Title: The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England

Author: Joseph Strutt

Editor: William Hone

Release date: May 17, 2015 [eBook #48983]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Christian Boissonnas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

INCLUDING THE

RURAL AND DOMESTIC RECREATIONS,

MAY GAMES, MUMMERIES, SHOWS, PROCESSIONS, PAGEANTS, & POMPOUS SPECTACLES

FROM

THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE PRESENT TIME.

BY JOSEPH STRUTT.

ILLUSTRATED BY

One Hundred and Forty Engravings.

IN WHICH ARE REPRESENTED

MOST OF THE POPULAR DIVERSIONS;

SELECTED FROM ANCIENT PAINTINGS.

A NEW EDITION, WITH A COPIOUS INDEX,

BY WILLIAM HONE,

AUTHOR OF THE EVERY-DAY BOOK, TABLE BOOK, YEAR BOOK, ETC.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THOMAS TEGG,

73, CHEAPSIDE.

1845.

J. Haddon, Printer, Castle Street, Finsbury.

There are two previous editions of Mr. Strutt's Sports and Pastimes of the People of England. The first appeared in 1801; the second, which was published in 1810, the year wherein the author died, was an incorrect reprint, without a single additional line. Both were in quarto, and as each of the plates, with few exceptions, contained several subjects referred to in different parts of the work, and as there were no paginal references on the plates, they were frequently embarrassing to the reader.

The present edition is of a more convenient size, and at one-sixth of the price of the former editions; and every engraving is on the page it illustrates.

To a volume abounding in historical and other interesting facts, an Index seemed indispensable; and a very copious one is annexed. The Two former editions were without.

[Pg vi] If Mr. Strutt had lived, I am persuaded he would have incorporated into the body of the work some notes, which were needlessly placed on the bottom margins. I have ventured to take them up into the pages; but without any undue alteration of the author's language.

I hope, therefore, that my aim to render this edition generally desirable and available, has been fully accomplished.

W. Hone.

Newington Green, 1830.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| A GENERAL ARRANGEMENT OF THE POPULAR SPORTS, PASTIMES, AND MILITARY GAMES, TOGETHER WITH THE VARIOUS SPECTACLES OF MIRTH OR SPLENDOUR, EXHIBITED PUBLICLY OR PRIVATELY, FOR THE SAKE OF AMUSEMENT, AT DIFFERENT PERIOD, IN ENGLAND. | PAGE |

| I. Object of the Work, to describe the Pastimes and trace their Origin—II. The Romans in Britain—III. The Saxons—IV. The Normans—V. Tournaments and Justs—VI. Other Sports of the Nobility, and the Citizens and Yeomen—VII. Knightly Accomplishments—VIII. Esquireship—IX. Military Sports patronized by the Ladies—X. Decline of such Exercises—XI. and of Chivalry—XII. Military Exercises under Henry the Seventh—XIII. and under Henry the Eighth—XIV. Princely Exercises under James the First—XV. Revival of Learning—XVI. Recreations of the Sixteenth Century—XVII. Old Sports of the Citizens of London—XVIII. Modern Pastimes of the Londoners—XIX. Cotswold and Cornish Games—XX. Splendour of the ancient Kings and Nobility—XXI. Royal and noble Entertainments—XXII. Civic Shows—XXIII. Setting out of Pageants—XXIV. Processions of Queen Mary and King Philip of Spain in London—XXV. Chester Pageants—XXVI. Public Shows of the Sixteenth Century—XXVII. Queen Elizabeth at Kenelworth Castle—XXVIII. Love of Public Sights illustrated from Shakspeare—XXIX. Rope-dancing, tutored Animals, and Puppet-shows—XXX. Minstrelsy, Bell-ringing, &c.—XXXI. Baiting of Animals—XXXII. Pastimes formerly on Sundays—XXXIII. Royal Interference with them—XXXIV. Zeal against Wakes and May-Games—XXXV. Dice and Cards—XXXVI. Regulation of Gaming for Money by Richard Cœur de Lion, &c.—XXXVII. Statutes against Cards, Ball-play, &c.—XXXVIII. Prohibitions of Skittle play—XXXIX. Archery succeeded by Bowling—XL. Modern Gambling—XLI. Ladies' Pastimes, Needle-work—XLII. Dancing and Chess-play—XLIII. Ladies' Recreations in the Thirteenth Century.—XLIV. The Author's Labours.—Character of the Engravings. | xv |

| BOOK I.

[Pg x] RURAL EXERCISES PRACTISED BY PERSONS OF RANK. |

|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| I. Hunting more ancient than Hawking—II. State of Hunting among the Britons—III. The Saxons expert in Hunting—IV. The Danes also—V. The Saxons subsequently and the Normans—VI. Their tyrannical Proceedings—VII. Hunting and Hawking after the Conquest—VIII. Laws relating to Hunting—IX. Hunting and Hawking followed by the Clergy—X. The manner in which the dignified Clergy in the Middle Ages pursued these Pastimes—XI. The English Ladies fond of these Sports—XII. Privileges of the Citizens of London to hunt;—private Privileges for Hunting—XIII. Two Treatises on Hunting considered—XIV. Names of Beasts to be hunted—XV. Wolves not all destroyed in Edgar's Time—XVI. Dogs for Hunting—XVII. Various Methods of Hunting—XVIII. Terms used in Hunting;—Times when to hunt | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| I. Hawking practised by the Nobility—II. Its Origin not well known;—a favourite Amusement with the Saxons—III. Romantic Story relative to Hawking—IV. Grand Falconer of France, his State and Privileges—V. Edward III. partial to Hawking;—Sir Thomas Jermin—VI. Ladies fond of Hawking—VII. Its Decline—VIII. How it was performed—IX. Embellishments of the Hawk—X. Treatises concerning Hawking;—Superstitious Cure of Hawks—XI. Laws respecting Hawks—XII. Their great Value—XIII. The different Species of Hawks, and their Appropriation—XIV. Terms used in Hawking—XV. Fowling and Fishing;—the Stalking Horse;—Lowbelling | 24 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| I. Horse-racing known to the Saxons—II. Races in Smithfield, and why—III. Races, at what Seasons practised—IV. The Chester Races—V. Stamford Races—VI. Value of Running-horses—VII. Highly prized by the Poets, &c.—VIII. Horse-racing commended as a liberal Pastime—IX. Charles II. and other Monarchs encouragers of Horse-racing;—Races on Coleshill-heath | 40 |

| BOOK II.

[Pg xi] RURAL EXERCISES GENERALLY PRACTISED. |

|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| I. The English famous for their Skill in Archery—II. The use of the Bow known to the Saxons and Danes—III. Form of the Saxon Bow, &c.—IV. Archery improved by the Normans—V. The Ladies fond of Archery—VI. Observations relative to the Cross-Bow—VII. Its Form and the Manner in which it was used—VIII. Bows ordered to be kept—IX. The decay of Archery and why—X. Ordinances in its Favour;—the Fraternity of St. George established—XI. The Price of Bows—XII. Equipments for Archery—XIII. Directions for its Practice—XIV. The Marks to shoot at—XV. The Length of the Bow and Arrows—XVI. Extraordinary Performances of the Archers—XVII. The modern Archers inferior to the ancient in long Shooting—XVIII. The Duke of Shoreditch, why so called;—grand Procession of the London Archers—XIX. Archery a royal Sport;—a good Archer, why called Arthur—XX. Prizes given to the Archers | 48 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| I. Slinging of Stones an ancient Art—II. Known to the Saxons—III. And the Normans—IV. How practised of late Years—V. Throwing of Weights and Stones with the Hand—VI. By the Londoners—VII. Casting of the Bar and Hammer—VIII. Of Spears—IX. Of Quoits—X. Swinging of Dumb Bells—XI. Foot Races—XII. The Game of Base—XIII. Wrestling much practised formerly—XIV. Prizes for—XV. How performed—XVI. Swimming—XVII. Sliding—XVIII. Skating—XIX. Rowing—XX. Sailing | 71 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| I. Hand-ball an ancient Game—The Ball, where said to have been invented—II. Used by the Saxons—III. And by the Schoolboys of London—IV. Ball Play in France—V. Tennis Courts erected—VI. Tennis fashionable in England—VII. A famous Woman Player—VIII. Hand-ball played for Tansy Cakes—IX. Fives—X. Ballon-ball—XI. Stool-ball—XII. Hurling—XIII. Foot-ball;—Camp-ball—XIV. Goff;—Cambuc;—Bandy-ball—XV. Stow-ball—XVI. Pall-mall—XVII. Ring-ball—XVIII. Club-ball—XIX. Cricket—XX. Trap-Ball—XXI. Northen-spell—XXII. Tip-cat | 91 |

| BOOK III.

