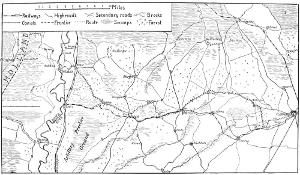

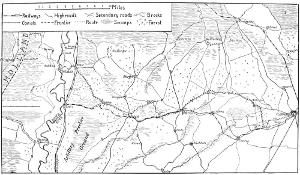

Transcriber’s Note: in web browsers, and in some e-readers, you will be able to click the map image for a larger version.

Map illustrating the Route of Author’s Escape.

The Dotted Line shows the Route taken.

Title: My Escape from Germany

Author: Eric A. Keith

Release date: July 23, 2015 [eBook #49509]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: in web browsers, and in some e-readers, you will be able to click the map image for a larger version.

Map illustrating the Route of Author’s Escape.

The Dotted Line shows the Route taken.

MY ESCAPE

FROM GERMANY

BY

ERIC A. KEITH

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1919

Copyright, 1920, by

The Century Co.

Published, January, 1920

There is an element of chance and risk about an attempt to escape from an enemy’s country which is bound to appeal to any one with a trace of sporting instinct. Viewed as a sport, though its devotees are naturally few and hope to become fewer, it has a technique of its own, and it may be better, rather than interrupt the course of my narrative, to say here something about this.

As always, appropriate equipment makes for ease. But its lack, since a prisoner of war cannot place an order for an ideal outfit, may be largely compensated for by personal qualities.

In considering the chances of success or failure, it must always be assumed that the route leads through a country entirely unknown to the fugitive. Yet this is not so great a disadvantage as one might suppose. Once free from towns and railways, a man with a certain knowledge of nature and the heavens, and with some powers of observation and deduction, can hardly fail to hit an objective so considerable as a fron[Pg vi]tier line, even if a hundred miles or so have to be traversed, provided he knows the position of his starting-point and is favored with tolerable weather.

With the sky obscured, he must at least have a pocket compass by which to keep his direction; though when the stars are visible it is easier and safer to walk by their aid.

Next in importance come maps. With fairly good maps, as well as a compass, the chances of evading discovery before approaching the frontier, with its zone of sentries and patrols, are, in my opinion, about even.

Another indispensable requisite is a water-bottle—a good big one. My own belief is that a man in tolerable condition—let us say good internment-camp condition—can keep going for from two to three weeks on no more food than he can pick up in the fields. But thirty hours without water will, in most cases, be too much for him. Under the tortures of thirst his determination will be sapped. I was, therefore, always willing to exchange the most direct route for a longer one which offered good supplies of water. In my final and successful attempt, when I was leader of a party of three and had to traverse a part of Germany where brooks and streams are rare, I always preferred taking the[Pg vii] risk of looking for fresh water rather than that of being without it for more than twenty hours between sources, relying in the meantime on what we had in our bottles.

The more clothing one can take along the better—within reason, of course. One is prepared to do without a good deal, but food must, if necessary, be sacrificed for a sweater and an oilsilk. Two sets of underclothing to wear simultaneously when the weather turns cold are a comfort. Beyond this, any one will naturally take such food as can be carried conveniently. Chocolate, hardtack and dripping, with a little salt, is, in my opinion, as much as one wants. Being a deliberate person, I usually managed to have enough of these in readiness before I even thought of other arrangements for the start.

People are very differently gifted with what might be called the out-of-door sense, though it is strong in some who have never really led an out-of-door life. Those who have this gift will know almost instinctively where to turn in an emergency, and will gather from the lie of the land information denied to those without it. This raises the question of companionship. As I am, fortunately, possessed of a fair share of this open-air sense, it was little handicap to[Pg viii] me to be alone on my first attempt. In fact, as long as I was using the railways, it was a distinct advantage. At critical moments a man can decide more quickly what to do, if he has only himself to think of, than when he has to consider and possibly to communicate with a companion, who may be contemplating a better but quite different solution. To know that it is only one’s own skin that is at stake gives one that promptness of decision which is itself the seed of success; the thought of involving another man in an error easily clogs the swiftness of one’s action.

On the march these conditions are reversed. One can walk only at night, and the approach of actual danger is best met by falling flat and keeping motionless, or else taking to one’s heels. It is under trying conditions just short of the actual peril of discovery that the soothing influence of a companion is of inestimable advantage. Cross-country walking tries one’s nervous forces to the utmost. Hour after hour passes, and no recognizable landmark appears. At last one gets the feeling of being condemned eternally to tramp over fields, skirt woods, and extricate oneself from an endless succession of morasses. In time the sky seems to reel and the compass-needle to point in all directions but the[Pg ix] right one. It is then that the voice of a friend, the touch of his hand, or merely the sound of his footsteps behind one, restores the sense of normality which, if one is alone, can be recovered only by a deliberate effort of will that is often very exhausting.

Before starting I always knew roughly what lay before me, and what I had to expect, until I met either with success or with complete failure by being captured. Even when the chances seemed to suggest it, I would never trust blindly to mere good luck, which I kept in reserve as an absolutely last resource. Once in hiding for the day, I usually worked out a detailed plan for the following night’s walk, and spent hours looking at the maps in order to impress on my mind a picture, as complete as possible, of the country directly in front of me and to each side of my route.

When this book was first published I pointed out, that “It is one of the penalties of an escape that, so long as others remain behind, it is impossible for obvious reasons to give too precise details, and often the moments one would most wish to describe have of necessity to be camouflaged from the observation of the enemy.” Now that the war is over and there is nothing to hinder it, I have been able to aug[Pg x]ment my original story with certain details originally omitted for reasons mentioned above. In its present form the book has been considerably enlarged and no detail of my escape has been omitted.

E.A.K.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | v | |

| PART I | ||

| I | The House of Bondage | 3 |

| II | Ruhleben: The Sheep and the Goats | 13 |

| III | The Sanatorium | 25 |

| IV | Planning the Details | 31 |

| V | A Glimpse of Freedom | 39 |

| VI | In Hiding | 52 |

| VII | Failure | 69 |

| VIII | A New Hope | 76 |

| IX | Breaking Prison | 91 |

| X | Caught Again! | 109 |

| XI | Under Escort | 120 |

| XII | The Stadtvogtei and “Solitary” | 126 |

| XIII | Classes and Masses in the Stadtvogtei | 146 |

| XIV | Prison Life and Officials | 154 |

| PART II | ||

| XV | A Fresh Attempt | 179 |

| XVI | From Berlin to Haltern | 190 |

| XVII | Westward Ho! | 202 |

| XVIII | The Game is Up | 218 |

| PART III | ||

| XIX | Footing the Bill | 233 |

| XX | Ruhleben Again | 251 |

| XXI | The Day | 265 |

| XXII | Order of March | 292 |

| XXIII | The Road Through the Night | 304 |

| XXIV | Crossing the Ems | 319 |

| XXV | The Last Lap | 333 |

| XXVI | Free at Last | 348 |

The date was April 7, 1916. The fat German warder backed out of my cell, a satisfied smile on his face; the door swung to, the great key clicked in the lock, and I was alone.

Prison once more! And only a bare three miles away was the frontier for which I had striven so hard—the ditch and the barbed wire that separated Germany, and all that that word means, from Holland, the Hook, the London boat, and freedom.

The game was lost. That was the kernel of the situation as it presented itself to me, sitting on my bed in the narrow, dark cell.

Vreden, where I thus found myself in prison, is a little town hardly three miles from the Dutch frontier, in the Prussian province of Westphalia. So near—and indeed a good deal nearer—had I got to liberty!

Twenty-four hours before, my first attempt to escape from Germany—which might be de[Pg 4]scribed with some justification as my third—had failed, and instead of being a free man in a neutral country, I was still a British civilian prisoner of war.

