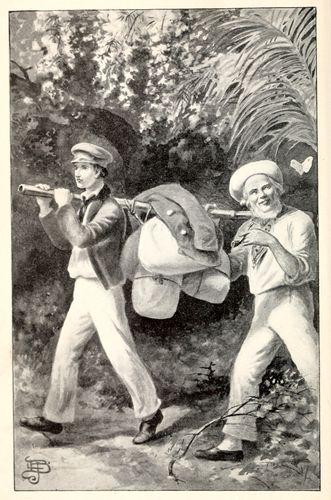

Walter and Bill tramping across the Isthmus.—Page 132.

Title: The Young Vigilantes: A Story of California Life in the Fifties

Author: Samuel Adams Drake

Illustrator: L. J. Bridgman

Release date: December 8, 2015 [eBook #50651]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard J. Shiffer and the Distributed

Proofreading volunteers at http://www.pgdp.net for Project

Gutenberg. (This file was produced from images generously

made available by The Internet Archive.)

Transcriber's Note

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including obsolete and variant spellings and other inconsistencies. Text that has been changed is noted at the end of this ebook.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE YOUNG VIGILANTES

A STORY OF CALIFORNIA

LIFE IN THE FIFTIES

BY

SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE

Author of "Watch Fires of '76," "On Plymouth Rock," "Decisive

Events in American History Series," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY L. J. BRIDGMAN

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD

1904

Published August, 1904

Copyright, 1904, by Lee and Shepard

All rights reserved

The Young Vigilantes

Norwood Press

Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Narrow Escape | 9 |

| II. | Walter Tells His Story | 18 |

| III. | And Charley Tells His | 30 |

| IV. | What Happened on Board the "Argonaut" | 37 |

| V. | One Way of Going to California | 45 |

| VI. | A Black Sheep in the Fold | 66 |

| VII. | The Flight | 82 |

| VIII. | Outward Bound | 100 |

| IX. | Across Nicaragua | 117 |

| X. | The Luck of Yankee Jim | 141 |

| XI. | Seeing the Sights in 'Frisco | 154 |

| XII. | An Unexpected Meeting | 165 |

| XIII. | In Which a Man Breaks into His Own Store, and Steals His Own Safe | 182 |

| XIV. | Charley and Walter go a-Gunning | 203 |

| XV. | The Young Vigilantes | 215 |

| XVI. | Ramon Finds His Match | 231 |

| XVII. | A Sharp Rise in Lumber | 241 |

| XVIII. | A Corner in Lumber | 250 |

| XIX. | Hearts of Gold | 262 |

| XX. | Bright, Seabury & Company | 274 |

| Page | |

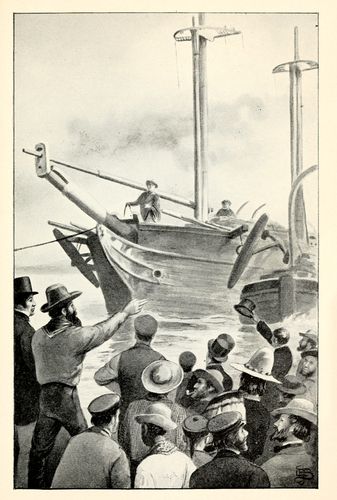

| Walter and Bill tramping across the Isthmus (Frontispiece.) | 132 |

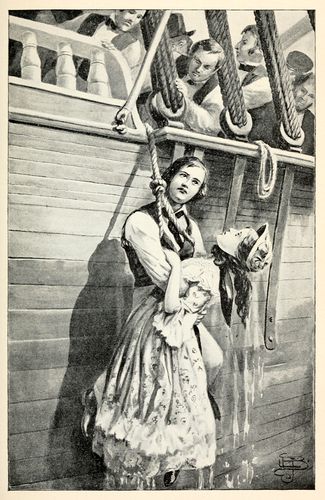

| Walter rescuing Dora Bright | 42 |

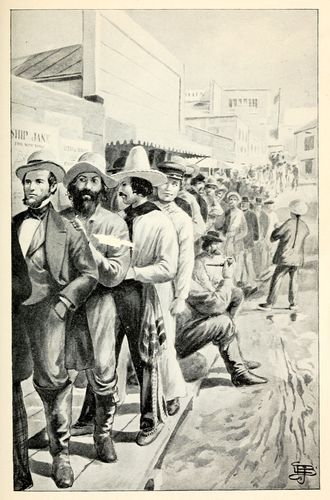

| Waiting for the opening of the mail | 160 |

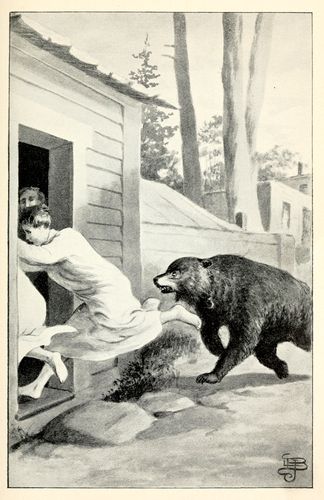

| The hunters hunted by a grizzly bear | 208 |

| Ramon made to give up his stealings | 236 |

| Arrival of the Southern Cross at Sacramento | 254 |

THE YOUNG VIGILANTES

From the Morning Post-Horn:

"As passenger train Number Four was rounding a curve at full speed, ten miles out of this city, on the morning of October 4, and at a point where a deep cut shut out the view ahead, the engineer saw some one, man or boy, he could not well make out which, running down the track toward the train, frantically swinging both arms and waving his cap in the air as if to attract attention. The engine-man instantly shut off steam, whistled for brakes, and quickly brought the train to a standstill.

"The engine-man put his head out of the[Pg 10] cab window. The conductor jumped off, followed by fifty frightened passengers, all talking and gesticulating at once; while the person who had just given the warning signal slackened his breakneck pace, somewhat, upon seeing that he had succeeded in stopping the train.

"'What's the matter?' shouted the impatient engine-man when this person had come within hearing.

"'What do you stop us for?' called out the little conductor sharply, in his turn, at the same time anxiously consulting the face of the watch he held in his hand.

"To both questions the young man seemed too much out of breath to reply, offhand; but turning and pointing in the direction whence he came, he shook his head warningly, threw himself down on the roadbed, as limp as a rag, and began fanning himself with his cap. After getting his breath a little, he made out to say, 'Bridge afire—quarter mile back. Tried put it out—couldn't. Heard[Pg 11] train coming—afraid be too late. Couldn't run another step.'

"'Get aboard,' said the conductor to him. 'Jake,' to the grinning engine-man, 'we'll run down and take a look at it. Get out your flag!' to a brakeman. 'Like as not Thirteen'll be along before we can make Brenton switch. All aboard!' The delayed train then moved on.

"As it neared the burning bridge it was clear to every one that the young man's warning had prevented a disastrous wreck, probably much loss of life, because the bridge could not be seen until the train was close upon it. All hands immediately set to work with pails extinguishing the flames, which was finally done after a hard fight. To risk a heavy train upon the half-burned stringers was, however, out of the question. Leaving a man to see that the fire did not break out again, the train was run back to the next station, there to await further orders. We were unable to learn the name of the young man to[Pg 12] whose presence of mind the passengers on Number Four owed their escape from a serious, perhaps fatal disaster. But we are informed that a collection was taken up for him on the train, which he, however, refused to accept, stoutly insisting that he had only done what it was his duty to do under the circumstances."

Thus far, the Morning Post-Horn. We now take up the narrative where the enterprising journal left off.

While the delayed train was being held for orders, the young man whose ready wit had averted a calamity stood on the platform with his hands in his trousers pockets, apparently an unconcerned spectator of what was going on around him. The little pug-nosed conductor stepped up to him.

"I say, young feller, what may I call your name?"

"Seabury."

"Zebra, Zebra," repeated the conductor,[Pg 13] in a puzzled tone, "then I s'pose your ancestors came over in the Ark?"

"I didn't say Zebra; I said Seabury plain enough," snapped back the young man, getting red in the face at seeing the broad grins on the faces around him.

"Don't fire up so. Got any first name?"

"Walter."

"Walter Seabury," the conductor repeated slowly, while scratching it down. "Got to report this job, you know. Say, where you goin'?"

"I'm walkin' to Boston."

"Shanks' mare, hey. No, you ain't. Get aboard and save your muscle. You own this train to-day, and everything in it. Lively now." The conductor then waved his hand, and the train started on. At the bridge a transfer was effected to a second train, and this one again was soon reeling off the miles toward Boston, as if to make up for lost time.

Being left to himself, young Seabury,[Pg 14] whom we may as well hereafter call by his Christian name of Walter, could think of nothing else than his wonderful luck. Instead of having a long, weary tramp before him, here he was, riding in a railroad train, and without its costing him a cent. This was a saving of both time and money.

