Title: A Middy's Recollections, 1853-1860

Author: Victor Alexander Montagu

Release date: May 31, 2015 [eBook #49101]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A MIDDY’S

RECOLLECTIONS

1853–1860

BY

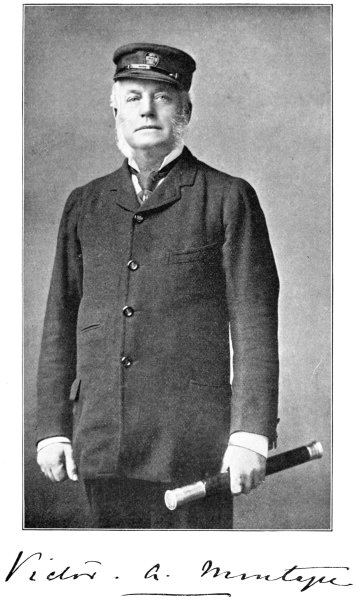

REAR-ADMIRAL THE HONOURABLE

VICTOR ALEXANDER MONTAGU

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1898

IN MEMORY OF

MY MOTHER

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Entering the Navy | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The “Princess Royal” | 9 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| War with Russia Declared | 26 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Crimea | 35 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Punishments in the Navy | 64 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Russia Collapses | 71 |

| CHAPTER VIIviii | |

| Leisure Hours | 77 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Some Distinguished Sailors | 86 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Play on Board; and some Duties | 95 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Pirate-Hunting; and a Dinner Party | 101 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| War with China Declared | 106 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

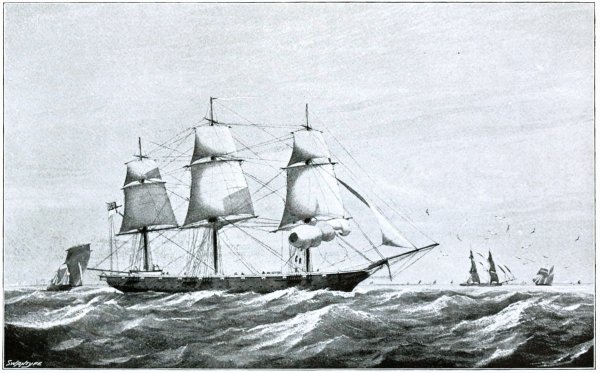

| The “Raleigh” Wrecked | 111 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| At War in China | 119 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| More Pirate Hunting | 139 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Indian Mutiny | 147 |

| CHAPTER XVIix | |

| The Naval Brigade at Work | 157 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Incidents of the Campaign | 167 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| A Touch-and-Go Engagement | 179 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| Compliments to the Naval Brigade | 193 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| Home Again | 199 |

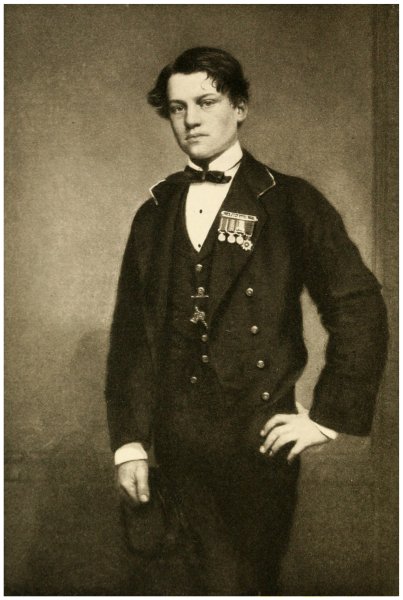

| The author as a Midshipman in 1856. From an oil painting | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

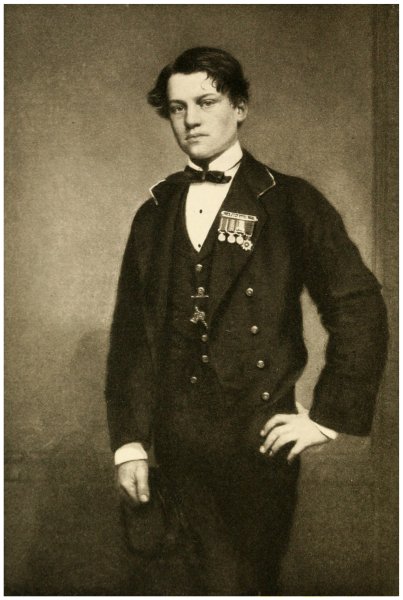

| The author as a Naval Cadet, 1853. From a miniature | 6 |

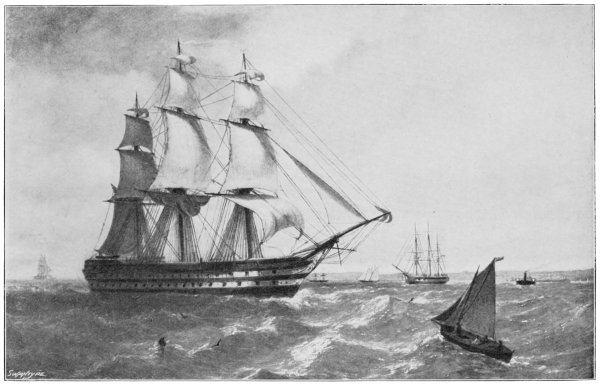

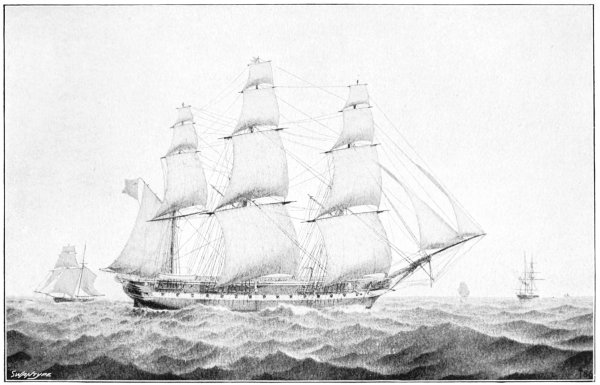

| H.M.S. “Princess Royal,” of 91 guns, 1853 | 10 |

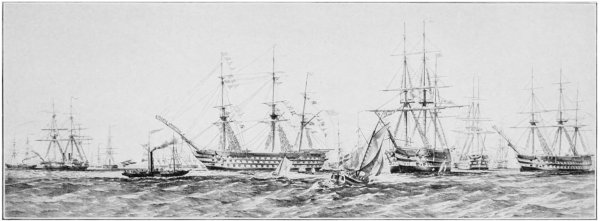

| The signal flying for war, and Fleet cheering | 26 |

| H.M.S. “Raleigh,” 50-gun sailing frigate, wrecked off Macao (China), the 14th April 1857 | 86 |

| The battle of Fatshan, showing the sinking of Commodore The Honourable Henry Keppel’s galley, 1st June 1857 | 128 |

| H.M.S. “Pearl,” 21-gun corvette | 148 |

| The author at the present day | 170 |

Born in April 1841, I was about six months more than twelve years old when I joined the Royal Navy. My father was the seventh Earl of Sandwich; my mother, a daughter of the Marquis of Anglesea, who commanded cavalry at Waterloo, and lost his leg by one of the last shots fired on that eventful day. It is said that when Lord Anglesea’s thigh was struck he happened to be riding by the side of the Duke of Wellington, and exclaimed, suddenly, “O the Devil! my leg is hit!” The Duke turned round, looked at him, and said, “The deuce it is!” His leg was shortly afterwards amputated. As all the surgeon’s knives had become blunt from the long day’s work, it took twenty minutes to perform the operation. I was the second of four sons, and was educated by a private tutor.

For some time before I was sent to sea, my father had often expressed a wish that, hailing2 from a naval family, one of his sons should select the Sea as his profession. Somehow or another, it devolved upon me to be the naval representative; and, though my father did not enforce this idea, I took it into my head that I should like it. My poor mother had misgivings. She loathed the sea, and could not bring herself to believe that any one else could endure its hardships. She was second to none, however, in her admiration of the Service.

No doubt I thought it a fine thing to don a naval uniform and wear a sword at my side at twelve and a half. A position of importance was assured. Of sea-life I knew but little. I had on several occasions, when staying at the Castle at Cowes (enjoying the hospitality of my grandfather, Lord Anglesea), sailed in his famous old cutter, the Pearl (130 tons); but beyond learning, when beating about the Solent, what sea-sickness was, my experience was naught. However, on the 15th of December 1853, I was gazetted a naval cadet in the Queen’s Navy.

