Title: Titan of Chasms: The Grand Canyon of Arizona

Author: C. A. Higgins

Charles Fletcher Lummis

John Wesley Powell

Release date: October 31, 2015 [eBook #50355]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan, the Mo-Ark

Regional Railroad Museum at Poplar Bluff, Missouri and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE TITAN OF CHASMS

By C. A. HIGGINS

THE SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER

By J. W. POWELL

THE GREATEST THING IN THE WORLD

By CHAS. F. LUMMIS

Fortieth Thousand

PASSENGER DEPARTMENT

THE SANTA FE

CHICAGO, 1903.

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. Bright Angel Creek and North Wall of the Canyon.

The Colorado is one of the great rivers of North America. Formed in Southern Utah by the confluence of the Green and Grand, it intersects the northwestern corner of Arizona, and, becoming the eastern boundary of Nevada and California, flows southward until it reaches tidewater in the Gulf of California, Mexico. It drains a territory of 300,000 square miles, and, traced back to the rise of its principal source, is 2,000 miles long. At two points, Needles and Yuma on the California boundary, it is crossed by a railroad. Elsewhere its course lies far from Caucasian settlements and far from the routes of common travel, in the heart of a vast region fenced on the one hand by arid plains or deep forests and on the other by formidable mountains.

The early Spanish explorers first reported it to the civilized world in 1540, two separate expeditions becoming acquainted with the river for a comparatively short distance above its mouth, and another, journeying from the Moki Pueblos northwestward across the desert, obtaining the first view of the Big Canyon, failing in every effort to descend the canyon wall, and spying the river only from afar.

Again, in 1776, a Spanish priest traveling southward through Utah struck off from the Virgin River to the southeast and found a practicable crossing at a point that still bears the name “Vado de los Padres.”

For more than eighty years thereafter the Big Canyon remained unvisited except by the Indian, the Mormon herdsman, and the trapper, although the Sitgreaves expedition of 1851, journeying westward, struck the river about 150 miles above Yuma, and Lieutenant Whipple in 1854 made a survey for a practicable railroad route along the thirty-fifth parallel, where the Santa Fe Pacific has since been constructed.

The establishment of military posts in New Mexico and Utah having made desirable the use of a waterway for the cheap transportation of supplies, in 1857 the War Department dispatched an expedition in charge of Lieutenant Ives to explore the Colorado as far from its mouth as navigation should be found practicable. Ives ascended the river in a specially constructed steamboat to the head of Black Canyon, a few miles below the confluence of the 4 Virgin River in Nevada, where further navigation became impossible; then, returning to the Needles, he set off across the country toward the northeast. He reached the Big Canyon at Diamond Creek and at Cataract Creek in the spring of 1858, and from the latter point made a wide southward detour around the San Francisco Peaks, thence northeastward to the Moki Pueblos, thence eastward to Fort Defiance, and so back to civilization.

That is the history of the explorations of the Colorado up to forty years ago. Its exact course was unknown for many hundred miles, even its origin being a matter of conjecture. It was difficult to approach within a distance of two or three miles from the channel, while descent to the river’s edge could be hazarded only at wide intervals, inasmuch as it lay in an appalling fissure at the foot of seemingly impassable cliff terraces that led down from the bordering plateau; and to attempt its navigation was to court death. It was known in a general way that the entire channel between Nevada and Utah was of the same titanic character, reaching its culmination nearly midway in its course through Arizona.

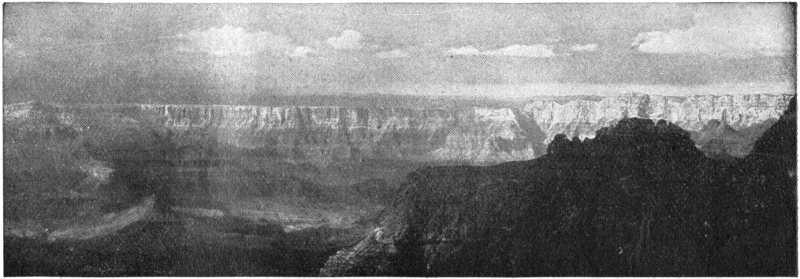

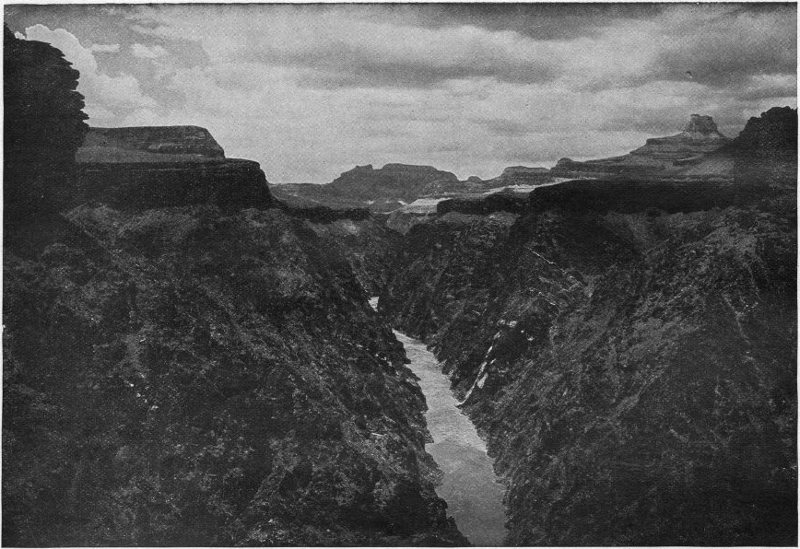

The Colorado, Foot of Bright Angel Trail.

In 1869 Maj. J. W. Powell undertook the exploration of the river with nine men and four boats, starting from Green River City, on the Green River, in Utah. The project met with the most urgent remonstrance from those who 5 were best acquainted with the region, including the Indians, who maintained that boats could not possibly live in any one of a score of rapids and falls known to them, to say nothing of the vast unknown stretches in which at any moment a Niagara might be disclosed. It was also currently believed that for hundreds of miles the river disappeared wholly beneath the surface of the earth. Powell launched his flotilla on May 24th, and on August 30th landed at the mouth of the Virgin River, more than one thousand miles by the river channel from the place of starting, minus two boats and four men. One of the men had left the expedition by way of an Indian reservation agency before reaching Arizona, and three, after holding out against unprecedented terrors for many weeks, had finally become daunted, choosing to encounter the perils of an unknown desert rather than to brave any longer the frightful menaces of that Stygian torrent. These three, unfortunately making their appearance on the plateau at a time when a recent depredation was colorably chargeable upon them, were killed by Indians, their story of having come thus far down the river in boats being wholly discredited by their captors.

Powell’s journal of the trip is a fascinating tale, written in a compact and modest style, which, in spite of its reticence, tells an epic story of purest heroism. It definitely established the scene of his exploration as the most wonderful geological and spectacular phenomenon known to mankind, and justified the name which had been bestowed upon it—The Grand Canyon—sublimest of gorges; Titan of chasms. Many scientists have since visited it, and, in the aggregate, a large number of unprofessional lovers of nature; but until a few years ago no adequate facilities were provided for the general sight-seer, and the world’s most stupendous panorama was known principally through report, by reason of the discomforts and difficulties, of the trip, which deterred all except the most indefatigable enthusiasts. Even its geographical location is the subject of widespread misapprehension.

Its title has been pirated for application to relatively insignificant canyons in distant parts of the country, and thousands of tourists have been led to believe that they saw the Grand Canyon, when, in fact, they looked upon a totally different scene, between which and the real Grand Canyon there is no more comparison “than there is between the Alleghanies or Trosachs and the Himalayas.”

There is but one Grand Canyon. Nowhere in the world has its like been found.

Stolid, indeed, is he who can front the awful scene and view its unearthly splendor of color and form without quaking knee or tremulous breath. An inferno, swathed in soft celestial fires; a whole chaotic under-world, just emptied of primeval floods and waiting for a new creative word; eluding all sense of perspective or dimension, outstretching the faculty of measurement, overlapping the confines of definite apprehension; a boding, terrible thing, unflinchingly real, yet spectral as a dream. The beholder is at first unimpressed by any detail; he is overwhelmed by the ensemble of a stupendous panorama, a thousand square miles in extent, that lies wholly beneath the eye, as if he stood upon a mountain peak instead of the level brink of a fearful chasm in the plateau, whose opposite shore is thirteen miles away. A labyrinth of huge architectural forms, endlessly varied in design, fretted with ornamental devices, festooned with lace-like webs formed of talus from the upper cliffs and painted with every color known to the palette in pure transparent tones of marvelous delicacy. Never was picture more harmonious, never flower more exquisitely 6 beautiful. It flashes instant communication of all that architecture and painting and music for a thousand years have gropingly striven to express. It is the soul of Michael Angelo and of Beethoven.

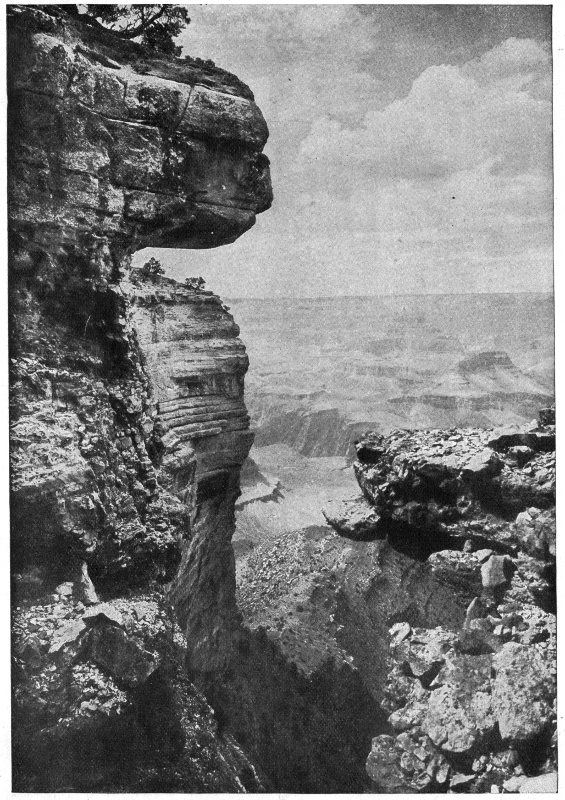

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. The River and the Canyon Wall.