Pretty soon the friendly conductor came down the aisle to where Walter sat, looking out of the car window. After giving him a sharp look, the conductor made up his mind that here was no vagabond tramp. "It's none of my business, but all the same I'd like to know what you're walkin' to Boston for, young feller?" he asked.

"Going to look for work."

"What's your job?"

"I'm a rigger." And his hands, tarry and cracked, bore out his story perfectly.

"Ever in Boston?"

"Never."

"Know anybody there?"

"Nobody."

"Got any of this—you know?" slapping his pocket.

At this question Walter flushed up. He drew himself up stiffly, smiled a pitying smile, and said nothing. His manner conveyed the idea that he really didn't know exactly how much he was worth.

"That's first-rate," the conductor went on. "Now, look here. You'll get lost in Boston. I'll tell you what. When we get in, I'll show you how to go to get down among the riggers' lofts. You're a rigger, you say?" Walter nodded. "They're all in a bunch, down at the North End, riggers, sailmakers, pump- and block-makers, and all the rest. Full of work, too, I guess, all on account of this Californy business. Everybody's goin' crazy over it. You will be, too, in a week."

By this time, the train was rumbling over the long waste of salt-marsh stretching out between the mainland and the dome-capped city, and in five minutes more it drew up with a jerk in the station, with the locomotive puffing[Pg 16] out steam like a tired racehorse after a hard push at the finish.

The conductor was as good as his word. He told Walter to go straight up Tremont Street until he came to Hanover, then straight down Hanover to the water, and then to follow his nose. "Oh, you can't miss it," was the cheerful, parting assurance. "Smell it a mile." But going straight up this street, and straight down that, was a direction not so easy to follow, as Walter soon found. The crowds bewildered him, and in trying to get out of everybody's way, he got in everybody's way, and was jostled, shoved about, and stared at, as he slowly made his way through the throng, until his roving eyes caught sight of the tall masts and fluttering pennants, where the long street suddenly came to an end. Walter put down his bundle, took off his cap, and wiped the perspiration from his forehead. Whichever way he looked, the wharves were crowded with ships, the ships with workmen, and the street with loaded[Pg 17] trucks and wagons. Casting an eye upward he could see riggers at work among the maze of ropes and spars, like so many spiders weaving their webs. Here, at least, he could feel at home.

Walter's first want was to find a boarding house suited to his means. Turning into a side street, walled in by a row of two-story brick houses, all as like as peas in a pod, he found that the difficulty would be to pick and choose, as all showed the same little tin sign announcing "Board and Lodging, by the Day or Week," tacked upon the door. After walking irresolutely up and down the street two or three times, he finally mustered up courage to give a timid pull at the bell of one of them. The door opened so suddenly that Walter fell back a step. He began stammering out something, but before he could finish, the untidy-looking girl sang out at the top of her voice: "Miss Hashall, Miss Hashall, there's somebody wants to see you!" She[Pg 19] then bolted off through the back door singing "I want to be an angel," in a voice that set Walter's teeth on an edge. To make a long story short, Walter soon struck a bargain with the landlady,—a fat, pudgy person in a greasy black poplin, wearing a false front, false teeth, and false stones in her breastpin. True, Walter silently resented her demanding a week's board in advance, it seemed so like a reflection upon his honesty, but was easily mollified by the motherly interest she seemed to take in him—or his cash.

Bright and early the next morning Walter sallied out in search of work. His landlady had told him to apply at the first loft he came to. "Why, you can't make no mistake," the woman declared. "They're all drove to death, and hands is scurse as hens' teeth, all on account of this Kalerforny fever what carries so many of 'em off. Don't I wish I was a man! I'd jest like to dig gold enough to buy me a house on Beacon Street and ride in my kerridge. You just go and spunk right[Pg 20] up to 'em, like I do. That's the way to get along in this world, my son."

Walter's landlady had told him truly. The demand for vessels for the California trade was so urgent that even worm-eaten old whaleships were being overhauled and refitted with all haste, and as Walter walked along he noticed that about every craft he saw showed the same sign in her rigging, "For San Francisco with dispatch." "Well, I'll be hanged if there ain't the old Argonaut that father was mate of!" Walter exclaimed quite aloud, clearly taken by surprise at seeing an old acquaintance quite unexpectedly in a strange place, and quickly recognizing her, in spite of a new coat of paint alow and aloft.

The riggers were busy setting up the standing rigging, reeving new halliards, and giving the old barky a general overhauling. Walter climbed on board and began a critical survey of the ship's rigging, high and low.

"What yer lookin' at, greeny?" one of[Pg 21] the riggers asked him, at seeing Walter's eyes fixed on some object aloft.

"I'm looking at that Irish pennant[1] on that stay up there," was the quick reply. This caused a broad smile to spread over the faces of the workmen.

[1] A strand of marline carelessly left flying by a rigger.

"You a rigger?"

"I've helped rig this ship."

"Want a job?"

"Yes."

"Well, here," tossing Walter a marline-spike, "let's see you make this splice." It was neatly and quickly done. "I'll give you ten dollars a week." Walter held out for twelve, and after some demurring on the part of the boss, a bargain was struck. Walter's overalls were rolled up in a paper, under his arm, so that he was immediately ready to begin work.

Being, as it were, in the midst of the stream of visitors to the ship, hearing no end of talk about the wonderful fortunes to be[Pg 22] made in the Land of Gold, Walter did not wholly escape the prevailing frenzy, for such it was. But knowing that he had not the means of paying for his passage, Walter resolutely kept at work, and let the troubled stream pass by. There was still another obstacle. He would have to leave behind him a widowed aunt, whose means of support were strictly limited to her actual wants. He had at once written to her of his good fortune in obtaining work, though the receipt of that same letter had proved a great shock to the "poor lone creetur," as she described herself, because she had freely given out among her neighbors that a boy who would run away from such a good home as Walter had, would surely come to no good end.

Walter had struck up a rather sudden friendship with a young fellow workman of about his own age, named Charley Wormwood. On account of his name he was nicknamed "Bitters." Charley was a happy-go-lucky sort of chap, valuing the world chiefly[Pg 23] for the amusement it afforded, and finding that amusement in about everything and everybody. Though mercilessly chaffed by the older hands, Charley took it all so good-naturedly that he made himself a general favorite. The two young men soon arranged to room together, and had come to be sworn friends.

One pleasant evening, as the two sat in their room, with chairs tilted back against the wall, the following conversation was begun by Charley: "I say, Walt, we've been together here two months now, to a dot, and never a word have you said about your folks. Mind now, I don't want to pry into your secrets, but I'd like to know who you are, if it's all the same to you. Have you killed a man, or broke a bank, or set a fire, or what? Folks think it funny, when I have to tell them I don't know anything about you, except by guess, and you know that's a mighty poor course to steer by. Pooh! you're as close as an oyster!"

Walter colored to his temples. For a short space he sat eyeing Charley without speaking. Then he spoke up with an evident effort at self-control, as if the question, so suddenly put, had awakened painful memories. "There's no mystery about it," he said. "You want to hear the story? So be it, then. I'll tell mine if you'll tell yours.

"I b'long to an old whaling port down on the Cape. I was left an orphan when I was a little shaver, knee-high to a toadstool. Uncle Dick, he took me home. Aunt Marthy didn't like it, I guess. All she said was, 'Massy me! another mouth to feed?' 'Pooh, pooh, Marthy,' uncle laughed, 'where there's enough for two, there's enough for three.' She shut up, but she never liked me one mite."

"An orphan?" interjected Charley. "No father nor mother?"

"I'll tell you about it. You see, my father went out mate on a whaling voyage in the Pacific, in this very same old Argonaut we've[Pg 25] been patchin' and pluggin' up. It may have been a year we got a letter telling he was dead. Boat he was in swamped, while fast to a whale—a big one. They picked up his hat. Sharks took him, I guess. Mother was poorly. She fell into a decline, they called it, and didn't live long. We had nothin' but father's wages. They was only a drop in the bucket. Then there was only me left."

"That was the time your uncle took you home?"

"Yes; Uncle Dick was a rigger by trade. He used to show me how to make all sorts of knots and splices evenings; and bimeby he got me a chance, when I was big enough, doin' odd jobs like, for a dollar a week, in the loft or on the ships. Aunt Marthy said a dollar a week didn't begin to pay for what I et. Guess she knew. Pretty soon, I got a raise to a dollar-half."

"But what made you quit? Didn't you like the work?"

"Liked it first-rate. Like it now. But I[Pg 26] couldn't stand Aunt Marthy's sour looks and sharp tongue. Nothing suited her. She was either as cold as ice, or as hot as fire coals. When she wasn't scolding, she was groaning. Said she couldn't see what some folks was born into this world just to slave for other folks for." A frown passed over Walter's face at the recollection.

"Nice woman that," observed the sententious Charley. "But how about the uncle?" he added. "Couldn't he make her hold her yawp?"

