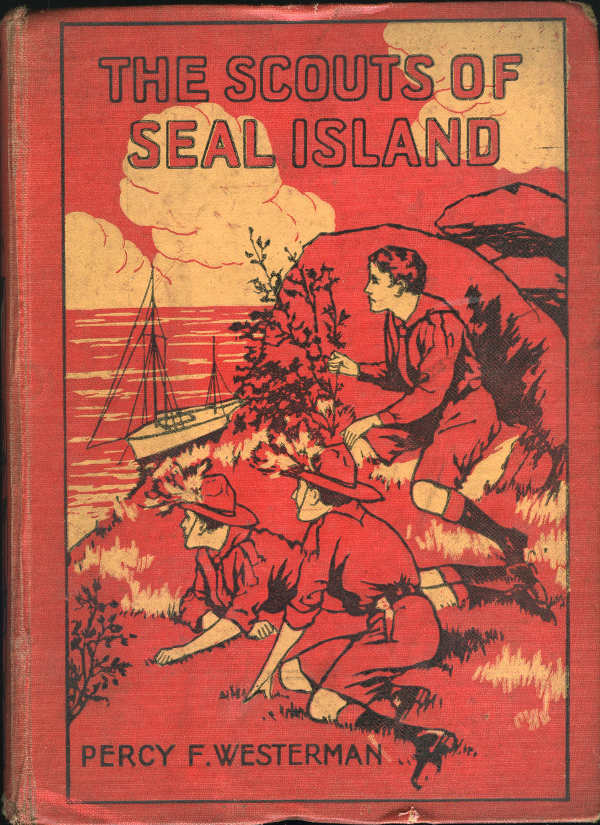

Title: The Scouts of Seal Island

Author: Percy F. Westerman

Illustrator: Ernest Prater

Release date: July 21, 2015 [eBook #49496]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by R.G.P.M. van Giesen

|

OTHER BOOKS FOR

YOUNG PEOPLE WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR |

|---|

| AESOP'S FABLES |

| ANDERSEN'S FAIRY TALES |

| BLOSSOM. A FAIRY STORY |

| BUNYAN'S PILGRIM'S PROGRESS |

| COUNT OF MONTE CRISTO |

| GRIMM'S FAIRY TALES |

| GULLIVER'S TRAVELS |

| JOHN HALIFAX, GENTLEMAN |

| MR. MIDSHIPMAN EASY |

| SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON |

| THE CHILDREN OF THE NEW FOREST |

| THE ENCHANTED FOREST |

| THE LITTLE FAIRY SISTER |

| THE LITTLE GREEN ROAD TO FAIRYLAND |

| THE WATER BABIES (KINGSLEY) |

| CHAP. | |

| I. | SIR SILAS DISAPPROVES |

| II. | DICK ATHERTON'S GOOD TURN |

| III. | THE PATROL LEADER'S DILEMMA |

| IV. | OFF TO SEAL ISLAND |

| V. | THE ARRIVAL |

| VI. | A SPOILT BREAKFAST |

| VII. | THE MYSTERIOUS FOOTPRINTS |

| VIII. | THE MISSING THOLE-PINS |

| IX. | AT THE LIGHTHOUSE |

| X. | THE WRECK |

| XI. | HOW CAME PAUL TASSH ON SEAL ISLAND? |

| XII. | THE BURGLARY |

| XIII. | FLIGHT |

| XIV. | PHILLIPS' DISCOVERY |

| XV. | THE EXPLORATION OF THE TUNNEL |

| XVI. | TRAPPED |

| XVII. | THE MYSTERIOUS YACHT |

| XVIII. | HOT ON THE TRAIL |

| XIX. | THE FIRST CAPTURE |

| XX. | A GOOD NIGHT'S WORK |

"Lads," exclaimed Scoutmaster Leslie Trematon, "I am sorry to announce a disappointment, but I trust you will receive the news like true Scouts and keep smiling."

The Scoutmaster paused to note the effect of his words. Practically every boy of the "Otter" and "Wolf" patrols knew what was coming, but one and all gave no sign of disgust at the shattering of their hopes. Two or three pursed their lips tightly, others set their jaws grimly, while a few looked at their comrades as if to gauge the state of their feelings on the matter.

"We must, I'm afraid, give up all hope of our Cornish trip and set our minds upon a fortnight's camp at or in the neighbourhood of Southend," continued Mr Trematon. "I had an idea, when I approached Sir Silas Gwinnear, that my application would be favourably considered, and that in less than a week's time you would be enjoying the pure bracing air of Seal Island. Unfortunately, Sir Silas does not see eye to eye with us. His opinion of Scouts in general is not a flattering one. Of course every man is entitled to his own opinion, but at the same time I sincerely trust that Sir Silas may be convinced that his estimate of the qualities of Scouts is inconsistent with facts. I would not hold your confidence if I did not read his letter to you. At the same time I feel sure you will make due allowances for the somewhat scathing strictures upon Boy Scouts in general."

Leslie Trematon, the third master of Collingwood College, was a tall, broad-shouldered muscular Cornishman of twenty-four years of age. He was just over six feet in height, his complexion was ruddy, though tanned by exposure to the sun, while his crisp, light brown hair and kindly blue eyes gave him a boyish appearance. He had been two years assistant master at Collingwood College, and, although a strict disciplinarian during school hours, was the idol of his scholars. Out of harness he was almost as one of them: full of spirit, keen on games, and sympathetic with lads who sought his confidence.

A little more than twelve months previously, Mr Trematon had raised four patrols of Scouts amongst the pupils of Collingwood College, and the troop was officially designated the 201st North London. Trematon saw possibilities in the Scout movement. His superior, the Rev. Septimus Kane, the dignified and somewhat old-fashioned Principal of the College, did not regard the newly raised Scouts in a favourable light. He set his face against new institutions; but, finally, on the Scoutmaster's representations he grudgingly consented to give the experiment a term's trial.

At the end of the first term he condescended to admit that the 201st Troop justified its existence. More recruits came in, and the school-games club flourished more than it had done before. Scouting went hand in hand with sport, and the Collingwood College football team attained a higher place in the junior league than it had since its formation.

The second term gave even better results. The whole school seemed infected with the spirit. There was more esprit de corps, the physical condition of the boys was decidedly on the improve, while the Midsummer Examination percentage of passes caused the Rev. Septimus to beam with satisfaction and the governors to bestow lavish praise upon their headmaster and his staff of assistants.

Even Monsieur Fardafet, the second French master, noticed the change in the boys' behaviour, and weeks went by without his having to complain to the Head about the conduct of certain irreconcilables who had hitherto been the worry and despair of his existence.

The fact was that the whole College was imbued with the principles of scoutcraft. Every boy realised that it was incumbent upon him to develop his individual character, and that it was impossible for his masters to confide in him if he failed to confide in them.

It had always been a strong point with the Rev. Septimus to impress upon his assistants the necessity of appealing to a boy's honour, but hitherto there had been a flaw in the working of the Head's scheme. The boys regarded any advance on their masters' part with suspicion. It was their firm belief that masters existed simply and solely for the purpose of driving in the dreary elements of knowledge. But when Mr Leslie Trematon arrived upon the scene matters began to improve, till, at the time our story opens, a state of harmony existed betwixt the masters and scholars of Collingwood College.

The number of patrols had now increased to ten. Of these the "Otters" and the "Wolves" were composed solely of boarder who, through various circumstances, were unable to spend their holidays in the home circle. Mr Trematon looked upon it as a pleasurable duty to give up a portion of his summer vacation to these two patrols, and, with this object in view, had approached Sir Silas Gwinnear to obtain his permission to have the use of Seal Island for a fortnight in August.

Sir Silas was a city magnate whose name was generally to the fore in every large commercial transaction that would bear close investigation. With the exception of a comparatively brief holiday, invariably spent on his large Cornish estate near Padstow, Sir Silas stuck closely to his business. He was a self-made man, whose wealth had been accumulated by sheer hard work and indomitable determination. In his earlier days he knew Mr Trematon's father intimately, and the young Scoutmaster took decorous advantage of this friendship to ask a boon for his Scouts.

Seal Island, which formed but a small portion of Sir Silas' estates, is situated off the north Cornish coast, being separated from the shore by a stretch of deep water barely a quarter of a mile in width. It is a little more than half a mile in length, and half that distance across its widest part. Roughly, the island resembles the shape of the body of a pig, the back being seawards. It is uninhabited, save for numerous rabbits and countless sea-birds. Its north-western side is honeycombed with caves; a romantic ruin, that tradition ascribes to the work of a saintly hermit, occupies the highest position, which is two hundred and fifty feet above the sea.

