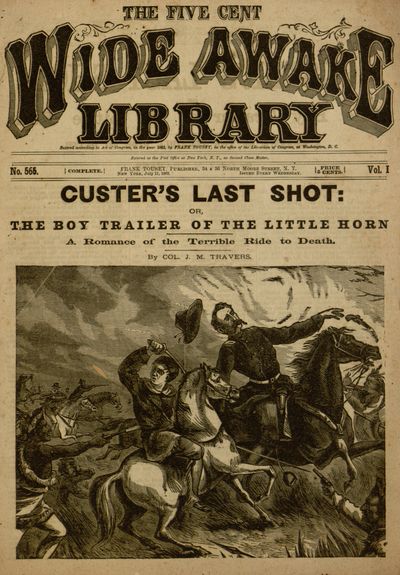

Title: Custer's Last Shot; or, The Boy Trailer of the Little Horn

Author: Col. J. M. Travers

Release date: June 26, 2015 [eBook #49286]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, by FRANK TOUSEY, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

Entered at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., as Second Class Matter.

|

No. 565. | { | COMPLETE. | } |

FRANK TOUSEY, Publisher, 34 & 36 North Moore Street, N. Y. New York, July 11, 1883. Issued Every Wednesday. | { | PRICE 5 CENTS. | } | Vol. I |

OR,

THE BOY TRAILER OF THE LITTLE HORN

A Romance of the Terrible Ride to Death.

By COL. J. M. TRAVERS.

The subscription price for The Wide Awake Library for the year 1882 will be $2.50 per year; $1.25 per 6 months, post paid. Address FRANK TOUSEY, Publisher, 34 and 36 North Moore Street, New York. Box 2730.

CUSTER'S LAST SHOT;

OR,

The Boy Trailer of the Little Horn.

A ROMANCE OF THE TERRIBLE RIDE TO DEATH.

By Col. J. M. TRAVERS.

CHAPTER I. THE YELLOW-HAIRED CAVALRY CHIEF ON THE WAR TRAIL.

CHAPTER II. SITTING BULL'S GANG OF RED MARAUDERS.

CHAPTER III. THE RECKLESS GALLOP IN THE JAWS OF DEATH.

CHAPTER IV. BRAVE CUSTER'S LAST SHOT.

CHAPTER V. HOW THE COMMAND PAID FOR IMMORTALITY.

CHAPTER VI. BOLLY WHERRIT'S BATTLE ON A SMALL SCALE.

CHAPTER VII. ROBBERS OF THE DEAD.

CHAPTER VIII. PANDY ELLIS' HOTTEST SCRIMMAGE.

CHAPTER IX. RED GOLIATH, THE GIGANTIC HERCULES.

CHAPTER X. ADELE.

CHAPTER XI. HOSKINS PAYS NATURE'S DEBT—ABOUT THE FIRST HE EVER DID.

CHAPTER XII. WHITE THUNDER ON THE RAMPAGE.

CHAPTER XIII. RENO'S RIFLE-PITS ON THE RIVER BLUFFS.

CHAPTER XIV. THE BOY TRAILER AT WORK.

CHAPTER XV. A MAN WHO NEVER BROOKED AN INSULT.

CHAPTER XVI. WHAT FATE HAS ORDAINED.

THE YELLOW-HAIRED CAVALRY CHIEF ON THE WAR TRAIL.

"Hold up yer hands thar, ye varmints. Ef his hair air gray I kin swar this chile's hand air as steddy and his eye as sure az they war twenty years ago. Bein' sich a heathen, I reckon ye don't know that wine improves wid age; ther older it air, ther better, an' I s'pose thar's a likeness between wine an' me, az ther feller sez. Keep them hands steddy, my red cock-o'-the-walk. Now, I'm goin' ter caterkize ye 'cordin' ter my own style. Fust and foremost, who air ye?"

The buckskin-clad hunter held his long rifle nicely poised, and the bead at the end was in a line with the object of his speech.

Under such peculiar circumstances the warrior (for his color proclaimed him an Indian) could do no less than remain quiet, although from his evident uneasiness it was plainly seen that he did so under protest.

Even in this sad predicament, the boasting qualities of his race seemed to be predominant.

"Ugh!" he ejaculated, slapping his dusky chest vigorously, "me big chief. Hunter must hear of Yellow Hawk. Big chief, great brave. Take much scalps. Hab hunter's in little while. What name? ugh!"

The leather-clad ranger gave a laugh that was not all a laugh, insomuch that it appeared to be a loud chuckle coming up from his boots.

His thin face was a little wrinkled, and the tuft of hair upon his chin of the same iron-gray color as the scalp mentioned by the redskin; but no one would be apt to judge, taking into consideration the man's strength and stubborn endurance, that he was over seventy years of age.

Yet such was the actual fact; for some fifty years this ranger had roamed the wild West from the frozen region of the polar seas to the torrid climes of the Isthmus; and everywhere had his name been reckoned a tower of honesty, strength and power.

Though probably few men had had half of his experience among the redskins of the mountains and prairies, there was something so charmingly fresh in the remark of his red acquaintance that made the ranger more than smile.

"Purty good fur ye, Yaller Hawk. I won't furgit yer name, and by hokey I reckon I'll plug ye yet, ef things keep on ther way they seem set on going. Az ter my name, thet's another goose. I don't s'pose ye ever hearn tell o' such a cuss az Pandy Ellis, now did ye?"

Again that queer chuckle, for the Indian had slunk back, his black eyes fastened upon the ranger's face, with a sort of dazed expression.

It appeared as though Pandy was known to him by report, if not personally.

"Ugh! Sharp shot! Heavy knife! Big chief! Ugh!"

"I reckon," returned the old ranger dryly.

Half a moment passed, during which neither of them spoke.

Pandy's grim features had resumed their usual aspect, and there was actually a scowl upon his face as he gazed steadily at the redskin.

"Chief," said he at length, "fur I reckon I kin b'lieve ye that fur an' say ye air a chief, I'm going ter ax ye sum questions, an' I want square answers to every wun o' them. Fust o' all, what'd ye shoot at me fur?" and Pandy glanced at his shoulder, where a little tear told where the bullet had gone.

"Me see through bushes; tink was Blackfoot squaw. Ugh!"

"Yas, I reckon. Werry plausible, az ther feller sez, but two thin. Wal, we'll let that pass, seein' az no harm war done. I forgive ye, chief. Receive a benediction, my red brother. Let that lie pass ter yer credit. Now, my painted scorpion, look me full in the eye. What hez Sitting Bull done wid my pard?"

This was uttered in a slow, but emphatic tone.

The Indian either could not or would not understand; he shook his head.

Pandy took a step forward, and his rifle was again raised menacingly.

"Looky hyar, ye lump o' dough, I'm inquirin' respectin' Bolly Wherrit, the big rover o' thar plains. White Thunder, do ye understand?"

Whether it was the hunter's threatening attitude that scared the warrior, or that he suddenly realized what was meant, can never be made manifest; certain it is he remembered just at this critical period.

"Ugh! mean White Thunder; him dead."

"Another lie. Now, redskin, how did he come ter die?" asked Pandy, who, although not believing this assertion, began to feel uneasy.

"Wagh! eat too much. Dine with Sitting Bull. No hab good tings afore; stuff full and burst. Run all ober. Ugh!" grunted this savage composedly.

"Thunder! thet air rich. How the ole man'll larf wen he hears it. Allers prided himself on bein' a light feeder; eat az much az a bird, him that I've seen git away wid a hull haunch o' venison while I war chawin' the tongue. Now, Yaller Hawk, allow me ter say I don't believe a word ye've sed; may be all is az true az Scripture, but I wouldn't like ter swar ye. I'll tell ye what I think. Bolly air a prisoner in yer camp. I tole him twar a fool's errand he started on, but a willing man must hev his way, az the feller sez, so he started widout me. I'm goin' into yer camp; tell Sitting Bull that I'll see him widin a week, and listen, Yaller Hawk. Does ther eagle car fur its mate? will thar she bar fight fur her cubs? Wal, I love Bolly Wherrit; he air my life, all I care about livin' fur. Mark my words, redskin; if any harm comes ter White Thunder, I swar Sitting Bull and his chiefs shall go under. Do yer hear? Then don't fail to report. That's all; ye can retire now, az ther cat sed when it had ther mouse by ther nape o' ther neck. Come, git, absquatulate, vamose the ranche."

