Title: The Mentor: Famous Composers, Vol. 1, Num. 41, Serial No. 41

Author: Henry T. Finck

Release date: September 9, 2015 [eBook #49921]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By HENRY T. FINCK

Author of “Wagner and His Works,” “Success in Music,” “Chopin,” “Grieg and His Music,” etc.

THE MENTOR

SERIAL No. 41

DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS

MENTOR GRAVURES

| FRÉDÉRIC FRANÇOIS CHOPIN | 1810-1849 |

| FELIX MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY | 1809-1847 |

| FRANZ PETER SCHUBERT | 1797-1828 |

| ROBERT SCHUMANN | 1810-1856 |

| FRANZ LISZT | 1811-1886 |

| JOHANNES BRAHMS | 1833-1897 |

While it is generally understood that the three great musical countries are Italy, Germany, and France, it must not be forgotten that Poland revolutionized the music of the pianoforte, the most popular and universal of all instruments. That small country looms up very big indeed in the history of the piano. Paderewski, the greatest pianist of our time, and one of the best composers (although his day as such has not yet come), is a Pole, and so is the pianist who ranks next to him, Josef Hofmann. Karl Tausig, in his day, was a piano giant; while three other Poles are well known to all music-lovers of our time,—Moszkowski and the Scharwenka brothers, all of them composers for the same instrument.

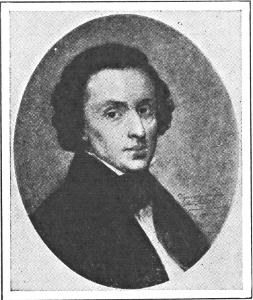

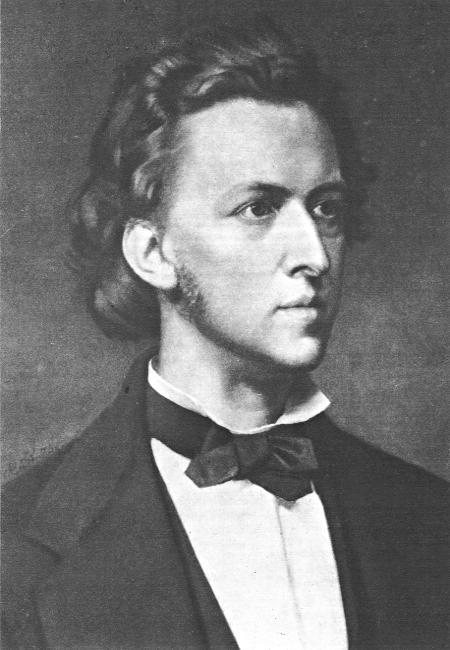

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

From a portrait made by Stattler, after original by Ary Scheffer.

Greatest of all the Poles, however, is Frédéric François Chopin. While his name is usually printed with the French accents, and the French are inclined to claim him as their own because his father emigrated from France to Poland, he himself was as thoroughly Polish in all his sympathies as his mother, and there is reason to believe that his paternal ancestors also came originally from Poland. Some of the traits that have endeared his music to all players and listeners—its elegance, its charm, its polished style—make it seem French; but the Poles also are noted for these same qualities; and in other respects Chopin’s music is as thoroughly and unmistakably Polish as it is an expression of his unique genius.

This is true particularly of his polonaises and his mazurkas. Polonaises seem to have been played originally at the coronation of Polish kings when the aristocrats were marching past the throne; while the mazurkas were quaint old folk dances. In Chopin’s pieces the aristocratic and the folk elements are artistically blended, and that is one of their principal charms. Like Luther Burbank’s wonderful new fruits, they unite the raciness of the soil with the qualities of his own creative genius.

THE CHOPIN MONUMENT

Why does an audience invariably applaud a Chopin valse enthusiastically, provided it is well played? Because the Chopin valse is both popular and artistic. No one thinks of the ballroom while it is heard: it is enjoyed because of its enchanting melody, its rhythmic swing, its elegance, and its exquisite harmonic changes. Why are his études applauded with no less fervor? Because, though modestly called studies, they are dazzling displays of skill and at the same time lofty flights of poetic fancy, astonishing in their originality, like most of his works. “Preludes,” he called more than two dozen of his short pieces; but they are so many precious stones, every facet polished by a master hand.

His splendid sonatas were for a long time underrated, because he refused to cut them according to traditional patterns; but in these days of musical free thinking we laugh at such objections and applaud his sonatas as much as his short pieces.

While the public loves Chopin for the reasons hinted at, experts hold him in highest honor also because he discovered the true language of the piano, which all the composers who came after him had to learn to speak. By his ingenious use of the pedal to combine “scattered” tones into chords he revealed an entirely new world of ravishing tone colors of extraordinary richness and variety. Quite new, too, were the dainty ornamental notes that here and there bedew his melodies like an iridescent spray. He created not only a new style of playing, but also pieces of new patterns, or forms; whereas most of even the greatest masters had contented themselves with accepted traditional forms and simply enlarging or improving them.

