Title: Across South America

Author: Hiram Bingham

Release date: June 6, 2016 [eBook #52248]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Rachael Schultz, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

|

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text. List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

By the Same Author

THE JOURNAL OF AN EXPEDITION ACROSS VENEZUELA AND COLOMBIA, 1906-07. With 133 illustrations and a map. Published by the Yale University Press.

ACROSS SOUTH AMERICA

AN ACCOUNT OF A JOURNEY FROM BUENOS

AIRES TO LIMA BY WAY OF POTOSÍ

WITH NOTES ON BRAZIL, ARGENTINA,

BOLIVIA, CHILE, AND PERU

BY

HIRAM BINGHAM

YALE UNIVERSITY

WITH EIGHTY ILLUSTRATIONS

AND MAPS

![[Image of the colophon unavailabl.e]](images/colophon.png)

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1911

{iv}

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY HIRAM BINGHAM

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published April 1911

{v}

THIS VOLUME IS

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

TO

THE MOTHER OF

SIX LITTLE BOYS

In September, 1908, I left New York as a delegate of the United States Government and of Yale University to the First Pan-American Scientific Congress, held at Santiago, Chile, in December and January, 1908-09. Before attending the Congress I touched at Rio de Janeiro and the principal coast cities of Brazil, crossed the Argentine Republic from Buenos Aires to the Bolivian frontier, rode on mule-back through southern Bolivia, visiting both Potosí and Sucre, went by rail from Oruro to Antofagasta, and thence by steamer to Valparaiso. After the Congress I retraced my steps into Bolivia by way of the west coast, Arequipa, and Lake Titicaca. Picking up the overland trail again at Oruro, I continued my journey across Bolivia and Peru, via La Paz, Tiahuanaco, and Cuzco, thence by mules over the old Inca road as far as Huancayo, the present terminus of the Oroya-Lima Railroad. At Abancay I turned aside to explore Choqquequirau, the ruins of an Inca fortress in the valley of the Apurimac; an excursion that could not have been undertaken at all had it not been for the very generous assistance of Hon. J. J. Nuñez, the Prefect of Apurimac, and his zealous aide, Lieutenant Caceres of the Peruvian army. I reached Lima in March, 1909.

The chief interest of the trip lay in its being an exploration of the most historic highway in South America, the old trade route between Lima, Potosí, and Buenos Aires. The more difficult parts of this{viii} road were used by the Incas and their conqueror Pizarro; by Spanish viceroys, mine owners, and merchants; by the liberating armies of Argentina; and finally by Bolivar and Sucre, who marched and countermarched over it in the last campaigns of the Wars of Independence.

Realizing from previous experience in Venezuela and Colombia that the privilege of travelling in a semi-official capacity would enable me to enjoy unusual opportunities for observation, I made it the chief object of my journey to collect and verify information regarding the South American people, their history, politics, economics, and physical environment. The present volume, however, makes no pretence at containing all I collected or verified. Such a work would be largely a compilation of statistics. The ordinary facts are readily accessible in the current publications of the ably organized Pan-American Bureau in Washington. Nevertheless, I have included some data that seemed likely to prove serviceable to intending travellers.

Grateful acknowledgment for kind assistance freely rendered in many different ways is due to President Villazon of Bolivia, the late President Montt of Chile, and President Leguia of Peru; to Secretary, now Senator, Root and the officials of the Diplomatic and Consular Service; to Professor Rowe and my fellow delegates to the Pan-American Scientific Congress; and particularly to J. Luis Schaefer, Esq., W. S. Eyre, Esq., and their courteous associates of the house of W. R. Grace & Co. Although business houses rarely take the trouble to make the{ix} path of the scientist or investigator more comfortable, it would be no easy task to enumerate all the favors that were shown, not only to me, but also to the other members of the American delegation, by Messrs. Grace & Co. and the managers and clerks of their many branches.

Acknowledgments are likewise due to the officials of the Buenos Aires and Rosario Railroad, the Peruvian Corporation, and the Bolivia Railway; and to Colonel A. de Pederneiras, Sr. Amaral Franco, Don Santiago Hutcheon, Sr. C. A. Novoa, Sr. Arturo Pino Toranzo, Dr. Alejandro Ayalá, Captain Louis Merino of the Chilean army, Don Moises Vargas, Sr. Lopez Chavez, and Messrs. Charles L. Wilson, A. G. Snyder, U. S. Grant Smith, J. B. Beazley, D. S. Iglehart, John Pierce Hope, Rankin Johnson, Rea Hanna, and a host of others who helped to make my journey easier and more profitable.

I desire also to express my gratitude, for unnumbered kindnesses, both to Huntington Smith, who accompanied me during the first part of my journey, and to Clarence Hay, who was my faithful companion on the latter part.

Some parts of the story have already been told in the “American Anthropologist,” the “American Political Science Review,” the “Popular Science Monthly,” the “Bulletin of the American Geographical Society,” the “Records of the Past,” and the “Yale Courant,” to whose editors acknowledgment is due for permission to use the material in its present form.

Hiram Bingham.

Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

20 November, 1910.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Pernambuco and Bahia | 3 |

| II. | Rio, Santos, and Brazilian Trade | 16 |

| III. | Buenos Aires | 29 |

| IV. | Argentine Independence and Spanish-American Solidarity | 46 |

| V. | The Tucuman Express | 60 |

| VI. | Through the Argentine Highlands | 69 |

| VII. | Across the Bolivian Frontier | 81 |

| VIII. | Tupiza to Cotagaita | 92 |

| IX. | Escara to Laja Tambo | 104 |

| X. | Potosí | 117 |

| XI. | Sucre, the de jure Capital of Bolivia | 133 |

| XII. | The Road to Challapata | 148 |

| XIII. | Oruro to Antofagasta and Valparaiso | 164 |

| XIV. | Santiago and the First Pan-American Scientific Congress | 180 |

| XV. | Northern Chile | 198 |

| XVI. | Southern Peru | 211 |

| XVII. | La Paz, the de facto Capital of Bolivia | 224 |

| XVIII. | The Bolivia Railway and Tiahuanaco{xii} | 241 |

| XIX. | Cuzco | 254 |

| XX. | Sacsahuaman | 272 |

| XXI. | The Inca Road to Abancay | 280 |

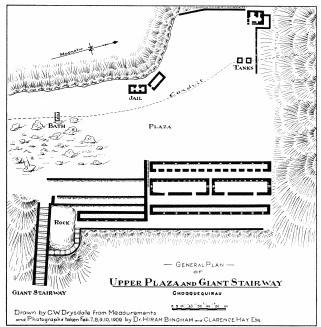

| XXII. | The Climb to Choqquequirau | 296 |

| XXIII. | Choqquequirau | 307 |

| XXIV. | Abancay to Chincheros | 324 |

| XXV. | Bombon to the Battlefield of Ayacucho | 341 |

| XXVI. | Ayacucho to Lima | 360 |

| XXVII. | Certain South American Traits | 379 |

| Index: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y, Z | 393 | |

The frontispiece and the illustration at page 20 are from photographs by Marc Ferrez. Those at pages 50, 216, 226, 232, 258, 298, 302, 324, 342, 346, 350, 354, and 362 are from photographs by Mr. C. L. Hay; and those at pages 150, 160, 170 from photographs by Mr. H. Smith.

ACROSS SOUTH AMERICA

There are two ways of going to the east coast of South America. The traveller can sail from New York in the monthly boats of the direct line or, if he misses that boat, as I did, and is pressed for time, he can go to Southampton or Cherbourg and be sure of an excellent steamer every week. The old story that one was obliged to go by way of Europe to get to Brazil is no longer true, although this pleasing fiction is still maintained by a few officials when they are ordered to go from Lima on the Pacific to the Peruvian port of Iquitos on the Amazon. If they succeed in avoiding the very unpleasant overland journey via Cerro de Pasco, they are apt to find that the “only feasible” alternative route is by way of Panama, New York, and Paris!

