FOR THE SUBSCRIBERS.

1904.

[2]

AN INDEX EXPURGATORIUS.

The man who marks or leaves with pages bent

The volume that some trusting friend has lent,

Or keeps it over long, or scruples not

To let its due returning be forgot;

The man who guards his books with miser’s care,

And does not joy to lend them, and to share;

The man whose shelves are dust begrimed and few,

Who reads when he has nothing else to do;

The man who raves of classic writers, but

Is found to keep them with their leaves uncut;

The man who looks on literature as news,

And gets his culture from the book reviews;

Who loves not fair, clean type, and margins wide—

Or loves these better than the thought inside;

Who buys his books to decorate the shelf,

Or gives a book he has not read himself;

Who reads from priggish motives, or for looks,

Or any reason save the love of books—

Great Lord, who judgest sins of all degrees,

Is there no little private hell for these?

Edition 352 copies.

12 on large paper. [3]

INTRODUCTION.

This pamphlet in its present form is the result of an inquiry into the characters represented in a historical grade of the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite, and the probability of their having existed at the date mentioned in the said grade. Few appeared to have any very clear notion of the relation of the characters to the period—Frederick II. being confounded with his grand-father, Frederick Barbarossa—and the date of the supposed foundation of the Order of Teutonic Knights, 1190, being placed as the date of the papacy of Oronata, otherwise Honorius III. Inquiry being made of one in authority as to the facts in the case—he being supposed to know—elicited the reply that the matter had been called to his attention some months previous by an investigator—now deceased—but the matter had been dropped. It was also surmised by the same authority that an error might have been made by one of the committee having ritualistic matter in charge—but he, having also been gathered to his fathers, was not available for evidence.

It is stated that the action took place when Frederick II. was Emperor of Germany, and Honorius III. presided over spiritual conditions; but this Pope, according to Haydn’s Dictionary of Dates, reigned 1216–1227, and the dissertation on the pamphlet names Gregory IX., successor to Honorius, (1227–1241) as the Pope against whom the treatise was written. The infamous book mentioned in the representation no one [4]seemed to have any knowledge of. Inquiry made concerning the treatise at various libraries supposed to possess it, and of various individuals who might know something of it, elicited but the information that it was purely “legendary,” that, “it had no existence except by title,” and that “it was an item of literature entirely lost.”

Having been a book collector and a close reader of book catalogs for over twenty-five years, I had never noted any copy offered for sale, but a friend with the same mania for books, had seen a copy mentioned in a German catalog, and being interested in “de tribus Impostoribus” for reasons herein mentioned, had sent for and procured the same—an edition of a Latin version compiled from a Ms. 1598, with a foreword in German. The German was familiar to him, but the Latin was not available.

About the same time I found in a catalog of a correspondent of mine at London, a book entitled “Les Trois Imposteurs. De Tribus Impostoribus et dissertation sur le livre des Trois Imposteurs, sm. 4to. Saec. XVIII.,” and succeeded in purchasing it.

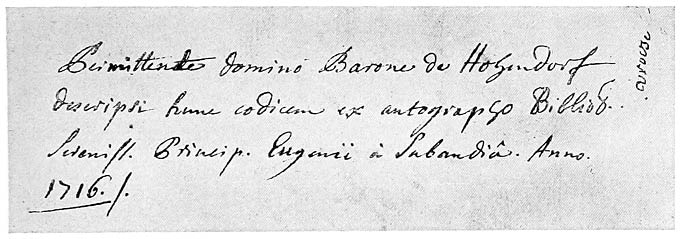

The manuscript is well written, and apparently by two different hands, which would be probable from the facts set forth in the “Dissertation.” A copy of the translation from the Latin is probably deposited in the library of Duke Eugene de Subaudio as set forth in the colophon at end of the manuscript.

The manuscript is written in the French of the period, and is dated in the colophon as 1716. The discovery of the original Latin document is mentioned in the “Dissertation” as about 1706. It has been annotated by another hand, as shown by foot notes, and several inserted sheets containing notes in still another [5]hand, were written evidently about 1746, as one of the sheets is a portion of a letter postmarked 4e Aout in latter year.

I append a bibliography from Weller’s Latin reprint of 1598 which will show that the pamphlet has “been done before”; but it will be noted that English versions are not so plenty as those in other tongues, and but one is known to have been printed in the United States.

I must acknowledge my indebtedness to Doctissimus vir Harpocrates, Col. F. Montrose, and Maj. Otto Kay for valued assistance in languages with which I am not thoroughly familiar, and also to Mr. David Hutcheson, of the Library of Congress, for favors granted.

Ample apologies will be found for the treatise in the several introductions quoted from various editions, and those fond of literary curiosities will certainly be gratified by its appearance in the twentieth century.

A. N. [7]

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

In 1846, Emil Weller published “De Tribus Impostoribus,” and also a later edition in 1876, at Heilbronn, from a Latin copy of one of the only four known to be in existence and printed in 1598. The copy from which it was taken, consisting of title and forty-six leaves, quarto, is at the Royal Library at Dresden, and was purchased for one hundred gulden.

The other three, according to Ebert in his “Bibliographical Lexicon,” are as follows: one in the Royal Library at Paris, one in the Crevanna Library and the other in the library of Renouard.

An edition was published at Rackau, in Germany, in 1598, and Thomas Campanella (1636), in his “Atheismus Triumphatus,” gives the year of its first publication as 1538.

Florimond Raimond (otherwise Louis Richeome,) claims to have seen a copy owned by his teacher, Peter Ramus, who died in 1572.

All the talk of theological critics that the booklet was first printed in the seventeenth century, is made out of whole cloth.

There is nothing modern about the edition of 1598. It may be compared, for example, with Martin Wittel’s print of the last decade of the sixteenth century, by which it is claimed that it could not have been printed then, as the paper and printing of that period closely resembles that of the eighteenth century.

With the exception of the religious myths, few [8]writings of the dark ages have had as many hypotheses advanced in regard to origin as there have been regarding this one.

According to John Brand it had been printed at Krakau, according to others, in Italy or Hungary as a translation of an Arabic original existing somewhere in France.

William Postel mentions a tract “de Tribus Prophetis,” and gives Michael Servetus, a Spanish doctor, as the author.

