Title: The Marryers: A History Gathered from a Brief of the Honorable Socrates Potter

Author: Irving Bacheller

Release date: September 30, 2015 [eBook #50088]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

Pointview, Conn.

To the Honorable Judges of Decency and Good Behavior the World Over:

My friend, the novelist, has prevailed upon me to write this brief in behalf of my country and against certain feudal tendencies therein. I have tried to tell the truth, but with that moderation which becomes a lawyer of my age 'and experience. It is bad manners to give a guest more wine than he can carry or more truth than he can believe. In these pages there is enough wine, I hope, for the necessary illusion, and enough truth, I know, for the satisfaction of my conscience. I hasten, to add that there is not enough of wine or truth to stagger those who are not accustomed to the use of-either. I warned the novelist that nothing could be more unfortunate for me than that I should betray a talent for fiction. He assures me that my reputation is not in danger.

CONTENTS

I.—IN WHICH MR. POTTER PRESENTS THE SINGULAR DILEMMA OF WHITFIELD NORRIS, MULTIMILLIONAIRE

II.—MY INTERVIEW WITH THE PIRATE

III.—IN WHICH A MAN IS SEEN HOLDING DOWN THE BUSHEL THAT HIDES HIS LIGHT

IV.—A RATHER SWIFT ADVENTURE WITH THE PIRATE

V.—IN WHICH WE HAVE AN AMUSING VOYAGE

VI.—WE ARRIVE IN THE LAND OF LOVE AND SONG

VII.—IN WHICH I TEACH THE DIFFICULT ART OF BEING AN AMERICAN IN ITALY

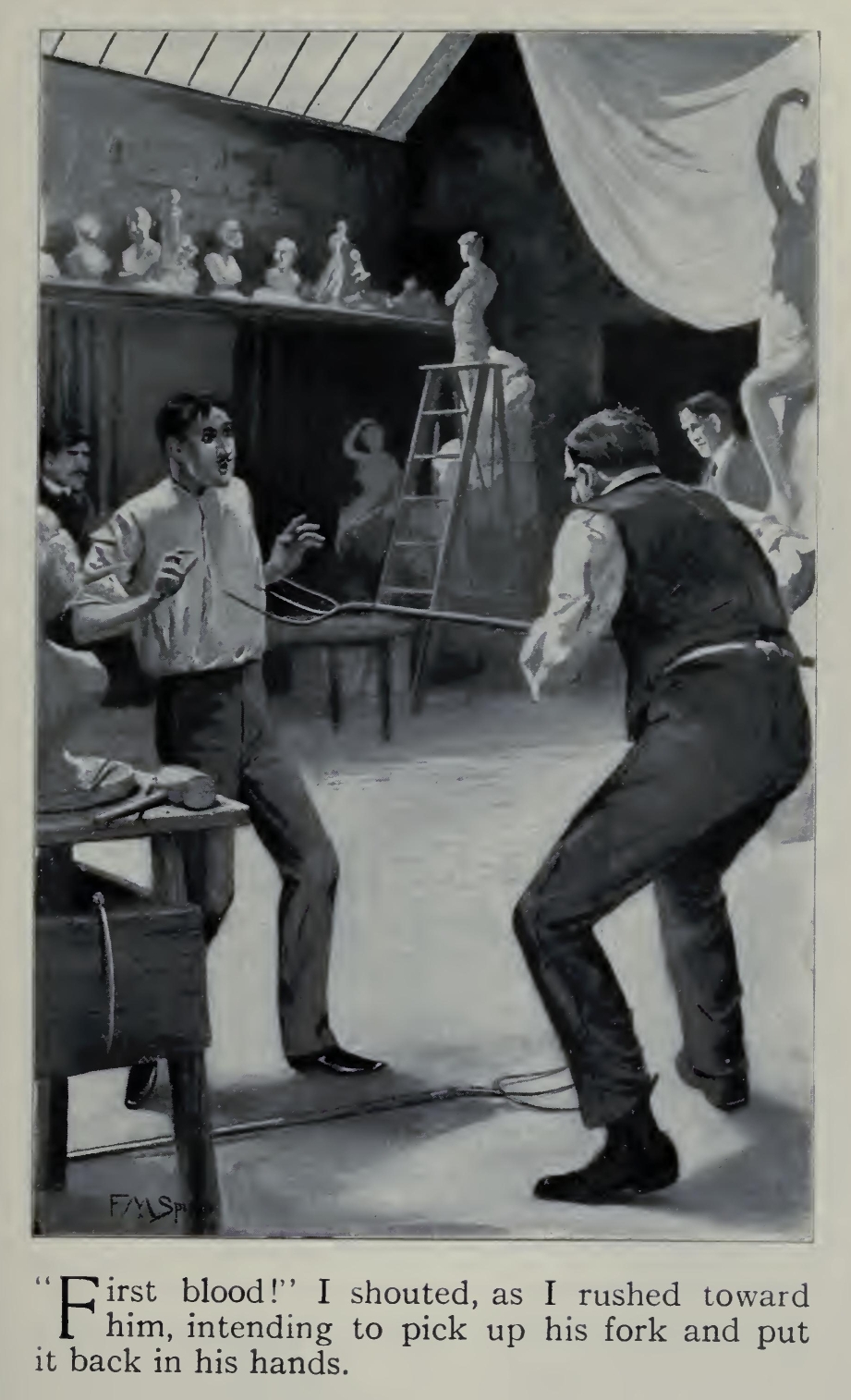

VIII.—I AGREE TO FIGHT A DUEL AND NAME A WEAPON WITH WHICH EUROPEAN GENTLEMEN ARE UNFAMILIAR

IX.—A MODERN AMERICAN MARRYER ENTERS THE SCENE

X.—A DAY OF ADVENTURES WITH TUSCAN ARTISTS AND OTHERS

XI.—IN WHICH WE GET INTO THE FLASH AND GLITTER OF HIGH LIFE

XII.—IN WHICH NORRIS TAKES HIS LIGHT FROM UNDER THE BUSHEL

XIII.—IN WHICH I FIGHT A DUEL WITH ONE OF THE OLDEST WEAPONS IN THE WORLD

XIV.—MISS GWENDOLYN DEFINES HER POSITION

XV.—SOMETHING HAPPENS TO THE MAN MUGGS

I HAVE just returned from Italy—the land of love and song. To any who may be looking forward to a career in love or song I recommend Italy. Its art, scenery, and wine have been a great help to the song business, while its pictures, statues, and soft air are well calculated to keep the sexes from drifting apart and becoming hopelessly estranged. The sexes will have their differences, of course, as they are having them in England. I sometimes fear that they may decide to have nothing more to do with each other, in which case Italy, with its alert and well-trained corps of love-makers, might save the situation.

Since Ovid and Horace, times have changed in the old peninsula. Love has ceased to be an art and has become an industry to which the male members of the titolati are assiduously devoted. With hereditary talent for the business, they have made it pay. The coy processes in the immortal tale of Masuccio of Salerno are no longer fashionable. The Juliets have descended from the balcony; the Romeos climb the trellis no more. All that machinery is now too antiquated and unbusinesslike. The Juliets are mostly English and American girls who have come down the line from Saint Moritz. The Romeos are still Italians, but the bobsled, the toboggan, and the tango dance have supplanted the balcony and the trellis as being swifter, less wordy, and more direct.

There are other forms of love which thrive in Italy—the noblest which the human breast may know—the love of art, for instance, and the love of America. I came back with a deeper affection for Uncle Sam than I ever had before.

But this is only the cold vestibule—the “piaz” of my story. Come in, dear reader. There's a cheerful blaze and a comfortable chair in the chimney-corner. Make yourself at home, and now my story's begun exactly where I began to live in it—inside the big country house of a client of mine, an hour's ride from New York. His name wasn't Whitfield Norris, and so we will call him that. His age was about fifty-five, his name well known. If ever a man was born for friendship he was the man—a kindly but strong face, genial blue eyes, and the love of good fellowship. But he had few friends and no intimates beyond his family circle. True, he had a gruff voice and a broken nose, and was not much of a talker. Of Norris, the financier, many knew more or less; of Norris, the man, he and his family seemed to enjoy a monopoly of information. It was not quite a monopoly, however, as I discovered when I began to observe the deep undercurrents of his life. Right away he asked me to look at them.

Norris had written that he wished to consult me, and was forbidden by his doctor to go far from his country house, where he was trying to rest. Years before he had put a detail of business in my hands, and I had had some luck with it.

His glowing wife and daughter met me at the railroad-station with a glowing footman and a great, glowing limousine. The wife was a restored masterpiece of the time of Andrew Johnson—by which I mean that she was a very handsome woman, whose age varied from thirty to fifty-five, according to the day and the condition of your eyesight. She trained more or less in fashionable society, and even coughed with an English accent. The daughter was a lovely blonde, blue-eyed girl of twenty. She was tall and substantial—built for all weather and especially well-roofed—a real human being, with sense enough to laugh at my jokes and other serious details in her environment.

