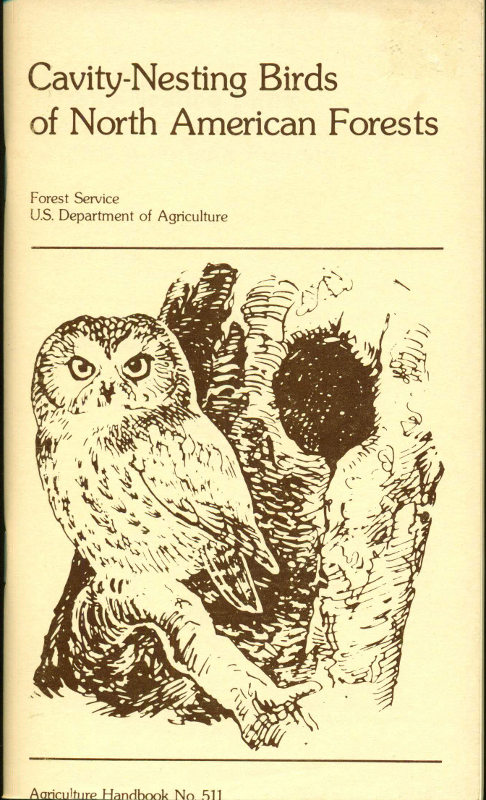

Title: Cavity-Nesting Birds of North American Forests

Author: Virgil E. Scott

Keith E. Evans

David R. Patton

Charles P. Stone

Illustrator: Arthur Singer

Release date: June 9, 2015 [eBook #49172]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

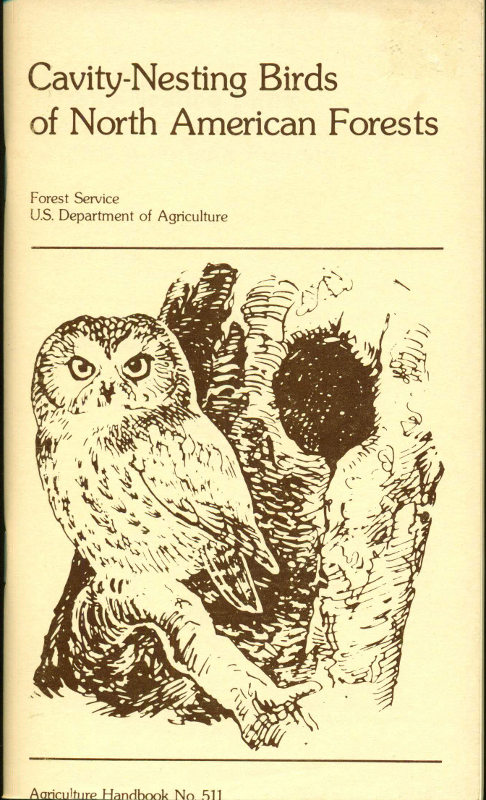

Cover sketch: Saw-whet owl, by Bob Hines of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Virgil E. Scott

Denver Wildlife Research Center

Keith E. Evans

North Central Forest Experiment Station

David R. Patton

Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station

Charles P. Stone

Denver Wildlife Research Center

Illustrated by

Arthur Singer

Agriculture Handbook 511

November 1977

Forest Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402

Stock No. 001-000-03726-9

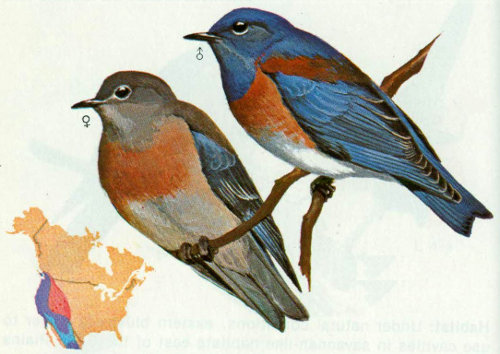

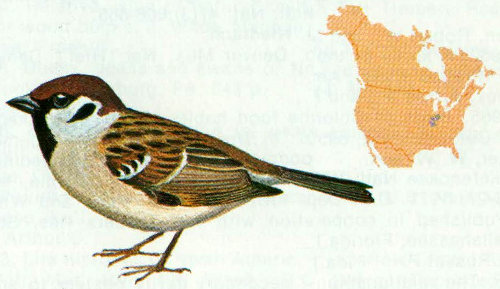

Habitat, cavity requirements, and foods are described for 85 species of birds that nest in cavities in dead or decadent trees. Intensive removal of such trees would disastrously affect breeding habitat for many of these birds that help control destructive forest insects. Birds are illustrated in color; distributions are mapped.

This Handbook is the result of a cooperative effort between the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Authors Scott and Stone are wildlife research biologists with the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Denver Wildlife Research Center. Scott is stationed in Fort Collins, Colorado. Authors Evans and Patton are principal wildlife biologists with the Forest Service’s North Central Forest Experiment Station and Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, respectively. Evans is stationed in Columbia, Missouri, in cooperation with the University of Missouri, while Patton is stationed in Tempe, Arizona, in cooperation with Arizona State University.

Special thanks are due Arthur Singer, who graciously donated the use of his illustrations from “A guide to field identification: Birds of North America,” by Robbins, Bruun, and Zim, which are reproduced here with permission of the Western Publishing Company. The distribution maps are also reproduced with the permission of Western Publishing Company. © Copyright 1966 by Western Publishing Company, Inc.

We would like to thank Kimberly Hardin, Beverly Roedner, Mary Gilbert, Steve Blair, and Michael, Leslie, and Mary Stone for their assistance in collecting literature. A special thanks to Jill Whelan for her assistance in literature searches, checking references and scientific names, and assembling this publication. The assistance of Robert Hamre in encouraging and guiding the preparation of this manuscript is acknowledged and very much appreciated.

Many species of cavity-nesting birds have declined because of habitat reduction. In the eastern United States, where primeval forests are gone, purple martins depend almost entirely on man-made nesting structures (Allen and Nice 1952). The hole-nesting population of peregrine falcons disappeared with the felling of the giant trees upon which they depended (Hickey and Anderson 1969). The ivory-billed and red-cockaded woodpeckers are currently on the endangered list, primarily as a result of habitat destruction (Givens 1971, Bent 1939). The wood duck was very scarce in many portions of its range, at least in part, for the same reason and probably owes its present status to provision of nest boxes and protection from overhunting.

Some 85 species of North American birds (table 1) excavate nesting holes, use cavities resulting from decay (natural cavities), or use holes created by other species in dead or deteriorating trees. Such trees, commonly called snags, have often been considered undesirable by forest and recreation managers because they are not esthetically pleasing, conflict with other forest management practices, may harbor forest insect pests, or may be fire or safety hazards. In the past such dead trees were often eliminated from the forest during a timber harvest. As a result, in some areas few nesting sites were left for cavity-nesting birds. Current well-intentioned environmental pressures to emphasize harvesting large dead or dying trees, if realized, would have further adverse effects on such ecologically and esthetically important species as woodpeckers, swallows, wrens, nuthatches, and owls—to name a few.

The majority of cavity-nesting birds are insectivorous. Because they make up a large proportion of the forest-dwelling bird population, they play an important role in the control of forest insect pests (Thomas et al. 1975). Woodpeckers are especially important predators of many species of tree-killing bark beetles (Massey and Wygant 1973). Bruns (1960) summarized the role of birds in the 2 forests:

Within the community of all animals and plants of the forest, birds form an important factor. The birds generally are not able to break down an insect plague, but their function lies in preventing insect plagues. It is our duty to preserve birds for esthetic as well as economic reasons ... where nesting chances are diminished by forestry work.... It is our duty to further these biological forces [birds, bats, etc.] and to conserve or create a rich and diverse community. By such a prophylactic ... the forests will be better protected than by any other means.

Several of the birds that nest in cavities tend to be resident (non-migrating) species (von Haartman 1968) and thus more amenable to local habitat management practices than migratory species. Nest holes may be limiting for breeding populations of at least some species (von Haartman 1956, Laskey 1940, Troetschler 1976, Kessell 1957). Bird houses have been readily accepted by many natural cavity nesters, and increases in breeding density have resulted from providing such structures (Hamerstrom et al. 1973, Strange et al. 1971, Grenquist 1965), an indication that management of natural snags should be rewarding.

Because nesting requirements vary by bird species, forest type, and geographic location, more research is needed to determine snag species, quality, and density of existing and potential cavity trees that are needed to sustain adequate populations of cavity-nesters. In a Montana study, for example, larch and paper birch snags were most frequently used by cavity-nesters (McClelland and Frissell 1975). The most frequently used trees were large, broken-topped larches (either dead or alive), greater than 25 inches diameter at breast height (dbh), and more than 50 feet tall. No particular snag density was recommended to managers. In the Pacific Northwest, Thomas et al. (1976) suggested about seven snags per acre to maintain 100 percent of the potential maximum breeding populations of cavity-nesters in ponderosa pine forests and six per acre in lodgepole pine and subalpine fir. In Arizona ponderosa pine forests, an average of 2.6 snags per acre (mostly ponderosa) were used by cavity-nesting birds (Scott, in press[1]). The most frequently used snags were trees dead 6 or more years, more than 18 inches dbh, and with more than 40 percent bark cover. The height of the snag was not as important as the diameter, but snags more than 46 feet tall had more holes than did shorter ones. Balda (1975) recommended 2.7 snags per acre to maintain natural bird species diversity and maximum densities in the ponderosa pine forests of Arizona.

Important silvical characteristics in the development of nesting cavities include (1) tree size, longevity, and distribution; (2) regeneration by sprouts, and (3) decay in standing trees (Hansen 1966). Although trees less than 14 to 16 inches dbh at maturity are too small to yield cavities appropriate for wood ducks, they may be important for smaller species. Aspen, balsam fir, bitternut hickory, ironwood, and other trees fall within this range. Short-lived species such as aspen and balsam fir usually form cavities earlier than longer lived trees. Since a major avenue of fungal infection is sprouts, sprouting vigor and the age at which sprouts are produced are important considerations in managing for cavity-producing hardwood trees. Cavity formation in oaks of basal origin is a slow process, but black oak is a good cavity producer as trees approach maturity because although the heartwood decays rapidly the sapwood is resistant (Bellrose et al. 1964). Basswood is a good cavity producer because of its sprouting characteristics. Baumgartner (1939), Gysel (1961), Kilham (1971), Erskine and McLaren (1972), and others presented information on tree cavity formation for wildlife species. More information on the role of decay from branch scars, cutting, and animal damage is needed for different species of trees so that positive management for snags may be encouraged.