The Capuchin Monk Joly, in Vol. III of his “Conference of Mysteries,” assures us that the Huguenot, Nic. Barnaud, in 1612, on account of an issue of “de Tribus Impostoribus,” was excommunicated as its author.

Johann Mueller, in his “Besiegten Atheismus,” (Conquered Atheism), mentions a certain Nachtigal who published at Hague, in 1614, “De Trib. Imp.,” and was therefore exiled.

Mosheim and Rousset accuse Frederick II as the author with the assistance of his Chancellor, Petrus de Vineis. Vineis, however, declares himself opposed even to the fundamental principles of the book, and in his “Epist. Lib. 1, ch. 31, p. 211,” says he never had any idea of it.

Others place the authorship with Averroes, Peter Arretin and Petrus Pomponatius. Heinrich Ernst accuses the above mentioned Postel. Postel attributes it to Servetus, who, in turn, places it at the door of the Huguenot Barnaud.

The instigator of the treatise, it is claimed, should have been Julius Cesar Vanini, who was burned at Toulouse in 1619, or Ryswick, who suffered at the stake in Rome in 1612. [9]

Other persons accused of the authorship are Macchiavelli, Rabelais, Erasmus, Milton (John, born 1608,) a Mahometan named Merula, Dolet, and Giordano Bruno.

According to Campanella, to whom the authorship was attributed occasionally, Muret, or Joh. Franz. Poggio, were responsible. Browne says it was Bernhard Ochini, and Maresius lays it to Johann Boccaccio.

The “three cheats” are Moses, Jesus and Mahomet, but the tracts of each of the latter alleged authors treat only of Moses, of whom they say that his assertions in Genesis will not hold water, and cannot be proved.

Weller, in his edition of 1876, speaking of the copy of 1598, says that this issue should never be compared with any of the foregoing.

Many authors have written “de Tribus Impostoribus” because they had some special object in view; for instance, John Bapt. Morinus, when he edited, under the name of Vincentius Panurgius, in Paris, 1654, an argument against Gassendi, Neure, and Bernier.

Joh. Evelyn with a “Historia de tribus hujus seculi famosis Impostoribus,” Padre Ottomano, Mahomed Bei, otherwise Joh. Mich. Cigala, and Sabbatai Sevi (English 1680, German 1669,)1 Christian [10]Kortholt “de Tribus Impostoribus Magnus,” (Kiel 1680 and Hamburg 1701,) against Herbert, Hobbes and Spinosa, Hadrian Beverland, Perini del Vago, Equitis de Malta, “Epistolium ad Batavum in Brittania hospitem de tribus Impostoribus,” (Latin and English 1709.)

Finally, Michael Alberti, under the name of Andronicus, published a “Tractatus Medico-historicus de tribus Impostoribus,” which he named the three great Tempters of Humanity: 1. Tea and Coffee. 2. Laziness. 3. Home apothecaries.

Cosmopoli Bey (Peter Martin Roman), issued at Russworn in Rostock in 1731, and a new edition of same treatise—De Trib. Imp.—1738 and 1756.

For a long time scholars confused the genuine Latin treatise with a later one. De la Monnoye fabricated a long dissertation in which he denied the existence of the original Latin edition, but received a well merited refutation at the hands of P. F. Arpe.

The false book is French—“La vie et l’esprit de Mr. Benoit Spinoza.”2 The author of the first part [11]was Hofrath Vroes, in Hague, and the second was written by Dr. Lucas. It made its first appearance at Hague 1719, and later in 1721, under the title “de Tribus Impostoribus,” des Trois Imposteurs. Frankfort-on-the-Main at the expense of the Translator (i. e. Rotterdam.)

Richard la Selve prepared a third edition under the original title of “The Life of Spinoza,” by one of his Disciples. Hamburgh (really in Holland,) 1735.

In 1768 there was printed by M. M. Rey, at Amsterdam, a new edition called a “Treatise of the Three Impostors;” immediately after another edition appeared at Yverdoner 1768, another in Holland 1775, and a later one in Germany 1777.

The contents of “L’esprit de Spinoza” (German) by Spinoza II, or Subiroth Sopim—Rome, by Widow Bona Spes 5770—(Vieweg in Berlin 1787,) are briefly Chap. I, Concerning God. Chap. II, Reasons why men have created an invisible Being which is commonly called God. Chap. III, What the word Religion signifies, and how and why so many of these Religions have crept into the world. Chap. IV, Evident truths. Chap. V, Of the Soul. Chap. VI, Of Ghosts, Demons, etc. Then follows fifteen chapters which are not in the treatise (? Edition 1598.) [12]

The following became known by reason of peculiarities of their diction: 1. Ridiculum et imposturae in omni hominum religione, scriptio paradoxa, quam ex autographo gallico Victoris Amadei Verimontii ob summam rei dignitatem in latinum sermonem transtulit ††† 1746. Which according to Masch consists of from five to six sheets and follows the general contents, but not in the order of the original edition. 2. A second. Quaedam deficiunt, s. fragmentum de libro de tribus impostoribus. Fifty-one pages is a fragment. 3. One mentioned by Gottsched. De impostoris religionum breve. Compendium descriptum ab exemplari MSto. quod in Bibliotheca Jo. Fried. Mayeri, Berolini Ao. 1716, publice distracta deprehensum et a Principe Eugenio de Sabaudio 80 Imperialibus redemptum fuit. (forty-three pages.) The greater part of the real book in thirty-one paragraphs, the ending of which is Communes namque demonstrationes, quae publicantur, nec certae, nec evidentes, sunt, et res dubias per alias saepe magias dubias probant, adeo ut exemplo eorum, qui circulum currunt, ad terminum semper redeant, a quo currere inceperunt. Finis.3 A German translation of this is said to be in existence. 4. According to a newspaper report of 1716, there also should exist an edition which begins: Quamvis omnium hominem intersit nosse veritatem, rari tamen boni illi qui eam norunt, etc.,4 and ends, Qui veritatis amantes sunt, multum solatii inde capient, et hi sunt, quibus placere gestimus, nil curantes mancipia, quae praejudicia oraculorum—infallibilium loco venerantur. [13]

5. Straube in Vienna made a reprint of the edition of 1598 in 1753.

6. A new reprint is contained in a pamphlet edited by C. C. E. Schmid and almost entirely confiscated, entitled: Zwei seltene antisupernaturalistische manuscripte. Two rare anti-supernaturalistic manuscripts. (Berlin, Krieger in Giessen, 1792.)

