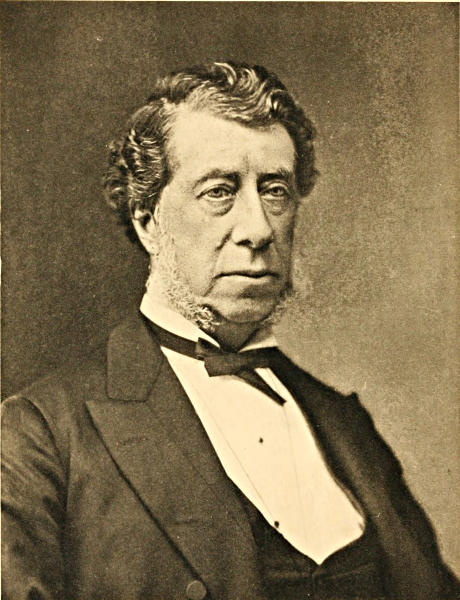

HAMILTON FISH

Title: Charles Sumner: his complete works, volume 17 (of 20)

Author: Charles Sumner

Release date: November 2, 2015 [eBook #50370]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: There is a printer’s error in footnote 102; the Statutes at Large volume reference is missing from the original.

HAMILTON FISH

Copyright, 1880,

BY

FRANCIS V. BALCH, Executor.

Copyright, 1900,

BY

LEE AND SHEPARD.

Statesman Edition.

Limited to One Thousand Copies.

Of which this is

Norwood Press:

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

Resolution in the Senate, December 7, 1868.

Whereas the inland postage on a letter throughout the United States is three cents, while the ocean postage on a similar letter to Great Britain, under a recent convention, is twelve cents, and on a letter to France is thirty cents, being a burdensome tax, amounting often to a prohibition of foreign correspondence, yet letters can be carried at less cost on sea than on land; and whereas, by increasing correspondence, and also by bringing into the mails mailable matter often now clandestinely conveyed, cheap ocean postage would become self-supporting; and whereas cheap ocean postage would tend to quicken commerce, to diffuse knowledge, to promote the intercourse of families and friends separated by the ocean, to multiply the bonds of peace and good-will among men and nations, to advance the progress of liberal ideas, and thus, while important to every citizen, it would become the active ally of the merchant, the emigrant, the philanthropist, and the friend of liberty: Therefore

Be it resolved, That the President of the United States be requested to open negotiations with the European powers, particularly with Great Britain, France, and Germany, for the establishment of cheap ocean postage.

Remarks in the Senate on his Death, December 18, 1868.

MR. PRESIDENT,—The visitor to the House of Commons, as he paces the vestibule, stops with reverence before the marble statues of men who for two centuries of English history filled that famous chamber. There are twelve in all, each speaking to the memory as he spoke in life, beginning with the learned Selden and the patriot Hampden, with Falkland so sweet and loyal, Somers so great as defender of constitutional liberty, and embracing in the historic group the silver-tongued Murray, the two Pitts, father and son, masters of eloquence, Fox, always first in debate, and that orator whose speeches contribute to the wealth of English literature, Edmund Burke.

In the lapse of time, as our history extends, similar monuments will illustrate the approach to our House of Representatives, arresting the reverence of the visitor. If our group is confined to those whose fame has been won in the House alone, it will be small; for members of the House are mostly birds of passage, only perching on the way to another place. Few remain so as to become identified with the House, or their service there is forgotten in the blaze of service elsewhere,—as was the case with Madison, Marshall, Clay, Webster, and Lincoln. It is not difficult to see who will find a place[Pg 3] in this small company. There must be a statue of Josiah Quincy, whose series of eloquent speeches is the most complete of our history before Webster pleaded for Greece,—and also a statue of Joshua R. Giddings, whose faithful championship of Freedom throughout a long and terrible conflict makes him one of the great names of our country. And there must be a statue of Thaddeus Stevens, who was perhaps the most remarkable character identified with the House, unless we except John Quincy Adams; but the fame of the latter is not of a Representative alone, for he was already illustrious from various service before he entered the House.

All of these hated Slavery, and labored for its overthrow. On this account they were a mark for obloquy, and were generally in a minority. Already compensation has begun. As the cause they upheld so bravely is exalted, so is their fame. By the side of their far-sighted, far-reaching, and heroic efforts, how diminutive is all that was done by others at the time! How vile the spirit that raged against them!

Stevens was a child of New England, as were Quincy and Adams; but, after completing his education, he found a home in Pennsylvania, which had already given birth to Giddings. If this great central State can claim one of these remarkable men by adoption only, it may claim the other by maternity. Their names are among its best glories.

Two things Stevens did for his adopted State, by which he repaid largely all her hospitality and favor. He taught her to cherish Education for the People, and he taught her respect for Human Rights. The latter lesson was slower learned than the former. In the prime[Pg 4] of life, when his faculties were in their highest vigor, he became conspicuous for earnest effort, crowned by most persuasive speech, whose echoes have not yet died away, for those Common Schools, which, more even than railways, are handmaids of civilization, besides being the true support of republican government. His powerful word turned the scale, and a great cause was won. This same powerful word was given promptly and without hesitation to that other cause, suffering then from constant and most cruel outrage. Here he stood always like a pillar. Suffice it to say that he was one of the earliest of Abolitionists, accepting the name and bearing the reproach. Not a child in Pennsylvania, conning a spelling-book beneath the humble rafters of a village school, who does not owe him gratitude; not a citizen, rejoicing in that security obtained only in liberal institutions founded on the Equal Rights of All, who is not his debtor.

When he entered Congress, it was as champion. His conclusions were already matured, and he saw his duty plain before him. The English poet foreshadows him, when he pictures

Slavery was wrong, and he would not tolerate it. Slave-masters, brimming with Slavery, were imperious and lawless. From him they learned to see themselves as others saw them. Strong in his cause and in the consciousness of power, he did not shrink from encounter; and when it was joined, he used not only argument and history, but all those other weapons by which a bad[Pg 5] cause is exposed to scorn and contempt. Nobody said more in fewer words, or gave to language a sharper bite. Speech was with him at times a cat-o’-nine-tails, and woe to the victim on whom the terrible lash descended!

Does any one doubt the justifiableness of such debate? Sarcasm, satire, and ridicule are not given in vain. They have an office to perform in the economies of life. They are faculties to be employed prudently in support of truth and justice. A good cause is helped, if its enemies are driven back; and it cannot be doubted that the supporters of wrong and the procrastinators shrank often before the weapons he wielded. Soft words turn away wrath; but there is a time for strong words as for soft words. Did not the Saviour seize the thongs with which to drive the money-changers from the Temple? Our money-changers long ago planted themselves within our temple. Was it not right to lash them away? Such an exercise of power in a generous cause must not be confounded with that personality of debate which has its origin in nothing higher than irritability, jealousy, or spite. In this sense Thaddeus Stevens was never personal. No personal thought or motive controlled him. What he said was for his country and mankind.

As the Rebellion assumed its giant proportions, he saw clearly that it could be smitten only through Slavery; and when, after a bloody struggle, it was too tardily vanquished, he saw clearly that there could be no true peace, except by new governments built on the Equal Rights of All. And this policy he urged with a lofty dogmatism as beneficent as uncompromising. The Rebels had burned his property in Pennsylvania, and there were weaklings who attributed his conduct to smart at[Pg 6] pecuniary loss. How little they understood his nature! Injury provokes and sometimes excuses resentment. But it was not in him to allow private grief to influence public conduct. The losses of the iron-master were forgotten in the duties of the statesman. He asked nothing for himself. He did not ask his own rights, except as the Rights of Man.

