TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the title page of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

THE SISTERS OF LADY JANE GREY

[Frontispiece

LADY KATHERINE GREY

(From the original painting, by an unknown artist, in the possession of Mrs. Wright-Biddulph, bearing the following inscription:)

“Now thus but like to change

And fade as dothe the flowre

Which springe and bloom full gay,

And wythrethe in one hour.”

THE SISTERS OF

LADY JANE GREY

AND THEIR WICKED GRANDFATHER

BEING THE TRUE STORIES

OF THE STRANGE LIVES OF CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF

SUFFOLK, AND OF THE LADIES KATHERINE AND

MARY GREY, SISTERS OF LADY JANE GREY,

“THE NINE-DAYS’ QUEEN”

BY

RICHARD DAVEY

AUTHOR OF

“THE SULTAN AND HIS SUBJECTS,” “THE PAGEANT OF LONDON,”

AND “THE NINE-DAYS’ QUEEN”

WITH 14 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

CHAPMAN AND HALL, Ltd.

1911

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

BRUNSWICK STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E.

AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

TO

THE MEMORY OF THE LATE

MAJOR MARTIN HUME

A GREAT HISTORIAN OF TUDOR TIMES

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY A STUDENT OF

THE SAME PERIOD OF OUR

NATIONAL HISTORY

PREFACE

The strange adventures of the Ladies Katherine and Mary Grey, although they excited great interest at the time of their happening, and were of immense contemporary political importance, are now almost unknown, even to professed students of Elizabethan history. The sad fate of these unfortunate princesses has paled before that of their more famous sister, Lady Jane Grey, who, although the heroine of an appalling tragedy, was rather the victim of others than of her own actions. In a sense, she was merely a lay-figure, whereas her sisters, especially Lady Katherine, who played an active part on the stage of history at a later period of life, and possessed an unusually strong personality, were entirely swayed by the most interesting of human passions—love. Lady Katherine was literally “done to death” by her infatuation for the young Earl of Hertford, the eldest son of that Protector Somerset who suffered death under Edward VI. The feline cruelty with which Queen Elizabeth tormented Lady Katherine, after the clandestine marriage with her lover was revealed, called forth the freely expressed condemnation of Chief Secretary Cecil, who denounced his royal mistress’s harshness in no measured terms.

It is said that Lady Willoughby d’Eresby, one of the faithful attendants on Katherine of Aragon, was so infuriated by Henry VIII’s courtship and marriage with Anne Boleyn, that she pronounced a terrible curse upon that wretched queen and the infant Elizabeth. If, through her intercession or incantations, she contrived to induce some evil spirit to inspire Henry VIII to make his famous but ill-considered Will, she certainly succeeded in adding very considerably to the discomfort of his celebrated daughter, who, during all her life, had to experience the consequences of an ill-judged testament, whereby Henry VIII, by passing over the legitimate claim to the succession, of his grandniece, Mary Queen of Scots, the descendant of his eldest sister, Margaret Tudor, widow of James IV of Scotland, in favour of the heirs of his youngest sister, Mary Tudor, Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk, opened a very Pandora’s box, full of more or less genuine claimants, after Elizabeth’s death, to the English Throne. The Spanish Ambassador enumerates a round dozen of these, all of whom, with the exception of Mary Stuart and Lady Katherine Grey, he describes as more or less incompetent place-seekers, not worth the butter on their bread, but who clamoured to obtain the queen’s recognition of what they believed to be their legal rights, and thereby added greatly to the general confusion. Of these claimants, Lady Katherine Grey was by far the most important, her right to the Crown being not only based on two Royal Wills—those of[ix] Henry VIII and Edward VI[1]—but, moreover, ratified by a special Act of Parliament. She therefore played a more conspicuous part in the politics of the early years of Elizabeth’s reign than is generally known, and, as a matter of fact, was rarely out of the queen’s calculations. In the first year of her reign, Elizabeth, wishing to be on the best of terms with her young cousins, not only admitted them to her privy chamber, but went so far as to recognize Lady Katherine as her legitimate successor, and even proposed to adopt her, calling her, in public, her “daughter.” For all this, there was no love lost between the queen and the princess. Lady Katherine, who had been intimate with the Countess of Feria, an Englishwoman by birth, and a close friend of Queen Mary, was strongly prejudiced against the Princess Elizabeth, who, she had been assured, was no daughter of Henry VIII, but a mere result of Anne Boleyn’s intimacy with Smeaton the musician. Notwithstanding, therefore, the queen’s advances, on more than one occasion Lady Katherine Grey, according to Quadra, the Spanish Ambassador, answered Elizabeth disrespectfully. It was not, however, until after the news of the clandestine marriage between Lady Katherine Grey and the Earl of Hertford reached her majesty, that she began to persecute the wretched girl and her husband, by sending them to the Tower—not, indeed, to “dungeons damp and low,” but to fairly[x] comfortable apartments, worthy of their high station, for which the earl, at least, had to pay handsomely. When, thanks to the carelessness or connivance of Sir Edward Warner, the lieutenant, the offending couple were allowed occasionally to meet, and Lady Katherine eventually gave birth to two sons, Elizabeth’s fury knew no bounds, and the young mother had to undergo an awful and lifelong penance as the result of her imprudence. That Elizabeth had good cause to object to the introduction into this world of a male successor, became unpleasantly apparent some ten years later, when the two boys were put forward as claimants to her Throne, and thereby came very near involving England in an ugly civil war.

The misfortunes of her elder sister do not seem to have impressed Lady Mary Grey, on whom the Crown devolved, according to the Wills of Henry VIII and Edward VI, in the event of Lady Katherine dying without issue. She was a dwarf, and married secretly Mr. Thomas Keyes, the “giant” Sergeant-Porter of Whitehall Palace, who “stood seven feet without his shoes.” When Elizabeth received the news of this “outrage” on the part of the youngest of the sisters Grey, her resentment was truly dreadful, though her indignation, in this instance, was almost justifiable, since there is nothing a great sovereign dislikes more than that any members of the royal family should expose themselves to ridicule. Lady Mary, by her unequal marriage, had dragged the great name of Tudor into the mire, and had rendered[xi] herself the laughing-stock of Europe! Elizabeth adopted in this case the same unpleasant treatment which she had administered to the recalcitrant Lady Katherine; but, fortunately for the little Lady Mary, Mr. Keyes died “of his torments,” at an early stage of proceedings, and his widow, having promised never to repeat her offence, by re-marrying with an ordinary mortal, let alone with a dwarf or a “giant,” was permitted to spend the rest of her short life in peace and plenty.

The character of Elizabeth does not shine for its wisdom or kindliness in these pages; and some incidental information concerning the mysterious fate of Amy Robsart, Leicester’s first wife, tends to prove that “our Eliza” was perfectly well aware of what was going on at Cumnor Hall, where, it will be remembered, the fair heroine of Scott’s magnificent novel, Kenilworth, died “of a fall downstairs,” which, at the time, was not generally considered accidental. The callous manner in which the queen announced this accident—if accident it was—to the Spanish Ambassador, is full of significance. Meeting him one day in a corridor at Hampton Court, she said to him very lightly, and in Italian: “The Lady Amy, the Lord Robert’s wife, has fallen downstairs and broken her neck.” A few days earlier the queen had asked the ambassador whether he thought there would be any harm in her marrying her servant, meaning Dudley. He ventured to remind her that there was an impediment to this[xii] scheme, as the Lord Robert’s wife was then still living. This impediment was soon removed!

Elizabeth’s openly expressed passion for the future Earl of Leicester, who was Lady Katherine Grey’s brother-in-law, damaged her reputation throughout Europe, and even jeopardized her Throne. The French Ambassador informs his sovereign that “the Queen of England is mad on the subject of the Lord Robert,” “she cannot live without him,” “their rooms communicate.” “I could tell your Majesty,” says the Spanish representative at our Court, in a letter to Philip II, “things about the Queen and the Lord Robert which baffle belief, but I dare not do so in a letter.” Strange to relate, however, no sooner was Amy Robsart dead, than Elizabeth’s behaviour to the Lord Robert, as he was generally called, underwent a considerable change. She was willing to retain him as a lover, but, after what had happened, she was too frightened of possible consequences, to accept him as a husband. It was only the beauty of his person that captivated the queen: otherwise, she recognized him to be what he really was—a fool. “You cannot trust the Lord Robert,”[2] she once complained to the French Ambassador, “any further than you see him. Il est si bête.” She was perfectly right, for, although she was perhaps never aware of the fact, the Spanish State Papers reveal that at one time Robert Dudley[3] was actually in correspondence,[xiii] through the Spanish Ambassador, with Philip II, to obtain his approval of the following astounding scheme, which, in abbreviated form, stands thus: “The Lord Robert is to marry the Queen, and, with Philip’s aid, they are to become Catholics, and work for the reconciliation of England to the Church, and the interests of Spain.” Comment is needless!

