TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

EVELYN BYRD

By GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON

AUTHOR OF “A CAROLINA CAVALIER,” “DOROTHY

SOUTH,” “THE MASTER OF WARLOCK,”

“RUNNING THE RIVER,” ETC., ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

CHARLES COPELAND

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1904,

BY

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON.

Published May, 1904.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co. — Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

Preface

THIS book is the third and last of a trilogy of romances. In that trilogy I have endeavoured to show forth the character of the Virginians—men and women.

In “Dorothy South” I tried to show what the Virginians were while the old life lasted—“before the war.”

In “The Master of Warlock” I endeavoured faithfully to depict the same people as they were during the first half of the Civil War, when their valour seemed to promise everything of results that they desired. In “Evelyn Byrd” I have sought to show the heroism of endurance that marked the conduct of those people during the last half of the war, when disaster stared them in the face and they unfalteringly confronted it.

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON.

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Stricken Corsage | 9 |

| II. | Owen Kilgariff | 29 |

| III. | Evelyn Byrd | 50 |

| IV. | The Letting Down of the Bars | 59 |

| V. | Dorothy’s Opinions | 70 |

| VI. | “When Greek meets Greek” | 79 |

| VII. | With Evelyn at Wyanoke | 102 |

| VIII. | Some Revelations of Evelyn | 118 |

| IX. | The Great War Game | 144 |

| X. | The Law of Love | 152 |

| XI. | Orders and “No Nonsense” | 167 |

| XII. | Safe-conduct of Two Kinds | 178 |

| XIII. | Kilgariff hears News | 185 |

| XIV. | In the Watches of the Night | 210 |

| XV. | In the Trenches | 216 |

| XVI. | The Starving Time | 224 |

| XVII. | A Gun-pit Conference | 242 |

| XVIII. | Evelyn’s Revelation | 269 |

| XIX. | Dorothy’s Decision | 277 |

| XX. | A Man, a Maid, and a Horse | 283 |

| XXI.[6] | Evelyn lifts a Corner of the Curtain | 294 |

| XXII. | Alone in the Porch | 302 |

| XXIII. | A Lesson from Dorothy | 318 |

| XXIV. | Evelyn’s Book | 327 |

| XXV. | More of Evelyn’s Book | 345 |

| XXVI. | Evelyn’s Book, Continued | 370 |

| XXVII. | Kilgariff’s Perplexity | 386 |

| XXVIII. | Evelyn’s Book, Concluded | 390 |

| XXIX. | Evelyn’s Vigil | 418 |

| XXX. | Before a Hickory Fire | 424 |

| XXXI. | The Last Flight of Evelyn | 432 |

| XXXII. | The End of it All | 434 |

Illustrations

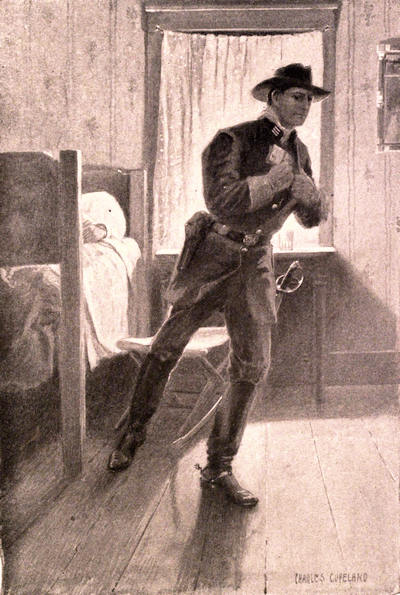

| “I already know what is in the papers” | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| “Who are you?” | 89 |

| “I may stroke his fur as much as I please” | 166 |

| Taking the papers from Campbell’s hand, passed out of the house without a word of farewell | 208 |

Evelyn Byrd

I

A STRICKEN CORSAGE

A BATTERY of six twelve-pounder Napoleon guns lay in a little skirt of woodland on the south bank of the Rapidan. It was raining, not violently, but with a soaking persistence that might well have made the artillery-men tired of life and ready to welcome whatever end that day’s skirmishing might bring to the weariness of living. But these men were veteran soldiers, inured to hardship as well as to danger. A saturating rain meant next to nothing to them. A day’s discomfort, more or less, counted not at all in the monotonously uncomfortable routine of their lives.

They had been sent into the woodland an hour or two ago, and had done a little desultory firing now and then, merely by way of disturbing[10] the movements of small bodies of the enemy who were being shifted about on the other side of the river.

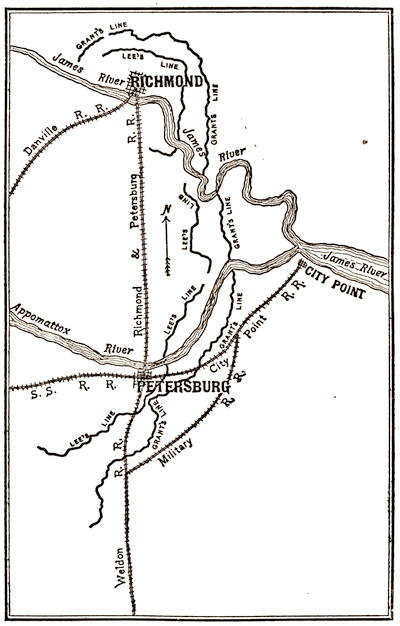

Just now the guns were silent, no enemy being in sight, and Captain Marshall Pollard being disposed to save his ammunition against the time, now obviously near at hand, when the new commander of the Federal forces, General Grant, should push the Army of the Potomac across the river to make a final trial of strength and sagacity with that small but wonderfully fighting Army of Northern Virginia directed by the master mind of Robert E. Lee.

But, while no enemy was within sight, there was a hornets’ nest of Federal sharp-shooters concealed in a barn not far beyond the river, and from their secure cover they were very seriously annoying the Confederate lines. The barn lay a little to the left of the battery front, but near enough for the sharp-shooters’ bullets to cut twigs from the tree under which Captain Marshall Pollard sat on horseback with Owen Kilgariff by his side. Still, the fire of the sharp-shooters was not mainly directed upon the woodland-screened battery, but upon the troops in the open field on Pollard’s left.

Presently Captain Pollard, with the peculiar deliberation which characterised all his actions, lowered his field-glass from his eyes, and, withdrawing a handkerchief from a rain-proof breast pocket, began polishing the mist-obscured lenses. As he did so, he said to Kilgariff:—

“Order one of the guns to burn that barn.”

As he spoke, both his own horse and Kilgariff’s sank to the ground; the one struggling in the agony of a mortal wound, the other instantly dead.

“And tell the quartermaster-sergeant to send us two more horses—good ones,” Captain Pollard added, with no more of change in his tone than if the killing of the horses at that precise moment had been a previously ordered part of the programme.

A gun was quickly moved up to a little open space. It fired two shots. The flames burst from the barn, and instantly a horde of sharp-shooters abandoned the place and went scurrying across an open field in search of cover. As they fled, the gun that had destroyed their lurking-place, and another which Captain Pollard had instantly ordered up, shelled them mercilessly.

It was then that Owen Kilgariff said:—

“That barn was full of fodder. Its owner had saved a little something against a future need, and now all the results of his toil have gone up in smoke. That’s war!”

“Yes,” answered Captain Pollard, “and the worst of it is that the man whose possessions we have destroyed is our friend, and not our enemy; again, as you say, ‘that’s war.’ War is destruction—whether the thing destroyed be that of friend or foe.”

Just then a new and vicious fire of skilled sharp-shooters broke forth from the mansion-house of the plantation to which the burned barn had belonged. It was an old-time colonial edifice. Marshall Pollard had spent many delightful days and nights under its hospitable roof. He had learned to love its historic associations. He knew and loved every old portrait that hung on its oak-wainscotted walls. He knew and loved every stick of its old, colonial, plantation-made furniture; its very floors of white ash, that had been polished every morning for two hundred years; and its mahogany dining-table, around which distinguished guests had gathered through many generations. All[13] these were dear to the peculiarly sympathetic soul of the scholar-soldier, Marshall Pollard, a man born for books, and set by adverse fate to command batteries instead; a man of creative genius, as his novels and poems, written after the war, abundantly proved, set for the time to do the brutal work of destruction. He remembered the library of that mansion, too, the slow accumulation of two hundred years. He had read there precious volumes that existed nowhere else in America, and that money could not duplicate, however lavishly it might be offered for books, of which no fellows were to be found except upon the sealed shelves of the British Museum, or in other great public collections from which no treasures are ever to be sold while the world shall endure.

