Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 988, December 3, 1898

Author: Various

Release date: December 27, 2015 [eBook #50773]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| Vol. XX.—No. 988.] | DECEMBER 3, 1898. | [Price One Penny. |

[Transcriber's Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

"OUR HERO."

VARIETIES.

BURNT WOOD DRAWING.

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

SOME PRACTICAL HINTS ON COSMETIC MEDICINE.

ANGELIE.

"SISTER WARWICK": A STORY OF INFLUENCE.

THREE SOUPS.

THE RULES OF SOCIETY.

LETTERS FROM A LAWYER.

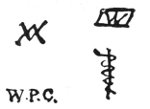

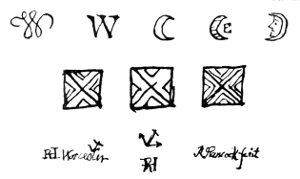

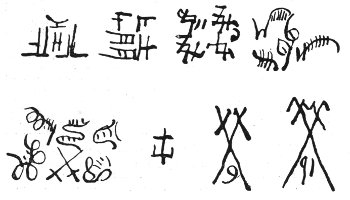

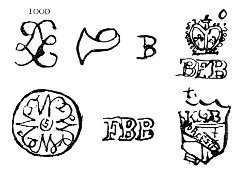

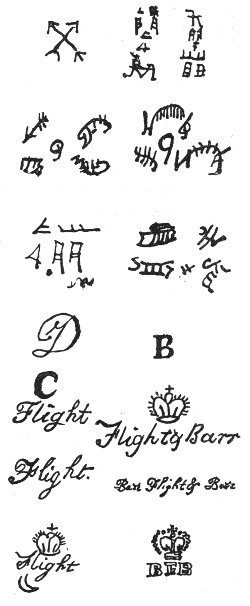

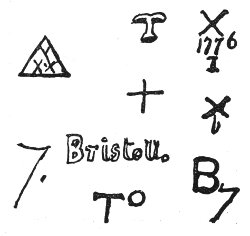

CHINA MARKS.

NEIGHBOURS.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

All rights reserved.]

A TALE OF THE FRANCO-ENGLISH WAR NINETY YEARS AGO.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "The Girl at the Dower House," etc.

Little rest could be allowed in those days to England's most gallant sons. Moore had a short time with those whom he loved best—with the mother especially, who was more to him than all the world beside—and again he was called away. In this year, 1797, a French invasion was already looked for, and he had to go, with an engineer officer, to survey the eastern coast, and to decide on preparations for such an invasion. After which he was despatched against Irish rebels in our unquiet sister-isle, there to be once more laid low with a severe illness.

Despite this attack he made himself so invaluable to the Lord-Lieutenant, Earl Cornwallis, one of his many personal friends, that when needed on the Continent by Sir Ralph Abercrombie, he could not at once be ordered thither. However, the need for his services became urgent, and English ministers appealed to Cornwallis, whose reply was:—

"I am sure you know me too well to suspect that any selfish consideration can weigh a moment with me against the general interests of the country. You shall have all the troops you ask, and General Moore, who is a greater loss to me than the troops. But he will be of infinite service to Abercrombie; and I likewise think it an object of the state that an officer of his talents and character should have every opportunity of acquiring knowledge and experience in his profession."

This was 1799, and ten thousand British troops were sent to Holland under Abercrombie. On October 2nd that engagement took place, to which the letters copied by Jack Keene bore reference. Moore received two wounds in the course of five hours' determined fighting. The first, in his leg, he quietly ignored; the second, in his face, felled him to the ground in a stunned condition. He and his men were then nearly surrounded by a strong body of the enemy, and Moore would have been made prisoner but that his men carried him off. He was assisted to the rear, and when his wounds had been dressed he rode ten miles back to his quarters, so faint with loss of blood that his horse had to be led, and he could barely keep his seat.

A few days later he very nearly put an end to his own life by accidentally drinking a strong sugar-of-lead lotion, used to bathe his cheek. Happily he kept his self-command, and the measures instantly taken prevented any ill result.

The letter from Sir Ralph Abercrombie to Dr. Moore had been written on the field of battle, which the commanding officer never left that night.

In the year 1800 Moore was again in the Mediterranean, and then came the memorable "Expedition to Egypt" under Abercrombie, Moore being once more under his old commander; and this time Ivor was again under Moore.

In a desperate action, which took place on March 20th, 1801, Moore was a second time wounded in the leg, and, as before, he fought resolutely on, disregarding it. Abercrombie, too, was shot in the thigh, but paid no heed, not even mentioning the fact until, the battle ended, he turned faint, and fell from his horse. The two friends never met again, for Abercrombie died of his wound before Moore was able to go to him. Moore's especial companion, Anderson, was also severely wounded, nearly losing his arm in consequence. Moore, writing home afterwards, said, "I never saw a field so covered with dead." But victory was with the English.

Then came the Peace of Amiens, and Moore returned to England in time to see once more his father, who was dying of old age and heart-disease. The Doctor's property was left between his wife and his six children, and Moore, not satisfied with his mother's jointure, insisted on giving her an additional annuity.

Thus for years the name of John Moore had been incessantly before the English public as the bravest of the brave, having become by this time the name beyond any other to which his countrymen would instinctively turn in any hour of national peril.

What was it about this remarkable man which so riveted the hearts of others to him? Not the hearts of women only, though his mother and sister idolised him, but vigorous men, stern soldiers, poured upon him a passion of devotion.

Buonaparte was adored and followed unto death by his soldiers, as a great Captain. Moore, in addition to this, was loved intensely as a man, with that love which strong men only give to strong men, and not to many of them. Wherever Moore turned he found this love. His own brothers lavished it upon him. The Duke of Hamilton was his ardent friend for life. Anderson was to him as Jonathan to David. The three gallant Napiers, Charles, George, and William, absolutely worshipped him. His French servant, François, forgot home and country for his sake. Private soldiers were ready to rush upon certain death if so they might save his life. Officers of rank, working with him, became almost inevitably his personal friends. The younger officers, under his command and training, so caught the infection of his high spirit, so responded to the influence of "their Hero," that by scores in after years they became prominent characters in the Army and leaders in the nation. He has been truly called "a king among men."

No doubt his striking personal appearance, his indescribable charm of manner—perhaps too his brilliant and witty conversational powers—had something to do with the matter. At the date when war again broke out, Moore, already a General, was only in his forty-third year—a man of commanding presence, tall and graceful, with a countenance of rare beauty. But those things which really lay at the foundation of this extraordinary control over others were,—the force of his character, the vivid enthusiasm of his purpose, the loftiness of his ideals, the simple grandeur of his life.

He had no doubt his enemies. What truly great man, who does not pander to the littlenesses of truly little men, ever fails to make some enemies? It could not be otherwise. His inviolable integrity, his blameless name, the splendid disdain with which he spurned everything false and mean—such qualities as these in Moore made some of a baser type turn from and even turn against one so infinitely more noble than themselves. But to men of a higher and purer stamp Moore was as the Bayard of the Middle Ages had been to a former generation, a knight sans peur et sans reproche, a model upon which they might seek to shape themselves.

With Ivor, as with many another, to have known Moore was to have been imbued for life with new aims, new ideals, new views of duty, new thoughts of self-abnegation. Not so much from what Moore might here or there have said, as from what he always was. To be under the man was in itself an inspiration.

Soon after Jack's departure for Sandgate, Admiral Peirce was called away on duty, and then the Bryces decided to flit eastward. Mrs. Bryce, who loved sensation, talked of a visit to Folkestone, a very tiny watering-place in those days, but within easy reach of Sandgate, and of Moore's Camp at Shorncliffe.

As a next move she offered to take Polly with her. Mrs. Fairbank demurred, and Mrs. Bryce insisted. Polly had kept up bravely under her separation from Ivor, but her pretty face had lost some of its colour, and no one could deny that the change might do her good. Mrs. Fairbank, thus advised, yielded, and Polly of course was charmed. Who would not have been so in her place? She would see Jack again, also Jack's Commander and England's Hero, General Moore. She would be distinctly{147} nearer to France, and therefore to Denham. She would be in the thick of all that was going on, and would hear the news of the hour at first hand. Moreover, Polly was young and loved variety. But what about Molly?

"Molly has her lessons to learn. She and I will be companions each to the other," Mrs. Fairbank decided.

Nobody saw aught to find fault with in the plan except Molly herself, and Molly said nothing. Under the circumstances no other seemed open, unless Polly were made to give up the change which she much needed.