A canyon, truly, but not after the accepted type. An intricate system of canyons, rather, each subordinate to the river channel in the midst, which in its turn is subordinate to the whole effect. That river channel, the profoundest depth, and actually more than 6,000 feet below the point of view, is in seeming a rather insignificant trench, attracting the eye more by reason of its somber tone and mysterious suggestion than by any appreciable characteristic of a chasm. It is perhaps five miles distant in a straight line, and its uppermost rims are nearly 4,000 feet beneath the observer, whose measuring capacity is entirely inadequate to the demand made by such magnitudes. One can not believe the distance to be more than a mile as the crow flies, before descending the wall or attempting some other form of actual measurement.

Mere brain knowledge counts for little against the illusion under which the organ of vision is here doomed to labor. Yonder cliff, darkening from white to gray, yellow, and brown as your glance descends, is taller than the Washington Monument. The Auditorium in Chicago would not cover one-half its perpendicular span. Yet it does not greatly impress you. You idly toss a pebble toward it, and are surprised to note how far the missile falls short. By and by you will learn that it is a good half mile distant, and when you go 7 down the trail you will gain an abiding sense of its real proportions. Yet, relatively, it is an unimportant detail of the scene. Were Vulcan to cast it bodily into the chasm directly beneath your feet, it would pass for a bowlder, if, indeed, it were discoverable to the unaided eye.

Yet the immediate chasm itself is only the first step of a long terrace that leads down to the innermost gorge and the river. Roll a heavy stone to the rim and let it go. It falls sheer the height of a church or an Eiffel Tower, according to the point selected for such pastime, and explodes like a bomb on a projecting ledge. If, happily, any considerable fragments remain, they bound onward like elastic balls, leaping in wild parabola from point to point, snapping trees like straws; bursting, crashing, thundering down the declivities until they make a last plunge over the brink of a void; and then there comes languidly up the cliff sides a faint, distant roar, and your bowlder that had withstood the buffets of centuries lies scattered as wide as Wycliffe’s ashes, although the final fragment has lodged only a little way, so to speak, below the rim. Such performances are frequently given in these amphitheaters without human aid, by the mere undermining of the rain, or perhaps it is here that Sisyphus rehearses his unending task. Often in the silence of night some tremendous fragment has been heard crashing from terrace to terrace with shocks like thunder peal.

The spectacle is so symmetrical, and so completely excludes the outside world and its accustomed standards, it is with difficulty one can acquire any notion of its immensity. Were it half as deep, half as broad, it would be no less bewildering, so utterly does it baffle human grasp.

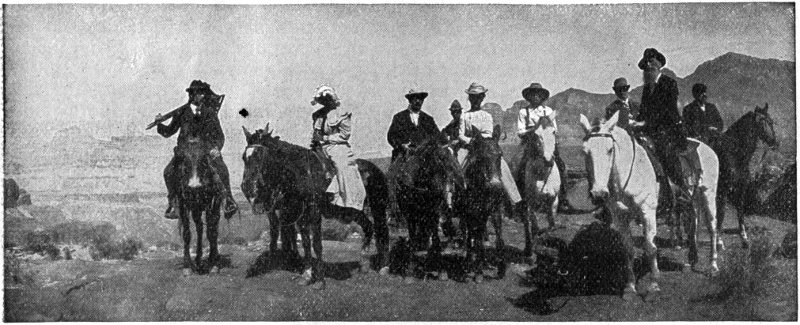

Only by descending into the canyon may one arrive at anything like comprehension of its proportions, and the descent can not be too urgently commended to every visitor who is sufficiently robust to bear a reasonable amount of fatigue. There are four paths down the southern wall of the canyon in the granite gorge district—Mystic Spring, Bright Angel, Berry’s and Hance’s trails. The following account of a descent of the old Hance trail will serve to indicate the nature of such an experience to-day, except that the trip may now be safely made with greater comfort.

For the first two miles it is a sort of Jacob’s ladder, zigzagging at an unrelenting pitch. At the end of two miles a comparatively gentle slope is reached, known as the blue limestone level, some 2,500 feet below the rim, that is to say—for such figures have to be impressed objectively upon the mind—five times the height of St. Peter’s, the Pyramid of Cheops, or the Strasburg Cathedral; eight times the height of the Bartholdi Statue of Liberty; eleven times the height of Bunker Hill Monument. Looking back from this level the huge picturesque towers that border the rim shrink to pigmies and seem to crown a perpendicular wall, unattainably far in the sky. Yet less than one-half the descent has been made.

Overshadowed by sandstone of chocolate hue the way grows gloomy and foreboding, and the gorge narrows. The traveler stops a moment beneath a slanting cliff 500 feet high, where there is an Indian grave and pottery scattered about. A gigantic niche has been worn in the face of this cavernous cliff, which, in recognition of its fancied Egyptian character, was named the Temple of Sett by the painter, Thomas Moran.

A little beyond this temple it becomes necessary to abandon the animals. The river is still a mile and a half distant. The way narrows now to a mere notch, where two wagons could barely pass, and the granite begins to tower 8 gloomily overhead, for we have dropped below the sandstone and have entered the archæan—a frowning black rock, streaked, veined, and swirled with vivid red and white, smoothed and polished by the rivulet and beautiful as a mosaic. Obstacles are encountered in the form of steep, interposing crags, past which the brook has found a way, but over which the pedestrian must clamber. After these lesser difficulties come sheer descents, which at present are passed by the aid of ropes.

The last considerable drop is a 40-foot bit by the side of a pretty cascade, where there are just enough irregularities in the wall to give toe-hold. The narrowed cleft becomes exceedingly wayward in its course, turning abruptly to right and left, and working down into twilight depth. It is very still. At every turn one looks to see the embouchure upon the river, anticipating the sudden shock of the unintercepted roar of waters. When at last this is reached, over a final downward clamber, the traveler stands upon a sandy rift confronted by nearly vertical walls many hundred feet high, at whose base a black torrent pitches in a giddying onward slide that gives him momentarily the sensation of slipping into an abyss.

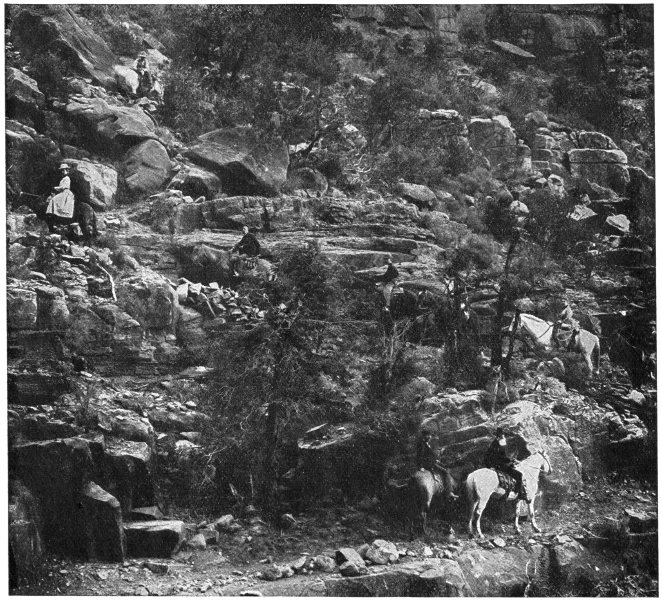

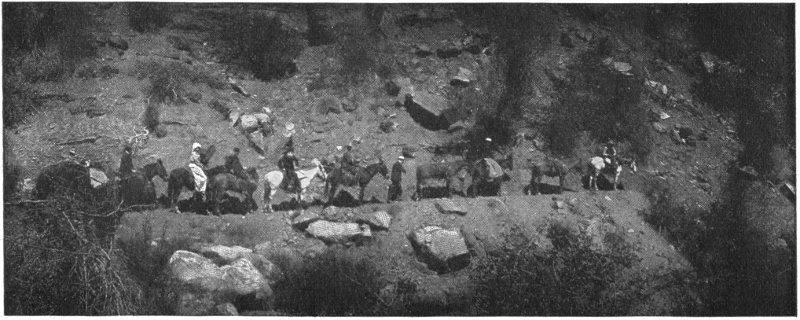

A Party on Bright Angel Trail.

With so little labor may one come to the Colorado River in the heart of its most tremendous channel, and gaze upon a sight that heretofore has had fewer witnesses than have the wilds of Africa. Dwarfed by such prodigious mountain shores, which rise immediately from the water at an angle that would deny footing to a mountain sheep, it is not easy to estimate confidently the width and volume of the river. Choked by the stubborn granite at this point, its width is probably between 250 and 300 feet, its velocity fifteen miles an hour, and its volume and turmoil equal to the Whirlpool Rapids of Niagara. Its rise in time of heavy rain is rapid and appalling, for the walls shed almost instantly all the water that falls upon them. Drift is lodged in the crevices thirty feet overhead.

For only a few hundred yards is the tortuous stream visible, but its effect upon the senses is perhaps the greater for that reason. Issuing as from a mountain side, it slides with oily smoothness for a space and suddenly breaks into violent waves that comb back against the current and shoot unexpectedly here and there, while the volume sways tide-like from side to side, and long curling breakers form and hold their outline lengthwise of the shore, despite the seemingly irresistible velocity of the water. The river is laden with drift (huge tree trunks), which it tosses like chips in its terrible play.

Standing upon that shore one can barely credit Powell’s achievement, in spite of its absolute authenticity. Never was a more magnificent self-reliance displayed than by the man who not only undertook the passage of Colorado River but won his way. And after viewing a fraction of the scene at close range, one can not hold it to the discredit of three of his companions that they abandoned the undertaking not far below this point. The fact that those who persisted got through alive is hardly more astonishing than that any should have had the hardihood to persist. For it could not have been alone the privation, the infinite toil, the unending suspense in constant menace of death that assaulted their courage; these they had looked for; it was rather the unlifted gloom of those tartarean depths, the unspeakable horrors of an endless valley of the shadow of death, in which every step was irrevocable.

Returning to the spot where the animals were abandoned, camp is made for the night. Next morning the way is retraced. Not the most fervid pictures of a poet’s fancy could transcend the glories then revealed in the depths of the canyon; inky shadows, pale gildings of lofty spires, golden splendors of sun beating full on façades of red and yellow, obscurations of distant peaks by veils of transient shower, glimpses of white towers half drowned in purple haze, suffusions of rosy light blended in reflection from a hundred tinted walls. Caught up to exalted emotional heights the beholder becomes unmindful of fatigue. He mounts on wings. He drives the chariot of the sun.

