Title: Liberation: Marines in the Recapture of Guam

Author: Cyril J. O'Brien

Release date: May 27, 2015 [eBook #49056]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

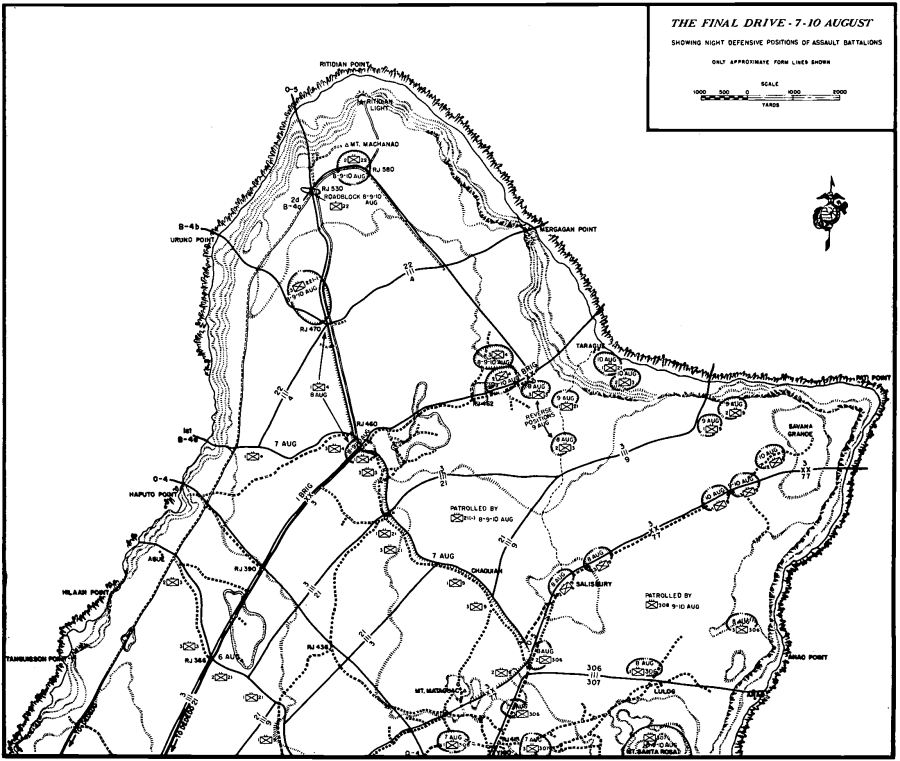

Transcriber’s note: Table of Contents added by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain. Some maps will show more detail in larger windows or when stretched.

Marines in

World War II

Commemorative Series

By Cyril J. O’Brien

by Cyril J. O’Brien

With the instantaneous opening of a two-hour, ever-increasing bombardment by six battleships, nine cruisers, a host of destroyers and rocket ships, laying their wrath on the wrinkled black hills, rice paddies, cliffs, and caves that faced the attacking fleet on the west side of the island, Liberation Day for Guam began at 0530, 21 July 1944.

Fourteen-inch guns belching fire and thunder set spectacular blossoms of flame sprouting on the fields and hillsides inland. It was all very plain to see in the glow of star shells which illuminated the shore, the ships, and the troops who lined the rails of the transports and LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank) which brought the U.S. Marines and soldiers there.

The barrages, which at daylight would be enlarged by the strafing and bombing of carrier fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes, were the grand climax of 13 days (since 8 July) of unceasing prelanding softening-up. Indeed, carrier aircraft of Task Force 58 had been blasting Guam airfields since 11 June, while the first bombardment of the B-24s and B-25s of the Fifth, Seventh, and Thirteenth Air Forces fell as early as 6 May.

Up at 0230 to a by-now traditional Marine prelanding breakfast of steak and eggs, the assault troops, laden with fighting gear, sheathed bayonets protruding from their packs, hurried and waited, while the loudspeakers shouted “Now hear this.... Now hear this.” Unit commanders on board the LSTs visited each of their men, checking gear, straightening packs, rendering an encouraging pat on a shoulder, and squaring away the queues going below to the well decks before boarding the LVTs (Landing Vehicles, Tracked).

Troops on the APAs (attack transports) went over the rail and down cargo nets to which they—weighed down with 40-pound packs as well as weapons—held on for dear life, and into LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel). These troops would transfer from the landing craft to LVTs at the reef’s edge, if all went as planned.

Aircraft went roaring in over mast tops and naval guns produced a continuous booming background noise. Climaxing it all was the voice of Major General Roy S. Geiger, commanding general of III Amphibious Corps, rasping from a bulkhead speaker:

You have been honored. The eyes of the nation watch you as you go into battle to liberate this former American bastion from the enemy. The honor which has been bestowed on you is a signal one. May the glorious traditions of the Marine Corps’ esprit de corps spur you to victory. You have been honored.

In the crowded, stifling well decks of the LSTs, the liberators climbed on board the LVTs and waited claustrophobic until the LST bow doors dropped and the tracked landing vehicles rattled out over these ramps into the swell of the sea. As the amphibian tractors circled (about 0615) near the line of departure, a flight of attack aircraft from the Wasp drowned out the whine of the amtrac engines and whirled up clouds of fire and dust, obscuring the landing beaches ahead. Eighty-five fighters, 65 bombers, and 53 torpedo planes executed a grass-cutting strafing and bombing sweep along all of the landing beaches from above the2 northern beaches of Agana, south for 14 miles to Bangi Point.

“My aim is to get the troops ashore standing up,” said Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly, Southern Attack Force (Task Force 53) commander, who earned the nickname “Close-in Conolly” during the Marshalls operations for his insistence on having his naval gunfire support ships firing from stations very close to the beaches.

Private First Class James G. Helt, a radioman with Headquarters and Service Company, 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, in the bow of an LVT moving towards shore, wondered, as did many others, if anything could still be alive on Guam? Ashore, Lieutenant Colonel Hideyuki Takeda, on the staff of the defending 29th Division, said the island could only be defended if the Americans did not land. In a diary, one Japanese officer noted that the only respite from the bombardment was a “stiff drink.”

The next best thing to a welcome mat for Marine assault waves had been laid by the audacious Navy Underwater Demolition Teams 3, 4, and 6, who cleared the beach obstacles. Navy Chief Petty Officer James R. Chittum of Team 3 noted that these pathfinders were usually close enough to draw small arms fire. At Asan, they exploded 640 wire obstacle cages filled with cemented coral, and at Agat they blew a 200-foot hole for unloading in the coral reef. Team 3, under Navy Reserve Lieutenant Thomas C. Crist, also removed half of a small freighter from a channel blocking the way of the Marines.

Swimmers as well as scouts, the “demos” reconnoitered right up on the landing beaches themselves. They left a sign for the first assault wave at Asan: “Welcome Marines—USO This Way.”

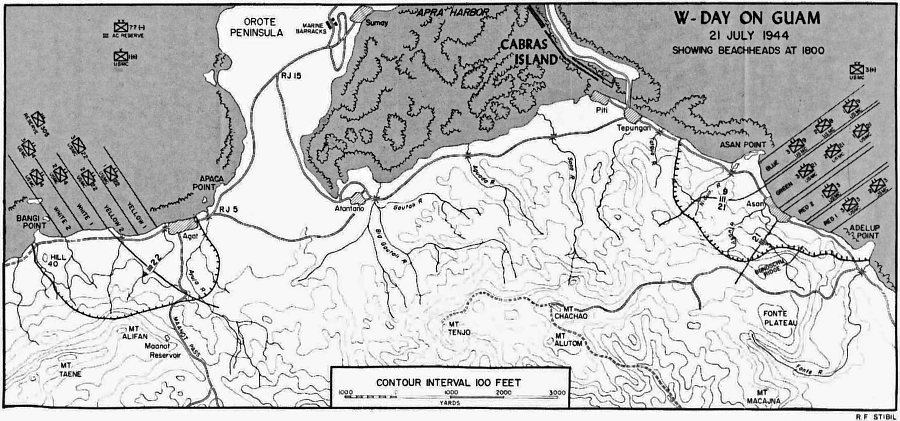

At 0730 a flare was shot in the air above the waiting flotilla and Admiral Conolly commanded: “Land the Landing Force.” At 0808, the first wave of the 3d Marine Division broke the circle of waiting LVTs to form a line and cross the 2,000 yards of water to the 2,500-yard-wide beach between Asan and Adelup points. At 0829, the first elements of the 3d Marine Division were on Guam. Three minutes later, 0832, lead assault troops of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade crossed the shelled-pocked strand at Agat, six miles south of the Asan-Adelup beachhead.

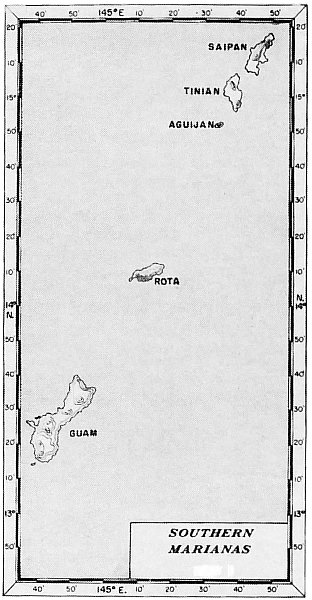

Guam, along with the Philippines, became a territorial possession of the United States with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1899, ending the Spanish-American War. Earlier, on 21 June 1898, First Lieutenant John Twiggs “Handsome Jack” Myers had led a party of Marines ashore from the protected cruiser Charleston to accept the surrender of the Spanish authorities, who didn’t know that a state of war then existed between Spain and the United States. Thus began a long Marine presence on Guam. The island, southernmost of3 the Marianas chain, was discovered by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, but not occupied until 1688 when a small mission was established there by a Spanish priest and soldiers. When control of the rest of the Mariana Islands, including Saipan and Tinian, all once German possessions, was given to Japan as a mandate power in 1919, Guam became an isolated and highly vulnerable American outpost in a Japanese sea.

This American territory, 35 miles long, nine miles at its widest and four at its narrowest, shaped like a peanut, with a year-long mean temperature of 79 degrees, fell quickly and easily in the early morning of 10 December 1941. Much of the Japanese attack on Guam came from her sister island of Saipan, 150 miles to the north.

The governor of Guam, Captain George J. McMillan (the island governor was always a U.S. Navy officer), aware that he could expect no reinforcement or relief, decided to surrender the territory to Japanese naval forces. Foremost in his mind was the fate of the 20,000 Guamanians, all American nationals, who would inevitably suffer if a strong defense was mounted. He felt “the situation was simply hopeless.” He sent word to the 153 Marines of the barracks detachment at Sumay on Orote Peninsula and the 80-man Insular Guard to lay down their arms. Even so, in two days of bombing and fighting, the garrison lost 19 men killed and 42 wounded, including four Marines killed and 12 wounded.