The biographies of the two princesses, Katherine and Mary Grey, are preceded by a few chapters dealing with Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Mary Tudor, their grandfather and grandmother. I have published these chapters, because they seem to me to complete the history of this strange family, and enable me to place before my readers a subject never before, I believe, treated in detail: that of the remarkable series of marriages of Charles Brandon, who, at the time that he was courting his king’s sister, had two wives living, one of whom, the Lady Mortimer, was destined to give him considerable trouble, and to vex his spirit and that of his consort not a little. I think I may claim to be the first writer on Tudor topics and times who has been able to determine who was this Lady Mortimer, Brandon’s first wife, and to trace her very interesting pedigree to a singular source. The story of Charles Brandon and of his clandestine marriage with Mary Tudor has been frequently related, and, indeed, it forms the subject of one of the last essays ever written by Major Martin Hume. Brandon’s earlier adventures, however, have entirely escaped the[xiv] attention of historians, and are only alluded to in a casual manner in most volumes on this subject. Brandon had a very interesting and complex personality, and the strange resemblance which existed between him and his master, King Henry VIII, forms not the least singular feature in his romantic career. This resemblance was not only physical, but moral. So great was it, from the physical point of view, that certain of his portraits are often mistaken for those of King Henry, to whom, however, he was not even remotely connected by birth. As to his moral character; his marriages—he had four wives, whilst a fifth lady, Baroness Lisle, was “contracted to him”—tend to prove that either Henry VIII influenced his favourite, or the favourite influenced his master, especially in matters matrimonial.

A brief account of Lady Eleanor Brandon and her heirs closes this volume, which I hope will receive from the public as indulgent and kindly a reception as did the story of Lady Jane Grey (The Nine-days’ Queen), of which the celebrated M. T. de Wyzewa, in a lengthy review in the Revue des Deux Mondes, did me the honour of saying that “Jamais encore, je crois, aucun historien n’a reconstitué avec autant de relief et de couleur pittoresque le tableau des intrigues ourdies autour du trône du vieil Henri VIII et de son pitoyable successeur, Edouard VI.”

It is my duty to state that I submitted the manuscript of this book for the consideration of the late Major Martin Hume, who had already done[xv] me the honour of editing my previous work, on Lady Jane Grey, for which he supplied an Introduction on the foreign policy of England during the reign of Edward VI and the “nine-days’ reign,” possibly one of the most brilliant essays on Tudor times he ever wrote. He was so much interested in the present volume, that he promised to write for it a similar introductory chapter; but, unfortunately, a few weeks after this kind offer of assistance was made, I received the sad news of his sudden death. Major Martin Hume, was, therefore, unable to carry his promise into effect; but in a letter which he wrote to me at an earlier period of our agreeable correspondence, he indicated to me several sources of information, of which I have gratefully availed myself.

The loss that historical literature sustained by the death of Major Hume was far greater than the general public, I think, realizes. He was a past-master in Tudor lore and history, and the future will, I trust, accord him that high position amongst our historians to which his work on the Spanish or Simancas State Papers should alone entitle him. In paying this, my poor tribute, to his memory as an historian, I can only add my sincere expression of profound regret at his loss as a personal friend.

In this volume—as well as in the previous one on Lady Jane Grey—I received considerable assistance, in the earlier stages of its compilation, from the celebrated Dr. Gairdner, and from my deeply regretted friend, the late Dr. Garnett.[xvi] I wish to acknowledge my debt of gratitude to these gentlemen; and to renew my thanks to the authorities of the Record Office, the Bodleian Library, and other libraries, public and private, for their unvarying courtesy.

In conclusion, I desire to express my appreciation of Mrs. Wright-Biddulph’s kindness in allowing me to publish in this work a reproduction of her unique portrait of Lady Katherine Grey. Lord Leconfield, likewise, gave me permission to reproduce several of the portraits in his magnificent collection at Petworth, but, unfortunately, his courteous offer came too late. None the less it merits acknowledgment in these pages.

Richard Davey.

Palazzo Vendramin Calergi, Venice.

August 1911.

Note.—The following brief account of Henry VIII’s Will may aid the reader in understanding the complications to which it gave rise. By this famous testament (dated 26th of December 1546 and revoking all his previous Wills), King Henry VIII provided that, in case he himself had no other children by his “beloved wife Katherine [Parr] or any other wives he might have thereafter,” and in the event of his only son, Edward [afterwards King Edward VI], who was to be his immediate successor, dying childless, that prince was to be succeeded by his eldest sister, Princess Mary; and if she, in turn, proved without offspring, she was to be succeeded by her sister, King Henry’s younger daughter, Elizabeth. Failing heirs to that princess, the Crown was to pass to the Lady Jane Grey and her sisters, Katherine and Mary Grey, successively, these being the daughters of Henry’s eldest niece, the Lady Frances Brandon, Marchioness of Dorset. In the event of the three sisters Grey dying without issue,[xvii] the Throne was to be occupied successively by the children of the Lady Frances’s sister, the King’s other niece, the Lady Eleanor Brandon, Countess of Cumberland. The Scotch succession, through Henry’s eldest sister, Margaret Tudor, Dowager Queen of Scotland, was set aside, and the name of the young Queen of Scots [Mary Stuart] omitted from the Will, preference being given to the Ladies Grey, the daughters of Henry’s niece, because he hoped that the betrothal of Mary Stuart, then only six years of age, to his son Edward, might be arranged, and the desired union of England and Scotland brought about in a natural manner. It is curious that Henry’s nieces, the Ladies Frances and Eleanor, are not named in the Will as possible successors to the Crown, although their children are. Probably the King thought that, considering the number of claimants in the field, both ladies would be dead, in the course of nature, long before they could be called upon to occupy the Throne.

In 1553 the Duke of Northumberland, then all powerful, induced Edward VI, in the last weeks of his reign, to make a Will, in which he set aside the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth, his sisters, even stigmatizing them as bastards, and thus reversing his father’s testament; and named Lady Jane Grey, his cousin, and in default of her, her sisters Katherine and Mary Grey, as his immediate and legitimate successors. The consequences of this unfortunate “Devise,” as it is called, were, as all the world knows, fatal to the Lady Jane and her family.

As the result of these two Royal Wills, the principal claimants to the Crown on Elizabeth’s death were, therefore, at the beginning of her reign, the following: firstly, Mary Queen of Scots, and her son, afterwards James I, who may be described as the legitimate pretenders; secondly, the Lady Margaret Lennox, step-sister to the Queen of Scots, and her two sons Darnley and Charles Lennox, and, eventually, the latter’s daughter, Arabella Stuart; thirdly, the Lady Katherine Grey and her two sons, and finally, in the event of their deaths, their aunt, the Lady Mary Grey. In case of all these princes and princesses leaving no issue, there remained the children and grandchildren of the Lady Frances’s sister, the Lady Eleanor Brandon, Countess of Cumberland, one of whom, at least, Fernando Strange, rendered himself and his claims distinctly troublesome to Elizabeth.

The queen had, moreover, to contend with the heirs of the Plantagenets, the members of the royal house of Pole, [xviii]who, in the person of the Earl of Huntingdon, hoped, at one time, to dethrone the queen, and, with the assistance of the ultra-Protestant party, reign in her stead.

