Cleveland, Ohio

MCMVI

[5]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLV

| Preface | 11 | |||||

Document of

1736

|

||||||

| Bibliographical Data | 89 | |||||

Appendix: Education in the Philippines

|

||||||

Table of Contents

[9]

ILLUSTRATIONS

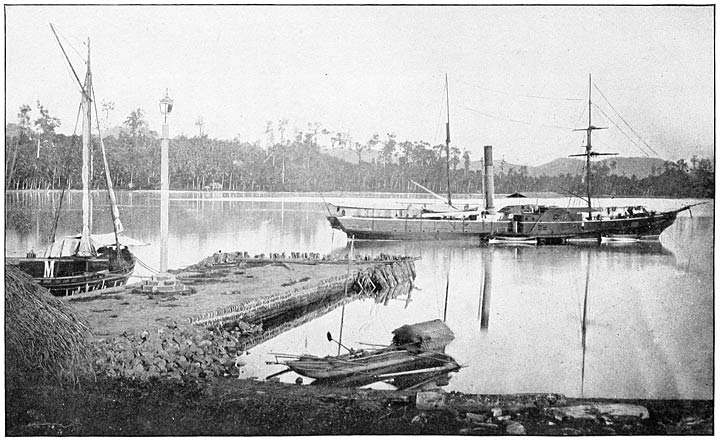

| View of port of Tacloban, in the island of Leyte; from photograph procured in Madrid | 33 | |||||

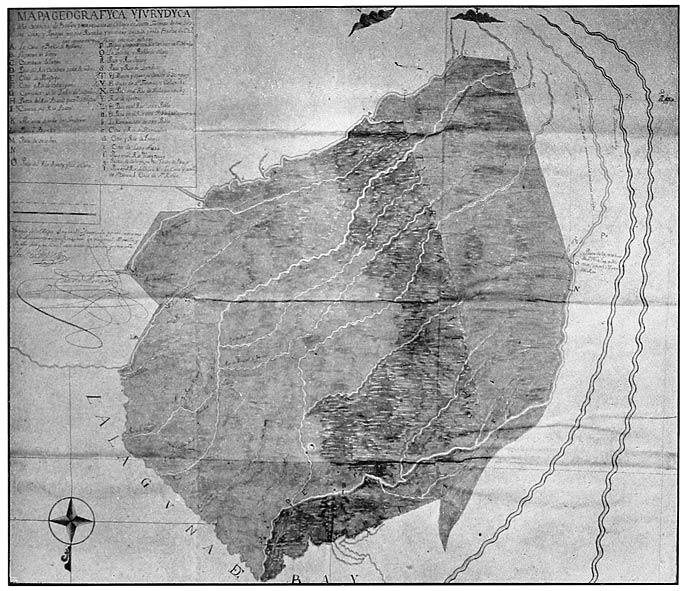

| Chart of the stockfarm of Biñán belonging to the college of Santo Tomás, of Manila, 1745; photographic facsimile from original manuscript by the land-surveyor, Francisco Alegre, in Archivo general de Indias, Sevilla | 143 | |||||

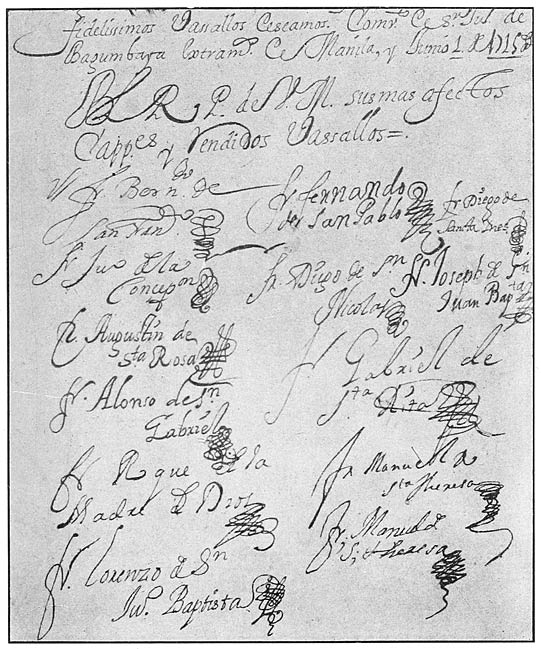

| Autograph signature of Juan de la Concepción, et al.; photographic facsimile from original MS. in Archivo general de Indias, Sevilla | 193 | |||||