"Oh, no better man ever stood. He was like a father to me—bless him!" (Walter's voice grew a little shaky here.) "But he showed the white feather to Aunt Marthy. Whenever she went into one of her tantrums, he would take his pipe and clear out, leaving me to bear the brunt of it.

"A good while after mother died, father's sea-chest was brought home in the Argonaut. There was nothing in it but old clothes, this watch [showing it], and some torn and greasy[Pg 27] sea-charts, with the courses father had sailed pricked out on 'em. Those charts made me sort o' hanker to see the world, which I then saw men traveled with the aid of a roll of paper, and a little knowledge, as certainly, and as safely, as we do the streets of Boston. You better believe I studied over those charts some! Anyhow, I know my geography." And Walter's blue eyes lighted up with a look of triumph.

"Bully for you! Then that was what started you out on your travels, was it?"

"No: I had often thought of slipping away some dark night, but couldn't make up my mind to it. It did seem so kind o' mean after all Uncle Dick had done for me. But one day (one bad day for me, Charley) a man came running up to the loft, all out of breath, to tell me that Uncle Dick had fallen down the ship's hatchway, and that they were now bringing him home on a stretcher. I tell you I felt sick and faint when I saw him lying there lifeless. He never spoke again.

"Shortly after the funeral, upon going to the loft the foreman told me that work being slack they would have to lay off a lot of hands, me with the rest. Before I went to sleep that night I made up my mind to strike out for myself; for now that Uncle Dick was gone, I couldn't endure my life any longer. I set about packing up my duds without saying anything to my aunt, for I knew what a rumpus she would make over it, and if there's anything I hate it's a scene."

"Me too," Charley vigorously assented. "Rather take a lickin'."

"Well," Walter resumed, "I counted up my money first. There was just forty-nine dollars. Lucky number: it was the year '49 too. I put ten of it in an envelope directed to my aunt, and put it on the chimney-piece where she couldn't help seeing it when she came into my room. Then I took a piece of chalk and wrote on the table top: 'I'm going away to hunt for work. When I get some, I'll let you know. Please take care of my[Pg 29] chest. Look on the mantelpiece. Good-bye. From Walter.'

"Then, like a thief, I slipped out of the house by a back way, in my stocking feet, and never stopped running till I was 'way out of town. There I struck the railroad. I knew if I followed it it would take me to Boston. And it did. That's all."

There was silence for a minute or two, each of the lads being busy with his own thoughts. Apparently they were not pleasant thoughts. What a tantalizing thing memory sometimes is!

But it was not in the nature of things for either to remain long speechless. Walter first broke silence by reminding Charley of his promise. "Come now, you've wormed all that out of me about my folks, pay your debts. I should like to know what made you leave home. Did you run away, too?"

At this question, Charley's mouth puckered up queerly, and then quickly broke out into a broad grin, while his eyes almost shut tight at the recollection Walter's question had summoned up. "It was all along of 'Rough on Rats,'" he managed to say at last.

"'Rough on Rats?'"

"Yes, 'Rough on Rats.' Rat poison. You just wait, and hear me through.

"I've got a father somewhere, I b'leeve. Boys gen'ally have, I s'pose, though whether mine's dead or alive, not knowin', can't say. We were poor as Job's turkey, if you know how poor that was. I don't. Anyway, he put me out to work on a milk and chicken farm back here in the country, twenty miles or so, to a man by the name of Bennett, and then took himself off out West somewhere."

"And you've never seen him since?"

"No; I ha'n't never missed him, or the lickin's he give me. Well, my boss he raised lots of young chickens for market. We was awfully pestered with rats, big, fat, sassy ones, getting into the coops nights, and killing off the little chicks as soon's ever they was hatched out. You see, they was tender. Besides eating the chicks they et up most of the grain we throw'd into the hens. The boss he[Pg 32] tried everything to drive those rats away. He tried cats an' he tried traps. 'Twan't no use. The cats wouldn't tech the rats nor the rats go near the traps. You can't fool an old rat much, anyhow," he added with a knowing shake of his head.

"Well, the boss was a-countin' the chicks one mornin', while ladling out the dough to 'em. 'Confound those rats,' he sputtered out; 'there's eight more chicks gone sence I fed last night. I'd gin something to red the place on 'em, I would.'

"'Uncle,' says I (he let me call him uncle, seein' he'd kind of adopted me like)—'uncle,' says I, 'why don't you try Rough on Rats? They say that'll fetch 'em every time.'

"'What's that? Never heer'd on't. How do you know? Who says so?' he axed all in one breath."

"'Anyhow, I seen a big poster down at the Four Corners that says so,' says I. 'The boys was a-talkin' about what it had done up[Pg 33] to Skillings' place. Skillings allowed he'd red his place of rats with it. Hadn't seen hide nor hair of one sence he fust tried it. Everybody says it's a big thing.'

"The old man said nothin' more just then. He didn't let on that my advice was worth a cent; but I noticed that he went off and bought some Rough on Rats that same afternoon, and when the old hens had gone to roost and the mother hens had gathered their broods under 'em for the night, uncle he slyly stirred up a big dose of the p'isen stuff into a pan of meal, which he set down inside the henhouse.

"Uncle's idea was to get up early in the mornin', so's to count up the dead rats, I s'pose.

"But he did not get up early enough. When he went out into the henhouse to investigate, he found fifteen or twenty of his best hens lying dead around the floor after eatin' of the p'isen'd meal.

"When I come outdoors he was stoopin'[Pg 34] down, with his back to me pickin' 'em up."

Walter laughed until the tears rolled down his cheeks, sobered down, and then broke out again. Charley found the laugh infectious and joined in it, though more moderately.

"Go ahead. Let's have the rest, do," Walter entreated. "What next?"

"I asked Uncle Bennett what he was goin' to do with all those dead hens. He flung one at my head. Oh! but he was mad. 'Just stop where you be, my little joker,' says he, startin' off for the stable; 'I've got somethin' that's Rough on Brats, an' you shall have a taste on't right off. Don't you stir a step,' shakin' his fist at me, 'or I'll give you the worst dressin' down you ever had in all your life.'

"While he was gone for a horsewhip, I lit out for the Corners. You couldn't have seen me for dust.

"I darsen't go back to the house and I had only a silver ninepence in my pocket and a[Pg 35] few coppers, but I managed to beg my way to Boston. Oh! Walt, it was a long time between meals, I can tell you. I slept one night in a barn, on the haymow. Nobody saw me slip in after dark. I took off my neckerchief and laid it down within reach, for it was hot weather on that haymow, and I was 'most choked with the dust I swallowed. I overslept. In the morning I heard a noise down where the hosses were tied up. Some one was rakin' down hay for 'em. I reached for my neckerchief, thinkin' how I should get away without being seen, when a boy's voice gave a shout, 'Towser! Towser!' and then I knew it was all up, for that boy had raked down my neckerchief with the hay, and he knew there was a tramp somewhere about.

"The long and short of it is, that the dog chased me till I was ready to drop or until another and a bigger one came out of a yard and tackled him. Then it was dog eat dog.

"When I got to Boston it was night. I had no money. I didn't know where to go.[Pg 36] Tired's no name for it. I was dead-beat. So I threw myself down on a doorstep and was asleep in a minnit. There was an alarm of fire. An ingine came jolting along. I forgot all about being tired and took holt of the rope, and ran, and hollered, with the rest. The fire was all out when we got there, so I went back to the ingine house, and the steward let me sleep in the cellar a couple of hours and wash up in the mornin'. But I'm ahead of my story. They had hot coffee and crackers and cheese when they got back from the fire. No cheese ever tasted like that before. Give me a fireman for a friend at need. I hung round that ingine house till I picked up a job. The company was all calkers, gravers, riggers, and the like. Tough lot! How they could wallop that old tub over the cobblestones, to be sure!"

And here Charley fell into a fit of musing from which Walter did not attempt to rouse him. In their past experiences the two boys had found a common bond.

Seeing that Walter also had fallen into a brown study, Charley quickly changed the subject. "See here, Walt!" he exclaimed, "the Argonaut's going to sail for Californy first fair wind. To-morrow's Sunday, and Father Taylor's goin' to preach aboard of her. He's immense! Let's go and hear him. What do you say?"

Walter jumped at the proposal. "I want to hear Father Taylor ever so much, and I shouldn't mind taking a look at the passengers, too."

Sunday came. Walter put on his best suit, and the two friends strolled down to the wharf where the Argonaut lay moored with topsails loosened, and flags and streamers fluttering[Pg 38] gayly aloft. The ship was thronged not only with those about to sail for the Land of Gold, but also with the friends who had come to bid them good-bye; besides many attracted by mere curiosity, or, perhaps, by the fame of Father Taylor's preaching. There was a perfect Babel of voices. As Walter was passing one group he overheard the remark, "She'll never get round the Horn. Too deep. Too many passengers by half. Look at that bow! Have to walk round her to tell stem from starn."

