Title: History of the Beef Cattle Industry in Illinois

Author: Frank Webster Farley

Release date: November 10, 2015 [eBook #50420]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

BY

FRANK WEBSTER FARLEY

THESIS

FOR THE

DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE

IN AGRICULTURE

IN

THE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE

OF THE

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS

1915

May 22, 1915

THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY

Frank Webster Farley

ENTITLED History of the Beef Cattle Industry in Illinois

______________________________________________________________

IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE

DEGREE OF Bachelor of Science in Agriculture

____________________________________________________

Henry P Rusk

Instructor in Charge

APPROVED: May 27, 1915

Herbert W. Mumford

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF Animal Husbandry

HISTORY OF THE BEEF CATTLE INDUSTRY IN THE STATE OF ILLINOIS

"As a whole, the surface of the State of Illinois is nearly level. The prairie regions which cover a large part of the state are only slightly rolling, except in those places where streams have worn valleys. These are shallow in the eastern and the northern parts of the state, deepening gradually as the great rivers are approached. Nearly all the waters of Illinois find their way to the Mississippi river. Along this river, as also along the larger streams of the state, the lands are cut into abrupt bluffs or sharp spurs which, nearing the sources of the streams, gradually become softened into rounded hillocks, sinking at last into the low banks. Through such waterways as these form, flow streams usually gentle in current, often sluggish, and sometimes becoming even stagnant. Over a large part of the state, ponds and "sloughs", or marshes, formerly abounded. In these the water was renewed only by the rains that fell occasionally. Under hot suns these ponds, having neither inlet nor outlet, quickly became foul, particularly where stock resorted to them to drink and cool themselves, as they did almost universally throughout the state a few years ago, and do even now in some parts.

"For years such ponds furnished the principal, almost the only, water supply for stock in large areas of this state.[Pg 2] The constant use of such impure water greatly injured the quality of the milk and butter of cows, and doubtless had a baneful effect upon the health of the animals that drank the foul water and those who used the milk and butter.

"With the drainage of the land and the introduction of a pure supply of water, came the disappearance of certain diseases of cattle and of human beings, particularly the so-called milk sickness and kindred maladies, and a marked improvement in the flavor and keeping qualities of milk and butter. Although the change thus far has been great, there are yet districts in which there has been little improvement in the conditions of the land, of the water supply, or of the people. Stock are still compelled to depend, for their water supply, upon streams and pools that almost invariably become stagnant in the warm and dry days of the latter part of summer each year."[1]

Inquiries addressed to hundreds of intelligent and careful observers, nearly all of whom were practical stockmen, elicited information showing the following:

| Number of Counties | District | Chief Source of Water Supply |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | Northwest or Postal District | Streams and wells; springs furnish a considerable part of it; few ponds used; three instances of tile drains. |

| Central Northern Counties | Wells chief source; springs, streams, and tiles used to a considerable extent. [Pg 3] | |

| Northeast Counties | Streams, wells, and springs used about equally. | |

| Eastern Counties | Wells chiefly; streams next; ponds and tile drains follow in the order named; nine instances of springs. | |

| Central Counties | Forty-nine districts report wells; forty report streams; thirty-five tile drains; twenty-five ponds; twenty-four springs. | |

| Western Counties | Wells and tile drains equal; springs next; ponds in a few instances. | |

| 4 | Southern Counties | Ponds and streams equal; six report wells; five report springs; four tile drains. |

| 21 | Central S. Counties | Ponds chiefly; streams next; wells next; springs and tiles in the order named. |

| Southeast and Southwest Counties | A like condition: ponds, streams, and springs. |

"From all parts of the state, correspondents wrote that the ponds and streams become stagnant in the warm months of summer, a few making exception of those years in which rainfall has been heavy during the summer months. Stagnant water is found more generally in the southern than in the northern part of Illinois; chiefly, perhaps, because the cultivation and drainage of the land has not become almost universal as it has in the northern districts."

In several counties artesian wells afford a most copious supply of water of good quality. In Iroquois and other eastern[Pg 4] counties, such wells have been bored to a depth of from 150 to 200 feet and obtained an unfailing flow of water impregnated with minerals. Stock show a strong liking for such water after becoming accustomed to its use, and it is the belief of those who have had opportunity for observing the effects of its continued use, that this mineral water serves to keep the animals free from disorders which formerly prevailed in that region. This seems to be especially apparent in regard to malarial disorders.

About 1820, the State of Illinois was being rapidly settled by people from the eastern states. Prior to this time, very few white settlements had been made in the state. These early pioneers, drawn from the population of the eastern states, were composed of almost all nationalities. They pushed their way across the mountains of Pennsylvania and Virginia in crude wagons, drawn by oxen, bringing with them their household goods and a few milk cows. They came into Illinois, built new homes, and laid out new fields on the broad, unsettled prairies.[2]

Beginning with the year of 1800, when there were only a few people in the state, the population has increased very rapidly, as is shown by the following statistics, taken from the United States Census[Pg 5] Report (special supplement for the State of Illinois):

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1790 | |

| 1800 | 5,641 |

| 1810 | 24,520 |

| 1820 | 147,178 |

| 1830 | 343,031 |

| 1840 | 685,866 |

| 1850 | 851,470 |

| 1860 | 1,711,951 |

| 1870 | 2,539,891 |

| 1880 | 3,077,871 |

| 1890 | 3,826,352 |

| 1900 | 4,821,550 |

| 1910 | 5,638,591 |

When Illinois was first settled, almost the whole of the middle and the northern parts of the state were covered with a rank growth of native grasses, which furnished an ample supply and variety of forage of fair quality. "In the southern districts were heavy forests, but in the central and northern sections were but few groves or other timber growths to afford shelter to stock." The prairie grasses that grew in the central and northern districts were usually devastated by fire during the fall. However, the general fencing and cultivation of the land put a stop to the burning of these dead grasses of the prairies, and soon groves of oaks sprang up and covered many uncultivated spots. The leaves which stayed on these trees throughout the winter until spring, furnished valuable shelter to stock from the raw winter winds.

At the beginning of the settlement of Illinois, very little attention was given to the cattle interest. The pioneer settlers, however, had brought a few milk cows with them from the eastern states, but these cows were kept for milk only, no thought being given to beef production. After a few years, a few pure bred cattle were brought in, at which time some attention was given to beef, as well as to milk production, not for the beef produced, however, but principally to give a ready market for their grain crops.

The practice of raising beef cattle to market grain continued from then until near the end of the nineteenth century, when cattle feeding was no longer profitable as a grain market, and the question was: "How much beef can be produced from a bushel of corn?"[4]

"Despite the seemingly adverse character of the climate, Illinois has been, for some time, little, if any, behind other leading states of the Union in stock growing. In 1850, this state stood sixth in milk cows, and seventh in work oxen and other cattle. In 1860, it was tenth in work oxen, fifth in milk cows, and second in other cattle. In 1870, it was twenty-sixth in work oxen, fourth in milk cows, and second in the supply of other cattle. In 1880, it stood thirty-sixth in work oxen, second in milk cows, and third in other cattle. Iowa then had 240,280 and Texas had 1,812,860 more cattle than Illinois.

"The average value of milk cows in Illinois in 1884 was $35, and of oxen and other cattle, it was $28.04, while the[Pg 7] average value of milk cows in Iowa was only $31.75, and of other cattle $26.00. The blood of the Shorthorns was used more largely than that of any other breed in the improvement of the cattle of the state. The first, and for some years, the only representatives of pure races of cattle in this state were Shorthorns, and to this date they exceed all other breeds in number."

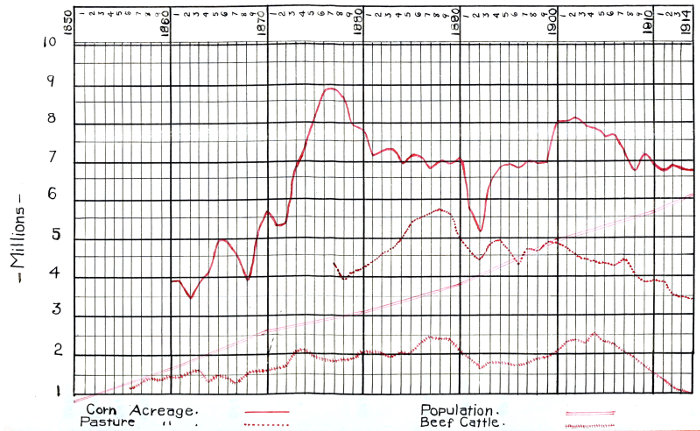

The growth of the cattle interest in the State of Illinois, from 1850 to 1884, inclusive, is shown by the following statistics, taken from the United States Census Reports. The first figures of close accuracy on the number of cattle in the state were those gotten in 1850.

| Year | Milch Cows | Work Oxen | Other Cattle | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Inc. % | No. | Inc. % | No. | Inc. % | No. | Inc. % | |

| 1850 | 294,671 | 76,156 | 541,209 | 912,036 | ||||

| 1860 | 522,634 | 77.3 | 90,380 | 18.6 | 970,799 | 79.4 | 1,583,813 | 73.6 |

| 1870 | 640,321 | 22.5 | 19,766 | -78.1 | 1,055,499 | 8.7 | 1,715,586 | 8.3 |

| 1880 | 865,913 | 35.2 | 3,346 | -83.0 | 1,515,063 | 43.5 | 2,384,322 | 38.9 |

| 1883 | 716,102 | -17.3 | 1,253,765 | -17.2 | 1,969,867 | -17.4 | ||

| 1884 | 919,404 | 17.7 | 1,471,191 | 17.3 | 2,390,595 | 21.3 | ||

[1] Report of the Bureau of Animal Industry, 1885, p. 362.

