Title: An American Patrician, or The Story of Aaron Burr

Author: Alfred Henry Lewis

Release date: May 1, 2016 [eBook #51911]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—FROM THEOLOGY TO LAW

CHAPTER II—THE GENTLEMAN VOLUNTEER

CHAPTER III—COLONEL BENEDICT ARNOLD EXPLAINS

CHAPTER IV—THE YOUNG FRENCH PRIEST

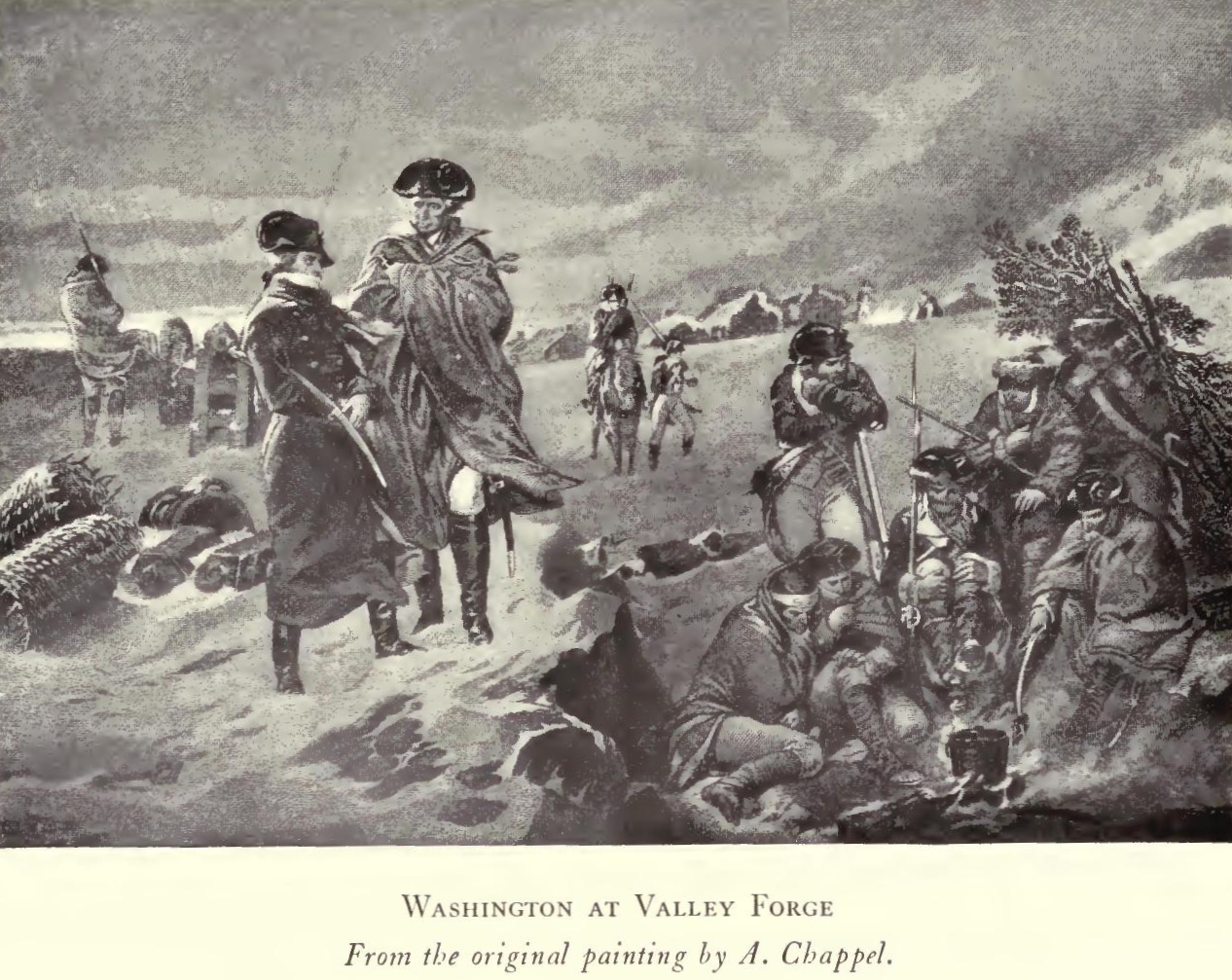

CHAPTER V—THE WRATH OF WASHINGTON

CHAPTER VI—POOR PEGGY MONCRIEFFE

CHAPTER VII—THE CONQUERING THEODOSIA

CHAPTER VIII—MARRIAGE AND THE LAW

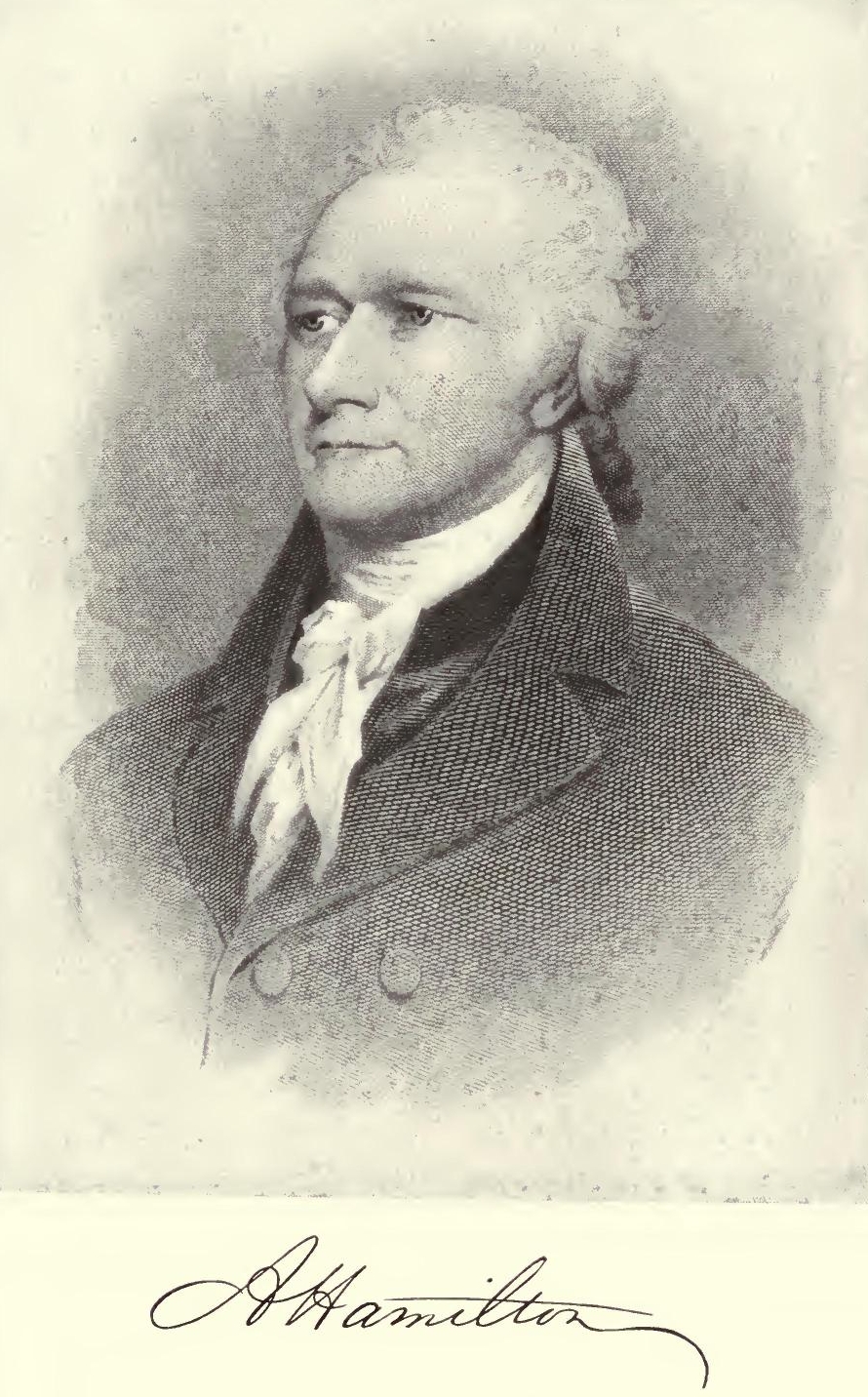

CHAPTER IX—SON-IN-LAW HAMILTON

CHAPTER X—THAT SEAT IN THE SENATE

CHAPTER XI—THE STATESMAN FROM NEW YORK

CHAPTER XII—IDLENESS AND BLACK RESOLVES

CHAPTER XIII—THE GRINDING OF AARON’S MILL

CHAPTER XIV—THE TRIUMPH OF AARON

CHAPTER XV—THE INTRIGUE OF THE TIE

CHAPTER XVI—THE SWEETNESS OF REVENGE

CHAPTER XVII—AARON I, EMPEROR OF MEXICO

CHAPTER XVIII—THE TREASON OF WILKINSON

CHAPTER XIX—HOW AARON IS INDICTED

CHAPTER XX—HOW AARON IS FOUND INNOCENT

CHAPTER XXI—THE SAILING AWAY OF AARON.

CHAPTER XXII—HOW AARON RETURNS HOME

CHAPTER XXIII—GRIEF COMES KNOCKING

CHAPTER XXIV—THE DOWNFALL OF KING CAUCUS

CHAPTER XXV—THE SERENE LAST DAYS

THE Right Reverend Doctor Bellamy is a personage of churchly consequence in Bethlehem. Indeed, the doctor is a personage of churchly consequence throughout all Connecticut. For he took his theology from that well-head of divinity and metaphysics, Jonathan Edwards himself, and possesses an immense library of five hundred volumes, mostly on religion. Also, he is the author of “True Religion Delineated”; which work shines out across the tumbling seas of New England Congregationalism like a lighthouse on a difficult coast. Peculiarly is it of guiding moment to storm-vexed student ones, who, wanting it, might go crashing on controversial reefs, and so miss those pulpit snug-harbors toward which the pious prows of their hopes are pointed.

