Title: Dick Kent with the Mounted Police

Author: M. M. Oblinger

Release date: November 11, 2015 [eBook #50431]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Rick Morris

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

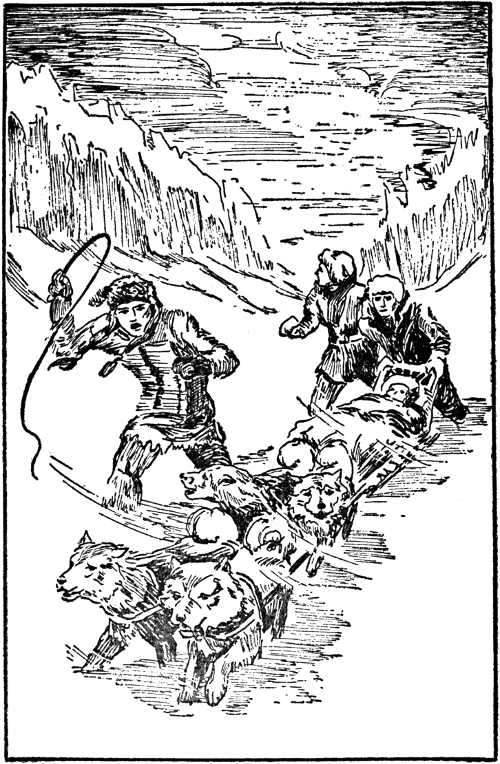

Wrapped in blankets, Sandy still lay on the hastily improvised sled. (Page 127)

By MILTON RICHARDS

AUTHOR OF

“Dick Kent in the Far North”

“Dick Kent with the Eskimos”

“Dick Kent, Fur Trader”

“Dick Kent and the Malemute Mail”

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Akron, Ohio New York

Copyright MCMXXVII

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Made in the United States of America

Dick Kent tossed aside the wolf trap he had been trying to repair, and turned to his chum, Sandy McClaren.

“Let’s go back to your Uncle Walter’s at Fort Good Faith,” said Dick restlessly. “It’s getting too quiet around here.”

Sandy McClaren’s big blue eyes turned from the marten pelt he had been scraping. “I’m with you, Dick. Uncle Walt needs us, too. He’s still having a lot of trouble with that outlaw, Bear Henderson.”

For a year after finishing school in the United States, Dick Kent and Sandy McClaren had been pursuing adventure two hundred miles north of Hay River Landing, Canada, where they had gone to visit Sandy’s uncle. Lately they had come to Fort du Lac at the invitation of Martin MacLean, the factor there. The savage northland already had woven its spell of dangerous adventure about them, but Fort du Lac had proved dull after the excitement of the more lawless trading post supervised by Sandy’s uncle on the northern fringe of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory.

Dick and Sandy had turned toward the big log store building where Martin MacLean bartered for furs, when they stopped dead, looking northeast along the trail that curved about a high headland of pine forest.

“What’s that?” cried Dick suddenly.

“Looks like an Indian runner!” Sandy exclaimed.

“I’ll tell Mr. MacLean,” Dick stretched his athletic legs toward the store.

The fur trader came out on Dick’s heels a moment later, his broad, bony frame and bearded face tense at the hint of trouble.

“It’s a runner all right,” confirmed the trader, watching the distant figure, which was rapidly approaching.

Presently a swarthy faced Indian, his coarse black hair streaming about his haggard features, fell almost exhausted into their arms.

“Help me carry him in,” Martin MacLean commanded. “He’s tuckered out. We’ve got to get him to talk. There’s trouble somewhere.”

They tugged the limp body of the runner into the store and lay him on several bales of fur. The trader hurried for stimulant, which he forced between the Indian’s teeth. The runner soon opened his eyes. All three bent over him as he spoke:

“Him Bear Henderson take um post—from Mister McClaren,” gasped the runner. “Tie um up. Kill all good Injuns!”

Dick Kent’s face paled as he turned to Sandy. “Henderson has captured your Uncle Walter!”

“Well, he’ll get his when the mounted police get there,” flared Sandy, his Scotch temper showing itself.

The factor of the post turned to them. They fell silent. “Boys, I can’t leave the post,” he said, “and I don’t trust any of the Indians around the store. Can I depend on you to go down the river and get Malcolm Mackenzie?”

“Can you!” Dick and Sandy chorused, “I should smile.”

“You know what this means,” the trader went on sternly. “Bear Henderson is a powerful man. There isn’t a doubt this runner was followed here. There may be men right here at Fort du Lac who are in sympathy with the outlaw. Henderson is plotting against the whole northern frontier held by Hudson’s Bay Company. It’s life or death.”

“We’ll do it!” Dick cried eagerly. “Tell us what to do.”

“All right then. You go by canoe down the river to Mackenzie’s Landing. Tell Mackenzie I asked him to go with you to the mounted police post at Fort Dunwoody. You know the trail that far. Malcolm knows it from the landing on. There’s a grub cache he might have forgotten. In case he has——” the boys followed MacLean behind the counter. From the strong box the trader drew a map. “Now here is our post,” the trader continued, indicating a dot on the rough map with a match end, while Dick and Sandy followed him attentively; “There’s Little Moose Portage, and further down Mackenzie’s Landing, the free trader’s post. Twenty miles further the river swings north and you leave the water and go by land. Then here’s where you strike the cache of food——”

Dick’s sudden, startled cry interrupted. “What was that at the window!”

“I didn’t see anything,” whispered Sandy.

“Sure you weren’t imagining something?” said the trader.

“I know I saw a face right there a moment ago,” Dick insisted, pointing to a window in the rear of the long store. “It seemed to be an Indian’s face which was covered with hideous scars.”

MacLean walked back and pulled the curtains shut over the window. He returned and went on explaining the location of the cache and the route to be taken to Fort Dunwoody.

Once started, Dick and Sandy were not long in preparing for the trip down the river to Mackenzie’s Landing. They cleaned and oiled their 30.30 Ross rifles, packed a canoe with flour, beans, bacon, coffee, salt, sugar and camp utensils, and saw that they were well supplied with ammunition.

On their last trip to the canoe from the storehouse, Sandy, too, had a singular surprise. But he did not cry out. Instead, he called softly to Dick, who was a little ahead of him.

“I saw the same face you saw behind those boxes over there on the landing,” Sandy said tensely. “Make believe we didn’t notice anything. Then we’ll pick up our rifles and walk down the river till we get where we can see behind the boxes.”

“All right,” Dick replied cooly, his dark eyes gleaming as they always did at the promise of excitement.

“Don’t shoot. Capture him,” Dick added, as they deposited their packs into the canoe, picked up their rifles and started off down the river bank, their eyes bent to the left.

When they had advanced far enough to see behind the boxes, they turned and looked. The face was gone! There was no one behind the packing boxes.

Sandy scratched his head. “Blame it, I know I saw somebody watching us.”

“Come on, we’ll look closer.” Dick led the way forward and they examined all the boxes, but found each one empty.

“Looks queer,” Dick admitted.

“Those Indians can disappear mighty suddenly,” Sandy said. “Let’s tell Mr. MacLean.”

They hurried back to the store. The trader plainly was deeply concerned over what they had to tell. “I tell you, boys, I hadn’t ought to let you make this trip,” he said, pacing back and forth. “Henderson has men here that I know nothing about. They say he has secret operatives all over the northern frontier. Sandy’s uncle never would forgive me if anything happened to you fellows. But I don’t see what else I can do. The mounted police must be notified.”

“Well, Sandy and I aren’t men,” Dick replied modestly, “but you know we’ve been in the north country for a year now and so far we’ve taken pretty good care of ourselves. Sandy’s Uncle Walter will tell you that.”

The trader surveyed Dick Kent’s stalwart figure and Sandy’s more stocky frame with a renewal of confidence. “Yes,” he concluded, “I believe you fellows will come out all right. Shake.”

Dick and Sandy gripped Martin MacLean’s hard hand. They felt a glow of admiration for the big “sourdough” who had so complimented two “chechakos,” or tenderfeet. The trader drew from his pocket a wallet of money and thrust it into Dick’s hand, with the remark it might come in handy for expenses.

An hour later the boys were gliding down the river, Dick in the stern steering, Sandy in front on the lookout for snags. The dark walls of spruce forest on either side closed in on them with a mysterious silence. They seemed to feel malevolent eyes watching them as they sheered the oily surface of the stream. The strange face both had seen at Fort du Lac remained in their memory and made them silent as they forged along with the current. It was the last warm days of fall; already a hint of winter was in the air, and with the threat of danger hovering about was combined another feeling of dread, as if the very atmosphere of the vast, lonely land heralded the approach of mercilessly cold weather.