I know not if he could be called orator. Perhaps, like Fox, he were better called debater. And yet I doubt if words were ever delivered with more effect than when, broken with years and decay, he stood before the Senate and in the name of the House of Representatives and of all the people of the United States impeached Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors in office. Who can forget his steady, solemn utterance of this great arraignment? The words were few, but they will sound through the ages. The personal triumph in his position at that moment was merged in the historic grandeur of the scene. For a long time, against opposition of all kinds, against misconceptions of the law, and against apologies for transactions without apology, he had insisted on impeachment; and now this old man, tottering to your door, dragged the Chief Magistrate of the Republic to judgment. It was he who did this thing; and I should do poor justice to his life, if on this occasion I failed to declare my gratitude for the heroic deed. His merit is none the less because other influences prevailed in the end. His example will remain forever.

In the House, which was the scene of his triumphs, I never heard him but once; and I cannot forget the noble eloquence of that brief speech. I was there by accident just as he rose. He did not speak more than[Pg 7] ten minutes, but every sentence seemed an oration. With unhesitating plainness he arraigned Pennsylvania for her denial of equal rights to an oppressed race, and, rising with the theme, declared that this State had not a republican government.[2] His explicitness was the more striking because he was a Representative of Pennsylvania. Nobody, who has considered with any care what constitutes a republican government, especially since the definition supplied by our Declaration of Independence, can doubt that he was right. His words will live as the courageous testimony of a great character on this important question.

The last earnest object of his life was the establishment of Equal Rights throughout the whole country by the recognition of the requirement of the Declaration of Independence. I have before me two letters in which he records his convictions, which are perhaps more weighty because the result of most careful consideration, when age had furnished experience and tempered the judgment. “I have,” says he, “long, and with such ability as I could command, reflected upon the subject of the Declaration of Independence, and finally have come to the sincere conclusion that Universal Suffrage was one of the inalienable rights intended to be embraced in that instrument.” It is difficult to see how there can be hesitation on this point, when the great title-deed expressly says that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. But this is not the only instance in which he was constrained by the habits of that profession which he practised so successfully. A great Parliamentarian of France has said:[Pg 8] “The more one is a lawyer, the less he is a Senator,”—Plus on est avocat, moins on est Sénateur. If Stevens reached his conclusion slowly, it was because he had not completely emancipated himself from that technical reasoning which is the boast of the lawyer rather than of the statesman. The pretension that the power to determine the “qualifications” of voters embraced the power to exclude for color, and that this same power to exclude for color was included in the asserted power of the States to make “regulations” for the elective franchise, seems at first to have deceived him; as if it were not insulting to reason and shocking to the moral sense to suppose that any unalterable physical condition, such as color of hair, eyes, or skin, could be a “qualification,”—and as if it were not equally offensive to suppose, that, under a power to determine “qualifications” or to make “regulations,” a race could be disfranchised. Of course this whole pretension is a technicality set up against Human Rights. Nothing can be plainer than that a technicality may be employed in favor of Human Rights, but never against them. Stevens came to his conclusion at last, and rested in it firmly. His final aspiration was to see it prevail. He had seen much for which he had striven embodied in the institutions of his country. He had seen Slavery abolished. He had seen the freedman of the National Capital lifted to equality of political rights by Act of Congress; he had seen the colored race throughout the whole land lifted to equality of civil rights by Act of Congress. It only remained that he should see them throughout the whole land lifted to the same equality in political rights; and then the promises of the Declaration of Independence would be all fulfilled. But he was called away before this final triumph.[Pg 9] A great writer of Antiquity, a perpetual authority, tells us that “the chief duty of friends is not to follow the departed with idle lamentation, but to remember their wishes and to execute their commands.”[3] These are the words of Tacitus. I venture to add that we shall best honor him we now celebrate, if we adopt his aspiration and strive for its fulfilment.

It is as Defender of Human Rights that Thaddeus Stevens deserves homage. Here he is supreme. On other questions he erred. On the finances his errors were signal. But history will forget these and other failings, as it bends with reverence before the exalted labors by which humanity has been advanced. Already he takes his place among illustrious names which are the common property of mankind. I see him now, as so often during life. His venerable form moves slowly and with uncertain steps; but the gathered strength of years is in his countenance, and the light of victory on his path. Politician, calculator, timeserver, stand aside! A hero-statesman passes to his reward.

Speeches in the Senate, January 12 and 15, 1869.

MR. PRESIDENT,—This discussion, so unexpectedly prolonged, has already brought us to see two things,—first, the magnitude of the interests involved, and, secondly, the simplicity of the principle which must determine our judgment. It is difficult to exaggerate the amount of claims which will be let loose to feed on the country, if you recognize that now before us; nor can I imagine anything more authoritative than the principle which bars all these claims, except so far as Congress in its bounty chooses to recognize them.

By the Report of the Committee on Claims[4] it appears that the house of Miss Sue Murphey, of Decatur, Alabama, was destroyed, so that not a vestige remained, by order of the commander at that place, on the 19th March, 1864, under instructions from General Sherman to make it a military post. It is also stated that Miss Murphey was loyal. These are the important facts. Assuming the loyalty of the petitioner, which I have been led to doubt, the simple question is, whether the Nation is bound to indemnify a citizen, domiciled in a Rebel State, for property in that State, taken for the building of a fort by the United States against the Rebels.

Here it is proper to observe three things,—one concerning the petitioner, and two concerning the property taken: first, that the petitioner was domiciled in a Rebel State, or, to use more technical language, in a State declared by public proclamation to be in rebellion; secondly, that the property was situated within the Rebel State; and, thirdly, that the property was taken under the necessities of war, and for the national defence. On these three several points there can be no question. They are facts which have not been denied in this debate. Thus far I confine myself to a statement of facts, in order to prepare the way for the consideration of the legal consequences.

Bearing in mind these facts, several difficulties which have been presented during this debate disappear. For instance, a question was put by a learned Senator [Mr. Davis, of Kentucky] as to the validity of an imagined seizure of the property of the eminent Judge Wayne, situated in the District of Columbia. But it is obvious that the facts in the imagined case of the eminent judge are different from those in the actual case before us. Judge Wayne, unlike the petitioner, was domiciled in a loyal part of the country; and his property, unlike that of the petitioner, was situated in a loyal part of the country. This difference between the two cases serves to illustrate the position of the petitioner. Because property situated in the District of Columbia and belonging to a loyal judge domiciled here could not be taken, it by no means follows that property situated in a Rebel State and belonging to a person domiciled there can enjoy the same immunity.

Behind the fact of domicile, and the fact that the property was situated in a Rebel State, is that other[Pg 12] fact, equally incontrovertible, that it was taken in the exigencies of war. The military order under which the taking occurred declares that “the necessities of the Army require the use of every building in Decatur,”—not merely the building in question, but every building; and the Report of the Committee says that “General Sherman had previously issued an order to fortify Decatur for a military post.” I might quote more to illustrate this point; but I quote enough. It is plain and indisputable that the taking was under an exigency of war. To deny this is to assail the military order under which it was done, and also the Report of the Committee.

Three men once governed the mighty Roman world. Three facts govern the present case, with the power of a triumvirate,—the domicile of the petitioner, the situation of the property, and the exigency of war. If I dwell on these three facts, it is because I am unwilling that either should drop out of sight; each is important. Together they present a case which it is easy to decide, however painful the conclusion. And this brings me to the principle which I said at the beginning was so simple. Indeed, let the facts be admitted, and it is difficult to see how there can be any question in the present case. But the facts, as I have stated them, are indubitable.