That house, with all its memories and all its treasures, must be destroyed. Marshall Pollard clearly understood the necessity, and he was altogether a soldier now, in spite of his strong inclinations to peace and civilisation, and all gentleness of spirit. Yet he found it difficult to order the work of destruction that it was his manifest duty to do. Presently, with bullets whistling about his ears, he turned to Owen[14] Kilgariff, and, in a tone of petulance that was wholly foreign to his habit, asked:—

“Why don’t you order the thing done? Why do you sit there on your horse waiting for me to give the order?”

Kilgariff understood. He was a man accustomed to understand quickly; and now that Captain Pollard had made him his chief staff officer, sergeant-major of the battery, his orders, whatever they might be, carried with them all the authority of the captain’s own commands.

Kilgariff instantly rode back to the battery and ordered up two sections—four guns. Advancing them well to the front, where the house to be shot at could be easily seen, he posted them with entire calm, in spite of the fact that a Federal battery of rifled guns stationed at a long distance was playing vigorously upon his position, and not without effect. The artillery-men in both armies had, by this late period of the war, become marksmen so expert that the only limit of the effectiveness of their fire was the limit of their range.

Half a dozen of Marshall Pollard’s men bit the dust, and nearly a dozen of his horses were killed, while Owen Kilgariff was getting the[15] four guns into position for the effective doing of the work to be done, although that process of placing the guns occupied less than a minute of time. Two wheels of cannon carriages were smashed by well-directed rifle shells, but these were quickly replaced by the extra wheels carried on the caissons; for every detail of artillery drill was an a-b-c to the veterans of this battery, and if the men had nerves, the fact was never permitted to manifest itself when there was work of war to be done.

Within sixty seconds after Owen Kilgariff rode away to give the orders that Marshall Pollard hesitated to give, four Napoleon guns were firing four shells each, a minute, into a mansion that had been famous throughout all the history of Virginia, since the time when William Byrd had been Virginia’s foremost citizen and the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe had ridden out to possess themselves of the regions to the west.

Half a minute accomplished the purpose. The mansion was in flames, the sharp-shooters who had made a fortress of it were scurrying to the cover of the underbrush a few hundred yards in rear, and Owen Kilgariff ordered the[16] guns to “cease firing” and return to the cover of the woodlands whence they had been brought forward for this service. Six of Marshall Pollard’s men lay stark and stiff on the little meadow which the guns had occupied. These were hastily removed for decent burial. Nine others were wounded. They were carried away upon litters for surgical attention.

These details in no way disturbed the battery camp. They were the commonplaces of war; so the men, unmindful of them, cooked such dinner as they could command, and ate it with a relish unimpaired by the events of the morning.

But Captain Marshall Pollard and his companion, Sergeant-major Owen Kilgariff, were not minded for dinner. Seeing the flames burst forth from the upper stories of the old colonial mansion, Kilgariff said to his captain:—

“I wonder if all those fellows got away? There may be a wounded man or two left in the house to roast to death. May I ride over there and see?”

“Yes,” answered Pollard, “and I will ride with you. But first order two of the guns to shell the sharp-shooters in the thicket yonder. Otherwise we may not get back.”

In spite of the heavy fire that the two guns poured into the thicket beyond the house, the sharp-shooters stood their ground like the veterans that they were, and Pollard and Kilgariff were their targets as these two swam the swollen river and galloped across the last year’s corn lands on their way to the burning house.

Arrived there, they hastily searched the upper rooms. Here and there they came upon a dead soldier, left by his companions to be incinerated in company with the portraits of old colonial notables and beautiful colonial dames that were falling from the walls as the ancient oaken wainscot shrivelled in the fire.

But no living thing was found there, and the two Confederates, satisfied now that there was no life to be saved, hurried down the burning stairway and out into the air, where instantly they became targets again for the sharp-shooters, not three hundred yards away.

As they were about to mount their horses, which had been screened behind a wall projection, Kilgariff suddenly bethought him of the cellar, and plunged down the stairway leading to it. He was promptly followed by his captain, though both of them realised the peculiar[18] danger of the descent at a time when the whole structure seemed about to tumble into that pit as a mass of burning timber. But they realised also that the cellar was the place where they were most likely to find living men too badly wounded to make their escape, and so, in spite of the terrible hazard, they plunged into the depths, intent only upon their errand of mercy.

A hasty glance around in the half-light seemed to reveal only the emptiness of the cavernous cellar. But just as the two companions were about to quit the place, in a hurried effort to save themselves, a great, blazing beam fell in, together with a massive area of flame-enveloped flooring, illuminating the place. As Kilgariff turned, he caught sight of a girl, crouching behind an angle of the wall. She was a tall, slender creature, and Kilgariff was mighty in his muscularity. There was not a fraction of a second to be lost if escape from that fire pit was in any wise to be accomplished. Without a moment’s pause, Kilgariff threw his arm around the girl and bore her up the cellar stairs, just as the whole burning mass of timbers sank suddenly into the space below.

His captain followed him closely; and, emerging from the flames, scorched and smoke-stifled, the three stood still for a moment, under the deadly fire of the sharp-shooters. Then, with recovered breath, they turned an angle of the wall, mounted their horses, and sped away toward the river, under a rifle fire that seemed sufficient for the destruction of a regiment. The shells from their own side of the line, shrieking above the heads of the three fugitives, made their horses squat almost to the ground; but with a resolution born of long familiarity with danger, the two soldiers sped on, Kilgariff carrying the girl on the withers of his horse and trying to shield her from the fire of the sharp-shooters by so riding as to interpose his own body between her and the swiftly on-coming bullets.

Finally the river was reached, and, plunging into it, the two horses bore their burdens safely across. Pollard might easily have been fifty yards in advance of his sergeant-major, seeing that he had the better horse, and that his companion’s animal was carrying double. But that was not Marshall Pollard’s way. Instead of riding as fast as he could toward the river and[20] the comparative safety that lay beyond it, he rode with his horse’s head just overlapping the flanks of the animal which bore the girl and her rescuer. In this way he managed to make of himself and his horse a protecting barrier between the enemy and the girl whom Kilgariff was so gallantly trying to bear to safety.

This was not a battle, or anything remotely resembling a battle. If it had been, these two men would not have left their posts in the battery. It was only an insignificant “operation of outposts,” which the commanders in the front of both armies that night reported as “some slight skirmishing along the outer lines.” On neither side was it thought worth while to add that fifty or sixty brave young fellows had been done to death in the “slight skirmishing.” The war was growing old in the spring of 1864. Officers, hardened by experience of human butchery on a larger scale, no longer thought it necessary to report death losses that did not require three figures for their recording.

When Pollard and Kilgariff reached the bit of woodland in which the battery had been posted for a special purpose, they found the guns already gone. The battery had been[21] ordered during their absence to return to its more permanent camp two or three miles in the rear, and in Captain Pollard’s absence his senior lieutenant had taken command to execute the order. It is the way of war that “men may come and men may go,” but there is always some one next in command to take the place of one in authority who meets death or is absent for any other cause. An army organisation resembles Nature herself in its scrupulous care for the general result, and in its absolute indifference to the welfare or the fate of the individual.

War is a merciless thing—inhuman, demoniacal, devilish. But incidentally it calls into activity many of the noblest qualities of human nature. It had done so in this instance. Having fired the house on the enemy’s side of the river, and having thus driven away a company of sharp-shooters who were grievously annoying the Confederate line, Captain Pollard’s duty was fully done. But, at the suggestion that some wounded enemy might have been left in the house to perish in the torture of the flames, he and his companion had deliberately crossed the river into the enemy’s country, and had[22] ridden under a galling fire to the burning building, as earnestly and as daringly intent upon their mission of mercy as they had been a little while before upon their work of slaughter and destruction.

“Man’s a strange animal,” sings the poet, and his song is an echo of truth.