7. There recently appeared through W. F. Genthe an edition, De impostura religionum compendium s. liber de tribus impostoribus, Leipsic, 1833.

8. Finally, through Gustav Brunet of Bordeaux an edition founded upon the text of the 1598 edition was produced with the title, de Tribus Impostoribus, MDIIC. Latin text collated from the copy of the Duke de la Valliere, now in the Imperial Library;5 enlarged with different readings from several manuscripts, [14]etc., and philologic and bibliographical notes by Philomneste Junior, Paris, 1861 (?1867). Only 237 copies printed, and is out of print and rare.

9. An Italian translation of the same appeared in 1864 by Daelli in Milan with title as above.

10. A Spanish edition also exists taken from the same source and under the same title. London (Burdeos) 1823.

Note. All the preceding Bibliography is from the edition of Emil Weller, Heilbronn 1876.—A. N.

The only edition known to have been printed in the United States was entitled “The Three Impostors.” Translated (with notes and illustrations) from the French edition of the work, published at Amsterdam, 1776. Republished by G. Vale, Beacon Office, 3 Franklin Square, New York, 1846, 84pp. 12o. A copy is in the Congressional Library at Washington.

From this I transcribe the following notes:

NOTE BY THE AMERICAN PUBLISHER.

We publish this valuable work, for the reasons contained in the following Note, of which we approve:

NOTE BY THE BRITISH PUBLISHER.

The following little book I present to the reader without any remarks on the different opinions relative to its antiquity; as the subject is amply discussed in the body of the work, and constitutes one of its most interesting and attractive features. The Edition from which the present is translated was brought me from [15]Paris by a distinguished defender of Civil and Religious Liberty: and as my friend had an anxiety from a thorough conviction of its interest and value, to see it published in the English Language, I have from like feelings brought it before the public, and I am convinced that it is eminently calculated to promote the cause of Freedom, Justice and Morality.

J. Myles.

PREFACE BY THE TRANSLATOR.

The Translator of the following little treatise deems it necessary to say a few words as to the object of its publication. It is given to the world, neither with a view to advocate Scepticism, nor to spread Infidelity, but simply to vindicate the right of private judgment. No human being is in a position to look into the heart, or to decide correctly as to the creed or conduct of his fellow mortals; and the attributes of the Deity are so far beyond the grasp of limited reason, that man must become a God himself before he can comprehend them. Such being the case, surely all harsh censure of each other’s opinions and actions ought to be abandoned; and every one should so train himself as to be enabled to declare with the humane and manly philosopher

“Homo sum, nihil humani me alienum puto.”

Dundee, September 1844.

The Vale production is evidently translated from an edition derived from the Latin manuscript which is the basis of the translation given in this volume. The variations in the text of each not being important, but [16]simply due to the different modes of expression of the translators—the ideas conveyed being the same.

The Treatise in Vale’s edition concludes with the following:

“Happy the man who, studying Nature’s laws,

Through known effects can trace the secret cause;

His mind possessing in a quiet state,

Fearless of Fortune, and resigned to Fate.”

—Dryden’s Virgil. Georgics Book II, l. 700.

There is also in the Library of Congress a volume entitled “Traité des Trois Imposteurs.” En Suisse de l’imprimerie philosophique—1793. Boards 3½ × 5¾ inches, containing the Treatise proper 112 pp. Sentimens sur le traite des trois imposteurs, (De la Monnaye) 32 pp. Response a la dissertation de M. de la Monnaye 19 pp. signed J. L. R. L. and dated at Leyden 1 Jan., 1716, to which this note is appended: “This letter is from Sieur Pierre Frederic Arpe, of Kiel, in Holstein, author of the apology of Vanini, printed at Rotterdam in 8o, 1712.” The letter contains the account of the discovery of the original Latin manuscript at Frankfort-on-the-Main, in substance much the same as the translation given in this edition.

In the copy at the Congressional Library, I find the following manuscript notes which may be rendered as follows: “Voltaire doubted the existence of this work, this was in 1767. See his letter to his Highness Monseigneur The Prince of ——. Letter V, Vol. 48 of his works, p. 312.”

See Barbier Dict. des ouv. anon. Nos. 18250, 19060, 21612.

De Tribus Impostoribus. Anon.

L’esprit de Spinosa trad. du latin par Vroes. [17]

In connection with this latter note, and observing the name written at end of the colophon of the manuscript from which the present edition is translated, it is probable that this same Vroese was the author of another translation.

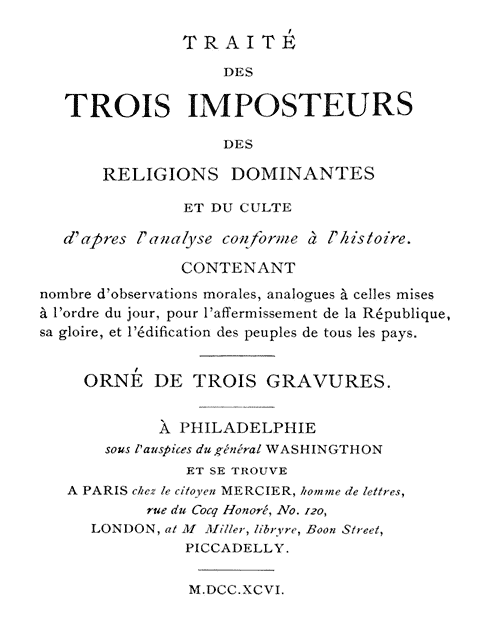

Another remarkable copy is contained in the Library of Congress, the title page of which is displayed as follows: [18]

TRAITÉ

DES

TROIS IMPOSTEURS

DES

RELIGIONS DOMINANTES

ET DU CULTE

d’apres l’analyse conforme à

l’histoire.

CONTENANT

nombre d’observations morales, analogues à celles mises à l’ordre du jour, pour l’affermissement de la République, sa gloire, et l’édification des peuples de tous les pays.

ORNÉ DE TROIS GRAVURES.

