THE EVENING WALK.

Engraved by H. G. Armstrong for Godey's Lady's Book.

Title: Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. 48, February, 1854

Author: Various

Editor: Sarah Josepha Buell Hale

Release date: May 27, 2016 [eBook #52168]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

February.

THE EVENING WALK.

Engraved by H. G. Armstrong for Godey's Lady's Book.

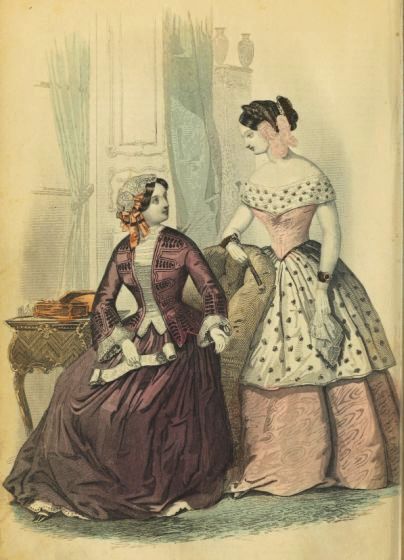

GODEY'S COLORED FASHIONS.

EMBROIDERED DRESSING GOWN.

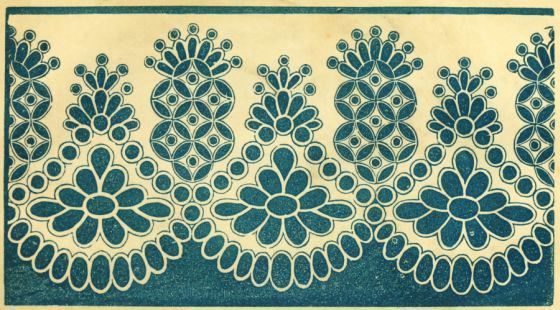

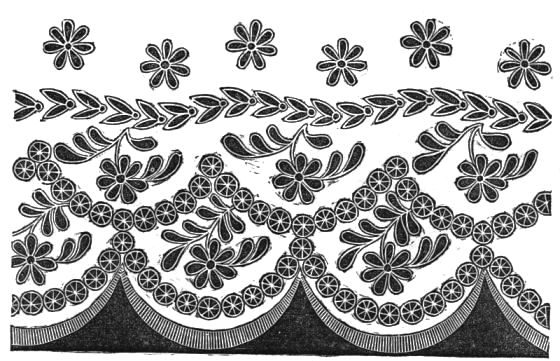

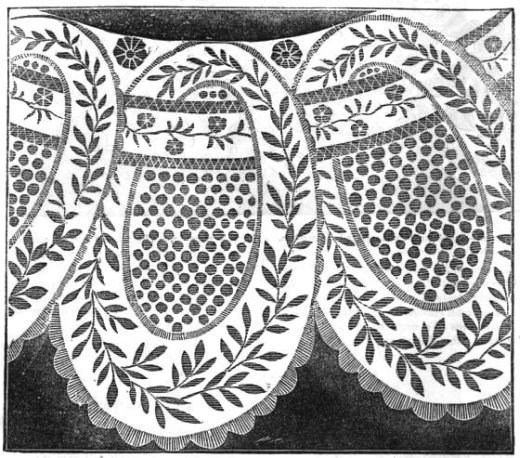

BRODERIE ANGLAISE FLOUNCING.

The Farm Yard.

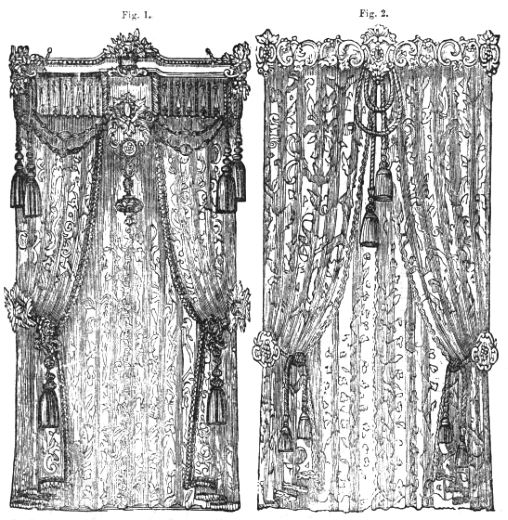

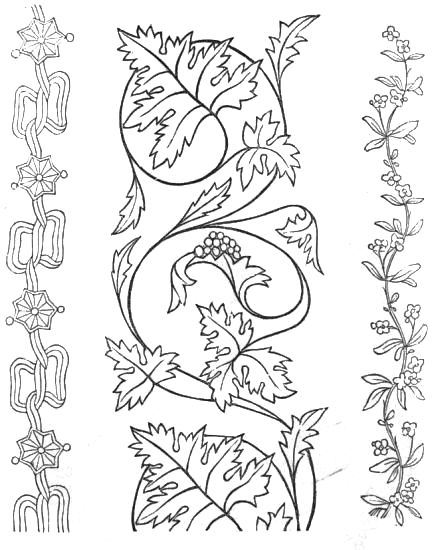

FOR DECORATING PARLOR WINDOWS

THE LATEST STYLES.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

From W. H. Carryl's celebrated depot for Curtains, Furniture Coverings, Window Shades, and all kinds of parlor trimmings, No. 169 Chestnut Street, corner of Fifth, Philadelphia. (For description, see page 166.)

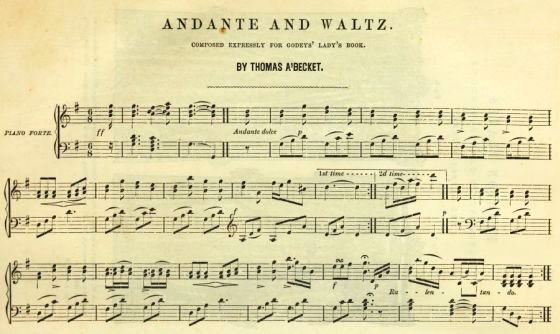

COMPOSED EXPRESSLY FOR GODEYS' LADY'S BOOK.

BY THOMAS A'BECKET.

[Listen]

[Listen]

THE MOSCOW WRAPPER.

[From the establishment of G. Brodie, No. 51 Canal Street, New York.]

PHILADELPHIA, FEBRUARY, 1854.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PEN AND GRAVER.

BOARDMAN & GRAY'S DOLCE CAMPANA ATTACHMENT PIANO-FORTES.

(Concluded.)

The Piano-Forte Action Regulator adjusts the action in all its operations. Those parts are supplied and fitted that are still wanting to complete it. The depth of the touch is regulated, the keys levelled, the drop of the hammer adjusted, and all is now seemingly in order for playing; but in Messrs. Boardman & Gray's Factory, the instrument has to undergo another ordeal in the way of regulating; for, after standing for several days or weeks, and being tuned and somewhat used, it passes into the hands of another and last regulator, who again examines minutely every part, readjusts the action, key by key, and note by note, until all is as it were, perfect. And now its tone must be regulated, and the "hammer finisher" takes it in charge, and gives it the last finishing touch; every note from the bass to the treble must give out a full, rich, even, melodious tone. This is a very important branch of the business; for great care and much experience are required to detect the various qualities and shades of tone, and to know how to alter and adjust the hammer in such a way as to produce the desired result. Some performers prefer a hard or brilliant tone; others a full soft tone; and others, again, a full clear tone of medium quality. It is the hammer-finisher's duty to see that each note in the whole instrument shall correspond in quality and brilliancy with the others. The piano-fortes of Messrs. Boardman & Gray are celebrated for their full organ tone, and for the even quality of each note; for the rich, full, and harmonious music, rather than the noise, which they make; and a discriminating public have set their stamp of approbation on their efforts, if we may judge by the great and increasing demand for their instruments.

The instrument, after being tuned, is ready for the ware-room or parlor.

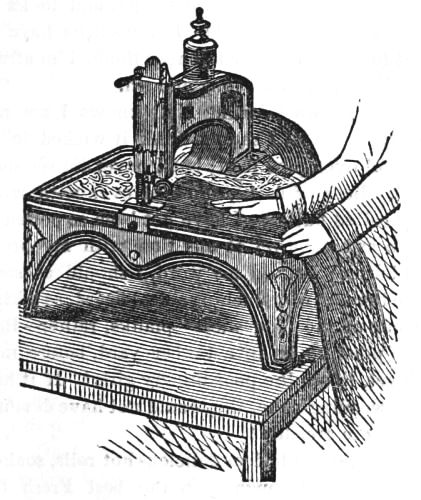

PIANO-FORTE ACTION REGULATOR.

But several operations we have purposely passed by, as it was our wish to give a clear idea of the structure of the piano-forte by exhibiting, from stage to stage, the progress of the manufacture of the musical machinery. Let us now look after the construction of the other parts of the instrument.

The "leg-bodies," as they come from the machine, are cut out in shape in a rough state, ready for being veneered (or covered with a thin coating of rosewood or mahogany); and, as they are of various curved and crooked forms, it is a trade by itself to bend the veneers and apply them correctly. The veneers are curved and bent to the shapes required while hot, or over hot irons, and then applied to the leg-bodies by "calls," or blocks of wood cut out to exactly fit the surface to be veneered. These calls are heated in the steam ovens. The surface of the leg having been covered with glue, the veneer is put on, and then the hot call is applied and screwed to it by large handscrews holding the veneer closely and firmly to the surface to be covered. The call, by warming the glue, causes it to adhere to the legs and veneer; and, when cold and dry, holds the veneer firmly to its place, covering the surface of the leg entire, and giving it the appearance of solid rosewood, or of whatever wood is used for the purpose. Only one surface can be veneered at a time, and then the screws must remain on until it is cold or dry; and, as the legs have many distinct surfaces, they must be handled many times, and, of course, much labor is expended on them. After all the sides are veneered, they must be trimmed, scraped, and finished, and all imperfections in the wood made perfect, ready for being varnished.