[2] United States Census Report and interviews with old settlers.

[3] Report of Bureau of Animal Industry, 1885, p. 365.

[4] Bureau of Animal Industry, 1885, p. 365-66

"When the farms of Illinois were first put into cultivation, the attention of the farmers was almost entirely devoted to grain raising. Wheat was cash and was the only product of the farm that could be sold for ready money. The virgin soils of the state gave to the pioneer large crop yields, but constant cropping soon began to tell on the soil and each year the crop yield became lighter. This depletion of the fertility of the soil by continuous cropping, together with a need for a near market for the grain crops, soon gave stimulus to an idea that cattle feeding would help restore the fertility of the soil and, at the same time, market the grain at home." From this time on, the production of beef in this state has been one of the most important phases of agriculture. In the southern part of the state, however, which was settled largely by French, and where the predominating cattle continued to be the mongrel bred stock, little attention was given to cattle feeding. These people turned their cattle out on the luxuriant grass and relied upon the meat and milk produced in that way.

"In the evolution or development of beef production that followed in Illinois and other corn-belt states, there has been two distinct stages, and it is now entering upon the third stage. The first stage was that in which cattle were fed to market corn, and also to increase the fertility of the soil, which was being[Pg 9] depleted by the continuous cropping. The second stage was that in which the ranges had been broken up and the object was not to raise cattle to market corn but to raise corn to make beef." The third stage, or that upon which the industry is now entering, is that of baby beef making.

Seventy or eighty years ago, and for several years afterward, cattle were bred and fed, not primarily for beef production, but to market corn. The farmers of those days were accustomed to say: "I'll make my corn walk to market," or "I'll condense my freight," or "I'll grow packages in which I can condense my corn and put in the hay and pastures as well." Statisticians figured that about six tons of corn could be put into one ton of pork, about ten tons into one ton of beef, and from twenty to twenty-five tons into one ton of butter. There were very few railroads in the state at that time and farmers were forced to haul their corn and wheat thirty and forty miles to reach a station. And while freight rates were extortionately high on corn and wheat in proportion to their cash value, railroads were racing with each other to get the livestock trade. They gave passes, rebates, and quick service, and many other things to get the patronage of the cattle feeders and shippers. The country roads in Illinois were bad, the bridges were few and poor, and the farmers, therefore, soon came to realize that their corn must walk to market if it gave them any profit.

"The growing of the so-called packages in which to condense[Pg 10] freight, and thereby sell corn to a better advantage, was an easy matter in those days. In the newer sections, away from the main lines of railroads, there was much open prairie land, which was covered with luxuriant grass. Cattle could be herded on this free grass on the prairies at a dollar a head from May to October, and then stalk fields could be had for ten cents an acre. Usually these stalk fields contained from twenty cents to thirty cents worth of corn per acre. The only expensive months for feeding were March and April, when either clover, timothy, or prairie hay had to be fed. The cost in the summer was only about twenty cents a month per head, in the winter about thirty-three cents. The total cost of growing a package was about $6.00."

The cattle herders in those days made contracts with the large operators to graze so many cattle at so much per head during the grazing season. The usual price for the entire season was from $1.00 to $1.50 per head. These cattle ranged from three to seven years old by the time they were ready for market and sold for about $25.00 per head.

An instance of the cattle herding industry, as it may be termed, is related by Mr. C. W. Yapp, now of Urbana, Illinois, who was one of the early herders in that country near Mahomet:

About 1855, at 13 years of age, Mr. Yapp began herding cattle for the then large cattle feeders of that part of the country. In the early spring of 1860, he started from Mahomet with a bunch of 12 cattle, to meet a large drove that was coming up from the southern part of the state. These cattle were native stock which had been collected over the state. The entire bunch[Pg 11] numbering around 900, were driven to Drummer's Grove, near Gibson City. There they were branded and herded on the open prairie during the spring and summer. In the fall, they were returned to the lots of the large feeders, where they were fed out during the winter. The feed during the winter consisted mostly of shocked corn.

Some of the large cattle feeders bought their packages to be filled with corn, while others grew them. In either case, the primary aim was not to make beef, but to market the corn crop at a much better price than would be obtained if the winter was spent in hauling the corn to market at the nearest town. Naturally, these feeders fed corn with a lavish hand. They fed from twenty to thirty pounds to a steer per day, and if the steer became gorged and mussed over it, it was thrown out to the hogs. They kept corn before their cattle all the time. They argued that if you want solid beef, beef that will weigh like lead, give the cattle nothing but corn and water. They wanted big packages, nothing less than two-year-old steers past would do, and three and four-year-olds were preferable. They wanted steers that would be at least four years old when ready for market and that would weigh from 1500 to 1600 pounds. These steers were desirable because they would hold more corn than the smaller ones. Very little attention was given to the finish of the steers sent to market. They were all driven out together regardless of the degree of finish. It was not until some time in the eighties and nineties that much attention was given to the degree of finish[Pg 12] in fat steers when sent to market.

After the open prairies became settled up and there was no more free grass at home, the feeders of Illinois and the adjoining states could buy their packages on the ranges on the plains west of the Mississippi river, or at the range cattle markets. Corn was still cheap and so were packages in the shape of stockers and feeders. The reason for this was that the great corn fields of Kansas and Nebraska were being opened up and the great national pastures from Canada to the Texas Panhandle had not yet become spotted and rendered useless by the homesteader. Speculation in semi-arid land had not set in, and the term "dry farming" had not been invented.

The great drouths caused the price of corn to fluctuate but the aggregate corn yield kept on increasing with increased acreage and usually the year following a drouth was one of superabundance of corn. Such was the year of 1895 following the drouth of 1894. The proportion of cattle per thousand population steadily increased. Meanwhile our cattle markets became centralized and were always full to overflowing. Everybody wondered where the cattle came from.

In the year of 1895, this system reached its climax. The question confronting the farmer at this time was: "Why did he continue growing corn and feeding cattle?" He grew corn because he could do it cheaply and more certainly than anything else. The farmer had begun to realize that the limit of good land watered by the rains of heaven would soon be reached. He would, therefore, hold on to his land and gain back all that he[Pg 13] had lost in fertility by growing corn in the increased price of land that was sure to come in the near future. He had been feeding cattle to sell his corn with the idea also that cattle feeding and cattle grazing were good for the land. The limit of good land was not reached, however, nearly so soon as he had expected and when it was reached, land advanced in price more rapidly than even the most optimistic had anticipated. The year of 1895 marks the end of the first stage of beef production in Illinois as well as in the other corn belt states.

The Summer That the Rain Came Not

In the nineties (1896), cattle feeding in Illinois and the other corn belt states entered upon the second stage of its evolution or development. The purpose of feeding cattle during this stage was not to market corn but to make beef. The great corn crop of 1895 and 1896, following the drouth of 1894, gave very cheap corn. Cattle were cheap also. During the two years 1896-1897, business was on a standstill the whole country over, but the next year, 1898, business started in full blast; cattle began to advance in price, and the demand for feeders increased. As a consequence, the whole country was scoured for them, but it was found that the choicest ones had been sold off in 1894, and the early part of 1895. Cattle feeders, anxious to secure cattle to fill their feed lots, turned to other sources for their supply. They went into Mexico, Oregon, Colorado, and Tennessee, and bought their feeder cattle. When cattle went[Pg 14] up in price, corn went up also, then labor began to gradually go up.

At that point began the advance in the value of land. The government had no more choice corn land. The two acres necessary to keep a cow during the summer and two more acres, the hay from which would keep her during the winter, doubled in price within the next fifteen years, but it did not increase in actual value as determined by the amount of grass or grain it would produce. It was at that time the people were confronted first with dear land, stockers, feeders, corn, hay, and beef. This all led the cattle feeders and the corn growers to begin studying out a method or system by which they could profitably grow corn to make beef instead of growing beef to market corn. The prices of fat cattle were very tempting, something unheard of ever before, but when it came to buying feeders, the margin was very little greater than it had been in previous years, and besides, corn was higher than it had ever been. The problem then was, how to get the most beef out of a bushel of corn.

