![[Image of the cove not available]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Birds useful and birds harmful

Author: Ottó Herman

J. A. Owen

Illustrator: Titusz Csörgey

Release date: March 25, 2016 [eBook #51553]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

![[Image of the cove not available]](images/cover.jpg)

|

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. (In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers]

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

Birds Useful and Birds

{i}

Harmful

Sherratt & Hughes

Publishers to the Victoria University of Manchester

Manchester: 34 Cross Street

London: 33 Soho Square, W.

THE BEARDED TIT.

See page 203.

BY

OTTO HERMAN

Director of the Royal Hungarian Ornithological Bureau, Budapest

AND

J. A. OWEN

Author of the “Country Month by Month,” etc.,

and Editor of all signed “A Son of the Marshes.”

Illustrated by T. Csörgey.

MANCHESTER

At the University Press

1909

| PAGE | |

| Preface | 1 |

| Chapter I. Useful or Harmful | 7 |

| Chapter II. The Structure of the Bird | 15 |

| Chapter III. Workers on the Ground | 25 |

| Barn or White Owl, Tawny or Wood Owl, Long-eared Owl, Short-eared Owl, Little Owl, the Rook, Hooded Crow, Carrion Crow, Raven, Jackdaw, Jay, Magpie, Quail, Black-headed Gull, Starling, Rose Starling, Waxwing. | |

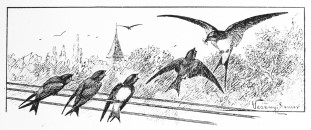

| Chapter IV. In the Air and on the Trees | 105 |

| Swallow, House Martin, Sand Martin, Swift, Nightjar or Fern Owl, Green Woodpecker, Greater Spotted Woodpecker, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Tree-Creeper, Nuthatch, Crossbill. | |

| Chapter V. The Farmer’s Summer Friends | 139 |

| Wryneck, Cuckoo, Hoopoe, Great Grey Shrike, Lesser Grey Shrike, Red-backed Shrike, Lesser Whitethroat, Blackcap, Nightingale, Redstart, Tree-Pipit, Wagtails, Great Reed Warbler, Willow Wren, Flycatchers, Wheatear, Stonechat, Bearded Reedling or Titmouse, the Titmouse Family.{viii} | |

| Chapter VI. Workers all the year round | 225 |

| House Sparrow, Tree Sparrow, Hedge Sparrow, Skylark, Kingfisher, Dipper, Song Thrush, Blackbird, Oriole, Robin, Wren, Chaffinch, Hawfinch, Bullfinch, Yellow Hammer, Turtle Dove. | |

| Chapter VII. Some Wildfowl | 283 |

| Lapwing, Common Curlew, Redshank, Green Sandpipers, Herons, Bitterns, Moorhen, Tern, Bean Goose, Wild Duck or Mallard, Pintail Duck, Shoveler, Great Crested Grebe. | |

| Chapter VIII. Some of the Falconidæ | 333 |

| Golden Eagle, Kite, Red-footed Falcon, Buzzard, Sparrow Hawk, Goshawk, Hobby, Kestrel, Marsh Harrier, Hen Harrier. | |

| Chapter IX. The Rational Protection of Birds | 369 |

| Index | 385 |

The systematic study of the economic value of birds in their relation to agriculture has been carried out in Hungary of late years more indefatigably than in most other parts of Europe. The natural resources of the country are indeed so largely dependent on agriculture that this is only what might have been expected.

The Royal Hungarian Minister, M. Darányi, who has proved himself so thorough and so capable a Director of his country’s interests in the direction of Agriculture—amongst other handbooks issued under his orders for popular use—commissioned the well-known naturalist, M. Otto Herman, to prepare the present work, which is intended to give to landowners, farmers, fruit-growers and gardeners such a knowledge of the action, beneficial and otherwise, of birds as would prevent the mistakes which have ended in some districts in our own country, in the wholesale destruction of some very useful species.{2}

The book is enriched by the drawings of a talented artist, M. Titus Csörgey, who, I need not say, is himself a skilled naturalist. These are so executed as to render it easy to the most casual observer to identify the various markings of the plumage as well as the mere form of the bird.

The work makes no pretence at being scientific in the ordinary sense of the word. It has been written with the view of providing a ready handbook for the farmer, the gardener, the student, and bird-lovers generally; and it embodies the result of exact data kept by correspondents of M. Herman’s department in all parts of the country; so that the observations on which its statements are grounded are the results of personal investigation and dissection.

In our country this study of the food of birds and the part they play in the economy of nature has not received the attention it demands. Yet it is one that affects the entire community. It is true that in journals here and there valuable papers on this subject have appeared, but it is felt that among the innumerable books on bird life which have been published of late years there has been a lack which this little volume may supply.

A few words as to myself and my present association with M. Herman. From my earliest childhood I have had a passionate love for birds and flowers. I remember looking with wondering delight on the velvety upturned faces of the variously tinted pansies that bordered the paths leading up to the door of a certain farmhouse where we stayed much in the summer-time, when I was just four years old,—wonder because our mother told us that God’s finger painted them and I used to think that He did it whilst we slept. Our father gave us{3} prizes for the one who could collect the greatest number of wild flowers and knew most about the trees. In the town I collected bird pictures, nursed an occasional wounded sparrow, kept my eyes open generally, and read much of William and Mary Howitt. Then came some years of school life—the last two of these in Germany, where the study of natural history has always received more attention than has hitherto been the case with us in England, and these were followed by a few years at home on the moorlands of Staffordshire. Later I had thirteen years of wandering in different parts of the Pacific—New Zealand, Tahiti, Hawaii, California, all of which strengthened my love of out-door life; and although my scientific knowledge was small, my acquaintance with nature and my love of nature have been ever growing.

As years advanced, and I was no longer able to go so far afield, it has been a great pleasure to me to collaborate with other naturalists—more than one of these—who, with greater opportunities for the practical observation of birds have combined scientific research. I have been glad to act as henchwoman to such—and to be, as it were, the little bird that in its playful and circling way follows the flight of the greater bird in the heavens.

And as I edited—with much gain to my own knowledge—the records of observations of the working naturalist styled “A Son of the Marshes,” so I am glad also to be able to present to our English readers these chapters on the Man and the Bird, and their relative significance in the great field of agriculture.

I visited M. and Madame Herman at their home in the beautiful Hungarian valley of Lillafüred, where his{4} summers are spent in the very heart of nature; and I learned and saw much with him there. He had lived as a boy among these mountains and valleys—his father having been the leading physician in the district. There, he had scoured the woods over which the Snake or Short-toed Eagle circled, climbed up to the Peregrine Falcon’s nest, and boated on the lovely little lake, watching the movements of the Osprey. But indeed his whole life has been devoted to the study of nature, and the fauna of his Country, and his many published writings have had a very large circulation there, as well as in Germany.

M. Herman laments the constantly decreasing number of birds in his native valley. In a spot where he once counted many a Flycatcher’s nest, only two pairs now breed. The Nightingales, formerly plentiful, have entirely forsaken this valley—the Titmice are lessening in numbers, and so on. Yet the masses show no inclination to destroy useful, insect-eating birds—although modern forestry, and gardening, which does not tolerate old trees, and the absence of sheltering hedges over the great Hungarian plains, render many birds—especially the migratory species—homeless.

Numbers of interesting species nest in and visit this valley, however. In winter that beautifully coloured, long-billed Rock-Creeper (Tichodroma muraria)—with wings rose-red above, dashed with white underneath, runs up the rock sides, as does the Tree Creeper on the tree trunks—a blithe, busy creature. This species is found in the same latitude, in rocky mountain ranges eastward, as far as Northern China. The great slanting rocky spurs, that gleam with rosy light, or pale blue, as the sun runs its daily course, this rock climber delights in. The{5} Rock Thrush breeds in the same ridges; the Long-tailed Tit has its nest there; near the ground in the woods, are the breeding-places of the familiar Coal-Tit; where fir-trees abound it is at home. The less welcome Red-backed Shrike pursues his cruel little methods here, lessening the numbers of more useful and more attractive birds. Waterfalls abound, and among the brooks, from stone to stone, trips the merry Dipper, showing his pretty breast and red underparts—building his large house near the running water, in whose pools fine trout are in plenty.