The desks are made by being so framed together as to give strength, then veneered, and, after being varnished and polished, are sawed out in beautiful forms and shapes by scroll saws, in the machine-shop. They have thus to pass through quite a number of processes before they are ready to constitute a part of a finished piano-forte. The same can be said of many other parts of the instrument that are made separate, and applied when wanted in the instrument, such as lyres, leg-blocks, or caps, &c. And, as each workman is employed at but one branch alone, and perfects his part, it is evident that, when put together correctly, the whole will be perfect. And, as Messrs. Boardman & Gray conduct their business, there are from twenty to twenty-four distinct kinds of work or trades carried on in their establishment. Thus, the case-maker makes cases; the leg-maker legs; the key-maker keys; the action-maker action; the finisher duts the action into the piano; the regulator adjusts it; and thus each workman bends the whole of his energies and time to the one branch at which he is employed. The result of this division of labor is strikingly shown in the perfection to which Messrs. Boardman & Gray have brought the art of piano-forte making, as may be seen in their superior and splendid instruments.

The putting together the different parts of the piano-forte, such as the top, the legs, the desk, the lyre, &c., to the case, constitutes what is called fly-finishing. The top is finished by the case-maker in one piece, and remains so until varnished and polished; then the fly-finisher saws it apart, and applies the butts or hinges, so that the front will open over the keys; puts on all the hinges; hangs the front or "lock-board" to the top; and completes it. He also takes the legs as they come from the leg-maker, and fits them to the case by means of a screw cut on some hard wood, such as birch or iron-wood, one end of which is securely fastened into the leg, and the other end screws into the bottom of the piano. The fly-finisher also puts on the castors, locks, and all the finishing minutiæ to complete the external furniture of the instrument, when it is ready for the ware-rooms, to which it is next lowered by means of a steam elevator, sufficiently large to hold a piano-forte placed on its legs, together with the workman in charge of it.

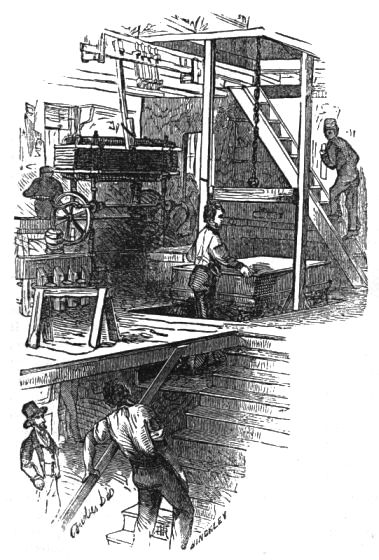

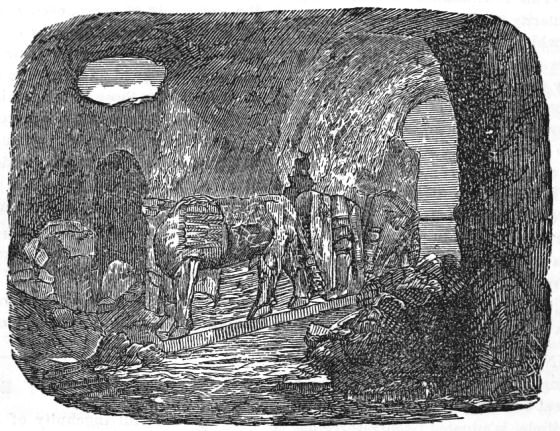

The following plate exhibits a piano-forte on the elevator passing from the fly-finisher's department to the ware-rooms. Of these steam elevators there are two, one at each end of the building; one for passing workmen, as well as lumber, to and from the machine-shop and drying-rooms, and one for passing cases and pianos up and down to the different rooms. Much ingenuity is shown in their construction, being so adjusted as to be sent up or down by a person on either floor, or by one on the platform, who, going or stopping at will, thus saves an immense amount of hard labor.

Water from the Albany water-works is carried throughout the building on to each floor, with sinks, hose, and every convenience for the workmen, so that they may have no occasion to leave the premises during the working hours. One thing we must not forget to point out, and that is the Top Veneering-Press, made on the plan of "Dicks's Patent Anti-Friction Press" (shown in the following engraving on the upper floor at left hand), and we believe the only press of the kind in the world. It was made to order expressly for Messrs. Boardman & Gray, and its strong arms and massive iron bed-plates denote that it is designed for purposes where power is required. It is used in veneering the tops for their piano-fortes, and it is warranted that two men at the cranks, in a moment's time, can produce a pressure of one hundred tons with perfect[103] ease. It is so arranged that the veneers are laid for several tops at one time. Tops made and veneers laid under such a pressure will remain level and true and perfectly secure. Messrs. Boardman & Gray have used this press upwards of eighteen months, and find that it works excellently, and consider it a great addition to their other labor-saving machines.

STEAM ELEVATOR, AND DICKS'S PATENT TOP VENEERING PRESS.

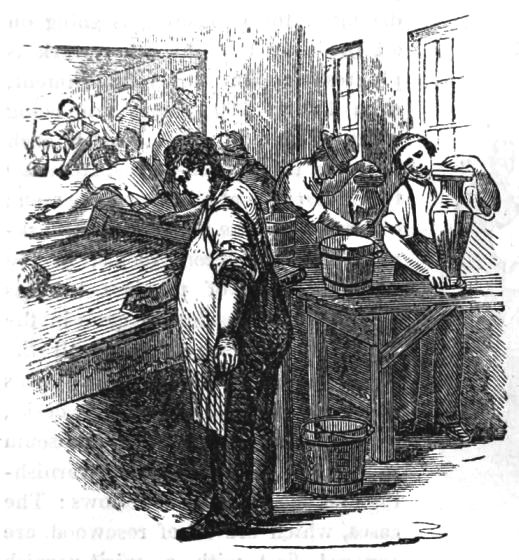

Having thus given a passing glance at most of the mechanical parts of the piano-forte, we will now examine the varnishing and polishing departments, consisting of some five or more large rooms. As the different layers of varnish require time to dry, it is policy to let the varnish harden while the workmen are busy putting in the various internal parts of the piano. Thus the case, when it comes from the case-maker, goes first to the first varnishing-room, and receives several coats of varnish; and, when the workman is ready to put in the sounding-board and iron frame, it is taken from the varnish-room to his department; and, when he has finished his work, it is again returned to the varnishing department, where it remains until the finisher wants it, who, when done with it, returns it to the varnishing-room. Thus, these varnishing-rooms are the store-rooms for not only the cases, but all the parts that are varnished; and the drying of the varnishing is going on all the time that the other work is progressing. In this establishment, from 150 to 200 pianos are being manufactured in the course of each day. In the varnish-rooms, from 100 to 150 cases are at all times to be seen; others are in the hands of the workmen in the different rooms, in the various stages of progress towards completion. Besides the cases in the varnish-rooms, we may see all the different parts of the pianos in dozens and hundreds, legs, lyres, tops, desks, bars, &c. &c., forming quite a museum in its way. The processes of varnishing and polishing are as follows: The cases, which are all of rosewood, are covered first with a spirit-varnish made with shellac gum, which, drying almost instantly, becomes hard, and keeps the gum or pitch of the rosewood from acting on the regular oil varnish. After the case has been "shellacked," it then receives its first "coat of varnish" and left to dry; and then a second coat is applied, and again it is left to dry. The varnish used is made of the hardest kind of copal gum, and prepared for this express purpose. It is called scraping varnish; it dries hard and brittle, and is intended to fill in the grain of the wood. When it becomes thoroughly dry and hard, these two coats are scraped off with a steel scraper. The case then receives several coats of another kind of varnish; when this is dried, it is ready for rubbing, which is effected by means of an article made of cloth fastened on blocks of wood or cork; and the varnish is rubbed on with ground pumice stone and water (a process somewhat similar to that of polishing marble). A large machine, driven by the engine, is used for rubbing the tops of pianos and other large surfaces. When the whole surface is perfectly smooth and even, it receives an additional coat of varnish. Each coat having become dry, hard, and firm, the surface receives another rubbing until it is perfectly smooth, when it receives a last flowing coat. After it is[104] thoroughly dried and hardened, it is ready for the polishing process, which consists in first rubbing the surface with fine rotten stone, and then polishing with the fingers and hands until the whole surface is like a mirror wherein we can

"See ourselves as others see us."

POLISHING AND RUBBING DEPARTMENTS.

In the preceding statement, we have simply given an outline of the mechanical branches of the business, and a general description of the lumber required, and its peculiar seasoning and preparation prior to use. Large quantities of rosewood are used for veneering and carved work, slipping, &c. Just now, this is the fashionable wood for furniture; nothing else is used in the external finish of the piano-fortes of Messrs. Boardman & Gray. A view of their large veneer-room would excite the astonishment of the novice. Rosewood is brought from South America, and is at present a very important article of commerce, a large number of ships being engaged in this trade alone, to say nothing of the thousands employed in getting it from its native forests for shipping, and the thousands more busy in preparing it for the market after it has reached this country. Much that is used by Messrs. Boardman & Gray is sawed into veneers, and prepared expressly for them at the mills at Cohoes, N. Y. They buy large quantities at a time, and, of course, have a large supply on hand ready for immediate use. They always select the most richly-figured wood in the market, believing that rich music should always proceed from a beautiful instrument. Thick rosewood is constantly undergoing seasoning for those portions which require solid wood. And one thing, dear reader, we would say; and that is, where rosewood veneers are put on hard wood well seasoned, and prepared correctly, they are much more durable than the solid rosewood would be, not being so liable to check and warp. They also make use of a large quantity of hardware in the form of "tuning pins"—upwards of a ton per year. Of iron plates they use some twenty-five tons. Their outlay for steel music wire amounts to hundreds of dollars per year; not to speak of the locks, pedal feet, butts and hinges, plated covering wire for the bass strings, bridge pins, centre pins, steel springs, and screws of various kinds and sizes, of which they use many thousand gross annually. Of all these, they must keep a supply constantly on hand, as it will not do for their work to stop for want of materials. A large capital is at command at all times; and, as many of these things require to be made expressly to order, calculation, judgment, and close attention are needed to keep all moving smoothly on.