"Oh, she'll get there fast enough," his companion replied. "She knows the way. Besides, you can't sink her. She's got lumber enough in her hold to keep her afloat if she should get waterlogged."

"That ain't the whole story by a long shot," a third speaker broke in. "Don't you remember the crack ship that spoke an old whaler at sea, both bound out for California? The passengers on the crack ship called out to the passengers on the old whaler to know if[Pg 39] they wanted to be reported. When the crack ship got into San Francisco, lo and behold! there lay the 'old tub' quietly at anchor. Been in a week."

Strange sight, indeed, it was to see men who, but the day before, were clerks in sober tweeds, farmers in homespun, or mechanics in greasy overalls, now so dressed up as to look far more like brigands than peaceful citizens; for it would seem that, to their notion, they could be no true Californians unless they started off armed to the teeth. So the poor stay-at-homes were given to understand how wanting they were in the bold spirit of adventure by a lavish display of pistols and bowie-knives, rifles and carbines. Poor creatures! they little knew how soon they were to meet an enemy not to be overcome with powder and lead.

Between decks, if the truth must be told, many of the passengers were engaged in sparring or wrestling bouts, playing cards, or shuffleboard, or hop-scotch, as regardless of[Pg 40] the day as if going to California meant a cutting loose from all the restraints of civilized life. The two friends made haste to get on deck. As they mingled with the crowd again, Walter exchanged quick glances with a middle-aged gentleman on whose arm a remarkably pretty young lady was leaning. Walter was saying to himself, "I wonder where I have seen that man before," when the full and sonorous voice of Father Taylor, the seaman's friend, hushed the confused murmur of voices around him into a reverential silence. With none of the arts and graces of the pulpit orator, that short, thick-set, hard-featured man spoke like one inspired for a full hour, and during that hour nobody stirred from the spot where he had taken his stand. Father Taylor's every word had struck home.

The last hymn had been sung, the last prayer said. At its ending the crowd slowly began filing down the one long, narrow plank reaching from the ship's gangway to the wharf. Nobody seemed to have noticed that[Pg 41] the rising tide had lifted this plank to an incline that would make the descent trying to weak nerves, especially as there were five or six feet of clear water to be passed over between ship and shore. It was just as one young lady was in the act of stepping upon this plank that two young scapegraces ahead of her ran down it with such violence as to make it rebound like a springboard, causing the young lady first to lose her balance, then to make a false step, and then to fall screaming into the water, twenty feet below.

Everybody ran to that side, and everybody began shouting at once: "Man overboard!" "A boat: get a boat!" "Throw over a rope!—a plank!" "She's going down!" "Help! help!" but nobody seemed to have their wits about them. With the hundreds looking on, it really seemed as if the girl might drown before help could reach her.

Both Charley and Walter had witnessed the accident: coats and hats were off in a jiffy. Snatching up a coil of rope, it was the work[Pg 42] of a moment for Walter to make a running noose, slip that under his arms, sign to Charley to take a turn round a bitt, then to swing himself over into the chains and be lowered down into the water on the run by the quick-witted Charley.

Meantime, the young lady's father was almost beside himself. In one breath he called to his daughter, by the name of Dora, to catch at a rope that was too short to reach her; in the next he was offering fifty, a hundred dollars to Walter if he saved her.

Walter rescuing Dora Bright.—Page 42.

Giving himself a vigorous shove with his foot, in two or three strokes Walter was at the girl's side and with his arms around her. It was high time, too, as her clothes, which had buoyed her up so far, were now water-soaked and dragging her down. Only her head was to be seen above water. At Walter's cheery "Haul away!" fifty nervous arms dragged them dripping up the ship's side. The young lady fell, sobbing hysterically, into her father's arms, and was forthwith hurried off into the[Pg 43] cabin, while Walter, after picking up his coat and hat, slipped off through the crowd, gained the wharf unnoticed, and with the faithful, but astonished, Charley at his heels, made a bee-line for his lodgings. Moreover, Walter exacted a solemn promise from Charley not to lisp one word of what had happened, on pain of a good drubbing.

"My best suit, too!" he ruefully exclaimed, while divesting himself of his wet clothes. "No matter: let him keep his old fifty dollars. Pretty girl, though. I'm paid ten times over. A coil of rope's a handy thing sometimes. So's a rigger—eh, Charley?"

Charley merely gave a dissatisfied grunt. He was very far from understanding such refined sentiments. Besides, half the money, he reflected, would have been his, or ought to have been, which was much the same thing to his way of thinking. And when he thought of the many things he could have done with his share, the loss of it made him feel very miserable, and more than half angry with[Pg 44] Walter. "Fifty dollars don't grow on every bush," he muttered. "Then, what lions we'd 'a' been in the papers!" he lamented.

"You look here. Can't you do anything without being paid for it? I'd taken thanks from the old duffer, but not money. Can't you understand? Now you keep still about this, I tell you."

Though still grumbling, Charley concluded to hold his tongue, knowing that Walter would be as good as his word; but he inwardly promised himself to keep his eyes open, and if ever he should see a chance to let the cat out of the bag without Walter's knowing it, well, the mischief was in it if he, Charley, didn't improve it, that was all.

The Argonaut affair got into the newspapers, where it was correctly reported, in the main, except that the rescuer was supposed to be one of the Argonaut's passengers, and as she was now many miles at sea, Mr. Bright, the father of Dora, as a last resort, put an advertisement in the daily papers asking the unknown to furnish his address without delay to his grateful debtors. But as this failed to elicit a reply, there was nothing more to be done.

Walter, however, had seen the advertisement, and he had found out from it that Mr. Bright was one of the Argonaut's principal owners. He therefore felt quite safe from discovery when he found himself reported as having sailed in that vessel.

Time moved along quietly enough with Walter until the Fourth of July was near at hand, when it began to be noised about that the brand-new clipper ship then receiving her finishing touches in a neighboring yard would be launched at high water on that eventful day. What was unusual, the nameless ship was to be launched fully rigged, so that the riggers' gang was to take a hand in getting her off the ways. Everybody was consequently on the tiptoe of expectation.

The eventful morning came at last. It being a holiday, thousands had repaired to the spot, attracted by the novelty of seeing a ship launched fully rigged. At a given signal, a hundred sledges, wielded by as many brawny arms, began a furious hammering away at the blocks, which held the gallant ship bound and helpless to the land. The men worked like tigers, as if each and every one had a personal interest in the success of the launch. At last the clatter of busy hammers ceased, the grimy workmen crept out, in twos and threes, from[Pg 47] underneath the huge black hull, and a hush fell upon all that vast throng, so deep and breathless that the streamers at the mast-head could be heard snapping like so many whiplashes in the light breeze aloft.

"All clear for'ard?" sang out the master workman. "All clear, sir," came back the quick response. "All clear aft?" the voice repeated. "Aye, aye, all clear." Still the towering mass did not budge. It really seemed as if she was a living creature hesitating on the brink of her own fate, whether to make the plunge or not. There was an anxious moment. A hush fell upon all that vast throng. Then, as the stately ship was seen to move majestically off, first slowly, and then with a rush and a leap, one deafening shout went up from a thousand throats: "There she goes! there she goes! hurrah! hurrah!" Every one declared it the prettiest launch ever seen.

Just as the nameless vessel glided off the ways a young lady, who stood upon a tall scaffold[Pg 48] at the bow, quickly dashed a bottle of wine against the stem, pronouncing as she did so the name that the good ship was to bear henceforth, so proudly, on the seas—the Flying Arrow. Three rousing cheers greeted the act, and the name. The crowd then began to disperse.

As Walter was standing quite near the platform erected for this ceremony, his face all aglow with the vigorous use he had made of the sledge he still held in his hand, the young lady who had just christened the Flying Arrow came down the stairs. In doing so, she looked Master Walter squarely in the face. Lo and behold! it was the girl of the Argonaut. The recognition was instant and mutual.

Walter turned all colors at once. Giving one glance at his greasy duck trousers and checked shirt, his first impulse was to sneak off without a word; but before he could do so he was confronted by Mr. Bright himself. Walter was thus caught, as it were, between[Pg 49] two fires. Oh, brave youth of the stalwart arm and manly brow, thus to show the white feather to that weak and timid little maiden!

Noticing the young man's embarrassment, Mr. Bright drew him aside, out of earshot of those who still lingered about. "So, so, my young friend," he began with a quizzical look at Walter, "we've had some trouble finding you. Pray what were your reasons for avoiding us? Neither of us [turning toward his daughter] is a very dangerous person, as you may see for yourself."

"Now, don't, papa," pleaded Dora. Then, after giving a sidelong and reproachful look at Walter, she added, "Why, he wouldn't even let us thank him!"

Walter tried to stammer out something about not deserving thanks. The words seemed to stick in his throat; but he did manage to say: "Fifty stood ready to do what I did. I only got a little wetting, sir."

