Title: Dick Kent at Half-Way House

Author: M. M. Oblinger

Illustrator: C. R. Schaare

Release date: April 24, 2016 [eBook #51848]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

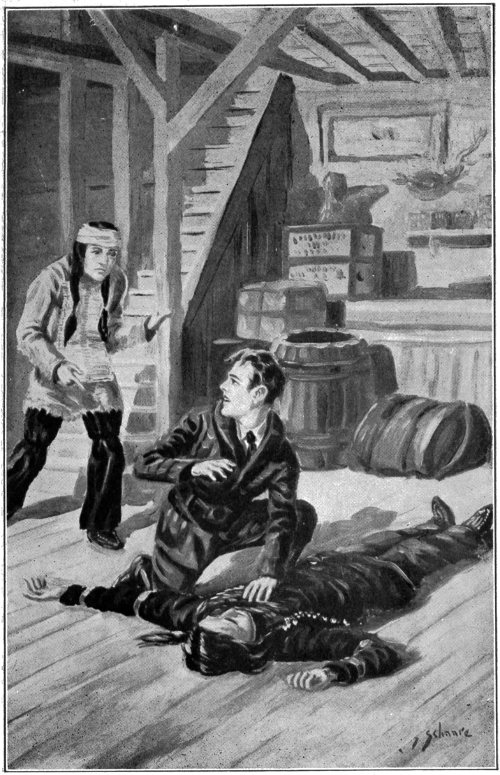

“Dick,” he trembled, “What happen? You shoot this man—you—” (Page 174)

By MILTON RICHARDS

Author of

“Dick Kent With the Mounted Police,”

“Dick Kent in the Far North,”

“Dick Kent With the Eskimos,”

“Dick Kent, Fur Trader,”

“Dick Kent With the Malemute Mail,”

“Dick Kent on Special Duty,”

“Tom Blake’s Mysterious Adventure,”

“The Valdmere Mystery,” etc.

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Printed in U. S. A.

STORIES OF ADVENTURE IN THE NORTH WOODS

FOR BOYS 12 TO 16 YEARS

By MILTON RICHARDS

Copyright, 1929

By A. L. BURT COMPANY

Printed in U. S. A.

Just before dusk, riding in on a slight swell, the canoe touched on the leeward side of the island. It was a wooded island, similar to a score of others that dotted that lake. There was little to differentiate it from its brothers except that in its very center the fir and balsam had graciously withdrawn to permit a huge shaft of solid rock to raise its head loftily and majestically skyward.

The three young men who disembarked from the canoe, stood looking toward the shaft with something like eagerness in their eyes. Then one of them spoke:

“There it is! The rock of the dinosaur!”

Another of the trio, a stockily built boy with light blue eyes and sandy complexion, removed a battered felt hat that had been crammed down over his well-shaped head and ran his fingers through a mop of corn-colored hair.

“Bones! Toma—bones!”

The remaining member of the party, swarthy, dark, soft-footed, agile as a panther, grinned as he stooped down to tie the strings of one of his moccasins.

“Mebbe this not right place after all,” he said.

The first speaker turned swiftly at this and regarded the stooping figure. What had induced Toma to make that remark? The description that had been given them by Mr. Donald Frazer, factor at Half Way House, fitted this island exactly: an island in a lake of many islands, an island with a tall rock. Dick Kent remembered as well as if it had been only yesterday.

“It’s three hundred miles northwest of here in a country of innumerable lakes,” the factor had directed them. “These lakes all drain into the Half Way River. They are all very close together, forming a sort of chain. Most of the lakes are dotted with a few islands, but there is one lake, near the center of the chain, that has more islands than all the rest—scores of small wooded islands. On one of these you will find a tall, spindling rock. The island with that rock is the island of the dinosaur.”

So remembering this conversation, Dick could not believe with Toma that they might have come to the wrong place. Here was the wooded island. Here was the spindling rock. Here was the lake of many islands.

“Why don’t you think it’s the right place?” he demanded.

The young Indian straightened up quickly, his eyes twinkling.

“Why you get so worried, Dick?” he inquired blandly. “I no say this the wrong place. Mebbe so, mebbe not. Plenty islands I see in other lakes an’ plenty rocks too.”

“But not a rock as tall as that one,” objected Sandy.

Dick nodded his head.

“Yes, and most of the other lakes we explored had only a few islands. This one tallies exactly with the description Mr. Frazer gave us.”

Toma grinned again.

“All right,” he waved their arguments aside. “What you say, we go see?”

The three boys pushed forward. The island was scarcely more than four or five acres in area. In a few minutes they reached the center, coming to a full stop near the base of the pinnacle. They found a peculiar formation here. In some prehistoric time a gigantic upheaval had thrust the underlying strata to a position very nearly perpendicular. In other words, layer upon layer of substratum had been lifted up out of the earth and exposed to view. Embedded in one of the layers of rock was the huge fossil of a prehistoric reptile. Its immense frame could be seen very distinctly from where the boys were standing. Supported by the rock, much of which had crumbled away, the skull of the dinosaur rested lightly against the side of the pinnacle and the bones of the rest of the body, still joined and intact, extended downward to the edge of a deep pit.

The effect of all this was ghastly. Staring at it, one was conscious of an indescribable feeling that the fleshless body of the dinosaur still retained life and that it had clambered out of the deep pit beneath it and was now endeavoring to climb the tall, spindling spire of granite. So lifelike and terrible indeed, did the primeval monster appear, that for a full five minutes the three boys stood there without as much as moving a muscle.

Suddenly the tension snapped as Dick burst into a roar of laughter. He laughed until the tears came into his eyes and coursed down his cheeks. He roared and slapped his thigh and sat down on a rock, swaying back and forth in a paroxysm of uncontrollable mirth.

Toma and Sandy stared at their chum in utter amazement. They surveyed each other blankly. They looked quickly over at the dinosaur in the belief that possibly they had overlooked something.

“See here,” began Sandy, “what in the name of common sense are you yowling about? If you can possibly see anything funny in that grewsome mass of bones your sense of humor is warped. Stop it, Dick! Stop it, I say before you drive me daft. Stop!”

Dick raised his head and wiped his eyes. He was still choking.

“You—you see nothing funny?” he gasped.

“I do not!”

“What do you think of our friend, the dinosaur?” and Dick indulged in another convulsive chuckle.

Sandy’s eyes flashed fire.

“Say—”

“Look at it! Look at it!” shrieked Dick. “Its size! Must weigh tons—tons, Sandy. And—we’ve come—three hundred miles—laboring under impression—going to carry it back on a raft.”

“Well—”

“On a raft,” continued Dick. “That thing on a raft. If you can, just get that picture in that slow mind of yours.”

Toma was grinning broadly now.

“The portages,” he wondered.

“Yes, think of carrying that huge skeleton over the portages.”

“Why it—it can’t be done,” stated the young Scotchman, beginning to see the light. “Absolutely out of question. We’ve come on a fool’s errand. Mr. Frazer must have—”

“Known it!” Dick took the words out of his chum’s mouth. “Of course, he knew it. Can’t you see, Sandy, we’ve been victimized, made the butt of one of the worst jokes I’ve ever heard of. No wonder they all grinned and acted so queerly when we left the post. By this time, half the people in this north country are laughing up their sleeves. It’s all a hoax. I’ll bet that London museum Mr. Frazer told us about hasn’t even made an offer for this dinosaur.”

“You mean the whole affair from beginning to end was planned by that fool and his friends?”

“Exactly.”

“And that we’ve not only lost what we thought was a chance to make a few hundred dollars but have become the laughing stock of—of—” Sandy choked and gurgled.

“Right again,” grinned Dick. “You’re learning fast.”

Sandy’s color drained from his cheeks and he sat down quickly, endeavoring to control the fierce gathering storm within.

“And you call that a good joke,” he inquired bitterly, “a friendly, decent joke that sent us packing through a hundred dangers at the risk of life and limb? You can laugh at that?”

“Well, what would you have me do? Sit down and cry? Not I. Might as well make the best of it. I’ll go back and laugh with ’em.”

“I laugh too,” said Toma. And he did.

Sandy continued to glower. He looked up at the dinosaur. Then he put his head in his hands and groaned.

Dick Kent had plenty of time that night to think about the crude joke Mr. Frazer, the factor at Half Way House, had played upon them. The factor must have known full well that the mammoth skeleton of the dinosaur could not be conveyed easily up the river on an ordinary raft. He must have known, too, of the utter impossibility of packing the huge creature over the thirteen portages that are to be found between the island of the granite shaft and the trading post, three hundred miles up the river.

