THE INVADED COUNTRY

Title: The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record

Author: Arnold Toynbee

Release date: December 18, 2015 [eBook #50716]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Larger versions of the maps can be viewed by clicking on each map in a web browser.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

An Historical Record

BY

ARNOLD J. TOYNBEE

LATE FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE,

OXFORD

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

MCMXVII

COPYRIGHT, 1917,

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The subject of this book is the treatment of the civil population in the countries overrun by the German Armies during the first three months of the European War. The form of it is a connected narrative, based on the published documents[1] and reproducing them by direct quotation or (for the sake of brevity) by reference.

With the documents now published on both sides it is at last possible to present a clear narrative of what actually happened. The co-ordination of this mass of evidence, which has gradually accumulated since the first days of invasion, is the principal purpose for which the book has been written. The evidence consists of first-hand statements—some delivered on oath before a court, others taken down from the witnesses without oath by competent legal examiners, others written and published on the witnesses’ own initiative as books or pamphlets. Most of them originally appeared in print in a controversial setting, as proofs or disproofs of disputed fact, or as justifications or condemnations of fact that was admitted. In the present work, however, this argumentative aspect of them has been avoided as far as possible. For it has either been treated exhaustively in official publications—the[vi] case of Louvain, for instance, in the German White Book and the Belgian Reply to it—or will not be capable of such treatment till after the conclusion of the War. The ultimate inquiry and verdict, if it is to have finality, must proceed either from a mixed commission of representatives of all the States concerned, or from a neutral commission like that appointed by the Carnegie Foundation to inquire into the atrocities committed during the Balkan War. But the German Government has repeatedly refused proposals, made both unofficially and officially, that it should allow such an investigation to be conducted in the territory at present under German military occupation,[2] and the final critical assessment will therefore necessarily be postponed till the German Armies have retired again within their own frontiers.

Meanwhile, an ordered and documented narrative of the attested facts seems the best preparation for that judicial appraisement for which the time is not yet ripe. The facts have been drawn from statements made by witnesses on opposite sides with different intentions and beliefs, but as far as possible they have been disengaged from this subjective setting and have been set out, without comment, to speak for themselves. It has been impossible, however, to confine the exposition to pure narration at every point, for in the original evidence the facts observed and the inferred explanation of them are seldom distinguished, and when the same observed fact is made a ground for diametrically opposite inferences by different witnesses, the difficulty becomes acute. A German soldier, say, in Louvain on[vii] the night of August 25th, 1914, hears the sound of machine-gun firing apparently coming from a certain spot in the town, and infers that at this spot Belgian civilians are using a machine gun against German troops; a Belgian inhabitant hears the same sound, and infers that German troops are firing on civilians. In such cases the narrative must be interpreted by a judgment as to which of the inferences is the truth, and this judgment involves discussion. What is remarkable, however, is the rarity of these contradictions. Usually the different testimonies fit together into a presentation of fact which is not open to argument.

The narrative has been arranged so as to follow separately the tracks of the different German Armies or groups of Armies which traversed different sectors of French and Belgian territory. Within each sector the chronological order has been followed, which is generally identical with the geographical order in which the places affected lie along the route of march. The present volume describes the invasion of Belgium up to the sack of Louvain.

Arnold J. Toynbee.

March, 1917.

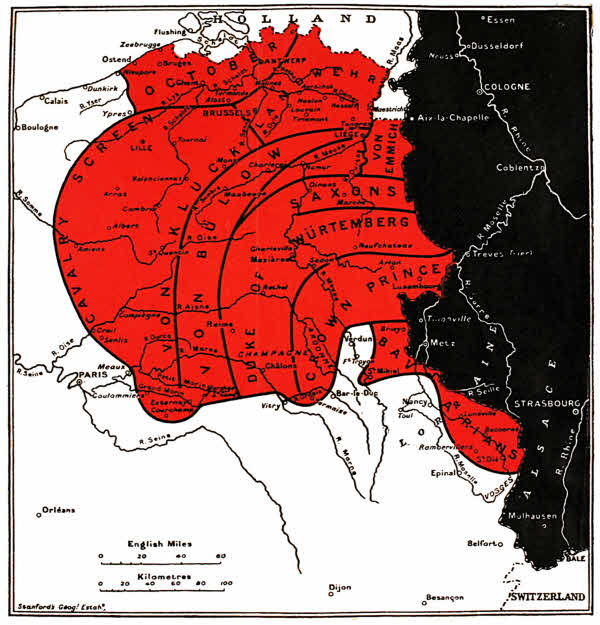

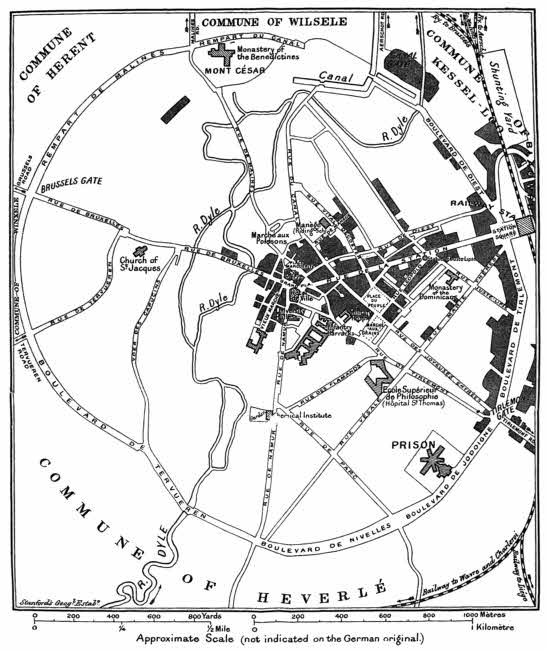

| FRONTISPIECE | The Invaded Country (Map) | |

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | v | |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | ix | |

| LIST OF MAPS | ix | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | x | |

| LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS | xi | |

| CHAPTER I.: THE TRACK OF THE ARMIES | 15 | |

| CHAPTER II.: FROM THE FRONTIER TO LIÉGE | 23 | |

| (i) | On the Visé Road | 23 |

| (ii) | On the Barchon Road | 27 |

| (iii) | On the Fléron Road | 31 |

| (iv) | On the Verviers Road | 37 |

| (v) | On the Malmédy Road | 38 |

| (vi) | Between the Vesdre and the Ourthe | 42 |

| (vii) | Across the Meuse | 44 |

| (viii) | The City of Liége | 46 |

| CHAPTER III.: FROM LIÉGE TO MALINES | 52 | |

| (i) | Through Limburg to Aerschot | 52 |

| (ii) | Aerschot | 57 |

| (iii) | The Aerschot District | 74 |

| (iv) | The Retreat from Malines | 77 |

| (v) | Louvain | 89 |

| THE INVADED COUNTRY | Frontispiece |

| THE TRACK OF THE ARMIES: FROM THE FRONTIER TO MALINES[3] | End of Volume |

| LOUVAIN, FROM THE GERMAN WHITE BOOK | End of Volume |

| PAGE | ||

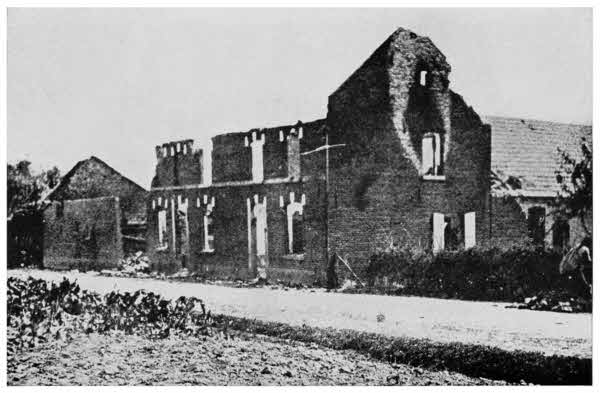

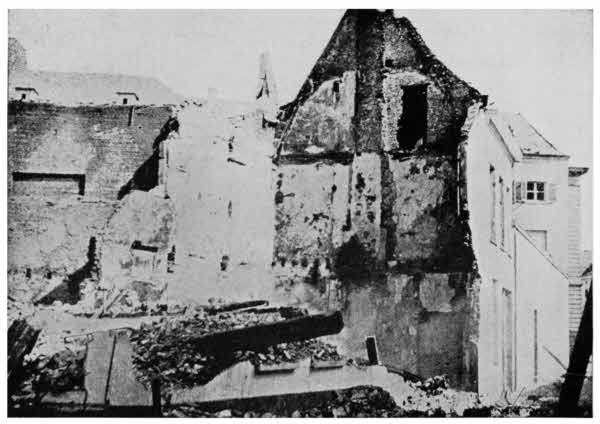

| 1. | Mouland | To face page 16 |

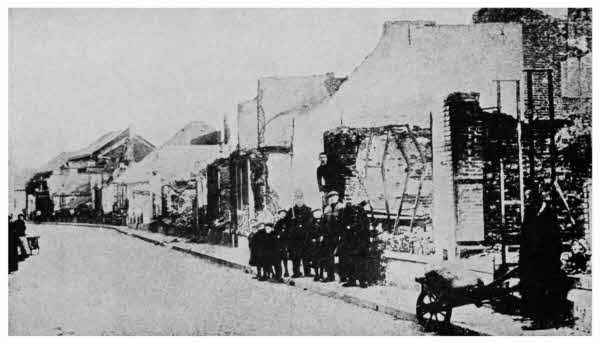

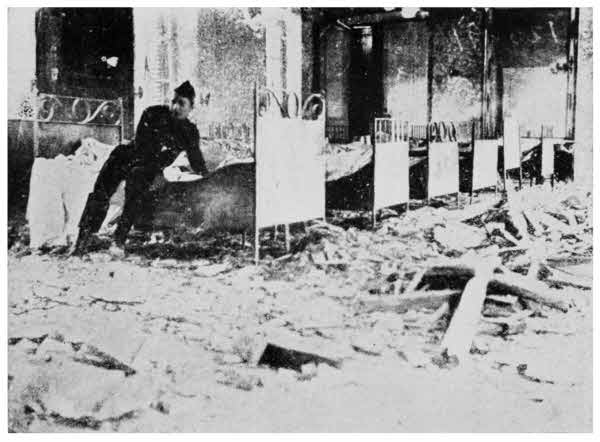

| 2. | Battice | 17 |

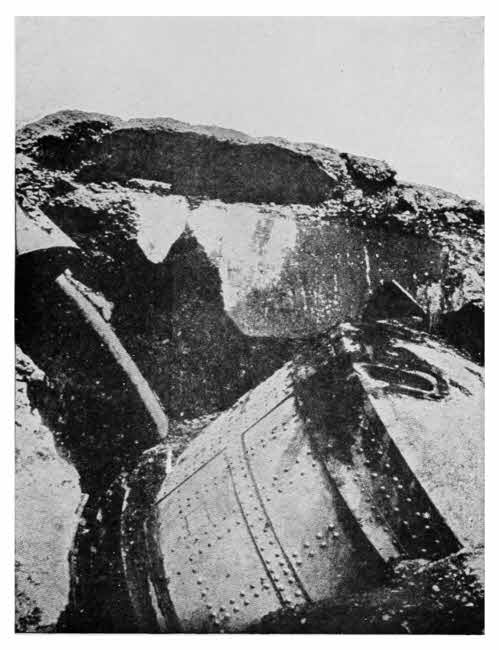

| 3. | Liége Forts: A Destroyed Cupola | 32 |

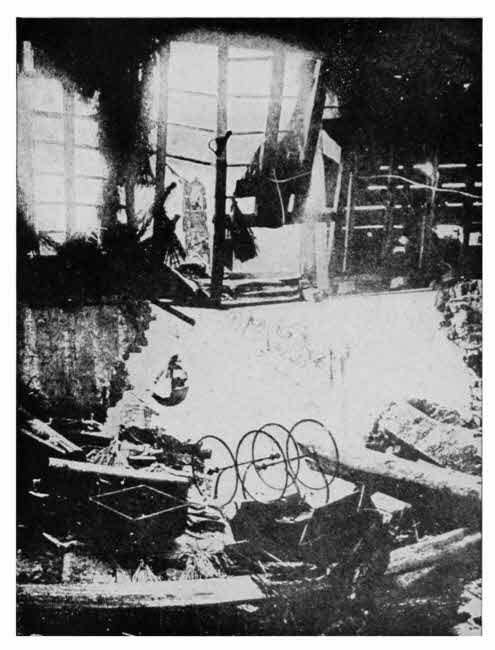

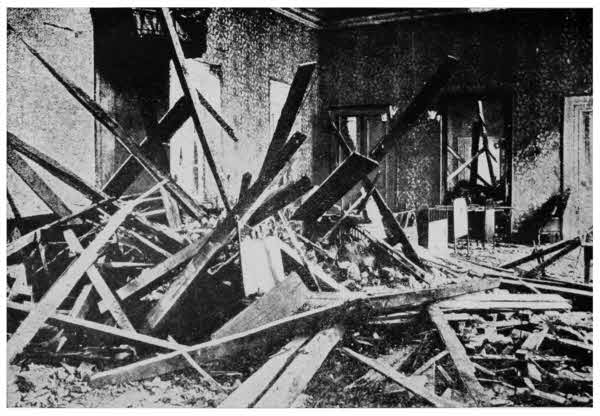

| 4. | Ans: An Interior | 33 |

| 5. | Ans: The Church | 48 |

| 6. | Liége: A Farm House | 49 |

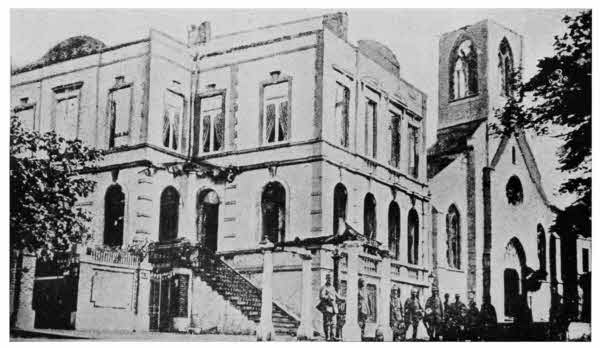

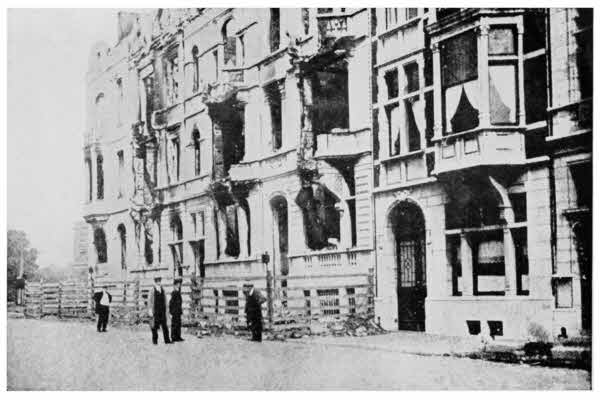

| 7. | Liége Under German Occupation | 52 |

| 8. | Liége Under the Germans: Ruins and Placards | 53 |

| 9. | Liége in Ruins | 60 |

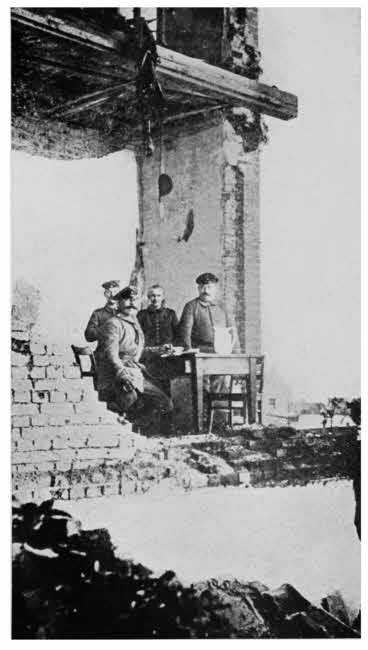

| 10. | “We Live Like God in Belgium” | 61 |

| 11. | Haelen | 64 |

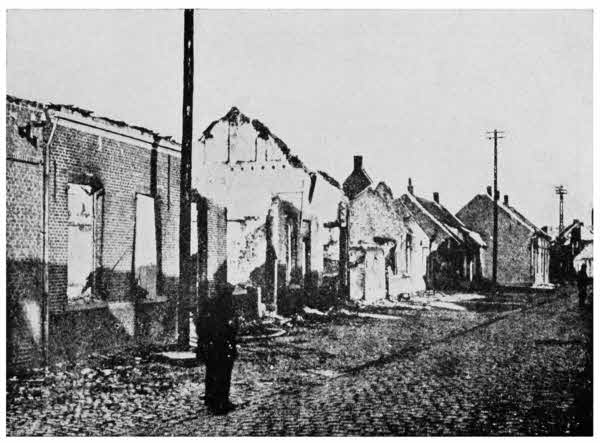

| 12. | Aerschot | 65 |

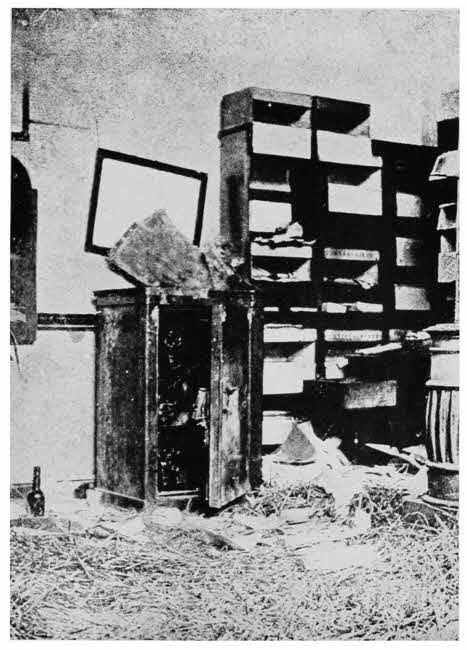

| 13. | Brussels: A Booking-Office | 80 |

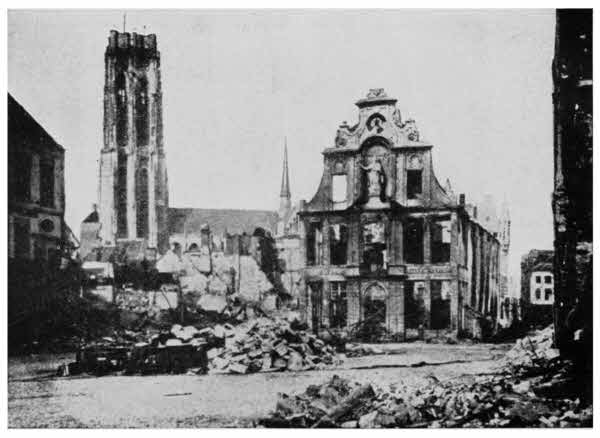

| 14. | Malines After Bombardment | 81 |

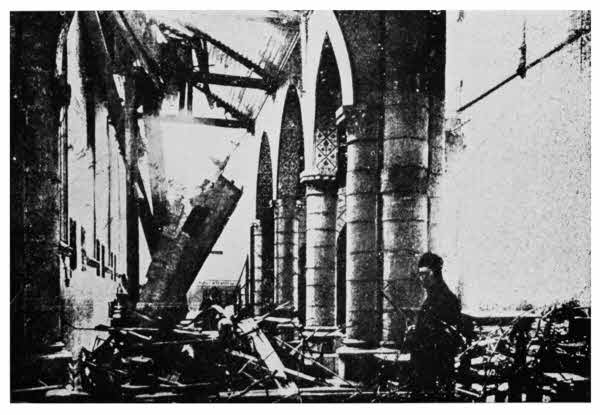

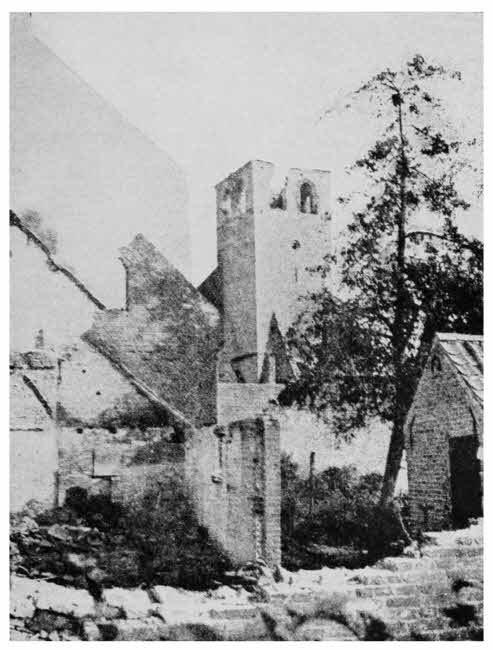

| 15. | Malines: Ruins | 84 |

| 16. | Malines: Ruins | 85 |

| 17. | Malines: Cardinal Mercier’s State-Room as a Red Cross Hospital | 92 |

| 18. | Malines: The Cardinal’s Throne-Room | 93 |

| 19. | Capelle-au-Bois | 96 |

| 20. | Capelle-au-Bois | 97 |

| 21. | Capelle-au-Bois: The Church | 112 |

| 22. | Louvain: Near the Church of St. Pierre | 113 |

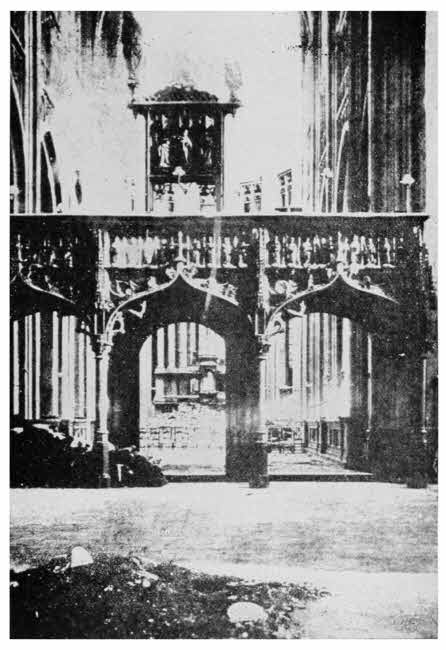

| 23. | Louvain: The Church of St. Pierre | 116 |

| 24. | Louvain: The Church of St. Pierre Across the Ruins | 117 |

| 25. | Louvain: The Church of St. Pierre—Interior | 124 |

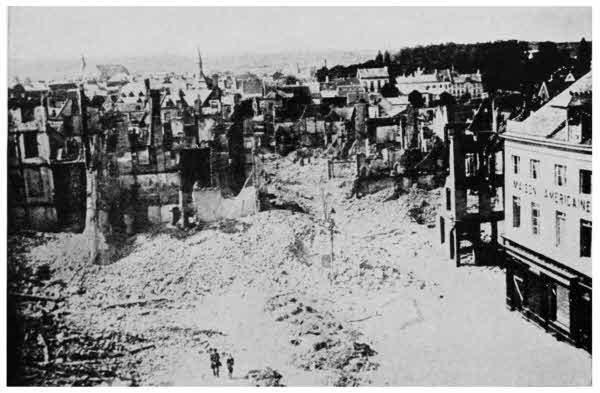

| 26. | Louvain: Station Square | 125 |

| Alphabet, Letters of the:— | |

| Capitals | Appendices to the German White Book entitled: “The Violation of International Law in the Conduct of the Belgian People’s-War” (dated Berlin, 10th May, 1915); Arabic numerals after the capital letter refer to the depositions contained in each Appendix. |

| Lower Case | Sections of the “Appendix to the Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages, Appointed by His Britannic Majesty’s Government and Presided Over by the Right Hon. Viscount Bryce, O.M.” (Cd. 7895); Arabic numerals after the lower case letter refer to the depositions contained in each Section. |

| Ann(ex) | Annexes (numbered 1 to 9) to the Reports of the Belgian Commission (vide infra). |

| Belg. | Reports (numbered i to xxii) of the Official Commission of the Belgian Government on the Violation of the Rights of Nations and of the Laws and Customs of War. (English translation, published, on behalf of the Belgian Legation, by H.M. Stationery Office, two volumes.) |

| Bland | “Germany’s Violations of the Laws of War, 1914-5”; compiled under the Auspices of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and translated into English with an Introduction by J. O. P. Bland. (London: Heinemann. 1915.) |

| Bryce | Appendix to the Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages appointed by His Britannic Majesty’s Government. |

| Chambry | “The Truth about Louvain,” by Réné Chambry. (Hodder and Stoughton. 1915.)[xii] |

| Davignon | “Belgium and Germany,” Texts and Documents, preceded by a Foreword by Henri Davignon. (Thomas Nelson and Sons.) |

“Eye-Witness” |

“An Eye-Witness at Louvain” (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. 1914.) |

| “Germans” | “The Germans at Louvain,” by a volunteer worker in the Hôpital St.-Thomas. (Hodder and Stoughton. 1916.) |

| Grondijs | “The Germans in Belgium: Experiences of a Neutral,” by L. H. Grondijs, Ph.D., formerly Professor of Physics at the Technical Institute of Dordrecht. (London: Heinemann. 1915.) |

| Höcker | “An der Spitze Meiner Kompagnie, Three Months of Campaigning,” by Paul Oskar Höcker. (Ullstein and Co., Berlin and Vienna. 1914.) |

| “Horrors” | “The Horrors of Louvain,” by an Eye-witness, with an Introduction by Lord Halifax. (Published by the London Sunday Times.) |

| Massart | “Belgians under the German Eagle,” by Jean Massart, Vice-Director of the Class of Sciences in the Royal Academy of Belgium. (English translation by Bernard Miall. London: Fisher Unwin. 1916.) |

| Mercier | Pastoral Letter, dated Xmas, 1914, of His Eminence Cardinal Mercier, Archbishop of Malines. |

| Morgan | “German Atrocities: An Official Investigation,” by J. H. Morgan, M.A., Professor of Constitutional Law in the University of London. (London: Fisher Unwin. 1916.) |

| Numerals, Roman lower case | Reports (numbered i to xxii) of the Belgian Commission (vide supra). |

| R(eply) | “Reply to the German White Book of May 10, 1915.”

(Published, for the Belgian Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

by Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1916.)

Arabic numerals after the R refer to the depositions contained in the particular section of the Reply that is being cited at the moment: e.g., R15 denotes the fifteenth deposition in the section[xiii] on Louvain in the Reply when cited in the section on Louvain in the present work; but it denotes the fifteenth deposition in the section on Aerschot when cited in the corresponding section here. The Reply is also referred to by pages, and in these cases the Arabic numeral denotes the page and is preceded by “p.” |