"Just so. But they didn't, all the same.[Pg 50] Come, we are not ungrateful. Can I depend on you to call at my office, 76 State Street, to-morrow morning about ten?"

"You can, sir," bowing respectfully.

"Very good. I shall expect you. Come, Dora, we must be going." Father and daughter then left the yard, but not until Dora had given Walter another reproachful look, out of the corner of her eye.

"Poor, proud, and sheepish," was the merchant's only comment upon this interview, as they walked homeward. Mentally, he was asking himself where he had seen that face before.

Dora said nothing. Her stolen glances had told her, however, that Walter was good-looking; and that was much in his favor. To be sure, he was plainly a common workman, and he had appeared very stiff and awkward when her father spoke to him. Still she felt that there was nothing low or vulgar about him.

Punctual to the minute, Walter entered[Pg 51] the merchant's counting room, though, to say truth, he found himself ill at ease in the presence of half a dozen spruce-looking clerks, who first shot sly glances at him, then at each other, as he carefully shut the door behind him. Walter, however, bore their scrutiny without flinching. He was only afraid of girls, from sixteen to eighteen years old.

Mr. Bright immediately rose from his desk, and beckoned Walter to follow him out into the warehouse. "You are prompt. That's well," said he approvingly. "Now then, to business. We want an outdoor clerk on our wharf. You have no objection, I take it, to entering our employment?"

Walter shook his head. "Oh, no, sir."

"Very good, then. I'll tell you more of your duties presently. I hear a good account of you. The salary will be six hundred the first year, and a new suit of clothes, in return for the one you spoiled. Here's a tailor's address [handing Walter a card with the order written upon it]. Go and get measured[Pg 52] when you like, and mind you get a good fit."

Walter took a moment to think, but couldn't think at all. All he could say was: "If you think, sir, I can fill the place, I'll try my best to suit you."

"That's right. Try never was beat. You may begin to-morrow." Walter went off feeling more happy than he remembered ever to have felt before. In truth, he could hardy realize his good fortune.

This change in Walter's life brought with it other changes. For one thing it broke off his intimacy with Charley, although Walter continued to receive occasional visits from his old chum. He also began attending an evening school, kept by a retired schoolmaster, in order to improve his knowledge of writing, spelling, and arithmetic, or rather to repair the neglect of years; for he now began to feel his deficiencies keenly with increasing responsibilities. He was, however, an apt scholar, and was soon making good progress. The[Pg 53] work on the wharf was far more to his liking than the confinement of the warehouse could have been; and Walter was every day storing up information which some time, he believed, would be of great use to him.

Time wore on, one day's round being much like another's. But once Walter was given such a fright that he did not get over it for weeks. He was sometimes sent to the bank to make a deposit or cash a check. On this particular occasion he had drawn out quite a large sum, in small bills, to be used in paying off the help. Not knowing what else to do with it, Walter thrust the roll of bills into his trousers pocket. It was raining gently out of doors, and the sidewalks were thickly spread with a coating of greasy mud. There was another call or two to be made before Walter returned to the store. At the head of the street Walter stopped to think which call he should make first. Mechanically he thrust his hand in his pocket, then turned as pale as a sheet, and a mist passed before his eyes.[Pg 54] The roll of bills was not there. A hole in the pocket told the whole story. The roll had slipped out somewhere. It was gone, and through his own carelessness.

After a moment's indecision Walter started back to the bank, carefully looking for the lost roll at every step of the way. The street was full of people, for this was the busiest hour of the day. In vain he looked, and looked, at every one he met. No one had a roll of bills for which he was trying to find an owner. Almost beside himself, he rushed into the bank. Yes, the paying teller remembered him, but was quite sure the lost roll had not been picked up there, or he would have known it. So Walter's last and faintest hope now vanished. Go back to the office with his strange story, he dared not. The bank teller advised his reporting his loss to the police, and advertising it in the evening editions. Slowly and sadly Walter retraced his steps towards the spot where he had first missed his employer's money, inwardly scolding[Pg 55] and accusing himself by turns. Vexed beyond measure, calling himself all the fools he could think of, Walter angrily stamped his foot on the sidewalk. Presto! out tumbled the missing roll of bills from the bottom of his trousers-leg when he brought his foot down with such force. It had been caught and held there by the stiffening material then fashionable.

Walter went home that night thanking his lucky stars that he had come out of a bad scrape so easily. He was thinking over the matter, when Charley burst into the room. "I say, Walt, old fel, don't you want to buy a piece of me?" he blurted out, tossing his cap on the table, and falling into a chair quite out of breath.

Walter simply stared, and for a minute the two friends stared at each other without speaking. Walter at length demanded: "Are you crazy, Charles Wormwood? What in the name of common sense do you mean?"

"Oh, I'm not fooling. You needn't be scared. Haven't you ever heard of folks buying pieces of ships? Say?"

"S'pose I have; what's that got to do with men?"

"I'll tell you. Look here. When a feller wants to go to Californy awful bad, like me, and hasn't got the chink, like me, he gets some other fellers who can't go, like you, to chip in to pay his passage for him."

"Pooh! That's all plain sailing. When he earns the money he pays it back," Walter rejoined.

"No, you're all out. Just you hold your hosses. It's like this. The chap who gets the send-off binds himself, good and strong, mind you, to divide what he makes out there among his owners, 'cordin' to what they put into him—same's owning pieces of a ship, ain't it? See? How big a piece'll you take?" finished Charley, cracking his knuckles in his impatience.

Walter leaned back in his chair, and burst[Pg 57] out in a fit of uncontrollable laughter. Charley grew red in the face. "Look here, Walt, you needn't have any if you don't want it." He took up his cap to go. Walter stopped him.

"There, you needn't get your back up, old chap. It's the funniest thing I ever heard of. Why, it beats all!"

"It's done every day," Charley broke in. "You won't lose anything by me, Walt," he added, anxiously scanning Walter's face. "See if you do."

Walter had saved a little money. He therefore agreed to become a shareholder in Charles Wormwood, Esquire, to the tune of fifty dollars, said Wormwood duly agreeing and covenanting, on his part, to pay over dividends as fast as earned. So the ingenious Charley sailed with as good a kit as could be picked up in Boston, not omitting a beautiful Colt's revolver (Walter's gift), on which was engraved, "Use me; don't abuse me." Charles was to work his passage out in the[Pg 58] new clipper, which arrangement would land him in San Francisco with his capital unimpaired. "God bless you, Charley, my boy," stammered Walter, as the two friends wrung each other's hands. He could not have spoken another word without breaking down, which would have been positive degradation in a boy's eyes.

"I'll make your fortune, see if I don't," was Charley's cheerful farewell. "On the square I will," he brokenly added.

The house of Bright, Wantage & Company had a confidential clerk for whom Walter felt a secret antipathy from the first day they met. We cannot explain these things; we only know that they exist. It may be a senseless prejudice; no matter, we cannot help it. This clerk's name was Ramon Ingersoll. His manner toward his fellow clerks was so top-lofty and so condescending that one and all thoroughly disliked him. Some slight claim Ramon was supposed to have upon the senior partner, Mr. Bright, kept the junior clerks[Pg 59] somewhat in awe of him. But there was always friction in the counting-room when the clerks were left alone together.

The truth is that Ramon's father had at one time acted as agent for the house at Matanzas, in Cuba. When he died, leaving nothing but debts and this one orphan child, for he had buried his wife some years before, Mr. Bright had taken the little Ramon home, sent him to school, paid all his expenses out of his own pocket and finally given him a place of trust in his counting-house. In a word, this orphaned, penniless boy owed everything to his benefactor.

As has been already mentioned, without being able to give a reason for his belief, Walter had an instinctive feeling that Ramon would some day get him into trouble. Fortunately Walter's duties kept him mostly outside the warehouse, so that the two seldom met.

One day Ramon, with more than ordinary cordiality, asked Walter to visit him at his[Pg 60] room that same evening In order to meet, as he said, one or two particular friends of his. At the appointed time Walter went, without mistrust, to Ingersoll's lodgings. Upon entering the room he found there two very flashy-looking men, one of whom was short, fat, and smooth-shaven, with an oily good-natured leer lurking about the corners of his mouth; the other dark-browed, bearded, and scowling, with, as Walter thought, as desperately villainous a face as he had ever looked upon.

"Ah, here you are, at last!" cried Ramon, as he let Walter in. "This is Mr. Goodman," here the fat man bowed, and smiled blandly; "and this, Mr. Lambkin." The dark man looked up, scowled, and nodded. "And now," Ramon went on, "as we have been waiting for you, what say you to a little game of whist, or high-low-jack, or euchre, just to pass away the time?"

"I'm agreeable," said Mr. Goodman, "though, upon my word and honor, I hardly[Pg 61] know one card from another. However, just to make up your party, I will take a hand."

