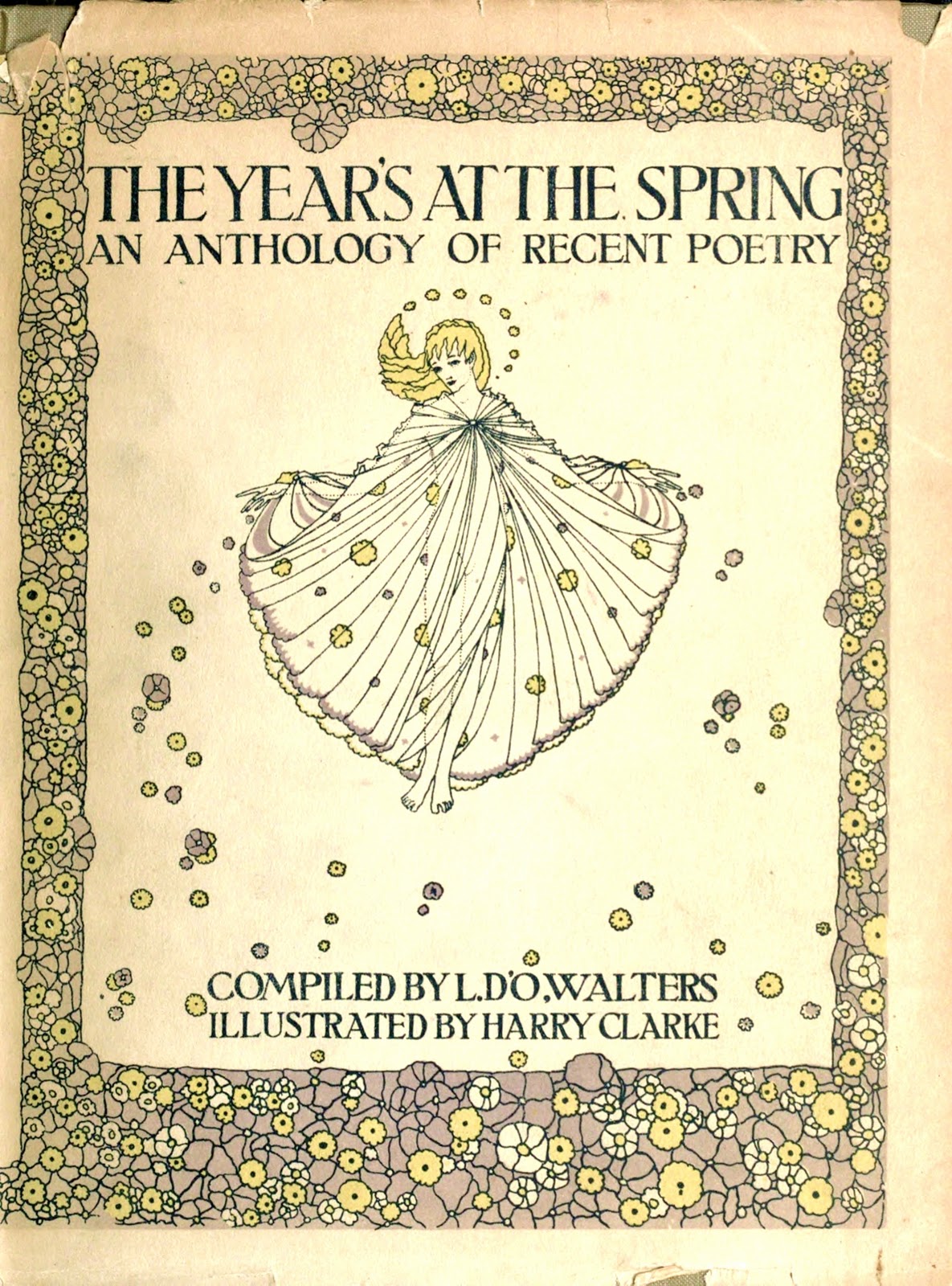

Title: The Year's at the Spring: An Anthology of Recent Poetry

Compiler: L. D'O. Walters

Author of introduction, etc.: Harold Monro

Illustrator: Harry Clarke

Release date: March 17, 2016 [eBook #51488]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annemie Arnst and Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Internet Archive)

The best poetry is always about the earth itself and all the strange and lovely things that compose and inhabit it. When a 'great poet' sets himself the task of some 'big theme' he needs only to hold, as it were, a magnifying glass to the earth. We who are born and live here like very much to imagine other worlds, and we have even mentally constructed such another in which to exist after dying on this one; but we were careful to make it a glorified version of our own earth, with everything we most love here intensified and improved to the utmost stretch of human imagination.

To each man his 'best poetry' is that which he is able most to enjoy. The first object of poetry is to give pleasure. Pleasure is various, but it cannot exist where the emotions or the imagination have not been powerfully stirred. Whether it be called sensual or intellectual, pleasure cannot be willed. It is impossible to feel happy because one wants to feel happy,[Pg 6] or sad because one wishes to feel sad. But such bodily or mental conditions may be induced from outside through a natural agency such as poetry, or music.

Now those dreary people who would maintain that poetry should deal (some say exclusively) with what they call 'big themes,' or 'the larger life', are merely advocating more use of the magnifying glass as against intensive cultivation of the natural eye. The poet is essentially he who examines carefully, and learns to know fully, every detail of common life. He seeks to name in a variety of manners, and to define, the objects about him, to compare them with other objects, near or remote, and to find, for the mere sake of enjoyment, wonderful varieties of description and comparison. When he imagines better places than his earth, or invents gods, the impersonation and combination of the fortunate qualities in man, he is then using the magnifying glass with talent, occasionally with rare genius. But the poet who seeks, without genius, to magnify is simply a fool who sees everything too big, and boasts, in the loudest voice he can raise, of his diseased eyesight.

One of the peculiarities, or perhaps rather the essential quality, of the lyrical poetry of to-day is a minute concentration on the objects immediately near it and an anxious carefulness to describe these in the most appropriate and satisfactory terms. Thus it is often accused of a neglect to sublimate the emotions, and many critics have been at pains to suggest that this affection for the nearest and that careful[Pg 7] description of natural events denotes a smallness of mental range. Be it noted, however, that the eye which does not look too far often sees most. It is remarkable that English lyrical poetry should have learnt in this period of religious uncertainty to clasp itself at least to a reality that cannot be questioned or doubted. So far its faith reaches. It expresses a trustfulness in what it can definitely perceive, it hardly ventures outside the circles of human daily experience, and in this capacity it reveals an excellence of many kinds, sincerity often, and, at worst, a playfulness which, if ephemeral, is amusing at any rate to those whom it is intended to amuse, and appropriately irritating to those whom it wants to annoy.

But the most noticeable characteristic of the verse of our present moment is its dislike of the aloofness generally associated with English poetry. About twice a century language consolidates: phrases which were once soft and new harden with use; words once of a ringing beauty become dry and hollow through excessive repetition. This state of language is not much noticed by people who have no special use for it beyond the expression of daily needs. Moreover, they make new colloquial words for themselves as required without forethought or difficulty. Poets, however, must consciously search for new words, and a tired condition of their language is to them a great difficulty. The Victorians were absolute spendthrifts of words: no vocabulary could keep pace with their recklessness; they bequeathed a language[Pg 8] almost ruined for sentimental purposes—words and phrases had acquired either such an aloofness that for a long time no one any more would trouble to reach up to them, or had become so thin and common that to use them would have been something like hack-sawing a piece of cotton.

Now in the anthology which follows we may notice a characteristic escape from these difficulties. Words have been brought down from their high places and compelled into ordinary use. This has been accomplished not so much through any new familiarity with the words themselves as by a certain naturalness in the attitude of the people employing them. Rupert Brooke's "Great Lover" is an example.

In short, these are the chief reasons why present-day poetry is readable and entertaining—that it deals with familiar subjects in a familiar manner; that, in doing so, it uses ordinary words literally and as often as possible; that it is not aloof or pretentious; that it refuses to be bullied by tradition: its style, in fact, is itself.

If an excuse is to be sought for the addition of this one more to the large number of existent collections of recent poetry, let it be in the nature of an explanation rather than an apology. Good, or even representative, poetry requires, in fact, no apology, but where the poems of some thirty-two different[Pg 9] authors have been extracted from their books and placed side by side in one collection, a discussion of the apparent aims of the anthologist may be interesting, and will perhaps lead to a fuller enjoyment of the collection thus produced.