[Pg xii] PASTIMES USUALLY EXERCISED IN TOWNS AND CITIES, OR PLACES ADJOINING TO THEM. |

|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| I. Tournament a general Name for several Exercises—II. The Quintain an ancient Military Exercise—III. Various Kinds of the Quintain—IV. Derivation of the Term—V. The Water Quintain—VI. Running at the Quintain practised by the Citizens of London; and why—VII. The Manner in which it was performed—VIII. Exhibited for the Pastime of Queen Elizabeth—IX. Tilting at a Water Butt—X. The Human Quintain—XI. Exercises probably derived from it—XII. Running at the Ring—XIII. Difference between the Tournaments and the Justs—XIV. Origin of the Tournament—XV. The Troy Game;—the Bohordicum or Cane Game—XVI. Derivation of Tournament;—how the Exercise was performed—XVII. Lists and Barriers—XVIII. When the Tournament was first practised—XIX. When first in England—XX. Its Laws and Ordinances—XXI. Pages, and Perquisites of the Kings at Arms, &c.—XXII. Preliminaries of the Tournament—XXIII. Lists for Ordeal Combats—XXIV. Respect paid to the Ladies—XXV. Justs less honourable than Tournaments—XXVI. The Round Table—XXVII. Nature of the Justs—XXVIII. Made in honour of the Fair Sex—XXIX. Great Splendour of these Pastimes;—The Nobility partial to them—XXX. Toys for initiating their Children in them—XXXI. Boat Justs, or Tilting on the Water—XXXII. Challenges to all comers | 111 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| I. Ancient Plays—II. Miracle Plays, Dramas from Scripture, &c. continued several Days—III. The Coventry Play—IV. Mysteries described—V. How enlivened—VI. Moralities described—The Fool in Plays, whence derived—VII. Secular Plays—VIII. Interludes—IX. Chaucer's Definition of the Tragedies of his Time—X. Plays performed in Churches—XI. Cornish Miracle Plays—XII. Itinerant Players, their evil Characters—XIII. Court-Plays—XIV. Play in honour of the Princess Mary's Marriage—XV. The Play of Hock Tuesday—XVI. Decline of Secular Plays—XVII. Origin of Puppet Plays—XVIII. Nature of the Performances—XIX. Giants and other Puppet Characters—XX. Puppet Plays superseded by Pantomimes—XXI. The modern Puppet-show Man—XXII. Moving Pictures described | 150 |

| CHAPTER III. [Pg xiii] | |

| I. The British Bards—II. The Northern Scalds—III. The Anglo-Saxon Gleemen—IV. The Nature of their Performances—V. A Royal Player with three Darts—VI. Bravery of a Minstrel in the Conqueror's Army—VII. Other Performances by Gleemen—VIII. The Harp an Instrument of Music much used by the Saxons—IX. The Norman Minstrels, and their different Denominations and Professions—X. Troubadours—XI. Jestours—XII. Tales and Manners of the Jesters—XIII. Further Illustration of their Practices—XIV. Patronage, Privileges, and Excesses of the Minstrels—XV. A Guild of Minstrels—XVI. Abuses and Decline of Minstrelsy—XVII. Minstrels were Satirists and Flatterers—XVIII. Anecdotes of offending Minstrels, Women Minstrels—XIX. The Dress of the Minstrels—XX. The King of the Minstrels, why so called—XXI. Rewards given to Minstrels—XXII. Payments to Minstrels—XXIII. Wealth of certain Minstrels—XXIV. Minstrels were sometimes Dancing Masters | 170 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| I. The Joculator—II. His different Denominations and extraordinary Deceptions—III. His Performances ascribed to Magic—IV. Asiatic Jugglers—V. Remarkable Story from Froissart—VI. Tricks of the Jugglers ascribed to the Agency of the Devil; but more reasonably accounted for—VII. John Rykell, a celebrated Tregetour—VIII. Their various Performances—IX. Privileges of the Joculators at Paris.—The King's Joculator an Officer of Rank—X. The great Disrepute of modern Jugglers | 197 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| I. Dancing, Tumbling, and Balancing, part of the Joculator's Profession—II. Performed by Women—III. Dancing connected with Tumbling—IV. Antiquity of Tumbling—much encouraged—V. Various Dances described—VI. The Gleemen's Dances—VII. Exemplification of Gleemen's Dances—VIII. The Sword Dance—IX. Rope Dancing and wonderful Performances on the Rope—X. Rope Dancing from the Battlements of St. Paul's—XI. Rope Dancing from St. Paul's Steeple—XII. Rope Dancing from All Saints' Church, Hertford—XIII. A Dutchman's Feats on St. Paul's Weathercock—XIV. Jacob Hall the Rope Dancer—XV. Modern celebrated Rope Dancing—XVI. Rope Dancing at Sadler's Wells—XVII. Fool's Dance—XVIII. Morris Dance—XIX. Egg Dance—XX. Ladder Dance—XXI. Jocular Dances—XXII. Wire Dancing—XXIII. Ballette Dances—XXIV. Leaping and Vaulting—XXV. Balancing—XXVI. Remarkable Feats—XXVII. The Posture-Master's Tricks—XXVIII. The Mountebank—XXIX. The Tinker—XXX. The Fire-Eater | 207 |

| CHAPTER VI. [Pg xiv] | |

| I. Animals, how tutored by the Jugglers—Tricks performed by Bears—II. Tricks performed by Apes and Monkeys—III. By Horses among the Sybarites—IV. In the thirteenth Century—V. In Queen Anne's Reign—VI. Origin of the Exhibitions at Astley's, the Circus, &c.—VII. Dancing Dogs—VIII. The Hare beating a Tabor, and learned Pig—IX. A Dancing Cock—The Deserter Bird—X. Imitations of Animals—XI. Mummings and Masquerades—XII. Mumming to Royal Personages—XIII. Partial Imitations of Animals—XIV. The Horse in the Morris dance—XV. Counterfeit Voices of Animals—XVI. Animals trained for Baiting—XVII. Paris Garden—XVIII. Bull and Bear Baiting patronised by Royalty—XIX. How performed—XX. Bears and Bear-wards—XXI. Baiting in Queen Anne's time—XXII. Sword Play. &c.—XXIII. Public Sword Play—XXIV. Quarter Staff—XXV. Wrestling, &c. in Bear Gardens—XXVI. Extraordinary Trial of Strength | 239 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| I. Ancient Specimens of Bowling—Poem on Bowling—II. Bowling-greens first made by the English—III. Bowling-alleys—IV. Long-bowling—V. Supposed Origin of Billiards—VI. Kayles—VII. Closh—VIII. Loggats—IX. Nine-pins—Skittles—X. Dutch-pins—XI. Four-corners—XII. Half-bowl—XIII. Nine-holes—XIV. John Bull—XV. Pitch and Hustle—XVI. Bull-baiting in Towns and Villages—XVII. Bull-running—At Stamford, &c.—XVIII. At Tutbury—XIX. Badger-baiting—XX. Cock-fighting—XXI. Throwing at Cocks—XXII. Duck-hunting—XXIII. Squirrel-hunting—XXIV. Rabbit-hunting | 266 |

| BOOK IV.

