Title: Third Reader: The Alexandra Readers

Author: W. A. McIntyre

John Dearness

John C. Saul

Release date: March 14, 2016 [eBook #51441]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Les Galloway and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE ALEXANDRA READERS

BY

W. A. McINTYRE, B.A., LL.D.

PRINCIPAL, NORMAL SCHOOL, WINNIPEG

JOHN DEARNESS, M.A.

VICE-PRINCIPAL, NORMAL SCHOOL, LONDON

AND

JOHN C. SAUL, M.A.

Authorized by the Departments of Education

for Use in the Schools of Alberta

and Saskatchewan

PRICE 45 CENTS

TORONTO

MORANG EDUCATIONAL COMPANY LIMITED

1908

Copyright by

MORANG EDUCATIONAL COMPANY LIMITED

1908

Copyright in Great Britain

| PAGE | ||

| Canada! Maple Land! | 9 | |

| The Shoemaker and the Elves | Jacob Grimm | 10 |

| Song of the Golden Sea | Jean Blewett | 13 |

| Work | Mary N. Prescott | 14 |

| Fortune and the Beggar | Ivan Kriloff | 15 |

| The Sprite | Frederick George Scott | 17 |

| A Crust of Bread | Selected | 19 |

| Two Surprises | Anonymous | 23 |

| The Rich Man and the Cobbler | Jean de la Fontaine | 25 |

| The Drought | R. K. Kernighan | 30 |

| The Eagle | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 31 |

| The Golden Windows | Laura E. Richards | 32 |

| A Song of Seasons | Elizabeth Roberts Macdonald | 36 |

| A Miser’s Treasure | Grace H. Kupfer | 38 |

| Drifted out to Sea | Rosa Hartwick Thorpe | 42 |

| The Daisy and the Lark | Hans Christian Andersen | 44 |

| The Splendor of the Days | Jean Blewett | 48 |

| Before the Rain | Thomas Bailey Aldrich | 49 |

| Webster and the Woodchuck | Selected | 50 |

| The Fairies of Caldon Low | Mary Howitt | 53 |

| The Last Lesson in French | Alphonse Daudet | 57 |

| The Brook Song | James Whitcomb Riley | 62 |

| The Better Land | Felicia Dorothea Hemans | 63 |

| Cædmon | Grace H. Kupfer | 65 |

| The Bluebell | Anonymous | 67 |

| Lullaby of an Infant Chief | Sir Walter Scott | 69 |

| The Minstrel’s Song | Maude Lindsay | 69 |

| The Use of Flowers | Mary Howitt | 746 |

| The Miller of the Dee | Charles Mackay | 76 |

| The Story of Moween | Selected | 77 |

| A Hindu Fable | John Godfrey Saxe | 81 |

| The Boy Musician | Bertha Leary Saunders | 83 |

| The Sparrows | Celia Thaxter | 87 |

| The Time and the Deed | Jean Blewett | 90 |

| The Flax | Hans Christian Andersen | 91 |

| Jeannette and Jo | Mary Mapes Dodge | 96 |

| The Maid of Orleans | Maude Barrow Dutton | 98 |

| Birds | Eliza Cook | 102 |

| The Owl | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 103 |

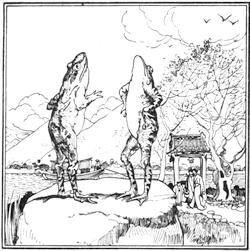

| Iktomi and the Coyote | Zitkala-S¨a | 104 |

| Golden Rod | Frank Dempster Sherman | 108 |

| November | Helen Hunt Jackson | 109 |

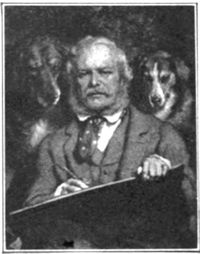

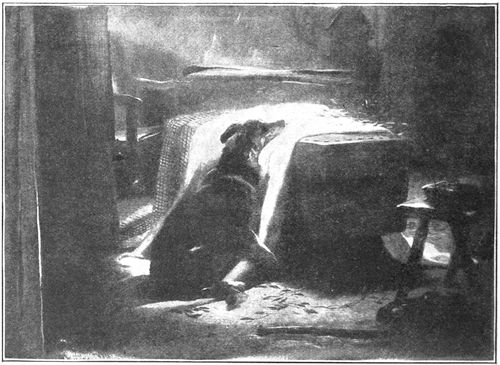

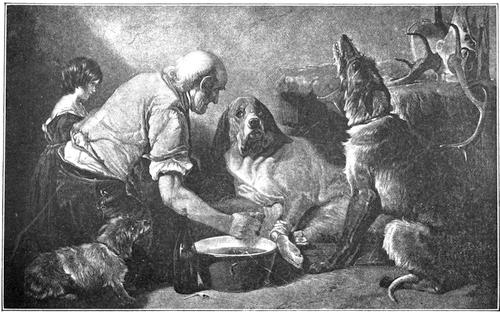

| Sir Edwin Landseer | Selected | 110 |

| The Two Church Builders | John Godfrey Saxe | 115 |

| How Siegfried made the Sword | Selected | 118 |

| Grass and Roses | James Freeman Clarke | 123 |

| The Wounded Curlew | Celia Thaxter | 124 |

| The Gold and Silver Shield | Selected | 125 |

| The White-throat Sparrow | Sir James D. Edgar | 128 |

| The Sandpiper | Celia Thaxter | 129 |

| Crœsus | James Baldwin | 131 |

| The Frost Spirit | John Greenleaf Whittier | 135 |

| A Song of the Sleigh | James T. Fields | 137 |

| The Christmas Dinner | Charles Dickens | 138 |

| Christmas Song | Phillips Brooks | 144 |

| Bergetta’s Misfortune | Celia Thaxter | 146 |

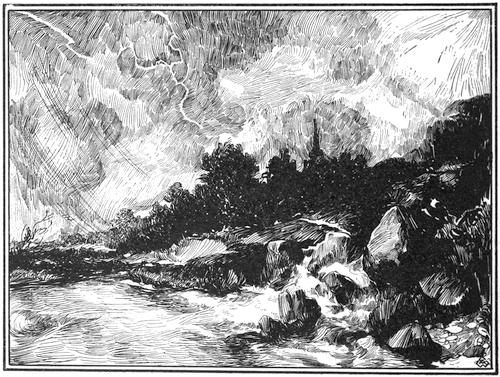

| Storm Song | Bayard Taylor | 150 |

| A Wet Sheet and a Flowing Sea | Allan Cunningham | 152 |

| The Indians | Selected | 153 |

| Speak Gently | David Bates | 157 |

| Daybreak | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 158 |

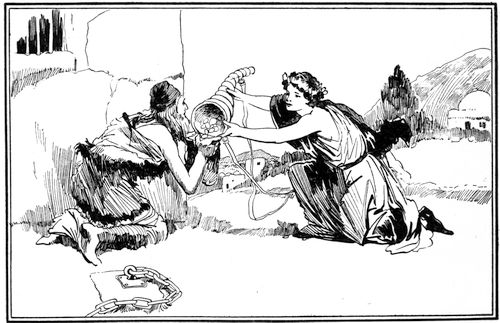

| The Choice of Hercules | James Baldwin | 159 |

| The Walker of the Snow | Charles Dawson Shanly | 1627 |

| The Frog Travellers | William Elliot Griffis | 165 |

| The Three Bells | John Greenleaf Whittier | 169 |

| How the Indian Knew | Selected | 171 |

| Hohenlinden | Thomas Campbell | 172 |

| The Clouds | Archibald Lampman | 174 |

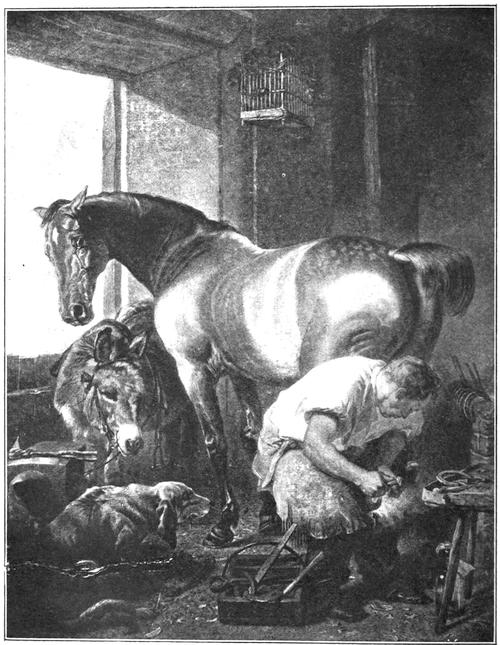

| Shoeing | Estelle M. Hurll | 175 |

| The Village Blacksmith | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 179 |