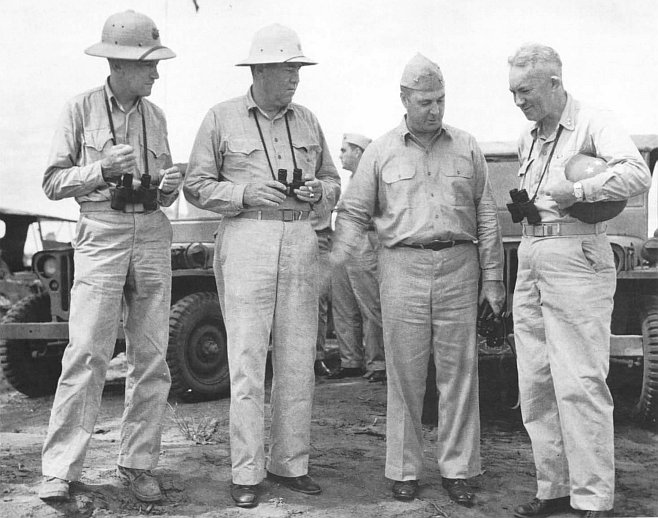

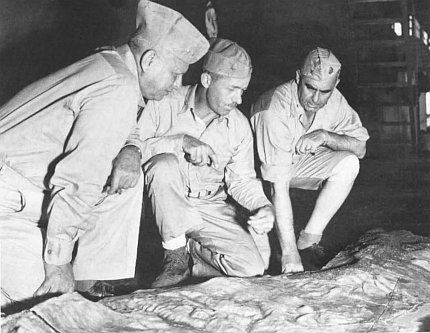

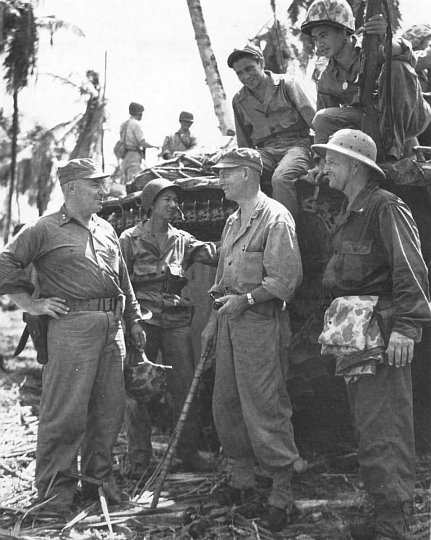

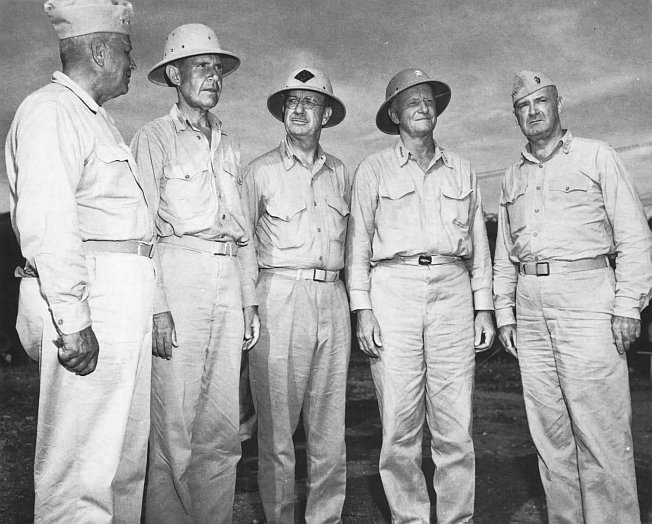

RAdm Richard L. Conolly, Southern Attack Force commander for the Guam landings, confers on Guadalcanal with the commanders of the Northern Attack Group during rehearsals prior to the departure for the Marianas target. From left to right: BGen Alfred H. Noble, assistant division commander, 3d Marine Division; Cdr Patrick Buchanan, USN, commander, Northern Transport Group; Adm Conolly; MajGen Allen Turnage, commanding general, 3d Marine Division.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 50235

In late 1943, both the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) and, later, the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) agreed to the further direction of the Pacific War. General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, was to head north through4 New Guinea to regain the Philippines. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Pacific Ocean Areas (CinCPac/CinCPOA), proposed a move through the Central Pacific to secure a hold in the Marianas. The strategic bombing of Japan would originate from captured fields on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. The new strategic weapon for these attacks would be the B-29 bomber, which had a range of 3,000 miles while carrying 10,000 pounds of bombs. The code name of the Marianas operation was “Forager.” The Central Pacific drive began with the landing on Tarawa in November 1943, followed by the landings in Kwajalein Atoll on Roi-Namur, Eniwetok, and Kwajalein itself.

In January 1944, Admiral Nimitz made final plans for Guam, and selected his command structure for the Marianas campaign. Accordingly, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the victor at Midway, was designated commander of the Fifth Fleet and of all the Central Pacific Task Forces; he would command all units involved in Forager.

Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner, who had commanded naval forces for the landings at Guadalcanal and Tarawa, headed the Joint Expeditionary Force (Task Force 51). Turner would also command the Northern Attack Force for the invasion of Saipan and Tinian. Admiral Conolly,5 who had commanded the invasion forces at Roi and Namur in the Marshalls, would head the Southern Attack Force (Task Force 53) assigned to Guam. Marine Major General (later Lieutenant General) Holland M. Smith, the Expeditionary Troops commander for the Marianas, would be responsible for the Northern Troops and Landing Force at Saipan and Tinian, essentially the Marine V Amphibious Corps (VAC). Major General Roy S. Geiger, an aviator who had conducted the Bougainville operation, was to command the Southern Troops and Landing Force, the III Amphibious Corps, at Guam.

D-Day for the invasion of Saipan had been set for 15 June. It was an important date also for the 3d Marine Division, commanded by Major General Allen H. “Hal” Turnage; the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade under Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr.; and the Army’s 77th Infantry Division under Major General Andrew D. Bruce. They were to land on Guam on 18 June, but the 3d Division and the brigade first would wait as floating reserve until the course of operations on Saipan became clear. The 77th would stand by on Oahu, ready to be called forward when needed.

Admiral Spruance kept the floating reserve well south and east of Saipan, out of the path of an expected Japanese naval attack. A powerful Japanese fleet, eager to close with the American invasion force, descended upon the Marianas. The opposing carrier groups clashed nearby in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, one of the major air battles of the war. The Imperial Navy lost 330 out of the 430 planes it launched in the fray. The clash (19 June), called “the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” was catastrophic for the Japanese and ended once and for all any naval or air threat to the Marianas invasion.

With the hard fighting on Saipan turning gradually but inevitably in favor of the American Marines and soldiers battling the Japanese, the U.S. Navy was ready to direct its attention to Guam, which was now slated to receive the most thorough pre-landing bombardment yet seen in the Pacific War. After weeks at sea, the 3d Division and the 1st Brigade were given a respite and a chance to go ashore to lose their “sea legs” after so long a period on board ships. The Task Force 53 convoy moved back to Eniwetok Atoll, whose huge 20-mile-wide lagoon was rapidly becoming a major forward naval base.

The Marines welcomed the break and the chance to walk on dry land on the small islands of the atoll. There was even an issue of warm beer to all those on shore. The Marine veterans of the fighting on Bougainville, New Georgia, and Eniwetok had a chance to look over the soldiers of the 305th Regimental Combat Team, which now came forward6 from Oahu to be attached briefly to the brigade for the landing on Guam, set for 21 July and designated W-Day. The rest of the Army contingent, the 77th Infantry Division, was well trained and well led, and was scheduled to arrive at the target on W plus 1, 22 July.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 90434

BGen Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., Commanding General, 1st Provisional Marine Brigade and his principal officers, from left, Col John T. Walker, brigade chief of staff; LtCol Alan Shapley, commander, 4th Marines; and Col Merlin T. Schneider, commander, 22d Marines, view a relief map of Guam for the brigade’s operation.

The 3d Marine Division, composed of the 3d, 9th, and 21st Marines (rifle regiments), the 12th Marines (artillery), and the 19th Marines (engineers and pioneers), plus supporting troops, numbered 20,238 men. It had received its baptism of fire on Bougainville in November and December 1943 and spent the intervening months on Guadalcanal training and absorbing casualty replacements. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, which was organized on Guadalcanal, was also a veteran outfit. One of its infantry regiments, the 4th Marines, was formed from the disbanded raider battalions which had fought in the Solomons. The other once-separate regiment, the 22d Marines, was blooded in the seizure of Eniwetok in February 1944. Both regiments had 75mm pack howitzer battalions attached, which now joined brigade troops. In all, the brigade mustered 9,886 men.

Corps troops of the III Corps was heavy with artillery and would use every gun. III Corps had three battalions of 155mm howitzers and guns and the 9th and 14th Defense Battalions, whose 90mm guns could and would fire at both air and ground targets.

For the handling of casualties, III Corps had a medical battalion, with equipment and supplies to operate a 1,500-bed hospital. In addition, the 1st Brigade had two medical companies; the 3d Division its own medical battalion; and the 77th Division a fully staffed and equipped Army field hospital. Each of the divisions had a medium tank battalion and a full complement of engineers, augmented by two Marine separate engineer battalions and two naval construction battalions (Seabees). Two amphibian tractor battalions and an armored amphibian battalion would carry the assault waves to shore. All in all, the III Amphibious Corps was prepared to land more than 54,000 soldiers, sailors, and Marines.

En route to Guam on board the command ship USS Appalachian (AGC 1), Marine III Amphibious Corps commander, MajGen Roy S. Geiger; his chief of staff, Col Merwin H. Silverthorn; and the Corps Artillery commander, BGen Pedro A. del Valle, all longtime Marines and World War I veterans, review their copy of the Guam relief map to assist in their estimates and plans for the operation.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 87140

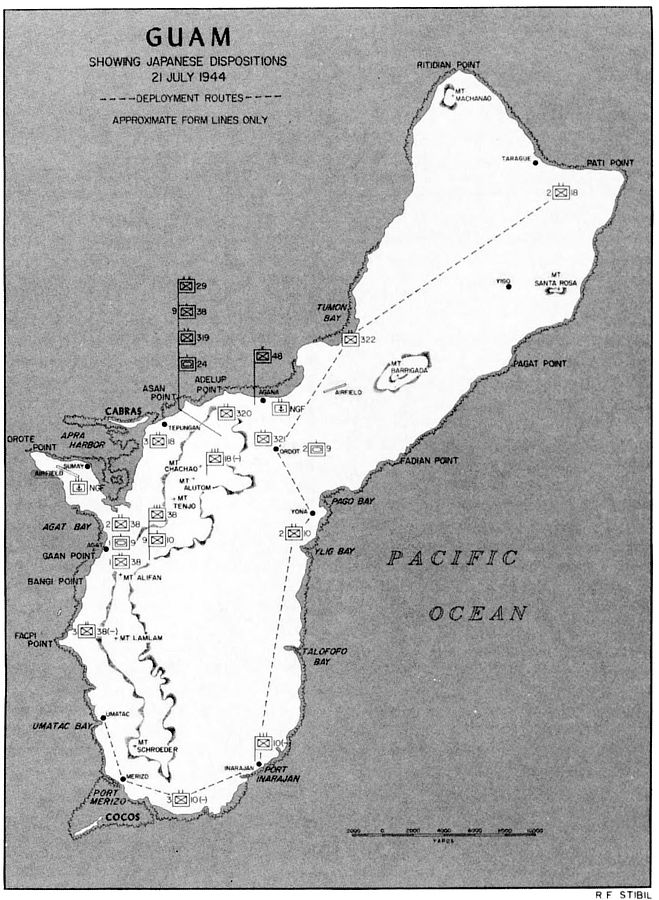

Waiting for the attack and sure7 that it would come, but not where, was the Japanese 29th Infantry Division under Lieutenant General Takeshi Takashina. The 29th had served in Japan’s Kwantung Army, operating and training in Manchuria until it was sent to the Marianas in February 1944. One of its regiments, the 18th, fell victim to an American submarine, the Trout, and lost 2,200 of its 3,500 men when its transport was sunk. Reorganized on Saipan, the 18th Infantry Regiment took two infantry battalions to Guam, together with two companies of tanks.