Given sufficient leisure to think the matter over, Dick decided that he did not blame Sandy one bit for the anger and bitterness that Frazer’s trickery had aroused. The young Scotchman had eaten his supper in a huff and later had retired to his blankets in a manner that was, to say the very least, thoroughly hostile and unfriendly. His actions indicated very plainly that he, for one, didn’t consider this business of the dinosaur as the sort of joke that could pass unnoticed or unforgiven, or that could be laughed down or yet dismissed with a shrug. It rankled and cut deep. Some day Mr. Frazer would hear about it.

Dick turned his eyes toward the campfire and watched the shadows creeping up to the bright circle its glimmering light made. He lay quite still, listening to the monotonous beat of the water around the shore of the island. He was dimly aware of the tall granite slab that thrust up its pointed head in cold disdain of the lowly trees under it. Far away somewhere a loon called out mockingly and derisively to its mate.

Sandy woke on the following morning in a better humor. Over a hot cup of tea and a crisp rasher of bacon, he apologized for his behavior on the previous night.

“I had no reason to be angry with you, Dick,” he stated contritely. “But you irritated me because you took it all so good-naturedly. It can’t be denied that the joke is on us, but you surely know that he went too far with it. He never should have permitted us to start out. Our time is worth something and we paid the factor a good stiff price for our grubstake. Then there are all those cumbersome tools we brought along—rock chisels, pickaxes, hatchets and what not. We paid for them out of our own hard-earned money. A very expensive practical joke, if you ask me.”

In the act of raising a cup of steaming beverage to his lips, Toma paused and his dark eyes fell upon Sandy’s face.

“Mebbe not so much joke like you think. Mebbe Mr. Frazer him not want us to stay at Half Way House any longer. Mebbe he think your Uncle Walter send us fellows down to spy on him an’ he no like that.”

Both Dick and Sandy started. They had never looked at the situation from quite that angle. The young Indian’s statement had induced a new train of thought. Come to think of it, why had Sandy’s uncle, Mr. Walter MacClaren, factor at Fort Good Faith and superintendent for the Hudson Bay Company for all that vast northern territory, sent them over to Half Way House in the first place? Sandy looked at Dick searchingly for another moment, then broke forth:

“Gee, I never thought about that. Toma, you’re too deep for us. I can begin to see now.”

Dick pursed his lips, scowling slightly.

“Mr. MacClaren said that the hunting was good up around Half Way House and that we’d enjoy our summer’s vacation there. He didn’t tell us that he was suspicious of Mr. Frazer. Naturally he wouldn’t. He wanted us to find that out for ourselves. Sandy,” he glanced eagerly across at his chum, “as far as you know, has Mr. Frazer a reputation for being much of a practical joker?”

Sandy put down his cup and proceeded to pour out his second helping of tea.

“No, I’ve never heard that he was. And certainly he doesn’t look the part. I wouldn’t call him frivolous. My impression of him has always been that he is inclined to be sort of taciturn, reserved and fairly uncommunicative.”

At this juncture, Toma again broke into the discussion.

“He not look like man that see anything to laugh about ever. I no like that fellow very much. I no like them friends he keep alla time hanging around the post. Look like bad men to me.”

On many occasions previously during their sojourn in the North, the two boys had come to place a good deal of reliance on the young Indian’s snap judgment. He had an almost uncanny ability to read character and of finding hidden traits, both good and bad, in the persons with whom he came in contact. Seldom did he err.

“He’s referring to Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum,” said Sandy. “Well, I don’t know as one could call them Frazer’s friends.”

“I see Mr. Frazer talk with them many times,” Toma wagged his head. “When I come close they hush up—don’t talk any more. An’ one time I see a light in Mr. Frazer’s room late, ’bout two o’clock, I think. An’ there through the window I see ’em. Wolf Brennan, McCallum, Frazer an’ two Indians I do not know.”

“Why didn’t you tell us this before?” demanded Dick.

That was the way with Toma—ever reticent. His uncommunicativeness often became a source of despair to his two chums.

“You no ask me.”

“But how did we know?” glared Sandy. “We weren’t up at two o’clock that night.”

“I no tell you that,” Toma explained, “because I think mebbe you no want to hear bad things about Mr. Frazer.”

“You cherub!” Sandy snorted.

“Sandy,” questioned Dick, “how does Mr. Frazer stand with the company?”

Sandy stirred the oatmeal, sugar and bacon grease together in what was to Dick an unappetizing mess.

“Uncle Walter never told me.”

“But haven’t you heard?” Dick persisted.

“No, I haven’t,” Sandy commenced to eat his favorite dish. “Uncle Walter never tells me anything about his business. He’s as close-mouthed as the average Scotchman, I guess.”

“There are some ways in which you do not resemble him in the least,” pointed out Dick, winking at Toma.

No more was said on the subject then. As soon as they had washed their breakfast dishes, Dick and Sandy went over for another view of the dinosaur, while Toma set out to explore the island. The dinosaur, in the bright morning sunlight, seemed to be as ugly and repellent as it had been in the evening’s shadows on the night before. Again they were awed by its presence. It seemed inconceivable that anything so huge and ugly had ever walked upon the earth.

“How’d you like to meet one of those things alive?” asked Sandy.

“Not for me. A bullet would probably flatten out on its scaly hide. At the best, it would feel like no more than a pin-prick. And Mr. Frazer told us we could bring that thing back on a raft. He must have known better, because he was here two years ago and saw it with his own eyes.”

“Of course, he knew better,” growled Sandy.

The bushes parted behind them. First Toma’s head was thrust through and then his body. He motioned to them eagerly.

“Come on,” he said. “I show you something. Come quick!”

They turned and followed him, finding it difficult to keep pace with him, so quickly did he go. They came presently to a fringe of willows not far from the western shore of the lake. The young Indian motioned them to be seated.

“Watch out there in the lake,” he commanded them. “Pretty soon you see something. Keep very quiet. No talk now.”

Both waited expectantly. Out ahead of them the lake rippled and sparkled. Suddenly a canoe glided within their range of vision—a canoe containing two occupants. Their paddles dipping in unison, the two men sat very straight, one in, the center and one in the stern, two mackinaw coated figures, two bearded white men whom the boys recognized instantly. In the excitement of the moment, Sandy jabbed his elbow in Dick’s ribs.

“Cracky!” he blurted out. “What’s up now? Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum! They’re coming here.”

But in this Sandy was mistaken. The canoe did not pause, did not waver. It swept in fairly close to the island then, as if it had suddenly changed its mind, it swerved sharply and continued on its course. The two men sat like statues until they were thirty or forty yards away. Then Wolf Brennan craned his thick, bull-like neck and looked back.

Even at that distance the boys caught the expression that distorted the man’s coarse features. A leer, a mocking, unfriendly grin, a diabolical, fiendish sneer!

Abruptly he turned and the paddle, gripped in his huge ape-like hands, glinted in the sunlight as it smote the gleaming water.

“Now what are they up to?”

Dick’s hands clenched as he spoke. He half rose from his kneeling position behind the willow copse and glared at Sandy as if he expected that that young man could answer the question.

“Yes, what are they up to?” he repeated in a low tense voice. “Messrs. Brennan and McCallum must be on our trail. And from the look that Wolf just now directed toward this island, they know we’re here. The whole thing is a puzzle to me. I don’t know what to think of it.”

“What I can’t understand,” said Sandy in a breathless voice, “is why they did not stop. They’ve gone right on. The reasonable and decent thing for them to do would be to come over and say ‘hello’. They might, at least, have shown that they were hospitable.”

“Wonder if Frazer sent them,” mused Dick.

Sandy pursed his lips and scowled as he looked out toward the flashing crests of water.

“I shouldn’t wonder,” he answered. “Now that we’ve found the little joker in this deal of the dinosaur, I’m inclined to think he has. Further than that, I’m prompted to believe that there was something more than the mere playing of a practical joke that induced Factor Frazer to get us to come out here. There must be some deviltry afoot at Half Way House. Our presence there isn’t wanted. He sent us up here on this wild goose chase to get us out of the way, and, working on this hypothesis, the next logical inference is that Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum have trailed us all the way up here.”

Dick motioned Sandy and Toma to follow him to the opposite side of the island. Arriving at their camp, he turned upon his two chums.