Pollard and Kilgariff rode on until the camp was reached. There Kilgariff pushed his horse at once to the tent of the surgeon, and delivered the girl into that officer’s keeping.

“Quick!” he said. “I fear she is terribly wounded.”

“No, no,” cried the girl; “I am not hurt. It is only that my corsage is—what you call stricken. Is it that that is the word? No? Then what shall I say? It is only that the bullet hurt what you call my stays. Truly it did not touch me.”

Just then Captain Pollard observed that Kilgariff’s left hand was wrapped in a piece torn from the front of the girl’s gown, and that the rude bandage was saturated with blood. Contrary to all military rule, the sergeant-major had been holding his reins in his right hand, and carrying the girl in the support of his left arm.[23] This awkwardness, as he was at pains to explain to the captain, had been brought about by the hurry of necessity.

“I grabbed the girl,” he explained, “without a thought of anything but the danger to her. The house timbers were already falling, and there was no time to be lost. When I got to my horse, the fire of the sharp-shooters was too severe to be trifled with when I had a girl to protect, so I mounted from the right side of my horse instead of the left, and continued to ride with her on my left arm and my bridle-rein in my right hand. I make my apologies, Captain.”

“Oh, confound your apologies!” ejaculated Captain Pollard. “What’s the matter with your left hand? Let the surgeon see it at once.”

“It is nothing of consequence,” answered the young man, stripping off the rudely improvised bandage. “Only the ends of a finger or two carried away. I had thought until a moment ago that the bullet had penetrated the young lady’s body. You see, Captain, I was holding her in front of me and clasping her closely around the waist with my fingers extended, the[24] better to hold her in her uncertain seat on the withers. So, when the bullet struck my fingers, I thought it had pierced her person. Thank God, she has come off safe! But by the time the surgeon is through with his work on my fingers, I shall have to use my right hand on the bridle for a considerable time to come, Captain.”

“You will have to go to the hospital,” said the surgeon.

“Indeed I shall do nothing of the kind.”

“Why not, Kilgariff?” asked Pollard, who had become mightily interested in the strange and strangely reserved young man whom he had made his sergeant-major.

“Why not? Why, because I’m not going to miss the greatest and probably the last campaign of the greatest war of all time.”

As he spoke, the captain turned away toward his tent, leaving Kilgariff to endure the painful operations of the surgeon upon his wounded hand, without chloroform, for there was none of that anæsthetic left among the supplies of this meagrely furnished field-hospital after the work already done upon the wounded men of that morning. Kilgariff endured the amputations without a groan or so much as a flinching,[25] whereat the surgeon marvelled the more, seeing that the patient was a man of exceptionally nervous constitution and temperament. When the bandages were all in place, the sergeant-major said simply:—

“Please let me have a stiff drink of spirits, Doctor. I am a trifle inclined to faintness after the pain.” That was absolutely the only sign the man gave of the fact that he had been enduring torture for nearly a half-hour.

Relighting his pipe, which he had smoked throughout the painful operation, Kilgariff bade the doctor good morning, and walked away to the tent which he and the captain together occupied.

In the meantime Captain Pollard had been questioning the girl as to herself, and getting no satisfactory answers from her, not so much because of any unwillingness on her part to give an account of herself, as seemingly because she either did not understand the questions put to her, or did not know what the answers to them ought to be.

“I’ll tell you what, Captain,” said Kilgariff, when Pollard had briefly suggested the situation to him, “Doctor Brent is at Orange Court[26] House, I hear, reorganising the field-hospital service for the coming campaign, and his wife is with him. Why not send the girl to her?”

“To Dorothy? Yes, I’ll send her to Dorothy. She will know what to do.”

He hastily summoned an ambulance for the girl to ride in, and still more hastily scribbled a note to Dorothy Brent—to her who had been Dorothy South in the days of her maidenhood before the war. In it he said:—

I am sending you, under escort, a girl whom my sergeant-major most daringly rescued this morning from a house on the enemy’s side of the river, after we had shelled and set fire to the place. She seems too badly scared, or too something else, for me to find out anything about her. You, with your womanly tact, will perhaps be able to gain her confidence and find out what should be done. If she has friends at the North to whom she should be returned, I will arrange with General Stuart to send her back across the river under a flag of truce. If she hasn’t any friends, or if for any other reason she should be kept within our lines, you will know what to do with her. I am helpless in such a case, and I earnestly invoke the aid of the very wisest woman I ever knew. When you see the girl—poor, innocent child that[27] she is—you, who were once yourself a child, and who, in growing older, have lost none of the sweetness and especially none of the moral courage of childhood, will be interested, I am very sure, in taking charge of her for her good.

Having despatched this note, and the girl, under escort, Pollard turned to Kilgariff, and abruptly asked:—

“Why did you call this coming campaign ‘the greatest and probably the last campaign’ of the war?”

“Why, all that seems obvious. The Army of the Potomac has at last found a commander who knows how to handle it, and both sides are tired of the war. Grant is altogether a different man from McClellan, or Pope, or McDowell, or Burnside, or Meade. He knows his business. He knows that the chief remaining strength of the Confederacy lies in the fighting force of the Army of Northern Virginia. He will strike straight at that. He will hurl his whole force upon us in an effort to destroy this army. If he succeeds, the Confederacy can’t last even a fortnight after that. If he fails, if Lee hurls him back across the Rapidan, broken and beaten as all his predecessors have been, the[28] North will never raise another army—if the feeling there is anything like what the Northern newspapers represent it to be. You see, I’ve been reading them all the while—but, pardon me, I meant only to answer your question.”

“Don’t apologise,” answered Pollard. And he wondered who this man, his sergeant-major, was—whence he had come, and how, and why. For Captain Marshall Pollard knew absolutely nothing about the man whom he had made his confidential staff-sergeant, his tent mate, his bedfellow, and the executant of all his orders. Nevertheless, he trusted him implicitly. “I do not know his history,” he reflected, “but I know his quality as a man and a soldier.”

II

OWEN KILGARIFF

THE relations between Pollard and Kilgariff were peculiar. In many ways they were inexplicable except upon the ground of instinctive sympathy between two men, each of whom recognised the other as a gentleman; both of whom were possessed of scholarly tastes combined with physical vigour and all that is possible of manliness; both of whom loved books and knew them intimately; and each of whom recognised in the other somewhat more than is common of intellectual force.

The history of their acquaintance had been quite unusual. Marshall Pollard had risen from the ranks to be now the captain of a battery originally organised and commanded by Captain Skinner, a West Point graduate who had resigned from the United States army many years before the war, but not until after he had seen much service in Mexico and in Indian warfare.[30] The battery had been composed at the outset of ruffians from the purlieus of Richmond, jailbirds, wharf-rats, beach-combers, men pardoned out of the penitentiary on condition of their enlistment, and the friends and associates of such men. It had been a fiercely fighting battery from the beginning. Slowly but surely many of the men who had originally constituted it had been killed in battle, and Virginia mountaineers had been enlisted to fill their places. In the meanwhile discipline of the rigidest military sort had wrought a wonderful change for the better in such of the men as survived from the original organisation. By the time that the battery returned to Virginia, after covering itself with glory at Gettysburg, it was no longer a company of ruffians and criminals, but it continued to maintain its reputation for desperate fighting and for cool, self-contained, and unfaltering courage. For those mountaineers of Virginia were desperately loyal to the fighting traditions of their race.

During the winter of 1863-4 Captain Pollard’s battery was stationed at Lindsay’s Turnout, on the Virginia Central Railroad a few miles west of Gordonsville. Indescribable, almost inconceivable[31] mud was the characteristic of that winter, and General Lee had taken advantage of it, and of the complete veto it placed upon even the smallest military operations, to retire the greater part of his army from the Rappahannock and the Rapidan to the railroads in the rear, where it was possible to feed the men and the horses, at least in some meagre fashion.

It was during this stay in winter quarters that Owen Kilgariff had come to the battery. Whence he came, or how he got there, nobody knew and nobody could guess. There were only two trains a day on the railroad; one going east, and the other going west. It was the duty of strong guards from Pollard’s battery to man the station whenever a train arrived and inspect the passports of every passenger who descended from the cars to the platform or passed from the platform to the cars. Owen Kilgariff had not come by any of the trains. That much was absolutely certain, and nobody knew any other way by which he could have come. Yet one evening he appeared in Pollard’s battery at retreat roll-call and stood looking on and listening while the orders for the night were being read to the men.