Some readers approach a volume of poems to criticize it, others with the object of gaining pleasure. To give pleasure is assuredly the object of this volume. Moreover, it is adapted to the tastes of almost any age, from ten to ninety, and may be read aloud by grandchild to grandparent as suitably as by grandparent to grandchild. It is an anthology of Poems, not of Names. For instance, though Thomas Hardy is on the list, the lyric chosen to represent him is actually more characteristic of the book itself than of the mind of that great and aged poet. It is, in fact, Christian in atmosphere. It is not a typical specimen of Mr Hardy's style. It shows him in that occasional rather sad mood of regret for a lost superstition. It is not the best of Hardy, but rather a poem admirably suited to the book, which also happens, as by chance, to be by the author of "The Dynasts" and "Satires of Circumstance."

The collection as a whole is modern, and all except eight of its authors are living and writing. Of those eight, five died as soldiers in the European War, and are represented mainly by what is known as 'War poetry.' Otherwise such poetry is fortunately absent. This absence may be justified[Pg 10] by the fact that most of the verse written on the subject of the War turns out, surveyed in cooler blood, to be, as any sound judge of literature must always have known, definitely and unmistakably bad. Much of it is by now, or should be, repudiated by its authors. It was too often "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings"; it too seldom originated from "emotion recollected in tranquillity."

Rupert Brooke's sonnets "The Dead" and "The Soldier" were popular almost from their first publication. They belong undoubtedly to the best traditions of English poetry. Julian Grenfell's "Into Battle," and, in a lesser, degree, the "Home Thoughts from Laventie" of Edward Wyndham Tennant, have acquired popularity among a larger number of folk than can be included in the general term 'literary circles.' Neither of the composers of these verses was a professional poet. Both were men of attractive personality and strong feeling, with education, taste, and an occasional impulse to write gracefully. Intrinsically either poem might as easily have been inspired by an Indian frontier raid as by a European war. They do not affect the traditions of English poetry by subject or by form. It will be found, as the years pass, that always fewer 'War poems' can still be read with pleasure, the incidents which gave rise to them having become dim in human memory. And these will not be read because of their association with the Great War, but for their qualities as poems and their power to stir enjoyment or surprise in the reader.

Consider those four melancholy lines by which Edward Thomas is here represented, remarkable for their concentration and for the crowd of images they can suggest. At present the words "where all that passed are dead" alone associate this poem with the War. But death comes through so many causes that twenty years from now a footnote would be needed if it were desired to emphasize that association.

J.E. Flecker's "Dying Patriot," one of his three poems in this book, was written in 1914 in Switzerland, where he was dying of consumption. It is certainly less a 'War poem' than the same author's "War Song of the Saracens."

The verses entitled "A Petition," by R. E. Vernède, are of a different kind. They are written in conventional Henley-Kiplingese, and contain too many incidents of a type of poetic expression that has been used to excess, as "wider than all seas," "to front the world," "quenchless hope" "All that a man might ask thou hast given me, England!" They are, nevertheless, useful in the collection as a set-off against the other 'War poems' and an instance of the more ephemeral type of patriotic verse.

Thus it would appear that the anthologist has displayed wisdom when including in this volume only few pieces that may be associated with the War, and those few (with one exception) on the score of their literary merit, and for no other reason.

Poets of to-day write individually less than their pre-decessors, and most of them are satisfied to publish only a proportion of what they write. None of the eight referred to above left us any great bulk of verse. Four at least, however, are becoming daily better known to the reading public, and of these Rupert Brooke and J. E. Flecker have already their dozens of conscious or unconscious imitators. The form, rhythm, or Eastern atmosphere of Fleckers poetry, the cynicism and wit of Brooke's, recur somewhat diluted in the verse of almost every young undergraduate. Neither Lionel Johnson nor Mary Coleridge has ever become so well known or received so much attention from the average plagiarist, while the reputation of Edward Thomas has been of slow and uncertain growth. Johnsons poetry is too intellectual for the average reader. The wonderful, small lyrics of Mary Coleridge are esoteric rather than general. Nevertheless, this anthology includes, most advisedly, a good poem by Johnson, one indeed which has had a quiet, but strong, influence on modern lyrical poetry, namely, the lines to the statue of King Charles at Charing Cross, and also a charming impression by Mary Coleridge.

"Street Lanterns" is a good example of that poetry of close observation to which reference has already been made. It is a small, careful description of a London scene. It assumes that the reader has observed as much, and that he[Pg 13] will enjoy to be reminded and brought back for a moment in imagination to autumn and street-mending. The advocate of 'big themes' will inevitably condemn such verse, for the poet has aimed at neither size nor grandeur, has indeed sought rather to diminish her subject than enlarge it.

This anthology, it has been remarked above, is one rather of particular poems than of well-known authors. Several names of repute are not to be found in the index. William Watson is only represented by "April," a little catch that might come to any man of feeling on a spring walk. To think in terms of these verses is at once not to mind having left an umbrella at home. Hilaire Belloc gives a sharp impression of early rising; he also sings in a great voice all the glories of his favourite part of England. W. H. Davies brings sheep across the Atlantic, and he talks to a kingfisher. Mrs Meynell contributes "The Shepherdess," that well-known description of a fine and serene mind, also two London poems, of which one is the lovely "November Blue." John Masefield is not to be read in his best style, but the three poems we find here are thoroughly English, full of the love of the island soil and of its sea, and are probably in the book for that reason. So much for some of the well-known contributors. Side by side with them we find the unknown name of H. H. Abbott, whose "Black and White" is a sketch of remarkable clarity and interest.

Death, so favourite a subject with poets, is seldom allowed to figure in this book. Betsey-Jane would insist on going to Heaven, but is told, in the charming verses by Helen Parry Eden, that it simply "would not do." The whole book is too full of pleasure and the experience of being alive: Betsey-Jane should read it. She might remember all her life the advice given on page 117, and be saved hundreds of pounds in lawyers' bills when she is grown up.

Let the reader turn to page 114. Here is the style in which good poetry prefers to teach, and by which it achieves more in eleven lines than a Martin Tupper in 11,000. Mr Pepler has written down only one sentence, charmingly improved by a series of most natural rhymes. It is a very nasty hit at the lawyer. He does not tell him he is not a 'gentleman', or anything so strong as that. He pays him what might be taken for a compliment. He assumes that he does understand his own job. Then he enumerates the things he does not understand. He attaches no blame: he makes a statement only; one that the lawyer certainly will not think worth arguing about, but that his client may advisedly take to heart.

Ralph Hodgson's "Stupidity Street" argues in somewhat the same manner. It does not suggest that anyone should become vegetarian, or that it is wrong to kill birds. It names a street and gives a reason for doing so. It is an angry little Poem, but impersonal.

"The Bells of Heaven," by the same author, simply chances[Pg 15] a hint that something might happen if something else did. It is a suggestion only, but made by one who knows what he thinks, and how to think it. Into a few lines a whole philosophy is concentrated.

Thus Pepler or Ralph Hodgson nudge peoples arms and draw attention to traditional stupidities.

Walter De la Mare puts the children to sleep with "Nod," or bewitches them with the Mad Prince's Song; or he takes us to an Arabia which never existed, but is one of those countries more beautiful than any we know, and therefore we love to imagine it.

Look at that full moon on page 53, which Dick saw "one night." Here is the possible experience of man, woman, child, dog, fox, bear—or even nightingale—all concentrated into the shortest and plainest account of something that happened to Dick. He and Betsey-Jane, though quite different in kind, belong to the same world. Betsey-Jane is plainly more romantic than Dick.

But, talking of the moon, we may turn back to Mr Chesterton on page 36. Here we find something incongruous in the collection: a poem that wishes deliberately to strike a note. The donkey is a much better fellow than Mr Chesterton seems to think: he does not ask for glorification, nor would he utter that boast of the last two lines. Would a man not rather "go with the wild asses to Paradise" than have the case for the donkey pleaded before him in this obtrusive manner?

Turn back four pages and you will find:

For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance,

And the merry love the fiddle,

And the merry love to dance.

This, by W. B. Yeats, represents a much pleasanter type of thought. In these verses of the Irish poet we have the gaiety of a man who, knowing all about religion, can afford not to be sentimental. And here is the spirit of the book.

The happiness of those who love the earth is so different from the pleasure by proxy of those that abide it in the idea of going to some Heaven afterward. Mr Yeats' "Fiddler of Dooney" is that type of fellow who accepts the symbolism of a national religion only in so far as it may help him to enjoy the condition of being alive. And in his "Lake Isle of Innisfree" he imagines a Paradise which is of the earth only. And he takes you there by reason of his own longing.

This anthology, as a whole, is romantic ; its language is simple; its philosophy is that of everyday life, and is entirely undisturbing. It contains a large proportion of poems by authors who write more particularly for children, such as P. R. Chalmers, Rose Fyleman, Queenie Scott-Hopper, and Marion St John Webb, or of children's poems by authors who do not actually specialize in that style, such as "The Ragwort,"[Pg 17] by Frances Cornford; "Cradle Song," by Sarojini Naidu; "Check," by James Stephens, and others. Two of its authors remain necessarily unmentioned here, namely, the compiler of the book and the writer of this Introduction.