Apart from the overwhelming sense of failure which oppressed me, I was not exactly physically comfortable. To start with, I wanted a change of clothing and a real bath. I had not had my boots off—except during several hours when I was walking in bare feet for the sake of silence—for over eight days, and for almost the same length of time I had not even washed my hands. The change of clothing was out of the question. The bath—One does not feel as if one has had a bath after an ablution in a tin basin holding a pint of water, with a cake of chalky soap the size of a penny-piece, and a towel which, but for texture, would have made a tolerable handkerchief. And no water to be spilled on the floor of the cell, mind you!

My prison bed was an old, wooden “civilian” one with a pile of paillasses on it, and the usual two blankets. It was fairly comfortable to lie on, as long as the numerous indigenous population left you alone, which they rarely did.

The warder—the only one, I believe, in the prison—had asked me immediately after my arrival whether or not I had any money on me.[Pg 5] When he heard I had not, his face fell. Since he could not make me profitable he made me useful, and put me to peeling potatoes in the morning, a job I liked very much under the circumstances.

The food in Vreden prison was scanty, barely sufficient. I was always moderately hungry, and ravenous when meal-time was still two or three hours off. Twice in four days I had an opportunity of walking for twenty minutes round the tiny prison yard, sunless and damp, where green moss spread itself in three untrodden corners, while the fourth was occupied by a large cesspool. The rest of my time I spent alone in my cell, now and again reading a few pages of Jules Verne’s “Five Weeks in a Balloon,” execrably translated into German and lent me by the warder. But mostly I was busy speculating about my immediate future, or thinking of the eighteen months of my captivity in Germany.

Technically, I was not being punished as yet for my escape. I was merely being kept under lock and key pending my removal back to Ruhleben camp or to a prison in Berlin, I did not know which. But if it was not punishment I was undergoing in the little frontier town, it was an excellent imitation of it.

Some experiences, exciting when compared with the dull routine of camp life, were still ahead of me; the journey to Berlin was something to look forward to, at any rate. But what would happen afterward? I did not know, for I flatly refused to believe in solitary confinement to the end of the war—the punishment which had been suggested as in store for unsuccessful escapers.

I had not escaped from Ruhleben, as my predecessors had. I had walked out of a virtually unguarded sanatorium in Charlottenburg, a suburb of Berlin, where British civilian prisoners of war, suffering from diseases and ailments which could not be properly combated in camp, were treated. Might not this give an earnest to a plea which was shaping in my mind? Could the Germans be persuaded to believe that I had acted under the influence of an attack of temporary insanity, caused by overwhelming homesickness? True, I had “gone away” well prepared; I had shown a certain amount of determination and tenacity of purpose. On the other hand, I had not destroyed any military property. Of course, I had damaged a good deal of property, but it wasn’t military property! A fine point, but an important one, especially in Germany.

These were the sort of reflections which mostly occupied my four days in Vreden prison, unreasoning optimism struggling desperately against rather gloomy common sense.

What I looked forward to most in the solitude of my cell was a meeting with my old friends in Ruhleben camp in the near future. The other escapers had all been returned to camp for a short time before they were taken to prison, to demonstrate to us ocularly the hopelessness of further attempts. Surely the Germans would do the same with me; and then I should get speech with one or two of my particular chums. For this I longed with a great longing, although I did not look forward to telling them that I had failed.

Only one of them knew the first links in the chain of events which connected my sensations of the first day of the war with the present, when I was restlessly measuring the length of my cell, or sitting motionless on the edge of the bed, staring with dull eyes upon the dirty floor. Under the pressure of my disappointment, and without the natural safety-valve of talk to a friendly soul, I naturally began to examine my experiences during the war, opening the pigeon-holes of my memory one by one, reliving an incident here, revisualizing a picture there, and[Pg 8] retracing the whole length of the—to me—most important developments leading up to my attempted escape.

When the storm clouds of the European war were gathering I was living in Neuss, a town on the left bank of the Rhine, between Düsseldorf, a few miles to the north, and Cologne, twenty miles to the south. I had been there a little over a year. Immersed though I was in business, I was by no means happy. I was distinctly tired of Germany, and was on the point of cutting short my engagements and leaving the “Fatherland.”

I had turned thirty some time before, and hitherto my life, although it had led me into many places, had been that of an ordinary business man. In spite of unmistakable roaming proclivities, it was likely to continue placidly enough. Then suddenly everything was changed.

One afternoon, about the 20th of July, I was standing in the enclosure of the Neuss Tennis Club, waiting for a game. The courts were close to a point where a number of important railway lines branched off toward Belgium and France. I was watching and wondering about the incessant traffic of freight-trains[Pg 9] which for days past had been rolling in that direction at about fifteen-minute intervals. They consisted almost exclusively of closed trucks.

Another member of the club pointed his racket toward one. “War material. Soldiers!” he said succinctly. With a sinking heart I gazed after the train as it disappeared from view. The political horizon was clouded, but surely it wouldn’t come to this! It couldn’t come to this. It was impossible that it should happen.

The police, always troublesome and inquisitive in Germany, seemed to be taking some unaccountable interest in me. Nothing was further from my mind than to connect this lively interest in an obscure individual like myself with anything so stupendous as a war.

And then it happened. War was declared.

I was warned not to leave the town without permission. I was eating my head off in idleness and anxiety. I hoped to be sent out of the country at short notice, but the order to pack up and be gone did not come. Instead, I was invited to call upon the inspector of police at 9 A.M. on the 27th of August. I obeyed. An hour later I was locked up in a cell of an old, evil-smelling, small prison. I did not know for what reason, beyond the somewhat incompre[Pg 10]hensible one of being a British subject. Nor did I know for how long. The inspector of police had answered my questions with an Oriental phrase: It was an order!

It appeared that the order referred to Britishers of military age only, which, according to it, began with the seventeenth and ended with the thirty-ninth year. Thus it came about that I made the acquaintance of three out of the six Englishmen then temporarily living in Neuss, but hitherto beyond my ken. They were all fitters of a big Manchester firm, Messrs. Mather & Platt Ltd., employed in putting up a sprinkler installation in the works of the International Harvester Co., an American concern in Neuss.

We were treated comparatively well in prison. Nevertheless, the days we had to pass in that old, evil-smelling house of sorrows were interminable. Most of our time we spent together, in a locked-up part of the corridor on the second floor. Outside it was glorious summer weather. All our windows were open to the breeze, which never succeeded in dispersing the stench pervading the whole building. Sitting on the uncomfortable wooden stools, or walking idly about, we smoked incessantly, read desultorily in magazines and books, and talked spasmodically. And always the air vibrated with the[Pg 11] faint, far-away, half-heard, half-sensed muttering of distant guns. The news in the German newspapers was never cheering to us.

As suddenly as we had been arrested we were released from prison after eleven days, and confined to the town.

There followed nine weeks of inactivity and endless waiting. For the first time I gave a fleeting thought to an attempt of making my way out of Germany by stealth. It hardly seemed worth while, as we were “sure of being exchanged sooner or later”! Twice I left the town for a few hours. On my return I always found the police fully conversant with every one of my moves, which showed how carefully they were watching me. Having always provided excellent explanations for my actions, I escaped trouble over these escapades.

As announced beforehand in the German press, we were arrested again on November 6, 1914. We passed four cheery days in the old familiar prison, and then came the excitement of our departure for Ruhleben camp, via Cologne, where we and a hundred and fifty other civilian prisoners, collected from the Rhine provinces, spent a night in a large penal prison.

Under a strong escort we were marched to the station at seven the following morning. Before[Pg 12] starting we had been told that there was only one punishment for misbehavior on transport—death! Misbehavior included leaving the ranks in the streets or leaning out of the windows when in the railway carriages.

Entraining at eight o’clock, we did not reach our final destination until twenty-three hours later. The first hour or so of our journey was tolerable. We were in third-class carriages. Having had hardly any breakfast, and no tea or supper the previous day, we soon became hungry and thirsty. But we were not even allowed to get a drink of water. Whenever the train drew into a station, the Red Cross women rushed toward our carriages with pots of coffee and trays of food, under the impression that we were Germans on the way to join our regiments. But they were always warned off by uniformed officials: “Nothing for those English swine.” We were evidently beyond the pale of humanity.