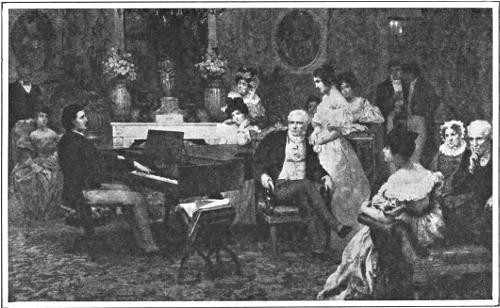

CHOPIN PLAYING IN THE SALON OF PRINCE RADZIWILL (1829)

When Paderewski plays a Chopin mazurka, he varies the pace incessantly, with most enchanting, poetic effect. This is called “tempo rubato.” It was used before Chopin, notably by opera singers; but it was through him that it became the accepted mode of interpreting all poetic music, not only for the piano, but for the orchestra. Thanks to Chopin’s influence, combined with that of Wagner and Liszt, no good pianist or orchestral conductor of our time performs a piece of music in monotonous metronomic time, except in a ballroom.

THE MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY HOUSE IN HAMBURG

Moses Mendelssohn, the father of Felix, was a banker. He added Bartholdy to the family name.

When Mendelssohn’s parents called him Felix they chose the right name for him; for Felix means happy, and throughout his life few things occurred to cast on him shadows of dark clouds like those which occasioned the gloomy moods of Chopin, Beethoven, Schumann, and Liszt. While Chopin also had his happy moments, a vein of sadness twines through most of his pieces. It is significant that of these pieces the one most often heard is the funeral march from one of his sonatas; whereas of Mendelssohn’s pieces the one most in vogue is the jubilant wedding march from his music to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Evidently there dwells in most souls a love of both the sad and the cheerful in art.

There was a time when Mendelssohn’s popularity was second to that of no other composer. His short piano pieces known as “Songs without Words” in particular enjoyed unbounded popularity, thanks to their tunefulness, which all could appreciate. The thing was overdone, and as in all such cases the inevitable reaction came, these pieces being looked on now as mere sentimental trifles. Paderewski, however, has shown that if played in the modern way they appeal as much as ever to music lovers. He has the audacity to use the tempo rubato, which Mendelssohn would have none of; but there is reason to think he would like it as used by Paderewski.

MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY MONUMENT, LEIPSIC

While the songs of Mendelssohn enjoyed for a generation as wide popular favor as his “Songs without Words,” it is not likely that they will ever recover their lost ground,—ground which they lost because, though tuneful, most of them are superficial. There is no doubt a good deal of “small talk” in many of Mendelssohn’s works, and small talk has no enduring value. But while the songs of this master are now neglected, his choral works, “St. Paul” and “Elijah,” still awe and thrill modern audiences, because in them, as in the oratorios of Handel and Bach, religious fervor is expressed in terms of noble music.

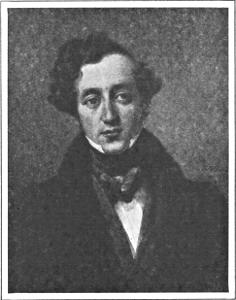

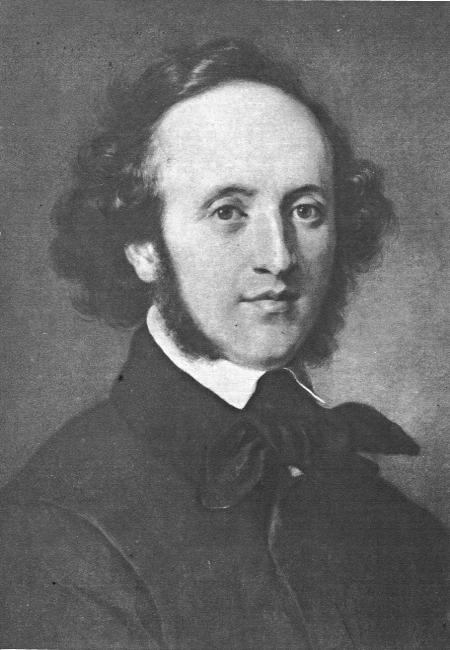

FELIX MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY

From a portrait painted by Horace Vernet. This is considered an excellent likeness of the composer. The face reflects his sunny disposition.

It is a curious and somewhat paradoxical fact that, while Mendelssohn’s personal sympathies were on the whole rather with the conservative classicists in the matter of form than with the modern progressives, by far the greatest of his works, particularly for orchestra, are those in which he heeds the modern craving for realism and program music, as illustrated in his “Fingal’s Cave” overture, the “Scotch” symphony, and the “Midsummer Night’s Dream” music. The overture to this is one of the marvels of music; for it is amazingly original from every point of view, though written by him when he was only seventeen years old.

It is commonly assumed that Italy is the land of melody; but Theodore Thomas used to maintain, and rightly, that the prince of melodists was the Austrian, Franz Schubert. Tunes flowed from his brain as spontaneously as water flows from a gushing well. He slept with his spectacles on, so as to lose no time when he jumped out of bed to jot down the melodies that came to him like inspirations from above. While he read a poem, the music suitable for it often sprang from his brain, Minerva-like.

