Title: The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments, of Great Britain

Author: John Evans

Release date: May 2, 2016 [eBook #51960]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Chris Curnow, RichardW, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments, of Great Britain, by John Evans

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/ancientstoneimpl00evaniala |

In presenting this work to the public I need say but little by way of preface. It is the result of the occupation of what leisure hours I could spare, during the last few years, from various and important business, and my object in undertaking it is explained in the Introduction.

What now remains for me to do is to express my thanks to those numerous friends who have so kindly aided me during the progress of my work, both by placing specimens in their collections at my disposal, and by examination of my proofs. Foremost among these must be ranked the Rev. William Greenwell, F.S.A., from whose unrivalled collection of British antiquities I have largely drawn, and from whose experience and knowledge I have received much assistance in other ways.

To Mr. A. W. Franks, F.S.A.; Mr. J. W. Flower, F.G.S.; Mr. W. Pengelly, F.R.S.; Colonel A. Lane Fox, F.S.A.; Mr. E. T. Stevens, of Salisbury; Messrs. Mortimer, of Fimber; Mr. Joseph Anderson, the Curator of the Antiquarian Museum at Edinburgh; and to numerous others whose names are mentioned in the following pages, my thanks must also be expressed.

The work itself will, I believe, be found to contain most of the information at present available with regard to the class of antiquities of which it treats. The subject is one which does not readily lend itself to lively description, and an accumulation of facts, such as is here presented, is of necessity dull. I have, however, relegated to smaller type the bulk of the descriptive {vi} details of little interest to the ordinary reader, who will probably find more than enough of dry matter to content him if he confines himself to the larger type and an examination of the illustrations.

Whatever may be the merits or defects of the book, there are two points on which I feel that some credit may be claimed. The one is that the woodcuts—the great majority of which have been specially engraved for this work by Mr. Swain, of Bouverie Street—give accurate representations of the objects; the other is, that all the references have been carefully checked.

The Index is divided into two parts; the first showing the subjects discussed in the work, the second the localities where the various antiquities have been found.

Now that so much more attention than formerly is being bestowed on this class of antiquities, there will, no doubt, be numerous discoveries made, not only of forms with which we are at present unacquainted, but also of circumstances calculated to throw light on the uses to which stone implements and weapons were applied, and the degree of antiquity to be assigned to the various forms.

I will only add that I shall gladly receive any communications relative to such discoveries.

JOHN EVANS.

Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead, May, 1872.

The undiminished interest taken by many archæologists in the subject to which this book relates seems to justify me in again placing it before the public, though in an extended and revised form. I am further warranted in so doing by the fact that the former edition, which appeared in 1872, has now been long out of print.

In revising the work it appeared desirable to retain as much of the original text and arrangement as possible, but having regard to the large amount of new matter that had to be incorporated in it and to the necessity of keeping the bulk of the volume within moderate bounds, some condensation seemed absolutely compulsory. This I have effected, partly by omitting some of the detailed measurements of the specimens, and partly by printing a larger proportion of the text in small type. I have also omitted several passages relating to discoveries in the caverns of the South of France.

I have throughout preserved the original numbering of the Figures, so that references that have already been made to them in other works will still hold good. The new cuts, upwards of sixty in number, that have been added in this edition are distinguished by letters affixed to the No. of the Figure immediately preceding them.

The additions to the text, especially in the portion relating to the Palæolithic Period, are very extensive, and I hope that all the more important discoveries of stone antiquities made in this country during the last quarter of a century are here duly recorded, and references given to the works in which fuller details concerning them may be found. In some cases, owing to the character of the {viii} objects discovered being insufficiently described, I have not thought it necessary to cite them.

I am indebted to numerous collectors throughout the country for having called my attention to specimens that they acquired, and for having, in many cases, sent them to me for examination. I may take this opportunity of mentioning that while the whole of the objects found by Canon Greenwell during his examination of British Barrows has been most liberally presented to the nation, the remainder of his fine collection of stone antiquities, so frequently referred to in these pages, has passed into the hands of Dr. W. Allen Sturge, of Nice.

The two Indices have been carefully compiled by my sister, Mrs. Hubbard, and are fuller than those in the former edition. They will afford valuable assistance to any one who desires to consult the book.

For the new woodcuts that I have had engraved I have been so fortunate as to secure the services of Messrs. Swain, who so skilfully cut the blocks for the original work. I am indebted for the loan of numerous other blocks to several learned Societies, and especially to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and to the Geological Society of London. Mr. Worthington Smith has also most liberally placed a number of blocks at my disposal.

It remains for me to express my thanks to those who have greatly aided me in the preparation of this edition, the whole of the proofs of which have been kindly read by Mr. C. H. Read, F.S.A., of the British Museum, as well as by some members of my own family. Dr. Joseph Anderson, of the National Museum at Edinburgh, has been good enough to read the parts relating to Scotland, while Professor Boyd Dawkins has gone over the chapter on Cave Implements, and Mr. William Whitaker has corrected the account of the discoveries in the River-drift. To each and all I am grateful, and as the result of their assistance I trust that, though not immaculate, the book may prove to be fairly free from glaring errors and inconsistencies.

JOHN EVANS.

Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead, May, 1897.

The Iron, Bronze, and Stone Ages — Bronze in use before Iron — Persistence of Religious Rites — Use of Stone in Religious Ceremonies — Stone Antiquities not all of the same Age — Order of Treatment . . . 1

Pyrites and Flint used for striking Fire — Strike-a-light Flints — The Gun-flint Manufacture — Gun-flint Production — Modes of producing Flakes — Pressigny Nuclei — Rough-hewing Stone-hatchets — Ancient Mining for Flint — Flint-mines at Grime’s Graves and Spiennes — Production of Arrow-heads — Flaking Arrow-heads — Arrow-flakers — Grinding Stone Implements — Methods of Sawing Stone — Methods of Boring Stone — Boring by means of a Tube — Progress in Modes of Manufacture . . . 14

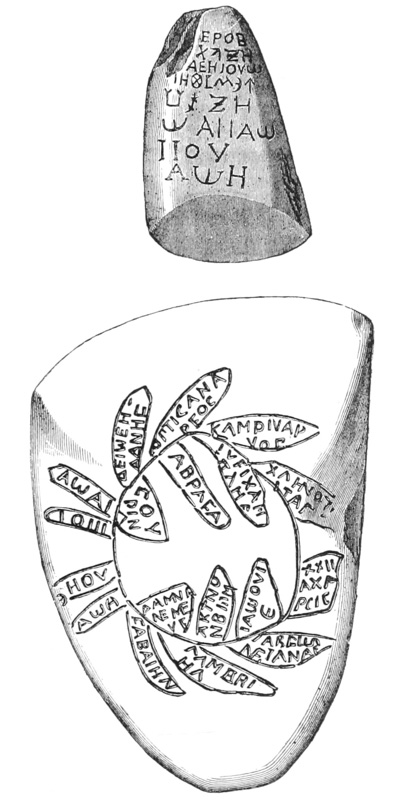

Belief in their Meteoric Origin — Regarded as Thunderbolts — Celt with Gnostic Inscriptions — Their Origin and Virtues — How regarded by the Greeks and Romans . . . 55

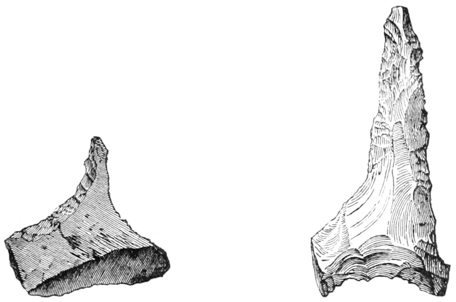

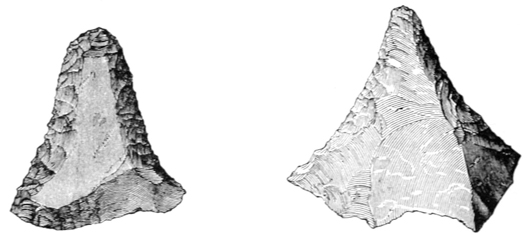

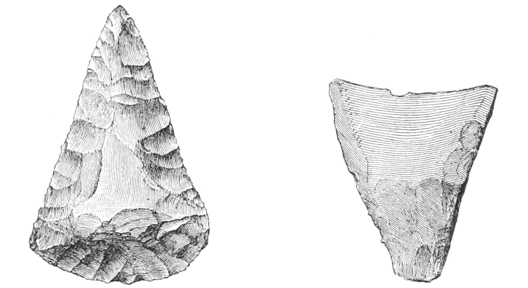

The Kjökken-Mödding Type — Some possibly Agricultural Implements — Some carefully Chipped — The Common Forms — Their abundance — Discoveries at Cissbury — Found in company with Polished Celts — Their probable Age . . . 67

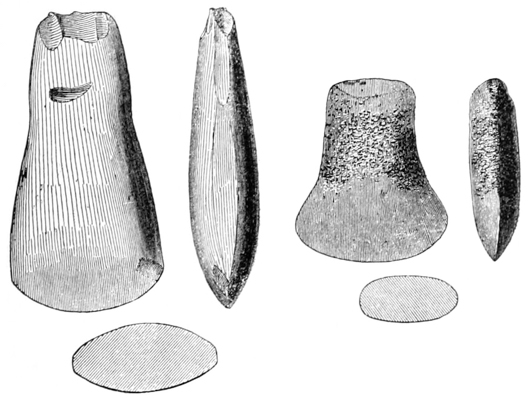

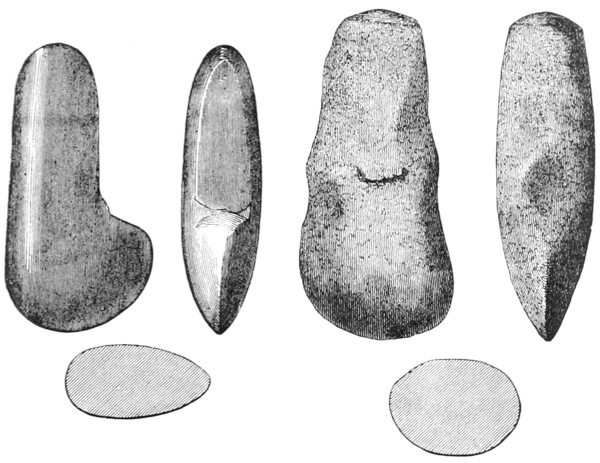

Pointed at the Butt-end — Of Elongated Form — Expanding at the Ends — Of Peculiar Forms — Their Occurrence in Foreign Countries . . . 87

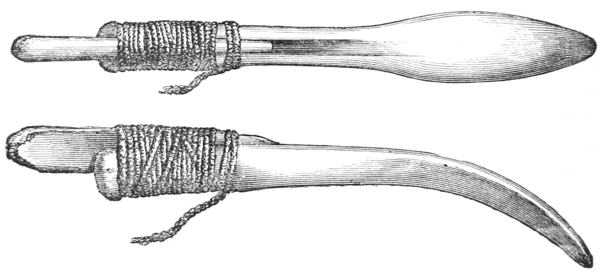

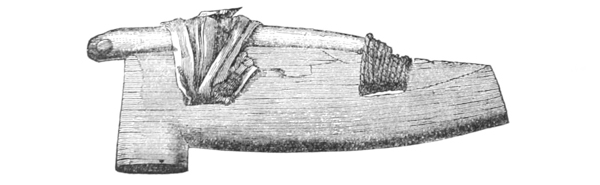

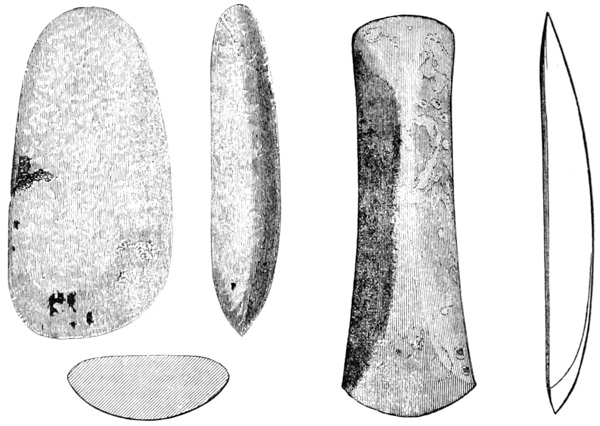

A Type common in the Eastern Counties — With the Surface ground all over — Expanding at the Edge — Of other Materials than Flint — The Thin and Highly-polished Type — With Flat Sides — With Flat Sides and Narrow Butt — With Flat Sides and Pointed Butt — Of Rectangular Section — Chisel-like and of Rectangular Section — Of Oval Section — Of Oval Section with Conical Butt — Of a Form common in France — Of Oval Section pointed at the Butt — With a Cutting Edge at each End — Sharp at both Ends — Polished Celts narrowing in the Middle — Used in the Hand without Hafting — Polished Celts of Abnormal types — Polished Celts with Depressions and Flutings — Circumstances under which they have been Found — Their Discovery with Objects of Later Date — Their Range in Time — Accompanying Interments — Manner in which Hafted — In their original Handles — Inserted in Sockets in the Hafts — Hafted with Intermediate Sockets — Compared with Axes of modern Savages — Mounted in Forked Hafts — Mounted on Wooden Hafts — Compared with Adzes of modern Savages — Mounted in Withes and Cleft Sticks — Modern methods of Hafting Axes . . . 98

Small Hand Chisels — Gouges rare in Britain — Bastard Gouges . . . 173

Sharp at both Ends — Expanding at one End — Pointed at one End — Adze-like in Character — Cutting at one End only — Used as Battle-axes — Ornamented on the Faces — Large and Heavy — A Large Form common in the North — Fluted on the Faces — Boring, the last Process — Axe-hammers hollowed on the Sides — Axe-hammers ornamented on the Faces — Frequently found in Barrows — But little used by modern Savages . . . 183

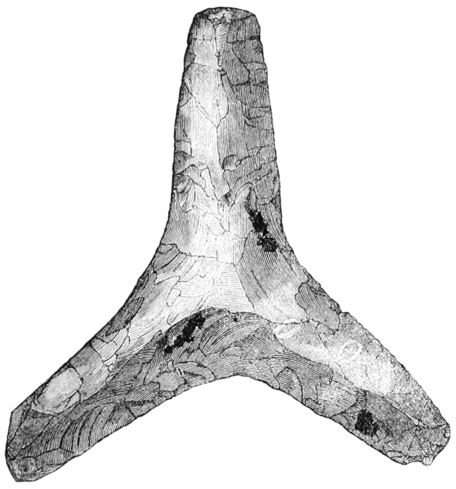

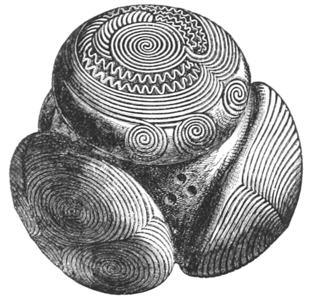

Of Peculiar Forms — Some of them Weapons, not Tools — Conical, Rounded at each End — Made from Pebbles with Natural Holes — Of an Ornamented Character — Made from Quartzite Pebbles — Purposes to which Applied — Mauls for Mining Purposes — Of Wide Range — Net-sinkers . . . 217

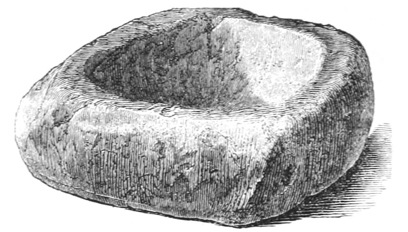

With Depressions on the Faces — With Cup-shaped Depressions — Ridged at the End — Made of Flint and Quartzite — Saddle-querns — Pestles and Mortars — From Shetland and Orkney — Various forms of Mortars — Hand-mills or Querns . . . 238

Uses for Sharpening Celts — Found in Barrows — Found with Interments — Pebbles with Grooves in them . . . 261

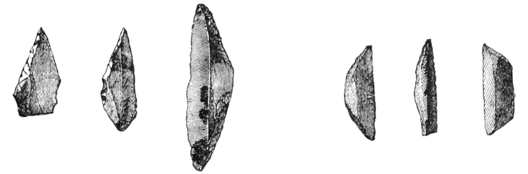

The Cone and Bulb of Percussion — Classification of Flakes — Polygonal Cores — Numerous in Ancient Settlements — Localities where Abundant — Not Confined to the Stone Period — The Roman Tribulum — In other parts of the World — The Uses of Flakes — Flakes ground at the Edge — Hafted Flakes — Flakes made into Saws — Serrated, as the Armature of Sickles . . . 272

Used in Dressing Hides — Horseshoe-shaped — Kite-shaped and Duck-bill-shaped — Some like Oyster Shells in Form — Double-ended and Spoon-shaped — Found with Interments — Evidences of Wear upon them — Found with Pyrites — The Modern form of Strike-a-light — Used with Pyrites for producing Fire — The Flat and Hollowed Forms . . . 298

Found in different Countries — Of Minute Dimensions . . . 321

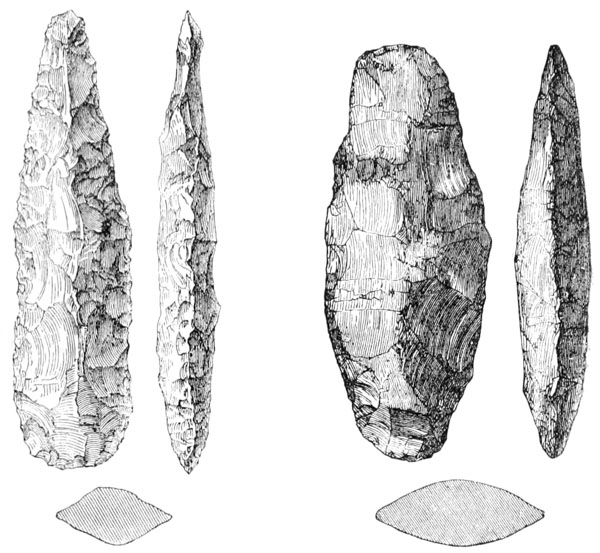

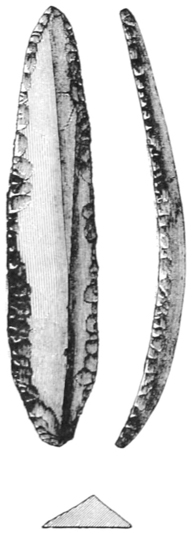

From different Countries — Some Trimmed Flakes, probably Knives — Knives from Barrows — Some possibly Lance-heads — Knives with one Edge blunt — Of Oval Form — Sharpened by Grinding — Of Circular Form — Of Semicircular and Triangular Form — The so-called “Picts’ Knives” — Like those of the Eskimos — Daggers or Lance-heads — With Notches at the Sides — Found in other Countries — Curved and Crescent-shaped Blades — Curved Knives, probably Sickles — Ripple-marked Egyptian Blades . . . 326

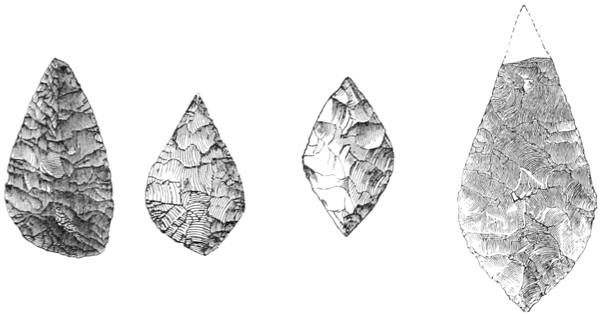

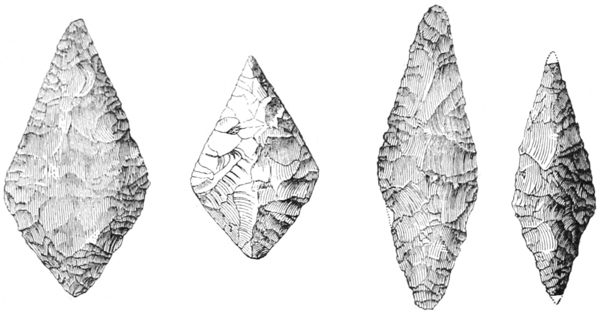

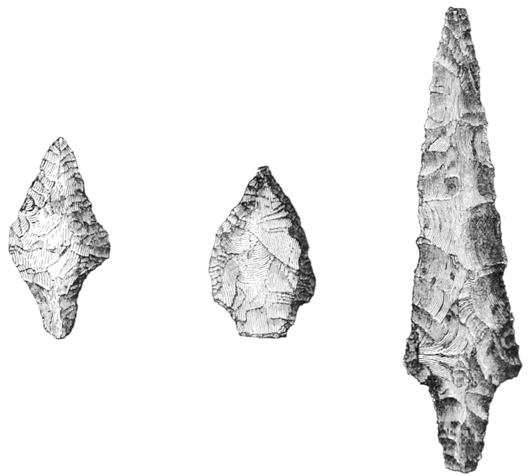

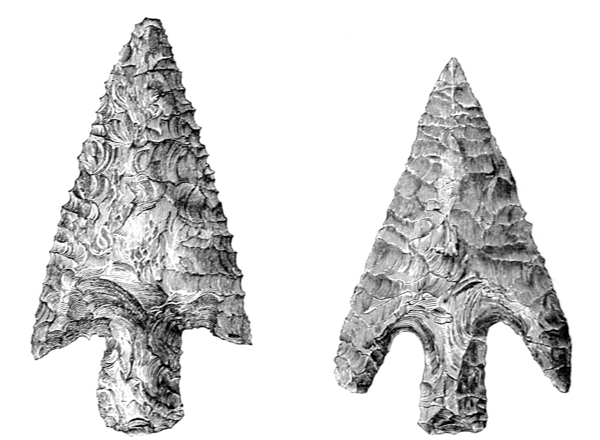

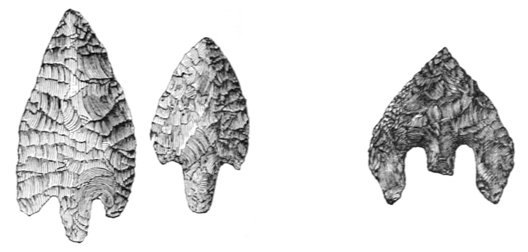

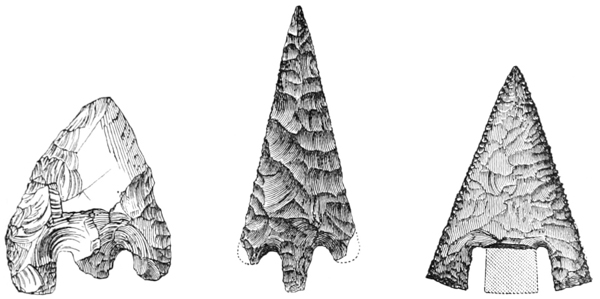

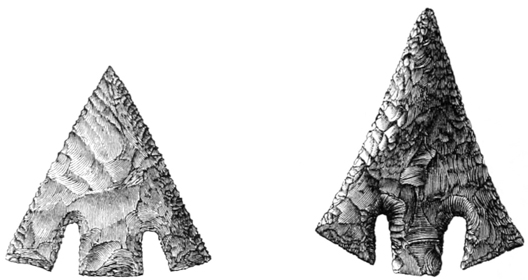

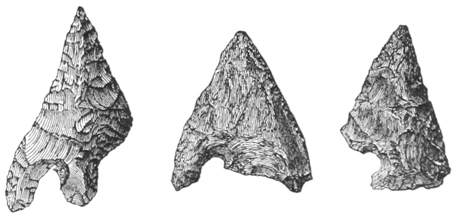

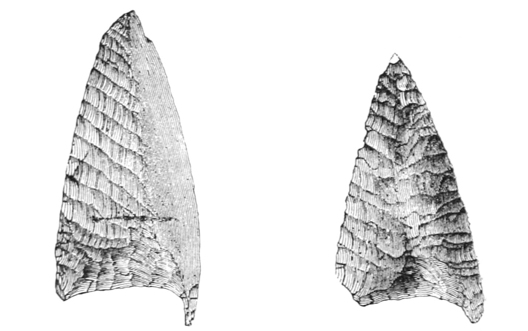

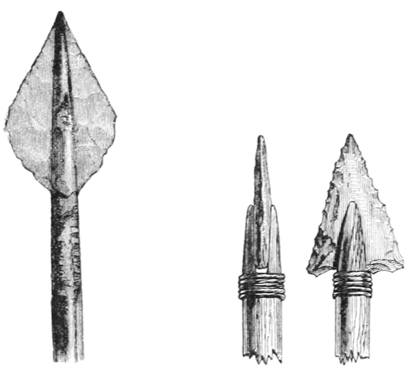

Their earliest occurrence — Thought to fall from the Heavens — Superstitions attaching to them — Worn as Amulets — An Egyptian Arrow — Javelin-heads — Leaf-shaped Arrow-heads — Leaf-shaped Arrow-heads pointed at both Ends — Lozenge-shaped Arrow-heads — Stemmed-Arrow-heads — Stemmed and Barbed Arrow-heads — Unusual Forms — Found in Scotland — Localities where found — The Triangular Form — Single-barbed Arrow-heads — The Chisel-ended Type — Found in Barrows — Irish and French Types — From various Countries — African and Asiatic Types — South American Types — How attached to their Shafts — Bows in Early Times . . . 360

Their probable Uses — Used for working in Flint . . . 412

Sling-stones Roughly Chipped from Flint — Ornamented Balls principally from Scotland — The use of “Bolas” . . . 417

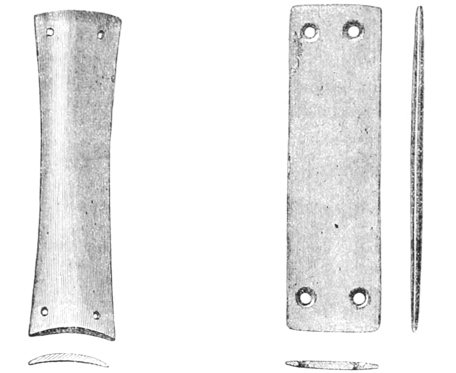

Wrist-guards or Bracers of Stone — The use of Arm-guards — Bone Lance-heads and Pins — Needles of Bone — Hoes of Stag’s Horn . . . 425

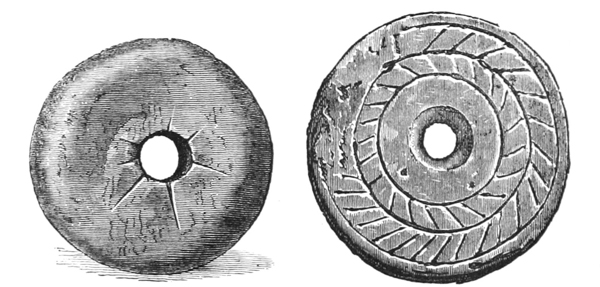

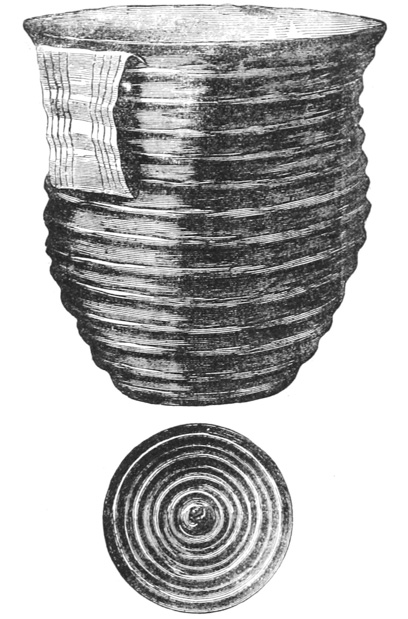

Superstitions attaching to Whorls — Uses of Perforated Discs — Use of Slick-stones — Stones as Burnishers and Weights — Stone Cups — Cups turned in a Lathe — Amber Cup — Vessels made of Stone . . . 436

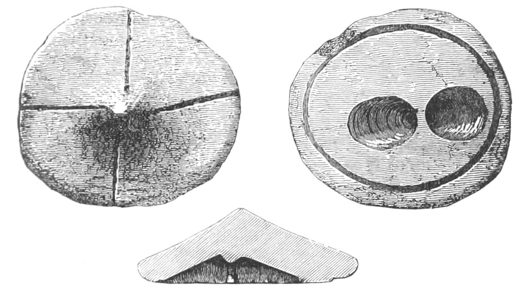

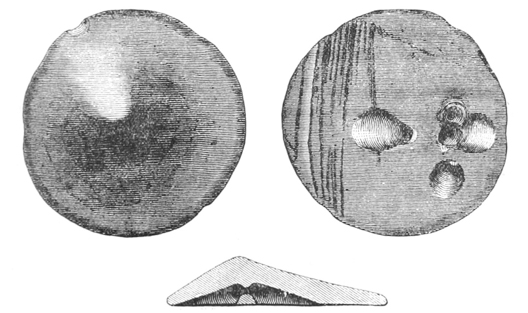

Buttons of Jet, Shale, and Stone — Buttons found in Barrows — Necklaces of Jet — Necklaces, Beads, Pendants, and Bracelets — Rings of Stone — Pebbles found in Barrows — Lucky Stones and Amulets — Conclusions as to the Neolithic Period . . . 452

Compared with those from the River-drift — Formation of Caverns — Deposition of Stalagmite — Different Ages of Caverns — Chronological Sequence of Caverns — Fauna of the Caves — Dean Buckland’s Researches — Kent’s Cavern, Torquay — Alteration in Structure of Flint — Trimmed Flakes from Kent’s Cavern — Scrapers from Kent’s Cavern — Cores and Hammers from Kent’s Cavern — Bone Harpoon-heads from Kent’s Cavern — Fauna of Kent’s Cavern — Animal Remains associated with Works of Art — Correlation of Kent’s Cavern with Foreign Caves — Brixham Cave — Trimmed Flakes from the Brixham Cave — The Wookey Hyæna Den — The Gower and other Welsh Caves — The Caves of Creswell Crags — General Considerations . . . 473

The Discoveries at Abbeville and Amiens — Discoveries on the Continent and in India — In the Valley of the Ouse — Biddenham, Bedford — Hitchin, Herts — Valleys of the Cam and the Lark — Bury St. Edmunds — Icklingham — High Lodge, Mildenhall — Redhill, Thetford — Santon Downham — Bromehill, Weeting — Gravel Hill, Brandon — Lakenheath — Shrub Hill, Feltwell — Hoxne, Suffolk — Saltley, Warwickshire — Possibility of their occurrence in the North of England — Gray’s Inn Lane, London — Highbury, London — Lower Clapton, Stoke Newington, &c. — Ealing and Acton — West Drayton, Burnham, Reading — Oxford and its Neighbourhood — Peasemarsh, Godalming — Valleys of the Gade and Colne — Caddington — No Man’s Land, Wheathampstead — Valley of the Lea — Valley of the Cray — Swanscomb and Milton Street — Ightham, Sevenoaks — Limpsfield, Surrey — Valley of the Medway — Reculver — Thanington, Kent — Canterbury and Folkestone — Southampton — Hill Head, Southampton Water — The Foreland, Isle of Wight — Bemerton, Salisbury — Fisherton and Milford Hill, Salisbury — Bournemouth and Barton Cliff — Valley of the Axe . . . 526

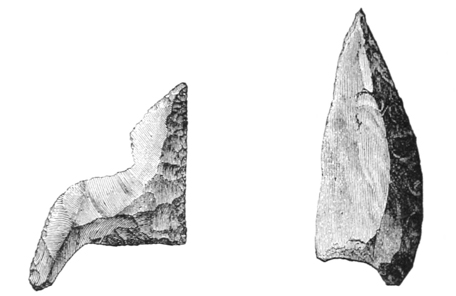

Flint Flakes — Trimmed Flakes — Pointed Implements — Sharp-rimmed Implements — Differ from those of Neolithic Age — Their occurrence in other parts of the World — Found in Africa and Asia — Their probable Uses — The Civilization they betoken — Characteristics of their Authenticity . . . 640

Hypothetical case of River-action — Origin of River Systems — Amount of Solid Matter in Turbid Water — Nature of Flood-deposits — Effects of Ground-Ice — Deposits left on the Slopes of Valleys during Excavation — Solvent power of Carbonic Acid — The results of the Deepening of Valleys — Actual Phenomena compared with the Hypothetical — The Denudation of the Fen Country — The Valley of the Waveney — The Valley of the Thames — Deposits in the South of England — Deposits near Salisbury — The Origin of the Solent — Deposits at Bournemouth — Breach through the Chalk-range South of Bournemouth — The Question of Climate — Evidence as to Climate — Association of Implements with a Quaternary Fauna — Scarcity of Human Bones in the River-drift — Attempts to formulate Chronological Data — Data from Erosion — Conclusion . . . 662

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY.

1. Egypt . . . 8

CHAPTER II.

ON THE MANUFACTURE OF STONE IMPLEMENTS IN PREHISTORIC TIMES.

CHAPTER III.

CELTS.

11.* Celt with Gnostic Inscription . . . 61

CHAPTER IV.

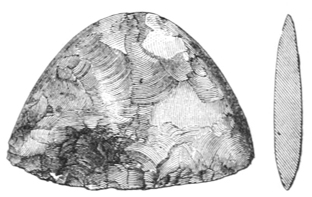

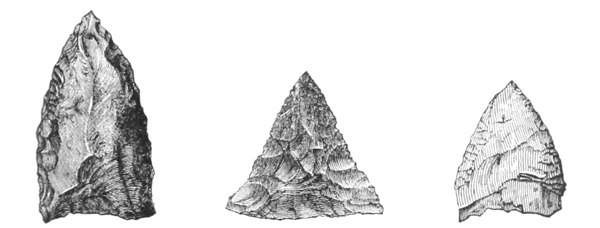

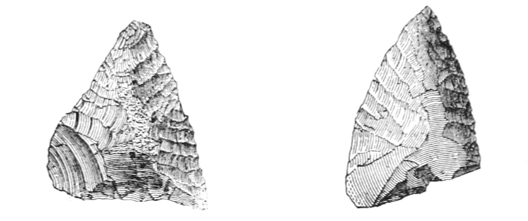

CHIPPED OR ROUGH-HEWN CELTS.

