Title: Troubled Waters

Author: Robert Leckie

Release date: October 31, 2015 [eBook #50353]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Troubled Waters, by Robert Leckie

SANDY STEELE ADVENTURES

Black Treasure

Danger at Mormon Crossing

Stormy Voyage

Fire at Red Lake

Secret Mission to Alaska

Troubled Waters

BY ROGER BARLOW

SIMON AND SCHUSTER

New York, 1959

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

INCLUDING THE RIGHT OF REPRODUCTION

IN WHOLE OR IN PART IN ANY FORM

COPYRIGHT © 1959 BY SIMON AND SCHUSTER, INC.

PUBLISHED BY SIMON AND SCHUSTER, INC.

ROCKEFELLER CENTER, 630 FIFTH AVENUE

NEW YORK 20, N. Y.

FIRST PRINTING

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 59-13882

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY H. WOLFF BOOK MFG. CO., INC., NEW YORK

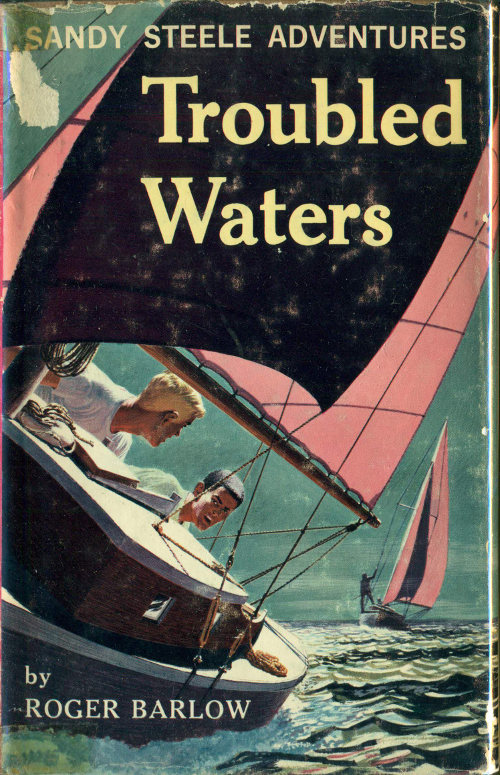

CLIFFPORT CALIFORNIA

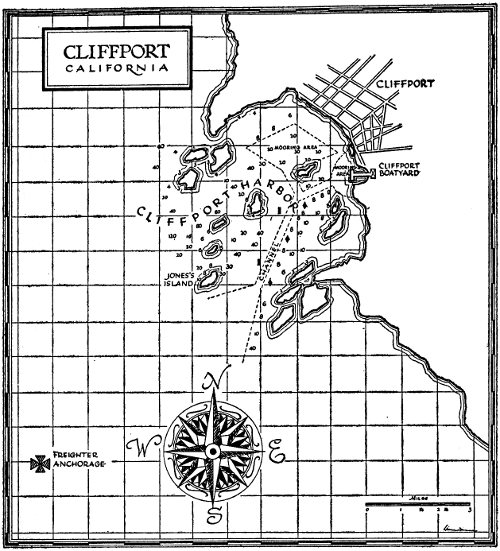

SLOOP

Sandy Steele slowly put down the phone and pushed his blond cowlick back from his brow. Excitement and confusion were mixed in equal parts in his expression as he turned to his father, John Steele, who stood leaning against his workbench, idly tossing a piece of quartz crystal in the air.

“Wow!” Sandy said. “Leave it to Uncle Russ to come up with a real surprise!”

“It certainly seems to be a habit of his,” John Steele smiled. “What do you think of this particular surprise?”

“I hardly know what to think,” Sandy answered. “The question is, what do you and Mother think? I mean, is it all right if I go—if I can find somebody to go with me?”

“Your mother and I discussed this with your Uncle Russ before he called you,” Sandy’s father said, “so I guess that’s one worry you don’t have to consider. The only problem you have is finding somebody who knows how to handle a boat, and who’ll be interested in making this trip with you.”

Wrinkling his forehead in thought, Sandy swung his gangling six-foot frame up on to the workbench next to his father. “How about you, Dad?” he asked. “Do you know anything about sailing a boat?”

His father shook his head. “Sailing is hardly a skill that a government field geologist needs to develop. My work is with rocks and minerals—the dryest kind of dry land. What I know about water, you could carve on granite and put in your watch pocket!”

“Geology didn’t make you into an inventor, a chemist, an electrical engineer, a carpenter and gosh knows what else,” Sandy answered, waving around him at the crowded workshop with its confusing mass of equipment. “I just thought you might have done some reading on this subject, too.”

John Steele smiled. “As the proud but confused owner of a new sailboat, one of the first things you’ll learn is that there’s a world of difference between theory and practice. I’ve been out on a boat a few times; years ago, though. I’ve also read some books on the subject, as you thought. But all I know is that I don’t know anything.” He put down the quartz crystal and moved away from the workbench. “No,” he said, “if you’re going to be able to accept your Uncle Russ’s offer of a sailboat as a gift, and if you’re going to sail it on a three-day trip down from Cliffport, you’ll have to find someone with practical knowledge to help you do it.”

Sandy frowned in concentration. “Finding a sailor in Valley View is going to be like finding a ski instructor in the Sahara Desert!” he said. “Why, this town is almost one hundred miles inland from the ocean!”

“That’s true,” John Steele said; “but it seems to me that I once heard you and one of your friends talking about sailing. If I’m not mistaken, it was Jerry James, and it sounded to me at the time as if he knew what he was talking about.”

“Of course!” Sandy said, slapping his forehead in exasperation. “I don’t know why I didn’t think of it! Jerry was a Sea Scout in Oceanhead before his family moved to Valley View. It’s just that he’s become so much a part of this town that I forget he didn’t grow up here with the rest of us. I think he was a Sea Scout for about three years, and he had been sailing before he ever joined up. I’m sure he can do it!”

“Well,” his father said, “you’d better hunt him up fast and find out whether he can and will. Your uncle expects us to call him back within a couple of hours to give him an answer, because he’s leaving the country in two days and he wants to get this settled before he goes.”

He had hardly finished his sentence before Sandy was out of the workshop, on his bike, and tearing down the tree-shaded street. He was sure that Jerry would be able to do it! He remembered their conversation well, now that his father had reminded him of it, and he recalled that Jerry had said that he practically grew up on boats, and that they were the only thing that he missed since moving to Valley View. In the close friendship that had grown up between them in the last couple of years, Sandy could not think of one time that Jerry had promised something that he did not deliver. If he said he could do something, he could do it! Sandy smiled, remembering Jerry’s early days in Valley View, his modest admission that he “could play a little baseball,” and his first day on the diamond. Jerry had immediately shown himself to be the best high school catcher in the county. With Sandy as pitcher, they had developed into an almost unbeatable battery.

As he pedaled toward the drugstore owned by Jerry’s father, Sandy hoped that they would be able to carry their teamwork on in this new venture. He could still hardly believe his Uncle Russ’s offer of a sailboat, provided he could find someone to teach him how to sail. Like most boys, he had read and enjoyed sea stories, although many of the words used were strange and meaningless to him. In his reading, he had often pictured himself at sea, steering a tall ship through white-capped seas. A confused series of sailing words went through his mind: bow, stern, helm, topgallant sails, mizzen, poop deck, quarter-deck, galley, batten the hatches, go aloft....

He was suddenly brought back to land as he narrowly missed running his bike into Pepper March, who refused to hurry for a mere bike. Putting the sea dreams firmly out of his mind, he continued more carefully until he pulled up in front of James’s Drugstore, where he put his bike in the rack under the green-and-white striped awning and hurried into the cool, vanilla-smelling store.

Jerry was behind the counter, making up a pineapple ice-cream soda for Quiz Taylor who, with two empty glasses in front of him, was impatiently waiting for the third.

Sandy climbed onto the stool next to the stubby Quiz and impatiently waited until Jerry was through making the soda. When the concoction was safely delivered into Quiz’s eager hands, Sandy said, “Jerry, I’ve got some real exciting news! In fact, it’s so exciting that I didn’t want to tell you while you still had that soda in your hands. I was afraid you’d toss the whole thing into the air!”

Having firmly secured both his friends’ attention, Sandy told them about the phone call from his Uncle Russ, the offer of the boat, the need for instruction and the whole story. When he had finished, Jerry’s lantern-jawed face was lit up with a 500-watt grin.

“It sounds as if this is going to be the best vacation of my life!” he said. “A boat! I can hardly wait to get going!”

