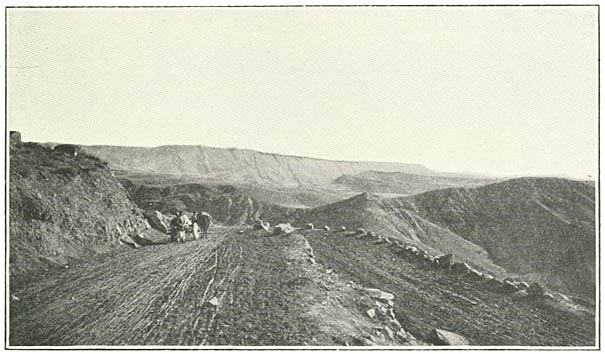

At five o’clock in the afternoon of the 4th

of October we set out for Edgmiatsin. It is a drive of about thirteen

miles across the plain. Our luggage was consigned to a waggon of the

post, and we ourselves enjoyed the luxury of a light victoria, drawn by

four horses abreast. They covered the distance in an hour and forty

minutes, although the road is in many places a mere track.

What a drive! It is so well within reach of Europe that

it ought to be included, like the journey to Italy, in the programme of

a liberal education. The railway will before long arrive at Erivan, and

then the pilgrimage will be still easier to undertake. Not all the

tourists in the world will disturb the harmony of this landscape; the

screeching trains, the loud hotels, the Babel of tongues will be lost,

like a flight of starlings, in this expanse. It is here that the spirit

of Asia is most intensely present—an inner sanctuary to those

outer courts through which the traveller may have wandered and never

crossed the threshold of this plain. And it is a spirit and an

influence which arouse deep chords within us and send them sounding

through our lives.

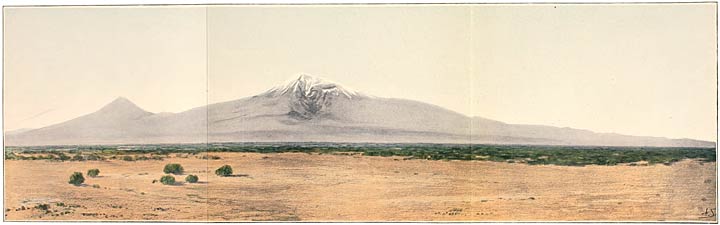

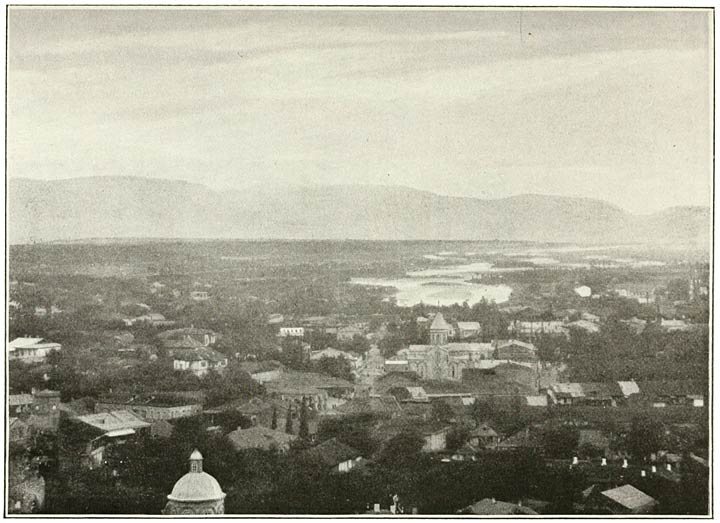

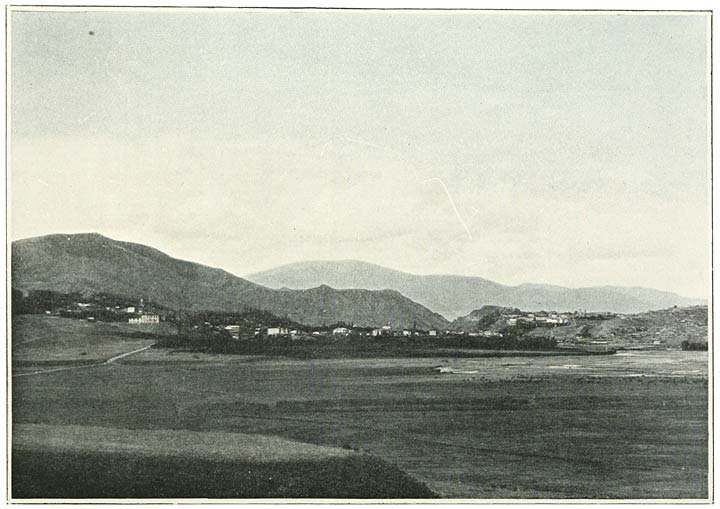

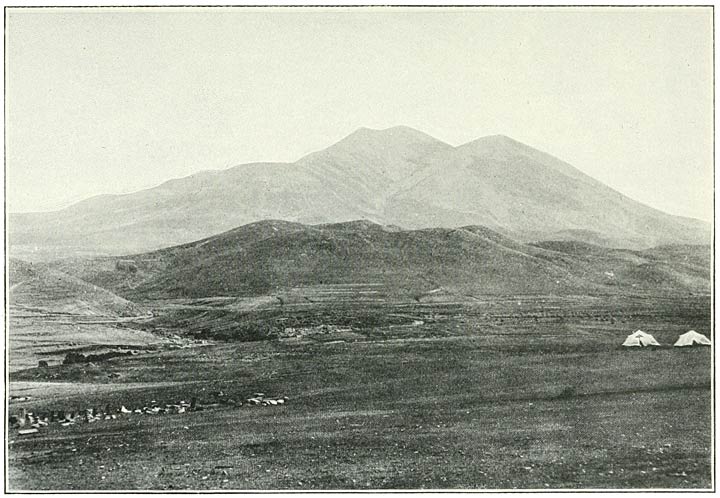

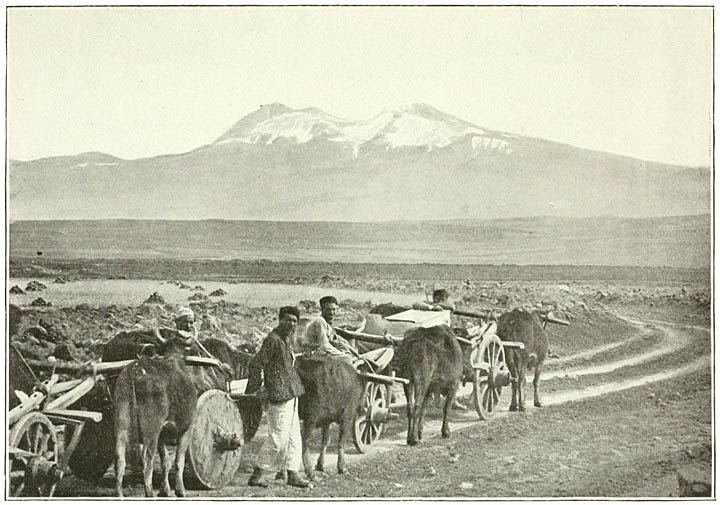

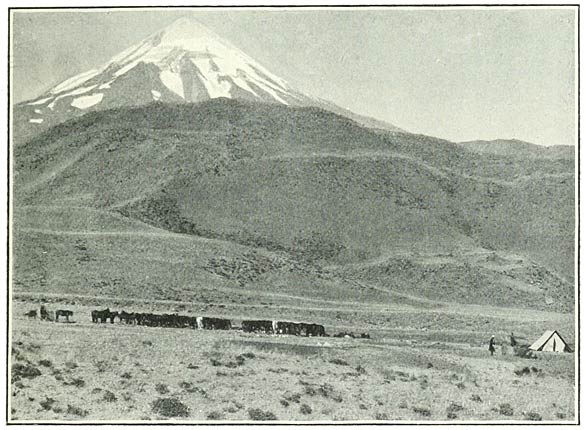

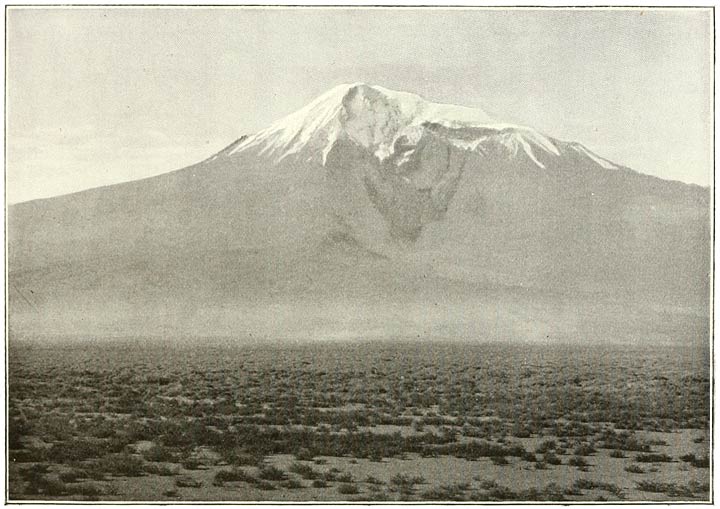

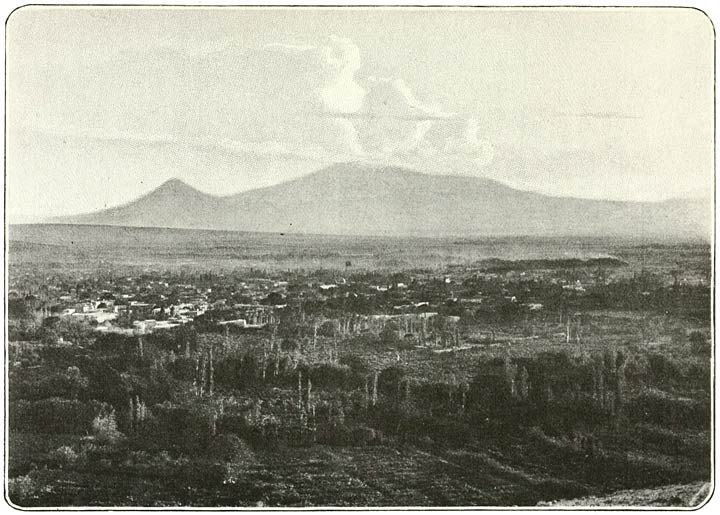

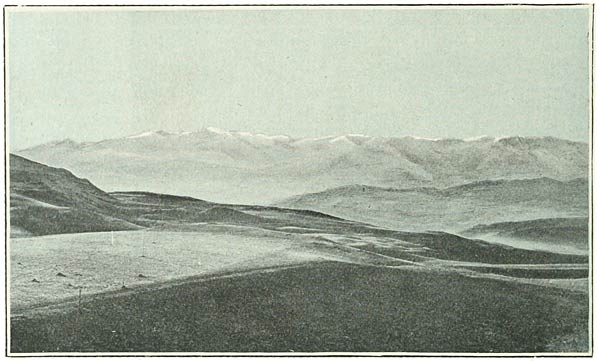

The landscape at once combines and accentuates the

salient features of the Asiatic highlands. There is the plain which was

once the bed of an inland sea. It stretches west and east without

visible limits; and this evening it has all the appearance of water. In

the west it is mirage which produces this effect. The long

north-western slope of the Ararat fabric assumes the character of a

dark and narrow promontory rising on an opposite shore. From the east,

beyond the train of the Little Ararat, a cold mist—may it be from

the Caspian?—is slowly wafted over the steppe, and the illusion

is complete. Into those liquid spaces sweep the basal vaultings of

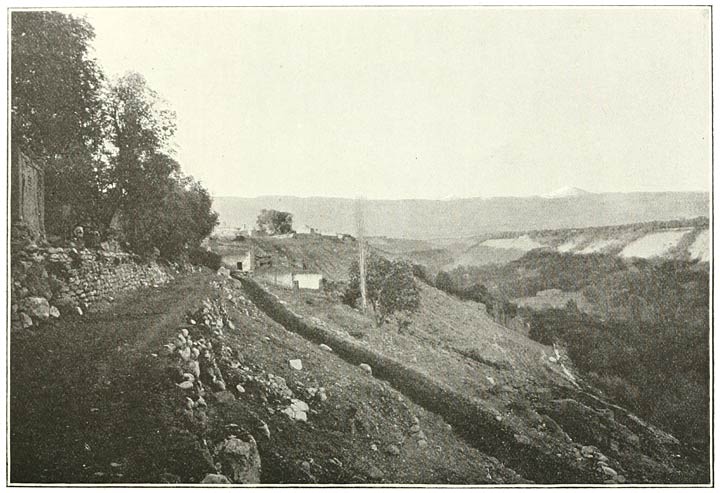

Alagöz—the boulder-strewn declivities [229]which we keep on our right hand, and which seem

to embody on a typical scale that quality of hopeless sterility which

is characteristic of vast portions of the continent. But the same vague

distance receives the Zanga, diffused into many channels, and lost

beneath luxuriant foliage. For over a quarter of an hour after leaving

Erivan we pass at a rapid trot between the walls of orchards; and in

places the water gushes from the conduits across the road. Once outside

this intricate zone the track wanders over the idle soil, skirting the

stony slopes in the north. In the opposite direction the plain blooms

with fields of cotton and rice, sustained by a small canal which

pursues a westerly course before it falls into the Araxes, if indeed it

flow so far.