Needless to say the Scouts voted that Seal Island was an ideal place to spend a holiday, and one and all looked for the expected reply.

And now Sir Silas Gwinnear had replied, and their hopes were dashed to the ground.

"I may as well let you hear what Sir Silas says," continued Mr Trematon. "You will then be able to know what some people think of us Scouts:—

"I must apologise for the slight delay that has arisen in replying to your letter of the 2nd.

"It is an unpleasant thing to have to refuse the request of the son of an old friend of mine, but in so doing I merely adhere to the principles I am about to explain.

"I give you my reasons. They may not meet with your approval, but they are certainly what I believe to be correct. In the first place, I strongly disapprove of the Boy Scout movement. To me, a man of strong commercial instincts, the whole scheme suggests militancy and is merely the thin end of the wedge of 'National Conscription,' which to a man of peace is utterly abhorrent.

"Nor can I see that any useful purpose can be served by grotesquely garbed youths running about the country with broomsticks in their hands and wild cat-calls on their lips. The very privacy of a country ramble is menaced by the apparition of an inquisitive youth in a Scout's hat peering through a gap in the hedge.

"To-day, too much time is wasted in outdoor amusements—in fact, in amusements of all sorts. The commercial vitality of the nation is seriously threatened. I can assure you that I've had the greatest difficulty in obtaining a suitable junior clerk. There were scores of applicants for the post, but in almost every case the lads wanted to know what holidays were given, and what the hours were on Saturdays—in order, I suppose, that they can go to football.

"By granting you permission to take your Scouts to Seal Island I realise that I should be tacitly violating my principles. It is not because of the damage the boys might do: there is very little to harm on the Island. I trust, therefore, that you will understand the reason of my refusal, and accept my assurance of regret at not being able to accede to your request.—Yours faithfully,

"Jolly hard lines, sir," exclaimed Jack Phillips, the Second of the "Otters." "Can't you write and explain that his ideas are wrong."

"Hardly," replied the Scoutmaster, with a smile. "Sir Silas does not ask for my opinion. All the same it is up to us to show him that he is in error. All great organisations are misunderstood by some, especially during the initial stages. Time alone will wear down opposition, and in due course I sincerely hope that Sir Silas may have cause to change his opinions. Meanwhile, lads, we must not be downhearted. I must say you appear to take the bad news in a true Scout-like spirit. Perhaps, after all, we will have almost as jolly a camp at Southend, although I am sorry we are not going to sample the glorious Cornish climate. But now let's to work: its bridge building to-night, and there's quite a lot to be done in the time."

Five minutes later the old gym., which the Rev. Septimus Kane had, as a token of appreciation, handed over to the sole use of the Scouts, was a scene of orderly bustle. For the time being the lads had put Seal Island from their minds.

On the following Wednesday afternoon Leader Dick Atherton, of the "Otters," was invited to his chum Gregson's to tea. Gregson was a day boarder whose people lived at Brixton. He wished very much to join the Scouts, but his parents strongly objected. This was a source of keen disappointment both to Gregson and Atherton, for instinctively they realised that there was bound to be an ever-widening gap in their friendship.

Dick Atherton was a good specimen of a British school-boy. He was sixteen years of age, fairly tall, and with long supple limbs and a frame that showed promise of filling out. At present he was, like a good many other lads of his age, growing rapidly. Plenty of outdoor exercise and an abundance of plain wholesome food had turned the scale, for instead of becoming a lank, over-studious youth he showed every promise of developing into a strong, muscular man.

One of the first to avail themselves of Mr Trematon's offer to become Scouts, Dick Atherton was by the unanimous vote of the patrol appointed Leader of the "Otters." He took particular pains to prove himself worthy of the honour his comrades had paid him, with the result that he soon gained his Ambulance, Cycling, Pathfinder, Swimming and Signalling badges.

Scoutmaster Trematon was strongly opposed to the idea of any lad hastily qualifying for badges merely for the sake of having the right sleeve decorated by a number of fanciful symbols; he preferred to find a Scout making himself thoroughly proficient, and keeping himself up to a state of efficiency in a comparatively few number of subjects, rather than a slipshod scramble for badges that could only be regarded in a similar light to the trophies of a "pothunter."

Dick Atherton, as did most of his comrades, saw the good sense of his Scoutmaster's wishes. Therein he laid the foundations of his success in after life: he specialised. It would be hard to find another Scout in the whole of the London Troops who could excel Atherton in any of the branches he had taken up. To the Scouts' motto "Be prepared" he instinctively added another, "Be thorough."

Shortly after six o'clock Atherton bade his friends farewell and started on his return journey to Collingwood College. It was imperative that he should be back before a quarter to eight in time for evening "prep."

A heavy mist, almost a fog, had settled down earlier in the afternoon, driving most people to the Tubes. Atherton, however, preferred to take a motor-bus.

As the vehicle was passing under the railway viaduct in the Waterloo Road it skidded on the greasy surface and dashing into the kerb smashed the nearside fore-wheel. The Scout promptly alighted, thinking that perhaps he might be of assistance. To his request the motorman curtly told him to "Chuck it and clear out," advice that Atherton deemed it expedient to carry out.

Just then he remembered that to-morrow was Fred Simpson's birthday. Simpson was the Leader of the "Wolves," and a jolly good sort, and Atherton resolved to spend the remainder of his weekly allowance in some small present for his chum. Stamp-collecting was one of Simpson's hobbies, and Atherton knew that it was his ambition to get a set of Servian "Death Masks."

"I saw a set in a shop in the Strand only last week," thought Atherton. "I'll take a short cut across Hungerford Bridge, buy the stamps if they are still to be had, and pick up the Tube at Charing Cross. There will be ample time if I make haste."

The approach to the bridge consists of a fairly steep wooden gangway with an abrupt turning at its upper end. The worn planks were slippery with mud, while, being close to the river, the mist seemed denser than ever. From the bridge it was just possible to see the outlines of the adjoining brewery and the tiers of heavy barges lying on the reeking mud, for the tide had almost ceased to ebb.

Less than half-way across the bridge Atherton saw the figures of two men. One was leaning over the low parapet, the other, hands in pockets and his hat stuck on the back of his head, was looking fixedly along the narrow footway. Suddenly the latter poked his companion in the ribs and pointed at the oncoming Scout; then both men turned and leant over the parapet as if interested in the swirl of yellow water twenty or thirty feet beneath them.

"What can their interest be in me, I wonder?" thought Atherton. "No use showing the white feather. I'll walk straight past them—but I'll 'Be prepared.'"

Somewhat to his surprise the two men took particular care to keep their faces averted. But swiftly as he walked by the Scout did not forget the value of unobtrusive observation.

"No. 1.—Height about five feet five, broad shouldered, short legs; back of neck dirty yellow, hair black and long, showing a tendency to curl. Clothes: a billy-cock hat, soiled stand-up collar, with a frayed yellow-and-black necktie showing above the back collar-stud, coat rusty black, circular patch of deep black material on left elbow; trousers grey, frayed at bottoms; boots pale yellow, badly in need of a clean, and much worn on the outside of each heel.

"No. 2.—Height five feet ten, back of neck red, iron-grey hair closely cut, shoulders bent, legs long, feet planted well apart. Cloth cap; blue woollen scarf, blue serge coat and trousers, black boots that had apparently been treated with dubbin. Should take him to be a seafaring man; more than likely a bargeman. I feel pretty certain that I could pick out these men in a crowd of——"

A stifled shout for aid was faintly borne to the Scout's ears. He stopped, turned, then without hesitation ran as hard as he could in the direction from which he had come. The mist hid the two men from his sight, while at the same time a light engine running slowly over the adjacent bridge threw out a dense cloud of steam that, beaten down by the moist atmosphere, made it impossible for Atherton to see more than a yard ahead.

Once more came the cry, this time nearer, but gurgling, as if the victim's mouth was being held by one of his assailants. Imitating a man's voice, the Scout shouted. Just then the cloud of steam was wafted away, and Atherton was able to see what was taking place.

The two men he had previously passed were struggling fiercely with a tall, elderly gentleman, who in spite of his grey hairs was strenuously resisting. Even as the Scout dashed up, the two rascals deliberately lifted their victim over the iron balustrade. There was a stifled shriek followed by a heavy plash, while the assailants bolted as fast as their legs could carry them.

Three or four pedestrians, looming out of the mist, promptly stood aside to let the hurrying men pass. The former made no attempt to stop the fugitives. All they did was to stand still and gaze after them till they were lost to sight.

"A man has been thrown into the river!" shouted Atherton. "Run down to the Charing Cross Pier and get them to send out a boat."

