CAPTAIN COLES’S NEW IRON TURRET-SHIP-OF-WAR.

Title: Knowledge for the Time

Author: John Timbs

Release date: July 25, 2015 [eBook #49524]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

CAPTAIN COLES’S NEW IRON TURRET-SHIP-OF-WAR.

A Manual

OF

READING, REFERENCE, AND CONVERSATION ON SUBJECTS OF LIVING INTEREST, USEFUL CURIOSITY, AND AMUSING RESEARCH:

HISTORICO-POLITICAL INFORMATION.

PROGRESS OF CIVILIZATION.

DIGNITIES AND DISTINCTIONS.

CHANGES IN LAWS.

MEASURE AND VALUE.

PROGRESS OF SCIENCE.

LIFE AND HEALTH.

RELIGIOUS THOUGHT.

Illustrated from the best and latest Authorities.

By JOHN TIMBS, F.S.A.

AUTHOR OF CURIOSITIES OF LONDON, THINGS NOT GENERALLY KNOWN, ETC.

LONDON:

Lockwood and Co., 7 Stationers’-hall Court.

MDCCCLXIV.

The great value of contemporary History—that is, history written by actual witnesses of the events which they narrate,—is now beginning to be appreciated by general readers. The improved character of the journalism of the present day is the best evidence of this advancement, which has been a work of no ordinary labour. Truth is not of such easy acquisition as is generally supposed; and the chances of obtaining unprejudiced accounts of events are rarely improved by distance from the time at which they happen. In proportion as freedom of thought is enlarged, and liberty of conscience, and liberty of will, are increased, will be the amount of trustworthiness in the written records of contemporaries. It is the rarity of these high privileges in chroniclers of past events which has led to so many obscurities in the world’s history, and warpings in the judgment of its writers; to trust some of whom has been compared to reading with “coloured spectacles.” And, one of the features of our times is to be ever taking stock of the amount of truth in past history; to set readers on the tenters of doubt, and to make them suspicious of perversions; and to encourage a whitewashing of black reputations which sometimes strays into an extreme equally as unserviceable to truth as that from which the writer started.

It is, however, with the view of correcting the Past by the light of the Present, and directing attention to many salient points of Knowledge for the Time, that the present volume is offered to the public. Its aim may be considered great in proportion to the limited means employed; but, to extend what is, in homely phrase, termed a right understanding, the contents of the volume are of a mixed character, the Author having due respect for the[v] emphatic words of Dr. Arnold: “Preserve proportion in your reading, keep your views of Men and Things extensive, and depend upon it a mixed knowledge is not a superficial one: as far as it goes, the views that it gives are true; but he who reads deeply in one class of writers only, gets views which are almost sure to be perverted, and which are not only narrow but false.”

Throughout the Work, the Author has endeavoured to avail himself of the most reliable views of leading writers on Events of the Day; and by seizing new points of Knowledge and sources of Information, to present, in a classified form, such an assemblage of Facts and Opinions as may be impressed with warmth and quickness upon the memory, and assist in the formation of a good general judgment, or direct still further a-field.

In this Manual of abstracts, abridgments, and summaries—considerably over Three Hundred in number—illustrations by way of Anecdote occur in every page. Wordiness has been avoided as unfitted for a book which has for its object not the waste but the economy of time and thought, and the diffusion of concise notions upon subjects of living Interest, useful Curiosity, and amusing Research.

The accompanying Table of Contents will, at a single glance, show the variety as well as the practical character of the subjects illustrated; the aim being to render the work alike serviceable to the reader of a journal of the day, as well as to the student who reads to “reject what is no longer essential.” The Author has endeavoured to keep pace with the progress of Information; and in the selection of new accessions, some have been inserted more to stimulate curiosity and promote investigation than as things to be taken for granted. The best and latest Authorities have been consulted, and the improved journalism of our time has been made available; for, “when a river of gold is running by your door, why not put out your hat, and take a dip?”[1]

The Author has already published several volumes of “Things not generally Known,” which he is anxious to supplement with the present Manual of Knowledge for the Time.

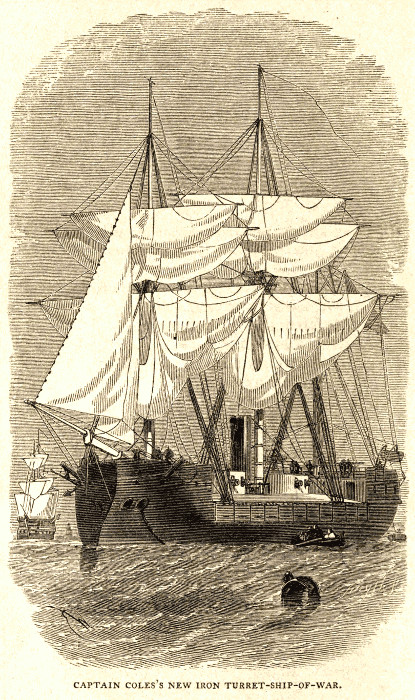

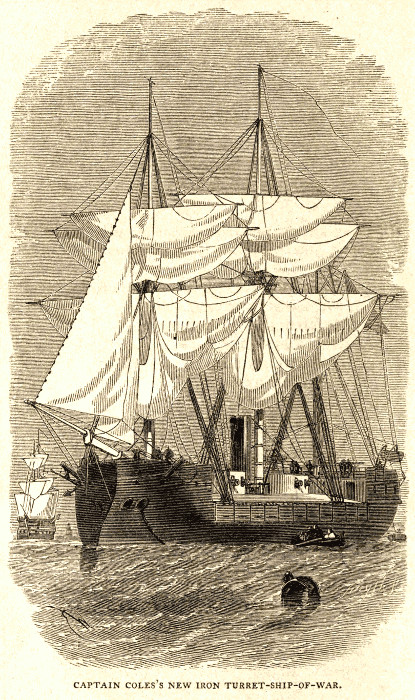

CAPTAIN COLES’S IRON TURRET-SHIP-OF-WAR.

The precise and best mode of constructing Iron Ships-of-War, so as to carry heavy guns, is an interesting problem, which Captain Coles believes he has already satisfactorily solved in his Turret ship, wherein he proposes to protect the guns by turrets. Captain Coles offered to the Admiralty so long ago as 1855 to construct a vessel on this principle, having a double bottom; light draught of water, with the power of giving an increased immersion when under fire; sharp at both ends; a formidable prow; her rudder and screw protected by a projection of iron; the turret being hemispherical, and not a turn-table, which was unnecessary, as this vessel was designed for attacking stationary forts in the Black Sea.

Captain Coles contributed to the International Exhibition models of his ship; admitting (he states) from 7 to 8 degrees depression. In two this is obtained by the deck on each side of the turret sloping at the necessary angle, to admit of the required depression; in the other two it is obtained by the centre of the deck on which the turret is surmounted being raised sufficiently to enable the shot, when the gun is depressed, to pass clear of the outer edge of the deck. A drawing published in 1860, of the midship section from which these models were made, also gives a section of the Warrior, by which it will be seen that supposing the guns of each to be 10 feet out of water, and to have the usual depressions of guns in the Navy (7 degrees), the Warrior’s guns on the broadside will throw the shot 19 feet further from the side than the shield ship with her guns placed in the centre, that being the distance of the latter from the edge of the ship: thus, with the same depression, the shield ship will have a greater advantage, this being an important merit of the invention,[vii] which Captain Coles has already applied to the Royal Sovereign. The construction of these turrets, the guns, and the turn-tables on which they are placed, with the machinery to work them, is very interesting; but its details would occupy more space than is at our command. (See Times, Sept. 8, 1863.)

Captain Coles, in a communication to the Times, dated November 4, 1863, thus urges the application of the turret to sea-going vessels, and quotes the opinion of the present Contractor of the Navy on the advantages his (Captain Coles’) system must have over the old one, in strength, height out of water, and stability, and consequent adaptation for sea-going ships. The Captain states:

“I believe I have already shown that on my system of a revolving turret, a heavier broadside can be thrown than from ships armed on the broadside; but it possesses this further advantage, that my turrets can be adapted to the heaviest description of ordnance; indeed, no other plan has yet been put in practice, while it is impossible to adapt the broadside ships to them, without the enlargement of the ports, which would destructively weaken the ships, and leave the guns’ crew exposed to rifles, grape-shot or shells.” Captain Coles then quotes the armaments of the Prince Albert (now constructing at Millwall,) and the Warrior, and shows that although the broadside of the Prince Albert is nominally reduced to 1120 lbs. (still in excess of the Warrior’s if compared with tonnage); it still gives this great advantage, that whereas late experiments have demonstrated that 4½-inch plates can be made to resist 68-pounder and 110-pounder shot, they have also shown that the 300-pounder smashes them when formed into a “Warrior target” with the greatest ease. The Prince Albert, therefore, can smash the Warrior, though the Warrior carries no gun that can injure her; nor can she, as a broadside ship, be altered to carry heavier guns.

