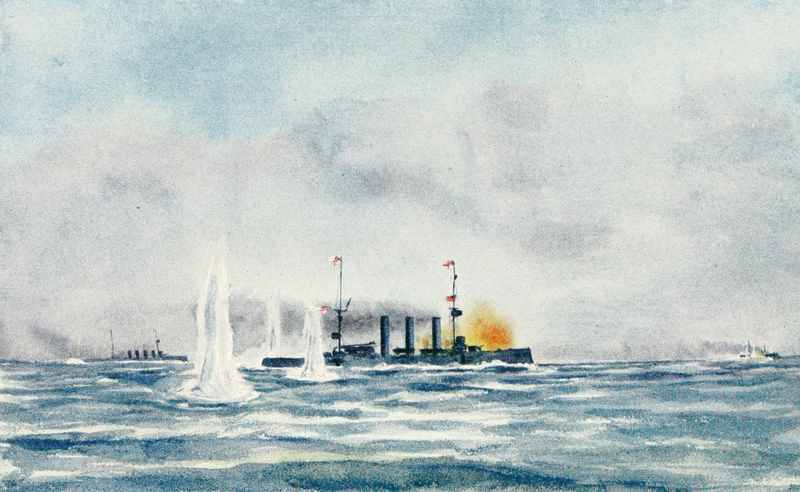

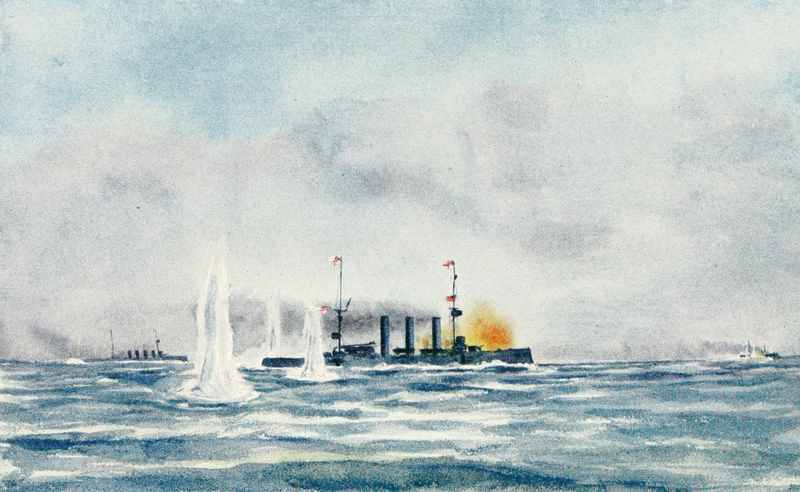

THE BATTLE OF THE FALKLAND ISLANDS, 8th DECEMBER, 1914

The "Cornwall" engaging the "Leipzig"

| From a | |

| Colour Drawing by | |

| Lieut.-Comm. H. T. Bennett, R.N. |

Title: The Battle of the Falkland Islands, Before and After

Author: Henry Edmund Harvey Spencer-Cooper

Release date: October 21, 2015 [eBook #50265]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by John Campbell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

The format of time in the original text has been retained. For example, 10.30 A.M. or 7.3 P.M.

Gun caliber in the original text is of the form 9.1" or sometimes 9·1". For consistency all calibers have been changed to the 9.1" (or 9.1-inch) form.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

| From a | |

| Colour Drawing by | |

| Lieut.-Comm. H. T. Bennett, R.N. |

The Battle of the

Falkland Islands

Before and After

By

Commander H. Spencer-Cooper

With Coloured Frontispiece

and Ten Maps and Charts

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1919

To the Memory

of the

Officers and Men

of the Royal Navy and the Royal Naval Reserve

who so gallantly gave their lives in the actions

described in this book

| Part I.—Exploits off South America | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| 1. | German Men-of-War in Foreign Seas | 3 |