“You watch the south bank, and I’ll watch the north,” Dick broke the silence when the landing at Fort du Lac had faded from view around a bend. “I think we’ll be followed by land if our suspicions are correct and there’s really some one on our trail.”

“They’ll have to follow by land for a ways anyway,” rejoined Sandy. “Mr. MacLean will see them if they use one of the canoes at the landing. But I suppose they have a canoe hidden somewhere along the river.”

“That’s about it,” Dick agreed. “We’ll keep sharp watch and be ready to duck if there’s any shooting.”

They paddled on silently for a quarter of an hour, making good time and keeping to the center of the stream. They were just passing a large heap of driftwood, lodged in an eddy near the north shore, when Sandy called Dick’s attention to something under the brush.

“What do you make of that light brown object just the other side of the little sand point sticking out into the river?” asked Sandy.

“I was looking at it myself,” responded Dick. “I thought it was a log with the bark off it at first, but it might be a canoe.”

“It looks a lot like a canoe—as if they tried to hide it under some brush but the brush sprung up after they left and exposed it.”

“We’ll turn in and see,” Dick plied his paddle lustily, and the light craft swerved toward the shore.

“Aren’t we taking an awful risk?” Sandy was cautious. “Suppose they’re close to us.”

“We’ll take a chance,” Dick returned. “Better take a chance now than have them catch up with us in that canoe. It’s plain they’re not here yet.”

Nerves keyed high at thought of the peril they might be floating into, Dick and Sandy bore swiftly into the sand point, and presently the bottom of the canoe grated on the gravel. Dick leaped out into the shallow water and beached the canoe, Sandy following closely.

“It’s a canoe sure enough!” Dick exclaimed when they reached the spot where they had seen the suspicious object.

“And they tried to hide it,” Sandy came back, as they drew nearer. “See the tracks in the mud? Say! That canoe hasn’t been there a day, if that!”

“You’re right!” Dick cried, “and right here and now we’re going to see that nobody chases us in this canoe.”

“Be careful,” Sandy cautioned.

“We’ll set her adrift,” Dick went on, unheeding Sandy’s precautions. “Here, Sandy, you grab the bow and I’ll get around behind and push. Soon as we get it out in the current it’ll float down where they can’t find it. We might sink it, but we’d have to tow it into the river and we haven’t time.”

Sandy fell to work with a will. The canoe was lodged in the mud rather securely and they strained for some minutes before it at last came loose with a suck and splash that nearly tumbled Sandy over. An instant later they had shoved the canoe out into the stream, where the current caught it and carried it past the sand point.

The young adventurers paused to gaze with satisfaction upon this blow they felt they had dealt the enemy, when a sound from the shore drew their startled attention.

“Listen,” whispered Dick.

They could hear a crashing among the trees. Looking toward the forest they could see nothing at first. Then suddenly, into a small clearing that led down to the river bank, burst three men, running and waving their rifles menacingly.

“Quick! The canoe!” cried Dick hoarsely. “Don’t stop to shoot. We’ve got to get away. They’re after that canoe. It’s the Indian with the scarred face!”

Sandy tumbled into the stern of the canoe in one flying leap, and as Dick shoved on the prow, he picked up his paddle and stroked backward. The canoe left the beach with a lunge, and Dick was nearly precipitated into the water as he leaped into his position in the bow. As they crouched to paddle, three shots sounded and bullets cut the water about them.

“Downstream fast,” shouted Dick. “Stay low, Sandy.”

Rifle balls were flying thick and fast as they rounded the sand point, paddling frantically after the canoe they had set adrift.

“Diable!” they could hear an enraged cry in French, as their pursuers found the canoe gone and the boys escaping.

Dick turned and looked back. All three of the men were kneeling with rifles leveled. “Duck!” he shouted to Sandy just in time.

The rifles cracked almost as one and two bullets ripped through the bottom of the canoe, plowing up splinters in their wake.

“We’ve sprung a leak,” called Sandy almost immediately. “Those shots have put the canoe out of commission!”

Dick glanced about at the bottom of the canoe. Sandy was right. The bullets had struck below the waterline and the river was gurgling in around the packs and blankets.

Dick Kent thought swiftly. There was no time to lose. The canoe was filling fast. Already it was growing perceptibly heavier. Ahead he could see the canoe they had set adrift. It was a long chance, but it was the only thing to be done, aside from swimming to the other shore and abandoning all their packs and camp equipment.

“Sandy!”

“What?” panted his chum.

“We’ve got to switch our packs into that empty canoe.”

“Catch it first, I’ll say!” cried Sandy.

They redoubled their efforts on the paddles. The drifting canoe was spinning slowly in the stream. Waterlogged as they were, they yet were slowly gaining on the empty craft. Out of rifle range from the sand point, the bullets of their pursuers no longer endangered them as they skipped across the water yards short of their mark.

Slowly they overhauled the empty canoe, and at last Dick reached out and grasped the prow, hauling it to the side of their own sinking craft. Dropping their paddles then, they straddled the two gunwales and with their legs held the canoes together while with all haste they transferred their dunnage. Working grimly and silently they had almost finished when the canoes began to whirl slowly in the current. Sandy lost his balance and toppled into the water, his hoarse shout of surprise muffled as the river closed over his head.

Sandy came up from the cold bath. Dick shouted encouragement, extending a paddle to his chum while he alone held the canoes together. In a moment, spluttering and shivering, Sandy crawled back into the loaded canoe.

The leaking canoe was rolling on its side when the last blanket was taken from it. The young men picked up their paddles and struck out with all speed. They feared their pursuers, since they no longer appeared on the sand point, had run back into the forest and were coming along the river bank into rifle range.

“B-r-r-r, that sure was no warm bath,” chattered Sandy.

“Keep paddling, and warm up,” Dick called over his shoulder. “We’ll go ashore and dry your clothes when we’re sure we’ve got away from them.”

No sooner were the words out of his mouth when a rifle shot sounded from the shore some distance behind them. A bullet whined over their heads and plunked into the river.

“There they go again!” cried Dick. “Let’s bear toward the other shore and see if we can’t get out of range.”

Crouching over their paddles they swerved to the right and gradually paddled out of range once more.

Until late in the afternoon the boys kept up a killing pace with the paddles. Sandy, warmed by the stiff exercise, would not permit Dick to go in shore on his account, and so they drew into the swift current above Little Moose Portage.

The canoe was beached on the shore opposite the one where the enemy had put in an appearance miles behind. It was an excellent camp site. They were only about three hundred yards above the rapids, whose swift current, filled with sharp stones, made it necessary to go on by land to a point where the river was less dangerous. They could hear the sound of the rushing water.

“We’ll keep sharp watch while we make camp,” said Dick. “Those fellows may have found another canoe and caught up with us.”

“Even if they come on by land they can’t be so very far behind,” Sandy added, shivering a little now that the warming work on the paddle was discontinued.

Dick and Sandy had paddled many miles that day and they were very tired. A year before they could not have kept on that far. But the north country had hardened their already healthy bodies, until they laughed at the exertion that would have put a southland boy flat on his back.

A campfire of pine cones and dead wood soon was crackling cheerily. Dick set on the coffee pot and mixed up some flapjacks while Sandy took off his moccasins and sox by the fire. By the time Sandy was fairly dry the meal was ready, and the boys fell to ravenously. Now and again they were startled by some sound from the forest, but each time the noise proved to be only that made by a wild animal investigating their campfire.

“We’ll take turns on watch tonight,” Dick said, sipping his last cup of coffee.

“Let’s draw straws for the first trick,” Sandy suggested.

“No,” Dick objected, “that ducking you had gave you the hardest day. I’ll take the first watch.”

Sandy wanted it otherwise, but Dick insisted.

“Well, if you’ll be sure to wake me up when my turn comes,” Sandy was already yawning, “it’s all right with me.”

Soon Sandy was rolled in his blankets, close by the fire, which was welcome indeed in the chill of the autumn evening.

Dick took a position in the shadow of a clump of willows where the firelight would not reveal him to any prowlers of the night that might investigate too closely. Here he squatted Indian fashion, his rifle across his knees. Many thoughts passed through his mind as the time slowly passed. That Sandy and he were on the most perilous mission of their lives he knew. But contrary to being frightened by impending danger, he was overjoyed. It was what he and Sandy had come north for—adventure. And they were getting it.

“We ought to get to Mackenzie’s Landing day after tomorrow,” he mused, talking low to himself to keep from going to sleep. It was too dangerous to walk about. “That means three or four more camps before we get a guide. Gee, I wish we could go on by ourselves. If Sandy or I only knew the country around Fort Dunwoody—but we’d get lost, and we can’t afford to lose any time with Sandy’s uncle in Bear Henderson’s hands. Wonder——”

Dick sat up suddenly, listening. It seemed to him that above the ripple of the river water and the low rumble of the distant rapids he heard the scrape of a canoe bottom on the gravel. His heart leaped and beat on painfully. What if some one stole their canoe, or crept up and attacked them! The thought galvanized him into action.