“I’ve been thinking of what you’ve just said, Sandy,” he remarked, as he began packing their luggage. “I want to tell you that I believe you’ve hit the nail on the head. Something underhanded is taking place at Half Way House. We’ve been sent out here to be kept in ignorance of what is going on. They know that all of us are attached to the Mounted Police reserve and it would be fatal to their plans to have us there at the post. Wolf Brennan and his pal are out here to watch us, to see that we do not return. I—”

The young Scotchman interrupted him.

“Hold on there a moment, Dick. I don’t know as I’d care to go that far. I gather from what you’ve just said that you mean they’ve been commissioned by Frazer to put us out of the way.”

Dick smiled. “No, I didn’t quite mean that, Sandy. I don’t think we’ll be murdered. Not that. As long as we stay on this island, or remain here in this vicinity, we’ll be safe enough. We might stay here all summer, and we’d never see them again, never be bothered, but—”

“Yes, yes,” said Sandy impatiently, “go on, Dick.”

“But,” continued Dick, “let us leave this island or this vicinity and then trouble aplenty.”

“You mean they’ll attempt to stop us if we start back for Half Way House?”

“Yes, that’s exactly what I mean,” said Dick. “They’ll harass us at every turn. I’m convinced of it. I won’t say they’ll resort to open violence if underhanded methods will avail.”

“Oh come, Dick, surely not.”

“As I live, I sincerely believe it. I wouldn’t put these thoughts in your mind, if I didn’t But I can easily prove my point.”

“How?”

“By starting back.”

“What—you mean right now?”

“No better time than now. If my suspicions are correct, we’ll run into some snag within the next day or two.”

“Is that why you were starting to pack that luggage?”

“Yes.”

Sandy tongued his cheek and in the bright light of that perfect morning he squinted at his chum. In that brief interval he did some quick thinking.

“Wait a minute, Dick,” he finally broke forth. “Let’s not be too hasty.”

“But I’m not hasty. No use staying here any longer that I can see. We’ve all agreed that it’s out of the question to bother with the dinosaur. There’s absolutely nothing we can do here unless it is to put in a few weeks fishing and hunting, and somehow,” Dick stroked back the hair from his forehead, “I’m in no mood for that. Let’s start back and see what happens.”

“No, I think I have a better plan. Let’s postpone that return trip until we’ve had a chance to interview Messrs. Brennan and McCallum.”

“Just what do you propose to do?”

“Well,” began Sandy, “I doubt if they are aware that we’ve seen them. We can jump into our canoe, slip down along the east side of the lake and come upon them in such a way that they’ll think our meeting is quite accidental. We’ll profess great surprise at seeing them. We’ll ask them point-blank what they are doing out here.”

Dick laughed. “Yes, and not learn a thing. They’ll have a very plausible story, don’t worry about that. And why go to all that trouble anyway? If you want to talk to them, Sandy, let’s jump in the canoe and overtake them at once.”

“All right. Just as you say. I’m ready.”

“What do you think about it?” Dick turned upon the young Indian.

Toma deliberated for nearly a minute. His eyes flecked and his gaze dropped.

“No harm we go see them. Take jus’ a few minutes an’ we find out what they say. Come on.”

They dragged their canoe down to the water and Sandy pushed off. The light craft bobbed and swayed for twenty feet through the blue, almost unruffled surface near shore, then headed straight out toward the gradually disappearing speck retreating in the distance. For fully ten minutes no one spoke. The little vessel leaped and darted through the blue, sparkling element. In another ten minutes the other canoe had grown appreciably larger. Between strokes, Dick puffed:

“Remember, Sandy, this is your suggestion. You’re the spokesman.”

“Leave it to me,” the other retorted. “I know just what I’m going to say.”

“Whatever you do,” Dick warned him, “don’t let them guess that we’re suspicious of them.”

“I won’t,” growled Sandy.

Thus it happened that when they pulled abreast of the smaller craft, it was Sandy who hailed them. The two men raised their paddles and permitted their canoe to be overhauled. There ensued an exchange of greetings.

“Why didn’t you stop?” asked Sandy.

“Stop?” Wolf Brendan rubbed his unshaven chin and stared questioningly. “Stop where?”

“Why, at the island, of course.”

Brennan continued to stare blankly, almost foolishly. He was a good actor.

“There’s a hull lot of islands in this here lake. What island do you mean?”

“The dinosaur’s island, of course. You saw us, didn’t you?”

“Nope, we didn’t see yuh. Knew yuh was up here, o’ course, getting them bones of that thar dinosaur, but we didn’t know just where—which island, I mean.”

“You weren’t very far behind us on the trail.”

“Nope, ’bout a day I guess. Seen your campfire along the trail. One was still smoking when we got to it.”

“We sort o’ half suspected we’d run across yuh somewheres,” McCallum interjected. “So this yere is the lake of the dinosaur? ’Magine yuh fellows will be pretty busy durin’ the next few weeks gettin’ them bones chipped out o’ the rock ready for shippin’.”

“No,” Sandy informed them, “we’re not going to bother with it. The thing’s too big for us to handle.”

“Yuh can build a big raft,” McCallum suggested.

“What about the portages?” There was a faint note of anger in Sandy’s voice.

“Yuh’ll have to pack it, o’ course,” McCallum said. “But it’s almost as easy to build a big raft as a small one.”

“The dinosaur’s skeleton is too big and too heavy to pack,” declared Sandy haughtily.

“Yuh don’t say.”

“It certainly is.”

“What yuh gonna do then?”

“We’ve given it up,” Sandy spoke harshly. “We’re starting back to Half Way House this afternoon.”

Wolf Brennan spat in the water and glanced inquiringly at the three occupants in the other canoe.

“If yuh fellows was right smart now, yuh wouldn’t give up so easily. There’s a lot o’ money to be made if yuh can manage to get that big lizard back where it can be took to one o’ the company’s steamers. If I was making a contract now,” Wolf Brennan spat in the water again, “I’m thinkin’ I’d move Heaven an’ earth afore I’d give up.”

Sandy glanced back at him.

“I’m not saying we’ll never get the dinosaur out. But if we do, it won’t be this summer and it won’t be on a raft one is required to pole up a river that has thirteen portages.”

“How else could yuh get it out?”

“I don’t know. We haven’t thought about that—yet. Perhaps this winter we may come to some definite conclusion.”

“So yuh’re goin’ back to Half Way House?”

“You bet we are.”

“Too bad.”

“And where are you going?” Sandy inquired innocently.

Wolf Brennan glanced at McCallum for a brief interval and between them passed a significant and knowing look.

“Sort o’ figured we’d go prospectin’ for a time.”

“Where?”

Brennan seemed to be hazy on this point. He coughed embarrassedly and looked again at his partner.

“’Tother side o’ the lake there’s some hills an’ we kind o’ thought we’d put in a week or two jus’ sort o’ looking’ around.”

“What side of the lake?” persisted Sandy.

“On the north side,” Brennan answered. “If yuh’re startin’ back for the post this afternoon, we may see yuh again.”

“I shouldn’t wonder. Because we are starting for the post this afternoon.”

Brennan blinked and again he looked at McCallum. Evidently this was McCallum’s cue for he spoke up.

“Mebbe if yuh’d stick around for a while,” he suggested, “the four of us could figure out some way to get out that dinosaur.”

“Five of us,” corrected Dick, speaking for the first time. “You’ve overlooked Toma.”

“Breeds don’t count.”

“This one here,” stated Dick furiously, stooping over and patting Toma on the shoulder, “is as good as any dirty, bewhiskered white man that ever came over the trail from Half Way House. You can take that statement in any way you see fit, McCallum.”

“Regular spit-fire, ain’t yuh?”

“I’m not accustomed to have my friends insulted.”

McCallum removed his hat and bowed gravely.

“I shore beg your pardon. I didn’t mean no offense. Along toward evening, me an’ Wolf will drop over to your little island and pay yuh our respects.”

“Suit yourself,” said Sandy, “but we won’t be there. As I’ve already told you, we’re starting back to Half Way House this afternoon.”

What Sandy read in McCallum’s eyes was a challenge, but it was Wolf Brennan who spoke.

“Mebbe,” he said.

The first night on their return trip to Half Way House the boys camped twenty miles south of the lake. Here they received their first set-back. In the morning they awoke to find their canoe was gone. Rage in their hearts, they gathered in a little group and stared at the place where it had been. They guessed immediately what had happened. After the first shock, Dick scowled and looked at his two chums.

“Well, we know where we stand now,” he declared grimly.

“Three against two,” blurted Sandy. “They can’t stop us.”

Dick mopped his moist forehead and dug the tip of one moccasin into the loose sand.