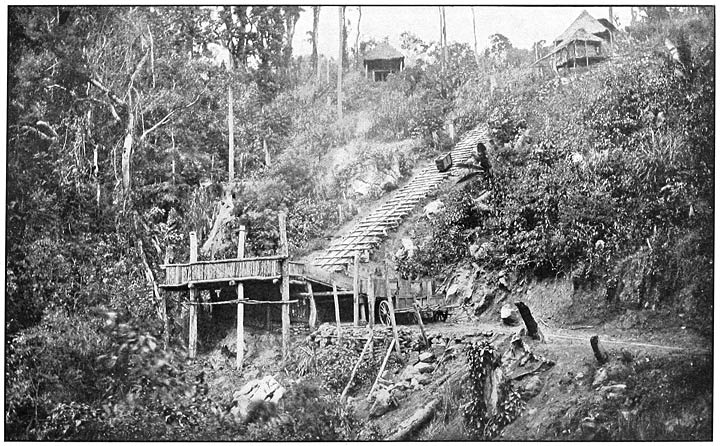

| A Cebú coal mine; from photograph procured in Madrid | 225 | |||||

[11]

PREFACE

The text proper of the present volume is entirely commercial. In the conclusion of the Extracto historial, is seen the continuance, between the merchants of Spain and the colonies, of the struggle for commercial supremacy. Demands and counter-demands emanate from the merchants of Cadiz and Manila respectively; and economic questions of great moment are treated bunglingly. The jealousy, envy, and distrust of the Cadiz merchants sees in the increasing prosperity of the Manila trade, especially that in Chinese silks, only their own ruin. The Manila merchants, on the other hand, who have the best of the controversy, quite properly object to an exchange of the silk trade for the exclusive right in the spice trade. The laws of supply and demand seem to be quite left out of consideration. The appendix is an attempt to show the influences and factors making for education in the Philippines during the Spanish régime, and the various educational institutions in the archipelago. In it one will see that, while apparently there has been great activity, results have been meager and superficial.

At the close of the preceding volume, we saw in the Extracto historial the “Manila plan” for regulating the commerce between the Philippines and [12]Nueva España, and its adoption (1726) by the Spanish government for a limited period. Three years later (July, 1729) Cadiz protests against this concession, complaining of the abuses practiced in the Manila-Acapulco trade, and of the injury done to Spanish commerce by the importation of Chinese silks into Nueva España. In consequence of this, an investigation is ordered in Acapulco and Mexico, from which it appears that the amount of Manila’s commerce is rapidly increasing; the viceroy therefore advises the home government to restrict it, as being injurious to the commercial interests not only of the mother-country but of Nueva España, especially in the matter of Chinese silks. Meanwhile, he notifies Manila that the galleon of 1734 must be laden in accordance with the old scheme, the five years’ term having expired. At this, Manila enters a vigorous protest, and demands that the permission of 1726 be continued to the islands. After much discussion pro and con, a royal decree is issued (April 8, 1734) to regulate that commerce; the viceroy’s order is revoked, the amount of trade permitted to Manila is increased, but otherwise the decrees of 1702, 1712, and 1724 shall be in force (with some minor changes). In the following year, Cadiz again complains of the Manila-Acapulco trade, and proposes that Chinese silks be excluded from it—offering, by way of compensation, to surrender to Manila the exclusive right to the spice trade in the American colonies. The royal fiscal disapproves this, for various practical reasons, and recommends that the whole matter be discussed at a conference in Mexico, attended by delegates from Manila and Cadiz. The Manila deputies place before the Council another [13]long memorial (dated March 30, 1735), refuting the arguments and denying the charges made by Cadiz; the latter’s offer of the spice trade in Nueva España is regarded as useless and in every way unsatisfactory. Cadiz answers these objections (June 1, 1735), and urges the court to cut off the trade of Manila in Chinese silks, adducing many arguments therefor. Again the fiscal refuses to endorse the policy of Cadiz; and the Council call (November 16, 1735) for a summary report of the entire controversy, with the documents concerned therein, preparatory to their final review and decision.