He dropped to his hands and knees, his rifle clutched in his right fingers. It was only a short distance to that part of the beach where they had dragged the canoe up out of the water. Dick crawled quietly along among the shadows to the fringe of undergrowth bordering the beach. At first the glare of the firelight in his eyes made all appear very dark by contrast, but gradually his vision was adjusted, and he could make out the vague form of the canoe.

“Wonder if it was only my imagination,” he mumbled, not seeing anything amiss. “But——” he caught his breath. The canoe had moved!

Sure enough, difficult as it was to see distinctly, he knew the canoe had rocked from side to side.

“What could it be?” he whispered, straining his eyes.

It seemed now that he could see a darker blot of darkness moving above the rim of the canoe, but he was not sure. There was but one thing to do—crawl out of the sheltering bushes and across the sand to a point from which he could ascertain just what was moving the canoe.

The decision made, Dick did not hesitate a moment. Half way to the canoe, he stopped and lay prone on his stomach, listening and watching. What little breeze there was blew from the canoe toward him, so that an animal would not easily detect his approach unless it heard him. Faintly, Dick could hear a scratching sound, as if some sharp instrument agitated the sand and gravel. He was more puzzled than ever.

He moved on again, drawing one knee cautiously after the other, careful that his rifle was ready for instant firing. Ten feet further and the scratching sound ceased suddenly. Dick was now within a few feet of the prow of the canoe. He stopped dead still, and, resting on his knees, raised his rifle.

“Who’s there?” he called sternly.

A sudden commotion followed. Around the prow of the canoe flashed two round glowing eyes, and a bearded, tuft-eared cat face. Dick’s rifle crashed. There was an inhuman squall of pain; a ball of fur and fury bounded high into the air and fell writhing, spitting and snarling within three feet of Dick, who leaped to one side.

“Hi! Hi! Dick, where are you?” It was Sandy calling from the campfire. He had been awakened by the gun shot.

“It’s all right, Sandy,” Dick called back, stooping over the animal he had killed. “Only a lynx scratching around the canoe. Come and take a look. Gosh! I must have hit him right between the eyes.”

Sandy came running up, and bent over the dead lynx. When the cat’s last struggles ceased, the boys hauled it into the firelight.

“I was scared half to death,” Sandy grinned sheepishly. “I was dreaming we were in Fort Good Faith with Uncle Walter and about a million wild Indians were whooping and shooting at the stockade.”

“You can bet your bottom dollar I didn’t feel so calm about the time that lynx came around the canoe and looked me in the eye,” Dick confessed. “I never took aim at all—just blazed away. Lucky shot I call it. I thought it was some one trying to steal our canoe.”

“What time is it?” Sandy inquired, getting up and stretching.

Dick drew out a fine watch which had been a graduation present. “Only ten o’clock,” he reported. “You can go back to bed, Sandy. My watch isn’t half done.”

The young adventurers talked a few minutes after Sandy was back in his blankets. But Sandy soon fell asleep. In spite of the excitement brought on by the killing of the lynx, Sandy was so tired that he went back to sleep almost immediately.

Dick looked down at the lynx. “He’s sure a beauty,” he whispered proudly. “I kind of wish I hadn’t killed him now. It’s a shame to kill animals when a fellow can’t use their fur or meat.”

He returned to his position in the shadow of the willows and sat there patiently until midnight, when it was time to awaken Sandy. The fire had died down and he heaped more wood on it. He never felt more wide awake in his life. Sandy was sleeping soundly.

“Sandy, you’re pretty tired,” Dick murmured, looking down at his chum, “and I feel just about as fresh as when we pitched camp. Guess I won’t wake you up—just let you sleep until morning.”

There was an affection like brotherhood between the two boys, who had been neighbors and chums from infancy up. And since Dick was two years older than Sandy, he often felt somewhat like an older brother would feel toward a younger. Perhaps this induced Dick to resume his watch without awakening Sandy.

When Dick sat down again he was sure he could stay awake all night, but the flicker of the firelight, the whispering silence of the forest, and the ripple of the river were like a pleasant lullaby. Before he knew it he was nodding, and presently he fell sound asleep. Head drooping over his knees, Dick slept unknowing, while the fire died down and the deep blackness of the northland night crept over the silent camp.

Sandy awakened with a start at four o’clock. It still was dark, as the days were shortening with the approach of winter. He did not know why Dick had not awakened him, and he was at first fearful that something had happened to his chum.

“Dick, Dick,” he called softly, sitting up in his blankets, trying to pierce the gloom with his eyes.

There came no answer. Quietly Sandy reached out and one hand closed on his rifle. The feel of the cold steel comforted him. He had begun to learn what an encouraging companion a firearm can be in those lonely climes where they are necessary if one would live long.

Arising, Sandy began a search of the camp and quickly came upon Dick, sound asleep a little way off.

“Ho, ho,” laughed Sandy mischievously, “I’ve got one on you now, old boy. Asleep on watch, huh. I’ll fix you.”

His fears relieved, Sandy’s sense of humor cropped out. He could not resist playing a good joke on his chum.

Sandy thought a moment, then hit upon an idea, which he quickly put into execution. The fire had gone out, and Sandy’s scheme was no other than to rebuild it so close to Dick that it would sizzle the sleeping lad’s chin.

Soon Sandy had the fire crackling and snapping within two feet of Dick’s face, as he lay on the pine needles where he had fallen over during the night.

Setting about breakfast, Sandy chuckled as he watched Dick begin to squirm and mutter in his sleep as the heat reached him.

At last Dick turned over, and flinging out one hand, almost plunged it into the fire. Sandy cried out sharply, and jumped forward to keep Dick’s hand out of the fire, when his chum leaped up wide awake.

“What! How——” Dick stammered, blinking his eyes.

Sandy doubled up with laughter. Dick soon saw the joke and joined Sandy in a hearty laugh. Then he quickly grew serious.

“That’s the worst thing I could have done,” Dick accused himself. “Suppose Henderson’s men had crept up on us while I was asleep. Sandy, I’ll never forgive myself for this. I can’t blame them for shooting soldiers that sleep on guard duty—after tonight.”

“Oh, never mind,” Sandy’s optimism came to the front. “What’s the difference. We’re safe and sound, aren’t we?”

“That doesn’t excuse me for neglecting my duty,” Dick insisted. But as he reached for the tin plate of bacon and camp bread that Sandy handed him, Dick cheered up. “What beats me,” he concluded, “is that I was going to let you sleep till morning, Sandy. Guess I wasn’t as tough as I thought I was.”

“That’s just like you,” Sandy retorted. “Just because you’re a couple of years older than I you think you ought to do all the heavy work.”

“Well, I’ll see that you do your night watching after this,” Dick promised. “And now we’d better get started. If those fellows kept on after us they’ve had just about time enough to catch up.”

It did not take the boys long to break camp. The trail that led along the bank past the dangerous Little Moose Rapids to safe water was on the other bank of the river, and Dick and Sandy prepared to paddle across. Once on the trail, they planned to shoulder their packs and the canoe for the jaunt over the portage. They shoved out the canoe without mishap and were cutting across the swift current of the Big Smokey river above the rapids, when on the other shore, at the point where they intended landing, Dick thought he saw a wisp of smoke ascending, as from a campfire recently extinguished.

“Sandy, do you see any one over there?” Dick called.

“I see a kind of smoke haze among those little spruce trees,” Sandy replied.

“You know what I think?” Dick went on, sturdily plying his paddle, “that gang is waiting for us over there. They’re in ambush. As soon as we get close in they’ll open fire. I’ll bet I’m right. If I am we don’t dare try to land.”

“Well, there’s no trail around the rapids on the side we camped,” Sandy returned. “We’d have to detour about twelve miles that way to get back to the Big Smokey.”

They were slowly drawing closer to the opposite bank, the swift current pulling them downstream a little in spite of their efforts. The boys were silent as they drew closer, undecided which way to turn, almost certain now that a warm reception awaited them on the portage trail landing. Suddenly Dick spoke cooly, but tensely:

“Backwater, Sandy. Don’t act excited. We don’t dare go on. I just saw two rifle barrels thrust over a hump of moss on a fallen tree.”

Sandy did not falter at the warning. He reversed his paddle, as Dick was doing, and the canoe came almost to a standstill.

“We’ll have to shoot the rapids!” Dick’s voice was like the snap of a whip as he made known his daring resolve.