The knight of the gloomy brow silently drew his chair up to the table, which was, at least, significant of his intentions.

Walter had no scruples about playing an innocent game of whist. So he sat down with the others.

The game went on rather languidly until, all at once, the fat man broke out, without taking his eyes off his cards, "Bless me!—why, the strangest thing!—if I were a betting man, I declare I wouldn't mind risking a trifle on this hand."

Ramon laughed good-naturedly, as he replied in an offhand sort of way: "Oh, we're all friends here. There's no objection to a little social game, I suppose, among friends." Here he stole an inquiring look at Walter. "Besides," he continued, while carelessly glancing at his own hand, "I've a good mind to bet a trifle myself."

Though still quite unsuspicious, Walter[Pg 62] looked upon this interruption of the harmless game with misgiving.

"All right," Goodman resumed, "here goes a dollar, just for the fun of the thing."

The taciturn Lambkin said not a word, but taking out a well-stuffed wallet, quietly laid down two dollars on the one that Goodman had just put up.

"I know I can beat them," Ramon whispered in Walter's ear. "By Jove, I'll risk it just this once!"

"No, don't," Walter whispered back, pleadingly, "it's gambling."

"Pshaw, man, it's only for sport," Ramon impatiently rejoined, immediately adding five dollars of his own money to the three before him.

Walter laid down his cards, leaned back in his chair, and folded his arms resolutely across his chest. "And the fat man said he hardly knew one card from another. How quick some folks do learn," he said to himself.

"Isn't our young friend going to try his luck?" smiled, rather than asked, the unctuous Goodman.

"No; I never play for money," was the quiet response.

Once the ice was broken the game went on for higher, and still higher, stakes, until Walter, getting actually frightened at the recklessness with which Ramon played and lost, rose to go.

After vainly urging him to remain, annoyed at his failure to make Walter play, enraged by his own losses, Ramon followed Walter outside the door, shut it behind them, and said in a menacing sort of way, "Not a word of this at the store."

"Promise you won't play any more."

"I won't do no such thing. Who set you up for my guardian? If you're mean enough to play the sneak, tell if you dare!"

Walter felt his anger rising, but controlled himself. "Oh, very well, only remember that I warned you," he replied, turning away.

"Don't preach, Master Innocence!" sneered Ramon.

"Don't threaten, Master Hypocrite!" was the angry retort.

Quick as a flash, Ramon sprang before Walter, and barred his way. All the tiger in his nature gleamed in his eyes. "One word of this to Mr. Bright, and I'll—I'll fix you!" he almost shrieked out.

With that the two young men clinched, and for a few minutes nothing could be heard but their heavy breathing. This did not last. Walter soon showed himself much the stronger of the two, and Master Ramon, in spite of his struggles, found himself lying flat on his back, with his adversary's knee on his chest. Ramon instantly gave in. Choking down his wrath, he jerked out, "There, I promise. Let me up."

"Oh, if you promise, so do I," said Walter, releasing his hold on Ramon. He then left the house without another word. He did not see Ramon shaking his fist behind[Pg 65] his back, or hear him muttering threats of vengeance to himself, as he went back to his vicious companions. Walter did wish, however, that he had given Ramon just one more punch for keeps.

So they parted. Satisfied that Walter would not break his promise, Ramon made all haste back to his companions, laughing in his sleeve to think how easily he had fooled that milksop Seabury. His companions were two as notorious sharpers as Boston contained. He continued to lose heavily, they luring him on by letting him win now and then, until they were satisfied he had nothing more to lose. At two in the morning their victim rose up from the table, hardly realizing, so far gone was he in liquor, that he was five hundred dollars in debt to Lambkin, or that he had signed a note for that sum with the name of his employers, Bright, Wantage & Company. He had found the road from gambling to forgery a natural and easy one.

Leaving Ingersoll to follow his crooked ways, we must now introduce a character, with whom Walter had formed an acquaintance, destined to have no small influence upon his own future life.

Bill Portlock was probably as good a specimen of an old, battered man-o'-war's man as could be scared up between Montauk and Quoddy Head. While a powder-monkey, on board the President frigate, he had been taken prisoner and confined in Dartmoor Prison, from which he had made his escape, with some companions in captivity, by digging a hole under the foundation wall with an old iron spoon. Shipping on board a British merchantman, he had deserted at the first neutral port she touched at. He was now doing[Pg 67] odd jobs about the wharves, as 'longshoreman; and as Walter had thrown many such in the old salt's way a kind of intimacy had grown up between them. Bill loved dearly to spin a yarn, and some of his adventures, told in his own vernacular, would have made the late Baron Munchausen turn green with envy. "Why," he would say, after spinning one of his wonderful yarns, "ef I sh'd tell ye my adventers, man and boy, you'd think 'twas Roberson Crushoe a-talkin' to ye. No need o' lyin'. Sober airnest beats all they make up."

Bill's castle was a condemned caboose, left on the wharf by some ship that was now plowing some distant sea. Her name, the Orpheus, could still be read in faded paint on the caboose; so that Bill always claimed to belong to the Orpheus, or she to him, he couldn't exactly say which. When he was at work on the wharf, after securing his castle with a stout padlock, he announced the fact to an inquiring public by chalking up the legend,[Pg 68] "Aboard the brig," or "Aboard the skoner," as the case might be. If called to take a passenger off to some vessel in his wherry, the notice would then read, "Back at eight bells." A sailor he was, and a sailor he said he would live and die.

No one but a sailor, and an old sailor at that, could have squeezed himself into the narrow limits of the caboose, where it was not possible, even for a short man like Bill, to stand upright, though Bill himself considered it quite luxurious living. There was a rusty old cooking stove at one end, with two legs of its own, and two replaced by half-bricks; the other end being taken up by a bench, from which Bill deftly manipulated saucepan or skillet.

"Why, Lor' bless ye!" said Bill to Walter one evening, "I seed ye fish that ar' young 'ooman out o' the dock that time. 'Bill,' sez I to myself, 'thar's a chap, now, as knows a backstay from a bullock's tail.'"

"Pshaw!" Then after a moment's silence,[Pg 69] while Bill was busy lighting his pipe, Walter absently asked, "Bill, were you ever in California?"

"Kalerforny? Was I ever in Kalerforny? Didn't I go out to Sandy Ager, in thirty-eight, in a hide drogher? And d'ye know why they call it Sandy Ager? I does. Why, blow me if it ain't sandy 'nuff for old Cape Cod herself; and as for the ager, if you'll b'leeve me, our ship's crew shook so with it, that all hands had to turn to a-settin' up riggin' twict a month, it got so slack with the shakin' up like."

"What an unhealthy place that must be," laughed Walter. Then suddenly changing the subject, he said: "Bill, you know the Racehorse is a good two months overdue." Bill nodded. "I know our folks are getting uneasy about her. No wonder. Valuable cargo, and no insurance. What's your idea?"

Bill gave a few whiffs at his pipe before replying. "I know that ar' Racehorse.[Pg 70] She's a clipper, and has a good sailor aboard of her: but heavy sparred, an' not the kind to be carryin' sail on in the typhoon season, jest to make a quick passage." Bill shook his head. "Like as not she's dismasted, or sprung a leak, an' the Lord knows what all."

The next day happened to be Saturday. As Walter was going into the warehouse he met Ramon coming out. Since the night at his lodgings, his manner toward Walter, outwardly at least, had undergone a marked change. If anything it was too cordial. "Hello! Seabury, that you?" he said, in his offhand way. "Lucky thing you happened in. It's steamer day, and I'm awfully hard pushed for time. Would you mind getting this check on the Suffolk cashed for me? No? That's a good fellow. Do as much for you some time. And, stay, on your way back call at the California steamship agency—you know?—all right. Well, see if there are any berths left in the Georgia. You[Pg 71] won't forget the name? The Georgia. And, oh! be sure to get gold for that check. It's to pay duties with, you know," Ramon hurriedly explained in an undertone.

"All right; I understand," said Walter, walking briskly away on his errand. He quite forgot all about the gold, though, until after he had left the bank; when, suddenly remembering it, he hurried back to get the coin, quite flurried and provoked at his own forgetfulness. The cashier, however, counted out the double-eagles, for the notes, without remark. Such little instances of forgetfulness were too common to excite his particular notice.

On that same evening, finding time hanging rather heavily on his hands, Walter strolled uptown in the direction of Mr. Bright's house, which was in the fashionable Mt. Vernon Street. The truth is that the silly boy thought he might possibly catch a glimpse of a certain young lady, or her shadow, at least, in passing the brilliantly lighted residence. It was, he admitted to[Pg 72] himself, a fool's errand, after walking slowly backwards and forwards two or three times, with his eyes fastened upon the lighted windows; and with a feeling of disappointment he turned away from the spot, heartily ashamed of himself, as well, for having given way to a sudden impulse. Glad he was that no one had noticed him.

