced laugh.

But if he is a woman, what can be his motive for masquerading thus? I cannot answer the question in any way. That a very young, very handsome and perfectly beardless youth should disguise himself as a woman might be conceived; in that way he would open a thousand doors that would otherwise remain obstinately closed to him, and the jest might lead him into a complication of adventures thoroughly Dædalian and enjoyable. In that way one can gain access to a woman who is closely guarded or carry a citadel by storm under cover of a surprise. But I cannot understand what advantage can accrue to a young and beautiful woman from travelling around the country in male attire: she can only lose by it. A woman is not likely to renounce thus the pleasure of being courted, flattered and adored; she would renounce life rather, and she would do wisely, for what is a woman's life without all that?—Nothing—or something worse than death. And I always wonder that women who are thirty years old, or have the small-pox, don't jump from the top of a steeple.

Notwithstanding all that, something stronger than all arguments cries out to me that he is a woman, and that she is the woman I have dreamed of, whom alone I am to love, and who is to love me alone;—yes, it is she, the goddess with the eagle glance, with the fair royal hands, who smiled condescendingly upon me from her seat on her throne of clouds. She has presented herself to me in this disguise to put me to the test, to see if I would recognize her, if my amorous gaze would penetrate the veils in which she has enveloped herself, as in the marvellous tales where fairies appear at first in the guise of beggars, then suddenly stand forth resplendent in gold and jewels.

I have recognized you, oh! my love! At sight of you my heart leaped in my breast as Saint-Jean leaped in the breast of Sainte-Anne, when she was visited by the Virgin; the air was filled with a blaze of light; I smelt the odor of divine ambrosia; I saw the train of fire at your feet, and I understood at once that you were not an ordinary mortal.

The melodious notes of Sainte-Cecilia's viol, to which the angels listened with delight, are hoarse and discordant compared with the pearly cadences that issue from your ruby lips; the youthful, smiling Graces dance incessantly about you; the birds, when you pass through the woods, murmur as they bend their little feathered heads in order to see you more clearly, and whistle their sweetest refrains to you; the amorous moon rises earlier to kiss you with her pale silver lips, for she has abandoned her shepherd for you; the wind is careful not to efface the delicate print of your dainty foot upon the sand; the fountain, when you lean over it, becomes smoother than crystal, for fear of wrinkling and disturbing the reflection of your celestial face; even the modest violets open their little hearts to you, and play countless little coquettish tricks from before you; the jealous strawberry is stung to emulation and strives to equal the divine carnation of your lips; the infinitesimal gnat hums joyously and applauds you by flapping his wings;—all nature loves and admires you, its loveliest work!

Ah! now I live!—hitherto I had been no better than a dead man: now I have thrown off my shroud, and I stretch out my two thin hands from the grave toward the sun; my blue spectre-like color has left me. My blood flows swiftly through my veins. The ghastly silence that reigned about me is broken at last. The black, opaque arch that weighed upon my brow is lighted up. A thousand mysterious voices whisper in my ear; lovely stars sparkle above me and carpet the windings of my path with their gold spangles; the marguerites smile sweetly on me and the bells tinkle my name with their little twisted tongues. I understand a multitude of things that I used not to understand, I discover marvellous affinities and sympathies, I know the language of the roses and the nightingales, and I can read fluently the book I could not even spell. I have discovered that I have a friend in yonder respectable old oak, covered with mistletoe and parasitic plants, and that the frail and languorous periwinkle, whose great blue eye is always overflowing with tears, has long cherished a secret, discreet passion for me:—it is love, it is love that has unsealed my eyes and given me the key to the enigma.—Love descended into the depths of the cavern where my cowering, drowsy soul was freezing to death; he took it by the hand and led it up the steep and narrow stairway to the outer world. All the doors of the prison were burst open and for the first time the poor Psyche came forth from the me in which she was confined.

