Title: Robert Emmet: A Survey of His Rebellion and of His Romance

Author: Louise Imogen Guiney

Release date: April 29, 2016 [eBook #51889]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

The following unscientific monograph, a sort of little historical descant, is founded upon all the accurate known literature of the subject, and also largely on the Hardwicke MSS. These, in so far as they relate to Emmet, the writer was first to consult and have copied, last winter, before they were catalogued. But while these sheets were in press, several interesting fragments from the MSS. appeared in the Cornhill Magazine for September, 1903, thus forestalling their present use. This discovery will condone the writer’s innocent claim, made on page 60, of printing the two letters there as unpublished matter.

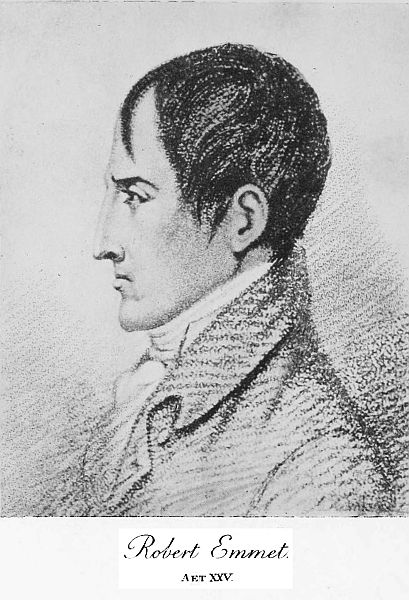

The portrait is after Brocas’s hurried court-room sketch, made the day before the execution. The original print is in the Joly Collection of the[viii] National Library of Ireland. The head is too sharp and narrow, and yet it bears a marked resemblance, far exceeding that of either of the other portraits, to some of Robert Emmet’s collateral descendants. On such good à posteriori evidence it was chosen.

Oxford, Dec. 9, 1903.

The four who lived to grow up of the seventeen children born to Robert Emmet, M.D., of Cork, later of Dublin, and Elizabeth Mason, his wife, were all, in their way, persons of genius. The Emmets were of Anglo-Norman stock, Protestants, settled for centuries in Ireland. The Masons, of like English origin, had merged it in repeated alliances with women of Kerry, where the Dane, the Norman, and later invaders from nearer quarters had never settled down to perturb the ancient Celtic social stream. Dr. Emmet was a man of clear brain and incorruptible honour. The mother of his children, to judge by her letters, many of which have been privately printed, must have been an exquisite being, high-minded, religious, loving, humorous, wise. Her eldest surviving son, Christopher[2] Temple Emmet, was named for his two paternal grandparents, Christopher Emmet of Tipperary and Rebecca Temple, great-great-granddaughter of the first Baronet Temple of Stowe, in Buckinghamshire. The mention of that prolific, wide-branching, and extraordinary family of Temple as forebears of the younger Emmets is like a sharply accented note in a musical measure. It has never been played for what it is worth; no annalist has tracked certain Emmet qualities to this perfectly obvious ancestral source. The Temples had not only, in this case, the bygone responsibility to bear, for in a marked manner they kept on influencing their Emmet contemporaries, as in one continuous mood thought engenders thought. Says Mr. James Hannay: “The distinctive ηθος of the Temples has been a union of more than usual of the kind of talent which makes men of letters, with more than usual of the kind of talent which makes men of affairs.” The Emmets, too, shared the “distinctive ηθος” in the highest degree. Added to the restless two-winged intelligence, they had the heightened soberness, the moral elevation, which formed no separate inheritance. The Temples were, and are, a race of subtle but somewhat[3] austere imagination, strongly inclined to republicanism, and to that individualism which is the norm of it. The Temple influence in eighteenth-century Ireland was, obliquely, the American influence: a new and heady draught at that time, a “draught of intellectual day.” If we seek for those unseen agencies which are so much more operative than mere descent, we cover a good deal of ground in remembering that Robert Emmet the patriot came of the same blood as Sidney’s friend, Cromwell’s chaplain, and Dorothy Osborne’s leal and philosophic husband. And he shared not only the Temple idiosyncrasy, but, unlike his remarkable brothers, the thin, dark, aquiline Temple face.

Rebecca Temple, only daughter of Thomas, a baronet’s son, married Christopher Emmet in 1727, brought the dynastic names, Robert and Thomas, into the Emmet family, and lived in the house of her son, the Dublin physician, until her death in 1774, when her grandchildren, Temple and Thomas Addis, were aged thirteen and ten, Robert being yet unborn. Her protracted life and genial character would have strengthened the relations, always close, with the Temple kin. Her brother Robert had gone in his youth from Ireland to Boston, where[4] his father was long resident; and there he married a Temple cousin. This Captain Robert Temple died on April 13, 1754, “at his seat, Ten Hills, at Boston, in New England.” His three sons, the eldest of whom, succeeding his great-grandfather, became afterwards Sir John Temple, eighth Baronet of Stowe, all settled in New England and married daughters of the Bowdoin, Shirley, and Whipple families—good wives and clever women. John Temple had been “a thorough Whig all through the Revolution,” and had suffered magnanimously for it. He had to forfeit office, vogue, and money; and little anticipating his then most improbable chances of a rise in the world, he forfeited all these with dogged cheerfulness, in the hour when he could least afford to do so. The latter-day Winthrops of the Republic are directly descended from him, and the late Marquis of Dufferin and Ava from his brother. A certain victorious free spirit, an intellectual fire, whimsical and masterful, has touched the whole race of untamable Temples, and the Emmets, the very flower of that race. Love of liberty was, in both Robert Emmet and in Thomas Addis Emmet, no isolated phenomenon, but[5] their strengthened and applied inheritance. Captain Robert Temple’s second son, Robert, came back with his wife, Harriet Shirley, after the Declaration of Independence, to Allentown, Co. Dublin. His widow eventually received indemnification for the loss of their transatlantic estates. It is thus proved that Robert Temple was a loyalist to some appreciable degree. Earlier and later, however, he did considerable thinking, cherished liberal principles, and had much to say of the rights of man and other large theses to his namesake first cousin, Robert Emmet, M.D., with whom he lived for eighteen months after his return. This community of ideas was further cemented by the marriage of Anne Western Temple, Robert Temple’s daughter, to Dr. Emmet’s eldest son, Temple Emmet. Dr. Emmet was faithful to the unpopular convictions which he found himself sharing in increased degree with his cousin. Up to 1783 he was always voluntarily abandoning one position of eminence after another, as he came to dissent from English rule in Ireland. He held among other offices that of State Physician; and from a bland condemnatory notice of his youngest son in The Gentleman’s Magazine for October 1803,[6] we learn that he was also physician to the Lord-Lieutenant’s household. It is clear, then, that he also began his career as a trusted Conservative. But as his opinions changed, he gave up, Temple-like and Emmet-like, every position and emolument inconsistent with them; when the ’98 broke out he had even ceased to practise his profession. He and his wife and their children felt alike in these matters so adversely and intimately affecting their chances of worldly success. The boys and the girl were brought up to think first of Ireland and her needs. An amicable satirist and distinguished acquaintance was wont facetiously to report Dr. Emmet’s administration of what the visitor named “the morning draught” to his little ones: “Well, Temple, what are you ready to do for your country? Would you kill your sister? Would you kill me?” For after this perilous early Roman pattern the catechism ran. Even if only a beloved joke, it would have been enough to seal the young Emmets for fanaticism, had not their good angels intervened. As it turned out, they were all of a singularly judicial cast. The only daughter, Mary Anne, had what used to be called, by way of adequate eulogy, a “masculine understanding,”[7] and wrote pertinently and well. Her husband was the celebrated barrister and devoted Irishman, Robert Holmes. He was the true friend and adviser of the whole Emmet family, and survived his wife, who died during his imprisonment in 1804, for five-and-fifty years. Of Dr. Emmet’s three sons, Temple, Thomas Addis, and Robert, the former had an almost incomparably high repute for “every virtue, every grace,” to quote Landor’s mourning line for another. It is no disparagement to him to say that this was partly owing to the pathos of so short a career, and to the fact that he died ten years before the great Insurrection, twelve before the Union; seeming to belong to a prior order of things, it was the easier to praise the Emmet who did not live long enough to get into trouble, at the expense of the Emmets who did.