We have rested together in a little cove on the lake at Hamar, which is overhung by luxuriant foliage; across the water, over the dense woods, floats a solitary Eagle—that seeks his quarry in the shades below. Otto Herman knew his breeding-place as a boy. Tradition says the nest is at least a hundred years old, yet each year the young are still fed there.

That Great Britain has still much to do in the direction of Bird Protection is definitely shown in a leaflet just issued (December, 1908) by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, of whose Council I have the honour to be a member. Of the 370 or 380 species placed on the list of “British birds,” scarcely 200 can now be justly termed British. I may be allowed to give you here some idea of the principal agents in this destruction of birds as set forth by our Society:—

“First, there are those who destroy for destruction’s sake; the boy who ravages the hedgerows in spring and delights in catapults, air-guns, and stones at all times; the lout with a gun; and the cockney sportsman. They are responsible for a vast amount of cruelty, especially{6} to nesting birds and nestlings; for the killing of various home-birds and migrants, and for the senseless shooting of sea-birds and occasionally of rare visitants.

“Secondly, the bird-catcher, responsible for the decrease of all those birds sought for caging, such as Goldfinch, Linnet, Siskin, Lark, etc. This class, like the first-named, requires dealing with, chiefly because of the intolerable amount of ill-treatment involved by the methods employed in the catching, transit, and sale of wild birds. The destruction of the useful Lapwing, and of the Skylark for the table, is also a point in need of attention; and in the same category may be placed the so-called sparrow-clubs, which encourage the indiscriminate killing of many species of small birds.

“Thirdly, the gamekeeper, responsible for the extinction, or extreme rarity of most of our large birds, especially predatory species and uncommon visitors.

“Fourthly, the private collector with a craze for rare British-taken birds and eggs, or, in the case of the humbler persecutor of beautiful species, for something to put in a glass case.

“Fifthly, the trader and the feathered woman, jointly responsible for the devastation wrought among the loveliest birds of all lands.”

We have included a few useful species here, which are only visitants to our country, but which, with more protection, might remain for part of the year with us regularly.{7}

The Hungarian Central Office for Ornithology was instituted in 1804, in accordance with a scheme submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture by Mr. Otto Herman, then a member of the Hungarian Parliament.

The rapid progress of economical affairs in the nineteenth century, particularly in its second half, had a perceptible influence upon the position occupied by the bird and insect fauna, a change which was felt in agriculture, and led to the formation of a new branch of science—ornithologia oeconomica.

The Hungarian Central Office for Ornithology took the new branch in hand, after its transfer from the sphere of the Ministry of Public Instruction to that of the Ministry of Agriculture, where M. de Darányi assigned an important place to practical experimental methods as a complement to strict science.

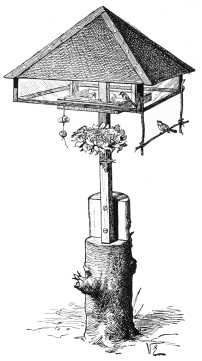

In the meantime Baron Hans von Berlepsch of Seebach developed his system for the protection and propagation of the most useful birds, the main points of which were the feeding and providing with nesting opportunities of such birds. Thereby bird protection was diverted into a rational direction, which met with hearty sympathy on the part of M. de Darányi; consequently the Hungarian Central Office for Ornithology included this branch of ornithology in the work it set itself to do.

The course followed by rational bird-protection in Hungary is as follows. It starts with the idea that{8} nature itself knows neither useful nor noxious birds, but only necessary ones, which have developed according to the laws of nature, and on the basis of their development are performing in the world of nature the work which is appropriate to their organism.

The manifold character of the work performed by birds is in harmony with the variety of these organisms.

The question of the usefulness and noxiousness of birds during the whole of the nineteenth century was treated only approximately, upon the assertions of authorities. When, later on, Congresses began to embrace the cause of bird-protection, and the question of the usefulness or noxiousness of each species assumed a rôle of the first importance, it turned out that there was no firm basis upon which to rely, in passing judgment. Eminent ornithologists were often at variance with regard to the usefulness or noxiousness of a particular species.

Where Nature is intact, the number of birds is automatically regulated in accordance with the natural development of their surroundings.

The conceptions of “useful” and “noxious” are merely human ones; and man can, by cultivation or the contrary, alter the normal conditions; and may, consequently, modify the character and habits of birds also. Agriculture on a large scale, modern forestry, the draining of territory—all these things alter the fundamental conditions of animal life, and in consequence of bird-life also; and if these modifications in respect of birds are injurious to man, it is in the interests of man to adapt them artificially for the benefit of birds; and if by cultivation man deprives useful birds of their natural nesting facilities, he ought to provide them with{9} artificial ones. This is the principle on which Baron von Berlepsch founded his system, which was accepted and applied in Hungary, together with the modifications required by special circumstances, or such as were introduced as the result of experience.

These principles apply chiefly to those species which remain with us during summer and winter alike, and which are useful to agriculture. But the international protection of birds is important as regards those useful species that are migratory, and, as they migrate, pass through countries where—as is the case in Italy—the birds are caught en masse, and where bird-catching is carried on as a trade.

The third international Ornithological Congress, held in Paris in 1900, decided that the Governments of the various European States should be called upon to have the food of birds made the object of special investigations, and to report the result, within a space of five years. When the fourth International Congress met, however, only Hungary and Belgium were able to report on the subject.

The publications of the Hungarian Ornithological Centre are founded upon the collection of data, divided into two main groups:—1. The Migration data, so-called historical, up to 1891, and again from that to the present day. 2. Foreign data, partly taken from literature, and Special data relating to one species, from the whole area of its habitation—the Cuckoo for instance.

The investigation of the economic rôle played by the Rook (Corvus frugilegus L.), which English landowners and farmers are beginning to feel is a matter of great importance, was begun by the Central Bureau in 1893; it is still going on. According to the results hitherto{10} attained, this bird does more good by destroying insects, and in particular the larvæ of insects living underground, than it does harm to the crops.

It is our endeavour in this little volume which we now offer to English readers, to give a faithful presentment of the good and the harm that the birds are known to do, from the agriculturist’s standpoint. But in this all depends on the attitude which the gardener and the farmer adopt towards the birds.

By throwing a single stone a lad can scare away a whole flock of rooks; and when these birds alight on a field where they do harm to grain, a man must not grudge a little labour in keeping them off; considering that the same bird that works harm at one season, will be a valuable ally at another, as well as a source of pleasure and interest.

The rook, the crow, and even the mischievous magpie, follow the plough as it turns up the brown furrows, with sharp eyes spying worms, larvæ and cockchafer grubs. Nothing escapes the attention of the bird. He picks here and there, and fills his crop with the worst enemies of the tiller of the fields—the various forms of insect life that lie dormant in the earth until the time arrives for each one to come forth and fulfil its life’s mission—much of which means injury to the fruit of man’s labour.

Starlings rise in flocks—a perfect cloud of them—to disperse, and again to assemble before settling on the pastures, where they will be busy all the day, for that part of the year when man needs their services most.

Later, in the cherry trees and among our own vines the starlings would do mischief enough. The rifled branches and stripped grape stems are a sorry sight for{11} the owner, who finds it hard to remember that God cares even for the sparrows. He tries to drive the thieves away, but they care little for the cries of the lads set to scare them. Little do they heed the rattles, feathers, rows of sticks with lines of thread—all the various flimsy inventions are useless; a gun will disperse them for the moment, but the cloud of pilferers is soon back again, and as busy as ever. At this juncture severe measures are justified. Even the most ardent bird-lover will not be foolish enough to protect every bird at all times and seasons. Yet it is only for a short season of the year that starlings are harmful, and for the greater part they are useful, in garden, field and meadow, from early morning until late evening, protecting growing blades of grass and coming seed and roots for the farmer, with unceasing labour. This is in the early spring; later they betake themselves to the pasture lands, where, on bright sunny mornings, they walk nimbly among the browsing cattle seeking their food in the form of crane fly and daddy-long-legs, in the shadow of the patient creatures. The gadflies, too, buzz about the bodies of the beasts, lay their eggs under the hide, boring into the flesh, tormenting and maddening the helpless cattle. The Hungarian herdsman is glad when he sees the starlings settle on his wide pastures.

