The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: The Wide World Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 131, February, 1909

Author: Various

Release date: January 28, 2016 [eBook #51061]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial Magazines,

Jonathan Ingram, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

418

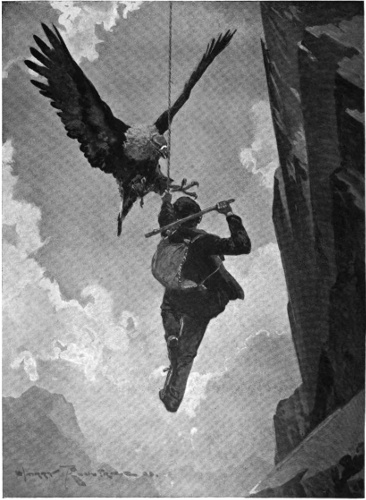

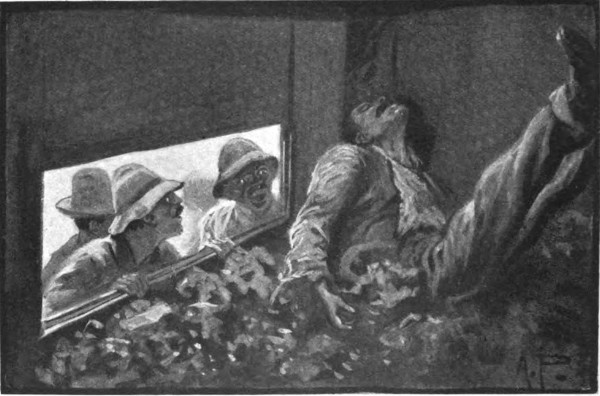

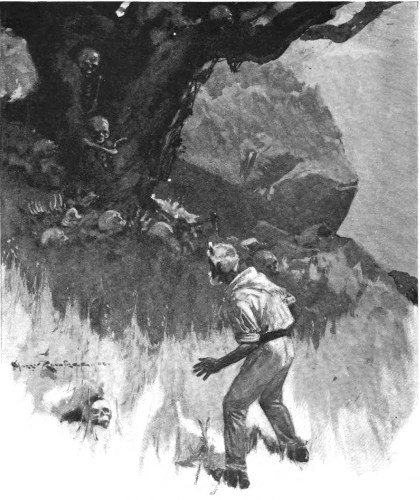

“WILLIAMS LASHED AT THE BIRD WITH HIS STICK.”

(SEE PAGE 424.)

419

Vol. XXII. FEBRUARY, 1909. No. 131.

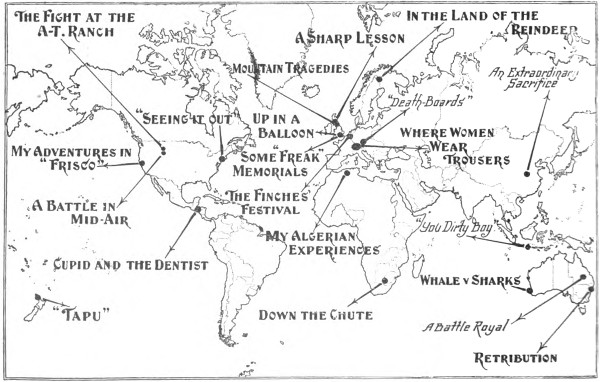

Another instalment of a fascinating budget of adventure narratives. This month we publish accounts of a fight to the death between a whale and a school of thresher sharks; a nest-robber’s terrible battle with an infuriated mother-eagle; and the nerve-trying experience which befell a Surrey cyclist while out for a Saturday afternoon spin.

Early on the morning of August 14th last, while engaged in building new quarters for the lighthouse-keeper at Breaksea Island, near Rottnest, Western Australia, the contractor and his men noticed a bull whale, with a cow and calf, passing the island some distance off. They watched them with interest for awhile, noting the immense size of the two parents and the methodical regularity with which columns of water rose from their blowholes, and then resumed their labours.

An hour or so later—about nine o’clock, to be exact—the men were startled by an extraordinary noise, apparently coming from the eastern end of the island, a noise unlike anything they had ever heard before. Dropping their tools and staring towards the east, they beheld such a sight as it falls to the lot of few people to witness. There, not five hundred yards from the shore, was being waged a battle to the death—a fight between the great cow whale previously seen and a school of thresher sharks. The calf was swimming about distractedly, but the old bull had disappeared, having basely deserted his family at the first approach of danger.

The sharks, as though acting in accordance with some preconcerted plan, had completely surrounded the two whales, and, apparently realizing that nothing was to be feared from the calf, concentrated all their efforts upon the cow. Again and again they charged in upon her, their jaws snapping, tearing at her mighty sides until the sea was red with blood. Meanwhile the cow lashed her tail furiously, hurling up sheets of reddened water and occasionally crashing down with terrific force upon one of her voracious opponents. Maddened with pain and rage, she dashed this way and that, but the sharks hung to her side with a persistency and ferocity that made the fascinated onlookers shudder. Now and again the wildly-lashing tail would catch one of the assailants, driving it beneath the waves—no doubt killed or disabled—but the remainder rushed in undismayed, tearing viciously at the mammal’s bleeding flanks or butting her with the force of battering-rams.

Presently the spellbound spectators realized two facts—firstly, that the calf had disappeared in the mêlée, and secondly, that, the tortured whale was undoubtedly becoming weaker. It was obvious that the unequal struggle could 420 421 422 have only one ending. Still, however, she fought on doggedly, winning admiration and sympathy by her exhibition of hopeless courage. Altering her tactics, by a supreme effort she hurled her whole great bulk clear of the water for a moment, and the fascinated onlookers beheld the sharks hanging from various parts of her gleaming body by their serrated teeth. Then down she went again, with a crash like thunder, and for an instant whale and sharks were buried amidst masses of foam, heavily coloured with the poor mammal’s life-blood. Rising again, she essayed another change of plan, making for the rocks and desperately striving to rub off the clinging sharks against their edges. But the threshers were equal to the occasion; while those on the outside maintained their grip, the others dived under their enemy and charged her anew, tearing at the whale’s side in an ecstasy of ferocity that was bloodcurdling to witness.

TERRIFIC BATTLE AT BREAKSEA

ISLAND.

WHALE KILLED BY THRASHER

SHARKS.

A THREE HOURS’ FIGHT.

A SEA OF BLOOD.

(By An Eye Witness.)

Much has been written about fights between the larger denizens of the sea, but it has fallen to the lot of very few to witness such a battle as one which took place off Breaksea Island on Friday, the 14th inst., between a school of thrasher sharks and a cow

A CUTTING FROM THE “WEST AUSTRALIAN,” OF PERTH,

W.A., REFERRING TO THE BATTLE BETWEEN A WHALE

AND THRESHER SHARKS.

Click here for image.

More and more feeble grew the whale’s struggles, and at last—to the heartfelt relief of the spectators, for her death-fight had been terrible to behold—the great body turned over and sank beneath the red-tinted water. The unequal battle was over, having lasted from nine o’clock until noon—as awe-inspiring a contest as man was ever privileged to witness. It is a thousand pities that there was no camera on the island to make a pictorial record of the struggle. The men went back to their work greatly impressed by the unique spectacle, and expressions of sympathy for the whale were heard on every side.

Forty-eight hours afterwards the whale’s carcass, which had in the meantime become distended with gas, rose to the surface, and exploded with a roar like a miniature powder-magazine, causing the startled people to flock to the shore to discover what had happened. On examination of the remains it was discovered that every shred of the outer flesh of the whale had been torn off by the sharks, who had now, doubtless, gone off to repeat their tactics upon some other hapless leviathan.

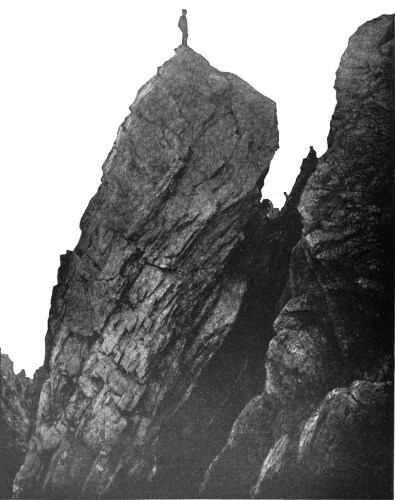

Swinging like a pendulum at the end of a two-hundred-and-fifty-foot rope against the side of a five-hundred-foot cliff, with jagged rocks far below, and nothing but one bare hand with which to fight off the fierce onslaught of an immense eagle, whose nest he was attempting to rob—this was the awful predicament in which Arthur Williams, a young man of Riverton, Wyoming, found himself one day early in June last year. With the welfare of her nestlings at stake, the great bird attacked the despoiler of her home with inconceivable fury, and only to a lucky chance does Williams owe his life.

Riverton is a new town on that portion of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indian reservation which was opened to settlement last year, and in the country thereabouts mountain lions, timber wolves, coyotes, eagles, bears, etc., are still to be found. The principal industry is sheep-raising, and continual warfare exists between the flockmasters and the wild things, especially the eagles, which annually kill and carry off hundreds of young lambs. Because of this heavy drain on their flocks, every shepherd and owner of sheep in Wyoming takes great pains to kill the birds and to destroy their nests whenever they are discovered.

Before the Indian reservation was formally opened to the whites for settlement, the flockmasters were permitted to graze their sheep over the country, and it gradually became known among the sheepmen that over in Lost Well Canyon there were a pair of eagles who made a speciality of devouring young lambs. Try as they might, however, the shepherds were unable to get a shot at either of these great birds, and for several years they were the terrors of the district.

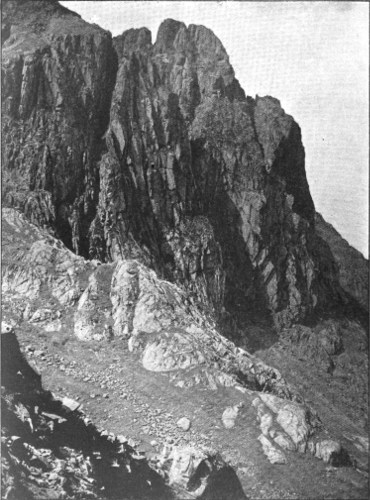

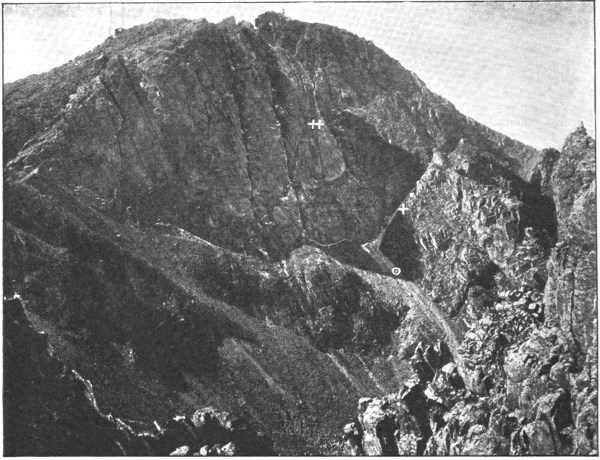

It was discovered that the old birds made their nest in a cleft in the face of a five hundred-foot perpendicular wall, which formed one side of the canyon. Here they safely raised brood 423 after brood of young ones, which were turned loose in due course to prey on the community.

Hunters, with their Winchester rifles, often lay in wait for the big birds, hoping to get a shot at them, but, with the proverbial keen eyesight of such creatures, the eagles detected the Nimrods and never came within gun-shot when the nest was being watched.