The doctor has a round, florid face, which, with his well-fed stomach, gives no hint of thin living. From the suave propriety of his cue to the silver buckles on his shoes, his atmosphere is wholly clerical. Just now, however, he wears a disturbed, fussy air, as though something has rubbed wrong-wise the fur of his feelings. He shows this by the way in which he trots up and down his study floor. Doubtless, some portion of that fussiness is derived from the doctor’s short fat legs; for none save your long-legged folk may walk to and fro with dignity. Still, it is clear there be reasons of disturbance which go deeper than mere short fat legs, and set his spirits in a tumult.

The good doctor, as he trots up and down, is not alone. Madam Bellamy is with him, chair drawn just out of reach of the June sunshine as it comes streaming through the open lattice. In her plump hands she holds her sewing; for she is strong in the New England virtue of industry, and regards hand-idleness as a species of viciousness. While she stitches, she bends appreciative ear to the whistle of a robin in an apple tree outside.

“No, mother,” observes the doctor, breaking in on the robin, “the lad does himself no credit. He is careless, callous, rebellious, foppish, and altogether of the flesh. I warrant you I shall take him in hand; it is my duty.”. “But no harshness, Joseph!”

“No, mother; as you say, I must not be harsh. None the less I shall be firm. He must study; he is not to become a preacher by mere wishing.”

Shod hoofs are heard on the graveled driveway; a voice is lifted:

“Walk Warlock up and down until he is cooled out. Then give him a rub, and a mouthful of water.”

Madam Bellamy steps to the window. The master of the voice is swinging from the saddle, while the doctor’s groom takes his horse—sweating from a brisk gallop—by the bridle.

“Here he comes now,” says Madam Bellamy, at the sound of a springy step in the hall.

The youth, who so confidently enters the doctor’s study, is in his nineteenth year. His face is sensitive and fine, and its somewhat overbred look is strengthened and restored by a high hawkish nose. The dark hair is clubbed in an elegant cue. The skin, fair as a girl’s, gives to the black eyes a glitter beyond their due. These eyes are the striking feature; for, while the eyes of a poet, they carry in their inky depths a hard, ophidian sparkle both dangerous and fascinating—the sort of eyes that warn a man and blind a woman.

The youth is but five feet six inches tall, with little hands and feet, and ears ridiculously small. And yet, his light, slim form is so accurately proportioned that, besides grace and a catlike quickness, it hides in its molded muscles the strength of steel. Also, any impression of insignificance is defeated by the wide brow and well-shaped head, which, coupled with a steady self-confidence that envelops him like an atmosphere, give the effect of power.

As he lounges languidly and pantherwise into the study, he bows to Madam Bellamy and the good doctor.

“You had quite a canter, Aaron,” remarks Madam Bellamy.

“I went half way to Litchfield,” returns the youth, smiting his glossy riding boot with the whip he carries. “For a moment I thought of seeing my sister Sally; but it would have been too long a run for so warm a day. As it is, poor Warlock looks as though he’d forded a river.”

The youth throws himself carelessly into the doctor’s easy-chair. That divine clears his throat professionally. Foreseeing earnestness if not severity in the discourse which is to follow, Madam Bellamy picks up her needlework and retires.

When she is gone, the doctor establishes himself opposite the youth. His manner is admonitory; which is not out of place, when one remembers that the doctor is fifty-five and the youth but nineteen.

“You’ve been with me, Aaron, something like eight months.”

The black eyes are fastened upon the doctor, and their ophidian glitter makes the latter uneasy. For relief he rebegins his short-paced trot up and down.

Renewed by action, and his confidence returning, the doctor commences with vast gravity a kind of speech. His manner is unconsciously pompous; for, as the village preacher, he is wont to have his wisdom accepted without discount or dispute.

“You will believe me, Aaron,” says the doctor, spacing off his words and calling up his best pulpit voice—“you will believe me, when I tell you that I am more than commonly concerned for your welfare. I was the friend of your father, both when he held the pulpit in Newark, and later when he was President of Princeton University. I studied my divinity at the knee of your mother’s father, the pious Jonathan Edwards. Need I say, then, that when you came to me fresh from your own Princeton graduation my heart was open to you? It seemed as though I were about to pay an old debt. I would regive you those lessons which your grandfather Edwards gave me. In addition, I would—so far as I might—take the place of that father whom you lost so many years ago. That was my feeling. Now, when you’ve been with me eight months, I tell you plainly that I’m far from satisfied.”

“In what, sir, have I disappointed?”

The voice is confidently careless, while the ophidian eyes keep up their black glitter unabashed.

“Sir, you are passively rebellious, and refuse direction. I place in your hands those best works of your mighty grandsire, namely, his ‘Qualifications for Full Communion in the Visible Church’ and ‘The Doctrine of Original Sin Defended,’ and you cast them aside for the ‘Letters of Lord Chesterfield’ and the ‘Comedies of Terence.’ Bah! the ‘Letters of Lord Chesterfield’! of which Dr. Johnson says, ‘They teach the morals of a harlot and the manners of a dancing master.’”

“And if so,” drawls the youth, with icy impenitence, “is not that a pretty good equipment for such a world as this?”

At the gross outrage of such a question, the doctor pauses in that to-and-fro trot as though planet-struck.

“What!” he gasps.

“Doctor, I meant to tell you a month later what—since the ice is so happily broken—I may as well say now. My dip into the teachings of my reverend grandsire has taught me that I have no genius for divinity. To be frank, I lack the pulpit heart. Every day augments my contempt for that ministry to which you design me. The thought of drawing a salary for being good, and agreeing to be moral for so much a year, disgusts me.”

“And this from you—the son of a minister of the Gospel!” The doctor holds up his hands in pudgy horror.

“Precisely so! In which connection it is well to recall that German proverb: ‘The preacher’s son is ever the devil’s grandson.’” The doctor sits down and mops his fretted brow; the manner in which he waves his lace handkerchief is like a publication of despair. He fixes his gaze on the youth resignedly, as who should say, “Strike home, and spare not!”

This last tacit invitation the youth seems disposed to accept. It is now his turn to walk the study floor. But he does it better than did the fussy doctor, his every motion the climax of composed grace.

“Listen, my friend,” says the youth.

For all the confident egotism of his manner, there is in it no smell of conceit. He speaks of himself; but he does so as though discussing some object outside of himself to which he is indifferent.

“Those eight months of which you complain have not been wasted. If I have drawn no other lesson from my excellent grandsire’s ‘Doctrine of Original Sin Defended,’ it has taught me to exhaustively examine my own breast. I discover that I have strong points as well as points of weakness. I read Latin and Greek; and I talk French and German, besides English, indifferently well. Also, I fence, shoot, box, ride, row, sail, walk, run, wrestle and jump superbly. Beyond the merits chronicled I have tried my courage, and find that I may trust it like Gibraltar. These, you will note, are not the virtues of a clergyman, but of a soldier. My weaknesses likewise turn me away from the pulpit.

“I have no hot sympathies; and, while not mean in the money sense, holding such to be beneath a gentleman, I may say that my first concern is not for others but for myself.”

“It is as though I listened to Satan!” exclaims the dismayed doctor, fidgeting with his ruffles.

“And if it were indeed Satan!” goes on the youth, with a gleam of sarcasm, “I have heard you characterize that arch demon from your pulpit, and even you, while making him malicious, never made him mean. But to get on with this picture of myself, which I show you as preliminary to laying bare a resolution. As I say, I have no sympathies, no hopes which go beyond myself. I think on this world, not the next; I believe only in the gospel according to Philip Dormer Stanhope—that Lord Chesterfield, whom, with the help of Dr. Johnson, you so much succeed in despising.”

“To talk thus at nineteen!” whispers the doctor, his face ghastly.

“Nineteen, truly! But you must reflect that I have not had, since I may remember, the care of either father or mother, which is an upbringing to rapidly age one.”

“Were you not carefully reared by your kind Uncle Timothy?” This indignantly.

“Indeed, sir, I was, as you say, well reared in that dull town of Elizabeth, which for goodness and dullness may compare with your Bethlehem here. It was a rearing, too, from which—as I think my kind Uncle Timothy has informed you—I fled.”

“He did! He said you played truant twice, once running away to sea.”

“It was no great voyage, then!” The imperturbable youth, hard of eye, soft of voice, smiles cynically. “No, I was cabin boy two days, during all of which the ship lay tied bow and stern to her New York wharf. However, that is of no consequence as part of what we now consider.”

“No!” interrupts the doctor miserably, “only so far as it displays the young workings of your sinfully rebellious nature. As a child, too, you mocked your elders, as you do now. Later, as a student, you were the horror of Princeton.”

“All that, sir, I confess; and yet I say that it is of the past. I hold it time lost to think on aught save the present or the future.”

“Think, then, on your soul’s future!—your soul’s eternal future!”

“I shall think on what lies this side of the grave. I shall devote my faculties to this world; which, from what I have seen, is more than likely to keep me handsomely engaged. The next world is a bridge, the crossing of which I reserve until I come to it.”

“Have you then no religious convictions? no fears?”

“I have said that I fear nothing, apprehend nothing. Timidity, of either soul or body, was pleasantly absent at my birth. As for convictions, I’d no more have one than I’d have the plague. What is a conviction but something wherewith a man vexes himself and worries his neighbor. Conclusions, yes, as many as you like; but, thank my native star! I am incapable of a conviction.”

The doctor’s earlier horror is fast giving way to anger. He almost sneers as he asks:

“But you pretend to honesty, I trust?”