An Indian's code is "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth."

Yellow Hawk had attempted the ranger's life, and he expected the latter to take his in just retaliation.

Therefore, he was not a little surprised at the words of his enemy, nor did his amazement retard his progress.

A moment and he was beyond the range of vision, having vanished among the trees.

Pandy Ellis, the trapper chief, was alone. He did not stay in his exposed position long, however, knowing full well the treacherous character of the foes he had to deal with, but plunging among the undergrowth himself, in a direction almost opposite to the one taken by the Indian, he made his way along, aiming for a certain spot.

This proved to be a small creek, on the further bank of which his horse was tethered.

Crossing over, the ranger mounted and rode away. The animal he bestrode was no mustang, but a tall, broad-breasted horse, capable not only of carrying heavy burdens and making fast time, but also of keeping up his pace.

Many years ago Pandy owned a quaint steed called Old Nancy, and in memory of that faithful equine friend had this animal been named.

Reaching the prairie, the ranger dashed out upon the open space and cantered along toward the north.

The grass was already high, and dotted here and there with beautiful wild flowers, that seemed to make the scene one of enchantment.

His gray eyes swept both the horizon and the ground before him with customary caution.

All at once the ranger brought Nancy to an abrupt halt, threw himself from the saddle and bent down to examine tracks in the soft earth.

"Glory! kin I b'lieve my eyes? A hull army o' 'em, az I'm a sinner. Ther report I heerd must be true then. My yallar-haired chief air on the war-trail, and when Custer gits on ther rampage thar's blood on ther moon."

SITTING BULL'S GANG OF RED MARAUDERS.

The slanting rays of the rising sun fell upon an immense Indian encampment that stretched for several miles along the left bank of the Little Horn, and could hardly have been less than a mile in width.

Doubtless such a gathering of redmen had not taken place for many years.

In addition to the several lodges composing the village proper, scores and even hundreds of temporary brush-wood shelters had been hastily constructed, which significant fact went to show that this immense assemblage of warriors, numbering very nearly three thousand, was a gathering from different tribes.

That mischief was intended by these warlike Sioux could be presumed from the fact of their being painted as for battle.

The sun had been shining for some time when two mounted Indians, coming from the plains away beyond the distant range of hills, appeared almost simultaneously on the high bluffs that lined the right bank of the river.

Dashing down the steep inclined plane they forded the Little Horn and rode directly into the village.

One lodge, more conspicuous than its fellows, was situated near the center of the place, and even an inexperienced eye might have discovered in it the resting-place of a great chief, even though the only conviction came from seeing the many sub-chiefs that hovered near by.

These two hard riders reached the lodge at nearly the same time, and throwing themselves to the ground, left their sweltering horses to take care of themselves, while they entered with that boldness the bearers of exciting news generally possess.

Old Sitting Bull was busily engaged in an earnest confab with some half dozen chiefs, and although he spoke only once in a while, his words were listened to respectfully by the rest.

All eyes were turned upon the new-comers, and a hush fell upon the assembly, for something seemed to tell them that great news was on the tapis. Yellow Hawk, (for this discomfited chief was one of the hard riders) managed to get in the[Pg 3] first word, and when it was known that the far-famed Pandy Ellis was in their immediate neighborhood, more than one of these dusky braves felt his heart beat faster, for there was a terrible meaning attached to the old ranger's honest name, for all evil-doers.

When, however, the second courier spoke, a wild excitement seized upon the chiefs.

Custer the hard fighter, the yellow-haired devil, whom they had always feared, was charging along their trail and aiming for the village like a thunderbolt, with his cavalry regiment at his back.

Indians are not accustomed to speaking their thoughts during times of excitement, but the news loosened their tongues, and for several moments a hubbub arose in the head chief's lodge.

In the midst of this several white men, garbed as Indians, but with their faces painted, entered.

A moment only was needed to become acquainted with the state of affairs, and then one of them, a squatty individual, who had long been a pest to the border, under the name of Black Sculley, spoke a few words in the ear of Sitting Bull.

Whatever he said does not concern my narrative, but it had its effect upon the chief, who immediately became calm, and made a motion toward one who stood at the entrance of the lodge as a sort of door-keeper.

This individual signaled the waiting chiefs outside, and in another moment fully forty well-known leading Sioux were clustered together.

Indian councils from the time of Red Jacket and Tecumseh back to time immemorial have been windy affairs, in which much eloquence and debate was needed to settle that which had already been decided before the argument commenced; for being natural born orators the red sons of the plains and forest liked to hear their own voices.

In contrast with these, this council was very brief, only lasting about five minutes.

This proved that their dealings with the whites had affected the redskins.

After the chiefs separated, there was a wild commotion in the immense village.

Horses neighed, dogs barked, men shouted, and the din was increased by the thunder of hoofs as squad after squad of mounted braves, led by their chiefs, dashed down to the river and forded it.

In a lodge not far removed from that of the great chief, a leather-clad ranger lay, bound hand and foot.

It was Bolly Wherrit, the old-time chum and friend of Pandy Ellis.

He had been taken prisoner, fighting against overwhelming numbers, and had lain here without food for over twenty-four hours.

What his fate would doubtless be the old ranger knew well enough, but he had faced death too often to flinch now.

Something seemed to trouble him, however, for he occasionally gave vent to a groan and rolled restlessly about.

"Cuss the thing," he muttered at length. "Bolly Wherrit, ye're growing inter yer second childhood; thar's eggscitin' times comin' off now, and hyar ye lie tied neck and heel. Didn't I hyar what them infernal renegades talked 'bout jest then. Custer, my pet, a-comin', tearin', whoopin' at this hyar town wid his cavalry. Lordy, won't the yaller-har'd rooster clean 'em out; don't I know him though. Wonder ef Major Burt air along. Why didn't I wait fur Pandy. T'ole man tole me I'd get inter trouble, but consarn the luck, in course a woman's at the head o' it. Cud I stand it wen that purty face, runnin' over wid tears, war raised ter mine, an' she a pleadin'? No, sir, fool or not, I'd run through fire fur a woman, 'cause I kain't never furget my mother. That gal is in this hyar village. 'Cause why? Sumfin tells me so, and I've hed that feeling afore. Beside, ain't ole Sittin' Bull hyar, and cudn't I swar I heerd the voice o' that white devil she tole me about, Pedro Sanchez she called him, right aside this lodge. Bolly Wherrit, thar's no good talking, ef ye don't get outen this place in an hour, ye'll never leave it alive, fur when Custer sails in he never backs out, and the reds hev a failing fur braining their prisoners, 'specially men folks. Now do ye set ter work, and show these red whalps that a border man air sumpin like a bolt o' lightning."

From the manner in which Bolly set to work, it would be supposed that he had been making efforts at freeing his arms for some time back, and had only stopped to rest while holding this one-sided conversation with himself.

Somehow or other he had found a piece of a broken bottle, and had been sawing away at the cord securing his hands with this, one end being thrust into the ground, and held upright in the proper position.

Although his wrists and hands were badly lacerated by this rough method, the ranger possessed the grit to persevere.

Ten minutes after his soliloquy his hands separated. Bolly gave a sigh of relief, held the bloody members up for inspection, and then, without an instant's delay, seized upon the sharp-edged glass.

It had taken him hours to free his arms, as he was unable to see, and his position, while working, exceedingly uncomfortable; the cord securing his feet he severed in a few minutes.

Something like a chuckle escaped his lips as he stood upright. There was a mighty stretching of those cramped and tired limbs, and then Bolly was ready for business.

An ardent desire had seized upon him to take part in the attack which brave Custer was sure to make.

Fastening the cords around his ankles in a way that looked very secure, but which was treacherous, the ranger lay down upon the ground.

With his hand he quietly raised one of the skins composing the lodge and peeped out.

The opening thus formed was not over a couple of inches in length, but his keen eyes could see everything that was passing.

A grim smile lit up the ranger's features, as he saw the wild excitement that reigned throughout the camp.