| The Search for a Western Sea | Helen Palk | 181 |

| The Moss Rose | F. A. Krummacher | 185 |

| Woodman, Spare that Tree! | George P. Morris | 186 |

| Dick Whittington | Selected | 187 |

| Somebody’s Mother | Anonymous | 195 |

| The Lord is my Shepherd | The Book of Psalms | 197 |

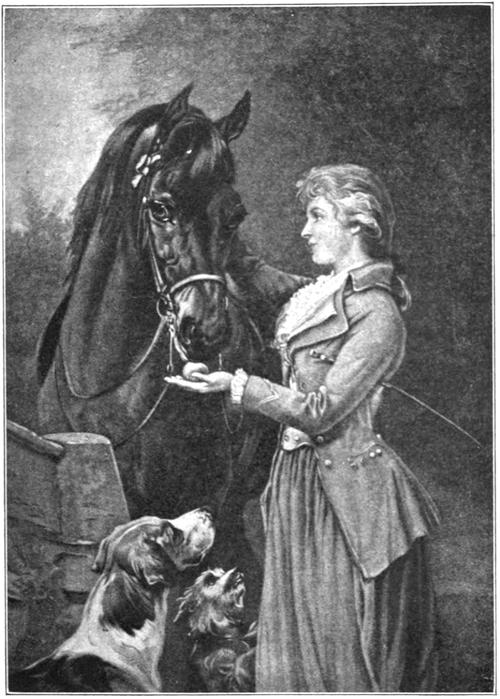

| Black Beauty’s Breaking In | Anna Sewell | 198 |

| The Door of Spring | Ethelwyn Wetherald | 204 |

| The Crocus’s Song | Hannah Flagg Gould | 206 |

| A Sound Opinion | Selected | 207 |

| The Soldier’s Dream | Thomas Campbell | 211 |

| March of the Men of Harlech | William Duthie | 212 |

| Hugh John Smith becomes a Soldier | Samuel R. Crockett | 213 |

| England’s Dead | Felicia Dorothea Hemans | 219 |

| A Child’s Dream of a Star | Charles Dickens | 221 |

| Excelsior | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 226 |

| The Sentinel’s Pouch | Selected | 228 |

| The Milkmaid | Jeffreys Taylor | 232 |

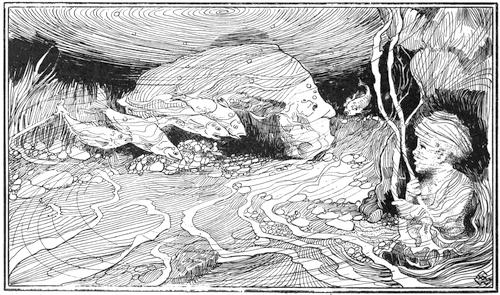

| Tom, the Water-baby | Charles Kingsley | 234 |

| An April Day | Caroline Bowles Southey | 241 |

| Pussy Willow | Anonymous | 243 |

| Laura Secord | Helen Palk | 244 |

| The Maple Leaf Forever | Alexander Muir | 249 |

| The Colors of the Flag | Frederick George Scott | 250 |

| How the Mountain was Clad | Björnstjerne Björnson | 252 |

| Lucy Gray | William Wordsworth | 256 |

| Beautiful Joe | Marshall Saunders | 259 |

| Somebody’s Darling | Marie Lacoste | 2678 |

| Home, Sweet Home | John Howard Payne | 269 |

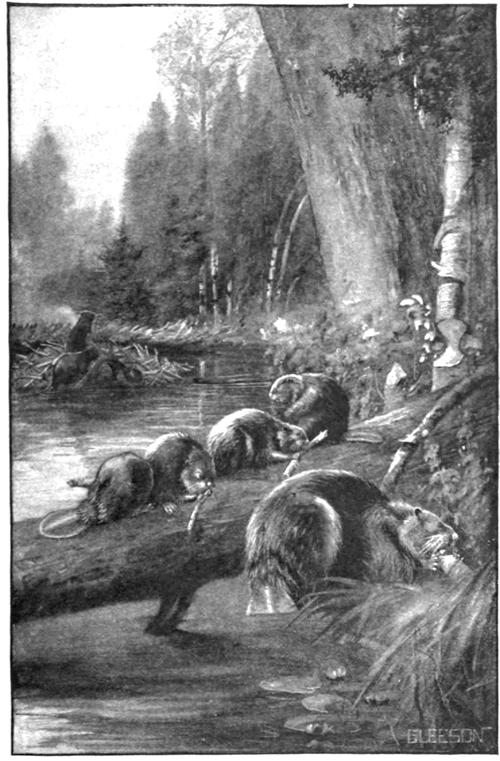

| The Beavers | Julia Augusta Schwartz | 270 |

| The Brook | Alfred, Lord Tennyson | 276 |

| The Little Postboy | Bayard Taylor | 278 |

| Hiawatha’s Friends | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 288 |

| The White Ship | Charles Dickens | 295 |

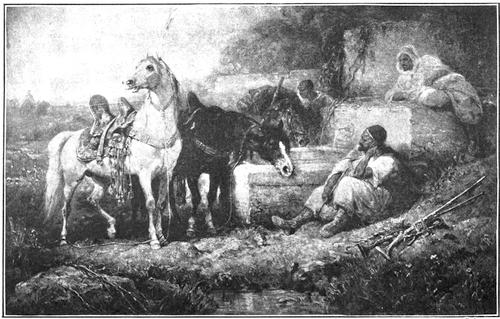

| The Arab and his Steed | Caroline Norton | 299 |

| A Bridge of Monkeys | Mayne Reid | 303 |

| We are Seven | William Wordsworth | 306 |

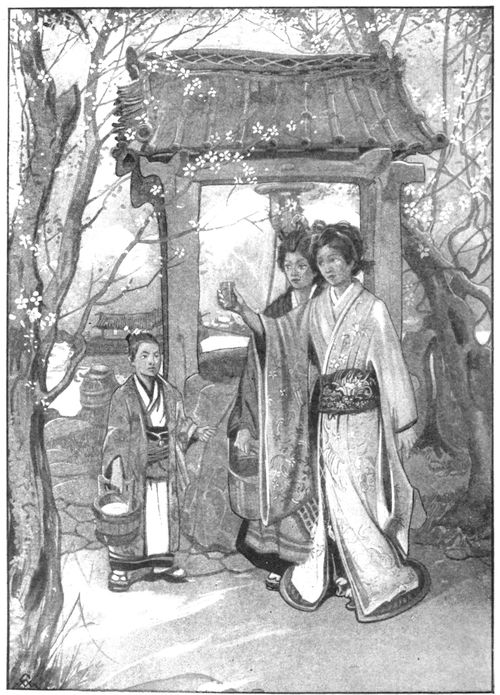

| The Mirror | From the Japanese | 309 |

| The Wreck of the Hesperus | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 314 |

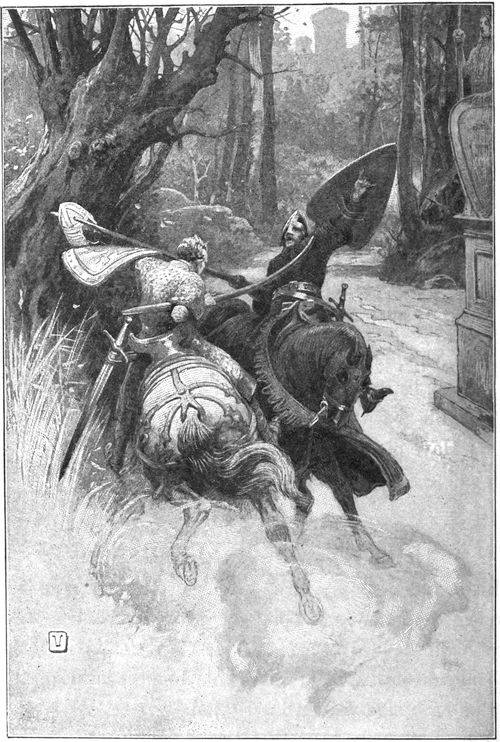

| The Black Douglas | Sir Walter Scott | 318 |

| Bruce and the Spider | Eliza Cook | 322 |

| The Old Man of the Meadow | Julia MacNair Wright | 325 |

| John Gilpin | William Cowper | 329 |

| A Forest Fire | Susannah Moodie | 340 |

| The Horses of Gravelotte | Gerok | 344 |

| Four-leaf Clovers | Ella Higginson | 346 |

| Aladdin | Arabian Nights’ Entertainment | 347 |

| The Rapid | Charles Sangster | 357 |

| Long Life | Horatio Bonar | 358 |

| Little Daffydowndilly | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 359 |

| The Earth is the Lord’s | The Book of Psalms | 369 |

| The Singing Leaves | James Russell Lowell | 370 |

| The Clocks of Rondaine | Frank R. Stockton | 374 |

| The Camel’s Nose | Lydia Huntley Sigourney | 384 |

| Lord Ullin’s Daughter | Thomas Campbell | 385 |

| God Save the King | 388 |

9

THIRD READER

10

There was once an honest shoemaker who worked very hard at his trade; yet through no fault of his own he grew poorer and poorer. At last he had only just enough leather left to make one pair of shoes. In the evening he cut out the leather so as to be ready to make the shoes the next day.

He rose early in the morning, and went to his bench. But what did he see? There stood the pair of shoes, already made. The poor man could hardly believe his eyes, and he did not know what to think. He took the shoes in his hand to look at them closely. Every stitch was in its right place. A finer piece of work was never seen.

Very soon a customer came, and the shoes pleased him so well that he willingly paid a higher price than usual for them. The shoemaker now had enough money to buy leather for two pairs of shoes. In the evening he cut them out with great care, and went to bed early so that he might be up in good time the next day. But he was saved all trouble; for when he rose in the morning, two pairs of well-made shoes stood in a row upon his bench.

Presently in came customers, who paid him a high price for the shoes, and with the money that he received, he bought enough leather to make four pairs of shoes. Again he cut the work out overnight and again he found it finished11 in the morning. The shoemaker’s good fortune continued. All the shoes he cut out in the day were finished at night. The good man rose early, and he was busy every moment of the day. Every pair found ready sale. “Never did shoes wear so long,” said the buyers.

One evening, about Christmas time, the shoemaker said to his wife, “Let us watch to-night and see who it is that does this work for us.” So they left a light burning and hid themselves behind a curtain which hung in the corner of the room. As soon as it was midnight there came two little dwarfs. They sat down upon the shoemaker’s bench, and began to work with their tiny fingers, stitching and rapping and tapping away. Never had the good shoemaker and his wife seen such rapid work. The elves did not stop till the task was quite finished, and the shoes stood ready for use upon the table. This was long before daybreak, and then they bustled away as quick as lightning.

12

The next day the shoemaker’s wife said to her husband: “These little folks have made us rich, and we ought to be thankful to them and do them a service in return. They must be cold, for they have nothing on their backs to keep them warm. I shall make each of them a suit of clothes, and you shall make some shoes for them.”

This the shoemaker was very glad to do. When the little suits and the new shoes were finished, they were laid on the bench instead of the usual work. Again the good people hid themselves in the corner of the room to watch. About midnight the elves appeared. When they found the neat little garments waiting for them, they showed the greatest delight. They dressed in a moment, and jumped and capered and sprang about until they danced out of the door and over the green.

Never were they seen again, but everything went well with the shoemaker and his wife from that time forward as long as they lived.—Jacob Grimm.

13

From “The Cornflower and Other Poems,” by permission.