Cloth is used for a variety of purposes in the establishment of Messrs. Boardman & Gray. It is made and prepared expressly for their use, from fine wool, of various thicknesses and colors, according to the use for which it is designed. Whether its texture be heavy or thick, firm or loose, smooth or even, soft or hard, every kind has its peculiar place and use. Here we would give a word of caution to the reader. So much cloth is used in and about the action of the piano-forte, that we must beware of the insidious moth, which will often penetrate and live in its soft folds, thereby doing much damage to the instrument. A little spirits of turpentine, or camphor, is a good protection against them.

Ivory is another article which is largely used. Being expensive, no little capital is employed in keeping an adequate supply at all times on hand.

And then there is buckskin of various kinds and degrees of finish, sand-paper, glue, and a variety of other things, all of which are extensively employed in the business.

So far, we have treated merely of materials and labor. We have said nothing of the science of piano-forte making. If, after all the pains taken in selecting and preparing the materials required, the scale of the instrument shall not be correctly laid down on scientific principles; that is to say, if the whole is not constructed in a scientific manner, we shall not have a perfect musical instrument. So the starting-point in making a piano-forte is in having a scale by which to work. This scale must be of the most[105] improved pattern, and laid out with the utmost nicety, and with mathematical precision. By the scale, we mean the length of each string, and the shape of the bridges over which it passes. The length of the string for each note, and its size, are calculated by mathematical rules, and perfected by numerous experiments; and by these experiments alone can perfection be attained in the manufacture of the instrument. Messrs. Boardman & Gray use new and improved circular scales of their own construction, in which they have embodied all the improvements which have from time to time been discovered. They are determined that nothing shall surpass, if anything equals, their Dolce Campana Attachment.

VIEW OF ONE OF BOARDMAN AND GRAY'S ORNAMENTAL FINISHED PIANO-FORTES.

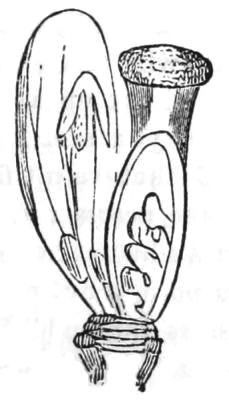

The great improvement of this age in the manufacture of the piano-forte is the Dolce Campana Attachment, invented by Mr. Jas. A. Gray, of the firm of Boardman & Gray, and patented in 1848 not only in this country, but in England and her colonies. It consists of a series of weights held in a frame over the bridge of the piano-forte, which is attached to the sounding-board; for the crooked bridge of the piano, at the left hand, is fast to and part of the sounding-board. The strings passing over, and firmly held to this bridge, impart vibration to the sounding-board, and thus tone to the piano. These weights, resting in a frame, are connected with a pedal, so that when the pedal is pressed down, they are let down by their own weight, and rest on screws or pins inserted in the bridge, the tops of which are above the pins that hold the strings, and thus control the vibrations of the bridge and sounding-board. By this arrangement, almost any sound in the music scale can be obtained, ad libitum, at the option of the pianist; and as it is so very simple, and in no way liable to get out of order, or to disturb the action of the piano, of course it must be valuable. But let us listen for ourselves. We try one of the full rich-toned pianos we have described, and, pressing down the pedal, the tone is softened down to a delicious, clear, and delicate sweetness, which is indescribably charming, "like the music of distant clear-toned bells chiming forth their music through wood and dell." We strike full chords with the pedal down, and, holding the key, let the pedal up slowly, and the music swells forth in rich tones which are perfectly surprising. Thus hundreds of beautiful effects are elicited at the will of the performer. This Dolce Campana Attachment is the great desideratum which has been required to perfect the piano-forte, and by using it in combination with the other pedals of the instrument, the lightest shades of altissimo, alternating with the crescendo notes, may be produced with comparative ease. Its peculiar qualities are the clearness, the brilliancy, and the delicacy of its touch. Those who, in the profession, have tested this improvement have, almost without an exception, given it their unqualified approbation; and amateurs, committees of examination, editors, clergymen, and thousands of others also[106] speak of it in terms of the highest praise. Together with the piano-forte of Messrs. Boardman & Gray, it has received ten first class premiums by various fairs and institutes. And we predict that but a few years will pass ere no piano-forte will be considered perfect without this famous attachment.

We must now examine its structure and finish. The attachment consists of a series of weights of lead cased in brass, and held in their places by brass arms, which are fastened in a frame. This frame is secured, at its ends, to brass uprights screwed into the iron frame of the piano; and the attachment frame works in these uprights on pivots, so that the weights can be moved up or down from the bridge. The frame rests on a rod which passes through the piano, and connected with the pedal; and the weights are kept raised off the pins or screws in the bridge by means of a large steel spring acting on a long lever under the bottom of the piano, against which the pedal acts; so that the pressing down of the pedal lets the attachment down on to its rests on the bridge, and thus controls the vibrations of the sounding-board and strings. The weights and arms are finished in brass or silver. The frame in which they rest is either bronzed or finished in goldleaf, and thus the whole forms a most beautiful addition to the interior finish of the piano-forte.

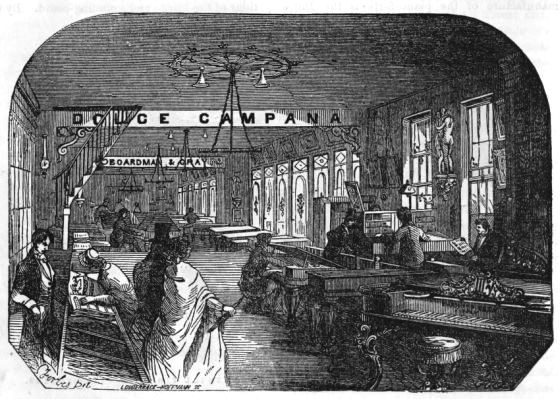

BOARDMAN AND GRAY'S STORE (INTERIOR VIEW), ALBANY, N. Y.

Messrs. Boardman & Gray have applied upwards of a thousand of these attachments to piano-fortes, many of which have been in use four and five years, and they have never found that the attachment injured the piano in any way. As their piano-fortes without the attachment have no superiors for perfection in their manufacture, for the fulness and sweetness of their tone, for the delicacy of their touch and action, it may easily be seen how, with this attachment, they must distance all competition.

And now, dear reader, we have attempted to show you how good piano-fortes are made; to give you an idea of the varied materials which are requisite for this purpose; and to describe the numerous processes to which they are subjected, before a really perfect instrument can be produced.

The manufacturing department is under the immediate supervision of Mr. James A. Gray, one of the firm, who gives his time personally to the business. He selects and purchases all the materials used in the establishment. He is thoroughly master of his vocation, having made it a study for life. No piano-forte is permitted to leave the concern until it has been submitted to his careful inspection. If, on examination, an instrument proves to be imperfect, it is re[107]turned to the workman to remedy the defect. He is constantly introducing improvements, and producing new patterns and designs, to keep up, in all things, with the progress of the age.

The senior partner of the firm, Mr. Wm. G. Boardman, attends to the sales, and gives his attention to the financial department of the business. Thus, the proprietors reap the benefit of a division of labor in their work, and each is enabled to devote his entire time and energies to his own duties. Their great success is a proof of their industry and honorable devotion to their calling. They are gentlemen in every sense of the word, esteemed by all who know them, and honored and trusted by all who have business connections with them. They liberally compensate the workmen in their employ, and act on the principle that the "laborer is worthy of his hire." Their workmen never wait for the return due their labor. Their compensation is always ready, with open hand. The business of the proprietors has increased very rapidly for the last few years, and, although they are constantly enlarging and improving their works, they find themselves unable to satisfy the increasing demand for their piano-fortes. Their establishment is situated at the corner of State and Pearl Streets, Albany, N. Y., well known as the "Old Elm-Tree Corner."

Their store is always open to the public, and constantly thronged with customers and visitors, who meet with attention and courtesy from the proprietors and persons in attendance. We would advise our readers, should business or pleasure lead them to the capital of the Empire State, to call on Messrs. Boardman & Gray at their ware-rooms, even though they should not wish to purchase anything from them; for they may spend an hour very pleasantly in examining and listening to their beautiful and fine-toned piano-fortes with the Dolce Campana Attachment.

INSTRUCTIONS.

Have your piano-forte tuned, at least four times in the year, by an experienced tuner; if you neglect it too long without tuning, it usually becomes flat, and troubles a tuner to get it to stay at concert pitch, especially in the country. Never place the instrument against an outside wall, or in a cold, damp room. Close the instrument immediately after your practice; by leaving it open, dust fixes on the sound-board and corrodes the movements, and, if in a damp room, the strings soon rust.

Should the piano-forte stand near or opposite a window, guard, if possible, against its being opened, especially on a wet or damp day; and, when the sun is on the window, draw the blind down. Avoid putting metallic or other articles on or in the piano-forte; such things frequently cause unpleasant vibrations, and sometimes injure the instrument. The more equal the temperature of the room, the better the piano will stand in tune.

Much has been said and written upon diet, eating and drinking, but I do not recollect ever noticing a remark in any writer upon breathing, or the manner of breathing. Multitudes, and especially ladies in easy circumstances, contract a vicious and destructive mode of breathing. They suppress their breathing and contract the habit of short, quick breathing, not carrying the breath half way down the chest, and scarcely expanding the lower portions of the chest at all. Lacing the bottom of the chest also greatly increases this evil, and confirms a bad habit of breathing. Children that move about a great deal in the open air, and in no way laced, breathe deep and full in the bottom of the chest, and every part of it. So also with most out-door laborers, and persons who take a great deal of exercise in the open air, because the lungs give us the power of action, and the more exercise we take, especially out of doors, the larger the lungs become, and the less liable to disease. In all occupations that require standing, keep the person straight. If at table, let it be high, raised up nearly to the armpits, so as not to require you to stoop; you will find the employment much easier—not one half so fatiguing, whilst the form of the chest and symmetry of the figure will remain perfect. You have noticed that a vast many tall ladies stoop, whilst a great many short ones are straight. This arises, I think, from the table at which they sit or work, or occupy themselves, or study, being of a medium height—for a short one. This should be carefully corrected and regarded, so that each lady may occupy herself at the table to suit her, and thus prevent the possibility or the necessity of stooping. It will be as well not to remain too long in a sitting position, but to rise occasionally, and thus relieve the body from its bending position. The arms could be moved about from time to time.

BY PAULINE FORSYTH.