Personally I was glad of the excuse to go the longer way, for I knew that the exceedingly comfortable new steamers of the Royal Mail Line were likely to carry many Brazilians and Argentinos, from whom I could learn much that I wanted to know. They proved to be most kind and communicative, and gave me an excellent introduction to the point of view of the modern denizen of the east coast whose lands have received the “golden touch” that comes{4} from foreign capital, healthy immigration, and rapidly expanding railway systems. I was also fortunate in finding on board the Aragon a large number of those energetic English, Scots, and French, whose well-directed efforts have built up the industries of their adopted homes, until the Spanish-Americans can hardly recognize the land of their birth, and the average North American, who visits the east coast for the first time, rubs his eyes in despair and wonders where he has been while all this railroad building and bank merging has been going on. If there were few Germans and Italians on board, it was not because they were not crossing the ocean at the same time, but because they preferred the new steamers of their own lines. I could have travelled a little faster by sailing under the German or the Italian flag, but in that case I should not have seen Pernambuco and Bahia, which the more speedy steamers now omit from their itinerary.

The Brazilians call the easternmost port of South America, Recife, “The Reef,” but to the average person it will always be known as Pernambuco. Most travellers who touch here on their way from Europe to Buenos Aires, prefer to see what they can of this quaint old city from the deck of the steamer, anchored a mile out in the open roadstead. The great ocean swell, rolling in from the eastward, makes the tight little surf boats bob up and down in a dangerous fashion. It seems hardly worth while to venture down the slippery gangway and take one’s chances at leaping into the strong arms of swarthy boatmen, whom the waves bring upward toward you with startling{5} suddenness, and who fall away again so exasperatingly just as you have made up your mind to jump.

Out of three hundred first-cabin passengers on the Aragon, there were only five of us who ventured ashore,—three Americans, a Frenchman, and a Scotchman. The other passengers, including several representatives of the English army—but I will say no more, for they afterwards wrote me that, on their return journey to England, the charms of Pernambuco overcame their fear of the “white horses of the sea,” and they felt well repaid.

Pernambuco is unquestionably one of the most interesting places on the East Coast. From the steamer one can see little more than a long low line of coast, dotted here and there with white buildings and a lighthouse or two. To the north several miles away, on a little rise of ground, is the ancient town of Olinda, founded by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, a hundred years before Henry Hudson stepped ashore on Manhattan Island. By the time that our ancestors were beginning to consider establishing a colony in Massachusetts, the Portuguese had already built dozens of sugar factories in this vicinity. Then the Dutch came and conquered, built Pernambuco and, during their twenty-five years on this coast, made it the administrative centre for their colony in northeast Brazil. Their capital, four miles north of the present commercial centre, is now a village of ruined palaces and ancient convents. The Dutch had large interests on the Brazilian seaboard and carried away quantities of sugar and other precious commodities, as is{6} set forth in many of their quaint old books. The drawings which old Nieuhof put in his sumptuous folio two centuries ago are still vivid and lifelike, even if they serve only to emphasize the great change that has come over this part of the world in that time.

Now, three trans-Atlantic cables touch here, and it is a port of call for half a dozen lines of steamers. The old Dutch caravels used to find excellent shelter behind the great natural breakwater, the reef that made the port of Recife possible. No part of the east coast of Brazil possesses more strategical importance, and modern improvements have deepened the entrance so that vessels drawing less than fifteen feet may enter and lie in quiet water, although the great ocean liners are obliged to ride at anchor outside. Tugs bring out lighters for the cargo, but the passengers have to trust to the mercy of the surf boats.

It took six dusky oarsmen to pull us through the surf and around the lighthouse that marks the northern extremity of the reef, into the calm waters of the harbor. On the black reef a few rods south of the lighthouse stands an antiquated castle, which modern guns would make short work of, but which served its purpose admirably by defending the port against the sea rovers of the seventeenth century. Opposite this breakwater, on two or three “sea islands” whose tidal rivers cut them off from the mainland, the older part of Pernambuco is built.

It was with a feeling of having miraculously escaped from the dangers of a very stormy voyage,{7} that we clambered up the slippery stone stairs of the landing stage and entered the little two-storied octagonal structure which serves the custom house as a place in which to examine incoming passengers. This took but a moment, and then we went out into the glaring white sunlight of this ancient tropical city and began our tour of inspection.

Immediately in front of us was a line of warehouses three or four stories high and attractively built of stone. They give the water-front an air of permanency and good breeding. Between them and the sea-wall there was a tree-planted, stone-paved area, the Rialto of Recife, where all classes, from talkative half-tipsy pieces of foreign driftwood to well-dressed local merchants, clad in immaculate white suits, congregate and gossip. Beyond the sea-wall a dozen small ocean steamers lay inside the harbor, moored to the breakwater; while numbers of smaller vessels, sloops, schooners, and brigantines were anchored near the custom house docks or in the sluggish Rio Beberibe, which separates Recife from the mainland.

As we wandered through the streets past the Stock Exchange, the naval station, and the principal business houses, we saw various sights: a poorly dressed Brazilian, of mixed African and Portuguese descent, carrying a small coffin on his head; barefooted children standing in pools of water left in the paved sidewalks by the showers of the morning; bareheaded women, with gayly colored shawls over their shoulders; neat German clerks dressed in glistening white duck suits; lounging boatmen in nonde{8}script apparel; and everywhere long, low drays loaded with bags of sugar, each vehicle drawn by a single patient ox whose horns are lashed to a cross-piece that connects the front end of the thills. Those who moved at all moved as if there were abundant time in which to do everything, and as though the hustle and bustle of lower New York never existed at all. The scene was distinctively Latin-American. One must be careful not to say “Spanish-American” here, for if there is one thing more than another that the Brazilian is proud of, it is that he is not a Spaniard and does not speak Spanish. However, the difference between the two languages is not so great and the local pride not so strong but that the obliging natives will understand you, even if you have the bad taste to address them in Spanish. They will reply, however, in Portuguese, and then it is your turn to be obliging and understand them, if you can.

West of Recife, on another island and on the mainland, are the other public buildings, parks, and the finest residences. A primitive tram-car, pulled by mules, crosses the bridge and jangles along toward the suburbs, which are quite pretty, although some of the houses strive after bizarre color-effects which would not be appropriate in the Temperate Zone. There are fairly good hotels here, and there is quite a little English colony. But it is not a place where the white man thrives. The daily range of temperature is very small, and it is claimed that the average difference between the wet and dry season is only three degrees.

From Pernambuco there radiate three or four{9} railways, north, west, and south. None of them are more than two hundred miles long, but all serve to gather up the rich crops of sugar and cotton for which the surrounding region is noted, and bring them to the cargo steamers that offer in exchange the manufactured products of Europe and America. If one may judge from the size of the custom house and the busy scene there, where half a dozen steam cranes were actively engaged in unloading goods destined to pay the annoyingly complex Brazilian tariff, the business of the port is very considerable. It seemed quite strange to see such mechanical activity and such a modern customs warehouse so closely associated with the narrow, foul-smelling streets of the old town. But it gives promise of a larger and more important city in the years to come, when the new docks shall have been built and still more modern methods introduced.

Yet even now there are over one hundred and fifty thousand people in the city, and the mercantile houses do a good business. The clerks move slowly, and there is little appearance of enterprise; but one must always remember, when inclined to criticise the business methods of the tropics, that this is not a climate where one can safely hurry. Things must be done slowly if the doer is to last any length of time. The commercial traveller who comes here full of brusque and zealous activity, will soon chafe himself into a fever if he is not careful. These are easy-going folk, and political and commercial changes do not affect them seriously. They are willing to stand governmental conditions that would be almost in{10}tolerable to us, and their haphazard methods of business are well suited to their environment. The European, although proverbially less adaptable than the American, is forced by keener competition at home to adjust himself as best he may to the local conditions here and elsewhere in South America. His American colleague, on the other hand, has as yet not felt the necessity of learning to meet what seems to him ridiculous prejudice.

