Title: Fort Jefferson National Monument, Florida

Creator: United States. National Park Service

Release date: September 14, 2015 [eBook #49968]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

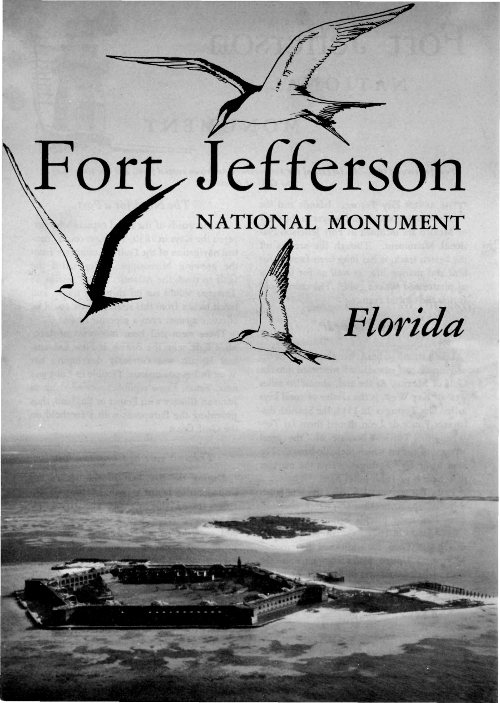

(Cover) Fort Jefferson from the air.

Fort Jefferson (1846-74), largest of the 19th-century American coastal forts, and one time “Key to the Gulf of Mexico.”

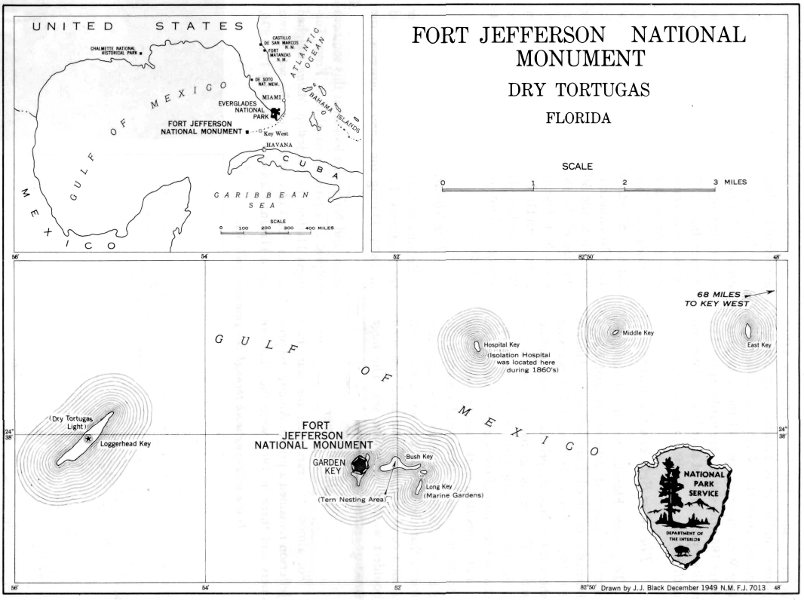

The seven Dry Tortugas Islands and the surrounding shoals and waters in the Gulf of Mexico are included in Fort Jefferson National Monument. Though the area is off the beaten track, it has long been famous for bird and marine life, as well as for legends of pirates and sunken gold. The century-old fort is the central feature.

Like a strand of beads hanging from the tip of Florida, reef islands trail westward into the Gulf of Mexico. At the end, almost 70 miles west of Key West, is the cluster of coral keys called Dry Tortugas. In 1513, the Spanish discoverer Ponce de León named them las Tortugas—the Turtles—because of “the great amount of turtles which there do breed.” The later name Dry Tortugas, warns the mariner that there is no fresh water here.

Past Tortugas sailed the treasure-laden ships of Spain, braving shipwreck and corsairs. Not until Florida became part of the United States in 1821 were the pirates finally driven out. Then, for additional insurance to a growing United States commerce in the Gulf, a lighthouse was built at Tortugas, on Garden Key, in 1825. Thirty-one years later the present 150-foot light was erected on Loggerhead Key.

In the words of the naval captain who surveyed the Keys in 1830, Tortugas could “control navigation of the Gulf.” Commerce from the growing Mississippi Valley sailed the Gulf to reach the Atlantic. Enemy seizure of Tortugas would cut off this vital traffic, and naval tactics from this strategic base could be effective against even a superior force.

There were still keen memories of Jackson’s fight with the British at New Orleans, and Britain was currently developing her West Indies possessions. Trouble in Cuba was near. Texas, a new republic, seemed about to form an alliance with France or England, thus providing the Europeans with a foothold on the Gulf Coast.