The educational appendix, which occupies most of this volume, opens with a petition from the Manila ecclesiastical cabildo, to the effect that no religious order be allowed to establish a university in Manila (as has been petitioned), as such a procedure would be prejudicial to the secular clergy, by reason of the fact that the religious would hold all the chairs in such institution. The petition also recommends that all ecclesiastical posts be given indiscriminately to members of all the orders until there are sufficient secular priests to hold them.

The second document, consisting of two parts, relates to the college of San José. The first part is the account by Colin in his Labor evangelica, and is a brief history of the institution from its foundation until 1663; the second is a compilation from various sources. The efforts of the Jesuits for a college are first realized through the Jesuit visitor, Diego Garcia, who is well assisted by Pedro Chirino. Luis Gomez, the first rector, secures the necessary civil and ecclesiastical permissions, in 1601. The college opens with thirteen fellowships, which are given to [14]the sons of influential citizens, a number soon increased to twenty. Rules and regulations are made for teachers and scholarships. As early as 1596, Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa has left directions in his will, in case either of his minor daughters dies, for the endowment of a college under the care of the Jesuits. One of his daughters dying, the will becomes operative, and in consequence, the second establishment of the college takes place February 28, 1610, the act of foundation being given. The Jesuits have some trouble in getting the funds decreed by the will, but are finally successful. In 1647, the college obtains the favorable decision as to right of seniority in its contest with the Dominican institution of Santo Tomás. The second part of this document traces (mainly by reference to and citation from original documents), the history of the college of San José from its foundation to the present time, necessarily mentioning much touched upon by Colin. The royal decree of May 3, 1722, granting the title of “Royal” to the college is given entire. The various fellowships in the college are enumerated. The expulsion of the Jesuits in 1768 has a direct bearing on the college, which is at first confiscated by the government, but later restored to the archbishop who lays claim to it. The latter converts it into an ecclesiastical seminary, thus depriving its students of their rights; but the king disapproves of such action, and the college is restored to its former status and given into the charge of the cathedral officials. Its later management does not prove efficient, and the college finally falls under the supervision of the Dominican university. In the decade between 1860 and 1870, the plans of making a professional school of it are [15]discussed, and in 1875 faculties of medicine and pharmacy are established there. The Moret decrees of 1870 secularize the institution, but the attempt is successfully blocked by the religious orders. Since American occupation of the islands, the question of the status of the college has been discussed before the government, and the case is still unsettled.

The next document, consisting of three parts, treats of the Dominican college and university of Santo Tomás. The first part is the account as given by Santa Cruz, and treats especially of the erection of the college into a university. After unsuccessful efforts made by the Dominicans with Pope Urban VII in 1643 and 1644 to obtain the pontifical permission for this step, it is at length obtained from Pope Innocent X in 1645. In 1648, the Audiencia and the archbishop give their consent to the erection. Rules and regulations are made by the rector of the new university, Fray Martin Real de la Cruz, in imitation of those of the university of Mexico. The second part of this document is the royal decree of March 7, 1785, granting the title of “Royal” to the institution, on condition that it never petition aid from the royal treasury. The third part is an account of the university by Fray Evarista Fernandez Arias, O.P., which was read at the opening of the university in 1885. He traces briefly the history of the foundation and growth of the college and university. Pope Paul V grants authority to it to confer degrees to its graduates for ten years, a permission that is later prolonged. The brief of Innocent X erecting the college into a university in 1645 is later extended by Clement XII in 1734. The first regulations of the university are revised in 1785, [16]when the faculties of law and theology are extended (the departments of jurisprudence and canon law having been established early in the eighteenth century). These laws are the ones still in force in 1885 except in so far as they have been modified by later laws. It becomes necessary to abolish the school of medicine and the chairs of mathematics and drawing. In 1836, the chair of Spanish law is created. Between the years 1837 and 1867 the question of reorganization is discussed. In 1870, the university is secularized as the university of the Philippines by the Moret decree, but the decree is soon repealed. The college of San José is placed definitely under the control of the university, and becomes its medical and pharmaceutical department. In 1876, a notarial course is opened, and in 1880, courses in medicine, pharmacy, and midwifery are opened. Since this date the college has had complete courses in superior and secondary education.