It was deemed advisable to send me to a school where boys were prepared for examination before joining the Navy. When it is remembered that one’s qualification consisted only in being able to master simple dictation from some English work, and arithmetic as far as the Rule of Three, this will seem incompatible with modern ideas. So it3 was, however; and I found myself, some time in October 1853, at the school of Mr. Eastman, a retired naval instructor who kept a house of about thirty boys in St. George’s Square, Portsea. This mansion I visited not long ago, and found it a tavern of the first quality.

If my memory serves me rightly, we did not indulge in much study at that school. We used to walk out to Southsea Common in twos and twos to play games, and, if opportunity offered, to have rows with what we called “the cads,” the youth of the town: a pastime which the usher encouraged.

It was a very rough school. The food was execrable; many of us were cooped up in the same room; and I have a vivid remembrance of the foot-pan which we were allowed to use only once a week. On birthdays, or other select occasions, the chosen few were regaled with very large junks of bread sparsely besmeared with butter, and tea in the parlour, about 4.30 P.M.; our host and hostess being at that time well into their second glass of toddy, and drowsy though attempting to amuse us with old sea stories.

Sometimes we were taken to the Dockyard. I well remember being much interested in watching a Russian frigate then in dock refitting, and wondering to myself why Russians looked so4 different from men of my own race, and why their ships carried such a curious scent. This reminds me that often in after years, when returning to my ship on a dark night and not being exactly sure of her position, I have been guided by the peculiar smell which you notice in passing under the stern of a foreign man-of-war. The perfume of each navy is distinct; and the position of a ship, which I recollected from the daytime, was often the means of putting me on my right course during a night’s pull.

I do not remember anything particularly worth recording during my six-weeks’ stay at that school. Only, on one occasion, about midnight, we were all aroused by the noise caused by the smashing of glass. Running out in our night-shirts into the street, we discovered that all the front plate-glass windows were broken. The master, in his fury, thought that open mutiny had broken out in school, and vowed vengeance on every bone in our bodies. It turned out that Mr. Eastman had been cramming some mates for their examination towards Lieutenancies, and that, as they had all signally failed, they had expressed their displeasure by breaking the windows. No clue was obtained at the time; but I happened to hear all about the affair when I joined my first ship. Three of the culprits were serving in that vessel, and told me the story.

5 Shortly after this, the time arrived when I was to present myself at the Royal Naval College to pass my examination. The nervous and sleepless nights! Though I felt perfectly capable of passing through the ordeal, the name of the Royal College overawed me. The thought of naval dons sitting in conclave over my work, with the possibility of their finding it defective, was as an evil dream. When the day arrived, two short hours sufficed to get me through. My arithmetic was faultless; and, though I spelt judgment without a d, my papers were said to be very good. In short, I had passed thus far with éclat.

Having qualified in mind, I found that the next performance was to qualify in body. Forthwith I was taken on board that glorious and venerable ship, the Victory, to be medically inspected. It was my first visit to this renowned ship; and how well I remember the thoughts that ran through my mind as I approached her! There was the hull exactly as it had been on the day of Trafalgar! I could not help picturing to myself those noble sides being pierced through and through with shot while the vessel was leading the line gallantly into action past the broadsides of the enemy.

Once on board, I was accosted by a rough Irish assistant-surgeon, who, without a word of warning or of good-morning, ejaculated, “What is your6 name? How old are you?” On my having meekly answered these questions to his apparent satisfaction, he said, in the gruffest of tones, “Strip, sir.” Having decency, I quietly asked, in the humblest of tones, “Do you wish me, sir, to pull off my trousers as well?” “Yes, sir,—everything,” was the answer. This was a trial. I was miserable about my braces’ buttons, afraid he would see that two were lacking (one in front and one behind); which might tell against my claim to respectability. How curious is it to find oneself remembering such details through life! Having denuded myself of everything,—which was very trying, particularly in a draughty cabin in December—I was put through various exercises; and, after being minutely examined as to wind, sight, hearing, and other gifts, I was told to dress and take away with me a formal certificate of health. I hated that man, and was glad to get back to school in order to prepare to leave for home on the following day.

THE AUTHOR AS A NAVAL CADET, 1853.

Swan Electric Engraving Co

Within a week from this time, I received my first official document. It ran:—

You are hereby directed to repair on board H.M. ship Princess Royal, now laying at Spithead, and report yourself on December the 15th. Should the Princess Royal not be laying at Spithead on the date mentioned, you will inquire at the Admiral’s office at the Dockyard, and you will be informed where H.M. ship may be.

7 This notice gave me a clear fortnight more at home. I had to get my outfit ready, and to pack up my sea-chest. My father had the sea-chest made by the house-carpenter, instead of relying on the outfitter who invariably supplied the necessary article according to regulation size. No doubt my father conceived the idea with the best possible intentions as to economy; but the chest was always an eyesore, and eventually it was cut down to proper dimensions by order of a very particular commanding officer, who could not stand seeing one chest an inch higher than the rest in the long row on the cockpit deck.

War with Russia was at this time expected. Writing so many years later, I can only attempt to describe, from memory, all I then thought, and the pride I felt that I should possibly see active service soon. There was an innate dread of leave-taking—of parting from home for the first time—more especially of separating myself from my mother, a lady beloved by all her children. That was a thought scarce bearable. Many who read those lines will realise too well how sad such moments are: perhaps the saddest that fall to one’s lot. Yet, painful as they are, they have their consolation: as showing the love between mother and son. The more this sentiment is impressed on the youthful8 mind, the greater the gain in after life; for when the mother is not present, there comes the echo of sweet counsel ringing in the heart, inspiring the wish to act as she would desire—she, the help and guidance in all trouble.

I joined the Princess Royal, commanded by my uncle, Lord Clarence Paget, and found that beautiful 91-gun line-of-battle ship lying at Spithead, preparing for sea. The family butler was deputed to see me safely on board and report on his return. He had been long a servant of my father—I believe he had been his valet at Cambridge;—and many were the hours he had spent with my brothers and myself ferreting and hunting with terriers; and we were all much attached to him.

It was blowing a fresh gale when we took our wherry from the Hard at Portsmouth, and the double-fare flag was flying on the official tower; but go we must, though our boatman seemed to suggest that we should have a bad time of it outside; and so it turned out, for, besides being drenched to the skin on a cold December day, the butler and I, when we got alongside the noble10 ship, were sea-sick. My first obeisance to the Quarter-Deck—(I had been warned to be very particular about this)—must have lacked finish. My troubles were not over with that ceremony. I had hardly finished saluting the officer of the watch when a blue-jacket fell from out of the main-rigging on to a quarter-deck gun within a yard of me. He was killed instantly, and the sight was very painful.

This was a sad beginning.

My next step was to go below and endeavour to look pleasant on being introduced to my messmates. Many were the eyes I felt glaring at me to see what the new cadet was made of. Didn’t this poor boy wish himself elsewhere? Once in my hammock that night, I was thankful to find myself in seclusion.

For several nights I was on the look-out for the cutting-down process that must be practised on me. I had not long to wait. “Cutting down,” I may explain, means that when you are fast asleep your hammock, either at one end or the other, is let down by the run. If it were let down by the head, your neck might be broken. To be suddenly aroused from sleep by finding yourself balancing by the head on a hard deck is not an enviable position. It was ordained only if the boy was obnoxious; but the alternative, as I found to my chagrin, is not pleasant. Luckily, a marine sentry11 came to my rescue. He helped to get my hammock up again, and condoled with me.

Those marines were fine fellows. They were always considered the special safeguard of the officers in a man-of-war. In case of mutiny or other trouble, they stood by the officers of the ship. In the Princess Royal I had, on joining, an excellent old soldier told off to look after me and be my servant. For many months after joining I was too small to swing myself into my hammock (I could not reach anything handy even by jumping), and he invariably came at the appointed time to give me a leg-up. I was much attached to him. Many a time, when some bigger midshipman took it into his head to take some of my washing water away for his own selfish use, my marine came to the rescue in support of his small master. Seven shillings a month were his wages, and on washing days, I think, he received an extra douceur. Poor man: he got into trouble later, and had to leave me. I recollect well going to visit him in irons, under charge of a sentry; he was then under sentence of four dozen lashes for having been drunk on board; and some years afterwards, while I was fitting out in a ship at Portsmouth, in passing along the road I heard the voice of this dear old Joey calling me by name; but so drunk was he that he could not follow me, and I escaped. Sometimes, when half-starved in the gun-12room mess, I went into my marine’s mess and got some ship’s biscuits, which, with pickled gerkins, I supped off. We certainly were shockingly fed in those days. Growing youths, much imbued with sea air, used to fare very badly; but when it is considered how little was paid in the shape of mess money it is no wonder. On joining you found £10 as an entrance fee; and the mess subscription was one shilling a day, with your rations thrown in. The rations were the same as those allowed to the ship’s company: a pound of very bad salt junk (beef), or of pork as salt as Mrs. Lot, execrable tea, sugar, and biscuit that was generally full of weevils, or well overrun with rats, or (in the hot climates) a choice retreat for the detestable cockroach. In one ship—I think it was the Nankin frigate—cockroaches swarmed. Sugar or any other sweet matter was their attraction; and at night, when they were on the move, I have seen strings of the creatures an inch and a half long making a route over you in your hammock. Some ships were overrun with them. Rats also were a dreadful nuisance: they invariably nested among the biscuit bags. We mids used to lie awake and watch them coming up at night from the hold on to the cockpit deck; and, well armed with shoes, hair-brushes, and so on, we persecuted them.