Another of the 29th’s regiments garrisoned Tinian and the remaining unit, the 38th Infantry, together with division headquarters troops, arrived on Guam in March. The other major Army defending units were the 48th Independent Mixed Brigade and the 10th Independent Mixed Regiment, both formed on Guam in March from a six-battalion infantry, artillery, and engineer force sent from the Kwantung Army. With miscellaneous supporting troops, the total Army defending force numbered about 11,500 men. Added to these were 5,000 naval troops of the 54th Keibitai (guard force) and about 2,000 naval airmen reorganized as infantry to defend Orote Peninsula and its airfield. General Takashina was in overall tactical command of the 18,500 Army and Navy defenders. His immediate superior, Lieutenant General Hideyoshi Obata, commanding the Thirty-first Army, was also on Guam, though not intentionally. Returning to his Saipan headquarters from an inspection trip to the Palau Islands, Obata was trapped on Guam by the American landing on Saipan. He left the conduct of Guam’s defense to Takashina.

The fact that the Americans were to assault Guam was no secret to its defenders. The invasion of Saipan and a month-long bombardment by ships and planes left only the question of when and where. With only 15 miles of potential landing beaches along the approachable west coast, the Japanese could not be very wrong no matter where they defended.

GUAM

SHOWING JAPANESE DISPOSITIONS

21 JULY 1944

Tokyo Rose said they expected us. On board ship, the Americans heard her and her pleasant beguiling voice on the radio. While she made threats of dire things to happen to invasion troops, she was never taken seriously by any of her American “fans.”

Major General Kiyoshi Shigematsu, shoring up the morale of his 48th Independent Mixed Brigade, told his men: “The enemy, overconfident because of his successful landing on Saipan, is planning a reckless and insufficiently prepared landing on Guam. We have an excellent opportunity to annihilate him on the beaches.”

Premier Hideki Tojo, supreme commander of the war effort for Japan, also had spirited words for his embattled commanders: “Because the fate of the Japanese empire depends on the result of your operation, inspire the spirit of officers and men and to the very end continue to destroy the enemy gallantly and persistently; thus alleviate the anxiety of the Emperor.”

Back to visit Guam a half century later, a former Japanese lieutenant said the tremendous American invasion fleet offshore had “paved the sea” and recalled what he thought on 21 July: “This is the day I will die.”

“Conditions,” said Admiral Conolly, “are most favorable for a successful landing.”

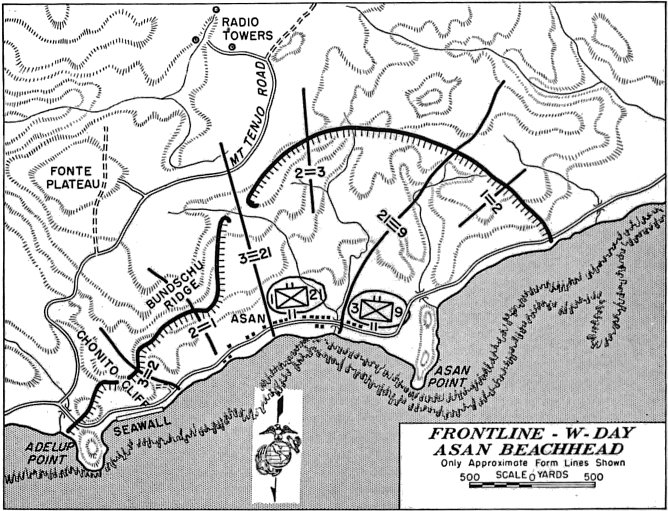

Troops of the 3d Marine Division landed virtually in the lap of the Japanese island commander, General Takashina, whose U-shaped cave command post, carved out of a sandstone cliff, overlooked the Asan-Adelup beachhead. The looming heights dominated the beaches, particularly on the left and center, where the 3d and 21st Marines were headed for the shore.

W-Day, 21 July 1944, opened as a beautiful day, but it soon turned hazy as the violent clouds of smoke, dust, and fire spiraled skyward. At 0808 an air observer shouted into his microphone: “First wave on the beach.” At 0833, the same airborne announcer confirmed the battle was on, with: “Troops ashore on all beaches.”

The 3d Marines under Colonel W. Carvel Hall struck on the far left of the 2,500-yard beachhead, the left flank of the division near Adelup Point. Ahead was Chonito Cliff, a ridge later named Bundschu Ridge, and high, difficult ground in back of which was the final beachhead line (FBHL), or first goal of the landing. The center, straight up the middle, belonged to the 21st Marines, under Colonel Arthur H. “Tex” Butler. The regiment would drive inland, secure a line of cliffs, and defend them until the division caught up and was ready to expand the beachhead outward. Under Colonel Edward A. Craig, the 9th Marines landed on the right flank near Asan Point, ready to strike inland over paddies to and across lower and more hospitable hills, but all part of the same formidable enemy-held ridgeline.

W-DAY ON GUAM

21 JULY 1944

SHOWING BEACHHEADS AT 1800

The 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel Walter Asmuth, Jr., caught intense fire from the front and right flank near Asan Point, and he had to call on tanks for assistance, but one company got to9 the ridge ahead quite rapidly and threw the defenders at Asan Point off balance, making the regiment’s advance easier. (It would also be up to the 9th Marines to take Cabras, a little island offshore and hard against Apra Harbor. This would be accomplished with a separate amphibious landing.) With its 2d and 3d Battalions in the lead, the 9th Marines drove through its initial objectives quickly and had to slacken its advance in order not to thin out the division’s lines.

Colonel Butler’s 21st Marines, in a stroke of luck which would later be called unbelievable, found two unguarded defiles on either side of the regiment’s zone of action. His troops climbed straight to the clifftops. No attempt was made to keep contact going up, but, on top, the 2d and 3d Battalions formed a bridge covering both defiles. The 1st Battalion swept the area below the cliffs.

The 12th Marines (Colonel John B. Wilson) was quickly on the beach, with its burdensome guns and equipment, and the 3d Battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Alpha L. Bowser, Jr., was registered and firing by 1215. By 1640 every battery was in position and in support of the advance. Captain Austin P. Gattis of the 12th Marines attributed the success of his regiment in setting up quickly to “training, because we had done it over, and over, and over. It was efficiency learned and practiced and it always gave the 12th a leg up.”

On the far left, the 3d Marines was getting the worst of the enemy’s increasing resistance. The regiment received intense mortar and artillery fire coming in and on the beaches, and faced the toughest terrain—steep cliffs whose approaches were laced with interlocking bands of Japanese machine gun fire. The cliffs were defended by foes who knew and used their weapons well. The Japanese, that close, would roll grenades right down the escarpment onto the Marines. Snipers could find protection and cover in the countless folds and ridges of the irregular terrain, and the ridgetops were arrayed like the breastworks of some nightmarish castle. It appeared that ten on top could hold off hundreds below.

Laden amphibious tractors carry troops of the 22d Marines in the assault wave to Yellow Beaches 1 and 2 south of Agat in the Southern Sector. Here, they would face murderous fire from Japanese guns at Gaan Point and from positions overlooking the beaches on Mount Alifan and Maanot Ridge. Gaan Point was not fully neutralized until 1330, W-Day.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 88093

One of the defenders, Lieutenant Kenichi Itoh, recalled that despite the terrible bombardment, he felt secure, that his countrymen could hold out for a long time, even win. After the war, recalling his feelings that eventful day in July 1944, the lieutenant considered it all a bad dream, “even10 absurd” to think that his forces could ever withstand the onslaught.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 88160

Upon reaching the beach, Marines quickly unload over the gunwales of the amtrac which brought them in and rushed off the beaches. As the frontlines advanced, succeeding waves of amphibian tractors will carry the troops further inland.

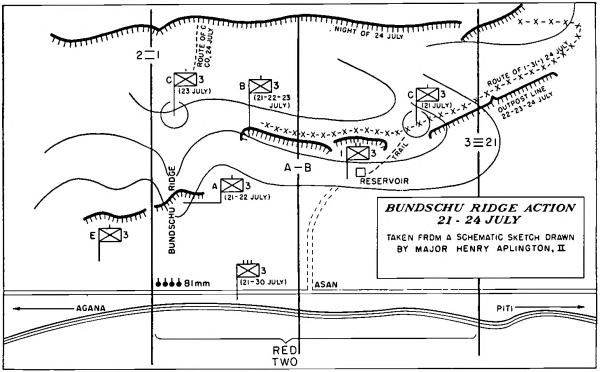

On W-Day, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph E. Houser’s 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, was on the extreme left of the line, facing Adelup Point, which, with Asan Point, marked the right and left flanks of the invasion beaches. Houser’s troops could seize the territory in his zone only with the support of tanks from Company C, 3d Tank Battalion, and half-track-mounted 75mm guns. Holding up the regimental advance was a little nose projecting from Chonito Ridge facing the invasion beach in the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines’ zone. Early on W-Day (about 1045), Captain Geary R. Bundschu’s Company A was able to secure a foothold within 100 yards of the crest of this promontory, but could not hold its positions in the face of intense enfilading machine gun fire. Captain Bundschu called for stretchers and corpsmen, then requested permission to disengage. Major Henry Aplington II, commanding the 1st Battalion, was “unwilling to give up ground in the tight area and told Captain Bundschu to hold what he had.”

Colonel Hall ordered the attack to continue in mid-afternoon behind a massive 81mm mortar barrage. None of the companies of Major Aplington’s battalion or Lieutenant Colonel Hector de Zayas’ 2d Battalion could gain any ground beyond what they already precariously held. Their opponent, the 320th Independent Infantry Battalion held fast.

A couple of hours later, Colonel Hall ordered another attack, with Companies A and E in the fore. Major Aplington recalled:

When the 1700 attack went off, it was no change. E made little progress and the gallant men of A Company attacked again and again, reached the top but could not hold. Geary Bundschu was killed and the company slid back to the former positions.

In the morning light of 22 July (W plus 1), that small but formidable Japanese position still held firmly against the 3d Marines’ advance. During the bitter fighting of the previous day, Private First Class Luther Skaggs, Jr., of the 3d Battalion, led a mortar section through heavy enemy fire to support the attack, then defended his position against enemy counterattacks during the night although badly wounded. For conspicuous gallantry and bravery beyond the call of duty, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. On the 22d, Private First Class Leonard F. Mason, a Browning automatic rifleman of the 2d Battalion, earned a posthumous Medal of Honor for single-handedly attacking and wiping out an enemy machine gun11 position which threatened his unit. Although wounded severely, he rejoined his fellow Marines to continue the attack, but succumbed to his fatal wounds.