At Little Moose Rapids the Big Smokey river plunged through a gorge nearly a half mile long before it finally came once more to a gentler incline where canoeing was safe. Only the most daring of canoeists ever risked piloting a frail craft through this treacherous stretch of water, and many who had dared had been drowned. Dick’s last minute resolution was one of desperation. Though he and Sandy were experts with the paddle, yet they never would have considered attempting to shoot any rapids had death or capture not threatened them.

“We’ll never make it!” the optimistic Sandy was shaken from his cheeriness by Dick’s desperate resolve.

“We’ve got to!” shouted Dick, as with one strong stroke of his paddle he swerved the canoe head on with the current, and they sped straight toward the gorge.

At the maneuver they heard an angry shout from the shore that had been their destination. Even at that distance they could detect the menace in that cry, and with added zeal they bent to their paddles.

Then a rifle cracked and a ball whistled across the water behind them. Another and another shot was fired while they sped on swifter and swifter.

“We’re getting out of range!” Dick cried.

“I hope so,” panted Sandy.

“They’re poor marksmen, anyhow,” Dick returned.

They both fell silent as they left one danger behind, only to face one almost as threatening.

The river swiftly narrowed and deepened as they swept down between the high walls of the gorge. A sullen roar of the water against the numerous rocks and against the solid walls could be heard. The canoe seemed to shoot ahead like a leaf on the wind. Louder and louder grew the sound of rushing water. Then the boys saw the first wave of foam and spray where the water whirled among several huge boulders.

Sandy was in the bow, Dick in the stern when they struck the first angry whirlpool.

“Use your paddle to push off the rocks,” shouted Dick above the rumble of the water.

They scudded past a huge, wet boulder, seemed almost flung against another, only to be whisked into a deep pool where it was all Dick and Sandy could do to keep the canoe from turning clear around. Out of the pool, they danced on once more. The rapids were clear of rocks for a space, but they were moving so fast that it seemed no time before they reached a giant buttress of stone that seemed to bar the way.

“Push off,” cried Dick. “I’ll backwater. Heave now. Here we go!”

They shaved the bluff so closely that the grind of the canoe upon the rock could be heard. The dash of water against the cliff showered down upon them, and the canoe took in a bucketful.

“Dip the water out!” shouted Dick, while they spun into another deep pool, the cliff behind them.

Sandy began frantically bailing out the water with his hat, while Dick desperately held the canoe bow against the current.

The gorge was deeper now, almost shutting out the early morning sunlight. All about spray flew in the air, like driving mist, and the roar of rushing water was almost deafening. The canoe was holding up well, yet its two occupants realized its frail shell would be shattered to atoms if but once it was thrown upon one of the countless rocks they seemed to miss by inches.

“I hope we don’t hit a waterfall,” shouted Sandy as he ceased bailing water and drew a long breath.

“Let ’er come,” responded Dick daringly, swerving the canoe this way and that with a lusty stroke of his paddle.

“Look out, another rock!”

Sandy turned from his bailing and grasped his paddle just in time. In a crouch he met the boulder with the end of the paddle and pushed. The canoe forged off to the left, dodged in between two other rocks, and once more they reached a space comparatively straight and free from obstructions. Like an arrow they shot onward.

The noise of the foaming water was fast increasing in volume. Dick feared a waterfall, and silently he nerved himself for it, and none too soon. Dashing down a narrow channel and bobbing around a curve like a cork on ocean waves, he saw ahead a mist of spray and the rumble of falling water burst upon his ears.

Sandy could not suppress a cry of terror, but white-lipped Dick managed to hold his breath for what was to come. “Hold tight!” he shouted to his chum. “I’ll hold her straight, and we’ll dive over. We’ve a chance. It’s not high.”

Straight toward the edge of the waterfall the canoe shot with terrific speed. The rumble of the water was frightful. Then they went over. One glimpse they had of the whirlpools boiling below the falls as the prow of the canoe swept over and the light craft leaped into the misty air, like a ski jumper.

It was only a short drop of about five feet, but when the canoe struck the churning water, it spun and spun about, wallowing in the foam. Dick and Sandy were drenched to the skin in a moment. All they could do was cling to the canoe, hoping against hope.

“Hang to that rock ahead, if we go under!” Dick cried, above the thunder of the falls.

“I can’t see!” Sandy shouted back, rubbing the water from his eyes and coughing.

Then the canoe struck something submerged, and turned over on its side, tipping Dick and Sandy into the boiling whirlpools.

Dick clung to the side of the canoe as the water washed over him. For an instant Sandy disappeared, then Dick saw him come up, also clinging to the canoe, which had not entirely turned over, but had shipped so much water that it was sinking.

Presently, canoe and swimmers were whipped into a deep pool below the falls, and Dick and Sandy began desperately flinging water out of their craft. A little later they crawled back into their canoe, wet as half drowned rats, and Dick pushed off into the center of the stream.

The worst was over. Below the falls the gorge widened out slowly and the current grew more sluggish. For a quarter of an hour they glided on silently without need of their paddles, except to keep the craft in the center of the stream.

“Whew! I hope we don’t run into any more rapids,” Sandy breathed more freely.

Dick emphatically agreed. “Next time,” said he, “I’ll prefer facing the bullets, I think. Gee, if the fellows back in the U. S. A. knew what we’d just gone through they’d have a fit.”

“They’ll never believe it,” Sandy opined.

“We’ll make ’em believe it if we live to tell it,” vowed Dick, pulling extra hard on his paddle and making the canoe leap forward like a live thing. “But, to change the subject, I guess we left the enemy behind this time.”

“I’ll say so,” Sandy came back, “but two duckings in two days isn’t fair. Where can I stop off and get dry?”

“I think we’d better keep moving till noon,” Dick advised. “Then we can kill two birds with one stone—eat and dry off too.”

Sandy saw the wisdom of this and fell silent, bending his energies to the paddle. They made good time until about noon, when they espied a sandy shoal ahead of them that promised plenty of dry firewood for a campfire. They drew in, beached the canoe and made camp. An hour later, dry again and in good spirits, they pushed off and went on down the river.

“Seems as if I smell burning wood in the air,” Dick remarked a couple of miles further on.

“I do too,” Sandy replied, “——must be a forest fire somewhere near.”

“Hope it’s not too near,” said Dick, “a forest fire would hold us up a while even if we are on the river. I’ve heard my father tell about the fires they used to have in Oregon. They’re no joke.”

Sandy was about to add what he knew of forest fires when they both sighted another canoe toiling upstream. At that distance they could not at first distinguish whether there was more than one in the canoe. However, they held any stranger they might meet a possible enemy, since Martin MacLean had told them how far-reaching was the hand of Bear Henderson, and so they prepared for hostility.

Slowly the two canoes drew together. Sandy quietly picked up his rifle, while Dick continued paddling. They could now see there was but one man in the canoe.

“Hello there,” Dick hailed.

The stranger waved a hand, ceased paddling, except to hold his canoe against the current, and waited for the boys to glide up. He was a tall man, with long, dark hair and a leathery face.

“Where you goin’?” he asked as the canoe prows touched.

“Mackenzie’s Landing,” Dick replied, seeing nothing hostile in the other’s demeanor, and seeing no reason why he should not reveal his destination, if not his errand.

“I got my grub stole back river a piece,” the stranger said, pointing over his shoulder with one thumb. “Have you fellers got plenty of grub?”

“Sure,” Dick answered. “Want to eat with us? Our grub’s a little wet, but it swallows all right.”

“I’d be obliged,” the stranger returned, “but mebbe you wasn’t figgerin’ to stop jest now.”

“We just had a snack,” Dick admitted, “but if you’re hungry we’ll split what we have.”

“I jest need enough to get me to Fort du Lac.”

“Fort du Lac!” Dick and Sandy chorused. “We just came from there!”

“So? Wal, it’ll be nigh three days canoein’ up river, an’ I’ll need grub. No time to hunt. You fellers didn’t happen to run across an Injun with a heap of scars on his face?” the man asked, searching their faces.

“A scar faced Indian!” Sandy exclaimed. “Why——”

“Well, yes,” Dick broke in with a warning look at his chum. “We noticed a fellow of that description at the fort. Didn’t think much about him,” Dick was cautious.

“You fellers needn’t be afraid to tell me all you know,” the stranger had noticed Dick’s reserve and his interruption of Sandy. “I ain’t publishin’ my business but my name’s Slade.”

“Not Malemute Slade, the scout for the mounted!” Dick exclaimed, for the man’s reputation as a scout was a fable in the north country, and many times he had heard it spoken with awe and admiration.

“There’s them call me Malemute Slade,” admitted the tall man cooly, “but what was that about this here scar faced Indian?”

Dick then related the queer experiences at the fort.

The canoes were permitted to drift on down the river while they talked. Malemute Slade listened attentively.