| 2. | The Policy of Admiral Count von Spee | 13 |

| 3. | British Men-of-War off South America | 19 |

| 4. | Life at Sea in 1914 | 28 |

| 5. | The Sinking of the "Cap Trafalgar" | 35 |

| 6. | The Action off Coronel | 45 |

| 7. | Concentration | 60 |

| 8. | Possibilities and Probabilities | 67 |

| Part II.—The Battle of the Falklands | ||

| 9. | Away South | 79 |

| 10. | Enemy in Sight | 87 |

| 11. | The Battle-Cruiser Action | 96 |

| 12. | The End of the "Leipzig" | 110 |

| 13. | The Sinking of the "Nürnberg" | 124 |

| 14. | Aftermath | 134 |

| 15. | The Psychology of the Sailor in Action | 141 |

| 16. | Von Spee's Aims and Hopes | 151 |

| 17. | The Parting of the Ways | 158 |

| 18. | The Last of the "Dresden" | 163 |

| [viii] | ||

| Part III.—Official Dispatches | ||

| 1. | The Action of H.M.S. "Carmania" | 169 |

| 2. | The Action off Coronel by H.M.S. "Glasgow" | 172 |

| 3. | Report by Vice-Admiral Count von Spee | 174 |

| 4. | The Battle of the Falkland Islands | 178 |

| 5. | The Surrender of the "Dresden" | 194 |

| Appendix | ||

| A List of the Officers serving in the Actions Recorded | 197 | |

| Index | 221 | |

| PAGE | |

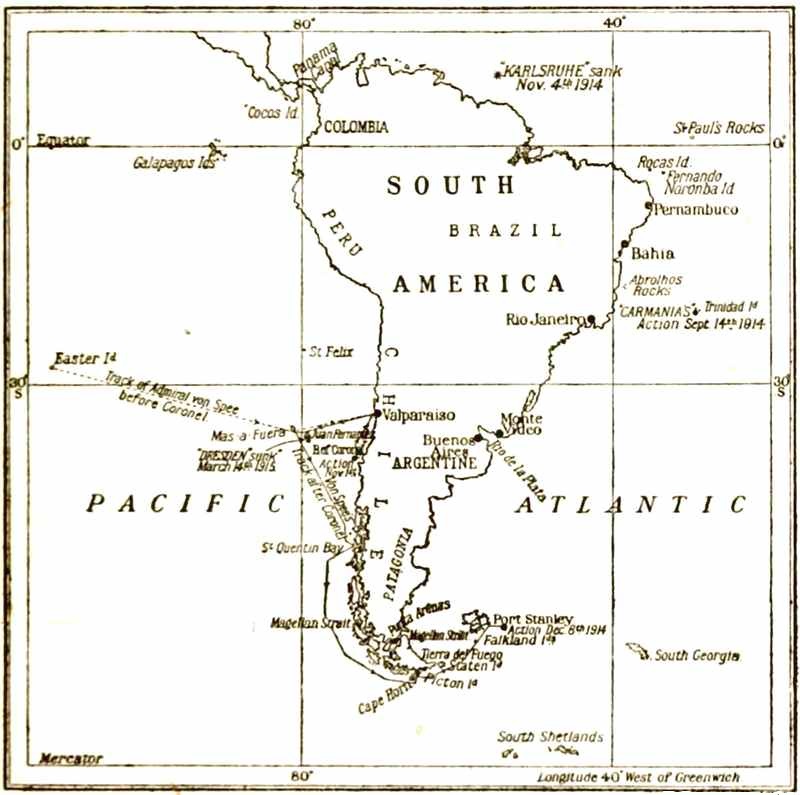

| The War Zone in Western Seas | 5 |

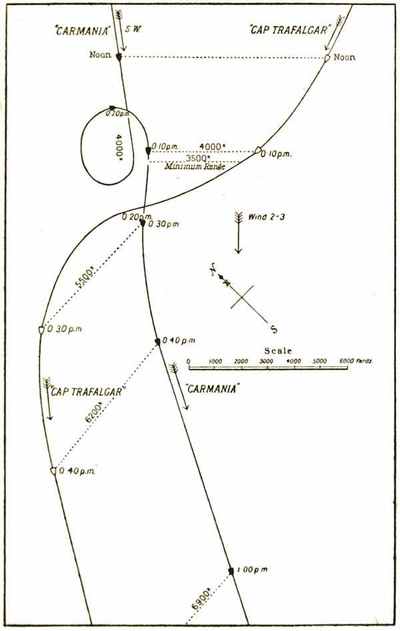

| Chart of Course in "Carmania"—"Cap Trafalgar" Duel | 39 |

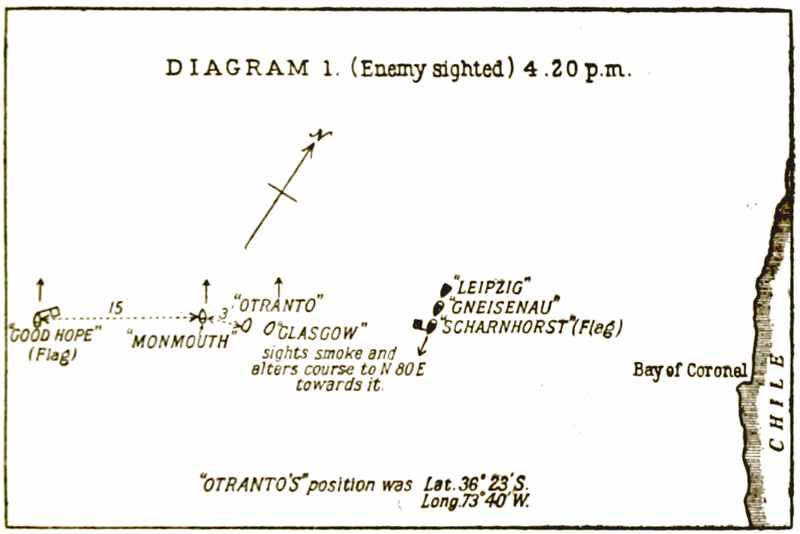

| The Coronel Action: Position when Enemy Sighted | 49 |

| The Coronel Action: Position at Sunset | 51 |

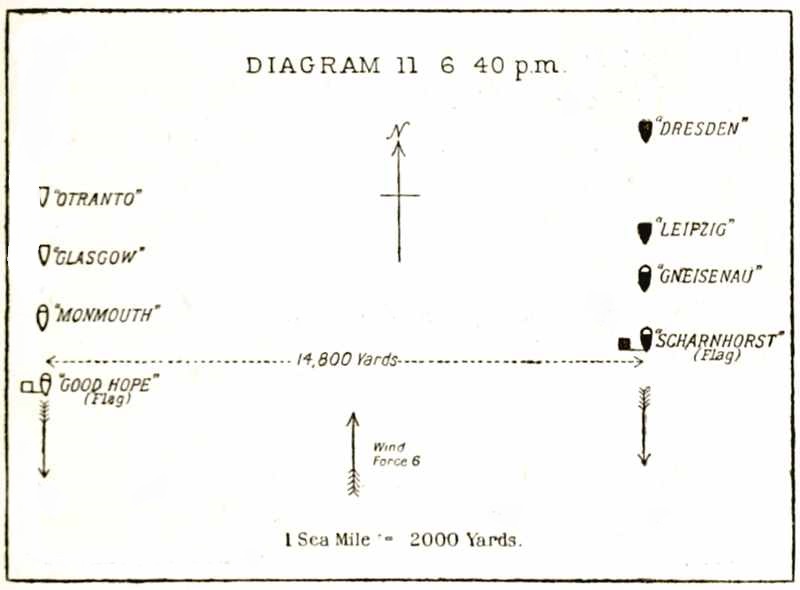

| Chart of "Cornwall" Action (Inset) | 79 |

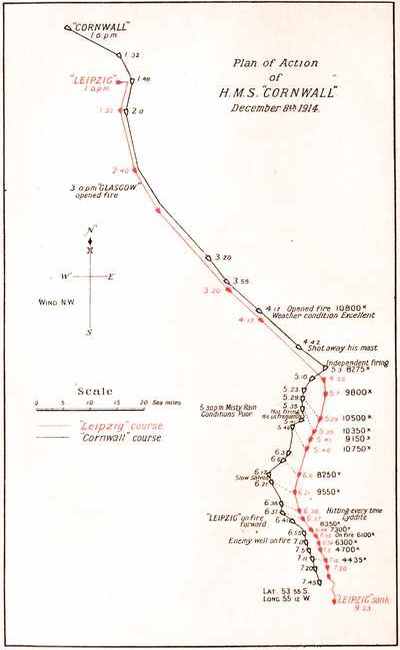

| Chart of Battle-Cruiser Action (Inset) | 79 |

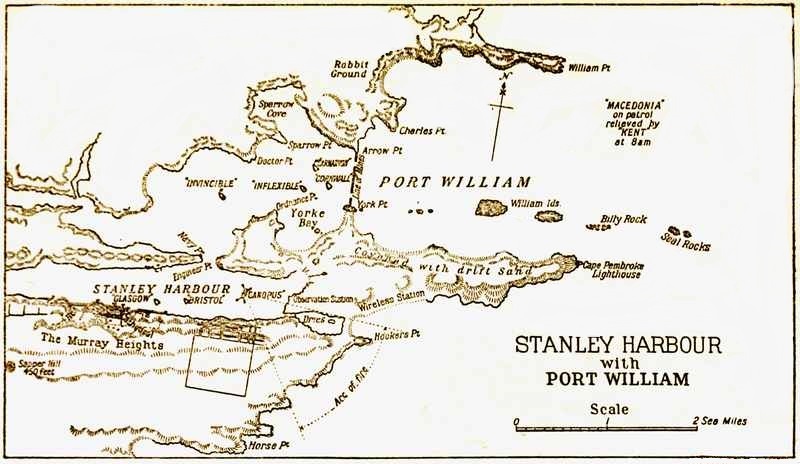

| Stanley Harbour: Positions of Warships | 83 |

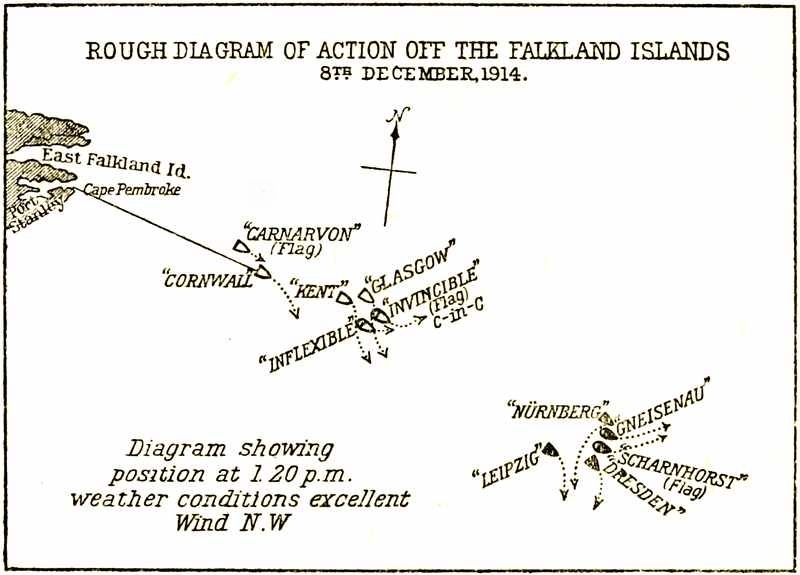

| Battle of the Falklands: Positions at 1.20 p.m. | 94 |

| Battle of the Falklands: Positions at 2.45 p.m. | 112 |

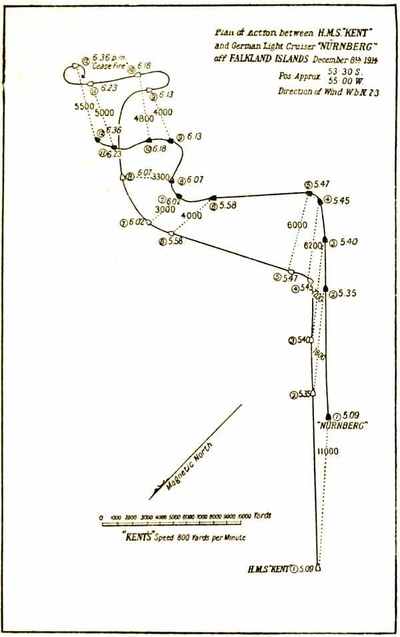

| Duel between "Kent" and "Nürnberg" | 127 |

This plain, unvarnished account, so far as is known, is the first attempt that has been made to link with the description of the Falkland Islands battle, fought on December 8th, 1914, the events leading up to that engagement.

In order to preserve accuracy as far as possible, each phase presented has been read and approved by officers who participated. The personal views expressed on debatable subjects, such as strategy, are sure to give rise to criticism, but it must be remembered that at the time of writing the exact positions of the ships engaged in overseas operations were not fully known, even in the Service.

The subject falls naturally into three divisions:

Part I. deals briefly with the movements of British and German warships, and includes the duel fought by the Carmania, and the action that took place off Coronel.

Part II. describes the Falkland Islands battle itself, and the subsequent fate of the German cruiser Dresden.

Part III. contains the official dispatches bearing on these exploits.

The words of Alfred Noyes have been referred to frequently, because they are in so many respects pro[xii]phetic, and also because of their influence in showing that the spirit of Drake still inspires the British Navy of to-day.

The author takes this opportunity of expressing his warmest thanks to those who have helped him in collecting information and in the compilation of this book.

"Meekly content and tamely stay-at-home

The sea-birds seemed that piped across the waves;

And Drake, bemused, leaned smiling to his friend

Doughty and said, 'Is it not strange to know

When we return, yon speckled herring-gulls

Will still be wheeling, dipping, flashing there?

We shall not find a fairer land afar

Than those thyme-scented hills we leave behind!

Soon the young lambs will bleat across the combes,

And breezes will bring puffs of hawthorn scent

Down Devon lanes; over the purple moors

Lav'rocks will carol; and on the village greens

Around the maypole, while the moon hangs low,

The boys and girls of England merrily swing

In country footing through the flowery dance.'"

—Alfred Noyes (Drake).

THE BATTLE OF THE

FALKLAND ISLANDS

"I, my Lords, have in different countries seen much of the miseries of war. I am, therefore, in my inmost soul, a man of peace. Yet I would not, for the sake of any peace, however fortunate, consent to sacrifice one jot of England's honour."—(Speech by Lord Nelson in the House of Lords, November 16th, 1802.)

We are now approaching the end of the third year of this great war,[1] and most Englishmen, having had some of the experience that war inevitably brings with it, will agree that the words which Nelson spoke are as true to-day as when they were uttered just over a century ago. Furthermore, as time and the war go on, the spirit of the whole British nation—be it man or woman—is put to an ever-increasing test of endurance, which is sustained and upheld by those two simple words, "England's Honour." An old platitude, "Might is Right," is constantly being quoted; but the nation that reverses the order is bound to outlast the other and win through to the desired goal. The justness of the cause, then, is the secret of our strength, which [4]will not only endure but bring success to our arms in the end.