Some people make it their business to pick anthologies to pieces, and they seem to enjoy themselves. "Why is this included?" they cry; "Why is that left out?"—a form of criticism nearly always beside the point. Inclusion or exclusion is in the taste and discretion of the anthologist.

This Introduction may, it is hoped, stimulate the reader of the poems which follow to think about them carefully in their relation to each other, and in their relation to English poetry as a whole. For though it has frequently been emphasized that the object of poetry (and particularly of lyrical poetry) is to give pleasure, it should nevertheless be added that intellectual pleasure cannot be gathered at random, or without certain preparation of the mind to receive it.

HAROLD MONRO

For permission to use copyright poems the Editor is indebted to :

The Authors—H. H. Abbott, Hilaire Belloc, P. R. Chalmers, G. K. Chesterton, Frances Cornford, W. H. Davies, Walter De la Mare, John Drinkwater, Rose Fyleman, W. W. Gibson, Robert Graves, Ralph Hodgson, Teresa Hooley, Margaret Mackenzie, Irene R. McLeod, John Masefield, Alice Meynell, Harold Monro, Sarojini Naidu, H. D. C. Pepler, James Stephens, Sir William Watson, Marion St John Webb, and W. B. Yeats.

The Literary Executors of Rupert Brooke, Mary E. Coleridge (Sir Henry Newbolt), James Elroy Flecker (Mrs Flecker), Julian Grenfell (Lady Desborough), Lionel Johnson (Mr Elkin Mathews), Edward Wyndham Tennant (Lady Glenconner), Edward Thomas (Messrs Selwyn and Blount), R. E. Vernède.

And the following Publishers, in respect of the poems selected :

Messrs Burns and Oates, Ltd.

Alice Meynell: Collected Poems.

Messrs Constable and Co., Ltd.

Walter De la Mare: The Listeners, Peacock Pie.

Messrs J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd.

[Pg 20]G. K. Chesterton: The Wild Knight.

Messrs Duckworth and Co.

Hilaire Belloc: Verses.

Mr A. C. Fifield

W. H. Davies: Collected Poems.

Messrs George G. Harrap and Co., Ltd.

E. J. Brady: The House of the Winds.

Queenie Scott-Hopper: Pull the Bobbin!

Marion St John Webb: The Littlest One.

Mr W. Heinemann, London, and the John Lane Company, New York

Sarojini Naidu: The Golden Threshold.

Messrs Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston

John Drinkwater: Poems by John Drinkwater.

Mr John Lane, London, and the John Lane Company, New York

Helen Parry Eden Bread and Circuses.

Edward Wyndham Tennant, by Pamela Glenconner.

Messrs Macmillan and Co., Ltd., London, and the Macmillan Company, New York

W. W. Gibson: Whin.

Ralph Hodgson: Poems.

J. Stephens: The Adventures of Seumas Beg, Songs from the Clay.

W. B. Yeats: Poems: Second Series.

The Macmillan Company, New York

John Masefield: Ballads and Poems.

Messrs Maunsel and Co.

P. R. Chalmers: Green Days and Blue Days.

Messrs Methuen and Co., Ltd.

Rose Fyleman: Fairies and Chimneys, The Fairy Green.

The Poetry Bookshop

H. H. Abbott: Black and White.

Frances Cornford: Spring Morning.

[Pg 21]R. Graves: Over the Brazier.

Messrs Sands and Co.

M. Mackenzie: The Station Platform, and Other Poems.

Mr Martin Seeker

J. E. Flecker: Collected Poems.

Francis Brett Young: Poems, 1916-1918.

Messrs Selwyn and Blount, London, and Messrs Henry Holt and Company, New York

Edward Thomas: Poems.

Messrs Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd.

J. Redwood Anderson: Walls and Hedges.

John Drinkwater: Swords and Ploughshares.

Messrs Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd., and the John Lane Company, New York

Rupert Brooke: 1914, and Other Poems.

Messrs T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd.

W. B. Yeats: Poems.

ARRANGED UNDER NAMES OF AUTHORS

ABBOTT, H. H.

Black and White 126

ANDERSON, J. REDWOOD

The Bridge 118

BELLOC, HILAIRE

The Early Morning 37

The South Country 38

BRADY, E. J.

A Ballad of the Captains 47

BROOKE, RUPERT

The Dead 60

The Great Lover 61

The Soldier 65

[Pg 24]

CHALMERS, P. R.

If I had a Broomstick 74

Roundabouts and Swings 75

CHESTERTON, G. K.

The Donkey 36

COLERIDGE, MARY E.

Street Lanterns 116

CORNFORD, FRANCES

In France 71

The Ragwort 72

DAVIES, W. H.

The Kingfisher 85

Sheep 86

DE LA MARE, WALTER

Arabia 51

Full Moon 53

Nod 54

The Song of the Mad Prince 56

DRINKWATER, JOHN

A Town Window 78

EDEN, HELEN PARRY

To Betsey-Jane, on her Desiring to go

[Pg 25]

Incontinently to Heaven 117

FLECKER, JAMES E.

Brumana 79

The Dying Patriot 80

November Eves 82

FYLEMAN, ROSE

Alms in Autumn 105

I Don't Like Beetles 107

Wishes 108

GIBSON, W. W.

Sweet as the Breath of the Whin 113

GRAVES, ROBERT

Star-Talk 83

GRENFELL, JULIAN

Into Battle 91

HARDY, THOMAS

The Oxen 128

HODGSON, RALPH

The Bells of Heaven 99

The Song of Honour 100

Stupidity Street 102

HOOLEY, TERESA

Sea-Foam 123

JOHNSON, LIONEL

By the Statue of King Charles at

[Pg 26]

Charing Cross 66

MACKENZIE, MARGARET

To the Coming Spring 103

MCLEOD, IRENE R.

Lone Dog 73

MASEFIELD, JOHN

Sea Fever 41

Tewkesbury Road 43

The West Wind 45

MEYNELL, ALICE

A Dead Harvest 57

November Blue 58

The Shepherdess 59

MONRO, HAROLD

Overheard on a Saltmarsh 94

A Flower is Looking through the Ground 96

Man Carrying Bale 97

NAIDU, SAROJINI

Cradle-Song 35

PEPLER, H. D. C.

The Law the Lawyers Know About 114

SCOTT-HOPPER, QUEENIE

Very Nearly! 109

[Pg 27]

What the Thrush Says 110

STEPHENS, JAMES

Check 69

When the Leaves Fall 70

TENNANT, E. W.

Home Thoughts in Laventie 88

THOMAS, E.

The Cherry Trees 98

VERNÈDE, R. E.

A Petition 124

WALTERS, L. D'O.

All is Spirit and Part of Me 115

WATSON, SIR WILLIAM

April 31

WEBB, MARION ST JOHN

The Sunset Garden 112

YEATS, W. B.

The Fiddler of Dooney 32

The Lake Isle of Innisfree 34

YOUNG, FRANCIS BRETT

February 121

The Lake Isle of Innisfree. Frontispiece

April 31

The Fiddler of Dooney 32

Cradle-Song 35

The Donkey 36

Sea Fever 41

A Ballad of the Captains 47,48

Arabia 51

The Song of the Mad Prince 56

The Shepherdess 59

The Dead 60

The Great Lover 62, 64

If I had a Broomstick 74

[Pg 30]

The Dying Patriot80, 82

Star-Talk 84

Overheard on a Saltmarsh 94

To the Coming Spring 103

Alms in Autumn 106

Very Nearly! 109

All is Spirit and Part of Me 115

Black and White 126

APRIL

April, April,

Laugh thy girlish laughter;

Then, the moment after,

Weep thy girlish tears!

April, that mine ears

If I tell thee, sweetest,

All my hopes and fears,

April, April,

Laugh thy golden laughter,

But, the moment after,

Weep thy golden tears.

WILLIAM WATSON

THE FIDDLER OF DOONEY

When I play on my fiddle in Dooney,

Folk dance like a wave of the sea;

My cousin is priest in Kilvarnet,

My brother in Moharabuiee.

I passed my brother and cousin:

They read in their books of prayer;

I read in my book of songs

I bought at the Sligo fair.

When we come at the end of time,

To Peter sitting in state,

He will smile on the three old spirits,

But call me first through the gate;

For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance,

And the merry love the fiddle,

And the merry love to dance:

And when the folk there spy me,

They will all come up to me,

With "Here is the fiddler of Dooney!"