Experiment stations had been doing work along that line for several years. They pointed out that the younger and smaller the animal is, the less will be the grain required to sustain the life-giving forces, or to run the machine, and a greater proportion will go to the building up of body tissue, hence the greater the profit in feeding young animals. Feeders began to drop out the two and three year old steers and replace them with baby beeves. Many feeders tried it but somehow or other they could not make it work according to the experimental evidence.[Pg 15] They found no profit in feeding any kind of cattle. Many feed lots became empty and blue grass and clover pastures were plowed up and put into corn fields. If corn was worth more outside of the steer than it was in the steer, the farmer argued, why feed cattle? The landlord could get more rent from corn land than from grass land devoted to cattle grazing; therefore, he saw no profit in building expensive barns, sheds, and fences for cattle feeding.

In the summer of 1907, business was flourishing and packers were in need of money. To meet their needs, they flooded the western banks with commercial paper. They bought so few cattle that the price fell off at least 30 per cent in three months' time. The loss accrued by such a rapid decline in the price of fat cattle was so great that it paid for the commercial paper that had been issued by the packers. Such conditions as these hastened the process of depleting the feed yards and decreasing the number of cattle on the market.

"The cattle have left central Illinois and the grain elevator now distinguishes the landscape. The vast blue grass pastures of the ante-bellum period have disappeared, and corn tillage is the principal occupation of the agrarian population. Down in Morgan and Sangamon counties, even recollections of the cattle trade, as it existed in the days of John T. Alexander and Jacob Strawn, are being rapidly affected. A few cattle come in from the west to be fattened on corn, but summer grazing is the exception and the interest of the occupant of the land centers, not in the cattle market quotations, but in the price of corn.[6]

"All the evidence seems to point toward the conclusions that another change in the corn belt system of beef production is imminent.

"One of two things will happen or Illinois will quit the cattle business. Either some new breeding and rearing center must be developed, or Illinois feeders must return to breeding their own feeder steers.

"I believe that Illinois will not quit the cattle business. There is too much at stake besides the mere success or failure of the cattle business alone. First of all, this country needs the beef. The greatest people of the earth have been meat eaters, and I believe that the American people will continue to eat meat and will pay the price necessary to make its production profitable.

"Another consideration of vital importance, but too broad a subject for discussion in this connection, is the value of livestock as an aid to the maintenance of soil fertility. Then, too, for the sake of our economic stability, the livestock interest of the country must be preserved and encouraged. Professor Herbert W. Mumford is my authority for the statement that 80 % of the corn grown in the United States is fed to livestock. Picture, if you can, the effect upon corn belt land value and our economic situation generally if the country suddenly lost this market for 80 % of its corn crop.

"Regarding the possibility of another breeding center being developed, it may be said that there are other sections that can produce feeders much more cheaply than Illinois. There[Pg 17] are large areas of cheap lands in some of the Gulf states with which Illinois could not compete in the production of feeder steers. But these sections are not interested in the production of cattle, and it is doubtful if the south ever produces a surplus of feeder steers. Hence, it seems that the probable solution of the whole question will be brought about by producing our own feeders.

"If Illinois does return to the cattle breeding business, it will not be on the old extensive scale that prevailed throughout the state a generation ago. Grass grown on these high priced lands is too expensive to be disposed of with so lavish a hand as it was thirty or forty years ago.

"A return to cattle breeding in Illinois will be coincident with a more general adoption of supplement for pasture. The use of smaller proportions of permanent pasture, more extensive use of rotated or leguminous pastures, the passing of the aged steers in our feed lots, and the inauguration of what may be called intensive systems of baby beef production."[7]

| Year | Number of Beef Cattle in Illinois |

|---|---|

| 1856 | 1 169 855 |

| 1857 | 1 351 209 |

| 1858 | 1 422 249 |

| 1859 | 1 336 565 |

| 1860 | 1 425 978 |

| 1861 | 1 428 362 |

| 1862 | 1 603 946 |

| 1863 | 1 684 892 |

| 1864 | 1 370 783 |

| 1865 | 1 568 280 |

| 1866 | 1 435 769 |

| 1867 | 1 486 381 |

| 1868 | 1 520 963 |

| 1869 | 1 584 445 |

| 1870 | 1 578 015 |

| 1871 | 1 611 349 |

| 1872 | 1 684 029 |

| 1873 | 2 015 819 |

| 1874 | 2 042 327 |

| 1875 | 1 985 155 |

| 1876 | 1 857 301 |

| 1877 | 1 750 931[Pg 19] |

| 1878 | 1 775 401 |

| 1879 | 1 862 265 |

| 1880 | 1 998 788 |

| 1881 | 2 045 366 |

| 1882 | 2 012 902 |

| 1883 | 1 959 867 |

| 1884 | 1 997 927 |

| 1885 | 2 166 059 |

| 1886 | 2 337 074 |

| 1887 | 2 480 401 |

| 1888 | 2 465 288 |

| 1889 | 2 398 191 |

| 1890 | 2 095 595 |

| 1891 | 1 853 318 |

| 1892 | 1 615 405 |

| 1893 | 1 812 924 |

| 1894 | 1 798 417 |

| 1895 | 1 782 158 |

| 1896 | 1 626 171 |

| 1897 | 1 753 371 |

| 1898 | 1 802 061[Pg 20] |

| 1899 | 1 886 933 |

| 1900 | 2 009 598 |

| 1901 | 2 372 710 |

| 1902 | 2 409 772 |

| 1903 | 2 325 980 |

| 1904 | 2 535 954 |

| 1905 | 2 301 519 |

| 1906 | 2 203 108 |

| 1907 | 2 065 816 |

| 1908 | 1 892 118 |

| 1909 | 1 691 686 |

| 1910 | 1 512 055 |

| 1911 | 1 473 741 |

| 1912 | 1 258 293 |

| 1913 | 1 170 628 |

"In reviewing the cattle breeding and the cattle feeding situation in Illinois in 1894, Mr. J. G. Imboden stated that the outlook was not very encouraging. The question was, "Are the men who are feeding the grain and fodder crop of the farm any worse off than those grain farmers who are selling their grain on the market, or even the butcher, the grocer, the boot[Pg 21] and shoe dealer, or the drygoods merchant?" They undoubtedly were not at that time. Competition was very close, profits small, and unless a business man was satisfied with a small profit, his competitor did the business. Such were the conditions that faced the cattle breeders and feeders at that time.

"From 5 % to 10 % of the feeding value of the crops on Illinois farms were left in the field; straw-stacks stood in the field where the thresher left them; stover stood on the field after the corn was husked, while on these same farms were stock that were shrinking from exposure and lack of feed."

The outlook for the feeder was very discouraging, but much more so for the breeder. There were no hopes for success for the breeder until the feeder had two or three years of success in order to make a market for the cattle that were bred. Strong efforts were being made to devise some methods of feeding the farm products more economically and in such a way as would mean more grain and better profits for the feeder.

"The cattle feeders of Illinois presumed that the time was nearing when feeder cattle of the best grade for grazing and feeding purposes would be hard to secure. While at that time there were plenty of cattle west of the Mississippi river, in Illinois there was a scarcity of breeding cattle to supply the demand. It was harder to buy a bunch of fifty uniformly good steers, throughout central Illinois especially, than it had been for fifteen years past. This was probably due to the fact that feeders had quit raising their feeding cattle and the breeders had changed from one breed to another in hopes of finding a breed[Pg 22] that would give them greater returns. Again, many breeders had become very careless of the merits of the cattle on their farm."[8]

"In 1881, Oatman Brothers, of Dundee, Illinois, built the first silo in the state. At the eighth annual meeting of the Illinois State Dairyman's Association, held at Dundee, Illinois, December 14-16, 1881, Mr. E. J. Oatman read an article on "Silos and Ensilage.""

Mr. Oatman stated that some agricultural paper in Chicago had been agitating the building of silos in Illinois and had tried to induce him to build one. The stories that the paper told about the value of ensilage as a feed sounded too good to be true. The idea of cutting up green fodder, packing it away in a hole, and expecting to see it come out in first class condition, in the dead of winter, seemed to be impossible. A great many objections arose to such "cow kraut" as some called it. It would heat, ferment, and rot; therefore it was a very difficult matter to make people see its value as a feed.

Mr. Oatman, however, visited the farm of Messrs. Whitman and Burrell at Little Falls, New York, on February 1, 1880, for the purpose of seeing their silo and the condition of their ensilage. He made a thorough investigation and thereupon became convinced that ensilage was a success. He returned home to his farm at Dundee and made preparations to build a silo. His first silo was 49 feet by 43 feet by 20 feet deep, dug out into the ground. It[Pg 23] was divided into three parts, all of which were made of concrete.