Having returned to the plateau, it will be found that the descent into the canyon has bestowed a sense of intimacy that almost amounts to a mental grasp of the scene. The terrific deeps that part the walls of hundreds of castles and turrets of mountainous bulk may be approximately located in barely discernible pen-strokes of detail, and will be apprehended mainly through the memory of upward looks from the bottom, while towers and obstructions and yawning fissures that were deemed events of the trail will be wholly indistinguishable, although they are known to lie somewhere flat beneath the eye. The comparative insignificance of what are termed grand sights in other parts of the world is now clearly revealed. Twenty Yosemites might lie unperceived anywhere below. Niagara, that Mecca of marvel seekers, would not here possess the dignity of a trout stream. Your companion, standing at a short distance on the verge, is an insect to the eye.

Still, such particulars can not long hold the attention, for the panorama is the real overmastering charm. It is never twice the same. Although you think you have spelt out every temple and peak and escarpment, as the angle of sunlight changes there begins a ghostly advance of colossal forms from the farther side, and what you had taken to be the ultimate wall is seen to be made up of still other isolated sculptures, revealed now for the first time by silhouetting shadows. The scene incessantly changes, flushing and fading, advancing into crystalline clearness, retiring into slumberous haze.

Should it chance to have rained heavily in the night, next morning the canyon is completely filled with fog. As the sun mounts, the curtain of mist suddenly breaks into cloud fleeces, and while you gaze these fleeces rise and dissipate, leaving the canyon bare. At once around the bases of the lowest cliffs white puffs begin to appear, creating a scene of unparalleled beauty as their dazzling cumuli swell and rise and their number multiplies, until once more they overflow the rim, and it is as if you stood on some land’s end looking down upon a formless void. Then quickly comes the complete dissipation, and again the marshaling in the depths, the upward advance, the total suffusion and the speedy vanishing, repeated over and over until the warm walls have expelled their saturation.

Long may the visitor loiter upon the verge, powerless to shake loose from the charm, tirelessly intent upon the silent transformations until the sun is low in the west. Then the canyon sinks into mysterious purple shadow, the far Shinumo Altar is tipped with a golden ray, and against a leaden horizon the long line of the Echo Cliffs reflects a soft brilliance of indescribable beauty, a light that, elsewhere, surely never was on sea or land. Then darkness falls, and should there be a moon, the scene in part revives in silver light, a thousand spectral forms projected from inscrutable gloom; dreams of mountains, as in their sleep they brood on things eternal.

In the fall of 1857 Lieutenant Ives, of the engineer corps of the army, ascended the Colorado River on a trip of exploration with a little steamer called the Explorer; he went as far as the mouth of the Rio Virgin. Falling back down river a few miles, Lieutenant Ives met a pack train which had followed him up the bank of the stream. Here he disembarked, and on the 24th of March started with a land party to explore the eastern bank of the river; making a long detour he ascended the plateau through which the Grand Canyon is cut, and in an adventurous journey he obtained views of the canyon along its lower course. On this trip J. S. Newberry was the geologist, and to him we are indebted for the first geological explanation of the canyon and the description of the high plateau through which it is formed. Doctor Newberry was not only an able geologist, but he was also a graphic writer, and his description of the canyon as far as it was seen by him is a classic in geology.

In 1869 Lieutenant Wheeler was sent out by the chief engineer of the army to explore the Grand Canyon from below. In the spring he succeeded in reaching the mouth of Diamond Creek, which had previously been seen by Doctor Newberry in 1858. Mr. Gilbert was the geologist of this expedition, and his studies of the canyon region during this and subsequent years have added greatly to our knowledge of this land of wonders.

In this same year I essayed to explore the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, together with the upper canyons of that stream and the great canyons of the lower portion of Green River. For this purpose I employed four rowboats and made the descent from what is now Green River station through the whole course of canyons to the mouth of the Rio Virgin, a distance of more than a thousand miles.

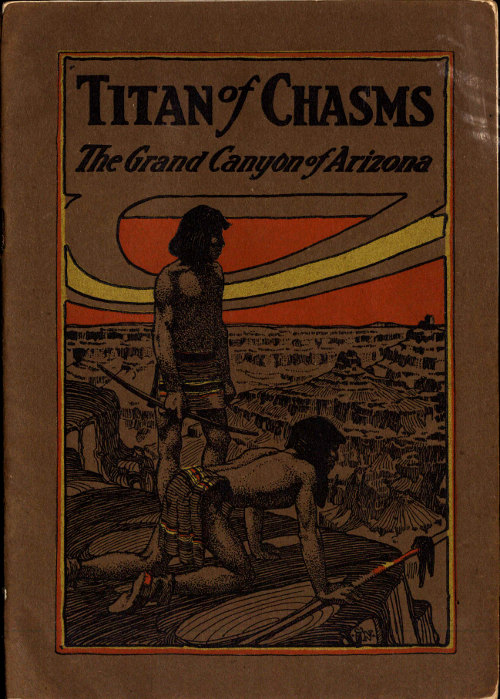

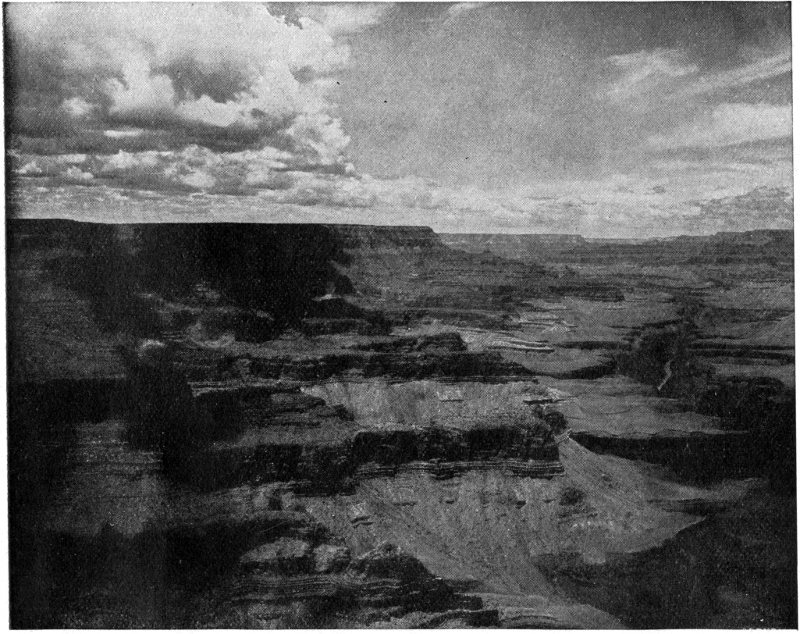

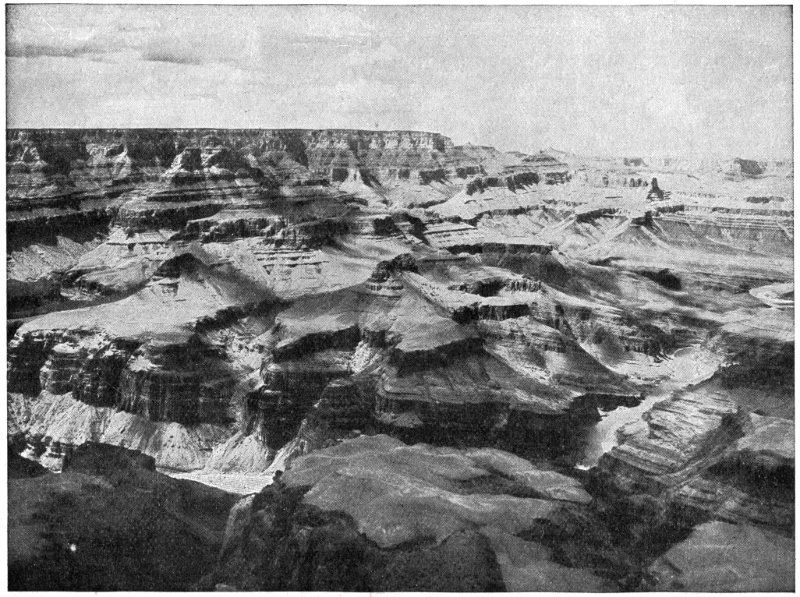

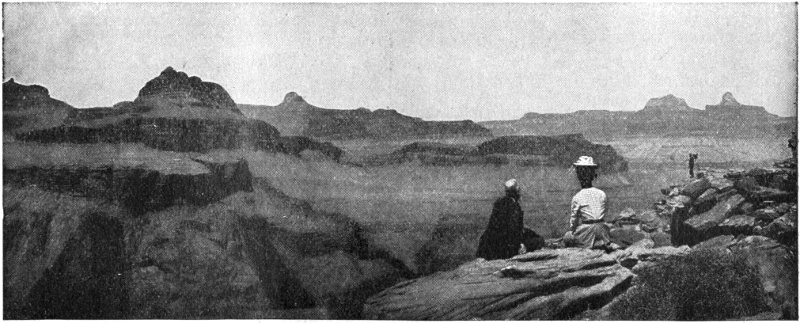

From Kaibab Plateau, Looking South.

In the spring of 1870 I again started with three boats and descended the river to the Crossing of the Fathers, where I met a pack train and went out with a party of men to explore ways down into the Grand Canyon from the north, and devoted the summer, fall, winter, and following spring to this undertaking.

In the summer of 1871 I returned to the rowboats and descended through Marble Canyon to the Grand Canyon of Arizona, and then through the greater part of the Grand Canyon itself. Subsequent years were then given to exploration of the country adjacent to the Grand Canyon. On these trips Mr. Gilbert, the geologist, who had been with Lieutenant Wheeler, and Capt. C. E. Dutton, were my geological companions. On the second boat trip, and during all the subsequent years of exploration in this region, Prof. A. H. Thompson was my geographical companion, assisted by a number of topographical engineers.

In 1882 Mr. C. D. Walcott, as my assistant in the United States Geological Survey, went with me into the depths of the Grand Canyon. We descended from the summit of the Kaibab Plateau on the north by a trail which we built down a side canyon in a direction toward the mouth of the Little Colorado River. The descent was made in the fall, and a small party of men was left with Mr. Walcott in this region of stupendous depths to make a study of the geology of an important region of labyrinthian gorges. Here, with his party, he was shut up for the winter, for it was known when we left him that snows on the summit of the plateau would prevent his return to the upper region before the sun should melt them the next spring. Mr. Walcott is now the Director of the United States Geological Survey.