[Pg xv] DOMESTIC AMUSEMENTS OF VARIOUS KINDS; AND PASTIMES APPROPRIATED TO PARTICULAR SEASONS. |

|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| I. Secular Music fashionable—II. Ballad-singers encouraged by the Populace—III. Music Houses—IV. Origin of Vauxhall—V. Ranelagh—VI. Sadler's Wells—VII. Marybone Gardens—Operas—Oratorios—VIII. Bell-ringing—IX. Its Antiquity—X. Hand-bells—XI. Burlesque Music—XII. Dancing—XIII. Its Antiquity, &c.—XIV. Shovel-board—XV. Anecdote of Prince Henry—XVI. Billiards—XVII. Mississippi—XVIII. The Rocks of Scilly—XIX. Shove-groat—XX. Swinging—XXI. Tetter-totter—XXII. Shuttle-cock | 286 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| I. Sedentary Games—II. Dice-playing;—Its Prevalency and Bad Effects—III. Ancient Dice-box;—Anecdote relating to false Dice—IV. Chess;—Its Antiquity—V. The Morals of Chess—VI. Early Chess-play in France and England—VII. The Chess-board—VIII. The Pieces, and their Form—IX. The various Games of Chess—X. Ancient Games similar to Chess—XI. The Philosopher's Game—XII. Draughts, French and Polish—XIII. Merelles, or Nine Mens' Morris—XIV. Fox and Geese—XV. The Solitary Game—XVI. Backgammon, anciently called Tables;—The different Manners of playing at Tables—XVII. Backgammon, its former and present Estimation—XVIII. Domino—XIX. Cards, when invented—XX. Card-playing much practised—XXI. Forbidden—XXII. Censured by Poets—XXIII. A Specimen of ancient Cards—XXIV. Games formerly played with Cards—XXV. The Game of Goose—and of the Snake—XXVI. Cross and Pile | 305 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| I. The Lord of Misrule said to be peculiar to the English—II. A Court Officer—III. The Master of the King's Revels—IV. The Lord of Misrule and his Conduct reprobated—V. The King of Christmas—of the Cockneys—VI. A King of Christmas at Norwich—VII. The King of the Bean—VIII. Whence originated—IX. The Festival of Fools—X. The Boy Bishop—XI. The Fool Plough—XII. Easter Games—XIII. Shrove-Tuesday—XIV. Hock-Tuesday—XV. May-Games—XVI. The Lord and Lady of the May—XVII. Grand May-Game at Greenwich—XVIII. Royal May-Game at Shooter's-hill— [Pg xvi] XIX. May Milk-Maids—XX. May Festival of the Chimney Sweepers—XXI. Whitsun-Games—XXII. The Vigil of Saint John the Baptist, how kept—XXIII. Its supposed origin—XXIV. Setting of the Midsummer Watch—XXV. Processions on Saint Clement's and Saint Catherine's day—XXVI. Wassails—XXVII. Sheep-shearing and Harvest-home—XXVIII. Wakes—XXIX Sunday Festivals—XXX. Church Ales—XXXI. Fairs, and their Diversions and Abuses—XXXII. Bonfires—XXXIII. Illuminations—XXXIV. Fireworks—XXXV. London Fireworks—XXXVI. Fireworks on Tower-hill, at Public Gardens, and in Pageants | 339 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| I. Popular manly Pastimes imitated by Children—II. Horses—III. Racing and Chacing—IV. Wrestling and other Gymnastic Sports—V. Marbles, and Span-counter—VI. Tops, &c.;—The Devil among the Tailors—VII. Even or Odd—Chuck-halfpenny;—Duck and Drake—VIII. Baste the Bear;—Hunt the Slipper, &c.—IX. Sporting with Insects;—Kites;—Windmills—X. Bob-cherry—XI. Hoodman-blind;—Hot-cockles—XII. Cock-fighting—XIII. Anonymous Pastimes;—Mock Honours at Boarding-schools—XIV. Houses of Cards;—Questions and Commands;—Handy-dandy;—Snap-dragon;—Push-pin;—Crambo;—Lotteries —XV. Obsolete Pastimes-XVI. Creag;—Queke-board;—Hand in and Hand out;—White and Black, and Making and Marring;—Figgum;—Mosel the Peg;-Hole about the Church-yard;—Penny-prick;—Pick-point, &c.;—Mottoes, Similes, and Cross-purposes;—The Parson has lost his Cloak | 379 |

A GENERAL ARRANGEMENT OF THE POPULAR SPORTS, PASTIMES, AND MILITARY GAMES, TOGETHER WITH THE VARIOUS SPECTACLES OF MIRTH OR SPLENDOUR, EXHIBITED PUBLICLY OR PRIVATELY, FOR THE SAKE OF AMUSEMENT, AT DIFFERENT PERIODS, IN ENGLAND.

In order to form a just estimation of the character of any particular people, it is absolutely necessary to investigate the Sports and Pastimes most generally prevalent among them. [Pg xviii] War, policy, and other contingent circumstances, may effectually place men, at different times, in different points of view, but, when we follow them into their retirements, where no disguise is necessary, we are most likely to see them in their true state, and may best judge of their natural dispositions. Unfortunately, all the information that remains respecting the ancient inhabitants of this island is derived from foreign writers partially acquainted with them as a people, and totally ignorant of their domestic customs and amusements: the silence, therefore, of the contemporary historians on these important subjects leaves us without the power of tracing them with the least degree of certainty; and as it is my intention, in the following pages, to confine myself as much as possible to positive intelligence, I shall studiously endeavour to avoid all controversial and conjectural arguments. I mean also to treat upon such pastimes only as have been practised in this country; but as many of them originated on the continent, frequent digressions, by way of illustrations, must necessarily occur: these, however, I shall make it my business to render as concise as the nature of the subject will permit them to be.

We learn, from the imperfect hints of ancient history, that, when the Romans first invaded Britain, her inhabitants were a bold, active, and warlike people, tenacious of their native liberty, and capable of bearing great fatigue; to which they were probably inured by an early education, and constant pursuit of such amusements as best suited the profession of a soldier; including hunting, running, leaping, swimming, and other exertions requiring strength and agility of body. Perhaps the skill which the natives of Devonshire and Cornwall retain to the present day, in hurling and wrestling, may properly be considered as a vestige of British activity. After the Romans had conquered Britain, they impressed such of the young men as were able to bear arms for foreign service, and enervated the spirit of the people by the importation of their own luxurious manners and habits; so that the latter part of the British history exhibits to our view a slothful and effeminate race of men, totally divested of that martial disposition, and love of freedom, which so strongly marked the character of their progenitors; and their [Pg xix] amusements, no doubt, partook of the same weakness and puerility.

The arrival of the Saxons forms a new epoch in the annals of this country. These military mercenaries came professedly to assist the Britons against their incessant tormentors the Picts and the Caledonians; but no sooner had they established their footing in the land, than they invited more of their countrymen to join them, and turning their arms against their wretched employers, became their most dangerous and most inexorable enemies, and in process of time obtained full possession of the largest and best part of the island; whence arose a total change in the form of government, laws, manners, customs, and habits of the people.

The sportive exercises and pastimes practised by the Saxons appear to have been such as were common among the ancient northern nations; and most of them consisted of robust exercises. In an old Chronicle of Norway, [1] we find it recorded of Olaf Tryggeson, a king of that country, that he was stronger and more nimble than any man in his dominions. He could climb up the rock Smalserhorn, and fix his shield upon the top of it; he could walk round the outside of a boat upon the oars, while the men were rowing; he could play with three darts, alternately throwing them in the air, and always kept two of them up, while he held the third in one of his hands; he was ambidexter, and could cast two darts at once; he excelled all the men of his time in shooting with the bow; and he had no equal in swimming. In one achievement this monarch was outdone by the Anglo-Saxon ᵹlıᵹman, represented by the engraving No. 50, [2] who adds an equal number of balls to those knives or daggers. The Norman minstrel Tallefer, before the commencement of the battle at Hastings, cast his lance into the air three times, and caught it by the head in such a surprising manner, that the English thought it was done by the power of enchantment. Another northern hero, whose name was Kolson, boasts of nine accomplishments in which he was well skilled: "I know," says he, "how to play at chess; I can engrave Runic letters; I am expert at my book; I know how to handle [Pg xx] the tools of the smith; [3] I can traverse the snow on skates of wood; I excel in shooting with the bow; I use the oar with facility; I can sing to the harp; and I compose verses." [4] The reader will, I doubt not, anticipate me in my observation, that the acquirements of Kolson indicate a much more liberal education than those of the Norwegian monarch: it must, however, be observed, that Kolson lived in an age posterior to him; and also, that he made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, which may probably account in great measure for his literary qualifications. Yet, we are well assured that learning did not form any prominent feature in the education of a young nobleman during the Saxon government: it is notorious, that Alfred the Great was twelve years of age before he learned to read; and that he owed his knowledge of letters to accident, rather than to the intention of his tutors. A book adorned with paintings in the hands of his mother, attracted his notice, and he expressed his desire to have it: she promised to comply with his request on condition that he learned to read it, which it seems he did; and this trifling incident laid the groundwork of his future scholarship. [5]

Indeed, it is not by any means surprising, under the Saxon government, when the times were generally very turbulent, and the existence of peace exceedingly precarious, and when the personal exertions of the opulent were so often necessary for the preservation of their lives and property, that such exercises as inured the body to fatigue, and biassed the mind to military pursuits, should have constituted the chief part of a young nobleman's education: accordingly, we find that hunting, hawking, leaping, running, wrestling, casting of darts, and other pastimes which necessarily required great exertions of bodily strength, were taught them in their adolescence. These amusements engrossed the whole of their attention, every one striving to excel his fellow; for hardiness, strength, and valour, out-balanced, in the public estimation, the accomplishments of the mind; and therefore literature, which flourishes best in tranquillity and retirement, was considered as a pursuit unworthy the notice of a soldier, and only requisite in the gloomy recesses of the cloister.