After the silo was finished, Mr. Oatman proceeded to fill it, which required thirteen days with a force of ten men, at a rate of about twenty-three tons per day. After it was filled, stone was placed on top, at the rate of about 150 pounds per square inch.

Mr. Oatman met with many discouragements with his new silo; the community at large thought it was a very foolish idea. Some said that if it did keep, the cattle would not eat it, and others still more radical, even hoped that he would lose it all, and said that any man who would try such a thing was crazy.

When the time came to open the silo, Mr. Oatman found that the silage was all fresh and nice with the exception of a few inches on top. His cattle took to it readily, and he found that it greatly increased the milk production of his dairy herd.[9]

The use of ensilage as a feed for beef and milk production has become so general in Illinois since the first silo was built in 1881 that ensilage is now one of the staple feeds. While there are a few people who still think that the use of ensilage in the production of beef is a fad, practically every one agrees that it is economical in the production of milk.

Ensilage is a roughage and not a concentrate, and its profitableness in a fattening ration depends not so much upon its nutritive value as upon its succulence and palatability, the steers' ability to consume large quantities of it, and the fact that it makes possible the utilization of all of the corn plant, a large proportion of which would be wasted.

Every year sees a more general adoption of ensilage as a roughage, and with the inauguration of the present intensive system of baby beef production, and where the baby beeves are raised on the farm on which they are to be fed, ensilage is the most economical feed that can be used in maintaining the breeding herd.

"The situation of Chicago in the great agricultural center of the United States brought it into prominence at an early day as the center of the live stock trade. This position it has never lost. However great may be the development of other sections of the country, Chicago can not fail to continue to be the leader in this class of business. Its location as a railroad center and its position as a distributing point is made secure by the steadiness of its growth and the magnitude of its present operations. There is greater competition in this market than in any other. The Chicago market is the purchasing point, not only for the local packers, large and small, the exporters, and the speculators, but also for a great number of smaller packing houses scattered over the country, and for the feeders and breeders of the most fertile and largest agricultural sections of the United States."[10]

Prior to the year of 1833, Chicago had no provisions to export, and as late as 1836, an actual scarcity of food there created a panic among the inhabitants.

The first shipment of cattle products from Chicago was made in 1841, by Newbury and Dale on the schooner, Napoleon, bound fo[Pg 25]r Detroit, Michigan. This shipment consisted of 287 barrels of salted beef and 14 barrels of tallow.

| Population: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Whites | 3989 | |

| Colored | 160 | |

| Males | 2579 | |

| Females | 1570 | |

| Total | 4149 | |

| Buildings: | ||

| Dwellings | 398 | |

| Drygoods stores | 29 | |

| Grocery stores | 26 | |

| Hardware stores | 5 | |

| Drug stores | 3 | |

| Churches | 5 |

There were two weekly papers published in Chicago at this time: The American, a whig paper, and the Democrat.

The first market in the way of stock yards in Chicago was located on the north branch of the Chicago river. These yards were used chiefly for swine. In 1836, the first cattle yards were opened on a tract of land near twenty-ninth street and Cottage Grove avenue. A few pens had been erected here to accommodate the cattle trade. The first scales for weighing livestock ever used in that country were used in these yards.[11]

In 1855, there were two regular stock yards in Chicago; one, called the Merrick Yard, is now known as the Sherman Yards, and the other was called the Bullshead Yard. A great many eastern people came to Chicago at this time to buy fat cattle to take back east. Most of the cattle they bought were driven over into Indiana to Michigan City, to be shipped on east. John L. Hancock was the only packer in Chicago at this time. Ice was not used, and packing was done during the cool seasons of the year.

One element of the success of Chicago as a market was the fact that stock might be pastured without charge on the prairies near the city, while the owners awaited favorable market conditions in the eastern states. The cattle were herded on the open prairies just outside of the city, and the buyers of Chicago rode out each day and bought the cattle in such numbers as they needed.

In 1865, the growth of the livestock traffic had increased so rapidly that the several railroad companies that centered in Chicago, together with the managers of the stock yards already existing, combined for the erection of the Union Stock Yards. These were opened for business on Christmas day, 1865.[12]

"The meat industry of Chicago, from the purchase of the livestock to the shipment of the meat, in either the fresh or the cured condition, is carried on at the Union Stock Yards, which are located near the outskirts of the city. The yards cover exactly a square mile of ground. One-half of this area is covered with cattle pens, and the other half by huge establishments of the[Pg 27] packing houses. The pens are surrounded by strong stockades, about shoulder high, and they are laid out in blocks with streets and alleys, in much the same fashion as an ordinary American town. The whole of this area, a half mile in width, and a mile in length, is paved with red brick; and here we see the first notable evidence of the effort to maintain the stock yards in a sanitary condition.

"The brick paving makes it possible to thoroughly clean both pens and streets, and this is done at regular and frequent intervals."[13]

"Whatever may have been the conditions in the past, it is a fact that today the greatest care is exercised in the shipment and handling of the stock from the time they leave the farms until they reach the packing houses. The price that the animals will bring in the pens depends upon the conditions they present under the eye of the buyer, who represents the packing houses, and it is to the interest of the farmers, the cattlemen, and the commission men, to whom the cattle are consigned at the yards, that they shall receive the best food and the most careful attention up to the very hour at which the sale is made. They are shipped in special stock cars, in which they are carried as expeditiously as possible to the stock yards, where they are unloaded and driven to the pens. Here they are at once fed and watered, each pen containing a feeding trough and a water trough, into which a stream of fresh water is kept running.

"The cattlemen consign their stock to the various commission houses, and for receiving and selling the stock, there is a[Pg 28] charge of, respectively, twenty-five cents and fifty cents a head. The purchase of the cattle is made by buyers, of whom each of the packing houses maintain a regular staff."

"About 1845, a bold editor left Buffalo, New York, then the greatest lake part of the country, and bravely ventured as far into the rowdy west as Chicago. Possibly the people here received him with generous hospitality; perhaps they treated him with something even more warming to the inner man; or it may be that as they filled him with solid chuck and, perhaps, with less solid refreshments, they took occasion to remark, with that modest and restrained hopefulness for which Chicago people have justly received credit, that Chicago was destined to become a town of some importance. Be that as it may, when that editor luckily found himself once more safe within his sanctum, he gave vent to his joy and overflowing gratitude by writing wild, enthusiastic predictions concerning the future of the town, which was then aspiring to rise above the rushes and wild rice of the Chicago river.

"Reckless of the opinion of the readers of his paper, perhaps trusting to their ignorance of the conditions of the out of the way place, this bold editor predicted that the day would come when Chicago would have an elevator capacious enough to hold 25,000 bushels of grain, and that in a single winter season, 10,000 cattle, and as many hogs, would be slaughtered and packed there.

"Beef packing was the leading industry of Chicago at that time, but no trustworthy statistics relating to the cattle traffic previous to 1851 have been preserved, and from 1851 until 1856[Pg 29] no account of the receipts of cattle were kept. This was probably due to the fact that a large number of those cattle that were brought to Chicago were held on the open prairies until sold to butchers to supply the requirements for local consumption. No accurate count of cattle disposed of in that way could well be obtained."

Statistics of the receipts of cattle at the Chicago Union Stock Yards from 1851 to 1913, inclusive, and the shipments from 1852 to 1884, inclusive:

| Year | Receipts | Shipments |

|---|---|---|

| 1851 | 22 566[14] | |

| 1852 | 25 708[14] | 77 |

| 1853 | 29 908[14] | 2 657 |

| 1854 | 36 888[14] | 11 221 |

| 1855 | 39 865[14] | 8 253 |

| 1856 | 39 950 | 22 205 |

| 1857 | 48 524 | 25 502 |

| 1858 | 140 534 | 42 638 |

| 1859 | 111 694 | 37 584 |

| 1860 | 177 101 | 97 474 |

| 1861 | 204 579 | 124 146 |

| 1862 | 209 655 | 112 745 |

| 1863 | 300 622 | 187 048 |

| 1864 | 303 726 | 162 446 |

| 1865 | 333 362 | 301 637 |

| 1866 | 393 007 | 263 693 |

| 1867 | 329 188 | 203 580[Pg 30] |

| 1868 | 324 524 | 215 987 |

| 1869 | 403 102 | 294 717 |

| 1870 | 532 964 | 391 709 |

| 1871 | 543 050 | 401 927 |

| 1872 | 648 075 | 510 025 |

| 1873 | 761 428 | 574 181 |

| 1874 | 843 966 | 822 929 |

| 1875 | 920 843 | 696 534 |

| 1876 | 1 096 745 | 797 724 |

| 1877 | 1 033 151 | 703 402 |

| 1878 | 1 083 068 | 699 108 |

| 1879 | 1 215 732 | 726 903 |

| 1880 | 1 382 477 | 886 614 |

| 1881 | 1 498 550 | 938 712 |

| 1882 | 1 582 530 | 921 009 |

| 1883 | 1 878 944 | 966 758 |

| 1884 | 1 817 697 | 678 341 |

| 1885 | 1 905 518 | |

| 1886 | 1 963 900 | |

| 1887 | 2 382 008 | |

| 1888 | 2 611 543 | |

| 1889 | 3 023 281 | |

| 1890 | 3 484 280 | |

| 1891 | 3 250 359 | |

| 1892 | 3 571 796[Pg 31] | |

| 1893 | 3 133 406 | |

| 1894 | 2 974 363 | |

| 1895 | 2 588 558 | |

| 1896 | 2 600 476 | |

| 1897 | 2 554 924 | |

| 1898 | 2 480 897 | |

| 1899 | 2 514 446 | |

| 1900 | 2 729 046 | |

| 1901 | 3 031 396 | |

| 1902 | 2 941 559 | |

| 1903 | 3 432 486 | |

| 1904 | 3 259 185 | |

| 1905 | 3 410 469 | |

| 1906 | 3 329 250 | |

| 1907 | 3 305 314 | |

| 1908 | 3 039 206 | |

| 1909 | 2 929 805 | |

| 1910 | 3 052 958 | |

| 1911 | 2 931 831 | |

| 1912 | 2 652 342 | |

| 1913 | 2 513 074 | |

| 1914 |

In April, 1869, a charter was granted by the state of Illinois to the East St. Louis Stock Yards Company. This company[Pg 32] was authorized to issue stock to an amount not to exceed $200,000. The original charter of the company, which later operated the National Stock Yards, fixed the capital stock thereof at $1,000,000, which was, subsequently, raised, by a vote of the stock holders, to an amount of $250,000, to meet the requirements of the rapidly growing business. When the National Stock Yards were completed, they were more convenient than were any others of their kind in the country.

[5] Wallaces' Farmer, 1913, and thesis by Garver, "History of Dairy Industry in Illinois."

[6] The Breeder's Gazette, July, 1913.

[7] Lecture by Professor H. P. Rusk on "Beef Production."

[8] The Breeder's Gazette, Feb. 1894.

[9] Thesis "History of the Dairy Industry in Illinois" by Garner, 1911.

[10] "Facts and Figures," by Wood Brothers, Live Stock Commission Merchants, Chicago, 1906, and Report of Bureau of An. Ind. 1884.

[11] Prairie Farmer, 1887, p. 160.

[12] Life of Tom C. Ponting.

[13] Scientific American—The Meat Industry of America, 1909.

[14] Estimated.

Previous to the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century, no droves of cattle were seen in the country west of Ohio. The first drove ever driven from Illinois was taken from Springfield, through Chicago, to Green Bay, Wisconsin, in 1825, by Colonel William S. Hamilton. Beginning with this date, the practice of collecting cattle into droves and driving them to market soon grew from a minor occupation into an industry within itself; beef cattle that were grown and fattened in Illinois were gathered together into large droves by men who made it a business, and were driven to the then great cattle markets on the sea board. Foremost among these early pioneer cattlemen were: Jacob Strawn, John T. Alexander, B. F. Harris, and Tom C. Ponting. In the scope of their operations, Jacob Strawn and John T. Alexander exceeded many of the conspicuous operators in the rise and fall of the range industry in this state. These men owned hundreds of acres of the prairie land of the state, on which they collected enormous droves of cattle. These cattle were grazed here throughout the spring and summer, then were fed during the winter. It was no uncommon occurrence for one of these operators to buy all the corn for sale during one season in three or four counties. The next spring these fat bullocks were trailed across the level country to the eastern mountain ranges, over which they climbed to reach Lancaster, Philadelphia, and New York. Cincinnati and Buffalo received a few of these cattle, but most of them were driven on through to the markets[Pg 34] on the sea board, where better prices were obtained. These cities bore about the same relation to the livestock traffic of those days as Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and St. Joseph bear to the cattle trade of today; they were the collecting points for the business and the slaughterers who bought them either salted the carcasses down in barrels and casks or sold them to local consumers. Other dealers, however, bought some of these cattle and drove them on to smaller towns nearer the coast. "In the census of 1850, it was recorded that Illinois alone sent 2,000 head of cattle each week to the New York market."

While the cattle barons represented a large part of the beef cattle trade of Illinois, there were hundreds of smaller dealers who fed only a few cattle each year which added materially to the magnitude of the beef cattle industry of the state. A few of these smaller operators were found in almost every section of the state, especially in the central and northern part.

Cattle trailing continued until lines of railroad connecting Illinois with the cities on the Atlantic coast were built. This made cattle trailing unnecessary and greatly stimulated the production of beef in the state by furnishing means for placing beef before the consumers of the east quickly and, at a much less cost than that of the old method. The long drives greatly decreased the weight of the animals, and, at the same time, the meat of carcasses was inferior to that of the cattle that were shipped by railroad, and slaughtered without having taken such a long drive.[15]

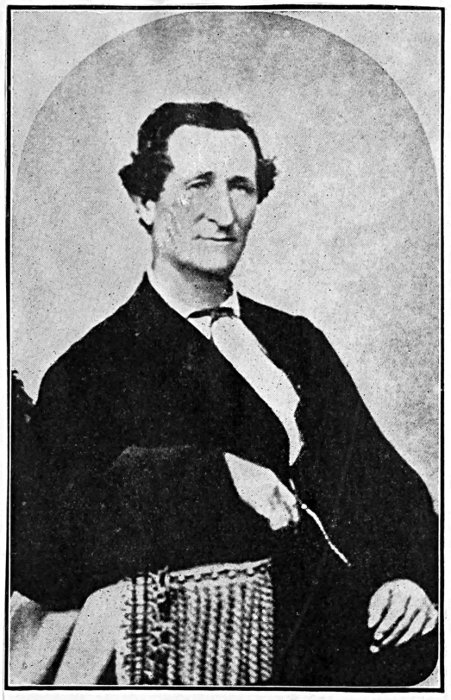

JOHN T. ALEXANDER.

"Among the cattle operators of Illinois, John T. Alexander was probably the greatest by reason of the magnitude of his transactions, but he was antedated by Jacob Strawn, who located in Morgan County in 1827. Alexander has been regarded as America's greatest cattleman in a commercial sense. In the strict sense of the term, he was a pastoralist and a trader, not an agriculturalist. His parents were native of Ireland, who migrated to Virginia in 1818, and in 1824 joined the exodus to the Mississippi Valley, settling in Jefferson County, Ohio. John T. Alexander was the oldest of a family of eleven children. His education was on the farm. He was endowed with that faculty called cattle sense. At the age of fifteen, he was entrusted, by his father, with the entire charge of a drove of cattle sent to Philadelphia. He sold them to advantage, collected the money, and took it safely home. At the age of seventeen, he was purchasing cattle in Illinois to replenish his father's Ohio pastures. It is related that his[Pg 36] search took him down into Sangamon county, where he was so struck with its natural advantages, from a cattle standpoint, that he determined to migrate."

In 1840, the Alexanders settled in Morgan county, then a cattle range bounded only by the horizon. Mr. Alexander accumulated a herd of steers, pastured them on the public domain, and for half a decade prospered in a moderate way. As the country became settled, it soon became evident that he must own land or get out of the cattle business as far as that locality was concerned. In 1848, he purchased 3,000 acres of land at prices ranging from 87 cents to $3.00 per acre. This land was adjoining the half section that he had originally homesteaded. In 1855, he acquired another 1,000 acres at $30.00 per acre. This indicated how rapidly the price of land was advancing. In 1857, he bought 700 acres more at $50.00 per acre, and in 1859, he acquired 1500 acres of the Strawn estate at $30.00 per acre. In 1864, he secured 853 acres at $60.00 to $70.00 per acre, making him the owner of 7,233 acres of the choicest land in Illinois. In 1866, he purchased the stock farm of Michael Sullivan in Champaign county, Illinois, containing 26,000 acres at $11.00 to $12.00 per acre.

It was during this period of purchase that John T. Alexander acquired the title of "cattle king." His transactions were on an enormous scale. His buyers searched every nook and cranny of the cattle producing region of the Mississippi valley, and Alexander, on the Wabash railroad in Morgan county, Illinois, was the largest cattle shipping station in the world. Entire[Pg 37] trains of cattle, destined for eastern markets, were daily loaded there and almost the entire population was on the Alexander pay roll. Thousands of other cattle, for which he paid but never saw, were loaded at innumerable points for eastern markets. From a pastoralist, he had emerged into a speculator on probably the most gigantic scale the live stock industry has ever witnessed. He ruled the markets of the East and was the Napoleon of the cattle trade. His name was more familiar to the West than that of Vanderbilt or A. T. Stewart. His annual cattle shipment for many years exceeded 50,000 head, and in 1868, reached 75,000. For a lengthy period, his sales on eastern markets exceeded $4,000,000 annually, and it is related that prior to his Champaign county purchase, an inventory of his assets showed 7,233 acres of land, averaging $75.00 per acre in value, $100,000 in bank, 7,000 cattle on his Morgan county pastures, and not a dollar of debt.