On these facts two questions arise: first, as to the rule of International Law applicable to property of persons domiciled in an enemy country; and, secondly, as to the applicability of this rule to the present case. Of the rule there can be no question; its applicability is sustained by reason, and also by authority from which there can be no appeal.

In stating and enforcing the rule I might array writers, precedents, and courts; but I content myself with a paragraph from a writer who in expounding the Laws of War is perhaps the highest authority. I refer to the Dutch publicist of the last century, Bynkershoek, whose work is always quoted in the final resort on these questions. This great writer expresses himself as follows:—

“Could it be doubted whether under the name of enemies may be understood also our friends who having been conquered are with the enemy, their city perhaps being occupied by him?… I should think that they also were to be so understood, certainly as regards goods which they have under the government of the enemy.… I know upon what ground others say the contrary,—namely, that our friends, although they are with the enemy, have no spirit of hostility to us; for that it is not of their free will that they are there, and that it is only from the animus that the case is to be judged. But the case does not depend upon the animus alone; because neither are all the rest of our enemy’s subjects, at any rate very few of them, carried away by a spirit of hostility to us; but it depends upon the right by which those goods are with the enemy, and upon the advantage which they afford him for our destruction.”[5]

Nothing could be stronger in determining the liability from domicile. Its sweeping extent, under the exigency of war, is proclaimed by this same writer in words of peculiar weight:—

“Since it is the condition of war that enemies are despoiled and proscribed as to every right, it stands to reason that everything found with the enemy changes its owner and goes to the Treasury.… If we follow the mere Law of War, even immovable property may be sold and its price turned into the Treasury, as in the case of movable property.”[6]

Here is an austere statement; but it was adopted by Mr. Jefferson as a fundamental principle in his elaborate letter to the British Minister, vindicating the confiscation of the property of Loyalists during the Revolution.[7] It was the corner-stone of his argument, as it has since been the corner-stone of judicial decisions. To cite texts and precedents in its support is superfluous. It must be accepted as the rule of International Law.

The rule, as succinctly expressed, is simply this,—that the property of persons domiciled in an enemy country is liable to seizure and capture without regard to the alleged friendly or loyal character of the owner.

Unquestionably there are limitations imposed by humanity which must not be transcended. A country must not be wasted, or buildings destroyed, unless under some commanding necessity. This great power must not be wantonly employed. Men must not become barbarians. But, if, in the pursuit of the enemy, or for purposes of defence, property must be destroyed, then by International Law it can be done. This is the rule. Vattel, while pleading justly and with persuasive examples for the preservation of works of art, such as temples, tombs, and structures of remarkable beauty, admits that even these may be sacrificed:—

“If for the operations of war, to advance the works in a siege, it is necessary to destroy edifices of this nature, one has undoubtedly the right to do so. The sovereign of the country, or his general, destroys them indeed himself, when the necessities or the maxims of war invite thereto. The governor of a besieged city burns its suburbs, to prevent the besiegers from obtaining a lodgment therein. Nobody thinks of blaming him who lays waste gardens, vineyards, orchards, in order to pitch his tent and intrench himself there.”[8]

This same rule is recognized by Manning, in his polished and humane work, less frequently quoted, but entitled always to great respect. This interesting writer expresses himself as follows:—

“It is clearly a belligerent’s right to destroy the enemy’s property as far as necessary in making fortifications.… Destruction of the enemy’s property is justifiable as far as indispensable for the purposes of warfare, but no further.”[9]

With the limitations which I have tried to exhibit, the rule is beyond question in the relations between nations. Do you call it harsh? Undoubtedly it is so. It is war, which from beginning to end is terrible harshness. Without the incidents sanctioned by this rule war would be changed, so that it would be no longer war. It was such individual calamities that Shakespeare had in mind, when he spoke of “the purple testament of bleeding war”; and it was such which entered into the vision of that other poet, when, in words of remarkable beauty, he pictured, by way of contrast, the blessings of peace:—

It only remains now to show that this rule of International Law is applicable to the present case. Of course, our late war was not between two nations; therefore it was not strictly international. But it was between the National Government, on one side, and a Rebellion which had become “territorial” in character, with such form and body as to have belligerent rights on land. Mark the distinction, if you please; for I have always insisted, and still insist, that complete belligerency on land does not imply belligerency on the ocean. As there is a dominion of the land, so there is a dominion of the ocean; and as there is a belligerency of the land, so there is also a belligerency of the ocean. Therefore, while denying to our Rebels belligerent rights on the ocean, I have no hesitation with regard to them on the land. But just in proportion as these are admitted, is the rule of International Law made applicable to the present case.

Against our Rebels the Nation had two sources of power and two arsenals of rights,—one of these being the powers and rights of sovereignty, and the other the powers and rights of war,—the former being determined by the Constitution, the latter by International Law. The Nation might pursue a Rebel as traitor or as belligerent; but whether traitor or belligerent, he was always an enemy. Pursuing him in the courts as traitor, he was justly entitled to all the delays and safeguards of the Constitution; but it was otherwise, if he was treated as belligerent. Pursuing him in battle, driving him from point to point, dislodging him from fortresses, expelling him from towns, pushing him back from our advancing line, and then building fortifications against him,—all this was war; and it was none the less[Pg 17] war because the enemy was unhappily our own countryman. A new law supplied the rule for our conduct,—not the Constitution, with its manifold provisions dear to the lover of Liberty, including the solemn requirement that nobody shall “be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law,” and then again that other requirement, that “private property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation.” All these were silent while International Law prevailed. The Rebellion had grown until it became a war; and as this war was among countrymen, it was a civil war. But the rule of conduct in a civil war is to be found in the Law of Nations.

I do not stop to quote the familiar views of publicists, especially of Vattel, to the effect that in a civil war the two parties are to be treated as “two different nations.”[11] Suffice it to say, that such is the judgment of all the authorities on International Law. But I come directly to the decisions of our Supreme Court, which recognize the rule of International Law as applicable to our civil war.

In the famous cases known as the Prize Cases, the Court expressly says:—

“All persons residing within this territory, whose property may be used to increase the revenues of the hostile power, are in this contest liable to be treated as enemies, though not foreigners.”[12]

Here is the rule of International Law applied directly to our civil war. In a later case the rule is applied with added emphasis and particularity:—

“We must be governed by the principle of public law, so often announced from this bench as applicable alike to civil and international wars, that all the people of each State or district in insurrection against the United States must be regarded as enemies.”[13]

Thus, according to our highest tribunal, the rule in civil war and international war is the same. By another decision of the Court, this same rule continues in force until the character of public enemy is removed by competent authority. On this point the Court declares itself as follows, in the Alexander cotton case:—

“All the people of each State or district in insurrection against the United States must be regarded as enemies, until, by the action of the Legislature and the Executive, or otherwise, that relation is thoroughly and permanently changed.”[14]

If the present case is to be settled by authority, this is enough. Here is the Supreme Court solemnly recognizing the rule of International Law, even to the extent of embracing under its penalties all the people of the hostile community, without regard to their sentiments of loyalty. This is decisive. You cannot decree the national liability in the present case without reversing these decisions. You must declare that the rule of International Law is not applicable to our civil war. There is no ground for exception. You must reject the rule absolutely.

Do you say that its application is harsh? Of course it is. But again I say, this is war; or rather, it is rebellion which has assumed the front of war. I do not make the rule. I have nothing to do with it. I take it as I find it, affirmed by great authorities of International[Pg 19] Law, and reaffirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Here I might stop; for the conclusion stands on reason and authority, each unanswerable; but I proceed further in order to relieve the case of all ambiguity. Of course instances may be adduced where compensation has been made to sufferers from an army, but no case like the present. If we glance at these instances, we shall see the wide difference.