“His name’s Many-Scar Jackson,” Slade told them when they had finished with their story. “He’s wanted for murder down the river a piece. But that’s nothin’ to this Henderson breakin’ loose. That’s news to me, an’ it’ll be news for the mounted maybe. I’ve heard rumors f’r a long time, but didn’t think much of it. A tough customer, Henderson. You fellers wants to watch y’r step. If I seen any of the gang that was foller’n you I’ll square up with ’em.”

In the keen eyes and the lean jaw of the far-famed Malemute Slade the boys saw that which made them confident that Slade could “square up” with most any one or any number.

“Tell the factor you saw us and that we’re all right—only got a ducking when we shot Little Moose Rapids,” Dick said.

Malemute Slade’s eyes lighted up. He looked with new respect at Dick’s wiry figure. “So you fellers shot the Little Moose an’ come through alive—wal, I swan. You must have toted a dozen rabbit’s feet.”

“Not a one,” Dick replied modestly, while Sandy grinned with pride.

“Y’r apt to have somethin’ worse on your hands afore you get to Mackenzie’s,” Malemute surprised them. “There’s a forest fire whoopin’ it up back a piece, an’ it’ll maybe hit the river afore you pass it. There’s a bit of smoke in the air now. Hey!”

Dick and Sandy started up and looked where Slade pointed.

Nearly four hundred yards down the river a stag had come down to drink and was standing half in and half out of the water. The canoes were slowly drifting down upon it.

“You fellers want a fresh haunch o’ venison f’r tonight?” queried Malemute.

“You bet!” Dick and Sandy chimed, “but the deer’s seen us and we can’t get close enough for a shot.”

“Reckon I can drop him from here,” Malemute Slade replied cooly.

“What!” Dick exclaimed incredulously.

Malemute’s only reply was slowly to raise his 45.70 lever action rifle to his shoulder. Dick and Sandy watched breathlessly. Motionless as a statue, the big man took aim before his rifle crashed. As the echo of the shot sounded in the silent forest, the stag leaped upward and fell into the river with a soundless splash.

“Now you fellers split your grub with me, an’ I’ll be goin’ on. If I had time I’d paddle down an’ cut a hunk off that deer. But I’ll have to be moochin’.”

Malemute Slade thought nothing of the wonderful exhibition of markmanship he had just made, and Dick and Sandy were awed to silence as they undid their packs and transferred half their food into the scout’s canoe.

Malemute Slade paid them in king’s coin for the provisions.

“You’ll probably see me again afore this Henderson business is over, but it’s hard tellin’,” was Malemute’s parting prophecy. “Au revoir.”

“Au revoir,” the boys sang out the French “so long,” and started on to where the stag had fallen.

Late that evening, making camp at a point they judged somewhere within fifty miles of Mackenzie’s Landing, the smoke of the forest fire was so strong it made them cough. They had paddled a little way up a small creek for the night, thinking to make themselves more secure from a possible night attack from Henderson’s men, who seemed so determined they should not get to the mounted police.

“I’m afraid we’re in for it,” Dick shook his head concernedly.

“It sure feels as if we were close to a fire,” Sandy agreed dubiously.

“Well, we’ll need all the sleep we can get at any rate,” Dick concluded, as he rolled into his blankets, and Sandy prepared for the first watch.

That night Dick slept fitfully. The place where they had camped was in a deep coulee, unwooded except for a few clumps of red willow. Straight above them, at the top of an almost perpendicular wall of red shale and crumbling sandstone, was a dark fringe, which marked the beginning of a mighty forest of spruce and jack pine. Moaning in his sleep, Dick sat up and commenced rubbing his eyes. Then he paused to stare in open-mouthed wonder.

The coulee was full of smoke. It floated around them in a ever thickening cloud, while above, plainly visible in the glare of the conflagration, sweeping down from the north, he beheld a thick, dense column of smoke, which seemed to span the coulee like a black bridge.

Ten feet away, Sandy, on sentinel duty, coughed and dug at his eyes. In alarm, Dick threw aside his blankets and crawled hurriedly forward to consult with his chum.

“Sandy!” he shouted, “the fire is all around us. We’ll die like rats in a trap if we stay here. Why didn’t you awaken me before? Let’s hurry back to the river and our canoe.”

“Can’t,” said Sandy laconically, “I’ve been watching that. There’s a belt of fire between us and the river. We should never have camped so far away from it.”

“Well, you know we thought we’d be safer from Henderson’s men up here,” Dick replied.

The boys could hear plainly the howling of the wind and the distant, thunderous roar of the fire. Accustomed as he had become to danger since his sojourn in the north, Dick could not overcome a sudden feeling of fear and apprehension.

“Where will we go?” shivered Sandy. “It seems to be all around us.”

“We’ve got to go through it somehow,” Dick answered, not altogether sure, himself, what ought to be done. “It’s dangerous to remain here any longer. What do you think is best?”

Sandy, eyes running water, scratched his head in perplexity.

“If we could get to the river,” he said, “we’d be safe. I don’t see any other way.”

A few moments later, two disconsolate figures clambered up the side of the coulee and struck off hurriedly at right angles with the fire. With a catch in his throat, Dick perceived the huge walls of flames bearing down upon them. For several miles, at least, they were cut off from the river. Even the sky glowed dully like a large orange disk through a thick blanket of smoke.

“What’s that!” exclaimed Sandy, suddenly starting back.

Something had shot past them through the underbrush—a heavy body, hurtling along in mute terror. Almost immediately came other bodies, small and large—rabbits scurrying almost between their legs; deer, jumping past in a wild stampede; bear and moose, crashing their way forward in a cumbersome, heart-stirring panic, as they ran from the fire.

“If they’re afraid, it’s about time we were,” Sandy declared grimly, through set teeth. “If this smoke gets any worse we’ll be suffocated in another ten minutes. My throat feels as if I had been drinking liquid fire for a week.”

Twenty feet away a flying ember settled down on the dry grass and immediately burst into flames. With the ever increasing velocity of the wind, similar patches of fire sprang up around them on every side.

“I’m afraid,” said Dick, fighting bravely against mounting despair, “that we’ll never make it. I never saw such a wind.”

Sandy did not reply. With handkerchiefs pressed to their noses and mouths, the boys struggled forward for another quarter of a mile.

By this time the heat had become terrific. Dick’s face felt as if it had been washed in a bucket of lye. Sandy’s cheeks were streaked with tears, not tears of grief, but tears of misery from smoke-tortured, bloodshot eyes.

“No use,” choked Sandy, plunging down a short embankment with Dick at his heels. “I’m about ready to quit. You see,” he explained, struggling with the lump in his throat, “I’m getting dizzier and dizzier every minute. This heat and smoke is getting me.”

Dick put out his hand with an assurance he did not feel, and patted his chum on the shoulder.

“Buck up,” Dick encouraged, “we’ll get out of this somehow. I tell you, Sandy, we’ve got to do it. Maybe this——”

Dick never finished what he was about to say. His foot slipped, and with a startled exclamation, he pitched forward, completely upsetting Sandy. In a moment both boys had rolled and slid down a steep bank. It seemed there was no end to the fall, and Dick’s heart almost failed him as he thought of what fate might meet them below. Perhaps they were rolling toward the brink of a cliff hundreds of feet high, perhaps they would fall into some rock cluttered canyon, or again, they might be drowned in some deep lake at the bottom of the bank.

Then they reached the bottom with a jarring impact that shook the breath from their bodies. When they recovered enough to look each other over, Dick was sitting upright, astride of Sandy, who lay in a crumpled, groaning heap under him. Dick heard, or thought he heard, the trickle of running water. His right foot felt pleasantly cool. When he put out his hand to investigate his fingers encountered water.

Sandy was half submerged in a tiny pool, and was sinking fast, before Dick could pull him back to safety. Dazed from the fall, Sandy sputtered a moment, then inquired excitedly:

“Have we got to the bottom?”

“I guess so,” replied Dick. “At any rate there seems to be a sort of creek running along here. Are you all right, Sandy?”

“Well, if I’m not, I soon will be,” answered Sandy, more cheerfully. “Wait till I get a drink of this water. Boy, I’m dry. Do you think we’ll be safe here?”

By way of answer, Dick pointed up to the wide belt of fire. “It’s closer than it was before. We’re protected down here from the heat and smoke, but that won’t last long. In two hours this place will be as hot as a stove. Our only chance is to keep on moving.”

“I hate to leave this water,” said Sandy, gulping large mouthfuls of it.

“I don’t intend leaving the water,” Dick assured him. “It’s just occurred to me that our best plan will be to follow this little creek. It’s probably fed from a spring and will eventually run either into a lake or river. Once we get into more water we’ll be pretty safe.”

Sandy thought Dick was right, and a few minutes later, greatly refreshed, they set out again, following the creek downstream.

Two miles further on the creek ran into a larger stream, and a little later as they hurried around a curve, Sandy, who was in the lead, gave vent to an exclamation of despair.