| S(omville) | “The Road to Liége,” by Gustave Somville. (English translation by Bernard Miall. Hodder and Stoughton. 1916.) |

| Struyken | “The German White Book on the War in Belgium: A Commentary,” by Professor A. A. H. Struyken. (English Translation of Articles in the Journal Van Onzen Tijd, of Amsterdam, July 31st, August 7th, 14th, 21st, 1915. Thomas Nelson and Sons.) |

N.B.—Statistics, where no reference is given, are taken from the first and second Annexes to the Reports of the Belgian Commission. They are based on official investigations.

THE GERMAN TERROR IN BELGIUM

When Germany declared war upon Russia, Belgium, and France in the first days of August, 1914, German armies immediately invaded Russian, Belgian, and French territory, and as soon as the frontiers were crossed, these armies began to wage war, not merely against the troops and fortifications of the invaded states, but against the lives and property of the civil population.

Outrages of this kind were committed during the whole advance and retreat of the Germans through Belgium and France, and only abated when open manœuvring gave place to trench warfare along all the line from Switzerland to the sea. Similar outrages accompanied the simultaneous advance into the western salient of Russian Poland, and the autumn incursion of the Austro-Hungarians into Serbia, which was turned back at Valievo. There was a remarkable uniformity in the crimes committed in these widely separated theatres of war, and an equally remarkable limit to[16] the dates within which they fell. They all occurred during the first three months of the war, while, since that period, though outrages have continued, they have not been of the same character or on the same scale. This has not been due to the immobility of the fronts, for although it is certainly true that the Germans have been unable to overrun fresh territories on the west, they have carried out greater invasions than ever in Russia and the Balkans, which have not been marked by outrages of the same specific kind. This seems to show that the systematic warfare against the civil population in the campaigns of 1914 was the result of policy, deliberately tried and afterwards deliberately given up. The hypothesis would account for the peculiar features in the German Army’s conduct, but before we can understand these features we must survey the sum of what the Germans did. The catalogue of crimes against civilians extends through every phase and theatre of the military operations in the first three months of the war, and an outline of these is a necessary introduction to it.

In August, 1914, the Central Empires threw their main strength against Belgium and France, and penetrated far further on this front than on the east and south-east. The line on which they advanced extended from the northern end of the Vosges to the Dutch frontier on the Meuse, and here again their strength was unevenly distributed. The chief striking force was[17] concentrated in the extreme north, and advanced in an immense arc across the Meuse, the Scheldt, the Somme, and the Oise to the outskirts of Paris. As this right wing pressed forward, one army after another took up the movement toward the left or south-eastern flank, but each made less progress than its right-hand neighbour. While the first three armies from the right all crossed the Marne before they were compelled to retreat, the fourth (the Crown Prince’s) never reached it, and the army of Lorraine was stopped a few miles within French territory, before ever it crossed the Meuse. We shall set down very briefly the broad movements of these armies and the dates on which they took place.

1. Mouland

2. Battice

Germany sent her ultimatum to Belgium on the evening of Aug. 2nd. It announced that Germany would violate Belgian neutrality within twelve hours, unless Belgium betrayed it herself, and it was rejected by Belgium the following morning. That day Germany declared war on France, and the next day, Aug. 4th, the advance guard of the German right wing crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked the forts of Liége. On Aug. 7th the town of Liége was entered, and the crossings of the Meuse, from Liége to the Dutch frontier, were in German hands.

Beyond Liége the invading forces spread out like a fan. On the extreme right a force advanced north-west to outflank the Belgian army covering Brussels[18] and to mask the fortress of Antwerp, and this right wing, again, was the first to move. Its van was defeated by the Belgians at Haelen on Aug. 12th, but the main column entered Hasselt on the same day, and took Aerschot and Louvain on Aug. 19th. During the next few days it pushed on to Malines, was driven out again by a Belgian sortie from Antwerp on Aug. 25th, but retook Malines before the end of the month, and contained the Antwerp garrison along the line of the Dyle and the Démer.

This was all that the German right flank column was intended to do, for it was only a subsidiary part of the two armies concentrated at Liége. As soon as Antwerp was covered, the mass of these armies was launched westward from Liége into the gap between the fortresses of Antwerp and Namur—von Kluck’s army on the right and von Bülow’s on the left. By Aug. 21st von Bülow was west of Namur, and attacking the French on the Sambre. On Aug. 20th an army corps of von Kluck’s had paraded through Brussels, and on the 23rd his main body, wheeling south-west, attacked the British at Mons. On the 24th von Kluck’s extreme right reached the Scheldt at Tournai and, under this threat to their left flank, the British and French abandoned their positions on the Mons-Charleroi line and retreated to the south. Von Kluck and von Bülow hastened in pursuit. They passed Cambrai on Aug. 26th and St. Quentin on the 29th; on the[19] 31st von Kluck was crossing the Oise at Compiègne, and on the 6th Sept. he reached his furthest point at Courchamp, south-east of Paris and nearly thirty miles beyond the Marne. His repulse, like his advance, was brought about by an outflanking manœuvre, only this time the Anglo-French had the initiative, and it was von Kluck who was outflanked. His retirement compelled von Bülow to fall back on his left, after a bloody defeat in the marshes of St. Gond, and the retreat was taken up, successively, by the other armies which had come into line on the left of von Bülow.