“Why, sir,” returns the youth, with an air which narrowly misses the patronizing, and reminds one of nothing so much as polished brass—“why, sir, honesty, like generosity or gratitude, is a gentlemanly trait, the absence of which would be inexpressibly vulgar. Naturally, I’m honest; but with the understanding that I have my honesty under control. It shall never injure me, I tell you! When its plain effect will be to strengthen an enemy or weaken myself, I shall prove no such fool as to give way to it.”

“While you talk, I think,” breaks in the doctor; “and now I begin to see the source of your pride and your satanism. It is your own riches that tempt you! Your soul is to be undone because your body has four hundred pounds a year.”

“Not so fast, sir! I am glad I have four hundred pounds a year. It relieves me of much that is gross. I turn my back on the Church, however, only because I am unfitted for it, and accept the world simply for that it fits me. I have given you the truth. As a minister of the Gospel I should fail; as a man of the world I shall succeed. The pulpit is beyond me as religion is beyond me; for I am not one who could allay present pain by some imagined bliss to follow after death, or find joy in stripping himself of a benefit to promote another.”

“Now this is the very theology of Beelzebub for sure!” cries the incensed doctor.

“It is anything you like, sir, so it be understood as a description of myself.”

“Marriage might save him!” muses the desperate doctor. “To love and be loved by a beautiful woman might yet lead his heart to grace!”

The pale flicker of a smile comes about the lips of the black-eyed one.

“Love! beauty!” he begins. “Sir, while I might strive to possess myself of both, I should no more love beauty in a woman than riches in a man. I could love a woman only for her fineness of mind; wed no one who did not meet me mentally and sentimentally half way. And since your Hypatia is quite as rare as your Phoenix, I cannot think my nuptials near at hand.”

“Well,” observes the doctor, assuming politeness sudden and vast, “since I understand you throw overboard the Church, may I know what other avenue you will render honorable by walking therein?”

“You did not give me your attention, if you failed to note that what elements of strength I’ve ascribed to myself all point to the camp. So soon as there is a war, I shall turn soldier with my whole heart.”

“You will wait some time, I fear!”

“Not so long as I could wish. There will be war between these colonies and England before I reach my majority. It would be better were it put off ten years; for now my youth will get between the heels of my prospects to trip them up.”

“Then, if there be war with England, you will go? I do not think such bloody trouble will soon dawn; still—for a first time to-day—I am pleased to hear you thus speak. It shows that at least you are a patriot.”

“I lay no claim to the title. England oppresses us; and, since one only oppresses what one hates, she hates us. And hate for hate I give her. I shall go to war, because I am fitted to shine in war, and as a shortest, surest step to fame and power—those solitary targets worthy the aim of man!”

“Dross! dross!” retorts the scandalized doctor. “Fame! power! Dead sea apples, which will turn to ashes on your lips! And yet, since that war which is to be the ladder whereon you will go climbing into fame and power is not here, what, pending its appearance, will you do?”

“Now there is a query which brings us to the close. Here is my answer ready. I shall just ride over to Sally, and her husband, Tappan Reeve, and take up Blackstone. If I may not serve the spirit and study theology, I’ll even serve the flesh and study law.”

And so the hero of these memoirs rides over to Litchfield, to study the law and wait for a war. The doctor and he separate in friendly son-and-father fashion, while Madam Bellamy urges him to always call her house his home. He is not so hard as he thinks, not so cynical as he feels; still, his self-etched portrait possesses the broader lines of truth. He is one whom men will follow, but not trust; admire, but not love. There is enough of the unconscious serpent in him to rouse one man’s hate, while putting an edge on another’s fear. Also, because—from the fig-leaf day of Eve—the serpent attracts and fascinates a woman, many tender ones will lose their hearts for him. They will dash themselves and break themselves against him, like wild fowl against a lighthouse in the night. Even as he rides out of Bethlehem that June morning, bright young eyes peer at him from behind safe lattices, until their brightness dies away in tears. As for him thus sighed over, his lashes are dry enough. Bethlehem, and all who home therein, from the doctor with Madam Bellamy, to her whose rose-red lips he kissed the latest, are already of the unregarded past. He wears nothing but the future on his agate slope of fancy; he is thinking only on himself and his hunger to become a god of the popular—clothed with power, wreathed of fame!

“Mother,” exclaims the doctor, “the boy is lost! Ambitious as Lucifer, he will fall like Lucifer!”

“Joseph!”

“I cannot harbor hope! As lucidly clear as glass, he was yet as hard as glass. If I were to read his fortune, I should say that Aaron Burr will soar as high to fall as low as any soul alive.”

YOUNG Aaron establishes himself in Litchfield with his pretty sister Sally, who, because he is brilliant and handsome, is proud of him. Also, Tappan Reeve, her husband, takes to him in a slow, bookish way, and is much held by his trenchant powers of mind.

Young Aaron assumes the law, and makes little flights into Bracton’s “Fleeta,” and reads Hawkins and Hobart, delighting in them for their limpid English. More seriously, yet more privately, he buries himself in every volume of military lore upon which he may lay hands; for already he feels that Bunker Hill is on its way, without knowing the name of it, and would have himself prepared for its advent.

In leisure hours, young Aaron gives Litchfield society the glory of his countenance. He flourishes as a village Roquelaure, with plumcolored coats, embroidered waistcoats, silken hose, and satin smalls, sent up from New York. Likewise, his ruffles are miracles, his neckcloths works of starched and spotless art, while at his hip he wears a sword—hilt of gilt, and sharkskin scabbard white as snow.

Now, because he is splendid, with a fortune of four hundred annual pounds, and since no girl’s heart may resist the mystery of those eyes, the village belles come sighing against him in a melting phalanx of loveliness. This is flattering; but young Aaron declines to be impressed. Polished, courteous, in amiable possession of himself, he furnishes the thought of a bright coldness, like sunshine on a field of ice. Not that anyone is to blame. The difference between him and the sighing ones, is a difference of shrines and altars. They sacrifice to Venus; he worships Mars. While he has visions of battle, they dream of wedding bells.

For one moment only arises some tender confusion. There is an Uncle Thaddeus—a dotard ass far gone in years! Uncle Thaddeus undertakes, behind young Aaron’s back, to make him happy. The liberal Uncle Thaddeus goes so blindly far as to explore the heart of a particular fair one, who mayhap sighs more deeply than do the others. It grows embarrassing; for, while the sighing one thus softly met accepts, when Uncle Thaddeus flies to young Aaron with the dulcet news, that favored personage transfixes him with so black a stare, wherefrom such baleful serpent rage glares forth, that our dotard meddler is fear-frozen in the very midst of his ingenuous assiduities. And thereupon the sighing one is left to sigh uncomforted, while Uncle Thaddeus finds himself the scorn of all good village opinion.

While young Aaron goes stepping up and down the Litchfield causeways, as though strutting in Jermyn Street or Leicester Square; while thus he plays the fine gentleman with ruffles and silks and shark-skin sword, skimming now the law, now flattering the sighing belles, now devouring the literature of war, he has ever his finger on the pulse, and his ear to the heart of his throbbing times. It is he of Litchfield who hears earliest of Lexington and Bunker Hill. In a moment he is all action. Off come the fine feathers, and that shark-skin, gilt-hilt sword. Warlock is saddled; pistols thrust into holsters. In roughest of costumes the fop surrenders to the soldier. It takes but a day, and he is ready for Cambridge and the American camp.

As he goes upon these doughty preparations, young Aaron finds himself abetted by the pretty Sally, who proves as martial as himself. Her husband, Tappan Reeve, easy, quiet, loving his unvexed life, from the law book on his table to the pillow whereon he nightly sleeps, cannot understand this headlong war hurry.

“You may lose your life!” cries Tappan Reeve.

“What then?” rejoins young Aaron. “Whether the day be far or near, that life you speak of is already lost. I shall play this game. My life is my stake; and I shall freely hazard it upon the chance of winning glory.”

“And have you no fear?”

The timid Tappan’s thoughts of death are ashen; he likes to live.

Young Aaron bends upon him his black gaze. “What I fear more than any death,” says he, “is stagnation—the currentless village life!”

Young Aaron, arriving at Cambridge, attaches himself to General Putnam. The grizzled old wolf killer likes him, being of broadest tolerations, and no analyst of the psychic.

There are seventeen thousand Americans scattered in a ragged fringe about Boston, in which town the English, taught by Lexington and Bunker Hill, are cautiously prone to lie close. Young Aaron makes the round of the camps. He is amazed by the unrule and want of discipline. Besides, he cannot understand the inaction, feeling that each new day should have its Bunker Hill. That there is not enough powder among the Americans to load and fire those seventeen thousand rifles twice, is a piece of military information of which he lives ignorant, for the grave Virginian in command confides it only to a merest few. Had young Aaron been aware of this paucity of powder, those long days, idle, vacant of event, might not have troubled him. The wearisome wonder of them at least would have been made plain.