Sandy sighed with relief. “Then you’re sure you can handle it?” he asked.

“That’s a good question,” Jerry said, running a hand over his close-cropped inky hair. “To tell you the truth, I don’t know because you haven’t told me yet what kind of a boat it is. There are plenty that I wouldn’t even say I could act as a decent crew member on. Do you know what kind it is?”

“Why ... why ... it’s a sailboat!” Sandy said. “I mean, that’s all I know about it. Does it make much difference?”

Jerry laughed. “There are almost as many different kinds of boats as there are people,” he said. “Nobody but a real Master Mariner would just answer that he could sail anything. It’s like being an airplane pilot. If you got your pilot’s license flying a Piper Cub, you wouldn’t be exactly ready to fly a four-engine jet bomber!”

“Still,” Quiz interrupted thoughtfully, “the principle remains the same in both. It’s simply a question of creating a high-speed airstream, so directed as to pass over and under an aerodynamically shaped surface which, because of the varying degree of arc and the cambered sections and angle of attack, produces a lift, drag and momentum proportional to the density of the air, the square of the speed and the area of the wing or airfoil. It’s simple! What’s more, a sailboat works the same way.” Looking pleased with himself, Quiz happily returned his attention to the pineapple soda.

“Why, Quiz!” Sandy said. “I didn’t know you could fly!”

“Fly!” Quiz looked up from his soda with a grimace. “The very thought of flying makes me sick. If I don’t hold on to the banister, I get dizzy when I go up to bed at night!”

All three boys laughed, for this side of Quiz’s personality was a standing joke with them. Quiz, formally known as Clyde Benson Taylor, was a virtual encyclopedia of obscure information. While he could tell you vast amounts about nearly every human activity, the very idea of taking part in an activity usually upset him.

“So much for theory,” Jerry said. “Now, to get back to the practical realities of sailing a boat—I’d have to know a few things about the kind of sailboat you have before I’d be willing to give an answer. There are all kinds of boats, of all different sizes. There are sloops, cats, cutters, yawls, ketches, schooners and a hundred variations. Did your Uncle Russ give you any idea of what he has for you?”

“I think he said it was a sloop,” Sandy said. “And he did say that while it was large enough to sleep on and take out on a cruise, it was a pretty small boat. He said that anyone who knew how to sail would know how to handle it.”

“That sounds right to me,” Jerry said. “I didn’t think that he’d want to start you off with a complicated rig or a big boat. If it’s the kind of thing I think it is, I’m sure I can sail it, and teach you too.”

“Will I have to learn all about yardarms and fore-topgallant sails and things like that?” Sandy asked, somewhat doubtfully.

“Not for quite a while,” Jerry laughed. “You’ve been reading too many books about pirates and whalers in the old days. You only find all those complicated sail and rigging names on the big square-rigged ships—the ones with three and four masts. If your boat is a sloop, it only has one mast, one mainsail, and a choice of maybe three other sails, flown one at a time with the mainsail. There’s nothing much to learn compared with the old full-rigged ships with up to four masts.”

“Five,” Quiz said.

“I never heard of one with more than four,” Jerry commented.

As if he were reading from a book buried deep in his pineapple soda, Quiz mumbled around the straws, “The steel ship Preussen was the only five-mast full-rigged ship ever built. It was 408 feet long, had masts 223 feet high, yardarms over 100 feet long and 47 sails totaling 50,000 square feet.”

Even though Sandy was used to this sort of thing from Quiz, he was more impressed than usual. “How would you like to come with us, Quiz?” he asked.

“Who, me?” Quiz looked shocked. “I don’t know the first thing about boats! No, thanks—I’ll stay safe ashore!”

The next half hour was spent in excitedly discussing the trip to come, the possibilities of sailing, the things Sandy would have to learn, and the equipment that he and Jerry would have to take along. Finally Sandy remembered that his Uncle Russ was expecting a phone call, and that Jerry still had to get his parents’ permission to make the trip. They agreed to go back to Sandy’s house and let John Steele make the call to Jerry’s father so that the adults could satisfy themselves about the wisdom of letting the boys take a three-day cruise for Sandy’s first trip.

Leaving Quiz in charge of the drugstore’s soda fountain, they quickly hiked to the Steele home, where Sandy’s father agreed to make the call.

Getting Jerry’s parents’ consent to the trip proved not to be a difficult task. Mr. and Mrs. James obviously had a good deal of confidence in Jerry’s ability to handle a sailboat, and both sets of parents felt that their level-headed sixteen-year-olds could take such a trip on their own. In short order, all of the details were worked out, and Sandy was once more on the long-distance phone to speak with his Uncle Russ in San Francisco.

“It’s okay!” he shouted, as soon as his uncle answered the telephone. “Jerry James, my best friend, used to be a Sea Scout and knows all about boats. His parents say he’s a good sailor. We’re ready to start any time you want!”

He listened for a minute to his uncle, then said, “Swell! We’ll be ready. And thanks a million for the boat!” Hanging up the phone, he turned to his father, mother and Jerry with a wide grin.

“Uncle Russ sure doesn’t waste any time,” he said. “He’s leaving now and expects to be down here tonight. He says that we’d better get all packed and ready, because he wants to take us up to Cliffport tomorrow morning, and we’ll have to leave here by six o’clock!”

“There’s one good thing about riding in this little sports car,” Sandy said, and laughed as he eased his cramped six-foot length out of his Uncle Russ’s low-slung red racer. “It’s going to make the sailboat seem as roomy as a yacht in comparison!”

Sandy pushed his cowlick out of his eyes and stretched as his uncle and his friend Jerry followed him out of the little car.

“Don’t worry about the size of the boat,” Jerry said. “I’ll guarantee that it’s going to seem pretty big and complicated, no matter how small it actually is, until you’ve learned how to sail it. In fact, you’re going to find that a boat is a whole new world, full of all kinds of new things to get used to. And from what your uncle told us about this one, it’ll be more than big enough to keep us both busy for a couple of summers to come.”

“I feel as if we’re in a whole new world already,” Sandy replied, “and we’re not even on board yet!” He looked about him at the beehive of activity that was the Cliffport Boat Yard. “I’ve never seen anything like this before!”

From all sides came the sounds of hammering and sawing, and the thin whine of electric sanders. The brisk, salty smell of the sea was mingled with the sharp odors of paint, varnish and turpentine and the peculiar, half-sweet smell of marine engine fuel.

Boats of every size and description were ranged about them. Towering high above them, resting in specially built cradles, were long hulls with deep, weighted keels like giant fins under them. Heavy frames and timbers held these boats upright, and ladders leaned against them to where their decks joined their sides, high overhead. Men scrambled up and down the ladders with tools and equipment, or sat on the scaffolds and frames, painting.

Smaller craft without keels were braced in cradles or frames on the ground, or lay bottoms up on racks made of heavy beams that looked like railroad ties. Some of the boats were having their bottoms scraped, some were being sanded, others were in the process of painting.

At one nearby boat, Sandy saw men hammering on the bottom of the hull with big wooden mallets. Jerry explained that these were calking hammers, and that they were used to drive oakum into the seams between the planks to make the boats watertight for sailing. When the boats were put in the water later on, he added, the planks would swell and form waterproof joints where the planks met.

On both sides, lines of railroad tracks led from the boat yard and the big sheds straight down to the water’s edge and on into the water. Boats on wheeled flatcars stood on the rails here and there, ready to be eased down the tracks into the water for launching. Jerry explained how, when the flatcars with their cradles had gone down the slope and were under water, the boats simply floated away from them. Then the launching device would be hauled back up the tracks for use on another boat.

Sandy looked about him in bewilderment at the variety of boats in the yard. There were small boats with one mast, larger ones with two, cabin cruisers with no masts at all, and one sleek, beautiful, black-hulled boat with three tall masts. He was just beginning to think that he had found some relationship between the size of the boat and the number of masts when he spotted what appeared to be one of the largest hulls in the boat yard, with one immense mast. Next to it was a far smaller boat with two. Sandy thought to himself that there didn’t appear to be any simple rules to the business of boat designing. All in all the bustling Cliffport Boat Yard was a thoroughly confusing sight for Sandy, and a pretty exciting one, too.

As a matter of fact, the entire last two days had been pretty confusing and exciting, Sandy reflected. Just two days ago, he had started on his spring vacation from Valley View High School with not a thing to do but loaf around home. Now, suddenly, he was the owner of a sailboat he had never seen, and he was preparing to take a two-hundred-mile cruise down the coast! A two-hundred-mile cruise—and he had never even been on board a sailboat!