"Ther askeered o' Custer; they know him mighty well, but by thunder they mean ter fight. It'll be the biggest Indian fight that this country ever saw, bust my buttons now ef 'twon't. Bolly Wherrit, ye must let t'other matter drop, and sail inter this, fur it'll be full o' glory and death."

Alas! how the words of the old ranger came true has been made manifest in a way that has caused the whole country to mourn.

Death was fated to ride triumphant in the ravine on the other shore; this valley would see such a red slaughter as the annals of Indian history have seldom presented.

Several hours passed on.

The warriors were too busy with other matters to even think of their prisoner just then, much less visit his secure quarters, and so Bolly was undisturbed.

Noon came and went.

The hot sun beat down upon the earth with great fury, but a gentle breeze in the valley did much toward cooling the air on this fatal twenty-fifth of June.

All at once the old trapper leaped wildly to his feet; this same light wind had carried to his ear the distant but approaching crash of firearms and the wild yells of opposing forces.

His frame quivered and seemed to swell with excitement.

"Yaller Har's at work. The best Indian fighter that ever lived hez struck ile. Bolly Wherrit, now's the time fur yer chance at glory. Whoop! hooray!"

With this shout the ranger burst out of the lodge like a thunderbolt, and not even giving himself an instant's time for reflection, hurled his body upon a guard who leaned idly against a post, listening to the sounds of battle.

THE RECKLESS GALLOP IN THE JAWS OF DEATH.

A column of mounted men wearing the national colors, and headed by a group of officers, were making their way in a westerly direction. In the advance rode a body of Crow Indians, and on either flank were the scouts of the regiment—over seven hundred in all, and some of the most gallant fighters on the plains.

Among that group of officers, every man of whom had honor attached to his name, rode one who seemed conspicuous both for his bearing and peculiar appearance. His form was rather slender, and indeed one might call it womanly, but the face above, with its prominent features, redeemed it from this characteristic. The features themselves might be styled classic in their strange light, having a Danish look. Surmounting this clearly cut face was the well-known yellow hair, worn long on the neck.

Such was the gallant Custer. He had always been a dashing cavalry leader, and with Crook and McKenzie rendered the Union efficient service under General Sheridan during the late unpleasantness.

The morning was half over when the command was ordered to halt for two reasons.

One of these was that his scouts had brought word that the large Indian village, whose presence in the vicinity had been strongly suspected, was only a short distance ahead; the other that a single horseman was sighted coming along their back trail at a furious gallop.

Custer had suspected this latter might be a bearer of dispatches from his commander, General Terry, from whom he had separated at the mouth of the Rosebud, the commander going up the river on the supply steamer Far West, to ferry Gibbons' troops over the water.

When, however, the horseman came closer, it was discovered that he was no blue coat, but a greasy leather-clad ranger. The individual rode directly up to the officers, and his quick gray eye picking out Custer, he extended a horny palm.

"Can I believe my eyes?" exclaimed the general; "gentlemen, let me make you acquainted with my old friend, Pandy Ellis, the best Indian fighter that ever raised a rifle, and one whom I am proud to shake hands with."

"Come, come, general, don't butter it too thick. Yer sarvint, gentlemen. I'm on hand ter see ther fun, wich air all I keer 'bout. Don't mind me no more than ef I warn't in these hyar diggin's," protested Pandy, modestly.

"We shall do no such thing, old friend. Colonel Cooke, we will now move onward to the assault," and Custer touched his spurs to his steed.

A few notes from the trumpeters, and the regiment was again in motion.

Onward at a gallop went the troops.

The valley of the Little Horn was reached, and where the great trail entered it, another halt was made.

Now the immense village was in sight: large bands of warriors made their appearance on all sides, some of them mounted, others on foot.

That there was serious business before them every man in that regiment saw by intuition; bloody work that would ring from one end of the land to the other, and yet how few of them suspected in what a terrible way it would end.

Custer was reckless; every military man has agreed upon that.

He possessed a willful trait in his character that at times showed itself, and when the occasion presented, as it was fated to do before this day was over, merged into an indomitable stubborn nature. This one serious fault was generally hidden beneath his dashing spirit, and it would be a difficult thing to have met a more social companion than this hero of the last Indian war.

There was something wrong about him on this day when he committed his fatal error.

United in a solid body, the regiment might have cut its way through the Indian camp, and in the end come out victorious.

Custer either considered his force stronger than it really was, or else underestimated the fighting powers of the enemy.

He was too confident, and, in order that the Indians should not escape, ordered Major Reno, with three companies, to enter the valley where the trail struck it.

The yellow-haired cavalry leader took five companies himself, numbering over three hundred men, with the avowed intention of entering the village some three miles further down.

Major Reno could offer no remonstrance to his superior officer, although perhaps he may have felt that this plan was a most dangerous one.

His lips and those of his fellow officers were sealed by military discipline. Not so, however, with Pandy Ellis.

He had gazed upon the tremendous Indian village as it could be seen from their elevated position with something akin to amazement. Never before in all its vast experience had the veteran ranger witnessed such a gathering of redskins, and his usually smiling face clouded with apprehension.

None knew the reckless, dashing nature of Custer better than Pandy, and he heard the orders for a division of the regiment with dismay.

He even ventured to remonstrate with the general, but the latter turned upon him fiercely, and, although his sudden anger suddenly cooled down without a word being spoken, the look was enough to inform the ranger that he was meddling with affairs in which he had no part.

All the censure of the rash act must fall upon one pair of shoulders, where the glory also rests.

Pandy fell a little behind when the detachment struck off behind the crest of the high bluffs marking the right bank of the Little Big Horn. The old fellow had grown more cautious in his advancing years, and although at one time, in his career, this daring assault would have filled him with thoughts of glory, it now had an effect quite the reverse. He could only deplore the fact that Custer would take no warning, but persisted in riding directly into the jaws of death. Duty seemed to stand out before the ranger, and dashing alongside the general, he once more begged him to consider the situation. Something was certainly wrong with the usually gentlemanly general.

"Old friend," said he, "if you fear for your own safety, there is plenty of time to join Reno yonder. If for my welfare, I beg of you to let the subject drop."

"General, if 'twar any other man az sed that, he shud never live ter see another sunrise. Ye know Pandy Ellis better than that," said the old man, reproachfully. Custer moved uneasily in his saddle.

"Forgive me, Ellis; I meant nothing. Some devilish humor seems to possess me to-day, and I must let it out in fight. Besides, there is no danger."

"No danger!" muttered Pandy, falling back again, "no danger. Cuss me ef thet don't sound odd. Three hundred agin three thousand! Taint like ther old days now; then reds war reds, but now az they've got rifles and kin use 'em better than our men, ther devils. Lord forgive me, but I must say that I never hearn o' sich a reckless thing. Pandy Ellis air a goin' ter see it through, though, ef he does go under. Time's 'bout nigh up anyhow, might az well larf an' grow fat, az ther feller sez. Don't think o' Bolly, but jist yell an' sail in. Hooray!" and the ranger gave a subdued shout as the wild excitement seized upon him.

Major Reno was left behind with his three companies. Further to the left, some two miles away, was Captain Belton with three more companies.

As Custer and his ill-fated three hundred rode gallantly away, vanishing behind the crown of the bluffs, some of those who remained may have entertained suspicions of the dreadful result that was soon to follow, but no time was granted to realize what these conjectures amounted to.

The Indians had gathered thickly on the opposite bank, and Major Reno at once gave the word to go forward.

Fording the river in the midst of a fire so deadly that several saddles were emptied, the soldiers reached the other shore. Once on terra firma they formed and then charged.

As the bugles rang out it was a glorious sight to see that compact body of men dash forward like an avalanche, clearing the way before them as if they were invincible.

Alas! that such a gallant charge should have been in vain.

Overwhelming numbers opposed the troops; the horses could not even move forward, and, brave to the core, the men threw themselves to the ground and fought on foot. It was a terrible struggle, but could not last long.

Finding that the number of the Indians was far more than had been even imagined, and realizing that to continue the struggle would mean the sacrifice of every man in the command, Major Reno reluctantly gave the order to remount, and the three companies crossed the river again under a harassing fire, sadly depleted in number.

Just then Captain Belton came up with his men, but seeing the madness of attempting to assail the infuriated horde of red demons, savage at their success and the sight of blood, he wisely retired, and joined Reno, who had taken up a position on one of the bluffs back of the river bank.