When Great Britain plunged into this Armageddon on August 4th, 1914, the only German squadron not in European waters was stationed in the Western Pacific, with its main base at Tsingtau. In addition there were a few German light cruisers isolated in various parts of the world, many of them being in proximity to British squadrons, which would point to the fact that Germany never really calculated on Great Britain throwing in her lot on the opposite side.

The recent troubles in Mexico accounted for the presence of both British and German cruisers in those waters, where they had been operating in conjunction with one another in the most complete harmony. As an instance, it might be mentioned that on August 2nd, 1914, one of our sloops was actually about to land a guard for one of our Consulates at a Mexican port in the boats belonging to a German light cruiser!

A short description of some of the movements of the German ships during the first few months of war will suffice to show that their primary object was to damage our overseas trade as much as possible. Further, since it is the fashion nowadays to overrate Germany's powers of organisation and skill, it will be interesting to observe that in spite of the vulnerability of our worldwide trade comparatively little was achieved.

The German squadron in China was under the command of Vice-Admiral Count von Spee. The outbreak[5] of war found him on a cruise in the Pacific, which ultimately extended far beyond his expectations. The two armoured cruisers Scharnhorst—in which Admiral von Spee flew his flag—and Gneisenau left Nagasaki on June 28th, 1914. Their movements southward are of no particular interest until their arrival on July 7th at the Truk or Rug Islands, in the Caroline group, which then belonged to Germany. After a few days they leisurely continued their cruise amongst the[6] islands of Polynesia. About the middle of the month the light cruiser Nürnberg was hastily recalled from San Francisco, and sailed on July 21st, joining von Spee's squadron at Ponape (also one of the Caroline Islands), where the three ships mobilised for war. On August 6th they sailed for an unknown destination, taking with them an auxiliary cruiser called the Titania.

The Mappa Co. Ltd London

Apparently they were somewhat short of provisions, particularly of fresh meat and potatoes, for it was said in an intercepted letter that their diet consisted mainly of "spun yarn" (preserved meat).

On August 22nd the Nürnberg was sent to Honolulu to get papers and to send telegrams, rejoining the squadron shortly afterwards. A day or two later she was again detached, this time to Fanning Island, where she destroyed the British cable station, cut the cable, rejoining the squadron about September 7th, apparently at Christmas Island. Hearing that hostile forces were at Apia (Samoan Islands), von Spee sailed southward only to find, on his arrival, that it was empty of shipping.

The squadron now proceeded eastward to the French Society Islands to see what stores were to be found there. Completing supplies of coal at Bora Bora Island, it suddenly appeared off Papeete, the capital of Tahiti, on September 22nd. A French gunboat lying in the harbour was sunk by shell-fire, the town and forts were subjected to a heavy bombardment, whilst the coal stores were set on fire. Calling in later at the Marquesas Islands, the German Admiral shaped his course eastward toward Easter Island, which was reached on October 12th.

The light cruiser Leipzig sailed from Mazatlan, an important town on the west coast of Mexico, on August 2nd. Ten days later she was reported off the entrance to Juan de Fuca Straits, between Vancouver and the mainland, but never ventured inside to attack the naval dockyard of Esquimalt. When war broke out the Canadian Government with great promptitude purchased two submarines from an American firm at Seattle; this was probably known to the Germans, and might account for their unwillingness to risk an attack on a port that was otherwise practically defenceless.

The Canadian light cruiser Rainbow, together with the British sloop Algerine, did excellent work on this coast. The former, in particular, showed much zeal in shadowing the Leipzig, though they never actually met.

The Leipzig achieved absolutely nothing worthy of note, although she remained on the west coast of America for a long time. It was not till the middle of October that she joined Admiral von Spee's squadron at Easter Island, without having caused any damage to the British Mercantile Marine.

The light cruiser Dresden was at St. Thomas, one of the larger of the Virgin Islands group, West Indies. She sailed on August 1st and proceeded straight to Cape Horn, only staying her career to coal at various places en route where she was unlikely to be reported. Crossing and re-crossing the trade route, she arrived on September 5th at Orange Bay, which is a large uninhabited natural harbour a few miles to the north-west of Cape Horn. Here she was met by a collier,[8] and stayed eleven days making adjustments to her engines. She evidently considered that she was now free from danger—we had no cruisers here at this period—for she continued her course into the Pacific, easing down to a speed of 8½ knots, and keeping more in the track of shipping. She met the German gunboat Eber on September 19th, to the northward of Magellan, and continued her way, apparently on the look out for allied commerce, but only succeeded in sinking two steamers before joining the flag of Admiral von Spee at Easter Island on October 12th. Altogether she sank three steamers and four sailing vessels, representing a total value of just over £250,000.

The light cruiser Karlsruhe, the fastest and most modern of the German ships on foreign service, was in the Gulf of Mexico at the commencement of the war. On her way to her sphere of operations in the neighbourhood of Pernambuco she was sighted on August 6th, whilst coaling at sea from the armed liner Kronprinz Wilhelm, by the British cruiser Suffolk. Admiral Cradock, who was then flying his flag in the Suffolk, immediately gave chase to the Karlsruhe, the Kronprinz Wilhelm bolting in the opposite direction. During the forenoon Admiral Cradock called up by wireless the light cruiser Bristol, which was in the vicinity, and, giving her the position of the Karlsruhe, ordered her to intercept the enemy. The Karlsruhe was kept in sight by the Suffolk for several hours, but was never within gun-range, and finally escaped from her by superior speed. It was a beautiful moonlight evening when the Bristol sighted her[9] quarry at 8 P.M., and a quarter of an hour later opened fire, which was returned a few moments later by the Karlsruhe, but it was too dark for either ship to see the results of their shooting. All the enemy's shots fell short, so that the Bristol incurred no damage. Both ships went on firing for fifty-five minutes, by which time the German had drawn out of range. Admiral Cradock signalled during the action, "Stick to it—I am coming"; all this time the Suffolk was doing her best to catch up, but never succeeded in reaching the scene of the first naval action in the world-war. The German disappeared in the darkness, and was never seen again by our warships.

In her subsequent raids on British commerce along the South Atlantic trade routes the Karlsruhe was, on the whole, successful, until she met a sudden and inglorious end off Central America. Her fate was for a long time shrouded in mystery, the first clue being some of her wreckage, which was found washed up on the shores of the island of St. Vincent in the West Indies. Some of her survivors eventually found their way back to the Fatherland and reported that she had foundered with 260 officers and men—due to an internal explosion on November 4th, 1914, in latitude 10° 07′ N., longitude 55° 25′ W. (See Map p. 5.)

In all she sank seventeen ships, representing a value of £1,622,000.

There remain three German armed merchant cruisers that claim our attention on account of their operations off South America. The Cap Trafalgar only existed for[10] a month before being sunk by the armed Cunard liner Carmania. A description of the fight is given in a subsequent chapter.

The Prinz Eitel Friedrich was more directly under the orders of Admiral von Spee, and acted in conjunction with his squadron in the Pacific until the battle of the Falkland Islands, when she operated on her own account against our trade with South America. She achieved some measure of success during the few months that she was free, and captured ten ships altogether, several of which, however, were sailing vessels. Early in March she arrived at Newport News in the United States with a number of prisoners on board, who had been taken from these prizes. She was badly in need of refit; her engines required repairs, and the Germans fondly imagined that they might escape internment. On hearing that one of her victims was an American vessel, public indignation was hotly aroused and but little sympathy was shown for her wants. Her days of marauding were brought to an abrupt termination, for the Americans resolutely interned her.

Lastly, there was the Kronprinz Wilhelm, which, as we have seen, was in company with the Karlsruhe when the latter was sighted and chased by the Suffolk only two days after war was declared. She was commanded by one of the officers of the Karlsruhe, and worked under her orders in the Atlantic. In fact, the German cruiser transferred two of her Q.F. guns to the armed merchantman, and they were mounted on her forecastle. She was skilful in avoiding our cruisers and literally fed upon her captures, being fortunate in obtaining[11] coal with fair frequency. In the course of eight months the Kronprinz Wilhelm captured and destroyed fifteen British or French ships, four of which were sailing vessels. It will be realised how small was the toll of our ships sailing these seas, especially when it is recollected that the main object of the Germans at this time was to make war on our maritime trade. Finally, sickness broke out on board and there were several cases of beriberi; moreover, the ship leaked and was in want of repairs, so on April 11th she also steamed into Newport News and was interned.

That the Germans did not approach the results they hoped for in attacking our commerce was in a large measure due to the unceasing activity of our cruisers, who forced the German ships to be continually on the move to fresh hunting grounds. Thus, although many of them escaped capture or destruction for some time, they were perpetually being disturbed and hindered in their work of depredation.

The exploits of the light cruisers Emden and Königsberg are outside the scope of this book, but the following brief summary may be of interest.

Sailing from Tsingtau on August 5th, with four colliers, the Emden apparently proceeded to cruise in the neighbourhood of Vladivostock, where she captured a Russian auxiliary cruiser and one or two merchant ships, before going south to make history in the Bay of Bengal. She was eventually brought to book off the Cocos Islands on November 9th, 1914, by the Australian light cruiser Sydney, in a very gallant action[12] which lasted over an hour and a half, when she ran herself ashore in a sinking condition on North Keeling Island. She sank seventeen ships all told, representing a total value of £2,211,000.

The Königsberg, at the commencement of hostilities, was lying at Dar-es-Salaam, the capital of what was formerly German East Africa. She sank the Pegasus, a light cruiser only two-thirds of her size and of much inferior armament, at Zanzibar on September 20th, but only succeeded in sinking one or two steamers afterwards. She was eventually discovered hiding in the Rufiji Delta in German East Africa, towards the end of October, 1914, where she was kept blocked up by our ships for nearly nine months. Finally, on July 11th, 1915, she was destroyed by gunfire by the monitors Severn and Mersey, who went up the river—the banks on both sides being entrenched—and reduced her to a hopeless wreck where she lay, some fourteen miles from the sea.