Such speculative operations, however, had the result of entailing financial embarrassment. In 1871, Alexander had to contract his business and part with his Champaign county property. This embarrassment was due to many causes, not the least serious of which was cattle mortality by splenetic fever, by which he lost $100,000. He also sustained heavy losses by shrinkage in cattle values, and the Champaign county investment proved disastrous. He also became involved in railroad complications. The railroads were keen competitors for the livestock traffic and in 1871, Alexander severed his relations with the Pennsylvania railroad, making a contract with the New York Central, by which[Pg 38] that company gave him a low rate conditional to a specified tonnage. By way of resentment, the Pennsylvania railroad put merely nominal rates into effect, thereby glutting eastern markets and crippling Alexander's trade, which had become so colossal as to be unwieldy. To carry on such gigantic operations, he was compelled to trust to innumerable assistants, many of whom proved to be either incompetent or unfaithful. Confronted with liabilities aggregating $1,200,000, he was forced to make an assignment, but his estate was sufficient not only to pay off every creditor, but leave him a large sum for a fresh start in life. It was while energetically engaged in retrieving his fortune that he died, in 1876.

Those survivors of John T. Alexander, who remember his activity as Illinois' greatest operator, describe him as being tall and commanding in appearance. Even at the time of his death, he was hale and youthful. He was of sanguine temperament, naturally impulsive, but quiet and non-assuming in manner, sparing in speech, and undoubtedly one of the great American captains of industry in his time, an outstanding figure in a trade that boasts many conspicuous men.

The old Alexander mansion in Morgan county, the greatest house in the countryside half a decade ago, remains in a somewhat dilapidated condition, and the decaying out-buildings convey a mournful hint of vanished greatness. Here, during Alexander's time, Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas, Richard Yates, and others, whose illustrious names adorn Illinois history, were the guests of America's greatest cattleman.

Jacob Strawn came from Ohio and settled in Morgan county in 1827, and a few years later was probably the most extensive cattle dealer in the world, but his operations were, to a large extent, local and his most distant shipping point, Saint Louis. His pastures in Morgan county embraced about 15,000 acres and his business reached its maximum about 1860.

Survivors of that period recall Strawn's free handed methods. He purchased cattle by the thousands, fixing the price on mere verbal description as to quality and weight. Frequently, at delivery time, nobody was on hand to receive the cattle, but they were driven into the Strawn pastures and left with confidence that payment would be prompt. Both Strawn and his successor, Alexander, were always ready to buy cattle, in fact they were the market of that period. Strawn was at the height of his career when John T. Alexander came on the scene. Strawn produced beef as a feeder and grazier; Alexander contracted cattle to be delivered in the future.[17]

Mr. T. C. Sterrett relates that in the summer of 1856 he came to Illinois and was informed that the largest cattle dealer in the state was Jacob Strawn, living near Jacksonville, in Morgan county. He visited Strawn's place and found a remarkably large brick house and was astonished at the amount of brick paving about the house. Mr. Strawn lived on a good farm at Orlean[Pg 40]s Station, east of Jacksonville. He owned a lot of good horses and Shorthorn cattle. Piloted by the foreman, Mr. Sterrett went out into a 1,200 acre pasture which was fenced with rails and stocked with a fine lot of cattle. He was very much struck with a hundred head of the finest general work horses that could be found anywhere. This band of horses and cattle, the good fences, and the general appearance of everything about the place, indicated the power and ability of the owner. Mr. Strawn was by far the greatest American cattleman of his time.[18]

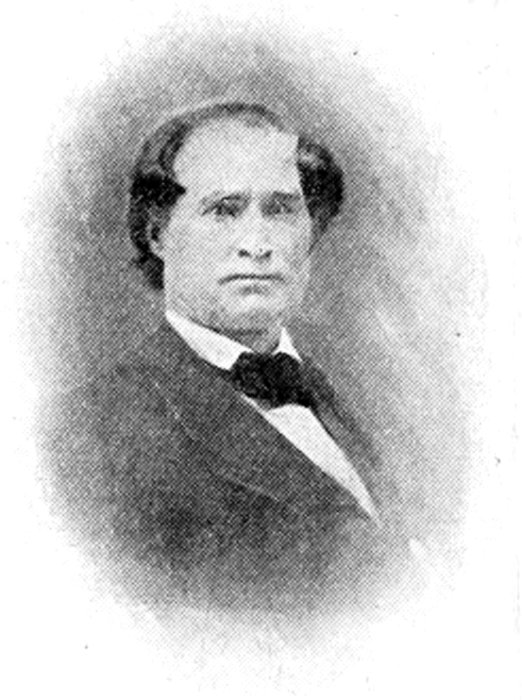

December 15, 1811—May 7, 1905

B. F. HARRIS at 55

"Benjamin Franklin Harris was born December 15, 1811, on a farm in the Shenandoah Valley, near Winchester and Harper's Ferry, in Frederick county, Virginia. He was the second of ten children of William Hickman Harris and Elizabeth Payne (own cousin of Dolly Payne Madison from England). His grandfather, Benjamin Harris, with two brothers, came from England and settled on the eastern shore of Maryland in 1726. The family were of Scotch-English extraction and Quakers; in this country becoming fighting Quakers, then Methodists. He grew to manhood on his father's Virginia farm, attending the country schools until sixteen years of age. At that time, President Jackson's attitude toward the United States bank so seriously affected values that wheat declined from $1.50 to 50 cents and Virginia farm land to less than one-third of its former price. [Pg 41]These declines so affected the father's obligations that Benjamin Franklin Harris and his brothers, each with a six horse team—in those days without railroads—went into the "wagoning" or freighting business, and for three years "wagoned" freight over that section and out through Pennsylvania and as far west as Zanesville, Ohio, in order to recoupe the father's losses."

On March 20, 1833, the Virginia farm had been sold at 40 % of its original cost, and in a one-horse gig and a two-horse carryall, the Harris family set out for Ohio, arriving at Springfield on April 8, and nearby, purchased and settled upon their new farm. It was during this year that Benjamin Franklin Harris commenced business for himself, buying and driving cattle overland to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and there disposing of them to cattle feeders.

In 1834, he started for Illinois via Danville, then through the present site of Sidney, and Urbana—where there was but one cabin—and on to what is now Monticello in Piatt county. During the ensuing years, he began to accumulate farming lands in Piatt and Champaign counties and to buy cattle throughout all this section as far south and west as Mt. Vernon, Vandalia, and Springfield. During several seasons, he bought for the purpose of feeding cattle, all the corn for sale in Macon, Sangamon, and Champaign counties. Each year, for nine years, he drove these cattle overland via Muncie, Indiana; Springfield, and Columbus, Ohio, into Pennsylvania, and some into New York and Boston, where they were sold.

When B. F. Harris came into this state, no streams were bridged, and there were only eleven families on the Sangamon river[Pg 42] from its source to the limits of Piatt county. Fifteen years later not a half dozen men had ventured their cabins a mile from the timber limits—the deer and the Indians were still at home here. In 1840, he visited Chicago, a town of 2000 people, on stilts in a swamp. Nineteen days were required for the trip and the corn and wheat he teamed there sold for 20 and 30 cents respectively. Fifteen years after he came, not 25 % of the land in these counties had passed from government ownership and the first railroad came twenty years later.

The operations of B. F. Harris in connection with the early beef cattle industry of Illinois were conducted more largely along the feeding lines than were those of John T. Alexander or Jacob Strawn. He bought, fed, and sold, from 500 to 2000 head of cattle annually for nearly three-quarters of a century. The Pittsburgh Live Stock Journal, May 8, 1905, in speaking of his death, referred to him as "The grand old man of the live stock trade—the oldest and most successful cattle feeder in the world." Everything to which he put his hand flourished. His judgment was so trustworthy that he made but few business mistakes. He did business on a cash basis and was never in debt. Operating on this basis, he was a rich man long before his race was run, and he enjoyed a period of ease and entire freedom from anxiety much longer than falls to the lot of most men who are counted fortunate in the world.