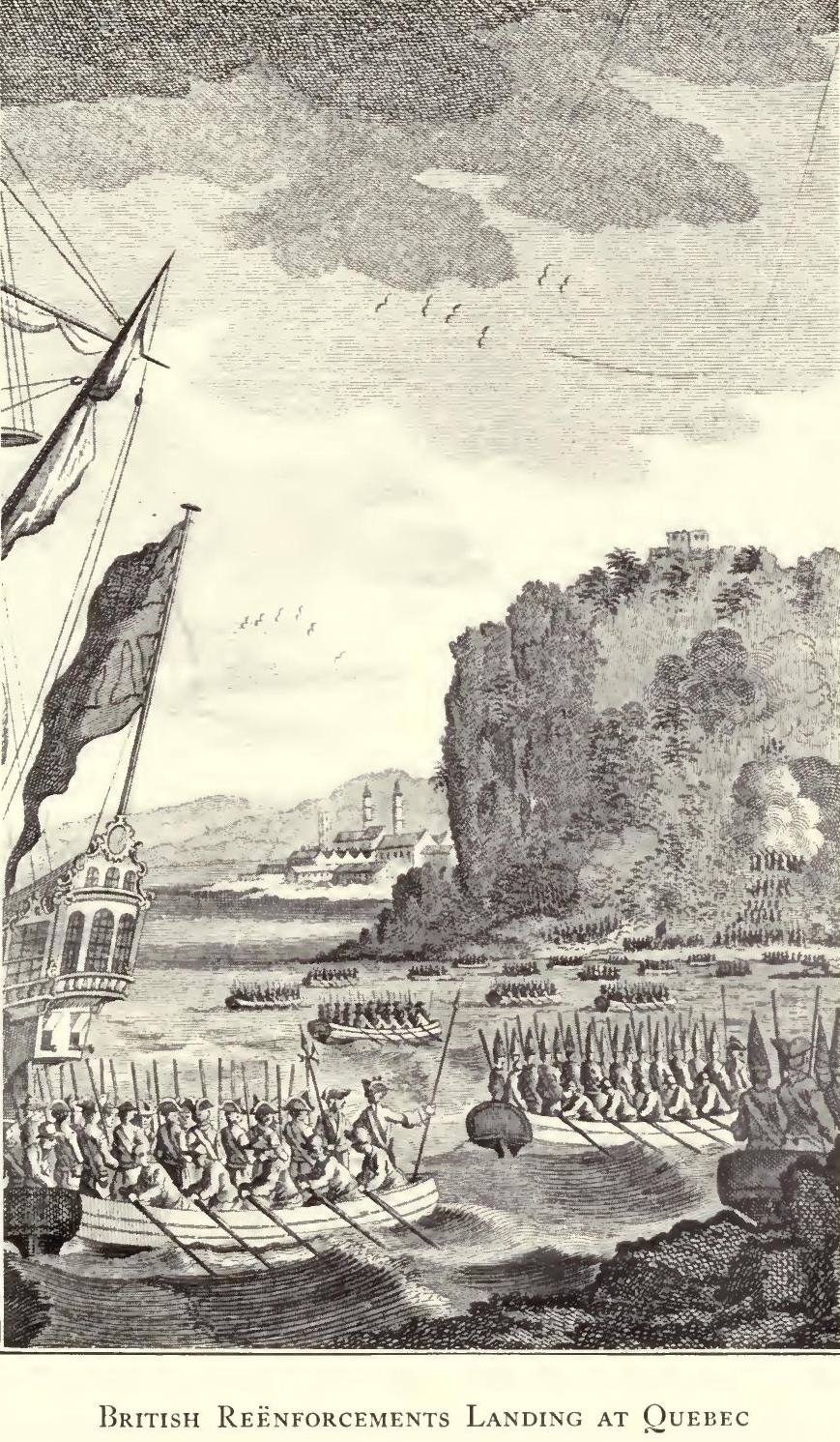

Young Aaron learns of an expedition against Quebec, to be led by Colonel Benedict Arnold, and resolves to join it. That all may be by military rule, he seeks General Washington to ask permission. He finds that commander in talk with General Putnam; the old wolf killer does him the favor of a presentation.

“From where do you come?” asks Washington, closely scanning young Aaron whom he instantly dislikes.

“From Connecticut. I am a gentleman volunteer, attached to General Putnam with the rank of captain.”

Something of repulsion shows cloudily on the brow of Washington. Obviously he is offended by this cool stripling, who clothes his hairless boy’s face with a confident maturity that has the effect of impertinence. Also the phrase “gentleman volunteer,” sticks in his throat like a fish bone.

“Ah, a ‘gentleman volunteer!’” he repeats in a tone of sarcasm scarcely veiled. “I have now and then heard of such a trinket of war, albeit, never to the trinket’s advantage. Doubtless, sir, you have made the rounds of our array!”

Young Aaron, from his beardless five feet six inches, looks up at the tall Virginian, and cannot avoid envying him his door-wide shoulders and that extra half foot of height. He perceives, too, with a resentful glow, that he is being mocked. However, he controls himself to answer coldly:

“As you surmise, sir, I have made the rounds of your forces.”

“And having made them”—this ironically—“I trust you found all to your satisfaction.”

“As to that,” remarks young Aaron, “while I did not look to find trained soldiers, I think that a better discipline might be maintained.”

“Indeed! I shall make a note of it. And yet I must express the hope that, while you occupy a subordinate place, you will give way as little as may be to your perilous trick of thinking, leaving it rather to our experienced friend Putnam, here, he being trained in these matters.”

The old wolf killer takes advantage of this reference to himself, to help the interview into less trying channels.

“You were seeking me?” he says to the youthful critic of camps and discipline.

“I was seeking the commander in chief,” returns young Aaron, again facing Washington. “I came to ask permission to go with Colonel Arnold against Quebec.”

“Against Quebec?” repeats Washington. “Go, with all my heart!”

There is a cut concealed in that consent, to the biting smart of which young Aaron is not insensible. However, he finds in the towering manner of its delivery something which checks even his audacity. After saluting, he withdraws without added word.

“General,” observes Washington, when young Aaron has gone, “I fear I cannot congratulate you on your new captain.”

“If you knew him better, general,” protests the good-hearted old wolf killer, “you would like him better. He is a boy; but he has an old head on his young shoulders.”

“The very thing I most fear,” rejoins Washington. “A boy has no more business with an old head than with old lungs or old legs. It is unnatural, sir; and the unnatural is the wrong. I want only heads and shoulders about me that were born the same day. For that reason, I am glad your ‘gentleman volunteer’”—this with a shade of irony—“goes to Quebec with that turbulent Norwich apothecary, Arnold. The army will be bettered just now by the absence of these lofty spirits. They disturb more than they help. Besides, a tramp of sixty days through the Maine woods will improve such Hotspurs vastly. There is nothing like a six-hundred mile march through an unbroken wilderness, with a fight in the snow at the far end of it, to take the edge off beardless arrogance and young conceit.”

What young Aaron carries away from that interview, as an impression of the big commander in chief, crops out in converse with his former college chum, young Ogden. The latter, like himself, is attached to the military family of General Putnam.

“Ogden, we have begun wrong as soldiers—you and I!” says young Aaron. “By flint and steel, man, we should have commenced like Washington, by hoeing tobacco!”

“Now this is not right!” cries young Ogden, in reproof. “General Washington is a soldier who has seen service.”

“Why,” retorts young Aaron, “I believe he was trounced with Braddock.” Then, warmly: “Ogden, the man is Failure walking about in blue and buff and high boots! I read him like a page of print! He is slow, dull, bovine, proud, and of no decision. He lacks initiative; and, while he might defend, he is incapable of attacking. Worst of all he has the soul of a planter—a plantation soul! A big movement like this, which brings the thirteen colonies to the field, is beyond his grasp.”

“Your great defect, Aaron,” cries young Ogden, not without indignation, “is that you regard your most careless judgment as final. Half the time, too, your decision is the product of prejudice, not reason. General Washington offends you—as, to be frank, he did me—by putting a lower estimate on your powers than that at which you yourself are pleased to hold them. I warrant now had he flattered you a bit, you would have found in him a very Alexander.”

“I should have found him what I tell you,” retorts young Aaron stoutly, “a glaring instance of misplaced mediocrity. He is even wanting in dignity!”

“For my side, then, I found him dignified enough.”

“Friend Ogden, you took dullness for dignity. Or I will change it; I’ll even consent that he is dignified. But only in the torpid, cud-chewing fashion in which a bullock is dignified. Still, he does very well by me; for he says I may go with Colonel Arnold. And so, Ogden, I’ve but time for ‘good-by!’ and then off to make myself ready to accompany our swashbuckler druggist against Quebec.”

IT is September, brilliant and golden. Newburyport is brave with warlike excitement. Drums roll, fifes shriek, armed men fill the single village street. These latter are not seasoned troops, as one may see by their careless array and the want of uniformity in their homespun, homemade garbs. No two are armed alike, for each has brought his own weapon. These are rifles—long, eight-square flintlocks. Also every rifleman wears a powderhorn and bullet pouch of buckskin, while most of them carry knives and hatchets in their rawhide belts.

As our rude soldiery stand at ease in the village street, cheering crowds line the sidewalk. The shouts rise above the screaming fifes and rumbling drums. The soldiers are the force which Colonel Arnold will lead against Quebec. Young, athletic—to the last man they have been drawn from the farms. Resenting discipline, untaught of drill, their disorder has in it more of the mob than the military. However, their eyes like their hopes are bright, and one may read in the healthy, cheerful faces that each holds himself privily to be of the raw materials from which generals are made.

Down in the harbor eleven smallish vessels ride at anchor. They are of brigantine rig, each equal to transporting one hundred men. These will carry Colonel Arnold and his eleven hundred militant young rustics to the mouth of the Kennebec. In the waist of every vessel, packed one inside the other as a housewife arranges teacups on her shelves, are twenty bateaux. They are wide, shallow craft, blunt at bow and stern, and will be used to convey the expedition up the Kennebec. Each is large enough to hold five men, and so light that the five, at portages or rapids, can shoulder it with the dunnage which belongs to them and carry it across to the better water beyond.

The word of command runs along the unpolished ranks; the column begins to move toward the water front, taking its step from the incessant drums and fifes. Once at the water, the embarkation goes briskly forward. As the troops march away, the crowds follow; for the day in Newburyport is a gala occasion and partakes of the character of a celebration. No one considers the possibility of defeat. Everywhere one finds optimism, as though Quebec is already a captured city.

Now when the throngs have departed with the soldiery, the street shows comparatively deserted. This brings to view the Eagle Inn, a hostelry of the village. In the doorway of the Eagle a man and woman are standing. The woman is dashingly handsome, with cheek full of color and a bold eye. The man is about thirty-five in years. He swaggers with a forward, bragging, gamecock air, which—the basis being a coarse, berserk courage—is not altogether affectation. His features are vain, sensual, turbulent; his expression shows him to be proud in a crude way, and is noticeable because of an absence of any slightest glint of principle. There is, too, an extravagance of gold braid on his coat, which goes well with the superfluous feather in the three-cornered hat, and those russet boots of stamped Spanish leather. These swashbuckley excesses of costume bear out the vulgar promise of his face, and guarantee that intimated lack of fineness.