One evening, at a large party, my attention was attracted by a tall, distinguished-looking young gentleman, whom I had never seen before. Though a stranger to me, he was evidently well known by most in the room, for he was speaking familiarly to several who stood near him, and bowing occasionally to others as they passed; yet all the time he was thus occupied, his eyes constantly sought the quiet corner to which, according to my usual habit, I had retreated. Strangers being rare in Louden, and gentlemen of his appearance remarkable in any place, I was at first disposed to gratify a natural curiosity with regard to him, but my eyes, sent out on their exploring expedition, met his so often, that at last, in a state of great confusion, I fastened them on the floor and resolved I would not raise them again for ten minutes. Meantime, I asked Virginia Percy, who was sitting by me, "Who that strange gentleman by the piano was? He looks like an officer," I continued.

"He is," she replied; "he is Lieutenant Marshall, a son of that Mr. Marshall who lives on the next plantation to us."

"Don't you know him?" asked I, surprised that, while greeting all his friends, he had not yet approached her.

"Oh, yes, of course," said she, quickly; "I have known him all my life."

Virginia, like most Southern girls, was a thorough-bred aristocrat, and I ascribed her evident want of appreciation of Lieutenant Marshall, and of interest in him, to the fact that his father's family, while respectable, did not belong to the "upper ten"—to use the only phrase that describes appropriately the class to which it refers—for they are distinguished neither by goodness, wit, nor birth, but they have become, by some concatenation of circumstances in this ever-shifting kaleidoscope of society, the upper stratum, and the position, once obtained, though it sometimes requires a severe struggle to gain it, is easy enough to keep.

"He is the most strikingly handsome man I ever saw," said I.

Virginia made no answer. Piqued at her indifference, and resolved to show my freedom from all narrow and illiberal prejudices with regard to society or position, I went on:—

"He has what handsome men so often want. They have generally something feminine about them; but he is essentially manly and dignified. I think that his expression would be perhaps a little too stern; only, when he speaks or even listens, his smile has so much warmth and kindness in it."

"You have seen a great deal in a little while," said Virginia.

"Yes, and under great difficulties too." Here I was interrupted by the approach of the person of whom we were speaking, accompanied by the lady of the house. He was introduced to me, and acknowledging Virginia's presence by a low bow, he seated himself by me and commenced a conversation. Much as I had admired him at a distance, this was an attention with which I would willingly have dispensed, for, naturally very shy, to attempt to entertain a stranger was distressing to me. Therefore, though I wondered a little that Virginia still retained her seat near me, so that she was obliged occasionally to join in the conversation with one whom she seemed to consider beneath her, yet I was pleased by her doing so, and attributed it to her friendship for me, and her consideration for my peculiarities.

During all the evening, Lieutenant Marshall paid me marked attention, so much so that, by the time we were ready to go home, I had become the target for all the jokes and witticisms that are kept laid up for such occasions. In a little place like Louden, where everybody knew everybody, and there was but little going on to talk about, any circumstance that would afford scope for harmless gossip and teasing was "nuts" to the good people, and before noon the next day it was generally understood, throughout Louden and its vicinity, that "Lieutenant Marshall was desperately smitten with Miss Forsyth."

My own vanity being thus supported by the openly expressed opinions of the discerning public, it is hardly to be wondered at if for a while I shared their delusion and their belief. But, being even then a little given to metaphysics and analytic investigations of all mental phenomena that fell under my notice, instead of putting the pretty rosebud that Mr. Marshall offered me next my heart, I set myself to[109] pulling it to pieces, and presently discovered that it was not a real rose at all, only a patchwork, scentless imitation.

In other words, I had ideas of my own on the subject of love. As the six-year-old New Yorker said, when he was asked if he had no one little girl whom he loved better than any one else in the world, "show me the boy of my age in New York that hasn't!" so I can say, show me the girl of seventeen who does not think herself an adept in all the signs and tokens of true love. And I soon settled it in my own mind, that, when brought to the test of severe and impartial criticism, Mr. Marshall did not exhibit one evidence of real love, beyond an apparent preference for my society. That the preference was apparent and not real his abstraction and indifference convinced me. At first, considering it a duty I owed to society to talk to those with whom I was thrown, unless they would kindly relieve me of this obligation, I tasked myself to weariness to find some topic of mutual interest between my constant attendant and myself. My remarks were all politely listened and replied to, and then he fell back into his state of reverie and silence. If there had not been a shade of melancholy about him, I should hardly have felt so patiently towards him for engrossing so much of my time, while his thoughts were evidently far away. But I had settled it in my own mind that he had been in love, and that the lady of his love had died—this accounted for his sadness and abstraction; and that some resemblance between the lost lady and myself attracted him to me.

This little romance gave him quite an interest to me, which was somewhat lessened by the discovery that he shared in the village love of gossip. I found that the only subjects that could interest him at all were the petty daily events that occurred to Virginia and myself, for we were constantly together. About these he was never weary of hearing, and would ask me the minutest questions, and by his pleased attention beguile me into long talks about such mere trifles that I used to blush to recall them, and then, as soon as I entered on some topic of higher or more general interest, it needed but little discernment to discover that courtesy alone prompted the attention he gave me.

At last I began to grow quite weary of attentions which I could not persuade myself were prompted by anything but recollections of the dead, and spoke of Lieutenant Marshall to Virginia, my only confidant, constantly, as "that tiresome man." Perhaps it was owing to her desire to relieve me of one of my heaviest burdens that she so often made one in our tête-à-têtes, and by infusing a great deal more spirit and life in our conversation, assisted me greatly. I do not know how it happened, but we both brightened wonderfully when Virginia joined us, and although I might have been half asleep with intense dulness a few moments before, I generally found myself very soon wide awake, and with auditors so attentive and easily pleased that I began to be quite uplifted with elevated ideas of my own newly developed conversational powers. One evening, there was a little gathering of young people in a house where the hostess did not approve of dancing. We were all seated in a stiff circle round the room doing our best to amuse and be amused by rational conversation. The appearance of things was very unpromising, and the lady of the house seemed quite uneasy; at last she proposed a promenade, and anything to break up the monotony was eagerly caught at. The ladies and gentlemen, like prisoners marching for exercise, were soon walking in at one door and out at another with great precision and order. I expected Mr. Marshall to ask me to join the staid procession, but perhaps marching seemed too much like work to him, for he proposed instead a game of backgammon. This had always appeared to me an uninteresting, rattling, flighty sort of a game; but to amuse so sorrow-stricken a man I would even have played checkers.

Before we had finished the first game, I felt a hand lightly resting on my shoulder, and looking round, saw Virginia seated close behind me. This was very kind in her, and I felt it to the depths of my heart. She was a great favorite in Louden, and to leave all who would have exerted themselves to please and amuse her, to sit quietly with me in a dull corner looking over a game of backgammon, was an effort of friendship of which I hardly thought that, in similar circumstances, I should have been capable. When the game was ended, I made a movement to close the board, but Mr. Marshall asked me so earnestly for one more, just one more, that I consented. However, I took an opportunity, while he was stooping to pick up some of the men that had dropped, to whisper. "You need not stay here, Virginia. You'll be dreadfully tired, and I don't mind much being left alone; there's Charles Foster looking quite distressed because you won't walk with him."

"No, dear," said Virginia, very affectionately, "there is not a person in the room I like half so well to stay with as you."

A stranger, far away from home, these words of affection from one whom I had loved from[110] the first, touched me powerfully, and almost involuntarily I pressed my lips to her cheek as it was bent towards me. Fortunately this little effusion passed unobserved, and Mr. Marshall and I resumed our game. But I turned several times to look at Virginia, attracted by a beauty in her that I had never noticed before. Her features were regular and her countenance pleasing, but her complexion was so colorless, and her expression so composed and unvarying, that I had never heard her called even pretty; but that night she looked positively beautiful. Her lips were crimson, her cheeks delicately flushed, and there was a glow and light over her whole face, and a glittering sparkle in her eye, as though some internal flame was informing her whole being with warmth and brightness. I did not wonder that Mr. Marshall was so struck by the change that his eyes rested often and admiringly upon her, so that he hardly seemed to know what he was doing.

"Virginia! Pauline! do come here," said a laughing girl, looking in from the piazza to which the whole party but our little group had retreated. I started up to obey the summons, for the sounds of merriment and laughter, mingled with the notes of a favorite negro melody, drew me with an irresistible attraction. Mr. Marshall and Virginia did not move.

"Finish my game for me, will you?" said I to Virginia; "I will return in a moment." But my moment lengthened into nearly half an hour, for four gentlemen of the party who were noted for their musical skill had been persuaded to send for their instruments and sing and play for us. This they did so well that it was with reluctance that at last I fulfilled my promise of returning.

Virginia was playing with the backgammon men as I entered, and Lieutenant Marshall was talking to her in a low tone.

"There he is, just as tiresome as ever," thought I; but we do not live in the palace of Youth now, so that I said, as I approached them—

"Well, which has been victorious?"

Virginia looked as though she had never heard of a game of backgammon, and it was a minute or two before I was answered. At last Mr. Marshall said—

"I was—that is, I mean Miss Virginia was"—and he did not seem exactly to know what he did mean.

"Do come out on the porch," said I, benevolently intending to relieve Virginia from a great bore; "we are having some delightful singing, and it is a very pleasant night." And I succeeded in inducing them both to accompany me.

That same evening, Virginia proposed to me to fulfil a promise we had made some time before of visiting her cousins Nannie and Bettie Buckley. I was very willing to do so, having conceived a great admiration for these ladies, which I am afraid had no better foundation than that they were very tall, and dressed more showily and expensively than any one that I had ever seen. Every summer they went to the North, where they enjoyed the reputation of being great heiresses, and consequently received much attention. Their father's wealth, though by no means so large as was supposed, was still ample enough to allow them to keep up their character as heiresses by a free expenditure at the principal shops in New York and Philadelphia, and they returned home with more magnificent brocades, flashy-looking cashmeres and bareges, and fantastic ball-dresses than would have sufficed for ten years at Louden. I do not think that my friends there appreciated them any the more highly on account of these brilliant robes, but I was still in that state of inexperience when "fine feathers make fine birds," and I was very much inclined to respond cordially to their warmly proffered offers of intimacy, and wondered that Virginia showed so little desire to seek the society of such relations. I was so pleased to find that she was at last willing to accompany me there, that I at once consented to go the next afternoon, spend Saturday and Sunday with the Misses Buckley, and return early on Monday morning.