We arrived at the big, plain, comfortable house just in time for luncheon. Norris met me at the door. He looked pale and careworn, but greeted me playfully, and I remarked that he seemed to be feeling his oats.

“Feeling my oats! Well, I should say so,” he answered. “No man's oats ever filled him with deeper feeling.”

Like so many American business men, his brain had all feet in the trough, so to speak, and was getting more than its share of blood, while the other vital organs in his system were probably only half fed.

At the table I met Richard Forbes, a handsome, husky young man who seemed to take a special interest in Miss Gwendolyn, the daughter. There were also the aged mother of Norris, two maiden cousins of his—jolly women between forty-five and fifty years of age—a college president, and Mrs. Mushtop, a proud and talkative lady who explained to me that she was one of the Mushtops of Maryland. Of course you have met those interesting people. Ever since 1627 the Mushtops have been coming over from England with the first Lord Baltimore, and now they are quite numerous. While we ate, Norris said little, but seemed to enjoy the jests and stories better than the food.

He had a great liking for good tobacco, and after luncheon showed me the room where he kept his cigars. There were thousands of them made from the best crops of Cuba, in sizes to suit the taste.

“Here are some from the crop of '93,” he said, as he opened a box. “I have green cigars, if you prefer them, but I never smoke a cigar unless it crackles.”

I took a crackler, and with its delicious aroma under my nose we went for a walk in the villa gardens. Some one had released a dozen Airedales, of whom my host was extremely fond, and they followed at his heels. I walked with the maiden cousins, one of whom said of Norris: “We're very fond of him. Often we sing, 'What a friend we have in Whitfield!' and it amuses him very much.”

And it suggested to me that they had good reason to sing it.

Norris was extremely fond of beautiful things, and his knowledge of both art and flowers was unusual. He showed us the conservatories and his art-gallery filled with masterpieces, but very calmly and with no flourish.

“I've only a few landscapes here,” he said, “things that do not seem to quarrel with the hills and valleys.”

“Or the hay and whiskers and the restful spirit beneath them,” I suggested.

I knew that he had bought in every market of the world, and had given some of his best treasures to sundry museums of art in America, but they were always credited to “a friend,” and never to Whitfield Norris.

On our return to the house he asked me to ride with him, and we got into the big car and went out for a leisurely trip on the country roads. The farmer-folk in field and dooryard waved their hands and stirred their whiskers as we passed.

“They're all my friends,” he said.

“Tenants and vassals!” I remarked.

“You see, I've helped some of them in a small way, but always impersonally,” he answered, as if he had not heard me. “I have sought to avoid drawing their attention to me in any way whatever.”

We drew up at a little house on a lonely road to ask our way. An Irish woman came to the car door as we stopped, and said:

“God bless ye, sor! It does me eyes good to look an' see ye better—thanks to the good God! I haven't forgot yer kindness.”

“But I have,” said Norris.

The woman was on her mental knees before him as she stood looking into his face.

No doubt he had lifted her mortgage or favored her in some like manner. Her greeting seemed to please him, and he gave her a kindly word, and told his driver to go on.

We passed the Mary Perkins's school and the Mary Perkins's hospital, both named for his wife. I had heard much of these model charities, but not from him. So many rich men talk of their good deeds, like the lecturer in a side-show, but he held his peace. Everywhere I could not help seeing that he was regarded as a kind of savior, and he seemed to regret it. Was he a great actor or—?

“It's a pity that I cannot enjoy my life like other men,” he interrupted, as this thought came to me. “None of my neighbors are quite themselves when they talk to me; they think I must be praised and flattered. They don't talk to me in a reliable fashion, as you do. You have noticed that even my own family is given to songs of praise in my presence.”

“Norris, I'm sorry for you,” I said. “They say that you inherited a fair amount of poverty—honest, hard-earned poverty. Why didn't you take care of it? Why did you get reckless and squander it in commercial dissipation? You should have kept enough to give your daughter a proper start in life. I have taken care of mine.”

“It began in the thoughtless imprudence of youth,” he went on, playfully. “I used to think that money was an asset.”

“And you have discovered that money is only a jackasset.”

“That it is, in fact, a liability, and that every man you meet is dunning you for a part of it.”

“Including the lawyers you meet,” I said. “Oh, they're the worst of all!” he laughed. “As distributors of the world's poverty they are unrivaled.”

He smiled and shook his head with a look of amusement and injury as he went on.

“Almost every one who comes near me has a hatchet if not an ax to grind. I am sick of being a little tin god. I seem to be standing in a high place where I can see all the selfishness of the world about me. No, it hasn't made me a cynic. I have some sympathy for the most transparent of them; but generally I am rather gruff and ill-natured; often I lose my temper. I have had enough of praise and flattery to understand how weary of it the Almighty must be. He must see how cheap it is, and if He has humor, as of course He has, having given so much of it to His children, how He must laugh at some of the gross adulation that is offered Him! But let us get to business.

“I invited you here to engage your services in a most important matter; it's so important that for many years I have given it my own attention. But my health is failing, and I must get rid of this problem, which is, in a way, like the riddle of the Sphinx. Some other fellow must tackle it, and I've chosen you for the job. Mr. Potter, you are to be, if you will, my trustiest friend as well as my attorney. For many years I have been the victim of blackmailers, and have paid them a lot of money.”

“Poverty is a good thing, but not if it's achieved through the aid of a blackmailer,” I remarked. “Try some other scheme.”

“But you must know the facts,” he went on. “At twenty-one I went into business with my father out in Illinois. He got into financial difficulties and committed a crime—forged a man's name to a note, intending to pay it when it came due. Suddenly, in a panic, he went on the rocks, and all his plans failed. He was up against it, as we say. There were many extenuating circumstances—a generous man, an extravagant family, of which I had been the most extravagant member; a mind that lost its balance under a great strain. He had risked all on a throw of the dice and lost. I'll never forget the hour in which he confessed the truth to me. It's hard for a father to put on the crown of shame in the presence of a child who honors him. There's no pang in this world like that. He had braced himself for the trial, and what a trial it must have been! I have suffered some since that day; but all of it put together is nothing compared to that hour of his. In ten minutes I saw him wither into old age as he burned in the fire of his own hell. When he was done with his story I saw that he was virtually dead, although he could still breathe and see and speak and walk. As I listened a sense of personal responsibility and of great calmness and strength came on me.

“I took my father's arm and went home with him and begged him not to worry. Then forthwith I went to police headquarters and took the crime on myself. My father went to paradise the next day, and I to prison. I was young and could stand it. They gave me a light sentence, on account of my age—only two years, reduced to a year and a half for good behavior. My Lord! It has been hard to tell you this. I've never told any one but you; not even my own mother knows the truth, and I wouldn't have her know it for all the world. I cleared out and went to work in California, in the mines. Suffered poverty and hardship; won success by and by; prospered, and slowly my little hell cooled down. But no man can escape from his past. By and by it overtakes him, and in time it caught me. A record is a record, and you can't wipe it out even with righteous living. It may be forgiven—yes, but there it is and there it will remain.

“I didn't marry, as you may know, until I was thirty-four. My wife was the daughter of a small merchant in an Oregon village. I had been married about a year when the first pirate fired across my bows—a man who had worked beside me at Joliet. I found him in my office one morning. He didn't know how much money I had, and struck me gently, softly, for a thousand dollars. It was to be a loan. I gave him the money; I had to. Why? Well, you see, my wife didn't know that I was an ex-convict, and I couldn't bear to have her know of it. I did not fear her so much as her friends, some of whom were jealous of our success. Why hadn't I told her before my marriage? you are thinking. Well, partly because I honored my father and my mother, and partly because I had no sense of guilt in me. Secretly I was rather proud of the thing I had done. If I had been really guilty of a crime I should have had to tell her; but, you see, my heart was clean—just as clean as she thought it. I hadn't fooled her about that. There had been nothing coming to me. Oh yes, I know that I ought to have told her. I'm only giving you the arguments with which I convinced myself—with which even now I try to convince myself—that it wasn't necessary. Anyhow, when I married it never entered my head that there could be a human being so low that he would try to fan back to life the dying embers of my trouble and use it for a source of profit. It never occurred to me that any man would come along and say: 'Here, give me money or I'll make it burn ye.'

“I foolishly thought that my sacrifice was my own property, and was beginning to forget it. Well, first to last, this man got forty thousand dollars out of me. He was dying of consumption when he made his last call, having spent the money in fast living. He wanted five thousand dollars, and promised never to ask me for another cent. He kept his word, and died within three months, but not until he had sold his pull to another scoundrel. The new pirate was an advertising agent of the Far West. He came to me with the whole story in manuscript, ready to print. He said that he had bought it from two men who had brought the manuscript to his office, and had paid five thousand dollars for it. He was such a nice man!—willing to sell at cost and a small allowance for time expended. I gave him all he asked, and since then I have been buying that story every six months or so. When anything happens, like the coming out of my daughter, this sleek-looking, plausible pirate shows up again, and, you see, I can't kick him out of my presence, as I should like to do. He always tells me that the mysterious two are demanding more money, so, like a bull with a ring in his nose, I have been pulled about for years by this little knave of a man. I couldn't help it. Now my nerves cannot endure any more of this kind of thing. My doctor tells me that I must be free from all worry; I propose to turn it over to you.”