Another life has become mine. I breathe through another's lungs, and the blow that should wound him would kill me.—Before this happy day I was like those stupid Japanese idols who are forever looking at their stomach. I was the spectator of myself, the pit at the comedy. I was acting; I watched myself live and listened to the beating of my heart as to the oscillations of a pendulum. That is the whole story. Images were reproduced in my distraught eyes; sounds fell upon my unheeding ear, but nothing from the outer world reached my soul. Nobody's existence was essential to me; indeed I doubted if there were any other existence than mine, nor was I quite sure even of that. It seemed to me that I was alone in the midst of the universe, and that all the rest was only smoke, images, vain illusions, fleeting apparitions destined to people that void.—What a difference!

And yet, what if my presentiment had misled me, if Théodore should prove to be in truth a man, as everybody believes him to be! Such marvellous beauty has sometimes been seen in man; extreme youth may assist the illusion.—It is something I will not think about, for it would drive me mad; the grain that fell yesterday into my sterile heart has already penetrated it, in every direction, with its thousand filaments; it has taken a strong hold there and it would be impossible for me to tear it out. It has already become a green and flourishing tree and its knotted roots have struck deep.—If I should be convinced beyond a doubt that Théodore is not a woman, alas! I cannot say that I should not love him still.

You were very wise, my sweet friend, to try and dissuade me from the plan I had conceived of seeing men near at hand, of studying them closely, before giving my heart to any one of them.—I have extinguished love, yes, even the possibility of love, within me forever.

What poor creatures we girls are; brought up with so much care, surrounded by a triple wall of virginal precautions and reticence;—allowed to hear nothing, to suspect nothing, our principal knowledge being to know nothing, in what strange misconceptions do we pass our lives and what deceitful chimeras lull us to sleep in their arms!

Ah! Graciosa, thrice accursed be the moment when the idea of this travesty first occurred to me; what horrors, what infamous vulgarity I have been compelled to witness or to listen to! what a treasure of chaste and priceless ignorance I have squandered in a short time!

It was a lovely moonlight night, do you remember? when we walked together at the foot of the garden, in that gloomy, unfrequented path, terminated at one end by a statue of a Faun playing the flute, a Faun without a nose and covered with a thick leprosy of greenish-black moss—and at the other end by an imitation vista drawn on the wall and half washed away by the rain.—Through the still sparse foliage of the elms we could see the twinkling stars and the curve of the silver sickle. The odor of young shoots and fresh flowers came to our nostrils from the flower-beds, borne upon the languid breath of a faint breeze; an invisible bird warbled a strange, languorous tune; we, like true girls, talked of love and lovers, of the handsome cavalier we had seen at mass; we shared the few notions of the world and of things that we had in our heads; we twisted and turned in a hundred ways a phrase we had heard by chance, the meaning of which seemed to us obscure and strange; we asked each other a thousand of the silly questions that the most perfect innocence alone can imagine.—What primitive poesy, what adorable nonsense in those furtive interviews of two little fools fresh from boarding-school!

You wanted for your lover a gallant, proud young man, with black hair and moustaches, long spurs, long plumes, and a long sword—a sort of amorous Hector—and you were all for the heroic and triumphant; you dreamed of nothing but duels and escalades, and marvellous devotion, and you would readily have thrown your glove in among the lions so that your Esplandian might go and pick it up. It was very comical to see a little girl as you were then, fair-haired and blushing, bending in the slightest breeze, declaim those noble tirades without taking breath, and with the most martial air imaginable.

I, although I was only six months older than you, was six years less romantic; the thing that interested me most was to know what men said among themselves and what they did when they went away from salons and theatres:—I felt that there were many dark, unsavory corners in their lives, carefully concealed from our eyes, which it was most important for us to know about. Sometimes, hiding behind a curtain, I watched from a distance the young gentlemen who came to the house, and it seemed to me at such times that I could detect something cynical and mean in their bearing, vulgar indifference or discourteous preoccupation which I no longer noticed when they had been admitted, and which they seemed to lay aside as if by enchantment at the threshold of the salon. All of them, young and old alike, seemed to me to have adopted a uniform conventional mask, conventional sentiments, and a conventional mode of speech, when they were in the presence of women.—From the corner of the salon where I sat up straight as a doll, my back not touching the back of my chair, pulling my bouquet to pieces in my fingers, I looked and listened; my eyes were cast down, and yet I saw everything to right and left, before and behind me:—like the fabulous eyes of the lynx, my eyes looked through walls, and I could have told what was taking place in the adjoining room.