It is clearly impossible to state with any exactitude the motives which governed von Spee's policy; but, in briefly reviewing the results, a shrewd idea of the reasons which led him to certain conclusions may be formed. Also, it will assist the reader to a conclusion on the merits and demerits of the strategy adopted, and will help him to follow more easily the reasons for some of the movements of our own ships described in the next chapter.

That Admiral von Spee did not return to Tsingtau at the outbreak of hostilities appears significant, since he was by no means inferior to our squadron, and wished to mobilise his ships. He, however, sent the Emden there with dispatches and instructions to the colliers about meeting him after she had escorted them to sea. Japan, it will be remembered, did not declare war till August 23rd, 1914, and therefore could scarcely have come into his earlier calculations. His action in continuing his cruise in the Southern Pacific, where he was handy and ready to strike at the French colonies[2] at the psychological moment of the outbreak of hostilities, gives the impression that he did not consider England's intervention probable.

Previous to the war, the Leipzig and Nürnberg had been detached to the West Coast of America, and it appears likely that von Spee was influenced in his decision to remain at large in the Pacific by this fact, as, before this dispersal of his squadron, he would have been distinctly superior to the British Fleet in the China Station at that time. Great care was taken by him to keep all his movements secret, and he appears to have avoided making many wireless signals.

The decision of the British Government to proceed with operations against the German colonies in the Southern Pacific must have had a determining effect on German policy; this decision was made at the very outset and allowed the enemy no time to make preparations to counter it. The value of the patriotism and loyal co-operation of the Dominions in building up their own Navy in peace time was now clearly demonstrated, Australia being the first of our Dominions to embark on this policy.

The German China squadron was inferior in strength to our ships in Australian waters, and could not afford to risk encountering the powerful battle-cruiser Australia with her eight 12-inch guns; consequently, von Spee was compelled to abandon the many colonies in Polynesia to their fate. Finally, the advent of Japan into the conflict left him little choice but to make his way to the eastward, since not to do so was to court almost certain destruction, while to move west and conceal his whereabouts was an impossibility. That von Spee felt his position to be precarious, and had difficulty in making up his mind what to do, is shown by[15] the slow and indecisive movement of his squadron at first.

The movements of the German light cruisers lead to the conclusion that they must have received orders to scatter so as to destroy our trade in various spheres. The Leipzig apparently patrolled the western side of North America, whilst the Karlsruhe took the South Atlantic, and so on.

Why the Dresden should have steamed over 6,000 miles to the Pacific instead of assisting the Karlsruhe is hard to explain, unless she had direct orders from the German Admiralty. She could always have joined von Spee later.

With the exception of the Emden, who operated with success in the Bay of Bengal, and the Karlsruhe, whose area of operations was along the junction of the South Atlantic and the West Indian trade routes, none of them succeeded in accomplishing a fraction of the damage that might reasonably have been expected at a time when our merchantmen were not organised for war and business was "as usual." It cannot be denied that the Emden's raids wholly disorganised the trade along the east coast of India. The local moneylenders—who are the bankers to the peasants—abandoned the coast completely, trade nearly came to a standstill, and the damage done took months to recover. In this case the effects could by no means be measured by an armchair calculation of the tonnage sunk by the Emden in pounds, shillings and pence.

The main anxiety of the German Admiral lay in the continuance of his supplies, which could only be assured[16] by careful organisation. This was rendered comparatively easy in South America, where every port teemed with Germans; the wheels of communication, through the agency of shore wireless stations, were well oiled by German money, and there were numerous German merchantmen, fitted with wireless, ready to hand to be used as supply ships or colliers.

It was thus of paramount importance that the German Squadron should be rounded up and annihilated before it could become a serious menace to our trade and that of our Allies. The other remaining light cruisers of the enemy, who were operating singly, could be dealt with more easily, since our ships could afford to separate in order to search for them, thus rendering it only a matter of time before they were destroyed.

What was the object, then, of the German Admiral? This was the all-important question that occupied the thoughts of all our naval officers in foreign parts. On the assumption that he would come eastwards, there appeared to be few choices open to him beyond the following:

(1) To bombard the seaports of our colonies on the west coast of Africa and to attack weakly defended but by no means valueless naval stations (such as St. Helena), at the same time operating against British and French expeditions going by sea against German colonies.

(2) To go to South Africa, destroy the weak British squadron at the Cape, and hang up Botha's expedition by supporting a rising against us in the South African Dominions.

(3) To endeavour to make his way home to Germany.

(4) To operate in the North Atlantic.

(5) To harass our trade with South America.

Both the first and second appeared quite feasible, but they had the twofold disadvantage of involving actions nearer England and of very possibly restricting the enemy a good deal in his movements; there are few harbours on this coast, and his every movement would become known in a region where we held the monopoly in methods of communication. Consequently, any success here was bound to be more or less short-lived. On the other hand, matters were undoubtedly very critical in these parts. De la Rey, when he was shot, was actually on his way to raise the Vierkleur at Potchefstroom, and any striking naval success which it would have taken us three weeks to deal with at the very least, might have just set the balance against us at this time in the minds of the waverers. Moreover, it would not have been difficult to ensure supplies from the German colonies.

The third may be dismissed as being extremely improbable at the outset, for it is difficult to run a blockade with a number of ships, and, for the enemy, it would too much have resembled thrusting his head into the lion's jaws. Besides, he could be of far greater service to his country in roaming the seas and in continuing to be a thorn in our side as long as possible.

The fourth will scarcely bear examination; cut off from all bases, he could hardly hope to escape early destruction.

The fifth seemed by far the most favourable to his[18] hopes, as being likely to yield a richer harvest, and, if successful, might paralyse our enormous trade with South America, upon which we were so dependent.

German influence was predominant as well as unscrupulous along the Brazilian coasts, which would render it easy to maintain supplies. To evoke sympathy amongst the smaller Republics would also come within his horizon. Finally, he could have had little idea of our strength in South Africa; whereas information gleaned from Valparaiso (which von Spee evidently considered reliable) as to the precise extent of our limited naval resources then on the east coast of South America, must have proved a deciding factor in determining his strategy.

Whichever course were adopted, it was practically certain that the German Admiral would move eastwards, either through the Straits of Magellan or, more probably, round the Horn to avoid having his whereabouts reported. That this occurred to the minds of our naval authorities before the action off Coronel took place is practically certain, but it is to be regretted that reinforcements to Admiral Cradock's squadron operating in South American waters were not sent there in time to prevent that disaster.

This, then, in brief, was the problem that presented itself to our commanders after the battle of Coronel took place, and no doubt influenced them in the choice of the Falkland Islands as a base, its geographical position making it almost ideal in the event of any move in that direction on the part of the Germans.

"If England hold

The sea, she holds the hundred thousand gates

That open to futurity. She holds

The highways of all ages. Argosies

Of unknown glory set their sails this day

For England out of ports beyond the stars.

Ay, on the sacred seas we ne'er shall know

They hoist their sails this day by peaceful quays,

Great gleaming wharves i' the perfect City of God,

If she but claims her heritage."

—Alfred Noyes (Drake).

Before attempting to give a description of the battle of the Falkland Islands, it is necessary to review very briefly the movements and dispositions of our ships, as well as the events preceding the battle, which include both the duel between the armed merchant cruiser Carmania and Cap Trafalgar and the action fought off Coronel on the coast of Chile by Admiral Cradock.

Our naval forces were scattered in comparatively small units all over the world when war broke out. Ships in various squadrons were separated from one another by great distances, and, with the exception of our Mediterranean Fleet, we possessed no squadron in any part of the globe equal in strength to that of von Spee.

Attention is directed to the positions of Easter Island, where the Germans had last been reported,[20] Valparaiso, Coronel, Magellan Straits, Staten Island, the Falkland Islands, Buenos Ayres, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, and the Island of Trinidad off the east coast of South America, since they occur continually in the course of this narrative.[3]

In the early part of 1914 Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, K.C.V.O., C.B., flying his flag in the Suffolk, was in command of the fourth cruiser squadron, which was then doing some very useful work in the Gulf of Mexico. On August 2nd he was at Kingston, Jamaica, and received information that the Good Hope was on her way out to become his flagship, so he sailed northwards to meet her. On the way he sighted and gave chase to the Karlsruhe on August 6th, as has been related. The Suffolk and the Good Hope met at sea ten days later, and the Admiral went on board the latter immediately and hoisted his flag.

Turning south, he went to Bermuda, called in at St. Lucia on August 23rd, and thence proceeded along the north coast of South America on his way to take up the command of a newly forming squadron of British ships patrolling the trade routes and protecting the merchant shipping in South American waters. At St. Lucia Admiral Cradock would probably have learned of the sailing of von Spee's squadron from Ponape on August 6th, and this accounts for his haste in making south in order to meet and form his ships together.

The squadron was gradually augmented as time went on, and in the months of September and October, 1914, consisted of the flagship Good Hope (Captain Philip [21]Francklin), Canopus (Captain Heathcoat Grant), Monmouth (Captain Frank Brandt), Cornwall (Captain W. M. Ellerton), Glasgow (Captain John Luce), Bristol (Captain B. H. Fanshawe), and the armed merchant cruisers Otranto (Captain H. McI. Edwards), Macedonia (Captain B. S. Evans), and Orama (Captain J. R. Segrave).