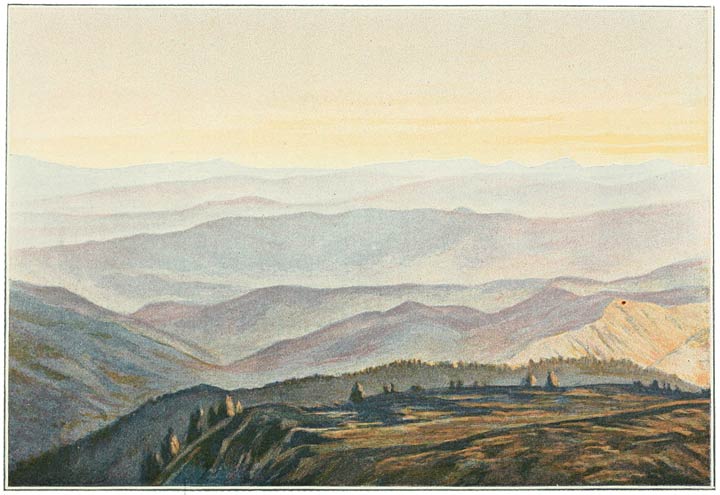

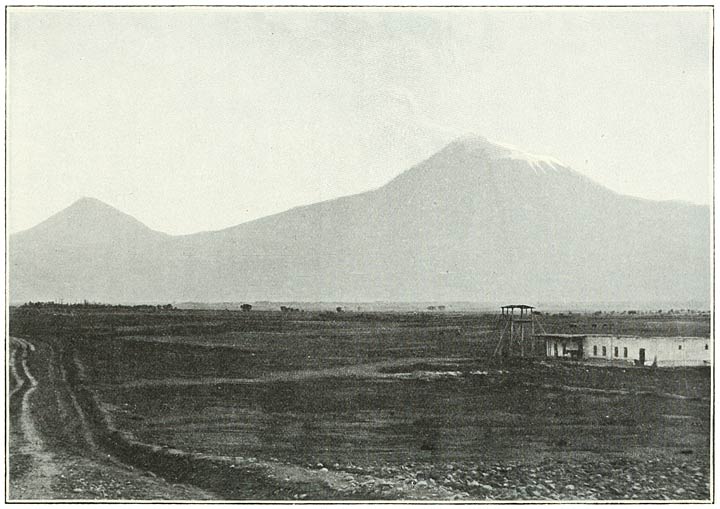

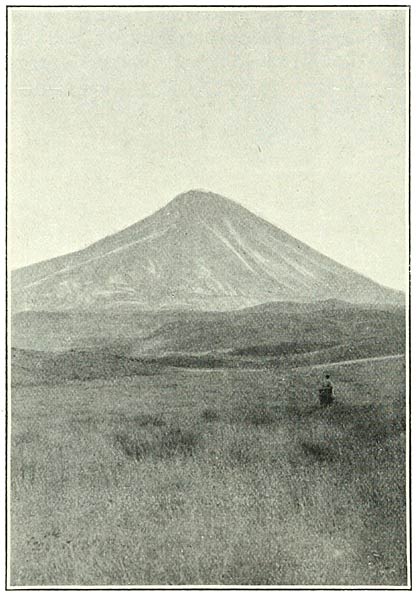

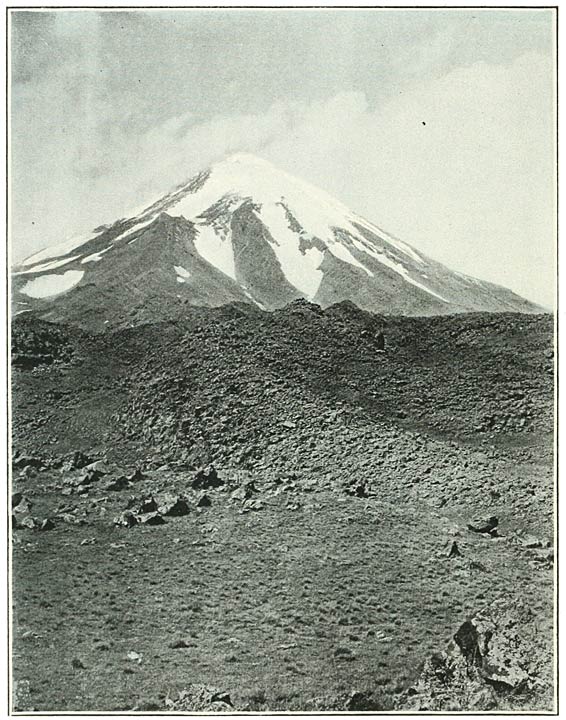

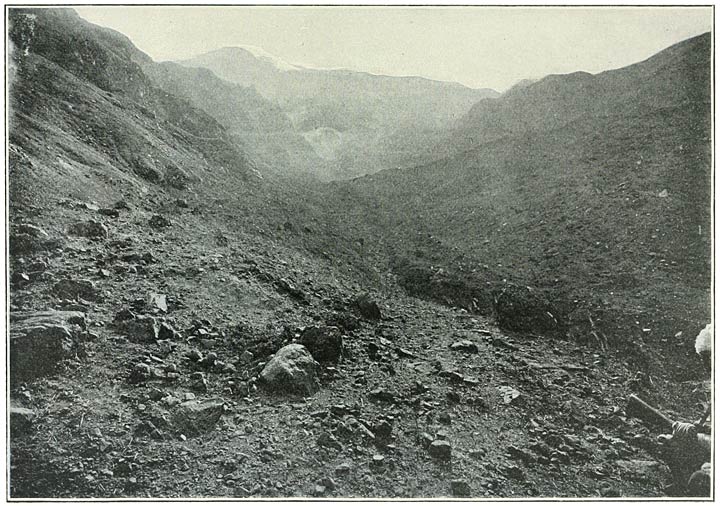

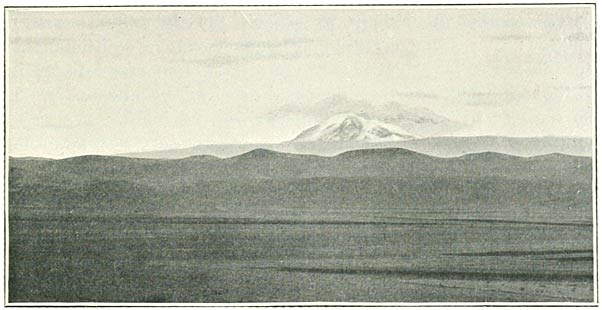

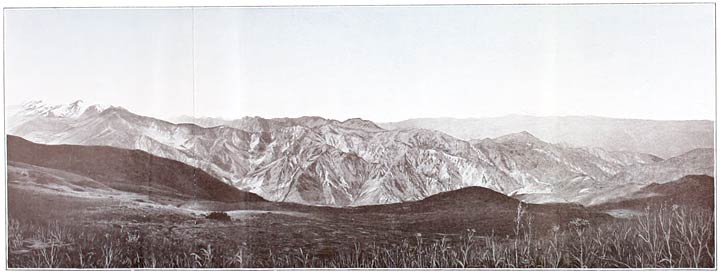

And there are the mountains of Asia—the volcanoes

with their vaulted summits, as well as those long ridges with their

serrated outline which represent the operation of less impetuous forces

through longer spaces of time. To this second category belongs the fine

chain on the west of Ararat which gains in definition as we proceed. It

stands a little back and behind the fabric of Ararat, and volcanoes too

have built themselves up upon this wall. But its rugged and tumbled

appearance is the feature which predominates, in striking contrast to

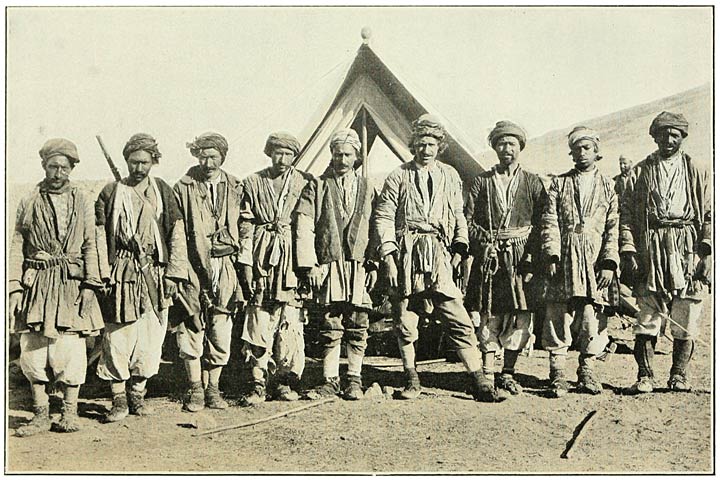

the symmetry of the mountain of the Ark. That giant overpowers the

lesser Ararat and appropriates their common base. One stands in wonder

at the force which could have rent that massive pedestal and opened the

yawning chasm which fronts the plain. Night creeps into those recesses,

where the blaze of a Kurdish camp-fire calls attention to the

extraordinary transparence of the air. The snow-fields, bare and cold

above the amber of the sunset, are already free of their coronal of

cloud. One full-puffed vapour still floats behind the uppermost

pinnacle; another clings to the bastion on the north-west. While we

admire this stately scene, made more impressive by the heavy silence, a

grove of trees rises from the steppe on our point of course. Two little

conical shapes just emerge above their outline, and are recognised as

the domes of Edgmiatsin.

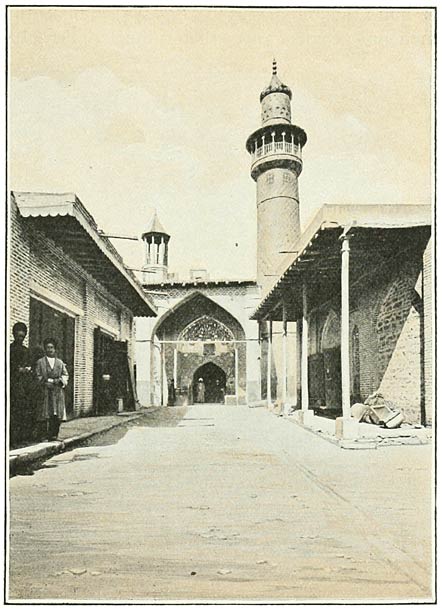

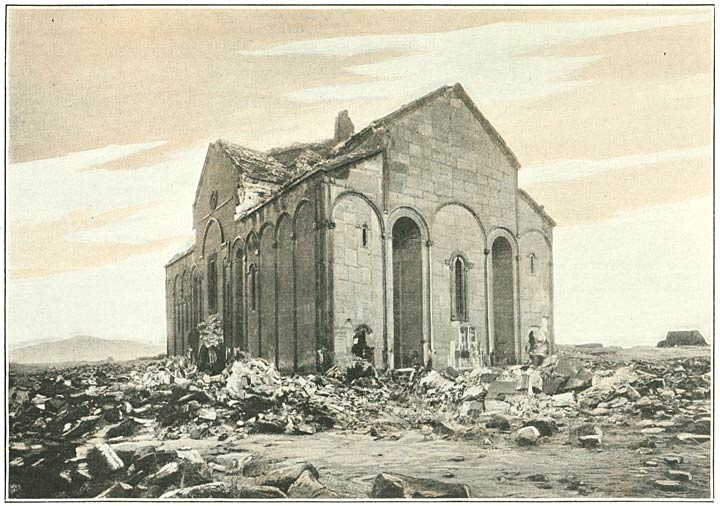

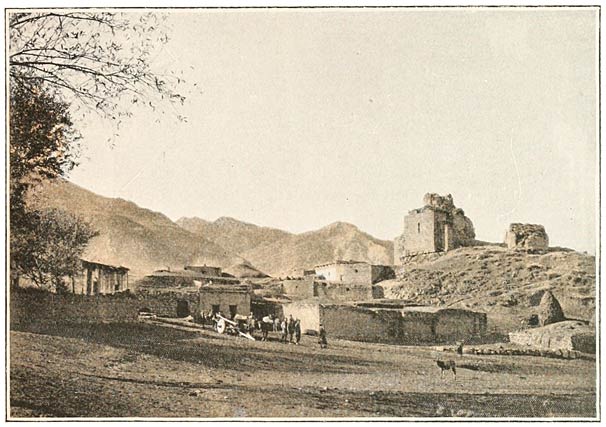

We pass through the thin plantation, sustained by

runnels derived from Alagöz, and come to a halt before the doorway

of a lofty mud wall with round towers at intervals. It might belong to

a Persian fortress; but it is the outer wall which surrounds the

cloister with the cathedral of St. Gregory. The massive gate is

[230]closed, and we thump and thump for some time in

vain. The parapet with its crumbling surface betrays no sign of the

life within. But there is just sufficient light to reveal the

surroundings of the fortified enclosure—a straggling village of

above-ground houses, outlying churches, poplars, dust.1

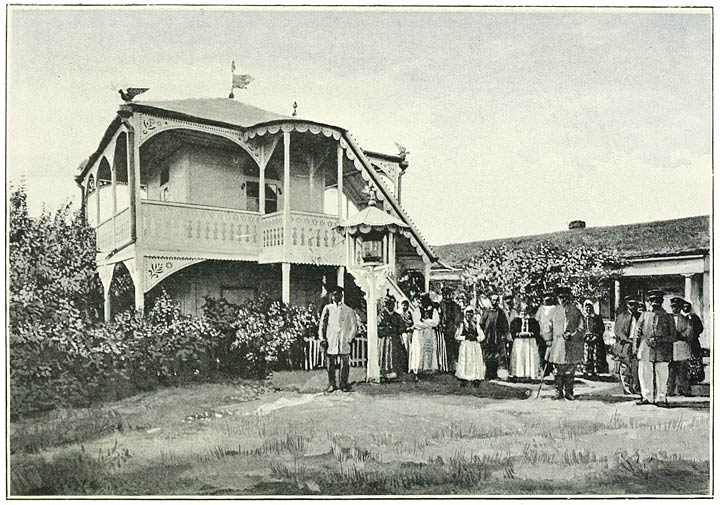

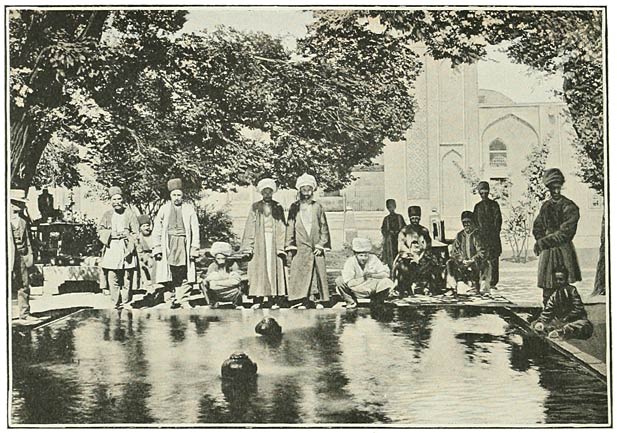

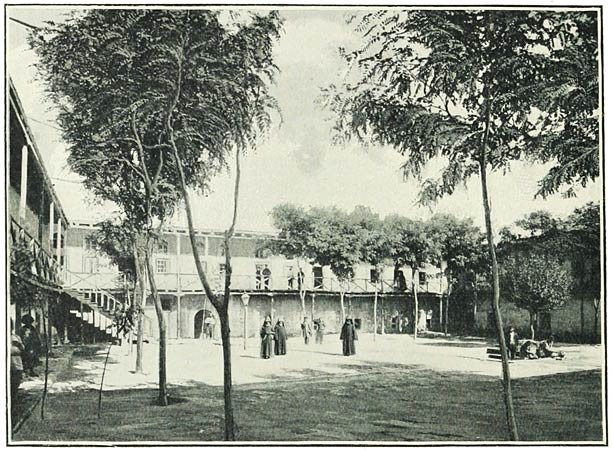

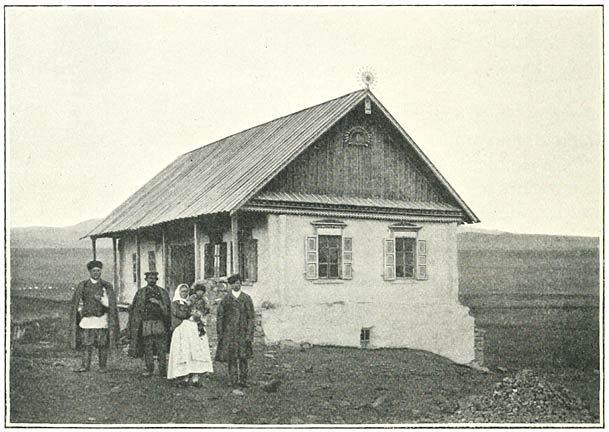

At last the hinges creak and the porter appears. We are

ushered into a court, like that of a college at Cambridge, adjoining

the great gate which is in the south wall. It is known as the

pilgrims’ court (Fig. 47). Low buildings,

rudely built, with a continuous wooden verandah, compose the

quadrangle. The windows are all lit up behind a line of young trees of

which the foliage rustles in the night air. Several figures may be

discerned on the steps of a basin of water in the centre of the court.

The place is all bustle and stir. Every room, so we are told, in the

whole monastery is occupied by as many people as it will hold. Quarters

have been reserved for us in the principal court; but we are not

expected until to-morrow. Sooner than [231]disturb the peace of

evening we retire to a room in the village where we erect our camp

beds. It is quite a dormitory. My immediate neighbour speaks English

and is a correspondent of the Daily News. He is an Armenian

gentleman who has come all the way from Tabriz, partly in the capacity

of delegate of his countrymen in the Persian city, and partly as the

representative of the London newspaper. He talks incessantly; his

companions do the same. The great event of the coming days will form an

epoch in their lives, and every incident will be indelibly imprinted

upon their memories. A thrilling and detailed narrative will be

despatched to London, where it will filter through the brain of the

sub-editor and issue in the form of a paragraph in small type.

But the newspaper will be to blame; for it is an event,

this consecration of the latest pontiff of the Armenian Church. It is

an event both by reason of the personality of the new katholikos and

because within recent years the fact has slowly dawned upon Europe that

the politics of Western Asia must react upon the Western peoples, and

that in those politics the Armenians are destined to play a part. The

Church is at the present day the only native institution which has been

preserved to that people. All their aspirations as human beings

desirous to live as human beings are focussed by that single

organisation. The broad democratic basis upon which reposes the

election of the patriarch invests him with a representative character.

Moreover he is not chosen by a section of his countrymen but by the

nation as a whole. The Armenians of Turkey and of Persia as well as

those within Russian territory contribute their suffrages. It is

therefore only natural that, in the absence of secular institutions,

the head of the Church should be much more than a merely spiritual

ruler, and should reflect and in no small measure be expected to

instruct the temporal hopes and fears of his flock.