13 Spithead, at the time I joined my ship, afforded an interesting spectacle. Men-of-war of all classes were gradually collecting, and the dockyards were very busy; but we were short of men—so much so that all available coastguard-men were requisitioned to complete our crews, which in those days were for the most part collected from the streets.

The war with Russia which (keen-sighted diplomatists warned our Government) must come, and that soon, necessitated active preparations. The newly-joined men were being trained in great-gun drill, and target practice was always going on.

My ship was a battleship of about 3400 tons, and said to be quite the prettiest of her class. We were afterwards styled the Pretty Royal; which so much pleased the middies that we all bought eyeglasses, and wore them, when not on duty, by way of swagger. We carried 32-pounders on the main and the upper deck, and 56-pounders on the lower deck, throwing hollow shot; with one solid 68-pounder on the forecastle. Our full-steam speed under favourable conditions was nine knots; but this speed under steam was of rare occurrence—eight knots was usual. We had a complement of 850 men and officers.

In the gun-room (or midshipmen’s) mess we numbered about twenty-four, all told. I grieve to say that we had a few very bad specimens of the14 British officer: bad both professionally and socially. Though discipline was generally very strict on deck and on duty, irregularities went on below that were winked at, and in later days would not have been tolerated. There was a remnant of the bad style of earlier days, without any of the higher qualities of the old naval officer to temper it. One heard now and then of notorious characters that seemed always just to escape retribution; though long before the end of the war three of my messmates, if not more, were “hoisted out” by court-martial or otherwise. Bullying also was common. On one occasion I was so much irritated by a lout of an Irish assistant-surgeon that I lost my poor little temper and gave him the lie. Being overheard by one of the senior mates, I was immediately kicked out of the gun-room and ordered to mess on my chest for three days. The punishment was carried out to the full. The most fiendish case of bullying it ever was my lot to endure was perpetrated by one Berkley. I glory now in presenting his name to the British people. He was one of the senior mates. It was his wont to regale himself with port wine and walnuts of an afternoon. On one occasion (possibly it may have been oftener) he sent for me, and he lashed me to a ring-bolt in the ship’s side, ordering me to say, “Down, proud spirit: up, good spirit, and make me a good boy.” I had to suit the action to the word by moving15 the hand and arm down and up the body. I had to repeat the formula a hundred times, while he jotted down my penances with a pencil on his slate. I have always considered myself lucky that I did not cross that man’s path in after life. In my last experience with this creature, I got the better of him. The Princess Royal was paying off, and the ship’s company and officers were hulked in one of the old ships in Portsmouth harbour. I think all our middies, except myself and two others, were away. A signal was made from the flagship for a midshipman to copy orders; and, though I was just going home on Admiralty leave, having packed my portmanteau and proceeded to change into mufti, Berkley sent for me to obey the summons for this signal, he knowing perfectly well that I was just about to go on shore. My answer to the message was that I would come up immediately, but that, as I had changed my uniform for mufti, I requested five minutes within which to don proper dress. In less than that time I had carried out my view of the matter by hailing a wherry under the stern port, popping my portmanteau into the boat, and telling the boatman to pull for his life to the Hard, keeping his boat well in a line with the stern of the hulk. Luckily, the tide was in my favour; but, to my horror, when nigh half-way to the Hard, I discovered the jolly-boat pulling after me like the very devil. “Give way,16 you beggar! Double fare! Only land me at the Hard before this infernal boat can overtake us!” We just did it. The portmanteau was whipped up on the boatman’s shoulders, and thrown into a fly that, luckily, saw the little game going on; and off we galloped to the station. I did him—Mr. Berkley:—that was all I wanted. He was promoted, and had left before I returned from leave; and from that day to this we have never crossed each other’s path.

One of the amusements with which the seniors entertained themselves was slitting the end of your nose open with a penknife. The idea was that you could not properly be a Royal, bearing the name of your ship, without a slight effusion of blood. The end of one’s nose was well squeezed, and thus there was little pain. A ceremony something after the style of blooding one over one’s first fox was gone through.

Every officer was limited in regard to his wine bill: you could not exceed a certain monthly sum. A middy was allowed about 15s.; the seniors, more; but, as many of them were of thirsty habit, some means had to be found to procure more wine or spirits after the bill was stopped, which usually occurred about the middle of the month. There were several methods. As on one occasion I had to suffer severely for the faults of others, I will tell a story.

17 The youngsters had to draw lots as to who should go and represent to a Naval Instructor fresh from one of the Universities that it was the birthday of some one in the gun-room, that his wine bill was stopped, and that he had no means of procuring any liquor if Mr. Verdant Green were not able to oblige by lending some. The lot fell upon me. I felt I was running fresh risks; but go I must. I soon found my man, and forthwith told my story and made my request. Instead of my being answered as I expected, by a “Yes” or by a “No,” my green friend went straight to the Commander’s cabin, tapped at his door, and in my hearing asked whether this were permissible, or in contravention to naval discipline and custom. The Commander settled the matter by ordering me to the mast-head on the spot and stopping my leave for six weeks. One would have thought the original delinquent would have pitied me on my return from the cross-trees; but I was told that I must have acted in a clumsy manner, and that I was a useless cub. The worst of an escapade such as this is that it gets you into the bad books of the Commanding Officer.

Soon after I had joined the Princess Royal, my uncle made me his A.D.C., and gave me charge of his 12-oared cutter, a boat which he preferred to the usual 6-oared galley. It was, I think, on the first occasion of my taking charge of this boat18 that I was sent into Portsmouth Harbour to fetch my captain and bring him off to Spithead. On my way to the King’s Stairs, while passing “the Point,” a locality (beset with public-houses) where the immortal Nelson left the English shore for the last time, the coxswain suddenly accosted me. “My sister,” he said, “keeps a pub close by, and it is quite the right thing that you should treat the boat’s crew to a glass of grog all round.” Feeling that I had plenty of spare time, and that it would be mean to refuse this very strong request, I gave permission to beach the boat, and forthwith produced the last of my pocket-money (a ten-shilling bit), in order that the crew might be regaled. They returned one man short. I could not wait to search for him, and I thought it just possible that his Lordship might not discover one oar minus: so I arranged that, on whichever side of the boat the captain took his seat, my vacant thwart should be on the other. All went well until we were nigh our ship; though I must own to many moments of anxiety during the long pull off to Spithead. Alas! He noticed the absence of a man as the men tossed their oars in. I could have died on the spot. Of course, we were all paraded on the quarter-deck. The coxswain made some plausible excuse; but I myself was threatened with immediate expulsion and watch-and-watch for a fortnight—four hours on duty and four hours19 off duty throughout the day and night. Within a few days, however, my uncle, having found a soft place in his heart, sent for me and let me off. I fancy that, being an old hand, he had seen how the land lay, and had taken pity on my youth, thinking that his coxswain had had more to do with the episode than I. Needless to state, the coxswain’s sister was a Mrs. Harris. She had been designed in order that a bad hat whom the coxswain and the crew detested should be given an opportunity to run. In later days, when the affair had well blown over, this information was imparted to me by the coxswain.