On May 23, 1856, his famous herd of one hundred cattle—the finest and heaviest cattle ever raised and fattened in one lot by one man—were weighed on his farm by Dr. Johns of Decatur, the president of the State Board of Agriculture. The average[Pg 43] weight of each of the hundred head was 2,378 pounds. Visitors to the number of 500 came from Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and this state to see these cattle, whose weight can never again be equalled. The following year, February 22, 1857, twelve of these cattle which he had retained and fed were shipped to Chicago. This remarkable bunch averaged 2,786 pounds. Clayborn and Alley, the most famous butchers in Chicago at that time, paraded them about Chicago's downtown streets.

Following is a copy of a pamphlet gotten out by Mr. Harris immediately after the sale of these cattle. (see next page)

The New York Tribune of October, 1853, refers to his prize winning drove of cattle averaging 1,965 pounds, displayed at the New York World's Fair then in session.

Every few years, he took cattle prizes or topped the market. Less than a year before his death, his 1,616 pound cattle topped the Chicago market for that season.

Mr. Harris died May 7, 1905, in his ninety-fourth year, still in strong mental and physical vigor, although at the age of fifty-three, he had retired from extremely active business life. He came in the day of ox teams and lived to ride over his farm with his son, grandsons, and great grandsons in an automobile. He voted for nineteen presidents, beginning with Henry Clay, and saw five generations of his family settled in Champaign county. He established the First National Bank in Champaign in 1865—the oldest bank in the county, and was its president at the time of his death.

In the issue of The Breeder's Gazette, May 24, 1905, is the following statement: "In literature, art, professional life, or politics, a man with a record of achievements equal to that of the late Benjamin Franklin Harris would deservedly have numerous biographers. Many a man has been made the subject of bulky biography who might not measure up to him on any score. This is not because the most inviting and interesting personalities are found outside the farmer's calling, but largely because until recent years agriculture as a vocation has not been adequately appreciated by the public. It has not been sufficiently dignified to become the source of life histories. Other professions have furnished the candidates for the Plutarchs, and contributed the heroes and heroines famous in fiction. Farming has been drawn on principally for Philistines. Its great men, its geniuses, its Harrises, have been overlooked by almost all writers worthy of putting their useful lives into books."

(Cont. on page 47.)

Record of the Best Hundred Head of Cattle Ever Fattened in One Lot in the United States.

STOCKMEN, ATTENTION

Who Can Beat This Record?

Weight of 100 head of Cattle, fatted by B. F. Harris, of Champaign County, Illinois:

| No. Cattle | Weight |

|---|---|

| 2 | 4718 |

| 2 | 4782 |

| 2 | 4340 |

| 2 | 4580 |

| 2 | 4582 |

| 2 | 4730 |

| 2 | 4764 |

| 2 | 4738 |

| 2 | 4880 |

| 2 | 4756 |

| 2 | 5150 |

| 2 | 4624 |

| 2 | 4582 |

| 2 | 5364 |

| 2 | 4828 |

| 2 | 5378 |

| 2 | 4864 |

| 2 | 4640 |

| 2 | 4694 |

| 2 | 4610 |

| 2 | 4776 |

| 2 | 4488 |

| 2 | 4572 |

| 2 | 4988 |

| 2 | 4634 |

| 2 | 4458 |

| 2 | 4920 |

| 2 | 4828 |

| 2 | 4702 |

| 2 | 4852 |

| 2 | 4464 |

| 2 | 4900 |

| 2 | 4634 |

| 2 | 4764 |

| 1 | 2690 |

| 2 | 4650 |

| 2 | 4806 |

| 2 | 4505 |

| 1 | 2548 |

| 2 | 4830 |

| 2 | 4762 |

| 2 | 4706 |

| 2 | 4854 |

| 2 | 4746 |

| 2 | 4700 |

| 2 | 4546 |

| 1 | 2516 |

| 2 | 4648 |

| 2 | 4724 |

| 2 | 4720 |

| 2 | 4732 |

| 1 | 2646 |

Average price sale, 7 cents

These cattle were weighed by Dr. Johns, President of State Agricultural Society.

Twelve of the large cattle out of 100 head, weighed May 23d, 1856, which was during the time of fattening:

| Black | 2424 |

| Red | 2340 |

| Pied | 2640 |

| M. Red | 2264 |

| Ch. Roan | 2522 |

| B. Red | 2574 |

| S. Roan | 2330 |

| C. Red | 2340 |

| S. White | 2360 |

| P. Red | 2486 |

| Long White | 2496 |

| M. Red | 2540 |

Same cattle weighed July 18, 1856:

| Black | 2526 |

| Red | 2480 |

| Pied | 2730 |

| M. Red | 2424 |

| Ch. Roan | 2654 |

| B. Red | 2646 |

| S. Roan | 2470 |

| C. Red | 2490 |

| S. White | 2430 |

| P. Red | 2630 |

| L. White | 2600 |

| M. Red | 2564 |

Same cattle weighed February 12th, 1857:

| Black | 2720 |

| Red | 2780 |

| Pied | 2990 |

| M. Red | 2640 |

| Ch. Roan | 2810 |

| B. Red | 2910 |

| S. Roan | 2680 |

| C. Red | 2770 |

| S. White | 2605 |

| P. Red | 2840 |

| L. White | 2810 |

| M. Red | 2880 |

Average, 2786¼ lbs.

Average age, 4 years

Weighed by B. F. Harris; sold for 8 cents per lb.

Largest steer in Illinois, weight 3524, 7 years old, raised by John Rising, fed by H. H. Harris.

Average weight of the 100 head, 2377 lbs.

The foregoing is a correct statement of a famous cattle sale which occurred in the City of Chicago, month of March, 1856.

The herd comprised 100 head of the finest and heaviest cattle ever raised and fattened in one lot by one man in the State of Illinois, or in the United States of America, or elsewhere, so far as the records go to show. These cattle were raised from[Pg 46] 1 and 2-year-old steers on my farm in Champaign County, Illinois, and fattened for the market in the years of 1855 and '56, their average age, at that time, being 4 years. They were weighed on my farm by Dr. Johns, of Decatur, Illinois, President State Agricultural Society. Said weights were witnessed by a large number of representative men from Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky and Illinois, to the number of five hundred, among whom were many professional cattle raisers and dealers, all of whom bore willing testimony to the average weight of the cattle, which was 2,377 lbs. per head. Out of this lot of 100 cattle, 12 head of the finest steers were selected and fed until the following February. They then showed an average weight of 2,786¼ lbs., and were sold to Messrs. Cliborn and Alby, of Chicago, at 8 cents per lb. The weight master kept a record of each draft as the cattle were weighed—one and two in a draft. A copy of said weights is herewith attached for the inspection of the general public; also copy of average gain at different periods.

On the 22d of February, 1857, the 12 steers sold to Cliborn and Alby, appropriately decorated with tri-colored ribbon, preceded by a band of music, were led through the principal streets of Chicago, followed by 100 butchers, mounted and uniformed. After this unique procession, the cattle were slaughtered by said Cliborn, and Alby, for the city markets, some of the beef selling as high as 50 cents per lb. Small packages of it were sent to customers in various parts of the United States, and even Europe, and sold, in some cases, as high as $1.00 per lb. These orders were given by these parties simply that they might say they had eaten of this famous premium beef.

B. F. Harris.

August 26, 1824-

"Tom Candy Ponting was born at Heyden farm, Parish of Kilsmeredo, near Bath, Somersetshire, England, August 26, 1824. He was the son of John Ponting and Ruth Sherron Ponting. The Pontings came into England with William the Conqueror, so were descendants of Normandy. The Ponting family were breeders of cattle and Tom Ponting has followed cattle breeding all of his life, both in England and in this country."

Tom Candy Ponting came to the United States in 1847, landing in New York City, and finally making his way to Etna, Ohio. Here he was employed by a Mr. Matthews, to sell mutton from a wagon in the market house in Columbus, where they attended twice a week. Mutton sold for 15 cents to 25 cents per quarter[Pg 48] in those days, while beef sold for 2½ cents to 3 cents per pound. After a short time, Mr. Ponting quit his job selling mutton, went to Columbus, bought a horse and saddle, and went into the country to buy cattle. The first cattle that he ever bought in the United States were eight head which he purchased from a Mr. Bishop eight miles northeast of Columbus, Ohio.

In the spring of 1848, Mr. Ponting, in company with a Mr. Vickery, another Englishman, visited Racine, Janesville, Watertown, Madison, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, looking for a location to start a butcher shop. Although there was plenty of need for butcher shops at these places, they did not locate because cattle were so scarce in the country. From Milwaukee, Mr. Ponting came to Chicago to study the situations there. He found no regular markets and only two places where they sold stock. While in Chicago, he met a Mr. Bradley, who had driven some cattle from McLean county, near Leroy. Mr. Bradley had sold all of his cattle except forty cows with calves. He sold these to Mr. Ponting, who drove them to Wisconsin and sold them to immigrants, a few at a time. He sold them for $15 to $25 per head and still made money. He returned to Chicago and again met Mr. Bradley, who had brought a boat load of sides of bacon up from Peoria. He had purchased this bacon from the farmers, hauled it to Peoria, and shipped it up the Illinois river to Chicago, where he sold it to grocery stores. This was the only means to dispose of the bacon put up by the farmers, as there was no hog packing done in Chicago at that time.