When the eggs have developed into maggots the birds alight on the backs of the beasts, to rid them of gadflies and batflies; and the cattle and sheep suffer their services gladly, knowing well that these good feathered friends will effectually extract their torturers without further irritation to the infested parts. A horse has been known to die from the exhaustion caused by the continuous action of parasitic creatures.{12}

Then, as regards the owl—that bird of the night, who shuns the light of the life-giving sun; for which reason man distrusts and persecutes him. The other birds also regard him with disfavour, and mob him when he ventures forth from his holes by day, big birds and little ones, in common dislike of the uncanny creature. They know full well that this is the nocturnal disturber of woods and fields, and they resent his ways and his manners.

When the twilight is over all and the birds of day have betaken themselves to rest, then most of the owls go forth to hunt for quarry. Noiselessly they flit over the quiet meadows and fields; with those eyes which shun the light they can detect through the dimness of evening the nest where small birds are, and this they rifle. And so in that respect they are harmful. The Short-eared owl will take birds from the size of a lark to that of a plover.

On the other hand, when mice have got the upper hand in house and barn, devouring and spoiling man’s provision, then every species of owl is welcome, even he the superstitious countryman calls the Death-bird. And, again, when the weather favours that pest the field-mouse, and the voles, and they swarm in meadows, cornlands and everywhere, so that the land is full of mouse-runs; from all sides comes that gentle singing from tiny throats and the farmer is at his wits’ end to know how to be rid of the plague. Then in Hungary the mouse buzzards circle by day over the pastures and fields, making war on the gnawing little beasts; and the whole night long the owls take up the same useful work. They fill their crops, each of them, with from twenty to thirty mice, fly to their several{13} trees to digest the meal, and you will find the pellets formed by the birds of the indigestible portions—bones and fur—in and about their nesting-holes. Harmful moths and beetles they also kill.

And so the Owls—barn, the tawny or wood-owl, the long and the short-eared—which in England are the only common species, are undoubtedly the agriculturalists’ good friends, and indeed friends of the whole human race; and many landowners now prohibit the use of the cruel pole-trap in their destruction. Richard Jefferies tells how 200 owls were taken in one pole-trap in a plantation of young fir in his time. Dr. Altum, a great mover in the cause of bird-protection, examined 210 of the wood-owl’s pellets and found in these the remains of 6 rats, 42 mice, 296 voles, 33 shrews, 48 moles, 18 birds and 48 beetles, besides a countless number of cockchafers.

And what can you find to say in favour of the Sparrow? I fancy I hear many a reader ask,—that ubiquitous bird whose impudence is everywhere proverbial. When sparrows in hosts settle down on the corn waiting to be harvested, not only filling their crops but uselessly beating the grain out of the ears, the case is bad, and it is hard then to recall all the good the same birds had done in devouring the seeds of harmful weeds, such as wild mustard, etc.—also to think of the cockchafers in the grub as well as winged—daddy-longlegs, caterpillars, turnip-moth, grubs of cabbage-moth and butterfly, and the moths of both currant and gooseberry. In towns, too, the sparrow is invaluable as a street scavenger. House-flies, those plagues indoors, maggots of fleas, eggs of cockroaches, spiders, centipedes,—all, and many other “small deer” that infest{14} stables, poultry-yards and other precincts of our homesteads the sparrow diligently seeks for.

It is true that the common sparrows multiply too fast and their numbers must be thinned down. This, many a bird-loving landowner and farmer does in various ways. The late Lord Lilford declared the most humane way was to pull down all the nests within man’s reach. There would still be plenty left, in inaccessible places. A humane farmer, the present writer knows in Hampshire, a great wheat-grower, gives the lads round threepence a score for all the sparrows’ eggs they can bring to him. Sparrow-clubs—save the mark!—are schools for cruelty. In one Lancashire parish which I know the vicar encourages the Jackdaw, allowing it to build even in his church steeple, because wherever that bird is, sparrows become more scarce, their young suiting that bird’s palate well. Man has foolishly upset the balance of nature by destroying the natural enemies of the sparrow. Take two neighbouring estates we know in Yorkshire; on the one sparrows, blackbirds, bullfinches and other birds are remorselessly shot during the fruit season; on the other the use of the gun is forbidden. In the garden and orchard of the latter there is always a far greater allowance of fruit than in those of the former.

Only where their natural enemies have become scarce ought man to set his wits to work to compass the destruction of a species.{15}

Let us now consider the bird’s bodily structure. Every child knows that the bird’s body is covered with feathers or down, and that what, in the case of mammals are fore-feet, in birds are wings with which they fly.

There are as many kinds of flight as there are kinds of birds. It depends for the most part on the nature of the bird, in a smaller degree on the structure of the wing.

The wing of the Swallow (Plate VIII.a) is pointed like that of the Peregrine Falcon, and is adapted for rapid flight. Both these birds secure their prey on the wing, and could not, therefore, live otherwise.

The wing of the Partridge is, on the contrary, rounded; this bird does not cut through the air, but can only raise itself in flight with rapid fluttering of the wings, and with a sudden loud “whirr” which makes considerable noise if the covey is a large one. The wing of the Partridge, therefore, is not at all adapted for enabling the bird to catch its prey flying, but only for moving from place to place, where it picks up its food walking.

From this we learn that the various kinds of wings correspond to various ways of flight and that each bird works out its destiny in its own way. It is suggestive of the organisation of an army, composed of cavalry, infantry, artillery, and other divisions. These also have different kinds of functions, which are necessary both{16}

individually and in combination, and the one cannot supply the place of the other.

So much for the wings. Now we will examine Plate IX., which shows heads and—what is the most important part of them—bills. We will take the illustrations in their proper order.

1. The bill of the Woodcock is shaped like a turner’s auger, the end greatly resembling the tip of a finger. With this the bird gropes for its food, and draws it out of the loose earth.

2. The bill of the Merganser has a hook at the point; it is toothed at the side, and is so well adapted to its purpose that no fish, however slippery, can escape.

3. The bill of the Hawfinch is conical, thick and strong, capable of cracking the hardest cherry stones.

4. The pretty Water-Wagtail has an awl-shaped bill, formed by Nature for the catching of gnats and other insects.

5. The Grey Heron has a bill which cuts like a knife. Woe to the most slippery tench if once caught within it!

6. The Curlew penetrates into the mud with its sickle shaped, slightly curved bill, and brings out of its depths the worms it feeds on.

7. The bill of the Long-tailed Tit is but a little point compared with those mentioned above, but all the same it is quite suitable for the bird, for only with such a tool could it pick the tiny insects out of the smallest cracks in the boughs.

8. The bill of the Goatsucker or Night-hawk is small, but the opening of the mouth is comparatively gigantic: it forms a yawning abyss, which, in the twilight and darkness of night, engulfs unwary insects.{18}

9. The bill of the Woodpecker may be compared to the adze which the Carpenter uses for chipping beams of wood. It is only by means of hard blows that this bird can get at the worms which it finds in decaying wood.

10. The Duck’s bill, on the other hand, is flat toothed at the side, exactly formed for straining the food which it gets out of the water.

11. The bill of the Gull is so formed that it can easily take up food from the surface of the water. Where Gulls arrive in large flocks, they eagerly follow the plough in the fields, and are then of great benefit.

12. The bill of the Crossbill is a valuable tool, with which he is able to pick out the seeds from between the scales of the fir cones.

13. The Ortolan splits hard seeds with the arch and the notch in its beak, as it were with nut-crackers.

14. The bill of the Avocet is in shape the opposite of the Curlew,—that of the former curving upwards, of the latter downwards.