Removal of snags is also known to reduce populations of some birds. For example, removal of some live timber and snags in an Arizona ponderosa pine forest reduced cavity-nesting bird populations by 50 percent (Scott[2]). Violet-green swallows, pygmy nuthatches, and northern three-toed woodpeckers accounted for much of the decline. A previously high population of swallows dropped 90 percent, and a low woodpecker population was eliminated. On an adjacent plot, where live trees were harvested but snags were left standing, cavity-nesters increased as they did on a plot where live trees and snags were undisturbed.

Foresters and recreation managers are now more aware of the esthetic and economic values of nongame wildlife, including cavity-nesting birds. In summer of 1977 the U.S. Forest Service established a national snag policy requiring all Regions and Forests to develop guidelines to “provide habitat needed to maintain viable, self-sustaining populations of cavity-nesting and snag-dependent wildlife species.” These guidelines are also to include “retention of selected trees, snags, and other flora, to meet future habitat requirements” (USDA Forest Service 1977). 4 Some Forest Service Regions had already established policies for snag management. For example, in 1976 the Arizona-New Mexico Region (USDA Forest Service 1976) recommended that three good quality snags be retained per acre within 500 feet of forest openings and water, with two per acre over the remaining forest. The policy also requires that provisions be made for continued recruitment of future snags; spike-topped trees with cavities and obvious cull trees should be left for future cavity nesters. Some foresters are now using tags to protect the more suitable snags from fuelwood cutters in high-use areas.

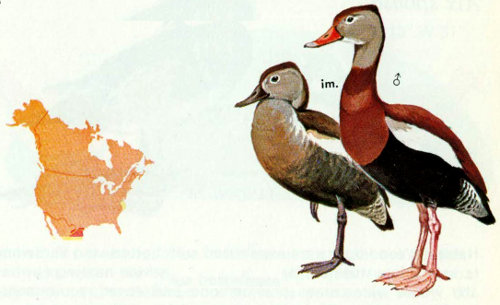

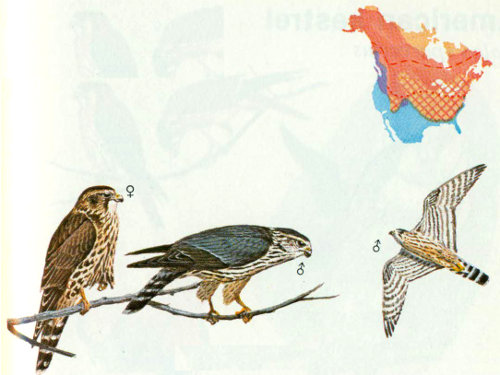

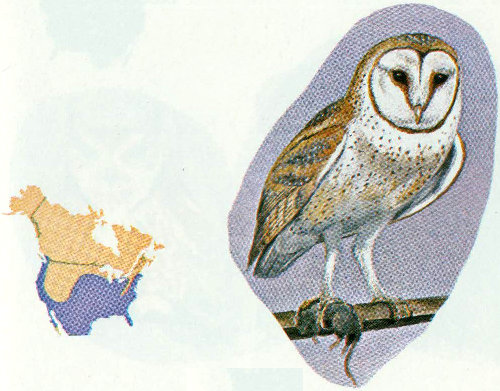

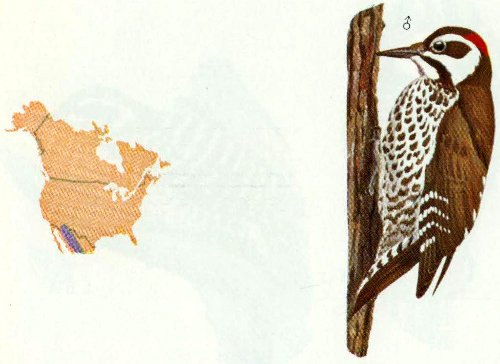

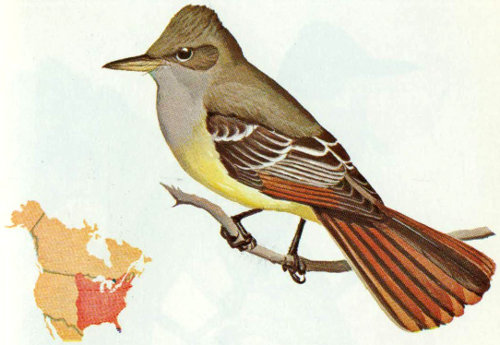

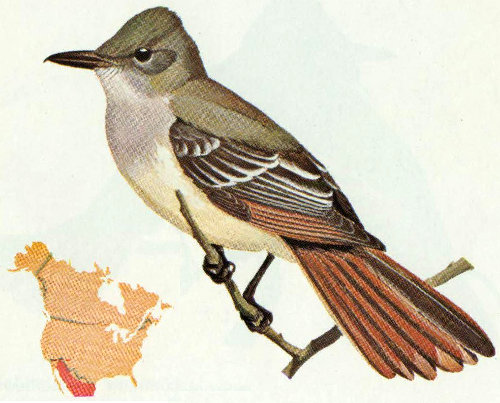

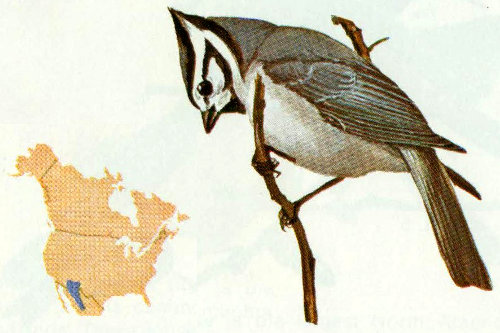

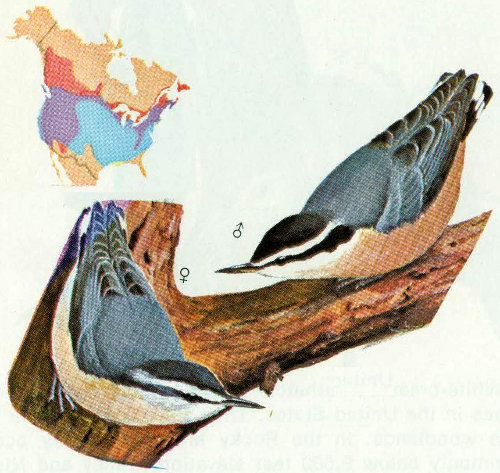

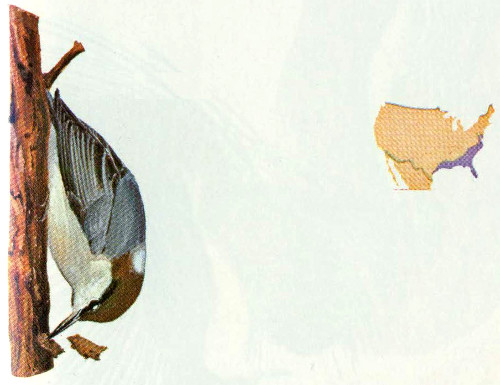

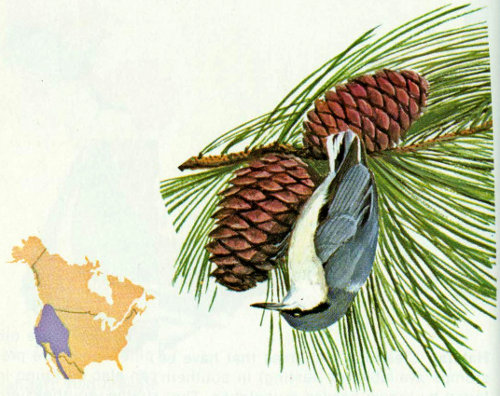

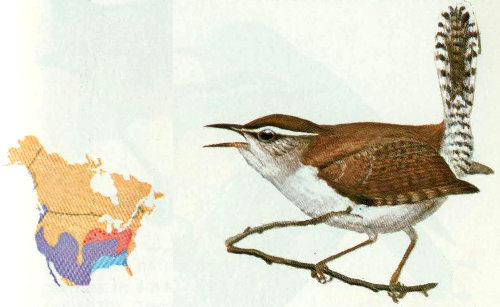

In this book, we have summarized both published data and personal observations on the cavity-nesting birds of North America in an attempt to provide land managers with an up-to-date, convenient source of information on the specific requirements of these birds. Bird nomenclature follows the American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist of North American Birds (fifth edition, with supplements). Bird illustrations and distribution maps are reprinted with permission of Western Publishing Co. from A Guide to Field Identification of Birds of North America by Robbins et al. (1966). The small range maps indicate where birds are likely to be found during different seasons. Summer or breeding range is identified in red, winter range in blue; purple indicates areas where the species may be found all year. Red cross-hatching identifies areas where migrating birds are likely to be seen only In spring and fall. Length measurements (L) are for birds in their natural position, while W indicates wingspan.

Percentages of the diet under “Food” in species accounts refer to volume, unless otherwise indicated. Since nestlings of most species require insect protein, “Major Foods” refers largely to adult diets. Appendices list common names of plants and animals mentioned in the text, with scientific names when they could be determined.

Habitat: Black-bellied whistling ducks (tree ducks) are found regularly in southern Texas and erratically elsewhere. Open woodlands, groves or thicket borders where ebony, mesquite, retama, huisache, and several species of cacti are dominant in freshwater habitat are preferred (Oberholser 1974, Meanley and Meanley 1958). Range extensions have been facilitated by flooding and impoundments.

Nest: Natural cavities in trees such as live oaks, ebony, willow, mesquite, and hackberry are preferred, but ground nests and nest boxes are sometimes used. The nest can be over land or water, but herbaceous vegetation under “land-bound” nests may be preferred to brush (Bolen et al. 1964). A perch near the cavity entrance may also be a factor in nest tree selection. Open and closed cavities are used. Nest cavities average 8.7 feet above ground or water and 23 inches deep, with 7.0 × 12.5 inch openings (Bellrose 1976). Nesting boxes should be 11 × 11 × 22 inches high at the front and tapered to 20 inches in the rear, with entrances 5 inches in diameter (Bolen 1967). Nest boxes should not be erected unless they are predator proof.

