Title: Five Minute Stories

Author: Laura Elizabeth Howe Richards

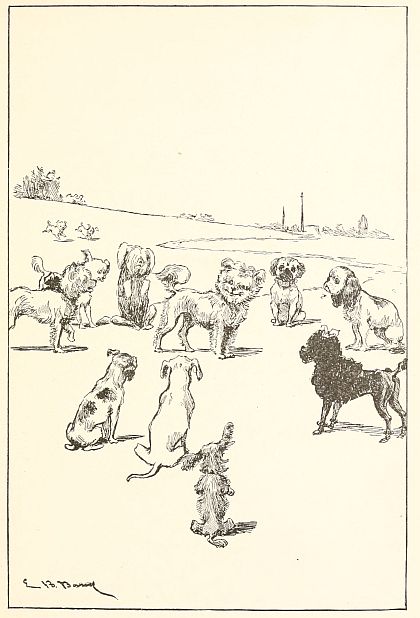

Illustrator: Etheldred B. Barry

Albertine Randall Wheelan

Release date: August 21, 2015 [eBook #49748]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

“Mrs. Richards has made for herself a little niche apart in the literary world, from her delicate treatment of New England village life.”—Boston Post.

“Seldom has Mrs. Richards drawn a more irresistible picture, or framed one with more artistic literary adjustment.”—Boston Herald.

“A perfect literary gem.”—Boston Transcript.

“Each is a simple, touching, sweet little story of rustic New England life, full of vivid pictures of interesting character, and refreshing for its unaffected genuineness and human feeling.”—Congregationalist.

“They are the most charming stories ever written of American country life.”—New York World.

“Had there never been a ‘Captain January,’ ‘Melody’ would easily take first place.”—Boston Times.

“The quaintly pretty, touching, old-fashioned story is told with perfect grace; the few persons who belong to it are touched in with distinctness and with sympathy.”—Milwaukee Sentinel.

A charming idyl of New England coast life, whose success has been very remarkable. One reads it, is thoroughly charmed by it, tells others, and so its fame has been heralded by its readers, until to-day it is selling by the thousands, constantly enlarging the circle of its delighted admirers.

The title most happily introduces the reader to the charming home-life of Dr. Howe and Mrs. Julia Ward Howe during the childhood of the author.

With true literary touch, she gives us the story of some of the salient figures of this remarkable period.

| PAGE | |

| Dedication | vii |

| Betty | 15 |

| Two Calls | 16 |

| A New Year Song | 19 |

| New Year | 20 |

| A Lesson Song | 24 |

| The Rubber Baby | 26 |

| The Red, White and Blue | 28 |

| Totty’s Christmas | 29 |

| A Certain Boy | 32 |

| The New Sister | 33 |

| Buttercup Gold | 35 |

| One Afternoon | 42 |

| The Stove | 43 |

| John’s Sister | 44 |

| New Year Song | 45 |

| What Was Her Name | 46 |

| A Lesson Song | 49 |

| The Patient Cat | 52 |

| Mathematics | 53 |

| By the Fading Light | 55 |

| Tobogganing Song | 58 |

| Song of the Tilt | 59 |

| The Lazy Robin | 60 |

| The Boy’s Manners | 62 |

| Merry Christmas | 66 |

| Rinktum | 67 |

| In the Tunnel | 69[x] |

| Practising Song | 71 |

| Queen Elizabeth’s Dance | 72 |

| A Storming Party | 74 |

| At the Little Boy’s Home | 75 |

| Then and Now | 76 |

| Pleasant Walk | 78 |

| A Great Day | 80 |

| A Pastoral | 82 |

| Riches | 84 |

| Poverty | 85 |

| The Best of All | 87 |

| A Study Hour | 89 |

| The Young Ladies | 90 |

| The Weathercock | 92 |

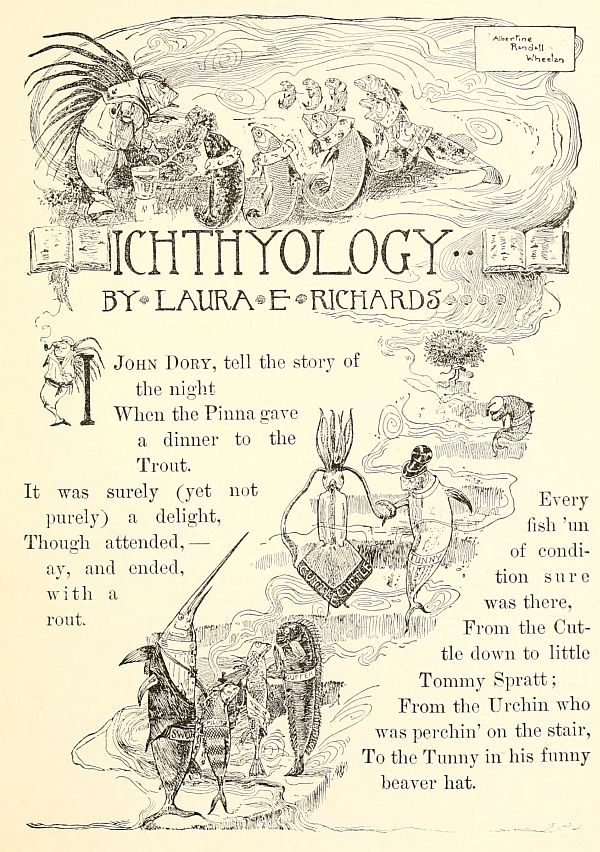

| Ichthyology | 93 |

| A Happy Morning | 98 |

| Lilies and Cat-Tails | 99 |

| The Metals | 104 |

| The Howlery Growlery Room | 109 |

| The Speckled Hen | 113 |

| The Money Shop | 116 |

| A Long Afternoon | 121 |

| The Jacket | 122 |

| The Fireworks | 124 |

| Jingle | 126 |

| See-Saw | 127 |

| Nancy’s Nightmare | 129 |

| Amy’s Valentine | 131 |

| Once Upon a Time | 133 |

| The Pathetic Ballad of Clarinthia Jane Louisa | 134 |

| A Day in the Country | 135 |

| Goosey Lucy | 136 |

| Goosey Lucy’s New Year’s Calls | 139 |

| Three Little Birds | 142 |

| The Quacky Duck | 143 |

| New Year Thoughts | 144 |

| Nonsense | 145 |

| The Singular Chicken | 147[xi] |

| The Clever Parson | 148 |

| The Purple Fish | 155 |

| Mr. Somebody | 157 |

| A Christmas Ride | 159 |

| A Funny Fellow | 161 |

| Woffsky-Poffsky | 162 |

| April and the Children | 163 |

| The Snowball | 165 |

| A Great Fight | 168 |

| Hallelujah! | 171 |

| Lullaby | 172 |

| Merry Christmas | 173 |

| The Little Dog with the Green Tail | 175 |

| Naughty | 180 |

| Hard Times | 180 |

| On the Steeple | 183 |

| Naughty Billy | 184 |

| A Lad | 184 |

| Saint Valentine’s House | 185 |

| The Gentleman | 187 |

| A Leap Year Boy | 190 |

| King Pippin | 193 |

| The Story of the Crimson Crab | 194 |

| Mother’s Riddle | 196 |

| King John | 197 |

| The Spotty Cow | 198 |

| The Button Pie | 199 |

| The Inquisitive Ducks | 200 |

| Queen Matilda | 202 |

| The Two-Shoes Chair | 203 |

| Ethelred the Unready | 205 |

| Poor Bonny | 205 |

| The Husking of the Corn | 209 |

| The Clever Cheese-Maker | 211 |

| The Spelling Lesson | 214 |

| The Person who Did Not Like Cats | 216 |

Beau Philip and Beau Bobby stood side by side on the doorstep of their father’s house. They were brothers, though you would hardly have thought it, for one was very big and one was very little.

Beau Philip was tall and slender, with handsome dark eyes, and a silky brown moustache which he was fond of curling at the ends. He wore a well-fitting overcoat, and a tall hat and pearl-gray kid gloves.

Beau Bobby was short and chubby, and ten years old, with blue eyes and yellow curls (not long ones, but funny little croppy locks that would curl, no matter how short he kept them). He wore a pea-jacket, and red leggings and red mittens.[17]

There was one thing, however, about the two brothers that was just the same. Each carried in his hand a great red rose, lovely and fragrant, with crimson leaves and a golden heart.

“Where are you going with your rose, Beau Bobby?” asked Beau Philip.

“I am going to make a New Year’s call,” replied Beau Bobby.

“So am I,” said Beau Philip, laughing. “We may meet again. Good-by, little Beau!”

“Good-by, big Beau!” said Bobby, seriously, and they walked off in different directions.

Beau Philip went to call on a beautiful young lady, to whom he wished to give his rose; but so many other people were calling on her at the same time that he could only say “good-morning!” to her, and then stand in a corner, pulling his moustache and wishing that the others would go. There were so many roses in the room, bowls and vases and jars of them, that he thought she would not care for his single blossom, so he put it in his buttonhole; but it gave him no pleasure whatever.