These armies had all crossed the Meuse south of the fortress of Namur, and, to retain connexion with them, von Bülow had had to detach a force on his left to seize the line of the Meuse from Liége to Namur and to capture Namur itself. The best German heavy artillery was assigned to this force for the purpose, and Namur fell, after an unexpectedly short bombardment, on Aug. 23rd, while von Bülow’s main army at Charleroi was still engaged in its struggle with the French.

The fall of Namur opened the way for German armies to cross the Meuse along the whole line from Namur to Verdun. The first crossing was made at Dinant on Aug. 23rd, the very day on which Namur fell, by a Saxon army, which marched thither by cross routes through Luxembourg; the second by the Duke of Würtemberg’s army between Mezières and Sedan; and the third by the Crown Prince of Prussia’s army[20] immediately north of Verdun. West of the Meuse the Saxons and Würtembergers amalgamated, and got into touch with von Bülow on their right. Advancing parallel with him, they reached Charleville on Aug. 25th, crossed the Aisne at Rethel on the 30th and the Marne at Châlons on the 4th, and were stopped on the 7th at Vitry en Perthois. The Crown Prince, on their left, did not penetrate so far. Instead of the plains of Champagne he had to traverse the hill country of the Argonne. He turned back at Sermaize, which he had reached on Sept. 6th, and never saw the Marne.

On the left of the Crown Prince a Bavarian army crossed the frontier between Metz and the Vosges. Its task was to join hands with the Crown Prince round the southern flank of Verdun, as the Duke of Würtemberg had joined hands with von Bülow round the flank of Namur. But Verdun never fell, and the Bavarian advance was the weakest of any. Lunéville fell on Aug. 22nd, and Baccarat was entered on the 24th; but Nancy was never reached, and on Sept. 12th the general German retreat extended to this south-easternmost sector, and the Bavarians fell back.

Thus the German invading armies were everywhere checked and driven back between the 6th and the 12th September, 1914. The operations which came to this issue bear the general name of the Battle of the Marne. The Marne was followed immediately by the Aisne, and the issue of the Aisne was a change from open to[21] trench warfare along a line extending from the Vosges to the Oise. This change was complete before September closed, and the line formed then has remained practically unaltered to the present time. But there was another month of open fighting between the Oise and the sea.

When the Germans’ strategy was defeated at the Marne, they transferred their efforts to the north-west, and took the initiative there. On Sept. 9th the Belgian Army had made a second sortie from Antwerp, to coincide with the counter-offensive of Joffre, and this time they had even reoccupied Aerschot. The Germans retaliated by taking the offensive on the Scheldt. The retaining army before Antwerp was strongly reinforced. Its left flank was secured, in the latter half of September, by the occupation of Termonde and Alost. The attack on Antwerp itself began on Sept. 27th. On the 2nd the outer ring of forts was forced, and on the 9th the Germans entered the city. The towns of Flanders fell in rapid succession—Ghent on the 12th, Bruges on the 14th, Ostend on the 15th—and the Germans hoped to break through to the Channel ports on the front between Ostend and the Oise. Meanwhile, each side had been feverishly extending its lines from the Oise towards the north and pushing forward cavalry to turn the exposed flank of the opponent. These two simultaneous movements—the extension of the trench lines from the Oise to the sea, and the German thrust across[22] Flanders to the Channel—intersected one another at Ypres, and the Battle of Ypres and the Yser, in the latter part of October, was the crisis of this north-western struggle. On Oct. 31st the German effort to break through reached, and passed, its climax, and trench warfare established itself as decisively from the Oise to the sea as it had done a month earlier between the Vosges and the Oise.

Thus, three months after the German armies crossed the frontier, the German invasion of Belgium and France gave place to a permanent German occupation of French and Belgian territories behind a practically stationary front, and with this change of character in the fighting a change came over the outrages upon the civil population which remained in Germany’s power. The crimes of the invasion and the crimes of the occupation are of a different order from one another, and must be dealt with apart.

The Germans invaded Belgium on Aug. 4th, 1914. Their immediate objective was the fortress of Liége and the passage of the Meuse, but first they had to cross a zone of Belgian territory from twenty to twenty-five miles wide. They came over the frontier along four principal roads, which led through this territory to the fortress and the river, and this is what they did in the towns and villages they passed.

The first road led from Aix-la-Chapelle, in Germany, to the bridge over the Meuse at Visé, skirting the Dutch frontier, and Warsage[4] was the first Belgian village on this road to which the Germans came. Their advance-guards distributed a proclamation by General von Emmich: “I give formal pledges to the Belgian population that they will not have to suffer from the horrors of war.... If you wish to avoid the horrors of war, you must act wisely and with a true appreciation of your duty to your country.” This was on the morning of Aug. 4th, and the Mayor of Warsage, M. Fléchet, had already posted a notice on the town-hall[24] warning the inhabitants to keep calm. All that day and the next the Germans passed through; on the afternoon of the 6th the village was clear of them, when suddenly they swarmed back, shooting in at the windows and setting houses on fire. Several people were killed; one old man was burnt alive. Then the Mayor was ordered to assemble the population in the square. A German officer had been shot on the road. No inquiry was held; no post-mortem examination made (the German soldiers were nervous and marched with finger on trigger); the village was condemned. The houses were systematically plundered, and then systematically burnt. A dozen inhabitants, including the Burgomaster, were carried off as hostages to the German camp at Mouland. Three were shot at once; the rest were kept all night in the open; one of them was tied to a cart-wheel and beaten with rifle-butts; in the morning six were hanged, the rest set free. Eighteen people in all were killed at Warsage and 25 houses destroyed.

At Fouron-St. Martin[5] five people were killed and 20 houses burnt. Nineteen houses were burnt at Fouron-le-Compte.[5] At Berneau,[6] a few miles further down the road, 67 houses (out of 116) were burnt on Aug. 5th, and 7 people killed. “The people of Berneau,” writes a German in his diary on Aug. 5th, “have[25] fired on those who went to get water. The village has been partly destroyed.” On the day of this entry the Germans had commandeered wine at Berneau, and were drunk when they took reprisals for shots their victims were never proved to have fired. Among these victims was the Burgomaster, M. Bruyère, a man of 83. He was taken, like the Burgomaster of Warsage, to the camp at Mouland, and was never seen again after the night of the 6th. At Mouland[7] itself 4 people were killed and 73 houses destroyed (out of 132).

The road from Aix-la-Chapelle reaches the Meuse at Visé.[8] It was a town of 900 houses and 4,000 souls, and, as a German describes it, “It vanished from the map.”[9] The inhabitants were killed, scattered or deported, the houses levelled to the ground, and this was done systematically, stage by stage.

The Germans who marched through Warsage reached Visé on the afternoon of Aug. 4th. The Belgians had blown up the bridges at Visé and Argenteau, and were waiting for the Germans on the opposite bank. As they entered Visé, the Germans came for the first time under fire, and they wreaked their vengeance on the town. “The first house they came to as they entered Visé they burned” (a 16), and they began to fire at random in the streets. At least eight civilians were[26] shot in this way before night, and when night fell the population was driven out of the houses and compelled to bivouac in the square. More houses were burnt on the 6th; on the 10th they burned the church; on the 11th they seized the Dean, the Burgomaster, and the Mother Superior of the Convent as hostages; on the 15th a regiment of East Prussians arrived and was billeted in the town, and that night Visé was destroyed. “I saw commissioned officers directing and supervising the burning,” says an inhabitant (a 16). “It was done systematically with the use of benzine, spread on the floors and then lighted. In my own and another house I saw officers come in before the burning with revolvers in their hands, and have china, valuable antique furniture, and other such things removed. This being done, the houses were, by their orders, set on fire....”

The East Prussians were drunk, there was firing in the streets, and, once more, people were killed. Next morning the population was rounded up in the station square and sorted out—men this side, women that. The women might go to Holland, the men, in two gangs of about 300 each, were deported to Germany as franc-tireurs. “During the night of Aug. 15-16,” as another German diarist[10] describes the scene, “Pioneer Grimbow gave the alarm in the town of Visé. Everyone was shot or taken prisoner, and the houses were burnt. The prisoners were made to march and keep up with[27] the troops.” About 30 people in all were killed at Visé, and 575 out of 876 houses destroyed. On the final day of destruction the Germans had been in peaceable occupation of the place for ten days, and the Belgian troops had retired about forty miles out of range.

That is what the Germans did on the road from Aix-la-Chapelle; but, before reaching Warsage, the road sends out a branch through Aubel to the left, which passes under the guns of Fort Barchon and leads straight to Liége. The Germans took this road also, and Barchon was the first of the Liége forts to fall. The civil population was not spared.

At St. André[11] 4 civilians were killed and 14 houses burnt. Julémont,[12] the next village, was completely plundered and burnt. Only 2 houses remained standing, and 12 people were killed. Advancing along this road, the Germans arrived at Blégny[13] on Aug. 5th. Several inhabitants of Blégny were murdered that afternoon, among them M. Smets, a professor of gunsmithry (the villagers worked for the small-arms manufacturers of Liége). M. Smets was killed in his house, where his wife was in child-bed. The corpse was thrown into the street, the mother and new-born[28] baby were dragged out after it. That night the population of Blégny was herded together in the village institute; their houses were set on fire. Next morning—the 6th—the women were released and the men driven forward by the German infantry towards Barchon fort. The Curé of Blégny, the Abbé Labeye, was among the number, and there were 296 of them in all. In front of Barchon they were placed in rows of four, but the fort would not fire upon this living screen, and they were marched away across country towards Battice, where five were shot before the eyes of the rest, and the curé kicked, spat upon, and pricked with bayonets. They were again driven forward as a screen against a Belgian patrol, and were kept in the open all night. Next morning 4 more were shot—two who had been wounded by the Belgian fire, and one who had heart disease and was too feeble to go on. The fourth was an old man of 78. The Germans tortured these victims by placing lighted cigarettes in their nostrils and ears. After this second execution on the 7th, the remainder were set free....