During the spring of 1908 the two old eagles were more successful than ever in raiding the flocks of the sheepmen, and accordingly a special effort was made to exterminate them. To that effort Arthur Williams owes the appalling adventure which befell him.

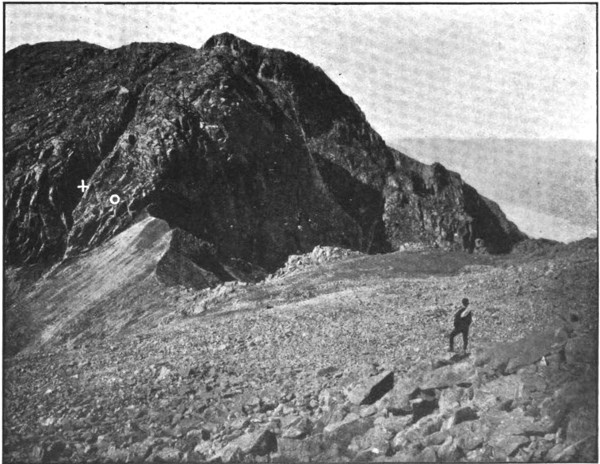

Williams and two friends made a trip out to Lost Well Canyon to investigate the chances of trapping the eagles in their nest. A ride of eight miles, over rough mountain trails, brought them to the canyon, half-way up the perpendicular side of which they saw the horizontal cleft in which the wise old birds had built their nest. At the foot of the cliff, directly under the cleft, was a pile of bones—the remains of lambs, thrown out of the nest by the eagles after they had been picked clean.

“We ain’t any nearer that nest down here than when we were at home,” remarked Williams to his comrades. “Nothing but a balloon or an airship can help us from down here. Let us go up to the top of the cliff and see what we can do from there.”

For two hours the three young men struggled to reach the top of the mountains. A wide détour was necessary, but at last this was accomplished and they stood on the brink of the cliff, half-way down which the eagles’ nest had been built.

“There’s nothing to be done from here, either,” said one of the men, despondently. “We might just as well go back home; we shall never reach that nest.”

While the men stood and talked, from far down below them there arose the shrill piping call of young birds.

“Young ones!” said Williams. “I wish we could get them alive; they would be worth money to us.”

“No use to bother; you’ll have to take it out in wishing,” said the third member of the party. “Come on; let’s go home.”

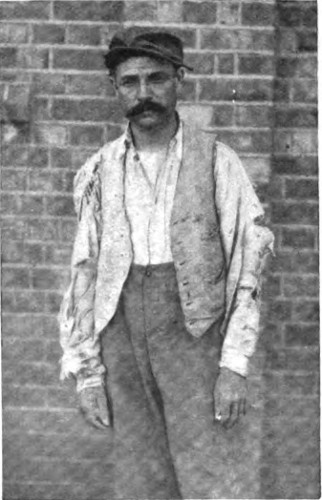

MR. A. E. WILLIAMS, WHO FOUGHT THE EAGLE

IN MID-AIR.

From a Photograph.

“All right. I’ll go home now, but I’m coming back to-morrow after those birds,” said Williams.

The next day found the three young men back at the cliff. They had mapped out a scheme whereby they hoped to get the young birds, and had brought with them seven hundred and fifty feet of stout rope, far more than enough to reach from the top of the cliff down to the bottom of the canyon. To make quite sure of this, however, they first lowered the rope, weighted with a stone, down the face of the rock, and saw that, while there yet remained a big coil at their feet, the weighted end of the rope rested on the floor of the canyon.

Then the rope was hauled back and a tight loop made in one end. This was paid out over the edge of the cliff until it hung directly in front of the eagles’ nest. The other end of the rope was hitched round a convenient tree.

During all this time the men kept close watch for the old eagles, but saw nothing of them.

“Off hunting lambs, I suppose,” said one of the young fellows.

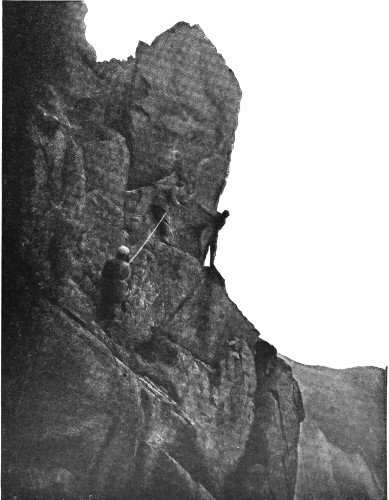

Then Williams stepped forward, laid hold of the rope, and quickly disappeared over the side, sliding slowly downward, using one leg, around which the line was wrapped, as a brake to keep himself from going too fast.

Across his shoulders was slung a stout bag, in which he intended placing the little eagles when he secured them. In one hand he carried a stout stick for use in an emergency: the other hand grasped the rope.

Down, down he went until just in front of the eyrie. Then he slipped one leg through the loop at the end of the cord and turned to look into the dark hole, where he could hear the eaglets “talking.”

Slowly he swung round, bracing his foot against the rocky wall, until he faced the cleft and could give his attention to the nest.

Suddenly, screaming wildly with rage and fright, out from the dark cleft came the old mother-bird. Like a stone from a catapult she flung herself at Williams’s face.

Dismayed by the suddenness of the attack, 424 Williams recoiled; his foot slipped from the wall, and his body spun round and out of reach as the huge bird went past him. He did not escape altogether scathless, for one claw, like a knife blade, cut across his cheek, and in an instant the blood was flowing from a cut half an inch deep.

Only a few yards did the old eagle fly; then she wheeled and, with the speed of an arrow, shot once more at the man hanging at the end of the rope before her nest.

This time Williams braced himself and, with his stout stick ready in his right hand, awaited the onslaught of the big bird. His left hand grasped the rope.

The eagle struck Williams on the head with her wing, and at the same moment Williams lashed at the bird with his stick. Such was the fury and strength of the creature, however, that the stick flew from Williams’s hand and went whirling through space to the bottom of the canyon, far below.

Again the eagle turned sharply and swooped down on the man, now left defenceless, with only a single bare hand to fight against the infuriated mother-bird’s sharp claws, powerful beak, and mighty wings.

Pecking, clawing, and striking stunning blows with her terrible wings, the big bird beat the air in front of Williams’s face, holding her position and tearing savagely at the head and face of the would be despoiler of her home. Her screams were incessant.

Meanwhile, on top of the cliff, there was utter consternation. The attention of one man was necessarily taken up with the rope, and a slip on his part meant instant death to Williams in the way of a fall to the rocks at the foot of the precipice. With a rifle in his hand the other man watched that nightmare fight in mid air, far below him. He could not shoot without endangering Williams even more than the eagle.

Just then things were going very badly with the nest-robber. Blood was flowing from a dozen cuts on his head and face, his hand was lacerated, the clothing about his shoulders was cut into ribbons. Moreover, he was half stunned, and but for the loop in the end of the rope would have fallen to his death. He had no time to give directions to his comrades, and simply had to fight the battle out alone.

MR. WILLIAMS AFTER HIS ENCOUNTER WITH THE EAGLE.

From a Photograph.

Presently the old bird darted away, preparing for another swoop at the defenceless man. When she was ten feet distant a rifle-shot rang out from the top of the cliff, and Williams knew his friends were doing what they could. But the old bird did not falter for a second, although a couple of feathers from her terrible right wing floated away on the wind. In his haste to send a second bullet downward the man with the rifle managed to “jam” the weapon, and with a despairing cry threw the now useless weapon to the ground.

The eagle returned to the attack with even greater fury, and for a few minutes Williams thought his last moments had arrived. But still he fought on, pulling great handfuls of feathers from the bird and beating at her desperately with his bare fist, receiving in return many cuts and slashes, as well as stunning blows from the madly-flapping wings. He was almost ready to loose his hold on the rope and go crashing down to the bottom of the canyon when the eagle suddenly wheeled away for another attack.

As she came back again, screaming and beating the air, something the size of Williams’s head struck her on the back, and down she went like a stone, whirling over and over. Williams’s friend above had hurled a small rock at the bird, and, luckily for Williams, the boulder had struck her fairly on the back, between the immense wings.

“Hold on tight and we’ll let you down to the bottom,” sang out the man at the top of the cliff, leaning far over. Then Williams showed the sterling stuff of which he was made. Though bleeding from a dozen wounds, breathless and exhausted, he was still determined to fulfil his errand.

“Hold me here until I get these little birds,” he shouted, feebly. “I came after them, and I’m going to have them.”

With that the plucky fellow crawled back into the niche, put the two little eaglets in his bag, thrust his leg through the loop, grasped the rope with both hands, and was safely lowered to the floor of the canyon.

Within a few feet of where he landed lay the old mother-eagle. Williams staggered over to 425 her and gave her a kick. To his amazement she moved, stood up on her feet, and flew away!

One of Williams’s companions came sliding down the rope, and reached him just as the injured man fainted from loss of blood and excitement. The punishment he had received was terrible, but fortunately his eyes had escaped injury.

After casting off the rope the third man made his way down the mountain to where Williams and his friend were. They managed to stop the flow of blood, and between them got the wounded man on his horse and brought him to Riverton. Williams spent several days in bed and was covered with bandages for two weeks, but received no lasting injuries.

As souvenirs of his terrible fight, he has two little eagles and a dozen or more big scars to show his friends.

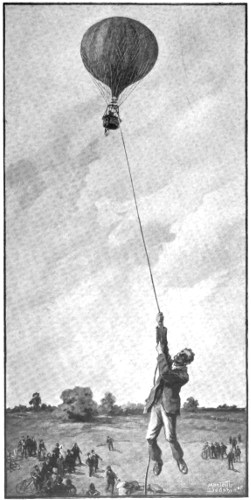

It was a delightful September afternoon some six years back—the close of a week during which there had been much discussion in the newspapers concerning a great balloon race versus cyclists, to be fought out on this identical Saturday. The late Rev. G. M. Bacon, of Newbury, the “ballooning parson,” and Mr. Percival Spencer, the well-known aeronaut, were to compete against Volunteer cyclists in an endeavour to settle the much-debated question as to whether, in time of war, a hostile balloon could escape from the speedy military wheelman. I am not a Volunteer, and certainly was at that time far from being a balloonist; I am less so now.

MR. A. SODEN, WHO HERE DESCRIBES

HIS EXPERIENCES IN A RUNAWAY

BALLOON.

From a Photo. by Sternberg & Co.,

Kingston-on-Thames.

At four-forty-five in the afternoon of this particular Saturday, while I was still debating what to do with myself, what should I see to the north-east but the war balloon, released from its anchorage at Stamford Bridge grounds, being carried by a gentle September breeze in the direction of Epsom. At all times the sight of a balloon excites peculiar interest, and I had soon made up my mind—I would try my hand at catching the aeronauts, and try to beat the military cyclists! I rushed for my machine, and was presently in full chase, pedalling fast through the lovely lanes of Malden. On and on I went, riding hard, alternately glancing at the road to see that all was clear and then at the balloon, calculating how high it was, how far away, and where it was likely to descend.

THE BOY WHO WAS WITH MR. SODEN IN

THE BALLOON.

From a Photograph.

Mile after mile I chased the drifting balloon, until at last, much to my joy, I saw that it was undoubtedly nearing the earth, and it eventually descended in a harvested field at Bookham. On approaching the balloon I soon discovered I was not alone, for cyclists representing various Volunteer regiments and civilian riders were there by the score; and a number of farm labourers who had been busy harvesting in the neighbouring fields also appeared on the scene, eager to inspect closely so formidable a beast as a war balloon.