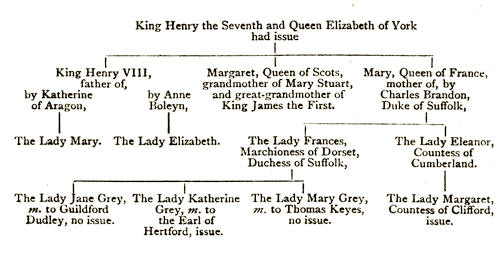

Table showing the heirs female, in remainder to the Crown, named in the Will of Henry VIII and the “Devise” of Edward VI:—

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| PREFACE | vii | |

| THE ORIGIN OF THE HOUSE OF TUDOR | xxiii | |

| CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF SUFFOLK | ||

| I | CLOTH OF FRIEZE | 3 |

| II | THE FRENCH MARRIAGE | 23 |

| III | CLOTH OF FRIEZE WEDS CLOTH OF GOLD | 49 |

| IV | THE LAST DAYS OF SUFFOLK AND OF THE QUEEN-DUCHESS | 67 |

| LADY KATHERINE GREY | ||

| I | BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD | 83 |

| II | LADY KATHERINE GREY AT THE COURT OF QUEEN MARY | 107 |

| III | THE PROGRESS OF LADY KATHERINE’S LOVE AFFAIRS | 128 |

| IV | QUEEN ELIZABETH AND HER SUCCESSION | 146 |

| V | THE CLANDESTINE MARRIAGE | 165 |

| VI | LADY KATHERINE AND HER HUSBAND IN THE TOWER | 181 |

| VII | LADY KATHERINE AT PIRGO | 199 |

| VIII | LADY KATHERINE AGAIN THE CENTRE OF INTRIGUES | 212 |

| IX | LADY KATHERINE’S LAST ILLNESS AND DEATH | 231 |

| LADY MARY GREY[xx] | ||

| I | EARLY YEARS | 255 |

| II | A STRANGE WEDDING | 262 |

| III | THE LAST YEARS OF LADY MARY | 282 |

| LADY ELEANOR BRANDON AND HER HEIRS | 293 | |

| INDEX | 305 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Lady Katherine Grey | Frontispiece |

| From the original painting, by an unknown artist, in the possession of Mrs. Wright-Biddulph, bearing the following inscription— | |

| “Now thus but like to change And fade as dothe the flowre Which springe and bloom full gay, And wythrethe in one hour.” |

|

| Facing page | |

| Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond | xxviii |

| From the original portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. | |

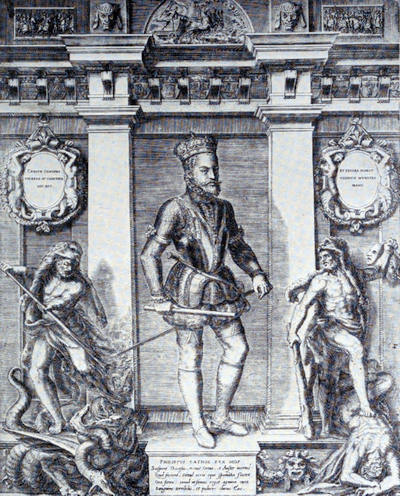

| Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk | 4 |

| From an engraving, after the original in the collection of His Grace the Duke of Bedford. | |

| Henry VIII (at the age of fifty-three) | 20 |

| From the original portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. | |

| Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Mary Tudor Taken Together | 50 |

| From an engraving, by Vertue, of the original portrait by Mabuse. | |

| Lady Monteagle (younger daughter of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk) | 62 |

| From an engraving after Holbein. | |

| Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk | 74 |

| From an engraving by Bartolozzi, of the original drawing, attributed to Holbein, in the King’s collection. | |

| Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, and Her Second Husband, Adrian Stokes | 104 |

| From an engraving by Vertue, after the original portrait by Lucas de Heere. | |

| Mary Tudor, Queen of England | 110 |

| From a little-known portrait by Antonio Moro, in the Escurial. | |

| Philip II, King of Spain[xxii] | 122 |

| From a contemporary Spanish print. | |

| Queen Elizabeth | 134 |

| From the original portrait, by F. Zucchero, at Hatfield. | |

| Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester | 156 |

| From the original portrait, by Zuccaro, in the National Portrait Gallery. | |

| William Cecil, Lord Burleigh | 214 |

| Sir Thomas Gresham | 278 |

| From a contemporary engraving. | |

THE ORIGIN OF THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

The amazing marriage of Katherine of Valois, widow of Henry V, with Owen Tudor, possibly accounts for much that was abnormal in the character of their royal descendants of the redoubted House of Tudor. The queen dowager was the daughter of the mad King Charles VI of France and of his licentious consort, Isabeau of Bavaria—bad blood, indeed; and Owen was a mere soldier of fortune. In his grandson Henry VII’s day, a goodly pedigree was discovered for him, which set forth that far from being a “mean born pup,” as was popularly reported, Owen was descended from Kenan, son of Coel, who was king of Britain, and brother of Helen, the mother of Constantine the Great. As to Owen ap Merideth ap Twydder or Tudor, good old Sandford affirms that “the Meanness of his Estate was recompensated by the Delicacy of his Person, so absolute in all the Lineaments of his Body, that the only Contemplation of it might make a Queen forget all other Circumstances”—which it did! Stowe, who lived near enough to those times to receive direct tradition concerning this brave soldier, says, in his Annals,[4] that[xxiv] he was “as ignorant as any savage.” Tall beyond the average, the founder of the House of Tudor carried himself with “a perfect grace.” He was well featured, with hair that was curly and “yellow as gold.” At an entertainment given in 1423, and attended, notwithstanding her recent bereavement, by the widowed queen, this Adonis, while in the act of executing an intricate pirouette, fell at the royal lady’s feet. Whether the passion kindled by this ludicrous accident was reciprocated, we are not told; but so ardent was it, on Katherine’s part, at least, that she soon afterwards clandestinely married the handsome Welshman.[5]

The enemies of the House of Tudor averred that this secret marriage never really took place, and it is a singular fact that no allusion whatever is made to it in the hearse verse originally placed over the tomb of Queen Katherine in Westminster Abbey, and quoted in full in the contemporary Chronicle of William of Worcester. But when Henry VII became king, this inscription was removed and another hearse verse, containing the following significant lines, was substituted and hung over his grandmother’s monument:—

“Of Owen Tudor after this,

The next son Edmund was,

O Katherine, a renowned Prince,

That did in Glory pass.

Henry the Seventh, a Britain Pearl,

A Gem of England’s Joy,

A peerless Prince was Edmund’s Son,

[xxvi]A good and gracious Roy.

Therefore a happy Wife this was,

A happy Mother pure,

Thrice happy Child, but Grandam she,

More than Thrice happy sure.”

For more than seven years, during which time she gave birth to four children, the queen’s household observed profound secrecy with respect to her marriage—a fact which honours the fidelity and discretion of its members.

Notwithstanding all these precautions, Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, who was regent during the minority of Henry VI, suspected the existence of something unusual, and, according to Sir Edward Coke,[6] forthwith framed a statute that “anyone who should dare to marry a queen dowager of these realms without the consent of king and council should be considered an outlaw and a traitor.” Spies were placed about the queen; but they either failed to discover anything unusual, or were bribed to secrecy: for the fact of the clandestine marriage was not really established until shortly before her death. When it became known, there must have been a terrible storm in the royal circle, for Owen was arrested and sent to Newgate, and the queen banished to Bermondsey Abbey,[7] where she died, six months[xxvii] later, on January 1, 1447, of a lingering illness and a broken heart. Katherine de la Pole, Abbess of Barking, took charge of the children, but she did not reveal their existence to Henry VI till some months after the queen’s decease, and then “only because she needed money for their sustenance.”

Meanwhile the London Chronicle, a most valuable contemporary document, thus relates the subsequent misadventures of the unfortunate Owen: “This year [1447] one Owen Twyder, who had followed Henry V to France, broke out of Newgate at searching time, the which Owen had privately married Queen Katherine and had four children by her, unknown to the common people until she was dead and buried.” Owen Tudor was three times imprisoned for marrying the queen, but each time he contrived to baffle the vigilance of his gaolers, only, however, to be promptly recaptured. As years went by, he came to be received into a certain measure of favour by his stepson, the king; and he fought so valiantly for the Lancastrian cause at Northampton, in 1460, that the king made “his well beloved squire Owen Tudyer” [sic] keeper of his parks in Denbigh, Wales.[8]

Later on, at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross,[xxviii] he again unsheathed his Agincourt sword in the Lancastrian cause, but, being taken prisoner by Edward IV, he was beheaded in Hereford market place. Many years later, by a strange and romantic concatenation of events, Edward’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth, married the fallen Owen’s grandson, Henry VII, thereby becoming the first queen of England of the Tudor line, and the great-grandmother of the Ladies Jane, Katherine and Mary Grey.

There was, it seems, a rugged grandeur about Owen Tudor, which stood him in lieu of gentle accomplishments. The physical power, persistent obstinacy and bluff address of his royal descendants may indeed have been derived from this fine old warrior; and from him surely it was that they inherited the magnificent personal appearance, the lofty stature, the fair complexion and leonine locks, that distinguished them from the dark but equally splendid Plantagenets. May we not also justly conclude that their violent passions were an inheritance transmitted to them by the amorous Katherine and her vicious mother?—passions which played so fateful a part in the tragic stories of Lady Katherine and Lady Mary Grey—the two younger sisters of the unfortunate “Nine-days’ Queen,” Lady Jane Grey.