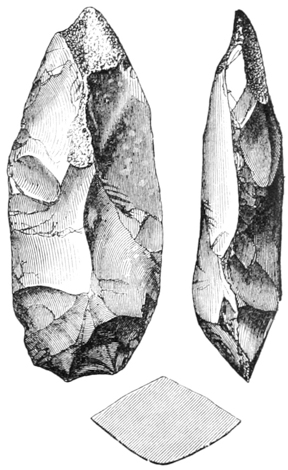

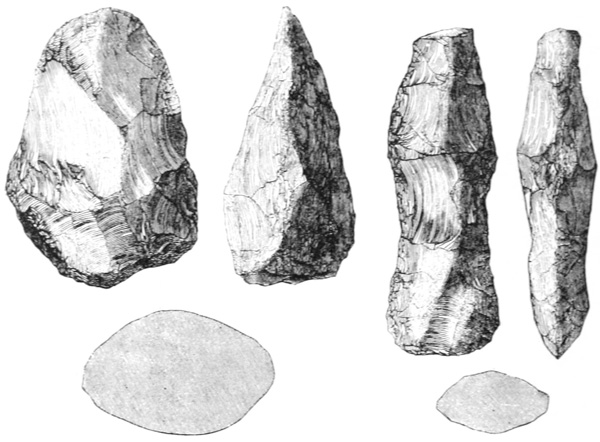

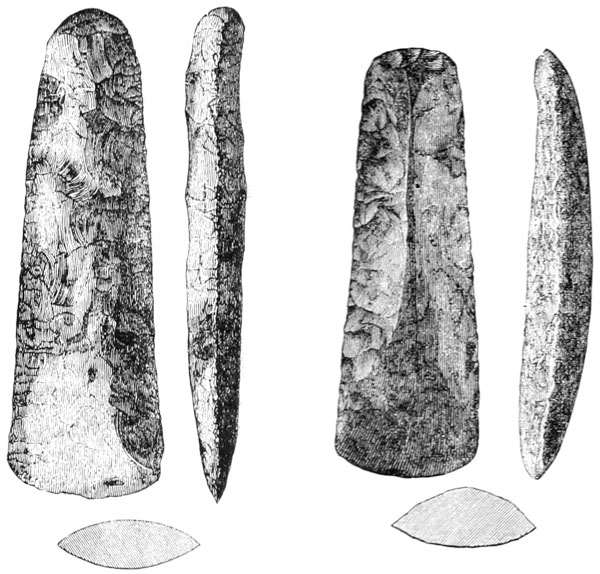

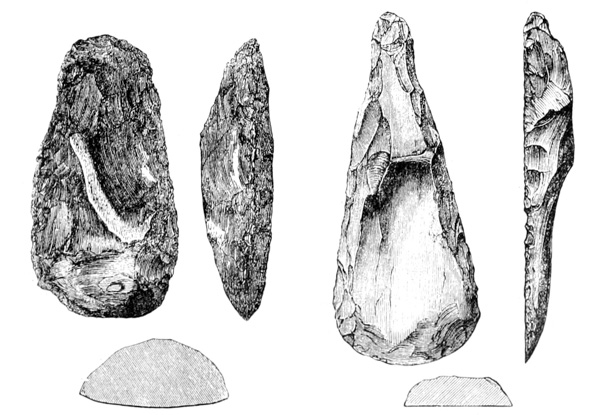

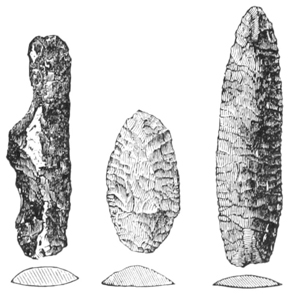

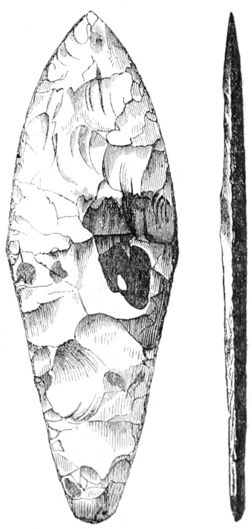

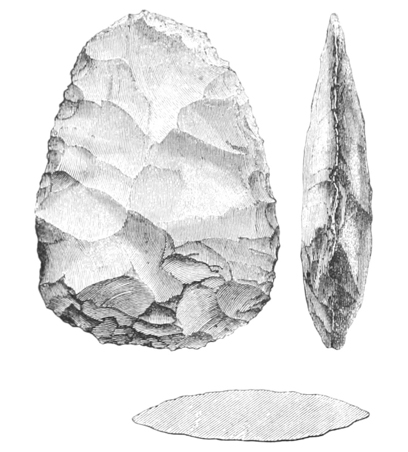

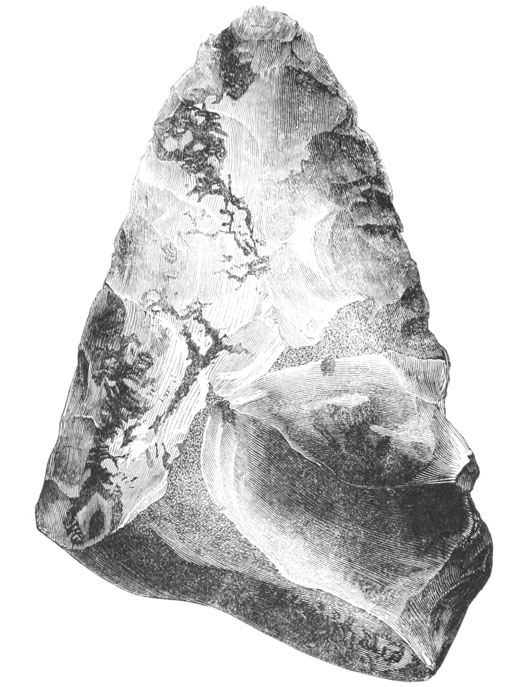

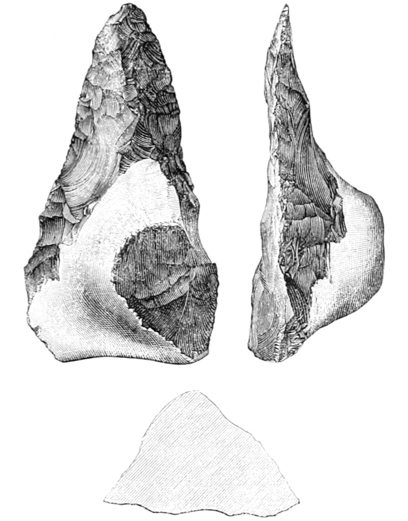

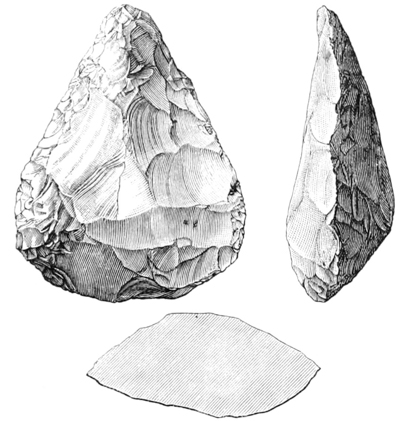

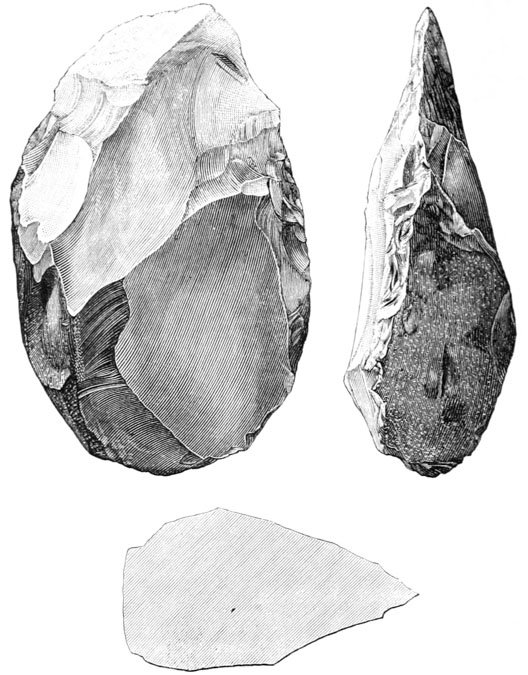

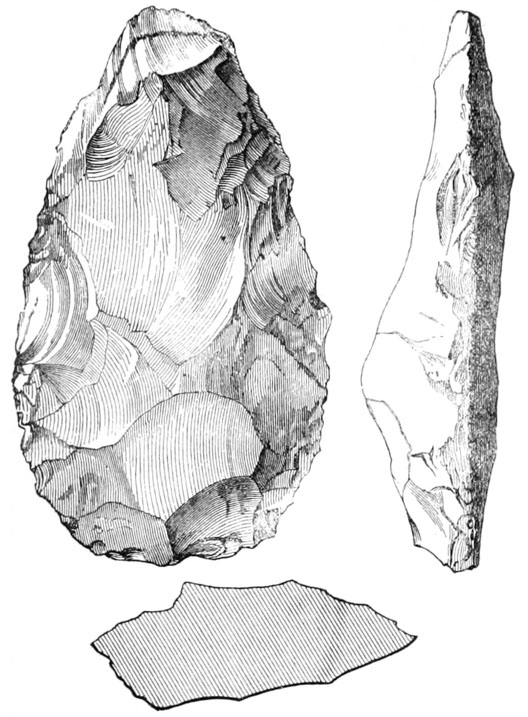

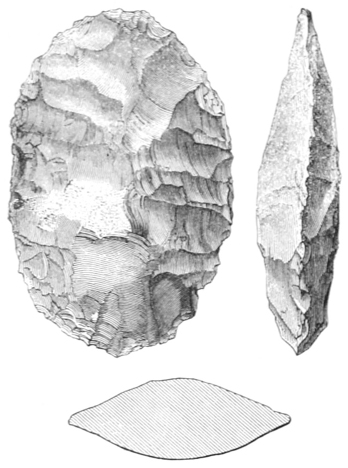

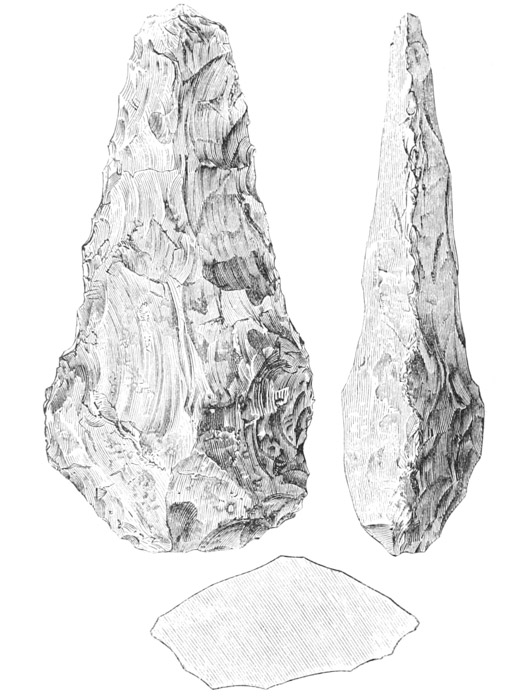

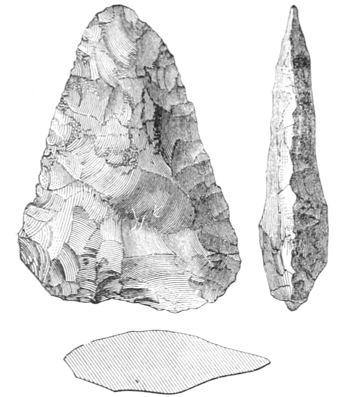

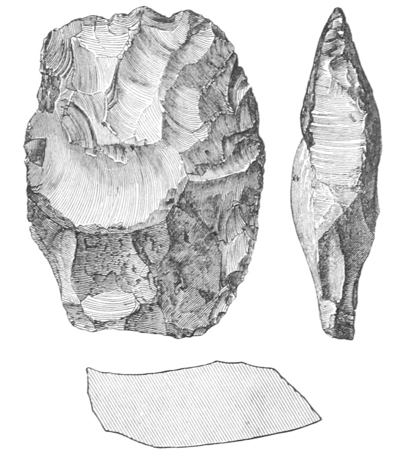

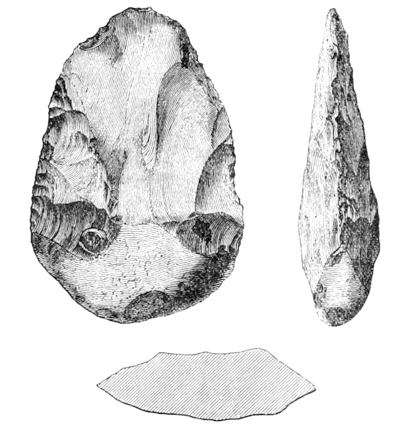

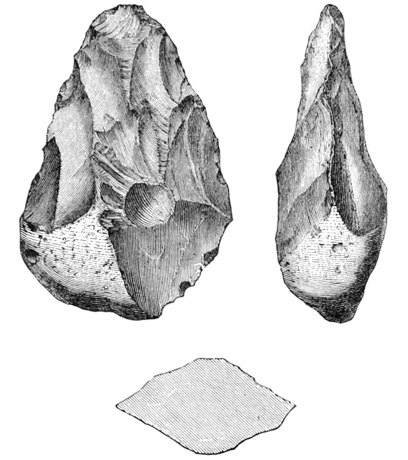

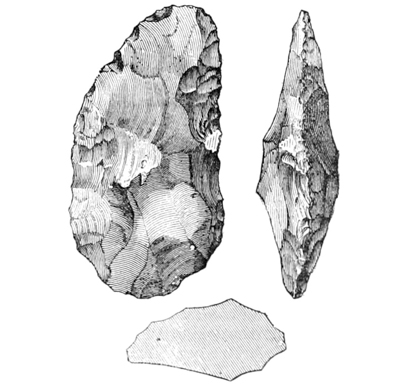

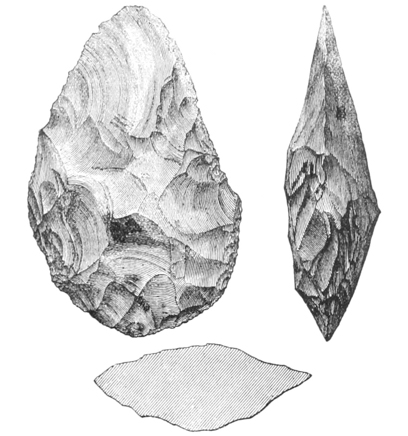

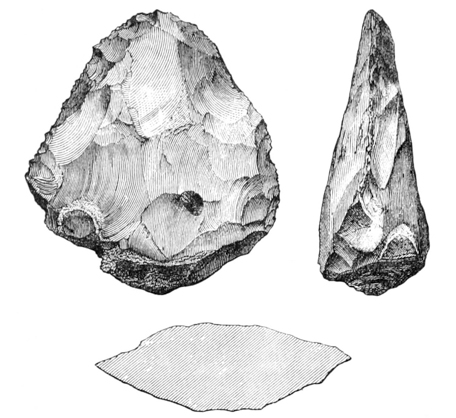

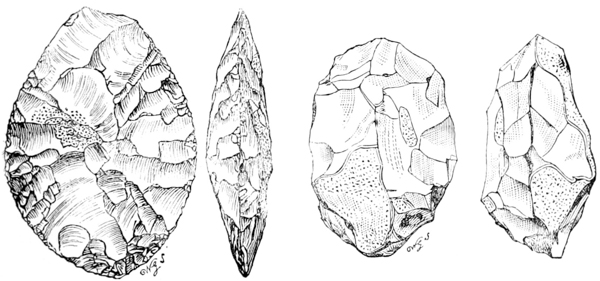

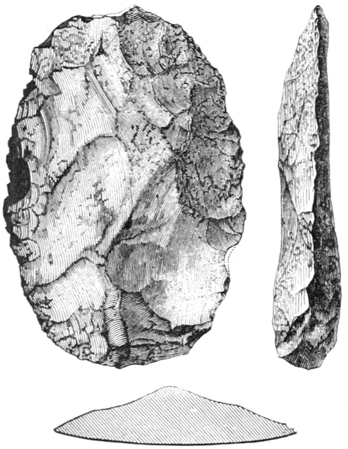

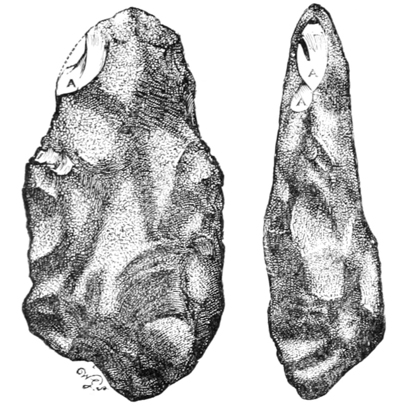

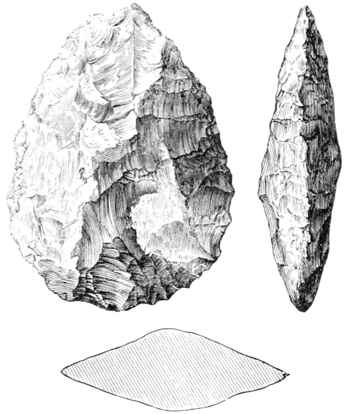

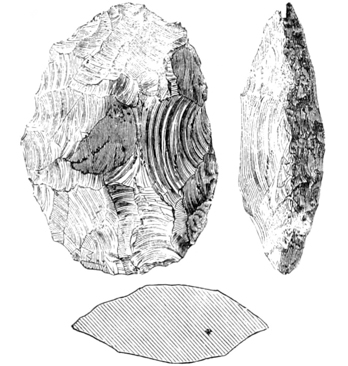

12. Near Mildenhall . . . 68

13. — — . . . 68

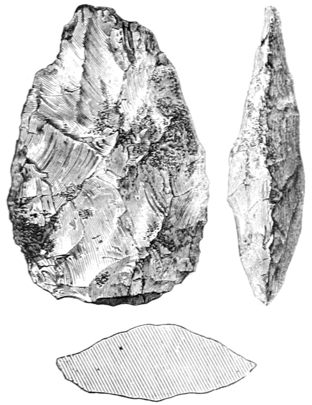

14. Near Thetford . . . 69

15. Oving, near Chichester . . . 70

16. Near Newhaven . . . 71

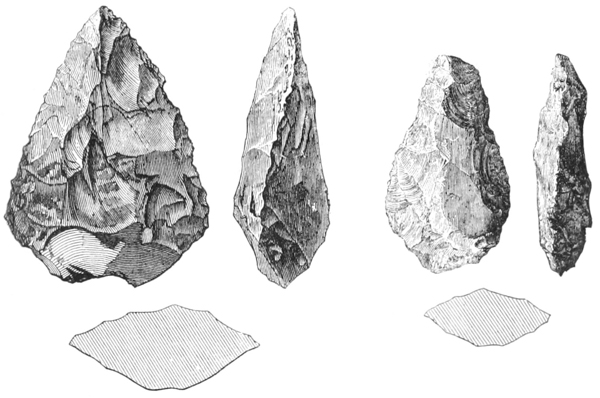

17. Near Dunstable . . . 72

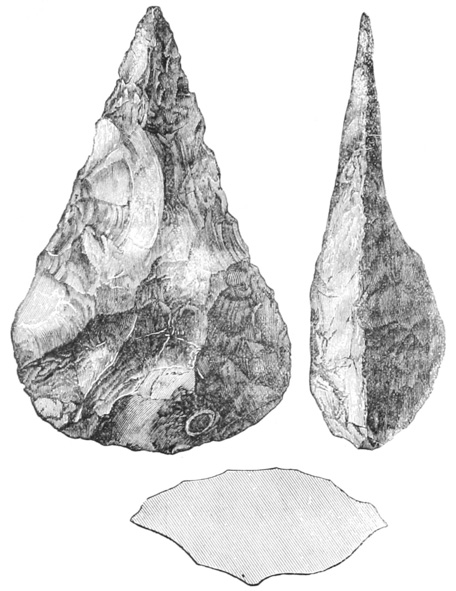

18. Burwell Fen . . . 72

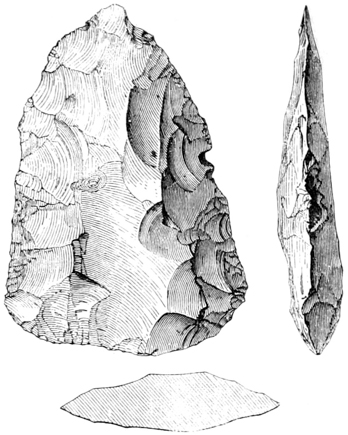

19. Mildenhall . . . 73

20. Bottisham Fen . . . 73

21. Near Bournemouth . . . 74

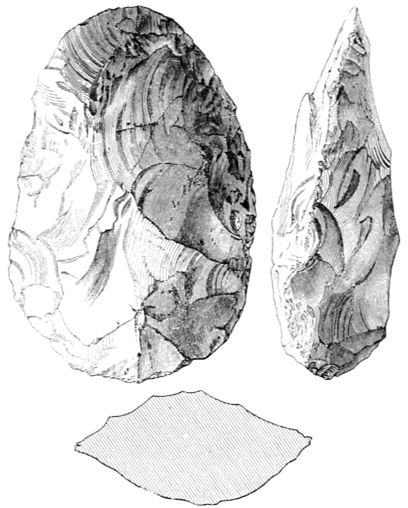

22. Thetford . . . 74

23. Reach Fen, Cambridge . . . 75

24. Scamridge, Yorkshire . . . 76

25.* Forest of Bere, near Horndean . . . 76

25A.* Isle of Wight . . . 77

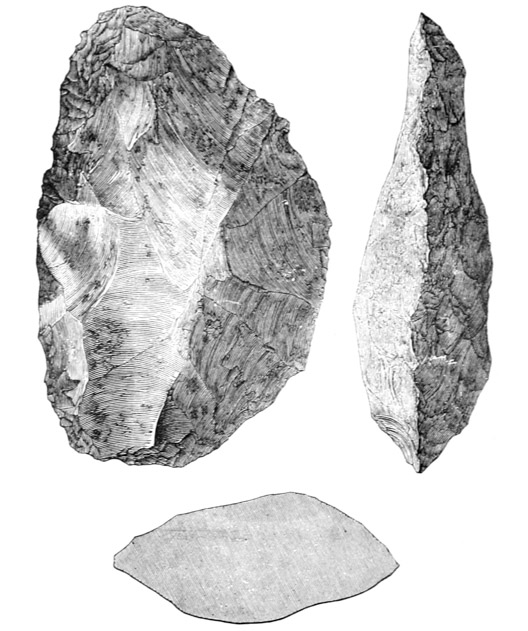

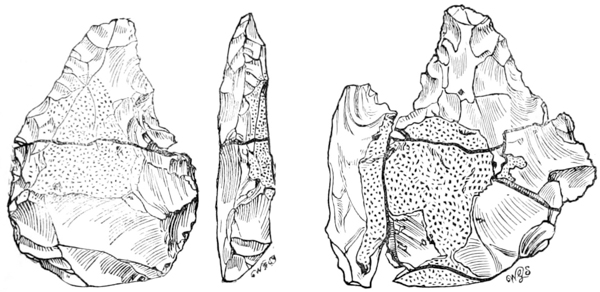

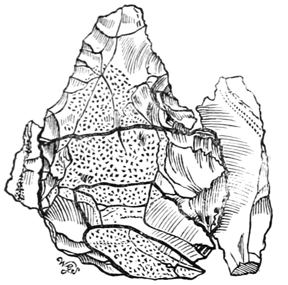

26. Cissbury . . . 81

27. — . . . 81

28. — . . . 82

29. — . . . 82

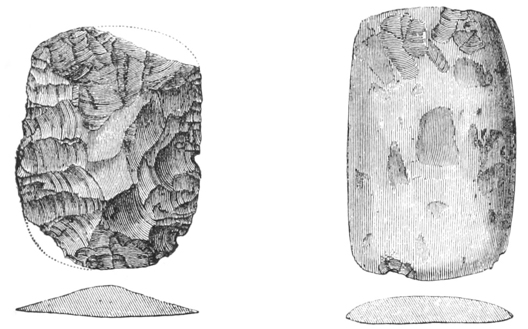

CHAPTER V.

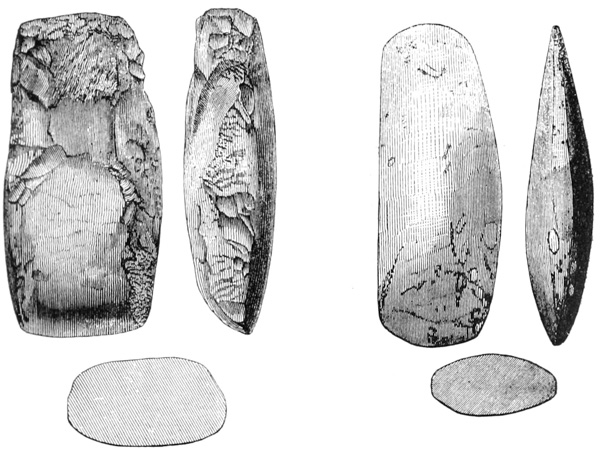

CELTS GROUND AT THE EDGE ONLY.