“Look at that!” he shouted. “The fire has cut in ahead of us.”

Sandy was right. Not more than a quarter mile downstream, the fire was raging on both sides of the creek, and even as they looked, a large jack pine, flaming to the top of its highest branches, swayed suddenly in the wind and went crashing forward in a shower of sparks and burning embers.

Sick at heart, the two young adventurers stood for a short time, scarcely daring to think of their predicament. Apparently there was little chance of escape, the main body of the fire behind them, another fire sweeping ahead.

“We’ve got to get through,” Dick muttered. “We’ll have to take a chance, Sandy. The fire ahead hasn’t been burning long and it’s not as far through it—maybe not more than a hundred yards. Somehow, I feel certain that this creek will take us straight on to the Big Smokey where we left the canoe.”

Sandy’s face brightened a little. “I believe you’re right, Dick. If a burning tree or branch doesn’t fall on us, we can make it. We’ll have to wade right down through the center of the stream. If it gets too hot we can dive under the water. I’m going to take off my shirt, soak it in water and breathe with it around my head.”

“A good idea,” approved Dick. “I’ll do it too.”

A half hour later, two boys emerged, wet and blackened, from a cloud of smoke and flame and advanced painfully along the creek to a point where it emptied into the Big Smokey river. Behind them thundered the terrible conflagration, getting closer every moment. Moose, deer and caribou stood trembling at the river’s edge, or struck boldly out into the stream. The boys turned north and followed the river for a mile before they discovered the object they sought. It was daylight now, though the smoke made it difficult to see far. Yet the light, graceful Peterboro canoe, loaded with supplies, did not miss their searching eyes. As they pushed it into the river and climbed in, Dick Kent gave voice to a fervent exclamation.

“We made it, Sandy!” he exulted, as he dipped his paddle once more into the bosom of the Big Smokey.

Sandy was about to share Dick’s rejoicing, when the movements of a huge brown bear, which had splashed into the water behind them, attracted his attention. The bear was swimming straight for the canoe.

“Shove out quick!” cried Sandy suddenly, but too late.

The brown bear, blinded by smoke, and thinking the canoe some log to cling to, clawed at the rim of the frail craft and pulled down. The canoe went over, spilling its contents into the river, while the bear, finding the craft unstable, swam on out into the river.

The plunge into the river revived both Dick and Sandy. Gasping, they came up for air, only to breathe the choking smoke and gases of the burning forest. They knew that the canoe was upside down and that their packs were in the bottom of the river. The bear was nowhere to be seen.

“Are you all right, Sandy?” called Dick, hoarsely.

“You bet,” Sandy replied, a bit faintly.

Among the burning brands sizzling in the water, and the flying sparks, they struggled with the canoe. In a few minutes they had righted it, though it was half full of water. The paddles, they could see, had gone with the packs.

“Look for a paddle!” shouted Dick. “They must be floating around somewhere.”

“There! I see one,” Sandy dived off as he spoke, and swam back quickly with a paddle in one hand.

But look as they did they could not locate the other paddle.

“We can’t look any longer. We’ll have to change off with one paddle,” Dick called a little later.

Dick paddling, they started on. The heat still was stifling, but they felt that the air was growing cooler. The wind seemed in their faces, which would tend to bear the fire back along the river. Wild animals of all kinds still could be seen in the water, wallowing along the shore or swimming the stream. But they had no more dangerous encounters with the frightened beasts.

Two hours of paddling, shifting the paddle back and forth between them as soon as one grew tired, and they came to a comparatively clear stretch of water. Here the fire was deeper in the forest, and had not eaten out to the bank yet. In greedy gasps, Dick and Sandy drew in the gusts of cool, pure air that were wafted over them.

“Look back, Sandy,” Dick called.

The whole sky was a mass of red flames behind them, and an ocean of smoke was rolling ceaselessly upward.

“Mackenzie’s Landing can’t be much further,” Sandy said when they had looked their last upon the great fire.

“No, we ought to make it by night. We’ll have to make it or camp without grub or blankets. I prefer going on,” Dick stated.

“So do I,” Sandy rejoined.

Some distance further on, as they rounded a huge bend in the stream, they could not suppress a cheer. In the distance they could see the shoulder of a high, barren bluff which was the ten-mile landmark on the trip to Mackenzie’s Landing.

It was late in the afternoon when in the distance they at last viewed the stockade and roofs of Malcolm Mackenzie’s trading post. Blackened and disheveled, nearly exhausted, they guided their canoe to the pier, where three half-breeds were watching them curiously. The half-breeds helped them secure their canoe, and listened without comment to some of their story of the eventful journey.

“Malcolm Mackenzie, he sick,” one of the half-breeds told them. “No can go. Him burned bad when fight with fire.”

“Did you hear that?” Dick turned to Sandy.

“Yes—just our luck. Now what?” Sandy returned, a little disheartened, as the half-breeds led the way into the stockade.

“We can talk to Mr. Mackenzie, can’t we?” Dick asked one of the men, as they entered the post.

“Yah, I guess.”

Presently, they were ushered into a room smelling of liniment and arnica. On a bunk lay Malcolm Mackenzie, his head and one arm swathed in bandages. Evidently he was suffering considerably from serious burns. He turned his head as the boys came in.

“Bear Henderson has captured Fort Good Faith,” Dick blurted out. “My friend’s uncle has been imprisoned. Mr. MacLean sent us to you. He said you would lead us to the mounted police post at Fort Dunwoody.”

“I’ve feared this,” Malcolm Mackenzie’s eyes narrowed, “but you see how it is with me, boys. I can’t travel. Got some bad burns while fighting that forest fire. But I can send an Indian who knows the trail.” He turned to one of the half-breeds, who was standing behind Dick and Sandy. “Send in Little John Toma,” he commanded.

A little later Dick and Sandy saw a young Indian enter. He was handsome in a dark, inscrutable way, and though not very tall, was powerfully built. He stood respectfully at attention, seeming more intelligent than many of his kind.

“Toma,” Mackenzie spoke, “I want you to lead these young men to Fort Dunwoody as fast as you can. Travel light. You ought to make it in four days if everything goes right.” He turned back to the boys. “Did MacLean say anything about a cache of grub along the way?”

“Yes,” Dick reached into his pocket and drew out the map the trader had drawn indicating the position of the cache of food on the trail to Fort Dunwoody.

Mackenzie took the map, glanced at it and handed it to Toma. “It’s on Limping Dog Creek,” said Mackenzie, “just where that gorge you follow intersects the stream. You know the place.” To Dick and Sandy: “Introduce yourselves and get acquainted. Toma will get everything ready for you to go on. Take a rest as soon as you eat. Oh, Calico, Calico!” he called to some one.

As the boys and Little John Toma passed out, a large, waddling Indian woman came in. They heard Mackenzie instructing her to get a meal ready for his visitors before the bear-skin curtain dropped behind them and they found themselves in the spacious living room of the post.

Dick and Sandy awkwardly introduced themselves to the young Indian who was to be their guide.

“Glad to meet,” Toma surprised them by saying, his teeth flashing whitely in a smile.

Dick and Sandy quickly felt that they were going to like Toma.

“I’ll bet he’s the son of a chief,” Sandy said to Dick, when the young Indian had gone, and they were busy at the wash bench, scrubbing off some of the smoke and ashes of the forest fire.

The boys ate heartily of the food the Indian woman placed before them on the rough board table. As soon as they were through they were shown to a comfortable bunk behind moose-hide curtains. Scarcely had they lay down when they fell into sound slumber.

It seemed to Dick Kent that he had only been asleep a moment when a hand, gently shaking his shoulder, awakened him. He looked up into the smiling face of Toma, the young guide.

“Time to go,” said Toma. “You wake up other fella.”

As the curtains fell, and Toma disappeared, Dick turned and shook Sandy.

An hour later they bid goodbye to Malcolm Mackenzie and wished him speedy recovery from his burns. The canoe lay ready packed with provisions at the landing when they arrived there. Toma was starting to push off. Dick and Sandy hopped in, and Toma sprang lightly into the bow.

“Now for Fort Dunwoody,” Dick breathed a sigh of relief.

“If I wasn’t an optimist,” Sandy added, “I’d say we aren’t there yet by a long shot.”

Toma silently sculled the craft into the center of the river, and they were once more floating down the stream. The boys marveled at Toma’s deftness with the paddle, though they themselves were experts. The young Indian seemed able to make the canoe fly with his quick, powerful strokes.

A half hour of paddling and the roofs of Mackenzie’s Landing had disappeared in the haze of the morning, and once more the walls of the silent spruce forest closed in on either side of them.