Looking at the maze of masts and rigging around him, Sandy sensed for the first time some of the complications of handling a boat. Laying a hand on his friend’s shoulder, he said, “Boy, Jerry, I sure hope you can sail this boat alone! If what I see around me is a sample, I’m afraid I’m going to be too confused to do more than just watch you and maybe ask a few simple-minded questions!”

“Don’t worry about it,” Jerry said with a grin. “It’s not anywhere near as complicated as it looks at first sight. I learned to handle a boat fairly well in just a few summers at the shore, plus some instruction in the Sea Scouts, and I didn’t even have my own boat so that I could sail regularly. One season of working your own boat will probably turn you into a first-rate skipper!”

Then Jerry frowned for a minute and ran his hand over his hair. “Speaking of being a skipper,” he began awkwardly, “you realize, I guess, that I’ll have to act as skipper of this boat at first? I mean, I know it’s your boat and all, but....”

Sandy laughed. “You go right ahead and take charge! I’ll be more than happy to take orders from you. After all, somebody on board has to be in charge, and it’s a good idea to have it be someone who knows what he’s in charge of!”

“Fine,” Jerry said, looking relieved. “If you just keep up that kind of attitude, you’ll be the best kind of a crew member that any skipper could ask for!”

Sandy’s Uncle Russ had been waiting by his car while the boys had been talking and taking in the sights, sounds and smells of the Cliffport Boat Yard. Now he moved over to join them. “The trunk of the car is open,” he said, “and your sea bags are in there. And that’s as much as I intend to do about it. I don’t know much about sailors, but if they’re anything at all like soldiers, they carry their own packs! Now let’s get going!”

The boys grinned sheepishly and ran to the back of the car to gather their equipment, and Russell Steele relaxed and dropped his mock military manner. An ex-general of the United States Army, he often kidded Sandy and his friends by pretending that they were soldiers in his command. This time, he reflected, it was very nearly true. In the same way that a general must feel a responsibility toward the men he sends out on a mission, Russell Steele felt responsible for Sandy and Jerry as they were preparing to set out on this trip.

After all, he reminded himself, the trip had been his idea, and the sailboat had been his present to Sandy. He had been using the boat during the last few months while doing some research on special underwater equipment for the government, and now he no longer had any need for it. As Vice President of World Dynamics Corporation, Russell Steele was in charge of the New Projects Division. World Dynamics was a sprawling concern with almost unlimited interests, often in the most secret kinds of affairs, and his work with it often called him to different parts of the world. He had found his stay in Cliffport a pleasant change from some of the remote and often primitive places he had been forced to settle in in the past. Now, however, he was off again, to one more secret destination. He wouldn’t be in a position to use a sailboat again for a long time to come.

Sandy’s Uncle Russ had been brought up on the seacoast of California. While his brother, Sandy’s father, had become fascinated with the rocks and geological formations of the nearby mountains and deserts, he had gone in the other direction to the shores of the Pacific. During nearly all of his boyhood he had puttered around boats and boat yards.

Although Russell Steele had spent most of his adult life in the Army (and maybe because of it) he had always had a soft spot in his heart for the sport of sailing. He had regretted that Sandy, his only nephew, lived inland in Valley View where he was unable to share in this enthusiasm. But Valley View was only a couple of hours from the seacoast and now that Sandy was old enough to drive a car, it would be possible for him to own and enjoy a sailboat.

Uncle Russ thought of all this, and then he wondered whether it had been a good idea to suggest that the boys bring the sloop all the way down from Cliffport on their very first sail. Still, he mused, Jerry seemed like a responsible lad, and he had said that he knew how to handle a boat well enough to make such a trip. And Sandy learned fast and was good with his hands. Well, the General thought to himself, we’ll just have to give them their heads and let them try it to see how they make out....

At that moment in his reflections, the boys joined him with their luggage, and all three started through the boat yard to the waterfront. As they picked their way through the clutter of boats, scrap lumber, railroad tracks and equipment, they passed close by the side of a boat standing on the ways about to be launched. Sandy ran his hand over the gleaming paintwork of the hull, and found that it was as smooth as glass. Jerry explained that great care was given to getting a smooth paint job, because the greatest force working against a boat to slow it down is the friction created by the water passing over the hull. Good racing boats, he told Sandy, are hauled out of the water to be cleaned and painted several times in a season.

Their walk had by now led them down to the water’s edge, where they walked along a weathered wharf. A light, early-morning haze made the colors of the sailboats that floated in the bay seem soft and pale. The water and the sky appeared to be one single surface, with no break or horizon line to indicate where one stopped and the other began. The boat-yard flag on its mast atop the main shed fluttered lazily in a mild breeze, and a gentle ground swell made soft, lapping sounds under the wharf.

Strolling along, they came to a long, steeply sloping gangway that descended to a floating dock, to which were tied several small sailboats that rocked quietly on the smooth swell of Cliffport Bay.

Russell Steele took his pipe out of his mouth and pointed with it. “See there?” he said. “The third sloop—the one with the white hull and the green decks and the varnished mast—that’s your new sailboat, Sandy, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I have.”

Before he had finished his sentence, Sandy and Jerry were down the steep gangway, racing along the floating dock to where the trim, white sloop was tied. Russ Steele smiled, replaced his pipe in his mouth, and followed at a pace almost as fast as the boys’.

“It’s a beauty!” Sandy panted, pushing his hair back from his eyes. “What slick lines! And look at how roomy the cabin is! And look at the height of the mast! And all that rigging!”

His grin faded, and a look of bewilderment spread across his face. “Boy, I can sure say that again! Just look at all that rigging! How am I supposed to know what to do with what and when to do it, Jerry?”

Jerry laughed, and jumped lightly into the small cockpit. “Come on board, skipper, and we’ll start your first sailing lesson by showing you around and telling you the names of things. It’s not half as complicated as it looks. In fact, this sloop rig is just about the simplest there is. As soon as you learn what to call things, you’ll have the hardest part of the lesson over with.”

Sandy followed Jerry into the cockpit, then paused to turn and face his uncle, who was still standing on the dock. “How about you, Uncle Russ?” he asked. “Will you stick around for a little while and take the first sail with us?”

“Thanks for asking, Sandy,” Russell Steele answered, “but much as I’d like to come along with you, I can’t manage it. I have to be back in my office this afternoon for an important conference. In fact, I’ll just about make it if I get started now. But before I get under way, and before you get carried away with the fine art of sailing, there are a few things that you’ll need to know.”

He talked rapidly and uninterruptedly for about five minutes and, when he had finished, Sandy appreciated for the first time how thoroughly well-organized his Uncle Russ was. His preparations for the boys’ trip had been complete in every last detail. Russell Steele’s practiced military mind had reviewed the situation and had missed nothing that might be needed.

The sailboat had been fully provisioned for more than a week of sailing, and had been equipped for every possible emergency as well as for a routine and pleasant cruise. The small cabin contained an alcohol cookstove and a good supply of canned food. Every locker and storage place was full, and everything put on board had been chosen with care and an eye for both comfort and necessity.

A complete tool chest was stowed in its cubby with several boxes of spare hardware, ship fittings, nuts and bolts, wire and odd tackle. A drawer under one of the bunks contained a whole assortment of fishing equipment. Another carried an odd mixture of things that the boys might want, even including clothespins for drying garments, and a sewing kit. A specially made bag contained another sewing kit, this one for sails and canvas repair.

In a narrow, hanging locker in the forward part of the cabin were two complete foul-weather suits consisting of waterproof pants and jackets with hoods. Below them were two pairs of sea boots.

Opposite this was the small enclosed “head,” sailor’s word for bathroom. No bigger than a telephone booth, it still managed to contain a toilet and a sink, plus a cabinet for medicines and first-aid supplies and another for towels, soap, toothbrushes and the like.

“The only things that you won’t find on board yet,” Russell Steele concluded, “are your sleeping bags and your air mattresses. I’ve ordered special ones that the local store didn’t have in stock, and they’re not due to arrive until tomorrow. For tonight, you’ll have to plan on sleeping ashore, but I’ve taken care of that for you, too. I’ve got a room reserved for you at the Cliffport Hotel. After tomorrow, you can sleep on board, like sailors.”

He scowled at his pipe for several seconds, as if he hoped to see in it some hint of anything that he might have forgotten to take care of, and he mentally checked each item again. Sails okay? Charts and navigating instruments in place? Food? Tools? Spare lines? Life jackets? Oars for the dinghy? Cleaning equipment? Sea anchor? Everything checked out. At last, satisfied that all was in good order, he smiled and clamped the pipe in his teeth again.