Temple Emmet, with his beautiful thought-burdened head, a little like the young Burke’s, passed by like a wonderful apparition in his day. His success at Trinity College was complete; it is said the examiners found their usual maximum of commendation, Valde bene, unequal to the occasion, and had a special O quam bene! given to him with his degree. This has a sort of historic parallel in[8] the incident at Wadham College, Oxford, just a century before, when Clarendon, Lord Chancellor of the University, set a kiss for eulogy upon the boyish cheek of John Wilmot, Master of Arts. Again serving as his own precedent, Temple Emmet became King’s Counsel at twenty-five. Two years later he was in his grave, whither his young wife quickly followed him. All his contemporaries qualified to appraise his worth, deplored him beyond common measure. Said the great Grattan, long after: “Temple Emmet, before he came to the Bar, knew more law than any of the judges on the Bench; and if he had been placed on one side and the whole Bench opposed to him, he could have been examined against them, and would have surpassed them all; he would have answered better both in law and divinity than any judge or bishop in the land.” His premature death called his next brother from the University of Glasgow, where he had just graduated in medicine, to the profession of the law.

The Emmet name was not destined to rise like a star where it had fallen, for bitter times were drawing nigh, and his own generosity and integrity were to bring Thomas Addis Emmet into fatal difficulties.[9] With a great number of other zealous spirits, he flung himself with all his force of protest against the legalised iniquities destroying Ireland. Examined before the secret committee of the House of Lords, August 10, 1798, the young man, then as always quietly intrepid, let fall brave prophetic words. Asked if he had been an United Irishman, he righted the tense in answering: “My Lords, I am one”; then he continued: “Give me leave to tell you, my Lords, that if the Government of this country be not regulated so that the control may be wholly Irish, and that the commercial arrangements between the two countries be not put upon a footing of perfect equality, the connection [with England] cannot last.” Lord Glentworth said: “Then your intention was to destroy the Church?” Mr. Emmet replied: “No, my Lord, my intention never was to destroy the Church. My wish decidedly was to overturn the Establishment.” Here Lord Dillon interrupted: “I understand you. And have it as it is in France?” “As it is in America, my Lords.” When the chance for self-expatriation came, when “to retract was impossible, to proceed was death,” Thomas Addis Emmet followed the ancestral trail, and founded a new family in his[10] approved America. The only one of his circle spared to continue the Emmet name, he came to flower sadly enough, because his hopes were broken, on what was not to him alien soil. Everyone knows the rest: how, admitted to the New York Bar by suspension of rules, without probation, he died in all men’s honour, in 1827, Attorney-General of the State.

Robert Emmet was even surer of an illustrious career. Alas! There is no documentary proof forthcoming for it as yet, but it is painfully probable that his little afterglow of a rebellion was long fostered, for reasons of their own, by great statesmen, and that their secret knowledge of it arose from Irish bad faith; that, in short, he was let dream his dream until it suited others to close the toils about him. The two or three highest in authority in Dublin, Lord Hardwicke chief among them, were kept ignorant as himself. Emmet was really victim and martyr. But to die prodigally at twenty-five, and to be enshrined with unwithered and unique passion in Irish hearts; to go down prematurely in dust and blood, and yet to be understood, felt, seen, for ever, in the sphere where “only the great things last,” is perhaps as enviable a[11] privilege as young men often attain. His is one of several historic instances in which those who have wrought little else seem to have wrought an exquisite and quite enduring image of themselves in human tradition. With none of the celebrities of his own nation can he in point of actual service, compare; but every one of them, whether known to ancient folk-lore or to the printed annals of yesterday, is less of a living legend with Thierry’s “long-memoried people,” than “the youngest and last of the United Irishmen,” “the child of the heart of Ireland.” A knot of peasants gathered around a peat fire in the long evenings, pipe in hand, are the busy hereditary factors of apocryphal tales beginning “Once Robert Emmet (God love him),” &c.; and a certain coloured print, very green as to raiment, very melodramatic as to gesture, hangs to-day in the best room of their every cabin, and stands to them for all that was of old, and is not, and still should be.

He was born March 4, 1778, in his father’s house in St. Stephen Green West, Dublin, now numbered 124-125. As a boy he was active out of doors, yet full of insatiable interest in books, and developed early his charming talent for drawing[12] and modelling. He was always rather grave than gay; but the best proof, if any were needed, that he had nothing of the prig in him, is that he was a favourite at school; the potential Great Man, in fact, to whom the others looked up. His one serious early illness was small-pox, which left his complexion slightly roughened. He entered Trinity College, in his native city, at fifteen. Either at this time, or just before, occurred an incident so characteristic as to be worth recording, for it illustrates both his power of mental concentration, and his still courage in facing the untoward haps of life alone. Like Shelley, he had a youthful fascination for chemistry. He had been dabbling with corrosive sublimate, not long before bedtime. Instead of going upstairs, he sat down, later, to figure out an allotted algebraic problem which, by way of whetting adventurous spirits, the author of the book in question acknowledged to be extremely difficult. Poring earnestly over the page, the boy fell to biting his nails. He instantly tasted poison, and pain and fear rushed on him. Without rousing a single person from sleep, he ran to the library, got down his father’s encyclopædia, turned to the article he needed, and learned that his antidote was[13] chalk and water; then he went in the dark to the coach-house where he had seen chalk used, got it, mixed and drank it, and returned to his interrupted task. His tutor could not fail to notice the agonised little face at breakfast. Robert confessed the mischance, and that he had lain perforce awake all night; but he added, modestly, that he had mastered the problem. One of Plutarch’s heroes, at that age, could hardly have done better. The antique world, with its heroic simpleness, was indeed Robert Emmet’s own ground. At Trinity he earned, without effort, a golden reputation, partly due to his scientific scholarship, partly to his goodness, partly, again, to his possession of a faculty of animated fluent speech, a faculty dear to the Irish, as to every primitive people. He had a presence noticeably sweet and winning, with “that gentleness so often found in determined spirits.” His classmate, Moore, the poet, bore witness long after to his “pure moral worth combined with intellectual power. . . . Emmet was wholly free from the follies and frailties of youth, though how capable he was of the most devoted passion events afterwards proved.” Mr. Charles Phillips wrote in 1818: “[Emmet at Trinity] was gifted[14] with abilities and virtues which rendered him an object of universal esteem and admiration. Every one loved, every one respected him; his fate made an impression on the University which has not yet been obliterated. His mind was naturally melancholy and romantic: he had fed it from the pure fountain of classic literature, and might be said to have lived not so much in the scene around him as in the society of the illustrious and sainted dead. The poets of antiquity were his companions, its patriots his models, and its republics his admiration. He had but just entered upon the world, full of the ardour which such studies might be supposed to have excited, and unhappily at a period in the history of his country when such noble feelings were not only detrimental but dangerous.”