The pair are Colonel Arnold and Madam

Arnold. She has come to see the last of her husband as he sails away. While they stand in the door, the coach in which she will make the homeward journey to Norwich pulls up in front of the Eagle.

As Colonel Arnold leads his wife to the coach, he is saying: “No; I shall be aboard within the hour. After that we start at once. I want a word with a certain Captain Burr before I embark. I’ve offended him, it seems; for he is of your proud, high-stomached full-pursed aristocrats who look for softer treatment than does a commoner clay. I’ve ordered a bottle of wine. As we drink, I shall make shift to smooth down his ruffled plumage.”

“Captain Burr,” repeats Madam Arnold, not without a sniff of scorn. “And you are a colonel! How long is it since colonels have found it necessary to truckle to captains, and, when they pout, placate them into good humor?”

“My dear madam,” returns Colonel Arnold as he helps her into the clumsy vehicle, “permit me to know my own affairs. I tell you this thin-skinned boy is rich, and what is better was born with his hands open. He parts with money like a royal prince. One has but to drop a hint, and presto! his hand is in his purse. The gold I gave you I had from him.”

As the coach with Madam Arnold drives away, young Aaron is observed coming up from the water front. His costume, while as rough as that of the soldiers, has a fit and a finish to it which accents the graceful gentility of his manner beyond what satins and silks might do. Madam Arnold’s bold eyes cover him. He takes off his hat with a gravely accurate flourish, whereat the bold eyes glance their pleasure at the polite attention.

Coach gone, Colonel Arnold seizes young Aaron’s arm, with a familiarity which fails of its purpose by being overdone, and draws him into the inn. He carries him to a room where a table is spread. The stout landlady by way of topping out the feast is adding thereunto an apple pie, moonlike as her face and its sister for size and roundness. This, and the roast fowl which adorns the center, together with a bottle of burgundy to keep all in countenance, invest the situation with an atmosphere of hope.

“Be seated, Captain Burr,” exclaims the hearty Colonel Arnold, as the two draw up to the table. “A roast pullet, a pie, and a bottle of burgundy, let me tell you, should make no mean beginning to what is like to prove a hard campaign. I warrant you, sir, we see worse fare in the pine wilderness of upper Maine. Let me help you to wine, sir,” he continues, after carving for himself and young Aaron. The latter, as cold and imperturbable as when, in Dr. Bellamy’s study, he shattered the designs of that excellent preacher by preferring law to theology and war to either, responds to this hospitable politeness with a bow. “Take your glass, Captain Burr. I desire to drink down all irritations. Yes, sir,” replacing the drained glass, “I may say, without lowering myself as a gentleman in your esteem, that, in giving you the order to see the troops aboard, I had no thought of affronting you.”

“It was not your orders to which I objected; it was to your manner. If I may say so, sir, it was a manner of intolerable arrogance, one which I shall brook from no man.”

“Tush, sir, tush! In war we must thicken our hides. We are not to be sensitive. We should not look in the camps for the manners of a king’s court. What you mistook for arrogance was no more than just a tone of command.”

Colonel Arnold’s delivery of this is meant to be conciliating. Through it, however, runs an exasperating vein of patronage, due, doubtless, to his superior rank, and those extra fifteen years wherein he overlooks young Aaron.

“Let us be plain, colonel,” observes young Aaron, studying his wine between eye and windowpane. “I hope for nothing better than concord between us. Also, every order you give me I shall obey. None the less I ask you to observe that I have no purpose of lowering my self-respect in coming to this war. As your subordinate I shall take your commands; as a gentleman, the equal of any, I must be treated as such.”

Colonel Arnold’s brow is red; but he fills his mouth with chicken which he drenches down with wine, and so restrains every fretful expression. After a moment filled of wine and chicken, he observes carelessly:

“Say no more! Say no more, Captain Burr! We understand one another!”

“There is no more to say,” returns young Aaron steadily. “And I beg you to remember that the subject is one which you, yourself, proposed. I am through when I state that, while I object to no man’s vanity, no man’s arrogance, I shall never permit him to transact them at the expense of my self-respect.”

Colonel Arnold turns the talk to what, in a wilderness as well as a fighting way, lies ahead. They linger over pullet and burgundy for the better part of an hour, and get on as well as should gentlemen who have no mighty mutual liking. As they prepare to go aboard, the stout landlady meets them in the hall. Her modest’ charges are to be met with a handful of shillings. Colonel Arnold rummages his pockets, wearing the while a baffled angry air; then he falls to cursing in a spirit truly military.

“May the black fiend seize me!” says he, “if my purse has not gone aboard with my baggage!”

Young Aaron pays the score with an indifference which does not betray a conviction that the pocket-rummaging is a pretence, and the native money-meanness of his coarse-faced colonel designed such finale from the first. Score settled, they repair to the water front. As the two depart, the stout landlady of the Eagle follows the retreating Colonel Arnold with shocked, insulted glance. She is a religious woman, and those curses have moved her soul.

“Blaspheming upstart!” she mutters. “And the airs he takes on! As though folk have forgotten that within the year he stood behind his Norwich counter selling pills and plasters!”

The eleven little ships voyage to the mouth of the Kennebec without event. The bateaux are launched, and the eleven hundred highhearted youngsters proceed to pole and paddle their way up the river. Where the currents are overswift they tow with lines from the banks. Finally they abandon the Kennebec, and shoulder the bateaux for a scrambling tramp across the pine-sown watershed. It takes days, but in the end they find themselves again afloat on the Dead River. This stream leads them to the St. Lawrence. It is the march of the century! These buoyant young rustics through the untraced wilderness have come six hundred miles in fifty days.

Woodmen born and bred, this long push through the forests is no surprising feat to these who perform it. They scarcely discuss the matter as they crouch about their camp fires. The big topic among them is their hatred of Colonel Arnold. From that September day in Newbury-port his tyranny has been in hourly expression. Also, it seems to grow with time. He hectors, raves, vituperates, until there isn’t a trigger finger in the command which does not itch to shoot him down. Disdaining to aid the march by carrying so much as a pound’s weight—as being work beneath his exalted rank—this Caesar of the apothecaries must needs have his special cooking kit along. Also his tent must be pitched with the coming down of every night. Men hungry and unsheltered all around him, he sees no reason why he should not sleep warmly soft, and breakfast and dine and sup like a wilderness Lucullus. Thereat the farmer youth grumble, and console themselves with slighting remarks and looks of contumely.

To these remarks and looks, Colonel Arnold is driven to deafen his ears and offer his back. It would be inconvenient to hear and see these things; since, for all his bullying attitude, he dare not crowd his followers too far. Their unbroken mouths are but new to the military bit; a too cruel pressure on the bridle reins might mean the unhorsing of our vanity-eaten apothecary. As it is, by twos and tens and twenties, the command dwindles away. Every roll call discloses fresh desertions. Wroth with their commander, resolved against the mean tyranny of his rule, when the party reaches the St. Lawrence, half have gone to a right-about and are on their way home. The feather-headed Colonel Arnold finds himself with a muster of five hundred and fifty where he should have had eleven hundred. And the five hundred and fifty with him are on the darkling edge of revolt.

“Think on such cur hearts!” cries Colonel Arnold, as he speaks with young Aaron of those desertions which have cut his force in two. “Half have already turned tail, and the other half are of a coward mind to follow their mongrel example. I would sooner command a brigade of dogs!”

“Believe me,” observes young Aaron, icily acquiescent, “I shall not contradict your peculiar fitness for the command you describe.”

Being thus happily delivered, young Aaron goes round on his imperturbable heel and strolls away, leaving the angry Colonel Arnold glaring with rage-congested eye.

“Insolent puppy!” the latter grits between his teeth.

He is heedful, however, to avoid the epithet in the presence of young Aaron; for, in spite of that rude courage which, when all is said, lies at the root of his nature, the ex-apothecary dreads the “gentleman volunteer,” with his black ophidian glance—so balanced, so hard, so vacant of fear!

It is toward the last of November; the valley of the St. Lawrence seems the home of snow. Colonel Arnold grows afraid of the temper of his people. As they push slowly through the drifts, their angry wrath against the Caligula who leads them is only too thinly veiled. At this, the insolent oppressions of our ex-apothecary cease; he seeks to conciliate, but the time is overlate.

Colonel Arnold goes into camp, and considers the situation. Even if his followers do not wheel suddenly southward for home, he fears that on some final battle day they will refuse to fight at his command. With despair gnawing at his heart, he decides to get word to General Montgomery, who has conquered and is holding Montreal. The giant Irishman is the idol of the army. Once he appears, the grumblings and mutinous murmurings will abate. The rebellious ones will go wherever he points, fight like lions at his merest word.

True, the coming of Montgomery will mean his own loss of command, and that is a bitter pill. Still, since he may do no better, he resolves to gulp it. Thus resolving, he calls young Aaron into conference. The uneasy tyrant hates young Aaron—hates him for the gold he has borrowed from him, hates him for his scarcely concealed contempt of himself. None the less he calls him into council. It is wisdom not friendship his case requires, and he early learned to value the long head of our “gentleman volunteer.”

“It is this,” explains Colonel Arnold, desperately. “We have not the force demanded for the capture of Quebec. We must get word to Montgomery. He is one hundred and twenty miles away in Montreal. The puzzle is to find some one, whom we can trust among these French-speaking native Canadians, who will carry my message.”

Young Aaron knots his brows. Colonel Arnold watches him anxiously, for he is at the end of his resources. Finally young Aaron consults his watch.