Among the vices of the Anglo-Saxons may be reckoned their [Pg xxi] propensity to gaming, and especially with the dice, which they derived from their ancestors; for Tacitus [6] assures us that the ancient Germans would not only hazard all their wealth, but even stake their liberty, upon the turn of the dice; "and he who loses," says the author, "submits to servitude, though younger and stronger than his antagonist, and patiently permits himself to be bound, and sold in the market; and this madness they dignify by the name of honour." Chess was also a favourite game with the Saxons; and likewise backgammon, said to have been invented about the tenth century. It appears moreover, that a large portion of the night was appropriated to the pursuit of these sedentary amusements. In the reign of Canute the Dane, this practice was sanctioned by the example of royalty, and followed by the nobility. Bishop Ætheric, having obtained admission to Canute about midnight upon some urgent business, found the king engaged with his courtiers at play, some at dice, and some at chess. [7] The clergy, however, were prohibited from playing at games of chance, by the ecclesiastical canons established in the reign of Edgar. [8]

The popular sports and pastimes, prevalent at the close of the Saxon era, do not appear to have been subjected to any material change by the coming of the Normans: it is true, indeed, that the elder William and his immediate successors restricted the privileges of the chase, and imposed great penalties on those who presumed to destroy the game in the royal forests, without a proper licence. [9] By these restrictions the general practice of hunting was much confined, but by no means prohibited in certain districts, and especially to persons of opulence who possessed extensive territories of their own.

Among the pastimes introduced by the Norman nobility, none engaged the general attention more than the tournaments and the justs. The tournament, in its original institution, was [Pg xxii] a martial conflict, in which the combatants engaged without any animosity, merely to exhibit their strength and dexterity; but, at the same time, engaged in great numbers to represent a battle. The just was when two knights, and no more, were opposed to each other at one time. These amusements, in the middle ages, which may properly enough be denominated the ages of chivalry, were in high repute among the nobility of Europe, and produced in reality much of the pomp and gallantry that we find recorded with poetical exaggeration in the legends of knight-errantry. I met with a passage in a satirical poem among the Harleian MSS. of the thirteenth century, [10] which strongly marks the prevalence of this taste in the times alluded to. It may be thus rendered in English:

While the principles of chivalry continued in fashion, the education of a nobleman was confined to those principles, and every regulation necessary to produce an accomplished knight was put into practice. In order fully to investigate these particulars, we may refer to the romances of the middle ages; and, generally speaking, dependence may be placed upon their information. The authors of these fictitious histories never looked beyond the customs of their own country; and whenever the subject called for a representation of remote magnificence, they depicted such scenes of splendour as were familiar to them: hence it is, that Alexander the Great, in his legendary life, receives the education of a Norman baron, and becomes expert in hawking, hunting, and other amusements coincident with the time in which the writer lived. Our early poets have fallen into the same kind of anachronism; and Chaucer himself, in the Knight's Tale, speaking of the rich array and furniture of the palace of Theseus, forgets that he was a Grecian prince of great antiquity, and describes the large hall belonging to an [Pg xxiii] English nobleman, with the guests seated at table, probably as he had frequently seen them, entertained with singing, dancing, and other acts of minstrelsy, their hawks being placed upon perches over their heads, and their hounds lying round about upon the pavement below. The two last lines of the poem just referred to are peculiarly applicable to the manners of the time in which the poet lived, when no man of consequence travelled abroad without his hawk and his hounds. In the early delineations, the nobility are frequently represented seated at table, with their hawks upon their heads. Chaucer says,

The picture is perfect, when referred to his own time; but bears not the least analogy to Athenian grandeur. In the romance called The Knight of the Swan, it is said of Ydain duchess Roulyon, that she caused her three sons to be brought up in "all maner of good operacyons, vertues, and maners; and when in their adolescence they were somwhat comen to the age of strengthe, they," their tutors, "began to practyse them in shootinge with their bow and arbelstre, [12] to playe with the sword and buckeler, to runne, to just, [13] to playe with a poll-axe, and to wrestle; and they began to bear harneys, [14] to runne horses, and to approve them, as desyringe to be good and faythful knightes to susteyne the faith of God." We are not, however to conceive, that martial exercises in general were confined to the education of young noblemen: the sons of citizens and yeomen had also their sports resembling military combats. Those practised at an early period by the young Londoners seem to have been derived from the Romans; they consisted of various attacks and evolutions performed on horseback, the youth being armed with shields and pointless lances, resembling the ludus Trojæ, or Troy game, described by Virgil. [15] These amusements, according to Fitz Stephen, who lived in the reign of Henry II., were appropriated to the season of Lent; but at other times they exercised themselves with archery, fighting with clubs and bucklers, and running at the quintain; and in the winter, when the frost set in, they would go upon the ice, and run against [Pg xxiv] each other with poles, in imitation of lances, in a just; and frequently one or both were beaten down, "not always without hurt; for some break their arms, and some their legs; but youth," says my author, "emulous of glory, seeks these exercises preparatory against the time that war shall demand their presence." The like kind of pastimes, no doubt, were practised by the young men in other parts of the kingdom.

The mere management of arms, though essentially requisite, was not sufficient of itself to form an accomplished knight in the times of chivalry; it was necessary for him to be endowed with beauty, as well as with strength and agility of body; he ought to be skilled in music, to dance gracefully, to run with swiftness, to excel in wrestling, to ride well, and to perform every other exercise befitting his situation. To these were to be added urbanity of manners, strict adherence to the truth, and invincible courage. Hunting and hawking skilfully were also acquirements that he was obliged to possess, and which were usually taught him as soon as he was able to endure the fatigue that they required. Hence it is said of sir Tristram, a fictitious character held forth as the mirror of chivalry in the romance entitled The Death of Arthur, that "he learned to be an harper, passing all other, that there was none such called in any countrey: and so in harping and on instruments of musike he applied himself in his youth for to learne, and after as he growed in might and strength he laboured ever in hunting and hawking, so that we read of no gentlemen who more, or so, used himself therein; and he began good measures of blowing blasts of venery, [16] and chase, and of all manner of vermains; [17] and all these terms have we yet of hunting and hawking; and therefore the book of venery, and of hawking and hunting, is called the Boke of Sir Tristram." In a succeeding part of the same romance, king Arthur thus addresses the knight: "For all manner of hunting thou bearest the prize; and of all measures of blowing thou art the beginner, and of all the termes [Pg xxv] of hunting and hawking thou art the beginner." [18] We are also informed, that sir Tristram had previously learned the language of France, knew all the principles of courtly behaviour, and was skilful in the various requisites of knighthood. Another ancient romance says of its hero, "He every day was provyd in dauncyng and in songs that the ladies coulde think were convenable for a nobleman to conne; [19] but in every thinge he passed all them that were there. The king, for to assaie him, made justes and turnies; and no man did so well as he, in runnyng, playing at the pame, [20] shotyng, and castyng of the barre, ne found he his maister." [21]

The laws of chivalry required that every knight should pass through two offices: the first was a page; and, at the age of fourteen, he was admitted an esquire. The office of the esquire consisted of several departments; the esquire for the body, the esquire of the chamber, the esquire of the stable, and the carving esquire; the latter stood in the hall at dinner, carved the different dishes, and distributed them to the guests. Several of the inferior officers had also their respective esquires. [22] Ipomydon, a king's son and heir, in the romance that bears his name, written probably at the commencement of the fourteenth century, is regularly taught the duties of an esquire, previous to his receiving the honours of knighthood; and for this purpose his father committed him to the care of a "learned and courteous knight called Sir 'Tholomew." Our author speaks on this subject in the following manner:

Here we find reading mentioned; which, however, does not appear to have been of any great importance in the middle ages, and is left out in the Geste of King Horne, another metrical romance, [24] which seems to be rather more ancient than the former. Young Horne is placed under the tuition of Athelbrus, the king's steward, who is commanded to teach him the mysteries of hawking and hunting, to play upon the harp,

to carve at the royal table, and to present the cup to the king when he sat at meat, with every other service fitting for him to know. The monarch concludes his injunctions with a repetition of the charge to instruct him in singing and music:

And the manner in which the king's carver performed the duties of his office is well described in the poem denominated the Squyer of Lowe Degree: [25]

Tournaments and justs were usually exhibited at coronations royal marriages, and other occasions of solemnity where pomp and pageantry were thought to be requisite. Our historians abound with details of these celebrated pastimes. The reader is referred to Froissart, Hall, Holinshed, Stow, Grafton, &c. who are all of them very diffuse upon this subject; and in the second volume of the Manners and Customs of the English are several curious representations of these military combats both on horseback and on foot.

One great reason, and perhaps the most cogent of any, why the nobility of the middle ages, nay, and even princes and kings, delighted so much in the practice of tilting with each other, is, that on such occasions they made their appearance with prodigious splendour, and had the opportunity of displaying their accomplishments to the greatest advantage. The ladies also were proud of seeing their professed champions engaged in these arduous conflicts; and, perhaps, a glove or riband from the hand of a favourite female might have inspired the receiver with as zealous a wish for conquest, as the abstracted love of glory; though in general, I presume, both these ideas were united; for a knight divested of gallantry would have been considered as a recreant, and unworthy of his profession.