“I think,” he said, “the only thing I’ve forgotten is the seagoing way to say goodbye!”

He settled for “Ahoy!” and “Smooth sailing!” and, brushing off Sandy’s thanks, walked briskly up the gangway without turning back.

The boys watched him as he turned the corner of the main shed and walked out of sight, then they gave all their attention to a close survey of their new floating home.

“Well, Jerry, what do you think of it?” Sandy asked his friend, as he cast a proud eye along the sleekly shaped length of the little sloop.

“Not ‘it,’” Jerry said. “You should say ‘her.’ You always call boats ‘she’ or ‘her,’ though I’ve never met a sailor who could tell you why.”

Jerry looked critically down the twenty-four-foot length of the sloop. “She looks really seaworthy,” he said, “and she looks pretty fast, too. Of course, this is not a racing boat, you know. They use this kind mostly for day sailing and for short cruises. Even so, she looks as if she’ll go. Of course, we can’t really tell until we’ve tried her, and I don’t think we’ll be ready to try anything fast for a little while yet.”

Noticing the flicker of disappointment that crossed Sandy’s face, Jerry added, “I’d rather have a boat like this than any racing machine ever built. And I’m not saying that just to make you feel better about not having a racer. There’s not much difference in actual speed between a really fast boat and an ordinary good boat of the same size. But there sure is a lot of difference in comfort. And I like my comfort when I go for a cruise.”

“Why should a racing boat be uncomfortable?” Sandy asked.

“It’s not uncomfortable for racing, or for day sailing,” Jerry answered, “but a racing boat of this size wouldn’t be fitted out for cruising at all. You see, to get the most speed out of a boat, designers make sure that the hull is kept as light as possible and as streamlined as possible, too. A light hull will ride with less of its surface in the water, and that cuts down on the amount of friction. You remember what I told you about friction before?”

Sandy nodded, and Jerry went on. “Streamlining the hull shape helps it to cut through the water without making a lot of waves at the bow to hold it back. Not only that, but to make the boat really as fast as possible, most designers want to streamline the decks, too. That way, even the air resistance is lowered. Well, when you streamline the hull, you make less cabin space below. Then when you streamline the decks, you have to lower the cabin roof so that it’s level with the decks. You can see that in a small boat like this, you wind up with no cabin at all.”

“I see,” Sandy said. “But how does the lightness of the hull affect comfort? I’m not so sure I understand that.”

“When you have a light hull,” Jerry replied, “it’s a good idea to keep it light. If you overload it, you lose the advantage you built into it in the first place. That means that you can’t carry all the stuff we have on board to make for comfortable, safe cruising. Our bunks, the galley, the head, the spare anchor, all the tools and supplies—it adds up to a lot of weight. If you want a really fast boat, you have to leave all that stuff behind.”

“Then if this were a racing boat,” Sandy said, “we wouldn’t have anything more than a small cockpit and a lot of deck, with a little storage space! No wonder you said you’d rather have a boat like this! But there’s one thing I’d still like to know. You said that there wasn’t much difference in real speed between a racing boat and an ordinary good boat. How much is ‘not much’?”

Jerry thought for a minute. “Well—” he said, at length—“I’d have to know a lot more about boat design than I know to give you an accurate answer, but I can give you a rough idea. This is a twenty-four-foot boat. If it were a racing hull, you might get eight and a half or maybe even nine knots out of it under ideal conditions. For practical purposes, you can figure eight or less. A knot, by the way, is a nautical mile, and it’s a little more than a regular mile. When you say eight knots, you mean eight nautical miles an hour.”

“But that’s not fast!” Sandy objected. “You said that’s what a fast racing boat would do!”

Jerry smiled. “Believe me, Sandy,” he said, “when your boat is heeling way over and your decks are awash and your sails are straining full of wind, it seems like an awful lot of speed! You’ll see when we get out today. Besides, speed is all relative. A really dangerous speed on a bike would seem like a slow crawl in a car.”

“I guess you’re right,” Sandy answered. “But you didn’t tell me how fast this boat will go, compared to a racer.”

“I think we’ll get five or six knots out of her,” Jerry replied thoughtfully. “That’s not fast, but it’s only a couple of knots slower than the fastest. You see now what I mean?”

Sandy nodded, then said, “I’m with you, Jerry. Now that I know a little bit about it, I sure think you’re right. I’d much rather have a boat we can sleep on and take on trips up and down the coast than a racer that doesn’t even go so fast! Besides, I’d be pretty foolish to think about any other kind of boat at all, wouldn’t I? I don’t even have the least idea of how to sail this one yet! Come on, Jerry, start showing me!”

As Jerry carefully explained the different parts of the rigging, the complicated-looking series of wires and ropes around the mast began to look a whole lot simpler to Sandy. The first thing he learned was that not much of the rigging moved or was used for actual sailing of the boat. The parts that didn’t move were called “standing rigging,” and if you eliminated them from your thoughts, it made the “running rigging” comparatively easy to understand.

“You have to learn about the rigging first,” Jerry said. “The idea is simple enough. The standing rigging is used to support the mast and keep it from bending to either side or to the front or back when the sails start to put pressure on it. The standing rigging is every line or cable you see that comes from the top of the mast or near it down to the outer edge of the deck or to the bow or stern.”

Sandy looked about the little sloop, and noticed that this seemed to take care of more than half of what he saw.

“The running rigging,” Jerry went on, “is used to raise and lower the sails and to control their position to catch the wind when you’re sailing. The lines that are used to raise and lower the sails on the mast are called halyards. They work just like the ropes on a flagpole. The other kind of running rigging—the lines used to control the way the sails set—are called sheets. You’d think that a sheet was a sail, wouldn’t you? It isn’t, though. It’s the line that controls a sail.”

“I think I understand so far,” Sandy said, “but don’t you think it would be easier for me to learn if we went out for a sail and I could see everything working?”

“Right,” Jerry said. “That’s just what I was going to say next. Telling you this way makes me feel too much like a schoolteacher!”

Jerry decided that it would not be a good idea to try to sail away from the dock, because the part of the harbor they were in was so crowded. There would be little room to maneuver with only the light morning winds to help them. The best thing to do, he concluded, was to move the boat to a less crowded part of the harbor. At the same time, he would teach Sandy the way to get away from a mooring. In order to do all this, Jerry explained, they would row out in the dinghy, towing the sloop behind them. Once out in open water, they would tie the dinghy behind them and pull it along as they sailed.

Together they unlashed the dinghy, which was resting on chocks on the cabin roof. Light and easy to handle, the dinghy was no trouble at all to launch, and in a minute it was floating alongside, looking like a cross between a canoe and a light-weight bathtub.

Getting into the dinghy carefully, so as not to upset its delicate balance, they untied the sloop from the dock. Then they fastened the bow line of the sloop to a ring on the stern of the dinghy, got out the stubby oars and started to row.

At first, it took some strong pulling at the oars to start the sailboat moving away from the dock, and Sandy feared that they would tip over the frail cockleshell of the dinghy. But once the sloop started to move, Sandy found that it took surprisingly little effort to tow it along. It glided easily behind them, its tall mast swaying overhead, as they rowed slowly out into the waters of Cliffport Bay.

“We’ll find an empty mooring, and tie up for a few minutes,” Jerry said. “I don’t think that anyone will mind. I want to show you the method we’ll use most of the time for getting under way.” He pointed to the anchorage area, or “holding ground,” as it was called, and Sandy noticed several blocks of painted wood floating about. They had numbers, and some had small flags on them. “Those are moorings,” Jerry explained. “They’re just permanent anchors, with floats to mark the spot and to hold up the end of the mooring line. Every boat owner has his own mooring to come in to. The people who own these empty moorings are probably out sailing for the day, and we won’t interfere if we use one for a while.”

Easing back on the oars, they let the sloop lose momentum and came to a natural stop near one of the moorings. They transferred the bow line from the dinghy to the mooring and made the sloop fast in its temporary berth. Then they climbed back on board and tied the dinghy behind them. Jerry explained that a long enough scope of line should be left for the dinghy so as to keep it from riding up and overtaking the sloop, as accidents of this sort have been known to damage the bow of a fragile dinghy.

This done, Jerry busied himself by unlashing the boom and the rudder to get them ready to use, while Sandy went below for the sail bags. These were neatly stacked in a forward locker, each one marked with the name of the type of sail it contained. He selected the ones marked “main” and “jib,” as Jerry had asked him to, and brought them out into the cockpit.