After this year I made no substantial additions to my geologic and scenic knowledge of the Grand Canyon, though I afterward studied the archæology to the south and east throughout a wide region of ruined pueblos and cliff dwellings.

Since my first trip in boats many others have essayed to follow me, and year by year such expeditions have met with disaster; some hardy adventurers are buried on the banks of the Green, and the graves of others are scattered at intervals along the course of the Colorado.

In 1889 the brave F. M. Brown lost his life. But finally a party of railroad engineers, led by R. B. Stanton, started at the head of Marble Canyon and made their way down the river as they extended a survey for a railroad along its course.

Other adventurous travelers have visited portions of the Grand Canyon region, and Mr. G. Wharton James has extended his travels widely over the region in the interest of popular science and the new literature created in the last decades of the nineteenth century. And now I once more return to a reminiscent account of the Grand Canyon, for old men love to talk of the past.

The Grand Canyon of Arizona and the Marble Canyon constitute one great gorge carved by a mighty river through a high plateau. On the northeast and north a line of cliffs face this plateau by a bold escarpment of rock. Climb these cliffs and you must ascend from 800 to 1,000 feet, but on their summit you will stand upon a plateau stretching away to the north. Now turn to face the south and you will overlook the cliff and what appears to be a valley below. From the foot of the cliff the country rises to the south to a great plateau through which the Marble and the Grand canyons are carved. This plateau terminates 14 abruptly on the west by the Grand Wash Cliffs, which is a high escarpment caused by a “fault” (as the geologist calls it), that is, the strata of sandstone and limestone are broken off, and to the west of the fracture they are dropped down several thousand feet, so that standing upon the edge of the plateau above the Grand Wash Cliffs you may look off to the west over a vast region of desert from which low volcanic mountains rise that seem like purple mounds in sand-clad lands.

On the east the great plateau breaks down in a very irregular way into the valley of the Little Colorado, and where the railroad ascends the plateau from the east it passes over picturesque canyons that run down into the Little Colorado. On the south the plateau is merged into the great system of mountains that stand in Southern Arizona. Where the plateau ends and the mountains begin is not a well-defined line. The plateau through which the Grand Canyon is cut is a region of great scenic interest. Its surface is from six to more than eight thousand feet above the level of the sea. The Grand Plateau is composed of many subsidiary plateaus, each one having its own peculiar and interesting feature.

The Kaibab Plateau, to the northeast of the Grand Canyon, is covered with a pine forest which is intercepted by a few meadows with here and there a pond or lakelet. It is the home of deer and bear.

To the west is the Shinumo Plateau in which the Shinumo Canyon is carved; and on the cliffs of this canyon and in the narrow valley along its course the Shinumo ruins are found—the relics of a prehistoric race.

To the west of the Shinumo Plateau is the Kanab Plateau, with ruins scattered over it, and on its northern border the beautiful Mormon town of Kanab is found, and the canyon of Kanab Creek separates the Shinumo Plateau from the Kanab Plateau. It begins as a shallow gorge and gradually increases in depth until it reaches the Colorado River itself, at a depth of more than 4,000 feet below the surface. Vast amphitheaters are found in its walls and titanic pinnacles rise from its depths. One Christmas day I waded up this creek. It was one of the most delightful walks of my life, from a land of flowers to a land of snow.

To the west of the Kanab Plateau are the Uinkaret Mountains—an immense group of volcanic cones upon a plateau. Some of these cones stand very near the brink of the Grand Canyon and from one of them a flood of basalt was poured into the canyon itself. Not long ago geologically, but rather long when reckoned in years of human history, this flood of lava rolled down the canyon for more than fifty miles, filling it to the depth of two or three hundred feet and diverting the course of the river against one or the other of its banks. Many of the cones are of red cinder, while sometimes the lava is piled up into huge mountains which are covered with forest. To the west of the Uinkaret Mountains spreads the great Shiwits Plateau, crowned by Mount Dellenbough.

Past the south end of these plateaus runs the Colorado River; southward through Marble Canyon and in the Grand Canyon, then northwestward past the Kaibab and Shinumo Canyon, then southwestward past the Kanab Plateau, Uinkaret Mountains to the southernmost point of the Shiwits Plateau, and then northwestward to the Grand Wash Cliffs. Its distance in this course is little more than 300 miles—but the 300 miles of river are set on every side with cliffs, buttes, towers, pinnacles, amphitheaters, caves, and terraces, exquisitely storm-carved and painted in an endless variety of colors.

The plateau to the south of the Grand Canyon, which we need not describe in parts, is largely covered with a gigantic forest. There are many volcanic 15 mountains and many treeless valleys. In the high forest there are beautiful glades with little stretches of meadow which are spread in summer with a parterre of flowers of many colors. This upper region is the garden of the world. When I was first there bear, deer, antelope, and wild turkeys abounded, but now they are becoming scarce. Widely scattered throughout the plateau are small canyons, each one a few miles in length and a few hundred feet in depth. Throughout their course cliff-dweller ruins are found. In the highland glades and along the valley, pueblo ruins are widely scattered, but the strangest sights of all the things due to prehistoric man are the cave dwellings that are dug in the tops of cinder cones and the villages that were built in the caves of volcanic cliffs. If now I have succeeded in creating a picture of the plateau I will attempt a brief description of the canyon.

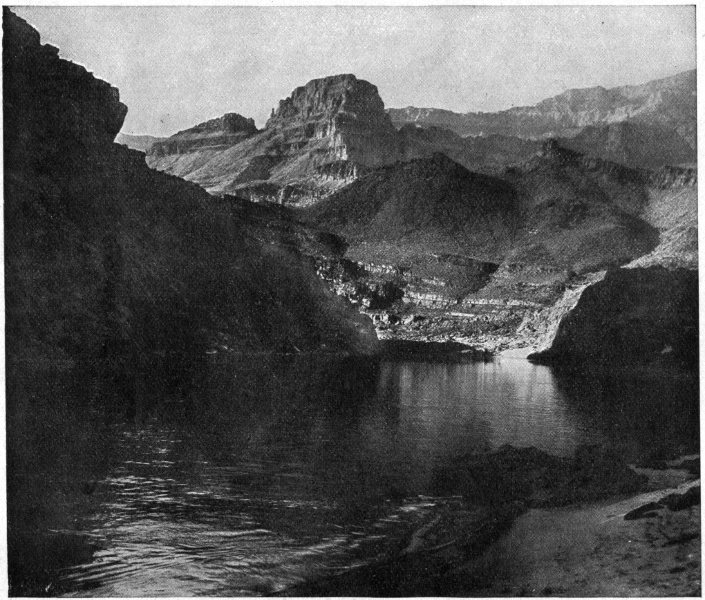

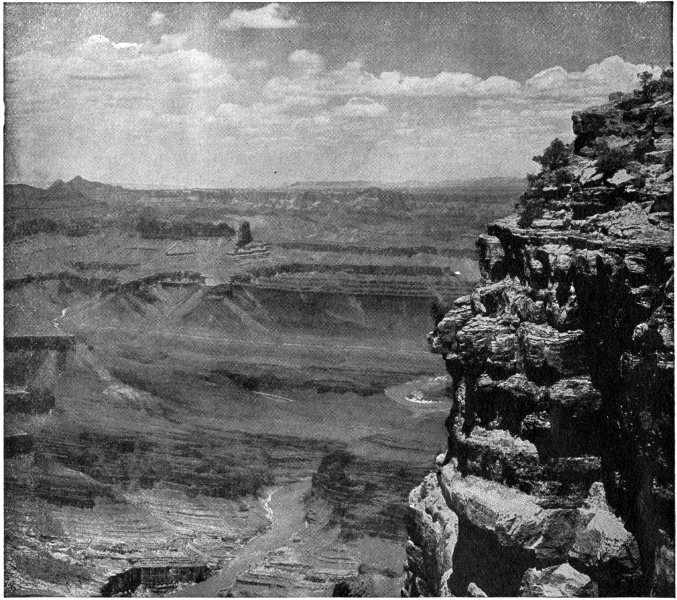

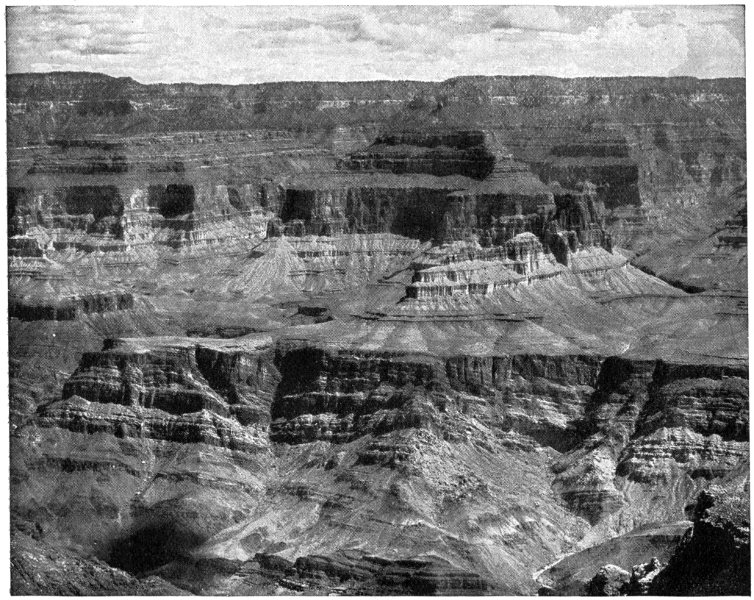

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. Bissell Point and Colorado River.

Above the Paria the great river runs down a canyon which it has cut through one plateau. On its way it flows with comparative quiet through beautiful scenery, with glens that are vast amphitheaters which often overhang great 16 springs and ponds of water deeply embosomed in the cliffs. From the southern escarpment of this plateau the great Colorado Plateau rises by a comparatively gentle acclivity, and Marble Canyon starts with walls but a few score feet in height until they reach an altitude of about 5,000 feet. On the way the channel is cut into beds of rock of lower geologic horizon, or greater geologic age. These rocks are sandstones and limestones. Some beds are very hard, others are soft and friable. The friable rocks wash out and the harder rocks remain projecting from the walls, so that every wall presents a set of stony shelves. These shelves rise along the wall toward the south as new shelves set in from below.