Emblematic of this Brazilian trade are the primitive little catamarans in which the fishermen of Recife venture far out into the great ocean. The frail little craft are only moderately safe, and at best can bring back but a small quantity of fish. They are most uncomfortable, and their occupants are kept wet most of the time by the waves that dash over them. Furthermore, a glimpse of them is as much of Pernambuco as most steamship passengers get. It is only by venturing and taking the trouble to go ashore that one can see the modern custom house dock on the other side of Recife, and learn the lesson of the possibilities of commerce here.

We left Pernambuco in the afternoon and reached the green hills of the coast near Bahia the next morning. The steamers pass near enough to the shore to enable one to make out, with the glasses, watering-places and pretty little villas that have been built on the ocean side of the peninsula by the wealthier citizens of Bahia. At the end of the promontory, just above the rocks and the breakers, is the picturesque white tower of a lighthouse. Unfortunately, it did not avail to save a fine German steamer that was{11} lying wrecked on the dangerous shoals near the entrance to the harbor when we passed in.

As we steamed slowly around the southern end of the low promontory, the city of Bahia gradually came into view, its large stone warehouses lining the water-front, its lower town separated by a steep hill, covered with gardens and graceful palms, from the upper city, conspicuous with the towers and cupolas of numerous churches and public buildings.

On the left, as one enters the harbor, rises the interesting island of Itaparica, which England once offered to take in payment of a debt due her by Portugal. It bears a resemblance to Gibraltar in more ways than one, but it was not destined to become a British stronghold. A favorite resort of the citizens of Bahia, it is called “the Europe of the poor,” because it has a genial climate and is frequented by those who cannot afford to cross the Atlantic.

As we leave it on our left, in front of us, and to the north, lies the magnificent bay that has given the city its name. It lacks the romantic mountains that make Rio so famous, yet its beautiful blue waters are most alluring, dotted as they are here and there with the white sails of fishing-boats and catamarans.

We have to anchor a mile from the shore, and a steam launch carrying the port officials soon comes alongside. The local boatmen, whose little craft, suited only to the quiet waters of the bay, bear no resemblance to the seaworthy surf boats of Pernambuco, line up at a distance of half a mile, awaiting the signal which permits them to hoist sail and race for{12} the steamer. It is a pretty sight, enlivened by the shouts of the boat crews. Some boats are loaded with delicious tropical fruits that are eagerly bargained for by our steerage passengers, most of whom are Spanish peasants on their way to harvest the crops of Argentina. Others are anxious to take us ashore. And after the usual delay, we make a deal with a boatman, a lazy fellow who wastes a lot of time trying to sail in against the wind while his more energetic competitors are rowing. On the way we pass half a dozen steamers and a few sailing vessels, and steer carefully between scores of huge lighters and dozens of smaller craft. In place of the steel steam cranes which we saw at Pernambuco, on the wharves are numerous wooden cranes worked by hand.

We land on slippery wooden stairs, and hurry across the blistering hot pavements of the street to rest for a few moments in the shade of the large warehouses and wholesale shops that crowd the lower town. Some of the signs are decidedly bizarre and scream as loudly for patronage as the limits of modern Frenchified Portuguese art will permit. There is none of the picturesqueness of Pernambuco, and we soon betake ourselves to one of the cog railways where, for a few cents, we are allowed to scramble into a bare little wooden passenger coach and be yanked up the steep incline by a cable that looks none too strong for its purpose. Once in the upper city, the narrow streets of commerce seem to be left behind, and we are in broader thoroughfares, with here and there a green park full of palms and other tropical plants. There are churches on every side,{13}

some of them wonderfully decorated and most attractive. Bahia is not quite so old as Pernambuco, its foundation dating only from the middle of the sixteenth century; but it early became the religious and intellectual centre of Portuguese-America, and it is still noted for its literature and culture, although long ago passed in the race by Rio.

The glaring white sunlight throws everything into bold relief and makes the shadows seem unusually dark and cool. On the corners of the streets are little folding stands bearing a heavy load of toothsome confectionery. Their barefooted coal-black owners, clad generally in white, lean against the iron posts of the American Trolley Car System and watch patiently for the trade that seems sure to come to him who waits. On every side one sees black faces.

In fact, Bahia is sometimes popularly spoken of as the “Old Mulattress,” in affectionate reference to the fact that more than ninety per cent of its two hundred thousand people are of African descent. For over two centuries Bahia monopolized the slave trade of Brazil. Her traders continued to be the chief importers of negroes down to the middle of the nineteenth century. It is said that as many as sixty thousand slaves were brought in within a single year.

We took one of the American-made trolleys and soon went whizzing along through well-paved streets and out into the suburbs. Here villas, fearfully and wonderfully made, like the baker’s best wedding cake in his shop window, attest to the local fondness for rococo extravagance. In general, however, the{14} principal buildings appear to be well built, and are frequently four or five stories in height.

The architecture of Bahia is decidedly Portuguese, much more so than that of Pernambuco, which still bears traces of its Dutch origin and even reminds one of Curaçao. Some of the villas in Bahia are strikingly like those in Lisbon. And there are other likenesses between the Portuguese capital and this ecclesiastical metropolis of Brazil. Both are situated on magnificent estuaries, and present a fine spectacle to the traveller coming by sea. Both have upper and lower towns, with hills so steep as to require the services of elevators and cog or cable railways to connect them. The upper town of each commands an extensive view of the shipping, the roadstead, and the surrounding country. But here the similarity ends; for Lisbon is built on several hills, while Bahia occupies but a single headland, the verdure-clad promontory which shelters the magnificent bay.

Bahia is the centre for a considerable commerce in sugar and cotton, cocoa and tobacco. These are brought to the port by land and water, but chiefly by the railroads that go north to the great river San Francisco and west into the heart of the state. There are many evidences of wealth in the city, and there is certainly an excellent opportunity for developing foreign trade. One looks in vain, however, for great American commercial houses like those which mark the presence of English, French, and German enterprise. Nevertheless the electric car line, with its American equipment, gives a promise of{15} things hoped for. And there is a decided air of friendliness toward Americans on the part of the Brazilians whom one meets on the streets and in the shops. There is none of that “chip on the shoulder” attitude which the Argentino likes to exhibit toward the citizens of the “United States of North America.” The Brazilian appears to realize that Americans are his best customers, and he is desirous of maintaining the most friendly relations with us.{16}

Two days’ sail from Bahia brought us within sight of the wonderful mountains that mark the entrance to the Bay of Rio de Janeiro. As one approaches land, the first thing that catches the eye is the far-famed Sugar Loaf Mountain which seems to guard the southern side of the entrance. Back of it is a region even more romantic, a cluster of higher mountains, green to their tops, yet with sides so precipitous and pinnacles so sharp one wonders how anything can grow on them. The region presents, in fact, such a prodigious variety of crags and precipices, peaks and summits, that the separate forms are lost in a chaos of beautiful hills.

The great granite rocks that guard the entrance to the harbor leave a passage scarcely a mile in width. At the base of the Sugar Loaf we saw a fairy white city romantically nestling in the shadow of the gigantic crag. It is the new National Exposition of Brazil.

Once safely inside the granite barriers, the bay opens out and becomes an inland sea, dotted with hundreds of islands, a landlocked basin with fifty square miles of deep water.

On the northern shores of the bay lies the town of Nictheroy, the capital of the state. Its name per{17}petuates the old Indian title of the bay, “hidden water.” The name of the capital of the Republic, on the south side of the bay, carries with it a remembrance of the fact that when first discovered, the bay was mistaken for the mouth of a great river, the River of January.