BRAVE CUSTER'S LAST SHOT.

—Charge of the Light Brigade.

The Crimean war may have presented its phases of reckless daring to the world, but I doubt if such a case as Custer's gallop to glory and death has been paralleled since the days of Leonidas and his deathless Spartans in the world-famed pass of Thermopylæ.

They literally rode to destruction, as may be seen when it is officially stated that not one regular soldier in the whole command lived through the battle.

After leaving the attack at the upper end of the village to Reno's case, Custer and his men struck along the route selected, at as rapid a pace as the nature of the ground permitted.

This line of travel was just beyond the crest of the high bluffs, and no doubt the leading principle that actuated the general into selecting it, was an idea that their movements might be concealed from the enemy.

In this, however, the project failed utterly, for great numbers of Indian scouts had posted themselves on the crags and their rifles kept up a continued musical refrain far from pleasant to the ears of the devoted band, more than one of whom threw up his arms and fell from his steed as the bitter lead cut home.

It was a dangerous ride, and yet in the face of this murderous fire these valiant men rode on, turning neither to the right nor the left, but keeping straight forward.

Now and then a trooper, exasperated beyond endurance by the fall of some dear comrade, would discharge his carbine at the Indians who showed themselves boldly on one side.

Owing to the rapid motion these shots were indifferently rewarded, only a few of the most expert hitting the objects of their aim.

On ordinary occasions old Pandy Ellis would have been one of the first to prove his markmanship, but something seemed to keep his attention riveted in one direction, and amidst the storm of hissing bullets, growing momentarily louder and more threatening, the prairie ranger rode as calmly as if indeed there was no danger.

But if our old friend paid little attention to this deadly discharge from all quarters, others made up for his lack of interest, and growls of dissatisfaction arose on all sides; not at their leader, but because it was almost impossible to return the fire of the enemy.

With his usual disregard for danger, Custer rode in the advance, where his form was a prominent mark for all concealed sharp-shooters; but the general, in spite of all, seemed to bear a charmed life.

He leaned forward in the saddle, and seemed to be scrutinizing some point of land, toward which his attention had been drawn by Bloody-Knife, one of his Crow scouts.

It was at this moment, after a gallop of nearly three miles after leaving Major Reno, that Custer gave a start and uttered an exclamation as a bullet grazed his flesh, making a slight but burning skin wound.

Aroused to action by this, his quick eye took in all the surroundings, and immediately the order was given to change the route.

Passing over the crown of the bluffs, the cavalry rushed down toward where the Little Big Horn ran noisily over its bed.

Indians seemed as thick as blackberries on a July day.

From every bush and rock they made their appearance, ugly-looking and determined on mischief.

All the way down to the level bank of the river men kept dropping, and with them horses, but in spite of it all the brave squad kept straight on.

Just at this moment a new form appeared among the blue coats.

Where he came from no one had the slightest idea, not even keen-eyed Pandy himself.

The first the ranger knew of it, he saw some one mounted on a white horse dash by him, and a boy dressed in the becoming suit of a hunter drew rein beside the yellow-haired chief.

Custer turned his head for the first time since changing the course of his troop, and his face expressed evident displeasure when he saw the boy.

"Mason, boy, you here?" the officer ejaculated.

The young fellow did not seem to pay any heed to the dismay that was plainly perceptible in the tones of the general.

"General," he almost shouted, putting out a hand to seize Custer's bridle, but which was impatiently put away by him, "to go forward is impossible. They are ten to your one."

"To retreat is also impossible, even if we wished it," said Custer, grimly.

It was indeed so; the command could never scale the bluffs again in the face of those defending them.

Again the boy appealed.

"General, the whole river bank is a mass of reds. It is a trap, an ambuscade. Turn back, or halt, if you value your life," he exclaimed.

Several of the officers were waiting for a reply; but Custer, firm and brave to the last, did not hesitate in his course.

He realized that a terrible error had been committed in dividing his troop; but he possessed the spirit to persist in his former plan, hoping to come out all right in the end.

His fellow officers saw the lips pressed firmly together.

Then came the one word:

"Forward!"

The foot of the bluffs was reached, and then the truth of the boy's assertion became manifest.

Another moment, and the gallant command was completely surrounded by a struggling, yelling mass of Indians, many of whom were mounted.

Then commenced the deadliest fight that has ever been known to take place on the plains.

All the attendant noises of a great battle, cannon excepted, could be found here.

The Sioux seemed crazy with both anger and delight; and many a poor fellow, struggling hard in the midst of this sea of humanity, was actually pulled from his horse into the arms of death.

There was no halt made at all.

The command kept compactly together, using their weapons as best they could, but never thinking of retreating.

On, on, was the cry; forward, the shout.

Being prevented from fording the river by the overwhelming force, Custer and his men rode along the shore.

Every second the number of opponents swelled, as those upon the heights came down upon the scene of action; and still the little band went on, trampling down and riding over those who would not get out of the way.

As a single man in a crowd is pushed hither and thither, like a feather floating on the water and at the mercy of the wind, so Custer and his command were drawn away from the river.

Everywhere was their trail marked by the dead, until it came to the slaughter-pen.

After leaving the water, the remnant of the gallant Seventh attempted to make a break out of this infuriated mass, but the tide had set in against them.

Five, ten minutes of this awful fighting, and then there came a time when retreat was utterly out of the question, much as they might have wished it. The Sioux had forced them into a ravine, and here was enacted the closing scene of the bloody drama.

Custer saw the inevitable finale; hope of a rescue there could be none, as Reno had received positive orders, and Terry and Crook were far away in different directions.

In this ravine they must die, then.

"My God!" exclaimed Custer, "we are trapped like foxes. To stay here means death. Forward, men, forward. Down with the hounds!"

Wounds counted as nothing at this dread moment; so long as a man could keep his seat, he was in good luck; it was the death bullet that told.

"My Heavens! the general's shot!" shouted a soldier close to Pandy Ellis.

Custer was reeling in his saddle; the film of death already showed itself in those clear eyes, but bracing himself, he discharged his revolver full in the face of Black Sculley, the renegade, who had given him his death-wound.

The scoundrel rolled over with a curse; Custer's last shot had done its work.

As the general fell from his saddle he was caught in the arms of the boy hunter, who had dismounted.

While the awful din raged around, and men were covering one another with blood, the soul of as gallant an officer as ever drew sword passed away to a better world.

Custer died at the head of his command.

HOW THE COMMAND PAID FOR IMMORTALITY.

Their valiant leader lying dead upon the ground, and men continually dropping on all sides, the remnant of the officers saw that the game was up. There was not one chance in a thousand for their escape, and the only thing that was left to them was to fight to the last gasp, to "pile the field with Moslem slain," and die as did Bowie and his friends at the Alamo, with the bodies of their enemies forming a breast-high bulwark around them.

"Down with the redfiends!"

It was brave Colonel Cook's last words, for hardly had he spoken before a lance knocked the red sword from his hand. Eager hands seemed to clutch at him on all sides, and in an instant he had disappeared, being pulled down among that surging crowd of savage devils.

Colonel Custer fought like a Hercules, but nothing could avail against such overwhelming numbers. In the confusion of the onslaught he had accidentally become separated a little from the rest, and although this may have hastened his death a trifle, in the end it made no difference. This gallant man was the next officer to fall. His horse was shot under him, and almost before he had reached the ground fate had overtaken him.

His comrade, Colonel Yates, uttered a heavy groan when Custer fell, and as if yet hoping against hope, turned his eyes towards the bluffs above. For once the brave man found himself wishing a fellow officer would commit a breach of discipline, and disobey orders. If Reno came up with the remaining seven companies they might be saved. Alas! the major never came, for about this time he was industriously engaged in defending himself against a horde of savage Sioux.

As moment after moment glided away, every spark of hope left the heart of Yates, and clenching his teeth, he turned his full attention upon the scene around him.

Indeed, it was enough to appall the stoutest heart to see that little band of brave men hemmed in on all sides by a surging mass of red demons, each one of whom seemed to feel the old desire for human blood so characteristic of the Indian race.