During the day’s bitter fighting, Colonel Hall tried to envelop the Japanese, using Companies A and C of Aplington’s battalion and Company E of de Zayas’. On regimental orders, Aplington kicked it off at 1150. It also got nowhere at first. Company A got to the top but was thrown off. Company E was able to move ahead very slowly. Probe after probe, it found Japanese resistance perceptibly weakening. By 1900, the men of E reached the top, above Company A’s position. The Japanese had pulled back. In the morning, a further advance confirmed the enemy withdrawal.

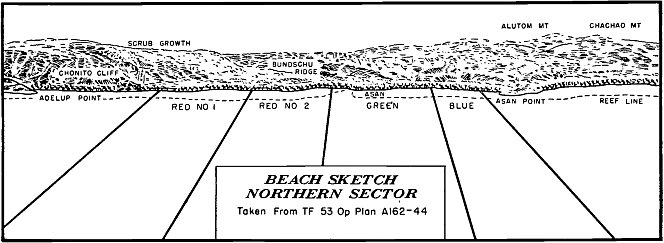

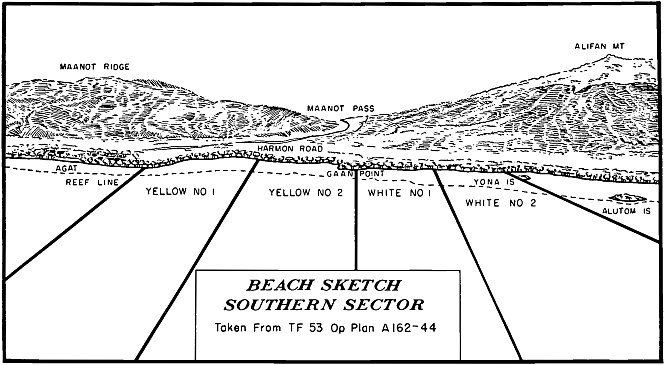

BEACH SKETCH

NORTHERN SECTOR

Taken From TF 53 Op Plan A162-44

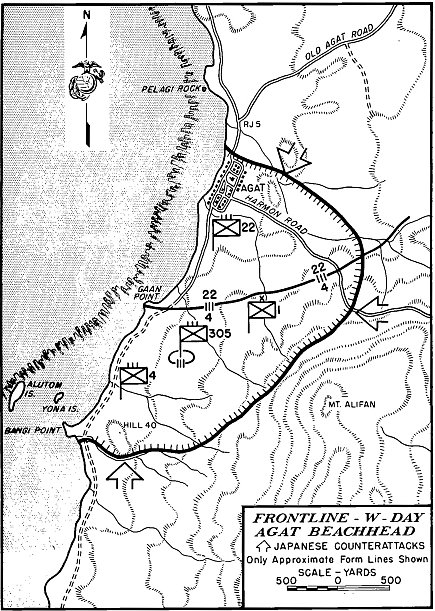

In the south at Agat, despite favorable terrain for the attack, the 1st Brigade found enemy resistance at the beachhead to be more intense than that which the 3d Division found on the northern beaches. Small arms and machine gun fire, and the incessant fires of two 75mm guns and a 37mm gun from a concrete blockhouse with a four-foot thick roof built into the nose of Gaan Point, greeted the invading Marines as the LVTs churned ashore. The structure had been well camouflaged and not spotted by photo interpreters12 before the landing nor, unfortunately, selected as a target for bombing. As a result, its guns knocked out two dozen amtracs carrying elements of the 22d Marines. For the assault forces’ first hours ashore on W-Day on the southern beaches, the Gaan position posed a major problem.

FRONTLINE—W-DAY

ASAN BEACHHEAD

Only Approximate Form Lines Shown

The assault at Agat was treated to the same thunderous naval gunfire support which had disrupted and shook the ground in advance of the landings on the northern beaches at Asan. When the 1st Brigade assault wave was 1,000 yards from the beach, hundreds of 4.5-inch rockets from LCI(G)s (Landing Craft, Infantry, Gunboat) slammed into the strand. It would be the last of the powerful support the troops of the brigade in assault would get before they touched down on Guam.

While the LVTs, the DUKWs (amphibious trucks), and the LCVPs were considerably off shore, there was virtually no enemy fire from the beach. An artillery observation plane reported no observed enemy fire. The defenders at Agat, however, 1st and 2d Battalions, 38th Infantry, would respond in their own time. The loss of so many amtracs as the assault waves neared the beaches meant that, later in the day, there would not be enough LVTs for the transfer of all supplies and men from boats to amtracs at the Agat reef. This shortage of tractors would plague the brigade until well after W-Day.

The damage caused to assault and cargo craft on the reef, and the precision of Japanese guns became real concerns to General Shepherd. Some of the Marines and most of the soldiers who came in after the first assault waves would wade ashore with full packs, water to the waist or higher, facing the perils of both underwater shellholes and Japanese fire. Fortunately, by the time the bulk of the 77th Division waded in, these twin threats were not as great because the Marines ashore were spread out and keeping the Japanese occupied.

The Japanese Agat command had prepared its defenses well with thick-walled bunkers and smaller pillboxes. The 75mm guns on Gaan Point were in the middle of the landing beaches. Crossfire from Gaan coordinated with the machine guns on nearby tiny Yona island to rake the beaches allocated to the 4th Marines under Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley. The 4th Marines was to establish its beachhead, and protect the right or southernmost flank. After bitter fighting, the 4th Marines forged ahead on the low ground to13 its front and cleared Bangi Point where bunker walls could withstand a round from a battleship. Lieutenant Colonel Shapley set up a block on what was to be known as Harmon Road leading down from the mountains to Agat. A lesson well learned in previous operations was that the Japanese would be back in strength and at night.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 94137

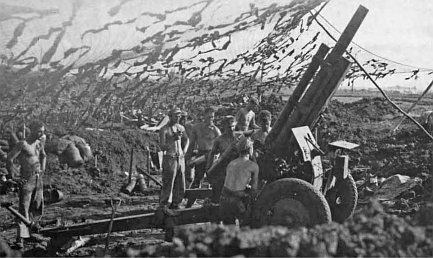

In quick order, the 105mm howitzers of LtCol Alpha L. Bowser’s 3d Battalion, 12th Marines, were landed and set up in camouflaged positions to support the attack.

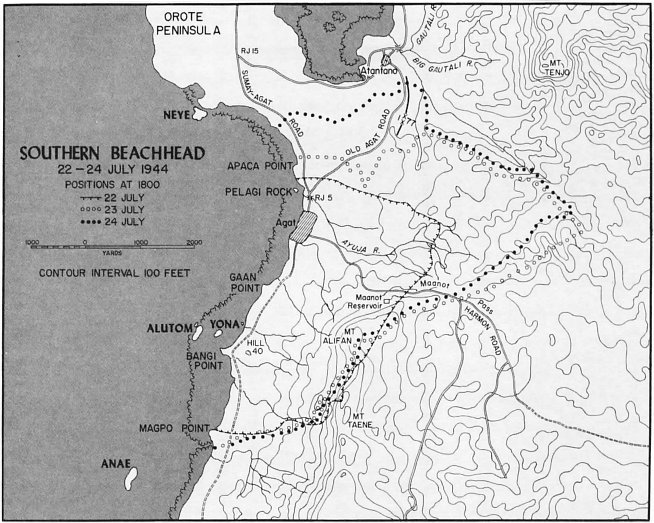

When the Marines landed, they found an excellent but undermanned Japanese trench system on the beaches, and while the pre-landing bombardment had driven enemy defenders back into their holes, they nonetheless were able to pour heavy machine gun and mortar fire down on the invaders. Pre-landing planning called for the Marine amtracs to drive 1,000 yards inland before discharging their embarked Marines, but this tactic failed because of a heavily mined beachhead, with its antitank ditches and other obstacles. However, the brigade attack ashore was so heavy, with overwhelming force the Marines were able to break through, and by 1034, the assault forces were 1,000 yards inland, and the 4th Marines’ reserve battalion had landed. After receiving extremely heavy fire from all emplaced Japanese forces, the Marines worked on cleaning out bypassed bunkers together with the now-landed tanks. By 1330, the Gaan Point blockhouse had been eliminated by taking the position from the rear and blasting the surprised enemy gunners before they could offer effective resistance. At this time also, the brigade command group was on the beach and General Shepherd had opened his command post.

BUNDSCHU RIDGE ACTION

21–24 JULY

TAKEN FROM A SCHEMATIC SKETCH DRAWN

BY MAJOR HENRY APLINGTON, II

The 22d Marines, led by Colonel Merlin F. Schneider, was battered by a hail of small arms and mortar fire on hitting its assigned beach, and suffered heavy losses of men and equipment in the first minutes. Private First Class William L. Dunlap could vouch for the high casualties. The dead, Dunlap recalled, included the battalion’s beloved chaplain, who had been entrusted with just about everybody’s gambling money “to hold for safekeeping,” the Marines never for a minute considering that he was just as mortal as they. The 1st Battalion, 22d Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Walfried H. Fromhold), had left its section of the landing zone and moved to the shattered town of Agat, after which the battalion would drive north and eventually seal off heavily defended Orote Peninsula, shortly to be the scene of a major battle.

The 22d Marines’ 2d Battalion, (Lieutenant Colonel Donn C. Hart), in the center of the beachhead, quickly and easily moved 1,000 yards directly ahead inland from the beach. The battalion could have gone on to one of the W-Day goals, the local heights of Mount Alifan, if American bombs had not fallen short, halting the attack.

Company A, 3d Marines, is in a perilous position on W-Day plus 1, 22 July, as it is held up on Bundschu Ridge on its way to Chonito Ridge at the top. The troops were halted by Japanese fire, which prevented immediate reinforcement.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 87396

The 1st Battalion moved into the ruins of Agat and at 1020 was able to say, “We have Agat,” although there was still small arms resistance in the rubble. By 1130 the battalion was also out to Harmon Road, which led to the northern shoulder of Mount Alifan. Even as Fromhold’s men made their advances, Japanese shells hit the battalion aid station, wounding and killing members of the medical team and destroying supplies.15 Not until later that afternoon was the 1st Battalion sent another doctor.

On the right of the landing waves, Major Bernard W. Green’s 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, ran head-on into a particularly critical hill mass (Hill 40) near Bangi Point, which had been thoroughly worked over by the Navy. Hill 40’s unexpectedly heated defense indicated that the Japanese recognized its importance, commanding the beaches where troops and supplies were coming ashore. It took tanks and the support of the 3d Battalion to claim the position.

Before dark on W-Day, the 2d Battalion, 22d Marines, could see the 4th Marines across a deep gully. The latter held a thin, twisted line extending 1,600 yards from the beach to Harmon Road. The 22d Marines held the rest of a beachhead 4,500 yards long and 2,000 yards deep.

At nightfall of W-Day, General Shepherd summed up to General Geiger: “Own casualties about 350. Enemy unknown. Critical shortages of fuel and ammunition all types. Think we can handle it. Will continue as planned tomorrow.”