The formal “capturing” of the balloonists by the soldiers was soon over, and then, at the urgent request of the onlookers, and to the intense delight of the local element, Mr. Spencer was good enough to grant permission for those who wished to go for short trips in the balloon, now held captive by the anchor-rope. There were many willing hands to relieve the balloon of ballast, grappling-irons, and sundries, and in a remarkably short time the great gas-bag was free of its accoutrements. A trail-rope was attached for those on the ground to hang on, to prevent the balloon from sailing away, and Mr. Spencer, with his usual foresight, arranged for parties of six to go up at a time. The passengers were given strict instructions that when the balloon touched ground each was to get out singly, so that there should be no sudden alteration of weight that would cause the balloon to shoot up again.

All went merrily, and several 426 car-loads went up, we on the ground hanging tight to the rope and hauling the great bag down on the word of command from Mr. Spencer. At length came the call, “The last time!” and in I jumped. There were five of us in the car, four men and a boy—a Volunteer, a farm labourer, and two others. Surely, I thought, as the great sphere began to rise, I am well repaid for my long ride by this novel experience. It was grand to be sailing up in the air with the ground gradually sinking away beneath us and our late companions becoming mere specks dotted about on the ground. At last we arrived at the end of our upward journey, and the men below began hauling at the trail-rope. Down we went, and presently touched ground. Then, contrary to all instructions, out jumped the Volunteer and a civilian named Tickner. As they leapt they collided with the men who held the controlling ropes, knocking them over and causing much confusion.

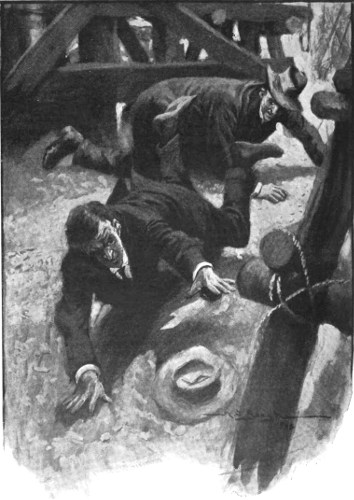

“HIGHER AND HIGHER WE WENT, WITH THE HAPLESS MAN DANGLING.”

The balloon, relieved of the heavy load, at once shot up again. There were wild cries of “Seize the rope!” “Hang on to her!” “Hold her down!” But all the shouts were of no avail; the balloon continued to rush upwards, while we peered helplessly over the edge of the car. Several men, realizing the dangerous position we were in, soaring up aloft at great speed, rushed into the middle of the crowd of excited onlookers and seized the trailing rope, but all to no purpose; it was now impossible to check the balloon’s rapid ascent. “Let go!” roared somebody, and by the sudden bound our car gave we knew the men had obeyed. All, that is, save one. He, Tickner, a hard-working, much-respected farm labourer, clung to the rope like a monkey, only to be drawn up into the air as the balloon rose. Higher and higher we went, with the hapless man 427 dangling two hundred feet below us and the crowd watching with horror in their eyes. Presently, when he was about eighty feet from the earth, the poor fellow’s strength gave out and he was compelled to let go, falling with an awful thud to the ground.

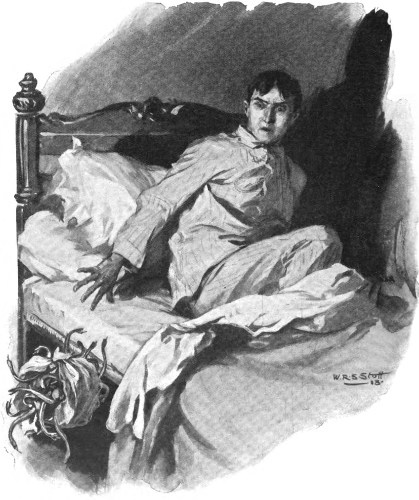

Then, for the first time since the accident, I found my tongue. “Good heavens! this is awful!” I cried. “Where shall we drop?” I could say no more, for my knees shook under me and my very blood seemed frozen with horror. Still, steadily and inexorably, the balloon continued to rise. I dared not look over the side, but I knew we must have reached a considerable altitude. What would happen to us, and should we ever see our homes again?

All this time the boy beside me, shivering with fright, yet not realising his desperate position, kept dinning into my ears in a whining monotone, “They’ve let us go! They’ve let us go!”

There was nothing to be seen around us now but mountains of clouds—clouds white, black, and grey. I saw them, and yet, somehow or other, I could not bring myself to realize what they meant. I could not think, but simply stood there, bewildered and dazed, leaning against the side of the car. On my right hand the boy still continued his maddening wail; on the left my second companion, a man, kept asking what his father and mother would think. Our peril seemed to have temporarily turned his brain.

2 SEPTEMBER 1902.

BALLON DISASTER.

A LEATHERHEAD LABORER KILLED.

THRILLING ADVENTURES OF AMATEUR AERONAUTS.

The ballon versus cyclists, which was arranged by the Rev. G. M. Bacon, of Newbury, the ballooning enthusiast, with the sanction of the War Office, and which took place from Stamford-bridge athletic grounds on Saturday, was, it was transpire, attended with an accident of a very serious character, resulting in the death of one man, injuries to several others, and an experience which three of those involved are never likely to forget as long as they live. The

A CUTTING FROM THE “MORNING LEADER”

REFERRING TO THE BALLOON DISASTER.

Click here for image.

I glanced at the altitude-registering instrument; we were up two thousand feet! Then, suddenly, without the slightest warning, my brain cleared, and I remembered the valve, the opening of which would cause the great gas-bag to descend. But where was it? Which was the valve-rope? The car seemed all ropes as I turned anxiously this way and that. I tried one after another, and at last, to my joy, I felt one give. Then I smelt the escaping gas, and knew that I had struck the right cord. Very soon I realized that our upward way was checked, and that instead we were descending. I do not know how long we took over the downward trip. I only remember that I pulled the rope, then slacked it, and so on alternately until we could faintly hear the shouts of those below. Presently the boy plucked up courage to look over the side of the car, and, wild with joy, called out that we were saved. Fortunately for us, there was practically no wind; we went up straight and came down straight, landing safely in a field only some two hundred yards from the spot where we ascended. I collapsed as they helped me out of the car, and the other man, directly he alighted, rushed headlong away—the ordeal had turned his brain.

Giving evidence before the coroner the following Monday at the inquest on poor Tickner, I still felt decidedly shaky, and to my dying day I shall never forget my trip in the runaway balloon.

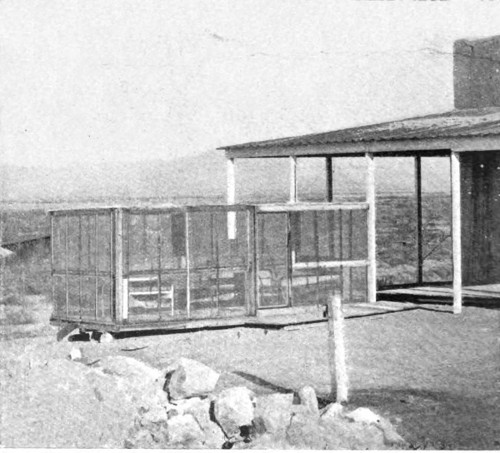

THE FIELD IN WHICH THE BALLOON DESCENDED.

From a Photograph.

428

When a man, especially a wealthy man, sets out to erect a memorial to something or somebody, there is no knowing what eccentricity he will not commit. Scattered up and down this country, as the writer shows, are a number of most remarkable memorials—“freaks” of the first water, from whatever standpoint one judges them.

Who shall impose limits on the intent and form of memorials? He would be a brave man indeed who attempted the task; yet, though it is very difficult to say precisely where the line should be drawn, there are a number of such things in existence which, judged by the commonly-accepted standards, are distinctly “freakish.” They range from public statues plain to all men to small stones in arcadian aloofness, and, as a whole, go far to justify the oft-repeated taunt of the “intelligent foreigner”—a taunt amounting to an implication—that memorials afford an outlet for much of the Englishman’s eccentricity and sheer “pig-headedness.”

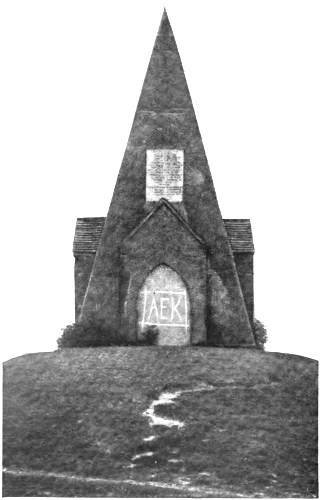

There are some very curious monuments to animals scattered over the countryside. The one with the most remarkable story crowns Farley Mount, near Winchester. Underneath it lies buried, as an inscription on the exterior records, “a horse, the property of Paulet St. John, Esq., that in the month of September, 1733, leaped into a chalk-pit twenty-five feet deep a-fox-hunting, with his master on his back, and in October, 1734, won the Hunters’ Plate on Worthing Downs, and was rode by his owner, and entered in the name of Beware Chalk Pit.” This inscription, which is a copy of the original, was restored by the Right Hon. Sir William Heathcote, Bart., in 1870. A duplicate is in the interior, which is provided with three seats intended for the accommodation of wayfarers.

A MONUMENT TO A HORSE THAT LEAPED INTO A CHALK-PIT AND AFTERWARDS WON A RACE.

From a Photograph.

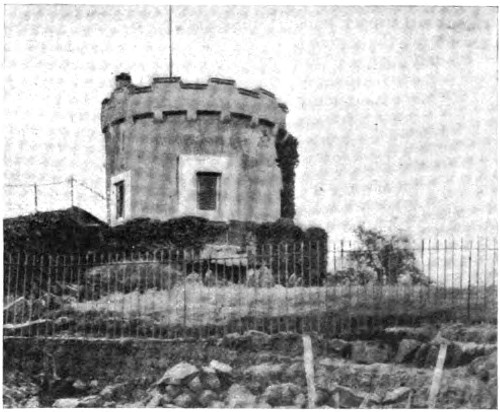

Of the memorials to dogs the most imposing of modern date is “Tell’s Tower,” a structure on the seashore near West Kirby, Cheshire. It is in honour of the Great St. Bernard dog, Tell, “ancestor of most of the rough-coated champions of England, and himself winner of every prize in the kingdom. He was majestic in appearance, noble in character, and of undaunted courage.” Built by the late Mr. J. Cumming Macdona, the tower is a sort of summer-house, in the base of which is a vault containing Tell’s remains, guarded by an effigy of that remarkable animal.

To a whole series of such freaks of commemoration there hangs a singular tale. In Oatlands Park, Weybridge, there are two or three scores of memorials to dogs. These animals, some of which have handsome epitaphs inscribed to their many virtues, are popularly supposed to have been pets of Frederica Duchess of York; but, as a fact, Her Royal Highness had not sufficient warm 429 affection to bestow a goodly portion on so many dumb creatures. What human being, indeed, ever had? She was presented with many dogs, which she could neither refuse without giving pain, nor keep unless the whole house was turned into kennels. So they were given a dose of opium, buried, and then commemorated in verse. But, while the Duchess was not so foolish as is generally believed by those who visit Oatlands, she was certainly responsible for the monuments.