14

15

One day a ragged beggar was creeping along from house to house. He carried an old wallet in his hand, and was asking at every door for a few cents to buy something to eat. As he was grumbling at his lot, he kept wondering why it was that people who had so much money were never satisfied, but were always wanting more.

“Here,” said he, “is the master of this house—I know him well. He was always a good business man, and he made himself wondrously rich a long time ago. Had he been wise he would have stopped then. He would have turned over his business to some one else, and then he could have spent the rest of his life in ease. But what did he do instead? He began building ships and sending them to sea to trade with foreign lands. He thought he would get mountains of gold.

“But there were great storms on the water; his ships were wrecked, and his riches were swallowed up by the waves. Now his hopes all lie at the bottom of the sea, and his great wealth has vanished like the dreams of a night. There are many such cases. Men seem never to be satisfied unless they can gain the whole world. As for me, if I had only enough to eat and to wear I would not wish anything more.”

Just at that moment Fortune came down the street.16 She saw the beggar and stopped. She said to him: “Listen! I have long desired to help you. Hold your wallet and I shall pour this gold into it. But I shall pour only on this condition: All that falls into the wallet shall be pure gold, but every piece that falls upon the ground shall become dust. Do you understand?”

“Oh, yes, I understand,” said the beggar.

“Then have a care,” said Fortune. “Your wallet is old; so do not load it too heavily.”

The beggar was so glad that he could hardly wait. He quickly opened his wallet, and a stream of yellow dollars was poured into it. The wallet soon began to grow heavy.

“Is that enough?” asked Fortune.

“Not yet.”

17

“Isn’t it cracking?”

“Never fear.”

The beggar’s hands began to tremble. Ah, if the golden stream would only pour forever!

“You are the richest man in the world now!”

“Just a little more,” said the beggar; “add just a handful or two.”

“There, it’s full. The wallet will burst.”

“But it will hold a little more, just a little more!”

Another piece was added and the wallet split. The treasure fell upon the ground and was turned to dust. Fortune had vanished.

The beggar had now nothing but his empty wallet, and it was torn from top to bottom. He was as poor as before.

—From the Russian of Ivan Kriloff.

The boy was lying under a big shady tree eating a large crust of bread. He had been romping with his dog in the garden, enjoying the sweet flowers and the bright sunshine. Now he rested in the cool shade of the apple-tree with the dog curled up at his feet. The birds were warbling their20 gayest songs in the topmost branches, and the leaves cast their dancing shadows on the soft carpet of green below.

As the dog was fast asleep, the boy had no one with whom to play. Just then a lady, beautifully dressed and holding a wand in her hand, stood before him. She smiled, and then placed her wand on the crust of bread, after which she at once vanished. She had no sooner gone than the boy rubbed his eyes in wonder, for the crust of bread was talking in a gentle voice.

“Would you like to hear my story?” it said. The boy nodded his head, as if to say yes, and the crust began:—

“Once upon a time I was a little baby seed. I lived in a large home called a granary. In this home were many other baby seeds just like me. No one could tell one from the other, as we all belonged to the same family and looked so much alike. We lived there very quietly until one day my sister cried, ‘Hark! do you hear that noise? The mice are coming!’ Then she told us the mice were fond of little grains of wheat, and that if they were to eat us we would never grow to be like our mother. We heard them many times after that, but we never saw them.

“One day a farmer came and put us into a large sack. It was so dark in the sack, and we lay so very near together that I thought we should smother. Soon I felt myself sliding. I tried to cling to the sack, but the other grains in their rush to the sunlight took me along with them.21 In our wild race we ran into a tube, and, going faster and faster, we soon fell into the seed-drill.

“Then I felt myself sliding again, for the seed-drill was moving forward. I could hear the driver call out in loud tones to the horses, ‘Get up!’ and round and round went the big wheels of the drill. All at once I went under cover in the rich ground. At first I did not like to be shut in from the sunlight. But one day when I heard the crows, I was glad that I was under the coverlet of the ground. I heard their cry of ‘Caw, caw,’ and how frightened I was! I knew that the crows were near, and that they liked the little baby wheat grains. This made me thank the farmer and Mother Nature for giving me such a good home. The crows could not find me, and by and by they flew away.

“Mother Nature now warmed me, and the rains fed me. I went to sleep, but one bright morning I awoke. The rain had been tapping on our great brown house, telling us to awake from our nap. I had grown so large while sleeping that my brown coat burst open. The sun had warmed my bed. I put a little white rootlet out and sent it down into the ground. The gentle spring breeze and the warm days brought my first blade into the sunlight above the ground, and peeping out I was glad to see everything growing fresh and green. I could see the tender sprouting grass and the opening buds. I could hear the bluebird’s song and the robin’s warble. I could smell the balmy air of spring.

22

“Mother Nature sent her children every day to help me. The rain came through the soil, and brought me food and drink. The sun fairies warmed my sprouting leaves, and the wind brought me fresh air. In June I wore a dainty green dress of slender, graceful leaves. As my sisters and I stood in the great field on the plain, and were wafted to and fro by the winds, we looked like the waves of the rolling deep.

“So I grew and grew, and one morning after the dew had given me my cool bath, and the sun fairies had dried my leaves, the south wind whispered her song to me, and I found myself a full-grown plant. I was proud of my spikelets of flowers, and now could wave with my sisters in the rolling seas of wheat. Down at the base of our little spikelets were seed cups in which slept the little baby seeds. The wind rocked them to sleep, and, sleeping, they grew to the full-sized wheat grain.

“By and by we became tall stalks of golden wheat, and the farmer was glad to look at us. When we were fully ripe, the great reaping-machine drawn by a number of horses came along and cut us down. Then we were picked up and sent whirling through the buzzing jaws of the thrasher. Our grains of wheat were screened from the chaff and straw, and fell into sacks. Then we were put on trains and transported to the mammoth granaries to be stored away until the flour-mills wanted us.

“At last we reached the mills. There we were turned23 into beautiful white flour and shipped to the market. So in time we, as flour, reached the housewife’s or baker’s well-stocked kitchen, where we were put into trays, and, being mixed with a little salt, yeast, and some water, were kneaded into loaves of bread and baked. This is the story of my life from a little grain of wheat until I became the crust of bread that you are eating.”

The sun was sinking in the west, the birds were winging their flight homewards, and night was fast coming on. The dog yawned, and, stretching himself out, was ready for another romp with his master. The boy awoke from his dream and hurried home to help with the evening meal, and to do his share of the world’s work.

—Selected.

From “The New Education Readers,” by permission of the American Book Company.

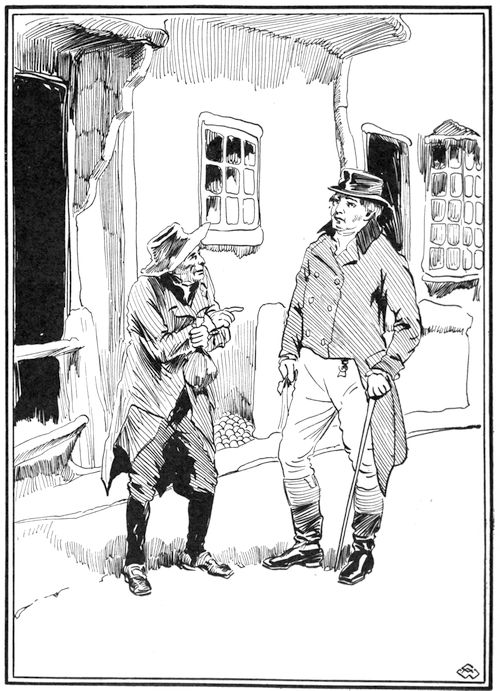

In old Paris, very rich people and quite poor people used to live close by each other. Up one stair might be found a very rich man; up two stairs a man not quite so rich; up three stairs a man who had not very much money. On the very lowest floor, a little below the street, were to be found the poorest folks of all. It was on this low floor that a cobbler used to live and mend shoes and sing songs. For he was a very happy cobbler, and went on singing all day, and keeping time with his hammer or his needle.

26

27

Up one stair, or on what is called the first floor, lived a very rich man, so rich that he did not know how rich he was—so rich that he could not sleep at nights for trying to find out how much money he had, and if it were quite safe.

Everybody knows that it is easier to sleep in the morning than at night. So nobody will wonder when I say that this rich man lay awake all night and always fell asleep in the morning. But no sooner did he fall asleep than he was wakened again. It was not his money that wakened him this time—it was the cobbler. Every morning, just as the rich man fell asleep the cobbler awoke, and in almost no time was sitting at his door, sewing away and singing like a lark.

The rich man went to a friend and said, ”I can’t sleep at night for thinking of my money, and I can’t sleep in the morning for listening to that cobbler’s singing. What am I to do?” This friend was a wise man, and told him of a plan.

Next forenoon, while the cobbler was singing away as usual, the rich man came down the four steps that led from the pavement to the cobbler’s door.

“Now here’s a fine job,” thought the happy cobbler. “He’s going to get me to make a grand pair of boots, and won’t he pay me well!”

But the rich man did not want boots or anything. He had come to give, not to get. In his hand he had a leather28 bag filled with something that jingled. “Here, cobbler,” said the rich man, “I have brought you a present of a hundred crowns.”

“A hundred crowns!” cried the cobbler; “but I’ve done nothing. Why do you give me this money?”

“Oh, it’s because you’re always so happy.”

“And you’ll never ask it back?”

“Never.”

“Nor bring lawyers about it and put me in prison?”

“No, no. Why should I?”

“Well, then, I’ll take the money, and I thank you very, very much.”

When the rich man had gone the cobbler opened the bag, and was just about to pour out the money into his leather apron to count how much it was, when he saw a man in the street looking at him. This would never do, so he went into the darkest part of his house and counted the hundred crowns. He had never seen so much money in his life before, but somehow he did not feel so happy as he felt he should.

Just then his wife came in quietly, and gave the poor29 cobbler such a fright that he lost his temper and scolded her, a thing he had never done in his life.

Next he hid the bag below the pillow of the bed, because he could see that place from the door where he worked. But by and by he began to think that if he could see it from the door so could other people. So he went in and changed the bag to the bottom of the bed. Two or three times every hour he went in to see that the bag was all right. His wife wanted to know what was the matter with the bed, but he told her to mind her own business. The next time she was not looking he slipped the bag into the bottom of an old box, and from that time he kept changing it about from place to place whenever he got a chance. If he had told his wife it would not have been so bad, but he was afraid even of her.