But in later years Molly often looked back with a shudder to those lonely autumn weeks.

Those were days of far severer imprisonment than are these, dungeons and chains being everyday matters. Molly had heard enough, even in her short life, of fettered and half-starved prisoners to cause her to be haunted by doleful visions.

In the daytime, when, by Mrs. Fairbank's desire, she was always fully occupied, it was easier to take a cheerful view of life; but Molly's time of misery began with nightfall. Often she would start out of a restless sleep, fancying that she saw Roy deep in some noisome underground cavern, with chains clanking on his wrists, while his big grey eyes appealed pitifully to her for help. Then she would hide her face, and would sob for an hour, and in the midst of her woe would come the sound of the old watchman shaking his rattle as he passed down the street, and calling out monotonously in sing-song tones, "Past one o'clock, and a fine starlight night." Or it might be, "Past three o'clock, and a rainy morning." Those old watchmen—"Charleys," as they were called—were the forerunners of our present police.

But of all this Molly said not a word to any human being. The only person whom she could have told was Polly.

In time a delightful letter arrived from Polly, written to Molly, telling how she and Mrs. Bryce had driven over from Folkestone to Sandgate, and had seen General Moore and Jack, and had inspected the preparations there made for a due welcome to Napoleon, when he should choose to make his appearance on British shores.

"And do but think, Molly," wrote Polly, "General Moore's dear old mother is down now at Sandgate, where she and her daughter have come to see again the General. For if Napoleon comes—and some say he will, and some say he will not—there must surely be hard fighting, and what that may mean none can tell beforehand. For sure it is, whatever happens, that General Moore will be in the thickest of the fight. And Jack tells me that when first Mrs. Moore arriv'd 'twas a touching sight indeed. She took her son into her arms, before all the Officers who were gather'd together, and burst into tears, doubtless thinking of the danger he must soon be in, and the many times he has been wounded. And not one present, Jack says, who did not testify his respect for her, nor his sympathy in her love for her heroic son.

"She has been at Sandgate for many weeks, and the General now urges her return home. For any day the French may make a move, and he wou'd fain have her away in a place of safety. But Mrs. Bryce and I have no fear, though all the world is in a great stir, waiting for the invaders to come. Jack wou'd love nothing better than to see the fleet of flat-bottomed boats approaching, that he might have a chance of fighting them and driving them back.

"I must tell you a story of Mr. William Pitt, who, being Warden of the Cinque Ports, has lately raised two regiments in this district, consisting of a thousand men each. He has often ridden over to General Moore's camp at Shorncliffe, and the two have talked together, General Moore telling his plans to Mr. Pitt. And one day Mr. Pitt said to General Moore, 'Well, Moore, but on the very first alarm of the enemy's coming, I shall march to aid you with my Cinque Port regiments, and you have not told me where you will place us.' Whereupon General Moore answered, 'Do you see that hill? You and yours shall be drawn up upon it, where you will make a most formidable appearance to the enemy, while I, with the soldiers, shall be fighting on the beach.' Mr. Pitt was excessively entertained with this reply, and laughed heartily.

"And that reminds me of another little tale which Jack told to me—not as to Mr. Pitt, but as to Mr. Fox. He was playing a game of cards one day, no long time agone, and on overhearing some story that was told, he threw his cards down, and cried out, 'Tell that again! I hear a good deal of General Moore, and everything good. Tell me that again.' But Jack could not say what it was that had been told, only he liked to know that Mr. Fox could so speak of one who is Mr. Pitt's friend. And though Mr. Pitt and General Moore be so intimate, yet General Moore will have it that he cares little which side shall be in power, so long only as the country is well governed. But some say that 'tis like to be no long time before we see Mr. Pitt once more at the head of the Government."

To this letter Molly sent a reply in her childish round handwriting, letting a little of her loneliness slip out, despite herself; and Mrs. Fairbank, much disturbed in mind on Polly's behalf, wrote also, suggesting arrangements for the greater safety of the people concerned.

(To be continued.)

Recipes for Mental Ailments.

Against fits of fury.—Go at once into the open air, far away from your neighbours, and shout to the wind, and tell it how foolish you are.

Against attacks of discontent.—Set out for the homes of the poor. Look at their narrow rooms, their hard beds, their poor clothes and shoes. Observe what is put on their breakfast, dinner and supper table. Ask what their earnings are, and calculate how you would fare with the same amount. When you get home again you will be no longer discontented.

Against despair.—Look at the good things God has given you in this world and remember the better things He has promised for the next. She who looks for cobwebs in the garden will find not only them but spiders as well. But she who goes to find flowers will return with perfumed roses.—From the German.

Thought and Action.

The ancestor of every action is a thought. Our dreams are the sequel of our waking knowledge.—Emerson.

A Lesson for a Choir-Singer.

One of the finest choral conductors whom this country has ever produced was Henry Leslie, whose choir was for many years one of the prominent features of musical London.

He was an autocrat, very difficult to satisfy, particular to nicety in regard to every phrase and mark of expression. He did not like to hear individual voices; the blending of the voices was his aim. There was a lady with a very rich contralto who gave him trouble in this way—her voice was heard separately. Mr. Josiah Booth, who was one of the members of the choir, says that he thinks Mr. Leslie had spoken to the lady privately, but without result. However, one day he said to her—

"You may have a very fine voice, but I don't want to hear it. I want to hear the choir."

"We went on singing," says Mr. Booth. "Sitting behind, I could not see the lady's face, but I guessed she was looking daggers at Mr. Leslie. At the next pause he fixed her with those searching eyes of his and said—

"'I've a great deal more reason to look like that than you have.'"

Chinese Doctors.

No pharmacopœia is more comprehensive than the Chinese, and no English physician can surpass the Chinese in the easy confidence with which he will diagnose symptoms that he does not understand. The Chinese physician who witnesses the unfortunate effect of placing a drug of which he knows little into a body of which he knows less, is not much put out: he retires sententiously observing, "there is medicine for sickness, but none for fate." "Medicine," says a Chinese proverb, "cures the man who is fated not to die." Another saying has it that "when Yenwang (the King of Hell) has decreed a man to die at the third watch no power will detain him to the fifth."

Doctors in China dispense their own medicines. In their shops you see an amazing variety of drugs; you will occasionally also see tethered a live stag which on a certain day, to be decided by the priests, will be pounded whole in a pestle and mortar. "Pills manufactured out of a whole stag slaughtered with purity of purpose on a propitious day" is a common announcement in dispensaries in China.

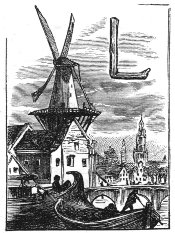

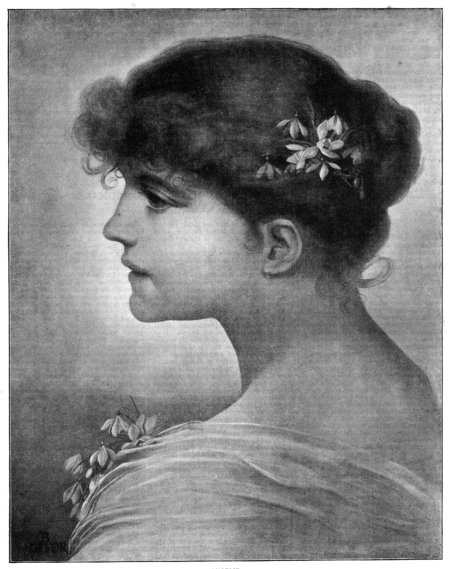

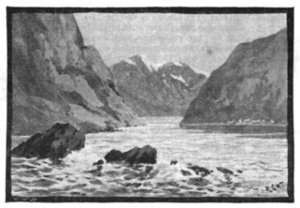

SUNSET OVER THE SEA.

(Burnt wood drawing in oak frame, by E. M. Jessop.)

Of all the graphic arts this is probably the most useful and durable. Under its old but ridiculous title of "poker work" it has flourished from time immemorial; gifted by some unknown genius with the modern name of Pyrography, it bids fair to become a universal favourite among the amusements of art-loving amateurs, but, owing to want of support, has not hitherto been much adopted by the professional artist who alone possesses the graphic skill, the power of technique and the breadth of execution which would do justice to such a beautiful art.

When we consider that nothing but fire or wanton mischief can really damage the pictures which may be produced in this work, and that the original cost of the materials for its production is so very slight, one marvels that so fine a medium for wall and furniture decoration has been so much neglected.