On the 10th Aug. the curé writes in his diary:

“There are now 38 houses burnt, and 23 damaged.

“Thursday the 13th: a few houses pillaged, two young men taken away.

“Friday, the 14th: a few houses pillaged.

“Friday night: the village of Barchon is burnt and the curé taken prisoner....”

The curé’s last notes for a sermon have survived: “My brothers, perhaps we shall again see happy days....” But on the 16th, before the sermon was delivered, the curé was shot. He was shot against the church wall, with M. Ruwet, the Burgomaster, and two brothers, one of them a revolver manufacturer who had handed over his stock to the German authorities (from whom he received two passes) and had been working for the Red Cross. After the execution the church was burnt down. The nuns of Blégny were shot at by Germans in a motor-car when they came out that day to bury the bodies. From the 5th to the 16th Aug., about 30 people were killed in the commune of Blégny-Trembleur, and 45 houses burnt in all.

The village of Barchon,[14] as the curé of Blégny records, was destroyed on the 14th—in cold blood, five days after the surrender of the fort. There was a battue by two German regiments through the village. The houses were plundered and burnt (110 burnt in all out of 146); the inhabitants were rounded up. Twenty-two were shot in one batch, including two little girls of two and an old woman of ninety-four. Thirty-two perished altogether, and a dozen hostages were carried off, some of whom were tied to field guns and compelled to keep up with the horses. On the 16th the Germans evicted the inhabitants of Chefneux,[15] and[30] shot 4 men. On the 17th they burned all the 22 houses in the hamlet. At Saives[16] they burned 12 houses, and shot a man and a girl.

We have the diary of a German soldier who marched down this branch road from Aubel when all the villages had been destroyed except Wandre,[17] which stood where the road debouched upon the Meuse.

“15th Aug.—11.50 a.m. Crossed the Belgian frontier and kept steadily along the high road until we got into Belgium. We were hardly into it before we met a horrible sight. Houses were burnt down, the inhabitants driven out and some of them shot. Of the hundreds of houses not a single one had been spared—every one was plundered and burnt down. Hardly were we through this big village when the next was already set on fire, and so it went on....

“16th Aug. The big village of Barchon set on fire. The same day, about 11.50 a.m., we came to the town of Wandre. Here the houses were spared but all searched. At last we had got out of the town when once more everything was sent to ruins. In one house a whole arsenal had been discovered. The inhabitants were one and all dragged out and shot, but this shooting was absolutely heart-rending, for they all knelt and prayed. But this got them no mercy. A few shots[31] rang out, and they fell backwards into the green grass and went to their eternal sleep.

“And still the brigands would not leave off shooting us from behind—that, and never from in front—but now we could stand it no longer, and raging and roaring we went on and on, and everything that got in our way was smashed or burnt or shot. At last we had to go into bivouac. Half tired out and done up we laid ourselves down, and we didn’t wait long before quenching some of our thirst. But we only drank wine; the water has been half poisoned and half left alone by the beasts. Well, we have much too much here to eat and drink. When a pig shows itself anywhere or a hen or a duck or pigeons, they are all shot down and slaughtered, so that at any rate we have something to eat. It is a real adventure....”

This was the temper of the Germans who destroyed Wandre. They burned 33 houses altogether and shot 32 people—16 of them in one batch.

There is another road from Aix-la-Chapelle to Liége, which passes through Battice and is commanded by Fort Fléron (Fort Fléron offered the most determined resistance of all the forts of Liége, and cost the Germans the greatest loss). The Germans marched through Battice on August 4th, and came under fire of the fort that afternoon. In the evening they arrested[32] three men in the streets of Battice, and shot them without charge or investigation.

The check to their arms was avenged on the civil population. “On the arrival of the German troops in the village of Micheroux,” states a Belgian witness (a 12), “during the time when Fort Fléron was holding out, they came to a block of four cottages, and having turned out the inhabitants, set the cottages on fire and burned them. From one of the cottages a woman (mentioned by name) came out with a baby in her arms, and a German soldier snatched it from her and dashed it to the ground, killing it then and there.”[18]

“The position was dangerous,” writes a German in his diary[19] on August 5th, from a picket in front of Fort Fléron. “As suspicious civilians were hovering round, houses 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 were cleared, the owners arrested (and shot the next day).... I shoot a civilian with my rifle, at 400 metres, slap through the head....”

3. Liége Forts: A Destroyed Cupola

4. Ans: An Interior

That day the curé of Battice[20]: (who had been kept under arrest in the open since the evening of the 4th) was driven, with the Mayor and one of the communal councillors, under the Belgian fire. On the 6th the German troops again retired on Battice in confusion, and the village was destroyed that afternoon. Shots were[33] fired indiscriminately and the houses set on fire. The first victim was a young man sitting in a café with his fiancée—he fell dead by her side. Three people were taken to the field to which the men of Blégny had been brought, and were shot with the five victims there. On the 7th they shot a workman who had been given a safe-conduct by a German officer to buy bread in a neighbouring village, and was on his way home with his wife. On the 8th they set the fire going again, to burn what still remained. They burned 146 houses and killed 36 people in Battice from first to last.

The town of Herve[21] lies a mile or so beyond Battice on the Fléron road, and was also traversed by the Germans on August 4th. The first to pass were officers in a motor car, and as they crossed the bridge they shot down two young men standing by the roadside—one was badly wounded, the other killed outright. In the evening they sent for the Mayor, accused the inhabitants of having fired on German troops, and threatened to shoot the inhabitants and burn the town to the ground. The Mayor and the curé spent the night going from house to house and warning the people to avoid all grounds of offence—before they had finished there were more shots fired indiscriminately (by the Germans), and more (civilian) wounded and dead. The Mayor and curé were then retained as hostages for the civilians’ good behaviour. On the 6th[34] the first house was burnt; on the 7th five men were shot in cold blood; on the 8th a fresh column of troops arrived from Aix-la-Chapelle, and these were the destroyers of Herve. “They fired indiscriminately in all quarters of the town,” says an eye-witness (a 2), “and in the Rue de la Station they shot Madame Hendrickx, hitting her at close range, although she had a crucifix in her hand—begging for mercy.” All through the 8th the shooting and burning went on, and on the 9th the fires were kindled again. “The Germans gave themselves up to pillage and loaded motor cars with everything of value they could find.” They burned and pillaged consecutively for ten days, and on the 19th and 20th fresh regiments arrived and carried on the work. Two hundred and seventy-nine houses were destroyed at Herve altogether, and 44 people killed. “On the road to Herve everything is burnt,” writes a German soldier (Reply p. 127) who passed when all was over. “At Herve, the same. Everything is burnt except a convent—everywhere corpses carbonised into an indistinguishable mass. (There are about a hundred, all civilians, and children among the number.) I only saw three people alive in the village—an old man, a sister of charity, and a girl.” The Belgian witness quoted above (a 2) records that “the German staff officers staying in his hotel told his wife that the reason why they had so treated Herve was because the[35] inhabitants of the town would not petition for a passage for the Germans at Fléron.”

In the villages between Herve and Fort Fléron the slaughter and devastation were, if possible, more complete. At la Bouxhe-Melen[22] there were two massacres—one on Aug. 5th and another on the 8th. In the second the people were shot down in a field en masse, and 129 were murdered altogether, as well as about 40 people herded in from the farms and hamlets of the neighbourhood. Sixty houses in la Bouxhe-Melen were destroyed. In the commune of Soumagne,[23] on a branch road to the south, the Germans killed 165 civilians and burned 104 houses down. When they entered Soumagne on Aug. 5th, they killed indiscriminately in the streets. “They broke the windows and broke the door,” writes a witness (a 5) who had taken refuge in a cellar. “My mother went out of the cellar door.... Then I heard a shot and my mother fell back into the cellar. She was killed.” This indiscriminate killing was followed up the same afternoon by the massacre of 69 civilians in a field called the Fonds Leroy. “The soldiers fired a volley and killed many, and then fired twice more. Then they went through the ranks and bayonetted everyone still living. I saw many bayonetted in this way” (a 4). One boy was shot and bayonetted in four places, and lay[36] several days among the dead, keeping himself alive on weeds and grass. This boy survived. In another field 18 were massacred in one batch, in another 19. “I saw about 20 dead bodies lying here and there along the road,” writes one of the witnesses (a 4). “One of them was that of a little girl aged 13. The rest were men, and most of them had had their heads bashed in.”—“I saw 56 corpses of civilians in a meadow,” deposes another. “Some had been killed by bayonet thrusts and others by rifle shots. In the heaps of corpses above mentioned was that of the son of the Burgomaster. His throat had been cut from ear to ear and his tongue had been pulled out and cut off.”

In the hamlet of Fécher the whole population—about 1,000 women, children and men—was penned into the church on Aug. 5th, and next morning the men (412 of them) were herded off as a living screen for the German troops advancing between the forts (the first man to come out of the church being wantonly shot down as an example to the rest). The 411 were driven by bye-roads to the Chartreuse Monastery, above the Meuse, overlooking the bridge into the city of Liége, and on the 7th they were planted as hostages on the bridge while the Germans marched across. They were held there without food or shelter or relief for a hundred hours. At Micheroux[24] 9 people were killed and 17 houses destroyed. These villages were all outside[37] the eastern line of forts, but the places inside the line, between the forts and Liége, were devastated to an equal degree. At Fléron[25] 15 civilians were killed and 152 houses destroyed.[26] At Retinnes[27] 41 civilians were killed and 118 houses destroyed.[26] At Queue du Bois[28] 11 civilians were killed and 35 houses destroyed. At Evegnée 2 civilians were killed and 5 houses destroyed. At Cerexhe[29] 4 women and children were burnt alive in a house, and 2 houses destroyed. At Bellaire[30] 4 people were killed and 15 houses destroyed. At Jupille[31] 8 people were killed and 1 house destroyed. These villages were saved none of the horrors of war by the surrender of the forts.

The Germans converged on the forts by more southerly roads as well. At Dolhain,[32] on the road from Eupen to Verviers, 28 houses were burnt on Aug. 8th and several civilians killed. At Metten,[33] near Verviers, a German soldier confesses that he and his comrades “were ordered to search a house from which shots had[38] been fired, but found nothing in the house but two women and a child.... I did not see the women fire. The women were told that nothing would be done to them, because they were crying so bitterly. We brought the women out and took them to the major, and then we were ordered to shoot the women.... When the mother was dead, the major gave the order to shoot the child, so that the child should not be left alone in the world. The child’s eyes were bandaged. I took part in this because we were ordered to do it by Major Kastendick and Captain Dultingen....”