“It is now ten o’clock,” he says. “Nothing can be done to-night. And yet I think I know the man for your occasion. By daybreak I’ll have him before you.”

THERE are many deserted log huts along the St. Lawrence. Colonel Arnold has taken up his quarters in one of these. It is eight o’clock of the morning following the talk with young Aaron when the sentinel at the door reports that a priest is asking admission.

“What have I to do with priests!” demands Colonel Arnold. “However, bring him in! He must give good reasons for disturbing me, or his black coat will do him little good.”

The priest is clothed from head to heel in the black frock of his order. The frock is caught in about the waist with a heavy cord. Down the front depend a crucifix and beads. The frock is thickly lined with fur; the peaked hood, also fur-lined, is drawn forward over the priest’s face. In figure he is short and slight. As he peers out from his hood at Colonel Arnold, his black eyes give that commander a start of uncertainty.

“I suppose you speak no French?” says the priest.

His accent is wretched. Colonel Arnold might be justified in retorting that his visitor speaks no English. He restricts himself, however, to an admission that, as the priest surmises, he has no French, and follows it with a bluff demand that the latter make plain his errand.

“Why, sir,” returns the priest, glancing about as though in quest of some one, “I expected to find Captain Burr here. He tells me you wish to send a message to Montreal.”

Colonel Arnold is alert in a moment; his manner undergoes a change from harsh to suave.

“Ah!” he cries amiably; “you are the man.” Then, to the sentinel at the door: “Send word, sir, to Captain Burr, and ask him to come at once to my quarters.”

While waiting the coming of young Aaron, Colonel Arnold enters into conversation with his clerkly visitor. The priest explains that he hates the English, as do all Canadians of French stock. He is only too willing to do Colonel Arnold any service that shall tell against them. Also, he adds, in response to a query, that he can make his way to Montreal in ten days.

“There are farmer and fisher people all along the St. Lawrence,” says he. “They are French, and good sons of mother church. I am sure they will give me food and shelter.”

The sentinel comes lumbering in, and reports that young Aaron is not to be found.

“That is sheer nonsense, sir!” fumes Colonel Arnold. “Why should he not be found? He is somewhere about camp. Fetch him instantly!”

When the sentinel again departs, the priest frees his face of the obscuring hood.

“Your sentinel is right,” he says. “Captain Burr is not at his quarters.”

Colonel Arnold stares in amazement; the priest is none other than our “gentleman volunteer.” Perceiving Colonel Arnold gazing in curious wonder at his clerkly frock, young Aaron explains.

“I got it five days back, at that monastery we passed. You recall how I dined there with the Brothers. I thought then that just such a peaceful coat as this might find a use.”

“Marvelous!” exclaims Colonel Arnold. “And you speak French, too?”

“French and Latin. I have, you see, the verbal as well as outward furnishings of a priest of these parts.”

“And you think you can reach Montgomery? I have to warn you, sir, that the work will be extremely delicate and the danger great.”

“I shall be equal to the work. As for the peril, if I feared it I should not be here.”

It is arranged; and young Aaron explains that he is prepared, indeed, prefers, to start at once. Moreover, he counsels secrecy.

“You have an Indian guide or two, about you,” says he, “whom I do not trust. If my errand were known, one of them might cut me off and sell my scalp to the English.”

When Colonel Arnold is left alone, he gives himself up to a consideration of the chances of his message going safely to Montreal. He sits long, with puckered lips and brooding eye.

“In any event,” he murmurs, “I cannot fail to be the better off. If he reach Montgomery, that is what I want. On the other hand, should he fall a prey to the English I shall think it a settlement of what debts I owe him. Yes; the latter event would mean three hundred pounds to me. Either way I am rid of one whose cool superiorities begin to smart. Himself a gentleman, he seems never to forget that I am an apothecary.”

Young Aaron is twenty miles nearer Montreal when the early winter sun goes down. For ten days he plods onward, now and again lying by to avoid a roving party of English. As he foretold, every cabin is open to the “young priest.” He but explains that he has cause to fear the redcoats, and with that those French Canadians, whom he meets with, keep nightly watch, while couching him warmest and softest, and feeding him on the best. At last he reaches General Montgomery, and tells of Colonel Arnold below Quebec.

General Montgomery, a giant in stature, has none of that sluggishness so common with folk of size. In twenty-four hours after receiving young Aaron’s word, he is off to make a junction with Colonel Arnold. He takes with him three hundred followers, all that may be spared from Montreal, and asks young Aaron to serve on his personal staff.

They find Colonel Arnold, with his five hundred and fifty, camped under the very heights of Quebec. The garrison, while quite as strong as is his force, have not once molested him. They leave his undoing to the cold and snow, and that starvation which is making gaunt the faces and shortening the belts of his men.

General Montgomery upon his arrival takes command. Colonel Arnold, while foreseeing this—since even his vanity does not conceive of a war condition so upside down that a colonel gives orders to a general—cannot avoid a fit of the sulks. He is the more inclined to be moody, because the coming of the big Irishman has visibly brightened his people, who for months have been scowls and clouds to him. Now the face of affairs is changed; the mutinous ones have nothing save cheers for the big general whenever he appears.

General Montgomery calls a conference, and Colonel Arnold comes with all his officers. At the request of young Aaron, the big general retains him by his side. This does not please the ex-apothecary, it hurts his self-love that the “gentleman volunteer” is so obviously pleased to be free of his company. At the conference, General Montgomery advises all to hold themselves in readiness for an assault upon the English walls.

“I cannot tell the night,” he observes; “I only say that we shall attack during the first snowstorm that occurs. It may come in an hour, wherefore be ready!”

The storm which is to mask the movements of General Montgomery does not keep folk waiting. There soon falls a midnight which is nothing save a blinding whirling sheet of snow. Thereupon the word goes through the camp.

The assault is to be made in two columns, General Montgomery leading one, Colonel Arnold the other. Young Aaron will be by the elbow of the big Irishman. By way of aiding, a feigned attack is ordered for a far corner of the English works.

As the soldiers fall into their ranks, the storm fairly swallows them up. It would seem as though none might live in such a tempest—white, ferociously cold, Arctic in its fury! It is desperate weather! the more desperate when faced by ones whose courage has been diminished by privation. But the strong heart of General Montgomery listens to no doubts. He will lead out his eight hundred and fifty against an equal force that have been sleeping warm and eating full, while his own were freezing and starving. Also, those warm, full-fed ones are behind stone walls, which the lean, frozen ones must scale and capture.

“I shall give you ten minutes’ start,” observes General Montgomery to Colonel Arnold. “You have farther to go than we to gain your position. I shall wait ten minutes; then I shall press forward.”

Colonel Arnold moves off with his column through the driving storm. When those ten minutes of grace have elapsed, General Montgomery gives his men the word to advance.

They urge their difficult way up a ravine, snow belt-deep. There is an outer work of blockhouse sort at the head of the defile. It is of solid mason work, two stories, crenelled above for muskets, pierced below for two twelve-pounders. This must be reduced before the main assault can begin.

As General Montgomery, with young Aaron on the right, the column in broken disorder at his heels, nears the blockhouse, a dog, more wakeful than the English, is heard to bark. That bark turns out the redcoat garrison as though a trumpet called.

“Forward!” cries General Montgomery.

The men respond; they rush bravely on. The blockhouse, dully looming through the storm, is no more than forty yards away.

Suddenly a red tongue of flame licks out into the snow swirl, to be followed by the roar of one of the twelve-pounders. In quick response comes the roar of its sister gun, while, from the loopholes above, the muskets crackle and splutter.

It is blind cannonading; but it does its work as though the best artillerist is training the guns at brightest noonday. The head of the assaulting column is met flush in the face with a sleet of grapeshot.

General Montgomery staggers; and then, without a word, falls forward on his face in the snow. Young Aaron stoops to raise him to his feet. It is of no avail; the big Irishman is dead.

The bursting roar of the twelve-pounders is heard again. As if to keep their general company, a dozen more give up their lives.

“Montgomery is slain!”

The word zigzags along the ragged column.

It is a daunting word! The men begin to give way.

Young Aaron rushes into their midst, and seeks to rally them. He might as well attempt to stay the whirling snow in its dance! The men will follow none save General Montgomery; and he is dead.

Slowly they fall backward along the ravine up which they climbed. Again the two twelve-pounders roar, and a raking hail of grape sings through the shaking ranks. More men are struck down! That backward movement becomes a rout.

Young Aaron loses the icy self-control which is his distinguishing trait. He buries the retreating ones beneath an avalanche of curses, drowns them with a cataract of scorn.

“What!” he cries. “Will you leave your general’s body in their hands?”

He might have spared himself the shouting effort. Already he is alone with the dead.

“It is better company than that of cowards!” is his bitter cry, as he bends above the stark form of his chief.

The English are pouring from the blockhouse. Still young Aaron will not leave the dead Montgomery behind. Now are the steel-like powers of his slight frame manifest. With one effort, he swings the giant body to his shoulder, and plunges off down the defile, the eager blood-hungry redcoats not a dozen rods behind.

THE gray morning finds the routed ones in their old camp by the St. Lawrence. Colonel Arnold’s assault has also failed. The ex-apothecary received a slight wound, and is vastly proud. It is his left arm that was hurt, and of it he makes a mighty parade, slinging it in a rich crimson sash.

Colonel Arnold, now in command, does not attempt another assault, but contents himself with maneuvering his slender forces on the plain in tantalizing view of the redcoat foe. He sends a flag of truce to the foot of the walls, with a sprightly challenge to their defenders, inviting them to come out and fight. The Quebec commander, being a soldier and no mad knight errant, refuses to be thus romantic. The winter is deepening; he will leave the vaporing Colonel Arnold to fight a battle with the thermometer. Also, General Burgoyne, at the head of an army, is pointed that way.