THE SCHUBERT MEMORIAL, VIENNA

It is this spontaneity of Schubert’s melodies that explains their vogue, their universal popularity. Strange to say, during his life (which, to be sure, was pathetically short) his wonderful songs were, with a few exceptions, neglected, partly because with his melodies there were associated harmonies and modulations which to us are ravishing, but which to his contemporaries were “music of the future.” The shrill dissonance of the child’s cry when he thinks the Erlking is seizing him in the death-grip was as revolutionary and as far ahead of the times as anything Wagner or Liszt ever wrote. It was Liszt, by the way, who directed the world’s attention to the marvels of Schubert’s songs by playing them in his matchless way on the piano. Seeing how they moved audiences, the singers then took them up, and more and more convinced the world that among song writers Schubert was indeed king.

SCHUBERT’S BIRTHPLACE, VIENNA

The composer was born here in 1797.

It is one of the strangest facts in musical history that the great masters who came before Schubert—while some of them (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven) wrote a considerable number of songs—reserved their best inspirations for their operas, symphonies, and sonatas. Schubert was the first who was willing to put his best into a “mere song,” and that helps to explain his appeal to all music lovers.

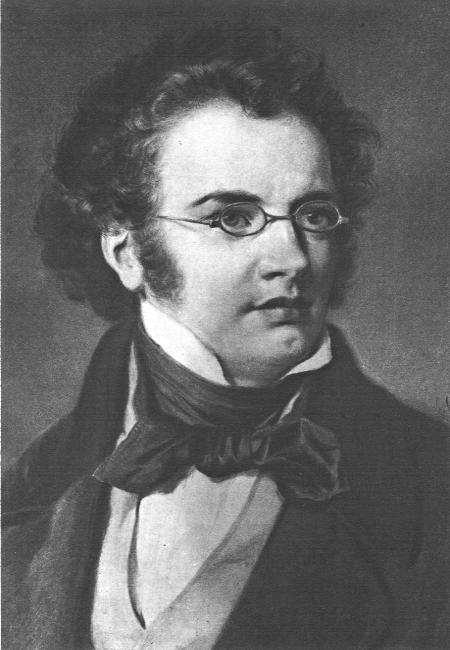

FRANZ SCHUBERT

From a portrait sketch made in 1825, by W. A. Rieder.

While he put of his best into his songs, there was plenty of it left for his instrumental pieces. Rubinstein considered his short pieces for piano even more marvelous than his songs, and among his symphonies there are two (the “Unfinished,” in two movements, and the ninth) that are as popular with high-class audiences as the best of Beethoven’s, which they even surpass in richness and novelty of orchestral coloring and in variety and novelty of modulation, while their melodic charm is as great as that of his songs.

While Schubert belongs to the romantic school, he did not follow all of its principal methods. In so far as he wrote chiefly short pieces and allowed them to crystallize into forms of their own (the variety of form in his songs is astonishing), he is a romanticist; but in writing instrumental pieces he did not associate poetic titles or stories with them. In this respect Schumann went far beyond him in the direction of realism and program music, and for this reason he is considered the most thoroughly romantic of the German masters.

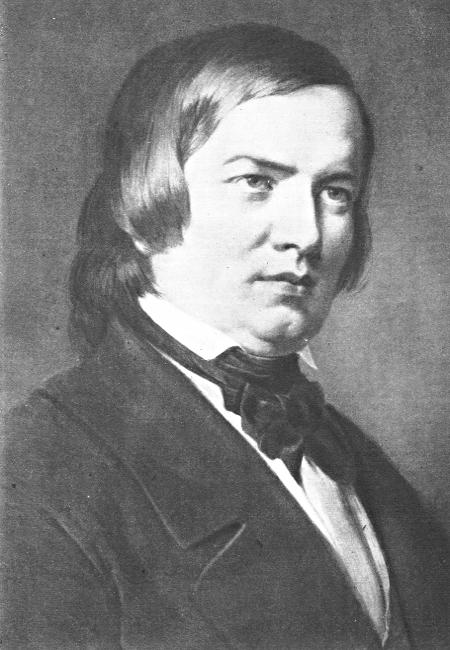

ROBERT SCHUMANN

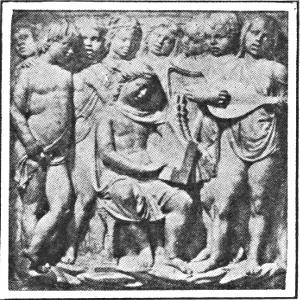

THE SCHUMANN MEMORIAL, BONN

In his early period, in particular, he seldom wrote a piece without suggesting in the title a poetic basis for it. It was his custom to issue his pieces in groups, with a general title for the group, like “Papillons” (Butterflies), “Kinderscenen,” “Faschingsschwank,” “Kreisleriana,” and a special title for each piece in the group, suggesting its message.