We were to go on horseback, and when the time arrived, I found that Virginia's brother and younger sister were to accompany us. We galloped on in that glow of spirits and enjoyment that riding on horseback so often imparts; when, as we passed Mr. Marshall's plantation, the Lieutenant, as though he had been expecting and waiting for us, opened the gate and joined us.

"That man is becoming a perfect bête noir to me," said I to Ellen Percy; "I can never go anywhere without him, lately."

I had hardly finished my speech, before it struck me that there was something a little peculiar in the greeting between Virginia and Lieutenant Marshall, and a half-formed, undefined suspicion rose in my mind. I banished it immediately, however, for I looked upon Virginia as the soul of truth, and if there had been anything between herself and the man who had been so openly attentive to me, I felt sure she would have told me. Therefore, much against my will, I allowed Ellen and George to ride on, whilst I checked my horse, as fond of a race as[111] its rider, to the slow pace that seemed to suit my other two companions. It was not long, however, before I intercepted one or two glances that "spoke volumes"—ten folios could not have revealed more to me—and all at once I was seized with the oppressive consciousness of being de trop. My next thought was how I should contrive to join Ellen, whose swift horse had carried her far in advance of us. I could think of no excuse that did not seem to me so transparent as to be more than useless. At last, murmuring some unintelligible words, I fairly ran off. Afterwards apologizing to Virginia for my abrupt mode of leaving her, saying that I had tried in vain to manage it more skilfully, she replied with some surprise—

"My dear, I thought you managed it beautifully, and so I have no doubt Lieutenant Marshall did."

"If he thought at all about it," answered I; and she smiled.

"Has it ever struck you—have you ever heard anything about Lieutenant Marshall's being in love with Virginia?" I asked, when I had overtaken Ellen.

"A long time ago I heard it talked about a little, but nothing has been said about it for the last year or two. I have always thought, though, that Virginia cared more about him than any one else."

"It is strange she never has alluded to him to me," said I; and I was inexpressibly pained at this want of confidence on her part, revealed at a time when I thought every feeling of her heart was laid bare to me. Nor could I reconcile the clandestine way in which they had carried on their love-affair, with the previous high opinion I had formed both of Virginia and Mr. Marshall, as persons of the highest integrity and principle. An indistinct feeling of annoyance at having been used as a blind, and of disappointment at the tarnish which had suddenly obscured, in my eyes, the bright purity of Virginia's character, prevented me for a time from enjoying my ride. But deeper griefs than mine would not long have been proof against the exhilaration produced by rapid motion, through southern woods, on a cool and balmy afternoon in early spring.

Nature has no secrets in that genial clime. She does not elaborate her delicate buds and leaflets within the closely enveloping bark until they burst suddenly upon you, full-formed and perfect, but her workshop is the open air, and one might almost fancy he could see her dainty fingers patiently adding, day by day, one touch after another, until her work is complete. I have watched the slow development of an oak, from the first red tassel to its full leaved glory, till I have felt quite sure that if, by any of those marvellous metamorphoses we read of in the old mythology, I should ever feel myself taking root and shape like it, I should know exactly what would be expected of me. And so, my eye caught and charmed by one beauty after another, of flower, or tree, or cloud, I had regained all my cheerfulness by the time we halted at the plantation, to allow the lovers to overtake us.

They had loitered so far behind, that we had to wait at least half an hour before they joined us, but we were forbearing, and said nothing to remind them of their want of consideration, though I am afraid my silence was as much owing to wounded feeling as anything else.

We were most cordially welcomed by Nancie and Bettie Buckley, but I was so surprised at the house and its furniture, that I hardly noticed our reception. Was it possible, thought I, that those gorgeously apparelled women came out of those low, poorly furnished rooms, with their stiff, old-fashioned chairs, and no carpets, no sofas—no silver forks at tea—in short, few of those little luxuries that long use makes almost necessaries. Virginia explained the incongruity to me by saying that cousin Tom, as she called old Mr. Buckley, refused to allow the least change to be made in their household arrangements. His daughters might travel and spend as much money as they pleased, but not one of their new-fangled notions were allowed to be introduced into the family. To make up for every other deficiency, there was a most bewildering number of servants of all ages and sizes. They ran about the house like tame kittens. Two accompanied me to my room at night, and three assisted, to my great embarrassment, at my morning toilet.

Mr. Buckley was a stout, uneducated, kind-hearted sort of a man, with a high appreciation of a mint-julep and a good cigar, and an intense dislike of Yankees. This was so much a part of his nature that he could not help expressing it even to me, and it was so genuine, that, notwithstanding my natural pride in my birthright, I caught myself insensibly sympathizing. Towards me personally, as a woman and a stranger, he evidently felt nothing but a sort of tender pity and concern. This he showed in the only way he could think of, by mixing me a very strong mint-julep, and urging me to drink it. I tried to please him—in fact, I had watched the process of making it, and thought I should like it; but the very first attempt I made, gave me such a fit of coughing, and came so near strangling me,[112] that I gave up; after that, we all sat down on the porch together until tea was ready, while Mr. Buckley smoked his cigar and looked hopelessly at me.

After tea, we returned to the porch and our conversation, and Mr. Buckley to his cigar. In the course of the evening, I missed Virginia and my recreant knight, and they did not appear until we were about separating for the night. Virginia and I were to occupy the same room; and hardly were we alone before she turned to me, exclaiming, with a vivacity and eagerness very unusual to her—

"Dear Pauline, how strange you must think my conduct has been lately, after what you have seen to-day! But let me explain it to you. I would have spoken openly to you weeks ago, if I had had anything to tell; but I have been kept as much in the dark as any one until to-day. When we were children, Philip—Mr. Marshall—and I were constantly together, and became very much attached to each other; so that when he went to West Point, though I was but about eleven years old, we were regularly and solemnly engaged. He did not return to Louden until he had graduated; for, you know, his father is poor, and they could not afford him the money for the journey. Then he came, he says, with the full intention of renewing our childish engagement, if he found me so disposed; but he thought he ought first to speak to my father about it, as I was still so young, and father objected so decidedly to anything of that kind being said to me then, that Philip consented to wait a little while. He came back in a year, and, as soon as father heard of it, he sent me down to New Orleans on a visit to my aunt. I don't know how I discovered the truth; but I did know very well the reason I was sent off so hastily, and felt very badly about it. Then father and Philip had another long talk, and Philip promised to wait until I was eighteen before he made any other attempt to speak to me about what father calls our ridiculous engagement."

"Oh," said I, "you were eighteen the day of Mrs. Simmons's party—last Wednesday."

"Yes; and Philip tried to have an explanation with me then; but he could not, for there were so many people about. He was determined, he said, this time not to see my father until he had spoken to me, and he asked me when he could see me alone for a little while. I told him we had been talking of visiting Nannie and Bettie for some time, and he said he would accompany us, as they were cousins of his, too—Virginia cousins, that is, not very near ones."

"What can be your father's objection to Mr. Marshall?" asked I.

"None at all to him; it is to his profession. He wants me settled near him. He says I am not strong enough to bear the wandering life and hardships I shall have to encounter as an officer's wife. I hope, though, that he will give his consent, now that he sees by our constancy how much we really do like each other. Just think, dear, until to-day, I have hardly had five minutes' uninterrupted conversation with Philip since I was eleven, and our engagement was never alluded to; and yet I never thought of liking any one else, and I was sure his feelings were unchanged; though, of course, until he told me so, I could not speak of it even to my dearest friend."

Before Virginia had finished her little romance, my feelings of annoyance were all lost in sympathy, and we passed the greater part of the night discussing the manner in which Mr. Percy would receive Mr. Marshall's third communication. Virginia seemed to have but little doubt of her father's consent, and neither had I; for I had not yet met a Southern father who had seemed able to refuse any child of his whatever she had fixed her heart upon.

But in this case we were both disappointed. Mr. Percy, usually calm and indulgent, seemed irritated and displeased to an uncommon degree when Mr. Marshall urged his request. He reminded the young officer that he was entirely dependent on his pay, which Mr. Percy said he considered barely enough for one person; told him that, owing to an unfortunate speculation in buying a plantation in Arkansas, which had turned out badly, and to the failure of his cotton crop for the last two years, he had become very much embarrassed, so that he should not be able to assist his daughter, if she married, for some time. He ended by repeating his former decision that, accustomed as Virginia had been to the ease and indulgences of a settled home, he was sure she could never endure the discomforts of a roving life. When she was twenty-one, she might judge for herself; until that time, he wished never to hear the subject mentioned again.

Mr. Marshall was very indignant, and tried to persuade Virginia to renew her engagement with him without her father's knowledge; but to this she would not consent, and he was soon afterwards obliged to return to his post.

Virginia was almost heartbroken at this sudden rupture of a tie that had been formed in her earliest childhood, and strengthened with every subsequent year. I tried to persuade her that[113] the three years which were to intervene before she could make her own decision would pass very quickly; but, hardly heeding my reasonings, she gave herself up to hopeless despair. She was sure, she said, her father never would consent to her union with Philip, and she would never marry without it. Besides, she did not expect to live to be twenty-one. Long before that time she should be in her grave.

At first, I paid no attention to these dismal forebodings, thinking them only the natural expressions of an affectionate heart suffering under such a great disappointment. But gradually I began to fear that they should be realized. She would not eat, and grew pale and pined, and her countenance began to wear an unearthly look of patient sorrow and resignation that I never observed without a pang. I knew that her parents had noticed the alteration in Virginia's health and spirits, for hardly a week passed that some pleasant little excursion or journey was not proposed to her. And thus the long warm summer wore away.

One afternoon, late in September, I received a note from her, saying that she had just returned from a visit to the Mammoth Cave, and would like to see me, to tell me about it. As I had not seen her for three weeks, I hastened to Mr. Percy's immediately, and running up to her room, entered without knocking at the half-open door.