Mr. Bradley wanted Mr. Ponting to go with him to McLean county, but as Illinois was known in those days as a very sickly state, Mr. Ponting was afraid to venture.

While in Chicago at this time, he met a Mr. Lewis and Mr. Heyworth who had come up from Vermilion county with a drove of cattle. Mr. Heyworth was taken sick here and Mr. Ponting was employed to assist Mr. Lewis in taking the cattle on to Milwaukee.

In the spring of 1849, Mr. Ponting went to Georgetown, Illinois, and there purchased about 300 head of cattle. He also bought a camping outfit, a yoke of oxen, employed a cook, and drove through with the cattle to Wisconsin. The cattle that got fat on the way were sold to the butchers, while those that were fit for milk cows were sold to the immigrants. During this same spring, when Mr. Ponting was in Vermilion county, he visited Mr. Lewis at Crabapple Grove, which is on the line of Vermilion and Edgar counties. This man and one of his neighbors had bought a drove of geese, drove them to Iowa, and traded them for steers. They drove the steers back to Vermilion county, fattened them, and the next spring built flat boats and shipped them to New Orleans. In the fall of this same year, he made several trips over the line into Illinois, in Stevenson county, buying fat sheep to drive to Milwaukee. There were no regular banks in Milwaukee, therefore all the money that was paid for stock was Mexican dollars and five franc pieces. Very little American silver money was seen at that time. The hotel rates in Milwaukee were very cheap; only $2.00 per week, with bitters before breakfast, free. Whiskey sold for 15 cents a gallon and was used liberally by stock drivers.

In March, 1850, Mr. Ponting rode on horseback from Milwaukee to Leroy, in McLean county, where he met with some men who were buying cattle to take back to California. He went from here to Christian county, where he bought a drove of cattle which cost him from $6 to $11 per head. In the spring, he drove them to Milwaukee. There had been very heavy rains that spring and rivers were very high, which made cattle driving very difficult.

In the spring of 1851, he purchased about 350 head of cattle, buying from Rochester, near Springfield, to the Wabash river. After gathering the cattle together, he pinned them up near the present site of Moweaqua. He bought these cattle very cheap and drove the entire herd to Milwaukee, where they were herded on the prairies near town until sold. He took a few in each week and sold them to the butchers. After finishing the season's work, he returned to Indiana to spend the winter.

In the summer of 1852, the cattle business in Wisconsin was dull. Money matters were very much changed; gold began to come in from California, and get into circulation. Mr. Ponting and his partner decided to go to Texas and buy their feeder cattle. They rode through to Hopkins county, Texas. Here they visited a Mr. Hart, one of the large cattle men in that country. They bought several hundred cattle and drove them back to Illinois, reaching Moweaqua in July of the next year. He put these Texas cattle on pasture until winter, when they were fed out on shocked corn. Mr. Ponting's partner went to Indiana and bought several hundred hogs to follow these cattle. They bought shocked corn,[Pg 51] paying about 50 cents a bushel for it. They would go into a piece of corn after it was dry enough and select two of the smallest shocks they could find. The owner would select two of the largest ones. These were shocked out and weighed, the average being taken as an average size shock. He bought about 40 acres from Mr. Dennison Sanders this way. The shocked corn was fed to the cattle in the same place each day, so that when it rained, the accumulation of stalks would keep the steers out of the mud. He drove this bunch of cattle to New York the next summer, where they were sold July 4, 1854.

In the spring of 1855, Mr. Ponting purchased a large drove of cattle, which together with some he had bought a few months before, were driven through to Chicago. Illinois was pretty well settled by this time, and it was unnecessary to take a camping outfit along. He stopped this drove of cattle near Pullman, put them out on the grass and took only a few into Chicago at a time. There had been a great change made in the Chicago market since Mr. Ponting was there two years before. There were two regular stock yards; the Merrick Yards, now known as the Sherman Yards, and the Bullshed Yards. In the fall of this year, he bought another bunch of cattle and drove them to Chicago in October. This time he stopped the cattle near the present site of Kankakee, and rode on into Chicago to learn the prospects for a market. They were then taken on to Chicago and left just outside the city to graze until they could be sold to the cattle dealers. This was the last bunch of cattle Mr. Ponting ever drove over land to Chicago, and it is probable that they were the last bunch ever driven from central Illinois. From this time on, the cattle were sent to market by[Pg 52] railroad. The next year, 1856, he shipped 110 head of cattle from Moweaqua, the first cattle ever shipped from that place.

In the early part of 1857, the cattle business was very flourishing and the packers said there would be a big demand for them that fall. Mr. Ponting contracted for 1000 head of cattle and about 1500 hogs before the season was over, but before he got them on the market, a panic came on, money became almost worthless, and he suffered a heavy loss.

In 1866, Mr. Ponting went to Abilene, Kansas, to buy some feeders. He purchased about 700, sold them the next spring, making a good profit. He repeated the Kansas purchase the next year with like success. In 1868, he took the cattle he had bought in Kansas to Albany. They numbered around 800. In 1870, he went back down into Texas and bought cattle as he had done in 1852. He found a herd of about 2500, out of which he bought all of the two and three year olds. These numbered about 850, for which he paid $16 per head. There had been a new railroad, just finished, from St. Louis through Missouri, close to the Indian Territory line to a place called Pierce City. The railroad officers had some agents trying to get a contract to carry these cattle, together with some other cattle belonging to Hall brothers, over the new road. They billed the cars, numbering 80 in all, with a contract to refund $50 per car. They did this to get the contract which made a big showing before some New York magnates, who were there at the time trying to buy stock in the new railroad.

In 1876, Mr. Ponting visited a Shorthorn sale at Springfield and bought several head of cattle with which he started a Shorthorn[Pg 53] herd. In the spring of 1880, he attended another Shorthorn sale at Chicago, where he bought a few more Shorthorns to add to his herd. Until his first purchase of Shorthorns, Mr. Ponting's operations had been entirely along the line of buying and feeding and although he did a small pure bred business from this time on, he continued his feeding operations as he had done in previous years, although probably not on as large a scale.

Mr. Ponting had not been in the Shorthorn business very long until he became interested in Herefords. In the fall of 1880, he visited the fair at St. Louis, where he purchased four Herefords. In the spring of the next year, Mr. W. H. Sotham of Guelph, Canada, bought four more Herefords for him. In the fall of 1882, he sold out all of his Shorthorns, thereby severing his relations with this breed.

In 1886, Mr. Ponting made a contract with the Wyoming Hereford Association to sell them 270 head of Hereford cattle, to be delivered in the spring of 1887. The firm paid for a part of them and Mr. Ponting took a note for a few more. About 60 were left on his hands and had to be sold for beef. As a result, he lost about $800 on the deal, which killed all of his profits.

Mr. Ponting continued in the Hereford business until 1903, when he decided to retire from actual business. In the summer, a gentleman came from Iowa and bought his entire Hereford cattle trade. He had at this time about 3700 acres of land, 1500 acres of which were in Christian county. He decided to divide his property among his children, keeping a sufficient amount to support Mrs. Ponting and himself. He bought a home in Moweaqua,[Pg 54] where he and Mrs. Ponting have lived happily ever since.

When Mr. Ponting came to Chicago in 1848, there was only one cattle market west of the Allegheny mountains, and that was at St. Louis. At that time, there were a good many cattle sold for the New Orleans market during the spring and winter, but the principal markets were New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia It took ninety days to make the trip to New York with cattle and the drovers had to wait until the roads settled in the spring before they started.

At Fort Worth, Texas, there was nothing but a large fort and force of United States soldiers to subdue the Indians around there. The present six big western markets have all been started since that time.

"While the magnitude of Mr. Ponting's operations was not as great as that of John T. Alexander, and although he probably never accumulated as much wealth as Benjamin F. Harris, he was successful and his operations extended over a greater period of time than any one of the early pioneer cattlemen of the state of Illinois. He operated throughout two of the stages of cattle feeding and has lived to see the beginning of the third."[20]

[15] Bureau of Animal Industry Report of 1885-86.

[16] The Breeder's Gazette, July 16, 1913.

His son, John T. Alexander, of Alexander, Ward & Co., commission men of Chicago, has been prominent in the cattle interests during the last 40 years.

[17] The Breeder's Gazette, July 16, 1913.

[18] The Breeder's Gazette. Aug. 6, 1913.

[19] This information was given by his grandson, Mr. B. F. Harris.

[20] Story of Tom Ponting's Life.