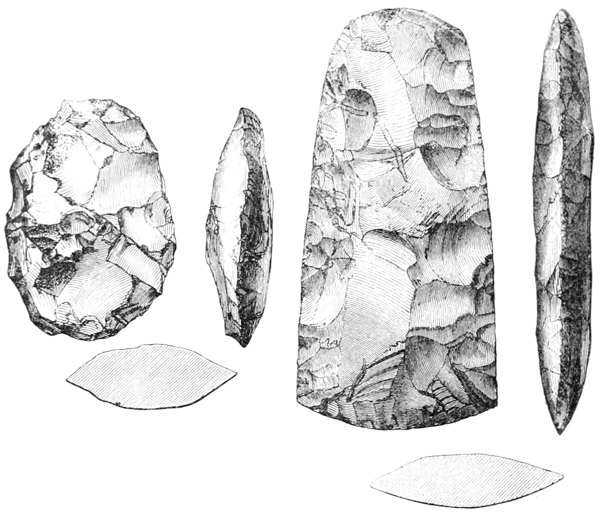

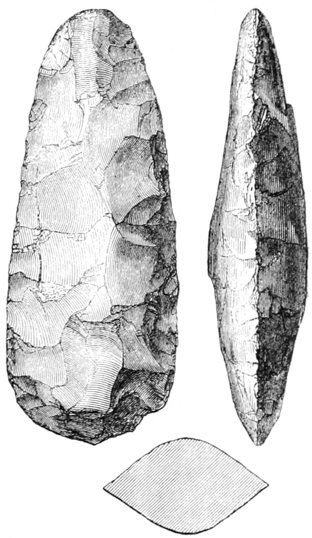

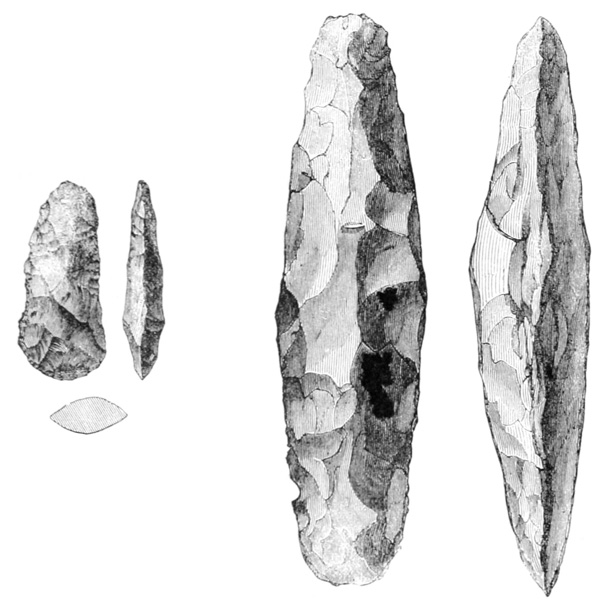

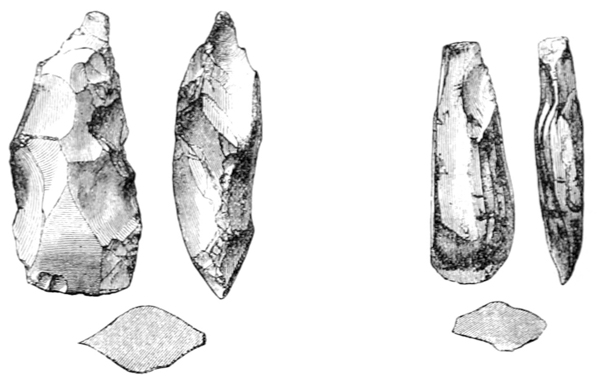

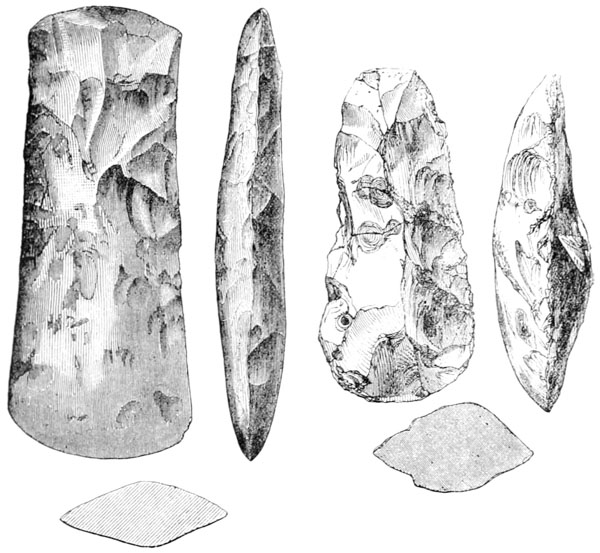

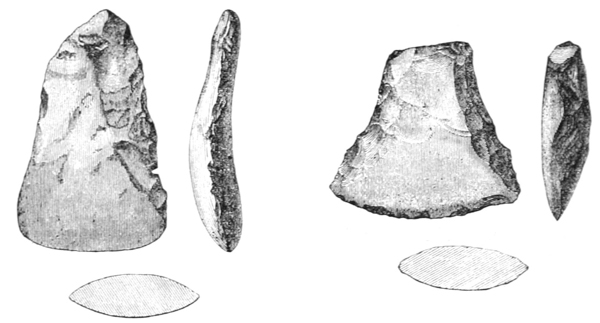

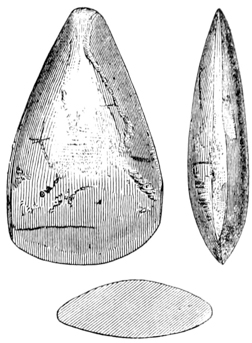

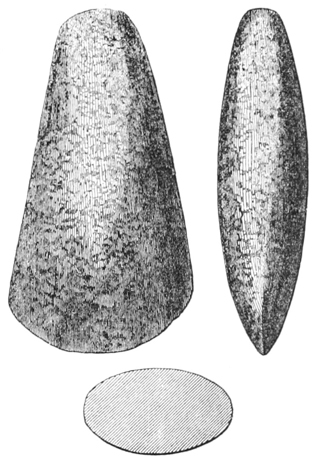

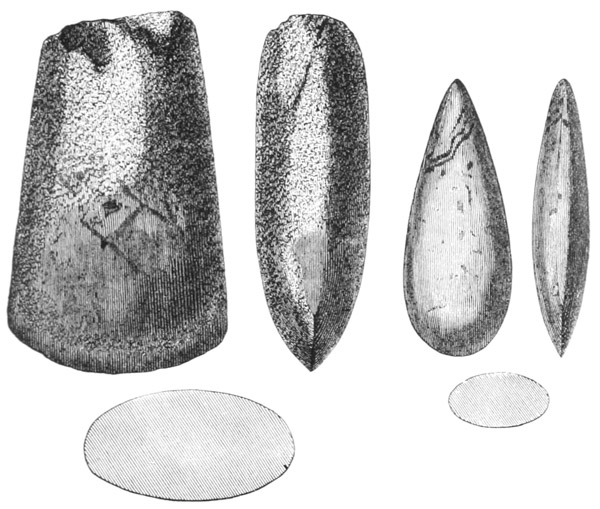

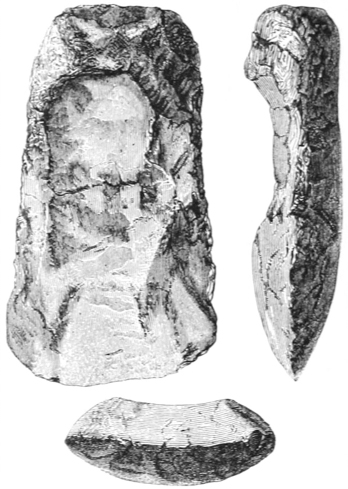

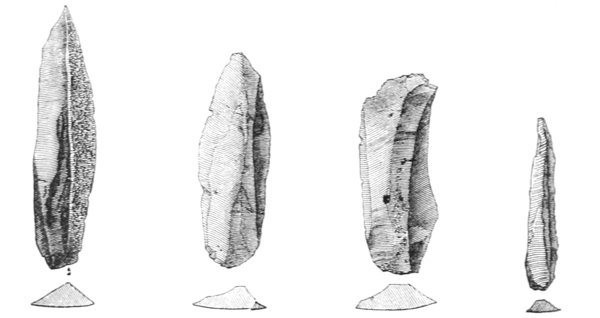

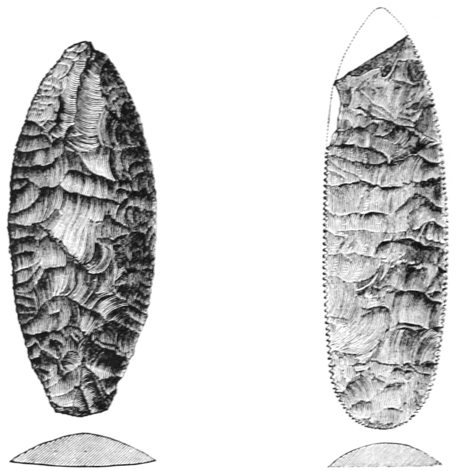

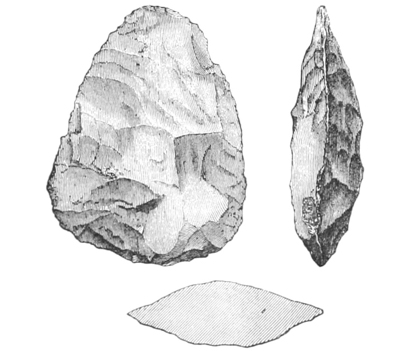

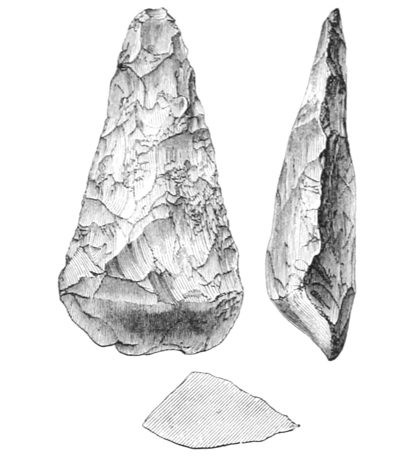

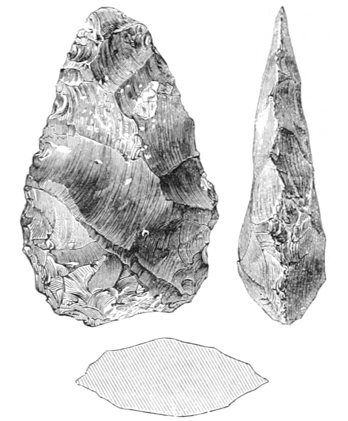

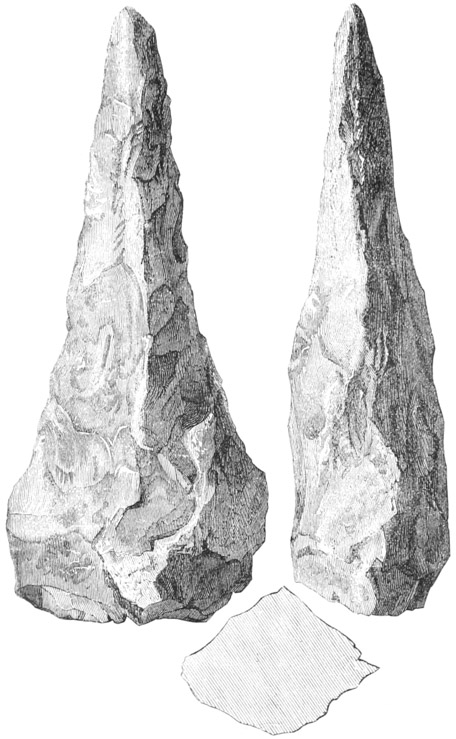

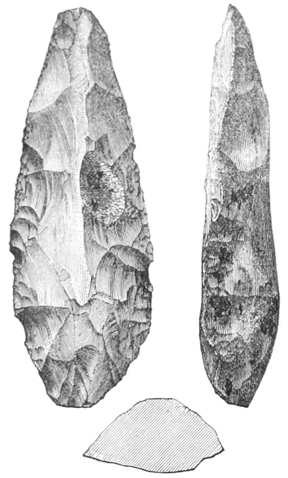

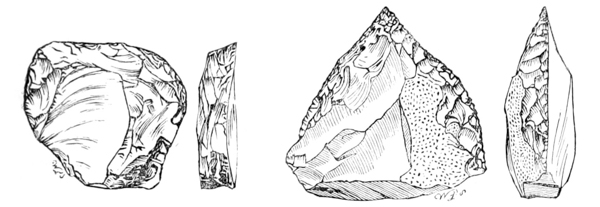

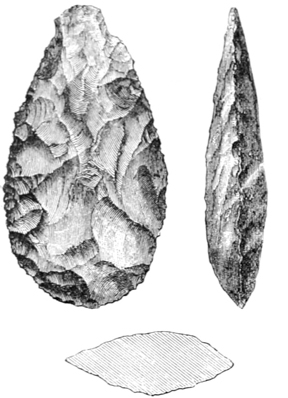

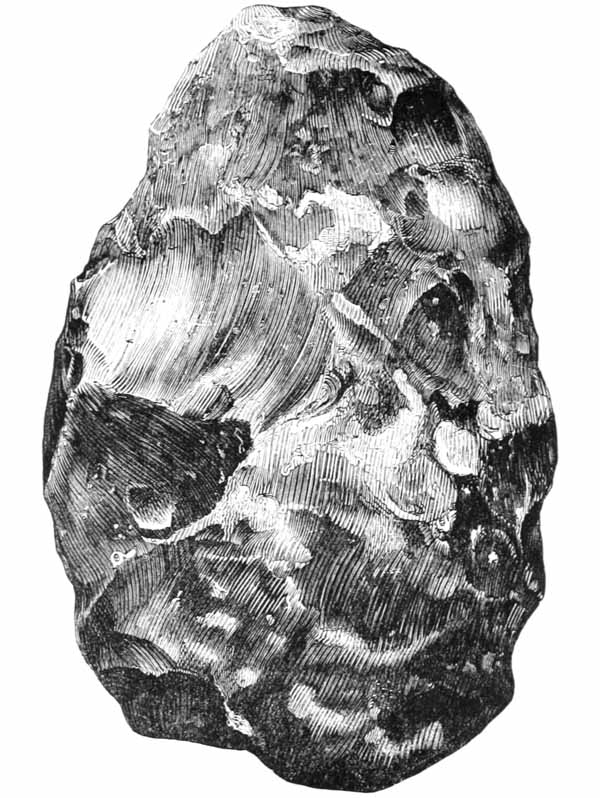

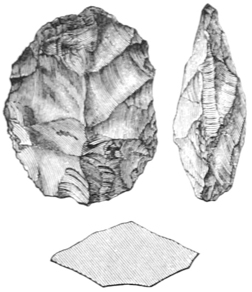

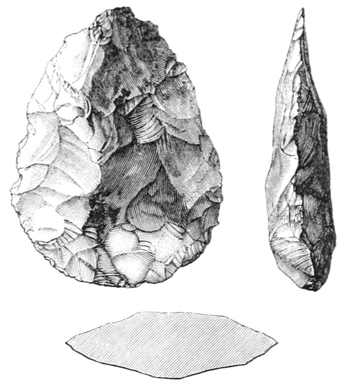

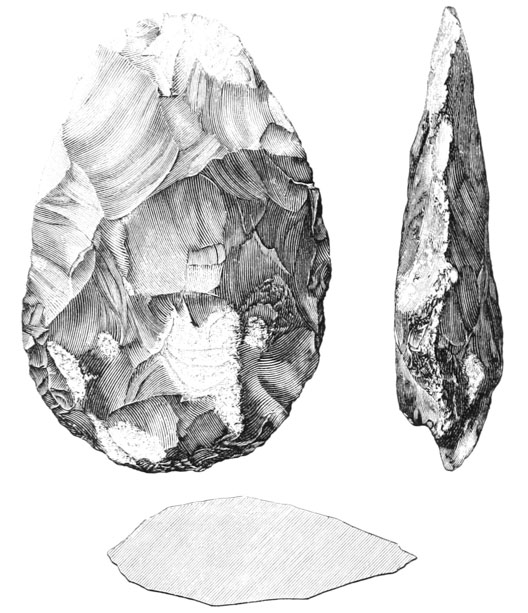

30. Downs near Eastbourne . . . 88

31. Culford, Suffolk . . . 88

32. Near Mildenhall, Suffolk . . . 88

33. Sawdon, North Yorkshire . . . 89

34. Weston, Norfolk . . . 90

35. Mildenhall . . . 91

35A. Reach Fen . . . 92

36. Burwell Fen . . . 93

37. Thetford . . . 93

38. Undley Common, Lakenheath . . . 94

38A. East Dean . . . 95

39. Ganton . . . 95

40. Swaffham Fen . . . 95

41. Grindale, Bridlington . . . 96

42. North Burton . . . 96

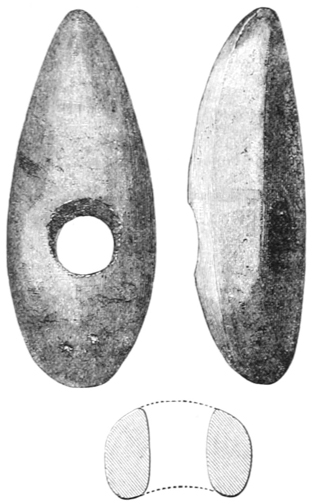

CHAPTER VI.

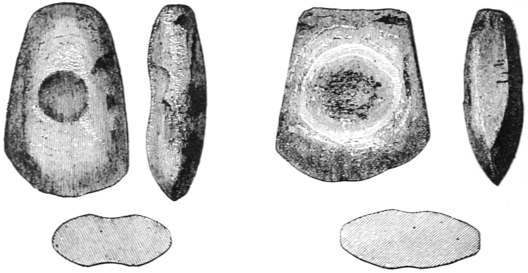

POLISHED CELTS.

