Title: Asmodeus; or, The Devil on Two Sticks

Author: Alain René Le Sage

Contributor: Jules Gabriel Janin

Illustrator: Tony Johannot

Translator: Joseph Thomas

Release date: February 8, 2016 [eBook #51145]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clare Graham and Marc D'Hooghe

When I first determined on the publication of a new edition of "The Devil on Two Sticks," I had certainly no idea of engaging in a new translation. I had not read an English version since my boyhood, and naturally conceived that the one which had passed current for upwards of a century must possess sufficient merit to render anything beyond a careful revision, before passing it again through the press, unnecessary. However, on reading a few pages, and on comparing them with the much-loved original, I no longer wondered, as I had so often done, why Le Diable Boiteux was so little[Pg viii] esteemed by those who had only known him in his English dress, while Gil Blas was as great a favourite with the British public as any of its own heroes of story. To account for this, I will not dwell on the want of literal fidelity in the old version, although in some instances that is amusing enough; but the total absence of style, and that too in the translation of a work by one of the greatest masters of verbal melody that ever existed, was so striking as to induce me, rashly perhaps, to endeavour more worthily to interpret the witty and satirical Asmodeus for the benefit of those who have not the inestimable pleasure of comprehending him in his native tongue—for, as Jules Janin observes, he is a Devil truly French.

In the translation which I here present, I do not myself pretend, at all times, to have rendered the words of the 'graceful Cupid' with strict exactness, but I have striven to convey to my reader the ideas which those words import. Whether I have succeeded in so doing is for others to determine; but, if I have not, I shall at all events have the satisfaction of failing in company,—which, I am told, however, is only an Old Bailey sort of feeling after all.

I have not thought it necessary to attempt the Life of the Author; it will be enough to me, for fame, not to have murdered one of his children. I have therefore adopted the life, character, and behaviour of Le Sage from one of the most talented of modern French writers, and my readers will doubtless congratulate themselves on my resolve. Neither have I deemed it needful to enter into the controversy as to the originality of this work, except by a note in page 162: and this I should probably not have appended, had I, while hunting over the early editions there referred to, observed the original dedication of Le Sage to 'the illustrious Don Luis Velez de Guevara,' in which are the following words: "I have already declared, and do now again declare to the world, that to your Diabolo Cojuelo I owe the title and plan of this work ...; and I must further own, that if the reader look narrowly into some passages of this performance, he will find I have adopted several of your thoughts. I wish from my soul he could find more, and that the necessity I was under of accommodating my writings to the genius of my own country had not prevented me from copying you exactly." This is surely enough to exonerate Le Sage from the many charges which have been urged against him; and I[Pg x] quote the concluding sentence of the above, because it is an excuse, from his own pen, for some little liberties which I have, in my turn, thought it necessary to take with his work in the course of my labours.

JOSEPH THOMAS.

| TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE. | vii |

| BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE OF LE SAGE. | xv |

CHAPTER I. | |

| WHAT SORT OF A DEVIL HE OF THE TWO STICKS WAS—WHEN AND BY WHAT ACCIDENT DON CLEOPHAS LEANDRO PEREZ ZAMBULLO FIRST GAINED THE HONOUR OF HIS ACQUAINTANCE. | 1 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| WHAT FOLLOWED THE DELIVERANCE OF ASMODEUS. | 15 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| WHERE THE DEVIL TRANSLATED THE STUDENT; AND THE FIRST FRUITS OF HIS ECCLESIASTICAL ELEVATION. | 20 |

| [Pg xii] | |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| STORY OF THE LOVES OF THE COUNT DE BELFLOR AND LEONORA DE CESPEDES. | 45 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| CONTINUATION OF THE STORY OF THE LOVES OF THE COUNT DE BELFLOR AND LEONORA DE CESPEDES. | 77 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| NEW OBJECTS DISPLAYED TO DON CLEOPHAS; AND HIS REVENGE ON DONNA THOMASA. | 104 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE PRISON, AND THE PRISONERS. | 116 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| OF VARIOUS PERSONS EXHIBITED TO DON CLEOPHAS BY ASMODEUS, WHO REVEALS TO THE STUDENT WHAT EACH HAS DONE IN HIS DAY. | 144 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE MADHOUSE, AND ITS INMATES. | 168 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| THE SUBJECT OF WHICH IS INEXHAUSTIBLE. | 201 |

| [Pg xiii] | |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| OF THE FIRE, AND THE DOINGS OF ASMODEUS ON THE OCCASION, OUT OF FRIENDSHIP FOR DON CLEOPHAS. | 218 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| OF THE TOMBS, OF THEIR SHADES, AND OF DEATH. | 224 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE FORCE OF FRIENDSHIP. | 241 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE SQUABBLE BETWEEN THE TRAGIC POET AND THE COMIC AUTHOR. | 277 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| CONTINUATION, AND CONCLUSION, OF THE FORCE OF FRIENDSHIP. | 289 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| THE DREAMERS. | 337 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| IN WHICH ORIGINALS ARE SEEN OF WHOM COPIES ARE RIFE. | 353 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| RELATING TO OTHER MATTERS WHICH THE DEVIL EXHIBITED TO THE STUDENT. | 365 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| THE CAPTIVES. | 378 |

| [Pg xiv] | |

CHAPTER XX. | |

| OF THE LAST HISTORY RELATED BY ASMODEUS: HOW, WHILE CONCLUDING IT, HE WAS SUDDENLY INTERRUPTED; AND OF THE DISAGREEABLE MANNER, FOR THE WITTY DEMON, IN WHICH HE AND DON CLEOPHAS WERE SEPARATED. | 394 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| OF THE DOINGS OF DON CLEOPHAS AFTER ASMODEUS HAD LEFT HIM; AND OF THE MODE IN WHICH THE AUTHOR OF THIS WORK HAS THOUGHT FIT TO END IT. | 410 |

I shall at once place Le Sage by the side of Molière; he is a comic poet in all the acceptation of that great word,—Comedy. He possesses its noble instincts, its good-natured irony, its animated dialogue, its clear and flowing style, its satire without bitterness, he has studied profoundly the various states of life in the heights and depths of the world. He is perfectly acquainted with the manners of comedians and courtiers,—of students and pretty women. Exiled from the Théâtre-Français, of which he would have been the honour, and less fortunate than Molière, who had comedians under his direction, and who was the proprietor of his own theatre, Le Sage found himself obliged more than once to bury in his breast this Comedy, from want of a fitting stage for its exhibition, and actors to represent it. Thus circumstanced, the author of "Turcaret" was compelled to[Pg xvi] seek a new form, under which he might throw into the world the wit, the grace, the gaiety, the instruction which possessed him. In writing the biography of such men, there is but one thing to do, and that is to praise. The more humble and obscure have they been in their existence, the greater is the duty of him who tells the story of their lives, to heap upon them eulogy and honour. This is a tardy justice, if you will, but it is a justice nevertheless; and besides, of what importance, after all, are these vulgar events? All these biographies are alike. A little more of poverty, a little less of misery, a youth expended in energy, a manhood serious and filled with occupation, an old age respected, honourable; and, at the end of all these labours, all these troubles, all these anguishes of mind and heart, of which your great men alone have the secret,—the Académie-Française in perspective. Then, are you possessed of mediocre talents only? all doors are open to you;—are you a man of genius? the door opens with difficulty;—but, are you perchance one of those excelling spirits who appear but from century to century? it may turn out that the Académie-Française will not have you at any price. Thus did it with the great Molière; thus also has it done for Le Sage; which, by-the-bye, is a great honour for the illustrious author of "Gil Blas."

René Le Sage was born in the Morbihan, on the 8th of May, 1668:[1] and in that year Racine produced "Les Plaideurs," and Molière was playing his "Avare." The father of Le Sage was a man slightly lettered,—as much so as could be expected of an honourable provincial attorney, one who lived from day to day like a lord, without troubling himself too much as to the future fortunes of his only son. The father died when the child was only fourteen years of age; and soon afterwards the youthful René lost his mother. He was now alone, under the guardianship of an uncle, and he was [Pg xvii]fortunate enough to be placed under the tutelage of those learned masters of the youth of the seventeenth century, the Jesuits who subsequently became the instructors of Voltaire, as they have been of all France of the great age. Thanks to this talented and paternal teaching, our young orphan quickly penetrated into the learned and poetical mysteries of that classic antiquity, which is yet in our days, and will be to the end of time, the exhaustless source of taste, of style, of reason, and of good sense. It is to praise Le Sage to say that he was educated with as much care and assiduity as Molière and Racine, as La Fontaine and Voltaire; they one and all prepared themselves, by severest study, and by respect for their masters, to become masters in their turn; and they have themselves become classic writers, because they reverenced their classic models,—which may, in case of need, serve as an example for the beaux-esprits of our own time.