During the first half of the 1800’s the United States began a chain of seacoast defenses from Maine to Texas. The largest link was Fort Jefferson, half a mile in perimeter and covering most of 16-acre Garden Key. From foundation to crown its 8-foot-thick walls stand 50 feet high. It has 3 gun tiers, designed for 450 guns, and a garrison of 1,500 men.

The fort was started in 1846, and, although work went on for almost 30 years, it was never finished. The U. S. Engineer Corps planned and supervised the building. Artisans imported from the North and slaves from Key West made up most of the labor gang. After 1861 the slaves were partly replaced by military prisoners, but slave labor did not end until Lincoln freed the slaves in 1863.

To prevent Florida’s seizure of the half-complete, unarmed defense, Federal troops hurriedly occupied Fort Jefferson (January 19, 1861), but aside from a few warning shots at Confederate privateers, there was no action. The average garrison numbered 500 men, and building quarters for them accounted for most of the wartime construction.

Little important work was done after 1866, for the new rifled cannon had already made the fort obsolete. Further, the engineers found that the foundations rested not upon a solid coral reef, but upon sand and coral boulders washed up by the sea. The huge structure settled, and the walls began to crack.

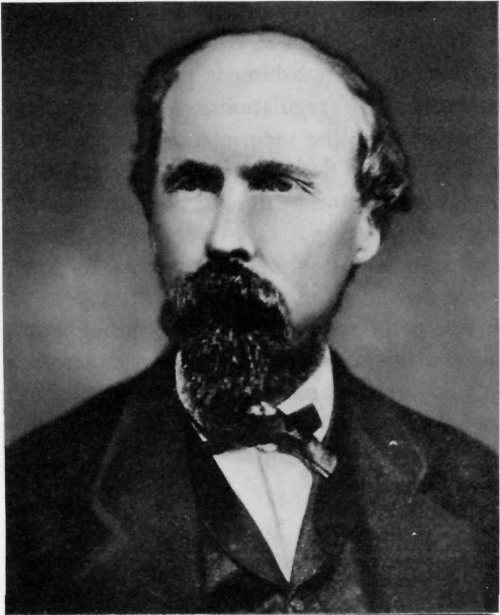

For almost 10 years after the war, Fort Jefferson remained a prison. Among the prisoners sent there in 1865 were the “Lincoln Conspirators”—Michael O’Loughlin, Samuel Arnold, Edward Spangler, and Dr. Samuel A. Mudd. Dr. Mudd, knowing nothing of President Lincoln’s assassination, had set the broken leg of the fugitive assassin, John Wilkes Booth. The innocent physician was convicted of conspiracy and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor.

Normally, Tortugas was a healthful post, but in 1867 yellow fever came. From August 18 to November 14 the epidemic raged, striking 270 of the 300 men at the fort. Among the first of the 38 fatalities was the post surgeon, Maj. Joseph Sim Smith. Dr. Mudd, together with Dr. Daniel Whitehurst, from Key West, worked day and night to fight the scourge. Two years later, Dr. Mudd was pardoned.

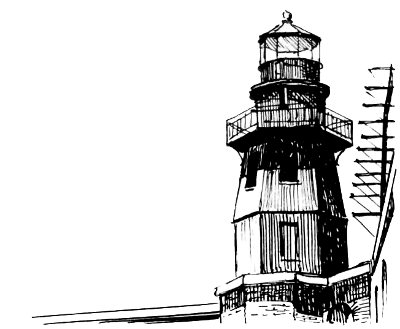

It is a mile-long walk through the gunroom galleries.

Because of hurricane damage and another fever outbreak, Fort Jefferson was abandoned in 1874. During the 1880’s, however, the United States began a naval building program, and Navy men looked at this southern outpost as a possible naval base. From Tortugas Harbor the battleship Maine weighed anchor for Cuba, and when she was blown up in Havana Harbor, on February 15, 1898, 3 the Navy began a coaling station outside the fort walls, bringing the total cost of the fortification to some 3½ million dollars. The big sheds were hardly completed before a hurricane smashed the loading rigs.