The Russian Government have not been slow in recognising

this fact; nor does the anxiety with which it is regarded in official

circles date from the contemporary prominence of the Armenian Question.

In the heyday of their relations with this Christian nation which

hailed them as liberators, and which was placed in the very centre of

the Mussulman peoples over which they were slowly establishing their

sway, the Russians lavished favours upon Edgmiatsin;2 and

rightly or wrongly they are now [232]accused by their Armenian

allies, become their subjects, of having excited hopes which, when they

had served the ends of Russian policy, were rudely and almost brutally

suppressed. It is certain that the Armenian inhabitants of the

provinces which now belong to Russia favoured the Russians in their

campaigns against Persia and Turkey at the risk of reprisals on the

part of their Mussulman masters. They smoothed the way for the

extension of the Russian Empire from the valley of the Kur to that of

the Araxes. The first great step in this direction was effected at the

commencement of the present century, when the kingdom of Georgia was

organised into a Russian province. The acquisition of Georgia afforded

the Russians a foothold upon the tableland, and brought them into

direct contact with the Persians and with the Turks. Their first battle

against the Persians was fought on the 20th of June 1804, and resulted

in the repulse of the Shah’s forces, which were led by his son,

the famous Abbas Mirza. This action took place in the immediate

neighbourhood of Edgmiatsin, and on the same day upon which was

celebrated the annual festival of St. Ripsime, one of the saints who

are the special glory of the cloister. The Armenians did not disguise

the direction of their sympathies, and attributed, the Russian victory

to the intervention of their Saint.3 Ten years later, when the

monastery was visited by Morier, the patriarch was wearing a high

Russian order, of which the star glittered on his purple robe.4

[233]

In 1828 Edgmiatsin was annexed to Russia after the

capture of Erivan from the Persians and as a result of the Treaty of

Turkomanchai. Throughout the wars which ensued with Turkey the

Armenians espoused the Russian cause; and one cannot doubt that their

assistance was of considerable benefit both to Paskevich during the

campaigns of 1828–29, and to Loris Melikoff, himself of Armenian

origin, in that of 1877.5 Little by little a certain

bitterness becomes appreciable in these honeymoon relations. The origin

or perhaps the reflection of this new feeling may be found in the

provisions of the important statute which defines the status of the

Armenian Church in Russia and regulates the constitution of Edgmiatsin.

This statute, which is generally known as the Polojenye, is

headed by the signature of the Tsar Nicholas and bears the date of

March 1836. It was translated for me by one of the monks. In some

respects it deals most liberally with the national Church. Her

congregations are accorded full liberty of worship, and her clergy are

relieved from all civil burdens. The principle of the election of the

katholikos by the whole Armenian people professing the national

religion is expressly recognised. The method of his election is

minutely prescribed. The national delegates assemble in the church of

St. Gregory, and submit two names to the Emperor, who makes the

appointment.6 On the other hand, in [234]true

Russian fashion, what is given with one hand is taken away with the

other. The synod of Edgmiatsin is an ancient institution which,

according to Armenian traditions, advises the katholikos, and may even

resist him should he desire to effect changes in matters intimately

affecting the national faith.7 The Polojenye emphasises

and develops the constitutional importance of this body, and places it

under the titular presidency of the Emperor. The decrees of the synod

are headed “By order of the Emperor of Russia”; and they

are submitted to a Russian procurator, resident at Edgmiatsin, who

examines into their validity. In matters of a purely spiritual nature

the katholikos takes counsel with the synod, but need not necessarily

accept its recommendations. But in all the general business of the

Church, as well as of the cloister, it is the synod which has

jurisdiction subject to the approval of the Minister of the Interior.

In the synod, which consists of eight priests resident at Edgmiatsin,

the katholikos has no more than a casting vote. It is true that he

might act by Bull. But such action, were it contrary to the resolutions

of the synod, would, as matters now stand, be revolutionary. In this

manner the katholikos is put into leading strings, of which the ends

are held by the officials on the banks of the Neva, duly instructed by

a professed and resident spy. [235]

Nor are the remaining provisions of this double-faced

instrument calculated to shed balm over the wounded dignity of the head

of the Church. It is the Emperor who appoints the members of the synod,

although the katholikos is entrusted with the important function of

submitting two names for the Imperial choice. It is not legal for the

pontiff to punish a member of the synod without the Imperial consent.

The same authority is necessary should he desire to suspend a bishop.

He may not leave the cloister for more than four months except with the

sanction of the Tsar. When a bishopric falls vacant he submits names to

the Emperor, with whom the appointment rests. Should the bishop desire

to go abroad for more than four months, application must be made to the

same high quarter. But perhaps the most serious because the most

insidious weapon against the independence of the national Church is the

provision which enacts that a year shall elapse between the death of a

katholikos and the election of his successor. This clause was accepted

with singular want of foresight at a time when travelling was even

slower than it is at the present day, and when it was difficult to

collect the delegates from Turkey and Persia within a lesser period. In

practice it is not easy for the new katholikos to take up his duties

until some time subsequent to his election; and, should further delay

be of advantage to the Government, the Tsar can always defer confirming

the choice of the representatives. Thus a vacancy in the Chair is

always accompanied by a long interregnum, during which the Government

plays off one party against the other, and succeeds in obtaining

whatever concessions may have been resisted during the preceding

pontificate.

An English traveller who visited Edgmiatsin the year

after the conclusion of this enactment found the synod with its Russian

procurator in full swing. The katholikos was at once reduced to a

position of president of the synod, and the synod to one of

subservience to Russian policy.8 Von Haxthausen speaks of

the procurator as a Russian and quite an autocrat; this was in

1843.9 At that time the pontiff Nerses was in occupation

of the Chair, and his conspicuous abilities were [236]regarded with suspicion by the Russian

authorities. His schemes for the higher education of the Armenians had

come to nothing owing to Russian opposition. But the hardest blow was

reserved for the year 1885, when the Katholikos Makar was appointed by

the Emperor in defiance of the expressed sentiments of the delegates of

the nation. It was then realised that the independence of the Church

was at an end. The ukase of investiture confirmed this pessimist view.

Instead of the usual wording “upon the recommendation of the

Armenian people,” the appointment was based “upon the

recommendation of the clergy.” Instead of the pictures from

Armenian history which adorned the ukase of the pontiff George, Russian

insignia and coats of arms enlivened the scroll. The constitutional

phrase has been restored to the ukase confirming the present pontiff,

but not the patriotic pictures!10

Still, in spite of the fetters which have been imposed

upon the actions of the katholikos, as much by the manner in which the

Polojenye is worked by the Russian bureaucracy as by the

provisions which that statute contains, the average Armenian and

especially the lower classes are immensely interested in the event of

the coming days. At Batum, at Kutais, at Alexandropol, at

Erivan—wherever we have been in the society of Armenians, talk

has centred upon the triumphal journey and the approaching consecration

of His Holiness Mekertich Khrimean. It is not only the ancient

ceremony, and it is not merely the assembling of delegates from all

parts of the Armenian world that appeals to the heart of the nation. It

is the personality and reputation of the man. The people forgets, but

it does not change. The imagination of the race still sees in the

holder of the pontifical office not alone or so much an archbishop or

katholikos—the keystone of the edifice of the Church—as a

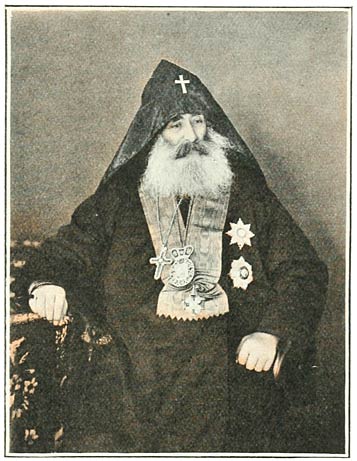

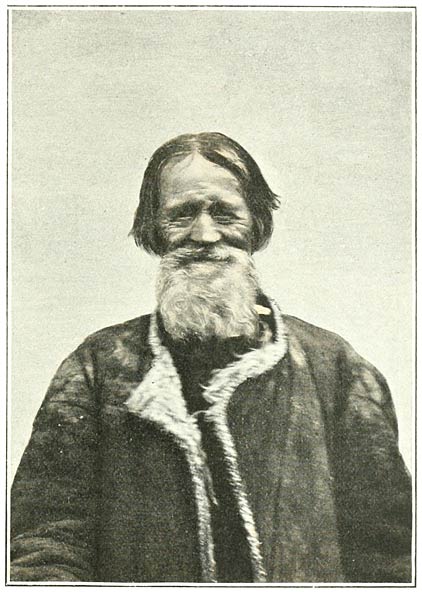

high priest in the old Biblical sense. Khrimean is the ideal of a high

priest. He is a figure which steps straight out from the Old

[237]Testament with all the fire and all the poetry.

At the ceremony of his consecration it seemed as if at the foot of

Ararat the ancient spirit were still alive, and that the holy oil which

descended upon that venerable head from the beak of the golden dove

anointed a law-giver to the people who announced the Divine Word. This

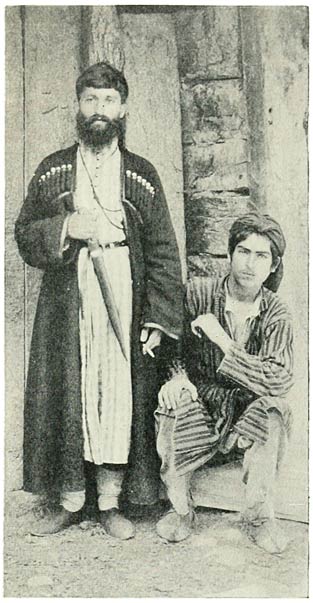

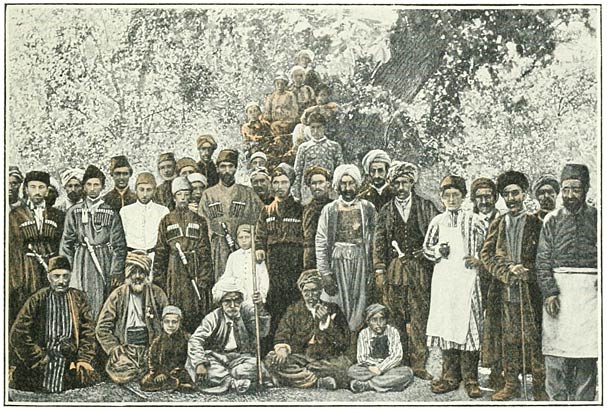

impression was in part derived from the Semitic cast of his features.

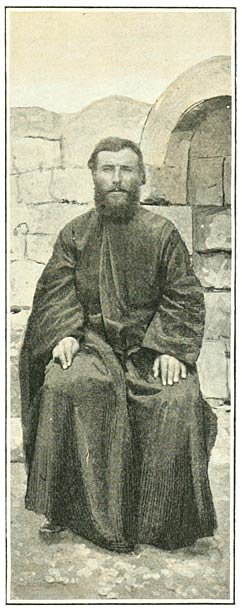

The large brown eyes and aquiline nose above a long and full beard, are

characteristics which we associate with the Jewish nation, but which

are not uncommon among the Armenians. What is more rare among this

people is the spirituality and refinement which is written in every

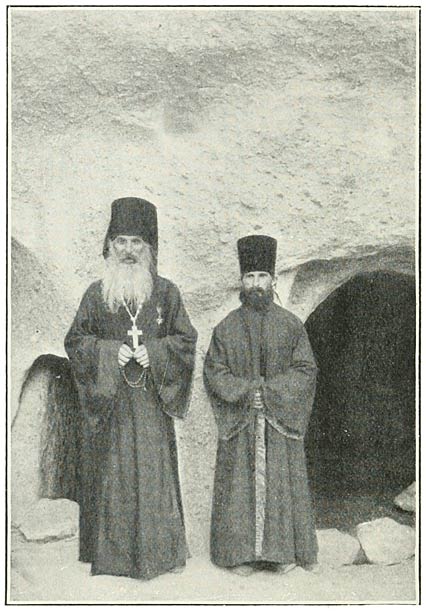

line of this handsome face (Fig. 48). But the

whole character of the man would seem to have been moulded upon a

Biblical model rather than upon that of the Christian hierarchy. He is

the tried statesman to whom the people look for guidance in the

abeyance of the kingly office. With him religion and patriotism are

almost interchangeable terms; and the strong reality which he has given

to the old Armenian history may be illustrated by an act which those

who lack sympathy with such a character might almost regard as

childish. In the cloister of Varag near Van, over which he has presided

for many years, are buried the remains of Senekerim, king of the Van

country, who abdicated his kingdom in favour of the Byzantine emperor,

Basil II., and retired to the town of Sivas in Asia Minor, which he

received in exchange. Over his tomb a wooden canopy had been erected

and decorated in a manner befitting royal rank. But such honours, paid

to so unworthy a monarch, shocked the keen sense [238]of

the patriot in Khrimean; he stripped the frame of its trappings and

ornaments, and the structure stands bare to this day. The simple

surroundings among which his life has been passed recall the setting of

a Bible story. At a later stage of our journey, when we arrived in the

town of Van, I was shown the house where he had resided and which he

has now devoted to a school for girls. As I alighted to visit the

school a man with the appearance and dress of a peasant stepped forward

to hold the reins of my horse. Yet this individual was none other than

the nephew of the Katholikos, and the brother of Khoren Khrimean, who

has accompanied his uncle to Edgmiatsin, and who does the honours of

the patriarchal household with so much dignity and natural grace.

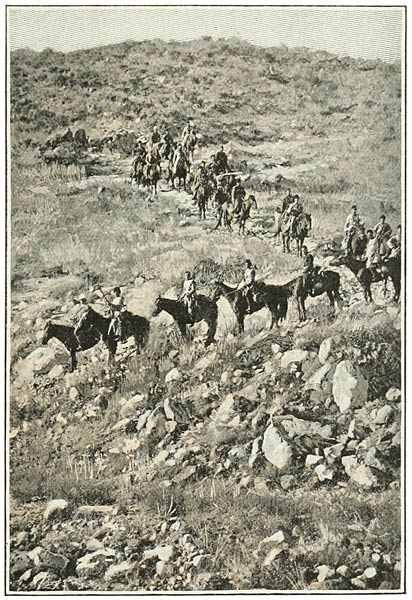

During our stay in Van, his native province, we were afforded an

instance of the magnetic influence which through a long life Mekertich

Khrimean has exercised upon his countrymen, and which takes the form of

superstitious veneration among the humble and the poor. As we were

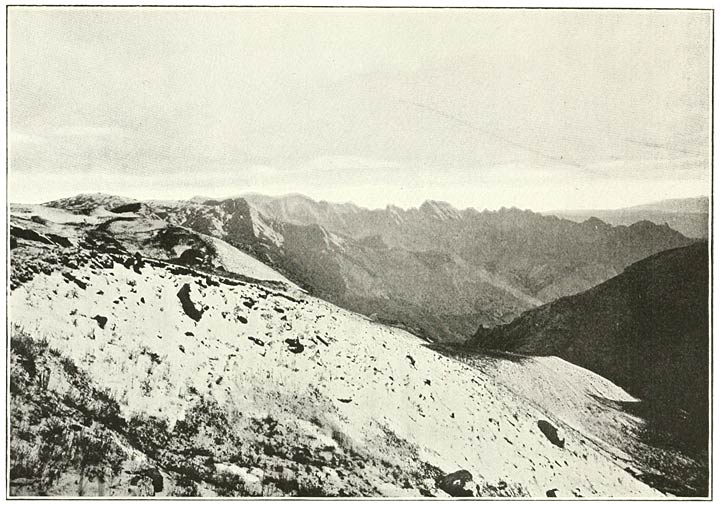

winding up the slopes of Mount Varag on our way to the ancient

monastery where he lived so long, teaching in the school which he had

founded within its walls, and often taking this very path from the

cloister to preach in the little church of Hankusner, on the outskirts

of the gardens of Van, our attention was called to a spot where an

assassin had lain in wait for him, deputed by his enemies to kill him

as he rode unaccompanied towards the town. The story is told that when

the man perceived him and raised his rifle to his shoulder, a sudden

fear seized his limbs, his arm shook like a wand; and he fell upon his

knees before his victim, whose look he had been unable to bear. As a

writer Khrimean has expressed through the vehicle of a prose which is

full of poetry and emotion conceptions of Scripture and thoughts upon

the troubles of his time which might have sprung from the warm

imagination of the early Christians in the East. He has often suffered

for the fire of his sermons, and he possesses both the style of the

consummate orator and the personal charm which keeps an audience under

a spell. He has for many years been in the forefront of the Armenian

movement; and it was he who pleaded the Armenian cause at the Congress

of Berlin. A people whose spirit has been crushed and whose manhood has

been degraded gather new life from such a teacher and learn to become

men. But perhaps the most striking quality in a character which is at

once complex and clear as the light of [239]day is the

ever-welling kindness and open-armed sympathy with which he shares the

troubles of his fellow-men. As the throng press round him, the holder

of their highest office, and endeavour to kiss his hand or gain a

glimpse of his face, the mind travels back to that solemn scene in

which the Greek king receives his stricken and distracted people:

“O my poor children, known to me, not unknown is the subject of

your prayer; well am I aware that you are sore afflicted all; yet,

though you suffer, there is not one among you who suffers even as I.