Making the mainsail ready to hoist, Sandy quickly got the knack of threading the sail slides onto the tracks on the mast and the boom. He worked at this while Jerry made the necessary adjustments to the halyards and fastened them to the heads of the sails. When this job was done, Sandy slid the foot of the sail aft along the boom, and Jerry made it fast with a block-and-tackle arrangement which was called the “clew outhaul.”

“Now,” Jerry said, when they had finished, “it’s time to hoist the mainsail!”

“What about the mooring?” Sandy asked. “Don’t you want me to untie the boat from it first?”

“Not yet,” Jerry answered. “We won’t do that until we’re ready to go.”

“But won’t we start going as soon as we pull up the mainsail?” said Sandy, puzzled.

“No,” Jerry said. “Nothing will happen when we hoist the sail. It’s like raising a flag. The flag doesn’t fill with wind and pull at the flagpole like a sail, does it? It just points into the wind and flutters. That’s just what the mainsail will do. You see, the boat is already pointing into the wind, because the wind has swung us around on the mooring. You look around and you’ll see that all the boats out here are heading in the exact same direction, toward the wind. When we hoist the sail, it’ll act just like a flag, and flap around until we’re ready to use it. Then we’ll make it do what we want it to by using the jib and controlling its position with the sheets. Look.”

Jerry hauled on the main halyard, and the sail slid up its tracks on the mast, squeaking and grating. As it reached the masthead, it fluttered and bellied loosely in the wind, doing nothing to make the boat move in any direction. Motioning to Sandy to take his place tugging at the halyard, Jerry jumped down into the cockpit.

The halyard ran from the pointed head of the sail up through a pulley at the top of the mast, then down to where Sandy was hauling on it. Below his hands, it passed through another pulley near Sandy’s feet, then back along the cabin roof. Jerry, from his position in the cockpit, grabbed the end of the halyard and hauled tight, taking the strain from Sandy. Then he tied it down to a wing-shaped cleat on the cabin roof near the cockpit.

This was done with a few expert flips of the wrist. The mainsail was up, and tightly secured.

“There,” Jerry said. “Now we’re almost ready. We won’t move at all until we get the jib up, and even then we won’t move unless we want to. When we want to, we’ll untie from the mooring and get away as neat as you please.”

They then took the jib out of its sail bag and made ready to hoist it. Instead of securing to the mast with slides on a track the way the mainsail had, the jib had a series of snaps stitched to its forward edge. These were snapped around the steel wire forestay, a part of the standing rigging that ran from the bow of the boat to a position high up on the mast. The jib halyard was fastened to the head of the jib, the snaps were put in place, and a few seconds of work saw the jib hanging in place, flapping before the mast. Then Jerry asked Sandy to pick up the mooring that they had tied to, and to walk aft with it.

“When you walk aft with the mooring,” Jerry explained, “you actually put some forward motion on the boat. Then, when you get aft and I tell you to throw the mooring over, you put the bow a little off the wind by doing it.”

Sandy untied the bow line from the mooring, and walked to the stern of the boat, holding the mooring float as he had been told. Then, when Jerry said “Now!” he threw the mooring over with a splash.

“With the jib flying and the boat free from the mooring and no longer pointing directly into the wind,” Jerry said, “the wind will catch the jib and blow our bow even further off. At the same time, I’ll steer to the side instead of straight ahead. As soon as our bow is pointing enough away from the wind, the breeze will strike our sails from one side, and they’ll start to fill. When the sails have caught the wind right, I’ll ease off on the rudder, and we’ll be moving ahead.”

By this time, the morning haze had “burned off” and the light breeze had freshened into a crisp, steady wind. As the head of the little sloop “fell away” from the direction from which the wind was coming, the sails swelled, the boat leaned slightly to one side, and a ripple of waves splashed alongside the hull. Sandy looked back and saw that the bow of the dinghy, trailing behind them, was beginning to cut a small white wave through the water.

“We’re under way!” Jerry cried. “Come on over here, skipper! You take the tiller and learn how to steer your boat while I handle the sails and show you what to do!”

Sandy slid over on the stern seat to take Jerry’s place, and held the tiller in the position he had been shown, while Jerry explained how to trim the sails and how to go where you wanted to go instead of where the wind wanted to take you.

“I’ll take care of the sail trimming,” Jerry said. “All you have to do is keep the boat heading on the course she’s sailing now. The wind is pretty much at our backs and off to the starboard side. You have to keep it that way, and especially keep the stern from swinging around to face the wind directly. It’s not hard to do. Just pick a landmark and steer toward it.”

He looked ahead to where a point of land jutted out some miles off the mainland. A lighthouse tower made an exclamation mark against the sky.

“Just steer a little to the right of that,” he said, “and we can’t go wrong.”

“What if the wind shifts?” Sandy asked. “How can we tell?”

Jerry pointed to the masthead, where a small triangular metal flag swung. “Just keep an eye on that,” he said. “It’s called a hawk, and it’s a sailor’s weathervane.”

“With one eye on the lighthouse and one eye on the masthead,” Sandy laughed, “I’m going to look awfully silly!”

He leaned back in the stern seat with the tiller tucked under his arm. The little sloop headed steadily for the lighthouse, steering easily. Every few seconds, Sandy glanced at the hawk to check the wind. He grinned and relaxed. He was steering his own boat! The sail towered tall and white against the blue sky above him and the water gurgled alongside and in the wake behind where the dinghy bobbed along like a faithful puppy.

“This is the life!” he sighed.

Jerry pointed out a handsome, white-hulled, two-masted boat approaching them. “Isn’t that a beauty?” he said. “It’s a ketch. On a ketch, the mainmast is taller than the mizzen. That’s how you tell the difference.”

“How do you tell the difference between the mainmast and the mizzen?” Sandy asked. “You’re going to have to start with the simplest stuff with me.”

“The mainmast is always the one in front, and the mizzen is always the one aft,” Jerry explained. “A ketch has a taller main; a schooner has a taller mizzen; a yawl is the same as a ketch, except that the mizzen is set aft of the tiller. Got it?”

Sandy shook his head and wondered if he would ever get all of this straight in his head. It was enough trying to learn the names of things on his own boat without worrying about the names of everything on other boats in the bay.

As the ketch sailed by, the man at her tiller waved a friendly greeting. The boys waved back and Sandy watched the big ketch go smoothly past, wondering how much harder it might be to sail a two-masted boat of that size than it was to sail a relatively small sloop such as his own. Certainly it could not be as simple as the sloop, he thought. Why this little sailboat was a whole lot easier than it had seemed to be at first. As a matter of fact....

“Duck your head!” Jerry yelled.

Not even stopping to think, Sandy dropped his head just in time to avoid being hit by the boom, which whizzed past barely a few inches above him! With a sharp crack of ropes and canvas, the sail filled with wind on the opposite side of the boat from where it had been a moment before, and the sloop heeled violently in the same direction. Jerry grabbed at the tiller, hauled in rapidly on the mainsheet, and set a new course. Then, calming down, he explained to Sandy what had happened.

“We jibed,” he said. “That means that you let the wind get directly behind us and then on the wrong side of us. The mainsail got the wind on the back of it, and the wind took it around to the other side of the boat. Because the sheets were let out all the way, there was nothing to restrain the sail from moving, and by the time it got over, it was going at a pretty fast clip. You saw the results!”

Jerry adjusted the mainsail to a better position relative to the wind, trimming it carefully to keep it from bagging, then he went on to explain. “A jibe can only happen when you’ve got the wind at your back. That’s called sailing downwind, or sailing before the wind, or running free. It’s the most dangerous point of sail, because of the chance of jibing. When the wind is strong, an uncontrolled jibe like the one we just took can split your sails, or ruin your rigging, or even snap your boom or your mast. Not to mention giving you a real bad headache if you’re in the way of that boom!”

“I can just imagine,” Sandy said, thinking of the force with which the boom had whizzed by. Then he added, “You said something about an ‘uncontrolled jibe,’ I think. Does that mean that there’s some way to control it?”

“I should have said an accidental jibe instead of an uncontrolled one,” Jerry said. “A deliberate or planned jibe is always controlled, and it’s a perfectly safe and easy maneuver. All you have to do is to haul in on the sheet, so that the boom won’t have any room for free swinging. Then you change your course to the new tack, let out the sail, and you’re off with no trouble.”

Sandy grinned. “I’m afraid that description went over my head as fast as the boom did—only a whole lot higher up!”