Food: Black-bellied whistling ducks are predominantly grazers (Rylander and Bolen 1974), but they can dabble and dive for aquatic food. Of 92 percent plant materials, sorghum and Bermudagrass predominated, with smartweeds, millets, water stargrass, and corn also occurring in one study (Bolen and Forsyth 1967). In some areas corn and oats are more important in the diet.

Habitat: Wood ducks are associated with bottomland hardwood forests where trees are large enough to provide nesting cavities and where water areas provide food and cover requirements (McGilvrey 1968). Requirements may be met in several important forest types, all of which must be flooded during the early nesting season: (1) southern flood plain, (2) red maple, (3) central flood plain, (4) temporarily flooded oak-hickory, and (5) northern bottomland hardwoods.

Nest: Optimum natural cavities are 20 to 50 feet above the ground with entrance holes of 4 inches in diameter, cavity depths of 2 feet, and cavity bottoms measuring 10 × 10 inches (McGilvrey 1968). Management for cavities more than a half mile from water is not recommended, and dead trees, other than cypress, do not usually contain usable cavities. Good densities of suitable wood-duck cavities have been recorded for many timber types (Bellrose 1976). Nest boxes are readily used by wood ducks, and their use may increase breeding populations, even if natural cavities are abundant, if predators are excluded. Measurements and placement of wood duck boxes have been well described (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1976, Bellrose 1976, McGilvrey 1968).

Food: Wood ducks consume large quantities of acorns, usually in flooded bottoms. Other mast and fleshy fruits also are eaten, as are waste corn and wheat (Bellrose 1976). Smartweed, buttonbush, bulrush, pondweed, cypress, ash, sweet gum, burweed, and arrow arum seeds are used by breeding birds. Skunk cabbage, coontail, and duckweed are also food items. Duckweed is also habitat for invertebrates in the diet (Grice and Rogers 1965).

Habitat: The breeding range of the common goldeneye generally coincides with the boreal coniferous forest in North America (Johnsgard 1975, Bellrose 1976). In a Minnesota study, 87 percent of breeding goldeneyes were found on large, sand-bottomed fish lakes (Johnson 1967), while in New Brunswick, this species preferred water areas with marshy shores and adjacent stands of old hardwoods (Carter 1958). In Maine, nests are found in mature hardwoods adjacent to lakes with rocky shores, hard bottoms, and clear water. Shoal waters less than 10 feet deep with an irregular shoreline provide brood shelter and protective vegetation necessary for duckling food (Gibbs 1961).

Nest: Common goldeneyes used and were more successful in open top or “bucket” cavities than in enclosed cavities in New Brunswick (Prince 1968). Most nests were in silver maples on wetter sites or American elms on drier sites and aspen in northern conifer forests. Nest trees averaged 23 inches in diameter with cavity dimensions of 8 inches in diameter and 18 inches deep; most entrances were 6 to 40 feet above ground (Prince 1968). Wooden nest boxes measuring 12 × 12 × 24 inches with elliptical entrances 3½ × 4½ inches were used extensively in Minnesota (Johnson 1967).

Food: Of 395 stomachs examined by Cottam (1939), crustaceans (32 percent), insects (28 percent), and molluscs (10 percent) were primary animal foods (total, 73.9 percent). Crabs, crayfish, amphipods, caddisfly larvae, water boatmen, naiads of dragonflies, damselflies, and mayflies were also found. Pondweed, wild celery, and seeds of pondweed and bulrushes were important plant materials.

Habitat: Barrow’s goldeneyes attain their highest breeding population levels in western North America on moderately alkaline lakes of small to medium size in parkland areas. Open water is a necessity throughout the range, but frequently goldeneyes favor a dense growth of submerged aquatics such as sago pondweed and widgeon grass. The abundance of aquatic invertebrates may be more important than nesting cavities in determining distribution (Johnsgard 1975).

Nest: This species is not an obligate tree nester, and has been reported to use holes in banks or lava beds, rock crevices, ground under shrubs and on islands, haylofts, crows’ nests, and the outer walls of peat shelters for sheep in Iceland (Harris et al. 1954). However, the usual site is in dead stubs or trees such as aspen, Douglas-fir, and ponderosa pine within 100 feet of water (Palmer 1976). Deserted pileated woodpecker or common flicker cavities enlarged by natural decay are readily used (Palmer 1976). Cavity entrances from 3.0 to 3.9 inches in diameter, cavity depths between 9.8 and 52.9 inches, and cavity diameters between 6.5 and 9.0 inches have been reported (Johnsgard 1975). Nest boxes have been used around high lakes in the Cascade Mountains (Bellrose 1976).

Food: Food of 71 adult Barrow’s goldeneyes consisted of 36 percent insects, 19 percent molluscs, 18 percent crustaceans, 4 percent other animals, and 22 percent plants (Cottom 1939). Naiads of dragonflies and damselflies, caddisfly and midge larvae, blue mussels, amphipods, isopods, and crayfish were important animal foods, and pondweeds and wild celery were primary plant foods.

Habitat: Buffleheads favor small ponds and lakes in open woodlands (Godfrey 1966). In British Columbia, most nesting is in the interior Douglas-fir zone while poplar communities are usually used in Alberta, and ponderosa pine types are preferred in California. Scattered breeding records in Oregon, Wyoming, and Idaho are primarily in subalpine lodgepole pine, and in Alaska (Erskine 1971) Engelmann spruce and cottonwood stands are used for nesting.

Nest: Of 204 nests observed from California to Alaska, 107 were in aspen trees, 44 in Douglas-fir, 14 in balsam poplar and black cottonwood, 12 in ponderosa pine, 11 in poplar, and 16 in a few other coniferous and deciduous trees (Palmer 1976). Buffleheads prefer unaltered flicker holes in aspen. Dead trees close to (within 220 yards) or in water are preferred, and “bucket” or open top cavities are rarely used (Erskine 1971). Forestry practices that leave stubs near water while clearing away most ground litter and slash that might hinder ducklings from reaching water are to be encouraged. Nest boxes used by captive buffleheads had entrances 2⅞ inches wide with cavities 7 inches in diameter and 16 inches deep (Johnsgard 1975).

Food: Buffleheads consume mostly animal material. Insects make up 70 percent of summer foods in freshwater habitat. Midge, mayfly, and caddisfly larvae, and naiads of dragonflies and damselflies are also consumed. Water boatmen are the most widely distributed, important food. Plant food was found in many stomachs but much was fiber and was probably taken while catching aquatic insects. Pondweed and bulrush seeds were frequently consumed plant items. Dragonfly and damselfly larvae are important in the diet of ducklings in all areas (Erskine 1971).

Habitat: Although hooded mergansers prefer wooded, clear water streams, they also use the wooded shorelines of lakes. Drainage of swamps and river bottoms, removal of snags, and other human activities have been detrimental to this species as they have been to wood ducks. Hooded mergansers are more easily disturbed by man and far more sensitive to a decline in water quality than are wood ducks. Breeding densities often seem more related to food abundance and availability than to nesting cavities (Johnsgard 1975).

Nest: Cavities at any height may be selected in any species of tree; the size and shape of the cavity are apparently not important (Bent 1923). Natural cavities chosen are similar to those used by wood ducks but with smaller optimum dimensions. Frequent use of nest boxes has been reported in Missouri, Mississippi, and Oregon (Bellrose 1976). In Oregon, boxes were placed 30 to 50 feet apart in sets of 8 (Morse et al. 1969). Some of the most southerly nesting records of this species are from wood duck nest boxes (Bellrose 1976).

Food: The food habits of hooded mergansers are not well known, but are apparently more diversified than those of common mergansers. Of 138 stomachs taken from various locations in the United States, rough fishes made up 24.5 percent, game fish and unidentified fish fragments 19.4 percent, crayfish 22.3 percent, other crustaceans 10.3 percent, and aquatic and other insects 13.4 percent (Palmer 1976). Acorns are sometimes eaten in large quantities. Frogs, tadpoles, and molluscs such as snails are also consumed.

Habitat: Common mergansers prefer cool, clear waters of northern boreal or western forests, although at times they have nested as far south as North Carolina and Mexico. Ponds associated with the upper portions of rivers in northern forested regions are often used (Johnsgard 1975). As with hooded mergansers, clear water is needed for foraging.

Nest: Although hollow trees are the usual location, ground nests under thick cover or in rock crevices are not uncommon. A wide variety of other locations have been reported such as chimneys, hawk nests, bridge supports, and old buildings. The species of tree used for nesting and the height of the cavity are apparently unimportant (Foreman 1976). Nest sites are usually close to water (Bellrose 1976) and are used repeatedly, probably by the same female (Palmer 1976). Artificial nest boxes have been accepted, especially in Europe. Preferred dimensions are 9.1 to 11 inches wide, and 33.5 to 39.4 inches high, with 4.7 × 4.7-inch entrances, 19.7 to 23.6 inches above the base of the nest box (Johnsgard 1975).

Food: Programs to reduce populations of this fish-eating merganser have increased trout and salmon production in several areas, at least temporarily. Generally, common mergansers are opportunistic feeders with salmon taken extensively in some areas and suckers, chubs, and eels in others. In warm-water areas, food is usually rough and forage fish such as carp, suckers, gizzard shad, perch, and catfish. In some areas, water plants, salamanders, insects, or molluscs may be important in the diet of this species (Palmer 1976).

Habitat: Turkey vultures soar over most of the forest types of the United States and southern Canada, with the exception of the pine and spruce-fir stands in the extreme northeastern United States. In search of food this common carrion eater makes use of the forest openings created by roads, powerline rights-of-way, clearcuts, and abandoned fields.

Nest: Preferred nest sites are often at a premium because of the bird’s large size and the shortage of large snags. The smell of carrion around the nest necessitates a well-protected site to lessen predator losses. The nest site is almost always at or near ground level (Bent 1937). Although nesting sites are commonly located in hollow trees or hollow logs lying on the ground, these vultures will nest on cliffs, in caves, and in dense shrubbery (Gingrich 1914, Townsend 1914). These birds will return to the same nesting site year after year unless the site has been severely disturbed (Jackson 1903, Kempton 1927).