When the military enthusiasm which so strongly characterised the middle ages had subsided, and chivalry was on the decline, a prodigious change took place in the nurture and manners of the nobility. Violent exercises requiring the exertions of muscular strength grew out of fashion with persons of rank, and of course were consigned to the amusement of the vulgar; and the education of the former became proportionably more soft [Pg xxviii] and delicate. This example of the nobility was soon followed by persons of less consequence; and the neglect of military exercises prevailed so generally, that the interference of the legislature was thought necessary, to prevent its influence from being universally diffused, and to correct the bias of the common mind; for, the vulgar readily acquiesced with the relaxation of meritorious exertions, and fell into the vices of the times, resorting to such games and recreations as promoted idleness and dissipation, by which they lost their money, and, what is worse, their reputation, entailing poverty and distress on themselves and their families.

The romantic notions of chivalry appear to have lost their vigour towards the conclusion of the fifteenth century, especially in this country, where a continued series of intestine commotions employed the exertions of every man of property, and real battles afforded but little leisure to exercise the mockery of war. It is true, indeed, that tilts and tournaments, with other splendid exhibitions of military skill, were occasionally exercised, and with great brilliancy, so far as pomp and finery could contribute to make them attractive, till the end of the succeeding century. These splendid pastimes were encouraged by the sanction of royalty, and this sanction was perfectly political; on the one hand, it gratified the vanity of the nobility, and, on the other, it amused the populace, who, being delighted with such shows of grandeur, were thereby diverted from reflecting too deeply upon the grievances they sustained. It is, however, certain that the justs and tournaments of the latter ages, with all their pomp, possessed but little of the primitive spirit of chivalry.

Henry VII. patronized the gentlemen and officers of his court in the practice of military exercises. The following extract may serve as a specimen of the manner in which they were appointed to be performed: "Whereas it ever hath bene of old antiquitie used in this realme of most noble fame, for all lustye gentlemen to passe the delectable season of summer after divers [Pg xxix] manner and sondry fashions of disports, as in hunting the red and fallowe deer with houndes, greyhoundes, and with the bowe; also in hawking with hawkes of the tower; and other pastimes of the field. And bycause it is well knowen, that in the months of Maie and June, all such disports be not convenient; wherefore, in eschewing of idleness, the ground of all vice," and to promote such exercises as "shall be honourable, and also healthfull and profitable to the body," we "beseech your most noble highness to permit two gentlemen, assosyatying to them two other gentlemen to be their aides," by "your gracious licence, to furnish certain articles concerning the feates of armes hereafter ensuinge:"—"In the first place; On the twenty-second daye of Maie, there shall be a grene tree sett up in the lawnde of Grenwich parke; whereupon shall hange, by a grene lace, a vergescu [27] blanke; upon which white shield it shal be lawful for any gentleman that will answer the following chalenge to subscribe his name.—Secondly; The said two gentlemen, with their two aides, shal be redye on the twenty-thirde daie of Maie, being Thursdaye, and on Mondaye thence next ensewinge, and so everye Thursday and Monday untill the twentieth daye of June, armed for the foote, to answear all gentlemen commers, at the feate called the Barriers, with the casting-speare, and the targett, and with the bastard-sword, [28] after the manner following, that is to saie, from sixe of the clocke in the forenoone till sixe of the clocke in the afternoone during the time.—Thirdly; And the said two gentlemen, with their two aiders, or one of them, shall be there redye at the said place, the daye and dayes before rehearsed, to deliver any of the gentlemen answeares of one caste with the speare hedded with the morne, [29] and seven strokes with the sword, point and edge rebated, without close, or griping one another with handes, upon paine of punishment as the judges for the time being shall thinke requisite.—Fourthly; And it shall not be lawfull to the challengers, nor to the answearers, with the bastard sword to give or offer any foyne [30] to his match, upon paine of like punishment.—Fifthly; The challengers shall bringe into the fielde, the said daies and tymes, all manner of [Pg xxx] weapons concerning the said feates, that is to saye, casting speares hedded with mornes, and bastard swords with the edge and point rebated; and the answerers to have the first choise." [31]

Henry VIII. not only countenanced the practice of military pastimes by permitting them to be exercised without restraint, but also endeavoured to make them fashionable by his own example. Hall assures us, that, even after his accession to the throne, he continued daily to amuse himself in archery, casting of the bar, wrestling, or dancing, and frequently in tilting, tournaying, fighting at the barriers with swords, and battle-axes, and such like martial recreations, in most of which there were few that could excel him. His leisure time he spent in playing at the recorders, flute, and virginals, in setting of songs, singing and making of ballads. [32] He was also exceedingly fond of hunting, hawking, and other sports of the field; and indeed his example so far prevailed, that hunting, hawking, riding the great horse, charging dexterously with the lance at the tilt, leaping, and running, were necessary accomplishments for a man of fashion. [33] The pursuits and amusements of a nobleman are placed in a different point of view by an author of the succeeding century; [34] who, describing the person and manners of Charles lord Mountjoy, regent of Ireland, in 1599, says, "He delighted in study, in gardens, in riding on a pad to take the aire, in playing at shovelboard, at cardes, and in reading of play-bookes for recreation, and especially in fishing and fish-ponds, seldome useing any other exercises, and useing these rightly as pastimes, only for a short and convenient time, and with great variety of change from one to the other." The game of shovelboard, though now considered as exceedingly vulgar, and practised by the lower classes of the people, was formerly in great repute among the nobility and gentry; and few of their mansions were without a shovelboard, which was a fashionable piece of furniture. The great hall was usually the place for its reception.

We are by no means in the dark respecting the education of the nobility in the reign of James I.; we have, from that monarch's own hand, a set of rules for the nurture and conduct of an heir apparent to the throne, addressed to his eldest son Henry, prince of Wales. From the third book of this remarkable publication, entitled ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΟΝ ΔΩΡΟΝ, or, a Kinge's Christian Dutie towards God," I shall select such parts as respect the recreations said to be proper for the pursuit of a nobleman, without presuming to make any alteration in the diction of the royal author.

"Certainly," he says, "bodily exercises and games are very commendable, as well for bannishing of idleness, the mother of all vice; as for making the body able and durable for travell, which is very necessarie for a king. But from this court I debarre all rough and violent exercises; as the foote-ball, meeter for lameing, than making able, the users thereof; as likewise such tumbling trickes as only serve for comœdians and balladines to win their bread with: but the exercises that I would have you to use, although but moderately, not making a craft of them, are, running, leaping, wrestling, fencing, dancing, and playing at the caitch, or tennise, archerie, palle-malle, and such like other fair and pleasant field-games. And the honourablest and most recommendable games that yee can use on horseback; for, it becometh a prince best of any man to be a faire and good horseman: use, therefore, to ride and danton great and courageous horses;—and especially use such games on horseback as may teach you to handle your armes thereon, such as the tilt, the ring, and low-riding for handling of your sword.

"I cannot omit heere the hunting, namely, with running houndes, which is the most honourable and noblest sort thereof; for it is a theivish forme of hunting to shoote with gunnes and bowes; and greyhound hunting [35] is not so martial a game.

"As for hawkinge, I condemn it not; but I must praise it more sparingly, because it neither resembleth the warres so neere as hunting doeth in making a man hardie and skilfully ridden in all grounds, and is more uncertain and subjec. to mischances; [Pg xxxii] and, which is worst of all, is there through an extreme stirrer up of the passions.

"As for sitting, or house pastimes—since they may at times supply the roome which, being emptie, would be patent to pernicious idleness—I will not therefore agree with the curiositie of some learned men of our age in forbidding cardes, dice, and such like games of hazard: [36] when it is foule and stormie weather, then I say, may ye lawfully play at the cardes or tables; for, as to diceing, I think it becommeth best deboshed souldiers to play at on the heads of their drums, being only ruled by hazard, and subject to knavish cogging; and as for the chesse, I think it over-fond, because it is over-wise and philosophicke a folly."

His majesty concludes this subject with the following good advice to his son: "Beware in making your sporters your councellors, and delight not to keepe ordinarily in your companie comœdians or balladines."