Virginia was sitting in the full light of an afternoon sun, whose rays were streaming in unobstructed by shutters or curtain, seemingly as if the occupant of the room had lost all thought of bodily comfort. Her eyes were fixed on a white cloud floating in the distant sky, and as the wind lifted the heavy bands of hair from her pallid temples, she looked so spiritualized and incorporeal, that I should hardly have been surprised if she had floated out to mingle with the clouds on which she was gazing.

"Why, Virginia, have you been sick?" I asked, after our first hurried greetings.

"No, dear; do I look badly?"

"Very," was my reply, sincere, if impolitic.

"I am rather glad to hear it," said Virginia, "though of course it will be painful to me to leave my father and mother, brothers and sisters; still, I have so little to look forward to in this world, that I cannot care to live. I feel, myself, that I am growing weaker every day, and that is one reason that I hurried home; I wanted to see you and leave some messages with you for Philip."

And Virginia went on to impress upon me a variety of tender messages I was to remember for Mr. Marshall. I tried to listen, but I hardly heard what she said, for I was revolving in my mind a bold undertaking. I knew that Mr. Percy loved his daughter devotedly, and that if once aware of her danger he would consent to any means that seemed necessary for her recovery. If I only dared to speak to him about it—but I stood somewhat in awe of him, which feeling I shared with his children and most of his younger acquaintances. He had a certain grand magnificent way with him that I have never seen, excepting in Southern planters, and but seldom in them. I imagine a Roman patrician may have awed the populace, and impressed the rude Gauls by somewhat the same air and bearing.

However, the longer I listened to Virginia's plaintive words and looked at her sorrowful face, the more I felt that my reverence for her father was being gradually lost in anger at what I considered his cruel regardlessness of her feelings. At last I left Virginia as abruptly as I had entered. I had seen Mr. Percy as I passed, attending to the grafting of some trees in the fruit orchard, and there I bent my steps.

He greeted me with a pleasant smile, and offered me a large Indian peach he had just gathered from the tree. It almost seemed as if he wished to propitiate me, for if I have a weakness it is for peaches—and this particular kind, with its deep red juicy pulp, was an especial favorite. But I took it almost unconsciously, and, looking at him earnestly, I said—

"Mr. Percy, Virginia is very ill."

He looked anxiously upon me.

"She will die," I continued, shaking my head at him.

"Why, Pauline, do you really think so?" asked he; and I could see that the alarm that had been half roused for some time was now thoroughly awake, and producing its effect.

"Yes, I do not see how she can recover—unless—"

"Unless what?"

"Unless you send for Lieutenant Marshall immediately."

"Don't you think Dr. Parkinson might do as well?" asked he.

"No," I answered, shortly, looking upon that question as most unkind trifling with mortal need.

Every one knows the effect that decided impulsive natures have on calm meditative ones. An act Mr. Percy had been trying to make up his mind to perform for some time, but had been putting off, in hopes that secondary measures might avail, he now consented to at once.

"I believe I shall have to do it," he said; "you may tell Virginia so."

My work was but half done. Mr. Percy was a most inveterate dawdle, to use Fanny Kemble's expressive word. If left to himself, the letter might be written in a week, but more probably would be put off for a month. If we lived in antediluvian times, this dilatory way of managing matters might be of little consequence, but life is too short now to afford the loss of even a few weeks' happiness.

"Could you not write to Mr. Marshall now? There is plenty of time to send it to the post-office before dark."

Mr. Percy smiled, and yielded to my request so far as to turn his steps towards the little building dignified with the name of his office, though I do not know what business he had to transact there. He loitered by the way in a manner that tired my patience to its utmost, and once murmured something about having time to graft another tree; but, heedless of his evident desire to escape, I walked on with resolute purpose, and, as you may have seen some stately vessel, with furled sail, submissively yielding herself up to be dragged into port by an energetic little steamer, so did Mr. Perry resign himself to the fate that had for once overtaken him—of doing the right thing at the right time—and seated himself at his writing-desk.

"How am I to know that Mr. Marshall has not changed his mind?" asked Mr. Percy, before beginning to write.

"Virginia showed me a letter just now that she received from him a few hours ago, in which he said that, although she would not consent to any engagement without your approval, he still and always should, as long as she remained single, consider himself bound by his boyish promise."

"Desperately romantic!" said Mr. Percy, and then the movement of his pen told me that he had commenced the epistle that was to put an end to so much sorrow.

Unable to remain quiet, I leaned out of the window, and beckoned to a servant I saw loitering at a little distance.

"Jack," said I, as he came near, "your master is writing a letter, wait here until it is finished, for he will want you to take it directly to the post-office."

The order to wait was one too congenial to his nature not to be readily obeyed, and discovering at a glance the capabilities for enjoyment and repose afforded by an inviting bed of hot sand in which the afternoon sun was expending its last fierce blaze, Jack threw himself down in it, and I had soon the satisfaction of seeing that he was sound asleep, and therefore in no danger of being out of the way when he was wanted.

"Would you like to read the letter, Miss Pauline?" asked Mr. Percy, when he had finished it.

I was very glad to avail myself of this permission. I found that it contained a cordial, though dignified invitation to Mr. Marshall to return to Louden, with a full consent to the engagement between Virginia and himself.

Giving the letter to Jack with directions to put it in the post-office without delay, I hurried to Virginia with the joyful tidings. I expected a burst of tears and an infinitude of thanks. Instead of either, when I had finished my story, she said, in a slightly aggrieved tone—

"I am sorry, Pauline, you told father I should certainly die unless he sent for Philip. It will make him think me so weak."

"Why, Virginia," I exclaimed, taken quite by surprise, "what should I have said?"

"You might have said that I was not very well, or something of that kind."

"And then he would have sent for Dr. Parkinson, and the only result would have been a few doses of calomel or quinine. No, dear, I never once thought of your not being well. I felt sure you would die, and I said so. I am sorry it troubles you, but I think it was the best thing I could do."

Virginia blushed the next time she saw her father, as if he had been her lover instead; but, as he said nothing to her on the subject, she gradually recovered from her embarrassment, and by the time Mr. Marshall joined her she had so far recovered her health as to be able to enjoy without a drawback what some people consider the happiest part of one's life.

Mr. Percy did not relinquish his desire to have his daughter settled near him, and one or two successful years enabled him to effect his wishes. Lieutenant Marshall was induced to resign from the army, and with his wife and six children he is now living and prospering on a plantation; and in the substantial person of Mrs. Marshall, anxious and troubled about many things in her household and maternal concerns, I find it hard to discover the least trace of the shadowy and ethereal girl who had seemed to me at one time much more a part of the spirit world than of this material sphere.

LESSON II.

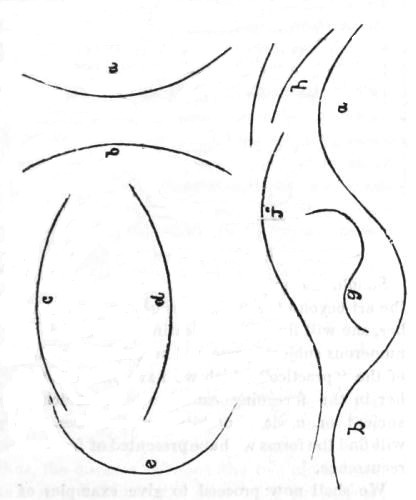

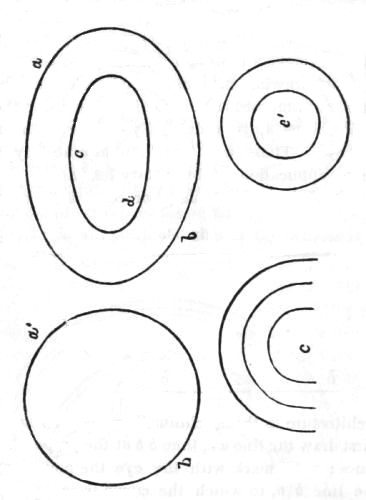

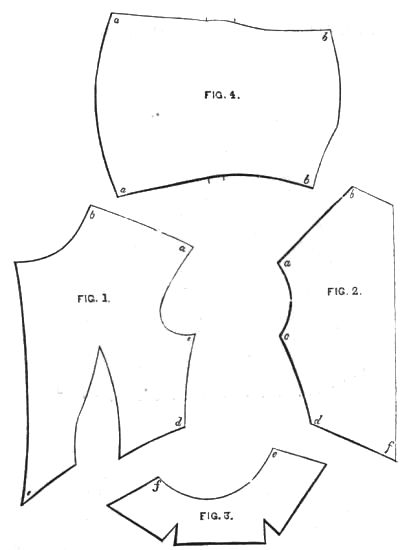

Fig. 11.

We now proceed to the drawing of curved lines, as in Fig. 11. And as these are the basis of innumerable forms, the pupil must not rest satisfied with a few attempts at forming them; she must try and try again, until she is able, with a single sweep, to draw them correctly. They must be done in one stroke, no piecing being allowed. Let the curved line a be first produced; beginning at the top, bring the arm or wrist down, so that at one operation the form may be traced; do this repeatedly, until the correct outline is attained at every trial. The pupil may next proceed to the curved line b, which is merely the line a in another position; then, after repeated trials, the lines c, d, e, g, and h may be drawn. These curves should be attempted to be drawn in all manner of positions, beginning at the top, then at the bottom, and making the curve upwards, and so on, until the utmost facility is attained in drawing them, howsoever placed. The curved line, generally known as the "line of beauty," f a b´, must next be mastered; it is of the utmost importance to be able to do this easily and correctly. In all these and the future elementary lessons, the pupil must remember that when failing to draw a form correctly, she should at once rub it out or destroy it, and commence a new attempt.

Fig. 12.

Having, then, acquired a ready facility in drawing the simple elementary curved lines, the pupil may next proceed to the combination of these, as exemplified in simple figures, as circles and ellipses, or ovals. First attempt to draw the circle a´ b, Fig. 12; beginning at a´, sweep round by the right down to b, then from b towards the left and up to a´, where the circle was first begun. The pupil may also try to draw it by going the reverse way to the above. We are quite aware that it will be found rather a difficult matter to draw a circle correctly at the first, or rather even after repeated attempts; but the pupil must not be discouraged; by dint of practice she will be able to draw circles of any size very correctly. We have seen circles drawn by hand so that the strictest test applied could scarcely point out an error in their outline, so correctly were they put in. Circles within circles may be drawn, as at c´; care should be taken to have the lines at the same distance from each other all round. The ellipse a b must next be attempted; this is a form eminently useful in delineating a multiplicity of forms met with in practice. Ovals within ovals may also be drawn, as at c d.