Since the early years of the sixteenth century, Rio has been conspicuous in the annals of discovery and conquest. Magellan touched here on his famous voyage round the world. The spot where he landed is now the site of a large hospital and medical school. French Huguenots attempted to find here a refuge in the time of the great Admiral Coligny. As one steams slowly into the harbor, one passes close to the historic island of Villegagnon, whose romantic story has been so graphically told by Parkman.

Hither came the King of Portugal, flying from the wrath of Napoleon. Here lived the good Emperor Don Pedro II, one of the most beneficent monarchs the world has ever seen. And into these waters are soon to come Brazil’s new Dreadnoughts, about which all the world has been speculating, and which have made Argentina almost forget the necessities of economic development in her anxiety to keep up with Brazil in the way of armament.

An elaborate system of new docks, that has been in the course of construction for a long time, has not been completed yet; so we anchor a mile or more from the shore, not far from a score of ocean steamers and half a hundred sailing vessels. Before the anchor falls we are surrounded by a noisy fleet of steam launches, whose whistles keep up a most in{18}fernal tooting. A score of these insistent screamers attempt to get alongside of our companion-way at the same time. In addition, half a hundred row-boats attack the ladder where some of the steerage passengers are trying to disembark.

We had heard, before entering the port, that there were several hundred cases of smallpox here, besides other infectious diseases. Yet this did not prevent everybody that wanted to, and could afford the slight cost of transportation, from coming out from the shore and boarding our vessel. Such a chattering, such a rustling of silk skirts and a fluttering of feathers on enormous hats, such ecstatic greetings given to returning citizens! Such ultra-Parisian fashions!

On shore we found the marks of modern Rio—electric cars, fashionable automobiles, well-paved streets, electric lights, and comfortable hotels—very much in evidence. Were it not for the blinding sunlight that fairly puts one’s eyes out in the middle of the day, one could readily forget one’s whereabouts. To be sure, if you go to look for it, there is the older part of the city which still needs cleaning up according to modern ideas of sanitation. But if you are content to spend your time in the fashionable end of the town or speeding along the fine new thoroughfares in a fast motor car, it is easy to think no more of Rio’s bad record as an unhealthy port.

The city of Rio is spread over a large peninsula that juts out from the south into the waters of the great bay. Across the peninsula, through the centre of the busiest part of the city, the Brazilians have{19} recently opened a broad boulevard, the Avenida Central. Fine modern business blocks have sprung up as if by magic, and the effect is most resplendent. The spacious avenue is in marked contrast with the very narrow little streets that cross it. One of them, the Rua Ouvidor, the meeting-place of the wits of Rio, is in many ways the most interesting street in Brazil. Here one may see everybody that is anybody in Rio.

At one end of the Avenida Central is Monroe Palace, which once did duty at an International Exposition, and more recently was the meeting-place of the third Pan-American Conference, made notable by the presence of Secretary Root. Beyond the showy palace to the east there are a number of little bays, semi-circular indentations in the shore, which have recently been lined with splendid broad driveways, where one may enjoy the sea breeze and a marvellous view over the inland sea to the mountains beyond.

At the far end of the new parkway rises the ever-present Sugar Loaf, at whose feet are the buildings of the National Exposition. They are wonderfully well situated, lying as they do on a little isthmus wedged in between two gigantic rocks, with the ocean on one side and the beautiful bay on the other. The buildings themselves are not particularly remarkable, being decorated in the gorgeous style of elaborate whiteness that one is accustomed to associate with expositions.

The crowds I saw there were composed exclusively of Brazilians, most of whom had apparently visited{20} the grounds many times and accepted them as the fashionable evening rendezvous. Each of the states of Brazil had a building of its own in which to exhibit its products, and there was a theatre, a “Fine Arts” building, a Hall of Manufactures, and a sad attempt at a Midway. An entire building was devoted to the manufactures and exports of Portugal. All other buildings were devoted to the states or industries of Brazil, making the prejudice in favor of the mother country all the more noticeable.

A change is coming over the foreign commerce of Rio. Twenty years ago, the largest importing firms were French and English. Many of these have practically disappeared, having been driven out by Portuguese, Italian, and German houses. The marked leaning toward goods of Portuguese origin is very striking and naturally difficult to combat.

Brazil has recently established in Paris an office for promoting the country and aiding its economic expansion. This office is publishing a considerable literature, mostly in French, and will undoubtedly be able to bring about an increase of European commerce and that immigration which Brazil so much needs. The completion of the new docks will greatly help matters.

But besides new docks Rio needs a reformed customs service. Every one is agreed that the most vexatious thing in Rio is the attitude of the custom house officials. Either because they are poorly paid or else simply because they have fallen into extremely bad habits, they are allowed to receive tips and gratuities openly. The result may easily be imagined.{21}

A few days after my arrival, an American naturalist, thoroughly honest but of a rather short temper, was treated with outrageous discourtesy, and his personal effects strewn unceremoniously over the dirty floor of the warehouse by angry inspectors, simply because he was unwilling to bribe them. There was no question as to his having any dutiable goods.

The population of Rio is variously estimated at between seven and eight hundred thousand, but her enthusiastic citizens frequently exaggerate this and speak in an offhand way of her having a million people. They are naturally reluctant to admit that Rio has any fewer than Buenos Aires.

The suburbs of Rio are remarkably attractive. On the great bay, dotted with its beautiful islands, are various resorts that take advantage of the natural beauties of the place, and cater to the pleasure-loving Brazilians. From various ports on the bay, railroads radiate in all possible directions, going north into the heart of the mining region and west through the coffee country to Saõ Paulo. The terminus of a little scenic railway is the top of one of the highest and most remarkable of the near-by peaks, the Corcovado. The view from the summit can scarcely be surpassed in the whole world. The intensely blue waters of the bay, the bright white sunlight reflected from the fleecy cumulous clouds so typical of the tropics, the verdure-clad hills, and the white city spread out like a map on the edge of the bay, combine to make a marvellous picture.

No account of Rio, however brief, would be com{22}plete without some reference to the “Jornal do Comercio,” the leading newspaper of Brazil, whose owner and editor, Dr. J. C. Rodriguez, is one of the most influential men in the country. In addition to guiding public opinion through his powerful and ably edited newspaper, he has had the time to attend to numerous charities and to the collection of a most remarkable library of books relating to Brazil. He has recently taken high rank as a bibliographer by publishing a much sought after volume on early Braziliana, basing his information largely on his own matchless collection.

Another well-edited paper is “O Paiz,” which like the “Jornal do Comercio” has its own handsome edifice on the new Avenida Central. A subscription to it for one year costs “thirty thousand reis”—a trifle over nine dollars! As in the case of other South American newspapers, its offices are far more luxurious and elaborate than those of their contemporaries in North America. These southern dailies give considerable space to foreign cablegrams, so much more, in fact, than do our own papers, that it almost persuades one that we are more provincial than our neighbors.

Santos, the greatest coffee port in the world and the only city in Brazil having adequate docking facilities, is a day’s sail from Rio. It is separated from the ocean by winding sea-rivers or canals. The marshes and flats that surround it, and the bleaching skeletons of sailing vessels that one sees here, are sufficient reminders of the terrible epidemics that have been the scourge of Santos in the past.{23} Stories are told of ships that came here for coffee, whose entire crews perished of yellow fever before the cargo could be taken aboard, leaving the vessel to rot at her moorings. All of this is changed now, and the port is as healthy as could be expected.

Yet the town is not attractive. It lacks the picturesque ox-drays of Pernambuco and the charming surroundings of Rio. The streets are badly paved and muddy; the clattering mule-teams that bring the bags of coffee from the great warehouses to the docks are just like thousands of others in our own western cities. The old-fashioned tram-cars, running on the same tracks that the ramshackle suburban trains use, are dirty but not interesting. Prices in the shops are enormously high. In fact, on all sides there is too much evidence of the upsetting influence of a great modern commerce.