The next document is one of unusual interest because it is the earliest attempt to form an exclusively royal and governmental educational institution in the Philippines—the royal college of San Felipe de Austria, founded by Governor Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera. The first part of this document, which consists of two parts, is an extract from Diaz’s Historia. Corcuera assigns the sum of 4,000 pesos annually from the royal treasury for the support of the twenty fellowships created, those preferences being designed for the best Spanish youth of Manila. The new institution is given into the charge of the Jesuits. The college is, however, suppressed at the close of Corcuera’s government, as it is disapproved by the king, the decree of suppression being inexorably [17]executed by Fajardo. The Jesuits are compelled to repay the 12,000 pesos that have been paid them for the support of the college for the three years of its existence. A later royal college, called also San Felipe, is created by order of Felipe V. The second part of the present document is condensed from notes in Pastells’s edition of Labor evangélica, and is a brief sketch of the founding, duration, and suppression of the institution founded by Corcuera. The latter founds it at the instance of the secular cabildo of Manila, and the charge of it is given to the Jesuits, although the Dominicans offer to dispense with the 4,000 pesos granted it from the royal treasury. Twenty fellowships and six places for Pampango servants are created by the act of foundation, December 23, 1640. The 4,000 pesos are met from Sangley licenses. An abstract of the rules of the new institution, thirty-three in all, is given. They cover the scholastic, moral, and religious life of the pupils. Corcuera’s letter of August 8, 1641, reporting the foundation and asking certain favors, is answered by the royal decree of suppression, which is entrusted to the new governor, Fajardo. The 12,000 pesos, which the Jesuits are ordered to pay, is repaid them (if they have paid it) by a royal decree of March 17, 1647, and the incident of the short-lived college is closed.

The following document—the summary of a letter from the famous Archbishop Pardo—is the answer to a royal decree ordering the education of natives for the priesthood. He states the inefficiency of the natives for that pursuit, and the necessity of sending religious from Spain. It is followed by a royal decree of June 20, 1686, directing the strict observance [18]of the laws for native schools and the study of Spanish in the Spanish colonies.

The college-seminary of San Clemente, or San Felipe, as it was called later, forms the subject of the next document, which consists of two parts. The first is a royal decree of March 3, 1710, in which the king disapproves of the methods employed in the founding of the seminary which he had ordered Governor Zabalburu to found with 8 seminarists. Instead of following orders, the governor allows the archbishop and the “patriarch” Tournon to establish the institution, which is thrown open to foreigners, and has over eighty instead of eight seminarists. This disobedience occasions the removal and transfer of Archbishop Camacho, and the foreigners are ordered to be expelled, and only sixteen Spanish subjects are to be allowed in the seminary as boarders, in addition to the eight seminarists. The second part of the document is from the Recollect historian, Juan de la Concepción. Governor Cruzat y Gongora, in answer to a royal decree recommending the establishment of a seminary, declares such to be unnecessary. Its foundation is, however, ordered, and is finally consummated, but the conditions of the actual founding, which was entrusted to the governor, are altered by the neglect of the latter and the intrusion of Tournon and the archbishop who work in concert. The king, hearing of the turn affairs have taken, not through direct communication, but through the papal nuncio, orders the refounding of the institution along the lines indicated by him, and the name is changed to San Felipe. The formal founding of the latter is left by the governor to Archbishop Francisco de la Cuesta, who draws [19]up new rules, but at the same time deprives the king of the private patronage, usurping it for himself, although it is a lay creation.