Next morning the rich man fell asleep as usual, and was not disturbed by the cobbler’s song. The next morning was the same, and the next, and the next. Everybody noticed what a change had come over the cobbler. He no longer sang. He did little work, for he was always running out and in to see if his money was all right; and he was very unhappy.

On the sixth day he made up his mind what to do. I think he talked it over with his wife at last, but I am not sure. Anyway, he went up his four steps, and then up the one stair that led to the rich man’s room. When he had30 entered, he went up to the table and laid down the bag, and said, “Sir, here are your hundred crowns; give me back my song.”

Next morning things were as bad as ever for the poor rich man, who had to remove, they say, to another part of Paris where the cobblers are not so happy.

—From the French of Jean de la Fontaine.

By special permission.

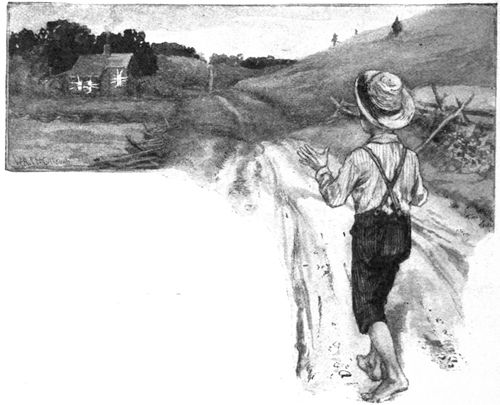

32

All day long the little boy worked hard, in field and barn and shed, for his people were poor farmers, and could not pay a workman; but at sunset there came an hour that was all his own, for his father had given it to him. Then the boy would go up to the top of a hill and look across at another hill that rose some miles away. On this far hill stood a house with windows of clear gold and diamonds. They shone and blazed so that it made the boy wink to look at them; but after a while the people in the house put up shutters, as it seemed, and then it looked like any common farm-house. The boy supposed they did this because it was supper-time; and then he would go into the house and have his supper of bread and milk and so to bed.

33

One day the boy’s father called him and said: “You have been a good boy, and have earned a holiday. Take this day for your own; but remember that God gave it, and try to learn some good thing.”

The boy thanked his father and kissed his mother; then he put a piece of bread in his pocket, and set out to find the house with the golden windows.

It was pleasant walking. His bare feet made marks in the white dust, and when he looked back, the footprints seemed to be following him, and making company for him. His shadow, too, kept beside him, and would dance or run with him as he pleased; so it was very cheerful. By and by he felt hungry; and he sat down by a brown brook that ran through the alder hedge by the roadside, and ate his bread, and drank the clear water. Then he scattered the crumbs for the birds, as his mother had taught him to do, and went on his way.

After a long time he came to a high green hill; and when he had climbed the hill, there was the house on the top; but it seemed that the shutters were up, for he could not see the golden windows. He came up to the house, and then he could well have wept, for the windows were of clear glass, like any others, and there was no gold anywhere about them.

A woman came to the door, and looked kindly at the boy, and asked him what he wanted.

34

“I saw the golden windows from our hilltop,” he said, “and I came to see them, but now they are only glass.”

The woman shook her head and laughed.

“We are poor farming people,” she said, “and are not likely to have gold about our windows; but glass is better to see through.”

She told the boy to sit down on the broad stone step at the door, and brought him a cup of milk and a cake, and bade him rest; then she called her daughter, a child of his own age, and nodded kindly at the two, and went back to her work.

The little girl was barefooted like himself, and wore a brown cotton gown, but her hair was golden like the windows he had seen, and her eyes were blue like the sky at noon. She led the boy about the farm, and showed him her black calf with the white star on its forehead, and he told her about his own at home, which was red like a chestnut, with four white feet. Then when they had eaten an apple together, and so had become friends, the boy asked her about the golden windows. The little girl nodded, and said she knew all about them, only he had mistaken the house.

“You have come quite the wrong way!” she said. “Come with me, and I shall show you the house with the golden windows, and then you will see for yourself.”

They went to a knoll that rose behind the farm-house,35 and as they went the little girl told him that the golden windows could be seen only at a certain hour, about sunset.

“Yes, I know that!” said the boy.

When they reached the top of the knoll, the girl turned and pointed; and there on a hill far away stood a house with windows of clear gold and diamond, just as he had seen them. And when they looked again, the boy saw that it was his own home.

Then he told the little girl that he must go. He promised to come again, but he did not tell her what he had learned; and so he went back down the hill, and the little girl stood in the sunset light and watched him.

The way home was long, and it was dark before the boy reached his father’s house; but the lamplight and firelight shone through the windows, making them almost as bright as he had seen them from the hilltop; and when he opened the door, his mother came to kiss him, and his little sister ran to throw her arms about his neck, and his father looked up and smiled from his seat by the fire.

“Have you had a good day?” asked his mother.

Yes, the boy had had a very good day.

“And have you learned anything?” asked his father.

“Yes,” said the boy. “I have learned that our house has windows of gold and diamond.”

—Laura E. Richards.

From “The Golden Windows,” by permission of Little, Brown & Company.

36

By permission of the publishers, L. C. Page & Co., Boston.

38

There once lived, in a little English town, a skilful linen weaver named Silas Marner. He was of a simple, trusting nature. He thought no wrong of anybody, and had never harmed any one in word or deed. Among his friends in the town there was one man whom he loved so dearly that he would gladly have given his life for him.

This man, however, far from being a true friend, acted most dishonestly and unfaithfully. Having committed a robbery himself, he cast the blame on Silas; and the weaver, who was too simple to see through the trick that had been played upon him, was forced to leave his native town, not only a disgraced, but a broken-hearted, man. The wickedness of the man whom he had thought his true friend, and the readiness of all his fellow-townsmen to believe evil of him, changed his whole nature and made him suspicious of and bitter against all men.

He wandered forth and settled at last in the village of Raveloe, far away from his old home. There he took up his abode in a little weather-beaten cottage at the outskirts of the town, and would have nothing to do with his neighbors beyond furnishing them with the fine linen he wove so well, and taking his pay in gold.

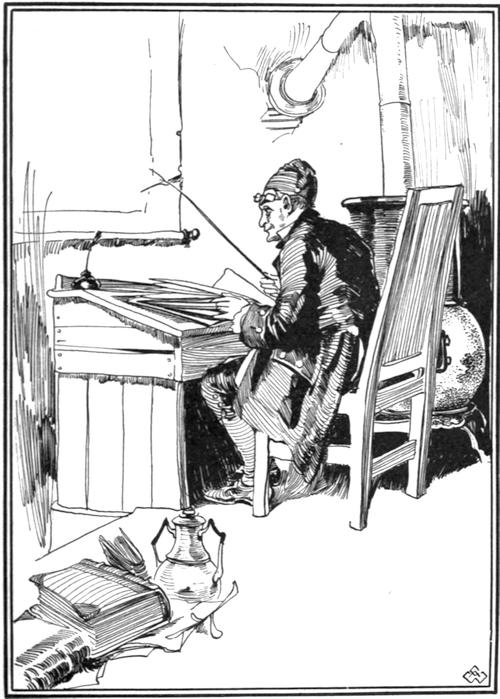

All day long he sat spinning at his loom, seeing no one and thinking only of his wrongs; and at night he had noth39ing to do but count his gold and watch with delight how the pile grew larger and larger every week. At last the gold, taking the place of his former interests, became the one thing in life he cared for. He hoarded it and gloated over it like a miser; and before long, though he still worked steadily at his loom, he thought no more of his work, but only of the gold it would bring him to add to his store. Thus passed his life for a long time.

But one evening when Silas had gone out to carry a bundle to a neighboring house, and had left his door ajar because he meant to be back in a short time, a thief, attracted by the light and the open door, entered the weaver’s hut and stole the bags of gold. When he returned, and, as usual, lifted the stone under which his treasure was hidden, he found nothing but the empty hole.

At first he could not believe that the money was gone. He hunted everywhere through his little cottage, turning again and again to the empty hole in the ground, to make sure that his eyes had not deceived him. When at last the truth forced itself upon him that his gold was really gone, he uttered a cry of anger and dismay, and rushed forth into the night, weeping and wailing and searching in vain for his lost treasure.

His neighbors, who soon heard what had happened, felt very sorry for him, and tried to show, by many little kind acts, their friendliness for the now desolate man. But he40 would have nothing to do with any of them. He shut himself up in his cheerless cottage, and though, from force of habit, he still worked at his loom, he had no longer any interest in life.

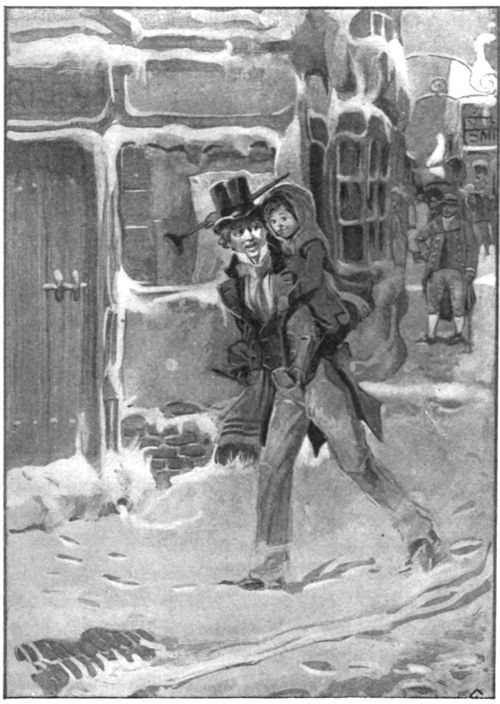

One bitterly cold night, Silas again had occasion to go out after dark. This time he left his door wide open, for now he had nothing left to lose. But while he was gone, a little golden-haired child, whose poor mother lay frozen to death in the snow on the roadside, had spied the light in Marner’s cottage and had crept to it for safety. Once inside the warm room, the child had fallen asleep, her golden head resting upon the very spot from which the miser’s treasure had been stolen.