For the grief you bear comes to each one alone—himself for

himself he suffers—and to none other else; but my soul mourns for

the State and for myself and you.”11

Side by side with personal relations of greater freedom

than I had anticipated towards this remarkable man, there grew up at

Edgmiatsin and during the course of subsequent travel a fairly intimate

acquaintance with the events of his life. He was born on the 5th of

April 1820; and it is therefore in his seventy-fourth year that he

ascends the throne of St. Thaddeus and of St. Gregory. His father and

uncle were well-to-do citizens of Van, who had come to be known under

the name of Khrimean because of a trade which they had conducted with

the Crimea. The young Mekertich had a single brother and no sisters;

and he appears to have been educated with some care by his uncle. His

youth and early manhood were devoted to secular pursuits. For five or

six years he acted in the capacity of an overseer in a weaving

business. But already in 1841 he had become a traveller and a thinker;

in that year he made a journey in the province of Ararat and visited

Edgmiatsin. At the age of twenty-five he married and in due course

became a father; but his wife died after giving birth to a daughter who

only lived to be six or seven years old. To a layman of intellectual

tastes among the Armenians of Turkey there is scarcely any other

profession open than the honourable but ill-paid calling of a teacher.

Shortly after his marriage Khrimean proceeded to the capital and earned

his living by private tuition. His first book appeared in 1850, and

consisted of a description in poetry of his travels in Ararat. The

period of his residence in Constantinople was diversified by further

journeys; to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, of which he published an

account; and to Cilicia, the seat of the latest Armenian dynasty, where

he remained some time as [240]a teacher in the convent of Sis.

In 1854 he returned to his native city, and in the following year took

orders and became a vardapet or monastic priest. It is at this

date that the more conspicuous portion of his life may be said to have

commenced. The pulpit gave full scope to his natural eloquence; while

the qualities of the student and writer, which he had carefully

cultivated, were displayed in the columns of a journal which he founded

about 1856 and named the Eagle of Vaspurakan, or of the province

of Van. The proceeds of the sale of this periodical, which was at first

printed at Constantinople, whither he had returned in 1855, enabled him

to purchase an instrument of great rareness in Turkey, which the

Armenians prize with the same childish affection and reverence as the

Persian highlanders value a rifle or sporting gun. Khrimean re-entered

Van with the title of abbot of the famous monastery which overlooks the

landscape of the city and the rock and the waters from the slopes of

Mount Varag. He came the proud possessor of a printing press, with

which to conquer the sloth of the faint-hearted among the laymen and

edify the crass ignorance of the priests.

In the good old times in Turkey one might read or write

what books one liked, and the freedom which was enjoyed by the average

individual might have excited the envy of the citizens of some of the

European states. When the abbot of Varag cast his stone into the

stagnant waters, the report woke little echo beyond the borders of his

native province and the ranks of his countrymen. But the waves which he

set in motion have never yet subsided; and who can tell upon what shore

of promise or disappointment they are destined to break and disappear?

If ever there was a good cause, such was the cause which he championed,

and no advocate could be more pure-minded than himself. His avowed

object and real aim was the elevation of the Armenians and their

preparation for the new era which he foresaw. That era he conceived as

one of national activity in the rapid decline of the Mussulman peoples

and the approach of new influences from the West. If we tax him with

having resuscitated a realised and played-out ideal—that national

ideal which is still the bane of our modern Europe, but which, except

perhaps in the case of some paradoxical German Professors, has lost its

hold upon educated minds, he might reply that it is the only talisman

with which to touch the Armenians, the most obstinate nationalists

which the world has ever seen. He might [241]further point to the

almost hopeless condition of the Ottoman Empire, and under his breath

he might suggest that the methods of Russian despotism were not such as

to excite the enthusiasm of a strongly individual people capable of

assimilating Western culture at first hand. Lastly, he might dwell upon

the fact that the Armenians have a long history, and that their

progress, to be solid and permanent, must be based on a revival of

consciousness in the dignity of their past.

But the inculcation of such doctrines in the minds of

his countrymen was sure to produce a ferment among a people who have

been regarded as the inferiors and almost as the slaves of the

Mussulmans for upwards of eight hundred years. It was imputed to him

that he was working to revive the old Armenian kingdom—a

consummation which a sensible Turk should regard with equanimity, since

the time necessary to attain this end would far exceed all possible

limits which he might assign to his solicitude for posterity. But

sensible people are a minority of the inhabitants of this globe, and

they are not numerous in the governing circles of the Ottoman Empire.

The great activity of the Abbot of Varag, who trained his youths in the

school of the cloister to conduct unaided the redoubtable magazine,

slowly aroused the suspicion of the authorities. His own party in the

Church supported him with much zeal, and another monastery, still more

famous, that of Surb Karapet above Mush plain, was added to his

spiritual administration. No sooner was he installed than a second

printing press was set up and another school founded. The Armenians of

the plain of Mush were edified by a new local journal, the Little

Eagle of Taron. In 1869 he was elected Patriarch of Constantinople,

a dignity which he only held for four years. The Turkish Government had

become alive to his great and growing popularity, and it was found

expedient that he should resign. Then came the tribulations of the

Russo-Turkish war, during which the new movement among the Armenians

cost them several little massacres and untoward events. When the

Congress met at Berlin the ex-patriarch, who had been busy with

literature, undertook, in concert with an archiepiscopal colleague, a

mission on behalf of his nation to the German capital. This was his

first visit to the West, and he extended his journey to Italy, France

and England. The result of his efforts and of those of Nerses,

Patriarch of Constantinople, was the insertion of the [242]well-known clause in the Treaty of Berlin

pledging Europe to supervise the execution of reforms in the Asiatic

provinces of Turkey inhabited by Armenians. Khrimean returned to his

native country the object of the resentment of the Ottoman authorities;

much of this portion of his life was spent in Van. But Armenian

discontent was spreading; the alarm of Government was increasing; and

in 1889 the eloquent preacher was sent to Jerusalem in honorary exile.

In the month of May 1892 he was elected to the primacy of the Armenian

Church. The Russian bureaucracy perhaps reflected that their safeguards

at Edgmiatsin were quite sufficient to bridle the vigour of a

septuagenarian. These shrewd diplomats therefore humoured the Armenians

in the matter, and the election was allowed to stand. The Sultan raised

difficulties about releasing the exiled prelate from his Ottoman

nationality and oath of allegiance. When this objection had been

overcome his consent was qualified by the condition that the

katholikos-elect should not pass through Constantinople. A year elapsed

in these parleyings. For two years the Armenian Church had been without

a head. During that period it had been ruled by the Russian procurator.

Now in the autumn the elect of the nation is at length presented to the

delegates who have assembled from all parts of the Armenian world. And

he comes from Russia, from the north, released from exile in Turkey at

the pressing instance of the Tsar. One must admire the extraordinary

cleverness of these Russian bureaucrats!

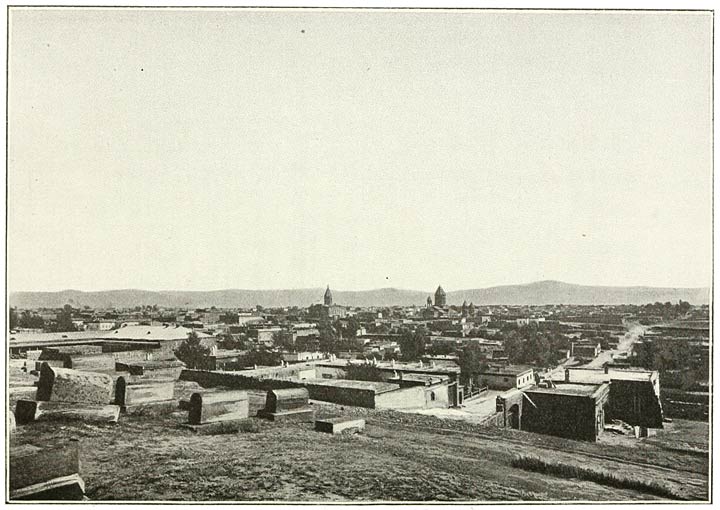

The sun was already high when we sallied forth from our

lodging, having with great difficulty prepared our breakfast in the

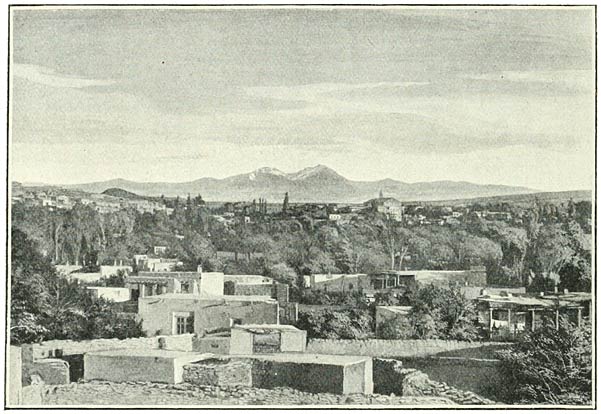

crowded room. We passed down the long and dusty street of the village,

which is dignified by the historical name of Vagharshapat. Nothing

remains of the capital of King Tiridates, which was built upon this

site or in the immediate neighbourhood. You are shown the remains of an

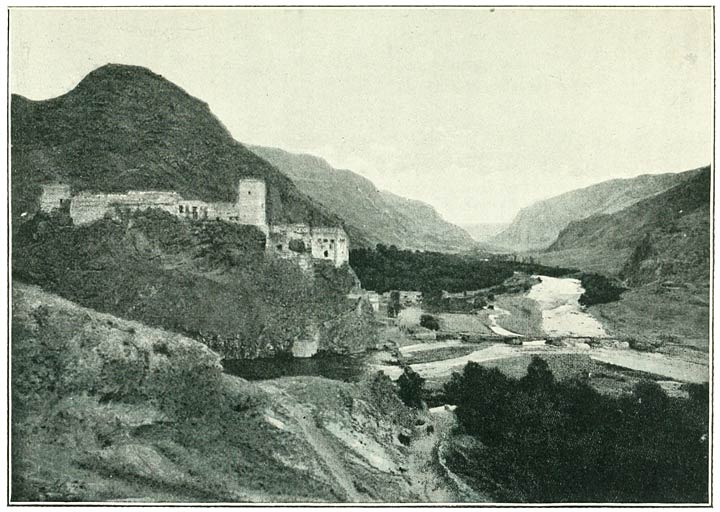

old bridge which spanned the Kasagh, or river of Vagharshapat, some

little distance north-west of the present settlement. The river has

changed its course since it was erected. But the character of the

masonry is rather that which was prevalent in the Middle

Ages—conglomerate piles, faced with carefully hewn and jointed

blocks of stone. Several shops bestow a modern appearance upon the

street, having windows and being disposed as in Europe. A commonplace

edifice with many windows and standing in private grounds recalls an

Institute in one of our provincial towns. It is the [243]Academy or Seminary. We entered the cloister