Helping to ensure that the Marines would stay on shore once they landed was a host of unheralded support troops who had been struggling since daylight to manage the flow of vital supplies to the beaches. Now, as17 W-Day’s darkness approached, the 4th Ammunition Company, a black Marine unit, guarded the brigade’s ammunition depot ashore. During their sleepless night, these Marines killed 14 demolition-laden infiltrators approaching the dump.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 91176

A Japanese cave position on the reverse slope of Chonito Ridge offered protection for the enemy from the prelanding bombardment and enabled them to reoccupy prepared positions from which they could oppose the advance of the 3d Marines.

Faulty communications delayed the order to land the Army’s 305th Regimental Combat Team (Colonel Vincent J. Tanzola), elements of the assault force, for hours. Slated for a morning landing, the 2d Battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. Adair did not get ashore until well after nightfall. As no amtracs were then available, the soldiers had to walk in from the reef. Some soldiers slipped under water into shellholes and had to swim for their lives in a full tide. The rest of the 305th had arrived on the beach, all wet, some seasick, by 0600 on W plus-1.

Colonel Tsunetaro Suenaga, commanding officer of the 38th Regiment, from his command post on Mount Alifan, had seen the Americans overwhelm his forces below. Desperate to strike back, he telephoned General Takashina at 1730 to get permission for an all-out assault to drive the Marines into the sea. He had already ordered his remaining units to assemble for the counterattack. The 29th Division commander was not at first receptive. Losses would be too high and the 38th Regiment would serve better defending the high ground and thereby threatening the American advance. Reluctantly however, Takashina gave his permission, and ordered the survivors to fall back on Mount Alifan if the attack failed, which he was certain it would. Eventually Colonel Suenaga was forced to share the general’s pessimism, for he burned his regiment’s colors to prevent their capture.

At the focal point of the enemy’s attack from the south, Hill 40, the brunt of the fighting fell upon First Lieutenant Martin J. “Stormy” Sexton’s Company K, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines. The enemy’s 3d Battalion, 38th Regiment coming north from reserve positions was still relatively intact. In the face of Japanese assaults, the company held, but just barely. Sexton recalls Lieutenant Colonel Shapley’s assessment of the night’s fighting: “If the Japanese had been able to recapture Hill 40, they could have kicked our asses off the Agat beaches.”

Major Anthony N. “Cold Steel” Walker, S-3 (operations officer) of the 3d Battalion, recalled that the18 Japanese, an estimated 750 men, hit the company at about 2130, with the main effort coming to the left or east of the hill. He remembered:

Finding a gap in our lines and overrunning the machine gun which covered the gap the enemy broke through and advanced toward the beaches. Some elements turned to their left and struck Hill 40 from the rear. K Company with about 200 men fought them all night long from Hill 40 and a small hill to the rear and northeast of Hill 40. When daylight came the Marines counterattacked with two squads from L Company ... and two tanks ... and closed the gap. A number of men from Company K died that night but all 750 Japanese soldiers were killed. The hill ... represents in miniature or symbolically the whole hard-fought American victory on Guam.

Along the rest of the Marine front, and in the reserve areas, the fighting was hot and heavy as the rest of the 38th attacked. Colonel Suenaga pushed his troops to attack again and again, in many cases only to see them mowed down in the light of American flares. No novice to Japanese tactics, General Shepherd had anticipated this first night’s attack and was ready.

BEACH SKETCH

SOUTHERN SECTOR

Taken From TF 53 Op Plan A162-44

Enemy reconnaissance patrols were numerous around 2130, trying to draw fire and determine Marine positions. Colonel Suenaga was out in front of the center thrust which began at 2330 after a brisk mortar flurry on the right flank of the 4th Marines. The Japanese came on in full force, yelling, charging with their rifles carried at high port, and throwing grenades. The Marines watched the dark shadows moving across the skyline under light of star shells from the ships. Men lined up hand grenades, watched, waited, and then reacted. The Japanese were all around, attempting to bayonet Marines in their foxholes. They even infiltrated down to pack-howitzer positions in the rear of the front lines. It was the same for the 22d Marines. A whole company of Japanese closed to the vicinity of the regimental command post. The defense here was held largely by a reconnaissance platoon headed by Lieutenant Dennis Chavez, Jr., who personally killed five of the infiltrators at point-blank range with a Thompson sub-machine gun.

Four enemy tanks in that same attack lumbered down Harmon Road. There they met a bazooka man from the 4th Marines, Private First Class Bruno Oribiletti. He knocked out the first two enemy tanks and Marine Sherman tanks of Lieutenant James R. Williams’ 4th Tank Company platoon finished off the rest. Oribiletti was killed; he was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for his bravery. Enemy troops of the 38th also stumbled into the barely set up perimeter of the newly arrived 305th Infantry and paid heavily for it.

After one day and night of furious battle the 38th ceased to exist. Colonel Suenaga, wounded in the first night’s counterattack, continued to flail at the Marines until he, too, was cut down. Takashina ordered the shattered remnants of the regiment north to join the reserves he would need to defend the high ground around Fonte Ridge above the Asan-Adelup beachhead. The general would leave his19 troops on Orote to fend for themselves.

The two days of fierce fighting on the left of the 3d Division’s beachhead in the area that was now dubbed Bundschu Ridge cost the 3d Marines 615 men killed, wounded, and missing. The 21st Marines in the center held up its advance on 22 July until the 3d Marines could get moving, but the men in their exposed positions along the top of the ridge, seized so rapidly on W-Day, were hammered by Japanese mortar fire, so much so that Colonel Butler received permission to replace the 2d Battalion by the 1st, which had been in division reserve. The 9th Marines met relatively little resistance as it overran many abandoned Japanese positions in its drive toward the former American naval base at Piti on the shore of Apra Harbor. The 3d Battalion, after a heavy barrage of naval gunfire and bombs, assaulted Cabras Island in mid-afternoon, landing from LVTs to find its major obstacle dense brambles with hundreds of mines.

General Turnage, assessing the situation as he saw it on the eve of 22 July reported to General Geiger:

Enemy resistance increased considerably today on Div left and center. All Bn’s of 3rd CT [combat team] have been committed in continuous attack since landing. 21st CT less 1 Bn in Div Res has been committed continuously with all units in assault. One of the assault Bn’s of 21st CT is being relieved on line by Div Res Bn today. Former is approx 40 percent depleted. Since further advance will continue to thin our lines it is now apparent that an additional CT is needed. 9th CT is fully committed to the capture of Piti and Cabras. Accordingly it is urgently recommended that an additional CT be attached this Div at the earliest practicable date.

Turnage did not get the additional regiment he sought. The night of W plus 1 was relatively quiet in the 3d Division’s sector except for the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, which repulsed a Japanese counterattack replete with a preliminary mortar barrage followed by a bayonet charge.

On the 23d, III Amphibious Corps Commander, General Geiger, well aware that the majority of Japanese troops had not yet been encountered, told the 3d Division that it was “essential that close contact between adjacent units be established by later afternoon and maintained throughout the night” unless otherwise directed. Despite the order to close up and keep contact, the 3d Division was spread too thinly to hold what it had seized in that day’s advance. When it halted to set up for the night, it was found that the distance between units had widened. When night fell, the frontline troops essentially held strongpoints with gaps between them covered by interlocking bands of fire.

Only Approximate Form Lines Shown

The 3d Marines reached the high ground of Bundschu Ridge on the20 23d and searched out the remaining Japanese stragglers. It was obvious that the enemy had withdrawn from the immediate area and equally plain that the Japanese hadn’t gone far. When patrols from the 21st Marines tried to link up with the 3d Marines, they were driven back by the fire of cleverly hidden machine guns, all but impossible to spot in the welter of undergrowth and rock-strewn ravines. All across the ridges that the Marines held, there were stretches of deadly open ground completely blanketed by enemy fire from still higher positions. On the night of the 23d, the 9th Marines made good progress moving through more open territory which was dotted by hills, each of which was a potential enemy bastion. A patrol sent south along the shoreline to contact the 1st Brigade took fire from the hills to its left and ran into an American artillery and naval gunfire concentration directed at Orote’s defenders. The patrol was given permission to turn back.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 87239

Mount Alifan looms over the men of the 4th Marines as they move through the foothills to the attack. In the background, a plane being used for observation keeps track of the front lines for controlling the fire of ships’ guns and supporting artillery.

On the 24th, the 3d and 21st Marines finally made contact on the heights, but the linkup was illusory. There were no solid frontlines, only strongpoints. No one could be certain that the Japanese had all been accounted for in the areas that had been probed, attacked, and now seemed secure. Every rifleman was well aware that more of the same lay ahead; he could see his next objectives looming to the front, across the Mount Tenjo Road, which crossed the high ground that framed the beachhead. Already the division had suffered more than 2,000 casualties, the majority in infantry units. And yet the Japanese, who had lost as many and more men in the north alone, were showing no signs of abandoning their fierce defense. General Takashina was, in fact, husbanding his forces, preparing for an all-out counterattack, just as the Marines, north and south, were getting ready to drive to the force beachhead line (FBHL), the objective which would secure the high ground and link up the two beachheads.

Since the American landings, Takashina had been bringing troops into the rugged hills along the Mount Tenjo Road, calling in his reserves from scattered positions all over the island. By 25 July, he had more than 5,000 men, principally of the 48th Independent Mixed Brigade and the 10th Independent Mixed Regiment, assembled and ready to attack.

The fighting on the 25th was as intense as that on any day since the landing. The 2d Battalion, 9th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Cushman, Jr., who was to become the 25th Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1972), was attached to the 3d Marines to bring a relatively intact unit into the fight for the Fonte heights and to give the badly battered21 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, a chance to rest and recoup. By nightfall, Cushman’s men had driven a salient into the Japanese lines, seizing the Mount Tenjo Road, 400 yards short of the Fonte objective on the left and 250 yards short on the right.

SOUTHERN BEACHHEAD

22–24 JULY 1944

During the day’s relentless and increasingly heavy firefights, the 2d and 3d Battalions of the 3d Marines had blasted and burned their way through a barrier of enemy cave defenses and linked up with Cushman’s outfit on the left. About 1900, Company G of the 9th Marines pulled back some 100 yards to a position just forward of the road, giving it better observation and field of fire. Company F had reached and occupied a rocky prominence some 150 yards ahead of Companies G and E, in the center of the salient. It pulled22 back a little for better defense, and held. Thus the scene was set for the pitched battle of Fonte Ridge, fought at hand-grenade range and in which casualties on both sides were largely caused by small arms fire at point-blank distances. It was in this action that leadership, doggedness, and organizational skill under fire merited the award of the Medal of Honor to the Commanding Officer of Company F, Captain Louis H. Wilson, Jr., who became the 26th Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1976, following in the footsteps of his former battalion commander.