[To face p. xxviii

MARGARET BEAUFORT, COUNTESS OF RICHMOND

(From National Portrait Gallery)

Soon after Queen Katherine’s decease, Henry VI brought his Tudor brethren into the royal circle. When the eldest, Edmund of Hadham, grew to manhood, he created him Earl of Richmond (November 23, 1452), with precedence of all other earls. This stalwart nobleman married the dwarfish Princess Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Beaufort, great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt by his last wife Catherine Swynford, and daughter and heiress of the last Duke of Somerset of the first creation. He was one of the pillars of the Lancastrian party, lending great help at the temporary restoration of Henry VI; afterwards, under Edward IV, he was compelled, with other Lancastrians, to seek safety in Brittany. He died shortly after his return to England, within a year of his marriage, leaving a son, who succeeded to his father’s title of Earl of Richmond, and eventually became King Henry VII. Edmund’s next brother, Jasper of Hatfield, so called from the place of his birth, was raised at the same time to the rank of Earl of Pembroke. He was with his father at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross; but escaped, and later, at the accession of Henry VII, he was created Duke of Bedford in the place of George Nevill, elder brother of the famous “Kingmaker,” whose titles and lands were confirmed in his favour. He died young in 1456 and was buried in St. David’s Cathedral. He never married, but left an illegitimate daughter, who became the wife of William Gardiner, a citizen of London. Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, was reputed to be their son. Owen, third son of Katherine of Valois and[xxx] Owen Tudor, embraced the religious life and lived a monk, at Westminster, into the first half of the sixteenth century. Their only daughter—who was blessed with the curious name of Tacina, and whose existence is ignored by most historians—married Lord Grey de Wilton, an ancestor of the ill-fated subjects of this book.

It is worthy of note that whereas most of the Tudor Princes were very tall, several of them, thanks to a well-known law of atavism, reverted to the tiny type of their ancestress, Margaret Plantagenet. Mary I was a small woman, and the three sisters Grey were not much above the height of average-sized dwarfs.

CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF SUFFOLK

CHAPTER I

CLOTH OF FRIEZE

It is a remarkable fact that, although Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, was, after Thomas More, Wolsey and the king himself, the most conspicuous personage at the court of Henry VIII, no authoritative biography of him exists, unless indeed it be a short, but very unimportant, monograph (written in Latin, at the end of the sixteenth century) now in the King’s Library at the British Museum. Suffolk outlived nearly all his principal contemporaries, except the king and the Duke of Norfolk, and his career, therefore, runs almost parallel with that of Henry VIII, whom he attended in nearly every event of importance, from boyhood to death. Brandon predeceased the king by only a few months. In person, he bore so striking a resemblance to Henry, that the French, when on bad terms with us, were wont to say that he was his master’s bastard brother. The two men were of the same towering height, but Charles was, perhaps, the more powerful; at any rate, King Henry had[4] good cause, on one occasion, to admit the fact, for Brandon overthrew and slightly injured him in a wrestling match at Hampton Court. Both king and duke were exceedingly fair, and had the same curly, golden hair, the same steel-grey eyes, planted on either side of an aquiline nose, somewhat too small for the breadth of a very large face. In youth and early manhood, owing to the brilliancy of their pink-and-white complexions, they were universally considered extremely handsome, but with the advent of years they became abnormally stout, and vainly tried to conceal their fat, wide cheeks, and double chins, with beards and whiskers. A French chronicler, speaking of Charles Brandon at the time that he was in Paris for the marriage of Mary Tudor to Louis XII, says he had never seen so handsome a man, or one of such manly power who possessed so delicate a complexion—rose et blanc tout comme une fille. And yet he was not the least effeminate, for of all the men of his day, he was the most splendid sportsman, the most skilful in the tilt-yard, and the surest with the arrow. He danced so lightly and so gracefully that to see him was a sight in which even Henry VIII, himself an elegant dancer, delighted.

[To face p. 4

CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF SUFFOLK

(From an engraving, after the original in the collection of His Grace the Duke of Bedford)

Unfortunately, so many physical advantages were not allied to an equal number of virtues; and here again, the resemblance between King Henry and his bosom friend is extraordinary. Both were equally cruel, selfish and unscrupulous, and both entertained the same loose ideas as to the sanctity of marriage—with this difference, however, that whereas King Henry usually divorced one wife before he took another, Charles had two wives living at one and the same time, from neither of whom was he properly divorced! What is most singular, too, is that he ventured to marry the king’s sister whilst his first wife was still living, and not as yet legally separated from him, whereby he might easily have been hauled before a justice as a bigamist, and his offspring by a princess of the blood royal of England, and dowager queen of France to boot, been declared illegitimate.

In addition to his great strength and exceptional ability as a commander, both on land and sea, Suffolk possessed a luxuriant imagination, which delighted in magnificent pageantry. In the halcyon days of Henry’s reign, long before the fires of Smithfield had shed their lurid glow over the city, Suffolk and his master devised sports and pastimes, masques and dances, to please the ladies.[9] Once he entered the tilt-yard dressed as a penitent, in a confraternity robe and[6] cowl of crimson velvet, his horse draped in cardinal-coloured satin. Assuming a humble attitude, he approached the pavilion in which sat the king and Queen Katherine, and in a penitential whine, implored her grace’s leave to break a lance in her honour. This favour being granted, he threw back his cloak, and appeared, a blaze of cloth of gold, of glittering damascened armour and sparkling jewels, to break sixteen lances in honour of the queen. Again, when Queen Mary was his bride, and the court went a-maying at Shooters Hill, he devised a sort of pastoral play, and with Jane Grey’s paternal grandfather, Thomas, Marquis of Dorset, disguised himself and his merry men as palmers, in gowns of grey satin with scallop-shells of pure gold and staves of silver. The royal guests having been duly greeted, the palmers doffed their sober raiment and appeared, garbed in green and gold, as so many Robin Hoods. They then conducted their Majesties to a glade where there were “pastimes and daunces,” and, doubtless, abundant wine and cakes. Much later yet, Brandon went, in the guise of a palmer, with Henry VIII, to that memorable ball given by Wolsey at Whitehall, at which Anne Boleyn won the heart of the most fickle of our kings.

The last half of the fourteenth century witnessed the beginning of the decline of feudalism[7] in England. The advance of education, and consequently of civilization, had by this time largely developed the commercial and agricultural resources of the country, and the yeoman class, with that of the country gentry, had gradually come into being. At the Conquest, the majority of the lands owned by the Saxons—rebels to Norman force—were confiscated and handed over to the Conqueror’s greater generals: to such men as William, Earl of Warren, or Quarenne, who seated himself in East Anglia, having, as his principal Norfolk fortress, Castleacre Castle, on the coast, not far from East Dereham. Its picturesque ruins still tower above those of the magnificent priory that the great William de Warren raised, “to the honour of God and Our Lady,” for monks of the Cluniac branch of the Benedictine Order. This Earl of Warren, who was overlord of a prodigious number of manors and fiefs in East Anglia, numbered, among the bonny men who came out of Picardy and Normandy in his train, two stalwart troopers: one haled from Boulogne-on-the-Sea, so tradition says—and is not tradition unwritten history?—and was known as “Thomas of Boulogne”; he settled at Sale, near Aylsham, in Norfolk, and was the progenitor of the Boleyns or Bullens, whose surname is an evident corruption of de Boulogne; the other[8] dropped his French patronym, whatever it was, and assumed the name of Brandon, after a little West Suffolk border town, in the immediate vicinity of the broad and fertile lands he had acquired.