[1] According to Moreri, in his "Grand Dictionnaire Historique," (folio, Paris, 1759,) and he cites as his authority M. Titon de Tillet's second supplement to the "Parnasse Français," Le Sage was born at Ruis in Brittany, in 1677. There is, however, every reason to believe that M. Jules Janin is correct, both as to the year and the place of his birth, notwithstanding that Mr. Chalmers, in his "Biographical Dictionary," while he assigns to the former the year 1668, places the latter at Vannes, as does also the "Biographie Universelle," which he appears to have followed.

But, when this preliminary education was completed, and when he left these learned mansions, all filled with Greek and Latin, all animated with poetic fervour, Le Sage encountered those terrible obstacles that await invariably, as he emerges from his studies, every young man without family, and destitute of fortune. The poet Juvenal has well expressed it, in one of his sublimest verses: "They with difficulty rise, whose virtues are opposed by the pinching wants of home."

"Haud facile emergunt, quorum virtutibus obstat

Res angusta domi."

But what matters poverty when one is so young,—when our hopes are so vast, our thoughts so powerful and rich? You have nothing, it is true; but the world itself belongs to you,—the world is your patrimony; you are sovereign of the universe; and around you, the twentieth year touches every thing with its golden wand. Your clear and sparkling eye may look in the sun's bright face as dauntless as the eagle's. It is accomplished: all the powers of your soul are awakened, all the passions of your heart join in one swelling choir, to chant Hosanna in excelsis! What matter then that you are poor! A verse sublime, a noble thought, a well-turned phrase, the hand of a friend, the soft smile of some bright-eyed[Pg xviii] damsel as she flits across your path,—there is a fortune for a week. Those who, at the commencement of every biography, enter into all sorts of lamentation, and deplore with pathetic voice the mournful destiny of their hero, are not in the secret of the facile joys of poetry, of the exquisite happiness of youth,—the simpletons! They amuse themselves in counting, one by one, the rags that cover yonder handsome form; and they see not, through the holes of the cloak which envelopes it, those Herculean arms, or that athletic breast! They look with pity on that poor young man with well-worn hat, and beneath that covering deformed they see not those abundant, black, and tended locks, the flowing diadem of youth! They will tell you, with heart-rending sighs, how happy Diderot esteemed himself, when to his crust of bread he joined the luxury of cheese, and how this poor René le Sage drank at his repasts but pure spring water;—a lamentable matter, truly! But Diderot, while he ate his cheese, already meditated the shocks of his "Encyclopædia"; but this same clear fountain from which you drink, at twenty, in the hollow of your hand, as pure, will intoxicate more surely than will, after twenty other years, alas! the sparkling produce of Champagne, poured out in cups of crystal.

This is sufficient reason why we should not trouble ourselves overmuch as to the early life of Le Sage; he was young and handsome, and as he marched, his head upturned like a poet, he met as he went along with those first loves which one always meets when the heart is honest and devoted. A charming woman loved him, and he let her love him to her heart's content; and, without concerning himself as to his good fortune, more than would master Gil Blas have done on a similar occasion, these first amours of our poet lasted just as long as such sort of amours ought to last—long enough that they should leave no subject for regret, not enough that they should evoke hatred. When, therefore, they had loved each other as much as they could, she and he, they separated, still to please themselves; she found a husband of riper age and better off than her lover; he took a wife more beauteous and less wealthy than his mistress. And blessings on the amiable and devoted girl who consented, with a joyous heart, to encounter[Pg xix] all the risks, all the vexations, and also to expose herself to the seducing pleasures of a poetic life! Thus Le Sage entered, almost without thinking of it, into that laborious life in which one must daily expend the rarest and most charming treasures of his mind and soul. As a commencement, he made a translation of the Letters of Calisthenes, without imagining that he was himself possessed of more wit than all the Greeks of the fourth century. The work had no success, and it ought not to have had. He who has the genius of Le Sage must create original works, or not meddle in the craft. To translate is a trade of manual skill—to imitate, is one of plagiary. However, the failure of this first book rendered Le Sage less proud and haughty; and he accepted, what he would never have done had he at once succeeded, a pension from M. l'Abbé de Lyonne. This pension amounted to six hundred francs; and thereupon the biographers of our author are in extacies at the generosity of the Abbé de Lyonne.

Six hundred francs! and when we reflect that had Le Sage lived in our day, depending only on his Théâtre de la Foire, he would have gained thirty thousand francs a year! In our days, a romance like "Gil Blas" would not be worth less than five hundred thousand francs; "Le Diable Boiteux" would have brought him a hundred thousand, at least: still, we must not be angry with M. l'Abbé de Lyonne, for having bestowed a pension of six hundred on the author of "Gil Blas." The abbé did more; he opened to Le Sage an admirable treasure of wit, of imagination, and of poetry; he taught him the Spanish tongue, that lovely and noble instructress of the great Corneille; and it is doubtless no slight honour for the language of Cervantes to have given birth in our land to "The Cid" and to "Gil Blas." You may imagine with what delight Le Sage accepted this instruction, and how perfectly at home he found himself in those elegant and gracious manners; with what good will he studied that smiling gallantry, that loyal jealousy; those duennas in appearance so austere, in reality so accessible; those lovely women, their feet ensatined, their head in the mantilla; those charming mansions, all carved without, and within all silence; those exciting windows, lighted by smiles above, while concerts murmur at their feet! You may imagine if he[Pg xx] adopted those lively and coquetish waiting-women, those ingenious and rascally valets, those enormous mantles so favourable to love, those ancient bowers so friendly to its modest blisses! Thus, when he had discovered this new world of poesy, of which he was about to be the Pizarro and the Fernando Cortes, and of which Corneille had been the Christopher Columbus, René le Sage clapped his hands for joy. In his noble pride, he stamped his feet on this enchanted land; he began to read, you may fancy with what delight, that admirable epic, "Don Quixote," which he studied for its grace, its charms, its poetry, its passion; putting for the time aside its satire, and the sarcasm concealed in this splendid drama, as weapons for a later use, when he should attack the financiers. Certainly, the Abbé de Lyonne never dreamt that he was opening to the light this exhaustless mine for the man who was to become the first comic poet of France—since Molière is one of those geniuses apart, of whom all the nations of the earth, all literary ages, claim alike with equal right the honour and the glory.

The first fruit of this Spanish cultivation was a volume of comedies which Le Sage published, and in which he had translated some excellent pieces of the Spanish stage. It contained only one from Lopez de Vega, so ingenious and so fruitful; that was certainly too few: there was in it not one of Calderon de la Barca; and that was as certainly not enough. In this book, which I have read with care, in search of some of those luminous rays which betoken the presence of the man of genius wherever he has passed, I have met with nothing but the translator. The original writer does not yet display himself: it is because style is a thing which comes but slowly; it is because, in this heart of comedy more especially, there are certain secrets of trade which no talent can replace, and which must be learned at whatever cost. These secrets Le Sage learned, as every thing is learned, at his own expense. From a simple translator as he was, he became an arranger of dramatic pieces, and in 1702 (the eighteenth century had begun its course, but with timid steps, and none could have predicted what it would become) Le Sage brought out at the Théâtre Français a comedy in five acts, "Le Point d'Honneur:" it[Pg xxi] was a mere imitation from the Spanish. The imitation had small success, and Le Sage comprehended not this lesson of the public; he understood not that something whispered to the pit, so reserved in its applause, that there was in this translator an original poet. To avenge himself, what did Le Sage? He fell into a greater error still: he set to work translating—will you believe it?—the continuation of "Don Quixote," as if "Don Quixote" could have a continuation; as if there were a person in the world, even Cervantes himself, who had the right to add a chapter to this famous history! Verily, it is strange, indeed, that with his taste so pure, his judgment so correct, Le Sage should have ever thought of this unhappy continuation. This time, therefore, again his new attempt had no success; the Parisian public, which, whatever may be said to the contrary, is a great judge, was more just for the veritable Quixote than Le Sage himself; and he had once more to begin anew. However, he yet once more attempted this new road, which could lead him to nothing good. He returned to the charge, still with a Spanish comedy, "Don César Ursin," imitated from Calderon. This piece was played for the first time at Versailles, and applauded to the skies by the court, which deceived itself almost as often as the town. Le Sage now thought that the battle at last was won. Vain hope! it was again a battle lost, for, brought from Versailles to Paris, the comedy of "Don César Ursin" was hissed off the stage by the Parisian pit, which thus unmercifully annihilated the eulogies of the court, and the first victory of the author. It was now full time to yield to the force of evidence. Enlightened by these rude instructions, Le Sage at last comprehended that it was not permitted to him, to him less than to all others, to be a plagiarist; that originality was one of the grand causes of success; and that to confine himself for ever to this servile imitation of the Spanish poets was to become a poet lost.