“That may be true. We have the advantage in numbers. But I’d also like to point out to you that even though that is so the odds are in their favor, nevertheless. We never know when to look for them. They’ll strike when we least expect it and always from under cover. They’ve already won the first round. Poling up the river in a raft is a tedious and disheartening undertaking. It will take us three times as long to reach our destination. I don’t know as I’m in favor of going on in that way.”

“Why not?”

“Too much danger.”

“Not any more danger than there was in the canoe,” objected Sandy.

“Probably not. But until this moment we haven’t been sure in our own minds that Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum have taken the offensive. Now we know. There’s absolutely no question about it. They’ve struck once and they’ll strike again too. The next time it may be a stray shot that will get one of us.”

“What do you mean by a stray shot?” demanded Sandy.

“If one of us gets killed it might as well be a stray shot, mightn’t it? I mean, it will be a difficult thing to prove that we were deliberately fired on and that those two miscreants did the firing.”

“You propose then to walk back?”

“Yes, I think it will be safer.”

“But they can shoot us just as well while we are going through the woods as they can if we were aboard a raft.”

“I don’t agree with you there. There’s no better mark that I can think of then three standing figures on a raft, no obstructions of any kind to check the progress of a bullet, the best sort of cover along the shore in which they can hide.”

“Well, I don’t mind walking,” said Sandy. “But what about our luggage here? We can’t carry all of that. I’m mighty glad now we left those tools back there at the island of the dinosaur.”

“I’d suggest that we make a cache, right here, of what we can not carry. If we are to travel swiftly, we ought not to pack more than fifty pounds each. Isn’t that right, Toma?”

The Indian nodded. “Not more than fifty pounds. That way we travel quick. Think much better like you say not to pole up river in raft. Next time Wolf Brennan him not be so easy on us.”

Sandy suddenly clapped his hands. His face brightened and he laughed gleefully.

“Cracky! I’ve just had an inspiration. We’ll beat them at their own game. We won’t set our course along the river. We’ll go a more roundabout way and put them off our trail entirely.”

“But how?” questioned Dick, greatly interested.

“I just happened to remember,” explained Sandy, “that sixty miles southwest of here is the Clear Spring River. It’s a large stream, fairly navigable. On this river, near what is called the Great Heart Portage, is an old trading post, now deserted, once the headquarters for an independent fur company. If I remember correctly, Uncle Walter said that this independent company has been out of business for something like eight years. But their stores and warehouses are still there. These have been made over into dwelling houses and are occupied by half-breeds and Indians during the winter months. If we proceed in a straight line toward this old trading post, we ought to reach it in two days. When we arrive there, the chances are, we may find Indians in the vicinity and may be able to purchase another canoe. If we do, we’ll proceed up the Clear Spring River to Halstead’s Island, which will bring us about fifteen miles west of Half Way House.” Sandy paused and regarded Dick and Toma questioningly. “What do you think of that for a plan?”

“Good,” declared Toma.

“I like it very much,” smiled Dick. “It ought to throw Brennan and McCallum completely off our trail. They’ll be waiting for us somewhere a short distance up the river and, when we fail to put in an appearance either by raft or on foot, they won’t know what has become of us. I doubt if they’ll ever tumble to the fact that we’ve gone over to the Clear Spring River. When they do come back here to investigate and stumble upon our trail, we’ll be so far away they won’t be able to overtake us.”

While Dick had been talking, Toma paced restlessly back and forth near the campfire. For some unexplainable reason, he felt uneasy. For several minutes now, he had been watching closely a thicket of elders as a cat might watch a mouse. On two different occasions the leaves and branches of the elders had stirred gently. A light breeze flowed down along the river valley, yet it was so vagrant and listless that it scarcely could be felt fanning one’s cheek. Yet he had distinctly seen the elders moving. His quick eye had noted this and his first thought had been that possibly a squirrel was playing there. Catching up his rifle, he strode straight over to the clustered thicket and parted the branches. As he peered within, for one fleeting moment he was under the impression that he had caught sight of something brown. Then he heard a stealthy movement, followed, by the unmistakable crackling of dry branches.

Pushing his way within the thicket, he paused to listen. He could hear no further sound. Yet something told him that that fleeting glimpse of something brown had not been of an animal but of a man—Wolf Brennan or McCallum!

He took a few steps forward, critically examining the ground. A barely audible sound escaped his lips. He stooped quickly over the faint imprint of a moccasined foot. Satisfied, his suspicions confirmed, he dashed on through the thicket, emerging at its farther side, just as two figures topped a low hill not thirty feet ahead. Toma raised his rifle to his shoulder in a lightning motion, then came a blinding explosion and the two men ducked their heads as a bullet whistled between them.

The skulkers did not hesitate for even a fraction of a second. They dashed down the hill toward the thicker growth just below. Just as they entered this welcome barrier, a second bullet clipped the leaves above their heads.

In the wild scramble that followed, Wolf Brennan lost his hat. Cursing, he started back for it when still another lead pellet whizzed past, so close to his face that he thought better of it, turned and plunged on after his companion.

Soon afterward, Toma strode back into camp as calmly as if nothing happened. His expression was reserved and dignified. Except for a faint sparkle in his eyes, one could never have guessed that only a short time before he had been so busy.

“What were you shooting at?” Dick and Sandy demanded.

The young Indian smiled faintly.

“A wolf,” he answered.

“Where did you see it? Pshaw, you’re joking,” accused Sandy. “A wolf! One seldom sees a wolf during the summer.”

“I see ’em wolf,” declared Toma, “an’ I shoot at him one, two, three times.”

“Yes, we heard you,” said Dick. “Hit him?”

“I not try very hard. I have lots fun scare that wolf. Wolf no good to eat unless one pretty near starve. Why for I kill him?”

“I’d kill a wolf any time I had a chance,” declared Dick. “I hate them.”

Sandy started to say something, then suddenly paused. Of a sudden his eyes had grown very round and he stared at Toma as if fascinated. He was looking straight at the young Indian’s hip pocket. From it a bulky object protruded. The object was brown and it was a little difficult to tell just what it was, nevertheless, Sandy had his suspicions. He strode forward quickly and yanked it from his chum’s pocket. He smoothed it and held it out for better inspection.

“Where did you get it?” he demanded.

At the sharp question, Dick turned and he, too, stood goggling.

“I no tell you a lie,” Toma explained. “That fellow him wolf all right—Wolf Brennan.”

Dick turned pale. “Did you kill him?” he cried in horror. “Tell the truth, Toma, you didn’t hit him, surely? You wouldn’t do that.”

“I just tell you I like make ’em run. Wolf Brennan, Toby McCallum do very fast run back there in the trees,” Toma pointed away in the direction he had just come. “Mebbe next time them fellows think twice before they try spy on our camp.”

For a brief interval, Dick and Sandy grinned over the mental picture of those two racing figures, but their mirth was short-lived. The same thought came to each at the same time.

“I’ll bet they heard what we were talking about,” gasped Sandy.

“Sure they did,” said Dick.

“In that case, no use going to Clear Spring River. Might as well go on the way we planned in the first place”—dolefully.

“Might as well.”

Toma, who had been gazing up and down along the shore, suddenly broke forth:

“What you think them fellows do with our canoe?”

“Set it adrift, of course,” grunted Sandy. “It’s probably miles away by this time. Might even have reached the Lake of Many Islands.”

Toma rubbed his forehead with a grimy hand.

“Mebbe not. Mebbe current take it close in to shore an’ that canoe not very far away this minute.”

“Possible, I’ll admit,” agreed Dick, “but not very probable. More likely they took it out here in mid-stream and sunk it.”

“If you fellow stay here,” suggested Toma, “I very willing to walk back to see if mebbe I find it.”

“No,” said Dick, “I wouldn’t want you to do that. I mean it isn’t fair that you should take all the risks and do all the work, Toma. Let’s toss a coin to see who goes.”

It was agreed. They tossed the coin and Dick lost. A few minutes later, carrying his rifle and a few emergency rations, he waved good-bye to his two chums and started out.

Dick had no definite plan in mind other than to proceed down the river in search of their missing canoe. As Toma had suggested, there was a possible chance that the unscrupulous Wolf Brennan and his partner had set the craft adrift, believing that it would be carried by the current into the Lake of Many Islands—out of sight and out of reach of their three young opponents. If this was the plan that Wolf had actually put into effect, there was still a frail chance for its recovery. It might have floated out of the main current and subsequently been washed ashore. If Dick were lucky, he might come upon it. It was a somewhat hopeless quest yet, under the circumstances, it might be well worth the effort.