It would have been a sight fit for a painter, and[Pg 5] yet what artist could do justice to the expression of mingled despair and courage that showed itself upon each face in that noble little band?

Ah, me! It was a terrible, terrible half-hour. Men in that gallant Seventh, who had been ordinary mortals before, now proved themselves heroes, and fought like tigers at bay.

There is something fearful in the look of a man who has given up every vestige of hope, and fights with that fierce courage born of despair; one can never expect to see it elsewhere.

"Boys, we've got to die here. Close up and let every man take half a dozen of these red fiends to eternity with him."

It was Captain Smith who yelled this out, and those who knew him best can believe it of the officer.

This was not his first Indian fight.

He had faced death before, but never would again.

Bronzed, bearded faces grew paler than usual, and perhaps some hands shook as the men thought of the loved ones at home.

God knows that they had cause to feel this weakness for a moment, when they realized that never again should their eyes behold those dear friends, and that this ravine in which they fought was doomed to be their field of death.

"Keep your faces towards the foe!" shouted Colonel Yates, bravely, and to himself he muttered the anxious prayer that could never be answered:

"Oh, heavens! that Crook was here, or Andy Burt and the Ninth."

But Crook and Gallant Major Burt were far away.

The Indians, incited by their chiefs, now prepared for a grand final rush.

Mr. Read, who had accompanied the expedition, was down; Colonel Keogh had vanished a long time before, and just at this critical juncture Captain Smith threw up his arms, and after reeling for an instant in his saddle, slipped to the ground.

Yates saw that the closing scene was at hand.

"Close up, men, close up! For God's sake, let every man keep his face towards them! The old Seventh will become famous!" he exclaimed.

Yes, indeed, famous at the dear cost of the utter extermination of almost half its number.

A yell, such as might have made the earth tremble, and the whole mass of warriors, mounted and on foot, came against the solid little phalanx like an avalanche.

Had the rush been from one quarter alone, the remnant of cavalry would have been swept out of existence like a flash, scattered here and there among their enemies; but as the press came from all sides at once, it only served to crush them closer together.

In union there is always strength.

Had the hundred cavalrymen now left been divided into small groups, they would have been all killed before ten minutes had passed by, but in a solid body they could resist for over half an hour.

Pandy Ellis was in the thick of it.

His blood was thoroughly aroused, and I doubt if any man in that ill-fated command killed half as many red-skins as did this gray-haired ranger.

When his rifle and pistols were empty, he slung the former to his back very coolly, and then, drawing the huge bowie-knife that had given him the name of Heavy Knife, he sailed in to conquer or die. Experienced in these matters, he had foreseen such a catastrophe, although even his vivid imagination had failed to paint such a serious calamity.

Pandy had expected to be forced into a retreat, but such a thing as having the whole command utterly annihilated never entered his head, until they were pushed into the ravine trap.

Even when he was fighting in the midst of the red-skins, a thought of the strange boy who had so suddenly disappeared among them, entered his head.

Custer had called him Mason, and seemed to feel some affection for him.

Pandy's eyes soon fell upon him. He had the general's revolver in his hand, and was seated on his horse, engaged in emptying it with commendable precision, making every shot tell.

When the ranger looked again, a few moments later, the boy had disappeared.

"Poor feller, he's done fur; an' yet it'll likely be ther fate o' us all," muttered Pandy, as he drove his keen blade home in the broad breast of a brave.

At such a dread time as this the eye of a participant could not take in the entire scene.

All that Pandy was sure of after Cooke fell pierced by many wounds, was that every member of that heroic band fought as if the strength and endurance of a dozen men was in his body.

For every blue-coat who fell, at least two Indians bit the dust.

Although the fight had grown more silent, now that nearly all the firearms were discharged, it was none the less deadly on that account.

Sabers, red with human gore, were flashed in the sun's bright rays, and urged to their deadly work by arms that seemed iron in their endurance.

Lances, tomahawks and keen knives opposed them, and now and then a rifle added its weight to the side of the Indians.

On each occasion, some poor fellow would totter in his saddle, and finding himself going, show the spirit that imbued his nature by making a last sweeping blow at the enemy who held such a tight grip on them all.

It was horrible to see how that devoted little band continually diminished in numbers.

There were hardly forty left now, and in ten minutes these had become less than twenty. The end was near at hand.

Yates still lived, although the only commissioned officer.

His face was very white, and streaked with blood, so that old Pandy, still fighting like a hero, hardly recognized the man who touched his arm.

"Old friend, try to escape and carry the news to Crook and Reno. If you succeed, tell them to let my folks know how I died, and that my last were of them. The old seventh has made a record that——"

It was never finished; the fatal bullet came, and as brave a man as ever presented his face to the foe succumbed to the inevitable.

Pandy seemed to hesitate an instant, then his powder-begrimed face lit up.

"I'll do it, bust my buttons. Might az wal die tryin' it az hyar. Good-bye, boys; I'm in fur death, or ter carry ther news ter Crook. Nancy, away wid ye," and the knife point sent the animal bounding among the Indians.

Ten minutes later and all was over. The ravine looked like a slaughter-pen in the daylight, and even when the Sioux, glutted with blood, searched among the heaps of slain for any who might live, the sun sank out of sight as if ashamed to look upon such a horrid scene, and a merciful darkness hurried to close over the ravine of death.

BOLLY WHERRIT'S BATTLE ON A SMALL SCALE.

When Bolly Wherrit threw himself upon the guard at his prison lodge, he was without a single weapon.

Besides this his hands and wrists were considerably lacerated by the cruel glass that had been the means of his gaining freedom, but he had no doubt regarding his ability to overcome the fellow, especially as he had the advantage of a surprise.

Finding himself so suddenly seized by the throat, the guard turned like a flash and attempted to use his arm, thinking to get the hunter in a bear's clasp, and then hold him till assistance came.

He counted without his host, however, as many folks are in the habit of doing.

Raised in the school of nature, very nearly the whole of his life being spent upon the plains in active warfare with the savage denizens thereof, it was not likely that Bolly would in his declining years lose the prompt discretion and agility that had marked his whole checkered career.

Perhaps that Indian thought a thunderbolt had seized hold of him, that is, if he took time to think at all, which is rather questionable, and in truth he would not have been far from the truth.

The way in which Bolly shook him by means of the hold upon his throat would have reminded one of a terrier and a rat.

So violent was the motion that the unlucky fellow's head was in danger of coming off, and when Bolly in the end dashed his clenched fist full in the red face, it ended the matter, for when he released his clasp the man dropped to the ground perfectly insensible.

To stoop over the fallen brave and transfer the fellow's weapon to his own person, was, for the ranger, but the work of a moment.

Quite a fine-looking rifle, of a modern pattern, a long, ugly-looking knife, a revolver and some ammunition were thus appropriated without compunction, for Bolly believed in the adage that "to the victor belong the spoils." Besides, had not this man or his friends made themselves owners of his articles of warfare without saying so much as "by your leave."

There were very few men left in the village; for one to remain idle when such deadly work was in progress at two separate points would have been a decided disgrace.

A dozen cavalrymen dashing in at the northern and western end of the village could have carried everything before them.

Not forty yards away from the prison lodge, some ten or twelve warriors were clustered, being wounded braves unable to take part in the great battle.

So interested were these worthies in what was passing before their eyes (for, standing on a little elevation, they could see the fight with Reno now drawing to an end, and the gallop to death of brave Custer and his men), that the little episode in their rear did not serve to attract their attention.

It was only when the ranger arose to his feet, after arming himself by means of the late guard's weapons, that one of the wounded braves happened to catch sight of him, and, giving the alarm to his companions, the whole of them started forward with a yell.

If they were to be deprived of a share in both of the fierce battles, why could they not get up a little affair of their own, a private entertainment, so to speak, whereby each individual participant on their side might share the excitement.

Unfortunately for them Bolly Wherrit proved too willing, and then again he wanted all the fun on his side of the house.

"Now fur sumpin rich. Calculate I kin wipe out them reds like a chalk mark. Old bruiser in front thar, take keer o' yerself."

The rifle proved to be a good one in the right hands, for as the report sounded, one of the approaching braves sprang wildly forward with a convulsive drawing up of the legs, and was met half way by death.

Then the revolver commenced its fearful work.