from a door on the north, through which we issued into an open space on

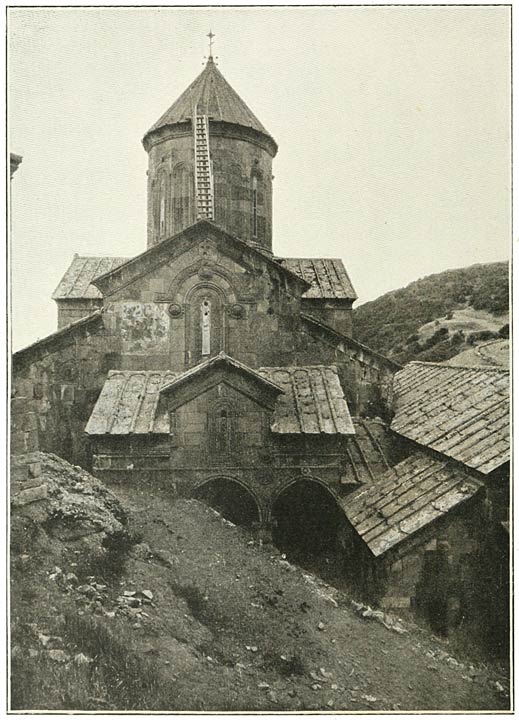

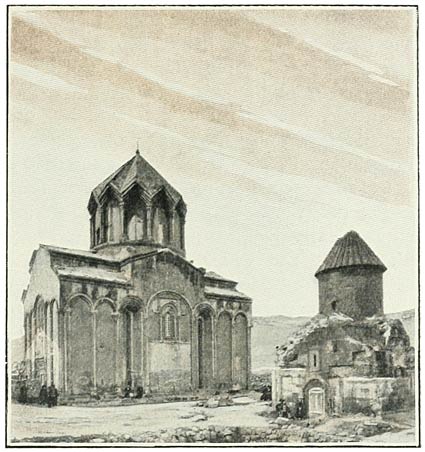

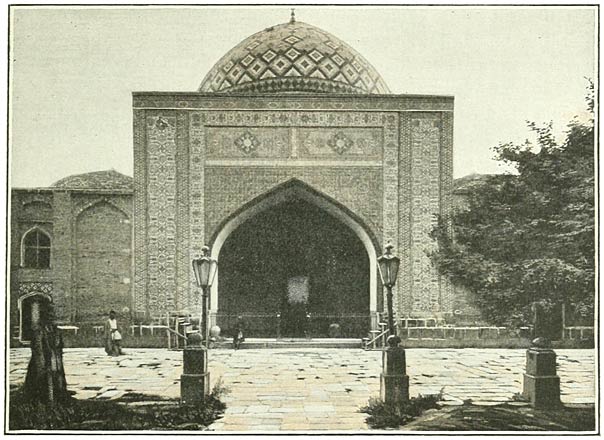

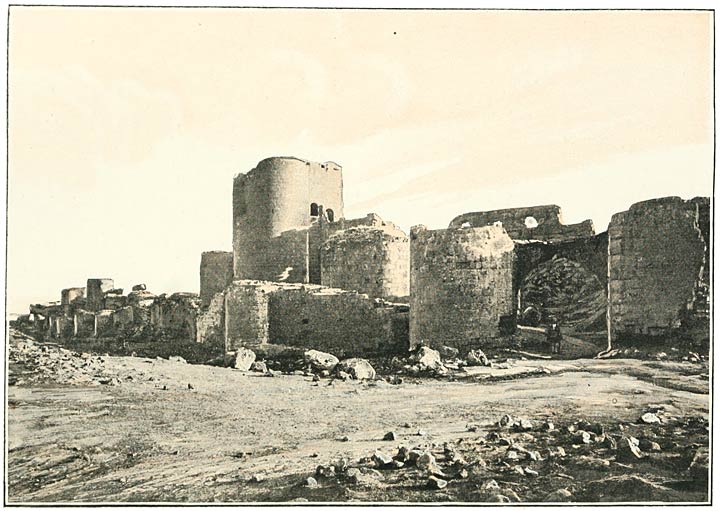

the west of the great court. A covered way conducted us to the

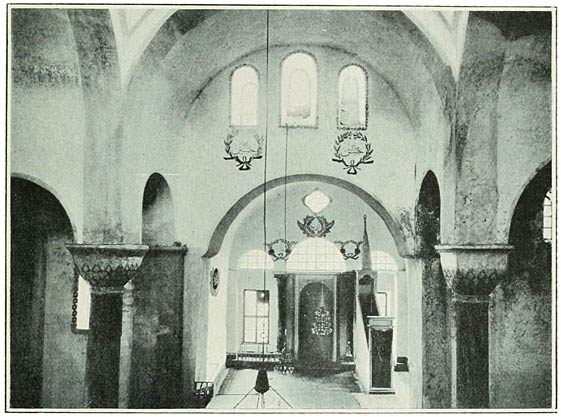

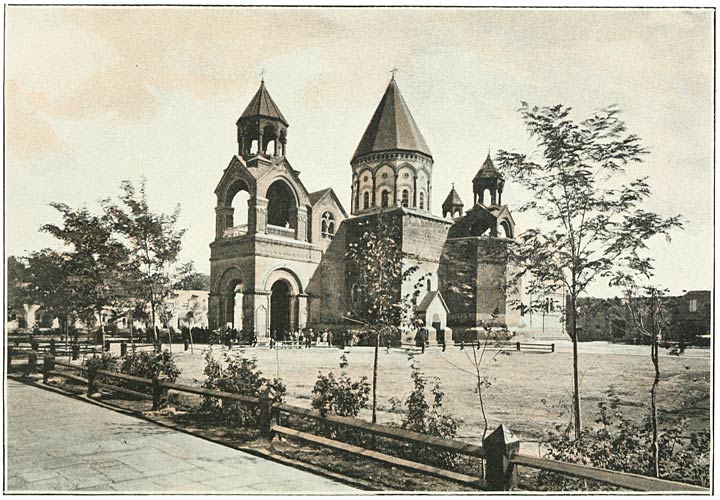

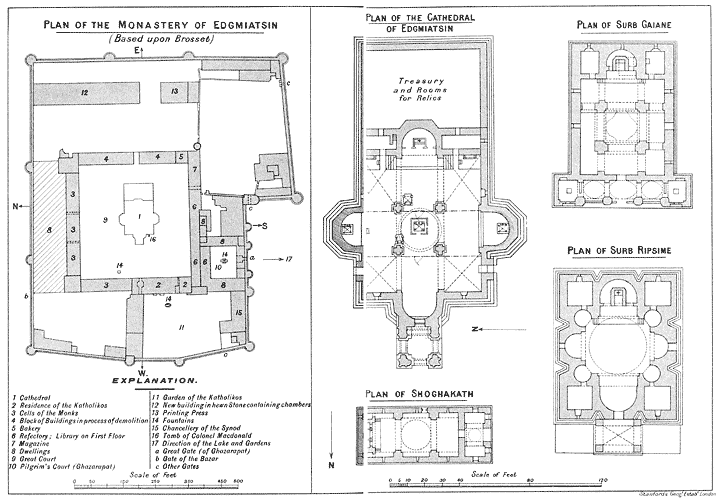

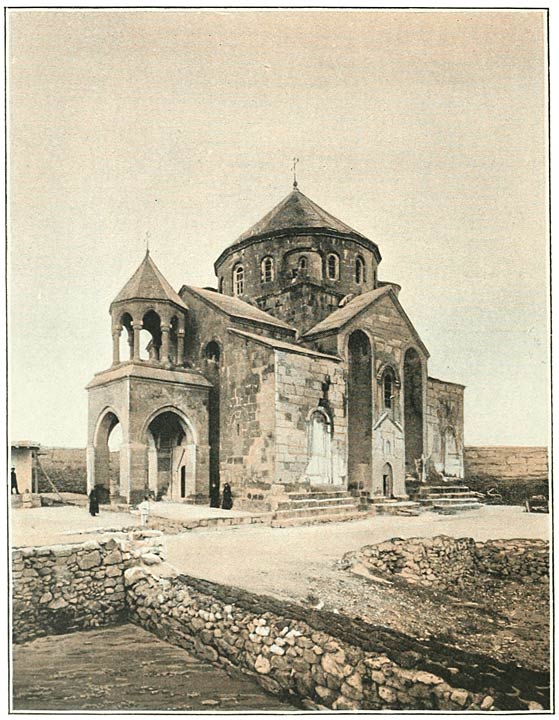

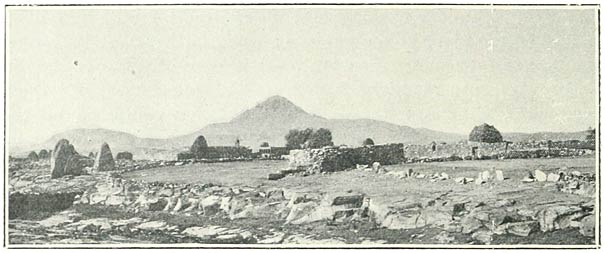

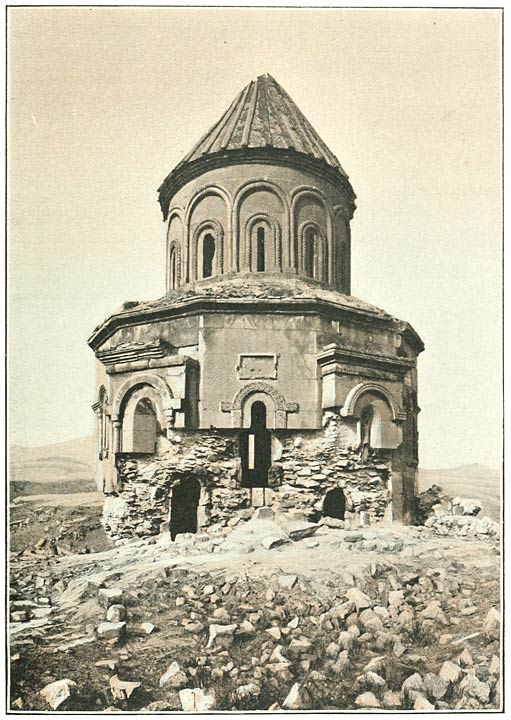

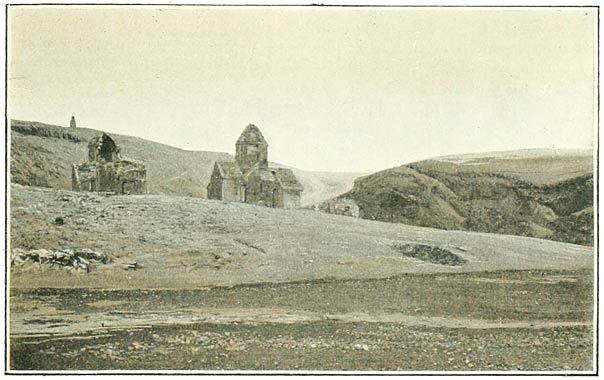

quadrangle, in the centre of which rises the cathedral (Fig. 49, taken from south-west).

Imagine the Old Court of Trinity College at Cambridge

without the gateway, the hall and chapel, and with a church of some

size placed in the centre where the fountain stands. All four sides of

the figure are defined by low buildings, resembling the dwellings which

constitute two sides of the Cambridge court. I had always understood

that our quadrangle at Trinity was the largest in the world; although I

believe some American university was building one a few inches bigger

not so very long ago. But the great court of Edgmiatsin perhaps already

makes the record; it has a length, from west to east, of 349 feet 6 inches, and a breadth of 335 feet 2 inches. These measurements I took

myself, much to the astonishment of the crowd which assembled; they

were at a loss to find a theory which might explain so strange an act.

The length will be very much increased in a short while, when the

condemned east side has disappeared. A fine row of stone buildings is

in course of erection, which will enlarge that dimension by many yards.

Our cousins across the Atlantic must bestir themselves.

The western side of the court on the south of the

covered way is devoted to the residence of the Katholikos, while the

block on the north of the same passage is occupied by the bishops.

There is no style or pomp about the pontifical dwelling; and it would

bear the same relation to the Master’s Lodge at Trinity as a

four-roomed cottage to a mansion. At the back is a little garden. The

north side consists of the rooms inhabited by the monks, and a terrace,

raised on pointed arches, extends from end to end. The building on the

east is in process of demolition, and, like its fellows on the two

sides which have already been described, is composed of comparatively

fragile material. I was given to understand that it had once housed the

seminary and printing press; a little bakery still occupies the

junction with the buildings on the south. These are constructed of

stone, and, although very plain, lend an air of solidity to the entire

quadrangle. Beginning on the west of this block we have first a long

refectory on the ground floor. Its dimensions are a length of

155 feet, and a breadth

of 16 feet 6 inches. But it is a very

[244]humble place when compared to the magnificent

dining halls at Cambridge, and it is not more than 14 feet in height. The ceiling is

vaulted, and like the walls is whitewashed over; the apartment is well

lit and is cool in summer. Two rows of narrow tables extend down it,

and on the west side is the throne and the canopy of the Katholikos,

both in carved wood. Should he join the monks at dinner, his table is

spread beneath the canopy. Parallel with this refectory and facing the

outhouses on the south is placed a similar chamber for the servants, a

part of the space upon the east being occupied by the kitchen. The

storey above the refectories is tenanted by the library, while the

eastern portion of the buildings is taken up by granaries and store

rooms both on the ground and upper floors.

Except for the pilgrims’ court, with adjacent

structures, and the garden of the Katholikos—the one on the

southern, the other on the south-western side—the space between

the outer wall and the great court is for the most part vacant ground.

What edifices there have been raised within it are of an unsubstantial

character, and may have been allowed to fall into ruin. The fine sites

which are thus forthcoming are being rapidly utilised, and I have

already referred to the row of buildings which will extend the great

court upon the east and which at the time of our visit were approaching

completion. In a line with this new block, in which red and grey stones

diversify the masonry, is situated further south the house which lodges

the printing press, a solid stone structure. The transformation of

Edgmiatsin from a residence of ignorant monks into a seat of education,

the home of cultured men, is proceeding year by year; and it is even

possible that the bricks and mortar, or, to speak more correctly, the

excellent masonry is in advance of the needs which it is intended to

supply. Wealthy Armenians are fond of endowing the famous cloister, for

which they do not need the incitement of meetings at some Devonshire

House. But the form of gift dearest to them is the erection of a

building, which stands there so that all may see. This preference for

the concrete and visible is deeply ingrained in them, and they are able

to gratify it owing to the great skill of the Armenian masons. Plans

were shown me which provided a palace for the Katholikos and the

rebuilding of the north side of the quadrangle. These, I believe, have

already been decided upon, one of our party at the private table of the

Katholikos having provided the greater part of the [245]funds. I was also invited to look at some very

elaborate drawings for the enlargement and adornment of the church. No

sooner had they been handed round than one of the guests of His

Holiness expressed his readiness to defray the cost. Speaking as one

who came fresh to Edgmiatsin, I did my best to dissuade the acceptance

of this last project. To enlarge the church would be to dwarf the fine

proportions of the court; indeed the contrary course would be

well-advised. One would not very much regret the abolition of the

portal, while the excrescence on the east, containing the treasury and

room of relics, should certainly be pulled down. His Holiness favoured

the idea of erecting a new church outside the walls, to supplement the

space available in the present building.

We were assigned a room in the condemned block on the

east of the quadrangle, wherein we spread our rugs and erected our camp

beds. It was 26 feet

square, with a lofty wooden ceiling, supported by two pillars of the

same material. The adjoining apartment was in process of demolition,

but, although without a roof, it served admirably as a kitchen, while

the flooring provided fuel for our fire. When all was in order we

should not have exchanged the results of our improvisation even for the

creations of the Cambridge upholsterer, mellowed in the hands of the

Cambridge bedmaker; while, as for living, was it not preferable to

possess the whole of our scapegrace cook than to share the services of

the most virtuous of gyps? Each day as we mounted our staircase, which

exactly recalled its sad Cambridge counterparts, I was struck by the

resemblance of my new surroundings to those among which I had grown up

in the Old Court of Trinity, with the sky and the fountain and the

adjacent cloister, where the glory of the foliage and lawn and river is

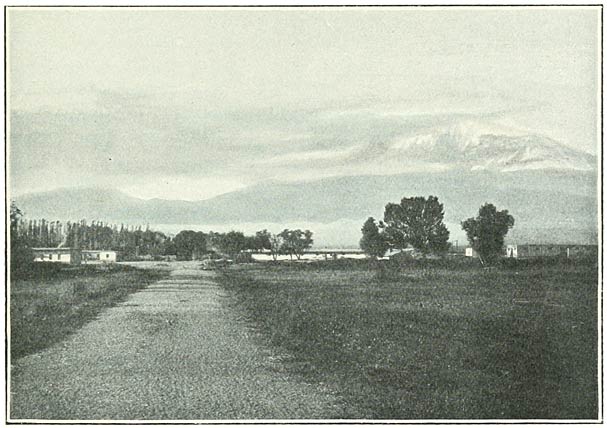

spread in mystery beyond the trellis screens.