To many lovers of Schumann these early pieces are still the dearest. He was more thoroughly romantic when he wrote them than he was in later years, when he came too much under the influence of Mendelssohn and the classical masters, and at the same time grew less original and spontaneous.

It is not difficult for those who have read the romantic and pathetic story of his life to connect the waning of his originality with the gradual coming on of the mental disease to which he finally succumbed. Fortunately the bulk of his works, including four admirable symphonies and some excellent chamber music,[A] notably the glorious quintet for piano and strings, was written before his creative power was weakened.

[A] Chamber music is the term used for pieces played by a group (“ensemble”) of instrumentalists too small to be called an orchestra. Most frequently these pieces are for a few players of string instruments (quartets, quintets, etc.), with or without piano. Program music is music that seeks to depict or suggest a thunderstorm, the babbling of a brook, or any incident, scene, or poetic fancy associated with it by the composer.

It has been said that Mendelssohn would have made five pieces with the material Schumann used for one. This highly concentrated quality of his music makes it more difficult to understand, and explains why his contemporaries did not appreciate him as they did Mendelssohn. It also helps to explain the better “keeping qualities” of Schumann’s music.

ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN

While Mendelssohn’s songs, for instance, have, as just stated, virtually disappeared from recital programs, Schumann’s are more popular than ever, and seldom today is a program printed without one or a group of them. The best, by far, of his songs are among the hundred he wrote during the year when he married Clara Wieck, after a long contest with her father for the possession of her heart, though it had belonged to him for years. The popularity of Schumann’s songs is due largely to their being the expression of this ardent love. Women have not yet written immortal songs; but they have inspired many of them.

Richard Wagner called Liszt “the greatest musician of all the ages.” He certainly was the greatest pianist of them all, unequaled to this day; but he was very much more than that. In all departments of music, except the opera and chamber music, he created a new epoch or opened new and glorious vistas; and his influence on the musicians of his time and those who came after him was as great as Wagner’s.

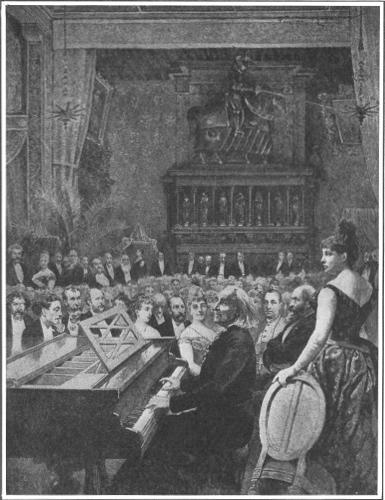

LISZT PLAYING AT THE HOME OF MADAME MUNKACSY

This picture, by the artist Frédéric Régamey, represents one of the brilliant assemblages in the salon of Madame Munkacsy, in Paris. In the picture are many portraits. Beside Liszt stands Madame Munkacsy, next to her Gounod, and grouped in the front are Saint-Saëns, Portales, Daudet and other notables. Munkacsy, the celebrated painter, stands at the back on the extreme left.

The strangest thing in Liszt’s extraordinary career is that when he was at the height of his fame as a pianist, and fabulous sums were offered him for recitals, he renounced his instrument, so far as concerts were concerned. For charity he would play occasionally, and for his friends and his pupils; but not for the paying public. This happened thirty-nine years before he died.

LISZT’S HOME IN WEIMAR

It was in this house that he spent his latter years.

Various motives prompted this action, one of them being that he preferred creative work. Thus it came about that the loss of his contemporaries in not hearing him play was our gain in enabling us to hear his songs, his piano pieces, his choral and orchestral compositions. Many of these are still “music of the future”; but their day is dawning.

At piano recitals, in America as in Europe, no composer’s pieces are now more favored than Liszt’s. Pianists usually place them at the end of the program; not only because they make a brilliant close, but because they prevent the audience from leaving before the end, as few or none want to miss these pieces.

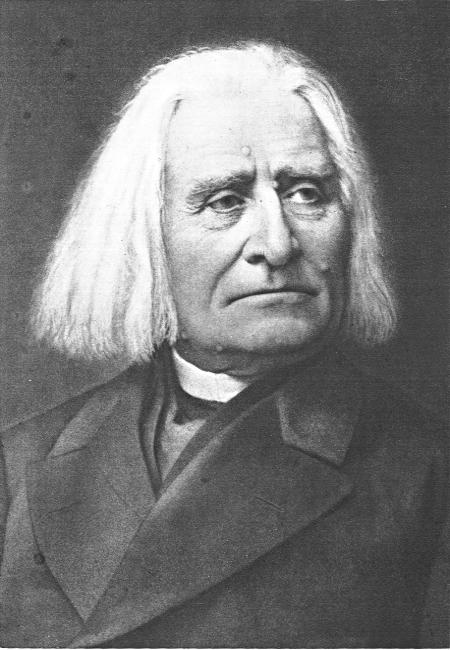

FRANZ LISZT

From a portrait of him in his youth painted by Ary Scheffer.

LISZT AT THE PIANO

From a photograph made late in life.