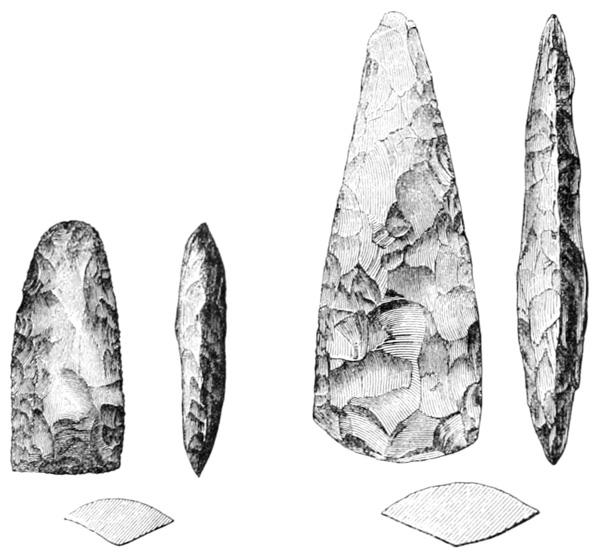

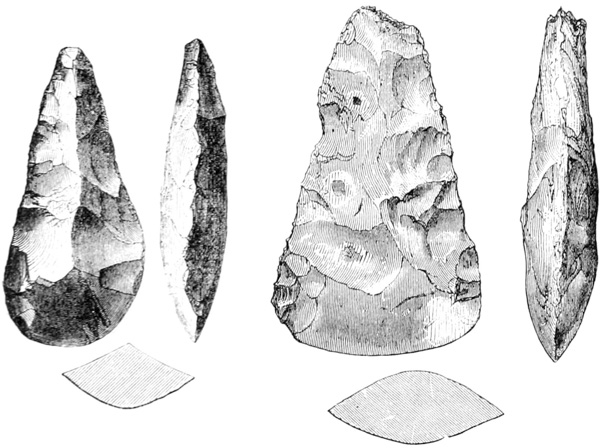

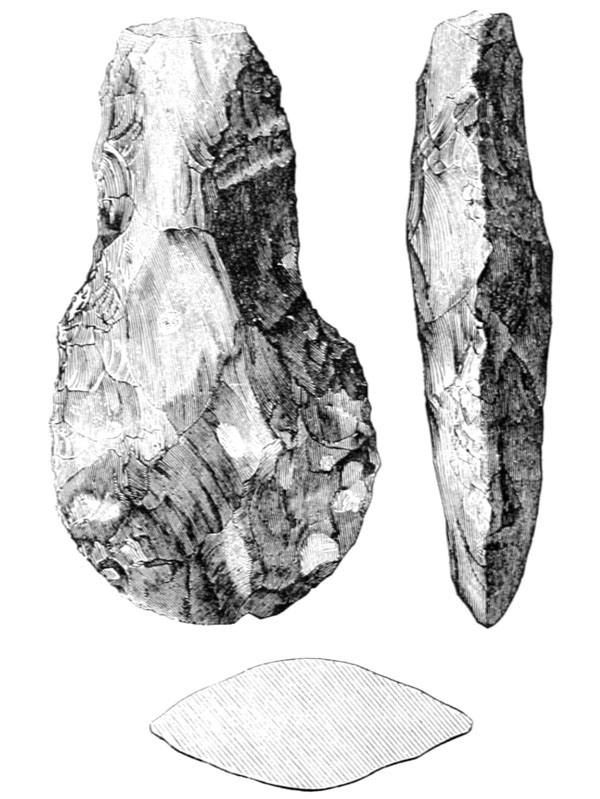

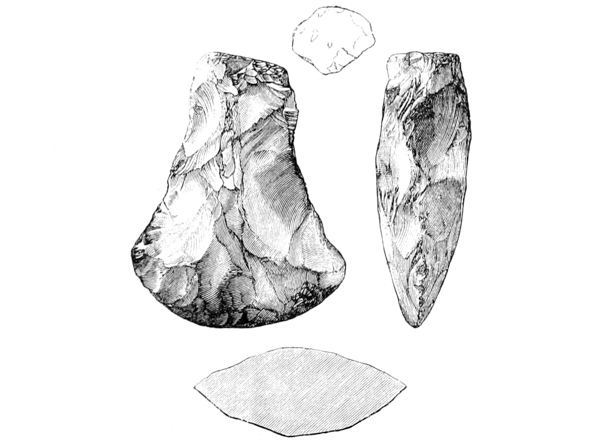

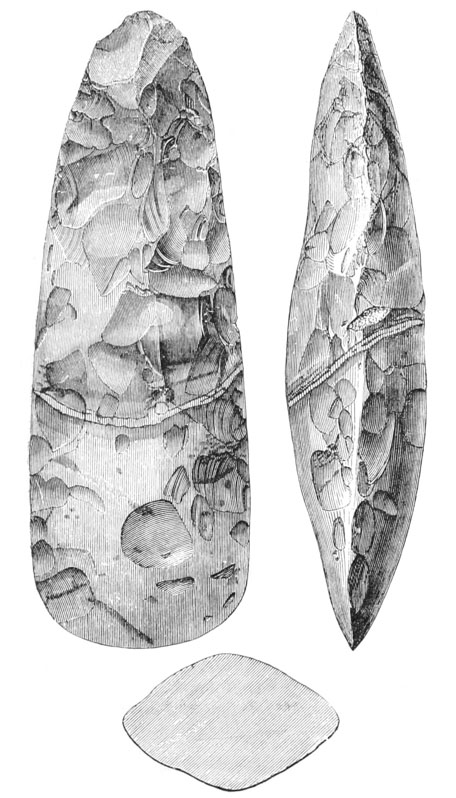

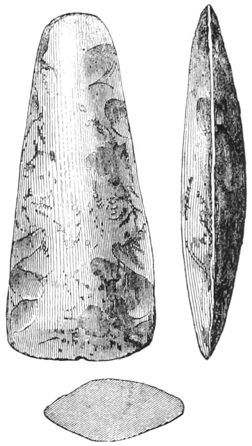

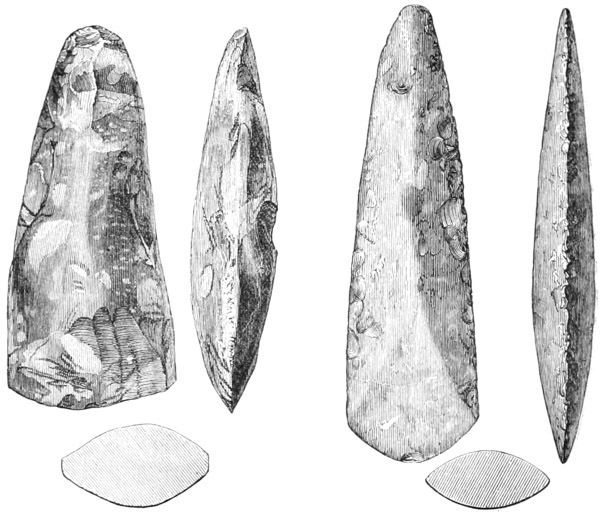

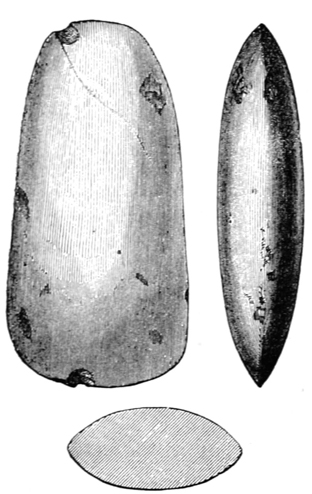

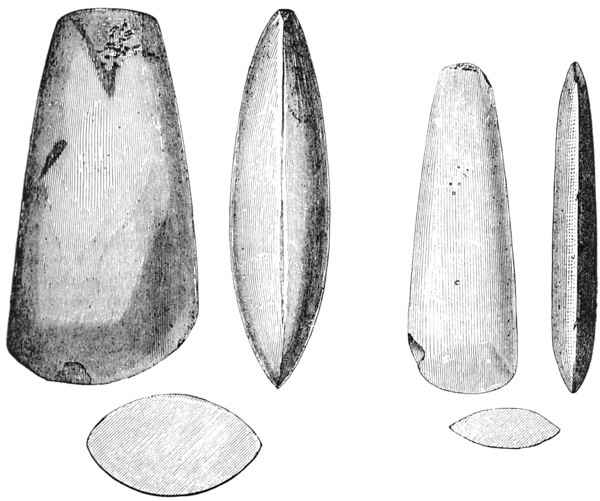

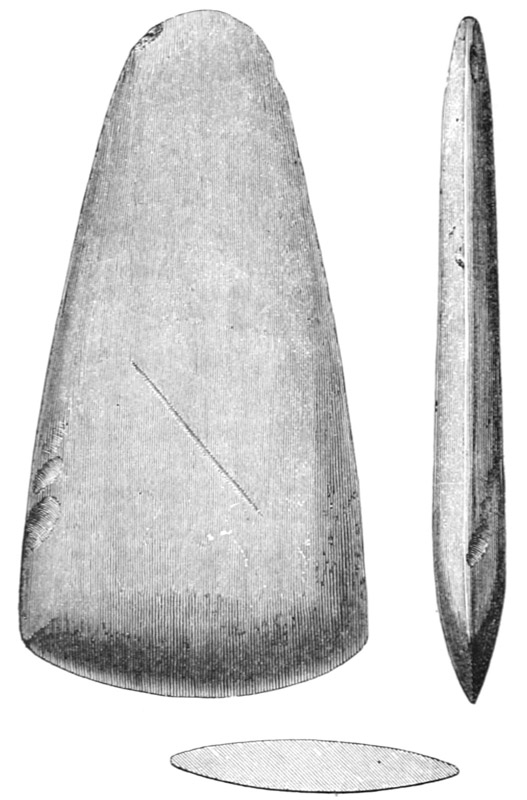

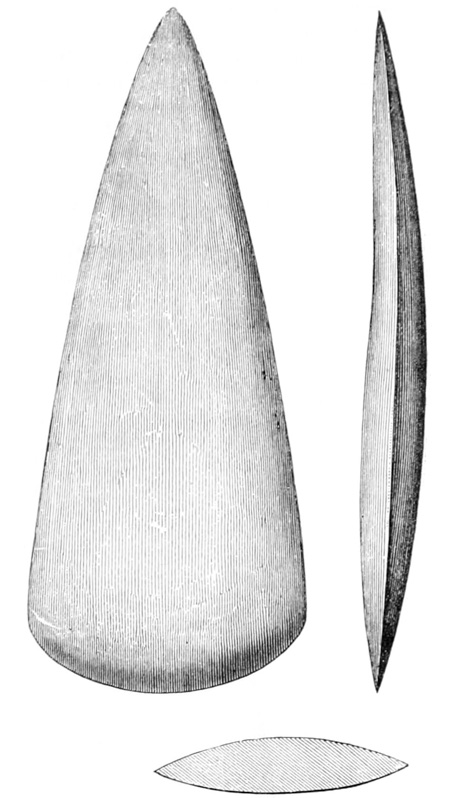

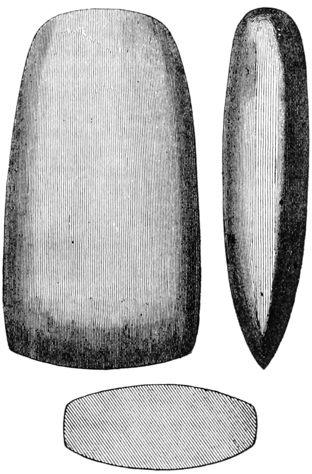

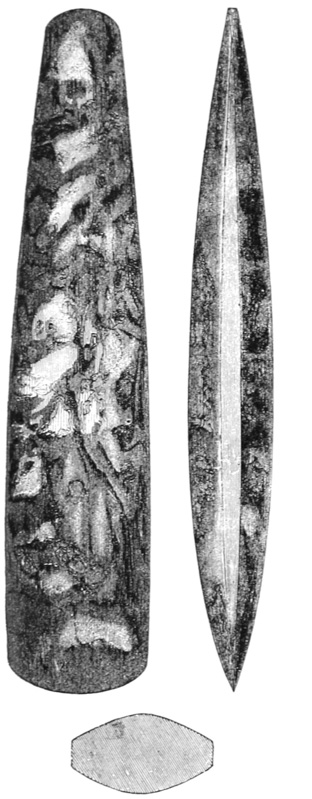

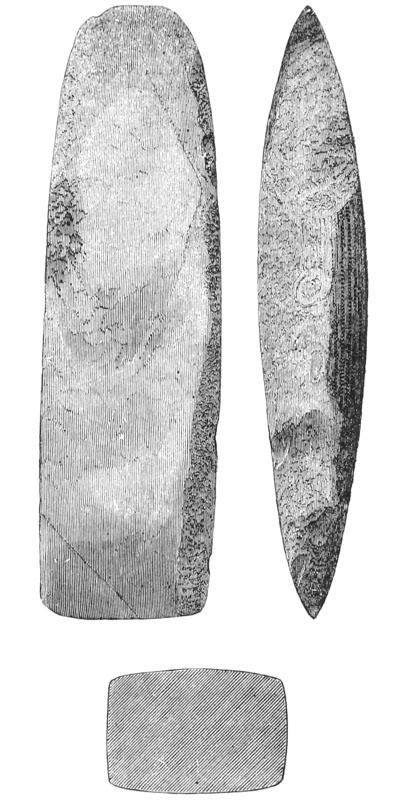

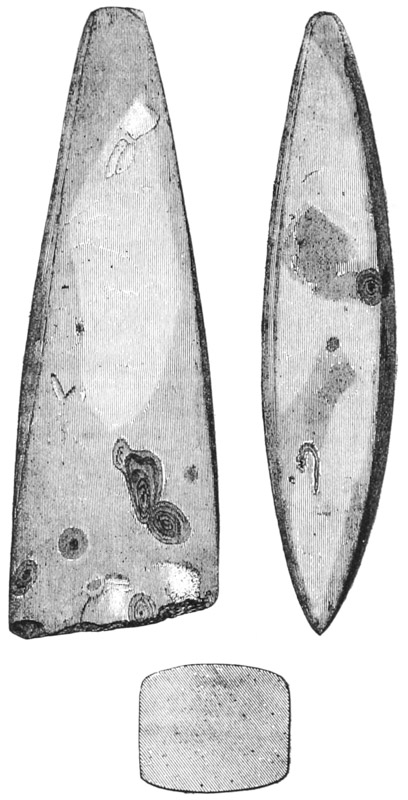

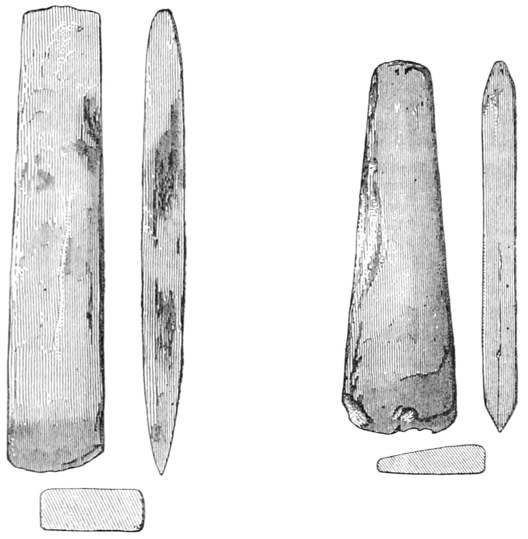

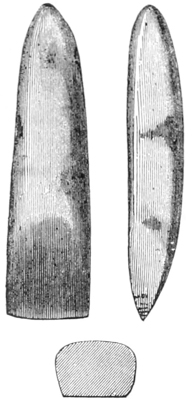

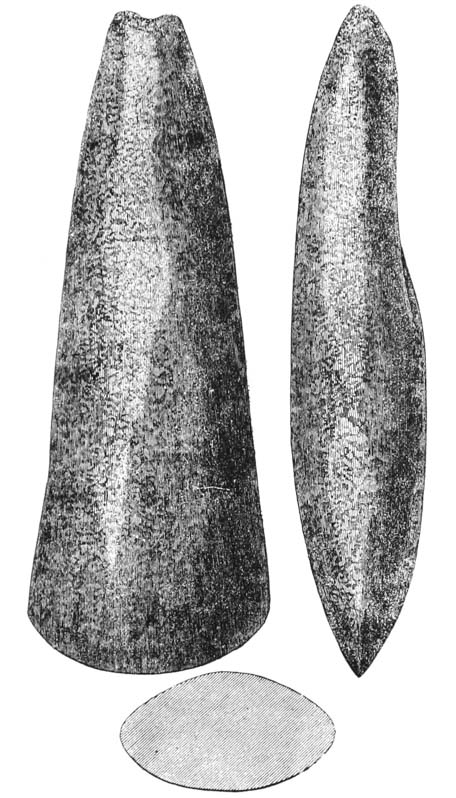

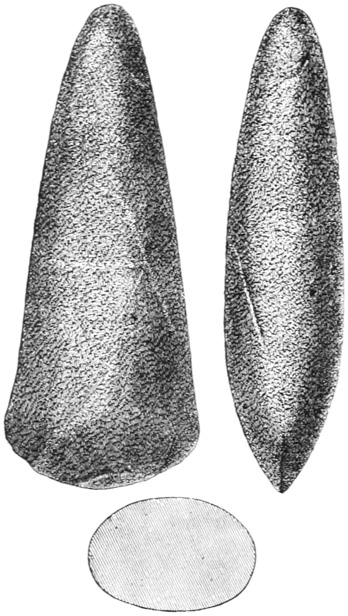

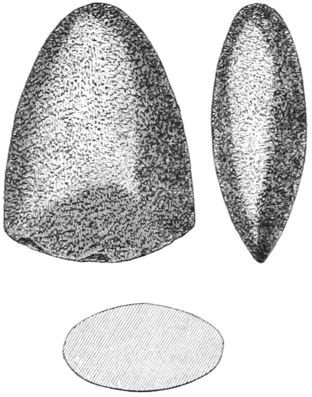

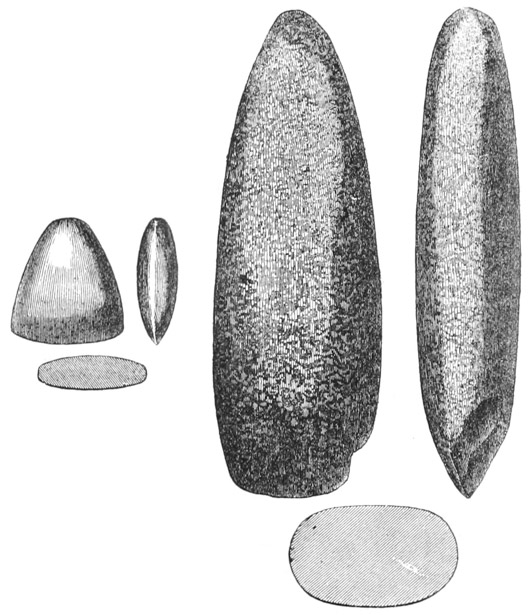

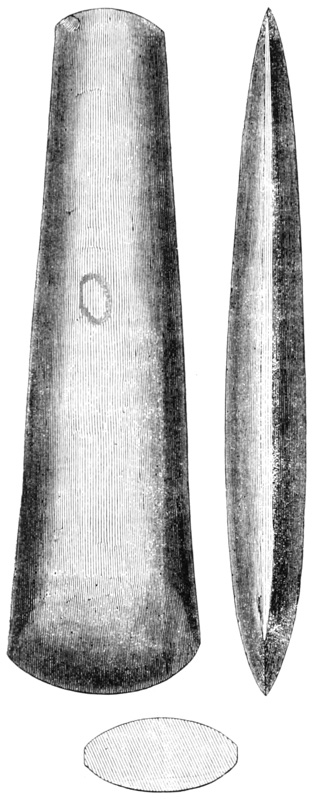

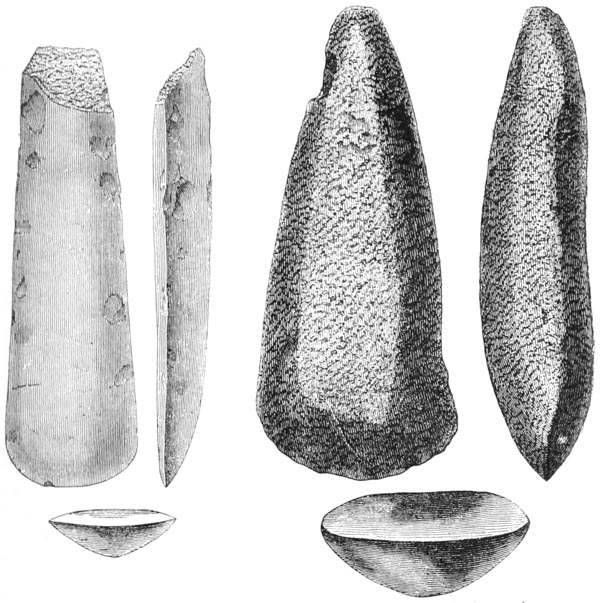

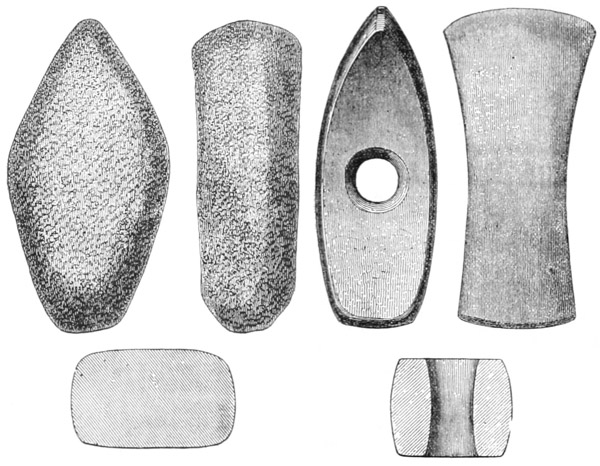

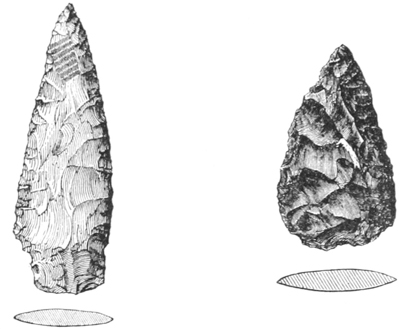

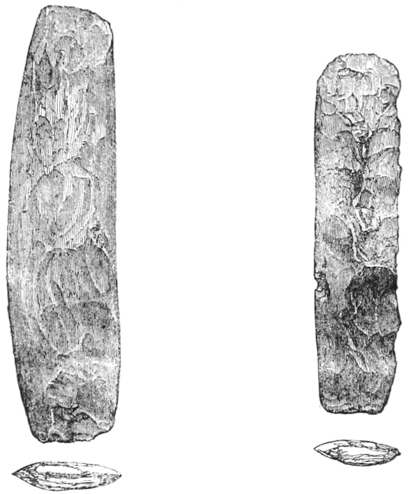

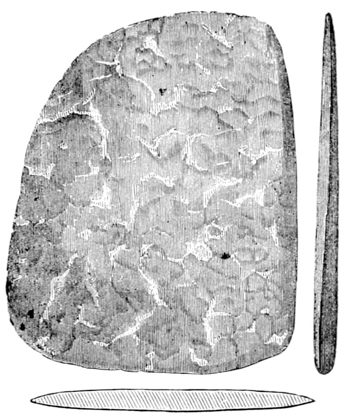

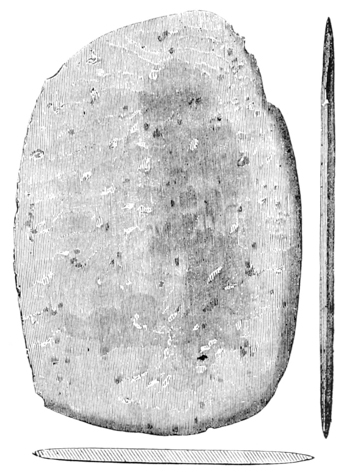

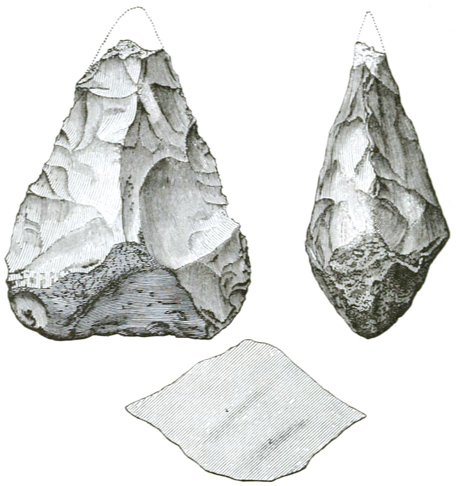

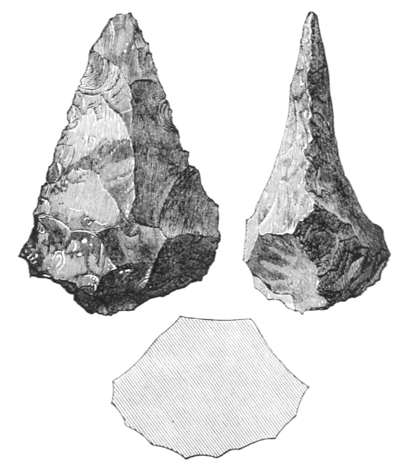

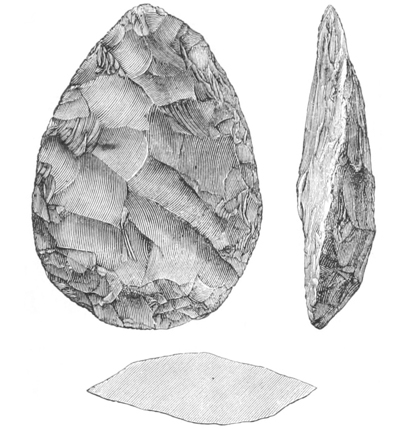

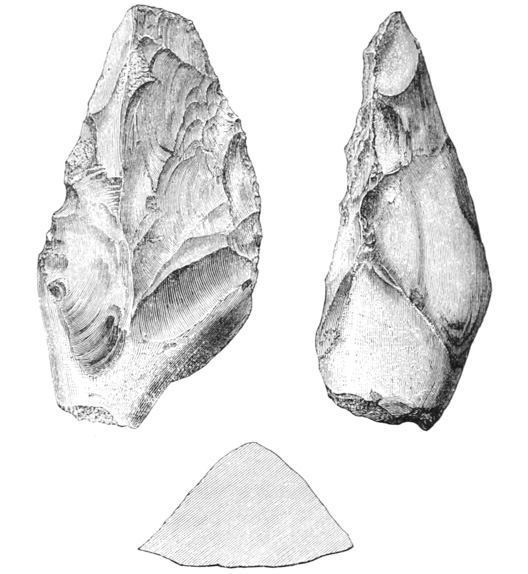

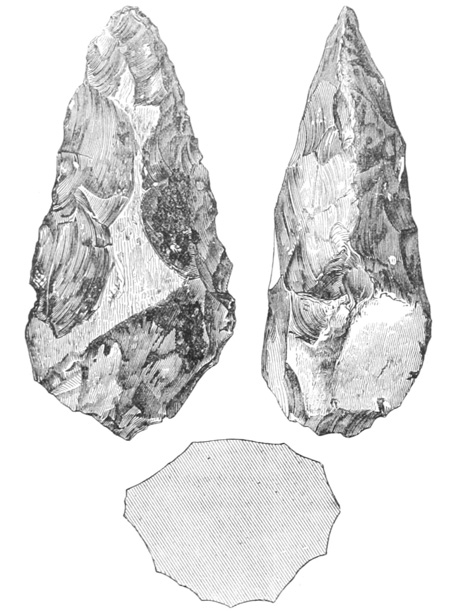

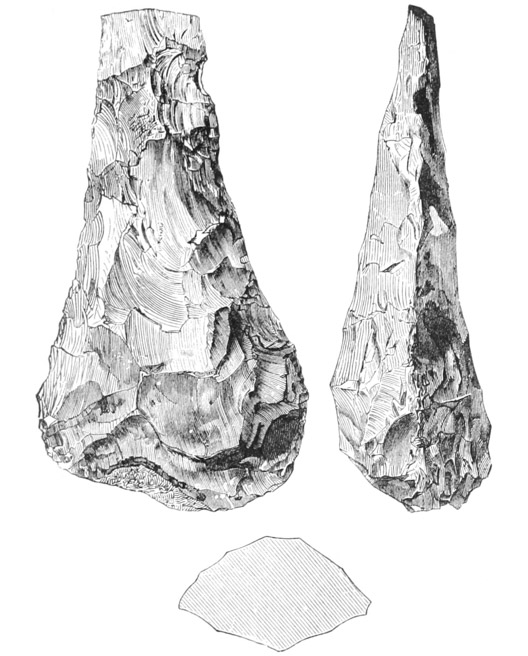

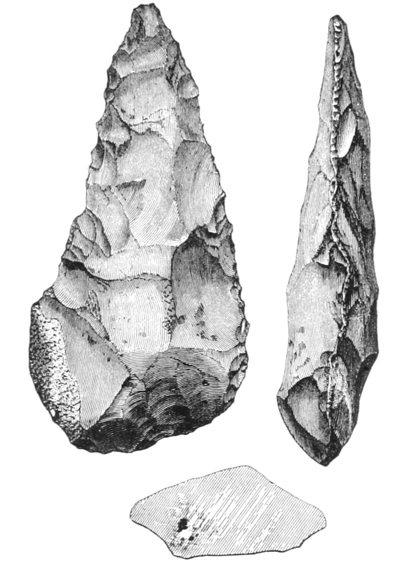

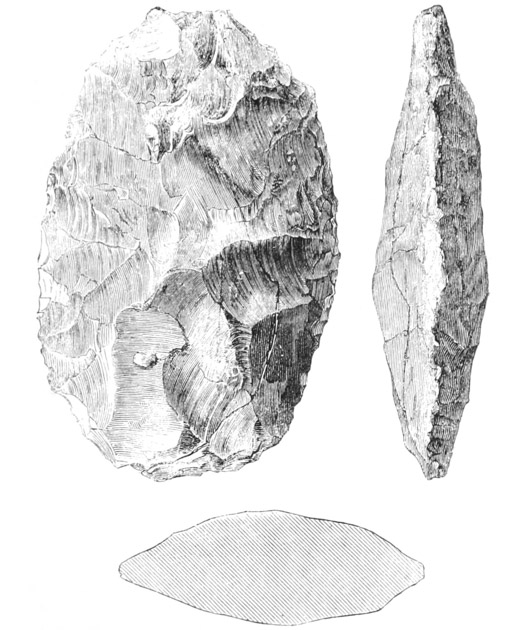

43. Santon Downham, Suffolk . . . 99

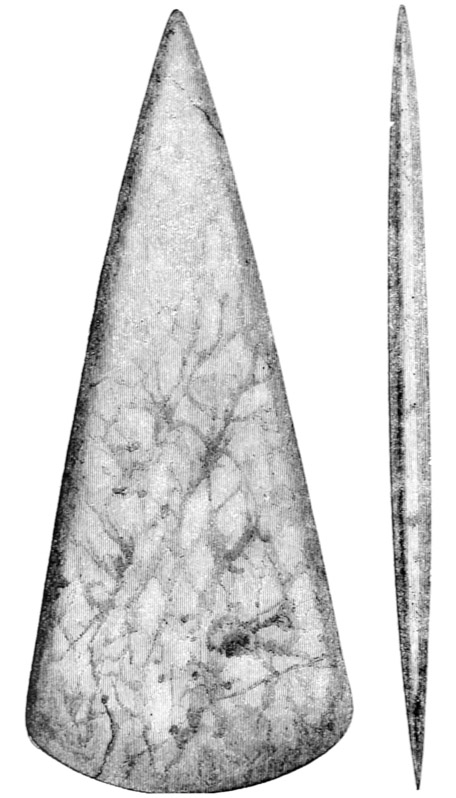

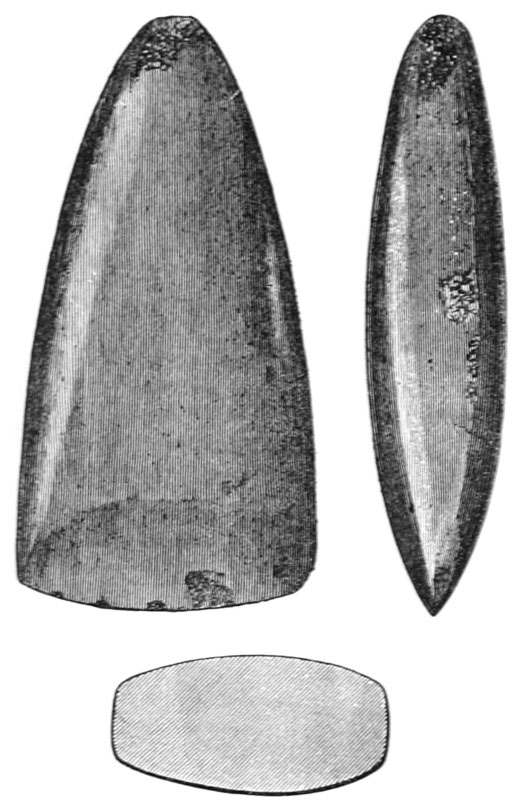

44. Coton, Cambridge . . . 101

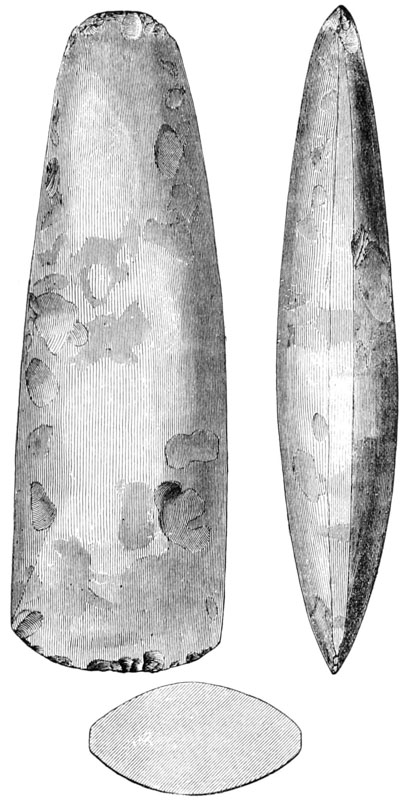

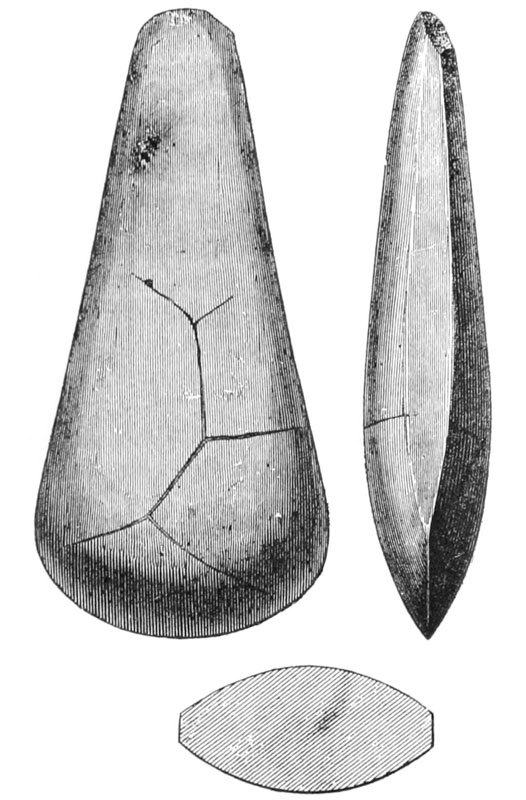

45. Reach Fen, Cambridge . . . 102

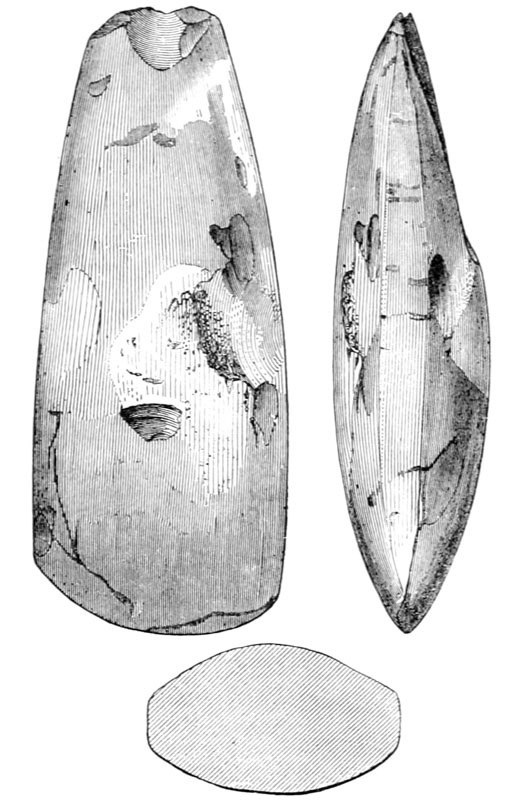

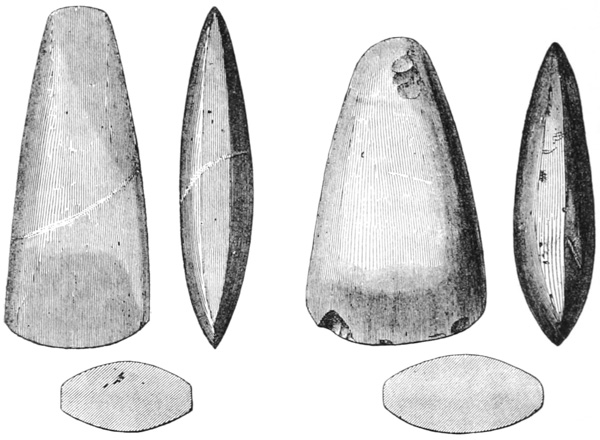

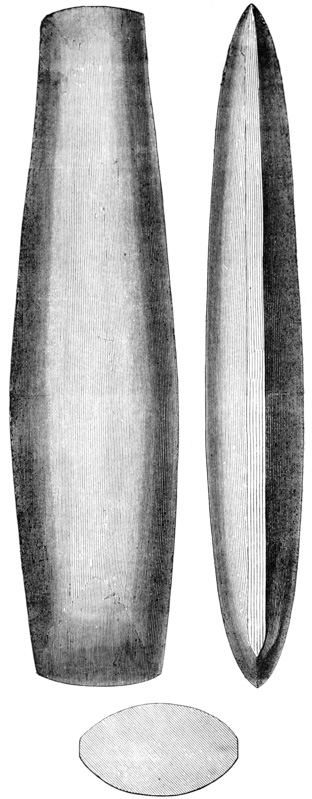

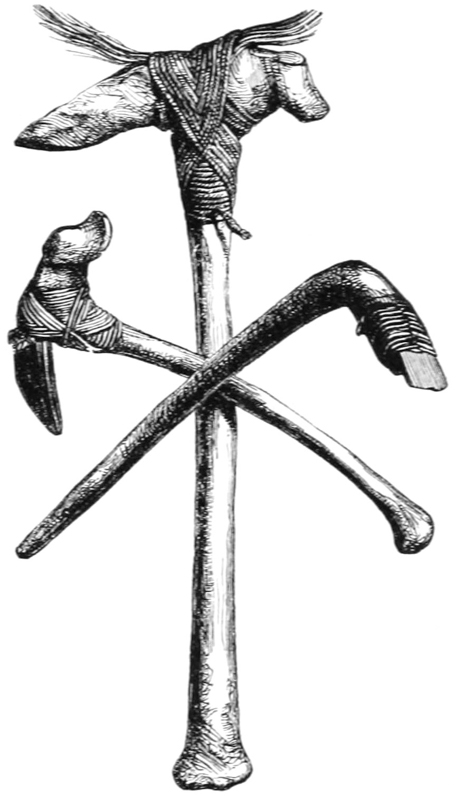

46. Great Bedwin, Wilts . . . 102

47. Burradon, Northumberland . . . 103

48. Coton, Cambridge . . . 104

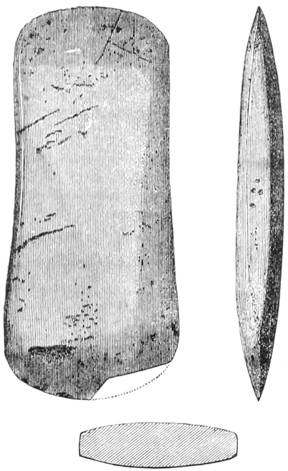

49. Ponteland, Northumberland . . . 105

50. Fridaythorpe, Yorkshire . . . 105

51. Oulston . . . 106

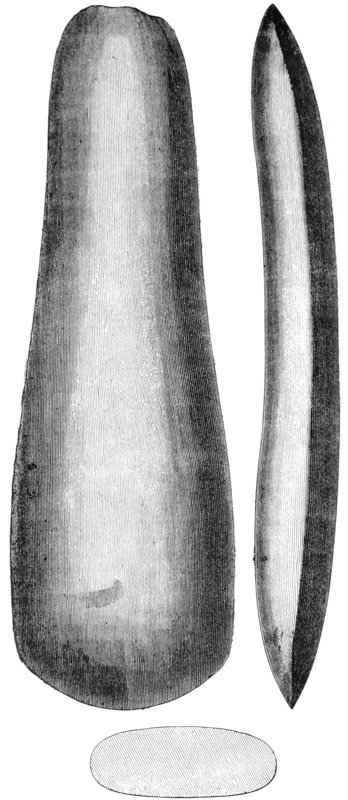

52. Burwell Fen . . . 107

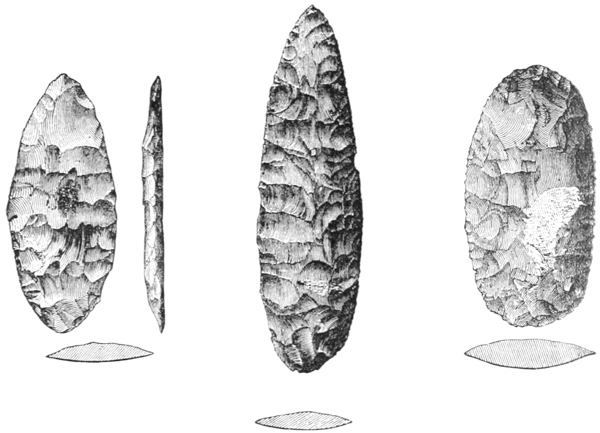

52A.* Berwickshire . . . 108

53. Botesdale, Suffolk . . . 111

54. Lackford, Suffolk . . . 112

55. Dalmeny, Linlithgow . . . 113

56. Sprouston, near Kelso . . . 114

57. Nunnington, Yorkshire . . . 115

58. Burradon, Northumberland . . . 116

59. Livermere, Suffolk . . . 116

60. Ilderton, Northumberland . . . 117

61. Near Pendle, Lancashire . . . 118

62. Ness . . . 119

63. Gilling . . . 120

64. Swinton, near Malton . . . 121

65. Scamridge Dykes, Yorkshire . . . 121

66. Whitwell, Yorkshire . . . 122

67. Thames, London . . . 123

68. Near Bridlington . . . 124

69. Lakenheath, Suffolk . . . 125

70. Seamer, Yorkshire . . . 126

71. Guernsey . . . 127

72. Wareham . . . 127

73. Forfarshire . . . 128

74. Bridlington . . . 129

75. Caithness . . . 129

76. Gilmerton, East Lothian . . . 131

77. Stirlingshire . . . 132

78. Harome . . . 133

79. Daviot, near Inverness . . . 134

80. Near Cottenham . . . 135

81. Near Malton . . . 135

82. Mennithorpe, Yorkshire . . . 136

83. Middleton Moor . . . 137

83A. Keystone . . . 137

84. Near Truro . . . 138

84A.* Slains . . . 138

85. Near Lerwick . . . 139

86. Weston, Norfolk . . . 139

87. Acklam Wold . . . 140

88. Fimber . . . 140

89. Duggleby . . . 141

90. Guernsey . . . 141

90A. Wereham . . . 142

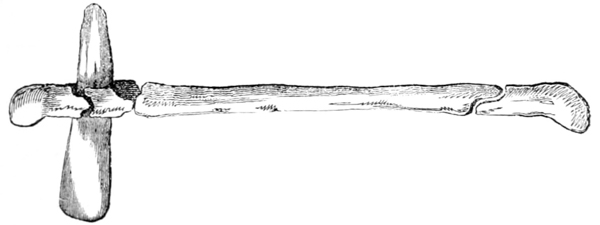

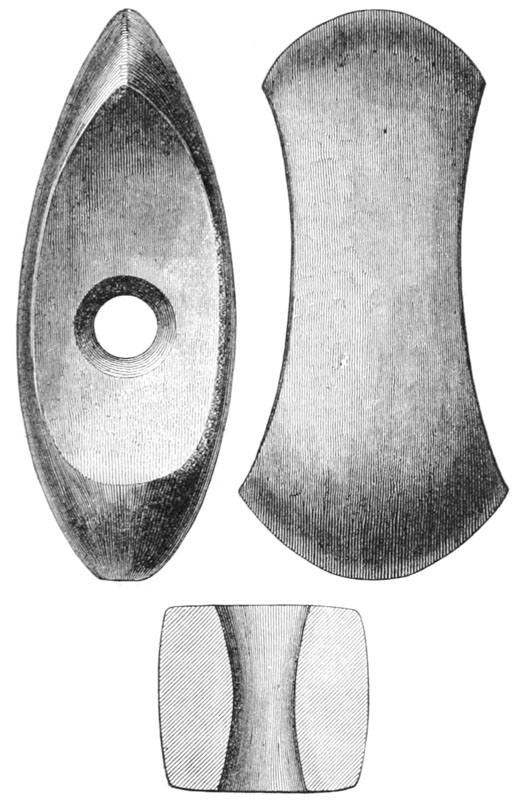

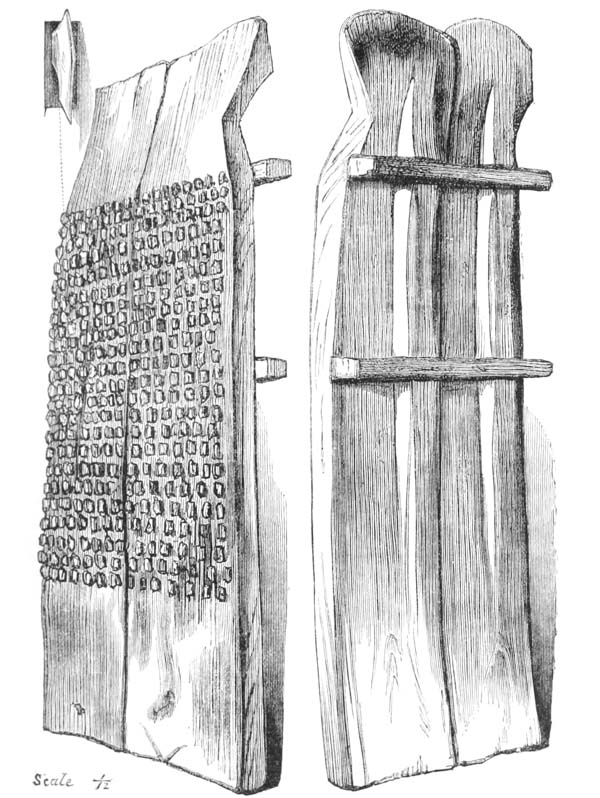

91.* Solway Moss . . . 151

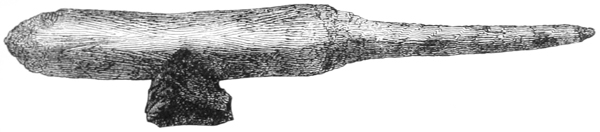

92. Cumberland . . . 153

93.* Monaghan . . . 154

94. Axe from the Rio Frio . . . 155

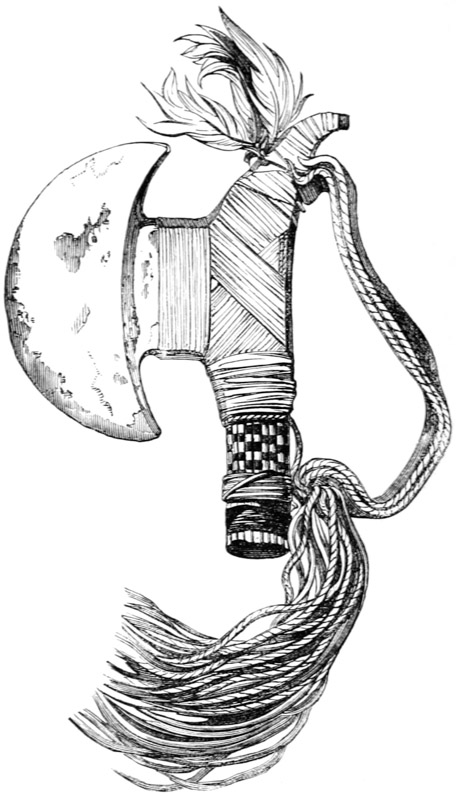

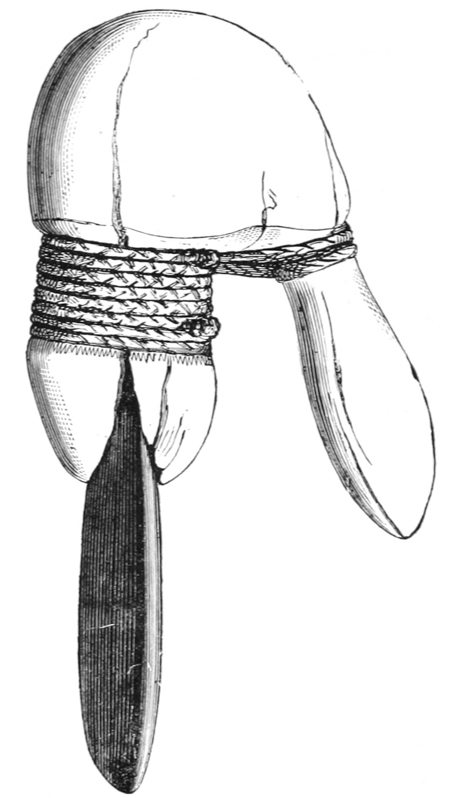

95.* War-axe—Gaveoë Indians, Brazil . . . 156

96. Axe of Montezuma II . . . 157

97. Axe—Nootka Sound . . . 158

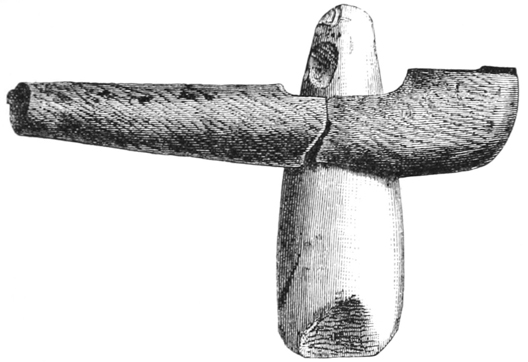

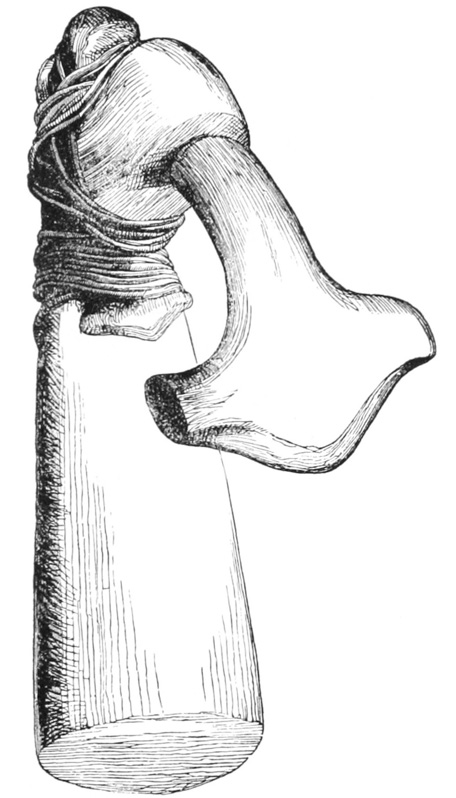

98. Axe in Stag’s-horn Socket—Concise . . . 159

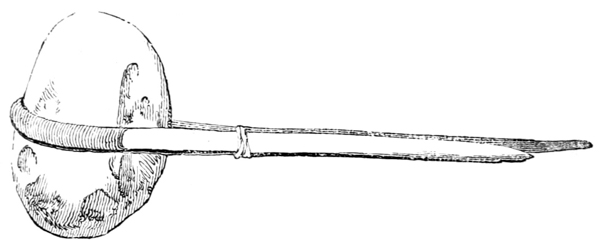

99. Axe—Robenhausen . . . 159

99A. Penhouet . . . 161

99B.* New Guinea . . . 161

99C.* — — Adze . . . 162

100. Axe—Robenhausen . . . 163

101. Schraplau . . . 163

102.* Adze—New Caledonia . . . 164

103.* Adze—Clalam Indians . . . 165

104.* South-Sea Island Axes . . . 166

105.* Axe—Northern Australia . . . 168

106.* Hatchet—Western Australia . . . 170

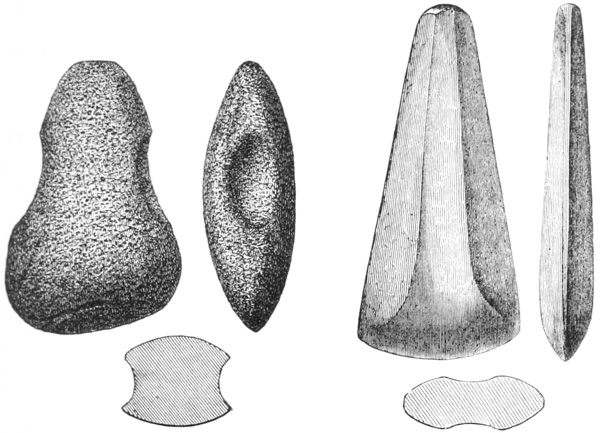

CHAPTER VII.

PICKS, CHISELS, GOUGES, ETC.

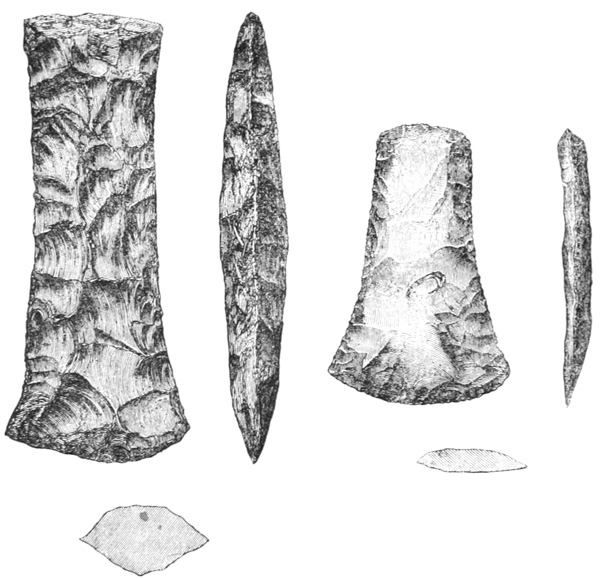

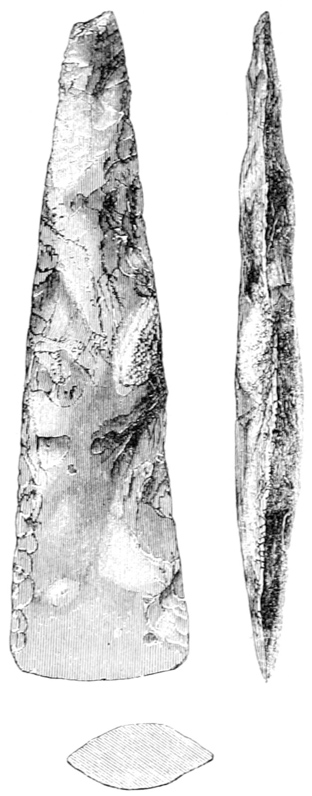

107. Great Easton . . . 173

108. Bury St. Edmunds . . . 174

109. Burwell . . . 175

110. Near Bridlington . . . 175

111. Dalton, Yorkshire . . . 176

112. Helperthorpe . . . 177

113. New Zealand Chisel . . . 178

114. Burwell . . . 179

114A. Westleton Walks . . . 179

115. Eastbourne . . . 180

116. Willerby Wold . . . 181

117. Bridlington . . . 181

CHAPTER VIII.

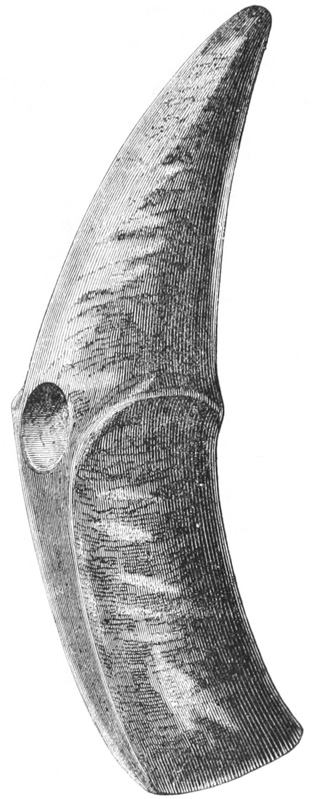

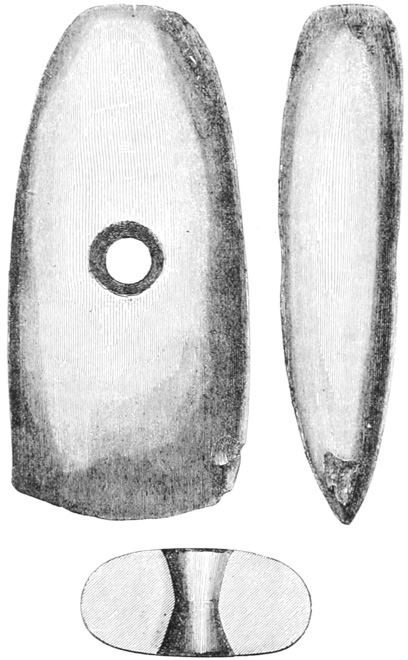

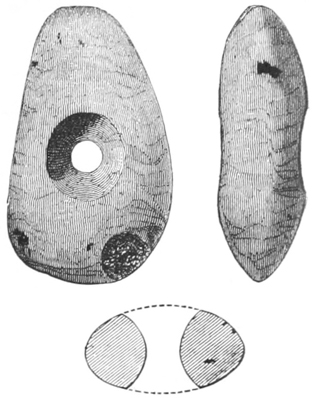

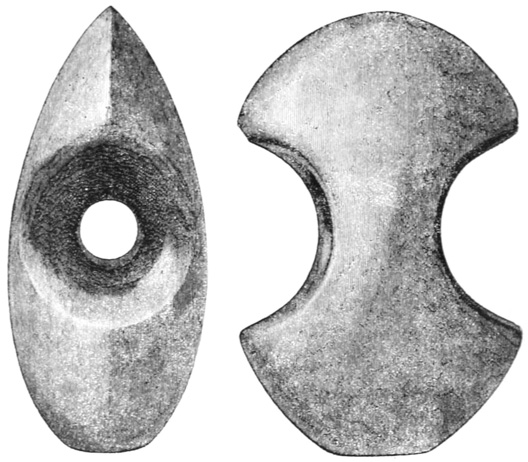

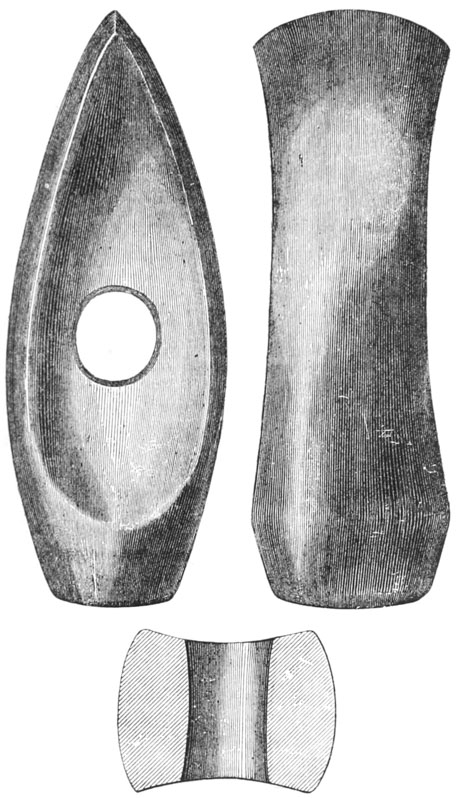

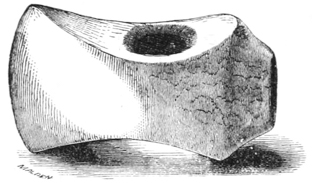

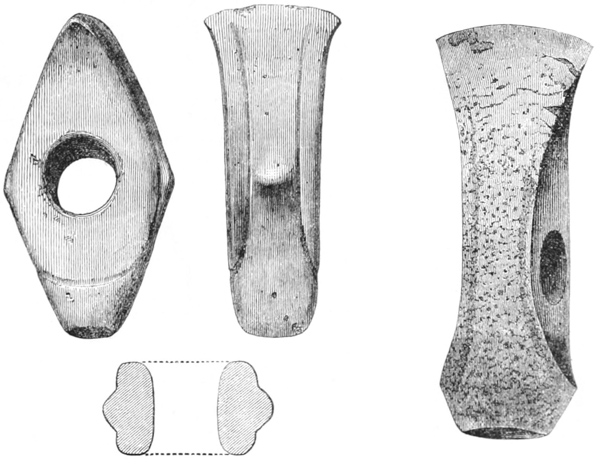

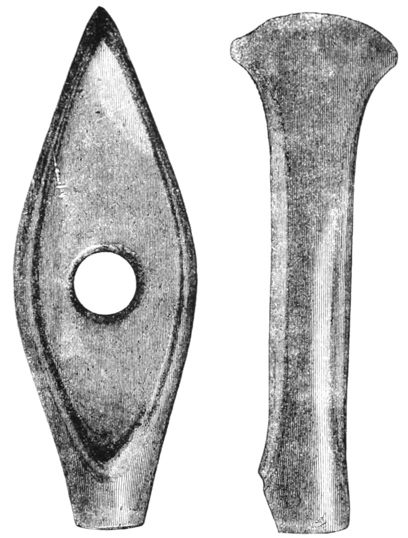

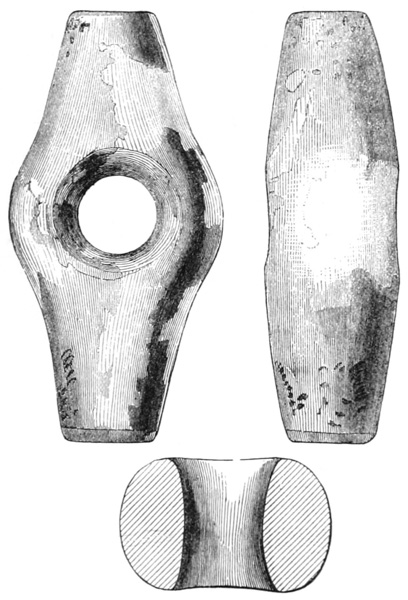

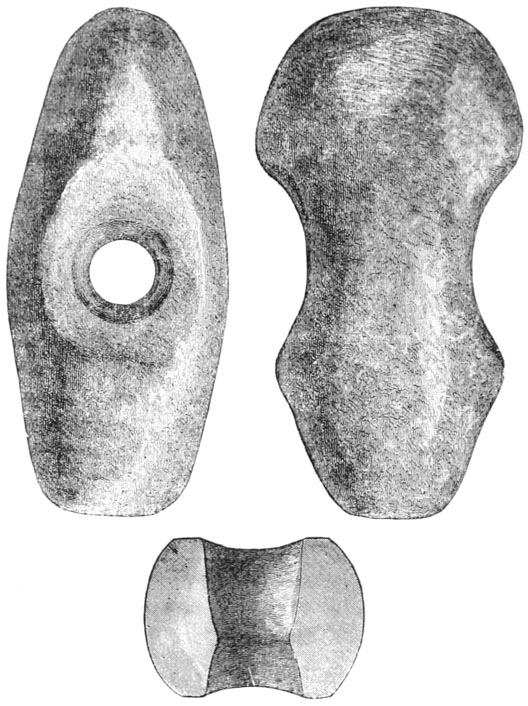

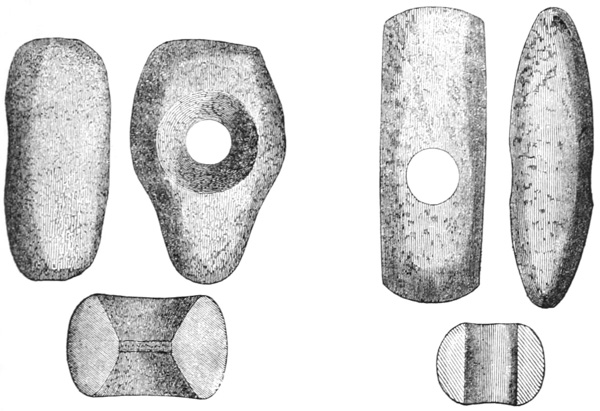

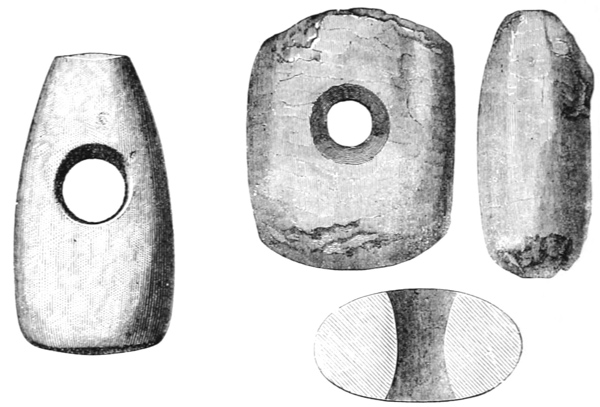

PERFORATED AXES.