I had also noticed a notable difference in the way they spoke to married women; there were none of the discreet, polite, playfully-childish sentences such as they addressed to me or my companions, but a more flippant sportiveness, less grave and more familiar manners, the significant reticence and circumlocutions that follow quickly from a corrupt nature that knows it has one similarly corrupt before it; I felt that there was an element of union between them that did not exist between us, and I would have given everything to know what that element was.

With what anxiety and frenzied curiosity did I follow with eye and ear the buzzing, laughing groups of young men who, after breaking through the circle at a few points, resumed their promenade, talking together and casting ambiguous glances as they passed. Incredulous sneering smiles flickered about their full lips; they had the appearance of laughing at what they had said and of retracting the compliments and words of adoration with which they had overwhelmed us. I did not hear their words; but I understood, from the movement of their lips, that they were talking a language that was unknown to me and that no one had ever used before me. Even those who had the most humble and submissive manner tossed their heads with very perceptible indications of ennui and rebellion;—a panting sound, like that made by an actor when he reaches the end of a long speech, escaped from their lungs in spite of them, and they would half turn on their heels as they left us, in an eager, hurried way that denoted inward satisfaction at being relieved from the severe task of being courteous and gallant.

I would have given a year of my life to listen, unseen, to one hour of their conversation. I frequently understood from certain attitudes, from an occasional gesture or an oblique glance in my direction, that I was the subject of conversation among them and that they were discussing either my age or my face. At such times I was on burning coals; the few indistinct words, the fragments of phrases that reached my ears at intervals, excited my curiosity to the highest pitch but could not satisfy it, and I fell into strange doubts and perplexities.

Generally what they said seemed to be favorable, and it was not that that disturbed me: I cared very little whether they thought I was beautiful; but the brief remarks whispered in the ear and almost always followed by long laughter and significant winks—those were what I would have liked to know about; and for one of those sentences spoken in an undertone behind a curtain or in the angle of a door, I would without regret have interrupted the sweetest and most delightful conversation in the world.

If I had had a lover, I would have liked much to know how he would have spoken of me to another man, and in what terms he would have boasted of his good fortune to his boon companions, with a little wine in his head and both elbows on the table.

I know now and in truth I am very sorry to know.—It is always so.

My idea was a mad one, but what is done is done and one cannot unlearn what one has learned. I did not listen to you, my dear Graciosa, and I am sorry for it; but one doesn't always listen to reason, especially when it issues from such a pretty mouth as yours, for, I don't know why it is, but one cannot believe that advice is good unless it is given by some old bald or gray head, as if having been a fool for sixty years could make you wise.

But all this tormented me too much, and I couldn't stand it; I was broiling in my little skin like a chestnut on the stove. The fatal apple was ripening in the foliage above my head, and I must needs bite into it at last, being at liberty to throw it away afterwards, if it seemed to me to have a bitter taste.

I did like fair-haired Eve, my dearest grandmother—I bit.

The death of my uncle, my only remaining kinsman, leaving me in control of my actions, I carried out the plan I had so long dreamed of.—My precautions were taken with the greatest care so that no one should suspect my sex: I had learned to use the sword and pistol; I was a perfect horsewoman and daring to a point that few equerries could equal; I made a careful study of the proper way of wearing a cloak and brandishing a crop, and in the course of a few months I succeeded in transforming a girl who was considered very pretty, into a youth who was much prettier and who lacked almost nothing except a moustache,—I turned what property I had into cash, and left the town, resolved not to return until I had acquired thorough experience.

It was the only way of solving my doubts: to have lovers would have taught me nothing, or at least it would only have afforded me incomplete information, and I wanted to study man thoroughly, to dissect him fibre by fibre with an inexorable scalpel, and to watch him, alive and palpitating, on my dissecting-table; for that, it was necessary to see him alone in his own house, off his guard, to go with him to walk, to the tavern and elsewhere.—With my disguise I could go everywhere without being noticed; no one would conceal his true character before me, all constraint and reserve would be laid aside, I should receive confidences—I would make false ones in order to receive true ones in return. Alas! women have read only the romance of man, never his history.