A long line of steamers lying at the docks taking on coffee is the characteristic feature of the place, and a booklet that has recently been issued to advertise the resources of Brazil bears on its cover a branch of the coffee tree, loaded with red berries, behind which is the photograph of a great ocean liner, into whose steel sides marches an unending procession of stevedores carrying on their backs sacks of coffee. It not only emphasizes Brazil’s greatest industry, but it is also thoroughly typical of Santos.

Most of the coffee is grown in the mountains to the north, and comes to Santos from Saõ Paulo on a splendidly equipped British-built railway. The line is one of the finest in South America. It rises rapidly through a beautiful tropical valley by a{24} gradient so steep as to necessitate the use of a cable and cogs for a large part of the distance. The powerhouses scattered at intervals along the line are models of cleanliness and mechanical perfection.

Notwithstanding the fact that America is by far the greatest consumer of Santos coffee, the greater part of the local enterprises are in British hands. The investment of British capital in Brazil is enormous. It has been computed that it amounts to over six hundred million dollars. Americans do not seem yet to have waked up to the possibilities of Brazilian commerce, or to the fact that the question of American trade with Brazil is an extremely important one.

It is only necessary to realize that the territory of Brazil is larger than that of the United States, that the population of Brazil is greater than all the rest of South America put together, and that Brazil’s exports exceed her imports by one hundred million dollars annually, to understand the opportunity for developing our foreign trade.

Brazil produces considerably more than half of the world’s supply of coffee, besides enormous quantities of rubber. The possibilities for increased production of raw material are almost incalculable. It is just the sort of market for us. Here we can dispose of our manufactured products and purchase what will not grow at home.

We have made some attempts to develop the field, even though our knowledge is too often limited to that of the delightful person who knew Brazil was “the place where the nuts come from!” We have{25}

little conception of the great distances that separate the important cities of Brazil and of the difficulties of transportation.

A story is told in Rio of an attempt to go from Rio to Saõ Paulo by motor, over the cart-road that connects the two largest cities in the Republic. The trip by railway takes about twelve hours. The automobile excursion took three weeks of most fearful drudgery. Needless to say, the cars did not come back by their own power.

It is more difficult for a merchant in one of the great coast cities of Central Brazil to keep in touch with the Amazon, than it is for a Chicago merchant to keep in touch with Australia.

Furthermore, to one who tries to master the situation, the coinage and the monetary system seem at first sight to present an insuperable obstacle. To have a bill for dinner rendered in thousands of reis is rather confusing, until one comes to regard the thousand rei piece as equivalent to about thirty cents.

Another and much more serious difficulty is the poor mail service to and from New York. To the traveller in South America, unquestionably the most exasperating annoyance everywhere is the insecurity and irregularity of the mails. The Latin-American mind seems to be more differently constituted from ours in that particular than in any other. He knows that the service is bad, slow, and unreliable. But it seems to make little difference to him, and the only effort he makes to overcome the frightfully unsatisfactory conditions is by resorting to the registered mail, to which he intrusts everything that is{26} of importance. Add to this fact the infrequency of direct mail steamers from the United States to the East Coast, and it may readily be seen where lies one of the most serious obstacles in the way of extending our commerce with Brazil.

A marked peculiarity of the Brazilian market is its extreme conservatism. Brazilians who have become accustomed to buying French, English, and German products are loath to change. American products are unfashionable. The Brazilian who can afford it travels on the luxuriously appointed steamers of the Royal Mail, and he and his friends regard articles of English make as much more fashionable and luxurious than those from the United States.

This is largely due to the lack of commercial prestige which we enjoy in the coast cities of Brazil. The Brazilians cannot understand why they see no American banks and no American steamship lines. Our flag never appears in their ports except as it is carried by a man-of-war or an antiquated wooden sailing vessel. To their minds this is proof conclusive that the American, who claims that his country is one of the most important commercial nations in the world, is merely bluffing.

Such prejudices can only be overcome by strict attention to business, and this attention our exporters have in large measure not yet thought it worth while to give. The agents that they send to Brazil rarely speak Portuguese, and are unable to compete with the expert linguists who come out from Europe. Frequently they even lack that technical{27} training in the manufacture of the goods which they are trying to sell, which gives their German competitors so great an advantage.

Still more important than commercial travellers in a country like Brazil, is the establishment of agencies where goods may be attractively displayed. An active importer told me that, in his opinion, the most essential thing for Americans to do was to maintain permanent depots or expositions where their goods could be seen and handled. Relatively little good seems to result from the use of catalogues, even when printed in the language of the country, owing to the insecurity of the mails and the absence of American banks or express companies which would insure the delivery of goods ordered.

Finally, it is disgraceful to be obliged to repeat the old story of American methods of packing goods for shipment to South America. This fact has been so often alluded to in many different publications that it might seem as though further criticism were unnecessary. Unfortunately, however, in spite of repeated protests, American shippers, forgetful of the almost entire absence of docks and docking facilities here, continue to pack their goods as if they were destined for Europe.

At most of the ports, lighters have to be used. These resemble small coal barges, into which the goods are lowered over the side of the vessel. Often more or less of a sea is running, and notwithstanding all the care that may be used the durability of the packing-cases is tested to the utmost. I saw a box containing a typewriter dumped on top of a pile{28} of miscellaneous merchandise, from which it rolled down, bumping and thumping into the farther corner of the barge. Fortunately, this particular typewriter belonged to a make of American machines whose manufacturers have learned to pack their goods in such form as to stand just that kind of treatment. The result is that one sees that brand of machine all over South America.

The American consul in Rio, Mr. Anderson, has been doing a notable service in recent years by sending north full and accurate reports of business conditions in Brazil, and our special agent, Mr. Lincoln Hutchinson, has written excellent reports on trade conditions in South America. To the labors of both these gentlemen I am greatly indebted for information on this subject.{29}

We left Santos late on a Tuesday afternoon, and after two pleasant days at sea entered the harbor of Montevideo on Friday morning. It was crowded with ships of all nations, and we were particularly delighted to see the American flag flying from three small steamers. Could it be possible that the flag which had been so conspicuous for its absence from South American waters, was regaining in the twentieth century the preëminence it had in the early years of the nineteenth? Alas, no; the boats were only government vessels in the lighthouse service, towing lightships from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. They had stopped here to coal, for Montevideo is a favorite port of call for steamers bound through the Straits of Magellan. Ever since the days when it was the home of active smugglers, who were engaged in defying Spain’s restrictive colonial policy, Montevideo has been a prosperous trading centre. To-day, clean streets, new buildings, electric cars, fine shops, elaborate window displays, well-dressed people, and excellent hotels mark it as modern and comfortable.

It is difficult to realize that this is the capital of Uruguay, “one of the most tumultuous of the smaller revolutionary states of South America.” The Amer{30}ican is chagrined to find that the Uruguayan gold or paper dollar is worth two cents more than our own. And the Englishman is most annoyed to find the “sovereign” at a discount. But chagrin gives way to frank amazement at the high prices which the Montevidean is willing to pay for his imported luxuries.

The republic is small but there is no waste land, and the railroads bring in quantities of wool and food-stuffs destined for the European market. More than three thousand steamers enter the port annually. Most of them belong to the eighteen British lines that touch here. No wonder the city is wealthy and has attractive shops and boulevards. To be sure, the harbor improvements, not completed yet, have been greatly retarded by the most flagrant kind of political graft. But what American city, from New York to San Francisco, has a clean record in this particular?

Splendidly equipped steamers, resembling our Fall River boats, ply nightly between Montevideo and Buenos Aires, in order to accommodate the increasing numbers who wish to do business in both cities.