“Then I shall wipe him off the slate,” I said. “They'll publish the facts.”

“Poor man!” I exclaimed. “You've got one big asset, and you're afraid to claim it. Nothing that you have ever done compares with that term in prison. Your charities have been large, but, after all, their value is doubtful except to you. The old law of evolution isn't greatly in need of your money. But when you went to prison you really did something, old man. The light of a deed like that shines around the world. Let it shine—if it must. Don't hide it under a bushel.”

“But not for all I am worth would I have my father's name dishonored, with my mother still alive,” he declared. “Now, as to myself, I am not so much worried. I could bear some disgrace, for it wouldn't alter the facts. I should keep my self-respect, anyhow. But when I think of my wife and children I admit that I am a coward. They're pretty proud, as you know, and the worst of it is they are proud of me. Their pride is my best asset. I couldn't bear to see it broken down. No, what I want is to have you manage this blackmail fund and keep all comers contented. What money you need for that purpose will be supplied to you.”

“In my opinion you're unjust to the ladies of your home,” I remarked.

“How?”

“You should treat them like human beings and not like angels,” I said. “It's their right to share your troubles. They'd be all the better for it.”

“Please do as I say,” he answered. “You must remember that they're all I've got.”

“Cheer up! I 'll do my best,” was my assurance. “But I shall ask you to let me manage the matter in my own way and with no interference.”

“I commit my happiness to your keeping,” he answered.

“I wonder that you have got off so cheaply,” I said. “I should think there might have been a dozen pirates in the chase instead of two.”

“Circumstances have favored me,” he explained. “I spent my youth in Germany, where I was educated. I had been in America only six months when my father failed. In those days I was known as Jackson W. Norris. In California I got into a row and had my nose broken. I was a good-looking man before that. Then, you see, it has been a rule of my life to keep my face from being photographed. Of course, the papers have had snap-shots of me; but no one who knew me as a boy would recognize this bent nose and wrinkled face of mine. I have discouraged all manner of publicity relating to me and kept my history under cover as a thing that concerned no one but myself.”

I had requested that our ride should end at the railroad-station, and we arrived there in good time for my train.

“I will ask Wilton, my pirate friend, to call on you,” he said.

“Let him call Friday at twelve with a note from you,” I requested.

Gwendolyn Norris and Richard Forbes were waiting at the station, the latter being on his way to town.

“Going back? You ought to know better,” I said.

“So I do, but business is business,” he answered.

“And there's no better business for any one than playing with a fair maid.”

“He knows that there's a tennis match this afternoon and a dance this evening, and he leaves me,” the girl complained.

“I shall have to take a week off and come up here and convince you that no man is fonder of fun and a fair maid,” said Forbes.

“I could do it in ten minutes,” I declared.

“But you have had practice and experience,” said Forbes.

“And you are more supple,” was my answer.

“I should hope so,” the girl laughed. “If all men were like Mr. Potter the world would be full of old maids. It took him thirty years to make up his mind to get married.”

“No, it took her that long—not me,” I answered, and the arrival of the train saved me from further humiliation.

On the way to town I got acquainted with young Forbes, and liked him. He was a big, broad-shouldered athlete, two years out of college. The glow of health and good nature was in his face. His blue eyes twinkled merrily as we sparred for points. He had a full line of convictions, but he didn't pretend to have gathered all the fruit on the tree of knowledge. He was the typical best product of the modern wholesale man factory—strong, modest, self-restrained, well educated, and thinking largely in terms of profit and loss. That is to say, he was sawed and planed and matched and seasoned like ten thousand other young men of his age. His great need had been poverty and struggle and individual experience. If he had had to climb and reach and fall and get up and climb again to secure the persimmon which was now in his hands, he would have had the persimmon and a very rare thing besides, and it's the rare thing that counts. But here I am finding fault with a thoroughly good fellow. It's only to clear his background for the reader, to whose good graces I heartily recommend the young man. His father had left him well off, but he had gone to work on a great business plan, and with rare talent for his task, as it seemed to me.

IT had been a misty morning, with slush in the streets. For hours the great fog-siren had been bellowing to the ships on the sound and breaking into every conversation. “Go slow and keep away!” it screeched, in a kind of mechanical hysterics.

I was sitting at my desk when Norris's pirate came in. I didn't like the look of him, for I saw at once that he was hard wood, and that he wouldn't whittle. He was a sleek, handsome, well-dressed man of middle age, with gray eyes, iron-gray hair and mustache, the latter close-cropped. Here, then, was Wilton—a man of catlike neatness from top to toe. He stepped softly like a cat. Then he began smoothing his fur—neatly folded his coat and carefully laid it over the back of a chair; blew a speck of dust from his hat, and tenderly flicked its brim with his handkerchief and placed it with gentle precision on the top of the coat. It's curious how the habit of taking care gets into the character of a gentleman thief. He almost purred when he said “Good morning.” Then he seemed to smell the dog, and stopped and took in his surroundings. His hands were small and bony; he felt his necktie, adjusted his cuffs with an outward thrust of both arms, and sat down. Without a word more he handed me the note from Norris, and I read it.

“Yes,” I said; “Mr. Norris has given me a brief history of your affectionate regard for him.”

He tried to take my measure with a keen glance. I looked serious, and he took me seriously.

“You see,” he began, in a low voice, “for years I have been trying to protect him from unscrupulous men.”

He gently touched the end of one forefinger with the point of the other as he spoke. His words were neatly said, and were like his clothing, neatly pressed and dusted, and calculated to present a respectable appearance.

“Tell me all about it,” I said. “Norris didn't go into details.”

“Understand,” he went on, gently moving his head as if to shake it down in his linen a little more comfortably, “I have never made a cent out of this. I have only kept enough to cover my expenses.”

It was the old story long familiar to me. The gentleman knave generally operates on a high moral plane. Sometimes he can even fool himself about it. He had climbed on a saint's pedestal and was looking down on me. It shows the respect they all have for honor.

“There are two men besides myself who know the facts, and I have succeeded so far in keeping them quiet,” he added.

“I don't know you, but you won't be offended if I assume that you're a man of honor,” I said.

In the half-moment of silence that followed the old fog-siren screeched a warning.

There was a quick, nervous movement of the visitor's body that brought his head a little nearer to me. The fur had begun to rise on the cat's back.

“There's nothing to prevent it,” said he, with a look of surprise.

“Save a possible element of professional pride,” was my answer.

“That vanishes in the presence of a lawyer,” said he.

It was a kind of swift and surprising cuff with the paw, after which I knew him better.

“But we're licensed, you know, and now, your reputation being established, I suggest that you are in honor bound to let us know the names of those men.”

“Excuse me! I'm above that kind of thing—way above it,” said he, with a smile of regret for my ignorance.

“Perhaps you wouldn't be above explaining.”

“Not at all. If I told you that, I would be as bad as they are. Why, sir, I would be the yellowest yellow dog in the country.”

“Frankness is not apt to have an effect so serious,” I said.

Again the points of his forefingers came together as he gently answered:

“You see, the first demand they made of me, after putting the story in my hands, was that I should never give out their names. I had to promise that.”

“Oh, I see. They've elected you to the office of Guardian Angel and Secretary of the Treasury. How did it happen?”

The query didn't annoy him. He was getting used to my sallies, and went on:

“It was easy and natural as drawing your breath. Those men knew that I had met Mr. Norris—that I was a man of his class, and could talk to him on even terms. They had got the story from a man now dead—paid him five hundred dollars for it. They wanted my help to make a profit, see? I had met Mr. Norris and liked him. He is one of Nature's noblemen. So I played a friendly part in the matter, and bought the story and turned it over to Mr. Norris for what it cost me, and he gave me two hundred dollars for my time. Unfortunately, they have turned out to be rascals, and we have had to keep them in spending money, and prosperity has made them extravagant. The whole thing has become a nuisance to me, and I wish I was out of it.”

“What do they want now?” I asked.

“Ten thousand dollars.”

That was all he said—just those three well-filled words—with a sad but firm look in his face and a neat little gesture of both hands. “When do they want it?”

“To-day; they're getting impatient.”

“Suppose you tell them that they'll have to practise economy for a week or so at least. I don't know but we shall decide to let them go ahead and do their worst. It isn't going to hurt Norris. He's been foolish about it; I'm trying to stiffen his backbone.” Wilton rose with a look of impatience in his face that betrayed him.

“Very well; but I shall not be responsible for the consequences.”

The cat had hissed for the first time, but he quickly recovered himself; the tender look returned to his eyes.

“I think you're foolish,” he began again, while his right forefinger caressed the point of his left. “These men are not going to last long. One of them has had delirium tremens twice, and the other is in the hospital with Bright's disease. They're both of them broke, and you know as well as I that they could get this money in an hour from some newspaper. It's almost dead sure that both of these men will be out of the way in a year or so. Norris wants to be protected, and it's up to you and me to do it.”