In addition to this shelving structure the walls are terraced and the cliffs of the canyon are set back one upon the other. Then these canyon walls are interrupted by side streams which themselves have carved lateral canyons, some small, others large, but all deep. In these side gorges the scenery is varied and picturesque; deep clefts are seen here and there as you descend the river—clefts furnished with little streams along which mosses and other plants grow. At low water the floor of the great canyon is more or less exposed, and where it flows over limestone rocks beautiful marbles are seen in many colors; saffron, pink, and blue prevail. Sometimes a façade or wall appears rising vertically from the water for thousands of feet. At last the canyon abruptly ends in a confusion of hills beyond which rise towering cliffs, and the group of hills are nestled in the bottom of a valley-like region which is surrounded by cliffs more than a mile in altitude.

From here on for many miles the whole character of the canyon changes. First a dike appears; this is a wall of black basalt crossing the river; it is of lava thrust up from below through a huge crevice broken in the rock by earthquake agency. On the east the Little Colorado comes; here it is a river of salt water, and it derives its salt a few miles up the stream. The main Colorado flows along the eastern and southern wall. Climbing this for a few hundred feet you may look off toward the northwest and gaze at the cliffs of the Kaibab Plateau.

This is the point where we built a trail down a side canyon where Mr. Walcott was to make his winter residence and study of the region; it is very complicated and exhibits a vast series of unconformable rocks of high antiquity. These lower rocks are of many colors; in large part they are shales. The region, which appears to be composed of bright-colored hills washed naked by the rain, is, in fact, beset with a multitude of winding canyons with their own precipitous walls. It is a region of many canyons in the depths of the Grand Canyon itself.

In this beautiful region Mr. Walcott, reading the book of geology, lived in a summerland during all of a long winter while the cliffs above were covered with snow which prevented his egress to the world. His companions, three young Mormons, longing for a higher degree of civilization, gazed wistfully at the snow-clad barriers by which they were inclosed. One was a draughtsman, another a herder of his stock, and the third his cook. They afterward told me that it was a long winter of homesickness, and that months dragged away as years, but Mr. Walcott himself had the great book of geology to read, and to him it was a winter of delight.

A half dozen miles below the basaltic wall the river enters a channel carved in 800 or 1,000 feet of dark gneiss of very hard rock. Here the channel is narrow and very swift and beset with rapids and falls. On the south and 17 southwest the wall rises abruptly from the water to the summit of the plateau for about 6,000 feet, but across the river on the north and west mountains of gneiss and quartzites appear, sometimes rising to the height of a thousand feet. These are mountains in the bottom of a canyon. The buttes and plateaus of the inter-canyon region are composed of shales, sandstones, and limestones, which give rise to vast architectural shelving and to pinnacles and towers of gigantic proportions, the whole embossed with a marvelously minute system of fretwork carved by the artistic clouds. Looking beyond these mountains, buttes, and plateaus vistas of the walls of the great plateau are seen. From these walls project salients, and deep re-entrant angles appear.

The whole scene is forever reminding you of mighty architectural pinnacles and towers and balustrades and arches and columns with lattice work and delicate carving. All of these architectural features are sublime by titanic painting in varied hues—pink, red, brown, lavender, gray, blue, and black. In some lights the saffron prevails, in other lights vermilion, and yet in other lights the grays and blacks predominate. At times, and perhaps in rare seasons, clouds and cloudlets form in the canyon below and wander among the side canyons and float higher and higher until they are dissolved in the upper air, or perhaps they accumulate to hide great portions of the landscape. Then through rifts in the clouds vistas of Wonderland are seen. Such is that portion of the canyon around the great south bend of the Colorado River past the point of the Kaibab Plateau.

In the last chapter of my book entitled “The Canyons of the Colorado” I have described the Grand Canyon in the following terms:

The Grand Canyon is a gorge 217 miles in length, through which flows a great river with many storm-born tributaries. It has a winding way, as rivers are wont to have. Its banks are vast structures of adamant, piled up in forms rarely seen in the mountains.

Down by the river the walls are composed of black gneiss, slates, and schists, all greatly implicated and traversed by dikes of granite. Let this formation be called the black gneiss. It is usually about 800 feet in thickness.

Then over the black gneiss are found 800 feet of quartzites, usually in very thin beds of many colors, but exceedingly hard, and ringing under the hammer like phonolite. These beds are dipping and unconformable with the rocks above. While they make but 800 feet of the wall or less they have a geologic thickness of 12,000 feet. Set up a row of books aslant; it is ten inches from the shelf to the top of the line of books, but there may be three feet of the books measured directly through the leaves. So these quartzites are aslant, and though of great geologic thickness they make but 800 feet of the wall. Your books may have many-colored bindings and differ greatly in their contents; so these quartzites vary greatly from place to place along the wall, and in many places they entirely disappear. Let us call this formation the variegated quartzite.

Above the quartzites there are 500 feet of sandstones. They are of a greenish hue, but are mottled with spots of brown and black by iron stains. They usually stand in a bold cliff, weathered in alcoves. Let this formation be called the cliff sandstone.

Above the cliff sandstone there are 700 feet of bedded sandstones and limestones, which are massive sometimes and sometimes broken into thin strata. These rocks are often weathered in deep alcoves. Let this formation be called the alcove sandstone.

Over the alcove sandstone there are 1,600 feet of limestone, in many places 18 a beautiful marble, as in Marble Canyon. As it appears along the Grand Canyon it is always stained a brilliant red, for immediately over it there are thin seams of iron, and the storms have painted these limestones with pigments from above. Altogether this is the red-wall group. It is chiefly limestone. Let it be called the red-wall limestone.

Above the red wall there are 800 feet of gray and bright red sandstone, alternating in beds that look like vast ribbons of landscape. Let it be called the banded sandstone.

And over all, at the top of the wall, is the Aubrey limestone, 1,000 feet in thickness. This Aubrey has much gypsum in it, great beds of alabaster that are pure white in comparison with the great body of limestone below. In the same limestone there are enormous beds of chert, agates, and carnelians. This limestone is especially remarkable for its pinnacles and towers. Let it be called the tower limestone.

These are the elements with which the walls are constructed, from black buttress below to alabaster tower above. All of these elements weather in different forms and are painted in different colors, so that the wall presents a highly complex façade. A wall of homogeneous granite, like that in the Yosemite, is but a naked wall, whether it be 1,000 or 5,000 feet high. Hundreds and thousands of feet mean nothing to the eye when they stand in a meaningless front. A mountain covered by pure snow 10,000 feet high has but little more effect on the imagination than a mountain of snow 1,000 feet high—it is but more of the same thing—but a façade of seven systems of rock has its sublimity multiplied sevenfold.

A Panoramic View of the Canyon.

Consider next the horizontal elements of the Grand Canyon. The river meanders in great curves, which are themselves broken into curves of smaller magnitude. The streams that head far back in the plateau on either side come down in gorges and break the wall into sections. Each lateral canyon has a secondary system of laterals, and the secondary canyons are broken by tertiary canyons; so the crags are forever branching, like the limbs of an oak. That which has been described as a wall is such only in its grand effect. In detail it is a series of structures separated by a ramification of canyons, each having its own walls. Thus, in passing down the canyon it seems to be inclosed by walls, but oftener by salients—towering structures that stand between canyons that run back into the plateau. Sometimes gorges of the second or third order have met before reaching the brink of the Grand Canyon, and then great salients are cut off from the wall and stand out as buttes—huge pavilions in the architecture of the canyon. The scenic elements thus described are fused and combined in very different ways.

We measured the length of the Grand Canyon by the length of the river running through it, but the running extent of wall can not be measured in this manner. In the black gneiss, which is at the bottom, the wall may stand above the river for a few hundred yards or a mile or two; then to follow the foot of the wall you must pass into a lateral canyon for a long distance, perhaps miles, and then back again on the other side of the lateral canyon; then along by the river until another lateral canyon is reached, which must be headed in the black gneiss. So for a dozen miles of river through the gneiss there may be a hundred miles of wall on either side. Climbing to the summit of the black gneiss and following the wall in the variegated quartzite, it is found to be stretched out to a still greater length, for it is cut with more lateral gorges. In like manner there is yet greater length of the mottled (or alcove) sandstone wall, and the red wall is still farther stretched out in ever-branching gorges.

To make the distance for ten miles along the river by walking along the top of the red wall it would be necessary to travel several hundred miles. The length of the wall reaches its maximum in the banded sandstone, which is terraced more than any of the other formations. The tower limestone wall is less tortuous. To start at the head of the Grand Canyon on one of the terraces of the banded sandstone and follow it to the foot of the Grand Canyon, which by river is a distance of 217 miles, it would be necessary to travel many thousand miles by the winding way; that is, the banded wall is many thousand miles in length.

For eight or ten miles below the mouth of the Little Colorado, the river is in the variegated quartzites, and a wonderful fretwork of forms and colors, peculiar to this rock, stretches back for miles to a labyrinth of the red-wall cliff; then below, the black gneiss is entered and soon has reached an altitude of 800 feet and sometimes more than 1,000 feet, and upon this black gneiss all the other structures in their wonderful colors are lifted. These continue for about seventy miles, when the black gneiss below is lost, for the walls are dropped down by the West Kaibab Fault and the river flows in the quartzites.

Then for eighty miles the mottled (or alcove) sandstones are found in the river bed. The course of the canyon is a little south of west and is comparatively straight. At the top of the red-wall limestone there is a broad terrace, 20 two or three miles in width, composed of hills of wonderful forms carved in the banded beds, and back of this is seen a cliff in the tower limestone. Along the lower course of this stretch the whole character of the canyon is changed by another set of complicating conditions. We have now reached a region of volcanic activity. After the canyons were cut nearly to their present depth, lavas poured out and volcanoes were built on the walls of the canyon, but not in the canyon itself, though at places rivers of molten rock rolled down the walls into the Colorado.

The canyon for the next eighty miles is a compound of that found where the river is in the black gneiss and that found where the dead volcanoes stand on the brink of the wall. In the first stretch, where the gneiss is at the foundation, we have a great bend to the south, and in the last stretch, where the gneiss is below and the dead volcanoes above, another great southern detour is found. These two great beds are separated by eighty miles of comparatively straight river.