Now, therefore, behold him, determined in his turn to be an original poet. This time he no longer copies, he invents; he arranges his fable to his mind, and seeks no further refuge in the phantasmagoria of Spain. With original ideas, comes to him originality of style; and he at last lights on that wondrous and imperishable dialogue which may be compared to the dialogue of[Pg xxii] Molière, not for its ease, perhaps, but unquestionably for its grace and elegance. He found at the same time, to his great joy, now that he was himself—that he walked in the footsteps of nobody, he found that the business was much more simple; this time he was at his ease in his plot, which he disposed as it pleased him; he breathed freely in the space which he had opened to himself; nothing constrained his march, any more than his poetical caprice. Well! at last then we behold him the supreme moderator of his work, we behold him such as the pit would have him, such as we all hoped he was.

This happy comedy, which is, beyond all doubt, the first work of Le Sage, is entitled "Crispin, Rival de son Maître." When he had finished it, Le Sage, grateful for the reception which the court had given to "Don César Ursin," was desirous that the court should also have the first hearing of "Crispin, Rival de son Maître." He remembered, with great delight, that the first applauses he had received had been echoed from Versailles! Behold him then producing his new comedy before the court. But, alas! this time the opinion of the court had changed: without regard for the plaudits of Versailles, the pit of the Paris theatre had hissed "Don César Ursin"; Versailles in its turn, and as if to take its revenge, now hissed "Crispin, Rival de son Maître." We must allow that, for a mind less strong, here was enough to confound a man for ever, and to make him comprehend nothing either as to the success or the failure of his productions. Happily, Le Sage appealed from the public of Versailles to the pit of Paris; and as much as "Crispin, Rival de son Maître" had been hissed at Versailles, so much was this charming comedy applauded at Paris. On this occasion, it was not alone to give the lie to the court, that the pit applauded; Paris had refound, in truth, in this new piece, all the qualities of true comedy,—the wit, the grace, the easy irony, the exhaustless pleasantry, a noble frankness, much biting satire, and a moderate seasoning of love.

As to those who would turn into accusation the hisses of Versailles, they should recollect that more than one chef-d'oeuvre, hissed at Paris, has been raised again by the suffrages of Versailles;—"Les Plaideurs" of Racine, for instance, which the court restored[Pg xxiii] to the poet with extraordinary applause, with the bursting laughter of Louis XIV., which come deliciously to trouble the repose of Racine, at five o'clock in the morning. Happy times, on the contrary, when poets had, to approve them, to try them, this double jurisdiction; when they could appeal from the censures of the court to the praises of the town, from the hisses of Versailles to the plaudits of Paris!

Now we behold René le Sage, to whom nothing opposes: he has divined his true vocation, which is comedy; he understands what may be made of the human race, and by what light threads are suspended the human heart. These threads of gold, of silver, or of brass, he holds them at this moment in his hand, and you will see with what skill he weaves them. Already in his head, which bears Gil Blas and his fortune, ferment the most charming recitals of "Le Diable Boiteux." Silence! "Turcaret" is about to appear,—Turcaret, whom Molière would not have forgotten if Turcaret had lived in his day; but it was necessary to wait till France should have escaped from the reign, so decorous, of Louis XIV., to witness the coming, after the man of the Church, after the man of the sword, this man without heart and without mind,—the man of money. In a society like our own, the man of money is one of those bastard and insolent powers which grow out of the affairs of every day, as the mushroom grows out from the dunghill. We know not whence comes this inert force,—we know not how it is maintained on the surface of the world, and nothing tells how it disappears, after having thrown its phosphorus of an instant. It is necessary, in truth, that an epoch should be sufficiently corrupt, and sufficiently stained with infamy, when it replaces, by money, the sword of the warrior, by money the sentence of the judge, by money the intelligence of the legislator, by money the sceptre of the king himself. Once that a nation has descended so low, as to adore money on its knees—to require neither fine arts, nor poesy, nor love, it is debased as was the Jewish people, when it knelt before the golden calf. Happily, of all the ephemeral powers in the world, money is the most ephemeral; we extend to it our right hand, it is true, but we buffet it with our left; we prostrate ourselves before it as it passes along,—yes; but when it has passed, we kick it with our foot![Pg xxiv] This is what Le Sage marvellously comprehended, like a great comic poet as he was. He found the absurd and frightful side of those gilded men who divide our finances, menials enriched overnight, who, more than once, by a perfectly natural mistake, have mounted behind their own coaches. And such is Turcaret. The poet has loaded him with vices the most disgraceful, with follies the most dishonouring; he tears from this heart, debased by money, every natural affection; and nevertheless, even in this fearful picture, Le Sage has confined himself within the limits of comedy, and not once in this admirable production does contempt or indignation take the place of laughter. It was then with good cause that the whole race of financiers, as soon as they had heard of Turcaret, caballed against this chef-d'oeuvre; the cry resounded in all the rich saloons of Paris; it was echoed from the usurers who lent their money to the nobles, and re-echoed by the nobles who condescended to borrow from the usurers; it was a general hue and cry.

"Le Tartufe" of Molière never met with greater opposition among the devotees than "Turcaret" experienced from financiers; and, to make use of the expression of Beaumarchais in reference to "Figaro," it required as much mind for Le Sage to cause his comedy to be played as it did to write it. But on this occasion, again, the public, which is the all-powerful manager in these matters, was more potent than intrigue; Monseigneur le Grand Dauphin, that Prince so illustrious by his piety and virtue, protected the comedy of Le Sage, as his ancestor, Louis XIV., had protected that of Molière. On this, the financiers, perceiving that all was lost as far as intrigue was concerned, had recourse to money, which is the last reason of this description of upstarts, as cannon is the ultima ratio of kings. This time again the attack availed not: the great poet refused a fortune that his comedy might be played, and unquestionably he made a good bargain by his resolve, preferable a hundred thousand times to all the fortunes which have been made and lost in the Rue Quincampoix.[2] The success of "Turcaret" (1709) was immense; the Parisian [Pg xxv]enjoyed with rare delight the spectacle of these grasping money-hunters devoted to the most cruel ridicule. What if Le Sage had deferred the production of this masterpiece! These men would have disappeared, to make room for others of the kind, and they would have carried with them into oblivion the comedy they had paid for. It would have been a chef-d'oeuvre lost to us for ever; and never, that we know of, would the good men on 'Change have dealt us a more fatal blow.

[2] In this street, in 1716, the famous projector Law established his bank; and the rage for speculation which followed, made it for a time the Bourse of Paris. A hump-backed man made a large fortune by lending himself as a desk, whereon the speculators might sign their contracts, or the transfer of shares. The Rue Quincampoix is still a leading street for business, but its trade is now confined to more honest wares, such as drugs and grocery.

Who would credit it, however? After this superb production, which should have rendered him the master of French comedy, Le Sage was soon compelled to abandon that ungrateful theatre which understood him not. He renounced,—he, the author of "Turcaret,"—pure comedy, to write, as a pastime, farces, little one-act pieces mingled with couplets, which made the life of the Théâtre de la Foire Saint Laurent, and of the Théâtre de la Foire Saint Germain. Unfortunate example for Le Sage to set, in expending, without thought, all his talent, from day to day, without pity for himself, without profit for anyone. What! the author of "Turcaret" to fill exactly the same office as M. Scribe; to waste his time, his style, and his genius upon that trifling comedy which a breath can hurry away! And the French comedians were all unmoved, and hastened not to throw themselves at the feet of Le Sage, to pray, to supplicate him to take under his all-powerful protection that theatre elevated by the genius and by the toils of Molière! But these senseless comedians were unable to foresee anything.

Nevertheless, if he had renounced the Théâtre Français, Le Sage had not abandoned true comedy. All the comedies which thronged his brain, he heaped them up in that grand work which is called "Gil Blas," and which includes within itself alone the history of the human heart. What can be said of "Gil Blas" which has not already been written? How can I sufficiently eulogise the only book truly gay in the French language? The man who wrote "Gil Blas" has placed himself in the first rank among all the authors of this world; he has made himself, by the magic of his pen, the cousin-german[Pg xxvi] of Rabelais and Montaigne, the grandfather of Voltaire, the brother of Cervantes, and the younger brother of Molière; he takes his place, in plenitude of right, in the family of comic poets, who have themselves been philosophers. In the same vein, he has further composed the "Bachelier de Salamanque," which would be a charming book if "Gil Blas" existed not, if above all, before writing his "Gil Blas," he had not written this charming book, "Le Diable Boiteux."

And now, sauve qui peut! the Devil is let loose upon the town, a devil truly French, who has the wit, the grace, and the vivacity of Gil Blas. Beware! Look to yourselves, you the ridiculous and the vicious, who have escaped the high comedy of the stage, for, by the virtue of this all-potent wand, not alone your mansions but your very souls shall in a twinkling change to glass. Beware! I say; for Asmodeus, the terrible scoffer, is about to plunge his pitiless eye into those mysterious places which you deemed so impenetrable, and to each of you he will reveal his secret history; he will strike you without mercy with that ivory crutch which opens all doors and all hearts; he will proclaim aloud your follies and your vices. None shall escape from that vigilant observer, who, astride upon his crutch, glides upon the roofs of the best secured houses, and divines their ambitions, their jealousies, their inquietudes, and, above all, their midnight wakefulness. Considered with relation to its wit without bitterness, its satire which laughs at everything, and with regard to its style, which is admirable, "Le Diable Boiteux" is perhaps the book most perfectly French in our language; it is perhaps the only book that Molière would have put his name to after "Gil Blas."