“Things always sound complicated when you describe them,” Jerry said, “but we’ll do a couple later, and you’ll see how it works.”

“Fine,” Sandy agreed. “But until we do, how can I keep from doing any more of the accidental variety?”

“The only way to avoid jibing,” Jerry replied, “is never to let the wind blow from the same side that the sail is set on. This means that if you feel the wind shift over that way, you have to alter your course quickly to compensate for it. If you don’t want to alter your course, then you have to do a deliberate jibe and alter the direction of the sail. All it means is that you have to keep alert at the tiller, and keep an eye on the hawk, the way I told you, so that you always know which direction the wind is blowing from.”

“I guess I was getting too much confidence a lot too soon,” Sandy admitted, shamefaced. “There’s obviously a lot more to this sailing business than I was beginning to think. Anyway, a jibe is one thing I won’t let happen again. I’ll stop looking at other boats for a while, and pay more attention to this one! There’s more than enough to look at here, I guess.”

Once more, Sandy cautiously took the tiller from Jerry. Then he grinned ruefully and said, “Just do me one favor, will you, Jerry?”

“Sure. What?”

“Just don’t call me ‘skipper’ any more. Not for a while, at least!”

“Just keep her sailing on this downwind course,” Jerry said. “Head for that lighthouse the way you were before, and keep an occasional eye on the hawk. As long as the wind isn’t dead astern, we shouldn’t have any more jibing troubles. As soon as we get out into open water, we’ll find an easier point of sail. We can’t do that until we’re clear of the channel, though. When we are, we’ll reach for a while, and then I’ll show you how to beat.”

“What’s reaching?” Sandy asked. “And what’s beating? And how do you know when we’re out of the channel into open water? And how do you even know for sure that we’re in the channel now? And how....”

“Whoa! Wait a minute! Let’s take one question at a time. A reach is when you’re sailing with the wind coming more from the side than from in front or from behind the boat. Beating is when the wind is more in front than on the side, and you have to sail into it. Beating is more like work than fun, but a reach is the fastest and easiest kind of a course to sail. That’s why I want to reach as soon as we’re out in open water where we can pick our direction without having to worry about channel markers.”

“How come reaching is the fastest kind of course to sail?” Sandy asked. “I would have guessed that sailing downwind with the wind pushing the boat ahead of it would be the fastest.”

“It sure seems as if it ought to work that way,” Jerry said with a grin. “But you’ll find that sailboat logic isn’t always so simple or easy. When you’re running free in front of the wind, you can only go as fast as the wind is blowing. When you’re reaching, you can actually sail a lot faster than the wind.”

“I’m afraid that I don’t understand that,” Sandy said. “How does it work?”

Jerry paused and thought for a minute. “You remember what Quiz said about the sailboat working like an airplane? Well, he made it sound pretty tough to understand, what with all his formulas and proportions, but actually he was right. A sail is a lot like an airplane wing, except that it’s standing up on end instead of sticking out to one side. Well, you know that the propellers on a plane make wind, and that the plane flies straight into that wind. You see, the wind that comes across the wing makes a vacuum on top of the wing surface, and the plane is drawn up into the vacuum. You get a lot more lift that way than if the propellers were under the wing and blowing straight up on the bottom of it.”

“I see that,” Sandy said. “And a propeller blowing under a wing would be pretty much the same as a wind blowing at the back of a sail. Right?”

“Right!” Jerry said, looking pleased with his teaching ability. “Now you have the idea. When you have a sail, like a wing standing up, the air that passes over the sail makes a vacuum in front and pulls the boat forward into it. Actually, the vacuum pulls us forward and to one side, the same as the wind from the propeller makes the plane go forward and up. We use the rudder and the keel to keep us going more straight than sideways.”

Sandy shook his head as if to clear away cobwebs. “I think that I understand now, but it’s still a little hazy in my mind. Maybe I’ll do better if you don’t tell me about the theory, and I just see the way it works.”

“Could be,” Jerry said. “There are lots of old-time fishermen and other fine sailors who have absolutely no idea of how their boats work, and who wouldn’t know a law of physics or a principle of aerodynamics if it sat on their mastheads and yelled at them like a sea gull! They just do what comes naturally, and they know the way to handle a boat without worrying about what makes it run.”

Still heading on their downwind course, they passed several small islands and rocks, some marked with lights and towers, some with bells or floating buoys. They seemed to slide by gracefully as the little sloop left the mainland farther behind in its wake.

“Before we get out of the channel,” Jerry said, “I want to show you some of the channel markers and tell you about how to read them. They’re the road signs of the harbors, and if you know what they mean and what to do about them, you’ll never get in any trouble when it comes to finding your way in and out of a port.”

He pointed to a nearby marker that was shaped like a pointed rocket nose cone floating in the water. It was painted a bright red, and on its side in white was painted a large number 4.

“That’s called a nun buoy,” Jerry told Sandy. “Now look over there. Do you see that black buoy shaped just like an oversized tin can? That’s called a can buoy. The cans and the nuns mark the limits of the channel, and they tell you to steer between them. The rule is, when you’re leaving a harbor, to keep the red nun buoys on your port side. That’s the left side. When you’re entering a harbor, keep the red nun buoys on your starboard side. The best way to remember it is by the three R’s of offshore navigating: ‘Red Right Returning.’”

Sandy nodded. “I understand that all right,” he said. “But what are the numbers for?”

“The numbers are to tell you how far from the harbor you are,” Jerry said. “Red nun buoys are always even-numbered, and black cans are always odd-numbered. They run in regular sequence, and they start from the farthest buoy out from the shore. For example, we just sailed past red nun buoy number 4. That means that the next can we see will be marked number 3, and it will be followed by a number 2 nun and a number 1 can. After we pass the number 1 can, we’ll be completely out of the channel, and we’ll have open water to sail in.”

“Do they have the same kind of markers everywhere,” Sandy asked, “or do you have to learn them specially for each port that you sail in?”

“You’ll find the same marks in almost every place in the world,” Jerry said. “But you won’t have to worry about the world for a long while. The important thing is that the marking and buoyage system is the same exact standard for every port in the United States and Canada.”

“What’s that striped can I see floating over there?” Sandy asked, pointing.

Jerry looked at the buoy. “That’s a special marker,” he answered. “All of the striped buoys have some special meaning, and it’s usually marked on the charts. They’re mostly used to mark a junction of two channels, or a middle ground, or an obstruction of some kind. You can sail to either side of them, but you shouldn’t go too close. At least that’s the rule for the horizontally striped ones. The markers with vertical stripes show the middle of the channel, and you’re supposed to pass them as close as you can, on either side.”

Another few minutes of sailing brought them past the last red buoy, and they were clear of the marked channel. From here on they were free to sail as they wanted, in any direction they chose to try.

For the next hour they practiced reaching. With the wind blowing steadily from the starboard side, the trim sloop leaned far to the port until the waves were creaming almost up to the level of the deck. Jerry explained that this leaning position, called “heeling,” was the natural and proper way for a sailboat to sit in the water. The only way that a boat could sail level, he pointed out, was before the wind. With the boat heeling sharply and the sails and the rigging pulled tight in the brisk breeze, Sandy really began to feel the sense of speed on the water, and understood what Jerry had told him about speed being relative.

After they had practiced on a few long reaches, Jerry showed Sandy how to beat or point, which is the art of sailing more or less straight into the wind.

“Of course you can’t ever sail straight into the wind,” Jerry said. “The best you can do is come close. If you head right into it, the sails will just flap around the way that they did when we were pointing into the wind at the mooring. You’ve got to sail a little to one side.”

“Suppose you don’t want to go to one side?” Sandy asked. “If the wind is blowing straight from the place you want to get to, what do you do about it?”

“You have to compromise,” Jerry replied. “You’ll never get there by aiming the boat in that direction. What you have to do is sail for a point to one side of it for a while, then come about and sail for a point on the other side of it for a while. It’s a kind of long zigzag course. You call it tacking. Each leg of the zigzag is called a tack.”

Sailing into the wind, they tacked first on one side, then on the other. Each time they came about onto a new tack, the mainsail was shifted to the other side of the boat, and the boat heeled in the same direction as the sail. The jib came about by itself, just by loosening one sheet and taking up on the other one. Soon Sandy was used to the continual shifting and resetting of the sails, and to the boom passing back and forth overhead.

Suddenly Sandy pointed and clapped Jerry on the shoulder with excitement. “Look!” he cried. “There’s a whole fleet of boats coming this way! They look just like ours! And they’re racing!”