Throwing off his coat and shoes the Scout climbed over a parapet and lowered himself till his whole weight was supported by his hands. There he hung for a brief instant. He realised that the drop was a long one, and in addition there was the possibility of falling not into the water but upon the deck of a barge that might at that moment be shooting under the bridge. In that case it might mean certain death, or at least broken limbs.

Shutting his eyes and keeping his legs tightly closed and straight out, Atherton released his hold and dropped. He hit the water with tremendous force, descending nearly ten feet. Instinctively he swam to the surface and, shaking the water from his hair and eyes, struck out down stream.

Twenty yards from him, and just visible in the murky atmosphere, he caught sight of a dark object just showing above the surface. The next moment it vanished. Putting all his energy into his strokes Atherton swam to the spot and, guided by the bubbles, dived. It seemed a forlorn hope, for at a few feet below the surface the thick yellow water was so opaque that he could not distinguish his hands as he struck out. For nearly half a minute the brave lad groped blindly. His breath, already sorely taxed by the force of his drop from the bridge, was failing him. He must come to the surface ere he could renew his vague search. Just as he was on the point of swimming upwards his left hand came into contact with a submerged object. His grip tightened. With a thrill of satisfaction he realised that he had hold of the victim of the outrage.

Thank Heaven, the surface at last! Turning on his back Atherton drew in a full breath of the dank yet welcome air, then shifting his grasp to the collar of the rescued man drew him face uppermost to the surface. To all appearance the old gentleman was dead. His eyes were wide open, his lips parted, his features were as white as his hair.

The Scout looked about him. His vision was limited to a circle of less than fifty yards in radius; beyond this the mist enveloped everything. The Embankment, the bridges, the Surrey side—all were invisible. But above the noise of the traffic on the Embankment and the rumble of the trains across the river came the dull roar of voices, for already a dense crowd had gathered almost as soon as the alarm had been given by the hitherto apathetic pedestrians on the foot-bridge.

"The wind was blowing down stream," thought Atherton. "If I keep it on my left I ought to strike shore somewhere, so here goes."

Still swimming on his back, and holding up the head of the rescued man, the Scout headed towards the Middlesex side. His progress was slow, for his burden was a serious drag, and his strength had already undergone a severe strain. His clothes, too, were a great impediment. Had it been clear weather Atherton would have been content to keep himself afloat till picked up by a boat, but he did not relish the idea of drifting aimlessly on the bosom of old Father Thames; his plan was to make for land, hoping to reach the Embankment somewhere in the neighbourhood of the steps by Cleopatra's Needle.

All this while, owing to a slight veering of the wind, Atherton was swimming, not towards the shore, but almost down stream. He wondered faintly why his feet had not yet touched the mud. More than once he thrust his legs down to their fullest extent, hoping to find something offering more resistance than water, but each time his hopes were not realised.

He was momentarily growing weaker. His movements were little more than mechanical, yet not for one instant did he think of abandoning his burden to save himself. His clothing seemed to hang about his limbs like lead. Ofttimes he had practised swimming in trousers, shirt and socks—for one of the Scouts' swimming tests is to cover fifty yards thus attired; but he had already covered more than four times that distance, while, in addition, he was heavily handicapped by having to tow another person.

Presently a dull throbbing fell upon the Scout's ears.

"A steamboat," he muttered. "Wonder if she'll come this way."

And expending a considerable amount of his sorely tried breath he shouted for aid. A sharp blast upon a steam-whistle was the response, while a hoarse voice bawled, "Where are you, my man?"

"Here," replied Atherton vaguely, for owing to the mist the direction in which the sound came from was quite unable to be located.

Fortunately the steamboat was heading almost down upon the nearly exhausted lad. Her bows, magnified out of all proportion, loomed through the misty atmosphere.

"Stop her!" shouted the coxswain to the engineer, then, "Stand by with your boathook, Wilson."

Losing way, the boat—one of the Metropolitan Police launches—was brought close alongside the rescuer and the rescued. The bowman, finding the lad within arm's length, dropped his boathook, and leaning over the gunwale, grasped Atherton by the shoulder. The coxswain came to his aid, and the victim of the outrage was hauled into safety.

Shivering under the stern canopy of the launch, Scout Atherton assisted the bowman in his work of restoring the half-drowned man to life. Before the craft reached Charing Cross Pier, the policeman was able to announce that there was yet hope.

Feeling dizzy and numbed Atherton stepped ashore.

"Can I help, sir?" he asked.

"You'd better run off home and get out of those wet clothes," replied the coxswain, a sergeant of police. "Do you feel equal to it, or shall we get you a cab?"

"I'm all right, I think," replied Atherton.

"Let's have your name and address," continued the sergeant, pulling out his notebook. "You're a plucky youngster, that you are."

Atherton was not at all keen on giving the particulars. Publicity was the thing he wished to avoid. He had done a good turn, and, Scout-like, he wanted, now that he could render no further assistance, to modestly retire from the scene.

His desire was gratified, for at that moment a doctor, two reporters and an ambulance man came hurrying down the incline leading to the pier. The doctor turned his attention to the still unconscious man, while the Pressmen tackled the sergeant in a most business-like manner.

Atherton seized the opportunity and slipped off.

The water was still dripping steadily from his things. He started into a run, partly to restore his numbed circulation and partly to get back to the spot where he had taken his venturesome dive, for he remembered that he had left his boots and coat on the bridge. By the time he reached the top of the three flights of stairs leading from the Embankment to the bridge his watery tracks were quite insignificant, and of the few people hurrying on their way home none noticed the hatless, coatless and bootless youth.

The crowd of curious spectators had dispersed. A rumour that the water police had picked up the body of the victim had resulted in a wild stampede along the Embankment. Atherton made his way to the place where he had dropped into the river. His coat and boots had vanished.

"I'm in a pretty fine mess!" he exclaimed, ruefully. "Dirty trick, sneaking a fellow's clothes, though. I wonder what the Head will say when I turn up late."

Atherton knew that if he journeyed to King's Cross otherwise than on foot he would be exposing himself to a great risk by taking cold, so adopting the "Scout's pace"—alternately walking and running twenty paces—he found himself at the Great Northern metropolitan station in very quick time.

Upon arriving at Collingwood College a slice of good luck awaited him. Jellyboy, the porter, was standing on the kerb beckoning frantically to a newsboy. The outer door was open, and the Scout slipped in unobserved.

Under ordinary circumstances he would have gone straight to his house master, but the desire to keep his good turn a secret caused him to make straight for the dormitory. Here he changed, placing his still damp clothes under his bed till he could find an opportunity of drying them.

"Prep." was over. Harrison, the junior science master had been in charge, and had not noticed Atherton's absence. The Scouts were assembling for the evening's instruction, and, not without curious glances from his chums, the Leader of the "Otters" joined them.

Somehow Atherton did not feel quite satisfied with himself. He began to realise that by avoiding publicity he had placed himself in a false position. By promptly giving the police a detailed description of the two assailants, the arrest of the culprits might have been speedily effected. Besides, he did not relish the stealthy tactics he had to adopt in returning to the College without being detected.

"I'll see Mr Trematon and tell him all about it," he declared. "It seems to me that I've made a pretty mess of things, so here goes."

"Well, Atherton, what do you want?" basked the Scoutmaster, as the Leader went up to him and saluted. "A suggestion for the camp, eh?"

"No, sir," replied Atherton. "I'm in a difficulty and want advice. Can I speak to you in the store-room, sir?"

"Certainly," assented Mr Trematon kindly. "Now, Atherton, what is it that's worrying you?"

The Scout told the story of his adventure, omitting nothing, although he put the account of his part of the rescue in as brief a form as possible.

"You had better come with me to the Head," said Mr Trematon, when Atherton had finished. "I think I can account for your reticence, and no doubt Mr Kane will see things in a similar light."

"Whatever possessed you to go without giving your name and address, Atherton?" asked the Rev. Septimus. "Don't you see you are putting obstacles in the way of the police?"

"I have thought of that since, sir," replied Atherton; "but at the time all I wanted was to make myself scarce."

"Make yourself scarce!" repeated the Head, reprovingly. "That is hardly the right way to express yourself:"

"Well, sir, you see I did not want any reward for my good turn."

"What a strange idea," remarked the Rev. Septimus Kane to his assistant.

"One of the principles of Scout law, sir; to do a brave action with the prime motive of self-advertisement is deprecated by all true Scouts."

"Yet I notice names of Scout heroes frequently figure in the Press," added the Head, musingly.

"Possibly not with their consent, sir."

"There are volumes in the meaning of the word 'possibly,' Mr Trematon. However, the best thing you can do is to take Atherton over to the police-station. Ask that his identity may be concealed if practicable. They will telephone the description of the two assailants to the other stations, and in that way a tardy assistance may be rendered to the Force. Don't wait, it is late already."