Such was this life, all filled with most delightful labour, as also with the most serious toil; thus did this man, who was born a great author, and who has raised to perfection the talent of writing, go on from chef-d'oeuvre to chef-d'oeuvre without pause. The number of his productions is not exactly known; at sixty-five years of age, he yet wrote a volume of mélanges, and he died without imagining to himself the glories which were reserved for his name. An amiable and light-hearted philosopher, he was to the end full of wit and good sense; an agreeable gossiper, a faithful friend, an[Pg xxvii] indulgent father, he retired to the little town of Boulogne-sur-Mer, where he became without ceremony a good citizen, whom everybody shook by the hand without any great suspicion that he was a man of genius. Of three sons who had been born to him, two became comedians, to the great sorrow of their noble father, who had preserved for the players, as is plainly perceptible in "Gil Blas," a well-merited dislike. However, Le Sage pardoned his two children, and he even frequently went to applaud the elder, who had taken the name of Monmenil; and when Monmenil died, before his father, Le Sage wept for him, and never from that time (1743) entered a theatre. His third son, the brother of these two comedians, was a good canon of Boulogne-sur-Mer; and it was to his house that Le Sage retired with his wife and his daughter, deserving objects of his affection, and who made all the happiness of his latest days.

One of the most affable gentlemen of that time, who would have been remarkable by his talents, even though he had not been distinguished by his nobility, M. le Comte de Tressan, governor of Boulogne-sur-Mer, was in the habit of seeing the worthy old man during the last year of his life; and upon that fine face, shaded with thick white hairs, he could still discern that love and genius had been there. Le Sage rose early, and his first steps took him to seek the sun. By degrees, as the luminous rays fell upon him, thought returned to his forehead, motion to his heart, gesture to his hand, and his eyes were lighted with their wonted fire: as the sun mounted in the skies, this awakened intelligence appeared, on its side, more brilliant and more clear; so much so, that you beheld again before you the author of "Gil Blas." But, alas! all this animation drooped in proportion as the sun declined; and, when night was come, you had before your eyes but a good old man, whose steps must be tended to his dwelling.

Thus died he, one day in summer. The sun had shown itself in heaven's topmost height on that bright day; and it had not quite left the earth when Le Sage called the members of his family around to bless them. He was little less than ninety when he died (1747).

To give you an idea of the popularity that this man enjoyed even[Pg xxviii] during his life-time, I will finish with this anecdote: When the "Diable Boiteux" appeared, in 1707, the success of this admirable and ingenious satire upon human life was so great, the public esteemed the lively epigrams it contains so delightful, that the publisher was obliged to print two editions in one week. On the last day of this week, two gentlemen, their swords by their sides, as was then the custom, entered the bookseller's shop to buy the new romance. A single copy remained to sell: one of these gentlemen would have it, the other also claimed it; what was to be done? Why, in a moment, there were our two infuriate readers with their swords drawn, and fighting for the first blood, and the last "Diable Boiteux."

But what, I pray you, had they done, were it a question then of the "Diable Boiteux" illustrated by Tony Johannot?

JULES JANIN.

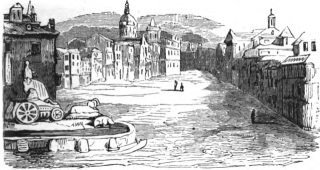

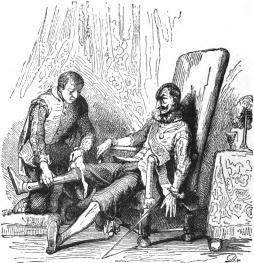

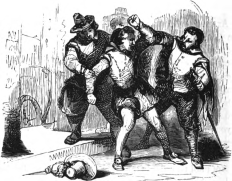

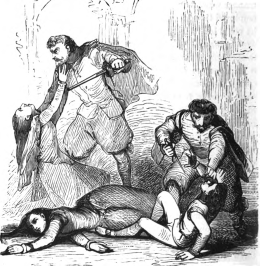

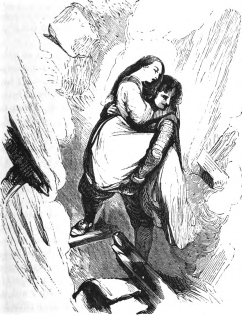

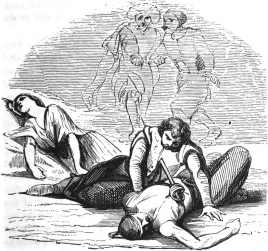

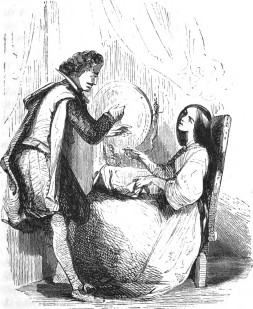

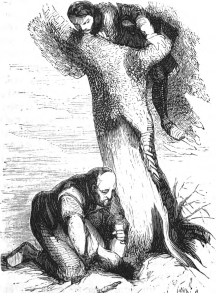

A night in the month of October covered with its thick darkness the famous city of Madrid. Already the inhabitants, retired to their homes, had left the streets free for lovers who desired to sing their woes or their delights beneath the balconies of their mistresses; already had the tinkling of guitars aroused the care of fathers, or alarmed the jealousy of husbands; in short, it was near midnight, when Don Cleophas Leandro Perez Zambullo, a student of Alcala, suddenly emerged, by[Pg 2] the skylight, from a house into which the incautious son of the Cytherean goddess had induced him to enter. He sought to preserve his life and his honour, by endeavouring to escape from three or four hired assassins, who followed him closely, for the purpose of either killing him or compelling him to wed a lady with whom they had just surprised him.

Against such fearful odds he had for some time valiantly defended himself; and had only flown, at last, on losing his sword in the combat. The bravos followed him for some time over the roofs of the neighbouring houses; but, favoured by the darkness, he evaded their pursuit; and perceiving at some distance a light, which Love or Fortune had placed there to guide him through this perilous adventure, he hastened towards it with all his remaining strength. After having more than once endangered his neck, he at length reached a garret, whence the welcome rays proceeded, and[Pg 3] without ceremony entered by the window; as much transported with joy as the pilot who safely steers his vessel into port when menaced with the horrors of shipwreck.

He looked cautiously around him; and, somewhat surprised to find nobody in the apartment, which was rather a singular domicile, he began to scrutinize it with much attention. A brass lamp was hanging from the ceiling; books and papers were heaped in confusion on the table; a globe and mariner's compass occupied one side of the room, and on the other were ranged phials and quadrants; all which made him conclude that he had found his way into the haunt of some astrologer, who, if he did not live there, was in the habit of resorting to this hole to make his observations.

He was reflecting on the dangers he had by good fortune escaped, and was considering whether he should remain where he was until the morning, or what other course he should pursue, when he heard a deep sigh very near him. He at first imagined it was a mere phantasy of his agitated mind, an illusion of the night; so, without troubling himself about the matter, he was in a moment again busied with his reflections.

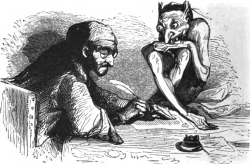

But having distinctly heard a second sigh, he no longer doubted its reality; and, although he saw no one in the room, he nevertheless called out,—"Who the devil is sighing here?" "It is I, Signor Student," immediately answered a voice, in which there was something rather extraordinary; "I have been for the last six months enclosed in one of these phials. In this house lodges a learned astrologer, who is also a magician: he it is who, by the power of his art, keeps me confined in this narrow prison." "You are then a spirit?" said Don Cleophas, somewhat perplexed by this new adventure.[Pg 4] "I am a demon," replied the voice; "and you have come in the very nick of time to free me from slavery. I languish in idleness; for of all the devils in hell, I am the most active and indefatigable."