Beau Bobby trotted away on his short legs till he came to a poor street, full of tumble-down cottages.

He stopped before one of them and knocked at the door. It was opened by a motherly looking Irish woman, who looked as if she had just left the washtub, as, indeed, she had.

“Save us!” she cried, “is it yersilf, Master Bobby? Come in, me jewel, and warm yersilf by the fire! It’s mortal cowld the day.”

“Oh, I’m not cold, thank you!” said Bobby. “But I will come in. Would you—would you like a rose, Mrs. Flanagan? I have brought this rose for you. And I wish you a Happy New Year. And thank you for washing my shirts so nicely.”[18]

This was a long speech for Beau Bobby, who was apt to be rather silent; but it had a wonderful effect on Mrs. Flanagan. She grew very red as she took the rose, and the tears came into her eyes.

“Ye little angil!” she said, wiping her eyes with her apron. “Look at the lovely rose! For me, is it? And who sint ye wid it, honey?”

“Nobody!” said Bobby. “I brought it myself. It was my rose. You see,” he said, drawing his stool up to the little stove, “I heard you say, yesterday, Mrs. Flanagan, when you brought my shirts home, that you had never had a New Year’s call in your life; so I thought I would make you one to-day, you see. Happy New Year!”

“Happy New Year to yersilf, me sweet jewel!” cried good Mrs. Flanagan. “And blessings go wid every day of it, for your kind heart and your sweet face. I had a sore spot in my heart this day, Master Bobby, bein’ so far from my own people; but it’s you have taken it away this minute, wid yer sweet rose and yer bright smile. See now, till I put it in my best chiny taypot. Ain’t that lovely, now?”

“Isn’t it!” cried Beau Bobby. “And it makes the whole room sweet. I am enjoying my call very much, Mrs. Flanagan; aren’t you?”

“That I am!” said Mrs. Flanagan. “With all my heart!”

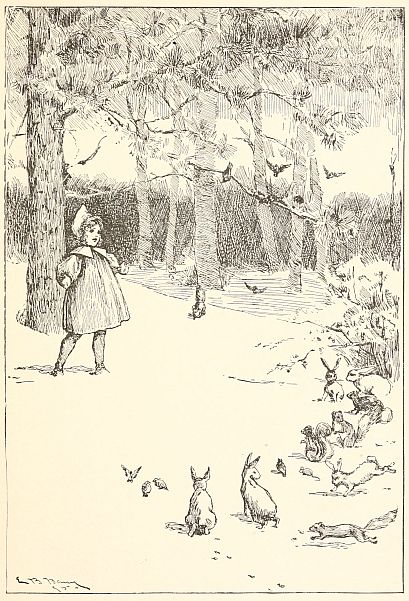

The little sweet Child tied on her hood, and put on her warm cloak and mittens. “I am going to the wood,” she said, “to tell the creatures all about it. They cannot understand about Christmas, mamma says, and of course she knows, but I do think they ought to know about New Year!”

Out in the wood the snow lay light and powdery on the branches, but under foot it made a firm, smooth floor, over which the Child could walk lightly without sinking in. She saw other footprints beside her own, tiny bird-tracks, little hopping marks, which showed where a rabbit had taken his way, traces of mice and squirrels and other little wild-wood beasts.

The Child stood under a great hemlock-tree, and looked up toward the clear blue sky, which shone far away beyond the dark tree-tops. She spread her hands abroad and called, “Happy New Year! Happy New Year to everybody in the wood, and all over the world!”

A rustling was heard in the hemlock branches, and a striped squirrel peeped down at her. “What do you mean by that, little Child?” he asked. And then from all around came other squirrels, came little field-mice, and hares swiftly leaping, and all the winter birds, titmouse and snow-bird, and many another; and they all wanted to know what the Child meant by her greeting, for they had never heard the words before.

“It means that God is giving us another year!” said the

Child. “Four more seasons, each lovelier than the last, just as

it was last year. Flowers will bud, and then they will blossom,

and then the fruit will hang all red and golden on the branches,[21]

[22]

[23]

for birds and men and little children to eat.” “And squirrels,

too!” cried the chipmunk, eagerly.

“Of course!” said the Child. “Squirrels, too, and every creature that lives in the good green wood. And this is not all! We can do over again the things that we tried to do last year, and perhaps failed in doing. We have another chance to be good and kind, to do little loving things that help, and to cure ourselves of doing naughty things. Our hearts can have lovely new seasons, like the flowers and trees and all the sweet things that grow and bear leaves and fruit. I thought I would come and tell you all this, because sometimes one does not think of things till one hears them from another’s lips. Are you glad I came? If you are glad, say Happy New Year! each in his own way! I say it to you all now in my way. Happy New Year! Happy New Year!”

Such a noise as broke out then had never been heard in the wood since the oldest hemlock was a baby, and that was a long time ago. Chirping, twittering, squeaking, chattering! The wood-doves lit on the Child’s shoulder and cooed in her ear, and she knew just what they said. The squirrels made a long speech, and meant every word of it, which is more than people always do; the field-mouse said that she was going to turn over a new leaf, the very biggest cabbage-leaf she could find; while the titmouse invited the whole company to dine with him, a thing he had never done in his life before.

When the Child turned to leave the wood, the joyful chorus followed her, and she went, smiling, home and told her mother all about it. “And, mother,” she said, “I should not be surprised if they had got a little bit of Christmas, after all, along with their New Year!”

The ascent of the Rubber Baby took place in the back yard on the afternoon of last Fourth of July. It was an occasion of great interest.

We were all in the yard,—Mamma, Papa, Tubby, Toots, Posy, Bunny, Bay and Mr. Bagabave. (This boy has another name, but he prefers Mr. Bagabave because he made it himself.)

There was also the best cousin, who is nine feet tall, more or less, and a kind gentleman who was a friend of the best cousin, and came to see that he did not hurt himself with the firecrackers.

Well, there we all were, and we fired crackers and torpedoes the whole afternoon without stopping. The best cousin and the kind gentleman did it to amuse the children, and the rest of us did it to amuse ourselves.

We had cannon-crackers a foot long; we had double-headers, which papa threw up in the air, oh, ever so far, so that they exploded long before they reached the ground. Then there were dear little crackers, very small and slender, just made for Bay, though it is quite strange that the Chinese people should have known about her, when she is so very young.

Now we fired off single crackers, great and small, with a bang and a bang and a bang-bang; then we put a whole bunch under a barrel, and they went snap, crack, crickety, crackety. Yes, it was delightful.

But Papa, who has lived long and fired many crackers, began to pine for something new, and he said, “Let us have an ascension!”

Then we took counsel, and Mr. Bagabave said, “We will send[27] up the Rubber Baby.” Now the Rubber Baby belonged to Bay, and she loved him; but when Bunny and Mr. Bagabave told her what a fine thing it was to get up in the world, and how many people would like to go up farther than the Rubber Baby would go, Bay consented, and went and brought the Rubber Baby, who smiled and thought little of the matter.

Then Papa brought the biggest cannon-cracker of all, and made a long fuse for it, and set it up in the ground; and over it he put a tomato can, and on the tomato can he set the Rubber Baby.

Now all was ready, and we all stood waiting for the final moment. I do not know what were the thoughts of the Rubber Baby at this moment, but we were all in a state of great excitement.

“Get out of the way, children!” cried Papa. “Run away, Bay! Get behind the maple-tree, Mr. Bagabave! She’s going. Now, then! One, two, three, and away!” and Papa touched off the fuse.

A moment of great suspense, a tremendous report, a dense cloud of smoke. Up soared the Rubber Baby, higher than the top of the big maple-tree, almost to the very clouds (or so Bay thought).

We watched in silent rapture; then, as the intrepid air-traveller came down, still smiling, a loud cheer broke from the whole crowd.

No, not from the whole crowd; there was one exception. The kind gentleman who came to keep the best cousin from hurting himself gave a howl so loud and clear that we all started, and ran to see what was the matter.

The poor gentleman had been holding a cannon-cracker, which he was going to fire just when Papa gave the signal for sending off the Rubber Baby. In the excitement of the moment[28] he forgot the cannon-cracker, and it went off in his hand, and burnt him quite badly.

We were all very sorry, not only for the poor gentleman’s own sake, but because now there was no one to see that the best cousin did not hurt himself.

A pretty young lady came, and tied up the poor gentleman’s hand so nicely with her soft handkerchief that he said he was glad the cracker had gone off in it.

The Rubber Baby said nothing, but sat still in the middle of the gravel walk. Perhaps it was waiting to see if some lovely young lady would come to cheer and comfort it; but no one came till little Bay took it up, wiped off the dust and powder, kissed it, and put it to bed.

Dorothy was all dressed to see the Fourth of July procession. She had on her white dress, her blue sash, and her red shoes. Her cheeks were red, too, and her eyes were blue, and when she pushed up her full muslin sleeves, she saw how white her fat little arms were as soon as you got past the sunburn. “I’se red, white and blue mine-self!” said Dorothy.