À PHILADELPHIE

sous l’auspices du général WASHINGTHON

ET SE TROUVE

A PARIS chez le citoyen MERCIER, homme de lettres, rue

du Cocq Honoré, No. 120,

LONDON, at M. Miller, libryre, Boon Street,

PICCADELLY.

M.DCC.XCVI.

Note.—This edition has undoubtedly been translated from the original Latin manuscript.—A. N.

Translation. Treatise of the Three Impostors of the governing Religions and worship, after an examination conformable to history, containing a number of moral observations, analogous to those placed in the order of the day for the support of the republic, its glory, and the edification of the people of all countries. Ornamented with three engravings. At Philadelphia under the auspices of General Washington, and may be found at Paris at the house of Citizen Mercier (Claude Francois Xavier6), man of letters, 120 Cocq Honoré street, and at London at Mr. Miller’s, bookseller, Boon street, Piccadelly, 1796. [19]

On the following page may be found the following:

LE PEUPLE

FRANÇAIS

RECONNANT

L’ÊTRE SUPRÊME

L’IMMORTALITÉ DE L’AME

ET LA LIBERTÉ DES CULTES

——7

TRAITÉ

DES

Religions Dominantes8

| Chapter | I. | Concerning God, | 6 | paragraphs. | ||

| Chapter | II. | Reasons, etc., | 11 |

|

||

| Chapter | III. | Religious, | 9 |

|

“Les prêtres ne sont pas ce qu’un vain peuple pense

Notre crédulité fait toute leur science.”

Priests are not what vain people think,

Our credulity makes all their science.

| Chapter | IV. | Moses, | 2 | paragraphs. | ||

| Chapter | V. | Jesus Christ, | 10 |

|

Paragraph 2. Politics; paragraph 6. Morals.

| Chapter | VI. | Mahomet, | 2 | paragraphs. | ||

| Chapter | VII. | Evident Truths, | 6 |

|

||

| Chapter | VIII. | The Soul, | 7 |

|

||

| Chapter | IX. | Demons, | 7 |

|

Facing page twenty-seven is a medallion copper plate of Moses, around which are these words (translated): “Moses saw God in the burning bush,” and beneath the following from Voltaire’s Pucelle (translated):

Alone on the summit of the mysterious mount

As he desired, he closed his fortieth year.

Then suddenly he appeared upon the plain

With buck’s horns9 shining on his forehead.

Which brilliant miracle in the mind of the philosopher

Created a prompt effect.”

In a note to par. II. occur the following lines which translated read:

“How many changes a revolution makes:

Heaven has brought us forth in happy time

To see the world——Here the weak Italian

Is frightened at the sight of a stole:

The proud Frenchman astonished at nothing

Boldly goes to defy the Pope at his capital

And the grand Turk in turban, like a good Christian,

Recites the prayers of his faith

And prays to God for the pagan Arab,

Having no thought of any kind of expedient

Nor means to destroy altars and idol worship.

The Supreme Being his only and sole support,

Does not exact for offering a single coin

From any sect, from Jew nor plebeian:

What need has He of Temple or archbishop?

The heart of the just and the general good

Shines like a brilliant sun on the halo of glory.”

Then follows a “Bouquet for the Pope”:

“Thou whom flatterers have invested with a vain title,

Shalt thou at this late day become the arbiter of Europe?

Charitable pontiff, and friend of humanity,

Having so many sovereigns as fathers of families, [21]

The successors of Christ, in the midst of the sanctuary

Have they not placed unblushingly, incest and adultery?

Be this the last of imposture and thy last sigh.

Do thyself more honor, esteem and pleasure,

Than all the monuments erected to the glory

Of thy predecessors in the temple of memory.

Let them read on thy tomb ‘he was worthy of love,

The father of the Church and oracle of the day.’”

On the following page is a copper plate profile portrait of Pius VI. surrounded by the words “Senatus Populus Que Romanus.” At the side Principis Ecclesiae dotes vis Cernere Magni. (Senate and People of Rome—Prince of the Church endowed with power and great wisdom.) Beneath:

“The talents of the learned and the virtues of the wise,

A noble and beneficent manner with which all are charmed,

Depict much better than this image

The true portrait of Pius VI.”

Facing page fifty-one is a copper plate portrait of Mahomet, and beneath this tribute:

“Know you not yet, weak and superb man,

That the humble insect hidden beneath a leaf

And the imperious eagle who flies to heaven’s dome,

Amount to nothing in the eyes of the Eternal.

All men are equal: not birth but virtue

Distinguishes them apart.”

Then there are inserted a number of verses, some of the titles reading:

- “Homage to the Supreme Being.”

- “Voltaire Admitted to Heaven.”

- “Homage to the Eternal Father.”

- “Bouquet to the Archbishop of Paris.”

- “Infinite Mercy—Consolation for Sinners.”

- “Lots of Room in Heaven.”

- “The Holy Spirit Absent from Heaven,” etc.

[22]

Concluding with “A Picture of France at the Time of the Revolution.”

“Nobility without souls, a fanatical clergy.

Frightful tax gatherers gnawing a plucked people.

Faith and customs a prey to designing persons.

A price set upon the head of the Chancellor (Maupeou).

The skeleton of a perfidious Senate.

Not daring to punish a parricidal conspiracy.

O, my country! O, France! Thy miseries

Have even drawn tears from Rome.10

If you have no Republic, and no pure legislators

Like exist in America, to deliver you from the oppression

Of a tyrannous empire of knaves, brigands and robbers;

Like the British cabinet and the skillful Pitt, chief of flatterers,

Who with his magic lantern fascinates even the wise ones.

This clique will soon be seen to fall, if the French become the conquerors

Of this ancient slavery, and show themselves the proud protectors

Of their musical Carmagnole.

In the name of kings and emperors, how much iniquity and horror

Which are recorded in history, cause the reader to shudder with fright.

The entrance of friends in Belgium, to the eyes of those who know,

Is it not an unique epoch?

And this most flattering tie, sustained by a heroic compact,

Will be the desire of all hearts.”

À BOSTON

under the protection of Congress.

Bound in this volume is a pamphlet entitled “La Fable de Christ devoilée.” Paris: Franklin Press. 75 Rue de Clery. 2nd year of the Republic. Also, [23]“Éloge non-funèbre de Jesus et du Christianisme. Printed on the débris of the Bastille, and the funeral pile of the Inquisition. 2nd year of Liberty, and of Christ 1791.”