1. The first instance is where property is taken by the Nation, or its representative, within its own established jurisdiction. Of course this is unlike that now before us. To cite it is only to perplex and mystify, not to instruct. Thus, a Senator [Mr. Willey, of West Virginia] has adduced well-known words from Vattel on the question, “Whether subjects should be indemnified for damages sustained in war,” “as when a field, a house, or a garden, belonging to a private person, is taken for the purpose of erecting on the spot a town-rampart, or any other piece of fortification.”[15] But this authority is not applicable to the present case, where the claimant is not what Vattel calls a “subject,” and the property was not within the established jurisdiction of the nation. It applies only to such cases as occurred during the War of 1812, where property was taken on the Canadian frontier or at New Orleans for the erection of a fortress,—or such a case as that which formed one of the military glories of the Count Rochambeau, when at the head of the French forces in our country. The story is little known, and therefore I adduce it now, as I find it in[Pg 20] the Memoirs of Ségur, one of the brilliant officers who accompanied the expedition.

The French squadrons were quitting their camp at Crompond, near the North River, in New York, on their way to embark for France. Their commander, fresh from the victory of Yorktown, was at the head of the columns, when a simple citizen approached, and, tapping him slightly on the shoulder, said: “In the name of the law you are my prisoner.” The glittering staff by which Count Rochambeau was surrounded broke forth with indignation, but the General-in-Chief restrained their impatience, and, smiling, said to the American citizen: “Take me away with you, if you can.” “No,” replied the simple representative of the law, “I have done my duty, and your Excellency may proceed on your march, if you wish to set justice at defiance. Some of your soldiers have cut down several trees, and burnt them to make their fires. The owner of them claims an indemnity, and has obtained a warrant against you, which I have come to execute.” The Count, on hearing this explanation, which was translated by one of his staff, gave bail, and at once directed the settlement of the claim on equitable grounds. The American withdrew, and the French squadrons, which had been arrested by a simple constable, proceeded on their march. This interesting story, so honorable to our country and to the French commander, is disfigured by the end, showing extortion on the part of the claimant. A judgment by arbitration fixed the damages at four hundred dollars, being less than the commander had at once offered, while the claimant demanded no less than three thousand dollars.[16]

Afterward, in the National Assembly of France, when that great country began to throb with republican life, this instance of submission to law was mentioned with pride.[17] But though it cannot lose its place in history, it cannot furnish a precedent of International Law. Besides being without any exigency of defence, the trespass was within our own jurisdiction, in which respect it differed precisely from the case on which we are to vote. I adduce it now because it serves to illustrate vividly the line of law.

2. Another instance, which I mention in order to put it aside, is where an army in a hostile country has carefully paid for all its supplies. Such conduct is exceptional. The general rule was expressed by Mr. Marcy, during our war with Mexico, when he said that “an invading army has the unquestionable right to draw its supplies from the enemy without paying for them, and to require contributions for its support,” that “the enemy may be made to feel the weight of the war.”[18] But General Halleck, after quoting these words, says that “the resort to forced contributions for the support of our armies in a country like Mexico, under the particular circumstances of the war, would have been at least impolitic, if not unjust; and the American generals very properly declined to adopt, except to a very limited extent, the mode indicated.”[19] According to this learned authority, it was a question of policy rather than of law.

The most remarkable instance of forbearance, under this head, was that of the Duke of Wellington, as he entered France with his victorious troops, fresh from the[Pg 22] fields of Spain. He was peremptory that nothing should be taken without compensation. His order on this occasion will be found at length in Colonel Gurwood’s collection of his “Dispatches.”[20] His habit was to give receipts for supplies, and ready money was paid in the camp. The British historian dwells with pride on the conduct of the commander, and records the astonishment with which it was regarded by both soldiers and peasantry, who found it so utterly at variance with the system by which the Spaniards had suffered and the French had profited during the Peninsular campaigns.[21] The conduct of the Duke of Wellington cannot be too highly prized. It was more than a victory. I have always regarded it as the high-water mark of civilized war, so far as war can be civilized. But I am obliged to add, on this occasion, that it was politic also. In thus softening the rigors of war, he smoothed the way for his conquering army. In a dispatch to one of his generals, written in the spirit of the order, he says, in very expressive language: “If we were five times stronger than we are, we could not venture to enter France, if we cannot prevent our soldiers from plundering.”[22] It was in a refined policy that this important order had its origin. Regarding it as a generous example for other commanders, and offering to it my homage, I must confess, that, as a precedent, it is entirely inapplicable to the present case.

Putting aside these two several classes of cases, we are brought back to the original principle, that there[Pg 23] can be no legal claim to damages for property situated in an enemy country, and belonging to a person domiciled there, when taken for the exigencies of war.

If the conclusion were doubtful, I should deem it my duty to exhibit at length the costly consequences from an allowance of this claim. The small sum which you vote will be a precedent for millions. If you pay Miss Sue Murphey, you must pay claimants whose name will be Legion. Of course, if justice requires, let it be done, even though the Treasury fail. But the mere possibility of such liabilities is a reason for caution on our part. We must consider the present case as if on its face it involved not merely a few thousands, but many millions. Pay it, and the country will not be bankrupt, but it will have an infinite draft upon its resources. If the occasion were not too grave for a jest, I would say of it as Mercutio said of his wound: “No, ’tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church-door; but ’tis enough.”

If you would have a practical idea of the extent of these claims, be taught by the history of the British Loyalists, who at the close of our Revolution appealed to Parliament for compensation on account of their losses. The whole number of these claims was five thousand and seventy-two. The whole amount claimed was £8,026,045, or about thirty-eight million dollars, of which the commissioners allowed less than half.[23] Our claimants would be much more numerous, and the amount claimed vaster.

We may also learn from England something of the spirit in which such claimants should be treated. Even[Pg 24] while providing for them, Parliament refused to recognize any legal title on their part. What it did was in compassion, generosity, and bounty,—not in satisfaction of a debt. Mr. Pitt, in presenting the plan which was adopted, expressly denied any right on grounds of “strict justice.” Here are his words:—

“The American Loyalists, in his opinion, could not call upon the House to make compensation for their losses as a matter of strict justice; but they most undoubtedly had strong claims on their generosity and compassion. In the mode, therefore, that he should propose for finally adjusting their claims, he had laid down a principle with a view to mark this distinction.”[24]

In the same spirit Mr. Burke said:—

“Such a mode of compensating the claims of the Loyalists would do the country the highest credit. It was a new and a noble instance of national bounty and generosity.”[25]

Mr. Fox, who was full of ardent sympathies, declared:—

“They were entitled to a compensation, but by no means to a full compensation.”[26]

And Mr. Pitt, at another stage of the debate, thus denied their claim:—

“They certainly had no sort of claim to a repayment of all they had lost.”[27]

So far as this instance is an example to us, it is only an incentive to a kindly policy, which, after prudent inquiry,[Pg 25] and full knowledge of the extent of these claims, shall make such reasonable allowance as humanity and patriotism may require. There must be an inquiry not only into this individual case, but into all possible cases that may spring into being, so that, when we act, it may be on the whole subject.