At 2 A.M. we disembarked at Hanover station, to wait two hours for another train. Here a bowl of very good soup was served out to us.

At 7 A.M. on the 12th of November our train drew up at a siding. We were ordered roughly to get out and form fours. It was dark and cold. A thin drizzling rain was falling. Hardly as cheerful as when we left Neuss, we entered Ruhleben camp.

Ruhleben! A ride in a trolley car of fifty minutes to the east, and one would have been in the center of Berlin. Toward the west the town of Spandau was plainly visible. Shall we ever forget its sky-line—the forest of chimneys, the tall, ugly outlines of the tower of the town hall, the squat “Julius” tower, the supposed “war treasury” of the Germans where untold millions of marks of gold were alleged to be lying!

Before the war the camp had been a trotting race-course, a model of its kind in the way of appointments. Altogether, six grand stands, a restaurant for the public, a club-house for the members of the Turf Club, administrative buildings, and eleven large stables, all solidly built of brick and concrete, illustrated German thoroughness.

These buildings, except the three smaller grand stands, clustered along the west and south sides of an oval track, which was not at first included in the camp area.

Since the beginning of the war the restaurant, the “Tea House” as it was called, at the extreme western end, and the large halls underneath the three grand stands next to it had been used to house refugees from eastern Prussia. Then, an assorted lot of prisoners of war and civilians interned, preponderantly Russian but with a sprinkling of British and French subjects, had taken their place. A few Russians were still there when we arrived but evacuated very soon after. Their departure made the camp exclusively British.

We were given breakfast. It consisted of a bowl of so-called coffee and a loaf of black bread. The bread was to last us two days. Then we were marched to our palatial residence, Stable No. 5. We set to work to remove the plentiful reminders of the former four-legged inhabitants and installed ourselves as best we might.

The stables contained twenty-four box-stalls and two tiny rooms for stable personnel on the ground floor, and two large hay-lofts above. Six men to a box-stall was the rule, and as many as could be packed into the lofts. I had experience in both quarters, for I slept in the loft for more than a week, and then moved into “Box No. 6,” where a space on the floor had become empty. My new quarters were, at first, much[Pg 15] less attractive than the loft. They offered, however greater possibilities for improvement.

For six weeks we slept on a stone floor covered by an inch or so of wet straw. We had just room enough to lie side by side. We could turn over, if we did so together. The “loftites” slept on boards with straw on top of them. Later we all got ticks into which we could pack the wet and fouling straw. To start with, there was no heating. Then steam-radiators were installed, and during this winter and the three following, the stone barracks were heated in a fitful kind of way. The locomobile boilers which furnished the steam, one for each three or four barracks, delivered it into the radiators from 10 A.M. to 12 noon and from 3 to 5 P.M.

At last the “boxites” received bedsteads. They consisted of a simple iron framework with three-quarter-inch boards as mattresses. On these we placed our ticks. The bed uprights had male and female ends which permitted the building of as many superimposed bunks as seemed practicable. Two sleeping-structures of three bunks each was the rule in the boxes.

The food we received from the Germans was insufficient at any time. The allowance per man for rations was sixty-five pfennigs per day—sixteen cents at the pre-war rate of exchange.[Pg 16] It was contracted for at this price by a caterer.

While food in Germany was plentiful we could buy additions to our rations at the canteen. This became gradually impossible. We didn’t mind that much, as parcels containing food and other necessities, but mainly food, began to arrive from England in ever-increasing number. Relatives of prisoners, the firms they had been working for, and trade-unions or other organizations to which they belonged started the ball rolling. But when the real need of the prisoners became known in Blighty, special organizations for the purpose of assisting them sprang up everywhere. As they were independent of one another their work to a great extent overlapped. The majority of the civilians interned received too much; here and there a man received nothing at all. Through the action of the British Government the work of the individual societies was coördinated in November, 1916. From that date, the Order of the Red Cross and St. John was in charge of all of the relief work for prisoners of war, and each prisoner received six parcels of food per lunar month, not counting two loaves of white bread per week.

As far as my experience goes, the German authorities made an effort to have these parcels reach their destination. During the latter part[Pg 17] of my imprisonment deliveries became somewhat irregular. Food was scarce at that time in some parts of Germany and commanded very high prices, and the theft of parcels naturally increased.

Ruhleben camp was administered, at first, by the German officers in charge, with the help of the interned. In the spring of 1916, all of the internal affairs of the camp were placed in the hands of the interned themselves, the Germans confining themselves to guard duties and general supervision.

Much has been published about prisoners’ camps in Germany. Horrible stories have been told about them, and these are in the main quite true. But camps differed from one another; nor were the conditions in a given camp always the same. I’m not suggesting gradual or steady improvement. But, just as camp commanders and regional military commanders differed, so did the treatment of their charges differ. As prisoners of war the men in Ruhleben camp were a pretty lucky lot. The choice flowers of Kultur bloomed elsewhere.

In the beginning of our internment hopes of a speedy exchange to England ran high, and so did rumors concerning it. They helped us to en[Pg 18]dure the hardships of the first few months, hardships which might have proved even less tolerable than they did without some such sheet-anchor of faith.

In spite of the misery of the first winter, however, the majority of the pro-English portion of the camp would at any time have refused a chance of living “free” in Germany under the conditions we experienced previous to our internment. This certainly was the prevailing opinion among my friends, as it was mine. In camp, at any rate, we could wag our tongues, and speak as we listed, if we took only ordinary precautions. We had congenial companions, and shared our joys and discomforts. As long as our health remained tolerable, who would not have preferred this to liberty among German surroundings? But when illness came upon us—and few escaped it altogether—it was rather a tough proposition.

The colonial Britishers were not at first considered to come under the heading “Englander.” Probably the Germans were waiting for the disruption of the British Empire and intended to further it by partial treatment of men from our colonies, for they let them remain at liberty until the end of January, 1915.[Pg 19] It was then that the colonials arrived in Ruhleben.

Later came the separation of the sheep from the goats! There was trouble in camp. It had started in a ridiculous manner. A young lad had been overheard saying something about “bloody Germans,” and this had been reported to the authorities by one of their spies. German self-esteem was horribly hurt, the more so as they misunderstood the epithet and interpreted it as “bloodthirsty.” Whispers of impending trouble had reached us, and we were not astonished when, one morning—I believe in February or March, 1915—the alarm bell sounded the “line up.” Each barracks separately formed up in a hollow square in front of its dwelling-place. And each barracks was addressed separately by the camp commander, Baron von Taube. He was in a perfect frenzy of rage when our turn came. Our barracks was one of the last spoken to, and how he managed to keep up the performance after so many repetitions is a thing I cannot easily understand.

“We shall be the victors in this war thrust upon us by your country!” he shouted at us.[Pg 20] “And here and now I fling your own expression back into your faces. Bloody Englishmen I call you! Bloody Englishmen!” He thumped his chest like a gorilla about to charge. He came near to foaming at the mouth. So far it was merely amusing. Then came the order: “All those who entertain friendly feelings toward Germany fall out and hand in your names.”

Our barracks was rather a mixed one, many of its inhabitants being pro-German in sentiment. In addition, good and loyal men all over the camp, whose financial interests were entirely in Germany, became panicky and went over to the other side in the futile hope of saving their property. When they had gone to the office, we others were dismissed. Excitedly we discussed what had happened. Many of us were deeply disturbed. They were those who thought they had flung their all into a well, as it were, by standing still when the pro-Germans fell out. But we all hoped that the others would be quartered apart from us.

Unfortunately that was not the case. They came back and lived among us for some time, their presence giving rise to many a quarrel.