No news was obtainable as to the whereabouts of the German squadron stationed in the Pacific, which consisted of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Emden, Nürnberg, and Leipzig, except that it was known that the two latter had been operating on the east side of the Pacific, and that the Emden was in the Bay of Bengal. The vaguest rumours, all contradicting one another, were continually being circulated, in which it is more than likely that German agents had a large share.

Admiral Cradock proceeded south in the middle of September to watch the Straits of Magellan, and to patrol between there and the River Plate, as he doubtless hoped to prevent the Karlsruhe and Dresden—which, when last heard of, were in South American waters—from attempting to effect a junction with their main squadron. With him were the Monmouth, Glasgow, and the armed Orient liner Otranto, in addition to his own ship the Good Hope, which, together with his colliers, had their first base in the Falkland Islands.

On hearing of the appearance of the Germans off Papeete and of the bombardment of the French colony there on September 22nd, it was apparently considered expedient to proceed to the west coast of South America in order to intercept the enemy. Accordingly, early[22] in October the Monmouth, Glasgow, and Otranto went round to the Pacific, diligently searching out the many inlets and harbours en route, and arrived at Valparaiso on October 15th, but only stayed a part of one day in order to get stores and provisions. They then went back southwards to meet the Good Hope and Canopus, vainly hoping to fall in with the Leipzig or Dresden on the way. The Good Hope reached the Chilean coast on October 29th, and all ships filled up with coal; the Canopus was due very shortly, and actually sighted our ships steaming off as she arrived.

In order to carry out a thorough and effective examination of the innumerable inlets that abound amongst the channels of Tierra del Fuego, in addition to the bays and harbours on both coasts of South America, it became necessary to divide up this squadron into separate units. To expedite matters, colliers were sent to meet our ships, so that valuable time should not be lost in returning to the base at the Falkland Islands. The first fine day was seized to fill up with coal, care always being taken to keep outside the three-mile territorial limit.

It must have been a trying and anxious time for both officers and men, while pursuing their quest, never knowing what force might suddenly be disclosed in opening out one of these harbours. From the weather usually experienced in these parts some idea may be formed of the discomforts. An officer in the Glasgow, writing of this period, says: "It blew, snowed, rained, hailed, and sleeted as hard as it is possible to do these things. I thought the ship would dive under alto[23]gether at times. It was a short sea, and very high, and doesn't suit this ship a bit. The Monmouth was rather worse, if anything, though not quite so wet. We were rolling 35 degrees, and quite useless for fighting purposes. The ship was practically a submarine."

Imagine, too, the position of the Otranto, searching these waters by herself, without the least hope of being able to fight on level terms with one of the enemy's light-cruisers. The words of one of her officers sum up the situation: "We finally got past caring what might happen," he said; "what with the strain, the weather, and the extreme cold, we longed to find something and to have it out, one way or the other."

When the depredations of the Karlsruhe became more numerous, the Admiralty dispatched ships—as could best be spared from watching other trade routes—to reinforce Admiral Cradock's command. Thus, what may be termed a second squadron was formed, consisting of the Canopus, Cornwall, Bristol, the armed P. & O. liner Macedonia, and the armed Orient liner Orama. This latter squadron carried out a fruitless search during September and October for the ever elusive Karlsruhe, but, so far as is known, did not succeed in getting near her, for she was never actually sighted. In the absence of orders from Admiral Cradock, the duties of Senior Naval Officer of this northern squadron frequently involved the consideration of matters of no little consequence. These duties primarily devolved upon the shoulders of Captain Fanshawe of the Bristol, who was succeeded on the arrival of the Canopus by Captain Heathcoat Grant. As the poor[24] state of the engines of the Canopus did not enable her to steam at any speed, she remained at the base and directed operations, forming a valuable link with her wireless. Orders, however, were received from Admiral Cradock which necessitated her sailing on October 10th in order to join his southern squadron, so that Captain Fanshawe was again left in command.

On October 24th the Carnarvon (Captain H. L. d'E. Skipwith) arrived, flying the flag of Rear-Admiral A. P. Stoddart, who, though acting under the orders of Admiral Cradock, now took charge of the sweeping operations necessitated by our quest. Admiral Stoddart had previously been in command of the ships operating along our trade routes near the Cape Verde Islands, where the Carnarvon had not long before made a valuable capture, the German storeship Professor Woermann, filled with coal and ammunition.

The comparatively large number of men-of-war mentioned is accounted for by the fact that at this time the Karlsruhe began to make her presence felt by sinking more merchant ships, which caused no little apprehension amongst the mercantile communities in all the ports on the north and east coasts of South America, Brazilian firms at this period refusing to ship their goods in British bottoms, although some British vessels were lying in harbour awaiting cargoes. The German ship's activities were mainly confined to the neighbourhood of St. Paul's Rocks, Pernambuco, and the Equator.

It is not easy to put clearly the disposition of the ships acting under Admiral Cradock at this time, nor[25] to give an adequate idea of the many disadvantages with which he had to contend. The difficulties of communication on the east coast of South America between his two squadrons were very great, on account of the long distances between them (often some thousands of miles and always greater than the range of our wireless). The only method found feasible was to send messages in code by means of passing British merchantmen—usually the Royal Mail liners. The inevitable result of this was that it was frequently impossible for Admiral Cradock to keep in touch with his northern squadron, and important matters of policy had thus to be decided on the spot, the Admiral being informed later.

On the rare occasions that our ships visited Brazilian ports, which were crowded with German shipping, the crews of these ships, having nothing better to do, would come and pull round our cruisers—in all probability cursing us heartily the while—much to the interest and amusement of our men. These visits could only take place at the most once every three months, when the opportunity of getting a good square meal at a civilised restaurant was hailed with delight by those officers who were off duty.

Our coaling base in these waters was admirably selected. There was sufficient anchorage for a large number of ships four or five miles from any land, but protected from anything but a heavy swell or sea by surrounding ledges of coral awash at low water. Sometimes colliers got slightly damaged by bumping against our ships when there was a swell, but in other respects[26] it suited its purpose excellently. The Brazilians sent a destroyer to investigate once or twice, but could find nothing to arouse their susceptibilities, for our ships were always well outside the three-mile limit. Our sole amusement was fishing, frequently for sharks.

Towards the latter part of August, the armed merchant cruiser Carmania (Captain Noel Grant) was sent out to join Admiral Cradock's squadron with coal, provisions, and a large quantity of frozen meat, which was sadly needed. She was ordered by him to assist the Cornwall in watching Pernambuco on September 11th, as it was thought that the German storeship Patagonia was going to put to sea on September 11th to join the Karlsruhe. On her way south she got orders to search Trinidad Island in the South Atlantic to find out whether the Germans were making use of it as a coaling base, and there fell in with the German armed liner Cap Trafalgar, which she sank in a very gallant action that is described in a subsequent chapter.

The armed merchant cruiser Edinburgh Castle (Captain W. R. Napier) was sent out from England with drafts of seamen and boys, as well as provisions and stores for our men-of-war in these waters. On her arrival at the base on October 12th, she was detained on service to assist in the sweep that had been organised to search for the Karlsruhe. Some of us have pleasant recollections of excellent games of deck hockey played on the spacious promenade deck during her all too short stay with us.

The Defence (Captain E. La T. Leatham) touched at[27] the base to coal on October 27th, being on her way south to join Admiral Cradock's southern command. She had to coal in bad weather, and perforated the collier's side in doing so, but succeeded in completing with coal in the minimum possible time under difficult conditions. Without loss of time she proceeded to Montevideo, but never got any farther, as it was there that the news of the Coronel disaster first reached her. Admiral Cradock hoped to find von Spee before the German light-cruisers Dresden and Leipzig joined the main squadron; but he also was most anxious to wait for the Defence. She would have made a very powerful addition to his squadron, and it seems a thousand pities that it was not possible to effect this junction before he quitted the eastern shores of South America for the Pacific.

The Defence was very unlucky, and had a great deal of hard work without any kudos; not till Admiral Sturdee's arrival did she leave to join the Minotaur on the Cape of Good Hope station, and the very day she arrived there got the news of the Falkland Islands battle! Having covered 23,000 miles in two and a half months, the disappointment at having missed that fight was, of course, intense. It is sad to think that few of her gallant crew are alive to-day, as she was afterwards sunk in the battle of Jutland.

The Invincible, flagship of Vice-Admiral F. C. Doveton Sturdee (Captain P. H. Beamish), the Inflexible (Captain R. F. Phillimore, C.B., M.V.O.), and the Kent (Captain J. D. Allen) enter the scene of operations later.

"A seaman, smiling, swaggered out of the inn,

Swinging in one brown hand a gleaming cage

Wherein a big green parrot chattered and clung

Fluttering against the wires."

—Alfred Noyes (Drake).

A short digression may perhaps be permitted, if it can portray the long days, when for months at a time little occurs to break the monotony of sea life. The reader may also experience the charitable feeling that, at the expense of his patience, the sailor is indulging in the "grouse" that proverbially is supposed to be so dear to him.

Of necessity, work on board ship in wartime must be largely a matter of routine; and, though varied as much as possible, it tends to relapse into "the trivial round, the common task." All day and all night men man the guns ready to blaze off at any instant, extra look-outs are posted, and there are officers and men in the control positions. The ship's company is usually organised into three watches at night, which take turns in relieving one another every four hours.