Thus we see that as with the wing, so with the bill,—each bird is furnished with the kind that is most suitable to its nature and habits.

The general law of adaptability to its purpose is also strikingly exemplified in the formation of the foot. Let us look at Plate X.

1. The foot of the Fieldlark has a spur-like nail on the back toe which is nearly straight, so that the bird can easily rest on the ground.

2. The Pheasant’s foot is just like that of the Hen; which enables it to walk and run.

3. The powerful, sharp claw of the Eagle strikes deeply into the flesh of its prey and holds it fast.{20}

4. The Sparrow Hawk strangles and crushes with its warty toes the birds on which it preys.

5. The foot of the Owl, as well as its bill, proves that it is a bird of prey.

6. The foot of the Swift is so constructed that it can cling to walls; it cannot walk or stand.

7. The toes of the Moor-or Water-hen are provided with skin-flaps, not altogether perfect for swimming, but excellent for wading and diving.

8. The Crested Grebe excels in diving, pushing sideways with its feet.

9. The foot of the Bustard has three toes, and hard soles, which enable it to run extremely well.

10. The four toes of the Cormorant are joined together by a web; it is a good diver, can swim under water, and can also roost on trees.

11. The Wild Duck has only three toes webbed together; its foot is, therefore, specially suited for propelling the bird on the surface of the water.

12. The toes of the Avocet are only partially joined together by webs; its legs are suitable only for wading, but can be used for swimming in case of need.

The variety and suitability to their purpose of wings, bills, and legs, show us that the feathered inhabitants of a neighbourhood form a community. A society of men would not be perfect if there were only men of one calling. A variety of workers is needed in human society, with a variety of tools, with which to perform a variety of necessary work, just as various birds with a varied construction of body perform their work in the open field of Nature.{22}

A few words as to the feathers of the bird. The perfectly developed feather consists of a quill which grows in the flesh, the stem becoming gradually thinner towards the top and having lesser feathers on either side, those on the one side of the

quill being narrower than those on the other half. The feathers overlap each other exactly and densely especially those which protect the main part of the body. At the end of the quill of the top feathers is a down which takes the place of our under-clothing, and which in the case of waterfowl prevents the water from penetrating to the body of the bird. There is also a pure down which is composed of numerous stems; this is close and thick and protects the binding together of the general plumage.

The down has its fine quill and a stem bearing the close down which in water fowls keeps the warmth of the body at an even temperature whether in or out of the water. It would be an error to suppose that the feathers grow in the skin without any order, simply close together. They are in point of fact divided into areas between which the flesh is generally{23} covered with down, and all is arranged in a system of grouping which, the feathers being rightly placed over one and another, does not in any way interfere with the movements of the body, each movement being in perfect conformity with this feather covering. The feathered areas can be moved independently with the aid of the muscles, and this renders the cleansing of the individual feathers easy and the removing of the fatty substance, which is a matter of great importance. If we watch we see that the bird moves the feathers separately in this cleansing process, drawing them through its beak, and so removing any bits of fat and oily substances that may have collected about the fat glands.

View of the back of the bird, showing the feather tracts.

The spaces between the tracts are covered with down.

The Barn Owl builds no regular nest, but lays its eggs in the walls of ruined castles, on the inner sills of towers, or in the dust and sweepings that collect in the corners of granaries. The clutch consists of five, occasionally seven, longish white eggs.

This bird likes always to be close to the abode of man; she likes to make her nest among the rafters of some warm barn and in other farm buildings, or in church tower or belfry; in hollow trees, a cleft in wall or cliff; semi-obscure corners, those even in broad daylight. There she sits, putting herself now and again in grotesque positions, and when that facial disk is stirred she appears to be, as the children say, “pulling faces” at you. One of the most industrious of hunters, she catches far more mice than she can devour. It is true she takes the bat, who has his own insect-destroying work to do; and when she has the chance she will cause havoc in the nest of a small bird. But this is only an occasional outbreak, and it must not weigh against the general good record of this most useful species. She takes living prey, and will only touch carrion under extreme stress of hunger.{26}

The Barn or White Owl is generally distributed throughout Great Britain. It suffered at one time most undeservedly from the ignorant prejudices of many gamekeepers, and of late years from the senseless fashion of women wearing the wings and head in their headgear—a crowning folly only perpetrated through that ignorant vanity which knows neither love nor pity.

Colonel Irby said that this Owl, which is most useful to man, can be preserved and increased by fixing an 18-gallon cask in a tree. The barrel should be placed on its side and have a hole cut in the upper part of the head for the Owls to enter; care must, however, be taken that Jackdaws do not take possession of the cask.

Our gamekeepers are beginning now to be convinced of the usefulness of the Owl, especially in view of the fact that so many young birds are taken by the Brown Rat, a favourite quarry with the Owl—not to speak of the Voles and Mice the bird devours. The late Lord Lilford told me that he had watched a nest of young Owls being fed by their parents in an old cedar tree in the rectory garden of a relative, and that on one occasion the old birds came bringing food to these seventeen times in half an hour by the clock, on that evening. There was a rickyard not far from the nest which was the Owls’ favourite hunting-ground. Mice were not plentiful there, but rats swarmed, and the pellets found under the nest were here composed almost entirely of the remains of the latter. In the South of France and in Spain this Owl is accused of drinking oil from lamps in the peasants’ houses and in the churches and chapels. The name given to it in the former country by the peasant of the Midi is Béou l’oli—bird that drinks oil. Attracted by the light of the lamps, the poor Owl{27} perhaps has entered, once in a way, and in its fright has upset a lamp. Superstition grows on very meagre fare. This ally of the agriculturalist has been ill-repaid for his services.

Butler writes:—

But why this is so who can tell? If the Barn Owl shows himself by day, Rooks and Starlings, Blackbirds, both species of Thrush, Chaffinches, Tits and Wrens will mob him; and he flies awkwardly from tree to tree, with dazed eyes and apparently “mazed,” as the country folks says, altogether, till he can find a hole in a tree where he can hide himself. He may well like hollows in trees—for, as the poet says, “the Owl, with all his feathers, is a-cold.” This is not hard to understand, for the breast feathers are so light and fluffy that the wind easily parts them, laying bare the shivering skin.

His frequent choice of an old dovecote as a home was misunderstood. The ignorant countryman thought it was in order to prey on the young pigeons that he selected a corner there, whereas—and Waterton was the first to record the bird’s reason, after watching the doings of a pair of Barn Owls in his dovecote—the Owls were{28} there to prey on the pigeons’ enemies, and Owls and Pigeons lived amicably together in the same home.

Lord Cathcart, in a paper contributed to the Royal Agricultural Society, said: “Our ancestors, wiser than we, always made in their great barns ingress for Owls—an owl-hole, with often a stone perch.” And the Rev. F. O. Morris tells of a pair of this species which lived in a barn near Norwich, and were so fearless that they would stay there whilst the men were threshing; they waited on the flails as rooks do on the plough, and if a mouse were dislodged by the removal of a sheaf they would pounce upon it without minding the men’s presence. They hunt mice amongst the stacks, too, in the farmyard, staying there all night often, if mice abound. As E. Newman says, “The farmer pays the price of a sack of grain for every Owl nailed to his barn door, because that Owl would have destroyed mice every night, and these mice, being relieved of their oppressive enemy, would, in a very short time, consume a sack of wheat, peas, or beans.”