His maneuverings ignored, his challenge declined, Colonel Arnold puts in an entire night framing a demand for the instant surrender of Quebec. This he is at pains to couch in terms of insult, peppering it from top to bottom with biting taunts. He closes with a threat that, should the English commander fail to lower his flag, he will conquer the city at the point of the sword, and put the garrison to disgraceful death by gibbet and halter. When he has completed this precious manifesto, he seeks out young Aaron, and commands him to carry it in person to the city’s gates. As Colonel Arnold tenders the letter, young Aaron puts his hands behind him.

“Before I take it, sir,” says he, “I should like to hear it read.”

Young Aaron’s contempt for the ex-apothecary has found increase with every day since the death of Montgomery. Those braggadocio maneuverings, the foolish challenge to come out and fight, have filled him with disgust. They shock by stress of their innate cheap vulgarity. He is of no mind to lend himself to any kindred buffoonery.

“Do you refuse my orders, sirrah?” cries Colonel Arnold, falling into a dramatic fume.

“I refuse nothing! I say that I shall carry no letter until I know its contents. I warn you, sir, I am not to be ‘ordered,’ as you call it, into a false position by any man alive.”

Young Aaron’s face is getting white; there is a dangerous sparkle in the black ophidian eyes. Colonel Arnold reads these symptoms, and draws back. Still, he maintains a ruffling front.

“Sir!” says he haughtily; “you should think on your subordinate rank, and on your youth, before you pretend to overlook my conduct.”

“My subordinate rank shall not detract from my quality as a gentleman. As for my youth, I shall prove old enough, I trust, to make safe my honor. I say again, I’ll not touch your letter till I hear it read.”

“Remember, sir, to whom you speak!”

“I shall remember what I mentioned at the Eagle Inn; I shall remember my self-respect.”

Colonel Arnold fixes young Aaron with a superior stare. If it be meant for his confusion, it meets failure beyond hope. The black eyes stare back with so much of iron menace in them, as to disconcert the personage of former drugs.

He feels them play upon him like two black rapier points. His assurance breaks down; his lofty determination oozes away. With gaze seeking the floor, his ruddy, wine-marked countenance flushes doubly red.

“Since you make such a swelter of the business,” he grumbles, “I, for my own sake, shall now ask you to read it. I would have you know, sir, that I understand the requirements as well as the proprieties of my position.”

Colonel Arnold tears open the letter with a flourish, and gives it to young Aaron. The latter reads it; and then, with no attempt to palliate the insult, throws it on the floor.

“Sir,” cries Colonel Arnold, exploding into a sudden blaze of wrath, “I was told in Cambridge, what my officers have often told me since, that you are a bumptious young fool! Many times have I been told it, sir; and, until now, I did you the honor to disbelieve it.” Young Aaron is cold and sneering. “Sir,” he retorts, “see how much more credulous I am than are you. I was told but once that you are a bragging, empty vulgarian, and I instantly believed it.”

The pair stand opposite one another, glances crossing like sword blades, the insulted letter on the floor between. It is Colonel Arnold who again gives ground. Snapping his fingers, as though breaking off an incident beneath his exalted notice, he goes about on his heel.

“Ah!” says young Aaron; “now that I see your back, sir, I shall take my leave.”

The winter days, heavy and leaden and chill, go by. Colonel Arnold continues those maneuverings and challengings, those struttings and vaporings. At last even his coxcomb vanity grows weary, and he thinks on Montreal. One morning, with all his followers, he marches off to that city, still held by the garrison that Montgomery left behind. Established in Montreal he comports himself as becomes a conqueror, expanding into pomp and license, living on the fat, drinking of the strong. And day by day Burgoyne is drawing nearer.

Broad spring descends; a green mist is visible in the winter-stripped trees. The rumors of Burgoyne’s approach increase and prove disquieting. Colonel Arnold leads his people out of Montreal, and plunges southward into the wilderness. He pitches camp on the river Sorel.

Since the incident of the letter, young Aaron has held no traffic, polite or otherwise, with Colonel Arnold. The “gentleman volunteer” sees lonesome days; for he has made no friends about the camp. The men admire him, but offer him no place in their hearts. A boy in years, with a beardless girl’s face, he gives himself the airs of gravest manhood. His atmosphere, while it does not repel, is not inviting. Men hold aloof, as though separated from him by a gulf. He tells no stories, cracks no jests. His manner is one of careless nonchalance. In truth, he is so much engaged in upholding his young dignity as to leave him no time to be popular. His bringing off the dead Montgomery, under fire of the English, has been told and retold in every corner of the camp. This gains him credit for a heart of fire, and a fortitude without a flaw. On the march, too, he faces every hardship, shirks no work, but meets and does his duty equal with the best. And yet there is that cool reserve, which denies the thought of comradeship and holds friendly folk at bay. With them, yet not of them, the men about him cannot solve the conundrum of his nature; and so they leave him to himself. They value him, they respect him, they hold his courage above proof; there it ends.

Young Aaron, aware of his lonely position, does nothing to change it. He is conceitedly pleased with things as they are. It is the old head on the young shoulders that thus gets in his way; Washington was right in his philosophy. Young Aaron, however, is as content with that head, as in those old Bethlehem days, when he patronized Dr. Bellamy, and declared for the gospel according to Lord Chesterfield.

None the less young Aaron is not wholly satisfied. As he idles about the camp by the Sorel, he feels that any present chance of conquering the fame and power he came seeking in this war is closed against him.

“Plainly,” counsels the old head on the young shoulders, “it is time to bring about a change.”

Colonel Arnold is smitten of surprise one afternoon, when young Aaron walks into his tent. He does his best to hide that surprise, as an emotion at war with his high military station. Young Aaron, ever equal to a rigid etiquette, salutes profoundly.

“Colonel Arnold,” says he, “I am here to return into your hands that rank of captain, which I hold only by courtesy. Also, I desire to tell you that I leave for Albany at once.”

“Albany!”

“My canoe is waiting, sir. I start immediately.”

“I forbid your going, sir!”

Colonel Arnold has recovered his breath, and makes this proclamation grandly. Privately, he is a-quake; for he does not know what stories young Aaron might tell in the south.

“Sir,” he repeats, “I forbid your departure! You must not go!”

“Must not?”

As though answering his own query, young Aaron leaves Colonel Arnold without further remark, and walks down to the river, where a canoe is waiting. The latter cranky contrivance is manned by a quartette of Canadians, who sit, paddle in fist, ready for the word to start.

At this decisive action, Colonel Arnold is roused. He springs to his feet and follows to the waiting canoe. Young Aaron has just taken his place.

“Captain Burr,” cries Colonel Arnold, “what does this mean? You heard my orders, sir! You must not go!”

Young Aaron is ashore like a flash. “Colonel Arnold,” says he, “it is quite possible that you have force enough at hand to detain me. Be warned, however, that the exercise of such force will have a sequel serious to yourself.”

“Oh, as to that,” responds Colonel Arnold sullenly, “I shall not attempt to detain you. I simply leave you to the responsibility of departing in the teeth of my orders, sir.”

In a moment young Aaron is back in the canoe; the four paddles churn the water into baby whirlpools, and the slight craft glides out upon the bosom of the Sorel.

Young Aaron encounters a party of Indians, and conquers their friendship with diplomatic rum. He reaches Albany, and tastes the delights of fame; for the story of Quebec has preceded him, and he finds himself a hero. Thereupon, while outwardly unmoved, he swells in the proud but secret recesses of his heart.

In New York he meets his college friend Ogden, who tells him that he has sold Warlock and spent the proceeds. Likewise, Colonel Troup explains how he received a thousand pounds for him from his estate, but was moved to borrow the half of it, having a call for such sum. Colonel Troup gives five hundred pounds to young Aaron, who receives it carelessly, the while assuring his debtor, as well as young Ogden, who spent the price of Warlock, that they are cheerfully welcome to his gold. At that, both young Ogden and Colonel Troup pluck up a generous spirit, and borrow each another fifty pounds; which sums our “gentleman volunteer” puts into their impoverished fingers, as readily as though pounds mean groats and farthings. For he holds that to be niggard of money is impossible to a soldier and a gentleman. Did not the knight-errant of old romaunts go chucking gold-lined purses right and left, into every empty outstretched hand? And shall not young Aaron be the modern knight-errant if he chooses? These are the questions which he puts to himself, as he ministers to the famished finances of his friends.

General Washington learns of the incident of the dead Montgomery. Having a conscience, he is distressed by the thought that he may have been harshly unjust, one Cambridge day, to our “gentleman volunteer.” The conscience-smitten general has headquarters in New York, and now, when young Aaron arrives, strives to make amends. He invites that youthful campaigner to a place upon his personal staff, with the rank of major. Young Aaron accepts, and becomes part of Washington’s military family. The general is living at Richmond Hill, a mansion which in after years young Aaron will buy and make his residence.

For six weeks young Aaron is with Washington. Sometimes he rides out with him; sometimes he writes reports and orders at his dictation; always he dislikes him. He finds nothing in the Virginian to invoke his confidence or compel his esteem. In the finale he detests him.

This latter mind condition is vastly built up by the lack of notice he receives from the ever-taciturn, often-abstracted, overworried Washington. The big general will sit for hours, with brows of thought and pondering eye, as heedless of young Aaron—albeit in the same room with him—as though our sucking Marlborough owns no existence. This irritates the latter’s pride; for he has military views which he longs to unfold, but cannot because of the grim wordlessness of his chief. He resolves to break the ice.

Washington is sitting lost in thought. “Sir,” exclaims young Aaron, boldly rushing in upon the general’s meditations, “the English grow stronger. Every day their fleet is augmented by new ships, bringing fresh troops. Eventually they will land and drive us from the city. When that time comes, it will be my advice to burn New York to the ground, and leave them naught save the charred ruins.”

Washington pays no attention; it is as though a starling spoke. Presently he mounts his horse, and soberly rides off to an inspection of troops. Young Aaron is mightily mortified, and, by way of reestablishing his dignity on the pedestal from which it has been thrust, neglects a line of clerical work that should claim his attention. Washington upon his return discovers this, and having a temper like gunpowder flashes into a rage.