And dance like a wave of the sea.

W. B. YEATS

THE LAKE ISLE OF INNISFREE

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight's all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet's wings.

I will arise and go now, for always, night and day,

I hear lake-water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart's core.

W. B. YEATS

CRADLE-SONG

From groves of spice,

O'er fields of rice,

Athwart the lotus-stream,

I bring for you,

Aglint with dew,

A little lovely dream.

Sweet, shut your eyes,

The wild fire-flies

Dance through the fairy neem;[1]

From the poppy-bole

For you I stole

A little lovely dream.

Dear eyes, good-night,

In golden light

The stars around you gleam;

On you I press

With soft caress

A little lovely dream.

SAROJINI NAIDU

[1] A lilac-tree (Hindustani).

THE DONKEY

When fishes flew and forests walked

And figs grew upon thorn,

Some moment when the moon was blood

Then surely I was born;

With monstrous head and sickening cry

And ears like errant wings,

The devil's walking parody

On all four-footed things.

The tattered outlaw of the earth,

Of ancient crooked will;

Starve, scourge, deride me: I am dumb,

I keep my secret still.

Fools! For I also had my hour;

One far fierce hour and sweet:

There was a shout about my ears,

And palms before my feet.

G. K. CHESTERTON

THE EARLY MORNING

The moon on the one hand, the dawn on the other:

The moon is my sister, the dawn is my brother.

The moon on my left and the dawn on my right.

My brother, good morning: my sister, good night.

HILAIRE BELLOC

THE SOUTH COUNTRY

When I am living in the Midlands

That are sodden and unkind,

I light my lamp in the evening:

My work is left behind;

And the great hills of the South Country

Come back into my mind.

The great hills of the South Country

They stand along the sea;

And it's there walking in the high woods

That I could wish to be,

And the men that were boys when I was a boy

Walking along with me.

The men that live in North England

I saw them for a day:

Their hearts are set upon the waste fells,

Their skies are fast and grey;

From their castle-walls a man may see

[Pg 39]The mountains far away.

The men that live in West England

They see the Severn strong,

A-rolling on rough water brown

Light aspen leaves along.

They have the secret of the Rocks,

And the oldest kind of song.

But the men that live in the South Country

Are the kindest and most wise,

They get their laughter from the loud surf,

And the faith in their happy eyes

Comes surely from our Sister the Spring

When over the sea she flies;

The violets suddenly bloom, at her feet,

She blesses us with surprise.

I never get between the pines

But I smell the Sussex air;

Nor I never come on a belt of sand

But my home is there.

And along the sky the line of the Downs

So noble and so bare.

A lost thing could I never find,

[Pg 40]Nor a broken thing mend:

And I fear I shall be all alone

When I get towards the end.

Who will be there to comfort me

Or who will be my friend?

I will gather and carefully make my friends

Of the men of the Sussex Weald,

They watch the stars from silent folds,

They stiffly plough the field.

By them and the God of the South Country

My poor soul shall be healed.

If I ever become a rich man,

Or if ever I grow to be old,

I will build a house with deep thatch

To shelter me from the cold,

And there shall the Sussex songs be sung

And the story of Sussex told.

I will hold my house in the high wood

Within a walk of the sea,

And the men that were boys when I was a boy

Shall sit and drink with me.

HILAIRE BELLOC

SEA FEVER

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel's kick and the wind's song and the white sail's shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea's face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray "and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

[Pg 42]I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gipsy life,

To the gull's, way and the whale's way where the wind's like a whetted

knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick's over.

JOHN MASEFIELD

TEWKESBURY ROAD

It is good to be out on the road, and going one knows not where,

Going through meadow and village, one knows not whither nor why;

Through the grey light drift of the dust, in the keen cool rush

of the air,

Under the flying white clouds, and the broad blue lift of the sky.

And to halt at the chattering brook, in the tall green fern at the brink

Where the harebell grows, and the gorse, and the foxgloves purple and

white;

Where the shy-eyed delicate deer come down in a troop to drink

When the stars are mellow and large at the coming on of the night.

[Pg 44]O, to feel the beat of the rain, and the homely smell of the earth,

Is a tune for the blood to jig to, a joy past power of words;

And the blessed green comely meadows are all a-ripple with mirth

At the noise of the lambs at play and the dear wild cry of the birds.

JOHN MASEFIELD

THE WEST WIND

It's a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds' cries;

I never hear the west wind but tears are in my eyes.

For it comes from the west lands, the old brown hills,

And April's in the west wind, and daffodils.

It's a fine land, the west land, for hearts as tired as mine,

Apple orchards blossom there, and the air's like wine.

There is cool green grass there, where men may lie at rest,

And the thrushes are in song there, fluting from the nest.

"Will you not come home, brother? You have been long away.

It's April, and blossom time, and white is the spray:

And bright is the sun, brother, and warm is the rain,

[Pg 46]Will you not come home, brother, home to us again?

The young corn is green, brother, where the rabbits run;

It's blue sky, and white clouds, and warm rain and sun.

It's song to a man's soul, brother, fire to a man's brain,

To hear the wild bees and see the merry spring again.

Larks are singing in the west, brother, above the green wheat,

So will you not come home, brother, and rest your tired feet?

I've a balm for bruised hearts, brother, sleep for aching eyes,"

Says the warm wind, the west wind, full of birds' cries.

It's the white road westwards is the road I must tread

To the green grass, the cool grass, and rest for heart and head,

To the violets and the brown brooks and the thrushes' song

In the fine land, the west land, the land where I belong.

JOHN MASEFIELD

A BALLAD OF THE CAPTAINS

Where are now the Captains

Of the narrow ships of old—

Who with valiant souls went seeking

For the Fabled Fleece of Gold;

In the clouded Dusk of Ages,

In the Dawn of History;

When the ringing songs of Homer

First re-echoed o'er the Sea?

Oh, the Captains lie a-sleeping

Where great iron hulls are sweeping

Out of Suez in their pride;

And they hear not, and they heed not,

And they know not, and they need not

In their deep graves far and wide.

Where are now the Captains

Who went blindly through the Strait,

With a tribute to Poseidon,

[Pg 48]A libation poured to Fate?

They were heroes giant-hearted,

That with Terrors, told and sung,

Like blindfolded lions grappled,

When the World was strange and young.

Oh, the Captains brave and daring,

With their grim old crews are faring

Where our guiding beacons gleam;

And the homeward liners o'er them—

All the charted seas before them—

Shall not wake them as they dream.

Where are now the Captains

From bold Nelson back to Drake,

Who came drumming up the Channel,

Haling prizes in their wake?

Where are England's fighting Captains

Who, with battle-flags unfurled,

Went a-rieving all the rievers

O'er the waves of all the world?

Oh, these Captains, all confiding

In the strong right hand, are biding

In the margins, on the Main;

They are shining bright in story,

They are sleeping deep in glory,

On the silken lap of Fame.

Here are now the Captains

Who regarded not the tears

Of the captured Christian maidens

Carried, weeping, to Algiers?

Yes, the swarthy Moorish Captains,

Storming wildly 'cross the Bay,

With a dead hidalgo's daughter.

As a dower for the Dey?

Oh, those cruel Captains never

Shall sweet lovers more dissever,

On their forays as they roll;

Or the mad Dons curse them vainly,

As their baffled ships, ungainly,

Heel them, jeering, to the Mole.

Where are now the Captains

Of those racing, roaring days,

Who of knowledge and of courage,

Drove the clippers on their ways—

To the furthest ounce of pressure,

To the latest stitch of sail,

'Carried on' before the tempest

[Pg 50]Till the waters lapped the rail?

Oh, the merry, manly skippers

Of the traders and the clippers,

They are sleeping East and West,

And the brave blue seas shall hold them,

And the oceans five enfold them

In the havens where they rest.

Where are now the Captains

Of the gallant days agone?

They are biding in their places,

And the Great Deep bears no traces

Of their good ships passed and gone.

They are biding in their places,

Where the light of God's own grace is,

And the Great Deep thunders on.

Yea, with never port to steer for,

And with never storm to fear for,

They are waiting wan and white,

And they hear no more the calling

Of the watches, or the falling

Of the sea rain in the night.

E. J. BRADY

ARABIA

Far are the shades of Arabia,

Where the Princes ride at noon,

'Mid the verdurous vales and thickets,

Under the ghost of the moon;

And so dark is that vaulted purple

Flowers in the forest rise

And toss into blossom 'gainst the phantom stars

Pale in the noonday skies.

Sweet is the music of Arabia

In my heart, when out of dreams

I still in the thin clear mirk of dawn

Descry her gliding streams;

Hear her strange lutes on the green banks

Ring loud with the grief and delight

Of the demi-silked, dark-haired Musicians

In the brooding silence of night.