When Emmet was in his twentieth year the so-called Rebellion, in which Wolfe Tone and Lord Edward Fitzgerald were leaders, broke out. In the agitation which led up to it and sustained it, Thomas Addis Emmet was deeply implicated, nor did his younger brother go unsinged by the travelling flame. Sitting once by the pianoforte in Thomas Moore’s rooms, listening to Let Erin Remember, he stood up suddenly, with a brief[15] pregnant speech, such as was habitual with him: “O that I were at the head of twenty thousand men, marching to that air!” As it was, he made one of the nineteen of her best spirits whom his University then thought fit to dismiss without benisons. One of these was no fiery undergraduate, but a Fellow and a famous scholar, Dr. Whitley Stokes. Their chief offence was that they had refused to tell what they knew of others who shared their outspoken opinions. There is no need here to dwell upon the memorable rising of 1798, or upon the rooted general opposition to that Union with Great Britain which wholesale bribery was so soon to consummate. One need but bear in mind that the Anglo-Irish (chiefly the Presbyterians and members of the dominant Church, the landed classes, who had nothing to gain and everything to lose by their championship of disenfranchised Catholics and the countless poor) came angrily to the fore as the defenders of nationalism, at a time when exile, the dungeon, and the axe, active for two generations, had deprived Ireland of the last of her native Jacobite gentry. Saurin, the great jurist, had written: “Whether it would be prudent in the people to avail themselves of that right would be[16] another question; but if a Legislative Union were forced on the country against the will of its inhabitants, it would be a nullity: . . . [To take issue with it] would be a struggle against usurpation, not resistance against law.” Emmet had only to cross the street from his College to hear the debates in either House of Parliament, to hear the like doctrine from Grattan in his glory; and with “malignants” of the loftiest character, like Lord Cloncurry, then the Rt. Hon. Valentine Lawless, he and his associated every day. It was inevitable, with such counsels of perfection brought to bear upon his daring and his entire disinterestedness, that Robert Emmet should attempt a popular emancipation, and succeed but in ruining himself. It was a poignant case of chronological and topographical misplacement. In his expulsion, or rather, withdrawal from College (for he had anticipated the action of the authorities), his father, of course, approved and stood by him, although Robert’s entry upon any professional career was fatally compromised. His “highly distinguished family, striking talents, and interesting manners,” could not mend that. He may even have taken at once the plain godly oath of the United Irishmen, and become an active agent for the cause.[17] Within the twelvemonth he had bestirred himself so effectually that a warrant was actually issued for his arrest. For some reason or other it was not put in force: even thus early there began to be woven about him the web of curious cross-purposes in which, in the end, he was to be caught and strangled. It became advisable to go to France, to see the First Consul and Talleyrand on an all-important matter. It would be well to reach a quiet place beyond espionage, where inhibited rites might go on. The young conspirator had military histories in process of annotation, plans of campaign in mountainous districts to perfect, seditious conferences to hold with colleagues and subordinates, and, incidentally, even poems to commit for his sad country’s sake. And there was another excellent reason why he found it convenient to go away.

One of Robert Emmet’s college mates was Richard, youngest son of the John Philpot Curran, “ugly, copious, full of wit and ardour and fire,” the Curran of “fifty faces and twice as many voices,” of Byron’s lasting admiration. Richard had a sister Sarah, aged not quite eighteen when Robert Emmet, three years her senior, fell in love with[18] her. Sentimental invention has placed their first meeting at a ball in a Wicklow country-house; but it would rather seem as if, in the compact society of a gay little city like Dublin before the Union, they must have known each other fairly well from childhood, especially as the two families were then acquainted. That fatal mutual affection was to endure long vicissitudes and to prove invincible.

We must infer from a passage in Mr. W. H. Curran’s Life of his father that Emmet’s reserve, for once, but imperfectly concealed evidences of some strong passion, political or extra-political, or both, from the oracular host of the Priory at Rathfarnham. Parenthetically, and without emphasis, Mr. Curran saw fit to warn his household against too implicit a cherishing of their engaging visitor. That Sarah’s interest in him was particular, that it was already awakened and deepening, seems never to have been surmised. According to such evidence as we have, it looks as though he had declared to her the state of his feelings before he went to Paris. It was not an hour, however, when Sarah dared to be happy. Her family had but just gathered together after a most harrowing break-up; she herself had been away for several years under the roof of a[19] beloved clergyman in Lismore, and her homecoming was recent. Her mother, how driven to that point of revolt we know not, had eloped in 1794 with a too sympathetic neighbouring vicar. Sarah was fourteen then, and of a peculiarly sensitive temperament; and she had worshipped her mother. Her sensitiveness was not allayed by her father’s increased mental aloofness from his family, after his misfortune. Incomparably genial, when he chose, to strangers, he visited his resentments in private upon his children, her children, especially upon his son Henry, who stood in lifelong dread of him. The one little daughter of his inordinate love, Gertrude, had died by accident at twelve years old.

Sarah’s sad young face was typically Irish, her noble and touching beauty stamped in every feature with irony, melancholy, and fatalism. To her lover, with his head full of all poetic ideas, she must have looked like the very spirit of Innisfail. His intensely sanguine and resolute nature may have kept him from reading in such a face their own common rune of sorrow. It is clear that his forgetting her, while he was absorbed in the grave business abroad, was out of the question. No one knows, he tells Mme. la Marquise de Fontenay, in one of his[20] few recovered letters, what his return to Ireland and to “the sorrows before him” is costing. Memories of the past (of that long-distanced past which is proper to blasted youth) must assail him; and it will be hard to affect that he has not known “tender ties, perhaps,” which he is forbidden to resume. The lad was writing in French, and does it in character. But then, as ever, he was radically sincere. His thoughts seem to have turned towards Dublin, from motives of filial duty. His father and mother had agreed to the elder brother’s first suggestion from Paris that Robert should be induced to go to America with him; and Robert felt that so generous a permission laid its own obligation on him not to accept the parting. Everything seemed to conspire to restore him to Ireland. And with his yet-to-be-liberated Ireland, like

“Flame on flame and wing on wing,”

shone the remote sweetness of Sarah Curran. He was told that revolutionary hopes were ripening fast; he was thus lured back in October, 1802. His absence had lasted nearly three years.

The separation had probably taught Sarah something more of her own heart. Immediately[21] Emmet’s visits to the Priory were resumed, as if in the general stream of homage which brought so many enthusiastic young men into Mr. Curran’s presence, at evening, to listen and gather wisdom. Dr. Emmet died in April, much lamented, and by his will Robert came into possession of considerable ready money. He spent it instantly, effectively, and entirely on preparations for armed resistance. No one suspected it; those in his confidence were yet faithful. Still less did others suspect the now plighted attachment, the innocent love hungry for joy, and yet hurried on to dark ends through devious and hidden ways. Mr. Curran’s strenuous opposition, on all grounds, was necessarily taken for granted, until some prodigious success should befall Emmet, and as if by a spell free the daughter who so feared her father. Sarah knew detail by detail of the conspiracy as it arose, and was fain with all her soul to encourage its progress. For the two sensitive creatures under so complicated a strain there passed an anxious and exciting year. The most disagreeable surprise of Mr. Curran’s life was yet to come before it ended.

Robert Emmet took lodgings under an assumed name in Butterfield Lane, in the suburb of Rathfarnham.[22] His agents came to him by night and reported their progress. The record of all he had meant to do, drawn up with manly composure at the brink of the grave, may be read elsewhere. As has been noted, his plan for the capture of Dublin and the summoning of the patriotic Members of Parliament was clearly founded on an inspiring precedent, that of the Revolution of 1640 in Portugal, when but two-score clever and resolute men served to deliver the whole country from the yoke of Spain. But when the hour of Ireland’s destiny struck, every clock-wheel went wrong. If the failure were not so piteous, because of one’s interest in the doomed wizard and his suddenly disenchanted wand, it would be grotesque. Emmet had studied with enormous industry, and arranged with masterly precision, directing, among pikes and powder in his dingy depôts, each needful move and counter-move for a concerted rising; he thought it strange that in every conceivable way, major and minor, the whole scheme simultaneously miscarried.