“I won’t waste more than a few hours,” Dick decided, as he picked his way along the rock-strewn shore. “If I don’t find it within five miles from camp, I’ll give up.”

At the end of an hour, his patience was rewarded. Turning a bend in the stream, his heart gave a quick leap. Two hundred yards ahead was what looked to be very much like the thing he sought. It was a canoe—that much he knew. It was close to shore, drifting idly, round and round a circular pool on his own side of the river. He emitted a fervid sigh of satisfaction and relief and bounded forward. Fifty feet from his objective he stopped short, his breath catching.

It was not their canoe at all. It was the one in which only the day before, he had seen Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum pass by the island of the dinosaur. The realization had come so unexpectedly that, for a time, Dick was almost too dazed and bewildered to collect his scattered wits.

So Brennan and his partner had lost their canoe, too? How had that happened? Had they left it partly in the water and partly on shore, and had the current succeeded in tugging it away? It seemed probable. The river played no favorites.

And then Dick saw something that caused his pulses to leap with excitement. In the white sand, twenty feet from where the craft was bobbing idly, were the marks made by the canoe when it had been beached, and around these marks were the unmistakable imprints of moccasined feet.

Dick could not suppress a grin of appreciation. Well-trained canoe that! A very obliging current! Caught in a net-work of in-shore eddies, moving round and round in a circle, the canoe was nearly as safe as if it had been dragged clear of the water and deposited in the white sand along the beach.

Coincident with this discovery, there came the realization that he was treading on dangerous ground. Having left their canoe here, very naturally the partners would return. Perhaps they already had. For all Dick knew to the contrary, right at this moment from behind some leafy ambuscade they might be watching his approach. The thought frightened him. He paused dead in his tracks, undecided what to do. After the reception Wolf had received back there at the boys’ camp, it was only reasonable to suppose that neither of the partners would hesitate about using their own weapons. On the other hand, if they were still lingering in the vicinity of the other camp or had paused to rest somewhere, he would be missing a golden opportunity if caution or the fear of a bullet kept him from making a closer approach.

Come to think of it, he was in as much danger here, a mere fifty yards from his goal, as he would be if he were actually at the side of the canoe. Already he was within rifle range. But they hadn’t fired. Were they waiting for him to come just a wee mite closer, or was it really true that they hadn’t yet arrived upon the scene?

For a full minute Dick stood there, unable to decide. His heart pounded like a trip-hammer. Three times he took a step forward and thrice he stopped short, in panic at the thought of what might happen to him if he could command the courage to go on.

And then, almost beside himself from the inactivity and suspense, he gathered together the fluttering, loose ends of a waning decision, gritted his teeth, and darted forward. Bounding along at top speed, in a few seconds he came abreast of the canoe, checked himself, then splashed out waist-deep into the water and clambered aboard.

He dropped his rifle, frantically seized one of the paddles and was half way out into the river before he was sufficiently recovered from his fright to realize that he had actually made good his escape. Yet he continued to paddle furiously. Never before had he bucked a current with such fierce and desperate ardor. He swept round the bend in the river, perspiration pouring from every pore, working with a dogged, automatic, machine-like regularity. Seemingly he could not, dare not ease up for even as much as a split-second.

On and on he raced. A thin, white line of foam trailed off in his wake. Now and again in his eager haste, his paddle scooped the water in the air behind him, where the freshening breeze caught it and whirled it away.

He was limp as a rag and utterly spent when he reached camp. Toma and Sandy, who stood watching him as he glided up to shore, blinked in amazement.

He had not the breath to answer their eager questions. He lay back in the stern, puffing, gasping, while the blood throbbed in his head with such insistence that for a time he actually believed that his temples would burst. His vision was somewhat obscured, too. Through a sort of haze he could perceive Sandy dancing wildly like a jungle savage.

“Dick, you lucky beggar!” shrieked the suddenly daft and madly plunging young maniac. “What’s the meaning of this? O boy! Cracky! If you haven’t turned the tables after all. What a come-back! I’ll bet if either one of ’em had gold teeth you’d have stolen them, too. Where’d you get it?”

Not yet able to speak intelligently, Dick pointed down the river.

“You did, eh?”

Dick nodded.

“Fight ’em?” Sandy persisted.

Dick shook his head.

“Well, that’s too bad. I was hoping that you had left them back there to nurse a couple of broken heads. Serve ’em right after what they did to our canoe.”

Dick sat up, his breathing now less violent.

“Ju—just what do you mean, Sandy? Have you found it?”

“You bet we have. Toma and I found it in your absence. It’s not down the river at all. It’s over there in the brush, just where they carried it after smashing it up with rocks. We must have slept like logs not to have heard them.”

Dick thrust his two arms into the water over the side of the canoe and commenced to bathe his hot, sweat-streaked face.

“Well, it doesn’t matter now. We have this.”

“Yes, thanks to you. What do you say we leave this accursed place before something else happens? Toma and I can bring over the luggage while you sit there and rest a bit. You need it. When we saw you first, I’m only exaggerating a little when I say you were travelling at the rate of twenty knots an hour.”

“I’ll admit I was frightened.”

“You must have been. Next time we want to get a little speed in a pinch, I’m going to frighten you myself.”

“Cut out the talking, Sandy, and let’s start. I’m afraid to linger here much longer. Don’t forget that we’ve stirred up a hornets’ nest by taking a flying shot at Messrs. Brennan and McCallum, and now have added insult to injury by appropriating their canoe.”

“Serves ’em right.”

“Please——”

Dick did not finish the sentence. A warning shout from Toma was followed instantly by a sinister crack of a rifle and the whine of a bullet. The young Indian came running, carrying part of the luggage. Dazed by the suddenness of the attack, they could not determine at first from whence the murderous leaden messenger had come. A second puff of smoke revealed the place the two outlaws were hiding. Sitting in the canoe, Dick returned their fire, while Sandy, strangely calm for him, sprang up the bank to fetch what remained of their provisions.

When they were ready to embark, the firing had ceased. But it was only a lull before the storm. Changing their position, this time creeping down closer to the shore, Wolf Brennan and his companion blazed away at the speeding, bobbing mark out there in the water. In order to save themselves, the three boys dropped their paddles and sprawled at full length in the bottom of the canoe.

“Whatever you do—keep down!” panted Dick.

Crack! Crack! Crack! Wood splintered around them. Running wild in the current now, their craft started down stream. Suddenly, water commenced pouring in through one side. They were sinking—and drifting as they sank. Calm though he was, Dick had a feeling that they were irretrievably lost. The water was like ice, chilling one to the marrow. The opposite shore was still a long distance away.

“Be ready!” Dick called sharply. “Swim! Keep under as much as possible!”

Like a man dying, the canoe gurgled and went down. A bullet spat in the water where it had been. A yell of triumph sounded from the shore.

“Dive!” shivered Dick. “We’ll make it!”

Drenched and exhausted, they waded ashore. They wrung the water out of their dripping garments, eyeing each other soberly. His mouth grim, Toma turned and waved defiance at their two enemies, who stood watching them from the opposite side.

Dick was too overcome, too utterly sick at heart even for speech. His mind dwelt upon their awful plight. No catastrophe, except death itself, could have been more terrible. Canoe, supplies, guns—everything they possessed—had gone to the bottom of the river. In one stroke, fate had delivered a fearful blow. They were face to face with starvation, that grimmest of all spectres of the wild. They were two hundred miles from the nearest trading post—and food. The country through which they must pass was unsettled, except for roving bands of Indians, and here and there, probably, a white hunter or prospector. Without rifles, it would be very difficult to obtain game. They had not even matches with which to light a fire.

Standing there, shivering and despondent, Sandy addressed his chums:

“We’re alive, and that’s about all. An hour ago the odds were in our favor. Not now. The tables have been turned. The advantage is theirs. At least, they have rifles and matches.”

Despondently, they turned out their pockets. Each of the boys had a hunting knife. Dick had three fish hooks and a line. Sandy produced a watch, compass, and an emergency kit containing bandages and medicine. Toma pulled out an odd assortment of articles, including three wire nails, a mouth-organ, a bottle of perfume, a mirror, and a package of dried dates. That was all, not counting a small amount of money which each one carried.

“The prospect doesn’t look very bright,” sighed Dick. “Fish will have to keep us alive until we get back to the post. Toma,” he turned eagerly upon the young Indian, “do you know how to start a fire without matches?”

“Yes,” Toma nodded.