After sunrise the increased visibility gives ample warning of any possible attack. The messdecks, guns, and ship generally are cleaned before breakfast, while the forenoon soon passes in perfecting the guns' crews[29] and controls, and in physical drill. After dinner at noon and a smoke, everyone follows the old custom of the sea, and has a caulk (a sleep)—a custom originated in the days of sailing ships who were at sea for long periods at a time, and watch and watch (i.e. one watch on and one off) had to be maintained both day and night. The men lie about the decks, too tired to feel the want of either mattresses or pillows. The first dog watch (4–6 P.M.) is usually given up to recreation until sunset, when it is time to go to night defence stations. Day in and day out, this programme is seldom varied except to stop and examine a merchant ship now and again.

Every ship met with on the high seas is boarded for the examination of its passengers and cargo, an undertaking often attended by some difficulty on a dark night. On approaching, it is customary to signal the ship to stop; if this is not obeyed at once, a blank round is fired as a warning; should this be disregarded a shotted round is fired across her bows, but it is seldom necessary to resort to this measure. At night these excursions have a strange, unreal effect, and our boarding officer used to say that when climbing up a merchantman's side in rough weather he felt like some character in a pirate story. Getting out of a boat, as it is tossing alongside, on to a rope ladder, is by no means an easy job, especially if the officer is inclined to be portly. The searchlight, too, turned full on to the ship, blinding the scared passengers who come tumbling up, frequently imagining they have been torpedoed, adds to the mysterious effect produced, whilst[30] the sudden appearance of the boarding officer in his night kit suggests a visit from Father Neptune. But any idea of comedy is soon shattered by the grumpy voice of the captain who has been turned out from his beauty sleep, or by the vehement objections of a lady or her husband to their cabin being searched. As a matter of fact, we were always met with the most unfailing courtesy, and the boat's crew was often loaded with presents of cigarettes or even chocolates, besides parcels of newspapers hastily made up and thrown down at the last moment.

Off a neutral coast the food problem is an everlasting difficulty, and as soon as the canteen runs out and tinned stores cannot be replenished, the menu resolves itself into a more or less fixed item of salt beef ("salt horse") or salt pork with pea soup. The old saying, "Feed the brute, if a man is to be kept happy," has proved itself true, but is one which at sea is often extraordinarily hard to follow, especially when it is impossible to get such luxuries as eggs, potatoes, and fresh meat. If flour runs out, the ship's biscuit ("hard tack"), which often requires a heavy blow to break it, forms but a poor substitute for bread; although it is quite good eating, a little goes a long way. The joy with which the advent of an armed liner is heralded by the officers cannot well be exaggerated; the stewards from all ships lose no time in trying to get all they can, and the memory of the first excellent meal is not easily forgotten.

The ever-recurring delight of coaling ship is looked forward to directly anchorage is reached. Coal-dust[31] then penetrates everywhere, even to the food, and after a couple of hours it seems impossible for the ship ever to be clean again. Nearly every officer and man on board, including the chaplain and paymasters, join in the work, which continues day and night, as a rule, until finished. If this takes more than twenty-four hours there is the awful trial of sleeping, clothes and all, covered in grime, for hammocks have to be foregone, else they would be quite unfit for further use. The men wear any clothes they like. In the tropics it is a warm job working in the holds, and clothes are somewhat scanty. A very popular article is a bashed-in bowler hat, frequently worn with white shorts, and a football jersey! There is, generally, a wag amongst the men who keeps them cheery and happy, even during a tropical rain storm. His powers of mimicking, often ranging from politicians to gunnery instructors, bring forth rounds of applause, and all the time he'll dig out like a Trojan.

The sailor is a cheery bird, and seldom lets an opportunity of amusement escape. On one occasion, when lying at anchor in the tropics, someone suggested fishing; after the first fish had been caught many rods and lines were soon going. A would-be wit enlivened matters by tying an empty soda-water bottle on to a rather excitable man's line while he was away, which met with great success on the owner crying out, "I've got a real big 'un here" as he carefully played it to the delight of everyone. Shark fishing was a favourite sport, and three were caught and landed in one afternoon; one of them had three small sharks inside it.

The band (very few ships had the good fortune to possess one) plays from 4.30 to 5.30 P.M., when Jack disports himself in Mazurkas and d'Alberts, and dances uncommonly well before a very critical audience. Some men are always busy at their sewing machines when off duty, making clothes for their messmates; this they call "jewing"; others are barbers, or bootmakers, and they make quite a good thing out of it. Now that masts and sails are things of the past, substitutes in the way of exercise are very necessary, particularly when living on salt food. Boxing is greatly encouraged, and if competitions are organised, men go into strict training and the greatest keenness prevails. A canvas salt-water bath is usually rigged, and is in constant demand with the younger men. The officers congregate in flannels on the quarter-deck playing quoits, deck tennis, or cricket; some go in for doing Swedish exercises, Müller, or club swinging, and, to finish up with, a party is formed to run round the decks.

The Admiralty are extraordinarily good about dispatching mails to our ships, but sudden and unexpected movements often make it impossible to receive them with any regularity. When war broke out everyone wondered how their folk at home would manage, whether money and food would be easily obtainable. In our own case we were moved from our original sphere of operations, and did not get our first mail till October 19th, over eleven weeks after leaving England, and many other ships may have fared even worse. Again, our Christmas mail of 1914 was not received till six months afterwards, having followed us to the Falkland Islands,[33] then back home, out again round the Cape of Good Hope, finally arriving at the Dardanelles. On this occasion one of the men had a pound of mutton and a plum pudding sent him by his wife; it can easily be imagined with what delight he welcomed these delicacies, which had been through the tropics several times, as did those others whose parcels were anywhere near his in the mail bag. It may appear a paltry thing to those who get their daily post regularly, but the arrival of a mail at sea is a very real joy, even to those who get but few letters. The newspapers are eagerly devoured, and events, whose bare occurrence may have only become known through meagre wireless communiqués, are at length made comprehensible.

Darkening ship at sunset is uncomfortable, more particularly in the tropics, when the heat on the messdecks becomes unbearable from lack of air. However, this is now much improved by supplying wind-scoops for the scuttles, fitted with baffles to prevent the light from showing outboard. Everyone sleeps on deck who can, risking the pleasures of being trodden upon in the dark, or of being drenched by a sudden tropical shower, when the scrum of men hastily snatching up their hammocks and running for the hatches equals that of any crowd at a football match. On moonless nights little diversions are constantly occurring. A certain officer, perfectly sober, on one occasion walked over the edge of the boat-deck into space, and then was surprised to find that he was hurt.

The hardships and anxieties of the life are probably overrated by people ashore. The very routine helps[34] to make the sailor accustomed to the strange and unnatural conditions, nearly all of which have their humorous side. As is the way of the world, we on the coast of South America all envied those in the Grand Fleet at this time, in modern ships fitted with refrigerating rooms and plenty of good fresh food; and they, no doubt, willingly would have changed places with us, being sick to death of the uneventful life, cold, rough weather, and constant submarine strain from which we were fortunately immune. Events took such a shape a few months later that those of us who were fortunate enough to be in the battle of the Falkland Islands would not have been elsewhere for all the world.

"When, with a roar that seemed to buffet the heavens

And rip the heart of the sea out, one red flame

Blackened with fragments, the great galleon burst

Asunder! All the startled waves were strewn

With wreckage; and Drake laughed: 'My lads, we have diced

With death to-day, and won!'"

—Alfred Noyes (Drake).

It has already been mentioned that the Carmania was ordered to search the Brazilian island of Trinidad (not to be confused with the British Island of the same name), which lies in the South Atlantic about 600 miles to the eastward of South America, and in about the same latitude as Rio de Janeiro. It was uninhabited at this time, and seemed a likely place for the Germans to use as a temporary coaling base; they have never had any compunction about breaking the laws of neutrality if it suited their purpose.

The following narrative is taken from the official report, supplemented by an account written by the author two days after the action from a description given him by the officers of H.M.S. Carmania.

Land was sighted on the morning of September 14th, 1914. A moderate breeze was blowing from the north-east, but it was a lovely day, with a clear sky and the sun shining. Shortly after 11 A.M. the masts of a vessel were observed, and on approaching nearer the Carmania[36] made out three steamers, apparently at anchor in a small bay that lies to the south-west of the island. One of these was a large liner, but the others were clearly colliers and had their derricks topped; they were probably working when they sighted us, and they immediately separated and made off in different directions before the whole of their hulls could be distinguished.

The large vessel was apparently a liner about equal in size,[4] having two funnels which were painted to resemble those of a Union Castle liner. After running away for a while, the larger steamer, which turned out to be the Cap Trafalgar (though this was not known for certain till weeks afterwards), altered course to starboard and headed more in our direction. She was then steering about south at what appeared to be full speed, while the Carmania was steaming 16 knots on a sou'-westerly course.

There could no longer be any doubt that she meant to fight, and the duel now ensued that has been so happily described by a gifted naval writer, the late Fred T. Jane, as "the Battle of the Haystacks." To my idea, it appears almost a replica of the frigate actions of bygone days, and will probably go down in history as a parallel to the engagement fought between the Chesapeake and Shannon. For gallantry, pluck and determination it certainly bears comparison with many of these actions of the past.

About noon she fired a single shot across the enemy's[37] bows at a range of 8,500 yards, whereupon he immediately opened fire from his after-gun on the starboard side. This was quickly followed on both sides by salvoes (all guns firing nearly simultaneously as soon as their sights came on to the target), so matters at once became lively.