"Very good sir. Do you want me——"

Mr Trematon's words were interrupted by a sharp knock at the study door, and in response to the Head's invitation Jellyboy, the porter, entered, followed by a stalwart constable.

"Good evening, sir," exclaimed the policeman, saluting. "I've been sent to make a few enquiries, sir; can I speak to you in private?"

"I do not think privacy is desirable, constable," replied the Rev. Septimus, who at times possessed a keen intuition. "You have called with reference to that case of attempted murder on Hungerford Bridge."

"You're right, sir," said the astonished policeman. "You'll excuse me, sir, but might I ask how you know?"

"Easily explained, constable. You have a parcel under your arm. It has been crushed. The brown paper covering has burst. I can see a portion of the contents: a boy's cap with the badge of Collingwood College. Since one of my pupils—this lad, as a matter of fact—has arrived without a cap, coat or boots, and has reported to me that he jumped into the Thames after a gentleman who was thrown over the bridge by a couple of roughs, it naturally follows that I can guess the nature of your errand."

"You are quite right, sir," said the constable, admiringly.

"I frequently am," rejoined the Head, complacently. "But to return to the point: has the identity of the victim been established?"

"Yes, sir, the gentleman is Sir Silas Gwinnear. You might have heard of him, sir."

Leslie Trematon gave an exclamation of surprise. Atherton, equally astonished, could hardly realise the news. It seemed like a dream. Only a few days previously Sir Silas had written expressing his opinion of the Scout movement in emphatic terms of disapproval, and now, by the irony of fate, he owed his life to a Scout's promptitude and bravery.

"What is the matter, Mr Trematon?" asked the Head, who could not fail to notice the Scoutmaster's ejaculation of astonishment.

"I happen to know Sir Silas, sir," he replied. "He was a friend of my father's. Only the day before yesterday he wrote to me."

"And how is Sir Silas?" asked the Rev. Septimus, addressing the policeman.

"Getting along finely, sir, considering he's not a young man by any means."

"And his assailants?"

"No trace of them, sir. One of our men found these articles of clothing and took them to the station. A letter addressed to Master Atherton was in one of the pockets, so the Inspector sent me here to make enquiries. Is this the lad, sir?"

"That is Atherton, constable."

"Look here, young gentleman, can you give us any information as to what occurred?"

The Scout accurately described the appearance of the two men whom he saw commit the assault. The policeman, hardly able to conceal his surprise at the detailed description, laboriously wrote the particulars in his notebook; the Head was also surprised at his pupil's sense of perception. Only Mr Trematon maintained a composed bearing. Inwardly he was proud that his instruction in scoutcraft had borne such good fruit.

"Let me see," remarked the Rev. Septimus. "Atherton is, I believe, a—er—Scout?"

"Yes, sir," assented the Scoutmaster.

"He ought to be a detective, sir," observed the constable. "Only it's a great pity he didn't inform us at once. We might have nabbed those rascals."

"He quite realises that," said the Head. "One thing, he has been the means of saving life under very trying circumstances. The capture of the assailants is, after all, a secondary matter. Trematon, you ought to be proud of your Scouts if they are all like this one."

"I trust they will prove themselves equal to the occasion should necessity arise, sir," replied the Scoutmaster.

"You'll be sure to get the Bronze Cross, Dick," exclaimed his chum, Phil Green, as he paused in his work of varnishing a tail-board to critically admire his handiwork.

"Don't talk rot," replied Atherton, for the congratulations of his fellow-scouts were beginning to be embarrassing. "Don't talk rot, and get on with your work. We've only four clear days, and this trek-cart is nothing like finished."

The lads were hard at work in the old gym. The place reeked of elm sawdust and varnish, for sixteen Scouts were all busily engaged in constructing a cart.

"What did it feel like when you jumped of the bridge?" asked Fred Simpson, the Leader of the "Wolves."

"I cannot explain; I simply dropped," replied Atherton. "Perhaps if I had hesitated, I might have funked it. But dry up, you fellows, I've had enough. Come on, Baker, are those linchpins finished yet?"

"The papers made a pretty fine story about you, Dick," said Green, returning to the charge. "'The Scout and the Baronet,' the report was headed. Funny that it was Sir Silas Gwinnear you rescued, wasn't it?"

"You'll be funnier still if you don't hurry up with that coat of varnish," exclaimed the Leader, with mock severity. "Stick to it, man; we want to be able to show Mr Trematon something by the time he returns."

Just then Jellyboy stalked in.

"Mr Atherton, you're wanted at once in the Head's study."

Atherton hurriedly washed his hands, smoothed his hair and donned his blazer over his Scout's uniform. It was the custom for the lads to wear their uniform during their work in the gym., after "prep." was over; but for the first time on record was a Scout in full war-paint summoned to see the Head. The Rev. Septimus took particular pains to avoid sending for any of his pupils except when in their ordinary clothes; but on this occasion the warning was evidently urgent.

"Come in," said the Head, briskly. "Atherton, this is Sir Silas Gwinnear."

The Scout could hardly recognise the stranger as the same person he had rescued. Sir Silas under ordinary everyday conditions was a tall, thin-featured man with grey hair and beard. He bore the stamp of a self-made merchant, for he was somewhat showily dressed, an obtrusive gold watch-chain of old-fashioned make with a heavy seal, a massive signet ring and a thick scarf-pin being the outward signs of his opulence. His manner was pompous; but in his deep-set grey eyes there lurked the suspicion of a kindly nature.

"Ah, good evening, Atherton," exclaimed the Baronet, rising and shaking the Scout's hand. "I am out and about, you see, thanks to your bravery, my dear young sir. I took the first opportunity of calling and thanking you personally for what you have done for me."

"I only did my duty, sir."

"And did it well, too, I declare. To get to the point, Atherton: I am a man of few words, but you will not find me ungrateful. If at any future time I can be of assistance to you don't hesitate to ask. I flatter myself that I have a fair share of influence. Meanwhile I don't suppose you will object to having a little pocket-money. School-boys, I believe, are always fond of tuck."

So saying, Sir Silas thrust his hand deep into his trousers' pocket and fished out a fistful of gold and silver coins. From these he selected five sovereigns and offered them to his youthful rescuer.

Atherton drew himself erect.

"No, thank you, sir," he said firmly but politely. "I cannot take the money."

"Cannot take the money!" repeated Sir Silas, hardly able to credit his sense of hearing. "Why not?"

"I am a Scout, sir, and a Scout is not allowed to receive any reward for doing a good turn."

"A Scout! Bless my soul, so you are!" exclaimed the Baronet, as his eyes noticed for the first time the lad's knotted handkerchief showing above his buttoned-up blazer, and his bare knees. "I am afraid I am not in sympathy with the Scout movement," he added bluntly.

"We have recently formed a troop as a kind of experiment," explained the Rev. Septimus, apologetically. "But I must admit, Sir Silas, that I have had no reason up to the present to regret my decision in granting Scouts to be enrolled from my pupils."

"Atherton's refusal to take a small present surprises me," said the Baronet. "Is that rule strictly adhered to?"

"I know very little about the rules and regulations of Scoutcraft," replied the Head. "Perhaps Atherton can answer your question."

"Well, is it?" asked Sir Silas abruptly. "Yes, sir," replied the Scout, rather relieved to find that the conversation had turned into a channel that was more to his liking than being the object of embarrassing congratulations.

"H'm. The upkeep of the movement costs money, I suppose. How do you manage? I always thought Scouts cadged to meet their expenses."

"No, sir, we are not allowed to cadge. That is also against regulations. We are self-supporting."

"How?"

"To take our own case, sir, all our pocket-money is paid into the troop funds at the beginning of the term. We have to be thrifty, that is also an obligation. We all do something to add to the funds."

"I gave the permission, Sir Silas," remarked the Head. "In a commercial training school like Collingwood College I think that judiciously supervised earnings tend to develop commercial instincts and teach lads the value of money at an age when they are apt to disregard it."

"That is so," agreed the baronet. "'Take care of the pence,' you know. But suppose, Atherton, a sum of money was presented to the troop funds, what would you do then?"

"Our Scoutmaster, Mr Trematon, could answer the question better than I, sir," replied the Scout.

"Trematon? Is he here? That's strange. He wrote to me the other day. I thought the name Collingwood College seemed familiar, but until this moment I failed to connect the two circumstances. He asked me to allow him to take a party of Scouts to my place in Cornwall—to Seal Island."

"Yes, sir."

"And I refused. I gave my reasons. I suppose you fellows called me all sorts of uncomplimentary names, eh?"