“TELL’S TOWER,” ERECTED TO THE MEMORY OF A ST. BERNARD DOG—IN THE

FOUNDATIONS IS A VAULT CONTAINING THE ANIMAL’S REMAINS.

From a Photograph.

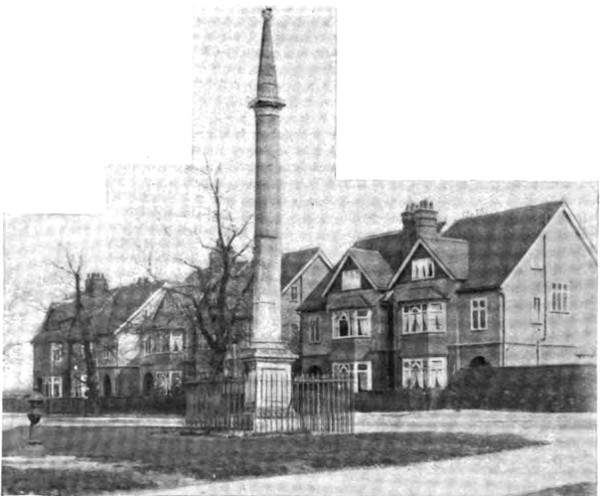

Strange, then, that her own memorial is the prime curiosity of Weybridge! Its history is this: After her death the inhabitants of the town were desirous of commemorating her thirty years’ residence among them, and it suddenly struck them that a way was ready to hand. Till about fifty years earlier there had stood in Seven Dials a pillar supporting a sundial which presented a face to each of the streets. It was from this adornment, indeed, that the classic district got its name. Believing that treasure was buried beneath the pillar, some night-birds threw it down and excavated beneath it, to find nothing. Rumour, they discovered, was a lying jade. The stones, instead of being set up again on their old site, were conveyed to Sayes Court, Addlestone, with a view to their re-erection there, but this was not done, the column remaining dismembered till the occupier of Oatlands died. Now this bit of London out of town the inhabitants resolved should be converted into a memorial of the Duchess. So the stones were purchased and set up on the green, with the substitution of a ducal crown for the block on which were the dials. This was used for some time afterwards as a mounting stone at an inn hard by. It then constituted a puzzle, because, though in Seven Dials—according to the testimony of everybody who described it—there were seven faces, the number on close examination proved to be only six.

THE “SEVEN DIALS” PILLAR, AT WEYBRIDGE, SURREY.

From a Photograph.

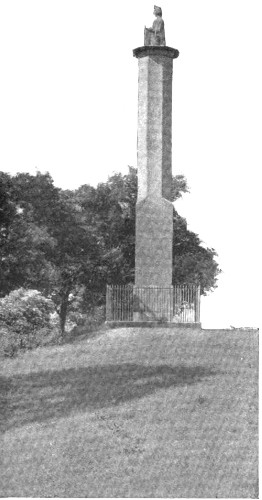

Another class of “freak” memorials have a twofold peculiarity: they are singular in themselves and are also remarkable by reason of the tardiness with which they were erected. Maud Heath’s Column, on Bremhillwick Hill, near Chippenham, is as good an instance as any. The title of the good lady to grateful remembrance is that she left a bequest by which a causeway 430 was constructed in 1474 from Chippenham to the shoulder of Bremhillwick Hill. Her claim was from the outset acknowledged, inscriptions along the route of the causeway expressing gratitude to her for having made it. But this was not enough for a former vicar of Bremhillwick. After pedestrians had for more than three centuries been called upon to bless the public-spirited lady, and had been told, moreover, precisely where her causeway began and where it ended, the vicar came to the conclusion that she ought to have a statue, and moved himself to that end. A preliminary difficulty was that no portrait of Maud Heath was known to exist; but ultimately, with the co-operation of the Marquess of Lansdowne, the clergyman triumphed, and the column on Bremhillwick Hill—which was set up in 1836—is the result. The sculptor of the statue on the top of it had to fall back on his imagination, and he represented a woman in fifteenth century costume, with a staff in her hand and a basket by her side.

A BELATED MONUMENT—IT WAS ERECTED IN 1836 TO THE MEMORY OF A

LADY WHO LIVED IN 1474, AND THE ARCHITECT HAD TO FALL BACK UPON HIS IMAGINATION FOR THE PORTRAIT!

From a Photograph.

A HIGHWAYMAN’S GRAVE AT BOXMOOR COMMON.

From a Photograph.

A belated memorial of a different class is at the head of a highwayman’s grave on Boxmoor Common. The knight of the road buried here, Snooks by name, was long a terror to travellers on the London road, which runs by his resting-place. At last, emboldened by many successes, he had the audacity to rob the Royal mail, whereupon he was hunted down, and eventually hanged near the scene of many of his crimes. He was, it is said, the last highwayman to suffer the extreme penalty in the district. Buried in unconsecrated ground, he was intended to be forgotten; but till about four years ago his grave was re-turfed periodically, and then a small stone, simply inscribed, “Robert Snooks, 1803,” was placed at its head. That tribute is one proof out of many that there is still a certain admiration for the race of which Dick Turpin is the popular hero. 431

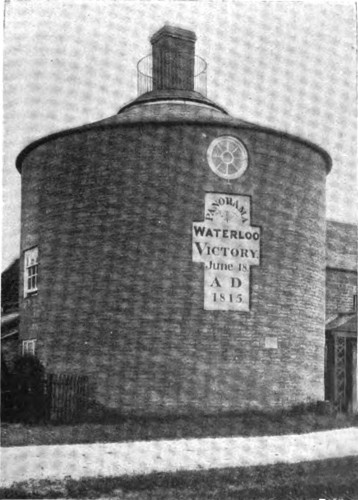

THE “ROUND HOUSE,” NEAR FINEDON, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE,

WHICH IS SUPPOSED TO OVERLOOK A TRACT OF COUNTRY

EXACTLY RESEMBLING THE FIELD OF WATERLOO.

From a Photograph.

Among our battle memorials are several of the “freak” order. The Round House, near Finedon, Northamptonshire, must certainly be so classified. Formerly an inn, it is now a dwelling, from the roof of which, it is said, there can be obtained a “panorama of Waterloo.” It was built on this spot, as a memorial of Wellington’s great victory, because the surrounding country is believed to be very much like the theatre of the momentous battle. There is a parallel duplicate in Kent. Crown Point, between Sevenoaks and Maidstone, takes its name from a place in Canada where Sir Jeffrey Amherst gained a great victory over the North American Indians. It is said to bear a remarkably close resemblance to its namesake.

Waterloo is also commemorated by an Alnwick memorial. Locally dubbed a “folly,” it stands on Camphill, where it is surrounded by tall fir trees, which prevent it from being seen except at close quarters. Its creator was the late Mr. H. S. Selby, whose object was to place on record the policy of Pitt, the victories of Wellington and Nelson, and the restoration of peace in 1814. He appears to have been doubtful afterwards whether the column would be sufficient to prevent all these events from being forgotten by posterity, because in celebration of the Battle of Waterloo he set up a beautiful statue of Peace in front of his mansion.

A HILL-TOP FREAK—THE COLUMN COMMEMORATES QUITE A LOT

OF THINGS, BUT IS SO SURROUNDED BY TREES AS TO BE

INVISIBLE SAVE AT CLOSE QUARTERS.

From a Photograph.

Still more singular a memorial of our fighting prowess is the Red Lion of Martlesham. The Red Lion, originally a ship’s figure-head, is now the sign of an inn at Martlesham, on the high road between Ipswich and Woodbridge, and is painted a most brilliant and 432 aggressive red. Indeed, “As red as the Red Lion of Martlesham” is a proverbial expression throughout East Suffolk. The grotesque object is a relic of a British victory over the Dutch in Sole Bay. It was brought inland as a trophy of our success, and was ultimately converted to its present use—that of an inn sign.

THE RED LION, OF MARTLESHAM, WHICH HAS GIVEN RISE TO A SUFFOLK PROVERB.

From a Photograph.

One of the best-known memorials of battles fought on English soil—the obelisk at Naseby—is a “freak,” and a strange one, too. Its distinction lies in the fact that it has misled thousands, including Carlyle and Dr. Arnold. “To commemorate,” so runs the inscription, “that great and decisive battle fought in this field on the XIV day of June, MDCXLV, between the Royalist Army, commanded by King Charles the First, and the Parliament Forces, headed by the Generals Fairfax and Cromwell ... this pillar was erected by John and Mary Frances Fitzgerald, Lord and Lady of the Manor of Naseby.” But nothing is more certain than that the battle was not fought in “this field.” It actually took place on Broadmoor, about a mile away. Appropriately, therefore, did Liston call the obelisk the “obstacle.” Edward Fitzgerald was conscious of this strange blunder, to which he refers in one of his letters (the monument, he says, “planted by my papa on the wrong site”), and which he proposed to remedy by removing the obelisk to the real battlefield. The scheme, however, was not carried out, presumably on the score of expense.

A MONUMENT IN THE WRONG PLACE—THE NASEBY MEMORIAL, WHICH DOES

NOT STAND UPON THE BATTLEFIELD AT ALL.

From a Photograph.

Besides the Round House, Finedon possesses a representative of a large class of “freak” memorials—those which bear no inscription, and the object of which is consequently doubtful. These differ from the many strange things which 433 serve as memorials without being plainly stamped as such. In Lancaster, for instance, a large horse-shoe is embedded in the middle of the roadway, and there is nothing to inform the stranger of its intent. It is actually there owing to a tradition that a horse ridden by John o’ Gaunt, the town’s patron saint, cast a shoe near the spot. The silent reminder of the incident—which, of course, has been renewed many times—was some years ago polished every morning. An eccentric man turned up with the utmost regularity, went down on his knees, and made it as bright as the proverbial new pin. Unfortunately his zeal was not admired by the authorities, who ultimately prosecuted him for obstructing the traffic.

A unique milestone, again, serves as a memorial. It stands in the hamlet of Newbold, Gloucestershire, and is surmounted by a cross. On the south side are the directions:—

And on the north face appears a “sermon in stone”:—

Nothing on the milestone denotes that it is intended to be a memorial, but a local gentleman, it is understood, erected it as such after the death of a member of his family.

There are, however, many memorials of conventional form which are much more puzzling than such “freaks.” Above the white horse at Cherhill, Wilts, is one on which not a single letter or figure appears. Several stories are told locally of its origin and purpose. Of the same cryptic character is the Finedon memorial—a pillar standing in a garden at the cross-roads. It is generally supposed to commemorate a mailcoach robbery which took place near the spot in or about the year 1810; but, as it was in existence before this event took place, the popular belief must be erroneous. The most probable theory is that it was set up during the rejoicings at the recovery of George III. from his illness. There was an ebullition of patriotism at that time, and before the fever subsided several memorials sprang up in different parts of the country.

WHAT IS IT? AN OBELISK WITHOUT AN INSCRIPTION.

From a Photograph.

Burial-grounds contain numerous “freak” memorials, notwithstanding that clergymen, as a rule, discountenance that form of eccentricity which strives after novelty in post-mortem advertisement. The most curious churchyard memorial in England, perhaps, is at Pinner. It resembles a church tower, and half-way up it a coffin projects on each side. Beneath, and 434 supporting the structure, are arches filled in with ironwork, bearing the words, “Byde-my-Tyme.” The “my” appears to stand for one William London, who was interred (or interned) here in 1809.

“’TWIXT EARTH AND SKY”—AN EXTRAORDINARY GRAVE IN PINNER CHURCHYARD.