Another closes the volume: “Lettres Philosophique sur St. Paul: sur sa doctrine, politique, morale, & réligieuse, & sur plusieurs points de la réligion chrétienne considerées politiquement.” (J. P. Brissot de Warville.) Translated from the English by the philosopher de Ferney and found in the portfolio of M. V. his ancient secretary. Neuchatel en Suisse 1783.

Note translated from the edition “En Suisse, de l’imprimerie philosophique,” 1793.

In a response to M. de la Monnoye, who laboriously endeavored to refute the existence of the treatise entitled “The Three Impostors,” and which reply in addition to M. de la Monnoye’s arguments appear in connection with some of the translations of the treatise, occurs the following introduction to the account of the discovery of the original manuscript: “I have by me a more certain means of overturning this dissertation of M. de la Monnoye, when I inform him that I have read this celebrated little work and that I have it in my library. I will give you and the public an account of the manner in which I discovered it, and as it is in my possession I will subjoin a short but faithful description of it.”

Here follows a summary of the contents and the Dissertation, in substance the same as our manuscript; the response concluding as follows:

“Such is the anatomy of this celebrated work. I might have given it in a manner more extended and [24]more minute; but besides that this letter is already too long, I think that enough has been said to give insight into the nature of its contents. A thousand other reasons which you will well enough understand, have prevented me from entering upon it to so great length as I could have done; “Est modus in rebus.”11

“Now although this book were ready to be printed12 with the preface in which I have given its history, and its discovery, with some conjectures as to its origin, and a few remarks which may be placed at its conclusion, yet I do not believe that it will live to see the day when men will be compelled all at once to quit their opinions and their imaginations, as they have quitted their syllogisms, their canons, and their other antiquated modes. As for me I will not expose myself to the Theological stylus13—which I fear as much as Fra-Poula feared the Roman stylus—to afford to a few learned men the pleasure of reading this little treatise; but neither will I be so superstitious, on my death bed, as to cause it to be thrown into the flames, which we are informed was done by Salvius, the Swedish ambassador, [25]at the peace of Munster. Those who come after me may do what seems to them good—they can not disturb me in the tomb. Before I descend to that, I remain with much respect, your most obedient servant,

J. L. R. L.

“Leyden, 1st January, 1716.”

This letter was written by Mr. Pierre Frederick Arpe, of Kiel, in Holstein; the author of an apology for Vanini, printed in octavo at Rotterdam, 1712.

[26]

1 The History of the Three Infamous Impostors of this Age.

1. Padre Ottomano, a pretended son of the Sultan of Turkey who flourished about 1650, and who latterly, under the above title, became a Dominican Friar.

2. Mahomed Bei, alias Joannes Michael Cigala, who masqueraded as a Prince of the Ottoman family, a descendant of the Emperor Solyman the Magnificent, and in other characters about 1660.

3. Sabbatai Sevi, the pretended Messiah of the Jews, “the Only and First-borne Son of God,” who amused the Jews and Turks about 1666. ↑

2 La vie et l’esprit de M. Benoit de Spinosa was published without the author’s name, in Amsterdam 1719. In the “Preface du Copiste” it is stated that the author of it is not known, but that if a conjecture might be permitted it might be said, perhaps with certitude, that the book is the work of the late Mr. Lucas, so famous for his Quintessences and for his manners and way of living.

Kuno Fischer, in his Descartes und seine Schule. Zweiter Theil, Heidelberg, 1889, p. 101, says:

“The real author of the work is not known with entire certainty; probably the author was Lucas, a physician at the Hague, notorious in his own day; others name as author a certain Vroese.”

Freudenthal, in his Die Lebensgeschichte Spinoza’s. Leipzig, 1899, writing of the various conjectures as to the authorship of the book, states that W. Meyer has lately sought to prove that Johan Louckers, a Hague attorney, was the author, but that the authorship had not been settled.

Oettinger in his Bibliographie Biographie Universelle, Bruxelles 1854, p. 1707, gives Lucas Vroese as the author.

It has also been suggested that Lucas and Vroese were two men and together wrote the book.

The authority for ascribing the book to Vroese, of whose life no particulars seem to have been recorded, appears to be the following passage in the Dictionnaire Historique, par Prosper Marchand, à la Haye, 1758, v. 1., p. 352:

“A la fin d’une copie manuscrit de ce Traité que j’ai vûe et lûe, on lui donne pour véritable Auteur a Mr. Vroese, conseiller de la cour de Brabant à la Haie, dont Aymon et Rousset retouchèrent le langage; et que ce dernier y ajouta la Dissertation ou Réponse depuis imprimée chez Scheurleer.”

The name “Vroese” appears at the side of the colophon at end of our translation, but probably as a reference only. ↑

3 This is probably a Latin edition of the original manuscript from which our translation was made.—Ed. ↑

4 See translation Chap. 1 “Of God,” first two lines. ↑

5 DISRAELI’S CURIOSITIES OF LITERATURE.

Title, “Literary Forgeries.”

“The Duc de la Valliere and the Abbe de St. Leger, once concerted together to supply the eager purchaser of literary rarities with a copy of “De Tribus Impostoribus,” a book, by the date, pretended to have been printed in 1598, though probably a modern forgery of 1698. The title of such a book had long existed by rumor, but never was a copy seen by man. Works printed with this title have all been proved to be modern fabrications—a copy however of the ‘introuvable’ original was sold at the Duc de la Valliere’s sale. The history of this volume is curious. The Duc and the Abbe having manufactured a text had it printed in the old Gothic character, under the title ‘De Tribus Impostoribus.’ They proposed to put the great bibliopobet, De Bure, in good humor, whose agency would sanction the imposition. They were afterwards to dole out copies at 25 louis each, which would have been a reasonable price for a book which no one ever saw! They invited De Bure to dinner, flattered and cajoled him, and, as they imagined at the moment they had wound him up to their pitch, they exhibited their manufacture—the keen-eyed glance of the renowned cataloguer of the ‘Bibliographie Instructive’ instantly shot like lightning over it, and like lightning, destroyed the whole edition. He not only discovered the forgery but reprobated it! He refused his sanction; and the forging Duc and Abbe, in confusion suppressed the ‘livre introuvable’; but they owed a grudge to the honest bibliographer and attempted to write down the work whence the De Bures derive their fame.” ↑