From the beginning of our national life Congress has been called to deal with claims for losses by war. Though new in form, the present case belongs to a long list, whose beginning is hidden in Revolutionary history. The folio volume of State Papers, now before me, entitled “Claims,” attests the number and variety. Even amid the struggles of the war, as early as 1779, the Rev. Dr. Witherspoon was allowed $19,040 for repairs of the college at Princeton damaged by the troops.[28] There was afterward a similar allowance to the academy at Wilmington, in Delaware, and also to the college in Rhode Island. These latter were recommended by Mr. Hamilton, while Secretary of the Treasury, as “affecting the interests of literature.”[29] On this account they were treated as exceptional. It will also be observed that they concerned claimants within our own jurisdiction. But on a claim for compensation for a house burnt at Charlestown for the purpose of dislodging the enemy, by order of the American commander at that point during the Siege of Boston, a Committee of Congress in 1797 reported, that, “as Government has not adopted a general rule to compensate individuals who have suffered in a similar manner, the Committee are of opinion that the prayer of this petition cannot be granted.”[30] At a later[Pg 26] day, however, after successive favorable reports, the claim was finally in 1833 allowed, and compensation made to the extent of the estimated value of the property destroyed.[31]

In 1815 a claimant received compensation for a house at the end of the Potomac bridge, which was blown up to prevent certain public stores from falling into the hands of the enemy;[32] and other claimants at Baltimore received compensation for rope-walks burnt in the defence of the city.[33] The report of a committee in another case says that the course of Congress “seems to inculcate that indemnity is due to all those whose losses have arisen from the acts of our own Government, or those acting under its authority, while losses produced by the conduct of the enemy are to be classed among the unavoidable calamities of war.”[34] This is the most complete statement of the rule which I find.

After the Battle of New Orleans the question of the application of this rule was presented repeatedly, and with various results. In one case, a claim for “a quantity of fencing” used as fuel by troops of General Jackson was paid by Congress; so also was a claim for damages to a plantation “upon which public works for the defence of the country were erected.”[35] On the other hand, a claim for “an elegant and well-furnished house” which afforded shelter to the British army and was[Pg 27] therefore fired on with hot shot, also a claim for damage to a house and plantation where a battery was erected by our troops, and on both of which claims the Committee, simultaneously with the two former, reported favorably, were disallowed by Congress.[36] In a subsequent case both the report and action seem to have proceeded on a different principle from that previously enunciated. At the landing of the enemy near New Orleans, the levee was cut in order to annoy him. As a consequence, the plantation of the claimant was inundated, and suffered damages estimated at $19,250. But the claim was rejected, on the ground that “the injury was done in the necessary operations of war.”[37] Certainly this ground may be adopted in the present case, while it must not be forgotten that in all the foregoing cases the claimants were citizens within our own jurisdiction, whose property had been used against a foreign enemy.

The multiplicity of claims arising in the War of 1812 prompted an Act of Congress in 1816 for “the payment for property lost, captured, or destroyed by the enemy.” In this Act it was, among other things, provided,—

“That any person, who, in the time aforesaid [the late war], has sustained damage by the destruction of his or her house or building by the enemy, while the same was occupied as a military deposit, under the authority of an officer or agent of the United States, shall be allowed and paid the amount of such damage, provided it shall appear that such occupation was the cause of its destruction.”[38]

Two years later it was found, that, in order to obtain the benefits of this Act, people, especially on the frontier of the State of New York, had not hesitated at “fraud, forgery, and perhaps perjury.”[39] Thereupon, the law, which by its terms was limited to two years, and which it had been proposed to extend, was permitted to expire; and it is accordingly now marked in our Statutes, “Obsolete.” But it is not without its lesson. It shows what may be expected, should any precedent be adopted by Congress to quicken the claimants now dormant in the South. “It is the duty of a good Government to attend to the morals of the people as an affair of primary concern.”[40] So said the Committee in 1818, recommending the non-extension of the Act. But this warning is as applicable now as then.

Among the claimants of the present day there are doubtless many of character and virtue. It is hard to vote against them. But I cannot be controlled on this occasion by my sympathies. Everywhere and in every household there has been suffering which mortal power cannot measure. Sometimes it is borne in silence and solitude; sometimes it is manifest to all. In coming into this Chamber and asking for compensation, it invites comparison with other instances. If your allowance is to be on account of merit, who will venture to say that this case is the most worthy? It is before us now for judgment. But there are others, not now before us, where the suffering has been greater, and where, I do not hesitate to say, the reward should be in proportion. This is an appeal for justice. Therefore do I say, in the name of justice, Wait!

January 15th, the same bill being under discussion, Mr. Sumner spoke as follows:—

There is another point, on which I forbore to dwell with sufficient particularity when I spoke before. It is this: Assuming that this claimant is loyal, I honor her that she kept her loyalty under the surrounding pressure of rebellion. Of course this was her duty,—nor more nor less. The practical question is, Shall she be paid for it? Had she been disloyal, there would have been no proposition of compensation. As the liability of the Nation is urged on the single ground that she kept her regard for the flag truly and sincerely, it is evident that this loyalty must be put beyond question; it must be established like any other essential link of evidence. I think I do not err in supposing that it is not established in the present case,—at least with such certainty as to justify opening the doors of the Treasury.

But assuming that in fact the loyalty is established, I desire to go further, and say that not only is the present claim without any support in law, but it is unreasonable. The Rebel States had become one immense prison-house of Loyalty; Alabama was a prison-house. The Nation, at every cost of treasure and blood, broke into that prison-house, and succeeded in rescuing the Loyalists; but the terrible effort, which cost the Nation so dearly, involved the Loyalists in losses also. In breaking into the prison-house and dislodging the Rebel keepers, property of Loyalists suffered. And now we are asked to pay for this property damaged in our efforts for their redemption. Our troops came down to break the prison-doors and set the captives free. Is it not unreasonable to expect us to pay for this breaking?

If the forces of the United States had failed, then would these Loyalists have lost everything, country, property, and all,—that is, if really loyal, according to present professions. It was our national forces that saved them from this sacrifice, securing to them country, and, if not all their property, much of it. A part of the property of the present claimant was taken in order to save to her all else, including country itself. It was a case, such as might occur under other circumstances, where a part—and a very small part—is sacrificed in order to save the rest. According to all analogies of jurisprudence, and the principles of justice itself, the claimant can look for nothing beyond such contribution as Congress in its bounty may appropriate. It is a case of bounty, and not of law.

It is a mistake to suppose, as has been most earnestly argued, that a claimant of approved loyalty in the Rebel States should have compensation precisely like a similar claimant in a Loyal State. To my mind this assumption is founded on a misapprehension of the Constitution, the law, and the reason of the case,—three different misapprehensions. By the Constitution property cannot be taken for public use without “just compensation”; but this rule was silent in the Rebel States. International Law stepped in and supplied a different rule. And when we consider how much was saved to the loyal citizen in a Rebel State by the national arms, it will be found that this rule is only according to justice.

I have no disposition to shut the door upon claimants. Let them be heard; but the hearing must be according to some system, so that Congress shall know the character and extent of these claims. Before the motion[Pg 31] of my colleague,[41] I had already prepared instructions for the Committee, which I will read, as expressing my own conclusion on this matter:—

“That the committee to whom this bill shall be referred, the Committee on Claims, be instructed to consider the expediency of providing for the appointment of a commission whose duty it shall be to inquire into the claims of the loyal citizens of the National Government arising during the recent Rebellion anywhere in the United States, classifying these claims, specifying their respective amounts, and the circumstances out of which they originated, also, the evidence of loyalty adduced by the claimants respectively, to the end that Congress may know precisely the extent and character of these claims before legislating thereupon.”

As this is a resolution of instruction, simply to consider the expediency of what is proposed, I presume there can be no objection to it.

Afterwards, on motion of Mr. Sumner, the bill, with all pending propositions, was recommitted to the Committee on Claims.

Speech in the Senate, January 23, 1869.

Mr. Hinds, while engaged in canvassing the State of Arkansas on the Republican side, was assassinated. The Senators of Arkansas requested Mr. Sumner to speak on the resolution announcing his death.