The reasons why the public is so enamoured of Liszt are not far to seek. While Chopin is, as Rubinstein called him, “the soul of the pianoforte,” because he makes it speak its own language as no one had made it speak before, Liszt’s piano music is no less idiomatic, and at the same time it is even richer in color and more varied in tonal power, or what musicians call “dynamic effects.” Not satisfied with the piano as such, Liszt converted it into a miniature orchestra, enabling the pianist to thunder or to whisper in tones not previously heard from that instrument.

Much of Liszt’s music, for both piano and orchestra, is program music: it tells its story in tones. In “St. Francis Walking on the Waves” one actually hears the waters, as in the orchestral “Mazeppa” one hears the galloping of the wild steed and the groans of the man tied on its back. The public likes music with such pictorial associations; but it would never have taken to Liszt’s program music as it has were it not at the same time good as music pure and simple,—interesting melodically, rhythmically, and harmonically.

Musicians, as well as the public, admire in Liszt’s orchestral works the same variety of new colors that enrich his piano music. They honor him for having created new forms of music in his symphonic poems, differing from symphonies as Wagner’s music-dramas differ from opera.

LISZT MONUMENT, WEIMAR

What the public likes best of all in Liszt’s works, however, is his Hungarian rhapsodies, in which the gipsy songs of love and war and every phase of life are “pianized” with marvelous art, one of the greatest charms of which is that it is absolutely unfettered and unconventional,—a real improvisation, like the playing of gipsies themselves.

THE BRAHMS MEMORIAL, VIENNA

Admirers of Liszt, and full-blooded Wagnerites, rarely care much for Brahms; while, conversely, the Brahmites look somewhat haughtily on those two composers, and all the other “progressives,” except Schumann, who is exempted, not only because there is a certain affinity between his music and that of their idol, but because he discovered Brahms, proclaiming him the “musical Messiah.” Brahms himself once signed a “protest” aimed against the Wagner-Liszt school; yet his bark was worse than his bite, for his works here and there show the influence of Wagner, and he liked some of Wagner’s operas.

Johannes Brahms is the god of the conservatives. He aimed, half-consciously, to carry on the traditions of Beethoven, and he had no use for modern realism and program music. His symphonies—the most delightful of which is the second—are marked simply numbers one, two, three, and four; and for his piano pieces he has no poetic titles after the manner of Schumann: they make their appeal by their own beauty, unadorned—and they have won a large audience of admirers.

Some of his songs everybody likes. They are on most programs, and are often redemanded. The music goes well with the words, and they are usually written most effectively for the voice, which makes the singers favor them too. But it is in his chamber music—trios, quartets, or sextets, for strings, with or without piano—that Brahms’ genius is most convincing. In this department he has composed many masterworks.

In general, it may be said that, while Brahms is melodically less spontaneous than some of the other masters, he excels most of them in the variety and originality of his rhythms.

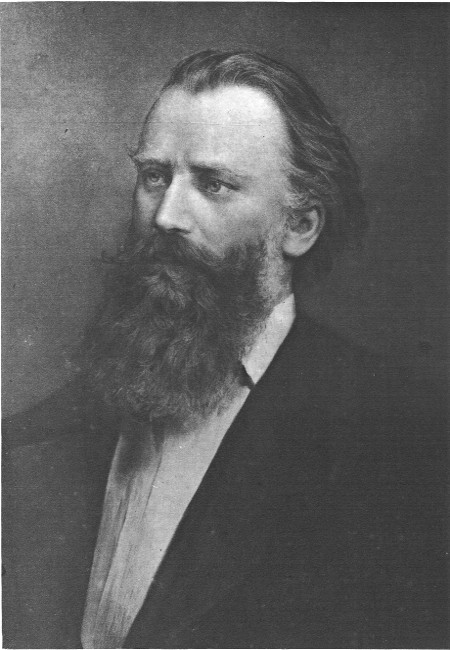

JOHANNES BRAHMS

From a special photograph by Maria Fetlinger.

SUPPLEMENTARY READING—“Chopin: The Man and His Music,” James Huneker; “The Life of Chopin,” Frederick Niecks; Article in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, “Mendelssohn,” S. S. Stratton; “Romantic Composers,” S. G. Mason; “Songs and Song Writers,” H. T. Finck; “Life of Schumann Told in His Letters,” May Herbert; “Franz Liszt,” James Huneker; “Life of Johannes Brahms,” Florence May; Articles on the Composers in Grove’s Dictionary.

THE MENTOR

ISSUED SEMI-MONTHLY BY

The Mentor Association, Inc.

381 Fourth Ave., New York, N. Y.

Volume 1 Number 41

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. FOREIGN POSTAGE, 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE, 50 CENTS EXTRA. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y., AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER. COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., PRESIDENT AND TREASURER, R. M. DONALDSON; VICE-PRESIDENT, W. M. SANFORD; SECRETARY, L. D. GARDNER.