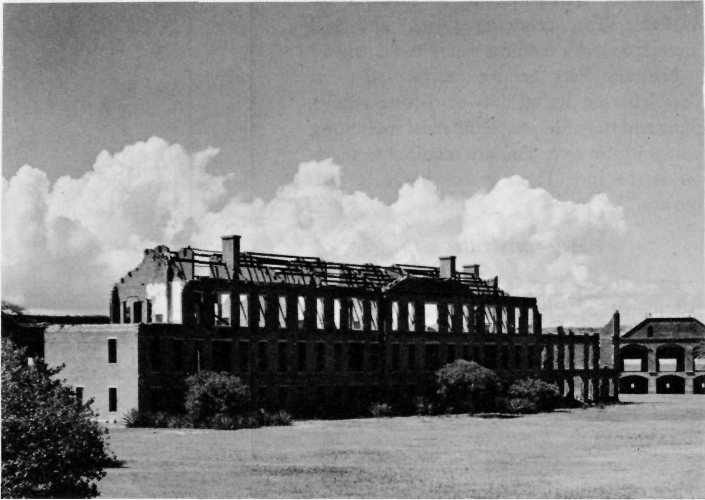

One of the first naval wireless stations was built at the fort early in the 1900’s, and, during World War I, Tortugas was equipped for a seaplane base. But as the military moved out again, fire and storms and salvagers took their toll, leaving the “Gibraltar of the Gulf” the vast ruin that it is today.

One of our great national wildlife spectacles occurs each year between May and September, when the sooty terns assemble on Bush Key for their nesting season. The terns come from the Caribbean Sea and west-central Atlantic Ocean and land by the thousands on Bush Key. Their nests are no more than depressions in the warm sand. The parents take turns shading their single egg from the sun. When the young are strong enough for continuous flight, the colony again heads southeastward to tropical seas.

The presence of these tropical oceanic birds at Tortugas was recorded by Ponce de León (1513), Capt. John Hawkins (1565), John James Audubon (1832), and Louis Agassiz (1858). During the early 1900’s, commercial egg-raiding reduced the colony to only 4,000 birds, but careful protection restored the strength of the colony; 120,000 birds are now recorded at the rookery. Several hundred noddy terns, similar to the sooty in habit and size, nest in the low shrubbery of Bush Key.

The great man-o’-war, or frigate, bird congregates here during the tern season to enjoy an easy existence on minnows pirated from the terns. With a wingspread of about 7 feet, the frigate is one of the most graceful of the soaring birds. Though rarely seen elsewhere in any number, as many as 200 glide endlessly on the thermal updrafts above the fort.

Blue-faced and brown boobies of the West Indies are year-round residents of Tortugas. Each summer a colony of a few hundred roseate terns, which normally inhabit the Atlantic seaboard north of Cape Hatteras, nest on Long Key. In season, a continuous procession of songbirds and other migrants fly over or drop off for rest at the islands, which lie across one of the principal flyways from the United States to Cuba and South America. Familiar gulls and terns of the north, as well as many migratory shore birds, spend the winter at Tortugas.

Ruins of the officers’ quarters.

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd.

The sooty tern shades its eggs from the hot sun.

The warm Gulf Stream waters support great reefs of coral and “forests” of marine plants, which in turn provide refuge for the myriad forms of animal life in nature’s aquarium. The visitor who is equipped with a glass-bottomed bucket or box can enjoy the sight of brilliant tropical fish and crustaceans in the crystal-clear waters of their native environment. Sport fishing is permitted in accordance with regulations, which may be obtained from the superintendent.

The native flora is tropical, principally mangrove, button-mangrove or buttonwood, bay cedar, seagrape, sea-lavender, purslane, and seaoats—all quite characteristic of the lower east coast of Florida.

The early residents, however, brought in many plants, including the feathery tamarind, gumbo limbo, Australian-pine, and coconut and date palms. Growing out of the ruins may be a pepper plant that came from a garden in Havana.

Fort Jefferson is 68 miles from Key West and is accessible only by boat. Landing of aircraft is prohibited because of the hazards to wildlife. However, there are no other restrictions that would interfere with your enjoyment of a rare experience. The area is an isolated wilderness, and you must provide for your own independent existence—no housing, meals, transportation, or supplies are available. The anchorage is large and well protected, and a landing wharf is available.

National Park Service representatives at Fort Jefferson are on duty to enforce regulations and to guide you to the most interesting points in the area. You are required to register at the fort. There is no charge for admission.

Fort Jefferson was declared a national monument by Presidential proclamation of January 4, 1935. The monument includes the Dry Tortugas Islands and a surrounding water area of about 75 square miles. Correspondence regarding the monument should be addressed to the Superintendent, Fort Jefferson National Monument, Key West, Fla.

FORT JEFFERSON NATIONAL MONUMENT;

DRY TORTUGAS; FLORIDA

High-resolution Map

United States Department of the Interior

Fred A. Seaton, Secretary

National Park Service, Conrad L. Wirth, Director

Reprint 1958

U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1958 O-467962

The National Park System, of which this area is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people.