Walter's queer actions, however, did not escape the attention of a certain lynx-eyed policeman, who, snugly ensconced in the shadow of a doorway, had watched his every step. The young man had gone but a short distance on his homeward way, when, as he was about crossing the street, he came within an ace of being knocked down and run over by a passing hack, which turned the corner at such a break-neck pace that there was barely time to get out of the way. There was a gaslight on this corner. At Walter's warning shout to the driver, the person inside the hack quickly put his head out of the window, and as quickly drew it in again; but in that instant[Pg 73] the light had shone full upon the face of Ramon Ingersoll.

The driver lashed his horses into a run. Walter stood stupidly staring after the carriage. Then, without knowing why, he ran after it, confident that if he had recognized Ramon in that brief moment, Ramon must also have recognized him. The best he could do, however, was to keep the carriage in sight, but he soon saw that it was heading for the railway station at the South End.

Out of breath, and nearly out of his head, too, Walter dashed through the arched doorway of the station, just in time to see a train going out at the other end in a cloud of smoke. In his eagerness, Walter ran headlong into the arms of the night-watchman, who, seeing the blank look on Walter's face, said, as he had said a hundred times before to belated travelers, "Too late, eh?"

"Yes, yes, too late," repeated Walter, in a tone of deep vexation. While walking home he began to think he had been making[Pg 74] a fool of himself again. After all, what business was it of his if Ramon had gone to New York? He might have gone on business of the firm. Of course that was it. And what right had he, Walter, to be chasing Ramon through the streets, anyhow? Still, he was sure that Ramon had recognized him, and just as sure that Ramon had wished to avoid being recognized, else why had he not spoken or even waved his hand? Walter gave it up, and went home to dream of chasing carriages all night long.

Walter went to the wharf as usual the next morning. In the course of the forenoon a porter brought word that he was wanted at the counting-room. When Walter went into the office, Mr. Bright was walking the floor, back and forth, with hasty steps, while a very dark, clean-shaven, alert-looking man sat leaning back in a chair before the door. This person immediately arose, locked the office door, put the key in his pocket, and then quietly sat down again.

Walter's heart was in his mouth. He grew red and pale by turns. Before he could collect his ideas Mr. Bright stopped in his walk, looked him squarely in the eye, and, in an altered voice, demanded sharply and sternly: "Ingersoll—where is he? No prevarication. I want the truth and nothing but the truth. You understand?"

Walter tried hard to make a composed answer, but the words would not seem to come; and the merchant's cold gray eyes seemed searching him through and through. However, he managed to stammer out: "I don't know, sir, where he is—gone away, hasn't he?"

"Don't know. Gone away," repeated the merchant. "Now answer me directly, without any ifs or buts; where, and when, did you see him last?"

"Last night; at least, I thought it was Ramon." The dark man gave his head a little toss.

"Well, go on? What then?"

"It was about nine o'clock, in a close carriage, not far from the Common." That, by the way, was as near to Mr. Bright's house as Walter thought proper to locate the affair.

Mr. Bright exchanged glances with the dark man, who merely nodded, but said never a word.

Thinking his examination was over, Walter plucked up the courage to say of his own accord, "I ran after the carriage as tight as I could; but you see, sir, the driver was lashing his horses all the way, so I couldn't keep up with it; and when I got to the depot the train was just starting."

"Pray, what took you to that neighborhood at that hour?" the silent man demanded so suddenly that the sound of his voice startled Walter.

If ever conscious guilt showed itself in a face, it now did in Walter's. He turned as red as a peony. Mr. Bright frowned, while the dark-skinned man smiled a knowing little smile.

"Why, nothing in particular, sir. I was only taking a little stroll about town, before going home," Walter replied, a word at a time.

"Yet your boarding place is at the other end of the city, is it not?" pursued Mr. Bright.

"Yes, sir, it is."

"Walter Seabury, up to this time I have always had a good opinion of you. This is no time for concealments. The house has been robbed of a large sum of money—so large that should it not be recovered within twenty-four hours we must fail. Do you hear—fail?" he repeated as if the word stuck in his throat and choked him.

"Robbed; fail!" Walter faltered out, hardly believing his own ears.

"Yes, robbed, and as I must believe by a scoundrel warmed at my own fireside. And you: why did you not report Ingersoll's flight before it was too late to stop him?"

Though shocked beyond measure by this[Pg 78] revelation, Walter made haste to reply: "Because, sir, I was not sure it was Ramon. It was just a look, and he was gone like a flash. Besides——"

"Besides what?"

"How could I know Ramon was running away?"

"Why, then, did you run after him? Are you in the habit of chasing every carriage you may chance upon in the street?" again interrupted the silent man.

Stung by the bantering tone of the stranger, Walter made no reply. Mr. Bright was his employer and had a perfect right to question him; but who was this man, and by what right did he mix himself up in the matter?

"Quite right of you, young man, to say nothing to criminate yourself; but perhaps you will condescend to tell us, unless it would be betraying confidence [again that cunning smile], if you knew that this Ingersoll was a gambler?"

The tell-tale blood again rushed to Walter's[Pg 79] temples, but instantly left them as it dimly dawned upon him that he was suspected of knowing more than he was willing to tell.

"Gently, marshal, gently," interposed Mr. Bright. "He will tell all, if we give him time."

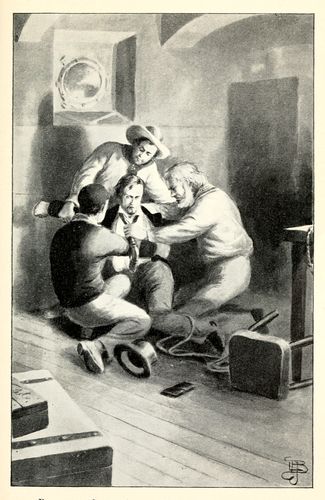

"One moment," rejoined the chief, with a meaning look at the merchant. "You hear, young man, this firm has been robbed of twenty thousand dollars—quite a haul. The thief has absconded. You tell a pretty straight story, I allow, but before you are many hours older you will have to explain why you, who have nothing to do with that department, should draw two thousand dollars at the bank yesterday; why, after getting banknotes you went back after gold," the marshal continued, warming up as he piled accusation on accusation; "why, again, you went from there to secure a berth in the Georgia, which sailed early this morning; and why you are seen, for seen you were, first watching Mr. Bright's house, and then arriving[Pg 80] at the station just too late for the New York express. Take my advice. Make a clean breast of the whole affair. If you can clear yourself, now is the time; if you can't, possibly you may be of some use in recovering the money."

Walter felt his legs giving way under him. At last it was all out. Now it was as clear as day how Ingersoll had so craftily managed everything as to make Walter appear in the light of a confederate. Now he knew why Ingersoll had wished to avoid being recognized. In a broken voice he told what he knew of Ingersoll's wrong-doings, excusing his own silence by the pledge he had given and received.

When he had finished, the two men held a whispered conference together. "Clear case," observed the marshal; "one watched your house while the other was making his escape."

"I'll not believe it. Why, this young man saved my daughter's life."

"Think as you like. At any rate, I mean to keep an eye on him." So saying, the marshal went on his way, humming a tune to himself with as much unconcern as if he had just got up from a game of checkers which he had won handily. At the street corner he hailed an officer, to whom he gave an order in an undertone, and then walked on, smiling and nodding right and left as he went.

Left alone with Mr. Bright, Walter stood nervously twisting his cap in both hands, like a culprit awaiting his sentence. It came at last. "Until this matter is cleared up," Mr. Bright said, "we cannot retain you in our employ. Get what is due you. You can go now." He then turned his back on Walter, and began busying himself over the papers on his desk.

Walter went out of the office without another word. He was simply stunned.

Walter walked slowly down the wharf, feeling as if the world had suddenly come to an end. Nothing looked to him exactly as it looked one short hour ago. He did not even notice that a policeman was keeping a few rods behind him. As he walked along with eyes fixed on the ground, a familiar voice hailed him with, "Why, what ails ye, lad? Seen a ghost or what?"

"Bill," said Walter, "would you believe it, that skunk of a Ramon has run off with a lot of the firm's money—to California, they say? And, oh, Bill! Bill! they suspect me, me, of having helped him do it. And I'm discharged. That's all." It was no use trying to keep up longer. Walter broke down completely at the sound of a friendly voice at last.

Bill silently led the way into the caboose. He first lighted his pipe, for, like the Indians, Bill seemed to believe that a good smoke tended to clear the intellect. He then, save for an occasional angry snort or grunt, heard Walter through without interruption. When the wretched story was all told Bill struck his open palm upon his knee, jerking out between whiffs: "My eye, here's a pretty kettle o' fish! Ruin, failure, crash, and smash. Ship ashore, and you all taken aback. Ssh!" suddenly checking himself, as a shadow darkened the one little pane of glass that served for a window. A policeman was looking in at them. Giving the two friends a careless nod, he walked slowly away.