MR. PRESIDENT,—It is with hesitation that I add a word on this melancholy occasion, and I do it only in compliance with the suggestion of others.

I did not know Mr. Hinds personally; but I have been interested in his life, and touched by his tragical end. Born in New York, educated in Ohio, a settler in Minnesota, and then a citizen of Arkansas, he carried with him always the energies and principles ripened under our Northern skies. He became a Representative in Congress, and, better still, a vindicator of the Rights of Man. Unhappily, that barbarism which we call Slavery is not yet dead, and it was his fate to fall under its vindictive assault. Pleading for the Equal Rights of All, he became a victim and martyr.

Thus suddenly arrested in life, his death is a special sorrow, not only to family and friends, but to the country which he had begun to serve so well. The void, when a young man dies, is measured less by what he has done than by the promises of the future. Performance itself is forgotten in the ample assurance afforded by character. Already Mr. Hinds had given himself[Pg 33] sincerely and bravely to the good cause. By presence and speech he was urging those great principles of the Declaration of Independence whose complete recognition will be the cope-stone of our Republic, when he fell by the stealthy shot of an assassin. It was in the midst of this work that he fell, and on this account I am glad to offer my tribute to his memory.

As the life he led was not without honor, so his death is not without consolation. It was the saying of Antiquity, that it is sweet to die for country. Here was death not only for country, but for mankind. Nor is it to be forgotten, that, dying in such a cause, his living voice is echoed from the tomb. There is a testimony in death often greater than in any life. The cause for which a man dies lives anew in his death. “If the assassination could trammel up the consequence,” then might the assassin find some other satisfaction than the gratification of a barbarous nature. But this cannot be. His own soul is blasted; the cause he sought to kill is elevated; and thus it is now. The assassin is a fugitive in some unknown retreat; the cause is about to triumph.

Often it happens that death, which takes away life, confers what life alone cannot give. It makes famous. History does not forget Lovejoy, who for devotion to the cause of the slave was murdered by a fanatical mob; and it has already enshrined Abraham Lincoln in holiest keeping. Another is added to the roll,—less exalted than Lincoln, less early in immolation than Lovejoy, but, like these two, to be remembered always among those who passed out of life through the gate of sacrifice.

Speech in the Senate, February 5, 1869.

The Senate having under consideration a joint resolution from the House of Representatives proposing an Amendment to the Constitution of the United States on the subject of Suffrage in the words following, viz.:—

“Article ——.

“Section 1. The right of any citizen of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of the race, color, or previous condition of slavery of any citizen or class of citizens of the United States.

“Sec. 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce by proper legislation the provisions of this Article.”—

Mr. Sumner offered the following bill as a substitute:—

Section 1. That the right to vote, to be voted for, and to hold office shall not be denied or abridged anywhere in the United States, under any pretence of race or color; and all provisions in any State Constitutions, or in any laws, State, Territorial, or Municipal, inconsistent herewith, are hereby declared null and void.

Sec. 2. That any person, who, under any pretence of race or color, wilfully hinders or attempts to hinder any citizen of the United States from being registered, or from voting, or from being voted for, or from holding office, or who attempts by menaces to deter any such citizen from the exercise or enjoyment of the rights of citizenship above mentioned, shall be punished by a fine not less than one hundred dollars nor more than three thousand dollars, or by imprisonment in the common jail for not less than thirty days nor more than one year.

Sec. 3. That every person legally engaged in preparing a register of voters, or in holding or conducting an election, who wilfully refuses to register the name or to receive, count, return, or otherwise give the proper legal effect to the vote of any citizen, under any pretence of race or color, shall be punished by a fine not less than five hundred dollars nor more than four thousand dollars, or by imprisonment in the common jail for not less than three calendar months nor more than two years.

Sec. 4. That the District Courts of the United States shall have exclusive jurisdiction of all offences against this Act; and the district attorneys, marshals, and deputy marshals, the commissioners appointed by the Circuit and Territorial Courts of the United States, with powers of arresting, imprisoning, or bailing offenders, and every other officer specially empowered by the President of the United States, shall be, and they are hereby, required, at the expense of the United States, to institute proceedings against any person who violates this Act, and cause him to be arrested and imprisoned or bailed, as the case may be, for trial before such court as by this Act has cognizance of the offence.

Sec. 5. That every citizen unlawfully deprived of any of the rights of citizenship secured by this Act, under any pretence of race or color, may maintain a suit against any person so depriving him, and recover damages in the District Court of the United States for the district in which such person may be found.

On this he spoke as follows:—

MR. PRESIDENT,—In the construction of a machine the good mechanic seeks the simplest process, producing the desired result with the greatest economy of time and force. I know no better rule for Congress on the present occasion. We are mechanics, and the machine we are constructing has for its object the conservation of Equal Rights. Surely, if we are wise, we shall seek the simplest process, producing the desired result with the greatest economy of time and force. How widely Senators are departing from this rule will appear before I have done.

Rarely have I entered upon any debate in this Chamber with a sense of sadness so heavy as oppresses me at this moment. It was sad enough to meet the champions of Slavery, as in other days they openly vindicated the monstrous pretension and claimed for it the safeguard of the Constitution, insisting that Slavery was national and Freedom sectional. But this was not so sad as now, after a bloody war with Slavery, and its defeat[Pg 36] on the battle-field, to meet the champions of a kindred pretension, for which they claim the safeguard of the Constitution, insisting also, as in the case of Slavery, upon State Rights. The familiar vindication of Slavery in those early debates was less sickening than the vindication now of the intolerable pretension, that a State, constituting part of the Nation, and calling itself “Republican,” is entitled to shut out any citizen from participation in government simply on account of race or color. To denominate such pretension as intolerable expresses very inadequately the extent of its absurdity, and the utterness of its repugnance to all good principles, whether of reason, morals, or government.

I make no question with individual Senators; I make no personal allusion; but I meet the odious imposture, as I met the earlier imposture, with indignation and contempt, naturally excited by anything unworthy of this Chamber and unworthy of the Republic. How it can enter here and find Senators willing to assume the stigma of its championship is more than I can comprehend. Nobody ever vindicated Slavery, who did not lay up a store of regret for himself and his children; and permit me to say now, nobody can vindicate Inequality and Caste, whether civil or political, the direct offspring of Slavery, as intrenched in the Constitution, beyond the reach of national prohibition, without laying up a similar store of regret. Death may happily come to remove the champion from the judgment of the world; but History will make its faithful record, to be read with sorrow hereafter. Do not complain, if I speak strongly. The occasion requires it. I seek to save the Senate from participation in an irrational and degrading pretension.

Others may be cool and indifferent; but I have warred[Pg 37] with Slavery too long, in all its different forms, not to be aroused when this old enemy shows its head under an alias. Once it was Slavery; now it is Caste; and the same excuse is assigned now as then. In the name of State Rights, Slavery, with all its brood of wrong, was upheld; and now, in the name of State Rights, Caste, fruitful also in wrong, is upheld. The old champions reappear under other names and from other States, each crying out, that, under the National Constitution, notwithstanding even its supplementary Amendments, a State may, if it pleases, deny political rights on account of race or color, and thus establish that vilest institution, a Caste and an Oligarchy of the Skin.