He was a singularly comely young man of[32] thirty years, or a little less—tall, rather slender, though very muscular, symmetrical in an unusual degree, and carrying his large and well-shaped head with the ease and grace of a trained athlete.

When the military function was ended and the men had broken ranks, Kilgariff approached Captain Pollard, and with a faultlessly correct military salute said:—

“Captain, I crave your permission to pass the night with some of your men. In the morning I think I shall ask you to enlist me in your battery.”

There was something in the man’s speech and manner which strongly appealed to Marshall Pollard’s sympathy and awakened his respect.

“You shall be my own personal guest for the night,” he said; “I can offer you some bacon and corn bread for supper, and a bundle of dry broom-straw grass to sleep upon. As for enlistment, we’ll talk further about that in the morning.”

The evening passed pleasantly. The stranger was obviously a gentleman to his finger tips. He conversed with rare intelligence and interest,[33] upon every subject that happened to arise among the officers who were accustomed to gather in the captain’s hut every evening, making a sort of club of his headquarters. Incidentally some one made reference during the evening to some reported Japanese custom. Instantly but very modestly Kilgariff said:—

“Pardon me, but that is one of many misapprehensions concerning the Japanese. They have no such custom. The notion arose originally out of a misunderstanding—a misinterpretation; it got into print, and has been popularly accepted ever since. Let me tell you, if you care to listen, what the facts really are.”

Then he went on, by eager invitation, to talk long and interestingly about Japan and the Japanese—matters then very slightly known—speaking all the while with the modest confidence of one who knows his subject, but who is in no sense disposed to display the extent of his knowledge.

Finally, inquiry brought out the modestly reluctant information that Kilgariff had been a member—though he avoided saying in what capacity—of Commodore Perry’s expedition[34] which compelled the opening of the Japanese ports, and that instead of returning with the expedition, he had somehow quitted it and made his way into the interior of the hermit empire, where he had passed a year or two in minute exploration.

All this was drawn out by questioning only, and in no case did Kilgariff go beyond the question asked, to volunteer information. Especially he avoided speaking of himself or of his achievements at any point in his conversation. He would say, “An American” did this, “An English-speaking man” saw that, “A foreigner had an experience,” and so forth. The first personal pronoun singular was almost completely absent from his conversation.

One of the lieutenants was a Frenchman, and to him Kilgariff spoke in French whenever that officer seemed at a loss to understand a statement made in English. The surgeon was a German, and with him Kilgariff talked in German about scientific matters, and in such fashion that the doctor said to Pollard next morning:—

“It is that this man an accomplished physician is, or I mightily mistaken am already.”

In the morning Owen Kilgariff warmly[35] thanked Captain Pollard for his entertainment, adding:—

“As one gentleman with another, you have been free to offer, and I free to accept, your hospitality. Be very sure that I shall not presume upon this after I become a common soldier under your command, as I intend to do this morning if I have your permission.”

Pollard protested that his battery was not a proper one for a man of Kilgariff’s culture and refinement to enlist in, explaining that such of the men as were not ex-criminals were illiterate mountaineers, wholly unfit for association on equal terms with him. For answer, Kilgariff said:—

“I am told that you yourself enlisted here, Captain, when the conditions were even less alluring than now.”

“Well, yes, certainly. But my case was peculiar.”

“Perhaps mine is equally so,” answered the man. “At any rate, I very much want to enlist under your command, in a battery that, as I learn, usually manages to get into the thick of every fight and to stay there to the end.”

A question was on Pollard’s lips, which he greatly wanted to ask, but he dared not. With the instinctive shrinking of a gentleman from the impertinence of personal questioning, Pollard found it impossible to ask this man how it happened that he was not already a soldier somewhere. And yet the matter was one which very naturally prompted questioning. The Confederate conscription laws had long ago brought into the army every able-bodied man in the South. How happened it, then, that this man of twenty-eight or thirty years of age, perfect in physique, had managed to avoid service until this fourth year of the war? And how was it, that one so manifestly eager now for service of the most active kind had been willing to keep out of the army for so long a time?

As if divining the thought which Captain Pollard could not bring himself to formulate, Kilgariff said:—

“Some day, perhaps, I shall be able to tell you how and why it is that I am not already a soldier. At present I cannot. But I assure you, on my honour as a gentleman, that there is absolutely no obstacle in the way of your enlistment of me in your command. I earnestly[37] ask you to accept me as one of your cannoniers.”

Accordingly, the man was enrolled as a private in the battery, and from that hour he never once presumed upon the acquaintance he had been privileged to form with the officers. With a scrupulosity greater than was common even in that rigidly disciplined command, he observed the distinction between officers and enlisted men. His behaviour indeed was that of one bred under the strict surveillance of martinet professors in a military school. He did all his military duties of whatever kind with a like attention to every detail of good conduct; always obeying like a soldier, never like a servant. That distinction is broad and very important as an index of character.

The officers liked him, and Pollard especially sought him out for purposes of conversation. The men liked him, too, though they felt instinctively that he was their superior. Perhaps their liking for him was in large part due to the fact that he never asserted or in any wise assumed his superiority—never recognised it, in fact, even by implication.

He nearly always had a book somewhere[38] about his person—a book borrowed in most cases, but bought when there was no opportunity to borrow, for the man seemed always to have money in plenty. Now and then he would go to a quartermaster or a paymaster with a gold piece and exchange it for a great roll of the nearly worthless Confederate notes. These he would spend for books or whatever else he wanted.

On one occasion, when the men of the battery had been left for thirteen bitterly cold days and nights with no food except a meagre dole of corn meal, Kilgariff bought a farmer’s yoke of oxen that had become stalled in the muddy roadway near the camp. These were emphatically “lean kine,” and their flesh would make very tough beef, but the toughest beef imaginable was better than no meat at all, and so Kilgariff paid what looked like a king’s ransom for the half-starved and wholly “stalled” oxen, got two of the men who had had experience in such work to slaughter and dress them, and asked the commissary-sergeant to distribute the meat among the men.

The next day he exchanged another gold piece for Confederate notes enough to paper[39] a goodly sized wall, and the men rightly guessed that for some reason, known only to himself, this stranger among them carried a supply of gold coin in a belt buckled about his waist. But not one of them ever ventured to ask him concerning the matter. He was clearly not a man to be questioned with regard to his personal affairs.

Thus it came about that Captain Pollard, who had made this man successively corporal, sergeant, and finally sergeant-major, solely on grounds of obvious fitness, actually knew nothing about him, except that he was an ideally good soldier and a man of education and culture.

Now that he had become sergeant-major, his association with the captain was close and constant. The two occupied the same tent or hut—when they had a tent or hut—messed together, slept together, and rode side by side whithersoever the captain had occasion to go on duty. They read together, too, in their idle hours, and talked much with each other about books, men, and affairs. But never once did Captain Pollard ask a personal question of his executive sergeant and intimate personal associate.

Nor did Kilgariff ever volunteer the smallest hint of information concerning himself, either to the captain or to anybody else. On the contrary, he seemed peculiarly to shrink even from the accidental or incidental revelation of anything pertaining to himself.

One day, in winter quarters, a gunner was trying to open a shell which had failed to explode when fired from the enemy’s battery into the Confederate lines. The missile burst while the gunner was handling it, and tore off the poor fellow’s hand. The surgeon had ridden away somewhither—nobody knew whither—and it was at least a mile’s distance to the nearest camp where a surgeon might be found. Meanwhile, the man seemed doomed to bleed to death. The captain was hurriedly wondering what to do, when Kilgariff came quietly but quickly, pushed his way through the group of excited men, knotted a handkerchief, and deftly bound it around the wounded man’s arm.

“Hold that firmly,” he said to a corporal standing by. “Watch the stump, and if the blood begins to flow again, twist the loop a trifle tighter, but not too tight, only enough to prevent a free hemorrhage—bleeding, I mean.”

Then, touching his cap brim, he asked the captain:—

“May I go to the surgeon’s tent and bring some necessary appliances? I think I may save this poor fellow’s life, and there is no time to be lost.”