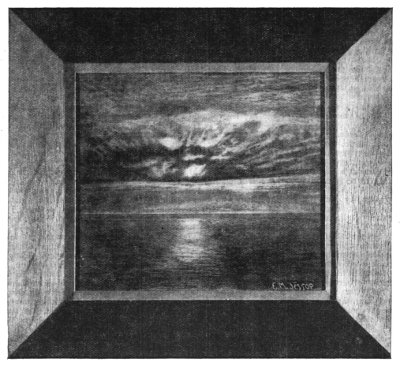

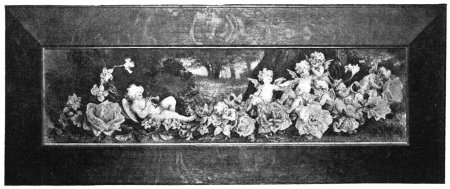

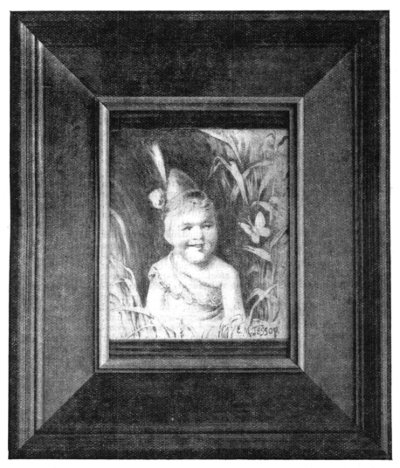

A SUMMER IDYLL.

(Burnt wood drawing in oak frame, by E. M. Jessop.)

In the specimens which I have recently had the honour to submit to H.R.H. The Princess of Wales, and which she was pleased to greatly admire, the materials used were of the very simplest. To be epigrammatic, were I asked how I did them, I could only reply,{149} "With a few boards, two old chisels and a little intelligence."

So now to our wood-work's foundation. In the first place never commence a drawing on any but sound, well-seasoned wood, as nothing could well be more trying to the temper than seeing the result of a month's work curling up like a roll of paper or splitting across in a manner which places it beyond repair. Any good whitish wood is suitable for burnt drawing; holly on account of its close grain being the best, but, like the best of everything, holly of the width required is also the rarest of woods. Next to holly comes sycamore, a fine hard wood; then chestnut. In one of the specimens here illustrated (the child's head) I have used an old drawing-board made of poplar with beech clamps at either end. Never use wood of less than three-eighths of an inch in thickness, the thin plaques sold by most shops being quite useless for works of any size on account of their liability to split and cockle. By the way, the cockling of a wood drawing can to a certain extent be remedied by exposing the concave side to heat and leaving it to cool between two flat surfaces with heavy weights on top.

And now to our tools. For drawings of any size suitable for the doors of cabinets or rooms, plaques to insert in oak dadoes, etc. (and it is in these we shall get our finest effects), the little machines heated by spirits of wine and other mediums are not of much use. It is, in fact, like using the smallest sable brushes for fresco painting. For my own work I mainly use wood-carving tools. The broadest chisels and gouges are the best, and the thicker the steel the better the tool, as it retains the heat for a longer period. Again, I always heat my tools in an ordinary coal fire, but it should be quite possible to get a small gas stove to give all the heat required in a perhaps more convenient manner.

I might here mention that your most used tool, which should be a broad blunt chisel, say three-quarters of an inch in width, ought to have its sharp corners carefully ground down before using it, as it is otherwise liable to burn ugly little black spots on the drawing.

With these explanations we will now proceed to the drawing itself, and here it is necessary to give a very strong caution at the outset; this is, always bear in mind that whatever marks you burn on your wood must absolutely remain there. There is no way of rubbing out, and to erase with a knife is to spoil the surface of your wood, as you cannot draw properly over a scratched surface. For this reason also you can only copy either your own or other people's drawings in burnt wood-work.

Having selected your copy first draw a careful pencil outline from it on the wood plaque. We will here, for example, say it is the drawing of the child's head reproduced. Heat a small tool sufficiently to mark a very light brown line on the wood (to ascertain heat keep a small piece of waste wood by your side), then carefully go over the outline of the head and mark in all the features. Now with soft india-rubber erase all pencil marks from the parts you have burnt, and make a fresh pencil indication of the shape of your shadows, and proceed slowly and carefully with the hot tool to build up coat by coat from the lightest to the darkest these same shadows, never forgetting that lights cannot be applied afterwards, but must be left out. A darker shade can always be added, but a light never. Now once more remove your pencil-marks and proceed to draw in your figure in the same manner as above described. Next comes the background to be lightly sketched in by the hot irons; and, after this, all pencil-marks may be removed and the picture carefully worked up tone by tone from the copy.

FRIVOLITY.

(Burnt wood drawing in ebony frame, by E. M. Jessop.)

In holding the tools (the handles of which may be covered with cork, or some non-conductor), it is necessary to remember that they should never be used to make pen-like strokes, but more of a pastel effect must be sought, as the soft-blurred appearance produced by gently drawing them along the wood gives the effect of old carved ivory, which is one of the chief charms of a fine burnt wood drawing. For instance, in the drawing of "Sunset over the Sea," I spent many hours in simply drawing a heated chisel slowly along the wood from end to end until I got the yellowish tone which now goes so well with its green oak frame. Here and there a white light had to be left. Its position was indicated to me by a pencil outline. For this drawing I had no sketch, it being entirely executed from memory. The main difficulty was to get the flat tones, without which it is impossible to indicate atmosphere and distance.

In the "Summer Idyll," given on the opposite page which is in size some thirty-six by ten inches, a great deal of the background effect was produced by using a small gas flame. This has to be done very slowly and carefully, as one is apt, if at all careless, to burn too deeply into the surface.

In conclusion, I may say that burnt wood drawing to be properly done requires both time and thought, it being a much more satisfactory result to produce one fine specimen by a month's labour than several odds and ends, which can only be compared with the daubs so often exhibited in shops as "painted by hand."

As to the applications of burnt wood work they are practically endless. Look, for instance at the mouldy, rickety, ill-designed, so-called antique chests so often sold at four times their original cost. For a very small sum a good carpenter will make you a really serviceable article with a framework of oak and white wood panels, which you can decorate with hot irons in such a manner as to make a truly beautiful piece of furniture. Again, for corner cupboards and cosy corners, panels of doors, etc., where is its peer to be found?

My last word is try but one carefully executed plaque, and I feel sure that you will not rest until you are making your home truly beautiful.

Ernest M. Jessop.

⁂ The original drawings from which these illustrations are taken were recently exhibited by desire to H. R. H. The Princess of Wales at Marlborough House, and H. R. H. was pleased to say that she had derived great pleasure from her inspection of them.

(All copyrights of drawings reserved by the artist.)

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of "Sisters Three," etc.

"Mrs. Saville was right—Peggy is a most expensive person!" cried Mrs. Asplin in dismay, when the bills for repairs came in, but when the Vicar suggested the advisability of a reproof, she said, "Oh, poor child; she is so lonely—I haven't the heart to scold her," and Peggy continued to detail accounts of her latest misfortune with an air of exaggerated melancholy, which barely concealed the underlying satisfaction. It required a philosophic mind to be able to take damages to personal property in so amiable a fashion; but occasionally Peggy's pickles took an irresistibly comical character. The story was preserved in the archives of the family of one evening when the three girls had been sent upstairs to wash their abundant locks and dry them thoroughly before retiring to bed. A fire was kindled in the old nursery which was now used as a sewing-room, and Mrs. Asplin, who understood nothing if it was not the art of making young folks happy, had promised a supper of roast apples and cream when the drying process was finished.

Esther and Mellicent were squatted on the hearth, in their blue dressing-gowns, when in tripped Peggy, fresh as a rose, in a long robe of furry white, tied round the waist with a pink cord. One bath towel was round her shoulders, and a smaller one extended in her hands, with the aid of which she proceeded to perform a fancy dance, calling out instructions to herself the while, in imitation of the dancing-school mistress. "To the right—two—three! To the left—two—three! Spring! Pirouette! Atti—tude!" She stood poised on one foot, towel waving above her head, damp hair dripping down her back, while Esther and Mellicent shrieked with laughter, and drummed applause with heel and toe. Then she flopped down on the centre of the hearth, and there was an instantaneous exclamation of dismay.

"Phew! What a funny smell! Phew! Phew! Whatever can it be?"