This perversity, which to careless observation seems so incomprehensible, is easily understood, when it is considered that the present generation grew up under an interpretation of the National Constitution supplied by the upholders of Slavery. State Rights were exalted and the Nation was humbled, because in this way Slavery might be protected. Anything for Slavery was constitutional. Such was the lesson we were taught. How often I have heard it! How often it has sounded through this Chamber, and been proclaimed in speech and law! Under its influence the Right of Petition was denied, the atrocious Fugitive Slave Bill was enacted, and the claim was advanced that Slavery travelled with the flag of the Republic. Vain are all our victories, if this terrible rule is not reversed, so that State Rights shall yield to Human Rights, and the Nation be exalted as the bulwark of all. This will be the crowning victory of the war. Beyond all question, the true rule under the National Constitution, especially since its additional Amendments, is, that anything for Human Rights is[Pg 38] constitutional. Yes, Sir; against the old rule, Anything for Slavery, I put the new rule, Anything for Human Rights.

Sir, I do not declare this rule hastily, and I know the presence in which I speak. I am surrounded by lawyers, and now I challenge any one or all to this debate. I invoke the discussion. On an occasion less important, Mr. Pitt, afterwards Lord Chatham, after saying that he came not “with the statute-book doubled down in dog’s-ears to defend the cause of Liberty,” that he relied on “a general principle, a constitutional principle,” exclaimed: “It is a ground on which I stand firm, on which I dare meet any man.”[42] In the same spirit I would speak now. No learning in books, no skill acquired in courts, no sharpness of forensic dialectics, no cunning in splitting hairs can impair the vigor of the constitutional principle which I announce. Whatever you enact for Human Rights is constitutional. There can be no State Rights against Human Rights; and this is the supreme law of the land, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

A State exercises its proper function, when, within its own jurisdiction, it administers local law, watches local interests, promotes local charities, and by local knowledge brings the guardianship of Government to the home of the citizen. Such is the proper function of the State, by which we are saved from that centralization elsewhere so absorbing. But a State transcends its proper function, when it interferes with those Equal Rights,[Pg 39] whether civil or political, which by the Declaration of Independence and repeated texts of the National Constitution are under the safeguard of the Nation. The State is local in character, and not universal. Whatever is justly local belongs to its cognizance; whatever is universal belongs to the Nation. But what can be more universal than the Rights of Man? They are for “all men,”—not for all white men, but for all men. Such they have been declared by our fathers, and this axiom of Liberty nobody can dispute.

Listening to the champions of Caste and Oligarchy under the National Constitution, and perusing their writings, I think I understand the position they take. With as much calmness as I can command, I note what they have to say in speech and in print. I know it all. I do not err, when I say that this whole terrible and ignominious pretension is traced to direct and barefaced perversion of the National Constitution. Search history, study constitutions, examine laws, and you will find no perversion more thoroughly revolting. By the National Constitution it is provided, that “the electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State Legislature,”—thus seeming to refer the primary determination of what are called “qualifications” to the States; and this is reinforced by the further provision, that “the times, places, and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations.” This is all On these simple texts, conferring plain and intelligible powers, the champions insist that “color” may be made[Pg 40] a “qualification,” and that under the guise of “regulations” citizens whose only offence is a skin not colored like our own may be shut out from political rights,—and that in this way a monopoly of rights, being at once a Caste and an Oligarchy of the Skin, is placed under the safeguard of the National Constitution. Such is the case of the champions; this is their stock-in-trade. With all their learning, all their subtlety, all their sharpness, this is what they have to say in behalf of an infamous pretension under the National Constitution. Everything from them begins and ends in a perversion of two words,—“qualifications” and “regulations.”

Now to this perversion I oppose point-blank denial. These two words are not justly susceptible of any such signification, especially in a National Constitution, which is to be interpreted always so that Human Rights shall not suffer. I do not stop now for dictionaries. The case is too plain. A “qualification” is something that can be acquired. A man is familiarly said to “qualify” for an office. Nothing can be a “qualification” which is not in its nature attainable,—as residence, property, education, or character, each of which is within the possible reach of well-directed effort. Color cannot be a “qualification.” If the prescribed “qualification” were color of the hair or color of the eyes, all would see its absurdity; but it is none the less absurd, when it is color of the skin. Here is an unchangeable condition, impressed by Providence. Are we not reminded that the leopard cannot change his spots, or the Ethiopian his skin? These are two examples of enduring conditions. Color is a quality from Nature. But a “quality” is very different from a “qualification.” A quality inherent in man and part of himself can never be a “qualification” in the[Pg 41] sense of the National Constitution. On other occasions I have cited authorities,[43] and shown how this attempt to foist into the National Constitution a pernicious meaning is in defiance of all approved definition, as it is plainly repugnant to reason, justice, and common sense.

The same judgment must be pronounced on the attempt to found this outrage upon the power to make “regulations,”—as if this word had not a limited signification which renders such a pretension impossible. “Regulations” are nothing but rules applicable to a given matter; they concern the manner in which a business shall be conducted, and, when used with regard to elections, are applicable to what may be called incidents, in contradistinction to the principal, which is nothing less than the right to vote. A power to regulate is not a power to destroy or to disfranchise. In an evil hour Human Rights may be struck down, but it cannot be merely by “regulations.” The pretension that under such authority this great wrong may be done is another illustration of that extravagance which the champions do not shrink from avowing.

The whole structure of Caste and Oligarchy, as founded on two words, may be dismissed. It is hard even to think of it without impatience, to speak of it without denouncing it as unworthy of human head or human heart. There are honorable Senators who shrink from any direct argument on these two words, and, wrapping themselves in pleonastic phrase, content themselves with[Pg 42] the general assertion, that power over suffrage belongs to the States. But they cannot maintain this conclusion without founding on these two words,—insisting that color may be a “qualification,” and that under the narrow power to make “regulations” a race may be broadly disfranchised. To this wretched pretension are they driven. And now, if there be any such within the sound of my voice, I ask the question directly,—Can “color,” whether of hair, eyes, or skin, be a “qualification” under our National Constitution? under the pretence of making “regulations” of elections, can a race be disfranchised? With all the power derived from both these words, can any State undertake to establish a Caste and organize an Oligarchy of the Skin? To put these questions is to answer them.

Such is the case as presented by the champions. But looking at the National Constitution, we shall be astonished still more at this pretension. On other occasions I have gone over the whole case of Human Rights vs. State Rights under the National Constitution. For the present I content myself with allusions only to the principal points.

It is under the National Constitution that the champions set up their pretension; therefore to the National Constitution I go. And I begin by appealing to the letter, which from beginning to end does not contain one word recognizing “color.” Its letter is blameless; and its spirit is not less so. Surely a power to disfranchise for color must find some sanction in the Constitution. There must be some word of clear intent under which this terrible prerogative can be exercised. This conclusion of reason is reinforced by the positive text[Pg 43] of our Magna Charta, the Declaration of Independence, where it is expressly announced that all men are equal in rights, and that just government stands only on the consent of the governed. In the face of the National Constitution, interpreted, first by itself, and then by the Declaration of Independence, how can this pretension prevail?

But there are positive texts of the National Constitution, refulgent as the Capitol itself, which forbid it with sovereign, irresistible power, and invest Congress with all needful authority to maintain the prohibition.

There is that key-stone clause, by which it is expressly declared that “the United States shall guaranty to every State in this Union a republican form of government”; and Congress is empowered to enforce this guaranty. The definition of a republican government was solemnly announced by our fathers, first, in that great battle-cry which preceded the Revolution, “Taxation without representation is tyranny,” and, secondly, in the great Declaration at the birth of the Republic, that all men are equal in rights, and that just government stands only on the consent of the governed. A Republic is where taxation and representation go hand in hand, where all are equal in rights, and no man is excluded from participation in the government. Such is the definition of a republican government, which it is the duty of Congress to maintain. Here is a bountiful source of power, which cannot be called in question. In the execution of the guaranty Congress may—nay, must—require that there shall be no Inequality, Caste, or Oligarchy of the Skin.