From a Photograph.

Legends cluster round this strange object. The stone coffin, according to the most circumstantial, contains the remains of a Scotch merchant, whose descendants retain his property as long as he “remains above ground.” Nothing definite, however, is known about the tomb. If its constructor wished to furnish posterity with an insoluble puzzle, he has succeeded to perfection.

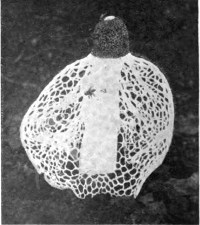

ANOTHER REMARKABLE MEMORIAL—A LIGHT BURNS IN THE TOWER NIGHT AND DAY.

From a Photograph.

Of the “freak” memorials in public cemeteries, a lighthouse is easily first. This is at Ulverston, and is not merely a stonemason’s model, for it actually contains a plate-glass lantern, in which a gas-jet is burning continuously day and night. The most remarkable thing about this elaborate token of affection, perhaps, is that it is not a glorified tombstone. It was erected by a daughter in memory of her father, who is buried elsewhere, and was placed on its present site because the two had paid several visits to Ulverston Priory. Neither had any real connection with the town. A feature which differentiates this handsome tribute from all, or nearly all, others is obvious, and that is the cost of maintenance consequent on the gas consumed in the lantern.

Public memorials include numbers of “freaks,” the singularity of some of which is greatly heightened by their surroundings. This is notably so in the case of a drinking fountain which stands in the middle of the East Anglian town of Swaffham. Unromantic as its environment is, this 435 structure is a modern heart shrine, containing as it does the cardiac organ of a local magnate, Sir William Bagge, who died in 1880. It was at his own request that his heart was deposited within the memorial, that he might remain after death, in a sense, in a place which he had loved so well in life.

A MODERN “HEART SHRINE,” AT SWAFFHAM, NORFOLK.

From a Photograph.

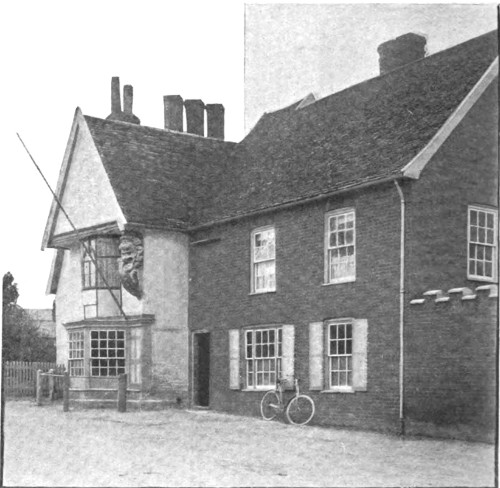

The last class of people to whom one would expect to see “freak” memorials are preachers, and yet there are two or three to such men. Decidedly the most picturesque, though not the most outré, is a massive chimney-stack at Coleman Green, Herts. It is preserved, as a tablet on it records, because in the cottage which was attached to it Bunyan occasionally preached.

“JOHN BUNYAN’S CHIMNEY” AT COLEMAN GREEN, HERTFORDSHIRE.

From a Photograph.

Strange as some of the foregoing memorials are, they are surpassed by certain monstrosities in private parks, which unquestionably contain the most remarkable “freaks” of the kind in England. In several cases the public are forbidden to enter such domains, not because it is feared that they commit damage, but in order that they shall not see some colossal absurdity of which the descendants of its creator are ashamed. Nearly the first thing one gentleman did, on entering into possession of the estate which he now holds, was to ascertain whether he had power to sweep off it a memorial which was ridiculed by the whole countryside and pointed out to every stranger to the district. Finding that he could not remove the eyesore, he at once gave orders that the park wall should be raised four feet all the way round! 436

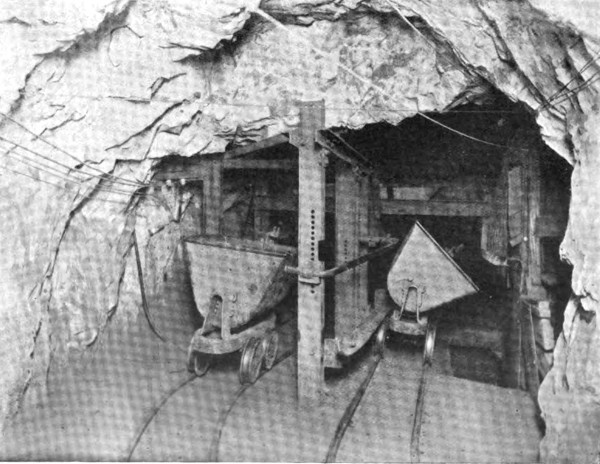

An account of a miraculous triple escape—an escape in which the odds were as a million to one on death. Mr. Wood’s adventure created quite a sensation in South Africa, for it is unique in the annals of the diamond fields. The photographs illustrating the story are published by kind permission of the general manager of the De Beers Consolidated Mines.

The following narrative, describing a miner’s miraculous escape from what appeared certain death, forms one of the most sensational episodes in the history of South African mining in general and of the world-famous De Beers Diamond Mines of Kimberley in particular. Miners who have spent many years in the wonderful underground workings of the Kimberley diamond mines, and who have become thoroughly familiar with the perils and thrilling incidents synonymous with underground mining, were dumbfounded at the truly unique experience which befell Mr. Charles Wood at the De Beers Company’s Wesselton Mine, Kimberley, South Africa, on Tuesday, 11th August, 1908. Mr. Wood’s story is here given as related to the author.

I am twenty-nine years of age, and have been for some years engaged in various capacities in the many departments of the underground workings of the Kimberley diamond mines. During that period I have witnessed many hairbreadth escapes from the innumerable perils of the treacherous subterranean workings, and have seen men launched into eternity in a single second by one or other of those unavoidable happenings which of necessity form part of the miner’s precarious occupation. Personally, however, I have been very fortunate, for my own mining experience has been uneventful—until last week, when I was the victim of a string of events probably unparalleled in the annals of the diamond mines.

On the morning of Tuesday, 11th August, 1908, I went to work as usual, and arrived at the mine shaft a few minutes before six o’clock, feeling in high spirits after a brisk and invigorating three-mile bicycle ride in a calm, bracing, and typical South African dawn, which heralded the commencement of a day that was to prove the most eventful and memorable of my life. Precisely as the mine “hooter” sounded, I, with several others, boarded the huge iron man-cage, and in another moment its human freight was being lowered some five hundred feet down the perpendicular shaft to the main working level of the mine.

Our destination was reached in due course, and the cage came to a standstill at the entrance to the main level, which here resembles a large arch-shaped room, about eighteen feet high and twenty-five feet wide, with sides and roof of solid rock. On the one side is the main vertical shaft, leading to the headgear on the surface above and to the further levels below, while directly opposite, and extending in a straight, horizontal line for nearly half a mile into the bowels of the earth, is the main tunnel to the mine, suggestive of some great corridor, with many side galleries and minor branch tunnels on either side, leading in contrary directions. There is a double track of rails, one for empties returning from the tips and the other for the loaded trucks, which are detached from the electric locomotives at an apex some thirty yards from the loading chute, and from which they run by gravitation, in sets of eight, along the “full-way,” round the left side of the shaft, to the automatic tips, which are situated immediately behind the shaft and on the opposite side of the main tunnel. Here the trucks are mechanically overturned and the contents discharged into the loading chute, a large steel receptacle some twenty feet deep, fifteen feet long, and four feet wide. From this point the trucks run along the “empty-way,” or right side of the shaft, in a semicircle towards the main tunnel, to be finally coupled to the locomotive, and drawn, in trains of sixteen, to the different passes to be reloaded.

In the mine I am known as the “tipman,” and my duties—directing the discharge of the diamond-laden “ground” into the chutes—commence when the trucks, laden with the “ground,” reach the automatic tips.

I was soon at my accustomed post, and before many minutes had elapsed the distant rumbling of the moving trucks in the tunnels became audible. The day’s operations had begun.

I am constantly engaged in superintending the working of the tipping arrangements, and in watching the running of trucks on the proper tracks, which here almost entirely encircle the main shaft, through which the “ground” is eventually raised to the surface in the giant hoisting skips. 437

On this particular morning I worked without the shortest break, and nothing interrupted the monotonous rolling of the trucks as they went backwards and forwards again and again to be refilled at the loading passes and emptied at the loading chutes, until nearly one o’clock, when, through a slight but unfortunate mishap, I became the victim of a catastrophe which now seems to me like some horrible nightmare, or the effect of temporary delirium, rather than an actual occurrence.

THE FIVE HUNDRED FEET LEVEL OF THE WESSELTON MINE, SHOWING AUTOMATIC TIPS AND TRUCK TIPPING INTO THE CHUTE INTO WHICH WOOD WAS THROWN.

From a Photo by J. A. Glennie, Kimberley.

As before-mentioned, the train of sixteen trucks is divided into two sets of eight trucks each. One set is emptied into No. 1 chute and the other into No. 2 chute. At about a quarter to one my attention was drawn to what appeared to be a slight irregularity in the tipping of the trucks at No. 2 chute. A train had just reached the tips, and the first set of eight trucks was emptied in the usual manner into No. 1 chute, while the second set was directed on to No. 2 chute.

As the last set of trucks passed round the “empty-way” I stepped on to the track, immediately over the No. 2 chute, in order to verify my suspicion that something was wrong. As I did so I heard a loud clattering noise, as of loaded trucks coming clown the “full-way” incline to the chute. I did not look to ascertain the cause of this noise at that moment, but an instant later I instinctively turned my head and looked up towards the entrance to the chute. Then, to my utter dismay and consternation, I saw, within a few feet, two fully-loaded trucks rushing headlong on to the No. 2 tip, where I was standing. In an instant the awful truth flashed through my brain. Only six trucks of the last set had tipped, two having become uncoupled up the incline, and here was I standing on the track immediately over the chute, without the remotest possibility of escape!

For a moment I was petrified with horror, and before I could make any arrangement the foremost of the two trucks had struck me full in the back, just above the hips, and I was precipitated violently into the chute, some twenty feet below, while at the same time, with a fearful, deafening noise, the two trucks overturned, and two tons of rock and hard blue “ground” came crashing into the chute on top of me. For a few seconds I was completely buried, but with a frantic effort I got the upper part of my body free, all the 438 time gasping wildly for breath, while temporarily deprived of sight by the mass of falling “ground,” and nearly asphyxiated by the immense cloud of dust, which seemed to hang over the chute like a pall.

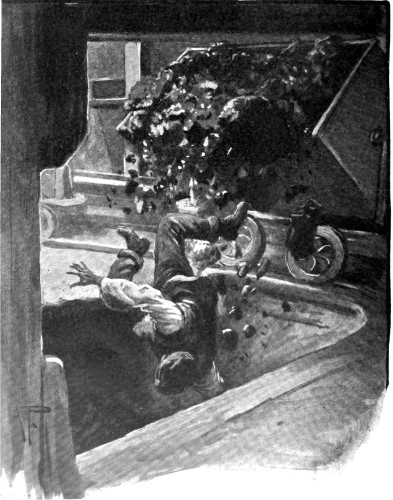

“I WAS PRECIPITATED VIOLENTLY INTO THE CHUTE.”