"I smelt it too. Peggy, what have you been doing? It's simply awful!"

"Hair-wash, I suppose, or the soap—I noticed it myself. It will pass off," said Peggy easily; but at that moment Mrs. Asplin entered the room, sniffed the air, and cried loudly—

"Bless me, what's this? A regular Apothecaries Hall! Paregoric! It smells as if someone had been drinking quarts of paregoric! Peggy, child, your throat is not sore again?"

"Not at all, thank you. Quite well. I have taken no medicine to-day."

"But it is you, Peggy—it really is!" Mellicent declared. "There was no smell at all before you came into the room. I noticed it as soon as the door was opened, and when you came and sat down beside us—whew! simply fearful!"

"I have taken no medicine to-day," repeated Peggy firmly. Then she started, as if with a sudden thought, lifted a lock of hair, sniffed at it daintily, and dropped it again with an air of conviction. "Ah, I comprehend! There seems to have been a slight misunderstanding. I have mistaken the bottles. I imagined that I was using the mixture you gave me, but——"

"She has washed her hair in cough mixture! Oh, oh, oh! She has mixed paregoric and treacle with the water! Oh, what will I do! what will I do! This child will be the death of me!" Mrs. Asplin put her hand to her side, and laughed until the tears ran down her cheeks, while Mellicent rolled about on the floor, and Esther's quiet "He, he, he!" filled up the intervals between the bursts of merriment.

Peggy was marched off to have her hair re-washed and rinsed, and came back ten minutes later, proudly complacent, to seat herself in the most comfortable stool and eat roast apple with elegant enjoyment. She was evidently quite ready to enlarge upon her latest feat, but the sisters had exhausted the subject during her absence, and had, moreover, a piece of news to communicate which was of even greater interest.

"Oh, Peggy, what y'think," cried Mellicent, running her words into each other in breathless fashion, as her habit was when excited, "I've got something beautiful to tell you. S'afternoon Bob got a letter from his mother to say that they were all coming down next week to stay at the Larches for the winter. They come almost every year, and have shooting-parties, and come to church and sit in the big square pew, where you can just see their heads over the side. They look so funny, sitting in a row without their bodies. Last year there was a young lady with them who wore a big grey hat—the loveliest hat you ever saw—with roses under the brim, and stick-up things all glittering with jewels, and she got married at Christmas. I saw her photograph in a magazine, and knew her again in a moment. I used to stare at her, and once she smiled back at me. She looked sweet when she smiled. Lady Darcy always comes to call on mother, and she and father go there to dinner ever so many times, and we are asked to play with Rosalind—the Honourable Rosalind. I expect they will ask you to go too. Isn't it exciting?"

"I can bear it," said Peggy coldly. "If I try very hard, I think I can support the strain."

The Larches, the country house of Lord Darcy, had already been pointed out to her notice; but the information that the family was coming down for the yearly visit was unwelcome to her for a double reason. She feared, in the first place, lest it should mean a separation from Bob, who was her faithful companion, and fulfilled his promise of friendship in a silent, undemonstrative fashion, much to her fancy. In the second place, she was conscious of a rankling feeling of jealousy towards the young lady who was distinguished by the name of the Honourable Rosalind, and who seemed to occupy an exalted position in the estimation of the Vicar's daughters. Her name was frequently introduced into conversation, and always in the most laudatory fashion. When a heroine was of a superlatively fascinating description, she was "Just like Rosalind;" when an article of dress was unusually fine and dainty, it would "do for Rosalind." Rosalind was spoken of with bated breath as if she were a princess in a fairy tale, rather than an ordinary flesh and blood damsel. And Peggy did not like it; she did not like it at all, for, in her own quiet way, she was accustomed to queen it among her associates, and could ill brook the idea of a rival. She had not been happy at school, but she had been complacently conscious that of all the thirty girls she was the most discussed, the most observed, and also, among the pupils themselves, the most beloved. At the vicarage she was an easy first. When the three girls went out walking, she was always in the middle, with Esther and Mellicent hanging on an arm at either side. Robert was her sworn vassal, and Max and Oswald her respectful and, on the whole, obedient servants. Altogether, the prospect of playing second fiddle to this strange girl was by no means pleasant. Peggy tilted her chin, and spoke in a cool, cynical tone.

"What is she like, this wonderful Rosalind? Bob does not seem to think her extraordinary. I cannot imagine a 'Miss Robert' being very beautiful, and as she is his sister, I suppose they are alike."

Instantly there arose a duet of protests.

"Not in the least. Not a single bit. Rosalind is lovely! Blue eyes, golden hair——"

"Down past her waist——"

"The sweetest little hands——"

"A real diamond ring——"

"Pink cheeks——"

"Drives a pony carriage, with long-tailed ponies——"

"Speaks French all day long with her governess—jabber, jabber, jabber, as quick as that—just like a native——"

"Plays the violin——"

"Has a lovely little sitting-room of her own, simply crammed with the most{151} exquisite presents and books, and goes travelling abroad to France and Italy and hot places in winter. Lord and Lady Darcy simply worship her, and so does everyone, for she is as beautiful as a picture. Don't you think it would be lovely to have a lord and lady for your father and mother?"

Peggy sniffed the air in scornful superiority.

"I am very glad I've not! Titles are so ostentatious! Vulgar, I call them! The very best families will have nothing to do with them. My father's people were all at the Crusades, and the Wars of the Roses, and the Field of the Cloth of Gold. There is no older family in England, and they are called 'Fighting Savilles,' because they are always in the front of every battle, winning honours and distinctions. I expect they have been offered titles over and over again, but they would not have them. They refused them with scorn, and so would I, if one were offered to me. Nothing would induce me to accept it!"

Esther rolled her eyes in a comical, sideway fashion, and gave a little chuckle of unbelief; but Mellicent looked quite depressed by this reception of her grand news, and said anxiously—

"But, Peggy, think of it! The Honourable Mariquita! It would be too lovely! Wouldn't you feel proud writing it in visitors' books, and seeing it printed in newspapers when you grow up? 'The Honourable Mariquita wore a robe of white satin, trimmed with gold!'"...

"Peggy Saville is good enough for me, thank you," said that young lady, with a sudden access of humility. "I have no wish to have my clothes discussed in the public prints. But if you are invited to the Larches to play with your Rosalind, pray don't consider me! I can stay at home alone. I don't mind being dull. I can turn my time to good account. Not for the world would I interfere with your pleasures!"

"But P—P—Peggy, dar—ling Peggy, we would not leave you alone!" Mellicent's eyes were wide with horror, she stretched out entreating hands towards the unresponsive figure. To see Peggy cross and snappish like any other ordinary mortal was an extraordinary event, and quite alarming to her placid mind. "They will ask you, too, dear! I am sure they will—we will all be asked together!" she cried; but Peggy tossed her head, refusing to be conciliated.

"I shall have a previous engagement. I am not at all sure that they are the sort of people I ought to know," she said. "My parents are so exclusive! They might not approve of the acquaintance!"

(To be continued.)

By "THE NEW DOCTOR."

THE HAIR.

It is often a great consolation to a girl who has but a plain face to possess a fine head of hair. One can understand how annoyed she must feel when her hair starts combing out in handfuls, and she sees her one good possession getting less and less every day.

There are very many causes why the hair should comb out, and as it is absolutely necessary to know which cause is at work before attempting to cure it, we will discuss briefly the chief causes that are common.

Undoubtedly the gravity of hair combing out is greatly exaggerated. If you comb out a few hairs every morning and save up the several combings to see how much hair you lose in the month, you will be surprised and annoyed at the result. Many girls do this and fancy that there is something wrong with the hair and that they are going bald.

It is natural for the hair to comb out. The life of a hair is of very varying duration, but it only lives a certain time. At the expiration of this time it dies, and a new hair springs from the same root. If it were not for this, what do you think would be the state of the hair at fifty?

Now let us look at the causes of the hair falling out excessively and the resulting condition—baldness.

When the health is disturbed, the hair often falls more rapidly than before. After severe illnesses it is not uncommon for the hair to fall out wholesale, often producing absolute baldness. In both these cases the hair almost invariably comes back as strong as before when the health has returned.

In men, age is a cause of baldness, and there is no reason to think that this cause acts less powerfully in the fair sex. Absolute baldness is not common in women, but their hair gets thinner and shorter after they have passed the meridian.