Jerry looked up in surprise. “They sure are racing! And they are just like this one! I guess I was wrong when I said they didn’t race this kind of boat. This must be a local class, built to specifications for local race rules. Boy, look at them go! I was wrong about not racing them, but I sure was right when I said that she looked fast!”

The fleet of sloops swept past, heeling sharply to one side, with the crews perched on the high sides as live ballast, and the water foaming white along the low decks which were washed over completely every moment or so. The helmsmen on the nearest of the boats grinned at them and waved an invitation to come along and join the regatta, but neither Jerry nor Sandy felt quite up to sailing a race just yet.

As they watched their white-sailed sisters fly down the bay, Sandy felt for the first time the excitement that could come from handling a boat really well. He turned to his own trim craft with renewed determination to learn everything that Jerry could teach him, and maybe, in due time, a whole lot more than that.

The next few hours were spent in happily exploring Cliffport Bay and trying the sloop on a variety of tacks and courses to learn what she would do. Eventually, the sun standing high above the mast, they realized almost at the same time that it was definitely time for lunch.

Jerry took the helm and the sheet while Sandy went below to see what the boat’s food locker could supply. In a few minutes, he poked his head out of the cabin hatch and shook it sadly at Jerry. “It looks as if Uncle Russ didn’t think of everything, after all. There’s plenty of food all right, but there’s not a thing on board to drink. The water jugs are here, but they’re bone-dry, and I’m not exactly up to eating peanut butter sandwiches without something to wash them down!”

“Me either!” said Jerry, shuddering a little at the thought. “Of course, we could settle on some of the juice from the canned fruits I saw in there, but we haven’t taken on any ice for our ice chest, and that’s all going to be pretty warm. In any case, we ought to have some water on board. I think we’d better look for a likely place near shore where we can drop anchor. Then we can take the dinghy in to one of the beach houses and fill up our jugs.”

“Good idea,” Sandy agreed. “And that way we can eat while we’re at anchor, and not have to worry about sailing and eating at the same time.”

Several small islands not too far away had houses on them, and the boys decided to set a course for the nearest one. As they drew near, they saw a sunny white house sitting on the crest of a small rise about a hundred yards back from the water. Below the house, a well-protected and pleasant-looking cove offered a good place for an anchorage. A floating dock was secured to a high stone pier, from which a path could be seen leading up to the house. It looked like an almost perfect summer place, set in broad green lawns, with several old shade trees near the house and with a general atmosphere of well-being radiating from everything.

They glided straight into the little cove, then suddenly put the rudder over hard and brought the sloop sharply up into the wind. The sails flapped loosely, and the boat lost some of its headway, then glided slowly to a stop.

On the bow, Sandy stood ready with the anchor, waiting for Jerry to tell him when to lower it. As the boat began to move a little astern, backing in the headwind, Jerry told Sandy to let the anchor down slowly.

“You never drop an anchor, or throw it over the side. After all, you want the anchor to tip over, and to drive a hook into the bottom. It won’t do that if it’s just dropped.”

When Sandy felt the anchor touch the bottom, he pulled back gently on the anchor line until he felt the hook take hold. Then, leading the line through the fair lead at the bow, he tied it securely to a cleat on the deck.

Loosening the halyards, they dropped first the jib and then the mainsail, rolled them neatly, and secured them with strips of sailcloth, called stops. Jerry pointed out that it was not necessary to remove the slides and snaps. That way, he explained, it would only be a matter of minutes to get under way when they wanted to. With the last stop tied and the boom and the rudder lashed to keep them from swinging, the sloop was all shipshape at anchor, rocking gently on the swell about fifty yards from the end of the floating dock.

“Let’s row the dinghy in to the dock and see if we can find somebody on shore,” Jerry suggested. “Of course, with no boats in here, there might not be anyone on the island right now, but I think that I saw a well up by the house, and I’m sure that no one would mind if we helped ourselves to a little water.”

But Jerry was wrong on both counts. There was somebody on the island, and he looked far from hospitable. In fact, the tall man who came striding down the path to the float where the boys already had the dinghy headed was carrying a rifle—and, what was more, he looked perfectly ready to use it at any minute!

“Turn back!” he shouted, as he reached the edge of the stone pier. “Turn back, I tell you, or I’ll shoot that dinghy full of holes and sink it right out from under you!” He raised the rifle deliberately to his shoulder and sighted down its length at the boys.

“Wait a minute!” Sandy shouted back. “You’re making a mistake! We just need to get some water to drink! We don’t mean any harm!”

The man lowered his rifle, but looked no friendlier than before. “I don’t care what you want,” he called, “but you can just sail off and get it some other place! This is my island and my cove. They’re both private property, and you’re trespassing here! Now turn that dinghy around and get back to your sailboat and go!”

This speech finished, he raised his rifle to the firing position once more and aimed it at the dinghy.

“All right, mister!” Jerry yelled back at him. “We’ll get going! But when we get back to the mainland, you can bet that we’re going to report you to the Coast Guard for your failure to give assistance! I’m not sure what they can do about it, but they sure ought to know that there’s a character like you around here! Maybe they’ll mark it on the charts, so that sailors in trouble won’t waste their time coming in here for help!”

As the boys started to turn the dinghy about, they heard a shout from the man on the pier. “Wait a minute!” he called. “There’s no need to get so upset. I’m sorry—but I guess I made a mistake after all. Row on in to the float and I’ll get you some water.”

Not at all sure that they were doing the wisest thing, but not wanting to anger the strange rifleman by not doing what he had suggested, they decided to risk coming to shore. After all, Sandy reasoned, he hadn’t actually threatened to shoot them—just the dinghy—and he couldn’t do much more harm from close up than from where they were. Besides, both boys were curious about the man and his island. They rowed to the floating dock and made the dinghy fast to a cleat.

“I’m sorry, boys,” the man with the rifle said pleasantly. “It’s just that I’ve been bothered in the past by kids landing here for picnics and swimming parties when I’m not here. They leave the beach a mess, and one gang actually broke into the house once, and stole some things. That’s why I don’t like kids coming around. I thought you were more of the same, but I figured you were all right when you said that you’d report to the Coast Guard. Those other kids stay as far away from the Coast Guard and the Harbor Police as they can.”

He smiled apologetically, but as Sandy started to climb up from the dinghy to the floating dock, his expression hardened once more.

“I said that I’d get you some water,” he said, “but I didn’t invite you to come ashore and help yourselves to it. You just stay right where you are in that dinghy, and hand me up your water jars. I’ll fill them up for you, and I’ll be back in a few minutes.”

More than a little puzzled, Jerry and Sandy handed up their two soft plastic gallon jugs. Their “host” took them under one arm, leaving the other hand free for his rifle which he carried with a finger lying alongside of the trigger. Without a word, the island’s owner walked off.

“I wonder what’s the matter with him,” Jerry said.

“I don’t know,” Sandy replied, “but whatever it is, we’d better do what he says, or something pretty bad might be the matter with us!”

Halfway up the path to the house, the tall man stopped, turned back, and looked hard at the boys before continuing on up the hill.

“Mind you do just what I said!” he shouted back over his shoulder. “You just stay in that dinghy, and don’t get any fancy ideas about exploring around. If I find you ashore, I’m still as ready as ever to use this gun!”

Unpredictable as the wind, the man was all smiles when he returned with the two jars filled with water. But he still had his gun.

“I’m glad to see you stayed put in your dinghy,” he said. “I kept an eye on you from the hill.” He handed down the plastic jugs to Sandy and added, “Sorry I acted so gruff, but you know how it is. I live all alone out here, and even though the island is only a little over a half mile from the mainland it’s a pretty isolated spot. I have to be careful of strangers. But I should have seen right away that you boys are all right.”

“Thanks,” said Sandy. “And thanks for filling our water jugs. We’re sorry we bothered you.”

They cast the dinghy free, rowed quickly back to the sloop and, as fast as they could manage it, raised the anchor, hoisted the sails and skimmed out of the cove. As they rounded the rocky point that marked the entrance to the cove, they looked back to where the island’s lone inhabitant was standing on the dock, watching them out of sight, his rifle still held ready at his hip.

“Boy, that’s a strange one!” Sandy said. “I wonder what he’s hiding on that island of his—a diamond mine?”

“You never can tell,” Jerry replied, “but it’s probably nothing at all. I guess the kind of man who would want to live all alone on an island away from people is bound to be pretty crazy about getting all the privacy he can. And as far as I’m concerned, he can have it. From now on, if we need anything, let’s head for the mainland!”