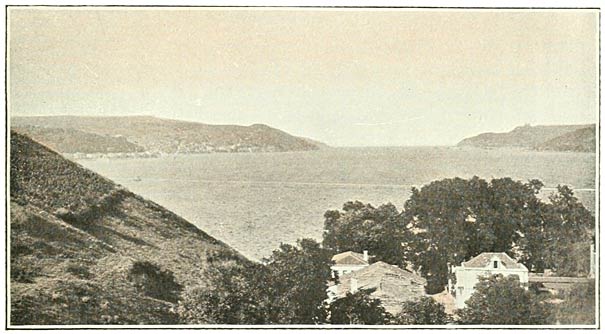

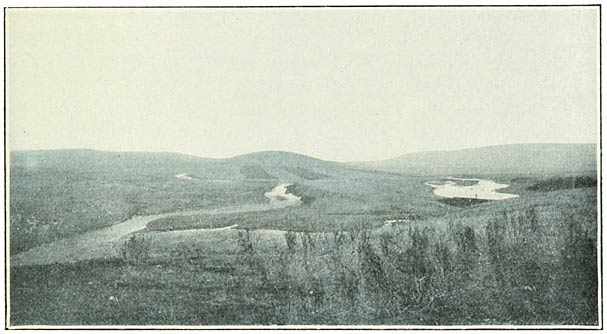

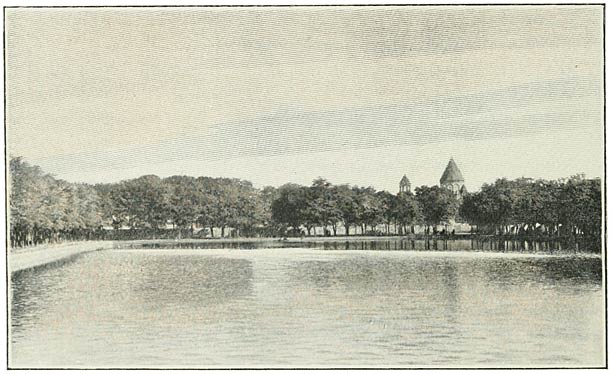

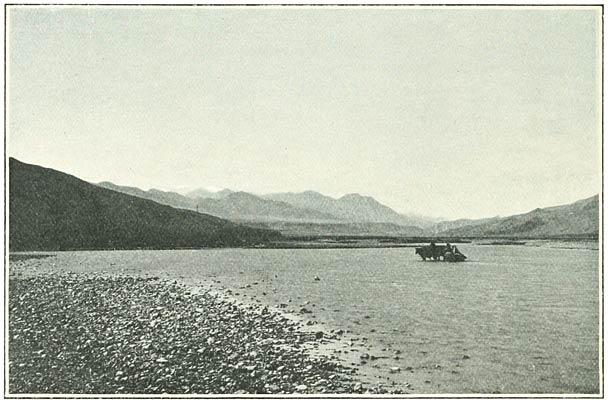

Even beneath this tropical sun the mind of man has

surpassed his difficulties; and just as the Cam has been converted from

a melancholy ditch into a brimming waterway, threading a landscape of

lawn and forest, so the Kasagh has been impressed into the service of

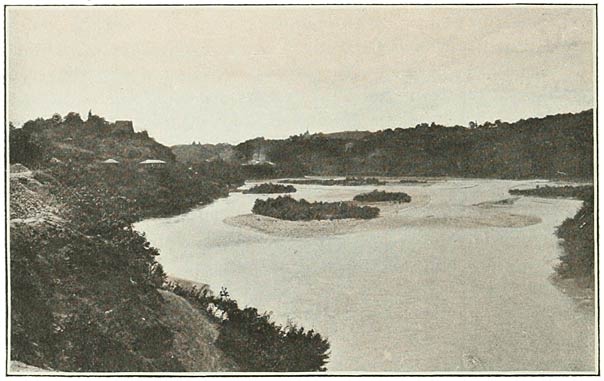

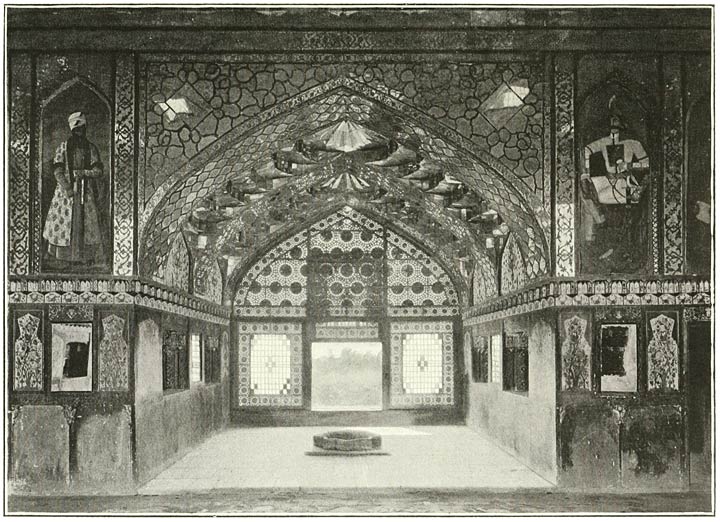

an artificial lake, bordered by shady avenues. Extremely pleasant is

the stroll round this spacious basin, which is due to the refinement of

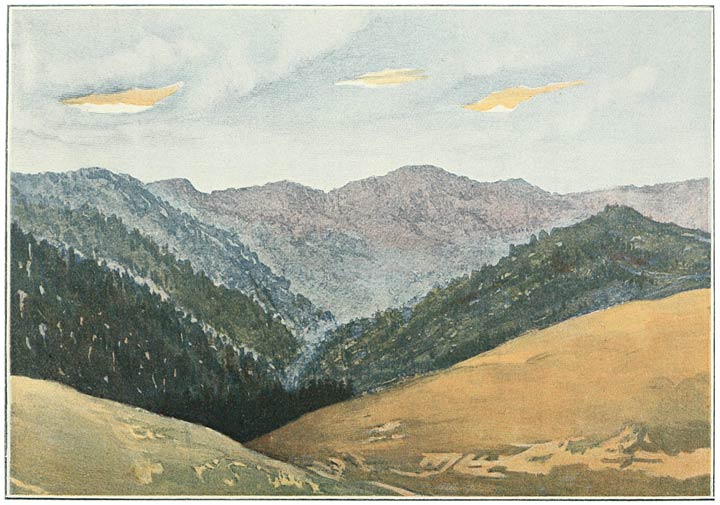

Nerses V. (1761–1857). It is situated just outside and south of

the cloister; and while from one side the view discloses the dome and a

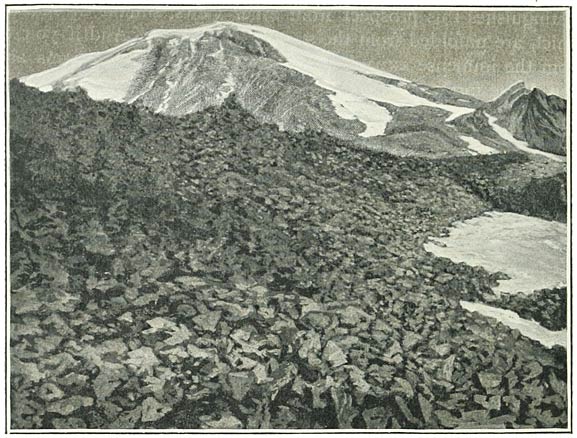

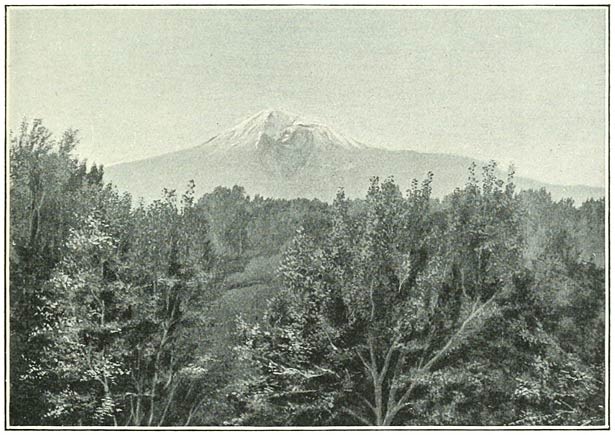

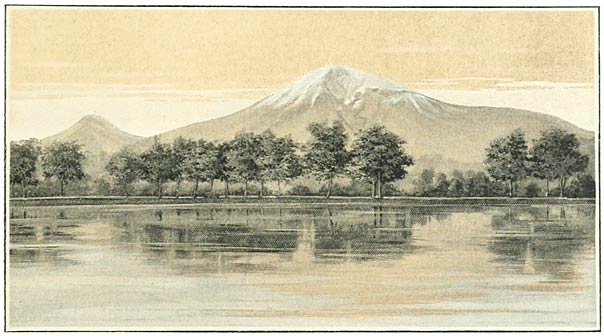

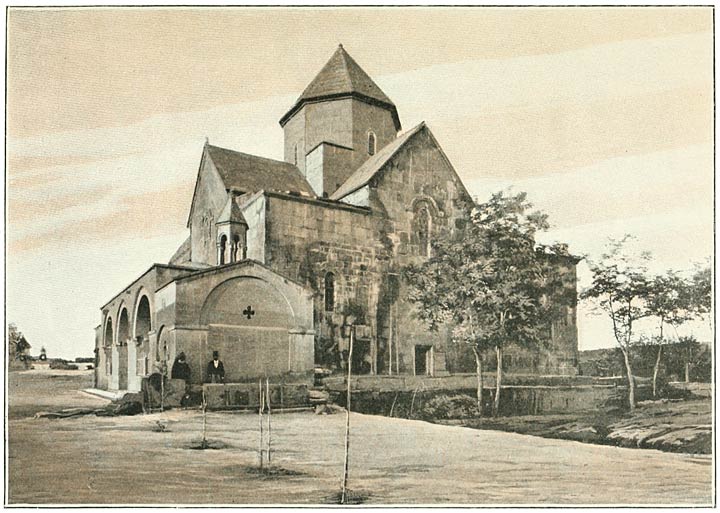

cupola of the cathedral (Fig. 50), on the other

it is the vault of Ararat and the pyramid [246]of the Lesser Ararat

that are outlined above the soft foreground of water and trees (Fig.

51). It was a pleasure to instance this work to

General Frese and my Russian acquaintances as bearing testimony to the

sense of security inspired by Russian rule. The cloister and even the

bazar are surrounded by walls worthy of a fortress, a relic from the

old Persian times. The Russians appear on the scene, and the imprisoned

monks disport in the open, which they make to bloom with luscious

groves.

On the morning following a restful day which introduced

us to our new environment I was invited to visit His Holiness. He had

arrived within the walls of the cloister during our sojourn on Ararat,

and it appeared that he had scarcely been able to leave his apartments

owing to the enthusiasm of the humbler among his admirers, who could

not be restrained from pressing round him whenever he walked abroad.

This enforced seclusion had developed a tendency to asthma; but with

this exception I found him in excellent health. Even the garden had

been invaded by the peasants, who would wait hour after hour to catch a

glimpse of their Hayrik—a term of endearment, signifying

little father, under which Khrimean is very generally known. Two

footmen in scarlet robes with blue sashes stood upon the flight of

steps or busied themselves with errands. I was ushered into a long

apartment, modestly furnished in European style, where I [247]was

received by an Armenian gentleman, of the handsome aquiline type of

face, who addressed me in fluent English. He had been interpreter to

the delegates to the Berlin Congress, and more recently had been much

in the society of the Katholikos, residing at Jaffa (Jerusalem). Baron

Serapion Murad—the first name is the equivalent of

Mr.—holds a position of the first importance in the counsels of

His Holiness at this juncture in his career. He is the shrewd man of

the world, who weighs you in the balance with a single glance of his

intelligent eyes. I appear to have emerged on the right side of the

scale; for his formidable scrutiny rapidly relaxed into an amiable

smile. We passed from this outer room into a chamber with a daïs

at the further side; and presently the Katholikos entered and mounted

the daïs, begging us be seated on two chairs which were placed on

the floor below, but quite close to his own arm-chair.

I do not remember having ever seen a more handsome and

engaging face; and I experienced a thrill of pleasure at the mere fact

of sitting beside him and seeing the smile, which was evidently

habitual to those features, play around the limpid brown eyes. The

voice too is one of great sweetness, and the manner a quiet dignity

with strength behind. The footmen and the daïs and the antechamber

were soon forgotten in this presence—forms necessary to little

men and perhaps useful to their superiors, though they are always

kicking them off when they are not stumbling among their folds. Happily

the temperament [248]of His Holiness is averse to all baubles;

the cross of diamonds was absent from his conical cowl, and his black

silk robe, upon which fell a beard which was not yet white, was

unrelieved by the star of his Russian order. These ornaments are

strangely out of place on such a figure, and their formulas out of

keeping with this character. I was closely questioned upon all the

incidents of our climb on Ararat; nor was it doubted that we had

reached the summit. In the old days such a pretension would have been

met with a smile. Then we passed to his sojourn in England, and I asked

his opinion of Mr. Gladstone, with whom he had enjoyed some

intercourse. He had been impressed, like so many others, with the

theological cast of that supple mind. The face contracted when we came

to speak of his life in the Turkish provinces; and he laid stress upon

the terrible reality of the sufferings of the Armenian inhabitants. All

the struggles and hopes and anguish of his strenuous days and sleepless

nights seemed to rise in the mind and choke the voice. Then he sank

back, with a sigh which seemed to regret them. “I have

come,” he said, “to the land of

Forgetfulness.”—And from the quadrangle came the sound of a

slowly-moving Russian anthem, and the measured step of a detachment of

Russian soldiers.

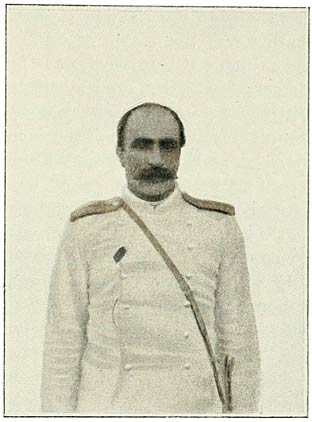

His Holiness invited me to take my meals in his private

dining-room, and expressed his regret that he would not be present

himself. It happened to be a fast day, and nothing was offered but

lentils and peas. But on the day following quite a banquet was spread

before us—salmon trout from Lake Sevan, delicious dolmas

of minced meat and rice bound together by tender cabbage leaves, and

the usual not very tasty chickens. At the head of the table sat the

vicar or substitute of the Katholikos, with M. Pribil on a special

mission representing the Emperor on his right hand, and General Frese

on his left. One or two Armenian notables were of the party, which,

however, consisted for the most part of bishops resident at Edgmiatsin.

All wore their black silk cowls during the meal. As one looked down the

line of clerics the aquiline type of face predominated—fine human

animals they seemed, with their pronounced features and limpid eyes and

the long beards which keep their colour and speak of a mind at ease.

One of the monks present spoke French fluently; but he had been

imported from the Crimea by the present Katholikos. His name was Khoren

Stephaneh. Many [249]a pleasant talk I had with him, but not

during dinner; they have too much respect in the East for their food

and cook to divert the tongue at such a time from its proper function.

What little ripples of conversation diversified the natural sounds of

the meal were due to that restless spirit of the West, which is always

asking questions and living several hours in advance of the actually

present time. I do not know that either of the high Russian

functionaries were much troubled by this particular product of Western

culture; but, if they were, they must have suffered from the inability

of their hosts to comprehend their language. The wine of the cloister

flowed freely, and was supplemented by European liqueurs. Then the

restless spirit broke bounds, attacking first the taciturnity of the

Governor of Erivan. The formula I had heard so often was the first to

take wing; and “How long are you staying here?” came across

the table in a somewhat loud voice. It was not the least unkindly

meant. Next the same little sprite perched upon M. Pribil, and

extracted several questions, which it let fly. When we rose from table

he engaged me in a discursive conversation which ranged freely over the

Armenian Question. He affirmed that the Armenians did not compose more

than one-fifth of the population of the Russian provinces south of

Caucasus.

The apartment was soon empty, every one retiring to

their siesta; but I strolled out and made my way to the humble monastic

buildings which adjoin the lonely church of Saint Gaiane. There I found

a new friend whom I had learnt to value, a young monk recently

ordained. Mesrop Ter-Mosesean belongs to the new school of clerics who

will before long remove that stigma of crass ignorance which still

attaches to the bulk of the Armenian priesthood. Men like Khrimean have

long perceived that in matters of education Germany occupies the first

position among the nations of the world. With greater insight than the

Turks, who send their young men to Paris—the very worst school

for the full-blooded Oriental—they encourage their promising

scholars to study in Germany, and find the necessary funds. The monk of

Gaiane had just returned from the German University, and he does credit

to the solid attainments which it supplies. He is a splendid physical

example of his race. Tall, with the bold features of the handsome type

which I have described, with a massive forehead and teeth white as

snow, he combines with these outward advantages a manner which is most

[250]winning and a simple, straightforward character.

Hours I spent in his little sitting-room during my sojourn, and I was

always sorry to come away. He occupies the post of librarian at

Edgmiatsin, and he is now busy with the compilation of a new and

comprehensive catalogue.12 On this occasion we walked

across to the library, and found it full of people. It is entered from

the side of the Katholikos’ garden. I was shocked by the

spectacle of valuable manuscripts lying open on a long table, and being

fingered by a promiscuous crowd. Such was the license of this national

festival. I noticed among them a New Testament of the tenth century,

bound in richly carved ivory sides. The type and pose of the Christ in

the centre of the one panel recalled that of a Roman emperor.13 Beautiful manuscripts of the thirteenth century

and a minutely illuminated missal of the seventeenth figured among the

treasures which any hand was allowed to soil.

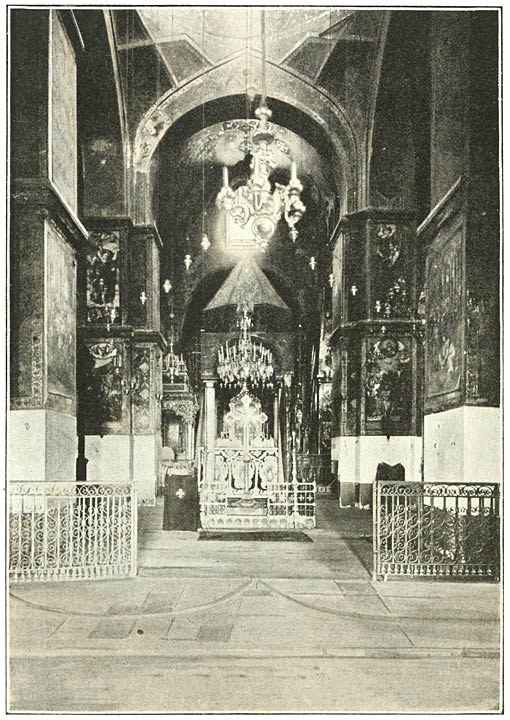

Evensong was at hand, and my companion and myself

entered the dimly-lit church. The Katholikos was already seated in the

throne with the canopy, attired in a rich white satin robe. The cross

of diamonds flashed from his cowl. Bishops and monks composed two rows,

extending to the daïs of the apse; they wore robes of yellow silk,

embroidered with coloured garlands of flowers. The congregation was

very numerous, but clustered in groups about the Katholikos; there was

no order or assignment of places, as with us. They sat or knelt upon

the floor. On either side of the lines of clerics were gathered the

choir, in gorgeous dresses, holding large and cumbrous books of

Armenian music. The priests conducting the service stood upon the

pavement of the church with their backs to the daïs. Above them

rose the shapes of crosses and gorgeous eikons, held aloft by their

attendants. Incense was scattered at intervals. I noticed that His

Holiness twice changed raiment, although I was at a loss to discover

when and where the transformation had taken place. The strongly nasal

chants hurt my unaccustomed ear, and I found it impossible to educate

my sympathy into communion with this show.