“What does this mean, sir?” he demands, angry to the eyes.

“Why, sir,” responds young Aaron coolly, “I should think it might mean that I brought a sword not a pen to this war.”

“You are insolent, sir!”

“As you please, sir. But since you say it, I must ask to be relieved from further duty on your staff.”

The big general stalks from the room. The next day he transfers young Aaron to the staff of Putnam.

“I’m sorry he offended you, general,” says the old wolf killer. “For myself, I’m bound to say that I think well of the boy.”

“There is a word,” returns Washington, “as to the meaning of which, until I met him, I was ignorant; that is the word ‘prig.’ It is strange, too; for he is as brave as Cæsar. I have it on the words of twenty. Yes, general, your ‘gentleman-volunteer’ is altogether a strangeling; for he is one of those anomalies, a courageous prig.”

ON that day when the farmers of Concord turn their rifles upon King George, there dwells in Elizabeth a certain English Major Moncrieffe. With him is his daughter, just ceasing to be a girl and beginning to be a woman. Peggy Moncrieffe is a beauty, and, to tell a whole truth, confident thereof to the verge of brazen. When her father is ordered to his regiment he leaves her behind. The war to him is no more than a riot; he looks to be back in Elizabeth before the month expires.

The optimistic Major Moncrieffe is wrong. That riot, which is not a riot but a revolution, spreads and spreads like fire among dry grass. At last a hostile line divides him from his daughter Peggy. This is serious; for, aside from forbidding any word between them, it prevents him sending what money she requires for her care. In her distress she writes General Putnam, her father’s comrade in the last war with the French. The old wolf killer invites the desolate Peggy to make one of his own household. When young Aaron leaves the staff of Washington, Peggy Moncrieffe is with the Putnams, whose house stands at the corner of Broadway and the Battery.

The family of the old wolf killer is made up of Madam Putnam and two daughters. Peggy Moncrieffe is received as a third daughter by the kindly Madam Putnam. Also, like a third daughter, she is set to the spinning wheel; for, while the old wolf killer fights the English, Madam Putnam and her daughters work early and late, with spinning wheel and loom, clothmaking for the continental troops. Peggy Moncrieffe offers no demur; but goes at the spinning and weaving as though she is as much puritan and patriot as are those about her. She is busy at the spinning when young Aaron is presented. And in that presentation lurks a peril; for she is eighteen and he is twenty.

Young Aaron, selfish, gallant, pleased with a pretty face as with a poem, becomes flatteringly attentive to pretty Peggy Moncrieffe. She, for her side, turns restless when he leaves her, to glow like the sun when he returns. She forgets the spinning wheel for his conversation. The two walk under the trees in the Battery, or, from the quiet steps of St. Paul’s, watch the evening sun go down beyond the Jersey hills.

Madam Putnam is prudent, and does not like these symptoms. She issues a whispered mandate to the old wolf killer, with whom her word is law. Thereupon he sends the pretty Peggy to safer quarters near Kingsbridge.

That is to say, the Kingsbridge refuge, to which pretty Peggy reluctantly retires, is safe until she arrives. It presently becomes a theater of danger, since young Aaron is not a day in discovering a complete military reason for visiting it. The old wolf killer is not like Washington; there are no foolish orders or tedious dispatches for his aide to write. This gives leisure to young Aaron, which he improves in daily gallops to Kingsbridge. It is to be feared that he and pretty Peggy Moncrieffe find walks as shady, and prospects as pleasant, and moments as sweet, as when they had the Battery for a promenade and took in the Jersey hills from the twilight steps of St. Paul’s. Also, the pretty Peggy no longer pleads to join her father; albeit that parent has just been sent with his regiment to Staten Island, not an hour’s sail away.

This contentment of the pretty Peggy with things as they are, re-alarms the prudence of Madam Putnam, who regards it as a sign most sinister. Having a genius to be military, quite equal to that of her old wolf-killing husband, she attacks this dangerously tender situation in flank. She gives her commands to the old wolf killer, and at once he blindly obeys. He dispatches young Aaron on a mission to Long Island. The latter is to look up positions of defense, so as to be prepared for the English, should they carry their arms in that direction.

In two days young Aaron returns, and makes an exhaustive report; whereat the old wolf killer breaks into words of praise. This duty discharged, young Aaron is into the saddle and off, clatteringly, for Kingsbridge. The old wolf killer sees him depart and says nothing, while a cunning twinkle dances in the old gray eye. Then the twinkle subsides, and is succeeded by a self-reproachful doubt.

“He might have married her,” he observes tentatively to Madam Putnam.

“Never!” returns that clear matron. “Your young Major Burr is too coolly the selfish calculating egotist. He would win her and wear her as he might some bauble ornament, and cast her aside when the glitter was gone. As for marrying her, he’d as soon think of marrying the rings on his fingers, or the buckles on his shoes.”

Young Aaron comes clattering back from Kingsbridge. His black eyes sparkle wickedly; his face, usually so imperturbable, is the seat of an obvious anger. Moreover, he seems chokingly full of a question, which even his ingenious self-confidence is at a loss how to ask. He gets the old wolf killer alone.

“Miss Moncrieffe!” he breaks forth. Then he proceeds blunderingly: “I had occasion to go to Kingsbridge, and was surprised to find her gone.” The last concludes with a rising inflection.

“Why, yes!” retorts the old wolf killer, summoning the innocence of a sheep. “I forgot to tell you that, seeing an opportunity, I yesterday sent little Peg to Staten Island under a flag of truce. She is with her father. Between us”—here he sinks his voice mysteriously—“I was afraid the enemy might find some way to use little Peg as a spy.” Young Aaron clicks his teeth savagely, but says nothing; the old wolf killer watches him with the tail of his eye.

The “gentleman volunteer” strides down to the sea wall, and takes a long and mayhap loving look at Staten Island, with the wind-ruffled expanse of bay between.

And there the romance ends.

Two days later young Aaron is sipping his wine in black Sam Fraunces’ long room, the picture of that elegant indifference which he cultivates as a virtue. Already the fancy for poor Peggy Moncrieffe has faded from the agate surface of his nature, as the breath mists fade from the mirror’s face, and he thinks only on how and when he shall lay down his title of major for that of lieutenant colonel.

The woman’s heart is the heart loyal. While he sips wine at Fraunces’, and weighs the chances of promotion, Peggy the forgotten finds in Staten Island another Naxos, and like another Ariadne goes weeping for that Theseus who has already lost her from out his thoughts.

It is unfortunate that, as aide to the old wolf killer, young Aaron is not provided with more work for hand and head. As it is, his unfilled hours afford him opportunity to think and talk unprofitably. He falls to criticising Washington to the old wolf killer; which is about as sapient as though he fell to criticising Madam Putnam to the old wolf killer.

“Of what avail,” cries young Aaron one afternoon, as he and his grizzled chief stroll in the Bowling Green—“of what avail for General Washington to hold the city, when he must give it up at last? New English ships show in the bay with the coming up of every sun. He would be wiser if he withdrew into the interior, and so forced the foe to follow him. This would lose them the backing of their fleet, from which they gain not only supplies, but what is of more consequence a kind of moral support.”

The old wolf killer looks at his opinionated aide for a moment. Then without replying directly, he observes:

“Just as the Christian virtues are faith, hope, and charity, so the military virtues are courage, endurance, and silence. And the greatest of these is silence. You ought always to remember that a soldier’s sword should be immeasurably longer than his tongue.”

Young Aaron reddens at what he feels is a rebuke. The following day, when he is directed to join General McDougal on Long Island, he is glad to go.

“He has had too little to do,” explains the old wolf killer to Madam Putnam. “Like all workless folk he is beginning to talk; and his is the sort of conversation that breeds enemies and brews trouble.”

Young Aaron is in the fight on Long Island. Upon the retreating back of that lost battle, he supervises the crossing of the troops to Manhattan. All night, cool and quick and vigilant, he labors on the Brooklyn side to put the men aboard the transports. When the last is across the East River, he himself embarks, bringing with him his horse, hog-tied, in the bottom of the barge. It is early dawn when he leads the released animal ashore on the Manhattan side. Mounting it, with two fellow officers, he rides northward at a leisurely gait, a half mile to the rear of the retreating army.

As young Aaron and his companions push north toward Kingsbridge, they come across the baggage and stores of a battery of artillery. The baggage and stores have been but the moment before abandoned.

“It looks,” observes young Aaron, who is as unruffled as upon the day when he laid down theology for law, to the horrified distress of Dr. Bellamy—“it looks as though the captain of that battery, whoever he is, has permitted these English in our rear to get unnecessarily upon his nerves. There is no such close occasion as to justify the abandonment of these stores. At least he should have destroyed them.”

Twenty rods beyond, he finds one of the battery’s guns. He points to the lost piece scornfully.

“There,” says he, “is the pure proof of some one’s cowardice!”

Spurring on, and led by the rumbling sounds of field guns in full retreat, he overtakes the timid ones who have thrown away baggage and gun. The captain who commands is a youth no older than young Aaron. As the latter comes up, the boy captain is urging his cannoneers to double speed.

“Let me congratulate you, captain,” observes young Aaron, extravagantly polite the better to set off the sneer that marks his manner, “on not having thrown away your colors. May I ask your name?”

“I, sir,” returns the artillery youth, as much moved of resentment at young Aaron’s sneer, as is possible for one in his perturbed frame, “I, sir, am Captain Alexander Hamilton.”

“And I, sir, am Major Burr. Let me compliment you, Captain Hamilton, for the ardor you display in carrying your battery forward. One might suppose from your headlong zeal that the English forces lie in that direction. I must needs say, however, that the zeal which casts away its stores and baggage, and leaves a gun behind, is ill considered.”