"Oh, no, sir. We were disappointed, of course. Mr Trematon was too, for he loves Cornwall, so he tells us. Now we are going to Southend instead."

"I suppose you wouldn't mind if I altered my decision?"

"Indeed, sir, it would be ripping," replied Atherton, enthusiastically.

"Well, I will write to Mr Trematon on the matter to-morrow," declared Sir Silas. "If you won't accept a pecuniary reward perhaps I can pay off a portion of my debt of gratitude to you in another way. All the same," he added, with a touch of pomposity, "I wish it to be clearly understood that the objections I have expressed to Mr Trematon I still believe in: but since you refuse any pecuniary reward I think I am justified in making this offer. I suppose there is no reason why you should decline this slight concession?"

"Thank you very much, sir," replied Atherton warmly. "In the name of the troop I thank you."

"No need for that," said Sir Silas grimly. "The troop, whatever that is—I suppose it has something to do with Scouts—has to thank you, not me. I will write to Mr Trematon this evening on the matter."

As soon as Leader Atherton was dismissed he ran as hard as he could out of the schoolhouse, and crossed the playground and burst excitedly into the old gym.

"I say, you chaps," he exclaimed, "it's all right after all. Sir Silas Gwinnear has reconsidered his decision and we have permission to camp out on Seal Island."

The roof echoed and re-echoed to the hearty cheer the Scouts raised, while little Reggie Scott, the Tenderfoot of the "Otters," showed his enthusiasm by attempting to dance a hornpipe on the back of the vaulting horse. His efforts came to an abrupt conclusion, and he rose from the floor dolefully rubbing the back of his head, while his comrades were unable to restrain their mirth.

In the midst of the uproar the Scoutmaster entered.

"What's all this, boys?" he inquired. "More play than work it looks like; and only a few days more before we go to Southend, and our preparations are not half made."

"No need to trouble about Southend, sir," said Fred Simpson, in an excited tone. "Atherton has seen Sir Silas, and we can go to Seal Island."

"Atherton has seen Sir Silas?" repeated Mr Trematon. "Come, Atherton, let me hear all about it."

"It is rather a pity that Sir Silas gives his consent under these conditions," he continued when the Scout had related what had occurred in the Head's study. "A gift grudgingly bestowed is but half a gift. No matter, lads; Atherton has made a good impression as a Scout, and I feel certain that the rest of us will leave no stone unturned to convince the baronet that Scouts are not what he imagines them to be. So it is to be Seal Island after all. I am glad, and I think you will agree with me that the possibilities of a thoroughly enjoyable fortnight under canvas are far greater there than at Southend. It was lucky I called in to see how you were getting on, for I meant to buy the tickets to-night. But now, lads, stick to your work, for I see there is still much to be done. Work first and play afterwards—and talk if you can without hindering each other."

For the next two days preparations were hurriedly yet methodically pushed forward. On the Friday the school broke up, the day boys and most of the boarders bidding goodbye to their studies for seven long weeks. Of the boarders who remained all belonged to the Scouts, and formed two patrols.

The "Otters," with Dick Atherton as Leader, were composed of Jack Phillips, Second; Phil Green and Tom Mayne, 1st class Scouts; Will Everest and George Baker, 2nd class Scouts; and Jim Sayers and Reggie Scott, the Tenderfoots.

The "Wolves" were made up of Fred Simpson, Leader; Harry Neale, Second; Jock Fraser, Arnold Hayes and Vernon Coventry, 1st class Scouts; Pat Coventry, 2nd class Scout; and Basil Armstrong, Tenderfoot. Little Dick Frost, the other Tenderfoot of the "Wolves," and one of the keenest of the troop, was the only one who was unable to go camping. His mother had written to the Head saying that as she considered her son a delicate lad, she did not wish him to run unnecessary risks by sleeping in the open. Even the Rev. Septimus smiled when he read the epistle, for Dick was really one of the toughest of a hardy set of lads.

Sir Silas kept his promise by writing to Mr Trematon, confirming the permission he had given to Atherton. In the letter he enclosed a railway pass to Wadebridge for seventeen persons, available for fifteen days.

"No doubt the laws of your organisation will permit you to accept the enclosed," he wrote. "Don't thank me, thank young Atherton. As regards Seal Island, I have written to my bailiff informing him that you are to have uninterrupted possession of the place for a fortnight. There are springs of fresh water, but fuel you will have to obtain from the mainland. Dairy produce is to be had of Trebarwith, the farmer who lives just outside Polkerwyck. You can shoot as many rabbits as you like, on the estate, but remember that the sea-birds are not to be killed or molested. Not only is it an offence against the law to kill birds, being close season, but I am strongly adverse from seeing these creatures harmed, so I sincerely trust that you will take strong measures to carry out my wishes in this respect. Should my keepers report any violation of this condition I will immediately give orders for your lads to quit the island."

Sir Silas' gift had relieved the Scouts of any possible pecuniary difficulty. For months they had put aside their pocket-money, paying into the troop funds for the purpose of defraying the cost of the camp training. For example, Tom Mayne and Coventry major earned sixpence a week for weeding the Head's garden. This sum was promptly paid in. Simpson and Everest had each won prizes in competitions organised by a leading boys' journal. In each case the articles were sold and the sums received added to the general fund. Every lad had done his utmost, and enough had been raised to pay for the railway fares. But there would be very little left when the expenses were met, and now the baronet's generous gift had made it possible for the Scouts to have a splendid holiday and still keep a balance in hand.

On the eve of the momentous journey to the west country, Leaders Atherton and Simpson, on behalf of the two patrols, sprang a little surprise upon their Scoutmaster. Unknown to Mr Trematon the Scouts had purchased a quantity of second-hand, yet serviceable, canvas, and from this they constructed a really smart and well-made ridge-tent suitable for one person. This they presented to the Scoutmaster as a token of appreciation from the "Otters" and the "Wolves."

For their camp equipment the Scouts had to exercise their wits. Their trek-cart was completed; their kit bags packed and stowed; their cooking utensils, truly Spartan in simplicity, were ready; but so far as sleeping accommodation was concerned the lads fully expected to have to construct rough shelters of brushwood and heather. Almost at the last moment the Scoutmaster of another North London Troop came to the rescue. The Collingwood College lads had more than once done his Scouts a good turn, and the opportunity arrived for their services to be reciprocated. The troop in question had just returned from a fortnight under canvas at Shoreham, and acting on their Scoutmaster's suggestion the Scouts lent three large bell-tents to the "Otters" and the "Wolves."

At length the eventful day arrived. The Scouts, all in full marching kit, fell in to be finally inspected by the Head. The trek-cart, filled to its utmost capacity, was placed in charge of Sayers and Armstrong—to be duly noticed and admired by the Rev. Septimus, who, a skilful amateur carpenter himself, always encouraged his pupils to take up carpentering for a hobby.

"Now, boys, I wish you all a very pleasant holiday," exclaimed the Head. "I have every reason to believe that you will do your best to enjoy yourselves and at the same time to keep up the credit of Collingwood College—and of the Scouts. I trust that you will have good weather, and that you will return safe and sound and ready to resume your studies with renewed keenness when the time comes. I will say no more, except perhaps that I wish I were coming with you."

The Scouts cheered at the last remark. They appreciated the Head's envy, but at the same time they were secretly glad that he was not accompanying them. There was a certain austerity about the Rev. Septimus that acted as a barrier betwixt master and scholar, a barrier that, out of school hours, did not exist between Mr Trematon and the lads.

The Head stepped up to Mr Trematon and shook hands.

"Scouts!" exclaimed the Scoutmaster. "Patrols right—quick march!"

The first stage of the long journey to Seal Island had begun.

It was four o'clock in the afternoon when the Scouts detrained at Wadebridge, the termination of their railway journey. Seven miles of hilly country separated them from the village of Polkerwyck. The afternoon was hot and sultry, there was no wind to cool the heated atmosphere; but braced up by the attractiveness of their novel surroundings the lads thought lightly of their march.

By some unexplained means the news of their impending arrival forestalled them, and at the station two Cornish troops, with drum and fife bands, awaited them. With typical kind-heartedness their west country brother-Scouts regaled their London visitors with tea, Cornish cream, pasties and other delicacies for which the Duchy is noted, while to still further perform their good turns they insisted upon dragging the camping party's trek-cart for nearly five miles.

It was a delicious march. Everything seemed strange to the visiting Scouts, and novelty was one of the chief delights of the holiday. The wild, moorland country, the quaint stone cottages, stone walls in place of hedges, the broad yet attractive dialect of the villagers, and last but not least their wholehearted hospitality, filled the lads with unbounded delight, while Mr Trematon, being in his native county, was as enthusiastic and light-hearted as his youthful companions.