If one could believe him as free as he believed himself, one might regret that he maintained too perfect a secrecy, and counted too much upon the elasticity of Irish impulse. He had been[23] careful to avoid what he thought the error of the United Irishmen in establishing too many posts for revolutionary action, and confiding knowledge of preliminaries to innumerable persons all over the country, some of whom would be almost certain to play him false. He worked in the dark, with but a dozen friends at his elbow, spending his money freely but heedfully on manufacturing and storing weapons of war in Dublin. He looked towards a moment when a disaffected legion would arise at a summons, like the men from the heath in The Lady of the Lake: a legion which he could arm and command and weld, in one magic moment, for Ireland’s regeneration. He leaned overmuch, not on human goodness, but on human intelligence in making opportunity: and it failed him. He was like the purely literary playwright labouring with the average theatre audience; he was never in the least, for all his wit, cunning enough to deal scientifically with a corporation on whom hints, half-tones, adumbrations, are thrown away; the law of whose being is still to crave a presentation of the “undisputed thing in such a solemn way.” As drama through its processes, act after act, does well to assume that we are all blockheads,[24] and then, as the case requires, to modify, so any flaming revolutionary genius would do well to trust nothing whatever to a moral inspiration only too likely to be non-existent. It is a terribly costly thing to be, as we say, equal to an emergency, before the emergency is quite ready to be equalled. And that was Emmet’s plight. A French fleet had been promised to begin military operations towards the end of August, but an unforeseen explosion in one of Emmet’s Dublin magazines led him to declare his toy war against the English Crown prematurely. The local volunteer troops were to be reinforced by others, well armed, from the outlying counties, at the firing of a rocket agreed upon; the Castle was to be seized as the chief move, and a Provisional Government, according to printed programme, set up. The time for assembling was hurriedly fixed for July 23, 1803, early in the evening. The gentlemen leaders and the trusty battalions failed to appear, kept away by mysterious quasi-authentic advices; appeared instead, as time wore on, many unknown, unprepossessing insurgents, the drunken refuse of the city taverns. The cramp-irons, the scaling-ladders, the blunderbusses, the fuses for the grenades, were not ready; signals had been delayed or suppressed; the[25] prepared slow-matches were mixed in with others; treachery was at work and running like fire in oil under the eyes of one who could believe no ill of human kind. Beyond Dublin, the Wicklow men under Dwyer, an epic peasant figure, received no message; the Wexford men waited in vain for orders all night; the Kildare men, whom Emmet meant to head in person, actually reached the city, and left it again. They had met and talked with him, and were not satisfied with the number and quality of the weapons, chiefly primitive inventions of his own; and because Dublin confederates were not produced for inspection (such was Emmet’s caution where others were concerned), the canny farmers returned homewards, spreading the ill word along the roads that Dublin had refused to act. Each imaginable prospect grew darker than its alternative. But the curtain had to rise now, let results be what they might. About nine o’clock, Emmet being in such a state of speechless agitation as may be conceived, one Quigley rushed in with the false report that the Government soldiery were upon them. There was nothing to do but sally forth in the hope of augmented numbers, once the move was made. The poor “General,” in his[26] green-and-white-and-gold uniform, at the head of some eighty insubordinates, took in the bitter situation at a glance: he foresaw how his holy insurrection would dwindle to a three-hours’ riot, how his dream, with all its costly architecture, was ending like snow in the gutter. Hardly had he set out on foot, with drawn sword, through the town, accompanied by the faithful Stafford and two or three associates, followed confusedly by the uncontrollable crowd, when an uproar rose from the rear; there was a sudden commotion which ended in wounds and death to a citizen and an officer; then the spirit of rowdyism, private pillage, and indiscriminate slaughter took the lead. While it ran high, Arthur Wolfe, Lord Kilwarden, Lord Chief-Justice, the one unfailingly humane and deservedly beloved judge in all Ireland, was killed. He was driving in from the country with his daughter and his nephew, the Rev. Richard Wolfe; finding the carriage stopped in Thomas Street, he put his grey head out at the window in the pleasant evening light, announcing the honoured name which, as he thought he knew, would be his passport through the maddest mob ever gathered. A muddle-brained creature, quite mistaken as to facts, and[27] acting in revenge for a wrong never inflicted, unmercifully piked him: a fate paralleled only by the unpremeditated assassination in our own time of that other kindest heart, Lord Frederick Cavendish. It is significant that some in the ranks afterwards made separately in court the unasked declaration that had they been near enough, Lord Kilwarden’s life should have been saved at the expense of their own. Such, indeed, was the general feeling. It has been carelessly stated that Emmet was not far from the scene of the outrage, and arrived, in a fury, just too late to prevent the second horror, the stabbing to death of Mr. Wolfe; and that it was he who took the unfortunate Miss Wolfe, to whom no violence was offered, from the carriage. But records now show conclusively that (as he once said) he had withdrawn from that part of Dublin before the murders came to pass. He had addressed his followers in Francis Street, setting his face against useless bloodshed, and made for the mountains hard by, commanding those who retained any sense of discipline to go along with him. A quick retreat was the only sagacious course to follow in this gross witless turmoil, so contrary to his purpose: for his printed manifesto had expressly[28] declared life and property were to be held sacred. His secret, up to this point, was practically safe, and his losses reparable. The “rebels” abroad that night were but diabolical changelings; he would break away with the few he could rely upon, nurse hope to life with the courage that never failed, and take his chances to fight again. He reached safety, unchallenged; Dwyer even then implored for leave to call out on the morrow his disappointed veterans for a new assay; but Emmet was firm. No lust of revenge on fate, no recoil from being thought, for one hot moment, a coward, could shake him from his shrewd and rational acceptance of present defeat. He had no personal ambition, no vicarious tax to pay it. Ireland could wait the truer hour. He seems never once to have bewailed aloud the miserable end of his own long minute study of military strategy, the foul check to aspirations founded in honour, and breathed upon by the dead of Salamis and Thermopylæ.

It is an almost incredible fact that the authorities, meanwhile, whether aware or unaware of the projected outbreak, were virtually off their guard, and the garrison was so little in condition to repel an onset that not a ball in the arsenal would fit the[29] artillery! Public attention in Great Britain was fixed on the difficulties with France, and this preoccupation everywhere affected social life. Dublin had been almost deserted on July 23; the Castle gates stood wide open, without sentries. Two entire hours passed before the detachments of horse and foot arrived to clear the streets. “Government escaped by a sort of miracle,” as The Nation remarked half a century after, “by a series of accidents and mistakes no human sagacity could have foreseen, and no skill repair.” Though there was treachery behind and before as we now see, Emmet, mournfully closing his summary of events, took no account of it. “Had I another week [of privacy], had I one thousand pounds, had I one thousand men, I would have feared nothing. There was redundancy enough in any one part to have made up in completeness for deficiency in the rest. But there was failure in all: plan, preparation, and men.” Three days after the abortive rising, the disturbance was completely over and the country everywhere quiet. The whole number of the slain was under fifty.

None among those who have written of Robert Emmet have noted for what reason the news of[30] the death of Lord Kilwarden must have been to him a last desperate blow. Quite apart from his natural horror of the blundering crime, he had the most intimate cause to lament it. Lord Kilwarden was the person in all the world whom John Philpot Curran most revered: “my guardian angel,” he was wont to call him, summing up in the words all his tutelary service of long years to a junior colleague. It would have gone hard with Mr. Curran, so high was partisan passion at the time, if, in his defence of the State prisoners during the terrible series of prosecutions in the ’98, he had not been protected, day after day, by the strong influence of Kilwarden. Emmet, if he could have leaned for once on a merely selfish motive, might have looked forward, as to the blackness of hell, to that hour when Curran should learn that his dearest friend’s indirect murderer was none other than his daughter’s betrothed lover. Apprehensions of danger to his sweetheart must have haunted Robert Emmet through the sleepless nights among the outlawed folk on the wild fragrant Wicklow hillsides. Below, in a little port, was a fishing-smack under full sail, which meant liberty and security, would he but abandon all and come away. But the[31] insistent beat of his own heart was to see his beautiful Sarah again; to learn how she looked upon him, or whether she would fly with him now that his first great endeavour was over, and only the rag of a pure motive was left to clothe his soiled dream and his abject undoing. It was a mad deed; but Robert Emmet, in relics of his tarnished regimentals, stole back to Dublin. He was so young that the adventure took on multiple attractions.

He hid himself in a house at Harold’s Cross, where he had masqueraded once before, when his country’s need constrained him. Now he was there chiefly because the road in front ran towards Rathfarnham, and because, at least, he could sometime or other watch his own dear love go by. A servant, a peasant wench who was devoted to him, Anne Devlin, carried letters under her apron to the Priory, carried letters “richer than Ind” back to the proscribed master. She was a neighbouring dairyman’s daughter, and her coming and going were unquestioned. Forty years after, in her pathetic old age, she told Dr. Madden how Miss Sarah’s emotion would all but betray her: “When I handed her a letter, her face would change so, one would hardly know her.” And again: “Miss Sarah[32] was not tall, her figure was very slight, her complexion dark, her eyes large and black, and her look was the mildest, the softest, and the sweetest look you ever saw!” All this is beautifully borne out by the Romney portrait, save that the pensive face which Romney must have begun to paint before the time of her betrothal (for after 1799 he painted hardly at all) is not olive-skinned and not black-eyed. The eyes are, in truth, very dark, but of Irish violet-grey. Every Anne Devlin in the world would have called them “black.” But one hastens to contradict a hasty phrase: there is but one Anne Devlin, a soul beyond price, who suffered afterwards and without capitulation, for her “Mr. Robert’s” sake, tortures of body and mind which read like those in the Acta Sanctorum. Her name will be with his when that “country shall have taken her place among the nations of the earth;” until then there is no fear but that those who care for him will keep a little candle burning to his most heroic friend.