“Well, that will help some. We haven’t any salt to eat with our fish, but in this sort of emergency I guess we can’t complain. One thing that pleases me, that makes all this endurable, is that Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum are not apt to bother us any more. We’re on opposite sides of the river, and by the time they can build a raft, we’ll be a good many miles ahead of them. If you fellows are willing, I’d just as soon walk all night.”

“But we can’t walk without food,” Sandy reminded him. “We must stop, catch a few fish, and make a fire. In time the sun will dry out our clothing, so we don’t need to worry about that.”

Toma led the way as they pushed on. It was late when they stopped. Dick immediately repaired to the river, where he caught four trout. In the meantime, Sandy watched Toma making a fire. It was a slow process. The young Indian walked up through the woods, and from the stem of a number of weeds he gathered a handful of pith. Next he procured dry moss, and, from the shore of the river, a hard rock about the size of a man’s hand. Proceeding with these materials to a place sheltered from the wind and handy to fuel, he squatted down, holding the rock in one hand and his knife in the other. With the ball of pith on the ground in front of him, working with incredible speed, he struck knife and rock together, sending a shower of red sparks upon the inflammable substance below.

Presently, it began to smoulder. Lying prone, he blew upon it gently. Delicate, fine pencils of smoke arose, then a tiny flame, no larger than that made by a match, flamed up from the pith. With a quick motion, still continuing to blow, Toma sprinkled over his embryo fire a quantity of dry moss. The little flame rose higher. He added a few tiny twigs and the outer husks of the weeds, from which he had taken the pith. Within five minutes their campfire was blazing brightly, and when Dick returned with the trout, he stood there staring in wonderment.

“Did you do that, Toma?”

“Yes, I do ’em.”

“What with?” Dick inquired curiously.

“The steel of his hunting knife and an ordinary rock,” explained Sandy. “Struck them together and made sparks. The sparks ignited a little ball of fluff he gathered from some weeds in the woods.”

“That not ordinary rock,” Toma pointed out. “That what Indian call fire-rock. Make spark easy. Not always you find rock like that. If I use different kind of rock, it take much longer.”

When they had eaten their supper, consisting of the four trout, baked over the fire, they all felt much more cheerful. Dick and Sandy spent an interesting half-hour receiving instructions in the art of fire making. Both soon discovered that it was not as easy as it looked. Each made several futile attempts before he finally succeeded. When they left camp, setting out upon their lonely night’s journey, much to the young Indian’s amusement, Dick took the fire-rock with him.

“We find plenty more rock like that along the river,” Toma told him. “Why you carry that extra load?”

“It’s not heavy,” Dick grinned. “Besides it fits nicely into my left hip-pocket. I don’t intend to take any chances about finding another rock as good as this. I know I can make a fire with this one and I might not be so fortunate with some other kind.”

Toma laughed again as they made their way through the enveloping spring twilight. The air was exhilarating and the quiet earth was touched with a solemn beauty. Not a breath of air stirred through the fir and balsam along the slope. A fragrant earth smell uprose from the rich soil. They passed shrubs that flamed with white and crimson flowers. Dick became so impressed with the loveliness of it all that for a time he quite forgot about their dilemma. Later, when he did remember it, it didn’t seem so terrible after all.

“We’ll fool them yet,” he announced cheerily. “If we can manage to get food as we go along, there’s no reason why we can’t arrive at Half Way House in time to upset Frazer’s plans.”

“We must do it,” replied Sandy soberly.

“It won’t be easy,” warned Dick.

“I know that. It makes me all the more anxious to succeed. I’m not very apt to forget this experience for a long time. If the factor really is up to some underhanded work—and the actions of Brennan and McCallum have indicated that pretty plainly—I, for one, intend to get to the bottom of it.”

“That’s the spirit,” applauded Dick. “We’ll show him. We’ll go till we drop. If anything happens to one of us, the other two must carry on.”

They paused at that and shook hands all around. Then they went on more grimly and doggedly. All night they tramped. When the early morning sun blazed a new trail across the blue field of the sky, they made a second camp, started another fire with flint and steel and devoured hungrily, almost ravenously, the six trout which Dick had the good fortune to catch in a deep, quiet pool near the shore of the river.

In catching the trout, Dick had used clams for bait. Watching him, the operation had given Sandy an idea. He set out along the shore, returning at the end of an hour with thirty large clams, which he placed in a hole he had scooped out in the sand.

“When we’ve had a few hours sleep,” he told Dick and Toma proudly, “I’ll roast these fellows in the hot ashes and we’ll have a change of diet.”

“Not a bad idea,” Dick rejoined. “I’m almost hungry enough to eat them right now.”

They slept longer than they had intended. It was late afternoon when they awoke. The warm sun, beating down upon their tired bodies, had kept them as warm and comfortable as if they had been wrapped in blankets. So refreshed were they when they had clambered up from their couches of white sand that Toma was moved to remark:

“Not bad idea to sleep daytime an’ travel night. At night fellow sleep by campfire with no blankets get cold. No rest good.”

“True,” agreed Dick. “We’ll do most of our travelling at night. Wish I knew what time it was. Too bad the water spoiled Sandy’s watch. By the look of that sun, I’d say it was about three o’clock in the afternoon.”

Toma squinted up at it and shook his head.

“Five o’clock,” he corrected. “Soon as we get something to eat, better tramp some more. Dick, you give ’em me fishhook and line an’ mebbe by time you an’ Sandy get fire ready an’ bake clams, I catch some more fish.”

Toma had better luck even than Dick. A few minutes before the clams were baked, he appeared upon the scene with eight speckled beauties, none of which weighed less than two pounds. They cleaned and baked them all, wrapped up five in Dick’s moose-hide coat, made a pack of it, and started out upon their journey.

They went jubilantly. It was many hours before the sun swung down toward the northwestern horizon. Just as the twilight waned and the half-night of the Arctic dropped its mantle over the earth, Toma, who was twenty yards in the lead, suddenly stopped short and threw up his hands, shouting for his two companions to hurry. When they reached his side, he pointed down at the loose sand at his feet.

“Go—ood Heavens!” stammered Dick.

In the sand, plainly distinguishable, were the imprints of naked human feet.

Who made those naked footprints in the sand? For hours afterward the boys puzzled over it, but could come to no satisfactory conclusion. Indians, as they well knew, seldom went barefoot. If, on the other hand, the tracks had been made by a white man, who was he and from whence had he come? Though they searched long and diligently for the remains of a campfire or other evidences of the stranger’s presence, none was to be found. The tracks could be followed for a distance of nearly a quarter of a mile along the shore, after which they turned away from the river and became lost in the thick moss that carpeted the woods.

Nor could they pick up the tracks again. Toma, whom nature and training had specially fitted for this kind of work, was forced to admit, finally, that even he was baffled. Given a little more time, he believed that he could find other imprints, but inasmuch as Sandy and Dick chafed at the delay already caused by the mysterious, barefoot stranger, he decided to concur with popular sentiment and try to think no more about it.

But it was not thus to be dismissed so lightly. The passing of time seemed only to add fresh interest to the puzzle. During the next two days it was the popular topic of discussion. New theories were advanced by one or other of the boys, argued over sometimes for hours, then relegated to the limbo of dead and forgotten things.

On the morning of the third day, however, while travelling over a rough section of country near the winding, interminable river, Dick was reminded again of the tracks. His own toes had worn through his moccasins. There was a hole about the size of a silver dollar in each one of his heels. In another day or so, he, too, would be walking barefoot, much as he dreaded to think of it, making those peculiar and tragic marks in the sand.

He glanced over at Sandy’s moccasins and noted with a sinking of the heart that his were even in worse condition than his own. Toma’s were in better shape, but also very badly worn. Soon they must all endure the torture of going unshod, or else cut up their moosehide coats and make new footgear.

None of the three wanted to part with his coat. The nights were often chilly and it would be a positive hardship to do without them.

“I’d almost as soon go barefoot,” declared Sandy.

“Yes, I know,” Dick’s face clouded, “but do you think we can endure these forced marches if our feet are cut and bruised? Mine are beginning to cause me untold suffering now. You, Sandy, are limping. No! Don’t try to deny it. I’ve been watching you. A few more bruises, a few more scratches and cuts, and we won’t be able to walk five miles a day. You may not have noticed it, but already we have begun to slacken down. I don’t believe we made more than eighteen miles yesterday. We put in the hours but we don’t seem to get the results. I’ll admit that it’s tough going through here, but we won’t find anything better until we reach the seventh portage.”

“I know it,” sighed the other. “Yet I hate to part with my coat. Say—where in the dickens has Toma gone?”