Owing to its very deep plumage, the Barn Owl looks larger than it is. Its eye is dark-coloured, almost black: its glance is directed forwards. The facial disk is very prominent; at rest, it is heart-shaped, and it is edged with white and rust-colour. The bill is yellowish in colour, and is slightly hooked. The legs are scantily feathered, and the toes almost bare: the claw of the middle toe is serrated along its inner edge. The body-plumage is soft as silk, and yielding, and thickly pearled with white and dark markings on the beautiful ash-grey back. The flanks are pale with a reddish tinge, in places very bright, and sprinkled with tiny pearl-like spots of light and dark colour.{29}

The Wood Owl, known also as the Brown or Tawny Owl, has the admirable trait of constancy, for it is said he mates for life and the pair return year after year to the same tree to nest. In the month of September you will hear him hooting in the woods more than at any other time of the year. He is not so constant in his choice of locality, but like many other birds he and his kind will disappear from a district without any apparent reason, to return to it again after a time. No doubt they follow their food supply; the small creatures they feed on—mice, rats, shrews, and squirrels—all disappear in the same fashion to re-appear elsewhere; the movements of these being no doubt ruled by the same conditions of suitable food, its scarcity or its plenty.

In spite of persecution the Tawny Owl is still fairly common in our own country wherever there are woods or crags suitable for its habitat. In the South of Scotland it is common, as well as in England and Wales. It is strange that it seems to be absent from Ireland. Here, in Ealing, where the present writer lives, its whoo-hoo, or, as Shakespeare has it, tu-whit and to-who, are heard regularly in one little spinney at the south-east corner of our suburb; and last summer—1908—a pair took up their abode in a garden, right in amongst the shady roads not very far from the Broadway.

The Tawny Owl breeds early; strong-flying young ones may be seen in April. A hollow oak tree or an elm is a favorite nesting site with it. The young are{30}

very easy to rear and to tame. The late Lord Lilford, who was perhaps our best authority on owls, stated that he had examined many pellets of the Tawny Owl, and although he more than once found the remains of young rabbits he could not accuse the bird of any serious poaching.

Living more in the woods the Brown Owl is less often observed than is the White Owl; also its plumage is darker, and this makes it often less visible, especially in the shade of the trees. When flying, his legs are stretched out behind, “as a balance to his heavy head,” White of Selborne remarked. The young ones, funny little balls of grey down, resemble, some one has said, “a pair of Shetland worsted stockings rolled up, such as might have belonged to Tam o’ Shanter.”

And this reminds us of Burns, who, when he bids the birds mourn for him, “Wha lies in clay, Wham we deplore,” sings:

But Shakespeare said of the Wood-Owl:

It was in 210 pellets of this species that Dr. Altum found the remains of 6 rats, 42 mice, 296 voles, 33 shrews, 48 moles, 18 birds, and 48 beetles, besides countless numbers of cockchafers.{32}

Brown Owls make very amusing pets and they are not hard to tame. They are less suspicious than other owls and become very companionable. R. Bosworth Smith, whose recent death was so much lamented by all bird-lovers, and who said: “Birds have been to me the solace, the recreation and the passion of a life-time,” told of one young brown owl which he brought up from the nest, which was very fond of music. It would make its way, through an open window on the ground floor, into the room in which a piano was being played and would even press closely against the case of the instrument. Dr. J. Cooper, Professor of Greek Language and Literature at Rutger’s College, New Brunswick, also told the same author that one morning in November of 1899 he found, on going to his lecture room, that a brown owl had somehow made its way into it, and had selected as a perch a huge framed photograph of Athens. It was, he remarks, an unlooked for illustration to both teacher and taught, of the proverbial expression “Owls to Athens.” And there she was, just over the Areopagus, the High Court of Athens, and she sat perched there four whole hours, that “bird of wisdom,” whilst the Professor gave as many lectures to successive classes of his pupils, quite undisturbed by the noise they made, coming and going. Before she disappeared, one of the lecturer’s brother-Professors had time to take a photograph of “the Bird of Pallas on her chosen throne.”

Description: In the adult male the upper parts are of variable shades of ash-grey, mottled with brown; there are large white spots on the outer webs of the wing-coverts; the tail is barred with brown and tipped with white; the under-parts are a buffish-white, mottled with{33} pale and streaked with dark brown. The disk about the face is greyish, having a dark brown border; the legs are feathered to the claws. The length of the bird is about 16 inches. The female is larger than the male and its plumage is a more rufous brown; but there are two varieties in this species, a red and a grey, the colour being independent of sex; the rufous form is more common in Great Britain. After the first greyish down of the nestlings they put on a more reddish brown than the adult birds have.{34}

In the wooded districts of Great Britain this handsome Owl is always to be found; the numbers bred here are augmented also by a considerable number which come to us in autumn from the Continent. It is a larger bird than the Short-eared species and it lives much in the same way as the Brown Owl. These two are not so fastidious in their way of feeding as the White Owl. It lives on small birds, rodents, bats, fish, reptiles and large insects. Some have accused it of taking birds up to the size of a Plover, but the late Lord Lilford stated that he had never heard any complaint of its destruction of game in those districts where it was comparatively common; the castings of this species which he examined were mainly composed of the remains of greenfinches, sparrows and field mice. It is often seen flying about by daylight and it has been known to pick up and carry off wounded birds. It is said to be much disliked by other birds—possibly the last mentioned habit may be at the bottom of this strong feeling on their part, also its appropriation of other birds’ nests. The note of the hungry young birds of this species is a loud mewing.

The prophet Isaiah had not very pleasant associations with Owls, it would seem. When speaking of desolated places, he says, “Owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there ... the screech owl also shall rest there ... the great owl make her nest....”

Alluding to the death of Julius Cæsar—or rather to the omens that preceded it—Shakespeare wrote:{36}

Of crook-backed Richard of Gloucester, too, he says:

Different parts of the White Owl’s body were supposed to possess different magical powers, and they have been used by many a rural imposter to breed awe in the credulous.

Happily all this is changed now excepting amongst a small ignorant minority. Of late years women who affected the fashion of wearing owls heads and wings on toques seemed likely to become the poor Owls’ worst enemy. Mr. Ward Fowler saw, not long ago, in a public house, this advertisement: “Wanted at once by a London firm, 1,000 owls.”

The late R. Bosworth Smith wrote: “The number of owls has been terribly diminished. Let them be encouraged and protected in every possible way. Let the gamekeeper be rewarded, as I have rewarded him myself, not for the owls he destroys, but for the owls he preserves.... Let the owl be regarded and protected in England as the stork is regarded and protected in Holland!”

The Long-eared Owl is 15 inches in length. The upper parts are a warm buff, mottled and pearled with brown and grey and streaked with dark brown, bill black, dark markings about the eyes, facial disk buff with greyish black margin and outer rim. The long erectile tufts are streaked with dark brown. The eyes{37} are a rich yellow. Under parts warm buff and grey with broad blackish streaks and small transverse bars. Legs covered to the toes with fawn coloured feathers. The eggs, four to six in number, are laid with us in an old squirrel’s drey or on the old nest of a Ringdove, a Magpie, Rook, Crow, or Heron’s nest; in Hungary often in that of a Buzzard or a Kite, with a few slight sticks and rabbits’ fur added. They are white, the surface smooth but not glossy. As a rule this species does not hoot like the Tawny Owl, but is rather silent.{38}

In Hungary Short-eared Owls appear in numbers with the Buzzards where field mice get the upper hand, and work with these grander birds. A peculiarity of the species is to crouch down to the earth like a hen when in danger. So confiding in nature is it that it falls an easy prey to the guns of those whom we call the “Sunday sportsmen,” to the great loss of the agriculturist. Large numbers of the Short-eared Owl arrive regularly in Great Britain from the Continent, to remain with us during the winter. This species is often termed the Woodcock Owl here, partly on account of its twisting flight it is supposed, and also because both birds make their appearance about the same time—some years in larger, some years in lesser numbers. A few pairs still breed in the eastern counties, but it nests more often in the north, in widely scattered parts of our moorland districts. In Scotland the species is common; but in Ireland it has not yet been recorded as breeding, although it is very common there in winter. I remember a relative telling me of a Short-eared Owl hovering much over a terrier he had out walking with him, one evening late, on Congleton Edge. Probably the bird had its young on some tuft of heather near them and was anxious as to the safety of these, and it would not have hesitated to attack the terrier had it been alone.