Some months afterward another separation of the sheep from the goats took place, much less dramatically, and this time the pro-Germans were quartered all by their sweet selves at one end of the camp.

In April, 1915, two men escaped from the hospital barracks, situated outside the barbed-wire enclosure, and but carelessly guarded. One of them became a great friend of mine later on.

When these two men escaped, I was playing with the idea myself. It was a very fine spring. In the afternoons I used to sit on the uppermost tier of the big grand stand. High up as I was, the factory buildings and chimneys toward the west, where Spandau lay, appeared dwarfed; and gazing across with my book on my knees, I had a sense of freedom. I used to dream extravagant dreams of flights in aëroplanes with Germany gliding backward beneath my feet, with the fat pastures of Holland unrolling from the horizon, with the gray glint of the sea appearing, and the shores of England lying rosy under a westering sun. And then, coming down to realities, I began seriously to speculate upon the chances of “getting through.”

I soon came to the conclusion that a companion was desirable, a good man who spoke German well, as I did; a man with plenty of common sense about him. I found one in April, T——, a native of the state of Kansas. Lack of money made an early attempt impossible. I had enough for myself, but my friend was dependent upon the five shillings per week relief money[Pg 22] paid by the British Government to those who had no resources of their own. I could not get hold of sufficient money for the two of us at once, so I set myself to accumulate gradually the necessary amount.

But the summer passed, the leaves began to turn yellow, and my pocket-book still contained less than I thought necessary.

In June of that year a successful escape from camp and from Germany by Messrs. Pyke and Falk set us all talking and wondering. Then, in quick succession, two serious attempts by a couple of men each failed. News was allowed to reach us that they would be kept in solitary confinement until the end of the war. This inhuman punishment was not actually put into effect, but the unfortunates got five months’ and four and a half months’ solitary confinement respectively, and after that indefinite detention in prison.

My companion and I heard only about the first sentence. It somewhat staggered us; but we decided that, as we did not intend to be caught, the punishment ought not to deter us, and that if we were caught we could stick it out as well as the next man.

The days were growing shorter, the nights[Pg 23] colder, the boughs of the trees barer, and conditions generally more unfavorable, and still we hung on. Then the military authorities began doubling the number of wire fences around the camp and erecting plenty of extra light-standards in the space between them. Also, the number of sentries was increased. All this decided us to have “a shot at it” there and then, before the additional fences were completed.

We had hoped for an overcast sky. Instead, the full moon was bathing the camp in light. Feeling anything but comfortable, we walked up to that part of the wire fence where we intended to scramble over. We were just getting ready, when a sentry came around the corner of the barracks outside the wire. We had never observed the man on that beat before. He stopped short, and his rifle came to the ready. “We’re camp policemen, if he asks,” I whispered to my companion. Lingering a moment as if in conversation, we then walked slowly away. We decided not to try again that night.

The next morning I was disgusted with myself and all the world. I talked it over with my companion, and he agreed with me that it was “no go” that year. Another week of light[Pg 24] nights would see the wire fences completed and the season so far advanced that the odds would be too heavy against us.

For some days I chewed the bitter cud of disappointment. Then I told my friend that I should be glad to go with him, if he had an opportunity, but that in the meantime I should take any chance, if one came to me, alone. He expressed approval.

Toward the end of November an old Scotsman, a member of my barracks (No. 5), was returned to camp from the sanatorium in Charlottenburg. I questioned him about the place. It appeared that no desperate illness was necessary to get there, as long as one was willing to pay for oneself instead of coming down upon the British Government funds ordinarily provided for that purpose.

This institution was a private medical establishment known as Weiler’s Sanatorium. The camp administration, by now in our own hands, had made arrangements with the proprietors to receive and treat such cases of illness or ill-health as could not be treated adequately in camp, where the accommodation in the infirmary, measured on civilized standards, was of the roughest.

Having a big scar on my left thigh, the only reminder of a perfectly healed compound fracture many years old, I believed sciatica a likely[Pg 26] complaint to acquire. Except in extreme cases no observable changes take place in the affected limb, and the statement of the patient is the only means of diagnosis. Forthwith I developed a gradually increasing limp. With it I got grumpy and ill-tempered, the limp preventing me from taking my usual exercise, and this soon had its effect.

At regular and short intervals I went to see the doctor. To start with, I got sympathy from him, and aspirin. But nothing did me any good, though I admitted to an occasional improvement when the weather was fine and dry. At last I was taken into the Schonungsbaracke and put under a severe course of sweating. I stuck it out, but came dangerously near throwing up the sponge before I was released at the end of a week of it. By that time I had made up my mind that my sciatica ought to be cured, at least temporarily.

I kept away from the doctor for some time, but after a fortnight, during which my limp had gradually increased again, I was back in the surgery. He admitted that under camp conditions a lasting cure, even of a mild case like mine, was hardly to be thought of; but since the Schonungsbaracke was full, there was nothing for me[Pg 27] “but to stay in bed as much as possible” and to swallow aspirin. This treatment suited me excellently well.

I kept hanging about the surgery complaining mildly until the first days of February, when the weather was rotten. I had a serious attack then. I knew the Schonungsbaracke to be still full, and this gave me the opportunity of asking to be transferred for treatment to the sanatorium.

My case being considered urgent, I left the camp the same afternoon, accompanied by a soldier and a box-mate of mine who had volunteered to carry my luggage—for I was unable, of course, even to lift it. With somewhat mingled feelings I looked my last upon Ruhleben for many a long day.

My new home had originally been intended for nervous cases only—a private lunatic asylum, to put it bluntly. The arrangement with the camp authorities for the treatment of all kinds of ailments among a population of over four thousand was taxing its capacity to the utmost. So many of our men were there at this time that they not only filled the original institution but were housed and treated in several dwellings leased by the proprietors in addition to the asylum.

This was a large building with an extensive[Pg 28] garden at 38 Nussbaum Allee, Charlottenburg. The appellation “Nussbaum Allee” distinguished it from the other houses, of which there were four, if I am not mistaken. I forget their names, however, with the exception of “Linden Allee.”

There were two classes of patients, whose food and accommodation differed according to the amount they paid, or which was paid for them by the British Government through the American Embassy. First-class treatment cost at that time twelve marks per day exclusive of medicines and special treatment. Without exception the expense had to be defrayed by the patient himself. In the second-class eight marks per day was charged. Neither class could expect private bedrooms for this, except where infectious ailments or other medical reasons made separate rooms imperative.

I had offered to pay my own expenses, to avoid delay by having my case referred to the American Embassy. It was a matter of indifference to me what class I was put into. The points of comfort I was looking for were easily opened windows, etc. I liked fresh air at any time, but now was particularly impressed by a theory of mine, that fresh air could be admitted in sufficient quantities only by windows not[Pg 29] too high from the ground and large enough to admit, or rather to give exit to, a fairly bulky man.

The windows looked all right, but, from my point of view, they were not. They had diamond panes set in cast-iron frames; and even if they opened, a dog could not have got out of the aperture. All the corridor doors were kept constantly locked. There was no passing from one part of the building to another without the help of a warder or a nurse. The idea of having to sleep in the same room with six or eight people, one or two of them seriously ill, did not appeal to me. One of them was always sure to be awake at night. Straightway I applied for first-class treatment, for this would get me sent to the “Linden Allee Villa,” where these lunatic-asylum precautions would probably be absent.

I was taken there in the course of the following morning. My assumption proved correct, for things were different. Twelve patients nearly occupied the available accommodation. The staff consisted of only a nurse and three servant girls, and no military guard was about the place. The biggest bedrooms contained three beds. A garden surrounded the house, accessible through at least three doors and a[Pg 30] number of windows of the ordinary French pattern. A low iron railing separated the garden from the streets, which in this part of the town were very wide, and which frequently had two causeways, lined with trees, and divided by stretches of lawn and thick shrubbery.

Not far from “Linden Allee” a big artery ran right into Berlin.