I know well the arguments of the champions. They insist that the definition of a Republican Government is to be found in the State Constitutions at the adoption[Pg 44] of the National Constitution; and as all these, except Massachusetts, recognized Slavery, they find that the denial of Human Rights is republican. But the champions forget that Slavery was regarded as a temporary exception,—that the slave, who was not represented, was not taxed,—that he was not part of the “body-politic,”—that the difference at that time was not between white and black, but between slave and freeman, precisely as in the days of Magna Charta,—that in most of the States all freemen, without distinction of color, were citizens,—and that, according to the history of the times, there was no State which ventured to announce in its Constitution a discrimination founded on color, except Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina,—this last the persevering enemy of republican government for successive generations; so that, if we look at the State Constitutions, we find that they also testify to the true definition.

There are words of authority which the champions forget also. They forget Magna Charta, that great title-deed called “the most august diploma and sacred anchor of English liberties,” where, after declaring that “there shall be but one measure throughout the realm,”[44] it is announced in memorable words, that “no freeman shall be disseized of his freehold or liberties but by legal judgment of his peers or by the law of the land,”[45] meaning, of course, the law of the whole land, in contradistinction to any local law. The words with which this great guaranty begin still resound: Nullus liber homo, “No freeman,” shall be denied the liberties which belong to freemen.

The champions also forget that “The Federalist,” in[Pg 45] commending the Constitution, at the time of its adoption, insisted, that, if the slaves became free, they would be entitled to representation. I have quoted the potent words before,[46] and now I quote them again:—

“It is only under the pretext that the laws have transformed the negroes into subjects of property, that a place is denied to them in the computation of numbers; and it is admitted, that, if the laws were to restore the rights which have been taken away, the negroes could no longer be refused an equal share of representation with the other inhabitants.”[47]

The champions also forget, that, in the debates on the ratification of the National Constitution, it was charged by its opponents, and admitted by its friends, that Congress was empowered to correct any inequality of suffrage. I content myself with quoting the weighty words of Madison in the Virginia Convention:—

“Some States might regulate the elections on the principles of Equality, and others might regulate them otherwise.… Should the people of any State by any means be deprived of the right of suffrage, it was judged proper that it should be remedied by the General Government.… If the elections be regulated properly by the State Legislatures, the Congressional control will very probably never be exercised. The power appears to me satisfactory, and as unlikely to be abused as any part of the Constitution.”[48]

The champions also forget that Chief Justice Taney, in that very Dred Scott decision where it was ruled that a person of African descent could not be a citizen of the[Pg 46] United States, admitted, that, if he were once a citizen, that is, if he were once admitted to be a component part of the body-politic, he would be entitled to the equal privileges of citizenship. Here are some of his emphatic words:—

“There is not, it is believed, to be found in the theories of writers on Government, or in any actual experiment heretofore tried, an exposition of the term citizen which has not been understood as conferring the actual possession and enjoyment, or the perfect right of acquisition and enjoyment, of an entire equality of privileges, civil and political.”[49]

Thus from every authority, early and late,—from Magna Charta, wrung out of King John at Runnymede,—from Hamilton, writing in “The Federalist,”—from Madison, speaking in the Convention at Richmond,—from Taney, presiding in the Supreme Court of the United States,—is there one harmonious testimony to the equal rights of citizenship.

If in the original text of the Constitution there could be any doubt, it was all relieved by the Amendment abolishing Slavery and empowering Congress to enforce this provision. Already Congress, in the exercise of this power, has passed a Civil Rights Act. It only remains that it should now pass a Political Rights Act, which, like the former, shall help consummate the abolition of Slavery. According to a familiar rule of interpretation, expounded by Chief Justice Marshall in his most masterly judgment, Congress, when intrusted with any power, is at liberty to select the “means” for its execution.[50] The Civil Rights Act came under the head of[Pg 47] “means” selected by Congress, and a Political Rights Act will have the same authority. You may as well deny the constitutionality of the one as of the other.

The Amendment abolishing Slavery has been reinforced by another, known as Article XIV., which declares peremptorily that “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” and again Congress is empowered to enforce this provision. What can be broader? Colored persons are citizens of the United States, and no State can abridge their privileges or immunities. It is a mockery to say, that, under these explicit words, Congress is powerless to forbid any discrimination of color at the ballot-box. Why, then, were they inscribed in the Constitution? To what end? There they stand, supplying additional and supernumerary power, ample for safeguard against Caste or Oligarchy of the Skin, no matter how strongly sanctioned by any State Government.

But the champions, anxious for State Rights against Human Rights, strive to parry this positive text, by insisting, that, in another provision of this same Amendment, the power over the right to vote is conceded to the States. Mark, now, the audacity and fragility of this pretext. It is true, that, “when the right to vote … is denied to any of the male inhabitants of a State, … or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion or other crime,” the basis of representation is reduced in corresponding proportion. Such is the penalty imposed by the Constitution on a State which denies the right to vote, except in a specific case. But this penalty on the State does not in any way, by the most distant implication, impair the plenary powers of Congress[Pg 48] to enforce the guaranty of a republican government, the abolition of Slavery, and that final clause guarding the rights of citizens,—three specific powers which are left undisturbed, unless the old spirit of Slavery is once more revived, and Congress is compelled again to wear those degrading chains which for so long a time rendered it powerless for Human Rights.

The pretension, that the powers of Congress, derived from the Constitution and its supplementary texts, were all foreclosed, and that the definition of a republican government was dishonored, merely by the indirect operation of the clause imposing a penalty upon a State, is the last effort of the champions. They are driven to the assumption, that all these beneficent powers have been taken away by indirection, and that a provision evidently temporary and limited can have this overwhelming consequence. They set up a technical rule of law, “Expressio unius est exclusio alterius.” It is impossible to see the application of this technicality. Because the basis of representation is reduced in proportion to any denial of the right to vote, therefore, it is argued, the denial of the right to vote is placed beyond the reach of Congress, notwithstanding all its plenary powers from so many sources. It is enough to say of this conclusion, that it is as strong as anything founded on the “argal” of the grave-digger in “Hamlet.” Really, Sir, it is too bad that so great a cause should be treated with such levity.

Mr. President, I make haste to the conclusion. Unwilling to protract this debate, I open the question in glimpses only. Even in this imperfect way, it is clearly seen, first, that there is nothing, absolutely nothing, in[Pg 49] the National Constitution to sustain the pretension of Caste or Oligarchy of the Skin, as set up by certain States,—and, secondly, that there is in the National Constitution a succession and reduplication of powers investing Congress with ample authority to repress any such pretension. In this conclusion, I raise no question on the power of States to regulate the suffrage; I do not ask Congress to undertake any such regulation. I simply propose, that, under the pretence of regulating the suffrage, States shall not exercise a prerogative hostile to Human Rights, without any authority under the National Constitution, and in defiance of its positive texts.

I am now brought directly to the proposed Amendment of the Constitution. Of course, the question stares us in the face, Why amend what is already sufficient? Why erect a supernumerary column?

So far as I know, two reasons are assigned. The first is, that the power of Congress is doubtful. It is natural that those who do not sympathize strongly with the Equal Rights of All should doubt. Men ordinarily find in the Constitution what is in themselves; so that the Constitution in its meaning is little more than a reflection of their own inner nature. As I am unable to find any ground of doubt, in substance or even in shadow, I shrink from a proposition which assumes that there is doubt. To my mind the power is too clear for question. As well question the obligation of Congress to guaranty a republican form of government, or the abolition of Slavery, or the prohibition upon States to interfere with the rights and privileges of citizenship, each of which is beyond question.