The Engraving represents Captain Coles’s Ship cleared for action, and the bulwarks down.

I.—Historico-Political Information, 1-56:

Politics not yet a Science, —The Philosopher and the Historian, 1. —Whig and Tory Ministries, 2. —Protectionists, —Rats, and Ratting, —The Heir to the British Throne always in Opposition, 4. —Legitimacy and Government, —“The Fourth Estate,” 5. —Writing for the Press, —Shorthand Writers, 7. —The Worth of Popular Opinion, 8. —Machiavelism, —Free-speaking, 9. —Speakers of the Houses of Parliament, 10. —The National Conscience, 11. —“The Nation of Shopkeepers,” 12. —Results of Revolutions, 13. —Worth of a Republic, —“Safe Men,” 14. —Church Preferment, —Peace Statesmanship, —The Burial of Sir John Moore, 15. —The Ancestors of Washington, 16. —The “Star-spangled Banner,” —Ancestry of President Adams, 18. —The Irish Union, 19. —The House of Bonaparte, 20. —Invasion of England projected by Napoleon I., 21. —Fate of the Duc d’Enghien, 24. —Last Moments of Mr. Pitt, 25. —What drove George III. mad, 27. —Predictions of the Downfal of Napoleon I., 29. —Wellington predicts the Peninsular Compaign, 30. —The Battle of Waterloo, 31. —Wellington’s Defence of the Waterloo Campaign, 32. —Lord Castlereagh at the Congress of Vienna, 33. —The Cato-street Conspiracy, 34. —Money Panic of 1832, 36. —A great Sufferer by Revolutions, —Origin of the Anti-Corn-Law League, 37. —Wellington’s Military Administration, 38. —Gustavus III. of Sweden, 39. —Fall of Louis Philippe, 40. —The Chartists in 1848, 41. —Revival of the French Emperorship, 43. —French Coup d’Etat Predictions, —Statesmanship of Lord Melbourne, 44. —Ungraceful Observance, 45. —The Partition of Poland, 46. —The Invasion of England, 47. —What a Militia can do, 48. —Whiteboys, 49. —Naval Heroes, —How Russia is bound to Germany, 50. —Count Cavour’s Estimate of Napoleon III., 51. —The Mutiny at the Nore, 52. —Catholic Emancipation and Sir Robert Peel, —The House of Coburg, 53. —A few Years of the World’s Changes, 55. —Noteworthy Pensions, 56.

II.—Progress of Civilization, 57-84:

How the Earth was peopled, 57. —Revelations of Geology, 58. —The Stone Age, 59. —What are Celtes? 60. —Roman Civilization of Britain, 61. —Roman Roads and British Railways, 62. —Domestic Life of the Saxons, 64. —Love of Freedom, 65. —The Despot deceived, [ix]—True Source of Civilization, 66. —The Lowest Civilization, —Why do we shake Hands? 67. —Various Modes of Salutation, 68. —What is Comfort? 69. —What is Luxury? —What do we know of Life? 70. —The truest Patriot the greatest Hero, —The old Philosophers, 71. —Glory of the Past, 72. —Wild Oats, —How Shyness spoils Enjoyment, 73. —“Custom, the Queen of the World,” 74. —Ancient Guilds and Modern Benefit Clubs, —The Oxford Man and the Cambridge Man, 75. —“Great Events from Little Causes spring,” 76. —Great Britain on the Map of the World, 80. —Ancient and Modern London, —Potatoes the national food of the Irish, 81. —Irish-speaking Population, —Our Colonial Empire, 82. —The English People, 84.

III.—Dignities and Distinctions, 85-102:

Worth of Heraldry, 85. —Heralds’ College, 86. —The Shamrock, —Irish Titles of Honour, 87. —The Scotch Thistle, 88. —King and Queen, 89. —Title of Majesty, and the Royal “We,” 90. —“Dieu et Mon Droit,” —Plume and Motto of the Prince of Wales, 91. —Victoria, 92. —English Crowns, —The Imperial State Crown, 93. —Queen’s Messengers, —Presents and Letters to the Queen, 95. —The Prince of Waterloo, —The See of London, 96. —Expense of Baronetcy and Knighthood, 97. —The Aristocracy, 98. —Precedence in Parliament, —Sale of Seats in Parliament, —Placemen in Parliament, 99. —New Peers, —The Russells, —Political Cunning, 100. —The Union-Jack, —Field-Marshal, 101. —Change of Surname, 102.

IV.—Changes in Laws, 104-144:

The Statute Law and the Common Law, 104. —Curiosities of the Statute Law, 105. —Secret of Success at the Bar, —Queen’s Serjeants, Queen’s Counsel, and Serjeants-at-Law, 107. —Do not make your Son an Attorney, —Appellate Jurisdiction of the House of Lords, 108. —Payment of an advocate, —Utter-Barristers, 109. —What was Special Pleading? —What is Evidence? 110. —What is Trial? —Trial by Jury, 111. —Attendance of Jurors, —The Law of Libel, 113. —Induction of a Rector, 115. —Benefit of Clergy, —The King’s Book, 116. —Compulsory Attendance at Church, 117. —The Mark of the Cross, —Marriage-Law of England, 118. —Marriage Fines, 119. —Irregular Marriages, 120. —Solemnization of Marriage, 123. —The Law of Copyright, 124. —Holding over after Lease, —Abolition of the Hop Duty, 125. —Customs of Gavelkind, —Treasure Trove, 126. —Principal and Agent, —Legal Hints, 129. —Vitiating a Sale, 130. —Law of Gardens, —Giving a Servant a Character, 131. —Deodands, 132. —Arrest of the Body after Death, —The Duty of making a Will, 133. —Don’t make your own Will, 134. —Bridewell, 135. —Cockfighting, 136. —Ignorance and Irresponsibility, —Ticket-of-Leave Men, 137. —Cupar and Jedburgh Justice, —What is to be done with our Convicts, 138. —The Game Laws, —The Pillory,[x] 139. —Death-Warrants, —Pardons, 140. —Origin of the Judge’s Black Cap, —The Last English Gibbet, 141. —Public Executions, 142.

V.—Measure and Value, 146-169:

Numbers descriptive of Distance, —Precocious Mental Calculation, 146. —The Roman Foot, 147. —The Peruvian Quipus, 148. —Distances measured, —Uniformity of Weights and Measures, 149. —Trinity High-water Mark, —Origin of Rent, 150. —Curiosities of the Exchequer, 151. —What becomes of the Public Revenue, 153. —Queen Anne’s Bounty, 154. —Ecclesiastical Fees, —Burying Gold and Silver, 155. —Results of Gold-seeking, 157. —What becomes of the Precious Metals? 158. —Tribute-money, 159. —The First Lottery, —Coinage of a Sovereign, 160. —Wear and Tear of the Coinage, —Counterfeit Coin, 161. —Standard Gold, —Interest of Money, 162. —Interest of Money in India, —Origin of Insurance, 163. —Stockbrokers, 164. —Tampering with Public Credit, —Over-speculation, 165. —Value of Horses, —Friendly Societies, 166. —Wages heightened by Improvement in Machinery, 167. —Giving Employment, —Never sign an Accommodation Bill, 168. —A Year’s Wills, 169.