6 The names are noted on title page in pencil. ↑

7 The French nation recognize the Supreme Being, the Immortality of the Soul, and the Freedom of Worship. ↑

8 Treatise of the Dominant Religions. ↑

9 In old prints Moses is always depicted with horns on his forehead. ↑

10 When they weep at Rome, they do not laugh in Paris. ↑

11 There is a measure in everything. ↑

12 As to the printing of the book they can bring forward no proof whatever of its having being done prior to this date (1716) and it is impossible to conceive that Frederick, surrounded as he was by enemies, would have circulated a work which gave a fair opportunity of proclaiming his infidelity. It is probable therefore that there were only two copies, the original one and that sent to Otho of Bavaria. J. L. R. L. ↑

13 This phrase is frequently employed to express ecclesiastical criticism. Its first application however had a more pungent meaning. The individual here alluded to having boldly assailed the errors of the Church was attacked one evening by an assassin. Fortunately the blow did not prove fatal; but the weapon (a stylus, or dagger, which is also the Latin name for a pen) having been left in the wound, on his recovery he wore it in his girdle labelled, “The Theological Stylus,” or Pen of the Church. The trenchant powers of this instrument have more frequently been employed to repress truth, than to refute argument. ↑

DISSERTATION ON THE BOOK OF THE THREE IMPOSTORS.

More than four hundred years have elapsed since this little treatise was first mentioned, the title of which has always caused it to be qualified as impious, profane and worthy of the fire. I am convinced that none of those who have mentioned it have read it, and after having examined it carefully, it can only be said that it is written with as much discretion as the matter would allow to a man persuaded of the falsehood of the things which he attacked, and protected by a powerful prince, under whose direction he wrote.

There have been but few scholars whose religious beliefs were dubious, who have not been credited with the authorship of this treatise.

Averroes, a famous Arabian commentator on Aristotle’s works, and celebrated for his learning, was the first to whom this production was attributed. He lived about the middle of the twelfth century when the “three impostors” were first spoken of. He was not a Christian, as he treated their religion as “the Impossible,” nor a Jew, whose law he called “a Religion for Children,” nor a Mahometan, for he denominated their belief “a Religion for Hogs.” He finally died a Philosopher, that is to say, without having subscribed to the opinions of the vulgar, and that was sufficient to publish him as the enemy of the law makers of the three Religions that he had scorned.

Jean Bocala, an Italian scholar of a happy disposition, and consequently not much imbued with [27]bigotry, flourished in the middle of the fourteenth century. A fable that he ventured in one of his works, concerning “Three Rings,” has been regarded as evidence of this execrable book whose author was looked for, and this was considered sufficient to attribute the authorship to him long after his death.

Michael Servetus, burned at Geneva (1553) by the pitiless persecution of Mr. John Calvin, he not having subscribed to either the Trinity or the Redeemer, it became proper to attribute to him the production of this impious volume.

Etienne Dolit, a printer at Paris, and who ranked among the learned, was led to the stake—to which he had been condemned as a Calvinist in 1543—with a courage comparable to that of the first martyrs. He therefore merited to be treated as an atheist, and was honored as the author of the pamphlet against the “Three Impostors.”

Lucilio Vanini, a Neapolitan, and the most noted atheist of his time, if his enemies may be believed, fairly proved before his judges—however he may have been convinced—the truth of a Providence, and consequently a God. It sufficed however for the persecution of his enemies, the Parliament of Toulouse, who condemned him to be burned as an atheist, and also to merit the distinction of having composed, or at least having revived, the book in question.

I am not sure but what Ochini and Postel, Pomponiac and Poggio the Florentine, and Campanella, all celebrated for some particular opinion condemned by the Church of their time, were for that reason accused as atheists, and also adjudged without trouble, the authors of the little truth for whom a parent was sought. [28]

All that famous critics have published from time to time of this book has excited the curiosity of the great and wise to determine the author, but without avail.

I believe that several treatises printed with the title “de Tribus Impostoribus,” such as that of Kortholt against Spinosa, Hobbes and the Baron Cherbourg; that of the false Panurge against Messieurs Gastardi, de Neure and Bernier have furnished many opportunities for an infinity of half-scholars who only speak from hearsay, and who often judge a book by the first line of the title. I have, like many others who have examined this work, done so in a superficial manner. Though I am a delver in antiquities, and a decipherer of manuscript, chance having caused the pamphlet to fall into my hands at one time, I avow that I gave neither thought to the production nor to its author.

Some business affairs having taken me to Frankfort-on-the-Main about the month of April, (1706), that is about fifteen days after the Fair, I called on a friend named Frecht, a Lutheran theological student, whom I had known in Paris. One day I went to his house to ask him to take me to a bookseller where he could serve me as interpreter. We called on the way on a Jew who furnished me with money and who accompanied us.

Being engaged in looking over a catalog at the book store, a German officer entered the shop, and said to the bookseller without any form of compliment, “If among all the devils I could find one to agree with you, I would still go and look for another dealer.” The bookseller replied that “500 Rix dollars was an excessive price, and that he ought to be satisfied with the 450 that he offered.” The officer told him to “go [29]to the Devil,” as he would do nothing of the sort, and was about to leave. Frecht, who recognized him as a friend, stopped him and having renewed his acquaintance, was curious to know what bargain he had concluded with the bookseller. The officer carelessly drew from his pocket a packet of parchment tied by a cord of yellow silk. “I wanted,” said he, “500 Rix dollars to satisfy me for three manuscripts which are in this package, but Mr. Bookseller does not wish to give but 450.” Frecht asked if he might see the curiosities. The officer took them from his pocket, and the Jew and myself who had been merely spectators now became interested, and approached Frecht, who held the three books.

The first which Frecht opened was an Italian imprint of which the title was missing, and was supplied by another written by hand which read

“Specchia della Bestia Triomphante.” The book did not appear of ancient date, and had on the title neither year nor name of printer.