“Personally I do not see the object,” I insisted. “Protecting him from one assault only exposes him to another.”

“You see, the daughter isn't married yet, and we'd better protect the name until she's out of the way, anyhow. That girl can go to Europe and take her pick. She's good enough for any title. But if this came out it would hurt her chances.”

“Mr. Wilton, I congratulate you,” was my remark.

“I thought you would see the point,” he answered, with a smile.

“I am thinking not of the point, but of your philanthropy. It is beautiful. Do you sleep well nights?”

“Very,” he answered, with a quick glance into my eyes.

“I should think that the troubles of the world would keep you awake.”

His face flushed a little, and then he smiled. “You lawyers have no suspicion of the amount of goodness there is in the world—you're always looking for rascals,” he said.

“But we have wandered. Let us take the nearest road to Rome. You say they must have money to-day.”

“Before three o'clock.”

“We'll give them ten thousand dollars—not a cent more. You must tell them to use it gently, for it's the last they'll get from us. To whom shall I draw the check?”

“To me—Lysander Wilton,” he answered, with a look of relief.

I gave him the check. He put on his coat and began to purr again; he was glad to know me, and rightly thought that he could turn some business my way.

As he left my office I went to one of the front windows and took out my handkerchief. The fog-whistle blew a blast that swept sea and land with its echoes. In a moment I saw a certain clever, keen-eyed man who was studying current history under the direction of Prof. William J. Bums come out of a door opposite and walk at a leisurely pace down the main street of Pointview toward the station. He was now taking the first steps in a systematic effort to see what was in and behind the man Wilton.

THE first thing I desired was the history of Wilton. He knew more about us than we knew about him, and that didn't seem to be fair or even necessary. In fact, I felt sure that his little world would yield valuable knowledge if properly explored. I knew that there were lions and tigers in it.

I learned that Wilton had proceeded forthwith to a certain apartment house on the upper west side of New York, in which he remained until dinner-time, when he came out with a well-dressed woman and drove in a cab to Martin's. The two spent a careless night, which ended at four a.m. in a gambling-house, where Wilton had lost nine hundred dollars. Next day, about noon, his well-dressed woman friend came out of the house and was trailed to a bank, where she cashed a check for five hundred dollars. We learned there that this woman was an actress and that her balance was about eighty-five hundred dollars.

Three months passed, and I got no further news of the man, save that he had gone to Chicago and that our trailers had gone with him.

“Our Western office now has the matter in hand,” so the agency wrote me. “They are doing their work with extreme care. Fresh men took up the trail every day, until one of our ablest became a trusted confidant of Wilton.”

The whole matter rested in the files of my office, and I had not thought of it until one day Norris sent for me and, on my arrival at his house, showed me a telegram. It was from the President of the United States, whose career he had assisted in one way and another. It offered him the post of Minister to a European court. The place was one of the great prizes.

“Of course you will accept it?” I said.

“I should like to,” he answered, “but isn't it curious that fame is one of the things which fate denies me. I wouldn't dare take it.”

I understood him and said nothing.

“You see, I cannot be a big man. I must keep myself as little as possible.”

“The joys of littleness are very great, as the mouse remarked at the battle of Gettysburg; but they are not for you,” I said. “He that humbleth himself shall be exalted.”

“He that humbleth himself shall avoid trouble—that's the way it hits me,” he said. “I could have been Secretary of the Treasury a few years back if I had dared. I must let everything alone which is likely to stir up my history. Suppose the President should suddenly discover that he had an ex-convict in his Cabinet? Do you think he could stand that, great as he is? He would rightly say that I had tricked and deceived and disgraced him. What would the newspapers say, and what would people think of me? Potter, I've made a study of this thing we call civilization. It's a big thing—I do not underestimate it—but it isn't big enough to forgive a man who has served his term.”

“Yes, I know; some of us are always looking for a thief inside the honest man,” was my answer. “We ought to be looking for the honest man inside the thief, as Chesterton puts it.”

“That's a good idea!” he exclaimed. “Find me one. I'd like to use him to teach this world a lesson. I'd pay you a handsome salary as Diogenes. If you succeed once I'll astonish you with generosity.”

“I should like to help you to get rid of some of this money of yours,” I said.

“You can begin this morning,” he went on. “I'm going to give you some notes for a new will. Suppose you sit down at the table there.”

I spent the rest of that day taking notes, and was astonished at the amount of his property and the breadth of his spirit. He had got his start in the mining business, and with surprising insight had invested his earnings in real estate, oil-lands, railroad stocks, and steel-mills.

“I have always believed in America, and America has made me rich,” he said to me.

“Before the Spanish War and in every panic, when no man seemed to want her securities, I have bought them freely, and I own them today. With our growing trade and fruitful lands I wonder that all thinking men did not share my confidence. If America had gone to smash I should have gone with her. I shall stick to the old ship.”

One paragraph of the will has begun to make history. It has appeared in the newspapers, but no account of my friend should omit it, and therefore I present its wording here:

“There are many points of greatness in the Christian faith, but the greatest of all is charity. I conceive that the best argument for the heathen is that of wheat and com. I therefore direct that the sum of five million dollars be set aside and invested by the trustees of this will and that its proceeds be applied to the relief of the distressing poverty of unconverted peoples, wherever they may be, in the discretion of said trustees; and when said relief is applied it shall be done as the act of 'A Christian friend in America.' It is my wish that wherever practicable in the judgment of said trustees this relief shall be applied through the establishment of industries in which the needy shall be employed at fair wages.”

I had finished my notes for the will, and my friend and I were sitting comfortably by the open fire, when his wife entered the room and sat down with us.

“Have you told Mr. Potter about the bank offer?” she inquired of her husband.

“No, my dear,” he answered.

“May I tell him?”

“Certainly.”

“Mr. Potter, the presidency of a great bank has been offered to my husband, and I think that he ought to take it.”

“Oh, I have work enough here at home—all I can do,” he said.

“But you will not have much to do there—only a little consulting once a week or so, and they say that you can talk to them here if you wish.”

“It's too much responsibility,” he answered.

“But it's so respectable,” she urged. “My heart is set on it. They tell me that, next to Mr. Morgan, you would be the greatest power in American finance. We should all be so proud of you.”

“I couldn't wish you to be any more proud of me,” he answered, tenderly.

“But, naturally, we want you to be as great as you can, Whitfield,” she went on. “This would mean so much to me and to Gwendolyn.”

He rose wearily, with a glance into my eyes which I perfectly understood, and went to his wife and kissed her and said:

“My dear, I am sure that Mr. Potter will agree with me.”

“Unreservedly,” was my answer.

I knew then that this ambitious woman was as ignorant as the cattle in their farmyard of the greater honors which he had declined.

She rose and left the room with a look of disappointment. How far the urgency of his wife and other misguided friends may have gone I know not, but I have reason to believe that it put him to his wit's ends.

I am sure that it was the most singular situation in which a lawyer was ever consulted. My client's high character had commanded the love and confidence of all who knew him well, and this love and confidence were pushing him into danger. His own character was the wood of the cross on which he was being crucified.

That week I appeared for Norris in a case of some importance in New York. One day in court a letter was put in my hands from the editor of a great newspaper. It requested that I should call upon him that day or appoint an hour when he could see me at my hotel. I went to his office.

“Is it true that Norris is to be our new minister to—?” he asked.

“It is not true,” I said.

“Is it true that he served a term in an Illinois prison?”

“Why do you ask?”

“For the reason that a story to that effect is now in this office.”

It was a critical moment, and I did not know how to behave myself.

“I mean that a man has submitted the story—he wishes to sell it,” he added.

“Forgive me if I speak a piece to you,” I said. “It will be short and to the point.”

As nearly as I could remember them I repeated the noble lines of Whitman:

“And still goes one, saying,

'What will ye give me and I will deliver this man unto

you?'

And they make the covenant and pay the pieces of silver,

The old, old fee... paid for the Son of Mary.

“If there's any descendant of Judas Iscariot on this paper I shall see to it that his name and relationship are made known,” I added.

“We have not bought the article, and it is not likely that we shall,” said he. “If you wish to answer my question I shall make no use of your words.”

There are times when one has to act and act promptly on his own judgment, and when the fate of a friend is in the balance it is a hard thing to do. So I quickly chose my landing and jumped.

“I have only this to say,” I answered. “Mr. Norris served a term in prison when he was a boy, but the facts are of such a nature that it wouldn't be safe for you to publish any part of them.”

I saw a query in his eye as he looked at me, and I went on:

“They are loaded—that's the reason—loaded to the muzzle, and they'd come pretty near blowing up your establishment. You know my reputation possibly.”

“Oh, very well.”

“Then you know that I am not in the habit of going off at half-cock. I tell you the facts would put you squarely on the Judas roll, and it isn't a popular part to play. Briefly, the facts are: Norris suffered for a friend, and that puts him on a plane so high that it isn't safe to touch him.”