In the following document, the college of San Juan de Letran is discussed. It is founded in 1640 by Juan Geronimo Guerrero, for the purpose of aiding and teaching poor orphan boys. Many alms are given for the work by charitable persons, and Corcuera grants some in the king’s name, and an encomienda in the Parián is given it. At the same time, a Dominican lay-brother undertakes the care of poor orphan boys in the porter’s lodge of the Manila convent. As Guerrero ages, finding it impossible to look after his orphan boys, he entrusts them to the care of the Dominican lay-brother, who has by this time formed a congregation under the name of San Pedro y San Pablo. The consolidation is known for some time by the latter name, although the transfer is made under the name of the College of San Juan de Letran, which is later definitely adopted. Rules for the college are made by Sebastian de Oquendo, prior of the Manila convent, which are revised later by the provincial chapter. After being housed for some years in the lower part of the convent, the college is moved into a house opposite the same; but that house being destroyed by the earthquake of 1645, a wooden building is erected outside the walls near the Parián. In 1669, finding their quarters uncomfortable, as the students are compelled to go to the university for their studies, the college is again moved inside the walled city. Priestly, military, and other professions are recruited from this institution.

A royal decree of June 11, 1792 requires the permission of the royal representative, and of those in [20]authority at the institutions of learning, for all students, men and women, attending any such institution subject to the royal patronage and protection, before the contraction of marriage. Another decree of December 22, 1792, directs the governor to observe the previous decrees concerning the teaching of Spanish in schools for the natives. Nothing but Spanish is to be spoken in the convents.

Conciliar seminaries are treated in a document of two parts. The first part is a decree of March 26, 1803, in regard to the three per cent discount which is ordered to be made from the salary of all parish priests for the maintenance of conciliar seminaries. A decree of July 30, 1802 is enclosed therein, which orders such collection, notwithstanding the objections raised by the parish priests; and the payment must be made in money. Special provisions are made in regard to the seminary of Nueva Segovia. The second part consists of extracts from various sources. The first two of the extracts relate to the five Roman Catholic conciliar seminaries, and give their status since 1862. The third extract is the provision made by the Aglipay or independent church of the Philippines for seminaries for the education of priests, and the plan for the studies to be carried on therein.

The Nautical school of Manila is also treated in two parts, the first being a decree of May 9, 1839, approving the new regulations for the pilots’ school of July 20, 1837; and the second extracts from various sources giving a brief history of this institution which is established first in 1820 by the Consulate of Commerce, and later taken under control of the government. This school is now maintained by the Americans. [21]

The boys’ soprano school is an interesting institution founded by Archbishop Rodriguez in 1742 for the purpose of furnishing boy singers to the cathedral. The education, which is chiefly musical, embraces training in both vocal and instrumental music, although on account of their tender age the boys are, as a general rule, debarred from using wind instruments. High merit is obtained by these boys.

Public instruction in the Philippines is discussed by Mas in the following document. He declares that the education of the Philippines is in a better state proportionally than it is in Spain. There are schools in each village, attendance at which is compulsory, except at seeding and harvest times. Expenses are met from the communal funds. Women also share in the education. The books commonly used are those of devotion. Besides communal and private schools there are also public institutions in Manila. Brief histories and descriptions are given of the following institutions: university of Santo Tomás; college of San José; college of San Juan de Letran; the charity school founded in 1817 by distinguished citizens; the nautical academy; the commercial school founded in 1840; seminary of Santa Potenciana, which was founded by a royal decree of 1589; Santa Isabel, founded by the confraternity of Misericordia, in 1632; beaterio of Santa Catalina de Sena, founded in 1696; beaterio de San Sebastian de Calumpang, founded in 1719; beaterio de San Ignacio, founded in 1699; beaterio de Santa Rosa, founded in 1750; and the beaterio de Pásig, or Santa Rita, founded in 1740.

This is followed by Mallat’s account, which uses Mas largely as authority. Mallat praises the advanced state of education in the Philippines, and [22]dwells at considerable length on their culture in poesy and music, and their allied branches of art; and gives in general a recast of the conditions of the educational influences in the archipelago.