Food: Turkey vultures are scavengers and carrion-eaters, often hunting along roads where animals have been struck by automobiles. They feed on snakes, toads, rats, mice, and other available animal matter. Often a dozen or more vultures will gather at and feed on a large carcass.

Habitat: The black vulture is found in the southern Great Plains, southeastern pine forests, oak-hickory forests, and intermediate oak-pine forests. It is a more southern species than the turkey vulture.

Nest: Like turkey vultures, black vultures nest under a wide variety of conditions. They use the nest site as found without adding nesting materials (Hoxie 1886, Bent 1937). Hollow stumps or standing trees are favorite nesting sites when they are available; otherwise, eggs are laid on the ground, often in dense thickets of palmetto, yucca, or tall sawgrass (Bent 1937). Nests have been reported in abandoned buildings.

Food: This carrion-eater is often found in towns and cities, feeding on animal wastes, scraps, or garbage. Forests are used primarily for roosting and nesting sites, whereas feeding is usually in more open areas and along highways, where animal carcasses are more plentiful.

Habitat: The peregrine falcon is found in tundra regions, northern boreal forests, lodgepole pine and subalpine fir, spruce-fir, southern hardwood-conifer, cold desert shrubs, and prairies—mainly in open country and along streams. It is also found around salt and freshwater marshes (Fyfe 1969, Hickey and Anderson 1969, Nelson 1969). This species is currently classified as “Endangered” in the United States.

Nest: Although the peregrine falcon is currently considered a cliff-nester, records indicate that it once nested in tree cavities (Goss 1878, Ridgway 1889, Ganier 1932, Bellrose 1938, Spofford 1942, 1943, 1945, 1947, Peterson 1948). The peregrine still uses cavities in broken-off trunks in Europe (Hickey 1942), but the hole-nesting population of America apparently disappeared with the felling of the great trees on which they depended (Hickey and Anderson 1969).

Food: The peregrine falcon feeds primarily on birds ranging in size from mallards to warblers, which are usually stunned or killed in flight. Mammals and large insects form only an insignificant portion of the diet (Bent 1938). White and Roseneau (1970) found remains of fish in the stomachs of peregrines in Alaska, and suggested that fish may be more common in some peregrine diets than the literature indicates.

Habitat: The merlin is usually found in open stands of boreal forest, Douglas-fir—sitka spruce, poplar-aspen-birch-willow, ponderosa pine—Douglas-fir, oak woodlands, and saltwater marshes (Craighead and Craighead 1940, Lawrence 1949, Brown and Weston 1961).

Nest: Like the peregrine falcon, most cavity nests for the merlin were reported before 1910, when it was nesting in cavities of poplars, cottonwoods, and American linden trees (Bendire 1892, Houseman 1894, Dippie 1895). The merlin usually uses tree nests built by other large birds (such as hawks, crows, and magpies) but sometimes nests on the ground under bushes or on cliffs and cutbanks.

Food: Brown and Amadon (1968) found that birds made up 80 percent (by weight) of the food for merlins, insects 15 percent, and mammals 5 percent. Ferguson (1922) examined 298 stomachs and found 4 mammals, 318 birds, and 967 insects. Birds found in the stomachs included small shorebirds, small game birds, and songbirds (which are normally captured in flight). Insect prey consisted of crickets, grasshoppers, dragonflies, beetles, and caterpillars (Bent 1938), while mammals included pocket gophers, squirrels, mice, and bats (Fisher 1893).

Habitat: The American kestrel is the smallest and most common falcon in North America, occurring in open and semi-open country throughout the continent. In the Rocky Mountain region, kestrels are most abundant on the plains, but do nest up to 8,000 feet elevation in the Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine, and pinyon-juniper forest types (Scott and Patton 1975, Bailey and Niedrach 1965). They have been observed on the highest peaks after the nesting season (Bailey and Niedrach 1965).

Nest: Nest sites vary greatly, but kestrels prefer natural cavities or old woodpecker holes. The following nest sites are reported in order of usage: common flicker holes, natural cavities, cavities in arroyo banks or cliffs, buildings, magpie nests, and man-made nesting boxes (Bailey and Niedrach 1965, Bent 1938, Roest 1957, Forbush and May 1939). Nest boxes, approximately 10 × 10 × 15 inches, should be located 10 to 35 feet above ground with a 3-inch entrance hole. Natural cavities or nest boxes should be available along edges of forest openings (Bailey and Niedrach 1965, Hamerstrom et al. 1973, Pearson 1936).

Food: Kestrels hunt from high exposed perches overlooking forest openings, fields, or pastures. Food consists primarily of insects (often grasshoppers), small mammals, and an occasional bird (Bent 1938).

Habitat: The barn owl inhabits most of the forest types in the United States except the higher elevation types in the Rocky Mountains. They are usually considered uncommon residents because their silent nocturnal habits render them undetectable by most casual observers. Barn owls are also birds of the open country, and adapt readily to areas occupied by man (Marti 1974).

Nest: Before the coming of man, barn owls nested in natural cavities in trees, cliffs, or arroyo walls, but now they also nest in barns, church steeples, bird boxes, mine shafts, and dovecotes (Bailey and Niedrach 1965, Reed 1897).

Food: Barn owls frequent areas where small mammals are plentiful; mice, voles, rats, gophers, and ground squirrels are major food items. Birds other than those such as house sparrows and blackbirds, which have communal roosts, are only rarely taken (Marti 1974).

Habitat: This small owl is found in most forest types below 8,000 feet elevation throughout the United States. Screech owls prefer widely spaced trees, interspersed with grassy open spaces, for hunting. Meadow edges and fruit orchards are favored throughout the eastern United States.

Nest: Like other owls, the male screech owl defends a nesting and feeding territory. Maples, apples, and sycamores with natural cavities or pines with woodpecker holes are preferred in the East (Bent 1938). Along the drainage systems of the plains areas, natural cavities or common flicker holes in cottonwood trees are preferred (Bailey and Niedrach 1965). Nest boxes in orchards or residential areas are often used. Hamerstrom (1972) recommended a nesting box 8 × 8 × 8 inches with a 3-inch entrance hole.

Food: Screech owls are among the most nocturnal owls and are rarely seen feeding. Major food items are mice and insects. Fisher (1893) examined 255 stomachs of screech owls and found birds in 15 percent of them, mice in 36 percent, and insects in 39 percent. Korschgen and Stuart (1972) found mostly small mammals in 419 screech owl pellets from western Missouri. The volume of the screech owl pellets was predominantly meadow mice, white-footed mice, and cotton rats.

Habitat: The small whiskered owl is generally found in the dense oak or oak-pine forests of southern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and into Mexico.

Nest: Nests have been reported in both natural cavities and old woodpecker holes located in oak, cottonwood, willow, walnut, sycamore, and juniper trees (Bent 1938). Karalus and Eckert (1974) suggest that white oak is one of the favorite nest sites, and that these small owls prefer to nest in cavities in the limbs of trees rather than in the trunk.

Food: Black crickets, hairy crickets, moths, grasshoppers, large beetle larvae, and centipedes are the principal elements of the diet (Jacot 1931). In addition to those mentioned by Jacot, Karalus and Eckert (1974) list praying mantids, roaches, cicadas, scorpions, and small mammals as part of the diet.

Habitat: The flammulated owl normally is not found in cutover forests or in pure stands of conifers but requires some understory or intermixture of oaks in the forest (Phillips et al. 1964). It occurs in ponderosa pine, spruce-fir, lodgepole pine, aspen, and pinyon-juniper forest types (Grinnell and Miller 1944, Karalus and Eckert 1974).

Nest: Nests are usually located in abandoned flicker or other woodpecker holes, but flammulated owls may take over occupied nests (Karalus and Eckert 1974). Their nests have been reported in pine, oak, and aspen snags (Bent 1938).

Food: The flammulated owl is almost entirely insectivorous, but it occasionally captures small mammals and birds. In the few stomachs that have been examined, items reported were various beetles, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, caterpillars, ants, other insects, spiders, and scorpions (Bent 1938). Kenyon (1947) examined the stomach contents of one owl and found 4 crane flies, 1 caddisfly, 7 moths, 11 harvestman spiders, and 1 long-horned grasshopper; the bird had apparently choked to death on the grasshopper.

Habitat: The hawk owl inhabits much of the northern poplar, spruce, pine, birch, tamarac, and willow forests where such forests are broken by small prairie burns and bogs (Henderson 1919).

Nest: Hawk owls usually nest in natural cavities or in enlarged holes of pileated woodpeckers and flickers. Nests have been reported in birch, spruce, tamarac, poplar snags (Henderson 1919, 1925, Bent 1938), and occasionally on cliffs or in crow’s nests.

Food: This owl hunts extensively during the day and feeds on small mammals, birds, and insects (Bent 1938). Mendall (1944) examined 21 hawk owl stomachs; all contained meadow or red-backed mice; two owls had also fed on shrews.

Habitat: The pygmy owl is found in most of the western wooded areas from western Canada into Mexico. It is probably most abundant in open coniferous or mixed forests and is reported specifically in ponderosa pine, mixed conifer, and fir-redwood-cedar forests.

Nest: This owl usually nests in old woodpecker holes ranging in size from those constructed by hairy woodpeckers up to and including those of the flickers from 8 to 75 feet above ground (Bent 1938).

Food: Mice and large insects are probably the most common prey of the pygmy owl, although other small mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles have been reported (Bent 1938). Brock (1958) found one vole, a deer mouse, and a Jerusalem cricket in the stomach of one bird and reported seeing another pygmy owl take a Nuttall’s woodpecker. We observed one pygmy owl in Arizona carrying a small vole. They have also been observed taking mice in the mountains west of Denver, and taking birds in the vicinity of feeders in Boulder, Colorado (Richard Pillmore pers. comm.[6]).

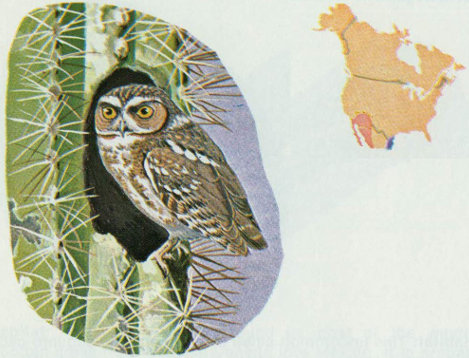

Habitat: This uncommon small owl inhabits the saguaro cactus in Sonoran deserts and wooded river bottoms near the Mexican border.