“On your word, Mr. Potter, I will do what I can to kill the story—now and hereafter,” said he. “The young man who wrote it is a decent fellow and will soon be in my employ. But of course Norris will decline to be put in high places.”

Even this enlightened editor saw that a man who had suffered prison blight was a kind of frost-bitten plum. I left him with a feeling of discouragement in the world and its progress.

Before a week had passed I was summoned to the home of Norris and found him ill in bed. He was in the midst of a nervous breakdown which had seemed to begin with a critical attack of indigestion. It wearied him even to sign and execute his will, and I saw him for only a few minutes, and not again for months.

He improved rapidly, and one day Gwendolyn Norris called at my office.

The family were sailing for Hamburg within a week to spend the rest of the winter at Carlsbad and Saint Moritz. She said:

“Father wishes me to begin my business career, and so I've been looking after the details, and you must tell me if there's anything that I have forgotten.”

I went over all the arrangements regarding cats and dogs and horses and tickets and hotel accommodations, and then asked, playfully:

“What provision have you made for the young men you are leaving?”

“There's only, one,” said she, with laughing eyes, “and he can take care of himself. He doesn't seem to need any of my help. But he's fine. I recommend him to you as a friend.”

“Yes, I understand. You want me to get his confidence and see that he goes to bed early and doesn't forget his friends.”

She blushed and laughed, and added:

“Or get into bad company!”

“You're a regular ward politician!” I said. “Don't worry. I'll keep my eye on him.”

“You don't even know his name,” she declared.

“Don't I? The name Richard is written all over your face.”

“How uncanny!” she exclaimed. “I'm going to leave you.” Then she added, with a playful look in her eyes, “You know it's a dangerous place for American girls who—who are unattached.”

“We don't want to frighten him.”

“It wouldn't be possible—he's awfully brave,” said she, with a merry laugh as she left me.

That was the last I saw of them before they sailed.

My friend had taken his doctor with him, and soon the latter wrote me from the mountain resort that Norris had improved, but that I must not appeal to him in any matter of business. All excitement would be bad for him, and if it came suddenly might lead to fatal results.

MIDWINTER had arrived when the checked current of our little history became active again. My wife had thought that our life in Pointview was a trifle sluggish, and we had been in town for two weeks. I had recommended the Waldorf-Castoria as being good for sluggish livers, but Betsey preferred the Manhattan. We were there when this telegram reached me from Chicago.

W. left for N. Y. this morning, broke. He will call on you. Important news by mail.

I expected to have some fun with him, and did.

The same mail brought the “important news” and a note from Wilton, which said:

I must see you within twenty-four hours. The need is pressing. Please wire appointment.

Many salient points in the career of Wilton lay before me. It's singular how much it may cost to learn the history of one little man. For half the sum that I was to pay for Wilton's record a commonplace intellect should have been able to acquire every important fact in the history of the world. Wilton, whose real name was Muggs, was wanted in Mexico for grand larceny, and very grand larceny at that, for he had absconded twelve years before with twenty thousand dollars belonging to the business in which he had been engaged. They had got their clue from a letter which he had carelessly left in his coat-pocket when he entered a Turkish bath, but of that part of the matter I need say no more. It was quite likely that he was wanted in other places, but this was want enough for my purpose.

It was Saturday, and Betsey had gone to Pointview; I was to follow her that evening for the week-end. No fog that day. The sun was shining in clear air.

When Wilton came my program had been arranged. It began as soon as he entered my room. The cat was purring when suddenly the dog jumped at her. It was the dog in my voice as I said:

“Good morning, you busted philanthropist! Why didn't you tell me at once that your name was Muggs. You might have saved me the expense of employing a dozen detectives to learn what you could have told me in five minutes. As a saint you're a failure. Why didn't you tell me that they wanted you down in Mexico?”

The cat was gone—jumped out of the open window, perhaps. I never saw her again. Muggs stood unmasked before me. He was a man now. His face changed color. His right hand went up to his brow, and then, as if wondering what it was there for, began deftly smoothing his hair, while his lower lip came up to the tips of his cropped mustache. His eyelids quivered slightly. The fingers in that telltale hand began to tremble like a flag of distress.

In a second, before he had time to recover, I swung again, and very vigorously.

“If you're going to save yourself you haven't a minute to lose. The detectives want that reward, and they're after you. They telephoned me not ten minutes ago. I'll do what I can for you, but I make one condition.”

“Excuse me,” he said, as he pulled himself together. “I didn't know that you had such a taste for history.”

“I love to study the history of philanthropists,” I said. “Yours thrilled me. I couldn't stop till I got to this minute. You're just beginning a new chapter, and I want you to give it a heading right now. Shall it be 'Prison Life' or 'In the Way of Reform'?”

Again the man spoke.

“As God's my witness, I want to live honest,” said he.

“Then I'll try to help you.”

I have always thought with admiration of his calmness as he looked down at me with a face that said, “I surrender,” and a tongue that said:

“May I use your bath-room for one minute?”

“Certainly,” was my answer.

He entered the bath-room and closed its door behind him.

I had begun to fear that he might have rashly decided to jump into eternity from my bath-room when he reappeared with no mustache and a gray beard on his chin. Then, as if by chance, he took my hat and gray summer top-coat from the peg, where they had been hanging, said “Good-by,” and walked hurriedly out of my door and down the corridor.

I had hesitated a little between my duty to Mexico and my duty to Norris, but I felt, and rightly, as I believe, that my client should come first, for I am rather human. But how about the reward? I thought. Well, that was none of my funeral. Shorn of his pull, he was now in the thorny path of the fugitive, and so I let him go.

I tried to work, but work was out of the question for me that morning. I went for a walk, and on my return sat down with my paper. Among the items in its cable news was the following:

Whitfield Norris and his family are at the Grand Hotel in Rome. His daughter, Miss Gwendolyn, whose beauty and wealth, as well as her amiable disposition, have attracted many suitors, is said to be engaged to the young Count Carola.

What I said to myself is not one of the things which should appear in a book, and I wish only to suggest enough of it here to put me on record.

Soon after one o'clock I was called to the 'phone by my secretary, who had followed Muggs when he left my room. At the time I gave my man his orders I did not know, of course, how my interview would turn out, and so, with a lawyer's prudence, I had decided to keep track of Muggs. When he settled down or left the city my young man was to report, and so:

“Hello,” came his voice on the telephone.

“Hello! What news?” I asked.

“Our friend has just sailed on the Caronia for England.”

“All right,” I said, and then: “Hold on! Find out if there is a fast ship sailing to-night, and if so engage good quarters for two.”

I sat down to get my breath.

“How deft and wonderful!” I whispered. “It takes a good lawyer to keep up with him.”

The man was on his way to Italy for another whack at Norris, and I had been thinking that he was broke. He would resume his philanthropic rôle in Italy and probably scare Norris to death. He had, of course, read that fool item in some paper. There was but one thing for me to do: I must get there first and meet him in the corridor of the Grand Hotel upon his arrival. Fortunately, my business was pretty well cleaned up in preparation for a long rest of which we had been talking.

I telephoned to Betsey that we should probably go abroad that night and that she must get her trunks packed and on the way to the city as soon as possible.

“But my summer clothes are not ready!” she exclaimed.

“Never mind clothes,” I answered. “Breech-cloths will do until we can get to Europe, and there's any amount of clothing for sale on the other side of the pond. Chuck some things into a couple of trunks and stamp 'em down and come on. We'll meet here at six.”

Then I thought of my talk with Gwendolyn, and telephoned to young Forbes and told him that I was going to Italy, and asked:

“Any message to send?”

“Sure,” said he. “I'll come down to see you.”

“We dine at seven,” I said.

“Put on a plate for me,” he requested.

I had scarcely hung up the receiver when the bell rang and my secretary notified me that he had engaged a good room on the Toltec, and would be at my hotel in twenty minutes.

I went down to the office and wrote a cablegram to Norris, in which I said that we were going over to see the country and would call on him within ten days.

To pay the charges I took out my pocket-book. There was no money in it. What had happened to me? There had been two one-hundred-dollar bills in the book when I had paid for last evening's dinner; now it held nothing but a slip of paper neatly folded. I opened it and read these words written with a pencil:

Thanks. This is the last call. M.

Then I remembered that yesterday's trousers had been hanging in the bath-room with my money in the right-hand pocket when Muggs was there. I had got the book and taken it with me when I went for a walk.

“He may be a busted philanthropist, but he's not a busted thief,” I mused.

BETSEY had been a bit disturbed by the swiftness of my plans. On her arrival in town she said to me:

“Look here, Socrates Potter, I'm no longer a colt, and you'll have to drive slower. What are you up to, anyway?”

“A surprise-party!” I answered. “Cheer up! It's our honeymoon trip. I've decided that after a man has married a woman it's his duty to get well acquainted with her. What's the use of having a breastful of love and affection and no time to show it. To begin with we shall have the best dinner this hotel affords.”

Our table, which had been well adorned with flowers, awaited us, and we sat down to dinner. Richard Forbes came while we were eating our oysters and joined us.