The shadows were lengthening as the "Otters" and the "Wolves" breasted the last hill. The lads had relapsed into comparative silence. The strangeness of their surroundings so filled them with keen joy that they could only march in subdued quietness and feast their eyes on the natural beauties of the country.

Suddenly Fred Simpson, who headed the march, stopped, and, raising his stetson on the end of his staff, gave a mighty shout. His example was followed by the others as they gained the summit of the hilly road. Almost beneath his feet, and extending as far as the eye could see, was the sea, bathed in all the reflected glory of the setting sun. Not one of the Scouts had previously seen the sun set in the sea: their knowledge of the seaside was confined to the Kentish and Essex coast towns where the orb of day appears to sink to rest behind the inland hills.

On either hand dark red cliffs cut the skyline, forming the extremities of Polkerwyck Bay. The headlands, fantastic in shape, reared themselves boldly to a height of nearly three hundred feet. On the easternmost point, appropriately named Beware Head, stood a tall granite lighthouse, the stonework painted in red and black bands. On the western headland—Refuge Point—stood the white-washed houses of the coastguard station. Between the headlands was Polkerwyck Bay, the village giving it its name nestling on either side of a small tidal estuary, and enclosed by a gorge so narrow and so deep that the Scouts imagined that they could throw a pebble from the road upon the stone roofs of the picturesque cottages.

Of the estuary, and separated from the land by a stretch of deep blue water, lay what appeared to be a small rock.

"Where's Seal Island, sir?" asked Atherton, who was the first to find his tongue.

"There," replied the Scoutmaster, pointing to the rock.

"Why, it's ever so small," cried several of the Scouts in a chorus.

"Large enough for us, lads," replied Mr Trematon with a hearty laugh. "Objects look deceptive when viewed from a height. Now, then, fall in! Sayers, Scott, Pat Coventry and Armstrong, follow the trek-cart with the drag ropes. You will want to keep it well in check going down the hill. Patrols—quick march!"

Down the zig-zag hill the Scouts made their way; at every step Seal Island seemed to get larger and larger, till at length the lads halted in the main and only street of Polkerwyck, where they were surrounded by all the available population: men, women and children to the number of about eighty.

"Welcome back to Polkerwyck, Mr Trematon, zur," exclaimed a hale, grey-headed fisherman, picturesquely attired in sou'wester (although the day was hot), blue jersey, tanned canvas trousers, and heavy sea-boots.

"Thanks, Peter Varco," replied the Scoutmaster, heartily shaking the old man's hand. "I am glad to see you again. You look just the same."

"Sure us old 'uns keep powerful hearty in these parts, Mr Trematon. Thanks be, I be middlin'. These be the Scouts, eh? Likely lads they be, although I reckon as they bain't up to our Cornish lads, eh, Mr Trematon? Squire's man, Roger Penwith, he comed down to see I yesterday. Says 'e, 'Squire has written to say Mr Trematon's Scouts are a' comin' to Seal Island, and Squire wants 'em looked after prop'ly-like.' 'Trust I to do my part,' says I, and sure enow I have a-done. The Pride of Polkerwyck—you'll remember 'er, Mr Trematon—is at your sarvice, an' the three small craft as well; so when you'm ready to go over along, them boats is ready."

"Thank you, Varco," said the Scoutmaster. "The sooner we get to the Island the better, for it is past sunset."

"And Roger Penwith 'e 'as placed a load or two o' firewood close alongside the landin' place, Mr Trematon. Thought as 'ow you'd be wantin' it."

"Good man, Mr Penwith!" ejaculated Mr Trematon. "We can find a place to store this cart, I suppose?"

"Sure there'll be a sight of room in yon hut," replied the fisherman.

"Unload the trek-cart, lads," ordered the Scoutmaster. "Keep each patrol's belongings apart. Atherton, will you take charge of one boat; Simpson, another; load the heavy gear into the third boat, and Phillips and Green will assist me in taking her across."

Hither and thither the Scouts ran, each with a set purpose, while the on-lookers watched with admiration as the baggage was unloaded and the trek-cart bundled at the double into the hut.

"Have you a key to the door, Mr Varco?" asked Everest, with characteristic caution, after the cart had been housed.

"Key, young man? What do 'e want wi' a key for, might I make so bold as to ax? Sure, us be all honest men in these parts," said Varco, in a tone of mingled reproof and pride.

At length the three boats were manned, and the Scoutmaster gave the word to push off and give way. Thanks to his early training Mr Trematon was thoroughly at home both on and in the water, and he had developed particular pains to instruct his lads in the art of managing a boat, till the style of the Collingwood College Scouts on the Highgate Pond became a subject of envy to most of the other troops in the district.

It was a ripping row. The only fault that the Scouts had to find was that it was far too short. The water was as calm as a mill-pond, although a faint roar betokened the presence of the customary ground-swell on the shore beyond the bay.

The Scouts landed in a sandy cove in the south-eastern side of the Island, where a winding footpath, that showed little signs of frequent image, wound its way up in a zig-zag fashion to the higher ground. The baggage was carried ashore, and the lads, having secured the boats' painters, prepared to convey their goods to the camping-place.

"You are not going to leave the boats like that, are you?" asked Mr Trematon.

"Aren't they all right, sir?" said Leader Simpson, inquiringly. "I made sure each painter was properly made fast with a clove-hitch, sir."

"Yes, that's all very well, but it is not good enough. You forget the rise of tide, which here exceeds fifteen feet at springs. Besides, it might come on to blow in the night, and even though the Island is sheltered from on-shore winds there would be sufficient swell to smash the boats to splinters. We must haul them well above high-water mark."

Back trooped the Scouts, and, taking up positions all round the first boat, tried to drag her up the steep incline; but as soon as the craft was clear of the water it was evident that the task was beyond them. The boat was heavily built, and all hands could not lift her forward another inch.

"Now what is to be done?" demanded Mr Trematon, with a view of testing the Scouts' practical knowledge.

"Put her on rollers, sir," suggested Jock Fraser.

"A good idea, but where are the rollers?"

"We can use our staves, sir."

"And spoil them by the rubbing of the boat's iron-bound keel. That would only be advisable in a case of necessity. To make use of the oars is open to a similar objection. Open that stern locker, Fraser. You'll find a powerful tackle there, if I'm not mistaken. Ah! There it is, and I can see a post driven in on purpose for hauling boats up."

The upper block was soon placed in position, and Fraser was about to bend the painter to the lower block when the Scoutmaster again called him to order.

"Won't do," he exclaimed. "You'll more than likely pull the stem out of her. Look at her forefoot, Fraser: do you see a hole bored through it?"

"Yes, sir," replied the Scout.

"Very well, then. There's a short iron bar in the locker. Thrust that through the hole and bend the block to it by this rope. That's it: now we can haul away, and the keel will take the strain. Four of you keep the boat upright and the rest tail on to the tackle."

By this means the heavy craft moved slowly arid surely, and was at length hauled above the line of dead seaweed that denoted the level of high-water spring tides. The remaining boats were treated in the same way, and the Scouts were free to proceed to the camping-ground.

Before ten o'clock the tents were pitched, a roaring camp fire threw its comforting glow upon the scene, and the two patrols were discussing their hard-earned and frugal supper with commendable avidity that betokened a healthy mind in a healthy body.

"Now, lads," exclaimed the Scoutmaster, as soon as the meal was concluded, "we must turn in. It has been a long day for us, and I don't suppose the majority of you will sleep very soundly the first night under canvas. But no talking, mind. There is a time for everything, and if talking is kept up those who might otherwise be able to sleep will be disturbed. Good-night!"

"Anyone awake?" enquired Mr Trematon softly, thrusting his head through the partially unlaced opening of the tent, where the eight "Otters" were lying like the spokes of a wheel, each lad's feet towards the tent-pole.

"I am, sir," replied Atherton and Green.

"Slip on your things and come out. I've a little job for you."

Without hesitation the two lads obeyed, and were soon blinking in the early morning sun. It was just after five o'clock—réveillé was to be at half-past six.

The air was keen and the dew still thick upon the short grass. The village of Polkerwyck was yet in shadow, for the sun had not risen sufficiently high to throw its slanting beams upon the deep-set hamlet. But already there were signs of activity, for several of the fishing boats that had been out all night had just returned and were landing their cargoes for conveyance to the nearest railway station. So still was the air that the reflections of the frowning cliffs and the deep browns of the tanned sails were faithfully reproduced in the placid water. The morning mist still lingered on the hill-tops, and drifted in ill-defined patches across the headlands that defined the limits of the bay.