They haunt me—her lutes and her forests;

No beauty on earth I see

But shadowed with that dream recalls

[Pg 52]Her loveliness to me:

Still eyes look coldly upon me,

Cold voices whisper and say—

"He is crazed with the spell of far Arabia,

They have stolen his wits away."

WALTER DE LA MARE

FULL MOON

One night as Dick lay half asleep,

Into his drowsy eyes

A great still light began to creep

From out the silent skies.

It was the lovely moon's, for when

He raised his dreamy head,

Her rays of silver filled the pane

And streamed across his bed.

So, for awhile, each gazed at each—

Dick and the solemn moon—

Till, climbing slowly on her way,

She vanished, and was gone.

WALTER DE LA MARE

NOD

Softly along the road of evening,

In a twilight dim with rose,

Wrinkled with age, and drenched with dew,

Old Nod, the shepherd, goes.

His drowsy flock streams on before him,

Their fleeces charged with gold,

To where the sun's last beam leans low

On Nod the shepherd's fold.

The hedge is quick and green with briar,

From their sand the conies creep;

And all the birds that fly in heaven

Flock singing home to sleep.

His lambs outnumber a noon's roses,

Yet, when night's shadows fall,

His blind old sheep-dog, Slumber-soon,

[Pg 55]Misses not one of all.

His are the quiet steeps of dreamland,

The waters of no-more-pain,

His ram's bell rings 'neath an arch of stars,

"Rest, rest, and rest again."

WALTER DE LA MARE

THE SONG OF THE MAD PRINCE

Who said, "Peacock Pie"?

The old King to the sparrow:

Who said, "Crops are ripe"?

Rust to the harrow:

Who said, "Where sleeps she now?

Where rests she now her head,

Bathed in eve's loveliness"?

That's what I said.

Who said, "Ay, mum's the word"?

Sexton to willow:

Who said, "Green dusk for dreams,

Moss for a pillow"?

Who said, "All Time's delight

Hath she for narrow bed;

Life's troubled bubble broken"?

That's what I said.

WALTER DE LA MARE

A DEAD HARVEST

IN KENSINGTON GARDENS

Along the graceless grass of town

They rake the rows of red and brown,—

Dead leaves, unlike the rows of hay

Delicate, touched with gold and grey,

Raked long ago and far away.

A narrow silence in the park,

Between the lights a narrow dark.

One street rolls on the north; and one,

Muffled, upon the south doth run;

Amid the mist the work is done.

A futile crop! for it the fire

Smoulders, and, for a stack, a pyre.

So go the town's lives on the breeze,

Even as the sheddings of the trees;

Bosom nor barn is filled with these.

ALICE MEYNELL

NOVEMBER BLUE

The golden tint of the electric lights seems to give a complementary

colour to the air in the early evening.

Essay on London

O heavenly colour, London town

Has blurred it from her skies;

And, hooded in an earthly brown,

Unheaven'd the city lies.

No longer standard-like this hue

Above the broad road flies;

Nor does the narrow street the blue

Wear, slender pennon-wise.

But when the gold and silver lamps

Colour the London dew,

And, misted by the winter damps,

The shops shine bright anew—

Blue comes to earth, it walks the street,

It dyes the wide air through;

A mimic sky about their feet,

The throng go crowned with blue.

ALICE MEYNELL

THE SHEPHERDESS

She walks—the lady of my delight—

A shepherdess of sheep.

Her flocks are thoughts. She keeps them white;

She guards them from the steep;

She feeds them on the fragrant height,

And folds them in for sleep.

She roams maternal hills and bright,

Dark valleys safe and deep,

Into that tender breast at night

The chastest stars may peep.

She walks—the lady of my delight—

A shepherdess of sheep.

She holds her little thoughts in sight,

Though gay they run and leap.

She is so circumspect and right;

She has her soul to keep.

She walks—the lady of my delight—

A shepherdess of sheep.

ALICE MEYNELL

THE DEAD

Blow out, you bugles, over the rich Dead!

There's none of these so lonely and poor of old,

But, dying, has made us rarer gifts than gold.

These laid the world away; poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene,

That men call age; and those who would have been,

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.

Blow, bugles, blow! They brought us, for our dearth,

Holiness, lacked so long, and Love, and Pain.

Honour has come back, as a king, to earth,

And paid his subjects with a royal wage;

And Nobleness walks in our ways again;

And we have come into our heritage.

RUPERT BROOKE

THE GREAT LOVER

I have been so great a lover: filled my days

So proudly with the splendour of Love's praise,

The pain, the calm, and the astonishment,

Desire illimitable, and still content,

And all dear names men use, to cheat despair,

For the perplexed and viewless streams that bear

Our hearts at random down the dark of life.

Now, ere the unthinking silence on that strife

Steals down, I would cheat drowsy Death so far,

My night shall be remembered for a star

That outshone all the suns of all men's days.

Shall I not crown them with immortal praise

Whom I have loved, who have given me, dared with me

High secrets, and in darkness knelt to see

The inenarrable godhead of delight?

Love is a flame;—we have beaconed the world's night.

A city:—and we have built it, these and I.

[Pg 62]An emperor:—we have taught the world to die.

So, for their sakes I loved, ere I go hence,

And the high cause of Love's magnificence,

And to keep loyalties young, I'll write those names

Golden for ever, eagles, crying flames,

And set them as a banner, that men may know,

To dare the generations, burn, and blow

Out on the wind of Time, shining and streaming....

These I have loved:

White plates and cups, clean-gleaming,

Ringed with blue lines; and feathery, faery dust;

Wet roofs, beneath the lamp-light; the strong crust

Of friendly bread; and many-tasting food;

Rainbows; and the blue bitter smoke of wood;

And radiant raindrops couching in cool flowers;

And flowers themselves, that sway through sunny hours,

Dreaming of moths that drink them under the moon;

Then, the cool kindliness of sheets, that soon

Smooth away trouble; and the rough male kiss

Of blankets; grainy wood; live hair that is

Shining and free; blue-massing clouds; the keen

Unpassioned beauty of a great machine;

The benison of hot water; furs to touch;

The good smell of old clothes; and other such—

The comfortable smell of friendly fingers,

Hair's fragrance, and the musty reek that lingers

About dead leaves and last year's ferns....

Dear names,

And thousand other throng to me! Royal flames;

Sweet water's dimpling laugh from tap or spring;

Holes in the ground; and voices that do sing;

Voices in laughter, too; and body's pain,

Soon turned to peace; and the deep-panting train;

Firm sands; the little dulling edge of foam

That browns and dwindles as the wave goes home;

And washen stones, gay for an hour; the cold

Graveness of iron; moist black earthen mould;

Sleep; and high places; footprints in the dew;

And oaks; and brown horse-chestnuts, glossy-new;—

And new-peeled sticks; and shining pools on grass;—

All these have been my loves. And these shall pass.

Whatever passes not, in the great hour,

Nor all my passion, all my prayers, have power

To hold them with me through the gate of Death.

They'll play deserter, turn with the traitor breath,

Break the high bond we made, and sell Love's trust

And sacramented covenant to the dust.

—Oh, never a doubt but, somewhere, I shall wake,

[Pg 64]

And give what's left of love again, and make

New friends, now strangers....

But the best I've known,

Stays here, and changes, breaks, grows old, is blown

About the winds of the world, and fades from brains

Of living men, and dies.

Nothing remains.

O dear my loves, O faithless, once again

This one last gift I give: that after men

Shall know, and later lovers, far-removed,

Praise you, "All these were lovely"; say, "He loved."

RUPERT BROOKE

THE SOLDIER

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

RUPERT BROOKE

BY THE STATUE OF KING CHARLES AT CHARING CROSS

Sombre and rich, the skies;

Great glooms, and starry plains.

Gently the night wind sighs;

Else a vast silence reigns.

The splendid silence clings

Around me: and around

The saddest of all kings

Crowned, and again discrowned.

Comely and calm, he rides

Hard by his own Whitehall:

Only the night wind glides:

No crowds, nor rebels, brawl.

Gone, too, his Court; and yet,

The stars his courtiers are:

Stars in their stations set;

[Pg 67]And every wandering star.

Alone he rides, alone,

The fair and fatal king:

Dark night is all his own,

That strange and solemn thing.

Which are more full of fate:

The stars; or those sad eyes?

Which are more still and great:

Those brows; or the dark skies?

Although his whole heart yearn

In passionate tragedy:

Never was face so stern

With sweet austerity.

Vanquished in life, his death

By beauty made amends:

The passing of his breath

Won his defeated ends.

Brief life and hapless? Nay:

Through death, life grew sublime.