It slowly dawned upon Walter that the man with the black rosette in his hat, whom he had seen at the office, had set a watch upon him. "Bill, you mustn't be seen talking to me," said Walter, rising to leave. "They'll think you are in the plot, too. Oh! oh! they dog me about everywhere."

The old fellow laughed scornfully. "That," he exclaimed, snapping his fingers, "for the hull b'ilin' on 'em. I've licked many a perleeceman in my time, and can do it again, old as I am. But we can be foxy, too, I guess. Listen. When I sees you comin', I'll go acrost the wharf to where that 'ar brig lays, over there. You foller me." Walter nodded. "I go up aloft. You follers. We has our little talk out in the maintop, free and easy like, and the perleeceman, he has his watch below."

When Walter reached his boarding house his landlady met him in the entry. She seemed quite flustered and embarrassed. "Oh, Mr. Seabury," she began, "I'm so glad you've come! Such a time! There has been an officer here tossing everything topsy-turvy in your room. He would do it, in spite of all I could say. I told him you were the best boarder of the lot; never out late nights, or coming home the worse for liquor, and always prompt pay. Do you think, he told me to[Pg 85] shut up, and mind my own business. Oh, sir, what is the matter? That ever a nasty policeman should came ransacking in my house. Goodness alive! why, if it gets out, I'm a ruined woman. Please, sir, couldn't you find another boarding place?"

This was the last straw for poor Walter. Without a word he crept upstairs to his little bedroom, threw himself down on the bed, and cried as if his heart would break.

Walter was young. Conscious innocence helped him to throw off the fit of despondency; but in so far as feeling goes, he was ten years older when he came out of it. It was quite dark. Lighting a lamp, he hastily threw a few things into a bag, scribbled a short note to his aunt, inclosing the check received when he was discharged, settled with the landlady, who was in tears, always on tap; took his bag under his arm, and after satisfying himself that the coast was clear, struck out a roundabout course, through crooked ways and blind alleys, to the wharf. For the life of him, he[Pg 86] could not keep back a little bitter laugh when he called to mind that this was the second time in his short life that he had run away.

The wharf was deserted. There was no light in the caboose; but upon Walter's giving three cautious raps, the door was slid back, and as quickly closed after him. "Well," he said, wearily throwing himself down on a bench, "here I am again. I've been turned out of doors now. You are my only friend left. What would you do, if you were in my place? I can't bear it, and I won't," he broke out impulsively.

"I see," said Bill, meditatively shutting both eyes, to give emphasis to the assertion.

"Nobody will give me a place now, with a cloud like that hanging over me."

Bill nodded assent.

"I can't go back to the loft where I worked before, to be pointed at and jeered at by every duffer who may take it into his head to throw this scrape in my face. Would you?"

As Bill made no reply, but smoked on in[Pg 87] silence, Walter exclaimed, almost fiercely, "Confound it, man, say something! can't you? You drive me crazy with all the rest."

This time Bill shook the ashes from his pipe. "What would I do? Why, if it was me I'd track the rascal to the eends of the airth, and jump off arter him, but I'd have him. And arter I'd cotched him, I'd twist his neck just as quick as I would a pullet's," was Bill's quiet but determined reply.

Walter simply stared, though every nerve in his body thrilled at the bare idea. "Pshaw, you don't mean it. What put that silly notion into your head? Why, what could I do single-handed and alone, against such a consummate villain as that? Where's the money to come from, in the first place?"

Bill watched Walter's sudden change from hot to cold. "Jest you take down that 'ar coffee-pot over your head." Walter handed it to him, as requested. First giving it a vigorous shake, which made the contents rattle again with a metallic sound, Bill then raised[Pg 88] the lid, showing to Walter's astonished eyes a mixture of copper, silver, and even a few gold, coins, half filling the battered utensil.

"Thar's a bank as never busts, my son," chuckled the old man, at the same time turning the coffee-pot this way and that, just for the pleasure of hearing it rattle. "What do you think of them 'ar coffee-grounds, heh? Single-handed, is it?" he continued, with a sniff of disdain. "I'll jest order my kerridge, and go 'long with ye, my boy."

It took some minutes for Walter to realize that Bill was in real, downright, sober earnest. But Bill was already shoving some odds and ends into a canvas bag to emphasize his decision. "Strike while the iron's hot" was his motto. Walter started to his feet with something of his old animation. "That settles it!" he exclaimed. "Since I've been turned out of doors, I feel as if I wanted to put millions of miles between me and every one I've ever known. Do you know, I think every[Pg 89] one I meet is saying to himself, 'There's that Walter Seabury, suspected of robbing his employers'? Go away I must, but I've found out from the papers that no steamer sails before Saturday, and to-day is Wednesday, you know. Where shall I hide my face for a day or two? How do I know they won't arrest me, if they catch me trying to leave the city? Oh, Bill, I can never stand that disgrace, never!"

Having finished with his packing, Bill blew out the light, pushed back the slide, and gave a rapid look up and down the wharf. As he drew in his head, he said just as indifferently as if he had proposed taking a short walk about town, "'Pears to me as if the correck thing for folks in our sitivation like was to cut and run."

"True enough for me. But how about you? They'll say that you were as deep in the mud as I am in the mire. Give it up, Bill. No, dear old friend, I mustn't drag you down with me. I can't."

"Bah! Talk won't hurt old Bill nohow. Bill's about squar' with the world. He owes just as much as he don't owe."

Walter was deeply touched. He saw plainly that it was no use trying to shake the old fellow's purpose, so forbore urging him further.

The old man waited a moment for Walter to speak, and finding that he did not, laid his big rough hand on the lad's shoulder and asked impressively, "Did you send off your chist to your aunt as I told ye to?"

"I did, an hour ago."

"An' did you kind o' explanify things to the old gal?"

"How could I tell her, Bill? Didn't she always say I would come to no good end? I wrote her that I was going away—a long way off—and for a long time. I couldn't say just how long. A year or two perhaps. My head was all topsy-turvy, anyhow."

"You didn't forgit she took keer on ye when ye war a kid?"

"I sent her the check I got from the store, right away."

"Then I don't see nothin' to—hender us from takin' that 'ar little cruise we was a-talkin' about."

It was pitch-dark when our two adventurers stepped out of the caboose. After securing the door with a stout padlock, Bill silently led the way to the stairs where he kept his wherry. Noiselessly the boat was rowed out of the dock, toward a light that glimmered in the rigging of an outward-bound brig that lay out in the stream waiting for the turning of the tide. Bill did not speak again until they were clear of the dock. "Yon brig's bound for York. I know the old man first-rate, 'cause I helped load her. He'll give us a berth if we take holt with the crew. Here we are." As he climbed the brig's side he set the wherry adrift with a vigorous shove of his foot.

A day or two after the events just described, Mr. Bright and the marshal met on the[Pg 92] street, the former looking sober and downcast, the latter smiling and elate. "What did I tell you?" cried the marshal, evidently well pleased with the tenor of the news he had to relate; "your protégé has gone off with an old wharf rat that I've had my eye on for some time."

"To tell you the whole truth, marshal, my mind is not quite easy about that boy," the merchant replied.

"Opportunity makes the thief," the officer observed carelessly.

"I'm afraid we've been too hasty."

"Perhaps so; but it's my opinion that when Ramon is found, the other won't be far off. I honor your feelings in this matter, sir, but my experience tells me that every rascal asserts his innocence until his guilt is proved. I've notified the police of San Francisco to be on the lookout for that precious clerk of yours. Good-day, sir."

When Mr. Bright returned to the store, on entering the office he saw an elderly woman,[Pg 93] in a faded black bonnet and shawl, sitting bolt-upright on the edge of a chair facing the door, with two bony hands tightly clenched in her lap. There was fire in her eye.

"That is Mr. Bright, madam," one of the clerks hastened to say.

"What can I do for you, madam?" the merchant asked.

The woman fixed two keen gray eyes upon the speaker's face, as she spoke up, quite unabashed by the quiet dignity of the merchant's manner of speaking.

"Well," she began breathlessly, "I'm real glad to see you if you have kept me waiting. Here I've sot, an' sot, a good half-hour. 'Pears to me you Boston folks don't get up none too airly fer yer he'lth. I was down here before your shop was open this mornin'. Better late than never, though."

The merchant bent his head politely. His visitor caught her breath and went on:

"I'm Miss Marthy Seabury. What's all this coil about my nevvy? He's wrote me[Pg 94] that he was goin' away. Where's he gone? What's he done? That's what I'd like to know, right up an' down." She paused for a reply, never taking her eyes off the merchant's troubled face for an instant.

"My good woman," Mr. Bright began in a mollifying tone, when she broke in upon him abruptly:

"No palaverin', mister. No beatin' the bush, if ye please. Come to the p'int. I left my dirty dishes in the sink to home, an' must go back in the afternoon keers."