As man after man lay down never to rise again, Bolly burst out into a wild, reckless laugh.

When the chambers were empty, only four men stood erect, and they looked as if they wished themselves anywhere but in their present situation.

Nothing daunted by the force of numbers, Bolly sprang towards them, holding his empty rifle in one hand and the long knife in the other.

Some stern duty appeared to call these four brave fellows in as many different directions, just then; at any rate they did not wait for the arrival of White Thunder, but dashed wildly away, forgetful alike of their wounded dignity, and their late dignified wounds. A shout from the old hunter caused them to expedite matters, and Bolly laughed at the ludicrous figures they cut.

A shrill neigh close by caused him to start. It was a well-remembered sound, and the hunter quickly turned his face in the direction from whence it came.

A horse, saddled and bridled, was fastened to a stake driven into the ground in front of a tent, and Bolly saw that it was his own lost steed. The animal had recognized its master, and had given token of its love for him.

With a few bounds Bolly was at the side of Black Bess.

As his hand fell caressingly upon the noble mare's mane, the skin serving as a door to the lodge was swept suddenly aside, and the next instant Bolly found himself face to face with Blue Horse, a noted chief, and an old enemy of his.

What this individual was doing in his lodge while his comrades fought and bled will, perhaps, never be known, and does not really affect the course of my narrative.

All that I wish to be positive about is the fact that he was there, and that for almost fully sixty seconds the foes glared at each other.

"Ugh! White Thunder! Blue Horse no forget ears," grunted the chief, as he put his hand to his belt and drew a revolver.

"Remember that ole scrimmage, eh, chief? Wal, I reckon I cud give ye another leetle reminder o' this happy occasion, seein' that yer is so partic'lar 'bout it," and the ranger laughed in the Indian's face.

Blue Horse angrily raised his weapon, but considerately refrained from firing. The reason of this clemency on his part was obvious.

Bolly held his empty revolver in his hand, and this had been thrown with tremendous force against the chief's head, which, not being made of iron, gave way, and the Sioux nation had to mourn the loss of another leader.

Bolly secured the revolver of Blue Horse, and was thinking of searching the village from one end to the other in order to accomplish the strange mission that had brought him to this part of the country, when a chorus of angry yells attracted his attention.

Upon investigation these were found to proceed from a score of mounted red men who were dashing along towards him, having evidently[Pg 6] been attracted by the cries of the four wounded warriors, who had fled after their little private amusement.

"Plague take the luck, I must git. Sich a good chance thrown away. Now, ye kin bet high on't, Bolly Wherrit's goin' ter have his own rifle back agin, an' resky that gal mighty soon. Whoa, Bess, whoa, old girl. Have they been treatin' ye bad? Away now, an' make the dust fly!"

Faithful Black Bess needed no second invitation, but darted away like an arrow shot from the bow, with Bolly swinging his rifle in the air, and shouting defiance to those who followed after.

His first thought was to make for the river and join the combatants on the other shore, but upon glancing across, such a mass of surging humanity met his gaze that Bolly was actually appalled. Besides, his pursuers were between himself and the water having come from that direction.

"Tarnal death! but it looks hot over thar. Reckon it must be Custer, for I swar no other man wud do sich a dare-devil thing. Ef they get outer thet hole, then I'll guv the general credit fur a heap o' smartness. Oh! yer imps o' Satan. 'Spect ter ketch me, hey? Wal, now we'll see what the hoss has ter say 'bout thet," muttered Bolly.

Actions often speak louder than words; if Black Bess could not talk, she certainly showed what she thought of the case by making a streak that promised to carry the ranger out of sight very shortly.

The last the score of Sioux saw of him he was waving his old hat in an affectionate farewell, and the exuberant shouts he gave utterance to came faintly across the level ground.

Bolly made at once for the hills, which he reached in a short time. Here we will leave the brave old ranger for a time, hatching up daring plans to carry out his singular mission, and return once more to that ravine of death where Custer and the last of his command fell beneath the fury of the Sioux and their renegade friends.

ROBBERS OF THE DEAD.

Night had closed over the scene of the terrible battle, but the darkness was not intense, as the stars shone out with unusual brilliancy, and the silver crescent of a new moon in the western sky lent its feeble aid.

The cold stars looked down upon a fearful sight; such an one as has not been seen in this fair land for many a year.

Hundreds of men and horses lying dead in that fatal ravine, and a trail of bodies leading almost in a circle, down to the river and then up the bluffs.

Valiant men lay here: heroes whose names shall ever be mentioned with proud honor by their surviving comrades; and yet what a price they paid for that worthless commodity to the dead—immortality.

Across the Little Horn could be heard the noises of a great camp, and once in a while the breeze bore the distant crack of firearms.

These last came from several miles to the south, where Major Reno had intrenched his command on the bluffs, and from hastily-constructed rifle-pits fought the enemy, who had posted themselves on the neighboring heights, where they could control his position.

Shadowy figures glided hither and thither over the field of battle, for that it was a battle, though a very uneven one, I do affirm, in spite of the constant appellation of massacre indulged in by the newspaper men.

The very word massacre brings to mind the idea of a wholesale butchery of helpless people. Historians are prone to be partial in its use.

We always find the affair termed a massacre when the Indians are victorious; but when the tables are turned it is "a splendid campaign," "a hard-fought battle," and "a glorious victory for the troops."

If the word massacre does not mean a one-sided butchery, then every world's battle has been such.

As to Custer's particular case, did he not move forward with the intention of attacking the village, and though every man fell, did they not slay at least their own number of redskins? Then this proves the affair a battle and not a massacre.

Having carried my point, I beg pardon for the digression.

These shadowy figures gliding over the scene of death were robbers of the slain, and having no compunctions of conscience, if a coveted ring refused to come off, the finger was at once severed in order to obtain the bauble.

Noble Custer and most of his officers lay close together, just as they had fallen.

Near by was a heap of slain, which included troopers, Sioux and horses.

One of the robbers of the dead approached this pile, and began pulling the bodies about in a promiscuous manner, his eyes busily engaged searching for plunder.

Under this pile a form lay, which, as the heavenly lights fell upon it, revealed the features of the boy who had been beside General Custer when he fell.

Something gleamed from the little finger of his left hand, and as this sparkled in the light of the moon, the prowler uttered a delighted exclamation that at once proved him to be a white man.

Seizing hold of the hand, he at once attempted to pull the diamond solitaire ring off, but this proving fruitless, he felt for his knife.

Just as this was drawn, his hand was tightly clutched by the one he held.

The truth of the matter was, that the boy had been rendered insensible by being struck with a bullet, that glanced from his forehead without breaking the bone.

Others, killed later in the desperate struggle, had fallen upon him, and here for several hours he lay at the door of death.

When the heap that pressed upon him had been removed by the robber, the fresh air served to partially revive him, and the twisting of his finger by the desperado finished the business.

Mason, as I shall call my boy hero, for Custer had given him that name when addressing him, opened his eyes.

By the dim light of the stars and the new moon combined, he saw the figure of a man kneeling over him.

That it was a white man was evident from his clothes and hat, and also the bushy beard.

A pair of fine cavalry boots, stolen from some unfortunate officer, were slung across his shoulders, and he seemed burdened down with all sorts of plunder.

Mason waited to see no more.

The wrenching at his finger ceased, the man uttered a curse, and began to draw his knife.

Then the whole horrible truth burst upon the boy's mind.

Under the impulse of the moment he tightened his clasp, and actually pulled himself to his feet by means of the renegade, and after this had been accomplished, released his hold.

The matter did not rest here.

Amazed at having the dead come to life in such an unexpected manner, as it seemed, the renegade uttered a cry and started back.

Custer's revolver was still held in the boy's right hand, just as it had been when he had fallen to the earth.

Whether a single load remained or not he could not tell, but quickly pulling up the hammer he raised the weapon.

When the robber of the dead, base craven that he was, saw this movement, he flung out his hands in an involuntary appeal for mercy, but the boy, after passing through such a bitter, bloody experience, could feel no pity for such as he.

The hammer fell, the crack came, and the bullet did its mission of retributive justice.

"My God! I'm done for. Curses on the young hound," half howled the renegade, reeling wildly in the effort to keep his feet, and at length plunging to the ground, where he lay covered with plunder, waiting for some other robber to relieve him as he had despoiled others.