An hour or two later symbols and eikons and tight little

[251]formulas were all blissfully asleep; and the

great court flooded over with good, healthy human spirits, released

from the restraints of the day. Bonfires were lit within it, from which

the leaping flames shot into the shadows of the church of the

Illuminator and revealed the circles of the dancers. From many a

brightly-lit room, given over to the pilgrims, came the shrill sounds

of the flute and the beats of the small drum. Hai-this and

Hai-that—the refrain and burden of every song celebrated the

glories of the sons of Hayk. In the street of Vagharshapat our friends

the musicians from Alexandropol were reaping a golden harvest. Was

there ever collected together a more motley crowd? They must have come

great distances. There were ladies from Akhaltsykh, with the pretty

fillets across the brow; there were frock-coats and uniforms. The

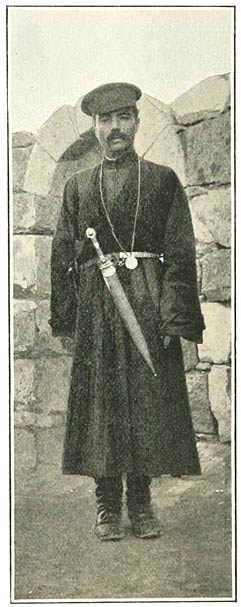

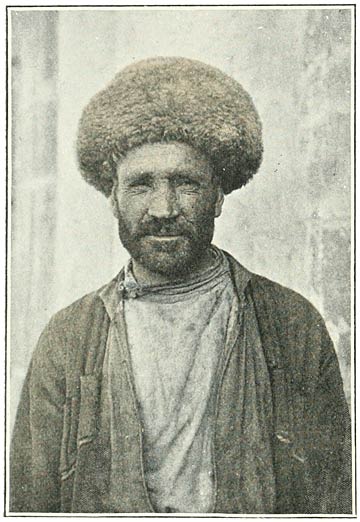

bright calicoes of peasant women enlivened the scene; some of the men,

the poorest class, wore their rough sheepskin hats, while the

better-to-do had donned low caps with a peak, like that of a naval

officer. Long before midnight quiet had settled upon the great

quadrangle, and nothing was heard but the plash of the fountain. But

sombre patches marked the spots where whole families were encamped;

while the steps all around the church and every niche and doorway were

black with the forms of serried human beings in every attitude of

slumber.

Next morning, the 8th of October, popular excitement was

at its highest, the central event which they had come to celebrate

being imminent. From the earliest dawn throngs of sheepskins and peak

hats and coloured calicoes had been busy reconnoitring the most

suitable positions; and, when the hour approached, all the roofs which

commanded a view of the portal, and a good part of the quadrangle

enjoying the same advantage, were densely packed with spectators. Rows

of Russian soldiers kept clear the approaches to the western or

principal entrance of the church. They wore dark green uniforms with

shoulder-straps of a faded pink, and peaked caps of white canvas.

Wesson and I made our way with difficulty to the residence of the

Katholikos, where, in the private room of Baron Murad, we set up the

camera right in face of the scene of the approaching ceremony. It had

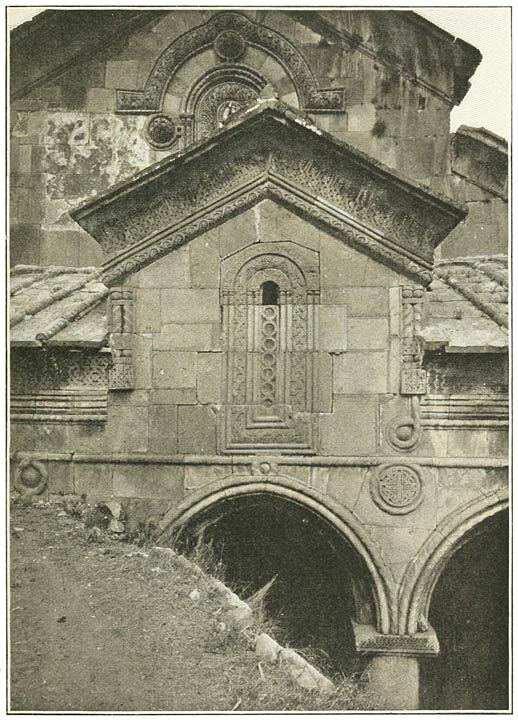

been decided to perform the rite of consecration upon a daïs in

front of the portal. This improvised wooden structure was covered with

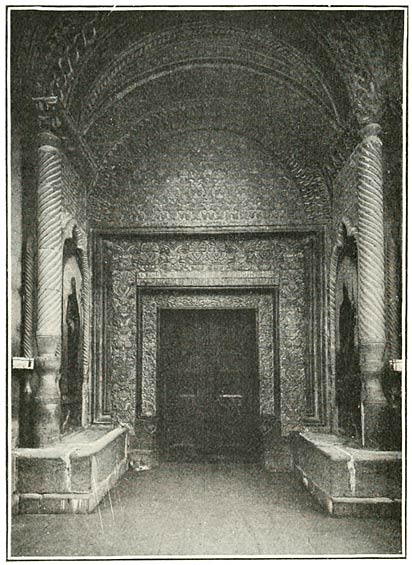

carpets and costly embroideries. Over the doorway of the portal were

emblazoned large Armenian letters upon a ground of cloth [252]or

canvas. The inscription reminded us that we were assembled upon the

actual site where Jesus Christ is believed to have descended from

heaven. The name of the cloister and cathedral is said to signify

“The Only-Begotten has descended”; and the text over the

doorway may be translated “The Only-Begotten has descended from

the Father, and the light of glorification with Him.” Upon a

higher plane, from the tower of the belfry, was suspended a banner,

embroidered with the device of the Katholikos and with the eagle of

Vaspurakan (Van). The device consisted of a mitre, surmounting the

figures of two angels, one carrying a cross and the other a pastoral

staff. These emblems crossed one another, and at the intersection was

placed an ornament of diamond shape peculiar to the Katholikos. The

eagle with the wings outspread was purely personal to Khrimean,

recalling the many links which attach him to Van. The scroll was to the

following effect:—“O God, the knower of hearts, protect for

long years our chief of shepherds (Hovapet) Mekertich

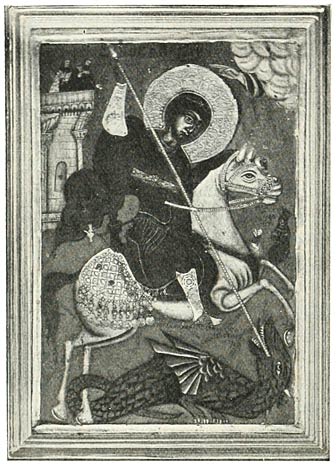

Hayrik.” Left and right of the daïs, in niches of the

façade of the portal, were exhibited two eikons, or religious

pictures, richly framed, of which that on the left—a Virgin and

Child—was a painting of very high merit, said to be of Byzantine

origin.

At a quarter to nine the procession is formed, and

proceeds from the pontifical residence down the avenue of soldiers to

the church door. The service which is held within the cathedral of the

Illuminator lasts for over an hour. The party assembled in our upper

chamber spend the time with conversation and in [253]gazing down upon the multitude. It consists of a

nun from Tiflis, a frock-coated teacher in a school of that city, and a

pretty woman of the rich Armenian bourgeoisie of

Tiflis, attired in a dress of Parisian model. The nun is a charming

woman, and we make great friends. She informs me that she is almost an

unique specimen of her order; the convent at Tiflis is perhaps a

solecism. Nunneries are not popular with the Armenians. I think my

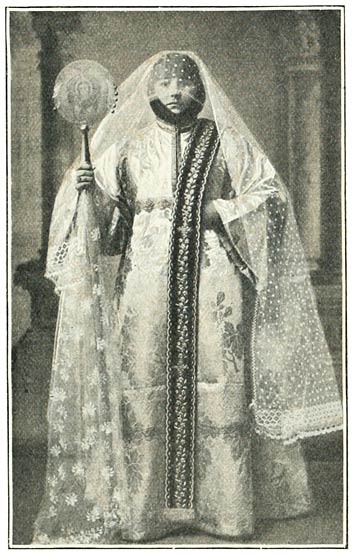

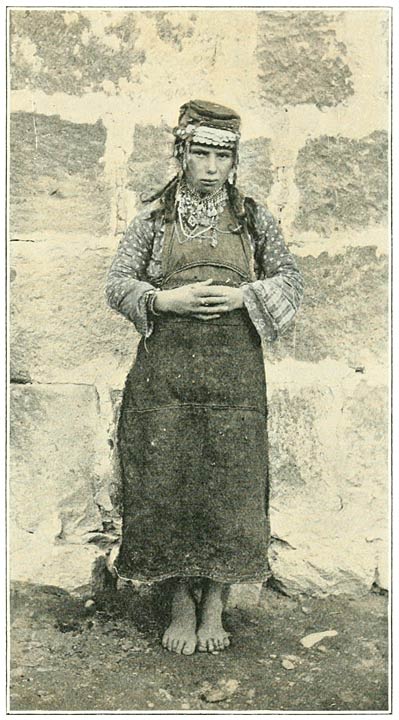

reader may appreciate the magnificent robes which belong to her office,

and of which, by her kindness, I am able to supply an illustration

(Fig. 52). I notice that among the women

assembled in the quadrangle the Armenian national dress is not often

seen. The Georgian head-dress—a band of black velvet, embroidered

with beads or jewels, across the temples, and a white silk kerchief

over the head—appears to predominate. This fact would show that

the greater number of those present have come from Tiflis and the

northern districts.

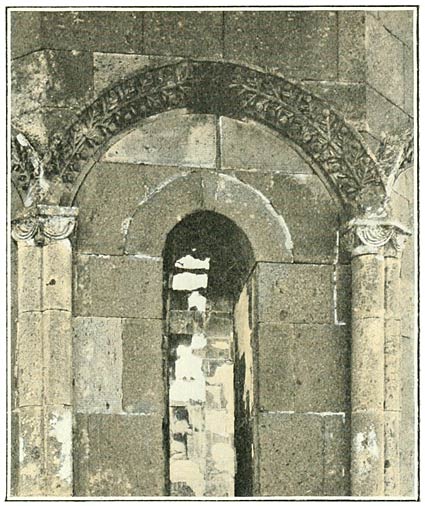

Just as we are getting a little bored with the finicking

architecture of the portal there is a movement and a rustle, and the

procession issues from the church. First to appear are the high Russian

officials in Court dress—M. Pribil, General Frese and the rest.

They take up position on the floor of the quadrangle in front of the

crowd, and face the still vacant daïs. Between them and this

central object room is left for the choir and deacons, who are

presently introduced. Hats are doffed in spite of the fierce sun. A

brief, intense pause, and the twelve bishops14 in gorgeous

attire mount the daïs from behind. They escort the venerable form

of the Katholikos, over whose head two attendants support a canopy of

crimson material, embroidered with gold lace. For a short space the

aged patriarch fronts the multitude in a standing posture; then sinks

on the carpet with his feet beneath his body in Eastern fashion. Erect

beside him, a bishop reads from a heavy volume. From time to time you

detect a movement of the deeply-bowed head of the seated figure, as a

particular passage is recited. Next a bishop advances, bearing in his

hands the image of a dove, wrought in gold. It is the receptacle of the

holy oil. In the southern apse of the cathedral stands a chest

containing a vase, in which is preserved [254]oil blessed by St.

Gregory. It is nothing, they say, but a mass of dry material. Of this

substance they take a pinch and mix it with consecrated oil, specially

prepared and scented with essence of flowers. Such is the liquid which

is allowed to flow from the beak of the dove upon the head of the

father of the nation. The bishops gather round, and each with his thumb

spreads the oil over the scalp, making the figure of a cross at the

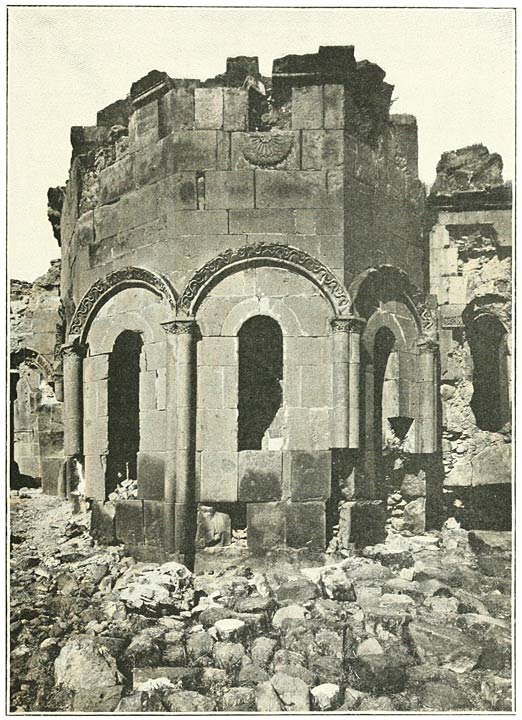

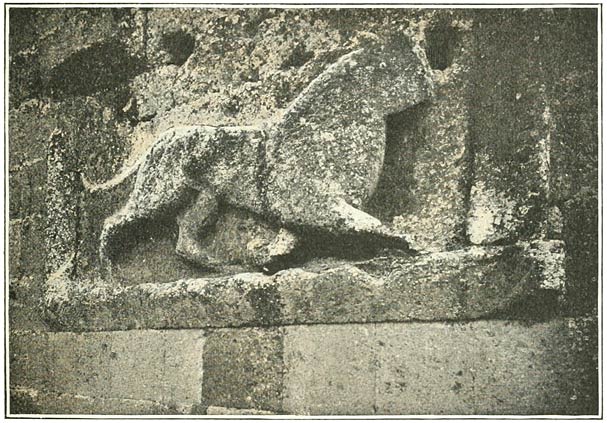

same time (Fig. 53). Then a mass of wool is

applied to the crown of the head, in the folds of a muslin veil which

is adjusted to fall over the face. The Katholikos rises after a brief

interval, places his feet in his embroidered slippers and with the

bishops re-enters the church. The ceremony has occupied a quarter of an

hour.

Some little time elapses, and the same procession leaves

the building, accompanying the anointed pontiff to his residence. The

choir sing from their great books the old Armenian chants15 with their loud lamentations and long shakes. The

band of the Russian regiment play a slow and solemn music, of which the

sweetness puts to shame the nasal choristers. They are mostly Armenians

in this band. These strains bring the rite to a conclusion, and we all

disperse to our various amusements or occupations.

The dinner “in hall” upon this festival of

the consecration was a very interesting incident. We were all to dine

in the refectory. When I entered, the long apartment was crammed. The

scholars of the Academy partook of the meal in the parallel chamber.