"Best part of the day, sir," said Atherton cheerfully, as he surveyed the scene of tranquillity.

"It is," assented Mr Trematon. "It makes one pity the sluggards who never see the sun rise. But I want you two to come with me across the Polkerwyck. Old Varco promised he'd have an old boat's mast ready for use as a flagstaff, and I want to commence our first day on Seal Island by saluting the flag."

It was now nearly high tide, and thanks to the steepness of the shore there was little difficulty in launching the smallest boat. The Scoutmaster steered, while Atherton and Green rowed.

"Isn't the water clear," said Green, looking over the side. "I wish we could have a bathe."

"All in good time," replied Mr Trematon. "There's a splendid bathing cove just past that point of the island, where there is hardly any current."

"How do we get there, sir?" asked Atherton. "The cliffs rise straight from the sea."

"There's a path leading to a cave, that in turn communicates with the sea. It used to be a favourite smugglers' haunt a century or more ago. Easy now, Green, we're nearly there."

The boat's forefoot grounded on the sand; Green jumped out and secured the painter, while the Scoutmaster and the Leader stowed the oars and sprang ashore.

"Here's the mast," said Mr Trematon, indicating a thirty-foot pole lying on the little stone quay. "I see Varco has rove some signal halliards—thoughtful man."

"It's a lump, sir," remarked Green. "How are we to get it into the boat? It will project ten feet at each end, and we will have no end of a job to row."

"I don't mean to place it in the boat. We'll tow it. Atherton, make this rope fast to that ring-bolt: we'll parbuckle the spar."

The Leader knew what his Scoutmaster meant. To push the mast over the edge of the quay would scratch the paint and roughen the wood. Making the end of his rope fast to a ring about a foot from the edge of the wharf, Atherton waited till Mr Trematon had performed a similar operation, the two ropes being twenty feet apart. Carefully the spar was rolled till it rested on the ropes, the "free ends" of which the Scoutmaster and Atherton held.

"Push the mast over the quay, Green," said Mr Trematon.

The pole, prevented from falling by the bights of the ropes, was now easily and slowly lowered into the water, and attached by its tapered end to the stern of the boat.

"That went smoothly enough, sir," said Green.

"Yes, two men can parbuckle a suitably-shaped object of thrice their combined weight. All the same it won't be such an easy task to haul the mast up the slope of Seal Island."

Upon landing on the Island, Atherton took the tapering end on his shoulder, Mr Trematon and Green supporting the heavier end.

"Don't keep step," urged the Scoutmaster, "or the mast will sway and possibly capsize us. Now, proceed."

It was no light work carrying the thirty-foot spar up the steep path, but dogged energy prevailed, and before it was half-past six the flagstaff was in position, ready for the hoisting of the Union Jack.

The first call on Hayes' bugle brought the Scouts from their tents. Baker and Pat Coventry, who overnight had been detailed for cooks, raced off' to construct earth ovens and light fires. Sayers, Scott, and Armstrong, the three Tenderfoots, marched off with buckets to bring a supply of water from the spring that the Scoutmaster had pointed out; Everest and Fraser took a boat and crossed to the mainland to procure milk, eggs and bacon from the farm; while the rest of the two patrols opened up tents and aired the bedding.

At seven, coffee and bread and butter were served out: not a standing meal, but merely a "stay" before breakfast. This was followed by prayers, then all hands fell in for bathing parade.

All except Atherton and Green were somewhat surprised when Mr Trematon led the way, not to the landing-place, but up hill in the direction of the ruined hermitage.

"What's that?" exclaimed young Armstrong, as a small brown animal with a tuft of white on its tail darted into a hole on the site of the path. "Why, I believe it's a rabbit."

"Look, there are dozens of them," added Everest, pointing to a hollow about two hundred yards off. "There they go as hard as they can."

"Yes, the Island is overrun with them, and so is most of Sir Gwinnear's estate. The farmers look upon them as a pest, and destroy as many as they can."

"Why pests, sir?" asked Phillips.

"Because they eat the grass that feed the sheep, nibble the young corn shoots, undermine hedges, and so on. Of course, they are not so numerous as in Australia, where agriculture is threatened with disaster by their depreciations. One day, Phillips, you can have a chance of shooting a few for our dinner. It will be necessary for you to get a gun licence before you can carry a gun. I'll see to that, however. But steady now: here's the entrance to our bathing cove."

"What, here, sir?" asked several of the lads in chorus, and in a tone of incredulity, for the place indicated by the Scoutmaster was a circular hole surrounded by a ruinous stone wall. "Yes: follow me. Mind where you tread. It's quite safe if you take reasonable precautions."

The shaft, a natural tunnel, was descended by means of a spiral path, in places less than three feet in width, a rusty iron handrail—a relic of the good old smuggling days—serving as a none too reliable protection.

At eighty feet from the summit a steeply shelving floor was reached, whence a long, irregular tunnel led seawards. For part of this distance the place was in almost total darkness, while the air was moist and chilly.

Presently the tunnel began to get lighter, and the rocky floor gave place to a carpet of smooth white sand, terminating at the water's edge.

"What a ripping bathing-place, sir," exclaimed Neale.

"Come on, lads, let's see who will be the first in," shouted Coventry major, hastily slipping off his scanty garments: an example that the others followed.

"Steady, boys," said the Scoutmaster. "Not so fast. I know that you can all swim more or less: but what precautions are you taking against accidents?"

"We're all together, sir," replied Coventry senior. "If needs be there is plenty of assistance ready."

"Quite so," assented Mr Trematon. "But that is hardly sufficient. I remember the case of a party of fifty soldiers bathing together. One of them suddenly sank without a shout, and he was not missed until the men paraded to march back to barracks. So I think we will have a boat out. The two Leaders and I will man the craft, and we can have our swim afterwards."

"A boat, sir? We will have to go back to the landing-place to fetch one."

"No need to do that. Come this way."

A few feet above high-water mark a side passage branched from the main tunnel, and within it was a small rowing boat about twelve feet in length, with oars and thole pins ready for use. A life-buoy and a length of rope lay under the sternsheets.

"This is one of Peter Varco's boats," said Mr Trematon. "He always keeps it here for the use of visitors who come to the place—Dollar Cove it is called—for bathing. He told me we could make use of it."

"Why is this called Dollar Cove, sir?" asked Basil Armstrong.

"They say a Spanish treasure ship was wrecked on the west side of Seal Island, and that her precious cargo was strewn over the bottom of the sea. Curiously enough the only coins ever washed ashore have been found at the mouth of this cove."

"Should we find any if we looked, sir?" asked Fraser.

"That I cannot say; but suppose instead of standing here in the cold we launch this boat?"

Soon the placid waters of the bathing-cove were disturbed by the splashing of the lads of the two patrols, and all were somewhat reluctant to hear Mr Trematon's voice calling for them to come and dress.

When the Scoutmaster and the Headers had had their swim the Scouts made their way to the top of the natural staircase, and, doubling, returned to the camp glowing with health and excitement.

Directly the bedding was replaced and the tents tidied, breakfast was served. The camp oven fires had been banked up, and a plentiful supply of hot water was instantly available. Eggs, boiled in salt water,—which, according to Mr Trematon's idea, were far more appetising than if done in fresh water—small flat loaves baked on hot ashes, and cocoa formed the repast.

"Whatever is the matter with you, Hayes?" asked Mr Trematon as the Scout gave a partly suppressed gurgle, rolled his eyes, and clutched his throat with both hands.

Without replying Hayes suddenly bolted, while the Scoutmaster and several of the Scouts followed to see what was amiss.

"The bread, sir," gasped Hayes, after several attempts to make him explain.

"The bread? What's wrong with it."

"It tastes horrible," replied the victim. "I feel awfully queer."

Just then young Coventry came running up, making similar grimaces to those of the first sufferer. He in turn was followed by little Reggie Scott, who, though undoubtedly equally as upset as his bigger comrades, kept himself more under control.

"It's the bread, sir," he announced, holding up half of one of the flat cakes. "I believe there's oil in it."

The Scoutmaster took the proffered bread and smelt it.

"You're right," he replied. "It is paraffin. What on earth have Baker and Pat Coventry been doing? Cheer up, you sufferers; you're not poisoned. Smile and look pleasant, and we'll hold a court-martial on the cooks."

Further examination revealed the fact that all the bread was tainted with the unpleasant odour of paraffin. On being questioned Pat Coventry replied that he took no part in making the dough, while Baker admitted that he had noticed an oily substance on the water when mixed with the flour.

"I skimmed it off, sir," he explained. "I didn't know that it was paraffin."

"Haven't you a nose? Why didn't you use your sense of smell?"