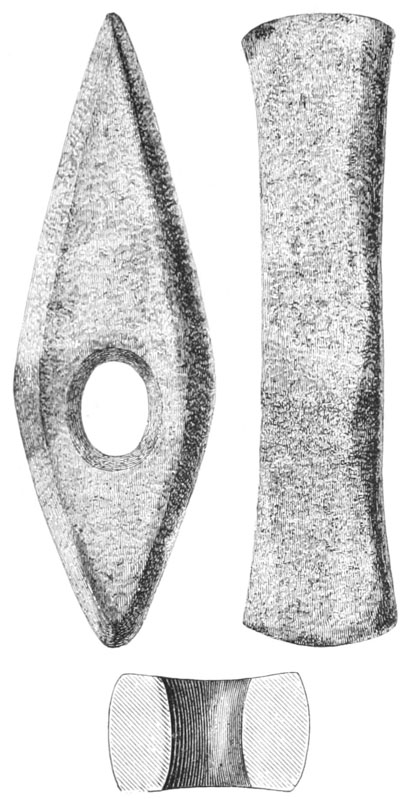

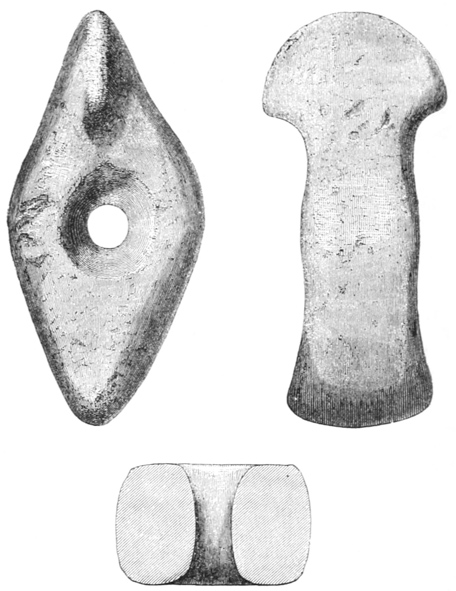

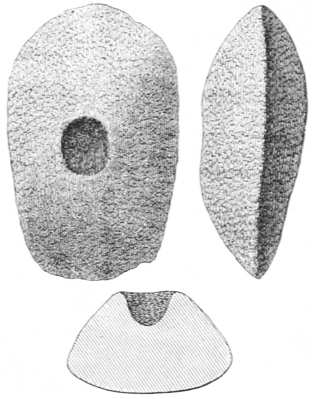

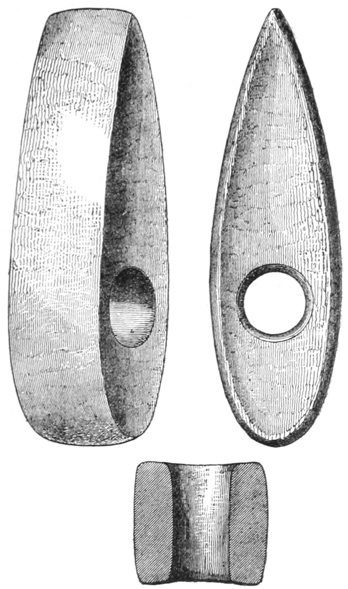

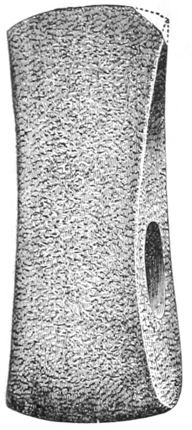

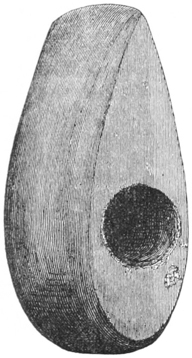

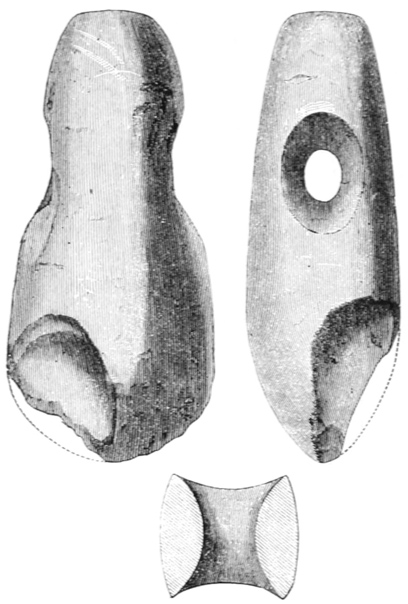

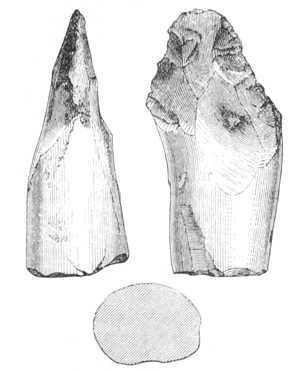

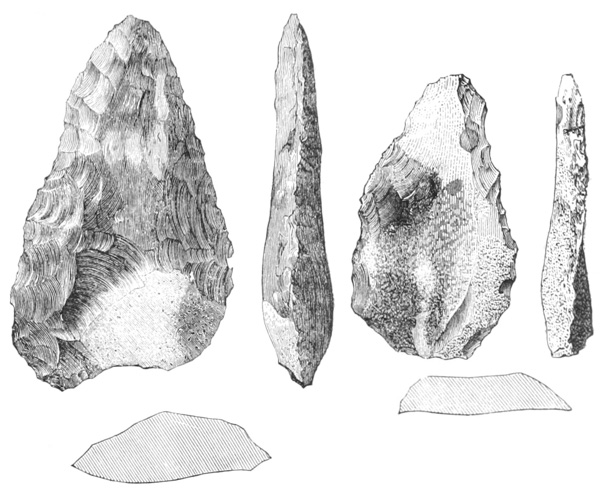

118. Hunmanby . . . 185

119.* Hove . . . 186

120. Llanmadock . . . 188

121. Guernsey . . . 189

122. Fireburn Mill, Coldstream . . . 190

123. Burwell Fen . . . 191

124. Stourton . . . 192

125. Bardwell . . . 193

126. Potter Brompton Wold . . . 194

127. Rudstone . . . 195

128. Borrowash . . . 196

129.* Crichie, Aberdeenshire . . . 197

130. Walsgrave-upon-Sowe . . . 199

131. Wigton . . . 201

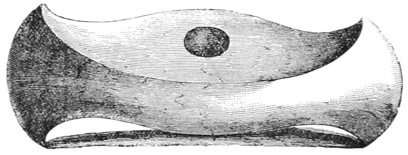

132. Wollaton Park . . . 203

133. Buckthorpe . . . 204

134. Aldro’ . . . 205

135. Cowlam . . . 206

136. Seghill . . . 207

136A.* Wick, Caithness . . . 208

137. Kirklington . . . 209

138.* Winterbourn Steepleton . . . 210

139. Skelton Moors . . . 211

140. Selwood Barrow . . . 211

140A.* Longniddry . . . 212

141. Upton Lovel . . . 213

142. Thames, London . . . 213

143. Pelynt, Cornwall . . . 214

CHAPTER IX.

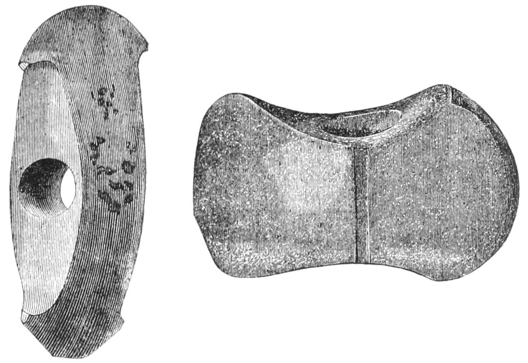

PERFORATED AND GROOVED HAMMERS.

144. Balmaclellan . . . 219

145. Thames, London . . . 219

145A.* Kirkinner . . . 220

146. Scarborough . . . 221

147. Shetland . . . 221

148.* Caithness . . . 222

149. Leeds . . . 222

150. Rockland . . . 223

151. Heslerton Wold . . . 224

152. Birdoswald . . . 225

153. Maesmore, Corwen . . . 226

154. Normanton, Wilts . . . 227

155. Redgrave Park . . . 228

156. Redmore Fen . . . 228

157.* Stifford . . . 229

158. Sutton . . . 231

159.* Ambleside . . . 236

CHAPTER X.

HAMMER-STONES, ETC.

160. Helmsley . . . 239

161. Winterbourn Bassett . . . 240

161A.* Goldenoch . . . 241

162. St. Botolph’s Priory . . . 242

163. Bridlington . . . 242

164. — . . . 243

165. — . . . 243

166. Scamridge . . . 246

167 & 168. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 248

168A.* Culbin Sands . . . 249

169. Bridlington . . . 249

170.* Holyhead . . . 251

171.* Ty Mawr . . . 253

172.* Holyhead . . . 254

173.* Pulborough . . . 254

174.* Shetland . . . 256

175.* — . . . 256

176.* — . . . 256

177.* — . . . 256

178.* — . . . 256

179.* — . . . 257

180.* Balmaclellan . . . 260

CHAPTER XI.

GRINDING-STONES AND WHETSTONES.

CHAPTER XII.

FLINT FLAKES, CORES, ETC.

188. Artificial Cone of Flint . . . 274

189. Weaverthorpe . . . 276

190. Newhaven . . . 278

191. Redhill, Reigate . . . 278

192. Icklingham . . . 278

193. Seaford . . . 278

194.* Tribulum from Aleppo . . . 285

195.* Admiralty Islands . . . 288

196. Charleston . . . 291

197. Nussdorf . . . 292

198. Australia . . . 293

199. Willerby Wold . . . 295

200. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 295

201. Scamridge . . . 296

202. West Cranmore . . . 296

CHAPTER XIII.

SCRAPERS.

203.* Eskimo Scraper . . . 298

204. Weaverthorpe . . . 300

205. Sussex Downs . . . 301

206. Yorkshire . . . 302

207. Helperthorpe . . . 302

208. Weaverthorpe . . . 302

209. Sussex Downs . . . 303

210. Yorkshire . . . 303

211. — Wolds . . . 303

212. — — . . . 304

213. Sussex Downs . . . 304

214. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 304

215. Sussex Downs . . . 305

216. — — . . . 306

217. — — . . . 306

218. Bridlington . . . 307

219. — . . . 307

220. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 307

221. — — . . . 308

222. French “Strike-a-light” . . . 314

223. Rudstone . . . 316

224. Method of using Pyrites and “Scraper” for striking a light . . . 317

225. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 319

226. — — . . . 319

226A. North of Ireland . . . 320

CHAPTER IV.

BORERS, AWLS, OR DRILLS.

CHAPTER XV.

TRIMMED FLAKES, KNIVES, ETC.

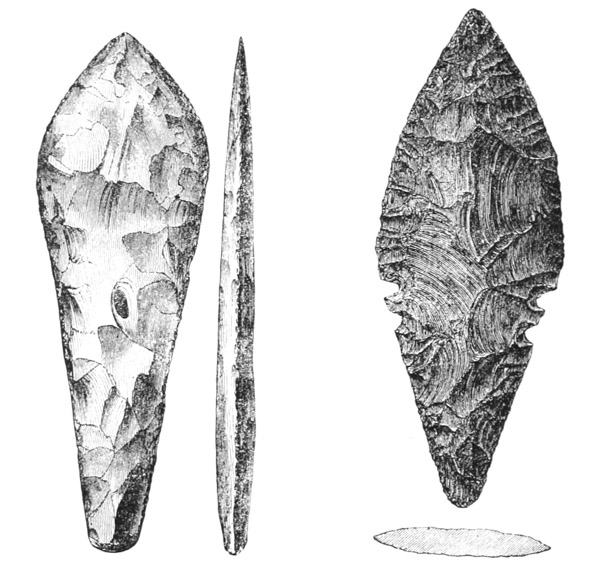

233. Cambridge (?) . . . 326

234. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 328

235. Yorkshire . . . 328

236. Bridlington . . . 329

237. Yorkshire . . . 329

238. Bridlington . . . 329

239. Castle Carrock . . . 329

240. Ford, Northumberland . . . 330

240A.* Etton . . . 330

241. Weaverthorpe . . . 331

242. Wykeham Moor . . . 331

243. Potter Brompton Wold . . . 332

244. Snainton Moor . . . 333

245. Ford . . . 333

246. Bridlington . . . 334

247. Cambridge Fens . . . 334

248. Scamridge . . . 335

249. Burwell Fen . . . 336

250. Saffron Walden . . . 336

251. Fimber . . . 337

252. Argyllshire . . . 338

253. Glen Urquhart . . . 338

254. Bridlington . . . 339

255. Overton . . . 339

256. Kempston . . . 340

256A. Eastbourne . . . 341

257. Kintore . . . 342

258. Newhaven, Derbyshire . . . 342

259. Harome, Yorkshire . . . 343

260. — — . . . 344

261. Crambe . . . 345

262. Walls, Shetland . . . 346

263. — — . . . 347

264. Lambourn Down . . . 349

265. Thames . . . 350

266. Burnt Fen . . . 350

267. Arbor Low . . . 352

267A. Sewerby . . . 355

268. Fimber . . . 356

269. Yarmouth . . . 356

270. Eastbourne . . . 357

CHAPTER XVI.

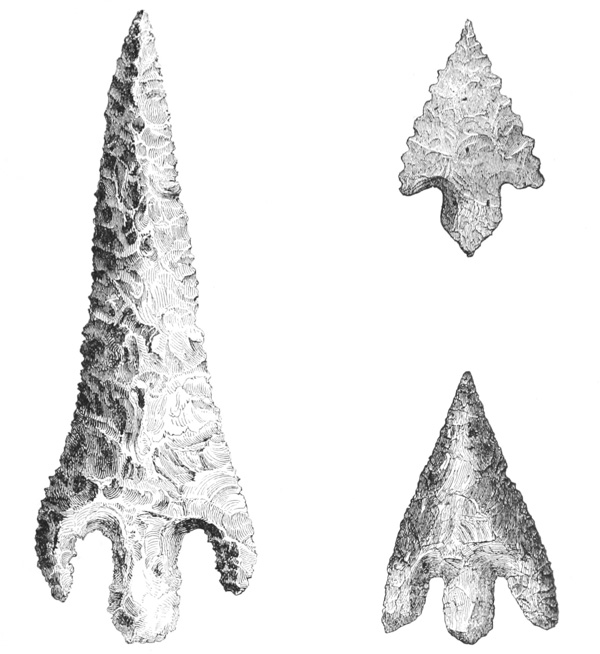

JAVELIN AND ARROW HEADS.

271.* Elf Shot . . . 365

272. Egypt . . . 369

273. Winterbourn Stoke . . . 371

274. — — . . . 371

275. — — . . . 371

276.* Calais Wold Barrow . . . 372

277.* — — — . . . 372

278.* — — — . . . 372

279.* — — — . . . 372

280. Icklingham . . . 373

281.* Gunthorpe . . . 373

282. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 373

283. — — . . . 374

284. Little Solsbury Hill . . . 374

285. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 374

286. Bridlington . . . 374

287 & 288. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 375

289. Lakenheath . . . 375

290 & 291. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 376

292 & 293. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 376

294. — — . . . 376

295.* Fyfield . . . 377

296. Bridlington . . . 378

297. Newton Ketton . . . 378

298 & 299. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 378

300. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 379

301. Amotherby . . . 379

302. Iwerne Minster . . . 379

303. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 380

304. — — . . . 380

305. Pick Rudge Farm . . . 380

305A. Ashwell . . . 381

306. Sherburn Wold . . . 381

307. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 381

308. — — . . . 381

309. — — . . . 381

310. — — . . . 381

311. — — . . . 381

312. — — . . . 381

313 & 314. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 382

314A. Icklingham . . . 382

315. Eddlesborough . . . 383

316. Reach Fen . . . 383

317. Isleham . . . 383

318. Rudstone . . . 384

318A. Dorchester Dykes . . . 384

319. Lambourn Down . . . 384

320. Fovant . . . 384

321. Yorkshire Moors . . . 385

322 & 323. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 385

323A.* Brompton . . . 386

324.* Isle of Skye . . . 387

325. Urquhart . . . 387

326. Aberdeenshire . . . 387

327. Glenlivet . . . 387

327A.* Philiphaugh . . . 388

328. Icklingham . . . 390

329. Langdale End . . . 390

330. Amotherby . . . 390

331. Weaverthorpe . . . 391

332. Lakenheath . . . 391

333. Yorkshire Wolds . . . 391

334. — — . . . 391

335. — — . . . 392

336. Bridlington . . . 392

337. — . . . 392

338. Fimber . . . 393

339. Hungry Bentley . . . 394

340.* Caithness . . . 394

341. Lakenheath . . . 395

342. Urquhart . . . 395

342A.* Fyvie, Aberdeenshire . . . 408

343. Switzerland . . . 408

344. Fünen, Denmark . . . 409

345.* Modern Stone Arrow-head . . . 409

CHAPTER XVII.

FABRICATORS, FLAKING TOOLS, ETC.

CHAPTER XVIII.

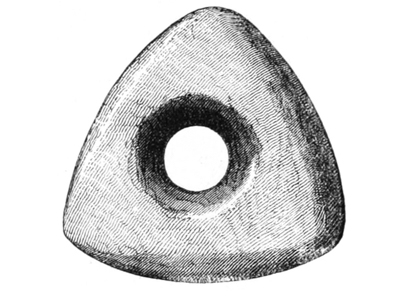

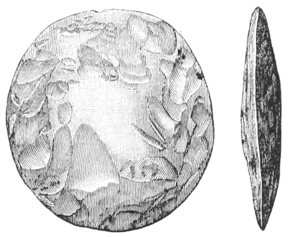

SLING-STONES AND BALLS.

CHAPTER XIX.

BRACERS, AND ARTICLES OF BONE.

CHAPTER XX.

SPINDLE-WHORLS, DISCS, SLICKSTONES, WEIGHTS, AND CUPS.

CHAPTER XXI.

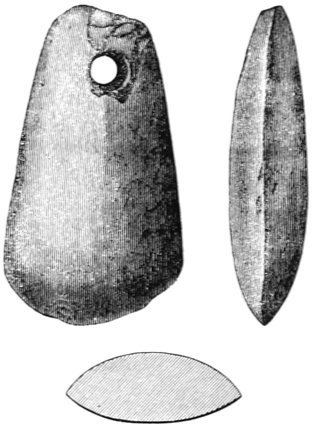

PERSONAL ORNAMENTS, AMULETS, ETC.

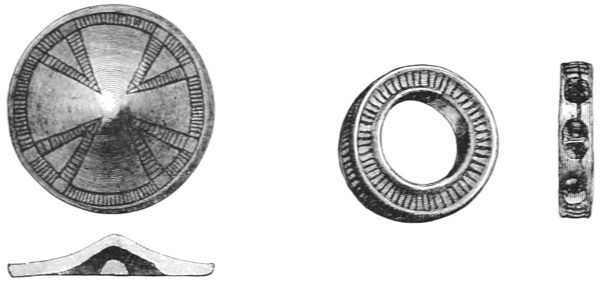

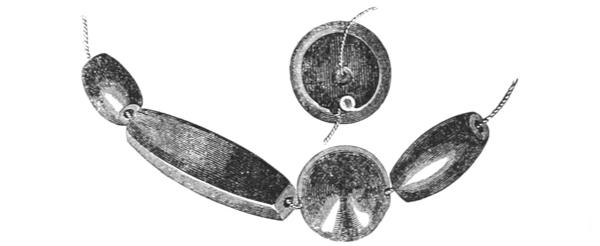

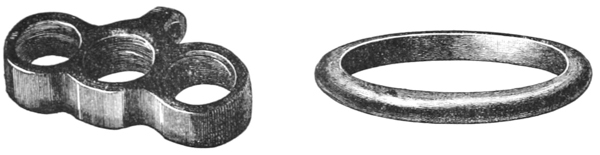

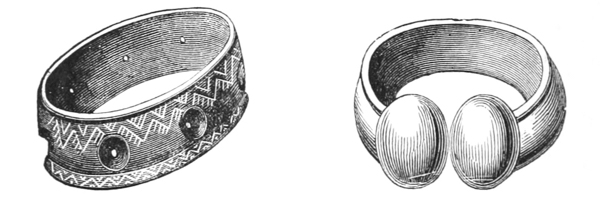

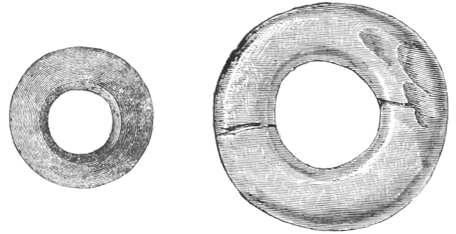

369. Butterwick . . . 453

370. — . . . 453

371. Rudstone . . . 454

372. — . . . 454

373. Crawfurd Moor . . . 454

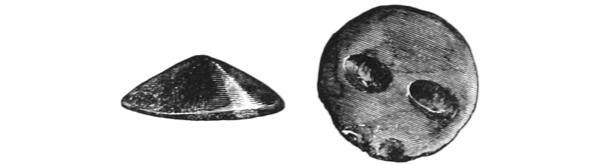

374.* Calais Wold Barrow . . . 455

375.* Assynt, Ross-shire . . . 457

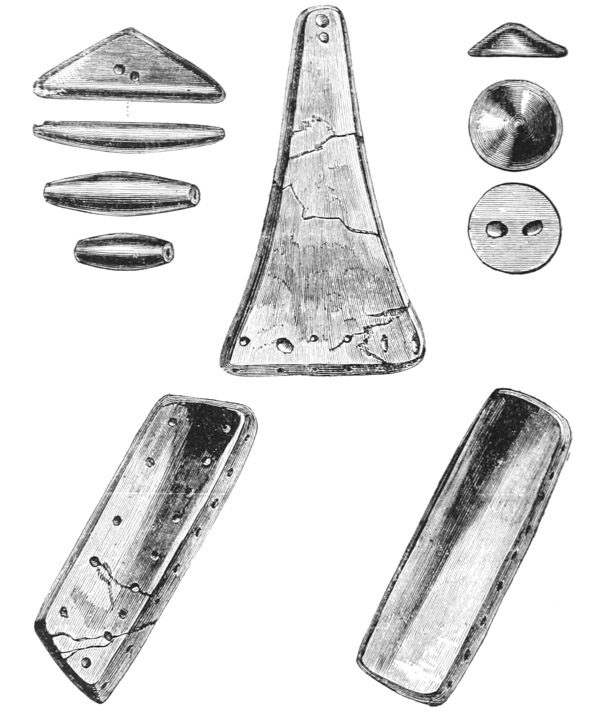

376.* Pen-y-Bonc . . . 458

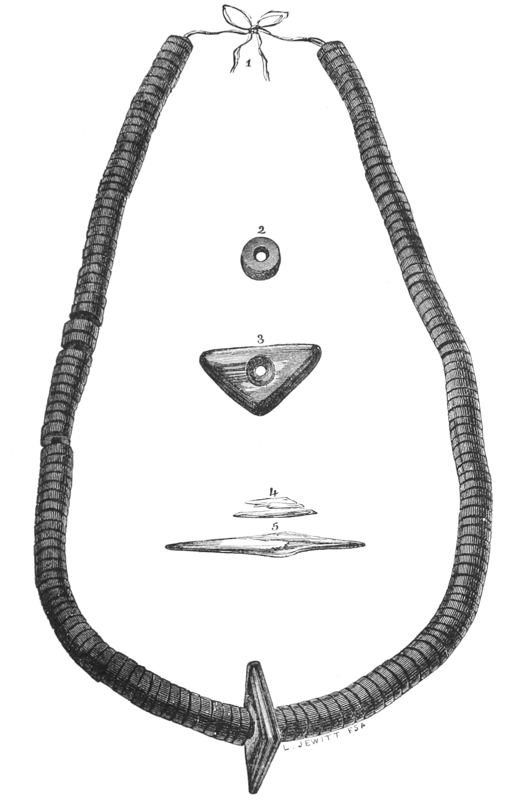

377.* Probable Arrangement of the Jet Necklace found at Pen-y-Bonc, Holyhead . . . 459

378.* Fimber . . . 461

379.* Yorkshire . . . 462

380.* — . . . 462

381. Hungry Bentley . . . 464

381A.* Heathery Burn Cave . . . 464

382.* Jet—Guernsey . . . 464

383.* Bronze—Guernsey . . . 464

384. Kent’s Cavern . . . 465

385.* Ty Mawr . . . 466

CHAPTER XXII.

CAVE IMPLEMENTS.

386. Kent’s Cavern . . . 493

387. — — . . . 493

388. — — . . . 494

388A.* — — . . . 495

389. — — . . . 496

390. — — . . . 496

391. — — . . . 498

392. — — . . . 499

393. — — . . . 499

394. — — . . . 500

395. — — . . . 500

396. — — . . . 501

397. — — . . . 501

398. — — . . . 502

399. — — . . . 502

400. — — . . . 502

401. — — . . . 503

402. — — . . . 503

403. — — . . . 505

404. — — . . . 505

405. — — . . . 505

406. — — . . . 506

407. — — . . . 506

408. — — . . . 506

409. Brixham Cave . . . 514

410. — — . . . 515

411. — — . . . 515

412. — — . . . 516

413.* Wookey Hyæna Den . . . 518

413A.* Robin Hood Cave . . . 522

413B.* — — — . . . 523

413C.* — — — . . . 523

413D.* — — — . . . 523

413E.* — — — . . . 523

413F.* — — — . . . 524

413G.* Church Hole Cave . . . 524

413H.* — — — . . . 524

CHAPTER XXIII.

IMPLEMENTS OF THE RIVER-DRIFT PERIOD.