On the 11th of February 1854, the Baltic Fleet was ready for sea. Three divisions (of squadrons) were formed, under Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Napier, Commander-in-Chief, Vice-Admiral Corry, and Rear-Admiral Chads; and a most imposing sight it was. Besides the line-of-battle ships, there were frigates and paddle-sloops. These frigates were lovely ships: the Imperieuse and the sister vessel, the Euryalus, were beautiful models, carrying 51 guns. There was a very fine 40-gun frigate whose name I cannot recall: she was commanded by one of the best and most popular officers in the service, Captain Yelverton. I had the honour, many years afterwards, of serving under him when he was Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean; and nothing could20 have exceeded the happiness of the fleet at that time. There was great rivalry in those days (and even long before) among some of the ships. Sail drill was the principal cause of it. The ships’ companies became so intensely jealous if one or more ships had completed an evolution in less time, that when general leave to go ashore was granted strict orders were given that leave should not be granted to those respective ships at the same time, for fear of a free fight between their men. I well recollect serious rows when they did meet one another. To my idea, nothing could have been finer than the display of competitive feeling. Some of the ships used to have all sorts of dodges (as we called them) to enable time to be saved during drill, and when I was Flag-Lieutenant on the station I was ordered to watch minutely, to see if all was fair play. The paddle-wheel sloops and frigates were comfortable vessels (one in particular, the Terrible, carrying 21 guns—and heavy ones they were). The Gorgon and the Basilisk rendered good service during the war. These were smaller, and carried 14 or 16 guns, I think. Of the liners, the Duke of Wellington, the flagship, bore the palm. She carried 131 guns, and was a beautiful sailer as well as steamer. The St. Jean D’Arc, of 101 guns, was a lovely ship. The Acre, commanded by Harry Keppel, was always what we termed our21 chummy ship: the Princess Royal was generally next her in the line.

Then came the great event of the day. The Queen arrived from Osborne in the Fairy, to review the Fleet before it weighed anchor. The very fact of Her Majesty announcing her intention to bid us Good-bye caused intense excitement through the Fleet, and I recollect well how highly this mark of honour was appreciated. We were all anchored in three lines, and the lovely little Fairy threaded her way through the ships as we manned yards and cheered to the echo. After this inspection the Queen summoned all her Admirals and Captains in command on board the Fairy, and personally took leave of them all. I was lucky enough to be present, as I had charge of my Captain’s cutter; and Her Majesty, on being told that one of her godsons was present, immediately ordered me to be sent for. It can be imagined that it was a most nervous moment for a boy of my age—scarcely thirteen—when I was hailed to go alongside the Fairy, as the Queen wished to see me. I remember well my coxswain pulling off a piece of flannel I had round my neck (as I was suffering from a severe sore throat, and the weather was very cold) before I left my boat to step over the side of the Queen’s yacht. After the Admirals and Captains had made their last obeisance, my turn came. Standing cap in hand, I made my bow;22 and Her Majesty said to me, “How do you do, Mr. Montagu? I have not seen you since you were quite a little boy;” and then asked after my mother, who had not many years previously been one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting. I then had the honour of shaking hands with His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, who was standing near, for the first time, and with the Princess Royal and the Princess Alice, all of whom said some kind words. I felt very proud indeed, after having got over my nervousness; and many were the interrogations when I returned on board. Yes: this was all a great honour; and so impressed was I at the time that nothing of this great reception has escaped my memory, nor the scene as I witnessed it at the time. His Royal Highness the Prince Consort also, I think, was on board; but I did not have the honour of seeing him. Shortly after this the Fleet weighed. Her Majesty placed herself at the head of the Fleet, and forthwith led us out to sea. When the Fairy left us a parting signal was flown on board the Fairy, the whole Fleet cheering Her Majesty’s departure. It was one of the grandest scenes imaginable: God be praised for having spared our gracious Sovereign to be reigning over her loving subjects still. In a man-of-war we are all constantly reminded of our Sovereign and the honour due to her station. At eight o’clock, when the colours are hoisted, the23 band plays our National Anthem, and all officers and men salute the colours as they are hoisted to the Peak. The Quarter-Deck is always saluted when officer or man comes on to it: simply because it is the Queen’s Quarter-Deck, and is honoured as such. At every mess, when the wine is passed round, our first duty is to recollect our Sovereign and raise our glasses to “The Queen (God bless her)!” All these matters tend to keep us in perpetual recollection of our Queen and the duties we owe to Her Majesty; and it is indeed a fine sentiment.

The Princess Royal called in at the Downs, and embarked an officer; and our last letters were sent on shore. On our way across the North Sea the Fleet was scattered in a fog. Our first rendezvous was Wingo Sound; and by degrees the ships rejoined, and we made that place our first anchorage. The ice farther north had not broken up: so there was a good deal of delay and cruising about.

The Fleet generally was sailing under very easy canvas (double-reefed topsails), as the wind was pretty strong, and we used to wear in succession after a few hours’ sail on one tack. Day after day this went on; and the only interest I took in it was in watching the ships while the evolution of wearing was going on: turning through the curve of a half circle, endeavouring to keep their proper distances apart. Of course, some of the ships24 carried more sail than others, as there was a material difference in their respective speeds. It was monotonous work, and, the weather being still cold and occasionally pretty rough, many of us suffered a good deal from sea-sickness and ennui. The paddle steamers used to ply across to Copenhagen, or other port, for fresh food; but I do not think the blue-jackets got much of this fare, and I know the gun-room mess did not. Indeed, we had a very wearisome fortnight during breezy weather, jogging about under easy sail off Gotska Sands. All was done in quite the old naval style, and gave me an insight into “the good old days.” A great deal of salt pork and salt junk, with a moderate allowance of water, was our fare; and all were desirous of pushing on.

I find myself writing about this time, evidently very homesick:—

People tell me I shall like the Service better as I get on, but one gives up home and all its joys for coming to sea, or otherwise for honour; one can do without honour but not without home, besides, why should I not get honour at home as well as at sea?

I quote this because it is curious to see how a boy’s mind wavers; for shortly afterwards, having seen a few shots fired at Hango at some Russian forts, I wrote home:—

I like the Service better every day. I begin to understand things, and they interest me.

We rode out a heavy gale in Kioge Bay, while some of the ships, dragging their anchors, were steaming ahead, with topmasts struck and two anchors down.

On the 14th of April, lying in this same bay, we suddenly saw a mass of bunting flying on board the Duke of Wellington. The signal, indeed, gave us great joy. It announced that “War was declared with Russia.” I shall never forget officers and men all rushing on deck helter-skelter. The blue-jackets were up the rigging in a jiffy, and cheer after cheer echoed through the Fleet. I believe the actual date of the Declaration was the 15th of March, just three weeks previously.

I shall not attempt to describe what are now well-known matters of history,—the events during the summer of 1854;—nor shall I speak of the do-nothing policy, which (with the exceptions of the storming and taking of Bomarsund, the destruction of grain stores in the Gulf of Bothnia, occasional scrimmages for fortified posts, and the hemming in of the Russian Fleet at Kronstadt) kept us inactive. Our chief, though a gallant man, did27 not seem to be gifted with much enterprise (possibly he was hampered by orders from home); but I do know that we all longed for some active service, and wished that the Russian ships would come out from under their batteries and give us a fair chance. We used to see them loosing their sails at their anchorage, and many were the surmises as to whether they intended to “sheet home” or only let them fall off the yards to dry.

They were, I think, nearly all sailing ships; though they had paddle-wheel steamers that occasionally would make a dash out at some yacht that had come out to see the fun, and had got in too close to the batteries. I fancy we must have felt as Nelson felt when blockading Toulon,—longing for his enemies to come out. But, after all, why should an enemy be expected to give battle with hopeless odds against him? Perhaps, on the other hand, the Russians wondered why we did not attack their forts. The explanation is that the channels were narrow, and what they called in those days “infernal machines” were supposed to have been laid down in those channels to obstruct the passage of our ships.

There were some pretty sights to be seen during that summer’s campaign. The two that struck my juvenile eyes most were the sailing of our huge Fleet through the Great Belt and the first28 meeting with the French Fleet. In the former case, imagine one long row of nearly twenty line-of-battle ships, several frigates, and a few sloops, tearing through the Belt, with a strong fair wind (there is a very clever picture of this scene drawn by Brierly, a famous marine artist of those days), the Duke of Wellington leading under close-reefed topsails, and some of the slower sailers carrying a press of canvas to enable them to keep their stations. It was amusing how we middies used to compare notes as to our respective sailing qualities, and argue, till we nearly came to blows, over details as to how one ship could spare another an extra reef in a topsail or a top-gallant sail, or the lee clew of a mainsail, as the case might be.

And what a lovely sight a line-of-battle ship was, under all plain sail—and still more lovely, to my mind, a handsome 50-gun frigate! Yes: one sometimes longs to see such sights again. One of the prettiest manœuvres I ever heard of in my time was done by the old Arethusa, a 50-gun sailing frigate. She attacked a fort off Odessa, in the Black Sea. Sailing in, she fired first one broadside; in tacking, she fired her bow guns; then she hove about, and fired her other broadside; wore round, and fired her stern guns. I do not know how many times this manœuvre was repeated; but it was a fine display of handling.