As I gradually gained control of my scattered senses I became aware of my miraculous escape from a terrible death, and with a shudder of horror realized that my situation was still one of extreme peril. In another second the doors of the chute would be opened, and I should either be plunged, with the great quantity of “ground” amidst which I lay, into the hoisting-skip below, or else crushed to a pulp by the next consignment of “ground” from the tip above. With almost superhuman strength I endeavoured to extricate 439 myself from the mass of “ground” by which I was well-nigh covered, and with all the power of which I was capable I shouted vociferously for help. It was all in vain, however; my cries for assistance were lost amidst the din of the constantly-moving trucks on the level above.

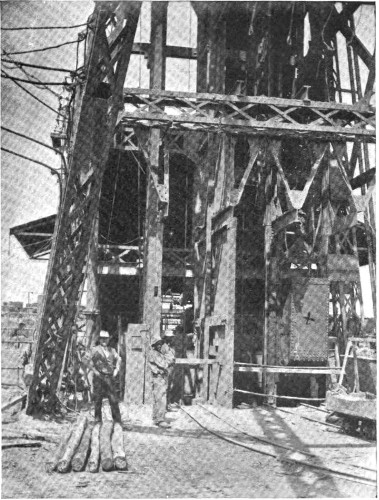

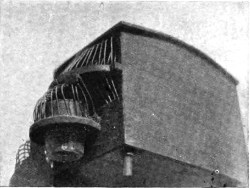

PORTION OF THE HEADGEAR SHOWING THE HOISTING-SKIP (INDICATED BY A CROSS) IN WHICH WOOD MADE HIS RAPID BUT UNCOMFORTABLE JOURNEY TO THE SURFACE.

From a Photo. by J. A. Glennie, Kimberley.

Just as I made another desperate attempt to free myself I heard the ominous creak of the levers, which foretold that the slides at the bottom of the chute were about to be opened, and—quite helpless and filled with an overwhelming despair—I resigned myself to my fate; I was doomed to a death from which there could be no possible escape. My whole frame was trembling with the fear of impending death, as, with a loud creak, the slides at the bottom of the chute separated, and I felt myself violently overturned and forced irresistibly through the opening. Thence I plunged head-first into the great hoisting-skip below, amidst the thunderous crash of the eight tons of blue “ground.” In a second the sliding doors of the chute had closed, the skip was loaded, and the relentless downpour of “ground” and hard lumps 440 ceased. I was again completely buried, but with a ferocious struggle managed to get my head uncovered.

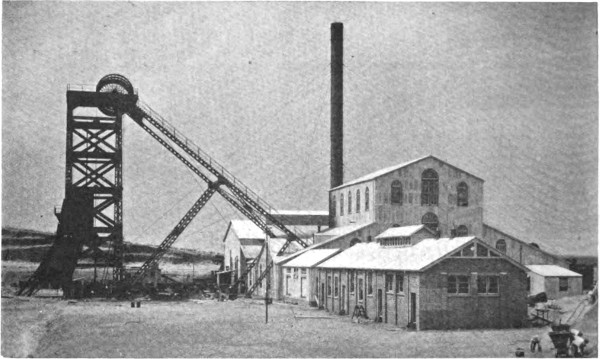

THE ENGINE-HOUSES AND HEADGEAR WHERE WOOD WAS HOISTED TO THE SURFACE.

From a Photo. by J. A. Glennie, Kimberley.

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

I, the undersigned, hereby certify that the account of my experience at Wesselton Mine, Kimberley, Cape Colony, as written by Mr. C. A. O. Duggan, is true and correct in every detail, and, further, I hereby give to Mr. C. A. O. Duggan the full and exclusive right to publish the particulars and account above referred to in any newspaper, periodical or magazine he may choose.

Charles Wood AS WITNESSES:— KIMBERLEY, S. A. 26th August, 1908. JJ Armstrong BW Freislich

The abovementioned copyright of Mr. Charles Wood’s experience at Wesselton Mine, Kimberley, C. C. is hereby given to the Proprietors of the “Wide World Magazine”, London, England.

MR. WOOD’S SIGNED STATEMENT VOUCHING FOR THE ACCURACY OF THIS STORY.

Click here for image.

Dazed and just able to realize my terrible situation, I gasped for breath, and, although quite oblivious of the nature and extent of my injuries, I was vaguely conscious that I was still alive, and that for the second time in a few minutes my life had been miraculously preserved. Securely pinned down by the tremendous weight of the “ground,” I lay unable to move, and after making a feeble and vain effort to shout for assistance, I gave up my futile struggle to free my aching body and sank down from sheer exhaustion, staring vacantly in the semi-darkness at an enormous, treacherous-looking boulder that had 441 lodged a few inches above me, and which appeared likely to find a fresh resting-place on my unprotected head at any moment.

For an instant there was a death-like stillness. Nearly distracted by the awful suspense, I lay helpless in the great iron skip, expecting each instant to feel the peculiar jerk of the hauling-rope that would mean the commencement of my lightning upward journey to the headgear on the surface, nearly six hundred feet above.

PORTION OF HEADGEAR SHOWING BOX LEVERS, WITH CHARLES WOOD STANDING ALMOST IMMEDIATELY UNDER THE LOADING-BOX WHERE HE WAS TAKEN OUT HEAD FIRST.

From a Photo. by J. A. Glennie, Kimberley.

What would be my fate when the skip tipped automatically on the surface? Should I be crushed to death or buried alive by the enormous quantity of “ground,” or should I meet with a more terrible death by being dashed to pieces against the steel sides or cross-bars of the loading-box, to be found later—a mangled and unrecognisable mass of humanity?

All these thoughts and countless vivid recollections of my childhood, boyhood, and early manhood flashed through my now disordered brain with startling rapidity, and I sobbed with anguish as I thought for a moment of my home, my children, and my wife, who was soon to be a widow and whom I should never see again. With a sickening terror I now grasped the fact that in a few seconds the great winding engine on the surface would be set in motion. Oh, the irony of it all! I had escaped death at the tip, and again at the loading-chute, only to end my existence when the skip eventually shot its eight-ton cargo into the steel loading-boxes above! Each moment now seemed a lifetime, and I prayed fervently that my suspense and agony might be ended.

At last the hauling-rope strained and tightened, and with a sudden jerk the skip started on its upward journey through the inky-black shaft, 442 gaining in rapidity at every yard, and each second carrying me nearer to death. The skip flew up at a terrific pace, and in a few seconds I was aware of its approach to the surface by the faint streaks of light that penetrated down the shaft. Another moment and I should be no more! The light of day became more and more intense, and with startling suddenness I shot out into the momentary and welcome brightness of the sunlight, past the level of the surface, and up to the automatic tip on the giant head-gear. Then, with a sharp click, the skip reached its tipping level and overturned, and I felt myself being thrown through space towards the yawning iron loading-boxes.

As the skip capsized I became unconscious, and was consequently spared the further mental torture consequent upon my precipitation into the yawning surface loading-boxes. At last, however, I opened my eyes, as if awakening from a profound sleep, and—amazed and utterly bewildered—gradually recognised that for the third time in as many minutes I had escaped a frightful death in a wonderful and miraculous manner. I found that I was lying awkwardly and with feet uppermost in the north side loading-box. While still trying to realize what had happened the slides of the box separated, and the next moment startled, anxious faces were peering in at me.

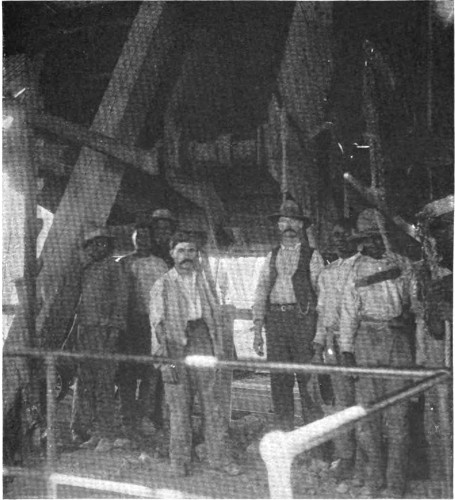

“STARTLED, ANXIOUS FACES WERE PEERING IN AT ME.”

CHARLES WOOD AS HE APPEARED AFTER HIS ALARMING

ADVENTURE.

From a Photo. by J. A. Glennie, Kimberley.

Gently the amazed men lifted me through the door and carried me to the mine change-house, where my injuries were promptly attended to. Incredible as it may seem, I was not seriously hurt, only suffering from several bruises about the body and from slight cuts on the head and above one eye. I was duly sent to the Kimberley Hospital, from which I was discharged eight days after the chapter of accidents here related, having completely recovered from the effects of my remarkable adventure. 443

There is a place up in the mountains of Switzerland where from time immemorial the women have worn the garb and done most of the work of their men-folk, who stop at home and smoke or mind the babies, while their be-trousered wives and daughters toil in the hayfields or among the live stock. In this article Miss Van der Veer describes a visit to this strange and little-known community.

Away up in the mountains of one of the most beautiful cantons of Switzerland, the Valais, the peasant women have for years found it expedient to don the garb of their men-folk and work in the hayfields and among the grazing cattle on the slopes, while their lords and masters lounge their days away in ease and the quiet of their log huts.

Curious to relate, they all seem perfectly contented with this inverted order of things—the men in particular. They brew the herbs, fry the tough-as-leather mountain meat, and look after the babies, while their buxom wives are wrestling with the sterner duties of field and stable.

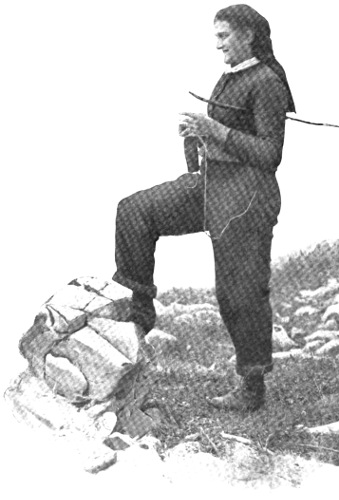

A SHEPHERDESS ON THE MOUNTAINS.

From a Photograph.

During the summer of 1908 I 444 spent some days in Champéry, the little village in the valley at the foot of the mountains where these strenuous women work and their lazy husbands smoke. At first I felt great disappointment at not seeing them about the village streets, but soon found that they seldom or never came down the mountain-side in their strange garb, or, at any rate, walked about the village in it. Tourists have become so numerous of recent years, and their curiosity so troublesome, that the village fathers have forbidden the women to come into the hamlet without skirts over their masculine nether garments. So whoever cares to behold them in the strange clothes of their choosing must scramble and toil their way up the mountain-side. On Sunday mornings it is highly entertaining to watch these women and young girls come down the zigzag footpaths to the tiny village chapel, where, just outside its doors, they halt and throw their skirts on over their heads in the most unconcerned fashion, as thoughtlessly as the fashionable dame gives her hat a furtive touch as she enters the church doors.