It is a terrifying thing to think of—a thing we do not think of—how profoundly ignorant we are of the life and conduct of those who seem to love us and whom we marry. Their real existence is as absolutely unknown to us as if they were inhabitants of Saturn or some other planet a hundred million leagues from our sublunary ball; you would say that they were of another species, and that there is not the least intellectual bond between the two sexes;—the virtues of one make the vices of the other, and the things that a man admires make a woman blush.

Our lives are transparent and may be penetrated at a glance.—It is easy to follow us from the house to the boarding-school, from the boarding-school back to the house;—what we do is a mystery to no one; every one can see our wretched crayon drawings, our bouquets in water-color, consisting of a pansy and a rose of the size of a cabbage, sweetly tied together by the stems with a bow of delicate-hued ribbon; the slippers we embroider for our father's or grandfather's birthday have nothing in themselves very occult or very disquieting.—Our sonatas and our romanzas are executed with all desirable lack of warmth. We are well and duly tied to our mother's apron-strings, and at nine o'clock, or ten at the latest, we go to our little white beds in our clean and virtuous little cells, where we are scrupulously bolted and padlocked in until the next morning. The most alert and most jealous sensitiveness could find nothing objectionable in that.

The clearest crystal is not so transparent as such a life.

The man who takes us knows what we have done from the moment we were weaned and even before, if he cares to carry his investigations so far.—Our life is not life, it is a sort of vegetating existence like that of moss and flowers; the freezing shadow of the maternal stalk hovers around us, poor, dwarfed rose-buds, who dare not open. Our principal business is to sit very straight, tightly laced and whaleboned, with our eyes properly downcast, and to outdo, in immobility and stiffness, mannikins and dolls on springs.

We are forbidden to speak, to join in the conversation farther than to answer yes and no if we are questioned. As soon as anything interesting is to be said we are sent away to practise on the harp or spinet, and our music masters are always at least sixty years old and take snuff disgustingly. The models hung in our rooms are anatomically very vague and evasive. The Greek gods, before making their appearance in young ladies' boarding-schools, take care to purchase very full box-coats at a second-hand clothing shop, and to be engraved in stipple, which makes them look like porters or cab-drivers and renders them but ill-adapted to excite our imaginations.

By dint of seeking to prevent us from becoming romantic, they make us idiots. The time when we are being educated is passed, not in teaching us something, but in preventing us from learning anything.

We are really prisoners, in body and mind; but a young man, free to do what he will, who goes out in the morning not to return until the next morning, who has money, who can earn money and dispose of it as he pleases—how could he justify his method of employing his time?—who is the man who would be willing to tell his beloved what he has done during the day and night?—Not one, even of those who are reputed the purest.

I sent my horse and my clothes to a little farm that I own at some distance from the town. I dressed myself, mounted and rode away, not without a strange oppression at the heart.—I regretted nothing, I left nothing behind, neither relatives nor friends, not a dog, not a cat, and yet I was sad, I almost had tears in my eyes; the farm, which I had never visited more than five or six times, had no sentimental attraction for me, and there was none of the fondness you sometimes feel for certain spots, which saddens you when you are obliged to leave them; but I turned two or three times to watch the spiral column of bluish smoke rising among the trees.

There I had left my title of woman, with my skirts and petticoats; in the chamber in which I had dressed were confined twenty years of my life, which were no longer to count and no longer concerned me. On the door might have been written:—"Here lies Madelaine de Maupin;"—for I was no longer Madelaine de Maupin, but Théodore de Sérannes,—and no one was to call me again by the sweet name of Madelaine.

The drawer in which my dresses, useless thenceforth, were placed, seemed to me like the coffin of my maidenly illusions;—I was a man, or at least I had the appearance of one; the maiden was dead.

When I had altogether lost sight of the tops of the chestnut-trees that surrounded the farm, it seemed to me that I was no longer myself but another, and I remembered my former acts as those of a stranger whom I had watched, or as the beginning of a novel which I had not finished reading.