These Brandons, then, had lived on their farm near Brandon for about four centuries, deriving, no doubt, a very considerable income from the produce of their fields and from their cattle. It is certain that they sent several members of their family to the Crusades; that one of them followed the Black Prince to Poitiers, and that yet another, a trooper, it is true, died on the field of Agincourt.[10] Somewhere in the last quarter of the fourteenth century, William, the then head of the family, apprenticed his son Geoffrey to a rich mercer of Norwich, a great commercial centre in those days, next to London and Bristol in importance, and doing what we should now call a “roaring trade” with Flanders, and through Flanders, with Venice and Florence, and even with the East. This Norwich Brandon having made a fortune, was seized with an ambition to attain still greater wealth and station for his son and[9] heir William; and hence it came about, that near the time King Henry VI ascended the throne, young Brandon arrived in London, apprenticed to a firm of mercers established near Great St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate Street. He was a pushing, shrewd, energetic, and very unscrupulous knave, who soon acquired great influence in the city and amassed corresponding wealth. Finally, he became sheriff, and was knighted by Henry VI. He purchased a large property in Southwark, and built himself a mansion, later known as Suffolk Court. During the Wars of the Roses he allied himself at first with the Yorkists, and lent Edward IV considerable sums of money, which, according to Paston, that monarch dishonestly refused to repay. This drove William to cast his fortunes with the Lancastrians and largely assist Henry VII, then simply Earl of Richmond, both with money and men, and so was held in high esteem by that monarch till his death, in the twelfth year of Henry’s reign. William Brandon married Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Robert Wingfield of Letheringham, whose mother was the daughter and co-heir of Sir Robert Goushall, the third husband of the dowager Duchess of Norfolk, widow of the first duke, who, dying in exile in Venice, was buried in the magnificent church of San Giovanni e Paolo. Even thus early, we see a[10] Brandon, the great-grandson of a Suffolk farmer, connecting himself with the noble houses of Wingfield, Fitzalan and Howard.[11]

At one time this gentleman was on very intimate terms with the renowned Sir John Paston, whose Letters throw so much light on the manners and customs of the age in which he lived; but the cronies fell out over some matter of business connected with Paston’s claim to the possession of Caistairs Castle, in which transaction, Paston declares, Brandon behaved like a blackguard—indeed, King Edward, to whom appeal was made, listed him as a “lyre.” During their intimacy, Paston, possibly over a tankard of ale at a merry dinner or supper party, had made some irreverent and coarse remarks about her grace of Norfolk, in the presence of Lady Brandon, who was the duchess’s grand-daughter. He had poked fun at the poor lady’s appearance when on the eve of adding her tribute to the population. Paston has recorded what he said, and it must be[11] confessed, that if Lady Brandon did repeat his vulgar jest to her august relation, that lady had every reason to feel indignant at such familiarity.

Whether it was repeated or not has never transpired, so perhaps we may suppose Lady Brandon was a prudent woman and kept her counsel. But Paston wrote to his brother to ask if he thought she might be trusted, or whether she was likely to have made mischief by repeating his ill-timed remarks to the duchess, her mother, adding a “lye or two of her own to help it out.”

Sir William Brandon, eldest son of the first William, and father of Charles Brandon, was never knighted, although usually styled by courtesy “Sir.” He married, when he was very young, Elizabeth, daughter and co-heir of Sir Henry Bruyn, or Brown,[12] by his wife, Elizabeth Darcy.[13] Sir William Brandon was standard-bearer to Henry VII at Bosworth Field, and there lost his life at the hand of Richard III, whilst gallantly defending his royal patron. Henry proved his gratitude by educating his only son, Charles, who, by his marriage with Mary Tudor, became the grandfather of Lady Jane Grey and her sisters[12] Katherine and Mary. Some historians have confused King Henry’s standard-bearer with a younger brother, Thomas Brandon, who married Anne Fiennes, daughter of Lord Dacre and widow of the Marquis of Berkeley, but had no children. He looms large (in every sense of the word, being of great height and bulk) in all the tournaments and jousts held in honour of the marriage of Katherine of Aragon with Prince Henry. He died, a very wealthy man, at his London house, Southwark Place, in 1502.

At four years of age the child Charles Brandon became playfellow to Arthur, Prince of Wales; but on the birth of the future Henry VIII, he was transferred to the younger prince as his companion. He may even have received his education with Henry, from Bernard André, historian and poet, or perhaps from Skelton, poet-laureate to Henry VII, who, with Dr. Ewes, had a considerable share in the instruction of the young prince. But there is reason to believe that Brandon, as a lad, did not spend so much time at court as has been generally stated, for his letters, phonetically spelt, in accordance with the fashion of his time, prove him to have spoken with a broad Suffolk accent; he must, therefore, have passed a good deal of his youth at Brandon, on the borders of Suffolk and Norfolk, where,[13] according to tradition, he was born. His letters, although the worst written and spelt of his day, are full, too, of East Anglianisms, which could only have been picked up by a man in his position through contact, in boyhood, with yokels and country-folk in general.

Charles, who grew up to be a remarkably fine youth, tall and “wondrous powerful,” began life virtually as an attendant in the royal household, though, as already stated, in due time he became Henry’s principal favourite and confidant. When little over twenty, he distinguished himself in a sea-fight off Brest, and was sent by Wolsey to join Henry VIII in his adventurous campaign to Therouanne. At the famous battle of the Spurs, he proved himself as brave a soldier as he had already shown himself to be a doughty sailor; but for all this merit he can scarcely be described as an honest gentleman, especially where ladies are concerned, and his matrimonial adventures were not only strange and complicated, but also exceedingly characteristic of the times in which he lived. In 1505/6, Charles Brandon became betrothed,[14] per verba de præsenti, to a young lady of good family, Anne Browne, third daughter of Sir Anthony Binyon Browne, K.G., governor of Calais, and of his wife, the Lady[14] Lucy Nevill, daughter and co-heiress of John Nevill, Marquis of Montagu, brother of the “Kingmaker,” Richard, Earl of Warwick. In 1506/7 this contract was set aside and the young gentleman married Margaret, the mature widow of Sir John Mortimer of Essex[15] (will proved, 1505).[15] And now came trouble. The Lady Mortimer, née Nevill (probably rather a tedious companion for so youthful a husband), was none other than the aunt of his first fiancée, Anne Browne, her sister being the Lady Lucy Nevill, who, as stated above, was the wife of Sir Anthony Browne and[16] mother of Anne. Brandon, therefore, probably with the aid of Henry VIII, about 1507, after having squandered a good deal of her fortune, induced the Archdeacon of London (in compliance with a papal bull) to declare his marriage with Lady Mortimer null and void, on the grounds that: Firstly, he and his wife were within the second and third degrees of affinity; secondly, that his wife and the lady to whom he was first betrothed (Anne Browne) were within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity—i.e. aunt and niece; thirdly, that he was cousin once removed to his wife’s former husband. After these proceedings, he married, or rather re-married, in 1508/11, in “full court,” and in the presence of a great gathering of relations and friends—and not secretly, as usually stated—the aforesaid Anne Browne, by whom he had two daughters, the eldest being born so soon after wedlock as to give rise to unpleasant gossip, probably started by Lady Mortimer. Anne, Lady Brandon, did not long survive her marriage, for she died in 1511/12; and in the following year (1513) her widower made a third attempt at matrimony, by a contract with his ward, the Lady Elizabeth Grey, suo jure Baroness Lisle, who, born in 1503/4, was only ten years of age; but the negotiations failed, though Brandon had been granted[17] the viscounty of Lisle, which title he assumed (May 15, 1513). As this lady absolutely refused him, he surrendered the patent of the title of Lisle in favour of Arthur Plantagenet, illegitimate son of Edward IV and husband of Lady Elizabeth Lisle, the aunt and co-heiress of the young lady he had wished to make his bride, and who, being free, gave her hand to Courtenay, Earl of Devon, who presently became Marquis of Exeter. This above-mentioned aunt, the other Lady Elizabeth, had married, in 1495, Edmund Dudley, the notorious minister of Henry VII, and became, about 1502, mother of that John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, who proved so fatal to Lady Jane Grey and her family.

Whilst he was still plodding through the labyrinth of his matrimonial difficulties, early in 1513, Charles Brandon was entrusted with a diplomatic mission to Flanders, to negotiate a marriage between Mary Tudor, the king’s youngest sister, and the young Archduke Charles of Austria, Infante of Spain, the most powerful and richest prince in Europe. On this occasion he displayed his majestic and graceful figure to such advantage in the tilt-yard, that the demonstrative expressions of admiration which escaped the proposed bridegroom’s aunt, Drayton’s “blooming duchess,” the most high and mighty Princess Margaret,[18] Archduchess of Austria, dowager Duchess of Savoy, and daughter of the Emperor Maximilian, evoked sarcastic comment from the illustrious company.