“I saw him around here only a few minutes ago,” Dick answered absent-mindedly, still absorbed with the pressing problem of footgear.

“No, you didn’t,” his chum flatly contradicted. “He’s been away a long time now—over an hour, I’m sure. I’m beginning to worry about him.”

“Probably away somewhere getting fish for breakfast,” Dick decided.

“He’s done that already.”

“You couldn’t lose that restless scamp if you tried, so stop worrying.”

“I can’t help it,” grumbled Sandy.

Dick suddenly sat up straight, the perplexed lines vanishing from his forehead.

“Say, I’ll bet I know. He’s gone off to snare rabbits. He’s been complaining a lot lately about our fish diet. I recall now that when we were walking along together early this morning he informed me that at our next stop he intended to set out some snares.”

“Don’t blame him one bit. I’m tired of this fish diet myself. Every time I wake up, I examine my body to see if I haven’t started to grow scales.”

Dick laughed. “Fish are called brain-food, Sandy. Don’t forget that. By the time we reach Half Way House, we’ll all be very learned and wise.”

“I much prefer to wallow along in ignorance,” Sandy retorted. “I hate fish. When we get home I never want to see another. Lately, about all I can think about is flapjacks and coffee and thick slices of white bread with a top covering of butter. Last night, or to be more exact, yesterday afternoon while I slept, I dreamed that Uncle Walter had just received one of those big plum puddings from England and that he made me a present of the whole of it.”

Sandy paused to moisten his lips.

“I never had such a vivid dream,” he went on. “At one sitting I ate the whole of it. It had dates and raisins in it, and currants and nuts, and there was a rich sauce that I kept pouring over it and—yum, yum—”

“Stop! Stop!” Dick shouted, vainly trying to shut out the appetizing picture. “You can tell the rest of that some other time when I’m in a better condition to appreciate it.”

“Well, if you won’t listen to me,” Sandy said aggrievedly, “I’m going to curl up here in the sun and go to sleep. Maybe I’ll dream about another plum pudding.”

“Think I’ll roll in too,” said Dick, smiling at the idiom.

Sans blankets or covering of any kind, even a coat, there was, of course, nothing to roll into. One simply stretched out in the sunshine, covered one’s face with a handkerchief to keep away the flies and fell away into deep slumber. He felt particularly tired today and decided that, as soon as Toma returned, he’d follow Sandy’s example. He lay back, his arms pillowed under his head, watching a few widely scattered fleecy clouds floating lazily along under the deep blue field of the sky.

He did not hear the young Indian steal quietly into camp more than two hours later, having fallen asleep in spite of himself. But when he did recover consciousness, Toma was the first person his eyes lighted upon. The Indian was standing less than twenty feet away, his back toward him, and he was busily absorbed in feeding a freshly-kindled fire. Something unusual about the native boy’s appearance immediately attracted Dick’s attention. He saw what it was. Toma, apparently, had rolled up his moose-hide trousers and had gone wading for clams. From his ankles to his knees his legs were bare.

“Did you get any clams, Toma?” Dick inquired sleepily. “How long have you been back? Why didn’t you wake me, Toma?”

The young Indian answered none of Dick’s questions. However, he smiled somewhat sheepishly as he turned around and faced his chum. Then Dick gave utterance to a prolonged exclamation of genuine astonishment. His eyes widened perceptibly. He sat up very quickly, contemplating Toma as one might contemplate a man from Mars.

“What in blue blazes have you done with the bottom of your pants?” gasped Dick.

“I cut ’em off,” answered Toma, flushing.

“Yes, I see you have—but why?”

By way of explanation, and not without a touch of the Indian’s native dignity, he strode over to a pile of driftwood and fished out of it two new moccasins. Excellent work, Dick could see at a glance; moccasins of which anyone might have been proud.

“Sew ’em all same like squaw,” said Toma.

“But you had no needle.”

“Make ’em needle out of stick,” came the prompt reply.

“But what about the sinew, Toma? You had no thread. How could you sew without thread?”

Toma hung his head. He hated to make this admission, but the truth must come out. Toma was always truthful.

“I use part of fish-line,” he explained.

“Part of the fish-line?” gurgled Dick.

“Yes, I use ’em part of the fish-line.”

“Well, I must admit that you made good use of it. There is really more than we require anyway. I’m glad for your sake, Toma. Who, beside yourself, would ever have thought of a stunt like that? They’ll come in mighty handy for you, of course, but won’t you feel cold, Toma? When the winds are chilly I’m afraid you’ll suffer.”

Toma shook his head, bit his lips and stared very hard at some imaginary object across the river. It was plain that he was keenly embarrassed and quite at a loss to know what to say. Finally, he found the words that he had been vainly striving for and quickly blurted them out:

“Dick, I no can stand it any longer to see Sandy all time limp. Mebbe two, three more days Sandy sit down and feet swollen so bad not walk any farther.”

He gulped, averted his eyes, then tossed the result of his handiwork over at the sleeper’s side. Dick took in the little tableau, feeling suddenly very sick and mean and miserable and selfish. He did not try to hide the tears that came into his eyes. Through a sort of mist he saw Sandy’s blurred form stretched out there on the sand. Then he glanced at Toma, who looked very ludicrous and silly standing there in his abbreviated trousers, the cool night wind blowing over his bare legs.

At that instant there popped into his mind the sarcastic utterance of one Toby McCallum:

“Breeds don’t count!”

Neither that day nor the following did the boys succeed in getting a single trout. It was an unforeseen calamity and they were wholly unprepared for it. At first, they could not understand it. They knew that the river teemed with fish. Up to this time, they had had no trouble in catching all they had required. That blazing hot noon when Sandy returned to camp empty-handed and reported that not one member of the countless schools of trout and white-fish, that literally darkened the stream, would rise to his bait, Dick could not believe his ears.

“You couldn’t have tried very hard, Sandy,” he chided him. “Here, give me that line. You never were much of a fisherman, that is the trouble with you. You haven’t the patience, Sandy.”

The young Scotchman relinquished the line, his eyes stormy.

“I’ll admit I’m no fisherman,” he blurted, “but please don’t tell me that I didn’t try, because I did, or that I haven’t the patience because I have. I’ve caught nearly as many trout on this trip as you have. But they aren’t biting today at all. I think the river must be bewitched.”

Dick smiled knowingly and confidently, unsheathed his hunting knife and cut a long alder pole. Then, winking at Toma, he hurried over to the river, sure in his belief that he’d show Sandy a thing or two about the gentle art of fishing.

He baited his hook and cast his line. Repeatedly he whipped the swift water, grinning. In a moment he’d feel that sharp tug, experience that old familiar thrill. Poor Sandy! At best, he was only a half-hearted fisherman, had never learned to love the sport, had never entered into it with the enthusiasm and spirit that made for proficiency. The minute passed, but he was not discouraged. Back and forth his line flipped over the water. The smile left his face. He scowled, swung in his line, walked fifty or sixty yards upstream and tried again.

An hour—two hours—he was very grim now, but he just couldn’t give up. There were fish here. He must get fish. They had no other food except clams and it was not possible to get many of them. Good Lord, what would happen if their one heretofore unfailing source of sustenance were cut off? Following their long tramp that previous night, they were all weak from hunger. He was so famished right now that he could even relish eating a dead crow. Despondently, he sat down on a rock, still whipping the water. A shadow appeared from behind him and he heard a voice:

“What’s the matter, Dick? No catch ’em one yet?”

Dick turned his head. He looked up into Toma’s serious face and gulped down a lump in his throat.

“I don’t understand it. I don’t understand it!” he wailed.

The young Indian regarded the river with a sober, thoughtful face.

“Long time I been ’fraid about this,” he sighed. “All the time I hope mebbe I’m wrong. River too swift here to get many fish. No pools along here. Trout keep in central current an’ hurry on to better feeding place down the river.”

“So that’s the reason. But, Toma, what are we going to do? We must eat, somehow, and for nearly thirty miles the river is just like this. Is it starvation? Has it come to that?”

“Mebbe not starve, but get mighty hungry.”

“Perhaps we could kill a few birds with stones,” Dick suggested hopefully.

“I know better plan than that. We do like Indians before white men come. I make ’em bows an’ arrows. Only trouble is we no shoot straight at first.”

“But what about the strings for our bows?”

“We use fish-line.”

Dick slid off the rock, his expression more hopeful.