A generation ago the traveller to Buenos Aires was obliged to disembark in the stream seven or eight miles from the city, proceed in small boats over the shallow waters, and then clamber into huge ox-carts and enjoy the last mile or two of his journey as best he could. Since then, extraordinary harbor improvements, costing millions of dollars, have been completed, and ocean steamers are now able{31}

to approach the city through dredged channels. Yet such has been the phenomenal growth of the port that the magnificent modern docks are already overcrowded and the handling of cargo goes on very slowly, retarded by many exasperating delays. The regular passenger and mail steamers are given prompt attention, however, and the customs house examination is both speedy and courteous, in marked contrast to that at Rio. In years to come, the two other important ports of Argentina—Rosario, higher up the Rio de la Plata, and Bahia Blanca, farther down the Atlantic coast—are destined to grow at a rapid rate because of the better docking facilities they will be able to afford.

Bahia Blanca in particular is destined to have a great future, as it is the natural outlet for the rapidly developing agricultural and pastoral region of southern Argentina.

Buenos Aires, however, will always maintain her political and commercial supremacy. She is not only the capital of Argentina, but out of every five Argentinos, she claims at least one as a denizen of her narrow streets. Already ranking as the second Latin city in the world, her population equals that of Madrid and Barcelona combined.

Hardly has one left the docks on the way to the hotel before one is impressed with the commercial power of this great city. Your taxicab passes slowly through crowded streets where the heavy traffic retards your progress and gives you a chance to marvel at the great number of foreign banks, English, German, French, and Italian, that have taken pos{32}session of this quarter of the city. With their fine substantial buildings and their general appearance of solidity, they have a firm grip on the situation. One looks in vain for an American bank or agency of any well-known Wall Street house. American financial institutions are like the American merchant steamers, conspicuous by their absence. The Anglo-Saxons that you see briskly walking along the sidewalks are not Americans, but clean-shaven, red-cheeked, vigorous Britishers.

In England they talk familiarly of “B.A.” and the “River Plate”; disdaining to use the Spanish words Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Buenos Aires. To hear them you might suppose they were speaking of something they owned, and you would not be so very far from the truth. What Mexico owes to American capital and enterprise, the countries and cities of the Rio de la Plata owe to Great Britain. British capitalists have not been slow to realize the possibilities of this great agricultural region. They know its potentiality as a food-producer, and they have covered it with a network of railways much as we have covered the prairies of Illinois and the plains of Kansas. Of the billion and a quarter dollars of British capital invested in Argentina, over seven hundred millions are in railways. Thousands of active, energetic young Englishmen, backed by this enormous British capital, have aided in the extraordinary progress which Argentina has made during the past generation.

In some ways this is an English colony. The majority of the people do not speak English, except in{33} the commercial district, and the Englishman is here on sufferance. But it is his railroads that tie this country together. It is his enterprises that have opened thousands of its square miles, and although the folly of his ancestors a century ago caused him to lose the political control of this “purple land,” the energy of his more recent forebears has given him a splendid heritage. Not only has he been able to pay large dividends to the British stockholders who had such great faith in the future of Argentina, he has made many native Argentinos wealthy beyond the dreams of avarice.

Land-owners, whose parents had not a single change of clothes, are themselves considering how many motor cars to order. Their patronage sustains the finely appointed shops which make such a brave display on Florida and Cangallo Streets. These streets may be so narrow that vehicles are only allowed to pass in one direction, but the shops are first class in every particular and include the greatest variety of goods, from the latest creations of Parisian millinery to the most modern scientific instruments. Fine book shops, large department stores, gorgeous restaurants, expensive to the last degree, emphasize the wealth and extravagance of the upper classes.

On the streets one may hear all of the European languages. In the business district it is quite as likely to be English as Spanish, and in the poorer quarters Italian is growing more common every day. The speech of the common people is nominally Spanish, very bad Spanish. In reality it is a hybrid{34} into which Portuguese, Italian, and Indian words and accents have entered to disfigure the beautiful Castilian.

When Rio cut her Avenida Central through the middle of her business district, she had in mind the Avenida 25 de Mayo of Buenos Aires, a typical imitation Parisian Boulevard that was opened not many years ago to facilitate traffic and beautify the city. On the Avenida, as in Rio, the leading newspaper has its luxurious home.

All the world has heard of “La Prensa” and its marvellously well-appointed building where distinguished foreigners are entertained, lectures are given, and all sorts of advertising dodges are featured. It was “La Prensa” that had the news of President Taft’s election two minutes after it was known in New York. Many Porteños, as the people of Buenos Aires are called, think the columns of “La Prensa” are too yellow and that its business methods are almost too modern. They prefer the more dignified pages of the “Nacion.”

The hotels on the Avenida are not up to the standard of three of those on the narrower thoroughfares. In fact, it would be hard to find more comfortable hostelries than the Grand or the Palace. The new Phœnix Hotel, one of the first skyscrapers to be erected here, promises even greater comforts and is to be the rendezvous of the British colony.

There are many theatres and they have a brilliant season, which begins in June. The pleasure-loving Porteños are willing to pay very high prices for the best seats, and managers can offer good{35}

salaries to tempt the best performers to leave Europe. Variety shows are popular and carried to an extreme with which we are not familiar in the United States. Some of them are poor copies of questionable Parisian enterprises. But even these are not as bad as the moving picture shows that have captured Buenos Aires. Public opinion is astonishingly lax in the southern capital. Exhibitions of shocking indecency are countenanced, that would no longer be tolerated in Europe or North America. In this matter Buenos Aires also offers a marked contrast to Santiago de Chile where morals are on a much higher plane, thanks to the Catholic Church, which unfortunately seems to have lost its grip here.

The Porteño has not only forgotten his religion, he seems also to have lost the pleasing manners of his Castilian ancestors. I have been in eight South American capitals and in none have I seen such bad manners as in Buenos Aires. Nowhere else in South America is one jostled so rudely. Nowhere else does one see such insolent behavior and such bad taste. Santiago, Lima, Bogotá, and Caracas seem to belong to a different civilization. To be sure, none of them are as rich and prosperous. But in all of them good society is a much more ancient concern than in this overgrown young metropolis.

Here the newly rich are in full sway and their ideas and instincts seem to predominate. On Sunday afternoon, all the world dashes madly out to the race course, where it exercises its passion for gambling to the fullest capacity. In the Jockey Club inclosure are gathered the youth and beauty, the{36} wealth and fashion of the city. And yet the ladies carry the artificial tricks of feminine adornment to such an amazing extent that it is almost impossible to realize that they belong to the fashionable world and not to the demi-monde. The races that I attended drew an audience of thirty thousand. One race had a first prize amounting to fifteen thousand dollars. The horses seemed to be of a rather heavier build than ours but they did not interest the spectators. Facilities for betting were provided on an elaborate scale. There were no bookmakers, and the odds depended entirely on the popular choice, as is commonly done in Europe. The gate receipts and the proceeds of the “percentage” are enormous and have enabled the Jockey Club to build one of the most luxurious and extravagant club houses in the world.

After the races, hundreds of motor cars and carriages promenade slowly up and down that part of the parkway which society has decreed shall be her rendezvous. Here one sees an astonishing display of paint and powder illuminating the faces of the devotees of a fashion which decrees that all ladies must have brilliant complexions. The effect is very unpleasant. I suppose it is simply another evidence of the newness of modern Buenos Aires. Very few wealthy families have a long-established social position. Culture and refinement are at a discount. Otherwise it is difficult to imagine how any society can tolerate such artificiality. This garish Sunday parade is quite a swing of the pendulum from the old days when Creole ladies, mod{37}estly attired in lovely black lace mantillas, walked quietly to church and home again, as they still do in most South American cities.

It is hardly necessary to speak of the more usual evidences of great wealth, palatial residences that would attract attention even in Paris and New York, charming parks beautifully laid out on the shores of the great Rio de la Plata, and a thousand luxurious automobiles of the latest pattern carrying all they can hold of Parisian millinery.