"I didn't think of it, sir."

"Well it cannot be helped now; another time, if you have any doubts, ask me. That's what I am here for," said Mr Trematon. "Serve out the biscuits, Atherton. The bread is useless. After breakfast we must find out how the paraffin got into the flour. But it's close on eight. Fall in."

The two patrols, staves in hand, lined up under their respective Leaders on either side of the flagstaff. The Union Jack was toggled to the halliards, and at the hour the ensign was slowly hoisted, while the Scouts stood alert and loyally saluted the Emblem of Empire.

"Sit easy!" ordered the Scoutmaster, and the Scouts sat down to listen to Mr Trematon's instructions.

"This is our first complete day in camp," he said, "and we can hardly hope to get into proper working order so soon. During the rest of the morning we must make more arrangements for our welfare. Coming in late last night we contented ourselves by merely pitching the tents. Had it rained, there would have been considerable discomfort on Seal Island, I fear. By this evening I hope to have the whole routine outlined, so that we may carry out our daily programme without a hitch. Simpson, I want you to take Armstrong and Hayes with you, cross to the mainland and purchase a sack of flour. Four of the 'Otters' will take spades and dig trenches round the tents and other holes where required. Four of the "Wolves" will attend on the cooks. and build a watertight hut for the kitchen. The rest of you can construct mattresses of bracken. You remember instruction was given on that subject only a few weeks ago. Now set to work and see how much you can do before one o'clock."

Calling the two cooks to accompany him, Mr Trematon walked over to the spot where the temporary ovens had been erected. A brief inspection showed the cause of the failure of the breakfast arrangements. In loading the boats for the journey across to Seal Island a can of paraffin had been dumped alongside the sack of flour, and the screw top of the former having worked loose a portion of the oil soaked into the flour.

During the rest of the morning the lads worked hard putting the camp in order. Trenches to drain the surface water in a possible heavy downpour of rain were dug round the tents; a mud and wattle hut, large enough to afford complete shelter for the cooks and their utensils, was erected; while a large tub was sunk in the little stream fed by the spring, so that a supply of fresh water was easily obtainable without having to make a lengthy journey to the fountain head.

The mattresses, too, were in a forward state. The frames of these were constructed of straight branches, the side pieces being five feet six inches in length, the head two feet, and the foot fifteen inches. By tapering the shape of the cots it was possible to arrange them systematically round the tent, so that each Scout slept with his feet towards the tent-pole. A coarse netting of thick twine filled the space between the cot frames, and through the meshes bracken was woven, forming a springy and comfortable couch, the frames being raised sufficiently to prevent the "sag," caused by the sleepers' bodies, from touching the ground.

For dinner, boiled bacon, cabbage and potatoes and suet pudding were provided, and the cooks of the day did themselves credit, as if to atone for the spoiling of the breakfast. True, Tom Mayne found a boiled caterpillar in his share of the cabbage, and Coventry minor all but swallowed a piece of string that had been mixed up with the suet, but as the Scoutmaster remarked such incidents are really blessings in disguise, since the lads afterwards carefully examined every portion of the dinner and thus prevented any undue haste in eating.

"It is certainly advisable that we should make ourselves thoroughly acquainted with our temporary domain," said Mr Trematon, after dinner was over. "It is now half past one. We will rest for half an hour and then set out for an exploration of Seal Island."

At the expiration of the stipulated time, preparations were made for the circuit of the Island. The "Otters" were ordered to take their staves, while to the "Wolves" was allotted the task of carrying several lengths of two-inch rope, iron crowbars, a pair of double "blocks" and a pair of single ones. Mr Trematon did not give the reason why these articles need be taken, and speculation as to their use ran high.

"Two lads must remain as camp orderlies," he remarked. "Who will volunteer? Remember a volunteer is worth two pressed."

There were several moments' hesitation. All were exceptionally keen on the trip, and the suggestion that two of them should remain did not appeal to them in a favourable light.

"I will, sir," said Atherton.

"No," rejoined the Scoutmaster. "The Leaders are exempt, since they are responsible to me for their patrols."

"I'll remain, sir," exclaimed Tom Mayne.

"That's good. Now, then, a volunteer from the 'Wolves.' That will be fair, won't it?"

Coventry major signified his willingness to stay, for although in different patrols the two lads were close chums.

"That's settled," continued Mr Trematon. "Now, orderlies, you must not go beyond the limits of the camp, except down to the landing-place. You are to receive any visitors that may come to the Island, and show them round, giving them any information as courteously as you can."

In high spirits the two patrols set out, their first halt being at the ruined oratory. Here Mr Trematon explained the use and nature of these buildings in mediaeval days, how that recluses devoted their lives to prayer and watching. No doubt many vessels in pre-Reformation days owed their safety to the friendly light that burned every night from hundreds of oratories scattered round the coast.

The ruins being situated on the highest part of the Island, the Scouts had an extensive view of the Cornish shore and of the expansive Bristol Channel. The day was clear, and the water was dotted with ships of all sizes, all looking like miniature boats in the distance. There were colliers, distinguishable by having their funnels well aft; tramps, rusty-sided, and with stumpy masts serving mainly to support the derricks for handling cargo; topsail schooners, in which most of the coast-wise trade between the smaller ports is now carried on; Bristol Channel pilot boats engaged in keen competition to pick up a job; and a host of small fishing boats from the neighbouring ports of St Ives and Padstow.

"How far can we see out to sea, sir?" asked Tenderfoot Scott.

"That depends mainly upon the clearness of the atmosphere. From the height on which we are now standing—250 feet—we might be able to see nearly twenty-one miles."

"It's very clear to-day, sir," observed Fraser.

"Yes, too clear for my liking," asserted the scoutmaster. "Tregantle Head—over twenty-five miles away—stands up quite plainly. That's a sure sign of wet weather and probably a storm in addition."

"A storm! Will there be any wrecks?" asked little Reggie Scott, eagerly. "Will we be able to see them if there are?"

"I trust not," replied the Scoutmaster, solemnly. "I have seen several wrecks, and it is not an experience to be desired. Now, lads, forward. Bear away to the right. I want you to see that part of the Island nearest to Beware Head."

Through a dense belt of gorse and bracken, out of which the startled rabbits scooted with amazing rapidity, the Scouts trooped till Mr Trematon called to them to halt. They were then within ten feet of the edge of the cliffs that here descend abruptly for a distance of one hundred and eighty feet.

"Don't ever go closer to the brink of the cliffs than this, unless you have a line round you," cautioned Mr Trematon. "The ground might crumble under you, although there is far less probability of doing so here—where the rocks are composed of granite—than on the south-eastern coast of England, where the cliffs are of chalk and soft sandstone."

From where they stood the Scouts could see almost the whole extent of water between the Island and Beware Head, a sheet of deep blue sea interspersed with patches of pale green denoting sandy bottom between the weed-covered rocks. Long oily rollers came tumbling inshore with unfailing regularity, breaking with a smother of foam against the base of the headland.

"What makes those rollers, sir?" asked Baker. "There's very little wind, and farther out the sea is quite calm."

"It's called a ground-swell, and is said to be caused by a storm many miles out to sea. Their presence is also an indication of the approach of bad weather. I don't want to dishearten you, lads, but we must 'Be prepared' for all emergencies, and if we are I don't think our holiday will be any less enjoyable."

"There's a signal from the lighthouse, sir," announced Atherton.

"Now, then, signallers: what do you make of that?" asked the Scoutmaster, as a burst of flags fluttered from a staff rising from the gallery of the lighthouse.

"We can't make out, sir," replied Phillips and Neale. "They are not spelling anything."

"No, it is in code. The combination of those three flags means a message which we could only interpret if we had a signal-code book. One of those vessels 'made her number '—that is, has reported herself on first sighting a British signal-station—and the information will be telegraphed to Lloyd's. See, there's a keeper on the gallery. Watch him through your pocket telescope, Phillips, and when he looks this way tell Neale to call him up."

"What shall I semaphore, sir?" asked the Second of the "Wolves."

"Ask him for permission to visit the lighthouse," replied Mr Trematon. "Then, if he says yes, ask what day and what time will be convenient."

"He's looking this way, sir," reported Phillips.

Standing well apart from his comrades, Neale "called up" the lighthouse. In a few moments Phillips announced that the man was looking towards them through a glass.

"He's acknowledged, sir," continued the Second of the "Otters." "Another man has taken the glass from him."

"Carry on," ordered the Scoutmaster, and Neale began semaphoring with considerable rapidity and accuracy.

Back came the reply: "The keepers of Beware Head lighthouse will be pleased to show the Scouts over the building any day between 9 A.M. and one hour before sunset."