When Silas entered the cottage and saw the glitter of gold on the floor, he was so startled that for a moment he stood stock-still. His first thought was that his treasure had been restored to him, and with a cry of joy he rushed forward to seize it. But instead of the cold, hard gold, he felt soft, warm curls; and the next minute the little child, who was awakened by his touch, began to cry.

Silas Marner, dazed as he was by the strange, living thing he had found in the place of his lost gold, did all he could to comfort the frightened little stranger; and soon, warm and no longer hungry, she was nestling her golden head against his arm, and laughing and babbling as contentedly as though she had always known her protector.

41

That was the beginning of a new happiness for Silas, much more satisfying than the miser’s love he had formerly felt for his gold. The lonely, helpless child aroused his pity and affection. As the mother was dead and no relatives came to claim the little girl, he decided to take care of her himself, and soon found himself loving her with a deep, fatherly tenderness.

He knew so little about children, however, that he needed the advice of a woman to help him bring up Eppie, as he had called the little girl; and so, gradually, he began to mingle more and more with the people of the village. As for the simple Raveloe folk, when they saw Silas Marner’s tenderness for the child, they felt that they had not really understood the lonely man. Before long all the villagers were on the best of terms with Silas and Eppie, and he had cast behind him all the hatred and bitterness that had led him to shun his fellow-men.

Eppie grew up strong and beautiful, and by the most tender love repaid Silas Marner for all his care of her through the years of her childhood. She had led him back to love and faith in human nature; and he never again regretted his lost treasure, which had been so richly replaced by the golden-haired child.

—Grace H. Kupfer.

From “Lives and Stories Worth Remembering,” by permission of the American Book Company.

42

By permission of the publishers.

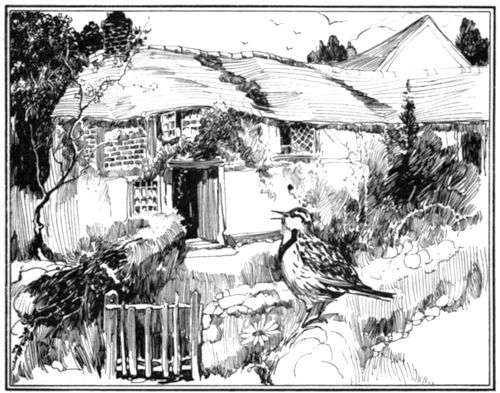

In the country, close by the roadside, stood a pleasant house. In front lay a little garden, enclosed by a fence, and full of blossoming flowers. Near the hedge, in the soft green grass, grew a little daisy. The sun shone as brightly and warmly upon her as it shone upon the large and beautiful garden flowers.

The daisy grew from day to day. Every morning she unfolded her white rays, and lifted up a little golden sun in the centre of her blossom. She never remembered how little she was. She never thought that she was hidden down in the grass, while the tall beautiful flowers grew in the garden. She was too happy to care for such things. She lifted her45 face towards the warm sun, she looked up to the blue sky, and she listened to the lark singing high in the air.

One day the little daisy was as joyful as if it were a great holiday, and yet it was only Monday. The little children were at school. They sat at their desks learning their lessons. The daisy, on her tiny stem, was learning from the warm sun and the soft wind how good God is. Then the lark sang his sweet song. “How beautiful, how sweet the song is!” said the daisy. “What a happy bird to sing so sweetly and fly so high!” But she never dreamed of being sorry because she could not fly or sing.

46

The tall garden flowers by the fence were very proud and conceited. The peonies thought it very grand to be so large, and puffed themselves out to be larger than the roses. “See how bright my colors are!” said the tulips. And they stood bolt upright to be seen more plainly. They did not notice the little daisy. She said to herself, “How rich and beautiful they are! No wonder the pretty bird likes them. I am glad I can live near them.”

Just then the lark flew down. “Tweet, tweet, tweet,” he cried, but he did not go near the peonies and tulips. He hopped into the grass near the lowly daisy. She trembled for joy. The little bird sang beside her: “Oh, what sweet, soft grass, and what a beautiful little flower, with gold in its heart and silver on its dress!” How happy the little daisy felt! And the bird kissed it with his beak, sang to it, and then flew up into the blue air above.

The daisy looked up at the peonies and the tulips, but they were quite vexed, and turned their backs upon her. She did not care, she was so happy. When the sun was set, she folded up her leaves and went to sleep. All night long she dreamed of the warm sun and the pretty little bird. The next morning, when she stretched out her white leaves to the warm air and the light, she heard the voice of the lark, but his song was sad. Poor little lark! He might well be sad: he had been made a prisoner in a cage47 that hung by the open window. He sang of the happy time when he could fly in the air, joyous and free.

Just then two boys came into the garden. They came straight to the daisy. One of them carried a sharp knife in his hand. “We can cut a nice piece of turf for the lark, here,” he said. And he cut a square piece of turf around the daisy, so that the little flower stood in the centre. He carried the piece of turf with the daisy growing in it, and placed it in the lark’s cage.

“There is no water here,” said the captive lark. “All have gone, and forgotten to give me a drop of water to drink. My throat is hot and dry. I feel as if I were burning.” And he thrust his beak into the cool turf to refresh himself a little with the green grass. Within it was the daisy. He nodded to her, and kissed her with his beak.

“Poor little flower! Have you come here, too?”

“How I wish I could comfort him,” said the daisy. And she tried to fill the air with perfume.

The poor bird lay faint and weak on the floor of the cage. His heart was broken. In the morning the boys came, and when they found the bird was dead, they wept many bitter tears. They dug a little grave for him, and covered it with flowers. The piece of turf was thrown on the ground.

The daisy had given her little life to make the captive bird glad.

—Hans Christian Andersen.

48

50

On a farm among the hills of New Hampshire, in the United States, there once lived a boy whose name was Daniel Webster. He was a tiny fellow for one of his age. His hair was jet black, and his eyes were so dark and wonderful that nobody who once saw them could ever forget them. He was not strong enough to help much on the farm; and so he spent much of his time in playing in the woods and fields. He loved the trees and flowers and the harmless wild creatures that made their homes among them.

But he did not play all the time. Long before he was old enough to go to school, he learned to read; and he read so well that everybody liked to hear him. The neighbors, when driving past his father’s house, would stop their horses and call for the boy to come out and read to them.

It happened one summer that a woodchuck made its burrow in the side of a hill near Mr. Webster’s house. On warm, dark nights it would come down into the garden and eat the tender leaves of the cabbages and other plants that were growing there. Nobody knew how much harm it might do in the end. Daniel and his elder brother Ezekiel made up their minds to catch the little thief. They tried this thing and that, but for a long time he was too cunning for them. Then they built a strong trap where the woodchuck51 would be sure to walk into it; and the next morning, there he was.

“We have him at last!” cried Ezekiel. “Now, Mr. Woodchuck, you’ve done mischief enough, and I’m going to kill you.” But Daniel pitied the little animal. “No, don’t hurt him,” he said. “Let us carry him over the hills, far into the woods, and let him go.” Ezekiel, however, would not agree to this. His heart was not so tender as his little brother’s. He was bent on killing the woodchuck, and laughed at the thought of letting it go.

“Let us ask father about it,” said Daniel.

“All right,” said Ezekiel; “I know what he will decide.”

They carried the trap, with the woodchuck in it, to their father, and asked what they should do.

“Well, boys,” said Mr. Webster, “we shall settle the question in this way. We shall hold a court here. I shall be the judge, and you shall be the lawyers. You shall each plead your case, for or against the prisoner, and I shall decide what his punishment shall be.”

Ezekiel, as the prosecutor, made the first speech. He told about the mischief that had been done. He showed that all woodchucks are bad and cannot be trusted. He spoke of the time and labor that had been spent in trying to catch the thief, and declared that if they should now set him free he would be a worse thief than before.

“A woodchuck’s skin,” he said, “may perhaps be sold for52 ten cents. Small as that sum is, it will go a little way towards paying for the cabbages he has eaten. But, if we set him free, how shall we ever recover even a penny of what we have lost? Clearly, he is of more value dead than alive, and therefore he ought to be put out of the way at once.”

Ezekiel’s speech was a good one, and it pleased Mr. Webster very much. What he said was true and to the point, and it would be hard for Daniel to make any answer to it.

Daniel began by pleading for the poor animal’s life. He looked up into his father’s face, and said:—

“God made the woodchuck. He made him to live in the bright sunlight and the pure air. He made him to enjoy the free fields and the green woods. The woodchuck has a right to his life, for God gave it to him.

“God gives us our food. He gives us all that we have. And shall we refuse to share a little of it with this poor dumb creature who has as much right to God’s gifts as we have?

“The woodchuck is not a fierce animal like the wolf or the fox. He lives in quiet and peace. A hole in the side of a hill, and a little food, is all he wants. He has harmed nothing but a few plants, which he ate to keep himself alive. He has a right to life, to food, to liberty; and we have no right to say he shall not have them.

“Look at his soft, pleading eyes. See him tremble with fear. He cannot speak for himself, and this is the only way53 in which he can plead for the life that is so sweet to him. Shall we be so cruel as to kill him? Shall we be so selfish as to take from him the life that God gave him?”

The father’s eyes were filled with tears as he listened. His heart was stirred. He did not wait for Daniel to finish his speech, but sprang to his feet, and as he wiped the tears from his eyes, he cried out, “Ezekiel, let the woodchuck go!”

—Selected.

56

I was very late that morning on my way to school, and was afraid of being scolded, as the master had told us he should question us on the verbs, and I did not know the first word, for I had not studied my lesson. For a moment I thought of playing truant. The air was so warm and bright, and I could hear the blackbirds whistling in the edge of the woods, and the Prussians who were drilling in the meadow behind the sawmill. I liked this much better than learning the rules for verbs, but I did not dare to stop, so I ran quickly towards school.

As I passed the mayor’s office, I saw people standing before the little bulletin-board. For two years it was there that we received all the news of battles, of victories, and defeats. “What is it now?” I thought, without stopping58 to look at the bulletin. Then, as I ran along, the blacksmith, who was there reading the bill, cried out to me, “Not so fast, little one, you shall reach your school soon enough.” I thought he was laughing at me and ran faster than ever, reaching the school yard quite out of breath.