The fashion of tying the hair with a ribbon or fillet will cause the hair to fall out by compressing it and therefore interfering with its nutrition. If you remove the fillet occasionally, it will do no harm to the hair. Curling the fringe with hot tongs is a very common cause of bald foreheads. If the tongs are used properly, that is, if they are not overheated, they will do little or no damage to the hair. But usually women curl their hair with tongs that are nearly red-hot, thereby singeing and killing the hair, which consequently falls out, and in the end leaves the forehead bare.

The commonest causes (and fortunately the easiest to remedy) of the hair falling out are affections of the scalp.

Dandruff, scurf or seborrhœa, as it is better named, is a condition of the scalp in which the sebaceous glands, which secrete the oil which lubricates the hair, are out of gear. They secrete too much oil of a very inferior quality. The hair loses its lustre, becomes brittle, usually dark in colour, breaks, falls out, and becomes covered with scurf. What this is exactly due to is not known. It is probably the result of a microbe. It usually becomes manifest about the age of thirteen or thereabouts, and may exist throughout life. It can hardly be called a disease, but if neglected may lead to the various forms of eczema that attack the scalp. The treatment for this condition is to wash the hair about once a week with the following lotion: Borax, one tablespoonful; carbonate of soda, one teaspoonful; glycerine, two tablespoonfuls, and water to the quart. After washing and drying the head well, rub into the scalp a very little sulphur ointment.

Often a girl will come complaining that her hair falls out from one part of her head, leaving a bald patch. This is called "alopœcia." Of its cause nothing is known. It is very common in girls when about fifteen years old, but it may occur at any age. The hair always grows again on the bald places, but it may not do so for a year or more. Painting the bald spot with a tincture of iodine is as good as anything, but it is Nature, and not drugs, that cures the affection.

The colour of the hair is extremely variable, and not uncommonly it changes from one colour to another in a very short time. The hair, like every other coloured organ in the body, obtains its colour from the iron in the blood. One would therefore think that taking iron or improving the circulation would darken the hair. It will not do so. In anæmia, where the iron in the blood is very deficient, the hair remains unaltered!

Severe emotion or sorrow will cause the hair to fade. Why it should do so we do not know, any more than why Father Time should meddle with it.

The only way in which the colour of the hair can be altered voluntarily is by external applications. No hair dye is really satisfactory, and most of them are dangerous. The hair will, however, sometimes change its colour completely without any external help.

The hair may lose its lustre from many causes. Dandruff is the commonest cause of this, but a very fertile factor in the causation of brittle lustreless hair is the constant employment of pomatums and greases to the hair. Nature supplies you with hair-oil of first-class quality. Every hair has two glands to secrete this oil (sebum). If you use an artificial grease (which can only be of a tenth-rate quality when compared with the natural substance), do you suppose the glands will go on working for nothing when the fruits of their labours are despised? Not they. They will strike work at once, and though they will resume their function if the external application is discontinued, it is better not to interfere with them at all. Girls with their long hair, however, need some form of application to keep the hair clean and glossy, and there is no objection to their using a really good substance, if they apply it to the hair itself and not to the scalp. You should never apply anything in the way of oil, grease, or pomatum to the roots of the hair, if it is healthy.

The applications of most value for the hair are the following:—

1. Brilliantine.—This is a pleasant emulsion, and it is very useful when the hair shows a tendency to fall out.

2. Bay Rum.—Occasionally I have seen this do good to the hair. Usually, however, it is better avoided.

3. Applications containing Cantharides are supposed to promote the growth of the hair. Possibly they do, but the action is not due to the Cantharides.

4. Rosemary is a nice clean preparation for the hair, and there are many good lotions containing this drug.

5. Marrow fat, Bear's grease, etc.—The solid fats are much used, and if you do not object to their messiness, they are not without merit.

6. Petroleum jelly, vaseline, etc.—These are simple, non-irritating, more or less inert substances, which may be applied to the ends of the hairs when a simple lubricant is necessary.

ANGELIE.

By WILLIAM T. SAWARD.

By H. MARY WILSON, Author of "In Warwick Ward," "In Monmouth Ward," "Miss Elsie," etc.

Sister Warwick was slowly rousing to the consciousness of the birth of another working-day. Her first sensation was weariness, her next a thought of surprise that the night had been passed without a summons to the side of one of the many beds in her ward, the third, and this with fully-awakened faculties, that her good Staff-nurse Carden was holding towards her the welcome tea-tray that her kind thoughtfulness never failed to bring with this earliest report of the "night duty."

Margaret Carden's hospital career had fulfilled the expectations of those who had watched it with loving, interested eyes. She had quietly and conscientiously worked her way from her probation through the three years of training, had done well, if not brilliantly, in her exams., and was now back again in the ward that was her "first love," so to speak. She was a staff-nurse on night duty.

She was very happy to be here. She loved little Sister Warwick—loved and respected and reverenced her. She could see through the brusque exterior that nettled some of the others, and could fully appreciate the noble heroism of her consistent, hard-working, unselfish life.

Sister Warwick was one who always felt the full responsibility of the life she had to live. Seven years before, after the governors of the hospital had offered her the coveted position of Sister of one of these hospital wards, she had written to her mother—

"It is very trying work beginning to be a Sister—more so than you can possibly imagine. To feel the whole weight of your domain weighing on you, a family of thirty to care for, and nurses to guide and train, is very appalling, very full of care."

And now, though she was used to her position, if experience was teaching her the wisest way to carry her cares, custom did not lighten them.

To-day she greeted her friend Carden with a smile and a "Good morning! What sort of a night have you had in the ward?"

"All has gone comfortably, Sister, except that Susie and Patty have both been troublesome again."

"Susie fretting for her mother, and Patty crying with the pain?"

"Yes, Sister, and really disturbing the others by being very noisy, poor mites."

"Perhaps there is some naughtiness in their crying. We must think what we can do. And Mrs. 13?"

"She is distinctly weaker, but she says the pain is less. How patient she is!"

And whereas within hospital walls it is the rule, not the exception, for the patients to show touching bravery and endurance in their pain, such an exclamation from a nurse was a special tribute to Mrs. 13's heroism. It was partly because before both Sister and nurse there rose in that moment a picture of what that poor woman's life had been. A dressmaker for some second-rate theatre, she had spent her days with ten or twelve other women in a room without a window, with the gas burning, and only the fireplace for ventilation.

"After tea, Sister, the women used to drop from their seats and faint away on the floor. We seemed not to mind after a bit, somehow."[1]

That had been the spiritless summing-up of the description which had so stirred the hearts of her listeners. And now she lay dying of the terrible disease that still baffles medical science, and seems to have no cure—and her patience did not fail!

Nurse Carden continued her report of the{154} other cases, and then, before leaving, said anxiously:

"You will be able to take your hours 'off duty' this afternoon, Sister? You know you did not last week."

Sister Warwick smiled. This staff-nurse of hers was bold in her determination to take care of her. None of the others ventured, except, perhaps, Nurse Greg; but she was promoted now, a Sister like herself—on her own level, in fact.

"You will, Sister," urged Margaret Carden again. "I know you are getting tired out."

"Not quite that," answered Sister Warwick, amused and touched. "But I do want a taste of the outside world, and if I possibly can, I mean to go."

With that the night nurse departed more contented, not hearing the sigh that followed the words, not knowing that it was want of confidence in her day staff-nurse—Nurse Hudson—that tied the Sister with so many anxious thoughts to her ward.

Sister Warwick and Sister Cumberland, which was the new title Nurse Greg had lately assumed with the donning of her dark stuff dress, met on the staircase in their bonnets and cloaks before eight o'clock. As their custom was, they walked together to the shortened morning service in the old parish church near the hospital gates. They had both learnt that the few quiet moments they spent there were "well invested," and they never passed out again into the whirl of their busy lives without an earnest prayer, first

and then for themselves, that they,

How better could they step into the daily routine than thus equipped?

Breakfast in their own rooms was followed by hours of occupation. Sister Warwick preferred to take her share of actual nursing with the rest.

Before the house-physician's visit was over a piteous wail from bed No. 12 rang through the ward.

"It do hurt so! I can't bear it—I can't!"

Sister Warwick knew that Patty had been spoilt at home, and that her pain was really bearable. She had tried petting. Now she felt that firmness with a flavour of severity would have to be applied.

Earlier in the morning, and in a happier moment, Patty had said insinuatingly—

"You don't know how I like eggs, Sister, or you'd give me one!" and she had answered—

"I will give you one, dear, but not while you do not try to be good and quiet. Patty must learn to bear her pain bravely like the rest. Anyhow, we will see what Mr. H—— (the house physician) says."