Dismissing the mysterious rifleman from their minds, they set out once more to enjoy the pleasures of a brisk wind, blue sky and a trim boat.

The afternoon went swiftly by as Sandy learned more and more about handling his boat, and about the boats they saw sailing near them. Jerry pointed out the different types of boats, explaining more fully than before that the ones with one mast were called sloops, the two-masted boats were called yawls, ketches and schooners. Telling one from the other was a matter of knowing the arrangement of masts. The ketches had tall mainmasts and shorter mizzens behind them. The yawls had even shorter mizzens, set as far aft as possible. Schooners, with taller mizzen than main, were relatively rare.

Jerry also pointed to varied types of one-masted boats. Not all of them, he told Sandy, were sloops, though most were. The sloops had their mast stepped about one third back from the bow. Cutters had their mast stepped nearly in the center of the boat. In addition, they saw a few catboats, with their single masts stepped nearly in the bows.

Learning all this, plus trying to absorb all that Jerry was telling him about harbor markers, sail handling, steering, types of sails and conditions under which each sail is used, Sandy found the time flying by. Almost before he realized it, the sun was beginning to set and the boats around them were all heading back up the channel to find their moorings and tie up for the night.

Everywhere they looked, the roadstead of Cliffport Bay was as busy as a highway. Sailboats of every description, outboard motorboats, big cabin cruisers, high-powered motor racers, rowboats, canoes, sailing canoes, kayaks, power runabouts, fishing excursion boats and dozens of other craft were making their way to shore.

The afternoon, which had started so brightly, had become overcast, and the sun glowed sullenly behind a low bank of clouds. The breeze which had been steady but light during the late afternoon hours, suddenly picked up force and became a fairly hard wind. It felt cold and damp after the hot day. Joining the homebound pleasure fleet, Sandy and Jerry picked their way through the now crowded harbor, back to Cliffport Boat Yard.

They arrived in a murky twilight, just a few minutes before the time when it would have become necessary for them to light the lanterns for the red and green running lights demanded by the International Rules of the Road.

The boys decided to drop anchor in the boat yard’s mooring area, rather than tow the boat back to the float where it had been tied. This would make it unnecessary to tow the sloop out again for the next day’s sailing, when they would start on the long trip home.

They dropped the sails, removed their slides and snaps on mast, boom and forestay, and carefully folded them for replacement in the sail bags. These were stowed below in their locker just forward of the cabin. Then Sandy and Jerry turned their attention to getting the boat ready for the night.

Sandy helped Jerry rest the boom in its “crutch,” a piece of wood shaped like the letter Y, which was placed standing upright in a slot in the stern seat. This kept the boom from swinging loose when the boat was unattended, and thus protected both the boat, the boom and the rigging from damage. All the running gear was then lashed down or coiled and put away, the sliding cabin door and hatch cover were closed in place, and the sloop was ready to be left.

“That’s what’s meant by ‘shipshape,’” Jerry said with satisfaction.

As the boys rowed the dinghy back to the float, they felt the first fat drops of rain and they noticed how choppy the still waters of the bay had become. Jerry cast a sailor’s eye at the ominously darkening sky.

“That’s more than evening coming on,” he said. “Unless I miss my guess, we’re in for a good storm tonight. To tell you the truth, I’m glad we’re staying ashore!”

They lifted the dinghy from the water, turned it over on the float and placed the stubby oars below it. Then, picking up their sea bags, they ran for the shelter of the shed as the first torrential downpour of the storm washed Cliffport in a solid sheet of blinding rain.

Later that night, after a change of clothes, dinner, and a movie at Cliffport’s only theater, the boys sat on their beds in the hotel room and listened to the howling fury of the storm. Raindrops rattled on the windowpanes like hailstones, and through the tossing branches of a tree they could see the riding lights of a few boats in the harbor, rocking violently to and fro. As they watched, the wind sent a large barrel bowling down the street to smash against a light pole, bounce off and roll, erratic as a kicked football, out of sight around a corner.

“It’s a good thing we anchored out,” Jerry said, watching this evidence of the storm’s power. “The boat could really have gotten banged up against the float if we had tied it up where it was before!”

“Do you think it’ll be safe where it is now?” Sandy asked anxiously.

“Oh, a little wind and water won’t bother a good boat,” Jerry answered. “After all, it was made for wind and water! Still....” He scowled and shook his head doubtfully.

“Still what?” Sandy said with alarm. “Is there something wrong with the way we left it?”

“Not really,” Jerry said. “I’m just worried about one thing. We’re not tied to a permanent mooring, the way the other boats around here are. That means that we might drag anchor in a storm as bad as this one, and if we happen to drag into deep water where the anchor can’t reach the bottom, the boat could drift a long ways off until it hooked onto something again. And there’s always the chance that it could get washed up on the rocks somewhere, first!”

With this unhappy thought in mind, the boys stared out the window for some time in silence as the storm continued unchecked. Finally, knowing that worry couldn’t possibly help, and that a good night’s sleep would prepare them to meet whatever the morning would bring, they turned out the lights and went to bed.

But, for Sandy, bed was one thing—sleep was another. Although Jerry managed to drop off to slumber in no time, Sandy lay a long time awake staring at the shadows of the tossing tree on the ceiling of the hotel room.

His mind was full of the events of the crowded day. It had been quite a day, starting with the ride in his uncle’s sports car, and proceeding to the new boat and learning to sail. Then the mysterious man on the island, keeping guard with his ever-present rifle, and concluding with a night of powerful storm. He reviewed all this, and mixed with his recollection his new worries about the safety of his boat. A series of images crowded his mind—a vision of the smart sloop lying smashed against some rocky piece of shore was mingled with a memory of the pleasures of his first day of sailing; and somewhere, behind and around all of his thoughts, was the unpleasantly frightening memory of the man with the gun, waiting on his hermit’s island.

All of this mingled in his mind with the sound of the storm until Sandy slipped into an uncertain, restless sleep—a sleep filled with vague, shadowy dreams, connected only by a sense that somewhere, something was wrong.

The next morning, when Sandy and Jerry awoke, the storm that had lashed Cliffport had vanished as if it, too, had been a bad dream.

Cliffport’s Main Street, which fronted the bay, was washed clean, and sparkled in the bright morning light. The bay waters themselves even looked cleaner than before, freshly laundered blue and white, with silver points of sunlight sprinkled over their peaceful surface. It was, in short, a perfect sailing day, and the boys could hardly wait to get down to the boat yard to see if the sloop had ridden the storm at anchor.

They dressed hurriedly in their sailing clothes—blue jeans, sneakers and sweat shirts—and bolted breakfast in the hotel coffee shop. Then, sea bags slung over their shoulders, they raced down the street to the Cliffport Boat Yard, rounded the corner of the main shed and, at the head of the gangway, came to a stop.

Sandy felt a sick, sinking feeling as he scanned the mooring area, searching vainly for a sight of his sloop. But where she had ridden at anchor the night before, there was only a patch of calm blue water.

It hardly seemed possible that she wasn’t there. The storm, on this bright, sunny morning, seemed never to have happened. Other boats rode peacefully at their moorings, apparently untouched by the night’s wild work. Life in the boat yard and on the bay went on as if nothing had occurred. But Sandy felt as if it were the end of the world.

Slowly and silently, the boys walked down the gangway to where their dinghy lay like a turtle, unharmed. They anxiously scanned the bay on all sides, searching for a mast that might be theirs, but to no avail. Then Jerry straightened up and clapped Sandy on the shoulder.

“Come on,” he said. “There’s no use standing here moping. The only thing to do now is to take out the dinghy and start to hunt.”

They launched the dinghy, put out the stubby oars, and rowed away from the float.

“Where do we look first?” Sandy asked.

“We’ll just go the way the wind went,” Jerry said. “Luckily, the storm came from the mainland and blew out to sea. That means there’s a good chance that the boat didn’t pile up on the shore. Of course, there are a lot of islands out there, and plenty of rocks, but there’s a lot more open water. With any luck we’ll find her floating safe and sound, somewhere out in the bay. I don’t think she could have gone too far dragging that anchor.”

They headed down the channel, taking occasional side excursions around some of the small islands whenever they saw, on the other side, a mast that could be theirs. But none of the boats they found was the right one. The hot sun made rowing even the light cockleshell of the dinghy unpleasant work. Sandy paused at the oars and pushed back his cowlick, then wiped his perspiring brow. He was beginning to fear that he would never again see his trim new sloop—unless he was to see it lying shattered on one of these rocky islands. Then, with dogged determination, he picked up his oars once more and bent his back to the task of rowing.