At this stage, the pupil ought to be able to draw combinations of straight and curved lines, as met with in many forms which may be presented to her in after-practice. The examples we intend now to place before her are all in pure outline, having no reference to picturesque arrangement, but designed to aid the pupil in drawing outlines with facility; and to prove to her, by a progression of ideas, that the most complicated forms are but made up of lines of extreme simplicity; that although in the aggregate they may look complicated, in reality, when carefully analyzed, they are amazingly simple. Again, although the pupil may object to them as being simple and formal—in fact, not picturesque or decorative enough to please her hasty fancy—she ought to recollect that, before being able to delineate objects shown to her eye perspectively, she must have a thorough knowledge of the method of drawing the outlines of which the objects are composed, and a facility in making the hand follow aptly and readily the dictation of the eye. These can be alone attained by a steady application to elementary lessons.

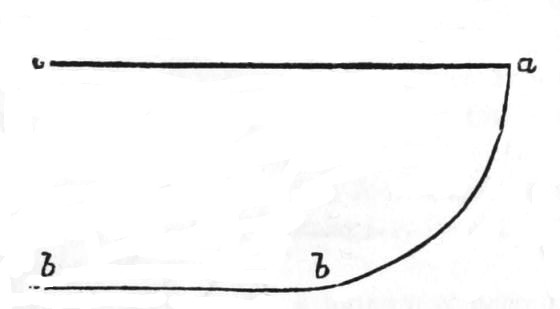

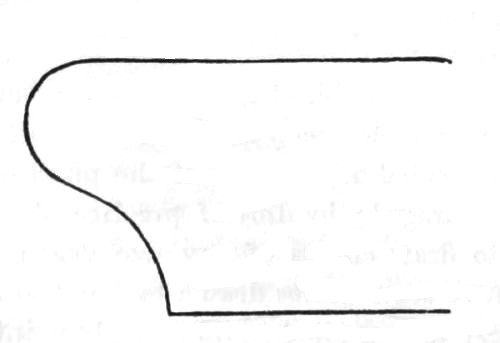

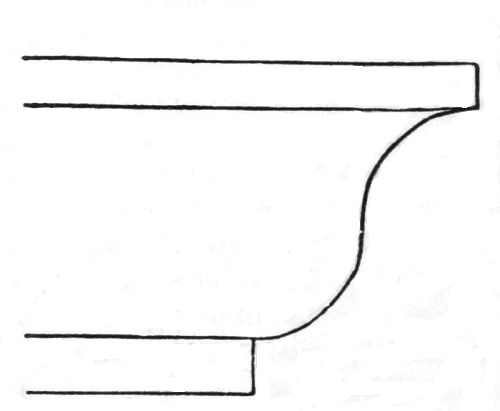

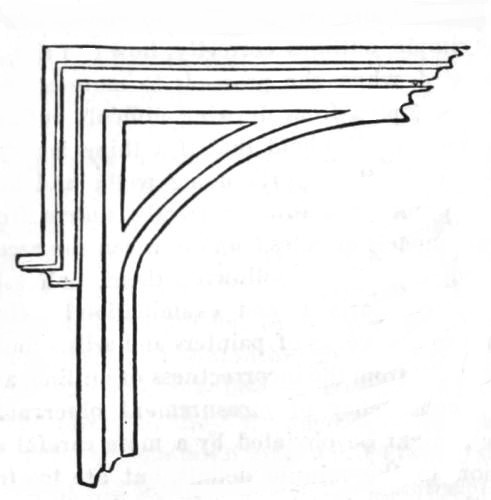

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13 is the moulding, or form known in architecture as the "echinus," or quarter-round. First draw the line a c, then b b at the proper distance; next mark with the eye the point b on the line b b, to which the curve from a joins; then put in the curve a b with one sweep. The curved portion of the moulding in Fig. 14, known as the "ogee," must be put in at one stroke of the pencil or chalk, previously drawing the top and bottom lines.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15 is the "scotia;" it is formed geometrically by two portions of a circle, but the pupil should draw the curve at once with the hand. It is rather a difficult one to draw correctly, but practice will soon overcome the difficulty.

Fig. 15.

Fig. 16 is termed the "cyma recta;" it affords an exemplification of the line of beauty given in Fig. 11.

Fig. 16.

Should the pupil ever extend the practice of the art beyond the simple lessons we have given her, she will find, in delineating the outlines of numerous subjects presented her, the vast utility of the "practice" which we have placed before her in the foregoing examples. In sketching ancient or modern architectural edifices, she will find the forms we have presented of frequent recurrence.

We shall now proceed to give examples of the combinations of the forms or outlines we have just noticed.

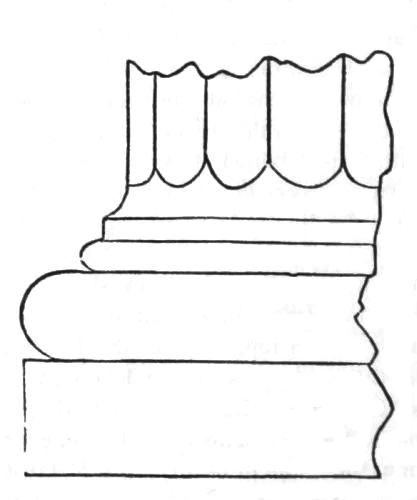

Fig. 17 is half of the base of an architectural order frequently met with, called the "Doric."

Fig. 17.

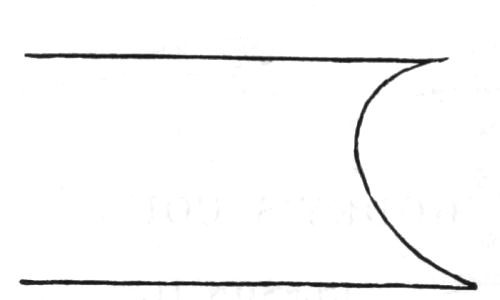

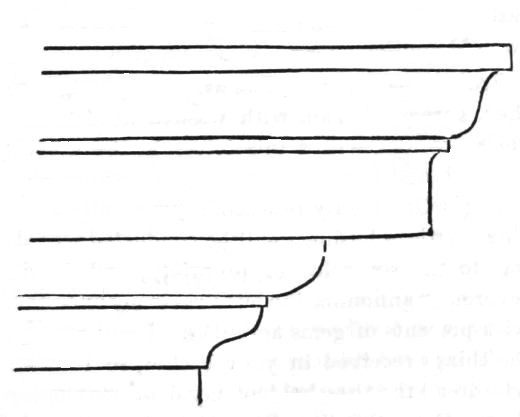

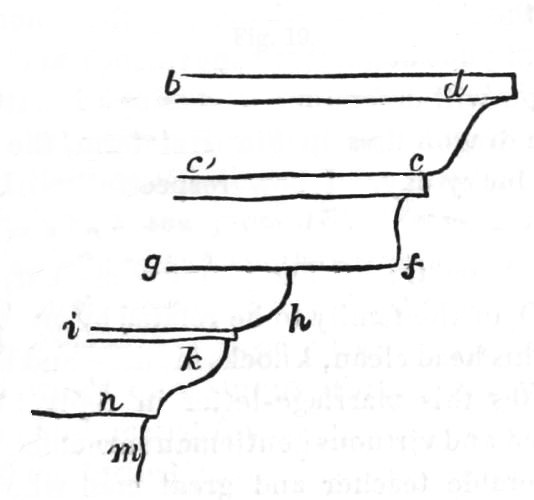

Fig. 18.

Fig. 19.

Fig. 18 affords an exemplification of the outline of part of a "cornice" belonging to the Tuscan order. Let us slightly analyze the supposed proceedings of the pupil in delineating this. Suppose Fig. 19 to be the rough sketch as first attempted. On examining the copy as given in Fig. 18, the pupil will at once perceive that the proportions are very incorrect; thus, the distance between the two upper lines, as at d, is too little, the fillet being too narrow; again, the point c, which regulates the extent of the curve from a, is too far from a, while the line c c´ is too near the line d; the space between c c´ and the line below it is too wide, and the line f is not perpendicular, but slopes outwards towards f; the distance between the line f g and the one immediately above it is also too narrow by at least one-third. Again, the point h, where the portion of the circle begins, is too near the point f; the line i is also too near that of f g; the outline of the curve is not correct, it being too much bulged out near the point k; the line n is not straight, and that marked m is too far from the extreme end of the line. The pupil has here indicated a method of analyzing her proceedings, comparing them with the correct copy, which she would do well, in her earlier practice, to use pretty frequently, until she is perfectly at home in correct delineation of outlines. It may be objected that this analysis is hypercriticism utterly uncalled for, from the simplicity of the practice; but let it be noted that if the pupil is not able, or unwilling to take the necessary trouble to enable her to draw simple outlines correctly, how can she be prevented, when she proceeds to more complicated examples, from drawing difficult outlines incorrectly? We hold that if a thing is worth doing at all, it is worth doing well; and how can a pupil do a thing correctly, unless from correct models or rules? and how can she ascertain whether she is following them, unless by careful comparison and examination? How often are the works of painters and artists found fault with, from the incorrectness of outline, and the inconsistency of measurement observable, which might be obviated by a more careful attention to the minute details, but are too frequently spurned at by aspiring artists; but of which, after all, the most complicated picture is but a combination? Thus the outline in Fig. 19 presents all the lines and curves found in Fig. 18, but the whole forms a delineation by no means correct; and if a pupil is allowed to run from simple lessons without being able to master them, then the foundation of the art is sapped, and the superstructure certainly endangered. Correct outlining must be attained before the higher examples of art can be mastered.

Fig. 20.