VI.—Progress of Science, 171-232:

What human Science has accomplished, —Changes in Social Science, 171. —Discoverers not Inventors, 172. —Science of Roger Bacon, 173. —The One Science, 174. —Sun-force, 175. —“The Seeds of Invention,” 176. —The Object of Patents, —Theory and Practice, —Watt and Telford, 177. —Practical Science, —Mechanical Arts, 178. —Force of Running Water, —Correlation of Physical Forces, —Oil on Waves, 180. —Spontaneous Generation, —Guano, —What is Perspective? 181. —The Stereoscope, —Burning Lenses, 182. —How to wear Spectacles, —Vicissitudes of Mining, 183. —Uses of Mineralogy, 185. —Our Coal Resources, —The Deepest Mine, 186. —Iron as a Building Material, 189. —Concrete, not new, —Sheathing Ships with Copper, 190. —Copper Smelting, —Antiquity of Brass, —Brilliancy of the Diamond, 191. —Philosophy of Gunpowder, —New Pear-flavouring, 192. —Methylated Spirit, 193. —What is Phosphate of Lime? —What is Wood? —How long will Wood last? 194. —The Safety Match, 195. —Pottery, —Wedgwood, 196. —Imposing Mechanical Effects, 197 —Horse-power, —The First Practical Steam-boat, 198. —Effect of Heavy Seas upon Large Vessels, 199. —The Railway, —Accidents on Railways, 200. —Railways and Invasions, 202. —What the English owe to naturalized Foreigners, 203. —Geological Growth, 204. —The Earth and Man compared, —Why the Earth is presumed to be Solid, —“Implements in the Drift,” 205. —The Centre of the Earth, 206. —The Cooling of the Earth, 207. —Identity of Heat and Motion, 208 —Universal Source of Heat, 209. —Inequalities of the Earth’s Surface, 210. —Chemistry of the Sea, 212. —The Sea: its Perils, 213. —Limitations of Astronomy, 214. —Distance of the Earth[xi] from the Sun, 215. —Blue Colour of the Sky, 216. —Beauty of the Sky, 217. —High Temperatures in Balloon Ascents, —Value of Meteorological Observations, Telegraph, and Forecasts, 218. —Weather Signs, 220. —Barometer for Farmers, 222. —Icebergs and the Weather, 223. —St. Swithun: his true History, 224. —Rainfall in London, 225. —The Force of Lightning, 226. —Effect of Moonlight, —Contemporary Inventions and Discoveries, 227. —The Bayonet, 228. —Loot, —Telegram, —Archæology and Manufactures, 229. —Good Art should be Cheap, 230. —Imitative Jewellery, 231. —French Enamel, 232.

VII.—Life and Health, 233-266:

Periods and Conditions of Life, —Age of the People, 233. —The Human Heart, —The Sense of Hearing, 234. —Care of the Teeth, —On Blindness, 235. —Sleeping and Dreaming, 236. —Position in Sleeping, —Hair suddenly changing Colour, 237. —Consumption not hopeless, 238. —Change of Climate, —Perfumes, 239. —Cure for Yellow Fever, —Nature’s Ventilation, 240. —Artificial Ventilation, —Worth of Fresh Air, 241. —Town and Country, 243. —Recreations of the People, —The Druids and their Healing Art, 244. —Remedies for Cancer, 245. —Improved Surgery, —Restoration of a Fractured Leg, 246. —The Original “Dr. Sangrado,” —False Arts advancing true, 247. —Brief History of Medicine, 248. —What has Science done for Medicine? 249. —Element of Physic in Medical Practice, 250. —Physicians’ Fees, —Prevention of Pitting in Small-pox, 251. —Underneath the Skin, 252. —Relations of Mind and Organization, 253. —Deville, the Phrenologist, 254. —“Seeing is believing,” 255. —Causes of Insanity, 256. —Brain-Disease, 257. —The Half-mad, 258. —Motives for Suicide, —Remedy for Poisoning, 259. —New Remedy for Wounds, —Compensation for Wounds, —The Best Physician, 260. —The Uncertainty of Human Life, 262.

VIII.—Religious Thought, 266-286:

Moveable Feasts, —Christmas, 266. —Doubt about Religion, 267. —Our Age of Doubt, 270. —A Hint to Sceptics, —What is Egyptology? 271. —Jerusalem and Nimroud, 272. —What is Rationalism? 273. —What is Theology? 274. —Religious Forebodings, 275. —Folly of Atheism, —The First Congregational Church in England, 276. —Innate Ideas, and Pre-existence of Souls, 277. —Sabbath of Professional Men, 278. —“In the Beginning,” 279. —The last Religious Martyrs in England, —Liberty of Conscience, 281. —Awful Judgments, —Christian Education, —The Book of Psalms, 283. —The Book of Job, 285.

| Great Precedence Question | 287 |

Mr. Buckle, in his thoughtful History of Civilization, remarks: “In the present state of knowledge, Politics, so far from being a science, is one of the most backward of all the arts; and the only safe course for the legislator is to look upon his craft as consisting in the adaptation of temporary contrivances to temporary emergencies. His business is to follow the age, and not at all to attempt to lead it. He should be satisfied with studying what is passing around him, and should modify his schemes, not according to the notions he has inherited from his fathers, but according to the actual exigencies of his own time. For he may rely upon it that the movements of society have now become so rapid that the wants of one generation are no measure of the wants of another; and that men, urged by a sense of their own progress, are growing weary of idle talk about the wisdom of their ancestors, and are fast discarding those trite and sleepy maxims which have hitherto imposed upon them, but by which they will not consent to be much longer troubled.”

“I have read somewhere or other,” says Lord Bolingbroke, “in Dionysius Halicarnassus, I think, that History is Philosophy teaching by Example.”

Walter Savage Landor has thus distinguished the respective labours of the Philosopher and the Historian. “There are,” Mr. Landor writes,[2] “quiet hours and places in which a taper may be carried steadily, and show the way along the ground; but you must stand a tip-toe and raise a blazing torch above your head, if you would bring to our vision the obscure and time-worn figures depicted on the lofty vaults of antiquity. The philosopher shows everything in one clear light; the historian loves strong reflections and deep shadows, but, above all, prominent and moving characters.”

In writing of the Past, it behoves us to bear in mind, that while actions are always to be judged by the immutable standard of right and wrong, the judgment which we pass upon men must be qualified by considerations of age, country, situation, and other incidental circumstances; and it will then be found, that he who is most charitable in his judgment, is generally the least unjust.

It is curious to find one of the silken barons of civilization and refinement, writing as follows. The polite Earl of Chesterfield says: “I am provoked at the contempt which most historians show for humanity in general: one would think by them that the whole human species consisted but of about a hundred and fifty people, called and dignified (commonly very undeservedly too) by the titles of emperors, kings, popes, generals, and ministers.”

Sir Humphry Davy has written thus plainly in the same vein: “In the common history of the world, as compiled by authors in general, almost all the great changes of nations are confounded with changes in their dynasties; and events are usually referred either to sovereigns, chiefs, heroes, or their armies, which do, in fact, originate entirely from different causes, either of an intellectual or moral nature. Governments depend far more than is generally supposed upon the opinion of the people and the spirit of the age and nation. It sometimes happens that a gigantic mind possesses supreme power, and rises superior to the age in which he is born: such was Alfred in England, and Peter in Russia. Such instances are, however, very rare; and in general it is neither amongst sovereigns nor the higher classes of society that the great improvers and benefactors of mankind are to be found.”—Consolations in Travel, pp. 34, 35.

The domestic history of England during the reign of Anne, is that of the great struggles between Whig and Tory; and Earl Stanhope, in his History of England, thus points out a number of precisely parallel lines of policy, and instances of unscrupulous resort to the same censurable set of weapons of party warfare, in the Tories of the reign of Queen Anne and the Whigs of the reign of William IV.

“At that period the two great contending parties were distinguished, as at present, by the nicknames of Whig and Tory. But it is very remarkable that in Queen Anne’s reign the relative meaning of these terms was not only different but opposite to that which they bore at the accession of William IV. In theory, indeed, the main principle of each continues the same. The leading principle of the Tories is the dread of popular licentiousness. The leading principle of the Whigs is the dread of royal encroachment. It may thence, perhaps, be deduced that good and wise men would attach themselves either to the Whig or to the Tory party, according as there seemed to be the greater danger at that particular period from despotism or from democracy. The same person who would have been a Whig in 1712 would have been a Tory in 1830. For, on examination, it will be found that, in nearly all particulars, a modern Tory resembles a Whig of Queen Anne’s reign, and a Tory of Queen Anne’s reign a modern Whig.

“First, as to the Tories. The Tories of Queen Anne’s reign pursued a most unceasing opposition to a just and glorious war against France. They treated the great General of the age as their peculiar adversary. To our recent enemies, the French, their policy was supple and crouching. They had an indifference, or even an aversion, to our old allies the Dutch. They had a political leaning towards the Roman Catholics at home. They were supported by the Roman Catholics in their elections. They had a love of triennial parliaments in preference to septennial. They attempted to abolish the protecting duties and restrictions of commerce. They wished to favour our trade with France at the expense of our trade with Portugal. They were supported by a faction whose war-cry was ‘Repeal of the Union,’ in a sister kingdom. To serve a temporary purpose in the House of Lords, they had recourse (for the first time in our annals) to a large and overwhelming creation of peers. Like the Whigs in May, 1831, they chose the moment of the highest popular passion and excitement to dissolve the House of Commons, hoping to avail themselves of a short-lived cry for the purpose of permanent delusion. The Whigs of Queen Anne’s time, on the other hand, supported that splendid war which led to such victories as Ramillies and Blenheim. They had for a leader the great man who gained those victories. They advocated the old principles of trade. They prolonged the duration of parliaments. They took their stand on the principles of the Revolution of 1688. They raised the cry of ‘No Popery.’ They loudly inveighed against the subserviency to France, the desertion of our old allies, the outrage wrought upon the peers, the deceptions practised upon the sovereign, and the other measures of the Tory administration.