And now, with this stormy outburst of weeping, came Sister Warwick's opportunity. She turned to Mr. H——, who was standing close by, and propounded this all-important egg-question.

He came with due gravity and looked down upon the sobbing child. His kind eyes were twinkling with amusement. He was well aware of Patty's character for tempestuosity. His voice was impressive almost to sternness.

"Yes, Sister," he said, "if she is a good girl, I think we may let her have a good egg, and shall we say if she's a bad girl, she shall have a bad egg?"

The solemn tones overawed Patty. She stopped crying and stared, and tried her hardest to think whether the punishment for her naughtiness was as terrible as it sounded.

With poor, home-sick, tired Susie, Sister Warwick had to try other measures. Susie was old enough to be reasoned with, and withal was not a coward in her pain—she was plucky there. But the peace of the ward and of the older patients must not be sacrificed to these wayward children.

So Sister Warwick, seated at her table in the ward, and having filled in her charts and completed other matters of business—such as signing a pass for a nurse's holiday—took a sheet of paper and wrote a letter as if to Susie's mother.

The words ran—

"Susie frets so for her home and for you, and is so especially unhappy after visiting day, that I must beg you not to come again until she can be quite good when you leave her."

She went to Susie's cot and read the sentence without a smile. Susie's eyes dilated, her lip quivered as she listened.

"Shall I post it, Susie?"

"Don't! Oh, please, Sister, don't!"

"Well, dear, it shall depend upon you whether it goes. See, I am going to pin it here on the curtain, where you can look at it. If you are good it shall not be sent."

And sent it never was.

There was much to do for Mrs. 13, and distressing though the work might be, admiration for her endurance and for the simple trust with which she accepted all her pain, as "the touch of God's finger laid on her in love," could only make the Sister's labours a pleasure and a privilege.

It was different when she turned to a bed at the end of the ward, a little apart from the others, where lay, unconscious, one of those sad cases, repulsive and loathsome, in which "the King's image" is disfigured almost beyond recognition by a life of sin and self-indulgence.

At one time Sister Warwick had found it hard to be as careful and tender with these—pity she never failed in. But one day the thought came to her that perhaps these poor souls were included in "the least of these My brethren"—that perhaps these words might mean sometimes those farthest removed from Him. After that the work for them was infinitely easier.

At one o'clock she was in her own room again, to find someone waiting for her there—a young student. His hands were loaded with "a sight for sair een"—a great bunch of buttercups and grasses.

"My mother is up in town to-day, Sister," he said, "and she asked me to bring these to you. They were picked only this morning and so are not at all battered, as you see."

"They are delightful; a real bit of the country for my poor 'children' to feast their eyes on."

Sister stretched out her hand for the golden posy, then an instinct prompted her to look more directly at the boy's face. His mother was her friend; she had promised to be an elder sister to this only son of hers, and she saw that her elder-sisterliness was wanted now.

She gave it—how wisely and strongly, yet tenderly, the young doctor only knew. It was a crisis in his career. He was afraid! How could he go on with the seeming inconsistencies that thronged him in his work? and there were other things.

Well, gradually it all came out. Somehow Sister Warwick understood, and she helped him to sort apparent contradictions and to smooth or explain difficulties. Not all, of course not! There must remain unfathomed mysteries in every profession. But he went away with a new light on his young face, and Sister Warwick with a sigh—not of regret but of humility—turned to her little table and her waiting lunch. She glanced up at the clock. Why, her half-hour had gone! The consulting physician might be here at any moment. She must put on a clean cap and apron and be ready. This done, there was left just time for a few mouthfuls of ham and bread and for a draught of milk, then the probationer's voice at her door was saying—

"Dr. W—— is here, please, Sister."

There was less for the doctors to do that day than usual, and it was not later than half-past two when, in bonnet and cloak, Sister Warwick began the little programme she had made for these "off hours."

Passing through the hospital gates, she took her way eastward until she reached the entrance to Pleasant Court.

Alas! Was there ever such a misnomer?

Insanitary, overcrowded, stifling, filthy, she wondered how any could live in such an atmosphere, and thought with pity of that poor ex-patient she had come to see, who had begged to come back here—"because it was home"—to die!

She climbed up the creaking stairs to an attic room, and her gentle tap was answered by a weak "Come in, please."

It was good to see how the wan face of the sick woman lit up at sight of her visitor, and to hear the glad "Oh, Sister, is it you?"

The poor, bare room was well swept and tidy, and the woman herself was as clean and orderly as she knew how to be. Months of hospital days had taught her much, and she had a husband tenderly anxious to please her by "doing for her" as carefully and as long as he could. Sister had been expected "one of these days," and she was touched to find, when she set to work to wash and dress an unhealed wound, that a ragged but clean towel was laid ready for her use afterwards.

Surgical duties performed, she sat beside Mrs. Sutton with her wasted hand in hers, listening to her laboured breathing and turning over a possibility in her mind.

"We'll try it!" she said suddenly out loud. And then, smiling at the woman's surprised expression, she went on. "What do you say to our getting a breath of fresh air together? Shall we have a drive?"

"Oh, Sister! Not really? Could I?"

Sister Warwick certainly had a way of sweeping aside difficulties when her mind was set to an end. She went to the nearest cab-stand, picked out the driver with care, and came back with the hansom to the entrance of the court. It could go no further.

A boy was found to hold the horse, and together she and cabby carried Mrs. Sutton down the old stairs. She was comfortably wedged into the corner of the seat with pillows, and a footstool was found for her feet. Then Sister gave the man her instructions—

"It is to be a shilling drive, please, and take us to see a bit of something green."

"Right you are, Nuss! Embankment's the place for we!"

Away they went—the air cool in their faces—until the sick woman began to draw long breaths of enjoyment, and even a little colour crept into her pale cheeks. Under the trees, with the glittering water on one side and patches of green grass within railings on the other. There was a laburnum in blossom. Some of the windows of the houses were bright with scarlet geraniums and marguerites. A donkey-cart came towards them laden with ferns and plants in bloom.

Mrs. Sutton's eyes feasted on it all. A few happy tears rolled down her cheeks. She had not hoped or thought to see these things until she rested in "the Park of God." And the sky was so blue! Heaven would be clearer to her imagination after this.

But Sister Warwick began to wonder when their driver meant to turn homewards. It{155} was a very long shilling's-worth already, and she had not wanted to spend more out of her slender purse. At last she pushed up the little trap-door.

"I think we had better be going back now," she said.

"Very well, Nuss. If you please."

But they had had at least a four-mile drive before they drew up at the court again and helped the tired but happy woman to her room once more.

When, with rough tenderness, he had given all the assistance he could, Sister Warwick followed the man on to the little landing. She offered him half-a-crown.

"I know it ought really to be more," she said.

He put back the coin.

"It's only a shilling, Nuss. I only meant it to be a shilling all along. Just let it be a shilling's-worth—now doo ee."[2]

She let him have his way. How could she resist him? And he stumped down the stairs smiling and proud, as if he had received a favour that afternoon. Well, perhaps he had!

There was time for Sister Warwick to pay another and a very different visit before she was due at the hospital for the Sisters' dinner. A visit to another court, but how different! What a contrast!

It is hard to believe that such dear old places are still left standing in the very heart of the great city. Sister Warwick passed through an archway into a flagged square and mounted a flight of steps leading to a quaint, old-fashioned house.

She turned before ringing the bell to look straight away through the large old iron gates on the opposite side of the square, at a long, delicious stretch of green—grass below, trees above. And far away—she fancied it might be really a quarter of a mile—a great flight of stone steps led down to the outer world again.

To those who live in the heart of the country—in the midst of all its delights and, above all, of its peace—this may not sound much to charm the gaze; but here, in the rush of the unending roar night and day, to find a comparative stillness is refreshing beyond everything.

To some natures the noise of London seems always dreadful. And it is true that the traffic never really ceases night or day, except perhaps for two or three hours on Saturday night, or rather Sunday morning. Even in this quiet square the sounds went on—cart succeeded cab, and omnibus followed on—without intermission. But it was all muffled and distant. The peace of it fell upon Sister Warwick's tired spirits.

Inside the house, too, there was more of this old-world feeling of un-hurry and rest. She was led through panelled passages to the long low drawing-room with its wide window-seats and great chintz-covered couches.