“All right, let’s set to work. I’ll help you, Toma. We’ll eat birds for dinner, squirrels—anything! Perhaps we might even be lucky enough to get a rabbit. If we don’t find something to eat pretty soon we’ll——”

The words died in his throat. On that instant back at camp, Sandy let out a scream—a ringing, pulsating, vibrant, piercing scream of terror. Looking back, they perceived Sandy tearing along toward them, arms and legs swinging, hat gone and the loose sides of his unbuttoned jacket billowing up in the wind.

While Dick stood there, wondering what it was all about, Toma stooped swiftly then straightened up, a rock in either hand, his cheeks the color of yellow parchment. At that moment, Dick caught sight of the apparition himself. His eyes popped and unconsciously he made a queer, choking noise in his throat. A thing that looked like a beast and yet, somewhat resembled a man, was making its way slowly down the steep bank toward their campfire. The horrible creature’s face was covered with a long black beard and the hair of his head straggled down over his eyes and fluffed out in a sinuous black wave around his shoulders.

It was a man undoubtedly—but what a man! A skin of some sort had been wrapped and tied around his torso, but both his arms and legs were quite naked. In every sense—a wild man. His huge frame supported bulging muscles. His chest expanded like a barrel. He walked with a gliding motion. His head rotated from side to side and, during the breathless silence that followed Sandy’s arrival, they could hear him clucking and grunting to himself.

The three boys waited there, rigid with terror. Never before had they seen a wild man. His awful appearance, his constant gibbering, his bobbing head and fearful eyes reminded Dick of gorillas and huge hairy apes, whose pictures he had often studied in his natural history book at school. When the hideous creature had turned from a momentary inspection of their campfire and commenced gliding toward them, with one accord they shrieked and fled.

They had no thought of their sore feet now, neither were they aware of the incessant, gnawing pains of hunger. In a great crisis of this sort, the mind has a peculiar tendency to become wholly subjective to the feelings of instinct. Instinct inherited from a thousand generations of jungle-prowling ancestors, told them to flee—and they fled.

Soon they headed away from the shore into the thickets of willow and jack-pine and began to climb the ascent that led away from the river, up and up, until right ahead they could see the somber, interminable green of the forest. It was cool here, a welcome coolness after the stiff climb. They were all panting for breath, fearful lest the wild man be still in pursuit of them. None of the boys wanted to meet him, cared about engaging in a hand to hand fight with that gorilla-like monster. So, plunging in the forest, they continued on, leaving the river far behind. At the end of a half hour, they swung south, guided by the sun, and continued their difficult journey in the direction of Half Way House.

When Dick felt perfectly sure that they were no longer being followed, he called a halt and brought up the subject closest to all of them.

“What about something to eat?” he inquired. “This will never do. We must eat. Toma, let’s put your plan into execution.”

“You mean ’em bows and arrows? All right, you get ’em fish-line.”

Dick handed it to him. With his hunting knife the young Indian set to work, cutting and fashioning the bows, while Dick and Sandy sharpened some straight sticks for arrows. Under Toma’s instructions, they tufted one end of each arrow with some tough, fibrous bark the young Indian found for them. In a little less than twenty minutes they were ready. Walking at a distance of about one hundred yards apart and, still moving south, they commenced to hunt.

Dick was not very hopeful. The first bird he saw, a bird that resembled a king-fisher, he shot at and missed. Five minutes later, his heart landed up in his throat as a rabbit scurried into his path and, for the second time he bent his bow and again he missed. He missed a squirrel that ran up a tree in front of him. Recovering his arrows each time, he took five shots at the squirrel and in the end lost sight of it. Every minute he was becoming more discouraged and more hungry. The arrows never went just where he expected. Usually, he was a foot or two wide of his mark, whether that mark was moving or stationary. After what seemed like an hour, he pressed over more to his right to discover if either of the others had had any better luck. There he found Sandy.

“How are you getting on?” he inquired eagerly.

Sandy turned his head. No need to ask him how he had fared. The discouraged lines in his face told the story. His words confirmed it.

“Dick, I’ve seen two rabbits and three grouse and I failed to get any of them. Think I’m too excited and eager. What did you get?”

“Nothing!” Dick’s eyes were tragic.

The young Scotchman averted his face.

“Cripes!” he choked.

When he turned toward Dick again the latter experienced a momentary feeling of utter discouragement and despair. Slow starvation—had it come to that? He noticed how gaunt and drawn his chum’s face was.

“Every minute that we have to spare, we must practice with these bows and arrows, Sandy,” Dick told him. “It’s our only salvation. In time we’ll grow expert in their use. I had a chance once to take up archery and now I wish I had.”

They heard a shout near at hand. The bushes parted and Toma plunged forward to join them. Toma was carrying something. What was it? Staring, Sandy suddenly let out a whoop and bounded forward to meet him.

“A porcupine!” he shouted. “Dick, Dick, come here! A porcupine and two rabbits! Thank God for that.”

Dick merely stood there, gasping—doubting the evidence of his own senses. A queer feeling swept through him. It was not merely joy at the successful outcome of their hunt, but a feeling of relief, of tension relaxed. The future did not look quite so dark now. With food they could make it. Good old Toma! Faithful ever, a wonderful help in time of stress or emergency.

All the boys contended that they had never tasted anything so good as that porcupine, which they roasted, Indian fashion, over the fire. When they had eaten they were actually happy. For nearly an hour Toma instructed them in the use of their bows and arrows. Then they sat down to decide what to do next.

“I don’t know what would be the best plan,” puzzled Dick, “keep on as we’re doing or retrace our steps to the river. What would you boys suggest?”

“Go back to the river,” answered Toma unhesitatingly.

“But why?” asked Dick.

“Follow the river,” explained Toma, “an’ then no chance we get lost. Bad to get lost now without grub, blankets. Pretty soon all our clothes wear out. What we do then?”

“Yes, that’s true,” agreed Dick. “There’s no danger of getting lost if we follow the river. The only thing I was thinking of, will we find as much game in the river valley as we will up here?”

“Not much difference,” returned Toma. “Hunting pretty much the same everywhere. It’s like what you call ’em—luck. If we lucky we see many things to shoot. If not see ’em, no luck. ’Nother thing, by an’ by, fishing get good again.”

Seeing the wisdom in all that Toma had said, they returned to the river valley without discussing the matter further. After partaking of the porcupine they had become more optimistic and were determined now to push on to their destination more hurriedly. It was agreed that not only would they walk all that night, but part of the next day before they made camp. They had still some of the roasted porcupine and rabbit, so it would not be necessary to stop long for lunch.

An hour later, breaking through a willow thicket, they perceived the slope leading to the river, descended it and continued along the shore. Occasionally, while they were marching, Dick and Sandy would test their marksmanship by firing at some object ahead, picking up the arrow again when they reached it. The interminable twilight of the Arctic made this possible and it was not long before each of the boys began to note a decided improvement in his marksmanship.

The feet of the three adventurers grew more sore and swollen through the passing of the hours. Yet they pushed doggedly on. They had walked so much that the action had become mechanical. Sometimes they plodded ahead with eyes half-closed, nearly asleep. The twilight faded and the day sprang forth. The gray morning mist lifted from the river. A hot sun threw its slanting rays across the strip of white sand along which the boys were proceeding.

Suddenly, Toma who was in the lead, stopped quickly, called sharply to his two chums and pointed ahead.

“Look!” he shouted.

On their side of the river, less than a quarter of a mile away, gently eddying among the tops of the spruce and balsam, were thin spirals of smoke.

“A campfire!” shrieked Sandy in wonder. “Oh boy, we’re in luck! Maybe we can get help—a canoe or a gun.”

Unmindful of his great weariness and tortured feet, he had started out on a dead run, when Dick called to him sharply.

“Just a minute, Sandy. Not so fast. It may be Wolf Brennan and Toby McCallum.”

Sandy stopped dead in his tracks.

“What’s that? Are you mad? If they had come up the river, we’d have seen them.”

“I’m not so sure. They might have passed us while we slept, or yesterday when we were in the woods after that experience with the wild man. One can never be too sure, Sandy. Our best plan is not to rush that camp, to make sure who they are before we let ourselves be seen.”

“That is right, Dick,” agreed Toma. “Brennan an’ McCallum very bad; also very clever fellow. No tell just where they may be now.”

Sandy, quick to see the wisdom propounded by his two friends, nodded in agreement while he waited for them to come up. They left the flat, sandy shore, where they could easily be seen, and proceeded thereafter through the jack-pine and willows farther up along the slope. Inside of twenty minutes they had approached to within a short distance of the place where the smoke was ascending.