Let us call this first great bend the Kaibab reach of the canyon, and the straight part the Kanab reach, for the Kanab Creek heads far off in the plateau to the north and joins the Colorado at the beginning of the middle stretch. The third great southern bend is the Shiwits stretch. Thus there are three distinct portions of the Grand Canyon: The Kaibab section, characterized more by its buttes and salients; the Kanab section, characterized by its comparatively straight walls with volcanoes on the brink, and the Shiwits section, which is broken into great terraces with gneiss at the bottom and volcanoes at the top.

The erosion represented in the canyons, although vast, is but a small part of the great erosion of the region, for between the cliffs blocks have been carried away far superior in magnitude to those necessary to fill the canyons. Probably there is no portion of the whole region from which there have not been more than a thousand feet degraded, and there are districts from which more than 30,000 feet of rock have been carried away; altogether there is a district of country more than 200,000 square miles in extent, from which, on the average, more than 6,000 feet have been eroded. Consider a rock 200,000 square miles in extent and a mile in thickness, against which the clouds have hurled their storms, and beat it into sands, and the rills have carried the sands into the creeks, and the creeks have carried them into the rivers, and the Colorado has carried them into the sea.

We think of the mountains as forming clouds about their brows, but the clouds have formed the mountains. Great continental blocks are upheaved from beneath the sea by internal geologic forces that fashion the earth. Then the wandering clouds, the tempest-bearing clouds, the rainbow-decked clouds, with mighty power and with wonderful skill, carve out valleys and canyons and fashion hills and cliffs and mountains. The clouds are the artists sublime.

In winter some of the characteristics of the Grand Canyon are emphasized. The black gneiss below, the variegated quartzite, and the green or alcove sandstone form the foundation for the mighty red wall. The banded sandstone entablature is crowned by the tower limestone. In winter this is covered with snow. Seen from below, these changing elements seem to graduate into the heavens, and no plane of demarcation between wall and blue firmament can be seen. The heavens constitute a portion of the façade and mount into a vast dome from wall to wall, spanning the Grand Canyon with empyrean blue. So the earth and the heavens are blended in one vast structure.

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. The Lower Gorge, Foot of Bright Angel Trail.

When the clouds play in the canyon, as they often do in the rainy season, another set of effects is produced. Clouds creep out of canyons and wind into other canyons. The heavens seem to be alive, not moving as move the heavens over a plain, in one direction with the wind, but following the multiplied courses of these gorges. In this manner the little clouds seem to be individualized, to have wills and souls of their own and to be going on diverse errands—a vast assemblage of self-willed clouds faring here and there, intent upon purposes hidden in their own breasts. In imagination the clouds belong to the sky, and when they are in the canyon the skies come down into the gorges and cling to the cliffs and lift them up to immeasurable heights, for the sky must still be far away. Thus they lend infinity to the walls.

You can not see the Grand Canyon in one view as if it were a changeless spectacle from which a curtain might be lifted, but to see it you have to toil from month to month through its labyrinths. It is a region more difficult to traverse than the Alps or the Himalayas, but if strength and courage are sufficient for the task, by a year’s toil a concept of sublimity can be obtained never again to be equaled on the hither side of paradise.

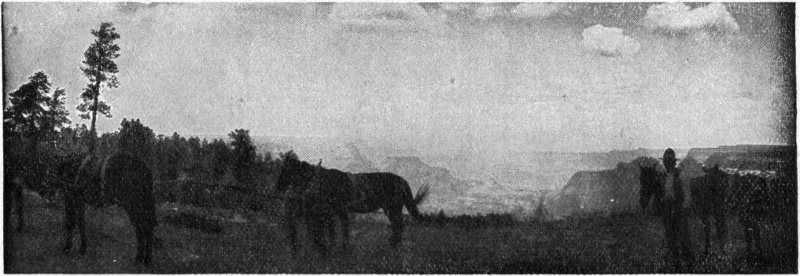

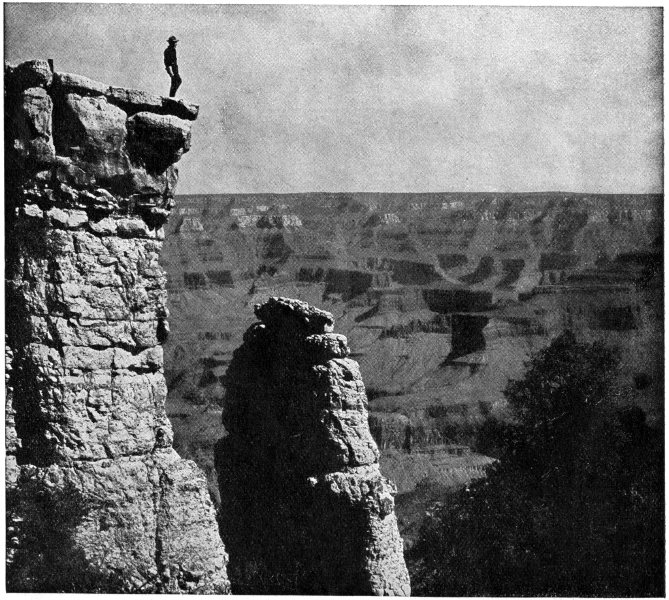

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. On Grand View Point.

“The greatest thing in the world.” That is a large phrase and an over-worked one, and hardened travelers do not take it lightly upon the tongue. Noticeably it is most glibly in use with those but lately, and for the first time, wandered beyond their native state or county, and as every province has its own local brag of biggest things, the too credulous tourist will find a superlative everywhere. And superlatives are unsafe without wide horizons of comparison.

Yet in every sort there is, of course, somewhere “the biggest thing in the world” of its kind. It is a good word, when spoken in season and not abused in careless ignorance.

I believe there is and can be no dispute that the term applies literally to several things in the immediate region of the Grand Canyon of Arizona. As I have more than once written (and it never yet has been controverted), probably no other equal area on earth contains so many supreme marvels of so many kinds—so many astounding sights, so many masterpieces of Nature’s handiwork, so vast and conclusive an encyclopedia of the world-building processes, so impressive monuments of prehistoric man, so many triumphs of man still in the tribal relation—as what I have called the Southwestern Wonderland. This includes a large part of New Mexico and Arizona, the area which geographically and ethnographically we may count as the Grand Canyon region. Let me mention a few wonders:

The largest and by far the most beautiful of all petrified forests, with several hundred square miles whose surface is carpeted with agate chips and dotted with agate trunks two to four feet in diameter; and just across one valley a buried “forest” whose huge silicified—not agatized—logs show their ends under fifty feet of sandstone.

The largest natural bridge in the world—200 feet high, over 500 feet span, and over 600 feet wide, up and down stream, and with an orchard on its top and miles of stalactite caves under its abutments.

The largest variety and display of geologically recent volcanic action in North America; with 60-mile lava flows, 1,500-foot blankets of creamy tufa 24 cut by scores of canyons; hundreds of craters and thousands of square miles of lava beds, basalt, and cinders, and so much “volcanic glass” (obsidian) that it was the chief tool of the prehistoric population.

The largest and the most impressive villages of cave-dwellings in the world, most of them already abandoned “when the world-seeking Genoese” sailed.

The peerless and many-storied cliff-dwellings—castles and forts and homes in the face of wild precipices or upon their tops—an aboriginal architecture as remarkable as any in any land.

The twenty-six strange communal town republics of the descendants of the “cliff-dwellers,” the modern Pueblos; some in fertile valleys, some (like Acoma and Moki) perched on barren and dizzy cliff tops. The strange dances, rites, dress, and customs of this ancient people who had solved the problem of irrigation, 6-story house building, and clean self-government, and even women’s rights—long before Columbus was born.

The noblest Caucasian ruins in America, north of Mexico—the great stone and adobe churches reared by Franciscan missionaries, near three centuries ago, a thousand miles from the ocean, in the heart of the Southwest.

Some of the most notable tribes of savage nomads—like the Navajos, whose blankets and silver work are pre-eminent, and the Apaches, who, man for man, have been probably the most successful warriors in history.

All these, and a great deal more, make the Southwest a wonderland without a parallel. There are ruins as striking as the storied ones along the Rhine, and far more remarkable. There are peoples as picturesque as any in the Orient, and as romantic as the Aztecs and the Incas of whom we have learned such gilded fables, and there are natural wonders which have no peers whatever.

At the head of the list stands the Grand Canyon of the Colorado; whether it is the “greatest wonder of the world” depends a little on our definition of “wonder.” Possibly it is no more wonderful than the fact that so tiny a fraction of the people who confess themselves the smartest in the world have ever seen it. As a people we dodder abroad to see scenery incomparably inferior.

But beyond peradventure it is the greatest chasm in the world, and the most superb. Enough globe-trotters have seen it to establish that fact. Many have come cynically prepared to be disappointed; to find it overdrawn and really not so stupendous as something else. It is, after all, a hard test that so be-bragged a wonder must endure under the critical scrutiny of them that have seen the earth and the fullness thereof. But I never knew the most self-satisfied veteran traveler to be disappointed in the Grand Canyon, or to patronize it. On the contrary, this is the very class of men who can best comprehend it, and I have seen them fairly break down in its awful presence.

I do not know the Himalayas except by photograph and the testimony of men who have explored and climbed them, and who found the Grand Canyon an absolutely new experience. But I know the American continents pretty well, and have tramped their mountains, including the Andes—the next highest mountains in the world, after half a dozen of the Himalayas—and of all the famous quebradas of the Andes there is not one that would count 5 per cent on the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. For all their 25,000-foot peaks, their blue-white glaciers, imminent above the bald plateau, and green little bolsones (“pocket valleys”) of Chile, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador; for all their tremendous active volcanoes, like Saugay and Cotopaxi; for all an earthquake activity 25 beside which the “shake” at Charleston was mere paper-doll play; for all the steepest gradients in the world (and Peru is the only place in the world where a river falls 17,000 feet in 100 miles)—in all that marvelous 3,000-mile procession of giantism there is not one canyon which any sane person would for an instant compare with that titanic gash that the Colorado has chiseled through a comparatively flat upland. Nor is there anything remotely approaching it in all the New World. So much I can say at first hand. As for the Old World, the explorer who shall find a gorge there one-half as great will win undying fame.