Nest: Nests are in abandoned woodpecker holes in mesquite, cottonwood, and saguaro cactus. Nest heights range from 10 to 40 feet above ground (Bent 1938, Karalus and Eckert 1974).

Food: The diet of the ferruginous owl consists primarily of small birds; however, insects, small mammals, invertebrates, reptiles, and amphibians are occasionally eaten (Karalus and Eckert 1974).

Habitat: The elf owl is restricted to the southwestern United States where it is found primarily in the saguaro cactus deserts, bottomland sycamore and cottonwood stands and in conifer-hardwood forests at high elevations.

Nest: One of the most common nest sites of the elf owl is in old woodpecker holes in saguaro cactus. It has also been reported nesting in cavities in sycamore, walnut, mesquite, and pine trees (Ligon 1967, Bent 1938, Hayes and James 1963). Cavities are usually located in snags or in dead branches of living trees.

Food: Elf owls feed almost entirely on insects, particularly beetles, moths, and crickets. They also feed on centipedes and scorpions and have been reported to take an occasional reptile (Ligon 1967).

Habitat: Barred owls are common in southern swamps and moist river bottoms of the Midwest, and less common but widespread in northern forests. These owls are found in all of the eastern forest types. Although they use white pine, these large owls prefer oak woods and mixed hardwood-conifer stands (Nicholls and Warner 1972). Preferred oak woods contain dead and dying trees for cavities and are free of dense understory, thus facilitating unobstructed flying and attacking of prey.

Nest: Natural cavities in hollow trees are preferred by barred owls. If these are unavailable, deserted crow, raptor, or squirrel nests are occasionally used (Pearson 1936, Bent 1938). Hollow trees used usually have hunting perches with good views. Recommended nest box size is 13 × 15 × 16 inches deep, with an entrance hole 8 inches in diameter (Hamerstrom 1972). Nest boxes will have a better chance of being used if they are placed near woods and streams.

Food: Barred owls are nocturnal hunters. More than half of the food items taken in western Missouri consisted of meadow mice, cottontail rabbits, and cotton rats (Korschgen and Stuart 1972).

Habitat: This uncommon owl occurs in most old-age conifer associations in the western United States. Forsman (1976) located 123 pairs in Oregon, and 95 percent occupied undisturbed old-growth conifer forests. Karalus and Eckert (1974) described the habitat as being dense fir forests, heavily wooded cliffsides, narrow canyons, and sometimes stream valleys well stocked with oak, sycamore, willow, cottonwood, and alder.

Nest: Forsman (1976) found spotted owls nesting in the holes of living old-growth conifers, particularly Douglas-fir. Nest trees typically had secondary crowns and broken tops caused by parasite infection. Cavities were located inside the tops of hollow trunks 62 to 180 feet above ground. Dunn (1901) reported spotted owls nesting in cavities in live and dead oak and sycamore trees. Spotted owls also nest in cavities in cliffs, and occasionally in abandoned nests of other large birds (Bent 1938).

Food: The major food items of the spotted owl are mammals and birds, with occasional insects and amphibians. Forsman (1976) found that mammals made up 90 percent of the total biomass taken; the major prey species were flying squirrels and wood rats. Marshall (1942) examined 23 pellets and stomach contents of 5 spotted owls and found 6 bats, 4 mice, 31 crickets, 12 flying squirrels, 1 mole, 1 shrew, 4 songbirds, 2 smaller owls, and 1 amphibian.

Habitat: This northern owl is normally found in the mixed conifer-hardwood forests of Canada (Peterson 1961). One juvenile reported in Colorado during August suggests that this owl may nest in the southern Rocky Mountains (Bailey and Niedrach 1965). Boreal owls are confined to evergreen woods and dense alder, white pine, and spruce forests.

Nest: Old flicker and pileated woodpecker holes are preferred, usually at a height of 10 to 25 feet (Fisher 1893, Preble 1908, Tufts 1925, Lawrence 1932). Conifer snags seems to be preferred for nest trees, although hardwoods have been used (Bent 1938).

Food: The main portion of the boreal owl’s diet consists of small rodents. Mendall (1944) examined the contents of 20 stomachs in Maine and found 73 percent mice (chiefly meadow voles) and 20 percent short-tailed shrews. Pigeons and grasshoppers made up the remaining 7 percent. In Ontario, Catling (1972) found 86.2 percent meadow voles, 5.6 percent deer mice, 4.2 percent star-nosed moles, 2.7 percent masked shrews, and 1.4 percent short-tailed shrews. Small birds, bats, insects, amphibians, and reptiles are also occasionally eaten (Karalus and Eckert 1974).

Habitat: Saw-whet owls are small, nocturnal hunters of the deep north woods. They nest in the Rocky Mountains up to about 11,000 feet (Bailey and Niedrach 1965). This widely distributed owl nests in most of the forest types throughout the northern half of the United States, but only rarely do they nest as far south as central Missouri.

Nest: These small owls prefer to nest in old flicker or other woodpecker holes (Bent 1938). Nesting habitat may be improving in areas where Dutch Elm disease has infested many elms, and woodpeckers have drilled nest holes (Hamerstrom 1972). Saw-whets will use nesting boxes if sawdust or straw is provided. Nest boxes should be 6 × 6 × 9 inches with a 2.5-inch entrance hole (Hamerstrom 1972).

Food: Saw-whet owls consume mostly small mammals and insects. Specific food items include mice, shrews, young squirrels, chipmunks, bats, beetles, grasshoppers, and occasionally small birds (Scott and Patton 1975, Burton 1973, Hamerstrom 1972, Bent 1938).

Habitat: Chimney swifts are found throughout the eastern half of the United States in wooded and open areas. They have adopted to man-made structures and are no longer dependent upon hollow trees for nesting and roosting.

Nest: Originally chimney swifts nested in hollow trees, especially sycamores. They now use chimneys, barn silos, cisterns, and wells (Pearson 1936). Their nests are made of twigs, which are glued to a vertical surface with saliva to form a “half-saucer” (Forbush and May 1939).

Food: Chimney swifts feed almost entirely on flying insects but will sometimes take small caterpillars hanging from tree branches or leaves (Forbush and May 1939).

Habitat: This small swift is most likely to be found in river valleys among dense Douglas-fir and redwood forests in the western United States.

Nest: Nests are usually located in tall hollow snags in burned or logged areas and are made from twigs (Peterson 1961, Robbins et al. 1966). Nests have been reported in unused chimneys and under building eaves (Bent 1940).

Food: Flying insects such as mosquitoes, gnats, flies, and small beetles captured in flight probably make up the entire diet (Bent 1940).

Habitat: Coppery-tailed trogons can be found along riparian streams and in pine-oak forests in Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and southern Texas.

Nest: Nests are found 12 to 40 feet above the ground in deserted large woodpecker holes (Bent 1940). Cottonwood and sycamore snags are usually selected for nests. Of the 34 species in the family Trogonidae, this is the only one that breeds in the United States (Wetmore 1964).

Food: There is little information on the food of these birds, but apparently both animal and vegetable matter are included in the diet. Bent (1940) reported on stomach contents of two birds. One contained adult and larvae of moths and butterflies; the other contained 68 percent insects and 32 percent fruits. Insect food included grasshoppers, praying mantids, stink bugs, leaf beetles, and larvae of hawk moth, sawfly, and miscellaneous other insects. Vegetable food consisted of fruits of cissus and red pepper and undetermined plant fiber.

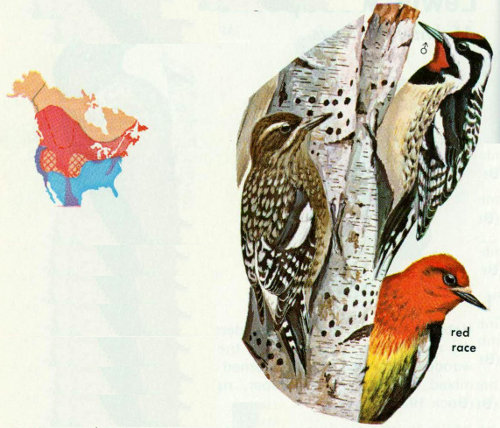

Habitat: Flickers are commonly found near large trees in open woodlands, fields, and meadows throughout North America. In winter, they occasionally seek shelter in coniferous woods or swamps. Previously three species were recognized: the yellow-shafted of the East, the red-shafted of the West, and the gilded of the southwestern desert. These are now considered a single species.

Nest: Flickers prefer to nest in open country or in lightly wooded suburban areas where park-like situations are plentiful (Bent 1939). Conner et al. (1975) reported that flickers usually nest in edge habitats and, in extensive forested areas, nest only in or around openings. Flickers excavate nest holes with a 2.75-inch entrance hole diameter in dead trees or dead limbs of many species of trees including aspen, cottonwood, oak, willow, sycamore, pine, and juniper. Nests are sometimes as high as 100 feet but usually between 10 and 30 feet (Scott and Patton 1975, Lawrence 1967).

Food: Sixty percent of common flicker food is animal matter. Of this, 75 percent is ants, more than taken by any other North American bird. Some flicker stomachs have contained over 2,000 ants. The rest of the insect material includes beetles, wasps, caterpillars, grubs, and crickets. The vegetable portion of the diet includes weed seeds, cultivated grain, and the fruit of wild shrubs and trees (Bent 1939, Forbush and May 1939).

Habitat: Forests of heavy timber and secondary growth consisting of mixed deciduous and coniferous trees are the preferred year-round habitat for pileated woodpeckers. These large woodpeckers have become less abundant over much of their former range where extensive agriculture or logging practices have eliminated large tracts of old growth forests. In the Ozarks, they are plentiful wherever extensive forests remain, preferring areas where past cutting practices (early 1900’s) have left scattered large cull trees throughout.

Nest: Pileated woodpecker nests have been found in beech, poplar, tulip-popular, birch, oak, hickory, maple, hemlock, pine, ash, elm, basswood, and aspen trees. Cavity heights range from 15 to 70 feet, with an entrance hole up to 4 inches in diameter (Hoyt 1941, 1957). Tall dead trees with smooth surfaces and few limbs are preferred. One tree may be used for several years, but rarely is a nest hole reused. This behavior provides cavities for other wildlife, including wood ducks, owls, and squirrels (Hoyt 1957). Timber stands with sawtimber of 15 to 18 inches dbh provide adequate habitat if there is a supply of dead and decaying trees (Conner et al. 1975).