The outlines of my plan of escape had been conceived almost a year before in Ruhleben, and had remained unaltered.

Generally speaking, the chances of success were so small that I was convinced it could be achieved only by the elimination of every unnecessary risk, and with a considerable amount of good fortune thrown in to make up for the unavoidable balance on the wrong side.

It must be remembered that we civilians were interned right in the center of Germany. There were three neutral countries to make for: Denmark, Holland, and Switzerland, distant from Ruhleben in that order. My choice fell upon Holland, which, from information I had obtained, seemed to offer the best opportunities.

Denmark, being only about a hundred and fifty miles away, had at first appeared very tempting. But the difficulty of crossing the Kiel Canal, the extraordinarily close watch kept all over Schleswig-Holstein and the frontier, lack of information about the state of affairs[Pg 32] along the Baltic coast, and the obvious difficulty of making a passage in a stolen boat to the nearest point on the Danish coast, twenty-five miles away, decided me against this plan. Switzerland was about six hundred miles distant, and the railway journey, with its attendant dangers, correspondingly long. Also, we had heard that part of the Swiss frontier, at least, was impregnably guarded. There remained Holland, about four hundred miles away.

In view of my thorough knowledge of German, I did not believe the railway journey an impossible undertaking. It appeared more feasible, at any rate, than the four-weeks’ tramp to the frontier with what scant food one could carry. Up to the last moment I tried to get information as to whether special passports were necessary for traveling on a train, and whether they would be inspected on taking the ticket, or during the journey. I had contradictory accounts about this.

Having arrived at the sanatorium, I very soon made up my mind to the following mode of procedure: A stay at the “Linden Allee” until the 30th of March would give me about four weeks in which to recruit my health, which was none of the best after a grueling winter in camp. Then, with a new moon on the 1st of April, a[Pg 33] succession of dark nights would be favorable for my purpose. On account of the weather, it might become advisable to delay the start a day or two; but if exceptionally wintry conditions should be prevailing then, a postponement until the moon had again changed through all her phases would become necessary. Trying to imagine conditions near the frontier, I had come to the conclusion that with snow on the ground, giving a considerable range of vision even during the darkest hours of the night, a successful passage through the sentry lines would be out of the question. On the other hand, the nights would be much shorter at the end of April, and this made me nervous lest such a postponement should be forced upon me. The task of getting out of the sanatorium and making my way into Berlin did not trouble me at all. It was as easy as falling off a log. Such of my things as I should deem necessary or very desirable for the exploit, I was going to take with me in a small leather Gladstone bag.

From newspapers I had learned that a train left Berlin for Leipzig at 7 A.M. My absence would probably not be discovered before the first breakfast, served in bed at 7:45 A.M. Thus I could be a good many miles away when the alarm reached headquarters.

Leipzig was not on my direct route toward the Dutch frontier, but it appeared very attractive as my first objective, partly for that reason. It is a big place, and a man could easily pass in the crowd there for a day, while the shops would allow me to complete my equipment with a compass and maps.

In Berlin the sale of the latter was prohibited except with a permit from the army corps commander. This ordinance was savagely enforced and probably strictly observed. Leipzig—the center of the German printing-trade, and, in the Kingdom of Saxony, not in Prussia—was the place where one could hope to obtain them, if anywhere.

In another way the fact of Leipzig being in a different state was in my favor. Any efforts of the Berlin police to recapture me would very likely be retarded if the case had to be handed over to a distinct and independent police organization.

I hoped that when I arrived in Dortmund, some time during the morning following my escape from the sanatorium, I could make my way by slow trains to the small town of Haltern.

This is situated in the northwestern corner of the province of Westphalia on the northern bank of the river Lippe. The nearest part of[Pg 35] Holland from there is only twenty-five miles distant as the crow flies, and no river of any size intervenes, an important consideration for the time of year I had fixed upon. Moreover, it is nowhere near the Rhine. As I had lived in the northern part of the Rhine province, the danger of being accidentally seen by a former acquaintance bade me keep away from that district.

There remained the smaller details of my plan to work out, file, and put together. Some of them were planned and executed before I left camp. For example, I had grown a beard during the winter 1915-16. This altered my appearance and lent itself to another alteration, back to the original. I bethought myself in the “Linden Allee” that the Germans would probably expect me to shave it off. A good reason for not doing so.

The universal practice of the Boches in both civil and military camps was to mark all the clothing of prisoners of war so distinctively that the status of the wearer could be recognized at a glance, if ever he got away. These marks consisted at first of stripes of vivid color painted down the seams of their trousers and around their arms, and fancy figures, circles, triangles, etc., on their backs. Later, stripes of brown material were sewn into the trousers and sleeves,[Pg 36] the original material having first been cut away.

This practice never obtained in Ruhleben, where we were allowed to wear what we liked. During two winters in camp I had made use of a very strong and warm suit of Manchester cord. It was now considerably the worse for wear, bleached by sun and rain and darkened again by mud and grease, rather conspicuous in its state of dilapidation, and, in camp, very distinctly connected with me. For months I had kept hidden in my trunk an inconspicuous gray jacket suit. When I went to the sanatorium it was packed away under other things at the bottom of my hand-bag. All the time at the villa I wore my cord suit, explaining that I had no other clothes, but was waiting for some on the way from England. I must have cut a very queer figure among my companions, but any one among them could conscientiously swear, after my departure, that I must have left in a brown cord suit, for, obviously, I had no other. The good ulster overcoat I intended to make use of could hardly give me away. Probably half a million similar ones were being worn in Germany at that time.

After the first week in March, winter set in again and held the land for a fortnight. Then,[Pg 37] abruptly, spring burst upon us—that glorious early spring of 1916 with its long succession of sunny, warm days and crisp, starlit nights.

A change in the number and distribution of the inmates had left me with only one companion in our bedroom. He was confined to bed with heart disease. I became rather nervous lest my unexpected disappearance and the following inevitable investigation should upset him. To minimize this possible shock I took him into my confidence.

As “the day” approached I got my things ready as unobtrusively as I could, gradually packing my small grip and finally destroying letters and private papers. It was then that my room-mate showed the first signs of unfeigned interest.

“Why,” he exclaimed, suddenly, “so you meant it, after all! Pardon my having been incredulous so far, but I’ve heard so many fellows talk about what they intended to do, without ever seeing anybody doing it that I didn’t quite realize you were the exception that proves the rule. Don’t worry about me, and the best of luck to you.”

The limp with which I had arrived at the sanatorium I had gradually relinquished as I announced improvements in my condition. It was[Pg 38] to be resumed on the journey as a sort of disguise, an unasked-for explanation for my not being in the army.

I had put aside some food, namely, a big German smoked sausage, still obtainable though very expensive, and containing a considerable amount of nourishment, a tin of baked beans, some biscuits, some chocolate, and a special anti-fatigue preparation. A green woolen shirt, a thick sweater, two pairs of socks, an extra set of underclothing, a stout belt, and a naval oilskin, filled the bag almost to the bursting-point. Watch, electric torch, knife, and money were to be carried on my person.

About this time my first monthly account was due from the sanatorium. I dared not ask for it, neither could I leave without paying. Apart from the moral aspect of vanishing and leaving an unsettled bill behind, such an act would certainly have resulted in criminal proceedings against me for theft or larceny, in the event of my being captured, and, according to the German application of the law where Englishmen were concerned, as certainly in conviction with a maximum sentence. So I decided to leave enough money in a drawer of my dressing-table to cover my bill.

Contrary to my expectations, I hardly felt any excitement during my last day at the “Linden Allee.” My mental attitude was rather a disinterested one, as if I were watching somebody else’s escape.