The discontinuation of bodily exercises afforded a proportionable quantity of leisure time for the cultivation of the mind; so that the manners of mankind were softened by degrees, and learning, which had been so long neglected, became fashionable, and was esteemed an indispensable mark of a polite education. Yet some of the nobility maintained for a long time the old prejudices in favour of the ancient mode of nurture, and preferred exercise of the body to mental endowments; such was the opinion of a person of high rank, who said to Richard Pace, secretary to king Henry VIII., "It is enough for the sons of noblemen to wind their horn and carry their hawke fair, and leave study and learning to the children of meaner people." [37] Many of the pastimes that had been countenanced by the nobility, and sanctioned by their example, in the middle ages, grew into disrepute in modern times, and were condemned as vulgar and unbecoming the notice of a gentleman. "Throwing the hammer and wrestling," says Peacham, in his Complete Gentleman, [Pg xxxiii] published in 1622, "I hold them exercises not so well beseeming nobility, but rather the soldiers in the camp and the prince's guard." On the contrary, sir William Forest, in his Poesye of Princelye Practice, a MS. in the Royal Library, [38] written in the year 1548, laying down the rules for the education of an heir apparent to the crown, or prince of the blood royal, writes thus:

However, I doubt not both these authors spoke agreeably to the taste of the times in which they lived. Barclay, a more early poetic writer, in his Eclogues, first published in 1508, has made a shepherd boast of his skill in archery; to which he adds,

Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy, published in 1660, gives us a general view of the sports most prevalent in the seventeenth century. "Cards, dice, hawkes, and hounds," says he, "are rocks upon which men lose themselves, when they are imprudently handled, and beyond their fortunes." And again, "Hunting and hawking are honest recreations, and fit for some great men, but not for every base inferior person, who, while they maintain their faulkoner, and dogs, and hunting nags, their wealth runs away with their hounds, and their fortunes fly away with their hawks." In another place he speaks thus: "Ringing, bowling, shooting, playing with keel-pins, tronks, coits, pitching of bars, hurling, wrestling, leaping, running, fencing, mustering, swimming, playing with wasters, foils, foot-balls, balowns, running at the quintain, and the like, are common recreations of country folks: riding [Pg xxxiv] of great horses, running at rings, tilts and tournaments, horse-races, and wild-goose chases, which are disports of greater men, and good in themselves, though many gentlemen by such means gallop quite out of their fortunes." Speaking of the Londoners, he says, "They take pleasure to see some pageant or sight go by, as at a coronation, wedding, and such like solemn niceties; to see an ambassador or a prince received and entertained with masks, shows, and fireworks. The country hath also his recreations, as May-games, feasts, fairs, and wakes." The following pastimes he considers as common both in town and country, namely, "bull-baitings and bear-baitings, in which our countrymen and citizens greatly delight, and frequently use; dancers on ropes, jugglers, comedies, tragedies, artillery gardens, and cock-fighting." He then goes on: "Ordinary recreations we have in winter, as cards, tables, dice, shovelboard, chess-play, the philosopher's game, small trunks, shuttle-cock, billiards, music, masks, singing, dancing, ule-games, frolicks, jests, riddles, catches, cross purposes, questions and commands, merry tales of errant knights, queens, lovers, lords, ladies, giants, dwarfs, thieves, cheaters, witches, fairies, goblins, and friars." To this catalogue he adds: "Dancing, singing, masking, mumming, and stage-plays, are reasonable recreations, if in season; as are May-games, wakes, and Whitson-ales, if not at unseasonable hours, are justly permitted. Let them," that is, the common people, "freely feast, sing, dance, have puppet-plays, hobby-horses, tabers, crowds, [39] and bagpipes:" let them "play at ball and barley-brakes;" and afterwards, "Plays, masks, jesters, gladiators, tumblers, and jugglers, are to be winked at, lest the people should do worse than attend them."

A character in the Cornish Comedy, written by George Powell, and acted at Dorset Garden in 1696, says, "What is a gentleman without his recreations? With these we endeavour to pass away that time which otherwise would lie heavily upon our hands. Hawks, hounds, setting-dogs, and cocks, with their appurtenances, are the true marks of a country gentleman." This character is supposed to be a young heir just come to his estate. "My cocks," says he, "are true cocks of the game—I make a match of cock-fighting, and then an hundred or two pounds are soon won, for I never fight a battle under." [Pg xxxv]

In addition to the May-games, morris-dancings, pageants and processions, which were commonly exhibited throughout the kingdom in all great towns and cities, the Londoners had peculiar and extensive privileges of hunting, hawking, and fishing: [40] they had also large portions of ground allotted to them in the vicinity of the city for the practice of such pastimes as were not prohibited by the government, and for those especially that were best calculated to render them strong and healthy. We are told by Fitz Stephen, in the twelfth century, that on the holidays during the summer season, the young men of London exercised themselves in the fields with "leaping, shooting with the bow, wrestling, casting the stone, playing with the ball, and fighting with their shields." The last species of pastime, I believe, is the same that Stow, in his Survey of London, calls "practising with their wasters and bucklers;" which in his day was exercised by the apprentices before the doors of their masters. The city damsels had also their recreations on the celebration of these festivals, according to the testimony of both the authors just mentioned. The first tells us that they played upon citherns, [41] and danced to the music; and as this amusement probably did not take place before the close of the day, they were, it seems, occasionally permitted to continue it by moonlight. We learn from the other, who wrote at the distance of more than four centuries, that it was then customary for the maidens, after evening prayers, to dance in the presence of their masters and mistresses, while one of their companions played the measure upon a timbrel; and, in order to stimulate them to pursue this exercise with alacrity, the best dancers were rewarded with garlands, the prizes being exposed to public view, "hanged athwart the street," says Stow, during the whole of the performance. This recital calls to my mind a passage in Spenser's Epithalamium, wherein it appears that the dance was sometimes accompanied with singing. It runs thus:

A general view of the pastimes practised by the Londoners soon after the commencement of the last century occurs in Strype's edition of Stow's Survey of London, published in 1720. [42] "The modern sports of the citizens," says the editor, "besides drinking, are cock-fighting, bowling upon greens, playing at tables, or backgammon, cards, dice, and billiards; also musical entertainments, dancing, masks, balls, stage-plays, and club-meetings, in the evening; they sometimes ride out on horseback, and hunt with the lord-mayor's pack of dogs when the common hunt goes out. The lower classes divert themselves at foot-ball, wrestling, cudgels, nine-pins, shovelboard, cricket, stow-ball, ringing of bells, quoits, pitching the bar, bull and bear baitings, throwing at cocks, and, what is worst of all, lying at alehouses." To these are added, by an author of later date, Maitland, in his History of London, published in 1739, "Sailing, rowing, swimming and fishing, in the river Thames, horse and foot races, leaping, archery, bowling in allies, and skittles, tennice, chess, and draughts; and in the winter scating, sliding, and shooting." Duck-hunting was also a favourite amusement, but generally practised in the summer. The pastimes here enumerated were by no means confined to the city of London, or its environs: the larger part of them were in general practice throughout the kingdom.

Before I quit this division of my subject, I shall mention the annual celebration of games upon Cotswold Hills, in Gloucestershire, to which prodigious multitudes constantly resorted. Robert Dover, an attorney, of Barton on the Heath, in the county of Warwick, was forty years the chief director of these pastimes. They consisted of wrestling, cudgel-playing, leaping, pitching the bar, throwing the sledge, tossing the pike, with various other feats of strength and activity; many of the country gentlemen hunted or coursed the hare; and the women danced. A castle of boards was erected on this occasion, from which guns were frequently discharged. "Captain Dover received [Pg xxxvii] permission from James I. to hold these sports; and he appeared at their celebration in the very clothes which that monarch had formerly worn, but with much more dignity in his air and aspect." [43] I do not mean to say that the Cotswold games were invented, or even first established, by captain Dover; on the contrary, they seem to be of much higher origin, and are evidently alluded to in the following lines by John Heywood the epigrammatist: [44]

Something of the same sort, I presume, was the Carnival, kept every year, about the middle of July, upon Halgaver-moor, near Bodmin in Cornwall; "resorted to by thousands of people," says Heath, in his description of Cornwall, published in 1750. "The sports and pastimes here held were so well liked by Charles II. when he touched here in his way to Sicily, that he became a brother of the jovial society. The custom of keeping this carnival is said to be as old as the Saxons."

Paul Hentzner, a foreign writer, who visited this country at the close of the sixteenth century, says of the English, in his Itinerary, written in 1598, that they are "serious like the Germans, lovers of show, liking to be followed wherever they go by whole troops of servants, who wear their master's arms in silver." [45] This was no new propensity: the English nobility at all times affected great parade, seldom appearing abroad without large trains of servitors and retainers; and the lower classes of the people delighted in gaudy shows, pageants, and processions.

If we go back to the times of the Saxons, we shall find that, soon after their establishment in Britain, their monarchs assumed great state. Bede tells us that "Edwin, king of Northumberland, lived in much splendour, never travelling without a numerous retinue; and when he walked in the streets of his own capital, even in the times of peace, he had a standard borne before him. This standard was of the kind called by the Romans tufa, [Pg xxxviii] and by the English tuuf: it was made with feathers of various colours, in the form of a globe, and fastened upon a pole." [46] It is unnecessary to multiply citations; for which reason, I shall only add another. Canute the Dane, who is said to have been the richest and most magnificent prince of his time in Europe, rarely appeared in public without being followed by a train of three thousand horsemen, well mounted and completely armed. These attendants, who were called house carles, formed a corps of body guards, or household troops, and were appointed for the honour and safety of that prince's person. [47] The examples of royalty were followed by the nobility and persons of opulence.