The quebrada of the Apu-Rimac is a marvel of the Andes, with its vertiginous depths and its suspension bridge of wild vines. The Grand Canyon of the Arkansas, in Colorado, is a noble little slit in the mountains. The Franconia and White Mountain notches in New Hampshire are beautiful. The Yosemite and the Yellowstone canyons surpass the world, each in its way. But if all of these were hung up on the opposite wall of the Grand Canyon from you the chances are fifty to one that you could not tell t’other from which, nor any of them from the hundreds of other canyons which rib that vast vertebrate gorge. If the falls of Niagara were installed in the Grand Canyon between your visits and you knew it by the newspapers—next time you stood on that dizzy rimrock you would probably need good field-glasses and much patience before you could locate that cataract which in its place looks pretty big. If Mount Washington were plucked up bodily by the roots—not from where you see it, but from sea-level—and carefully set down in the Grand Canyon, you probably would not notice it next morning, unless its dull colors distinguished it in that innumerable congress of larger and painted giants.

All this, which is literally true, is a mere trifle of what might be said in trying to fix a standard of comparison for the Grand Canyon. But I fancy there is no standard adjustable to the human mind. You may compare all you will—eloquently and from wide experience, and at last all similes fail. The Grand Canyon is just the Grand Canyon, and that is all you can say. I never have seen anyone who was prepared for it. I never have seen anyone who could grasp it in a week’s hard exploration; nor anyone, except some rare Philistine, who could even think he had grasped it. I have seen people rave over it; better people struck dumb with it, even strong men who cried over it; but I have never yet seen the man or woman that expected it.

It adds seriously to the scientific wonder and the universal impressiveness of this unparalleled chasm that it is not in some stupendous mountain range, but in a vast, arid, lofty floor of nearly 100,000 square miles—as it were, a crack in the upper story of the continent. There is no preparation for it. Unless you had been told, you would no more dream that out yonder amid the pines the flat earth is slashed to its very bowels, than you would expect to find an iceberg in Broadway. With a very ordinary running jump from the spot where you get your first glimpse of the canyon you could go down 2,000 feet without touching. It is sudden as a well.

But it is no mere cleft. It is a terrific trough 6,000 to 7,000 feet deep, ten to twenty miles wide, hundreds of miles long, peopled with hundreds of peaks taller than any mountain east of the Rockies, yet not one of them with its head so high as your feet, and all ablaze with such color as no eastern or European landscape ever knew, even in the Alpen-glow. And as you sit upon the brink the divine scene-shifters give you a new canyon every hour. With each degree of the sun’s course the great countersunk mountains we have been watching fade away, and new ones, as terrific, are carved by the westering shadows. It is like a dissection of the whole cosmogony. And the purple shadows, the dazzling lights, the thunderstorms and snowstorms, the clouds and the rainbows that shift and drift in that vast subterranean arena below your 26 feet! And amid those enchanted towers and castles which the vastness of the scale leads you to call “rocks,” but which are in fact as big above the river-bed as the Rockies from Denver, and bigger than Mount Washington from Fabyan’s or the Glen!

The Grand Canyon country is not only the hugest, but the most varied and instructive example on earth of one of the chief factors of earth-building—erosion. It is the mesa country—the Land of Tables. Nowhere else on the footstool is there such an example of deep-gnawing water or of water high-carving. The sandstone mesas of the Southwest, the terracing of canyon walls, the castellation, battlementing, and cliff-making, the cutting down of a whole landscape except its precipitous islands of flat-topped rock, the thin lava table-cloths on tables 100 feet high—these are a few of the things which make the Southwest wonderful alike to the scientist and the mere sight-seer.

That the canyon is not “too hard” is perhaps sufficiently indicated by the fact that I have taken thither ladies and children and men in their seventies, when the easiest way to get there was by a 70-mile stage ride, and that at six years old my little girl walked all the way from rim to bottom of canyon and came back on a horse the same day, and was next morning ready to go on a long tramp along the rim.

Copyright, 1899, by H. G. Peabody. The North Wall from Grand Scenic Divide.

There is only one way by which to directly reach the Grand Canyon of Arizona, and that is via the Santa Fe (The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway System).

There are three ways of reaching the Canyon from the Santa Fe—rail from Williams, private conveyance from Flagstaff and Peach Springs.

The route from Flagstaff is not available in winter. The Peach Springs route is open in winter, but now little used. The bulk of the travel is via Williams, sixty-five miles north to Bright Angel—open all the year.

There are but three points from which an easy descent may be made of the south wall to the granite gorge of the Grand Canyon:

1. At Grand View, down Berry’s (Grand View) or Hance’s (Red Canyon) trails.

2. At Bright Angel, down Bright Angel Trail.

3. At Bass’ Camp, down Mystic Spring Trail.

While the canyon may be reached over trails at other places outside of the district named (such as Lee’s Ferry Trail, by wagon from Winslow; Moki Indian Trail, by way of Little Colorado Canyon; and Diamond Creek road to Colorado River from Peach Springs station), most tourists prefer the Bright Angel, Grand View, and Bass’ Camp routes, because of the superior facilities and views there offered. The Peach Springs route is the only other one now used by the public to any extent.

It is near Grand View that Marble Canyon ends and the Grand Canyon proper begins. Northward, a few miles away, is the mouth of the Little Colorado Canyon. Here the granite gorge is first seen.

Bright Angel is approximately in the center, and Bass’ Camp at the western end of the granite gorge. By wagon road it is eighteen miles from Bright Angel east to Grand View, and twenty-three miles west to Bass’ Camp.

In a nutshell, the Grand Canyon at Grand View is accounted most sublime—a scene of wide outlooks and brilliant hues; at Bright Angel, deepest and most impressive—a scene that awakens the profoundest emotions; at Bass’ Camp, the most varied—a scene of striking contrasts in form and color.

Each locality has its special charm. All three should be visited, if time permits, as only by long observation can one gain even a superficial knowledge of what the Grand Canyon is. To know it intimately requires a longer stay and more careful study.

Because of recent improvements in service the Grand Canyon of Arizona may now be visited, either in summer or winter, with reasonable comfort and without any hardship. No one need be deterred by fear of inclement weather or a tedious stage ride. The trip is entirely feasible for the average traveler every day in the year.

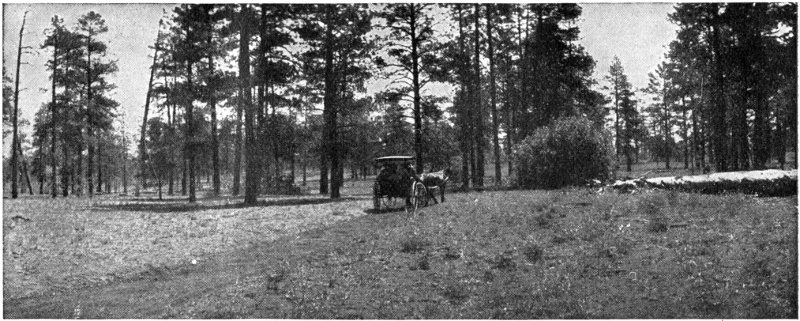

Leaving the Santa Fe transcontinental train at Williams, Arizona, passengers change in same depot to a local train of the Grand Canyon Railway, which leaves Williams daily, and arrives at destination after a three hours’ run.

Williams is a busy town of 1,500 inhabitants, 378 miles west of Albuquerque, on the Santa Fe. Here are located large sawmills, smelters, numerous well-stocked stores, and railroad division buildings. Prior to the disastrous fire in July, 1901, there were several excellent hotels. The one not destroyed affords good accommodations; it has been recently enlarged and otherwise improved.

There is usually ample time at Williams, between trains, for the ascent of Bill Williams Mountain, which rises near the town to a height of 9,000 feet. Tourists will find the trip thoroughly enjoyable. It can be made in five hours on horseback in perfect safety. The trail is an easy one, first leading through a gently sloping path of pines, then steeply up to the wind-swept summit alongside a pretty stream bordered by thickets of quaking aspens. Chimney Rock, with its eagle’s nest, is a noteworthy rock formation. On the summit is buried the historic pioneer scout, Bill Williams. From his resting-place there is a wide outlook, embracing, on clear days, the wall of the Grand Canyon, Verde River, Chino Valley, Jerome, Hell Canyon, Seligman, Ash Fork, and many neighboring peaks.

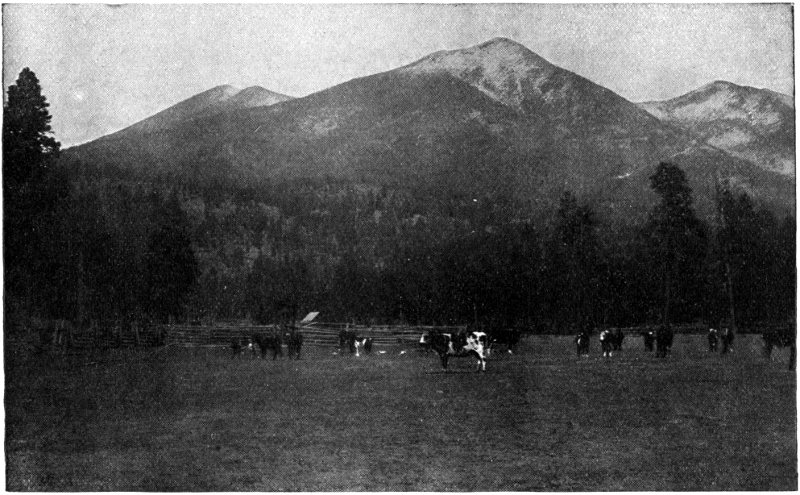

The railroad track to the canyon is remarkably smooth for a new line. It is built across a slightly rolling mesa, in places thickly wooded, in others open. The snow-covered San Francisco Peaks are on the eastern horizon. Kendricks, Sitgreaves, and Williams mountains are also visible. Red Butte, thirty miles distant, is a prominent local landmark. Before the terminus is reached the train climbs a long, high ridge and enters Coconino Forest, which resembles a natural park. The route here is amid fragrant pines, over low hills, and along occasional gulches and “washes.” Taken under the favorable conditions which generally prevail at this high altitude, the journey is a novelty and a delight.

The hotel at head of Bright Angel Trail is reached early in the evening. The tourist then finds himself on the verge of a high precipice, from which is obtained by moonlight a magnificent view of the opposite wall and of the intervening crags, towers, and slopes. The suddenness, the surprise, the revelation come as a fitting climax to a unique trip. After nightfall the air becomes cold, for here you are 7,000 feet above the sea; yet the absence of humidity, peculiar to these high altitudes, makes the chill less penetrating than on lower levels. By day, in the sunshine, there is usually a genial warmth—then overcoats, gloves, and wraps are laid aside.