Speak after sentence? Yea:

And to the end of time.

Armoured he rides, his head

[Pg 68]Bare to the stars of doom:

He triumphs now, the dead,

Beholding London's gloom.

Our wearier spirit faints,

Vexed in the world's employ:

His soul was of the saints;

And art to him was joy.

King, tried in fires of woe

Men hunger for thy grace:

And through the night I go,

Loving thy mournful face.

Yet when the city sleeps;

When all the cries are still:

The stars and heavenly deeps

Work out a perfect will.

LIONEL JOHNSON

CHECK

The night was creeping on the ground;

She crept and did not make a sound

Until she reached the tree, and then

She covered it, and stole again

Along the grass beside the wall.

I heard the rustle of her shawl

As she threw blackness everywhere

Upon the sky and ground and air,

And in the room where I was hid:

But no matter what she did

To everything that was without,

She could not put my candle out.

So I stared at the night, and she

Stared back solemnly at me.

JAMES STEPHENS

WHEN THE LEAVES FALL

When the leaves fall off the trees

Everybody walks on them:

Once they had a time of ease

High above, and every breeze

Used to stay and talk to them.

Then they were so debonair

As they fluttered up and down;

Dancing in the sunny air,

Dancing without knowing there

Was a gutter in the town.

Now they have no place at all!

All the home that they can find

Is a gutter by a wall,

And the wind that waits their fall

Is an apache of a wind.

JAMES STEPHENS

IN FRANCE

The poplars in the fields of France

Are golden ladies come to dance;

But yet to see them there is none

But I and the September sun.

The girl who in their shadow sits

Can only see the sock she knits;

Her dog is watching all the day

That not a cow shall go astray.

The leisurely contented cows

Can only see the earth they browse;

Their piebald bodies through the grass

With busy, munching noses pass.

Alone the sun and I behold

Processions crowned with shining gold—

The poplars in the fields of France,

Like glorious ladies come to dance.

FRANCES CORNFORD

THE RAGWORT

The thistles on the sandy flats

Are courtiers with crimson hats;

The ragworts, growing up so straight,

Are emperors who stand in state,

And march about, so proud and bold,

In crowns of fairy-story gold.

The people passing home at night

Rejoice to see the shining sight,

They quite forget the sands and sea

Which are as grey as grey can be,

Nor ever heed the gulls who cry

Like peevish children in the sky.

FRANCES CORNFORD

LONE DOG

I'm a lean dog, a keen dog, a wild dog, and lone;

I'm a rough dog, a tough dog, hunting on my own;

I'm a bad dog, a mad dog, teasing silly sheep;

I love to sit and bay the moon, to keep fat souls from sleep.

I'll never be a lap dog, licking dirty feet,

A sleek dog, a meek dog, cringing for my meat,

Not for me the fireside, the well-filled plate,

But shut door, and sharp stone, and cuff, and kick, and hate.

Not for me the other dogs, running by my side,

Some have run a short while, but none of them would bide.

O mine is still the lone trail, the hard trail, the best,

Wide wind, and wild stars, and the hunger of the quest!

IRENE R. McLEOD

IF I HAD A BROOMSTICK

If I had a broomstick, and knew how to ride it,

I'd fly through the windows when Jane goes to tea,

And over the tops of the chimneys I'd guide it,

To lands where no children are cripples like me;

I'd run on the rocks with the crabs and the sea,

Where soft red anemones close when you touch;

If I had a broomstick, and knew how to ride it,

If I had a broomstick—instead of a crutch!

PATRICK R. CHALMERS

ROUNDABOUTS AND SWINGS

It was early last September nigh to Framlin'amon-Sea,

An''twas Fair-day come to-morrow, an' the time was after tea,

An' I met a painted caravan adown a dusty lane,

A Pharaoh with his waggons cornin' jolt an' creak an' strain;

A cheery cove an' sunburnt, bold o' eye and wrinkled up,

An' beside him on the splashboard sat a brindled tarrier pup,

An' a lurcher wise as Solomon an' lean as fiddle-strings

Was joggin' in the dust along is roundabouts and swings.

"Goo'-day," said'e; "Goo'-day," said I; "an' 'ow d'you find things go,

[Pg 76]An' what's the chance o' millions when you runs a travellin' show?"

"I find," said'e, "things very much as 'ow I've always found,

For mostly they goes up and down or else goes round and round."

Said'e, "The job's the very spit o' what it always were,

It's bread and bacon mostly when the dog don't catch a'are;

But lookin' at it broad, an' while it ain't no merchant king's,

What's lost upon the roundabouts we pulls up on the swings!

"Goo' luck," said'e; "Goo' luck," said I; "you've put it past a doubt;

An' keep that lurcher on the road, the gamekeepers is out";

'E thumped upon the footboard an' 'e lumbered on again

To meet a gold-dust sunset down the owl-light in the lane;

An' the moon she climbed the'azels, while a night-jar seemed to spin

[Pg 77]That Pharaoh's wisdom o'er again, is sooth of lose-and-win;

For "up an' down an' round," said'e, "goes all appointed things,

An' losses on the roundabouts means profits on the swings!"

PATRICK R. CHALMERS

A TOWN WINDOW

Beyond my window in the night

Is but a drab inglorious street,

Yet there the frost and clean starlight

As over Warwick woods are sweet.

Under the grey drift of the town

The crocus works among the mould

As eagerly as those that crown

The Warwick spring in flame and gold.

And when the tramway down the hill

Across the cobbles moans and rings,

There is about my window-sill

The tumult of a thousand wings.

JOHN DRINKWATER

BRUMANA

Oh shall I never never be home again?

Meadows of England shining in the rain

Spread wide your daisied lawns: your ramparts green

With briar fortify, with blossom screen

Till my far morning—and O streams that slow

And pure and deep through plains and playlands go,

For me your love and all your kingcups store,

And—dark militia of the southern shore,

Old fragrant friends—preserve me the last lines

Of that long saga which you sung me, pines,

When, lonely boy, beneath the chosen tree

I listened, with my eyes upon the sea.

[Continued]

JAMES ELROY FLECKER

THE DYING PATRIOT

Day breaks on England down the Kentish hills,

Singing in the silence of the meadow-footing rills,

Day of my dreams, O day!

I saw them march from Dover, long ago,

With a silver cross before them, singing low,

Monks of Rome from their home where the blue seas break in foam,

Augustine with his feet of snow.

Noon strikes on England, noon on Oxford town,

—Beauty she was statue cold—there's blood upon her gown:

Noon of my dreams, O noon!

Proud and godly kings had built her, long ago

With her towers and tombs and statues all arow,

With her fair and floral air and the love that lingers there,

And the streets where the great men go.

Evening on the olden, the golden sea of Wales,

When the first star shivers and the last wave pales:

O evening dreams!

There's a house that Britons walked in, long ago,

Where now the springs of ocean fall and flow,

And the dead robed in red and sea-lilies overhead

Sway when the long winds blow.

Sleep not, my country: though night is here, afar

Your children of the morning are clamorous for war:

Fire in the night, O dreams!

Though she send you as she sent you, long ago,

South to desert, east to ocean, west to snow,

West of these out to seas colder than the Hebrides I must go

Where the fleet of stars is anchored and the young Star-captains glow.

JAMES ELROY FLECKER

NOVEMBER EVES

November Evenings! Damp and still

They used to cloak Leckhampton hill,

And lie down close on the grey plain,

And dim the dripping window-pane,

And send queer winds like Harlequins

That seized our elms for violins

And struck a note so sharp and low

Even a child could feel the woe.

Now fire chased shadow round the room;

Tables and chairs grew vast in gloom:

We crept about like mice, while Nurse

Sat mending, solemn as a hearse,

And even our unlearned eyes

Half closed with choking memories.

Is it the mist or the dead leaves,

Or the dead men—November eves?

JAMES ELROY FLECKER

STAR-TALK

"Are you awake, Gemelli,

This frosty night?"

"We'll be awake till reveille,

Which is Sunrise," say the Gemelli,

"It's no good trying to go to sleep:

If there's wine to be got we'll drink it deep,

But rest is hopeless to-night,

But rest is hopeless to-night."

'Are you cold too, poor Pleiads,

This frosty night?"

"Yes, and so are the Hyads:

See us cuddle and hug," say the Pleiads,

"All six in a ring: it keeps us warm:

We huddle together like birds in a storm:

It's bitter weather to-night,

It's bitter weather to-night."

"What do you hunt, Orion,

This starry night?"

"The Ram, the Bull and the Lion,

[Pg 84]And the Great Bear," says Orion,

"With my starry quiver and beautiful belt

I am trying to find a good thick pelt

To warm my shoulders to-night,

To warm my shoulders to-night."