The second incident to which I have alluded29 was our meeting the French Fleet for the first time. They were under sail, and remained hove to, with their main topsail to the mast, as we, the English Fleet, steamed in one long line across their bows. We hoisted the French Tricolour at the main, and they, to return the compliment, hoisted the English Ensign, while the bands played the National Anthem as we passed. It was a beautiful calm day, and the sight glorious. Yes: here we were, allies, bent on the same cause near at hand, and past days obliterated from memory. When at anchor together the two Fleets formed a most imposing sight: forests of masts covering the seas, and at eight o’clock, or when the colours were hoisted in the morning, the bands of the Fleets playing each the other’s National Anthem.

Apropos of bands: I shall never forget finding, while lying at anchor in the pleasant little landlocked harbour of the Piræus, off Athens, eight or ten vessels of different nationalities. At eight o’clock in the morning, as the colours went up, all our respective bands played one another’s National Anthem. The music was discordant. There was a great deal of etiquette as to which anthem was to be played first. Ultimately it was arranged that we should begin with the Hellenic air, and that the others should follow according to seniority of the ships present; but soon the discord became30 pronounced. It took the best part of half-an-hour to complete the set.

While the Fleet was cruising off Hango (a fairly strong position of the enemy’s) several of our paddle steamers were sent in to reconnoitre, and soon became engaged with the forts. My Captain, Lord Clarence Paget, could not stand a distant view of this engagement: so he ordered his boat to be manned, and we pulled in the direction of the ships engaged. We only had the satisfaction of gazing at some highly-elevated shells that exploded far above our heads, though some of the fragments fell into the water, unpleasantly near. The engagement ended in smoke, though a few losses occurred on board the paddle steamers; and, to our astonishment, the Fleet retired. I could not see the object of this mild display.

The attack of Bomarsund, later, was a success. The authorities had taken a considerable time to make up their mighty minds when to begin the bombardment. There was an idea that we could not subdue the place without troops. Thus, we waited long for the arrival of 10,000 French troops, which were brought up the Baltic on board some obsolete old 3-deckers in tow of steamers. It took some doing to lay Bomarsund low. We landed blue-jackets and marines, and heavy ordinance from the Fleet, and threw up a few batteries on the flank of the largest fort; and on a given day our smallest31 2-deckers and paddle frigates were sent in to demolish the place. The forts were blown sky-high, and the Russians suffered heavily.

We fraternised with the French Fleet. Each ship in our squadron had its own particular chum, and, besides exchange of dinners, many were the orgies at night. The nights being very short, two, three, four in the morning was not an unusual hour for boats, with lively occupants returning to their respective ships, to pass to and fro.

The Princess Royal always fraternised with the French liner, the Austerlitz, a very fine screw 2-decker of 90 guns. I scarcely set foot ashore during the cruise. Excepting at Led Sound (where we lay waiting for the French troops), there was little opportunity of a run. An immense deal of drill went on, and boat duty was constant. Thus one’s education was entirely neglected: the Naval Instructor, the midshipmen’s instructor, was voted a secondary consideration. Let me refer to boat duty for a moment. Great excitement prevailed when the mails arrived from England. All eyes were watching for the signal 768, implying “Send boat for letters.” Then came a regular race, every boat pulling its best to the flagship for mails and parcels; and, as it was a case of First come first served, the slow-going boats had sometimes to wait two or even three hours for their mails if, as was32 usual, many ships were present. I have seen as many as thirty or forty boats waiting alongside the Duke of Wellington.

Soon after the fall of Bomarsund, the Princess Royal was sent to Revel, to join the sailing squadron then lying at anchor, or cruising off that port; and after this, in October, my uncle, knowing that there was little chance of my seeing any more active service (and as I was not in very good health), took the opportunity of transferring me to his old friend Harry Eyere’s ship, the St. George, a sailing 3-decker of 120 guns.

The sailing squadron had received orders to leave for England: so in October four beauties—the Neptune (120 guns), the St. George (120), the Monarch (84), and the Prince Regent (90)—made for England; and a very interesting and instructive sail we had down the North Sea. The second in command on board my ship was Paddy May, a very fine seaman of the old school, a man whose name was much respected in the Service. Everything was done quite in the old style; and thus I can fairly claim the distinction of having belonged to the old school—anyhow to the remains of it—as all the ships of this squadron were minus engines and boilers.

The Monarch was far away the fastest ship, though in a breeze the Prince Regent held her pretty close. Off the island of Bornholm we were33 caught in a fresh gale; and, the St. George being a very crank old craft, it was deemed advisable to send our upper-deck carronades down into the hold. As we were short of water and provisions, the extra weight of these guns below counteracted our want of ballast. A 3-decker in a gale of wind was rather a curious being. Under close-reefed topsails you could not lay her near enough the wind to enable her to meet the seas comfortably. The effect of the wind on her huge sides was to drive her bodily and very fast to leeward: in fact, you simply drifted.

It was pleasant to watch these ships speeding gaily on their course for England. We carried on when the weather permitted. The Monarch was generally in the van, showing us a high turn of speed. At sunset, or soon after, we collected and sailed in two lines; and, as was customary, took in a reef or two of the topsails, to make all snug for the night. When daylight broke every stitch was set again.

On arrival in England we anchored at Spithead. My father was soon on board to greet me. He asked permission for me to land with him. Being virtually invalided, I was allowed to pack up my “traps” and accompany him ashore. I can so well remember telling him that I had not had a real good wash for weeks, and that before I was taken to my mother, who was then residing at34 Ryde, he must purchase me a clean shirt, as I was ashamed of appearing in a crumpled garment washed in salt water, and not even ironed or starched. Forthwith we went to a public bath, and six new shirts were bought from the nearest establishment to make me presentable to my mother, as I could not bear the idea of her not seeing me at my best.

Thus ended my share in the Baltic Campaign. I was much disappointed at having seen so little active service. Both officers and men shared that feeling. Sir Harry Keppel and my Captain were always urging the Commander-in-Chief to do something. The campaign seemed to have been conducted in a half-hearted manner; but memorable signals were sent up. One in particular caused feeling: “Sharpen your cutlasses, lads. The day is our own.” This was made about sunset. Goodness knows what we were to have a try at on the morrow. All we do know is that nothing came of it; and it looked rather peculiar. I fancy that our Chief was much hampered by the Government of the day. Perhaps he thought it would be very hazardous to attack strongly fortified positions, such as Kronstadt and Sveaborg, with little chance of doing much damage, or of compelling the Russian Fleet to come out. Thus all our time was devoted to a strict blockade: a slow game at the best of times.

Our ships had some experience of attacking forts (in the Black Sea) on the 17th of October 1854. We did not damage the forts. On the other hand, we received a good dose in return: wooden walls and granite forts are different things. Then, again, the combined Fleets must indeed have paralysed the Russian Fleet, which was so much inferior. But it was a pity that when we sailed for the Baltic (and still more so when we got there) we were led to think of mighty deeds in store for us. When our medals were presented to us, with the bit of blue and yellow ribbon, many felt that they had not deserved them: and the trinkets were kept in hiding.

I remained in England until the following January. Then, being quite re-established in health, I received orders to rejoin the Princess Royal off Sebastopol. It was while I was at home that the news of Balaclava and Inkerman arrived.36 Many of our friends and relations were laid low on those battlefields. I can well recall the wave of mixed joy and sorrow that swept over England as the detailed accounts came slowly to hand. My uncle, Lord George Paget, at the head of his regiment, the Fourth Light Dragoons, commanded the second line in that fatal and memorable charge, where his regiment was well-nigh destroyed. It was to him, as he was riding off the field, that were addressed those words by the French Marshal, which have since passed into proverbial use: “C’est magnifique; mais cela n’est pas la guerre.” One of Lord George’s troopers, who (I think) was his servant, was made prisoner, and for some reason was taken before the Tzar of Russia. Observing the man standing six foot two in his stockings, His Imperial Majesty inquired what regiment he had belonged to, and, being told that he was in a Light-Cavalry regiment, said, “Well, if you are a Light-Cavalry man, what the devil are the heavies?”

I took passage to the Crimea in a hired transport, and we sailed from Plymouth early in January 1855. We carried a few troops, and a large quantity of stores for the army. Touching at Gibraltar and Malta, we arrived at Constantinople after a three weeks’ passage.

I shall never forget my first sight of the entrance to the Golden Horn. Those who have seen it37 will bear me out when I say that of its kind the view is second to none in the world. It was a beautiful still morning, and as the sun rose and reflected its golden rays on all the minaret towers and the great edifice of St. Sophia, one seemed in fairyland. The caiques, the colouring, the costumes, and the novelty of this oriental scene—all enchanted me.

Before leaving England I had been told to quit the transport at Constantinople, and to report myself on board the Carodoc, the man-of-war appointed to our Ambassador as his despatch vessel. I was most kindly received by dear old Derriman, the Captain, who told me to present myself up at the Embassy, where Lord Stratford de Redcliffe wished me to stay until I could get a passage to rejoin my ship on the Black Sea.