On Brandon’s return, Henry VIII, probably with a view to facilitating a possible alliance between his favourite and the dowager of Savoy, to universal surprise and some indignation, created his “well-beloved Charles Brandon,” Duke of Suffolk, a title until quite recently held by the semi-regal, but dispossessed house of de la Pole,[16] and further presented him with the vast territorial apanage of that family, which included Westhorpe Hall, near Bury St. Edmunds; Donnington Castle, the inheritance of Chaucer’s granddaughter, the first Duchess of Suffolk; Wingfield Castle, in Suffolk; Rising Castle in Norfolk; and Lethering Butley in Herefordshire.[17]

In the summer of 1513, while the king was sojourning at Tournay, he received a visit from the Archduke Charles of Castile and Austria, and his aunt, the Dowager Duchess of Savoy, Regent of the Netherlands. These august personages came to congratulate the English monarch on the capture of Tournay from their mutual enemy, Louis XI of France. At this time the Austro-Spanish archduke still hoped to secure the hand of the King of England’s handsome sister, Mary[20] Tudor, who had accompanied her brother to France. Henry did his best to ingratiate himself with the regent, a handsome lady with a foolish whimpering expression, who, if we may judge her by her portrait in the Museum at Brussels, was most apt to credit anything and everything that flattered her fancy. The king and his favourites, indeed, to amuse her, behaved less like gentlemen than mountebanks. Henry danced grotesquely before her and played on the giltrone, the lute and the cornet for her diversion, and his boon companions followed their master’s example and exhibited their accomplishments as dancers and musicians. The contemporary Chronicle of Calais contains a most amusing account of the way Henry and Charles made game of the poor dowager, who betrayed her too evident partiality for the latter. Brandon actually went so far on one occasion as to steal a ring from her finger; “and I took him to laugh,” says Margaret of Savoy, describing this incident,[18] “and said to him that he was un larron—a thief—and that I thought the king had with him led thieves out of his country. This word larron he could not understand.” So Henry had to be called in to explain it to him. His Majesty next contrived a sort of love-scene between the pair, in which he made Duchess Margaret a very laughing-stock, by inducing her to repeat after him in her broken English the most appalling improprieties, the princess being utterly ignorant of the meaning of the words she was parroting. To lead her on, Suffolk, who was not a good French scholar, made answer, at the king’s prompting, to the princess’s extraordinary declarations, in fairly respectable French. At last, however, the good lady realized the situation, and, rising in dudgeon, declared Brandon to be “no gentleman and no match for her,”[19] and thus he lost his chance, though he never lost, as we shall presently see, the great lady’s friendship.

[To face p. 20

HENRY VIII AT THE AGE OF 53

(From National Portrait Gallery)

This silly prank on the English king’s part was, no doubt, the final cause of the rupture of the proposed alliance between Mary Tudor and the Archduke Charles of Castile. Be this as it may, it was at Tournay that Mary was reported to have first fallen a victim to the blandishments of Suffolk, who, while fooling the regent, was covertly courting his dread patron’s sister. He flattered himself that the king, loving him so tenderly as a friend, would readily accept him as a brother-in-law. In this he was mistaken. Henry had other views for Princess Mary’s future;[22] and no sooner was the Austro-Spanish match broken off,[20] thanks to certain political intrigues too lengthy and intricate to recapitulate here, than he set to work to arrange a marriage between Mary and King Louis XII,[21] who, although generally described as “old,” was at this time not more than fifty-three years of age. His appearance, however, was most forbidding; he suffered from the deformity of elephantiasis, and was scarred by some scorbutic disease, “as if with small-pox.”[22]

CHAPTER II

THE FRENCH MARRIAGE

The negotiations for this incongruous marriage, which united, for the first time since the Norman Conquest, a British princess to a French king, proceeded very slowly, for Henry knew well that his sister would reluctantly sacrifice her youth to so ugly and sickly a bridegroom: thus, according to the late Major Martin Hume, the first intimation of the proposal Mary received was not until after a tournament held at Westminster on May 14, 1514.

This tournament, in the open space between the ancient Palace and the Abbey, was magnificent in the extreme. Never before had there been seen in England so many silken banners, canopies, and tents of cloth of silver and gold. Queen Katherine of Aragon watched the tilting from a pavilion of crimson damask, embroidered with golden pomegranates, the emblems of her native country. Beside her sat Princess Mary, a pink-and-white beauty, with hair of amazing length shimmering down her back, and held in position[24] by a band of jewels that encircled her graceful head. Behind the princess many great ladies occupied the roomy chairs of state—the Countess of Westmorland and her lovely Nevill daughters, the Lady Paulet, the Lady of Exeter, the Lady de Mowbray, the Duchess of Norfolk, the Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, sister of the Duke of Norfolk and mother of the future Queen Anne, the “old Lady” of Oxford, and the Princess Margaret Plantagenet, that fated Countess of Salisbury who in after years was hacked to death by order of her most affectionate nephew, King Henry VIII, now in the full bloom of early manhood. There was a great nodding of glittering hoods and rustling of silken gowns, and whispering and tittering amongst this bevy of high and mighty dames, unto whom many a gallant knight and lordly sire conveyed his homage and the latest gossip of the day. Over the multi-coloured crowd fell the golden haze of a lovely October afternoon. Farther away from the throng of lords and ladies, the hearty citizens of London pressed against the barriers, whilst rich burghers, and British and foreign merchants, with their wives and daughters, filled the special seats allotted to them, that commanded a finer view of the towers of Westminster than did the richer canopies of the court folk. Itinerant vendors of sweetmeats, apples, nuts[25] and cakes, hawked their wares up and down the free spaces, whilst ballad-mongers sang—or rather shouted—their ditties, just as their descendants do, whenever there is a show of sport or pastime in our own day. Men and maidens cheered lustily as knight after knight, armed cap-à-pie, pranced his steed before the delighted spectators, even as we parade our horses before the race at Epsom, Sandown or Ascot.

The expressed hope was, of course, that the English knights should vanquish the French noble prisoners who had been set at liberty shortly before the tilt, so that they might join in the sport. The champions among them were the Duc de Longueville and the Sire de Clermont. The trumpets sounded, a hush fell upon the noisy gathering, all eyes were turned in one direction, as two stalwart champions entered the lists. They were garbed as hermits, the one in a black satin cloak with a hood, the other in a white one. With all the punctilious observance demanded by established rule and etiquette, these hermits, who rode mighty chargers caparisoned in silver mail, advanced towards the royal pavilion and made obeisance. On a sudden, off fell their cloaks and hoods, to reveal the two handsomest men in Europe, to boot, Henry, King of England, and Charles, Duke of Suffolk, clad from head to[26] foot in silver armour, damascened in gold by Venetian armourers. Long white plumes flowed from the crests of their gilded helmets. Behind the British champions rode two other fine fellows, bearing standards on which figured in golden letters the motto: “Who can hold that will away?” On reading this motto, the fair bent, the one to the other, to discuss its meaning. Did it refer to the young King of Castile and Flanders; or to the fact that Charles Brandon, as it was whispered about, was venturing to raise his eyes so high as to meet those of the Emperor Maximilian’s daughter, Margaret of Austria? It was said, too, that the Lady Mary, the king’s sister, liked not the motto; for even then she had conceived a wild though secret passion for the splendid son of a Suffolk squire.

The English (God and St. George be praised!) won the day; the Duc de Longueville was defeated “right honourably,” and so, too, was the Sire de Clermont. The silken kerchief, the gilded cup and the wreath of laurel were for Charles Brandon; and the princess, the Beauty Queen of the day, presented them to him as he knelt before her. Katherine of Aragon bestowed the second prize, a cup of gold, on her husband, who had vanquished Clermont.

Immediately after the jousts, Mary Tudor[27] learnt, to her exasperation, that her hand was destined, not for the Spanish prince, the future Emperor Charles V, nor for the Suffolk gentleman, but for the decrepit and doomed King of France. She was too much of a Tudor to accept her fate with meekness, and King Henry soon found he had set himself a difficult task to conciliate his sister, and obtain her consent to what was even then considered a monstrous match. She swore she would not marry his French majesty, unless her brother gave her his solemn promise that she should marry whom she listed when she became a widow. The king answered that, by God! she might do as she listed, if only she pleased him this time. He urged that King Louis was prematurely aged, and not likely, so he had been told, to live many months. Besides, he was passing rich, and the princess would have more diamonds, pearls and rubies than she had hairs on her head. Henry even appealed to her patriotism. England needed peace; the prolonged wars between France and England had exhausted both, and it was deemed advisable that the French should be made to understand, by this happy event, that the enmity which had existed so long had ceased at last. It was to be a thorough entente cordiale on both sides. None the less, when they got to know of it, both the[28] English and the French cracked many an indelicate jest over this unnatural alliance. The bride, it will be remembered, was still in her teens, and beautiful: the bridegroom-elect was fifty-three and looked twenty years older, the most disfiguring of his complication of loathsome diseases being, as we have seen, elephantiasis, which had swollen his face and head so enormously that when, on her arrival in France, Mary first beheld her future consort, she drew back, with an unconcealed cry of horror. For some days Mary seemed obdurate, despite Henry’s promise that, on the death of the French king, she might marry whom she listed. But at last she allowed her brother’s persuasive arguments to prevail, so that, dazzled by the prospect of becoming the richest and grandest princess in Europe, she finally, but reluctantly, consented to marry King Louis.