Food: Insects make up more than 70 percent of the food of pileated woodpeckers. Ants (especially carpenter ants) and beetles are the major food items. In the fall, dogwood berries, wild cherries, acorns, and other wild fruit are included in the diet (Bent 1939).

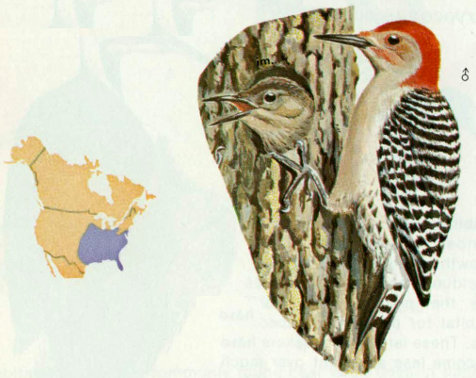

Habitat: Red-bellied woodpeckers are common throughout southeastern forest types. This bird has habits similar to those of the red-headed woodpecker, except that the red-headed prefers open woodlands, farm yards, and field edges whereas the red-bellied prefers larger expanses of forest. Bailey and Niedrach (1965) reported that the red-bellied woodpecker is extending its range westward up the river valleys of the Great Plains.

Nest: These woodpeckers most commonly excavate nest holes in dead limbs of living trees. Excavations were found in a wide variety of tree species, and ranged from 33 to 72 feet above ground (Reller 1972). Cavities are usually located in mature timber stands. Between September and January, males and females roost in separate holes. Often one of the roost holes (usually that of the female) becomes the nest site (Kilham 1958).

Food: Although primarily insectivorous, red-bellied woodpeckers consume more vegetable matter than most woodpeckers. Insects that are eaten include ants, adult and larval beetles, and caterpillars. Vegetation eaten includes grain, berries, and fruits of holly, dogwood, and poison ivy. Acorns and berries are stored in crevices in the fall (Kilham 1963, Bent 1939).

Habitat: The golden-fronted woodpecker’s preferred habitat is mesquite and riparian woodlands in Texas and Oklahoma. Cooke (1888) listed this species as an abundant resident of the lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas, in 1884.

Nest: Nesting behavior of the golden-fronted is similar to that of the red-bellied woodpecker (Pearson 1936). Tall trees of pecan, oak, and mesquite are the major species used for nesting (Bent 1939). Occasionally fence posts, telephone poles, and bird boxes are used (Reed 1965).

Food: The diet of the golden-fronted woodpecker consists of both insects and vegetable matter. Grasshoppers make up more than half of the animal matter and other insects include beetles and ants (Pearson 1936, Bent 1939). Vegetable matter consumed consists of corn, acorns, wild fruits, and berries (Bent 1939).

Habitat: This woodpecker is found on desert mesas in association with creosote bush, mesquite, and saguaro cactus from central Arizona to edges of adjacent states. It is also common in river bottoms and in foothill canyons among cottonwoods, willows, and sycamores.

Nest: The Gila woodpecker excavates holes in saguaro cacti for nests. Cottonwoods, willows, and mesquites are also used at higher elevations (Bent 1939, Ligon 1961).

Food: The diet of the Gila woodpecker consists of ants, beetles, grasshoppers, fruits from saguaro cactus, and mistletoe berries (Bent 1939). This woodpecker has been reported to remove eggs from the nests of various songbirds.

Habitat: Red-headed woodpeckers prefer to nest and roost in open areas. Farmyards, field edges, and timber stands that have been treated with herbicides or burned are preferred habitats. Redheads are attracted to areas with many dead snags and lush herbaceous ground cover, but not to woods with closed canopies. They are found throughout the East and along wooded streams of the prairie to eastern Colorado and Wyoming. Competition for nesting space is often intensive where starlings are abundant (Bailey and Niedrach 1965).

Nest: Red-headed woodpeckers most commonly excavate holes in the trunks of dead trees. Holes are excavated from 24 to 65 feet above the ground and the 1.8-inch diameter entrance hole often faces south or west (Reller 1972). These woodpeckers may excavate new holes each year, or use old nest sites.

Food: Red-headed woodpeckers consume about half animal matter (mostly insects) and half vegetable matter. Occasionally the eggs or the young of other birds are destroyed. Although a wide variety of vegetable matter is consumed, acorns from pin oak comprise a large portion of the winter diet. Nuts are stored whole or in pieces in cracks and crevices in bark, and in cavities which are sealed with bits of bark when full. These birds also store insects (especially grasshoppers) along with acorns in cavities and crevices (Kilham 1963, Bent 1939).

Habitat: The acorn woodpecker is a common resident of mixed oak-pine woodland and adjacent open grassland from Oregon along the Pacific Coast to the southwestern United States.

Nest: Acorn woodpeckers are communal nesters, and the young are fed by the entire group (Wetmore 1964). They usually excavate holes in ponderosa pine, but live and dead oaks of various species, sycamore, cottonwood, and willow are also used for nests. Their old holes are important for secondary cavity nesters such as small owls, purple martins, violet-green swallows, nuthatches, house wrens, and kestrels (Bent 1939).

Food: As the name implies, acorn woodpeckers feed mostly on acorns which are stored in holes drilled in communal trees. Sap from several species of oaks also is consumed from midwinter to summer (MacRoberts and MacRoberts 1972). About 25 percent of the diet is insects, including grasshoppers, ants, beetles, and flies (Bent 1939). Almonds, walnuts, and pecans are eaten when they are available.

Habitat: Open or parklike ponderosa pine forest is probably the major breeding habitat of the Lewis’ woodpecker. These woodpeckers also nest in burned over stands of Douglas-fir, mixed conifer, pinyon-juniper, riparian, and oak woodlands (Bock 1970).

Nest: The Lewis’ woodpecker generally excavates its own nest cavity, but will use natural cavities or holes excavated in previous years. Bock (1970) summarized the following nest data: height range 5 to 170 feet; 47 nests in dead stubs and 17 in live trees; 29 nests in conifers, 31 in cottonwood and sycamore, 6 in oaks, 2 in power poles, 1 in juniper, and 1 in catalpa. At Boca Reservoir, California, 10 of 11 nests were in dead ponderosa pines, and the other was in a hollow section of a living pine.

Food: Insects, including flies, ladybird beetle larvae, tent caterpillars, ants, and mayflies, were the primary food of Lewis’ woodpeckers during spring and summer (Bock 1970). Fruits and berries were the most frequently used food in late summer and fall, while winter food consisted mostly of acorns and almonds gathered and stored in crevices of dead trees, power poles, and oak bark. Hadow (1973) reported that, on snowy days when insects were inactive, Lewis’ woodpeckers in southeastern Colorado spent 99 percent of their feeding time feeding from caches of acorns and corn kernels.

Habitat: The yellow-bellied sapsucker (sometimes called red-naped) is most abundant along streams in mixed hardwood-conifer forests. It is also found in ponderosa pine, aspen, mixed conifer, lodgepole pine, and in mixed stands of fir-larch-pine.

Nest: Yellow-bellied sapsuckers usually nest in cavities in snags or live trees with rotten heartwood. Aspen seems to be the preferred species (Howell 1952, Lawrence 1967, Kilham 1971), but nests have also been found in ponderosa pine, birch, elm, butternut, cottonwood, alder, willow, beech, maple, and fir (Bent 1939). Kilham (1971) noted that nest trees were often infected by the Fomes fungus. Nest height varies from 5 to 70 feet above ground. The same nest tree is often used repeatedly, but a new cavity is excavated each year.

Food: Sap is eaten throughout the year by the yellow-bellied sapsucker, but the amount taken and tree species used vary seasonally (Tate 1973, Lawrence 1967). The birds regularly tap one or two “favorite trees” in their area; Oliver (1970) found that these tend to be trees which have been wounded (by logging, porcupines, etc.). About 80 percent of the insect food taken consists of ants (McAtee 1911). Other insects in their diet include beetles and wasps, but none of the woodboring larvae. The fruits of dogwood, black alder, Virginia creeper, and blackberries are included in the small portion of vegetable matter eaten (Bent 1939).

Habitat: This sapsucker prefers mixed conifer-hardwood forests of the Rocky Mountain region but also inhabits the subalpine spruce-fir-lodgepole zone, and ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, and aspen forests.

Nest: The choice of tree species for nesting seems to differ between regions. Bent (1939), Packard (1945), Bailey and Niedrach (1965), Burleigh (1972), and Jackman (1975) reported Williamson’s sapsuckers nesting primarily in conifers. Other authors (Rasmussen 1941, Hubbard 1965, Tatschl 1967, Ligon 1961, Crockett and Hadow 1975) found a preference for aspens. Of 57 nests in Colorado examined by Crockett and Hadow (1975), 49 were in aspens, especially aspens infected by the Fomes fungus; where pines were used, there were no suitable aspen sites nearby. In Arizona, we found 17 nests in aspen snags, 3 in aspens with dead tops, and 1 nest in a live aspen.

Food: The diet of Williamson’s sapsuckers is made up of 87 percent animal and 13 percent vegetable material (Bent 1939). Most of the animal food taken is ants, and most of the vegetable material is cambium. Like the yellow-bellied sapsucker, the Williamson’s sapsucker feeds on sap, especially in spring, and picks out “favorite trees” which it taps regularly (Oliver 1970).

Habitat: Hairy woodpeckers are residents of nearly all types of forest from central Canada south.

Nest: Live trees in open woodlands are preferred nesting sites of hairy woodpeckers. This species makes a nest entrance that exactly fits its head and body size (1.6 to 1.8 inches). Because this size also seems very convenient for starlings and flying squirrels, hairy woodpeckers are often troubled with invasions (Kilham 1968a, Lawrence 1967). Hairy woodpeckers will often excavate the entrance so it is camouflaged or hidden, such as on the underside of a limb. Nest heights vary from 15 to 45 feet but are commonly approximately 35 feet high. Hairies will often use the same hole year after year.