Usually, at the beginning of school, a loud noise could be heard from the street. Desks were being opened and closed, and lessons repeated at the top of the voice. Occasionally the heavy ruler of the master beat the table, as he cried, “Silence, please, silence!” I hoped to be able to take my seat in all this noise without being seen; but that morning the room was quiet and orderly. Through the open window I saw my schoolmates already in their places. The master was walking up and down the room with the iron ruler under his arm and a book in his hand. As I entered he looked at me kindly, and said, without scolding, “Go quickly to your place, little Franz; we were just going to begin without you. You should have been here five minutes ago.”

I climbed over my bench and sat down at once at my desk. Just then I noticed, for the first time, that our master wore his fine green coat with the ruffled frills, and his black silk embroidered cap. But what surprised me more was to see some of the village people seated on the benches at the end of the room. One of them was holding an old spelling-book on his knee; and they all looked sadly at the master.

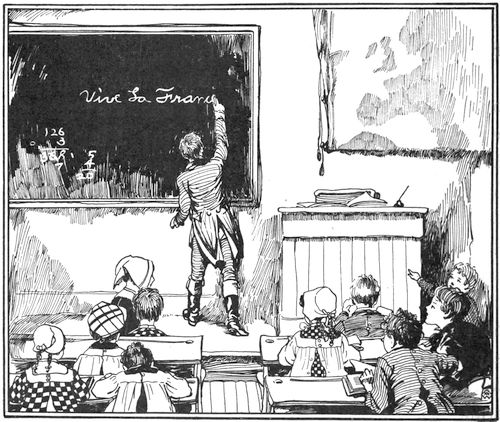

While I was wondering at this, our schoolmaster took his59 place, and in the same kind tone in which he had received me, he said: “My children, this is the last time that I shall give you a lesson. An order has come from Berlin that no language but German may be taught in the schools of Alsace and Lorraine. A new master will come to-morrow who shall teach you in German. To-day is your last lesson in French. I beg of you to pay good attention.”

These words frightened me. This is what they had posted on the bulletin-board, then! This is what the blacksmith was reading. My last lesson in French! I hardly knew how to write, and I never should learn now. How I longed for lost time, for hours wasted in the woods and fields, for days when I had played and should have studied. My books that a short time ago had seemed so tiresome, so heavy to carry, now seemed to me like old friends. I was thinking of this when I heard my name called. It was my turn to recite. What would I not have given to be able to say the rules without a mistake? But I could not say a word and stood at my bench without daring to lift my head. Then I heard the master speaking to me.

“I shall not scold you, little Franz. You are punished enough now. Every day you have said to yourself: ‘I have plenty of time. I shall learn my lesson to-morrow.’ Now you see what has happened.”

Then he began to talk to us about the French language, saying that it was the most beautiful tongue in the world,60 and that we must keep it among us and never forget it. Finally he took the grammar and read us the lesson. I was surprised to see how I understood. Everything seemed easy. I believe, too, that I never listened so well; and it seemed almost as if the good man were trying to teach us all he knew in this last lesson.

The lesson in grammar ended, we began our writing. For that day the master had prepared some new copies, on which were written, “Alsace, France; Alsace, France.” They seemed like so many little flags floating about the61 schoolroom. How we worked! Nothing was heard but the voice of the master and the scratching of pens on the paper. There was no time for play now. On the roof of the schoolhouse some pigeons were softly cooing, and I said to myself, “Shall they, too, be obliged to sing in German?”

From time to time, when I looked up from my page, I saw the master looking about him as if he wished to impress upon his mind everything in the room.

After writing, we had a history lesson, and then the little ones recited. Oh, I shall remember that last lesson!

Suddenly, the church clock struck the hour of noon. The master rose from his chair. “My friends,” said he, “my friends,—I—I—” But something choked him; he could not finish the sentence. He turned to the blackboard, took a piece of chalk, and wrote in large letters, “Vive la France!” Then he stood leaning against the wall, unable to speak. He signed to us with his hand: “It is ended. You are dismissed.”

—From the French of Alphonse Daudet.

62

By permission of the publishers, The Bobbs-Merrill Company. Copyright, 1901.

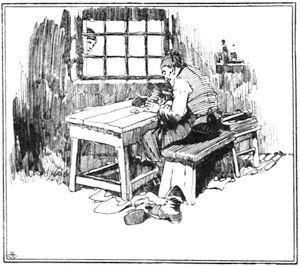

65

On one of the dark, rugged cliffs that jut out into the sea from the eastern part of England, stood, many centuries ago, the monastery of Whitby. At this time the people of England were still very ignorant. Only the monks and nuns knew how to read or write. The rest of the people were either warriors, or else simple-minded shepherds and farmers.

In this monastery lived a servant whose duty it was to attend to the sheep and cattle. In the evenings, very often, his companions were in the habit of gathering together in the common hall or banquet room. There it was the custom, while the feast was going on, for each one in turn to take the harp as it was passed around the table, and make up some simple song to entertain his friends. Although these people knew nothing about reading or writing, they were wonderfully clever at singing songs and accompanying themselves on the harp.

Only the herdsman who attended to the sheep and cattle, and whose name was Cædmon, could never sing. So whenever the feasting time came, and his comrades began to pass the harp from one to another, he, being ashamed of his lack of skill, would leave the banquet hall to go alone to the little house where he slept.

One night, after he had left his comrades, and had at66tended to all the wants of the cattle under his care, he, as usual, went to sleep, and in his sleep he had a wonderful dream. He dreamed that to his door came a beautiful youth, with a light shining about his head, who said to him, “Cædmon, sing for me.” Cædmon answered: “But thou knowest I cannot sing. That is why I left my companions in the banquet hall, and came here to my lonely hut.” “Try,” said the beautiful youth, “and thou shalt find that thou canst sing.” Then Cædmon in wonder asked, “What shall I sing about?”—”Sing of the beauty of the world, and the glory of the stars and the skies, and of all that is on the earth,” was the answer.

Then in his sleep Cædmon sang a beautiful song, just as the youth had commanded him. But the strangest thing was that when he awoke he remembered every word of the song, and not only that, but he found he could sing a song about any thought that came into his mind; whereas, formerly, he had never been able to sing at all.

Wonderful, indeed, all this seemed to the humble shepherd. He told his companions about his dream, and they led him to the abbess, who was chief in the monastery, and bade him sing his songs for her.

So he sang. All the wise monks came to hear him, and tears came into their eyes at the beauty of his song; for when he sang, the sky and the earth and the sea these men had known all their lives seemed suddenly to be filled with67 a new glory. They all said that Cædmon had received a wonderful gift from God, and that he must use it in a holy way.

From that day on some one else guarded the sheep and the cattle in the monastery of Whitby; and the former shepherd learned to read and write, and became one of the monks of the abbey. Many and beautiful and holy were the songs he wrote. They were written in Anglo-Saxon, the language spoken by the ancestors of the English people, and this simple shepherd, Cædmon, who was the first of the Anglo-Saxon poets, was therefore really the father of all English poetry.

—Grace H. Kupfer.

69

Once in the olden time a king called his heralds together to hear his bidding. And all the swift runners gathered before the king, each with a trumpet in his hand. And the king sent them forth into every part of the kingdom to sound their trumpets and to call aloud:—

“Hear, O ye minstrels! Our gracious king bids ye come to his court and play before the queen.”

70

The minstrels were men who went about from castle to castle and from palace to cot, singing beautiful songs and playing on harps. Wherever they roamed they were always sure of a welcome. They sang of the brave deeds that the knights had done, and of wars and battles. They sang of the mighty hunters that hunted in the great forests. They sang of fairies and goblins, of giants and elves. And because there were no storybooks in those days, everybody, from little children to the king, was glad to see them come.

When the minstrels heard the king’s message, they made haste to the palace; and it so happened that three of them met on the way and decided to travel together.

One of these minstrels was a young man named Harmonious; and while the others talked of the songs that they would sing, he gathered the wild flowers that grew by the roadside.

“I can sing of drums and battles,” said the oldest minstrel, whose hair was white, and whose step was slow.

“I can sing of ladies and their fair faces,” said the youngest minstrel. But Harmonious whispered, “Listen! listen!”

“Oh! we hear nothing but the wind in the tree-tops,” said the others. “We have not time to stop and listen.”

Then they hurried on and left Harmonious; and he stood under the trees and listened, for he heard the wind singing of its travels through the wide world. It was telling how it raced over the blue sea, tossing the waves and rocking71 the white ships. It sang of the hill where the trees made harps of their branches, and of the valleys where all the flowers danced gayly to its music. And this was the chorus of the song:—

Harmonious listened until he knew the whole song. Then he ran on, and soon reached his friends, who were still talking of the grand sights that they were to see. “We shall behold the king, and we shall speak to him,” said the oldest minstrel. “And we shall see his golden crown and the queen’s jewels,” added the youngest.

Now their path led them through the wood, and as they talked, Harmonious said, “Hush! listen!” But the others answered: “Oh! that is only the sound of the72 brook, trickling over the stones. Let us make haste to the king’s court.”

But Harmonious stayed to hear the song that the brook was singing, of journeying through mosses and ferns and shady ways, and of tumbling over the rocks in shining waterfalls, on its way to the sea.

Thus sang the little brook. Harmonious listened until he knew every word of the song, and then he hurried on.

When he reached the others, he found them still talking of the king and the queen, so he could not tell them of the brook. As they talked, he heard something again that was wonderfully sweet, and he cried, “Listen! listen!”

“Oh! that is only a bird,” the others replied. “Let us make haste to the king’s court.”

But Harmonious would not go, for the bird sang so joyfully that Harmonious laughed aloud when he heard the song. It was singing a song of green trees; and in every tree there was a nest, and in every nest there were eggs.

73

“Thank you, little bird,” said Harmonious; “you have taught me a song.” And he made haste to join his comrades.

When they had come into the palace, they received a hearty welcome, and were feasted in the great hall before they came into the throne room. The king and queen sat on their thrones side by side. The king thought of the queen and the minstrels; but the queen thought of her old home in a far-off country, and of the butterflies she had chased when she was a little child.