Mr. Ogilvie-Grant, in Lyddeker’s “R. Natural History,” says: “It is a curious circumstance that,{40} although the number of eggs laid by this bird (the Short-eared Owl) is generally four, yet, when food is unusually abundant, as during a lemming-migration, the number in a clutch will rise to seven or eight, and during the recent vole plague in Scotland larger numbers were recorded, reaching as many as thirteen.”

As many as ten and twelve eggs were often found on some hill farms where these Owls remained feeding all the winter and commenced nesting in March, the birds in many cases nearing a second brood.

Mr. Colles, of Higher Broughton, Manchester, speaking of the Short-eared Owl, said in a letter to his friend (R. Bosworth Smith): “You will remember that a few years ago certain parts of the country (Scotland) were infested with voles to such an extent that the sheep would not eat grass over thousands of acres of moorland. It was some two years after they had been at their worst that my son and I were fishing in St. Mary’s Loch; and one day, about noon, while I was crouching down between the high banks of the Meggett, to keep out of sight of the fish, a Short-eared Owl skimmed over the top of the bank directly to the place where I was; and I can assure you that no exaggerated comic picture of an Owl I had ever seen affected me as did this one. Its eyes looked to me as large as saucers, and the bird seemed a perfect ogre. A few days later we were fishing one of the tributaries of the Tweed near its source, and had to walk a mile or so, on almost flat moorland, where there was hardly a bush, much less a tree, to be seen. Wherever there was rise enough in the ground to form a little bank the soil was perfectly honeycombed with what appeared miniature colonnades or rather cloisters, and we caught{41} frequent glimpses of the voles within, as they flitted along their galleries. When we were well into this dreary place a couple of Short-eared Owls positively mobbed us, and as we walked along, with our fishing-rods over our shoulders they followed us till we reached a dry gully, where they became even more demonstrative, coming well within point of our rods. On both occasions the hour was between eleven and twelve o’clock and the sun was shining brilliantly.”

The Short-eared Owl is fierce and bold in defence of her young. She will attack larger animals than herself. In the Hawaiian Islands she has always been much admired because of her fine qualities, and was indeed one of the old tutelary deities of the natives.

This Owl is from 14 to 15 inches in length. The ear-feathers are short, the irides yellow, bill black, black about the eyes, and the facial disk is browner than in the last-named species; the plumage of the upper parts is more blotched than streaked; the buff tint is more decided. The ear-tufts, though erectile, are short, and not seen except when the bird is excited. Under-parts streaked lengthwise with blackish-brown, but have no transverse bars. The young are browner and darker and more boldly marked, and tawny on the under parts, iris paler than in the adult.{42}

The Little Owl makes its nest where it has its ordinary dwelling-place; that is to say, in hollows, behind beams, sometimes even under bridges. The clutch of eggs is four to five, and they are almost perfectly round. The young are covered with white down.

This is a friendly little species; it likes to get under the house-roof, into barns and towers; retires also into the hollow of a tree and clefts in old masonry. A capital mouse-hunter, it feeds also largely on insects, and haunts the lawns to get out the earthworms. In winter it catches birds at roost, getting numbers of Thrushes, also mice and other small mammals. When the chase is prolonged till daylight the small birds mob the Little Owl, surrounding him in numbers. They dare not meddle with him because of his sharp claws, but they scold and chatter at him as a shameless thief. Bird-catchers profit by this, and they fasten him to a bough to act as a lure. There is in Hungary a superstition that no one dies where this Little Owl appears and utters his cry of Kooweek, kooweek! which comes down from the gables or the attic windows of the house.

The numbers of the Little Owl have been increasing in England of late. Mr. Meade-Waldo informed me that in the neighbourhood of Penshurst, near his own home, in Kent, he had seen as many as sixteen Little Owls perched on the telegraph wires on the line between two{44} stations. This gentleman has always been known to be a lover and a protector of this species.

In Leadenhall Market there are often cages full of them which have been brought over from Holland. They make delightful house pets and good mousers indoors. “I have one of my own,” says A Son of the Marshes, “and I set him down as a bird of priceless value, for he has the power to make me laugh when I should be least in the mood for it.... Jan Steen and Teniers introduced him into their pictures. In that of ‘The Jealous Wife,’ for instance, there is the Little Owl perched on the window shutter contemplating an aged man holding sweet converse with a young woman, presumably his niece. The old woman, his wife, has also her head in the opening, taking in the scene wrathfully. My own bird is at liberty. This he uses to the best of his ability, making the third member of our small household.”

The Little Owl is about eight inches long, but seems bigger than it is because of its large head and soft plumage: its body is compressed in form. Bill and iris are yellow, legs clad with hair-like feathers, toes almost bare. The short tail is hardly visible beneath the points of the wings. The back is greyish-brown, spotted with white; the belly whitish, with long brown markings.{45}

The Rook lives in flocks and breeds in great colonies. Its nest is smaller and looser than that of the Hooded Crow. Five or six nests one above another, are often found in one tree—sometimes as many as eighteen. It pairs somewhat late, in Hungary, but already in April may be found three to five eggs of a pale green colour spotted with grey and blue. These are smaller than those of the Hooded Crow.

The Rook spends the greater part of its life in its native home, often in huge crowds, numbering many thousands, which divide up during the day to seek food in different parts of the neighbourhood. During the breeding time they are divided according to the breeding places. This bird is the most zealous follower of the ploughman, and by its great number destroys an enormous quantity of noxious creatures—the cockchafer being its most coveted delicacy. It covers, with its flocks, the freshly ploughed field, and if they are sown, picks up the grains that are lying about. It bores into the soft earth of the meadows and cornfields, for destructive grubs, and pulls up the withered plants in order to secure the caterpillar or wireworm which has destroyed the roots. This has caused the Rook to be suspected of plundering the fields, but the question has not yet been settled, and the general inclination is in the bird’s favour. The fact is that even in Hungary, where the Rook exists in millions, the people generally are indifferent about it. Early sowing, while there is{46}

sufficient insect food for the birds, is the best protection from its mischief, and this is good for the services it performs.

A knowledge of the habits of the Rook is important, because the bird is closely associated with husbandry, and with its well organised work deeply affects the interests of the husbandman. While the Hooded Crow roams about the district with the Jackdaw, thousands of Rooks cover the corn-fields; they settle also on fallow ground, on the freshly ploughed field, on the sprouting crops, and on the turnip-field. It is this appearance in vast numbers which mainly distinguishes the Rook from the Hooded Crow, which otherwise its habits closely resemble.

In regard to this bird also, different views are held. Whilst the scientific agriculturist considers it useful, the old-fashioned husbandman is convinced that it is harmful. Here again, therefore, must a just verdict be given, between two opposing parties—but this verdict must be impartial. Various things are said of the Rook—but it is not true that it picks the seed out of the earth, so that the spoiled seed has to be ploughed in again. It only takes the seed which has been imperfectly covered by the harrow,—and the reploughing is only an empty complaint, for no one ever heard tell of a particular village, or farm, where reploughing had to be performed on account of the Rooks. The farmer who keeps his eyes open before he gives an opinion knows that the Rook digs his beak into the ground because he hopes to find worms there. Sometimes it is shot, in order to be set up as a scarecrow, but they say nothing of what may be found in its crop, should it be opened; this, however, is just what is necessary in order to ascertain{48} the truth—although the other conditions of its life must also be taken into account.