Food: Hairy woodpeckers prefer to feed on insects on dead and diseased trees (Bent 1939). Approximately 80 percent of the diet is animal matter; adult and larval beetles, ants, and caterpillars are the most frequently eaten items. The primarily insect diet is supplemented with fruit, corn, acorns, hazelnuts, and many other species (Beal 1911, Bent 1939). The males forage in trees away from the nest for large insects (usually borers) located deep in the wood. Females forage close to the nest on the surface of trees, shrubs, or on the ground for small prey (Kilham 1968a).

Habitat: Downy woodpeckers inhabit most of the wooded parts of North America. They are absent or rare in the arid deserts, and not common in the densely forested regions. Favorite habitat includes open woodland, hammocks, orchards, roadside hedges, farmyards, and urban areas (Bent 1939). Occasionally, these birds nest at elevations above 9,000 feet in the central Rockies (Bailey and Niedrach 1965). Most populations are considered nonmigratory; however, there is some movement from north to south and from high elevations to the plains during winter.

Nest: Downy woodpeckers resemble common flickers in many of their nesting habits. Both prefer to excavate near the tops of dead trees in fairly open timber stands. They generally excavate new cavities each year in the same tree, but do not usually use cavities of other birds or reuse old cavities (Lawrence 1967). In the fall, these birds excavate fresh holes to use as winter roosts (Kilham 1962). Nest holes are normally 8 to 50 feet above the ground with an entrance hole 1.2 to 1.4 inches in diameter (Bent 1939).

Food: The diet is about 75 percent animal and 25 percent vegetable material. Animal material consists mostly of economically harmful insects. Kilham (1970) found that beetles, mostly wood-boring larvae, made up 21.5 percent of the diet. Other materials included ants (21 percent), caterpillars (16.5 percent), weevils (3 percent), and fruit (6 percent). Like hairy woodpeckers, downy woodpeckers have been credited with reducing forest pests (MacLellan 1958, 1959, Olson 1953).

Habitat: Ladder-backed woodpeckers are commonly found in mesquite and deciduous woodland along streams in desert regions of the Southwest.

Nest: Ladder-backed woodpecker nests are located in a variety of trees such as mesquite, screw bean, palo verde, hackberry, china tree, willow, cottonwood, walnut and oak, usually from 2 to 30 feet above ground. Saguaro cactus, yucca stalks, and branches are sometimes used for nests, as are telephone poles and fence posts (Bent 1939, Phillips et al. 1964).

Food: Insects, especially larvae of wood-boring beetles, caterpillars, and ants, are major food items. The ladder-backed woodpecker also has been reported to eat the ripe fruit of saguaro cactus (Bent 1939).

Habitat: This western woodpecker is an inhabitant of oak woodlands, riparian woods, and chapparal west of the Sierras in California.

Nest: From a literature survey and personal observations, Miller and Bock (1972) summarized the following nest-tree data for 57 nests: 23 percent in oak, 19 percent in willow, 18 percent in sycamore, 16 percent in cottonwood, and 12 percent in alder. Cavities were excavated in dead limbs and trunks of trees, from 3 to 45 feet above ground.

Food: About 80 percent of the diet of Nuttall’s woodpecker is insects, including 28 percent beetles, 15 percent hemipterans, 14 percent lepidopteran larvae, and 8 percent ants (Beal 1911). Most of the insects are gleaned from trunk and limb surfaces or captured on the wing (Short 1971). Wild fruits, poison oak seeds, and occasional acorns make up the vegetable portion of the diet. Nuttall’s woodpeckers in California have been known to take almonds, occasionally robbing the caches of Lewis’ woodpeckers (Emlen 1937, Bock 1970).

Habitat: Arizona woodpeckers are found in live oak and oak-pine forests and canyons from 4,000 to 7,500 feet in Arizona and New Mexico.

Nest: The Arizona woodpecker excavates holes in dead branches of living trees, primarily walnuts, oaks, maples, and sycamores. One nest was reportedly located in a mescal stalk (Bent 1939).

Food: This woodpecker’s diet probably consists largely of the adult and larval stages of insects, with some fruit and acorns, but few details of food items have been reported (Bent 1939).

Habitat: Red-cockaded woodpeckers need open, mature (at least 60 year old) pine forest with a high fire occurrence (Bent 1939, Jackson 1971, Hopkins and Lynn 1971). Pine species used during breeding season include: longleaf (Crosby 1971), slash (Lowry 1960), loblolly (Sprunt and Chamberlain 1949), and shortleaf (Sutton 1967). Red-cockaded woodpeckers are on the national “Endangered species” list.

Nest: These woodpeckers prefer living pines infected with red heart rot for nesting. These trees have a soft, easily excavated interior with a living exterior, leaving the tree less susceptible to destruction by fire than a dead tree. Cavities can often be reused for at least 20 years and for several years by the same pair (Ligon 1971). The height of cavity is influenced by the location of red heart infection and the height and density of undergrowth (Crosby 1971). The majority of cavities face west, and, when found in leaning trees, are generally on the low side (Beckett 1971, Baker 1971).

Food: Insects make up the major portion of the diet of red-cockaded woodpeckers. Beal (1911) and Beal et al. (1916) examined 99 stomachs and found 86 percent insects and 14 percent vegetable matter, mostly mast. Beetle larvae (16 percent) and ants made up an important part of the year-round diet. The corn earworm can be a major food source during several weeks where conditions are suitable (Ward 1930). Plant material recorded being eaten includes wax myrtle, magnolia, poison ivy, wild grape, pokeberry, blueberry, wild cherry, black gum, and pecan (Beal 1911, Baker 1971, Ligon 1971).

Habitat: Open ponderosa pine forest from Washington to central California is the primary habitat of the white-headed woodpecker, but it also occurs in sugar pine, Jeffrey pine, and red and white fir forests (Grinnell and Miller 1944).

Nest: This woodpecker seems to prefer dead pines, but nests have also been found in live and dead fir, oak, and aspen. White-headed woodpeckers usually excavate a new nest cavity every year and often excavate several holes before selecting one to nest in (Bent 1939). Average nest height is 8 feet above ground.

Food: White-headed woodpeckers feed primarily on pine seeds during the winter and early spring, and on insects during the summer. Tevis (1953) determined that 60 percent of the annual diet was pine seeds and 40 percent was insects. Ants made up half of the insect food; other insects taken were woodboring beetles, spiders, and fly larvae (Beal 1911, Grinnell and Storer 1924, Ligon 1973).

Habitat: The conifer forests of the north are preferred, but this three-toed woodpecker is not abundant even in its favorite habitat. Forest types include mixed conifer, lodgepole pine, white fir, subalpine fir, tamarack swamps, boreal spruce-balsam fir, Douglas-fir, and mixed hardwood-conifer.

Nest: This species usually excavates its cavities in snags or live trees with dead heartwood, especially in areas that have been burned or logged (Bent 1939). Nests are usually in spruce, balsam fir, pines, or Douglas-fir, although maple, birch, and cedar have been used.

Food: The food of this species is similar to that of the northern three-toed woodpecker. Beal (1911) found 75 percent of the food to be woodboring beetle larvae, mainly long-horned beetles and metallic woodboring beetles. Weevils and other beetles, spiders, and ants are eaten along with some wild fruit, mast, and cambium. Beal estimated that each three-toed woodpecker annually consumed 13,675 woodboring beetle larvae.

Habitat: This highly beneficial woodpecker is most common in coniferous forests of the West, but does occur occasionally in the Northeast.

Nest: The northern three-toed woodpecker excavates nest cavities each year in standing dead trees or in dead limbs of live trees with rotted heartwood (Jackman and Scott 1975). Their nest cavities have been reported in pine, aspen, spruce, and cedar trees (Bent 1939). In Arizona, we found two nests in ponderosa pine snags.

Food: The northern three-toed woodpecker is probably one of the most important birds in combating forest insect pests in the western United States. Massey and Wygant (1973) found that spruce beetles comprised 65 percent of their diet in Colorado. During the winter when other foods were scarce, the spruce beetle made up 99 percent of the food taken. West and Speiers (1959) reported that both species of three-toed woodpeckers in northeastern United States feed on elm bark beetles, which carry Dutch elm disease. Koplin (1972) estimated that 20 percent of an endemic and 84 percent of an epidemic spruce beetle population in Colorado were consumed by three species of woodpeckers, the most important of which was the northern three-toed. Other foods include ants, woodboring and lepidopteran larvae, fruits, mast, and cambium (Beal 1911, Massey and Wygant 1973).

Habitat: Cooke (1888) and Bent (1939) described the largest of the North American woodpeckers as rare, shy, and found only in the heaviest timber in virgin cypress and bottomland forest of the South. Tanner (1942) described ivory-billed woodpecker habitat as heavily forested and usually flooded alluvial land bordering rivers, made up of oaks, cypress, and green ash. The most recent sightings (between 5 and 10 pairs) have been made in bottomland hardwoods that have been cut over but still have some large, mature trees (Dennis 1967). They are included on the national “Endangered species” list.

Nest: Nest cavities of this species have been recorded in almost every species of tree occurring within the ivory-bill’s habitat (Greenway 1958). The squarish holes (Dennis 1967) are high, 16 to 65 feet, and in the trunks of living or dead trees (Greenway 1958, Forbush and May 1939).

Food: Ivory-billed woodpeckers could be of economic importance except for their small numbers (Greenway 1958). The woodboring larvae making up a third of their diet (Beal 1911) are injurious to trees (Pearson 1936), and are most abundant in areas where recently dead and dying trees are numerous because of flooding, fire, insect attacks, or storms. The birds stay as long as there are abundant larvae (Dennis 1967). They also eat fruit of magnolia and pecan trees (Beal 1911).

Habitat: The sulphur-bellied flycatcher is a common occupant of riparian habitat with sycamore trees in deep canyons from 5,000 to 7,500 feet elevation in the Huachuca Mountains of Arizona.

Nest: Invariably the nest of this species, made from leaf stems (Peterson 1961), is built in a natural cavity in a large sycamore at a height between 20 and 50 feet above the ground. The cavity normally is a knothole where a large branch has broken off (Bent 1942). At least one member of each pair may return to the same nest site each year.

Food: Little information has been published on the food habits of this flycatcher, but insects caught in the air are undoubtedly the major items. Apparently small fruits and berries also are eaten (Bent 1942).