But Verviers and the Verviers road remained comparatively unscathed. Far worse was done by the Germans who descended on the Vesdre from Malmédy, south-eastward, over the hills.

Francorchamps,[34] the first Belgian village on the Malmédy road, was sacked on Aug. 8th, four days after the first German troops had passed through it unopposed, and again on Aug. 14th by later detachments. At Hockay,[35] near Francorchamps, the curé was shot. In Hockay and Francorchamps 13 people were killed altogether, and 25 houses burnt. “M. Darchambeau, who was wounded (in the cellar of a burning house), asked a young officer for mercy. This young[39] officer of barely 22, in front of the women and children, aimed his revolver at M. Darchambeau’s head and killed him.”

The fate of Pepinster[36] is recorded in a German diary: “Aug. 12th, Pepinster, Burgomaster, priest, and schoolmaster shot; houses reduced to ashes. March on.” As a matter of fact, the three hostages were not shot, but reprieved. The Burgomaster of Cornesse[37] was shot in their stead (a 33, 34)—“an old man and quite deaf. (He was only hit in the leg, and a German officer came up and shot him through the heart with his revolver.)” Five houses in Cornesse were burnt. At Soiron,[38] on Aug. 4th, the Germans bivouacking there fired on one another, and eight German soldiers were wounded or killed. “But the officers,” deposes a German private[39] who was present at the scene, “in their anxiety to prevent the fact of this blunder from being reported, hastened to pretend that it was really the civilians who had fired, and gave orders for a general massacre. This order was carried out, and there was terrible butchery. I must mention that we only killed the males, but we burned all the houses.” At Olnes[40] the curé and the communal[40] secretary were shot on Aug. 5th, and the schoolmaster the same evening, in front of his burning house, with his daughter and his two sons. Only two members of the schoolmaster’s family were spared. In the hamlet of St. Hadelin,[41] which came within the radius of Fort Fléron’s guns, there was a wholesale massacre on the same date. Early in the day the Germans “requisitioned” 300 bottles of wine; later they drove a crowd of people from St. Hadelin, Riessonsart, and Ayeneux, to a place called the Faveu, and shot down 33. The remainder were forced to haul German artillery towards the forts, but these were partly released next day, and partly massacred at the Heids d’Olne. Twenty inhabitants of Ayeneux were massacred in a batch elsewhere. Sixty-two civilians were murdered altogether in the commune of Olne, and 78 houses destroyed—40 in St. Hadelin and 38 in Olne itself.

At Forêt[42] the Germans burned a farm and killed two of the farmer’s sons on Aug. 5th as they entered the place. They drove the farmer and his two surviving sons in front of them as a screen. The schoolmaster and two others were shot outside the village. “At Forêt,” states the German soldier quoted above,[43] “we found prisoners—a priest and five civilians, including a boy of 17. Pillage began ... but we were shelled ... and moved off to the next village. The[41] house doors were at once broken in with the butt-ends of muskets. We pillaged everything. We made piles of the curtains and everything inflammable, and set them alight. All the houses were burnt. It was in the middle of this that the civilian prisoners of whom I have spoken were shot, with the exception of the curé.” (The curé, too, was shot that night.)[44] “A little further on, under the pretext that civilians had fired from a house (though for my own part I cannot say whether they were soldiers or civilians who fired), orders were given to burn the house. A woman asleep there was dragged from her bed, thrown into the flames, and burnt alive....”

Thirteen people in all were killed at Forêt, and 6 houses destroyed. At Magnée[45] 18 houses were destroyed and 21 people killed. The German troops in Magnée were caught by the fire from the Fléron and Chaudfontaine forts, and they revenged themselves, as elsewhere, on the civilians, shooting people in batches and burning houses and farms. This was on Aug. 6th, and at Romsée,[46] on the same day, 34 houses were burnt and 31 civilians murdered—some of them being driven as a screen in front of the German troops under the fire of Fort Chaudfontaine.

The same outrages were committed between the Vesdre and the Ourthe. At Louveigné,[47] on Aug. 7th, the Germans, retreating from their attack on the southern forts, looted the drink-shops, fired in the streets, and accused the civilians of having shot. A dozen men (two of them over 70 years old) were imprisoned as hostages in a forge, and were shot down, when released, like game in the open. That evening Louveigné was systematically set on fire with the same incendiary apparatus that was used at Visé, and the curé was dragged round on the foot-board of a military motor-car to watch the work. There were more murders next day. The total number of civilians murdered at Louveigné was 29, and there were 77 houses burnt. The devastation impressed the German soldiers who passed through Louveigné on the following days. “Louveigné has been completely burnt out. All the inhabitants are dead,” writes a German diarist on Aug. 9th. “March to Louveigné,” another records on Aug. 16th. “Several citizens and the curé shot according to martial law, some not yet buried—still lying where they were executed, for everyone to see. Stench of corpses everywhere. Curé said to have incited the inhabitants to ambush and kill the Germans.”—“Bivouac! Rain! Burnt villages! Louveigné!”[43] another exclaims on Aug. 17th. “We marched and bivouacked in the rain, in an orchard with a high hedge round it, full of fruit-trees. There was an abandoned house in front of it. The door, which was locked, was broken in with an axe. The traces of war—burnt houses, weeping women and children, executions of franc-tireurs—showed us the ruthlessness of the times. We could not have done otherwise.... But how many have to suffer with others, how many innocent people are shot by martial law, because there is no detailed enquiry first....”

At Lincé,[48] in the commune of Sprimont, a German officer was wounded when the troops returned in confusion from before the southern forts of Liége. The Germans forbade an autopsy to discover by what bullet the wound had been caused, and condemned two civilians with a proven alibi to be shot. All the next morning the destruction went on. Houses were burnt, the curé was mishandled, a farmer and his son were shot down at their farm gate, a girl of twelve received four bullets in her body. The execution of the hostages took place in the afternoon. Sixteen men were shot, of whom 7 were more than 60 years old. At Chanxhe,[49] on Aug. 6th, hostages from Poulseur were bound in ranks to the parapet of the bridge over the Ourthe, and kept there several days while the Germans[44] filed across. “We were tortured by hunger and thirst,” writes one of them. “We shivered at night. And then, of necessity, there was the filth.... At the end of the bridge the women were pleading with the Germans in vain, and the children were crying.” On the 5th two civilian captives were shot on the bridge, and their bodies thrown into the river, and two more (one aged 70) were shot on the 7th. In the commune of Poulseur, from which these hostages came, 7 civilians were killed and 25 houses destroyed. In the commune of Sprimont 67 houses were destroyed and 48 civilians killed. At Esneux 26 houses were destroyed and 7 civilians killed.

Meanwhile, the Germans had crossed the Meuse at Visé, and were descending on Liége from the north. At Hallembaye, in the commune of Haccourt,[50] 18 people were killed. There were women, children and old men among them, and also the curé,[51] who was bayonetted on his church threshold as he was removing the sacrament. In the commune of Haccourt 80 houses were destroyed, and 112 hostages were carried away into Germany. Hermalle-sous-Argenteau[52] was plundered on Aug. 15th, and 9 houses destroyed. There[45] was a mock execution of hostages in the presence of women and children, and 368 men of the place were imprisoned in the church for 17 days. At Vivegnis[53] 6 civilians were shot on Aug. 13th, and 45 houses destroyed the day after. The Germans fired on the inhabitants through the windows and doors, and two men were thus killed in a single household. At Heure-le-Romain[54] the population was confined in the church on Aug. 16th (it was Sunday) and compelled to stand there, hands raised, under the muzzle of a machine-gun. Seven civilians were shot at Heure-le-Romain that day, including the Burgomaster’s brother and the curé,[55] who were roped together and shot against the church wall. All through the 16th and 17th the sack continued; on the 18th fresh troops arrived and completed the work by systematic arson and the slaughter of 19 people more. Twenty-seven civilians were killed at Heure-le-Romain altogether and 84 houses destroyed. At Hermée,[56] on Aug. 6th, the Germans, caught by the fire of Fort Pontisse, revenged themselves by shooting 11 civilians, including old men of 76 and 82 years. On the 14th, the day after the surrender of the fort, the inhabitants of Hermée were driven from their homes and the village systematically burnt, 146 houses out of 308 being destroyed. In the[46] village itself, as apart from the outlying hamlets of the commune, only two or three houses were left standing. At Fexhe-Slins, near Hermée, 3 people were killed. Twenty-three were killed, and 13 houses destroyed, in the hamlet of Rhées in the commune of Herstal.[57]

Thus the Germans plundered private property, burned down houses, and shot civilians of both sexes and all ages, on every road by which they marched upon Liége—from the north-east, the south-east, and the north. One thousand and thirty-two civilians[58] were shot by the Germans in the whole Province of Liége, and 3,173 houses were destroyed in two arrondissements (those of Liége and Verviers) alone out of the four of which the Province is made up.

Twenty-nine of these civilians were killed and 55[59] of the houses destroyed in the city of Liége itself—on August 20th, a fortnight after it had fallen into the German Army’s possession. The Germans entered Liége on August 7th. Their entry was not opposed by Belgian troops, and arms in private hands had already been called in by the Belgian police.[60] The Germans[47] found themselves in peaceful occupation of a great industrial city, caught in the full tide of its normal life. There was nothing to suggest outrage, still less to excuse it, in their surroundings there; their conduct on August 20th was deliberate and cold-blooded. The Higher Command was faced with the problem of holding a conquered country, and wanted an example. The troops in garrison were demoralised by the sudden change to idleness from fatigue and danger, and were ready for excitement and pillage.

“Aug. 16th, Liége,” writes a German soldier in his diary.[61] “The villages we passed through had been destroyed.

“Aug. 19th. Quartered in University. Gone on the loose and boozed through the streets of Liége. Lie on straw; enough booze; too little to eat, or we must steal.

“Aug. 20th. In the night the inhabitants of Liége became mutinous. Forty persons were shot and 15 houses demolished. Ten soldiers were shot. The sights here make you cry.”