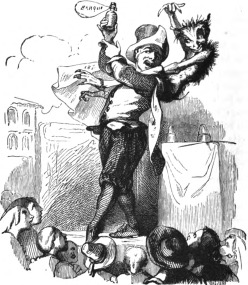

These words somewhat alarmed Signor Zambullo; but, as he was naturally brave, he quickly recovered himself, and said in a resolute tone: "Signor Diabolus, tell me, I pray you,[Pg 5] what rank you may hold among your brethren. Are you an aristocrat, or a burgess?" "I am," replied the voice, "a devil of importance, nay, the one of highest repute in this, as in the other world." "Perchance," said Don Cleophas, "you are the renowned Lucifer?" "Bah," replied the spirit; "why, he is the mountebank's devil." "Are you Uriel then?" asked the Student. "For shame!" hastily interrupted the voice; "no, he is the patron of tradesmen; of tailors, butchers,[Pg 6] bakers, and other cheats of the middle classes." "Well, perhaps you are Beelzebub?" said Leandro. "Are you joking?" replied the spirit; "he is the demon of duennas and footmen." "That astonishes me," said Zambullo; "I thought Beelzebub one of the greatest persons at your court." "He is one of the meanest of its subjects," answered the Demon; "I see you have no very clear notions of our hell."

"There is no doubt then," said Don Cleophas, "that you are either Leviathan, Belphegor, or Ashtaroth." "Ah! those three now," replied the voice, "are devils of the first order, veritable spirits of diplomacy. They animate the councils of princes, create factions, excite insurrections, and light the[Pg 7] torches of war. They are not such peddling devils as the others you have named." "By the bye! tell me," interrupted the Scholar, "what post is assigned to Flagel?" "He is the soul of special pleading, and the spirit of the bar. He composes the rules of court, invented the law of libel, and that for the imprisonment of insolvent debtors; in short, he inspires pleaders, possesses barristers, and besets even the judges.

"For myself, I have other occupations: I make absurd matches; I marry greybeards with minors, masters with[Pg 8] servants, girls with small fortunes with tender lovers who have none. It is I who introduced into this world luxury, debauchery, games of chance, and chemistry. I am the author of the first cookery book, the inventor of festivals, of dancing, music, plays, and of the newest fashions; in a word, I am Asmodeus, surnamed The Devil on Two Sticks."

"What do I hear," cried Don Cleophas; "are you the famed Asmodeus, of whom such honourable mention is made by Agrippa and in the Clavicula Salamonis? Verily, you have not told me all your amusements; you have forgotten the best of all. I am well aware that you sometimes divert yourself by assisting unhappy lovers: by this token, last year only, a young friend of mine obtained, by your favour, the good graces of the wife of a Doctor in our university, at Alcala." "That is true," said the spirit: "I reserved that for my last good quality. I am the Demon of voluptuousness, or, to express it more delicately, Cupid, the god of love; that being the name for which I am indebted to the poets, who, I must confess, have painted me in very flattering colours. They say I have golden wings, a fillet bound over my eyes; that I carry a bow in my hand, a quiver full of arrows on my shoulders, and have withal inexpressible beauty. Of this, however, you may soon judge for yourself, if you will but restore me to liberty."

"Signor Asmodeus," replied Leandro Perez, "it is, as you know, long since I have been devoted to you: the perils I have just escaped will prove to you how entirely. I am rejoiced to have an opportunity of serving you; but the vessel in which you are confined is undoubtedly enchanted, and I should vainly strive to open, or to break it: so I do not see clearly in what manner I can deliver you from your bondage. I am not much used to these sorts of disenchantments; and,[Pg 9] between ourselves, if, cunning devil as you are, you know not how to gain your freedom, what probability is there that a poor mortal like myself can effect it?" "Mankind has this power," answered the Demon. "The phial which encloses me is but a mere glass bottle, easy to break. You have only to throw it on the ground, and I shall appear before you in human form." "In that case," said the Student, "the matter is easier of accomplishment than I imagined. But tell me in which of the phials you are; I see a great number of them, and all so like one another, that there may be a devil in each, for aught I know." "It is the fourth from the window," replied the spirit. "There is the impress of a magical seal on its mouth; but the bottle will break, nevertheless." "Enough," said Don Cleophas; "I am ready to do your bidding. There is, however, one little difficulty which deters me: when I shall have rendered you the service you require, how know I that I shall not have to pay the magician, in my precious person, for the mischief I have done?" "No harm shall befall you," replied the Demon: "on the contrary, I promise to content you with the fruits of my gratitude. I will teach you all you can desire to know; I will discover to you the shifting scenes of this world's great stage; I will exhibit to you the follies and the vices of mankind; in short, I will be your tutelary demon: and, more wise than the Genius of Socrates, I undertake to render you a greater sage than that unfortunate philosopher. In a word, I am yours, with all my good and bad qualities; and they shall be to you equally useful."

"Fine promises, doubtless," replied the Student; "but if report speak truly, you devils are accused of not being religiously scrupulous in the performance of your undertakings." "Report is not always a liar," said Asmodeus, "and this is an[Pg 10] instance to the contrary. The greater part of my brethren think no more of breaking their word than a minister of state; but for myself, not to mention the service you are about to render me, and which I can never sufficiently repay, I am a slave to my engagements; and I swear by all a devil holds sacred, that I will not deceive you. Rely on my word, and the assurances I offer: and what must be peculiarly pleasing to you, I engage, this night, to avenge your wrongs on Donna Thomasa, the perfidious woman who had concealed within her house the four scoundrels who surprised you, that she might compel you to espouse her, and patch up her damaged reputation."

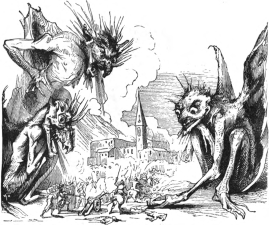

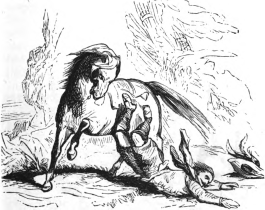

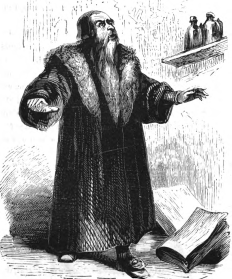

The young Zambullo was especially delighted with this last promise. To hasten its accomplishment, he seized the phial; and, without further thought on the event, he dashed it on the floor. It broke into a thousand pieces, inundating the apartment with a blackish liquor: this, evaporating by degrees, was converted into a thick vapour, which, suddenly dissipating, revealed to the astonished sight of the Student the figure of a man in a cloak, about two feet six inches high, and supported by two crutches. This little monster had the legs of a goat, a long visage, pointed chin, a dark sallow complexion, and a very flat nose; his eyes, to all appearance very small, resembled two burning coals; his enormous mouth was surmounted by a pair of red mustachios, and ornamented with two lips of unequalled ugliness.

The head of this graceful Cupid was enveloped in a sort of turban of red crape, relieved by a plume of cock's and peacock's feathers. Round his neck was a collar of yellow cloth, upon which were embroidered divers patterns of necklaces and earrings. He wore a short white satin gown, or tunic, encircled[Pg 11] about the middle by a large band of parchment of the same colour, covered with talismanic characters. On the gown, also, were painted various bodices, beautifully adapted for the display of the fair wearers' necks; scarfs of different patterns, worked or coloured aprons, and head-dresses of the newest fashion;—all so extravagant, that it was impossible to admire one more than another.

But all this was nothing as compared with his cloak, the[Pg 12] foundation of which was also white satin. Its exterior presented an infinity of figures delicately tinted in Indian ink, and yet with so much freedom and expression that you would have wondered who the devil could have painted it. On one side appeared a Spanish lady covered with her mantilla, and leering at a stranger on the promenade; and on the other a Parisian grisette, who before her mirror was studying new airs[Pg 13] to victimize a young abbé, at that moment opening the door. Here, the gay Italian was singing to the guitar beneath the balcony of his mistress; and there, the sottish German, with vest unbuttoned, stupefied with wine, and more begrimed with snuff than a French petit-maître, was sitting, surrounded by his companions, at a table covered with the filthy remnants of their debauch. In one place could be perceived a Turkish bashaw coming from the bath, attended by all the houris of his seraglio, each watchful for the handkerchief; and in another an English gentleman, who was gallantly presenting to his lady-love a pipe and a glass of porter.

Besides these there were gamesters, marvellously well portrayed; some, elated with joy, filling their hats with pieces of gold and silver; and others, who had lost all but their honour, and willing to stake on that, now turning their sacrilegious eyes to heaven, and now gnawing the very cards in despair. In[Pg 14] short, there were as many curious things to be seen on this cloak as on the admirable shield which Vulcan forged for Achilles, at the prayer of his mother Thetis; with this difference however,—the subjects on the buckler of the Grecian hero had no relation to his own exploits, while those on the mantle of Asmodeus were lively images of all that is done in this world at his suggestion.

Upon perceiving that his appearance had not prepossessed the student very greatly in his favour, the Demon said to him, smiling: "Well, Signor Don Cleophas Leandro Perez Zambullo, you behold the charming god of love, that sovereign master of the human heart. What think you of my air and beauty? Confess that the poets are excellent painters." "Frankly!" replied Don Cleophas, "I must say they have a little flattered you. I fancy, it was not in this form that you won the love of Psyche." "Certainly not," replied the Devil: "I borrowed the graces of a little French marquis, to make her dote upon me. Vice must be hidden under a pleasing veil, or it wins not even woman. I take what shape best pleases me; and I could have discovered myself to you under the form of the Apollo Belvi, but that as I have nothing to disguise from you, I preferred you should see me under a figure more agreeable to the opinion which the world[Pg 16] generally entertains of me and my performances." "I am not surprised," said Leandro, "to find you rather ugly—excuse the phrase, I pray you; the transactions we are about to have with each other demand a little frankness: your features indeed almost exactly realise the idea I had formed of you. But tell me, how happens it that you are on crutches?"