I recalled complacently a thousand little details, whose childish innocence brought to my lips an indulgent smile, sometimes a little mocking, like that of a young rake listening to the Arcadian, pastoral confidences of a school-boy of thirteen; and, at the moment I was parting from them forever, all my girlish and young-womanish follies flocked to the roadside, making friendly gestures to me and sending me kisses with the tips of their white, tapering fingers.

I put spurs to my horse to fly from this enervating emotion; the trees flew swiftly by on the right hand and the left; but the madcap swarm, buzzing louder than a swarm of bees, rushed along the paths beside the road, calling: "Madelaine! Madelaine!"

I struck my horse a sharp blow on the neck which made him double his speed. My hair stood out almost straight behind my head, my cloak was in a horizontal position, as if the folds had been carved out of stone, our pace was so swift; I looked back once and saw, like a tiny white cloud far away on the horizon, the dust that my horse's feet had raised.

I stopped a moment.

In an eglantine bush, on the edge of the road, I saw something white moving, and a voice, clear and soft as silver, struck my ear:—"Madelaine, Madelaine, where are you going so far from home, Madelaine? I am your virginity, my dear child; that is why I have a white dress, a white crown and a white skin. But why do you wear boots, Madelaine? I thought that you had a very pretty foot. Boots and short-clothes and a great plumed hat like a cavalier going to the war! Why that long sword that strikes and bruises your thigh? You have a strange outfit, Madelaine, and I am not sure if I ought to accompany you."

"If you are afraid, my dear, go back to the house, water my flowers and take care of my doves. But really you are wrong, you would be safer in these garments of stout cloth than in your gauze and fine linen. My boots prevent any one from seeing if I have a pretty foot; this sword is to defend myself and the plume waving in my hat is to frighten away the nightingales that come to sing false songs of love in my ear."

I continued my journey; in the sighs of the wind I thought I could recognize the last bar of the sonata I had learned for my uncle's birthday, and in a great rose that showed its full-blown head above a low wall, the model of the rose I had painted so often in water-colors; as I rode by a house I saw the phantoms of my curtains waving at a window. My whole past seemed to be clinging to me to prevent my going forward and arriving at a new future.

I hesitated two or three times, and I turned my horse's head the other way.

But the little blue snake, curiosity, softly hissed insidious words into my ear, and said to me:—"Go on, go on, Théodore; it is a good opportunity to learn; if you don't learn to-day, you will never know.—And will you bestow your noble heart, at random, on the first honest and passionate exterior?—Men conceal some very extraordinary secrets from us, Théodore!"

I started off at a gallop.

The short-clothes were on my body and not in my mind; I had a very unpleasant feeling, a sort of shiver of fear, to call it by its right name, at a dark place in the forest; a gunshot, fired by a poacher, almost made me faint. If it had been a highwayman, the pistols in my holsters and my long sword would certainly have been of small use to me. But gradually I recovered and paid no farther attention to it.

The sun sank slowly beneath the horizon like the lights in a theatre which are turned down when the performance is at an end. Rabbits and pheasants crossed the road from time to time; the shadows lengthened and all distant objects were tinged with red. Certain parts of the sky were of a most soft, deep lilac, others of a pale lemon or orange; the birds of night began to sing, and a multitude of curious sounds arose from the woods: the little remaining light faded away, and it became quite dark,—darker because of the shadow cast by the trees. And I, who had never been out alone at night, was in the midst of a great forest at eight o'clock! Can you imagine it, my Graciosa,—I who used almost to die of fear at the foot of the garden? My fright returned with ten-fold force and my heart beat terribly fast; it was with great satisfaction, I confess, that I saw the lights of the town for which I was bound gleaming and twinkling on a hillside. As soon as I saw those bright specks—like little earthly stars they were—my fright passed away completely. It seemed to me that those unthinking lights were the open eyes of so many friends watching for me.

My horse was no less content than I, and, scenting the sweet odors of a stable, more agreeable to him than the perfume of all the marguerites and wood strawberries on earth, he trotted straight to the Hôtel du Lion-Rouge.

Chapter X — The inn-keeper approached to ask me what I wanted for supper.

He was a pot-bellied man, with a red nose, wall-eyes, and a smile that made the circuit of his head. At every word he uttered he showed a double row of pointed teeth with spaces between, like an ogre's.