One does not need to be told that this is a city of electric cars, telephones, and taxis. These we take for granted. But there is a characteristic feature of the city that is unexpected and striking: the central depots for imported thoroughbreds. Only a few doors from the great banks and railway offices are huge stables where magnificent blooded horses and cattle, sheep and pigs, which have brought records of distinguished ancestry across the Atlantic, are offered for sale and command high prices.

These permanent cattle-shows are the natural rendezvous of the wealthy ranchmen and breeders who are sure to be found here during a part of each day while they are in town. So are foreigners desirous of purchasing ranches and reporters getting news from the interior. The cattle-fairs offer ocular evidence of the wealth of the modern Argentino and the importance of the pastoral industry. There are over a hundred million sheep on the Pampas. Cattle and horses also are counted by the millions.

The problems of Argentine agriculture and animal industries are being continually studied by the{38} great land-owners, who have already done much to improve the quality of their products.

During my stay in Buenos Aires, it was my privilege to visit an agricultural school in one of the neighboring towns. The occasion was the celebration of its twenty-fifth anniversary. The festivities were typically Spanish-American. An avenue of trees was christened with appropriate ceremonies, being given the name of the anniversary date. To each tree a bunch of fire-crackers had been tied. At the beginning and end of the avenue a new sign-post bearing its name had been put up and veiled with a piece of cheese cloth. A procession consisting of the officials of the school and of the National University of La Plata, with which the school is affiliated, alumni and visitors, formed at the school-buildings after the reading of an appropriate address, and marched down the new avenue following the band. As we progressed, the signs were unveiled and the bunches of fire-crackers touched off. At the far end, in a grove of eucalyptus trees, a collation was served, and we were entertained by having the fine horses and cattle belonging to the school paraded up and down. The school has an extensive property, is doing good work, and shows a practical grasp of the needs of the country.

Argentina has worked hard to develop those industries that are dependent upon stock-raising. The results have amply justified her. The exportation of frozen meat from Argentina amounts to nearly twenty million dollars annually. Only re{39}cently one of the best known packing-houses of Chicago opened a large plant here and is paying tribute to the excellence of the native stock. Every year Argentina sends to Europe the carcasses of millions of sheep and cattle as well as millions of bushels of wheat and corn, more in fact than we do. Of all the South American republics, she is our greatest natural competitor, and she knows it. Nevertheless, she lacks adequate resources of iron, coal, lumber, and water power, and notwithstanding a high protective tariff, can never hope to become a competitor in manufactured products. Argentina exports more than three times as much per capita as we do, and must do so in order to pay for the necessary importation of manufactured goods. It also means that she will always find it to her advantage to buy her goods from England, France, and Germany, where she sells her food-stuffs. Brazil can send us unlimited amounts of raw materials that we cannot raise at home, while at present Argentina has little to offer us. Yet we are already buying her wool and hides, and before long will undoubtedly be eating her beef and mutton, as England has been doing for years.

The banks of Buenos Aires have learned to be extremely conservative. For a long time this city was a favorite resort of absconding bank cashiers from the United States, and stories are told of many well-dressed Americans who have come here from time to time without letters of introduction but with plenty of money to spend, who have been kindly received by the inhabitants, only to prove{40} to be undesirable acquaintances. What we consider “old-fashioned and antiquated” English bank methods are the rule, and it frequently takes a couple of hours to draw money on a letter of credit even when one has taken the pains to notify one’s bankers beforehand that the letter was to be used in South America. Personally, I have found American Express checks extremely useful in all parts of South America and have had no difficulty in getting them accepted in Buenos Aires. In the interior it is more difficult unless one comes well introduced. But the necessity for letters of introduction is quite generally recognized all over the continent. Strangers who have “neglected to supply themselves with credentials,” frequently turn out to be fugitives from justice.

Another local peculiarity noticeable also in Chile, is that many of the citizens bitterly begrudge us our attempted monopoly of the title of “Americans.” They catalogue us at all possible times under “N” instead of “A.” They also speak of us as North Americans or as “Yankis,” and they call our Minister the “North American Minister,” quite ignoring the existence of Mexico and Canada.

Certain Americans who are desirous of securing an increase of our trade with South America and of placating in every possible manner the South Americans, overlooking the practical side of the question, have acquiesced in the local prejudice and speak of themselves as North Americans, even though they do not address their letters to the “United States of North America.”{41}

The fact that the South American refuses to grant us our title of “Americans” is really an indirect compliment. It is chiefly owing to the industry and intelligence of the citizens of the United States, that the word “American” has come to have a complimentary meaning,—far more complimentary in fact than it had fifty years ago when distinguished foreigners were wont to use that adjective as a peculiarly opprobrious epithet. With this change in the significance of the term has come a natural desire on the part of the South Americans to apply it to themselves. They reason that they have as good a right, geographically, to the term as we have, and they wilfully forget that each of their republics has in its legal title a word which conveniently and euphoniously characterizes its citizens. The people of the United States of Brazil are called Brazilians, and those of the United States of Mexico are Mexicans by the same right that those of the United States of America are Americans. To be sure, the world generally thinks of our country as the United States, quite forgetful that there are several other republics of the same name. It is a pity that a euphonious appellation cannot be manufactured from one or both of those two words. We cannot distinguish ourselves by the title “North American,” as that ignores the rightful claim to that title which the denizens of the larger part of this continent, the Mexicans and Canadians, have in common with us. It is difficult to see how we are to avoid calling ourselves Americans even if it gives offence to our neighbors. It is not a point of{42} great importance and it seems to me that in time, with the natural growth of Chile and the Argentine Republic, their citizens will be so proud of being called Chilenos or Argentinos that they will not begrudge us our only convenient and proper title.

There is another point, however, in their criticism of us which is more reasonable and on which they might be accorded more satisfaction. I refer to that part of our foreign policy known as the Monroe Doctrine. Many a Chileno and Argentino resents the idea of our Monroe Doctrine applying in any sense to his country and declares that we had better keep it at home. He regards it as only another sign of our overweening national conceit. And on mature consideration, it does seem as though the justification for the Monroe Doctrine, both in its original and its present form, had passed. Europe is no longer ruled by despots who desire to crush the liberties of their subjects. As is frequently remarked, England has a more democratic government than the United States. In all the leading countries of Europe, the people have practically as much to say about the government as they have in America. There is not the slightest danger that any European tyrant will attempt to enslave the weak republics of this hemisphere. Furthermore, such republics as Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru no more need our Monroe Doctrine to keep them from being robbed of their territory by European nations than does Italy or Spain. If it be true that some of the others, like the notoriously lawless group in Central America, need to be looked after{43} by their neighbors, let us amend our outgrown Monroe Doctrine, as has already been suggested by one of our writers on international law, so as to include in the police force of the Western Hemisphere, those who have shown themselves able to practice self-control. With our lynchings, strikes, and riots, we shall have to be very careful, however, not to make the conditions too severe or we shall ourselves fail to qualify.

The number of “North Americans” in Buenos Aires is very small. While we have been slowly waking up to the fact that South America is something more than “a land of revolutions and fevers,” our German cousins have entered the field on all sides.

The Germans in southern Brazil are a negligible factor in international affairs. But the well-educated young German who is being sent out to capture South America commercially, is a power to be reckoned with. He is going to damage England more truly than Dreadnoughts or gigantic airships. He is worth our study as well as England’s.

Willing to acquaint himself with and adapt himself to local prejudices, he has already made great strides in securing South American commerce for his Fatherland. He has become a more useful member of the community than the Englishman. He has taken pains to learn the language thoroughly, and speak it not only grammatically but idiomatically as well; something which the Anglo-Saxon almost never does. He has entered into the social life of the country with a much more gracious{44} spirit than his competitors and rarely segregates himself from the community in pursuing his pleasures as the English do. His natural prejudices against the Spanish way of doing things are not so strong.