Habitat: Great crested flycatchers are common in deciduous and mixed woods east of the Rockies. They were originally a deep forest bird, but with increases in forest clearing and thinning operations, fewer and fewer cavities are available. They seem to be adapting well to less densely forested areas, areas treated with herbicides, and forest-field edge situations (Hespenheide 1971, Bent 1942).

Nest: Great crested flycatchers use natural cavities or excavations made by other species. Nests are found in a variety of tree species anywhere from 3 to 70 feet above the ground (mostly below 20 feet). They build a bulky nest, and therefore prefer deep cavities. Before constructing a nest, they will generally fill a deep cavity with trash to a level of 12 to 18 inches from the top. They are well known for their habit of including a snake skin in the nest or dangling it from the cavity opening (Bent 1942).

Food: Food habit studies have shown that great crested flycatchers eat 94 percent animal and 6 percent vegetable material. Most frequently eaten are butterflies, beetles, grasshoppers, crickets, katydids, bees, and sawflies. Vegetable matter is mainly wild fruits. Most food is caught in flight in the usual flycatcher fashion (Bent 1942).

Habitat: Desert saguaros, deciduous woodlands and riparian vegetation in the Southwest are the preferred habitats of the Wied’s crested flycatcher.

Nest: Nests made from twigs, weeds, and trash are built in abandoned woodpecker holes in saguaro cacti at a height from 5 to 20 feet above the ground. Sycamores, cottonwoods, and fence posts are used occasionally (Bent 1942).

Food: The diet of this species is similar to that of other crested flycatchers, consisting mostly of beetles, flying insects, and perhaps some berries and fruits (Bent 1942).

Habitat: The ash-throated flycatcher occupies dense mesquite thickets, oak groves, saguaro cactus, riparian vegetation, and pinyon-juniper forests. It ranges from Washington to the southwestern United States and Texas.

Nest: The ash-throated flycatcher is not particularly specific in tree selection as long as it has a cavity. Woodpecker holes, exposed pipes, and nest boxes have been used. Mesquite, ash, oak, sycamore, juniper, and cottonwood are common nest trees (Bent 1942).

Food: The diet of this species consists mainly of animal material. Beetles, bees, wasps, bugs, flies, caterpillars, moths, grasshoppers, spiders, etc., make up about 92 percent of the diet. Mistletoe, berries, and other fleshy fruits account for the remainder (Bent 1942).

Habitat: Olivaceous flycatchers are found in dense oak thickets, pinyon-juniper forests, and along canyon streams in Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

Nest: Nests are located in natural cavities or abandoned woodpecker holes. Oaks are preferred, but nests also have been reported in ash and sycamore trees (Bent 1942).

Food: Limited evidence on food habits of this species indicates that the major food items are small insects including grasshoppers, termites, mayflies, treehoppers, miscellaneous bugs, moths, bees, wasps, and spiders (Bent 1942).

Habitat: Moist deciduous or coniferous forests and areas near running water with tall trees are favored by the western flycatcher (Grinnell and Miller 1944).

Nest: Western flycatchers sometimes nest in cavities, but use a variety of nest sites. Davis et al. (1963) found four nests in natural cavities in willows and oaks, and six behind flaps of bark in sycamores and willows. Nests are often reported in natural rock crevices, on tree limbs and crotches, and on ledges of buildings (Bent 1942, Davis et al. 1963, Beaver 1967).

Food: Almost all of the food of the western flycatcher is insects captured on the wing. An examination of 23 stomachs showed 31 percent flies, 25 percent beetles, 23 percent lepidopterans (including pupae and adults of spruce budworms), and 17 percent hymenopterans (Beaver 1967).

Habitat: Ponderosa pine affords the favorite habitat for violet-green swallows (Bailey and Niedrach 1965), but they are also found in aspen-willow and spruce-aspen forests. They prefer open or broken woods or the edges of dense forests.

Nest: Violet-green swallows nest in holes, cavities, and crevices in a variety of situations. Where birds are abundant, the demand for nest sites is sometimes greater than the supply, and practically any available cavity may be used. These swallows have been reported to use old nests of cliff swallows and even burrows of bank swallow (Bent 1942). Winternitz (1973) reported violet-greens using old woodpecker holes in live aspen as nesting sites, but in Arizona, we found them nesting primarily in old woodpecker holes in ponderosa pine snags. We found one in the dead top of an aspen, 5 in dead tops of ponderosa pine, and 26 in ponderosa pine snags. Nest heights ranged from 16 to 80 feet and averaged 43 feet.

Food: Apparently, the diet of this species is exclusively insects taken on the wing. It includes leafhoppers, leaf bugs, flies, flying ants, and some wasps, bees, and beetles (Bent 1942). In Colorado, Baldwin (pers. comm.[7]) found that insects made up 99 percent of the stomach contents of six violet-green swallows. Flies were the most abundant insect found. Scolytid beetles, seed and leaf bugs, miscellaneous insects, and a few spiders were also found.

Habitat: Tree swallows breed throughout North America from the northern half of the United States north to the limit of tree growth. They are migrants throughout the Central and Southern states and winter primarily in Central America.

Nest: Tree swallows prefer to nest in natural cavities and old woodpecker holes—usually near water. The lack of natural cavities, competition for existing cavities, and the availability of nest boxes, have resulted in a shift in nesting preferences to nest boxes in the eastern United States (Bent 1942, Low 1933, Whittle 1926). Bluebird boxes and purple martin houses are frequently used. Tree swallows are not colonial, but will nest within 7 feet of each other, if there are adequate meadows, marsh, or water area available for feeding (Whittle 1926). Woodpecker holes in aspen, spruce, and pine are the most common nest sites in the West (Bailey and Niedrach 1965).

Food: This species is the first of the swallows to arrive in the north in the spring, and the last to depart in the fall. Because tree swallows can subsist on seeds and berries, they are not as dependent upon insects as are other swallows. They are partial to waxmyrtle and bayberry where these are available. Plant food proportions in the diet are 1 percent in spring, 21 percent in summer, 29 percent in fall, and 30 percent in winter (Martin et al. 1951, Forbush and May 1939).

Habitat: The natural nesting population of purple martins prefer open woodlands or cutover forests where suitable snags remain. Purple martins have been reported in oak, sycamore, ponderosa pine, Monterey pine, spruce, and fir forests of California (Grinnell and Miller 1944). In the Southwest, the purple martin breeds in the ponderosa pine belt and in the saguaro cactus desert.

Nest: The western purple martin has not adapted to nesting in boxes as well as the eastern form (Bunch 1964), and much of the western population depends upon holes made by woodpeckers, usually in tall pines in relatively open timber stands (Bent 1942). Martins also nest in old woodpecker holes in saguaro cactus. We have recorded 21 nests near Cibecue, Arizona, all in ponderosa pine snags. Nests ranged from 25 to 35 feet above ground. Nest compartments in martin houses should be 6 × 6 × 6 inches with an entrance hole 2½ inches in diameter 1 inch above the floor. The boxes should be 15 to 20 feet above ground.

Food: The purple martin feeds on the wing, and nearly all the diet is insects, although some spiders are taken (Beal 1918). Johnston (1967) examined the stomach contents of 34 martins collected in April, May, June, and August in Kansas. Beetles, true bugs, flies, bees, and wasps were the important food items. Although the purple martin has been credited for feeding on large numbers of mosquitoes (Bent 1942), it was not documented by the two food habit studies mentioned.

Habitat: Black-capped chickadees nest throughout southern Canada and the northern half of the United States. In Missouri, the black-capped chickadee generally nests north of the Missouri River and the Carolina chickadee nests south of the River. The breeding range extends farther south at higher elevations of the Rocky and Appalachian Mountain ranges than in non-mountainous areas. In Colorado, black-caps are most abundant in the ponderosa pine and aspen forests (Bailey and Niedrach 1965).

Nest: Chickadees nest in cavities but roost anywhere convenient, generally not in cavities (Odum 1942). The most suitable nesting sites are stubs with partially decayed cores and firm shells. They usually excavate their own cavities, but will use natural cavities or nest boxes. Black-caps will occasionally nest in a cavity they used the previous year after making some alterations. Preferred nesting sites throughout the eastern forests are tree species that occur in the early seral stages but that are short lived and persist in the intermediate stages as decaying stubs (Odum 1941, Brewer 1961).

Food: The diet of the black-capped chickadee is comprised of 70 percent animal and 30 percent vegetable matter. Mast, chiefly from coniferous trees, and fruits of bayberry, blackberry, blueberry, and poison ivy make up the bulk of the vegetable matter. Animal material eaten (mostly insects) includes caterpillars, eggs, moths, spiders, and beetles. Winter diet is primarily larvae, eggs, katydids, and spiders (Bent 1946, Martin et al. 1951).

Habitat: The Carolina chickadee, which inhabits the southeastern forests, is a slightly smaller version of the black-capped chickadee. In Missouri, the Carolina chickadee nests south of the Missouri River throughout the Ozarks.

Nest: The nesting habits of the black-capped and Carolina chickadees are quite similar. They occasionally nest in natural cavities or deserted holes of woodpeckers, but commonly excavate their own nest cavity in decaying wood of dead trunks or limbs of deciduous trees (Bent 1946). Black-capped and Carolina chickadees line their nesting cavities with fine grasses and feathers.

Food: Food habits of the Carolina chickadee are also very similar to those of the black-capped chickadee. Food consists of insects and a variety of fleshy fruits and seeds (Bent 1946).

Habitat: This species inhabits pine and spruce forests from 7,000 to 10,000 feet elevation just inside the United States in the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona and the Animas Mountains of New Mexico (Phillips et al. 1964).

Nest: Mexican chickadees excavate nest holes in dead trees or branches. One nest was found in a willow stub about 5 feet above the ground (Bent 1946).

Food: No information on diet was found in the literature.

Habitat: This common little chickadee can be found in most coniferous forests of the West from 6,000 to 11,000 feet (Bent 1946).

Nest: Mountain chickadees usually nest in natural cavities or abandoned woodpecker holes, and probably do not excavate their own cavities if suitable ones are available (Bent 1946). Winternitz (1973) reported five nests in live aspen and one in a dead aspen, 6 to 15 feet above ground. In Arizona, we have found five nests in live aspen, three in aspen snags, two in ponderosa pine snags, and one in a white fir snag.