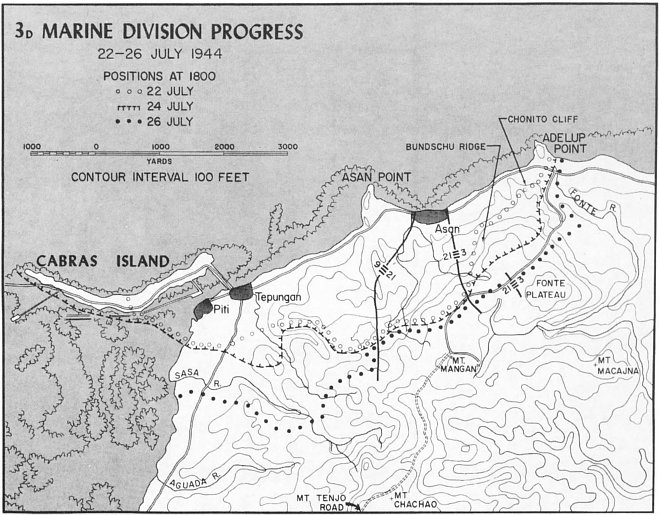

3D MARINE DIVISION PROGRESS

22–26 JULY 1944

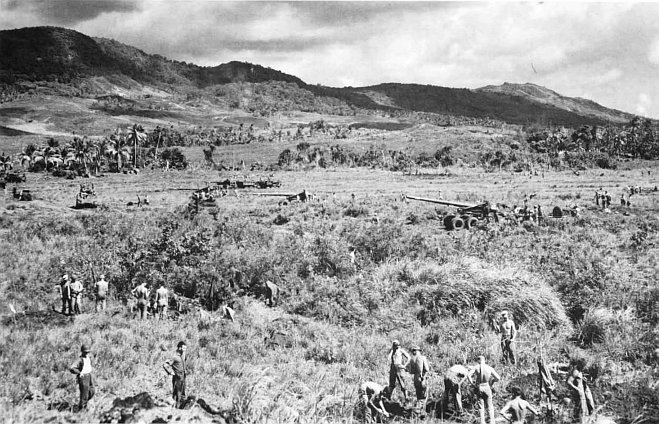

In the aftermath of the Japanese counterattack, bodies of the attackers were strewn on a hillside typical of the terrain over which much of the battle was fought.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 91435

Captain Wilson was wounded three times leading his own attacks in the intense crux of this Fonte action, and as his citation relates: “Fighting fiercely in hand-to-hand encounters, he led his men in furiously23 waged battle for approximately 10 hours, tenaciously holding his line and repelling the fanatically renewed counterthrusts until he succeeded in crushing the last efforts of the hard-pressed Japanese....”

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 93106

Long Toms of Battery A, 7th 155mm Gun Battalion, III Corps Artillery, were set up in the open 500 yards from White Beach 2 in the shadow of the mountain range secured by the 4th Marines and the Army’s 305th Infantry after heavy fighting.

Captain Wilson organized and led the 17-man patrol which climbed the slope in the face of the same continued enemy fire to seize the critical high ground at Fonte and keep it.

A half century later, Colonel Fraser E. West recalled the engagement at Fonte as bitter, close, and brisk. As a young officer, he commanded Company G, and reinforced Wilson’s unit. West joined on Company F’s flank, then reconnoitered to spot enemy positions and shared the night in a common CP with Captain Wilson.

In late afternoon of the 25th, a platoon of four tanks of Company C, 3d Tank Battalion, had made its way up to the Mount Tenjo Road and gone into position facing the most evident Japanese strongpoints. At the height of the battle by Wilson’s and West’s companies to hold their positions, First Lieutenant Wilcie A. O’Bannon, executive officer of Company F, managed to get down slope from his exposed position and bring up two of these tanks. By use of telephones mounted in the rear of the tanks to communicate with the Marines inside, Lieutenant O’Bannon was able to describe targets for the tankers, as he positioned them in support of Wilson’s and West’s Marines. West recalled the tanks came up with a precious cargo of ammunition. He and volunteers stuffed grenades in pockets, hung bandoleers over their shoulders, pocketed clips, carried grenade boxes on their shoulders, and delivered them all as they would birthday presents along the line to Companies G and F and a remaining platoon of Company E. Major West was also able to use a tank radio circuit to call in naval gunfire, and guarantee that the terrain before him would be lit all night by star shells and punished by high explosive naval gunfire.

On the morning of 26 July, 600 Japanese lay dead in front of the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines positions. But the battle was not over. General Turnage ordered the military crest of the reverse slope taken. There would be other Japanese counterattacks, fighting would again be hand-to-hand, but by 28 July, the capture of Fonte was in question no longer. Companies E, F, and G took their objectives on the crest. Lieutenant Colonel Cushman’s battalion in four murderous days had lost 62 men killed and 179 wounded.

It was not any easier for the 21st Marines with its hard fighting in the morning of the 25th. Only by midafternoon did that regiment clear the front in the center of the line. The 2d Battalion, 21st Marines, had to deal with a similar pocket of die-hards as that which had held up the24 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, on Fonte. Holed up in commanding cave positions in the eastern draw of the Asan River, just up from the beachhead, the Japanese were wiped out only after repeated Marine attacks and close-in fighting. The official history of the campaign noted that “every foot of ground that fell to Lieutenant Colonel [Eustace R.] Smoak’s Marines was paid for in heavy casualties, and every man available was needed in the assault....”

The 9th Marines under Colonel Craig made good progress on the 25th from its morning jump-off and reached the day’s objective, a line running generally along the course of a local river (the Sasa) by 0915. The 9th Marines had taken even more ground than was planned. General Turnage was then able to reposition the 9th Marines for the harder fighting on the beleaguered left. The 2d Battalion pulled out of position to reinforce the 3d Marines and the remaining two battalions spread out a little further in position.

The determined counterattack that hit the 3d Marines on the night of 25–26 July was matched in intensity all across the 3d Division’s front. It wasn’t long before there were enemy troops roaming the rear areas as they slipped around the Marine perimeters and dodged down stream valleys and ravines leading to the beaches.

Major Aplington, whose 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, now constituted the only division infantry reserve, held positions in the hills on the left in what had been a relatively quiet sector. Not for long, he recalled:

With the dark came heavy rain. Up on the line Marines huddled under ponchos in their wet foxholes trying to figure out the meaning of the obvious activity on the part of the opposing Japanese. Around midnight there was enemy probing of the lines of the 21st [Marines], and slopping over into those of the 9th [Marines].... All was quiet in our circle of hills and we received no notification when the probing increased in intensity or at 0400 when the enemy opened ... his attack.... My first inkling came at about 0430 when my three companies on the hills erupted into fire and called for mortar support. I talked to the company commanders and asked what was going on to be told that there were Japanese all around them ... the Japanese had been close. Three of my dead had been killed by bayonet thrusts.

In the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, sector, Private Dale Fetzer, a dog handler assigned with his black Labrador Retriever alerted Company C. The dog, Skipper, who had been asleep in front of his handler’s foxhole suddenly bolted upright, alerting Fetzer. Skipper’s nose was pointed up and directly toward Mount Tenjo. “Get the lieutenant!” called handler Fetzer, “They’re coming.”

At about 0400, the Japanese troops poured down the slopes in a frenzied banzai attack. Japanese troops had been sighted drinking during the afternoon in the higher hills, and some of these attackers appeared drunk. Marine artillery fire had immediately driven them to cover then, but they apparently continued to prepare for the attack.

In the area of the 21st Marines,25 along a low ridge not far from the critical Mount Tenjo Road, the human wave struck hard against the 3d Battalion and the Japanese actually seized a machine gun which was quickly recaptured by the Marines. The 3d Division was holding a front of some 9,000 yards at the time, and it was thinnest from the right of the 21st Marines to the left of the 9th Marines. Much of that line was only outposted. The 3d Battalion, 21st Marines, held throughout. Some of the raiders got through the weakly manned gap between the battalions. They charged harum-scarum for the tanks, artillery, and ammunition and supply dumps. The attack seemed scattered, however, and unorganized. The fighting was fierce, nonetheless, and it shattered the hastily erected Marine roadblock between the battalions.

Some of the attackers got through the lines all along the front. A group of about 50 reached the division hospital. Doctors evacuated the badly wounded, but the walking wounded joined with cooks, bakers, stretcher bearers, and corpsmen to form the line that fought off the attackers. One of the patients, Private First Class Michael Ryan, “grabbed up the blanket covering me and ran out of the building without another stitch on.” He had to run with a wounded foot through crossfire to reach some safety.

Lieutenant Colonel George O. Van Orden (3d Division infantry training officer), on orders from General Turnage, assembled two companies of the 3d Pioneer Battalion to eliminate this threat. In three hours the pioneers killed 33 of the assailants and lost three of their own men. The 3d Medical Battalion had 20 of its men wounded, but only one patient was hit and he was one of the defenders.

For many men in the furious and confused melees that broke out all over the Marine positions, the experience of Corporal Charles E. Moore of the 2d Platoon, Company E, 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, wasn’t unique. His outfit held a position about a quarter mile from Fonte Plateau. He recalled:

We set up where a road made a sharp turn overlooking a draw. It was the last stand of the second platoon. There were three attacks that night and by the third there was nobody left to fight, so they broke through. They came in droves throwing hand grenades and hacked up some of our platoon. In the26 morning, I had only ten rounds of ammunition left, half the clip for my BAR. I was holding those rounds if I needed them to make a break for it. I had no choice. Everybody was quiet, either dead or wounded. The Japanese came in to take out their dead and wounded, and stepped on the edge of my foxhole. I didn’t breath. They were milling around there until dawn then they were gone.

As Lieutenant Colonel Cushman, evaluating the action later, said:

With the seizure of Fonte Hill, the capture of the beachhead was completed. In the large picture, the defeat of the large counterattack on the 26th by the many battalions of the 3d Division who fought valiantly through the bloody night finished the Jap on Guam.... What made the fighting for Fonte important was the fact that [the advance to the north end of the island] could not take place until it was seized.

The enemy attack failed in the south also, and in the south it was just as much touch and go at times. The Japanese sailors on Orote were just as determined as the soldiers at Fonte to drive the Americans from Guam.

The 22d Marines had driven up the coast from Agat in a series of hard-fought clashes with stubborn enemy defenders. The 4th Marines had swept up the slopes of Mount Alifan and secured the high ground overlooking the beachhead. By the 25th, the brigade was in line across the mouth of Orote Peninsula facing a formidable defensive line in depth, anchored in swamps and low hillocks, concealed by heavy undergrowth,27 and bristling with automatic weapons.

Sherman mediums from the 3d Tank Battalion lumber up the long incline from the Asan beachhead towards the scene of battle around Fonte and X-Ray Ridges.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 93640

The 77th Infantry Division had taken over the rest of the southern beachhead, relieving the 4th Marines of its patrolling duties to the south and in the hills to the west. The division’s artillery and a good part of the III Corps’ big guns hammered the Japanese on Orote without letup. Just in case of enemy air attack, the beach defenses from Agat to Bangi Point were manned by the 9th Defense Battalion. There were not too many Japanese planes in the sky, and so the antiaircraft artillerymen could concentrate on firing across the water into the southern flank of the enemy’s Orote positions. On Cabras Island, the 14th Defense Battalion moved into position where it could equally provide direct flanking fire on the peninsula’s northern coast and stand ready to elevate its guns to fire at enemy planes in the skies above.