She went and stood on the top doorstep, which was very near the street. Pretty soon the trumpets began to sound and the drums to beat, first far away, then nearer and nearer. At last the procession came round the corner. First the drum-major, with his huge bearskin cap, tossing his great gilded stick about; then came the musicians, puffing away with might and main at their great brass horns and trumpets, and banging away at their[29] drums and kettle-drums. It was a splendid noise; but they were really playing a tune, the “Red, White and Blue.”

The standard-bearer dipped his flag as he passed Dorothy’s house, for there was a great flag draped over the doorway, and red, white and blue streamers running up to the windows, and Dorothy waved a little flag as she stood on the top doorstep. “Three cheers for the red, white and blue!” sang the soldiers as they marched by.

“Sank you!” said Dorothy, spreading out her frock and patting her sash. “I’se the red, white and blue! See mine sash!”

The soldiers laughed and cheered.

Then came a soldier who looked straight up at Dorothy, and held out his arms, though without stopping. And it was Dorothy’s own Papa!

In less than half a minute Dorothy was in his arms, and he had caught her up, and put her on his shoulder.

Dorothy waved her flag, and jumped up and down on Papa’s shoulder, and cried, “Three cheers for the red, white and blue! three cheers for me!” and all the soldiers shouted and cheered and laughed, and so Dorothy and the procession went on their way all through the village.

They call me Totty, because I am small. I had a funny Christmas, and Mamma said I might tell about it.

I have the scarlet fever, and I live all alone with my Mamma in her room. Nobody comes in ’cept the doctor, and he says he sha’n’t come any more to see a girl who feels as well as I do.[30]

Mamma wears a cap and an apron, and we have our own dishes, just like play, and she washes them in a bright tin pan, and then I have the pan for a drum, and beat on it till she says she shall fly.

I always stop then, for I do think I should be frightened to see Mamma fly. Besides, she might fly away.

Well, yesterday was Christmas, and I could get out of bed and sit up in a chair; it was the first time.

So I sat up to dinner, and it was a partridge, but we played it was a turkey. There was jelly and macaroni, and for desert we had grapes and oranges. Mamma made it all look pretty, and Papa gave her roses through the door, and she put them all over the table.

When she had washed the dishes, she turned the big chair round so that I could look out of the window, and Hal and John came out on the lawn and made a snow-man for me to look at.

It was a fine man, with two legs and two arms, and they kept playing he was the British, and knocking his head off.

Mamma told me I mustn’t turn round till she said I might, but I didn’t want to, anyhow, the man was so funny.

I heard Papa whispering at the door, and I did want to see him, but I knew I couldn’t, ’cause the other children haven’t had the fever: and then I heard things rustle, paper and something soft, like brushing clothes.

They went on rustling, oh, a long time! and there was jingling, too, and I began to want to turn round very much indeed; but I didn’t, of course, ’cause I said I wouldn’t.

At last Mamma came up softly and tied something over my eyes, and told me to wait just a minute; and it really did not seem as if I could.

Then she turned the chair round, and took the thing off my eyes, and—what do you think was there?[31]

A Christmas tree! A dear little ducky tree, just about as big as I am, and all lighted with red and blue candles, and silver stuff hanging like fringe from the branches, and real icicles. (No! Mamma says they are glass, but they look real. They are in a box now, and I can play with them.)

And everything on the tree was for me. That makes a rhyme. I often make them.

There was a lovely doll, all china, with clothes to take off and put on, and buttons and buttonholes in everything. I have named her Christine, because that is the most like Christmas of any name I know.

And a tin horse and cart, and a box of blocks, and a lovely white china slate to draw on, and a box of beasts, not painted, all carved, just like real beasts, and a magnet-box, with three ducks and two swans and four goldfish and a little boat, all made of tin, and lots of oranges and a lovely china box full of cream candy (the doctor said I might have it if Aunt May made it, and she did), and a box of guava jelly, and a little angel at the top, flying, all of white china.

And everything will wash except the things to eat, ’cause everything I play with has to be burned up, unless it can be washed, so they all gave me washing things.

Even Christine has china hair, and all her clothes are white, so they can be boiled, and so can she, and Mamma says it won’t hurt her at all.

So I never had a nicer Christmas, though, of course, I wanted the other children; but then, I had Mamma, and of course they wanted her, poor dears!

And nobody need be afraid to read this story, ’cause it is going to be baked in the oven before it is printed.

“Look carefully!” said the kind Nurse, turning down a corner of the flannel blanket. “Don’t touch her, dears, but just look.”

The children stood on tiptoe and peeped into the tiny red face. They were frightened at first, the baby was so very small, but Johnny took courage in a moment.

“Hasn’t she got any eyes?” he asked. “Or is she like kittens?”

“Yes; she has eyes, and very bright ones, but she is fast asleep now.”

“Look at her little hands!” whispered Lily. “Aren’t they lovely? Oh, I do wish I could give her a hug!”

“Not yet,” said Nurse. “She is too tender to be hugged. But Mamma sends word that you may give her something,—a name. She wants you and Johnny to choose the baby’s name, only it must not be either Jemima, Keziah or Keren-Happuch.”

The Nurse went back into Mamma’s room, and left Johnny and Lily staring at each other, too proud and happy to speak at first.

“Let’s sit right down on the floor and think!” said John. So down they sat.

“I think Claribel is a lovely name!” said Lily, after a pause. “Don’t you?”

“No!” replied Johnny, “it’s too girly.”

“But baby is a girl!”

“I don’t care. She needn’t have such a very girly name. How do you like Ellen?”[34]

“Oh, Johnny! why, everybody’s named Ellen. We don’t want her to be just like everybody. Now Seraphina is not common.”

“I should hope not. I should need a mouth a yard wide to say it. What do you think of Bessie?”

“Oh, Bessie is very well, only—well, I should be always thinking of Bessie Jones, and you know she isn’t very nice. I’ll tell you what, Johnny! suppose we call her Vesta Geneva, after the girl Papa told us about yesterday.”

“Lily, you are a perfect silly! Why, I wouldn’t be seen with a sister called that! I think Polly is a nice, jolly kind of name.”

“Well, I don’t.”

“You needn’t get mad if you don’t. Cross-patch!”

“You’re perfectly horrid, John Brown; I sha’n’t play with you any more.”

“Much I care, silly Lily!”

“Well!” said Nurse, coming in again, “what is the name to be, dears? Mamma is anxious to know.”

Two heads hung very low, and two pairs of eyes sought the floor and stayed there. “Shall I tell you,” the good Nurse went on, taking no notice, “what I thought would be a very good name for baby?”

“Oh yes! yes! do tell us, ’cause we can’t get the right one.”

“Well, I thought your mother’s name, Mary, would be the very best name in the world. What do you think?”

“Why, of course it would! We never thought of that. Oh, thank you, Nurse!” cried both voices, joyously. “Dear Nurse! will you tell Mamma, please?”

Nurse nodded, and went away smiling, and Lily and John looked sheepishly at each other.

“I—I will play with you, if you like, Johnny, dear.”

“All right, Lil.”

Oh! the cupperty-buts! and oh! the cupperty-buts! out in the meadow, shining under the trees, and sparkling over the lawn, millions and millions of them, each one a bit of purest gold from Mother Nature’s mint. Jessy stood at the window, looking out at them, and thinking, as she often had thought before, that there were no flowers so beautiful. “Cupperty-buts,” she had been used to call them, when she was a wee baby-girl and could not speak without tumbling over her words and mixing them up in the queerest fashion; and now that she was a very great girl, actually six years old, they were still cupperty-buts to her, and would never be anything else, she said. There was nothing she liked better than to watch the lovely golden things, and nod to them as they nodded to her; but this morning her little face looked anxious and troubled, and she gazed at the flowers with an intent and inquiring look, as if she had expected them to reply to her unspoken thoughts. What these thoughts were I am going to tell you.

Half an hour before, she had called to her mother, who was just going out, and begged her to come and look at the cupperty-buts.

“They are brighter than ever, Mamma! Do just come and look at them! golden, golden, golden! There must be fifteen thousand million dollars’ worth of gold just on the lawn, I should think.”

And her mother, pausing to look out, said, very sadly,—

“Ah, my darling! if I only had this day a little of that gold, what a happy woman I should be!”[36]

And then the good mother went out, and there little Jessy stood, gazing at the flowers, and repeating the words to herself, over and over again,—

“If I only had a little of that gold!”

She knew that her mother was very, very poor, and had to go out to work every day to earn food and clothes for herself and her little daughter; and the child’s tender heart ached to think of the sadness in the dear mother’s look and tone. Suddenly Jessy started, and the sunshine flashed into her face.

“Why!” she exclaimed, “why shouldn’t I get some of the gold from the cupperty-buts? I believe I could get some, perfectly well. When Mamma wants to get the juice out of anything, meat, or fruit, or anything of that sort, she just boils it. And so, if I should boil the cupperty-buts, wouldn’t all the gold come out? Of course it would! Oh, joy! how pleased Mamma will be!”