Her friend, whose home it was, rose to greet her, and she was at once taken in hand, thrust into the softest lounge, plied with tea, and told to "laze." She was not even permitted to talk; but her thoughtful hostess, having supplied all her wants, went to a little chamber-organ at the far end of the room and played softly and quietly such things as refresh body and soul in one—bits of Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn. She passed from one to the other, and Sister Warwick lay and listened with closed eyes—all her responsibilities and anxieties wiled from her for the time.

Was this unusual hour of rest sent to brace her for what was to come that night and the following day? She thought so herself when, later, she looked back at the events of those forty-eight hours.

At the Sisters' dinner that evening, Miss Jameson, the Sister of the Nurses' Home, gave her a summons to the Matron's house for a discussion on some improvement to be made in the nurses' uniform. She was to go when her ward work was over—medicines superintended, prayers read, the change of nurses made for the night.

She hurried back to it all, and with quiet steps was passing between the long rows of beds sooner than was her wont.

Nurse Hudson was settling the patients for the night. A long, thin, languid-looking girl was sitting up in bed No. 10 while her pillows were being arranged and her sheet straightened.

Sister paused to look. The smile she had for the patient quickly faded to sternness as she turned to the nurse.

"What are you doing?" she said in her sharpest tones. "Allowing a typhoid to sit up! Nurse, you know better than that!"

She laid the girl down on the pillows again herself, and then stood silently by while the bed was finished.

Nurse Hudson flushed crimson. But she had no excuse ready, and presently her superior passed on down the ward, registering in her indignant mind another of many carelessnesses she had noticed. She knew that Ellen Hudson was particularly anxious for her own pleasure to get away punctually that evening. But to risk a case in order to do her work more quickly—the selfishness of the act hurt the Sister's pride in the nursing profession. So thoroughly angry did she feel that she wondered whether she could command herself sufficiently to speak a calm reproof before the nurse left the ward that evening. She was very conscious that a biting sarcasm in her fault-finding had often alienated the confidence of her nurses, and she was now striving hard to mete out to them a more kindly and less impatient justice.

Mrs. 13 was watching her with loving eyes as she went to and fro.

"Patty has been a better girl this afternoon, Sister," she said, when she came within hearing, "ever so much better. I expect she is afraid of the bad egg!"

The laugh did Sister Warwick good, and Patty fell asleep that night with the sound of commendation in her ears, and with a virtuous determination "to be a better gairl to-morrow, too."

"Ain't the buttery-cups beeootiful, Sister? They minds me of home. I was a country girl onst, and picked my hands full of them when I was little. But, bless ye, I ain't been out of London since I married. I've 'most forgotten what the country looks like."

It was Granny 20 who was speaking, as Sister bandaged her leg and helped to tidy her for the night.

"We will put that right before long, Granny, see if we don't. You shall pick flowers and get sunburnt with the best of us. Fancy not seeing the grass and the flowers, and hearing the birds sing, for fifty years! How could you bear it?"

"Well, it's true, Sister. I ain't been further than London Bridge all that time. And there! bless ye, I'm 'most afraid to try it now."

But Sister Warwick thought of the beautiful grounds round the Hospital Convalescent Home, which was not so very far away. Granny 20 was getting well fast—a credit to them all. She should renew her acquaintance with "great Nature's pictures" before very long.

The day had been hot; but a cool mist or fog covered the shadowed houses as Sister Warwick lay down that night. Nurse Carden was on duty again; with that knowledge the Sister fell quickly asleep, at ease for the safety of all.

(To be concluded.)

Ingredients.—One oxtail, one large carrot, two onions stuck with cloves, one turnip, four sticks of celery, four mushrooms, half a parsnip, a bunch of herbs, two blades of mace, twelve black peppercorns, three ounces of butter, one dessertspoonful of red currant jelly, two quarts and a half of water, a wine-glass of sherry, three ounces of fine flour, salt.

Method.—Wash the oxtail and chop it; put it in a saucepan and cover with cold water; bring to the boil and throw the water away. Fry the oxtail gently in the butter until it is a good brown; prepare the vegetables and slice them and put them in a saucepan with the oxtail, water, herbs, mace, salt and peppercorns; put on the lid and simmer gently for five hours. Strain the stock and skim off the fat; pick out the meat and put it aside to keep hot; pick out the vegetables and pound them finely, add the stock by degrees, return to the stove and re-heat; melt the rest of the butter in a small frying-pan and stir in the flour, fry it a good dark brown over the fire, stir in a little of the hot soup and add this thickening to the soup; add the sherry and red currant jelly and the pieces of oxtail, and serve.

Ingredients.—One pound of ox kidney, half each of carrot, turnip, onion and parsnip, two sticks of celery, one tomato, one bay leaf, one sprig of parsley, one dessertspoonful of Harvey's sauce, a little browning, one quart of water or stock, one ounce of butter, pepper and salt.

Method.—Wash the kidney and cut away any fat; cut it in dice and fry gently in the butter; prepare the vegetables, cut them in pieces and put them in a saucepan with the kidney, bay leaf, parsley, water or stock and salt. Put on the lid and let all simmer gently for four hours; strain off the soup, pick out the pieces of kidney and put them aside to keep hot. Return the stock to the saucepan, add the Harvey's sauce and the browning; put back the pieces of kidney, re-heat and serve.

Ingredients.—One large onion, one apple, one tablespoonful of good curry powder, one ounce of flour, half an ounce of grated cocoanut, a few drops of lemon juice, one dessertspoonful of red currant jelly, one dessertspoonful of chutney, salt, one quart of chicken or veal stock, three ounces of butter, one ounce and a half of cornflour, some well boiled rice.

Method.—Skin the onion, slice it and pound it in a mortar; chop and pound the apple. Mix the curry powder smoothly with half a teacupful of cold water, melt the butter in a stewpan, stir in the curry powder and water and the pounded onion; cook and stir until the water cooks away and the onion browns in the butter; add the apple, cocoanut, chutney, salt and the stock (warm); put on the lid and simmer for half an hour; rub through a sieve, mix the flour with a little cold stock, re-heat the soup and when it boils stir in the flour; add the lemon juice and red currant jelly; hand well-cooked rice with this soup.

By LADY WILLIAM LENNOX.

My last paper on the rules of Society ended with some remarks upon dinner-parties and the conversation thereat; but although the article thus finished, my observations did not, and must therefore be continued into this chapter. A silent dinner is a very depressing function, so much so indeed that among the disadvantages of living alone must be counted solitary meals, as not only saddening in their effect upon the mind, but provocative of bad digestion in the body; and even if we dine in company, but the company of dull, stupid, or at any rate unconversable people, the result is much the same as though we had sat down in solitude. It behoves us therefore, each and all, to try and prevent this evil and also make the dinner pleasant by taking a middle course—as is usually wisest with regard to most things in life—and neither to be like a ghost, speechless and casting the metaphorical wet blanket over the assembled guests; nor, on the other hand, to remind everybody of the whirling of a mill by the never-ceasing clatter of our tongue.

A clever hostess will do her best to secure some few good talkers at her table, in order that no pauses of sufficient length to give a sense of uncomfortable silence may occur; nothing more than those little gaps in conversation poetically supposed to be caused by "Angels passing." We are not all geniuses in the talking line, but we are bound to take our share, so far as in us lies, in contributing to brightness and cheerfulness at table; only, of course, young girls are not expected to bring themselves prominently forward in that way, and young or old it should not be forgotten that a "voice soft, gentle and low, is an excellent thing in woman," and that a shrill laugh, or an exclamation so highly pitched that it pierces through the ordinary hum of sound, is anything but agreeable or attractive. Also, it should be remembered that dinners are meant to be enjoyed, and men especially feel aggrieved if they are exposed to a constant fire of words, worst of all if those words resolve themselves into questions which require answers. Chilly soup, tepid fish, and entrées bolted for want of time to eat them properly, produce feelings of anger which even beauty itself can hardly stand against, if the beauty's chatter has caused the annoyance, that is to say. So it is wise to let your neighbour on either hand enjoy his dinner in peace, undisturbed by too much conversation, although at the same time he must not be allowed to suppose that a dumb doll dressed in pretty clothes is sitting beside him.

Do not crumble your bread over the tablecloth by way of inspiration, if you think you ought to say something and can find nothing; do not play with your wine-glasses either, until, very likely, you upset one of them; nor drop your dinner-napkin, gloves, etc., which makes a commotion and is rather a bore.

Such small things seem hardly worth mentioning, but tricks of any kind are to be avoided, as they generally give the impression of awkwardness.