Late that night they camped some twenty miles from the trading post, in a little clearing at the river’s edge. Toma mentioned “bear sign,” and so they hung up their flour and bacon on a tree bough for fear a bear might get it.

Sandy kept first watch while Toma and Dick slept.

It was a dark night. Only the stars were out, and when the fire died down Sandy scarcely could see a dozen paces from the camp. Occasionally he glanced into the shadows, listening to the mysterious sounds of the forest, and starting up at each crackle of a twig or rustle of undergrowth.

Sandy wondered if the men on their trail had been thrown off, and imagined what he would do if they would suddenly attack. As he thought of the dangers threatening Dick and him, his hand tightened on his rifle.

It was nearly eleven o’clock, the time he was to call Toma for the second watch, when Sandy became conscious of some sinister presence. Before he really saw or heard anything, he shivered and looked fearfully about into the gloom of the forest.

A scratching and grunting noise attracted his attention to the tree where they had hung up the flour and bacon. It seemed he could hear the shuffle of heavy feet and the wheeze of giant lungs as he listened intently.

“I won’t call Dick and Toma,” thought Sandy. “It may be only my imagination. I’ll go see what it is.”

Heart beating wildly, Sandy commenced to creep toward the point he had heard the noises. He could see nothing in the dark, yet as he strained his eyes it seemed to him that one portion of the blackness was blacker than the rest.

Suddenly, he heard the crashing of a splintered tree bough. A low, vibrating growl followed, and Sandy dropped upon his stomach. There came a slapping, thumping sound, then an angry growling and tussling. The dark blot lurched downward. Sandy raised his rifle and blazed away at the shape. A rambling roar rose in the night.

“Dick! Toma!” cried Sandy, as he turned about and fled, hearing behind him the rush of a heavy body pursuing him.

Toma and Dick were already on their feet when Sandy rushed toward them out of the gloom.

“It’s a bear, a giant bear!” cried Sandy. “Run! I’ve wounded him!”

The angry roar behind Sandy was all that was needed for Dick and Toma to take to their heels with alacrity.

“Get up tree, get up tree!” Toma called to them.

Faster than they ever before had climbed a tree, Dick and Sandy shinned up one in the dark. The bear charged beneath them in the underbrush. The huge beast wheeled on finding his prey had taken to the trees and circled the trunk which supported Dick and Sandy. Toma’s calm voice came through the gloom from a near-by tree:

“Him grizzly all right,” Toma told them. “You stay in tree. I get down to rifle pretty quick.”

“You surely must have wounded the bear,” Dick whispered to Sandy. “I’ve heard they won’t attack unless they’re wounded.”

“I don’t know what I did,” Sandy came back breathlessly. “I just blazed away and ran. Believe me, I don’t want to go down there again while that monster is wandering around looking for me. He’d chew us up in about two bites and a half.”

Dick knew that Sandy’s caution bump was working again, and he smiled in the dark. He did not intend to let Toma go down after the bear alone. Yet he believed the young Indian would protest if he revealed his intentions.

“Got your rifle?” Dick called to Toma, not intimating his resolution.

“I got gun,” Toma called back.

“I wish I’d thought to bring mine along,” Dick muttered, “but then it takes an Indian to shin up a tree with a heavy rifle in his hand I suppose. Anyway I have my knife.”

“Don’t go down, Dick,” whispered Sandy, as the bear crashed about in the brush below them.

“Nonsense, Sandy, I’ve got as much chance as Toma. We can’t let that bear wreck our camp. That’s what he’s up to.”

“Then I’ll go down too,” Sandy stubbornly decided.

They could not hear Toma’s movements with the bear making so much noise, but Dick suspected the guide already had slipped down from his tree and was stalking the wounded grizzly, perhaps close enough to get in a fatal shot.

Presently, they could hear the bear make off into the gloom toward the campfire. When Dick and Sandy dropped down out of the tree, the bear seemed to be on the other side of the campfire, clawing and mouthing over their dunnage.

“You better stay up in the tree,” Dick said.

“Not on your tintype,” Sandy snapped. “If you go, I go.”

“Well, then, we’ve got to get our guns,” said Dick. “Mine’s right where I got out of my blankets.”

“Seems to me I dropped mine just before I started climbing the tree,” Sandy was feeling around in the dark. “Yes, here it is,” was his triumphant call.

Toma seemingly had vanished. Since his last words, they had heard nothing more from him. Dick judged the guide was stalking the bear from some other direction. At any moment he expected to hear the report of the Indian’s rifle, and see the flash of it in the gloom.

Sandy alone armed, save for Dick’s hunting knife, the boys began a stealthy advance toward the camp where they could hear the bear slashing and groveling about, evidently in some pain, for they were sure now that Sandy’s shot had taken effect.

The coals of the campfire shed a faint glow. As the boys drew nearer, on hands and knees, they could see the bulk of the grizzly outlined. He seemed a mammoth of his kind, and indeed was a fearful beast to meet in the forest.

“I’ll bet he’s wrecked our camp outfit,” Dick muttered. “Careful, Sandy, don’t get too close. Let’s wait till he gets away from the fire a little further, then I can get my rifle.”

Scarcely were the words out of his mouth, when Toma’s rifle crashed in the dark on the left, and Dick and Sandy saw a streak of flame, and heard the roar of the bear, plainly hard hit. The grizzly rose upon his hind legs and turned toward the spot he believed his enemy was hidden. Then Sandy leveled his rifle and fired, drawing bead as best he could just under the huge beast’s forelegs.

At this second shot, the bear seemed undecided just which way to charge. He stopped, his head turning from side to side, growling horribly, not hit hard enough to fall.

Toma shot again, then Sandy. The grizzly dropped to all fours, and began clawing at his breast. Toma shot again from another position. The bear rose up again with a roar of pain and rage and started for Dick and Sandy, who turned to flee. Then the big beast, without any apparent reason whatsoever, wheeled about and made off into the forest in the opposite direction.

“He’s hit hard!” cried Dick, hurrying forward.

Toma came out of the gloom like a shadow. “He go off die,” said the Indian. “Be careful he no come back. I go see where he go.” Toma disappeared after cautioning the boys to stay where they were until he returned.

The minutes passed slowly while Dick and Sandy waited the return of Toma. Finally Dick grew impatient and was about to go on to the campfire for his rifle, when Toma appeared again, as if he had risen out of the earth.

“She all right,” Toma reported. “Him keep going. Him die somewhere.”

Relieved, Dick and Sandy approached the campfire. Toma already was heaping on more wood. As the flames leaped upward, and the light chased away some of the surrounding shadows, Dick and Sandy breathed freely once more. However, sleep was far from them after the narrow escape from being clawed by the wounded bear. They ventured about to see what damage the big grizzly had effected.

They found Dick’s and Toma’s blankets torn to shreds. The coffee pot was crushed flat and the sugar sack broken open, its contents scattered.

Dick hurried to the bough where they had hung the flour and bacon. “Hey, look here—Sandy, Toma!”

They joined Dick. The bough had been broken down; the flour was scattered about as if the sack had exploded; the bacon was gone. Searching about in the gloom they found hunks of chewed rind among the pine needles. Only one small chunk of bacon was left, and this they preserved in one of their knapsacks.

“Him no hungry,” Toma grunted, “him play. Him chew bacon up, spit him out.”

“Well, he did us plenty of damage all right,” Dick said ruefully.

“Looks like we were in for a hungry spell,” Sandy added, resignedly.

“Humph! We have bear steak for breakfast,” Toma exclaimed significantly.

“That’s what I call justice,” Dick laughed.

All three went back to the campfire then and squatted around the crackling flames. The excitement had loosened Toma’s tongue, it seemed, and he began telling stories of other bears he had known, and whom his father had known. Dick and Sandy listened with rapt interest to the simple tales of the young Indian.

Almost the balance of the night passed with Toma’s droning voice relating thrilling adventures among the tribes in the far north. Toward dawn Sandy turned in for an hour or so of rest, but Toma and Dick remained awake.

The sun had scarcely topped the distant forest skyline when Dick and Toma awakened Sandy, and all three gathered up what they could of the wreckage remaining of their provisions.

“Now we gettum bear steak,” Toma said.

In single file they followed the gliding figure of the guide, as he set off on the trail of the grizzly.

“See that track!” Dick exclaimed presently, pointing with his rifle at a spot of soft leaf-mold.

“It’s a bear track, all right,” conceded Sandy, “—and look! There’s blood on that bush.”

“We sure hit him a lot of times—I mean you and Toma,” Dick corrected. He felt disappointed that he had not actually been in on the killing of the bear, since he had had no rifle. But the thrill of trailing a wounded grizzly made him forget.

Toma seemed to follow the trail as if by instinct. Where Sandy and Dick could see no sign whatever, Toma went unerringly forward, always with that gliding, noiseless, pigeon-toed pace, that seemed tireless, though it was kept up with an ease and speed that made Dick and Sandy run.