“Such were the Tories and such were the Whigs of Queen Anne. Can it be doubted that, at the accession of William IV., Harley and St. John would have been called Whigs; Somers and Stanhope, Tories? Would not the October Club have loudly cheered the measures of Lord Grey, and the Kit-Cat find itself renewed in the Carlton?”

The defence of the Whigs against these imputations seems to be founded upon the famous Jesuitical principle, that the end justifies the means. They do not deny the facts, but they assert, that while the Tories of 1713 resorted to such modes of furthering the interests of arbitrary power, they have employed them in advancing the progress and securing the ascendancy of the democracy.

This name was given to that section of the Conservative party which opposed the repeal of the Corn-laws, and which separated from Sir Robert Peel in 1846. A “Society for the Protection of Agriculture,” and to counteract the efforts of the Anti-Corn Law League, gave the name to the party. Lord George Bentinck was their leader from 1846 till his death on September 21, 1848. The administration under Lord Derby not proposing the restoration of the corn-laws, this society was dissolved February 7, 1853.

James, in his Military Dictionary, 1816, states:—

“Rats are sometimes used in military operations, particularly for setting fire to magazines of gunpowder. On these occasions, a lighted match is tied to the tail of the animal. Marshal Vauban recommends, therefore, that the walls of powder-magazines should be made very thick, and the passages for light and wind so narrow as not to admit them (the rats).”

The expression to rat is a figurative term applied to those who at the moment of a division desert or abandon any particular party or side of a question. The term itself comes from the well-known circumstance of rats running away from decayed or falling buildings.—Notes and Queries, 2 S., No. 68.

Horace Walpole somewhere remarks, as a peculiarity in the history of the Hanover family, that the heir-apparent has always been in opposition to the reigning monarch. The fact is true enough; but it is not a peculiarity in the House of Hanover. It is an infirmity of human nature, to be found, more or less, in every analogous case of private life; but our political system developes it with peculiar force and more remarkable effects in the[5] Royal Family. Those who cannot obtain the favours of the father will endeavour to conciliate the good wishes of the son; and all arts are employed, and few are necessary, to seduce the heir-apparent into the exciting and amusing game of political opposition. He is naturally apt enough to dislike what he considers a present thraldom, and to anticipate, by his influence over a faction, the plenitude of his future power. This was the mainspring of the most serious part of the political troubles of the last century: let us, however, hope that it will never be revived; and this we are encouraged to hope from our improved Constitution, as well as from the improved education of our Royal Family.

It is an unguarded idea of some public writers that “the Sovereign holds her crown not by hereditary descent but by the will of the nation.” This doctrine is too frequently stated in and out of Parliament; and without qualification or explanation it would be apt to breed mischief in the minds of an ignorant and excited multitude, if the instinctive feelings of common sense did not invariably correct the popular errors of theorists.

“They who have studied the Constitution attentively hold that her Majesty reigns by hereditary right, though her predecessor in 1688 received the Crown at the hands of a free nation. To refer to the right of election, which can be exercised only during a revolution, and to be silent on hereditary right, is to lower the Regal dignity to the precarious office of the judges when they held their patents durante bene placito. Suppose a nation so divided that one casting vote would carry a plebiscite, changing the form of government, or the dynasty, and there would be a practical illustration of a principle—if principle at all—which, when taken as a broad palpable fact, is undeniable in the founder of a dynasty, but when erected into a legal theory it becomes neither more nor less than a permanent code of revolution. Hence the successor of that founder, if his power be not supported by military despotism, is invariably a staunch advocate of his indefeasible hereditary right, though originally derived from the consent of the nation.”—Saturday Review.

The Press has been described as the Fourth Estate of the realm; but it is not so. If we remember rightly, it was Lord Stanley who characterized it as a second representation of the Third Estate.[6] This is nearer the mark, though it is not exactly true, seeing that the press represents, or professes to represent, all the three estates. Its influence on the State is a fact either not acknowledged at all or acknowledged as an evil to be held in check by stringent laws and safeguards. Its place of power is not defined by any written Constitution, and its acts are in our day controlled, for the most part, by no written statute, but only by its own good sense. In its modes of expression, the newspaper press of our country usually keeps far within the bounds which the law prescribes; it voluntarily prescribes for itself a law which has no authority save that of taste. There is not a greater power under the Constitution than this press, which is indeed the source of power to much besides itself. What would public meetings be without the press? Within the present century the method of influencing public opinion by means of great gatherings of the people under the direction of leagues and associations has been perfected. It is a method which derives its momentum from the multiplication of reports. It is a matter of indifference to an orator what or where is his audience, provided through the reporters he can address all England. The Press has thus neutralized one of the evils of democracy as it was known in the olden time. A democratic Assembly meant a rabble, a packed multitude of noisy citizens into which the more quiet and thoughtful class of people did not care to venture. In the democratic Assemblies now every man in England virtually sits. We have good seats, for we are at our own firesides with the newspapers in our hands. In the quiet of our chosen retreats we listen to the “cheers,” and the “hear, hear,” and the laughter which the speech of the orator evokes, and we can calmly measure the words of the demagogue. Upon the very manner of public speaking, too, we imagine that the system of newspaper reporting has had some effect. If we may judge by the very imperfect reports which we have of speeches delivered in the last century, orators were then more inflated and inflammatory in their style than they are now, the momentary impression which they created was beyond anything we can now conceive, and if eloquence is to be judged from its immediate effect they were greater masters of the art than any we can now boast of. If this appears a hard thing to say, when we have such orators among us as Lord Derby, Mr. Gladstone, Mr. Bright, and Mr. Disraeli, let us remember the other side of the question—let us take into account that our contemporary first-class orators speak with the full knowledge that in cool blood their speeches will be read word for word[7] on the morrow. They know right well that much of the bombast which might safely be addressed to an admiring and heated audience will expose them only to ridicule when it is reduced to print. Insensibly a more sober standard of oratory is thus established, to the great gain of our deliberative assemblies, and acting as some check upon rhetorical demagogues.—Times.

The organization of a great Newspaper establishment is a remarkable result of practical ability profiting by accumulated experience; but an account of the progress and development of the system is as tedious as a history of the iron manufacture or of the cotton trade. A readable narrative must include matters of more human interest than tables of figures which represent the successive numbers of copies and of advertisements; and although newspapers, like power-looms, may not have sprung into existence of themselves, the names of their obscure founders and managers are deservedly forgotten. Mr. Perry’s name is still known in consequence of his connexion with the old Whig party; Mr. Stuart enjoys a parasitic fame as the employer of Coleridge and of Mackintosh; and the late Mr. Walter exhibited an effective sagacity in the conduct of his business which places him on a level with the Arkwrights and Boltons of manufacturing history. It would not be worth while to extend the list of able editors and spirited proprietors. Successful men of business must be contented to make their own fortunes and to benefit the world at large, without desiring the supererogatory reward of posthumous fame. When the gods, in Schiller’s apologue, had given away the earth and the sea, they reserved the barren sky for the portionless poet; and ever since, the lightest touch of genius, the smallest act which indicated inherent greatness, has been found to retain its place in the memory of men long after capitalists and mechanical inventors have joined the multitude of the dead; abierunt ad plures. The clever lecturer who employs himself in diffusing information on the mechanism of watches probably finds the attention of his audience flag when he attempts to delineate the qualities and virtues of deceased generations of watchmakers.—Saturday Review.

Stenography, or the art of short writing, is generally stated to have been invented by Xenophon, the historian; first practised[8] by Pythagoras; and reduced to a system by the poet, Ennius. To this art we owe full reports of the proceedings in Parliament. The system of Gurney was employed for this purpose; shorthand notes upon which were found among the Egerton MSS.