It is easy to observe the behaviour of Rooks, because they always move and act in flocks. These flocks are dissolved only in cold snowy winters, when the birds, tired of the cold and lack of food, come into the villages. When the early spring ploughing begins, part of them follow the plough; the flock spreads itself over the freshly ploughed land and they snap up the grubs of the destructive insects which escape from the newly-turned clods. This then is useful work. They also settle on the sown land and pick up the seeds which the harrow has left on the surface, but at the same time devour the insects which the harrow has turned up. There is no harm in this. In a short time the full spring has come and the immature insects have developed into other forms—then the Rook begins to think of building its nest. Its young are not fed on seeds, for at that time there are none to be had, but exclusively on insects—which again is a great and useful work. Then the flock spreads over the neighbourhood, leaving their sleeping-place in the morning in a body, and betaking themselves to different parts of the district; and it may be remembered that separate flocks repeatedly visit the same spot, and work there; as, for instance, one point in a great stretch of cornland, where in the track of the birds lie many uprooted plants, which the farmer generally looks upon as due to the mischief of the Rooks. When insect life has become stronger, they settle on the meadows, where they eagerly hunt for crickets and grasshoppers; then they return to the ploughed fields and destroy the insects that have been disturbed—and this is useful work. It is true that later on they visit any heaps of cut corn{49} that may lie in their way, and in this way do harm, but the greater number of the flock pick up the fallen grains in the stubble field, and a few follow the carts which carry the corn, and pick up any that is dropped. There is no harm in this, as these ears would in any case be lost to the farmer. At the time of the hay harvest they settle on the ridges of cut grass and hunt for crickets and grasshoppers, for these creatures have then no cover, and easily fall a prey to the birds. The Rook also attacks the young maize and fruit, but it has not skill in this respect and cannot do much harm. The harm done is outweighed a thousandfold by the good which it does in the destruction of insects. The black army of birds lights also upon the turnip crops just at the time when these valuable plants are covered with masses of the “turnip caterpillar.” By the destruction of this pest they do the farmer invaluable service.

This sanitary work continues into the late autumn as long as the caterpillars, the Rook’s favourite food, remain. The Rook may do serious damage during the autumn sowing, especially if it is thin, and sown and harrowed so late that the caterpillars have disappeared, not so much, however, that the field must be ploughed up; at the worst there would remain only one or two unproductive spots, and we know that corn grows in tufts, and if it is not thinned by the Rooks it must be done by the farmer, so that the corn is not choked by its own abundance.

When the hard part of winter comes, the flocks of Rooks seek towns and villages, where they spend the nights on the roofs of houses in order to shelter themselves from the icy wind; during the day they steal from{50} the barns and granaries, or, if the opportunity offers, they get at the bundles of straw which they pull about to try and find a stray ear of corn.

This much is certain that the principal food of the Rook consists of insects and grubs, which it gets not only from the surface of the earth, but also from beneath it, when the bird sees from the colour of the fading plant that a grub is gnawing at its root. This is the meaning of the uprooted plants; and why one flock after another so often visits the same cornfields. It is a sure sign that the wireworm or some similar pest is busy with its depredations. Here again the work of the Rook is a blessing.

There are neighbourhoods where the farmer makes a great fuss about a grain or two of wheat or maize, as if he must be ruined by the damage. I repeat that the bird has earned its few grains by its other work; indeed, without its useful services these grains would probably never have grown.

The lesson we learn then is as follows:—The Rook lives principally and preferably on insects, grubs and worms, and so long as these are procurable, it does not look for grain—therefore, the spring sowing should be performed as late as possible, when the insects have developed, and the Rook can find its natural food; in autumn the sowing should be done as early as possible while there are still some insects to be found. The further actions of this bird are protective, for it attacks the gnawing maggots that live in the ground. These facts can be verified by dissection of the bird, when the stomach is often found to be full of wire-worms.

None the less researches into the habits of the rook{51} require to be more thoroughly worked out, and this must not be lost sight of.

. . . . . . . . . . .

I asked a tenant farmer in our own Midlands his views on the subject of Rooks and the following, with some slight editing of my own, was what he sent me. I give it in full as although there may be some repetition of the foregoing statements, it has special interest as coming from one of our English farmers.

A recent writer from the sportsman’s point of view speaks of the Rook as “this black robber,” and he says that there is no practical difference of opinion as to the question whether his benefits outweigh his depredations. Now, as a farmer, I confidently affirm that he does much more good than harm. He will sometimes uproot vegetables in getting at the worms round their roots. It is true also that he often robs the nests of the pheasant and the partridge; but, as I could easily show, he does far more good to the general community by furthering the labours of agriculturists, on whom so much depends, than harm to the sport of our leisured classes.

A more social bird even than the gregarious starling, he flies in flocks, feeds in flocks, and builds in flocks. His everyday life may appear to be an uneventful one to the outside world, and most commonplace; yet it is full of adventure and of joy tempered with sorrows. Apparently a grave bird, he is brimful of humour and, at times, as full of play as a titmouse. Like all other links in the seemingly endless chain of nature, he is the victim of circumstances: without much ado he could count up his sincere friends, but his enemies are beyond his conception of numbers.

From his winter homing quarters he comes with his{52} company during February to inspect the colony of breeding nests which he regards as his peculiar domain, going back as night approaches to his sleeping-place until all is ready for the family life to begin. Rookeries vary, of course, greatly in size; one may be as a city or large town, again there will be a village, and here and there a small hamlet. There are in my own fields one of about a hundred and thirty nests, one of sixty, one of eight, and another of four nests. Of these latter I have some views of my own. I believe them to be those of odd and outlawed individuals who follow the other companies hither, but are socially considered as pariahs. My nearest neighbours are those of the sixty-two-nest village, and my last census-taking records about sixty-two married couples and thirty-six or more odd or unmated birds. These are all, of course, adult birds, their numbers reckoned before the young were hatched out.

The odd birds may some of them be outlaws, as I said before, but the majority of them are not vagabonds by any means. They only happen to belong to that numerous enough class amongst humans—those who have been forced by some just cause or impediment into a life of celibacy. As the rook does not mate until it is nearly two years old, a number of the single birds are, therefore, simply lusty young bachelors. The few individuals whom I sum up as ne’er-do-weels or unfortunates—I know personally three of these at the present moment—are to be recognised by the shabby, neglected, and generally unkempt appearance of their plumage, and some other of the many outward signs of a past henpecked existence. I am ignorant of the life history of these; perhaps if we knew all about them we should look upon them as objects of pity rather than of reproach.{53} Now and again I notice that a few old birds in our colony appear to be dissatisfied with everybody and everything; and imaginary grievances, political and social, often lead to a segregation scheme. This is how I have accounted for my hamlet of four nests. The general run of our odd, or celibate, birds is, however, good in character; they help in the building of the nests and even in feeding the sitting birds. For the wedded pairs April is a most trying time: if the season be a dry one, or frost sets in, food is scarce. Insects and worms are deep in the earth; the farmer is engaged in sowing his spring corn, oats, and barley. The rooks prefer a diet of insects, worms and grubs, but these are hard to get at times; the spring beans are just peeping through, and the sitting hen asks for food. The cock bird ventures too long in the beanfield, and as he skims over the hedge with a bean or two in his pouch a shot is heard; the faithful mate of the sitting bird is brought down to mother earth, and the farmer feels that he has one enemy the less. Personally I would not shoot a bird if you gave me a sovereign for it. The old bird may, and does, grieve, but the news of her loss is soon at the rookery, and her food is brought to her by a new mate. Thus there is a place taken in the rookery by one of our odd birds, and there is a bachelor less in the community. I have known many a bird die about this time through over-zeal—a slave to love and duty. If April prove seasonable and mild with showers, worms are plentiful, and the farmer’s gun remains in its place over the kitchen chimneypiece.

Often during the building season the rookery is disturbed by discordant notes, accompanied by a great fluttering of wings; there is a big row in the township;{54} not a duel over a “squaw”: the rook is a philosopher, and the ritual of love-making and matrimony are of the simplest. The bother will be over divergent interests or a disputed claim, for there is a recognised right of property—not ground-rent to pay, but a specified limit for nest-room has been accorded. The trouble occurs mostly with young birds wishing to place their nests too near to an old nest. A parish council is called, with the result that the disputants’ nests are soon scattered to the winds, and the claimant and the defendant may both have to begin a new foundation. Sometimes there is a disturbance on a more limited scale: one between very near neighbours or blood-relations—a family jar, in fact. One pair of birds do their very best to pull the sticks from the nest of another pair: each of the contending parties will do all they can to prevent the other from building.