That great man made a deep impression on me. Tall and upright, he was as fine a figure as ever stepped: a man of perfect features and iron will: a grand seigneur; and the world knew it. He kindly told me to make myself at home, and to remain at the Embassy until he was ready to start in the Carodoc for the Crimea. He was going to the front to hold an Investiture of the Bath, and would probably sail in two or three days. This gave me intense pleasure: I rejoiced at the prospect of becoming acquainted with Constantinople. Lady Stratford de Redcliffe and her38 charming daughters made things doubly pleasant. That most lovely and engaging of women, Lady George Paget, my cousin (aunt by marriage), also was staying at the Embassy. Among the staff of the Embassy were many men who made their marks in after life—Odo Russell, Allison, Count Pisani, and others,—from whom, one and all, I received the kindest attention. It was indeed an interesting time: I saw everything, and had a sort of general lascia passare.

I was soon called upon to assist in the correspondence department at the Embassy, and many were the despatches which I copied. Every one was overwhelmed with business, and I was only too glad to render what assistance I could. His Lordship was often at work most of the night, receiving and dictating despatches; his breakfast hour varied from nine to twelve, according to his hours of rest. The Embassy at Constantinople in those days was, I imagine, a position of unique and supreme importance in diplomacy. The postal and the telegraphic services were in their infancy. In copying Lord Stratford’s despatches I was not long in discovering how frequently he acted on his own initiative and responsibility, without reference to the powers that were at home. No such independence would now be tolerated, nor would it be possible. It is one thing to recommend your views before the home authorities for39 approval; quite another, to act on the spur of the moment, and to take the sole responsibility on your own shoulders, as Lord Stratford did. The Turks held him in unbounded fear and respect.

The Bosphorus was a great sight. Ships of war were passing to and fro; transport and provision ships were constantly going and coming. With Lady Stratford, I went over to Scutari Hospital to see the crowds of wounded and invalids from the front, and was presented to Miss Nightingale. How she worked!

Constantinople in those days was purely Turkish. Modern customs were not in vogue: the Frank dress was infrequent. The bazaars were rough and uncivilised. Not until some time after the war was there any marked improvement in the customs of the natives. Trade soon became more general, and, owing to freer intercourse with foreigners, the more enlightened Turk began to shake off the lethargic Eastern style, adapting himself to the more modern ways of civilisation. I doubt much whether the change has produced good results as far as the Turk is concerned.

While awaiting the Ambassador’s departure for the Crimea, I made excursions to the environs. The sweet waters of Asia were most interesting. Rowed about in the Embassy caique, I visited most of the palaces, gardens, and other places40 worth seeing. Everything was novel. Englishmen were at that time held in high esteem by the Turk. “Buono Johnnie” was the cry everywhere, and nothing could have exceeded the Turk’s rude civilities. I was much amused at the way the kavasses cleared the road for one. When you were walking in the bazaars, or in the streets, which were crowded, men and women were sent flying on the approach of your kavass, who generally wielded a big stick. And the swarms of dogs—how curious it all seemed to my young imagination!

The Carodoc soon sailed, and in less than thirty-six hours we found ourselves steaming into Balaclava harbour, which was almost landlocked. On passing the towering perpendicular cliffs I could not help picturing to myself the scene of carnage of the previous October, when so many vessels, with their living freights, were lost during a frightful gale on that iron-bound coast. Before we got in I caught a distant sight of Sebastopol and the large allied Fleets at anchor off the coast. My ship was lying in Kazatch Bay. As there was no chance of joining her for a few days, His Excellency asked me to accompany him in his daily expeditions to the front. We were a goodly party. All the ladies from the Embassy accompanied us. We rode or drove to all the battlefields and objects of interest at the front,41 lunching generally at some Headquarter Staff, and on one occasion at Lord Raglan’s. The battlefield of Inkerman was still full of débris. I was astonished to see so many boots lying about—and poor fellows’ bones as well. I carried off a Russian musket, besides other small articles.

At Lord Raglan’s I came across Frank Burgesh—afterwards Lord Westmorland—looking as handsome and as fresh as he was when hunting with the Fitz-William hounds.

Subsequently we visited the ground of the famous Balaclava charge, and saw some of the remains of the shattered cavalry. The few horses surviving were in a sorry plight. Their manes and tails were much reduced: actually the horses, from sheer hunger, had been gnawing one another. Lord George Paget had scarcely any horses fit for duty the day after the charge. The Tenth Hussars, with splendid horses, had just arrived from India, and, mustering strong, were much more numerous than the whole of the Light Brigade.

On one occasion, while I was with Lord Stratford, there was a review of 25,000 French troops; and I was much struck by their soldier-like bearing.

Within a few days I rejoined my ship, then lying off Sebastopol, delighted with all I had seen, and with Lord Stratford’s kindness to me. Once42 on board again, I soon shook down among old messmates and friends. There had been many changes among the officers; but my best friend, Dick Hare, was still there. The three bad officers had been weeded out. Consequently, our mess was comfortable.

In a letter to my mother I remarked that I much preferred the Black Sea to the Baltic, and that I felt happier—more reconciled to the Service. There was always the sure expectation of seeing active service, and possibly of being in the thick of it.

The duties assigned to me were to keep daily the morning and in the evening the six-to-eight watch. This went on without a break for eight months. I soon became accustomed to getting up at 4 A.M., and in the fine summer months it was pleasant to paddle about the decks during the washing process. When the ship’s company went to breakfast, at three bells (5.30 A.M.), I could get three-quarters of an hour to myself, alone in the gun-room, for my cup of ship’s cocoa and biscuit; to be followed by reading or writing letters, pondering over my letters from home, and a glance at my Prayer Book, as to which I remembered my mother’s last injunctions.

How much I relished my 5 A.M. cocoa! A hungry middy does enjoy it; though it takes the sharp edge off the eight o’clock breakfast, which43 consisted of (perhaps) a piece of toughest beef-steak—any part of the animal being dignified by that name. The poor animals, which had ploughed Turkish soil for many a long year, were slaughtered the afternoon before, between two guns, on the main deck. When we were not favoured with these mighty bullocks, it was a case of salt pork or junk (salt beef); these were usually chopped up into square bits, and curried with a ghastly yellow powder. Sometimes we had boxes of grub (as it was called) sent out from home; the grub was much appreciated, and we usually shared it with our chums. Mostly it consisted of jams, potted meats, and preserved milk; but in those days potted meats were in their infancy, and nothing like so good as now. The condensed milk, though to a certain extent welcomed, was nasty stuff: some of the midshipmen preferred spreading it on their bread to putting it in their tea.

During the daytime my duties were very various. We were supposed to go to the Naval Institute for two or three hours in the forenoon; but going was a rare occurrence. There was much duty to be done away from the ship in boats—provisioning, coaling, landing stores for the front, besides attending constant signals from the Flag-Ship. This, together with gun drilling and other exercises, took up a great deal of one’s time.

Occasionally I got a day’s leave. Then I went44 to the front, and dined with some pal in the Brigade of Guards or other regiment, shared his tent for a night, and had a peep at the trenches next day. We could see a good deal of the fighting from the ship: the sorties at night were lit up by bursting shells. By its lighted fuze I often watched the trajectory of the shell while circling through the air, beautifully timed to burst on approaching the ground.

Having to be up so early every morning, I was generally in my hammock by 9.30 P.M. (sometimes earlier), and often fell asleep while the band was playing on the main deck, hard by the officers’ smoking resort. Smoking was kept uncommonly strict in those days. The hours of the ship company’s meals were the only times allowed during the daytime; in the evenings, from after evening quarters until just before the rounds were gone, at 9.30; and no officer could smoke until he was eighteen. I became an inveterate smoker, and once was within an ace of being turned out of the Excellent, gunnery-ship at Portsmouth (while undergoing my examination), for smoking with another fellow on the extreme fore part of the main deck, a locality well known to the naval officers. The sentry smelt the fumes, and reported us. We had tried to get out of a scuttle; but it was considerably too small, and we had to surrender, feeling it was all up, and that we should45 have to suffer next day. However, somehow we got off with a deuce of a wigging.