Jessy’s actions always followed her thoughts with great rapidity. In five minutes she was out on the lawn, with a huge basket beside her, pulling away at the buttercups with might and main. Oh! how small they were, and how long it took even to cover the bottom of the basket. But Jessy worked with a will, and at the end of an hour she had picked enough to make at least a thousand dollars, as she calculated. That would do for one day, she thought; and now for the grand experiment! Before going out she had with much labor filled the great kettle with water, so now the water was boiling, and she had only to put the buttercups in and put the cover on. When this was done, she sat as patiently as she could, trying to pay attention to her knitting, and not to look at the clock oftener than every two minutes.

“They must boil for an hour,” she said; “and by that time all the gold will have come out.”[37]

[38]

[39]Well, the hour did pass, somehow or other, though it was

a very long one; and at eleven o’clock, Jessy, with a mighty

effort, lifted the kettle from the stove and carried it to the open

door, that the fresh air might cool the boiling water. At first,

when she lifted the cover, such a cloud of steam came out that

she could see nothing; but in a moment the wind blew the

steam aside, and then she saw,—oh, poor little Jessy!—she

saw a mass of weeds floating about in a quantity of dirty, greenish

water, and that was all. Not the smallest trace of gold,

even in the buttercups themselves, was to be seen. Poor little

Jessy! she tried hard not to cry, but it was a bitter disappointment;

the tears came rolling down her cheeks faster and faster,

till at length she sat down by the kettle, and, burying her face

in her apron, sobbed as if her heart would break.

Presently, through her sobs, she heard a kind voice saying, “What is the matter, little one? Why do you cry so bitterly?” She looked up and saw an old gentleman with white hair and a bright, cheery face, standing by her. At first, Jessy could say nothing but “Oh! the cupperty-buts! oh! the cupperty-buts!” but, of course, the old gentleman didn’t know what she meant by that, so, as he urged her to tell him about her trouble, she dried her eyes, and told him the melancholy little story: how her mother was very poor, and said she wished she had some gold; and how she herself had tried to get the gold out of the buttercups by boiling them. “I was so sure I could get it out,” she said, “and I thought Mamma would be so pleased! And now—”

Here she was very near breaking down again; but the gentleman patted her head and said, cheerfully, “Wait a bit, little woman! Don’t give up the ship yet. You know that gold is heavy, very heavy indeed, and if there were any it would be at the very bottom of the kettle, all covered with the weeds, so[40] that you could not see it. I should not be at all surprised if you found some, after all. Run into the house and bring me a spoon with a long handle, and we will fish in the kettle, and see what we can find.”

Jessy’s face brightened, and she ran into the house. If any one had been standing near just at that moment, I think it is possible that he might have seen the old gentleman’s hand go into his pocket and out again very quickly, and might have heard a little splash in the kettle; but nobody was near, so, of course, I cannot say anything about it. At any rate, when Jessy came out with the spoon, he was standing with both hands in his pockets, looking in the opposite direction. He took the great iron spoon and fished about in the kettle for some time. At last there was a little clinking noise, and the old gentleman lifted the spoon. Oh, wonder and delight! In it lay three great, broad, shining pieces of gold! Jessy could hardly believe her eyes. She stared and stared; and when the old gentleman put the gold into her hand, she still stood as if in a happy dream, gazing at it. Suddenly she started, and remembered that she had not thanked her kindly helper. She looked up, and began, “Thank you, sir;” but the old gentleman was gone.

Well, the next question was, How could Jessy possibly wait till twelve o’clock for her mother to come home? Knitting was out of the question. She could do nothing but dance and look out of window, and look out of window and dance, holding the precious coins tight in her hand. At last, a well-known footstep was heard outside the door, and Mrs. Gray came in, looking very tired and worn. She smiled, however, when she saw Jessy, and said,—

“Well, my darling, I am glad to see you looking so bright. How has the morning gone with my little housekeeper?”[41]

“Oh, mother!” cried Jessy, hopping about on one foot, “it has gone very well! oh, very, very, very well! Oh, my mother dear, what do you think I have got in my hand? What do you think? oh, what do you think?” and she went dancing round and round, till poor Mrs. Gray was quite dizzy with watching her. At last she stopped, and holding out her hand, opened it and showed her mother what was in it. Mrs. Gray was really frightened.

“Jessy, my child!” she cried, “where did you get all that money?”

“Out of the cupperty-buts, Mamma!” said Jessy, “out of the cupperty-buts! and it’s all for you, every bit of it! Dear Mamma, now you will be happy, will you not?”

“Jessy,” said Mrs. Gray, “have you lost your senses, or are you playing some trick on me? Tell me all about this at once, dear child, and don’t talk nonsense.”

“But it isn’t nonsense, Mamma!” cried Jessy, “and it did come out of the cupperty-buts!”

And then she told her mother the whole story. The tears came into Mrs. Gray’s eyes, but they were tears of joy and gratitude.

“Jessy dear,” she said, “when we say our prayers at night, let us never forget to pray for that good gentleman. May Heaven bless him and reward him! for if it had not been for him, Jessy dear, I fear you would never have found the ‘Buttercup Gold.’”

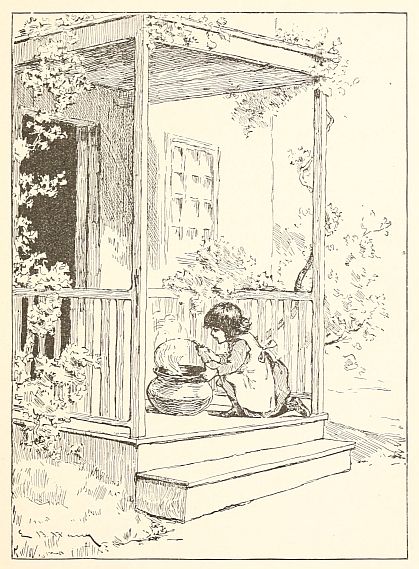

Betty has a real stove, just as real as the one in the kitchen, if it is not quite so big. It has pots and kettles and a frying-pan, and a soup-pot, and the oven bakes beautifully, and it is just lovely! I went to spend the afternoon with her yesterday, and we cooked all the time, except when we were eating. First, we made soup in the soup-pot, with some pieces of cold goose, and we took some to Auntie (she is Betty’s mother), and she said it was de-licious, and took two cups of it. (They were doll’s cups; Betty says I ought to put that in, but I don’t see any need.) Then we made scrambled egg and porridge, and baked some custard in the oven, and it was just exactly like a big custard in the big cups at home. The cake was queer, so I won’t stop to tell about that, though Rover ate most of it, and the rest we crumbled up for the pigeons, so it wasn’t wasted; but the best of all was the griddle-cakes. Oh, they were splendid! The griddle is just the right size for one, so they were as round as pennies, and about the same size; and we had maple syrup on them, and Maggie the cook said she was so jealous (she called it “jellies”) that she should go[44] straight back to Ireland; but I don’t believe she will. I don’t feel very well to-day, and Betty wasn’t at school, either. But I don’t think it had anything to do with the griddle-cakes, and I am going to play with Betty again to-morrow,—if Mamma will let me.

“Wake up!” said an old gentleman, dressed in brown and white, as he gently shook the shoulder of a young lady in green, who was lying sound asleep under the trees. “Wake up, ma’am! it is your watch now, and time for me to take myself off.”

The young lady stirred a very little, and opened one of her eyes the least little bit. “Who are you?” she said, drowsily. “What is your name?”

“My name is Winter,” replied the old man. “What is yours?”

“I have not the faintest idea,” said the lady, closing her eyes again.

“Humph!” growled the old man, “a pretty person you are to take my place! Well, good-day, Madam Sleepyhead, and good luck to you!”

And off he stumped over the dead leaves, which crackled and rustled beneath his feet.[47]

As soon as he was gone, the young lady in green opened her eyes in good earnest and looked about her.

“Madam Sleepyhead, indeed!” she re-echoed, indignantly. “I am sure that is not my name, anyhow. The question is, What is it?”

She looked about her again, but nothing was to be seen save the bare branches of the trees, and the dead, brown leaves and dry moss underfoot.

“Trees, do you happen to know what my name is?” she asked.

The trees shook their heads. “No, ma’am,” they said, “we do not know; but perhaps when the Wind comes, he will be able to give you some information.”

The girl shivered a little, and drew her green mantle about her and waited.

By and by the Wind came blustering along. He caught the trees by their branches, and shook them in rough, though friendly greeting.

“Well, boys!” he shouted, “Old Winter is gone, is he? I wish you joy of his departure! But where is the lady who was coming to take his place?”

“She is here,” answered the trees, “sitting on the ground; but she does not know her own name, which seems to trouble her.”

“Ho! ho!” roared the Wind. “Not know her own name? That is news, indeed! And here she has been sleeping, while all the world has been looking for her, and calling her, and wondering where upon earth she was. Come, young lady,” he added, addressing the girl with rough courtesy, “I will show you the way to your dressing-room, which has been ready and waiting for you for a fortnight and more.”

So he led the way through the forest, and the girl followed,[48] rubbing her pretty, sleepy eyes, and dragging her mantle behind her.