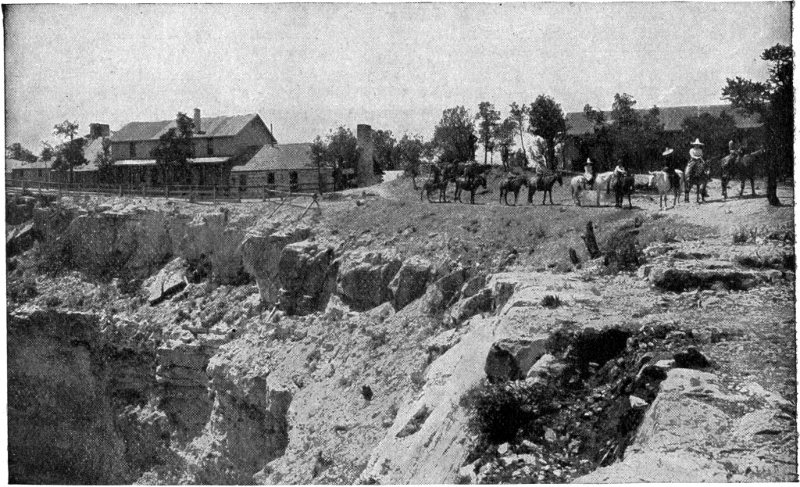

The Bright Angel Hotel is managed by Mr. M. Buggeln, who also controls the stage line, trail stock, guides, etc. The hotel comprises a combination log and frame structure of eight rooms, with three frame annexes containing forty-six sleeping rooms, and (for summer use) several rows of tents, all clustered on the rim and surrounded by pines and spruces. Each room in the annexes has one or two beds, a stove, dressing table, and Navajo rugs. In the log-cabin part of the main edifice are two large rooms. One is used for reception purposes, being warmed by means of an old-fashioned fireplace and tastefully carpeted with Indian rugs, also furnished with capacious rocking chairs and a piano; the other of these two rooms is for the office.

Good meals are prepared by expert cooks and served in a pleasant dining-room. In a word, the hotel facilities are good, far better than one might expect to find for the reasonable rate charged. There is no “roughing it”; everything is homelike and comfortable. One must not, however, expect all the city luxuries. A telephone and telegraph line directly connects the hotel with the outer world at Williams.

Note.—A fine modern hotel of fifty rooms, with cottage annexes, to be known as Bright Angel Tavern, will be built in this vicinity during 1903 and managed by Mr. Fred Harvey. It will be a permanent affair and will provide all the latest conveniences.

While one ought to remain at least a week, a stop-over of three days from the transcontinental trip will allow practically two days at the canyon. One full day should be devoted to an excursion down Bright Angel Trail, and the other to walks and drives along the rim. Another day on the rim—making a four-days’ stop-over in all—will enable visitors to get more satisfactory views of this stupendous wonder.

The trail here is perfectly safe and is generally open the year round. In midwinter it is liable to be closed for a few days at the top by snow, but such blockade is only temporary. It reaches from the hotel four miles to the top of the granite wall immediately overlooking the Colorado River. At this point the river is 1,200 feet below, while the hotel on the rim is 4,300 feet above. The trip is commonly made on horseback, accompanied by a guide; charges for trail stock and services of guide are moderate. A strong person, accustomed to mountain climbing, can make the round trip on foot in one day, by starting early enough; but the average traveler will soon discover that a horse is a necessity, especially for the upward climb.

Eight hours are required for going down and coming back, allowing two hours for lunch, rest, and sight-seeing. Those wishing to reach the river leave the main trail at Indian Garden Spring and follow the downward course of Willow and Pipe creeks. Owing to the abrupt descent from this point, part of the side trail must be traversed on foot. Provision is made for those wishing to camp out at night on the river’s edge.

The famous guide, John Hance, is now located at Bright Angel.

If much tramping is done, stout, thick shoes should be provided. Ladies will find that short walking skirts are a convenience; divided skirts are preferable, but not essential, for the horseback journey down the zigzag trail. Traveling caps and (in summer) broad-brimmed straw hats are useful toilet adjuncts. Otherwise ordinary clothing will suffice. A good field glass and camera should be brought along.

Bright Angel Hotel.

The round-trip ticket rate, Williams to Grand Canyon and return, is only $6.50. Adding $6 for two days’ stay at Canyon Hotel, $1 for part of a day at hotel in Williams, $1.50 for probable proportion of cost of guide, $3 for trail stock, and the total necessary expense of the three days’ stop-over is about $18 for one person; each additional day only adds $3 to the cost for hotel.

Stop-overs will be granted at Williams on railroad and Pullman tickets if advance application is made to train and Pullman conductors. Trunks may be stored in the station at Williams free of charge by arrangement with ticket agent.

Grand View (previously mentioned) may be reached in summer by private conveyance from Flagstaff, a distance of seventy-five miles; or at any time of the year by stage from Bright Angel, sixteen miles along the rim. The rate for round trip, Bright Angel to Grand View, is $2.50 to $5 each person, according to size of party. While Flagstaff is an interesting place to visit—with its near-by cliff and cave dwellings and San Francisco Peaks—and the trip thence to the Grand Canyon is a novel one, distance and time are such that most travelers prefer to go in by railroad from Williams.

Grand View Hotel is a large, rustic structure, built near the head of Berry’s Trail and about three miles from Hance’s Trail, in the midst of tall pines and overlooking the mighty bend of the Colorado. This is the point to which visitors were conducted in the days of the old stage line from Flagstaff.

It is noted for its wide views of the Coconino Forest and Painted Desert, as well as for the beautiful forms and color of the canyon itself. A favorite trip here is to go down one trail and up the other. The hotel accommodations are quite good; capacity, forty guests; rate, $3 per day.

At the western end of the granite gorge is Mystic Spring Trail, an easy route down to the Colorado River and up the other side to Dutton’s Point and Powell’s Plateau. The magnificent panorama eastward from Havasupai Point takes in fifty miles of the canyon, while westward is the unique, table-like formation which characterizes the lower reaches of the river. The views from both rims are pronounced by noted artists and explorers to be unequaled.

Present accommodations at Havasupai Hotel (Bass’ Camp), near head of this trail, are fairly good, consisting of a cabin, several tents, and good trail stock; wholesome meals are served in comfortable style. A new hotel is to be built here during 1903. Bass’ Camp is now reached by stage from Coconino, a station on the Grand Canyon Railway, or one may take a team direct from Bright Angel.

A visit should be made to the Havasupai Indian village in Cataract Canyon. Any bona fide tourist can procure an introductory letter from the railroad agent at Williams or Grand Canyon. On presenting same to the U. S. Indian agent at Supai, permission will be granted to enter the reservation. This is an unique trip of about forty miles, first by wagon across a timbered plateau, then on horseback down precipitous Topocobya Trail, along the rocky floors of Topocobya and Cataract canyons, deep in the earth, to a place of gushing springs, green fields, and enchanting waterfalls. Here live the Havasupai Indians, one of the most interesting tribes in Arizona. The round trip from Bright Angel or Bass’ Camp is made in three or four days at an expense of $35 to $50 each for a party of three persons.

The trip in winter from Peach Springs station down to the Colorado River, through Diamond Creek Canyon, is most enjoyable. Owing to the low altitude here (4,780 feet at Peach Springs and approximately 2,000 feet at the river) the air is usually balmy from November to April; in summer the heat is a considerable drawback.

A journey of but twelve miles leads you through a miniature Grand Canyon with scenery increasingly sublime. On either side are abrupt walls and wonderfully suggestive formations—castles, domes, minarets. On your left, glancing backward, is an exact reproduction of Westminster Abbey.

This comparatively easy jaunt brings you by team to the very brink of the swift-rolling Colorado, whereas by the other Grand Canyon gateways you are landed on the rim and must go down thousands of feet by a steep trail. The outlook here is restricted to the river itself and the great walls rising precipitously from its banks—a scene well worth while, but not so impressive as the wide sweep of the canyon visible from the rim.

Following Diamond Creek to its source you may walk along the bed of the stream between walls thousands of feet high and glistening in the white sunlight as if varnished. The upper part of Diamond Creek is a veritable terrace of fern bowers, luxuriant vegetation, crystal cascades, and sequestered meadow parks.

The town itself is an interesting place, prettily situated in the heart of the San Francisco uplift and surrounded by a pine forest.

Its hotels, business houses, lumber mills, and residences denote thrift. On a neighboring hill is the Lowell Observatory, noted for its many contributions to astronomical science.

San Francisco Peaks.

Eight miles southwest from Flagstaff—reached by a pleasant drive along a level road through tall pines—is Walnut Canyon, a rent in the earth several hundred feet deep and three miles long, with steep terraced walls of limestone. Along the shelving terraces, under beetling projections of the strata, are scores of quaint cliff dwellings, the most famous group of its kind in this region. The larger abodes are divided into several compartments by cemented walls, many parts of which are still intact. It is believed that these cliff dwellers were of the same stock as the Pueblo Indians of to-day and that they lived here about 800 years ago.

Nine miles from Flagstaff and only half a mile from the old stage road to the Grand Canyon, upon the summit of an extinct crater, the remarkable ruins of the cave-dwellers may be seen.

The magnificent San Francisco Peaks, visible from every part of the country within a radius of a hundred miles, lie just north of Flagstaff. There are three peaks which form one mountain. From Flagstaff a road has been constructed up Humphrey’s Peak, whose summit is 12,750 feet above sea level. It is a good mountain road, and the entire distance from Flagstaff is only about ten miles. The trip to the summit and back is easily made in one day.

The Santa Fe has published a new and beautiful book on the Grand Canyon. It contains articles by Hamlin Garland, Harriet Monroe, Robert Brewster Stanton, Chas. S. Gleed, John L. Stoddard, Charles Dudley Warner, R. D. Salisbury, “Fitz Mac,” Nat M. Brigham, Joaquin Miller, Edwin Burritt Smith, David Starr Jordan, C. E. Beecher, Henry P. Ewing, and Thomas Moran, as well as the authors represented in this pamphlet. The book has more than a hundred pages, illustrated with half-tones and portraits; the cover is from a painting of the Canyon by Thomas Moran, and is lithographed in seven colors. It will be forwarded on receipt of fifty cents.

A beautiful and unique color picture of the Grand Canyon, mounted to show all its colors as in nature, may be had for twenty-five cents.

Address W. J. BLACK,

Gen’l Passenger Agent, A., T. & S. F. Ry., CHICAGO.

Ad. 71—2-3-03. 10M.