The shorthand-writer of the House of Commons states in his Evidence before the Select Committee on Private Bill Legislation that he receives two guineas a-day for attendance before committees to take notes of the evidence, and 9d. per folio of 72 words for making a copy from his notes. In 1862, he received for business thus done for the committees on private Bills 6667l., consisting of 1682l. for attendance fees and 4985l. for the transcripts; this does not include the charges in respect of committees on public matters. He is appointed for the House of Lords also. So much of the business as he cannot execute by his own establishment he transfers to other shorthand writers on rather lower terms, but he himself keeps a staff of ten shorthand writers. Each of these has at least one clerk who can read his shorthand; but the most efficient course is found to be that he have two such clerks, each of whom (and himself also), taking in hand a portion of the notes, dictates to quick writers, so that the mode of transcribing is by writing from dictation, and not by copying. There is a great strain and pressure in order to get the transcript to the law-stationers in time for the requisite number of copies to be ready when the committee meet next morning. In the height of the session, the witness mentions, he provides refreshments for about fifty persons employed at his office during the evening, many of them until midnight, and often later.

Popular Opinion is generally founded on the most prominent and the most striking, but for that reason, often the most superficial feature in the interesting object of which a knowledge is pretended. That Cromwell had a wart on his nose; that Byron had a club-foot, which gave him more anxiety than the critiques on his poems; that the head of Pericles was too long, for which reason the sculptors always made his bust helmeted, while that of Julius Cæsar was bald, which made it doubly grateful to that great commander to have his brow encompassed with an oaken wreath, or the coveted kingly diadem; such prominent and superficial accessories of personal appearance, in the case of well-known characters, will often be familiar to thousands who know nothing more of the persons so curiously characterized. But[9] these, so far as they go, are true; they are accurate knowledge, not mere opinion. Even vulgar opinion is not so often altogether false as it is partial and inadequate, and therefore unjust. Of Mahomet, for instance, everybody knows that he was the prophet of an intolerant religion, which its most sincere professors have always most zealously propagated with the sword. This is quite true; but it is far from embracing the whole truth with regard to the religion of the Koran; and he who with the inconsiderate haste of popular logic, uses this accurate knowledge about a fraction of a thing, as if it were the just appreciation of the whole, falls not the less certainly into the region of mere delusion; for though the thing that he believes is true, it is not true as he gives it currency. He is in fact doing a thing in the region of ideas which is equivalent to passing a farthing for a guinea; an act whereby he swindles the public and himself very nearly as much as if he were to pass off a piece of painted pasteboard for the same value.—Professor Blackie; Edinburgh Essays, 1856.

It has been well said of Machiavelli, that he has the credit or discredit of having been the first to erect into a science, and reduce it to theory, the art of obtaining absolute power by deception and cruelty; and of maintaining it afterwards by the simulation of leniency and virtue. In political history, he was the first who gave at once a general and a luminous development of great events in their causes and connexion.

Sir Walter Raleigh, in his History of the World, says:—“The doctrine which Machiavel taught unto Cæsar Borgia, to employ men in mischievous actions, and afterwards to destroy them when they have performed the mischief, was not of his own invention. All ages have given us examples of this goodly policy; the latter having been apt scholars in this lesson to the more ancient, as the reign of Henry VIII. here in England can bear witness; and therein especially the Lord Cromwell, who perished by the same unjust law that himself had devised for the taking away of another man’s life.”

Archbishop Whately, in his very able Lecture on Egypt, referring to the writers on Public Affairs at home, reprehends the practice of exaggerating, with keen delight, every evil that they[10] can find, inventing such as do not exist, and keeping out of sight what is good. An Eastern despot, reading the productions of one of these writers, would say that, with all our precautions, we are the worst governed people on earth; and that our law-courts and public offices are merely a complicated machinery for oppressing the mass of the people; that our Houses of Lords and Commons are utterly mismanaged, our public men striving to repress merit, and that our best plan would be to sweep away all those, as, with less trouble, matters might go on better, and could not go on worse. Charges of this nature cannot be brought publicly forward in the Turkish Empire. In Cairo, a man was beheaded because he made too free a use of his tongue. He was told not to be speaking of the insurrection in Syria, and had dared to be chatting of the news; and there are other countries, also, where because such charges are true, it would not be safe to circulate them. But these writers do not mean half what they set forth. They heighten their descriptions to display their eloquence; but the tendency of such publications is always towards revolution, and the practical effect on the minds of the people is to render them incredulous. They understand that these overwrought representations are for effect, and they go about their business with an impression that the whole is unreal. If one of these writers were visited himself with a horrible dream that he was a peasant under an Oriental despot, that he was taxed at the will of the Sovereign, and had to pay the assessment in produce, valued at half the market-price, that he was compelled to work and receive four-fifths of his low wages in food consisting of hard, sour biscuit—let him then dream that he had spoken against the Ministry, and that he finds himself bastinadoed till he confesses that he brought false charges; that his grown-up son had been dragged off for a soldier, and himself deprived of his only support, and he would be inclined to doubt whether ours is the worst system of Government.

The late Sir George Cornewall Lewis, in a communication which appeared in Notes and Queries, in the week of the author’s lamented death, states the following:

“In modern legislative chambers it has been customary for the Chamber to appoint one of its own members as president. In the English House of Lords the Lord Chancellor is President by virtue of his office. Although a member of the executive Government, and holding his office at the pleasure of the Crown, he is nevertheless a high judicial officer, and is[11] deemed to carry his judicial impartiality into the performance of his presidential functions. In general, however, the president of a legislative chamber is not, according to modern practice, a member of the executive Government. He is an independent member of the legislature, who is appointed by the chamber, and holds his office at its pleasure, such as the Speaker of the English House of Commons.

“The principal functions of the Speaker of the House of Commons were not originally (as the title of his office indicates) what they are at present. The House of Commons were at first a set of delegates summoned by the Crown to negotiate with it concerning the payment of taxes. They might take advantage of the position of superiority which they temporarily occupied to remonstrate with the Crown about certain grievances, upon which they were generally agreed. In this state of things it was important that they should have an organ and spokesman with sufficient ability and knowledge to state their views, and with sufficient courage to contend against the displeasure of the Crown. The helpless condition of a large body which is called upon to conduct a negotiation without any appointed organ is well described by Livy. When the Roman plebeians seceded to the Mount Aventine, after the Decemvirate, the Senate sent three ambassadors to confer with them, and to propose three questions. ‘Non defuit,’ says Livy, ‘quid responderetur; deerat qui daret responsum, nullodum certo duce, nec satis audentibus singulis invidiæ se offerre’ (iii. 50). Since the Revolution of 1688, and the increased power of the House of Commons, the functions of the Speaker have undergone a change. His chief function has been no longer to speak on behalf of the House; that which was previously his accessary has become his principal duty. He has been simply chairman of the House, with the function of regulating its proceedings, of putting the question, and of maintaining order. The Speaker of the House of Commons is now virtually disqualified by his office from speaking; but as their debates have become more important, his office of moderator of these debates has acquired additional importance.

“The position of the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons was similar to that of the Speaker of the English House (see Lord Mountmorres’s History of the Irish Parliament, vol. i. p. 71-79); but in Scotland the three estates sat as one House; there was no separate House of Commons, and the Lord Chancellor presided over the entire assembly.” (See Robertson’s History of Scotland, b. 1, vol. i. p. 276, ed. 1821.)

When we come to the proofs from fact and historical experience, we might appeal to a singular case in the records of our Exchequer, viz., that for much more than a century back, our Gazette and other public advertisers have acknowledged a series of anonymous remittances from those who, at some time or other, had appropriated public money. We understand that no corresponding[12] fact can be cited from foreign records. Now, this is a direct instance of that compunction which our travelled friend insisted on. But we choose rather to throw ourselves upon the general history of Great Britain: upon the spirit of her policy, domestic or foreign; and upon the universal principles of her public morality. Take the case of public debts, and the fulfilment of contracts to those who could not have compelled the fulfilment; we first set this precedent. All nations have now learned that honesty in such cases is eventually the best policy; but this they learned from our experience, and not till nearly all of them had tried the other policy. We it was who, under the most trying circumstances of war, maintained the sanctity from taxation of all foreign investments in our funds. Our conduct with regard to slaves, whether in the case of slavery or of the Slave Trade—how prudent it may always have been we need not inquire—as to its moral principles they went so far ahead of European standards that we were neither comprehended nor believed. The perfection of romance was ascribed to us by all who did not reproach us with the perfection of Jesuitical knavery; by many our motto was supposed to be no longer the old one of divide et impera, but annihila et appropria. Finally, looking back to our dreadful conflicts with the three conquering despots of modern history, Philip II. of Spain, Louis XIV., and Napoleon; we may incontestably boast of having been single in maintaining the general equities of Europe by war upon a colossal scale, and by our counsels in the general congresses of Christendom.—De Quincey.