Curiously enough, the enemy's first few shots fell short, ricocheting over, and then, as the range decreased, they went clean over the hull, in consequence of which our rigging, masts, funnels, derricks, and ventilators all suffered, though the ship's side near the waterline—the principal anxiety—was so far intact. Some of the Carmania's first shots, which were fired at a range of 7,500 yards, were seen to take effect, and she continued to score hits afterwards with moderate frequency. The port battery was engaging his starboard guns at this period, so that he was on her port hand, and a reference to the plan will show that she was ahead on bearing. The range was rapidly decreasing since they were both on converging courses, but unfortunately the German ship had the speed of her, for the Cunarder could only do 16 knots, due largely to a lack of vacuum in the condensers. As far as could be judged the Cap Trafalgar was steaming between 17 and 18 knots. (See Diagram, p. 39.)

At 4,500 yards, two of our broadsides were seen to hit all along the waterline. As the range decreased to 4,000 yards the shot from the enemy's pom-poms (machine guns), fired with great rapidity, began to fall like hail on and all round the ship; this induced Captain Grant to alter course away with promptitude, thus open[38]ing out the range and bringing the starboard battery into play. The port 4.7-inch guns—they were all over twenty years old—were by this time wellnigh red-hot. That the enemy did not apprehend this manœuvre was demonstrated by his erratic fire at this moment, when the Britisher was enabled to bring five guns into action to his four through being able to use both the stern guns. It was now that the German suffered most heavily, the havoc wrought in such a short time being very noticeable. He then turned away, which brought the two ships nearly stern on to one another; two of his steam pipes were cut by shell, the steam rising into the sky, he was well on fire forward, and had a list to starboard.

The Mappa Co. Ltd London

One of his shells, however, had passed through the captain's cabin under the fore bridge, and although it did not burst it started a fire, which rapidly became worse; unhappily no water was available to put it out, for the fire main was shot through, while the chemical fire extinguishers proved of little use. All water had to be carried by hand, but luckily the fire was prevented from spreading over the ship by a steel bulkhead, together with an ordinary fire-proof swing door, which was afterwards found to be all charred on one side. Nevertheless it got a firm hold of the deck above, which broke into flame, so the fore-bridge had to be abandoned. The ship had now to be steered from the stern, and all orders had to be shouted down by megaphone both to the engine rooms and to this new steering position in the bowels of the ship, which was connected up and in operation in fifty-seven seconds! To reduce the effect of the fire the vessel was kept before the wind,[40] which necessitated turning right round again, so that the fight resolved itself into a chase.

The action was continued by the gun-layers, the fire-control position being untenable due to the fire, so each gun had to be worked and fired independently under the direction of its own officer. Among the ammunition supply parties there had been several casualties and the officers, finding it impossible to "spot" the fall of the shell, owing to the flashes from the enemy's guns obscuring their view from so low an elevation, lent a hand in carrying the ammunition from the hoists to the guns. In these big liners the upper deck, where the guns are mounted, is approximately 70 feet above the holds, whence the ammunition has to be hoisted and then carried by hand to the guns—a particularly arduous task.

Crossing, as it were, the enemy was at this time well on the starboard bow, but firing was continued until the distance was over 9,000 yards, the maximum range of the Carmania's guns. Owing to his superior speed and a slight divergence between the courses, the distance was gradually increasing all the time, and at 1.30 he was out of range. His list had now visibly increased, and his speed began to diminish, probably on account of the inrush of water through his coaling ports. It was surmised that there had not been sufficient time to secure these properly, for he had evidently been coaling at the time she arrived upon the scene.

Towards the end the Cap Trafalgar's fire had begun to slacken, though one of her guns continued to fire to the last, in spite of the fact that she was out of range.[41] It became patent that she was doomed, and her every movement was eagerly watched through field-glasses for some minutes by those not occupied in quenching the fire. Suddenly the great vessel heeled right over; her funnels being almost parallel to the surface of the sea, looked just like two gigantic cannon as they pointed towards the Carmania; an instant later she went down by the bows, the stern remaining poised in mid-air for a few seconds, and then she abruptly disappeared out of sight at 1.50 P.M., the duel having lasted an hour and forty minutes.

There were no two opinions about the good fight she had put up, and all were loud in their praise of the gallant conduct of the Germans.

One of the enemy's colliers was observed approaching this scene of desolation in order to pick up survivors, some of whom had got away from the sinking ship in her boats. The collier had been flying the United States ensign, evidently as a ruse, in the hope that the Carmania might be induced to let her pass without stopping her for examination. It was, however, impossible to interfere with her owing to the fire that was still raging in the fore part of the ship. This kept our men at work trying to get it under, and necessitated keeping the ship running before the wind, the direction of which did not permit of approaching the spot in order to attempt to pick up survivors.

Smoke was now seen away to the northward, and the signalman reported that he thought he could make out the funnels of a cruiser. As the Cap Trafalgar, before sinking, had been in wireless communication[42] with some German vessel, it was apprehended that one might be coming to her assistance. As the Carmania was totally unfit for further action, it was deemed advisable to avoid the risk of another engagement, so she steamed off at full speed in a southerly direction.

As soon as the collier and all that remained of the wreckage of the Cap Trafalgar was lost to view the gallant Cunarder was turned to the north-westward in the direction of the anchorage. She was unseaworthy, nearly all her navigational instruments and all the communications to the engines were destroyed, making the steering and navigation of the ship difficult and uncertain. When wireless touch was established, the Cornwall was called up and asked to meet and escort her in. But as she had only just started coaling she asked the Bristol to take her place. The next day the Bristol, which was in the vicinity, took the Carmania along until relieved the same night by the Cornwall, which escorted her on to the base, where temporary repairs were effected.

One of the enemy's shells was found to have passed through three thicknesses of steel plating without exploding, but in spite of this it set fire to some bedding which caused the conflagration under the fore bridge. Where projectiles had struck solid iron, such as a winch, splinters of the latter were to be seen scattered in all directions. The ship was hit seventy-nine times, causing no fewer than 304 holes.

There were 38 casualties. Five men were killed outright, 4 subsequently died from wounds, 5 were seriously wounded and 22 wounded—most of the latter were only slightly injured. All the casualties occurred on[43] deck, chiefly among the guns' crews and ammunition supply parties. No one below was touched, but a third of those employed on deck were hit.

The following remarks may be of interest, and are taken from the author's letters, written on September 16th, after having been shown over the Carmania:

"When I went on board this morning, I was greatly struck by the few fatal casualties considering the number of holes here, there, and everywhere. Not a single part of the upper deck could be crossed without finding holes. A remarkable fact was that only one officer, Lieutenant Murray, R.N.R., was hurt or damaged in any way, although the officers were in the most exposed positions, and the enemy's point of aim appeared to be the fore bridge.

"They had only three active service ratings on board; some of the gunlayers were old men, pensioners from the Navy.

"One of the senior officers told me that the first few rounds made him feel 'a bit dickey,' but that after that he took no notice of the bigger shells, though, curiously enough, he thoroughly objected to the smaller pom-poms which were 'most irritating.' He added that the men fought magnificently, and that the firemen worked 'like hell.' As flames and smoke from the fire on deck descended to the stokeholds by the ventilators instead of cool air, the states of things down below may easily be imagined.

"One chronometer was found to be going in spite of the wooden box which contained it having been burnt.

"The deeds of heroism were many.

"I liked the story of the little bugler boy, who had no more to do once the action had commenced, so he stood by one of the guns refusing to go under cover. As the gun fired he shouted: 'That's one for the blighters!' And again: 'There's another for the beggars—go it!' smacking the gunshield the while with his hand.

"Again one of the gunlayers, who lost his hand and also one leg during the engagement, insisted upon being held up when the German ship sank, so as to be able to cheer. I talked to him, and he waggled his stump at me quite cheerily and said, 'It was well worth losing an arm for.'

"It is good to feel that the spirit of our forefathers is still active in time of need."

"Then let him roll

His galleons round the little Golden Hynde,

Bring her to bay, if he can, on the high seas,

Ring us about with thousands, we'll not yield,

I and my Golden Hynde, we will go down,

With flag still flying on the last stump left us

And all my cannon spitting the fires

Of everlasting scorn into his face."

—Alfred Noyes (Drake).

The wanderings of the German squadron in the Pacific have been briefly traced as far as Easter Island, where it arrived on October 12th, 1914, and found the Dresden. The Leipzig, which had been chased from pillar to post by British and Japanese cruisers, and succeeded in eluding them, joined up shortly after to the relief of the German Admiral.

The contractor at Easter Island, an Englishman named Edwards, who supplied the Germans with fresh meat and vegetables, was a ranch-owner, and had no idea that war had even been declared. One of his men, in taking off provisions to the ships, discovered this amazing fact, which had carefully been kept secret, and informed his master. The account was not settled in cash, but by a bill made payable at Valparaiso. The German squadron sailed for Mas-a-Fuera a week later, so the ranch-owner took the earliest opportunity of[46] sending in his bill to Valparaiso, where it was duly honoured, vastly to his astonishment and relief.

For the reasons already adduced, it seemed almost certain that Admiral von Spee would make his way round South America. That there was a possibility of his descending upon Vancouver and attacking the naval dockyard of Esquimalt is acknowledged, but it was so remote as to be scarcely worthy of serious consideration. The three Japanese cruisers, Idzuma, Hizen, and Asama, were understood to be in the eastern Pacific at this time, and this was probably known to the German Admiral. The risk, too, that he must inevitably run in attacking a locality known to possess submarines was quite unjustifiable; besides, he had little to gain and everything to lose through the delay that must ensue from adopting such a policy.