At every house where Emmet lived, as “Mr. Huet” or “Mr. Ellis,” during his fugitive and perilous months, he had his romantic trap-doors, and removable wainscots, and sliding panels. Even at Casino, his own home in the country, closed after[33] his father’s death, with its summer-house and decaying garden, he provided like subterfuges and inventions of his own, for he had a turn for mechanism as well as for the plastic arts. It is hard to be both a hunted rebel and an anxious lover, to have equal necessity for staying in and for sallying forth! Just so had “Lord Edward,” dear to every one who knew him, managed to exist, in and out of a hole, before his seizure and death. It has been justly said that “a system of government which could reduce such men as Robert Emmet and Lord Edward Fitzgerald to live the life of conspirators, and die the death of traitors, is condemned by that alone.” It seems hardly possible but that Robert and his Sarah made out to meet again, as they had met after the lamentable no-rising, when for a night and a morning he had lingered in the alarmed city before escaping into the mountains. One may be not far wrong in believing that the girl was by this time too overwrought, dismayed, and grief-stricken, to come to any immediate decision about joining him, and breaking away while there was yet opportunity. He must have realised fully the alternative, whether she did so or not, that to remain in Ireland was but to beckon on his fate. At any rate, on[34] August 23, at his humble dining-table, he was suddenly apprehended. The informer has never been discovered; from the Secret Service Money books we know that he received his due £1000. The captor was Major Sirr, the unloved fowler of that other young eagle of insurrection but just mentioned, Lord Edward Fitzgerald. He was able to recognise Emmet by the retrospective description obligingly furnished by Dr. Elrington, Provost of Trinity, of an undergraduate whom he had not loved. The captive was bound and led away, bleeding from a pistol wound in the shoulder. He had tried to get off, and some rough treatment followed, for which apologies were tendered. “All is fair in war,” said the prince of courtesy. The Earl of Hardwicke, then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, writes two days after, in his usual covertly kind way, of the arrest of young Emmet, now consigned to Kilmainham Gaol on the charge of high treason. “I confess I had imagined that he had escaped,” he says to his brother, his confidential daily correspondent. “His having remained here looks as if he had been in expectation of a further attempt.” Not yet was the Lord Lieutenant aware of the love-story intertwined with the one-man insurrection.

When enclosed in his cell, Emmet became the object of apparent concern and affection on the part of two acquaintances: the accomplished advocate and litterateur, Mr. Leonard M’Nally, and Dr. Trevor, Superintendent of Prisons. If these persons had stepped out of an ancient epic or some fancied tragedy to show what human genius could do by way of creating hypocrites, no plaudit ever yet given could be worthy of the play. They were both moral monsters, paragons of evil, beyond the Florentine or Elizabethan imagination. How they played with the too noble and trusting creature in their hands, how they tricked him with illusory plans of escape, and beguiled him into inditing documents which were promptly handed over to headquarters, need not detain us, though it supplies a long thrilling chapter in the humanities. Emmet’s first move was to empty his pockets of coin for the gaoler, under the man’s promise that he would carry in person a communication to Miss Curran. The recipient was not that distracted maid, but the Attorney-General. The Lord Lieutenant wrote to the Hon. Charles Yorke on September 9 as follows: “A curious discovery has been made respecting Emmet, the particulars of which I have not time to detail to[36] you fully. There were found upon him two letters from a woman, written with a knowledge of the transactions in which he had been engaged, and with good wishes for the success of any future attempt. He has been very anxious to prevent these letters being brought forward, and has been apprehensive that the writer was arrested as well as himself. Till yesterday, however, we were entirely ignorant of the person who had written these letters, which are very clever and striking. The discovery was made last night by a letter from Emmet, intercepted on its passage from Kilmainham Prison to Miss Sarah Curran, youngest daughter of Curran the lawyer. Wickham has seen him, and he professes entire ignorance of the connection; but I think he must decline being counsel for Emmet in a case in which his daughter may be implicated. It is a very extraordinary story, and strengthens the case against Emmet.” A rumour of the fate of his letters was allowed to reach Emmet, and cut him to the quick. He wrote at once begging that the third letter (surely with news of his arrest, and with such assurances and sorrowful endearments as the occasion called for), might not be withheld; and in exchange for the service demanded, knowing that[37] the Government already feared what that eloquent tongue might have to say in court, he offered to plead guilty, and go dumb to the grave. He who had staked so much on the purity of his public motive, he who cared only, and cared fiercely, for the clearing of his name from the misconceptions of posterity, he who was one of the elect souls loving his love so much because he loved honour more—he, Robert Emmet, was willing to forfeit every chance of his own vindication for the sake of the sad girl brought into abhorrent publicity by his rashness. He said he had injured her; he pleaded for the delivery of the letter, and offered his own coveted silence as the price of it. “That was certainly a fine trait in his character,” said Grattan, who looked upon him as a visionary broken justly upon the wheel of things ordained. Sarah never received her letter. But the discovery that there had been a correspondence between herself and the arch-rebel was a highly important-looking circumstance, and with all apologies to its distinguished owner, the Priory at Rathfarnham was ordered to be searched. Mr. Curran was not at home, but he returned in season to meet Major Sirr and the armed escort riding down his drive-way, and aglow with virtuous wrath at the[38] possibility of suspicion alighting upon him or his, he went to clear himself before the Privy Council. Though his action secured its ends, being voluntary and merely formal, it was a singular humiliation to the paternity concerned. But the culminating shock he had to endure arose from another cause. Sarah’s apartments had been searched; Emmet’s glowing letters, openly alluding to his purposes, had been seized, and tied up and carried away. Here was complicity indeed! and the knowledge of it came upon him like a thunderbolt.

Within a few days, towards the end of this month of August, Mr. Curran himself received a letter from Robert Emmet. It was neither signed nor dated, and opened abruptly, waiving all formalities, not from any hidden defiance, but from entire absorption in the mournful retrospect it called up. As we know from Lord Hardwicke’s communication, Emmet had retained Mr. Curran for his counsel, and it was thought fitting that the latter should decline the brief for the defence. Of course Mr. Curran threw it up; no man could have done otherwise. But his general turmoil, and the apparent motives of it, are not a particularly noble spectacle. The young prisoner, meanwhile, had something to say to him.