When I got into bed at the usual time, I immediately fell asleep, having first made up my mind to wake at 3:30 A.M. I awoke an hour sooner, and went to sleep again. It was close on four o’clock when I opened my eyes for the second time. Getting up noiselessly, I carried the Gladstone and a big hand-bag containing my clothes, boots, etc., into the bath-room on the first floor. There I lathered my shaving brush and shaved a few hairs off my left forearm, leaving the safety-razor on the washstand, uncleaned, to create the impression that I had shaved off my beard. I dressed as rapidly as I could, throwing my pajamas on the floor and leaving generally a fair amount of disorder behind me. A breathless trip to the loft of the house to conceal my cord suit behind some beams[Pg 40] was executed with as much speed and caution as I could manage. With my bag in one hand and my boots round my neck, I descended again by the light of the electric torch, slipped into my overcoat in the hall, and, snatching my hat from the rack, entered the dining-room. From there a French window gave upon a porch to which a few steps led up from the garden. The window offered no resistance and, fortunately, the protecting roller-blind was not down. A few women, probably ammunition workers, passed the house, and when they were out of hearing I stepped out.

It was still dark, though the dawn was heralded in the east. In a spot previously selected for the reason that it was screened by bushes, and from which I could survey the street without being seen, I got over the fence. I had barely done so when a cough sounded some distance behind me. With a chill racing up and down my spine, I walked on. Turning the near corner, I threw a hasty glance over my shoulder, but could see no one. Nevertheless, I thought it wise to walk back on my tracks around several blocks, before I made for the big thoroughfare which led toward Berlin.

A number of people were about, men and women, going to work. Keeping on, I came[Pg 41] after a lapse of about fifteen minutes to a station of the Elevated. It was now five o’clock.

When I went up the steps to the booking-hall, night was slowly withdrawing before the vanguard of the approaching day. The electric lights in the streets flashed once and were dead. In the station they were beginning to show pale and ineffective.

To my relief, people were entering the station with me. Obviously, there was a service of trains this early, though I had been in doubt about it till then. The taking of a ticket to Friedrich Strasse Station, one of the chief stations in Berlin, cost me some agitation. It meant the first test of my ability to “carry on.”

“Friedrich Strasse! Ten minutes to six! I must find the restaurant and have breakfast.” There is no sense in neglecting the inner man; no experienced campaigner will voluntarily risk it.

Friedrich Strasse was a most uncomfortable place to be in. It swarmed with soldiers, and its intricate passages and stairs were plastered with placards: “Station Provost Marshal,” “Military Passport Office,” “Passports to be shown here,” “For Military only.”

At last I found a snug little waiting-room and restaurant, where I got a fairly decent meal, in[Pg 42]cluding eggs, which at the time were still obtainable without ration-cards, and rolls, for which I ought to have delivered up some bread-tickets, but didn’t. As soon as I had a chance, I bought a newspaper and some cigarettes. Either might help one over an awkward moment.

The train for Leipzig left from a station I knew nothing about except the name. The easiest way for me to get there was by cab. A number of these were standing in front of Bahnhof Friedrich Strasse.

“Anhalter Bahnhof,” I said curtly to the driver of the first four-wheeler on the rank. Cabby mumbled something about Marke through a beard of truly amazing wildness. Then only did I recollect that it is necessary before taking a cab from a station rank in Berlin to obtain a brass shield, with its number, from a policeman stationed inside the booking-hall. Back I went, overcoming as best I might the terrifying aspect of the blue uniform close to me. Fortunately, the man was extraordinarily polite for a Prussian officer of the law, and inquired solicitously what particular kind of cab I should like, and whether it was to be closed or open. It was to be closed.

I had twenty minutes to spare after I[Pg 43] alighted from the cab in front of my destination. This station appeared less crowded than the former one, although a considerable number of soldiers were in, or passing through, the big hall. The moment had come when one of the main points of my plan was to be put to the test. Could I obtain a long-distance ticket without a passport? I waited until several people approached the booking-office, then lined up behind them. One of them asked for a second-class ticket to Leipzig, and got it without any formality. I considered myself quite safe when I repeated his demand.

The train, a corridor-express, was crowded. The hour was early for ordinary people, and nobody seemed in the least talkative. To guard against being addressed, I had bought enough German literature of the bloodthirsty type to convince anybody of my patriotic feelings, but I hardly looked at it. I was too much interested in watching the country flashing past the window and in speculating upon what it would be like near the Dutch frontier.

At Leipzig, where we arrived at 9:30 A.M., I had my little Gladstone taken to the cloak-room by a porter, to give more verisimilitude to my limp. For the same reason I made it my first business to buy a stout walking-stick at the[Pg 44] nearest shop. After that I got a good luminous compass, whose purchase was another test case. When it was treated as an everyday transaction by the man behind the counter my spirits rose, and the acquisition of maps appeared a less formidable undertaking. Nevertheless, I resolved to leave their purchase to the afternoon. Should I find that suspicion was aroused by my request for “a good map of the province of Westphalia,” I intended to nip away on the earliest train, if I could reach the station unarrested.

The rest of the morning I spent limping through the town, keeping very much on the alert all the time. The tortuous, narrow streets of the inner town, with their old high-gabled houses in curious contrast with the modern buildings and clanging tram-cars, were a delight to me as well as a difficulty; the latter in so far as I had to keep account of my whereabouts, the better to be able to act swiftly in an emergency. Gradually I got into more modern streets, wide and straight. In passing I had made a mental note of a likely-looking restaurant to have lunch in later on.

At last I found myself in a public park, where I rested on a seat for some time. A shrewd wind, which whistled through the bare branches[Pg 45] of the trees, made me wrap myself tighter in my greatcoat.

I started to walk back to the restaurant at midday, following for the greater part of the way in the wake of three fat and comfortable-looking burghers, who were deciding the war and the fate of nations in voices loud enough for me to follow their conversation, although thirty paces behind. In the restaurant I had a meal, somewhat reduced in quality and quantity, for a little more than I should have paid in peace times. Over a cigarette I then started to look up my evening train in the time-table I had bought at the station. Unable to find what I wanted, I grew hot and cold all over. I had by no means speculated upon having to stay in any town overnight, and should not have known how to act had I been forced to do so. This question had to be settled there and then, so I went to the station and the inquiry office. I was told that I could get a train at 7:50 or 8 P.M.—I forget which—to Magdeburg, and from there catch the express for the west to Dortmund.

The first part of the afternoon I spent in several cafés, unhappy to be within four walls, yet wanting to rest as much as possible. Toward five o’clock I nervously set forth to buy the maps and some other less important things. I passed[Pg 46] several booksellers’ shops with huge war-maps displayed in the windows, but my feet, seemingly of their own volition, carried me past them. When I finally plucked up enough courage to enter a shop, my apprehension proved quite unnecessary. I came away with a fine motor-map and another one, less useful generally but giving some additional information. After that the rest of my equipment was rapidly acquired: a pair of night binoculars, wire-clippers, a knapsack, a very light oilskin, and a cheap portmanteau to carry these things in. By a fortunate chance I saw some military water-bottles in a shop window, which reminded me that I had nearly overlooked this very important part of a fugitive’s rig-out. I got a fine aluminum one.

By this time it was getting dark. The best way of spending what remained of my time in Leipzig was to have a leisurely meal in the station restaurant.

While I was waiting to be served, a well-dressed man at a table opposite attracted my attention. He came into the room soon after me, and seemed to take a suspicious interest in my person. He stared at me, openly and otherwise. When he did the former, I tried to outstare him. After he had twice been worsted in[Pg 47] this contest he kept a careful but unobtrusive watch over the rest of the people in the restaurant, but took no further notice of me, not even when I crossed the room later on to buy at the counter as many sweet biscuits and as much chocolate as I dared. After that I sat reading a book with a lurid cover whereon a German submarine was torpedoing a British man-of-war among hectic waves. Taking advantage of the short-sightedness implied by my glasses, I held it close to my eyes, so that onlookers might have the benefit of the soul-inspiring cover, and look at that instead of my face.