The “treaty of marriage” between Louis XII and Mary Tudor was signed at London by the representatives of both parties on August 7 (1514); and the marriage by proxy, according to the custom of the time, took place in the Grey Friars’ Church at Greenwich, before Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, the Bishops of Winchester and Durham, and others, on August 13. The recently liberated Duc de[29] Longueville represented the French king, whereas the Duke of Orleans gave the bride the ring; afterwards the primate pronounced a brief panegyric of the young queen’s virtues, and those of her august spouse, whom he described as the best and greatest prince in Europe.

The bride left England’s shores on October 2, after a tearful leave-taking of her brother and sister-in-law, King Henry and Queen Katherine. The chronicles of those far-off times, ever delighting in giving the minutest details, inform us that she was “terrible sea-sick” before she arrived at Boulogne, where a pious pageant had been prepared to greet her. Above the drawbridge of the port, suspended in mid-air, was a ship, painted with garlands of the roses of England mingled with the fleur-de-lys of France, and bearing the inscription, Un Dieu, Un Roy, Une Foy, Une Loy: “One God, One King, One Faith, One Law.” In this ship stood a young girl—“dressed like the Virgin Mary,” as the chronicler tells us—together with two winged children, supposed to be angels. The young lady represented Notre Dame de Boulogne, the patroness of the city, and bore the civic gift, destined for the princess, consisting of a silver swan, whose neck opened, to disclose a golden heart weighing sixty écus. So violently raged the storm, that the heavy vessel, instead[30] of riding gracefully into the harbour, stuck on a sandbank, and the future Queen of France, dripping with sea-water, had to be carried ashore by Sir Christopher Gervase. On reaching land, she was met by the Heir Presumptive of her new dominions, François, Duc de Valois, the Dukes of Alençon and Bourbon, and the Counts de Vendôme, de Saint-Pol, and de Guise, supported by the Abbots of Notre Dame and of St. Wulmer, accompanied by their monks wearing copes, and bearing, enclosed in gold and silver shrines, all the relics from their respective churches. In the presence of this goodly company, the ship containing the aforesaid representative of Our Lady of Boulogne was lowered to the ground, and the young lady addressed the princess “en rhétoricque,” otherwise French verse, welcoming her to Boulogne, and presenting her with the city’s gift. Mary then proceeded to the Church of Notre Dame, and after praying there awhile, she was, so says our chronicler, “agreeably occupied in admiring all the rich and royal offerings that formed the principal attraction of the Church.” And gorgeous and wonderful indeed must it have been, before the vandal greed of King Henry’s troops had sacked the shrine. The Treasury contained nearly a hundred gold and silver reliquaries, eighteen great silver images,[31] most of them containing relics, “eleven hearts and a great number of arms and legs, both in gold and silver” (votive offerings), twenty dresses and twelve mantles of very precious stuffs, “for the use of the holy Image.” The altar of the Blessed Virgin was especially magnificent. Seven lamps, four in silver and the rest of gold, burnt incessantly before the Madonna, who held in one hand a golden heart, whilst the other supported a figure of the Infant Jesus, who clasped in His chubby hand a bouquet of “golden flowers,” amongst which was “a carbuncle of a prodigious bigness”; the pillars and columns round this altar were sheathed in “blades of silver”: “in short,” says the chronicler, “everything which was in this chapel could challenge comparison with the richest and most renowned objects that antiquity ever had.” Such was the splendour that enchanted and bewildered our Princess Mary, who after offering to Our Lady of Boulogne a gift consisting of “a great arm of silver, enamelled with the arms of France and England, and weighing eight marcs,” proceeded on her way to Abbeville, near which city she was met, in the forest of Ardres, by King Louis, mounted on a charger and attended by a glittering train of lords and attendants.

To the young and beautiful Mary, who had[32] only just recovered from a violent sea-sickness, this first meeting with her future lord and master must indeed have been painful. As she afterwards admitted, she had never before seen a human being so horribly ugly. It is not therefore to be wondered at that she should have uttered the exclamation of horror above mentioned. King Louis, for his part, was in the best of humours; never merrier. He was very plainly dressed, and was evidently bent on correcting, by his munificence and good temper, whatever unfavourable impression might be created by his unfortunate appearance. Before arriving at the place of meeting, Princess Mary had changed her travelling gown for a weighty robe covered with goldsmith’s work “like unto a suit of armour.” So awkward and stiff was this costume, that when the princess, in accordance with etiquette, attempted to descend from her litter to bend the knee before her royal spouse, she found she was unable to do so, and was in great distress until the deformed king gallantly begged her not to attempt so complicated a manœuvre, and won a grateful smile from his embarrassed bride.

The marriage took place on Monday, October 9 (1514), at Abbeville, in the fine old Church of St. Wolfran, and is one of the most gorgeous functions recorded of those pageant-loving times.[33] Something mysterious must have happened at Abbeville, for, according to the Bishop of Asti, the marriage was consummated by proxy—a weird ceremony in which the Marquis de Rothelin (representing King Louis), fully dressed in a red suit, except for one stocking, hopped into the bride’s bed and touched her with his naked leg; and the “marriage was then declared consummated.” Possibly, considering the rickety state of his health, this was all the married life, in its more intimate form, that, fortunately, Mary Tudor ever knew so long as Louis XII lived. As an earnest of his affection, however, the sickly king presented his spouse with a collection of jewels a few days after the marriage, amongst these being “a ruby almost two inches long and valued at ten thousand marks.”

In the meantime, there had been some unpleasantness between the French monarch and the Earl of Worcester, the English ambassador, about the presence in France of one of the queen’s maids, Mistress Joan Popincourt. The question of her fitness to accompany the princess was first raised before Mary left our shores, to reach its culminating point whilst the new queen was resting at Boulogne, at which time King Louis (then at Abbeville) had an interview with Worcester on the subject. The trouble is said[34] to have originated in the fact that Mistress Popincourt had behaved herself with considerable impropriety,—at least that was the accusation the English envoy laid before his majesty of France; but if we read between the lines of the letters and documents connected with this side-plot, we learn that it was Mistress Popincourt who had first attempted to negotiate the marriage of her mistress with King Louis by means of the Duc de Longueville, whilst that nobleman was still imprisoned in the Tower of London. As the negotiations had succeeded, even through another medium, she considered herself entitled to some recompense for her share in the affair, and probably attempted to blackmail the king; at any rate, for one reason or another, he was so furious with her, that on the occasion in question, he told Worcester never to “name her any more unto me.” “I would she were burnt,” he added; “if King Henry make her to be burnt, he shall do but well and a good deed!” Mary, however, held the recalcitrant Popincourt in the highest esteem. None the less, King Louis decided that she should be there and then sent back to England, but whether with a goodly recompense to soothe her disappointment is not recorded. Maybe she, who had done so much to further the royal match, found herself better off than[35] the other unfortunate attendants on Princess Mary, who, being dismissed after her arrival at Abbeville, were stranded, penniless. Some of these misguided ladies had, says Hall, “been at much expense to wait on her [Princess Mary] to France, and now returned destitute, which many took to heart, insomuch some died by the way returning, and some fell mad.”[23]