Now it was a very singular thing that whatever the green mantle touched, instantly turned green itself. The brown moss put out little tufts of emerald velvet, fresh shoots came pushing up from the dead, dry grass, and even the shrubs and twigs against which the edges of the garment brushed broke out with tiny swelling buds, all ready to open into leaves.

By and by the Wind paused and pushed aside the branches, which made a close screen before him.

“Here is your dressing-room, young madam,” he said, with a low bow; “be pleased to enter it, and you will find all things in readiness. But let me entreat you to make your toilet speedily, for all the world is waiting for you.”

Greatly wondering, the young girl passed through the screen of branches, and found herself in a most marvellous place.

The ground was carpeted with pine-needles, soft and thick and brown. The pine-trees made a dense green wall around, and as the wind passed softly through the boughs, the air was sweet with their spicy fragrance. On the ground were piled great heaps of buds, all ready to blossom; violets, anemones, hepaticas, blood-root, while from under a huge pile of brown leaves peeped the pale pink buds of the Mayflower.

The young girl in the green mantle looked wonderingly at all these things. “How strange!” she said. “They are all asleep, and waiting for some one to waken them. Perhaps if I do it, they will tell me in return what my name is.”

She shook the buds lightly, and lo! every blossom opened its eyes and raised its head, and said, “Welcome, gracious lady! welcome! We have looked for you long, long!”

The young girl, in delight, took the lovely blossoms, rosy and purple, golden and white, and twined them in her fair locks,[49] and hung them in garlands round her white neck; and still they were opening by thousands, till the pine-tree hollow was filled with them.

Presently the girl spied a beautiful carved casket, which had been hidden under a pile of spicy leaves, and from inside of it came a rustling sound, the softest sound that was ever heard.

She lifted the lid, and out flew a cloud of butterflies.

Rainbow-tinted, softly, glitteringly, gayly fluttering, out they flew by thousands and thousands, and hovered about the maiden’s head; and the soft sound of their wings, which mortal ears are too dull to hear, seemed to say, “Welcome! welcome!”

At the same moment a great flock of beautiful birds came, flying, and lighted on the branches all around, and they, too, sang, “Welcome! welcome!”

The maiden clasped her hands and cried, “Why are you all so glad to see me? I feel—I know—that you are all mine, and I am yours; but how is it? Who am I? What is my name?”

And birds and flowers and rainbow-hued butterflies and sombre pine-trees all answered in joyous chorus, “Spring! the beautiful, the long-expected! Hail to the maiden Spring!”

When the spotted cat first found the nest, there was nothing in it, for it was only just finished. So she said, “I will wait!” for she was a patient cat, and the summer was before her. She waited a week, and then she climbed up again to the top of the tree, and peeped into the nest. There lay two lovely blue eggs, smooth and shining.

The spotted cat said, “Eggs may be good, but young birds are better. I will wait.” So she waited; and while she was waiting, she caught mice and rats, and washed herself and slept, and did all that a spotted cat should do to pass the time away.

When another week had passed, she climbed the tree again and peeped into the nest. This time there were five eggs. But the spotted cat said again, “Eggs may be good, but young birds are better. I will wait a little longer!”

So she waited a little longer and then went up again to look. Ah! there were five tiny birds, with big eyes and long necks, and yellow beaks wide open. Then the spotted cat sat down on the branch, and licked her nose and purred, for she was very happy. “It is worth while to be patient!” she said.

But when she looked again at the young birds, to see which one she should take first, she saw that they were very thin,—oh, very, very thin they were! The spotted cat had never seen anything so thin in her life.

“Now,” she said to herself, “if I were to wait only a few days longer, they would grow fat. Thin birds may be good, but fat birds are much better. I will wait!”[53]

So she waited; and she watched the father-bird bringing worms all day long to the nest, and said, “Aha! they must be fattening fast! they will soon be as fat as I wish them to be. Aha! what a good thing it is to be patient.”

At last, one day she thought, “Surely, now they must be fat enough! I will not wait another day. Aha! how good they will be!”

So she climbed up the tree, licking her chops all the way and thinking of the fat young birds. And when she reached the top and looked into the nest, it was empty!!

Then the spotted cat sat down on the branch and spoke thus, “Well, of all the horrid, mean, ungrateful creatures I ever saw, those birds are the horridest, and the meanest, and the most ungrateful! Mi-a-u-ow!!!!”

There was only one chapter more to finish the book. Bell did want very much indeed to finish it, and to make sure that the princess got out of the enchanted wood all right, and that the golden prince met her, riding on a jet-black charger and leading a snow-white palfrey with a silver saddle for her, as the fairy had promised he would.

She did want to finish it, and it seemed very hard that she should be interrupted every minute.

First it was dear Mamma calling for a glass of water from her sofa in the next room, and of course Bell sprang with alacrity to answer that call.

But then baby came, with a scratched finger to be tied up, and then Willy boy wanted some more tail for his kite, and[56] he could not find any paper, and his string had got all tangled up.

Then came little Carrie, and she had no buttons small enough for her dolly’s frock, and did sister think she had any in her work-basket?

So sister looked, and Carrie looked, too, and between them they upset the basket, and the spools rolled over the floor and under the chairs, as if they were playing a game; and the gray kitten caught her best spool of gold-colored floss, and had a delightful time with it, and got it all mixed up with her claws so that she couldn’t help herself, and Bell had to cut off yards and yards of the silk.

At last it was settled, and the little girl supplied with buttons, and Bell sank back again on the window-seat, so glad that she hadn’t been impatient, and had seen how funny the kitten looked, so that she could laugh instead of scold about the silk.

“And when the golden prince saw the Princess Merveille, he took her hand and kissed it, for it was like the purest ivory and delicately shaped. And he said—”

Tinkle! tinkle! went the door-bell, and Bell, with a long sigh, laid down the book and went to the door, for Mary was out. It was old Mr. Grimshaw.

“Good-day, miss!” he said, with old-fashioned courtesy, “I have come to borrow the third volume of ‘Paley’s Evidences.’ I met your worthy father, and he was good enough to say that you would find the book for me. I am of the opinion that he mentioned the right-hand corner of the third shelf in some bookcase; I do not rightly remember in which room.”

Bell showed the old gentleman into the study and brought him a chair, and looked in the right-hand corners of all the shelves; then she looked in the left-hand corners; then she[57] looked in the middle; then she looked on Papa’s desk, and in it and under it.

Then she looked on the mantel-piece, and in the cupboard, and in the chairs, for there was no knowing where dear Papa would put a book down when his thinking-cap was on. All the time Mr. Grimshaw was delivering a lecture on Paley, and telling her on what points he disagreed with him, and why; and Bell felt as if a teetotum were going round and round inside her head.

At last, in lifting Papa’s dressing-gown, which hung on the back of a chair, she felt something square and heavy in one of the pockets; and—there was the third volume of “Paley’s Evidences.”

She handed it to Mr. Grimshaw with her prettiest smile, and he went away thinking she was a very nice, well-mannered little girl.

And so she was; but—oh dear! when she got back to the window-seat the daylight was nearly gone.

Still, the west was very bright, and perhaps she could just find out.

“And he said, ‘Princess, my heart is yours! Therefore, I pray you, accept my hand, also, and with it my kingdom of Grendalma, which stretches from sea to sea. Ivory palaces shall be yours, and thrones of gold; mantles of peacock feathers, with many chests of precious stones.’ So the princess—”

“Bell!” called Mamma from the next room. “It is too late to read, dear! Blindman’s Holiday, you know, is the most dangerous time for the eyes. So shut the book, like a dear daughter!”

Bell shut the book, of course; but a cloud came over her pleasant face, and two little cross sticks began beating a tattoo on her heart.[58]

Just at that moment came voices under the window,—Carrie and Willy boy, talking earnestly. “Would a princess be very pretty, do you suppose, Willy? prettier than Bell?”

“Ho!” said Willy, “who cares for ‘pretty?’ She wouldn’t be half so nice as Bell. Why, none of the other fellows’ sisters—”

They passed out of hearing; and even so the cloud passed away from Bell’s brow, and she jumped up and shook her head at herself, and ran to give Mamma a kiss, and ask if she would like her tea.

The mother robin woke up in the early morning and roused her three children.

“Breakfast time, my dears!” she said; “and a good time for a flying lesson, besides. You did well enough yesterday, but to-day you must do better. You must fly down to the ground, and then I will show you how to get worms for yourselves. You will soon be too old to be fed, and I cannot have you more backward than the other broods.”

The young robins were rather frightened, for they had only had two short flying lessons, taking little flapping flutters among the branches. The ground seemed a long, long way off!

However, two of them scrambled on to the edge of the nest, and after balancing themselves for a moment, launched bravely out, and were soon standing beside their mother on the lawn, trembling, but very proud.

The third robin was lazy, and did not want to fly. He thought that if he stayed behind and said he was sick, his[61] mother would bring some worms up to him, as she had always done before. So he sat still in the nest, and drooped his head.

“Come along!” cried the mother robin. “Come, Pecky! Why are you sitting there alone?”

“I—don’t feel very well,” said Pecky. “I don’t feel strong enough to fly.”

“Oh!” said his mother, “then you had better not eat any breakfast, and I will send for Doctor Woodpecker.”