"Why," replied the Demon, "many years ago, I had an unfortunate difference with Pillardoc, the spirit of gain, and the patron of pawnbrokers. The subject of our dispute was a stripling who came to Paris to seek his fortune. As he was capital game, a youth of promising talents, we contested the prize with a noble ardour. We fought in the regions of mid-air; and Pillardoc, who excelled me in strength, cast me on the earth after the mode in which Jupiter is related by the poets to have tumbled Vulcan. The striking resemblance of our mishaps gained me, from my witty comrades, the sobriquet of the Limping Devil, or the Devil on Two Sticks, which has stuck to me from that time to this. Nevertheless, limping as I am, I am tolerably quick in my movements; and you shall witness for my agility.

"But," added he, "a truce to idle talk; let us get out of this confounded garret. My friend the magician will be here shortly; as he is hard at work on rendering a handsome damsel, who visits him nightly, immortal. If he should surprise us, I shall be snug in a bottle in no time; and it may go hard but he finds one to fit you also. So let us away! But first to throw the pieces, of that which was once my prison, out of the window; for such 'dead men' as these do tell tales."

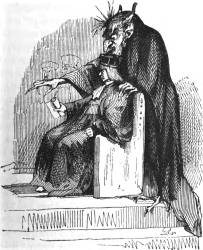

"What if your friend does find out that you are 'missing?'" "What!" hastily replied the Demon; "I see you have never studied the Treatise on Compulsions. Were I hidden at the[Pg 17] extremity of the earth, or in the region where dwells the fiery salamander; though I sought the murkiest cavern of the gnomes, or plunged in the most unfathomable depths of the ocean, I should vainly strive to evade the terrors of his wrath. Hell itself would tremble at the potency of his spells. In vain should I struggle: despite myself should I be dragged before my master, to feel the weight of his dreaded chains."

"That being the case," said the Student, "I fear that our intimacy will not be of long duration: this redoubtable necromancer will doubtless soon discover your flight." "That is more than I know," replied the Spirit; "there is no foreseeing what may happen." "What!" cried Leandro Perez; "a demon, and ignorant of the future!" "Exactly so," answered the Devil; "and they are only our dupes who think otherwise. However, there are enough of them to find good employment for diviners and fortune-tellers, especially among your women of quality; for those are always most eager about the future who have best reason to be contented with the present, which and the past are all we know or care for. I am ignorant, therefore, whether my master will soon discover my absence; but let us hope he will not: there are plenty of phials similar to the one in which I was enclosed, and he may never miss that. Besides, in his laboratory, I am something like a law-book in the library of a financier. He never thinks of me; or if he does, he would think he did me too great an honour if he condescended to notice me. He is the most haughty enchanter of my acquaintance: long as he has deprived me of my liberty, we have never exchanged a syllable."

"That is extraordinary!" said Don Cleophas; "what have you done to deserve so much hatred or scorn?" "I crossed him in one of his projects," replied Asmodeus. "There was a chair vacant in a certain Academy, which he had designed for a friend of his, a professor of necromancy; but which I had destined for a particular friend of my own. The magician set to work with one of the most potent talismans of the Cabala; but I knew better than that: I had placed my man in the service of the prime minister; whose word is worth a dozen talismans, with the Academicians, any day."

While the Demon was thus conversing, he was busily engaged in collecting every fragment of the broken phial; which having thrown out of the window, "Signor Zambullo," said he, "let us begone! Hold fast by the end of my mantle, and fear nothing." However perilous this appeared to Leandro Perez, he preferred the possible danger to the certainty of the magician's resentment; and, accordingly, he fastened himself as well as he could to the Demon, who in an instant whisked him out of the apartment.

Cleophas found that Asmodeus had not vainly boasted of his agility. They darted through the air like an arrow from the bow, and were soon perched on the tower of San Salvador. "Well, Signor Leandro," said the Demon as they alighted; "what think you now of the justice of those who, as they slowly rumble in some antiquated vehicle, talk of a devilish bad carriage?" "I must, hereafter, think them most unreasonable," politely replied Zambullo. "I dare affirm that his majesty of Castile has never travelled so easily; and then for speed, at your rate, one might travel round the world nor care to stretch a leg."

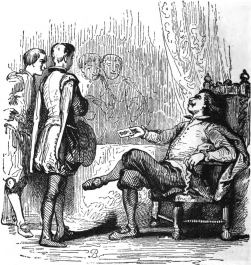

"You are really too polite," replied the Devil; "but can you guess now why I have brought you here? I intend to show you all that is passing in Madrid; and as this part of the town is as good to begin with as any, you will allow that I could not[Pg 21] have chosen a more appropriate situation. I am about, by my supernatural powers, to take away the roofs from the houses of this great city; and notwithstanding the darkness of the night, to reveal to your eyes whatever is doing within them." As he spake, he extended his right arm, the roofs disappeared, and the Student's astonished sight penetrated the interior of the surrounding dwellings as plainly as if the noon-day sun shone over them. "It was," says Luis Velez de Guevara, "like looking into a pasty from which a set of greedy monks had just removed the crust."

The spectacle was, as you may suppose, sufficiently wonderful to rivet all the Student's attention. He looked amazedly around him, and on all sides were objects which most intensely excited his curiosity. At length the Devil said to him: "Signor Don Cleophas, this confusion of objects, which you regard with an evident pleasure, is certainly very agreeable to look upon; but I must render useful to you what would be otherwise but a frivolous amusement. To unlock for you the secret chambers of the human heart, I will explain in what all these persons that you see are engaged. All shall be open to you; I will discover the hidden motives of their deeds, and reveal to you their unbidden thoughts.

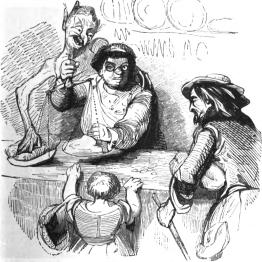

"Where shall we begin? See! do you observe this house to my right? Observe that old man, who is counting gold and silver into heaps. He is a miserly citizen. His carriage, which he bought for next to nothing at the sale of an alcade of the Cortes, and which to save expense still sports the arms of its late owner, is drawn by a pair of worthless mules, which he feeds according to the law of the Twelve Tables, that is to say, he gives each, daily, one pound of barley: he treats them as[Pg 22] the Romans treated their slaves—wisely, but not too well. It is now two years since he returned from the Indies, bringing with him innumerable bars of gold, which he has since converted into coin. Look at the old fool! with what satisfaction he gloats over his riches. And now, see what is passing in an adjoining chamber of the same house. Do you observe two young men with an old woman?" "Yes," replied Cleophas, "they are probably his children." "No, no!" said the Devil, "they are his nephews, and, what is better in their opinion, his heirs. In their anxiety for his welfare, they have invited a sorceress to ascertain when death will take from them their[Pg 23] dear uncle, and leave to them the division of his spoil. In the next house there are a pair of pictures worth remarking. One is an antiquated coquette who is retiring to rest, after depositing on her toilet, her hair, her eyebrows and her teeth; the other is a gallant sexagenarian, who has just returned from a love campaign. He has already closed one eye, in its case, and placed his whiskers and peruke on the dressing table.[Pg 24] His valet is now easing him of an arm and one leg, to put him to bed with the rest."

"If I may trust my eyes," cried Zambullo, "I see in the next room a tall young damsel, quite a model for an artist. What a lovely form and air!" "I see," said the Devil. "Well! that young beauty is an elder sister of the gallant I have just described, and is a worthy pendant to the coquette who is under the same roof. Her figure, that you so much[Pg 25] admire, is really good; but then she is indebted for it to an ingenious mechanist, whom I patronise. Her bust and hips are formed after my own patent; and it is only last Sunday that she generously dropped her bustle at the door of this very church, on the occasion of a charity sermon. Nevertheless, as she affects the juvenile, she has two cavaliers who ardently[Pg 26] dispute her favour;—nay, they have even come to blows on the occasion. Madmen! two dogs fighting for a bone.

"Prithee, laugh with me at an amateur concert which is performing in a neighbouring mansion; an after-supper offering to Apollo. They are singing cantatas. An old counsellor has composed the air; and the words are by an alguazil, who does the amiable after that fashion among his friends—an ass who writes verses for his own pleasure, and for the punishment of others. A harpsichord and clarionet form the accompaniment; a lanky chorister, who squeaks marvellously, takes the treble,[Pg 27] and a young girl with a hoarse voice the bass." "What a delightful party!" cried Don Cleophas. "Had they tried expressly to get up a musical extravaganza, they could not have succeeded better."