“I did not expect you to be my counsel. I nominated you, because not to have done so might have appeared remarkable. Had Mr. ——[1] been in town, I did not even wish to have seen you, but as he was not, I wrote to you to come to me at once. I know that I have done you very severe injury, much greater than I can atone for with my life; that atonement I did offer to make before the Privy Council by pleading guilty if those documents were suppressed. . . . My intention was not to leave the suppression of those documents to possibility, but to render it unnecessary for anyone to plead for me, by pleading guilty to the charge myself. The circumstances that I am now going to mention I do not state in my own justification. When I first addressed your daughter I expected that in another week my own fate would have been decided. I knew that in case of success many others would look on me differently from what they did at that moment; but I speak with sincerity when I say that I never was anxious for situation or distinction myself, and I did not wish to be united to one who was. I spoke to your daughter, neither expecting nor (under those circumstances) wishing that there [40]should be a return of attachment, but wishing to judge of her dispositions, to know how far they might be not unfavourable or disengaged, and to know what foundation I might afterwards have to count on. I received no encouragement whatever. She told me she had no attachment for any person, nor did she seem likely to have any that could make her wish to quit you. I stayed away till the time had elapsed, when I found that the event to which I allude was to be postponed indefinitely. I returned, by a kind of infatuation, thinking that to myself only was I giving pleasure or pain. I perceived no progress of attachment on her part, nor anything in her conduct to distinguish me from a common acquaintance. Afterwards I had reason to suppose that [political] discoveries were made, and that I should be obliged to quit the kingdom immediately. I came to make a renunciation of any approach to friendship that might have been formed. On that very day she herself spoke to me to discontinue my visits; I told her it was my intention, and I mentioned the reason. I then for the first time found, when I was unfortunate, by the manner in which she was affected, that there was a return of affection, and that it was too late to retreat. My[41] own apprehensions also I afterwards found were without cause; and I remained. There has been much culpability on my part in all this, but there has also been a great deal of that misfortune which seems uniformly to have accompanied me. That I have written to your daughter since an unfortunate event [the arrest], has taken place, was an additional breach of propriety for which I have suffered well; but I will candidly confess that I not only do not feel it to have been of the same extent, but that I consider it to have been unavoidable after what had passed. For though I shall not attempt to justify in the smallest degree my former conduct, yet, when an attachment was once formed between us (and a sincerer one never did exist), I feel that, peculiarly circumstanced as I then was, to have left her uncertain of my situation would neither have weaned her affections nor lessened her anxiety; and looking upon her as one whom, if I lived, I hoped to have had my partner for life, I did hold the removing of her anxiety above every other consideration. I would rather have the affections of your daughter in the back settlements of America, than the first situation this country could offer without them. I know not whether this will be any extenuation of my[42] offence; I know not whether it will be any extenuation of it to know that if I had that situation in my power at this moment I would relinquish it to devote my life to her happiness; I know not whether success would have blotted out the recollection of what I have done; but I [do] know that a man with the coldness of death on him need not to be made to feel any other coldness, and that he may be spared any addition to the misery he feels, not for himself, but for those to whom he has left nothing but sorrow.”

It is apparent from this page that the great Mr. Curran had not withheld from one under misfortune some crumbs of that verbal opulence for which he was famous. Emmet’s disclaimer of any eagerness on Sarah’s part in reciprocating his devotion is a knightly one. The interpretation of her maidenly conduct, purely chivalric, was designed to exculpate her in her over-lord’s eyes.

Poor Sarah, thus rudely informed by events of her Robert’s arrest, in an hour of unprecedented torment, did not lack the tender consideration from the Chief Secretary and the Attorney-General, which her innocent misery deserved. Lord Hardwicke, too, directed that no action of any kind should be taken against[43] her. But the stress of this last summer day was too much for her after the intense emotional life she had been bearing so long alone. In the breath of her love’s exposure and of her father’s anger head and heart seemed to break together, and for months to come she was to be wholly and most mercifully exempt from the “rack of this rough world.” On September 16, the Home Secretary was able to felicitate the Lord Lieutenant from Whitehall on his generous treatment of the implicated rebel at the Priory: “Your delicacy and management,” he says, “with regard to the Curran family is highly applauded. The King is particularly pleased with it. It is a sad affair. Mademoiselle seems a true pupil of Mary Wollstonecraft.” This, of course, amounts to the accusation that gentle little Sarah, with her sweet eyes and her “most harmonious voice,” was guilty of doing her own thinking, and of doing it, which was worst of all, upon political matters. It supplies us, at any rate, with evidence of the wide and deep grounds for Emmet’s true passion for the girl whose national ideals could so fearlessly keep pace with his own. Heart and brain, soul and body, she would have been his perfect mate. Her father’s harshness was the one element needed to perfect[44] Sarah’s desolation. Her real life closed without conscious pain, and remained for a decent space buried. She never had to look in the face the day of Emmet’s death, the all-significant day “under her solemn fillet;” for that had tiptoed past her while her reason slept. The good sister Amelia, afterwards Shelley’s friend and portrait-painter in Italy, as soon as Sarah could be moved, took her away from the intolerable home, and left her with loving Quaker friends, the Penroses of Cork. During all the time of her affliction and illness at the Priory, Mr. Curran is said never to have looked upon his youngest daughter’s face; and from the hour of her leaving Dublin, presumably under an allowance made for her support, he seems neither ever to have sent her a message, nor to have thought of her again.

There are several historic instances of a like fatherliness in fathers, a century ago. Mr. Curran doubtless felt outraged in every fibre, and not more indignant at the independent conduct of his meek domestic vassal than at the astounding ignorance in which she had contrived to keep him. Yet there were powerful pleas for compassion in such a case inherent in his own history. In early manhood he[45] himself had figured as collaborator in a similar headlong falling in love, a similar breach of parental discipline. John Philpot Curran had been for a short time tutor in the family of a fellow-Whig, Dr. Richard Creagh of Creagh Castle, near Spenser’s Doneraile, when with Miss Creagh, a young lady of beauty and of moderate fortune, he contracted a private marriage. The discovery brought on storms; but on further reflection Dr. Creagh saw fit to forgive the offenders, to receive them once more beneath his roof, and even to allow his daughter’s portion to be expended without stint on Mr. Curran, until he had completed his legal studies in London, and begun to establish his inevitable ascendancy at the Bar. The match, however, seems never to have been a happy one. Conjugal differences seldom lack their annotation. Without adopting the adjective missiles of either faction, let it suffice to say that they parted, in the summary fashion of which we are already aware. Mr. Curran had earned a right, he may have thought, to his opinion of women. The memory of his calamity may well have operated to make him both excessively exacting as to female behaviour and pitiless towards any supposed violation of it. In one touching story[46] of domestic ruin, at least, he had a deplorable influence. Mr. W. J. Fitzpatrick, in his Life, Times, and Contemporaries of Lord Cloncurry, records that after the Lady Cloncurry’s trespass, her generous husband would have taken her back, “were it not for his well-beloved J——n P——t C——n, who urged him, in strong and persuasive language, to the contrary.” Moreover, an Irish father is as likely as not to cherish spacious ideas of his own governing prerogative, and refuse to be tied in the matter to “anything so temporal,” as Lowell says in another application, “as a responsibility.” Mr. Curran could have bespoken for his children other destinies if they had ever known freedom of the heart at home.

Again, his attitude towards Emmet may have seemed to him no exaggerated hatred, but the mere tribute of virtuous scorn. In that, however, he was self-deceived. To any publicist in Ireland with the seed of compromise in him, even if the compromise never amounted to the smallest sacrifice of actual principle, Robert Emmet’s straight career must have been like a buffet in the face. Naked logic was Emmet’s element, and the expedient his negligible quantity. Every agitation sincerely founded[47] on a popular need breeds, in time, its extremists. They are the glory and the difficulty of all reform. It might have been said of Emmet, as at the outset of the Oxford Movement it was said of Hurrell Froude, that “the gentleman was not afraid of inferences.” Curran’s thoughts dwelt in no such simplified worlds. Like all the best Irishmen of his blazingly brilliant day, he was for Parliamentary Reform and Catholic Emancipation, and against the Union. It was even he who appeared to defend the revolutionists of 1798, who had obtained the writ of habeas corpus for Wolfe Tone on the very morning set for his execution under court-martial (a reprieve frustrated by suicide), and who was the first to plead, though with vain eloquence, at the bar of attainder for the Fitzgerald heirs. But though his convictions seemed close enough to Emmet’s, there was wide variance in their bearing and momentum. Initial or generic differences take on an almost amatory complexion when contrasted with those springing from the final consideration in like minds. Both men vehemently desired the framing of fresh good laws, and the unhampered operation of existing good laws, for Ireland. To Curran, incorruptible as he was, England was an excellent general superintendent[48] and referee to set over the concerns of other nations, including his own, provided that she could be got to abstain scrupulously from undue interference, and hold tenure under a more than nominal corporal withdrawal. Poor Emmet’s ideal of Irish independence was remote enough from this. He had read somewhere that his country used to be a proud kingdom, and not a petted province. Surely, Curran in his latter years, when he “sank” (the word is Cloncurry’s, and used of his friend) to office, could have no patience with a Separatist son-in-law. But the Master of the Rolls continued to be a great man, and Emmet at twenty-five ceased to be a fool.