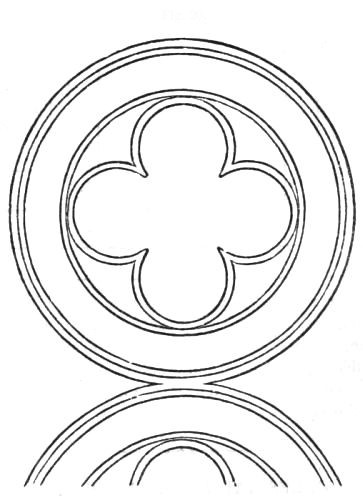

Fig. 20 is an outline sketch of the ornament called a quatre-foil, frequently met with in architectural and artistic decoration. It will be a somewhat difficult example to execute at first, but it affords good and useful practice.

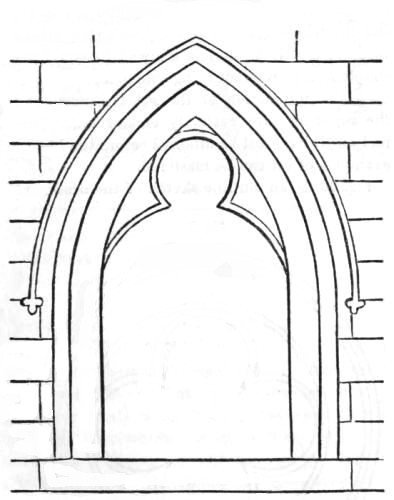

Fig. 21 is part of the arch and mullion of a window.

Fig. 22 is an outline sketch of a Gothic recess in a wall.

Fig. 21.

Fig. 22.

The reader will perceive that in all the foregoing designs, although consisting of pure outline, there exists a large amount of practice, which, if she has carefully mastered, will be of eminent service to her in the higher branches of the art.

In the Celestial Empire, love matters are managed by a confidant, and the billets-doux written to one another by the papas. At Amoy, a marriage was recently concluded between the respectable houses of Tan and O; on which occasion the following epistles passed between the two old gentlemen:—

From Papa Tan: "The ashamed young brother, surnamed Tan, with washed head makes obeisance, and writes this letter to the greatly virtuous and honorable gentleman whose surname is O. I duly reverence your lofty door. The marriage business will be conducted according to the six rules of propriety, and I will reverently announce the business to my ancestors with presents of gems and silks. I will arrange the things received in your basket, so that all who tread the threshold of my door may enjoy them. From this time forward the two surnames will be united, and I trust the union will be a felicitous one, and last for a hundred years, and realize the delight experienced by the union. I hope that your honorable benevolence and consideration will defend me unceasingly. At present the dragon flies in Sin Hai term, the first month, lucky day. I bow respectfully. Light before. Tan."

From Papa O: "The younger brother, surnamed O, of the family to be related by marriage, washes his head clean, knocks his head and bows, and writes this marriage-letter in reply to the far-famed and virtuous gentleman surnamed Tan, the venerable teacher and great man who manages his business. 'Tis matter for congratulation the union of 100 years. I reverence your lofty gate. The prognostic is good, also the divination of the lucky bird. The stars are bright, and the dragons meet together. I, the foolish one, am ashamed of my diminutiveness. I for a long time have desired your dragon powers: now you have not looked down upon me with contempt, but have entertained the statements of the match-maker, and agree to give Kang to be united to my despicable daughter. We all wish the girl to have her hair dressed, and the young man to put on his cap of manhood. The peach-flowers just now look beautiful, the red plum also looks gay. I praise your son, who is like a fairy horse who can cross over through water, and is able to ride upon the wind and waves; but my tiny daughter is like a green window and a feeble plant, and is not worthy of becoming the subject of verse.

"Now, I reverently bow to your good words,

and make use of them to display your good

breeding. Now, I hope your honorable benevolence

will always remember me without end.

Now the dragon flies in the Sin Hai term, first

month, lucky day. Obeisance! May the future

be prosperous. O."

BY T. S. ARTHUR.

CHAPTER I.

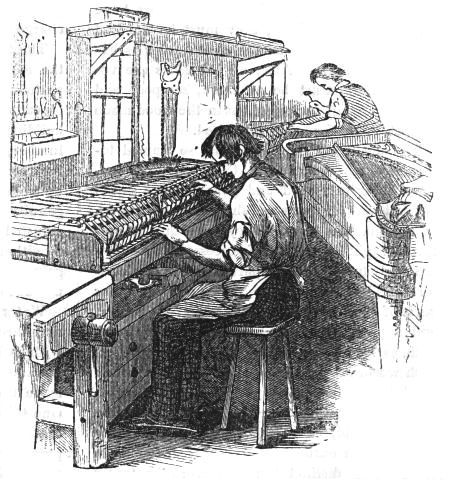

Needle-work, at best, yields but a small return. Yet how many thousands have no other resource in life, no other barrier thrown up between them and starvation! The manly stay upon which a woman has leaned suddenly fails, and she finds self-support an imperative necessity; yet she has no skill, no strength, no developed resources. In all probability, she is a mother. In this case, she must not only stand alone, but sustain her helpless children. Since her earliest recollection, others have ministered to her wants and pleasures. From a father's hand, childhood and youth received their countless natural blessings; and brother or husband, in later years, has stood between her and the rough winds of a stormy world. All at once, like a bird reared from a fledgling in its cage, and then turned loose in dreary winter time, she finds herself in the world unskilled in its ways, yet required to earn her bread or perish.

What can she do? In what art or profession has she been educated? The world demands service, and proffers its money for labor. But what has she learned? What work can she perform? She can sew. And is that all? Every woman we meet can ply the needle. Ah! As a seamstress, how poor the promise for her future! The labor market is crowded with sewing women, and, as a consequence, the price of needle-work—more particularly that called plain needle-work—is depressed to mere starvation rates. In the more skilled branches, better returns are met; but, even here, few can endure prolonged application—few can bend ten, twelve, or fifteen hours daily over their tasks, without fearful inroads upon health.

In the present time, a strong interest has been awakened on this subject. The cry of the poor seamstress has been heard; and the questions, "How shall we help her?" "How shall we widen the circle of remunerative employments for women?" passes anxiously from lip to lip. To answer this question is not our present purpose. Others are earnestly seeking to work out the problem, and we must leave the solution with them. What we now design is to quicken their generous impulses. How more effectively can this be done than by a life-picture of the poor needlewoman's trials and sufferings? And this we shall now proceed to give.

It was a cold, dark, drizzly day in the fall of 18—, that a young female entered a well-arranged clothing store in Boston, and passed with hesitating steps up to where a man was standing behind one of the counters.

"Have you any work, sir?" she asked, in a low, timid voice.

The individual to whom this was addressed, a short, rough-looking man, with a pair of large black whiskers, eyed her for a moment with a bold stare, and then indicated, by half turning his head and nodding sideways towards the owner of the shop, who stood at a desk some distance back, that her application was to be made there. Turning quickly from the rude, and too familiar gaze of the attendant, the young woman went on to the desk, and stood, half frightened and trembling, beside the man from whom she had come to ask the privilege of toiling for little more than a crust of bread and a cup of cold water.

"Have you any work, sir?" was repeated in a still lower and more timid voice than that in which her request had at first been made.

"Yes, we have," was the gruff reply.

"Can I get some?"

"I don't know. I'm not sure that you'll ever bring it back again."

The applicant endeavored to make some reply to this, but the words choked her; she could not utter them.

"I've been tricked in my time out of more than a little by new-comers. But I don't know; you seem to have a simple, honest look. Are you particularly in want of work?"

"Oh yes, sir!" replied the applicant, in an earnest, half-imploring voice. "I desire work very much."

"What kind do you want?"

"Almost anything you have to give out, sir?"

"Well, we have pants, coarse and fine roundabouts, shirts, drawers, and almost any article of men's wear you can mention."

"What do you give for shirts, sir?"

"Various prices; from six cents up to twenty five, according to the quality of the article."

"Only twenty-five cents for fine shirts!" returned the young woman, in a surprised, disappointed, desponding tone.

"Only twenty-five cents? Only? Yes, only twenty-five cents! Pray, how much did you expect to get, Miss?" retorted the clothier, in a half sneering, half offended voice.

"I don't know. But twenty-five cents is very little for a hard day's work."

"Is it, indeed? I know enough who are thankful for even that. Enough who are at it early and late, and do not even earn as much. Your ideas will have to come down a little, Miss, if you expect to work for this branch of business."

"What do you give for vests and pantaloons?" asked the woman, without seeming to notice the man's rudeness.

"For common trowsers with pockets, twelve cents; and for finer ones, fifteen and twenty cents. Vests about the same rates."

"Have you any shirts ready?"

"Yes, a plenty. Will you have 'em coarse or fine?"

"Fine, if you please."

"How many will you take?"

"Let me have three to begin with."

"Here, Michael," cried the man to the attendant who had been first addressed by the stranger, "give this girl three fine shirts to make." Then turning to her, he said, "They are cotton shirts, with linen collars, bosoms, and wristbands. There must be two rows of stitching down the bosoms, and one row upon the wristband. Collars plain. And remember, they must be made very nice."

"Yes, sir," was the reply, made in a sad voice, as the young creature turned from her employer and went up to the shop-attendant to receive the three shirts.

"You've never worked for the clothing stores, I should think?" remarked this individual, looking her in the face with a steady gaze.

"Never," replied the applicant, in a low tone, half shrinking away, with an instinctive aversion for the man.

"Well, it's pretty good when one can't do any better. An industrious sewer can get along pretty well upon a pinch."

No reply was made to this. The shirts were now ready; but, before they were handed to her, the man bent over the counter, and, putting his face close to hers, said—

"What might your name be, Miss?"

A quick flush suffused the neck and face of the girl, as she stepped back a pace or two, and answered—

"That is of no consequence, sir."

"Yes, Miss, but it is of consequence. We never give out work to people who don't tell their names. We would be a set of unconscionable fools to do that, I should think."

The young woman stood thoughtful for a little while, and then said, while her cheek still burned—

"Lizzy Glenn."

"Very well. And now, Miss Lizzy, be kind enough to inform me where you live."

"That is altogether unnecessary. I will bring the work home as soon as I have finished it."

"But suppose you should happen to forget our street and number? What then?"