"Did you hear that, Great She-bear,

This frosty night?"

"Yes, he's talking of stripping me bare,

Of my own big fur," says the She-bear.

"I'm afraid of the man and his terrible arrow:

The thought of it chills my bones to the marrow,

And the frost so cruel to-night!

And the frost so cruel to-night!"

"How is your trade, Aquarius,

This frosty night?"

"Complaints is many and various,

And my feet are cold," says Aquarius,

"There's Venus objects to Dolphin-scales,

And Mars to Crab-spawn found in my pails,

And the pump has frozen to-night,

And the pump has frozen to-night."

ROBERT GRAVES

THE KINGFISHER

It was the Rainbow gave thee birth,

And left thee all her lovely hues;

And, as her mother's name was Tears,

So runs it in thy blood to choose

For haunts the lonely pools, and keep

In company with trees that weep.

Go you and, with such glorious hues,

Live with proud Peacocks in green parks;

On lawns as smooth as shining glass,

Let every feather show its mark;

Get thee on boughs and clap thy wings

Before the windows of proud kings.

Nay, lovely Bird, thou art not vain;

Thou hast no proud ambitious mind;

I also love a quiet place

That's green, away from all mankind;

A lonely pool, and let a tree

Sigh with her bosom over me.

WILLIAM H. DAVIES

SHEEP

When I was once in Baltimore

A man came up to me and cried,

"Come, I have eighteen hundred sheep,

And we will sail on Tuesday's tide.

"If you will sail with me, young man,

I'll pay you fifty shillings down;

These eighteen hundred sheep I take

From Baltimore to Glasgow town."

He paid me fifty shillings down,

I sailed with eighteen hundred sheep;

We soon had cleared the harbour's mouth,

We soon were in the salt sea deep.

The first night we were out at sea

Those sheep were quiet in their mind;

The second night they cried with fear—

[Pg 87]They smelt no pastures in the wind.

They sniffed, poor things, for their green fields,

They cried so loud I could not sleep:

For fifty thousand shillings down

I would not sail again with sheep.

WILLIAM H. DAVIES

HOME THOUGHTS IN LAVENTIE

Green gardens in Laventie!

Soldiers only know the street

Where the mud is churned and splashed about

By battle-wending feet;

And yet beside one stricken house there is a glimpse of grass,

Look for it when you pass.

Beyond the Church whose pitted spire

Seems balanced on a strand

Of swaying stone and tottering brick

Two roofless ruins stand,

And here behind the wreckage where the back-wall should have been

We found a garden green.

The grass was never trodden on,

[Pg 89]The little path of gravel

Was overgrown with celandine,

No other folk did travel

Along its weedy surface, but the nimble-footed mouse

Running from house to house.

So all among the vivid blades

Of soft and tender grass

We lay, nor heard the limber wheels

That pass and ever pass,

In noisy continuity, until their stony rattle

Seems in itself a battle.

At length we rose up from our ease

Of tranquil happy mind,

And searched the garden's little length

A fresh pleasaunce to find;

And there, some yellow daffodils and jasmine hanging high

Did rest the tired eye.

The fairest and most fragrant

Of the many sweets we found,

Was a little bush of Daphne flower

[Pg 90]

Upon a grassy mound,

And so thick were the blossoms set, and so divine the scent,

That we were well content.

Hungry for Spring I bent my head,

The perfume fanned my face,

And all my soul was dancing

In that lovely little place,

Dancing with a measured step from wrecked and

shattered towns

Away . . . upon the Downs.

I saw green banks of daffodil,

Slim poplars in the breeze,

Great tan-brown hares in gusty March

A-courting on the leas;

And meadows with their glittering streams, and silver

scurrying dace,

Home—what a perfect place!

EDWARD WYNDHAM TENNANT

INTO BATTLE

The naked earth is warm with Spring,

And with green grass and bursting trees

Leans to the sun's gaze glorying,

And quivers in the sunny breeze;

And Life is Colour and Warmth and Light,

And a striving evermore for these;

And he is dead who will not fight;

And who dies fighting has increase.

The fighting man shall from the sun

Take warmth, and life from the glowing earth;

Speed with the light-foot winds to run,

And with the trees to newer birth;

And find, when fighting shall be done,

Great rest, and fullness after dearth.

All the bright company of Heaven

Hold him in their high comradeship,

The Dog-star and the Sisters Seven,

[Pg 92]Orion's Belt and sworded hip.

The woodland trees that stand together,

They stand to him each one a friend,

They gently speak in the windy weather;

They guide to valley and ridges' end.

The kestrel hovering by day,

And the little owls that call by night,

Bid him be swift and keen as they,

As keen of ear, as swift of sight.

The blackbird sings to him, "Brother, brother,

If this be the last song you shall sing

Sing well, for you may not sing another;

Brother, sing."

In dreary, doubtful, waiting hours,

Before the brazen frenzy starts,

The horses show him nobler powers;

O patient eyes, courageous hearts!

And when the burning moment breaks,

And all things else are out of mind,

And only Joy of Battle takes

[Pg 93]Him by the throat, and makes him blind—

Though joy and blindness he shall know,

Not caring much to know, that still,

Nor lead nor steel shall reach him, so

That it be not the Destined Will.

The thundering line of battle stands,

And in the air Death moans and sings;

But Day shall clasp him with strong hands,

And Night shall fold him in soft wings.

JULIAN GRENFELL

OVERHEARD ON A SALTMARSH

Nymph, nymph, what are your beads?

Green glass, goblin. Why do you stare

at them?

Give them me.

No.

Give them me. Give them me.

No.

Then I will howl all night in the reeds,

Lie in the mud and howl for them.

Goblin, why do you love them so?

They are better than stars or water,

Better than voices of winds that sing,

Better than any man's fair daughter,

Your green glass beads on a silver ring.

Hush, I stole them out of the moon.

[Pg 95][Illustration: "GIVE ME YOUR BEADS. I DESIRE THEM. NO."]

Give me your beads. I desire them.

No.

I will howl in a deep lagoon

For your green glass beads, I love them so.

Give them me. Give them.

No.

HAROLD MONRO

A FLOWER IS LOOKING

THROUGH THE GROUND

A flower is looking through the ground,

Blinking at the April weather;

Now a child has seen the flower:

Now they go and play together.

Now it seems the flower will speak,

And will call the child its brother—

But, oh strange forgetfulness!—

They don't recognize each other.

HAROLD MONRO

MAN CARRYING BALE

The tough hand closes gently on the load;

Out of the mind, a voice

Calls 'Lift!' and the arms, remembering well

their work,

Lengthen and pause for help.

Then a slow ripple flows from head to foot

While all the muscles call to one another:

'Lift!' and the bulging bale

Floats like a butterfly in June.

So moved the earliest carrier of bales,

And the same watchful sun

Glowed through his body feeding it with light.

So will the last one move,

And halt, and dip his head, and lay his load

Down, and the muscles will relax and tremble.

Earth, you designed your man

Beautiful both in labour and repose.

HAROLD MONRO

THE CHERRY TREES

The cherry trees bend over and are shedding

On the old road where all that passed are dead,

Their petals, strewing the grass as for a wedding

This early May morn when there is none to wed.

EDWARD THOMAS

THE BELLS OF HEAVEN

'T Would ring the bells of Heaven

The wildest peal for years,

If Parson lost his senses

And people came to theirs,

And he and they together

Knelt down with angry prayers

For tamed and shabby tigers

And dancing dogs and bears,

And wretched, blind pit ponies,

And little hunted hares.

RALPH HODGSON

THE SONG OF HONOUR

I climbed a hill as light fell short,

And rooks came home in scramble sort,

And filled the trees and flapped and fought

And sang themselves to sleep;

An owl from nowhere with no sound

Swung by and soon was nowhere found,

I heard him calling half-way round,

Holloing loud and deep;

A pair of stars, faint pins of light,

Then many a star, sailed into sight,

And all the stars, the flower of night,

Were round me at a leap;

To tell how still the valleys lay

I heard a watch-dog miles away,

And bells of distant sheep.

I heard no more of bird or bell,

The mastiff in a slumber fell,

I stared into the sky,

As wondering men have always done

Since beauty and the stars were one,

[Pg 101]Though none so hard as I.

It seemed, so still the valleys were,

As if the whole world knelt at prayer,

Save me and me alone;

So pure and wide that silence was

I feared to bend a blade of grass,

And there I stood like stone.

[Continued]

RALPH HODGSON

STUPIDITY STREET>

I saw with open eyes

Singing birds sweet

Sold in the shops

For the people to eat,

Sold in the shops of

Stupidity Street.

I saw in vision

The worm in the wheat,

And in the shops nothing

For people to eat;

Nothing for sale in

Stupidity Street.