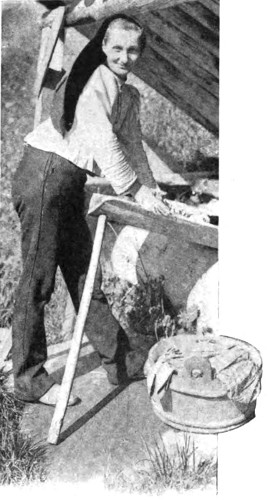

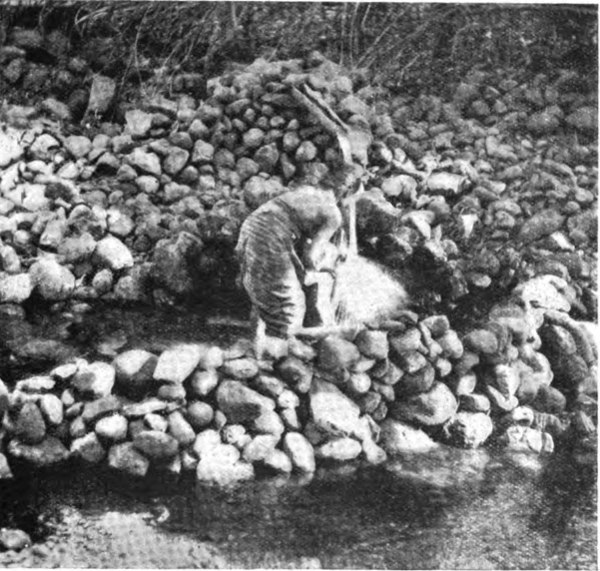

WASHING-DAY.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

It is difficult to trace the origin of this strange custom of the Champéry dames donning masculine nether garments. When one asks the peasants about it they do their best to look reflective, but always end in declaring that “it was always so.” “Our men-folk like best the fires, and we like best the fields,” is about the only intelligible explanation I could get out of them. They are fine, sturdy-looking beings, mostly red-cheeked and strong of limb, and many of the younger ones are strikingly handsome.

COOKING THE DINNER.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

One can scarcely call their costume a becoming one, though it certainly looks better than one would expect, and, after the first novelty of 445 seeing them wears off, its absolute suitability disarms criticism.

MOWING ON THE HILLSIDE.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

The most amusing thing about it is that the upper part of the costume remains feminine—the ordinary rough bodice of the peasant woman, often in bright colours of red or blue, worn with the most nondescript cut of trousers, of the “home-made” variety. That such a costume is necessary for women who take upon themselves the work of their men-folk in such a region of the world is quite apparent to any woman who attempts to follow them at their work for even ten minutes.

OFF TO THE VILLAGE.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

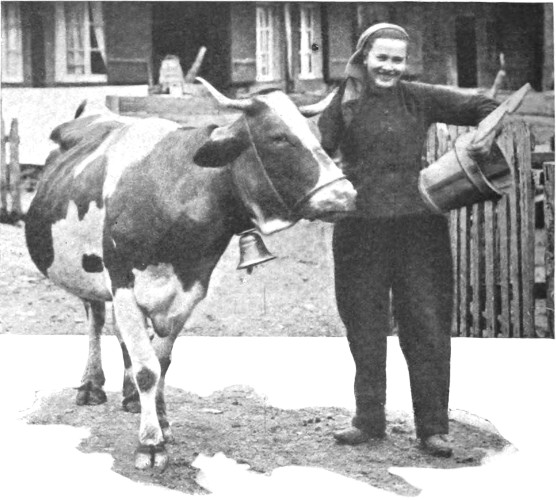

AMONG THE COWS ON THE MOUNTAIN PASTURES—THE WOMEN DO ALL THE MILKING AND BUTTER-MAKING.

From a Photograph.

The constant tramping along rough mountain ways and following cows over dangerously narrow ledges, the cutting of hay on inclines so acute as to be seemingly almost perpendicular, the going in search of lost sheep in thickets and snowdrifts, are but a few of the things which make the tyranny of skirts altogether impossible. 446 These women do not seem to mind in the least being stared at and questioned as to their clothes. In fact, they rather feel the pride of distinction their garments confer upon them. “We have never known any others,” they say quite simply, “so why should we feel queer in them? Besides, we all prefer them to skirts.”

A BE-TROUSERED MILKMAID.

From a Photograph.

The most surprising thing is that, in spite of their male attire, the women do not walk or sit in the masculine manner. Anyone can see at a glance that they are women in men’s clothes, though some green—very green—tourists often make ridiculous mistakes. At a mountain hut I once heard an English traveller declare that he never heard of men doing the family knitting until he came over the pass where these people live. He had evidently not the faintest suspicion that he had come across the men-garbed women of the mountain region, for they often sit knitting as they herd the sheep and cows on the hillsides.

Another thing that strikes one absurdly is that, while wearing trousers, these women nearly always sit sideways on horseback and get over fences by first mounting to the top rail and sliding down women-fashion, instead of striding over man-fashion. In truth, I observed no end of evidence that the inconsistency of the weaker sex cannot be quenched by anything so delectable as clothes.

One morning, when a heavy mist hung over the mountain-tops, quite obscuring everything, I sat outside the comfortable little chalet where a happy family of four sturdy daughters, with their mother, donned trousers every morning and disappeared up the mountain-side to work, while their stalwart “Pap,” as they called him, pottered round the house, pipe in mouth.

I could hear the women sharpening their scythes now and again, and catch snatches of mountain ditties as they sang at their mowing. Later on, as the mist lifted, I walked up to where they were working, and the first thing I 447 noticed was that their trousers were so long as to be quite dripping with mud, just as their skirts would have been had they worn them. When the old man went out he turned his up.

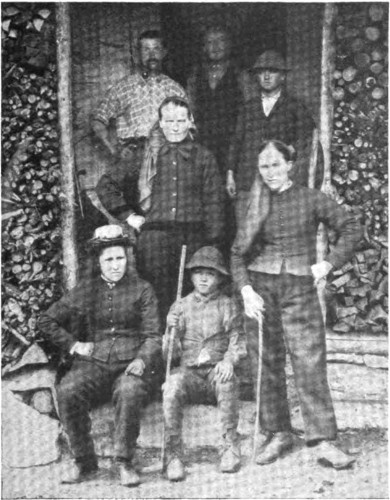

A FAMILY GROUP.

From a Photograph.

Another feminine absurdity is the wearing of a long sort of toga, which trails down their backs and gets in the way whenever they bend over or go through the tangles of the mountain wood.

“Why don’t you wear a cap or small felt hat like the men?” I asked an old woman once.

“We have always covered our heads so,” was her explanation—an explanation, in her opinion, that was all-sufficing; peasants from one generation to another do everything simply because their forefathers did the same.

A HALT FOR REST.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

One would imagine that on Sundays and fête days these women, particularly the young ones, would yield to the eternal feminine instinct of assuming the finery of their sex, but not they. Rest-time and feast-time always finds them in their usual garments. They have better-looking ones for these occasions, I confess, but they have no hankering for the trammels of skirts even during their courting hours. I was highly amused at seeing the pretty girls sauntering along the picturesque trails with their sweet-hearts’ arms around their waists, looking to the casual stranger for all the world like two young men gone “loony.”

One can scarcely imagine a wedding-party with bride and groom dressed in the same kind of garments, but I have seen one in the mountains, when the bride wore a white bodice, white trousers, and a bunch of white violets in her hair! She was as pretty as a picture, too, despite the attire, and quite as blushing and shy as any bride out of a convent.

The man of her choice, a perfect giant of a peasant, was resplendent in native costume, the chief glory of which, a green waistcoat with large brass buttons, could be seen a long way off.

Most of the weddings of recent years have been held in the little chapel of the village down 448 in the valley, where the regulation “slip over” skirt is donned at the chapel door, to be discarded before the tramp up the mountain-side is begun.

One day I was told in the village that a funeral was to be held in the little mountain settlement above Champéry, and I trudged up the zigzag pathway as hurriedly as the occasion would allow, for I confess to having a penchant for witnessing these mournful conclaves in every foreign country I may visit.

I had no trouble in discovering the house of mourning, as a crowd of peasants hung about the door. Soon the little procession, headed by the priest and his attendants, filed out of the door and moved with solemn chant down the mountain-side towards the little churchyard below.

On inquiry, I learned that the departed one was the elderly husband of a bent and weather-beaten old peasant woman, who tottered along in faded black garments, the nether portion of which looked for all the world as if she had donned the “left-overs” of her dear departed. On her head was a crisp new crape toga, however, and as she hobbled along I confess that she made a pathetic as well as an incongruous figure.

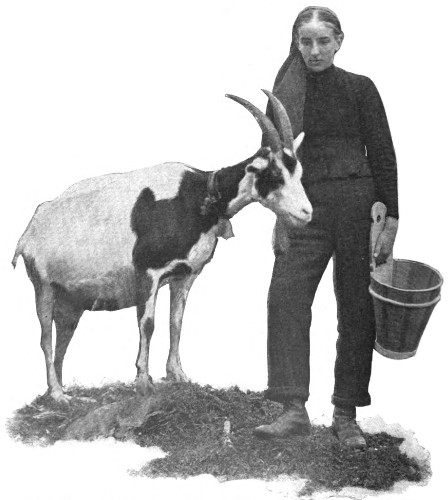

THE VILLAGERS POSSESS LARGE HERDS OF FINE MILCH-GOATS, WHICH THE WOMEN LOOK AFTER WHILE THEIR MEN-FOLK STOP AT HOME.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

Despite the fact that the women work hard out of doors, summer and winter, exposed to the worst of weathers, they are mostly long-lived and seldom know what illness is. I often saw them working in the hayfields with their babies lying blinking in the sunlight near by. At noon they lounged under the trees, talking mother-foolishness to the wee things, and their queer garments never seem so hideous and 449 altogether distasteful as when they are nursing the children.

The lack of even the simplest understanding of remedies for either illness or accident has always struck me as most remarkable among the Swiss peasantry. They may live several hours’ journey away from a doctor or chemist without ever making the least attempt at learning what to do for even the simplest ailments.

I once knew one of these Champéry women to have sunstroke so badly that she became quite unconscious, and continued so long in that state that I was certain she would die.

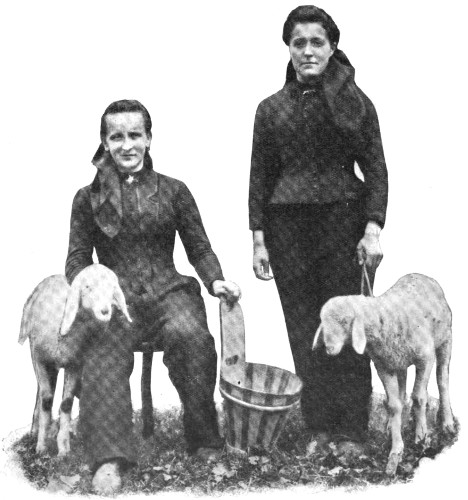

“MARY HAD A LITTLE LAMB”—THIS PHOTOGRAPH SHOWS CLEARLY THE “HOME-MADE” CUT OF THE TROUSERS AND THE CURIOUS HEAD-DRESS WORN BY THE WOMEN.

There were any number of old men and women gathered round wailing, but none of them seemed to know what to do in such a case. The woman’s mother suggested giving her a cup of coffee, which was attempted, most of it being spilt over her. Then someone took off her shoes and began slapping the soles of her feet with a piece of board.

I chanced to have a “first aid” case with me, and—greatly to the distrust of the peasants—administered what suitable remedies I had; I also insisted on one going post-haste down the valley for a medical man. But they would do nothing except wail and shake their heads. Finally the patient came round all right, saying that her head “felt full of hot things,” and the next morning, when I called to inquire after her, I found that she was at work in the hayfields, hatless, under the scorching sunlight, as usual. At another time a little child of three was taken with convulsions from having eaten 450 too much cheese, and died without having anything done to save the little creature; the old women simply wagging their heads wisely and muttering something about their all “going” when taken like that. With them it is evidently a case of the survival of the fittest.