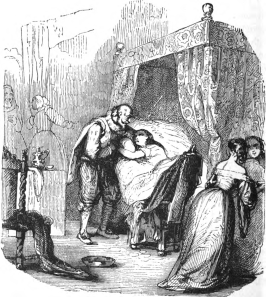

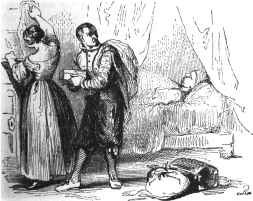

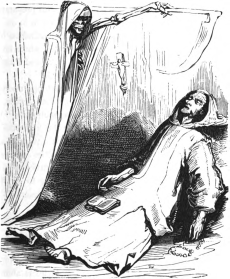

"Cast your eyes on that superb mansion," continued the Demon; "and you will perceive a nobleman lying in a splendid apartment. He has, near his couch, a casket filled with billets-doux; in which he is luxuriating, that the sweet nothings they contain may lull his senses gently to repose. They ought to be dear to him, for they are from a signora he adores; and who so well appreciates the value of her favours, that she will soon reduce him to the necessity of soliciting the exile of a viceroyalty, for his own support. Let us leave him to his slumbers, to watch the stir they are making in the next house to the left. Can you distinguish a lady in a bed with red damask furniture? Her name is Donna Fabula. She is of high rank, and is about to present an heir to her spouse, the aged Don Torribio, whom you see by her side, endeavouring to soothe the pangs of his lady until the arrival of the midwife. Is it not delightful to witness so much tenderness? The cries of his dear better-half pierce him to the soul: he is overwhelmed with grief; he suffers as much as his wife. With what care,—with what earnestness does he bend over her!" "Really," said Leandro, "the man does appear deeply affected; but I perceive, in the room above, a youngster apparently a domestic, who sleeps soundly enough: he troubles himself not for the event." "And yet it ought to interest him," replied Asmodeus; "for the sleeper is the first cause of his mistress's sufferings.

"But see,—a little beyond," continued the Demon: "in that low room, you may observe an old wretch who is anointing[Pg 28] himself with lard. He is about to join an assembly of wizards, which takes place to-night between San Sebastian and Fontarabia. I would carry you thither in a moment, as it would amuse you; but that I fear I might be recognised by the devil who personates the goat."

"That devil and you then," said the Scholar, "are not good[Pg 29] friends?" "No, indeed! you are right," replied Asmodeus, "he is that same Pillardoc of whom I told you. The scoundrel would betray me, and soon inform the magician of my flight." "You have perhaps had some other squabble with this gentleman?" "Precisely so," said the Demon: "some ten years ago we had a second difference about a young Parisian who was thinking of commencing life. He wanted to make him a banker's clerk; and I, a lady-killer. Our comrades settled the dispute by making him a wretched monk. This done, they reconciled us: we embraced; and from that time have been mortal foes."

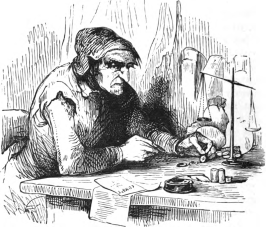

"But, have done with this belle assemblée," said Don Cleophas; "I am not at all curious to witness it: let us continue our scrutiny into what is before us. What is the meaning of those sparks of fire which issue from yonder cellar?" "They proceed from one of the most absurd occupations of mankind," replied the Devil. "The grave personage whom you behold near the furnace is an alchymist; and the flames are gradually consuming his rich patrimony, never to yield him what he seeks in return. Between ourselves, the philosopher's stone is a chimera that I myself invented to amuse the wit of man, who ever seeks to pass those bounds which the laws of nature have prescribed for his intelligence.

"The alchymist's neighbour is an honest apothecary, who you perceive is still at his labours, with his aged wife and assistant. You would never guess what they are about. The apothecary is compounding a progenerative pill for an old advocate who is to be married to-morrow; the assistant is mixing a laxative potion; and the old lady is pounding astringent drugs in a mortar."

"I perceive, in the house facing the apothecary's," said[Pg 30] Zambullo, "a man who has just jumped out of bed, and is hastily dressing." "Pshaw!" replied the Spirit, "he need not hurry himself. He is a physician; and has been sent for by a prelate who since he has retired to rest—about an hour—has absolutely coughed two or three times.

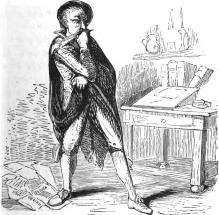

"But look a little further, in a garret on the right, and try if you cannot distinguish a man half dressed, who is walking up and down the room, dimly lighted by a single lamp." "I see," said the Student; "and so clearly that I would undertake to furnish you with an inventory of his chattels,—to wit, a truckle-bed, a three-legged stool, and a deal table; the walls seem to be daubed all over with black paint." "That exalted personage," said Asmodeus, "is a poet; and what appears to you black paint, are tragic verses with which he has ornamented his apartment, being obliged, for want of paper, to commit his effusions to the wall." "By his agitation and phrenzied air, I conclude he is now busily engaged on some work of importance," said Don Cleophas. "You are not far[Pg 31] out," replied the Devil: "he only yesterday completed the last act of an interesting tragedy, intitled The Universal Deluge. He cannot be reproached with having violated the unity of place, at all events, as the entire action is limited to Noah's ark.

"I can assure you it is a first-rate drama: all the animals talk as learnedly as professors. It of course must have a dedication, upon which he has been labouring for the last six hours; and he is, at this moment, turning the last period. It will be indeed a masterpiece of adulatory composition: every social and political virtue; every grace that can adorn; all that tends to render man illustrious, either by his own deeds or those of[Pg 32] his ancestors, are attributed to its object;—never was praise more lavishly bestowed, never was incense burnt more liberally." "For whom, then, of all the world, is so magnificent an apotheosis intended?" "Why," replied the Demon, "the poet himself has not yet determined that; he has put in every thing but the name. However, he hopes to find some vain noble who may be more liberal than those to whom he has dedicated his former productions; although the purchasers of imaginary virtues are becoming every day more rare. It is not my fault that it is so; for it is a fault corrected in the wealthy patrons of literature, and a great benefit rendered to the public, who were certain to be deluged by trash from the Swiss of the press, so long as books were written merely for the produce of their dedications.

"Apropos of this subject," added the Demon, "I will relate to you a curious anecdote. It is not long since an illustrious lady accepted the honour of a dedication from a celebrated novelist, who, by the bye, writes so much in praise of other women, that he thinks himself at liberty to abuse the one peculiarly his own. The lady in question was anxious to see the address before it was printed; and not finding herself described to her taste, she wisely undertook the task, and gave herself all those inconvenient virtues, which the world so much admires. She then sent it to the author, who of course had weighty reasons for adopting it."

"Hollo!" cried Leandro, "surely those are robbers who are entering that house by the balcony." "Precisely so," said Asmodeus; "they are brigands, and the house is a banker's. Watch them! you will be amused. See! they have opened the safe, and are ferreting everywhere; but the banker has been before them. He set out yesterday for Holland, and has taken with him the[Pg 33] contents of his coffers for fear of accidents. They may make a merit of their visit, by informing his unfortunate depositors of their loss."

"There is another thief," said Zambullo, "mounting by a silken ladder into a neighbouring dwelling." "You are mistaken there," replied the Devil; "at all events it is not gold he seeks. He is a marquis, who would rob a young maiden of the name, of which, however, she is not unwilling to part.[Pg 34] Never was 'stand and deliver' more graciously received: he of course has sworn he will marry her, and she of course believes him; for a marquis's 'promises' have unlimited credit upon Love's Exchange."

"I am curious to learn," interrupted the Student, "what that man in a night-cap and dressing-gown is about. He is writing very studiously, and near him is a little black figure, who occasionally guides his hand." "He is a registrar of the civil courts," replied the Demon; "and to oblige a guardian, is, for a consideration, altering a decree made in favour of the ward: the gentleman in black, who seems enjoying the sport, is Griffael the registrars' devil." "Griffael, then," said Don Cleophas, "is a sort of deputy to Flagel; for, as he is the spirit of the bar, the registrars are doubtless included in his department." "Not so," replied Asmodeus; "the registrars have been thought deserving of their peculiar demon, and I assure you they find him quite enough to do."

"Near the registrar's house, you will perceive a young lady on the first floor. She is a widow; and the man, whom you see in the same room, is her uncle, who lodges in an apartment over hers. Admire the bashfulness of the dame! She is ashamed to put on her chemise before her aged relative; so, modestly seeks the assistance of her lover, who is hidden in her dressing-room.