On another occasion I infuriated my senior officer by smoking while on duty. I was serving in the Mediterranean under that great disciplinarian, Sir William Martin (nicknamed Pincher Martin). I was officer of the guard, and had a long nasty pull round from the Grand Harbour at Valetta to the quarantine harbour, to get the Admiral’s despatches from the P. and O. steamer. It was a blowy cold night: so I allowed all my boat’s crew to light their pipes. On arriving at Admiralty House with the Commander-in-Chief’s bag of despatches, I was kept waiting in the hall while the old gentleman was at dinner. After his meal, the Admiral descended the staircase, and, in his usual curt way, said, “You are the officer of the guard, I presume? What sort of a night is it?” I having answered his questions, he said, “You have been smoking, sir!”—“Yes, sir: I have. I have had a long pull—and a very wet one—round from the other harbour.” “This is very disgraceful,” quoth he: “I will see about this to-morrow.” However, I heard no more of it. I always thought that the restriction as to smoking was carried much too far in the Navy. When I commanded ships, I used to allow much more licence than the Queen’s Regulations authorised, and I never found cause to repent of the indulgence. Smoking was considered46 a great solace and help, and many a dull afternoon was got through by my officers and men over their pipes. The custom of the Service was to allow a sort of half-holiday on Thursday afternoon. The pipe went, “Make and mend clothes.” That was a curious definition of a half holiday; but on those occasions every one was allowed to smoke, and it was a dies non with the ship’s company.

At 9 P.M. the youngsters, as a rule, were supposed to leave the gun-room; the signal for this arrangement was called “Sticking a Fork in the Beam.” I cannot remember ever seeing one so placed; but that was the adopted term. After a boy had passed his four yearly exams he was considered an oldster, and assumed a position of more importance. The chief benefit attached to his promotion was an extension of limited wine and extra bill. At ten, in harbour, gun-room lights were put out. The master-at-arms (the chief of the ship’s police) came round with his lantern, and was supposed to see the gun-room cleared of its inmates. If the seniors were singing, and there was some particular hilarity going on, the master-at-arms might be requested to ask for an extra half-hour’s lights. He would then go to the officer of the watch for permission. Much depended on the conscience of the officer.

The gun-room officers always dined at noon at sea, and at two or half-past two in harbour; but by47 degrees these hours became later, though it depended a good deal on the view which the Captain took of the arrangements. Dinner at noon and a wretched tea at about 5 P.M. made a boy feel mortal hungry by 7 or 7.30: so the steward was generally in requisition for a pot of sardines or for a lobster. This was considered an extra; and, as you were limited to 15s. a month of extras, one had to be very careful, and to economise one’s consumption. A certain amount of gambling went on over these extras. We “read” for each article; which, being interpreted, means that, instead of tossing up as to who should be charged for the supper, you selected the number of a letter of a specified line on a page—e.g., two two right, or three three left (as the case might be): the nearest letter to A won the supper. At Malta, sometimes, I have been away all day getting biscuit from the factory and filling launch after launch with bags of biscuits: so I used to lunch off newly-made biscuit and raw carrots or parsnips that were en route on board. I relished the provender: a middy’s digestion is pretty tough. It was considered a great honour to be asked to dine when at sea with the Captain. If one’s stock of clean white shirts was exhausted, one generally pulled out all the worn shirts and selected the best to wear at his table. At half-past two in the afternoon watch any middy on duty told the officer of his watch that he was asked to dine with the Captain,48 and no power on earth could prevent you from leaving the deck. Occasionally the Ward Room officers asked one to dine, which was a more enjoyable invitation, as you usually sat next to your pal lieutenant or officer, who was in the habit of lending you his cabin, or generally looked after your interests. It was a great boon having a cabin to fall back on, and when fatigued to be able to rest on a comfortable bed. Otherwise there was nothing but a hard teak deck to lie on, and a sextant box, or (what we often used) a couple of nautical almanacks for a pillow.

On many of our Sundays, while blockading Sebastopol, with everything quiet on deck and below, and perhaps not a shot being fired from the land batteries, I have gone down into the gun-room and seen rows of middies, mates, and other officers stretched out all over the deck fast asleep—and in the fore-part of the ship most of the ship’s company. Sailors are adepts at sleeping in quiet moments. Small blame to them; for when at sea a constant watch and watch for weeks and months is kept, and there is little continuous rest. I always thought it hard lines that after keeping the middle watch—from midnight to 4 A.M.—you had to be out of your hammock by 6.30. Often turning in wet and cold at four, you could not get off to sleep, particularly in bad weather, because of the noise; and just as you dozed off you heard the solemn grunt of your49 hammock-man, “Turn out, sir: it’s five bells” (6.30 A.M.); and the longer you kept him waiting, the shorter was his breakfast hour. How one could have wished him farther—anywhere but bothering one! And then his dirty hands pulling your sheets and pillows about, so as to place them away properly in the hammock, and that it should appear on deck in its proper shape to be stowed in the hammock-netting, well scrutinised by some very strict officer of the watch or mate of the deck! Woe betide you if the hammock looked too full of bedding, or in excess of what his critical eye might notice! I have often seen an unfortunate sleepy mid roll out of his hammock, cover himself with a blanket or a rug, and give himself another hour or so of rest by lying on the top of his chest, his own little home; but not much comfort attached to it if you were over four foot six in height.

What I used to hate most—in hot weather especially—was that morning evolution of crossing yards at eight o’clock. Just washed and dressed, perhaps in a clean pair of duck trousers, up you had to go to the main or fore-top, running up tarred rigging, or (just as bad) finding the rigging full of coal-dust and smoke. One often came down positively black, hot, and uncomfortable, one’s trousers ruined; and there you were, for perhaps the rest of the day, as another wash was out of the question. In after days wiser heads—50at any rate, officers with more forethought—left off making you wear your ducks on this particular occasion, and the comfort and convenience was a great boon to officers and men. But somehow, in my early days at sea, very little was studied as to convenience and comfort for officers and men.

In much later days I was serving in a line-of-battle ship belonging to the Channel Fleet. We wintered at Portland. It happened to be a very severe winter—so much so that at times our rigging and sails were frozen. Twice a week the ship’s company had to wash their clothes, which generally took from an hour to an hour and a half. Consequently, the routine was put a little out of joint. Time had to be made up somehow. The usual hour to turn out was at 5 or 5.30 A.M., to wash decks; but on washing mornings I have seen the men turned out at 7 bells in the middle watch (3.30), on a freezing morning, to scrub hammocks and wash clothes, with nothing but a wretched lanthorn and a farthing dip to see by; and this was the only light for ten or a dozen men to wash their clothes by. After this the decks had to be washed in icy cold water, and at 6.30 these wretched frozen men consoled themselves with breakfast of cocoa and ship’s biscuit—possibly with bread and butter, if the bum-boat had come alongside; but, as it generally blew a gale, Mr. Bum-boat did not appear so early. I can vouch for these remnants51 of barbarism: I was what was termed Mate of the Main Deck, and had to be up to see the business carried out.

During May the combined fleets sailed on an expedition to Kertch, at the entrance of the Sea of Azov. We left some ships to remain off Sebastopol; but the bulk went to Kertch, and shipped a goodly quantity of troops. The Princess Royal took on board the 90th Regiment of the line, besides detachments.

We expected opposition to our landing; but, as light-draught vessels could easily command and cover the landing, no Rooskies appeared to oppose us. We soon had our army ashore on a sandy beach not many miles from Kertch itself. Next day, while we were on the line of march, my uncle, Lord Clarence, happened to be in close conversation with Sir Edmund Lyons, when the Commander-in-Chief, suddenly observing me near at hand, called me up, and said, “Here, youngster: can you talk French?” On my answering “Yes,” he said, “Go at once and find the French General in Command” (pointing me out the direction in which I should find him), “and tell him that I wish the English Jack to be hoisted alongside the Tricolour as soon as that fort is captured. Mind and say so very civilly and in your best French.” Off I ran as fast as my legs would carry me across the plain. Singling out52 what appeared to me to be a body of French Staff-Officers, I asked the first among them to point me out the General in Command. Luckily, that potentate was among the bunch of officers. I felt nervous and shy; but, mustering up courage, I stood, cap in hand, delivering my orders. To my horror, he seemed to demur, and asked me a heap of questions before he at last consented and desired me to inform the Admiral that his wishes should be carried out. I had been told to bring back an answer; but for the life of me I could not find the Commander-in-Chief for a long time. However, when I did find him he seemed pleased. He said, “I see the Union Jack is up alongside the French flag. Well done, my boy! What’s your name, and who is your father? Tell your Commander I am much pleased with you.” I did feel proud.

There was no opposition at Kertch, and that evening part of the troop bivouacked in the town and suburbs.