One by one the minstrels played before them. The oldest minstrel sang of battles and drums, and the soldiers of the king shouted with joy. The youngest minstrel sang of ladies and their fair faces, and all the ladies of the court clapped their hands.

Then came Harmonious. And when he touched his harp and sang, the song sounded like the wind blowing, the sea roaring, and the trees creaking. Then it grew very soft, and sounded like a trickling brook, dripping on stones and running over little pebbles. And while the king and queen and all the court listened in surprise, Harmonious’s song grew sweeter, sweeter, sweeter. It was as if you heard all the birds in spring. And then the song was ended.

The queen clapped her hands, and the ladies waved their handkerchiefs, and the king came down from his throne to74 ask Harmonious if he came from fairy-land with such a wonderful song. But Harmonious answered:—

Now all the minstrels looked up in surprise when they heard these words from Harmonious; and the oldest minstrel said to the king: “Harmonious is surely mad! We met no singers on our way to-day.” But the queen said: “That is an old, old song. I heard it when I was a little child, and I can name the singers three.” And so she did. Can you?

—Maude Lindsay.

From “Mother Stories,” by permission of Milton Bradley Company.

76

This is a story a hunter told me as we sat by the camp-fire on the top of the mountain, after a day’s climb through the woods:—

“When I was a child, my home was on the edge of a great forest. There were but few people near us, and not a town for miles and miles. Many wild animals lived in the woods, which were so wide and deep that most of the animals had never seen a human being.

“One day my father and a neighbor were out hunting. There was no breeze, and the woods were very still. They were walking down a hillside, stepping quietly over the fallen78 trunks and dry leaves, when suddenly, ‘Look! look!’ my father whispered to his companion.

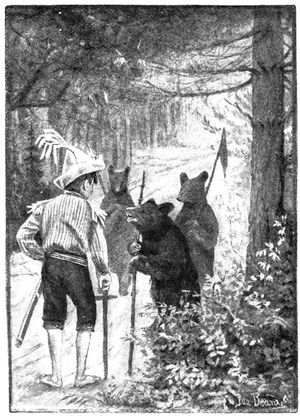

“A strip of water gleamed through the trees, and a mother bear and three cubs were walking along the shore. The bear caught the sound or the scent of some one near, for she stopped, rose on her hind legs, and snuffed the air, and all the little bears did exactly what she did. ‘We have surprised Bruin giving her children a lesson,’ said my father. But as he turned to speak, and before he could say a word to prevent, his companion had shot the mother bear. She tumbled down on the sand, and the little bears began to whimper and cry.

“Father never spoke to that man again, though he was a neighbor; and a neighbor means a good deal when the nearest one lives two miles away.

“The cubs were brave fellows; they did not run away even79 when the men went up to them, but stayed by their mother, whimpering a little. ‘It was pitiful to see them,’ father said. He was not willing to go away and leave the little fellows, for they were too small to take care of themselves; and now they had no mother to teach them bear language and bear ways. He picked up one and carried it, and the others followed. So he brought the three bears home to be my playmates, and glad I was to see them. They cried at first and missed their mother; but they soon became accustomed to living with people. What frolics we had! Every morning we would scamper up and down the road. When some one called in to the house and I ran in, they would come running and tumbling after me. We played house and school and soldier together, and though I often wished they could talk with me, in every other way they were good comrades.

“They were always good-natured. You have heard a dog growl over a bone; the bears preferred lumps of sugar, which they took without growling. How they liked sweet things! They would come into the pantry and beg for cake; and when my mother wanted to give us all a treat, she would make molasses candy.

“Did we sell them? No, sir! Father said their mother had been so cruelly treated that they deserved extra kindness, and they were free to come and go as they would.

“One morning I woke up to find that two of them had80 gone off to the woods,—their natural home. Only Moween had chosen to stay with us rather than to go with his brothers. He lived with us until he was a big bear. Sometimes he would roam into the woods to find honey, but he always came back. I used to like to go nutting with him, for he would climb up the tree and shake the branches until the nuts came pattering down.

“One afternoon a German, leading a bear by a chain, stopped at the house. He had lost his way, and we asked him to rest and spend the night with us. He explained in broken English that he had been travelling about the country with his dancing bear. The bear danced for us, but Moween seemed frightened and ran away when he saw the newcomer. The dancing bear, on his part, seemed afraid of Moween. However, at supper-time, Moween returned, and the bears seemed to make friends. What they said to each other I do not know, but when morning came both bears were gone. The dancing bear had slipped his chain. Their trail led into the forest, and we followed it a mile or two, but did not find them.

“This time my pet bear did not come back. Every spring I used to expect him, for when the maple trees were tapped, we had ‘sugarings off’ which were always feasts for Moween. But I have not seen him since, though I never see a bear without wishing that he were my old playmate, Moween.”

—Selected.

By permission of the Outlook Magazine.

81

83

There was a time, long ago, when people believed that fairies hovered over a sleeping babe, and gave to the little one the charm of beauty, or the joy of strength, or the power of genius.

If this were true, then fairies must have visited the cradle of little Wolfgang Mozart. We might easily believe that one of them said, “I shall give thee a loving heart;” and that another whispered, “Thou shalt delight in sweet sounds; music shall be thy language.”

The little Mozart lived in Germany more than a hundred years ago. His father was a musician, and his sister, Anna, had already made rapid progress in music. At all of her lessons the baby brother was an interested listener, and he often amused himself in trying to repeat the exercises he had heard. Before he was four years old, he began to compose music. His little pieces were written for him by his father, in a book which was kept for that purpose.

One Sunday the father came home from church and

found Wolfgang at a table busy over a piece of paper. His[Pg 84]

[Pg 85]

fat little hand grasped the pen with much firmness, and at

every visit to the ink-bottle he plunged it to the very bottom.

The paper was very badly blotted with ink, but the baby

composer calmly wiped away the blots with his finger and

wrote over them.

“What are you doing there?” asked his father.

“Writing a piece of music for the piano,” replied Wolfgang.

“Let me see it.”

“No, no, it is not ready!”

The father took up the paper, and laughed at the big blots and the notes which were scarcely readable. But upon looking over the work more carefully, he saw that it was written according to rule, and that it was a wonderful composition for so young a child.

The father now devoted all his time to the education of his two children. They progressed so rapidly that they were a marvel to their native town. When Anna was ten years old and Wolfgang six, they were taken by their father and mother to Vienna, and there the Emperor listened to their music. The courtiers and the royal family praised the gifted children and filled their hands with costly presents.

Soon after their return home, a noted violinist called to ask Herr Mozart’s opinion of some new music. As they were about to practise the different parts, little Wolfgang begged to play second violin.

86

“You cannot join our rehearsal,” said his father. “You have had no instruction on the violin.”

“I do not need any lessons to play second violin,” the boy persisted.

“Run away and do not disturb us,” was the father’s reply, and the little boy walked out of the room, crying bitterly. The visitor begged that the child be permitted to play with him, and Wolfgang was called back.

“Play then,” said the father; “but play very softly.”

The child was comforted. He brushed away his tears and began playing, softly at first, as he had been commanded; then he forgot everything but the notes before him, and the music swelled higher and higher. All were amazed, and tears of gladness stood in the father’s eyes.

Another concert tour was planned, and Wolfgang and his sister travelled with their parents from city to city, giving concerts at the courts of kings. Great crowds went to hear them, and everywhere they were greeted with enthusiasm and delight.

When Wolfgang was eleven years old, he went to Italy to study music. The fair, slender lad was looked upon as a marvel by the Italian musicians. The father and son reached Rome at the time of the great Easter festival. A beautiful piece of music had been set apart as sacred to this yearly service. For two hundred years it had been carefully guarded, and all musicians were forbidden to copy87 it. Wolfgang listened intently; and when he came again the next day to the church, he brought with him a folded paper on which he had written from memory the whole of the sacred music.

“Truly such wonderful gifts come from Heaven!” said the priests, in awe and admiration.

Mozart remained for nearly two years in Italy, studying with the finest musicians and hearing the best music. After his return to his native land, he continued his musical studies and gave his whole life to his art.

It seems impossible that the boy, who in his early years received such honors, should in his manhood meet poverty and neglect. Such was Mozart’s sad fortune, but in spite of his discouragements he struggled on, and became one of the greatest of musical composers. He has given to the world a wealth of beauty that has made his name immortal.—Bertha Leary Saunders.

91

The flax was in full bloom; it had pretty little blue flowers as delicate as the wings of a moth, or even more so. The sun shone, and the showers watered it, so that it became very beautiful.

“People say that I look exceedingly well,” said the flax, “and that I am so fine and long, that I shall make an excellent piece of linen. How fortunate I am! it makes me so happy; it is such a pleasant thing to know that something can be made of me. How the sunshine cheers me, and how sweet and refreshing is the rain! no one in the world can feel happier than I do.”

One day some people came, who took hold of the flax and pulled it up by the roots; this was painful. Then it was laid in water as if they intended to drown it, and, after that, placed near a fire as if it were to be roasted; all this was very shocking.

“I cannot expect to be happy always,” said the flax; “I must have my trials, and so learn what life really is.” And certainly there were plenty of trials in store for the flax.92 It was steeped, and roasted, and broken, and combed; indeed, it scarcely knew what was done to it.

At last it was put on the spinning-wheel. “Whirr, whirr,” went the wheel, so quickly that the flax could not collect its thoughts.

“Well, I have been very happy,” he thought in the midst of his pain, “and must be contented with the past;” and contented he remained till he was put on the loom, and became a beautiful piece of white linen. All the flax, even to the last stalk, was used in making this one piece. “How wonderful it is that, after all I have suffered, I am made something of at last; I am the luckiest person in the world—so strong and fine; and how white, and what a length! This is something different from being a mere plant and bearing flowers. I cannot be happier than I am now.”

After some time, the linen was taken into the house, placed under the scissors, and cut and torn into pieces, and then pricked with needles. This certainly was not pleasant; but at last it was made into garments.

“See now, then,” said the flax, “I have become something of importance. This was my destiny; it is quite a blessing. Now I shall be of some use in the world, as every one ought to be; it is the only way to be happy.”