The bishops, the monks, the delegates composed a sombre assembly,

stretching in rows of long perspective down the tables. A single

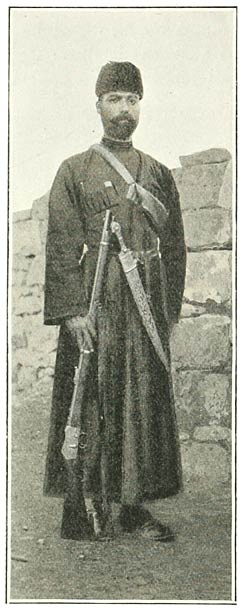

exception to this dark apparel was furnished by a delegate from

Karabagh, who was seated next myself. He wore his national

dress—a spare black tunic, fastened at the neck, displaying the

front and sleeves of a light blue silken vest. His face was large and

expressive of great resolution, especially the chin, which, like the

cheeks, was shaved. The bronze complexion heightened the whiteness of

the bold moustache. One was reminded of the best type of peasant

proprietors in Europe; and, indeed, a view of the faces round one

confirmed [255]that favourable impression which one receives

from the society of Armenians in their native country. There is

depicted a striking union of force of character with intelligence. In

the midst of these reflections the Katholikos enters the building, and

we all rise from our seats. He sits on his throne beneath the canopy,

and a monk ministers to his needs. On either side stands a scarlet

footman with a blue sash; the choir are drawn up behind. After the

first course His Holiness rises, wearing his cowl and the glittering

cross, and proposes the toast of the Emperor. It is a delight to hear

him speak. He has all the personal fascination of Mr. Gladstone. Dinner

proceeds as the catalogue of toasts is gone through, and between each

toast European melodies are sung by the choir, and songs by an Armenian

tenor of repute. The health of the Emperor is received with cries of

Oura; but the remaining toasts without exception with the

Armenian cheer of Ketsze! the equivalent of the French

Vive! In proposing the health of M. Pribil His Holiness recites

the various occasions upon which that functionary has come to

Edgmiatsin to attend the consecration or the funeral of a Katholikos.

Turning to his guest with a winning smile, he begs him to defer his

next ceremonial visit until after the lapse of a moderate interval.

In the evening the whole quadrangle was illuminated with

strings of coloured glasses containing candles. They made a very pretty

show. At intervals huge firebrands threw a lurid light upon the

buildings. The numerous choir of the Academy was marshalled in the

court, including many ladies. The programme comprised several cantatas

and some concerted music, and the standard was fairly high. But it

appears difficult to eliminate the nasal pronunciation. The

music-master was a great swell with his inspired look and flowing hair.

The band discoursed the waltzes of the immortal Strauss. Before eleven

all sound was hushed save the plash of the fountain, and darkness

unrelieved had settled upon the scene. I made my way to the rooms of

His Holiness and ascertained that he would receive me in spite of the

lateness of the hour.

I found him reclining on a wooden couch in a bare

white-washed apartment; a single rug was suspended upon the wall beside

the couch. Such is the bed and such the furniture natural to the object

of all this pomp, which I do not doubt is profoundly distasteful to

such a character. He took my hand in his, and [256]we

sat together for some time, the office of interpreter being, I think,

performed by Dr. Arshak Ter Mikelean. Our talk ranged over many

subjects; but I should have preferred to sit still, look in those eyes

and hear that voice. I think we both felt that we were very near each

other; and religion is a subtler thing than can be defined in creeds

and dogmas or embodied in what the world calls “views.”

On the following days the state of tension was gradually

relaxed; the cloister settled down to ordinary life, and it was

possible to examine the churches at one’s ease. These are

actually four in number, although in Mohammedan times the district was

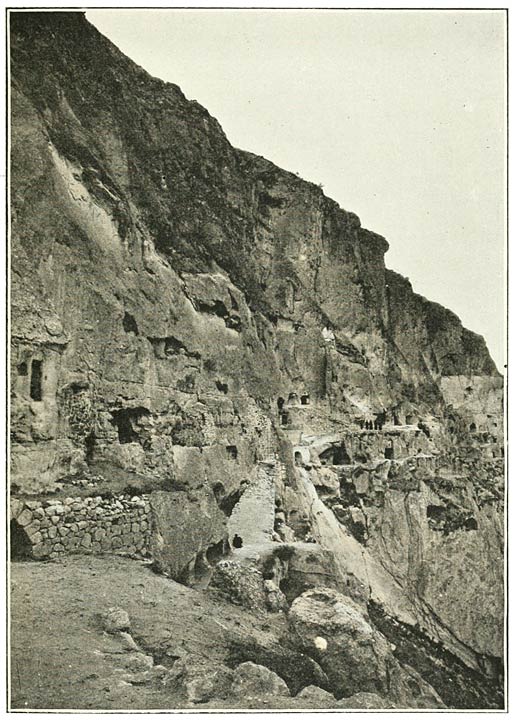

known under the name of Uch Kilisa, or Three Churches.16 Their origin is bound up with a legend which

plays such a considerable part in the history of the Armenian Church

that, before passing to a description of them, it may not be

inappropriate to instruct or amuse my readers with this curious

story.17

Towards the close of the third century, while Tiridates

was on the throne of Armenia, the Emperor Diocletian

(284–305),18 in search of a beauteous spouse, sent

artists into all parts of his empire to depict the charms of suitable

candidates for the imperial embrace. Now there happened to be in Rome a

convent of nuns of austere life, of which the superior was called

Gaiane. Under her charge was a virgin of surpassing beauty and of royal

lineage, whose name was Ripsime. The artists entered her retreat by

force, committed her lineaments to their tablets, and sent the portrait

with several others to their master. The emperor had no sooner gazed

upon the image of the high-born virgin than he fell violently in love.

No pains were spared to hurry forward the preparations for the

marriage, and the wretched bride was in despair. Her vow of chastity

and the [257]hatred she felt for the persecutor of her sect

encouraged her to adopt the counsels of despair. She took to flight,

attended by Gaiane and a numerous company of the nuns; and after many

wanderings the band arrived upon the banks of the distant Araxes, in

the outskirts of the Armenian capital of Vagharshapat. There they

discovered a secluded retreat in a place which served as a store for

vats, the city possessing extensive vineyards. One of their number was

versed in the art of the manufacture of glass objects; she made glass

pearls, and their price defrayed the cost of their daily

sustenance.

Meanwhile the emperor had despatched messengers in every

direction, and a Roman ambassador arrived at the court of the Armenian

king. He was the bearer of a letter to that monarch from his master,

who related how the Empire was suffering from the misdeeds of the

Christians, and in particular how a beautiful virgin whom he himself

had desired to marry had been abstracted by her infatuated co-sectaries

and taken into the territory of his Armenian ally. The emperor begged

his beloved colleague to track the party out, and, with the exception

of the wondrous virgin, to put them all to death. As for the lovely

fugitive, it would only be necessary to send her back; but the missive

added, with an amiability truly worthy of an emperor, that the king

might keep her if overcome by her charms.

As might be expected, no time was lost on the part of

Tiridates to institute and elaborate the search. The band was found;

the beauty of Ripsime needed no identification; and the fame of it

attracted a multitude of all ranks—princes and nobles, shoulder

to shoulder with the common people, closing round her under the sting

of licentious desire. The nuns raised their hands to heaven and drew

their veils about their faces; and perhaps this display of modesty

averted their ruin. Early on the following morning there arrived from

the palace magnificent litters and costly robes, the design of the king

being to take to wife the Christian maiden and make her queen of the

Armenians. But at this juncture a peal of thunder carried terror into

all hearts, and a voice was heard descending from the sky. It was the

voice of the Saviour, adjuring the nuns to take courage and remain firm

for the glorification of His name among the peoples of the north.

“Thou Ripsime,” it proceeded, “hast been cast out

(ἐξερρίφθης)

with Gaiane and thy companions from the realm of death into that of

eternal life.” Meanwhile the thunder had [258]caused a panic among the assembled people, and

the king’s officers hastened to the royal presence, bringing a

written report of all they had heard. But the monarch hardened his

heart, and, since she refused the pomp he offered, gave orders that the

maiden should be taken by force and brought to the royal

apartments.

These directions were executed, but not without

difficulty; the pious virgin was of stalwart frame, and the soldiers

were obliged to drag her along the ground, or carry her struggling in

their arms. When they had placed her in the king’s chamber, and

it was announced that the king had entered, the people outside the

palace feasted and danced and sang. But their rejoicings were

premature; for the intrepid Roman maiden was more than a match even for

the powers of so redoubtable an antagonist. Tiridates was widely famed

for physical strength and deeds of prowess; yet, although he persisted

in his suit for not less than seven hours, he was at last compelled

through sheer exhaustion to give in. The offices of Gaiane were

invoked; she consented to speak, but her counsels were addressed to

confirming the courage of her companion. Her Latin speech was

understood by some among those present; they took stones and tore her

face and broke her teeth. After a brief repose the king returned, and

again endeavoured to overcome the girl’s obstinacy; but after a

long struggle the inspired amazon was a second time victorious; she

threw the king (ἔρριψεν),

destroyed his diadem, and dismissed him from the chamber, fainting and

gathering around him his tattered robes.

A tender respect for the honour of women is a virtue of

Christian origin, which the romance of Western chivalry converted into

a cult of the fair sex. But the king of Armenia was an Oriental, a

heathen and a barbarian; nor had he been instructed in the code which

precludes the sentiment of humiliation in the vanquished where the

victor is possessed of a female form. His passion as a lover was

overcome by his fury as a thwarted despot; the virgin had fled from the

palace, but his savage emissaries were soon on her track. The

unfortunate maiden directed her steps to the retreat where the vats

were stored, and gave the alarm to her companions. All those present,

excepting one who was stricken with illness, accompanied her flight.

But when they had reached some rising ground near the road which led to

Artaxata, they were overtaken, bound with [259]cords and put to

death with great cruelty. With Ripsime there perished thirty-two of her

attendants, while the poor nun who had been left behind presently met

the same fate. The martyrdom of Gaiane and of two companions took place

on the following day and was attended with tortures which I should

shudder to commit to paper.

Not many days after this tragedy its author was visited

by the vengeance of heaven; a demon entered his body, and, like his

prototype of Babylon, the king of Armenia was turned into an animal

eating grass. In the form of a wild boar he resisted all attempts to

confine him; and similar punishments overtook the royal family and

attendants. At length the sister of the king, by name Khosrovidukht,

beheld in the watches of night a vision. A man with a radiant face

appeared and addressed her, to the effect that the only remedy was to

send to the town of Artaxata and summon thence a prisoner named

Gregory. When she related the vision people shook their heads, and

attributed it to the incipient madness of the princess. For Gregory,

who was once an honoured servant of King Tiridates, had been cast by

the tyrant into a deep pit, on account of his profession of

Christianity, not less than fifteen years ago. Would even his bones be

forthcoming from such a place? But when several times the vision had

been repeated, and the princess renewed her insistence, a great noble

was despatched to the place where the pit was situated, near the town

of Artaxata. A rope was let down into the cavern; and, to the

astonishment of all, there emerged a human form, blackened to the

colour of coal. It was none other than St. Gregory.

The saint was met by the king and nobles, foaming and

devouring their flesh, as he approached the city along the road from

Artaxata. Sinking on his knees, he obtained from heaven the restoration

of their reason, although not of their human forms. His next care was

the burial of the martyrs; he found their bodies, lying where they

fell, and still untouched by corruption after the lapse of nine days.

No dog or beast or bird had approached the remains. St. Gregory took

them with him to the place where the vats were stored; and for

sixty-six days he sojourned in that place, instructing the king and

nobles. After the lapse of that period he related to them a vision

which he had beheld during the middle watches of the night. The royal

party had come at sunrise to prostrate themselves before the holy

man.

During his vigil, while his mind was revolving the

recent acts [260]of Divine grace, a violent peal of thunder,

followed by a terrible rumbling sound, had fallen upon his startled

sense. The firmament opened as a tent opens, and from the heaven

descended the form of a man, radiant with celestial light. The name of

Gregory was pronounced; the saint looked upon the face of the man, and

fell trembling to the ground. Enjoined to raise his eyes, he beheld the

waters above the firmament cloven and parcelled apart like hills and

valleys, extending beyond the range of sight. Streams of light poured

down from on high upon the earth, and, with the light, innumerable

cohorts of shining human figures with wings of living flame. At their

head was One of terrible face whom all followed as the supreme ruler of

the host; He bore in his hand a golden mallet, and, alighting on the

ground in the centre of the city, struck with His mallet the crust of

the broad earth. The report of the blow penetrated into the abysses

below the earth; far and near all inequalities of the surface were

smoothed out, and the land became a uniform plain.

And the saint perceived in the middle of the city, near

the palace of the king, a circular pedestal made of gold and of the

size of a large plateau, upon which was reared an immensely lofty

column of fire with a cloud for capital, surmounted by a flaming cross.

As he gazed he became aware of three other pedestals. One rose from the

spot where the holy Gaiane suffered martyrdom; a second from the site

of the massacre of Ripsime and her companions; and the third from the

position occupied by the magazine of vats. These pedestals were of the

colour of blood; the columns were of cloud, and the capitals of fire.

The crosses resembled the cross of the Saviour, and might be likened to

pure light. The three columns were equal in height one with another,

but a little lower than that which rose near the royal palace. Upon the

summits of all four were suspended arcs of wondrous appearance; and

above the intersection of the arcs was displayed an edifice with a

dome, the substance being cloud. On the arcs stood the thirty-seven

martyrs, figures of ineffable beauty attired in white robes; while the

crown of the figure above the edifice was a throne of Divine fashioning

surmounted by the cross of Christ. The light of the throne mingled with

the light of the cross and descended to the bases of the columns.

When Gregory had related this vision he bade all present

gird up their loins and lose no time in erecting chapels to the

martyred virgins, where their remains might be deposited. Thus the

saints [261]might intercede for the afflicted king and

people and assist them to become healed. Forthwith the multitude set to

work, collected stones and bricks and cedar-wood; and, under the

guidance of the saint, constructed three chapels after a prescribed

design. One was placed towards the north and on the east of the city,

on the spot where Ripsime and her companions met their death. The site

of the second was further south, where the Superior Gaiane was

massacred; while that of the third was close to the magazine of vats.

These they built and adorned with lamps of gold and silver, with

candelabra of which the flames were never quenched. Coffins were made

for the remains of the martyrs; but no man was suffered to touch these

relics, for none had been baptized. The saint himself and in solitude

consigned the bodies to their receptacles. And when this was done he

fell on his knees and prayed for the healing of the king, that haply

the king might share in the work. The prayer was granted, and the horn

fell from the royal hands and feet. To the monarch was assigned the

task of digging tombs in the chapels to receive the coffins of the

martyrs; and his consort, the queen Ashkhen, together with his sister

Khosrovidukht, were associated with him in the work. The return of his

vigour was signalised on the part of the king by a labour worthy of the

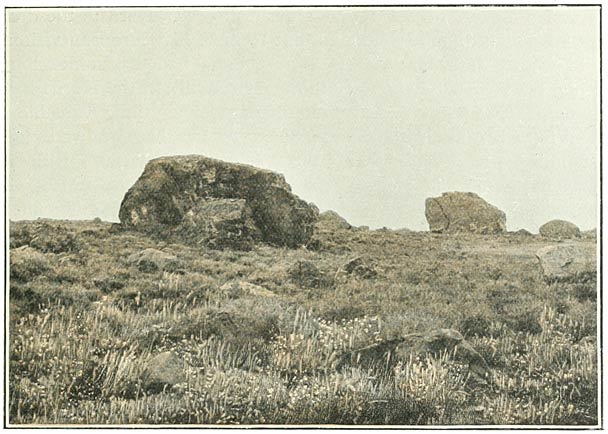

patriarch Hayk. He made a journey to the summit of Ararat, which the

compiler rightly observes would occupy seven days.19 When he

had completed this feat, he was seen bearing upon his shoulders eight

blocks of stone of gigantic size which he had taken from the crest of

the mountain. These he placed before the threshold of the chapel of the

martyred Ripsime in expiation of the unholy battle which he had

waged.20 In this manner all was accomplished according to

the vision of St. Gregory; while, as for the locality where had stood

the column of fire on the golden pedestal, it was surrounded by the

saint with a high wall and heavy gates; the sign of the cross was

erected within it, that the pilgrims might there worship the