“Oh no, please don’t!” cried Pecky, and down he fluttered to the lawn.

“That’s right!” said the mother robin, approvingly. “I thought there was not much the matter with you. Now bustle about, my dear! See how well your brother and sister are doing! I declare, Toppy has got hold of a worm as long as himself. It will get away from him—no, it won’t! There! he has it now! Ah! that was a good mouthful, Toppy. You will be a fine eater!”

Pecky sat still, with his head on one side. He felt quite sure that if he waited and did nothing, his mother would take compassion on him and bring him some worms. There were Toppy and Flappy, working themselves to death in the hot sun. He had always been his mother’s favourite (so he thought, but it was not really so), and he was quite sure that she would not let him go hungry.

So he gave a little squeak, as if quite tired out, and put his head still more on one side, and shut his eyes, and sat still. Now his mother did not see him at all, for her back was turned, and she was eating a fine caterpillar, having no idea of waiting on lazy birds who were old enough to feed themselves.

But some one else did see Master Pecky! Richard Whittington, the great gray cat, had come out to get his breakfast, too,[62] and he saw the lazy robin sitting still in the middle of the lawn with his eyes shut.

Richard could not have caught one of the others, for they all had their wits about them, and their sharp black eyes glanced here and there, and they were ready to take flight at a moment’s notice.

But Richard Whittington crept nearer and nearer to the lazy robin. Suddenly—pounce! he went. There was a shrill, horrified squeak, and that was the last of poor Pecky Robin.

The mother robin and her two other children flew up into the tree and grieved bitterly for their lost Pecky, and the mother did not taste a single worm for several hours.

But Richard Whittington enjoyed his breakfast exceedingly; and he was as good-natured as possible all day, and did not scratch the baby once.

The Boy was going out to Roxbury. He was going alone, though he was only five years old. His Aunt Mary had put him in the horse car, and the car went directly past his house; and the Boy “hoped he did know enough to ask somebody big to ask the conductor to stop the car.”

So there the Boy was, all alone and very proud, with his legs sticking straight out, because they were not long enough to hang over,—but he did not mind that, because it showed his trousers all the better,—and his five cents clutched tight in his little warm hand.

Proud as he was, the Boy had a slight feeling of uneasiness somewhere down in the bottom of his heart. His Aunt Mary[63] had just been reading “Jack and the Bean-stalk” to him, and he was not quite sure that the man opposite him was not an ogre. He was a very, very large man, about twelve feet tall, the boy thought, and at least nine feet round. He had a wide mouth, full of sharp-looking teeth, and he rolled his eyes as he read the newspaper. He was not dressed like an ogre, and he carried no knife in sight; but it might be in one of the pockets of his big gray coat.

Altogether, the Boy did not like the looks of this man at all, but nobody else seemed to mind him. A pretty girl sat down close beside him,—a plump, tender-looking young girl,—but the big man took no notice of her or anybody else, and kept on reading his newspaper and rolling his eyes.

So the Boy sat still, only keeping a good lookout, so that if this formidable person should pull out a knife, or begin to grind his teeth and roar, “Fee! fi! fo! fum!” he could slip off the seat and out at the door before his huge enemy could get upon his feet.

The car began to fill up rapidly. Soon every seat was occupied, and several men were standing up. One of them trod, by accident, on the ogre’s toe,—the Boy could not help calling him the ogre, though he felt it might not be right,—and he gave a kind of growl, which made the Boy quiver and prepare to jump; but his eyes never moved from his newspaper, so the Boy sat still.

By and by a poor woman got in, with a heavy baby in her arms. She looked very tired, but though there were several other men sitting down beside the big gray one, no one moved to give the woman a seat.

The boy remembered his manners, and knew that he ought to get up; but then came the thought, “If I get up, I shall be close to the ogre, for there is no standing-room anywhere else.[64] I am wedged so close between these two ladies that I can hardly get out: and if I do, there cannot possibly be room for that large woman.”

The Boy gave heed to this thought, though he knew in his heart that it did not make any difference. Just then the tired woman gave a sigh and shifted the heavy baby to the other arm.

The Boy did not wait any longer, but slipped at once down from his seat. “Here is a little room, ma’am!” he said, in his clear, childish voice. “There isn’t enough for you, but you might put the baby down, and rest your arms.”

At that moment the car gave a lurch, and the Boy lost his balance and fell forward,—right against the knees of the ogre.

“Hi! hi!” said the big man, putting aside his newspaper, “what’s all this? Hey?”

The Boy could not speak for fright; but the poor woman answered, “It’s the dear little gentleman offering me his seat for the baby, sir! The Lord bless him for a little jewel that he is!”

“Hi! hi!” growled the big man, getting heavily up from his seat and still holding the boy’s arm, which he had grasped as the child fell, “this won’t do! One gentleman in the car, eh? And an old fellow reading his newspaper! Here, sit down here, my friend!” and he helped the woman to his seat, and bowed to her as if she were a duchess. “And as for you, Hop-o’-my-thumb—” Then he stooped and took the Boy up, and set him on his left arm, which was as big as a table. “There, sir!” he said, “sit you there and be comfortable, as you deserve.”

The Boy sat very still; indeed, he was too frightened to move. Since the man had called him Hop-o’-my-thumb, he was quite sure that he must be an ogre; perhaps the very ogre from whom Hop and his brothers escaped. The book said he died, but books do not always tell the truth; Papa said so.[65]

When the big man began to feel in the right-hand pockets of his gray coat, the child trembled so excessively that he shook the great arm on which he sat.

The man looked quickly at him. “What is the matter, my lad?” he asked; and his voice, though gruff, did not sound unkind. “You are not afraid of a big man, are you? Do you think I am an ogre?”

“Yes!” said the boy; and he gave one sob, and then stopped himself.

The gray man burst into a great roar of laughter, which made every one in the car jump in his seat.

Still laughing, he drew his hand from his pocket, and in it was—not a knife, but a beautiful, shining, golden pear. “Take that, young Hop-o’-my-thumb,” he said, putting it in the Boy’s hands. “If you will eat that, I promise not to eat you,—not even to take a single bite. Are you satisfied?”

The boy ventured to raise his eyes to the man’s face; and there he saw such a kind, funny, laughing look that before he knew it he was laughing, too.

“I don’t believe you are an ogre, after all!” he said.

“Don’t you?” said the big man. “Well, neither do I! But you may as well eat the pear, just the same.”

And the Boy did.

(Air: “Es Regnet.”)

Will was digging a tunnel in the long drift. It was the longest drift that Will had ever seen, and he had meant to have Harry help him, but now they had quarrelled, and were never going to speak to each other as long as they lived, so Will had to begin alone.

He dug and dug, taking up great solid blocks of snow on his shovel, and tossing them over his shoulder in a workman-like manner. As he dug, he kept saying to himself that Harry was the hatefullest boy he ever saw in his life, and that he was glad he shouldn’t see anything more of him. It would seem queer, to be sure, not to play with him every day, for they had always played together ever since they put on short clothes; but Will didn’t care. He wasn’t going to be “put upon,” and Master Harry would find that out.

It was a very long drift. Will had never made such a fine tunnel; it did seem a pity that there should be no one to play with him in it, when it was done. But there was not a soul; for that Weaver boy was so rude, he did not want to have anything to do with him, and there was no one else of his age except Harry, and he should never see Harry again, at least not to speak to.

Dig! dig! dig! How pleasant it would be if somebody were digging from the other end, so that they could meet in the middle, and then play robbers in a cave, or miners, or travellers lost in the snow. That would be the best, because Spot could be the faithful hound, and drag them out by the hair, and have a bottle of milk round his neck for them to drink. Spot was[70] pretty small, but they could wriggle along themselves, and make believe he was dragging them. It would be fun! but he didn’t suppose he should have any fun now, since Harry had been so hateful, and they were never—no, never going to speak again, if it was ever so—

What was that noise? Could it be possible that he was getting to the end of the drift? It was as dark as ever,—the soft, white darkness of a snowdrift; but he certainly heard a noise close by, as if some one were digging very near him. What if—

Willy redoubled his efforts, and the noise grew louder and louder; presently a dog barked, and Will started, for he knew the sound of the bark. Just then the shovel sank into the snow and through it, and in the opening appeared Harry’s head, and the end of Spot’s nose. “Hullo, Will!” said Harry.

“Hullo, Harry!” said Will.

“Let’s play travellers in the snow!” said Harry. “This is just the middle of the drift, and we can be jolly and lost.”

“All right!” said Will, “let’s!”

They had a glorious play, and took turns in being the traveller and the pious monk of Saint Bernard; and they both felt so warm inside, they had no idea that the thermometer was at zero outside.

[A] This last line is not true, little girls; but it is hard, you know, to find good reasons for practising.

It was at Stirling Castle. People who did not know might have called it the shed, but that would show their ignorance. On the ramparts was mustered a gallant band, the flower of Scotland, armed with mangonels, catapults, and bows and arrows; below were the English, with their battering-rams and culverins and things. Ned was the English general, and led the storming party, and I was his staff, and Billy was the drummer, and drummed for the king. The Scottish general was Tom, and he had on Susie’s plaid skirt for a kilt, and his sporran was the rocking-horse’s tail that had come off.