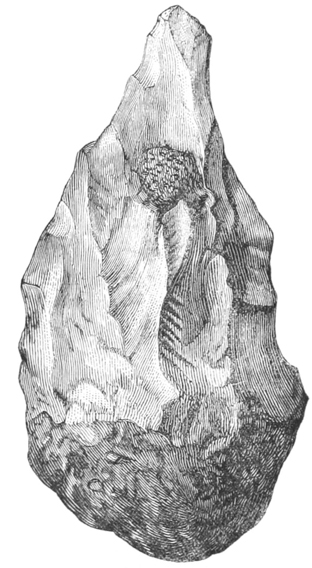

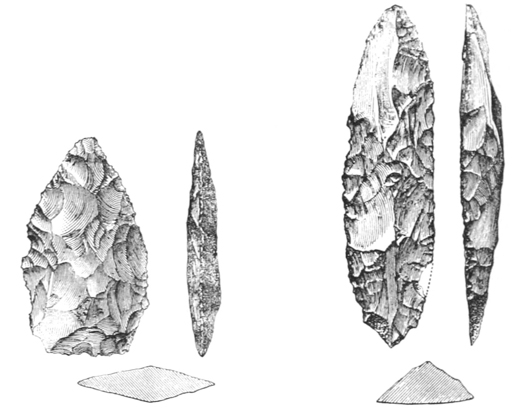

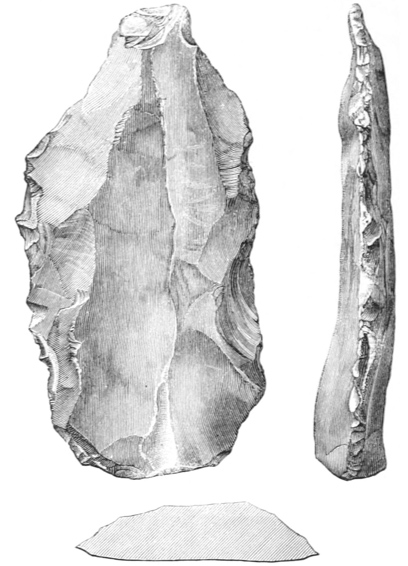

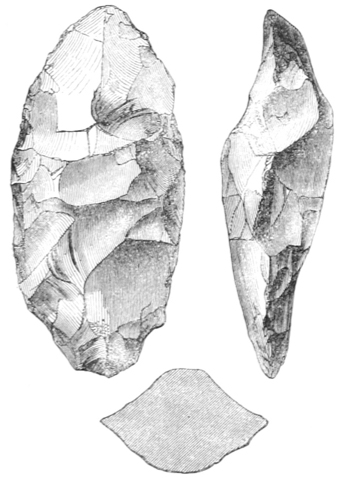

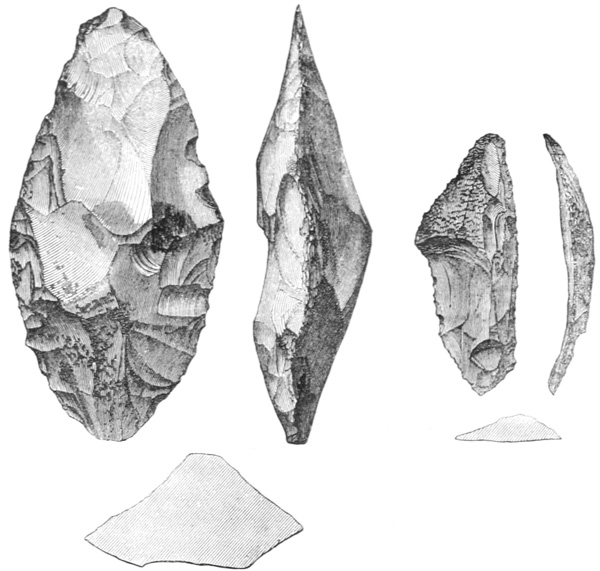

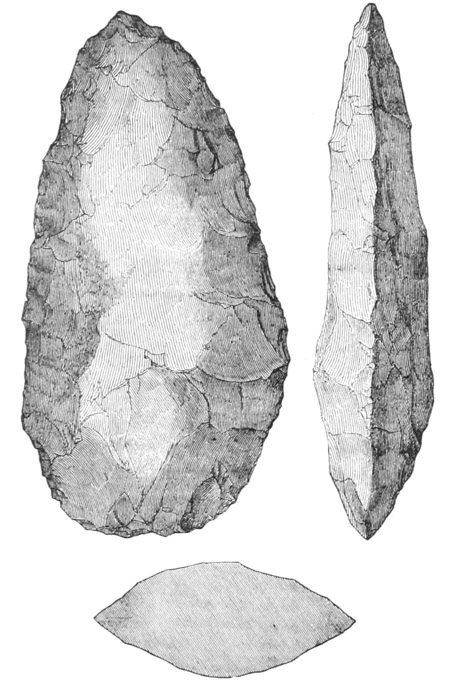

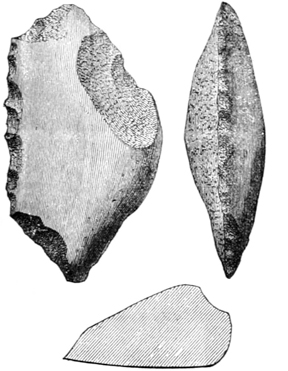

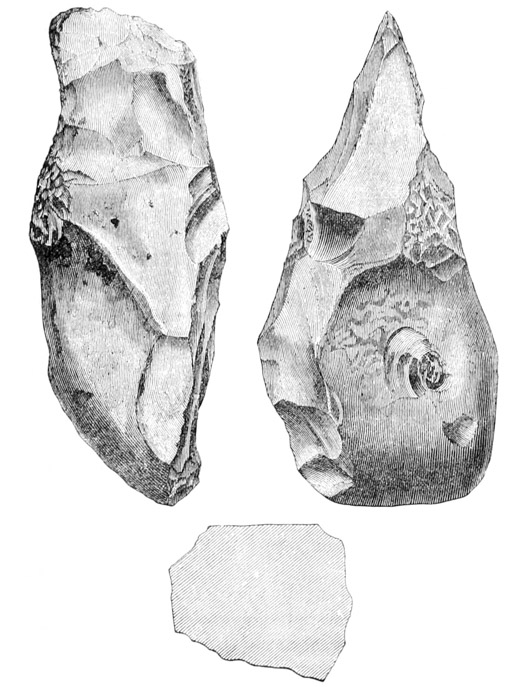

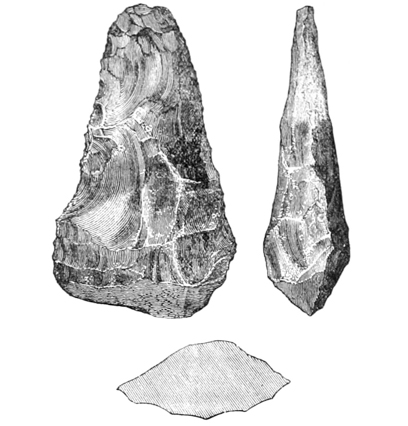

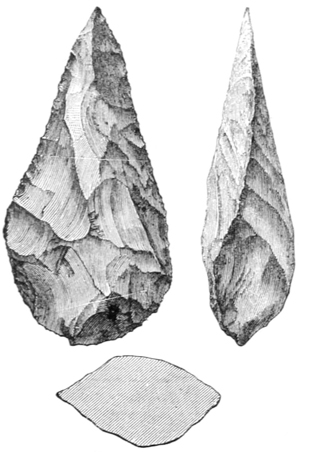

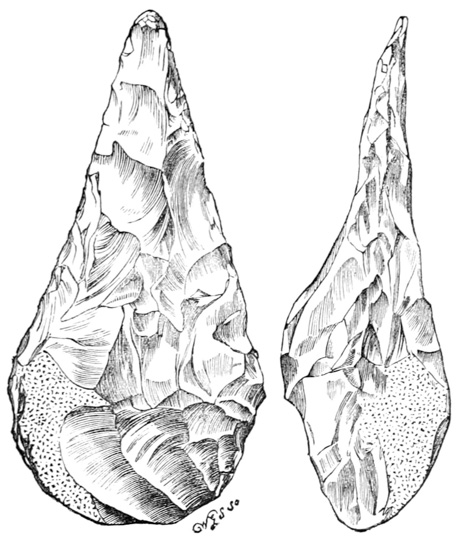

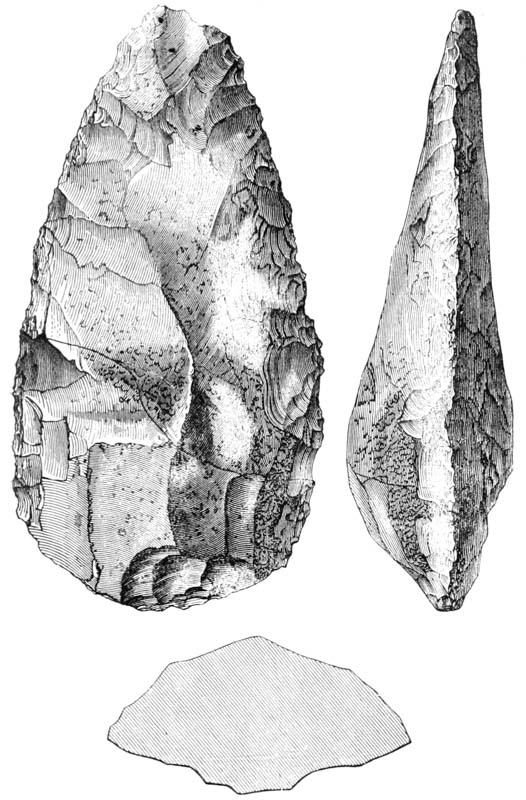

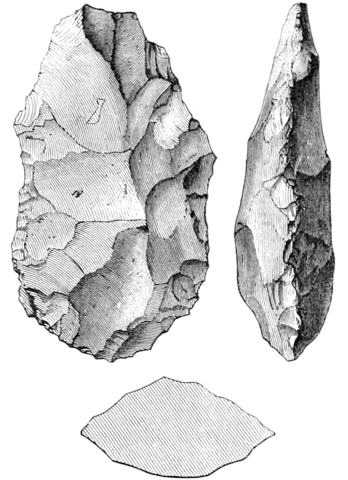

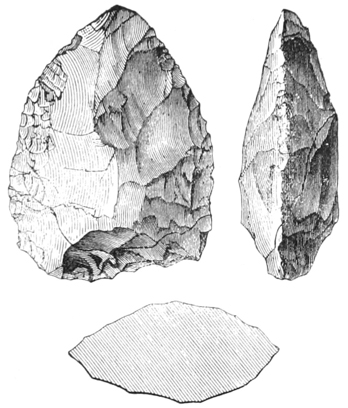

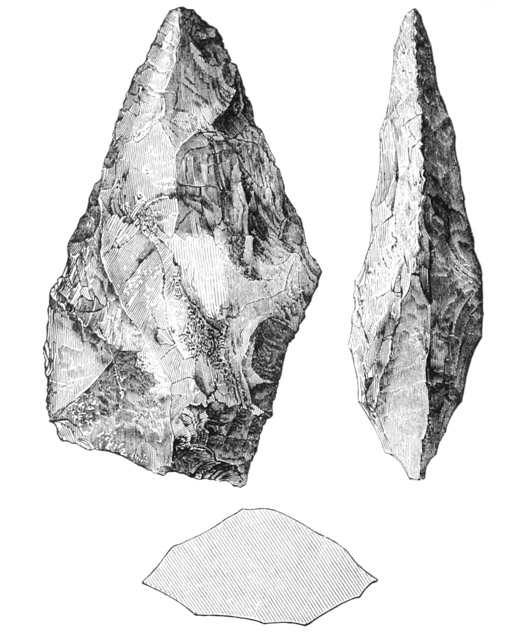

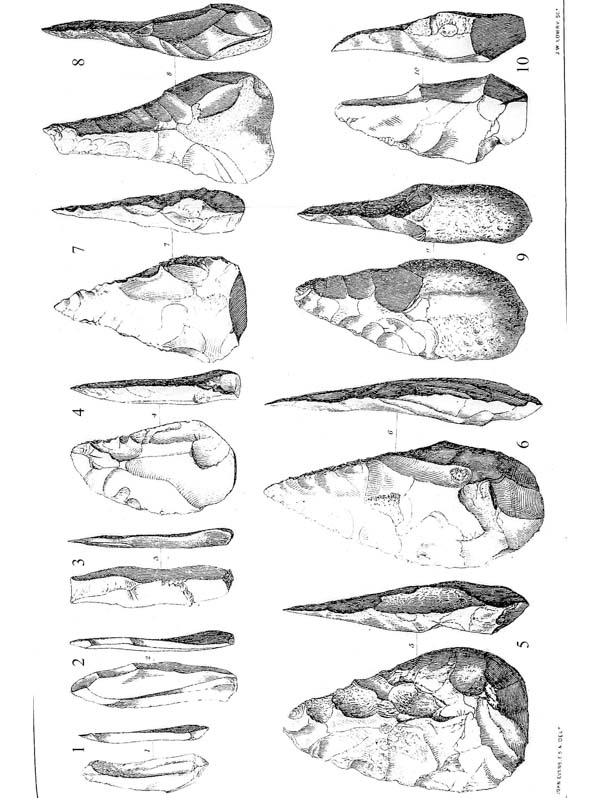

414. Biddenham, Bedford . . . 532

415. — — . . . 533

416. — — . . . 534

417. — — . . . 534

418. — — . . . 535

418A. Hitchin . . . 537

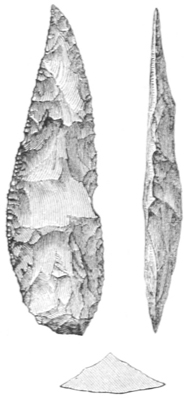

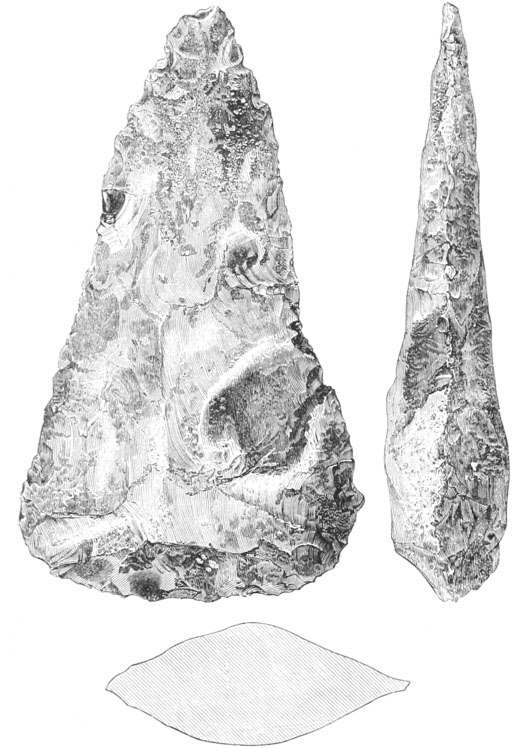

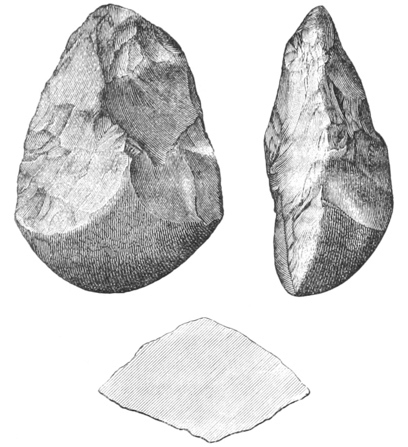

419. Maynewater Lane, Bury St. Edmunds . . . 540

419A. Grindle Pit, Bury St. Edmunds . . . 541

419B. Bury St. Edmunds . . . 542

419C. Nowton, near Bury St. Edmunds . . . 543

419D. Westley, near Bury St. Edmunds . . . 544

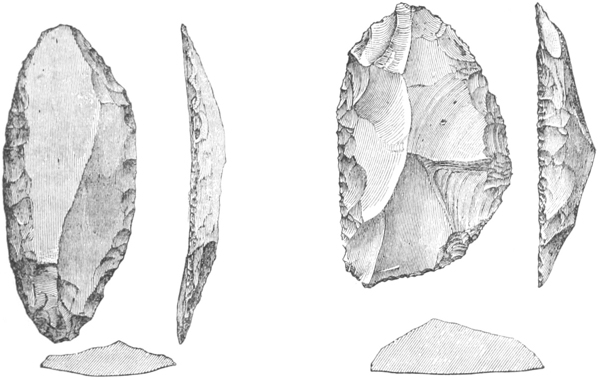

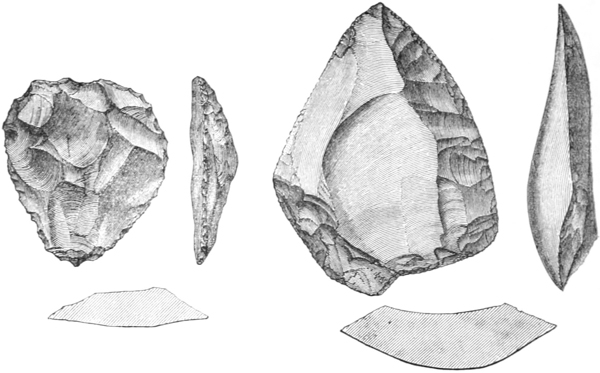

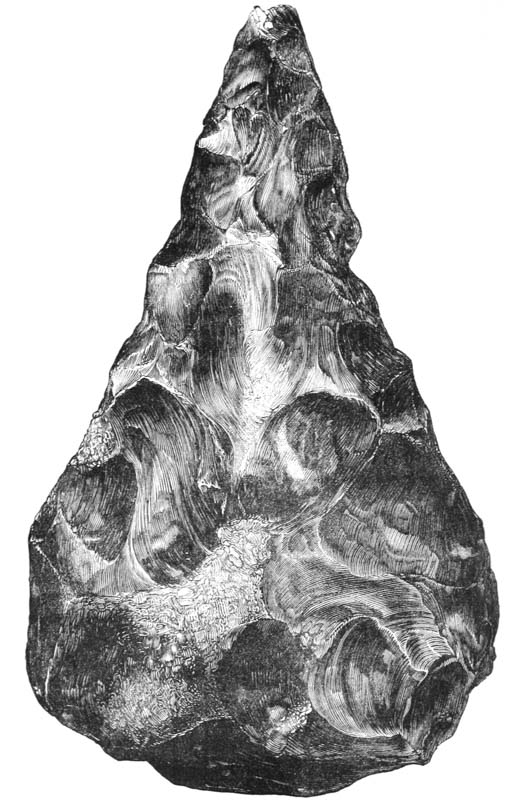

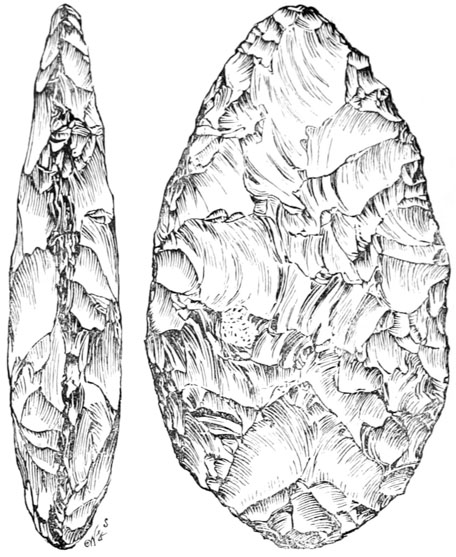

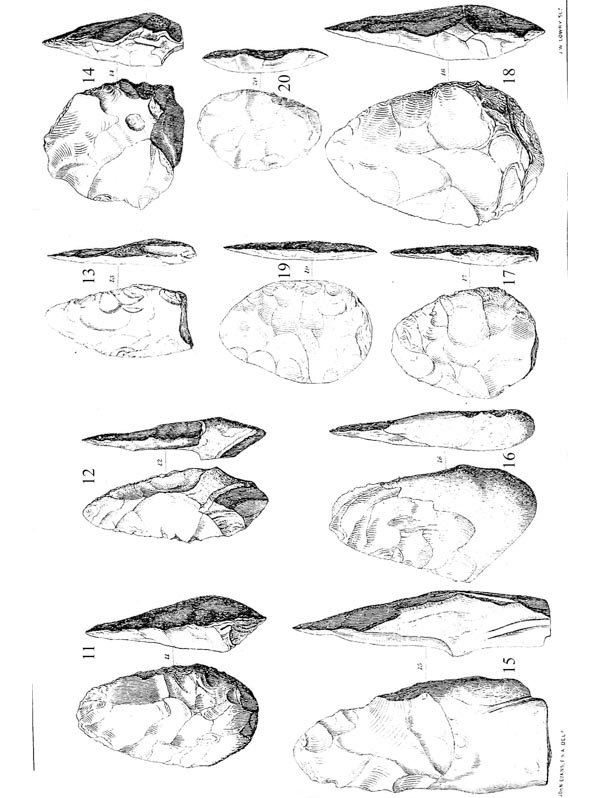

420. Rampart Hill, Icklingham . . . 545

421. Icklingham . . . 546

422. — . . . 546

423. — . . . 547

424. — . . . 548

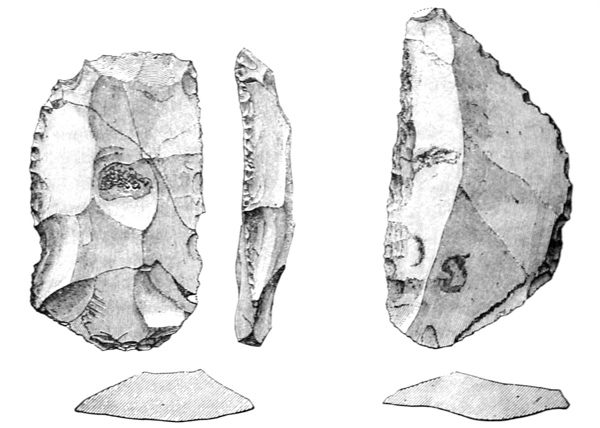

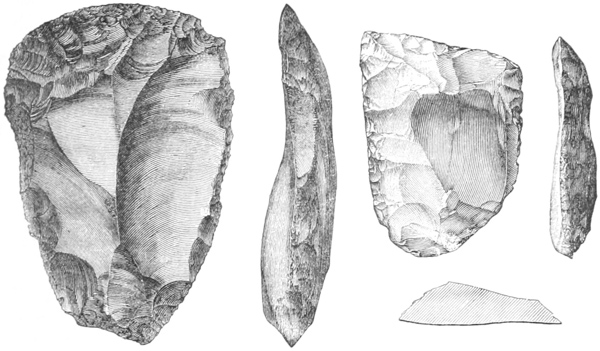

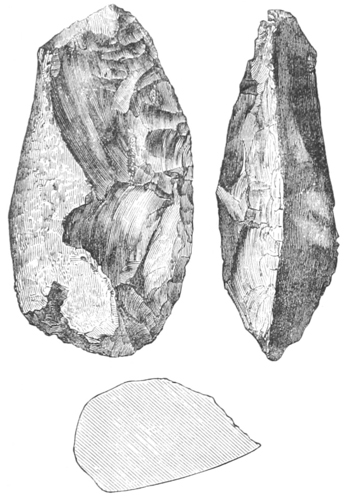

425. High Lodge . . . 548

426. — — . . . 549

426A. — — . . . 549

427. Redhill, Thetford . . . 552

428. — — . . . 553

429. — — . . . 554

430. — — . . . 555

431. — — . . . 555

432. Whitehill, Thetford . . . 556

433. Santon Downham . . . 557

434. — — . . . 558

435. — — . . . 559

436. — — . . . 560

437. — — . . . 561

438. Bromehill, Brandon . . . 562

439. Gravel Hill, Brandon . . . 563

440. — — — . . . 564

441. — — — . . . 564

442. — — — . . . 565

443. — — — . . . 566

444. Valley of the Lark, or of the Little Ouse . . . 567

445. Shrub Hill, Feltwell . . . 570

446. — — — . . . 570

447. — — — . . . 571

448. — — — . . . 571

449. Hoxne . . . 575

450. — . . . 576

450A. Saltley . . . 579

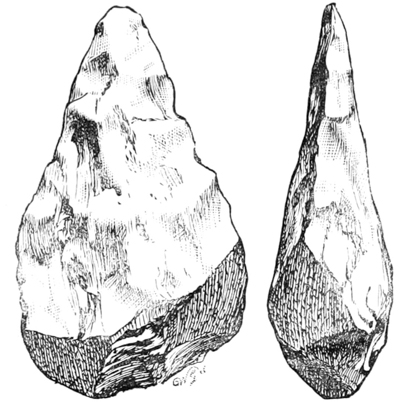

451. Gray’s Inn Lane . . . 582

452. Hackney Down . . . 583

453. Highbury New Park . . . 585

453A.* Lower Clapton . . . 587

453B.* Stamford Hill . . . 588

453C.* Stoke Newington Common . . . 588

453D.* — — — . . . 589

454. Ealing Dean . . . 590

455. Peasemarsh, Godalming . . . 595

455A.* Caddington . . . 599

455B.* — . . . 599

455C.* — . . . 600

455D.* — . . . 600

455E.* — . . . 601

455F.* — . . . 601

455G.* — . . . 601

455H.* Wheathampstead . . . 601

456. Dartford Heath . . . 606

456A. Bewley, Ightham . . . 609

457. Reculver . . . 612

458. Near Reculver . . . 614

459. — — . . . 615

460. Reculver . . . 616

461. — . . . 616

462. Studhill . . . 618

463. Thanington . . . 619

464. Canterbury . . . 620

464A.* — . . . 621

464B. Folkestone . . . 622

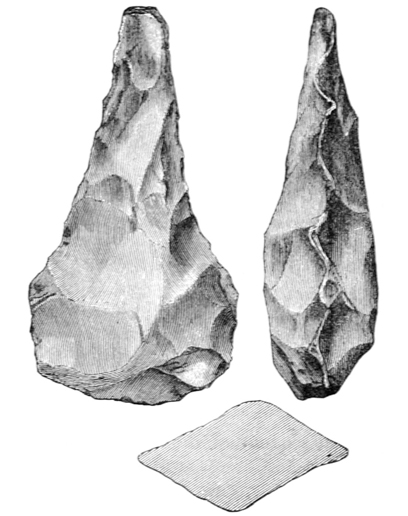

465. Southampton . . . 623

466. Hill Head . . . 625

467. The Foreland, Isle of Wight . . . 627

468. Lake . . . 628

469. Bemerton . . . 629

470. Highfield . . . 629

471. Fisherton . . . 630

472. Milford Hill, Salisbury . . . 633

473. Fordingbridge . . . 634

474. Boscombe, Bournemouth . . . 635

475. — — . . . 636

476. Bournemouth . . . 637

477. Broom Pit, Axminster . . . 638

In the following pages I purpose to give an account of the various forms of stone implements, weapons, and ornaments of remote antiquity discovered in Great Britain, their probable uses and method of manufacture, and also, in some instances, the circumstances of their discovery. While reducing the whole series into some sort of classification, as has been done for the stone antiquities of Scandinavia by Worsaae, Montelius, and Sophus Müller, for those of France by Messrs. Gabriel and Adrien de Mortillet, and for those of Ireland by Sir William Wilde, I hope to add something to our knowledge of this branch of Archæology by instituting comparisons, where possible, between the antiquities of England and Scotland and those of other parts of the world. Nor in considering the purposes to which the various forms were applied, and the method of their manufacture, must I neglect to avail myself of the illustrations afforded by the practice of modern savages, of which Sir John Lubbock and others have already made such profitable use.

But before commencing any examination of special forms, there are some few general considerations on which it seems advisable to enter, if only in a cursory manner; and this is the more necessary, since notwithstanding the attention which has now for many years been devoted to Prehistoric Antiquities, there is seemingly still some misapprehension remaining as to the nature and value of the conclusions based upon recent archæological and geological investigations.

At the risk therefore of being tedious, I shall have to notice once more many things already well known to archæologists, but which, it would appear from the misconceptions so often evinced, even by those who speak and write on such matters, can hardly be too often repeated.

Not the least misunderstood of these subjects has been the {2} classification of the antiquities of Western Europe, first practically adopted by the Danish antiquaries, under periods known as the Iron, Bronze, and Stone Ages; the Iron Age, so far as Denmark is concerned, being supposed to go back to about the Christian era, the Bronze Age to embrace a period of one or two thousand years previous to that date, and the Stone Age all previous time of man’s occupation of that part of the world. These different periods have been, and in some cases may be safely, subdivided; but into this question I need not now enter, as it does not affect the general sequence. The idea of the succession is this:—

1. That there was a period in each given part of Western Europe, say, for example, Denmark, when the use of metals for cutting-instruments of any kind was unknown, and man had to depend for his implements and weapons on stone, bone, wood, and other readily accessible natural products.

2. That this period was succeeded by one in which the use of copper, or of copper alloyed with tin—bronze—became known, and gradually superseded the use of stone for certain purposes, though it continued to be employed for others; and

3. That a time arrived when bronze, in its turn, gave way to iron or steel, as being a superior metal for all cutting purposes; which, as such, has remained in use up to the present day.

Such a classification into different ages in no way implies any exact chronology, far less one that would be applicable to all the countries of Europe alike, but is rather to be regarded as significant only of a succession of different stages of civilization; for it is evident that at the time when, for instance, in a country such as Italy, the Iron Age may have commenced, some of the more northern countries of Europe may possibly have been in their Bronze Age, and others again still in their Stone Age.

Neither does this classification imply that in the Bronze Age of any country stone implements had entirely ceased to be in use, nor even that in the Iron Age both bronze and stone had been completely superseded for all cutting purposes. Like the three principal colours of the rainbow, these three stages of civilization overlap, intermingle, and shade off the one into the other; and yet their succession, so far as Western Europe is concerned, appears to be equally well defined with that of the prismatic colours, though the proportions of the spectrum may vary in different countries. [1] {3}

The late Mr. James Fergusson, in his Rude Stone Monuments, [2] has analyzed the discoveries made by Bateman in his exploration of Derbyshire barrows, and on the analysis has founded an argument against the division of time into the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages. He has, however, omitted to take into account the fact that in many of the barrows there were secondary interments of a date long subsequent to the primary.

I have spoken of this division into Periods as having been first practically adopted by the Danish school of antiquaries, but in fact this classification is by no means so recent as has been commonly supposed. Take, for instance, the communication of Mahudel to the Académie des Inscriptions of Paris [3] in 1734, in which he points out that man existed a long time in different countries using implements of stone and without any knowledge of metals; or again, the following passage from Bishop Lyttelton’s [4] “Observations on Stone Hatchets,” written in 1766:—“There is not the least doubt of these stone instruments having been fabricated in the earliest times, and by barbarous people, before the use of iron or other metals was known, and from the same cause spears and arrows were headed with flint and other hard stones.” A century earlier, Sir William Dugdale, in his “History of Warwickshire,” [5] also speaks of stone celts as “weapons used by the Britons before the art of making arms of brass or iron was known.” We find, in fact, that the same views were entertained, not only by various writers [6] within the last two centuries, but also by many of the early poets and historians. There are even biblical grounds for argument in favour of such a view of a gradual development of material civilization. For all, including those who invest Adam with high moral attributes, must confess that whatever may have been his mental condition, his personal equipment in the way of tools or weapons could have been but inefficient if no artificer was instructed in brass and iron until the days of Tubal Cain, the sixth in descent from Adam’s outcast son, and that too at a time when a generation was reckoned at a hundred years, instead of at thirty, as now. {4}

Turning, however, to Greek and Roman authors, we find Hesiod, [7] about B.C. 850, mentioning a time when bronze had not been superseded by iron:—

Lucretius [8] is even more distinct in his views as to the successive Periods:—

So early as the days of Augustus it would appear that bronze arms were regarded as antiquities, and that emperor seems to have commenced the first archæological and geological collection on record, having adorned one of his country residences “rebus vetustate ac raritate notabilibus, qualia sunt Capreis immanium belluarum ferarumque membra prægrandia quæ dicuntur gigantum ossa et arma heroum.” [9]

We learn from Pausanias [10] what these arms of the heroes were, for he explains how in the heroic times all weapons were of bronze, and quotes Homer’s description of the axe of Pisander and the arrow of Meriones. He also cites the spear of Achilles in the temple of Pallas, at Phaselis, the point and ferrule of which only were of bronze; and the sword of Memnon in the temple of Æsculapius, at Nicomedia, which was wholly of bronze. In the same manner Plutarch [11] relates that when Cimon disinterred the remains of Theseus in Scyros he found with them a bronze spear-head and sword.

There is, indeed, in Homer constant mention of arms, axes, and adzes of bronze, and though iron is also named, it is of far less frequent occurrence. According to the Arundelian marbles, [12] it was discovered only 188 years before the Trojan war, though of course such a date must be purely conjectural. Even Virgil preserves the unities, and often gives bronze arms to the heroes of the Æneid, as well as to some of the people of Italy—

The fact that in the Greek [14] language the words χαλκεύς and χαλκεύειν remained in use as significant of working in iron affords a very strong, if not an irrefragable argument as to bronze having been the earlier metal known to that people. In the same way the continuance in use of bronze cutting implements in certain religious rites—as was also the case with some stone implements which I shall subsequently mention—affords evidence of their comparative antiquity. The Tuscans [15] at the foundation of a city ploughed the pomærium with a bronze plough-share, the priests of the Sabines cut their hair with bronze knives, and the Chief Priest of Jupiter at Rome used shears of the same metal for that purpose. In the same manner Medea has attributed to her both by Sophocles and Ovid [16] a bronze sickle when gathering her magic herbs, and Elissa is represented by Virgil as using a similar instrument for the same purpose. Altogether, if history is to count for anything, there can be no doubt that in Greece and Italy, the earliest civilized countries of Europe, the use of bronze preceded that of iron, and therefore that there was in each case a Bronze Age of greater or less duration preceding the Iron Age.

It seems probable that the first iron used was meteoric, and such may have been that “self-fused” mass which formed one of the prizes at the funeral games of Patroclus, [17] and was so large that it would suffice its possessor for all purposes during five years. Even the Greek word for iron (σίδηρος) may not improbably be connected with the meteoric origin of the first known form of the metal. Its affinity with ἀστήρ, often used for a shooting star or meteor, with the Latin “sidera” and our own “star” is evident.

Professor Lauth, [18]

moreover, interprets the Coptic word for iron,

,

as “the stone of heaven” (Stein des Himmels)

which implies that in Egypt also its meteoric origin was

acknowledged.

,

as “the stone of heaven” (Stein des Himmels)

which implies that in Egypt also its meteoric origin was

acknowledged.

Among the Eskimos [19] of modern times meteoric iron has been employed for making knives. Where an excess of nickel is present, the meteoric iron cannot well be forged, [20] but Dana seems to be right in saying, as a general rule it is perfectly malleable.

Some, however, are of opinion that during the time that bronze was employed for cutting instruments, iron was also in use for {6} other purposes. [21] At the first introduction of iron the two metals were, no doubt, in use together, but we can hardly suppose them to have been introduced simultaneously; and if they had been, the questions arise, whence did they come? and how are we to account for the one not having sooner superseded the other for cutting purposes?

Another argument that has been employed in favour of iron having been the first metal used, is that bronze is a mixed metal requiring a knowledge of the art of smelting both copper and tin, the latter being only produced in few districts, and generally having to be brought from far, while certain of the ores of iron are of easy access and readily reducible, [22] and meteoric iron is also found in the metallic state and often adapted for immediate use. The answer to this is, first, that all historical evidence is against the use of iron previously to copper or bronze; and, secondly, that even in Eastern Africa, where, above all other places, the conditions for the development of the manufacture of iron seem most favourable, we have no evidence of the knowledge of that metal having preceded that of bronze; but, on the contrary, we find in Egypt, a country often brought in contact with these iron-producing districts, little if any trace of iron before the twelfth dynasty, [23] and of its use even then the evidence is only pictorial, whereas the copper mines at Maghara are said to date back to the second dynasty, some eight hundred years earlier. Agatharchides, [24] moreover, relates that in his time, circa B.C. 100, there were found buried in the ancient gold mines of Egypt the bronze chisels (λατομίδες χαλκᾶι) of the old miners, and he accounts for their being of that metal by the fact that at the period when the mines were originally worked the use of iron was entirely unknown. Much of the early working in granite may have been effected by flint tools. Admiral Tremlett has found that flakes of jasper readily cut the granite of Brittany. [25]

To return, however, to Greece and Italy, there can, as I have already said, be little question that even on historical grounds we must accept the fact that in those countries, at all events, the use of bronze preceded that of iron. We may therefore infer theoretically that the same sequence held good with the {7} neighbouring and more barbarous nations of Western Europe. Even in the time of Pausanias [26] (after A.D. 174) the Sarmatians are mentioned as being unacquainted with the use of iron; and practically we have good corroborative archæological evidence of such a sequence in the extensive discoveries that have been made of antiquities belonging to the transitional period, when the use of iron or steel was gradually superseding that of bronze for tools or weapons, and when the forms given to the new metal were copied from those of the old. The most notable relics of this transitional period are those of the ancient cemetery at Hallstatt, in the Salzkammergut, Austria, where upwards of a thousand graves were opened by Ramsauer, of the contents of which a detailed account has been given by the Baron von Sacken. [27] The evidence afforded by the discoveries in the Swiss lakes is almost equally satisfactory; but I need not now enter further into the question of the existence and succession of the Bronze and Iron Ages, on which I have dwelt more fully in my book on Ancient Bronze Implements. [28]

I am at present concerned with the Stone Age, and if, as all agree, there was a time when the use of iron or of bronze, or of both together, first became known to the barbarous nations of the West of Europe, then it is evident that before that time they were unacquainted with the use of those metals, and were therefore in that stage of civilization which has been characterized as the Stone Age.

It is not, of course, to be expected that we should discover direct contemporary historical testimony amongst any people of their being in this condition, for in no case do we find a knowledge of writing developed in this stage of culture; and yet, apart from the material relics of this phase of progress which are found from time to time in the soil, there is to be obtained in most civilized countries indirect circumstantial evidence of the former use of stone implements, even where those of metal had been employed for centuries before authentic history commences. It is in religious customs and ceremonies—in rites which have been handed down from generation to generation, and in which the minute and careful repetition of ancient observances is indeed often the essential religious element—that such evidence is to be sought. As has already been observed by others, the transition from ancient to venerable, from venerable to holy, is as natural as it is universal; {8} and in the same manner as some of the festivals and customs of Christian countries are directly traceable to heathen times, so no doubt many of the religious observances of ancient times were relics of what was even then a dim past.

Whatever we may think of the etymology of the word as given by Cicero, [29] Lactantius, [30] or Lucretius, [31] there is much to be said in favour of Dr. E. B. Tylor’s [32] view of superstition being “the standing over of old habits into the midst of a new and changed state of things—of the retention of ancient practices for ceremonial purposes, long after they had been superseded for the commonplace uses of ordinary life.”

Such a standing over of old customs we seem to discover among most of the civilized peoples of antiquity. Turning to Egypt and Western Asia, the early home of European civilization, we find from Herodotus [33] and from Diodorus Siculus, [34] that in the rite of embalming, though the brain was removed by a crooked iron, yet the body was cut open by a sharp Ethiopian stone.