The trial came off before Lord Norbury, Mr. Baron George, and Mr. Baron Daly on September 19, 1803, at the court-house in Green Street. It is an extraordinary circumstance that it lasted eleven hours in a crowded room, the prisoner standing for all that time in the dock without proper food or rest. Mr. Emmet firmly refused to call any witnesses, to allow any statement by his counsel, or to furnish any comment upon the evidence. Long afterwards, Mr. Peter Burrowes told Moore of the continual check put upon his own attempts to disconcert[49] those who were giving testimony. “No, no,” Emmet would protest, “the man is speaking the truth.” The indictment was in part strengthened by the reading in court of passages of his own captured love-letters to Miss Curran. Thanks to the consideration of the Attorney-General the reading was brief and as non-committal as possible, Miss Curran’s name being of course suppressed. The Attorney-General (Mr. Standish O’Grady) showed, throughout the poor girl’s troubles, a most fatherly solicitude towards her, and pleaded for her with her own father, without appreciable results.

Emmet had other annoyances to bear. Mr. Conyngham Plunkett, as counsel for the Crown, took an unfair advantage of the silence of the counsels for the prisoner (Messrs. Ball, Burrowes, and M’Nally), and delivered at great length a very able oration, in which, more Hibernico, he had rather more to say of the Creator of men, and of His implicit support of the existing Government, than was strictly necessary; neither did he forget to recommend “sincere repentance of crime” to “the unfortunate young gentleman.” And when Emmet himself was invited to speak, and did so, or would[50] have done so, to really magnificent purpose, he was causelessly and continually interrupted by the presiding judge, lectured on the virtues and the standing of his long-deceased elder brother, and on the abominable anomaly of “a gentleman by birth” associating with “the most profligate and abandoned . . . hostlers, bakers, butchers, and such persons!” A sprig of lavender was handed him by some woman in the close court-room; it was snatched away as soon, on the groundless suspicion that it had been poisoned by one who would save the youth from his approaching fate. The jury, without leaving the box, brought in a verdict of guilty. It was to them a clear case. As the Earl of Hardwicke wrote to his brother, the Honourable Charles Yorke, “it was unanimously admitted that a more complete case of treason was never stated in a court of justice.” Of Emmet himself he adds conclusively: “He persisted in the opinions he had entertained, and the principles in which he had been educated.”

It was late in the evening when the Clerk of the Crown, following the usual form, ended: “Prisoner at the bar, what have you therefore now to say why judgment of death and execution should not be awarded against you according to law?” Emmet[51] was weary, but had body and mind under triumphant control, and he filled the next half-hour with words which were overwhelming at the time, and will never fail to thrill the most casual reader who can discern in them the victory of the human spirit over the powers which crush it. It is an immortal appeal. The rich phrases, the graceful, quick gestures, were unprepared and born of the moment. We are told that Emmet walked about a little, or stood bending hither and thither, in his earnestness. “He seemed to have acquired a swaying motion, when he spoke in public, which was peculiar to him; but there was no affectation in it.” It was a habit which the young man shared with a great contemporary singularly free from mannerisms: the Grattan to whom he used to listen, spell-bound, in his early years. Emmet has been misreported in one important particular. He had a fine understanding of the uses of irony; but it is his praise that he was also scrupulously, persistently, and invincibly courteous. To know him is to know that sentences such as those figuring in some reports of his speech, about “that viper,” meaning (Mr. Plunkett), or “persons who would not disgrace themselves by shaking your (that is, Lord Norbury’s)[52] blood-stained hand,” are, as attributed to him, all but impossible. The truth seems to be that his admirers, finding him unaccountably lacking in invective, and the vituperative power of the Gael, have amended, between them, this evidence of his undutiful shortcomings. It were a pity to summarise or paraphrase that living rhetoric, so fit in its place. We are disposed to forget nowadays that emotional speech is natural speech: its many and seemingly exuberant colours are but primal and legitimate, whereas it is our subdued daily chatter which is artificial. Emmet did not occupy himself with refuting the charge of having revolted against existing political conditions with “the scum of the Liberties behind him,” for he had a concern more intimate. It had been reported broadcast, and it had been taken for granted at the trial, that he had become an agent of France because he sought to deliver the country over to French rule. Hopeless, there and then, of being understood on the main issue, he was determined to make himself plain in this. He admitted that he had indeed laboured to establish a French alliance, but expressly under bond that aided Ireland, once freed, should be as completely independent of France as he would[53] have her of England. He sought, as he said, such a guarantee as Franklin had secured for America. For the reassertion of his own position as a patriot, Emmet spent his last energies. Like some few other selfless reformers known to history, he had taken little pains to proclaim himself, and in consequence had been translated into terms of expected profit and personal ambition, in the generalising minds of bystanders. It was nothing to him to go to his untimely grave legally convicted of Utopianism, precipitation, madness, or even of monstrous wickedness; but why he had plunged into such folly, or such crime, or such pure passion for freedom, as the case might be, seemed to demand some explanation from the person best qualified to give it. To risk that his informing intent should be misread hereafter, was more than he could bear. And thus it came about that, reserved as he always was, humble as he always was, he blazed out at last, and feared not to base himself proudly on “my character.” The word recurs: its numerical strength is almost equal to that of the beloved other one, “my country.” This was clearly a tautologous egotist, this young belated Girondin, to those who knew him not. As he talked on, in his beautiful[54] round tones, into the night, the dingy lamps begun to sputter as if tired of their unexpected vigil. “My lamp of life is nearly extinguished,” he said, looking sadly down. And then: “My race is run. The grave opens to receive me, and I sink into its bosom. I have but one request to make, at my departure from this world: it is the charity of its silence. Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice nor ignorance asperse them. Let them rest in obscurity and peace; let my memory remain in oblivion, and my tomb remain uninscribed, until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country shall have taken her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done.” There was perceptible emotion in every breast but his, when sentence of death by hanging and beheading was given at half-past ten o’clock, and ordered to take place next day.

Emmet’s strong slight frame had stood the long ordeal perfectly, and his mood had wings. He whispered cheerfully through the grating: “I shall be hanged to-morrow!” as he passed John Hickson’s cell on his way back to his own.

We know he read the Litany there; and he also indulged a turn for secular, and even profane employment. In fact, it pleased Mr. Robert Emmet to draw himself (he drew exquisitely) as a posthumous serial in two parts. Some one found and recognised the grim R. E., head, the disconcerted R. E., body, on separate scraps of paper: they lay on his little table, when all was over, witnesses to the detached humour possible to an easy conscience. His industry was great during the few remaining hours. He possessed a lock of his absent Sarah’s hair, which she may have given him years before: this he wished to wear in his dying hour. As he sat plaiting it minutely, and tenderly fastening it into the fold of his velvet stock, he was noticed and questioned. Fearing that the treasure might be taken from him, he said that his occupation was “an innocent one.” The only persons allowed to see him were the chaplains and M’Nally, the fine flower of infamy, happy in Government pay, who to the end played with success the part of the assiduous friend. It was he who brought to Emmet on his final morning the news, then ten days old, of his mother’s death. The son took it, as he took all his losses, with what Mr. W. H.[56] Curran briefly calls his “unostentatious fortitude.” After an instant of silence he looked up and found his voice. “It is better so,” he answered quietly. Her delicate proud heart had broken at the menace hanging over her darling: that much he had divined at once. She had written, during that last year, that she was “a parent supremely blest” in the virtues and dispositions of her children.