Years passed away; and at last the linen was so worn it could scarcely hold together. “It must end very soon,93” said the pieces to each other. “We would gladly have held together a little longer, but we must not forget that there is an end to all things.” And at length they fell into rags and tatters, and thought it was all over with them, for they were torn to shreds, and steeped in water and made into a pulp, and dried, and they knew not what besides, till all at once they found themselves beautiful white paper.

“Well, now, this is a surprise; a glorious surprise, too,” said the paper. “I am now finer than ever, and I shall be written upon, and who can tell what fine things I may have written upon me? This is wonderful luck!” And sure enough, the most beautiful stories and poetry were written upon it. Then people heard the stories and poetry read, and it made them wiser and better; for all that was written was sensible and good, and a great blessing was contained in the words on the paper.

“I never imagined anything like this,” said the paper, “when I was only a little blue flower, growing in the fields. How could I imagine that I should ever be the means of bringing knowledge and joy to men? I cannot understand it myself, and yet it is really so. I suppose now I shall be sent on my travels about the world, so that people may read me. It cannot be otherwise; indeed, it is more than probable, for I have more splendid thoughts written upon me than I had pretty flowers in olden times. I am happier than ever.”

94

But the paper did not go on its travels. It was sent to the printer, and all the words written upon it were set up in type, to make a book, or rather hundreds of books; for so many more persons could gain pleasure from a printed book than from the written paper; and if the paper had been sent about the world, it would have been worn out before it had got half through its journey.

“This is certainly the wisest plan,” said the written paper; “I really did not think of that. I shall remain at home and be held in honor, like some old grandfather, as I really am to all these new books. They shall do some good. I could not have wandered about as they do. Yet he who wrote all this has looked at me as every word flowed from his pen upon my surface. I am the most honored of all.”

Then the paper was tied in a bundle with other papers, and thrown into a tub that stood in the wash-house. “After work, it is well to rest,” said the paper. “Now I am able for the first time to think of my life and all the good that I have done. What shall be done with me now, I wonder? No doubt I shall still go forward.”

Now it happened one day that all the paper in the tub was taken out, and laid on the hearth to be burnt. People said it could not be sold at the shop, to wrap up butter and sugar, because it had been written upon. The children in the house stood round the stove; for they wished to see the paper burn, because it flamed up so prettily, and after95wards, among the ashes, so many red sparks could be seen running one after the other, here and there, as quick as the wind.

The whole bundle of paper had been placed on the fire, and was soon alight. “Oh, oh!” cried the paper, as it burst into a bright flame. It was certainly not very pleasant to be burning; but when the whole was wrapped in flames, the flames mounted up into the air, higher than the flax had ever been able to raise its little blue flower; and they gleamed as the white linen had never been able to gleam. All the written letters became quite red in a moment, and all the words and thoughts turned into fire.

“Now I am mounting straight up to the sun,” said a voice in the flames, and it was as if a thousand voices echoed the words; and the flames darted up through the chimney, and went out at the top. Nothing remained of the paper but black ashes with the red sparks dancing over them. The children thought that this was the end, but the sparks sang, “The most beautiful is yet to come.”

—Hans Christian Andersen.

96

98

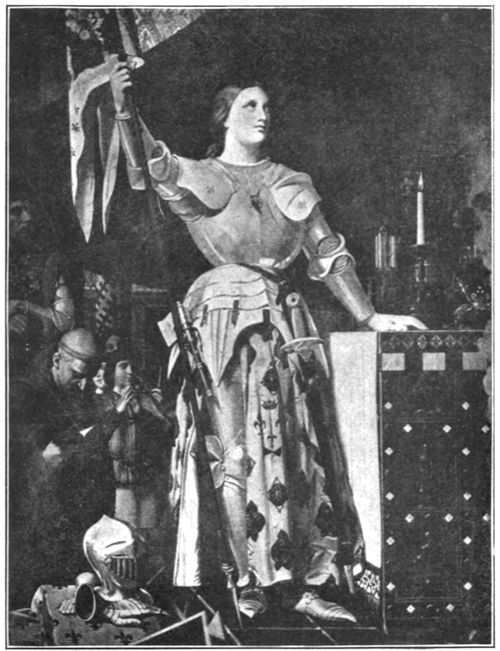

In the midst of those terrible times, during which for one hundred years England and France were at war, there was born in the little village of Domrémy a peasant girl, named Jeanne d’Arc. When she was old enough she used to tend her father’s sheep, and as she sat on the hillside, watching them day by day, she often looked out over the ruined houses and blackened fields and wondered if the English would ever come again to frighten her people and burn their peaceful homes. Her father, too, feared the same, and so taught his little daughter to ride a horse and to use simple weapons.

Later she heard that the dreaded English were back in

France, not in her own village, but besieging the brave town

of Orleans. News came that the Dauphin, who was now

governing France, dared not go to Rheims to be crowned,

because the English troops held the place. One day as

Jeanne sat musing over all these rumors, wishing that she

were a man so that she might go and fight for her country,

she saw a vision and heard voices bidding her leave her home

and deliver the Dauphin from his enemies, so that he might

be crowned king. So loudly and so plainly did she hear

these voices that she felt she must go to the French court at

once. She was so poor that she thought at first that she

must go afoot, but some kind neighbors gave her a horse.

Then she put on men’s clothing, instead of her coarse red[Pg 99]

[Pg 100]

dress, cut off her long black hair, and rode bravely off

alone.

Ingres

Jeanne d’Arc

The journey was long and perilous, for the country was still full of robbers and free lances, but when it was over she found that her troubles had only begun. The nobles met her strange story with laughter and scorn, and refused to let her see the king. But finally her sweetness and gentle manner prevailed, and she was led into the presence of her sovereign. The story runs that the king, to test her, had put on the simple robe of a courtier, and stood among the rest of the nobles when Jeanne entered. But Jeanne went to him, without hesitation, saluted, and said:—

“In God’s name, it is you, sire, and none other.”

There she stood, a simple shepherd lass, who could neither read nor write, before a roomful of men of noble birth; but she was not afraid, for she brought with her the faith that she was to save France. Gradually, her soft voice, ringing with enthusiasm and loyalty, aroused the king and his lords, and he granted Jeanne her request—she was to go and relieve Orleans.

He gave her a big horse and pure white armor, and she herself sent for a sword having five crosses on the blade, that she had seen in a dream lying behind an altar in a certain church.

But at Orleans the people who were defending the city mistrusted her. They tried to hide their plans from her,101 and made a secret attack in the night on the enemy. But the shouts of war woke her from her sleep. She hastily called for her horse and galloped into the midst of the fight. The soldiers cheered her wildly, and now even the unwilling captains were forced to listen to her. In the days that followed, Jeanne, though twice wounded, was always at the front, urging on the French and terrifying the English, who took her for a witch. She entered Orleans on Friday, and a week from the following Sunday the English had turned their backs forever on the city.

Jeanne did not linger to enjoy her triumph. Amid the tears of joy and the cheering of the people, she rode out of the city the next day to perform the rest of her task,—to crown the Dauphin king of France. From far and near people came to see her, and a large army sprang up around her and the king, eager to march towards Rheims. Still the court delayed, for the nobles were jealous of Jeanne’s glory, but she was firm in her faith and the people were with her.

The French first attacked the English who were holding Troyes. After a six days’ siege the king was discouraged, for the food was growing very scarce, but Jeanne begged him to hold out two days longer. When he agreed, she mounted her horse and led the attack against the town. The English, in terror, opened their gates before the assault began. Thus the last difficulty was surmounted and the army marched safely102 to Rheims. Here the king was crowned in the big cathedral, the brave young peasant girl standing by his side.

Jeanne was now ready to go back to her father and mother, and the tending of her sheep, but the voices still called her to drive the English from the land. She stayed with the king and army, trying to hasten an attack on the English. But the indolent king, listening to idle tales from his jealous nobles, forgot all Jeanne had done for him and France, and began to believe that she was a witch. At last Jeanne was captured by the enemy. The English believed her to be a witch and tried her for sorcery. The French king made no effort to ransom her, and she was condemned to be burned at the stake. The sentence was carried out, and thus the poor peasant girl gave up her life for the ungrateful country she had saved from ruin.

—Maude Barrow Dutton.

From “Little Stories of France,” by permission of the American Book Company.

Afar off upon a large level land, a summer sun was shining bright. Here and there over the rolling green were tall bunches of coarse gray weeds. Iktomi in his fringed buckskins walked alone across the prairie with a black bare head glossy in the sunlight. He walked through the grass without following any well-worn footpath.

From one large bunch of coarse weeds to another he wound his way about the great plain. He lifted his foot lightly and placed it gently forward like a wildcat prowling noiselessly through the thick grass. He stopped a few steps away from a very large bunch of wild sage. From shoulder to shoulder he tilted his head. Still farther he bent from side to side. Far forward he stooped, stretching his long thin neck like a duck, to see what lay under a fur coat beyond the bunch of coarse grass.

A sleek gray-faced prairie wolf! his pointed black nose tucked in between his four feet drawn snugly together; his handsome bushy tail wound over his nose and feet; a coyote105 fast asleep in the shadow of a bunch of grass!—this is what Iktomi spied. Carefully he raised one foot and cautiously reached out with his toes. Gently, gently he lifted the foot behind and placed it before the other. Thus he came nearer and nearer to the round fur ball lying motionless under the sage grass.

Now Iktomi stood beside it, looking at the closed eyelids that did not quiver the least bit. Pressing his lips into straight lines and nodding his head slowly, he bent over the wolf. He held his ear close to the coyote’s nose, but not a breath of air stirred from it.

“Dead!” said he at last. “Dead, but not long since he ran over these plains! See! there in his paw is caught a fresh feather. He is nice fat meat!” Taking hold of the paw with the bird feather fast on it, he exclaimed, “Why, he is still warm! I’ll carry him to my dwelling and have a roast for my evening meal. Ah-ha!” he laughed, as he seized the coyote by its two fore paws and its two hind feet and swung him overhead across his shoulders. The wolf was large and the teepee was far across the prairie. Iktomi trudged along with his burden, smacking his hungry lips together. He blinked his eyes hard to keep out the salty perspiration streaming down his face.

All the while the coyote on his back lay gazing into the sky with wide-open eyes. His long white teeth fairly gleamed as he smiled and smiled.

106