We talked of many things, and while we were eating our dessert I sailed into the subject nearest my heart by saying:

“I kind o' guessed that you'd want to send a message.”

“How did you know it?” he asked.

“Oh, by sundry looks and glances of your eye when I saw you last.”

“They didn't deceive you,” said he. “Tell them that they may see me in Rome before long. Miss Norris was kind enough to say in a letter that they would be glad to see me. I haven't answered yet. You might gently break the news of my plan and let me know how they stand it.”

“I'll give them your affectionate regard—that's as far as I am willing to go—and I'll tell them to prepare for your presence. If they show evidence of alarm I'll let you know. I kind o' mistrust that you may be needed there and—and wanted.”

“No joking now!” he warned me.

“Those titled chaps are likely to get after her, and I may want you to help me head 'em off. You'd be a silly feller to let them grab the prize.”

“The trouble is my fortune isn't made,” said he. “I'm getting along, but I can't afford to get married yet.”

“Don't worry about that,” I begged him. “Our young men all seem to be thinking about money and nothing else. Quit it. Keep out of this great American thought-trust. Any girl that isn't willing to take hold and help you make your fortune isn't worth having. Don't let the vine of your thoughts go twining around the money-pole. If you do they'll make you a prisoner.”

“But she is used to every luxury.”

“And probably will be glad to try something new. Her mama is not looking for riches, but noble blood, I suppose. Norris's girl looks good to me—nice way of going, as they used to say of the colts. We ought to be able to offer her as high an order of nobility as there is in Europe.”

“I'm very common clay,” the boy answered, with a laugh.

“And the molding is up to you,” I said, as we rose to go.

“Tell them that Gwendolyn's heart is American territory and that I shall stand for no violation of the Monroe Doctrine,” said he.

We bade him good-by and went aboard the steamer in as happy a mood as if we had spent six months instead of six hours getting ready. So our voyage began.

Going over we felt the strong tides of the spirit which carry so many of our countrymen to the Old World. The Toltec was crowded with tourists of the All-Europe-in-three-weeks variety. There were others, but these were a small minority. Every passenger seemed to be loaded, beyond the Plimsoll mark, with conversation, and in the ship's talk were all the spiritual symptoms of America.

We chose partners and went into the business of visiting. The sea shook her big, round sides, immensely tickled, I should say, by the gossip. Our ship was a moving rialto. We swapped stories and exchanged sentiments; we traded hopes and secrets; we cranked up and opened the gas-valve and raced into autobiography. Each got a memorable bargain. We were almost dishonest with our generosity.

“Ship ahoy!” we shouted to every man who came our way and noted his tonnage and cargo, his home port and destination.

How American! God bless us all!

Within forty-eight hours it seemed to me that everybody knew everybody else, except Lord and Lady Dorris, who were aboard, and the adoring group that surrounded them.

The big, wide-world thought-trust was well represented in the smoking-room. There were business men and boys just out of college, all expressing themselves in terms of profit and loss—the wealth of this or that man and how he got it, the effect of legislation upon business, and all that kind of thing. Thirty-five years ago such a company would have been talking of the last speeches of Conkling and Ingersoll or the last poems of Whittier and Tennyson.

There were many keynotes in the conversation. If one sat down with a book in the reading-room he would abandon it for the better display of human nature in the crowd around him. There were some twoscore women all talking at the same time, each drenching the other in the steady flow of her conversational hose. The plan of it all seemed to be very generous—everybody giving and nobody receiving anything. I used to think that among women talk was for display or relief, and whispering for the transfer of intelligence. Since I got married I know better: women have a sixth sense by which they can acquire knowledge without listening in a talk-fest. They miss nothing.

It was interesting to observe how the edges of the conversations impinged upon one another, like the circles made by a handful of pebbles flung from a bridge into water. Now and then some strong-voiced lady dropped a rock into the pool, and the spatter went to both shores. The spray advertised the thought-trusts of the women:

“I felt so sorry for poor Mabel! There wasn't a young man in the party.”

“It was a capital operation, but I pulled through.”

“Yes, I've wanted to go to Italy ever since I saw 'Romeo and Juliet.' Those Italians are wonderful lovers.”

“It was so ridiculous to be throwing her at his head, and she with a weak heart and only one lung!”

“I don't know how I spend it, but somehow it goes.”

“Oh, they have been abroad, but anybody can do that these days.”

“Poor man! I feel sorry for him—she's terribly extravagant.”

“We don't see much of our home these days.”

“My twentieth trip across the ocean.”

“Our children are in boarding-schools, and my husband is living at his club.”

I wanted to smoke and excused myself from Betsey and went out on the deck, now more than half deserted, and stood looking off at the night. Family history was pouring out of the state-room windows, and I could not help hearing it. Grandma, slightly deaf, was saying to her daughter:

“Lizzie must be more careful when those young men come to the door. This morning she wasn't half dressed when she opened it.”

“Oh yes, she was.”

“No, she wasn't; I took particular notice. And every morning she wets her hair in my perfumery. Then, sadly, It's almost gone.”

I knew enough about the sins of Lizzie, and moved on and took a new stand.

An elderly lumber merchant from Michigan was saying to his companion in a loud voice:

“Yes, I retired ten years ago. I am studying the history of the world—all about the life of the world, especially the life of the ancients.”

I moved on to escape a comparison of the careers of Alexander and Napoleon, and settled down in a dusky corner near which a lady was giving an account of the surgical operations which had been performed upon her. So the conversation, which had begun at daybreak, went on into the night. It was all very human—very American.

The Litchmans of Chicago had rooms opposite ours. Every night six or eight pairs of shoes, each decorated with a colored ribbon to distinguish it from the common run of shoes, were ranged in a row outside their door. The lady had forty-two hats—so I was told—and all of them were neatly aired in the course of the voyage. The upper end of her system was not a head, but a hat-holder.

Their family of four children was established in a room next to ours. As a whole, it was the most harmonious and efficient yelling-machine of which I have any knowledge. Its four cylinders worked like one. At dinner it filled its tanks with cheese and cakes and nuts and jellies and milk, and was thus put into running order for the night. It is wonderful how many yells there are in a relay of cheese and cake and nuts and jelly and milk. When we got in bed the machine cranked up, backed out of the garage, and went shrieking up the hill to midnight and down the slope to breakfast-time, stopping briefly now and then for repairs.

A deaf lady next morning declared that she had heard the fog-whistles blowing all night.

“Fog-whistles! We didn't need 'em,” said Betsey.

It was a symptom of America with which I had been unfamiliar.

We were astonished at the number of manless women aboard that ship. Many were much-traveled widows whose husbands had fallen in the hard battles of American life; some, I doubt not, like the battle of Norris, with hidden worries that feed, like rats, on the strength of a man.

Many of the women were handsome daughters and sleek, well-fed mamas whose husbands could not leave the struggle—often the desperate struggle—for fame and fortune.

There were elderly women—well upholstered grandmamas—generally traveling in pairs.

One of them, a slim, garrulous, and affectionate lady well past her prime, was immensely proud of her feet. She was Mrs. Fraley, from Terre Haute—“a daughter of dear old Missouri,” she explained. It seemed that her feet had retained their pristine beauty through all vicissitudes, and been complimented by sundry distinguished observers. One evening she said to Betsey:

“Come down to my state-room, dearest dear, and I will show you my feet.”

She always seemed to be seeking astonishment, and was often exclaiming “Indeed!” or “How wonderful!” and I hadn't told any lies either.

We met also Mrs. Mullet, of Sioux City, a gay and copious widow of middle age, who appeared in the ship's concert with dark eyes well underscored to give them proper emphasis. She was a well-favored, sentimental lady with thick, wavy, brown hair. Her thoughts were also a bit wavy, but Betsey formed a high opinion of her. Mrs. Mullet was a neat dresser and resembled a fashion-plate. Her talk was well dressed in English accents. She often looked thoughtfully at my chin when we talked together, as if she were estimating its value as a site for a stand of whiskers. It was her apparent knowledge of art which interested Betsey. She talked art beautiful, as Sam Henshaw used to say, and was going to Italy to study it.

There were schoolma'ams going over to improve their minds, and romping, sweetfaced girls setting out to be instructed in art or music, beyond moral boundaries, and knowing not that they would take less harm among the lions and hyenas of eastern Africa. When will our women learn that the centers of art and music in Europe are generally the exact centers of moral leprosy?

There were stately, dignified, and inhuman people of the seaboard aristocracy of the East—the Europeans of America, who see only the crudeness of their own land. They have been dehorned—muleyed into freaks by degenerate habits of mind and body. A certain passenger called them the “Eunuchs of democracy,” but I wouldn't be so intemperate with the truth. One of them was the Lady Dorris, daughter of a New York millionaire, who came out of her own apartments one evening to peer laughingly into the dining-saloon, and say:

“I love to look at them; they're so very, very curious!”

Yes, we have a few Europeans in America, but I suspect that Europe is more than half American.