Mr. M’Nally was intimate with Mr. Curran, for whom he had an affection as genuine as he was capable of feeling. It was like “Janus” Wainewright’s affection for Charles Lamb, and as exempt from the poison-cup otherwise dealt impartially to divers and sundry. It is possible, therefore, that Mr. M’Nally chose to acquaint his much-deceived client with the true state of Sarah’s health: a life-in-death which also was surely “better so.” But this is mere conjecture, as Emmet would never have inquired; rather than name his “nut-brown maid,” the truly “banished man” would still have endured all the inner turmoil of lonely love,

No credit need be given to the tale that as Emmet[57] went forth to his death through the Dublin streets, a young lady, believed to be Miss Curran, was seen in a carriage despairingly taking leave of him, and fluttering a handkerchief until he was out of sight, when she sank in a swoon. It is not the fashion of persons of deep feeling, save on the stage, to have recourse at solemn moments to fluttering handkerchiefs. If any young lady interested in Robert Emmet were abroad in a carriage on that autumn morning, it would be his only sister, Mrs. Holmes, fated to outlive him but one melancholy year. As for poor lovely Sarah, she had disappeared like an underground stream during his last weeks and days, ever since her letters were seized as spoils of war. Major Sirr is believed to have destroyed them all, in due course, not without a flow of tears! The sweet lady was indeed an object of pity; and Emmet, putting in never a stroke of conscious work, had a most unaccountable faculty for melting hearts. The reign of Sensibility was not over; able-bodied persons in 1803 were only beginning to be carried out of the pit, more dead than alive, when Mrs. Siddons played. But something in Emmet’s uncomplaining presence overcame stern men habituated to political offenders. The honest turnkey at Kilmainham fell fainting at his feet, only[58] to hear the affectionately-proffered good-bye; and it was generally noticed that Lord Norbury, facing him, could with difficulty steady his voice, though he was popularly believed to revel in pronouncing capital sentence.

Emmet busied himself with letters in his cell. He slept and ate as usual; and his firm handwriting witnessed the unshaken soul within. Several of his last letters have been recovered; two or three have been published, in Mr. W. H. Curran’s Life of his illustrious father, in Dr. Madden’s moving but chaotic Memoirs of the United Irishmen, and elsewhere. On the day set for his execution Robert Emmet wrote to his old friend Richard Curran:—

“My dearest Richard: I find I have but a few hours to live; but if it was the last moment, and the power of utterance was leaving me, I would thank you from the bottom of my heart for your generous expressions of affection and forgiveness to me. If there was any one in the world in whose breast my death might be supposed not to stifle every spark of resentment, it might be you. I have deeply injured you; I have injured the happiness of a sister that you love, and who was formed to give happiness to every[59] one about her, instead of having her own mind a prey to affliction. Oh, Richard! I have no excuse to offer, but that I meant the reverse: I intended as much happiness for Sarah as the most ardent love could have given her. I never did tell you how much I idolised her. It was not with a wild or unfounded passion, but it was an attachment increasing every hour, from an admiration of the purity of her mind, and respect for her talents. I did dwell in secret upon the prospect of our union; I did hope that success, while it afforded the opportunity of our union, might be a means of confirming an attachment which misfortune had called forth. I did not look to honours for myself; praise I would have asked from the lips of no man: but I would have wished to read, in the glow of Sarah’s countenance, that her husband was respected. My love, Sarah! it was not thus that I thought to have requited your affection. I did hope to be a prop round which your affections might have clung, and which would never have been shaken; but a rude blast has snapped it, and they have fallen over a grave. This is no time for affliction. I have had public motives to sustain my mind, and I have not suffered it to sink; but there have been moments in my imprisonment[60] when my mind was so sunk by grief on her account that death would have been a refuge. God bless you, my dearest Richard. I am obliged to leave off immediately. Robert Emmet.”

This touching letter has been printed before, but the two which follow, long lost and newly found, have never been made public. The original letters seem to have disappeared. The contemporary copies figure in the Hardwicke or Wimpole collection, which has very recently been made accessible to readers by the issue of the current Catalogue of Additional Manuscripts at the British Museum. The shorter of them was intended by Emmet for Thomas Addis Emmet and his wife Jane Patten, his brother and sister-in-law. With it was sent a long historical document, called An Account of the late Plan of Insurrection in Dublin, and the Causes of its Failure. Hurriedly penned, in order to give the beloved relatives a unique and direct knowledge of all that the writer had meant and missed, it is a masterly detailed statement, as free from all traces of morbidity, or even of agitation, as if it had been drawn up “on happy mornings with a morning heart,” in the tents of victory.[61] Thanks to the practised duplicity of Dr. Trevor, to whose care it was confided, Mr. Thomas Addis Emmet, then in Paris, never received it; he complained bitterly of its suppression, and was only towards the close of his life enabled to read it through the medium of the press. But neither he nor any of his American descendants, inclusive of the distinguished compiler of the quarto, privately printed in New York, entitled The Emmet Family, seems to have suspected the existence of the little personal note in which the Account was enclosed. The official draft of it figures in Hard. MS. 35,742, f. 197:—

“My dearest Tom and Jane: I am just going to do my last duty to my country. It can be done as well on the scaffold as in the field. Do not give way to any weak feelings on my account, but rather encourage proud ones that I have possessed fortitude and tranquillity of mind to the last.

“God bless you, and the young hopes that are growing up about you. May they be more fortunate than their uncle, but may they preserve as pure and ardent an attachment to their country as he has done. Give the watch to little Robert; he[62] will not prize it the less for having been in the possession of two Roberts before him. I have one dying request to make to you. I was attached to Sarah Curran, the youngest daughter of your friend. I did hope to have had her my companion for life; I did hope that she would not only have constituted my happiness, but that her heart and understanding would have made her one of Jane’s dearest friends. I know that Jane would have loved her on my account, and I feel also that, had they been acquainted, she must have loved her for her own. None knew of the attachment till now, nor is it now generally known; therefore do not speak of it to others. [I leave her][2] with her father and brother; but if those protectors should fall off, and that no other should replace them, [take][2] her as my wife, and love her as a sister. Give my love to all friends.”

It is to be feared that “little Robert” (the eldest of the children, afterwards Judge Robert Emmet of New York) did not receive his legacy. According [63]to what testimony can be gathered, the watch which Emmet carried to the last was either presented to the executioner, or passed over to him with some understanding which has not transpired. Poor Emmet’s seal, a beautiful design of his own for the United Irishmen, went safely into friendly keeping; but most of his personal belongings worn on the scaffold, including his high Hessian boots and the stock with the precious hair sewed inside the lining, were actually sold at auction in Grafton Street, Dublin, during December, 1832. In this letter to his brother and sister, how piercing is the “I did hope,” iterated to them as to Richard Curran! It reminds us what a network of beneficent will and forethought made up that intense nature, and how the perishing leaf was but in the green. When the Lord Lieutenant, in the course of his industrious correspondence with his brother, sent to him, as a literary curio, a copy of Robert Emmet’s letter (Robert himself being newly dead), in reference to it, he hastens to add this significant sentence: “The letter to his brother will not be forwarded; but the passage respecting Miss Sarah Curran has been communicated to her father.” The Chief Secretary and Lord Hardwicke were joint contrivers[64] of what seems to us (from the point of view of the most helpless of the persons chiefly concerned) an unnecessary if not unfeeling move. And Mr. Curran promptly replied to the former, the Right Honourable William Wickham, on the morrow (Hard. MS. 35,703, f. 158):—

“Sir: I have just received the honour of your letter, with the extract enclosed by desire of His Excellency. I have again to offer to His Excellency my more than gratitude, the feelings of the strongest attachment and respect for this new instance of considerate condescension. To you also, sir, believe me, I am most affectionately grateful for the part that you have been so kind as [to] take upon this unhappy occasion; few would, I am well aware, perhaps few could, have known how to act in the same manner.

“As to the communication of the extract, and the motive for doing so, I cannot answer them in the cold parade of official acknowledgment; I feel on the subject the warm and animated thanks of man to man, and these I presume to request that Lord Hardwicke and Mr. Wickham may be pleased[65] to accept: it is, however, only justice to myself to say, that even on the first falling of this unexpected blow, I had resolved (and so mentioned to Mr. Attorney-General), that if I found no actual guilt upon her, I would act with as much moderation as possible towards a poor creature that had once held the warmest place in my heart. I did, even then, recollect that there was a point to which nothing but actual turpitude or the actual death of her parent ought to make a child an orphan; but even had I thought otherwise, I feel that this extract would have produced the effect it was intended to have, and that I should think so now. I feel how I should shrink from the idea of letting her sink so low as to become the subject of the testamentary order of a miscreant who could labour, by so foul means and under such odious circumstances, to connect her with his infamy, and to acquire any posthumous interest in her person or her fate. Blotted, therefore, as she may irretrievably be from my society, or the place she once held in my affection, she must not go adrift. So far, at least, ‘these protectors will not fall off.’