Whether they resulted from the pent-up life of the soldiers and sailors, or from the mere longing for a spree, I do not know; but the looting and breaking into cellars, and the consequent trouble, were very discreditable. I supposed it was one of the horrors of war. Among other officers, I was sent ashore next day to patrol the streets with a strong picket, and endeavour to keep53 the inhabited houses free from molestation. I took many disorderly men of both armies prisoners, as well as lusty Jacks of the Fleet. However, fair and square looting seemed to be winked at. Our mids went ashore, and bagged no end of cases of champagne. On a subsequent occasion my respected uncle did not scruple at having a wretched old piano taken on board the Princess Royal by way of enabling his dear little nephew to keep up his music! We lay some little time off Kertch while our gun-vessels and launches of the Fleet were employed playing wholesale destruction of grain and stores in the Sea of Azov; and they had some sharp fighting into the bargain.

I used to land occasionally, and in strolling about the camps came across old friends that I did not even know to be attached to the army before Sebastopol. Two of them were old cricketing friends: so, no doubt, we got on the noble game and cricket grounds many miles away.

On the 24th of May the Fleet weighed—or part of it, bound to a very strongly fortified place, Anapa, where we expected heavy fighting. Splinter netting was got up; masts and yards were struck; everything was made ready for an attack. Next morning, when approaching this place, the Hannibal, line-of-battle ship, was sent on ahead to look out and report by signals whether the forts were ready for us. To our dismay (I thought54 so then), we found the forts evacuated, and partly blown up. They were excessively strong, and stood on a very commanding position on high cliffs. We should have had our work cut out to subdue them. How bloodthirsty the middies were! I suppose I was too young to realise the horrors of a naval action, and of seeing our decks strewn with killed and wounded. I never could understand why the Russians blew up and deserted the place. On landing, soon after anchoring, we could readily observe the strength of the place. Some of the works were blown up, and the guns were spiked or taken away—possibly buried. Leave to land was granted; but on no account were we to enter the forts—for fear of slow matches and explosions.

We fraternised with some very picturesque Circassians. I longed to buy some of their accoutrements, which they seemed ready and willing to sell; but, alas! I had no money with me. However, a happy thought struck me. I happened to be wearing a new pair of duck trousers. Thinking that I might tempt them with the shiny brace buttons, I went round a corner and cut the trinkets off. The effect was magical, and enabled me to purchase some of the cartouche-cases in which they carried their powder slung round their waists, or sewn into their rough coats across their chests. They say that exchange is55 no robbery. The aphorism was well illustrated. Soon we were back again to our old anchorage off Sebastopol, feeling that we had had a wild-goose chase. Indeed, we were all beginning to be weary of not having the chance of distinguishing ourselves from on board our respective ships. Luckily, my uncle was of an enterprising nature. He formed an idea that it would be a good thing to worry the forts by firing into them after dark. To do this, it was necessary to have leading lights on the coast, so as to guide the ships in at night; and these he placed on the sea-coast on the extreme left of the French position.

The Admiral lent him a paddle-sloop, the Spitfire, commanded by an able officer, one Spratt; and for several nights I accompanied my uncle while the operations were going on. Our only danger was that we might be discovered by the Russian guard-boats that were always prowling about outside the harbour mouth. Somehow, they never saw us. After a week’s work at placing the lights, everything was in readiness for the night attack. The lights were very ingeniously placed, showing different colours on different bearings; and when on these bearings we knew our approximate distance from the fort at the harbour’s mouth.

On the night of the 16th of June the Miranda frigate, commanded by Captain Lyons, supported56 by rocket boats, was sent in to attack the forts. Unfortunately, the enemy got his range—owing to the illumination caused by the rockets, which lit up the whole scene. Poor Lyons was killed, and there was considerable loss besides, and the incident ended in being somewhat a failure. The intention of these night attacks was to worry the enemy, and keep the sailors and gunners down at the forts instead of their assisting in the siege batteries up at the front.

Next night, that of the 17th of June, came our turn in the Princess Royal. My Captain begged to be allowed to go in alone, so as not to attract the fire of the forts by too great a display of firing, such as that of the previous night. Of course, this sort of affair under cover of darkness makes it a mere question of luck whether we should be sunk, or seriously mauled, or escape scot-free. The enemy could fire at random only. We were not blessed in those days with search-lights: in fact, there was nothing to give the enemy a clue to our distance, and they could not lay their guns with any certainty: whilst, we being directed to fire in broadsides only, there would naturally be no continuous firing to assist their gunners in laying the guns.

We cleared for action at 9 P.M. that evening, hove in our cable, and awaited the signal to weigh. How wearisome each half hour seemed!57 We longed to have the business over. We waited and waited the signal; but half hour after half hour passed, and nothing happened. So we could only lie down at our guns and take a snatch of sleep—or make the attempt, at any rate. I wonder what many of us thought over during those weary half hours, and whether our minds were far away? Not a light was allowed. All was still, and in utter darkness. The only light to be seen on board was in the binnacle compass on the poop. I recollect well running up and down constantly to the poop to find out the latest news, and convey it below, because at one time we began to despair of the attack coming off that night.

My uncle was calmly walking the poop, in close conversation with the Commander, and awaiting the signal to weigh. At last, at midnight, up went the signal, by lanterns: “Weigh and proceed.” All was bustle in an instant; though beyond the links grinding in at the hawse pipe not a sound was to be heard—no boatswain’s whistle: absolutely nothing. We were soon under weigh, and off at slow speed. The lights which we placed were plainly visible as we steamed in. It was a most exciting moment as we gradually approached the enemy’s huge batteries. The men were already at their guns, and we had placed a few more from our port batteries over to the star-board side, in order to give them not only58 46 but also 50 or more shots from our star-board broadside.

Having got our bearings on with the lights (coloured large lanterns), we steamed on until a certain light showed red: then we knew our approximate distance, and that it was time to fire. Up to this time I had been constantly sent down with messages to the officers at their quarters, in order to make sure that no mistake could possibly be made; and the Captain arranged to give the order himself for the broadside to be fired at the exact moment.

I was on the poop by the Captain’s side. Suddenly he asked whether all was ready below—the guns being elevated to 1200 yards and loaded with shell. The answer was, “Yes, sir.” He said, “Stand by.” A few seconds of suspense followed. When the order to fire was given, off went the roar of these guns simultaneously from our whole broadside; and in a few seconds I saw the most lovely illumination of the whole front of Fort Constantine. Our shells had burst beautifully. On the face of the fort, for an instant or so, I could plainly see the embrasures (so to speak) lit up, and, indeed, the whole face of the fort.

A minute or two elapsed before any fire was returned. First came one or two shots; then gradually more; until they began pounding away to their hearts’ content, firing red-hot shot, shells,59 and chain shot, the latter to cut our rigging. The shells I could plainly see coming over us, some few bursting short; but the enemy must have estimated our range to be 200 yards farther out, for hundreds passed over us, cutting our rigging unmercifully. Had we been that distance farther out to sea we should indeed have got a proper mauling. It was great luck, indeed, that our hull was hit only five times. We lost only two killed and five wounded: all at one gun under the poop: just below where my Captain and I were standing.

I shall never forget an idiot of a signalman who, on hearing the crash, yelled out to me, “Look out, sir: the mast is coming down by the run.” This shot certainly made great havoc. After knocking these poor chaps over, it tore up some planks on our quarter-deck, smashed part of the mast, and made a hole in the stern of our boom boat in its passage overboard to the other side. For a quarter of an hour or more these shots and shells came very thick. We loaded for another broadside, but suddenly got into unpleasant shoal water: so we had to turn tail. I believe our orders were not to run any risks, and not to fire more than one or two broadsides if the enemy got our range: after all, our purpose was served in worrying the forts. Though the engagement was exciting, I felt glad when we got out of range. It certainly was too hot to be pleasant.

60 When the retreat from quarters was sounded, there was a general call for the steward; and (now two o’clock in the morning) potted lobster, tinned salmon, and sardines were eagerly devoured. Many a yarn about the details of the night passed between us. We were afterwards told that the whole Fleet had been watching the affair, which was described as lovely in the distance. Next day we buried our dead outside at sea. Some people think that being sewn up in a hammock with two shots tied to the foot of it, and being launched overboard, is the best way of being buried. I do not. I hated seeing the bodies slipped overboard out of a port from a grating during the funeral service.

For a fortnight we had cholera in the Fleet pretty badly. I think we lost eleven poor chaps in our ship alone. Many others were seized, but got over it. Our men generally fell ill about daybreak or soon after. I have seen them, seized with the horrid cramp, tumble down while decks were being washed. The best precaution was to make every one as cheerful as possible, so as to keep the devil out of the mind. The band used to play off and on all day; while games and smoking were allowed ad lib.

By the next mail I wrote to my mother, describing the night attack; and saying:—

I have no wish to go into action again, if I can keep out of it. We were the first line-of-battle ship that has been in at night—and so close! How jealous the Acres must be [alluding to the St. Jean D’Acre, our chummy ship, commanded by Henry Keppel]. I have earned the Black Sea medal.