RALPH HODGSON

TO THE COMING SPRING

O punctual Spring!

We had forgotten in this winter town

The days of Summer and the long, long eves.

But now you come on airy wing,

With busy fingers spilling baby-leaves

On all the bushes, and a faint green down

On ancient trees, and everywhere

Your warm breath soft with kisses

Stirs the wintry air,

And waking us to unimagined blisses.

Your lightest footprints in the grass

Are marked by painted crocus-flowers

And heavy-headed daffodils,

While little trees blush faintly as you pass.

The morning and the night

You bathe with heavenly showers,

And scatter scentless violets on the rounded hills,

Drop beneath leafless woods pale primrose posies.

With magic key, in the new evening light,

[Pg 104]

You are unlocking buds that keep the roses;

The purple lilac soon will blow above the wall

And bended boughs in orchards whitely bloom—

We had forgotten in the Winter's gloom ...

Soon we shall hear the cuckoo call!

MARGARET MACKENZIE

ALMS IN AUTUMN

Spindle-wood, spindle-wood, will you lend me, pray,

A little flaming lantern to guide me on my way?

The fairies all have vanished from the meadow and the glen,

And I would fain go seeking till I find them once again.

Lend me now a lantern that I may bear a light

To find the hidden pathway in the darkness of the night.

Ash-tree, ash-tree, throw me, if you please,

Throw me down a slender branch of russet-gold keys.

I fear the gates of Fairyland may all be shut so fast

That nothing but your magic keys will ever take me past.

I'll tie them to my girdle, and as I go along

[Pg 106]My heart will find a comfort in the tinkle of their song.

Holly-bush, holly-bush, help me in my task,

A pocketful of berries is all the alms I ask :

A pocketful of berries to thread in golden strands

(I would not go a-visiting with nothing in my hands).

So fine will be the rosy chains, so gay, so glossy bright,

They'll set the realms of Fairyland all dancing with delight.

ROSE FYLEMAN

I DON'T LIKE BEETLES

I don't like beetles, tho' I'm sure they're very good,

I don't like porridge, tho' my Nanna says I should;

I don't like the cistern in the attic where I play,

And the funny noise the bath makes when the water runs away.

I don't like the feeling when my gloves are made of silk,

And that dreadful slimy skinny stuff on top of hot milk;

I don't like tigers, not even in a book,

And, I know it's very naughty, but I don't like Cook!

ROSE FYLEMAN

WISHES

I wish I liked rice pudding,

I wish I were a twin,

I wish some day a real live fairy

Would just come walking in.

I wish when I'm at table

My feet would touch the floor,

I wish our pipes would burst next winter,

Just like they did next door.

I wish that I could whistle

Real proper grown-up tunes,

I wish they'd let me sweep the chimneys

On rainy afternoons.

I've got such heaps of wishes,

I've only said a few;

I wish that I could wake some morning

And find they'd all come true!

ROSE FYLEMAN

VERY NEARLY!

I never quite saw fairy-folk

A-dancing in the glade,

Where, just beyond the hollow oak,

Their broad green rings are laid:

But, while behind that oak I hid,

One day I very nearly did!

I never quite saw mermaids rise

Above the twilight sea,

When sands, left wet,'neath sunset skies,

Are blushing rosily:

But—all alone, those rocks amid—

One night I very nearly did!

I never quite saw Goblin Grim

Who haunts our lumber room

And pops his head above the rim

Of that oak chest's deep gloom:

But once—when Mother raised the lid—

I very, very nearly did!

QUEENIE SCOTT-HOPPER

WHAT THE THRUSH SAYS

Come and see! Come and see!"

The Thrush pipes out of the hawthorn-tree:

And I and Dicky on tiptoe go

To see what treasures he wants to show.

His call is clear as a call can be—

And "Come and see!" he says:

"Come and see!"

"Come and see! Come and see!"

His house is there in the hawthorn-tree:

The neatest house that ever you saw,

Built all of mosses and twigs and straw:

The folk who built were his wife and he—

And "Come and see!" he says:

"Come and see!"

"Come and see! Come and see!"

Within this house there are treasures three:

So warm and snug in its curve they lie—

[Pg 111]Like three bright bits out of Spring's blue sky.

We would not hurt them, he knows; not we!

So "Come and see!" he says:

"Come and see!"

"Come and see! Come and see!"

No thrush was ever so proud as he!

His bright-eyed lady has left those eggs

For just five minutes to stretch her legs.

He's keeping guard in the hawthorn-tree,

And "Come and see!" he says:

"Come and see!"

"Come and see! Come and see!"

He has no fear of the boys and me.

He came and shared in our meals, you know,

In hungry times of the frost and snow.

So now we share in his Secret Tree

Where "Come and see!" he says:

"Come and see!"

QUEENIE SCOTT-HOPPER

THE SUNSET GARDEN

I can see from the window a little brown house,

And the garden goes up to the top of the hill.

And the sun comes each day,

And slips down away

At the end of the garden an' sleeps there ... until

The daylight comes climbing up over the hill.

I do wish I lived in the little brown house,

Then at night I'd go out to the garden, an' creep

Up ... up ... then I'd stop,

An' lean over the top,

At the end of the garden, an' so I could peep,

And see what the sun looks like when it's asleep.

MARION ST JOHN WEBB

SWEET AS THE BREATH OF THE WHIN

Sweet as the breath of the whin

Is the thought of my love—

Sweet as the breath of the whin

In the noonday sun—

Sweet as the breath of the whin

In the sun after rain.

Glad as the gold of the whin

Is the thought of my love—

Glad as the gold of the whin

Since wandering's done—

Glad as the gold of the whin

Is my heart, home again.

WILFRID WILSON GIBSON

THE LAW THE LAWYERS KNOW ABOUT

The law the lawyers know about

Is property and land;

But why the leaves are on the trees,

And why the winds disturb the seas,

Why honey is the food of bees,

Why horses have such tender knees,

Why winters come and rivers freeze,

Why Faith is more than what one sees,

And Hope survives the worst disease,

And Charity is more than these,

They do not understand.

H. D. C. PEPLER

ALL IS SPIRIT AND PART OF ME.

A greater lover none can be,

And all is spirit and part of me.

I am sway of the rolling hills,

And breath from the great wide plains;

I am born of a thousand storms,

And grey with the rushing rains;

I have stood with the age-long rocks,

And flowered with the meadow sweet;

I have fought with the wind-worn firs,

And bent with the ripening wheat;

I have watched with the solemn clouds,

And dreamt with the moorland pools;

I have raced with the water's whirl,

And lain where their anger cools;

I have hovered as strong-winged bird,

And swooped as I saw my prey;

I have risen with cold grey dawn,

And flamed in the dying day;

For all is spirit and part of me,

And greater lover none can be.

L. D'O. WALTERS[Pg 116]

STREET LANTERNS

Country roads are yellow and brown.

We mend the roads in London Town.

Never a hansom dare come nigh,

Never a cart goes rolling by.

An unwonted silence steals

In between the turning wheels.

Quickly ends the autumn day,

And the workman goes his way,

Leaving, midst the traffic rude,

One small isle of solitude,

Lit, throughout the lengthy night,

By the little lantern's light.

Jewels of the dark have we,

Brighter than the rustic's be.

Over the dull earth are thrown

Topaz, and the ruby stone.

MARY E. COLERIDGE

TO BETSEY-JANE, ON HER DESIRING

TO GO INCONTINENTLY TO HEAVEN

My Betsey-Jane, it would not do,

For what would Heaven make of you,

A little, honey-loving bear,

Among the Blessed Babies there?

Nor do you dwell with us in vain

Who tumble and get up again.

And try, with bruised knees, to smile—.

Sweet, you are blessed all the-while

And we in you: so wait, they'll come

To take your hand and fetch you home,

In Heavenly leaves to play at tents

With all the Holy Innocents.

HELEN PARRY EDEN

THE BRIDGE

Here, with one leap,

The bridge that spans the cutting; on its back

The load

Of the main-road,

And under it the railway-track.

Into the plains they sweep,

Into the solitary plains asleep,

The flowing lines, the parallel lines of steel—

Fringed with their narrow grass,

Into the plains they pass,

The flowing lines, like arms of mute appeal.

A cry

Prolonged across the earth—a call

To the remote horizons and the sky;

The whole east-rushes down them with its light,

And the whole west receives them, with its pall

Of stars and night—

[Pg 119]The flowing lines, the parallel lines of steel.

And with the fall

Of darkness, see! the red,

Bright anger of the signal, where it flares

Like a huge eye that stares

On some hid danger in the dark ahead.

A twang of wire—unseen

The signal drops; and now, instead