For a half mile they wound among the trees, beginning to come upon spots where the bear had dropped down to rest. At these points the blood was drying in large clots. Finally, approaching a fallen tree, they came upon the grizzly, stone dead!

Dick and Sandy were about to cheer, yet the actual sight of the bear made them a little sad. The great monarch of the forest never again would proudly tread the forest aisles. Yet the boys felt a certain satisfaction in having won in a battle with such a powerful foe.

Toma immediately began skinning one haunch of the great bear. “Him old and tough,” grunted Toma, “but we cook um long time. That make um tender.”

Dick laughed. “The old boy will make stringy eating.”

“I wish we could take his hide,” Sandy sighed.

“It sure would knock the eyes out of the fellows back home,” Dick said.

“No time to skin,” Toma interrupted. “Hide too heavy carry. Mister Mackenzie say mus’ travel light.”

“Yes, it’s impossible for us to have the old fellow’s hide, but that’s no reason why we can’t have his scalp.” Suiting his action to his words, Dick drew his sharp hunting knife and stooped over the head of the wilderness king. With Sandy’s help they took the old grizzly’s scalp, ears and all, as a trophy.

“It’s yours and Toma’s,” Dick smiled, when they had finished. He held the scalp out to Sandy.

Sandy’s eyes lightened. “Let Toma have the scalp. I’ll take the claws.”

Dick’s hunting knife once more came into play. The bear’s claws measured as long as five inches, and Sandy was exceedingly proud as he at last pushed them into a side pocket of his leather coat.

Toma was waiting when they had finished. The guide had his knapsack filled with the tenderest steaks he could cut.

At a jog trot they set out for the river and their campsite, and soon they were grilling bear steaks over the fire.

When they broke camp they had provisions for two scanty meals, including some of the bear steaks which they saved from breakfast. The canoe packed, they once more set out down the river.

“We make um grub cache tomorrow,” Toma encouraged them. “Get um plenty grub there.”

Late that afternoon, without mishap they reached a point where Toma said they must abandon their canoe and go on by land, since the river swung off in another direction. They carefully hid their canoe in some underbrush along with two others left by a party that had recently gone on ahead of them, and started out on foot.

Dick and Sandy were very tired long before Toma showed signs of slowing up, but they gamely stuck to the pace without complaint.

They were angling down the side of a long ravine, toward a spring, which Toma muttered would be a good place to camp, when of a sudden, the guide stopped dead.

“Hide quick!” Toma whispered, with a significant gesture of one sinewy brown hand.

Dick and Sandy crouched.

“Think um bad fellas ahead,” Toma explained. “You stay here. I go ahead; look um over.”

Dick and Sandy were glad to sink down and rest their weary legs. But the warning in Toma’s voice did not escape them. They were keyed to sharp watchfulness as Toma dropped to his hands and knees and disappeared silently among the bushes.

Dick and Sandy had crouched in hiding for upwards of a half hour before Toma returned. He came as he had gone, silently, like a ghost almost, so stealthy were his movements, so clever his woodcraft.

“What did you find?” whispered Dick, anxiously.

“Two, t’ree—five bad fellas,” Toma counted on his fingers. “One Pierre Govereau lead um. They got um spring for tonight. We go round um. Got to. Them fellas friends Bear Henderson. They watch um trail for police. ’Fraid police go to Fort Good Faith.”

Dick and Sandy exchanged glances. Their weariness was temporarily forgotten in this new peril. They began to understand the far-reaching power of the man who had captured Sandy’s uncle and had taken possession of Fort Good Faith on the edge of the northern wilderness.

“We go,” Toma urged, his only excitement revealed by the swift movements of his eyes as they roved this way and that.

Silently the Indian guide melted into the underbrush, Dick immediately behind him, Sandy in the rear. For nearly two hundred yards they went onward, almost at snail’s pace. It was twilight now. Long shadows of tree and bush stretched everywhere.

At last Toma signaled for them to stop. Dick and Sandy dropped flat. Not more than three hundred feet ahead a campfire twinkled through the trees, and, motionless, between them and the fire, stood a silent figure, with rifle on his shoulder. It was a guard. Dick divined the figure, so like the tree trunk against which it stood, had even escaped the sharp eyes of Toma at first.

Four men were sitting around the campfire, and they could hear the mutter of gruff voices. Once or twice a louder than usual exclamation in French arose above the other sounds. It seemed the leader of the party was haranguing his men, or disciplining one of them.

Suddenly Dick started and clutched Sandy’s arm.

“That guard!” he exclaimed under his breath. “It’s the scar faced Indian!”

Sandy paled a little. It seemed almost impossible that the Indian could have gotten ahead of them. His appearance was as mysterious as had been their glimpses of him at Fort du Lac and along the Big Smokey river.

Toma was motioning for them to bear to the right. They crawled off after the guide in that direction.

Neither Dick nor Sandy knew which of them made too much noise, or revealed some part of his body, yet they had crawled no further than a dozen paces when the guard moved, turned and looked straight at them. Toma, watching over his shoulder, fell flat, Dick and Sandy following his example. Had they been seen?

The guard, his rifle ready for use, started slowly toward them. Tensely, Dick and Sandy watched Toma for a sign as to what course to take. They saw Toma slowly turn to his side. The guide swung his rifle to his shoulder as he lay.

Just as the guard cried out, Toma fired.

The scar faced Indian whirled, dropped his rifle and fell to his knees, clutching at one shoulder. Dick and Sandy got a glimpse of the men at the fire leaping up and snatching their rifles, as they took to their heels after Toma.

For several minutes they sprinted in the wake of the young Indian’s flying heels, hearing behind the crash of their pursuers through the underbrush, and their cries to one another.

Then, before a hollow tree, half covered by the dead branches of a lightning-blasted pine tree, Toma halted suddenly. He motioned to them to follow and disappeared into the half-obscured hole in the tree. Dick and Sandy slipped in after him. There was barely enough room in the tree for three to stand upright, but they managed to crowd in, while Toma quickly arranged the dead branches over the hole until their hiding place was entirely covered from view.

The distant shouts grew louder, as the men beat the brush looking for them. Two came closer and closer, until at last they stopped before the hollow tree, so near that the three hidden feared their heavy breathing might be heard.

“I thought I saw ’em go this way,” one said, in a harsh voice.

“Mebbe so,” the other, apparently an Indian, answered. “It look like they jump in air an’ fly away.”

“Pierre sure will give us the devil if we let ’em get away,” said the first. “Can’t blame him. Henderson will skin him alive if these trails aren’t kept clean of Hudson’s Bay men and mounties.”

“I see bush move over d’er!” the Indian ejaculated.

The two men moved off in another direction, and the boys in the hollow tree breathed easier.

“No go yet,” Toma advised. “Wait till all quiet.”

The minutes passed slowly while they waited in their cramped position. The shouts of the searchers grew fainter as they apparently abandoned the chase. Presently all was still. Toma peeped out through the branches covering the entrance to the hollow tree. After looking carefully about, the guide pushed back the branches and stepped out. Dick and Sandy followed. They were learning lessons in woodcraft every hour from this child of the forest.

“I think we ought to go back to the camp, steal up close and see if we can’t learn something of your Uncle Walter, Sandy,” Dick announced.

“Is it worth the risk?” Sandy came back. “Can’t we do better by hurrying on to Fort Dunwoody?”

“It’s true we can’t do much without the aid of the mounted police,” Dick studied. “Yet I’d like to know, if it’s possible, just what has been done with your uncle—how they’re treating him.”

Dick asked Toma what he thought of trying to learn something by eavesdropping. “If you think um best thing do,” Toma replied. “That scar face got best ears of all. He wounded now. Not much good; what say I try?”

“No, you’ve done plenty of this already, Toma,” Dick was firm. “I’ll go this time. You wait here where you can cover me with your guns if I am detected.”

Toma, assured Dick was determined to go, grunted his assent, and a moment later Dick disappeared into the bushes on his perilous venture. Sandy and Toma crawled back to within gunshot of the camp, where the men had gathered again, gesticulating to one another, plainly undecided what to do.

When Dick left his chum and the guide he realized the danger he faced. Yet he knew any information he might gain would be more than valuable to the police when once he got in touch with them. Govereau’s men were talking so loudly that he had little trouble in overhearing them. The leader’s heavy voice broke out in French, which disappointed Dick, for he knew very little French. Then Govereau changed to broken English, evidently for the benefit of a member of his band who did not understand French.

“We go on queeck, ketch them,” Govereau was saying. “Sure t’ing them fella are zee ver’ ones come from Fort du Lac. That devil Many-Scar an’ them others—they let zem get through Little Moose, I bat. We go.”