We passed to the second, which was a manuscript without title, the first page of which commenced “OTHONI illustrissimo amico meo charissimo. F. I. s. d.” This embraced but two lines, after which followed a letter of which the commencement was “Quod de tribus famosissimis Nationum Deceptoribus in ordinem. Justu. meo digesti Doctissimus ille vir, que cum Sermonem de illa re in Museo meo habuisti exscribi curavi atque codicem illum stilo aeque, vero ac puro scriptum ad te ut primum mitto, etenim ipsius per legendi te accipio cupidissimum.”

The other manuscript was also Latin, and without title like the other. It commenced with these words—from Cicero if I am not mistaken: “An. I. liber [30]de Nat. Deor. Qui Deos esse dixerunt tantu sunt in Varietate et dissentione constituti ut eorum molestum sit dinumerare sententias. Altidum freri profecto potest ut eorum nulla, alterum certi non potest ut plus unum vera fit. Summi quos in Republica obtinnerat honores orator ille Romanus, ea que quam servare famam Studiote curabat, in causa fuere quod in Concione Deos non ansus sit negare quamquam in contesta Philosophorum, etc.”

We paid but little attention to the Italian production, which only interested our Jew, who assured us that it was an invective against Religion. We examined several phrases of the latter by which we mutually agreed that it was a system of Demonstrated Atheism. The second, which we have mentioned, attracted our entire attention, and Frecht having persuaded his friend, whose name was Tausendorff, not to take less than 500 Rix dollars, we left the bookseller’s shop, and Frecht, who had his own ideas, took us to his inn, where he proposed to his friend to empty a bottle of good wine together. Never did a German decline a like proposition, so Frecht immediately ordered the wine, and asked Tausendorff to tell us how these manuscripts fell into his possession.

After enjoying his portion of six bottles of old Moselle, he told us that after the victory at Hochstadt1 and the flight of the Elector of Bavaria, he was one of those who entered Munich, and in the palace of His Highness, he went from room to room until he reached the library. Here his eyes fell by chance on the package of parchments with the silk cord, and believing them to be important papers or curiosities, he could not resist the temptation of putting them in his pocket. [31]He was not deceived when he opened the package and convinced himself. This recital was accompanied by many soldier-like digressions, as the wine had a little disarranged the judgment of Tausendorff. Frecht, who, during the story, perused the manuscript, took the chance of a refusal by asking his friend to allow him to take the book until the next day. Tausendorff, whom the wine had made generous, consented to the request of Frecht, but he exacted a terrible oath that he would neither copy it or cause it to be done, promising to come for it on Sunday and empty some more bottles of wine, which he found to his taste.

This obliging officer had no sooner left than we commenced to decipher it. The writing was so small, full of abbreviations, and without punctuation, that we were nearly two hours in reading the first page, but as soon as we were accustomed to the method we commenced to read it more easily. I found it so accurate and written with so much care, that I proposed to Frecht an equivocal method of making a copy without violating the oath which he had taken: which method was to make a translation. The conscience of a theologian did not but find difficulties in such proposal, but I removed them as I could, assuming the sin myself, and in the end he consented to work on the translation which was finished before the time fixed by Tausendorff.

This is the way in which this book came into our hands. Many would have desired to possess the original but we were not rich enough to buy it. The bookseller had a commission from a Prince of the House of Saxony, who knew that it had been taken from the library at Munich, and he was to spare no effort to secure it, if he found it, by paying the 500 [32]Rix dollars to Tausendorff who went away several days after, having regaled us in his turn.

Passing to the origin of the book, and its author, one can hardly give an account of either only by consulting the book itself in which but little is found except for the base of conjecture. There is only a letter at the beginning, and which is written in another character from the rest of the book, which gives any light. We find it addressed OTHONI, Illustrissimo. The place where the manuscript was found, and the name OTHO put together warrants the belief that it was addressed to the Illustrious Otho, lord of Bavaria. This prince was grandson of Otho, the Great; Count of Schiren and Witelspach from whom the House of Bavaria and the Palatine had their origin. The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa2 had given him Bavaria for his fidelity, after having taken it from Henry the Lion to punish him for his inconsistency in taking the part of his enemies. Louis I. succeeded his father, Otho the Great, and left Bavaria—in the possession of which he [33]had been disturbed by Henry the Lion—to his son Otho, surnamed the Illustrious, who assured his possession by wedding the daughter of Henry. This happened about the year 1230, when Frederick II., Emperor of Germany, returned from Jerusalem, where, at the solicitation of Pope Gregory IX., he had pursued the war against the Saracens, and from whence he returned irritated to excess against the Holy Father who had incensed his army against him, as well as the Templars and the Patriarch of Jerusalem, until the Emperor refused to obey the Pope.

Otho the Illustrious recognizing the obligations that his family were under to the family of the Emperor, took his part and remained firmly attached to him, notwithstanding all the vicissitudes of fortune of Frederick.

Why these historical reminiscences? To sustain the conjecture that it was to this Otho the Illustrious that this copy of the pamphlet of the Three Impostors was addressed. By whom? This is why we are led to believe that the F. I. s. d. which follows L’amico meo carissimo, and which we interpret FREDERICUS. [34]Imperator salutem Domino. Thus this would be by The Emperor Frederick II., son of Henry IV. and grandson of Frederick Barbarossa, who, succeeding to their Empire, had at the same time inherited the hatred of the Roman Pontiffs.3

Those who have read the history of the Church and that of the Empire, will recall with what pride and arrogance the indolent Alexander III. placed his foot on the neck of Frederick Barbarossa, who came to him to sue for peace. Who does not know the evil that the Holy See did to his son Henry VI., against whom his own wife took up arms at the persuasion of the Pope? At last Frederick II. uniting in himself all the resolution which was wanting in his father and grandfather, saw the purpose of Gregory IX., who seemed to have marshalled on his side all the hatred of Alexander, Innocent and Honorius against his Imperial Majesty. One brought the steel of persecution, and the other the lightning of excommunication, and furiously they vied with each other in circulating infamous libels. This, it seems to me, is warrant sufficient to apply these happenings to the belief that this book was by order of the Emperor, who was incensed against religion by the vices of its Chief, and written by the Doctissimus vir, who is mentioned in the [35]letter as having composed this treatise, and which consequently owes its existence not so much to a search for truth, as to a spirit of hatred and implacable animosity.