The captain gave permission, of course, and a few minutes later Kilgariff returned with a score of things needed. Kneeling, he arranged them on the ground. Then he examined the wounded man’s pulse, and with a look of satisfaction saturated a handkerchief with chloroform from a bottle he had brought. He then turned again to Captain Pollard, saying:—

“Will you kindly hold that over the man’s nose and mouth? And will you put your finger on his uninjured wrist, observing the pulse-beats carefully? Tell me, please, if any marked change occurs.”

“Why, what are you going to do?” asked the captain.

“With your permission, I am going to amputate this badly shattered wrist. There is no time to be lost.”

With that, he set to work, pausing only to[42] direct one of the corporals to keep the men back and prevent too close a crowding around the patient.

With what seemed to Captain Pollard incredible quickness, Kilgariff amputated the arm above the wrist, took up the arteries, and neatly bandaged the wound. Then he bade some of the men bear the patient on a litter to his hut, and place him in his bunk. He remained by the poor fellow’s side until the effects of shock and chloroform had subsided. Then he returned to his quarters quite as if nothing out of the ordinary routine had happened.

Captain Pollard had seen enough of field surgery during his three years of active military service to know that Kilgariff’s work in this case had been done with the skill of an expert, and his astonishment over this revelation of his sergeant-major’s accomplishment was great. Nevertheless, he shrank from questioning the man about the matter, or saying anything to him which might be construed as an implied question. All that he said was:—

“I thank you, Kilgariff, and congratulate you! You have saved a good man’s life this[43] day, and God does not give it to many men to do that.”

“I hope the surgeon will find my work satisfactory,” responded the sergeant-major. “Is there any soup in the kettle, Tom?”—addressing the coloured cook. “Bring me a cup of it, please.”

The man’s nerves had gone through a fearful strain, of course, as every surgeon’s do when he performs a capital operation, and the captain saw that Kilgariff was exhausted. He offered to send for a drink of whiskey, but Kilgariff declined it, saying that the hot soup was quite all he needed. The bugle blowing the retreat call a moment later, Kilgariff went, quite as if nothing had happened, to call the roll and deliver the orders for the night.

A little later the surgeon returned and was told what had happened. After looking at the bandages, and without removing them, he muttered something in German and walked away to the captain’s quarters. He was surgeon to this battery only, for the reason that the company was for the time detached from its battalion, and must have a medical officer of its own.

Entering the captain’s quarters, the bluff but emotional German doctor grasped Kilgariff’s hand, and broke forth:—

“It is that you are a brother then as well as a frient already. Why then haf you not to me that you are a surgeon told it? Ach! I haf myself that you speak the German forgot. It is only in the German that I can what I wish to tell you say.”

Then in German the excited doctor went on to lavish praise upon the younger man for his skill. Presently the captain, seeing how sorely Kilgariff was embarrassed by the encomiums, came to his relief by asking:—

“Have you taken off the bandages, Doctor, and examined the wound?”

“Shade of Esculapius, NO! What am I, that I should with such a bandaging tamper? One glance—one, what you call, look—quite enough tells me. This the work of a master is—it is not the work with which for me to interfere. The man who those bandages put on, that man knows what the best masters can teach. It is not under the bandages that I need to look to find out that. Ach, Herr Sergeant-major, I to you my homage offer. Five[45] years I in the hospitals of Berlin am, and four years in Vienna. In the army of Austria I am surgeon for six years. Do I not know?”

Then the doctor began to question Kilgariff in German, to the younger man’s sore embarrassment. But, fortunately for his reserve, Kilgariff had the German language sufficiently at his command to parry every question, and when tattoo sounded, the excited surgeon returned to his own quarters, still muttering his astonishment and admiration.

In the morning Captain Pollard asked Kilgariff to ride with him, in order that they two might the better talk together. But even on horseback Pollard found it difficult to approach this man upon any subject that seemed in the least degree personal. It was not that there was anything repellent, anything combative, and still less anything pugnacious in Kilgariff’s manner; for there was never anything of the sort. It was only that the man was so full of a gentle dignity, so saturated with that reserve which a gentleman instinctively feels concerning his own affairs that no other gentleman wishes to intrude upon them.

Still, Pollard had something to say to his sergeant-major on this occasion, and presently he said it:—

“I did not know until yesterday,” he began, “that you were a surgeon, Kilgariff.”

“Perhaps I should not call myself that,” interrupted the man, as if anxious to forestall the captain’s thought. “One who has knocked about the world as much as I have naturally picks up a good many bits of useful information—especially with regard to the emergency care of men who get themselves hurt.”

“Now listen to me, Kilgariff,” said Pollard, with determination. “Don’t try to hoodwink me. I have never asked you a question about your personal affairs, and I don’t intend to do so now. You need not seek by indirection to mislead me. I shall not ask you whether you are a surgeon or not. There is no need. I have seen too much with my own eyes, and I have heard too much from our battery surgeon as to your skill, to believe for one moment that it is of the ‘jack-at-all-trades’ kind. But I ask you no questions. I respect your privacy, as I demand respect for my own. But I want to say to you that this army is badly in need of surgeons,[47] especially surgeons whose skill is greater than that of the half-educated country doctors, many of whom we have been obliged to commission for want of better-equipped men. I learn this from my friend Doctor Arthur Brent, who tells me he is constantly embarrassed by his inability to find really capable and experienced surgeons to do the more difficult work of the general hospitals. He said to me only a week ago, when he came to the front to reorganise the medical service for this year’s campaign, that ‘many hundreds of gallant men will die this summer for lack of a sufficient number of highly skilled surgeons.’ He explained that while we have many men in the service whose skill is of the highest, we have not nearly enough of such to fill the places in which they are needed. Now I want you to let me send you to Doctor Brent with a letter of introduction. He will quickly procure a commission for you as a major-surgeon. It isn’t fit that such a man as you should waste himself in the position of a non-commissioned officer.”

Not until he had finished the speech did Pollard turn his eyes upon his companion’s face. Then he saw it to be pale—almost cadaverous.[48] Obviously the man was undergoing an agonising struggle with himself.

“I beg your pardon, Kilgariff,” hastily spoke Captain Pollard, “if I have said anything to wound you; I could not know—”

“It is not that,” responded the sergeant-major. But he added nothing to the declaration for a full minute afterward, during which time he was manifestly struggling to control himself. Finally recovering his calm, he said:—

“It is very kind of you, Captain, and I thank you for it. But I cannot accept your offer of service. I must remain as I am. I ought to have remained a private, as I at first intended. It is very ungracious in me not to tell you the wherefore of this, but I cannot, and your already demonstrated respect for my privacy will surely forbid you to resent a reserve concerning myself which I am bound to maintain. If you do resent it, or if it displeases you in the least, I beg you to accept my resignation as your sergeant-major, and let me return to my place among the men as a private in the battery.”

“No,” answered Pollard, decisively. “If the army cannot have the advantage of your service in any higher capacity, I certainly shall not let[49] myself lose your intelligence and devotion as my staff-sergeant. Believe me, Kilgariff, I spoke only for your good and the good of the service.”

“I quite understand, Captain, and I thank you. But with your permission we will let matters remain as they are.”

All this occurred about a week before the events related in the first chapter of this story.

III

EVELYN BYRD

WHEN the girl whom Kilgariff had rescued from the burning building was delivered into Dorothy Brent’s hands, that most gracious of gentlewomen received her quite as if her coming had been expected, and as if there had been nothing unusual in the circumstances that had led to her visit. Dorothy was too wise and too considerate to question the frightened girl about herself upon her first arrival. She saw that she was half scared and wholly bewildered by what had happened to her, added to which her awe of Dorothy herself, stately dame that the very young wife of Doctor Brent seemed in her unaccustomed eyes, was a circumstance to be reckoned with.

“I must teach her to love me first,” thought Dorothy, with the old straightforwardness of mind. “Then she will trust me.”

So, after she had hastily read Pollard’s note and characterised it as “just like a man not to find out the girl’s name,” she took the poor, frightened, fawnlike creature in her arms, saying, with caresses that were genuine inspirations of her nature:—

“Poor, dear girl! You have had a very hard day of it. Now the first thing for you to do is to rest. So come on up to my room. You shall have a refreshing little bath—I’ll give it to you myself with Mammy’s aid—and then you shall go regularly to bed.”