There are proofs of German premeditation—warnings from German soldiers to civilians on whom they were billeted,[62] and an ammunition waggon which drew up at 8.0 a.m. in the Rue des Pitteurs, and twelve[48] hours later disgorged the benzine with which the houses in that street were drenched before being burnt.[63]

“The city was perfectly quiet,” declares a Belgian witness,[64] “until about 8.0 p.m. At about 9.15 p.m. I was in bed reading when I heard the sound of rifle-fire.... The noise of the firing came nearer and nearer.” The first shot was fired from a window of “Emulation Building,” looking out on the Place de l’Université, in the heart of the town.[65] The Place was immediately crowded with armed German soldiers, firing in the air, breaking into houses, and dragging out any civilians they could find. First nine men (5 of them Spanish subjects) were shot in a batch, then 7 more.[66] “About 10.0 p.m. they were shooting everywhere. About 10.30 p.m. several machine guns were firing and artillery as well.” (The artillery was firing on private houses from the opposite side of the Meuse.[67]) “About 11.0 p.m. I saw between 45 and 50 houses burning. There were two seats of the fire—the first at the Place de l’Université (8 houses—I was close by at the time), the second across the Meuse on the Quai des Pecheurs, where there were about 35 houses burning. I heard a whole series of orders given in German, and also bugle calls, followed by the cries[49] of the victims, and I saw women with children running about in the street, pursued by soldiers....” (a 28).

5. Ans: The Church

6. Liége: A Farm House

The arson was elaborate. In the Rue des Pitteurs the waggon loaded with benzine moved from door to door.[68] “About 20 men were going up to each of the houses. One of them had a sort of syringe, with which he squirted into the house, and another would throw a bucket of water in. A handful of stuff was first put into the bucket, and when this was thrown into the house there was an immediate explosion” (a 31). At the Place de l’Université, when the Belgian fire-brigade arrived, they were forbidden to extinguish the fire, and made to stand, hands up, against a wall (a 28, 29). Later they were assigned another task. “About midnight,” states a witness (a 30), “a whole heap of civilian corpses were brought to the Hôtel de Ville on a fire-brigade cart. There were 17 of them. Bits were blown out of their heads....”

As the houses caught fire the inmates tried to escape. The few who reached the street were shot down (a 24, 26). Most were driven back into the flames. “At about 30 of the houses,” a witness states (a 31), “I actually saw faces at the windows before the Germans entered, and then saw the same faces at the cellar windows after the Germans had driven the people into the cellars.” In this way a number of men and women[50] were burnt alive.[69] In some cases the Germans would not wait for the fire to do their work for them, but bayonetted the people themselves. In one house, near the Episcopal Palace,[70] two boys were bayonetted before their mother’s eyes, and then the man—their father and her husband. Another man in the house was wounded almost to death, and the Germans were with difficulty prevented from “finishing him off,” next morning, on the way to the hospital. An orphan girl, who lodged in the same house, was violated.

Next morning, August 21st, the district round the University Buildings on either side of the Meuse was cleared of its inhabitants—such inhabitants as survived and such streets as still stood. The people were evicted at a few hours’ notice, and not allowed to return for a month.[71] The same day a proclamation was posted by the German authorities: “Civilians have fired on the German soldiers. Repression is the result.”[72] The indictment was not convincing, for “Emulation Building,” from which the first shot was fired on the night of the 20th, had been cleared of its Belgian occupants some days before and filled entirely with German soldiers. Later the German Governor of Liége shifted his ground, and laid the blame on Russian students “who had been a burden on the[51] population of the city.”[73] A clearer light is thrown on the outbreak of August 20th by what occurred on the night of August 21st-22nd. “Aug. 22nd, 3 a.m., Liége,” writes a German in his diary. “Two infantry regiments shot at each other. Nine dead and 50 wounded—fault not yet ascertained.” But in the other diary, quoted before, the incident is thus recorded under the same date: “August 21st. In the night the soldiers were again fired on. We then destroyed several houses more.” The soldiers fire, the civilians suffer reprisals, but the Germans’ object is gained. The conquered population is terrorised, the invaders feel secure. “On August 23rd everything quiet,” the latter diarist continues. “The inhabitants have so far given in.

“August 24th. Our occupation is bathing, and eating and drinking for the rest of the day. We live like God in Belgium.”

The first German force to push forward from Liége was the column commissioned to mask the Belgian fortress of Antwerp on the extreme right flank of the German advance. From the bridges of the Meuse this column marched north-west across the Province of Limburg. Belgian patrols met the advance-guard already at Lanaeken on August 6th, driving civilians in front of it as a screen.[74] The invaders were obsessed with the terror of franc-tireurs. At Hasselt,[75] on August 17th, they made the Burgomaster post a proclamation advising his fellow-citizens “to abstain from any kind of provocative demonstration and from all acts of hostility, which might bring terrible reprisals upon our town.

“Above all you must abstain from acts of violence against the German troops, and especially from firing on them.

“In case the inhabitants fire upon the soldiers of the German Army, a third of the male population will be shot.”

7. Liége Under German Occupation

8. Liége Under the Germans: Ruins and Placards

At Tongres,[76] on August 18th, the Germans carried threats into action. The population was driven out bodily from the town, and the town systematically plundered. At least 17 civilians were killed (including a boy of 12), and a number of houses were burnt. “On August 18th,” writes a German in his diary, “we reach Tongres. Here, too, it is a complete picture of destruction—something unique of its kind for our profession.”[77]—“Tongres,” writes another on the 19th, “A quantity of houses plundered by our cavalry.” A captured letter from the hand of a German army-doctor reveals the pretext on which this was done. “The Belgians have only themselves to thank that their country has been devastated in this way. I have seen all the great towns attacked and the villages besieged and set on fire. At Tongres we were attacked by the population in the evening when it was dark. An immense number of shots were exchanged, for we were exposed to fire on four sides. Happily we had only one man hit—he died the following day. We killed two women, and the men were shot the day after.” There is no disproof here of the Belgian affirmation that the shots were fired by the Germans themselves.

This outbreak at Tongres on August 18th was not an isolated occurrence. On the same day the Germans[54] shot down the Burgomaster’s wife and a lawyer at Cannes,[78] and two men and a boy at Lixht,[79] a few miles north-west of the Visé bridge. But Limburg suffered little compared to Brabant, into which the Germans next advanced.

Haelen, where their advance-guard was severely handled by the Belgian Army on August 12th, lies close to the boundary between the two provinces, and they took vengeance on the civil population of Brabant for this military reverse.

“The Germans came to Schaffen,”[80] the curé reports, “at 9.0 o’clock on August 18th. They set fire to 170 houses. A thousand inhabitants are homeless. The communal building and my own residence are among the houses burnt. Twenty-two people at least were killed without motive. Two men (mentioned by name) were buried alive head downwards, in the presence of their wives. The Germans seized me in my garden, and mishandled me in every kind of way.... The blacksmith, who was a prisoner with me, had his arm broken and was then killed.... It went on all day long. Towards evening they made me look at the church, saying it was the last time I should see it. About 6.45 they let me go. I was bleeding and unconscious.[55] An officer made me get up and bade me be off. At several metres distance they fired on me. I fell down and was left for dead. It was my salvation....

“All the houses were drenched, before burning, with naphtha and petrol, which the Germans carry with them....”

On the German side, there is the ordinary excuse. “Fifty civilians,” writes a diarist, “had hidden in the church tower and had fired on our men with a machine-gun.[81] All the civilians were shot.”

The curé mentions that the Germans found the church door locked, broke it in, and then found no one there.

At Molenstede, another village in the Canton of Diest, 32 houses were burnt and 11 civilians killed. In the whole Canton 226 houses were burnt, and 47 people killed in all.

The Germans were also advancing by a more southerly road from Tongres through St. Trond. At St. Trond,[82] the first Uhlans killed 2 civilians in the street and wounded others. At Budirgen they killed 2 civilians and burned 58 houses, at Neerlinter one and 73. In the Canton of Léau they killed 19 civilians altogether, and 174 houses were destroyed.

At Haekendover, in the Canton of Tirlemont, they killed one civilian, burned 32 houses and pillaged 150 (out of 220 in all). At Tirlemont itself, they killed three civilians and burned 60 houses. At Hougaerde,[83] when they entered the village, they drove the curé of Autgaerde before them as a screen, and he was killed by the first bullet from the Belgian troops, who were defending the road from behind a barricade. Four civilians were killed at Hougaerde, 100 houses pillaged, and 50 destroyed. In the whole Canton of Tirlemont the Germans killed 18 civilians, and burned 212 houses down.

At Bunsbeek they killed 4 people and burned 20 houses, at Roosbeek 3 and 42. “After Roosbeek,” a German diarist notes,[84] “we began to have an idea of the war; houses burnt, walls pierced by bullets, the face of the tower carried away by shells, and so on. A few isolated crosses marked the graves of the victims.” At Kieseghem[85] the Germans used civilians as a screen again, and killed two more when they entered the village. At Attenrode they killed 6 civilians and burned 17 houses, at Lubbeck 15 and 46. In the Canton of Glabbeek 35 civilians were killed from first to last, and 140 houses destroyed.

The Germans marched into Aerschot[86] on the morning of Aug. 19th, driving before them two girls and four women with babies in their arms as a screen.[87] One of the women was wounded by the fire of the Belgian troops, who had posted machine guns to dispute the Germans’ entry, but now withheld their fire and retired from the town. The Germans encountered no further resistance, but they began to kill civilians and break into houses immediately they came in. They bayonetted two women on their doorstep (c 27). They shot a deaf boy (c 1) who did not understand the order to raise his hands. They shot 5 men they had requisitioned as guides (R. No. 3). They fired at the church (c 18). They fired at people looking out of the windows of their houses (R. No. 5). The Burgomaster’s son, a boy of fifteen, was standing at a window with his mother and was wounded by a bullet in the leg (R. No. 11). They killed people in their houses. Six men, for instance, were bayonetted in one house (R. No. 15). They dragged a railway employé from his home and shot him in a field (R. No. 2). “I went back home,” states a woman who had been seized by the Germans and had escaped (c 18), “and found my husband lying dead outside it. He had been[58] shot through the head from behind. His pockets had been rifled.”