Should you happen to go down to dinner with the master of the house, it is as well to let your hostess have a chance of catching your eye to give the signal when she wishes to leave the table, but never on any account fall into the mistake which I once heard was made by a woman who ought to have known better. She imagined that the lady of the house was very inexperienced and was sitting on an unconscionable time because she did not know when to go, and so she, the guest, actually took it upon herself to push her own chair back a little, with a glance at her hostess; but the latter, looking steadily at her presuming acquaintance, said very quietly, "I do not think I made a move, Mrs. ——" and sat on for another ten minutes.

As regards evening parties there is not much to say. You speak to the hostess at the head of the stairs where she stands to receive her guests, and then you wander through the rooms, and enjoy yourself, till you descend for supper or depart altogether. There is no need to look for the lady of the house to say good-bye. She has, most probably, left her post long before and is wandering about among the company.

The next thing I will mention is country house visiting, which is very pleasant as a rule, especially to people young enough not to mind the open doors and windows, the large rooms—innocent of fires sometimes when dwellers in towns would have lit them—and long corridors down which a fine north-easter pursues you.

Take plenty of wraps, therefore, unless it is the very middle of summer; but this is by the way.

I will suppose that you arrive at your destination dressed in a neat travelling costume all in good order; no buttons off gloves or boots, no untidy straps about the handbag—of splendid dressing-bags I am not speaking.

You are shown into an apartment—very likely a big hall used in the day as a drawing-room—where you find perhaps several, perhaps only one or two, people, and the mistress of the house may ask whether you would like to see your room at once, or, if it is near tea-time, if you will stay and have a cup first? I believe that in New York and other places in America the custom in this respect differs from our own, and that the newly-arrived visitor is not brought face to face with the house party until she has had an opportunity of tidying her hair, brushing her gown, and generally smartening herself up, after which she can appear with an "equal mind," untroubled by any misgivings as to the results of the journey upon her looks. In my opinion, that arrangement is a great improvement on our way of doing things; but, however, as it is, you sit travel-tossed and more or less crumpled up, talking to anybody you know, and possibly, if by nature shy, with an embarrassing consciousness of being mentally criticised by some of those present whom you do not know. In such circumstances the most important matter is to keep still. If you have ever watched actors on the stage, you must have noticed that they never shuffle and move about without intending it. It is one of the first lessons, in fact, that amateurs have to learn, simply to stand or sit still. Nothing has a worse effect than the look of "not knowing what to do with your arms and legs," so do, therefore, refrain from twisting your feet about under your chair, fidgeting with your bracelets, or letting the spoon fall out of your saucer. If your gloves are off, do not begin to think about your hands getting red, for, if you do, they are pretty certain to fulfil your fears by becoming so. Nervousness has more to do with that than is generally imagined.

Whoever saw a pair of scarlet hands before them when they were alone?

Just call to mind the fact that there is no real reason why you should feel "all anyhow" because you are in a strange house among strangers, and try to be natural in manner and pleasant to everybody.

One thing very necessary to cultivate when on a visit is the habit of punctuality. In London, where people come long distances, with the chance of a "block," or finding the street up, or some other obstacle to progress, a liberal margin is allowed as to time, and dinner at a quarter to eight means eight. But in the country the hour named is the hour intended, and in some houses the striking of the gong and the appearance of the butler throwing open the doors for dinner are nearly simultaneous, while in others the guests have five minutes' grace after the gong sounds in which to get downstairs and into the drawing-room. In any case they should all have assembled before dinner is announced, for few things annoy the master of the house more than to see stragglers come in when the soup, and perhaps even the fish, has been already served.

The same rule applies to all arrangements which are not "movable feasts." Luncheon, for instance, is usually at a fixed hour, and so is breakfast in some houses, though not in all. If you are to ride or drive, or whatever it is, be ready to the minute, and do not give trouble by having to be sent for. To give no unnecessary trouble either to guests or servants is, indeed, a good motto to bear in mind, for nobody likes to be "put about," and a woman who gives a lot of trouble, whether from thoughtlessness or from an idea that by requiring a great deal of attention and waiting upon she makes herself interesting and of more importance, will find out her mistake sooner or later, and learn that fetching cushions and smelling-bottles is not an amusing occupation for her friends, and that ringing the bell without good reason only sends servants, especially other people's servants, into a bad temper.

When you come down to breakfast you need not go round and shake hands with everybody. Speak to the lady of the house and anybody you know close by, and a few little bows and smiles will do the rest. Be careful in going to or from the dining-room to wait your turn, and not walk out before those who ought to precede you. Sometimes when the same people are making a longish stay in the house, they draw lots to decide who shall go in with whom by way of variety instead of having always the same partner. Pieces of paper are numbered, two sets alike, and drawn just before dinner, the guests then pairing off according to their numbers, so that a woman or girl with no particular position may find herself in the place of honour at the table, but even so it would be extremely bad taste in her to leave the dining-room first.

When talking do not mention the name of the person you are addressing every time you speak. It has a tiresome effect upon the ear to hear perpetually "Yes, Mrs. ——" "No, Mr. ——" "Do you think so, Lady ——?" "How fine it is to-day, Mr. ——!"

No hard-and-fast rule can be laid down as to how often the name should be mentioned—for,{157} of course, it must be sometimes—but a little careful attention to ordinary conversation will teach you more than any written remarks could, and your own instinct must guide you further in the avoidance of little faults of the kind.

A matter of importance when visiting is to try never to be in the way when you are not wanted, and never out of it when you are wanted. Do not, for example, sit down and make an unrequired third in a conversation carried on between two people who are evidently quite content with each other's society, for they will only wish you anywhere, and, unless you have the constitution of a rhinoceros, the freezing atmosphere will soon bring to your mind a certain proverb which says that "Two's company, but three's none."

Do not insist upon speaking of something which interests you specially when, perhaps, nobody else cares very much about it; and, more than all, do not talk about yourself, your likes and dislikes, your health, etc., etc. It may not be pleasant, but the fact remains that nineteen people out of twenty feel not the smallest interest in you or your concerns except in so far as the outcome is agreeable to them, and this not exactly from want of heart so much as from want of time to stop and consider you, when there are so many others near and dear to them to be thought of. At all events, so it is, and any person who hangs about a room when she might as well go out of it, or worries people by airing her own opinions when nobody wishes to hear them, is decidedly in the way, and neither more nor less than a bore. This rock, i.e., being de trop, may be called the Scylla, while another of quite a contrary kind may be styled the Charybdis in the sea of Society, and both must be steered clear of if the voyage is to be pleasant and successful. The former is the rock on which active and energetic people split, and the latter often makes shipwreck of the more meditative and indolent natures, inclined to let things slip by, unobservant of what is required of them, or, if aware of it, too fond of their own comfort and repose to respond. Judgment and tact are essential in order to avoid running against one or other of these rocks, and perhaps the best preventive of mistakes in the matter will be found in remembering to "do as you would be done by," because, keeping that in mind, you will have only to make a shrewd guess as to what others would like in the same circumstances. Now and then doubtless in carrying out this rule some self-denial is involved, as, for instance, when lawn-tennis, or croquet, or even a walk, is proposed, and you, caring little for physical exertion at any time, and very anxious, moreover, to finish a book you are deep in, feel for a moment disposed to be churlish and refuse to join. Well, then comes in the remembrance of what is due to others, and you put the best face you can on it, get your hat, and go. Or on a wet day somebody wants to play billiards, or battledore and shuttlecock, or something, and you would rather work at a drawing or run through a song or two in the little boudoir where you will disturb nobody, but you are wanted to help brighten up the dreary day, and your private inclinations have to be sacrificed to the good of others. Another thing—— But my paper is growing rather lengthy, and, lest I should be voted a bore and go to pieces on the rock Scylla, I think my remarks had better end here for to-day, the remainder of them, not many now, being laid by for another occasion.

(To be continued.)

The Temple.

My dear Dorothy,—So you have decided on commencing your married life in a flat—a very wise decision on your part. In the first place, in a flat you know exactly what your position is as regards rent, whereas a house entails constant expense for repairs, to say nothing of rates and taxes.

It is true that, if the people on the floor above you indulge in clog-dancing all the day whilst the occupiers of the floor below practise the cornet à piston half-way into the night, you might find that the drawbacks of a flat were unendurable; but I do not think that you are likely to suffer quite such a terrible experience as I have depicted.

Another advantage of a flat is that, if you want to run down to the country or the seaside for the week's end, or for even a longer period, you can lock up your flat and start off gaily; but with a house on your hands it is a very different matter.