A superior order of December 2, 1847, legalizes in Spain degrees taken in the educational institutions of the colonies, and vice versa; and professions authorized in one country may be practiced in the other, on sufficient proof. A short document on the academy of painting, sculpture, and engraving, compiled from various sources, follows. This academy was founded in 1849 by the Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País, and reorganized in 1892. Another document, also compiled from various sources, treats of the Ateneo municipal, which is an outgrowth of the old Escuela pía, which was given into the control of the Jesuits upon their return to the Philippines in 1859. The latter school receives its present name in 1865. Its expenses are defrayed by the community of Manila.

A document taken from Apuntes interesantes asserts that the university has many enemies, not because the Dominicans are in control of it, but because they believe the study of law unadvisable therein. Such a view is anti-liberal. The writer believes that the Filipinos would give better results in medicine and surgery, and the advisability of a medical school could be sustained, but that medicine and even pharmacy which are both sorely needed in the islands could be established in the university. Foreign professors should be allowed to enter. Superstitions, abuses, and ignorance abound in regard to medicine and pharmacy among the natives. Drugs are allowed to be sold by peddlers, and adulterations [23]are frequent. Parish priests are called in to act as physicians but often only after the native doctor, who works mainly with charms, has been unable to combat the ailment of his patient. But for all his inefficiency, the natives prefer their mediquillo to the priest. Many reforms are needed. The naval school, the author declares, is poorly organized and directed. The graduates aspire only to fine berths and are not content to accept what is really within their powers. The school could profitably be reorganized into a school for training pilots exclusively for the coasting trade. Primary instruction, so far as the government is concerned, is in an incipient state. Spanish is taught only in Manila and some of the suburbs; but there are schools for boys in the native dialects, and some as well for girls. The government salaries are not sufficient and priests and officials find it necessary to determine means for buildings, etc., and salaries are even paid from the church funds. There is no suitable director for primary education, but in reading, writing, and religion, the children are more advanced than those of Spain. The government has tried to improve the instruction in the Spanish language, and has succeeded somewhat. The writer advises the government to introduce all the improvements possible, and to extend the normal school, which has but slight results at present. Teachers are needed, also.

Montero y Vidal in Archipiélago filipino, gives a recast of educational conditions in 1886. He shows that public instruction is somewhat widespread, but that it is lacking in efficiency. He gives some statistics, but they are inadequate, owing to the inefficiency of the public officials. The native lawyers [24]are poor and they sow discord against Spain. He strongly recommends industrial education.

The following document on girls’ schools in Manila and the provinces contains much of interest. This account, taken from the Dominican report of 1887, describes and gives a list of the schools of Santa Isabel, Santa Rosa, Santa Catalina, and La Concordia, or school of the Immaculate Conception. In these schools primary and secondary education are given. An account is also given of the school of San José of Jaro which was opened first in Iloílo in 1872, but closed in 1877 for lack of funds, and was soon thereafter reëstablished in Jaro through the intermediation of the bishop. The convent of San Ignacio, founded in 1669, is directed by the Jesuits, but after their expulsion is taken charge of by the provisor of the archbishop. It has had a school since 1883. Various other institutions where instruction is given to girls are mentioned.

The school of agriculture, both under Spanish and American dominion, is discussed in the next document. First established in 1889 by the Spanish government for theoretical and practical instruction, the school has not had great success. Various agricultural stations are established in various provinces by the government to supplement the work of the school. Since American occupation the work has been taken up, and appropriations made for the building of a school in the rich agricultural island of Negros.

The last document of this volume, a state discussion (1890) as to the reorganization of education in the university of Santo Tomás (signed among others by the famous Maura) suggests the arguments advanced [25]by both the civil and ecclesiastical governments in the Philippines. The questions under discussion are: 1. Whether the ministry has a right to reorganize education in the university without considering the religious order of the Dominicans. 2. Whether the university may offer legal opposition, and by what means. The conclusions reached are: 1. The ministry cannot apply the funds and properties of the university of private origin to any institution that it organizes; and hence cannot reorganize education in the university. 2. Should the ministry do so, then the university may take legal means to oppose such determination, the best method being through the ordinary court of common law. This is a highly interesting document, in view of the vital legal educational questions touched upon, some of which may have application in the present San José college case. The educational appendix will be concluded in VOL. XLVI.

The Editors

October, 1906. [27]