A bright light shone through the leaded windows of the hotel, whose tin sign swung from right to left and moaned like an old woman, for the north wind was beginning to freshen.—I turned my horse over to a groom and entered the kitchen.

An enormous fire-place at the end of the room swallowed in its black and red maw a bundle of fagots at every mouthful, and on each side of the andirons, two dogs, almost as large as men, sat on their hind-quarters, roasting themselves with all imaginable phlegm, content to raise their paws a little and heave a sort of sigh when the heat became more intense; but they certainly would have preferred to be reduced to charcoal rather than move back an inch.

My arrival did not seem to please them, and I tried in vain to make their acquaintance by patting them on the head several times; they cast stealthy glances at me that boded no good.—That astonished me, for animals generally take to me.

The inn-keeper approached to ask me what I wanted for supper.

He was a pot-bellied man, with a red nose, wall-eyes, and a smile that made the circuit of his head. At every word he uttered he showed a double row of pointed teeth with spaces between, like an ogre's. The huge kitchen-knife that hung at his side had a doubtful look, as if it might serve several different purposes. When I had told him what I wanted, he went up to one of the dogs and kicked him. The dog got up and walked toward a sort of wheel and went inside with a piteous, complaining air and a reproachful glance at me. At last, seeing that there was no hope for him, he began to turn the wheel and thereby the spit on which the chicken was impaled that was to furnish my supper.—I resolved to throw him the scraps as a reward for his trouble, and looked about the kitchen while the repast was preparing.

The ceiling was formed of huge oaken beams, all discolored and blackened by the smoke from the fire-place and the candles. On the sideboards pewter plates more highly polished than silver shone in the darkness, and white crockery with blue flowers.—The numerous rows of well-scoured saucepans along the walls reminded one not a little of the antique bucklers that we see hung in rows along the sides of Greek or Roman triremes—forgive me, Graciosa, the epic magnificence of that simile. One or two buxom servant-maids were moving around a great table, arranging plates and forks, music more agreeable than any other when one is hungry, for the hearing of the stomach then becomes keener than that of the ear. Take it for all in all, despite the landlord's Christmas-box mouth and saw teeth, the inn had a very honest and pleasing appearance; and even had his smile extended a fathom farther and his teeth been three times as long and white, the rain began to patter against the window-panes and the wind to howl in a fashion to take away all desire to depart, for I know nothing more depressing than the groaning of the wind on a dark and rainy night.

An idea came to me that made me smile—it was that no one in the world would have come to look for me where I was.

Indeed, who would have dreamed that little Madelaine, instead of being tucked away in her warm little bed, with her alabaster night-light beside her, a novel under her pillow, her maid in the adjoining closet, ready to run to her at the least nocturnal fright, was rocking to and fro in a straw chair in a country inn twenty leagues from her home, her booted feet resting on the andirons and her little hands buried jauntily in her pockets?

Yes, Madelinette has not remained like her companions, her elbows lazily resting on the balcony rail, between the window jasmine and volubilis, watching the violet fringe of the horizon across the plain or some little rose-colored cloud moving gently in the May breeze. She has not carpeted mother-of-pearl palaces with lily leaves, to furnish quarters for her chimeras; she has not, like you, lovely dreamers, arrayed some hollow phantom in all imaginable perfections; she has sought to compare the illusions of her heart with the reality; she has chosen to know men before giving herself to a man; she has left everything, her lovely dresses of bright-colored silks and velvets, her necklaces, her bracelets, her birds and her flowers; she has voluntarily renounced humble adoration, gallant speeches, bouquets and madrigals, the pleasure of being considered lovelier and better adorned than you, the sweet name of woman, everything that was part of her, and has started all alone, the brave girl, to travel the world over to learn the great science of life.

If people knew that, they would say that Madelaine was mad.—You said so yourself, my dear Graciosa;—but the real mad women are they who toss their hearts to the wind and sow their love at random on the stones and on the rocks, without knowing if a single seed will germinate.