A favorite phrase of ours has just come home to us in an oddly altered form. Its character has been completely reversed, and yet its value remains much the same. The phrase that we used referred to one of the advantages offered by The Mentor Association. We stated that The Mentor gives the facts that people ought to know and want to know about a subject, and we pointed out that a reader of The Mentor would find himself in a position to talk intelligently about many subjects that he had not understood before. Most people like to talk about things that they have come to know. We reckoned without one thoughtful reader, however, for he has come back at us with this: “I like The Mentor and it helps me. The more I read it the more I realize the value of having knowledge ready at hand. But it does not make me feel like talking more on various subjects, rather like talking less and listening more.”

And so our phrase, completely changed in color, returns to us. We are satisfied—let our reader be assured of that—for the phrase is just as valuable in the form in which it returns as in that in which we sent it out. We congratulate our reader. He is on the way to the greater benefits in the field of knowledge. He wants to know in order to grow rather than to show.

It is a great satisfaction to us to have readers bring home a phrase, especially when they amplify the idea themselves. Some time ago we called attention to the value of the odd moment, and we cited the case of a French woman who had employed so profitably her odd moments that in the course of a few years she had read during those moments an astonishing number of standard works. This has brought to mind several other striking illustrations of industry in cultivating the odd moment. Madame de Staël was a keen minded woman, actively interested in the public affairs of her time—and withal a very cultivated woman. In the midst of troublous social and political conditions she was a vigorous, energetic figure, and during all her activities she managed to accumulate a fund of information that was a source of amazement to her friends. “How do you gather all this knowledge?” she was once asked. “What time do you find to read? You seem to us to be busily engaged through all your working hours.” “You forget my sedan chair,” was Madame de Staël’s answer. While being carried in her chair she had as a companion a book or some bit of profitable reading, with which she mentally capitalized those brief intervals in her busy day.

We have been informed that a very eminent American preacher read no less than one hundred books in the course of three years, at his dining table. During that period of time he had always a book beside him at the table, and, whenever delays occurred, he would advance a few pages. The inference from this is that the divine was either a very fast reader, or that his table service was very slow; but in either case the results accomplished are an impressive demonstration of the value of the odd moment.

Suppose, now, that the essential information from lengthy books should be put into an article of not over 2,500 words, by a competent authority, and this material be put before you in a simple, readable manner, accompanied by illustrations. Would not that be the best possible mental fare for the odd moment? That is what The Mentor does. In the course of a year a reader of The Mentor gets the substance of the contents of many books. And it takes only a few minutes to read a single number of The Mentor.

FRANZ LISZT

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number One in The Mentor Reading Course

In Franz Liszt the lamp of genius burned brightly, and it lighted many halls in the Temple of Music. He was the most versatile of great musicians. He was the supreme pianoforte virtuoso. He was a conductor and champion of Wagner’s “music of the future,” teacher of great pianists, writer on music and musicians, and a composer of pianoforte pieces, songs, symphonic orchestral pieces, cantatas, masses, psalms, and oratorios.

He was born in Raiding, Hungary, October 22, 1811. At an early age, through the financial aid of a Hungarian magnate, he began a life of study. He first played in public at the age of eleven, and at thirteen made a tour through Switzerland, Paris, and the French provinces. He also went to England. At fifteen he was teaching and spending much of his time reading the religious, political, and literary works of his time. He was especially interested in the Saint Simonists and the romantic mysticism of Enfantin and the teachings of Abbe Lamennais. Defying public censure, he played compositions of Beethoven and Weber, a daring thing in those days.

His development as a virtuoso began in 1831, when Paganini, the famous violinist, first went to Paris. The success of Chopin, together with Paganini’s art, inspired him to practise. He transcribed many pieces, with a view to getting the effect of Paganini’s violin caprices on the piano, and perfect his own technic. He transcribed Berlioz’s “Symphonic Fantastique,” which ultimately led to the composition of his Symphonic Poems.

A few years later (1835) he met Comtesse d’Agoult, whose pen name was Daniel Stern, a friend and would-be rival to George Sand. Their friendship was world famous, and it exerted a great influence on the life and art of Liszt.

A patent of nobility was conferred upon him by the Emperor of Austria, and a sword of honor, from the magnates of Hungary, was presented to him in the name of the nation in 1840.

He then made a concert tour of all the leading cities in Europe, and made a great deal of money, much of which he gave to charity. In 1845 he completed the Beethoven Statue at Bonn, at his own expense, as the funds for this memorial had been accumulating very slowly.

Immediately following this period he began an active writing career, during which he wrote articles of permanent value on the early operas of Wagner and the work of Berlioz. He was one of the earliest supporters of Wagner, and remained loyal to him through life. He wanted to found a school of composers as well as pianists, and started a movement at Weimar which resulted in a private production of Wagner’s “Lohengrin” and “Tannhäuser,” as well as many pieces of Schumann, Weber, Schubert, Berlioz, and others.

Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein was collaborating with him at this time on many works. She was desirous of marrying the musician, who did not care to be joined to her, and to escape the match he retired to Rome, where he was ordained in 1865 by Cardinal Hohenlohe, and joined the Franciscan order. He received pupils gratis, and taught for several months of each year at the Hungarian Conservatory, Budapest. The last ten years of his life were spent at Bayreuth, where he died July 31, 1886.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

FELIX MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number Two in The Mentor Reading Course

The life of Felix Mendelssohn strikes one because of its remarkable activity, begun at a very early age. The son of a wealthy banker, he was born at Hamburg on February 3, 1809. As the French occupied Hamburg in 1811, it was necessary for the Mendelssohn family to move to Berlin, where Felix received his first training from his mother.

At the age of eleven Felix was composing with extraordinary rapidity, producing sixty pieces during the first year of composition, and the next year he was writing opera.

The Mendelssohn family had established the custom of holding musical festivals in the dining room of their home on alternate Sunday mornings. The music was rendered by a small orchestra under the direction of Felix. For each of these festivals the boy had some new composition. Thus, at the festival on his fifteenth birthday a private performance of his first three-act opera was held.

At the age of sixteen his father took him to Paris, where he met Rossini and Meyerbeer and other well known composers. With these men he worked and discoursed on music as if he were their equal in experience.

When only a little over seventeen he completed “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” which made an immediate success. During 1829 the composer made his first of ten trips to England, where “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was produced. On this occasion the director of the performance left the entire score in a coach on his return from the theater; but Mendelssohn wrote another from memory without a single error.

The next few years were full of activity. Mendelssohn produced many compositions, and filled the position of director of music, first at Düsseldorf, then at the Gewandhaus, Leipsic. The latter position was the highest honor in the German music world.

In 1837 he was married to Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud, whom he took on his concert tours, and it was during a tour in England with her that he received a call to Berlin from the king of Prussia. He left Berlin with the title of Kapellmeister.

The worry of his Berlin duties, a number of which he frankly told the king he could not fill, on account of the work at the Gewandhaus, began to wear on his health. Despite his weakened condition, he continued to do things. In 1843 he opened a college of music. Three years later he introduced Jenny Lind at the Gewandhaus, and then made a tour with her in England.

His activity was telling on his failing health, and when he reached Frankfort in 1847, returning from England, the news of his sister Fanny’s death caused him to collapse in the street. Five weeks later he had sufficiently recovered to take a trip with his family to Interlaken, where he remained until September, when he returned to Leipsic and lived in privacy.

On October 9 he asked Madam Frege to sing his latest songs. She left the room to get some lights, and on her return found him insensible. He lingered until November 4, when he died in the presence of his wife, his brother Paul, and three friends. A cross marks the site of his grave in Berlin.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

FRANZ PETER SCHUBERT

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number Three in The Mentor Reading Course

Of all the great masters of music, Franz Schubert had the least instruction of any. His life was full of the gloom and sorrow that surrounded so many of the earlier composers.

He was born in Vienna, January 31, 1797, one of a family of fourteen, nine of whom died in infancy. His first music lessons were given by his father on the violin and by his brother on the pianoforte. In 1808 he was sent to preparatory school; but could not stay after 1813, as he had failed in examinations. Although the Emperor of Austria offered him a scholarship, he refused it.

He began composing at the age of sixteen, and at twenty-five had written over 600 pieces. He had much difficulty with the publication of his works; but finally succeeded in making a commission arrangement with a publishing house.

Just how he lived from 1813 to 1818 no one knows. His music was not published until after that time, and he never appeared in public. It was not until the middle of 1818 that he was engaged as teacher for the family of Johann Esterházy. He called on Beethoven with some songs that he had dedicated to that great master. Beethoven was so deaf that all conversation had to be carried on by pencil and paper. Schubert was so bashful that Beethoven’s first remark about some of the variations caused him to lose his head. He rushed from the house in terror. This was in 1822.

The next two years were full of disappointment; for he met with failure at the first production of “Alfonso and Estrella.” This broke down his health. He left Vienna with the Esterházys for six months, and returned in somewhat better health.

By 1826 there was some demand for his songs, but an almost total ignoring of his larger works. His application for Kapellmeister was rejected, and also that for director in the Haftheater. Just before Beethoven’s death he paid a second visit, and found the great master favorably inclined toward his work. Three weeks later he was pallbearer at Beethoven’s funeral.

March 26, 1828, was the date of his first public concert of his own compositions. This netted him one hundred and sixty dollars. In the fall of the same year he fell ill, and died November 19. He was buried in Währing, “three places higher up than Beethoven.” A marble tomb with a bust of the composer placed between two columns marks his grave.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

ROBERT SCHUMANN

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number Four in The Mentor Reading Course

Although Schumann had begun to take a hand at composition before he was seven years old, he did not begin a real study of music until he was twenty. He was born at Zwickau, June 8, 1810, and lived there until 1826, when he began the study of law at the University of Leipsic. He wrote verse when at the university, and read more poetry and literature than law. In 1830, he took up the study of music under two masters. Herr Wieck was his teacher of pianoforte, and Heinrich Donn of composition.