Other civilians (the civil population was already accused of having fired) were collected as hostages,[88] and driven, with their hands raised above their heads, to an open space on the banks of the River Démer. “There were about 200 prisoners, some of them invalids taken from their beds” (c 1). There was a professor from the College among them (R. No. 9), and an old man of 75 (c 15). After these hostages had been searched, and had been kept standing by the river, with their arms up, for two hours, the Burgomaster was brought to them under guard,[89] and compelled to read out a proclamation, ordering all arms to be given up, and warning that if a shot were fired by a civilian, the man who fired it, and four others with him, would be put to death. It was a gratuitous proceeding, for, several days before the Germans arrived, the Burgomaster (like most of his colleagues throughout Belgium) had sent the town crier round, calling on the population to deposit all arms at the Hôtel-de-Ville, and he had posted placards on the walls to the same effect (c 4, 7). A priest drew a German officer’s attention to these placards (c 20), and the Burgomaster himself had already given a translation of their contents to the German commandant[59] (R. No. 11). That officer[90] disingenuously represents this act of good faith as a suspicious circumstance. “To my special surprise,” he states, “thirty-six more rifles, professedly intended for public processions and for the Garde Civique, were produced” (from the Hôtel-de-Ville). “The constituents of ammunition for these rifles were also found packed in a case.” But the only weapon still found in private hands on the morning of Aug. 19th was a shot gun used for pigeon shooting (c 1), and when the owner had fetched it from his home the hostages were released. Yet at this point 4 more civilians were shot down, two of them father and son—the son feeble-minded (c 15).

The Germans quartered in Aerschot were already getting out of hand. “I saw the dead body of another man in the street,” continues the witness (c 15) quoted above. “When I got to my house, I found that all the furniture had been broken, and that the place had been thoroughly ransacked, and everything of value stolen. When I came out into the street again I saw the dead body of a man at the door of the next house to mine. He was my neighbour, and wore a Red Cross brassard on his arm....”

The Germans gave themselves up to drink and plunder. “They set about breaking in the cellar doors, and soon most of them were drunk” (R. No. 15).—“An officer came to me,” states another witness (c 7),[60] “and demanded a packet of coffee. He did not pay for it. He gave no receipt.”—“They broke my shop window,” deposes another. “The shop front was pillaged in a moment. Then they gutted the shop itself. They fought each other for the bottles of cognac and rum. In the middle of this an officer entered. He did not seem at all surprised, and demanded three bottles of cognac and three of wine for himself. The soldiers, N.C.O.’s and officers, went down to the cellar and emptied it....” Not even the Red Cross was spared. The monastery of St. Damien, which had been turned into an ambulance, was broken into by German soldiers, who accused the monks of firing and tore the bandages off the wounded Belgian soldiers to make sure that the wounds were real (R. No. 16). “Whenever we referred to our membership of the Red Cross,” declares one of the monks, “our words were received with scornful smiles and comments, indicating clearly that they made no account of that.”

9. Liége in Ruins

10. “We Live Like God in Belgium”

About 5.0 p.m. Colonel Stenger, the commander of the 8th German Infantry Brigade, arrived in Aerschot with his staff. They were quartered in the Burgomaster’s house, in rooms overlooking the square. Captain Karge, the commander of the divisional military police, was billeted on the Burgomaster’s brother, also in the square but on the opposite side. About 8.0 p.m. (German time) Colonel Stenger was standing on the Burgomaster’s balcony; the Burgomaster, who had just[61] been allowed to return home, was at his front door, offering the German sentries cigars, and his wife was close by him; the square was full of troops, and a supply column was just filing through, when suddenly a single loud shot was fired, followed immediately by a heavy fusillade. “I very distinctly saw two columns of smoke,” writes the Burgomaster’s wife (R. No. 11), “followed by a multitude of discharges.”—“I could perceive a light cloud of smoke and dust,” states Captain Karge,[91] who was at his window across the square, “coming from the eaves of a red corner house.” In a moment the soldiers massed in the square were in an uproar. “My yard,” continues the Burgomaster’s wife, “was immediately invaded by horses and by soldiers firing in the air like madmen.”—“The drivers and transport men,” observes Captain Karge, “had left their horses and waggons and taken cover from the shots in the entrances of the houses. Some of the waggons had interlocked, because the horses, becoming restless, had taken their own course without the drivers to guide them.” Another German officer[92] thought the firing came from the north-west outskirts of the town, and was told by fugitive German soldiers that there were Belgian troops advancing to the attack. A machine-gun company went out to meet them, and marched three kilometres before it discovered that there[62] was no enemy, and turned back. “About 350 yards from the square,” states the commander of this unit,[93] “I met cavalry dashing backwards and transport waggons trying to turn round.... I saw shots coming from the houses, whereupon I ordered the machine guns to be unlimbered and the house fronts on the left to be fired upon.”

Who fired the first shot? Who fired the answering volley? There is abundant evidence, both Belgian and German, of German soldiers firing in the square and the neighbouring streets; no single instance is proved, or even alleged, in the German White Book, of a Belgian caught in the act of firing. “The situation developed,” deposes Captain Folz,[94] “into our men pressing their backs against the houses, and firing on any marksman in the opposite house, as soon as he showed himself.” But were they Belgians at the windows, or Germans taking cover from the undoubted fire of their comrades, and replying from these vantage points upon an imaginary foe? “Near the Hôtel-de-Ville,” continues Captain Folz, “there stood an officer who had the signal ‘Cease Fire’ blown continuously.[95] Clearly this officer desired in the first place to stop the shooting of our men, in order to set a systematic action on foot.”

The German soldiers’ minds had been filled with lying rumours. “I heard,” declares Captain Karge, “that the King of the Belgians had decreed that every male Belgian was under obligation to do the German Army as much harm as possible....

“An officer told me he had read on a church door that the Belgians were forbidden to hold captured German officers on parole, but had to shoot them....

“A seminary teacher assured me” (it was under the threat of death) “definitely, as I now think that I can distinctly remember, that the Garde Civique had been ordered to injure the German Army in every possible way....”

Thus, when he heard the shots, Captain Karge leapt to his conclusions. “The regularity of the volleys gave me the impression that the affair was well organised and possibly under military command.” It never occurred to him that they might be German volleys commanded by German officers as apprehensive as himself. “Everywhere, apparently,” he proceeds, “the firing came, not from the windows, but from roof-openings or prepared loopholes in the attics of the houses.” But if not from the windows, why not from the square, which was crowded with German soldiers, when a moment afterwards (admittedly) these very soldiers were firing furiously? “This” (assumed direction from which the firing came) “is the explanation of the smallness of the damage done by the shots to men and[64] animals,” and, in fact, the only victim the Germans claim is Colonel Stenger, the Brigadier. After the worst firing was over and the troops were getting under control, Colonel Stenger was found by his aide-de-camp (A 2), who had come up to his room to make a report, lying wounded on the floor and on the point of death. Captain Folz (A 5) records that “the Regimental Surgeon of the Infantry Regiment No. 140, who made a post-mortem examination of the body in his presence on the following day, found in the aperture of the breast wound a deformed leaden bullet, which had been shattered by contact with a hard object.” It remains to prove that the bullet was not German. The German White Book does not include any report from the examining surgeon himself.

Meanwhile, the town and people of Aerschot were given over to destruction. “I now took some soldiers,” proceeds Captain Karge, “and went with them towards the house from which the shooting”—in Captain Karge’s belief—“had first come.... I ordered the doors and windows of the ground floor, which were securely locked, to be broken in. Thereupon I pushed into the house with the others, and using a fairly large quantity of turpentine, which was found in a can of about 20 litres capacity, and which I had poured out partly on the first storey and then down the stairs and on the ground floor, succeeded in setting the house on fire in a very short time. Further, I had ordered the[65] men not taking part in this to guard the entrances of the house and arrest all male persons escaping from it. When I left the burning house several civilians, including a young priest, had been arrested from the adjoining houses. I had these brought to the square, where in the meantime my company of military police had collected.

“I then ... took command of all prisoners, among whom I set free the women, boys and girls. I was ordered by a staff officer to shoot the prisoners. Then I ordered my police ... to escort the prisoners and take them out of the town. Here, at the exit, a house was burning, and by the light of it I had the culprits—88 in number, after I had separated out three cripples—shot....”

11. Haelen

12. Aerschot

These 88 victims were only a preliminary batch. The whole population of Aerschot was being hunted out of the houses by the German troops and driven together into the square. They were driven along with brutal violence. “One of the Germans thrust at me with his bayonet,” states one woman (c 9), “which passed through my skirt and behind my knees. I was too frightened to notice much.”—“When we got into the street,” states another (c 10), “other German soldiers fired at us. I was carrying a child in my arms, and a bullet passed through my left hand and my child’s left arm. The child was also hit on the fundament.... In the hospital, on Aug. 22nd, I saw[66] three women die of wounds.”—“In the ambulance at the Institut Damien,” reports the monk quoted above, “we nursed four women, several civilians and some children. A one-year-old child had received a bayonet wound in its thigh while its mother was carrying it in her arms. Several civilians had burns on their bodies and bullet wounds as well. They told us how the soldiers set fire to the houses and fired on the suffocating inhabitants when they tried to escape.”

As elsewhere, the incendiarism was systematic. “They used a special apparatus, something like a big rifle, for throwing naphtha or some similar inflammable substance” (c 19).—“I was taken to the officer in command,” states a professor (c 14). “I found him personally assisting in setting fire to a house. He and his men were lighting matches and setting them to the curtains.”—“We saw a whole street burning, in which I possessed two houses,” deposes a native of Aerschot, who was being driven towards the square. “We heard children and beasts crying in the flames” (c 2). A civilian went out into the street to see if his mother was in a burning house. He was shot down by Germans at a distance of 18 yards (c 5). Another householder (R. No. 5) threw his child out of the first-floor window of his burning house, jumped out himself, and broke both his legs. His wife was burnt alive. “The Germans with their rifles prevented anyone going to help this man, and he had to drag himself along with[67] his legs broken as best he could” (c 19).—“The whole upper part of my house caught fire,” declares another (R. No. 13), “when there were a dozen people in it. The Germans had blocked the street door to prevent them coming out. They tried in vain to reach the neighbouring roofs.... The Germans were firing on everyone in the streets....”

By this time the Germans were mostly drunk (c9) and lost to all reason or shame. Two men and a boy stepped out of the door of a public-house in which they had taken refuge with others. “As soon as we got outside we saw the flash of rifles and heard the report.... We came in as quickly as we could and shut the door. The German soldiers entered. The first man who entered said, ‘You have been shooting,’ and the others kept repeating the same words. They pointed their revolvers at us, and threatened to shoot us if we moved” (c 4).

In another building about 22 captured Belgian soldiers (some of them wounded) and six civilian hostages were under guard. They were dragged out to the banks of the Démer and shot down by two companies of German troops. “I was hit,” explains one of the two survivors (a soldier already wounded before being taken prisoner), “but an officer saw that I was still breathing, and when a soldier wanted to shoot me again, he ordered him to throw me into the Démer. I clung to a branch and set my feet against the stones[68] on the river-bottom. I stayed there till the following morning, with only my head above water....” (R. No. 8).