O Graciosa! that is a thought I have never had without dismay: to have loved some one who was not worthy! to have shown one's heart all naked to impure eyes and allowed a profane creature to enter its sanctuary! to have mingled its limpid stream for some time with a muddy stream!—However perfectly they may be separated, some trace of the slime always remains, and the stream can never recover its original transparency.

To think that a man has kissed you and touched you; that he has seen your body; that he can say: "She is thus and so; she has such a mark in such a place; her mind runs upon this or that theme; she laughs for this thing and weeps for that; her dreams are like this; I have in my portfolio a feather from the wings of her chimera; this ring is made from her hair; a bit of her heart is folded into this letter; she caressed me so, and these are her usual words of endearment."

Ah! Cleopatra, I understand now why you always had the lover with whom you had passed the night killed in the morning.—Sublime cruelty, for which, formerly, I could find no imprecations strong enough! Great voluptuary, how well you understood human nature, and what deep purpose there was in that savagery! You did not choose that any living man should divulge the mysteries of your bed; the words of love that flew from your lips were not to be repeated.—Thus you retained your pure illusion. Experience did not tear away, bit by bit, the charming phantom you had cradled in your arms. You chose to be separated from him by a sudden blow of the axe rather than by slow distaste.—What torture, in very truth, to see the man one has chosen belying every moment the idea one has conceived of him; to discover in his character a thousand pettinesses you did not suspect; to discover that what had seemed to you so beautiful through the prism of love is really very ugly, and that he whom you had taken for a true hero of romance is, after all, only a prosaic bourgeois, who wears slippers and a dressing-gown!

I have not Cleopatra's power, and if I had it, I certainly should not have the strength to use it. And so, being neither able nor desirous to cut off my lovers' heads upon getting up in the morning, and being no more inclined to endure what other women endure, I must needs look twice before taking a lover; and that is what I propose to do three times rather than twice, if I should have any desire for one, which I very much doubt after what I have seen and heard; unless, however, I should meet in some blessed unknown country a heart like my own, as the novels say—a pure, virgin heart which has never loved and which is capable of loving, in the true sense of the word; which is not, by any manner of means, an easy thing to find.

Several cavaliers entered the inn; the storm and the darkness had prevented them from continuing their journey.—They were all young, the oldest certainly not more than thirty; their clothes indicated that they belonged to the upper classes, and, even without their clothes, their insolent familiarity and their manners would have made it sufficiently evident. There were one or two who had interesting faces; all the others had, in a greater or less degree, that sort of jovial brutality and careless good-humor which men display among themselves, and which they lay aside completely when they are in our presence.

If they could have suspected that the slender youth half-asleep on his chair in the chimney-corner was by no means what he appeared to be, but a young girl, a morsel for a king, as they say, certainly they would very soon have changed their tone, and you would have seen them swell out and spread their feathers on the instant. They would have approached me with repeated reverences, legs straight, elbows out, a smile in their eyes and mouth and nose and hair and their whole attitude; they would have emasculated the words they used and would have spoken only in velvet and satin phrases; at my slightest movement they would have acted as if they were going to stretch themselves out on the floor by way of carpet, for fear that my tender feet might be bruised by its inequalities; every hand would have been held out to support me; the softest chair would have been placed in the most desirable position;—but I had the outward appearance of a pretty boy and not of a pretty girl.

I confess that I was almost on the point of regretting my petticoats, when I saw how little attention they paid me.—I was deeply mortified for a moment; for from time to time I forgot that I was now wearing man's clothes, and I had to remind myself of it in order to avoid an attack of bad temper.

I sat there, not saying a word, with folded arms, apparently watching with close attention the chicken on the spit, which was turning browner and browner, and the unfortunate dog whose rest I had so unluckily disturbed, who was struggling away in his wheel like several devils in the same holy-water vessel.

The youngest of the party brought his hand down on my shoulder with a force that made me wince, on my word, and extorted from me a little involuntary shriek, and asked me if I would not prefer to sup with them rather than all alone, as several could drink better than one.—I answered that it was a pleasure I should not have dared to hope for, and that I would be very glad to do it. Our places were laid together and we took our seats at the table.

The panting dog, after swallowing an enormous dipperful of water with three laps of his tongue, resumed his post opposite the other dog, who had not stirred any more than if he had been made of porcelain,—the new-comers, by a special dispensation of Providence, not having ordered chicken.