Last summer I was in Champéry at the time of the great Swiss national holiday, when everybody celebrates Swiss freedom by making as much noise as possible during the day and lighting huge bonfires at night. Everyone was dressed in holiday finery, many of the younger women appearing in grey-check trousers and hats with artificial flowers! One happy family party, consisting of the father and mother and four children, had evidently a decided fondness for royal purple—or perhaps this was the colour of their clan—for the six of them, even to the babe in arms, were arrayed in the purple of kings and emperors!

The baby in particular attracted my interest insomuch that I ventured to take the little creature in my arms in the hope that I might slip it out of the cartridge-like swaddling-case in which these poor little wretches are carried about. I might just as well have tried to pull off the muzzle of a gun; the babe was as tightly fixed in his terribly hot case as though it were a vice. And yet I doubt not he will grow into a fine stalwart son of the mountains, though how they ever manage to expand or lengthen at all is a mystery to me.

I once sat talking to an old goatherd who certainly looked as if he had sat in the same nook in the mountains for at least a century. He was so bent and rheumaticky-looking that I quite failed to see how he could possibly make his way along the steep and slippery paths. His “old woman,” as he called her, was off down the valley gathering faggots. “She be a great worker,” he told me, and never got tired the way he did. I asked him if he liked the idea of the women doing most of the hard work; he answered by saying that it “was their way.” It suited the women to work at the hay, he seemed to think; and, besides, they hadn’t to smoke, which was evidently sufficient occupation for the men.

This old man had never seen a railway until this last summer, when a branch line was run on to the village of Champéry, at the foot of his mountain home. I asked him what he thought of it, and he grumbled out a long tale of how it had already killed a lot of goats and sheep!

Any sort of progress is looked upon with the greatest prejudice and suspicion by these people, who will undergo any fatigue and discomfort rather than change the routine of centuries.

Coming down a mountain path one evening, I ran into a party of peasant girls toiling up with huge baskets of provisions strapped to their backs. In the half light I mistook them for men from their garb, but coming nearer I recognised their red togas, and later their women’s voices.

A MOUNTAIN IDYLL.

From a Photo. by Jullien Bros.

Stopping to talk with them, I found that they were of the well-to-do natives who owned cows and mules, but they seldom thought of taking the mules along to carry up the provisions or themselves.

It had always been the custom of their women to make pack-baskets out of their backs, and they would never think of doing otherwise. It is not easy to get these people to talk of themselves to strangers; they often resent being asked questions about their work and ideas.

Yet the young women take interest in the pretty clothes of strangers. One of them came up to me and touched a blue lapis-lazuli ring I was wearing, her eyes simply devouring it, and the other trinkets I wore of the same stone. Finally, she exclaimed that she liked them very much, and also the frock of the same colour. I am quite certain there was a momentary pang of feminine envy in her heart, and a hatred for her own incongruous garments. 451

By Captain G. F. Pugh.

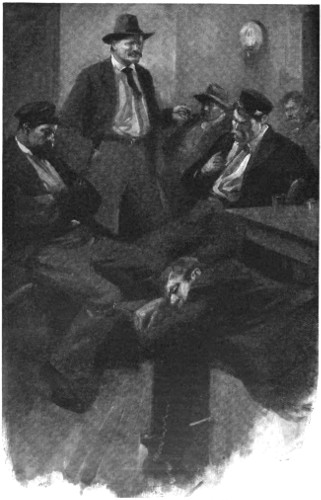

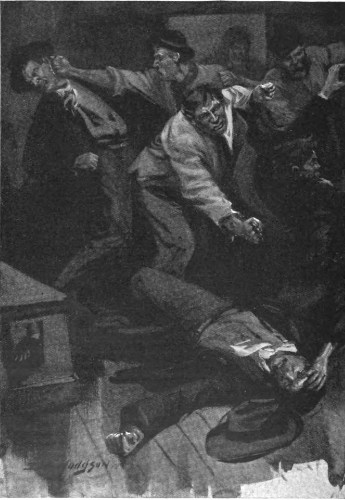

A story of the bad old “shanghaiing” days, showing how a villainous crimp had the tables turned upon him in dramatic fashion. Captain Pugh heard the first part of the story while in Newcastle, N.S.W., as mate of a ship, and its sequel upon a return voyage.

In 1872 Newcastle, New South Wales, was a busy, thriving little seaport. The harbour was full of large sailing ships, loading and waiting to load coal, and bound chiefly to China, San Francisco, and the Pacific Coast ports.

Very few of these ships had their full complement of seamen on board. Most of the sailors deserted during the vessels’ stay in port—and one cannot blame them, when it is remembered that the pay in these ships from British ports was two pounds ten a month, with the poorest quality of food that it was possible for the ship-owner to buy, and only just sufficient of that to keep body and soul together.

The pay out of the Australian ports was, for homeward-bounders, five pounds ten, and in the coast and inter-Colonial traders seven pounds a month, with a sufficiency of good, nourishing food. In addition to the inducements offered by the coast traders, there was plenty of work to be found on shore, for the Queensland, Victorian, and South Australian goldfields were in full swing. The consequence was that there was great difficulty in getting men to man the ships when they were ready for sea.

Like most seaports in those days of sailing-ships, the town was full of sailors’ boarding-houses. The tactics and ways of procuring men employed by the proprietors of these places were not such as would stand the light of day, but nevertheless they did a thriving business.

One of the most noted characters in the town was a boarding-house keeper named Dan Sullivan, a scoundrel to the backbone. He was notorious for the number of men he had “shanghaied” out of the port, but, strange to say, he had gained a certain amount of power in the town, and shipmasters requiring men were, under the circumstances, compelled to deal with him, although at the same time many of them had the utmost contempt for the fellow.

Sullivan kept a low-class drinking saloon with a free-and-easy dancing-room attached to it. The boarders lived in the rooms overhead. This was the only dancing saloon in the town, and was thronged with sailors every night. The liquor sold was, needless to say, vile stuff, but men who have been living for months on weevily biscuit and “salt-horse” have very little taste left in their mouths, and as long as the decoction was hot and came out of a bottle it passed muster.

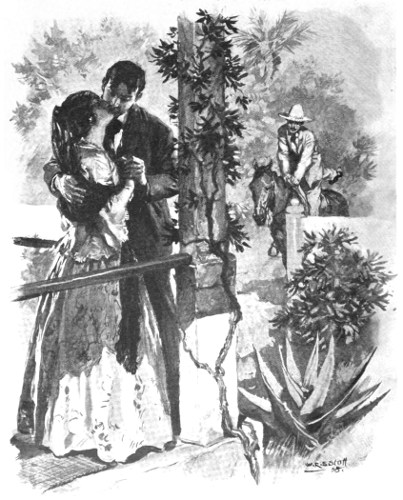

Sullivan was an adept at drugging liquor, and he always kept materials at hand for that purpose. Just a little tobacco ash dropped in the glass when pouring out the drinks, and the thing was done. When he required a few sailors for a ship ready to sail, he picked out the likeliest men in the room—usually strangers—and when the seamen, hot and thirsty with dancing, ordered drinks through the women who acted as waitresses, these Delilahs would bring the prepared stuff, and soon the men would feel muddled and sleepy and would go into the side room and sink down on the benches.

Sullivan would then slip in among them.

“Halloa, mates! What’s the matter? Feel queer, eh? Ah, it’s the dancing and the hot weather. I’ll send you a good tot that will put you all right.”

He would then send one of the girls in with a good glass of hot whisky—drugged, and that would be all the men would know for some time. When they came to their senses they found themselves in a strange ship, out of sight of land, without a stitch of clothes beyond what they stood up in. Of course, there was generally a row, but it invariably ended in their turning to work and making the best of a bad bargain. 452

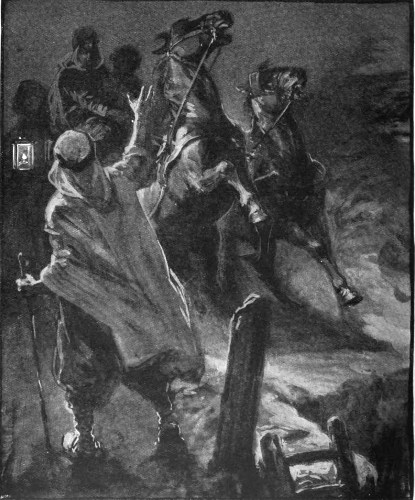

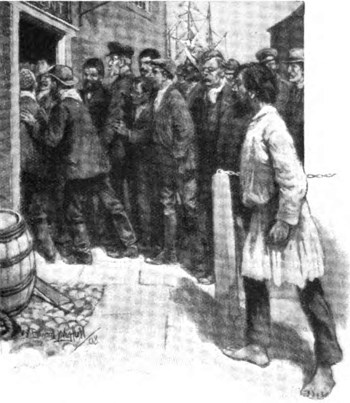

“HALLOA, MATES! WHAT’S THE MATTER?”

One day in February, 1872, it happened that there were three British ships lying at the buoys, loaded and ready to sail, but each was in want of a few seamen to make up her complement. Not a man could be got at the shipping-office for love or money—the news of a fresh gold-field on the Barrington had reached Newcastle that morning, and all the disengaged men had made tracks for that district. So the only possible way to get hands for the vessels ready to sail was to obtain them from the ships that had lately arrived, and which would have some time to wait for a loading berth.

The captains of the ships at the buoys sent for Sullivan, and arranged with him to supply them with four men each that night, as the trio would sail at the turn of the tide. When Sullivan got back on shore, he sent some of his runners to quietly let the crews of the ships in harbour know there was to be a free concert and dance at his place, with plenty of whisky into the bargain.

When night came the saloon was packed with seamen, and among the lot were six fine young American sailors from the ship Jeremiah Crawford, of New Bedford. Now, New Bedford ships are very often “family ships”—that is to say, the captain, officers, and seamen are related to each other. Of the six young fellows who went to this dance, two were nephews of the captain, one was a relative of the mate, and the others were related to members of the crew.

Long before the dance was over there were several seamen lying helplessly drugged in the side room. Just before midnight, and while the dance was still going on, Sullivan and his fellow-crimps removed the helpless men down to a boat, and took them off to the ships at the 453 buoys. Then Sullivan pocketed his blood-money, and before daylight the vessels were at sea under all plain sail.

The following day, when the six American seamen did not turn up on board the Jeremiah Crawford, inquiries were quietly made, and it was soon found out what had become of them; they had been among the twelve men “shanghaied” aboard the three waiting ships. The men’s shipmates, boiling with anger, wanted to go and wreck Sullivan and his saloon, but the captain called all hands aft, and from the poop told them they must not let it be known that they knew where their shipmates were.

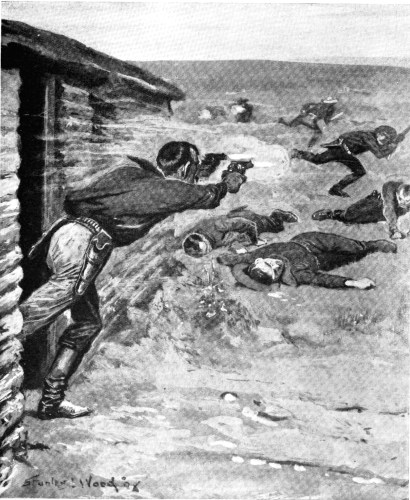

“I know how you feel over it,” he said, “and I know how I feel too, but I intend to pay that rascal in his own coin. Those Britishers are off to ‘Frisco, and we are bound there, too; and you can bet your bottom dollar I mean to make the ship move when we start. And what is more, I intend to take that rascal Sullivan with me!”