The 5,000 Japanese defenders on Orote took part in General Takashina’s all-out counterattack and it began in the early morning hours of 26 July. The attackers stormed vigorously out of the concealing mangrove swamp and the response was just as spirited. Here, as in the north, there was evidence that some of the attackers had fortified themselves with sake and there were senseless actions by officers who attacked the Marine tanks armed only with their samurai swords. There were deadly and professional attacks as well, with Marines bayoneted in their foxholes. There was one attendant communications breakdown obliging Captain Robert Frank, commanding officer of Company L, 22d Marines, to remain on the front relaying artillery spots to the regimental S-2 and thence to brigade artillery.

The artillery response was intense and effective. The fire was “drawn in closer and closer toward our front lines; 26,000 shells were thrown into the pocket [of attackers] between midnight and 3 a.m.” The screaming attacks came at 1230, then again at 0130, and at 0300. At daylight the muddy ground in front of the Marine positions was slick with blood. More than 400 Japanese bodies were sprawled in the driving rain.

General Shepherd, secure in the knowledge that his frontline troops, 4th Marines on the left, 22d Marines on the right, had withstood the night’s banzai attacks in good order, directed an attack to be launched at 0730. But first there would be another artillery preparation. At daybreak it opened with the 77th Infantry Division’s 105s and 155s, the brigade’s 75s, the defense battalion’s 90s, and whatever guns the 12th Marines could spare. It was one of the more intense preparations of the campaign. Major Charles L. Davis, S-3 of 77th Division Artillery, recalled how, on the request of General Shepherd, he had turned the heavy 155mm battalion and two 105mm battalions around to face Orote to soften the Japanese positions. The 155s and 105s battered well-prepared positions, and ripped the covering, protection, and camouflage from bunkers and trenches. Pieces of men soon hung in trees. Marines saw that this fire counted and made it a point to return to congratulate and thank the 77th’s artillery section leaders.

The advance, when it came, only went 100 yards before it was addressed by a blistering front of machine gun and small arms fire. Enemy artillery fire came falling almost simultaneously with the cessation of American support, leaving the Marines to think the fire was from their own guns, a favorite Japanese ruse. For a moment there, the Japanese return fire on the 22d Marines disorganized its forward move. It was about 0815 before the attack was on again in full force, spearheaded by Marine and Army tanks.

Immediately to the front of the 22d Marines was the infernal mangrove swamp from where the banzai attack had been mounted the night before. It was still manned heavily by Japanese, was dense, and the only means of penetrating it was by a 200-yard-long corridor along the regimental boundary which was covered by Japanese enfilade fire and could only be navigated with the cover of tanks. The armor gunners and commanders directed their fire just over the head of prone Marines and into the gunports of enemy pillboxes. By 1245, Colonel Schneider’s regiment had worked its way through all bottlenecks past the mangrove swamps, destroying bunkers with demolitions and flamethrowers. The 4th’s assault battalions kept pace with this advance, finding somewhat easier terrain but just as determined defenders. By evening the brigade had advanced 1,500 yards from its jump-off line. Both regiments, weary, wary, and waiting, dug in with an all-around defense.

Again, there was a heavy pre-attack barrage on the 27th and the Marines were stopped again before they’d gone 100 yards. The 3d Battalion,29 4th Marines, facing a well-defended ridge, a coconut grove, and a sinister clearing, was nearing the sentimental and tactically important goals of the old Marine barracks, its rifle range, and the runways of Orote airfield. With heavy tank support, the 22d Marines surged forward past the initial obstacles and by afternoon had reached positions well beyond the morning’s battles. On the left of the 4th Marines, where resistance was lighter, the assault was led by tanks that beat down the brush. While inspecting positions there, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel D. Puller, the 4th’s executive officer and brother of famed Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, was killed by a sniper.

By mid-afternoon, the 4th Marines’ assault elements broke out of the grove just short of the rifle range, only to stall in a new complex at dug-in defenses and minefields. Strangely, and yet not unusual in the climax of a losing engagement, a Japanese officer emerged to brandish his sword at a tank. It was easier than ritual suicide.

The horror of the American guns again must have been too much for the Japanese defending the immediate front. Surprisingly, they just cut and ran from their strong, well-defended positions. The elated Marines, who did not care why the enemy ran—just that they ran—now dug in only 300 yards from the prized targets. Their capture would wait for tomorrow, 28 July. The Japanese were now squeezed into the last quadrant of the peninsula. All of their strongly entrenched defenses had failed to hold. The Orote airfield, the old Marine barracks, the old parade ground which had not felt an American boot since 10 December 1941, were all about to be retrieved.

General Shepherd sounded a great reveille on 28 July for what was left of the Japanese naval defenders: a 45-minute air strike and a 30-minute naval gunfire bombardment, joined by whatever guns the 77th Division, brigade, and antiaircraft battalions could muster. At 0830 the brigade would attack for Orote airfield.

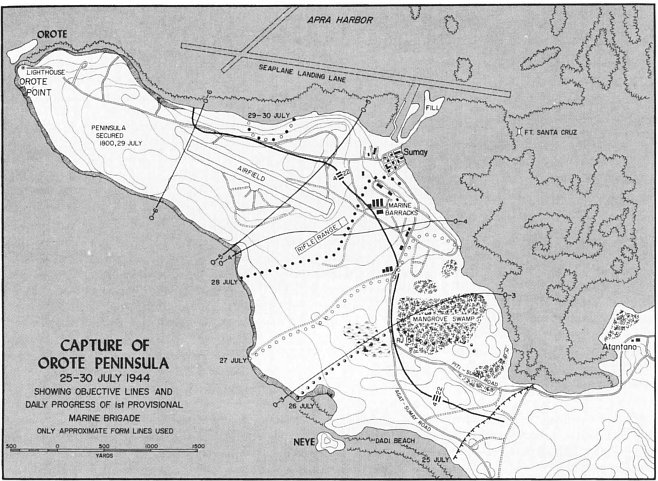

CAPTURE OF

OROTE PENINSULA

25–30 JULY 1944

SHOWING OBJECTIVE LINES AND DAILY PROGRESS OF 1st PROVISIONAL MARINE BRIGADE

ONLY APPROXIMATE FORM LINES USED

Colonel Schneider’s 22d Marines would take the barracks and Sumay and Colonel Shapley’s 4th Marines would take the airfield and the rifle range. Japanese artillery and mortar fire had diminished, but small arms and machine guns still spoke intensely when the Marines attacked. At this bitter end, the Japanese were evoking a last-ditch stubbornness. American tanks were called up but most had problems with visibility and control. Wherever the thick scrub brush concealed the enemy,30 Major John S. Messers’ 2d Battalion, 4th Marines called for increased tank support when one of his companies began taking heavy casualties. In response to General Shepherd’s request, General Bruce sent forward a platoon of Army tank destroyers and a platoon of light tanks to beef up the attack.

General Shepherd wanted the battle over now. He ordered a massive infantry and tank attack which kicked off at 1530 on the 28th. The Japanese did not intend to oblige this time by quitting; this was do or die. By nightfall all objectives were in plain sight, but there were still a few hundred yards to be gained. The Marines stood fast for the night, hoping the Japanese would sacrifice themselves in counterattack, but no such luck occurred.

When the attack resumed on the 29th, after the usual Army and Marine artillery preparation and an awesomely heavy air strike, Army and Marine tanks led the way onto the airfield. Resistance was meager. By early afternoon, the airfield was secured and the 22d Marines had occupied what was left of the old Marine barracks. A bronze plaque, which had long been mounted at the entrance to the barracks, was recovered and held for reinstallation at a future date.

The Japanese found this latest advance difficult to accept. Suicides were many and random. Soldiers jumped off cliffs, hugged exploding grenades, even cut their own throats.

Private First Class George F. Eftang, with the 4th Marines’ supporting pack howitzer battalion, saw the suicides: “I could see the Japanese jumping to their deaths. I actually felt sorry for them. I knew they had families and sweethearts like anyone else.”

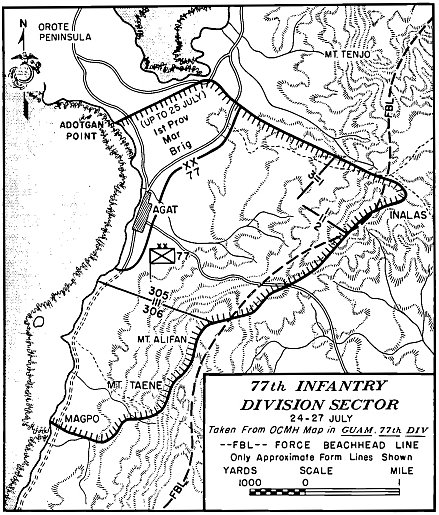

77th INFANTRY

DIVISION SECTOR

24–27 JULY

Taken From OCMH Map in GUAM, 77th DIV

Only Approximate Form Lines Shown

While the embattled peninsula still swarmed with patrols, Admiral Spruance; Generals Smith, Geiger, Larsen (the future island commander), and Shepherd; Colonels Shapley and Schneider, and others who could be spared, arrived for a ceremonial flag raising and heartfelt tribute to an old barracks and those Marines who had made it home. General Shepherd called it hallowed ground and told the distinguished assemblage, which included a hastily cleaned-up honor guard of brigade troops: “you have avenged the loss of our comrades who were overcome by a numerically superior force three days after Pearl Harbor. Under our flag this island again stands ready to fulfill its destiny as an American fortress in the Pacific.”

Many of the Marines standing at attention, watching the historic ceremony, could only thank God that they were still alive. At the end of this ceremony, engineers moved onto the airfield to clear away debris and fill the many shell and bomb holes.

Only six hours after the first bulldozer clanked onto the runways, a Navy torpedo bomber made an emergency landing. Soon the light artillery spotting planes were regularly flying from them.

The capture of Orote Peninsula had cost the brigade 115 men killed, 721 wounded, and 38 missing in action. The enemy toll of counted dead was 1,633. It was obvious that on Orote as at Fonte, there were many Japanese still unaccounted for and presumably ready still to fight to prevent the island’s capture.

With the breakthrough at Fonte and failure of Takashina’s mass counterattack, the American positions could be consolidated. The 3d and 21st Marines squared away their31 holds on heights and the 9th Marines (July 27–29) pushed its final way up to Mount Alutom and Mount Chachao.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 88153

A Marine uses a flamethrower on a Japanese-occupied pillbox on what had been the Marine golf course on Guam, adjoining the Marine Barracks on Orote Peninsula.

The most serious resistance to occupying the Mount Alutom-Mount Chachao massif and securing the Force Beachhead Line (FBHL) across the hills was a surprisingly strong point at the base of Mount Chachao. Major Donald B. Hubbard, commanding the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines (replacing Lieutenant Colonel Asmuth, wounded on W-Day), called down artillery, and, after the barrage, his Marines attacked with grenades and bayonets. They destroyed everything that stood in their path. When that fight was over, Major Hubbard’s battalion counted 135 Japanese dead. As the assault force pushed up these commanding slopes, the Marines could spot men of Company A of the 305th Infantry atop Mount Tenjo to the west. Lieutenant Colonel Carey A. Randall’s 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, then moved up and made contact with the Army troops. Originally, Mount Tenjo had been in the 3d Division zone, but General Bruce had wanted to get his men on the high ground so they could push ahead along the heights and not get trapped in the ravines. He also wanted to prevent the piecemeal commitment of his division and to preserve its integrity.