Mason sank to the ground immediately, and it was not until several moments had passed by that he ventured to raise his head and look around.

Not an object was stirring near him.

If the marauders of the dead had noticed the shot at all, they had taken it for granted that it was fired by one of their number at a wounded cavalryman, and the shout given by the victim of the bullet went far to corroborate this idea.

As he looked, Mason saw one of those shadowy forms skulking about and bending over the dead.

Fearful lest he should meet with one such and be murdered for want of weapons, he crawled over to where the renegade lay and secured his revolver.

Not content with this, he quietly proceeded to reload the empty chambers of the one he had taken from the holsters of Custer's saddle.

When this was done, he felt content, and arose to his feet.

Although he could see in the immediate vicinity, all appeared dark and gloomy a hundred yards away, and the bluffs could only be distinguished because they were outlined against the star-bedecked sky after the manner of a silhouette.

Which way to go was a puzzler.

Beyond the ravine he could hear the murmur of the river, and knew that on the other shore was the camp of the Sioux.

Once clear of this slaughter-pen and his ideas would flow more naturally, for it was impossible to think calmly while the mutilated bodies of friends lay around on every side.

To say a thing was to do it with Custer's boy friend.

He seemed to know that the general must be near by, and was led instinctively to his body.

A horse had fallen upon Custer's lower limbs, but the heavy weight had given him no pain, for he had been beyond that when the animal was shot.

I cannot positively say that the tears came from the boy's eyes, as some of my readers might deem that an unmanly proceeding, though God knows the poor fellow had cause enough to weep, with his best and only friend lying dead before him.

That he lifted the general's cold hand and kissed it repeatedly, while murmuring a farewell, I can and do affirm.

A moment more and he was stealthily making his way along the ravine, heading toward the river.

A vague notion that a horse was necessary to his future movements had intruded itself upon his brain, and although his plan of obtaining one was as yet illy defined, it constantly gained ground.

Once a dark form suddenly rose up in front of him, but the greasy Indian got no further than the drawing of his knife, when Mason's revolver sounded his death note, and without even a groan he sank beside the dead man whom he had been in the act of despoiling when disturbed by the boy's approach.

Avoiding all others whom he saw, Mason soon left the ravine behind him, and passing over the intervening ground, where a few bodies were scattered promiscuously about, he stood upon the river bank.

There was something soothing in the steady hum of the water which appeared to steady the boy's disturbed mind, and for almost half an hour he stood leaning against a tree that bent over the river, and engaged in dreamy fancies.

He had almost forgotten his notion of getting a remount in place of the one lost during the bloody skirmish.

Sad thoughts had crowded into his mind.

Of all that gallant band, was he the only survivor?

It seemed so, indeed; but Mason did not know of the supreme effort made by old Pandy Ellis, the prince of bordermen.

The boy's reverie was becoming almost unbearable, when it was disturbed by what appeared to be the flash of a paddle further up the stream.

PANDY ELLIS' HOTTEST SCRIMMAGE.

Valliant old Pandy Ellis, the veteran ranger of the prairies, was not the man to give up hope easily. He had been in many a tight scrape before, and had kept a bright face when the best of men might have given up in despair.

But there was something so fearful in the horrible struggle, where human efforts however strong seemed puny as an infant's, that the ranger might well be pardoned for shutting his teeth grimly and resolving to die hard.

There were actually tears in his eyes as he gave one last glance back at that sadly depleted little band, where noble Yates still shouted out encouraging words, and wielded his bloody sword with an untiring arm.

It was the last ever seen of this detachment of the gallant Seventh alive; and although the old ranger were to live his whole life over again, he could never forget that scene.

His hands were fully occupied in defending his person against the many weapons raised against it.

During the next five minutes Pandy had the hottest little scrimmage that ever fell to his lot.

On every side nothing met his eye but a mass of red faces, bearing the most devilish looks he could imagine, and the owners of which were trying their best to stab or shoot the rider.

Boldly he plunged into the thick of them.

Nancy trampled many under her feet, and bore her inevitable wounds with the air of a martyr, than which she could not well do otherwise, belonging as she did to such a renowned hero.

Guns cracked about him, bullets whistled close to his head, and cut into his flesh; lances, knives and tomahawks were thrust up at him with vengeful intent, and yet this veteran urged his horse forward, armed only with a knife as a serviceable weapon, with which he seemed to keep himself surrounded by a wall of steel through which it was next to impossible to force a passage.

How many men he and his horse killed between them during that five minutes' fearful[Pg 7] ride, Pandy could not even guess after it was over, for his mind was in a whirl, and he did mechanically the work that was needed, just as a set machine might have done; but it must certainly have been dozens.

Some men might have deemed it impossible to force a way on horseback through that mass of excited redskins. Colonel Yates had deemed it so, but to Pandy nothing was accepted as beyond the power to do, until an attempt had been made, and Yates' last words to him proved that the officer must have either placed more confidence in the ranger's dash than his own, or else had resolved to die with his brave boys at any risk.

It was over at last, this brief but exciting ride of the prairie man's, encompassed on all quarters by death.

As horse and rider burst out of that maddened throng as a strong swimmer buffets the billows of the mighty deep, Pandy drew a long breath.

Not that the danger was over by any means. Here were dozens of Sioux braves outside of the melee, and these seeing an enemy emerge from the mass of struggling combatants, made a rush at him. Pandy uttered a taunting laugh and dashed away like a bird, for although Nancy was breathing hard from her exertions, she was equal to what the occasion demanded.

The ranger after clearing about a third of a mile, turned to one side and rode up a pass that led to the other side of the bluffs.

Reaching the crest, he passed along until almost even with the ravine of death. Then he paused for a last glimpse. Alas! all was over.

Yates too had fallen, and not one of his men could be seen alive; all that was visible seemed to be a sea of red men rushing pell-mell over the battle-field.

Old Pandy was visibly affected.

"God help me! I never seen such a thing in my life. The hull crowd wiped out az clean az a whistle. What's goin' ter become o' us all at this hyar rate. Custer, Cooke, Yates, Keogh, all gone. Bust my buttons ef these reds ain't woke up wid sum o' ther old fire. My hate fur 'em war dyin' out, but it only needed this ter kindle it wus nor ever. I'll have revenge for this day's work; Custer shall never lie in his grave without satisfaction; an' ef ther pesky Government won't take it in hand, dash me, Bolly Wherrit's ther chap ter stick by me. We'll go on ther war path, an' by ther heavens above, if Sitting Bull don't pay dear fur this, then it's because two ole trappers will hev gone under. Tarnal Snakes an' critters! but it makes me tearin' mad. I must let out my spleen or bust; jist a parting card afore I go, ter let 'em know what's comin' in ther future."

It took but a couple of moments to load his rifle and revolvers.

His presence was not even suspected until the gun sent its clear detonation echoing over the hills.

A commotion was visible among the crowd below, and cries of pain reached the ranger's ear that were sweet music to him just then.

Without wasting any more time, he emptied all the chambers of his revolver, and then turning his horse's head, gave a loud hurrah, and vanished from view, feeling a hundred per cent. better after making a start in what he was pleased to term his death roll.

Some thirty yards below the crest of the bluffs, the way was easily traveled, and what few difficulties presented themselves were speedily overcome by such an enterprising individual as the ranger.

In a short time Pandy came to Custer's back trail.

It was quite deserted now, save by the dead, for after the cavalry had passed, the Indians followed after in order to have a hand in the battle which they knew would take place when the troops attempted to storm the village.

The crags that had so lately echoed with the cracks of Indian rifles as their owners lay in ambush, were silent now, and as Pandy rode along he could not help thinking how different it would have all been, had headstrong Custer cast aside his willful mood, and listened to the advice of one who had his best interest at heart.

It was while in this contemplative mood that Pandy suddenly became aware of the fact that a body of Indians were dodging about and among the rocks in front of him.

To retreat was almost impossible, as he would doubtless receive a bullet in the back.

Making what might be termed the best of a bad bargain, Pandy took the bridle between his teeth, and holding a revolver in each hand, urged Nancy forward at a gallop.