“But,” queried the doubting girl, “is it permitted to—”

“Oh, yes, I know you are faint with hunger, and you shall have your breakfast as soon as Dick can get it ready. Queer, isn’t it, to take breakfast at three o’clock in the afternoon? But you shall have it in bed, with nobody to bother you. Fortunately we have some coffee, and Dick is an expert in making coffee. I taught him myself. I don’t know, of course, how much or how little experience you have had with servants, but I have always found that when I want them to do things in my way, I must take all the trouble necessary to teach[52] them what my way is. Get her shoes and stockings off quick, Mammy.”

“I have had little to do with servants,” said the girl, simply, “and so I don’t know.”

“Didn’t you ever have a dear old mammy? queried Dorothy, thus asking the first of the questions that must be asked in order to discover the girl’s identity.

“No—yes. I don’t know. You see, they made me swear to tell nothing. I mustn’t tell after that, must I?”

“No, you dear girl; no. You needn’t tell me anything. I was only wondering what girls do when they haven’t a good old mammy like mine to coddle them and regulate them and make them happy. Why, you can’t imagine what a bad girl I should have been if I hadn’t had Mammy here to scold me and keep me straight. Can she, Mammy?”

“Humph!” ejaculated the old coloured nurse. “Much good my scoldin’ o’ you done do, Mis’ Dorothy. Dere nebber was a chile so cantankerous as you is always been an’ is to dis day. I’d be ’shamed to tell dis heah young lady ’bout your ways an’ your manners. Howsomever, she kin jedge fer herse’f, seein’ as she fin’s you[53] heah ’mong all de soldiers, when you oughter be at Wyanoke a-givin’ o’ dinin’-days, an’ a-entertainin’ o’ yer frien’s. I’se had a hard time with you, Mis’ Dorothy, all my life. What fer you always a-botherin’ ’bout a lot o’ sick people an’ wounded men, jes’ as yo’ done do ’bout dem no-’count niggas down at Wyanoke when dey done gone an’ got deyselves sick? Ah, well, I spec dat’s what ole mammies is bawn fer—jes’ to reg’late dere precious chiles when de’re bent on habin’ dere own way anyhow. Don’ you go fer to listen to Mis’ Dorothy ’bout sich things, nohow, Mis’—what’s yer name, honey?”

“I don’t think I can tell,” answered the girl, frightened again, apparently; “at least, not certainly. It is Evelyn Byrd, but there was something else added to it at last, and I don’t want to tell what the rest of it is.”

“Then you are a Virginian?” said Dorothy, quickly, surprised into a question when she meant to ask none.

“I think so,” said the girl; “I’m not quite sure.”

She looked frightened again, and Dorothy pursued the inquiry no further, saying:—

“Oh, we won’t bother about that. Evelyn[54] Byrd is name enough for anybody to bear, and it is thoroughly Virginian. Here comes your breakfast”—as Dick knocked at the door with a tray which Mammy took from his hands and herself brought to the bed in which the girl had been placed after her bath. “We won’t bother about anything now. Just take your breakfast, and then try to sleep a little. You must be utterly worn out.”

The girl looked at her wistfully, but said nothing. She ate sparingly, but apparently with the relish of one who is faint for want of food, the which led Dorothy to say:—

“It was just like a man to send you on here without giving you something to eat.”

“You are very good to me.” That was all the girl said in reply.

When she had rested, Dorothy sitting sewing in the meanwhile, the girl turned to her hostess and asked:—

“Might I put on my clothes again, now?”

“Why, certainly. Now that you are rested, you are to do whatever you wish.”

“Am I? I was never allowed to do anything I wished before this time—at least not often.”

The remark opened the way for questioning, but Dorothy was too discreet to avail herself of the opportunity. She said only:—

“Well, so long as you stay with me, Evelyn, you are to do precisely as you please. I believe in liberty for every one. You heard what Mammy said about me. Dear old Mammy has been trying to govern me ever since I was born, and never succeeding, simply because she never really wanted to succeed. Don’t you think people are the better for being left free to do as they please in all innocent ways?”

There was a fleeting expression as of pained memory on the girl’s face. She did not answer immediately, but sat gazing as any little child might, into Dorothy’s face. After a little, she said:—

“I don’t quite know. You see, I know so very little. I think I would like best to do whatever you please for me to do. Yes. That is what I would like best.”

“Would you like to go with me to my home, and live there with me till you find your friends?”

“I would like that, yes. But I think I haven’t any friends—I don’t know.”

“Well,” said Dorothy, “sometime you shall tell me about that—some day when you have come to love me and feel like telling me about yourself.”

“Thank you,” said the girl. “I think I love you already. But I mustn’t tell anything because of what they made me swear.”

“We’ll leave all that till we get to Wyanoke,” said Dorothy. “Wyanoke, you should know, is Doctor Brent’s plantation. It is my home. You and I will go to Wyanoke within a day or two. Just as soon as my husband, Doctor Brent, can spare me.”

The girl was manifestly losing something of her timidity under the influence of her new-found trust and confidence in Dorothy, and Dorothy was quick to discover the fact, but cautious not to presume upon it. The two talked till supper time, and the girl accompanied her hostess to that meal, where, for the first time, she met Arthur Brent. That adept in the art of observation so managed the conversation as to find out a good deal about Evelyn Byrd, without letting her know or suspect that he was even interested in her. He asked her no questions concerning herself or her past, but drew[57] her into a shy participation in the general conversation. That night he said to Dorothy:—

“That girl has brains and a character. Both have been dwarfed, or rather forbidden development, whether purposely or by accidental circumstances I cannot determine. You will find out when you get her to Wyanoke, and it really doesn’t matter. Under your influence she will grow as a plant does in the sunshine. I almost envy you your pupil.”

“She will be yours, too, even more than mine.”

“After a while, perhaps, but not for some time to come. I have much more to do here than I thought, and shall have to leave the laboratory work at Wyanoke to you for the present. You’d better set out to-morrow morning. The railroads are greatly overtaxed just now, as General Lee is using every car he can get for the transportation of troops and supplies—mainly troops, for heaven knows there are not many supplies to be carried. I have promised the surgeon-general that the laboratory at Wyanoke shall be worked to its full capacity in the preparation of medicines and appliances, so you are needed there at once. But under present[58] conditions it is better that you travel across country in a carriage. I’ve arranged all that. You will have a small military escort as far as the James River. After that, you will have no need. How I do envy you the interest you are going to feel in this Evelyn Byrd!”

IV

THE LETTING DOWN OF THE BARS

NOT many days after Pollard’s fruitless talk with Kilgariff, the sergeant-major asked leave, one morning, to visit Orange Court House. He said nothing of his purpose in going thither, and Pollard had no impulse to ask him, as he certainly would have been moved to ask any other enlisted man under his command, especially now that the hasty movements of troops in preparation for the coming campaign had brought the army into a condition resembling fermentation.

When Kilgariff reached the village, he inquired for Doctor Brent’s quarters, and presently dismounted in front of the house temporarily occupied by that officer.

As he entered the office, Arthur Brent raised his eyes, and instantly a look of amazed recognition came over his face. Rising and grasping[60] his visitor’s hand—though that hand had not been extended—he exclaimed:—

“Kilgariff! You here?”

“Thank you,” answered the sergeant-major. “You have taken my hand—which I did not venture to offer. That means much.”

“It means that I am Arthur Brent, and glad to greet Owen Kilgariff once more in the flesh.”

“It means more than that,” answered Kilgariff. “It means that you generously believe in my innocence—jail-bird that I am.”

“I have never believed you guilty,” answered the other.

“But why not? The evidence was all against me.”

“No, it was not. The testimony was. But between evidence and testimony there is a world of difference.”

“Just how do you mean?”

“Well, you and I know our chemistry. If a score of men should swear to us that they had seen a jet of oxygen put out fire, and a jet of carbonic acid gas rekindle it from a dying coal, we should instantly reject their testimony in favour of the evidence of our own knowledge. In the same way, I have always rejected the[61] testimony that convicted you, because I have, in my knowledge of you, evidence of your innocence. You and I were students together both in this country and in Europe. We were friends, roommates, comrades, day and night. I learned to know your character perfectly, and I hold character to be as definite a fact as complexion is, or height, or anything else. I had the evidence of my own knowledge of you. The testimony contradicted it. Therefore I rejected the testimony and believed the evidence.”