Well, there was lots of snow on the roof,—I mean the ramparts, and they hurled it down on our heads, and we played ours was Greek fire, and hit them back like fun, I tell you. There was quite a mountain down below, where Andrew, the chore-man, had shovelled off the deep snow; and we stood on this, and it was up to my waist, and I played it was gore, because in Scott they are always wading knee-deep in gore, and I thought I would get ahead of them and go in up to my waist.

I hit General Montrose (that was Tom) with a splendid ball of Greek fire, and it was quite soft, and a lot of it got down his neck, and you ought to have seen him dance. He called me a dastardly Sassenach, and I thought at first he said “sausage,” and was as mad as hops, but afterward I didn’t care.

Then Ned called for volunteers to storm the castle, and we all ran to the ladder; but Ned climbed up the spout, ’cause he can shin like sixty, and he got up before we did. He took the warder by the throat, just like the Bold Buccleugh in “Kinmont[75] Willie,” and chucked him right off the roo—ramparts into the gore. That made Montrose mad as a hornet, and he rushed on Ned, and they got each other round the waist, and went all over the roof, till at last they got too near the edge, and over they both went. Billy was scared at that and stopped drumming, but I drew my mangonel (Susie says that isn’t the right name, but I don’t believe she knows) and rushed on the Scottish troops, which were only Jimmy Weaver, now that Montrose and the warder were gone. I got Jimmy down, and put my knee on his chest and shouted, “Victory! the day is ours! Saint George for England!”

But then I heard somebody else yelling, and I looked over the ramparts, and there was Montrose with his knee on Ned’s chest, waving his culverin and shouting, “Victory! the day is ours! Saint Andrew for Scotland!”

I was perfectly sure that our side had beaten, and Tom was absolutely certain that he had won a great victory; but just then mother called us in to tea, so we could not fight it over again to decide. Anyhow, Montrose got so much Greek fire down his neck that he had to change everything he had on, and I didn’t have to change a thing except my stockings.

It was a very hot day, and the little boy was lying on his stomach under the big linden tree, reading the “Scottish Chiefs.”

“Little Boy,” said his mother, “will you please go out in the garden and bring me a head of lettuce?”

“Oh, I—can’t!” said the little boy. “I’m—too—hot!”[76]

The little boy’s father happened to be close by, weeding the geranium bed; and when he heard this, he lifted the little boy gently by his waistband, and dipped him in the great tub of water that stood ready for watering the plants.

“There, my son!” said the father. “Now you are cool enough to go and get the lettuce; but remember next time that it will be easier to go at once when you are told as then you will not have to change your clothes.”

The little boy went drip, drip, dripping out into the garden and brought the lettuce; then he went drip, drip, dripping into the house and changed his clothes; but he said never a word, for he knew there was nothing to say.

That is the way they do things where the little boy lives. Would you like to live there? Perhaps not; yet he is a happy little boy, and he is learning the truth of the old saying,—

(A disquisition on the use of gunpowder, by Master Jack.)

“Where are you going, Miss Sophia?” asked Letty, looking over the gate.

“I am going to walk,” answered Miss Sophia. “Would you like to come with me, Letty?”

“Oh yes!” cried Letty, “I should like to go very much indeed! Only wait, please, while I get my bonnet!”

And Letty danced into the house, and danced out again with her brown poke bonnet over her sunny hair.

“Here I am, Miss Sophia!” she cried. “Now, where shall we go?”

“Down the lane!” said Miss Sophia, “and through the orchard into the fields. Perhaps we may find some strawberries.”

So away they went, the young lady walking demurely along, while the little girl frolicked and skipped about, now in front, now behind. It was pretty in the green lane. The ferns were soft and plumy, and the moss firm and springy under their feet. The trees bent down and talked to the ferns, and told them stories about the birds that were building in their branches; and the ferns had stories, too, about the black velvet mole who lived under their roots, and who had a star on the end of his nose.

But Letty and Miss Sophia did not hear all this; they only heard a soft whispering, and never thought what it meant.

Presently they came out of the lane, and passed through the orchard, and then came out into the broad, sunny meadow.

“Now, Letty,” said Miss Sophia, “use your bright eyes, and[79] see if you can find any strawberries! I will sit under a tree and rest a little.”

Away danced Letty, and soon she was peeping and peering under every leaf and grass blade; but no gleam of scarlet, no pretty clusters of red and white could she see. Evidently it was not a strawberry meadow. She came back to the tree, and said,—

“There are no strawberries, at all, Miss Sophia, not even one. But I have found something else. Wouldn’t you like to see it? Something very pretty.”

“What is it, dear?” asked Miss Sophia. “A flower? I should like to see it, certainly.”

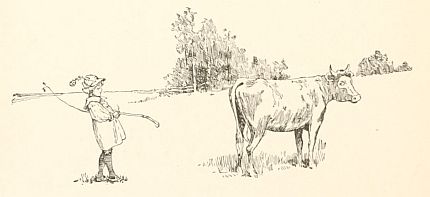

“No, it is not a flower,” said Letty; “it’s a cow.”

“What?” cried Miss Sophia, springing to her feet.

“A cow,” said Letty, “a pretty, spotted cow. She’s coming after me, I think.”

Miss Sophia looked in the direction which Letty pointed, and there, to be sure, was a cow, moving slowly toward them. She gave a shriek of terror; then, controlling herself, she threw her arms around Letty.

“Be calm, my child!” she said, “I will save you! Be calm!”

“Why, what is the matter, Miss Sophia?” cried Letty in alarm.

Miss Sophia’s face was very pale, and she trembled; but she seized Letty’s arm, and bade her walk as fast as she could.

“If we should run,” she said, in a quivering voice, “it would run after us, and then we could not possibly escape. Walk fast, my child! Don’t scream! Try to keep calm!”

“Why, Miss Sophia!” cried the astonished child, “you don’t think I’m afraid of that cow, do you? Why, it’s—”

“Hush! hush!” whispered Miss Sophia, dragging her along,[80] “you will only enrage the creature by speaking aloud. I will save you, dear, if I can! See! we are getting near the fence. Can’t you walk a little faster?”

“Moo-oo-ooo!” said the cow, which was now following them at a quicker pace.

“Oh! oh!” cried Miss Sophia. “I shall faint, I know I shall! Letty, don’t faint too, dear. Let one of us escape. Courage, child! Be calm! Oh! there is the fence. Run, now, run for your life!”

The next minute they were both over the fence. Letty stood panting, with eyes and wide mouth open; but Miss Sophia clasped her in her arms and burst into tears.

“Safe!” she sobbed. “My dear, dear child, we are safe!”

“Yes, I suppose we are safe,” said the bewildered Letty. “But what was the matter? It was Uncle George’s cow, and she was coming home to be milked!”

“Moo-oo-oo!” said Uncle George’s cow, looking over the fence.

“Children,” asked Miss Mary, the teacher, “do you know what day this is?”

“Yes, ma’am!” cried Bobby Wilkins, looking up with sparkling eyes.

“Does any one else know?” asked Miss Mary.

No one spoke. The boy John knew very well what day it was, but he was off in the clouds, thinking of William the Conqueror, and did not hear a word Miss Mary said. Billy Green knew, too, but he had been reproved for chewing gum in class,[81] and was in the sulks, and would not speak. Of course Joe did not know, for he never knew anything of that kind; and none of the girls were going to answer when the boys were reciting. So Bobby Wilkins was the only one who spoke.

“It is a day,” said Miss Mary, looking round rather severely, “which ought to waken joy in the heart of every American, young or old.”

Bobby felt his cheeks glow, and his heart swell. He thought Miss Mary was very kind.

“It is a day,” she went on, “to be celebrated with feelings of pride and delight.”

Bobby felt of the bright new half-dollar in his pocket, and thought of the splendid kite at home, and of the cake that mother was making when he came away. He had not wanted to come to school to-day, but now he was glad he had come. He had no idea that Miss Mary would feel this way about it. He looked round to see how the others took it, but they all looked blank, except the boy John, who was standing on the field of Hastings, and whose countenance was illumined with the joy of victory.

“It is a day,” said Miss Mary, with kindling eyes (for the children were really very trying to-day), “which will be remembered in America as long as freedom and patriotism shall endure.”

Bobby felt as if he were growing taller. He saw himself in the President’s chair, or mounted on a great horse, like the statues of Washington, holding out a truncheon.

“One hundred and eighteen years ago to-day,” cried Miss Mary—

“Oh! oh my, it ain’t!” cried Bobby Wilkins, springing up. “It’s only seven.”

“Bobby, what do you mean?” asked Miss Mary, looking at[82] him severely. “You are very rude to interrupt me. What do you mean by ‘seven?’”

“My birthday,” faltered Bobby. “I ain’t a hundred anything, I’m only seven.”

“Come here, dear!” said Miss Mary, holding out her hand very kindly. “Come here, my little boy. I wish you very many happy returns, Bobby dear! but—but I was speaking of the battle of Bunker Hill.”