His steamers are just as luxurious and comfortable as the new English boats. It is said that even if the element of danger that always exists at sea is less on the British lines, the German boats treat their passengers with more consideration, giving them better food and better service. No wonder the Spanish-American likes the German better than he does the English or American. Already the English residents in Buenos Aires, who have regarded the River Plate as their peculiar province for many years, are galled beyond measure to see what strides the Germans have made in capturing the market for their manufactured products and in threatening their commercial supremacy. And neither English nor Germans are going to hold out a helping hand or welcome an American commercial invasion.

Meanwhile the Argentinos realize that their country cannot get along without foreign capital, much as they hate to see the foreigner made rich from the products of their rolling prairies.

Politically, Buenos Aires and Argentina are in the control of the native born. They have a natural aptitude for playing politics, and they much prefer it to the more serious world of business. This they are quite willing to leave to the foreigner.

They realize also that they greatly need more immigrants. The population is barely five per square{45} mile, and as a matter of fact, is practically much less than that for so large a part of the entire population is crowded into the city and province of Buenos Aires. Consequently they are doing all they can to encourage able-bodied immigrants to come from Italy and Spain.

And the immigrants are coming. My ship brought a thousand. Other ships brought more than three hundred thousand in 1908. Argentina is not standing still. Nor is she waiting for “American enterprise.” During 1908 considerably more than two thousands vessels entered the ports of the republic. Four flew the American flag.{46}

On the 25th of May, 1910, the Argentine nation in general, and Buenos Aires in particular, observed with appropriate ceremonies the one hundredth anniversary of their independence. Great preparations were made to insure a celebration that should suitably represent the importance of the event.

In 1810 Buenos Aires had been a Spanish colony for two hundred and fifty years following her foundation in the sixteenth century. But the Spanish crown had never valued highly the great rolling prairies drained by the Rio de la Plata. There were no mines of gold or silver here, and Spain did not send her colonists into far-away America to raise corn and wine that should compete with Spanish farmers at home. Buenos Aires was regarded as the end of the world. All persons and all legitimate commerce bound thither from Spain were obliged to go by way of Panama and Peru, over the Andes, across the South American continent, before they could legally enter the port of Buenos Aires. The natural result of this was the building up of a prosperous colony of Portuguese smugglers in southern Brazil. Another result was that no Spaniards cared to live{47} so far away from home if they could possibly help it, and society in Buenos Aires was not nearly so brilliant as in the fashionable Spanish-American capitals of Lima, Santiago, or Bogotá.

During the closing years of the eighteenth century the Spaniards became convinced of their short-sighted policy and made Buenos Aires an open port. The English were not slow to realize that this was one of the best commercial situations in South America, and that far from being the end of the world, as the Spaniards thought, it was a natural centre through which the wealth of a large part of South America was bound to pass. The great Mr. Pitt, who was most interested in developing British commerce with South America, felt that it would probably be necessary to introduce British manufactures in the wake of a military expedition, and decided to seize Buenos Aires, which was so poorly defended that it could easily be captured by a small resolute force.

Accordingly in June, 1806, an attack was made. The Viceroy, notwithstanding repeated warnings, had made no preparations to defend the city, and it was captured without difficulty. There was great rejoicing in London at the report of the victory, but it was soon turned to dismay by the news of a disgraceful and unconditional surrender. The sudden overthrow of the English was due largely to the ability of a local hero named Liniers who played successfully on the wounded pride of the Porteños.

The significance of the episode is that it gave to the Porteños the idea that the power of Spain could{48} be easily overthrown, and that they actually had the courage and strength to win and hold their own independence.

Hardly had the city recovered from the effects of its bombardment by the English before events, destined to produce a profound change throughout South America, commenced to attract attention in Spain. Napoleon inaugurated his peninsula campaigns, and the world beheld the spectacle of a Spanish king become the puppet of a French emperor. In July, 1809, a new Viceroy, appointed by the Spanish cortes then engaged in fighting against Napoleon, took possession of the reins of government in Buenos Aires. In the early months of 1810, Napoleon’s armies were so successful throughout the Spanish peninsula that it seemed as if the complete subjection of Spain was about to be accomplished.

On May 18, the unhappy Viceroy allowed this news from Spain to become known in the city. At once a furor of popular discussion arose. Led by Belgrano and other liberal young Creoles, the people decided to defy Napoleon and his puppet king of Spain as they had defied the soldiers of England. On the 25th of May, the Viceroy, frightened out of his wits, surrendered his authority, and a great popular assembly that crowded the plaza to its utmost capacity appointed a committee to rule in his stead. So the 25th of May, 1810, became the actual birthday of Argentina’s independence, although the acts of the popular government were for six years done in the name of Ferdinand, the deposed king of Spain, and the Act of Independence{49} was not passed by the Argentine Congress until 1816.

No sooner had Buenos Aires thrown off the yoke of Spain than she began an active armed propaganda much as the first French republic did before her. Other cities of Argentina were forcibly convinced of the advantages of independence, and the armies of Buenos Aires pressed northward into what is now southern Bolivia. It was their intention to drive the Spanish armies entirely out of the continent, and what seemed more natural than that they should follow the old trade route which they had used for centuries, and go from Buenos Aires to Lima by way of the highlands of Bolivia and Peru. But they reckoned without counting the cost. In the first place the Indians of those lofty arid regions do not take great interest in politics. It matters little to them who their masters are. Furthermore, their country is not one that is suited to military campaigns. Hundreds of square miles of arid desert plateaux ten or twelve thousand feet above the sea, a region suited only to support a small population and that by dint of a most careful system of irrigation, separated by frightful mountain trails from any adequate basis of supplies, were obstacles that proved too great for them to overcome. Their little armies were easily driven back. On the other hand, when the royalist armies attempted to descend from the plateaux and attack the patriots, they were equally unsuccessful. The truth is that southern Bolivia and northern Argentina are regions where it is far easier to stay at home and defend one’s self than{50} to make successful attacks on one’s neighbors. An army cannot live off the country as it goes along, and the difficulties of supplying it with provisions and supplies are almost insurmountable. The first man to appreciate this was José San Martin.

It is not too much to say that San Martin is the greatest name that South America has produced. Bolivar is better known among us, and he is sometimes spoken of as the “Washington of South America.” But his character does not stand investigation; and no one can claim that his motives were as unselfish or his aims as lofty as those of the great general to whose integrity and ability the foremost republics of Spanish South America, Argentina, Chile, and Peru, owe their independence.

San Martin was born of Spanish parents not far from the present boundary between Argentina and Paraguay. His father was a trusted Spanish official. His mother was a woman of remarkable courage and foresight. His parents sent him to Spain at an early age to be educated. Military instincts soon drew him into the army and he served in various capacities, both in Africa and later against the French in the peninsula. He was able to learn thoroughly the lessons of war and the value of well-trained soldiers. He received the news of the popular uprising in Argentina while still in Spain, and soon became interested in the struggles of his fellow-countrymen to establish their independence. In 1812 he returned to Buenos Aires where his unselfish zeal and intelligence promptly marked him out as an unusual leader. The troops under him{51}

became the best-drilled body of patriots in South America.

After witnessing the futile attempts of the patriots to drive the Spanish armies out of the mountains of Peru by way of the highlands of Bolivia, he conceived the brilliant idea of cutting off their communication with Spain by commanding the sea power of the West Coast. He established his headquarters at Mendoza in western Argentina, a point from which it would be easy to strike at Chile through various passes across the Andes. Here he stayed for two years governing the province admirably, building up an efficient army, organizing the refugees that fled from Chile to Mendoza, making friends with the Indians, and keeping out of the factional quarrels that threatened to destroy all proper government in Buenos Aires. In January, 1817, his army was ready. He led the Spaniards to think that he might cross the Andes almost anywhere, and succeeded in scattering their forces so as to enable him to bring the main body of his army over the most practical route, the Uspallata Pass.