In the middle ages, the love of show was carried to an extravagant length; and as a man of fashion was nothing less than a man of letters, those studies that were best calculated to improve the mind were held in little estimation.

The courts of princes and the castles of the great barons were daily crowded with numerous retainers, who were always welcome to their masters' tables. The noblemen had their privy counsellors, treasurers, marshals, constables, stewards, secretaries, chaplains, heralds, pursuivants, pages, henchmen or guards, trumpeters, and all the other officers of the royal court. [48] To these may be added whole companies of minstrels, mimics, jugglers, tumblers, rope-dancers, and players; and especially on days of public festivity, when, in every one of the apartments opened for the reception of the guests, were exhibited variety of entertainments, according to the taste of the times, but in which propriety had very little share; the whole forming a scene of pompous confusion, where feasting, drinking, music, dancing, tumbling, singing, and buffoonery, were jumbled together, and mirth excited too often at the expense of common decency. [49] If we turn to the third Book of Fame, a poem written by our own countryman Chaucer, we shall find a perfect picture of these tumultuous court entertainments, drawn, I doubt not, from reality, and perhaps without [Pg xxxix] any exaggeration. It may be thus expressed in modern language: Minstrels of every kind were stationed in the receptacles for the guests; among them were jesters, that related tales of mirth and of sorrow; excellent players upon the harp, with others of inferior merit [50] seated on various seats below them, who mimicked their performances like apes to excite laughter; behind them, at a great distance, was a prodigious number of other minstrels, making a great sound with cornets, shaulms, flutes, horns, [51] pipes of various kinds, and some of them made with green corn, [52] such as are used by shepherds' boys; there were also Dutch pipers to assist those who chose to dance either "love-dances, springs, or rayes," [53] or any other new-devised measures. Apart from these were stationed the trumpeters and players on the clarion; and other seats were occupied by different musicians playing variety of mirthful tunes. There were also present large companies of jugglers, magicians, and tregetours, who exhibited surprising tricks by the assistance of natural magic.

Vast sums of money were expended in support of these absurd and childish spectacles, by which the estates of the nobility were consumed, and the public treasuries often exhausted. But we shall have occasion to speak more fully on this subject hereafter. [54]

The pageantry and shows exhibited in great towns and cities on occasions of joy and solemnity were equally deficient in taste and genius. At London, where they were most frequently required, that is to say, at the reception of foreign monarchs, at the processions of our own through the city of London to Westminster previous to their coronation, or at their return from abroad, and on various other occasions; besides such as occurred at stated times, as the lord-mayor's show, the setting of the midsummer watch, and the like, a considerable number of [Pg xl] different artificers were kept, at the city's expense, to furnish the machinery for the pageants, and to decorate them. Stow tells us that, in his memory, great part of Leaden Hall was appropriated to the purpose of painting and depositing the pageants for the use of the city.

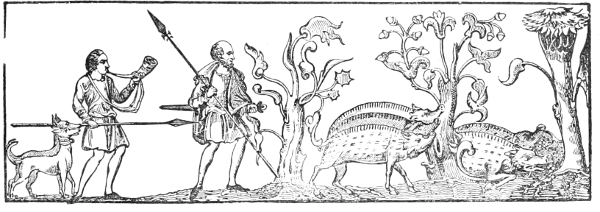

The want of elegance and propriety, so glaringly evident in these temporary exhibitions, was supplied, or attempted to be supplied, by a tawdry resemblance of splendour. The fronts of the houses in the streets through which the processions passed were covered with rich adornments of tapestry, arras, and cloth of gold; the chief magistrates and most opulent citizens usually appeared on horseback in sumptuous habits and joined the cavalcade; while the ringing of bells, the sound of music from various quarters, and the shouts of the populace, nearly stunned the ears of the spectators. At certain distances, in places appointed for the purpose, the pageants were erected, which were temporary buildings representing castles, palaces, gardens, rocks, or forests, as the occasion required, where nymphs, fawns, satyrs, gods, goddesses, angels, and devils, appeared in company with giants, savages, dragons, saints, knights, buffoons, and dwarfs, surrounded by minstrels and choristers; the heathen mythology, the legends of chivalry, and Christian divinity, were ridiculously jumbled together, without meaning; and the exhibition usually concluded with dull pedantic harangues, exceedingly tedious, and replete with the grossest adulation. The giants especially were favourite performers in the pageants; they also figured away with great applause in the pages of romance; and, together with dragons and necromancers, were created by the authors for the sole purpose of displaying the prowess of their heroes, whose business it was to destroy them.

Some faint traces of the processional parts of these exhibitions were retained at London in the lord mayor's show about twenty or thirty years ago; [55] but the pageants and orations have been long discontinued, and the show itself is so much contracted, that it is in reality altogether unworthy of such an appellation. [Pg xli]

In an old play, the Historie of Promos and Cassandra, part the second, by George Whetstone, printed in 1578, [56] a carpenter, and others, employed in preparing the pageants for a royal procession, are introduced. In one part of the city the artificer is ordered "to set up the frames, and to space out the rooms, that the Nine Worthies may be so instauled as best to please the eye." The "Worthies" are thus named in an heraldical MS. in the Harleian Library: [57] "Duke Jossua; Hector of Troy; kyng David; emperour Alexander; Judas Machabyes; emperour Julyus Cæsar; kyng Arthur; emperour Charlemagne; and syr Guy of Warwycke;" but the place of the latter was frequently, and I believe originally, supplied by Godefroy, earl of Bologne: it appears, however, that any of them might be changed at pleasure: Henry VIII. was made a "Worthy" to please his daughter Mary, as we shall find a little farther on. In another part of the same play the carpenter is commanded to "errect a stage, that the wayghtes [58] in sight may stand;" one of the city gates was to be occupied by the fowre Virtues, together with "a consort of music;" and one of the pageants is thus whimsically described:

The stage direction then requires the entry of "Two men apparelled lyke greene men at the mayor's feast, with clubbs of fyreworks;" whose office, we are told, was to keep a clear passage in the street, "that the kyng and his trayne might pass with ease."—In another dramatic performance of later date, Green's Tu Quoque, or the City Gallant, by John Cooke, published in 1614, a city apprentice says, "By this light, I doe not thinke but to be lord mayor of London before I die; and have three pageants carried before me, besides a ship and an unicorn." The following passage occurs in Selden's Table Talk, under the article Judge, "We see the pageants in Cheapside, the lions [Pg xlii] and the elephants; but we do not see the men that carry them we see the judges look big like lions; but we do not see who moves them."

In the foregoing quotations, we have not the least necessity to make an allowance for poetical licence: the historians of the time will justify the poets, and perfectly clear them from any charge of exaggeration; and especially Hall, Grafton, and Holinshed, who are exceedingly diffuse on this and such like popular subjects. The latter has recorded a very curious piece of pantomimical trickery exhibited at the time that the princess Mary went in procession through the city of London, the day before her coronation:—At the upper end of Grace-church-Street there was a pageant made by the Florentines; it was very high; and "on the top thereof there stood foure pictures; and in the midst of them, and the highest, there stood an angell, all in greene, with a trumpet in his hand; and when the trumpetter who stood secretlie within the pageant, did sound his· trumpet, the angell did put his trumpet to his mouth, as though it had been the same that had sounded." A similar deception but on a more extensive scale, was practised at the gate of Kenelworth Castle for the reception of queen Elizabeth. [59] Holinshed, speaking of the spectacles exhibited at London, when Philip king of Spain, with Mary his consort, made their public entry in the city, calls them, in the margin of his Chronicle, "the vaine pageants of London;" and he uses the same epithet twice in the description immediately subsequent; "Now," says he, "as the king came to London, and as he entered at the drawbridge, [on London Bridge,] there was a vaine great spectacle, with two images representing two giants, the one named Corineus, and the other Gog-magog, holding betweene them certeine Latin verses, which, for the vaine ostentation of flatterye, I overpasse." [60] He then adds: "From the [Pg xliii] bridge they passed to the conduit in Gratious-street, which was finely painted; and, among other things," there exhibited, "were the Nine Worthies; of these king Henry VIII. was one. He was painted in harnesse, [61] having in one hand a sword, and in the other hand a booke, whereupon was written Verbum Dei. [62] He was also delivering, as it were, the same booke to his sonne king Edward VI. who was painted in a corner by him." This device, it seems, gave great offence; and the painter, at the queen's command, was summoned before the bishop of Winchester, then lord chancellor, where he met with a very severe reprimand, and was ordered to erase the inscription; to which he readily assented, and was glad to have escaped at so easy a rate from the peril that threatened him; but in his hurry to remove the offensive words, he rubbed out "the whole booke, and part of the hand that held it." [63]

The Nine Worthies appear to have been favourite characters, and were often exhibited in the pageants; those mentioned in the preceding passage were probably nothing more than images of wood or pasteboard. These august personages were not, however, always degraded in this manner, but, on the contrary, they were frequently personified by human beings uncouthly habited, and sometimes mounted on horseback. They also occasionally harangued the spectators as they passed in the procession.