"In the same house with the registrar lives a stout graduate, who has been lame from his birth, but who has not his equal[Pg 36] in the world for pleasantry. Volumnius, so highly spoken of by Cicero for his delicate yet pungent wit, was a fool to him. He is known throughout Madrid as 'the bachelor Donoso,' or 'the facetious graduate;' and his company is sought by old and young, at the court and in the town: in short, wherever there is, or should be, conviviality, he is so much the rage, that he has discharged his cook, as he never dines at home; to which he seldom returns until long after midnight. He is at present with the marquis of Alcazinas, who is indebted for[Pg 37] this visit to chance only." "How, to chance?" interrupted Leandro. "Why," replied the Demon, "this morning, about noon, the graduate's door was besieged by at least half-a-dozen carriages, each sent for the especial honour of securing his society. The bachelor received the assembled pages in his apartment, and, displaying a pack of cards, thus addressed them:—'My friends, as it is impossible for me to dine in six places at one time, and as it would not appear polite to show an undue preference, these cards shall decide the matter. Draw! I will dine with the king of clubs.'"

"What object," said Don Cleophas, "has yonder cavalier, who is sitting at a door on the other side of the street? Is he waiting for some pretty waiting-woman to usher him to his lady's chamber?" "No, no," answered Asmodeus; "he is a young[Pg 38] Castilian, whose modesty exceeds his love; so, after the fashion of the gallants of antiquity, he has come to pass the night at his mistress's portal. Listen to the twang of that wretched guitar, with which he accompanies his tender strains! On the second floor you may behold his inamorata: she is weeping as she hears him;—but it is for the absence of his rival.

"You observe that new building, which is divided into two wings. One is occupied by the proprietor, the old gentleman whom you see now pacing the apartment, now throwing himself into an easy chair." "He is evidently immersed in some grand project," said Zambullo: "who is he? If one may judge by the splendour which is displayed in his mansion, he is a grandee of the first order." "Nevertheless," said Asmodeus, "he is but an ancient clerk of the treasury, who has grown old in such lucrative employment as to enable him to amass four millions of reals. As he has some compunctions of conscience for the means by which all this wealth has been acquired, and as he expects shortly to be called upon to render his account in another world, where bribery is impracticable, he is about to compound for his sins in this, by building a monastery; which done, he flatters himself that peace will revisit his heart. He has already obtained the necessary permission; but, as he has resolved that the establishment shall consist of monks who are extremely chaste, sober, and of the most Christian humility, he is much embarrassed in the selection. He need not build a very extensive convent.

"The other wing is inhabited by a fair lady, who has just retired to rest after the luxury of a milk bath. This voluptuary is widow of a knight of the order of Saint James, who left[Pg 39] her at his death her title only; but fortunately her charms have secured for her valuable friends in the persons of two members of the council of Castile, who generously divide her favours and the expenses of her household."

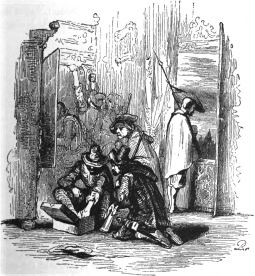

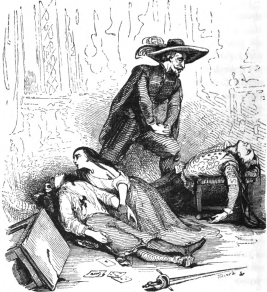

"Hark!" cried the Student; "surely I hear the cries of distress. What dreadful misfortune has occurred?" "A very common one," said the Demon: "two young cavaliers have been gambling in a hell (the name is a scandal on the infernal regions), which you perceive so brilliantly illuminated. They quarrelled upon an interesting point of the game, and I naturally drew their swords to settle it: unluckily, they were equally skilful with their weapons, and are both mortally wounded. The elder is married, which is unfortunate; and the younger an only son. The wife and father have just come in time to receive their last sighs; and it is their lamentations that you hear. 'Unhappy boy,' cries the fond parent over the still breathing body of his son, 'how often have I conjured thee to renounce this dreadful vice!—how often have I warned thee it would one day cost thee thy life. Heaven is my witness, that the fault is none of mine!' Men," added the Demon, "are always selfish, even in their griefs. Meanwhile the wife is in despair. Although her husband has dissipated the fortune she brought him on their marriage; although he has sold, to maintain his shameful excesses, her jewels, and even her clothes, not a word of reproach escapes her lips. She is inconsolable for her loss. Her grief is vented in frantic exclamations, mixed with curses on the cards, and the devil who invented them; on the place in which her husband fell, and on the people who surround her, and to whom she fondly attributes his ruin."

"How much to be lamented," interrupted the Student, "is[Pg 40] the love of gaming which possesses so large a portion of mankind; in what an awful state of excitement does it plunge its victims. Heaven be praised! I am not included in their legion." "You are in high feather," replied the Demon, "in another, whose exploits are not much more ennobling, and scarcely less dangerous. Is the conquest of a courtezan a glory worth achievement? Is the possession of charms[Pg 41] common to a whole city worth the peril of a life? Man is an amusing animal! The vision of a mole would enable him to discover the vices of his fellows, while that of the vulture could scarce detect a folly of his own. But let us turn to another affecting spectacle. You can discern, in the house just beyond the one we have been contemplating, a fat old man extended on a bed: he is a canon, who is now in a fit of apoplexy. The two persons, whom you see in his room, are said to be his nephew and niece: they are too much affected by his situation to be able to assist him; so, are securing his valuable effects. By the time this is accomplished, he will be dead; and they will be sufficiently recovered, and at leisure, to weep over his remains.

"Close by, you may perceive the funeral of two brothers;[Pg 42] who, seized with the same disorder, took equally successful but different means of ensuring its fatality. One of them had the most utter confidence in his apothecary; the other eschewed the aid of medicine: the first died because he took all the trash his doctor sent him; the last because he would take nothing." "Well! that is very perplexing," said Leandro; "what is a poor sick devil to do?" "Why," replied Asmodeus, "that is more than the one who has the honour of addressing you can determine. I know, for certain, that there are remedies for most ills; but I am not so sure that there are good physicians to administer them when necessary."

"And now I have something more amusing to unriddle. Do you not hear a frightful din in the next street? A widow of sixty was married this morning to an Adonis of seventeen; and all the merry fellows of that part of the town have assembled to celebrate the wedding by a concert of pots and pans, marrow-bones and cleavers." "You told me," said the Student, "that these matches were under your control: at all events, you had no hand in this." "No, truly," answered the Demon, "not I. Had I been free, I should not have meddled with them. The widow had her scruples; and has married for no better reason than that she may enjoy, without remorse, the pleasures she so dearly loves. These are not the unions I care to form; I prefer troubling people's consciences to setting them at rest."

"Notwithstanding this charming serenade," said Zambullo, "it seems to me that it is not the only concert performing in the neighbourhood." "No," said the cripple; "in a tavern in the same street, a lusty Flemish captain, a chorister of the French opera, and an officer of the German guard are singing a trio. They have been drinking since eight in the morning;[Pg 43] and each deems it a duty to his country, to see the others under the table."

"Look for a moment on the house which stands by itself, nearly opposite to that of the apoplectic canon: you will see three very pretty but very notorious courtezans enjoying themselves with as many young courtiers." "They are, indeed, lovely!" exclaimed Don Cleophas. "I am not surprised that they should be notorious: happy are the lovers who possess them! They seem, however, very partial to their present companions: I envy them their good fortune." "Why, you are very green!" replied the Demon: "their faces are not disguised with greater skill than are their hearts. However prodigal of their caresses, they have not the slightest tenderness for their foolish swains; their affection is bounded to the purses of their lovers. One of them has just secured the promise of a liberal establishment; and the others are prepared with[Pg 44] settlements which they are in expectation of securing ere they part. It is the same with them all. Men vainly ruin themselves for the sex: gold buys not love. The well-paid mistress soon treats her lover as a husband: that is a rule which I found necessary to establish in my code of intrigue. But we will leave these fools to taste the pleasures they so dearly purchase; while their valets, who are waiting in the street, console themselves with the pleasing anticipation of enjoying them gratis."

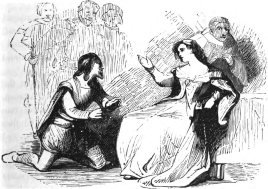

"Tell me," interrupted Leandro Perez, "what is passing in that splendid mansion on the left. The house is filled with well-dressed cavaliers and ladies; and all seems dancing and conviviality. It is indeed a joyous festival." "It is another wedding," said Asmodeus; "and happy as they now are, it is not three days since that house witnessed the deepest affliction. It is a story worth hearing: it is rather long, certainly; but it will repay your patience." The Devil then began as follows.

Leonora de Cespedes was passionately beloved by the young Count de Belflor, one of the most distinguished nobles of the court. He had, however, no thoughts of suing for her hand; the daughter of a private gentleman might command his love, but had no pretensions in his eyes to rank above his mistress; and such was the honour he designed for her.