A porter, whom I had tipped sufficiently to make it worth his while, came to fetch my luggage and see me into the train, where I had a compartment to myself. As soon as we were moving, I executed a wild but noiseless war-dance to relieve my overcharged feelings, and then had my first good look at the maps.

At Magdeburg I had only a few minutes to wait for the express to Belgium, which was to arrive at midnight. It turned out to be split into three sections, following each other at ten-minute intervals. I took the first of the trains. The second-class compartment I entered was occupied by an officer of the A. M. C. and two non-commissioned officers. The latter soon left us,[Pg 48] having bribed the guard, so it seemed, to let them go into the first-class. In this way the medical officer and I had the whole compartment to ourselves. We lay down at full length, and I slept with hardly an interruption until 4:30, half an hour before the train was due at Dortmund.

At Dortmund the waiting-room I went to was almost empty. I left my luggage in the care of a waiter, and went out to have a wash and brush-up. This expedition gave me an opportunity to learn something about the station before I got a fresh ticket. I saw that to do this I should have to pass ticket-gates which were in charge of an extraordinarily strong guard with fixed bayonets. The importance of Dortmund as a manufacturing town, coupled with its situation in the industrial district of the West, the vulnerable point of Germany, explained these precautions.

Back in the waiting-room, a liquid called coffee and a most unsatisfactory kind of war bread had to take the place of a Christian breakfast. From the time-table I learned that there was a local train to Wanne at about 6:30. It just missed connection with another one from Wanne to Haltern, if I recollect rightly. The prospect of having to wait over two hours in a small town on the edge of the industrial district, before I[Pg 49] could get a train, was not particularly inviting, but there was no alternative. My ticket was taken only at the last minute; then Dortmund was left behind.

For most of the way to Wanne I traveled in the company of two young civilians, massively built and pictures of health. When they had left I hastily packed my impedimenta in the new portmanteau, leaving the Gladstone empty, with the intention of depositing it in a cloak-room as the best means of getting rid of it without leaving a clue.

Having arrived at Wanne at eight o’clock, I handed my two pieces of luggage in at the cloak-room window, asking for a separate ticket for each.

The man behind the counter, to whom I took a great dislike from that moment, stared at me in silence for some seconds, until I could no longer stand it, and started a lame explanation: I wanted to leave the small bag for a friend of mine to fetch later on from whom I had borrowed it in the town about a week ago, name of Hugo Schmidt. The other I would take away with me as soon as my business in Wanne was finished. The fib sounded unconvincing enough to my own ears. The wooden face of my antagonist on the other side of the window gave[Pg 50] no indication of thoughts or emotions. All that mattered really was that he gave me two tickets, and that I found myself in the street still unarrested but feeling unaccountably hot.

Walking as briskly as my limp would permit, I wandered about the streets, diving into a factory yard here and the hall of an office building there, as if I were a commercial traveler, taking good care not to linger long enough for other people to become interested in me.

All the time I felt uncomfortable and dissatisfied with my performance at the station and the pretense I was putting up, and thus it came about that the photograph of a friend of mine in Ruhleben disintegrated under my fingers in my pocket, to be dropped bit by bit into the road, lest, if I were arrested, the original should get into trouble.

It was a relief when ten o’clock was past and train-time approached. I got my portmanteau from my friend in the cloak-room, who was fortunately busy with other people, and got into an empty compartment. Between stations, during the twenty-minute run, I looked at my maps, to form an idea of how best to get out of Haltern in the right direction.

This small town is about half a mile from the station, which is an important railway junction.[Pg 51] I was quite unacquainted with this part of the province of Westphalia. The maps showed it as not too thickly populated, with plenty of woods dotted all over it, and plenty of water.

The train thundered over the big railway bridge crossing the river Lippe and drew into the station, and I, feeling pretty good, landed on the platform with something like a skip and a jump, until I recollected my leg. Then slowly I limped after the other people the train had disgorged. In front of me I could see the church steeple rising above the roofs of the compact little town in the middle distance. Half-way toward it I passed a detachment of English Tommies sitting on top of a fence, smoking pipes and cigarettes. About an equal number of Poilus were standing close to them, laughing and criticizing the appearance of the passing women. The only guard I could discover was leaning sleepily against a tree on the opposite side of the road. I suppressed an almost overwhelming desire to exchange greetings, and passed them instead with a stony stare.

It was a sunny, warm day, and there was no difficulty about finding one’s bearings. In the market-place a sign “To Wesel” directed me up a narrow street of humble dwellings on my left. Just outside the town a number of roads met. Without looking at the directions on a mile-stone, I surveyed the country before me for suggestions as to my next move. The most important thing was to get to cover as quickly as possible, and to withdraw from the sight of man. Never mind about striking the right route now. That could wait until a thorough study of the maps gave me a better grasp of the situation. The most favorable-looking road led past a number of cottages and then ran in a northwesterly direction between a low range of hills. A footpath branching off toward a copse on my left seemed to offer the double attraction of a solitary walk and a short cut to a hiding-place. It took me about a hundred yards along the rear of the cottages, and then rejoined the[Pg 53] parent road at a point where the woods came down to it.

As soon as a corner of the copse sheltered me, I gave a last look up and down the deserted road, and a moment later the branches of the half-grown firs closed crackling behind me.

Loaded as I was with a thick overcoat and a heavy bag, I was fairly bathed in perspiration before I had penetrated sufficiently far into the thicket to feel safe. The branches were so interlaced that only the most realistic wormlike wriggle was effective as a means of propulsion, and even then progress was accompanied by a crackling noise which I was anxious to avoid.

Satisfied at last, I stood up and looked about me. From the pin-pricks of light toward the east, I concluded that the spot I stood on was not far from the margin of the copse where it bordered upon a plowed field. On all other sides was a dead wall of brown and green. Underfoot the ground was sopping wet, for the spring sun had no power as yet to penetrate down to where the brown needles and a tangle of black and moldering grass of last year’s growth would soon be covered by the shoots of the new spring. Wet and black, the lower branches of the young trees were things of the past, but higher up they stretched their arms[Pg 54] heavenward clothed in their dark green needles. The tops of the firs were glistening like green amber where they swayed slightly in the clear sunlight, forming delicate interlacing patterns beneath the pale spring sky.

Resting and preparing for my night’s walk, or poring over my maps, I spent the day there. A mouthful of food now and again was all I could swallow, for I was parched with thirst. The fast walk in the warm sun had started it, and the knowledge that there was no chance of assuaging it before the small hours of the next morning made it worse. I had not dared to fill my water-bottle at any of the stations for fear of being seen and arousing suspicion.

Most of the day my ears were continually on the alert, not so much from fear of discovery as for sounds which might convey useful information. The road leading past my hiding-place seemed little used; the rumble of a cart reached me only very occasionally. From the shrill cries of playing children, and the cackling of hens, I surmised the existence of several farmhouses farther along.

Before lying down I had put on my second set of underwear and discarded my white shirt, collar, and tie, for a green woolen shirt and a dark muffler, which did away with any but neutral col[Pg 55]ors on my person. Oilskins, oilsilks, overcoat, food, etc., were to be packed in the knapsack on breaking camp. Whatever would be wanted during the march, such as compass, maps, electric torch, and a small quantity of biscuits and chocolate, I stowed away in convenient pockets. The maps I cut into easily handled squares, discarding all the superfluous parts. When the sun had disappeared and gloom was gathering under the trees, I slung the water-bottle from my belt, the binoculars from my neck, and then crept to the edge of the copse, there to wait for the night.

Concealed behind some bushes, I watched the road, which gradually grew more indistinct. The roofs of the town, huddled in the hollow, lost their definite outlines. One after another lights sprang up behind the windows. The children’s voices became fewer, then ceased. Sound began to carry a great distance; the rumble of a railway train, the far-away barking of a dog. Twinkling stars came out in the heavens. It was time to start.