Then there was Mr. Pike, the lumber king, from Prairie du Chien, who stroked his whiskers when he talked to me and looked me over from head to toe as if calculating the amount of good timber in me. He had retired, jumped from the lumber business into ancient history, and was now reporting the latest news from Tyre and Babylon.

In this environment of character we proceeded with nothing to do but observe it, and with no suspicion that we were being introduced to the persons of a drama in which we were to play our parts in Italy.

So now, then, the orchestra has ceased playing and the curtain is up again, and, with all these people on the stage, in the middle of the ocean word goes around the decks that there is a ship off the port side very near us. We look and observe that we are passing her. It is the Caronia, and we ride the seas with a better sense of comfort, knowing that Wilton is behind us.

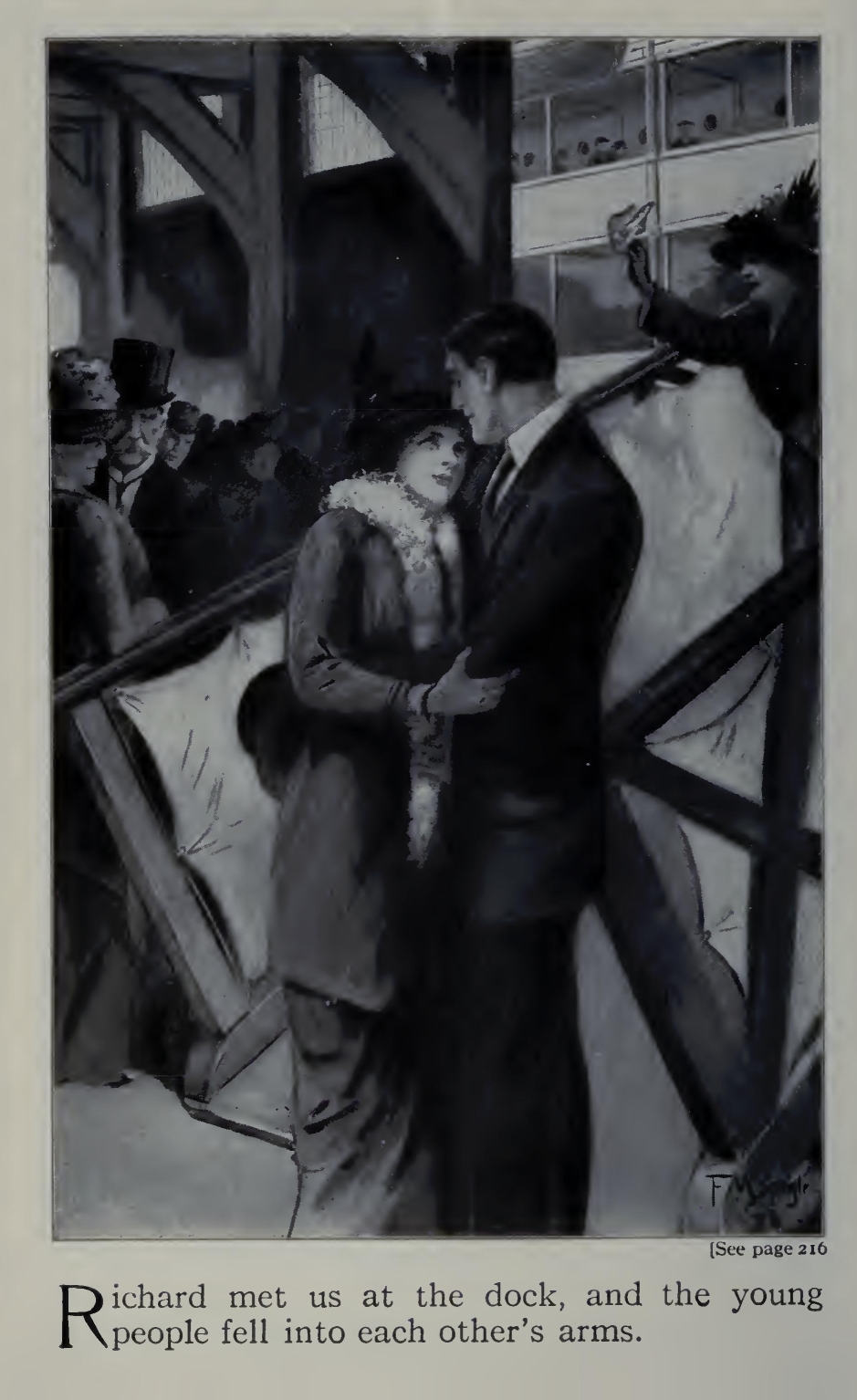

HERE we are in Rome on the tenth day of our journey at three in the afternoon! Jiminy Christmas! How I felt the need of language! I had given my leisure on the train to the careful study of a conversation-book, but the conversation I acquired was not extensive enough to satisfy every need of a man born in northern New England. It was too polite. There were a number of men who quarreled over us and our baggage in the station at Rome, and I had to do all my swearing with the aid of a dictionary. I found it too slow to be of any use. We were rescued soon by Mrs. Norris and her footman, who took us to the Grand Hotel. Gwendolyn met us in the hall of their apartment, and I delivered Forbes's message.

“You may kiss me!” she exclaimed, joyously.

“I do it for him,” I said.

“Then do it again,” said she.

That's the kind of a girl she was—up and a-coming!—and that's the kind of a man I am—obliging to the point of generosity at the proper moment.

The reputation of the Norrises gave us standing, and we were soon marching in step and sowing our francs in a rattling shower with the great caravan of American blood-hunters.

Norris himself was in better health than I had hoped to find him, and three days later he drove me to Tivoli in his motor-car.

As we were leaving the hotel the porter said to Norris:

“An American gentleman called to see you about an hour ago. He was very urgent, and I told him that I thought you had gone to Tivoli.”

“Not gone, but going,” said Norris. “There's a grain of truth in what you said, but I suppose you meant well.”

He handed the porter a coin and added:

“You must never be able to guess where I am.”

In the course of our long ride across the Campagna I made my report and he made his. I told the whole story of Muggs and how at length the man had given me a good, full excuse for my play-spell.

“I suppose that he will be after us again here,” said Norris.

“Don't worry,” I answered; “you'll find me a capable watch-dog. It will only be necessary for me to bark at him once or twice.”

“You're an angel of mercy,” said my friend. “I couldn't bear the sight of him now. It isn't the money involved; it's his devilish smoothness and the twitch of the bull-ring and the peril I am in of losing my temper and of doing something to—to be regretted.”

“Let me be secretary of your interior also,” I proposed, and added: “I can get mad enough for both of us, and I have a growing stock of cuss words.”

My assurance seemed to set Norris at rest, and I called for his report.

“Mine is a longer story,” he began. “First we went to Saint Moritz—beautiful place, six thousand feet up in the mountains—and it agreed with me. We found two kinds of Americans there—the idle rich who came to play with the titled poor and the homeless. Everywhere in Europe one finds homeless people from our country—a wandering, pathetic tribe of well-to-do gipsies. Among the idle rich are maidens with great prospects and planning mamas, and rich widows looking for live noblemen with the money of dead grocers, rum merchants, and contractors. They're all searching for 'blood,' as they call it.

“'I can't marry an American,' one of them said to me; 'I want a man of blood. These men are of ancient families that have made history, and they know how to make love, too.'

“Impoverished dukes, marquises, princes, barons, counts, from the purlieus of aristocratic Europe, throng about them. These noblemen are professional marryers, and all for sale. The bob-sled and the toboggan are implements of their craft, symbols of the rapid pace. Unfortunately, they are often the meeting-place of youthful innocence and utter depravity, of glowing health and incurable disease. Maidens and marquises, barons and widows, counts and young married women, traveling alone, sit dovetailed on bob-sleds and toboggans, and, locked in a complex embrace, this tangle of youth and beauty, this interwoven mass of good and evil, rushes down the slippery way. In the swift, curving flight, by sheer hugging, they overcome the tug of centrifugal force. It is a long hug and a strong hug. Thus, courtship is largely a matter of sliding.

“Then there are the dances. I do not need to describe them. At Saint Moritz they go to the limit. Fifteen years ago when Chuck Connors and his friends practised these dances in a Bowery dive respectable citizens turned away with disgust. Since then the idle rich who explore the underworld have begun to imitate its dances, which were intended to suggest the morals of the dog-kennel and the farmyard and which have achieved some success in that direction. Unfortunately, the idle rich are well advertised. If they were to wear rings in their noses the practice would soon become fashionable.

“Well, you see, it was no place for my girl. I sent her away with Mrs. Mushtop to Rome, but not until a young Italian count had got himself in love with my money.”

“Count Carola?” I asked.

“Count Carola!” said he. “How did you know?”

“Saw it in the paper.”

“The paper!” he exclaimed. “God save us from the papers as well as from war, pestilence, and sudden death.”

“Is the count really shot in the heart?” I ventured to ask.