The same species of shows, but probably not upon so extensive a scale, were exhibited in other cities and large towns throughout the kingdom. I have now before me an ordinance for the mayor, aldermen, and common councilmen of the city of Chester, to provide yearly for the setting of the watch, on the eve of the festival of Saint John the Baptist, a pageant, which is expressly said to be "according to ancient custome," consisting of four giants, one unicorn, one dromedary, one luce, [64] one camel, one ass, one dragon, six hobby-horses, and sixteen naked boys. This ordinance among the Harleian MSS. [65] is dated 1564. In another MS. in the same library, it is said, "A. D. 1599, Henry Hardware, esq. the mayor, was a godly and zealous man;" he [Pg xliv] caused "the gyauntes in the midsomer show to be broken," and "not to goe; the devil in his feathers," alluding perhaps to some fantastic representation not mentioned in the former ordinance, "he put awaye, and the cuppes and cannes, and the dragon and the naked boys." In a more modern hand it is added, "And he caused a man in complete armour to go in their stead. He also caused the bull-ring to be taken up," &c. But in the year 1601, John Ratclyffe, beer-brewer, being mayor, "sett out the giaunts and midsommer show, as of oulde it was wont to be kept." [66] In the time of the Commonwealth this spectacle was discontinued, and the giants, with the beasts, were destroyed. At the restoration of Charles II. it was agreed by the citizens to replace the pageant as usual, on the eve of the festival of St. John the Baptist, in 1661; and as the following computation of the charges for the different parts of the show are exceedingly curious, I shall lay them before the reader without any farther apology. We are told that "all things were to be made new, by reason the ould modells were all broken." The computist then proceeds: "For finding all the materials, with the workmanship of the four great giants, all to be made new, as neere as may be lyke as they were before, at five pounds a giant the least that can be, and four men to carry them at two shillings and six pence each." The materials for the composition of these monsters are afterwards specified to be "hoops of various magnitudes, and other productions of the cooper, deal boards, nails, pasteboard, scaleboard, paper of various sorts, with buckram, size cloth, and old sheets for their bodies, sleeves, and shirts, which were to be coloured." One pair of the "olde sheets" were provided to cover the "father and mother giants." Another article specifies "three yards of buckram for the mother's and daughter's hoods;" which seems to prove that three of these stupendous pasteboard personages were the representatives of females. There were "also tinsille, tinfoil, gold and silver leaf, and colours of different kinds, with glue and paste in abundance." Respecting the last article, a very ridiculous entry occurs in the bill of charges, it runs thus: "For arsnick to put into the paste to save the giants from being eaten by the rats, one shilling and fourpence." But to go on with the estimate. "For the new making the city mount, called the maior's mount, as auntiently it was, and for hireing of bays for the same, and a man to carry it, three [Pg xlv] pounds six shillings and eight pence." The bays mentioned in this and the succeeding article was hung round the bottom of the frame, and extended to the ground, or near it, to conceal the bearers. "For making anew the merchant mount, as it aunciently was, with a ship to turn round, the hiring of the bays, and five men to carry it, four pounds." The ship and new dressing it, is charged at five shillings; it was probably made with pasteboard, which seems to have been a principal article in the manufacturing of both the moveable mountains; it was turned by means of a swivel attached to an iron handle underneath the frame. In the bill of charges for "the merchant's mount," is an entry of twenty pence paid to a joyner for cutting the pasteboard into several images. "For making anew the elephant and castell, and a Cupid," with his bow and arrows, "suitable to it," the castle was covered with tinfoil, and the Cupid with skins, so as to appear to be naked, "and also for two men to carry them, one pound sixteen shillings and eightpence. For making anew the four beastes called the unicorne, the antelop, the flower-de-luce, and the camell, one pound sixteen shillings and fourpence apiece, and for eight men to carry them, sixteen shillings. For four hobby-horses, six shillings and eightpence apiece; and for four boys to carry them, four shillings. For hance-staves, garlands, and balls, for the attendants upon the mayor and sheriffs, one pound nineteen shillings. For makinge anew the dragon, and for six naked boys to beat at it, one pound sixteen shillings. For six morris-dancers, with a pipe and tabret, twenty shillings."

The sports exhibited on occasions of solemnity did not terminate with the pageants and processions: the evening was generally concluded with festivity and diversions of various kinds to please the populace. These amusements are well described in a few lines by an early dramatic poet, whose name is not known; his performance is entitled A pleasant and stately Morall of the Three Lordes of London, black letter, no date: [67]—

[Pg xlvi] The "cresset light" was a large lanthorn placed upon a long pole, and carried upon men's shoulders. There is extant a copy of a letter from Henry VII. to the mayor and aldermen of London, commanding them to make bonfires, and to show other marks of rejoicing in the city, when the contract was ratified for the marriage of his daughter Mary with the prince of Castile. [68]

These motley displays of pomp and absurdity, proper only for the amusement of children, or to excite the admiration of the populace, were, however, highly relished by the nobility, and repeatedly exhibited by them, on extraordinary occasions. One would think, indeed, that the repetitions would have been intolerable; on the contrary, for want of more rational entertainments, they maintained for ages their popularity, and do not appear to have lost the smallest portion of their attraction by the frequency of representation. Shows of this kind were never more fashionable than in the sixteenth century, when they were generally encouraged by persons of the highest rank, and exhibited with very little essential variation; and especially during the reign of Henry VIII. [69] His daughter Elizabeth appears to have been equally pleased with this species of pageantry; and therefore it was constantly provided for her amusement, by the nobility whom she visited from time to time, in her progresses or excursions to various parts of the kingdom. [70] I shall simply give the outlines of a succession of entertainments contrived to divert her when she visited the earl of Leicester at Kenelworth castle, and this shall serve as a specimen for the rest.

Her majesty came thither on Saturday the ninth of July, 1575; [71] she was met near the castle by a fictitious Sibyl, who promised peace and prosperity to the country during her reign. Over the first gate of the castle there stood six gigantic figures with trumpets, real trumpeters being stationed behind them, [Pg xlvii] who sounded as the queen approached. This pageant was childish enough, but not more so than the reason for its being placed there. "By this dumb show," says my author, "it was meant that in the daies of king Arthur, men were of that stature; so that the castle of Kenelworth should seem still to be kept by king Arthur's heirs and their servants." Laneham says these figures were eight feet high. Upon her majesty entering the gateway, the porter, in the character of Hercules, made an oration, and presented to her the keys. Being come into the base court, a lady "came all over the pool, being so conveyed, that it seemed she had gone upon the water; she was attended by two water nymphs, and calling herself the Lady of the Lake, she addressed her majesty with a speech prepared for the purpose." The queen then proceeded to the inner court, and passed the bridge, which was railled on both sides, and the tops of the posts were adorned with "sundry presents and gifts," as of wine, corn, fruits, fishes, fowls, instruments of music, and weapons of war. Laneham calls the adorned posts "well-proportioned pillars turned:" he tells us there were fourteen of them, seven on each side of the bridge; on the first pair were birds of various kinds alive in cages, said to be the presents of the god Silvanus; on the next pair were different sorts of fruits in silver bowls, the gift of the goddess Pomona; on the third pair were different kinds of grain in silver bowls, the gift of Ceres; on the fourth, in silvered pots, were red and white wine with clusters of grapes in a silver bowl, the gift of Bacchus; on the fifth were fishes of various kinds in trays, the donation of Neptune; on the sixth were weapons of war, the gift of Mars; and on the seventh, various musical instruments, the presents of Apollo. The meaning of these emblematical decorations was explained in a Latin speech delivered by the author of it. Then an excellent band of music began to play as her majesty entered the inner court, where she alighted from her horse, and went up stairs to the apartments prepared for her.

On Sunday evening she was entertained with a grand display of fireworks, as well in the air as upon the water.

On Monday, after a great hunting, she was met on her return by Gascoigne the poet, so disguised as to represent a savage man, who paid her many high-flown compliments in a kind of dialogue between himself and an echo.

On Tuesday she was diverted with music, dancing, and an interlude upon the water.

[Pg xlviii] On Wednesday was another grand hunting.