As to the nests, we all know how busily the rooks set to work to repair these after a gale of wind has wrought some havoc in their colonies; but I do not think it is equally well known that they are curiously weather-wise, and they scent the coming storm and set to work to repair and strengthen before the imminent gale has been evident to the farmer. I have noticed that fact; the Rook’s powers of sight and hearing are remarkable.

At the end of the breeding-season comes the farmers’ rook-shooting, which I, for one, never take part in: I have too much regard for the labours of both the adult and the young birds. About the roots of each of the turnip-plants there may gather scores of wireworms, which eat the turnips; in the crops of young birds which have been shot are found myriads of these wireworms, or it may be that they are filled with grubs of various{55} sorts, the larvæ of cockchafers, etc. In fact, in my opinion—that of a tenant farmer who is forced to make things pay—all the Rook’s acts of depredation ought to be forgotten if we carefully consider the great services he renders to the agriculturist. Beetles, tipula (Daddy Longlegs grubs), warble grubs, oak-leaf roller caterpillars, and the caterpillars of the diamond-backed moth he devours. The game-preserver may grudge the birds their plundering of his nests, but the farmer is in gratitude bound to spare them. A lot of young birds at the rook-shooting time are still unable to take a flight of any distance, but others are, happily for themselves, able to fly well. I am persuaded that the old parent birds often—foreseeing a shooting raid—get these out of the way, and so they secure life for a number of their young who might have been sacrificed. They betake themselves in parties to their rootings about the elms upon outlying pastures. Daily they grow stronger on the wing, and learn the ways and means of living.

Like all long-lived creatures, the Rook is temperate in eating, and he is capable of going a long time without food—a faculty which stands him in good stead during hard winters. In a long frost or a prolonged drought he is a most determined robber, and when he is on what he knows to be forbidden ground, he posts a sentinel to give warning of the approaching farmer or watcher. He is known to take the eggs of such favourite birds as the thrush and the blackbird, whose nests are open, and therefore soon discovered and plundered. But this is no doubt where his proper food is scarce; and if man had not been so eager in the destruction of some of our birds of prey, who are the natural enemies of him and his, Rooks would be less plentiful in some districts.{56} Still, I for one have no desire to see their numbers decrease, so certain am I of their value; and I believe this bird will become even more valuable as time goes on.

The Rook is somewhat smaller than the Hooded Crow; the beak more slender, rather straighter; the base of it in mature age bare, and covered with a kind of white scurf. The entire bird is black with a steely-blue and purple gloss. The feet black and thick, the claws strong, the sole rough; it walks better than the Hooded Crow. The beak of the young bird is not bare, the nostrils being covered with bristly feathers. The bareness first appears when the bird begins to dig in the ground for its food.

The Hooded Crow walks well, with head erect, moving its tail right and left as it goes. Its flight is easy, using comparatively little movement of the wings. This Crow usually makes its nest in the tops of high trees, preferably in one standing alone in a field; but sometimes on rocks. It does not build in colonies but usually settles alone, though occasionally two or three pairs will build on the edge of a wood or in a small plantation. The nest consists of twigs, roots, and grass; the hollow of the nest being safely lined; in the spring it contains four to six eggs of a light green colour speckled with grey and brown marks.

In mild seasons this bird has been known to pair, as early as the end of February, but the usual time is March. Then the construction and arrangements of the nest begins. The female bird, only, sits on the eggs; the male guards the nest and provides the food. When near the nest, he is a courageous, even daring bird, able to keep off such enemies as the Hawk or the Eagle. His cry is “kár, kár.”

The Hooded Crow is a clever intelligent bird. It easily adapts itself to circumstances; the wave-lashed rock, or the icy peak, are as acceptable to it as green meadows, or the palms and sycamores of Egypt; the woods, as welcome as the heart of the snug village, as the tiny garden round a peasant’s hut. It is omnivorous; so long as it can find food in forest or field, on the sea shore or river bank, it avoids the proximity of man; but when winter comes, it settles near inhabited districts and{58}

highroads, in order to seize upon anything eatable, however bad its condition.

And now let us investigate its actions, which divide men into two camps, one of which states that the Hooded Crow is harmful, the other that it is serviceable. First, as to the harm. It is true that this bird considers a young chicken a great delicacy, and so, takes one when it has a chance. But this happens very rarely, for the good mother-hen flies at the marauder, and raises a cry that brings out the people of the house to see what is the matter, and the Crow has to beat a retreat, without having secured its prey—or run the risk of having a wing broken by a stone, a rolling-pin, or other missile. Should it succeed in securing a chicken, then indeed it has done harm, but this happens so rarely, that the housekeeper does not make much account of it. It is also true that it attacks the timid little hares in the fields, and if the mother is absent, the young ones are quickly destroyed, and torn to pieces by two or three blows of the strong beak. In this case it is the sportsman who is most annoyed, for the farmer is no friend of the hare, which does great harm in the winter by gnawing the fruit trees. It is a known fact also that the Crow robs the nests of birds which are built on the ground in the fields, when it finds them. This also is harm, but the little birds exhibit wonderful instinct in hiding their nests, so that even the sharp-eyed Crow can rarely find one, especially when we consider that its attention is constantly being diverted from the search by a fat cricket or grasshopper, or a mouse slipping hurriedly by. Neither can it be denied that when the ears of maize are young and soft the Crows opens the husk with its beak and regales itself with the milky juice. This is indeed{60} mischievous, but the harm is only local. A few farmers track it down, others do not, for about this time the bird begins to mend his ways. It cannot be denied either that it pecks young fruit of all kinds, and later pulls it off the trees, and if not driven away, considerable damage is done, especially if the orchard lies within a district where Crows abound. It is evident then that the gamekeeper must be allowed a little license, for where game is bred and preserved, especially in such places as Pheasant runs, the Crow may do much damage among the young birds; but why is the gamekeeper there, if not to scare away the feathered thieves with his gun? Once having experienced such a fright the Crow does not often return to the same place.

And now let us consider the bird’s good deeds.

The ploughman would be indeed unwise were he to scare away the Crow, that, following in the furrow of the plough, picks out from the freshly turned clods, the worms, grubs, and maggots, which are the farmer’s worst enemies; nor do the evicted tenants of overturned mouse-nests escape the strong beak of the bird;—and how busy it is when a plague of mice occurs, as it does in some seasons! Then occurs a wholesale massacre, and if this visitation happens in winter, the snow bears evident traces of the Crow’s sanguinary work.

It is also useful among the sheep and cattle, settling on their backs, and destroying the parasites that attack them. The beasts leave it undisturbed knowing that it is doing them good service. Neither must we forget that in villages, near human habitations it does excellent scavengering work. It knows the precise time at which the remnants of food are usually thrown out from the cottage on the rubbish heap, and waits on the roof, till{61} the moment arrives when it can pounce on the promising morsels, which it carries away; thus removing what would otherwise soon have become putrid. In winter when pigs are killed, the Crows wait, among the neighbouring trees, for their share.

The only remaining question, then, is, in which part of the year this bird is harmful, and in which serviceable, and how long does each of these periods last. The destructive period is really of short duration, for the chickens soon grow into hens, the leverets become hares, the young birds leave the nests, the maize hardens, and ripe fruit lasts but a little while. That is to say, the destructive period lasts but a few weeks. And what does the Hooded Crow do for the rest of the year? It destroys insect pests, cleanses and purifies, and by its continuous activity, does a service to man, which no other creature could do.

Wherever and whenever this bird does harm it must be driven off, but not destroyed. The hens must be kept from roving, and the orchard must be watched. If it will not be scared away then it must be shot. But when busy in the furrow, the field, or the dunghill, let it be left in peace, for it is doing a beneficent work. Neither nature nor man can do without the Hooded Crow, and for this reason it must be treated indulgently.

The head, wings, tail, feet and throat of this bird are black, but not glossy; the lower breast, under-parts, and back ashen grey; the grey colour of the back forms a kind of mantle,—hence the name Mantle—or Hooded Crow. The strong curved beak is black, the nostrils covered by bristly feathers; the eyes dark brown; the feet strong and armed with thick scales, the soles rough.{62}