The vessels engaged in the action off Coronel, with their armament, etc., were:[5]

| Names | Tonnage | Armament | Speed | Completion |

| Good Hope | 14,100 | 2—9.2" | 23.5 | 1902 |

| 16—6" | ||||

| Monmouth | 9,800 | 14—6" | 23.3 | 1903 |

| Glasgow | 4,800 | 2—6" | 25.8 | 1910 |

| 10—4" | ||||

| Otranto (armed liner) | 12,000 gross | 8—4.7" | 18 | 1909 |

| Speed of squadron 18 knots. | ||||

| Names | Tonnage | Armament | Speed | Completion |

| Scharnhorst | 11,420 | 8—8.2" | 22.5 | 1908 |

| 6—5.9" | ||||

| 20—3.4" | ||||

| [47] Gneisenau | 11,420 | 8—8.2" | 23.8 | 1908 |

| 6—5.9" | ||||

| 20—3.4" | ||||

| Leipzig | 3,200 | 10—4.1" | 23 | 1906 |

| Dresden | 3,544 | 12—4.1" | 27 | 1908 |

| 4—2.1" | ||||

| Nürnberg | 3,396 | 10—4.1" | 23.5 | 1908 |

| 8—2.1" | ||||

| Speed of squadron 22.5 knots. | ||||

It will be noticed that our two armoured cruisers were respectively six and five years older than the Germans'. Our armament was much inferior in size, number, and quality on account of the later designs of the enemy's artillery. The range of the German 4.1-inch guns was nearly equal to that of our 6-inch guns. But perhaps the greatest point in favour of the enemy was the fact that Cradock's ships, with the exception of the Glasgow, were only commissioned at the outbreak of war, and had had such continuous steaming that no really good opportunity for gunnery practices or for testing the organisation thoroughly had been possible, whilst von Spee's had been in commission for over two years and had highly trained crews, accustomed to their ships.

The following account has been compiled from personal information received from officers who took part, from letters that have appeared in the Press, from a translation that has been published of Admiral von Spee's official report, and from the official report made by Captain Luce of the Glasgow.

Admiral Cradock, as we have seen, joined the remainder of his little squadron with the exception of[48] the Canopus off the coast of Chile on October 29th. The latter was following at her best speed. The squadron proceeded northwards, whilst the Glasgow was detached to Coronel to send telegrams, a rendezvous being fixed for her to rejoin at 1 P.M. on November 1st.

No authentic news of the movements of the Germans was available at this time; in fact, the last time that von Spee's squadron had been definitely heard of was when it appeared off Papeete and bombarded the town toward the end of September. That the enemy might be encountered at any moment was of course fully realised, but it was hoped that either the Dresden and Leipzig or the main squadron might be brought to action separately, before they were able to join forces. Time was everything if this was to be brought about, so Admiral Cradock pushed on without delay. The anxiety to obtain news of a reliable character may be imagined, but only the vaguest of rumours, one contradicting the other, were forthcoming. Reports showed that the German merchant shipping in the neighbourhood were exhibiting unwonted signs of energy in loading coal and stores, but this gave no certain indication of the proximity of the entire squadron.

Rejoining the British squadron at sea on November 1st, the Glasgow communicated with the Good Hope. Our ships had recently been hearing Telefunken[6] signals on their wireless, which was proof that one or more enemy warships were close at hand. About 2 P.M., therefore, the Admiral signalled the squadron to spread on a line bearing N.E. by E. from the Good Hope,[49] which steered N.W. by N. at 10 knots. Ships were ordered to open to a distance of fifteen miles apart at a speed of 15 knots, the Monmouth being nearest to the flagship, the Otranto next, and then the Glasgow, which was thus nearest the coast.

There was not sufficient time to execute this manœuvre, and when smoke was suddenly sighted at 4.20 P.M. to the eastward of the Otranto and Glasgow, these two ships were still close together and about four miles from the Monmouth. The Glasgow went ahead to investigate and made out three German warships, which at once turned towards her. The Admiral was over twenty miles, distant and out of sight, and had to be informed as soon as possible, so the Glasgow returned at full speed, warning him by wireless, which the Germans endeavoured to jam, that the enemy was in sight.

The squadron reformed at full speed on the flagship, who had altered course to the southward, and by 5.47 P.M. had got into single line-ahead in the order: Good Hope, Monmouth, Glasgow, and Otranto. The enemy, in similar formation, was about twelve miles off.

For the better understanding of the movements which follow, it may be stated that the ideal of a naval artillerist is a good target—that is, a clear and well defined object which is plainly visible through the telescopic gunsights; the wind in the right direction, relative to the engaged side, so that smoke does not blow across the guns, and no sudden alterations of course, to throw out calculations. The tactics of a modern naval action are in a large measure based on these ideals, at any rate according to the view of the gunnery specialist.

It is evident that it was Admiral Cradock's intention to close in and force action at short range as quickly as possible, in order that the enemy might be handicapped by the rays of the lowering sun, which would have been behind our ships, rendering them a very poor target for the Germans as the squadrons drew abeam of one another. He therefore altered course inwards towards the enemy, but von Spee was either too wary or too wise, for he says in his report that he turned away to a southerly course after 5.35, thus declining action, which the superior speed of his squadron enabled him to do at his pleasure. The wind was south (right ahead), and it was blowing very fresh, so that a heavy head sea was encountered, which made all[51] ships—especially the light-cruisers—pitch and roll considerably. It seems very doubtful whether the Good Hope and Monmouth were able to use their main deck guns, and it is certain that they could not have been of any value. This would mean that these two ships could only fire two 9.2-inch and ten 6-inch guns on the broadside between them, instead of their whole armament of two 9.2-inch and seventeen 6-inch guns.

There was little daylight left when Admiral Cradock tried to close the Germans, hoping that they would accept his challenge in view of their superior strength.

At 6.18 Admiral Cradock increased speed to 17 knots, making a wireless message to the Canopus, "I am about to attack enemy now." Both squadrons were now on parallel courses approximately, steering south, and[52] about 7½ miles apart. A second light cruiser joined the German line about this period; according to von Spee's report the Scharnhorst was leading, followed by the Gneisenau, Leipzig, and Dresden.

As the sun sank below the horizon (about 6.50 P.M.) the conditions of light became reversed to our complete disadvantage; our ships were now lit up by the glow of the sunset, the enemy being gradually enshrouded in a misty haze as the light waned. Admiral Cradock's last hope of averting defeat must have vanished as he watched the enemy turning away; at the best he could only expect to damage and thus delay the enemy, while it was impossible to withdraw. He had no choice but to hold on and do his best, trusting in Providence to aid him. In judging what follows it should be kept in mind that in the declining light even the outlines of the enemy's ships rapidly became obliterated, making it quite impossible to see the fall of our shots in order to correct the range on the gunsights; on the other hand, our ships showed up sharply against the western horizon and still provided good targets for the German gunners. Von Spee in his report says his "guns' crews on the middle decks were never able to see the sterns of their opponents, and only occasionally their bows." This certainly implies that the upper deck gunners could see quite well, whilst we have information from Captain Luce's report that our ships were unable to see the enemy early in the action, and were firing at the flashes of his guns.

Accordingly, as soon as the sun disappeared, von Spee lost no time in approaching our squadron, and[53] opened fire at 7.4 at a range of 12,000 yards. Our ships at once followed suit with the exception of the Otranto, whose old guns did not admit of her competing against men-of-war at this distance. The German Admiral apparently endeavoured to maintain this range, so as to reap the full advantage of his newer and heavier armament, for the two 9.2-inch guns in the Good Hope were the only ones in the whole of our squadron that were effective at this distance with the possible exception of the two modern 6-inch guns in the Glasgow. Von Spee had, of course, calculated this out, and took care not to close until our armoured cruisers were hors de combat.

The Germans soon found the range, their fire proving very accurate, which was to be expected in view of the reputation of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau for good shooting—the former had won the gold medal for the best average. These armoured cruisers concentrated their fire entirely on our two leading ships, doing considerable execution. In addition, they had a great stroke of luck, for in the first ten minutes of the engagement a shell struck the fore turret of the Good Hope, putting that 9.2-inch out of action. The Monmouth was apparently hit several times in rapid succession, for she was forced to haul out of the line to the westward, and her forecastle was seen to be burning furiously, but she continued to return the enemy's fire valiantly. This manœuvre caused her to drop astern, and compelled the Glasgow, who now followed on after the Good Hope, to ease speed to avoid getting into the zone of fire intended for the Monmouth.

It was now growing dark, but this did not deter both squadrons from continuing to blaze away as hard as they could; in fact, the fight was at its height; the German projectiles were falling all round and about our ships, causing several fires which lit them up with a ghostly hue. The heavy artillery of the enemy was doing great damage, and it was evident that both the Good Hope and Monmouth were in a bad way; the former sheered over unsteadily towards the Germans, returning their fire spasmodically, whilst the latter had a slight list and from her erratic movements gave the impression that her steering arrangements had been damaged. The results of our shooting could not be distinguished with accuracy, though von Spee mentions that the Scharnhorst found a 6-inch shell in one of her storerooms, which had penetrated the side and caused a deal of havoc below but did not burst, and also that one funnel was hit. The Gneisenau had two men wounded, and sustained slight damage.

At 7.50 P.M. a sight of the most appalling splendour arrested everyone, as if spellbound, in his tussle with death. An enormous sheet of flame suddenly burst from the Good Hope, lighting up the whole heavens for miles around. This was accompanied by the noise of a terrific explosion, which hurled up wreckage and sparks at least a couple of hundred feet in the air from her after funnels. A lucky shot had penetrated one of her magazines. "It reminded me of Vesuvius in eruption," said a seaman in describing this spectacle. It was now pitch dark, making it impossible for the opposing vessels to distinguish one another. The Good Hope[55] was never heard to fire her guns again, and could not have long survived such a terrible explosion, though no one saw her founder.