At 8:30 I scrambled out of my hiding-place and gained the road, where I set my face toward the west after a last glance at Haltern with its points of light. Two farmhouses, perfectly dark even at this early hour of the night, soon[Pg 56] lay behind me. Here the forest came down to the road on my left while fields bordered it on the right, and, perhaps eighty yards distant, the wooded hills arose. Whether it was a sort of sixth sense which gave me warning, I do not know, but a strong feeling that I was not safe on the road made me walk over the fields into the shadow of the trees, from where I could watch without being seen. My figure had hardly merged into this dark background, when silently a shadowy bicycle rider flitted along the road, going in my direction. He carried no lamp, and might have been a patrol.

The going on the plowed fields being rather difficult, I soon grew impatient of my slow progress and returned to the road, proceeding along it in perfect serenity henceforth. It rose gradually. Checking its direction by a glance at the stars now and again, I soon noticed a decided turn to the northwest. This proved beyond doubt that it could not be the turnpike to Wesel, which throughout its length ran due west.

After perhaps an hour of hard going, a sign-post loomed ghostly white through the darkness, to spring into sharp relief in the light from the torch. “Klein Recken 2½ hours,” it read. A consultation of the map then showed that I was on a far more favorable road than I had antici[Pg 57]pated, and that a brook flowing close to the hither side of the village of Klein Recken might be reached at about midnight, if I kept my speed. I needed no further inducement.

I was now ascending the last spur of the hills which had fronted me on coming out of Haltern. My way lay mostly through woods, with occasional clearings where the dark outlines of houses and barns showed against the sky. Only occasionally was a window feebly lit as if by a night-light. Often dogs gave warning of my approach and spread the alarm far and wide.

It was a most glorious night, the sky a velvet black, the stars of a brilliancy seldom seen in western Europe. Their luster seemed increased when I found myself hedged in by a tall forest through which the road wound as through a cañon. A bright planet hung fairly low just in front of me, and in the exuberance of my feelings I regarded it as my guiding star.

On the ascent the night air was deliciously cool, not cold, with occasional warmer puffs laden with the scent of pines, the unseen branches and sere leaves of which whispered softly. Seldom have I felt so great a sense of well-being as I had during the first hours of that night. Never again while I was in Germany—whether in camp, in prison, or on other[Pg 58] ventures—did I feel quite so happy, so free from all stress, so safe.

Just before coming to the top of the ridge I found another sign-post pointing one arm into the forest as the shortest route to Klein Recken. The light of the torch revealed a narrow footpath disappearing into impenetrable blackness. I eased myself of my knapsack and rested for ten minutes, eating some biscuits and chocolate, which made me more thirsty than ever. It must have been colder than I thought, for on resuming my burden I found it covered with a thin sheet of ice.

Striking into the footpath, I found a rather liberal use of the torch necessary. The path descended steeply at first, then more gradually. The tall timber changed to smaller trees and thickets. An occasional railway train rumbled in the distance; yet for over an hour the country was empty of human dwellings. Then several houses, widely apart, announced the neighborhood of a village. A tinkling sound made me lengthen my already swinging stride until I stood on a stone bridge. The low murmur of water below was very pleasant in my ears. But that was not the only sound. Something was stirring somewhere, but my dry tongue and throat would not be denied any longer. Clam[Pg 59]bering over a barbed-wire fence into a meadow, I looked for a place from which I could reach the stream, which had steep banks. Engaged in tying my water-bottle to my walking-stick to lower it into the water, I heard footsteps approaching. The darkness was sufficient concealment, and I merely kept motionless as two men crossed the bridge, one of whom, from the scraps of talk I could distinguish, appeared to be the village doctor, who was being fetched to a patient.

When they had gone, I lowered my water-bottle. It seemed a very long time filling, the bubbles breaking the surface with a wonderfully melodious sound. And then I drank and drank, filled it again, and almost emptied it a second time. When I turned away, it was hanging unwontedly heavy against my hip.

In front of me was Klein Recken. The road I had been following up to now terminated here. It was miles to the north of where I expected to be at this time, when I started out, but that much nearer to the frontier. My plans for the night had been upset by my getting on this favorable road, nor could I look at my maps. The use of the torch so near to habitations was out of the question. I had a pretty good idea, however, of what I should have seen, had I dared.

A railway line ran through the village. After crossing this, I should have to trust to my guiding star and to my ability to work across-country.

Instead of the level crossing I was looking for, I came unexpectedly upon a tunnel in a very high embankment. With bated breath I tiptoed through, more than half expecting to meet a sentry on the other side. The footpath which emerged from it proved an unreliable guide. It soon petered out and left me stranded in front of a barbed-wire fence and a ditch. The cross-country stretch was on.

The going over plowed fields was easy in comparison, but they formed only a part of the country I was traveling over. Frequent patches of forest forced me to skirt them, with time lost on the other side to make the necessary corrections. Repeatedly I sank half-way to my knees into slough and water. Several casts were often necessary to get round these places, for, overgrown with weeds, and in the darkness, the swampy pieces looked like firm meadows. For a time, a sort of wall formed of rough stones accompanied me, with marshy ground on one side and forest on the other. It seemed to run in all directions. As soon as I lost it, I came upon it again. I kept going as fast as[Pg 61] possible all the time; yet hour after hour passed, and still the bewildering procession of woods and fields, swamps and meadows continued.

A phenomenon of which I was ignorant at the time, but which is well known to sailors, kept me busy conjecturing. It is an impression one gets at night, on level ground, or at sea, that one is going decidedly up-hill. In my case this introduced a disturbing factor into my calculations as to my position.

After tacking through a forest over checker-board clearings the meaning of which was hidden from me, for they were hardly paths or roads, I came out upon a path, and heard water bubbling out of the bank on my right. “More haste less speed. Take it easy,” I murmured to myself, dropping the haversack. Then I bent down to the spring and, having drunk as much as I needed, and eaten a mouthful of food, I did some of the hardest thinking of my life.

So far as I recollect, my watch showed just 3:20 A.M. I went minutely over all my movements since leaving Klein Recken. Although the road, which I expected would lie across my course, had not yet materialized, I was confident that I had kept my direction fairly well. It was the impossibility of calculating one’s speed[Pg 62] across-country which caused the uncertainty as to my whereabouts.

Fortunately, there was no doubt that a turnpike was not many miles to the north of me. To reach it, and thus ascertain my position, meant leaving the present route to the frontier. With less than two hours of darkness before the dawn, which would force me into hiding, the former factor was of far greater importance than the latter.

My nerves had been getting a little shaky under the stress. I had to press my hands to my head in order to think logically, and to exert all my will-power to keep my heart steady. Oh, for a companion! The effort cleared my brain and soothed me. I was almost cheerful when I went on.

Opposite a farmhouse, the path divided and my way became a miry and deeply rutted cart track. Past another farm, it entered a swampy meadow through a gate and disappeared. Savage at being tricked again, I wheeled round to look for the other fork of the track, but was arrested by seeing a light in the window of the farmhouse where a big dog had given the alarm when I passed. This was the last straw. Clenching my teeth, I crouched behind the hedge, an insensate fury making my ears sing.[Pg 63] For the moment, having lost all control of myself, I was more than ready to meet man or dog, or both, and fight it out on the spot. But that feeling passed quickly.

The noise of a door being opened came to my ears. A lantern was borne from the house and obscured again. Another door opened, and the footsteps of a horse sounded on cobbles, followed by the jingling of harness. Then a cart started out into the dark. Where a cart could go there must be a road; so I followed after, stumbling over ruts and splashing through puddles, and running when the horse broke into a trot.

The cart drew up in front of a building, of which I could see only patches of the front wall where the lantern light struck. Followed the noise of heavy things dumped into the vehicle. Then it started again—back toward where I was standing. Thoroughly exasperated, I turned on my heel and walked back over the road I had come, careless whether I was seen or not. I soon drew away, tried to work round in a circle, and presently came upon a road once more.