In the Præludia to the Chronicon Albeldense, attributed to Bulcidius, Bishop of Salamanca, a Spanish writer at the end of the ninth century, we find the following singular refutation of an ungraceful compliment hitherto paid to us by our Gallic neighbours. In a paragraph headed De Proprietatibus Gentium, we see the tables turned in our favour:—“1. Sapientia Græcorum; 2. Fortia Gothorum; 3. Consilia Chaldæorum; 4. Superbia Romanorum; 5. Ferocitas Francorum; 6. Ira Britannorum; 7. Libido Scotorum; 8. Duritia Saxonum; 9. Cupiditas Persarum; 10. Invidia Judæorum; 11. Pax Æthiopum; 12. Commercia Gallorum!” This discovery seems to be invested with an additional interest at a time when our Allies very handsomely acknowledge that they have hitherto laboured under a mistake in their estimate of our national peculiarities.

Sir George Cornewall Lewis, in his last work, On the Best Form of Government, has this summary: “There are some rare cases in which a nation has profited by a revolution. Such was the English Revolution of 1688, in which the form of the Government underwent no alteration, and the person of the King was alone changed. It was the very minimum of a revolution; it was remarkable for the absence of those accompaniments which make a revolution perilous, and which subsequently draw upon it a vindictive reactionary movement. The late Italian revolution has likewise been successful; by it the Italian people have gained a better government and have improved their political condition. It was brought about by foreign intervention; but its success has been mainly owing to the moderation of the leaders in whom the people had the wisdom to confide, and who have steadily refrained from all revolutionary excesses. The history of forcible attempts to improve governments is not, however, cheering. Looking back upon the course of revolutionary movements, and upon the character of their consequences, the practical conclusion which I draw is that it is the part of wisdom and prudence to acquiesce in any form of government which is tolerably well administered, and affords tolerable security to person and property. I would not, indeed, yield to apathetic despair, or acquiesce in the persuasion that a merely tolerable government is incapable of improvement. I would form an individual model, suited to the character, disposition, wants, and circumstances of the country, and I would make all exertions, whether by action or by writing, within the limits of the existing law, for ameliorating its existing condition and bringing it nearer to the model selected for imitation; but I should consider the problem of the best form of government as purely ideal, and as unconnected with practice, and should abstain from taking a ticket in the lottery of revolution, unless there was a well-founded expectation that it would come out a prize.”

Sir William Hamilton has well observed that[14] “No revolution in public opinion is the work of an individual, of a single cause, or of a day. When the crisis has arrived, the catastrophe must ensue; but the agents through whom it is apparently accomplished, though they may accelerate, cannot originate its occurrence. Who believes that but for Luther or Zwingli the Reformation would not have been? Their individual, their personal energy and zeal, perhaps, hastened by a year or two the event but had the public mind not been already ripe for their revolt, the fate of Luther and Zwingli, in the sixteenth century, would have been that of Huss and Jerome of Prague in the fifteenth. Woe to the revolutionist who is not himself a creature of the revolution! If he anticipate, he is lost; for it requires, what no individual can supply, a long and powerful counter-sympathy in a nation to untwine the ties of custom which bind a people to the established and the old.”

Mr. Baron Alderson is described as having a temper too calm for the stormy floor of the House of Commons; but he studied politics as a science, from a safe distance; and his letters contain his opinions on some points expressed with a very deliberate care. To Mrs. Opie, who had been writing against Republics and Republican Government, he says: “I entirely agree with your view of a Republic. As long as men are so wicked, it is an impossibility for it to be a lasting government, for it does not govern, but obey. America is no exception to this rule. In the first place, at its commencement, I believe it was a remarkably moral population; and so the evils would not at first appear. And, since that time, the immensity of its territory has enabled its most active and least self-restrained population to expand itself with less inconvenience. But will the thing last? When the wilderness is peopled, will not the wickedness, which is now expended on the Indians and the weak without observation, become intolerable, and a government strong enough to protect, be the result? Such a one, I think, will hardly be a republic, but, I fear, a despotism, for men always run into extremes. Lynch law is, in fact, an ill-regulated despotism.”

Dean Hook, in his Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, has the following judicious observations upon appointments of this practically useful class:

“Among the archbishops,” says the Dean, “there are a few eminent rulers distinguished as much for their transcendent abilities as for their exalted station in society; but as a general rule they have not been men of the highest class of mind. In all ages the tendency has very properly been, whether by election or nomination, to appoint ‘safe men;’ and as genius is generally innovating and often eccentric, the safe men are those who, with certain high qualifications, do not rise much above the intellectual average of their contemporaries. They are practical men rather than philosophers and theorists, and their impulse is not to perfection but quieta non movere. From this very circumstance their history is the more instructive; and, if few among the archbishops have left the impress of their mind upon the age in which they lived, we may in their biography read the character of the times which they fairly represent. In a missionary age we find them zealous but not enthusiastic; on the revival of learning, whether in Anglo-Saxon times or in the fifteenth century, they were men of learning, although only a few have been distinguished as authors. When the mind of the laity was devoted to the camp or the chase, and prelates were called to the administration of public affairs, they displayed the ordinary tact and diplomatic skill of professional statesmen, and the necessary acumen of judges; at the Reformation, instead of being leaders, they were the cautious followers of bolder spirits; at the epoch of the Revolution they were anti-Jacobites rather than Whigs; in a latitudinarian age they have been, if feeble as governors, bright examples of Christian moderation and charity.”

Lord Chancellor Thurlow, on reading Horsley’s Letters to Dr. Priestley, at once obtained for the author a Stall at Gloucester, saying that “those who supported the Church should be supported by it.”

There is nothing more wholesome for both the people and their rulers, than to dwell upon the excellence of those statesmen whose lives have been spent in the useful, the sacred, work of Peace. The thoughtless vulgar are ever prone to magnify the brilliant exploits of arms, which dazzle ordinary understandings, and prevent any account being taken of the cost and the crime that are so often hid in the guise of success. All merit of that shining kind is sure of passing current for more than it is really worth; and the eye is turned indifferently upon, or even scornfully from, the unpretending virtue of the true friend to his species, the minister who devotes all his cares to stay the worst of crimes that can be committed, the last of calamities that can be endured by man.

It had been generally supposed that the interment of General Sir John Moore, who fell at the Battle of Corunna, in 1809, took place during the night; a mistake which, doubtless, arose from the justly-admired lines by Wolfe becoming more widely known and remembered than the official account of this solemn event in[16] the Narrative of the Campaign, by the brother of Sir John Moore. In Wolfe’s monody, the hero is represented to have been buried

an error of description which has, doubtless, been extended by many pictorial illustrations of the sad scene, “darkly at dead of night.” The Rev. J. H. Symons, who was chaplain to the brigade of Guards attached to the army under Moore’s command, and who attended the hero in his last moments, relates that during the battle Moore was conveyed from the field into the quarters on the quay at Corunna, where he was laid on a mattress upon the floor, and the chaplain remained with him till his death. During the night, the body was removed to the quarters of Colonel Graham, in the citadel, by the officers of his staff; whence it was borne by them, assisted by Mr. Symons, the chaplain, to the grave which had been prepared for it on one of the bastions of the citadel. It being now daylight, the enemy had discovered that the troops had been withdrawing and embarking during the night; a fire was soon opened by them, upon the ships which were still in the harbour; the funeral service was, therefore, performed without delay, under the fire of the enemy’s guns; and, there being no means to provide a coffin, the body of the general,

With his martial cloak around him,

was deposited in the earth, the Rev. Mr. Symons reading the funeral service.

While America feels a just pride in having given birth to George Washington, it is something for England to know that his ancestors lived for generations upon her soil. His great-grandfather emigrated about 1657, having previously lived in Northamptonshire. The Washingtons were a Northern family, who lived some time in Durham, and also in Lancashire, whence they came to Northamptonshire. The uncle of the first Lawrence Washington was Sir Thomas Kitson, one of the great merchants, who, in the reigns of Henry VII. and VIII., developed the wool-trade of the country, which depended mainly on the growth of wool, and the creation of sheep-farms in the midland counties. That he might superintend his uncle’s transactions with the sheep proprietors, Lawrence Washington settled in Northamptonshire, leaving his own profession of a barrister. He soon[17] became Mayor of Northampton, and at the dissolution of the monasteries, being identified with the cause of civil and religious liberty, he gained a grant of some monastic land, including Sulgrave. In the parish of Brington is situated Althorp, the seat of the Spencers: the Lady Spencer of that day was herself a Kitson, daughter of Washington’s uncle, and the Spencers were great promoters of the sheep-farming movement. Thus, then, there was a very plain connexion between the Washingtons and the Spencers.