Evidently King Louis was determined not to have too many Englishwomen in attendance upon his wife, or, as he put it, “to spy upon his actions,” for fresh difficulties arose, even after the Popincourt incident was closed, and he and the princess had been united in matrimony. According to arrangement, certain of the queen’s ladies were to return to England forthwith, but King Louis and his English monitor, the Duke of Norfolk, settled the matter by ordering that all Mary’s[36] train of young English gentlewomen and maidens, with the exception of the Lady Anne Boleyn[24] and of three others, were to return home. This was bad enough, but Mary was still more distressed to find that her confidential attendant and nurse, Mother Guildford, was very unceremoniously packed off with the rest. “Moder” or “Mowder” Guildford, as the queen was pleased to call her, was the wife of Sir William Guildford, controller of the royal household, who eventually stood godfather to that unfortunate Guildford Dudley who became the husband of Lady Jane Grey. If we may believe King Louis, he had certainly some justification for wishing Lady Guildford out of his sight, since she exasperated him to such an extent that he told Worcester that “rather than have such a woman about my wife, I would liever be without a wife.... Also, “he continued, “I am a sickly body, and not at all times that I would be merry with my wife like I to have any strange woman with her, but one that I am well acquainted with, afore whom I durst be[37] merry.” The king went on to pathetically relate the story of his own and his wife’s sufferings under Lady Guildford’s iron rule. “For as soon as she came on land,” says he, “and also when I was married, Lady Guildford began to take upon her not only to rule the queen, but also that she should not come to me, but she should remain with her, nor that no lady or lord should speak with the queen but she [Lady Guildford] hear it. Withal she began to set a murmur and banding among the ladies of the French court.” The “Moder” Guildford episode induced Mary to write several letters home, one to Henry VIII and another to Wolsey, complaining of the treatment she had received with respect to the dismissal of her attendants. In these she speaks in no measured terms of the Duke of Norfolk, who, as we have seen, had the matter in hand: “I would to God,” she exclaims in the letter to Henry VIII, “that my Lord of York [Wolsey] had come with me instead of Norfolk, for then I am sure I should not have been left as I am now!” In fact, she cast the whole blame of the incident on the shoulders of the Duke of Norfolk, whom she ever afterwards disliked for his share in it. Nevertheless, “Mowder” Guildford was sent back to England, to the great distress and grief of her royal mistress, who was preparing to have a[38] violent scene on the subject with her rickety husband, when the latter came into her chamber, accompanied by two attendants bearing a tray so heaped with rubies, diamonds and pearls, that the cloud of anger instantly passed from the queen’s brow, and her sunny smiles beamed afresh, when she heard the politic and courteous monarch say, “I have deprived you of one treasure, let me now present you with another.” And then he placed a collar of immense pearls round her neck, and taking a heap of jewels in his big hands, dropped them into her lap. “I will have no Guildfords, Popincourts, or other jades to mar my cheer or to stand betwixt me and my wife,” he continued laughingly; “but I intend to be paid for my jewels, and each kiss my wife gives me shall cost me a gem.” On this the covetous Mary kissed him several times, to the number of eight, which he counted, and punctually repaid by giving her eight enamelled buttons surrounded by large pearls. By this amorous playfulness, the astute Louis succeeded in making his queen so contented with her lot, that she presently told Worcester that “finding she was now able to do as she liked in all things,” she thought she was better without Lady Guildford, and would decline to have her back again in France. Mary not only forgave King Louis his share in the[39] business, but personally nursed him through an attack of gout, which beset him at Abbeville, and delayed the royal departure from that town until October 31, when the quaint cavalcade resumed its journey towards St. Denis.

It was one continuous pageant in every village and town through which the royal cortège passed, between Abbeville and St. Denis. Even in villages and hamlets, children dressed as angels, with golden wings, met the fair queen, to present to her pretty gifts of fruit and flowers. It took the king and queen and their escort six days to reach St. Denis, spending the nights either in episcopal palaces or in the splendid abbeys which lined the way. Although the French greeted the queen heartily, it was noticed that they “became overcast and sour” as they looked on the magnificent but defiant figure of the Duke of Suffolk, as he rode, in his silver armour, on the right side of the queen’s litter, whilst on the left cantered that stalwart nobleman, Thomas Grey, first Marquis of Dorset, who was destined by a curious and unexpected event to become the grandfather of Her Majesty’s ill-fated grandchildren, the Ladies Jane, Katherine and Mary Grey. At last, early in the morning of Sunday, November 5, the English princess passed up the splendid nave of St. Denis, escorted by all that[40] was highest and mightiest in French chivalry. The Duc de Longueville, the Duc d’Alençon, the Duke of Albany, Regent of Scotland, the Duke of Bourbon, and the Count de Vendôme, preceded her, bearing between them the regalia. Mary followed, escorted by the Duke of Valois, and clothed in a mantle of cloth of gold. She wore such a prodigious quantity of jewels that a number of them had to be removed in the sacristy before she was able to proceed with the innumerable ceremonies of the day. The new queen was anointed by the Cardinal de Pré, who also presented her with the sceptre and “verge of justice.” When, after more ceremony than prayer, the cardinal had placed the crown of France upon her brow, Prince Francis of Valois led Her Majesty to a throne raised high above the choir, whence in solitary state she glanced down upon the throng of prelates, priests and noblemen and noblewomen who crowded the chancel and the altar-steps, and overflowed into the nave and transepts. There she sat alone, for weak and sickly King Louis could do no more than witness the coronation, contenting himself by obtaining a view of it from a small closet window above the high altar.

The following day, at noon, Queen Mary passed on to Paris, whither King Louis had preceded[41] her earlier in the morning. On this occasion she did not occupy a litter, but rode by herself in a species of carriage designated “a chaise or chair,” embellished with cloth of gold, and drawn by two milk-white horses with silver reins and harness. Her Majesty, all in white and gold, did not wear the crown of France, but merely a diadem of pearls, from beneath which streamed her luxuriant tresses. Pressing round the queen’s chariot, rode the pick of the nobility of France, followed by the Scotch Guard and a detachment of German mercenaries. Pageants and allegories greeted the royal progress at every turn. When close to Paris, the queen’s train was met by three thousand Parisian students, law officers and representatives of the city council, who chanted in chorus a quaint song, still extant, in which Mary is likened to the Queen of Sheba and Louis XII to King Solomon. Over the portcullis of the Porte St. Denis was erected a ship, containing “mountebanks” representing Henry VIII in the character of Honour, and Princess Mary as Ceres, whilst an actor, wearing King Louis’s own gorgeous robes, offered “Ceres” a bunch of grapes, and was popularly held to personate Bacchus!

In the midst of what we should now consider a circus-like cavalcade, the queen, escorted by[42] a thousand horsemen bearing flaring torches, passed round the quays of Paris, brilliantly illuminated for the occasion, to her resting-place at the Conciergerie, where, we are informed, she was so dead tired that, after the official reception by King Louis and subsequent banquet, she fell asleep and had to be carried to her nuptial chamber. Here, so it is stated, King Louis did not receive her, since he was fast asleep already in his own bedchamber at the Louvre, whither he had retired many hours earlier. He was awake pretty early the next day, for at nine o’clock he breakfasted with the queen, having previously presented her with a bouquet of gems, the flowers being made of coloured stones and the leaves of emeralds. The king never left his bride the whole of that day, and it was observed that whenever he gazed upon her, he would put his hand to his heart and heave a deep sigh. Nothing can be imagined more ludicrous, and at the same time more pathetic, than the ardour of this poor, hopelessly love-sick monarch for his beautiful wife, who, thorough Tudor as she was, never missed an opportunity of fleecing him of jewels and trinkets, to such an extent as at last to excite the indignation of the court.

The coronation festivities closed with jousts in which “my lorde à Sofehoke,” as the Marquis[43] of Dorset calls him in a letter,[25] got “a little hurt in the hand.” In this same epistle the marquis adds that King Louis considered that Suffolk and his English company “dyd shame aule (all) Franse.” They did such execution indeed that, as the chroniclers complacently remark, “at every course many dead were carried off without notice taken.” The exasperation of the French against Suffolk grew so great—or was it due, as tradition suggests, to Francis of Valois’s personal jealousy of the British duke?—that they commissioned, contrary to all etiquette of tourney, an abnormally powerful German trooper to kill him by treachery in the lists. Suffolk, however, saw through the mean trick, and refusing to treat such a ruffian according to chivalric rules, gripped him by the scruff of the neck, and punched his head with much heartiness, to the ill-concealed satisfaction of the spectators.

It does not require much imagination to divine what were the thoughts of the lusty young queen, as she watched the prowess of her triumphant lover in the tilt-yard, and mentally contrasted his manly beauty with the wreck that was her husband, who lay on a couch at her side, “grunting and groaning.” He, poor man, was ever graciously courteous, and expressed his delight[44] whenever, in her enthusiasm, the lovely queen, regardless of etiquette, rose to her feet and leant over to applaud the British champions as they rode by her canopy of state. “Ma mie,” cried old Louis, “your eyes brighten like stars when the English succeed. I shall be jealous.” “Fie!” returned the queen with an arch smile, “surely there is no chance for the French today, since, fortunately for my countrymen, your majesty is too unwell to join in the fray?”