This conjecture may be further confirmed by remarking that this book was never mentioned only since the régime of that Emperor, and even during his reign it was attributed him, since Pierre des Vignes, his secretary, endeavored to cast this false impression on the enemies of his master, saying that they circulated it to render him odious.

Now to determine the Doctissimus vir who is the author of the book in question. First, it is certain that the epoch of the book was that which we have endeavored to prove. Second, that it was encouraged by those accused of its authorship, possibly excepting Averroes, who died before the birth of Frederick II. All the others lived a long time, even entire centuries after the composition of this work. I admit that it is difficult to determine the author only by marking the period when the book first made its appearance, and in whatever direction I turn, I find no one to whom it could more probably be attributed than Pierre des Vignes whom I have mentioned.

If we had not his tract “De poteste Imperiali,” his other epistles suffice to show with what zeal he entered into the resentment of Frederick II. (whose Secretary he was) against the Holy See. Those who have spoken of him, Ligonius, Trithemus and Rainaldi, furnish such an accurate description of him, his condition and his spirit, that after considering this I cannot remark but that this evidence favors my conjecture. Again, as I have remarked, he himself spoke of this book in his epistles, and he endeavored to accuse the [36]enemies of his master to lessen the clamor made to encourage the belief that this Prince was the author. As he had taken the greater part, he did not greatly exert himself to lessen the injurious noise, so that if the accusation was strengthened by passing for a long time from mouth to mouth it would not fall from the Master on his Secretary, who was probably more capable of the production than a great Emperor, always occupied with the clamors of war and always in fear of the thunders of the Vatican. In one word, the Emperor, however valiant and resolute, had no time to become a scholar like Pierre des Vignes, who had given all the necessary attention to his studies, and who owed his position and the affection of his Master entirely to his learning.

I believe that we can conclude from all this, that this little book Tribus famosissimus Nationum Deceptoribus, for that is its true title, was composed after the year 1230 by command of the Emperor Frederick II. in hatred of the Court of Rome: and it is quite apparent that Pierre des Vignes, Secretary to the Emperor, was the author.4

This is all that I deem proper for a preface to this little treatise, and as it contains many naughty allusions, to prevent that in the future, it may not be again attributed to those who perhaps never entertained such ideas.

2 Frederick Barbarossa was Emperor of Germany in 1152 and was drowned during Crusade in Syria June 10, 1190. He created Henry the Lion (? Henry VI.) Duke of Bavaria in 1154, expelled him in 1180, and Henry died 1195.

Otho the Great, Count of Witelspach, was made Duke of Bavaria 1180, and died 1183. He was the grandfather of Otho the Illustrious, who gained the Palatinate and was assassinated in 1231. He married the daughter of Henry the Lion about 1230.

Henry VI succeeded to the Empire on death of his father, Frederick Barbarossa, 1190, and died 1195—that is if Henry the Lion and Henry VI are identical.

Frederick II, son of Henry VI, began to reign (?) 1195, and was living 1243.

The succession of Popes during the period 1152–1254 (Haydn’s Dict. of Dates), was as follows:

Anastasius IV, 1153, Adrian IV, 1154, (Nicholas Brakespeare, the only Englishman elected Pope. Frederick I. prostrated himself before him, kissed his foot, held his stirrup, and led the white palfrey on which he rode.)

Alexander III. 1159, (Canonized Thomas à Becket and resisted Frederick I.) Victor V. 1159, Pascal III. 1164, Calixtus III. 1168, Lucius III. 1181.

Urban III. 1185, (opposed Frederick I.) Gregory VIII. (2 months) 1187. Clement III. 1187, proclaimed third Crusade.

Celestin III. 1191. Innocent III. 1198, excommunicated John, King of England. Honorius III. 1216, learned and pious. Gregory IX. 1227, preached new Crusade. Celestine IV. 1241. Innocent IV. 1243–1254 (opposed Frederick II.).

If Frederick II. caused pamphlet to be written about 1230, it could not have been burned by Honorius III., who reigned as Pope 1216–1227, but by Gregory IX., who reigned 1227–1241, who sent Frederick II. to the Crusades, upset his affairs while he was gone, and against whom the “Dissertation” says the pamphlet was written. ↑

3 Carlyle, in his “History of Frederick II. of Prussia, called Frederick the Great,” mentions Hermann von der Saltza, a new sagacious Teutschmeister or Hochmeister (so they call the head of the Order) of the Teutonic Knights, a far-seeing, negotiating man, who during his long Mastership (A. D. 1210–1239,) is mostly to be found at Venice and not at Acre or Jerusalem.

He is very great with the busy Kaiser, Frederick II., Barbarossa’s grandson, who has the usual quarrels with the Pope, and is glad of such a negotiator, statesman as well as armed monk. A Kaiser not gone on the Crusade, as he had vowed: Kaiser at last suspected of free thinking even:—in which matters Hermann much serves the Kaiser.—People’s Edition, Boston, 1885, Vol. 1, p. 92. ↑

4 Pierre des Vignes, suspected of having conspired against the life of the Emperor, was condemned to lose his eyes, and was handed over to the inhabitants of Pisa, his cruel enemies: and where despair hastened his death in an infamous dungeon where he could hold intercourse with no one. ↑

[37]

Frederick Emperor

to the very Illustrious Otho

my very faithful Friend,

Greeting:

I have taken the trouble to have copied the Treatise which was made concerning the Three Famous Impostors, by the learned man by whom you were entertained on this subject, in my study, and though you have not requested it, I send you the manuscript entire, in which the purity of style equals the truth of the matter, for I know with what interest you desired to read it, and also I am persuaded that nothing could please you more.

It is not the first time that I have overcome my cruel enemies, and placed my foot on the neck of the Roman Hydra whose skin is not more red than the blood of the millions of men that its fury has sacrificed to its abominable arrogance.

Be assured that I will neglect nothing to have you understand that I will either triumph or perish in the attempt; for whatever reverses may happen to me, I will not, like my predecessors, bend my knee before them.

I hope that my sword, and the fidelity of the members of the Empire; your advice and your assistance will contribute not a little. But nothing would add more if all Germany could be inspired with the sentiments of the Doctor—the author of this book. This is much to be desired, but where are those capable of accomplishing such a project? I recommend to you our common interests, live happy. I shall always be your friend.

F. I. [38]