For three generations the Washingtons remained at Sulgrave, taking rank among the nobility and gentry of the county. Then their fortunes failed: they were obliged to part with Sulgrave, and retired to Brington, under, as it were, the wing of the Spencer family. From this depression the Washingtons recovered by a singular marriage. The eldest son of the family had married the half-sister of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, which at this time was not an alliance above the pretensions of the Washingtons: they rose into great prosperity. The emigrant, above all others of the family, continued to be on intimate terms with the Spencers, down to the very eve of the Civil War; he was knighted by James I. in 1623, and in the Civil War took the side of the king. The emigrant who left England in 1657, we leave to be traced by historians on the other side of the Atlantic.

“George Washington, without the genius of Julius Cæsar or Napoleon Bonaparte, has a far purer fame, as his ambition was of a higher and a holier nature. Instead of seeking to raise his own name, or seize supreme power, he devoted his whole talents, military and civil, to the establishment of the independence and the perpetuity of the liberties of his own country. In modern history no man has done such great things without the soil of selfishness or the stain of a grovelling ambition. Cæsar, Cromwell, Napoleon, attained a higher elevation, but the love of dominion was the spur that drove them on. John Hampden, William Russell, Algernon Sidney, may have had motives as pure, and an ambition as sustained, but they fell. To George Washington alone, in modern times, has it been given to accomplish a wonderful revolution, and yet to remain to all future times the theme of a people’s gratitude, and an example of virtuous and beneficent power.”—Earl Russell’s Life and Times of Charles James Fox.

The people of the United States understand little of the proper form, proportion of size, number of stripes even, of their own national flag, the “Star-spangled Banner.”

The standard for the army is fixed at six feet and six inches, by four feet and four inches; the number of stripes is thirteen—viz., seven red and six white. It will be perceived that the flag is just one-half longer than it is broad, and that its proportions are perfect when properly carried out. The first stripe at the top is red, the next white, and so down alternately, which makes the last stripe red. The blue field for the stars is the width and square of the first seven stripes—viz., four red and three white. These seven stripes extend from the side of the field to the extremity of the flag; the next stripe is white, extending the entire length of it, and directly under the field; then follow the remaining stripes alternately. The number of stars on the field is now thirty-one, and the Army and Navy add another star on the admission of a new State into our glorious union. In some respects, the “Banner” resembles the flag of the Sandwich Islands.—American journal.

John Adams, second President of the United States of America, is commonly but erroneously represented to have been the son of a cobbler. Now, he was the son of a clergyman. His descent would have graced any Court in Europe. He was descended from one of the oldest families in Devonshire and Gloucestershire, one of whom sat as an English Baron in the Parliaments of Edward the First. His father, Adam Fitzherbert, was lineally descended from the ancient Counts de Vermandois. Lord ap-Adam’s wife (the ancestress of this second President of America) was the daughter and sole heiress of John Lord de Gournay, of Beverston Castle, Gloucestershire, the representative of the ancient House of Harpitré de Gournai, a branch of the great house of “Yvery,” which was connected with every Sovereign house in Europe. It would be difficult to find a higher descent. The late Mr. Edward Adams, M.P., of Middleton Hall, Carmarthenshire, was a descendant of the elder branch of this family; and Mr. Anthony Davis, of Misbourne House, Chalfont Saint Giles, Bucks, is its representative.

It was after the exhaustion caused by the Rebellion in Ireland, that Pitt brought forward his project of the Union, and Lord Cornwallis successfully accomplished it. Mr. Massey describes at great length the means by which, in Castlereagh’s phrase, “the fee simple of Irish corruption was bought;” and the Irish Parliament, like Tarpeia, perished beneath the weight of stipulated bribery. No person acquainted in the least with history, or having any regard for Ireland, will fail to rejoice at the success of a measure which relieved her instantly from a worthless Legislature, and by incorporating her with Great Britain assured her the prospect of just government. But the delay in the grant of Catholic Emancipation, which Pitt had intended to accompany the Union, retarded for many years its benefits; and another part of the Minister’s scheme, a State provision for the Catholic priesthood, remains to this day unaccomplished. Pitt incurred a heavy responsibility on this account. It appears certain from the Castlereagh correspondence that the Irish Catholics supported the Union on something like an implied pledge that they should obtain their political rights; and on this ground, and on that, besides, of the State necessity for emancipation, Pitt can hardly escape the censure of history for not having insisted more strongly in carrying out his policy as a whole, and especially for having, in 1805, consented not to press the subject on the King when he formed his second brief Administration. It is doubtful, however, Mr. Massey observes, whether Pitt could at any period have extorted compliance from George III., or, indeed, from the people of England; and, though his conduct in this matter was not chivalrous as an individual, he may have conceived, as a public man, that he had satisfied honour by his resigning in 1801, and that afterwards he would have not been justified in depriving the country of his services for the sake of a policy impracticable at the moment.—Times review of Massey’s Hist. England.

The published Correspondence of Lord Cornwallis gives, with painful minuteness, the details of management and bribery by which the Union between Great Britain and Ireland was carried to a conclusion; but most readers of the history of the period are satisfied with knowing that the Union was a political necessity, that the parties to be dealt with in effecting it—the Irish Parliament and its patrons—were utterly corrupt, and that persuasion was the only method which it was possible to employ. The result was inevitable. The Government bid high, and as it bid the[20] vendors raised their prices, and still the Government bid higher. At last the owners of seats were gorged with the sum of 15,000l. for each disfranchised borough, and the whole amount of compensation thus extorted reached the magnificent figure of 1,260,000l. We can hardly be thankful enough that Lord Grey’s Government had the firmness to resist the application of so inconvenient a precedent in the Reform Bill of 1832.

The Moniteur in 1862 contained five columns on the pedigree of Bonaparte, from Anno Domini 1170, when the first of that name headed an Italian league at Treviso against the German invaders under Frederic Barbarossa. John Bonaparte signs a treaty at Constance on behalf of Italy, and writes himself consul, being in fact le premier consul of his race, in 1182. Two centuries after the Bonaparte escutcheon on their house in St. Andrew’s-square, at Treviso, is ordered to be broken by Venice; and 440 years afterwards that republic is suppressed by a Bonaparte at the treaty of Campo Formio. Details are given of the family’s removal to Florence, San Miniato, and Corsica; of the sack of Rome, at which Jacopo Bonaparte assisted in 1520, and of a comedy, La Vedova, from the pen of another about the same period. Muratori’s Antiquitates Italicæ, vols. 8, 9, and 12, folio, contain numerous diplomatic documents signed by members of this stirring house, ever active in all the revolutions of mediæval Italy. The Moniteur becomes quite an enthusiast about the land that produced this chosen race. The oddest revelation is the fact, that Mala-parte was the original name before 1170, just as it was of the Bolognese family Malatesta, the change having been voted by popular acclaim in public assembly at Treviso. So far the Moniteur. But it might be added that the Beauharnais family, through which the present Emperor comes, had undergone a precisely similar change of name at the request of Marie Antoinette. That house had been known for ages in Poitou as Seigneurs de Bellescouilles, an appellation not quite fitting the Court at Versailles, and altered accordingly. It is rather remarkable that Napoleon I., in the Moniteur of 22nd Messidor, an XIII., 1805, had scouted all idea of ancestry, and ordered a formal declaration to be inserted that his house dated from Marengo, quoting the lines of La Fontaine—“Rien n’est dangereux qu’un sot ami,” meaning the person who had drawn out his pedigree.

The Register of the Imperial family is a large folio volume, bound in red velvet, and having at the corners ornaments of silver-gilt, with the family cipher ‘N’ in the centre. It was commenced in 1806, and the first entry made was the adoption of Prince Eugène by the Emperor. The second, made the same year, relates to the adoption of the Princess Stephanie de Beauharnais, who died Grand Duchess of Baden, and who was cousin of the Empress Joséphine. Next comes the marriage of the Emperor Napoleon I.; then several certificates of the birth of Princes of the family, and lastly of the King of Rome, which closes the series of the certificates inscribed under the reign of the First Emperor. This register was confided to the care of Count Regnault de Saint-Jean-d’Angely, Minister and Councillor of State, and Secretary of the Imperial family. It was to him, under the First Empire, as it is now to the Minister of State under the Second, that was reserved the duty of drawing up the procès verbaux of the great acts relative to Napoleon. At the fall of the First Empire, Count Regnault de Saint-Jean-d’Angely carefully preserved the book, which at his death passed into the hands of the Countess, his widow. That lady handed it over to the President of the Republic when Louis Napoleon was called by universal suffrage to the Imperial throne.