“Believe me,” answered Kilgariff, “I am grateful to you for that. I did not expect it. I ought to, but I did not. If I had reasoned as soundly as you do, I should have known how you would feel. But I am morbid perhaps. Circumstances have tended to make me so.”

“Come with me to my bedroom upstairs,” said Arthur Brent. “There is much that we must talk about, and we are subject to interruption here.”

Then, summoning his orderly, Arthur Brent gave his commands:—

“I shall be engaged with Sergeant-major Kilgariff upstairs for some time to come, and I must not be interrupted on any account. Say[62] so to all who may ask to see me, and peremptorily refuse to bring me any card or any name or any message. You understand.”

Then, throwing his arm around his old comrade’s person, he led the way upstairs. When the two were seated, Arthur Brent said:—

“Tell me now about yourself. How comes it that you are here, and wearing a Confederate uniform?”

“Instead of prison stripes, eh? It is simple enough. By a desperate effort I escaped from Sing Sing, and after a vast deal of trouble and some hardship, I succeeded in making my way into the Confederate lines. Thinking to hide myself as completely as possible, I enlisted in a battery that has no gentlemen in its ranks, but has a habit of getting itself into the thick of every fight and staying there. You know the battery—Captain Pollard’s?”

“Marshall Pollard’s? Yes. He is one of my very best friends. But tell me—”

“Permit me to finish. I wanted to hide myself. I thought that as a cannonier in such a battery I should escape all possibility of observation. But that battery has very little material out of which to make non-commissioned[63] officers. Very few of the men can read or write. So it naturally came about that I was put into place as a non-commissioned officer, and I am now sergeant-major, greatly to my regret. In that position I must be always with Captain Pollard. When I learned that he and you were intimates, and that your duty often called you to the front, I saw the necessity of coming to you to find out on what terms you and I might meet after—well, in consideration of the circumstances.”

Arthur Brent waited for a time before answering. Then he stood erect, and said:—

“Stand up, Owen, and let me look you in the eyes. I have not asked you if you are innocent of the crimes charged against you. I never shall ask you that. I know, because I know you!”

“I thank you, Arthur, for putting the matter in that way. But it is due to you—due to your faith in me—that I should voluntarily say to you what you refuse to ask me to say. As God sees me, I am as innocent as you are. I could have established my innocence at the critical time, but I would not. To do that would have been to condemn—well, it would have involved—”

“Never mind that. I understand. You made a heroic self-sacrifice. Let me rejoice only in the fact that you are free again. You are enlisted under your own name?”

“Of course. I could never take an alias. It was only when I learned that you and Captain Pollard were friends—”

“But suppose you fall into the hands of the enemy? Suppose you are made prisoner?”

“I shall never be taken alive,” was the response.

“But you may be wounded.”

“I am armed against all that,” the other replied. “I have my pistols, of course. I carry an extra small one in my vest pocket for emergencies. Finally, I have these”—drawing forth two little metallic cases, one from the right, the other from the left trousers pocket. “They are filled with pellets of cyanide of potassium. I carry them in two pockets to make sure that no wound shall prevent me getting at them. I shall not be taken alive. Even if that should happen, however, I am armed against the emergency. Two men escaped from Sing Sing with me. One of them was shot to death by the guards, his face being[65] fearfully mutilated. The other was wounded and captured. The body of the dead man was identified as mine, and my death was officially recorded. I do not think the law of New York would go behind that. But in any case, I am armed against capture, and I shall never be taken alive.”

A little later Arthur Brent turned the conversation.

“Let us talk of the future,” he said, “not of the past. I am reorganising the medical staff for the approaching campaign. I am sorely put to it to find fit men for the more responsible places. My simple word will secure for you a commission as major-surgeon, and I will assign you to the very best post at my disposal. I need just such men as you are—a dozen, a score, yes, half a hundred of them. You must put yourself in my hands. I’ll apply for your commission to-day, and get it within three days at most.”

“If you will think a moment, Arthur,” said the other, “you will see that I could not do that without dishonour. Branded as I am with a conviction of felony, I have no right to impose myself as a commissioned officer upon[66] men who would never consent to associate with me upon such terms if they knew.”

“I respect your scruple,” answered Doctor Brent, after a moment of reflection, “but I do not share it. In the first place, the disability you mention is your misfortune, not your fault. You know yourself to be innocent, and as you do not in any way stand accused in the eyes of the officers of this army, there is absolutely no reason why you should not become one of them, as a man conscious of his own rectitude.

“Besides all that, we are living in new times, under different conditions from those that existed before the war. It used to be said that in Texas it was taking an unfair advantage of any man to inquire into his life before his migration to that State. If he had conducted himself well since his arrival there, he was entitled to all his reserves with regard to his previous course of life in some other part of the country. Now a like sentiment has grown strong in the South since this war broke out. I don’t mean to suggest that we have lowered our standards of honourable conduct in the least, for we have not done so. But we have revised our judgments as to what constitutes[67] worth. The old class distinctions of birth and heritage have given place to new tests of present conduct. There are companies by the score in this army whose officers, elected by their men, were before the war persons of much lower social position than that of a majority of their own men. In any peacetime organisation these officers could never have hoped for election to office of any kind; but they are fighters and men of capacity; they know how to do the work of war well, and, under our new and sounder standards of fitness, the men in the ranks have put aside old social distinctions and elected to command them the men fittest to command. The same principle prevails higher up. One distinguished major-general in the Confederate service was a nobody before the war; another was far worse; he was a negro trader who before the war would not have been admitted, even as a merely tolerated guest, into the houses of the gentlemen who are to-day glad to serve as officers and enlisted men under his command. Still another was an ignorant Irish labourer who did work for day’s wages in the employ of some of the men to whom he now gives orders,[68] and from whom he expects and receives willing obedience. I tell you, Kilgariff, a revolution has been wrought in this Southern land of ours, and the results of that revolution will permanently endure, whatever the military or political outcome of the war may be. In your case there is no need to cite these precedents, except to show you that the old quixotism—it was a good old quixotism in its way; it did a world of good, together with a very little of evil—is completely gone. There is no earthly reason, Kilgariff, why you should not render a higher and better service to the Confederacy than that which you are now rendering. There is no reason—”

“Pardon me, Arthur; in my own mind there is reason enough. And besides, I am thoroughly comfortable as I am. You know I am given to being comfortable. You remember that when you and I were students at Jena, and afterward in the Latin Quarter in Paris, I was always content to live in the meagre ways that other students did, though I had a big balance to my credit in the bank and a large income at home. As sergeant-major under our volunteer system, I am the intimate associate not only of Captain[69] Pollard, whose scholarship you know, but also of all the battery officers, some of whom are men worth knowing. For the rest, I like the actual fighting, and I am looking forward to this summer’s campaign with positively eager anticipations. So, if you don’t mind, we will let matters stand as they are. I will remain sergeant-major till the end of it all.”

With that, the two friends parted.

V

DOROTHY’S OPINIONS

IT was not Arthur Brent’s habit to rest satisfied in the defeat of any purpose. He was deeply interested to induce Owen Kilgariff to become a member of the military medical staff. Having exhausted his own resources of persuasion, he determined to consult Dorothy, as he always did when he needed counsel. That night he sent a long letter to her. In it he told her all he knew about the matter, reserving nothing—he never practised reserve with her—but asking her to keep Kilgariff’s name and history to herself. Having laid the whole matter before that wise young woman, he frankly asked her what he should do further in the case. For reply, she wrote:—

I am deeply interested in Kilgariff’s case. I have thought all day and nearly all night about it. It seems to me to be a case in which a man is to be saved who is well worth saving. Not that I regard[71] service in the ranks as either a hardship or a shame to any man, when the ranks are full of the best young men in all the land. If that were all, I would not have you turn your hand over to lift this man into place as a commissioned officer.