“Oh, he likes her as any man likes a pretty, bright-eyed girl,” Norris went on, “but it was a part of my money that he wanted most. I had kept her out of that crowd, and the young man hadn't met her. He had only stood about and stared at us, and had finally asked for an introduction to me, which I refused, greatly to my wife's annoyance. The young man followed them to Rome, but I didn't know that he had done so until I got there. They went around seeing things, and everywhere they went the count was sure to go. Followed them like a dog, day in and day out. Isn't that making it a business? His eyes were on them in every room of every art-gallery. One day, when they stood with some friends near the music-stand in the Pincio Gardens, the count approached Mrs. Mushtop. You know Mrs. Mushtop; she is a good woman, but a European at heart and a worshiper of titles. I didn't suppose that she was such a romantic old saphead of a woman. This is what happened: the count took off his hat and greeted her with great politeness. She was a little flattered. My daughter turned away.

“'I suspect, myself, that you are the young lady's chaperon,' said he.

“'Yes, sir.'

“'I am in love with the beautiful, charming young lady. It is so joyful for me to look at her. I am most unhappy unless I am near her. I have the honor to hand you my card; I wish you to make the inquiry about my family and my character. Then I hope that you will permission me to speak to her.'

“Think of Mrs. Mushtop standing there and letting him go on to that extent.

“She said, 'It would do no good, for I believe that she is engaged.'

“'That will make not any difference,' he insisted, with true Italian simplicity; I will take my chances.'

“She foolishly kept his card, but had the good sense to turn away and leave him.

“Mrs. Norris went on to Rome for a few days while I stayed at Saint Moritz with my physician, mother, and secretary. You know women better than I do, probably. Most of them like that Romeo business; that swearing by the sun, moon, and stars—those cosmic, cross-universe measurements of love. I don't know as I blame them, for, after all, a woman's happiness is so dependent on the love of a husband.

“Well, those women got their heads together, and my wife thought that, on the whole, she liked the looks of the count. He was rather slim and dusky, but he had big, dark eyes and red cheeks and perfect teeth and a fine bearing. So they drove to Florence, where he lived, and investigated his pedigree and character. It was a very old family, which had played an important part in the campaigns of Mazzini and Cavour, but its estate had been confiscated after the first failure of the great Lombard chief, and its fortunes were now at a low ebb. One of the count's brothers is the head waiter in a hotel at Naples. He had sense enough to go to work, but the count is a confirmed gentleman who rests on hopes and visions. He reminds me of a house standing in the air with no visible means of support.

“However, the investigation was satisfactory to my wife, and she invited the young man to dinner at her hotel. The ladies were all captivated by his charm, and there's no denying that the young fellow has pretty manners. It's great to see him garnish a cup of tea or a plate of spaghetti with conversation. His talk is pastry and bonbons.

“When I came on I found them going about with him and having a fine time. Under his leadership my wife had visited sundry furniture and antique shops and invested some five thousand dollars, on which, I presume, the count received commissions sufficient to keep him in spending-money for a while. I didn't like the count, and told them so. He's too effeminate for me—hasn't the frank, upstanding, full-breasted, rugged, ready-for-anything look of our American boys. But I didn't interfere; I kept my hands off, for long ago I promised to let my wife have her way about the girl. That reminds me we have invited young Forbes to come over and spend a month with us.”

“Likely young fellow,” I said.

“None better,” said he; “if he had sense enough to ask Gwen to marry him I'd be glad of it. I have refused to encourage the affair with the count, but we find it hard to saw him off. We drove to Florence the other day, and he followed us there and back again. He's a comer, I can tell you; we can see him coming wherever we are. I swear a little about it now and then, and Gwen says, 'Well, father, you don't own the road.' And Mrs. Norris will say: 'Poor fellow! Isn't it pitiful? I'm so sorry for him!'

“His devotion to business is simply amazing—works early and late, and don't mind going hungry. In all my life I never saw anything like it.”

We had arrived at Tivoli, and as he ceased speaking we drew up at Hadrian's Villa and entered the ruins with a crowd of American tourists. An energetic lady dogged the steps of the swift-moving guide with a volley of questions which began with, “Was it before or after Christ?” By and by she said: “I wouldn't like to have been Mrs. Hadrian. Think of covering all these floors with carpets and keeping them clean!”

I left Norris sitting on a broken column and went on with the crowd for a few minutes. I kept close to the energetic lady, being interested in her talk. Suddenly she began to hop up and down on one leg and gasp for breath. I never saw a lady hopping on one leg before, and it alarmed me. The battalion of sightseers moved on; they seemed to be unaware of her distress—or was it simply a lack of time? I stopped to see what I could do for her.

“Oh, my lord! My heavens!” she shouted, as she looked at me, with both hands on her lifted thigh. “I've got a cramp in my leg! I've got a cramp in my leg!”

I supported the lady and spoke a comforting word or two. She closed her eyes and rested her head on my arm, and presently put down her leg and looked brighter.

“There, it's all right now,” said she, with a shake of her skirt. “Thanks! Do you come from Michigan?”

“No.”

“Where do you hail from?”

“Pointview, Connecticut.”

“I'm from Flint, Michigan, and I'm just tuckered out. They keep me going night and day. I'm making a collection of old knockers. Do you suppose there are any shops where they keep 'em here?”

“Don't know. I'm just a pilgrim and a stranger and am not posted in the knocker trade,” I answered.

The crowd had turned a corner; and with a swift good-by she ran after it, fearful, I suppose, of losing some detail in the domestic life of Hadrian.

So on one leg, as it were, she enters and swiftly crosses the stage. It's a way Providence has of preparing us for the future. To this moment's detention I was indebted for an adventure of importance, for as she left me I saw Muggs, the sleek, pestiferous Muggs, coming out of the old baths on his way to the gate. He must have been the man who had called to see Norris that morning. He turned pale with astonishment and nodded.

“Well, Muggs, here you are,” I said.

He handled himself in a remarkable fashion, for he was as cool as a cucumber when he answered:

“I used to resemble a lot of men, and some pretty decent fellows used to resemble me, but as soon as they saw me they quit it—got out from under, you know. Even my photographs have quit resembling me.”

“Well, you have changed a little, but my hat and overcoat look just about as they did,” I laughed. .

“If I didn't know it was impossible I would say that your name was Potter,” said he.

“And if I knew it was impossible I would swear that your name was Muggs,” I answered.

“Forget it,” said he; “in the name of God, forget it. I'm trying to live honest, and I'm going to let you and your friends alone if you'll let me alone. Now, that's a fair bargain.”

I hesitated, wondering at his sensitiveness.

“You owe us quite a balance, but I'm inclined to call it a bargain,” I said. “Only be kind to that hat and coat; they are old friends of mine. I don't care so much about the two hundred dollars.”

“Thanks,” he answered with a laugh, and went on: “I've given you proper credit on the books. You'll hear from me as soon as I am on my feet.”

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

He answered: “Ever since I was a kid I've wanted to see the Colosseum where men fought with lions.”

“I am sure that you would enjoy a look at Hadrian's Walk,” I said, pointing to the tourists who had halted there as I turned away.

So we parted, and with a sense of good luck I hurried to Norris.

“I've got a crick in my back,” I said. “Let's get out of here.”

We proceeded to our motor-car at the entrance.

“This ruin is the most infamous relic in the world,” said Norris, as we got into our car; “it stands for the grandeur of pagan hoggishness. Think of a man who wanted all the treasures and poets and musicians and beauties in the world for the exclusive enjoyment of himself and friends. Millions of men gave their lives for the creation of this sublime swine-yard. Hadrian's Villa, and others like it, broke the back of the empire. I tell you, the world has changed, and chiefly in its sense of responsibility for riches. Here in Italy you still find the old feudal, hog theory of riches, which is a thing of the past in America and which is passing in England. We have a liking for service. I tell you, Potter, my daughter ought to marry an American who is strong in the modem impulses, and go on with my work.”

NORRIS had overtaxed himself in this ride to Tivoli and spent the next day in his bed.

“My conversation often has this effect,” I said, as I sat by his bedside. “Forty miles of it is too much without a sedative. You need the assistance of the rest of the family. Let Gwendolyn and her mother take a turn at listening.”

“That's exactly what I propose. I want you to look after them,” he said. “They need me now if they ever did, and I'm a broken reed. Be a friend to them, if you can.”

I liked Norris, for he was bigger than his fortune, and you can't say that of every millionaire. Not many suspect how a lawyer's heart can warm to a noble client. I would have gone through fire and water for him.

“If they can stand it I can,” was my answer. “A good many people have tried my friendship and chucked it overboard. It's like swinging an ax, and not for women. One has to have regular rest and good natural vitality to stand my friendship.”

“They have just stood a medical examination,” he went on. “I want you and Mrs. Potter to see Rome with Gwendolyn and her mother and give them your view of things. Be their guide and teacher. I hope you may succeed in building up their Americanism, but if you conclude to turn them into Italians I shall be content.”

“There are many things I can't do, but you couldn't find a more willing professor of Americanism,” I declared.

So it happened that Betsey and I went with Gwendolyn and her mother for a drive.