A Correspondent of the Literary Gazette writes: “I have been afforded an opportunity of examining many of the letters of Napoleon which figure in the Imperial collection; and I assure you that the commission charged with the duty of saying what should and what should not be published, had a most arduous task to perform. For of all the ‘cramped pieces of penmanship’ that were ever seen his are the most cramped and unintelligible. The manner in which the letters are formed would frighten a writing-master into fits, and the lines never run straight, whilst not unfrequently they come into collision. And what is singular is that a great many of the words are grossly misspelt, and that others are only half-written. O vanity of human genius! O triumph for dull little schoolboys! The man who conquered more kingdoms than Alexander knew not orthography!”

The 9th volume of the Correspondance de Napoléon I., published at Paris, in 1862, brings to light, for the first time, the whole of his schemes for invading England, which he planned in 1803, when he led a mighty host to Boulogne, in the hope of repeating the scene of the Conquest. The following passage in this volume shows how Napoleon struggled to remove his inferiority in fleets:

“Collect 3000 workmen at Antwerp. Wood, iron, and materials can be brought there from the North. War is no impediment to shipbuilding at Antwerp. If we are three years at war, we must build there not less than 25 ships of the line. Anywhere else this would be impossible. We must have a powerful fleet; and we should not have less than 100 ships of the line. We must also commence building frigates and smaller vessels. St. Domingo cost us 2,000,000f. a month; the English having captured it, this sum must be appropriated to the increase of our navy.”

Such were the conditions of this attack; and such the forces with which Napoleon expected “to conquer the world in London;” and his letters to Soult, to Bruix, to Déeres must convince the reader that he was in earnest in his scheme of “planting the tricolour on the Tower.” The problem for Napoleon to solve was how to transport across the Channel an army of 150,000 men, with horses, cannon, baggage, and equipments, in spite of the naval superiority of England. In these first preparations we must allow he succeeded beyond our worst expectations. Within fourteen months from the commencement of the war he had gathered within ten leagues of our coast, and had placed beyond the power of attack, a flotilla mounting 2000 guns, and able to transport his superb army, which, though numbering 150,000 men, could embark in less than a single tide, and were fully trained for a naval encounter.

So far, at least, as regards the Government, it must be confessed that our preparations to meet this attack were unequal to the danger. In the Channel especially—the point menaced—the naval arrangements made by the Admiralty were very faulty and even ridiculous. Such a Power as England should never have allowed the flotilla to assemble at Boulogne at all; and when it had assembled it should have been assailed by a mass of gunboats and light vessels, which we might have sent out in enormous numbers. Yet the Admiralty persisted in encountering the flotilla with 18 and 12-pounder frigates, which drew too much water to close the shore, and, at long range, were no match for their powerfully armed, though small antagonists; the result was that on no occasion were we able to damage the enemy seriously, and that on some we suffered severely.

In England as well as in France it was thought that the flotilla was to risk the passage unaided, its heavy armament suggesting the notion that Napoleon believed it a match for our fleet in the narrow strait between Dover and Calais. We now know, however, that this was an error, and that Napoleon never intended to embark unless supported by a covering squadron, which, having for a time the command of the Channel, would completely protect the flotilla and the army. In order to have the mastery of the[23] Channel for the forty-eight hours required for the transit, the problem was so to manœuvre his fleets as to bring a superior force off Boulogne, in spite of the numerous English squadrons which watched or blockaded them in all their harbours. He devised a twofold scheme for this end, adapted to the circumstances of the seaboard, and which experience proved to be feasible.

This volume, however, proves sufficiently that, brilliant as were Napoleon’s designs, he could not inspire Villeneuve and Ganteaume with the daring energy of Nelson and Cochrane, or make British seamen of his sailors. The want of discipline, the timidity, and the inexperience, of which there are proofs, explain how Napoleon’s deep-laid designs were brought to an end on the day of Trafalgar.

However, in 1805, Napoleon renewed his invasion scheme, the details of which he thus narrates in the 11th volume of his Correspondance, 1863:

“I wished to bring together forty or fifty sail of the line by operating their junction from Toulon, Cadiz, Ferrol, and Brest; to move them all together to Boulogne; to be there for a fortnight master of the Channel; to have 150,000 men and 10,000 horses encamped on the coast, with a flotilla of nearly 4000 vessels, and then, upon the arrival of my fleet, to embark for England and seize London.... To secure a prospect of success it was necessary to collect 150,000 men at Boulogne, with the flotilla, and an immense materiel, to embark the whole, yet to conceal my plan. I accomplished this though it appeared impossible, and I did so by reversing what seemed probable.”

Thus, in the spring of 1805 Napoleon collected within ten leagues of our shores a flotilla of nearly 4000 vessels, which, moored under the batteries of Boulogne, and armed with very heavy cannon, had long repelled our attempts to destroy them. Encamped around lay the veteran legions which had been selected for the descent, and had been trained with such care to embark and expedite the passage, that Napoleon writes, “150,000 men with a due proportion of guns and horses could within four tides effect a landing.”

His plan was marked with much ingenuity. The aspect of an armed flotilla induced our Admiralty to think that Napoleon relied on it alone to cross; and they felt assured that when at sea, three or four ships would suffice to destroy it. Accordingly, our Channel fleet was reduced to a force of not more than six sail; and the mass of the British Navy was employed either in blockading the enemy’s squadrons or in distant expeditions on the ocean. Could, therefore, one of the blockaded fleets effect its junction[24] with another, and penetrate into the unguarded Channel, a temporary ascendancy at sea might be gained, under cover of which the flotilla could cross and ferry over the French army.

It is only in this volume that we see how nearly Napoleon’s design succeeded so far as regards the descent, and also what were the causes of its failure. Whatever we may think of his project as a whole, it must be allowed that in August, 1805, when Villeneuve put to sea from Ferrol, the Emperor had good reason to expect that his Admirals would fulfil their mission:—

“The squadrons of Nelson and Calder have joined the fleet off Brest, and Cornwallis has been foolish enough to send twenty sail to blockade the French fleet off Ferrol. On the 17th of August—that is, three days after our squadron left Ferrol, Calder left Brest for Ferrol with a northerly wind. What a chance was there for Villeneuve! He could either, by keeping a wide offing, avoid Calder, reach Brest, and fall upon Cornwallis, or with his thirty sail-of-the-line beat Calder’s twenty, and acquire a decided preponderance. So much for the English, whose combinations are so talked of.”

In England the Whigs laughed at the idea of the invasion as a ministerial bugbear. “Can anything equal,” says Lord Grenville in 1804, “the ridicule of Pitt riding about from Downing-street to Wimbledon, and from Wimbledon to Cox-heath, to inspect military carriages, impregnable batteries, and Lord Chatham’s reviews? Can he possibly be serious in expecting Bonaparte now?” So also wrote Fox a year afterwards—“The alarm of invasion here was most certainly a groundless one, and raised for some political purpose by the Ministers.” Whatever the Whigs might then think, there is no doubt now as to Bonaparte’s intentions. “Let us be masters of the Channel for six hours, and we are masters of the world,” are his famous words. His design to invade this country was never relinquished, was cherished as the darling scheme of his life, until within a month or two before Pitt’s death, when the battle of Trafalgar destroyed his hopes for ever.—Selected and abridged from reviews in the Times.

While the First Consul was meditating the descent upon England, in 1804, his life and government were imperilled by the conspiracy of Georges, Moreau, and Pichegru. The Duc d’Enghien, as is well known, was the innocent victim of this affair, having been arrested on neutral territory, and shot in a ditch, without a trial, in order to strike the Bourbons with terror. While the printed account shows that the plot was a formidable[25] one, that the death of Napoleon and a counter-revolution were really not remote contingencies, and that there were some slight grounds to suspect an intrigue between Dumouriez and the Duke, it also impliedly acquits that Prince of any share in the main conspiracy, and throws the guilt of his cruel fate exclusively on the First Consul. From the list of charges against the Duke, entirely in Napoleon’s writing, it is plain that he did not possess any proofs, sufficient even for the tribunal of Vincennes to convict the prisoner of a design against his life.