I learned, from some sentences that escaped them, that they were on their way to the court, which was then at—, where they expected to meet other friends. I told them that I was a young gentleman just from the University, on my way to visit my kins-men in the provinces by the true student's road, that is to say the longest he can find. That made them laugh, and after some comments on my innocent and artless appearance, they asked me if I had a mistress. I answered that I knew nothing about mistresses, whereat they laughed still louder. Bottle succeeded bottle with great rapidity; although I was careful almost always to leave my glass full, my head was a little heated, and, not losing sight of my idea, I managed to turn the conversation upon women. It was no difficult task; for, after theology and æsthetics, it is the subject upon which men talk most freely when they are drunk.

My companions were not exactly drunk, they carried their wine too well for that; but they began to enter upon moral discussions that had no end and to rest their elbows unceremoniously on the table.—One of them had gone so far as to put his arm about the extensive waist of one of the maid-servants, and was nodding his head most amorously; another swore that he should burst on the spot, like a toad that has been made to take snuff, unless Jeannette would let him give her a kiss on each of the great red apples that served her as cheeks. And Jeannette, not wishing that he should burst like a toad, gave him permission with very good grace and did not even check a hand that stole audaciously between the folds of her neckerchief into the moist valley of her breast, very insecurely guarded by a little golden cross, and not until he had exchanged some words with her in an undertone did he allow her to remove the dishes.

And yet they were habitués of the court and young men of refined manners, and unless I had seen it myself I should never have thought of accusing them of such familiarity with servants at an inn.—It is probable that they had just left charming mistresses, to whom they had sworn the mightiest oaths known to man: upon my word, it would never have occurred to me to request my lover not to sully lips on which I had placed mine, by contact with the cheeks of a clumsy wench.

The rascal seemed to take as much pleasure in that kiss as if he had kissed Phyllis or Oriana; it was a loud kiss, solidly and honestly bestowed, and left two little white marks on the fiery cheek of the damsel, who wiped them away with the back of the hand that had just been washing the dishes.—I do not believe that he had ever bestowed one so naturally affectionate on the chaste deity of his heart.—That was his thought apparently, for he said in an undertone and with a disdainful shrug:

"To the devil with thin women and high-flown sentiments!"

That moral maxim seemed to suit the party, and all nodded their heads approvingly.

"Faith," said another, following out the same line of thought, "I am unlucky in everything. Messieurs, allow me to inform you, under seal of the most profound secrecy, that I, who speak to you, have a passion at this moment."

"Oho!" exclaimed the others. "A passion! That is depressing to the last degree. What are you doing with a passion?"

"She's a virtuous woman, messieurs; you must not laugh, messieurs; for, after all, why shouldn't I have a virtuous woman? Have I said anything ridiculous?—I say, you over there, I'll throw the house at your head, if you don't have done."

"Well! what then?"

"She is mad over me:—she's the dearest soul in the world; speaking of souls, I know what I'm talking about, I know at least as much about 'em as I do about horses, and I give you my word that hers is the first quality. She is all exaltation, ecstasy, devotion, self-sacrifice, refinements of tenderness, everything that you can imagine that is most transcendent; but she has hardly any breast, indeed she has none at all, like a girl of fifteen at the outside.—She's pretty enough; has a well-shaped hand and pretty foot; she has too much mind and not enough flesh, and sometimes I long to drop her. Damnation! a man doesn't lie with a mind. I'm very unlucky; pity me, my dear friends."—And, made maudlin by the wine he had drunk, he began to weep hot tears.

"Jeannette will console you for the misfortune of lying with sylphs," said his neighbor, pouring him out a bumper; "her soul's so thick that you could make other women's bodies out of it, and she has flesh enough to cover the carcasses of three elephants."

O pure and noble woman! if you knew what is said of you, in wine-shops, regardless of everything, before people he does not know, by the man you love best in the world and for whom you have sacrificed everything! how shamelessly he undresses you, and with base effrontery abandons you all naked to the vinous gaze of his companions, while you sit sadly at your window, your chin resting in your hand, watching the road by which he should return to you!