There was something in the manner of this undaunted man's facing death again after his recent escape and great exertions, that would have enlisted the admiration of even an enemy.

As he advanced, the redskins vanished altogether, and Pandy was beginning to believe they had gone altogether, when he heard a singular but well-known whoop that made him draw rein with an exclamation of surprise.

At the same instant a tall Indian stepped into view from behind a bowlder and advanced boldly toward the ranger.

The latter seemed to recognize him, for a smile illuminated his bronzed and blood-stained countenance.

It was Eagle Eye, the Crow chief, whose hand Pandy pressed so warmly.

The Crow scouts of the expedition were some of his braves, but the chief had missed seeing the ranger before.

They were old friends, having hunted and trapped together a whole season several years before.

"Brother been in the big fight; much hurt?" said the chief, looking with dismay at the ranger's many wounds, which he seemed to regard as so many scratches, although some of them were very serious.

"Yes, I war thar, chief, an' 'twar ther hottest time o' my life. Did ye see it?"

"We reached the hilltop too late to take part. Custer gone up and all his men? Ugh! it was a heap big fight. How brother get away?"

"Wal, ye see," said Pandy, tying a rag over one of his worst wounds, and sitting with one leg over the saddle, "we war jist about goin' under, an' I'd 'cluded not to survive the boys, when Yates asked me ter make an attempt ter git away ter carry the news ter Mary, az ther feller sez, so I done it. Kin tell ye more about it another time, chief. Just now I want ter git ye ter do sumpin important. Know where Terry air?"

The chief pointed in the direction whence lay the distant Yellowstone, as Pandy well knew, and the ranger beamed his satisfaction.

"I reckon ye're correct, chief. Now, what I want is that ye send a couple o' yer men ter tell the gineral this sad news, an' git him ter hurry on hyar, fur I heerd firing down below, an' ef Reno hain't met Custer's fate he's in a bad fix anyhow. I intend ter jine him wharever he may be an' stand ther consequences. Chief, I'm off. Remember I depend on ye," and waving his hand toward his red friend, Pandy Ellis disappeared in the growing shadow that told of the coming night.

RED GOLIATH, THE GIGANTIC HERCULES.

Mason, General Custer's boy friend, leaned forward still more, relying on the hold he had upon the tree bending over the water, when that unmistakable sound, the dip of a paddle, reached his ears.

Underneath him the water of the Little Horn gurgled and plashed among the stones jutting out from the bank; close by a melancholy owl tried to make night hideous with its solemn declarations of warning, and once in a while the barking of dogs in the great village could be heard; but to these usual noises the boy paid little heed, as he had heard them for some time past.

The silver crescent still held forth in the western sky, and its meager light, augmented by the united force of stars, proved sufficient to see the opposite shore of the river, which at this point was rather narrow.

Could the boy's mental faculties have given him warning that it was not a common foe he was about to see?

There have been many occasions when persons of fine perceptions and susceptibility have realized, seemingly by tuition alone, that those whom they bear no love for are in the vicinity.

With some people this delicate sense of knowing what even the eyes and ears fail to tell becomes an art.

Many a deaf and blind man can tell, even the instant he enters the room, whether it be occupied or not, no matter how quiet those within may render themselves.

I only state this to defend my position when saying that young Mason appeared to suspect that a foe of more than common caliber was approaching.

Of course one cannot be positive as to what he thought, but at any rate the boy leaned out further than ever, and was fully engrossed in the steady but light dip of the paddle.

Whoever this night traveler was, his movements proclaimed him to be a man habitually addicted to caution.

This the boy quickly discovered, for although the canoe was undoubtedly approaching him, yet the steady dips of the paddle seemed to grow fainter if possible, or at least no louder.

Soon, by judging from the sounds he was enabled to place the exact position of the descending canoe, and a few seconds later a moving object crossed his range of vision.

That this was a boat, and that this craft contained but one person, soon became manifest as it drew nearer the concealed watcher.

The man stood erect near the stern, and held lightly poised in one hand the long paddle he had just been using.

Even in the dim light one would think an ancient giant, or at least a modern pocket edition of the famous Goliath whom David, the shepherd boy, slew with a stone, had appeared.

The colossal proportions reared themselves at least seven feet high, and being bulky in proportion the man presented a formidable aspect, such as would at sight appall a common foe.

Mason uttered a low exclamation and gave a companion start of surprise when the figure loomed into view; but after this one indication of his feelings he remained as motionless as a form of bronze.

There was no mistaking that person whom he was now looking upon; even a casual glance would have been sufficient to impress the face and figure indelibly on any mind, and surely the eyes of hate are more susceptible of retaining an object they dislike than others.

Hate was a feeble word when used in connection with the feeling our boy friend entertained towards this giant in the canoe, and if there was a word that combined fierce detestation, aversion, and a bitter longing to hack a man to pieces, together with a trifle of respect for his prowess, I should use it; but every one knows how weak the English language is in adjectives, compared with the scorching Italian.

The giant's back was toward the bank where Mason had concealed himself, and, judging from his appearance, he was closely scrutinizing the opposite shore as if intent on discovering something that required time to reveal.

At this point the river was rather swift, owing to its narrow bed, and his rapid motion seemed to interfere sadly with his study of the other bank, for he muttered several impatient words to himself in a voice that made Mason grit his teeth like a maniac when he heard it; for this verified what suspicions the sight of the form had raised.

Downward came the canoe with the current, and urged also by the impetus given by the last few dips of the paddle.

It was within a dozen feet of the spot where Mason hugged the tree-trunk, when the man threw up an arm bare to the shoulder and as knotty as the gnarled limb of an oak, and seized upon a branch that bent affectionately toward the cool water of the river. Instantly the canoe was halted in its downward course, as if a wall of stone had been suddenly reared in front of it, and remained swinging to and fro, with the water gurgling about the stern.

The giant now leaned down, and appeared to look up and down the stream as if searching for something.

This latter, which had been invisible to him while descending the stream, proved the opposite from his present post of observation, as the low ejaculation of surprise manifested.

"There it is as I expected; one, two, three a score of fires. The Indian village undoubtedly. Now, there's work before you if you expect to see that money, and such a sum ain't picked up every day these times. I've seen it when I'd a risked my life for a tenth of the gold. It's as plain as daylight; after that battle and victory, old Sitting Bull and his men 'll keep a loose camp. All that I'm afraid of are those sharp devils, Santee and Crazy Horse, for they've got such a spite against me I'd have a nice time if taken.

"Then I believe that Cheyenne chief, Black Moccasin, is here, and he bears me a grudge for that affair on the Platte.

"But what's the odds; I'm used to running risks on a lone hand, and it's in me to win or lose all. I'll cross here, leave the boat, and bring back the gal, if I have to search every lodge in the place," saying which the man let go of his hold on the branches, and gave a sweep of his paddle that startled the canoe towards the opposite bank, which at this point was low and sweeping.

Mason gave a convulsive movement when he heard that word "gal" mentioned.

"It is Red Goliath, and he has come from him for her."

These muttered words were all that he spoke; after that his lips remained as close and immovable as the clasps of a vise.

A few more sweeps of the paddle, almost noiselessly given, served to bring the canoe to the opposite shore, which the prow struck with a slight grating sound.

Laying down the paddle, the giant leaped upon the shore, and grasping the canoe pulled it upon the pebbly bench so that it could not be carried away by the action of the water.

As he turned around after doing this thing, a[Pg 8] dark shadowy form arose beside him, where it had up to this time crouched in the obscurity.

Other ears than the boy's had heard the suspicious dip of the paddle, and eyes that were hostile to his cause had witnessed the crossing of the giant.

Mason from his position saw this form rise up, and he realized the danger of the late oarsman, but not by word or deed did he attempt to warn the giant who was his deadly foe.

There was no necessity for a warning, however, for Red Goliath saw the uprising of the tall form that seemed almost to rival his own.

This modern giant and Hercules possessed a fierce nature, similar to that of a wild beast, and on stated occasions his thirst for blood became almost a mania, that could only be quenched in the life fluid of some one.

Perhaps one of these moods was coming upon him even then.

A looker-on would have been inclined to think so upon hearing the growl of satisfaction he gave utterance to.

When foemen worthy of each other's steel come in contact, there is seldom much time lost in skirmishing.