Poor Bobby! Miss Mary shook her head at the children over his shoulder, as he sat in her lap, as a sign not to laugh, but I suppose they could not help it. They did laugh a good deal,—all except the boy John, who was watching Harold die, and feeling rather sober in consequence.

“Mamma,” said Mabel, “I am very glad we are rich!”

Mamma looked up with a little smile; she was patching Freddy’s trousers, and had just been wondering whether they would last till spring, and if not, how she was to get him another pair.

“Yes, Mabel dear,” she said. “We are very rich in some things. What were you thinking about when you spoke?”

“I was thinking how dreadful it would be to be hungry,” replied Mabel, thoughtfully. “I mean terribly hungry, like people in a shipwreck. Why, just to be a little hungry, the way Freddy and I get sometimes, makes me feel all queer inside; and besides, it makes me cross and horrid. So then I wondered how it would feel to be really hungry, and not to be sure that you were going to have good bread and milk for supper; and that made me feel so glad that we were rich.”

Mamma was silent for a few minutes. She was thinking of a house to which she took some work the day before. She had passed through the dining-room, and there, at the carved table, sat a little girl with her supper before her,—delicate rolls, and cold chicken, and raspberry jam, and hot cocoa in a china cup all covered with roses, and creamy milk in a great silver mug.

The child was about Mabel’s age, but her face wore a very different expression. She had pushed her chair back, and was crying out that she would not eat cold chicken. She wouldn’t, she wouldn’t, she wouldn’t! so there now! The nurse might just as well take it away, and she was a horrid cross old thing![85] Mamma was going to have partridge for dinner, and she wanted some of that, and she would have it.

Then, when the nurse shook her white-capped head and said, “No miss! your Mamma said you were to have the chicken; so now eat it, like a good girl, and you shall have some jam,” the child flew at her like a little fury, and slapped and pinched her. That was all that Mabel’s Mamma saw, but as she thought of it, and then looked at her little maiden, with a sweet face smiling over her blue pinafore, she smiled again, very tenderly, and said,—

“Yes, dear, it is a very good thing to be rich, if it is the right kind of riches. Go now, darling, and get the bread and milk; set the table, and then call Freddy in to supper.”

It was a lovely day in June, and the poor little girl was going out. She was so poor that she had to go in a great big carriage, with two fat, slow horses and a sleepy driver, who got very angry if you asked him to drive a little faster. She was dressed in a white frock, frilled and flounced, and she had a fashionable little hat on her head, which stuck up in front, so that the wind was always catching it and blowing it off. She had tight kid gloves on her little hands, and beautiful little bronze kid boots on her feet; so you see she was very poor indeed.

The carriage rolled slowly along through the park, and the little girl saw many other poor children, also sitting in carriages, with tight kid gloves and kid boots; she nodded to them,[86] and they to her, but it was not very interesting. By and by they left the park, and drove out into the country, where there were green fields, with no signs to keep people off the grass. The grass was full of buttercups, and in one field were two little girls, running about, with their hands full of the lovely golden blossoms, laughing and shouting to each other. One had a pink calico dress on, and the other a brown gingham, and they were barefooted, and their sunbonnets were lying on the grass. The poor little girl looked at them with sparkling eyes.

“Oh, Mademoiselle!” she cried, “may I get out and run about a little? See what a good time those children are having! Do let me jump out, please!”

“Fi donc, Claire!” said the lady who sat beside her. She was a thin, dark lady, with sharp, eager black eyes, and not a pleasant face. “Fi donc! What would madame, your mother, say, if she heard you desiring to run in the fields like the beggar children? Those children—dirty little wretches!—are barefooted, and it is evident that their hair has never known the brush. Do not look at them, child! Look at the prospect!”

“I don’t care about the prospect!” said the poor child. “I want some buttercups. We never have buttercups at our house, Mademoiselle. I wish I might pick just a few!”

“Assuredly not!” cried Mademoiselle, her eyes growing blacker and sharper. “Let you leave the carriage and run about in the mire, for the sake of a few common, vulgar flowers? Look at your dress, Claire! Look at your delicate shoes, and your new pearl-colored gloves! Are these the things to run in the dirt with? I will not be responsible for such conduct. Sit still, and when we reach home the gardener shall pick you some roses.”

“I don’t want roses!” said the poor little girl, sighing wearily. “I am tired of roses. I want buttercups!”[87]

She sighed again, and leaned back on the velvet cushions; the carriage rolled on. The barefoot children gazed after it with wondering eyes.

“My!” said one, “wasn’t she dressed fine, though!”

“Yes,” said the other; “but she looked as if she was having a horrid time, poor thing.”

“Poor thing!” echoed the first child.

“I mean to have the best time this Fourth of July that I ever had in my life,” said the Big Boy. Then all the other big boys clustered round him to hear what the good time was to be, and the little boy sighed and wished he were big, too. The big boys did not tell him what they were going to do, but I know all about it, so I can tell. They made a camp in the Big Boy’s room, which is out in the barn. One boy brought a comforter, and another brought a pair of blankets; and there was an old spring mattress up in the loft, so that with the Big Boy’s own bed, which could hold two (if you kept very still and didn’t kick the other fellow out), they did very well indeed. The Big Boy’s mother, knowing something of boys, had set out a lunch for them, crackers and cheese, and gingerbread and milk, so there was no danger of starvation.

Of course they were busy in the early part of the evening, buying their firecrackers and torpedoes, their fish-horns and all their noisy horrors (for you must understand that this was the night before the Glorious Fourth); but by nine o’clock they were all assembled in the barn, ready to have the very best time[88] in the world. First they ate some lunch, and that was good; then they thought they would take a nap, just for an hour or so, that they might not be sleepy when the time came. Two of them lay down on the Big Boy’s bed, and two on the old spring mattress, and two on the floor; but it did not make much difference where they began their nap, for when the boys’ mother took a peep at them about ten o’clock, she found them all lying in a heap on the floor, sound asleep, though the Thin Boy was groaning in his sleep because the Fat Boy was lying across his neck.

Suddenly the Big Boy awoke with a start, and looking at his watch, found that it was half past eleven. Hastily he roused the sleepers, and there was a hurrying and scurrying, a hunting for caps, a snatching up of horns and slow-match. Then softly they stole down the barn stairs, and away they went to the old church, and up they climbed into the belfry. The sexton had left the door unlocked, having been a boy himself once; so there they waited till twelve o’clock came. Ah! what a grand time they had then, “ringing the bells till they rocked the steeple;” but it only lasted an hour, and then there was all the rest of the night. They went here and they went there, and when they grew hungry they went back to the barn and finished the lunch; and then they tried to go to sleep again, but they kept falling about so, it was no use, so they waited till they thought their own houses would be open, and then they went home, and the Big Boy crept into his bed and slept till noon.

But the Little Boy woke up at six o’clock, and jumped up like a lark, and got his torpedoes and firecrackers, and was very cheerful, though he did sigh just once when he thought of the big boys. He turned the gravel-sweep into a battle-field, and made forts and mines for the firecrackers, and then he cracked and snapped and fizzed and blazed—at least the firecrackers[89] did—all the morning. He only burned his fingers twice and his trousers five times, and that was doing very well. He had a glorious day; and his mother thought—but neither the Little Boy nor the Big Boy agreed with her—that the best part of all was the good night’s sleep beforehand.

The young ladies had a reception this afternoon, and a charming occasion it was. The guests were invited for four o’clock, and when I came in at five the party was in full swing.

Clare was the hostess,—lovely Clare, with her innocent blue eyes and gentle, unchanging smile. The nursery was transformed into a bower of beauty, and Clare was standing by a chair, holding out her hand with a gracious gesture of welcome.[91] Alida received with her, and she looked charming, too, only she was so much smaller that she had to be stood up on a box to bring her to a level with Clare’s shoulder. Alida is a remarkable doll, because she can open and shut her eyes without lying down or getting up; and Betty sat on the floor behind her and pulled the strings, so that she waved her long eyelashes up and down in the most enchanting manner.

All the dolls were in their best clothes, except Jack the sailor, who cannot change his suit, because it is against his principles; and I must say they made a pretty party. The tea-things were set out on the little round table, all the best cups and saucers, and the pewter teapot that came from Holland, and the gold spoons; and there was real cocoa, and jam, and oyster crackers, and thin bread and butter.

Rosalie Urania presided at the tea-table, and poured the cocoa with such grace that no one would have suspected her of being helped a little by Juliet (Juliet is not a doll), who was hidden behind the table.

“Will you have a cup of cocoa?” asked Rosalie, sweetly, as Mr. Punchinello approached her with his most elegant bow.

“With pleasure, lovely maiden!” was the courtly reply. “From your hands what would not your devoted Punchinello take?”

He bowed and smiled again (indeed, he was always smiling), while Rosalie, blushing (it was a way she had), lifted the pewter teapot, and deftly filled one of the pretty cups.

“He’ll take a licking from my hands if he doesn’t look out!” growled Jack, the sailor, who is jealous of Punchinello, and loves Rosalie Urania.