Although he had already composed a great deal, it was not until after 1840 that he studied harmony. Friends calling on him and his wife one evening said that they found the master and his wife “studying Cherubini’s counterpoint for the first time.”

His opportunity to become a virtuoso was lost when he lamed the fourth finger of his right hand while trying a stunt in practising. Schumann believed that he could train himself to reach beyond an octave by the use of his fourth finger, and it was in an attempt to do this that he disabled his hand.

With his pianoforte master Wieck, he founded a music journal, which he edited alone from 1835 to 1844. He attempted concerts in Vienna in 1838; but failed and returned to Leipsic. In 1840 he received the degree of Ph. D. from the University of Jena. He married Clara Wieck in the same year; although her father objected strongly to the match. His wife, under the name of Clara Schumann, became one of the most famous pianists and teachers in Europe. So the musician’s fame went to his wife; while Schumann made fame for himself as a composer. He became teacher of score reading in the college that Mendelssohn founded at Leipsic in 1843, and in 1847 conducted the Liedertafel. In 1850 he succeeded Ferdinand Hiller as general music director of Düsseldorf.

Owing to insanity, which threatened him as early as 1833, he had to resign in 1853, and in 1854 he jumped into the Rhine. He was committed to an asylum at Endenish, where he died July 29, 1856. He was buried in Bonn. A simple headstone marks his grave.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number Five in The Mentor Reading Course

“Imagine a delicate man of extreme refinement of mien and manner, sitting at the piano and playing with no sway of body and scarcely any movement of the arms, depending entirely upon his narrow, feminine hands and slender fingers!”

This is the picture of Chopin as seen by an amateur pupil. This great pianist, the inspiration of Liszt and the expounder of Polish dance music and national songs, was born at Zela Zowa Wola, near Warsaw, March 1, 1809. He was supported at college at Warsaw by an annuity of one hundred and twenty dollars, the gift of Prince Antoine Radziwill, who had written music for Goethe’s “Faust.”

The friendship of the prince is what brought Chopin into the circle of the most graceful and refined society of the early nineteenth century, that of Poland.

At nineteen Chopin made his début as a pianist in Vienna. Robert Schumann heard him play his first piece, “Don Giovanni Fantasie,” which led him to remark that the pianist was “the boldest and proudest spirit of the times.” Just after this same concert the leading German musical journal said, “M. Chopin has placed himself in the first rank of pianists,” and praised “his delicacy of touch, his rare mechanical dexterity, and the splendid clearness of his phrasing.”

In 1831 he stopped at Paris when on his way for an intended tour in England. He stayed there and made that city his permanent home. It was at this time that he met Madame Dudevant, better known by her literary pseudonym, George Sand, who was destined to have a great influence on his life.

Six years later, in failing health, he went to Majorca, where he recovered for a time, due to the constant attention and tender care of George Sand. However, in 1840 the pulmonary disease attacked him again, and the last years of his life were a constant struggle against ill health.

Chopin brought a new spirit into music, a new feeling and a new technic into piano playing. He was regarded with admiration not unmixed with awe. As his life drew near its end the music world watched and worshiped him as it might a divine spirit. He died October 17, 1849.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

JOHANNES BRAHMS

FAMOUS COMPOSERS

Monograph Number Six in The Mentor Reading Course

The life of Johannes Brahms was an unsettled and wandering one. It was not until his later years that he chose a definite city for his home.

He was born in Hamburg, May 7, 1833, the son of a double-bass player in a theater, who was his first teacher. His life was uneventful until the age of twenty, when he began his public career with a concert tour in company with Remenyi, the Hungarian violinist.

Joachim, the famous student of Mendelssohn, attended the concert at Göttingen, where Brahms was to play the “Kreutzer” sonata of Beethoven. The piano turned out to be a semitone below the required pitch. Brahms played the piece from memory, transposing it from A to B flat. Joachim discerned what the feat implied, and after the concert introduced himself to the pianist, laying the foundation of a lifelong friendship, through which Brahms met Liszt and Schumann. The latter, after hearing but a few of his compositions, pronounced him “the master of the music of the future.”

The Prince of Lippe-Detmold engaged him as choir director and music master in 1854. He kept the position a few years and then resigned. He then wandered about, giving occasional concerts at Hamburg and Zurich. In 1863 he was appointed director of the Singakademie; but resigned within a year.

He seems to have had no public activity or settled work for the next four years, when he went on a concert tour with Joachim, and later with Stockhausen. In 1871 he began to direct the concerts of the “Gesellschaft der Musik-freunde,” which he continued to do until 1874. He spent the remainder of his life in Vienna, whence he took journeys to Italy in the spring and Switzerland in the summer.

He refused to go to England to take an honorary degree, Doctor of Music, offered by Cambridge University. In 1881 the University of Breslau conferred an honorary Ph. D. on him. Before his death he was granted two more honors. He was created a knight of the Prussian order, “Pour le Mérité,” in 1886, and he gained the freedom of his town in 1889. He died at Vienna, April 3, 1897.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1, No. 41, SERIAL No. 41

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.