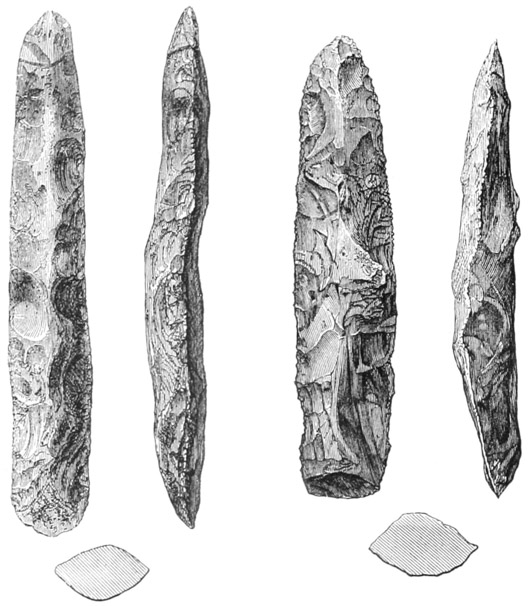

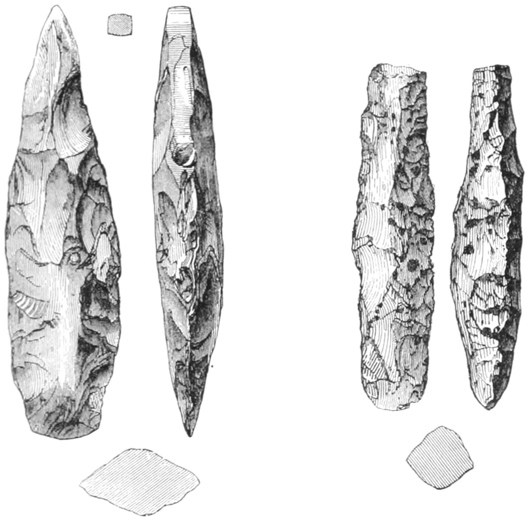

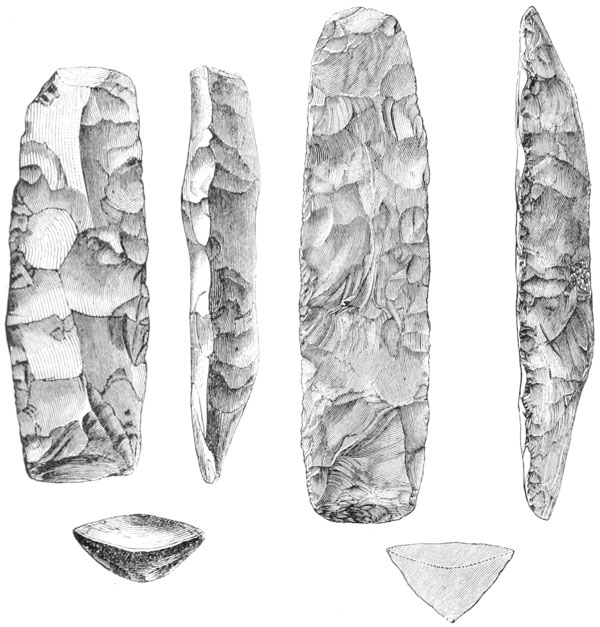

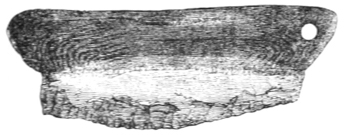

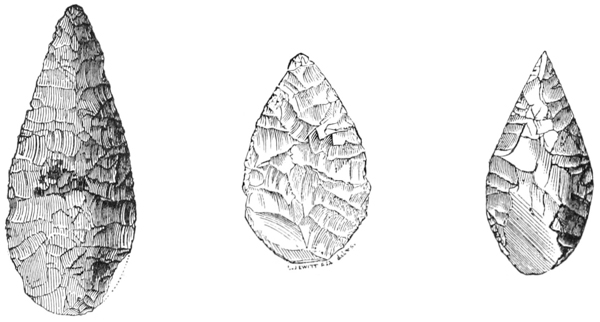

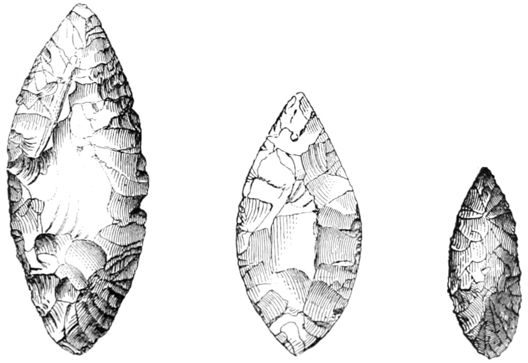

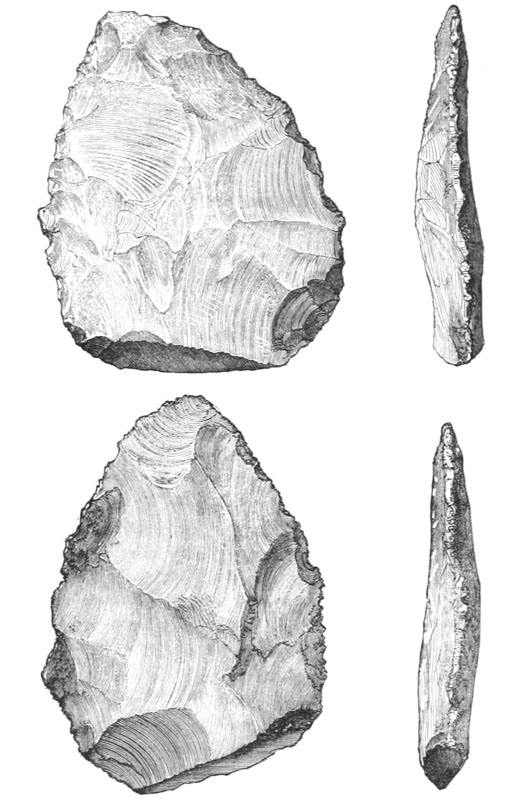

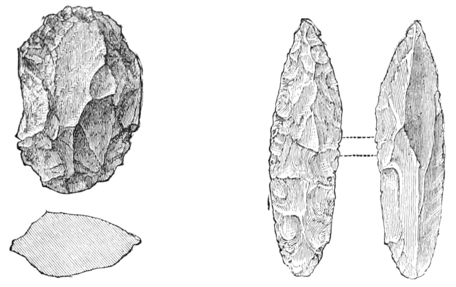

In several European museums are preserved thin, flat, leaf-shaped knives of cherty flint found in Egypt, some of which will be mentioned in subsequent pages. In character of workmanship their correspondence with the flint knives or daggers of Scandinavia is most striking. Many, however, are provided with a tang at one end at the back of the blade, and in this respect resemble metallic blades intended to be mounted by means of a tang driven into the haft.

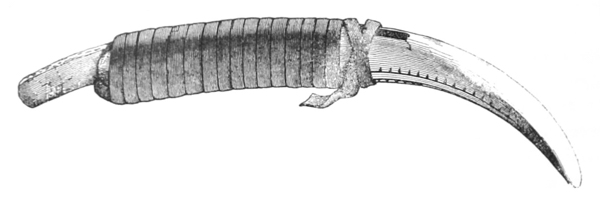

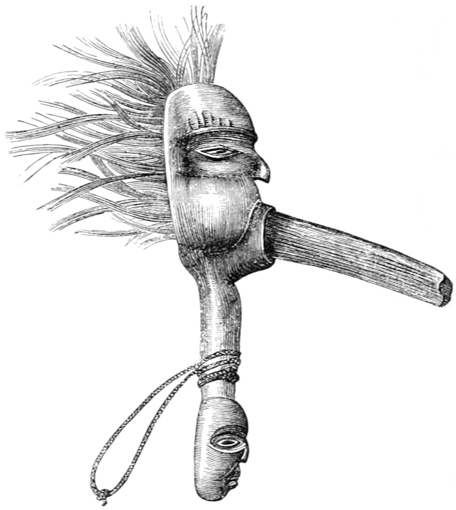

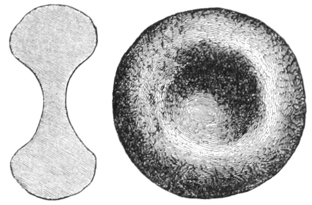

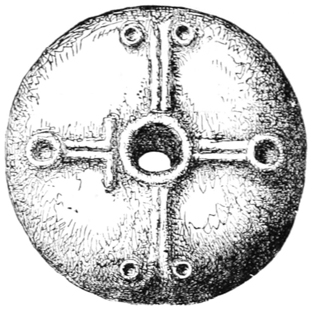

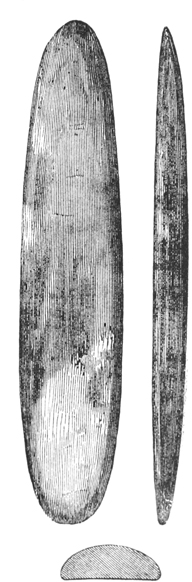

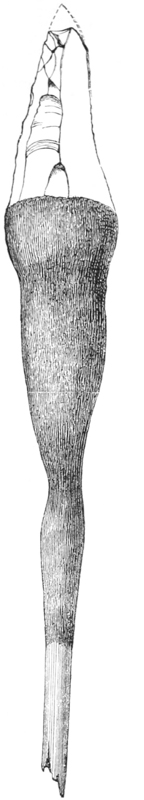

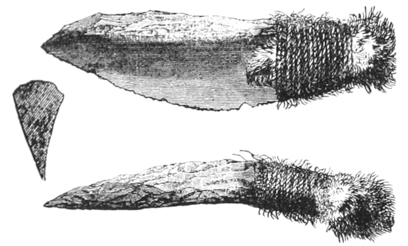

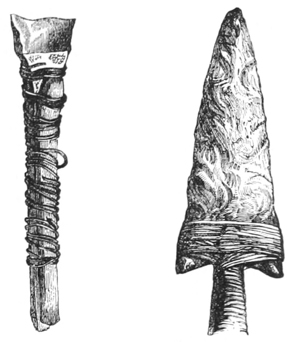

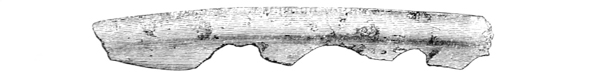

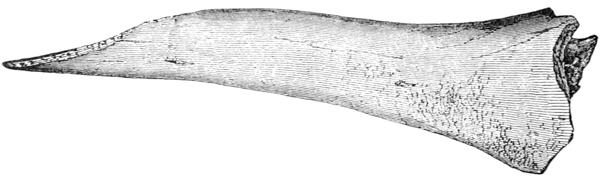

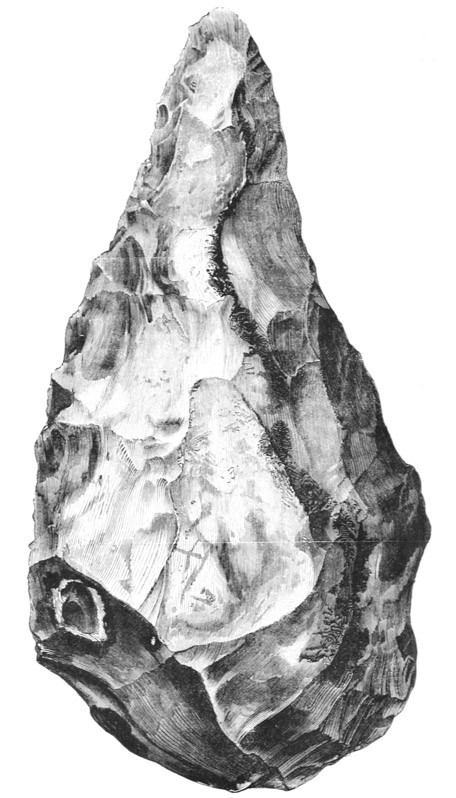

In the British Museum is an Egyptian dagger-like instrument of flint, from the Hay collection, still mounted in its original wooden handle, apparently by a central tang, and with remains of its skin sheath. It is shown on the scale of one-fourth in Fig. 1. There is also a polished stone knife broken at the handle, which bears upon it in hieroglyphical characters the name of PTAHMES, an officer.

Curiously enough the bodies of the chiefs or Menceys of the Guanches in Teneriffe [35] were also cut open by particular persons set apart for the office with knives made of sharp pieces of obsidian. {9}

The rite of circumcision was among those practised by the

Egyptians, but whether it was performed with a stone knife, as

was the case with the Jews when they came out of Egypt, is not

certain. Among the latter people, not to lay stress on the case of

Zipporah, [36]

it is recorded of

Joshua, [37]

that in circumcising the

children of Israel he made use of knives of stone. It is true that,

in our version, the words

are translated sharp knives,

which by analogy with a passage in Psalm lxxxix. 44 (43 E.V.), is

not otherwise than correct; but the Syriac, Arabic, Vulgate, and

Septuagint translations all give knives of

stone; [38]

and the latter

version, in the account of the burial of Joshua, adds that they laid

with him the stone knives (τὰς μαχαίρας τὰς πετρίνας) with which

he circumcised the children of Israel—“and there they are unto

this day.” Gesenius (s. v.

are translated sharp knives,

which by analogy with a passage in Psalm lxxxix. 44 (43 E.V.), is

not otherwise than correct; but the Syriac, Arabic, Vulgate, and

Septuagint translations all give knives of

stone; [38]

and the latter

version, in the account of the burial of Joshua, adds that they laid

with him the stone knives (τὰς μαχαίρας τὰς πετρίνας) with which

he circumcised the children of Israel—“and there they are unto

this day.” Gesenius (s. v.

)

observes upon the passage, “This

is a circumstance worthy of remark; and goes to show at least,

that knives of stone were found in the sepulchres of Palestine, as

well as in those of north-western

Europe.” [39]

In recent times the

Abbé Richard, in examining what is known as the tomb of

Joshua at some distance to the east of Jericho, found a number of

sharp flakes of flint as well as flint instruments of other

forms. [40]

)

observes upon the passage, “This

is a circumstance worthy of remark; and goes to show at least,

that knives of stone were found in the sepulchres of Palestine, as

well as in those of north-western

Europe.” [39]

In recent times the

Abbé Richard, in examining what is known as the tomb of

Joshua at some distance to the east of Jericho, found a number of

sharp flakes of flint as well as flint instruments of other

forms. [40]

Under certain circumstances modern Jews make use of a fragment of flint or glass for this rite. The occurrence of flint knives in ancient Jewish sepulchres may, however, be connected with a far earlier occupation of Palestine than that of the Jews. It was a constant custom with them to bury in caves, and recent discoveries have shown that, like the caves of Western Europe, many of these were at a remote period occupied by those unacquainted with the use of metals, whose stone implements are found mixed up with the bones of the animals which had served them for food. [41]

Of analogous uses of stone we find some few traces among classical writers. Ovid, speaking of Atys, makes the instrument with which he maimed himself to be a sharp stone,

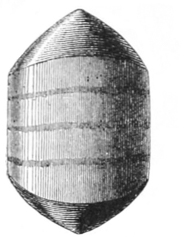

The solemn treaties among the Romans were ratified by the {10} Fetialis [42] sacrificing a pig with a flint stone, which, however, does not appear to have been sharpened. “Ubi dixit, porcum saxo silice percussit.” The “religiosa silex” [43] of Claudian seems rather to have been a block of stone like that under the form of which Jupiter, Cybele, Diana, and even Venus were worshipped. Pausanias informs us that it was the custom among the Greeks to bestow divine honours on certain unshaped stones, and ΖΕΥΣ ΚΑΣΙΟΣ is thus represented on coins of Seleucia in Syria, while the Paphian Venus appears in the form of a conical stone on coins struck in Cyprus. The Syrian god from whom Elagabalus, the Roman emperor, took his name seems also to have been an unhewn stone, possibly a meteorite.

The traces, however, of the Stone Age in the religious rites of Greece and Rome are extremely slight, and this is by no means remarkable when we consider how long the use of bronze, and even of iron, had been known in those parts of Europe at the time when authentic history commences. We shall subsequently see at how early a period different implements of stone had a mysterious if not a superstitious virtue assigned to them. I need only mention as an instance that, in several beautiful gold necklaces [44] of Greek or Etruscan workmanship, the central pendant consists of a delicate flint arrow-head, elegantly set in gold, and probably worn as a charm. Nor is the religious use of stone confined to Europe. [45] In Western Africa, when the god Gimawong makes his annual visit to his temple at Labode, his worshippers kill the ox which they offer, with a stone.

To come nearer home, it is not to be expected that in this country, the earliest written history of which (if we except the slight account derived from merchants trading hither), comes from the pen of foreign conquerors, we should have any records of the Stone Age. In Cæsar’s time, the tribes with which he came in contact were already acquainted with the use of iron, and were, indeed, for the most part immigrants from Gaul, a country whose inhabitants had, by war and commerce, been long brought into close relation with the more civilized inhabitants of Italy and Greece. I have elsewhere shown [46] that the degree of civilization which must be conceded to those maritime tribes far exceeds what is accorded by popular belief. The older occupants of Britain, who {11} had retreated before the Belgic invaders, and occupied the western and northern parts of the island, were no doubt in a more barbarous condition; but in no case in which they came in contact with their Roman invaders do they seem to have been unacquainted with the use of iron. Even the Caledonians, [47] in the time of Severus, who tattooed themselves with the figures of animals, and went nearly naked, carried a shield, a spear, and a sword, and wore iron collars and girdles; they however deemed these latter ornamental and an evidence of wealth, in the same way as other barbarians esteemed gold.

But though immediately before and after the Christian era the knowledge of the use of iron may have been general throughout Britain, and though probably an acquaintance with bronze, at all events in the southern part of the island, may probably date many centuries farther back, it by no means follows, as I cannot too often repeat, that the use of stone for various purposes to which it had previously been applied should suddenly have ceased on a superior material, in the shape of metal, becoming known. On the contrary, we know that the use of certain stone weapons was contemporary with the use of bronze daggers, and the probability is that in the poorer and more inaccessible parts of the country, stone continued in use for many ordinary purposes long after bronze, and possibly even iron, was known in the richer and more civilized districts.

Sir William Wilde informs us that in Ireland [48] “stone hammers, and not unfrequently stone anvils, have been employed by country smiths and tinkers in some of the remote country districts until a comparatively recent period.” The same use of stone hammers and anvils for forging iron prevails among the Kaffirs [49] of the present day. In Iceland [50] also, perforated stone hammers are still in use for pounding dried fish, driving in stakes, for forging and other purposes; “knockin’-stones” [51] for making pot-barley, have till recently been in use in Scotland, if not still employed; and I have seen fruit-hawkers in the streets of London cracking Brazil nuts between two stones.

With some exceptions it is, therefore, nearly impossible to say whether an ancient object made of stone can be assigned with {12} absolute certainty to the Stone Period or no. Much will depend upon the circumstances of the discovery, and in some instances the form may be a guide.

The remarks I have just made apply most particularly to the weapons, tools, and implements belonging to the period more immediately antecedent to the Bronze Age, and extending backwards in time through an unknown number of centuries. For besides the objects belonging to what was originally known by the Danish antiquaries as the Stone Period, which are usually found upon or near the surface of the soil, in encampments, on the site of ancient habitations, and in tumuli, there are others which occur in caverns beneath thick layers of stalagmite, and in ancient alluvia, in both cases usually associated with the remains of animals either locally or entirely extinct. In no case do we find any trace of metallic tools or weapons in true association with the stone implements of the old ossiferous caverns, or with those of the beds of gravel, sand, and clay deposited by the ancient rivers; and, unlike the implements found upon the surface and in graves, which in many instances are ground or polished, those from the caves, and from what are termed by geologists the Quaternary gravels, are, so far as at present known, invariably chipped only, and not ground, besides as a rule differing in form.

This difference [52] in the character of the implements of the two periods, and the vast interval of time between the two, I pointed out in 1859, at the time when the discoveries of M. Boucher de Perthes, in the Valley of the Somme, first attracted the attention of English geologists and antiquaries. Since then, the necessity of subdividing what had until then been regarded as the Stone Age into two distinct stages, an earlier and a later, has been universally recognized; and Sir John Lubbock [53] has proposed to call them the Palæolithic and the Neolithic Periods respectively, terms which have met with almost general acceptance, and of which I shall avail myself in the course of this work. In speaking of the polished and other implements belonging to the time when the general surface of the country had already received its present configuration, I may, however, also occasionally make use of the synonymous term Surface Period for the Neolithic, and shall also find it convenient to treat of the Palæolithic Period under two subdivisions—those of the River-gravels and of the {13} Caves, the fauna and implements of which are not in all cases identical.

In passing the different kinds of implements, weapons, and ornaments formed of stone under review, I propose to commence with an examination of the antiquities of the Neolithic Period, then to proceed to the stone implements of human manufacture discovered imbedded with ancient mammalian remains in Caverns, and to conclude with an account of the discoveries of flint implements in the Drift or River-gravels in various parts of England. But before describing their forms and characters, it will be well to consider the method of manufacture by which the various forms were produced.

In seeking to ascertain the method by which the stone implements and weapons of antiquity were fabricated, we cannot, in all probability, follow a better guide than that which is afforded us by the manner in which instruments of similar character are produced at the present day. As in accounting for the vast geological changes which we find to have taken place in the crust of the earth, the safest method of argument is by referring to ascertained physical laws, and to the existing operations of nature, so, in order to elucidate the manufacture of stone implements by the ancient inhabitants of this and other countries, we may refer to the methods employed by existing savages in what we must judge to be a somewhat similar state of culture, and to the recognized characteristics of the materials employed. We may even go further, and call in aid the experience of some of our own countrymen, who still work upon similar materials, although for the purpose of producing different objects from those which were in use in ancient times.

So far as relates to the method of production of implements formed of silicious materials, there can be no doubt that the manufacture of gun-flints, which, notwithstanding the introduction of percussion-caps, is still carried on to some extent both in this and in neighbouring countries, is that best calculated to afford instruction. The principal place in England where the gun-flint manufacture is now carried on, is Brandon, on the borders of Norfolk and Suffolk, where I have witnessed the process. I have also seen the manufacture at Icklingham, in Suffolk, where thirty years ago, gun-flint factories existed, which have now I believe {15} been closed. They were also formerly manufactured in small numbers at Catton, near Norwich. At Brandon, in 1868, I was informed that upwards of twenty workmen were employed, who were capable of producing among them from 200,000 to 250,000 gun-flints per week. These were destined almost entirely for exportation, principally to Africa. On July 18th, 1890, the Daily News [55] gave the number of workmen at Brandon as thirty-five.

Some other sites of the gun-flint manufacture in former times are mentioned by Mr. Skertchly, as for instance, Clarendon near Salisbury; Gray’s Thurrock, Essex; Beer Head, Devon; and Glasgow; besides several places in Norfolk and Suffolk.

In France the manufacture of gun-flints is still carried on in the Department of Loir et Cher, [56] and various other localities are recorded by Mr. Skertchly. [57]

In proof of the antiquity of the use of flint as a means of producing fire, I need hardly quote the ingenious derivation of the word Silex as given by Vincent of Beauvais:—“Silex est lapis durus, sic dictus eò quod ex eo ignis exiliat.” [58] But before iron was known as a metal, it would appear that flint was in use as a fire-producing agent in combination with blocks of iron pyrites (sulphide of iron) instead of steel. Nodules of this substance have been found in both French and Belgian bone-caves belonging to an extremely remote period; while, as belonging to Neolithic times, to say nothing of discoveries in this country, which will subsequently be mentioned, part of a nodule of pyrites may be cited which was found in the Lake settlement of Robenhausen, and had apparently been thus used. [59] In our own days, this method of obtaining fire has been observed among savages in Tierra del Fuego, and among the Eskimos of Smith’s Sound. [60] The {16} Fuegian tinder, like the modern German and ancient Roman, consists of dried fungus, which when lighted is wrapped in a ball of dried grass and whirled round the head till it bursts into flames. Achates, as will shortly be seen, is described by Virgil as following the same method.

The name of pyrites (from πῦρ) is itself sufficient evidence of the purpose to which this mineral was applied in early times, and the same stone was used as the fire-giving agent in the guns with the form of lock known as the wheel-lock. Pliny [61] speaks of a certain sort of pyrites, “plurimum habens ignis, quos vivos appellamus, et ponderosissimi sunt.” These, as his translator, Holland, says, “bee most necessary for the espialls belonging unto a campe, for if they strike them either with an yron spike or another stone they will cast forth sparks of fire, which lighting upon matches dipt in brimstone (sulphuratis) drie puff’s (fungis) or leaves, will cause them to catch fire sooner than a man can say the word.”

Pliny also [62] informs us that it was Pyrodes, the son of Cilix, who first devised the way to strike fire out of flint—a myth which seems to point to the use of silex and pyrites rather than of steel. The Jews on their return to Jerusalem, under Judas Maccabæus, “made another altar and striking stones they took fire out of them and offered a sacrifice.” [63] How soon pyrites was, to a great extent, superseded by steel or iron, there seems to be no good evidence to prove; it is probable, however, that the use of flint and steel was well known to the Romans of the Augustan age, and that Virgil [64] pictured the Trojan voyager as using steel, when—

And again, where—

In Claudian [66] we find the distinct mention of flint and steel—

At Unter Uhldingen [67] a Swiss lake station where Roman pottery was present, was found what appears to be a steel for striking a {17} light. However the case may have been as to the means of procuring fire, it was not until some centuries after the invention of gunpowder that flints were applied to the purpose of discharging fire-arms. Beckmann, [68] in his “History of Inventions,” mentions that it was not until the year 1687 that the soldiers of Brunswick obtained guns with flint-locks, instead of match-locks, though, no doubt, the use of the wheel-lock with pyrites had in some other places been superseded before that time.

I am not aware of there being any record of flints, such as were in use for tinder-boxes, [69] having been in ancient times an article of commerce: this, however, must have been the case, as there are so many districts in which flint does not naturally occur, and into which, therefore, it would have by some means to be introduced. Even at the present day, when so many chemical matches are in use, flints are still to be purchased at the shops in country places in the United Kingdom; and artificially prepared flints continue to be common articles of sale both in France and Germany, and are in constant use, in conjunction with German tinder, or prepared cotton, by tobacco-smokers. At Brandon [70] a certain number of “strike-a-light” flints are still manufactured for exportation, principally to the East and to Brazil—they are usually circular discs, about two inches in diameter. These flints are wrought into shape in precisely the same manner as gun-flints, and it seems possible that the trade of chipping flint into forms adapted to be used with steel for striking a light may be of considerable antiquity, and that the manufacture of gun-flints ought consequently to be regarded as only a modification and extension of a pre-existing art, closely allied with the facing and squaring of flints for architectural purposes, which reached great perfection at an early period. However this may be, it would seem that when gun-flints were an indispensable munition of war, a great mystery was made as to the manner in which they were prepared. Beckmann [71] says that, considering the great use made of them, it will hardly be believed how much trouble he had to obtain information on the subject. It would be ludicrous to repeat the various answers he obtained to his inquiries. Many thought that the stones were cut down by grinding them; some conceived that {18} they were formed by means of red-hot pincers, and many asserted that they were made in mills. The best account of the manufacture with which he was acquainted, was that collected by his brother, and published in the Hanoverian Magazine for the year 1772. At a later date the well-known mineralogist Dolomieu [72] gave an account of the process in the Mémoires de l’Institut National des Sciences, and M. Hacquet, [73] of Leopol, in Galicia, published a pamphlet on the same subject. The accounts given by both these authors correspond most closely with each other, and also with the practice of the present day, though the French process differs in some respects from the English. [74] This has been well described by Dr. Lottin. [75] The flints best adapted for the purpose of the manufacture are those from the chalk. They must, however, be of fair size, free from flaws and included organisms, and very homogeneous in structure. They are usually procured by sinking small shafts into the ground until a band of flints of the right quality is reached, along which low horizontal galleries, or “burrows,” as they are called, are worked. For success in the manufacture a great deal is said to depend upon the condition of the flint as regards the moisture it contains, those which have been too long exposed upon the surface becoming intractable, and there being also a difficulty in working those that are too moist. A few blows with the hammer enable a practised flint-knapper to judge whether the material on which he is at work is in the proper condition or no. Some of the Brandon workmen, however, maintain that though a flint which has been some time exposed to the air is harder than one recently dug, yet that it works equally well, and they say further, that the object in keeping the flints moist is to preserve the black colour from fading, black gun-flints being most saleable.

A detailed account, by Mr. Skertchly, of the manufacture of gun-flints, with an essay on the connection between Neolithic art and the gun-flint trade, forms an expensive memoir of the geological survey, published in 1879; but it seems well to retain the following short account of the process.

The tools required are few and simple:—

1. A flat-faced blocking, or quartering hammer, from one to {19} two pounds in weight, made either of iron or of iron faced with steel.

2. A well-hardened steel flaking hammer, bluntly pointed at each end, and weighing about a pound, or more; or in its place a light oval hammer, known as an “English” hammer, the pointed flaking hammer having been introduced from France.

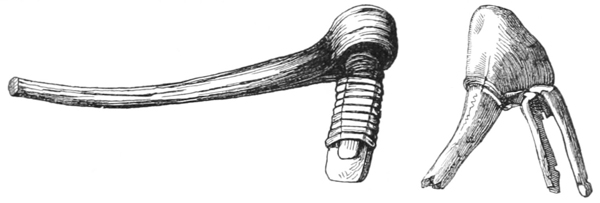

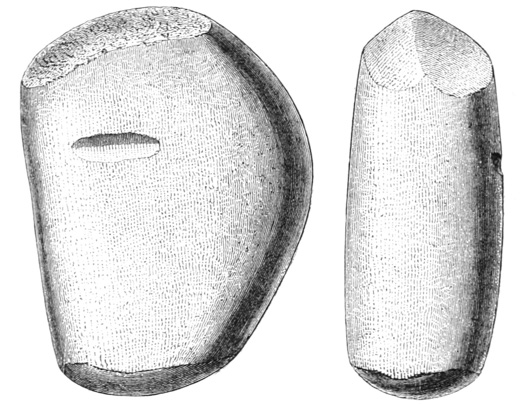

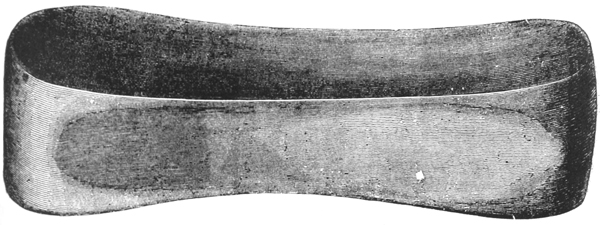

3. A square-edged trimming or knapping hammer, which may either be in the form of a disc, or oblong and flat at the end, made of steel not hardened. In England, this hammer is usually made from a portion of an old flat file perforated to receive the helve, and drawn out at each end into a thin blade, about 1 ⁄ 16 of an inch in thickness; the total length being about 7 or 8 inches.

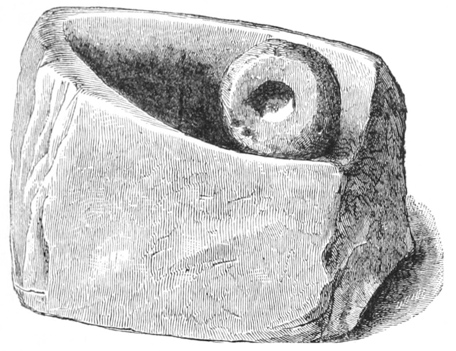

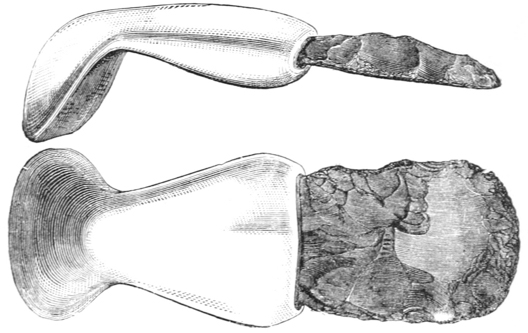

4. A chisel-shaped “stake” or small anvil set vertically in a block of wood, which at the same time forms a bench for the workman. In England, the upper surface of this stake is about 1 ⁄ 4 inch thick, and inclined at a slight angle to the bench.