Conservative estimates put the Japanese dead as a result of the counterattack at 3,200 men. The loss of Takashina’s infantry officers, including General Shigematsu, who had commanded the 48th Independent Mixed Brigade, was held to be as high as 96 percent. Takashina himself fell to the fire from a machine gun on an American tank as he was urging survivors out of the Fonte position and on to the north to fight again. With Takashina’s death, tactical command of all Japanese forces remaining on Guam was assumed by General Obata. He had only a few senior officers remaining to rally the surviving defenders and organize cohesive units from the shattered remnants of the battalions that had fought to hold the heights above the Asan-Adelup beaches.

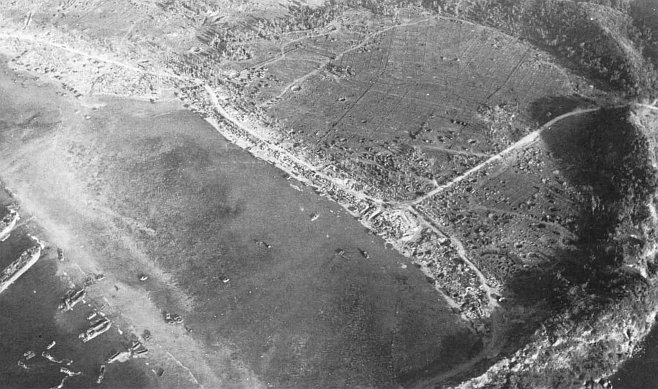

This Japanese airstrip on Orote Peninsula was one of the prime objectives of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade in its zone. Pockmarks on the strip resulted from the aerial, ships’ gunfire, and artillery bombardments directed at this target.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 88134

All through the night of 28 July, Japanese troops trudged along the paths that led from Fonte to Ordot, finding their way at times by the light32 of American flares. At Ordot, two traffic control points guided men toward Barrigada, where three composite infantry companies were forming, or toward Finegayan, where a force of five composite companies was to man blocking positions. As he fully expected the Americans to conduct an aggressive pursuit on the 29th, General Obata ordered Lieutenant Colonel Takeda to organize a delaying force that would hold back the Marines until the withdrawal could be effected.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 88152

A tank-infantry team from the 4th Marines advances slowly through the dense scrub growth that characterized the terrain in the regiment’s zone on Orote Peninsula. The attack moved forward yard by yard until the objective was secured.

Contrary to the Japanese commander’s expectations, General Geiger had decided to rest his battle-weary troops before launching a full-scale attack to the north. The substance of his orders to the 3d and 77th Divisions on 29 July was to eliminate the last vestiges of Japanese resistance within the FBHL, organize a line of defense, and patrol in strength to the front. With capture of the beachhead line and its critical high ground and the annihilation of great numbers of Japanese, the turning point of the Guam campaign had been reached.

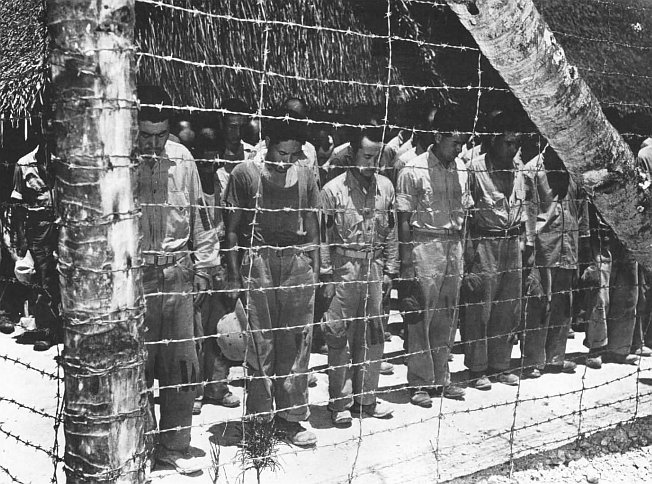

Yet, few Japanese had surrendered and those captured were usually dazed, wounded, or otherwise unable to resist. Almost all of the enemy died fighting, even when their lives were lost without sense or purpose. Still, a substantial number of troops from the 29th Division were still not accounted for.

General Geiger’s intelligence sections could only list about one quarter of the estimated soldier-sailor strength that had been on the island, and he needed to make certain that his rear was secure from attack before heading north after the enemy. Captured Japanese documents and prisoners of war, and sightings from aircraft, all indicated to Geiger that the Japanese had withdrawn to the north to better roads, denser and more concealing jungle, and commanding terrain for strongpoints.

To ensure that his rear area was not threatened, General Geiger had the 77th Division detail patrols to scour the southern half of Guam, repeating and intensifying the searches the brigade had made. These soldiers, as the Marines before them, found Guamanians everywhere, some in camps established by the Japanese, others on their farms and ranches. The natives, some surprised to see Americans so soon after the landings, reported the presence of only small bands of Japanese and often only single soldiers. It became increasingly evident that the combat units that remained were in the north, not the south. The best estimates of their strength ranged around a figure of 6,000 men.

Obata had expected a hasty pursuit, and set up strong rear guards to give time for his retreating forces to organize. Victory was no longer even a hope, but the Japanese could still extract a painful cost. General Geiger, who had a little time now, could give his troops a rest and move into attack positions across the width of the island. Strong and frequent patrols were sent out to find routes cross33 country and glimpse clues of enemy strength and dispositions.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 93468

Marines bypass two smoldering Japanese light tanks, knocked out of action by Marine Sherman medium tanks on the road to Sumay on Orote Peninsula.

Obata organized delaying defenses to include the southwest slopes of Mount Barrigada, midway across the island from Tumon Bay, and the little town of Barrigada itself, barely 20 houses. On all approaches to his final defensive positions near Mount Santa Rosa, in the northwest corner of the island, he organized roadblocks at trail and road junctions, principally at Finegayan and Yigo, and concealed troops in the jungle to interdict the roads which were the only practical approach routes to the northern end of the island. The Japanese commander felt sorely besieged, and as his notes later revealed: “the enemy air force seeking our units during daylight hours in the forest, bombed and strafed even a single soldier.” Perhaps even more damaging than the air attacks were artillery and naval gunfire bombardments brought down on men, guns, trenches, anything, by the Navy, Marines, and Army spotter planes which were constantly overhead.

Marine artillerymen, members of Battery C, 7th 155mm (Long Toms) Gun Battalion, III Amphibious Corps Artillery, take advantage of a lull in fire missions to swab the bore of their gun. Soon after, the gun was back in battery firing missions.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 91347

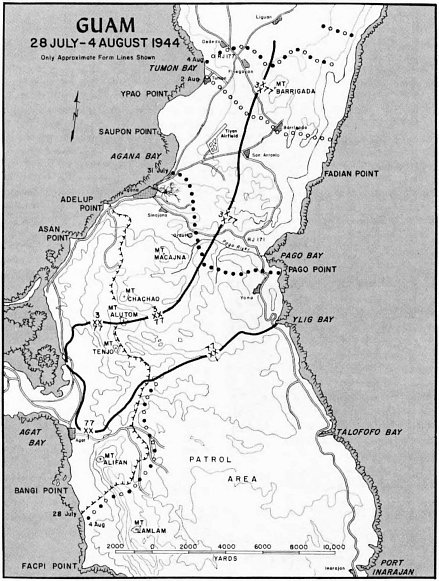

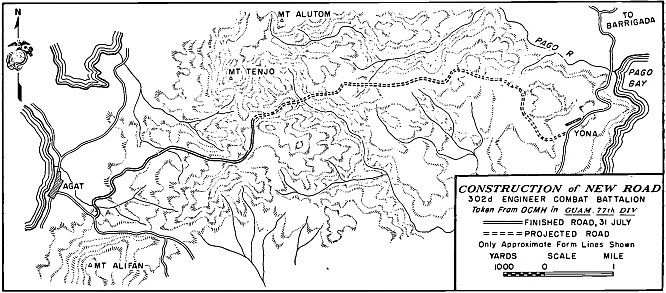

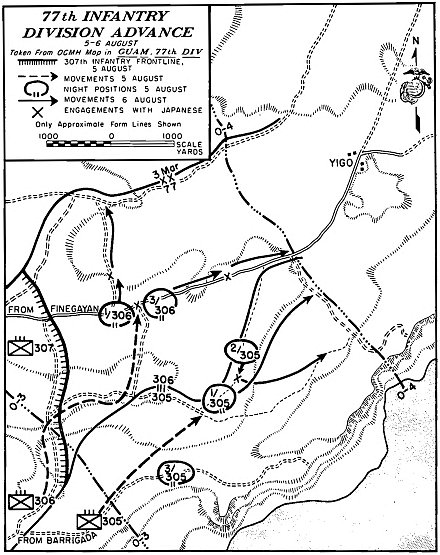

III Corps’s Geiger knew Obata’s probable route of retreat and drew up a succession of objectives across the island which would incrementally seize all potential enemy strongpoints. Jump-off for the drive north was 0630 31 July with the 3d Marine Division on the left and the 77th Infantry Division on the right, dividing the island down the middle. The Marine zone would include the island capital of Agana, the Japanese airfield at Tiyan, Finegayan, and the shores of Tumon Bay. The 77th would have Mount Barrigada, Yigo, and Mount Santa Rosa in its zone. The 1st Marine Brigade relieved the 77th Division of the defense of the southern portion of the FBHL and would continue to patrol the southern half of Guam. As the Corps attack moved northward and the island widened, the brigade would eventually take part in the drive to the extreme north coast of the island.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 93543

Fleet Marine Force, Pacific commander LtGen Holland M. Smith, right, stands with the leaders of the successful retaking of Orote Peninsula. From left to right, LtCol Alan Shapley; BGen Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr.; and Col Merlin F. Schneider.

The 3d Division reached Ordot in the center of its zone where Obata had directed some of his survivors. The 3d Battalion, 21st Marines, ran into them and one of their pillboxes, which the Marines thoroughly gutted. The Americans also accounted for 15 infantrymen and two light tanks which were the targets of M-1s and bazookas.

The honor of liberating Agana fell to the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines. The riflemen entered the town’s ruins treading carefully, sizing up the stark, dusty building walls for snipers. A few enemy riflemen emerged from behind concrete outcroppings then dropped back into eternity. The Japanese guards were stragglers, the wounded, or a few foolish enough to stay. In one house, a Marine opened a closet to reveal a Japanese officer, sword in hand. The Marine slammed the door, riddled it with an automatic rifle, and didn’t bother to look again. The once-beautiful old Plaza de Espana was in American hands 15 minutes after the town was entered. By noon it was secured.

The 1st and 2d Battalions, 3d Marines, moved along to the critical Agana-Pago Road. At 1350 the 21st Marines was right up there with them after the few engagements with pillboxes, snipers, and tanks. By 1510, Colonel Craig’s 9th Marines on the division’s right was partially across the road and seized the remaining portion of that highway in its sector on the next day. Hard-surfaced, with two lanes across the midriff of the island, the Agana-Pago Road would prove critical in winning the battle of Guam.