If I interpret the matter aright, Kilgariff is simply morbid, and if you can induce him to take the place you have pressed upon him, you will have cured him of his morbidity of mind. And I think you can do that. You know how I contemn the duello, and fortunately it seems passing out of use. In these war times, when every man stands up every day to be shot at by hundreds of men who are not scared, it would be ridiculous for any man to stand up and let one scared man shoot at him, in the hope of demonstrating his courage in that fashion.

That is an aside. What I want to say is, that while the duello has always been barbarous, and has now become ridiculous as well, nevertheless it had some good features, one of which I think you might use effectively in Owen Kilgariff’s case. As I understand the matter, it was the custom under the code duello, sometimes to call a “court of honour” to decide in a doubtful case precisely what honour required a man to do, and, as I understand, the decision of such a court was final, so far as the man whose duty was involved was concerned. It was deemed the grossest of offences to call in question the conduct of a man[72] who acted in accordance with the finding of a court of honour.

Now why cannot you call a court of honour to sit upon this case? Without revealing Kilgariff’s identity—which of course you could not do except by his permission—you could lay before the court a succinct but complete statement of the case, and ask it to decide whether or not the man concerned can, with honour, accept a commission in the service without making the facts public. I am sure the verdict will be in the affirmative, and armed with such a decision you can overcome the poor fellow’s scruples and work a cure that is well worth working.

Try my plan if it commends itself to your judgment, not otherwise.

Little by little, I am finding out a good deal about our Evelyn Byrd. Better still, I am learning to know her, and she interests me mightily. She has a white soul and a mind that it is going to be a delight to educate. She has already read a good deal in a strangely desultory and unguided fashion, but her learning is utterly unbalanced.

For example, she has read the whole, apparently, of the Penny Cyclopædia—in a very old edition—and she has accepted it all as unquestionable truth. Nobody had ever told the poor child that the science of thirty years ago has been revised and enlarged since that time, until I made the point clear to her singularly[73] quick and receptive mind in the laboratory yesterday. She seems also to have read, and well-nigh committed to memory, the old plays published fifty or sixty years ago under the title of The British Drama, but she has hardly so much as heard of our great modern writers. She can repeat whole dialogues from Jane Shore, She Stoops to Conquer, A New Way to Pay Old Debts, High Life Below Stairs, and many plays of a much lower moral character; but even the foulest of them have manifestly done her no harm. Her own innocence seems to have performed the function of the feathers on a duck’s back in a shower. She is so unconscious of evil, indeed, that I do not care to explain my reasons to her when I suggest that she had better not repeat to others some of the literature that she knows by heart.

I still haven’t the faintest notion of her history, or of whence she came. She is docile in an extraordinary degree, but I think that is due in large measure to her exaggerated sense of what she calls my goodness to her. Poor child! It is certain that she never before knew much of liberty or much of considerate kindness. She seems scarcely able to realise, or even to believe, that in anything she is really free to do as best pleases her, a fact from which I argue that she has been subject always to the arbitrary will of others. She is by no means lacking in spirit, and I suspect that those others who have arbitrarily dominated her[74] life have had some not altogether pleasing experiences with her. She is capable of very vigorous revolt against oppression, and her sense of justice is alert. But apparently she has never before been treated with justice or with any regard whatever to the rights of her individuality. She has been compelled to submit to the will of others, but she has undoubtedly made trouble for those who compelled her. At first with me she seemed always expecting some correction, some assertion of authority, and she is only now beginning to understand my attitude toward her, especially my insistence upon her right to decide for herself all things that concern only herself. The other day in the laboratory, she managed somehow to drop a beaker and break it. She was about to gather up the fragments, but, as the beaker had been filled with a corrosive acid, I bade her let them alone, saying that I would have them swept up after the day’s work should be done. She stood staring at me for a moment, after which she broke into a little rippling laugh, threw her arms around my neck, and said:—

“I forgot. You never scold me, even when I am careless and break things.”

I tried hard to make her understand that I had no right to scold her, besides having no desire to do so. It seemed a new gospel to her. Finally she said, more to herself than to me:—[75] “It is so different here. There was never anybody so good to me.”

Her English is generally excellent, but it includes many odd expressions, some of them localisms, I think, though I do not know whence they come. Occasionally, too, she frames her English sentences after a French rhetorical model, and the result is sometimes amusing. And another habit of hers which interests me is her peculiar use of auxiliary verbs and intensives. Instead of saying, “I had my dinner,” she sometimes says, “I did have my dinner,” and to-day when we had strawberries and cream for snack, she said, “I do find the strawberries with the cream to be very good.”

Yet never once have I detected the smallest suggestion of “broken English” in her speech, except that now and then she places the accent on a wrong syllable, as a foreigner might. Thus, when she first came, she spoke of something as excellent. I spoke the word correctly soon afterward, and never since has she mispronounced it. Indeed, her quickness in learning and her exceeding conscientiousness promise to obliterate all that is peculiar in her speech before you get home again, unless you come quickly.

The girl doesn’t know what to make of Mammy. That dearest of despots has conceived a great affection for this new “precious chile,” and she tyrannises over her accordingly. She refused to let her get up the other[76] morning until after she had taken a cup of coffee in bed, simply because no fire had been lighted in her room that morning. And how Mammy did scold when she learned that Evelyn, thinking a fire unnecessary, had sent the maid away who had gone to light it!

“You’se jes’ anudder sich as Mis’ Dorothy,” she said. “Jes’ case it’s spring yo’ won’t hab no fire to dress by even when it’s a-rainin’. An’ so you’se a-tryin’ to cotch yo death o’ cole, jes’ to spite ole Mammy. No, yo’ ain’t a-gwine to git up yit. Don’t you dar try to. You’se jes’ a-gwine to lay still till dem no-’count niggas in de dinin’-room sen’s you a cup o’ coffee what Mammy’s done tole ’em to bring jes’ as soon as it’s ready. An’ de next time you goes fer to stop de makin’ o’ you dressin’-fire, you’se a-gwine to heah from Mammy, yo’ is. Jes’ you bear dat in mind.”

Evelyn doesn’t quite understand. She says she thought we controlled our servants, while in fact they control us. But she heartily likes Mammy’s coddling tyranny—as what rightly constructed girl could fail to do? Do you know, Arthur, the worst thing about this war is that there’ll never be any more old mammies after it is ended?

I’m teaching Evelyn chemistry, among other things, and she learns with a rapidity that is positively astonishing. She has a perfect passion for precision, which[77] will make her invaluable in the laboratory presently. Her deftness of hand, her accuracy, her conscientious devotion to whatever she does, are qualities that are hard to match. She never makes a false motion, even when doing the most unaccustomed things; and whatever she does, she does conscientiously, as if its doing were the sum of human duty. I am positively fascinated with her. If I were a man, I should fall in love with her in a fashion that would stop not at fire or flood. I ought to add that the girl is a marvel of frankness—as much as any child might be—and that her truthfulness is of the absolute, matter-of-course kind which knows no other way. But these things you will have inferred from what I have written before, if I have succeeded even in a small way in describing Evelyn’s character. I heartily wish I knew her history; not because of feminine curiosity, but because such knowledge might aid me in my effort to guide and educate her aright. However, no such aid is really necessary. With one so perfectly truthful, and so childishly frank, I shall need only to study herself in order to know what to do in her education.

There was a postscript to this letter, of course. In it Dorothy wrote:—

Since this letter was written, Evelyn has revealed a totally unsuspected accomplishment. She has been conversing with me in French, and such French! I[78] never heard anything like it, and neither did you. It is positively barbaric in its utter disregard of grammar, and it includes many word forms that are half Indian, I suspect. It interests me mightily, as an apt illustration of the way in which new languages are formed, little by little, out of old ones.

There was much else in Dorothy’s letter; for she and her husband were accustomed to converse as fully and as freely on paper as they did orally when together. These two were not only one flesh, but one in mind, in spirit, and in all that meant life to them. Theirs was a perfect marriage, an ideal union—a thing very rare in this ill-assorted world of ours.

VI

“WHEN GREEK MEETS GREEK”

AT midnight on the 3d of May, 1864, a message came to General Lee’s headquarters. It told him only of an event which he had expected to occur about this time. Grant was crossing the river into the Wilderness, his army moving in two columns by way of the two lower fords.