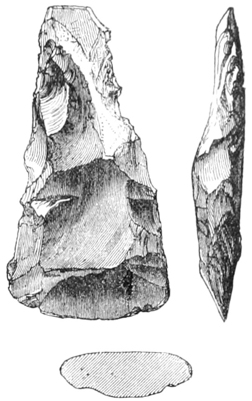

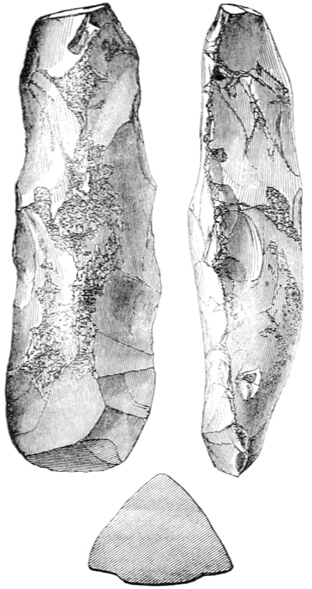

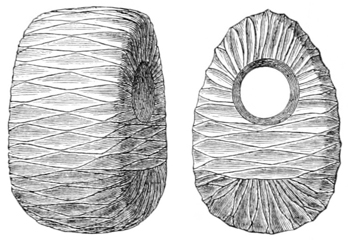

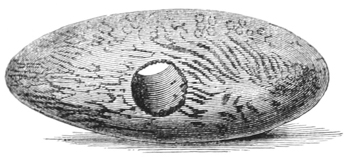

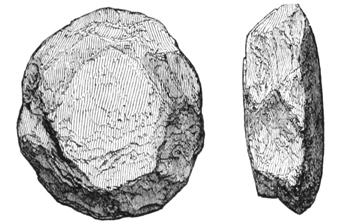

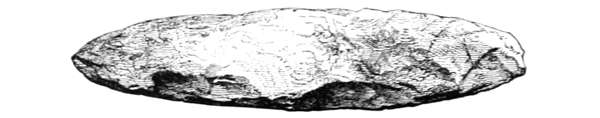

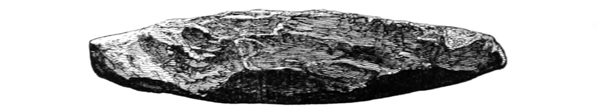

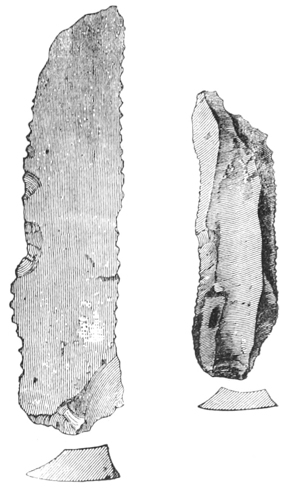

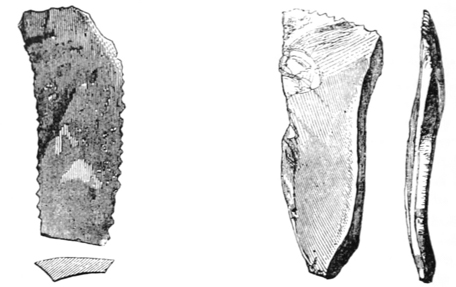

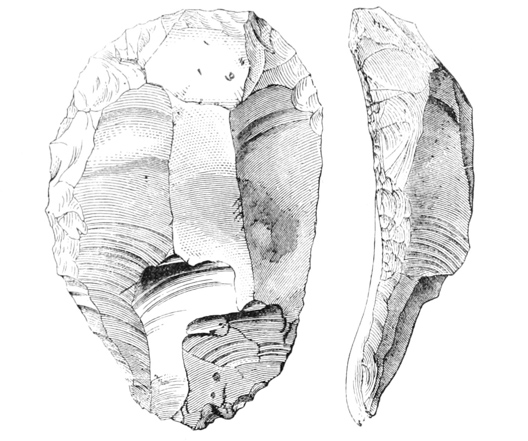

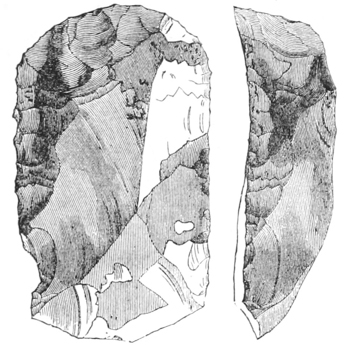

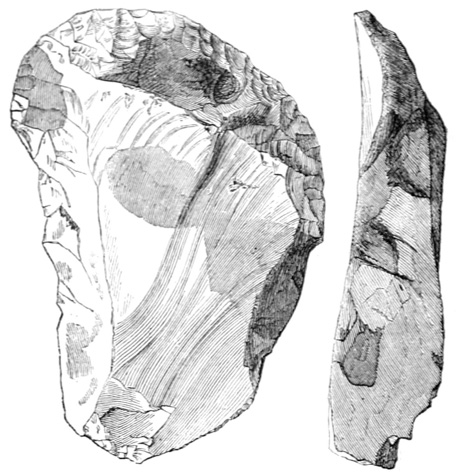

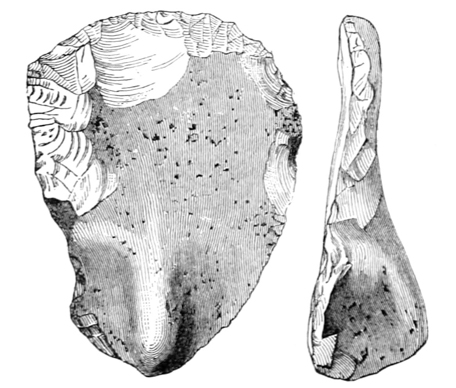

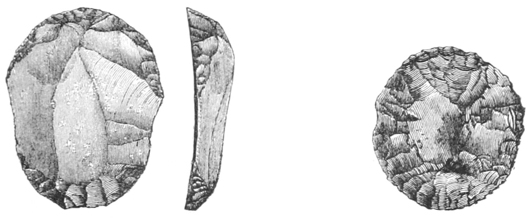

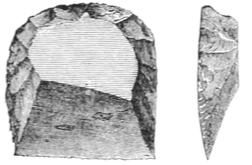

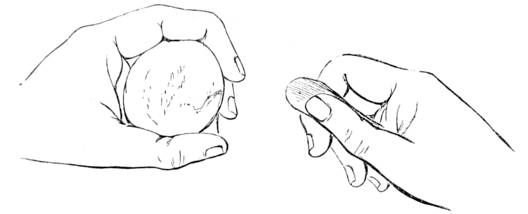

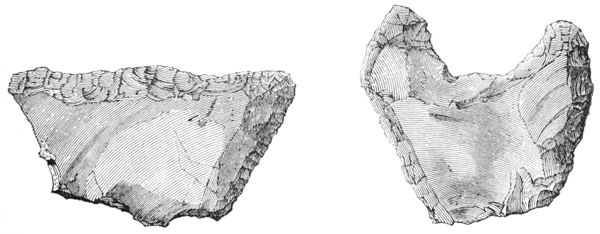

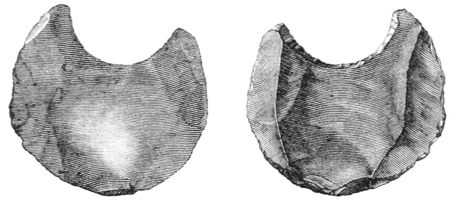

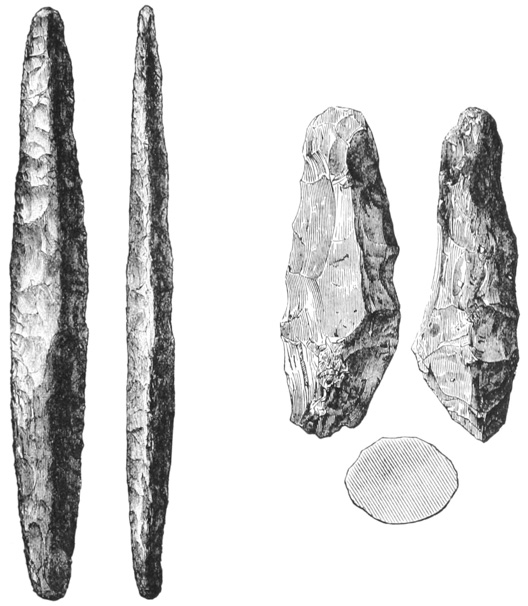

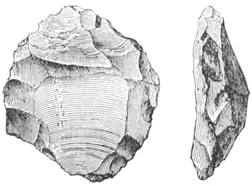

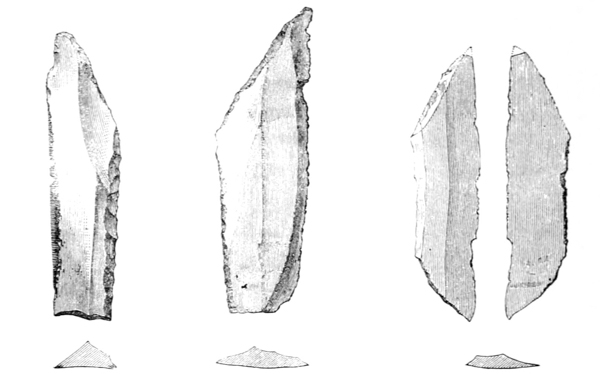

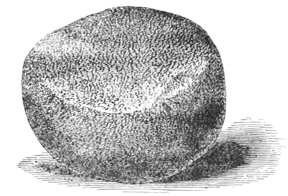

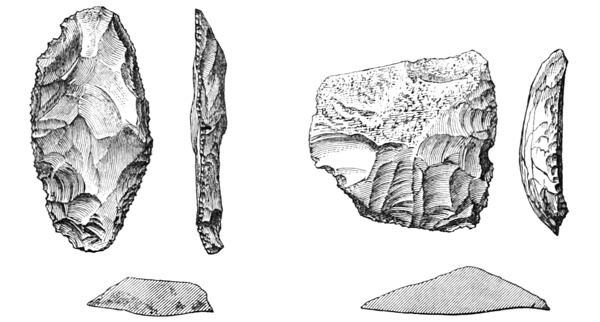

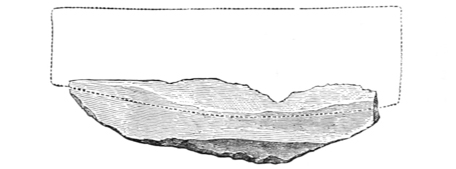

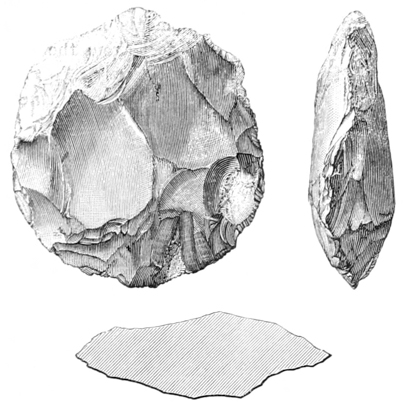

The method of manufacture [76] is as follows:—A block of flint is broken by means of the quartering hammer in such a manner as to detach masses, the newly-fractured surfaces of which are as nearly as possible plane and even. One of these blocks is then held in the left hand, so that the edge rests on a leathern pad tied on the thigh of the seated workman, the surface to be struck inclining at an angle of about 45°. A splinter is then detached from the margin by means of the flaking hammer. If the flint is of good quality, this splinter may be three or four inches in length, the line of fracture being approximately parallel to the exterior of the flint. There is, of course, the usual bulb of percussion, or rounded protuberance at the end, [77] where the blow is given, and a corresponding depression is left in the mass of flint. Another splinter is next detached, by a blow given at a distance of about an inch on one side of the spot where the first blow fell, and then others at similar distances, until some portion of the block assumes a more or less regular polygonal outline. As the splinters which are first detached usually show a portion of the natural crust of the flint upon them, they are commonly {20} thrown away as useless. The second and succeeding rows of flakes are those adapted for gun-flints. To obtain these, the blows of the flaking hammer are administered midway between two of the projecting angles of the polygon, and almost immediately behind the spots where the blows dislodging the previous row of flakes or splinters were administered, though a little to one side. They fall at such a distance from the outer surface as is necessary for the thickness of a gun-flint. By this means a succession of flakes is produced, the section of which is that of an obtuse triangle with the apex removed, inasmuch as for gun-flints, flakes are required with the face and back parallel, and not with a projecting ridge running along the back.

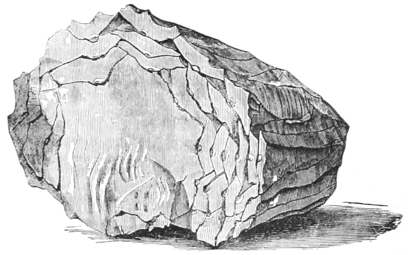

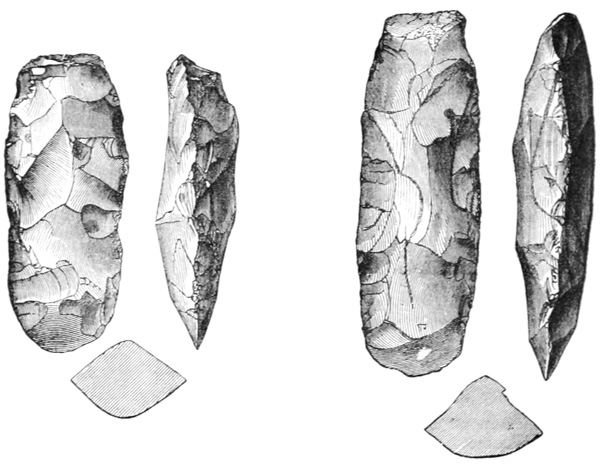

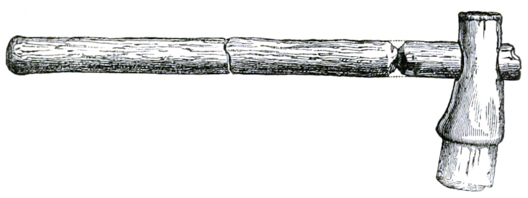

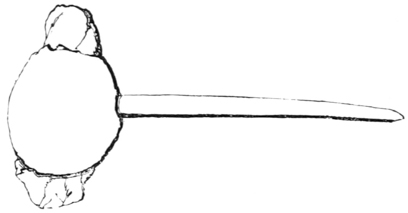

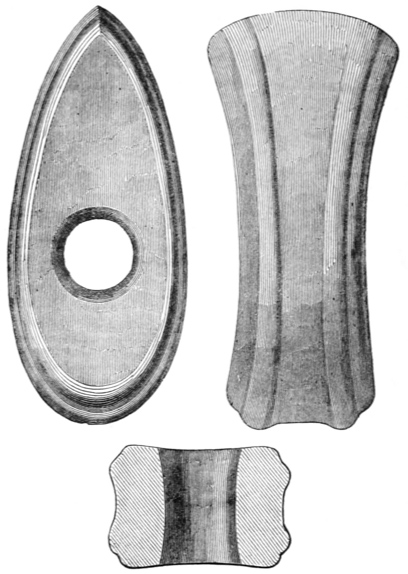

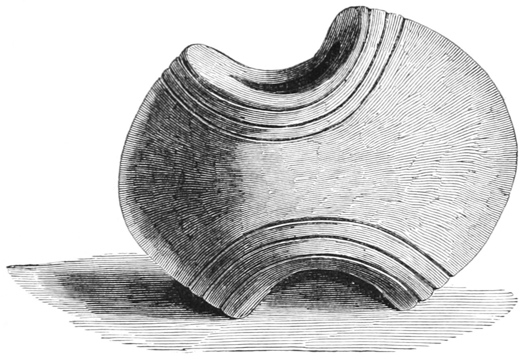

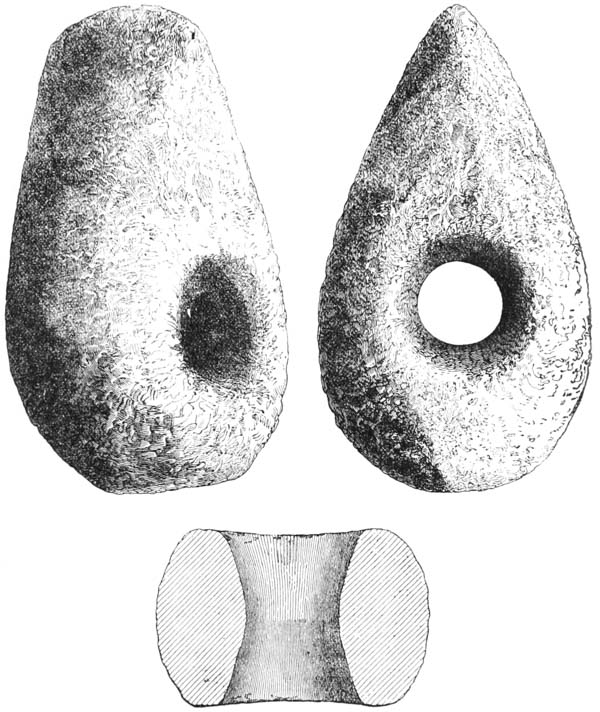

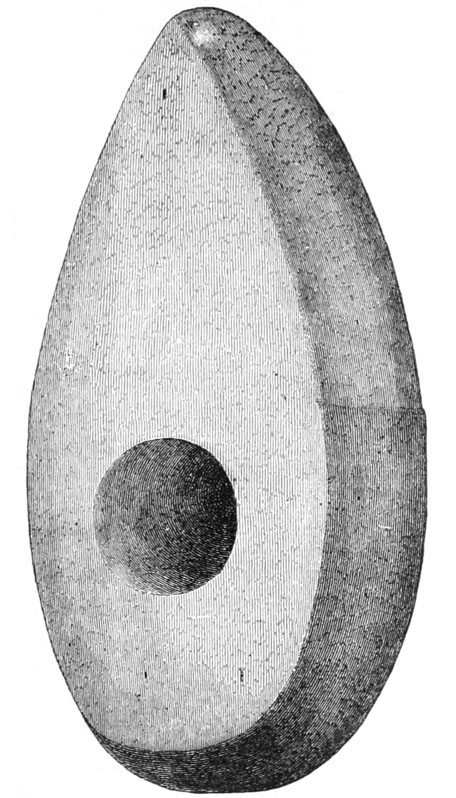

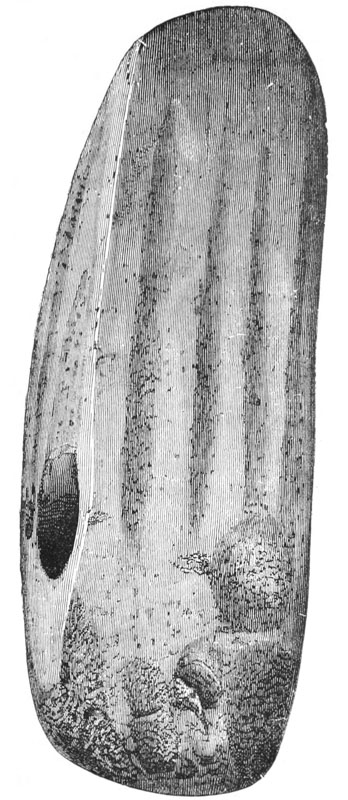

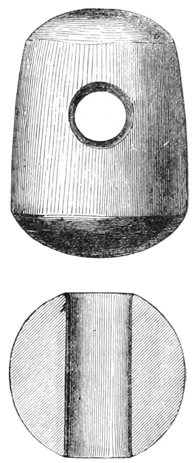

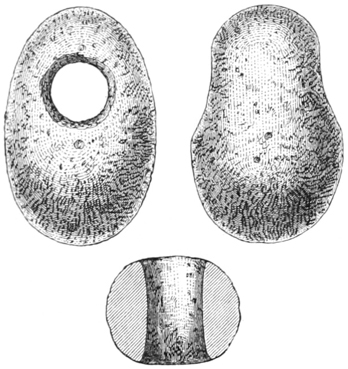

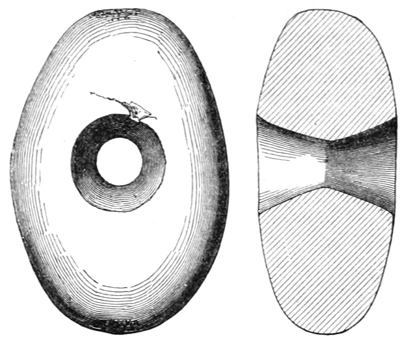

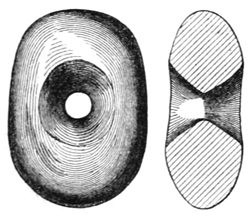

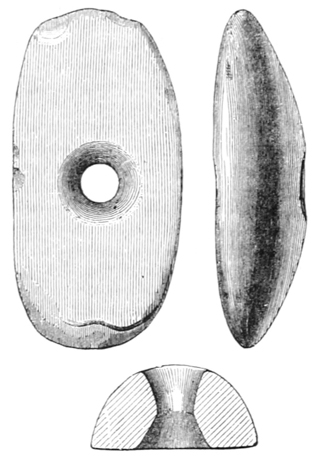

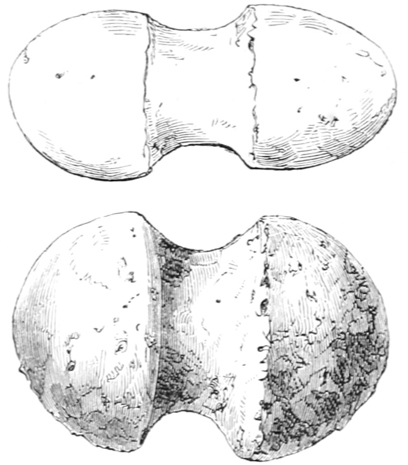

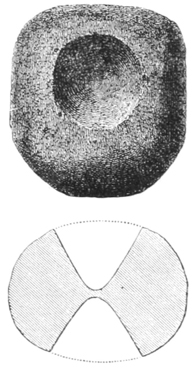

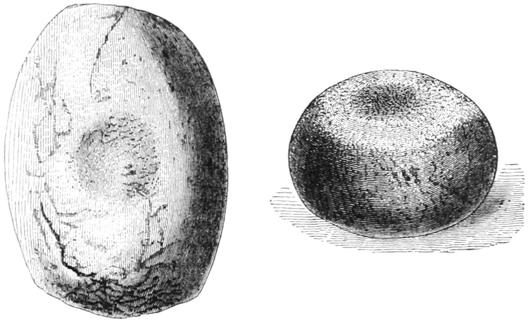

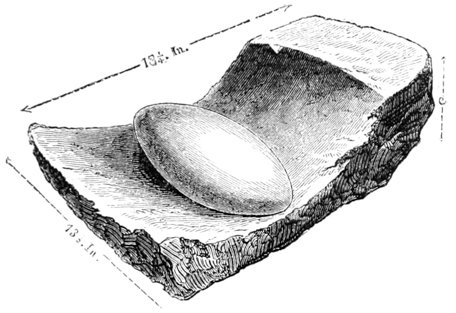

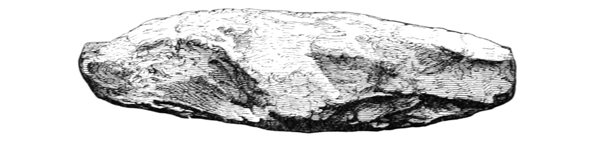

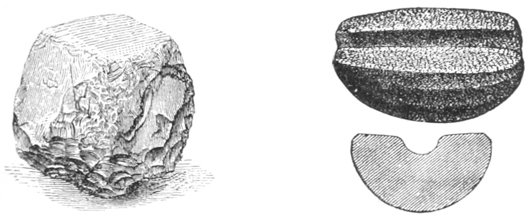

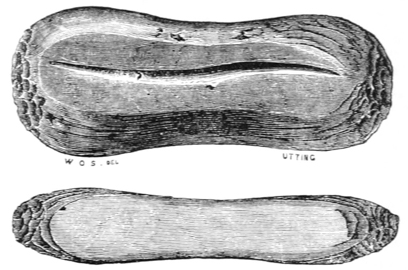

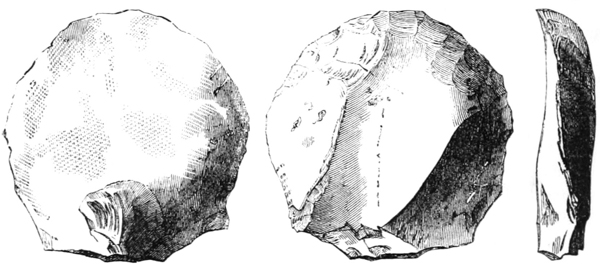

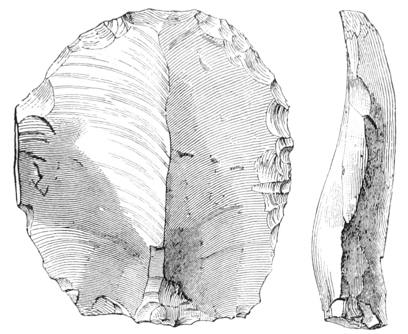

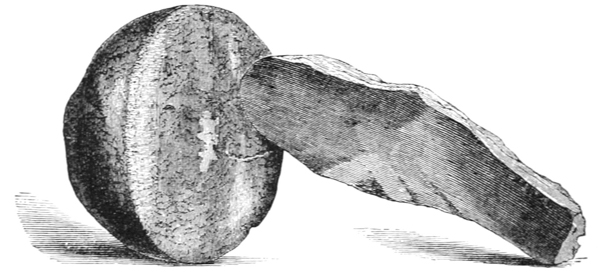

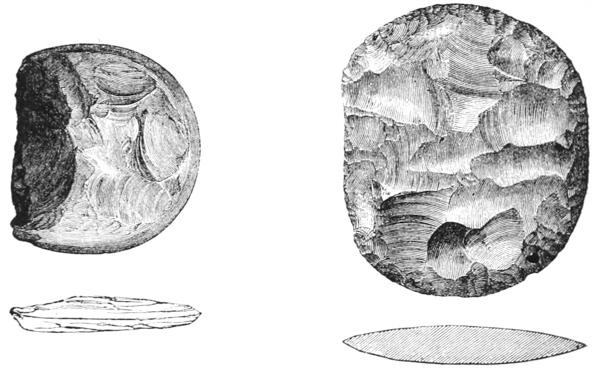

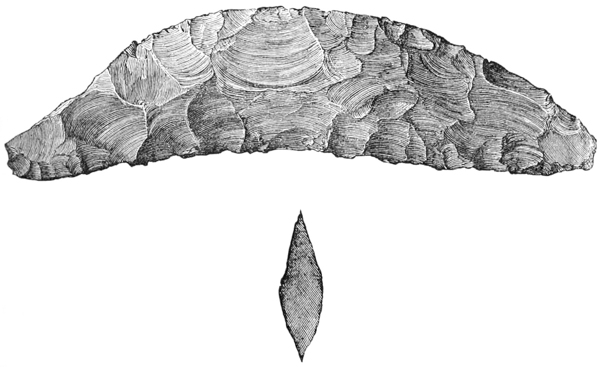

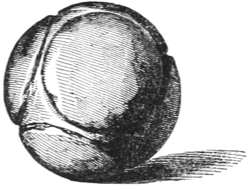

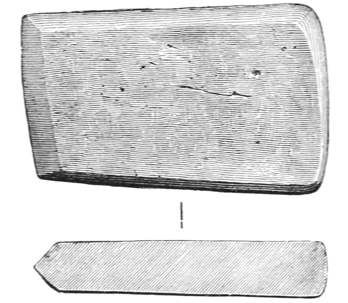

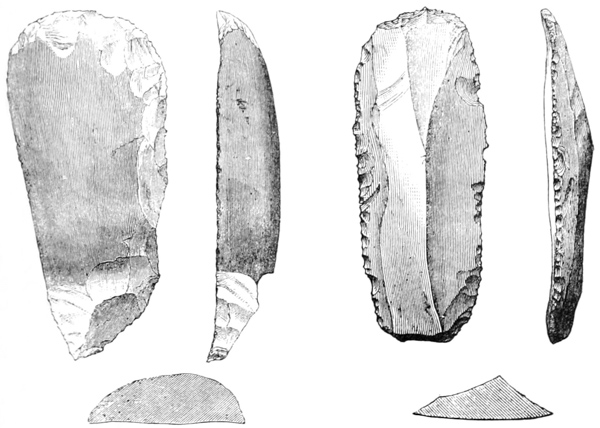

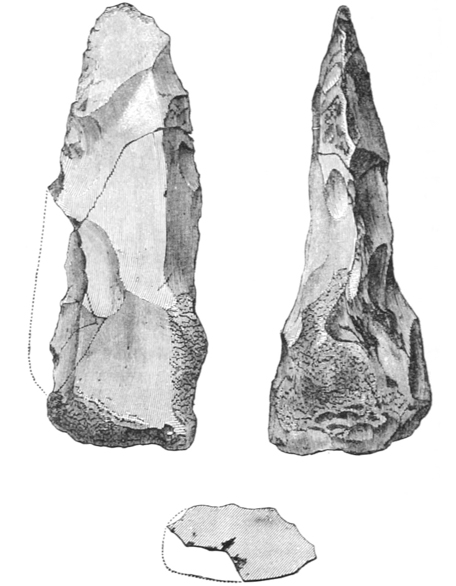

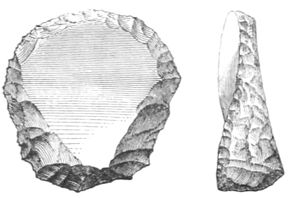

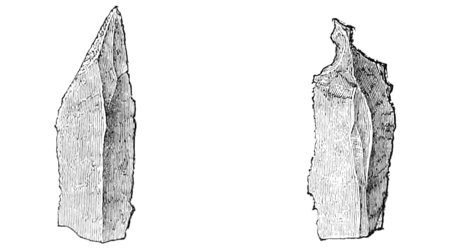

Fig. 2, representing a block from which a number of flakes adapted for gun-flints have been detached and subsequently returned to their original positions around the central core or nucleus, will give a good idea of the manner in which flake after flake is struck off. Mr. Spurrell and Mr. Worthington Smith have succeeded in building up flakes of Palæolithic date into the original blocks from which they were struck. The former has also replaced ancient Egyptian flakes, [78] the one upon the other. Mr. F. Archer has likewise restored a block of flint from Neolithic flakes [79] found near Dundrum Bay, county Down.

To complete the manufacture of gun-flints, each flake is taken in the left hand, and cut off into lengths of the width required, by means of the knapping hammer and the stake fixed in the bench. The flake is placed over the stake at the spot where it is to be cut, {21} and a skilful workman cuts the flake in two at a single stroke. The sections of flakes thus produced have a cutting edge at each end; but the finished gun-flint is formed by chipping off the edge at the butt-end and slightly rounding it by means of the fixed chisel and knapping hammer, the blows from which are made to fall just within the chisel, so that the two together cut much in the same manner as a pair of shears. Considerable skill is required in the manufacture, more especially in the production of the flakes; but Hacquet [80] says that a fortnight’s practice is sufficient to enable an ordinary workman to fashion from five hundred to eight hundred gun-flints in a day. According to him, an experienced workman will produce from a thousand to fifteen hundred per diem. Dolomieu estimates three days as the time required by a “caillouteur” to produce a thousand gun-flints; but as the highest price quoted for French gun-flints by Hacquet is only six francs the thousand, it seems probable that his calculation as to the time required for their manufacture is not far wrong. Some of the Brandon flint-knappers are, however, said to be capable of producing sixteen thousand to eighteen thousand gun-flints in a week. Taking the lowest estimate, it appears that a practised hand is capable of making at least three hundred flint implements of a given definite form, and of some degree of finish, in the course of a single day. If our primitive forefathers could produce their worked flints with equal ease, the wonder is, not that so many of them are found, but that they do not occur in far greater numbers.

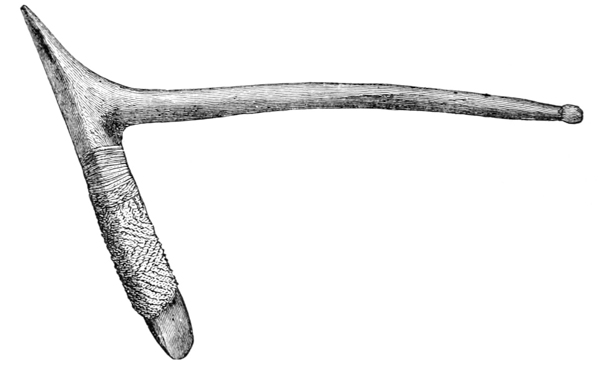

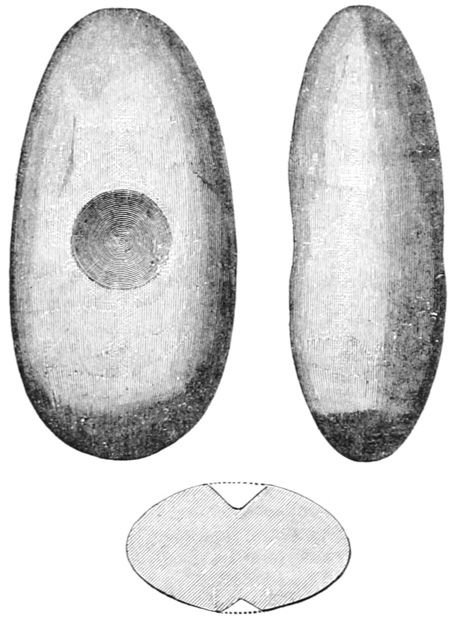

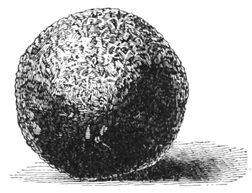

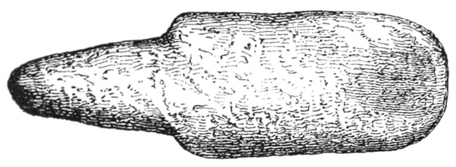

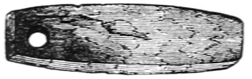

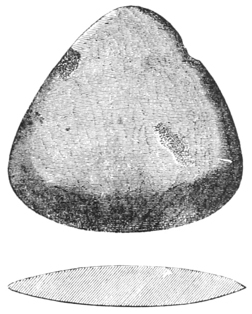

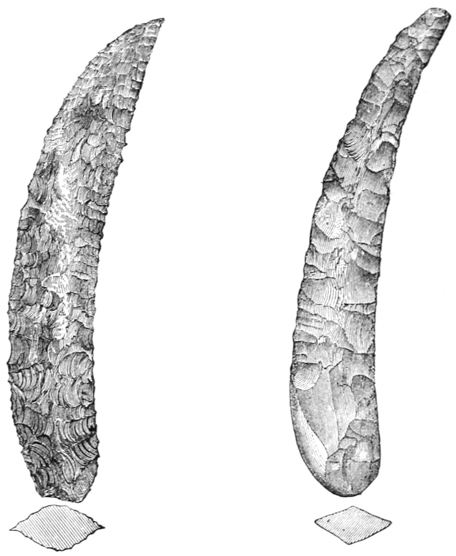

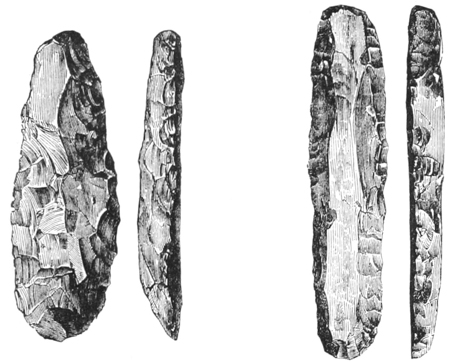

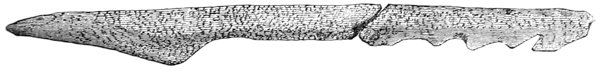

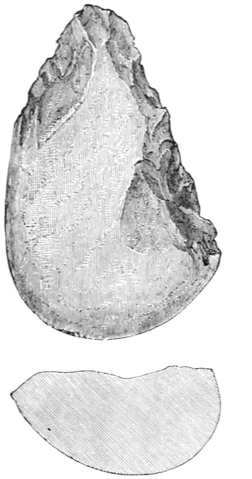

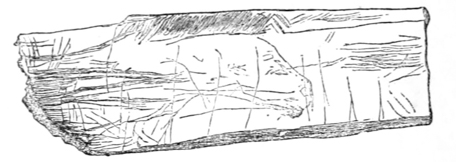

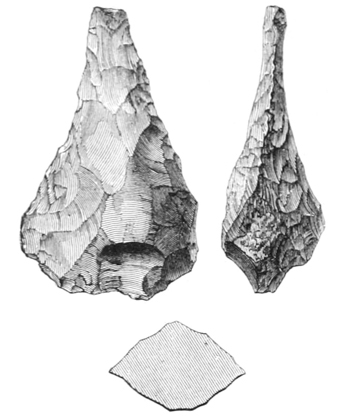

An elegant form of gun-flint, showing great skill in surface flaking, is still produced in Albania. A specimen, purchased at Avlona [81] by my son, is shown in Fig. 2A. Some gun-flints and strike-a-lights are formed of chalcedony or agate, and cut and polished.

The ancient flint-workers had not, however, the advantages of steel and iron tools and other modern appliances at their command; and, at first sight, it would appear that the {22} production of flakes of flint, without having a pointed metallic hammer for the purpose, was a matter of great difficulty, I have, however, made some experiments upon the subject, and have also employed a Suffolk flint-knapper to do so, and I find that blows from a rounded pebble, judiciously administered, are capable of producing well-formed flakes, such as, in shape, cannot be distinguished from those made with a metallic hammer. The main difficulties consist—first, in making the blow fall exactly in the proper place; and, secondly, in so proportioning its intensity that it shall simply dislodge a flake, and not shatter it. The pebble employed as a hammer need not be attached to a shaft, but can be used, without any preparation, in the hand. Professor Nilsson tried the same method long ago, and has left on record an interesting account of his experience. [82]